|

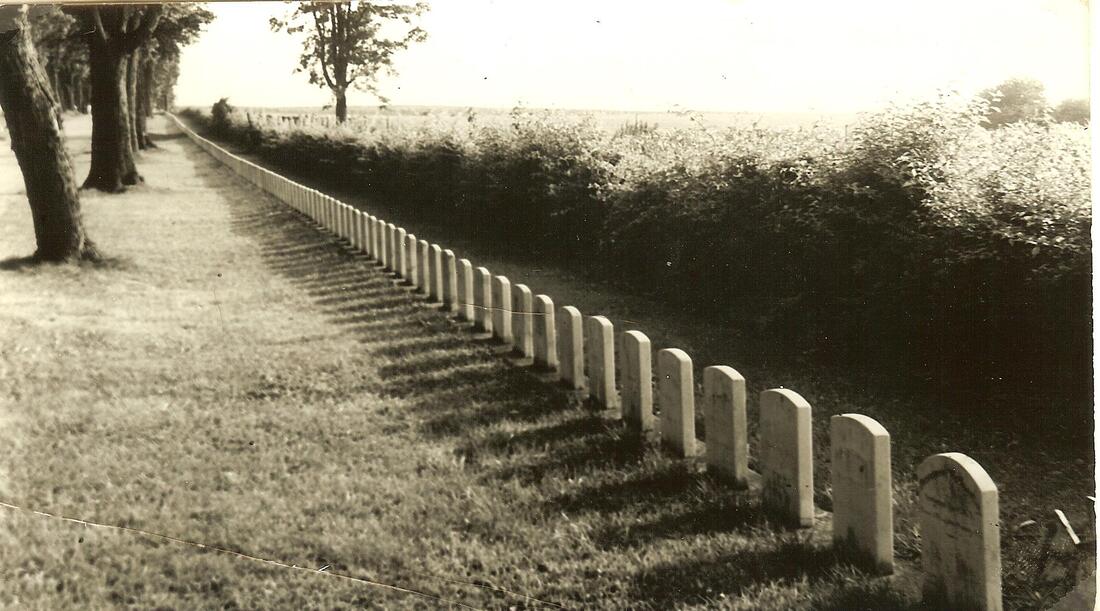

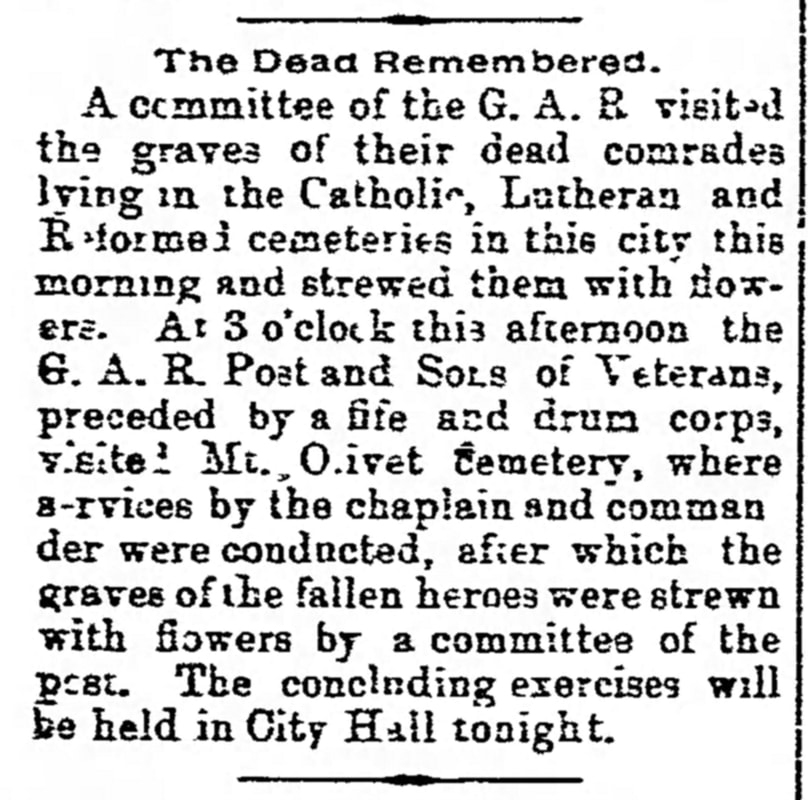

The first Memorial Day, as we know it, was held 150 years ago on May 30th, 1868. This holiday began after the American Civil War as “Decoration Day,” a ceremony to place flowers on the graves of those who had given their lives in America's bloodiest war. Here in Frederick, it would quickly evolve into one of Mount Olivet Cemetery’s busiest days of visitation. This fact continues to this day, however, veterans of multiple 20th century world wars and worldly conflicts are also honored—now on the last Monday of May each year. Mystery surrounds the origin of this custom. One version credits Southern women who began decorating graves in 1865. On May 1st, 1865, a Northern abolitionist named James Redpath, who had come to Charleston, South Carolina to organize schools for freed slaves, led black children to a cemetery for Union soldiers killed in the fighting nearby to scatter flowers on their graves.  Congress awarded the village of Waterloo, NY the distinction for holding the first Memorial Day, however this is also questionable. Union veterans apparently decorated the graves of fallen comrades on May 5th, 1866 but this wasn’t originally designed to be an annual tradition, just something that would be nice to do a year after the war’s end. We will get to “1868” in a moment, but here’s what was happening in Frederick’s historic “garden” cemetery. Hundreds of Union soldiers once had Frederick’s Mount Olivet Cemetery as their first original “resting place.” Many would be dis-interred and moved to Antietam National Cemetery in Sharpsburg in 1868. By in large, most all of the Confederate soldiers that died in local hospitals and buried in Mount Olivet would remain so for eternity. In fact the number (of Confederates) in Mount Olivet actually grew significantly higher a decade and a half after the Civil War. In the South, women formed Ladies Memorial Associations to dis-inter soldiers from nearby battlefields and rebury them locally with dignity. Frederick had one such group, responsible for spearheading a drive to bring to the cemetery more than 408 former Southern soldiers originally buried on the farms and environs that made up the Battle of Monocacy (fought on July 9th, 1864.) The remains of these men were buried in a mass grave, placed at the end of a row containing 311 Confederate graves. The Ladies Monumental Association of Frederick also erected a statue to symbolically stand guard over these Southern soldiers numbering over 700. Associations of these kinds became the sponsors of Confederate Memorial Days, which varied in date according to the height of the local flower season, from April in the Deep South to late May in Virginia. On the “northern” flipside, Gen. John A. Logan of Illinois founded the Grand Army of the Republic in 1866. This entity grew into a politically powerful veterans' organization consisting of former Union soldiers and sailors. In 1868, Logan ordered all G.A.R. posts to decorate the graves of Union soldiers on May 30th, the optimum time for flowers in the North. That first year, 103 posts held Memorial Day services, a number that grew to 336 in 1869 and continued to increase afterwards. Now we had a solid holiday in hand. What soon became known as Memorial Day spread to towns, cities and crossroads communities in both North and South. Interestingly, Waterloo, NY changed their decoration date to May 30th in 1868—“chicken, or the egg,” I ask.

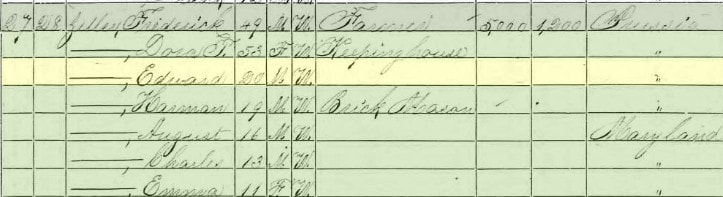

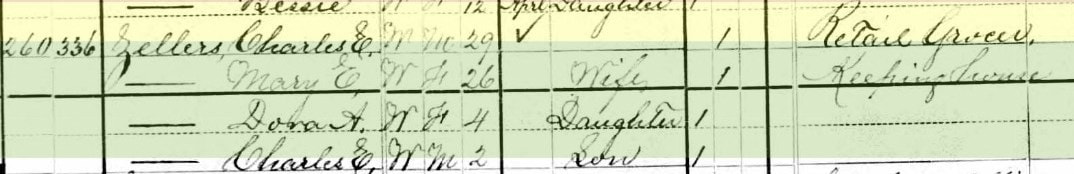

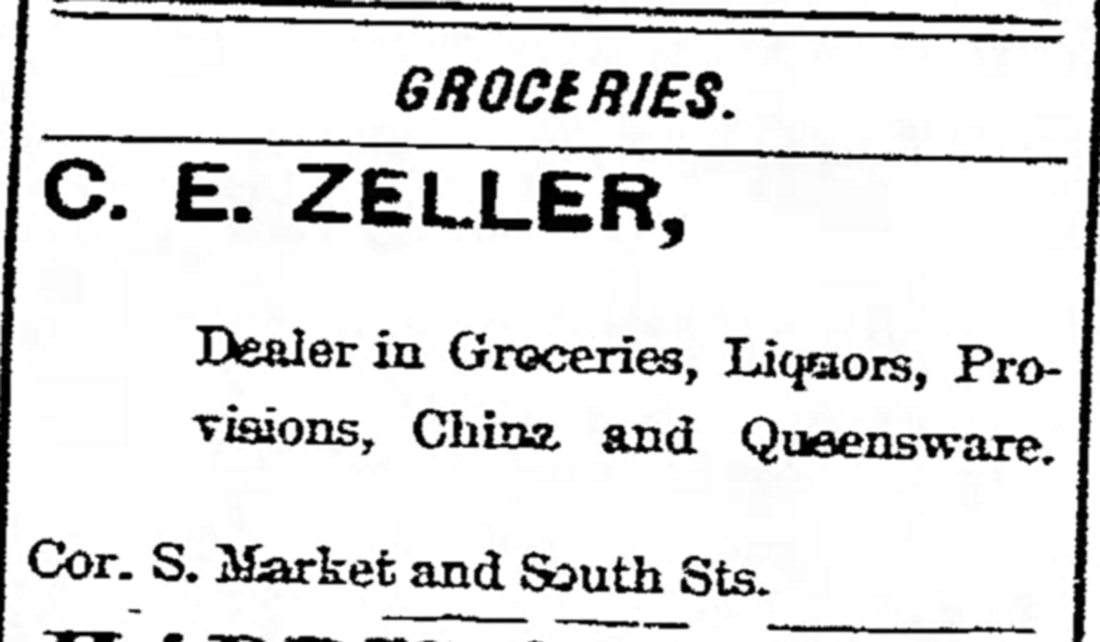

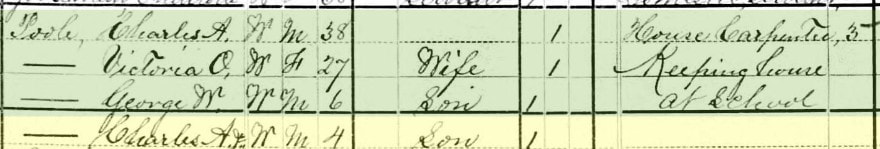

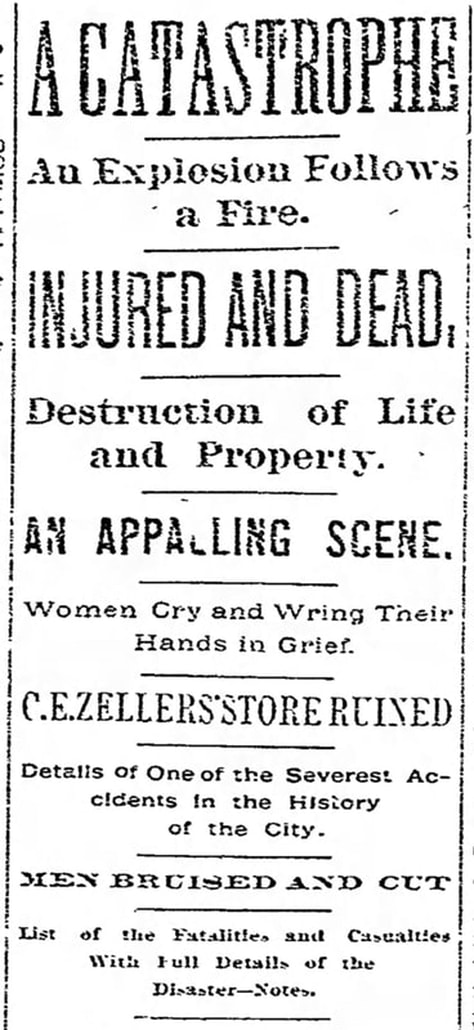

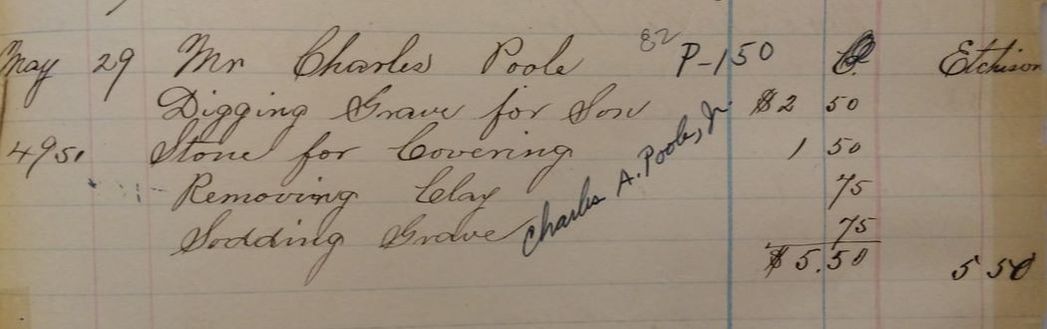

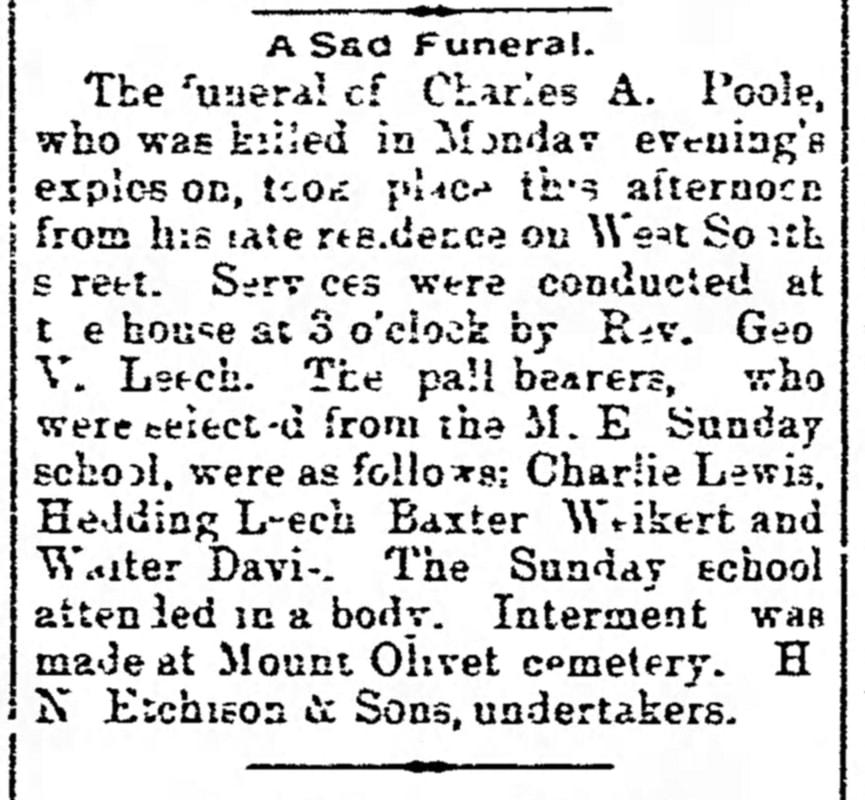

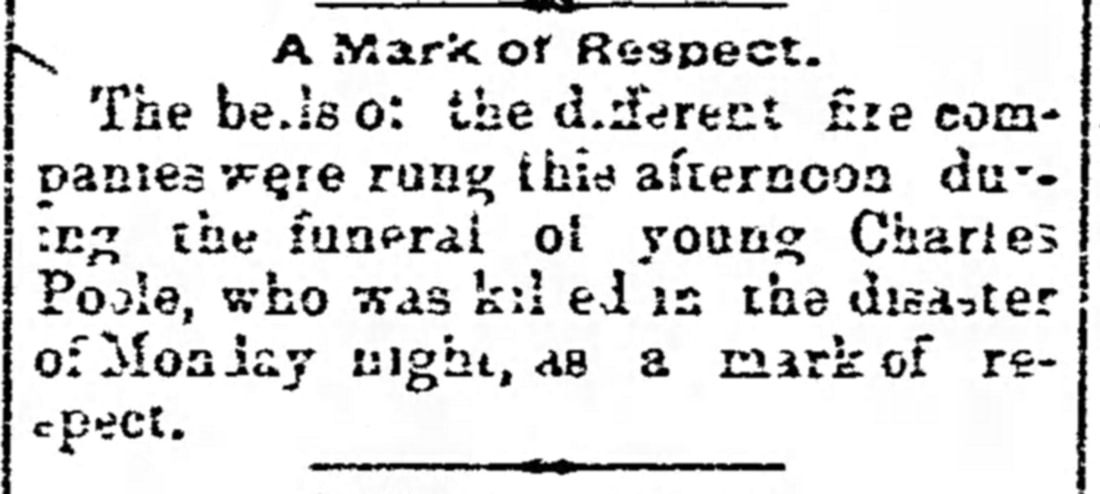

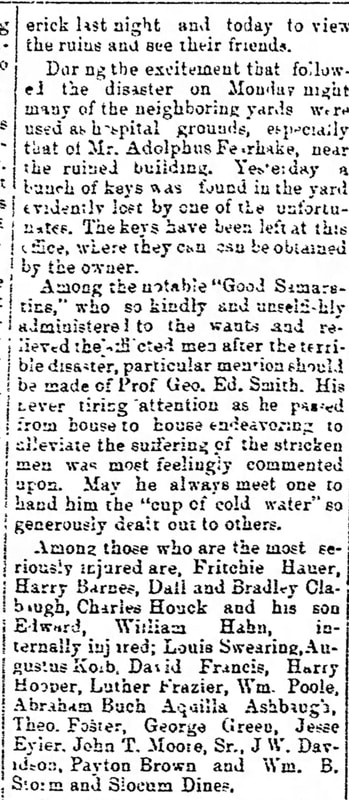

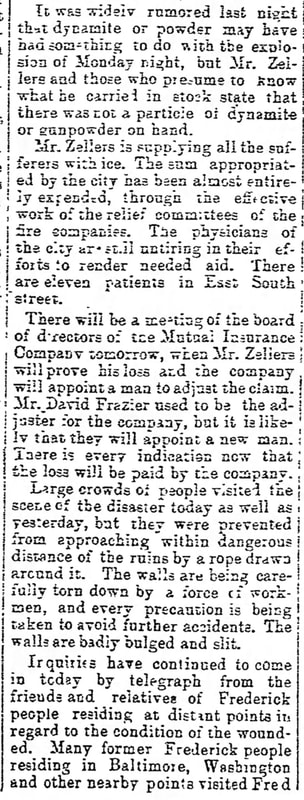

Meanwhile, a short distance away, another solemn memorial ceremony would begin at 3pm in a home located just blocks from the cemetery on W. South Street. This was the funeral of 12-year-old Charles A. Poole, Jr. The boy had been killed two days prior in one of Frederick City’s worst accidental tragedies. Thankfully the event, known as the Zeller’s Store explosion, would only claim one life—it could have easily taken many more. Zellers Store Charles Edward Zellers was a 37 year-old merchant who ran a grocery store on the northeast corner of S. Market and E. South St. A native of Frederick City, he was the son of German immigrants John Frederick and Dorothea Zellers. The Zellers arrived in the US from Odelsheim, Hesse-Cassel (Prussia) in the year1853. Born November 7th, 1850, Charles was one of four children and attended local schools in town. He grew up on E. South Street , near today's intersection with S. Carroll, and would eventually wed Mary E. Baer in 1875. They would have eventually have eight children, although three never reached adulthood. Mr. Zellers was a dealer in groceries, liquors, provisions, and dinner plates and accessories ranging from wood ware, queens ware, china and willow ware. His store was located on the northeast corner of S. Market and E. South streets. He had occupied this location for years, perhaps as early as 1880, if not earlier. Young Charles A. Poole, Jr. lived in the vicinity of the store on S. Market St., and later W. South St. in Frederick. In the spring of 1888, the 12 year-old house carpenter’s son of was in the employ of Charles Zellers, working at the market. On that fateful day of May 28th, young Charles Poole made a mistake which would cost him his life. It almost cost the lives of several townspeople as well, however this would not be the case. The heroes of the day involved several local fire companies who contained the blaze and administered care to the wounded sea of bystanders. Here is the story as told by the Frederick Daily News edition of May 29th, 1888: “One of the most terrible disasters that has ever occurred in this city happened last evening at quarter of seven o’ clock. The result is the destruction of the extensive retail grocery store of Charles Edward Zellers, situated at the northeast corner of Market and South streets, the killing of Charles A. Poole, Jr., a lad of about 11 years and the injury of upward of seventy men, white and colored, ranging in age from twelve to sixty years. About half past six last evening, Mr. Zellers sent a young lad employed at the store to draw five gallons of gasoline from a barrel in the cellar beneath the rear warehouse. It is stated that the lad in the endeavoring to use a lantern for the purpose of performing the duty upon which he had been sent accidentally ignited some of the gasoline that had leaked from the barrel. The lad immediately rushed from the cellar and an alarm of fire was given. Smoke issued from the windows of the cellar and soon filled the store room and adjoining house. The family of Mr. Zellers was promptly removed from the building. The general alarm of fire which had been sounded brought the members of the three fire departments on the scene with their apparatus. The first stream of water had hardly been thrown before a low rumbling sound, followed by a terrible sharp concussion, told the terrible story of one of the explosion usual in the case of fires at such places, where combustible material is stored in the cellar for sale. Of the ten or fifteen barrels of oil, gasoline and whiskey in the cellar at the time it is believed that all exploded but five or six. The wall of the warehouse fronting on South Street was laid over into the street, the roof was thrown back into the yard, the entire lower front of the building, consisting of heavy plate glass doors and windows was hurled in small atoms across Market Street into the midst of a crowd of spectators. Scarcely had the noise, dust and smoke of the explosion cleared away that the air was filled with the cries of frightened and weeping women, calling for their sons, husbands and brothers. For the space of 15 minutes, the scene was one of the utmost sadness and horror and many of the brave men who had entered the building to fight the flames emerged from the ruins cut, bruised and with broken limbs, while the groans of those who had been caught in the debris could be heard for half a square. As soon as possible the work of rescuing the injured and dying was commenced. The houses of those residing in the neighborhood were thrown open to the unfortunates and as soon as the physicians of the city could be summoned, the work of caring for the wounded began. On all sides the expression was that of horror. It is quite certain that the people of quiet Frederick were never before witnesses to so severe a catastrophe.” (NOTE: I've included another article with more on the aftermath of the event at the end of this blog). Charles A. Poole, Jr. had made it up from the basement and sounded the warning to others. Sadly he was killed when struck by falling debris from the explosion. His neck was broken. Although initial reports predicted more fatalities, this did not come to fruition. It was estimated that nearly 110 people were treated by local physicians, including 31 members of the United Fire Company, the first responders to the scene. One of these was Uncle Joe Walling, the featured star of an earlier "Stories in Stone" writing from 2017. Walling was the man who made several cross-country treks by foot and horse. Poole's body would be brought to Mount Olivet from his home on W. South Street. His burial occurred amidst the Memorial Day related exercises being held at Mount Olivet on that day in late May, 1888.

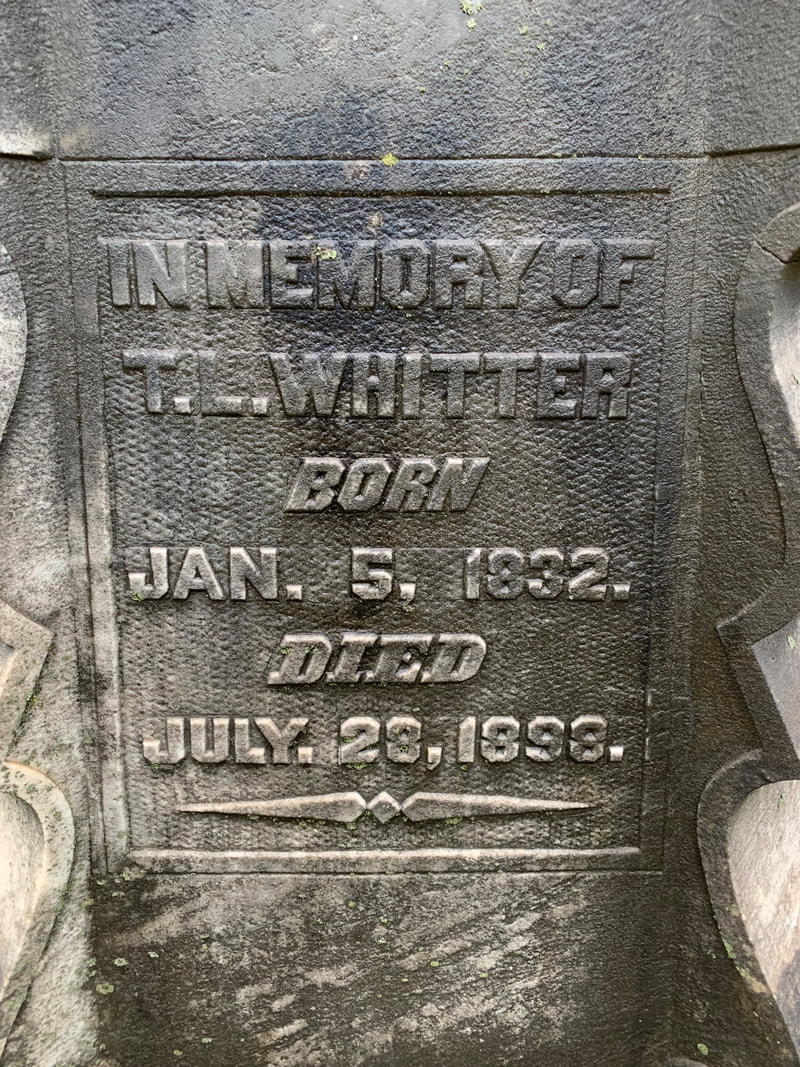

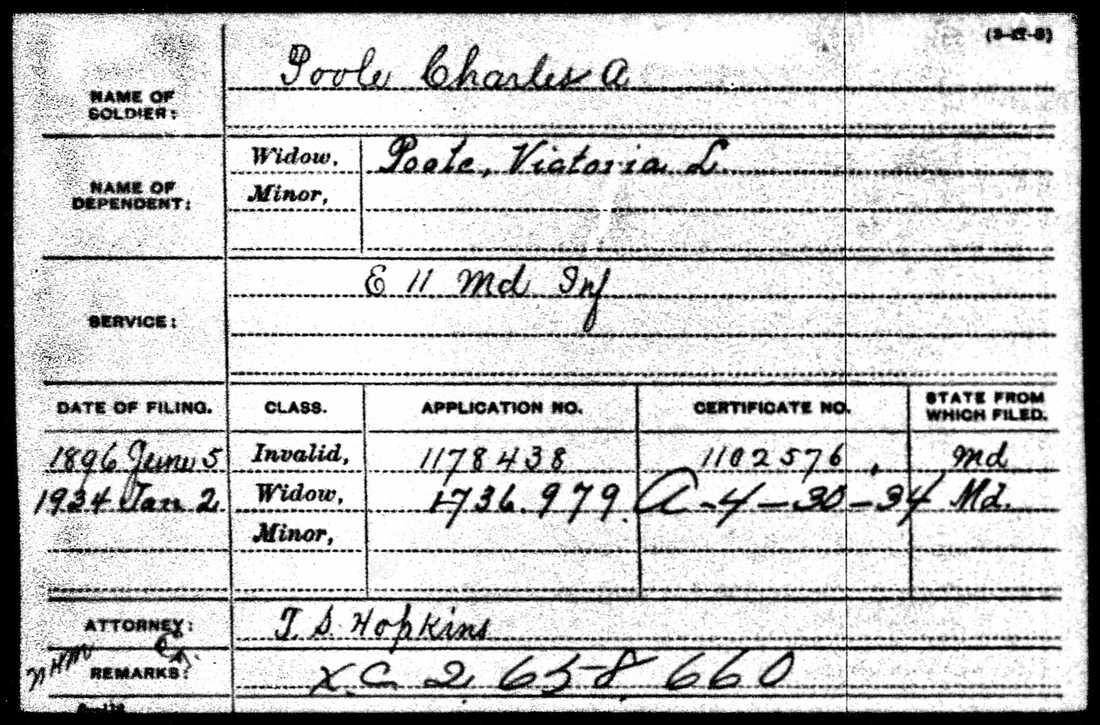

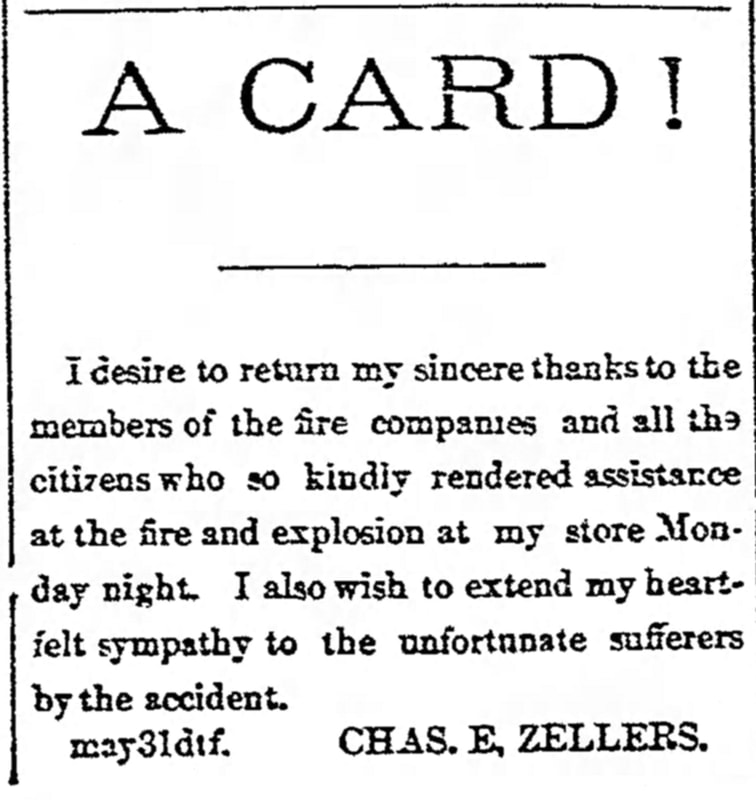

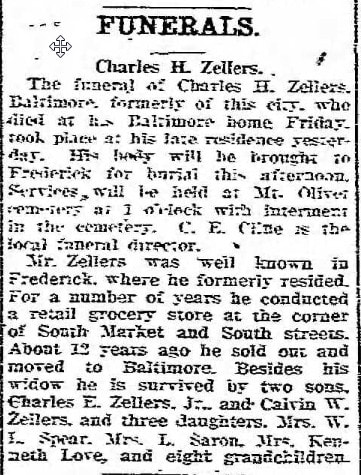

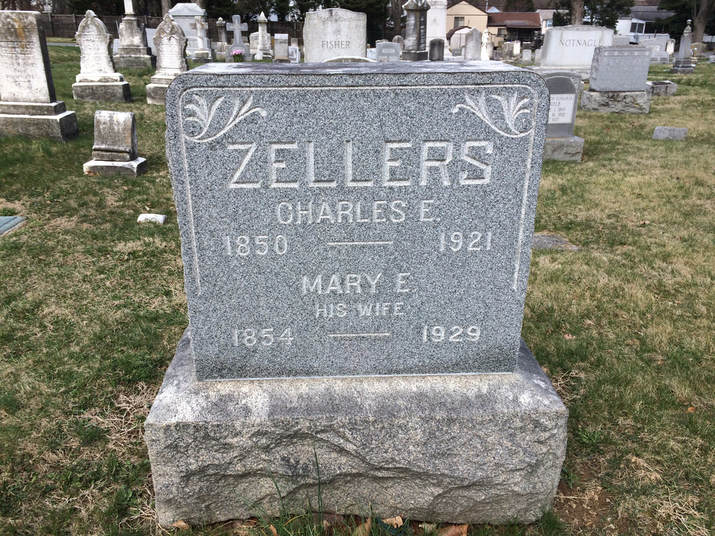

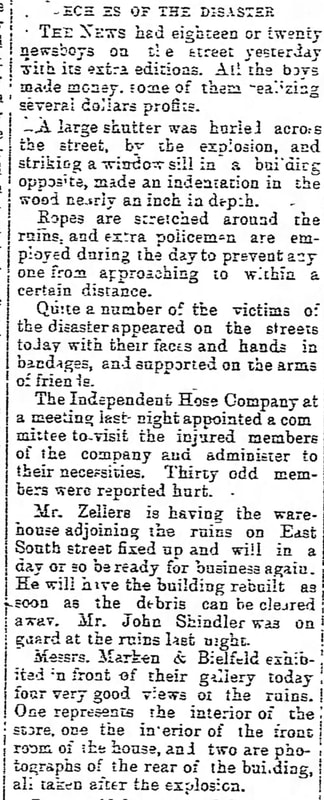

Along the way through my research, I found it fitting that Poole’s father was a Union veteran with Company E of the 11th Maryland Infantry Regiment. Dying in October of 1933, the elder Poole would live to endure 45 "memorial days" marking his son's premature death. He would join his son in the family lot within the cemetery’s Area P. Wife Victoria would follow a year later. As for Charles Zellers, both his commercial building and merchandise had been under-insured. The day after the catastrophe, a team of volunteers worked carefully to remove debris on the premises. Zellers needed to reopen as fast as possible. He would do this, and it was reported in the newspaper that a special cornerstone was placed that included photographs and newspaper accounts of the May disaster. Zellers and wife Mary continued to run the downtown market until the early 1900’s. They would relocate to Baltimore in 1909. Charles E. Zellers lived to be 70, and his body returned to Frederick for burial at Mount Olivet in 1921. (Area R/Lot 27).  I've deducted that the original family farm of Charles E. Zeller's parents (John Frederick and Dorothea Zellers) was located just east of the intersection of E. South and S. Carroll streets near the FCPS Headquarters. A mortgage record shows that the family built 6 townhouses on the south side of E. South St. almost to the brickyard property of B.F. Winchester @1875. This was commonly referred to as "Zeller's Row." Aftermath article from the Frederick News (May 30, 1888), giving updates on many of the townspeople injured in the Zeller's Store explosion. Special thanks to "Jeep" Abrecht, Jr. for his great assistance with this story.

3 Comments

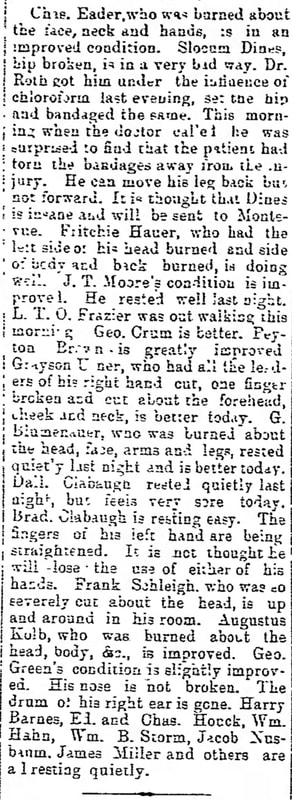

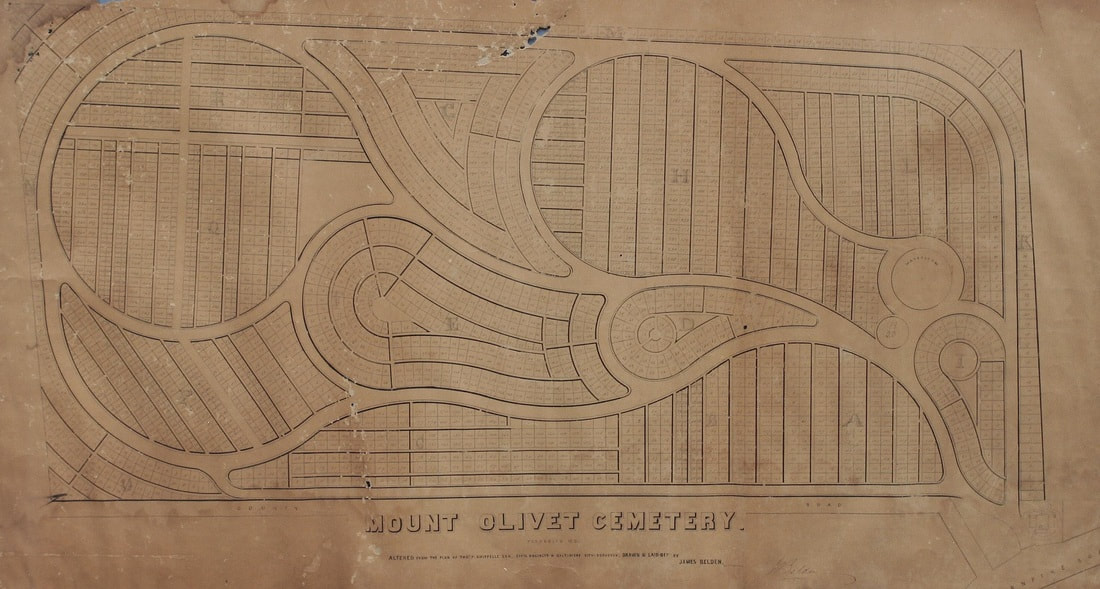

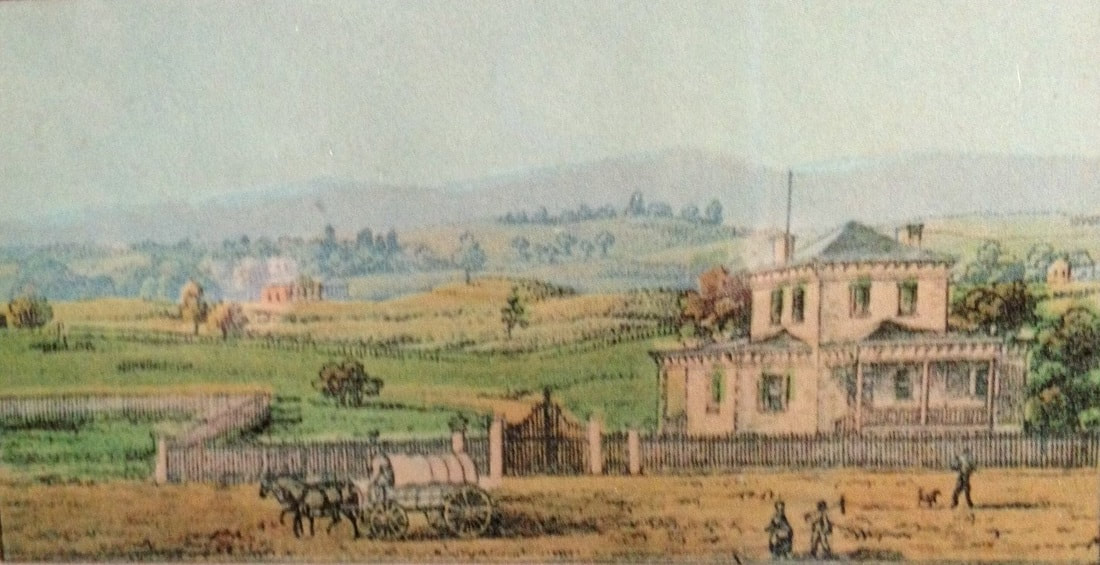

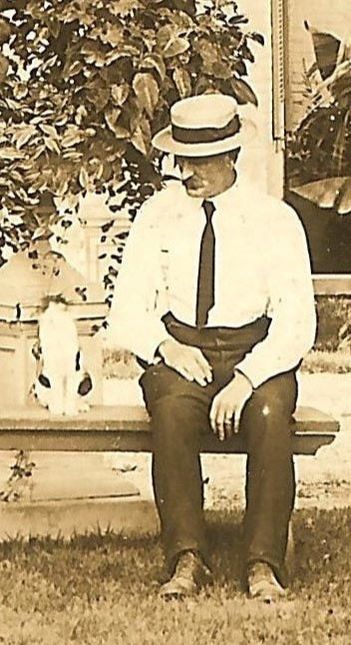

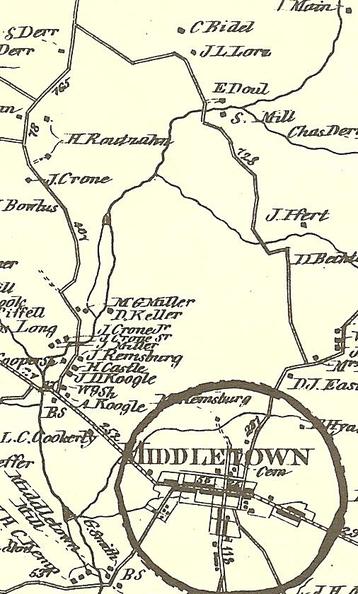

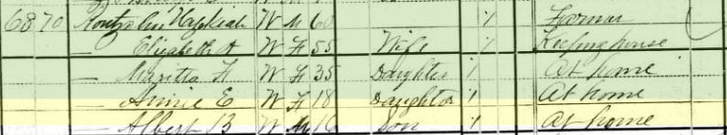

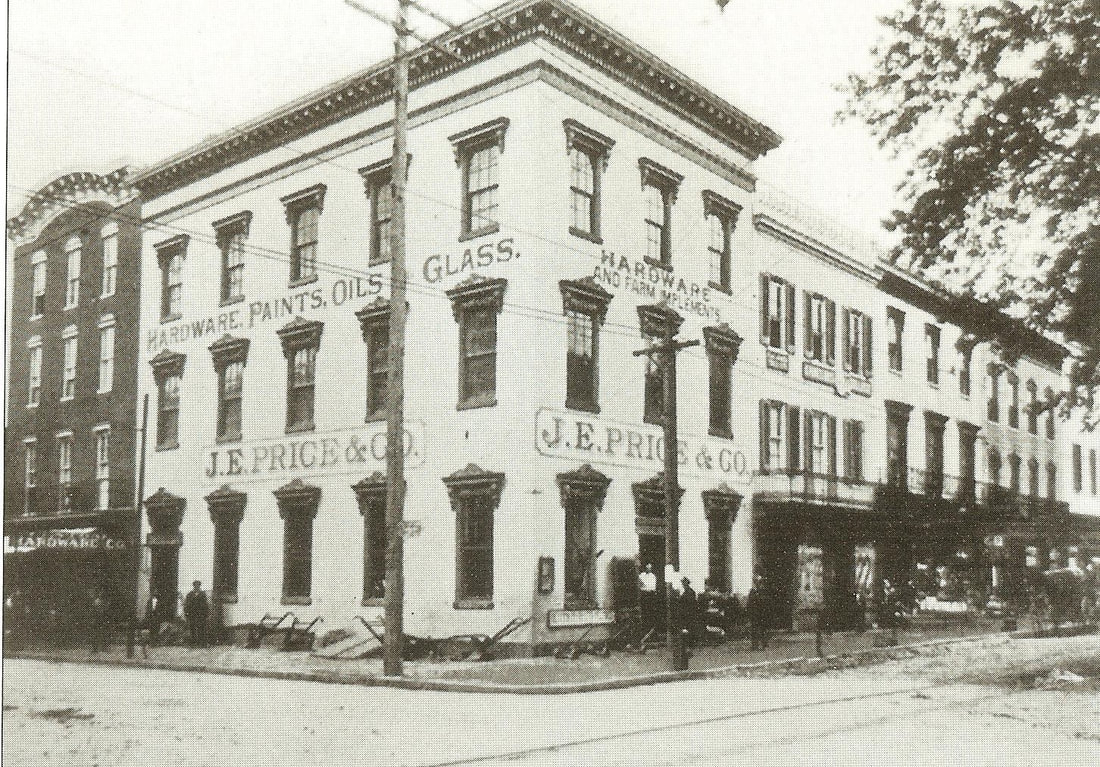

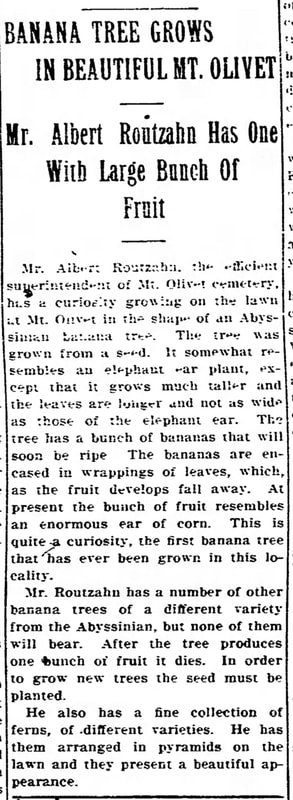

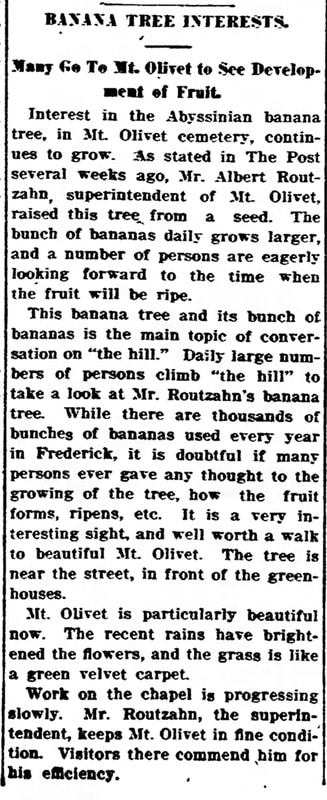

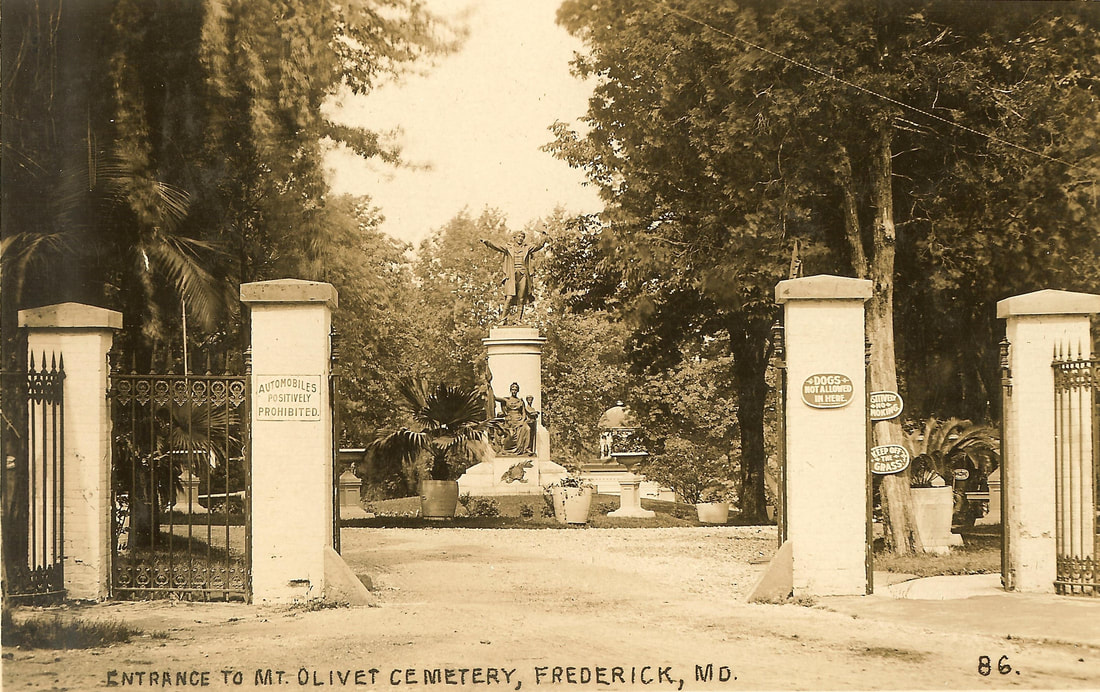

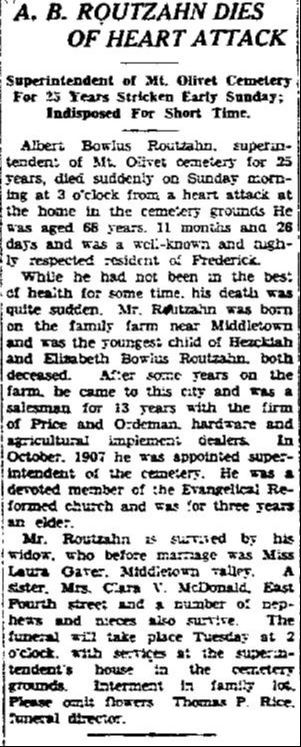

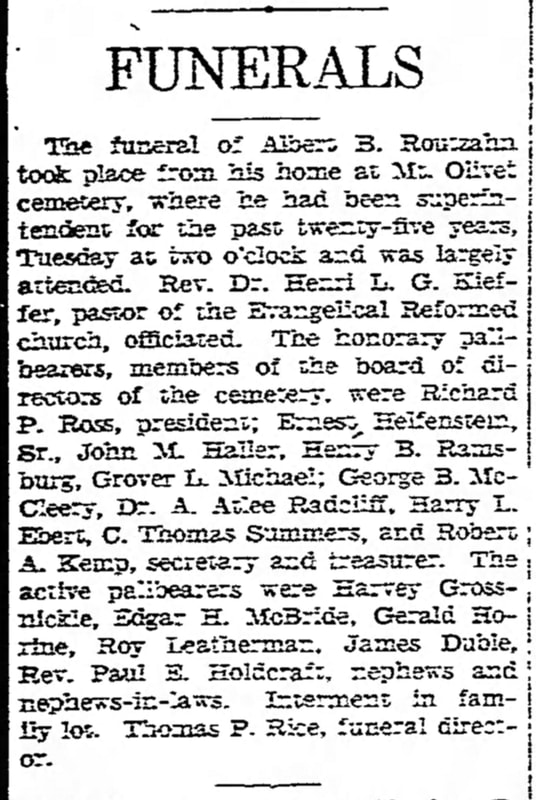

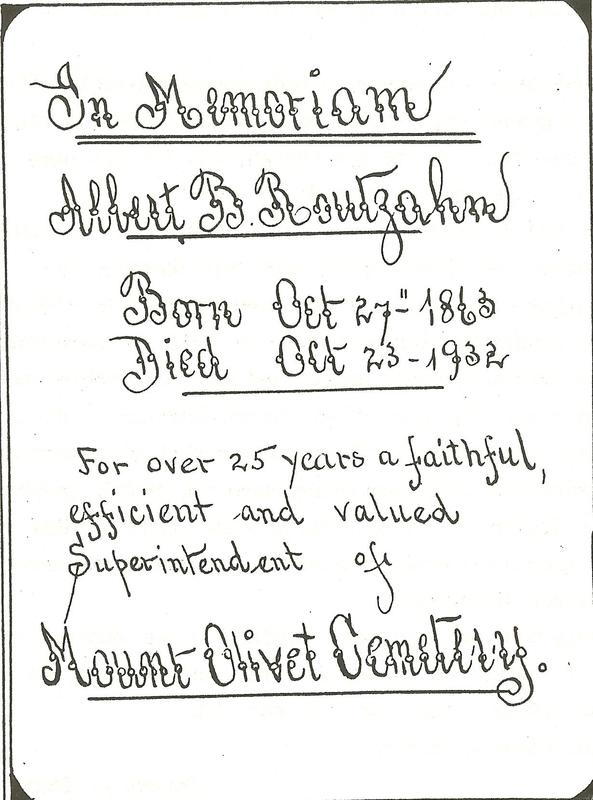

Question: If April showers bring May flowers, then what do intense May showers bring… other than flooded basements, closed roads, un-mowed lawns and canceled baseball games? Here in Frederick we will just have to wait and see as we have been deluged by an unusually high rain amounts of late. This past weekend, Mount Olivet Cemetery participated in the popular Beyond the Garden Gates Garden Tour put on by Celebrate Frederick in conjunction with the City of Frederick’s Office of Special Events. You may be saying to yourself, “Hey, wait a minute! I thought this was an annual tour of featured backyard gardens of Downtown Frederick homeowners? Why is a cemetery part of it?” Well, the answer may sound contrived to some, but will be crystal clear to others—Mount Olivet Cemetery is a special burying ground, known as a “rural,” or “garden” cemetery. The Charter of Mount Olivet Cemetery was recorded among the Land Records of Frederick County on October 4th, 1852. Thirty-two acres were purchased through stock sales, and a rural architect from Baltimore named James Belden was hired to design and lay-out Frederick's new burying ground. This would be located on the far outskirts south of downtown, even past the ancient Hessian Barracks on Cannon Hill. The cemetery was dedicated on May 23rd, 1854 amidst great fanfare, and received its first interment on May 28th, 1854. The "rural" or "garden" cemetery movement was a new school of thought, having origins in the large cities of the northeast. The first of this genre in the United States is Mount Auburn Cemetery, located on the line between Cambridge and Watertown, Massachusetts roughly four miles west of Boston. Dedicated in 1831 and set with classical monuments in a rolling landscaped terrain, Mount Auburn marked a distinct break with Colonial-era burying grounds and church-affiliated graveyards. The appearance of this type of landscape coincides with the rising popularity of the term "cemetery," derived from the Greek for "a sleeping place." This language and outlook eclipsed the previous harsh view of death and the afterlife embodied by old graveyards and church burial plots. The "garden" cemetery movement promoted larger, park-like spaces on the outskirts of town. These grounds were planned as public spaces from their inception, and provided a place for all citizens to enjoy refined outdoor recreation amidst art and sculpture. Elaborate gardens were planted, tree-lined and family outings to the cemetery became popular social activities. Mount Olivet certainly filled this role here in Frederick, at a time period before Baker and Gambrill parks, and museums such as the Historical Society of Frederick County and the National Museum of Civil War Medicine.  Queen Victoria of England (1819-1901) Queen Victoria of England (1819-1901) Victorian Style, "the Language of Flowers"and Symbolism Mount Olivet’s grounds are made up of hundreds of individual lots, each belonging to individual families. Though little more than cleared farmland in the beginning, early depictions show that many hedges were installed to delineate these property lines and young trees were planted to break the heat of the summer sun. Today these saplings are towering giants that pay homage to all who have passed beneath them. The families continued developing their lots and pictures from the turn of the century show the refinement that had occurred. Walls, fountains and ornate iron fences had been added to grace the gardens. The Victorian Period (1837-1901) defines the period of Queen Victoria's reign over Great Britain. This measured era of both European and American history brought a fascination with the natural world and a keen interest in plants. It became quite fashionable to decorate one's home with exotic, often tropical, plants. This would carry over to cemeteries as well. Palm trees and other rare species (to Maryland) would become part of the Mount Olivet landscape here, necessitating the cemetery's first greenhouse, built to "winter" these tender plants in addition to growing flowers. Many plants and flowers were symbolic to those of the Victorian Age, either through their ‘language of flowers’ or religious beliefs. Lilies, symbolizing resurrection, weeping willows for sorrow and palm fronds and laurel to indicate triumph of the soul are frequently seen on grave markers. A bouquet could be used to send a private message telling of one’s love. You could also see these plants growing nearby within the cemetery, and in other cases, actually carved in stone on monuments.  Frederick News (Sept. 27, 1907) Frederick News (Sept. 27, 1907) Superintendent Routzahn The cemetery’s managers met in late September, 1907 in order to select a new superintendent. Mount Olivet’s original superintendent was William T. Duvall who served from 1854 until his death in 1886. The job of caring for a “garden” cemetery was much different than that of the traditional church sexton of past history. A sexton was an officer of a church, congregation, or synagogue charged with the maintenance of its buildings and/or the surrounding graveyard. Yes, he had charge of burials, but unlike the cemetery keeper, he was also charged with caring for “living things,” if you catch my drift. These were things like trees, plants and flowers. Mount Olivet’s Superintendent Duvall was followed by Edward Herwig (1887-1893) and Daniel Jerome Michael (1893-1907). After a 17-year stint, Mr. Michael was forced to give up his duties due to health reasons in late September of 1907. The Board of Managers acted quickly in filling the position with a capable candidate. They found what would prove a very good choice in Albert B. Routzahn. Albert Bowlus Routzahn was born near Middletown on October 27th, 1863 on the family farm of parents Hezekiah Routzahn and Elizabeth (Bowlus) Routzahn. This was located northwest of Middletown on the east side of Old Hagerstown Road between the intersections with current day Palmer and Station roads. From census records, he appears to have been the youngest of eight children who would live into adulthood. Albert attended local schools of the area and continued working on the Routzahn farm until the death of his father in 1891. He had married Miss Laura Gaver two years earlier on Valentine’s Day, 1889. The young couple would relocate to Frederick sometime around 1892-93, and can be found living with Albert’s mother and sister at 162 W. Patrick St. Today, this property is the site of the Serenity Tea Room, the original townhouse having been demolished years ago. Albert took up work as a salesman for the successful firm of Price & Ordeman, a hardware and agricultural implements dealer located on the southwest of Frederick’s Square Corner. This is the current-day site of Colonial Jewelers. The ability to grow and nurture plants was certainly in Albert B. Routzahn’s blood, and he likely had regular contact with Mount Olivet’s previous superintendent and administrators in relation to purchasing tools, equipment and perhaps gardening supplies. Albert found himself at the helm of the cemetery in the fall of 1907. It was an exciting time of new growth, both figuratively and literally, for Mount Olivet under Superintendent Routzahn. One year after Routzahn took the job, the Board of Managers decided to build a greenhouse on the cemetery grounds. Perhaps this was a reward for good service by the new head employee, who was chock-full of new and innovative ideas. He certainly made an impact over his first two-and-a-half years on the job as his salary was raised to $50/month at the annual meeting of the Board of Managers in May, 1910. A series of old photographs taken around 1910-11 still survive, and give a visual impression of the grounds and structures long gone. These include exquisite plantings, the public vault and the original superintendent’s house. In the year 1911, the above-ground portion of the public vault was removed, and the current-day, Key Memorial Chapel was constructed on the space. Contract builder Harlan W. Hagan also busied himself at this time with dismantling the superintendent’s house in favor of reconstructing a larger home for the cemetery’s keeper. Meanwhile, a nearby house was rented by the company for Mr. and Mrs. Routzahn to reside temporarily. An additional title would be bestowed on Albert Routzahn in May of 1913. He became Mount Olivet’s “Landscape Gardener“ in what appears from the cemetery Minute Books to be a separate position in addition to superintendent. Better yet, it came with a salary of $20/month. Routzahn was the first to regularly mow the grass at the cemetery, creating a “gorgeous, green velvet carpet” as reported by one newspaper. Anecdotes like this had earned a bit of local celebrity for the superintendent over the previous few years. Articles hyped his experimental plantings of exotic flowers, ferns and palms on the cemetery grounds. Stories in local newspapers heaped praise on the “master gardener of Frederick’s City of the Dead” as residents were encouraged to see the superintendent’s hand-work and creations for themselves. Apparently Routzahn would use that new greenhouse to the utmost as “winter storage” for his tropical specimens. The superintendent’s top attention getters came from seeds and shoots planted in 1910. These were banana trees, the gift of Luther Derr, superintendent of the Maryland House of Corrections. The plants came to full “fruition” and there exists visual proof to go along with several newspaper articles dating to 1911-12. The Historical Society of Frederick County, better known these days as Heritage Frederick, has a photograph postcard in their rich collection of historic images that dates to 1911, showing one Superintendent Routzahn’s prized accomplishments. And speaking from a Frederick history perspective, Albert Routzahn also supervised the re-interment of Barbara Fritchie in the summer of 1913 from the German Reformed Burying Ground (present-day Memorial Park) to Mount Olivet. A fine monument would be dedicated the following year. Also in 1914, Superintendent Routzahn received an interesting, new charge from his Board of Managers at a meeting held on July 9th, 1914: “It was resolved that the President of the Company be directed to provide at the expense of the Company, a flag of the United States. And direct the Superintendent to keep the flag afloat over the grave of Francis Scott Key from May 30th to September 25th in each and every year, and on all National holidays. To renew and replace the flag from time to time as may be necessary.”  Frederick News (Aug. 15, 1923) Frederick News (Aug. 15, 1923) I couldn’t glean much more about the life of Albert B. Routzahn, outside the fact that he served on the Board of Directors of the Home Building and Loan Association of Frederick in 1914. In the mid 1920’s, advertisements appear touting offerings from the Frederick City Peach Orchard, of which Mr. Routzahn was proprietor. This was located on the property north of the cemetery between Fox’s Alley and South Street. Albert Routzahn kept himself most busy by caring for the cemetery. And this is where he died at 3 o’clock on the afternoon of October, 23rd, 1932. Although reports said that he had been ill of late, Routzahn’s death just four days shy of his 69th birthday came as a surprise to the community. He would be buried in a grave in Area R, among newly laid out sections by his own hand just a few decades earlier. His wife Laura would join him in Area R’s Lot 73 upon her death in 1951. Jacob Bowlus Routzahn was more than just a superintendent of Mount Olivet, he was a man who breathed life into the cemetery and tended its growth—things not particularly synonymous with burying grounds of old, yet the essence of the “garden” cemetery movement. Today, there are no banana trees or exotic palms on the property at present. However, the cemetery’s greenhouse has been home over the last few months to tropical waterlilies, part of the amazing aquatic garden that takes over Carroll Creek Park each summer. The program goes by the name of “Color on the Creek.” Dr. Peter Kremers and his talented staff of volunteers have been cultivating plants from the Amazon and other remote locations in a series of water troughs recently constructed within the Mount Olivet greenhouse. I find it ironic that traditional lilies of the land variety are said to symbolize resurrection. I guess you could apply this meaning to the water variety as well…a lily is a lily isn’t it? Regardless, I’m sure Superintendent Routzahn would be pleased at this recent partnership—one which adds to Downtown Frederick’s “garden-like” beauty and grandeur.

|

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed