|

Like so many of these “Stories in Stone,” I seem to just fall into them by accident every once in a while. Something usually catches my eye, be it an interesting name, an intriguing newspaper story, an anecdote from a visitor or family historian, a trigger relating to one of my past research projects, or in this week’s case—it’s “the stone” itself that got me thinking. Mid-last week, I found myself walking around Area B, one of Mount Olivet’s oldest sections, not far from the cemetery’s main entrance. I was taking photographs of World War I veteran graves for our www.MountOlivetVets.com website when a large monument came clearly into view. It was roughly 12-foot tall and I had never really taken notice of it before. The memorial is a very attractive marble monument, with intricate architectural features and topped with a shaft with an urn at the top. Around the shaft is a sculpted laurel wreath which is said to represent great distinction and “victory over death,” in the form of eternity or immortality.

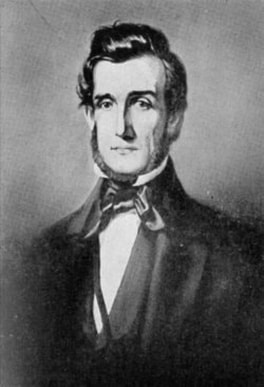

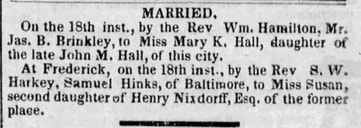

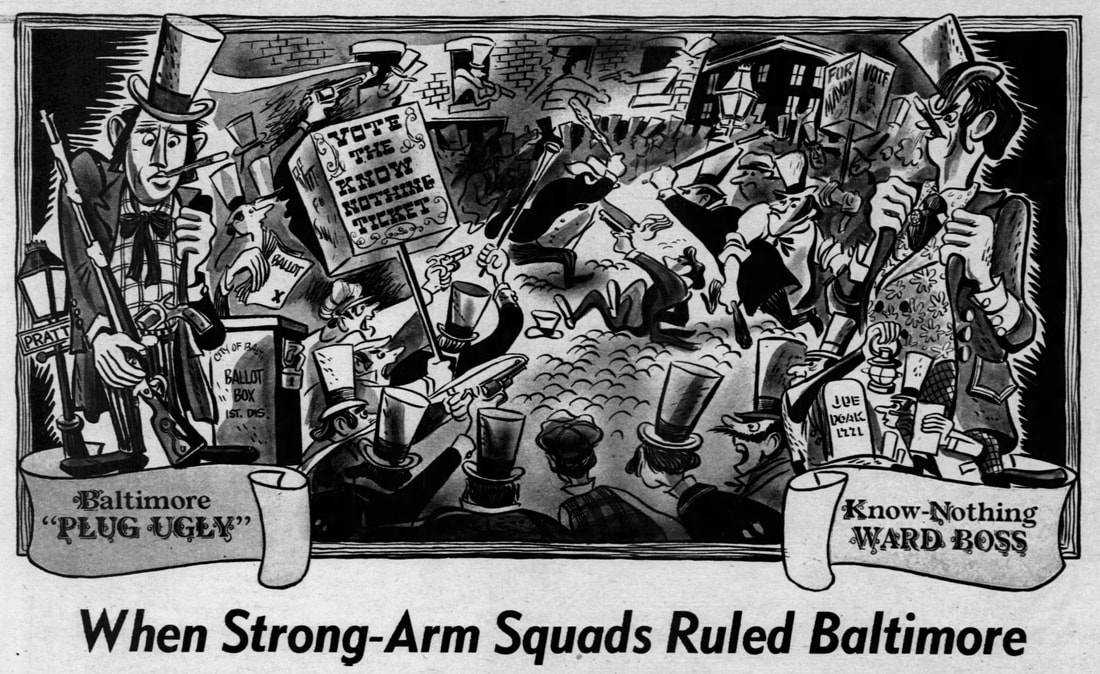

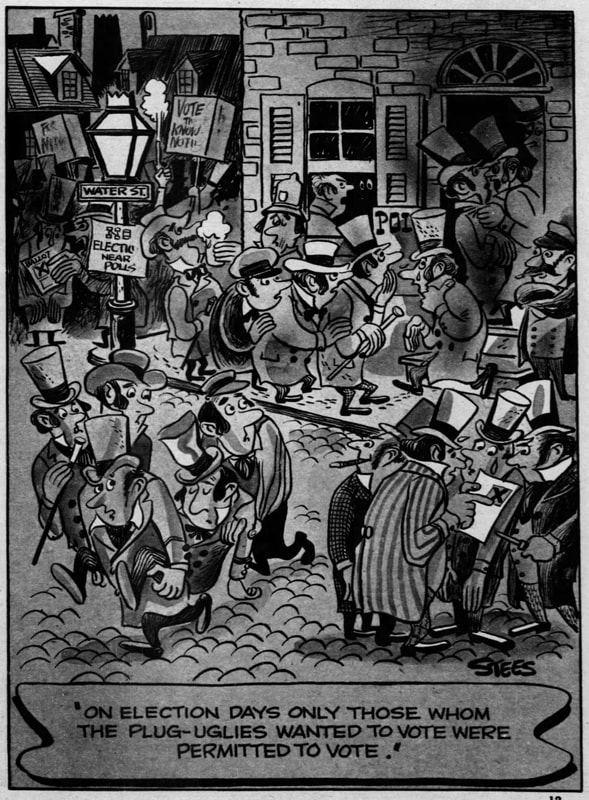

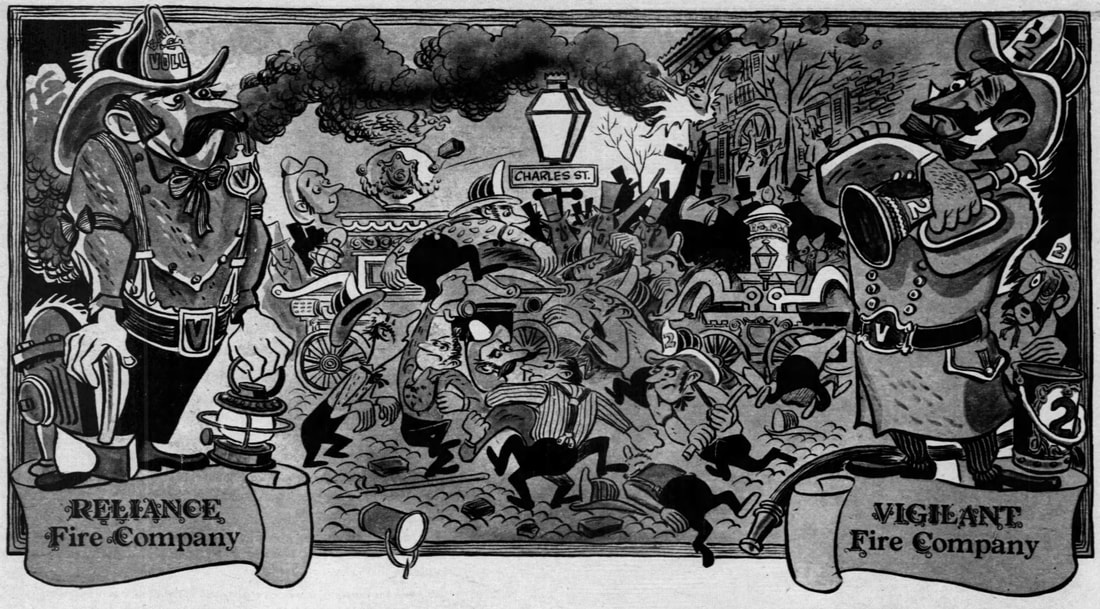

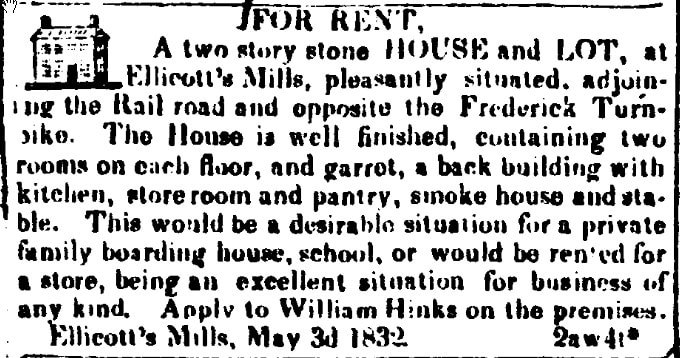

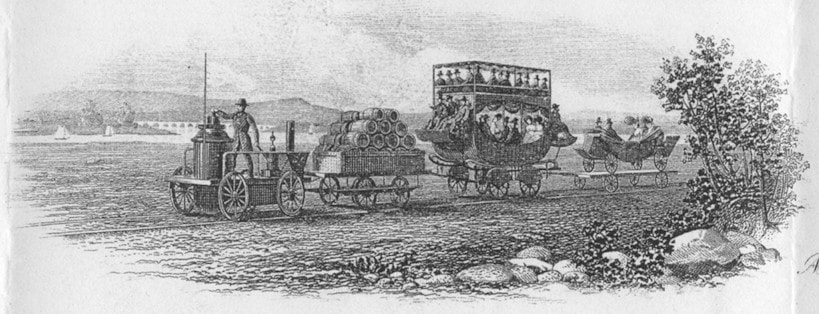

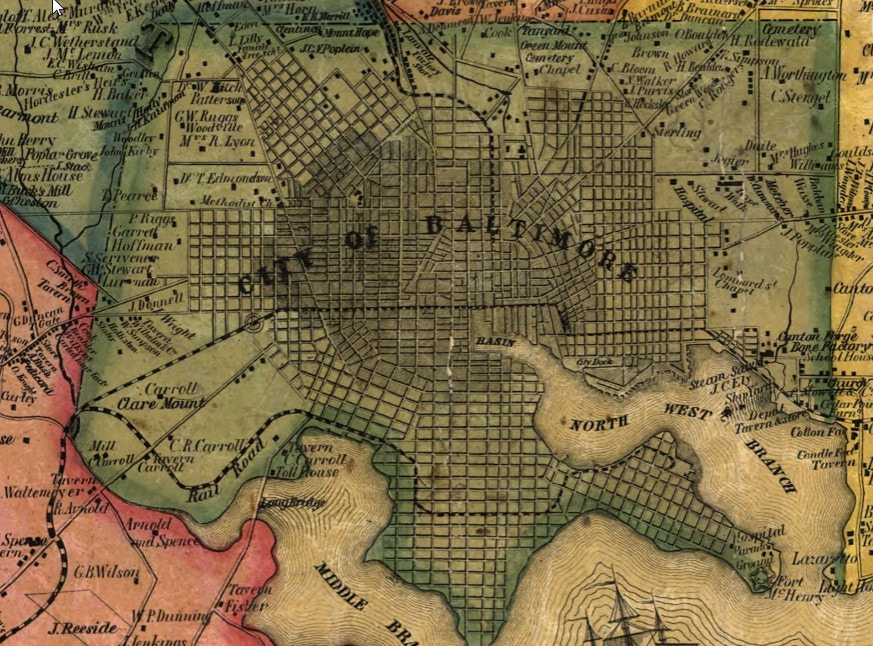

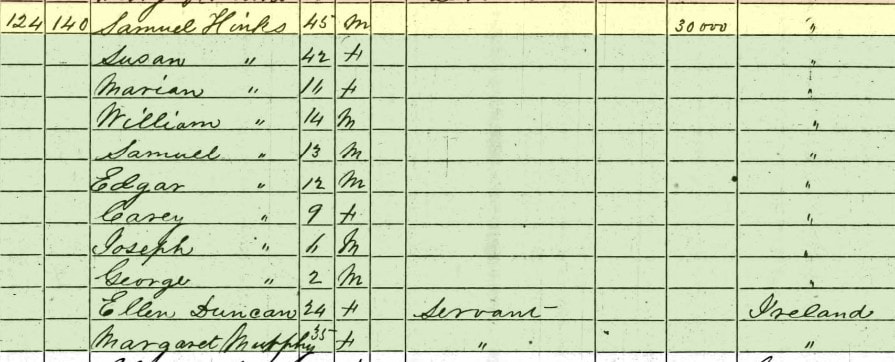

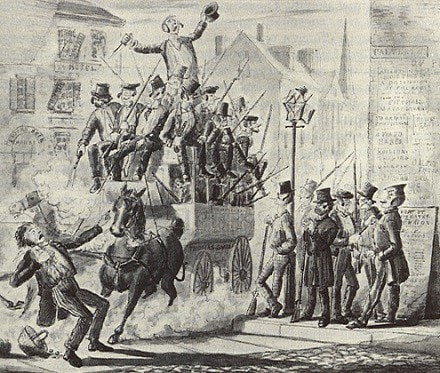

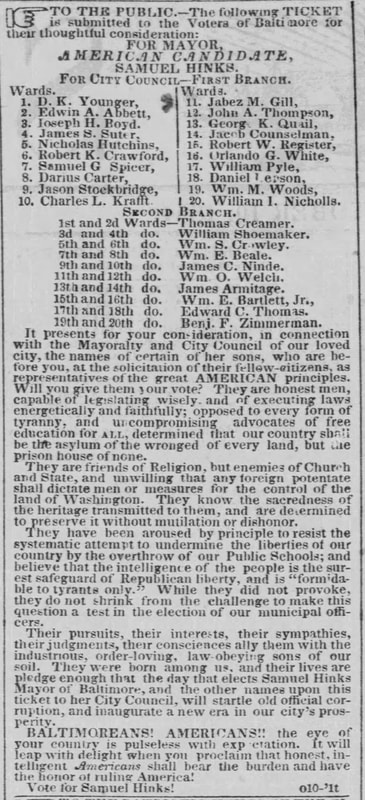

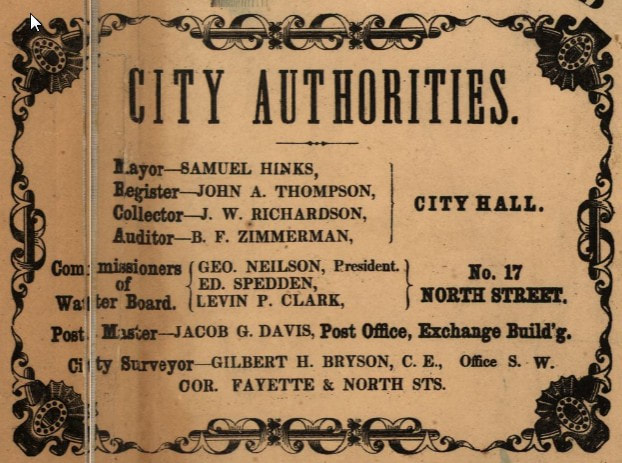

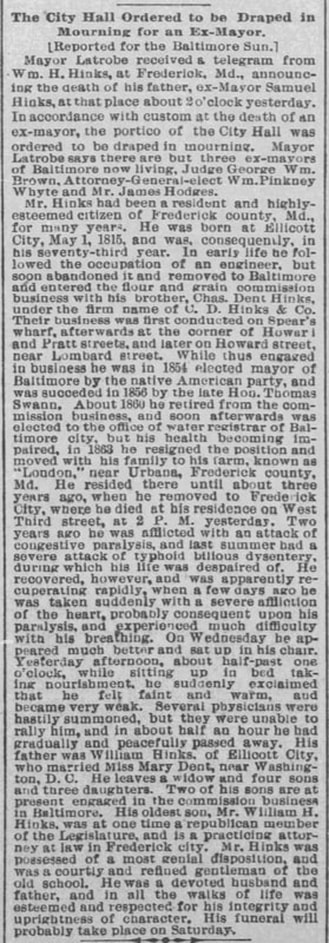

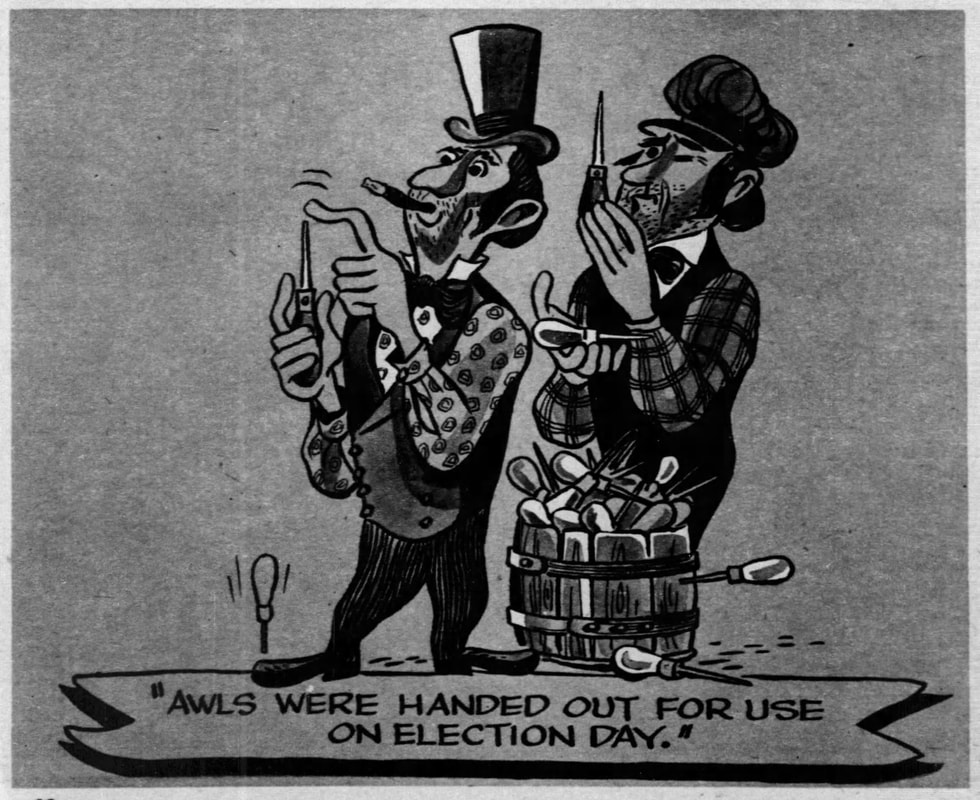

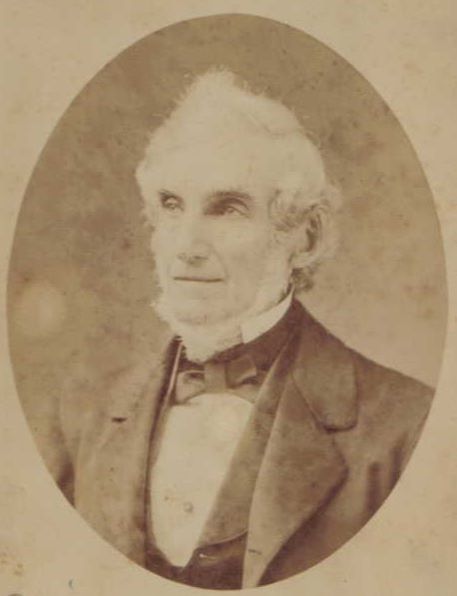

Samuel Hinks (1815-1887) MSA SC 3520-12475 Biography: Samuel Hinks was Mayor of Baltimore from November 13th, 1854, to November 10th, 1856. During this administration an ordinance authorizing the erection of a new City Jail was passed and the contract for the building was signed. The waterworks, which supplied Baltimore, were acquired from the Baltimore Water Company and a Water Department was organized to operate the system as a municipal plant. An ordinance passed during the latter part of this administration provided for taking water from several mill-dams on the Jones Falls and Stony Run, conducting this water to a reservoir and thus supplying the City. Other legislation authorized the construction of a new Western Female High School, Fayette, near Paca Street; two other school buildings and establishing a floating school for training youths for nautical pursuits. Provision was made for placing iron bridges over Jones Falls at Pratt, at Gay and at Baltimore Streets, and for a new market house for Lexington Market from Paca to Greene Streets. Legislation to open large portions of Hanover and Eager Streets was approved. A Councilmanic resolution was passed requesting Congress to establish a Marine Hospital at Baltimore. Agents representing the City in executing the McDonogh will were named and directors for the school (McDonogh) were appointed. Authority to sell the City's interest in the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was granted. A resolution petitioning the Legislature against a bill then pending to erect the Long Bridge over the Patapsco River and Middle Branch was passed. The bridge, however, was built and but recently razed, being replaced by the new Hanover Street structure. The House of Refuge (Maryland School for Boys) on Frederick Road was opened. One of Mayor Hinks' messages contained a proposal to sell Richmond and Cross Street Markets.  Samuel Hinks Samuel Hinks The Continued Search The Maryland archives page gave me a pretty good start. I was fascinated with the fact that we had a mayor of Baltimore buried here in Mount Olivet, something likely not known by cemetery staff and local historians over the last century. My questions now centered around the obvious: “Why was he buried here in Frederick, and not Baltimore?”; “Did he die here?”; “Was he originally from Frederick?”; “Are other family members buried within Mount Olivet?” I knew I’d soon be looking at such local sources such as Mount Olivet’s cemetery records, Ancestry.com, T.J.C. Williams History of Frederick County, and Jacob Engelbrecht’s Diary. Before I did, however, I wanted to see what the Wikipedia page for Samuel Hinks had to say. It was definitely less flattering than the State Archives biography, possessing the innuendo that Hinks perhaps acquired his job by “mob rule,” both literally, and figuratively. Here is what Wikipedia had to say: Samuel Hinks was born in Ellicott City, May 1st, 1815. In early life he followed the occupation of steam engineer. Removing to Baltimore he entered the grain and flour commission business, later establishing a partnership with his brother, Charles Dent Hinks. Samuel Hinks was elected Mayor by the "American Party" in 1854. In 1860 he retired from the grain commission business and shortly thereafter was elected Water Registrar, which position he held until 1863. He died November 30th, 1887. In 1854 Samuel Hinks was elected Mayor of Baltimore, standing as a candidate for the nationalist anti-Catholic “American Party.” Members of the party were popularly known as "Know-Nothings" because, when asked about their secret organizations, their members were said to reply "I know nothing.” I learned that this led to something referred to as the Know-Nothing Riot of 1856. I quickly switched gears to find out what that was all about. The Know Nothing Riot of 1856 (courtesy of Wikipedia) During the mid-1850s, public order in Baltimore had been threatened by the election of candidates of the American Party. As the 1856 Mayoral elections approached, Samuel Hinks was pressed by Baltimorians to order the militia of General George H. Steuart in readiness to maintain order, as widespread violence was anticipated. Hinks duly gave Steuart the order to ready the militia, but he soon rescinded it. In the event, violence broke out on polling day, with shots exchanged by competing mobs. In the 2nd and 8th wards, several citizens were killed, and many wounded. In the 6th ward, artillery was used, and a pitched battle fought on Orleans St between gangs of Know Nothings and rival Democrats, raging for several hours. The result of the election, in which voter fraud was widespread, was a victory for the Know Nothing candidate, Thomas Swann, by around 9,000 votes. Swann duly succeeded Hinks as Mayor of Baltimore. Wow, this info all came to me thanks to curiosity in wanting to know who was buried under that handsome monument in Area B of Mount Olivet. I would have been simply satisfied with his accomplishments as mayor, but I had learned that this was a man embroiled in an amazing time in our history—the eve of American Civil War. Baltimore would serve as a microcosm of what was taking place on the national stage. Civil War Connections A few years ago, I had the once in a lifetime opportunity to work with some of the best Maryland Civil War authors and historians, as I assisted in producing a film documentary with Maryland Public Television entitled “Maryland’s Heart of the Civil War.” One of the “on-camera” commentators for the project was a great historian named Daniel Carroll Toomey. Dan recently served as special curator for the B&O Railroad Museum in Baltimore throughout the 150th Sesquicentennial commemoration of the “war between the states.” One of the topics I asked Dan to talk about (within the documentary) was the infamous Baltimore Riot of 1861, commonly called the "Pratt Street Riots.” This was a civil conflict that took place on Friday, April 19, 1861, on Pratt Street, in Baltimore. The combatants were anti-war "Copperhead" Democrats (the largest party in Maryland) and other Southern/Confederate sympathizers on one side, and members of Massachusetts (and some Pennsylvania) state militia regiments en-route to the national capital at Washington. These men came to Baltimore via the railroad as they had been called up to protect the Union capital in response to recent actions at Fort Sumter and the secession of states. The fighting began at the President Street Railroad Station, spreading throughout President Street and subsequently to Howard Street, where it ended at the Camden Street Station. The riot produced the first deaths by hostile action in the American Civil War and is nicknamed the "First Bloodshed of the Civil War.” The gangs of Baltimore played a large role in the violence, thus resulting in Baltimore being put under martial law for the duration of the ensuing war. Federal Hill was constructed by the Union Army, and large artillery guns were pointed at Baltimore’s harbor and center city area as a deterrent. Dan Toomey shared with viewers the fact that Baltimore was often seen as the northernmost “Southern city,” having more in common with Richmond (154 miles away) than with Philadelphia, only 89 miles distant. Add to that a penchant for raucous gang activity, and you surely have a powder keg on your hands. So seldom do we see unhappiness with particular politics actually escalate into anger and irrational behavior. I’m being sarcastic of course.  In case you are interested in learning more about the Pratt Street Riots, click on the following link to see our MPT interview with Dan Toomey regarding the April 19th, 1861 event: https://vimeo.com/95439373 I set out to glean some information on gang makeups in Baltimore preceding the 1861 Pratt Street event. I also had a small visual in my head from modern times, in which many of us saw a more recent riot play out 154 years later live on our television and electronic device screens just three years ago on April 27th, 2015. This ugly episode was brought in response to the death of 26-year-old Freddie Gray at the hands of officers with the Baltimore City Police Department. Following Gray’s funeral, civil disorder intensified with looting and burning of local businesses and a CVS drug store, culminating with a state of emergency declaration by the governor. Maryland National Guard was deployed to Baltimore, and a curfew was established. Another major period of unrest and upheaval occurred 50 years ago this month in Baltimore with the infamous race riots of 1968. This followed the April 4th assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. Mobtown To get a feel for the earlier Civil War period that preceded the Civil Rights movement by a century, there is no better illustrative tool than the 2002 Martin Scorsese film “Gangs of New York” starring Leonardo DiCaprio and Daniel Day-Lewis. Saying this feature includes a pretty violent depiction of large city “gang life” of the mid-nineteenth century is an understatement. As the title implies, this movie is about New York City’s historic gangs that were centered in the Five Points area of lower Manhattan. Elements of ruthless crime and political corruption pepper this film, amidst the legendary historical event of the New York City Draft Riots of July 13-16th, 1863. So what was the “gang atmosphere” like in Baltimore at the time of Samuel Hinks’ rise to power in the 1850’s? Well, I checked another source to learn more about Baltimore’s earlier nickname, the one before “Charm City.” It was known as “Mobtown.” The earliest print documentation of the term Mobtown occurs in an 1838 copy of The Baltimore Sun; yet, it is said that by that time the name was already well established. One of the earliest tales comes from the turmoil of the American Revolution in 1777. A group of anti-British Baltimoreans called the Whig Club congregated outside the home of William Goddard. Goddard was the editor of the Maryland Journal who expressed pro-British sentiments. The mob forcefully removed him from his home and tarred and feathered him in the street. In response to the violence of the Whig Club, then Governor of Maryland stated the following on April 17, 1777 “all bodies of men associating together… for the purpose of usurping any of the powers of government, and presuming to exercise any powers over the persons or property of any subject of this State, or to carry into execution any of the laws thereof on their own authorities, unlawful assemblies.” A similar attack would happen to Federalist publisher Alexander Contee Hanson who successfully warded off a mob during the War of 1812. Ironically, Baltimore would erupt in riot in protest again in 1835 and 1839 in addition to the aforementioned 1856 and 1861 unfortunate events—all connected with local and national political developments. As stated before, Samuel Hinks was associated with the Know Nothing faction. To review, this group earned its name because members answered that they “knew nothing” when questioned by authorities regarding their aggressive activities. The Know-Nothings were particularly strong in Baltimore, where they included groups in the majority of wards with such unusual and colorful names as the Blood Tubs, McGonigan’s Rip Raps, Natives, Rough Skins, Tigers, Black Snakes, Wampanoags, Regulators, Double-Pumps, Hunters, American Rattlers, Butt Enders, Blackguards and so on. I found other great sources for information on these gangs courtesy of the Baltimore Sun with an article from May, 1951 by Ernest V. Baugh, Jr.; and by content provided on the Baltimore City Police Department website. The following is an excerpt from the history section of the website: “Gangs of young men parade public thoroughfares, armed with knives and revolvers,” wrote the Baltimore Sun in 1857, describing the makeup of these groups, which relied on violence and intimidation. “Collisions have been frequent between Americans and citizens of Irish and German extraction. The most bitter hostility has been encouraged between native and foreign-born citizens.” One of the most notorious gang of Know-Nothings in Baltimore was called the Plug Uglies. In 1857, the Washington Star called it “as pestilent and scrofulous a brood of scoundrels as hell itself could vomit from its vilest crater.” Growing out of the Mount Vernon Hook-and-Ladder Company—an all-volunteer firefighting group—the Plug Uglies were nasty, contemptible political gangsters who generally ran with McGonigan’s Rip Raps and often tangled with any Democrats in the city. According to folklore, the name “Plug Ugly” possibly refers to a specific gang member who was considered ugly to look upon but generous with his tobacco plugs—an inverse of the expression “ugly plug” or the “ugly blows” the gang delivered in its fights. Eventually, the term would be linked to anyone who was considered a “rowdy.” Members took pride in their brutal actions, even composing songs about their “valor” and strength. One such ditty was entitled “The Plug Uglies!” The song praises the gang’s ability to help elect or run out particular political candidates, including mayoral candidates, as well as former president Millard Fillmore, who ran an unsuccessful reelection campaign in 1856 as the American Party candidate. During the election, he only carried Maryland. In 1858, Maryland would receive its governor, Thomas Holliday Hicks, courtesy of the American Party and its Know Nothings. Although it may sound strange today to hear of a firefighting company described as violent, members of the Plug Uglies’ Mount Vernon Hook-and-Ladder Company were just as likely to get into a fight with a rival company while on the scene to extinguish a fire. As flames raged and threatened surrounding buildings, the firefighters would regularly ignore their duties to engage in “battle royales” with one another, using their axes, picks, hooks and even the street cobblestones and sidewalk bricks. In fact, some of the members were accused of starting several fires. So our Samuel Hinks must have quite an individual to have gained the support of the Plug Uglies, at least in that municipal election of 1854. Samuel Hinks (before Baltimore mayoral term) TJC Williams’ “History of Frederick County” states that Samuel Hinks was a native of Frederick County, where he was born on May 1st, 1815. This already contradicts the Wikipedia biography which claims that he was born in Ellicott City. Samuel’s father, William Hinks was associated with Ellicott City, however, and the town’s namesake progenitors—the Ellicott brothers. William Hinks was a machinist who would supposedly serve as superintendent of the Ellicott Mills operation. Through further research, I found that, in the year 1823, William Hinks purchased a stone dwelling structure from the trustees of John Ellicott. The location is on the eastern approach to Ellicott Mills coming from Baltimore on the famed roadway that would become known as the National Pike. This building is still standing and is commonly referred to as the Bridge Market house.  In 1828, William Hinks received a contract from the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad “to lay the first track, on about seven and a half miles, of the second division, next above Ellicott’s Mills.” This was a big deal as the famed railway broke ground on July 4th, 1828. It would reach Frederick in December, 1831. I read that Mr. Hinks also had a hand in the design of the first railway carriages, pulled at first by horses, and then by the initial iron steam engine developed by Peter Cooper and named “the Tom Thumb.” Samuel Hinks is said to have worked for the B & O as a “steam engineer,” which seems to make perfect sense as his childhood home was next to the tracks, built in part by his father. He next moved to Baltimore and joined his brother, Charles Dent Hinks, in operating the firm C. D. Hinks & Company, a flour and grain dealer that had a siding connecting to the B & O. The Hinks brothers were known for their “forceful personalities,” which helped give their business in prosperity and prestige. Apparently Samuel “directed the affairs of the establishment with an ability, foresight and sagacity that stamped him as a man of high executive and business capacity. Within no time, he would become highly active in Baltimore civic causes, politics and political circles.  Baltimore Sun (Oct 20, 1842) Baltimore Sun (Oct 20, 1842) On October 17th, 1842, Samuel would marry a local Frederick girl by the name of Susan Nixdorf. They would go on to have seven children, the first, a boy named William Henry, in 1844. In 1845, Samuel Hinks became treasurer for the Relief of the Poor in Baltimore’s 12th Ward. He would eventually take up residence in the city’s 14th Ward.

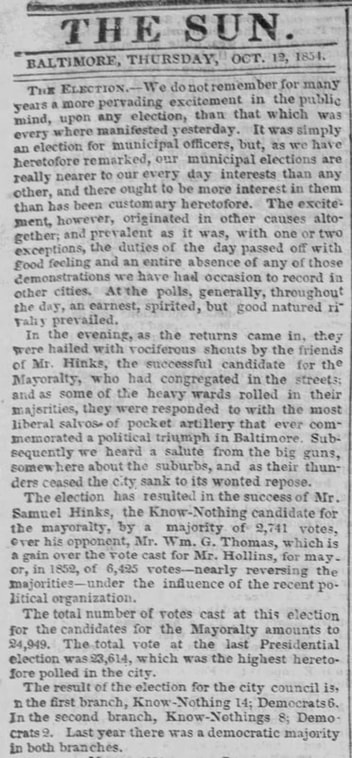

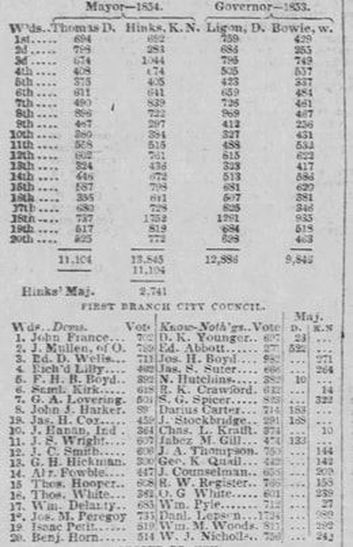

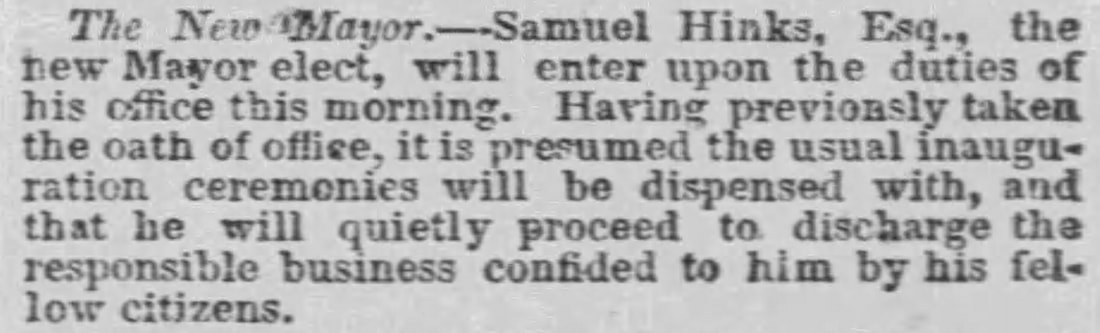

The Hinks brothers were entrenched in this group, belonging to a secret lodge. Up to this point, Samuel Hinks had never held a public office. He announced his candidacy only two weeks before the mid-October election, and followed by doing little if no campaigning. Even the convention that nominated him was held in secret. On Wednesday, October 11th, Hinks won by a margin of 2,741 votes—13,845 to 11,104 over Democratic challenger William G. Thomas. The total vote tally in this municipal election had even bested the presidential election of the previous year. Hinks’ victory came as an utter shock to the Democrats who had controlled the city for the past decade.

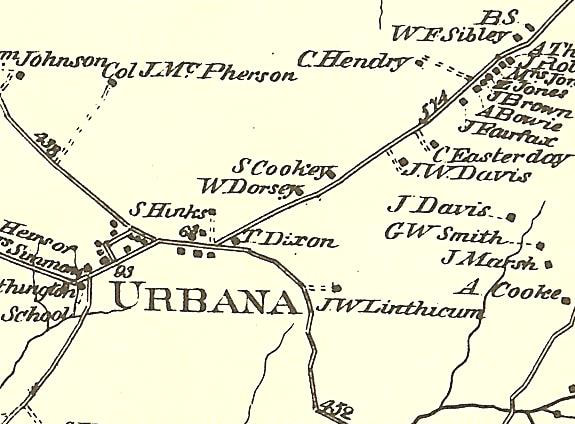

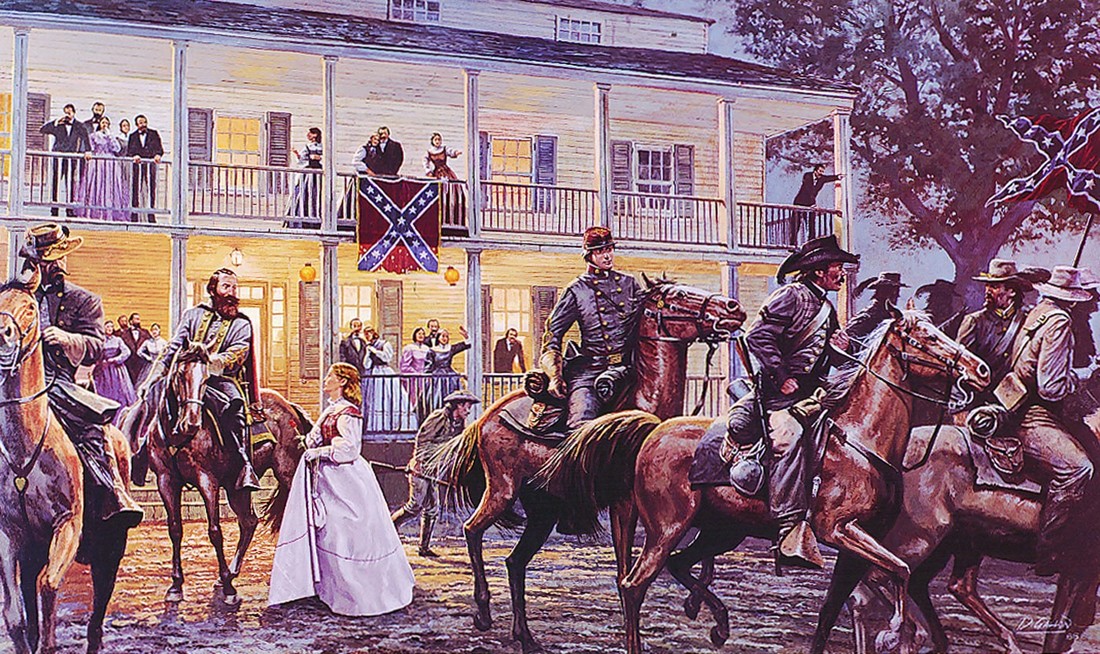

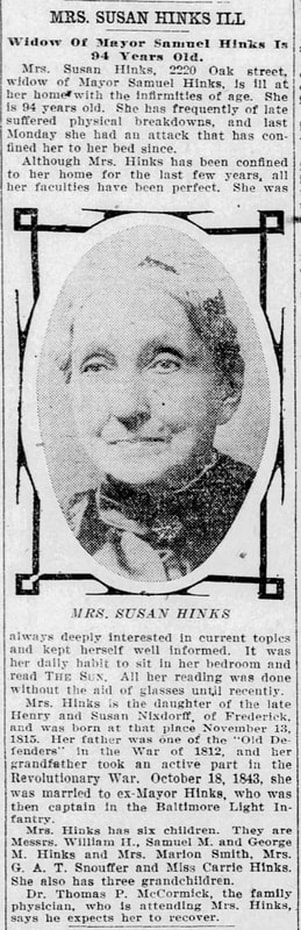

It was business as usual again for the Know Nothings. In opposition, Baltimore’s pro-slavery segment consisted of an uneasy coalition of “conservative businessmen, partisan Democrats, and beleaguered immigrant groups that had spent six years battling Know Nothing Rule.” These groups united to form the Reform party to challenge the Know Nothings in 1859. They would regain control in 1860—just in time for the Civil War. Samuel Hinks (after Baltimore mayoral term) In 1860, Samuel Hinks retired from the grain commission business and shortly thereafter was elected Water Registrar of Baltimore. In addition, he was a director of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. He even was nominated for president of the railroad, but lost convincingly to incumbent John W. Garrett. In 1863, Hinks experienced health issues, necessitating him to give up his municipal post. He also made the decision that country life would help him regain his health. He moved to Frederick County, and to the former 128-acre estate owned by Susan’s Nixdorf family, more recently known as the Dudderar Farm. Today, this comprises the Villages at Urbana subdivision. For his domicile, Samuel Hinks would purchase the neighboring Landon Academy structure (Landon House), scene of J.E.B. Stuart's Sabres and Roses Ball in September, 1862.  He settled into the role of country farmer quite nicely, far from the intricacies of Baltimore. Hinks used the opportunity to further groom his oldest son, William Henry, in the art of politics. William H. Hinks (1844-1912) had worked in the family grain business in Baltimore as a teenager, but would go on to study law at the University of Maryland, graduating in 1872. He moved to Frederick with his parents and was admitted to the Frederick Bar. William H. Hinks would gain election as a state delegate representing Frederick County to the Maryland General Assembly for two terms, 1875-79. In 1895, he was nominated to be a Republican candidate for Mayor of Frederick. Ironically, he would lose by a total of 11 votes. Shortly thereafter, he was nominated for State’s Attorney and elected. As for Samuel, he stayed active in Frederick affairs, moving to Frederick City’s West Third Street after selling his Urbana estate to Luke Tiernan Brien in 1883. He would die four years later on November 30th, 1887. Hinks obituary was featured in several newspapers around the state and many attended his funeral service at Mount Olivet, held Saturday, December 3rd. Susan would live to the ripe age of 92, joining her husband under the shadow of their fine monument on May 5th, 1909. William H. Hinks and second wife Janet Chase Hinks would also be laid to rest in Area B/Lot 21.

1 Comment

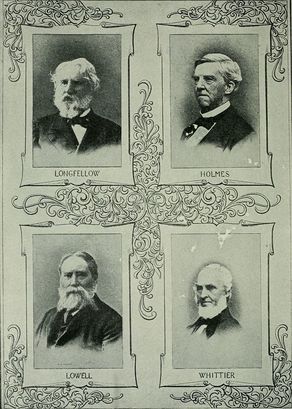

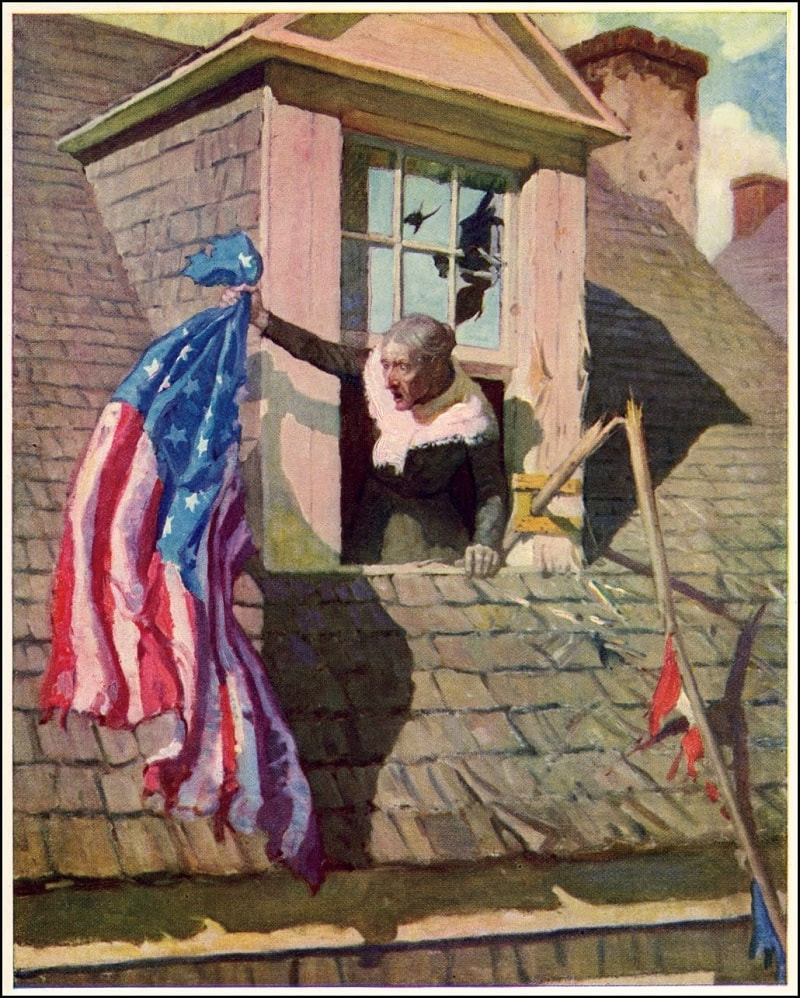

Mount Olivet Cemetery serves as the final resting place to a true legend in American broadcasting. His name is Edward Heston Walker. Some may not be familiar with the name, but man, you should have heard Ed Walker on the radio during an illustrious career spanning six and a half decades! Long before the advent of television, there was radio—the very first broadcast medium. Radio became popular in the early 1920’s and over the next few decades, home devices became readily available to the populous. It was not uncommon to find families of varying socio-economic levels gathered around a home radio in evenings and intently listening to things such as popular variety shows, presidential addresses, and boxing matches. This was reminiscent of earlier generations in the mid-19th century who regularly assembled around the fireplace at night to read aloud classic works by New England-based poets such as Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, William Cullen Bryant, James Russell Lowell, Oliver Wendell Holmes and a man with special ties to Frederick—John Greenleaf Whittier. They were fittingly known as the “Fireside Poets,” and had gained great popularity by presenting domestic themes and messages of morality within conventional poetic forms. In other words, this was a great way to get children of all ages to take history-themed “moral medicine.” Through a rhyming couplets and lyrical cadence, kids and adults alike could "joyfully" learn about historical events, all the while conjuring up amazing scenes in the mind's eye of participants. Among the most popular of these offerings were Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride,” Holmes’ “Old Ironsides,” and who can forget a little ditty about Frederick, Maryland by John Greenleaf Whittier entitled “Barbara Frietchie.” The latter presented readers and listeners around the country (and world) an opportunity to entertain (in their brain) our aesthetic local surroundings that included “meadows rich with corn,” green-walled hills” and “clustered spires.” These visuals were simply a backdrop for the theatrics at hand which involved our brave nonagenarian reportedly waving her Union flag in the face of Gen. Stonewall Jackson and the Confederate Army. John Greenleaf Whittier, the Quaker abolitionist from Amesbury, Massachusetts, painted quite a dramatic picture of Barbara Fritchie’s defiant stand from the second-story dormer window of her home on W. Patrick Street. Shots were fired at her, actually breaking the staff, but 95-year old Barbara remained unshaken and vigilant. Whittier’s pen, and poem, put Frederick on the map “so to speak,” and countless visitors from across the world yearned to see the location with their own two eyes. One such would be the future Prime Minister of Great Britain—Sir Winston Churchill. Churchill learned the "Barbara Frietchie" poem as a boy, as it was oftentimes a staple taught in Britain's grade schools. In 1943, while en-route to the presidential retreat with President Roosevelt, he would get the chance to feast his eyes on the actual home of Whittier's heroine—Frederick, Maryland.

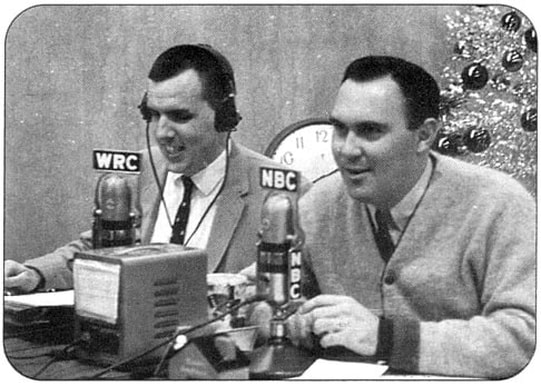

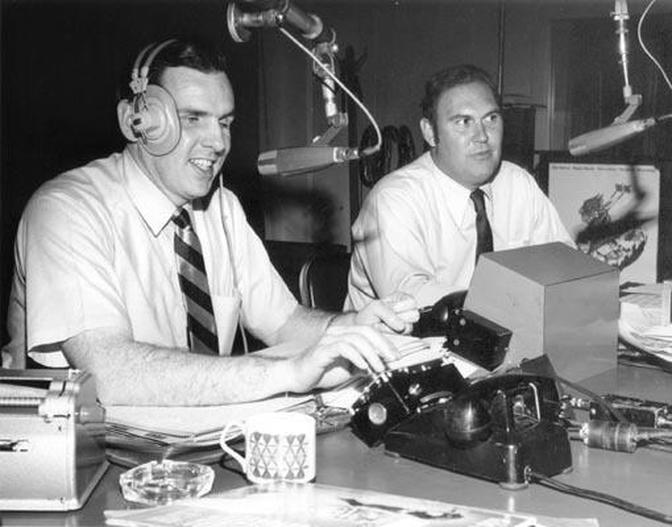

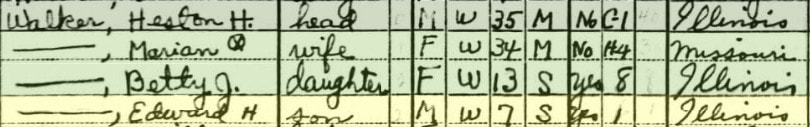

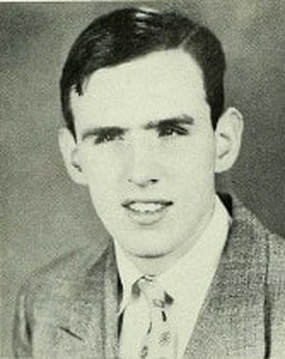

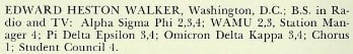

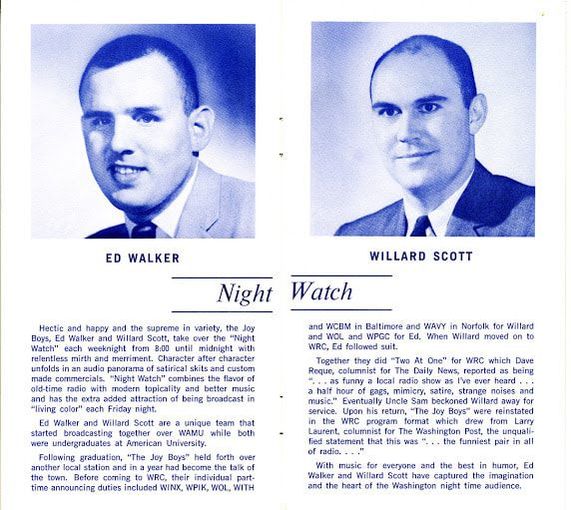

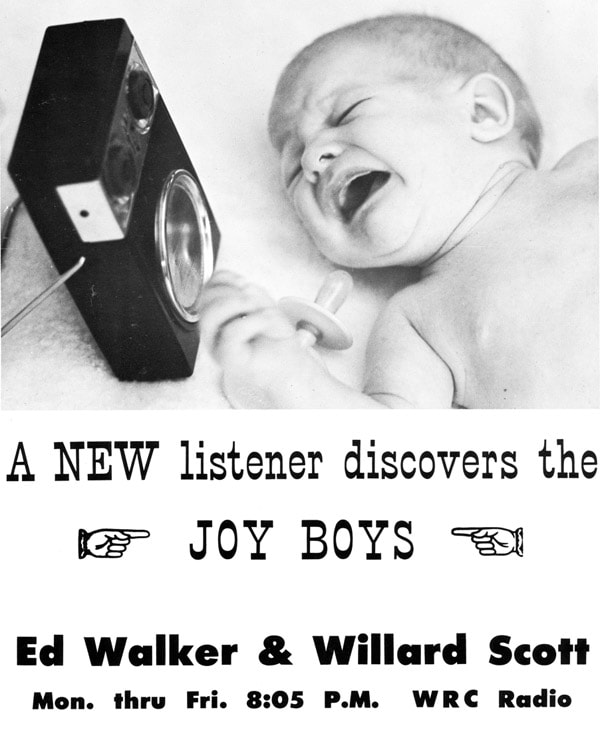

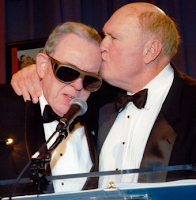

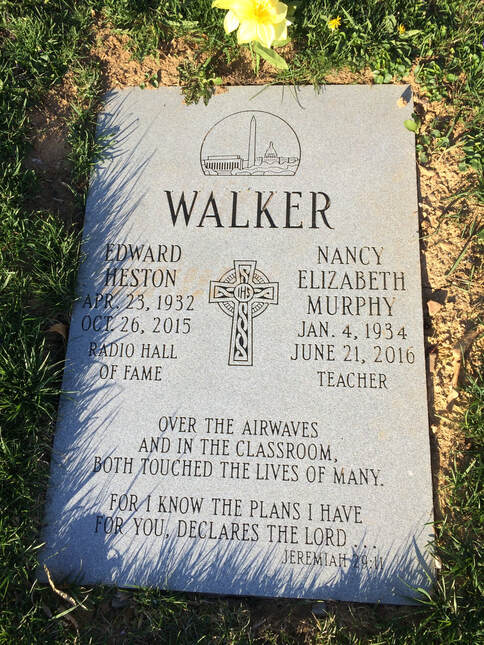

In late 1989, I began a job with our local cable company (Frederick Cablevision) which had a small television production unit. For me, this would eventually turn into a 17-year career at the helm of local Cable channel 10. Aiding in my departure from future radio pursuits was my fascination with historical documentary television. Ironically, this would come in part due to a documentary on the history of radio by documentarian extraordinaire, Ken Burns. The work in question was his 1992 follow-up to his legendary “The Civil War,” entitled “Empire of the Air: The Men who Made Radio.” The end result is that this history of radio made me love the medium of television even more than I had before. And it was television’s popularity in the 1950’s and onward that supplanted radio, or at least what we know as “the Golden Age of Radio.” In 1980, a British music group called The Buggles had the distinct honor of having their song "Video Killed the Radio Star" be the first-ever music video played on an upstart cable television network called MTV. I guess it’s safe to use the old adage: “What comes around, goes around” I guess, because this is what radio did to the popularity of those“Fireside Poets” earlier in the century. Now radio is still around today, and is remains an important mode of news, information, sports and entertainment for listeners engaged in the act of driving where eyeballs should be on the road, not a video screen. Conversely, over the years, as families began to gather around the television, home usage of radio declined as people yearned for visual stimulation to go along with the audio. However, the growth of automobile travel helped bolster radio's importance, as it still does today. Satellite radio has offered additional opportunities over the last two decades, much in the same vein as what cable television did to mainstream broadcast television and its original handful of channels, based, of course, on the technological ability to pick up signals with an antenna. The Golden Age Old-time radio, sometimes referred to as the Golden Age of Radio, was the medium of choice for scripted programming, variety and dramatic shows. According to a 1947 survey, 82 out of 100 Americans were radio listeners. A variety of new entertainment formats and genres were created for the new medium, many of which later went to television such as mystery serials, soap operas, radio plays, quiz shows, variety hours, play by play sports, children’s shows and variety hours. Long about the 1950’s, commercial radio programming shifted to more narrow formats of news, talk, sports and music. It was around this time that two, local college students from the DC metro area first met while attending American University. Both would become legendary in the field of radio broadcasting, one day becoming enshrined in the National Radio Hall of Fame, located in Chicago. These young men had an uncanny knack for writing and performing sketch comedy on the radio, and like the “Fireside Poets” of yore, each could easily conjure up amazing visuals in the mind’s eye of their listeners. This was particularly fascinating in the case of one of the duo, Ed Walker, a gentleman who had been blind since birth. His partner is a little more well-known because of his years as the original, “loveable” weatherman on NBC’s Today Show—Willard Scott. Ed Walker died in late October, 2015 and was buried here in Mount Olivet nearly a month later. He was born April 23rd, 1932. He was not a Frederick native—but married one however, and that's what brought him to Frederick's "garden cemetery." Ed's beloved wife, Nancy, passed just over eight months after her husband. She was the daughter of Frederick plumber Charles F. Murphy. Mr. Murphy opened his popular business in 1953 after working many years under other Frederick plumbing contractors. He was aided by his wife Kathleen and the business grew to include their sons, a son-in-law, daughter-in-law and a grandson. The business still exists today, located off Rosemont Ave/Yellow Springs Road (near the Old Farm Shopping Center) Originally from Illinois, Walker moved with his family to Washington, DC as a boy. As the first blind student accepted by American University, Ed Walker went on to help found WAMU-AM in 1951. He would later help secure the 4,000 watt transmitter from WGBH in Boston that launched WAMU-FM on October 23, 1961. After graduation from American University, Ed Walker and Willard Scott teamed up for the "Joy Boys Radio Program," a nightly drive-time offering of NBC-owned WRC radio in Washington, DC. The tandem performed in this capacity from 1955-1974, the final two years being on WWDC. Scott routinely sketched a list of characters and a few lead lines setting up a situation, which Walker would commit to memory or make notes on with his Braille typewriter. In a 1999 article recalling the Joy Boys at the height of their popularity in the mid-1960s, The Washington Post said Walker and Scott "dominated Washington, providing entertainment, companionship, and community to a city on the verge of powerful change.” It wasn't just a professional relationship between the two men, as Ed Walker and Willard Scott were said to have been "closer than most brothers." I found a fabulous biography online in the form of Ed’s obituary, magnificently written and published in the Washington Post. Here is a glimpse of the wonderful life of a true radio pioneer, one I would have emulated as a child, and surely respect and appreciate as a learned adult.  Edward Heston Walker Washington Post Obituary Ed Walker, who amused and entertained a generation of Washington-area listeners as half of “The Joy Boys” radio team with Willard Scott and spent 65 years on the local airwaves as a deejay, news host and genial raconteur, died Oct. 26 at a retirement community in Rockville, just hours after his final broadcast. He was 83. Mr. Walker had been undergoing treatment for cancer, said his daughter, Susan Scola. A lifelong radio connoisseur, Mr. Walker became one of its most skillful practitioners over his long career. For the past quarter century, he hosted a popular weekly radio-nostalgia program, “The Big Broadcast,” on public radio station WAMU-FM (88.5). Each week, he invited listeners to “settle back, relax and enjoy,” as he discussed and introduced replays of such golden-age programs as “Yours Truly, Johnny Dollar,” “Dragnet” and “Gunsmoke.” He recorded his last “Big Broadcast” on Oct. 13 from a hospital bed while being treated at Sibley Memorial Hospital in Washington. Mr. Walker listened to the final broadcast Sunday night on WAMU, surrounded by his family, a few hours before his death, according to the station. Born blind, Mr. Walker grew up with radio as his constant companion from an early age. By age 8, he was operating a low-power radio transmitter in his family’s basement, beaming music to his neighbors’ houses down the block. He would go on to spend almost all of his adult life involved in the medium in some way, all of it on stations in Washington. It was “The Joy Boys” — a gently humorous, somewhat anarchic and broadly popular daily program — for which Mr. Walker is perhaps most fondly remembered. Mr. Walker and Scott became friends while working on American University’s campus radio outlet, WAMU, then an AM station. They got their professional start in 1952 doing short comedy bits on a weekend radio show on WOL called “Going AWOL.” In 1955, they moved to daytime on NBC-owned WRC with a show called “Two at One.” When the show became a local hit, they moved into the evening hours as “The Joy Boys.” Mr. Walker conjured up a series of characters and situations, some of them topical. He did the voices of such characters as Old Granddad and Bal’more Benny (“the poet of the Patapsco”) while Scott played the straight man. They parodied NBC’s leading newscast, “The Huntley-Brinkley Report” with “The Washer-Dryer Report” and a popular soap opera with a continuing bit called “As the Worm Turns.” The duo took “Joy Boys” from the nickname used by student radio technicians at an engineering school in Washington, Scott said. For years, they used a jaunty theme song: “We are the joy boys of radio; we chase electrons to and fro.” The program traded off the improvisational skills of the two men and their on-air chemistry. Scott was typically the writer of their bits, which were roughed out in outline rather than fully scripted. Mr. Walker was the “talent,” according to Scott, who would take the comedy in unexpected directions. “We were like brothers,” said Scott, who would go on to become the weatherman on NBC’s “Today” show, in an interview. “I never had a better friend.” “The Joy Boys” would feature occasional guests; over the years, these included comedian Bill Cosby, “Get Smart” actor Don Adams and novelist and quiz-show panelist Fannie Flagg. As Mr. Walker recounted on his final “Big Broadcast,” the duo scored an interview in 1968 with the radio, TV and film star Jack Benny and performed a brief sketch with him. One of Mr. Walker’s characters was Mr. Answer Man, who served up lame jokes in a monotone. “What was the inspiration for the song ‘Melancholy Baby’?” a listener from Falls Church once asked. “The composer had a girlfriend with a head like a melon and a face like a collie,” Mr. Walker replied. “Hence ‘Melancholy Baby.’ ”As Scott said in an interview in 1999, “The Joy Boys’ bits were corny; for the most part, they were terrible. But there was a certain spirit.” A link to radio’s classic era of family-friendly entertainment, “The Joy Boys” aired on WRC from 1955 to 1972, and on WWDC from 1972 to 1974. It was cancelled by WWDC to make way for the station’s switch to rock music, a change that reflected the growing dominance of baby boomers over Washington’s, and the nation’s, popular culture. Mr. Walker went on to work at radio stations WPGC and WMAL and television stations WJLA and Newschannel 8. Among the programs he hosted on WMAL was “Play It Again,” a retrospective of music from the big band era. He also hosted a weekly magazine show for NPR aimed at the disabled called “Connection.” In 1990, Mr. Walker took over hosting another kind of nostalgia show, “The Big Broadcast.” The program had begun as “Recollections” in 1964 by John Hickman, who had appeared from time to time on “The Joy Boys” as a performer. When Hickman’s health began to fail, he asked Mr. Walker to take over the program. Edward Heston Walker was born in Fairbury, Ill., on April 23, 1932. His family moved from Forrest, Ill., to Washington when he was 4. His father, a former railroad telegrapher, joined the federal Railroad Retirement Board. His earliest memories involved listening to the radio. He recalled ringing a toy cowbell as small child along with the performers and audience he’d hear on a program called “The National Barn Dance.” “Most kids [got] a kick out of comic books, and funny papers and stuff like that” he said in an interview with NPR’s StoryCorps in 2012. “To me, radio is it. The sound effects to me were most important. . . . I absorbed [the medium] very well because I was listening very intently.” Mr. Walker graduated in 1950 from the Maryland School for the Blind in Baltimore and was the first blind student to attend American University. The District’s vocational rehabilitation agency, which funded his college scholarship, wanted him to study sociology in order to become a social worker, one of the few professional career paths open to the blind at the time. Mr. Walker insisted on pursuing a career in broadcasting. He completed his communications degree in 1954. Besides his daughter, of Potomac, survivors include his wife of 58 years, Nancy Murphy Walker of Rockville; and eight grandchildren. Another daughter, Carole Potter, died in 2004. Long after “The Joy Boys,” he continued to work with Scott when his old friend was on “Today.” Among other duties, Mr. Walker handled the crush of people seeking recognition for a friend or relative celebrating their 100th birthday. Mr. Walker helped produce the short tributes that Scott read on the air. Mr. Walker never attempted to conceal his blindness, but he didn’t often speak about it on the air. “When I first got into this business, I never let it be known on the air that I didn’t see,” he told The Washington Post in 1985. “Not that I was ashamed of it. It was in my mind that if I was going to be successful in this business, it was because I was a good performer, not because people felt sorry for me.” From his earliest days on the air, he used a Braille typewriter to produce scripts. While on the air, he kept his left hand on a Braille clock to maintain the precise timing necessary to hit the “marks” for commercials or the end of his show, said Lettie Holman, program director at WAMU, who worked with Mr. Walker for years. He was so skilled that most listeners were surprised when they learned, often many years into his career, that he was blind. He was inducted into the National Radio Hall of Fame in 2009 as a local-radio "pioneer."  Ed and Nancy Walker Ed and Nancy Walker Final Resting Place Ed Walker was preceded in death by a daughter, Carole Walker Potter (1962-2004), also buried in Mount Olivet. He left behind his wife of 58 years (Nancy) and another daughter, Susan, and a slew of grandchildren. Nancy M. (Murphy) Walker died on June 21st, 2016. She was a beloved schoolteacher in Montgomery County Public Schools for 40 years, teaching at Bradley Elementary, Westbrook Elementary and finally Somerset Elementary before retiring in 2004. Nancy had attended Towson University before moving to Bethesda, Maryland. She was active as a deacon and volunteer at her church, Fourth Presbyterian in Bethesda, and was also a volunteer at Sibley Hospital. Ed and Nancy are buried in the Murphy family plot located in Mount Olivet's Area GG (Lot 207) beneath a fine, flat monument. This memorial announces their professional accomplishments--ones that certainly brought joy to the countless thousands of listeners and students they inspired, and entertained, along the way.

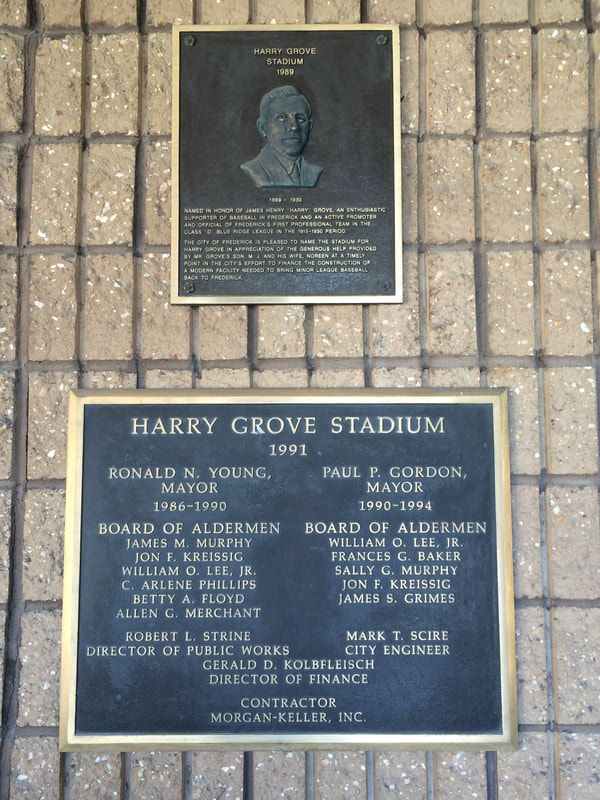

(Note: I've included a few video link buttons below featuring Ed Walker tributes and radio skits.)  Every spring, one can count on three consistent things being in bloom—trees, flowers and baseball. A place you can certainly find the latter is Frederick's Nymeo Field at Harry Grove Stadium. It's a cumbersome title for a sport venue but we are used to names of this variety with Oriole Park at Camden Yards just 45 minutes to the east. Although, when you think about it, Oriole Park is self-explanatory, and Camden Yards is a geographic locator based on history—the former train and freight yards of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. What is Nymeo? Who was Harry Grove? And how are they related? For starters, Nymeo is a federal credit union. Harry Grove was a former Frederick resident. Both can be said to be "key" supporters of Frederick baseball. That's simple enough, isn't it? Well, I will let you research Nymeo on your own time, but I'm happy to tell you about Harry Grove, as he is among the 40,000 residents of Mount Olivet Cemetery. Let's start with briefly exploring Frederick's strong affinity for the national pastime, one that dates back to the 1800’s. A perusal of old newspapers can yield box scores from “days of old” featuring local teams of all varieties and names. I found one called the Crickets. In 1907, Frederick had a semi-professional ball team, named the Hustlers, in the Sunset League which lasted until 1911. Three years later, a meeting occurred on April 6th, 1914 at Frederick's original YMCA location on the corner of W. Church and Court streets. This is the site of an M&T Bank branch parking lot today. Anyway, the meeting brought together "a body of national game enthusiasts at what is considered the most enthusiastic baseball rally ever held in this city" according to the Frederick Post. The purpose of the meeting was to temporarily organize a Frederick baseball association and appoint temporary committees and officers to draft plans and prepare for a permanent organization. The true aim of this event was to gage the level of interest the community had in having a paid baseball squad—a professional team. Seventy-five season tickets would be sold to accomplish this task. The chief promoter of this effort was Col. E. Austin Baughman, a Frederick native and prominent resident who would serve as Maryland's Motor Vehicle Commissioner from 1916-1935. By the colonel's side was a 45-year-old man, short in stature, but a giant in business acumen and his love for the baseball diamond. His name was James Henry "Harry" Grove. Both men made a motion to send a committee (representing Frederick's interest in having a professional baseball team) to an upcoming meeting to be held in Hagerstown. This group wanted a local team to be part of an established, four-six team, organized, Class D league. Or it would also consider having an independent team. The push was successful and Frederick would receive another semi-pro squad in a league, at first that only included teams from Frederick, Hagerstown and Martinsburg (WV). This was known as the aptly named Tri-City League. Plans would soon be underway to form a professional baseball league featuring these three teams, and three additional clubs (Chambersburg (PA), Gettysburg (PA) and Hanover (PA). They needed to gain official recognition by the National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues. Thus, in 1915, the Blue Ridge League was born. The Frederick team would take the nickname of Hustlers, but would also be known as the Champs and Warriors too during the 15 year history of the Class D, Blue Ridge League.  Seventy-four years after that "enthusiastic meeting of April, 1914," Frederick City acquired a professional baseball franchise from the mecca of Little League Baseball—Williamsport, PA. This happened in April, 1988. A firm called Baseball and Sports Associates, Inc. successfully negotiated to get this team into the Carolina League (of minor league baseball) as a Class A ball club of the Baltimore Orioles. Actually, the AA affiliate (Williamsport) went to Hagerstown and the A affiliate (Hagerstown Suns) came to Frederick in a "triple-play" of sorts. Many locals didn't want the Frederick franchise to keep the name Suns, in hopes for something new and perhaps, "Frederick-centric." Some pulled for the name of the original Frederick team—Hustlers, but a negative connotation with an adult magazine title may possibly have nixed that idea or so said Frederick News-Post sports reporter in an article dated November, 1988. Finally the team received its name a month later. It paid homage to our hometown hero Francis Scott Key, the man who gave us “the Star-Spangled Banner”— the greatest song baseball has ever known, with “Take Me Out to the Ballgame” a close second, of course. As an aside, other potential team names that received consideration were the Frederick Spires and the Frederick Fritchies.

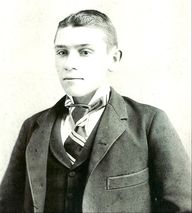

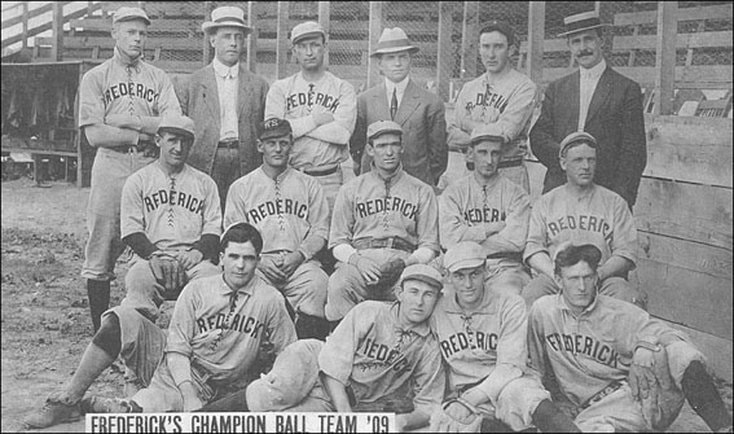

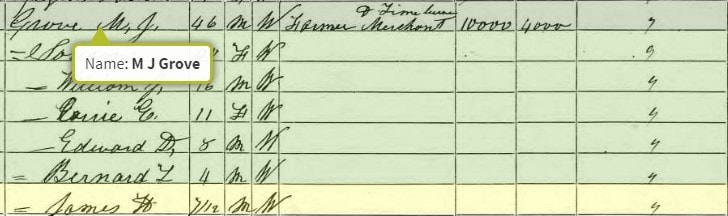

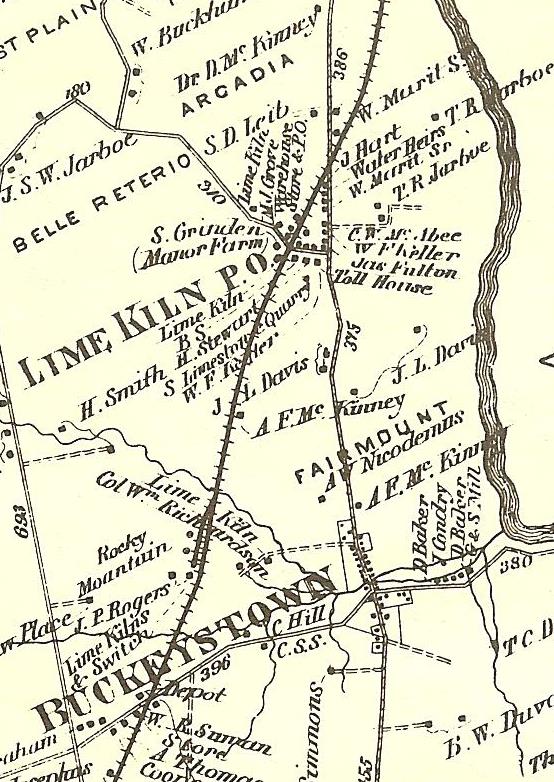

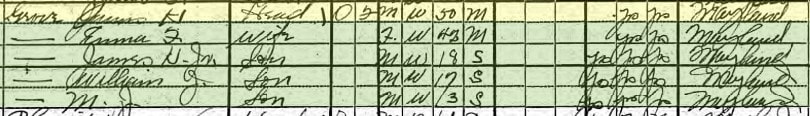

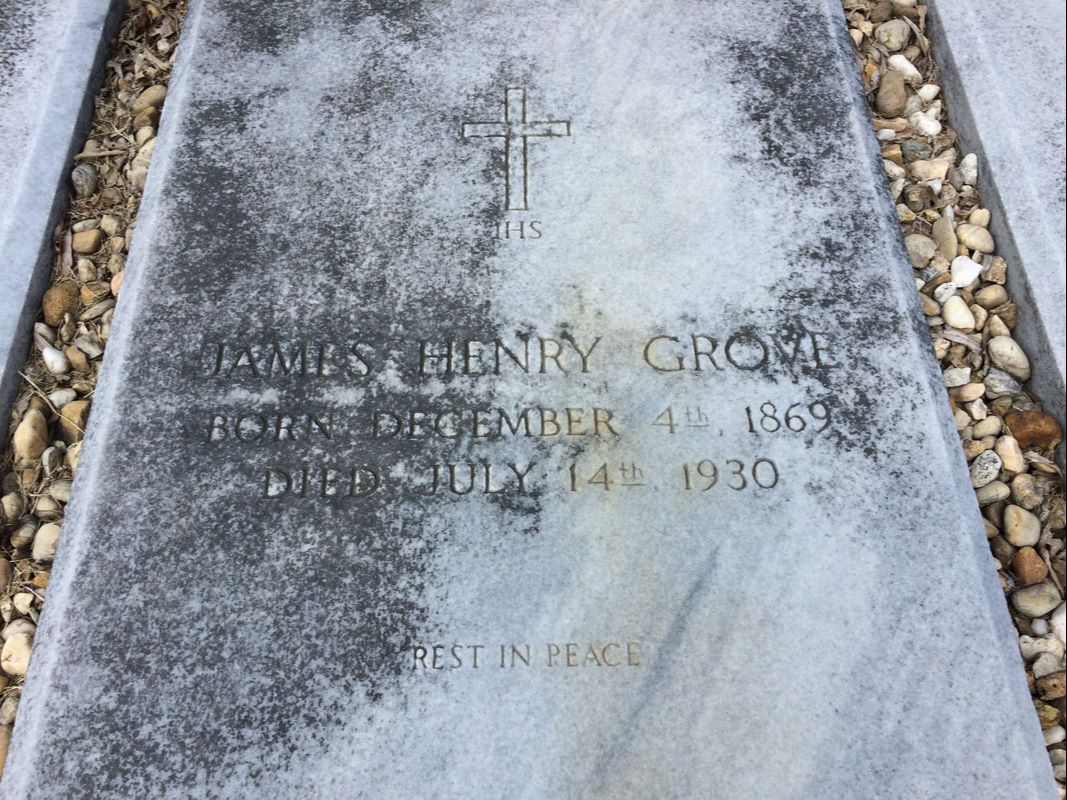

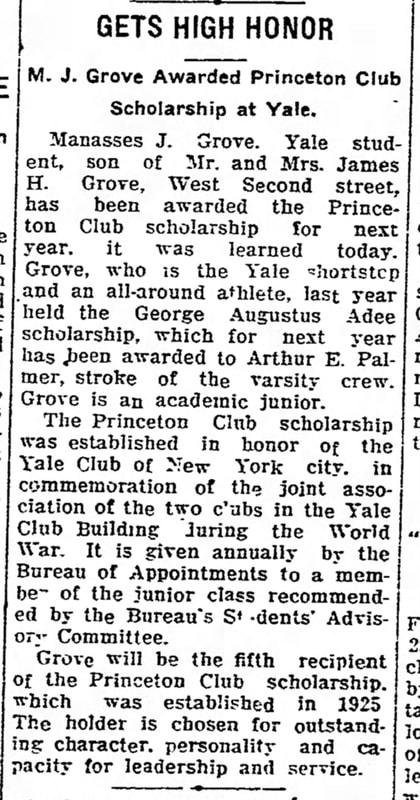

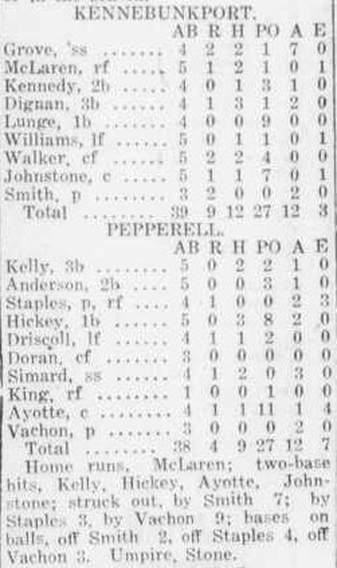

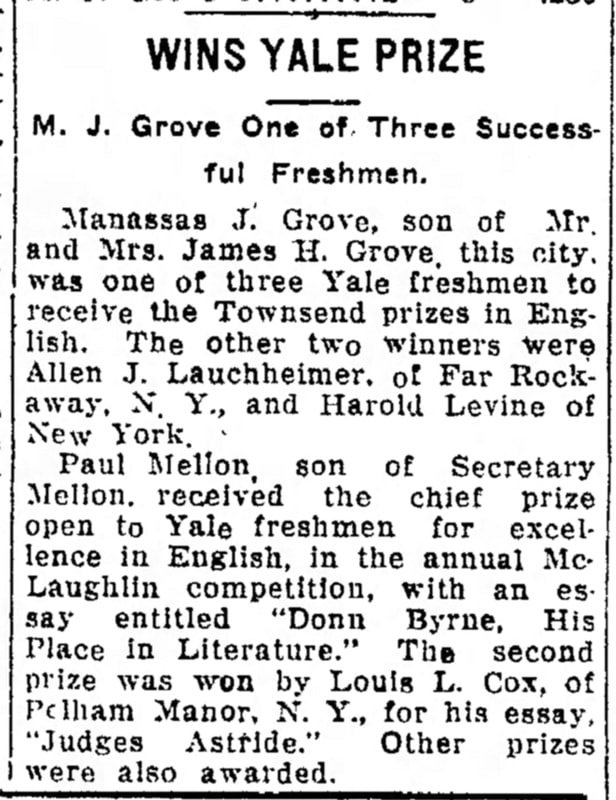

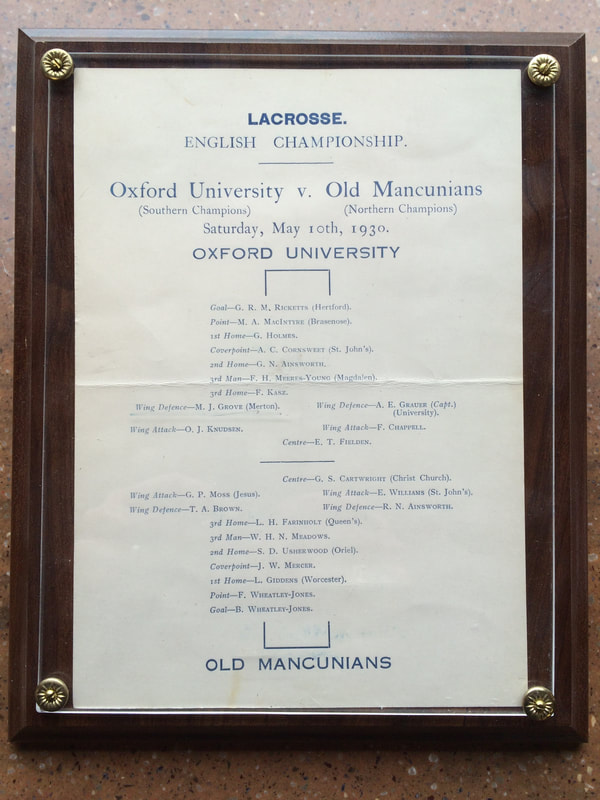

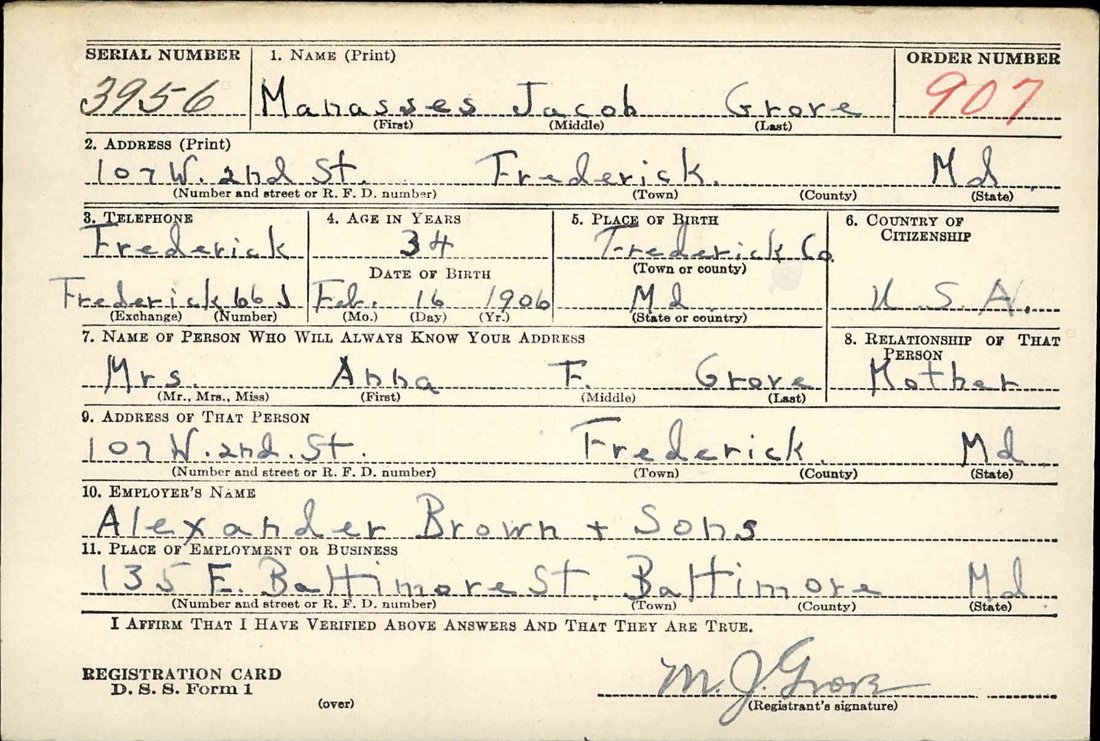

“In an April 1990 interview in the Baltimore Sun, Mr. Grove told sports reporter Thom Loverro: “My father was very active in baseball. After we read about the $250,000 needed for the stadium and how a donor could name it, my wife and I thought it would be a very nice thing to do. My father was really an avid baseball fan and always supported baseball around here.”  Young "Harry" Grove (c. 1886) Young "Harry" Grove (c. 1886) James Henry “Harry” Grove James Henry Grove was born in southern Frederick County on December 4th, 1869. He was the son of Manassas Jacob Grove, the man responsible for starting the M. J. Grove Lime Company in 1858. This operation was located at Lime Kiln, about five miles south of Downtown Frederick, on Carrollton Manor, just west of the Buckeystown Pike. The company produced crushed stone, lime and allied products and was one of the first road building firms in the state. Harry, as he came to be known, grew up at Lime Kiln vicinity and attended local public schools, culminating with the Frederick College located on Counsel Street. Soon after, he began his career in “the family business,” eventually serving as manager of the Frederick plant and director of the company, having additional operation locations elsewhere. The Tercentenary History of Maryland (published in 1925) states that the company was one of the largest in the country. “He (Grove) now has charge of the company’s interest in Frederick, an important and responsible position, requiring all of the aptitude for commercial work and business acumen of a successful executive and administrator. Thoroughly progressive in his methods, Mr. Grove has been no small factor in the development and extension of the Grove manufacturing interests. Mr. Grove married Anna Forsythe of Howard County on June 12th, 1900. The couple would be the proud parents of three boys: James Henry, Jr. (born May 12th, 1901), William Jarboe Grove (b. January 19th, 1903) and the fore-mentioned stadium donor of $250,000, Manassas Jacob Grove (born February 16th, 1906). The Tercentenary History of Maryland continues: “Mr. Grove has taken an interest in the commercial development of Frederick aside from the advancement of affairs of his own family firm, and has given of his capital and time in support of other business enterprises, among them the Mountain City Garage, which conducts one of the largest auto supply and repair stations in the city. He is president of the company. Politically Mr. Grove is a staunch supporter of the party of Andrew Jackson and is ever willing to lend his support to the democratic cause. He is a Roman Catholic in religious faith, a member of St. John’s parish of this city and a Knight of Columbus. Fraternally he is also affiliated with the Benevolent Protective Order of Elks, belonging to Frederick Lodge. Harry Grove was a big sports fan. He influenced a love for athletics in his boys. Son William Jarboe played baseball and football at Frederick High School, and college baseball at Cornell University. James Henry, Jr. particularly enjoyed outdoor activities such as golf, hiking and fishing. M. J. “Jacob” would become the top athlete in the family, but more on that in a moment. Harry was “intensely interested” in baseball—especially on the local level. He became associated with Frederick pro-ball clubs, including the Hustlers, from the onset as a founder, and board member.and continued his affiliation with the team up through the time of his death.  1909 Frederick team with Harry Grove pictured in center of back row with fancy hat (4th from left). Col. E. Austin Baughman is pictured second from left. Future American League umpire Richard "Dick" Nallin is the gentleman standing to the right of Grove. Ironically Nallin would eventually live only two doors down from Grove on W. 2nd Street. Mr. Grove died at his residence located at 107 W. Second Street on July 14th, 1930. He was only 61. Grove first started feeling ill after a July 4th outing with friends. He would eventually suffer a stroke, which rendered him in critical condition before succumbing to a cerebral hemorrhage. James Henry “Harry” Grove was duly laid to rest in Mount Olivet Cemetery’s Area LL/Lot 210. The location is roughly 300 yards from home plate of his namesake stadium.  M. J. "Jacob" Grove during his playing days at Yale M. J. "Jacob" Grove during his playing days at Yale Harry's Son M.J. Born in 1906, at Lime Kiln, M. J. "Jacob" Grove was named for his grandfather, Manassas J. Grove (1824-1907). M. J. "Jacob" Grove was a member of the first co-educational class that graduated from Frederick High School. He excelled in track events, lettered in four sports his senior year and was awarded a Silver Cup as the best all-around athlete in Frederick County. Jacob graduated from Yale University where he played varsity baseball for three years and competed in track as a broad jumper. It should come as no surprise that he would hold the school’s record for stolen bases from 1929 up through the early 1990’s. He also held the record for most consecutive games with a hit (21). He hit two grand slams as a member of Kennebunkport (Maine) Collegians in 1926.

M. J. Grove (c. 1945) M. J. Grove (c. 1945) Grove worked for the investment banking firms of Brown Brothers, Harriman & Co. in New York. He then worked at Alexander Brown & Sons of Baltimore. In May 1941, he was drafted into the Army. He was commissioned as a lieutenant in the US Navy, following the attack on Pearl Harbor. He served at naval aviation training stations during the war, principally as officer-in-charge of the Naval Light Preparatory School in Austin, Texas from 1943-44 and as a member of the staff of the Chief of Naval Training at Pensacola, until his discharge as a lieutenant commander, USNR in 1945. M. J. “Jacob” Grove married Miss Noreen Grote of Brenham, TX. On May 1st, 1945 in Walnut Grove, CA, a suburb of Sacramento. The couple came to back to Maryland where he joined the Mercantile Trust Company of Baltimore. Grove was elected Vice President in 1947, and remained until 1955. After a brief stint of teaching at Catonsville High School, the Groves moved back to Noreen’s home and the Lone Star state. Jacob Grove would work in the endowment Office of the University of Texas (Austin) as an investment specialist from 1957 until his retirement in 1971. Jacob and Noreen would again return to Maryland (and Frederick) in 1984. They would take up residence at Crestwood Village Senior Community, just a short drive from the Key’s baseball home named after his father. On the beautiful night of June 8th, 1993, M. J. Grove enjoyed a night at Harry Grove Stadium, taking in a game in which the Keys were hosting the Durham Bulls. This was no ordinary game, however. At Mr. Grove's side was a very important guest, the President of the United States, George Herbert Walker Bush. The two men had plenty in common to talk about aside from their love of baseball. Both had attended Yale, and served in the Navy during the World War. Both also had connections to Kennebunkport, Maine and the state of Texas. Noreen passed in 1996 at the age of 85. M. J. Grove would relocate to Homewood at Crumland Farms. He would die seven years later on September 17th, 2003 at Frederick Memorial Hospital. Grove's body would be buried next to his parents and two brothers (William Jarboe Grove died in February, 1997; and James Henry Jr. died in 1990). You know, on any given game night, you can stand at the Francis Scott Key monument and hear the National Anthem being sung at Grove Stadium. In the same vein, one can also hear the "crack of the bat" and the "roar of the crowd" from the vantage point of the Grove family burial lot in Mount Olivet. Some things are just meant to be. Thanks again to these two gentlemen and the extended Grove family for their part in providing us with a fine stadium for our hometown team, now celebrating its 30th anniversary. Very special thanks should go out to Ms. Helen Haerle of Middlebury, Vermont, a granddaughter of J. Harry Grove and niece of M. J. "Jacob" Grove. She provided the several family pictures used in this piece. I'd also like to thank Kim Selby at the YMCA of Frederick County who assisted me in getting images from the Alvin G. Quinn Sports Hall of Fame collection.

|

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed