|

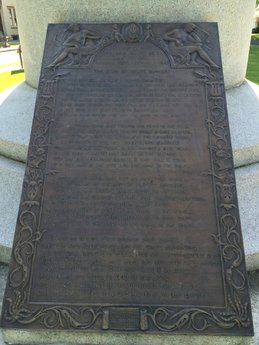

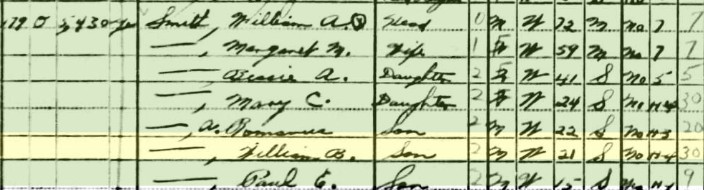

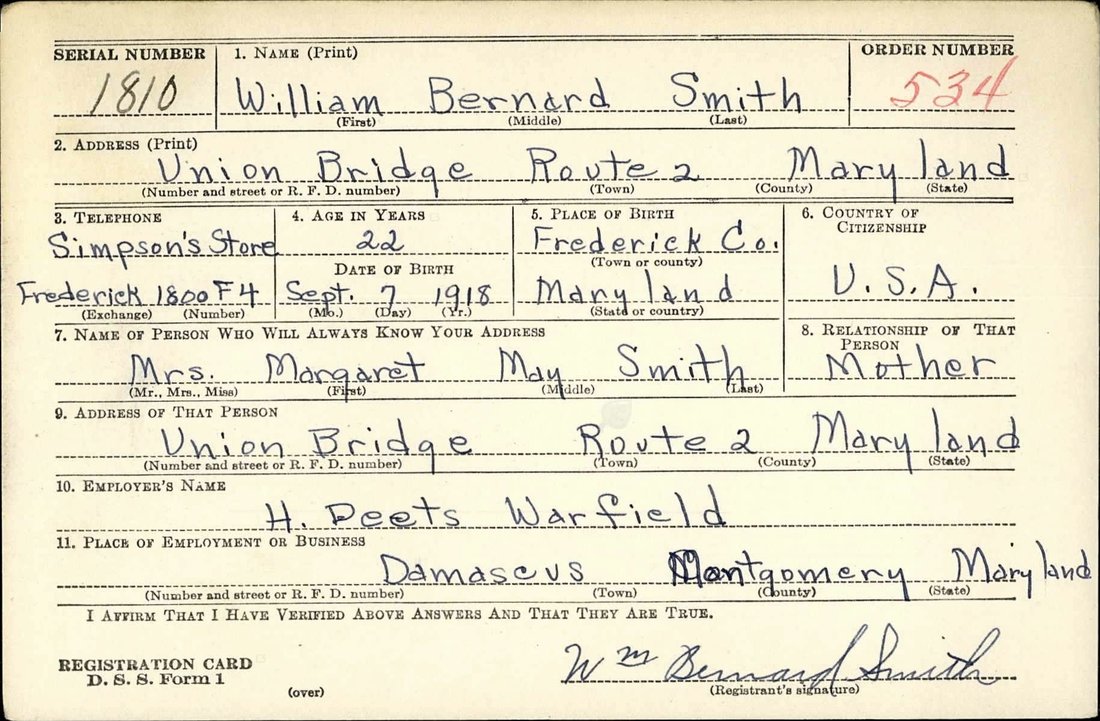

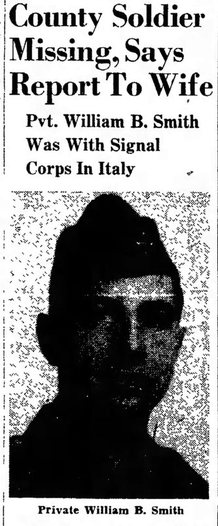

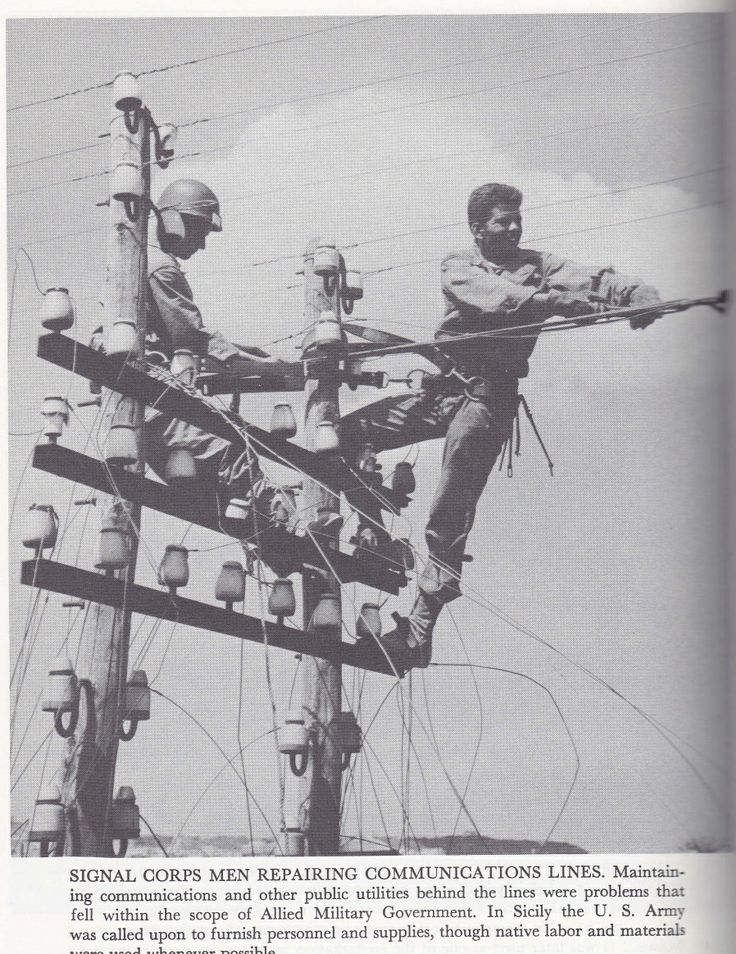

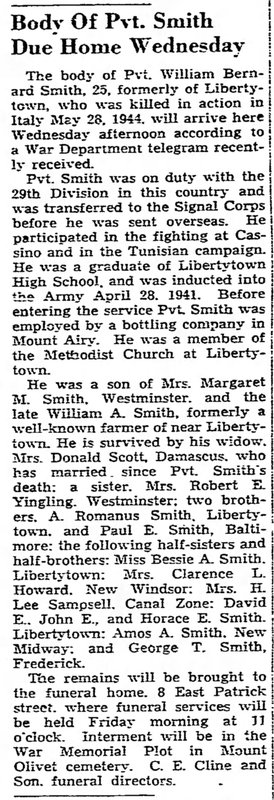

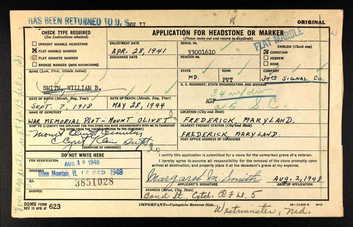

“The flame of love shall burn into our hearts the memory of our noble dead.” These are words written upon the World War II Memorial, located within Mount Olivet Cemetery’s Section EE. The monument, first erected in 1947, is: “dedicated to the Men and Women of Frederick County who, by their unselfish devotion to duty, have advanced the American ideals of liberty and the universal brotherhood of man.” Memorial Day originated in 1868. First known as Decoration Day, the observance took form in the year 1868 when the Grand Army of the Republic established it as a time for the nation to decorate the graves of the Union war dead with flowers. Confederate veteran groups would follow suit with their own day of honoring former soldiers lost in the conflict. By the 20th century, one day was chosen to solemnly commemorate all Americans who lost their lives in military service—Memorial Day. Over the years, people have made regular pilgrimages to visit cemeteries and memorials on this federal holiday, particularly to honor those who have died in military service. In many cases, volunteers place American flags on graves of veterans within cemeteries of varying sizes, big and small. Public ceremonies of remembrance are generally held by veterans service organizations and municipalities.  Mount Olivet is no stranger to the abovementioned activity, dating back to the 1860’s. To this day, annual Memorial Day observances have taken place within the cemetery’s hallowed grounds. For decades, the American Legion Francis Scott Key Post #11 has held a program in the shadow of their namesake’s memorial by the front of the cemetery. This takes place at 12 noon. Earlier in the morning, and in the rear of the cemetery, local Frederick County based chapters of the Daughters of the American Revolution, Sons of the American Revolution, along with Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War have organized ceremonies to honor veterans “at rest” in Mount Olivet’s mausoleum complex. This is a more recent tradition with a start time of 10am. The cemetery is peppered with small US flaglets, placed one week earlier by American Legion members and (Legion) baseball players. Flags are flown at half-mast, Taps is played and wreaths adorn the Francis Scott Key monument and the World War II Memorial. At the latter, poppy flower pedals can be found adorning the 30 military issued markers of men buried within the monument itself. One of these men died 73 years ago on May 28th, 1944. A Boy from Libertytown William Bernard Smith was born September 7th, 1918. He grew up on a farm in Libertytown owned by his parents William A. and Margaret Smith. A graduate of Libertytown High School, he found employment with a bottling company in nearby Mount Airy. One month before his 23rd birthday, Smith entered the US Army in April of 1941. Originally a member of the 29th Division, William B. Smith was transferred to the Signal Corps before being sent to the overseas Mediterranean and Middle East Theater of war. He arrived in late March 1943 and stationed in North Africa in June. He would participate in the Tunisian campaign and then landed in Italy. The push north by allied forces was slow and steady.

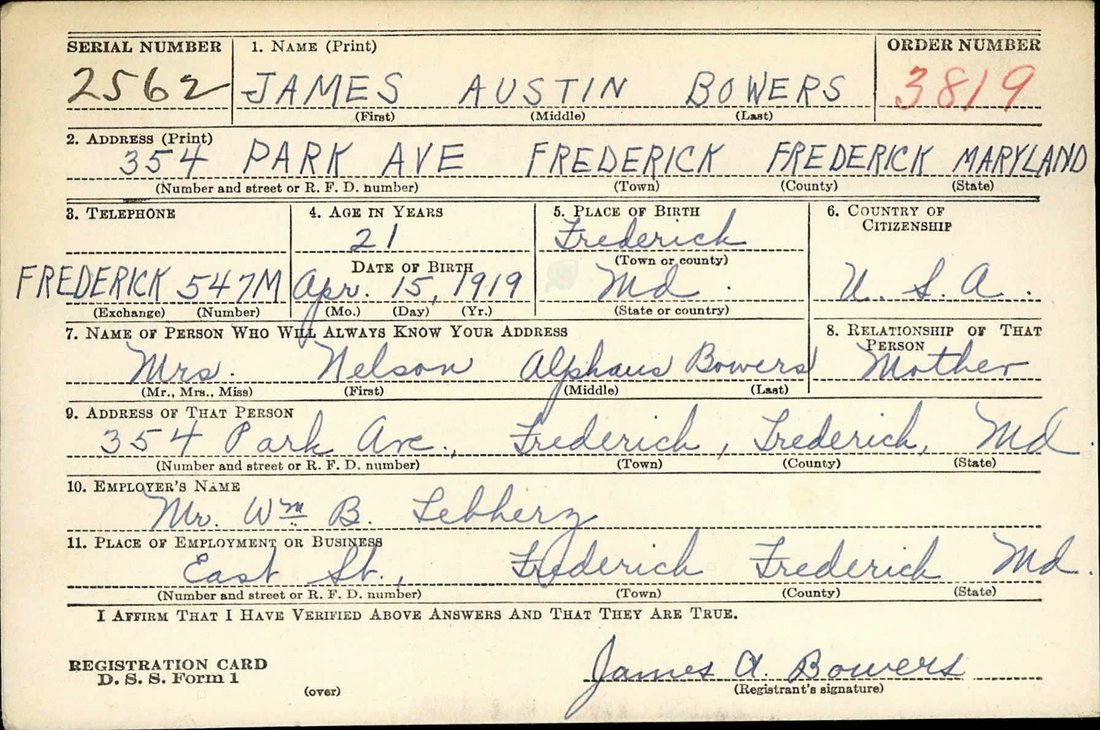

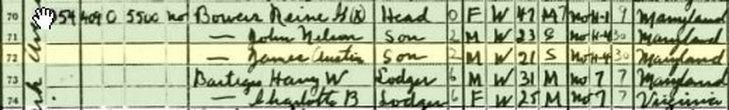

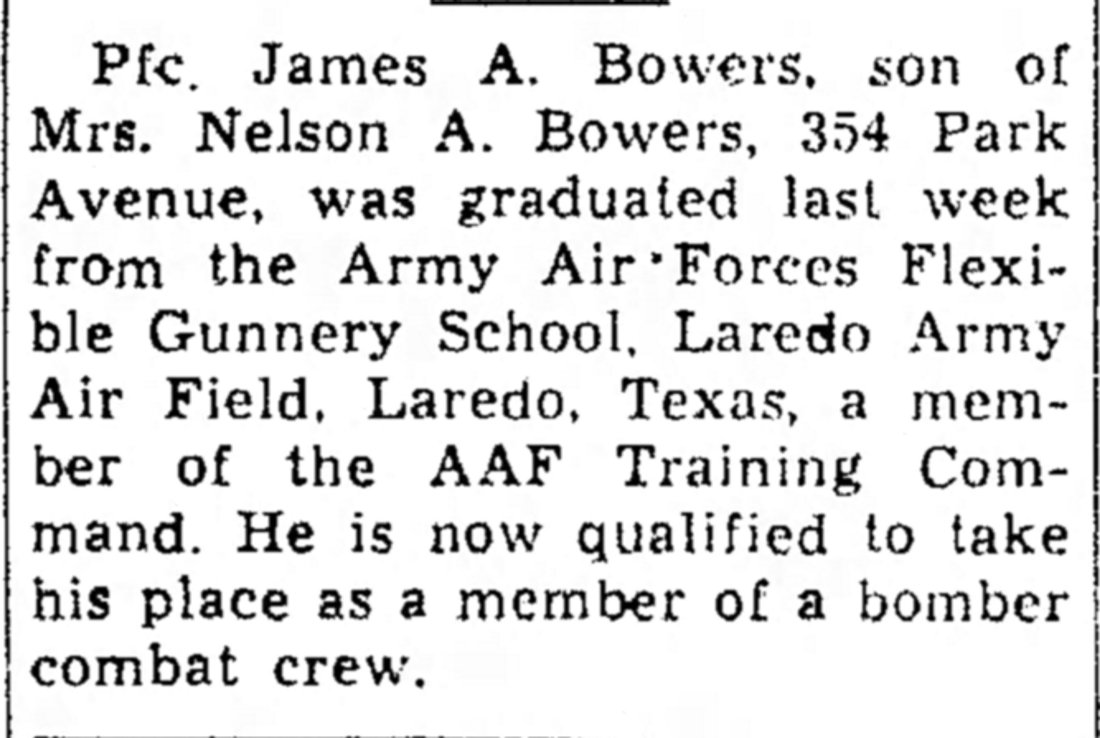

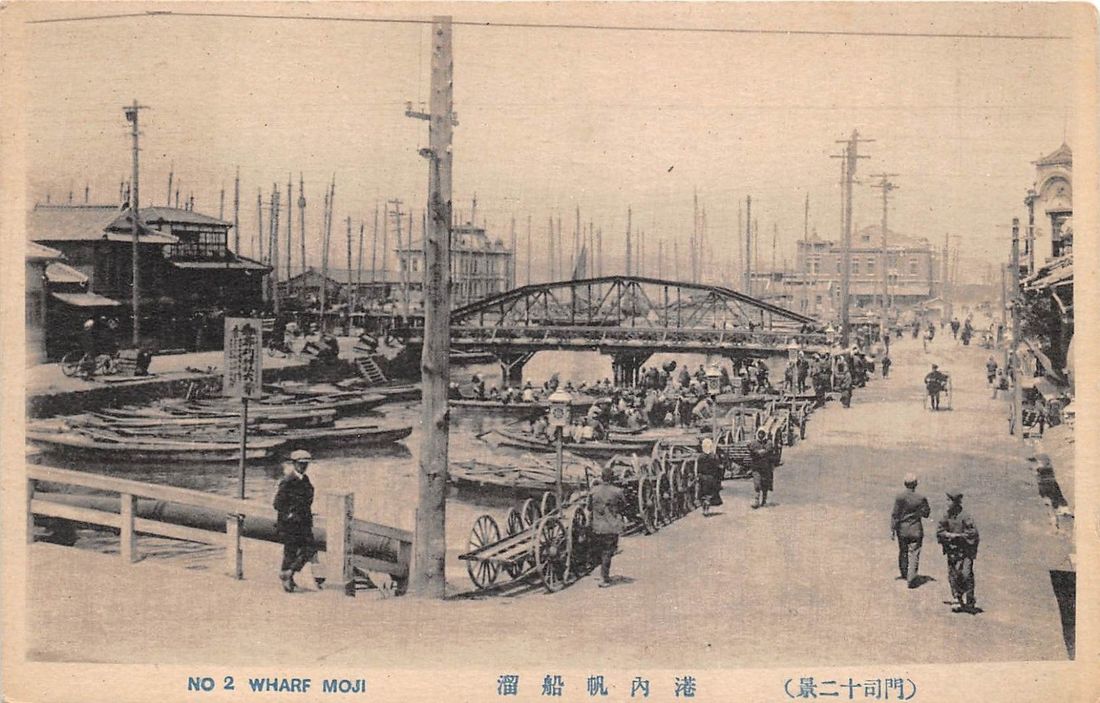

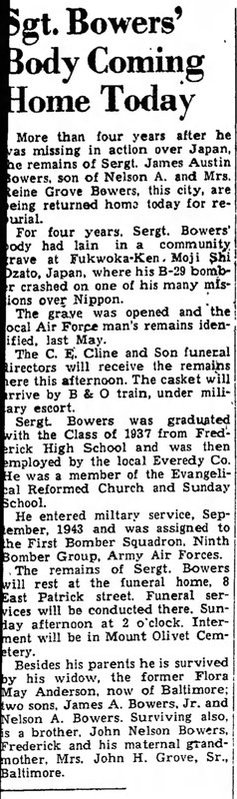

A Fear of the Unknown As the Smith family sadly experienced the one-year anniversary of William’s death, another Frederick resident would lose his life in the Western Theater of Japan on May 28th, 1945. This serviceman’s wife and mother had heard nothing from their loved one for weeks. Suspicion and concern arose as he had written home once or twice weekly. In late June, a telegram came stating that he was missing in action.” Unlike William B. Smith, the fate of this soldier would not be learned by his family until May of 1949. Sgt. James Austin Bowers was a gunner on a B-29 Superfortress, which crashed near the Japanese village of Fukuoka-Ken Moji Shi Ozato. Today, this locale is known as Moji, Kitakyushu. Villagers apparently recovered the bodies of those servicemen on board and buried them in a common grave. It wasn’t until 1949, when American Grave Registration Personnel discovered the gravesite, that Sgt. Bowers remains were identified. They were removed from Japan and reinterred in a US government cemetery located in Korea. Sgt. Bowers was born April 15th, 1919 in Frederick. The son of Nelson A. and wife Reine Grove Bowers lived at 354 Park Avenue in Frederick and attended Frederick High School, graduating in 1937. He was employed by the local Everedy Company. Bowers married a Frederick girl (Flora May Taylor) and relocated to Baltimore after taking a job at the Rustless Iron and Steel Company. He had two sons: James A. Bowers, Jr. and Nelson A. Bowers. Bowers entered the military in September, 1943 and was assigned to the First Bomber Squadron, Ninth Bomber Group, Army Air Forces. He reached the Mariana islands in January 1945, the site of a major allied airfield base. From here, Bowers would take part in several missions over Japan, one of which involved the destruction of a large arsenal in Osaka in March, 1945. One of Bower’s letters home recounted, “the blast was so great that some of the B29’s were hurled into the air upside down but were soon righted and returned to their base.”  An image of a B-29 is shot down by enemy fire An image of a B-29 is shot down by enemy fire The mission, in which Bowers lost his life, was supposedly a low altitude mining mission which set out from the Marianas Island of Tinian on May 27th, 1945. Bowers crew was aboard the aptly named “Tinney Anne.” A gentleman named Mike Adams from Hutto, Texas wrote an online article about Stan Black, the commanding pilot of Sgt. Bower’s B-29, and his last mission. The following is an excerpt: “Stan Black and crew were on the list to be the last plane out of Tinian at 17:11 that day. The name of the mission was “Starvation 1” and it required one hundred two B-29s and crews. Three crews and aircrafts would be lost that night, 33 men. After action reports tell us that Aircraft Commander Stanley Black was over his target at about 23:30 that night when a riverboat with mounted searchlights and anti-aircraft guns opened fire on the Tinny Anne. Another crew first saw his aircraft illuminated in the searchlight and attempting evasion maneuvers. Those were not so effective in a B-29. The same crew further observed only four muzzle blasts from the riverboat but they must have been well placed. Two of the AA shells exploded only 20 feet from his port wing folding it up like it had a hinge on it. Thus began the fall from 6,200 feet. Fortunately, it only takes a brief time for a B-29 to go down from that altitude as compared to 25,000 feet. Not so fortunately, it leaves much less time for any crewmember to escape. One did, a young man with a big happy smile by the name of Charlie Palmer. Two or three crewmembers from the other aircraft saw Charlie’s parachute open. No other chutes were seen that night. The B-29 burned as it fell thus providing a bright light as air whipped the aviation fuel into an intense and hot burning white light. Were their other chutes, they would have been seen. Other crews in other B-29s were able to follow Aircraft Commander Stanley Black, along with his heroic crew, all the way down to the water. Later they would all comment how bright that fire light was. It went out almost completely as the B-29 hit the water. Nevertheless, some fire still burned on the water’s surface as the other B-29s turned under the night’s moonlight and flew towards home. They were all thinking of home again, and while they would not talk about it, it had come to call that night. I believe some of them were thinking about Stan Black and his brave crew. Eleven more men lost in one Great War that produced a million heroes and heroines all over this world."* *This amazing article from May, 2011 can be accessed at: https://huttobusinessupdate.wordpress.com/2011/05/27/last-plane-off-tinian-ben-nicks-and-stan-black-two-brothers-in-arms/ Although this article says that the Superfortress crashed into the water, other reports say the aircraft crashed into a nearby mountain. Relics have been found here, and supposedly traced to the "Tinney Anne."

Mount Olivet's WWII Monument Mount Olivet's WWII Monument And speaking of hometowns, let us not forget men like William B. Smith and James A. Bowers who made the ultimate sacrifice. These gentleman once walked the same Frederick streets, beneath the fabled “Clustered Spires” as we walk today. They enjoyed the same pastoral views of Catoctin Mountain and its surrounding rolling farmland. Perhaps they swam or fished the Monocacy and Carroll Creek. Is it likely that both were inspired with patriotism while visiting the Francis Scott Key Monument within Mount Olivet? If you think of nothing else this Memorial Day, please say a prayer of thanks to these former residents who gave their lives on May 28th 1944 and 1945 respectively. They join countless others who did the same, making it possible for us today to enjoy not only the Frederick pleasures listed above, but all of life’s treasures. “Take up our quarrel with the foe: To you from failing hands we throw The torch; be yours to hold it high. If ye break faith with us who die We shall not sleep, though poppies grow In Flanders fields.” (from John McRae’s “In Flander’s Fields”)

1 Comment

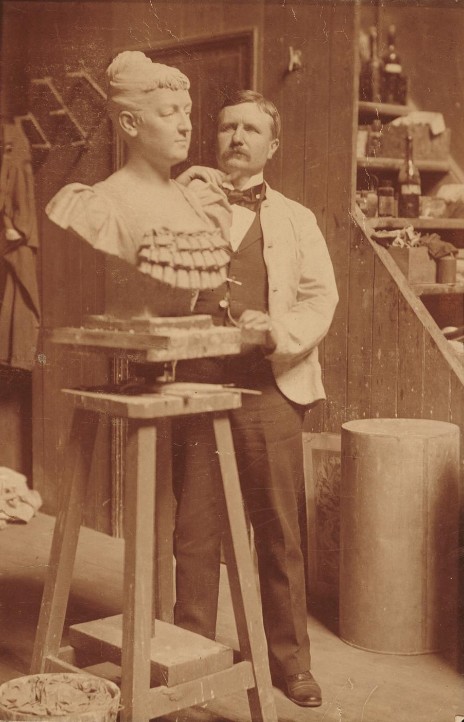

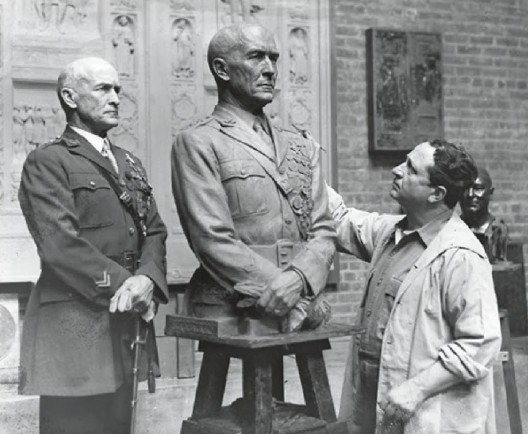

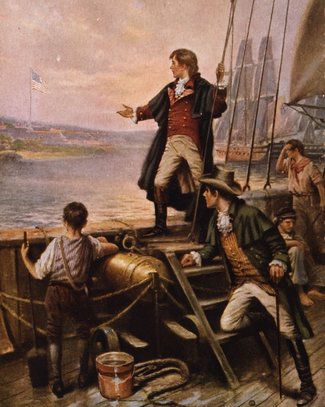

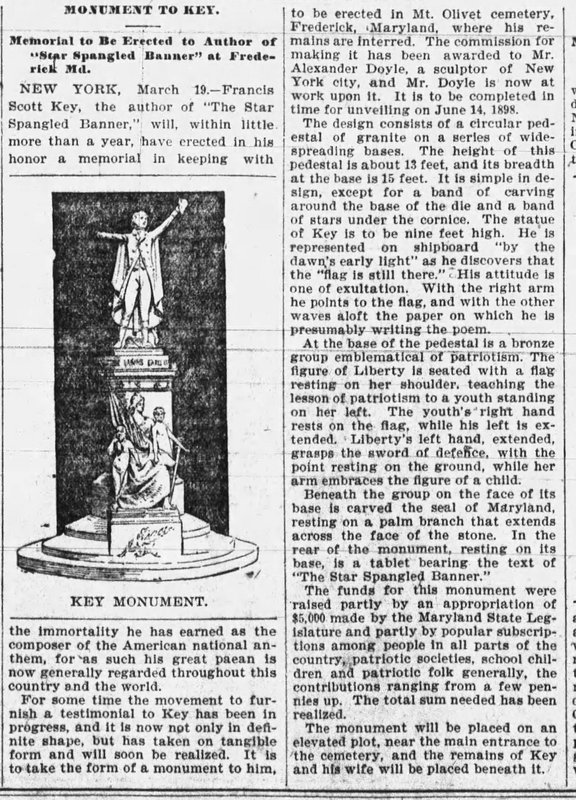

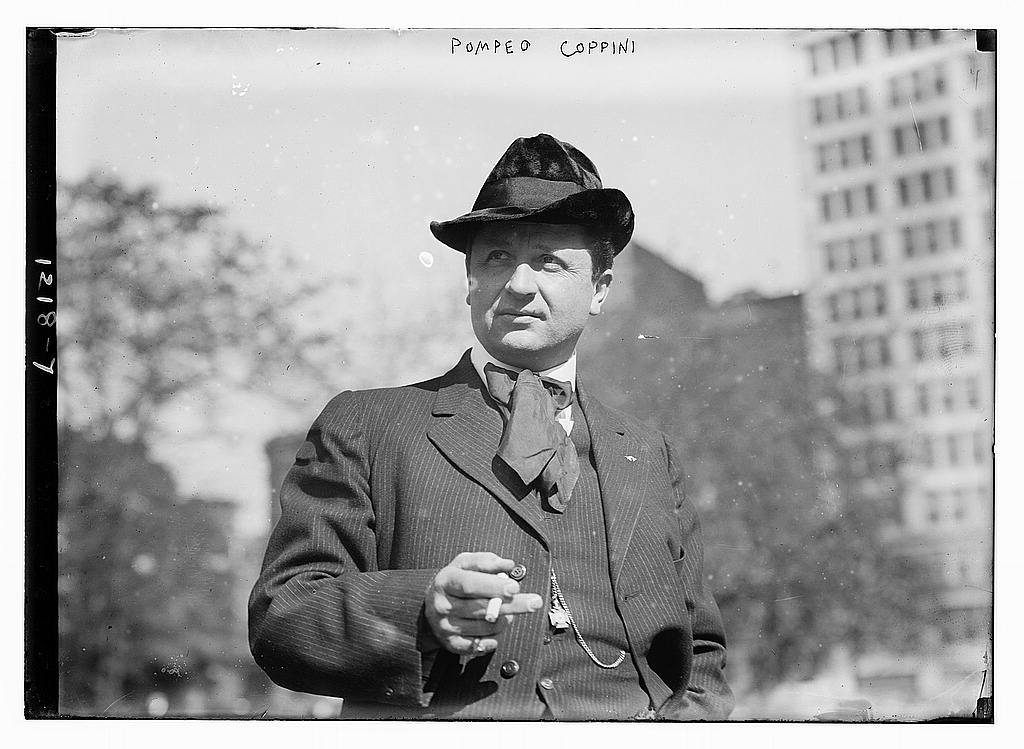

Moglia, Italy (c. 1900) Moglia, Italy (c. 1900) This past week marked the 147th birthday of Pompeo Coppini. While the name may not be familiar to many, this Italian immigrant had a hand, both literally and figuratively, in creating one of Frederick’s most iconic and visited landmarks—the Francis Scott Key Monument. The memorial lies just within the front gates of Mount Olivet Cemetery and features a 9-foot bronze sculpture of the author of “The Star-Spangled Banner, “placed atop a 15-foot granite shaft. Pompeo Luigi Coppini was born May 9th, 1870 in the small village of Moglia near the river Po in northwest Italy. This is located in Mantua within the Lombardy region. He was the son of Giovanni and Leandra Coppini. His father was a musician. The bulk of Coppini’s childhood would be spent surrounded by great works of art as the family made their residence in Florence. At the age of 10, Pompeo was hired to make ceramic horses after he had been taken under the wing of an unknown local artist. The family had recently changed apartments, now living adjacent a sculptor’s studio. Using marble and alabaster, this neighbor carved small objects and figurines for sale to tourists and art shops. Young Pompeo was influenced by the artist and others in his employ at the studio. Here, Coppini would receive encouragement toward a craft that would define his life.  The Academy of Fine Arts, home of Michelangelo's David statue (Florence, Italy) The Academy of Fine Arts, home of Michelangelo's David statue (Florence, Italy) At 16, Pompeo Coppini’s natural talent was becoming quite evident. He entered the Accademia di Belle Arte (Florence's renown Academy of Fine Arts), studying under Italian sculptor Augusto Rivalta. Slated as an 8-year course program, Pompeo graduated in just three years with highest honors in 1889. He briefly opened a sculpting studio, which soon failed. Coppini found that he was moving too fast, and perhaps his accelerated pace through art school was a mistake, as he should have gained a stronger foundation. Disheartened, the young sculptor spent the next two years in the service of the Italian Army. After discharge, he took on a series of odd jobs to make a living. These included tutor, hydraulic engineer, sign painter, waiter and bookkeeper. Eventually, Pompeo had saved enough money to open a second studio where he crafted busts, and made models for commercial houses. In 1894, he was called into military service again, to quell a revolt in Sicily. When he returned to his studio, he realized that there was little work for him to make it on his own. There was a glut of self-employed artists wherever he went—he soon thought that perhaps it would be more advantageous to work in the employ of someone else, just as he had done through adolescence. Pompeo found work in a town called Pietrasanta, a coastal town in northern Tuscany. Pietrasanta grew in importance during the 15th century, mainly due to its connection with marble. Michelangelo was the first sculptor to recognize the beauty of the local stone. Amidst the backdrop of a place named after the saint deemed to be the rock on which Jesus built his church, Coppini soon had his life calling reaffirmed. He too would build his career on “pietra/petra,” the latin word for stone. Coppini was given an assignment to model a large marble monument destined for shipment to America. This was to take the form of an 8-foot high winged angel, which was eventually placed within a cemetery in Boston, Massachusetts. Was he modeling his own guardian angel? The project inspired something special within the struggling young artist. Looking back at this episode, Pompeo declared: “I believe that the thought had a magnetic effect on me to dream that someday I might emigrate there myself, and that my desire made me work toward that end from that time on.” Coppini began saving up money for an Atlantic passage, along with garnering letters of reference. Not yet 26 years-old, he boarded the S.S. Kaiser Wilhelm II with a trunk and two suitcases and set sail for the United States. He arrived on March 5th, 1896. Pompeo Coppini now found himself in New York City with $40 in his pocket, and possessed a definitive lack of mastery for the English language. This combination almost caused him to starve to death. He found lodging within a tenement apartment building, packed full of fellow Italian immigrants. Pompeo rented his room for $2/week. Next door was a saloon that served meals for a nickel.  Roland H. Perry (1870-1941) Roland H. Perry (1870-1941) Pompeo was introduced through an acquaintance to a young, emerging sculptor named Roland Hinton Perry. He soon found himself working on a recent contract awarded to Perry which featured the production of sculptures to be installed within a fountain monument. This would be installed beside the Library of Congress in Washington, DC. Coppini and Perry conversed regularly in French, the only language shared by both men. Perry, himself had limited sculpting experience, but was known for his communication skills and efficiency with deadlines. The project’s completion was necessary in one year’s time, before the new library’s grand opening to the public. Coppini offered Perry his services, regardless of weekly salary. When finished, the pair had produced the Fountain of Neptune, completed according to schedule to meet a November 1st, 1897 opening. Immediately after finishing this project with Perry, Coppini checked back in with Alexander Doyle to see if he was in need of his services. Doyle had things covered at the moment, but said that he had been receiving several recent requests for proposals for projects. One such had come from Frederick, Maryland in which the Key Monument Association was looking for an able sculptor to craft a fitting monument to be placed over Francis Scott Key’s grave in Mount Olivet Cemetery. Doyle had to explain to the young Italian who Francis Scott Key was, and how he came about writing “The Star-Spangled Banner” during the War of 1812, while held upon a ship of truce. Both men were intrigued by the subject, however Pompeo was not capable of entering the project competition due to his unfamiliarity with the English language. On the flipside, Doyle was run down physically and mentally, results from juggling a heavy workload. He was desperately looking forward to his family’s annual summer vacation in Maine.

Coppini and Doyle agreed that an allegorical sub-sculpture should be placed below Key at the base of the monument. This came in the form of three figures symbolizing American Patriotism. The central figure was “Columbia,” the female personification of the United States. She is flanked by two boys—one standing with a downward sword and representing defense (in battle). The other child figure depicts music and song, as a small lyre is placed in hand. Working in tandem, these figures tell the story of how “The Star-Spangled Banner” song came about, and remains relevant—extreme patriotism demonstrated through a song written during, and about, an important defensive stand to defend our country’s flag.

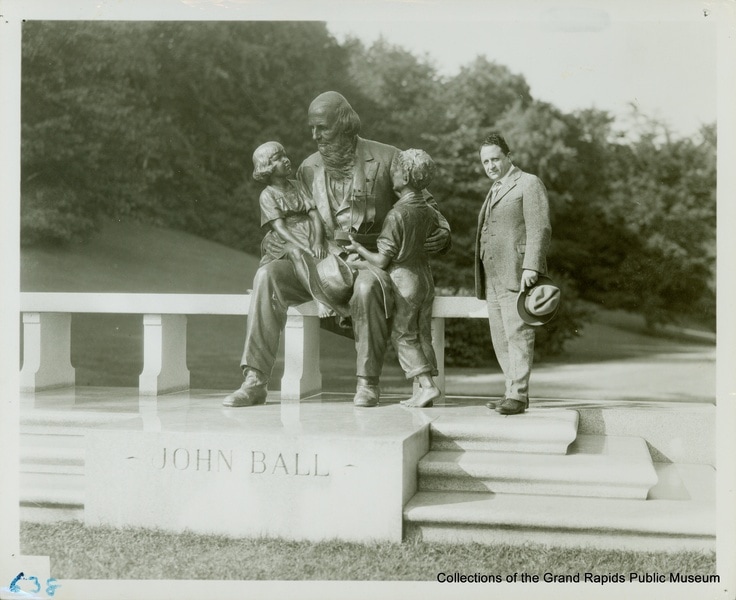

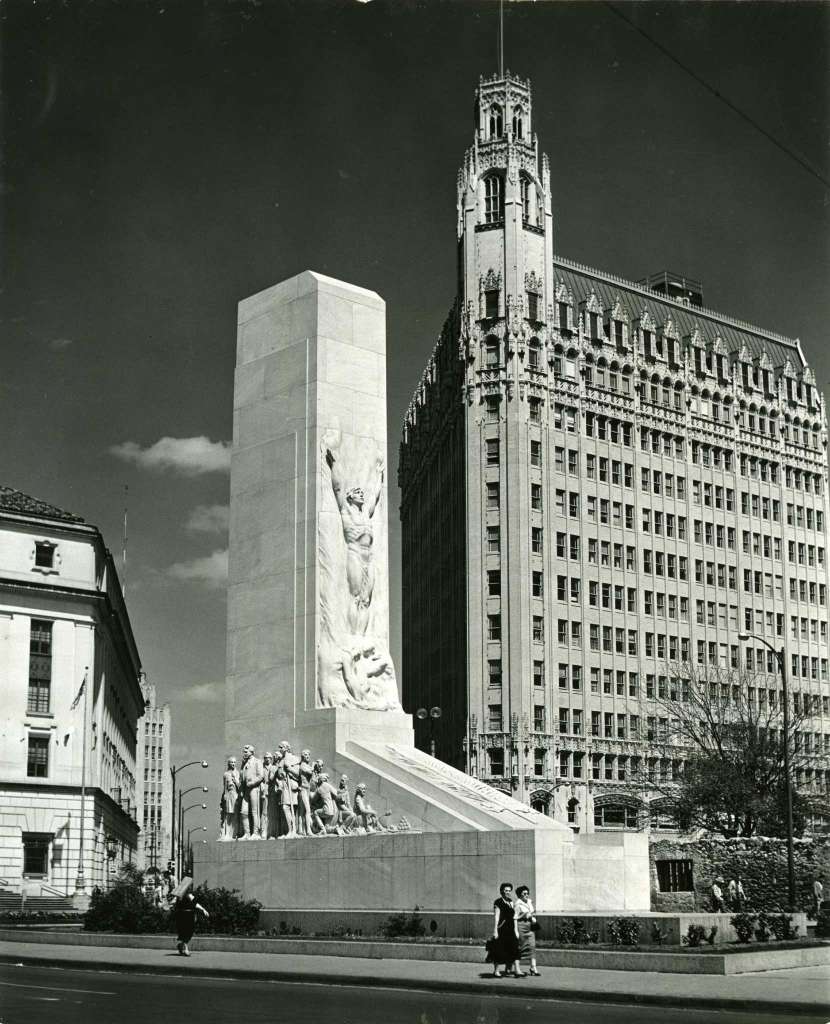

Often overlooked by visitors, another important element of the Key monument is the inclusion of the entire text of the “Star-Spangled Banner,” including all four stanzas. This can be found at the base, on the back side of the monument. It also presented Pompeo Coppini with one of the project’s greatest challenges as he had to accomplish this task while lacking the ability to read or write English. In an interview he spoke of this dilemma: “All the lettering of ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ tablet in the back of the memorial were modeled by me in clay and copied from a print of the National Anthem, letter by letter, before I was able to read a word of it, but knowing its meaning as Sculptor Alexander Doyle translated them for me, as he could speak and write Italian as well as I, having spent part of his youth and schooling in Carrara, where his father owned some marble quarries.” The Key monument, with its multiple sculptures, was put in place during the summer of 1898, and unveiled at a huge public dedication on August 9th, 1898. This was just 29 months after Pompeo Coppini had first stepped on American soil with $40 in his pocket and a desperate anxiety of whether or not he would continue life as an artist. With this project, Coppini had solidified his reputation as a capable and talented artist. In time he would climb into the eventual ranks as one of America’s greatest sculptors. You could also say that the Key monument project put an end to a period of bitter difficulties and desperation. Once again a “guardian angel” would come out of a project. “Columbia in bronze,” herself filled him with the supreme faith in America as the land of opportunity, and the land of promise. “Columbia in the flesh,” would be his lifetime companion, confidante and “petra.” Years later Coppini would remark to a newspaper reporter in an interview: “Though I am Italian born, I am American reborn.”  Pompeo Coppini moved to Texas in 1901, and became a US citizen just one year later. He began receiving commissions to sculpt the figures of multiple historic monuments for the state’s capitol grounds, working for the next 15 years in San Antonio. Coppini collaborated with other American sculptors in Texas, some of which became his students and protégés. He opened up his own art school in 1945, still operating today as the Coppini School of Fine Arts in San Antonio. His works are displayed everywhere from the Texas State Capitol to the University of Texas to Baylor University to Mexico City. Pompeo and Lizzie Coppini continued keeping a residence in San Antonio, but would also live (and work) in New York and Chicago. In 1931, Pompeo Coppini was “knighted” by the Italian government for his contribution of Italian art in the United States, receiving the Commendatore of the Order of the Crown of Italy. Three years later, he was honored by the Texas Centennial Committee commissioning him to design the Texas Centennial Half Dollar. He also served briefly in the art department of Trinity University in San Antonio. In all, Pompeo Coppini is represented in his adopted new country by 36 public monuments, 16 portrait statues, and nearly 75 portrait busts. One of his proudest life accomplishments came with his helping to save the legendary Alamo from commercial development. Coppini won the commission to construct “The Alamo Cenotaph,” in 1939. Towering 60-feet high and located adjacent the surviving buildings of the Alamo itself, San Antonio's "Alamo Cenotaph" pays tribute to the men who died defending the ancient mission in 1836 rather than surrender to overwhelming odds. The word cenotaph depicts an empty tomb. According to tradition, the Alamo Cenotaph marks the spot where the slain defenders of the fortified mission were piled after the battle and burned in great funeral pyres. The remains were later collected by local citizens and today are thought to be located in a marble casket at nearby San Fernando Cathedral. Titled "The Spirit of Sacrifice," the Cenotaph was created by Coppini from a design envisioned by architect Carlton Adams. Begun in 1937, the project took two years to complete and is itself now a historical treasure. Pompeo Coppini died in San Antonio on September 26th, 1957. He was buried in Sunset Memorial Park in a crypt of his own design. Wife Lizzie would only live seven weeks longer, dying in December (1957).

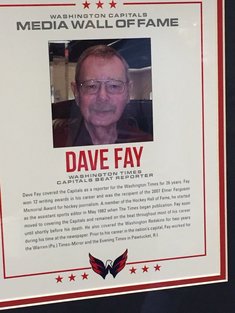

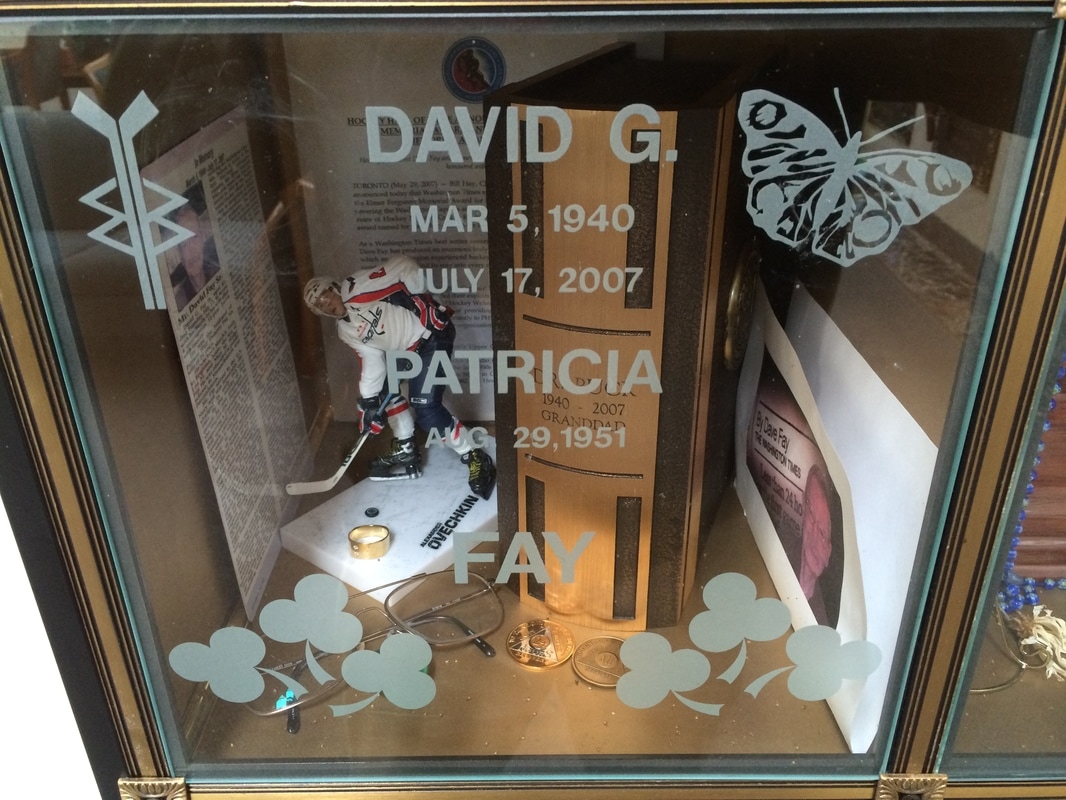

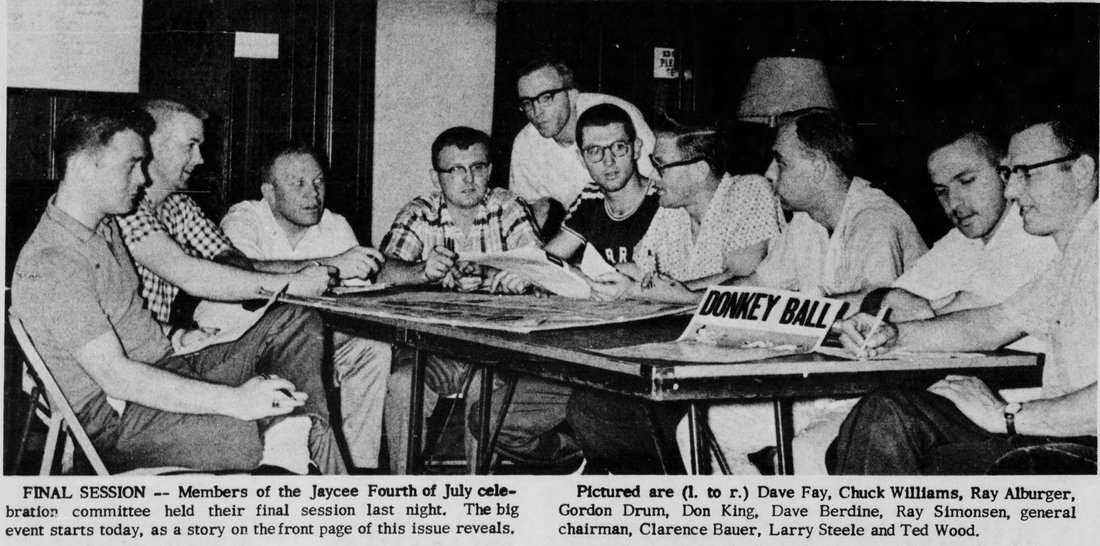

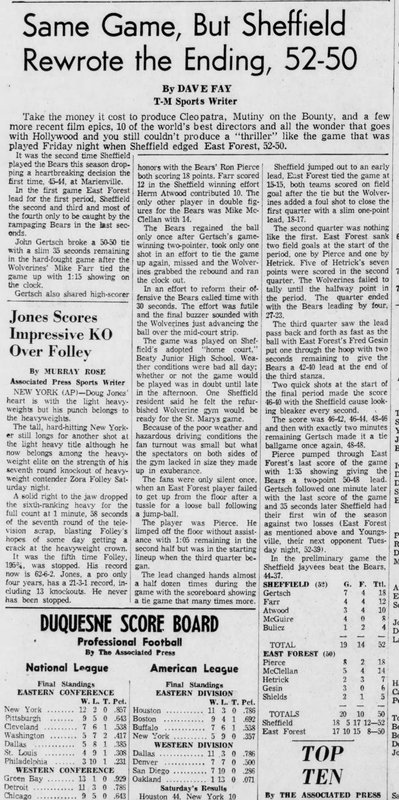

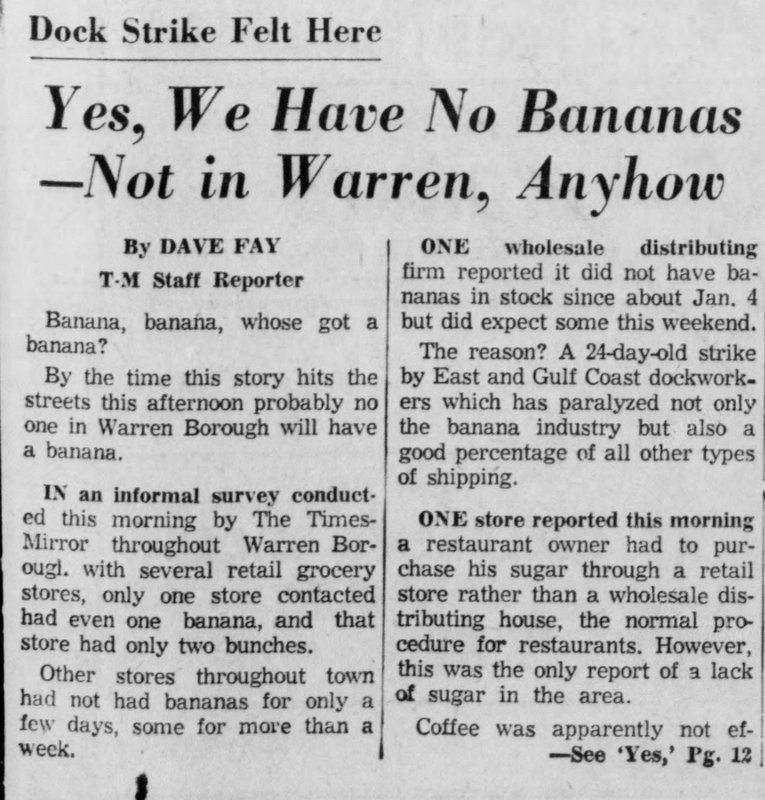

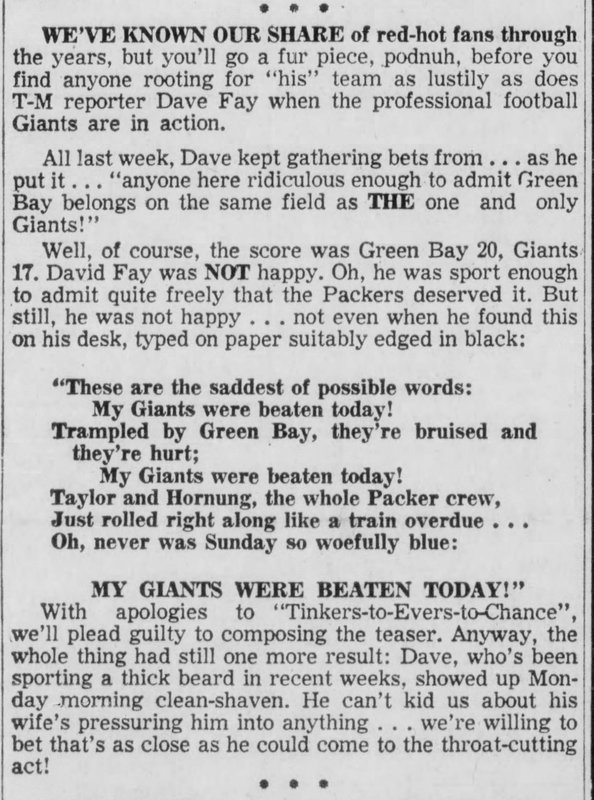

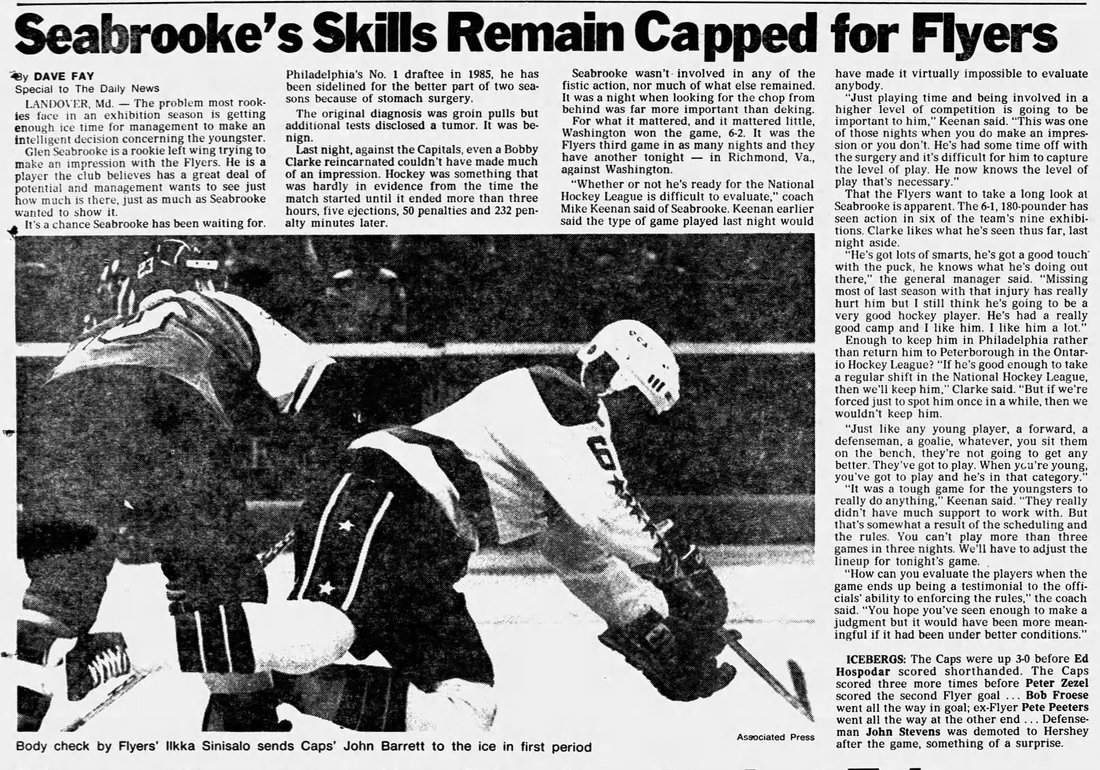

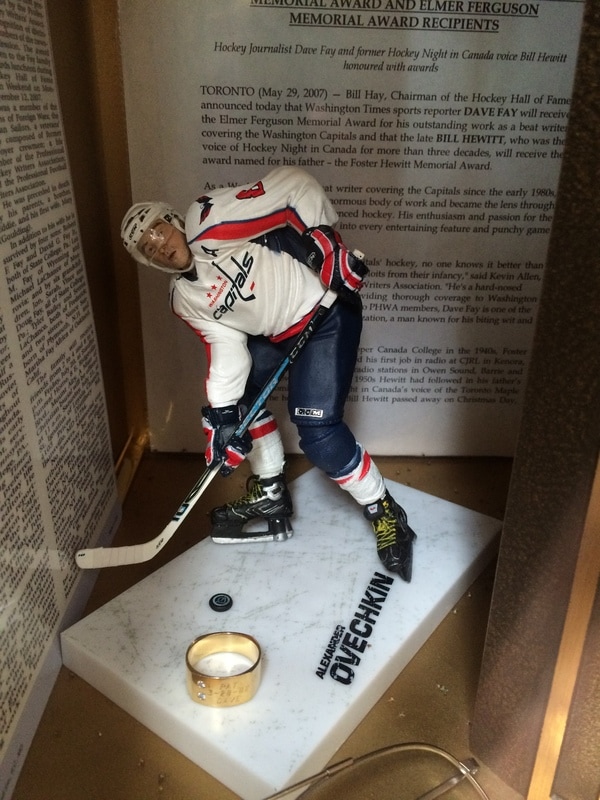

Back in his native Moglia, Italy, the town would name a main thoroughfare after the artist: “Pompeo Coppini Avenue.” Here in Frederick, Maryland we have a beautiful monument depicting the man who penned our national anthem. Tens of thousands have visited the site over the past (nearly) 120 years, and many more will continue to do so into the future. Coppini's triumph is Mount Olivet's "petra." Not bad for an immigrant who came to this country with nothing, but left so many treasures behind.  NOTE TO READERS: This article was originally published in May, 2017 after the Caps lost in the playoffs to Pittsburgh. We are proudly re-posting this article about sportswriter David Fay as the Capitals are still playing hockey in June...a first for the franchise! At the time of posting (June 1, 2018) the Caps and upstart Las Vegas Knights are tied at one game each for the Stanley Cup Championship, a best of 7-game series. Well, it’s been another tough season finish for the Washington Capitals and their loyal fans. They “rocked the red” until the bitter end Wednesday night, losing in game 7 of the second round of the playoffs to their archnemesis, the Pittsburgh Penguins. The most crushing blow was the “déjà vu” aspect: the Caps were eliminated from Stanley Cup contention last year in the second round, by the same team, and on the same exact date of May 10th! To add insult to injury, they had won the President’s Trophy, both this season and last. This award, presented by the NHL (National Hockey League) goes to the team that finishes with the most points (i.e. best record) during the regular season. Unfortunately, this does not heal the wound of failing to attain the coveted Stanley Cup. Oh well, what can you do? There’s always next season, but that is a small consolation for the players, fans and even local sports media that follow the team. Among Mount Olivet’s interred population of 40,000, I venture to say that hundreds were former hockey fans, along with likely some players, recreational or collegiate. I can’t say with certainty who these people are, as I don’t have documentation. Sometimes we can easily spot team allegiance as many granite and marble monuments (in the new section of course) display sports logos carved in stone such as the Redskins, Ravens, Orioles and Terps. Other gravesites are adorned with small flags and pennants of the deceased favorite team. When it comes to the Washington Capitals, I haven’t personally seen any examples of expressed fan adoration throughout Mount Olivet’s outside grounds. However, it’s a different story within our central Mausoleum Chapel, located to the rear of the cemetery. Here, one will find an outstanding connection to the Washington Caps, and professional hockey for that matter, amidst a vast collection of mausoleum tombs and niches. Most of these spaces have granite or marble coverings and are adorned with bronze plaques, but on the chapel’s interior south wall, stand columns of glass-front niches. This inurnment innovation has been around for 40 years, however many people know nothing about it. Gall front niches are somewhat like “shadow-box” displays, giving families the ability to personalize a final resting place with decorative (cremation) urns, photos and other mementos. These items work in tandem to create a unique “visual” memorial, painting more of a picture of the deceased for not only loved ones left behind, but descendants yet to come. Like many other visitors, my eye was suddenly captivated by niche space 26-D just inside the chapel doors. This occurred during my first look around in the chapel well over a year ago. Although the name was foreign to me, it was the contents of niche that grabbed me including a miniature statuette of Capitals star player and team captain Alex Ovechkin, a pair of eyeglasses, wedding ring and custom bronze urn in the form of a book, with the moniker of “Dr. Puck” etched on the spine. I’m not an engaged hockey fan, but have great respect for the sport and have seen about a half dozen professional hockey games in the past, most involving the Caps. I had recalled once hearing the name of Dr. Puck before, referenced by an announcer on a Washington sports radio station. He was held in esteem as an expert on Washington Capitals hockey. I was immediately inspired to perform a Google search on the niche’s inhabitant, David G. Fay. Born March 5th, 1940 in Brighton, Massachusetts, “Dave” was the son of parents Leo and Mary Fay. He received a public school education in both his native state, and later Pennsylvania. After graduation, he would serve in the US Navy and was honorably discharged in 1981. From here he gained employment with the Warren Times-Mirror newspaper (Warren, Pennsylvania), thus launching a career in journalism that would span nearly half a century.  Dave Fay worked in his field as both a manager and as an editor/writer, but it appears that he felt much more at home with the latter. Employers included the Pennsylvania Mirror (State College, PA), the Evening Times (Pawtucket, Rhode Island) and the Washington Times. For the final 25 years of his life, he was the Times’ undisputed, resident hockey expert as he served as beat reporter for the Capitals. His reputation grew across the region and country as authentic, honest and passionate about his craft. Just days after his death on July 17, 2007, former Times colleague Dan Daly wrote: “And Dr. Puck, as he came to be known, was very much a real man…in both the “real” sense and the “man” sense. There wasn’t a phony bone in his body, but there was spine enough for two people—spine enough to wage, without complaint, a 12-year battle with cancer before it took him from us Tuesday night at 67.” Over his career, Dave Fay covered every sport imaginable. I did a search of the internet subscription site newspapers.com and found several examples of Fay’s earliest work at the Warren Times-Mirror. Here were stories ranging from high school football, baseball and basketball to track and field, swimming and bowling. I even found articles in which he reported on boxing, hurling and "donkey ball." I also found non-sports-related stories penned by Fay. He eventually gained his own editorial forum entitled Fay’s Corner. Dave Fay’s early writing employed sophistication, creativity, and a pinch of sarcasm from time to time. It would only get better over time.  In 1981, Dave Fay served in the Sports Department of the Washington Times—a member of the newspaper’s inaugural staff. He covered the Capitals as beat reporter for all but two of his years in their employ. The others were spent on the Redskins, one of which included their 1991 Super Bowl run. Although football had always been his favorite sport growing up, apparently as a fan of the New York Giants, he quickly embraced a passion for professional ice hockey. He also earned a reputation for being “old school,” a stickler for details and oftentimes, a grumpy “curmudgeon.” At the start of his hockey tenure, Fay wrote an anonymous column in which he took a “tongue in cheek” approach with players and reporting on events in pro hockey. He used as his source an alter-ego by the name of Dr. Puck. Eventually readers, and players, caught on that it was indeed Fay himself. Once the proverbial “cat was out of the bag,” Fay decided to own the name, exemplified by obtaining custom license plates for his car. Dr. Puck and Dave Fay were now synonymous.  In his July 2007 op-ed piece, Dan Daly continued his eulogy for David Fay: “I’m not sure what bon-mots, if any, Dave planned for his gravestone, but I’d suggest: “What’s my deadline tonight?” Right to the end, he was filing copy, working-class Irishman that he was. With him, it was never about the language, about performing literary loop-de-loops; it was about clarity and accuracy and completeness—the fundamentals. Nobody who has covered the Caps in this town has been more plugged in or more passionate than he. That’s why he was recently chosen as the recipient of the Elmer Ferguson Award, the biggest honor in hockey journalism, and will live on in the Hockey Hall of Fame.” Dave Fay was the recipient of 12 writing awards, culminating with the Elmer Ferguson Award. Sadly, he passed away four months before the induction ceremony into the Hockey Hall of Fame by the Professional Hockey Writer’s Association. Announced earlier in the year, Dave knew of his achievement and could take pride in the legacy of his life’s professional work. His wife Pat traveled to Toronto in November (2007) to accept the tremendous honor posthumously on behalf of her husband. A press release (dated May 29th, 2007) adorns the back of Dave’s niche. Although professional sports-writing took Dave Fay to Canada, the Soviet Union and throughout the United States, he made his home in Monrovia in eastern Frederick County. This is where he spent his final days, working as long as he could. In addition to hockey, he was blessed with something far more important—a loving wife, four sons, daughters-law, six grandchildren and a host of friends and colleagues that loved and respected him. I’m sure the Washington Capitals occupy a great place in all their hearts, and how could they not with Dave Fay already there.

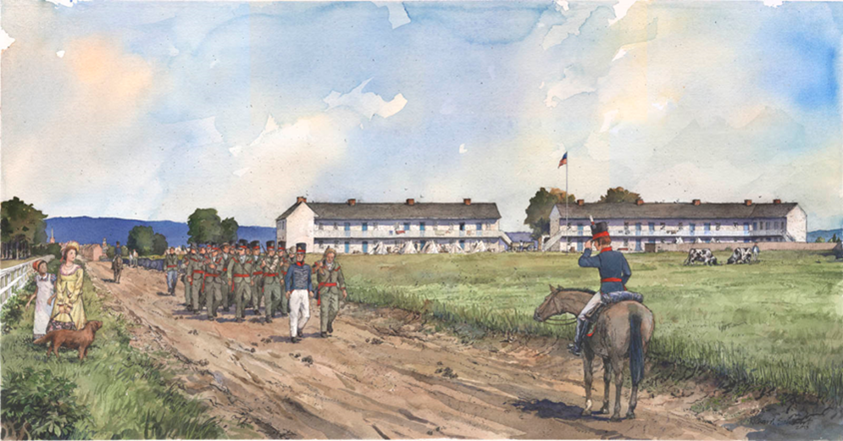

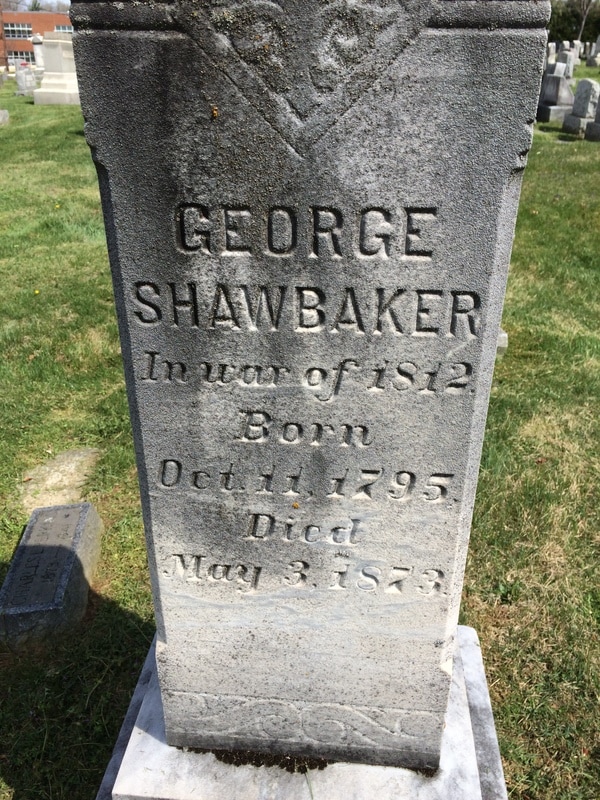

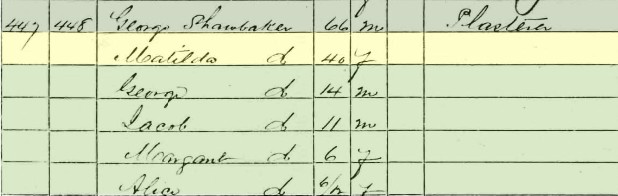

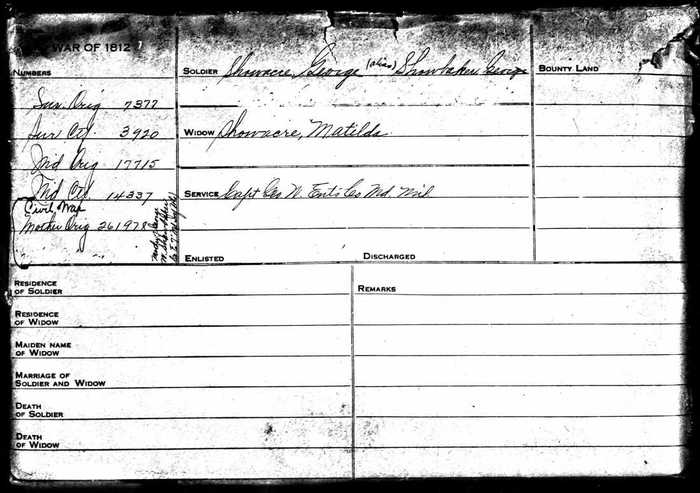

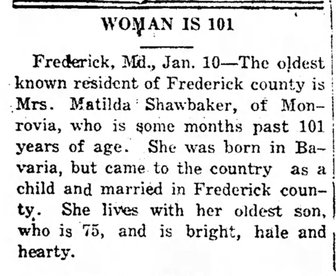

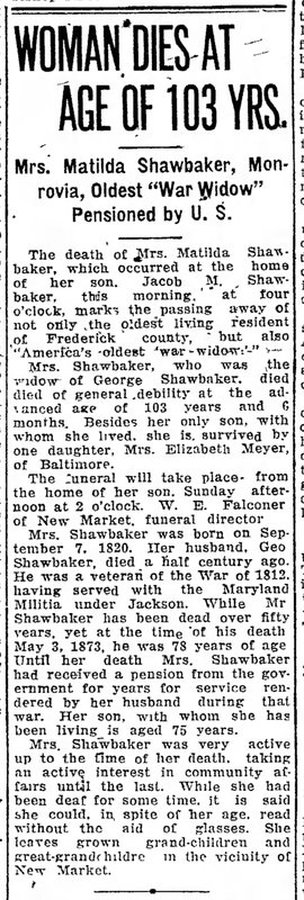

On an old page on Capitals Insider website, I found another July 2007 report of Dave Fay’s passing. In the online comments below the story I found the following entry from a lifelong Caps fan: “Truly a great man who loved the game and the Capitals organization enough to be honest, when perhaps maybe they didn't want him to be. Rest in peace, Dave. We'll see you at center ice someday.” This week’s subject is Matilda Shawbaker. In the early 1920’s up to her death in 1924, she held the distinction of being the oldest woman in Frederick County, and “oldest-living war widow.” Then for many years following, she would be the eldest female laid to rest in Mount Olivet. Maybe not the most flattering of accomplishments, but her extended age brought along with it plenty of notoriety. Matilda Shawbaker was a German immigrant, and married the son of an earlier German immigrant to the area. Her father-in-law was, however, an “accidental tourist” to Frederick, not coming here of his own volition. You could say the army brought him here, both literally and figuratively—just another one of several military ties in the storied life of Matilda Shawbaker. Mrs. Shawbaker’s name jumped out at me, as I had once interviewed her great-grandson back in 1994 for a historical video documentary called Frederick Town. The gentleman was Mr. William E. Main, and he made mention of his “great-grandmother Shawbaker” on more than a few occasions within the course of our on-camera discussion. I had forgotten all about this “history connection” until recently preparing notes for a “Frederick in the 1700’s” course I was hired to teach based on the documentary I had produced 20 + years back. In this course we covered the genesis of Frederick-Town, the brainchild of Annapolis businessman/politician/land speculator Daniel Dulany. We also explored the area’s subsequent growth and rise in importance thanks to hearty, industrious settlers who melded cultures to create the special place we call home today. Among these early residents were “Old-Line” English and Scots-Irish families from southern Maryland, Dutch colonists from the area of Kingston, New York, and Germans from the southeastern part of William Penn’s colony. We also had several German immigrants who came directly from the “Vaterland” without original intent to settle in a town (and county) named for the German-born prince, Frederick , a man who would never get his chance to wear the bejeweled crown as monarch of Great Britain. Yes, Frederick is named for Frederick Louis, Prince of Wales, son of King George II, and father of King George III. The latter was the same guy our 12 immortal Frederick County justices defied with their November 23rd, 1765 Repudiation of the Stamp Act. Eight years later, George III would be incensed by an infamous “tea party” in Boston, and then a major “declaration” in Philadelphia in 1776. These three events centered on the fundamental problem of taxation without representation. In my assessment, I can think of a handful of things worse than taxation that our early settlers and immigrants had to deal with during the 1700’s. Old World situations such as political tyranny, oppression of the masses, depressed economies, religious persecution, starvation and enemy attacks served as fodder for folks to leave their ancestral homes and brave crossing the Atlantic. Once here, they had to embrace a plethora of other hardships–but apparently “the juice was worth the squeeze,” a favorite proverb often quipped by a beloved former boss of mine. Germans would continue to come to America in the 1800’s for several of the same reasons they came in the previous century. One of these was Matilda Kiefer (Shawbaker). Matilda Kiefer (also spelled Keefer) was born in Bavaria on September 7th, 1820. According to a newspaper interview in 1922, she never knew where actually in Bavaria she was actually from. After the death of her mother in Germany, Matilda’s father, Adam Kiefer, brought his children to the United States around 1831 and settled in Frederick County in the Buckeystown District. He likely could have come to live amongst relatives already here in the area, as the Keifer/Keefer family operated a mill at a location in between present day Ballenger Creek Pike, and New Design Road—on the Ballenger Creek itself (east of Tuscarora High School). Adam Kiefer promptly remarried and young Matilda became well-versed in home endeavors and excelled as a seamstress. From Jacob Engelbrecht’s diary, I found that the Kiefer’s lived in the vicinity of St. Josephs-on-Carrollton Manor Church. On March 10, 1837, Matilda’s stepmother, Adelia Kiefer, died. Three days later, Matilda’s father Adam died. (I found an online record in the Frederick Equity records showing that neighbor George Thomas became guardian for Matilda’s step-sisters (Adelia) Margaret and Sophia).  The Frederick "Hessian" Barracks, located on the campus of the Maryland School for the Deaf. The Frederick "Hessian" Barracks, located on the campus of the Maryland School for the Deaf. On Christmas Eve, 1844, Matilda married George Shawbaker, a man 15 years her elder. Shawbaker was a native-born American, but the son of a former German mercenary soldier who did not come to the country with the purpose of staying. To tell the truth, he was even less keen on becoming a member of the military in the first place. He wasn’t alone as there were countless countrymen just like him who were forced to enter into mercenary fighting, an unfortunate dilemma which beset many native German people in Europe at the time of the American Revolution. A mercenary is a person who takes part in an armed conflict who is not a national, or party to the conflict and is "motivated to take part in the hostilities by desire for private gain.” Mercenaries generally fight for money or other recompense instead of fighting for ideological interests, whether they agree with or are against the existing government. The taxes levied on the 13 colonies in the years preceding the American Revolution were a result of Great Britain desiring compensation for their role in protection (of the colonies) during the French and Indian War (1754-1763). In this supposed “seven-year” affair, the bulk of the leaders were British subjects, however, the majority of front-line soldiers were from Ireland and Scotland—mercenary soldiers. The British government found that it was easier to borrow money and hire an army from elsewhere than recruit and raise it themselves from their own loyal populous. The situation would be repeated just over a decade later in the American Revolution and brings to mind a well-versed term in Frederick lore and history—“Hessian.” The strange noun turned adjective has adorned our colonial-era Frederick Barracks (located on the grounds of the Maryland School for the Deaf) since the early 1780’s. This was the time when Hessians began populating the prison garrison, as well as Frederick, but certainly not by desire and design at first.  A German peasant being pressed into military service A German peasant being pressed into military service The term "Hessians" refers to the approximately 30,000 German troops hired by the British to help fight during the American Revolution. They were principally drawn from the German state of Hesse-Cassel, although soldiers from other German states also saw action in America. King George II, son Frederick (Prince of Wales) and grandson George III hailed from the House of Hanover, a German royal dynasty that ruled the Electorate and then the Kingdom of Hanover. This powerful bloodline provided the ruling monarchs of Great Britain, Ireland and the United Kingdom until the death of Queen Victoria in 1901. The Hessians made up one-quarter of the troops the British sent to America. They usually entered the British service as entire units, and fought under their own German flags, commanded by their usual officers, and wearing their existing uniforms. The largest contingent came from the state of Hesse, which supplied about 40% of the German troops who fought for the British. The large number of troops from Hesse-Kassel led to the use of the term Hessians to refer to all German troops fighting on the British side. The others were rented from other small German states. Many of these men were pressed into Hessian service. Deserters were summarily executed or beaten by an entire company. Traditionally, the Hessian prisoners of war were put to work on local farms, as was the case with many who would be marched to Frederick for captivity after the battles of Saratoga and Yorktown. They were oftentimes loosely guarded and worked on local farms (owned by German immigrants or the children of German immigrants). German culture and tradition abounded, as did the language which is said to have been more commonly spoken in the streets of Frederick than English into the early 1800’s. There was also an abundance of attractive German farmer’s daughters and German craftsmen’s daughters as well. Couple this with crappy conditions back home and the real possibility of being sold back into military service by royal forces, and Frederick, Maryland looked like a very inviting prospect for a new lease on life. One of these Hessians was Adam Shawbaker (aka Schabaker, Schawacker, Showacre, Showbaker, Shouhoker, Shawacker). Adam was born around 1749 in Hesse-Kasssel. He fought for the Hessian forces under the British and was captured at the Battle of Yorktown in the fall of 1781. Adam would be brought to Frederick and imprisoned in the barracks here. He was released in April, 1783 by paying 83 Spanish dollars which allowed him to remain in America. Much of the money to do this came from local German families as a means of building the labor force, and/or keeping daughters happy. Adam met Anna Barbara Schnautiegel and married her on February 7th, 1787. Adam settled in Frederick Town, but appears to have moved to the Middletown area as some of his children were baptized at the Lutheran church there. He would have three sons (Adam, Jacob and George) and a daughter (Maria Barbara).

Private George Shawbaker served in the 3rd Regiment, Maryland Militia, under Captain George W. Ent from August 24th to September 30th, 1814. It would be 30 years before he married Matilda. The couple had seven children: George William Shawbaker (1846 - 1869) Jacob Michael Shawbaker (1848 - 1924) Mary Matilda Shawbaker (1850-1853) Margaret Elizabeth (Shawbaker) Meyer (1853 - 1928) Ann Matilda ("Alice") Shawbaker (1859-1918)  Frederick's "Hessian Barracks" (c. 1870's) Frederick's "Hessian Barracks" (c. 1870's) The family resided for some time in the same place that George’s father called home when he was brought to Frederick in the fall of 1781—the Hessian Barracks. This was sometime in the 1850s through 1860s when the barracks grounds also served home to the Frederick County Cattle Show and Agricultural Exhibition, known today as the Great Frederick Fair. The county-wide livestock gala and craft fair was the brainchild of the Farmers Club, soon to change its name to the Frederick County Agricultural Society. The first edition of this annual event commenced in October of 1853. The Shawbakers may likely have been caretakers of the grounds during this period. In the 1860 census, George is listed as a plasterer, and it is a good bet that he performed restorations on the barracks originally built to quarter enemy soldiers—such as his own father nearly 75 years earlier. Matilda stuck to her household duties and child rearing, all the while making time for her favorite pastime of knitting, needlework and crocheting. On one occasion, she was approached by the Agricultural Exhibition’s Board of Managers to make a large US flag to fly above the barracks during the next year’s event. She obliged and was paid in the form of getting to keep the surplus material. With this, she made her own flag. Matilda’s great-grandson recounted a story of this flag to me back in 1994. He said that Matilda and her family prized the flag, especially in the years immediately after it was made. The Agricultural Exhibition was put on hold from 1862-1867 due to the American Civil War. The Shawbakers were ardent Unionists and Matilda and George’s son George W, followed in his father’s steps by fighting to preserve the Union. He was only 17, when he joined Company E of the 7th Maryland Regiment. Matilda’s flag had to be hidden on more than one occasion as large contingents of the Confederate Army overtook Frederick in September of 1862 (battles of South Mountain and Antietam), and again in July 1864 (Battle of Monocacy). Matilda secured her flag in the ashes of her “ten plate” stove during one of these events. Another time, she buried the standard in her garden plot where she marveled as soldiers practically walked over top of it.  George W. Shawbaker George W. Shawbaker Son George W. Shawbaker made it through the war, although he was wounded at the Battle of the Wilderness in May of 1864. Complications from these injuries led to an early death in 1869, at the age of 22. Matilda’s brother Nicholas Kiefer also fought for the Union, but died while in captivity at Libby Prison in Richmond. Another brother, George Kiefer, actually fought for the Confederacy. The flag Matilda had made would be handed down in the family to future generations. Its special importance was renewed in 1917 when the United States went to war against Matilda’s native country of Germany. She would have five grandsons participating in this heartbreaking “world war.”  Matilda passed on March 7th, 1924, having reached the age of 103 years and 6 months. She was buried next to her husband and her first four children in the family lot at Mount Olivet (Area L/Lot 152). Many Fredericktonians claim descendancy from this unique wave of German immigrants that chose to stay in Frederick after their imprisonment during the American Revolution. It’s a great story, and one that brought Independence and freedom to more than just American colonists. It’s also amazing trace a family like George and Matilda Shawbaker’s that were so eager to fight in future conflicts to keep and preserve that independence for the “land of the free.” All the while, these individuals had the knowledge that their ancestor, Adam Schabacker, was forced to fight in a war that offered him nothing more than a paycheck.  Photo taken in 1995 of Matilda Shawbaker's grandson Mr. William E. Main (1919-2006) Photo taken in 1995 of Matilda Shawbaker's grandson Mr. William E. Main (1919-2006) Mr. William E. Main continued the legacy through distinguished service in World War II, followed by a career with the Army. He enlisted in Company "A," 115th Infantry, in November 1940 and in April 1942 entered the Infantry Officer Candidate School at Ft. Benning, Georgia. After being commissioned in July 1942, he served in the 309th Infantry, 78th Division, at Camp Butner, North Carolina, until ordered overseas in 1943, where he served in the China-Burma-India Theater, on the staff of Gen. Joseph Stillwell, and as a Liaison Officer to the Chinese Army until the end of World War II. He participated in the release and repatriation of American, British and Dutch P.O.W.s from the Japanese Prison Camp at Mukden Manchuria. Mr. Main was employed by the Department of the Army as a Nuclear Weapons Effects Analyst and Strategic Planner from 1950 until his retirement in 1974. He served from 1951 until 1965 with the 163rd Military Police Battalion of the District of Columbia National Guard, as a Company Commander, Battalion Operations Officer and Battalion Executive Officer. William E. Main also donated Matilda’s flag to the City of Frederick, where it is displayed on the second floor of City Hall. I want to conclude with an interesting finding. The laws of Germany today say that it is an offense "to recruit" German citizens "for military duty in a military or military-like facility in support of a foreign power.” Furthermore, a German who enlists in an armed force of a state that he or she is not a citizen, risks the loss of his or her citizenship.

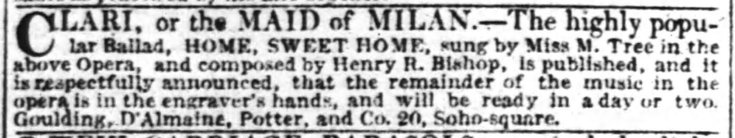

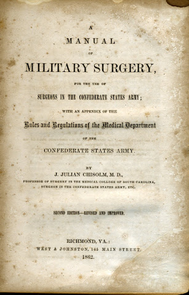

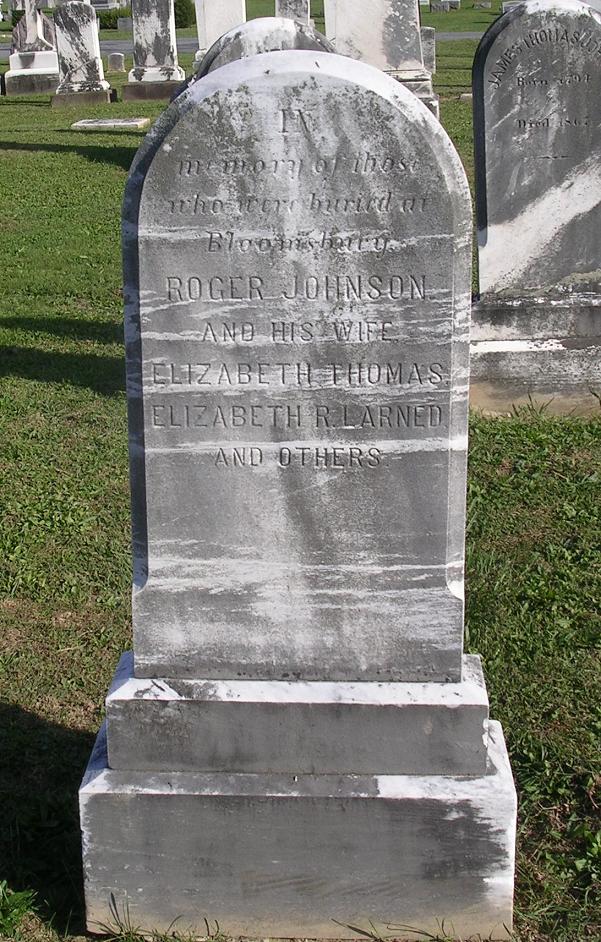

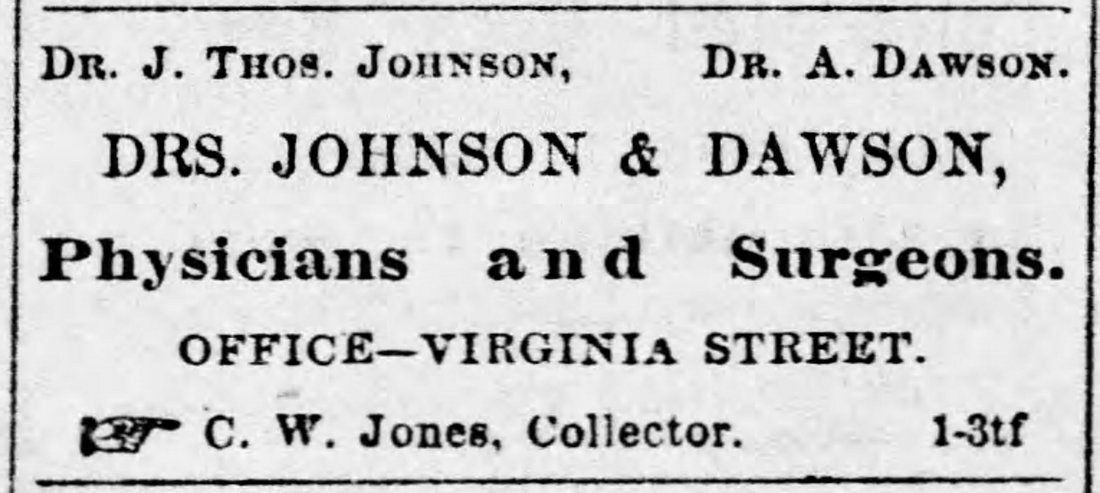

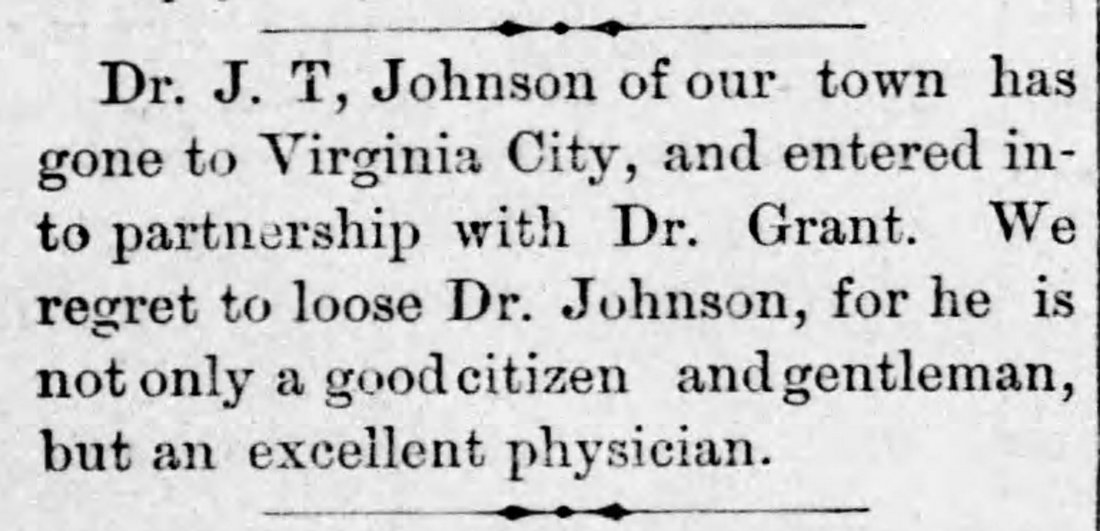

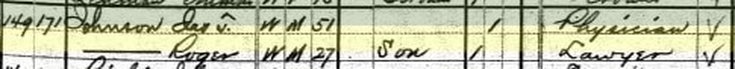

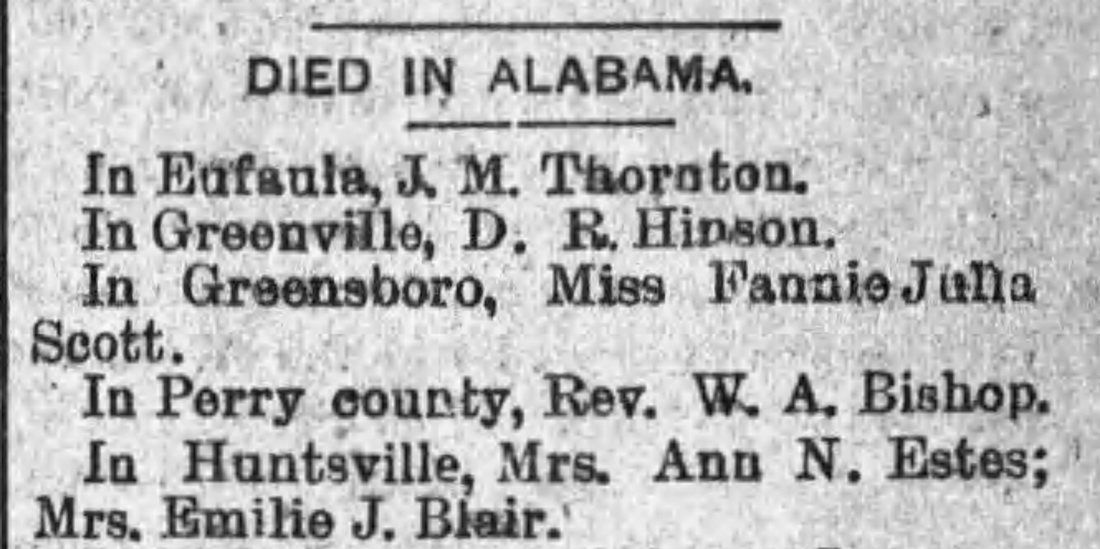

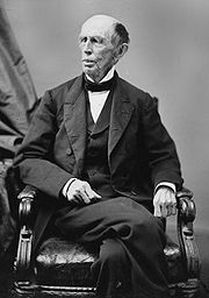

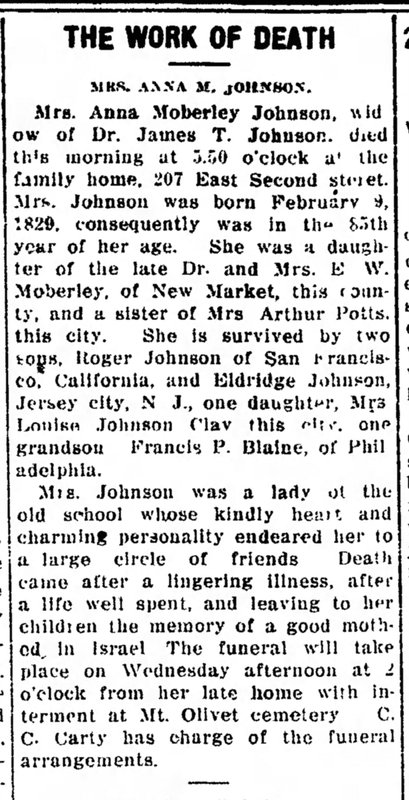

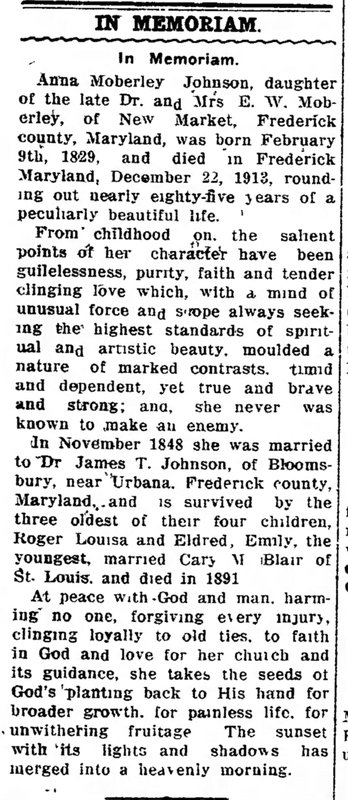

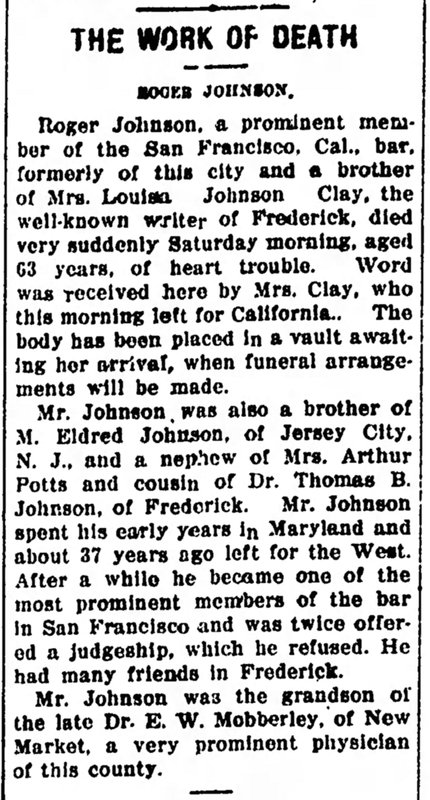

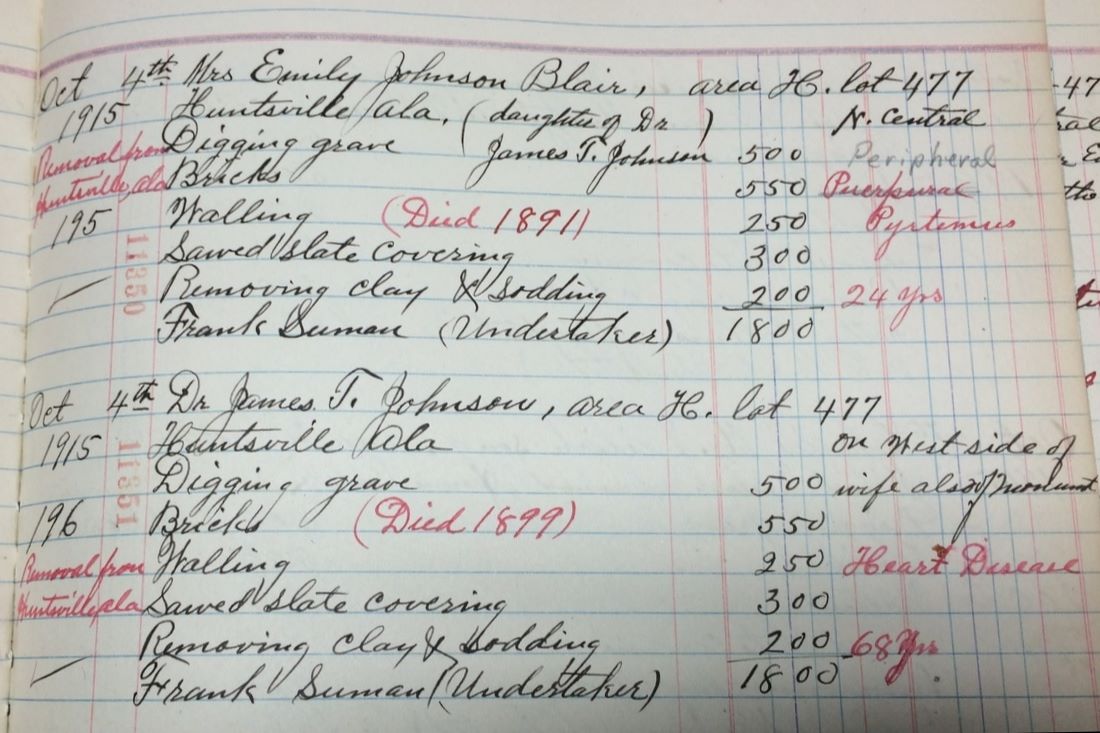

George Washington gave this message to his Continental Army soldiers before the first major engagement of the Revolutionary War, the Battle of Long Island: “Remember, officers and Soldiers, that you are Freemen … Remember how your Courage and Spirit have been despised, and traduced by your cruel invaders, though they have found by dear experience at Boston, Charlestown and other places, what a few brave men contending in their own land, and in best of causes can do, against base hirelings and mercenaries.” “Home Sweet Home” means different things to different people. In researching the origin of this popular expression, I found roots lying with a popular song dating back to 1823. "Home, Sweet Home" is a song adapted from American actor and dramatist John Howard Payne's 1823 opera Clari, or the Maid of Milan. The song's melody was composed by Englishman Sir Henry Bishop with lyrics by Payne. Mid pleasures and palaces though we may roam Be it ever so humble, there's no place like home A charm from the skies seems to hallow us there Which seek thro' the world, is ne'er met elsewhere Home! Home! Sweet, sweet home! There's no place like home There's no place like home! An exile from home splendor dazzles in vain Oh give me my lowly thatched cottage again The birds singing gaily that came at my call And gave me the peace of mind dearer than all Home, home, sweet, sweet home There's no place like home, there's no place like home! Interest in the song was strong in both Great Britain as well as the United States. When published separately, “Home, Sweet Home” quickly sold 100,000 copies, making considerable profits for both publishing companies and the producers of the opera. Soon, the song would be performed publicly by stage entertainers and in school-related concerts and recitals. In 1852 Henry Bishop "relaunched" the song as a parlor ballad, and it became very popular in the United States throughout the American Civil War and after.  Advertisement for "Home Sweet Home" appearing in the London Times (May 20, 1823) Advertisement for "Home Sweet Home" appearing in the London Times (May 20, 1823) In this week’s piece, I’d like to introduce readers to a branch of a family that obviously cherished Frederick, Maryland as “Home, Sweet Home” for a final resting place. Their surname of Johnson is synonymous with not only Frederick, but Maryland as well. Residing in various places around the country, several bodies were brought back to a newly created family plot in Mount Olivet in the year 1915. Dr. James Thomas Johnson (Jr.) was born June 26th, 1828 in Port Tobacco, Charles County, Maryland. He was the son of James Thomas Johnson and Emily Newman, and a great-grandson of Roger Johnson (1749-1831). You may recall that Roger Johnson was the one-time owner/operator of Bloomsbury Forge on Bennett’s Creek in southeastern Frederick County. He also was the kid brother of Maryland’s first elected governor, Thomas Johnson, Jr.  Now back to our subject James T. Johnson. His education was begun at the Frederick Academy and he went on to graduate in 1850 from Princeton (New Jersey). After graduation, Johnson studied medicine with his father and advanced his knowledge at the University of Maryland, gaining his degree in 1852. The young physician married Miss Anna Mobberly of New Market, the daughter of Dr. E. W. Mobberly. James T. Johnson opened his practice in Frederick at this time and enjoyed great success until the beginning of hostilities connected with the American Civil War. Dr. Johnson was outspoken in his support of the Southern Cause, and this would lead him to enter the service of the Confederacy as an assistant surgeon of the provisional army. He would quickly rise up in rank to hold the title of surgeon. Johnson was elevated again to the position of medical purveyor of the army, and then Chief Purveyor of the Army in 1862. In this role, Dr. Johnson had control of the hospitals and medical supplies for the entire army, involving an outlay of 1.5 million dollars/month with his principal depot being headquartered at Charlotte, North Carolina. He would hold this position until the war’s end in 1865. Dr. Johnson would come back to Frederick, but was not welcomed back with open arms by the majority of the Union-siding populace. Diarist Jacob Engelbrecht made mention of return in June, 1865, starting off his passage with: “Another batch of returned Rebels from our country have returned within a few weeks, viz J. D. Cockrill, Doctor J. T. Johnson, Richard Norris, Sergeant Michael P. Galligher, Carl Hoffman, Amos Scott….” This “homecoming” likely prompted the physician to take his practice elsewhere. And that he did, traveling across the country to make his new start. Newspaper advertisements show Johnson bouncing between Virginia City and Reno, Nevada in the 1870’s. This stint was capped by Johnson becoming a health officer for the state of Nevada, established in 1864. By the end of the decade, Dr. Johnson and son Roger would be listed in the 1880 US census. They were now living together in San Rafael, Marin County, California. "Doc" Johnson would leave northern California in 1885, however Roger would live out the balance of his life in nearby San Francisco, practicing law over the next three decades. He would not marry. Dr. Johnson next relocated to Decatur, Alabama, and served as health officer there until 1891. He would move to nearby Huntsville and hold the position of Health Officer of Madison County until the evening of August 9, 1899. After attending to his duties that day, the doctor would take supper with his wife. He would suffer a stroke shortly after, causing his death at the age of 68.

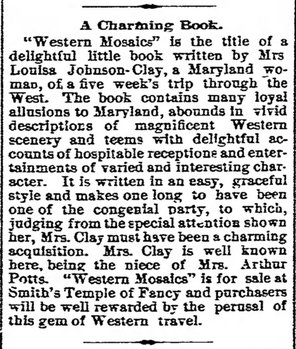

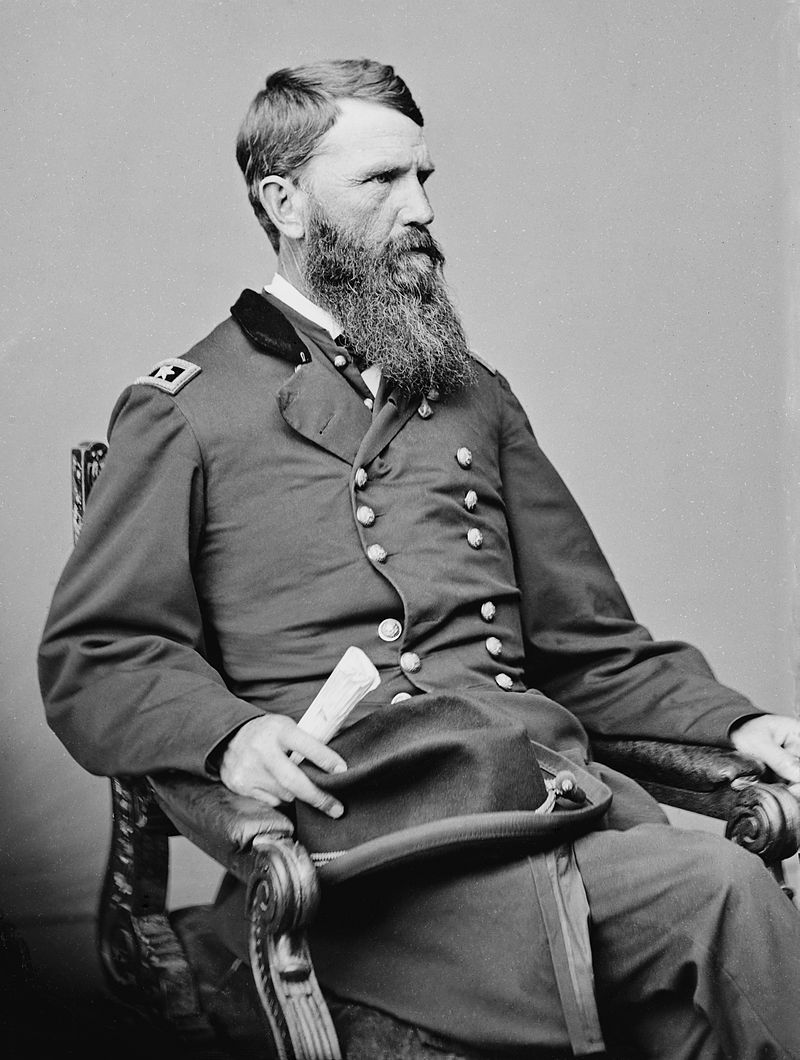

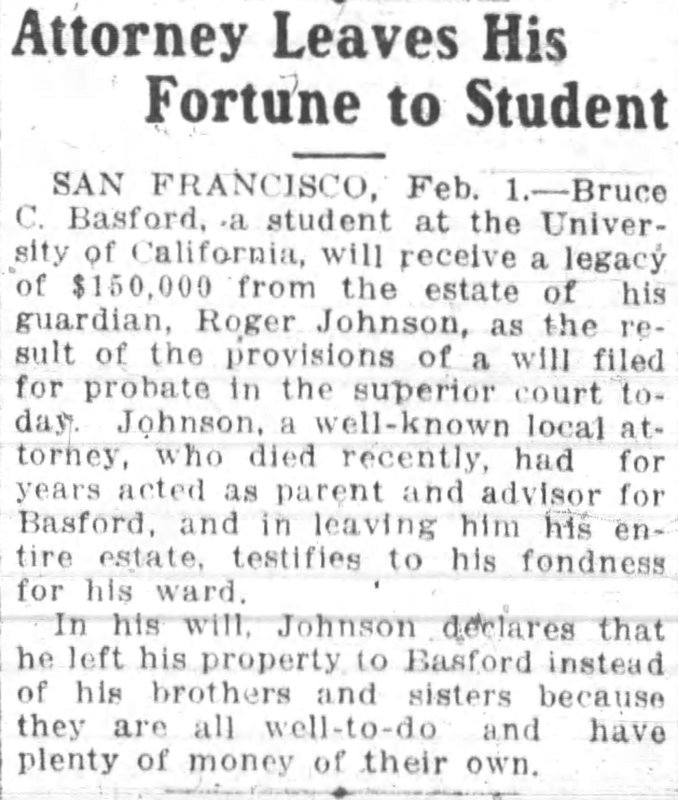

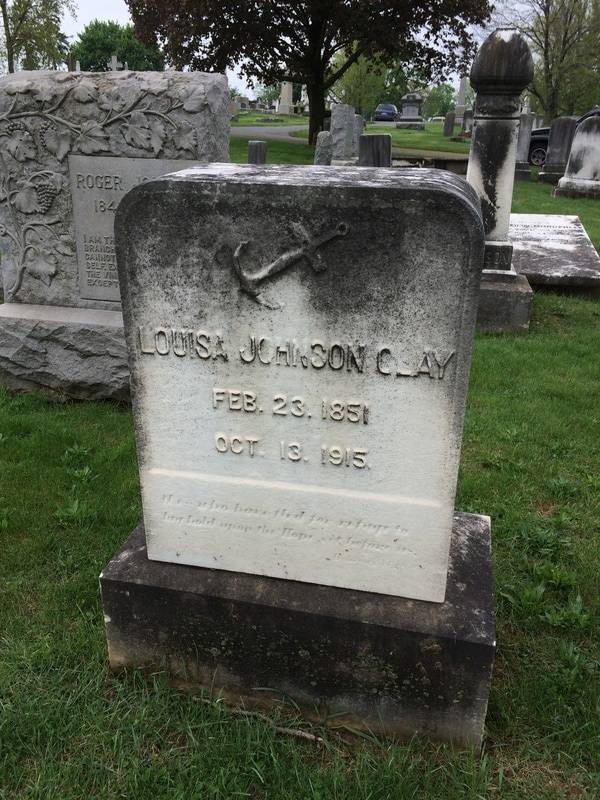

Mr. Blair was the son of famous Union Civil War Gen. Frank Preston Blair. Blair’s father also served as a US congressman from Missouri. Cary had come from a high pedigree family as well. His grandfather was Kentucky newspaper editor and politician Francis Preston Blair, who, in 1840, came across a mica-flecked spring near, what is today, Georgia Avenue near the Washington, DC line. The location today is Acorn Park at Blair Mill Rd., Newell St. and East-West Highway. The elder Blair decided he liked the location so much that he would acquire the property surrounding the spring and build a summer home for his family, away from the sweltering, malaria-infested confines of the capital city. Mr. Blair constructed a 20-room mansion on the parcel and called it “Silver Spring.” Cary’s uncle, Montgomery Blair, represented Dred Scott in the landmark Supreme Court case and served as mayor of St. Louis and Postmaster General under President Lincoln. Emily (Johnson) Blair gave birth to a son, Francis Preston Blair III, on September 3, 1891. She would endure complications from the childbirth and developed Puerperal Pyrexia, dying just over two weeks later on September 19th, 1891. Cary Blair would not recover from his wife’s premature death, and lived a reclusive existence in Colorado and Texas until his own death in 1944. Son Francis was adopted and raised in Philadelphia by Cary’s brother, dying himself in London in 1943.  Frederick News (Dec. 16, 1892) Frederick News (Dec. 16, 1892) Shortly after Dr. Johnson’s death, wife Anna M. Johnson and surviving daughter Louisa (Johnson) Clay would relocate to Maryland from Alabama. Named for her ancestral cousin and former First Lady (Louisa Johnson, wife of John Quincy Adams), Louisa married Huntsville attorney William Lewis Clay (1852-1911). William L. Clay was also a one-time secretary of the Alabama State Senate. Louisa won some notoriety of her own as an author, compiling a 70-page book called Western Mosaics, which chronicled a five-week trip through the west. She was also responsible for writing The Spirit Dominant: A Life of Mary Hayes Chynoweth. Ms. Chynoweth was a noted philanthropist and faith healer, responsible for establishing the True Life Church. It seems that the union between Mr. and Mrs. Clay was not the epitome of “Sweet Home Alabama.” They would divorce, likely the impetus for Louisa and her mother to return home to Frederick, Maryland. Once back, they first lived on East Patrick Street, and later can be found living at 207 East Second Street (in the household of William and Margaret Young) by the time of the 1910 census. Anna Mobberly Johnson died a few days before Christmas (December 22) of 1913, and was buried on Christmas Eve. The mother and daughter had bought lots at Mount Olivet Cemetery, but would acquire more than two for their personal needs. These were located next to the gravesite of Mrs. Johnson's parents and brother, all three dying in the 1870's and 1880's. In death, the James T. Johnson family would be carefully brought back together in Frederick. Roger Johnson died January 13th, 1915. Louisa personally went to San Francisco to make the necessary plans for disinterment and cross-country travel. On March 18th, Roger was laid to rest next to his mother. A bachelor with no heirs, Roger Johnson’s estate made national headlines as he left $200,000 in trust to a young student at the University of California at Berkeley. During the ongoing months of 1915, various stories described illnesses besetting Louisa, but full recoveries were always the case—at least until October of that year. The month started with two more reburials within Mount Olivet. On October 4th, the bodies of Dr. James T. Johnson and Emily Johnson Blair traveled back to Frederick from Huntsville, Alabama and were brought through the main gates. They were destined for reburial in the family plot on Area H/Lot 477.

|

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed