|

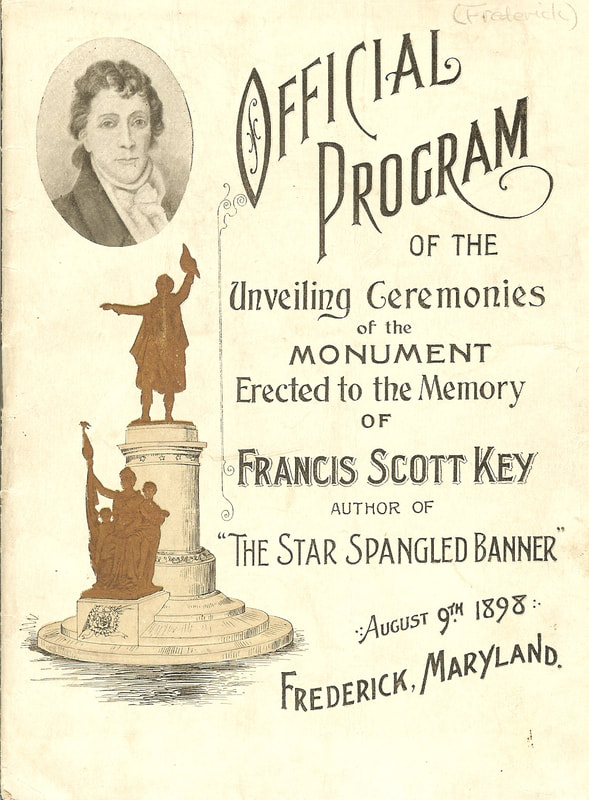

Let’s be frank, this week’s story is a bittersweet tale and barker for further knowledge through the documentary film medium. (Trust me, as I know a little bit about the process.) We feature two interesting figures in American history, both named Frank, and both buried within Mount Olivet. Interestingly, this cemetery was not either man's original burying place. There are plenty of similarities between both of these “gentle” men. Each rose to the heights of their professions, but are said to have had doubts about their work on the eves of “life-changing” events. Frank and Frank also had affinities for their families, one boasting eleven children, the other three. Each loved his wife, wholeheartedly, but died many miles away from their loving arms. Lastly, each of these fellows had intricate ties to the federal government, and their fame can be traced to secret missions during wartime—and each involving a place named after our county's third secretary of war, James McHenry (1753-1816). Each suddenly found themselves as captives. In one case, an individual was freed, and soon triumphed through this experience. In the other, a man was lost, creating an intricate mystery related to national security that still exists to this day. To the victor, go the spoils. The “Frank” that starred in the success story has been remembered fondly by history as a patriot of the highest order—a fact put into motion by a song that still serves as his legacy today. His overnight stardom led to good things for his family, and advancement in his career. He was a lawyer who came to advise the US president and other national leaders. He eventually became the District Attorney for Washington DC, a post that had him arguing cases before the Supreme Court. His final resting spot here in Mount Olivet is adorned by a fine monument standing 24’ tall at the entrance of the cemetery—you can’t miss it. Much has been written and produced on his life and times, including a recent miniseries on public television. His reputation and that of his legendary song have taken a few hits, or should I say “kneels,” of late, but both are still held as treasures by his hometown of Frederick, the State of Maryland and the Smithsonian Institution. On the other hand, the second “Frank” was a renowned scientist, brought to Frederick from his native Wisconsin to work at Fort Detrick on biological warfare and weapons research. His journey would be ill-fated, with a rise to notoriety based principally on a fall, or a jump—one that would extinguish his life, and alter that of his family, forever. Memory of this man and his work appear to have been erased, or covered-up following his death. He is buried towards the back of the cemetery, close to the mausoleum complex. His gravesite is simple, marked by a bronze plaque that bearing his name and vital dates. The marker has oxidized and turned greened over the six decades since his death. Although this has tarnished, the mark and reputation of this man continues to do the opposite thanks to has continued to the research work performed of his son Eric, countless reporters, and most recently by an Academy-award winning documentarian. My job here is merely to give introductions to the fact that the mortal remains of these notable figures lie here in Mount Olivet, hopefully both in peace. At the end of the story, I invite you to watch, and learn more about these gentleman and their lives, times and deaths. From there, you are warmly welcome to visit their gravesites and pay respects. Operation Anthem Without a doubt, the most well-known, and most-written about, person in Mount Olivet Cemetery is Francis Scott Key. As a 33-year-old lawyer, he found himself on a special mission and unfortunately, in the wrong place, at the wrong time on the day of September 13th, 1814. The Frederick native had studied law, making it his life-long profession. He was top use his skills and work experience to rescue a friend and fellow American who had been captured during the British invasion of the nation’s capital during the War of 1812.  Frank Key, as he was known to friends and family, also took great pride in being an amateur poet. His skill as a lawyer is what brought him to Baltimore just days before, as he and a government agent successfully gained the release of a US prisoner captured by the British military. However, it would be his penchant for prose that would take precedence as he departed Maryland’s principal city on September 15th. If you know your history, Key and Col. John Skinner, an American agent for prisoner exchange, had convinced British high command to free Dr. William Beanes to their custody. However, the British were readying to wage an assault on Baltimore which would result in a 25-hour bombardment on Fort McHenry. The three Americans, (Skinner, Frank and Beanes) had front row seats of the bombardment as they would be detained aboard a British sloop until the battle was over. The Maryland Defenders held the fort, and thus Baltimore, throughout the day of September 13th and the night of the 14th amid deplorable conditions of wind and rain.

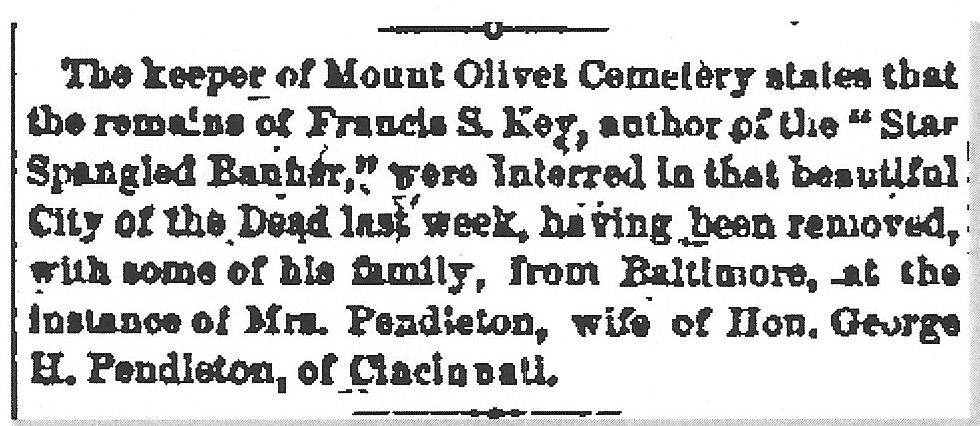

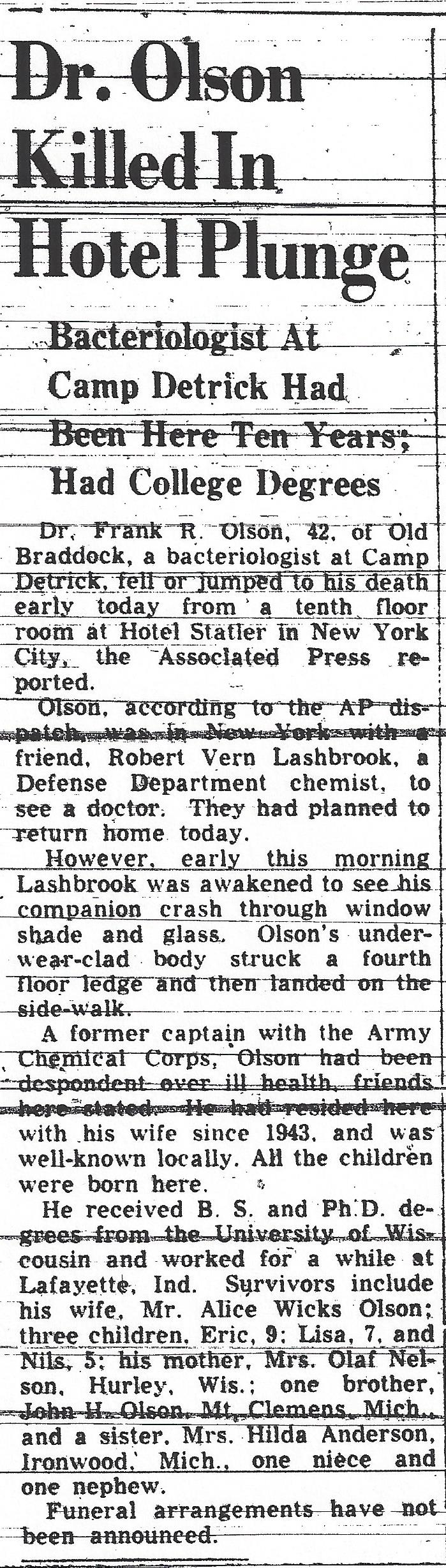

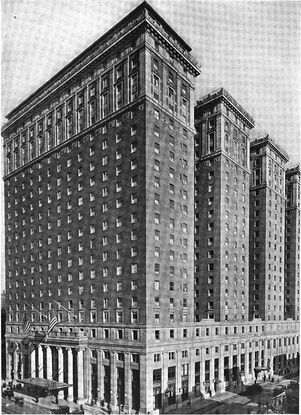

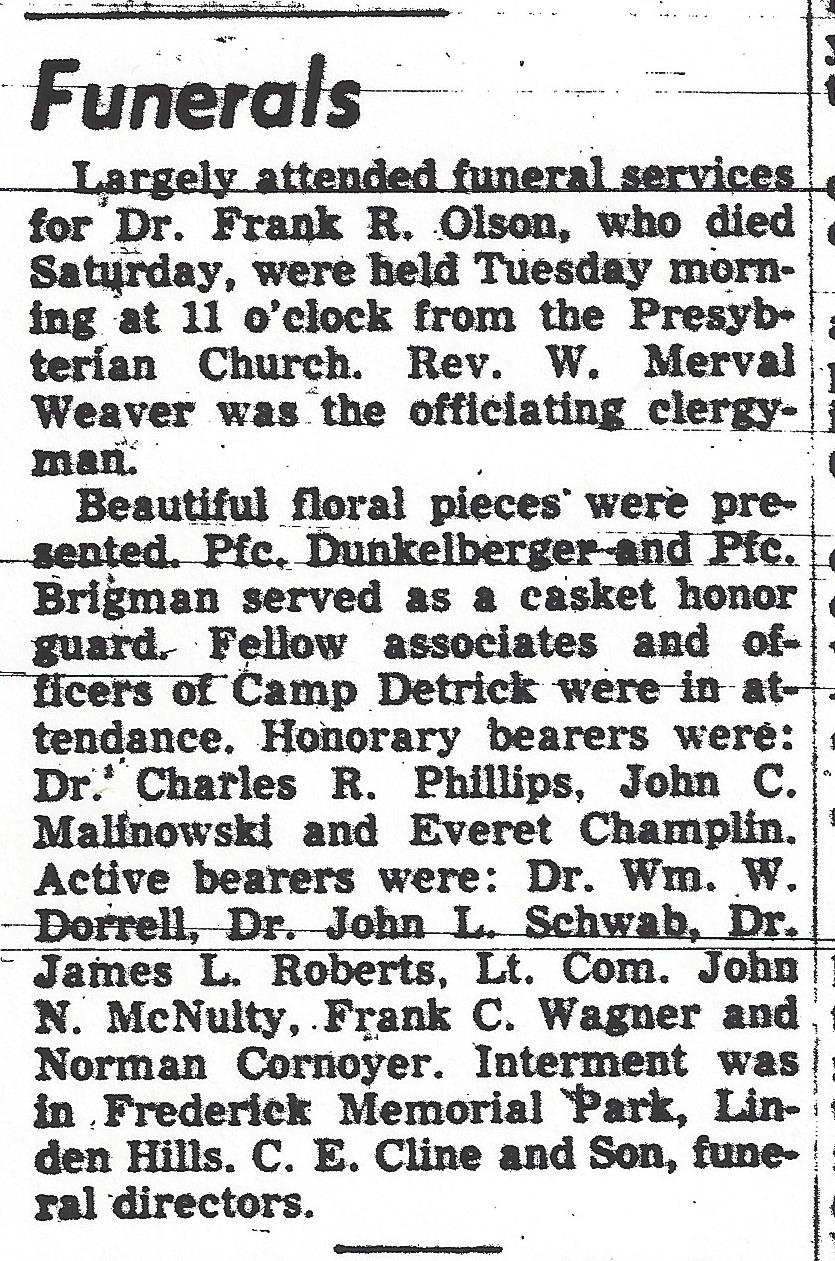

A few years ago, filmmaker Phillip J. Marshall zeroed in on the life and times of Frank Key with a multipart series he was producing for Maryland Public Television (MPT). He employed a method called participatory documentary, which features the filmmaker interacting with his or her social actors, participating in shaping what happens before the camera. Marshall took this to a new level as he speaks to re-enactors as if they are the actual historical figures he is chronicling. He includes some dry humor in his approach as well. It’s a bit different and quirky, but truly a novel way to bring history alive for the viewer. Produced by Kismetic Productions, funders of this project include some folks associated with Key’s hometown of Frederick—the Delaplaine Foundation, George and (the late) Bettie Delaplaine and Mike and Marlene Young. I can proudly say that this is the same group of local individuals who also helped me make my mark as a history documentarian. The program is really a collection of two documentaries hosted by filmmaker Marshall: F. S. Key and the Song that built America and the 3-part F.S. Key: After the Song. Phillip Marshall travels in Keys’ footsteps around the state and beyond, visiting many of the places where Key would have actually stood, some drastically changed by time. The documentary also includes interesting reenactments, historian commentators and interviews with prominent people in Key’s life, such as his wife Mary Tayloe Lloyd Key, his wife. Frank called her "Polly," and she is also buried here by his side in Mount Olivet. Here is a link to the film’s trailer: Logo with link to trailer promo http://ww2.mpt.org/station_relation/FSK/Video/FSKey_Broadcast_Promo-HD1080p.mov Operation Artichoke Operation Artichoke was a CIA project that researched interrogation methods during the Cold War period following World War II. This entity arose in August 20th, 1951 out of another operation entitled Project Bluebird, which was being run by the CIA’s Office of Scientific Intelligence. A memorandum by Richard Helms to CIA director Allen Dulles indicated that Operation Artichoke became Project MK-Ultra on April 13th, 1953. Frederick’s Fort Detrick played a role, as did several scientists and researchers who worked on the base. One of these was Dr. Frank Rudolph Olson, born July 17th, 1910 in a small town named Hurley located in Iron County, Wisconsin. Seven months into Project MK-Ultra, a group of men from the CIA held a retreat of sorts at Deep Creek Lake in western Maryland’s Garrett County. Ironically, this occurred at the small hamlet of McHenry. Dubbed by the official CIA papers as the “Deep Creek Rendezvous,” this trip would turn out to be the central turning point in a major government scandal after Dr. Olson would plunge to his death from a window on the 13th floor of New York City’s Hotel Statler.  Dr. Olson with wife Alice and children (L-R) Eric, Lisa and Nils (courtesy Olson family) Dr. Olson with wife Alice and children (L-R) Eric, Lisa and Nils (courtesy Olson family) The entertainment company Netflix recently released a 6-part documentary hybrid series, named Wormwood, on Frank Olson’s mysterious and untimely death following his visit to Deep Creek Lake in November, 1953. Olson’s passing was determined a suicide, and his wife Alice, and three children were left with broken hearts, and more questions than answers in the death of their loved one. The family remained in Frederick, living in Braddock Heights. Dr. Frank Olson was originally buried in Frederick Memorial Park, located high atop Linden Hills west of downtown Frederick. Here his body would remain until 2002.

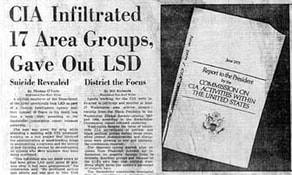

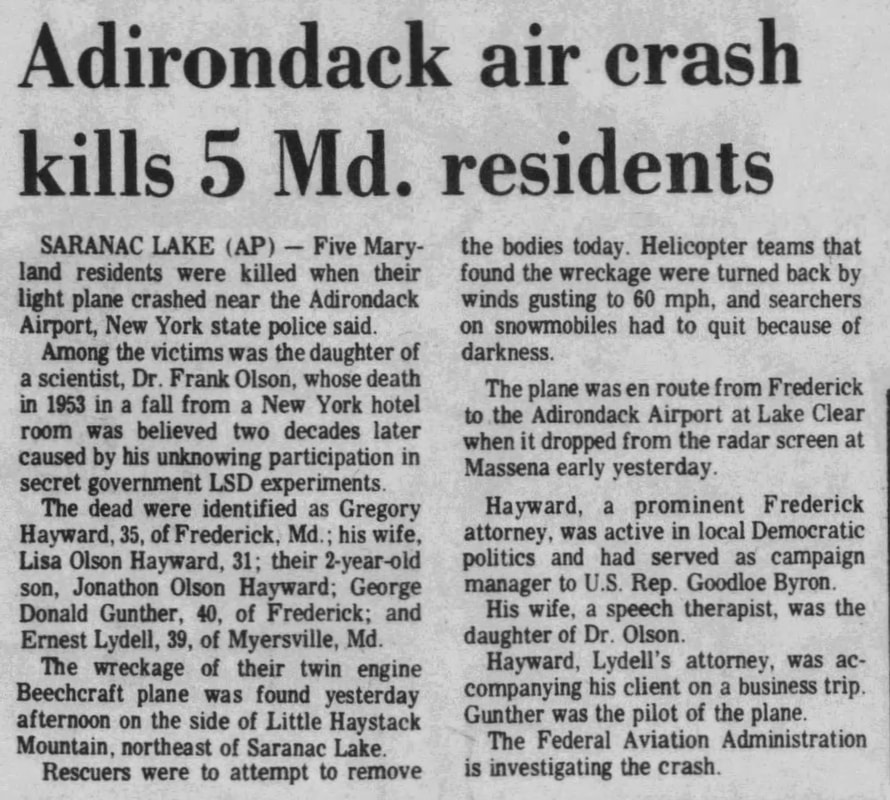

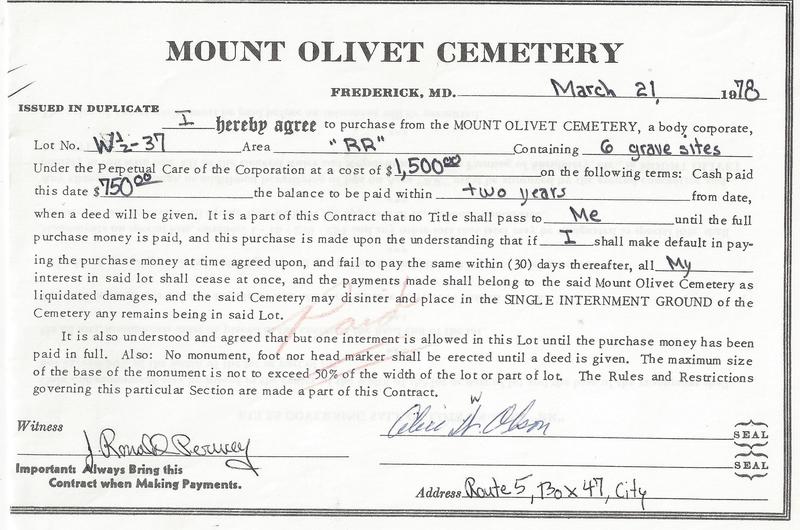

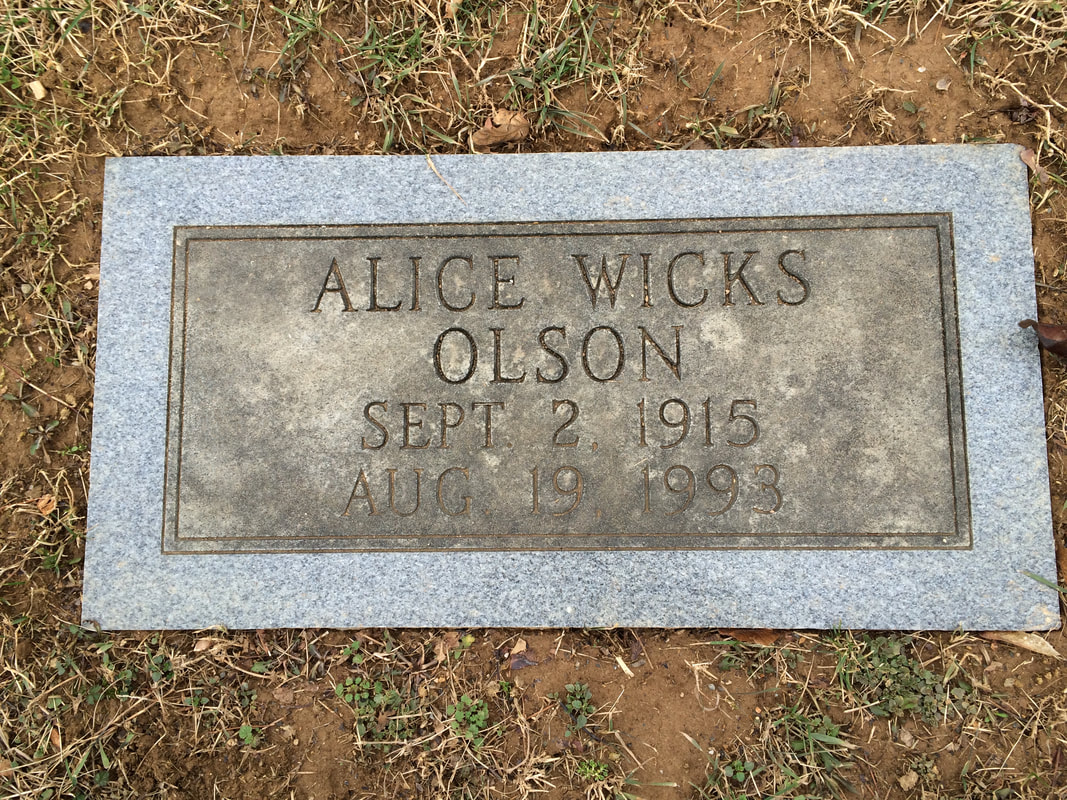

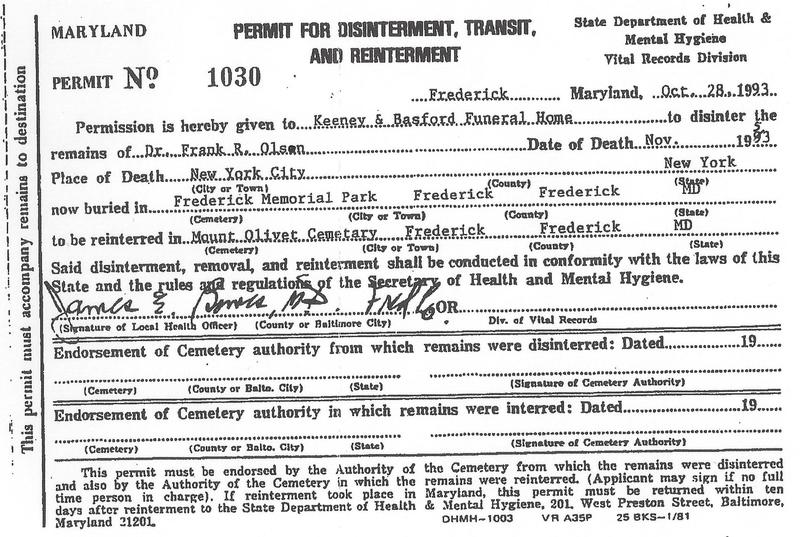

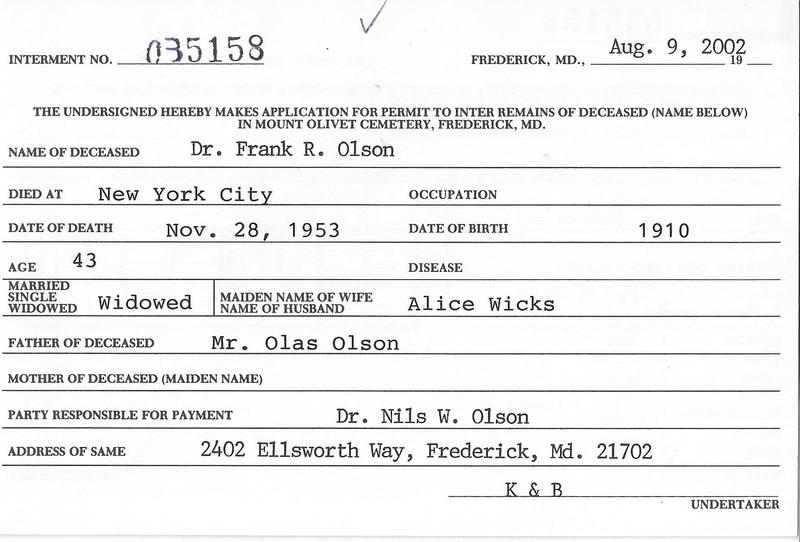

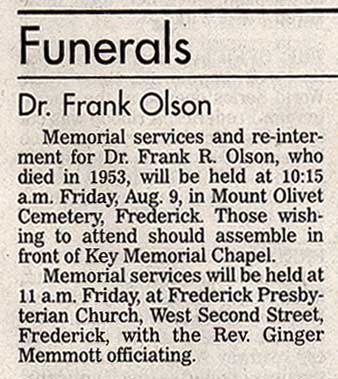

The Washington Post carries a front page story saying that the just-released Rockefeller Commission Report on the CIA includes description of an “Army scientist.” (June 11, 1975) The Washington Post carries a front page story saying that the just-released Rockefeller Commission Report on the CIA includes description of an “Army scientist.” (June 11, 1975) I recall first hearing about the whole Frank Olson tragedy as a young boy in the mid-seventies. My family had come to Frederick (from Delaware) in 1974, after my father began a job at Fort Detrick with the National Cancer Institute as a journal editor. He was interested in the case as it resurfaced in 1975, and I recall him trying to explain Dr. Olson’s mysterious death to me as a 9 year-old. I also remember marveling at an edition of Nightline with Ted Koppel that chronicled the case and showed scenes of Fort Detrick and surrounding Frederick, while interviews were conducted with Olson family members. It all came together in my 8th grade-year as a student at Gov. Thomas Johnson Junior High school in 1981 when Mrs. Olson, herself, spoke to our Health Class about the dangers of alcohol and drug addiction. I can still see the pain in this amazingly strong woman’s face as she recounted the deaths of her husband, daughter and young grandson. Alice Olson died in 1993 of pancreatic cancer. She would be laid to rest in Mount Olivet, in a lot she had purchased back in 1978 to place the bodies of Lisa, Greg and Jonathan Hayward. When researching this piece, I found that Alice’s obituary was carried in the country’s leading papers including the Washington Post and New York Times. I was fascinated to learn from these accounts that after Frank’s death, Mrs. Olson counseled alcoholics and drug addicts in our community. The Alice Olson House, a center for women recovering from drug and alcohol addiction was named in her honor. Today the family name still exists for this cause with the Olson House for Men.  Eric Olson (courtesy Netflix) Eric Olson (courtesy Netflix) Closure has still never come to son Eric Olson, a man who has dedicated his life in pursuit of the truth of what really happened in the early morning hours of November 23rd, 1953. His persistence is remarkable, as he continues to search for new clues to prove that his father's death was no accident. He has written extensively on the subject, resulting in a a very informative website (www.FrankOlsonProject.org), along with being the premise for a documentary produced by the BBC in 2002 and aptly titled Code Name Artichoke. On June 2, 1994, Eric and brother Nils had their father’s body disinterred in order to conduct further autopsy research at a forensic research laboratory under the direction of James E. Starrs (George Washington University's Law Center). The study answered some questions, but certainly not all. After completion, Dr. Olson’s body was brought here to Mount Olivet to be buried by Alice’s side in Area RR, Lot 37. This event, like that of the disinterment, brought media coverage to the cemetery on August 9th, 2002. Ironically, this was 104 years to the exact day of the unveiling of the Francis Scott Key Monument—August 9th, 1898.  If you’re unfamiliar with the Frank Olson case, or even if you’ve heard it all before, Wormwood is something to behold. The 6-part miniseries was directed by Academy-award winner, Errol Morris, a master in the investigative documentary field. His claim to fame is the critically acclaimed The Thin Blue Line, produced in 1988. Morris uses dramatic reenactments, with stars like Peter Sarsgaard as Frank Olson, interviews from Eric Olson and others who have been involved, footage from government forums, and uncovered government documents to give the viewers perhaps the most complete version of possible events and evidence. Here’s the official Trailer for Netflix’ Wormwood, but you will need a subscription to watch the 6-part mini-series: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b01DL8DTUGM  Mary Tayloe Lloyd (Polly) Key (1784-1859) Mary Tayloe Lloyd (Polly) Key (1784-1859) Deep Creek Lake Before I send you off into cyberspace with links to the fine documentaries on Frank Key and Frank Olson, I want to leave you with one additional connection between these two men. It has to do with the vicinity of Deep Creek Lake in Garrett County. Deep Creek was the place where Frank Olson’s demise began. It has represented a profound mystery and sadness for the Olson clan. In stark contrast, this would be a locale emitting much joy, peace solitude and remembrance for family members of Francis Scott Key. Apparently "Polly" Key and daughter Elizabeth (Howard) (whom Francis was visiting when he died in 1843) ventured here by train over a decade following FSK's death. Like Mrs Olson, Polly Key's life a mother was without incident as she too had lost three sons to tragedy: Edward to an accidental drowning (1822), Daniel to a duel(1836) and Phillip Barton Key was gunned down in broad daylight near the White House by US Sen. Daniel Sickles (1859). The Keys/Howards stayed at resorts located near the fore-mentioned McHenry-Oakland until granddaughter Alice McHenry Key purchased a residence here in 1870. This lodge would become home to the Star-Spangled Banner author’s grandchildren and great-grandchildren. The family’s residence had a tremendous impact on making the area a fashionable resort throughout the late 19th and early 20th century.  Elizabeth (Key) Howard (1803-1897) Elizabeth (Key) Howard (1803-1897) A story written by another Key granddaughter, Julia McHenry Howard, tells of the impetus of the Key family coming to the area: "In 1857, Mrs. Charles Howard (Elizabeth Phoebe Key) and her children and her mother, the widow of Francis Scott Key, were spending a very hot summer in the hotel at the Relay. The B. & O. had not been running through to the Ohio River, and to see the late afternoon train come through from the west was quite an event. One afternoon, a steward, formerly a butler in Mrs. Howard's home, stepped off the coach for a minute, and recognizing Mrs. Howard, told her that they had, that morning, come through a place where the ladies were walking up and down the platform wearing blankets, shawls, and the station railing was hung with rattlesnake skins. Next morning Mrs. Howard and Mrs. F. S. Key boarded the train for Oakland. They stayed for some weeks at the old Glades Hotel. In 1858, they went again, doubtless taking other members of the family with them. This time they stayed on a farm, known as Bitzer's near where the road to Monte Vista leaves the old West Union road. Mrs. Francis Scott Key died early in 1859, but Mrs. Charles Howard and various members of her family returned. They were already taking root in Oakland."  Howard Family Crypt in Old St. Paul's Cemetery (Baltimore) Howard Family Crypt in Old St. Paul's Cemetery (Baltimore) In 1893, Elizabeth Phoebe Key Howard (Key’s daughter) celebrated her 90th birthday in Oakland. All day a stream of visitors poured in, people from Oakland and Deer Park. A large dinner party was given that night. We have a debt of thanks to give Mrs. Howard, as she was person said to have given the family’s consent for her father’s body to be moved from the Howard family vault at Old St. Paul’s Cemetery to Mount Olivet some 27 years earlier. In 1897, Elizabeth Howard died in Garrett County. Her body was sent back to Baltimore by train, where her coffin was covered by an American Flag made of red, white and blue flowers. She would be laid to rest in that same Howard Family vault that once held the remains of her father and mother. Link to streaming video:

F.S. Key and the Song that built America http://www.pbs.org/video/mpt-specials-fs-key-and-song-built-america/ Website to purchase FS Key: After the Song mini-series: www.fskusa.org Netflix official website for Wormwood: https://www.netflix.com/title/80059446 Eric Olson’s website: http://www.frankolsonproject.org/Contents.html Link to streaming video of the BBC’s 2002 documentary: Codename Artichoke http://www.cultureunplugged.com/documentary/watch-online/play/9586/Code-Name-Artichoke

4 Comments

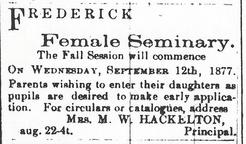

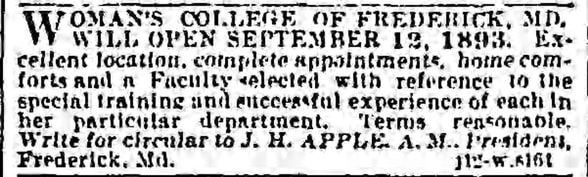

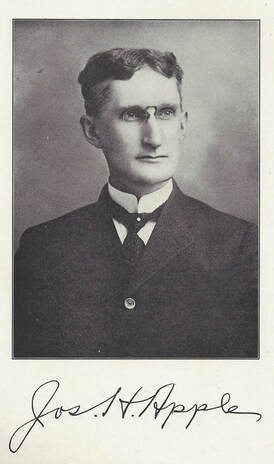

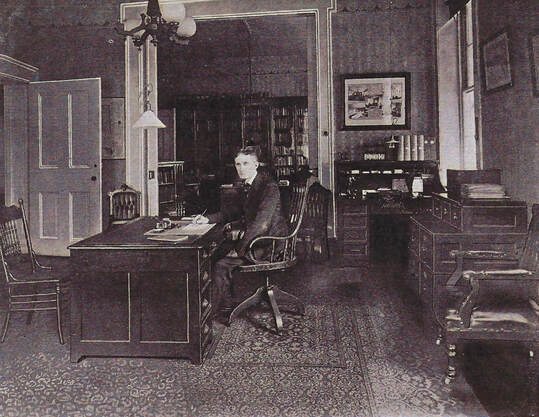

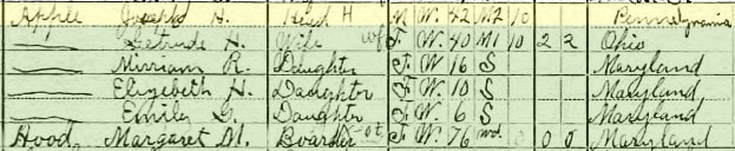

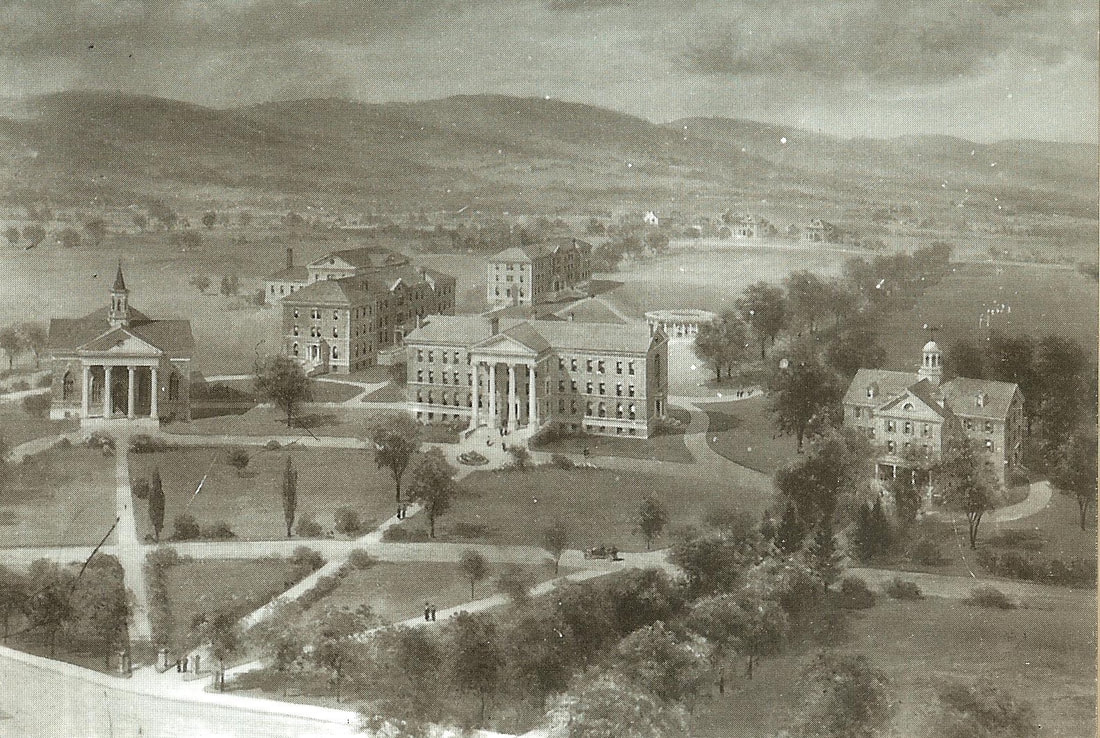

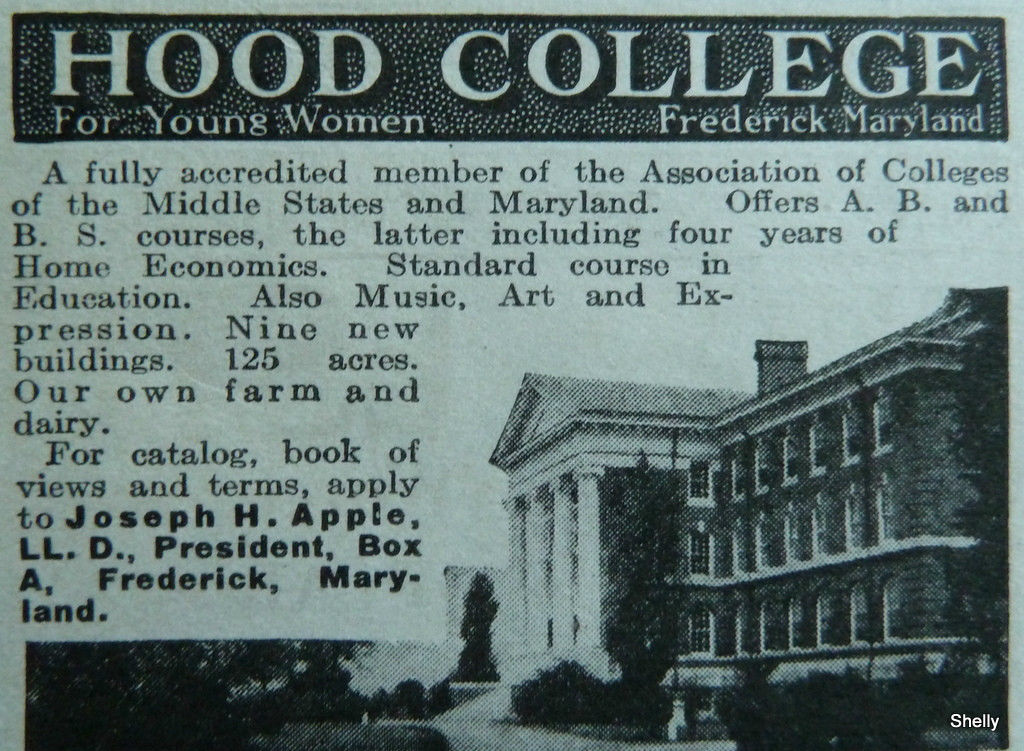

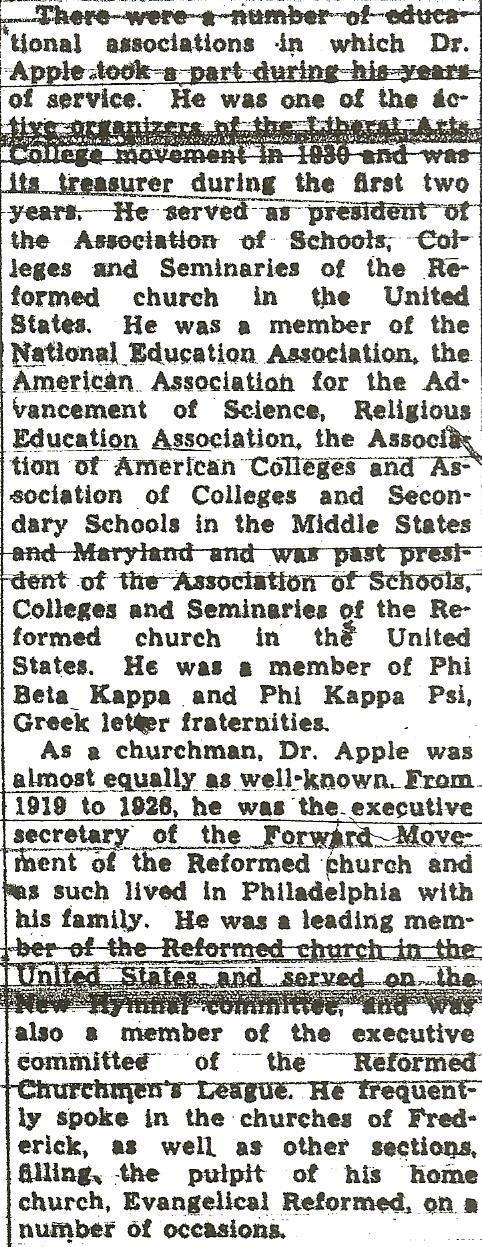

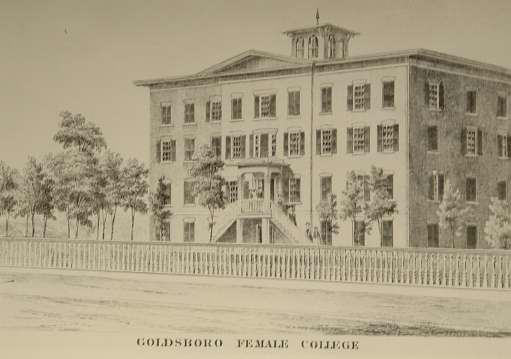

I was talking to an elderly gentleman in his nineties the other day, and I had to smile when he referred to some local youths responsible for vandalism to his car as “a few bad apples." I had not heard this throwback expression in a while, one comparable to the legendary “good-for-nothings” and “ne’er do wells.” I still revel when seeing any of these in print while conducting research work in old newspaper stacks and microfilm. The collective moniker (“A few bad apples") usually comes about when mayhem and misconduct rears its ugly head, and one chooses not to blame the larger group for the ill-intensions of a subset of said group or organization. The saying is rooted in ancient times, and its comparison between humans and apples is a welcomed break from the overused comparison apples to oranges. The literal meaning of the proverb comes from the message that one shouldn’t throw out a basket, bushel or barrel of apples, just because a few appear to be bad or rotten. Benjamin Franklin, however, muddied the waters with his charge of “guilt by association” as he popularized the expression "the rotten apple spoils his companion," a line credited to William Shakespeare where he used the expression “rotten apples” to signify “bad companions” (“Taming of the Shrew”). And then there are the Osmonds with their 1970 apple-oriented hit, but I don’t think we need to go there.  An apple atop the Apple family plot in Frederick's Mount Olivet Cemetery An apple atop the Apple family plot in Frederick's Mount Olivet Cemetery On the other hand, we also have another popular saying that puts emphasis on the good apples, not the bad. The old Welsh proverb reads: “An apple a day keeps the doctor away.” Its message provides the sage advice that eating fresh fruits and vegetable will provide one a healthier life. The expression dates to the 1860’s where it was originally spoken as “Eat an apple on going to bed, and you’ll keep the doctor from earning his bread.” Apparently the shortened version arose in print in the early 20th century, 1913 to be exact, based on the first published findings of this phrase. It’s only fitting that here in Frederick, in that same year of 1913, one could find in print a nice “conjugation” of the featured fruit and professional calling found in the fore-mentioned proverb. Yes, indeed, we had our own “Dr. Apple,” and he was creating something extremely special on the northwest side of town. He, my friends, was a very good apple.  The Frederick Female Seminary The Frederick Female Seminary Dr. Joseph Henry Apple first came to our fair town in 1893. His sole purpose—employment. A few weeks back, we featured a story on Professor William Von Steinman, a beloved former music teacher at the Frederick Female Seminary, one of the foremost and progressive education facilities for women in the country during the 19th century. The school was located within Winchester Hall, our seat of county government today, taking its name from the school’s original founder, Hiram Winchester. Winchester served as principal here from 1843-1863, at which time the school closed due to the American Civil War. The seminary re-opened in 1865 under a new leader, Thomas McMullen Cann, who remained here until 1873. In my Von Steinman piece, I made mention of the school’s next two principals, the husband and wife team of James H. Hackleton (principal from 1873-1877) and his wife Maria Hackleton (serving from 1877-1885). Mrs. Hackleton eventually moved to South Carolina to be closer to her daughters, opening the door for the last individual to hold the title of principal of the Frederick Female Seminary. This was Dr. William Purnell who served in this capacity until 1893. A “healthy” change came with Dr. Apple in the summer of 1893. It was at this time that the Potomac Synod of the Reformed Church of the United States was looking for a girls’ school in the local area to end the co-educational status of its Mercersburg College in Pennsylvania. The Synod had already received four other proposals for a women’s college located south of the Mason-Dixon Line when the board of trustees of the Frederick Female Seminary offered up the facilities at Winchester Hall to the religious group. An arrangement was made with the Potomac Synod to lease the school’s property here in Frederick, which now ceased to operate as a separate school. The Reformed Church Synod appointed a board of directors which, in turn, created the Woman’s College of Frederick. The first term of the exciting venture commenced with 112 students in September 1893 under the leadership of Dr. Apple’s administrative staff of fourteen. The new educator from Pennsylvania would be at the helm for the following 40 September academic year launches. Midway through Dr. Apple’s epic tenure, the Woman’s College would expand greatly, gaining a spacious new location to call home and a name change to Hood College. These results should be credited to Dr. Apple as much as they are to namesake benefactress Margaret Elizabeth Scholl Hood. Joseph Henry Apple Many others have written fine pieces on the tremendous achievements and life contributions of Dr. Joseph H. Apple. I, however, will shed some light on his death and burial here in Mount Olivet. But first, here’s the happy stuff in the form of a biography taken from Hood College’s website: "Joseph Henry Apple was born in Rimersburg, Pennsylvania, in 1865, the youngest son of Elizabeth Geiger and Joseph Henry Apple, a teacher and minister. An 1885 graduate of Franklin and Marshall College, he was called to be the President of the Woman’s College of Frederick in May of 1893 from Pittsburgh Central High School where he was enjoying a successful teaching career. Encouraged by his first wife, Mary Rankin Apple, to heed the call, Dr. Apple was to stay in Frederick and serve as president of the College for the ensuing 41 years. Upon his retirement in 1934, he was the oldest living college president in continuous active service at a single institution in the United States. Dr. Apple dedicated his life to the work of establishing the campus at its current location, constructing fourteen buildings and setting the high standards for academic excellence that continue to this day. A man of great vision and high purpose, he was noted for his persistence, dauntless determination and natural leadership ability. During his tenure, Hood grew from a small female seminary with an uncertain future to a campus of 125 acres, 14 buildings, 27 administrative staff, 57 faculty, and 500 students. He awarded diplomas to 1,591 students during his presidency. Not only did Dr. Apple give his life to Hood College, but so did the members of his family. Miriam Rankin Apple, the daughter of Dr. Apple and his first wife, graduated from Hood in 1914. She served as librarian in the library that bears her father’s name from 1914 to 1950, with the exception of a two-year leave of absence. Born in 1893, her life span coincided with the early life span of the College. She was noted in her grace, charm, and friendly disposition. The Miriam Apple Memorial Room in the library is dedicated to her memory and houses the archival treasures of the College. A second daughter, Charlotte, died as a child. Mary Rankin Apple died in 1896. In 1898 Dr. Apple married his second wife, Gertrude Harner Apple, who was employed by the College as an English instructor and is credited with establishing Hood’s literary magazine, The Herald. Additionally, Mrs. Apple was responsible for supervising the planting of many of the original trees, shrubs, and flowers which contribute to the extraordinary beauty of Hood’s campus. Gertrude and Joseph Henry Apple had three children. Two daughters: Elizabeth Apple McCain ’23 and Emily Apple Payne ’24, and a son, Joseph Henry Apple, Jr. The dedication of the Apple family to the life and work of the College is unparalleled. We owe much to this family. Their courage, vision, leadership, dedication, and commitment have resulted in a lasting legacy."  Margaret E. S. Hood (1833-1913) Margaret E. S. Hood (1833-1913) In his first year on the job, Dr. Apple properly, and professionally, built a relationship of trust with Margaret Elizabeth Scholl Hood, a former student of the Frederick Female Seminary (1847-1849). It was in 1893 that Mrs. Hood would put her faith (and money) in Dr. Apple’s leadership abilities by creating a $25,000 endowment in the name of her late husband, James Mifflin Hood. Years later, she would be invited by Dr. Apple to live at the school. He certainly made Mrs. Hood feel at home, becoming more than just an alumnus, but actually part of the institution itself. So much so, she would return the favor. In her will, she made arrangements to donate property (formerly known as Groff Park) and give an additional $30,000, which would be the impetus for President Joseph Henry Apple to begin building Shriner Hall and Alumnae Hall. In light of her many contributions, Dr. Apple led the charge to have the school’s charter amended to change the name of the Woman’s College of Frederick to Hood College. This occurred in October, 1912. Mrs. Hood would pass a few short months later on January 13th, 1913. As it was Mrs. Hood who gave her money and name to the institution for higher learning, it was Joseph Henry Apple who actually built it. The new campus opened in 1915, and the rest, as they say, is history.

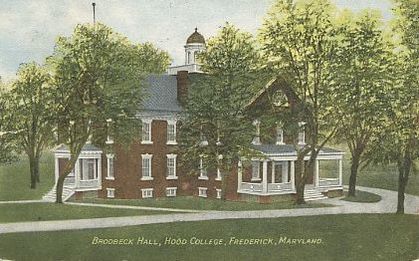

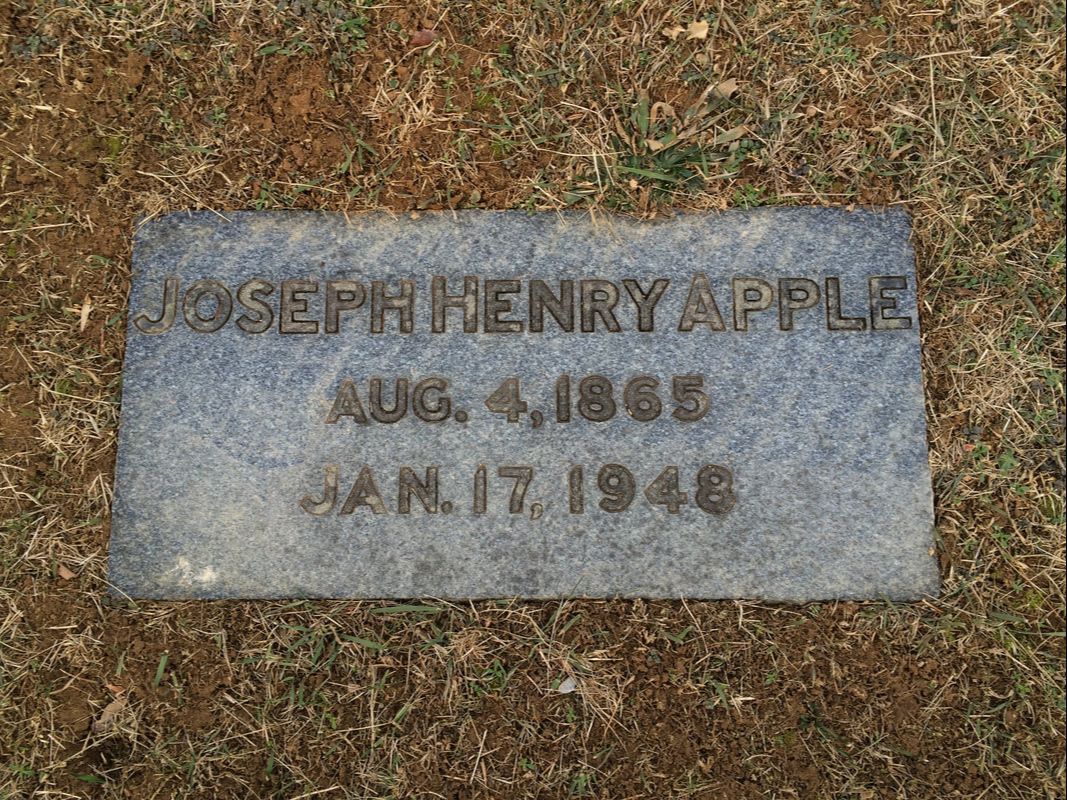

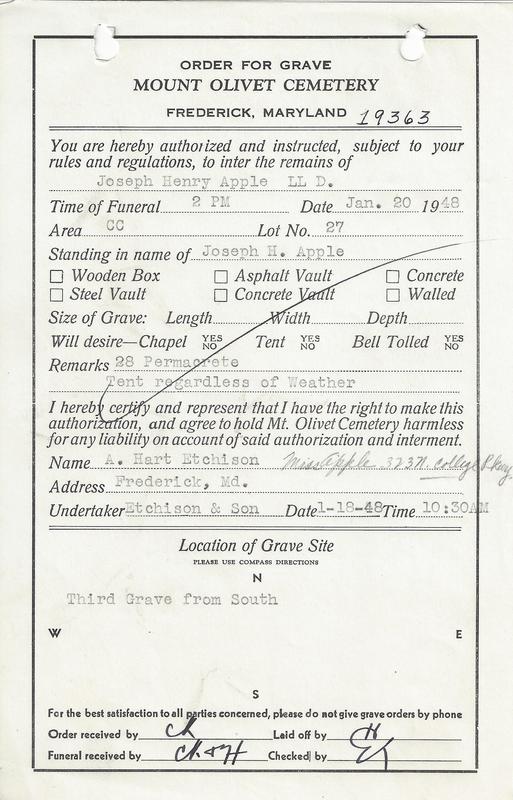

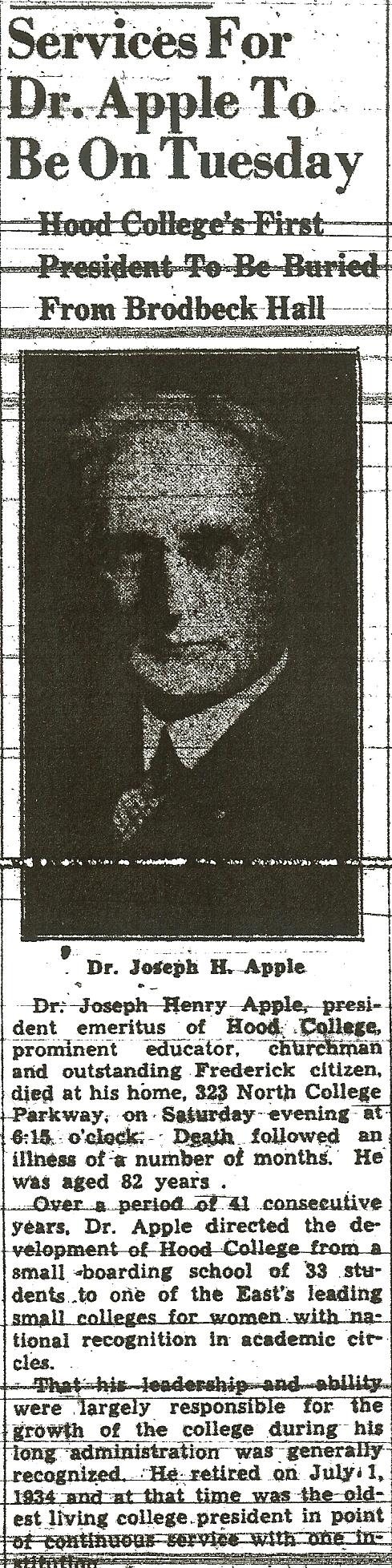

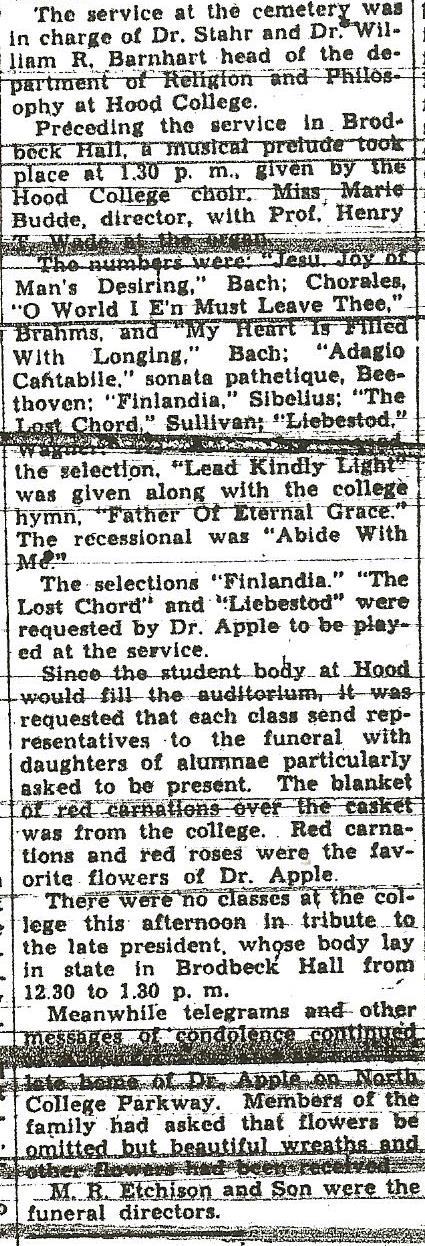

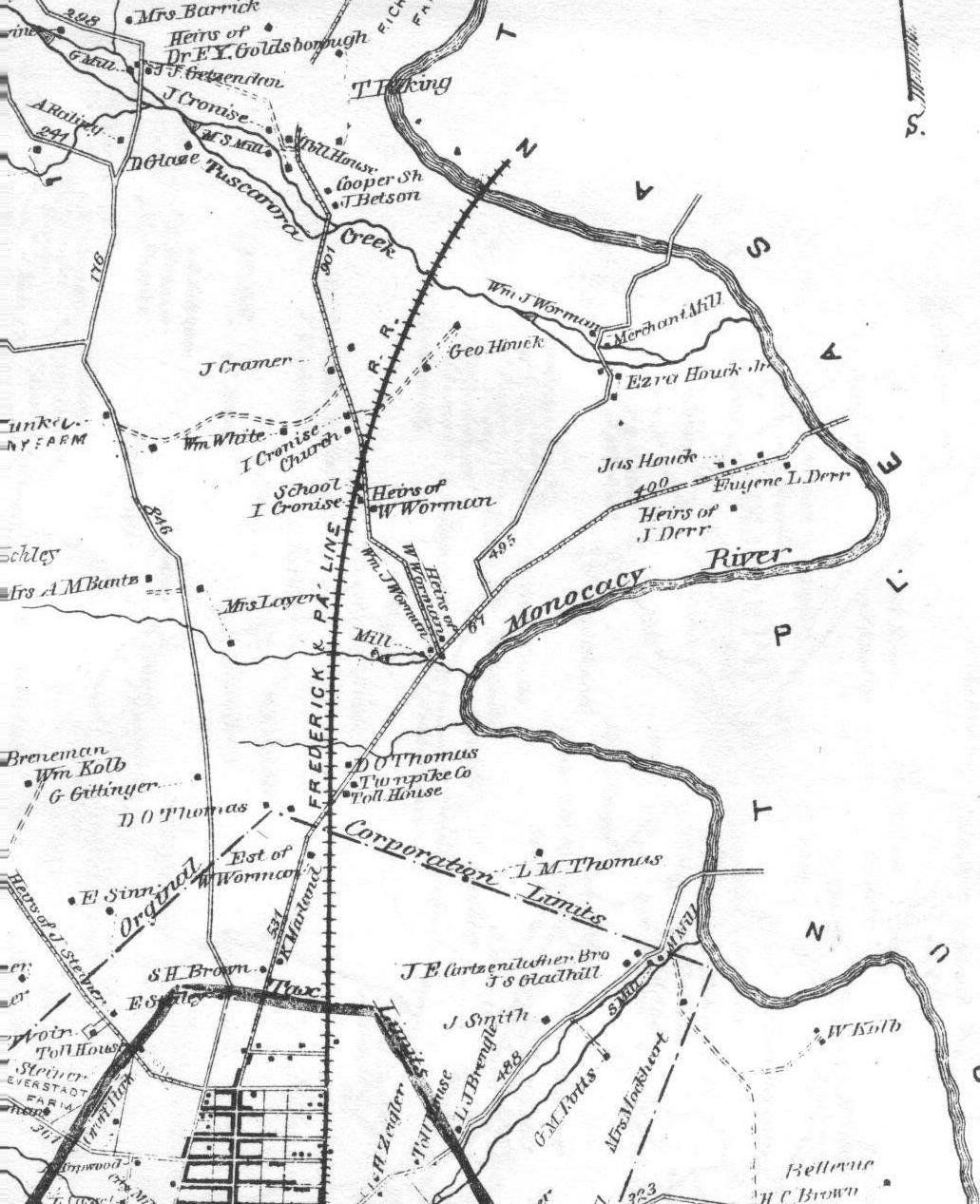

Dr. J. H. Apple (1865-1948) Dr. J. H. Apple (1865-1948) Dr. Apple was likely keenly aware of the 35th anniversary of his dear friend Mrs. Hood’s death on January 13th, 1948. At this time, he had been ill for a number of months. His own final bell would toll just four days later on Saturday, January 17th, 1948. Dr. Apple died at home, across the street from Hood's main entrance off Rosemont Avenue. The college and Frederick had lost Joseph Henry Apple at the age of 82. The local papers carried Dr. Apple’s obituary, along with several glowing tributes from community leaders and former students (I've included his obit at end of the story). The longtime educator had requested to be buried in his academic robe. January 20th was the day of the funeral. After a service at Brodbeck Hall, the original building of Hood’s new campus, the good doctor’s body would be laid to rest in Mount Olivet's Area CC, Lot 27. The family burial lot had been purchased two years earlier, and the remains of daughter Charlotte Apple had been relocated here from her original burial spot in Area L, found in the older section of the cemetery. I found that Charlotte had died in 1902 of diphtheria at the tender age of seven. Sadly, over the next decade, Dr. Apple would be joined by his daughter Miriam (1950), wife Gertrude (1953) and son Joseph, Jr. the latter dying as a result of a heart attack at age 48. Another one of Dr. Apple’s would be buried in the family plot in 1996, Emily Apple Payne. This one, good apple certainly made Frederick a healthier and better place, and Mount Olivet is proud to have people of his magnitude within its gates. Hood College is equally proud, celebrating its 125th anniversary in 2018.  Frederick News (Oct 28, 1929) Frederick News (Oct 28, 1929) In my research, I found yet another ironic and mystical connection. Dr. Apple’s remaining daughter, Elizabeth Apple, would marry Pittsburgh native Russell H. McCain in 1926. Russell was raised by his uncle, Elmer D. McCain, and the family came from western Pennsylvania in that pivotal year of 1913, the year Dr. Apple began Hood College. The McCains located west of Frederick along the National Pike (US 40) and started a farm operation that would take their name—McCain Orchards. And their specialty product was....you guessed it, apples! Later the name was changed to Hillcrest Orchards. The fruit trees are gone today, but one can still enjoy a tasty slice of pie or apple cheesecake at the Mountain View Diner or an apple-crisp sundae at Roy Rogers located adjacent McCain Drive—once serving as the farm lane that bisected the property . People often ask me what is the oldest burial stone marker in Mount Olivet Cemetery? It’s a great question, but one whose answer is not rooted in the cemetery’s first interment of 1854, or the cemetery's first monument. Ironically, it has a direct connection with the word stone, itself, not to mention being that of the builder of Frederick’s oldest known house. If you guessed the Brunner family (Schifferstadt built ca. 1758), you’d be wrong. It’s the gravestone, or grabstein, of Jacob Steiner (1713-1748). And in case you didn’t take German in high school, “stein” is the German word for stone. To understand the significance of this unique cemetery marker, one can also look at the significance of the house Jacob Steiner left behind, the archaic centerpiece of one of Frederick’s prime residential developments. Both are true stories left in stone. Master of Mill Pond I was intrigued to see a recent story in the Frederick News announcing the formation of the Mill Pond House Ruins Committee, a group taking aim to further preserve and interpret the “mortal remains” of what most likely represents Frederick’s oldest known house. The article states that City of Frederick planning officials are aiming to take the ruins over as part of a parkland dedication agreement with the developers of Worman’s Mill, located in the northeast portion of the city, just off MD route 26 and Monocacy Boulevard. Thankfully the remnants were not bulldozed with the creation of the Worman’s Mill community a few decades back. You can find them safely secured behind a chain link fence, located off a bicycle/walking trail that traverses the Worman’s Mill Conservancy property. This locale is bounded by Tuscarora Creek and Mill Race Road, and is also in close proximity to the Monocacy River to the northeast.  Dedra Salatrik with the ruins in the background (photo courtesy of the Frederick News-Post) Dedra Salatrik with the ruins in the background (photo courtesy of the Frederick News-Post) Unfortunately, all that exists of the original Mill Pond House are the chimney and a few of the structure’s stone walls. The current location of the remains of the Mill Pond House can be found on the Worman’s Mill Conservancy property (abutting the fore mentioned Mill Race Road and the Tuscarora Creek). We are lucky that multiple residents, past and present, have taken a great interest in the architectural importance of the house, and the life of its original builder. Neighboring Worman’s Mill resident Dedra Salitrik, a master gardener, became enamored with the Mill Pond House when she and husband, John, bought their home on Mill Race Road. The Salitrik residence actually backs to the ruins, and gave inspiration for their purchase at this location. The couple immediately started doing detective work on the structure, eventually receiving permission from the Wormald Development Company to go inside the chain-link fence and build a pollinator garden to attract birds and bees. They went on to enhance the ruins with plantings of elderberries, winterberry holly, milkweed and turtlehead. As for context on this old house, Worman’s Mill resident and historian Heidi Sproat wrote the following introductory piece on the Worman Mill Conservancy’s website: Jacob Stoner, a German settler to Frederick, MD built the Mill Pond House around 1746, before the Revolutionary War, on a site along the Old Annapolis Road. It was a prime example of half-timber and wattle-and-daub construction typical of late medieval dwellings in the valley of the Upper Rhine in Germany. In fact, it was the only known house in the East German or Palatine style ever built in Maryland. The house was constructed entirely of peg and rail construction; there were no nails used. The house was built forty feet wide and thirty feet deep and had two stories. While the original house was constructed using a technique known as "waddle and daubing," the ground floor was made of both sandstone and limestone. Incredibly, there was a vaulted cellar and spiral stairs. The house resembled what we refer to today as English Tudor. After Jacob Steiner’s (Stoner’s) death in 1748, the Mill Pond House, and surrounding property, was held by the Frederick County court and eventually transferred to his children in 1767. His wife had died the same year, leaving minor aged children. Jacob’s eldest son, John, inherited the Mill Pond parcel and continued to operate his father’s mill. Mill Pond was sold out of the family in 1798 (the time of John’s death) to William Potts, who would eventually convey the property to namesake Moses Worman on April 3, 1811. I have had the pleasure of knowing two of the leading contemporary authorities on Jacob Stoner and his Mill Pond House. One is my friend Patricia “Pat” Ogden, a historian, genealogist and master docent at Schifferstadt Architectural Museum. Pat has researched and presented on the Mill Pond House and Jacob Steiner in recent years, and serves as a key member of the Mill Pond House Ruins Committee. The other individual of note is no longer with us, however my work office is within 100 yards of his gravesite. His name was Claggett Jones (1924-2004). Claggett Jones, a Washington DC native and World War II veteran, took a great interest in the Mill Pond House and its history. After his retirement from the Department of Commerce, Mr. Jones moved to Frederick with his wife Jean, taking up residence in the Worman’s Mill community. Back in 1995, he was kind enough to provide me with a copy of an old article from 1951 which included photographs of the ancient structure for use in my documentary film series Frederick Town. A few years later, we invited Claggett to be a guest for a special feature on Young at Heart, one of our GS Communication’s Cable 10 television programs. He spoke on the Mill Pond House and shared a spectacular two-foot square model of the structure which he and lifelong friend and neighbor Wes Stewart had meticulously crafted in his basement. Jacob Steiner (Stoner) One of the area’s earliest settlers, Jacob Steiner (Stoner), was one of six men who tried to buy Tasker’s Chance in the late 1730’s. Tasker’s Chance was a parcel of 7,000 acres patented to Annapolis businessman and politician Benjamin Tasker in June 1727. It was eventually conveyed to Frederick Town’s founder, Daniel Dulany, and would constitute the bulk of the land that the City of Frederick sits on today. Of the 19 individuals in 1746 who initially received deeds from Dulany, only Steiner received more than one parcel. He held three lots, all located northeast of the newly laid-out town. Steiner operated a grain mill near the mouth of the Tuscarora Creek and named his lands Bear Den, The Barrens, and Mill Pond. It was on this latter tract that Jacob Steiner erected a late medieval-style stone and timber dwelling in 1746. Not much more is documented about Jacob Steiner’s arrival to this country from Germany, or his early years here. He was born in 1713 and married Magdalena Glattacker (1715-1748) in 1733. It is likely that Jacob arrived in Philadelphia and settled west of the city like many of his German brethren of the era. He would eventually come to Maryland and the Monocacy River Valley in the late 1730’s. In the year 1740, Jacob Steiner was naturalized with sons John and Jacob (Jr).  Trinity Chapel (ca. 1950) Trinity Chapel (ca. 1950) Jacob Steiner would not see the growth of Frederick, dying in 1748 at the age of 35. He would be laid to rest in the first graveyard associated with the German Reformed Church. This was located behind the site of the congregation’s first church structure in the first block of West Church Street. The place of worship would eventually be enhanced in the form of Trinity Chapel which still exists today. The burying ground stretched from behind the church, southward to West Patrick Street. The former McCrory's Store, today’s Maryland Ensemble Theater building (31 W. Patrick St.), occupies the footprint today. The congregation eventually built a second graveyard at the corner of Bentz and West Second streets, the site of Memorial Park. With the opening of Mount Olivet in 1854, many churches were relieved of the burden of not having adequate burial space. In some cases, folks bought lots in Mount Olivet and decided to move their ancestors into newly purchased lots from other cemeteries. Sometimes this was by choice, and other times by necessity as various congregations were making decisions to expand church structures, build support buildings or simply sell off downtown graveyard properties for lucrative offers made for residential and commercial purposes. This was the situation with for the German Reformed Church’s first cemetery. Coincidentally, the church’s second cemetery, original resting place of the famed Barbara Fritchie, was condemned by the City of Frederick in the 1920’s, and repurposed as Memorial Park in which soon became home to a fine World War I monument, erected in 1924.

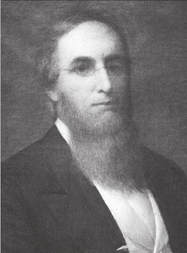

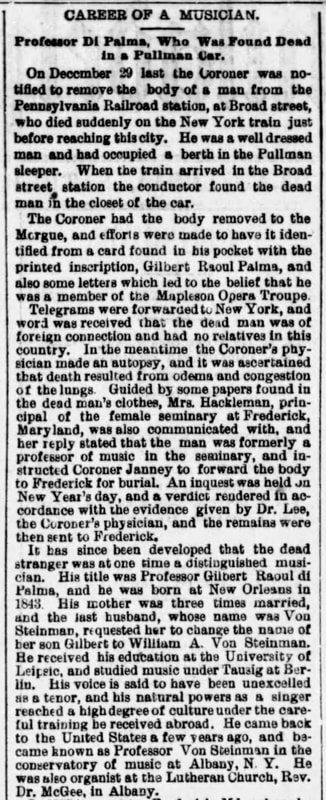

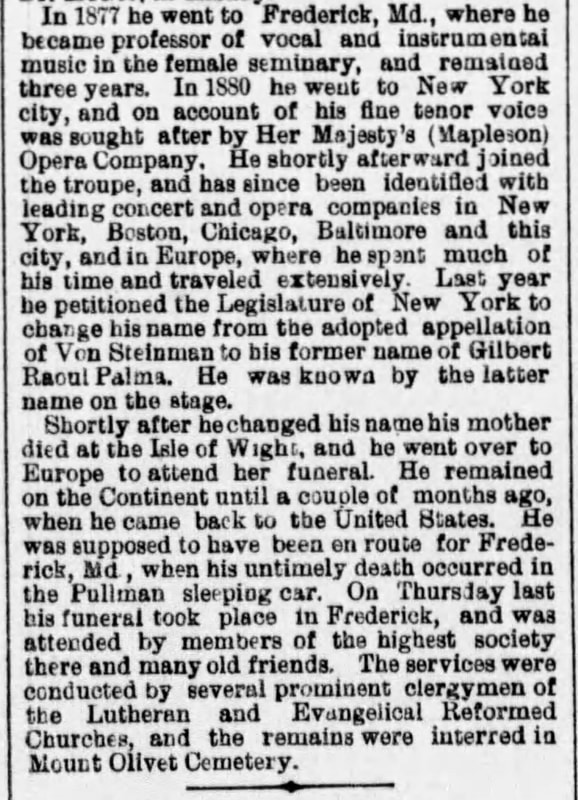

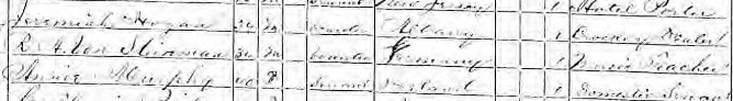

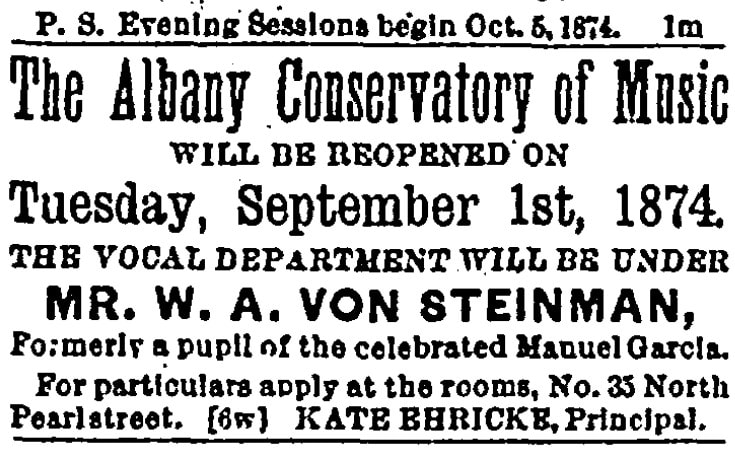

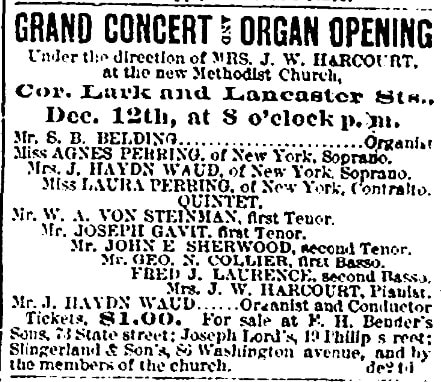

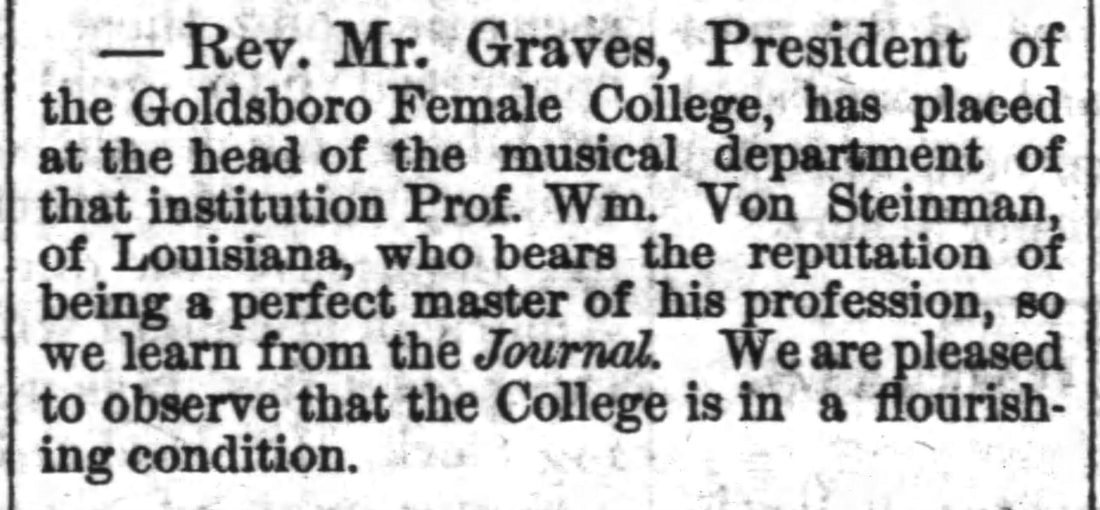

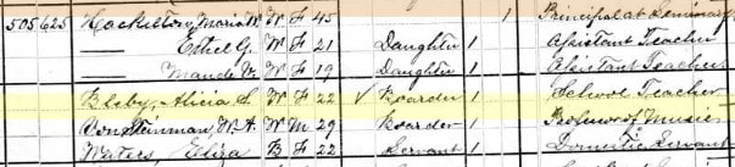

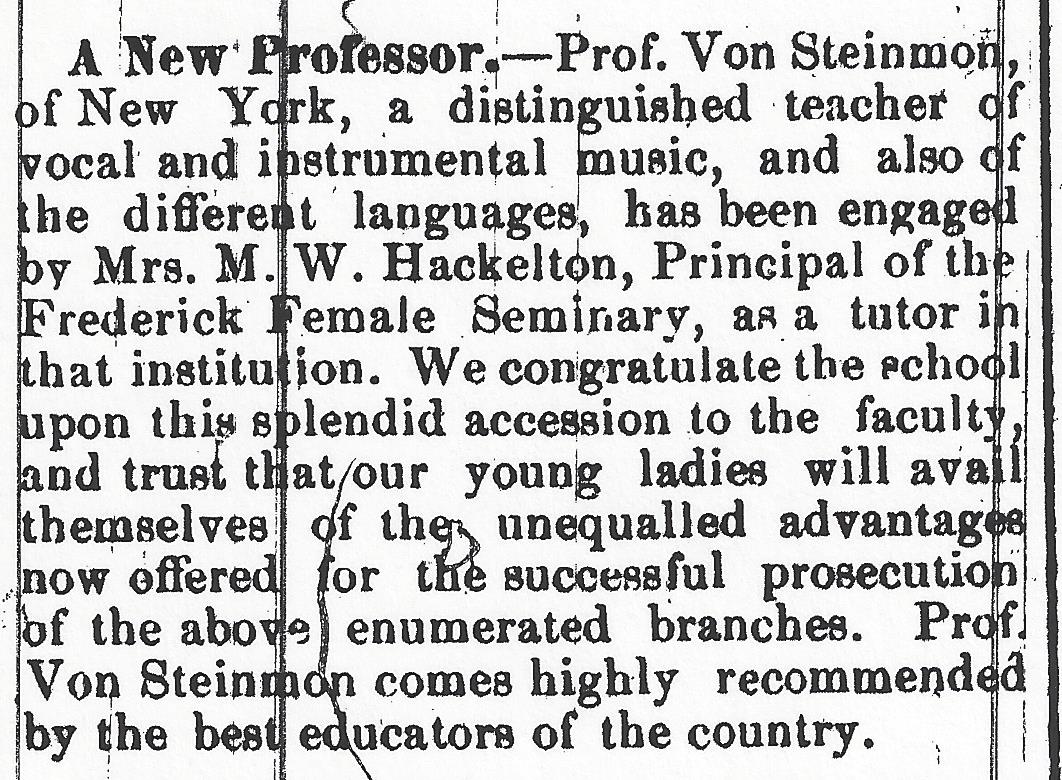

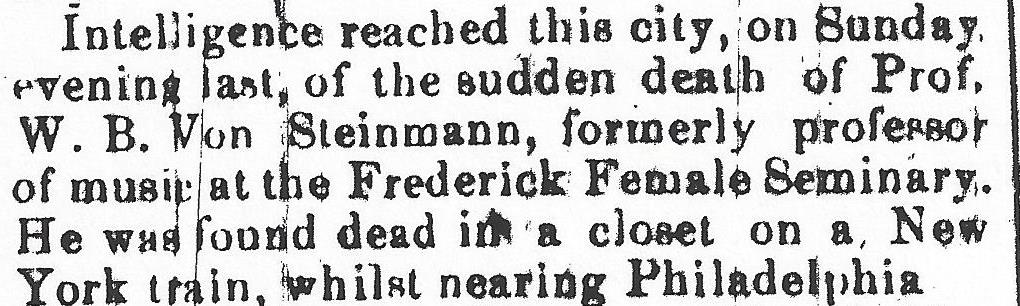

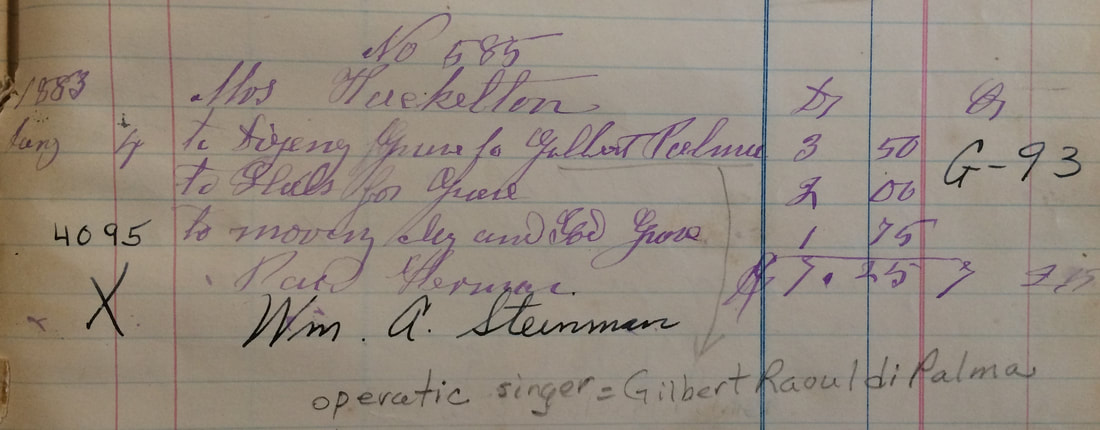

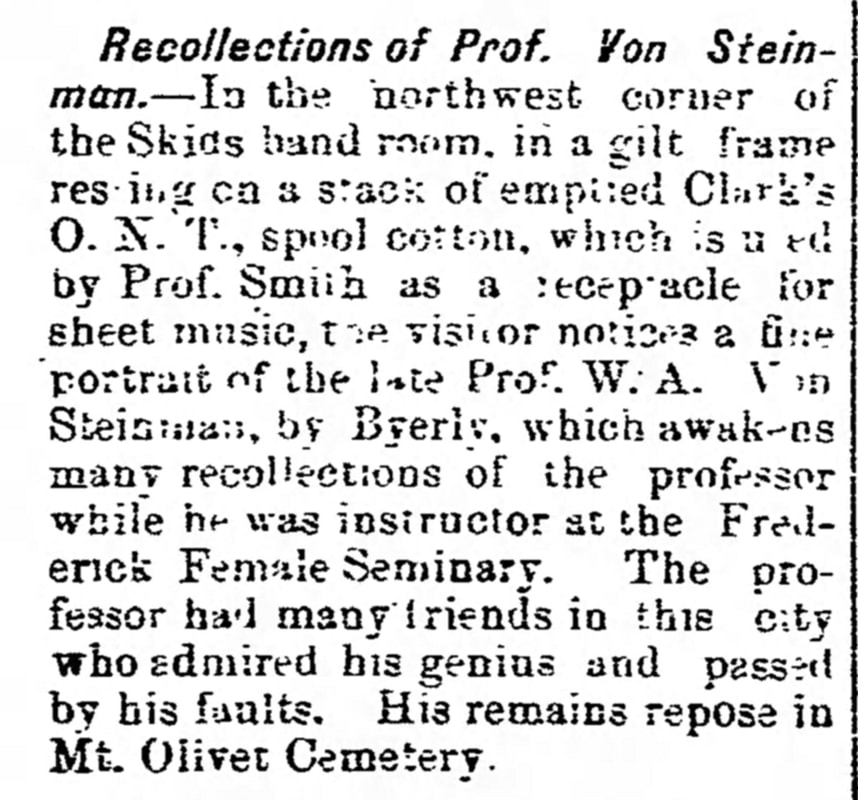

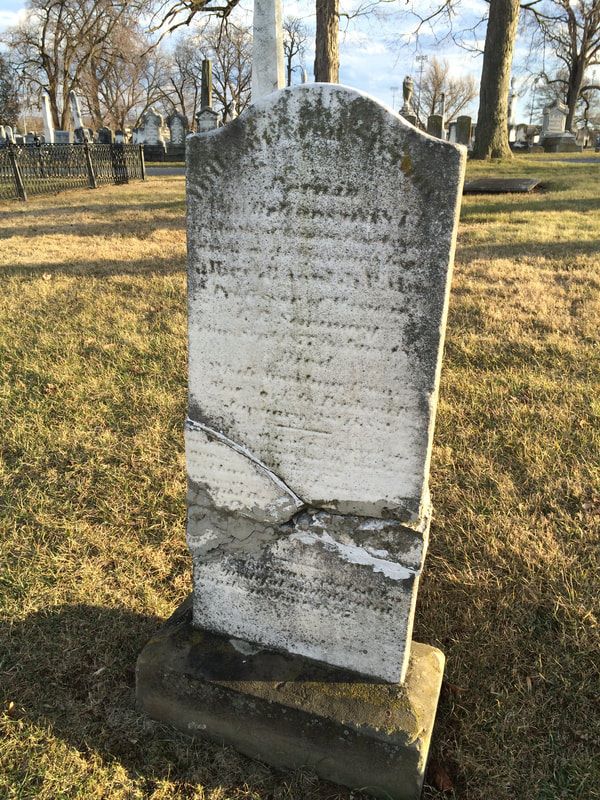

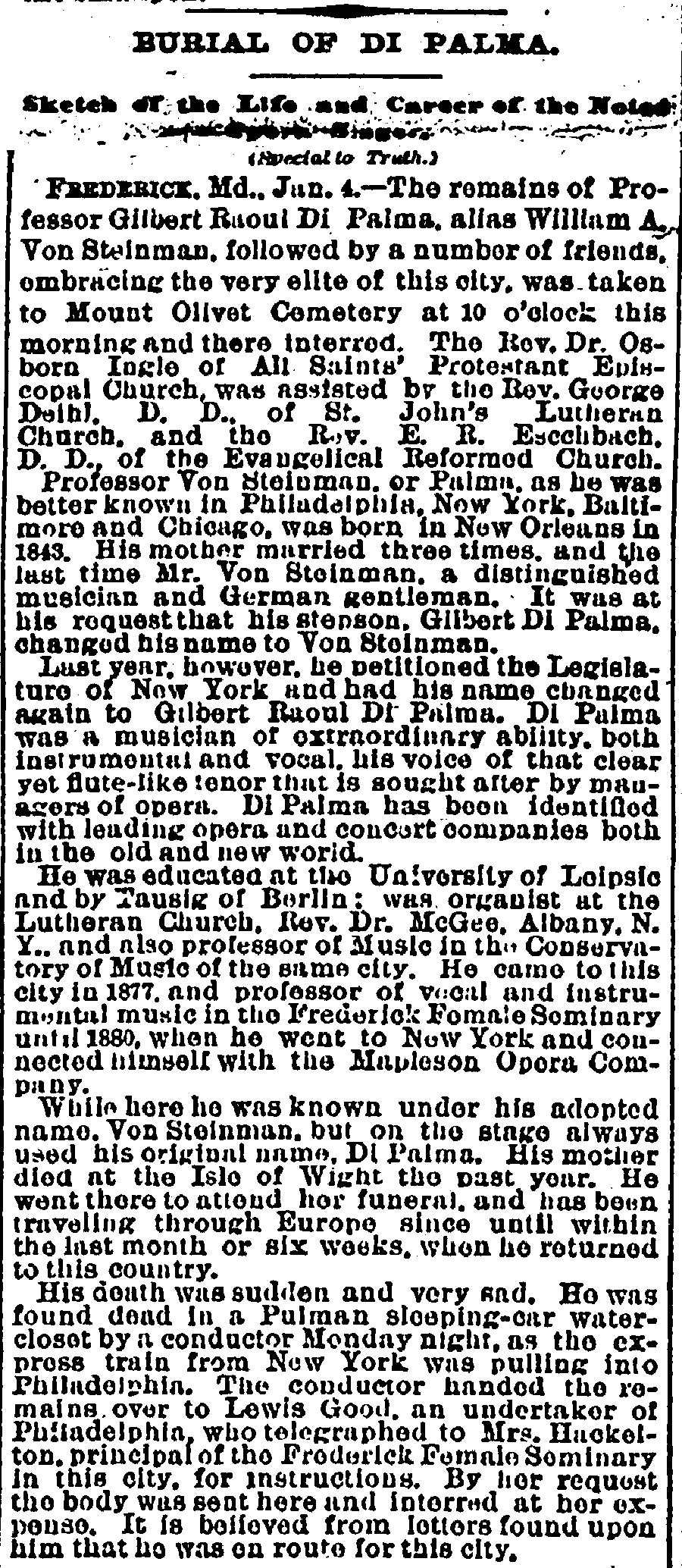

Replacement memorial stone for Jacob Steiner Replacement memorial stone for Jacob Steiner Our cemetery records do not show the removal or reburial of Jacob Stoner in Mount Olivet. Based on the time of his death, one of the earliest in Frederick Town’s history, his mortal remains are likely one with the earth that comprises the original German Reformed burying ground. Steiner's beautifully crafted tombstone was moved to Mount Olivet, likely in 1923 with the other family stones. Back in 2014, Jacob's grave stone was moved to the basement of the Key Memorial Chapel for safekeeping after descendant Roland Steiner and family of Howard County had new memorial stones crafted for Jacob Steiner and others whose stones had been disintegrating. The intent of Mr. Steiner was to preserve what is likely the oldest surviving tombstone in Frederick. With our new Preservation and Enhancement Fund, we hope to make a thorough restoration for the future and have the stone available for public display. Jacob Steiner is one with Frederick, and his original grave stone and some of the stone work associated with his magnificent home at Mill Pond have survived the test of time. One day, two summers back, I was walking around Mount Olivet Cemetery, taking scenic images for our website. While out and about, my curiosity was suddenly piqued by a well-aged, marble monument containing a tremendous amount of text carved on its face. The gravestone was about 3-foot tall, and appeared to have been the recipient of numerous repairs over the years. I could made out a few dates, and what I thought was the decedent’s name—William A. Von Steinman. When I got back to my office, I looked up William Von Steinman in our network interment database. I found basic vital information such as birth and death, but more importantly found an entry in the notes section that read as follows: Born in New Orleans, LA. Occupation: Professor of Music at Frederick Female Seminary who studied under of operatic singer Gilbert Raoul di Palma. The death records of the Evangelical Lutheran Church, Frederick, Md. recorded his full name (Prof. W. H. Von Steinman), age (39y2m), death date (Dec. 30, 1882) and burial date (Jan. 4, 1883). I thought it was ironic that this professor had been born in 1843, the same year the Frederick Female Seminary was originally opened. I immediately performed a Google word search on Gilbert Raoul di Palma (a name that also appears on the face of Von Steinman’s tombstone) to gauge his importance in the history of opera, thinking this could be a neat tie-in for a future blog story. Sadly, I found nothing. I then pulled out the heavy “research guns,” and began scouring online/digitized newspapers of the 19th century to see if Gilbert Raoul di Palma had taught and/or performed in the United States, likely in New Orleans. Then “Bingo!"— I had hit the “history geek researcher” jackpot on my first try. The top Google entry included not only di Palma’s name, but also that of Von Steinman! This article appeared in the Philadelphia Inquirer edition of January 6, 1883. I soon learned two fascinating things about my subject: Mr. di Palma and William Von Steinman were one in the same; and this enigmatic man (with fancy monikers) was not only a mystery to me, he (and his true identity) had been at the center of a larger puzzle and subsequent police investigation at the time of his untimely death—he had died at the age of 39 while traveling on a train between New York City and Philadelphia.  Leipzig Music Theater Leipzig Music Theater The Inquirer article was a Godsend, and told me everything I needed to know—well almost everything. I found that the story of William Von Steinman was run in newspapers in New York City, Chicago, Buffalo and even Racine, Wisconsin. Although I couldn’t find funeral coverage in any of our available local Frederick papers, I did find an article in a New York offering, reprinting a story that first originated here. (I’ve inserted at the end of this story). I wanted to go a bit further, yearning to learn three things, in particular: 1.)What was the exact timeline of Von Steinman’s life in reference to residences?; 2.)Why/how did he come to Frederick and the town’s seminary?; and 3.) Why is he buried in Mount Olivet as opposed to other locations? There was no “Big Easy” in trying to find details of the early life in New Orleans of one William Von Steinman/Gilbert di Palma. I couldn’t find any di Palmas in census records (1840’s-1870’s), as the closest match was a Gilbert Detour of French descent, aged 17 and living in the Fifth Ward of New Orleans in the 1860 US Census. In the dwelling next door, I found a James Dejour from Sicily. In an 1850’s New Orleans’ newspaper, I found the name of a Hermann Steinman attached to a political petition of support for a certain candidate. I could not put my finger on Gilbert di Palma’s assumed Italian roots, or the Bohemian influence inflicted by his step-father resulting in his name change. As can be seen by the Inquirer article, this individual spent time in Europe, attending what would become the Music Conservatory in Leipsig, oldest in Germany, and receiving piano instruction under the great Carl Tausig (1841-1871), Franz Liszt's most esteemed pupil. Europe was certainly a better option for the Von Steinman family in the decade of the 1860’s, as opposed to spending time stateside in New Orleans during the turbulent time of the American Civil War. The first tangible census record on our mystery man comes in 1875 with the New York State Census taken in that year. Mr. Von Steinman can be found living in Albany, New York as a boarder in Ward 7. His listed profession is that of music teacher, but his birthplace is shown as New Orleans, but rather Germany. Perhaps his birth in New Orleans was just a technicality as his parents (or simply his mother) was simply traveling through at the time. I started thinking that the professor either came from tremendous wealth, or was a total sham, taking fancy names suitable to propel a fledgling career as a successful music teacher/musician. Apparently, this time period included Von Steinman petitioning the New York legislature to have his name legally changed back to Gilbert di Palma, again, a great self-marketing ploy for an aspiring tenor. I deduce that the professor’s time in Albany ranged from late 1874-mid 1877, as many local newspapers articles and advertisements mention him often in relation to concert performances. I did find that he had been hired to teach music at another school prior to his tenure in upstate New York. This occurred in 1873, as his employer was the Goldsboro Female Seminary, located in New Bern, North Carolina. I had to smile in finding this tidbit, because the earlier mentioned Baron Christoph Von Graffenried was the founder of New Bern in 1710—the first Swiss settlement in the New World. Anyway, I digress (as usual).  J. H. Hackleton (1817-1877) J. H. Hackleton (1817-1877) The Hackleton Connection Further investigation showed me that William Von Steinman came to Frederick in the summer of 1877, in preparation for the upcoming school year in the employ of the Frederick Female Seminary—a fact that could have been learned earlier had the gravestone been more legible. It was a melancholy time for the Frederick institution, preparing for its 35th academic year of existence. The previous April, the school’s principal, James Harvey Hackleton, suddenly expired one week after celebrating his 60th birthday. Professor Hackleton had come to Frederick in 1873 with an impressive resume. Along with his wife, Maria (Williams) Hackleton, a noted professor in her own right, the Maine natives had previously administered like female seminaries in his home state and schools in the South, most recently in Memphis, Tennessee. Upon Principal Hackleton’s death, Maria assumed her husband’s chief leadership role at the institution. The transition was reported to have been quite smooth, and Mrs. Hackleton would remain in this position until 1885, aided by her two daughters, staff members of the Frederick Female Seminary who would marry into local Frederick families (McPherson and Parsons). Maria Hackleton would move to Greenville, South Carolina and continue her profession as principal of the Classical School for Young Ladies.  In an article appearing September 17th, 1877 in the Frederick Examiner newspaper, Mrs. Hackleton received praise for bringing Professor William Von Steinman onto her staff. It seems that the new music teacher’s reputation had certainly preceded him. Thus began Von Steinman’s four- year stint at the Frederick Female Seminary, where he soon became beloved by students and fellow citizens alike. I presume the young man meant a great deal to Mrs. Hackleton as well, as he likely did much to enhance the prestige of the school, while also bolstering the skills of Hackleton’s daughters, who appear to have had musical talents and aspirations of their own.  Col. Mapleson Col. Mapleson From the newspaper articles, I assume that William Von Steinman left the school, or took a sabbatical in fall 1880 to follow his perceived true dream as a professional musician. He became part of the Royal Opera Troupe led by Col. James Henry Mapleson, an English opera impresario and leading figure in the development of opera production, and the careers of singers in London and New York City in the second half of the 19th century. The company gave autumn and spring seasons at the New York Academy (10 weeks in the fall and 5-8 in the spring) and toured, appearing regularly in Philadelphia, Boston, Detroit, Cincinnati, Chicago, Cleveland, Buffalo, Syracuse and Albany. Other cities included St Louis, Baltimore, Washington, Pittsburgh, Toronto and Indianapolis. Mapleson’s continental repertory was fairly standard and featured operas by Italian composers such as Donzetti, Rossini and Verdi as well as translations of works by the likes of Gounod, Bizet and Wagner. So this explains the years of Von Steinman’s life during 1881 and 1882.

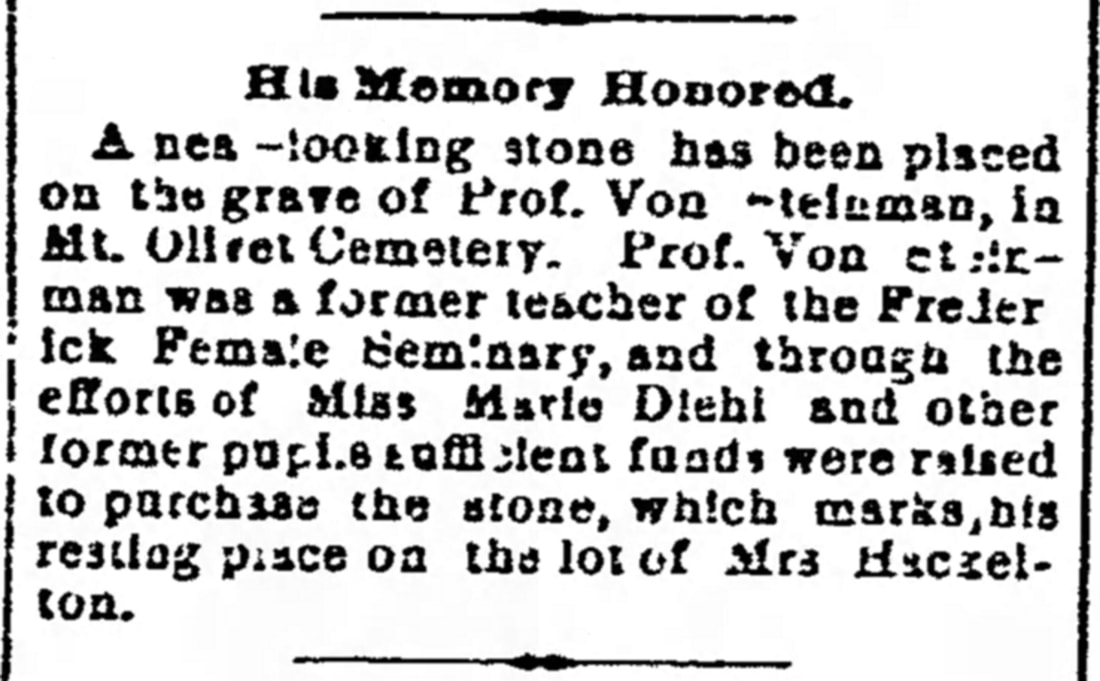

Mount Olivet Superintendent, Ron Pearcey, and I recently ventured out to make a rubbing of the gravestone, with the hope of gleaning more of the text content that couldn’t be read by the human eye—or at least mine. We were able to find that under his arching name of William A. Von Steinman (at the top of the stone), the following information is included: Born in New Orleans in 1843 Performed under the name of Gilbert Raoul di Palma Professor of Music at the Frederick Female Seminary from Sept 1877 to Nov 1880 Died while traveling from New York to Frederick January 3, 1883 Erected by his Grateful and Devoted Pupils in June 1899. Even with the rubbing we couldn’t decipher a biblical passage. We also note here that the death date of January 3, 1883 is incorrect, as it was actually December 29th (the time of the discovery aboard the train). January 3rd is likely the day that proper identification was made, however, the official Pennsylvania death certificate gives December 30th as the death date of Gilbert Raoul di Palma. I found a few remembrances of Professor Von Steinman in later papers. In 1889, an advertisement announced that a benefit concert was being planned to raise funds to place the fitting grave monument for the former music teacher. This would eventually become a reality nearly a decade later in 1897. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed