|

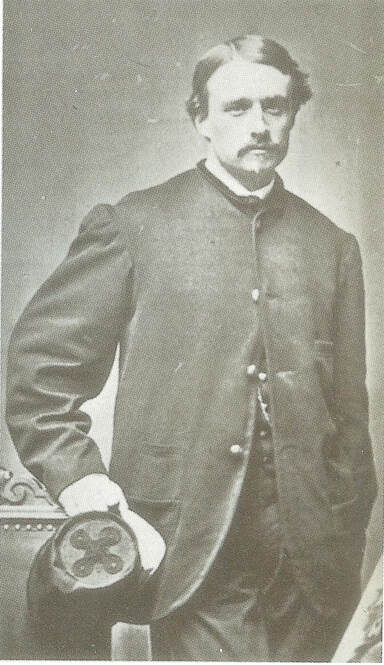

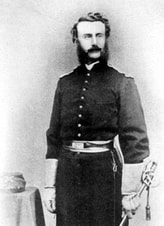

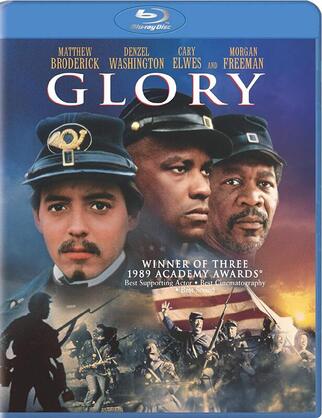

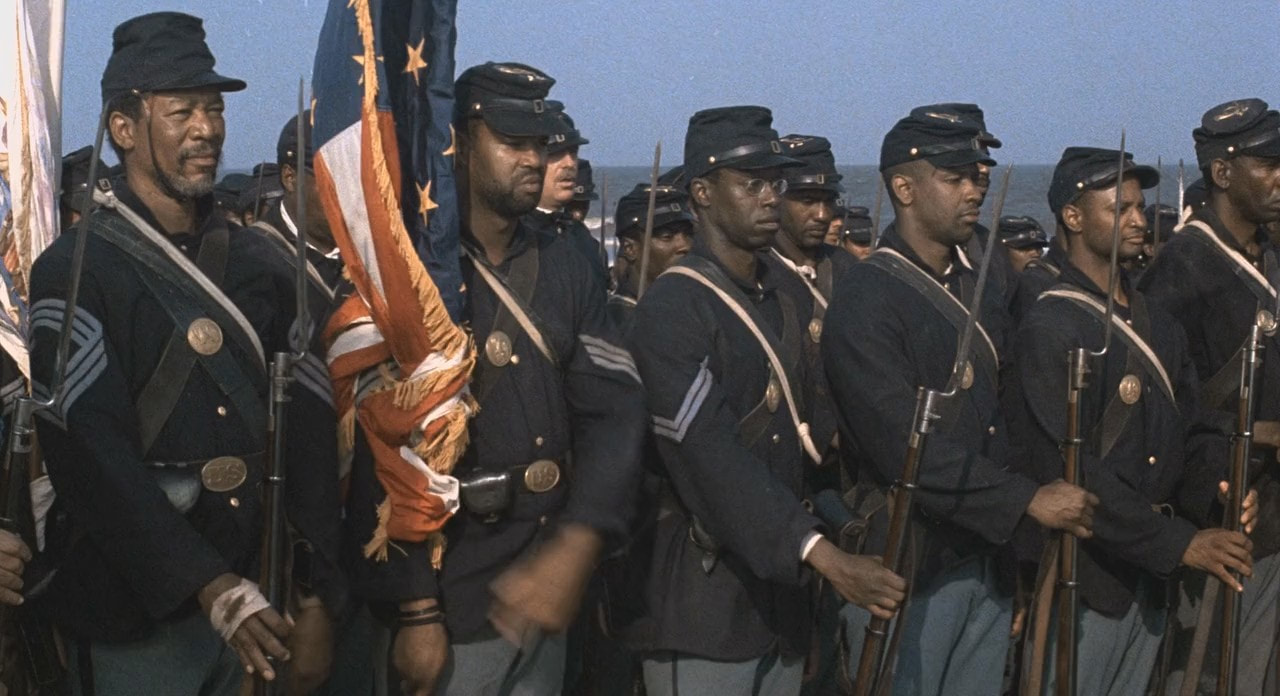

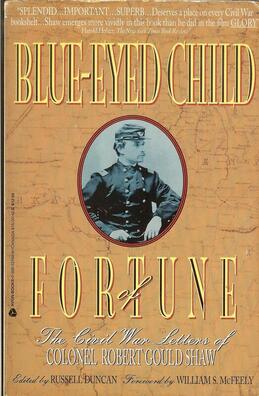

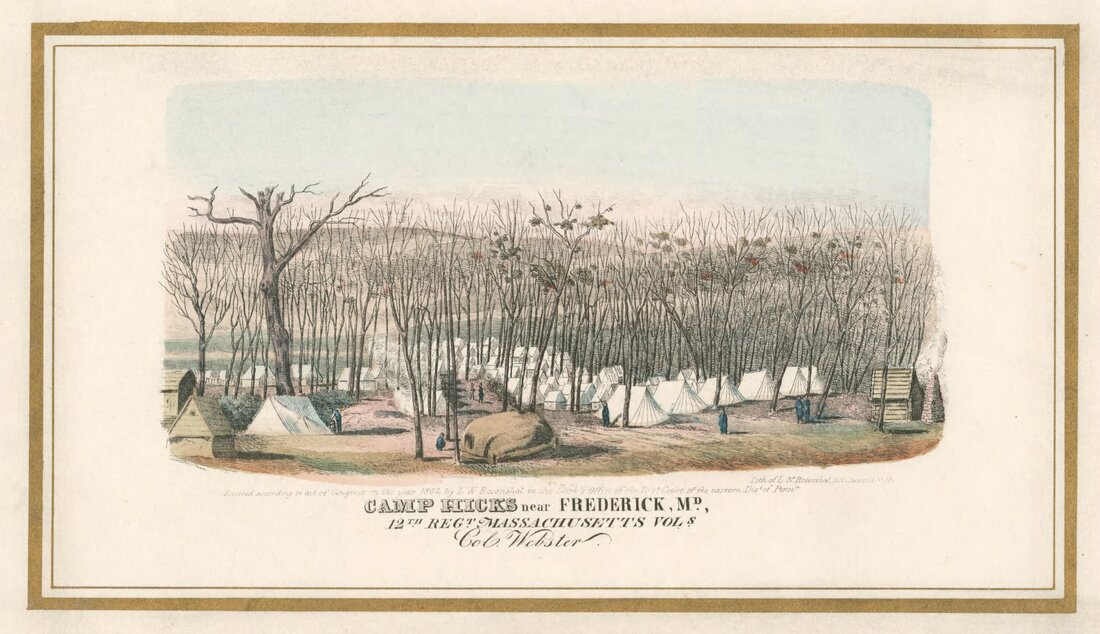

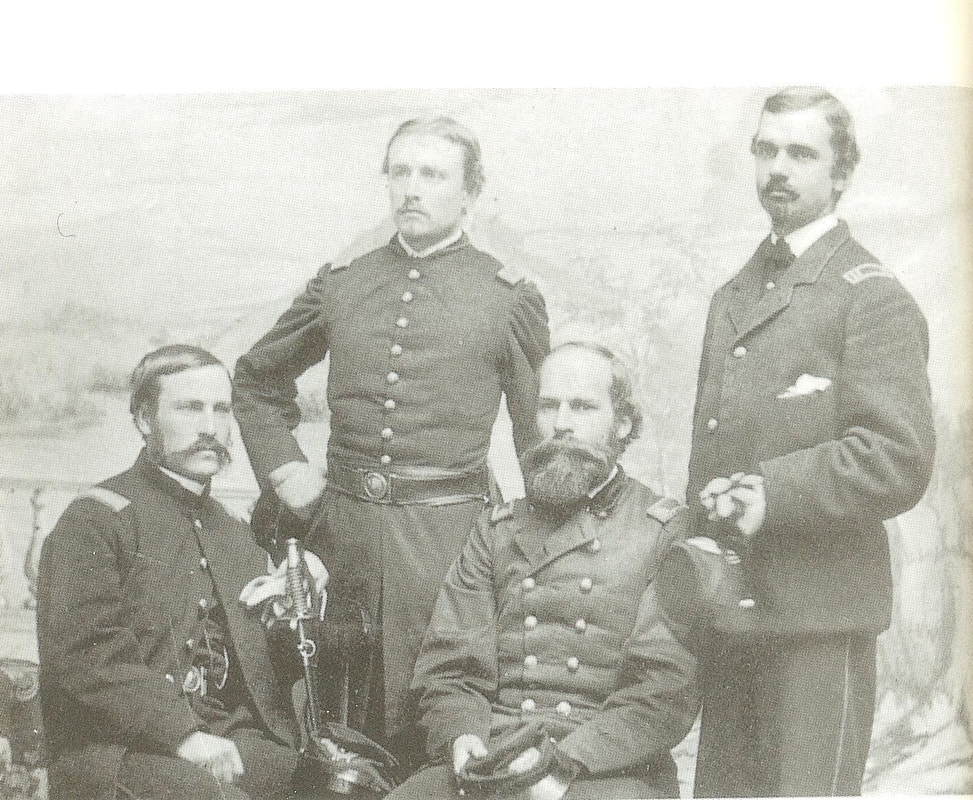

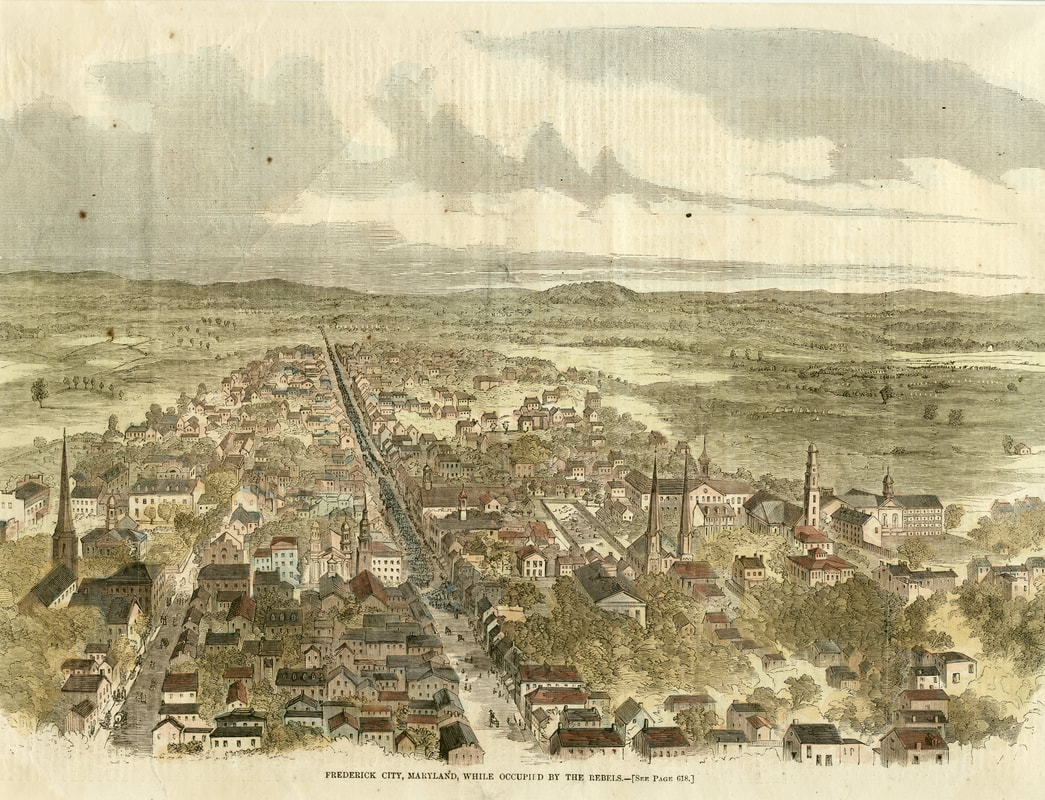

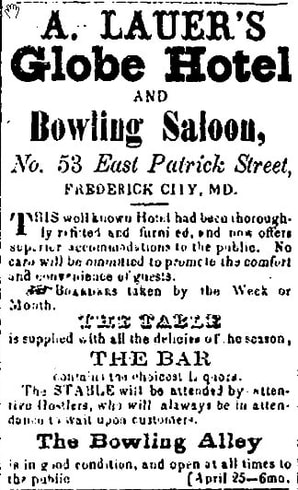

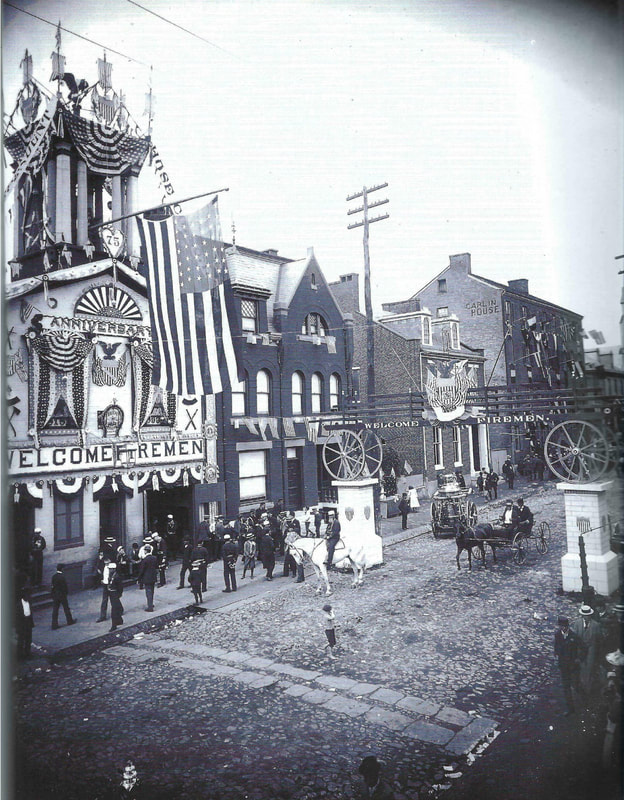

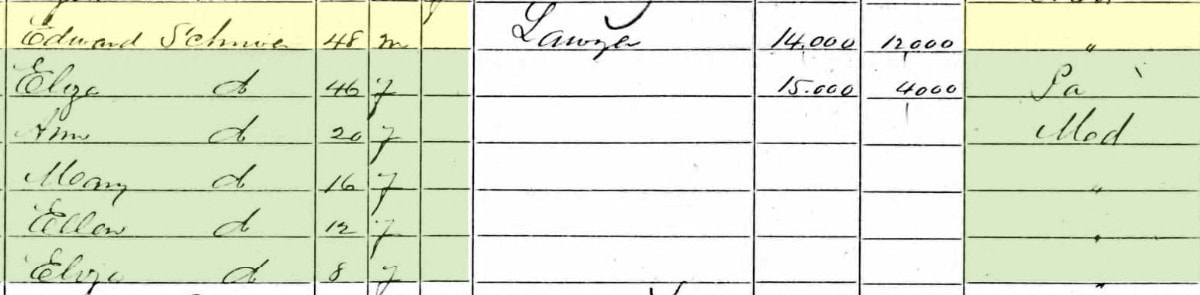

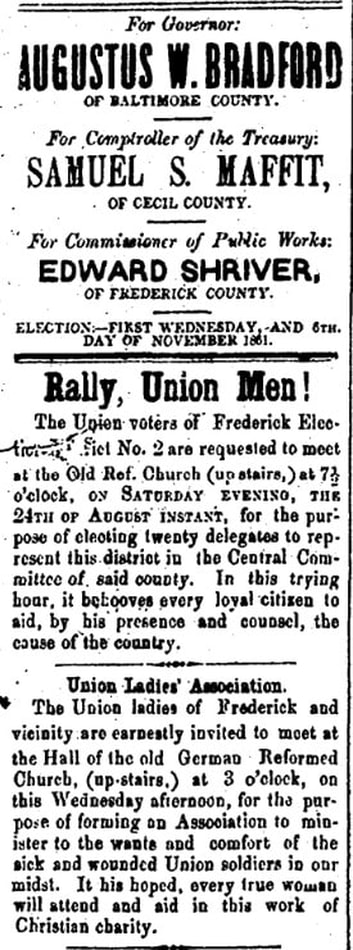

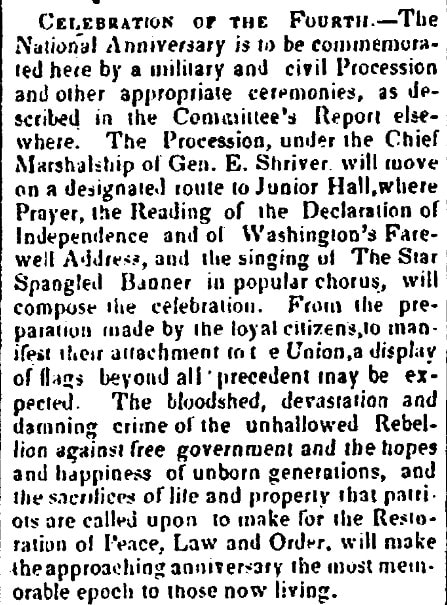

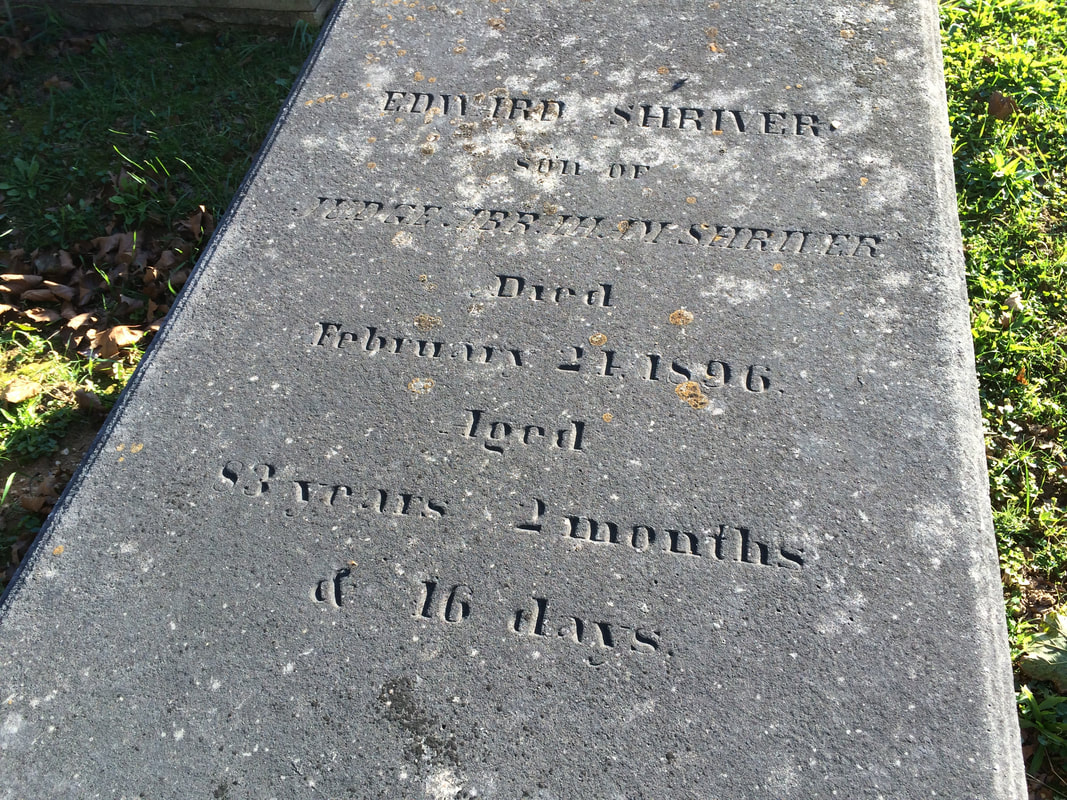

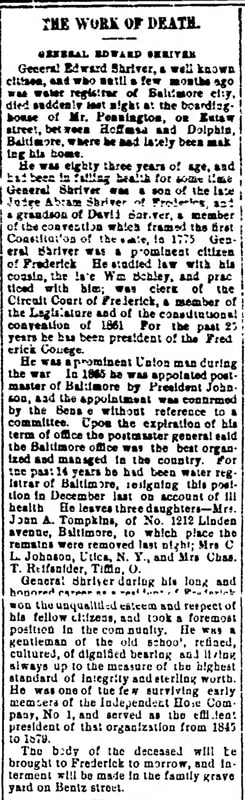

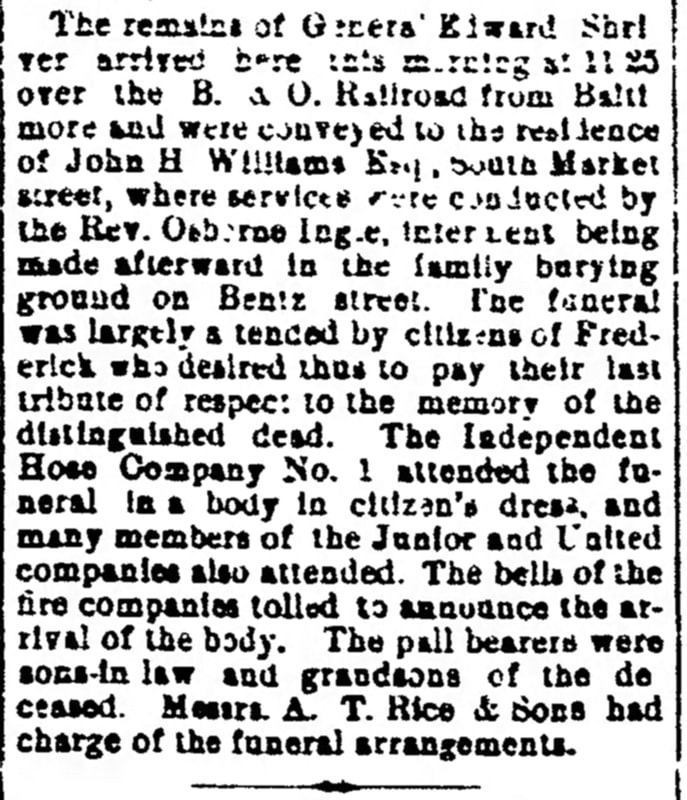

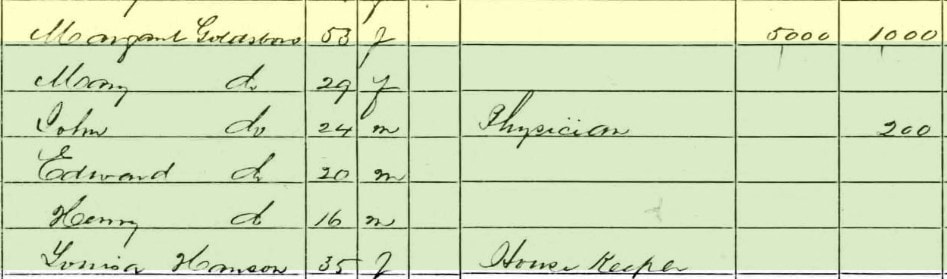

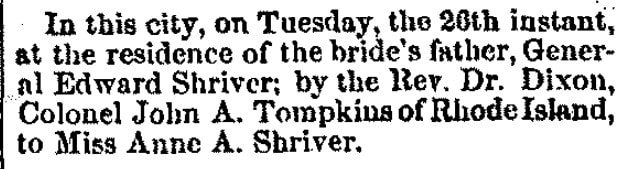

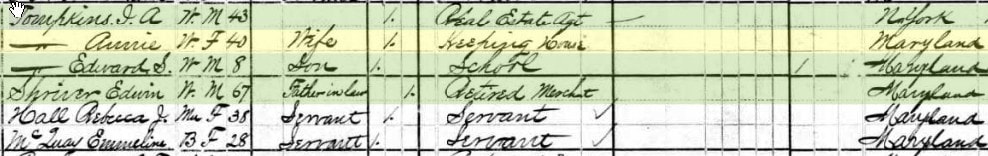

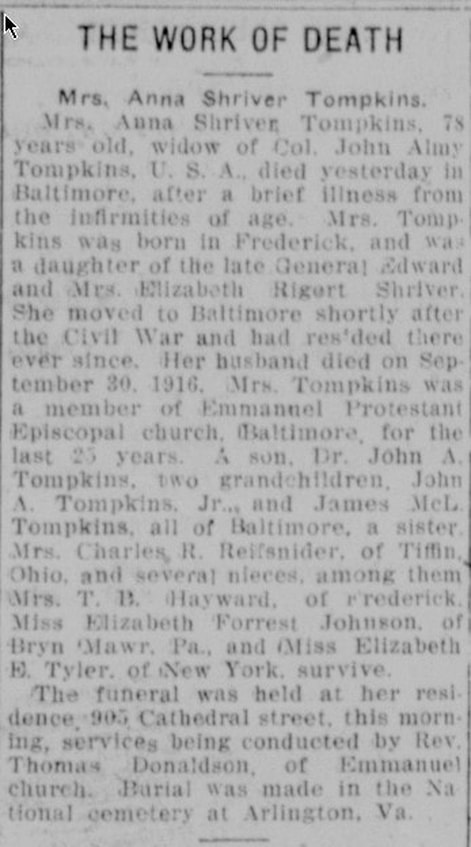

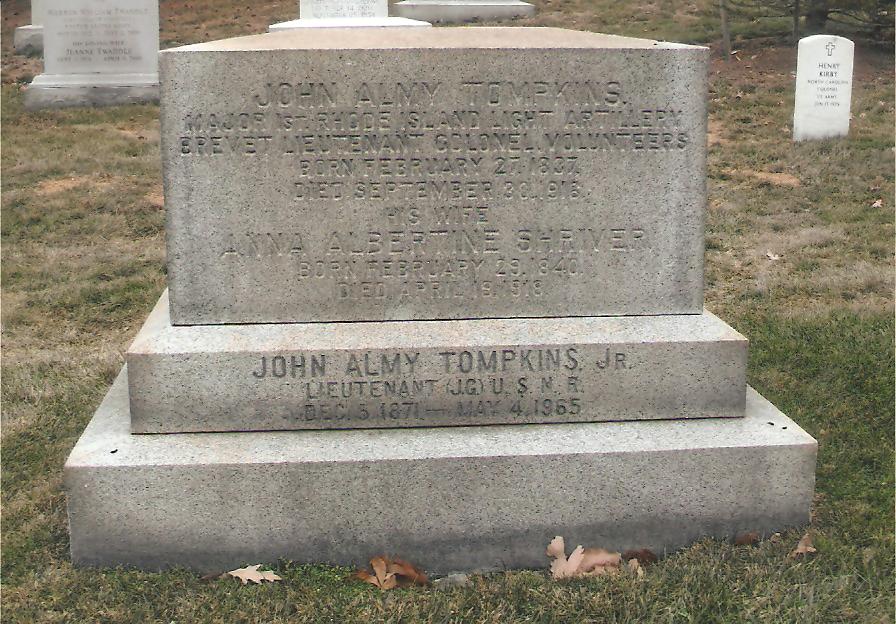

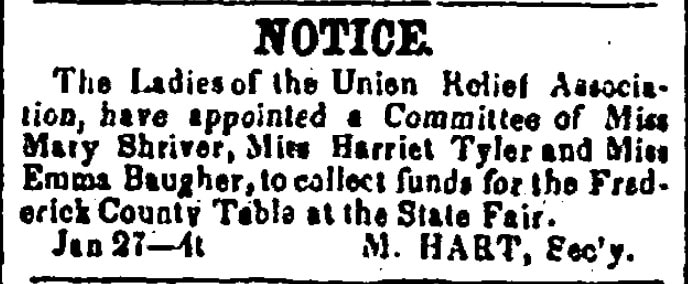

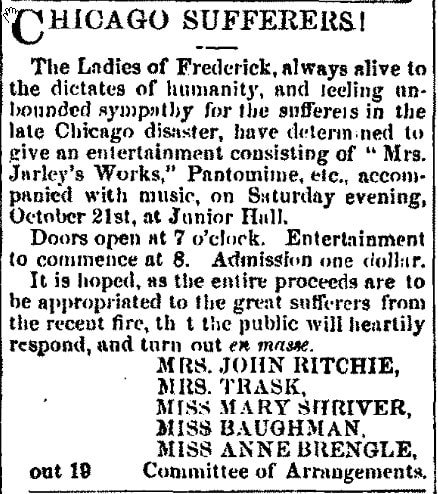

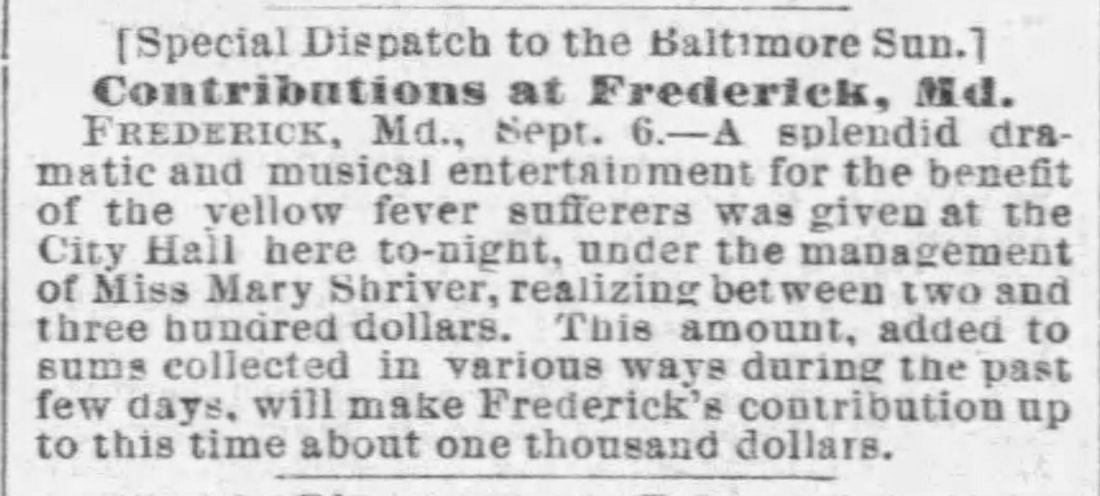

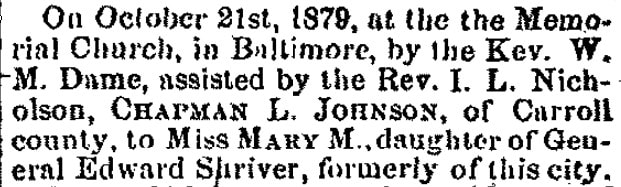

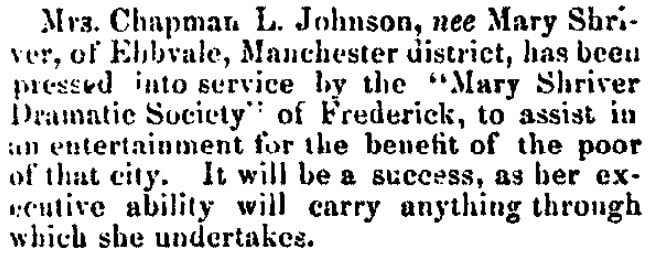

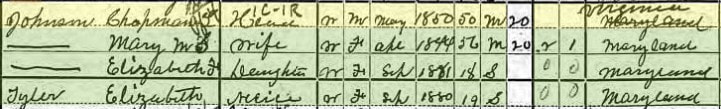

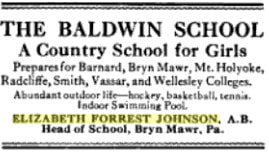

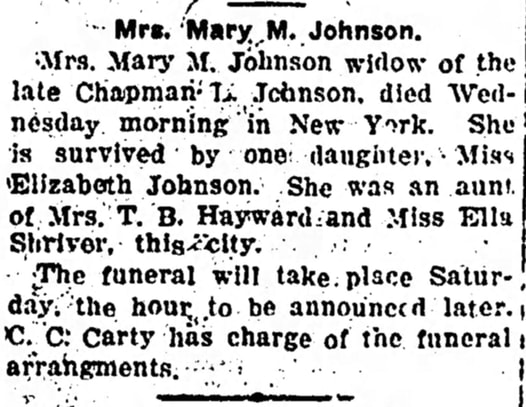

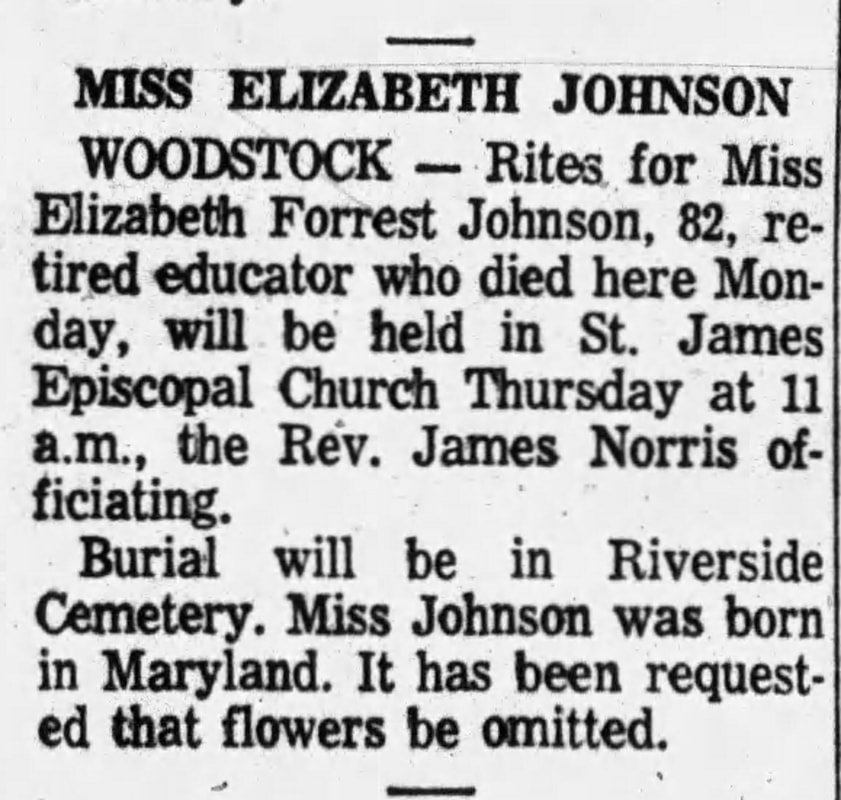

Well this year's Black History Month has one extra day in it this year, which gives me the opportunity to squeak-in and give context to a unique story with links to Mount Olivet on this final day. This two-part odyssey has nothing to do with a person of color, per se, but connects Frederick to one of the most interesting white characters found in the story of struggle for freedom and equality related to the American Civil War—Robert Gould Shaw. We are lucky to have several incredible, well-produced, historical motion pictures about warfare within reach. Many tell the story from the perspective of the human experience more so than simply battle strategies and execution. Examples include the recent Academy-award nominated 1917, along with classics such as Apocalypse Now and Saving Private Ryan. The HBO miniseries John Adams is also among my favorites as it gives a more authentic view of the American Revolution and shows the frailties and quirks of our founding fathers. Add to that list a movie which debuted 30 years ago and became an instant classic— Glory. This film, directed by Edward Zwick, chronicles the legendary 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, the Union Army's second African-American regiment in the American Civil War. It stars Matthew Broderick as Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, the regiment's commanding officer, and Denzel Washington, Cary Elwes, Andre Braugher and Morgan Freeman as fictional members of the 54th. For many viewers that grew up in the 1980s like myself, part of the magic of this movie was seeing this virtually unknown hero (Col. Shaw) played by high-school slacker “Ferris Bueller.” The film depicts the soldiers of the 54th from the formation of their regiment to their heroic actions at the Second Battle of Fort Wagner. The screenplay by Kevin Jarre was based on the books Lay This Laurel by Lincoln Kirstein and One Gallant Rush by Peter Burchard, and the personal letters of Shaw. Glory was nominated for five Academy Awards and won three, including Best Supporting Actor for Denzel Washington. It won many other awards from, among others, the British Academy of Film and Television Arts, the Golden Globe Awards, the Kansas City Film Critics Circle, the Political Film Society, and the NAACP Image Awards. The film premiered in limited release in the United States on December 14, 1989, and in wide release on February 16, 1990, making $27 million on an $18 million budget. So what does this have to do with Mount Olivet and Frederick? Well, Col. Robert Gould Shaw was stationed here in Frederick before he received his own glory on the battlefield. He walked our streets, stayed in homes and interacted with our citizenry—some of which reside here in the cemetery for eternity.  Robert Gould Shaw as part of the 7th New York State National Guard (Mass Historical Society) Robert Gould Shaw as part of the 7th New York State National Guard (Mass Historical Society) Robert Gould Shaw (1837-1863) If you have seen the movie, you may recall that it opens on the nearby battlefield of Antietam in nearby Sharpsburg on the morning of September 17th, 1862. Shaw, then a 2nd lieutenant, is felled by a bullet in the early morning fighting at the Cornfield. Here is some background information on the man, courtesy of Wikipedia: Shaw was born in Boston to abolitionists Francis George and Sarah Blake (Sturgis) Shaw, who were well-known Unitarian philanthropists and intellectuals of Scottish descent. The Shaws had the benefit of a large inheritance left by Shaw's merchant grandfather and namesake Robert Gould Shaw (1775–1853). Shaw had four sisters— Anna, Josephine (Effie), Susanna, and Ellen (Nellie). When Shaw was five years old, the family moved to a large estate in West Roxbury, adjacent to Brook Farm. During his teens he traveled and studied for some years in Europe. In 1847, the family moved to Staten Island, New York, settling among a community of literati and abolitionists while Shaw attended the Second Division of St. John's College, a preparatory school, at Fordham. These studies were at the behest of his uncle Joseph Coolidge Shaw, who had been ordained as a Roman Catholic priest in 1847. He converted to Catholicism during a trip to Rome, in which he befriended several members of the Oxford Movement, which had begun in the Anglican Church. Robert began his high school-level education at St. John's in 1850, the same year that Joseph Shaw began studying there for entrance into the Jesuits. In 1851, while Shaw was still at St. John's, his uncle died from tuberculosis. Aged 13, Shaw had a difficult time adjusting to his surroundings and wrote several despondent letters home to his mother. In one of his letters, he claimed to be so homesick that he often cried in front of his classmates. While at St. John's, he studied Latin, Greek, French, and Spanish, and practiced playing the violin, which he had begun as a young boy. He left St. John's in late 1851 before graduation, as the Shaw family departed for an extended tour of Europe. Shaw entered a boarding school in Neuchâtel, Switzerland where he stayed for two years. Afterward, his father transferred him to a school with a less strict system of discipline in Hanover, Germany, hoping that it would better suit his restless temperament. While in Hanover, Shaw enjoyed the greater degree of personal freedom at his new school, on one occasion writing home to his mother, "It's almost impossible not to drink a good deal, because there is so much good wine here." While Shaw was studying in Europe, Harriet Beecher Stowe, an abolitionist friend of his parents, published her novel Uncle Tom's Cabin (1854). Shaw read the book multiple times and was moved by its plot and anti-slavery attitude. Around the same time, Shaw wrote that his patriotism had been bolstered after encountering several instances of anti-Americanism among some Europeans. He expressed interest to his parents in attending West Point or joining the Navy. Because Shaw had had a longstanding difficulty with taking orders and obeying authority figures, his parents did not view this ambition seriously. Shaw returned to the United States in 1856. From 1856 until 1859 he attended Harvard University, joining the Porcellian Club, and the Hasty Pudding Club, but he withdrew before graduating. He had been a member of the class of 1860. Shaw found Harvard no easier to adjust to than any of his previous schools and wrote to his parents about his discontent. After leaving Harvard in 1859, Shaw returned to Staten Island to work with one of his uncles at the mercantile firm Henry P. Sturgis and Company. He found work life at the company office as disagreeable as some of his other experiences. With the outbreak of the American Civil War, Shaw volunteered to serve with the 7th New York Militia. On April 19th, 1861, Private Shaw marched down Broadway in lower Manhattan as his unit traveled south to man the defense of Washington, D.C. Lincoln's initial call up asked volunteers to make a 90-day commitment, and after three months Shaw's new regiment was dissolved. Following this, Shaw joined a newly forming regiment from his home state, the 2nd Massachusetts Infantry. On May 28th, 1861, Shaw was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the regiment's Company H. A great way to examine this man (at this time and beyond) is through the book Blue-Eyed Child of Fortune: The Civil War Letters of Colonel Robert Gould Shaw. This work was edited by Russell Duncan and published Avon Books in 1992. In July of 1861, his regiment was sent to today’s panhandle area of West Virginia where he encamped at Martinsburg, Charles Town and Harpers Ferry. In early fall, Shaw and his fellow “Bay Staters” were encamped in Montgomery County, primarily Darnestown, with forays at Muddy Branch and Seneca Creek. In December, the 2nd Massachusetts came to Frederick to set up winter quarters. The chosen place was located roughly three miles east of Frederick City, just across the Monocacy River in the vicinity of Linganore Road in what one soldier called “a beautiful wooded area on a hill.” The government called this site Cantonment Hicks after the Maryland governor (Thomas Holyday Hicks), but the soldiers would refer to it more lovingly as “Camp Hicks.” Here, troops had tents and built some small, wooden barracks, each boasting iron coal stoves. Robert Gould Shaw wrote the following letter home on December 8th, 1861. Camp Hicks near Frederick, Md December 8, 1861 My dear Effie, Your weekly & welcome letter came yesterday. I look for it regularly now and shall be much disappointed the first time it misses, if such a thing can be imagined after your long & faithful regularity. I didn’t have time to write again from Seneca, before we left, as I said I should, for the order to march came at 12 ½ A.M. We got off early in the morning. It was tout ce qu’il y a de plus unpleasant to be waked up at Midnight, the weather icy cold, to wake up in their turn the cooks, & see about rations. We had a good two days march, for the cold weather kept us going. The roads didn’t soften even at noon. The day after we arrived it changed and we have had almost an Indian summer for 5 days, during which time we have made ourselves comfortable & can defy Jack Frost when he comes again. Yesterday I went into Frederick to see Capt Mudge who has been ill for about 3 weeks. I found him much better & was coming out, not having any acquaintances top visit when I fell in with Copeland & it turned out to be a fortunate rencontre for me. He took me to a house where I was presented to two young ladies & we shortly sallied forth all together & after picking up Mrs. Copeland, another lady & Capt. Savage, we repaired to a bowling alley where we had a perfectly jolly time all the afternoon. We then took a walk, after which we went home to the house of the afore-mentioned young ladies, & took tea. In the evening there was a great deal of playing on the piano & chorus singing, in which latter we all howled, & made as much noise as we could. I can’t describe to you my sensations at sitting once more in a nice parlor & seeing real ladies with petticoats about. I had hardly realized before that for 5 months we had been living like gypsies & seeing only men, I had really not spoken to a lady since we left New York. These two are daughters of Genl Shriver, a Union man here, who was very active in helping break up the Maryland legislature 2 months ago. One of them is a very nice girl indeed, I should think, if one can judge on so short an acquaintance. She sings very well too. The letter goes on about other things at camp, but of key interest to me here is the mention of downtownFrederick—in particular, fascinating elements include a bowling establishment and the Shriver family. I found a bowling alley advertised in a Frederick newspaper from 1866 and located within the Globe Hotel of Mr. A. Lauer and located at 53 E. Patrick Street. I’m not sure when it originated, but there was also a bowling lane located within the Independent Hose Company on East Church Street. I am well aware of Col. Edward Shriver and made mention of him in an earlier “Story in Stone” published back in October of 2018. The blog dealt with eyewitnesses to the legendary John Brown Raid of Harpers Ferry in October, 1859. Edward Shriver was born on December 8th, 1812, the second son of Judge Abraham and wife Ann Margaret Shriver. The colonel was a Frederick lawyer who in 1854 had provided the Agricultural Society of Frederick County with the land that has served home to the Great Frederick Fair to this day. Shriver served in Maryland’s House of Delegates from 1843-1845 and was asked to serve as Secretary of State by two different governors, but declined. Between 1851 and 1857, he was a clerk of the Frederick County Court. Edward Shriver was also active in the Maryland Militia, and became colonel of the Sixteenth Regiment. In the fall of 1859, Col. Shriver quickly began assembling the three town companies of militia, and went to Harpers Ferry by train to survey the chaotic scene for himself, before bringing the larger militia contingent on the scene. He would oversee the Frederick men as the group holds claim to being the first responders on the scene, and successfully kept Brown “holed up” in the engine house until Robert E. Lee and his US Marines arrived from Washington, DC. Col. Shriver even talked personally with Brown, hearing his demands regarding the hostages he had taken, including one Frederick man who is buried in our cemetery by the name of George Brengle Shope. The Shrivers lived in the house that still stands today at 114 N. Court Street, diagonally northeast of Court Square. This was a convenient location for Col. Shriver’s occupational pursuits and likely housed his law business, as it still serves that purpose today as a sign above the front door calls it the Court Square Law Building. Sadly, Edward Shriver lost his wife, Elizabeth Lydia (Riegart), on December 2nd, 1860. The widower had the task of raising four daughters into adulthood, amidst his busy working and civic life. During the outbreak of the Civil War, Shriver, called a “staunch Unionist,” helped mobilize the citizenry of town and assisted Governor A. W. Bradford in administering the draft and served as the governor’s judge advocate for matters pertaining to conscription. Shriver also has received credit for preventing the meeting of a Maryland Secession Legislature. Through devotion to the Union, he would pick up the moniker of “General” along the way. After the war, Col. Shriver would be appointed postmaster of Baltimore by President Andrew Johnson, a job he held from 1866-1869. He also would serve as registrar of Baltimore’s water department. He died In Baltimore at his residence on Eutaw Street on February 24th, 1896. He was first buried in the Shriver family burial plot, once located on the west side of N. Bentz Street, south of Rockwell Terrace. This was an extension of the old German Reformed Graveyard, today comprising Frederick’s Memorial Park. The entire family plot would be removed to Mount Olivet on May 11th, 1904, and now these burials can be found in the northern part of Area MM (Lot 23). Here, he was buried beside his wife Elizabeth. But what of the Shriver daughters mentioned by Robert Gould Shaw? These were the ones that accompanied Shaw in the bowling foray, and a walk about town to follow. This culminated in a return to the Shriver household in which the hostesses engaged the 24-year-old Massachusetts’ soldier in singing and gave him the warm visual of ladies in petticoats? From the letter, we can sense that one, in particular, caught Lt. Shaw’s eye as he referred to her as “a very nice girl indeed, I should think, if one can judge on so short an acquaintance. She sings very well too.” Well the 1860 US census shows that the Shrivers had four daughters. Two, Ellen and Eliza, can be ruled out because they would have been far too young in late 1861. That leaves Anna Albertine Shriver (b. 1840) and Mary Margaret Shriver (b. 1844).  John A. Tompkins John A. Tompkins Anna (aka Annie) seems like the first choice as she was 21 at this time. She would marry Col. John A. Tompkins of New York in 1867. Perhaps Anna fits the description because it’s obvious she fancied a military man like her father? As a captain in 1862, John Almy Tompkins commanded Battery A, 1st Rhode Island Artillery at the Battle of Antietam. His battery was part of the Second Corps attack toward the Sunken Road, also known as Bloody Lane. Captain Tompkins and his men fired over 1,000 rounds of ammunition in about three hours and withstood a Confederate infantry attack right into their guns that led to hand to hand fighting. Tompkins and the 1st Rhode Island had visited Frederick the previous summer of 1861, encamped for a night at the Hessian Barracks from June 17th-18th. He would participate in some of the most famous battles in the war including the Wilderness, Fredericksburg and Gettysburg. After the war, Mr. Tompkins served as Superintendent of the Baltimore Chrome Works, and later became a real estate broker in Baltimore. In the 1880 census, the Tompkins can be found living on Linden Avenue. Note that Anna’s father is living with her at this residence. Anna died in April of 1918 and is buried with her husband in Arlington Cemetery. Mary Shriver is the only other option for Col. Shaw’s possible “Frederick crush.” She was born on April 18th, 1844, making her 17-and-a-half at the time of the December 7th excursion with Col. Shaw—certainly not out of the question. From what I have gleaned of Mary, she seemed to have been an incredibly kind woman as there are several articles describing her as such through her benevolent work during the war and beyond. Not only did she raise money and volunteer to care for wounded soldiers, she also headed up relief missions to help the victims of the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, and was director of Frederick’s Poor Fund for many years. She seems to have possessed theatrical talent as she helped produce and present entertainments that served as fundraisers in town. Mary wouldn’t marry until later in life, October of 1879 to be exact. Her groom was Chapman Love Johnson (1850-1915), a schoolteacher from Richmond, Virginia. She may have met him through her vast array of relatives living in Carroll County, site of her family’s ancestral home of Union Mills. The Johnsons would reside in the hamlet of Ebbvale, just outside Manchester and northeast of Westminster. They had one daughter, Elizabeth Forrest Johnson, and eventually removed to Utica, New York. Chapman was later employed as a civil engineer. Chapman Johnson passed in Lansdale, PA as the Johnsons were staying with their daughter at that place. Elizabeth, a 1902 graduate of Vassar College (Poughkeepsie, NY) had just been hired as head of the Baldwin School in Bryn Mawr and founded in 1888 by namesake Florence Baldwin. This was a private school for girls offering educational instruction from pre-K through 12th grade. The Johnson’s daughter took the reins from Ms. Baldwin, herself. Mary Margaret Shriver Johnson died four years later in New York on November 5th, 1919 at the age of 75. She would be buried next to her husband on Mount Olivet’s Area MM/Lot 2. Their graves are roughly fifteen yards from Mary’s parents.  Perhaps it’s a good thing that Mary, if she was indeed the apple of Col. Shaw’s eye for one cold, December day in Frederick in 1861, charted a different life for her life away from Glory’s famed Robert Gould Shaw. Her daughter, Elizabeth, would lead and grow the Baldwin School for 26 years until stepping down in 1941. The school thrives today, thanks in part to the tremendous fundraising, marketing and recruiting done by Miss Johnson. Today it boasts a strong theater and music departments and an extensive computer lab located in a recently renovated wing named for the former leader. The chief fundraising arm of the institution is fittingly named "The Elizabeth Forrest Johnson Society." Miss Johnson never married, but moved on to making further educational contributions at the Woodstock Country School in Woodstock, Vermont. The school which closed its doors in 1980, had a library that bore Miss Johnson’s name, and she is buried in nearby Riverside Cemetery. Look for my “part two” of this story next week as I share a few more connections to Col. Robert Gould Shaw, Frederick places and Mount Olivet residents

0 Comments

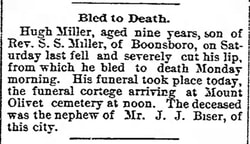

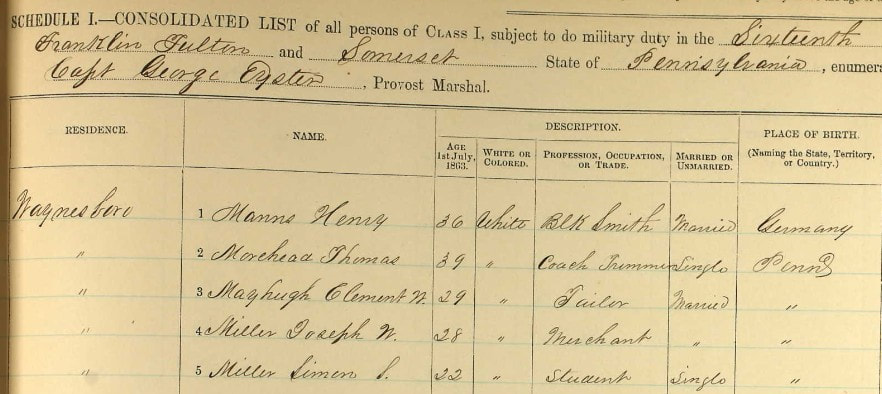

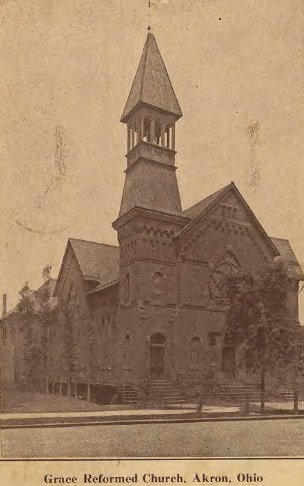

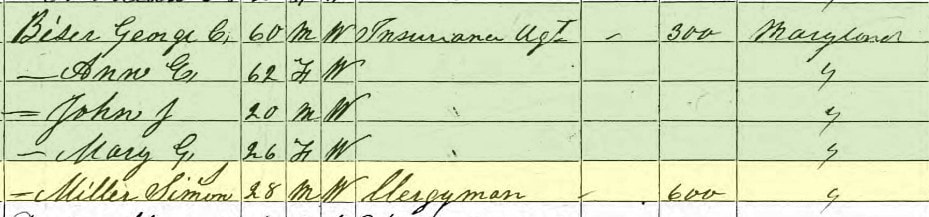

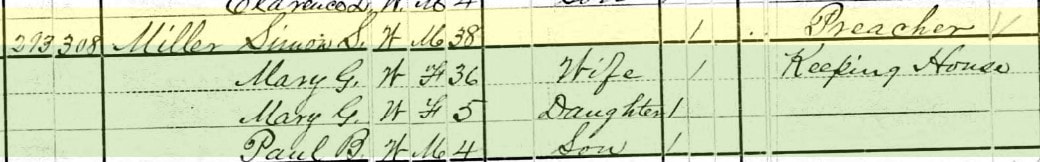

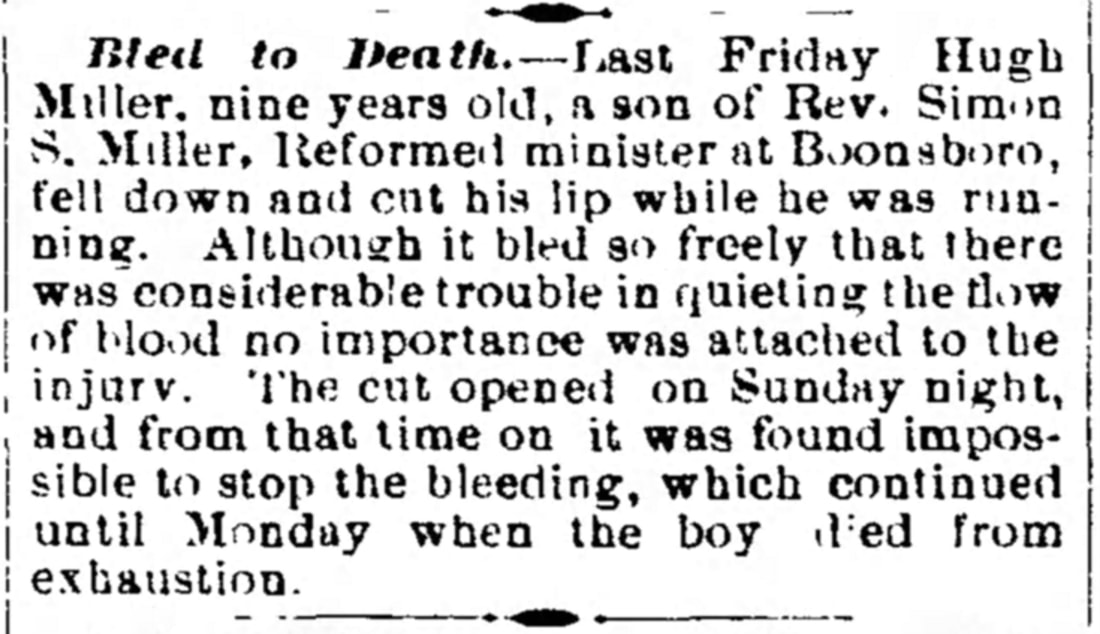

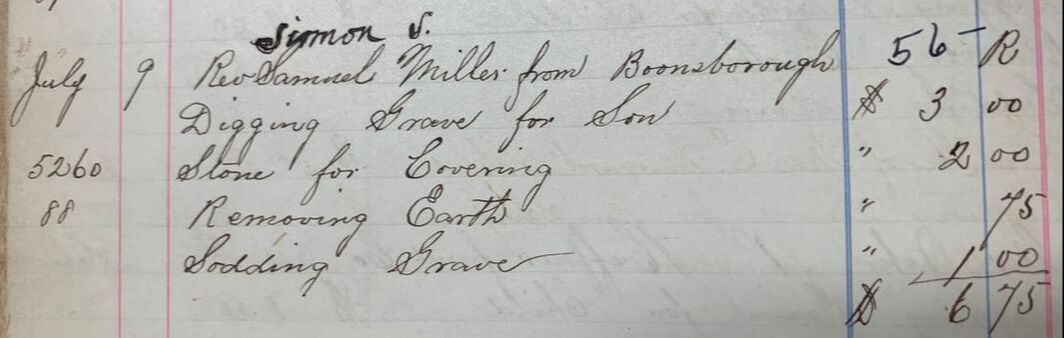

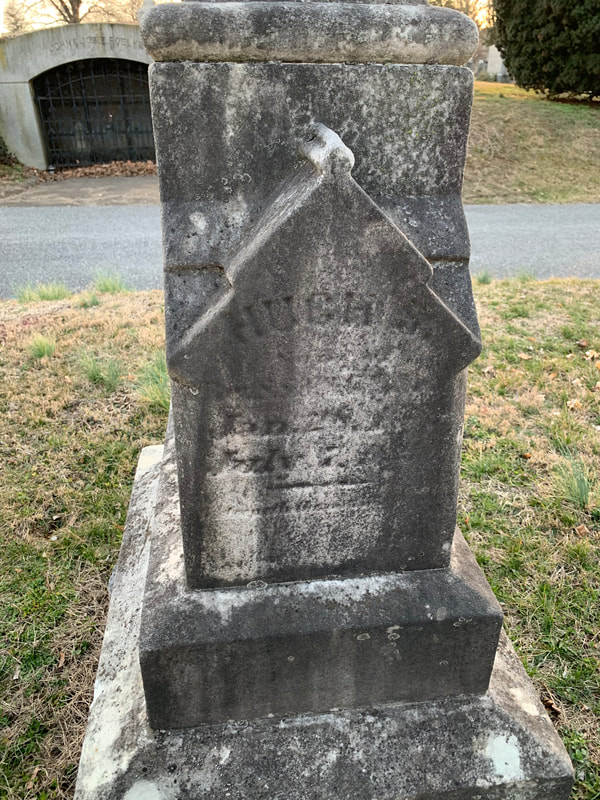

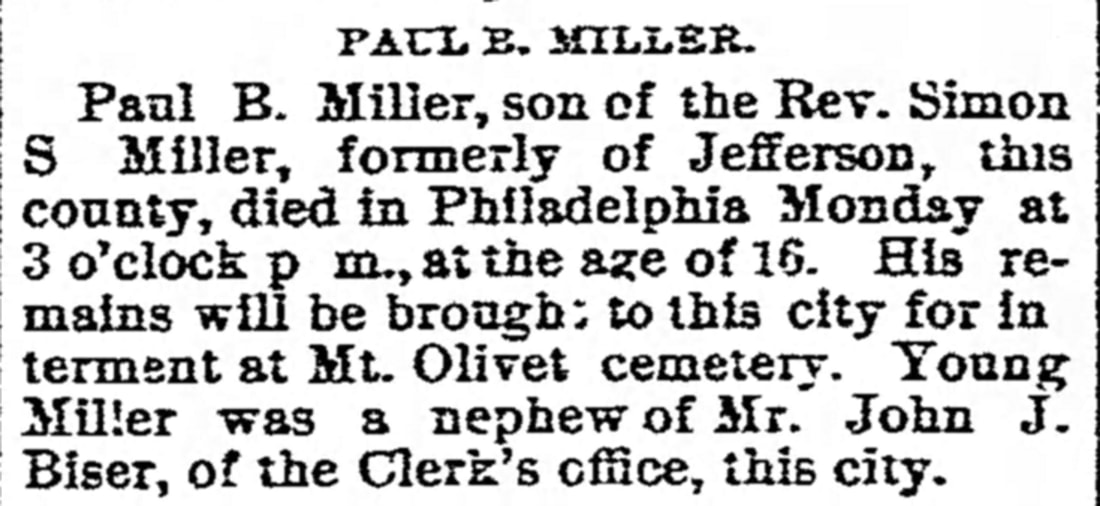

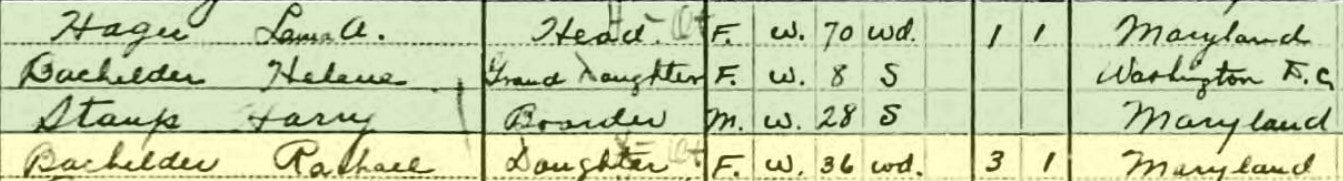

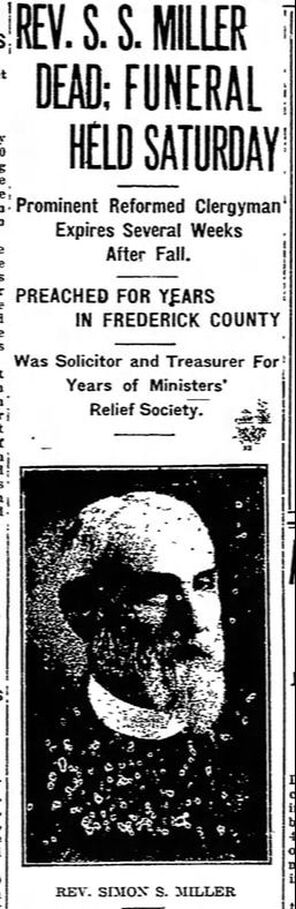

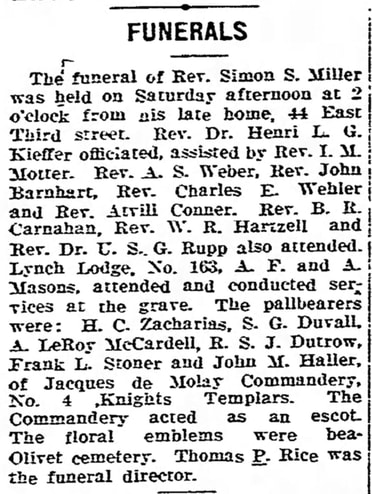

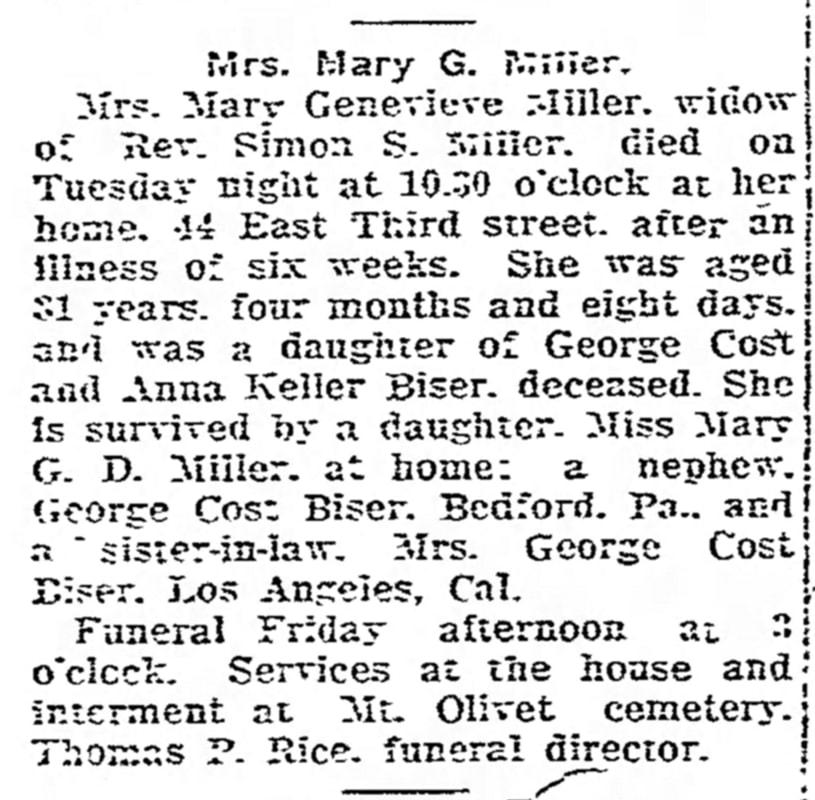

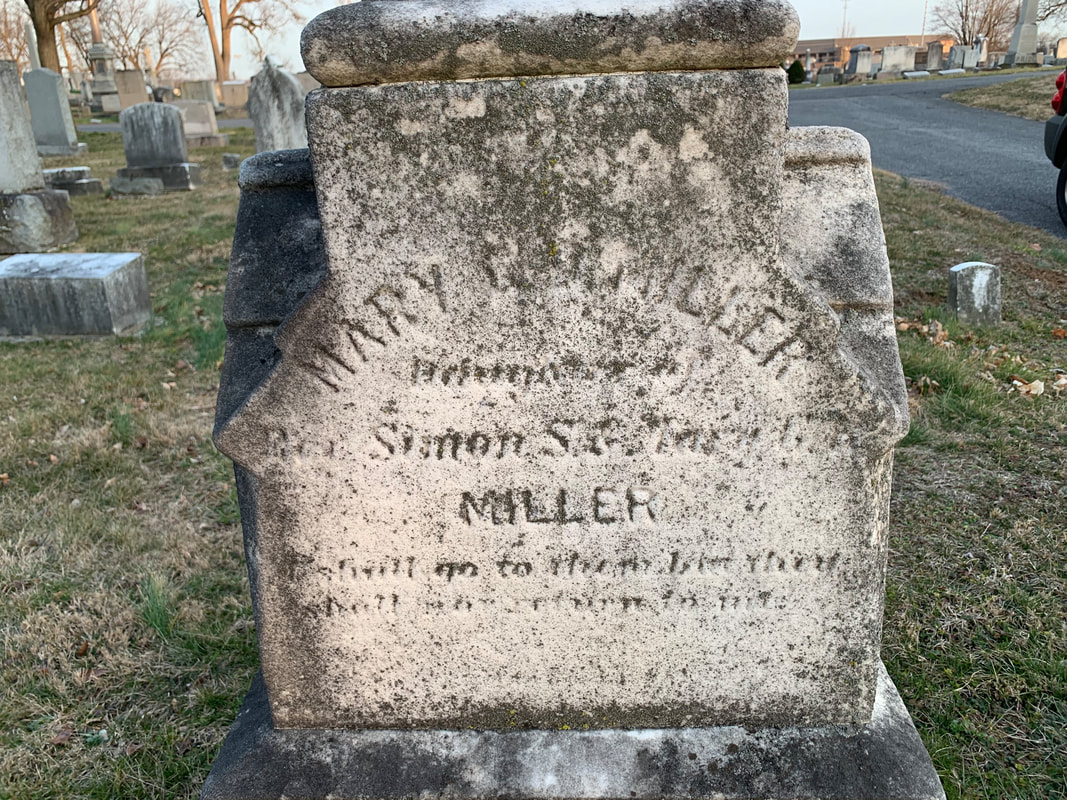

Well, our story title this week can signal someone’s tragic demise one of three ways: the result of an unfortunate loss of footing or balance; being caught unprepared in an extreme, below average temperature situation in September, October or November that could result in frostbite or worse; encountering a geologic novelty while swimming or boating at a place where water flows over a vertical drop or a series of steep drops in the course of a stream or river. I probably have most readers somewhat intrigued at this point, especially with the oddity involved with the latter two consequences. However, this week’s story is pretty straightforward, however, complete with a little twist, two in fact. Rev. Simon Schweigarde Miller was a minister in the German Reformed faith tradition. He was born in Waynesboro, Pennsylvania on February 22nd, 1842, the son of Henry Miller (1805-1848) and Elizabeth von Schweigarde (1808-1881). His great-grandfather (John Adman Heilman, Jr.) was a commissioned lieutenant who commanded men in the Battle of Long Island during the American Revolution. He was part of the famed “Flying Camp” that included regiments from Pennsylvania, Delaware and Maryland. Many Frederick men were part of this military formation employed by the Continental Army in late 1776, chief among them was Thomas Johnson, Jr., who would go on to become Maryland’s first governor. Simon Miller was living in Lancaster, PA, a student at Franklin and Marshall College, when the American Civil War broke out. He was registered for the draft but his calling differed from his great-grandfather’s as he would graduate from college in 1862, and follow-up his education in divinity school, attending the Reformed Seminary in Mercersburg until 1864. He was ordained at this time and took his first charge at Grace Church in Akron, Ohio. In the 1870 census, Rev. Miller is duly listed as a clergyman and living in the household of George C. Biser, an insurance agent. Mr. Biser would become Miller’s father-in-law, as daughter Mary Genevieve Biser would become the minister’s wife in 1874. At this time, the couple moved to Boonsboro, where Rev. Miller took the lead of Trinity Reformed which still stands today as the oldest UCC/German Reformed congregation in the tri-state area. The Millers would welcome three children while here: Mary Genevieve (1876), Paul Biser (1877), and Hugh Schweigarde (1884). It’s because of the Miller’s youngest child, that I “landed” on this family and topic for this week’s story. While perusing a local newspaper, I came across the following sad article.  Frederick News (July 9, 1890) Frederick News (July 9, 1890) A terrible happenstance for any family to have to endure, as the headline, not surprising of the time, certainly caught my attention. It was not uncommon for headings of this nature, as ghastly, and straightforward consequences were commonplace in describing fatalities. I guess the Frederick News editor wasn’t to blame as I found the same headline in the Hagerstown paper as well. A few more details of the accident were revealed which makes me assume that this paper carried the story first, although a day behind as it seems. Simon ventured to Frederick and paid then cemetery superintendent $6.75 for opening and closing a grave space. The young boy was brought to Mount Olivet was placed in the Biser family plot located in Area R/Lot 56. This section is easily found as it is only a few yards away from the Roelkey family crypt. The unfortunate tragedy that beset Rev. Miller and his family at this place, likely prompted him to tender his resignation a month later. He would leave the site of sadness, and return to his native Pennsylvania. St. Petersburg (Pennsylvania) would be the scene of his new congregation. In the Illustrated Portfolio of Western Pennsylvania Reformed Churches, published in 1896, the following was said about Rev. Miller by author J. N. Naly in relation to his leadership at St. Petersburg Reformed Church: "The congregation was without a regular pastor for about two years. Then they issued a call to the Rev. Simon Miller. Bro. Miller suceeded, however in establishing confidence, and raised about $2,500 with which the interior of the church was remodeled and frescoed, and the remaining debt was cancelled. His pastorate closed on the 30th day of April, 1895." In 1893, the Miller’s 16-year-old son, Paul, had died in Philadelphia. I was unable to find the true cause. His body had been sent to Frederick to be buried alongside Paul’s younger brother, Hugh.  Mount Pleasant Reformed Mount Pleasant Reformed The well-traveled clergyman would next take charge of the Daniel Stein Memorial Home in Myerstown, PA. This was a facility for retired German Reformed ministers and their spouses. Rev. Miller would serve as superintendent of the Stein House for four years before returning to Maryland and Frederick County. He would preach at Mount Pleasant Reformed Church for two years before a semi-retirement in Frederick, while filling-in as a substitute pastor for congregations in need. Rev. Miller took up residence at 44 E. Third Street in downtown Frederick. This rowhouse is on the southeast corner of E. Third and Maxwell Alley. However, this would be the scene of a second terrible fall for the Miller clan. It happened in April 1924. From another article, a few days later, it seemed as if the aged minister was recovering nicely from his broken hip. This news, like Rev. Miller, would be short lived. Rev. Simon S. Miller would join his son Hugh, who had predeceased him 34 years earlier, thanks in part, to a deadly fall. Wife Mary died the following year. I was relieved to see that it was not the result of a fall or tumble.

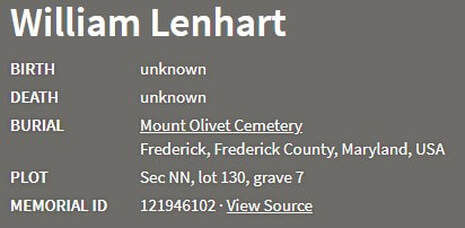

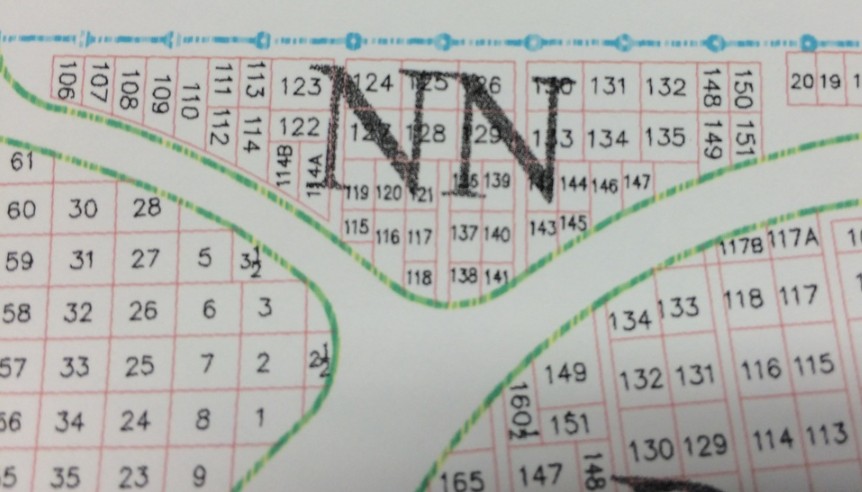

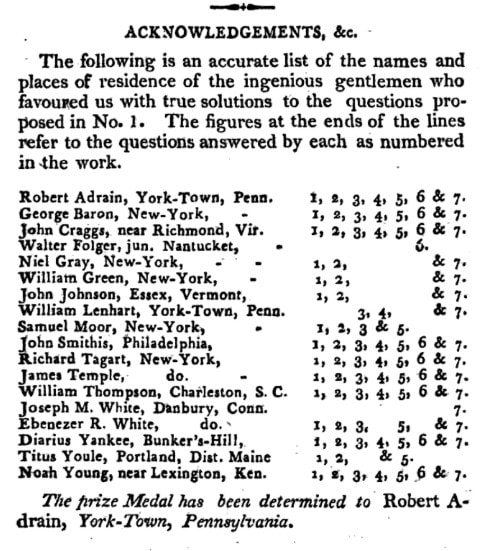

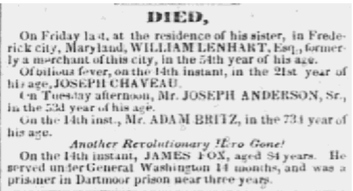

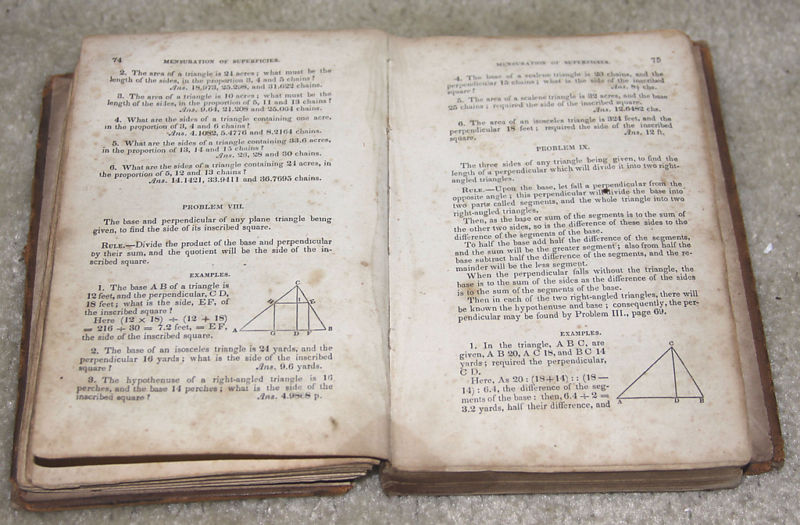

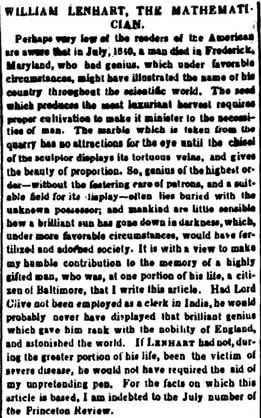

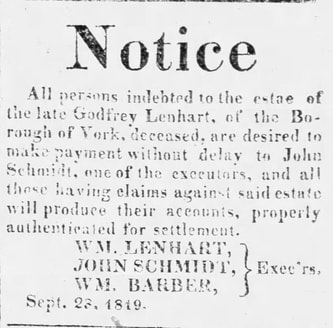

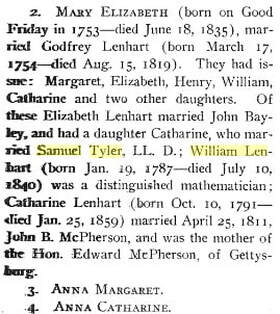

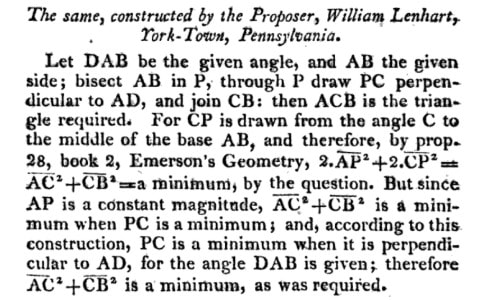

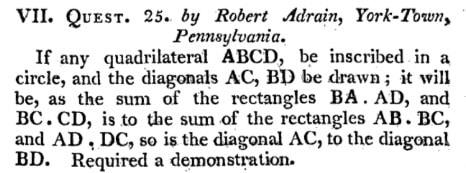

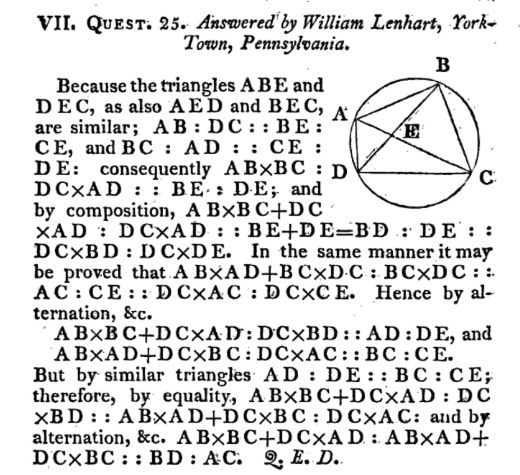

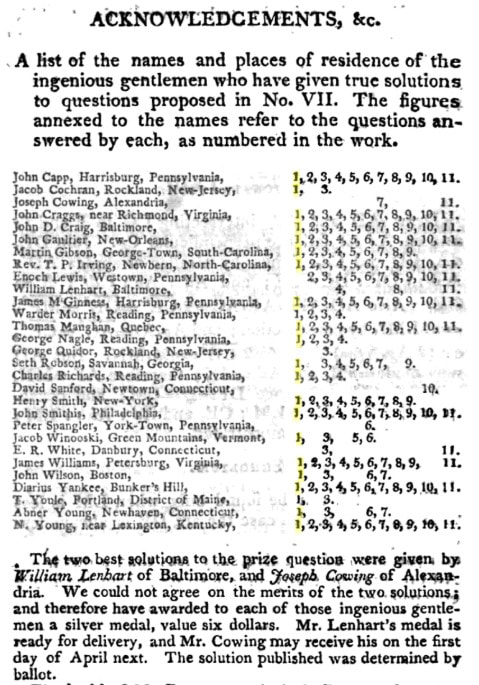

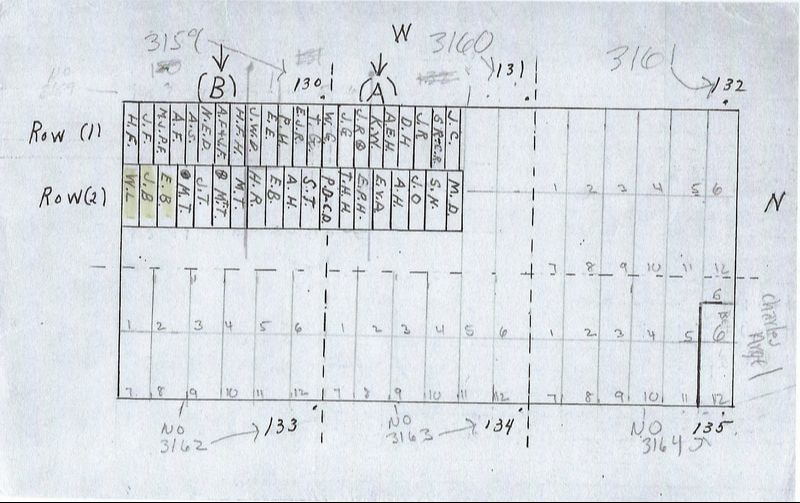

Well, with St. Valentine’s Day having recently hit us again, it’s nearly impossible to avoid images of hearts, roses, greeting cards and candy—specifically chocolate . And with the latter, the most popular chocolate chosen for this commercially-hyped day of “love-reckoning,” isn’t the typical household variety such as Hershey Bars, M & M’s or Reeses Cups (my personal favorite). No, no, no, we’re talking the “top shelf” stuff, packaged of course in box form, with an assortment of delicacies. Whether it’s a familiar name like Godiva, Lindt, Whitman’s or Russell-Stover, I’m always reminded of the legendary line from Forrest Gump—“Life is like a box of chocolates. You never know what you’re going to get.” However, when it comes to candy, I think I’d be more satisfied sometimes with plain ol’ Reeses Cups—but it’s the thrill of the quest, I guess, that makes boxed-chocolate something exciting. As I near my four-year anniversary working for Mount Olivet, I reflect upon the great satisfaction I've had in writing these “Stories in Stone” blog articles—this is number 140. The most gratifying part of it for me can also be explained by that Forrest Gump quote, however with one simple difference by interchanging the word life with the word death--“Death is like a box of chocolates. You never know what you’re going to get.” A few years ago, I wrote the following to describe my articles: “They are essays about former Frederick residents buried within Mount Olivet’s gates. Yes, some of these individuals stand out for their achievements. Others can be remembered for misfortunes. All in all, most of those “resting in peace” just lived simple, ordinary lives. To borrow a line from George Bailey in Frank Capra’s legendary film It’s a Wonderful Life: “Just remember Mr. Potter, that this rabble that you’re talking about...they do most of the working and paying and living and dying in this community.” We can just assume that the people here that you've never heard of before, simply lived ordinary, average lives. However, I have found that not to be the case, over and over again. That point hit home again last weekend while falling into a subject topic by pure accident. It is the genesis for this story here. I had been researching online within old Virginia newspapers of the early 1800s in hopes to learn more about my previous "Story in Stone" profile, artist John J. Markell. Out of the blue, a front- page article in the Staunton Spectator and General Advertiser caught my eye. Under the bold headlines MIscellany and Interesting Biography, appeared an extensive, two-column ode to a gentleman named William Lenhart, the Mathematician. Mr. Lenhart apparently had been living in Frederick, Maryland, before his death at the same place in the summer of 1840. I was certainly intrigued by seeing the words “Frederick, Maryland” in the story, and much more than I was in seeing “mathematician.” I’ll be the first person to tell you that I love numbers, especially as they pertain to history—dates, population totals, ages, casualty numbers, etc. I don’t mind basic arithmetic and entry-level statistics, but higher math in its various forms (ie: algebra, geometry, trigonometry, calculus, number theory and mathematical physics) scares the hell out of me. It’s a good thing I married a high school math teacher, who, ironically, has very little use, or interest, for history. “The Math Guy” With 40,000 former residents in my midst at Mount Olivet, roughly the same population as our state capital of Annapolis, I still pass countless gravesites without a thought, as their names are still nothing more than “names in stone.” With that said, I was certainly hoping that William Lenhart was possibly one of our own since he lived, and died, in Frederick back in the early 19th century. One minor conundrum was knowing that Mount Olivet opened in 1854, 14 years after Lenhart’s death. However, many of those early Frederick residents that had been buried in the existing church-owned graveyards of that era, would eventually be moved to Mount Olivet by the early 1900s. When I found that article in the Staunton newspaper, I was at home with no immediate access to Mount Olivet’s interment database. I will share a tip here with those finding themselves in the same predicament of wanting to check if someone is buried in a certain cemetery or not. Simply search the inventory of a particular burying ground on the www.FindaGrave.com site via the internet. It’s certainly not “fool-proof,” as some graves haven’t been added yet by hard-working volunteers, but generally most gravesites are included that have markers. In respect to Mount Olivet, here’s some basic math: our Find-a-Grave page shows that 34,058 interments have been added—that’s 73%! I simply typed "Lenhart" into the name search option and found the following result as part of a long list of Lenharts. Normally, I would be very disappointed to find this result. However, with this particular research mission, I became ecstatic because just in the sheer fact of getting this return, I now knew that there was a statistical chance and probability of William Lenhart, (Mathematician) being buried in our cemetery. Although there were no birth or death dates listed here, and no photo of tombstone (if one at all), I held optimism because here was a William Lenhart that could be him. I wish I could tell you the odds at the outset of this being a perfect match, but I already painfully divulged my math deficiencies earlier. Another source of delight for me (in looking at the scant Find-a-Grave entry for William Lenhart) was the fact that his grave location was listed as Area NN/Lot 130/Grave 7. This particular area is shaped somewhat like a small triangle on the cemetery’s western perimeter, only about 30 yards from the landmark Barbara Fritchie and Thomas Johnson monuments in the middle of Mount Olivet (in Area MM). Here, three local church congregations of yore bought property around 1907 and made arrangements to move bodies from former downtown churchyards. Interments from Frederick's former Methodist graveyard (once located at the SE corner of E. 4th St and Middle Alley) occupy the south side of the triangle (left). Evangelical Lutheran holds the center of NN, with these bodies coming from the second burying ground of the congregation, once located on the SE corner of E. Church Street extended and East Street (today's Everedy Square vicinity). Frederick’s Presbyterian Church holds the northern (right) portion closest to Confederate Row, roughly 30 yards away. In particular, bodies occupy lots 130-135 as shown on the above map section. I will tell you more on that church cemetery's history later. The William Lenhart I had just found on Find-a-Grave is shown as occupying Area NN/Lot 130, and because of this, I now knew that although loosely documented, this man had died before 1854, and had been buried elsewhere in town before being brought here. I would also soon lean that he had been previously buried in another part of Mount Olivet before coming to this current spot. Now I found the rationale to devote time to solve the problem: Does the Mount Olivet William Lenhart = William Lenhart, the Mathematician? I now had reason to read through a very lengthy article about a “math guy” in an effort to “solve my equation” or “prove my postulate” of these two being one and the same. After perusing the article, I engaged in the painful task of transcribing the lengthy two-column article for your reading pleasure. This had first appeared in print within the Baltimore American and Commercial Advertiser of October 2nd, 1841 (nearly a month earlier than it had appeared in the Staunton, VA newspaper). With no further adieu, here it is in its entirety as I think that this author’s presentation, although extremely lengthy and embellished, runs circles around anything I could wordsmith for telling his story:  WILLIAM LENHART, THE MATHEMATICIAN. Perhaps very few of the readers of The American are aware that in July, 1840, a man died in Frederick, Maryland, who had genius, which under favorable circumstances, might have illustrated the name of his country throughout the scientific world. The seed which produces the most luxuriant harvest requires proper cultivation to make it minister to the necessities of man. The marble which is taken from the quarry has no attractions for the eye until the chisel of the sculptor displays its tortuous veins, and gives the beauty of proportion. So, genius of the highest order—without the fostering care of patrons, and a suitable field for its display—often lies buried with the unknown possessor; and “mankind are little sensible how a brilliant sun has gone down in darkness, which, under more favorable circumstances, would have fertilized and adorned society. It is with a view to make my humble contribution to the memory of a highly gifted man, who was, at one portion of his life, a citizen of Baltimore, that I write this article. Had Lord Clive not been employed as a clerk in India, he would probably never have displayed that brilliant genius which gave him rank with the nobility of England, and astonished the world. If Lenhart had not, during the greater portion of his life, been the victim of severe disease, he would not have required the aid of my unpretending pen. For the facts on which this article is based, I am indebted to the July number of the Princeton Review. William Lenhart was the son of a respectable silversmith, of York, Pennsylvania, where he was born in 1787. His education received but little attention, until when he was about fourteen years old. Dr. Adrain,—then obscure, but since so extensively known as a mathematician,—opened a school in York, and young Lenhart became one of his pupils. Owing perhaps to the scanty means of his father, he did not remain at school more than eighteen months: yet in that short period, the rock was smitten and the waters of genius flowed out in an abundant stream. Adrain soon discovered the great mathematical talents of his pupil; and assumed towards him much of the relation of a companion in study. At this time he evinced life disposition of his mind by making in miniature, with great perfection, various machines which he had seen—fire engines, water mills, &.c. Before he left the school of Mr. Adrain, he became a contributor to the “Mathematical Correspondent,” a periodical published in New York. When he was about seventeen, he became a clerk in a store in Baltimore. I have no means of ascertaining the house in which he was placed. At that time, he was remarkable for the beauty of his person and the agreeableness of his manners. Having become tired with selling goods, he entered on the discharge of some duties in the office of Sheriff. In both these situations he was—as he continued through life—unequalled as a penman. While he remained in Baltimore, he occupied his leisure hours with reading and mathematical studies; and also made contribution to the “Mathematical Correspondent,” and the “Analyst,” published by Dr. Adrain in Philadelphia. When only seventeen, he obtained a medal for the solution of a mathematical prize question. After remaining in Baltimore about four years, Lenhart undertook the care of the books in the commercial house of Messrs. Hassinger and Reese, of Philadelphia. On account of his abilities, his employers doubled his salary at the end of the first year. His books were models of book-keeping, and the accounts he made out for foreign merchants were long kept by them as forms. As a clerk and book-keeper he was unrivalled. Such was the estimation in which he was held by the house, that after three years they offered him a partnership, by the terms of which they were to supply the capital, as his eminent personal services were considered by them as an equivalent. During this period, he cultivated mathematical science. Young Lenhart was now about twenty-four years old; and thus far his career—considering the difficulties with which he had to contend—had been one of great prosperity and promise. As to the remainder, “shadows, clouds and darkness rest, upon it.” It gives me pain to record the events of his subsequent life. When the pride of the forest is preyed upon by the worm, we are not pained by its gradual decay. The rude tempest passes by audit falls in the beauty of its foliage, the majestic oak, as it stands upon the mountain top, maybe splintered by the lightning; but our feelings of regret, as we survey the prostrate trunk, are absorbed by the contemplation of the power of the Almighty. We have different emotions when it has been scathed, and withers, and every wind of Heaven blows through its leafless branches. Deep must have been the anguish of Lenhart as he contemplated his situation, and felt that the bright prospects of his life were overcast almost as soon as the morning sun had arisen But he calmly bowed his head to the stroke; and his noble spirit enabled him to endure with a martyr’s patience, that which in the amount of suffering surpassed the torture and the flame. Before Mr. Lenhart entered upon his duties, as a partner in the house of Messrs. Hassinger and Reese, he made a visit to his father at York. While taking a drive in the country, his horse ran away, breaking the carriage and his leg was fractured. After his recovery he returned to Philadelphia. While pitching quoits he was attacked with excruciating pain in the back, and partial paralysis of the lower extremities. He was under the care of Drs. Physick and Parish for eighteen months; and after they had exhausted all their skill, they told him his case was hopeless. The injury he sustained, when thrown from his carriage was probably the cause of his spinal affliction. Had any other circumstance been required to make his cup of misery overflow, it would have been derived from the fact that he was at this time engaged to be married to a most interesting young lady; they having been mutually attached from early life. His sufferings during the subsequent sixteen years were indescribable: the intervals of pain being employed with light literature and music. In the latter art he made great proficiency, and was supposed to be the best chamber flute player in this country. He composed variations to some pieces of music, expressive of the anguish produced by the disappointment of his fondly cherished hopes of domestic happiness: and these he would perform with such exquisite feeling as deeply to affect all who heard him. In 1828, having so far recovered as to walk with difficulty—he again fractured his leg by a fall. His sufferings at this time were almost too great for human nature lo endure. From this period the greater portion of his time was passed with a sister in Frederick, Maryland. The progress of his disease paralyzed his lips, and he could no longer amuse himself by playing on the flute: and as light literature did not give sufficient employment to his active mind, he relieved the tedium of his confinement by the pursuit of mathematical science. It was under such unfavorable circumstances that he made those advances in abstruse science which have conferred immortality on his name. A year before his death he thus wrote to a friend: the beauty of the sentence will be appreciated by the mathematical reader :—“My afflictions” he says “appear to me to be not unlike an infinite series, composed of complicated terms, gradually and regularly increasing—in sadness and suffering—and becoming more and more involved; and hence the abstruseness of its summation; but when it shall be summed in the end, by the Great Arbiter and Master of all, it is to be hoped that the formula resulting, I will be found to be not only entirely free from surds, but perfectly pure and rational, I even unto an integer.” From 1812 to 1828, Mr. Lenhart was oppressed to such a degree by complicated afflictions, that he did not devote his attention to mathematical science. After the latter period, he resumed these studies, for the purpose of mental employment; and contributed various articles to the mathematical journals. In 1836 the publication of The Mathematical Miscellany was commenced in New York: and his fame was established by his contributions to that journal. I do not design to enter on a detail of his profound researches —He attained an eminence in science of which the noblest intellects might well be proud; and that too as an amusement, when suffering from afflictions which, we might suppose, would have disqualified him for intellectual labor. It will be sufficient for my purpose to remark, that he has left behind him a reputation as the most eminent Diophantine Algebraist that ever lived. The eminence of this reputation will be estimated when it is recollected that illustrious men—such as Euler, Lagrange and Gauss—are his competitors for fame in the cultivation of the Diophantine Analysis. Well might he say that he felt as if he had been admitted into the sanctum sanctorum of the Great Temple of Numbers, and permitted to revel amongst its curiosities.  Dr. Robert Adrain (1775-1843) Dr. Robert Adrain (1775-1843) Notwithstanding his great mathematical genius, Mr. Lenhart did not extend his investigations into the modern analysis and the differential calculus, as far as he did into the Diophantine Analysis. He thus accounts for it:—“My taste lies in the old fashioned pure Geometry, and the Diophantine Analysis, in which every result is perfect; and beyond the exercise of these two beautiful branches of the mathematics, at my time of life, and under present circumstances, I feel no inclination to go.” The character of his mind did not entirely consist in its mathematical tendency, which was developed by the early tuition of Dr. Adrain. Possessed as he was of a lively imagination—a keen susceptibility to all that is beautiful in the natural and intellectual world—wit and acuteness—it is manifest that he wanted nothing but early education and leisure to have made a most accomplished scholar. He was also a poet. One who knew him well says:—“He has left some effusions which were written to friends as letters, that for wit, humor, sprightliness of fancy, pungent satire, and flexibility of versification, will not lose in comparison with any of Burns' best pieces of a similar kind.” Mr. Lenhart was very cheerful and of a sanguineous temperament; full of tender sympathies with all the joys and sorrows of his race, from communion with whom he was almost entirely excluded. Like all truly great and noble men, he was remarkable for the simplicity of his manners. That word, in its broad sense, contains a history of character. He knew he was achieving conquests in abstruse science, which had not been made by the greatest mathematicians; yet he was far from assuming anything in his intercourse with others. During the autumn of 1839, intense suffering and great emaciation indicated that his days were almost numbered, His intellectual powers did not decay; but like the Altamont of Young, he was "still strong to reason, still mighty to suffer.” He indulged in no murmurs on account of the severity of his fate.—True nobility submits with grace to that which is inevitable. Caesar has claims on the admiration of posterity for the dignity with which, when he received the dagger of Brutus, he wrapped his cloak around his person, and fell at the feet of Pompey’s statue. Lenhart was conscious of the impulse of his high intellect, and his heart must have swelled within him when he contemplated the victories he might have achieved, and the laurels he might have won. But then he knew "his lot forbade" that he should leave other than “short and simple annals” for posterity. He died at Frederick, Maryland, on the 10th of July, I840, with the calmness imparted by Philosophy and Christianity. Religion conferred upon him her consolations in that hour, when it is only by religion that consolation can be bestowed: and as he sank into the darkness and silence of the grave, he believed there was another and a better world, in which the immortal mind will drink at the very fountainhead of knowledge, unencumbered with the decaying tabernacle of clay, by which its lofty aspirations are here confined as with chains. The life of William Lenhart is not without its moral. Of him it may with great appropriateness be said: “Genius will be fired with new ardour, as it beholds the triumphs of his intellect over the difficulties of science, amid so many disadvantages and discouragements; and misfortune, disappointment and disease, will be reconciled to their lot, as they view the afflictions with which he was scourged from youth to the grave.''—Baltimore American. S. C. All I could say, during and after reading this, was “Wow!” My head quickly filled with several new research questions, along with potential methods to attempt to answer each. Who was this article’s author, simply referred to as “S.C.?” What more did the referenced Princeton Review article have to say about Lenhart? What exactly were Lenhart’s disabilities, and how were they caused exactly? Who was Lenhart’s sister, and where did Lenhart live in Frederick? Were there any direct heirs to Lenhart or his immediate kin (as it appears Lenhart never married or had children)? What religion was Lenhart (hopefully Methodist, Lutheran or Presbyterian)? The answers to these problems would surely give me my answer.  Clock made by Godfrey Lenhart (c. 1777) Clock made by Godfrey Lenhart (c. 1777) “Show Your Work” My wife (the math teacher) always stresses to her students that one of the most important aspects of solving a math problem is to “show your work,” letting others know how you reached a particular answer to a problem. I will follow suit and share my "work" with you as well. You’ve already witnessed my first steps in scouring the Staunton newspaper article for clues, while tracking down the original article in the Baltimore American. I next went to Ancestry.com to search for a potential Family Tree that would include William Lenhart the Mathematician. I found one immediately, and learned parental names: Godfrey Lenhart (1754-1819), who I successfully verified as a prominent silversmith and noted grandfather clockmaker in York, PA. William's mother was Mary Elizabeth Harbaugh (1753-1824). The Family Tree was a little shaky, so I sought out other genealogical histories of the Harbaugh family that could be found on the internet. One such gave me exactly what I was searching for, including the knowledge that Mary Elizabeth (Harbaugh) Lenhart was a daughter of early Swiss immigrant Yost Harbaugh. Her brothers, George, Ludwig and Jacob, left York in 1760 and brought their families to northwestern Frederick County. Settling in the vicinity of today’s Sabillasville, their last name soon became synonymous with the locale still known as Harbaughs Valley. And just in case you were wondering, Baltimore Ravens head football coach John Harbaugh is a descendant of this same family. William Lenhart had a sister named after his mother. Mary Elizabeth Lenhart, who somehow met a gentleman named John Bayly. I found that Bayly operate a store in the first block of West Patrick Street which sold linens, broadcloths, groceries and seasonable goods. I'm assuming that the family lived above or behind the store, as was commonplace in the early 1840s. The Bayley’s had a daughter named Catharine, who would marry a noted former Fredericktonian, Samuel Tyler (1809-1879). Mr. Tyler was a lawyer, author and Georgetown College professor. I was already familiar with some of Tyler’s other writings, including a memoir of Roger Brooke Taney. I now surmise that Samuel Tyler was S.C., the original newspaper memorial's writer, as Mr. Lenhart was his wife’s uncle. (I can’t explain S.C. instead of S.T. but perhaps we can chalk it up to a typo).

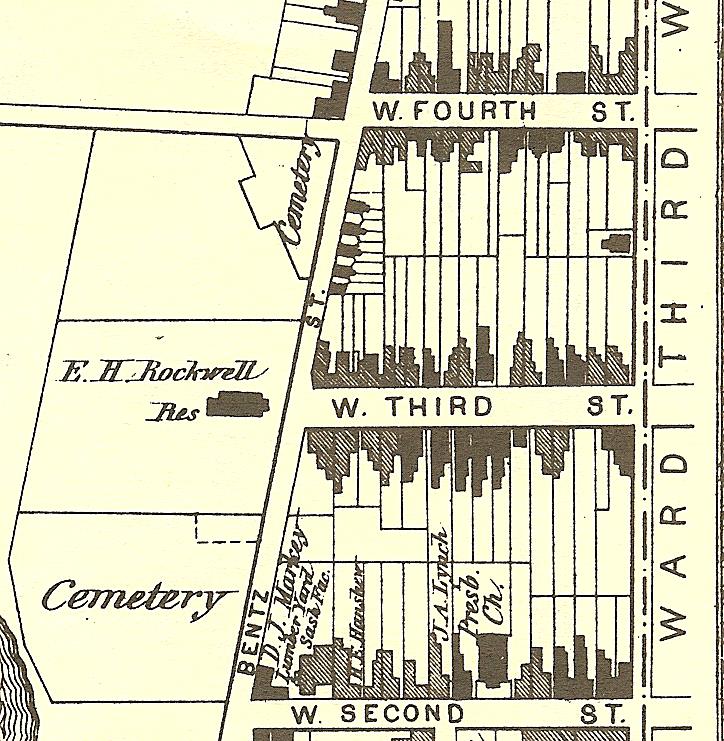

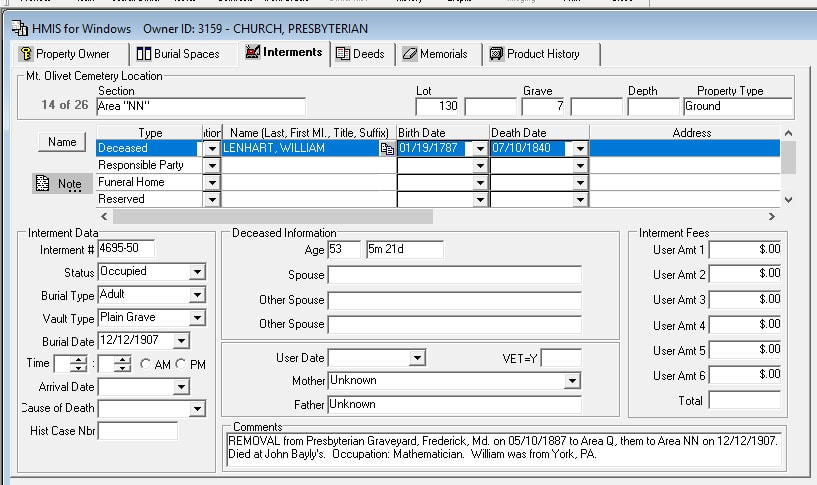

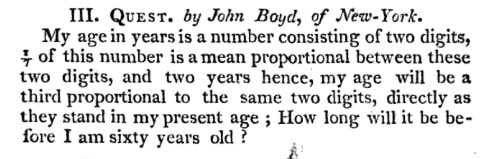

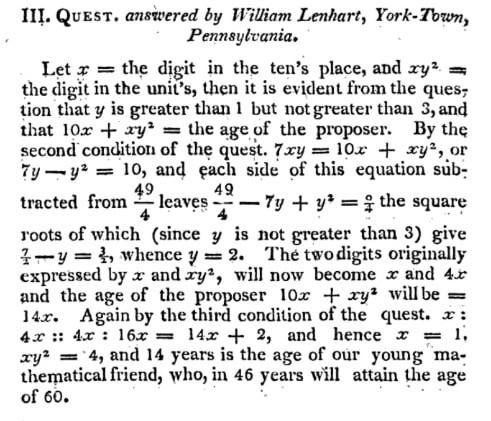

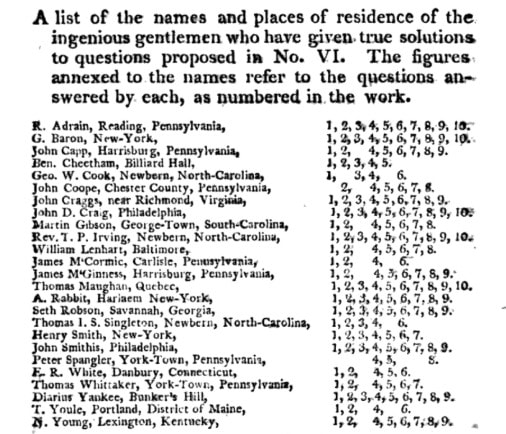

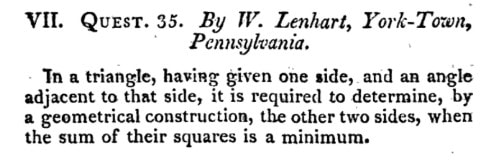

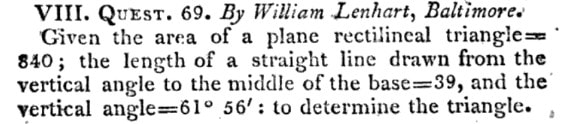

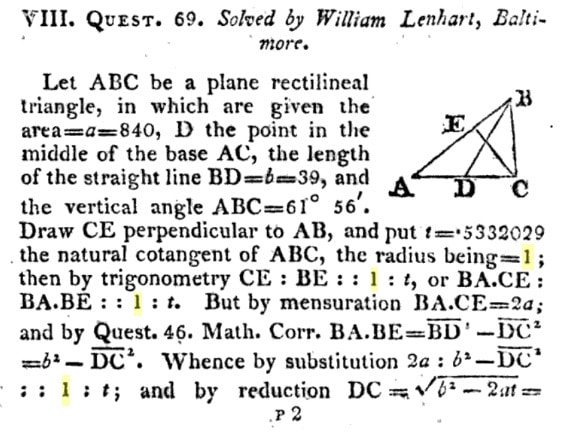

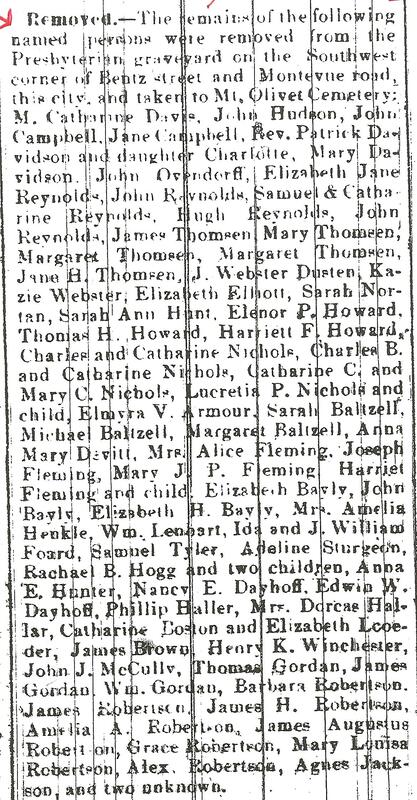

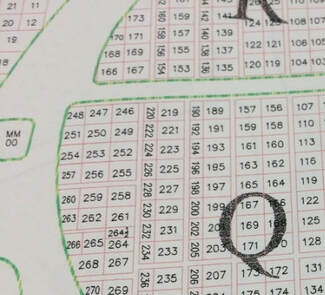

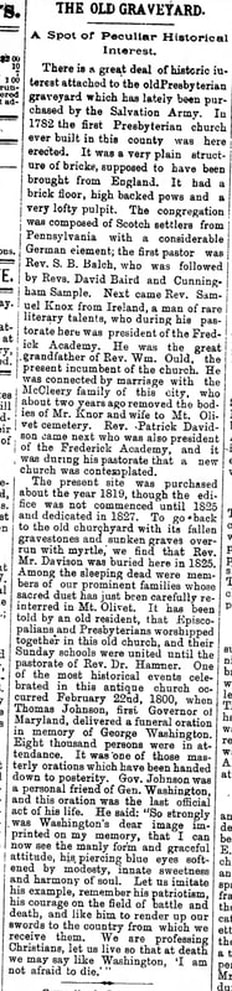

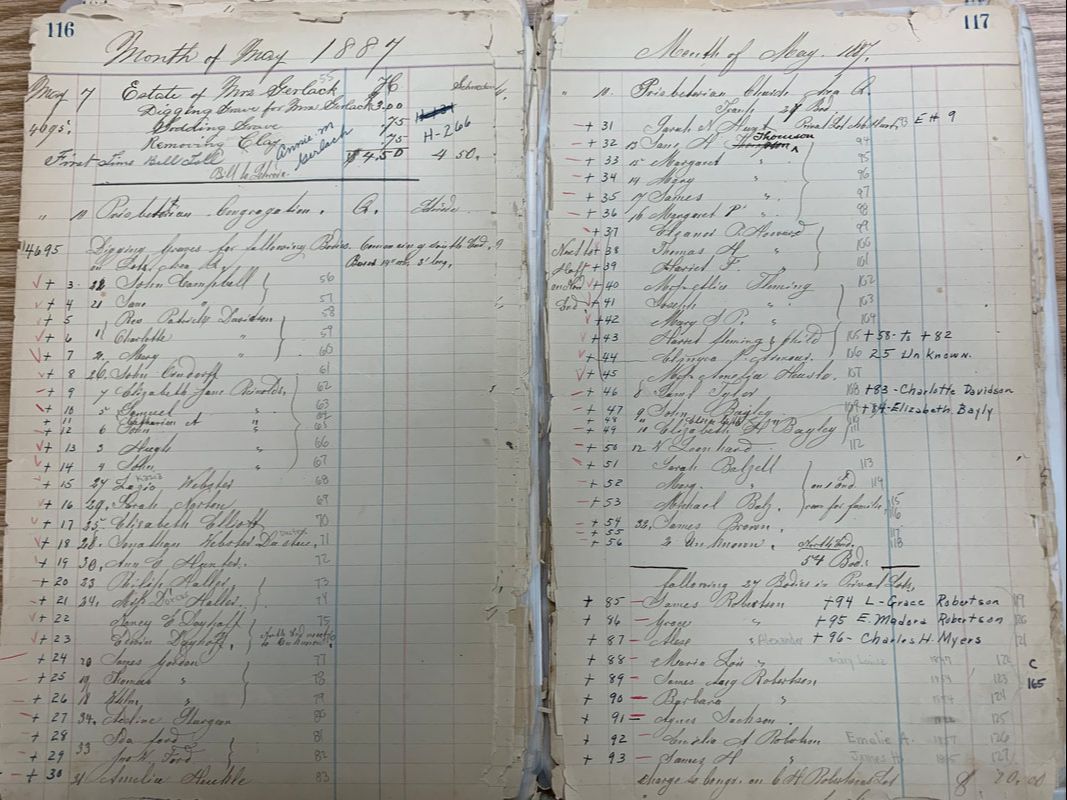

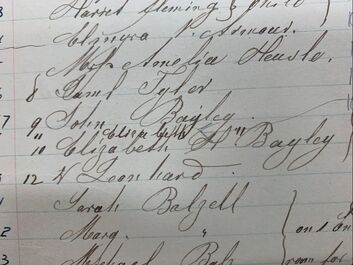

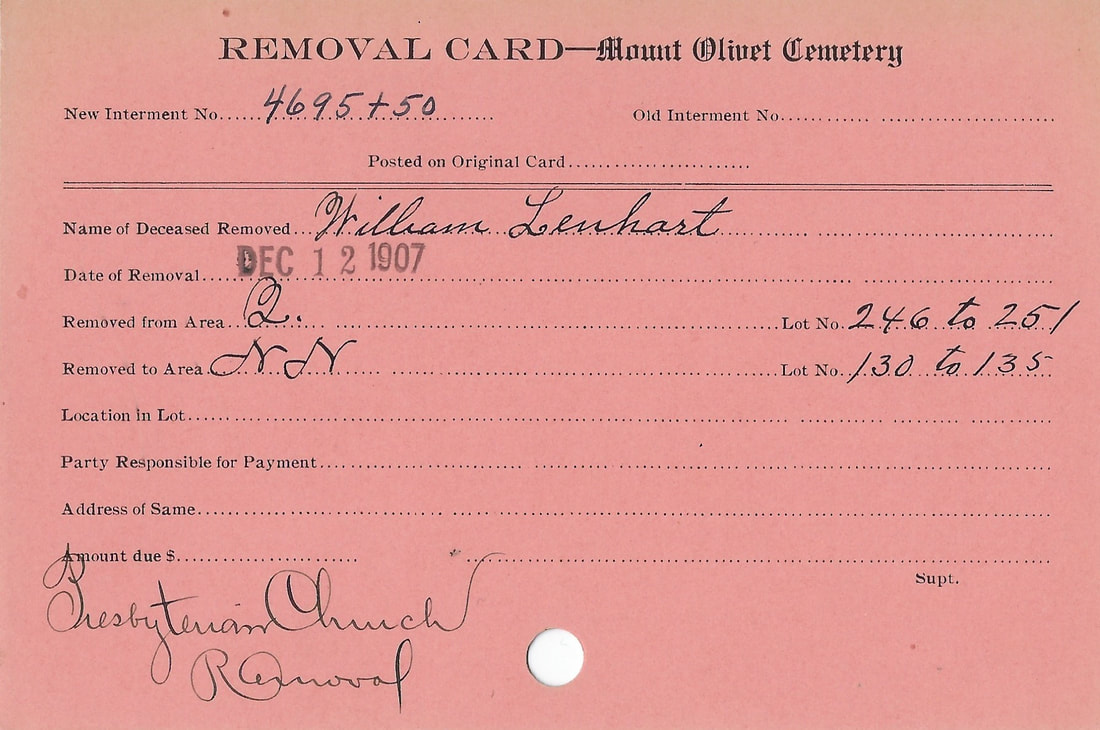

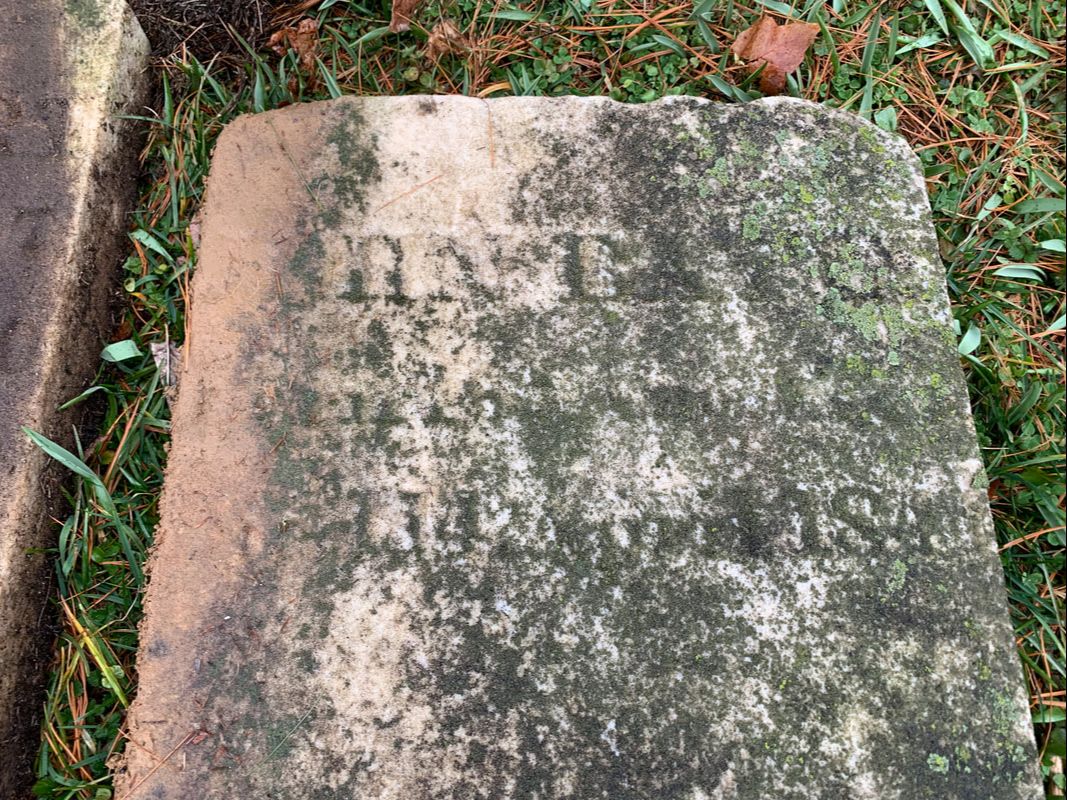

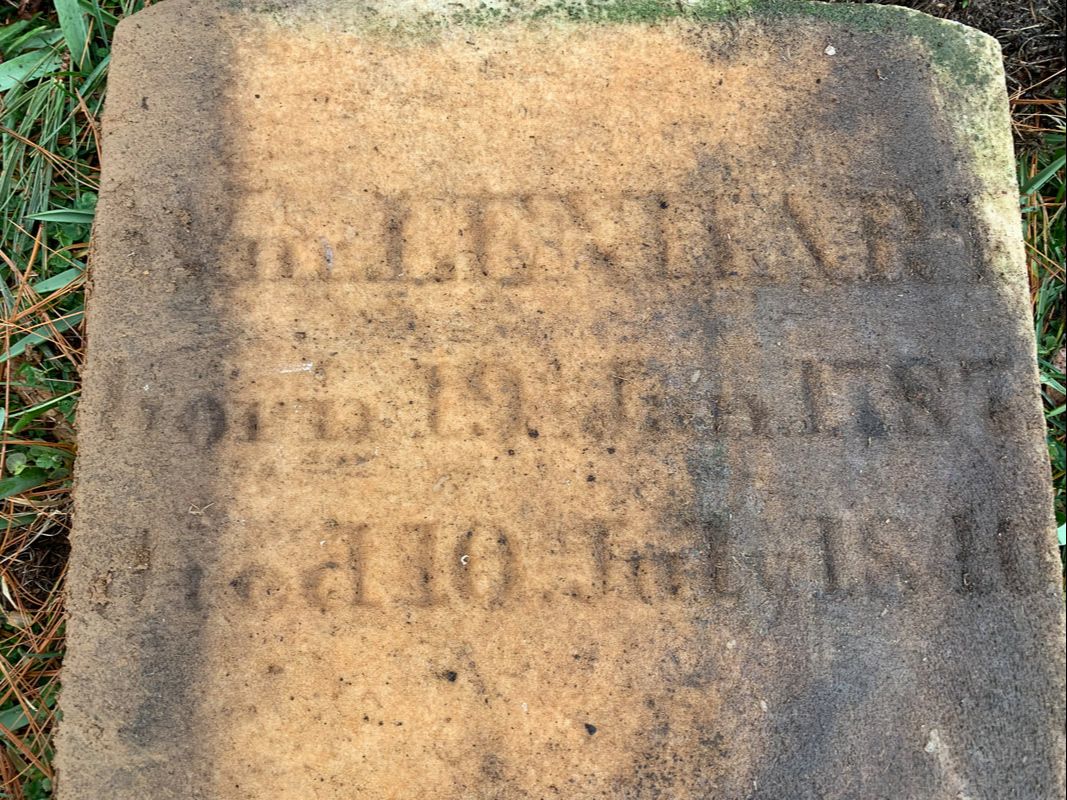

I quickly returned to Find-a-Grave and found both John and Mary Bayly buried in Mount Olivet. No pictures of stones either, but elation struck me when I found that they, too, were residing in Area NN, Lot 130, graves 7A and 8. I had successfully proven the relationship between Lenhart brother and sister (now a Bayly), and more so, decedent and famed mathematician! Of course, when I came into work on Monday, our database included information pertaining to Area NN's William Lenhart ranging from vital dates, to stating the fact that he was a removal from Frederick’s Presbyterian Cemetery on May 10th, 1887. Our data also had him as hailing from York, PA, dying at the residence of John Bayly, and, finally listed as an occupation that of a mathematician. Oh well, “What doesn’t kill you, makes you stronger” as they say—an interesting expression to recite as a full-time employee of a cemetery, for sure! Several old math journals from the 19th century mention Lenhart’s heroics answering prize questions offered up in monthly publications like the Mathematical Correspondent under the leadership of editor George Baron. The Correspondent presented problems to subscribers inviting them to solve and send in answers, which if correct, would be published in upcoming volumes. Lenhart was a regular contributor of both questions/problems, and answers. The following clippings come from the pages of various editions of The Mathematical Correspondent (1804).  I really didn't find much more on William Lenhart in old newspapers. Town diarist Jacob Engelbrecht recorded the mathematician's death, but not anything more. Lenhart’s name came up in several online searches connected with scholarly articles on math and its history in America. A particular interest to me was exploring how modern academics viewed William Lenhart today? I found an impression of his legacy in an article on early American mathematics journals, in which D.E. Zitarelli writes: When it comes to the study of mathematics in this country, we describe six of its major contributors, two of whom are known somewhat (Robert Adrain and Robert M. Patterson), but the other four seem to have slipped into obscurity in spite of accomplishments that deserve more recognition (William Lenhart, Enoch Lewis, John Gummere, and John Eberle). In 2005, Lenhart was ranked as the 7th top problemist of the early 1800s by Zitarelli , a bonafide expert on the subject having published his 2019 book entitled: A History of Mathematics in the United States and Canada: Volume 1: 1492–1900. An online journal article from the periodical Historia Mathematica (aka The International Journal of History of Mathematics) found at (https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/82122927.pdf) and entitled: The Fading Amateur: William Lenhart and 19th-Century American Mathematics by Edward R. Hogan of East Stroudsburg University (East Stroudsburg, PA). This work was published in 1990 by the Academic Press. Dr. Hogan writes: "There were amateur mathematicians in the United States after William Lenhart (1787-1840); there still are today. But Lenhart, although strictly an amateur in the sense that he neither received nor sought to receive revenue from his mathematical work, was one of the leading American mathematicians of his generation. He is the last person, to my knowledge, who was both. Lenhart was highly regarded by his countrymen. By the time of his death, he was heralded as a mathematician of extraordinary ability. Samuel Tyler, although not a scientist, was one of the foremost Baconians in America and Lenhart’s nephew by marriage. He said of his uncle’s contributions to the Mathematical Miscellany: “They have gained for him a reputation as the greatest Diophantine Algebraist that ever lived; and this is no mean renown, when it is considered that a Euler, a Lagrange, and a Gauss are his competitors." Such words might be dismissed as exaggerated praise from family and friends, but others with far more mathematical knowledge gave Lenhart similar compliments. Probably the most impressive came from Charles Gill, a competent, if self-taught, mathematician. He wrote to Lenhart: “No one will now deny that you have done more with the Diophantine analysis than any man who ever lived." In addition, the mathematical astronomer Daniel Kirkwood described Lenhart as an “eminent mathematician” and cited Gill’s evaluation, implying his agreement." Dr. Hogan also shed a bit more light on how William Lenhart suffered his life altering afflictions. After being offered a partnership in a business firm in 1812, Lenhart went home on a holiday to see his family, friends, and fiancee, and met with a freak accident. He was taking a ride in a gig when he passed by a traveling menagerie. The roar of a lion in the caravan frightened his horse, and Lenhart, thrown from his gig, fractured a leg and seriously injured his back. He never recovered; for the rest of his life he suffered extreme pain, exacerbated by a second fracture of the same leg.  Daniel Kirkwood (1814-1895) Daniel Kirkwood (1814-1895) The article goes on, but I think you are now likely feeling overwhelmed. I certainly am at this point in writing, and am starting to have uncomfortable flashbacks to certain math classes in my high school and college career. A final article of note was found in math periodical entitled The Analyst (Volume II, No. 6). A piece in this November, 1875 edition was penned by a colleague and friend of Lenhart’s, the fore-mentioned astronomer Daniel Kirkwood. The professor recounted that Lenhart was extremely fond of smoking cigars, owned a small library of books with some volumes dating to the early 1700s, and oftentimes replied to math publications with solution submissions to math questions under pseudonyms because he had found various ways to solve problems. He used the name Diophantus on a number of occasions, and more surprisingly answered as a supposed female contributor as well—using the name Mary Bond of Frederick Town, MD.  Frederick's Presbyterian Church on W. 2nd Street (c. 1900) Frederick's Presbyterian Church on W. 2nd Street (c. 1900) The Gravesite My last task was to seek out Lenhart’s exact gravesite. Since there was no picture on the Find-a-Grave website, I pondered if our local math genius was simply buried in an unmarked grave? This was often common as the re-interment process was quite complicated. Many graves were unmarked in former cemeteries, and old stones from the early 19th and 18th centuries didn’t hold up well in some instances. Those deemed shabby, were oftentimes banned from public display in the once- uppity places like our sparkling new “garden cemetery” during its earlier days. Some ragged stones hit the trash heap, others were buried. This would happen regularly when certain families "ponied" up the funds to have new stones made, and sometimes elaborate family memorials crafted, as replacements. Our records are pretty good here at Mount Olivet, and extensive work has been done over the years to document interments in places like Area NN in an effort to compensate reburials lacking gravestones or any other kind of marking. An interesting wrinkle in this particular re-interment case relates to the Presbyterian Cemetery removal of 1887. The church graveyard in question was originally located at the southwest corner of Dill and N. Bentz streets. Various clergy members and other VIP's would be buried behind the church itself, located on W. Second Street. The majority of burials of this congregation were placed in the other graveyard. Back in the day, Dill Avenue was originally known as New Cut Road. Upkeep for these cemeteries was difficult and costly for churches, especially when the burial business was now going to Mount Olivet—a well-established professional cemetery in town.  The old Presbyterian graveyard is located on this 1873 Titus Atlas map near the upper left of this image at the intersection of N. Bentz Stand Dill Ave (as it becomes W. 4th Street to the east). The larger burying ground below the E. H. Rockwell residence is the former German Reformed Cemetery, today known as Memorial Park Many congregations simply bought land in the form of lots within Mount Olivet, in an effort to transfer their own graveyard inhabitants. Since 1854, individuals had been removed here and there across town from various churchyards and associated graveyards and brought to the new cemetery by families with the means to do so. Mount Olivet was "the place to be,” even in death. Younger generations purchased extra lots in an effort to remove bodies from elsewhere in an effort to reunite themselves one day with parents, grandparents and other members of extended family in one location. The Presbyterian Church bought lots 246-251 in Area Q in 1887, just across from the Barbara Fritchie monument. Bodies were brought from the former burial ground—among them William Lenhart, his sister and brother-in-law (the Baylys) and buried on May 10th. I would find their names among those appearing in a newspaper article from the May 18th, 1887 edition of the Frederick Examiner which reported the mass removal from Frederick’s Presbyterian graveyard. You may recall, that earlier in the story, I gave Area NN as the location of William Lenhart’s grave, not Area Q? In December of 1907, a decision was made to rebury the Presbyterian bodies in Q (hailing from the old graveyard on N. Bentz) in Area NN. The move was only about 30 yards away. So William Lenhart was buried three times, a charming way to be handled in death. Armed with cemetery diagrams, I went to Area NN to find Lenhart’s grave and subsequent gravestone. All the while, I said to myself, “If this guy doesn’t have a stone, can I actually call this a “Story in Stone?” This was a logical question that I’m sure would make Lenhart and a host of ancient Greek math philosophers smile for sure. Once on the scene, I sadly went to the spot where Lenhart and the Baylys were supposed to be located. I found nothing but unmarked grave here. I double and triple checked the area and maps, but still with no success. Upon closer examination, I noted two downed-headstones, innocently leaning behind the row in front that Lenhart and the Baylys were supposed to be within. I strained to read a faded name on the top of these two stones, after brushing off debris. I then found the name "John Bayly.” I was once again very excited, well, you know, not as happy as at the birth of my son, but pretty happy. I carefully pulled that stone off the other to expose the second gravestone leaning underneath Bayly’s. Bingo!!!--it was that of William Lenhart, and I won’t confirm, or deny, that I may have done some sort of crazy math celebratory dance, then and there, in Area NN. I next carefully laid both stones out in the places they were supposed to occupy. I questioned the whereabouts of Mrs. Bayly’s gravestone, as it was visible, yet noted on the old diagram I held. I then thought perhaps she didn’t have one, or shared her husband's. The next morning, I made a visit to the gravesite to see the stone faces of the Lenhart and Bayly monuments. I had hoped overnight rain showers had helped clean off additional mud and debris. I soon flagged down our assistant grounds foreman, Rob Reeder, who was passing by the Area. I told him a bit of the story and how I found these stones stacked behind other graves. I also asked if he would kindly re-set the Lenhart and Bayly stones in place sometime in the coming months? He said sure, and even told me that he could do this later that same day. I certainly was expecting an answer of March or April. Excavation work began later that morning, and the original bases of each stone were found, having been placed within a cement trough. This method was responsible for serving as a foundation for the entire row of vintage stones from the former Presbyterian cemetery. I was called to the scene a short while later as a third stone foundation was found in the spot where Mary Elizabeth Bayly appears on lot maps. This was the base of a missing stone. Another search ensued and her gravestone (somewhat illegible) was found in two pieces, hidden behind the back row of Presbyterian congregation monuments and against the perimeter fence. The bottom piece of Elizabeth Bayly's stone fit against the foundation base like a "Cinderella shoe." Unfortunately though, erosion had rounded the major break area showing that this marker had been broken for a very long time, perhaps 50-60 years and never repaired. The other stones (Lenhart and Mr. Bayly) must have fallen more recently, but sometime before 2013, at which time the Find-a-Grave contributor posted the additions of William Lenhart and the Baylys to the Find-a-Grave website without photographs. I’m proud to say that in less than one week, we discovered a famous mathematician buried in Mount Olivet, found out more about his life and times, and set into motion the repair and resetting of his tombstone. This is the essence of our Mount Olivet Preservation and Enhancement Fund with a 3-part mission to preserve the history, structures and gravestones of our amazing cemetery. Our newly-formed Friends of Mount Olivet membership group will further this mission as volunteers will assist in documenting and assisting in the "resurrection" of fallen and damaged stones, while helping to raise needed project funds and support to benefit our historic monuments and memorials through repair.

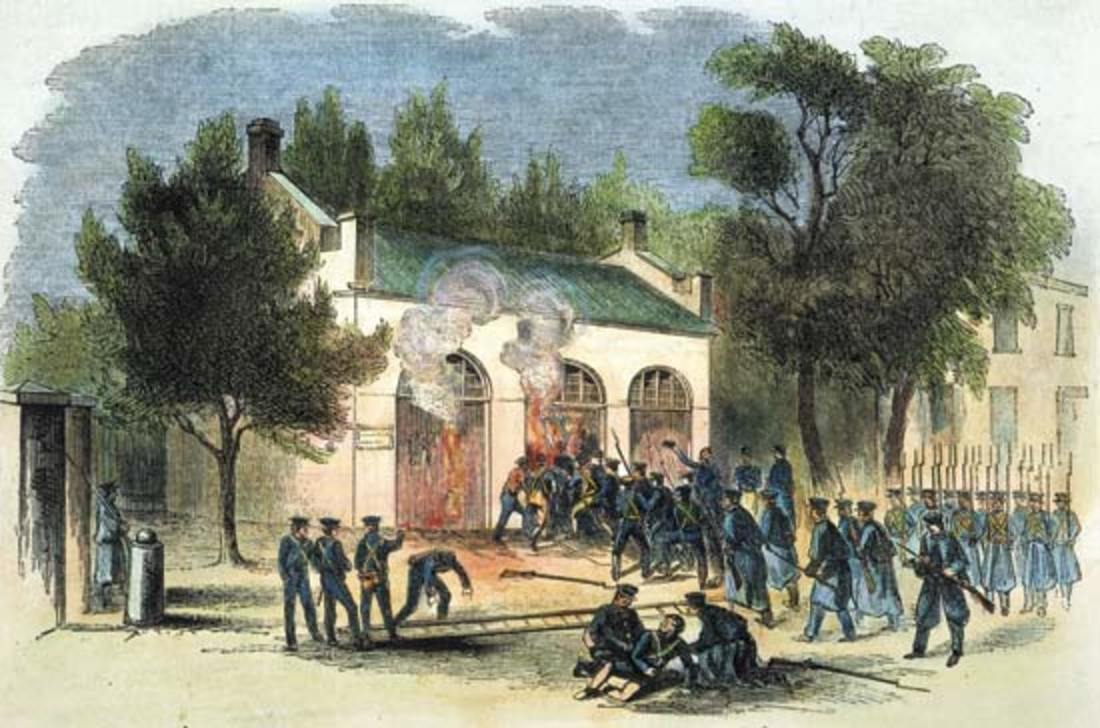

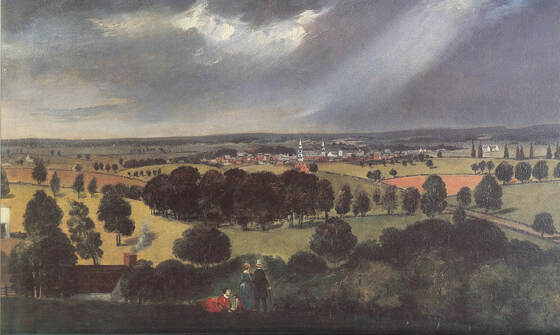

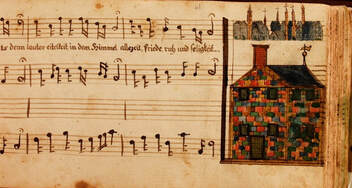

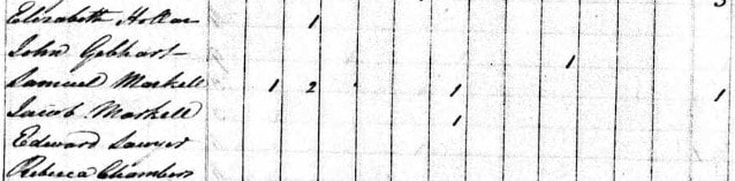

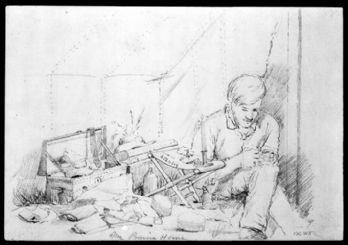

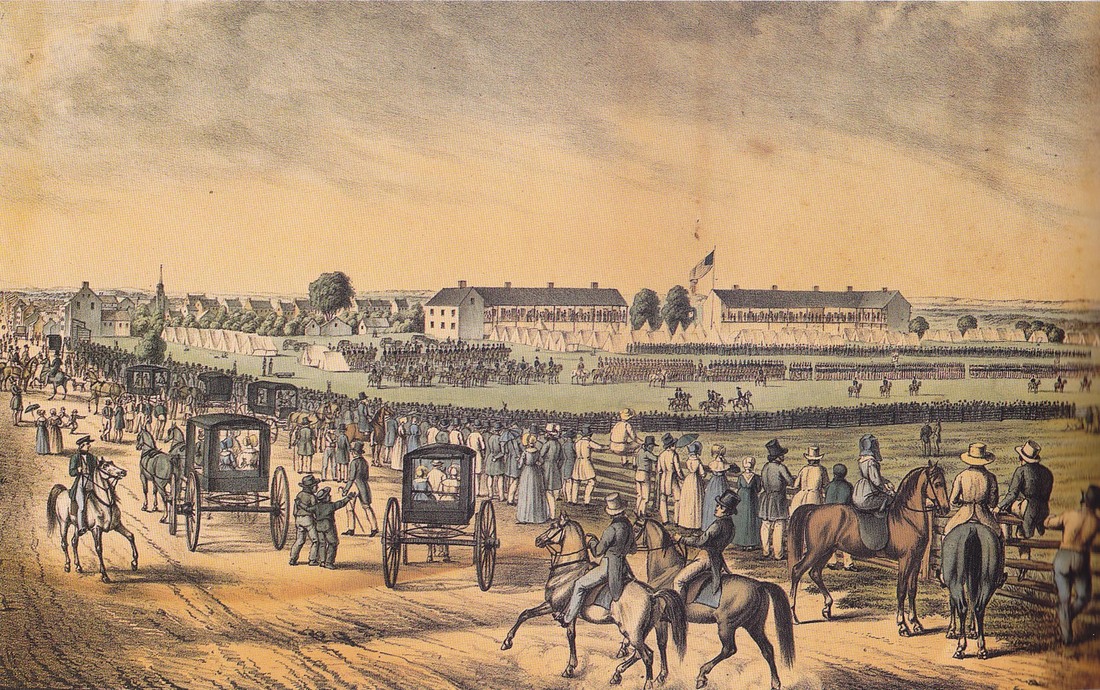

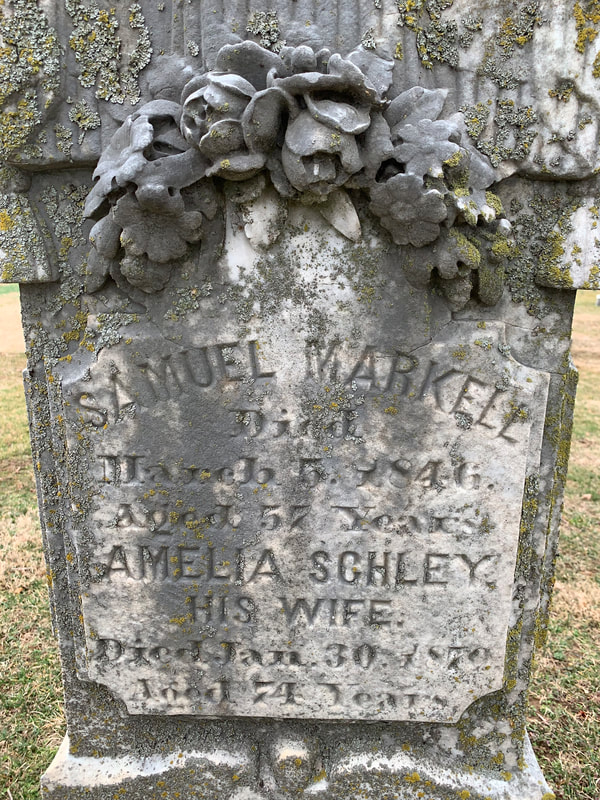

It has been said that each of us dies two deaths. The first is when the physical body ceases to exist. The second is when you are forgotten, and disappear from the written and spoken record. I’d say that we successfully brought William Lenhart back to life—a great "addition" to our varied cemetery population. Just like a box of chocolates, you never know what you’re going to get.  J. T. Schley J. T. Schley When you have over 40,000 individuals buried in a cemetery, you are bound to have a few that possessed above average artistic ability over their lifetimes. As some of subjects of these “Stories in Stone” articles have left their legacy in the form of hand-signed letters or documents, interesting houses of their own design, advertising memorabilia, mentions in faded newspapers, and their names on various street signs within the city and county, the artists leave their precious work behind—visions that once encompassed their minds, and in some cases, very souls. To name just a few, representatives of this profession and buried here include Helen Smith, David Yontz, Florence Doub and John Ross Key, grandson of the guy with the most famous memorial in the cemetery—sculpted by another artist of renown by the name of Pompeo Coppini. Among the earliest painters that can be found in Mount Olivet is John Johnston Markell. He was born on June 17th, 1821, the son of Samuel and Amelia Schley Markell. His great-grandfather, John Thomas Schley (1712-1790), was one of Frederick’s first settlers-having built the town’s first house and serving as schoolmaster and choirmaster for the German Reformed Church. An artist in his own right, Schley was a master of Fraktur, a calligraphic hand of the Latin alphabet and any of several blackletter typefaces derived from this hand. Samuel Markell (1789-1846) was one of three brothers living in Frederick (John and Jacob) at the time of his wedding in 1815. He and wife Amelia would have five children, our subject John Johnston being the third-born in order. These included: William Warren Markell (1816-1839), Thomas Maulsby Markell (1818-1902), John J., Catherine Markell (1827-1907), and Amelia S. Markell (1833-1910). The Markell family resided in the vicinity of S. Market and W. South streets, one time owning the property on the south side of South between Market and present day Broadway Avenue. Marilyn Veek, my amazing research assistant, scoured old land records and found Samuel living at 203 S. Market Street, a location his wife and children would live out their lives as well. I’m assuming that young John received his education at the Frederick Academy, where his father had been appointed to teach the Introductory School in 1809. In 1827, Mr. Markell would oversee the Third Department, which I'm guessing would denote secondary education. As for artistic talent, Markell was self-taught as a painter. Perhaps he gained inspiration from miniature portraits of his parents painted at the time of their wedding. A depiction of Amelia Schley Markell dates to March 9th, 1815 and was done by the Swiss itinerant artist David Boudon. John J. Markell was only 17 years old when he painted his first self-portrait in 1838 in Philadelphia. Even at an early age, he clearly knew he was an artist, and holds, in his hand, several brushes to identify himself as an artist. By 1839, at the age of 18, he was found living in Leesburg, Va., and advertising his services as a “Portraits and Landscape Painter.” Markell had embarked upon the life of an itinerant portrait artist, travelling to various locations and offering his unique services to the local population. A bit of information regarding this profession can be gleaned from a book entitled: A Most Perfect Resemblance at Moderate Prices: The Miniatures of David Boudon by Nancy E. Richards and published by the University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, Inc. The author states that the field of portrait painting in which John J. Markell entered was highly competitive and traditional customers/patrons were those of middle and upper middle class. In the early 19th century of Markell’s era, painters charged $100 for full length portraits, $50 for half-length, and $6 to $20 for miniatures done on ivory, some going on to be encased within a locket. Other services included profile likenesses which could be performed from $6-$8 and silhouettes were a true bargain at just 6 cents each. John J. Markell’s accomplishments as an artist are especially noteworthy because he only lived to age 23. This, however, also adds to the issue of having only a scarce bit of information on him. Markell left behind at least eleven portraits, seven landscapes, one lithograph and three other paintings to study and enjoy today. For quite some time now, I have been familiar with three vivid local landscape scenes, two depicting major incidents in Frederick’s history. Note: all three works can be found in some form as part of the Heritage Frederick archival collection. View of Frederick from Prospect Hill This 1844 landscape piece may look familiar as it was utilized as the cover of an anniversary calendar produced for Frederick’s 250th commemoration back in 1995. John J. Markell painted this scene of the Frederick City skyline looking northeast from a vantage point atop Prospect Hill (and the vicinity of the aptly named Prospect Hall mansion). Rolling farmland and clusters of trees are beautifully portrayed here as storm clouds gather overhead. One can see the picket fence-lined Jefferson Pike starting at the right of the artist’s work and extending into town as it still does today. The one church spire most evident in this work is that of Trinity Chapel of the German Reformed Church. This was home church of Markell’s family going back to the time relatives immigrated here in the mid-1700s. Courthouse Fire On March 31st, 1842, a fire broke out near Court House Square on Record Street at the residence of Dr. William Tyler. Burning embers were carried by blustery conditions to other nearby dwellings. One such was the Frederick Academy located directly across the street to the slight northeast of the Tyler residence. Another key building of interest also was affected—the County Courthouse to the southeast. The belfry of the seat of government, which formerly stood on the same footprint as today’s Frederick City Hall, was ignited but thanks to the work of town fire companies and residents participation in bucket brigades, the building was saved. John J. Markell did not let pass the opportunity to paint from memory his eyewitness account of a very scary moment. Apparently this was done in the form of a banner and was in the possession of the Independent Fire Hose Company for many years. Unfortunately, the courthouse would burn to the ground 19 years later, possibly thought to be the work of arsonists with Southern sympathies at the advent of the American Civil War. Camp Frederick, 1843 A watercolor (that would became a popular lithograph obtained by local residents) by Markell depicts a military encampment that occurred June 6-10th, 1843 on the grounds of the Frederick Barracks, better known to locals as the Hessian Barracks. Today this is the site of the campus of the Maryland School for the Deaf. In the work, Markell skillfully produced images of the varying companies that participated. These included men from Fort McHenry, Hanover, Hagerstown, Sharpsburg and Frederick. It was quite an attraction as throngs of local citizens lined S. Market Street to get a glimpse of the happenings of this major military force assembled. Markell's vantage point for this work would put him at Mount Olivet's front gate, however the cemetery would not come into existence until a decade later. A more intensive self-portrait of John J. Markell arrived at Heritage Frederick some years ago from California. Former curator and Executive director of the Museum of Frederick County’s history, Heidi Campbell-Shoaf had been eagerly awaiting this treasure to add to the local collection.  In a newsletter article she wrote of the oil portrait: “Markell painted himself posed with the tools of his trade, an oval artist’s palette and a collection of brushes. He wears the typical male attire for the 1840s, a black frock coat with white shirt and black cravat; a red vest adds a touch of color to his ensemble. His hair, nearly chin-length as was the fashion at the time, flips up ever so slightly at the ends and falls to either side of his left ear. Stylistically, Markell’s self-portrait is much like his other paintings, confident brush strokes and clear color choice with a minimum of detail in the clothing results in an image that appears somewhat flat to the eye. Though aspects of his art lacks definition, he skillfully executes the 5’oclock shadow shading his chin and cheeks. The painting we have is signed not once but three times on the back of the canvas as was Markell’s custom to do. Recycling or reusing the canvas is the most likely reason for the multiple signatures. The first reads ‘John J. Markell, Del., Frederick MD, May 10, 1843’ and is crossed out, then ‘Bathing Lady,’ John J. Markell, Del., Frederick MD, August 13, 1843’ is written and also crossed out, finally, “John J. Markell, Del., Frederick MD, February 7, 1844’ remains.” I was able to peruse the online Art Inventories Catalog database of the Smithsonian’s American Art Museums and found reference listings for many of Markell’s known works. I was interested to see several portraits done of family members including his parents and siblings. (NOTE: I was not able to see any images of these, but hope that I will be contacted in the future by someone who has a Markell piece and finds this story on the internet. I have included a rundown from the database at the very end of this blog.) John J. Markell would die later that year in 1844 on December 2nd. This apparently occurred in nearby Hagerstown. John was likely buried in the German Reformed Cemetery that once stood at the northwest corner of W. 2nd and Bentz streets. Today this is the site of Memorial Park. He also could have been buried behind Trinity Chapel, as his Schley ancestors were among the founders of the German Reformed congregation here. Our records show that John J. Markell and his father were re-interred in Mount Olivet in April of 1866. The gravesite is in Area D/Lot 71. The artist’s mother would be laid to rest in this same lot in January, 1870. Siblings including older brother Thomas (d. 1902), who worked as a cashier at a local bank, and sisters Catharine (d. 1907) and Amelia (d. 1910) would join them here too.  The memory of John Johnston Markell is kept alive and well thanks to the fore-mentioned Heritage Frederick. To recognize the work of this young artist, the entity holds an annual contest to encourage local high school students to depict, through art, an aspect of the county’s history. The contest is funded by the John Markell Memorial Art Contest Fund, administered by the Community Foundation of Frederick County, with additional support from the Frederick Art Club. Cash prizes are awarded to three winners. John Johnston Markell Aug 24, 1838 Oil Painting IAP 7300001

(A Self-Portrait) View Near Fishkill Jan 1835 Watercolor IAP 7300002 Men on Horses unknown Watercolor IAP 7300003 Man of the unknown Oil Painting IAP 7300004 Markell Family Woman of the unknown Oil Painting IAP 7300005 Markell Family Landscape unknown Oil Painting IAP 7300006 George Markell unknown Oil Painting IAP 7300007 Sophia Schley Markell unknown Oil Painting IAP 7300008 John Johnston Markell Oct 4, 1839 Oil Painting IAP 7300009 (A Self-Portrait) Landscape with unknown Oil Painting IAP 73000010 People, Dog and Castle Landscape with Cows unknown Oil Painting IAP 73000011 St. John Roman 1840 Oil Painting IAP 73000012 Catholic Church John Johnston Markell Feb 7, 1844 Oil Painting IAP 73000013 (A Self-Portrait) Jacob Byerly 1843 Oil Painting IAP 73000014 Samuel Markell 1842 Oil Painting IAP 73000015 Mrs. Samuel Markell 1842 Oil Painting IAP 73000016 (Amelia Schley) George Markell unknown Oil Painting IAP 73000018 Sophia Markell unknown Oil Painting IAP 73000019 Jacob Markell February 7, 1839 Oil Painting IAP 73000021 Cupid on a Dolphin January 1, 1839 Oil Painting IAP 73000022 Infant Savior March 1840 Oil Painting IAP 73000023 The Painter’s Sister March 30, 1839 Oil Painting IAP 73000024 |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed