|

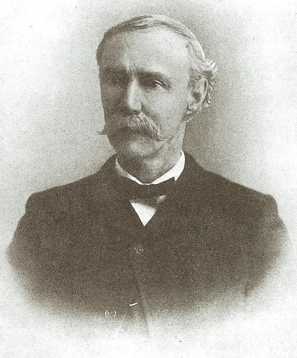

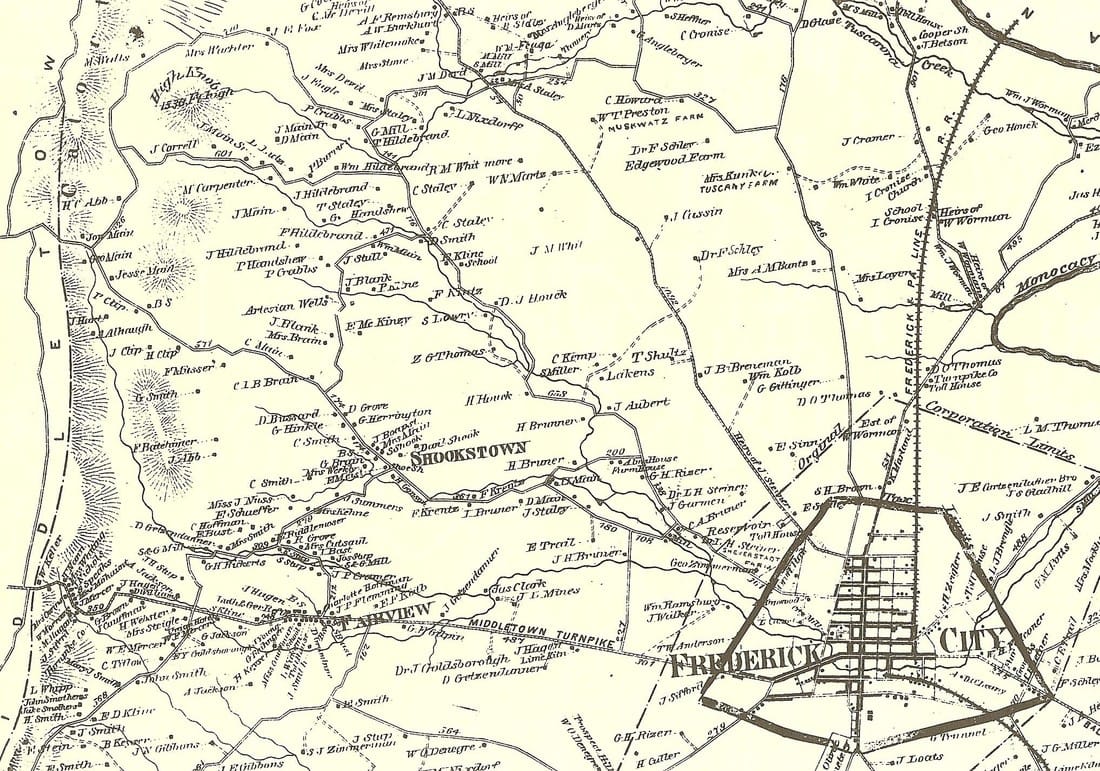

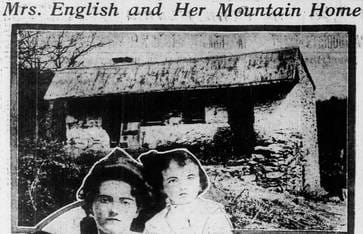

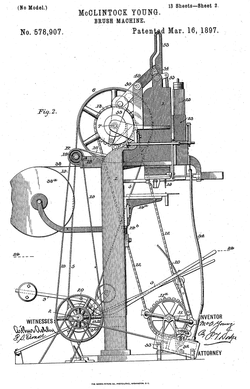

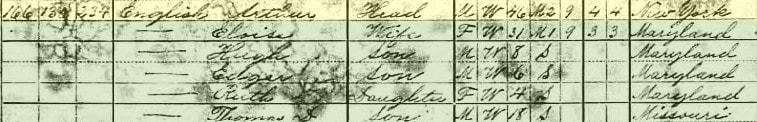

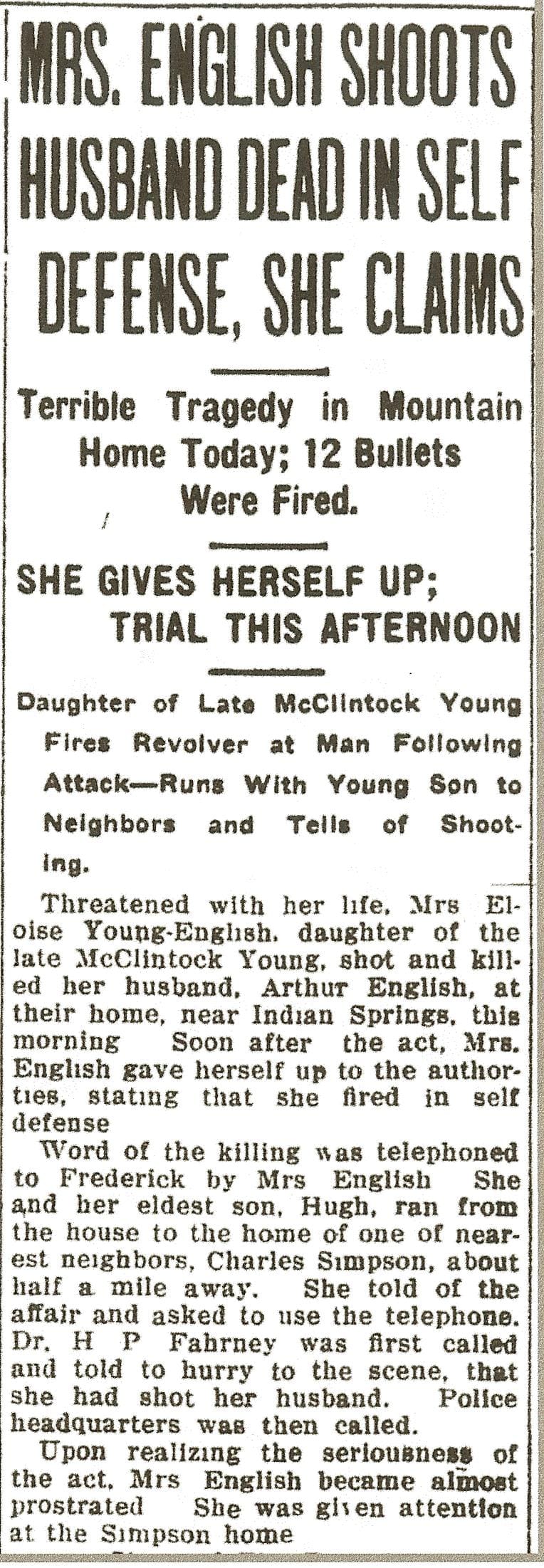

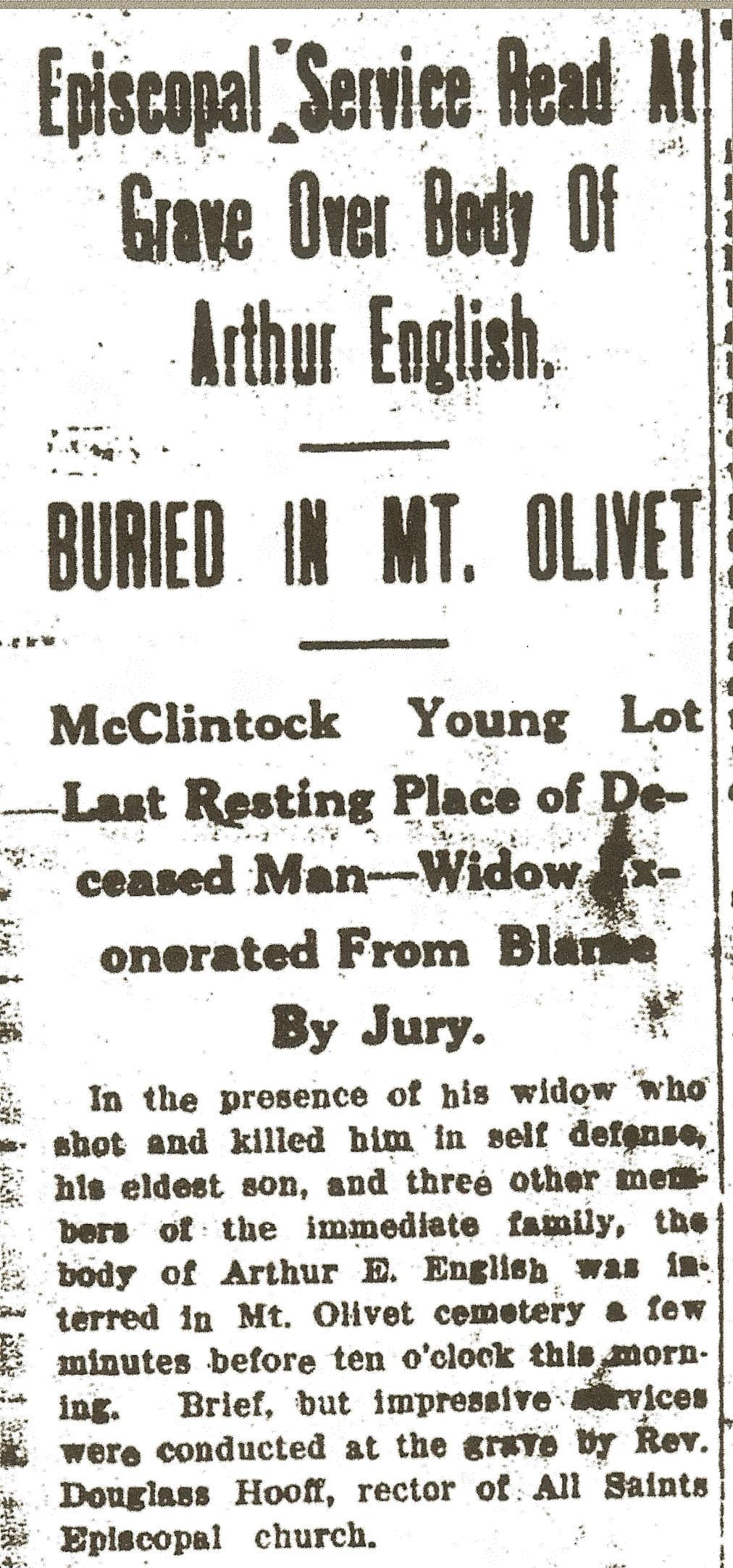

A new year can represent a fresh start—and many of us have been busy constructing resolutions, all part of a strategic plan to re-invent ourselves in 2017. It’s so simple, all we have to do is push the restart button at 12 midnight on New Years Eve, and voila! Well it’s not always as easy as it sounds. If nothing else, it’s good for the psyche to have hope and optimism at their highest peaks this time of year. So here’s to better days in times ahead. And singing Robert Evans 1788 poem (put to song) is always sure to give us that boost of confidence: Should auld acquaintance be forgot, And never brought to mind? Should auld acquaintance be forgot, And auld lang syne! Exactly 100 years ago, on New Year’s Eve (1916), I would venture to guess that mixed emotions were clouding the head of at least one Frederick resident who is today buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery. This was Mrs. Eloise N. English, a 39-year-old widow who had made national headlines earlier in the year. She had been given the task of guiding her four children through a bittersweet holiday season without their father, Eloise's late husband. She thought to herself that the new year of 1917 would surely be better for both herself and the children.  The southeast corner of W. 2nd and N. Court streets (c. 1870's). The Young household is the second townhouse to the right (located at 222 N. Court). The large house on the corner once belonged to Frederick lawyer Gen. Bradley Tyler Johnson who led Confederate troops during the Civil War. The southeast corner of W. 2nd and N. Court streets (c. 1870's). The Young household is the second townhouse to the right (located at 222 N. Court). The large house on the corner once belonged to Frederick lawyer Gen. Bradley Tyler Johnson who led Confederate troops during the Civil War. Eloise Newman Young was born on September 3rd, 1877. She came into the world a decade and a half after her parents and fellow residents had experienced trying events connected to the the American Civil War. Frederick, Maryland had been “one vast hospital” in the words of noted town diarist Jacob Engelbrecht. Union General Hospital No. 1 (which occupied the Hessian Barracks grounds across S. Market Street from the cemetery), the churches, public buildings and many private homes were filled with dying, wounded and sick soldiers from both armies North and South. The 1870’s was a time of prosperity, reconciliation, and rebuilding. Frederick was reinventing itself, the closest it would ever come to having an industrial revolution. And the Young family was playing a major role. Eloise embarked on a privileged childhood in the Courthouse Square area of Frederick. She didn’t want for much and had the best education that could be had here. Eloise learned first-hand the importance of ingenuity and thus possessed the power to re-invent herself. A guiding influence was her father, a manufacturer who garnered over 100 patents in his lifetime. Over time, he came to be known as Frederick’s greatest inventor. He helped Eloise in many ways, but none more important than on a dark, snowy day in March of 1916.  McClintock Young, Sr. (1801-1863) McClintock Young, Sr. (1801-1863) McClintock Young, Jr., Eloise’s father, was born June 25th, 1836 in Washington, DC. His own father was a politician and received an appointment to the position of Chief Clerk of the United States Treasury. He would be called upon to be Acting Director of the Treasury several times during the Jackson administration. Ironically, Young briefly worked under short-lived Secretary of the Treasury Roger Brooke Taney, but that’s a story for another day. Taney, however, may have influenced the elder McClintock Young to send sons McClintock Jr. and Alexander to Frederick to possibly attend the Frederick Academy, once located on Council Street. Both boys can be found living here in a boarding house in the 1850 census.  McClintock Young, Jr. (1836-1913) McClintock Young, Jr. (1836-1913) McClintock Young, Jr. was a tinkerer from a “young” age. In 1849, at 12 years-old, he constructed a fire engine that could throw a stream of water more than 40 feet in the air. After graduation from St. John’s College in Annapolis, McClintock Young, Jr. opened a foundry on Frederick City’s south-end, on the corner of South Street and Broadway. He soon married Louisa Mary Moberly of New Market and started a family. Young continued to make the world better through mechanized means, earning patents for steam engines, saw mills, and sewing machines. He also designed such useful things as a box-making machine and an ink eraser. His big invention came with a “self-rake” mechanism that he sold to the McCormick Harvester Company. This would remain a pivotal part of the firm’s famed reaper machines for more than half of a century. The light bulb continued to turn on within McClintock Young’s head. Ironically, he would earn a great payday in 1870 from the Diamond Match Company, who purchased the patent for an automated match-making machine. The relationship grew as McClintock Young and two executives of the Diamond Company founded the Palmetto Brush Company here in Frederick in 1886. Young had come up with a machine that could turn palm trees into scrub brushes, and would design several more variations on his original. By the next year, McClintock Young’s original foundry location became the home of the Ox Fibre Brush Company. Due to the business’ great success with customers here and abroad, a new plant would be built on East Church Street extended (today the site of Goodwill Industries). The company would long outlive Mr. Young into the mid 1900’s. McClintock Young’s “brush with success” would not stop here. He patented a hinge-making machine that lead to bicycles with pedals powering rear wheels instead of the existing early technology of the late 1800’s that featured “front-wheel drive.” Aside from that, Young was highly involved in the civic and fraternal clubs of town and most importantly, raised three daughters into adulthood, including Eloise who was only nine when her mother passed in 1886. It’s hard to keep a good man down, but the brilliant light within McClintock Young, Jr. finally faded after a three-year illness on August 1, 1913. He was buried in Mount Olivet amidst a great number of family, friends and admirers. One of the many gifts Eloise would receive from her father was a small, rustic dwelling with property located on Catoctin Mountain. This was in the vicinity of Indian Springs, roughly four miles northwest of downtown Frederick. Bought around 1890, this was a favorite place to hunt for her father. Fellow Frederick businessman DC Winebrenner owned a neighboring farm about a mile distant that was a regular scene of society gatherings. That would continue with later owners of note including James H. Gambrill, Jr. and Charles R. Simpson. The Young family's mountain house was simple, made of stone and said to have “stood on a bluff in an isolated section of the rugged mountain land.” It was quite a departure from the fine Frederick townhouse on North Court Street that Eloise had grown up in, not to mention her posh surroundings in New York City. Eloise had left Frederick around 1900 after marrying Arthur English, a one-time assistant US attorney for the Department of the Interior, now in private practice. Mr. English was a native New Yorker, extremely well-educated, and the son of a pseudo-celebrity. His father Thomas Dunn English was a former New Jersey congressman and the author or a popular song entitled “Ben Bolt.” Doors were opened for Eloise’s husband but he was also a diligent worker—but some said too diligent. He was licensed to practice in New York, Washington DC and several other states. In 1910, the couple could be found living in an apartment building located at 166 State Street in Brooklyn, blocks from the approach to the famous bridge that connects to lower Manhattan. Here, residing with the family was Arthur’s son Thomas from a previous marriage. (Arthur’s first wife Lucy died in 1895.)  Eloise (Young) English, pictured with two of her children. Eloise (Young) English, pictured with two of her children. At the time of her father’s death (1913), Eloise and Arthur had four children: two boys (Hugh b. 1901) (Edgar b. 1904) and two girls (Ruth Bird b. 1905) and (Louise b. 1912). “Home life” slowly changed Eloise’ opportunity to be a New York socialite. She became more centered on raising her children, a burden that seemed to be falling more on her shoulders as husband Arthur spent more and more time on his profession and less time at home. By year’s end 1915, Eloise and her children were residing at the Indian Springs mountain farmstead on the outskirts of Frederick. Friends and neighbors claimed that the relationship between husband and wife was beyond strained, the couple spent more time living apart than together. Arthur could often be found back in New York, as Eloise now found some semblance of civility up on Catoctin Mountain, but more so from being away from Arthur.  The approximite location of Indian Springs can be seen on the 1873 Titus Atlas of Frederick County within the Frederick District (later Tuscarora District). The author believes that the approximate location of the Young-English residence was in the upper left of the map, noted as the residence of J. E. Fox, an earlier owner. This is located a short distance west of the present day home of the Tuscarora Archers, Archery Lane on Etzler Road. Arthur made a brief visit to be with his family over the Christmas holidays. However, he would not return until the second week of March in the new year of 1916. No one could attest to the tone of the family’s reunion, but a glimpse can be garnered by the events that would unfold one week later— events that would change the lives of every member of the English family.  A photo of the English cabin home on Etzler Road appearing in the Philadelphia Inquirer of March 21, 1916. A photo of the English cabin home on Etzler Road appearing in the Philadelphia Inquirer of March 21, 1916. On Saturday, March 18th, 1916, Eloise watched out the window in sadness and dismay as Arthur forced sons Hugh and Edgar to chop wood during inclement weather. The story goes that Hugh had been ill of late, and Eloise did not want him in the frigid elements on this particular afternoon. She went outside and asked Arthur if he would give Hugh a reprieve, perhaps choosing a lesser chore like cleaning wood indoors instead. At this request, Arthur erupted and began regaling Eloise, not happy with her intervention. Eloise returned to the house quite shaken. This had not been an isolated incident as it was later reported that she regularly endured verbal beatings from her sharp-tongued husband. Things must have been more tense than normal, as Eloise felt compelled to retreat upstairs to retrieve a most practical gift given to her as a young girl by her father—a small revolver pistol. She hid this in her dress, sensing the dire possibility that it may be needed for protection for both herself and the children. She returned downstairs and took to washing dishes. Arthur English reappeared indoors after completing a myriad of outside tasks. Once again face to face with Eloise, he restarted his diatribe, scolding Eloise for up-rating him and his directive for the boys regarding the wood. She tried to reason that Hugh had been sick, and thought it better that he be assigned a less rigid task. At this, Arthur flew into an uncontrollable rage. Eloise took to her knees, begging her husband to calm down, all the while, ten-year-old daughter Ruth was watching a horrific drama play out before her very eyes. Arthur grabbed a hammer and began smashing furniture, heirlooms and china wear. Eloise continued to beg him to stop, which made him even angrier. He then smashed a glass cabinet and obtained the revolver kept within. He took hold and boldly uttered to Eloise: “I will finish you!” Eloise quickly shot first, emptying all five chambers of her gun into her husband. She then picked up his gun and did the same supposedly. Not knowing the damage inflicted, she quickly gathered all four children and fled, traveling a distance of a mile and a half through the snowy woods to a neighbor’s home. She had shot Arthur through the heart and in four other places, dropping him in the middle of the family’s dining room. At the home of Charles R. Simpson, Eloise told the story of what had just transpired. She did not know Arthur’s condition and the damage done by her volleys as she calmly telephoned for a physician to attend to her fallen husband. She next called police headquarters to report her actions in response to Arthur’s threat to her life, and requested a warrant for his arrest. At once, other neighbors were summoned to help. Eloise English would be exonerated by a coroner’s jury the evening after she and three of her children testified to Arthur English’s alleged brutality and frequent threats to kill her. Neighbors, friends and relatives backed the story fully. One day later, Arthur’s body was laid to rest, just ten feet beyond the grave of Eloise’s beloved father. Eloise English was now free of the abuse, threats, and violence. Thomas English, came to Frederick immediately to be with Eloise and the children and attended the funeral service on March 20th at Mount Olivet. He is reported to have offered to take his step-mother and step-siblings in, and provide for their welfare back in Brooklyn. Eloise, however, would kindly decline the offer. She chose not go back to the dwelling in Indian Springs, staying for a time at the home of her older sister Helen Young Johnson and husband Baker. In time she would return, and operated a truck farm with help from her children and a hired hand named Keefer Kline. She successfully raised her children into adulthood, but would never remarry. Eloise died in a Baltimore nursing home of February, 2nd, 1959. She was buried in the family plot (area H lot 483), next to her father, and not husband Arthur. Today, one can find three of Eloise's four children buried next to their protective mother—Louisa English Wemple (d. 1978), Hugh English (d. 1985)and Ruth Bird (d. 1999). As a ten-year-old child, the latter had proved the most significant witness to the case. Ruth Bird English would go on to earn a bachelor’s degree from Hood College and her master’s from the University of Pennsylvania. She taught for 32 years in private schools and may also be remembered as a reference librarian for C. Burr Artz Library. She would never marry. Eloise Newman (Young) English had reinvented her own life, and that of her children. Her father, Frederick’s remarkable inventor, would be proud. One hundred years ago today, as she stood ready to “re-invent” herself, I wonder if she reflected on the original lyrics of Robert Woods “Auld Lang Syne.” Or, rather, did she know that Woods had borrowed from an earlier poem written in 1711 by James Watson entitled “Auld Long Syne”: Should Old Acquaintance be forgot, and never thought upon; The flames of Love extinguished, and fully past and gone: Is thy sweet Heart now grown so cold, that loving Breast of thine; That thou canst never once reflect On old long syne. Special thanks to Mr. Ron Twenty who shared this modern-day picture of the English family's cabin.

3 Comments

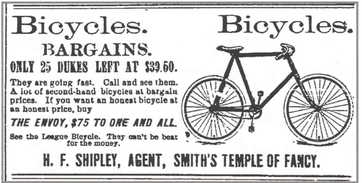

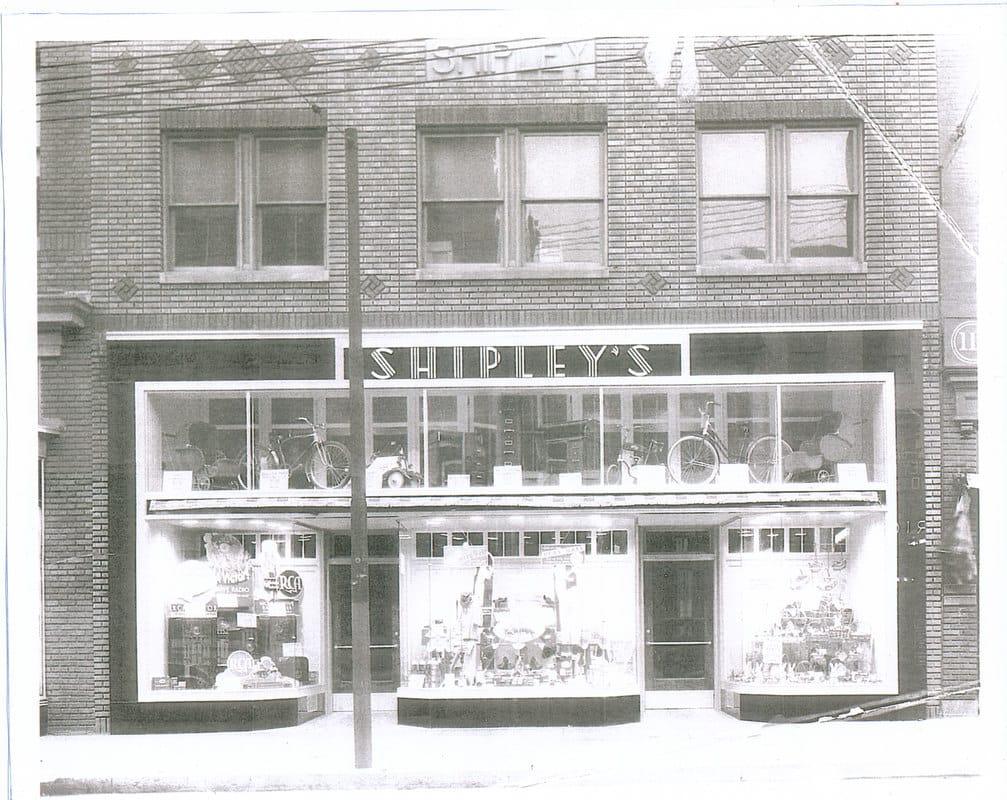

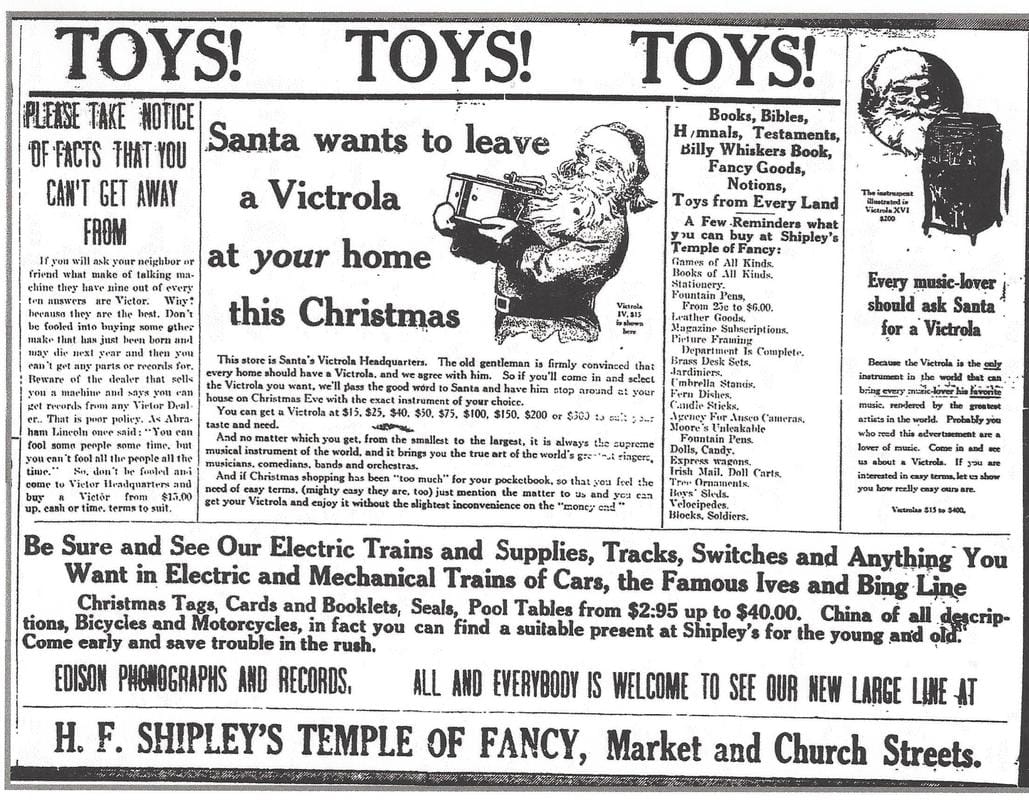

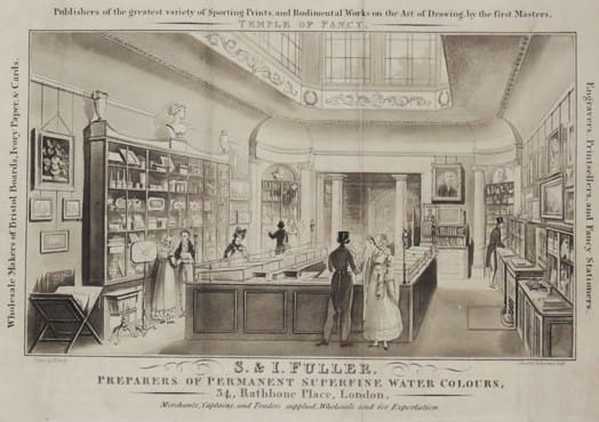

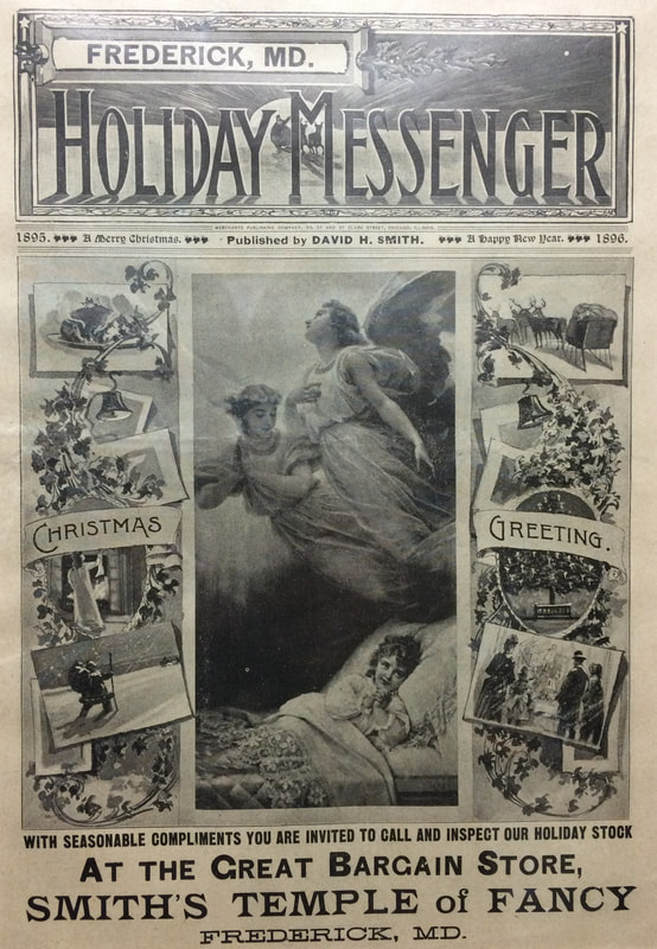

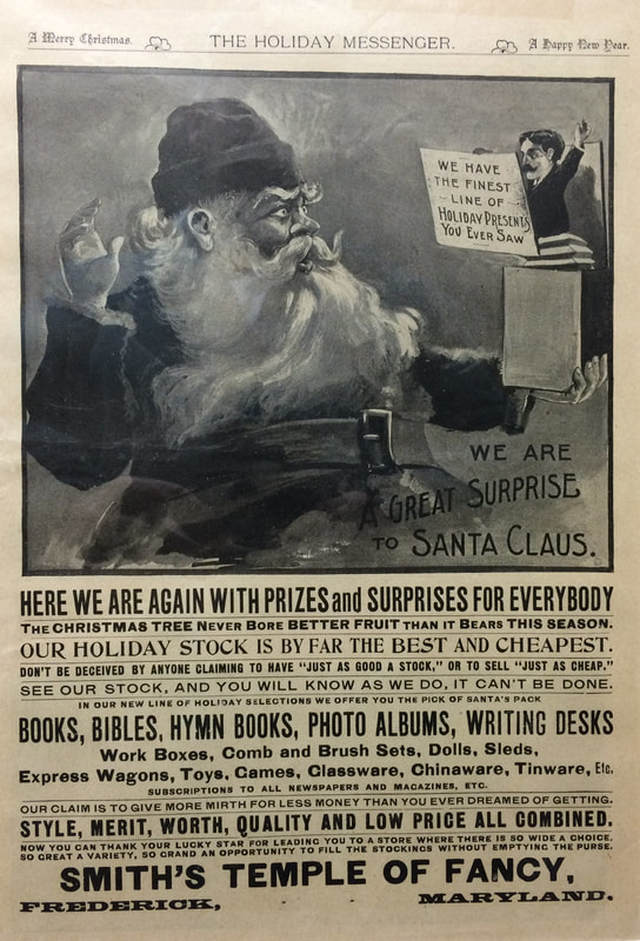

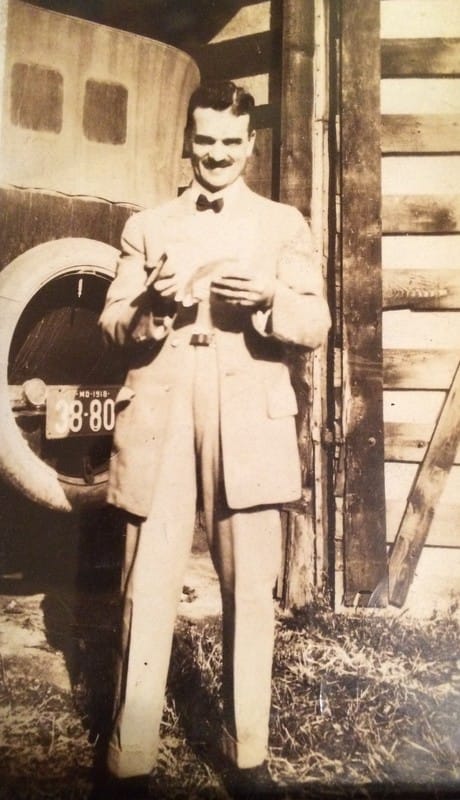

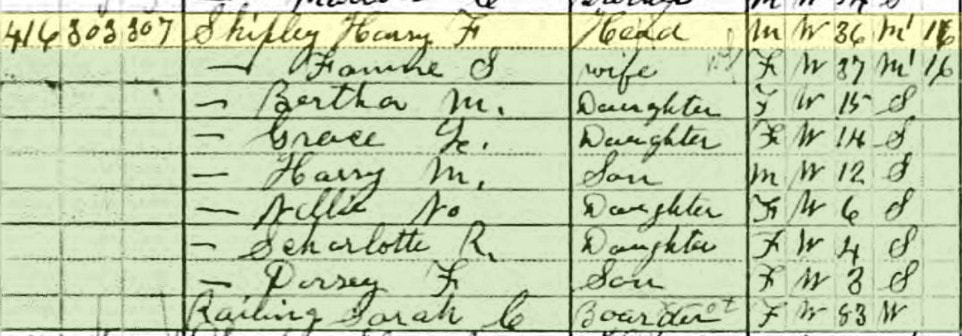

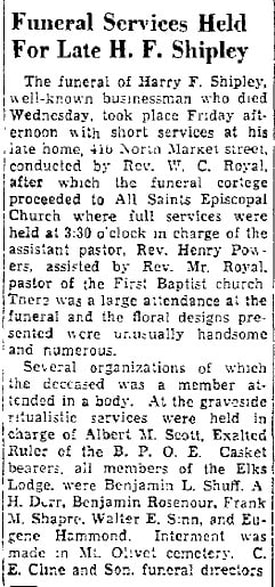

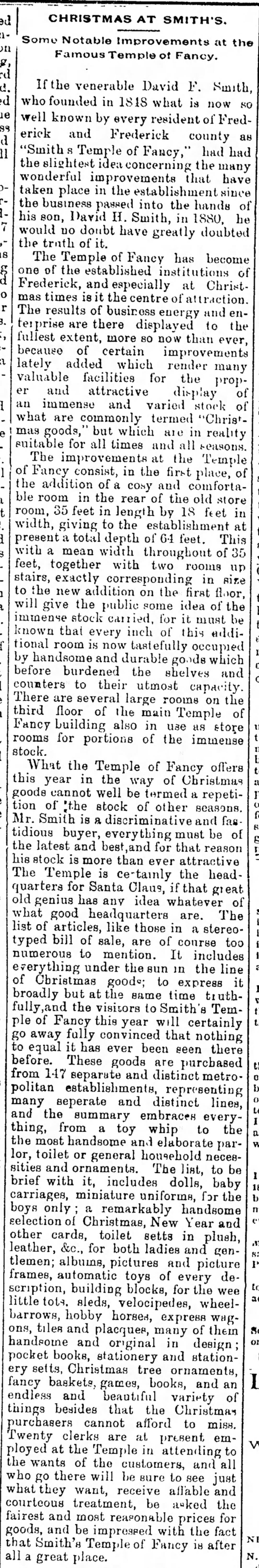

There is nothing more enjoyable during the holiday season than frantically finding the right gift for loved ones, all the while navigating crowded stores and co-mingling with equally stressed, fellow shoppers. Was it always like this? Gift giving at Christmas has been around for quite some time, and so has the pressure of buying presents. However, when it’s all said and done, nothing beats the joy involved in showing appreciation to friends, family and work colleagues through this selfless act. Unless, of course, you are forced to make a return—but that’s a whole other issue. Everything is relative, and it always will be. I have the good fortune of being a parent to four boys, currently ranging in age from 15 to 10. They each have different interests, so I usually experience eclectic quests for gifts. In general, I have a harder time searching for adults. Researching and acquiring “kid toys” and gadgets has been quite enjoyable, an experience that commonly takes me back to my own childhood and the magical Christmastimes of my youth. While I fondly recall gatherings with family, church services and delicious meals and sweets, what I remember best is the array of toys over the years. Interestingly, I have even bought some of the same gifts for my guys that I received as presents from my parents “back in the day.” Of course, technological advances have changed “toys” drastically since my childhood. However, this isn’t the case with many items such as dolls, basic sporting equipment (bats, balls, gloves), toy soldiers and bicycles. As I stare down my 50th birthday, coming in just a few short weeks, I can’t help but think of what my parents endured at Christmastime, shopping for me and my brothers. I then think of my grandparents shopping for their kids( my parents), and further back to my great-grandparents approach to Christmas as young parents themselves. That takes me back a century. If we were to go back in time to 1916, where would we go to shop for yuletide gifts and toys? I searched the newspaper archives and found that Frederick had a bevy of downtown stores, bustling with holiday shoppers in the weeks and days leading up to Christmas. One merchant, above the rest, caught my attention through whimsical advertisements for toys and gifts of all kinds. Best of all, the name of the business was also mysterious, yet awe inspiring—H.F. Shipley’s Temple of Fancy. As for H. F. Shipley, he was born Harry Franklin Shipley on October 23, 1874 on Frederick’s W. South Street, the son of J. Frederick and Margaret (Baer) Shipley. With his father employed as a general laborer, young Harry had a humble upbringing as the second oldest of ten children. His childhood can be exemplified by a family story of Harry commonly waiting along the railroad tracks in an effort to retrieve lost pieces of coal (that would fly off train cars) for his family to utilize for heating the house. Now, what is a “Temple of Fancy.” Merriam-Webster defines fancy (items/goods) as novelties, accessories, or notions that are primarily ornamental or designed to appeal to taste, or fancy, rather than being essential. There was actually a renowned “Temple of Fancy” in London, opened in 1810 by two brothers, Samuel and Joseph Fuller. This had become one of the leading print publishing businesses of the Regency and early Victorian periods, selling watercolors, lithographs, sporting prints, and fancy stationary to the masses. Today our lives are cluttered with “fancy,’ but back in earlier days, novelty items were just that—novelties. This included items such as Christmas Cards, holiday decorations/ornaments, lights, candy, and nouveau accoutrements that made life grander. Looking back 200 years in Frederick’s history, you’d be hard-pressed to find “fancy” items in 1816. Frederick folks back then were just happy to still have their own country of United States, recently having had to fend off the pesky British again in the War of 1812. The “national pike” ran through town, and was the first federally funded road project, bringing travelers, settlers, farm output and western exploited natural resources through town like never before. Outside of that, everyone just worked hard for subsistence, mostly growing their own food and making clothes and whatever else they needed. You saved up money to buy necessities—like nails, shoes and coal. Slowly but surely, specialty shops began opening as goods could be more easily transported from the larger cities. I’m guessing that holidays like Christmas were “less than fancy” for young Harry F. Shipley and his siblings, especially when compared to others in the community. Perhaps this precipitated a curious wonderment in his mind, or at the very least gave him the inspiration to change the course for his own children one day and future generations. Harry bettered his lot, and that of his family, by going to work—at the age of 11. Shipley's grandson Matt shared with me the story that H.F (as he is affectionately known to the family) first worked at a grocery store in town. When he was seeking employment to meet the basic needs of his family, a woman named Sarah C. railing at the establishment took pity on the youngster and hired him. Harry soon gained employment from Mr. David H. Smith, a well-known merchant who operated one of the most colorful and interesting businesses in town, surely making him the envy of his peers. This was Smith’s Temple of Fancy, located on the northeast corner of E. Church and N. Market streets in a building known to locals as Coppersmith's Hall.This veritable “tasting room” for the visual senses brought in plenty of profit (or should I say Proffitt). It was originally begun by Smith’s father, printer and compositor David F. Smith. David F. Smith was born and raised in Frederick but left town for love and employment, marrying a Baltimore girl (Susan Ford) and working in that city. He was employed by the Baltimore Sun and other newspapers before going into business for himself. The elder Smith operated a stationary and book shop on Gay Street in Baltimore before returning to his hometown and opening his Temple of Fancy in 1848. I’m assuming Mr. Smith's store was modeled after the London enterprise of the Fuller brothers. The younger David H. Smith would take hold of the operation in 1880 and add greatly to a business that specialized in selling items such as commercial art prints, cards and stationary. He was an excellent marketer and the store's reputation seemed to be very well-known. An article from the Frederick Daily News, dated December 16, 1886, sung the praise of the establishment under the heading "Christmas at Smith’s:" The Temple of Fancy has become one of the established institutions of Frederick, and especially at Christmastime, it is the center of attraction. The article went on to say “The Temple is certainly the headquarters for Santa Claus, if that great old genius has any idea of what good headquarters are.” The article boasted that Smith's Temple of Fancy featured “goods purchased from 147 separate and distinct metropolitan establishments, representing many separate and distinct lines, and the summary embraces everything from a toy whip to the most handsome and elaborate parlor, toilet or general household necessities or ornaments.” (See this article in its entirety below at end of article)  Harry F. Shipley would pass his formative years in the employ of Mr. Smith. His job had him extending Christmas Spirit to kids of all ages. Still a kid, himself, the young clerk was in the position of sharing keen advice to parents on the latest, greatest toys. I’m sure he also gave pointers on obtaining lumps of coal for stocking stuffers to parents of “naughty” kids. In the mid 1890's, Harry was given the job as bicycle agent for the firm. The wheeled machines were all the rage, and advertisements under Shipley's name regularly appeared in the local paper. After 11 years of working for Mr. Smith, 22 year-old Harry struck out on his own in conjunction with another former co-worker, George S. C. Bopst (also buried here in Mount Olivet). This was 1897, and their new venture came to be known as Shipley and Bopst. Bicycles and motorcycles would be a specialty of the business, along with other sporting goods. They would eventually acquire the Temple of Fancy business name from David H. Smith when the latter left for another job opportunity in 1901. Eleven more years would pass in Harry’s life before another major “business” change. He bought out Bopst on January 1, 1909. From that point on, Shipley conducted the business under his own family name and would eventually be aided by sons Harry M. and Dorsey F. Shipley.  The Shipley Building located at 105 N. Market St. in Frederick houses Firestone's Culinary Tavern today The Shipley Building located at 105 N. Market St. in Frederick houses Firestone's Culinary Tavern today Harry F. Shipley was an active sportsman, fraternalist and ardent Democrat. His employment could definitely be called a “life’s work” for he spent 50 years at the same Frederick location. Well actually, there was a slight change of venue as Harry had erected a new building at 103-107 N. Market St., making it one of the largest stores of its kind in Maryland. The structure still bears his family name today on its upper brick façade, but is better known as the home to Firestone’s Restaurant. In keeping with tradition, I understand that Firestone’s official name is Firestone’s Culinary Tavern—certainly a much “fancier” moniker. In 1912, he signed an agreement to lease the first floor of the corner building next door at 101 North Market and West Church streets. He made major improvements to the structure including the large expanses of plate glass windows that still exist today, adorning the Tasting Room Restaurant. H. F. Shipley’s Temple of Fancy remained the "go-to" Christmas headquarters for decades to come. It was usually decorated for the latest holiday, and carried a wide variety of merchandise ranging from toys, athletic goods, radios, and notions. It was one of the first to carry phonographs and records. Harry remained active, and beloved in the community. The “family discount” on store items must have come in handy, as he had 15 children to buy for at Christmas. He was twice married, beginning at the ripe age of 20. His first wife was Fannie Easterday (1873-1915) and second Mary Cramer. The Shipleys resided at 416 N. Market St. in Downtown Frederick. Another member of this household was not a family member by blood, but by friendship, compassion and love. This was the widowed Sarah C. Railing. When learning that the lady who helped him get his first job (at age 11 in the grocery store) was down on her luck with no place to go, H.F. took her into his home in the 1890's. Ms. Railing would live with the Shipleys until her death in February, 1920 at the age of 93. Harry was a member of All Saints Church, belonged to the Junior Fire Company, No. 2, King David Lodge of the International Order of Odd Fellows, Sons of American Revolution, Frederick Lions Club (Charter Member), Frederick County Fish and Game Association and the Elks Club. “You better watch out You better not cry Better not pout I'm telling you why Santa Claus is coming to town” And so starts one of our nation’s most beloved and beholden Christmas songs, albeit a connection to commercial Christmas in nature. The tune’s overarching appeal is due to its incentive-laden, and mesmerizing, threat to children everywhere this special time of year. For that very reason, aside from the catchy hook, it has been a holiday favorite to parents as well as children since being first sung by Eddie Cantor on a radio show in November, 1934. Santa Claus continues to come to towns across the nation and world, and Frederick, Maryland is no different. I’m sure that there are several inhabitants of Mount Olivet who helped forge “Christmas Magic” for youngsters in our past. However, one is a bonafide certainty—Charles Edward Winpigler.

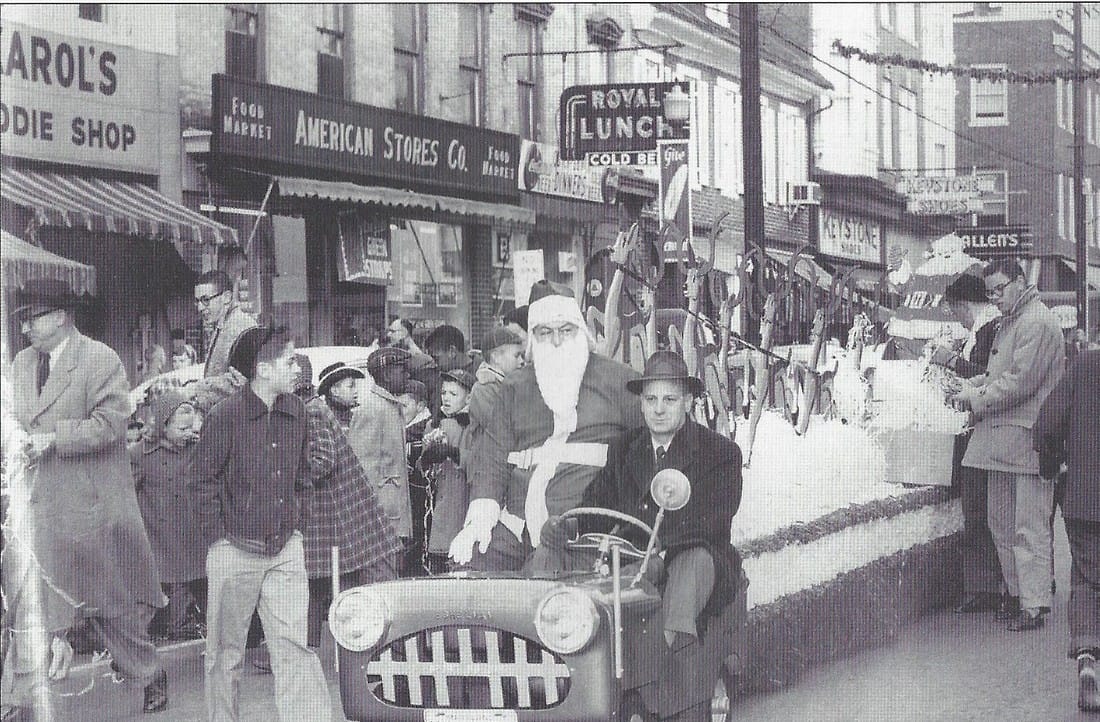

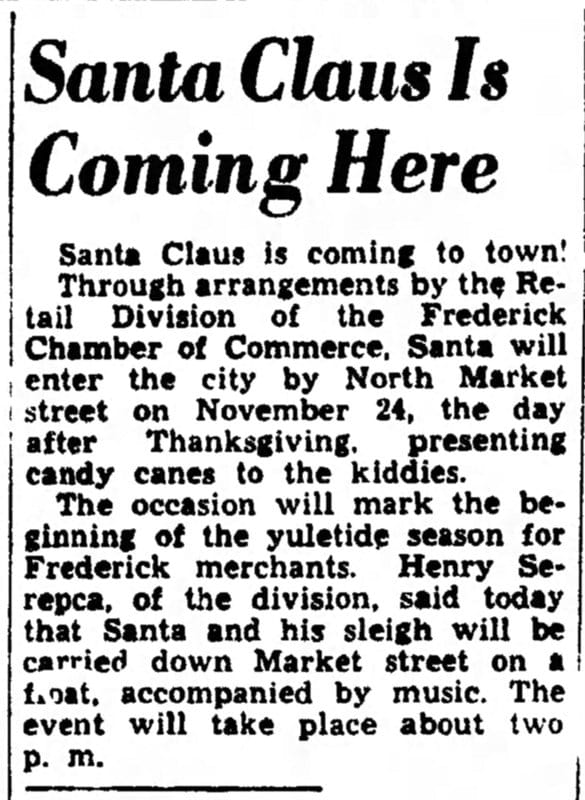

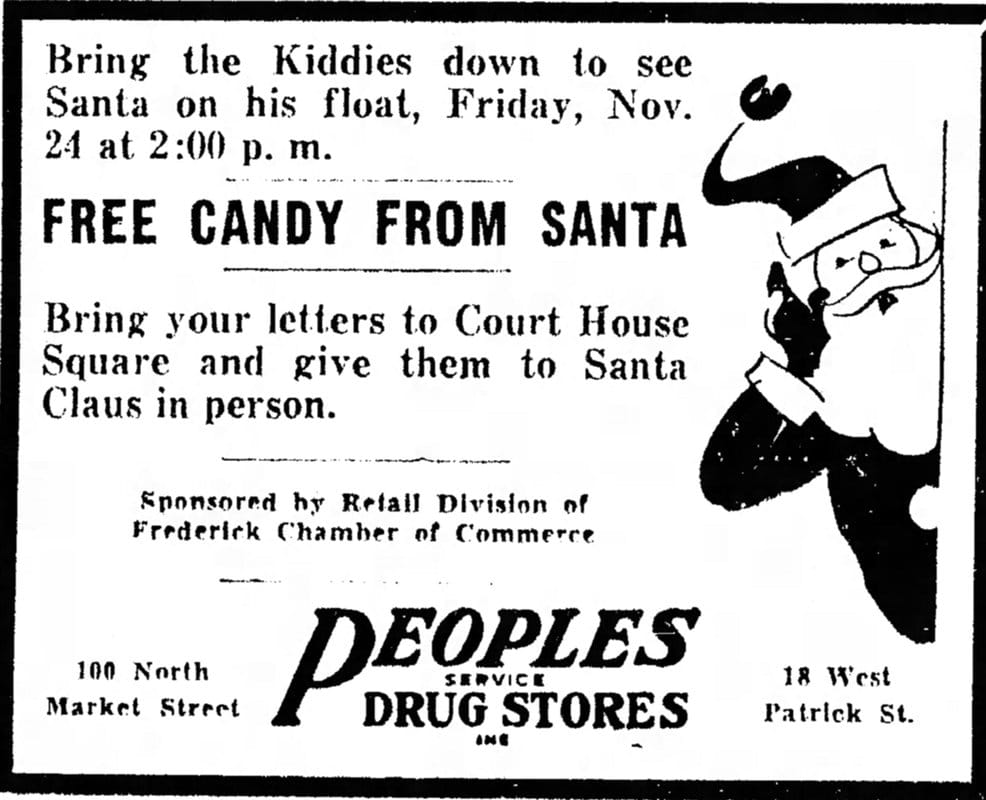

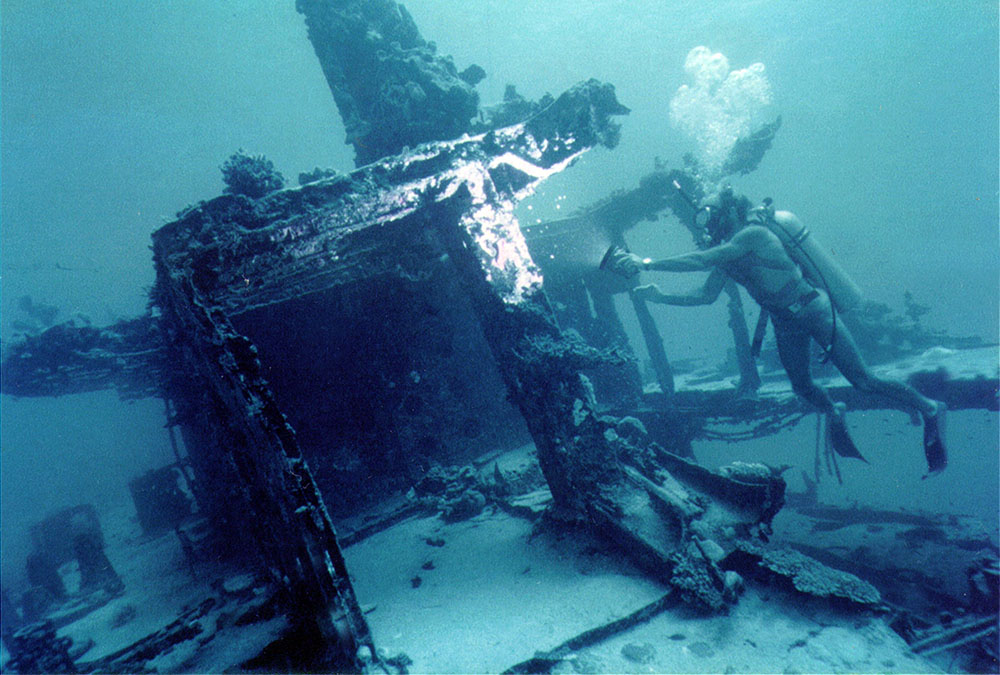

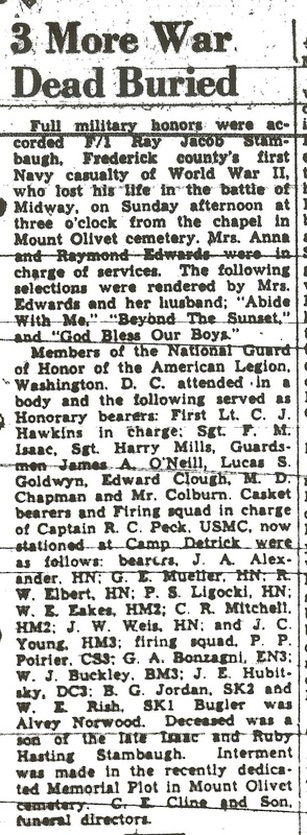

Local news articles from the 1950’s and 60’s talk of Mr. Winpigler’s, pardon, Mr. Santa Claus’ appearances at local civic club Christmas parties and merchant hostings. One of Ed’s earliest experiences came in late November, 1950 when the Frederick Chamber of Commerce brought Santa to town for a parade to kick-off the Christmas shopping season. The date was Friday, November 24, the day after Thanksgiving and Santa made the trip from the North Pole to North Market Street. He continued to proceed south on downtown Frederick’s main thoroughfare, before turning west on West All Saints Street and culminating at Court Square. Thousands of residents were in attendance and lined the street. “Santa’s sleigh” paused briefly at each block to hand out candy and collect Christmas “wish lists” from mesmerized boys and girls. Thus followed a great tradition for Frederick, the roots of today’s annual Kris Kringle Procession.  1955 image of Ed Winpigler's masterful portrayal 1955 image of Ed Winpigler's masterful portrayal Playing jolly “Ole Saint Nick” was a part well-tailored for a man rich in experience of “making his list, checking it twice and finding out who's naughty and nice.” This based on the fact that Ed Winpigler had 13 children (seven daughters and six sons) and 28 grandchildren. He would even boast 9 great-grandchildren at the time of his death. So what’s a few hundred more from the youth population of Frederick? An article from the January 19, 1961 edition the Frederick News recounted Mr. Santa Claus’ recent assignment with the Frederick Memorial Hospital’s Ladies Auxiliary: “…all ladies on the first and second floors of the hospital were given corsages left over from the Snow Ball. All floors were decorated at Christmas and Edward Winpigler as Santa Claus made rounds of every room giving appropriate gifts to each patient. The toys for the children were donated by Sears Roebuck and Co.”  Gravesite of Charles Edward Winpigler and wife Inez in Mount Olivet (Section EE lot 226) Gravesite of Charles Edward Winpigler and wife Inez in Mount Olivet (Section EE lot 226) Through his charitable service as Mr. Santa Claus, it’s safe to say that Ed Winpigler made an impression on kids—from one to ninety-two. C. Edward Winpigler would pass away 19 years later while at that same Frederick Memorial Hospital. However, he had held on to share and inspire holiday joy for family and friends for one last Christmas. He died one week later on New Year’s Eve, December 31st, 1979. If you have remembrances of Ed Winpigler, “Mr. Santa Claus,” or other “Santas” (interred at Mount Olivet Cemetery) please share with us in our comments section. We also can add additional photos to the story.  President Roosevelt addresses Congress President Roosevelt addresses Congress Seventy-five years ago, citizens of Frederick listened intently to radios as the following words were spoken by their defiant president, Franklin Delano Roosevelt as he addressed Congress and the nation on Monday, December 8, 1941: “Yesterday, December 7th, 1941—a date which will live in infamy—the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan. The United States was at peace with that nation and, at the solicitation of Japan, was still in conversation with its government and its emperor looking toward the maintenance of peace in the Pacific. Indeed, one hour after Japanese air squadrons had commenced bombing in the American island of Oahu, the Japanese ambassador to the United States and his colleague delivered to our Secretary of State a formal reply to a recent American message. And while this reply stated that it seemed useless to continue the existing diplomatic negotiations, it contained no threat or hint of war or of armed attack. It will be recorded that the distance of Hawaii from Japan makes it obvious that the attack was deliberately planned many days or even weeks ago. During the intervening time, the Japanese government has deliberately sought to deceive the United States by false statements and expressions of hope for continued peace. The attack yesterday on the Hawaiian islands has caused severe damage to American naval and military forces. I regret to tell you that very many American lives have been lost. In addition, American ships have been reported torpedoed on the high seas between San Francisco and Honolulu. Within an hour of this speech, Congress passed a formal declaration of war against Japan and officially brought the U.S. into World War II. Everyday life would be changed forever. And for many young men of the time, life would be cut drastically short on the seas and islands of the Pacific, battlefields of Europe and deserts of Africa among others.  Dedication of World War II Monument, May 30, 1948 Dedication of World War II Monument, May 30, 1948 As we commemorate this, the 75th anniversary of the bombing of Pearl Harbor, we reflect on those service men and women who put their lives on the line, specifically those connected to the Hawaiian Islands bombings. Over 200 soldiers, sailors and pilots from Frederick lost their lives in World War II. A monument to their memory lies within Mount Olivet Cemetery, originally dedicated on May 30, 1948. The double-columned monument, made of Indiana limestone, features a central obelisk containing the names of 219 individuals from all parts of Frederick County. Atop this pilaster is a sculpted eternal flame of gold, below which read: “The flame of love shall burn into our hearts the memory of our noble dead.” The remains of 30 veterans, who died in the line of duty, are buried in a semi-circular design around the monument, marked by flat, military issue stone markers. One of these slabs of marble rests over the body of Ray Jacob Stambaugh.  Jacob Stambaugh held the rank of fireman/first class Jacob Stambaugh held the rank of fireman/first class Jacob Stambaugh was serving at the United States naval base at Pearl Harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii Territory on the morning of December 7, 1941. Commencing at 7:48am (Hawaiian time), the base was attacked by 353 Imperial Japanese fighter planes and bombers launched from nearby aircraft carriers. Luckily, Jacob Stambaugh (fireman/1C) survived the assault without injury. He was stationed aboard the USS Tucker (DD-374), a Mahan-class destroyer assigned to the US Battle Fleet in San Diego, California that routinely operated along the West Coast and in the Hawaiian Islands. Stambaugh's ship had come to Pearl Harbor following a good will tour to New Zealand and was berthed at the East Loch of Pearl Harbor while undergoing overhaul. The ship did not receive much damage, as it was in the position however to shoot down four enemy planes that morning. Born March 17, 1921, Jacob Stambaugh was a native of Jimtown, near Thurmont. He was a former student and standout baseball player who attended the Buckingham School that once operated south of Buckeystown (today part of Claggett Center). He joined the Navy in 1939.  For the months following the Pearl Harbor disaster, Jacob Stambaugh saw duty in other parts of the Pacific. The USS Tucker escorted convoys between the West Coast and Hawaii. She then did escort work to American Samoa, the Fiji Islands, New Caledonia, and Espiritu Santo, New Hebrides. This latter island, today known as Vanuato, is where Stambaugh would lose his life. Newspaper accounts of the time reported that Stambaugh’s death was connected to the Battle of Midway which occurred in June of 1942. This wasn’t so. He was actually reported missing in action in early September, 1942. An article in the Frederick News and dated October 3rd, 1942 confirmed Stambaugh’s death at the age of 21 years of age. He would be the first World War II Naval casualty from Frederick County. I consulted our Mount Olivet records and found a notation in the file that Stambaugh was aboard the USS Tucker at the time of his death on August 4th, 1942, saying he died during the Battle of Midway. I questioned this and went online in search of the USS Tucker. I soon found the following account that documented an event that occurred on August 3, 1942 off the South Pacific island of New Hebrides: “The Tucker entered the harbor at Espiritu Santo's western entrance, leading the cargo ship SS Nira Luckenbach, unaware they had entered a minefield laid earlier by US Navy minelayers. After striking at least one mine, the destroyer was almost torn in two at the No. 1 stack, killing all three of the crew in the forward fireroom. The rest of the crew survived but Tucker did not. The destroyer slowly settled in the water and sank. An investigation revealed that the USS Tucker had not been given information about the existence of the minefield.” Jacob Stambaugh was one of the three men killed that fateful night. He was originally buried in the Espiritu Santo American Military Cemetery located on the US naval base located on the island. Six and-a-half years after his death, Ray Jacob Stambaugh would be repatriated and returned home to Frederick County (summer of 1948), just one week after the momentous dedication of Mount Olivet’s World War II monument. He goes down in the history books as the first WWII Naval casualty from Frederick County, and a lasting local connection to that “infamous day” in early December, 1941. Check out a touching YouTube video featuring vintage film made of a WWII military grave detail at Espiritu Santo Military Cemetery where Ray Jacob Stambaugh was first interred https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EnksOA4sSeM

|

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed