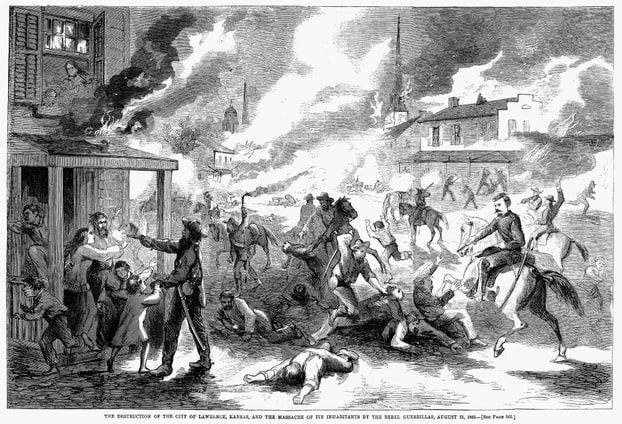

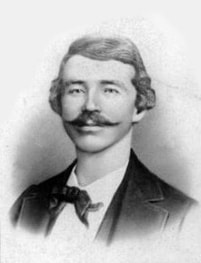

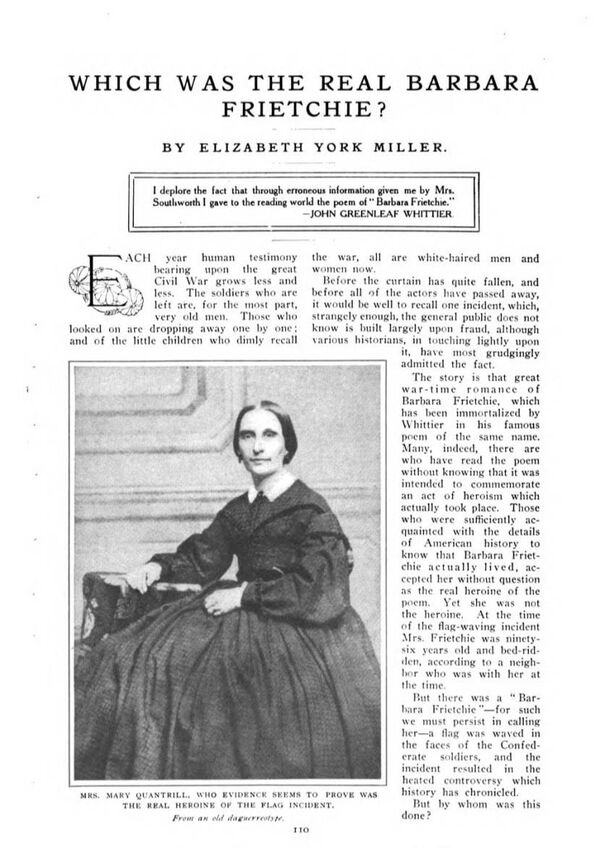

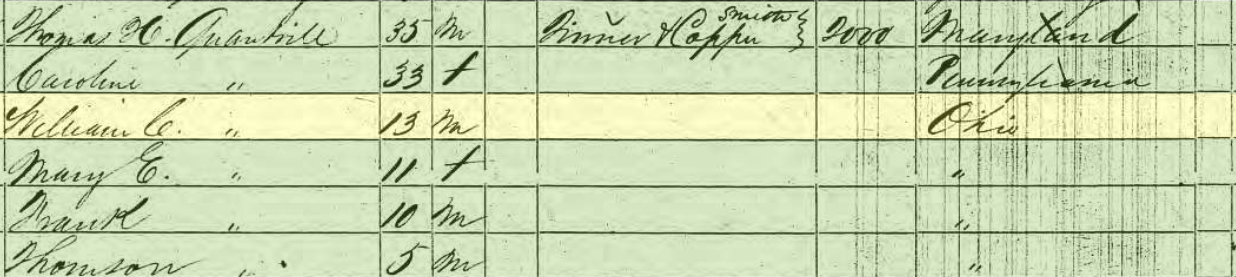

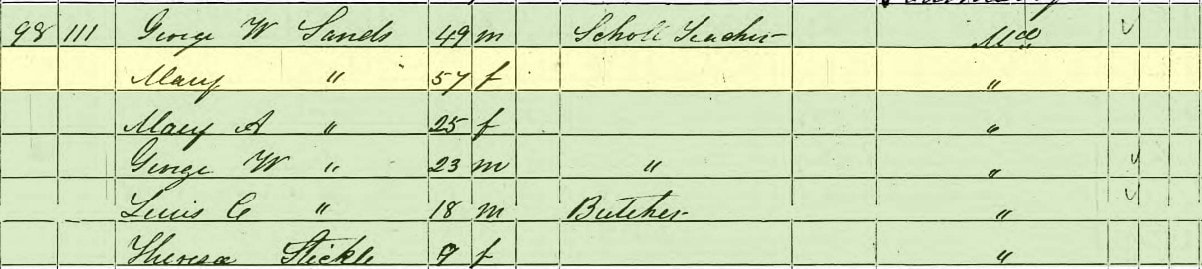

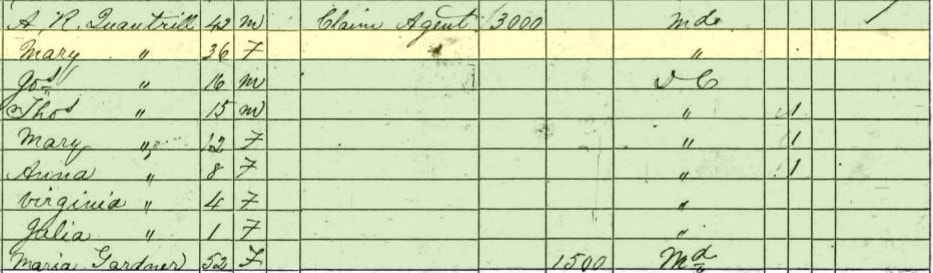

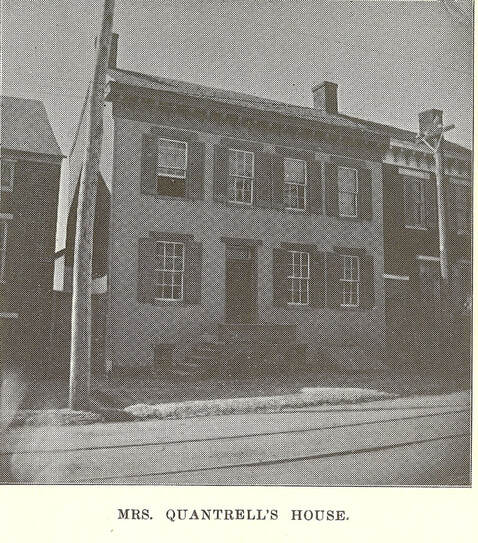

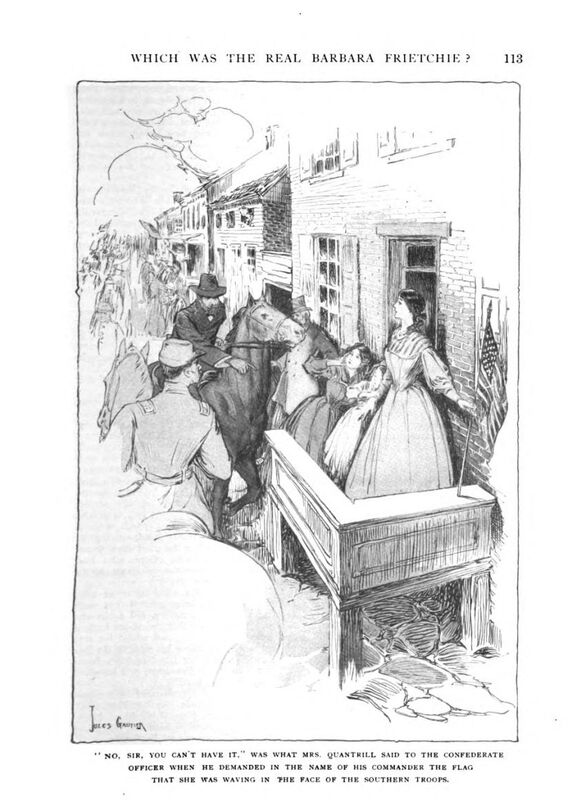

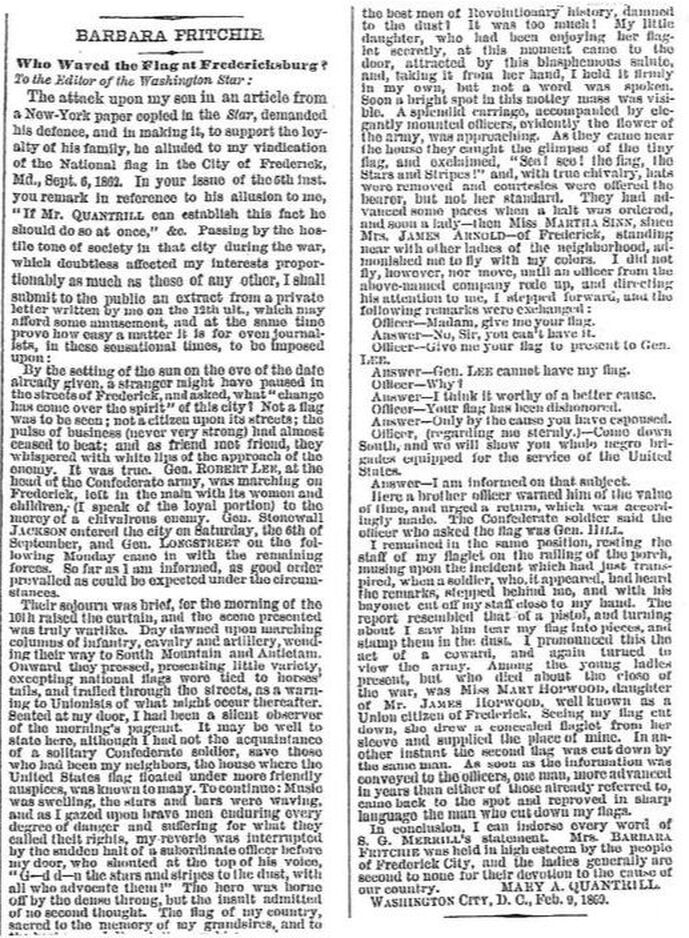

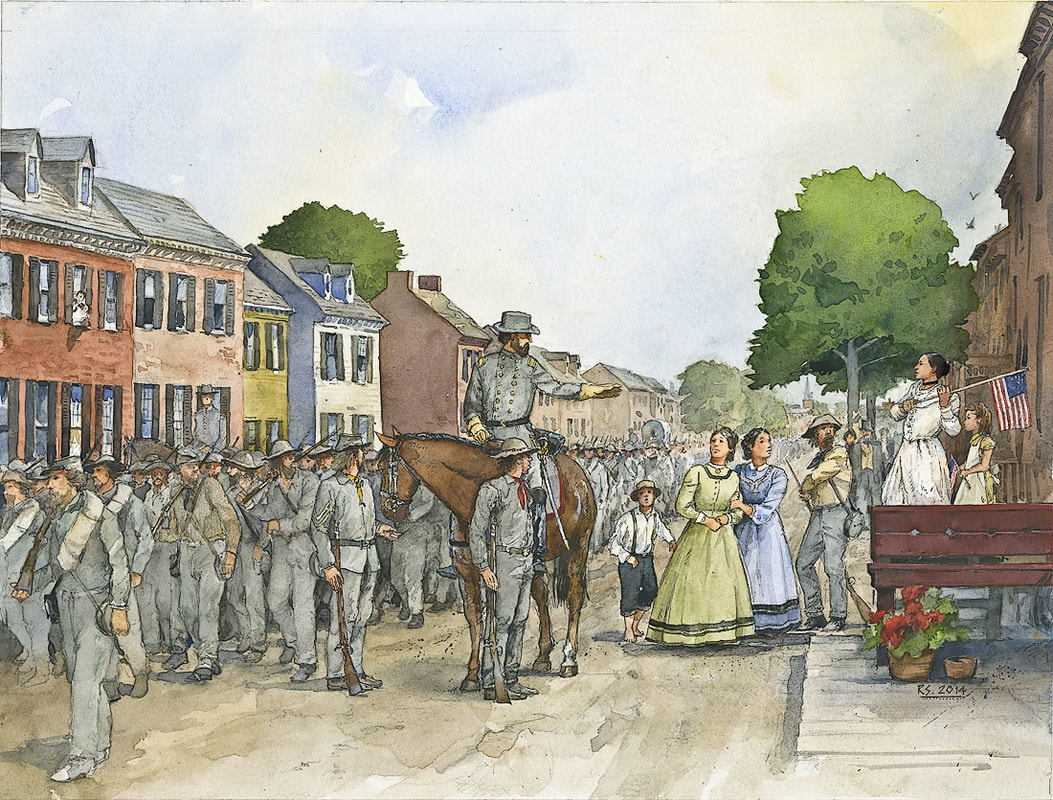

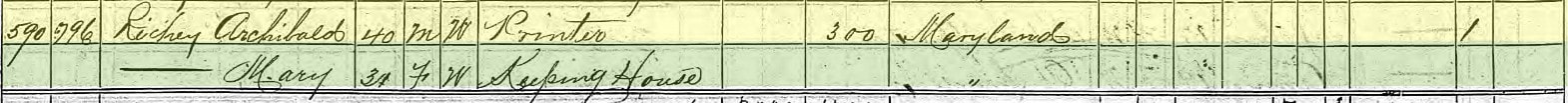

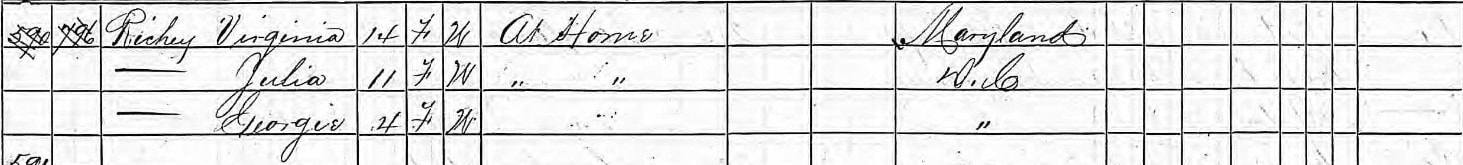

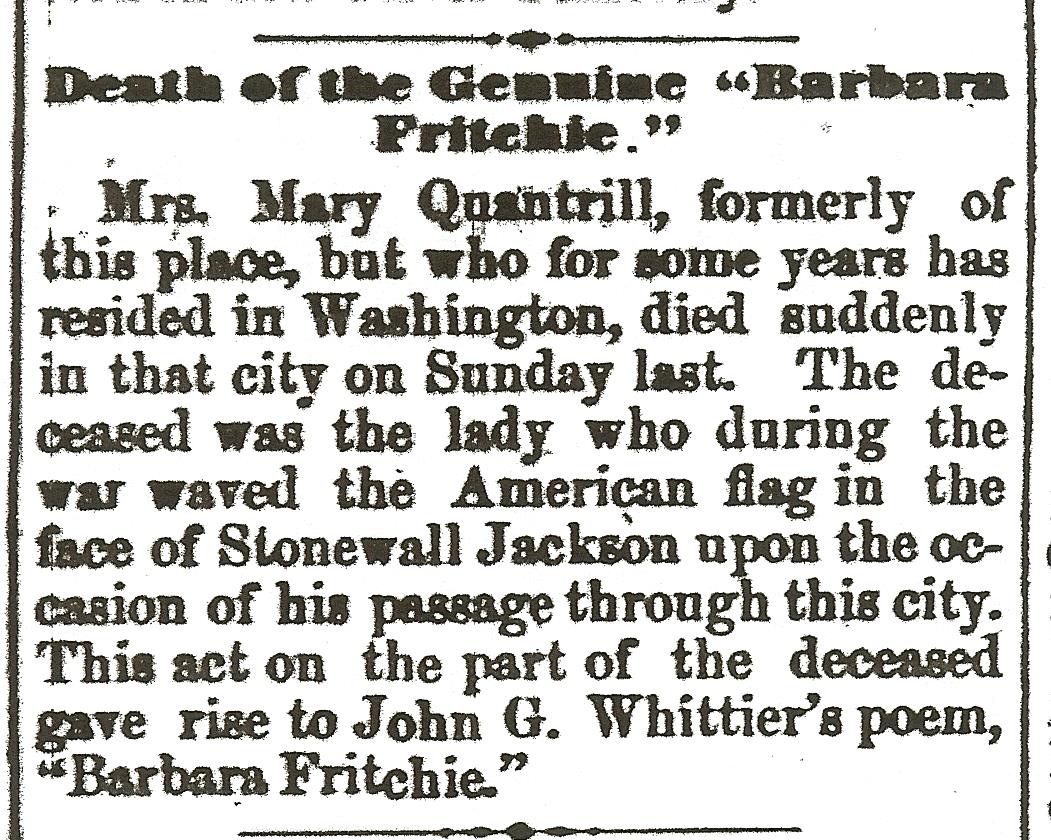

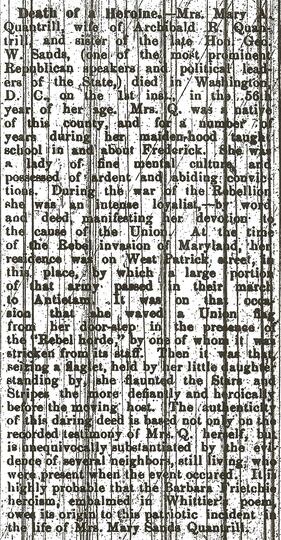

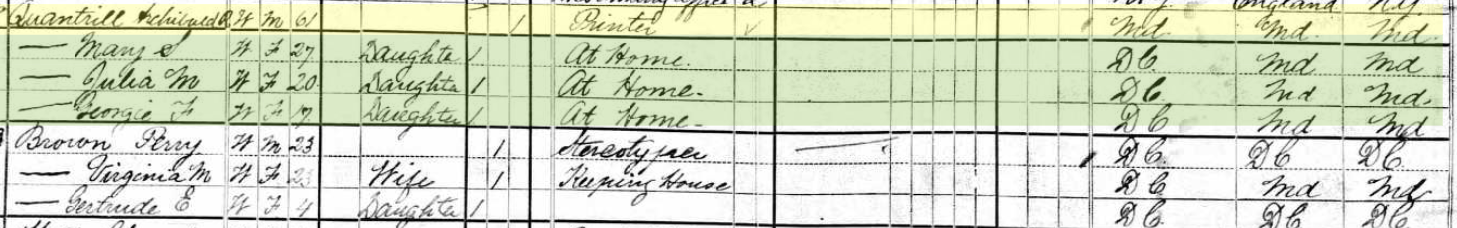

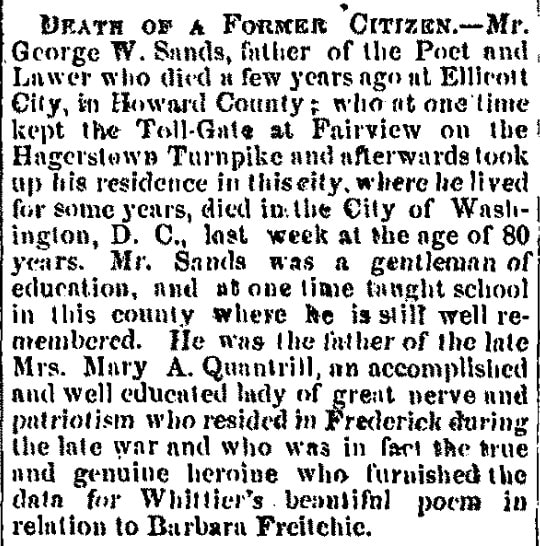

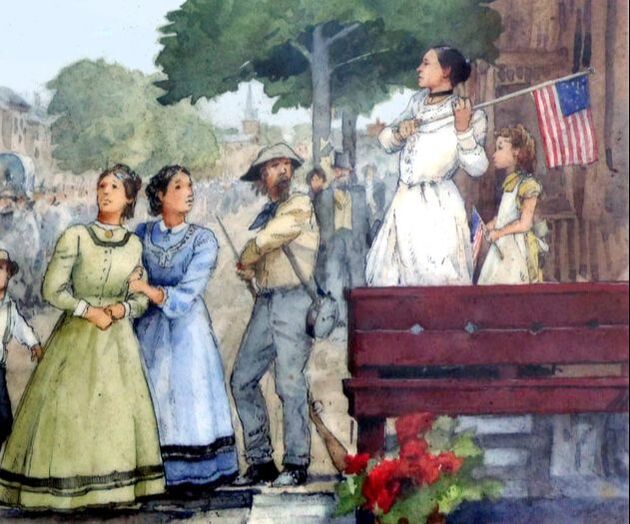

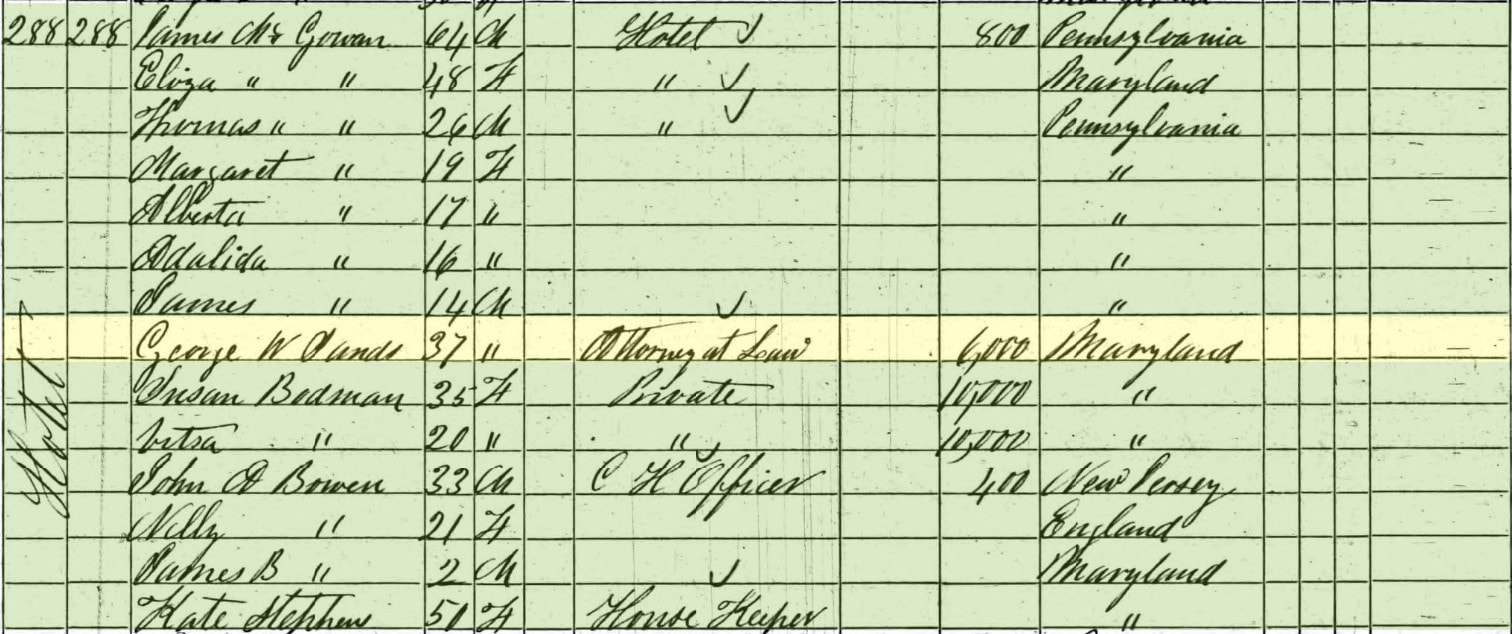

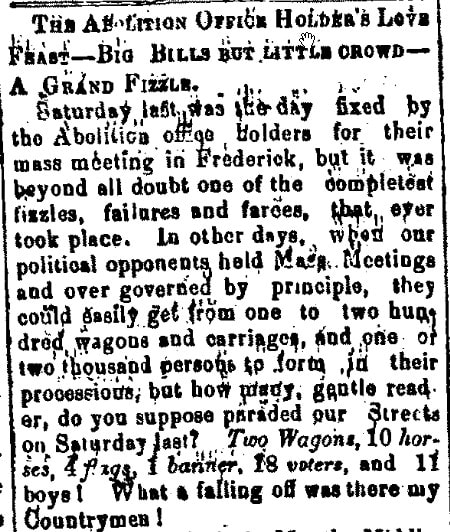

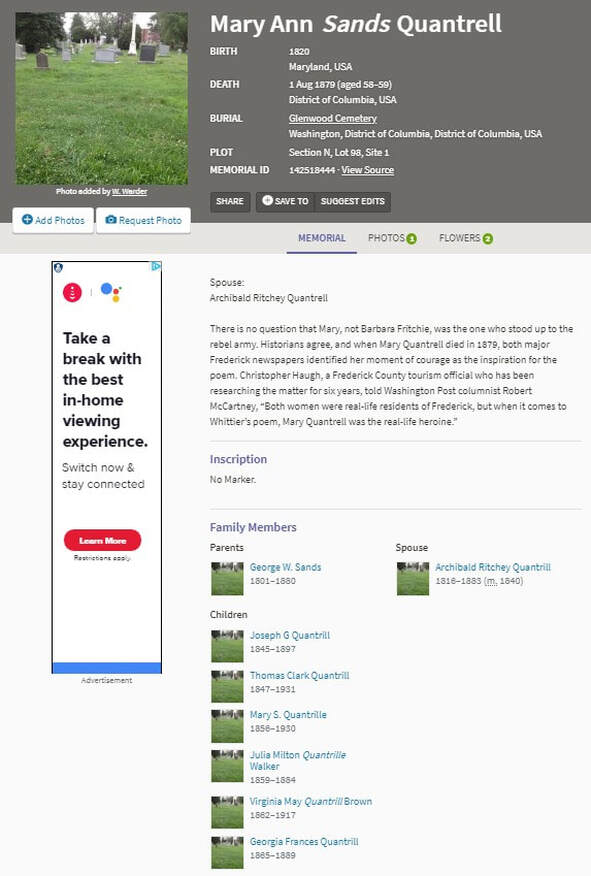

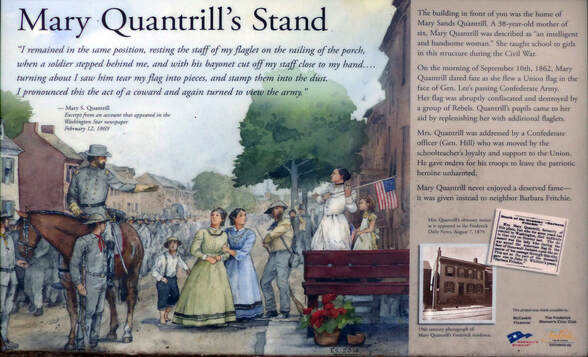

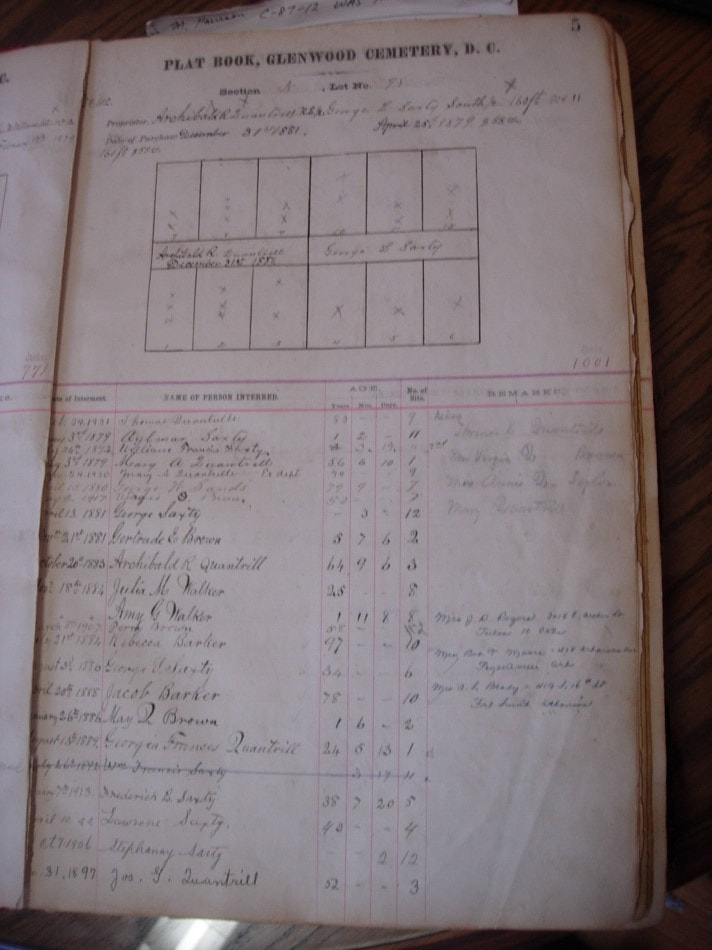

Well, I made it into this month’s edition of Frederick Magazine. Better yet, I was interviewed by writer Kate Poindexter in her fine story about Barbara Fritchie entitled “Legendary Tale.” Of course, I’ve been studying the nuances of the Fritchie episode for over 25 years, as it is has certainly been one of my favorite local research topics. Those who know me also are aware that I’m always up for challenging and busting age-old myths, and new ones too. But, I will confess, I get just as much satisfaction in proving myths true as well. As you may have seen (in the Frederick Magazine article), or already know otherwise, the Barbara Fritchie tale consists of many twists, turns and layers. It also possesses an interesting cast of supporting characters as well, featuring two other viable “flag-waving” understudies who could have easily been blessed with the lasting fame that Dame Fritchie has received. One of these ladies, Nannie (Nancy) Crouse, hailed from Middletown but eventually spent all her adult life a short distance from the cemetery as she lived in the first block of West South Street. Like Barbara, she is buried next to her husband (John Bennett) here in Frederick’s Mount Olivet Cemetery in Area B/Lot 2. The other “flag-toting Barbara” in question has always been shrouded in mystery and controversy. She also just happens to be one of my sentimental favorite individuals from our county’s rich heritage story. Her name is Mary Quantrill. Mary Quantrill lived a sad and desperate life after the events that played out in September of 1862 and were compounded by writers and reporters for many years to follow. Writer and humorist Mark Twain is responsible for saying: “Never let the truth get in the way of a good story.” This is so fitting to sum up the downfall of Mrs. Quantrill. You see, she was a victim of “cancel culture,” a century and a half before it was even a thing. This was the result of her situation not getting the press and embellishment garnered by Fritchie by a well-known poet who was deeply connected in the media of his time. However, there’s something about Mary that also “did her in” so to speak—a highly controversial surname. As rare as the last name of Quantrill still is, it had, at that time, gained an unpopular reputation thanks to a nephew living out west. Mary would never meet this individual during her lifetime. William Clarke Quantrill Quantrill's Raiders were the best-known of the pro-Confederate partisan guerrillas (also known as "bushwhackers") who fought in the American Civil War. Their leader was William Clarke Quantrill (1837-1865) and the gang included legendary outlaws Jesse James, brother Frank James, and Cole Younger. Early in the war, Missouri and Kansas were nominally under Union government control and became subject to widespread violence as groups of Confederate bushwhackers and anti-slavery Jayhawkers competed for control. The town of Lawrence, Kansas, a center of anti-slavery sentiment, had outlawed Quantrill's men and jailed some of their young women. In August 1863, Quantrill led an attack on the town, killing more than 180 civilians, supposedly in retaliation for the casualties caused when the women's jail had collapsed. Many of those slaughtered in broad daylight included young boys whose ability to hold a firearm resulted in their executions by “the Raiders.” William Clarke Quantrill was born at Canal Dover, Ohio. His father was Thomas Henry Quantrill, formerly of Hagerstown, Maryland, and his mother was Caroline Cornelia Clark, a native of Chambersburg, Pennsylvania. The oldest of twelve children (four of whom died in infancy), Quantrill endured a tempestuous childhood. By the time he was sixteen, he found himself teaching school in Ohio. A year later (1854), his abusive father died of tuberculosis, leaving the family with a huge financial debt. Quantrill's mother had to turn her home into a boarding house in order to survive. During this time, Quantrill helped support the family by continuing to work as a schoolteacher, but he left home a year later and headed to Illinois where he took up a job in the lumberyards, unloading timber from rail cars. One night while working the late shift, he killed a man. Authorities briefly arrested Quantrill even though he claimed that he had acted in self-defense. Since there were no eyewitnesses, and the victim was a stranger who didn’t know anyone in town, William was set free. Nevertheless, the police strongly urged him to leave the town of Mendota (Illinois) where he was living. William Clarke Quantrill continued his career as a teacher, moving to Fort Wayne, Indiana in February 1856. The school district was impressed with Quantrill's teaching abilities, but the wages remained meager. Quantrill journeyed back home to Canal Dover that fall, with no more money in his pockets than when he had left. The frustrating experience seems to have struck a nerve with the young educator, as he would leave his classroom for a drastically different life—as a slave catcher. William Clarke Quantrill joined a group of bandits who roamed the Missouri and Kansas countryside and apprehended escaped slaves. Later, the group became Confederate soldiers, who were referred to as "Quantrill's Raiders.” It was a pro-Confederate partisan ranger outfit that was best known for its often brutal guerrilla tactics, which made use of effective American Indian field and combat skills. Quantrill is often noted as influential in the minds of many bandits, outlaws and hired guns of “the Old West” as it was being settled. In May 1865, Quantrill was mortally wounded in combat by Union troops in Central Kentucky in one of the last engagements of the Civil War. He died of wounds in June. Meanwhile, the James brothers formed their own gang and conducted robberies for years as a continuing insurgency in the region. Miss Sands William Clarke Quantrill’s grandfather, Captain Thomas Quantrill, spent considerable time in Frederick, primarily at the old Hessian Barracks grounds—land that once graced the fields located across from our cemetery’s front gate. A British immigrant who raised a company of soldiers in Hagerstown for the War of 1812, Captain Quantrill was described as “a brave soldier” who participated (and was injured) in the Battle of North Point in Baltimore in September, 1814. Thomas Quantrill would eventually move to Washington, DC with his family following his wife’s death. His oldest son, Thomas Henry Quantrill (William Clarke Quantrill’s father) would move to Stark Ohio to open a blacksmith business. Meanwhile, Thomas Henry’s younger brother, named Archibald Richey Quantrill, spent the bulk of his life in Washington DC, and would eventually go into the newspaper business, serving as a printer and compositor for the National Intelligencer. Archibald would marry his second wife, Mary Ann Sands, on February 8th, 1854. Mary Ann Sands was born in Hagerstown on January 21st, 1823. She was the oldest of three children born to George Washington and Mary Ann (Cronise) Sands who were married in Hagerstown in August of 1821. The family moved to Frederick County and resided in the northwestern part of the county first, eventually making their way to Frederick City. They would reside in a rented dwelling in the 200 block of West Patrick Street, just a short distance up the hill and west from the Barbara Fritchie household. This Sands family can be found back to the 1830 census as living in Frederick. Mary’s father was listed as a school teacher in the 1850 census and also as an esquire, serving later as a judge in the city court of Lacon, Illinois. He apparently had an interest in writing poetry too. The Sands family consisted of three children with Mary as the oldest, followed by two brothers: George, Jr. and Louis . The older of the two, George W. Sands, Jr. (@1824-1874), would become a lawyer and politician. Louis would relocate to Suffolk County, New York (Long Island) and work for the railroad and later became a patent dealer. Our lead subject, Mary Quantrill, married Archibald Quantrill in 1854 and can be found living in Washington DC’s 1st Ward in the 1860 census, with husband Archibald’s profession listed as that of a claims agent. The family at this time included six children, four of which from Mr. Quantrill’s first marriage to a Frederick native named Mary Westenberger. By September of 1862, Mary would be back in Frederick and residing in her earlier home of 220 West Patrick St. in Frederick. With the serious threat to the Union’s “Capital City” during wartime, Archibald thought it best that Mary and their children reside in Frederick with Mary’s elderly mother, as Washington was thought to be a prime target for Confederate attacks. Mary's father was living in Illinois at this time. The elder Mrs. Sands is listed as blind in the 1860 census, so perhaps Mary was also involved in care-giving for her mother as well. Regardless, Archibald Quantrill remained in Washington at this time. During the Civil War, several accounts say that Mary Quantrill operated a small private school from the home on West Patrick at this time. “Mrs. Quantrill at the time of the incident was a handsome woman,” says author William E. Connelly in his 1909 biography of William Clarke Quantrill entitled Quantrill and the Border Wars. Connelley goes on to state that Mary Quantrill was the “The True Heroine” of the day (not Barbara Fritchie), and that “Mrs. Quantrill appears to have been a woman of superior intelligence. She has for many years a teacher in Frederick, and was a frequent contributor to the “Evening Herald” of York (PA). It is said that she always felt keenly the injustice Whittier had done her.” Archibald Quantrill was proven wrong in early September, 1862, when Frederick was the first, major Northern town Gen. Robert E. Lee would bring his Rebel Army of Northern Virginia, after crossing the Potomac River. Many are familiar with the fact that the Confederates were basically given a cold reception here at that time, save for a smattering of southern-leading residents. Not getting the assistance he had hoped for, Gen. Lee headed west toward South Mountain and Washington County, utilizing the National Pike to transport his large fighting force. West Patrick Street was part of this great road, and Mary Quantrill would have a front row seat for the Confederate parade out of town which began in the early morning hours of Wednesday, September 10th. She even had her Union flag proudly displayed from a railing on her front porch to give the Rebel horde a proper “send-off.” Mrs. Quantrill made a lot of noise that particular day, and was certainly noticed by soldiers, officers and a number of her Patrick Street neighbors. However, she didn’t make a lasting name for herself—or should I say, she didn’t receive help from a Georgetown novelist (E.D.E.N Southworth) or Quaker poet from Massachusetts (John Greenleaf Whittier). In late summer of 1863, these literary luminaries had an Abolitionist agenda to tend to, and fast-tracked a work of prose that featured Mary’s feisty neighbor—the nonagenarian who lived a football field’s length down the street whose name rhymes with “bitchy.” Yes, the name of Barbara Fritchie (or Frietchie) would ring true as not only Frederick’s heroine, but that of a nation—or at least the part of it that was still intact as the Union at that time. So, what exactly transpired on September 10th, 1862 in the 200 block of West Patrick Street? Well I have enclosed a vital article which appeared in the Washington Star newspaper (Washington D.C.). This particular letter to the editor was re-published in the New York Times on February 15th, 1869. A pretty colorful scene, wouldn’t you agree? Regardless, Dame Fritchie had died in December, 1862 and never lived to enjoy (or possibly refute) her fame, as she died at age 96, eleven months before the poem was published in the Atlantic Monthly Magazine October, 1863. The above newspaper clipping from 17 years later (1869) provides incredible context to Mary’s interaction with boisterous Confederates on that “Cool September morn.” Mary’s son, Thomas C. Quantrill had been mistakenly admonished in a Washington newspaper for being associated with the infamous Missouri Raider, William Clarke Quantrill. Thomas pointed out the error and exclaimed that he knew the man only as well as the general public knew the man. Thomas offered that he had volunteered for US Army duty in advance of the First Battle of Bull Run but was rejected due to physical limitations. In expressing his devotion to the Union, and not Confederacy, he made mention of his mother's heroics in Frederick on the morning of September 10th, 1862. He thought his mother had stood humble and tight-lipped long enough and should get at least some credit and accolades for her heroic role played in Frederick during the Civil War. This renewed interest in Barbara Fritchie came at a time when the original Fritchie house was being razed by the Frederick municipality in an effort to combat Frederick flood measures for Carroll Creek. Mary Quantrill had moved back to the nation’s capital in either 1863 or 1864. She was unable to escape the constant adoration her former neighbor (Barbara) continued to receive posthumously. And amazingly, no one definitively saw Barbara harass the Confederates on that fateful day, including our famed diarist, Jacob Engelbrecht, who lived directly across from the Fritchie house. He would make a journal entry in October of 1863 upon reading Whittier's Barbara Frietchie poem in a newspaper, commenting that this was the first he had heard of such an event and puzzled as he had watched the Confederate Army pass his door that entire day without a monumental incident occurring across the street. Mary Quantrill lived a lonely and broke life in her later years. In my initial research on Mary Quantrill back in 2007, I lost track of Mary save for the newspaper items I had found above. I could not find her in the 1870 US census. After countless attempts utilizing the popular internet site Ancestry.com, I finally found the family in question under the name of Archibald and Mary Richey. The infamy associated with the Quantrill family name, thanks to the exploits of William Clarke Quantrill, must have been too overwhelming for a peaceful existence free of criticism in the nation’s capital. Archibald’s middle name would serve as a less auspicious identifier. Mary Ann (Sands) Quantrill died on August 1st, 1879, and I have surmised it was likely from depression and a broken heart. The actual cause on the death certificate is cardiac-related so I’m not entirely off in my medical assessment. Mary is not buried in Mount Olivet, but rather Glenwood Cemetery in Washington, DC. Sadly, her “Story in Stone” has never been fully told, as she is buried in an unmarked grave. As a matter of fact, most of her immediate family has the same predicament. I have often wondered if this was a result of “cancel culture” for being thought of as a “want to be” hell bent on riding on Barbara’s coattails, or worse yet trying to steal the fame belonging to the defiant and deceased 95 year-old? Or were her detractors simply upset with that pesky Quantrill name, and the familial relation to one of the baddest men in the entire country? I think it was a lethal combination of both. One of the most gratifying finds in my “search for Mary Quantrill” came in the form of obituaries in the Frederick papers. As not to influence your judgment, I will simply present both from our two Frederick newspapers of record of that time. By the 1880 census, the Quantrill family name would reappear in print again as Archibald and three daughters (Mary, Julia and Georgie) are found living on K Street in the Northeast part of the District of Columbia.

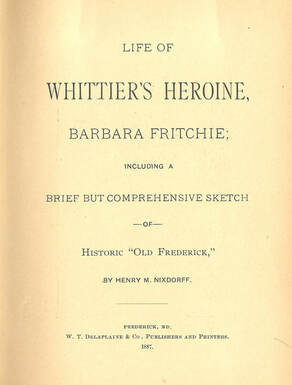

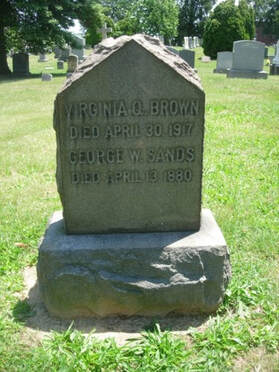

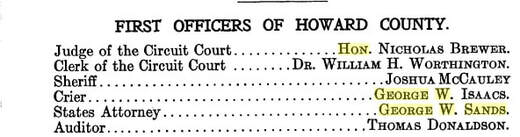

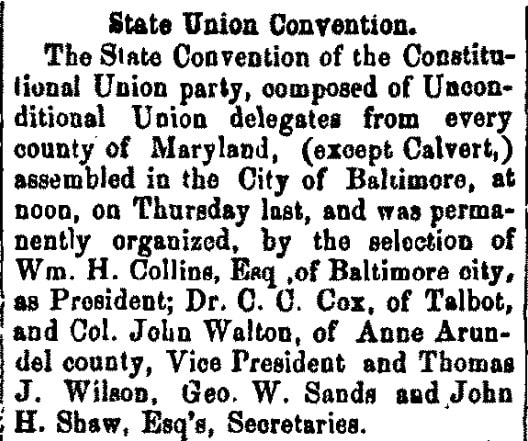

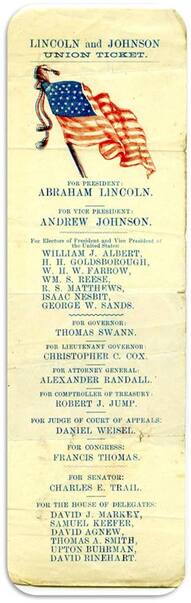

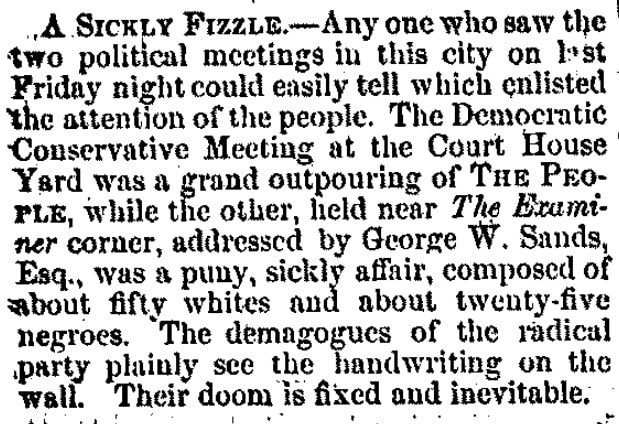

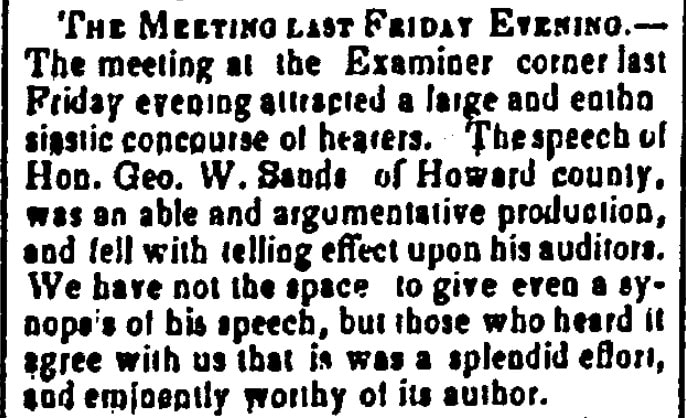

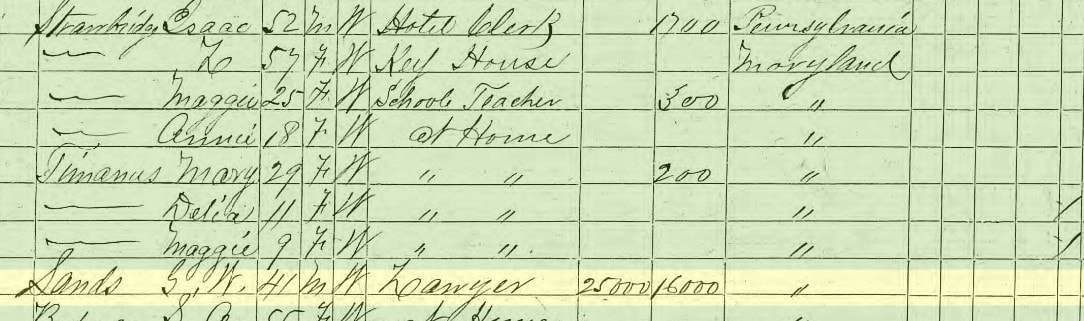

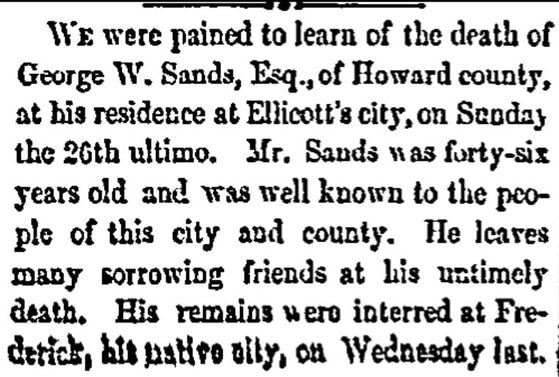

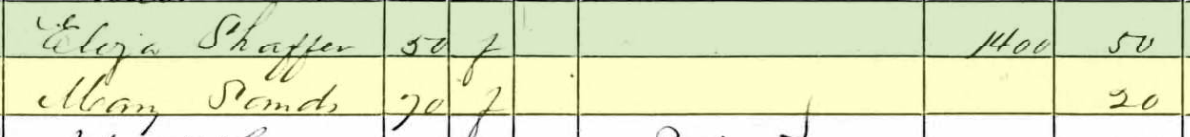

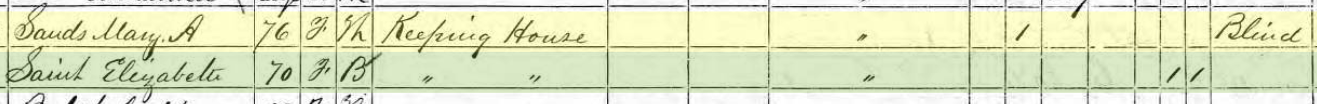

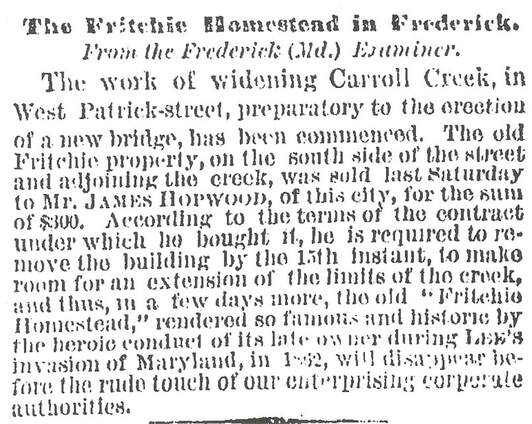

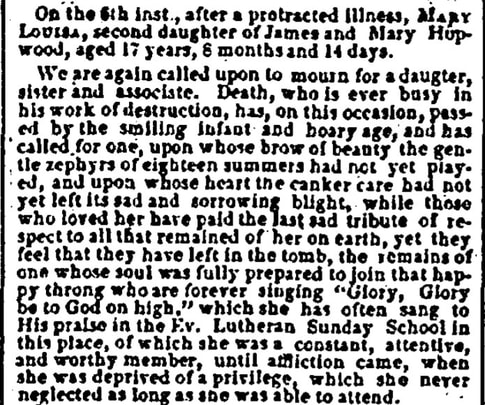

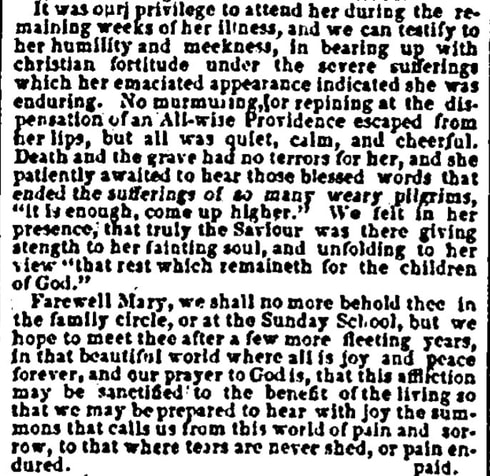

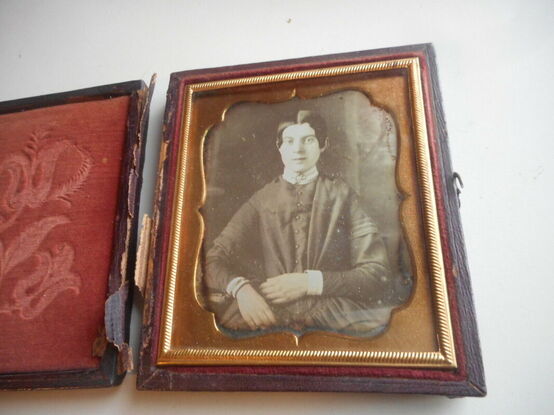

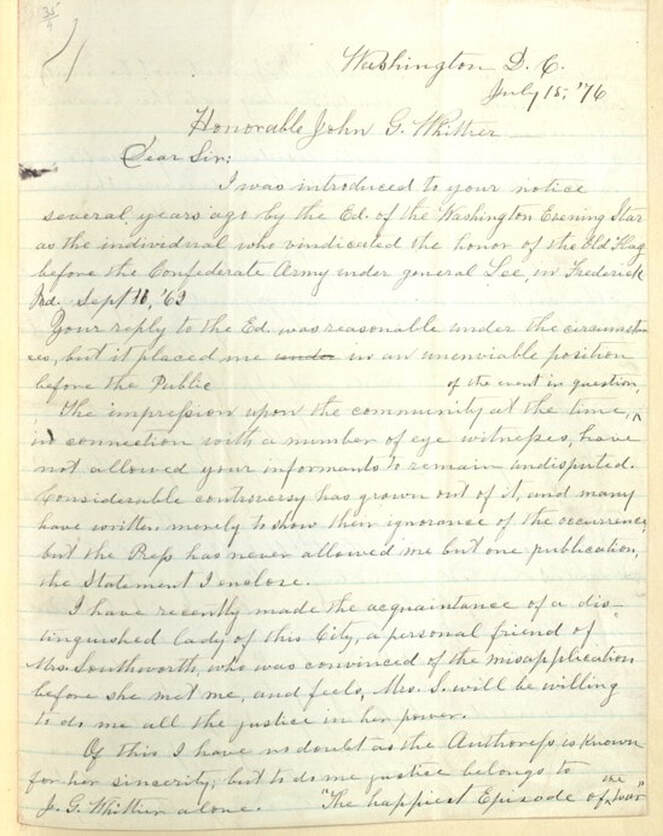

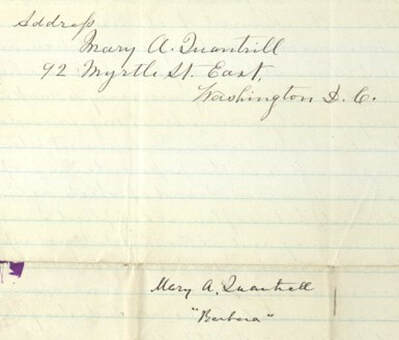

Mount Olivet and Mary Quantrill What we do have here in Mount Olivet are some close connections to Mary Quantrill. One of which is her brother, George W. Sands Jr. Mr. Sands had been practicing his legal career in Howard County and would become States attorney for the county by the mid-1850s. He would be elected state delegate from that county and, unlike his midwestern cousin William Clarke Quantrill, served as an outspoken Unionist and opponent to slavery. Sands would participate as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention of 1864 and was quite active in constructing the third state constitution of Maryland which abolished slavery, taking effect November 1st, 1864. He was also a US collector of internal revenue under President Lincoln. George W. Sands, Jr. died on July 28th, 1874 and was buried in Mount Olivet’s Area H/Lot 156 Strangely, he too is buried in an unmarked grave. Our records show that he is definitely here in space #3, and has two unknown individuals buried to each side of him. Could one of these graves be his (and Mary’s) mother (Mary Ann Sands)? I continue to search for the answer as our cemetery records books cannot confirm Mary Sands being here, or anywhere else in Frederick. She is definitely not recorded being at Glenwood in DC with husband George, Sr. or her daughter and the rest of the Quantrill family. Mary Sands is found in the census of that year and residing with a woman named Eliza Shaffer, perhaps a relation of some sort. Mrs. Shaffer was widowed at the time. A decade later, Mrs. Sands was living with a 70 year-old black woman named named Elizabeth Saint. I decided to see if Mrs. Shaffer was buried in Mount Olivet and I discovered from our records that an Elizabeth Matthews Shafer was buried here in March,1867, but her gravesite is listed as unknown. So I ask the question again, could Mrs. Sands and Mrs. Shaf(f)er be buried in Area H/Lot 156 with George W. Sands, Jr.? I found Mrs. Sands' husband was elsewhere during both these census years, but I haven't found him yet. I'm assuming he was either in Illinois, or in Ellicott City as his obituary claims he was a one-time resident of the Howard County town.  Grave of James Hopwood Grave of James Hopwood The Hopwoods As I said earlier, the Sands home was on the south side of the 200 block of West Patrick Street, about 50 yards west of the Bentz Street intersection. I found that the family had been renting this home for years from landlord, James H. Hopwood (1811-1883). Mr. Hopwood was one of the city’s busiest construction contractors. He also was heavily connected to the flag-waving incidents at hand. James and wife Mary Ann Hopwood lived a few doors west (234 W. Patrick St.) from Mary Quantrill and were the parents of a few of Mary Quantrill’s students. Of particular interest is Mary Hopwood (b. 1847), Mary’s oldest student and referenced by name in Mrs. Quantrill’s first person narrative of her experience on September 10th, 1862. Shortly after Barbara Fritchie’s death in December, 1862, her heirs sold their famous relative’s house to a Mr. George Eissler for use as a dyeing and scouring business. In late July of 1868, a disastrous flood washed away part of the old Fritchie property and caused the home to be condemned by the city. Mr. Eissler moved to a new home across the street, and the Fritchie house was put up for auction. The town fathers under Barbara’s Southern leaning grandnephew, Frederick Mayor Valerius Ebert, were interested in widening Carroll Creek at this location. The original Fritchie household was purchased from the city for $300 in early April and, upon the terms of sale, was fully dismantled and removed by May 15th of 1869 amidst the protest of the Frederick Examiner’s editor and others around the country. Jacob Engelbrecht even comments on this in his diary. It is fascinating to note that the sole bidder and eventual new owner of the property would also be the man in charge of the demolition operation of said heroine’s home. Simple “addition by subtraction” as James H. Hopwood’s wrecking ball would help initiate flood control overtures in an effort to help tame Carroll Creek. I’m thinking that Mr. Hopwood and other leaders in town had simply heard enough about Barbara Fritchie over a seven-year span. Mr. Hopwood was awarded the 1869 bid to dismantle the original Fritchie house and, afterwards, would build a two-story brick house on the property and was responsible for building a new wooden bridge over Carroll Creek at this location. He was surely in the Quantrill camp of loyalty as his daughter had been a hero as well, standing beside Mrs. Quantrill in her defiance of the Confederate Army earlier in the decade. The bittersweet part of the story here is that Mary died at age 17 on October 6th, 1864. She would be forgotten by the history books as well. Mrs. Davis Some of the Ebert children (Barbara Fritchie’s grandnieces) were also students of Mrs. Quantrill and under her tutelage on that fateful day in September, 1862. T.J.C. Williams History of Frederick County, published in 1910, contains a biography that makes specific reference to Mrs. Quantrill as a teacher. This can be found in the biography of Samuel Davis, a miller and storekeeper in Fountain Mills (New Market district). It is stated that he was married to Rebecca Maria Ebert (b.1850), a former student and next-door neighbor to Mary Quantrill. At the end of his bio, the author makes a point to say: “In the connection it might be said that Rebecca Ebert, (daughter of John Ebert and second wife Ann Fritchie), was a pupil of Mary Quantrill, who was really the woman who waved the flag which occasioned Whittier’s famous poem.” Ironically, Mrs. Davis’ maternal grandmother was Maria Rebecca (Fritchie) Ebert, sister of John Caspar Fritchie. John Caspar Fritchie was Barbara (Hauer) Fritchie’s husband of course. You may also recall Rebecca (Ebert) Davis’ brother named William Augustus Ebert of whom I wrote a story titled “The Lost Whitesmith” back in November, 2020. William accidentally shot himself while performing a repair on a pistol. The wound proved fatal and his grave can be found in the same plot of his sister (Area G/Lot 202). I missed out on bidding successfully for his photo which was up for auction on eBay. However, another photo of a young girl was up for auction at the same time from this family. I assume that this could be Rebecca Ebert in earlier days of the 1860s, however it could have been another sister as well.  Nixdorff's Affidavit Mary’s first-hand account is corroborated by another neighbor, a man named Henry M. Nixdorff who operated a general store a half block east of Mary’s home on West Patrick Street. The location was the same as the former Jennifer’s Restaurant (owned by Jennifer Dougherty), and most recently known as Le Parc Bistro. Mr. Nixdorff was the son of one of our War of 1812 soldiers buried in the cemetery. He was an intimate friend of Mrs. Fritchie and felt compelled to write a book in 1887 entitled Life of Whittier’s Heroine Barbara Fritchie. In this work, the author defended Ms. Fritchie’s real-life persona as a patriotic woman, kind neighbor and God-fearing Christian above all. This offering, with its personal anecdotes and colorful depictions of the aged town character, countered the more fact driven/no nonsense book written by Caroline W. H. Dall entitled Barbara Frietchie: A Study. Nixdorff’s book which underwent subsequent re-publishings, included an account of the Quantrill event that goes as follows: “I happened to look up the street, and saw a very intelligent lady, a neighbor, standing on her front porch, with a small Union flag in her hand waving it and making apparently the most earnest remarks to a Confederate officer who had ridden his horse over on the pavement up to the porch where she was standing. I was afterward assured by those who had the pleasure of being present that such glowing words of patriotism fell from the lips of Mrs Quantrell that the officer looked on and listened with wonder and surprise, and whilst he was present would not allow his men to do her the least of harm. After his departure however, some of the soldiers belonging to the army came and knocked the flag from her hand, breaking the staff into several pieces.” Mr. Nixdorff even went so far to have five neighbors, who had apparently witnessed the event up close and personal, sign a statement that said his account was genuine. I found all five of the signers buried here in Mount Olivet: Mrs. Matilda (Hauer) Fleming (1820-1887), Mrs. Harriet “Hallie” M. (Fleming) McDonald (1848-1906), Mrs. Kate (Hauer) Cashour (1850-1891), Nicholas Hughes Fleming (1852-1913), William W. Fleming (1854-1926). Mr. Nixdorff is buried in Area B/Lot 1. This man was connected to all three flag-wavers as he was close friends with Barbara Fritchie as mentioned, and helped exonerate Mary Quantrill. The last connection is to Nannie (Crouse) Bennett, who just happens to be buried in the next lot over. Another neighbor and eyewitness who kept the heroic story of Mary Quantrill alive for friends and later generations of family was a lady named Laura A. (Hiteshew) Railing (1843-1923). Mrs. Railing lived with her husband George across the street from the Sands home on West Patrick Street. She told the story to whoever would listen up to her dying days. These witnesses to history just saw Mrs. Quantrill as a mirage, a woman who displayed great bravery and then suddenly disappeared shortly thereafter, never to return. She was an enigma of sorts to those who heard the story. One more nugget I’d like to add. In the year 1876, Mary fruitlessly tried to get aid from author John Greenleaf Whittier in the form of clearing her name and admitting that she perhaps was owed the same fame as Ms. Fritchie. Three years before her death, she was in poor health, and literally destitute as being unhire-able due to the court of public opinion and favor which had turned against her. I saw this letter with my own eyes in the collection of the Quaker Reading Library at Swarthmore College in Philadelphia. The piece was exquisitely written by this highly gifted woman. My heart sank at the very end as it seems that Whittier, himself, inscribed a solemn sobriquet beneath Mary's name on the back of the letter—“Barbara.” As stated earlier, Mary’s final resting place is an unmarked grave in Glenwood Cemetery in Northeast Washington, DC, off Lincoln Ave. Look for the lone stone on the Quantrill lot belonging daughter Virginia (Quantrill) Browne, who participated in the underplayed flag-waving incident as well. A few years ago someone pointed out to me that Mary’s grave had been added to the internet’s FindaGrave site within Glenwood’s interments. He said that I had a hand in this occurrence which made me quite happy. As I said, I have developed an incredible fondness for this unsung historical figure of Frederick’s past. If only she was buried in Mount Olivet, I could do more. I’ve been to her gravesite three times down at Glenwood. The last time was back in 2015. It was a Sunday morning and I had just dropped off my stepson Jack at Reagan National as he was flying to Orlando with classmates for a marching band trip at DisneyWorld. When I drove closer to the Quantrill family plot, snow flurries began falling. I parked, and walked over to the hallowed ground of my old friend from countless hours of study and deduction. I immediately felt the pity for Mary all over again. As I stood there, I felt inclined, however, to tell Mary a bit of good news since I had last visited her. Thanks to some grant money I had obtained, and a generous contribution from a local financial planner (Scott McCaskill) with help from the Frederick Womens Civic Club, there was now an interpretive wayside marker in front of her old house in Frederick (220 W. Patrick St). Her story could now be learned by those passing by. As I turned to walk away, I could have sworn I heard a woman’s voice faintly say, “That’s great history boy, now work on getting me a proper tombstone.”

2 Comments

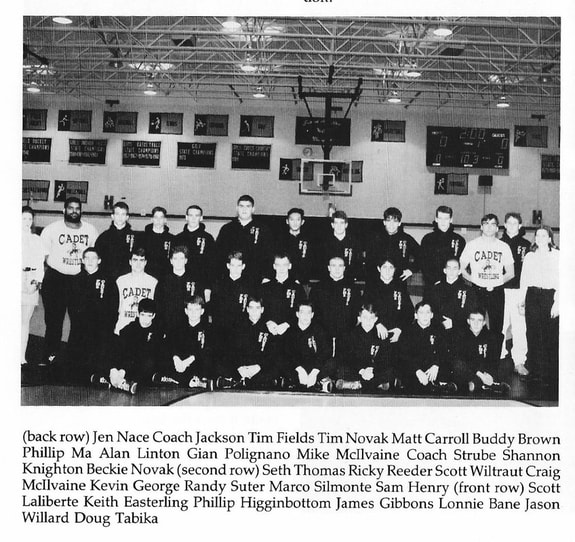

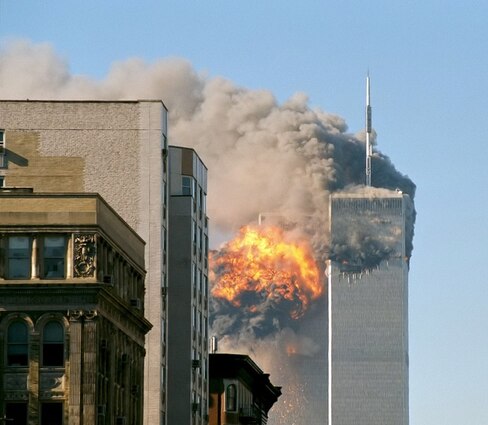

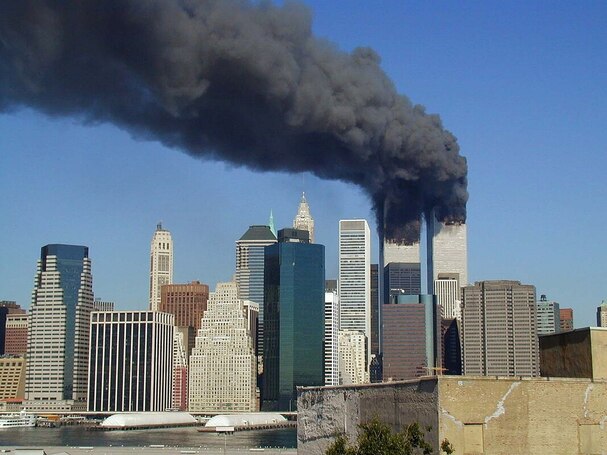

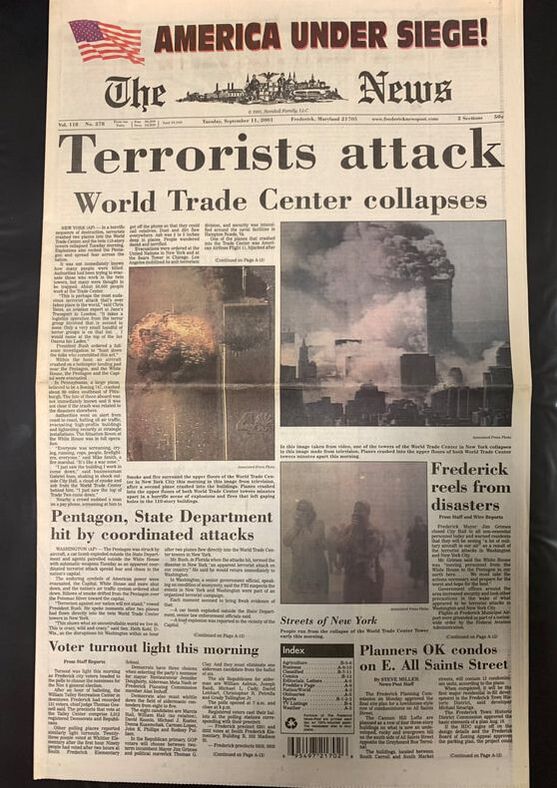

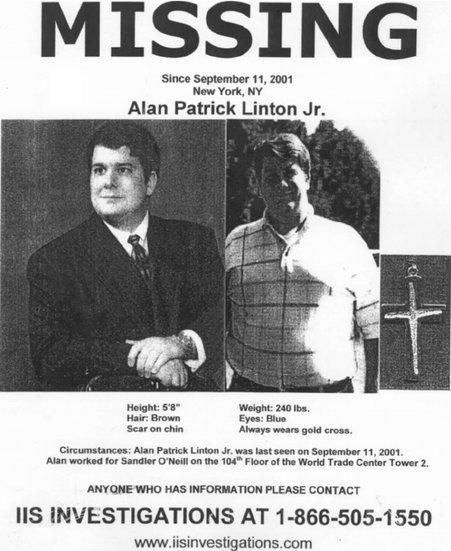

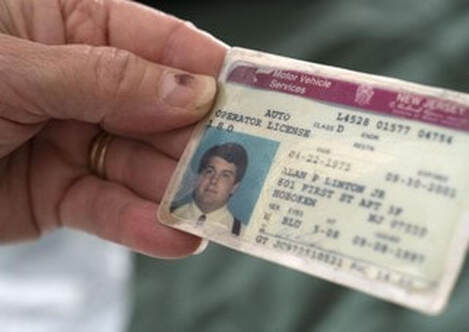

Almost everyday coming to (or leaving) work, I’m usually reminded of the September 11th tragedy that beset our country back in 2001. In my case, I would have to say it isn’t due to the fact that my employer is a cemetery, as I pass countless gravestones and markers on my commute through Mount Olivet and it’s eight miles of memorial drives and roadways. No, the reason for my “memory jog” can be blamed on a beautiful monument made of African Jet-Black granite and sitting on a corner lot at the entrance circle to our mausoleum chapel complex. Under this 7300-pound memorial is the gravesite of Frederick County’s only victim of the New York portion of the infamous September 11th terrorism act that toppled both behemoth towers of the World Trade Center. I would like to add here that our county had two additional casualties on that fateful day: Chief Warrant Officer William Ruth, age 57, and Lt. Cmdr. Ronald J. Vauk, age 37. Both of these individuals were Mount Airy residents and died in Washington, DC as employees of the U.S. Pentagon. Here in Mount Olivet, just 50 yards out my office window, is a monument to the everlasting memory of Alan Patrick Linton, Jr., a Frederick native, born April 22nd, 1975. Alan attended local public schools and was a graduate of Frederick High School. He grew up on the same grounds formerly farmed by his ancestors living along, and within the vicinity, of Ballenger’s Creek, just southwest of downtown Frederick City and near Adamstown. Alan was a classmate of my co-worker, Sales Manager Rick Reeder here at the cemetery. Rick recently found, and lent me, his 1993 yearbook allowing me another source in which to understand and illustrate Alan in his high school days. He was a bright student and admirable member of the football and wrestling teams. He graduated from FHS in spring 1993 and next headed to Pittsburgh's Carnegie-Mellon University earning a dual degree in business and economics. 20th Anniversary As our nation solemnly remembers the 20th anniversary of that frightening day in September, 2001, the magnitude will certainly be weighing heavier on the minds of those who were directly affected by the devastation and loss incurred. Here at home, it should be obvious that it will be a day to reflect and endure (just like the previous 18 anniversaries) for Alan’s parents, A. Patrick, Sr. and Sharon Lynn Linton, along with Alan's siblings... Laura and Scott. Alan Patrick Linton Jr. was only 26 years old, in the prime of his life, and working in the heart of Manhattan’s Financial District as an assistant manager and fixed-income analyst for Sandler O'Neill & Partners. His condominium home was across the Hudson River in Jersey City. I’m wondering if his office window offered a view of his New Jersey domicile, as I know his legendary workplace commanded views of all the City’s iconic surrounding landmarks such as Wall Street, the Battery, Ellis Island, the Statue of Liberty, the Brooklyn Bridge, the Empire State Building and the legendary five boroughs. This was one of the chief perks of employment in a high-rise building like the south tower of the World Trade Center. I recall my own visit a few years earlier in which I ventured to the “Top of the World Observatory” to take in the 360-degree view of New York City. This was on the 110th floor of Tower Number 2. However, that blessing became a curse on that beautiful September morn as hijacked airliners were purposefully flown into each of the twin towers as the deadliest single terrorism act the world had ever witnessed. Our former Carrollton Manor resident was working on the building's 104th floor when United Airlines Flight 175 crashed into floors 75-85 of the South Tower at 9:03am. Everyone aboard the plane, and hundreds in the building, died instantly as a result. Alan was trapped above the carnage, and those of us who witnessed this tragedy unfold before our very eyes on live television further saw the collapse of this architectural masterpiece just 56 minutes after the initial impact of the plane. The North tower would collapse at 10:28am.  Sharon and Pat Linton (Photo courtesy of Frederick News-Post) Sharon and Pat Linton (Photo courtesy of Frederick News-Post) I had the opportunity to talk to Mr. and Mrs. Linton last week. I knew they would be interviewed by the local paper and other outlets as has become an annual tradition, so I wanted to ask a few different questions. What truly intrigued me was an explanation for the beautiful monument and burial in Mount Olivet. Pat Linton said that he and his wife are very religious, as was son, Alan. As members of Frederick Church of the Brethren, Alan attended church regularly from childhood up to his death as he often came home to Frederick most weekends. Pat said that he’d come home Friday nights and leave Sunday nights, many times at the urging of his parents after dinner. He was a true homebody. Sharon Linton spent the first seven years hoping her son was still alive somewhere, perhaps suffering from memory loss or like malady. The family received a few of Alan’s belongings that he had on him on that September day twenty years ago. One such was his Maryland driver’s license found several blocks away from the South Tower. Federal investigators also delivered to the family some of their beloved son’s mortal remains including a part of the forearm. These were buried in the Linton plot during a small, private graveside service at Mount Olivet in fall of 2005. Even though reality of situation (regarding his ultimate survival) eventually sunk in, the Lintons relied on their Christian faith and believed their son was in a safe place, “somewhere better” as Pat, a former bank executive, would quietly exclaim. He went on to say that this led to the choice of a cross and flowers design to be etched upon the grave monument. To further the theme, two flower vases project from the gravestone’s face and are changed seasonally by the family. Speaking of family, the Lintons have a relatively large one, and with Alan’s passing they gave serious consideration to their own burial plans. They would purchase a large corner lot for themselves positioned in Area TJ/Lot 2. This is located along the entry drive directly in front of the original chapel mausoleum building which first erected in 1997. They couldn’t tell me why they had chosen this particular granite stone hailing from southern Africa for the family monument into the future, but were extremely happy and proud of their choice. They plan to join their son in this noble location when their respective times come. Pat told me that Mount Olivet was a natural choice, as it represented “home.” He went on to say: “My wife’s parents, Howard and Edith Moss, are buried in Mount Olivet. Alan’s other set of grandparents, my parents Jack Thomas Linton and wife Betty Mae (Thomas) Linton) are also here, along with my son’s great-grandparents (Russell Herbert “Brownie” Linton and Edith Marie Brandenburg).” I found the Moss’ on Area SS/Lot81, only about 100 yards from Alan’s grave. The Linton relatives were roughly 200 yards away in Mount Olivet’s Area GG/Lot 254. Interestingly, many local genealogists and family historians may recall that Jack and Betty Linton maintained a room in their home dedicated to the extensive obituary collection started by Jacob M. Holdcraft, who spent decades documenting the cemeteries and graveyards of Frederick culminating in the book entitled Names in Stone. The Lintons maintained the collection from 1972-June, 2010. About the same distance away to the north lies the final resting place of Alan’s paternal grandmother’s parents, his great-grandparents Russell Cephas Thomas and wife Bertha Mae Zimmerman. This is in Area T/Lot 119. Russell was the son of John Franklin Thomas, buried elsewhere in The Manor Cemetery (aka Church Hill Cemetery) near the family’s ancestral home at Adamstown. This is located on Ballenger Creek Pike across the street from St. Matthew’s Lutheran Church.  In his 1921 work The History of Carrollton Manor, author William Jarboe Grove wrote of the family: “The Thomas family forms so large a part of the early history of Carrollton Manor, that I am compelled, on account of space, to give only a brief account of this large family, who, by their industry and thrift, have prospered and left a splendid name and record for prosperity. These pioneers were among the very first settlers of Carrollton Manor. About 1750 three brothers emigrated here from Germany; John, Peter and Valentine. John was born in 1731 and settled on the old homestead near Adamstown. His descendants still hold the land. John had four children among whom was Henry Thomas of J. born October 18, 1765 on the old homestead. His whole life was spent in clearing timber and cultivating the land. Mr. Thomas married November 22, 1790 Ann Margaret Ramsburg. They had five children. Their son George Thomas of H., was born May 3, 1798 and lived on the old homestead during his early life, and by his industry and frugality acquired several other farms. He was a self-made man and took up at home the study of mathematics, and was recognized as an expert surveyor, all of which he taught himself through perseverance and practice.  In 1968, the German Thomas Cemetery, originally located on a farm about a mile away, was removed to Manor Cemetery (aka Church Hill Cemetery). Many date from the late 1700s. They are arranged in a row beside the guardrail on the right edge of the cemetery. Across Ballenger Creek Pike is St. Matthew's Church Cemetery.

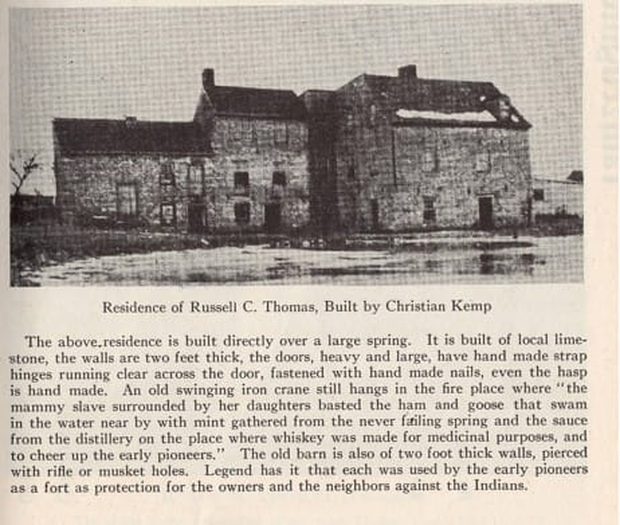

George Thomas married three times. With third wife Julia Ann Hargett, he had the above-mentioned John Franklin Thomas in 1843, our subject Alan Linton, Jr.’s great-great grandfather. The old Thomas homestead of three generations starting with Alan's great-grandfather, John Franklin Thomas, still stands on Ballenger Pike. This was originally constructed by early German immigrant Christian Kemp around 1750. It eventually wound up in the Thomas family in 1910 and was passed down to son Russell C. Thomas and then to daughter Betty (Thomas) Linton and son-in-law Jack Linton. it is still owned within the family today, now by Alan’s sister, Laura. Alan’s childhood home is immediately to the north. Across the street are former Thomas family farmlands that were developed into the community aptly named “Linton at Ballenger.” The main drive in is named Alan Linton Boulevard. There is also a Jack Linton Drive and a Betty Linton Trail. Pat and Sharon Linton recounted that Alan said he hoped to someday earn enough money to give to philanthropic purposes which eventually became the impetus for the Linton family’s generous contribution to the Religious Coalition. Their gift in Alan’s memory helped establish the Exodus Program and the Coalition naming its emergency shelter in his honor. This is located on DeGrange Street on the west side of downtown Frederick. The Linton family has visited the memorial at New York’s “Ground Zero” where they made rubbings of Alan's name. They still hold special birthday dinners on his birthday. "He's always with us." remarked Pat Linton at the end of our conversation. Please keep this special family and the memory of an equally special young man in your thoughts as we experience this landmark 20-year anniversary. Alan Patrick Linton, Jr.’s grave monument will always serve as a tangible reminder of a horrific event in our history, but one in which we can learn invaluable lessons when it comes to the resolve and resiliency of a family to continue moving forward despite the hardest of losses. Alan's grave also symbolizes the resolve and resiliency of the United States of America and its people in continuing to move forward as well. We Shall Never Forget Let the world always remember, That fateful day in September, And the ones who answered duty's call, Should be remembered by us all. Who left the comfort of their home, To face perils as yet unknown, An embodiment of goodness on a day, When men's hearts had gone astray. Sons and daughters like me and you, Who never questioned what they had to do, Who by example, were a source of hope, And strength to others who could not cope. Heroes that would not turn their back, With determination that would not crack, Who bound together in their ranks, And asking not a word of thanks. Men who bravely gave their lives, Whose orphaned kids and widowed wives, Can proudly look back on their dad, Who gave this country all they had. Actions taken without regret, Heroisms we shall never forget, The ones who paid the ultimate price, Let's never forget their sacrifice. And never forget the ones no longer here, Who fought for the freedoms we all hold dear, And may their memory never wane, Lest their sacrifices be in vain. -Alan W. Jankowski Special thanks to Laura (Linton) Anspach for the many family ancestor photos found on her Linton family tree on Ancestry.com.

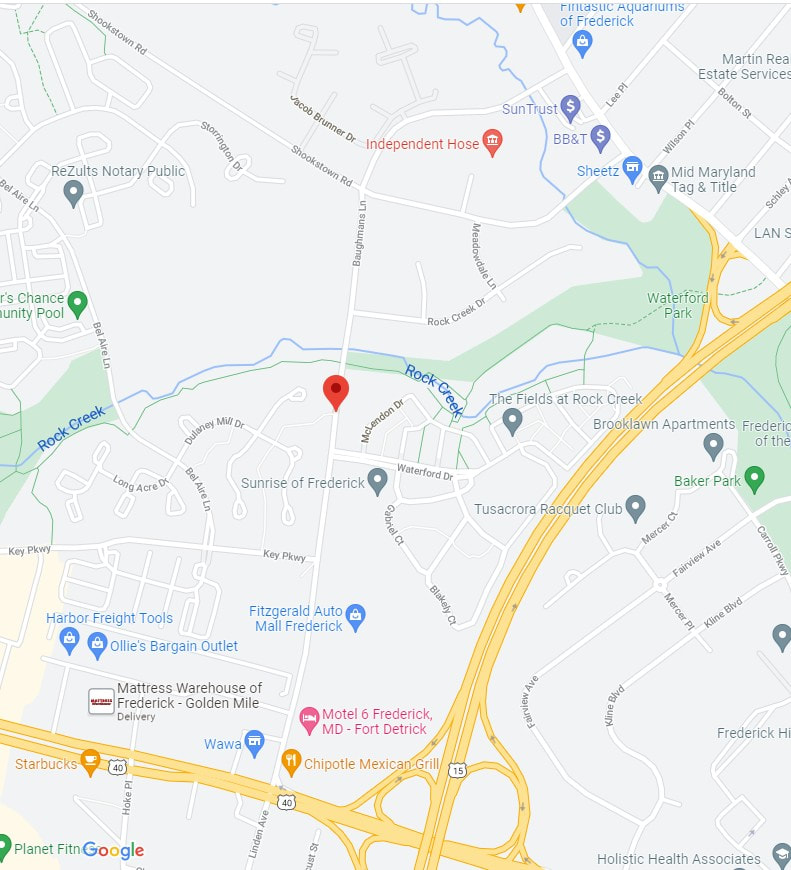

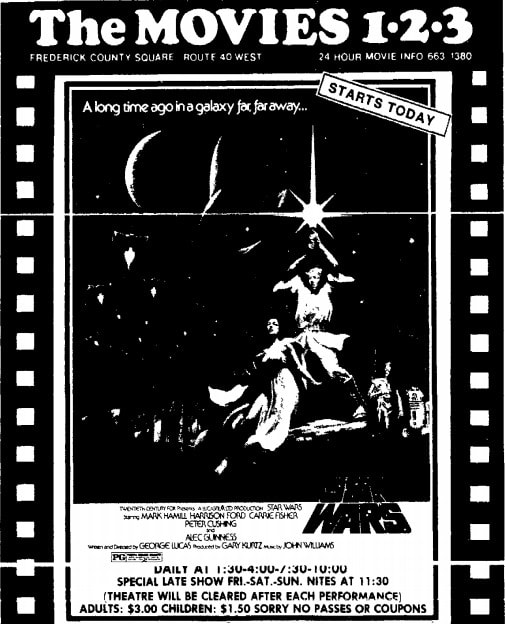

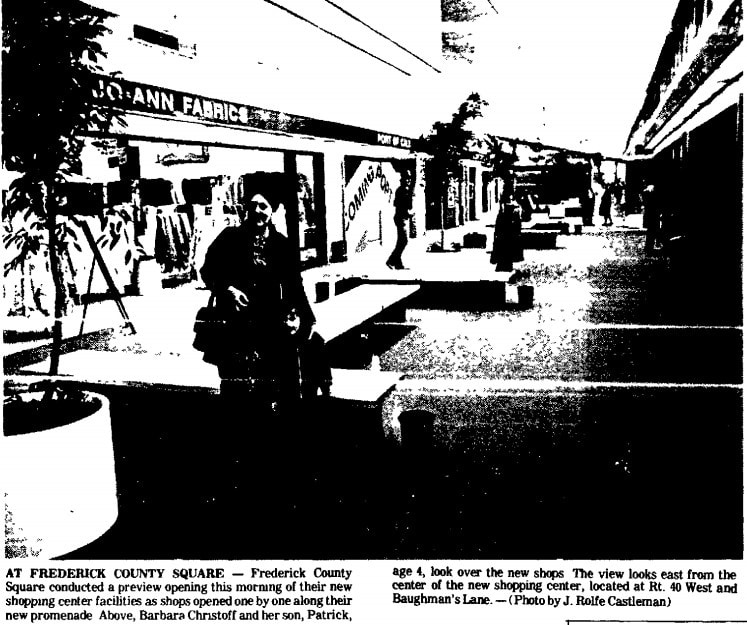

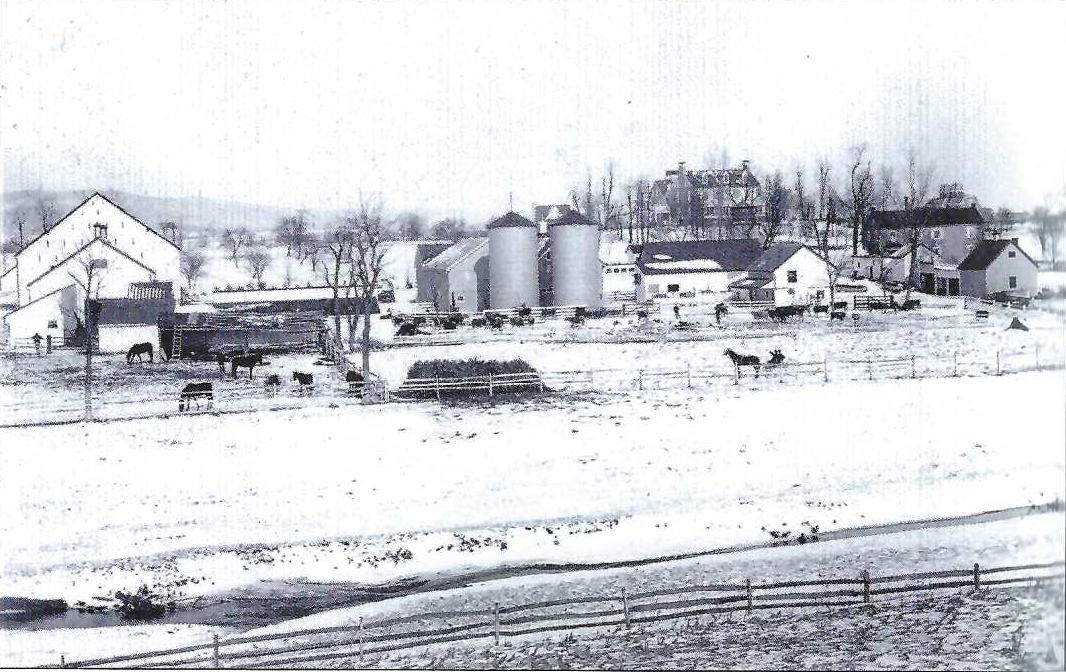

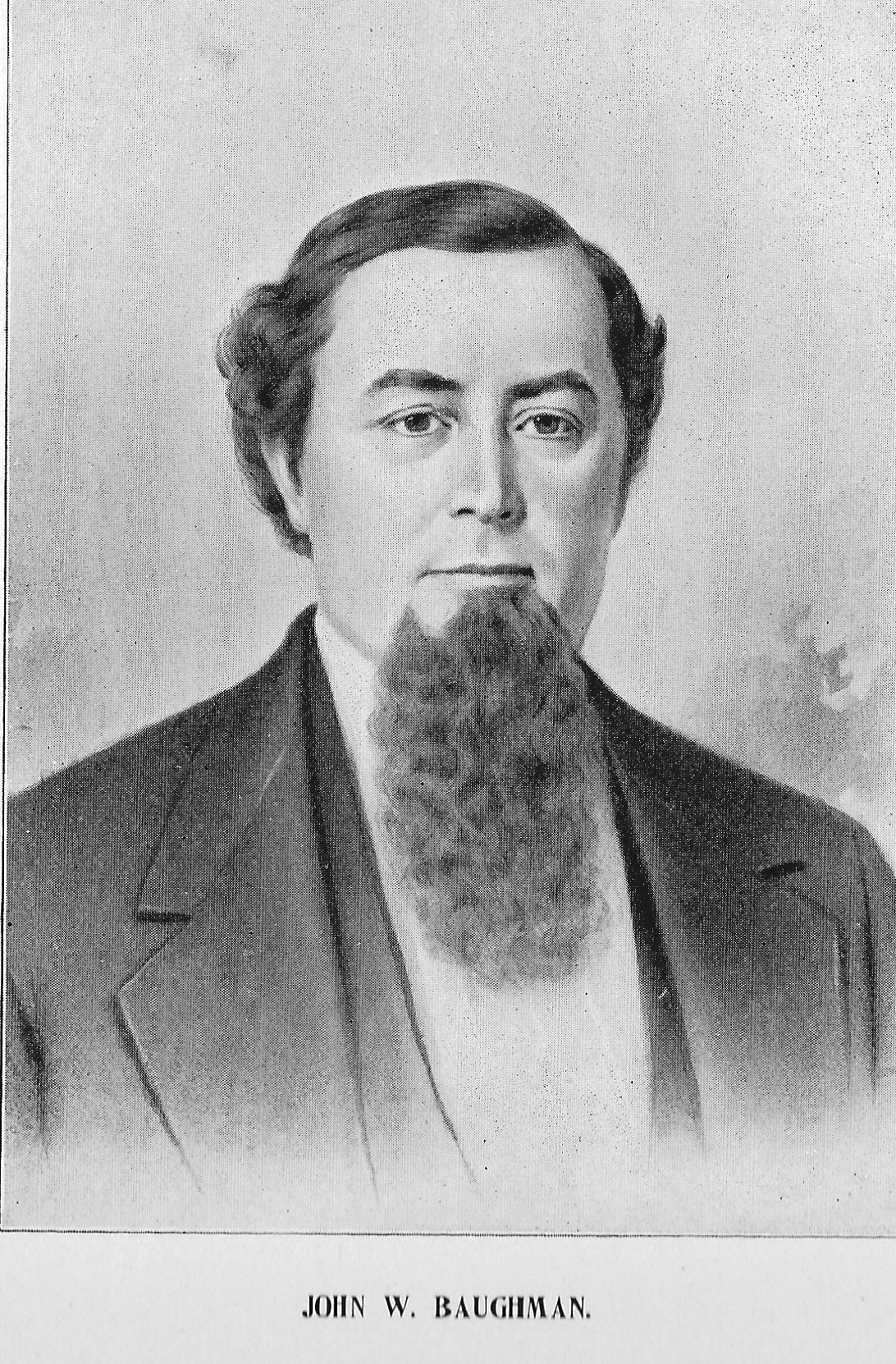

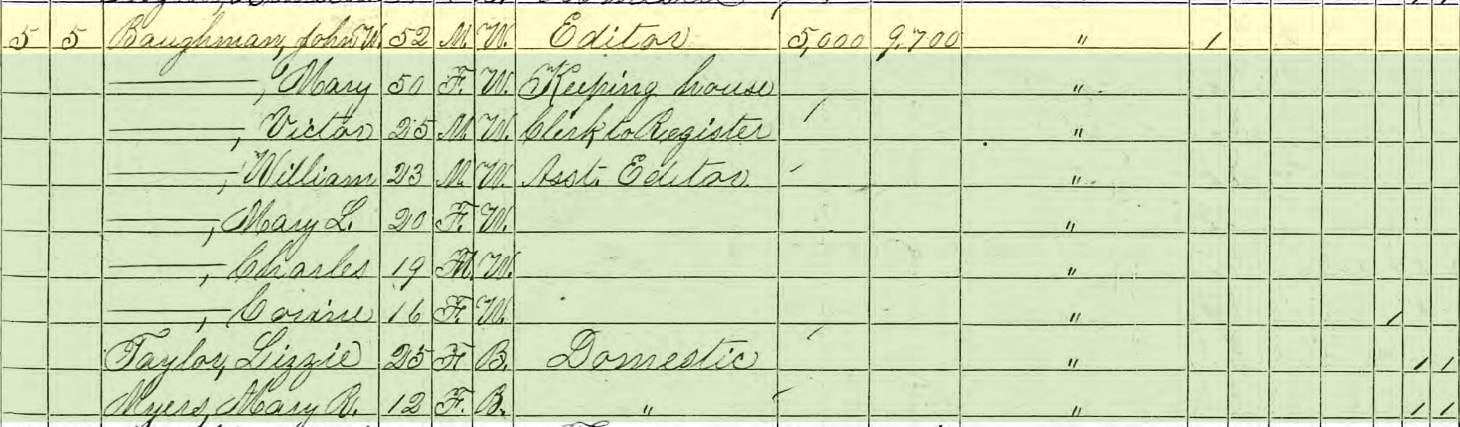

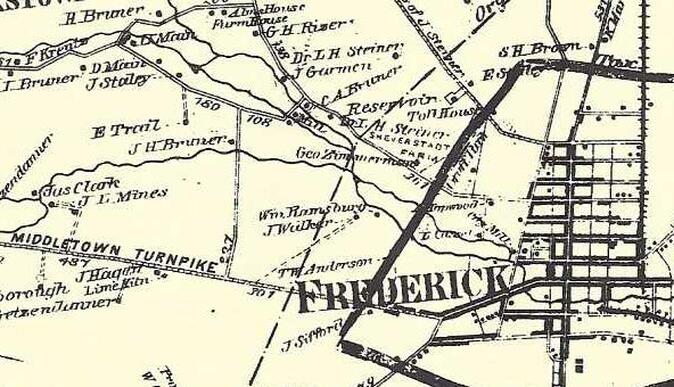

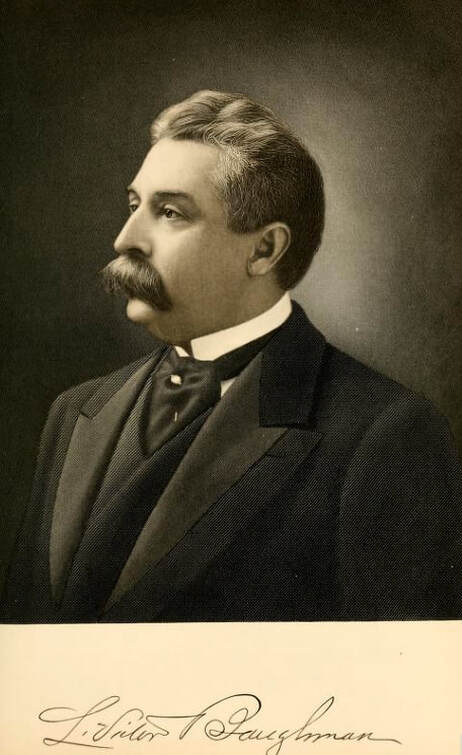

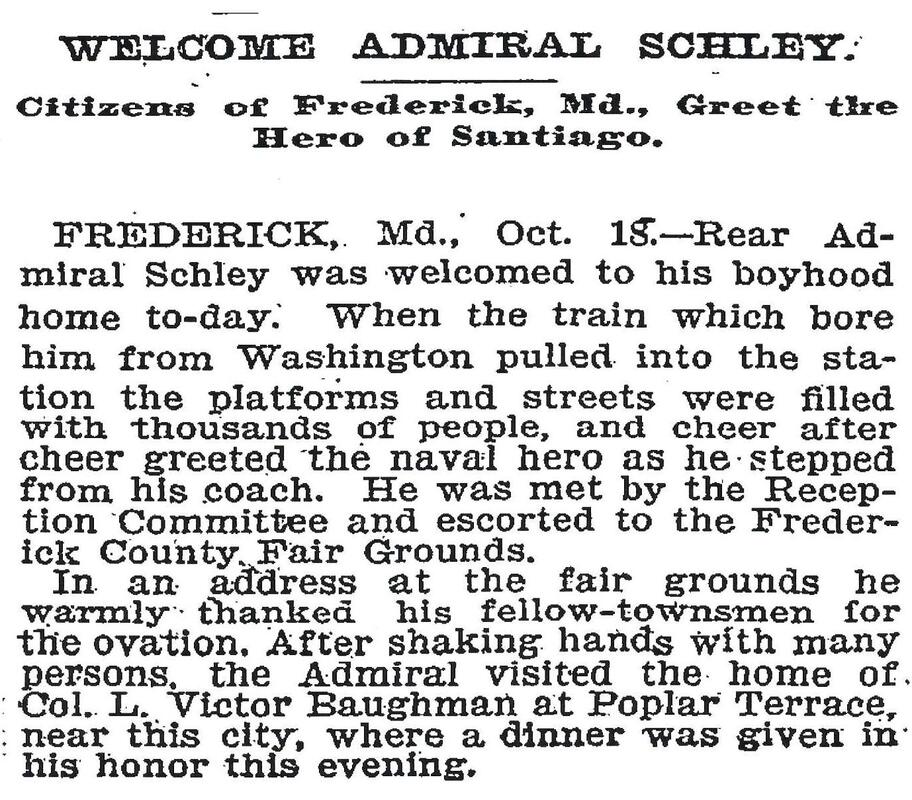

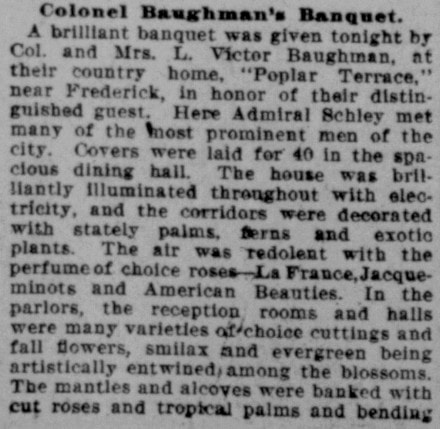

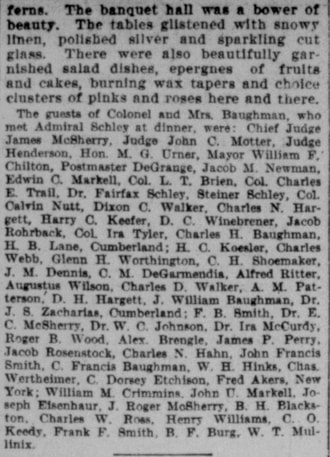

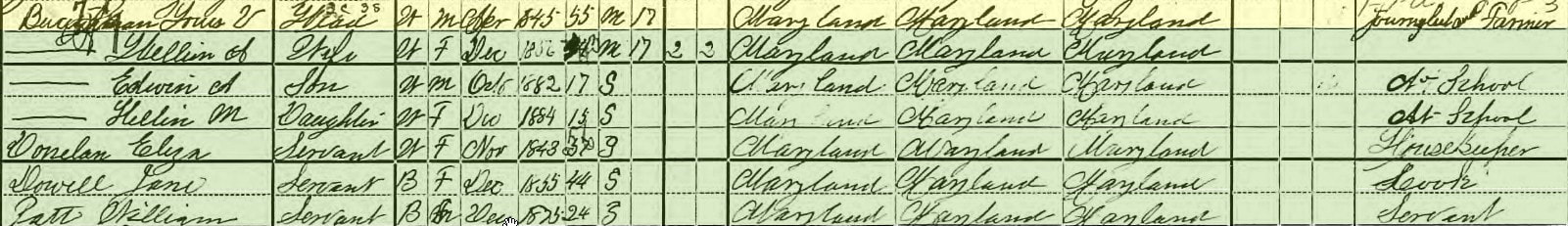

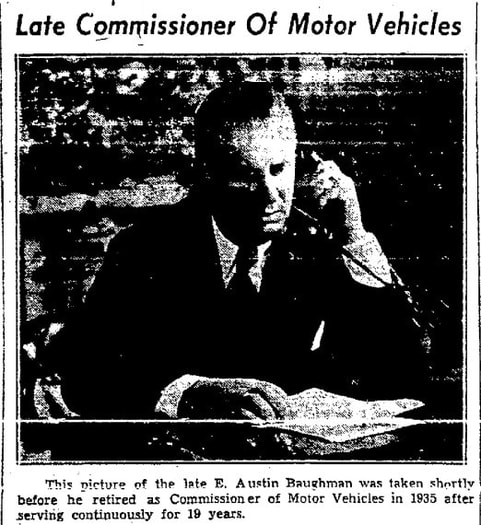

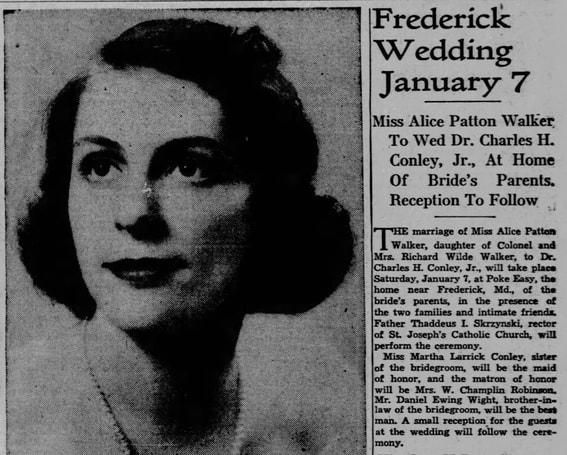

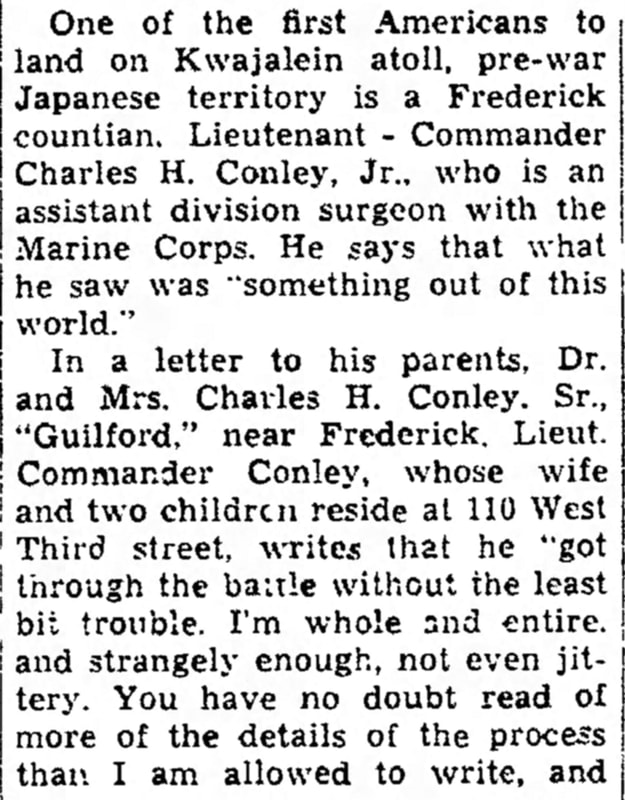

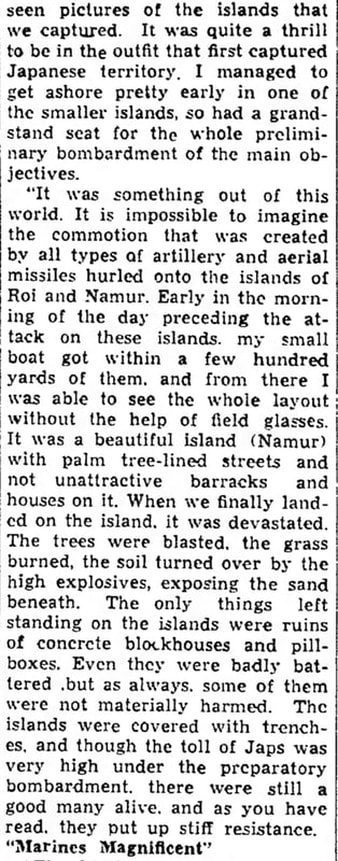

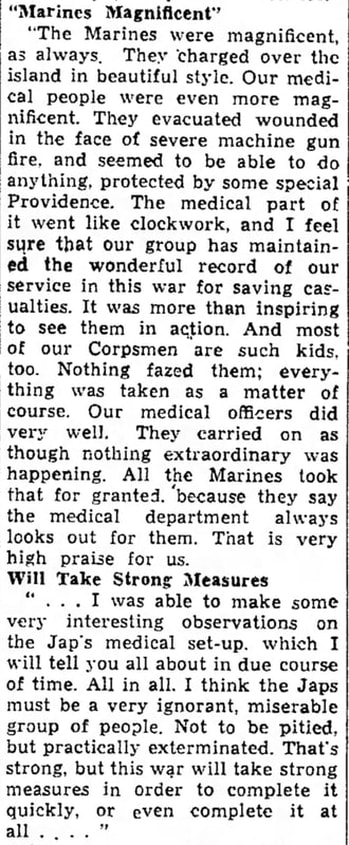

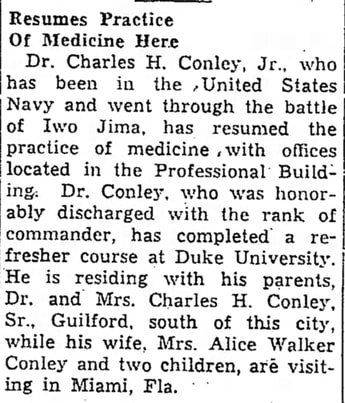

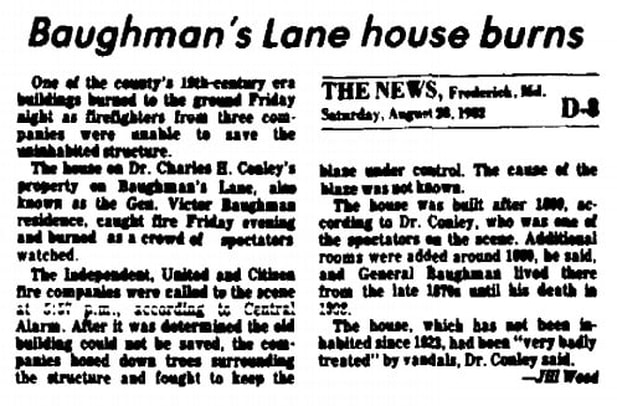

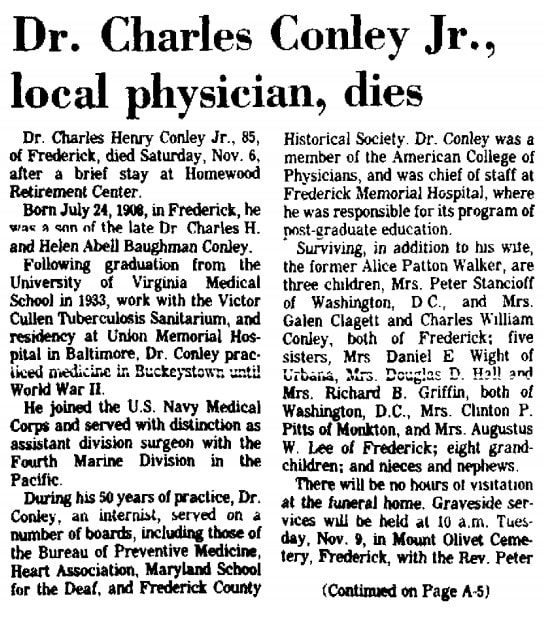

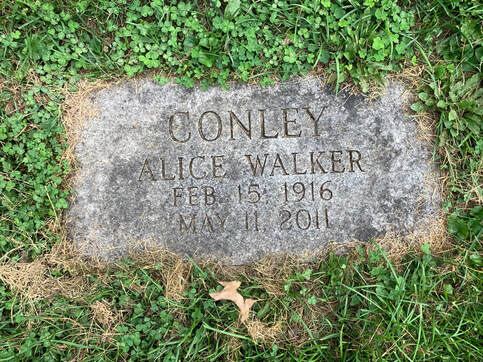

Throughout the summer, I have been watching the slow transformation of a once-grand estate from our community’s past into a new housing development. Such is often the case of progress and necessity in our highly sought-after town and county. This parcel sits along a distinct stretch of “suburban” Frederick City roadway, positioned west of one of the trickiest thoroughfares in town to pronounce, but certainly not to drive. I’m talking about Baughmans Lane. Go ahead, give it your best shot!— “Bawman’s Lane,” “Bogman’s Lane,” “Bowman’s Lane,” “Bowkman’s Lane.” Well, the family in question is of Germanic origin, and I found that the name derives from Bachmann. It was softened and anglicized, resulting in the “ch” being replaced by “ugh.” The proper pronunciation in this particular case is “Bachman’s Lane,” or I would gladly accept “Bawkman’s Lane.” Not to sound like a hypocrite, but I will tell you that my last name (Haugh) is pronounced “Haw” and is of Scottish and Irish origin. Many locals are familiar with the German variety of my surname, associating it with many earlier Dutch residents hailing from the Ladiesburg vicinity near the Monocacy River border with Carroll County, a stone's throw from Keymar, birthplace of our cemetery’s best known graveholder. Of course, Ladiesburg is the home of Haugh’s Church Road, pronounced “Hawk’s Church Road.” This popular transportation connector (northwest of historic downtown) was a Godsend at the time my family's arrival to Frederick and our new home in the Indian Springs area in 1974. Baughmans Lane joined West Patrick Street (US Route 40) and Shookstown Road, as well as Rosemont Avenue. At that time, there were no other roads to intersect Baughmans Lane, save for Rock Creek Drive. Key Parkway, Waterford Drive, Rock Creek Drive, or Jacob Brunner Drive all came later. Outside of a couple houses at the site of the fore-mentioned intersection of Baughmans and Shookstown Road, you couldn’t find much along this stretch of pavement until you got to the ends. Anchored on Rosemont Avenue was the Campbell family-owned gas station and a small, car dealer/garage on opposite corner. At the bustling other end (of Baughmans Lane), there was the Holiday Inn Hotel and the aptly named Holiday Cinemas (aka $1.99) movie theater next door. The stalwart was the former State Police Barrack B that once proudly stood on the locale of today's Wawa convenience store. No one ever connected with the original Tasker's Chance land patent of the mid 1700s could ever imagine the emergence and scope of a housing development that would one day take the same name some 250 years later. One more trivial, side note, the shopping center behind the old police barrack was new here as well in the spring of 1973. Named Frederick County Square, this suburban, retail oasis was made possible by the purchase of a piece of the Conley farm for the purpose, helping to create the legendary "Golden Mile" which also boasted the Frederick Towne Mall and Frederick Shoppers World opening at this same time. The Conley farm would also give birth to the Taskers Chance community decades later. A convenient, side entrance off Baughmans Lane gave my parents access to Frederick County Square and their grocery store of choice, Giant Foods in its first Frederick location. Also here was our favorite "go-to" pizza place (Vince’s Pizza), the K-Mart, a Burger King and an indoor mall which boasted a few specialty stores, a restaurant, and best of all, a “state-of-the-art” movie theater where I first saw the original Star Wars movie when initially released. Yes, these memories are all lumped together and somehow are conjured up when I think about Baughmans Lane in my warped memory bank. So where does the name of Baughman (for the lane) come from? Well, that’s a simple answer that cannot be debated—the Baughman family, prominent one-time residents of a fine, 19th century estate named “Poplar Terrace,” later named the Belle Aire Farm by Baughman descendants by the name of Conley. The long farm lane that led to the home (from the Old National Pike (US 40)) originally served for that very purpose—as it was actually Baughman’s Lane. The former mansion was lost to a fire in the 1980s, but several existing farm-related structures including a tenant house, mill house and others are on the exact site of current construction that will transform the remaining 32-acre lot into a major housing development. The Belle Air Farm Planned Neighborhood projects 220 homes (townhouses and single-family units) to be built between Baughmans Lane and Bel Aire Lane to the west. Most recently, the property was still owned by the Conley family. I find it ironic that the Baughmans lived here along Rock Creek, and there was a mill here going back to Colonial times. This ties-in nicely to the Baughman family name. According to a website entitled bachmannbaughmanhistory.com, author J. Ross Baughman writes: “In German, “Baughman” means "Man of the Brook" or "One Who Dwells by the Stream." Some have guessed that the original namesake of this name built his house by a stream and became known for that, perhaps making his living there too, running a ferry service, toll bridge or water wheel mill.” I will briefly introduce both the Baughmans and Conleys here in this week’s “Story in Stone.” I have long been acquainted with Gen. Louis Victor Baughman (1845-1906) and his father, John W. Baughman (1815-1872), as notable Frederick characters of our county’s past. Both were former editors of the Frederick Citizen newspaper. Sadly, I can’t claim either gentleman being buried here at Mount Olivet Cemetery as they, and their wives, are resting in peace at St. John’s Catholic Cemetery in downtown (Frederick between E. Third and E. Fourth streets). Two of Gen. Baughman’s sons (Edwin Austin and Louis Victor) are also interred at St. John’s, but a daughter, Helen Abell (Baughman) Conley (1884-1964), is buried here at Mount Olivet. She married Dr. Charles Henry Conley (1876-1956). Five (of six) of the Conley’s children are also interred here in our historic garden cemetery on the southside of downtown Frederick. One of these, Charles, Jr., would inherit his grandfather Col. Louis Victor Baughman’s fine home of “Poplar Terrace” and surrounding grounds. He would also concoct the new name of Belle Aire Farm. Before I give you some backstory on these folks, let me start by telling you just a bit more on the mansion and farm residence that made Baughmans Lane a reality. Hold on tight, as I’m going to throw plenty of names at you. As part of Benjamin Tasker’s 7,000 acre tract, aptly named “Tasker’s Chance” in 1725, it is interesting to note that the Belle Aire Farm is actually surrounded by a housing community of the same name—Tasker’s Chance as I mentioned earlier. It was built by the Kettler Brothers Corporation just a few decades ago. Going back to Frederick’s start, the Dulany family owned this property (as part of a much larger tract that included the land comprising Prospect Hall to the south. Eventually this fell into the hands of the Johnsons (of Gov. Thomas Johnson fame), and then in 1799 went to Col. John McPherson (1760-1829) who has been mentioned in this blog on numerous occasions as he is buried in Mount Olivet's Area E. Col. McPherson’s heirs then sold the property to Edward N. Trail (1798-1876), father of Col. Charles Edward Trail, one of the founders of Mount Olivet back in 1852. Still with me so far? Note that a J. H. Bruner (John H. Brunner) seems to be residing at the site of the Mill House adjacent Baughman's Lane and to Rock Creek (which flows under Baughmans Lane). This structure should be familiar to those who travel this road regularly as it practically adjoins the roadbed. I’ve read that this old building is planned to be salvaged and relocated from its original spot which is positive news, but also a necessity for the old lane to carry increased traffic in the future. After Edward Trail died in 1876, his wife, Lydia (Ramsburg) Trail (1802-1884), left the land to son Charles E. Trail (1825-1909). Col. Trail was a prominent businessman and known for his own, impressive mansion built in downtown Frederick on East Church Street (today the site of the Keeney-Basford Funeral Home). Trail didn’t keep the former “McPherson property" long, selling the 250-acre estate in 1882 to his brother in-law, Cyrus G. Helfenstein (1828-1895). It was Mr. Helfenstein who built the "Poplar Terrace" mansion that Louis Victor Baughman would inherit and eventually hand down to Louis Victor Baughman and last resident, Dr. Charles H. Conley, Jr. Louis Victor Baughman According to the Baltimore Sun Almanac of 1907, Louis Victor Baughman was one of the most popular men in Maryland of his time, and was known as the “Little General,” or “Colonel Vic.” He was called the "little Napoleon of Western Maryland." Born in 1845, he attended public and private schools in Frederick, followed by Mount St. Mary's College in Emmitsburg. From 1857 to 1861 he was an appraiser of the port of Baltimore. During the Civil War, he served in Company D, First Regiment of Maryland Confederate Cavalry, attaining the rank of colonel. Years later, the governor of Maryland would give him a political promotion to the rank of general. After the war, Baughman practiced law in Brooklyn, NY for a time with former Maryland governor (and Frederick resident) Enoch Louis Lowe. Beginning in 1872, he became managing editor of the Frederick Citizen, a democratic paper founded by his father. Baughman was a leader for the Democratic Party in the state, serving at different times as a member of the Democratic county committee of Frederick County, the State Democratic Committee, and the National Democratic Committee. He served as state comptroller for four years and president of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal and was president of the Frederick, Northern & Gettysburg Electric Railway Company after 1898. As busy as he kept himself professionally, it comes as no surprise that Col. Baughman would marry later in life. His bride was Helen Abell whom he tied the knot in 1881. The former Miss Abell was the daughter of Arunah S. Abell, founder of the Baltimore Sun newspaper. Of particular interest to many blog readers will be the fact that Gen. Baughman was a noted horseman. During his tenure of ownership of “Poplar Terrace,” he transformed the old McPherson property into a country manor with a well-known and respected horse and cattle operation consisting of agricultural buildings that were constructed by Baughman for that very purpose. He also had constructed an elaborate half-mile racing track here and a casino. “Poplar Terrace” was quite a showplace. I wrote an earlier blog back in 2015 which chronicled early cycling here in Frederick County. An interesting event occurred over the July 4th weekend of 1897 in which Frederick City hosted several bicycling contests at different locations within town, most at the Athletic Park. That Saturday afternoon of the long weekend, cyclists found themselves feted and treated to entertainment at the estate of Gen. Baughman. Additional races, tandem and of the single wheel variety took place on Baughman’s horse track. He personally awarded nice silver trophies to the victors. Two years later, national military hero and Frederick native, Admiral Winfield Scott Schley returned home to receive an incredible welcome. While here, he attended the annual Great Frederick Fair, was given a special excursion run on the new Frederick electric trolley system and was thrown an incredible luncheon party at Gen. Baughman’s residence on Rock Creek. Although business and politics often took him away from Frederick, Baughman was said to have been the happiest at home at "Poplar Terrace." At his farm, Baughman also is said to have entertained such notables as James Cardinal Gibbons, archbishop of Baltimore, and national politician William Jennings Bryan who passed through Maryland on his first presidential campaign tour. Louis Victor Baughman passed in 1906 after a two-month illness at the age of 61. Son Edwin Austin Baughman (1882-1946), inherited the property from his father and through his last will and testament would later donate land at the corner of Baughman’s Lane and US40 for the old state police barracks (previously mentioned). This is only fitting because "Austin" Baughman served as commissioner of the Maryland Motor Vehicle Commission during its formative years after being appointed to the post by the state governor in 1916. He became the first commissioner of the new State Police which originated within the Motor Vehicle Commission. Austin served until 1935, never married and had no direct heirs. Following his death in 1946, "Poplar Terrace" and remaining land went to Austin's nephew, Charles H. Conley Jr. (1908-1993). Charles Henry Conley, Jr. Charles grew up on his parent’s fine manor estate of Guilford, located off another recognizable thoroughfare which began as a simple farm lane connecting to the Old Georgetown Pike (MD355). Of course, I’m talking about today’s Guilford Drive, gateway to Frederick’s first Wal-Mart, Frederick Commons Shopping Center (Kohl’s Best Buy, etc) and further west, the Conley Corporate Center. I will save the story of Charles’ father (Charles Henry Conley, Sr.) for another day, but feel compelled to make "able" mention of Charles, Jr’s. mother, Helen Abell (Baughman) Conley, born December 4th, 1884 and died October 21st, 1964. She grew up at “Poplar Terrace” and regularly traversed Baughmans Lane throughout her lifetime. She would marry her husband in December, 1905.  Frederick News (June 17, 1933) Frederick News (June 17, 1933) Charles Jr. was Helen’s second born and only son out of six children. He would attend St. Johns School in Frederick for high school and went to the University of Virginia to get his degree in medicine. He began practicing medicine in Buckeystown soon after. Dr. Conley Jr. went on to become a prominent doctor in the area, who worked on behalf of the Frederick County Health Department, Federated Charities, the Record Street Home and the Maryland School for the Deaf. He married Alice Patton Walker, a native of Nebraska, in January, 1939. The couple lived first in Buckeystown, then moved to downtown Frederick. During World War II, Dr. Conley enlisted in the US Naval Reserve and his father had to come out of retirement to take charge of his patients. The younger Dr. Conley served as assistant division surgeon. Charles, Jr. returned from the war unscathed, but opted to take a medical refresher course at Duke University. He and the family would eventually move to the "Poplar Terrace" estate west of town. It doesn’t appear that Dr. Conley had the same passion and drive for the "Poplar Terrace" property as his grandfather (Victor Louis Baughman). However, that may not be completely true—as no one ever demonstrated a like zeal for this slice of Frederick than did Gen. Baughman. It was during the Conley family habitation, that the stately manor house was destroyed by fire in late August. 1982. This prompted the couple to move into the tenant house built by the McPhersons. As a young teenager, I recall my father driving me by the property and seeing the smoke still smoldering the day after the fire. The good doctor died on November 6th, 1993. His death made front page news and he was remembered fondly with a well-attended funeral, and the respect of countless peers and residents. His wife Alice Patton (Walker) Conley (b. 1916) passed in 2011. Post-Conleys The vacant property fell into disrepair over the years, but I've always tried sneaking a peak up the gated entry lane off of Baughmans Lane when passing by. Development planning and demolition requests have appeared in the local newspaper and internet over the last decade. I can thank these, along with genealogy blogs for many of the fine visuals and photographs used to illustrate this story here. It was inevitable, and I'm just glad we had this scenic portion of the old and original, tree-lined Baughmans Lane for as long as we did. Dr. Conley’s grandfather, Louis Victor Baughman" gave this parcel a lasting reputation which seems to now be in its final chapter. However, although commonly mispronounced by newcomers and lifelong residents alike, the old lane will always succeed in keeping the Baughman name alive regardless of the new neighborhood development that will take over what was left of a once-grand estate. Meanwhile, our connection at Mount Olivet comes with having practically everyone who resided on the site of Poplar Terrace/Belle Aire Farm, with the exception of namesake Louis Victor Baughman and wife Helen. Their daughter is here though (Helen Abell (Baughman) Conley) and so are others from McPhersons to Trails, Helfensteins to the next generation of Conleys. The latter of which, Charles Henry Jr., and wife Alice, quietly repose next to Charles Jr's. parents and a sibling in a fine corner lot on the northwest section of Mount Olivet’s Area DD within Lot #1. I'm tempted to lobby to name the roadway in front of the family lot "Conway's Lane."

|

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed