|

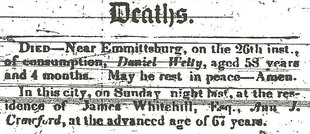

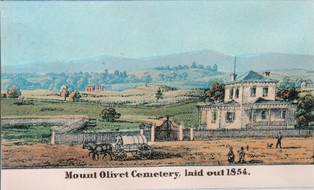

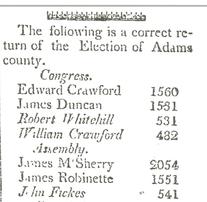

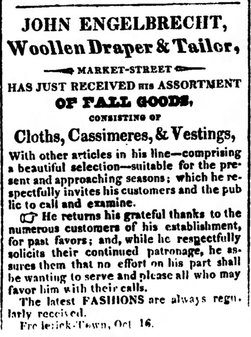

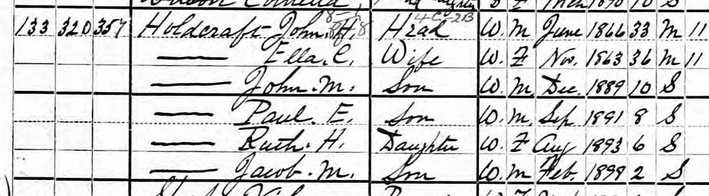

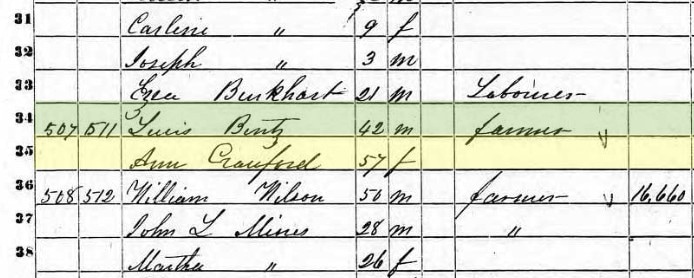

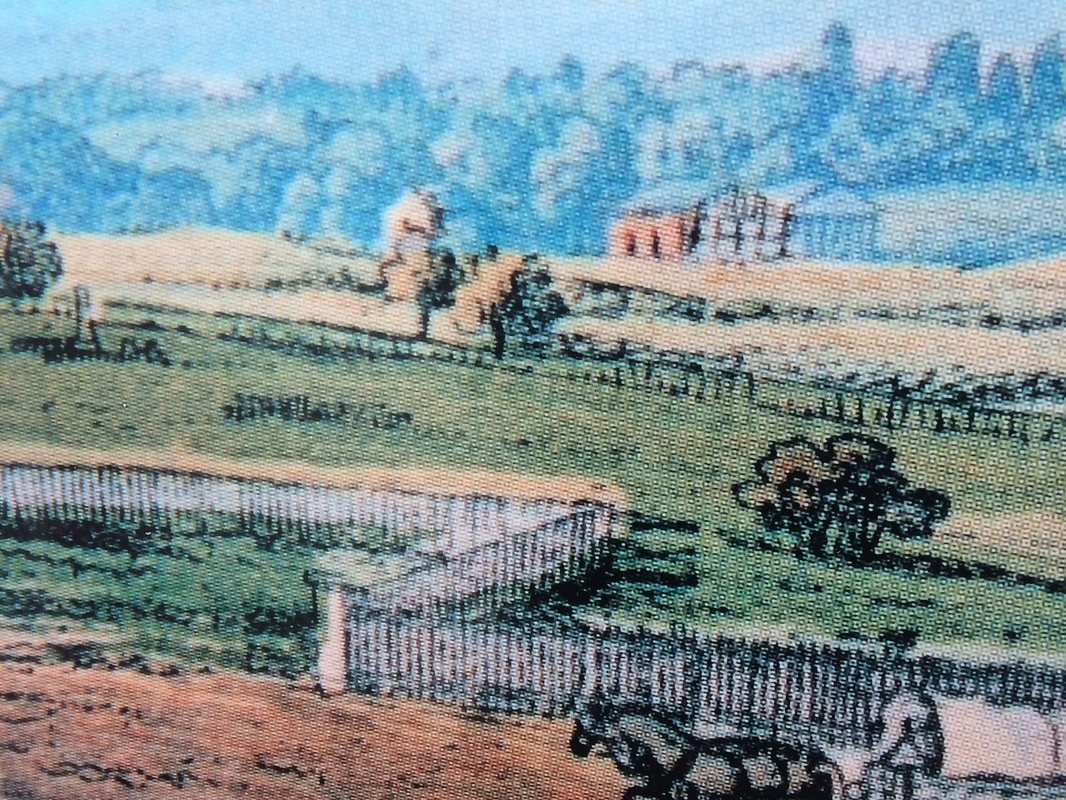

The last few blogs have centered on important “firsts” for Frederick’s Mount Olivet Cemetery. A few weeks back, I pointed out the first monument erected in the burying ground, dedicated in early 1854 to the memory of two maiden sisters—Kate and Mary Norris by their loving parents. Last week, we introduced William Thomas Duvall, the first cemetery superintendent. History and trivia books are filled with the names of people responsible for “famous firsts.” Most of us are familiar with luminaries of the past such as Adam and Eve, Christopher Columbus, George Washington, John Hancock, Charles Lindbergh, Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, the Wright Brothers, Jackie Robinson, Sandra Day O’Connor and Neil Armstrong—but does the name Ann Crawford mean anything to you? I guess it’s always noteworthy to be the first individual to accomplish something unique or special. This individual is seen as a trailblazer, pioneer, or legend. Plus it’s especially thought provoking in this day in age where “participation trophies” are trumping “placement honors.” That said, however, I don’t think everyone would aspire to holding the superlative the abovementioned Ann Crawford possesses—that of being “first person buried” in Frederick’s Mount Olivet Cemetery. This occurred on May 29th, 1854.  Frederick diarist extraordinaire, Jacob Engelbrecht (1797-1878) Frederick diarist extraordinaire, Jacob Engelbrecht (1797-1878) Although this history milestone failed to make front page news back in the mid-nineteenth century, the event did receive its own entry in John T. Scharf’s History of Western Maryland (1882) and of greater value, was recorded for posterity’s sake within the legendary diary of Jacob Engelbrecht: The first corpse buried on the New Cemetery — Mrs. Ann Crawford, who died at the house of Mr. James Whitehill on Sunday evening May 28, 1854 was buried, on “Mount Olivet Cemetery.” This was the burial on the cemetery since they dedicated it….Reverend Alexander E. Gibson officiating Minister (of Methodist Episcopal Church). Jacob Engelbrecht Tuesday May 30, 1854 7’oclock AM  Mrs. Crawford's obituary as it appeared in the Frederick Examiner (May 31, 1854) Mrs. Crawford's obituary as it appeared in the Frederick Examiner (May 31, 1854) That’s basically all we know from the written record on Mrs. Ann Crawford. Her scant, 23-word obituary appearing in the Frederick Examiner doesn’t add much more, however it does provide her middle initial of “J,” and that she was 67 years old at the time of death.  Scene of Mount Olivet Cemetery in 1854, from Sachse lithograph of the same year Scene of Mount Olivet Cemetery in 1854, from Sachse lithograph of the same year I have been working off and on for nearly seven years trying to find out more about this “first-rate” woman. Since 2012, I have taken hundreds of visitors to Ann Crawford’s grave site located in Area A, lot 58. To me, it has always seemed a logical place to begin our candlelight strolls of the historic grounds. In these nocturnal outings, (held throughout October each year), I shine my flashlight on Mrs. Crawford’s grave marker, and emphasize her novel achievement. I then ask guests to visualize what the scene of her burial ceremony must have looked like. I ask, “What did the new cemetery grounds look like in 1854, less than a decade before the American Civil War would be fought, and in this area?” The scenic view, framed by Catoctin Mountain to the west, consisted of a picturesque landscape full of rolling hills—the former farmland covered with maintained grass, trees and freshly laid out dirt lanes zig-zagging throughout. It was a place of tranquility, at the time located “far south” of bustling downtown Frederick City.  Conducting a cemetery tour, the author points out the grave of Ann Crawford. Conducting a cemetery tour, the author points out the grave of Ann Crawford. I then ask visitors to “fast-forward” back to present-day Frederick. That’s when I dramatically shine my flashlight into the distance, illuminating a backdrop full of marble and granite grave stones and funerary monuments. I make the statement, “Mrs. Crawford was the only one here on that day in late May, 1854, now there are tens of thousands.” I next share the fact that today’s cemetery population of nearly 40,000 interments within Mount Olivet rivals the living population of our state capitol of Annapolis. This usually elicits more than a few “oohhhs, and ahhhs.” Unfortunately, I haven’t garnered much more on Mrs. Ann J. Crawford after an exhaustive search of my usual repositories and historical resource haunts. But here’s what I can tell you. Ann Crawford can be found living in Frederick’s 8th ward at age 53. This is in the 1850 census, just four years prior to her death. She was in the South Market Street area home of 42-year-farmer/horse breeder Lewis Bentz, a recent widower. I have no idea how long Mrs. “C” had been living there, and in what capacity? Was she caregiving, consoling, convalescing or courting? If the latter is true, I guess you could say “cougaring” based on the age difference between tenants—but I digress.  Frederick's "Faith House," formerly the residence of James Whitehill Frederick's "Faith House," formerly the residence of James Whitehill It’s been long claimed that Mrs. Crawford was a maid/housekeeper for hire. Whatever the case, Ann Crawford would be found in a different domicile at the time of her death in 1854. This occurred in the home of prominent Frederick businessman, James Whitehill on the southwest corner of N. Market and 8th streets. Mr. Whitehill will certainly be the focus of a future blog as he was one of Mount Olivet’s founders and a charter member of the Board of Managers. His successful furniture-making operation on East Patrick Street once stood on the location of today’s Museum of Civil War Medicine. James Whitehill often receives credit for helping care for and bury Mrs. Crawford within the new cemetery, but it’s interesting to note that the lot she was laid to rest in a lot owned by the Methodist Episcopal Church of Frederick. Both facts raise the question: Was Mrs. Crawford destitute at the time of her death? A unique irony lies in the fact that James Whitehill’s home, the last residence of Mrs. Crawford, is located at 731 N. Market Street. In December, 2016, this building was recently opened as the Frederick Rescue Mission’s “Faith House,” a temporary shelter for homeless women and children. A brief note in the cemetery’s lot records states that Ann Crawford worked as a maid for James and Ann Whitehill at the time of her death. We know she died at his house, but what was the rationale for her living there? This is a good assumption, if, indeed, she had played that role previously for Lewis Bentz and simply changed employers. We have no idea of knowing this for sure.  1812 election results for Adams County (PA) appearing in the October 21, 1812 edition of the Adams Sentinel (Gettysburg, PA) 1812 election results for Adams County (PA) appearing in the October 21, 1812 edition of the Adams Sentinel (Gettysburg, PA) Now, here’s an opposite of extremes, an apocryphal story I have heard from fellow local Frederick historian/researcher Larry Moore. He has heard that Mrs. Crawford was the second wife of a prominent physician from Pennsylvania. When the Doctor died as a result of a buggy accident, she was cut out of the will by the physician’s children from his first marriage. She then went to live with a sister in Carroll County (Maryland) and had a son who went to Baltimore after marrying into the McPherson family. Once having a high social status through marriage, Ann Crawford was forced to earn her own way, working as a maid here in Frederick. I have not been able to find any direct connection or documentation on Ann Crawford in Ancestry .com databases, marriage licenses, etc. My biggest challenge is not knowing Ann’s maiden name. I have wondered if perhaps Ann Crawford could have been a relative of either James Whitehill or wife Ann Whitehill. James Whitehill’s ancestors were quite prominent in south central Pennsylvania in the late 1700’s and early 1800’s. Some of these men served as politicians, such as US Congressman Robert Whitehill (1738-1813). The name might not mean much to you, but he should receive partial credit for the Bill of Rights, the first 10 amendments found in the US Constitution. It wasn't all James Madison! The Whitehills were intertwined with prominent Crawfords of areas such as Adams County to Frederick County's immediate north. These too served in various levels of government. One such was Dr. William Crawford whose biography reads as follows: Hon. William P. Crawford, M.D., was born in Paisley, Scotland, in 1760, received a classical education, studied medicine at the University of Edinburgh, Scotland, and received his degree in 1791; emigrated to York County (now Adams County), and located near the present site of Gettysburg, purchased a farm on Marsh Creek in 1795, and spent the remainder of his life there practicing medicine among his friends, with the exception of intervals in which he was elected to office. He was an associate judge, and was elected to represent York district in the Eleventh Congress, in 1808, as a Democrat or Republican, as the name was then generally termed. He was re-elected to the Twelfth Congress to represent York District and to the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Congresses to represent a new district formed, of which Adams County was a part, serving continuously from 1809 to 1817, after which he resumed the practice of medicine. He died in 1823. Mrs. Edward McPherson is a granddaughter of Dr. Crawford. History of Cumberland and Adams Counties, Pennsylvania Chicago: Warner, Beers & Co., 1886  Ross-Mathias mansions on Frederick's Council Street, built by Col. John McPherson and John Brien 1815-1817 Ross-Mathias mansions on Frederick's Council Street, built by Col. John McPherson and John Brien 1815-1817 In digging deeper, I was ecstatic to learn that Dr. William P. Crawford had a wife named Ann! However, she died in 1860 and is buried with the physician in Gettysburg’s Evergreen Cemetery. But could she be a daughter-in-law? It doesn’t seem likely. Of other interest with this biography, is the mention of Edward McPherson, who married Dr. William Crawford’s granddaughter, Annie D. Crawford (daughter of John S, Crawford). Another Ann Crawford, but far too young to be our Ann Crawford! Edward McPherson was a leading lawyer of the Gettysburg area and also served terms in the United States Congress. The name McPherson conjures up a potential connection to another early Frederick transplant (and family) from the Adams County area— Col. John McPherson. You may recall that it was Col. John McPherson, who along with son-in-law John Brien, built the beautiful Council Street townhomes in Frederick’s Courthouse Square. Both men also operated the Catoctin Furnace for a period. Could Mrs. Crawford have any ties to them? Although known slaveholders, the need for a maid for this family and relatives is not far-fetched.  Engelbrecht tailoring advertisement from the Frederick Town Herald newspaper (Nov. 13, 1830) Engelbrecht tailoring advertisement from the Frederick Town Herald newspaper (Nov. 13, 1830) A final theory on Mount Olivet’s “first lady” comes from cemetery superintendent of 50+ years, J. Ronald Pearcey. Ron told me that he had heard that Ann Crawford was the wife of a tailor. Her husband had a business here in Frederick in the early 19th century, which was located in a building owned by none other than Mr. James Whitehill. Mr. Crawford passed away, leaving Mrs. Crawford to work as a domestic for local families. I have yet to find this gentleman, and Ron didn’t get his first name, but I did find this passage in Jacob Engelbrecht’s diary, written in 1827: Died last night in the year of her age Mrs. Crawford consort of Mr. Crawford of this county and mother of James and Joshua Crawford who now live with John & George Engelbrecht. Sunday, February 11th 1827 4pm Since this Mrs. Crawford died in 1827, I pose the question, “Could this Mrs. Crawford be the mother-in-law of our Mrs. Ann Crawford?” Was Ann Crawford’s husband either James or Joshua? It’s likely far-fetched because James and Joshua are likely just children, perhaps teenagers, at this time. If there was a relationship with our Mrs. Crawford (age 34 in 1827), we would have another “cougar-type” relationship in the making. It is possible, I guess, not to mention the fact that James and Joshua could have been tailors. The reason I say this stems from the fact that the abovementioned John and George Engelbrecht were brothers of diarist Jacob Engelbrecht. Their profession, like his, was that of a tailor. Were James and Joshua apprenticed in tailoring by their hosts? To tie-up this blog up with a pretty bow, I offer my deepest apologies to you the reader. I’m sorry I couldn’t shed anything more definitive about Mrs. Crawford, and am open to any leads or information anyone can offer.

I guess the “Story in Stone” here is that Ann J. Crawford’s life is simply defined by her death, leading to her May 29th burial in Mount Olivet, the very first--with thousands to follow. This is all she had to do to make history.

3 Comments

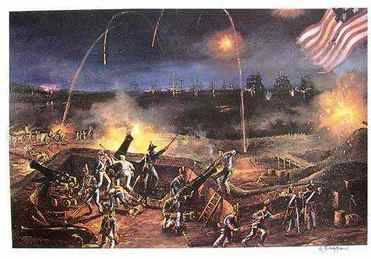

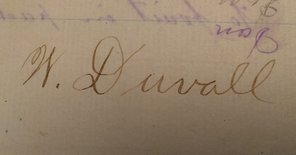

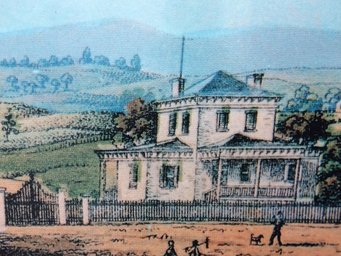

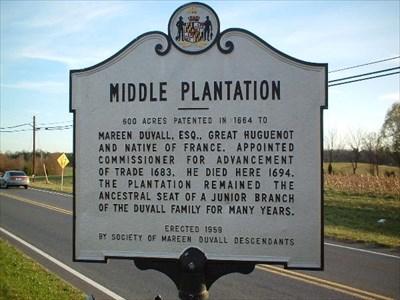

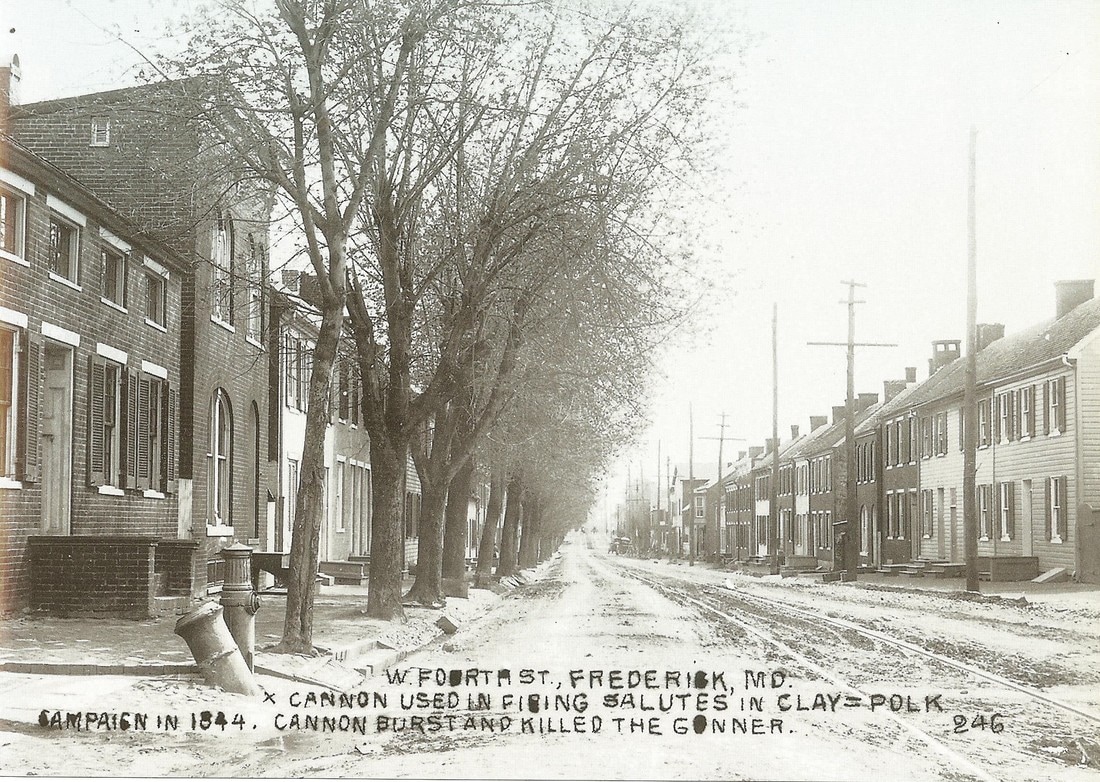

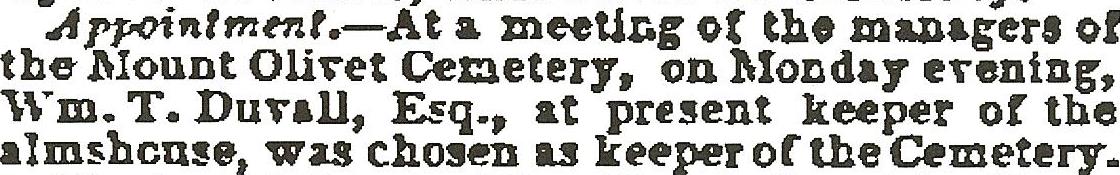

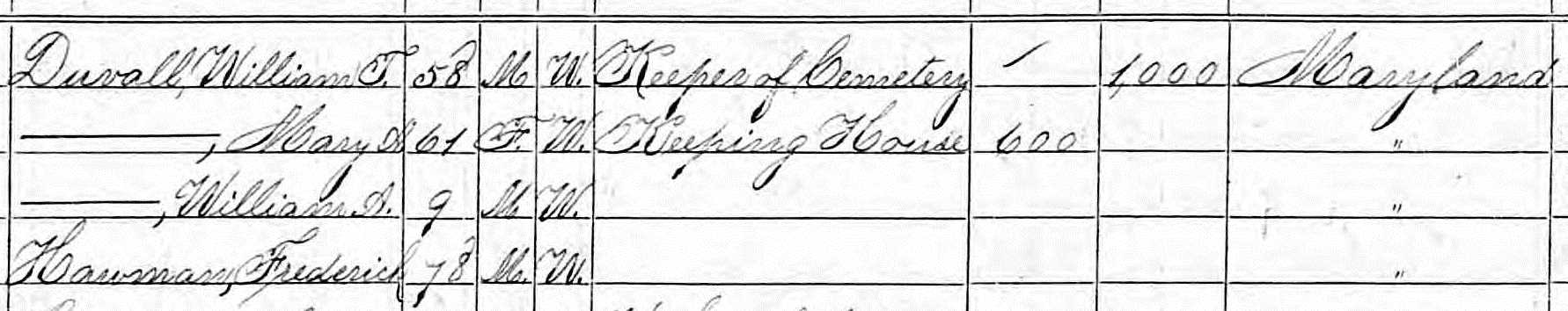

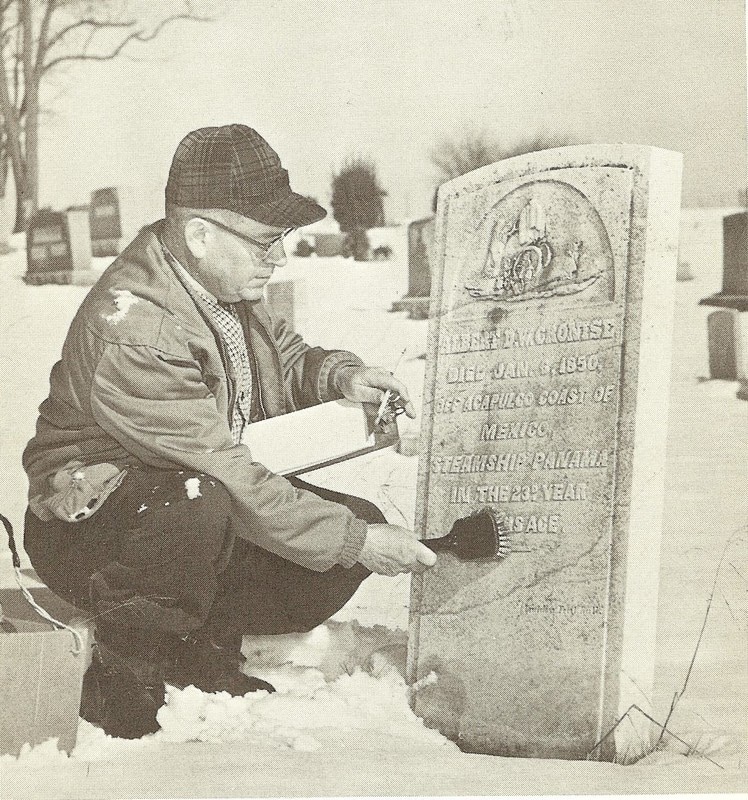

A popular expression used when someone dies is that they are “going home.” In this vein, “going home” simply means that the deceased is heading to heaven, to reunite with their God, along with a host of previously departed family members and friends such as parents, grandparents and cousins. This same expression could have taken on a unique, and somewhat comical, meaning if it had been uttered at the death of Frederick resident William T. Duvall, who passed on September 19th, 1886. Mr. Duvall was “going home,” but in a way, he was already there. His gravesite in Mount Olivet would be located only fifty yards from his home residence and work office of the previous 33 years. William Thomas Duvall was born during a turbulent time in American history in which Great Britain was trying to undo that which the founding fathers, Continental Army and countless others had fought so hard to gain in 1776—independence. Duvall’s birth on January 23rd, 1813 came at a time when the main theater of conflicts associated with the War of 1812 was occurring in Canadian provinces and American lands within the Great Lakes territory. In anticipation of warfare possibly taking place in and around the nation’s capital, local militia units organized and would regularly practice and drill. This was often the scene at the old Hessian Barracks and surrounding grounds atop the aptly named Barracks Hill, later known as Cannon Hill. British marauders harassed towns along the Chesapeake bay throughout the summer of 1813. As William T. Duvall turned one and a half years old in August, 1814, British forces sailed up the bay and ruthlessly sacked Washington, DC, burning the White House. The aggressors next set their sights on Baltimore, at the time, one of the largest and most important cities in the country. The Charm City defenders held their ground at Fort McHenry and thwarted the advance of the enemy, thanks in part to many Frederick veterans that would one day repose in Mount Olivet. Perhaps, William’s parents sang him to sleep each night with a catchy little song about the flag, written by a Frederick native named Key? Who knows? William T. Duvall’s father was never too keen on the British. He came from French lineage, his great-great grandfather having been born in Normandy and came to this country in 1650. The family progenitor Mareen DuVall (1630-1694) immigrated to Maryland as an indentured servant but worked his way up the ladder, providing quite a home for his family by the end of the 17th century. This estate was called Middle Plantation, located in Anne Arundel County. This is the area of present day Davidsonville, south of Crofton. Others direct descendants of this prosperous early immigrant include actor Robert Duvall, former vice-president Dick Cheney, and former presidents Harry S. Truman and Barrack Obama. Mareen Duvall is the latter's 9th great grandfather. The grandfather of William T. was John Duvall, a military captain during the American Revolution. He would live and die in his home county of Anne Arundel, but one of his sons, Marsh Mareen Duvall II (1768-1828), would leave to make a new home in burgeoning Frederick, Maryland. Information is scarce, but Marsh Mareen Duvall II would marry Sarah Stallings, 17 years his junior, in January of 1811. Two years later, the couple would welcome son William Thomas into the world. Three known children followed. I wasn’t able to glean much about William T’s childhood, other than his family were members of Evangelical Lutheran Church. His father was buried in the church’s graveyard located between East Church and 2nd streets upon his death in 1828. William T. Duvall got married in the same church in March, 1835. Another melancholy Duvall family burial would follow in 1844. William T.’s younger brother, Upton Duvall, would make national news in newspapers across the country in late November of that year. He played the lead role in one of the most "explosive" events in Frederick history. Upton was killed by Cannon Hill’s namesake cannon, after he and friends decided it would be fun to fire a celebratory blast in honor of presidential candidate James K. Polk. Polk had just narrowly defeated Henry Clay, heralded today as one of the greatest senators and statesman in US history. Instead of using typical shot materials, the group of Polk fanatics decided to make a symbolic and sarcastic statement with their actions by filling the artillery piece with clay. Upon a misfiring attempt, Upton approached the cannon to see what went wrong, and at that moment the weapon exploded, instantly killing the young man. Ironically it would be Upton Duvall, who would soon be placed in a grave, his corpse forever surrounded by the clay soil of Frederick’s Lutheran graveyard. (Note: for more on this incident see clipping at end of story)  William T. Duvall had married Mary Ann Rebecca Hawman, a local girl whose father was a Revolutionary War soldier, and her brother served as a member of the Frederick militia during the War of 1812. Fittingly, the new couple named their first born son William Luther Duvall (1838-1902), giving homage to both father and the father of their chosen religion. Sadly, two subsequent sons to William and Rebecca would die in late January, 1847—Frederick age 7, and Louis Hawman Duvall, age 5. These boys died six days apart, likely from a communicable disease. The couple’s fourth child, a daughter, named Harriett was born in 1844, but would also pass in her youth at the age of 16 in 1860. A fifth child, Julia Ann would live a full life, marrying David Ashbaugh. William T. gained employment as a weaver, having learned his trade from a gentleman named Daniel Boyd. In early 1852, he entered into a new profession. William Duvall was appointed to the position of Keeper of the Frederick County Almshouse located northwest of the City. This charitable housing facility provided Frederick residents (typically elderly citizens who could no longer work to earn enough to pay rent) a place to live. It is better remembered as the predecessor to the Montevue Home, and featured its own burying ground referred to as “the Potter’s Field.” Exactly two years later, William T. Duvall would make yet another job switch, but this one would last a lifetime. It was recorded for posterity’s sake by Frederick’s legendary diarist Jacob Engelbrecht: “Mr. William T. DuVall was on Monday evening the 6th instant, appointed keeper of “Mount Olivet Cemetery” of this city—the first keeper—no person is yet buried there—The house (dwelling)is not quite finished.” —Jacob Engelbrecht (Wednesday, February 9, 1854) On February 6th, 1854, Mount Olivet’s Board of Managers made a choice for their new cemetery’s gate keeper, also known as a superintendent. Thirteen names had been submitted for the position. Duvall’s prior experience at the almshouse, and handling of the premature deaths of his young children could have given him the “leg up” on other candidates. He garnered the necessary votes on the third round of balloting and staved off competitors for the post: W. Greentree, Harman Butler, George W. Cromwell and Samuel Haller.  The first Superintendent's House at Mount Olivet (built 1854) The first Superintendent's House at Mount Olivet (built 1854) The cemetery board set the gate keeper’s beginning salary at $20.00 per month which also included a major perk—the use of the dwelling house, rent-free, effective April 1, 1854. This structure had just been completed and was located adjacent the main entry gate and fronting on South Market Street. One year later, April 1, 1855, Superintendent Duvall reported a total of 172 interments within Mount Olivet. His job performance was rewarded with a pay raise as he was bumped up to $275/year. He would guide the general operation and improvements to Mount Olivet for 33 years until his death on Sunday, September 19th, 1886. During Mr. Duvall’s tenure, hundreds of colleagues, neighbors and family members would pass through Mount Olivet’s gate. Many other former Frederick residents that had been buried in the older church cemeteries of town were also moved to the “new” rural cemetery under his watch. When his work on Earth was done, he had buried 4,879 persons. Among these were veterans and combatants of the American Revolution, War of 1812 and Civil War. And let’s not forget a fellow named Francis Scott Key, who was reinterred from Baltimore under the superintendent’s utmost care. William T. Duvall’s own certificate of burial numbered 4,880. Duvall died in the Superintendent’s house, a site that would host his wake and funeral in the immediate days to follow. On Wednesday afternoon, September 22, 1886, William T. Duvall’s body was easily moved roughly fifty yards to his final resting place, a lot already containing the three children he had been forced to bury. He would forever remain within the location of his employ from that point into eternity. (Author's note: I am very interested in obtaining an image of William Thomas Duvall for interpretive use by the cemetery. Please contact me if you should ever find one, or know someone who might, thanks!) The article below was carried in the Frederick Examiner's edition of November 27, 1844. The story was carried in several newspapers across the country including Boston, Vermont and Louisiana to name a few.

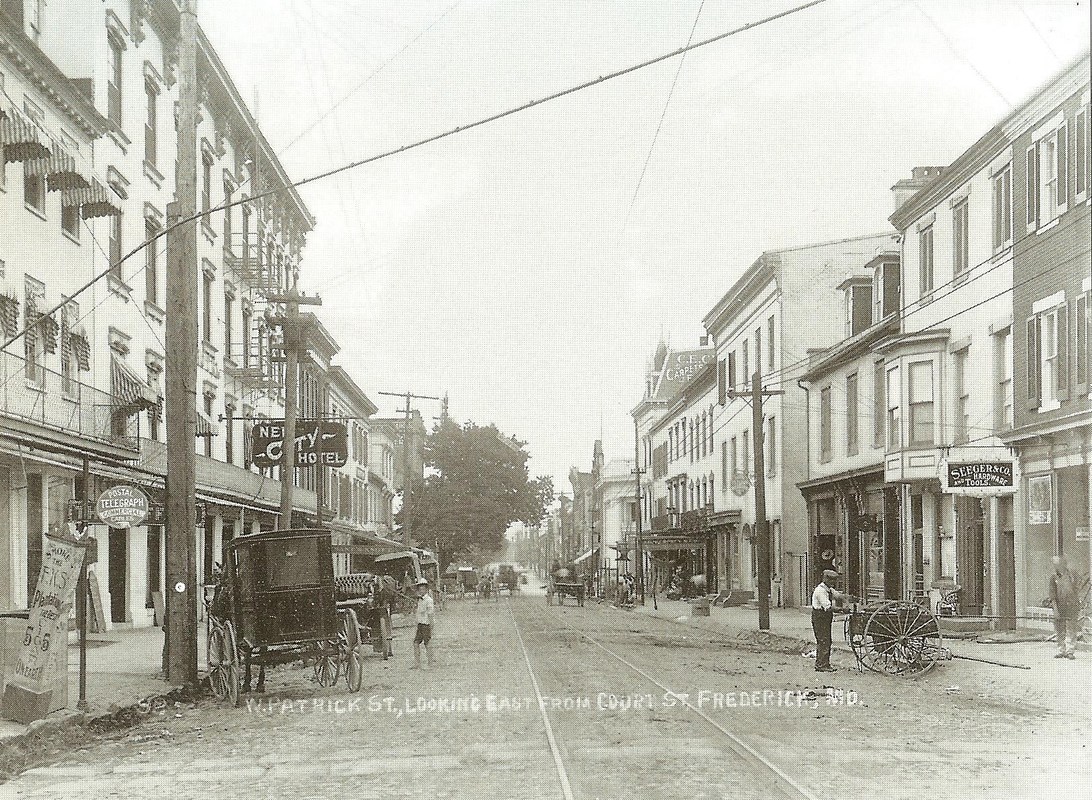

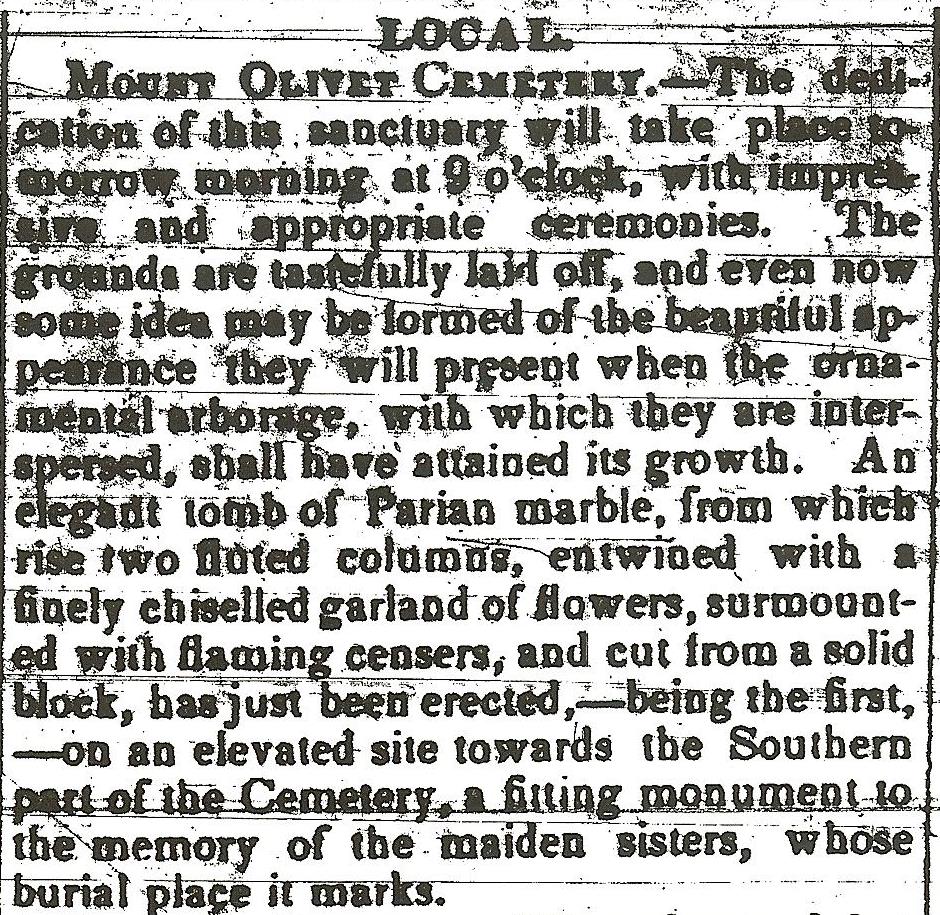

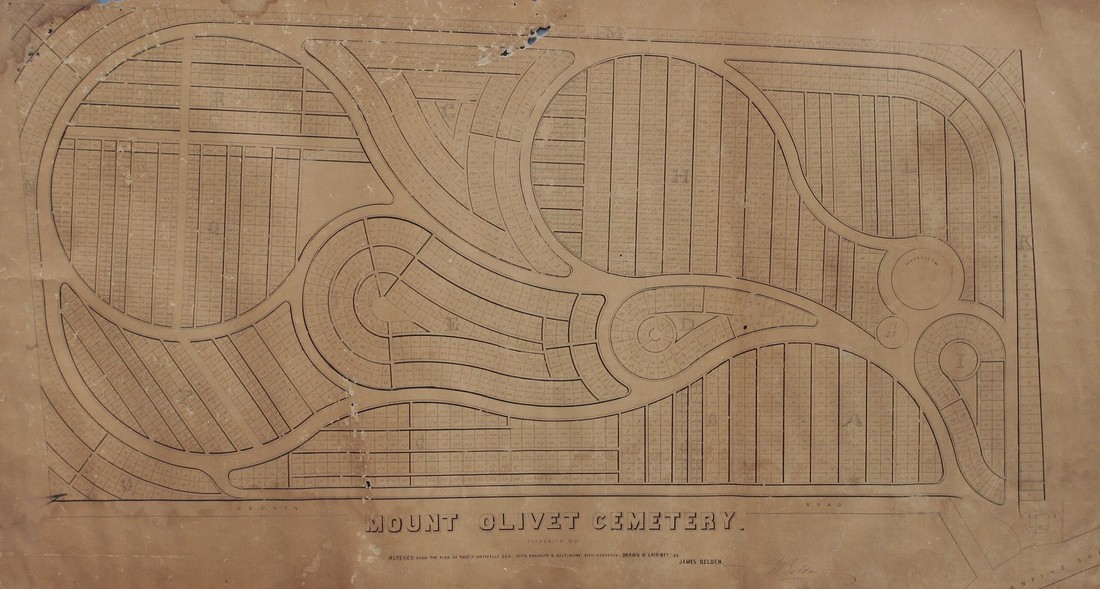

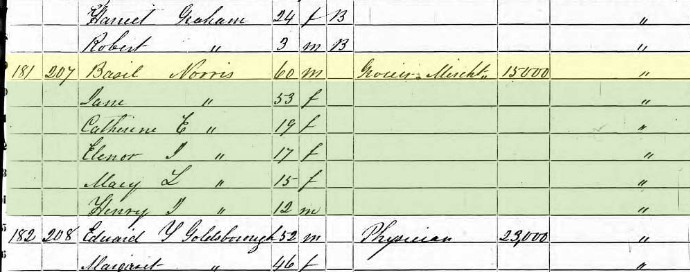

Since January is the first month, I’d figure we’d spend the next few weeks on subjects relating to firsts for the cemetery. This week, we will pick up last week’s conversation regarding grave markers and stones.The most famous monument is clearly that of Francis Scott Key, but I was surprised to find some cousins actually had the "first." Up until last summer, no one could speak to the subject of first grave monument to appear in Mount Olivet Cemetery. Now I don’t know if people spent a great deal of time on this query, but it makes for an interesting trivia question among local history buffs. My imagination was first sparked when I stumbled upon a news article relating to the cemetery’s official opening in 1854. I found the following piece in the Frederick Town Herald newspaper, dated May 10 (1854): So with no photograph, or “name in stone,” to go on, I set out to find this “elegant tomb of Parian marble.” But first, I had to figure out what Parian marble was? I soon discovered that Parian marble is: “a fine-grained, semi-translucent/pure-white and entirely flawless marble quarried during the classical era on the Greek island of Paros in the Aegean Sea. It was highly prized by ancient Greeks for making sculptures.” The geology/origin hint given by Wikipedia didn’t really help that much, but the news article’s geographical description of the gravestone’s location (within the cemetery) certainly did. I had to find an elevated site on the southern side of the cemetery. I knew that the obvious high-water mark (literally and figuratively) of the cemetery is the area of present-day Founder’s Garden, between areas “G,” “F” and “Q.” Once the site of an observation tower and waterworks (something we will surely discuss in a future blog), this location boasts its prominence as the highest elevation point in Downtown Frederick. That’s right, I said it—this Downtown Frederick’s highest peak! And with the name Mount Olivet, this is the closest we come to legitimizing our landform moniker—aside from biblical connotations of course. Many of the community’s most prominent residents of the late 19th and early 20th century would be laid to rest here atop the mountain-like hill. The iron-railed Potts family lot, the cemetery’s only “gated community,” is here as well. During the early decades of Mount Olivet, this locale would also represent the western boundary of the cemetery, as the grounds only encompassed one-third of what they do today. I simply started my search on the apex of the hill, intending to scour the southern slope, area “F.” I began looking for “two fluted columns, entwined with a finely chiseled garland of flowers, surmounted by flaming censers.” If you were wondering what a censer is, it’s a container in which incense is burned, typically during a religious ceremony. Amazingly, I didn’t have to go far as I found something that fit the bill within seconds. It was adjacent a cemetery lane that runs through the center of the cemetery. I had traveled by this monument regularly by car, but more so when conducting walking tours through the grounds. So I now had something that fit the newspaper article’s given location and description, now I had to check the interments buried beneath. You will recall that the clipping stated that this monument was placed to honor “the memory of two maiden sisters.” This was it! Mary Louisa Norris (b. 12/26/1834) died less than a week after her seventeenth birthday, on New Years Day, 1851. Eleven months later, Mary’s older sister Catherine Elizabeth “Kate” Norris would meet the same fate on November 11th (1851). She was just 23 years of age. Both young ladies were originally laid to rest in the old All Saint’s Burying Ground, located between East all Saints Street and Carroll Creek. Today this is at the top of another hill in downtown Frederick, one that overlooks an amphitheater and provides commanding views of the Community Bridge to the east, and William O. Lee Unity Bridge to the west. Plans for the creation of Mount Olivet would occur the next year (1852) with the founding of the Mount Olivet Cemetery Association. The girls’ grieving parents, Basil Norris and Jane (Charlton) Norris (1797-1871) decided that the new garden-style cemetery would be a more fitting resting place for two young women in the “spring” of their lives. Basil Norris (1788-1865) was a successful Frederick merchant who operated a grocery store for many years in the first block of West Patrick Street across from the City Hotel. Mrs. Norris was a first cousin of Francis Scott Key. (Basil Norris would purchase the City Hotel in 1854. The popular lodging site stood here until being replaced later by the Francis Scott Key Hotel.)  (c.1910) view of the first block of W. Patrick St. (looking east). The author believes the former Norris residence and grocery store were located in the twin three-story townhomes to the right of photograph. Charles F. Seeger would later start his hardware business at this location of 32 W. Patrick St. The Patrick Center sits on this site today. Rain and thunderstorms delayed Mount Olivet’s official dedication ceremony on May 11th. It would be rescheduled for May 23rd, 1854. Less than a month later, the Norris sisters would be carefully exhumed from All Saints Cemetery and brought to the Norris family lot in the town’s new burying ground. A beautiful monument was waiting their arrival, standing as a beacon to their memory, high atop Mount Olivet Hill. A biblical inscription (taken from Old Testament, second book of Samuel 1:23) can be found at the bottom of the monument. It reads:

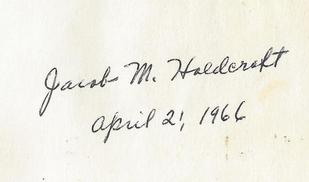

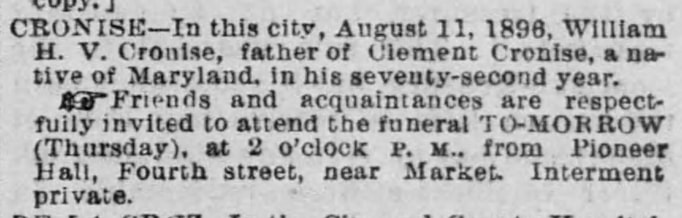

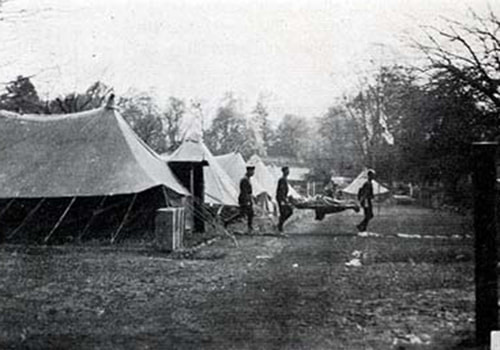

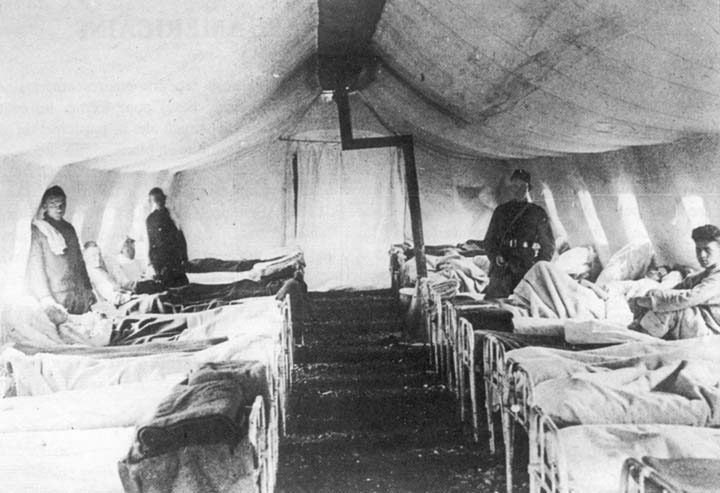

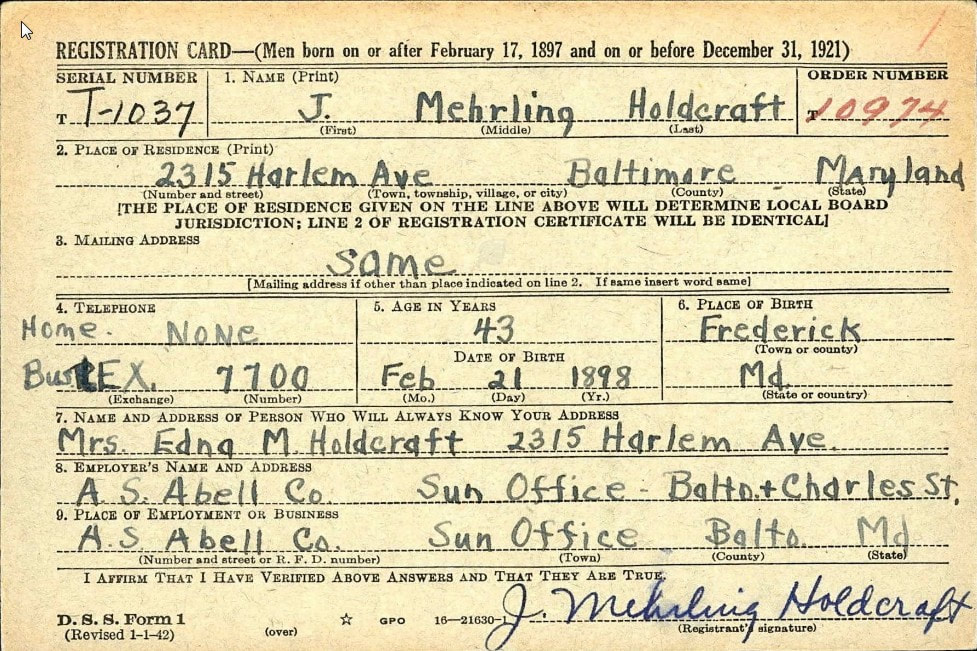

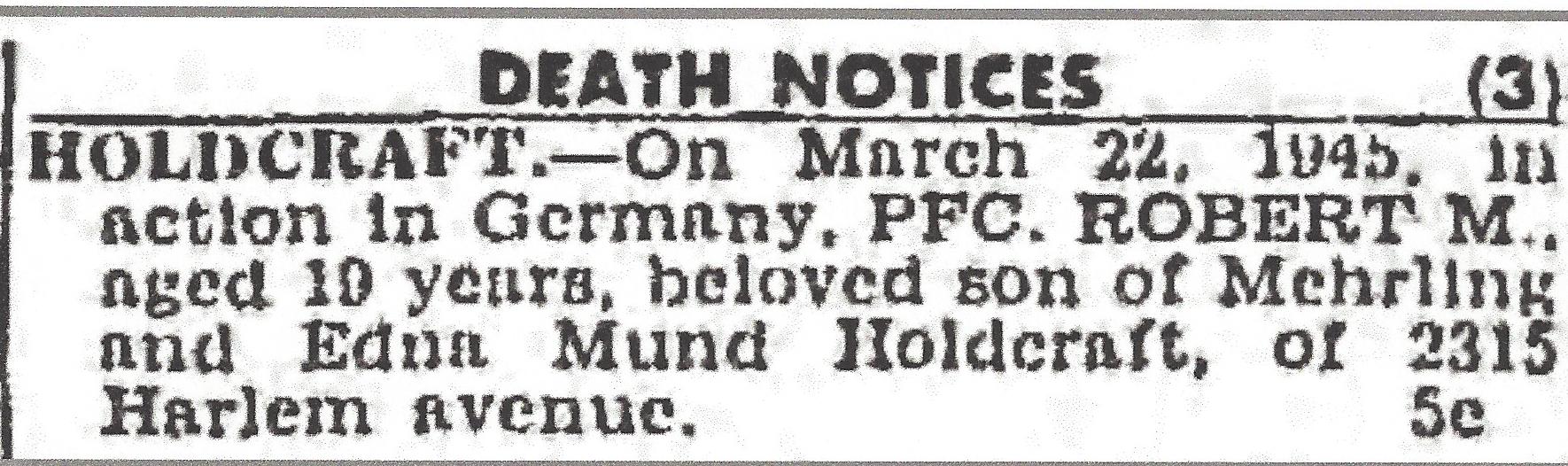

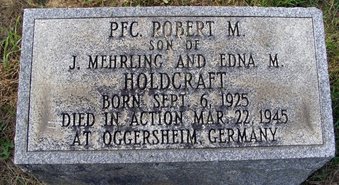

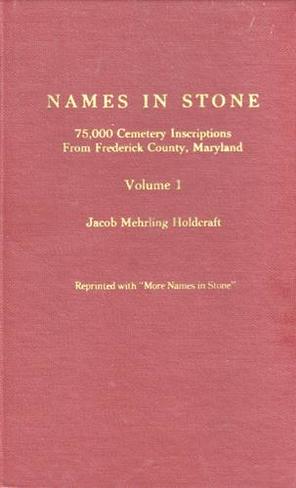

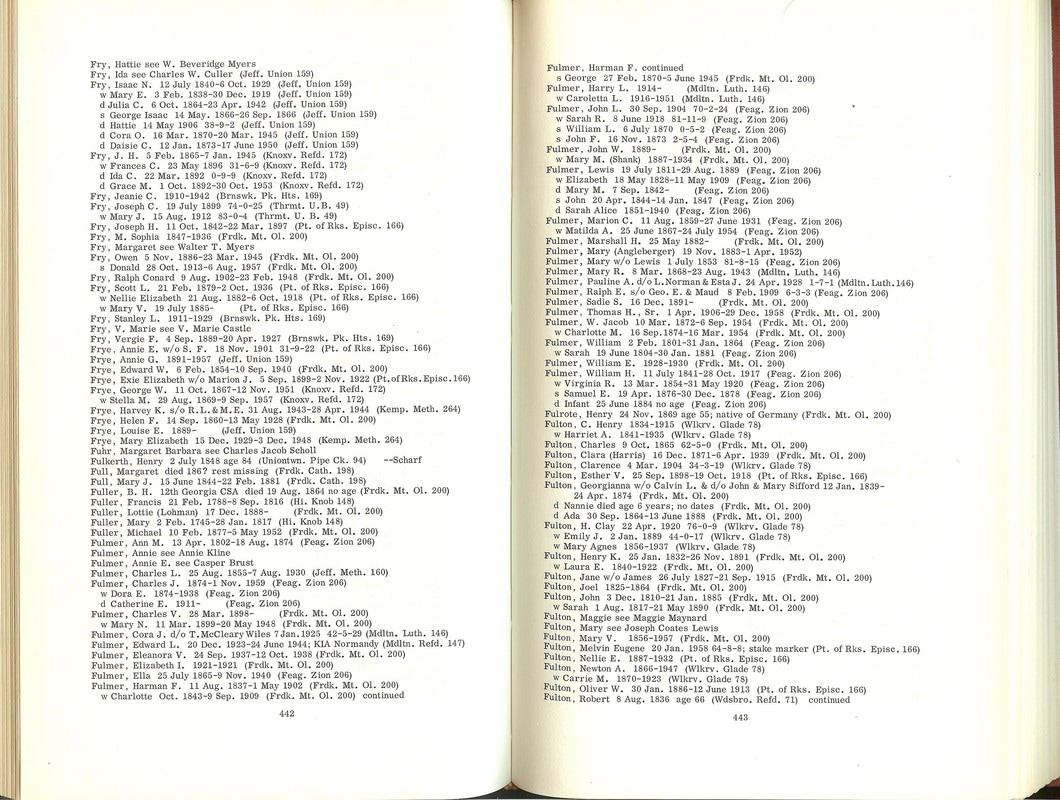

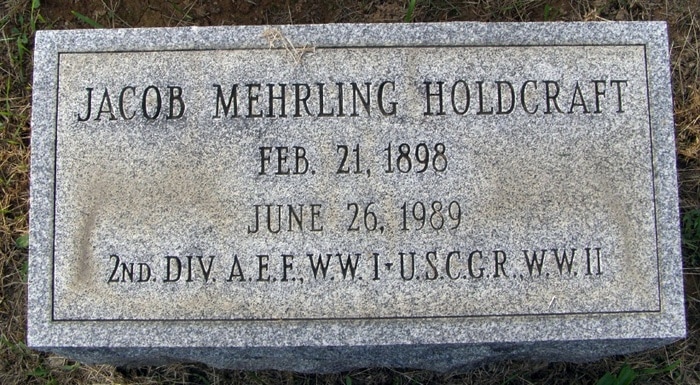

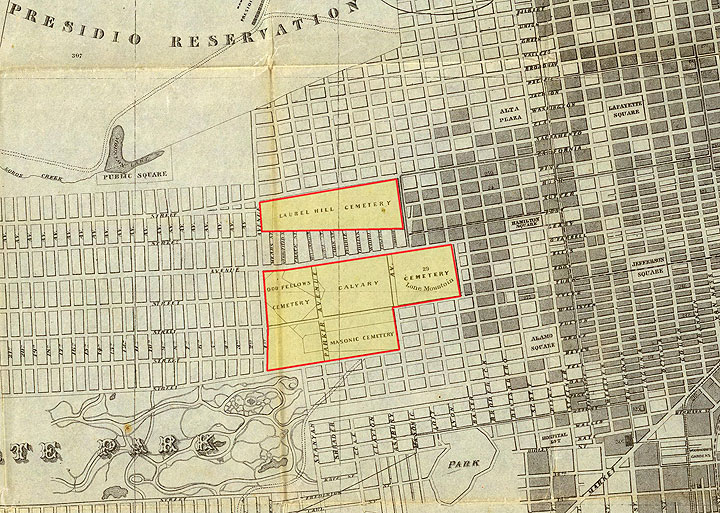

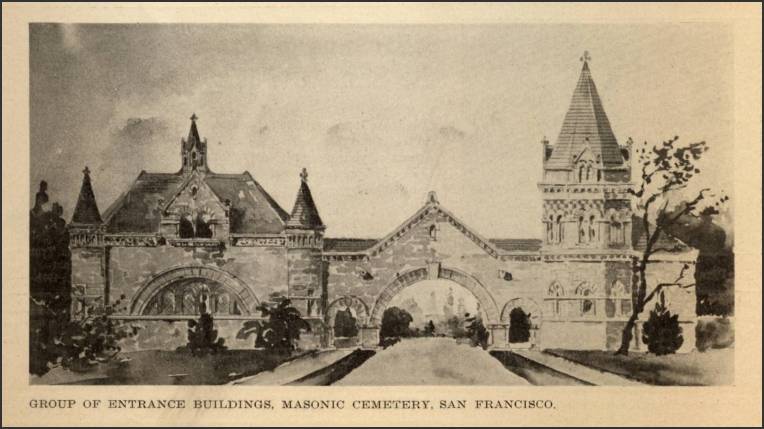

“They were lovely and pleasant in their lives, and in their death they were not divided.” Unfortunately, Mr. and Mrs. Norris would be forced to endure more heartache eight years later on July 1st, 1862, with the death of son Henry J. Norris who worked as a clerk in the family store. They erected another magnificent monument to the 25 year-old, placed to the immediate right of the Norris sisters. The stone depicts a broken column, a popular Victorian period design symbolic of a life cut short. The name of this blog is “Stories in Stone.” I began the weekly feature for the Mount Olivet Cemetery website and Facebook page back in early November, 2016. Since that time, people have remarked to me: “Oh what a clever name for your articles.” And I certainly agree! These are essays about former Frederick residents buried within Mount Olivet’s gates. Yes, some of these individuals stand out for their achievements. Others can be remembered for misfortunes. All in all, most of those “resting in peace” just lived simple, ordinary lives. To borrow a line from George Bailey in Frank Capra’s legendary film It’s a Wonderful Life: “Just remember Mr. Potter, that this rabble that you’re talking about...they do most of the working and paying and living and dying in this community.” While I will occasionally touch on local greats who made the national history books such as Francis Scott Key, Barbara Fritchie and Thomas Johnson, Jr., I’ve been most inspired by researching lesser known folks, or individuals that shouldn’t have been forgotten over time. At least, I have the opportunity to introduce (or reintroduce) them to readers here in this fashion.  I can’t walk through this cemetery without my head on a swivel. Monikers are everywhere, and jump out at me, left and right. I try to process these from my past experiences with research, documentary and writing work. I’m quick to recall that this man owned a department store downtown, that lady was a nurse during the Civil War, this individual was mayor of Frederick in the early 1800’s, that child was killed in the big fire, etc. With 40,000 former residents in my midst, roughly the same population as our state capital of Annapolis, I do pass countless gravesites without a thought, as their names are nothing more than “names in stone.” However, as I have found, they are much more than that. Grave markers, monuments, and tombstones are tributes to, and representations of, past lives. Each provides a tangible connection to the deceased. From a religious perspective, I’ve been taught that the spirit of our loved ones will always be with us, and are “watching from above.” However, these works in granite and marble are tangible, standing as a tribute to a life once lived, be it spectacular, common or “rabble.” Grave stones can bring a sense of reality and closure for some people, and for others serve to keep the memory of that person alive. Each and every day, I see individuals coming to Mount Olivet to plan and purchase monuments for themselves and loved ones who have passed. Some designs are playful, others are serious. Most can best be described as traditional. I also get to see the joy of discovery as family history chasers and historians complete pilgrimages here from around the country, to come as close to “face to face” as possible with ancestors they have heard stories about since childhood, or others just recently discovered on Ancestry.com. And to explain my statement of “face to face,” there are many situations in which a decedent’s photograph does not survive. In this case, a grave marker is the closest thing to visualize that individual. I often think of the extended family that gathered around a particular gravesite here for a funeral 150 years ago in the mid-1800’s, or maybe one in the early 1900’s or 1950’s. Those people were on hand to say goodbye and shed tears for their dearly departed. As time passed, later generations would gather for each of them as their own funerals took place. As I learn more about the lives of Mount Olivet’s residents through researching this blog and stories told to me by visiting descendants regarding their relatives, I certainly see that those interred here are much more than “names in stone.” Hence, they are Stories in Stone. I commonly find myself stopping and paying respects to more and more of these people who gave us the Frederick (city and county) we know and love today. I have only met them through perusing old photos, newspaper articles and census records. Thanks to gravestones and monuments, I know where they are, so to speak. One of Mount Olivet's inhabitants was very poignant to the research and history work I have been performing over the last 25+ years. He’s also the inspiration for the title of my blog. His name, Jacob M. Holdcraft.  1900 census showing Holdcraft family in Frederick 1900 census showing Holdcraft family in Frederick Jacob Mehrling Holdcraft was born on February 21st, 1898 in Frederick. He grew up on East Church Street (extended), the son of—you guessed it, a one-time tombstone salesman. Jacob’s father, John H. Holdcraft, was a native of Massachusetts who married a local girl named Ella C. Mehrling. Ella was the daughter of a butcher and was reputed to have been born in the original Barbara Fritchie house in 1863. Jacob grew up with eight siblings, but another, Nelson, had died from pneumonia as an infant two days before Christmas in 1896. The Holdcraft children went to local schools and be brought up in the Lutheran religion. The family attended Evangelical Lutheran Church, just a few blocks from home, and were highly active members. Jacob’s older brother Paul would attend seminary and became an ordained minister in the United Brethren Church. He served with distinction (mostly in Baltimore) up until his death in 1971. A sister Ruth (Mackley) married and lived in Thurmont where she played the role of longtime organist for Trinity United Church of Christ. Both siblings were linked to helping conduct funerals through their religious callings. With an 8th grade education, Jacob set out to work. He served as a paperboy for the Frederick News and would also perform duties as a brush maker at the Ox-Fibre Brush Factory (today the site of Goodwill Industries). He served the country overseas in World War I. Holdcraft joined the Regular US Army three days after Independence Day on July 7th, 1917. Five months later he was shipped to France. A month later he would receive a promotion to Private First Class and assigned to the 15th Field Hospital. Jacob Holdcraft would see much of the eastern part of the country including the Toulon-Troyon Sector, the Chateau-Thierry Sector, the Marbach Sector, and the Limey Sector. The Frederick native would also see the terrible carnage of war as he performed his duties throughout dangerous conflicts such as the battles at Aisne-Marne, St. Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne. He would head home in early August 1919, and was honorably discharged on August 13th. Holdcraft soon returned in peacetime, participating in the Army of Occupation in Germany following the conflict.  Jacob M. Holdcraft Jacob M. Holdcraft After his return home, he would eventually move to the big city of Baltimore, in the early 1920’s, finding work in the printing department of the Baltimore Sun newspaper. He also found Edna May Mund, who would soon be his new bride. Jacob M. Holdcraft had left Frederick, but Frederick would never leave him. The couple started a family in “Charm City,” welcoming their first child, Robert Mehrling Holdcraft in September of 1925. A daughter (Elaine) and another son (John) would follow before 1930. Jacob, or "Mehrl" as he was also called, would work his career in the newspaper business, serving as a compositor— a person who arranges type for printing or keys text into a composing machine. Later in his career with the Sun, he would serve as a proofreader.  Grave of Nelson R. Holdcraft (3/5/1896-12/23/1896) Grave of Nelson R. Holdcraft (3/5/1896-12/23/1896) Jacob Holdcraft most certainly read and performed his share of typing in obituaries. This led to an unusual leisure pursuit of “proofreading” compositing of a different sort—recording the names and birth/death date information on tombstones. He said that this new hobby grew out of his interest in his relatives and ancestors. Jacob's brother Nelson had died two years before his own birth, and surely captured his imagination. In addition, trips to visit the graves of early ancestors located in the county led rise to thoughts regarding the fate of the many pioneers who had passed through life and died without leaving any trace on Earth. He didn’t know it the time, but Jacob Holdcraft would embark on a 35-year odyssey of recording the existing tombstones of all of his native Frederick County’s cemeteries, churchyards and family burying grounds. What started as an aid to his own family genealogical research, became something that would help countless others with their research, including myself. Jacob’s venture was soon bittersweet as he would have to record the vital information of his own parents. His mother died in 1935, and his father two years later in 1937. Both are interred in Mount Olivet in the family lot within Area LL. Another World War was looming, and Jacob volunteered for the US Coast Guard. The events of the conflict consumed the Sun newspaper. However, nothing truly prepared a seasoned, war veteran and parent for what would come next—the heart-wrenching task of documenting a relative killed in the line of duty with the US Army during World War II. This was Jacob's first-born son, Robert, aged 19-years, 6 months and 16 days. He was killed in action by an artillery shell blast on March 22nd, 1945 in Oggersheim, Germany. Robert’s body was shipped home to be laid to rest in the Holdcraft lot in Mount Olivet. I can only assume that this tragic event further inspired Jacob on continuation with his “monumental” hobby. He likely had overwhelming feelings of empathy for the parents of any veteran lost in the line of duty, not to mention, any young person whose grave he recorded from that point forward. Perhaps this event, more than any other, propelled his hobby as an opportunity to fill the heavy void, while soothing the pain that Robert’s death created in his life. In a newspaper interview from the 1960’s about his research, Jacob said, “Not only was it a fascinating hobby, but it gave me “quiet” and restful hours in the great outdoors.”  Jacob Holdcraft would document cemetery inscriptions for the next two decades into the mid-1960’s, devoting most of his weekend, each and every week. In the end, he held the amazing distinction of visiting more individual graves in Frederick County than anyone before, and likely anyone since—75,000. With help from Dr. John P. Dern of California, Jacob compiled his findings alphabetically and in 1966 had his work published in a two volume, 1301-page masterpiece, aptly titled Names in Stone. The preface was penned by noted Frederick County genealogist, historian and author Millard Milburn Rice, a great choice in my opinion as I, myself, visited Mr. Rice in 1994 to gain advice and guidance before embarking on my 10-hour video documentary entitled Frederick Town (1995). In Names in Stone, Mr. Rice wrote: “In short, the information in these books may be relied upon within the limits of human fallibility and the ravages of time which are forever making inscriptions undecipherable. And I am sure all who find herein names heretofore possibly long sought will feel, as I do, a debt of gratitude to Jacob Mehrling Holdcraft for completion of such a difficult task.  Jacob Holdcraft gave Mount Olivet cemetery one of the first published editions of Names in Stone. The "compiler" autographed the fly leaf. Jacob Holdcraft gave Mount Olivet cemetery one of the first published editions of Names in Stone. The "compiler" autographed the fly leaf. Names in Stone has been a key resource for genealogists and historians ever since, especially in an era that pre-dated the family history resources associated with the internet. At 68-years old, Jacob, referring to himself as the book’s compiler, had produced the first Frederick-based Find-a Grave site in book form. He had dedicated more than half his life to the project. But he wasn’t done yet. In 1972, Holdcraft published a sequel entitled More Names in Stone. This 3,000 name addendum to his earlier work, focused on the former lands of Frederick County, now comprised as Carroll County. Amidst, sudden failing eyesight, Jacob added to our resource base. In his touching preface, he lamented that he still didn’t make it to all the graves existing in the county and went further by stating his hope for the work to go on saying: “and that ultimate continuation of my work may yet be undertaken by younger eyes.” Jacob Mehrling Holdcraft’s name went in stone in 1989. He passed away at his residence of Meridian-Catonsville Nursing Home (Catonsville, MD) having lived 91 years, 4 months and 5 days. His was "A Wonderful Life,” one that impacted genealogists and historians he would never know. A Monumental Story Through the years, certain grave markers stood out in Jacob’s mind. He had his picture taken for the inside cover of Names in Stone at one of these, located in a small cemetery named Bush Creek United Brethren, also known as Pleasant Hill Cemetery (see header picture for this article at top). This was the grave of Albert D. W. Cronise (1827-1850). In the year 1849, Cronise embarked on an amazing adventure with his older brother, William H. V. Cronise. They were heading to San Francisco to take part in the legendary California “Gold Rush.” The 23-year-old son of Rev. Jacob Cronise would not reach his destination, dying aboard the steamship Panama, off the coast of Acapulco, Mexico.  Pacific Mail Fleet steamer like the one the Cronise brothers traveled upon to San Francisco in 1849-50. Pacific Mail Fleet steamer like the one the Cronise brothers traveled upon to San Francisco in 1849-50. The alleged story (as told in letters home from brother William to his father) was that Albert took ill from a fever soon after his ship left the isthmus of Panama. He would soon perish on January 6, 1850. His last wishes, conveyed to William, were for his body to be returned to Monrovia and buried in Pleasant Hill Cemetery, for many years under his father’s charge. William successfully preserved Albert’s body in a barrel full of alcohol collected from his ship mates. The vessel made a successful trip to San Francisco, but Albert’s body was quickly decomposing due to the poor quality of the alcohol. Thus, William had his brother buried in San Francisco, but promised his parents that he would return to Frederick County with Albert’s remains. He eventually fulfilled his brother’s last wish as Albert’s body traveled the 2,800 miles back to Monrovia, Maryland where it was buried in Pleasant Hill Cemetery. Albert’s fine gravestone features a depiction of the steamer Panama on its face—a true “story in stone.”  William H. V. Cronise obituary as it appeared in the San Francisco Call newspaper of August 12, 1896. William H. V. Cronise obituary as it appeared in the San Francisco Call newspaper of August 12, 1896. As for William Cronise, he married and became a successful merchant and entrepreneur in San Francisco, passing on his opportunity to be buried and memorialized in the family lot at Pleasant Hill with Albert and his parents. He died in August, 1896 and was buried with his wife in her family lot within San Francisco’s Pioneer Hill/Masonic Cemetery. Ironically, five years later in 1901, the San Francisco City Board of Supervisors condemned this cemetery and others in the city's northwestern section as potential places of pestilence, outlawing new burials within the city limits. Many of the cemeteries suffered and fell into disrepair...truly a case of benign neglect as many businessmen lobbied to have bodies reinterred elsewhere to free up valuable real estate. This came to fruition in 1937 as tens of thousands of bodies were dug up and moved to Colma in neighboring San Mateo County. Unless the deceased’s family had enough money to pay for a careful relocation of their loved ones’ graves, bodies were dug up and moved. This was the fate of thousands of burials, including William H. V. Cronise. Unfortunately, very few gravestones made it out “alive,” accompanying their intended remains. The University of San Francisco sits atop William's former burying ground today.  Large scale removal of bodies from San Francisco cemeteries (1937). Large scale removal of bodies from San Francisco cemeteries (1937). Orphaned tombstones were used for park gutters, miscellaneous municipal stonework, street bollards, support subsurface to create the on and off ramps for the Golden Gate Bridge and filler to bolster San Francisco Bay sea walls. It’s ironic that Albert’s gravesite, 167 years later, stands as a lasting memorial of the young man’s great quest to be a 49er in the virgin hills of California, not to mention the 2,800-mile post-mortem adventure back home experienced by his corpse. Meanwhile, William’s body is unmarked, no name in stone above his grave for future descendants and curiosity seekers to research or cherish. I guess you can say that William Cronise “left his heart in San Francisco,” but no one will ever be able to find it! |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed