|

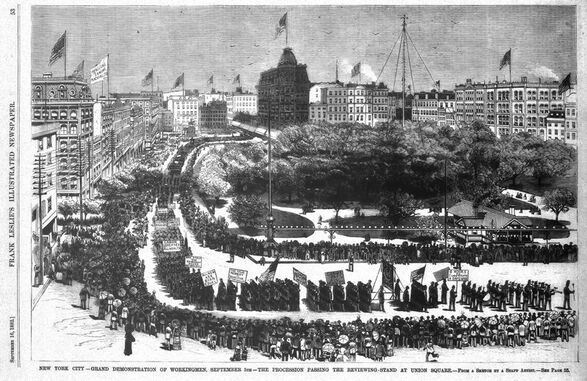

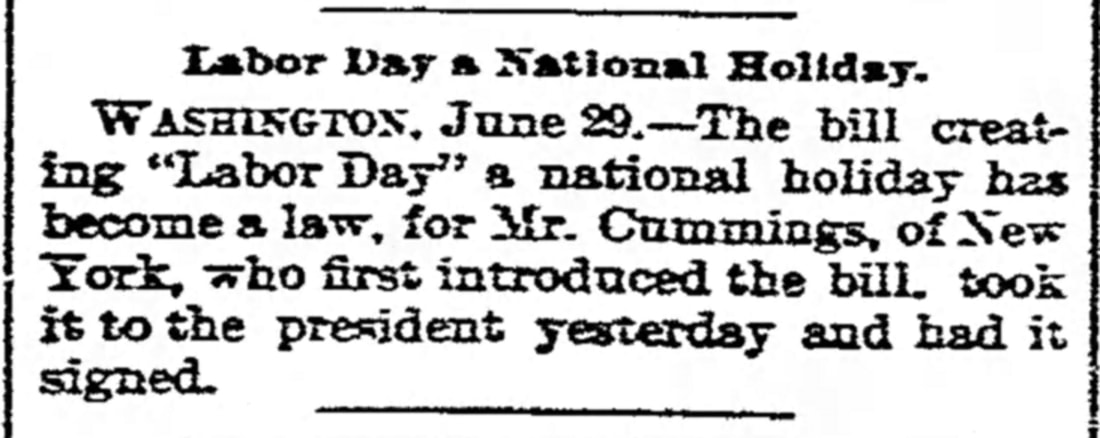

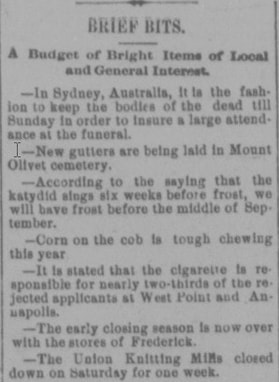

Labor Day, the public holiday celebrated annually on the first Monday in September, honors the American labor movement and the power of collective action by laborers—the lifeblood of the workings of our society. According to the Department of Labor's official description, “Labor Day is dedicated to the social and economic achievements of American workers, and constitutes a yearly national tribute to the contributions workers have made to the strength, prosperity, and well-being of our country." Of course, many folks these days have lost sight of the true meaning behind this day, simply because it sometimes gets lost as the depressing “pack-up” day of a long weekend (Labor Day Weekend). Worse yet, Labor Day sadly signals the "unofficial end of summer" as most annual family vacations have already been taken, and children are heading back to school. In addition, traditional fall activities and sports are set to soon commence, leaving behind the outdoor recreational opportunities such as picnics and amusement park visits afforded by warm, sunny weather. Here in our area, the temperature begins to cool at this time, and one of the major associations with summer is severely affected by the change of season—that of visiting the beach. It’s no wonder that the leading destination for Labor Day weekend involves ocean resorts. Naturally, this is due to the fact that a return of warmer weather (especially dictating higher temperatures suitable for ocean water swimming and sunbathing) will not come for another eight months. Let’s get back to the origin of the Labor Day holiday. Beginning in the late 19th century, the trade union and labor movements grew. Trade unionists proposed that a day be set aside to celebrate labor. In 1882, "Labor Day" was promoted by the Central Labor Union and the Knights of Labor, which organized and executed a parade in New York City. In 1887, Oregon became the first state of the United States to make Labor Day an official public holiday. I found a first mention of “Labor Day” in our local paper that same year, and in 1888, the September 4th edition of the Frederick Daily News carried several articles on its front page chronicling celebrations and parades held in major cities throughout the nation. It would eventually become an official federal holiday in 1894, and at this time, 30 states including Maryland officially celebrated Labor Day. Interestingly, the Frederick Daily News included the following brief, and seemingly sarcastic, remarks about the new holiday in an edition published by the firm and its staff of employees on Monday, September 3rd— Labor Day itself.

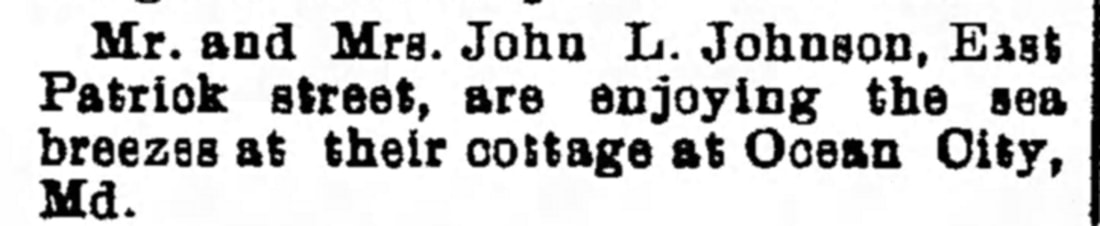

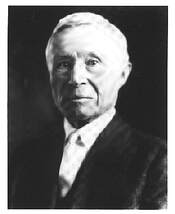

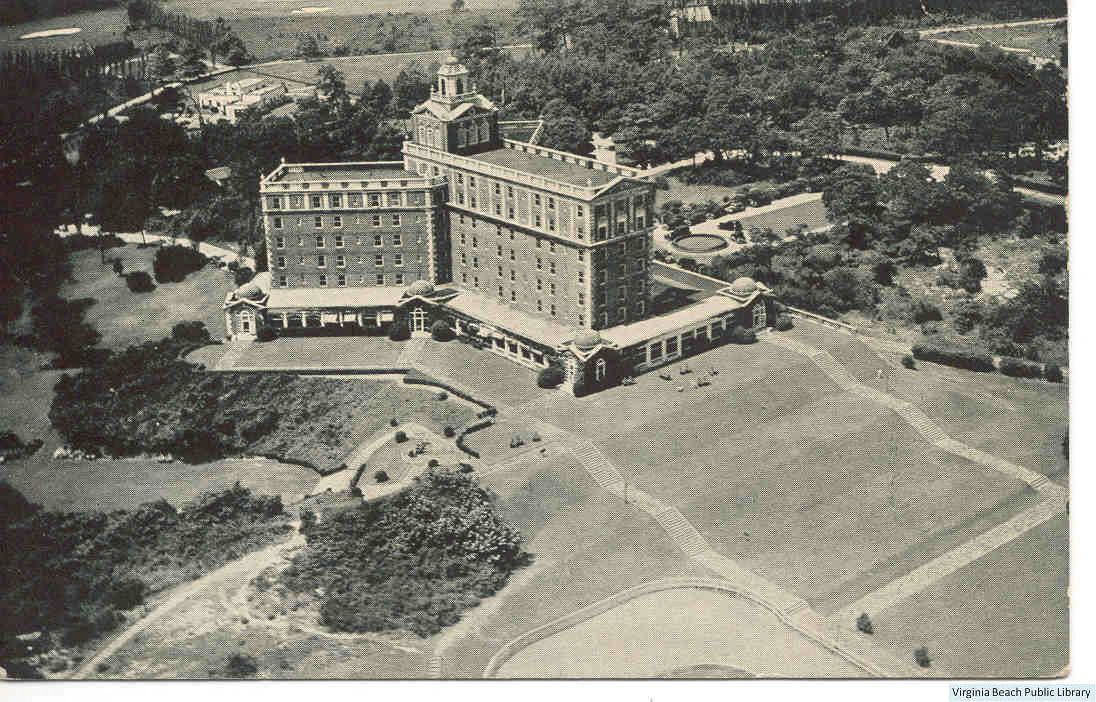

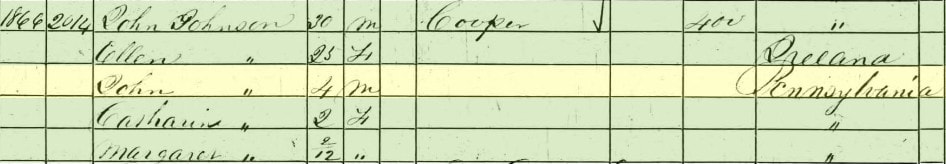

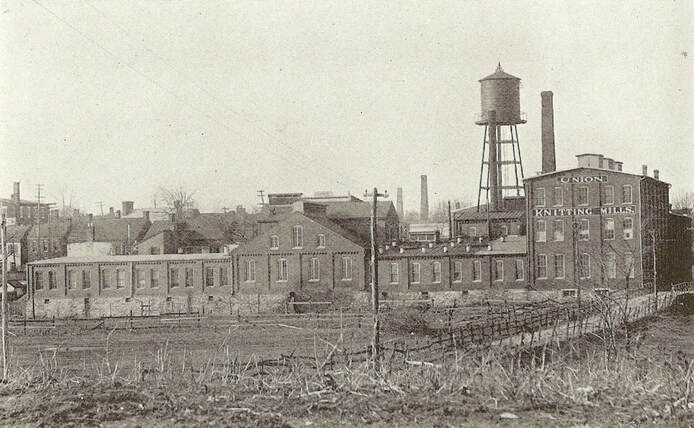

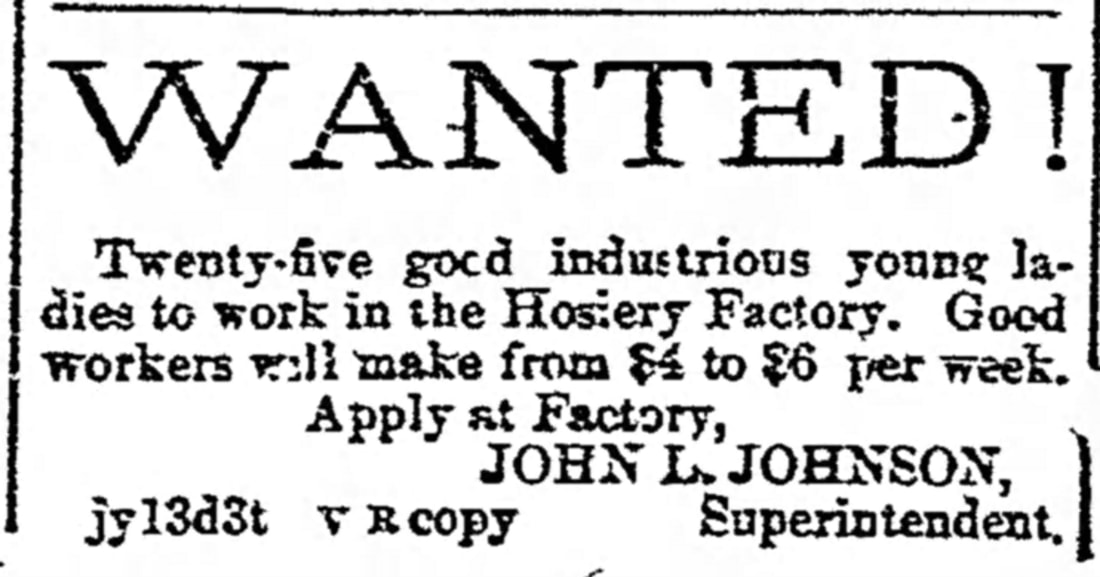

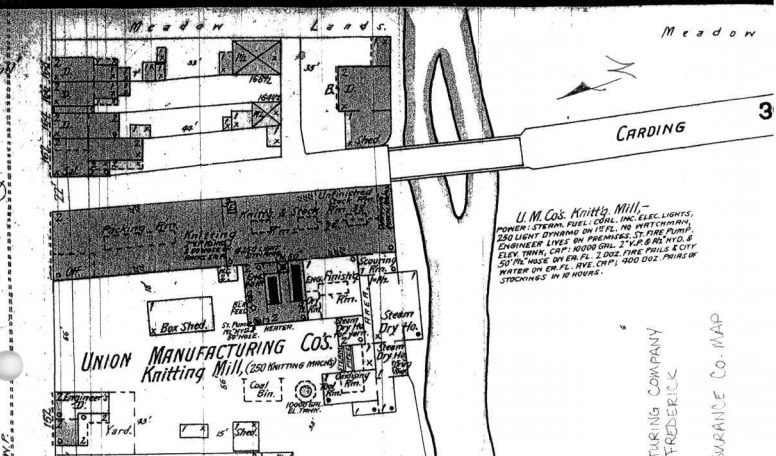

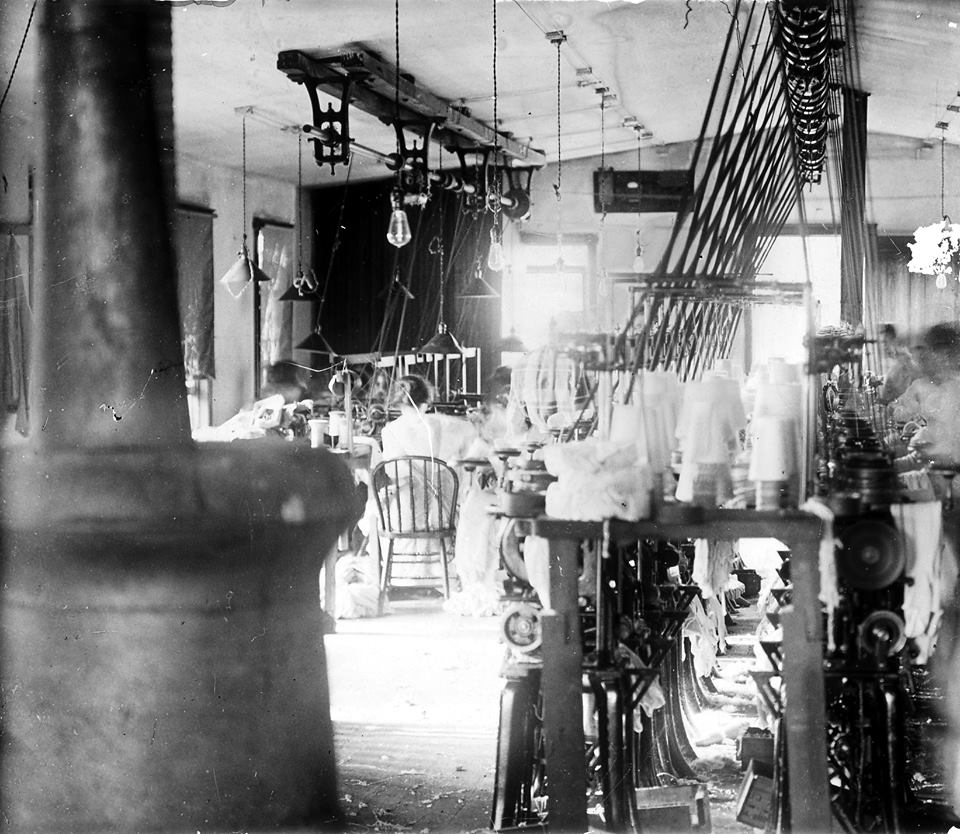

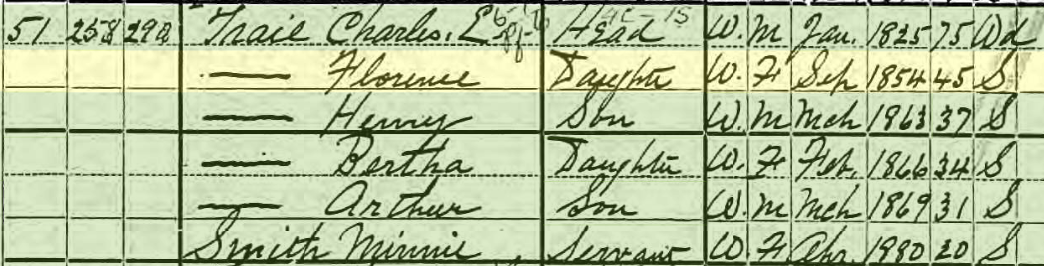

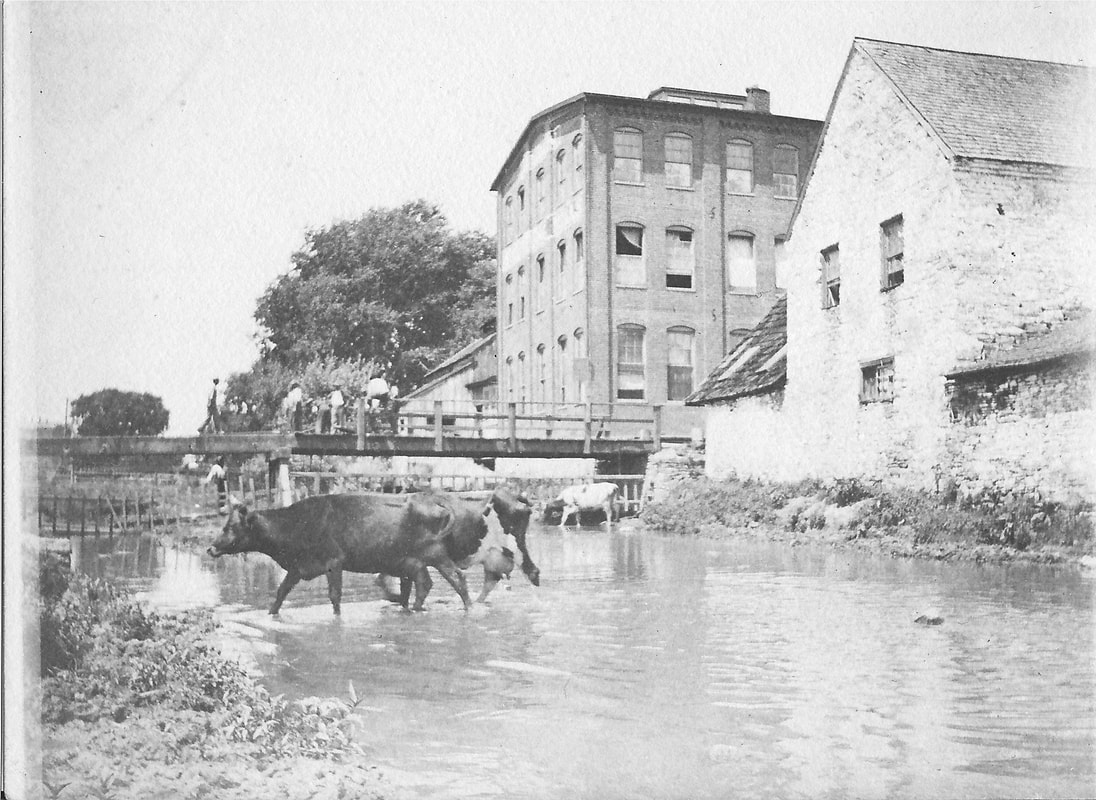

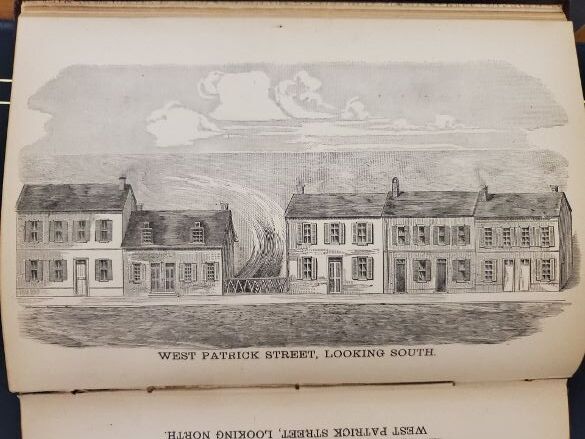

Now, for decades there had existed small-scale industries here in Frederick such as grain mills, canneries, tanneries, lumberyards and iron works, however the spirit of unionized labor was non-existent as opposed to its presence in the aforementioned cities in our region. One reason, I was told years ago, hinges on the fact that the founding families of town wanted to keep big industry out of Frederick, as exemplified by only allowing a train spur-line here coming up from Monocacy Junction. Now think about how the railroad influenced Baltimore, Hagerstown, Martinsburg and Cumberland, giving rise to more factories and industrial pursuits because of the transportation component? It did the same for Brunswick and Thurmont on a smaller scale, of course. In time, however, a shift away from the train to vehicular shipping (on a system of interstate highways) had serious negative consequences on the former places the railroad had transformed. Frederick, however remained virtually unscathed. I was excited to find several mentions of a local captain of industry who seemed to have made a ritual out of going to the beach around Labor Day weekend. His name was John L. Johnson and he was the managing superintendent of the Union Knitting Mill, formerly known as the Frederick Seamless Hosiery Company. Mr. Johnson would travel to the Maryland seashore regularly throughout summer, having built a beach cottage in old Ocean City, and came to own multiple farms on the Isle of Wight Bay in West Ocean City near Drum Point (north of the route 50 bridge). In fact, in that edition of the Frederick Daily News from September 3rd, 1894, I found John L. Johnson’s staff of employees had actually been given the week off. The irony of it all is that this industrial complex was one of the first, and only, large operations in Frederick’s history, and had come to have the word “Union” in its name. Of course at the time, “Union” had several meanings, but not “labor union,” which were the initiators behind the holiday of Labor Day. At the time, this particular company did not have an organized labor union, but decades later, calls for one, would serve as the undoing, or dare I say, un-stitching of the Union Knitting Mills—one of Frederick’s largest employers from 1887-1957. The Beachcombing Industrialist I have always had an incredible love of the beach, and am not alone. Stories of early industrialist who loved the shore have interested me as well. I have made trips to Jekyll Island, Georgia where the world’s wealthiest families vacationed— most notably the Morgans, Vanderbilts and Rockefellers. In fact, beer-brewing legend, Adolph Coors, escaped the Rockies and Colorado to spend time at Virginia Beach. Unfortunately, he chose to take his life here in June of 1929 by jumping out of a window of the Cavalier Hotel at which he was lodging. Thirteen years of the Prohibition had taken its toll on the legendary beer-maker from Germany. John Llewellyn Johnson just plain loved the ocean. He was one of the leading citizens of our town at the turn of the 19th century. He not only made an impact here in western Maryland, but also played a role in the early development of Maryland’s pride of the eastern shore, the aforementioned Ocean City. John L. Johnson had no connection to the Frederick family connected to our state’s first governor. He was born just a few days prior to the summer solstice, on June 18th, 1856 in Philadelphia. His father, John Porter Johnson, was a cooper by trade and veteran of the Civil War. John’s mother was a woman named Ellen Gillmore Johnson, and like her husband, is said to have come from old families associated with New Jersey. I learned from John L. Johnson’s biography found in Volume II of Williams & McKinsey’s "History of Frederick County, MD" (1910) that the one-day Frederick resident had grown up in “the City of Brotherly Love.” Apparently, he was sent to Massachusetts in his youth and learned knitting in a knitting mill under his uncle. Upon reaching adulthood, John went to Bristol, PA at which place he took charge of the aptly named Bristol Knitting Mills. After some time, Johnson returned to Philadelphia and worked under the employ of Blood Brothers as an overseer. Later, he would be employed by E. Sutro & Company. His next career move would come in 1887, at which time he would be brought to Frederick, Maryland to head an endeavor concocted by some of the towns leading business entrepreneurs. This was the Frederick Seamless Hosiery Company. The following narrative can be found online as part of the Maryland Historical Trust inventory of historic properties (NO FHD-1300): The Frederick Seamless Hosiery was founded in 1887 by five Frederick businessmen, David Lowenstein, Thomas H. Haller, John Baumgardner, George H. Zimmerman, and M.E.Getzendanner with $5,000 in capital. It was first established in the four-story Etchison building at 34-36 East Patrick Street and the primary product was men's half hose. Soon the business outgrew the building and in 1888 the partners bought the site of the former Vulcan Iron Works at 340 East Patrick Street and began building a new factory. In 1889, the Frederick Seamless Hosiery was reorganized and renamed The Union Manufacturing Company and took up residence in the newly constructed building.

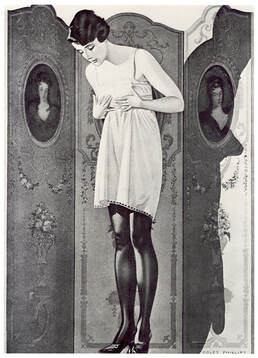

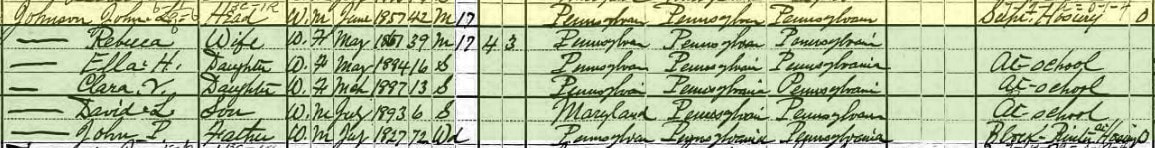

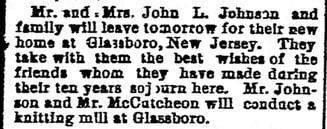

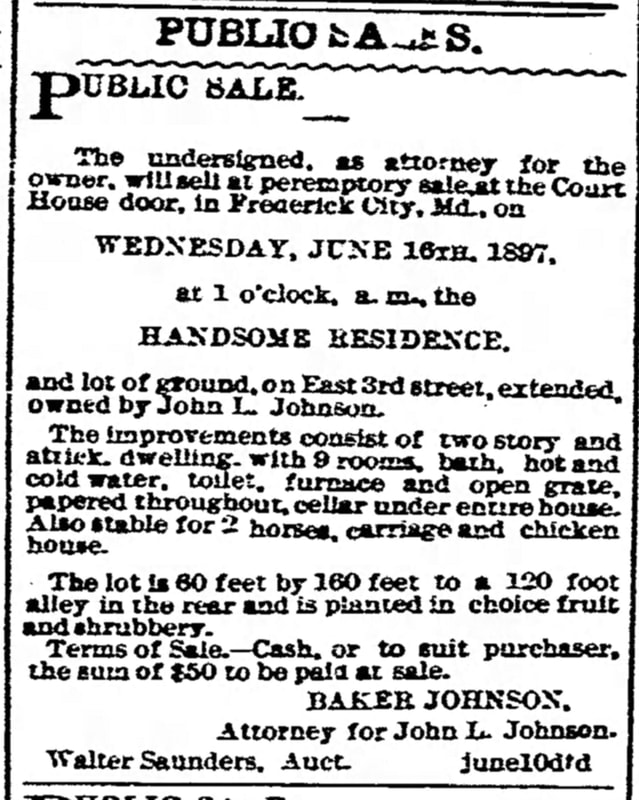

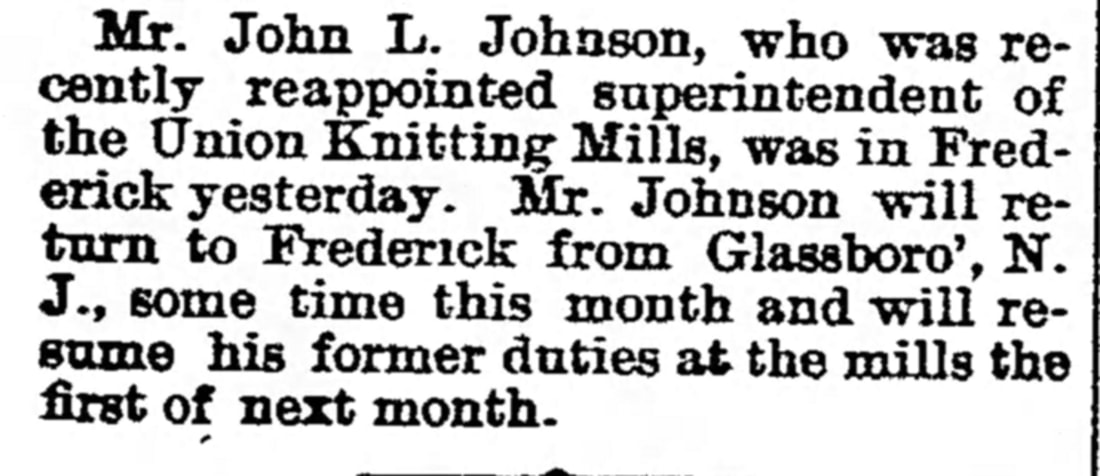

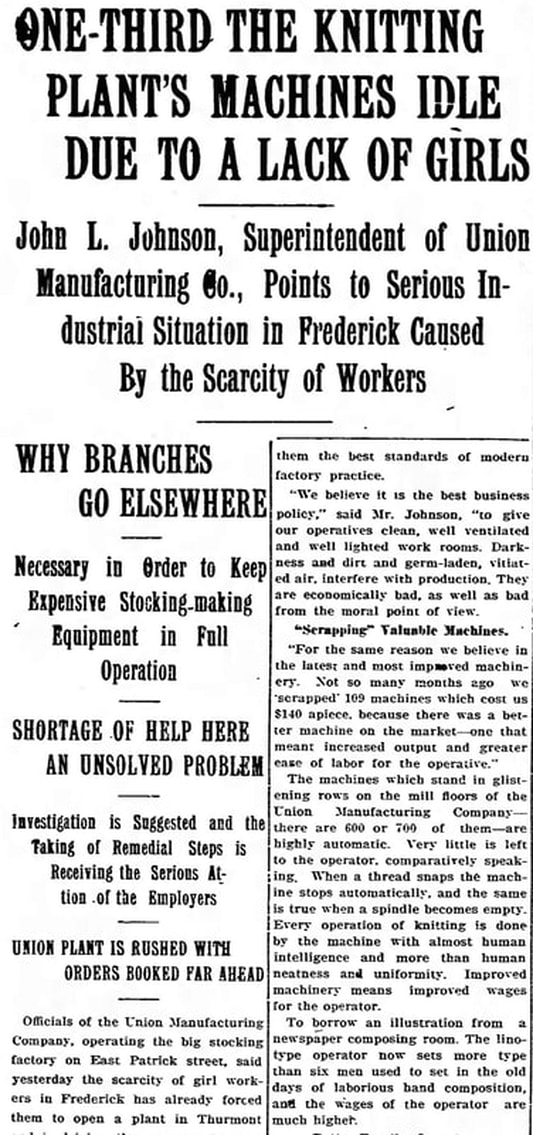

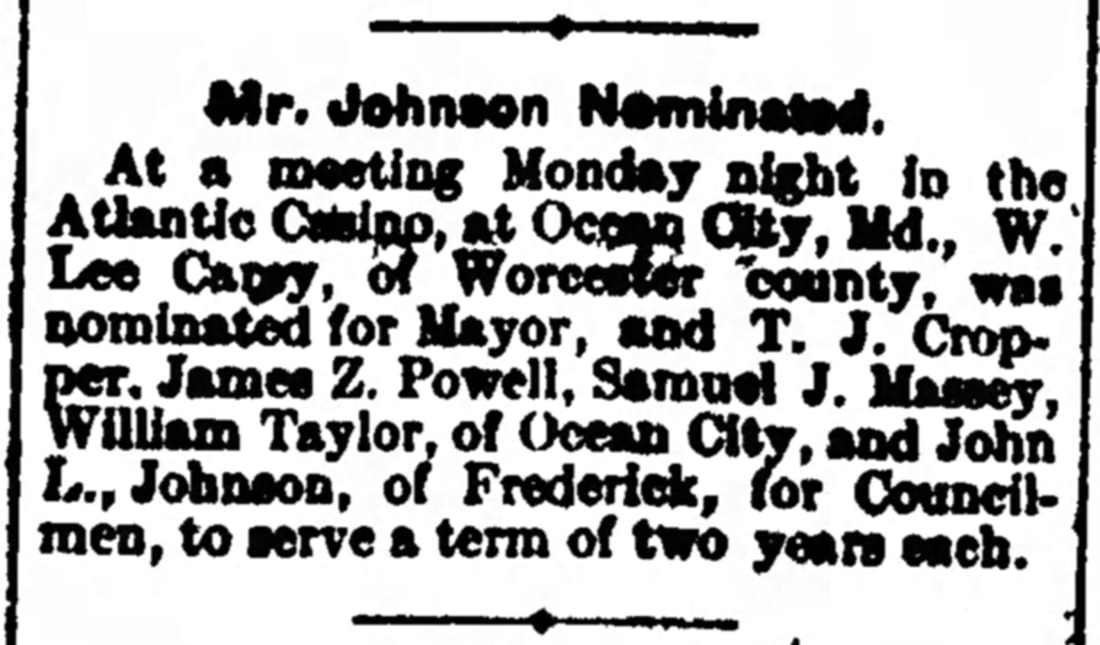

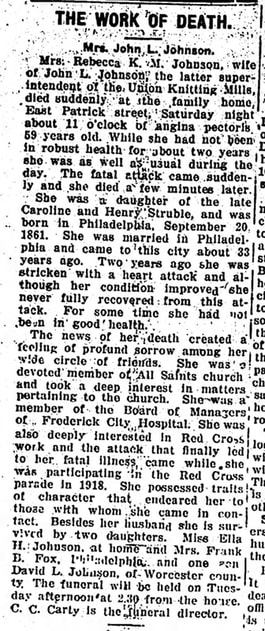

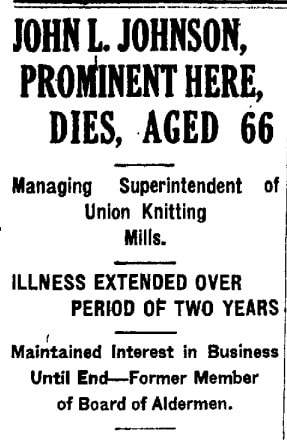

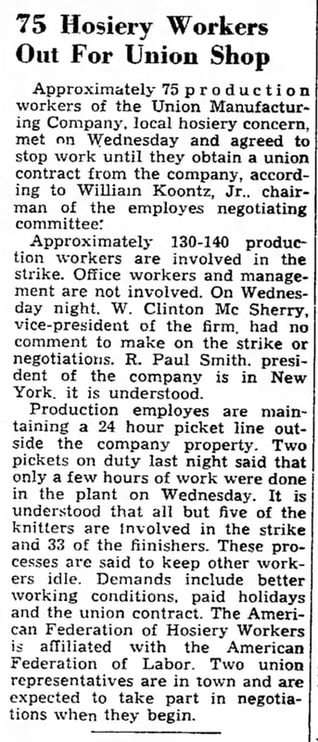

As previously stated, John L. Johnson was made managing superintendent of the firm, and also became a shareholder. The Williams & McKinsey History of Frederick states that “much of the success achieved is due to the great ability with which Mr. Johnson has discharged the duties devolving upon him.” The biography goes on to say: “He has been engaged in the knitting business all his life, and has thoroughly mastered all the details of that industry. He is strictly a self-made man, and owes his success in life to close application to business, and to his sober, temperate habits. Mr. Johnson has not given all his time to the knitting business, but has been active along other lines. He has always been a stanch supporter of the Republican party and, at the municipal elections in June, 1910, was chosen a member of the board of Alderman of Frederick City which is strongly Democratic. Fraternally, he is a member of Columbia Lodge, No. 58, A.F. and A.M.; Enoch Royal Arch Chapter, No. 23; Jacques De Molay Commandery, No. 4, Knights Templar, of Frederick; LuLu Mystic Shrine, of Philadelphia; Frederick Lodge No. 684, Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks; the Manufacturers Club of Philadelphia; and the Sons of the American Revolution. John L. Johnson was married to Rebecca Kay Maree Struble, of Philadelphia, Pa. They have three children: Ella H., Clara V., and David L. In religion, he is a member of the Episcopal Church. On their move from Philadelphia, the Johnson family first took up residence on a lot sold to them by business partner David Lowenstein. This was on East Third Street extended. Interestingly, I found news clippings that reported that Mr. Johnson had actually left Frederick with his family in 1897 and moved to Glassboro, NJ, where he and a partner opened a like-knitting operation to the Union Knitting Mills. During the spring of 1897, the Glassboro factory opened with twenty new machines and it’s said the female workers became very efficient with the machines. The factory did well and even gave their employees a week paid vacation, which at the time was very rare. This was a trademark of John L. Johnson's management style.  Wm O. McCutcheon (1858-1952) Wm O. McCutcheon (1858-1952) Ironically, the partner was destined to make a name for himself in the annals of Frederick manufacturing history, but not in the production of clothing but in the realm of canning, but would not occur until the late 1930s. He was Johnson’s brother-in-law, the husband of his wife’s sister, Annie. His name was William Oscar McCutcheon, also a native of Philadelphia and an experienced stocking weaver. A few years prior, Mr. and Mrs. Johnson encouraged the McCutcheons to move to Frederick and put William's talents to work for the Union Knitting Mills. Both families would leave for Jersey, but would eventually return to the town of clustered spires.  McCutcheon's Apple Press McCutcheon's Apple Press John L. Johnson came back in 1899 and took up residence on E. Patrick St. Mr. McCutcheon and family moved to Barnesville, Ohio where he managed a knitting mill there. The McCutcheons would return to Frederick where William managed the Colt-Dixon Canning Company for decades. In 1938, he would locate a used apple cider press on Wisner Street, exactly across from the Union Knitting Mills. Here, along with his son Robert and daughter in law Helen, he would found what would become McCutcheon Apple Products, an operation that continues to thrive today, generations later. The first decade of the new century saw measured growth under Johnson's leadership, however problems would arise at the beginning of the second decade. In particular, 1911 and 1912 would be trying times as Johnson and the knitting operation experienced a shortage of workers. This prompted the company to establish satellite operations of the Union Knitting Mills in Emmitsburg and Thurmont. Johnson's Personal Life A good manager always makes time to “recharge” his or her batteries by partaking in times of rest and relaxation. Mr. Johnson made countless trips to Ocean City. He also seems to have encouraged co-management and other Frederick business leaders to do the same as I found many clippings of the Johnsons entertaining guests at their beach cottage. I also presume that Johnson had a hand in designing the annual beach outings for the Union Company’s employees. A lasting tradition included an annual trip to Tolchester Beach on the eastern shore of the Chesapeake, located west of Chestertown in Kent County. Johnson spent enough time in Worcester County as to have been elected to the city council of Ocean City in 1908. In previous years he had been part of a board which planned the building of the famed Ocean City pier. This project was completed in 1907 and had a major effect in encouraging visitors and business to the beach resort. Rebecca Johnson died in 1920. Like her husband, she had also served her community well as one of the early Board of Managers of the Frederick City Hospital. Mr. Johnson had her buried in a lot located in Area Q (`Lot 182). Here, the Johnsons had earlier buried an infant son (John Llewellyn Johnson, Jr.) in 1892, and John's father in 1905. John L. Johnson found himself in poor health at the time of Rebecca’s death. He was diagnosed with cancer and underwent progressive treatments for the day including radium treatments. He died at home a week after celebrating his 66th birthday on June 27th, 1922. His body would be laid to rest in Mount Olivet two days later. The Legacy of Union Manufacturing And what became of the company Johnson labored for over a 35 year period? We can return to the Maryland Historical Trust report for the proverbial “rest of the story:” As the Great Depression set-in, the knitting mill found itself in good stead having purchased new rayon knitting machines. By 1935, rayon stockings with the seam running up the back of the leg were becoming the fashion so the factory continued to prosper and the building expanded to keep pace. Then, in 1937, Dupont Industries successfully developed nylon thread. The Union Manufacturing Company had been a good customer of Dupont's in the past and was offered a chance to experiment with the new fiber that same year. After several days of trial and error, in the spring of 1937, the Union Manufacturing Company produced the first nylon stocking in the world. The new stocking was a hit and soon the knitting mill was turning out over one million pairs of women's stockings annually. Hose from the Union knitting mill was being sold all over the world under the brand names of Wonder Hose and Ever Wear. Unfortunately, the success did not last. Following World War II, fashions changed again and the seamless variety of stocking was back in style. The company was caught unprepared, they did not have the machinery to produce the new kind of hose. Business dropped off and workers were let go and hours cut back. In 1959 the Union Manufacturing Company and another local business, the Everedy Company, merged to form the Union-Everedy Co. After the merger, Union stopped making hosiery, and the knitting machines were sold. In 1962, Meadows Van and Storage purchased the building  A fuller picture of the demise of the company in the 1950’s can be found in a wonderful history compiled in 1997 by authors Joseph Ford, Lynne Wells and Melissa Conroy and entitled: "The History of the Union Manufacturing Company from 1887 to 1957" and published by Fredericktowne Printing and Graphics. The authors say that there was “an external force that caused the tensions to erupt. In 1952, the American Federation of Hosiery workers approached the workers and attempted to organize them. ‘The salesmen told us they could sell hosiery if it had a union label,’ said (former employee ) Mrs. Grace Baker. It made sense to some of the workers, who believed that the company work conditions were due to decreased profitability arising from the inability to market the factory’s hosiery. Yes, it made little sense to the management who still believed they were doing the community a favor by continuing business in spite of decreased profitability. The tension between management and the workers came as a surprise to many who had seen the relationship between the two in a positive light. A Norwegian visiting the factory had once commented, ‘The most striking feature about American manufacturing is its mass production and the second thing is the relationship between people in the mill…you can’t have high efficiency without the relationship…This cooperative spirit between management and labor is really outstanding here.’  John Lewelynn Johnson can be credited with setting the early tone for this endeavor and creating a corporate culture that bred efficiency and high quality of product. Things turned turbulent in March, 1952, thirty years after Johnson’s death. Employees went on strike, one of the first work demonstrations in Frederick’s history, not to mention one of the largest. This also created a problem for the city as 27 police officers had to be assigned to the scene, culminating with the mayor requesting that the Union Manufacturing Company’s management close down the plant until the strike was settled. The strike is said to have ended quietly, but the damage had been done as the relationship between management and laborers would never be the same afterwards. The company limped forward for another seven years, however the end came to producing hosiery in mid August of 1959. Employees helped pack up the machines and after a 72-year run in stockings (pun intended), the knitting operation John L. Johnson helped built went quiet. Labor Day and the Union Knitting Mills no longer were connected.

2 Comments

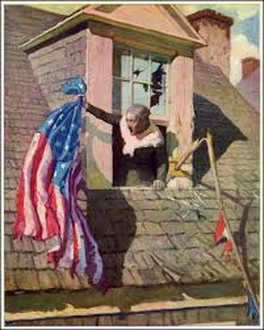

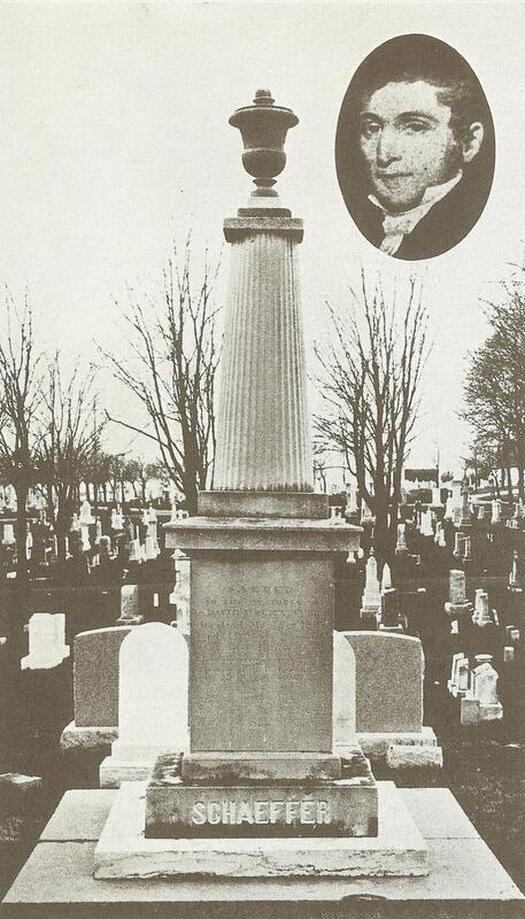

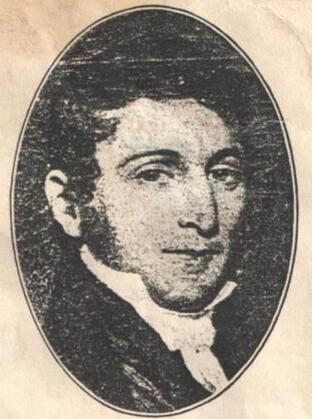

“Listen, my children, and you shall hear Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere, On the eighteenth of April, in Seventy-Five: Hardly a man is now alive Who remembers that famous day and year. He said to his friend, “If the British march By land or sea from the town to-night, Hang a lantern aloft in the belfry-arch Of the North-Church-tower, as a signal-light,– One if by land, and two if by sea; And I on the opposite shore will be, Ready to ride and spread the alarm Through every Middlesex village and farm, For the country-folk to be up and to arm. Many of us grew up with this poem, the work of fireside poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow more than a century and a half ago. But, does anyone know of an impressive “ride” that occurred here in Frederick, Maryland on the twenty-fifth of August, in 1814? “Paul Revere’s Ride” was written in 1860 on the eve of the American Civil War, first appearing in The Atlantic Monthly Magazine. Interestingly, and possibly by design, a friend and fellow poet from Massachusetts named John Greenleaf Whittier would have a similar work published in The Atlantic just three years later. As Longfellow made a household name out of Boston silversmith Paul Revere, Whittier did the same with a former resident of our fair city of Frederick—her name was Barbara Fritchie. However, in both cases, fame did not come to either subject until after their respective deaths. A bit of embellishment had been employed. You see, there is this thing called “poetic license,” which is defined as: the freedom to depart from the facts of a matter or from the conventional rules of language when speaking or writing in order to create an effect. And who best to demonstrate poetic license than Longfellow and Whittier—poets themselves!  William Dawes, Jr. William Dawes, Jr. Sadly, two other individuals, William Dawes, Jr. (1745-1799) of Boston and Mary Quantrill (1824-1879) of Frederick, never made the history books, while their counterparts have been “revered” for over a century and a half. Thanks again go to Wadsworth and Whittier. Hey, I just want to make it clear that I’m not here to challenge the patriotism of Paul or Barbara. Mr. Revere demonstrated his loyalty to the Sons of Liberty, and Dame Fritchie to the Union. Both poems (“Paul Revere’s Ride” and “The Ballad of Barbara Frietchie” made major impacts on our cultural identity as a country and explore the spirit of the civilian population in respect to our American Revolution and Civil War.  Today, Barbara Fritchie rests in peace within the confines of Mount Olivet, her grave topped by an impressive monument with Whittier’s poem etched on a bronze tablet. Nearly 80 or so yards to the north is another impressive monument marking the gravesite that of a local minister that old Dame Fritchie surely knew. He did not preach at her particular church (German Reformed), but was instead connected to Frederick’s Lutheran congregation. His name was David Frederick Schaeffer. Although this name doesn’t conjure up patriotism and the vision of flag-waving among lifelong Fredericktonians, one could make the case that Rev. Schaeffer could be considered our town’s “Paul Revere.” Rev. Schaeffer David Frederick Schaeffer was born in Carlisle, Pennsylvania on July 22nd, 1787. His parents were Frederick David Schaeffer and Rosina Rosenmiller, both German immigrants. His father was a Lutheran clergyman, as were his brothers Frederick Christian, Charles Frederick, and Frederick Solomon. As you can see, this family had a penchant for “Frederick,” through and through! By the way, I recently learned that the name Frederick is said to mean “peaceful.” Our subject spent much of his youth in Germantown, PA, once located northwest of Philadelphia, but today encompassed by “the City of Brotherly Love.” David graduated from the University of Pennsylvania in 1807, where he studied theology with Justus Henry Christian Helmuth, John Frederick Schmidt, and his own father. Young Schaeffer was ordained by the Pennsylvania Ministerium in 1812, although he had received his license to preach earlier in 1808. On July 17th of that same year (of 1808), Schaeffer became pastor of Frederick, Maryland’s Evangelical Lutheran congregation. Five days after his arrival, he would celebrate his 21st birthday.  The young minister came into a situation in which the congregation, for the most part, had experienced an adversarial relationship with their former, permanent pastor, a Rev. Frederick William Jaminsky. Jaminsky served from 1802 until July, 1807 at which time he honorably resigned his charge. An illustration of Schaeffer’s pastorate in Frederick can be gleaned from a book titled “A History of the Evangelical Lutheran Church: 250 years 1738-1988,” written by Abdel Ross Wentz and Francis E. Reinberger: If the Synod could now fill its own order and supply Frederick with a “peace-loving and capable pious pastor” there was every reason to expect that the church would share that enthusiasm for progress that was now beginning to mark the American nation as a whole and to lead it out into larger undertakings in the name of Jehovah….The period of waiting was over. The time of short pastorates was past. A long constructive period. The Frederick church, like the nation in general, was about to enter upon a new stage of its history. This new era in the life of the American nation covered the first forty years in the nineteenth century. It was marked by the rapid growth of patriotism and the national spirit. It severed the bonds that tied the Americans to their European masters, and it gave them independence in fact as the Revolutionary War had given them independence in name. This development of a new American culture applied not only to politics but to the religious and intellectual life as well. It enlarged the vision of individual Christians and it pushed back the horizons of the Churches as bodies. It led the Churches to face squarely the vast practical Christian tasks presented by the sudden territorial expansion and rapid numerical growth of the nation. This new temper of the times helps explain the general trend of events in the Frederick Lutheran Church during the period.” Rev. Schaeffer would prove a perfect match for the town, and county, that shared his middle name. He is said to have “entered his field with enthusiasm,” and possessed “an attractive personality, for he was well educated, trained in the courtesies and properties of life, tall and sturdy. His clear strong voice was a special asset in the pulpit. He had the dignified bearing of a clergyman and the natural grace of a gentleman. Even in his youth he never lacked poise. His unfailing kindliness of disposition attracted to him people of all stations and ages.” One such who was attracted to Rev. Schaeffer was Elizabeth Krebs of Philadelphia, whom he married in the year 1810. The couple would go on to have six children.

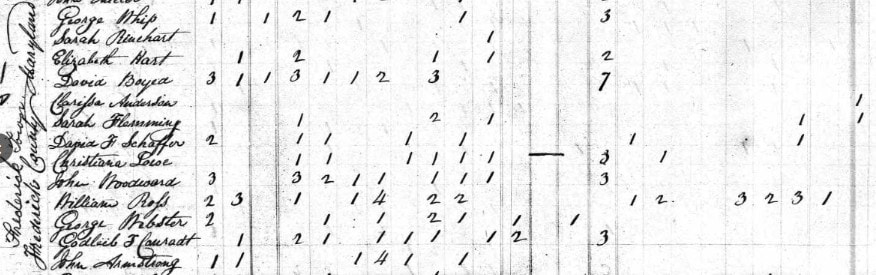

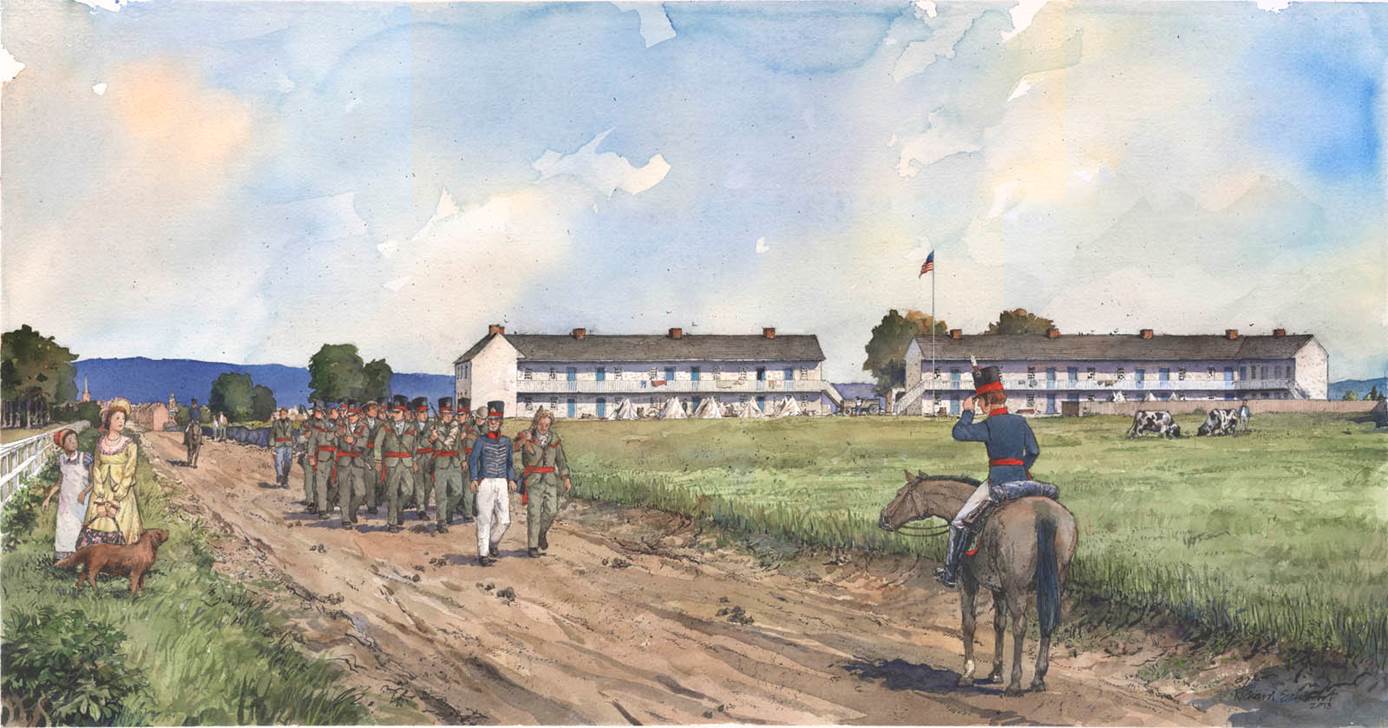

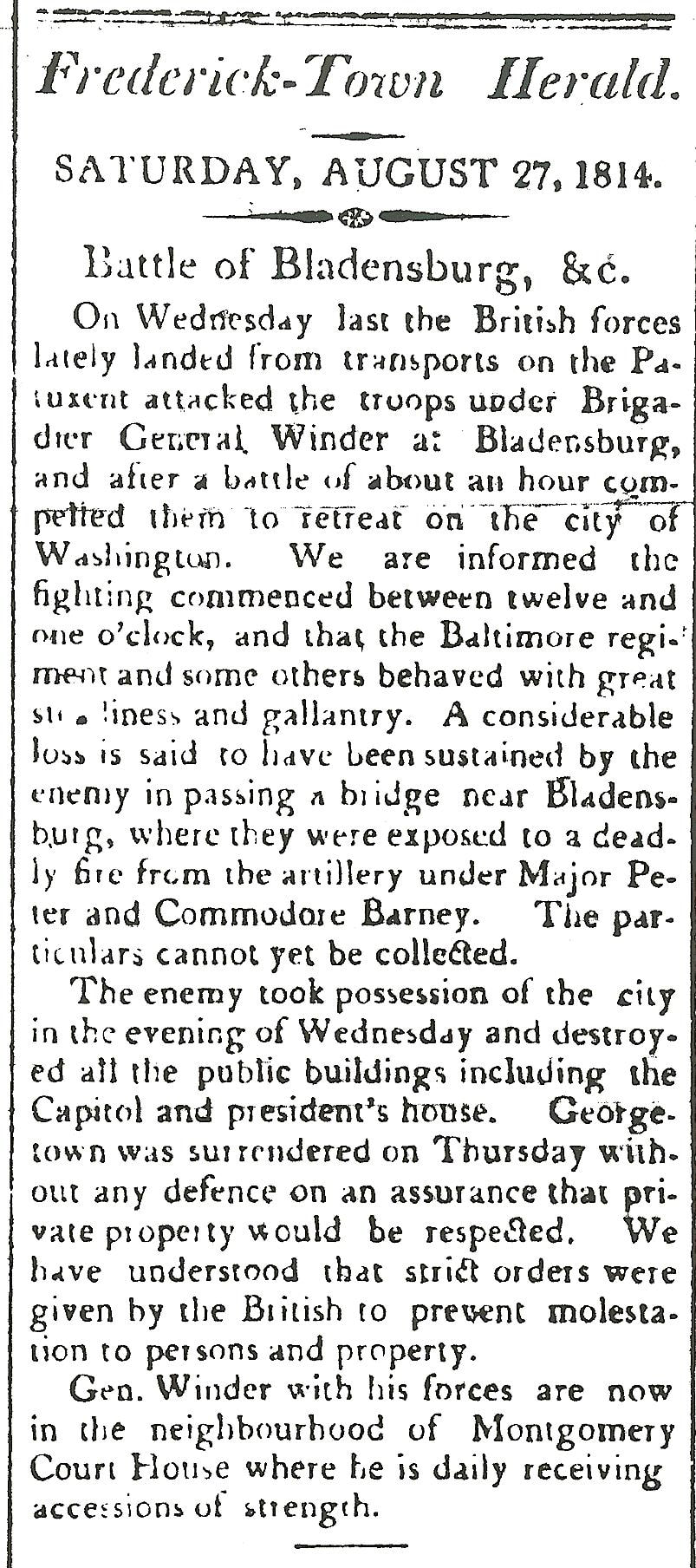

“The Perilous Fight” The winds of war were swirling shortly after David Schaeffer’s arrival here in Frederick. Great Britain was certainly “stirring the pot” of antagonism, but no one anticipated the fact that things would eventually escalate into a "Second War of Independence,” lasting from 1812 to 1815. One of the major issues during the first decade of the 19th century featured the practice of "impressment" on the high seas. This involved forcing men to serve in the armed forces through violence. The British Royal Navy vigorously practiced this method of replacing its sailors by taking United States citizens from American ships—not cool. In addition, Britain was also making attempts to limit American trade with France (with whom Britain was currently at war). This caused tensions to eventually boil over into a declaration of war by the United States in June, 1812. Battles between the two countries (and their respective Native-American allies) were primarily fought on the U.S.-Canadian border over the first two years of the war. This included locations such as Detroit and Niagara, as Canada was then a British territory. At least one bright highlight was the capture (and subsequent burning) of the major town of York in Ontario, Canada by US forces. We know this place today as Toronto. All the while, the United States did not have much of a major standing army at the time. Across the country, local men would be asked to comprise companies in an effort to form and bolster state militias. Frederick was no exception, as the Secretary of War demanded that quotas be filled for the defense and protection of major towns such as Baltimore and the state capital of Annapolis in our case. One of our local commanders included Major Ezra Mantz. He, in turn, had two local brothers, part of one of the town’s founding families. Captain Stephen Steiner oversaw a company of infantry and Captain Henry Steiner oversaw a company of artillery. A frequent place of military activity was the Frederick (Hessian) Barracks (today's site of the Maryland School for the Deaf). Here, troops would be mustered and take part in drilling and other training exercises. Outside of that, things were relatively quiet in the mid-Atlantic region and these citizen soldiers had ample opportunity to tend to their crops and respective trades as the war raged on elsewhere. That would all change in early 1814. Napoleon Bonaparte and his French Army would be defeated by spring, allowing the British to turn more of their attention to the United States. In mid-August of 1814, the British sailed up the Chesapeake Bay and disembarked on Maryland’s western shore at Benedict with the goal of capturing Washington, DC. This occurred on August 19th and the entire region was thrown into a full state of alarm and panic as you could imagine. The state militia scrambled to defend the nation’s capital and met the enemy at Bladensburg on Wednesday, August 24th. One such participant was Francis Scott Key, a lawyer who once dreamed of becoming a minister. During the battle, Key was living in Georgetown and served as an aide for the District of Columbia’s militia commander. The Battle of Bladensburg resulted in an embarrassing defeat of American forces under General William Winder. The blunder allowed the British Army to subsequently march into nearby Washington DC and set fire to public buildings, including the presidential mansion (later to be rebuilt and renamed as the White House) and Capitol over August 24th and 25th. Worse yet, this act of war was primarily performed in retaliation for the earlier torching of York (Toronto) by the United States. This had a major effect on American morale as the British had succeeded in destroying the very symbols of American democracy and spirit. At this moment in late August, 1814, the British sought to swiftly end the war, and with it, the “American Independence” that was first declared back on July 4th, 1776. As you can imagine, excitement was heightened here at home when news of the defeat and destruction reached Frederick. Our standing militia companies departed for Bladensburg and Washington on Thursday, August 25th under the leadership of the previously mentioned Capt. Henry Steiner, and another officer named George Washington Ent. Unfortunately, we had no mayor at the time for guidance or moral support as Frederick Town had not quite been incorporated, an event that would occur in 1817. So, you can guess who residents now turned to for guidance and support since our key military leaders were rushing toward the scenes of battle? That’s right—the local clergy. Now 27 years old, Rev. Schaeffer had “commanded” the respect of not only his Lutheran flock, but many other residents of Frederick.  Jacob Engelbrecht Jacob Engelbrecht We can get a feel for the mood of the day from two written accounts—one found in the local newspaper of the day and the other from our esteemed resident/diarist Jacob Engelbrecht, merely a teenager at the time. Englebrecht’s description would not be recorded until 42 years later( June of 1856), but it still provides documented proof of a unique happenstance involving Rev. Schaeffer: “War of 1812. The following is the Muster Roll (copy) of Captain John Brengle’s Company of Volunteers, which Company was raised in four hours, by marching through the streets of Frederick, August 25, 1814, (the day after the Battle of Bladensburg, on which day we received the news) headed by Captain Brengle & by the side, with them, rode the Reverend David F. Schaeffer, encouraging the men to volunteer…” Somewhat like Paul Revere, our Rev. David Frederick Schaeffer helped warn the "masses" that “the British were coming” and moreso urged residents to aid in repulsing this threat to America’s independence. Brengle, a large farm-owner from just east of town, was a seasoned militia veteran and upon hearing the threat to the capital became intent on raising additional men. Rev. Schaeffer is said to have rode alongside the company for three miles on their departure out of town that same day as they headed south on the Old Georgetown Pike. He delivered a parting address and offered a prayer with the soldiers all kneeling. Apparently, Captain Brengle’s Company is said to have encountered a messenger around the present vicinity of Clarksburg who told them that Washington had been lost and that the British were now setting their sights on Baltimore. At that point, Brengle is said to have re-directed his troops eastward. These men would eventually participate in the Battle of Baltimore a few weeks later on September 13th and 14th.  It’s not exactly known why or how John Brengle sought out our Rev. Schaeffer, particularly made more intriguing because the Brengle family was part of the Frederick’s German Reformed congregation. Regardless, the charisma and leadership qualities of the young minister helped result in the official tally of 73 men garnered for the additional local militia company. One final aside is a comical anecdote that Captain John Brengle got caught up in the excitement of the day and failed to notify his family that he had raised a volunteer company, and had even left Frederick for battle. In the bigger picture of “cause and effect,” the US flag, coupled with the relentless bravery shown by Baltimore’s defenders ( made up of Frederick’s own, including men inspired by Rev. Schaeffer), helped give impetus for the writing of a song, often confused to be a poem, by the fore-mentioned Francis Scott Key. The British were thwarted in “Charm City” and our Independence maintained. Rev. Schaeffer had played an interesting part in this drama—and did so as a civilian. The same can be said for FSK at this time, Paul Revere nearly forty years earlier, and Barbara Fritchie 48 years later.

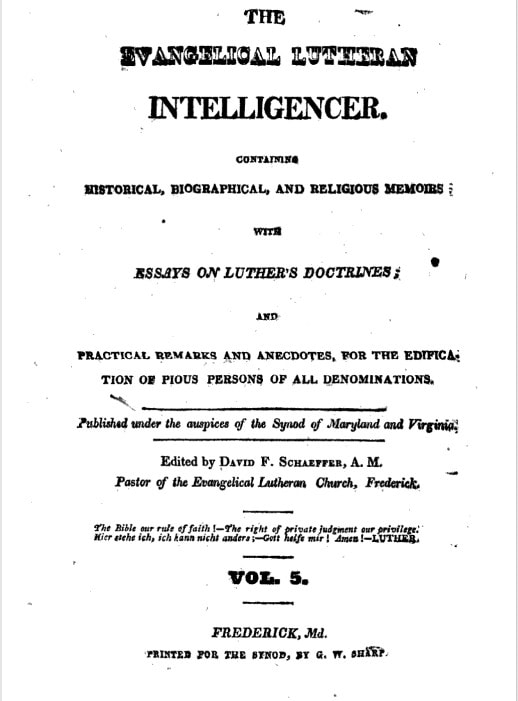

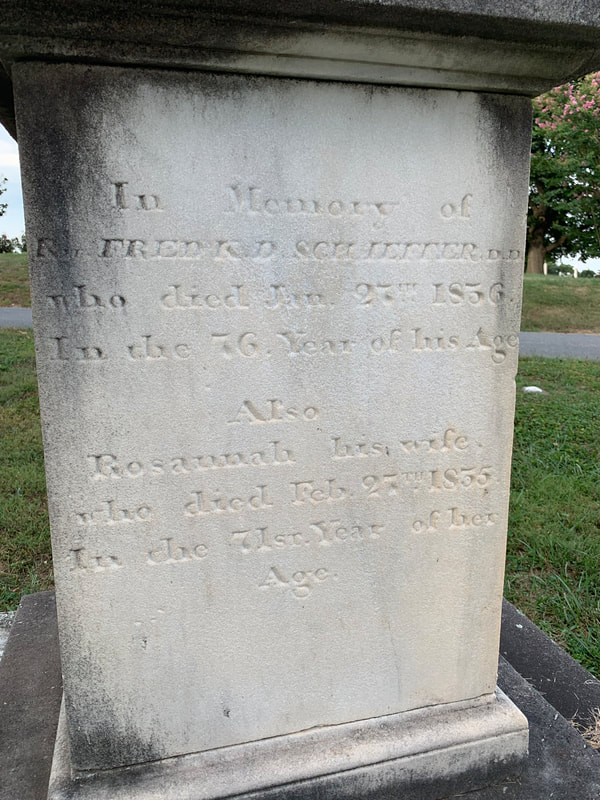

Back to the Pulpit As things returned to a new normal in Frederick, Rev. Schaeffer continued his recruiting ways, but these draftees were men and women intended for church pews, not battle trenches. He had a major goal of gaining more young people, particularly children, into the folds of the church. In 1820, Schaeffer initiated the first Sunday School at Frederick, known as the "Mathenian Association." In 1825, he helped lead a major restoration project to the aging chapel, resulting in the congregation boasting the largest auditorium in town. The timing could not have been any better as the year 1826 marked a very important time of patriotic fervor for not only the country, but Frederick as well—the fiftieth anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence on July 4th, 1826. Just as he had done twelve years earlier, Rev. Schaeffer rallied the community with his participation and leadership in hosting a commemorative celebration at the newly refurbished (and expanded) church. A newspaper of the day reported the work of the “Great Baby Waker” cannon and related exercises of the day: “The dawn of the day was announced by the thundering voice of the big black war dog who in the year 1783 was brought to Frederick to celebrate the restoration of peace and echo ever since has occupied his lonely station on Barracks Hill. He roused the inhabitants from their slumbers and bade them prepare to celebrate the Jubilee of Freedom. The enlivening strains of the bands of instrumental music stationed in the steeples, which broke upon the ear like a salutation from the celestial spheres; the brisk and animated rattle of the drums with the shrill tones of the fife silenced at intervals for a moment by the thundering peals of artillery together with the gay streamers that flaunted in the breeze, all imparted to the scene an interest such as was suited to the occasion….At an early hour at the east end of Market Street the procession was formed. The procession moved down Market Street, up Patrick Street, through Court Street, and thence to the Evangelical Lutheran Church. On entering the door, the choir sung an anthem suited to the occasion and the ceremonies were commenced by an appropriate address to the Throne of Grace by the Rev. Samuel Helfenstine. Thomas W. Morgan, Esquire, read the Declaration of Independence prefaced by a brief but suitable exordium. He was followed by L. P. W. Balch, Esquire, who pronounced an oration abounding with patriotic and benevolent sentiments.” It was a proud day for all in attendance, as I strongly sense that a 59 year-old local woman named Barbara Fritchie was in attendance, especially based on her strong patriotic leanings. It must have been a proud day for Rev. Schaeffer. From 1826 until 1831 David F. Schaeffer was the editor of the first English-language periodical established in the Lutheran Church in the United States, the Lutheran Intelligencer. Also in 1826, Schaeffer took an active part in the establishment of the Lutheran Theological Seminary at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. The reverend was one of the founders of the General Synod of the Lutheran Church (1821), and served as its secretary from 1821-1829, and its president from 1831-1833. In 1836, Schaeffer received the degree of Doctor of Divinity (D.D.) from St. John's College in Annapolis, MD. Besides a large number of doctrinal and other articles in the Lutheran Intelligencer, he published various addresses and sermons.  It was also in the year 1836 that a major setback occurred, one that involved Rev. Schaeffer feeling the need to resign his post due to health reasons. The congregation was reluctant to let Dr. Schaeffer go, as hope was held out that he would eventually overcome his present situation with rest as the reverend was not even 50 years old at this time. Meanwhile, Schaeffer kept getting unanimously elected by the congregation in votes to fill his vacancy. He repeatedly and respectfully declined, stating that he was significantly ill and the elections were unconstitutional. Finally, his resignation was accepted with deep regret in early 1837. Mrs. Elizabeth Schaeffer would die in February of that year, and her husband would succumb to his maladies on May 5th 1837, one day after the church’s Ascension Day . On the night of the 5th, Jacob Engelbrecht recorded the event for posterity in his diary: “Died this evening about 5 o’clock aged 49 years, 9 months & 13 days, The reverend David Frederick Schaeffer, D.D. Pastor of the Lutheran Church of this place for upwards of 28 years, from 1808 to 1836. He was born (in Germantown, Pennsylvania I believe) “July 22, 1787,” so he told me on the 22nd July 1833.” A month later, Engelbrecht would again mention Rev. Schaeffer in his diary: The funeral sermon of the late Reverend David F. Schaeffer, D.D. was preached yesterday forenoon in the Lutheran Church by the reverend Charles Philip Krauth, one of the professors of the Theological Seminary, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania to an over-crowded church. The reverend Doctor Hazelius, now of Salem, North Carolina preached last night in the Lutheran church in the English Language.” (Friday, June 5, 1837 )  Once again, I harken back to the fine history book of Frederick’s Evangelical Lutheran Church written at the time of its 250th anniversary in 1988. The following summation concludes several chapters on Schaeffer’s impact and accomplishments here in Frederick: “Dr. Schaeffer’s life was not a long one if measured in years. But in his ministry, all of it spent in Frederick, was abundant. Even the figures would suggest a great volume of labors and a large harvest. He preached at Frederick about 5,000 sermons, baptized over 2,000 infants, catechized and confirmed about 1,400 people, married about 2,000 couples and conducted 1,600 funeral services.” Rev. Schaeffer was buried in the congregational cemetery, once located at the southeast corner of East Church and East streets. Today, the site is marked by Everedy Square. His remains once rested alongside those of his wife under the shadow of a fine monument erected by the congregation. Also in this grave plot, were buried his esteemed father and dutiful mother who had both died within the preceding two years. In the early 1900’s, Rev. Schaeffer, his wife and parents were moved to Mount Olivet along with the impressive monument. This likely occurred in 1903 at the time of death of Schaeffer’s daughter Caroline 1827-1903). The eternal resting place of these exceptional early leaders of the Lutheran Church in Frederick (and abroad) is located in Area Q/Lot 10. In case you were curious, the Evangelical Lutheran Church eventually sold the land that constituted their second burying ground, causing the majority of the inhabitants to be transferred here to Mount Olivet. The good reverend’s name lives on as part of the Evangelical Lutheran Church campus. Fronting on E. 2nd Street, a new Sunday School building was constructed in 1891 and carries the name the Schaeffer Center. Within the adjacent church, two windows (on the east side) are memorials to the Rev. David Frederick Schaeffer, D.D. and feature Martin Luther and St. Paul. These were placed here in 1924 by grandson, Mr. George Frederick Hane, of Washington, DC.

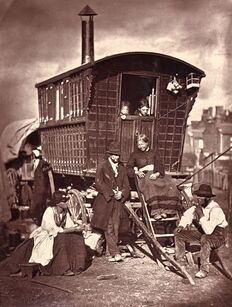

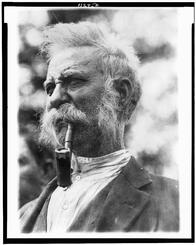

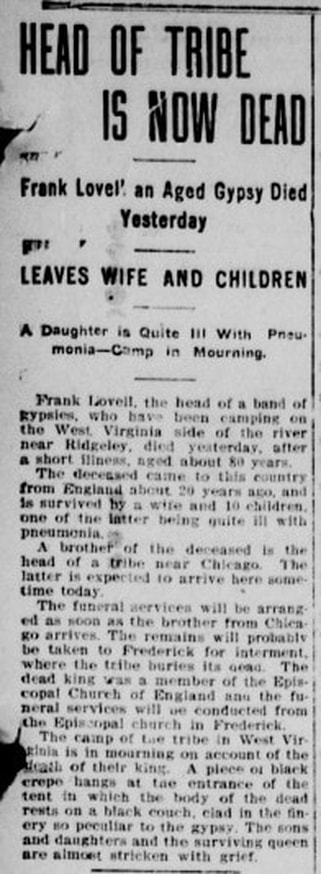

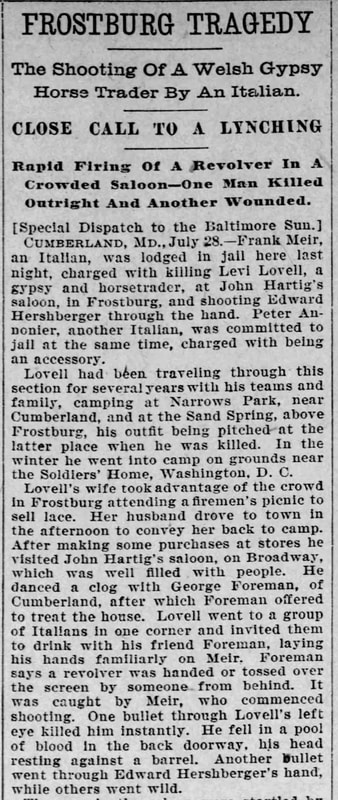

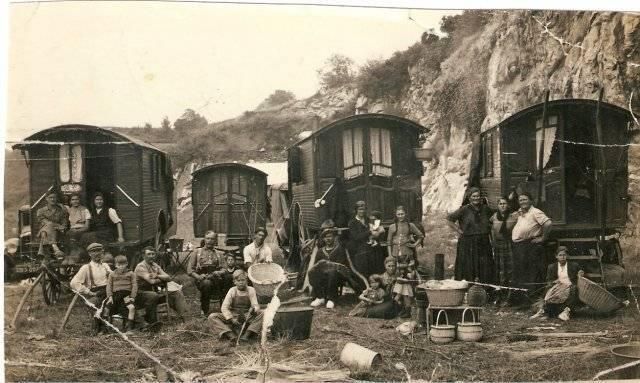

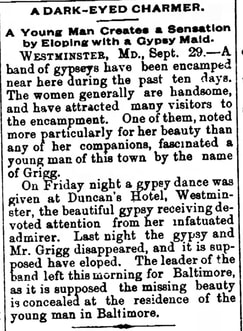

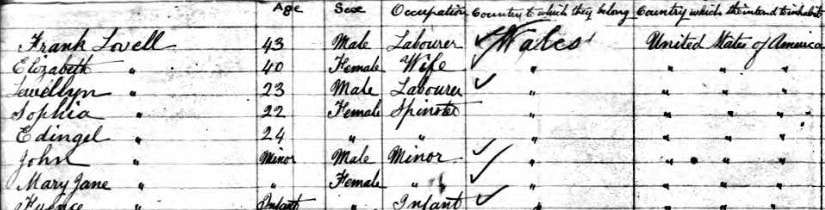

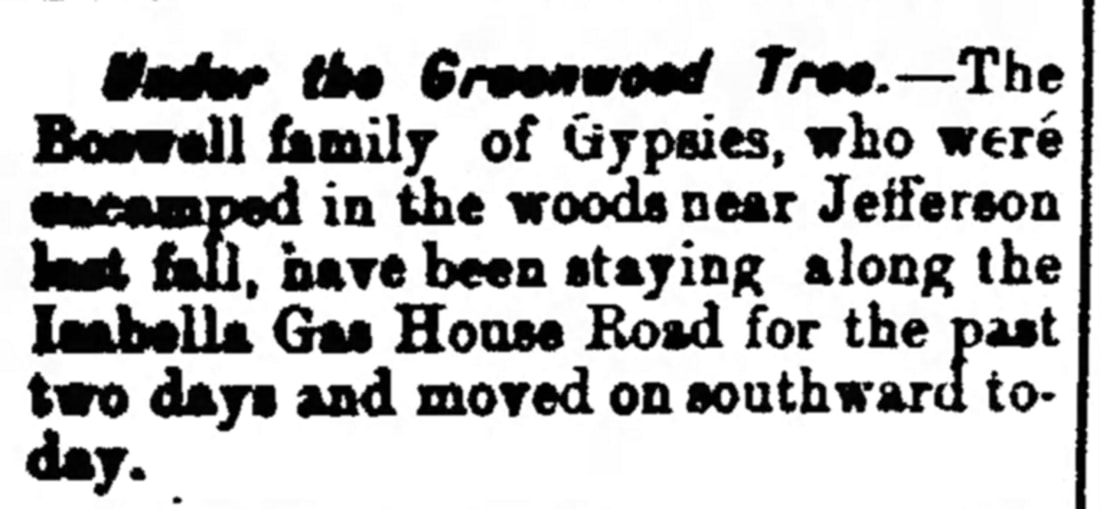

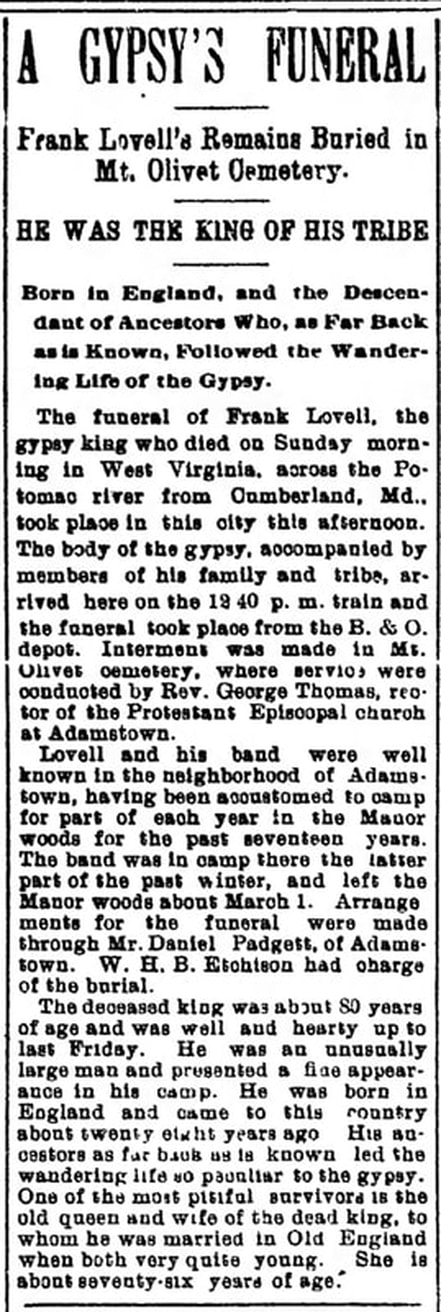

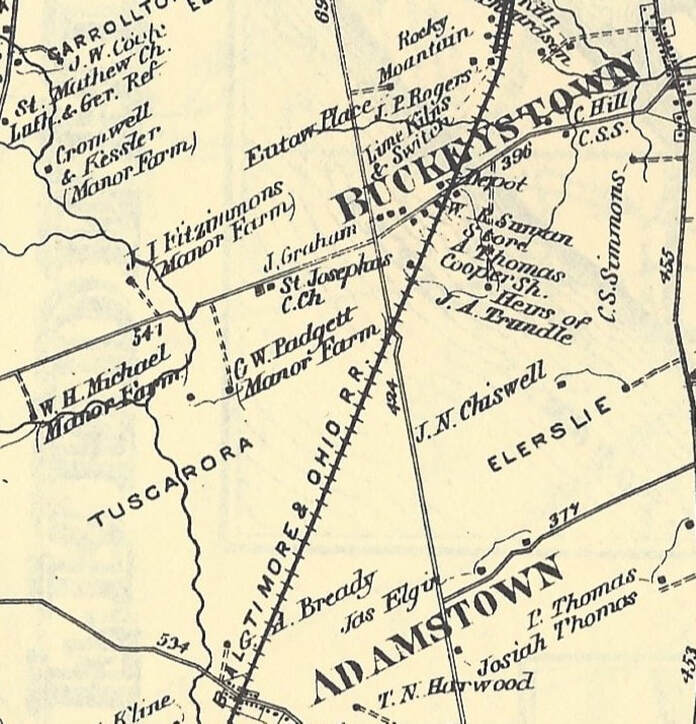

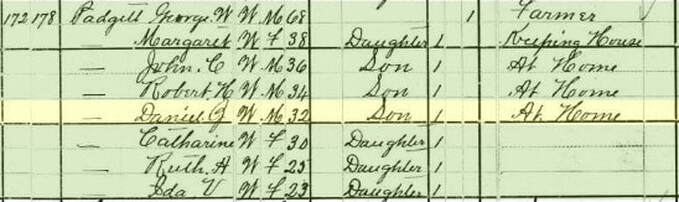

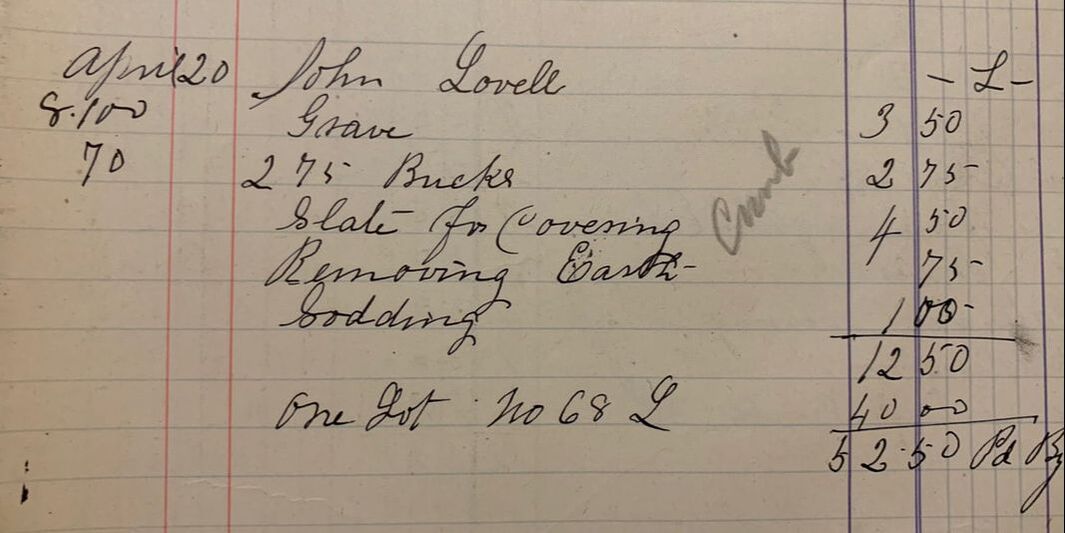

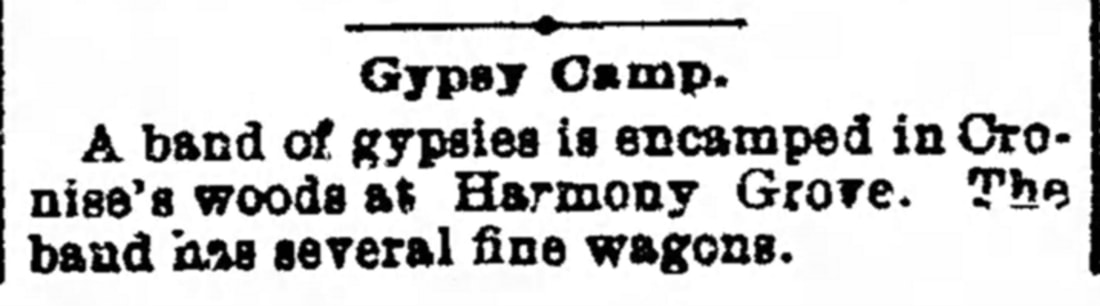

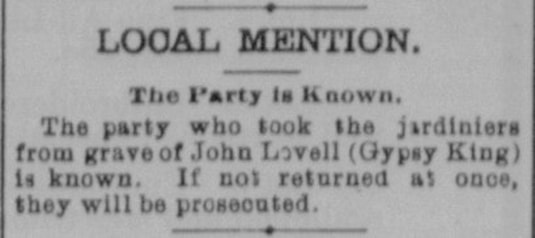

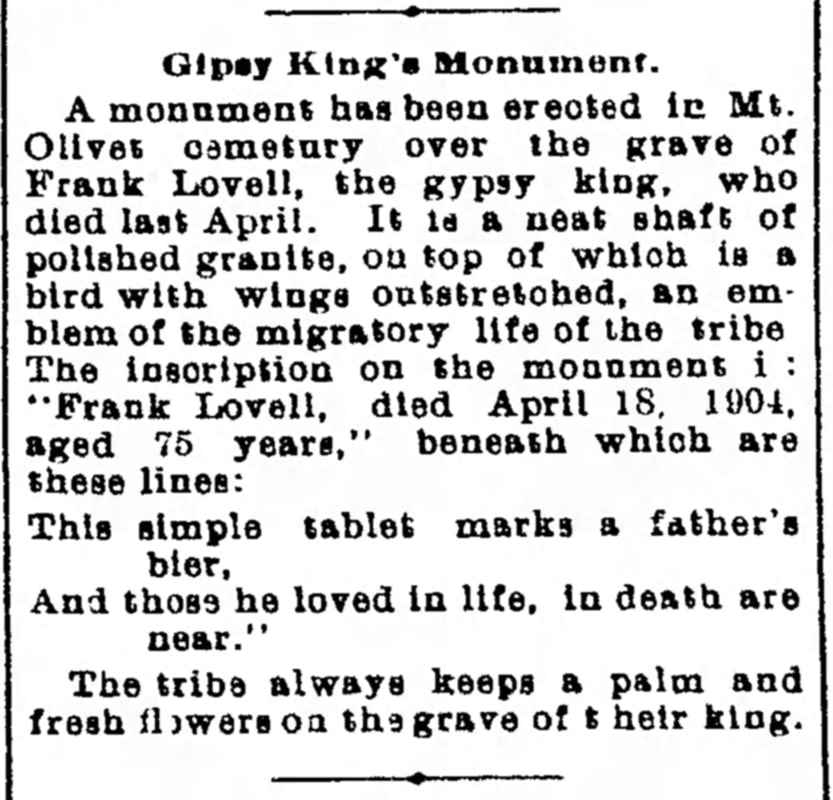

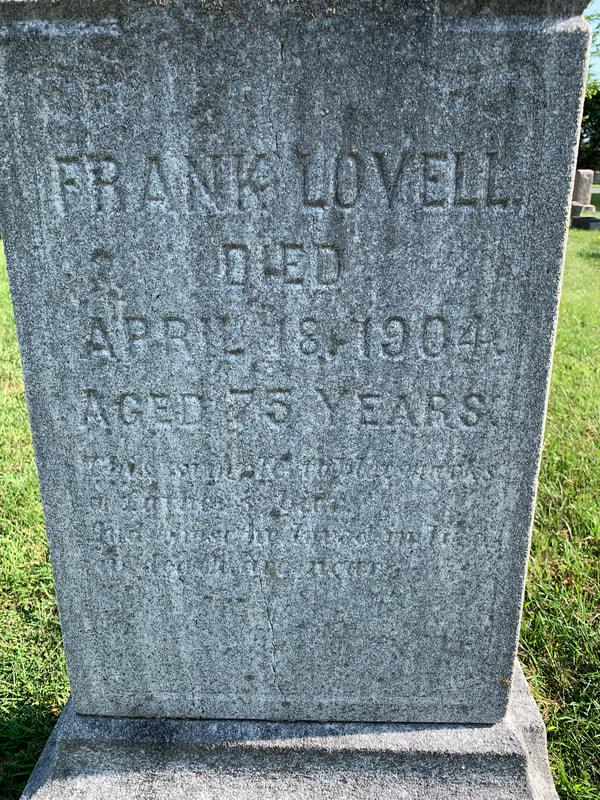

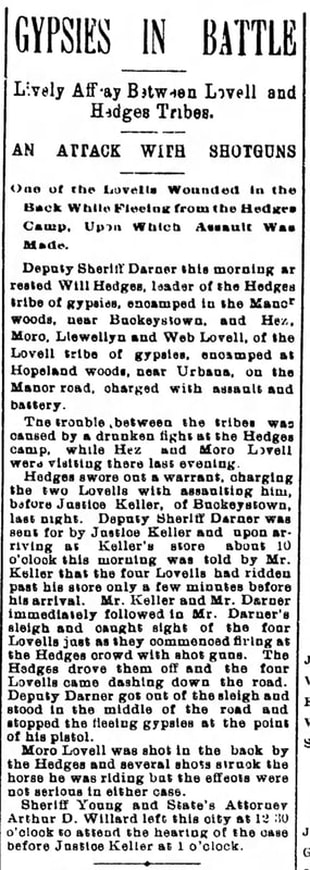

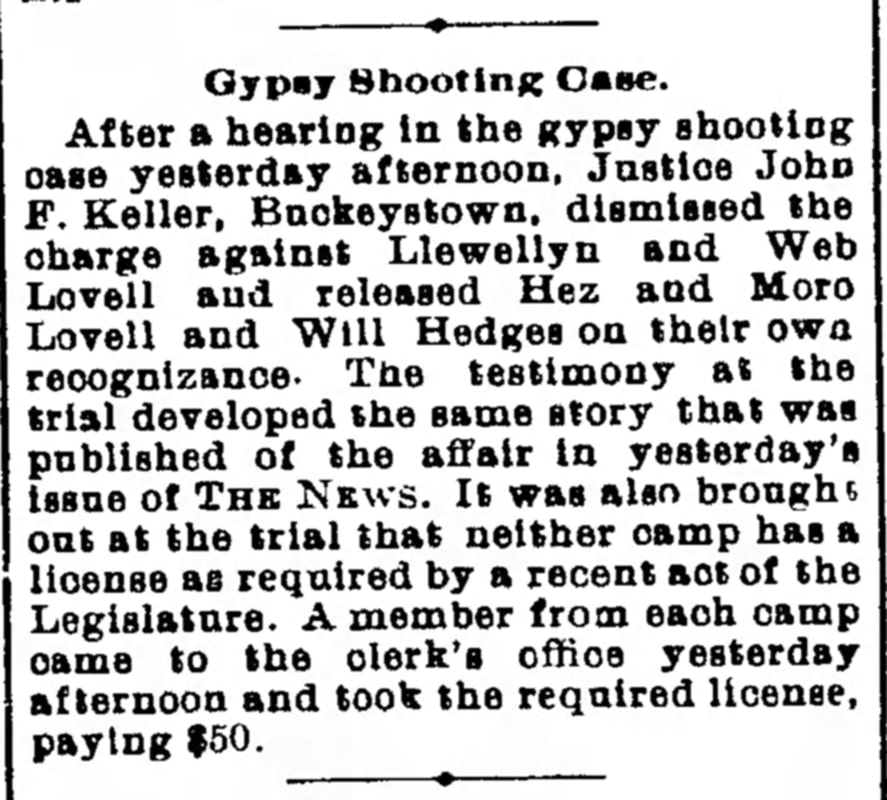

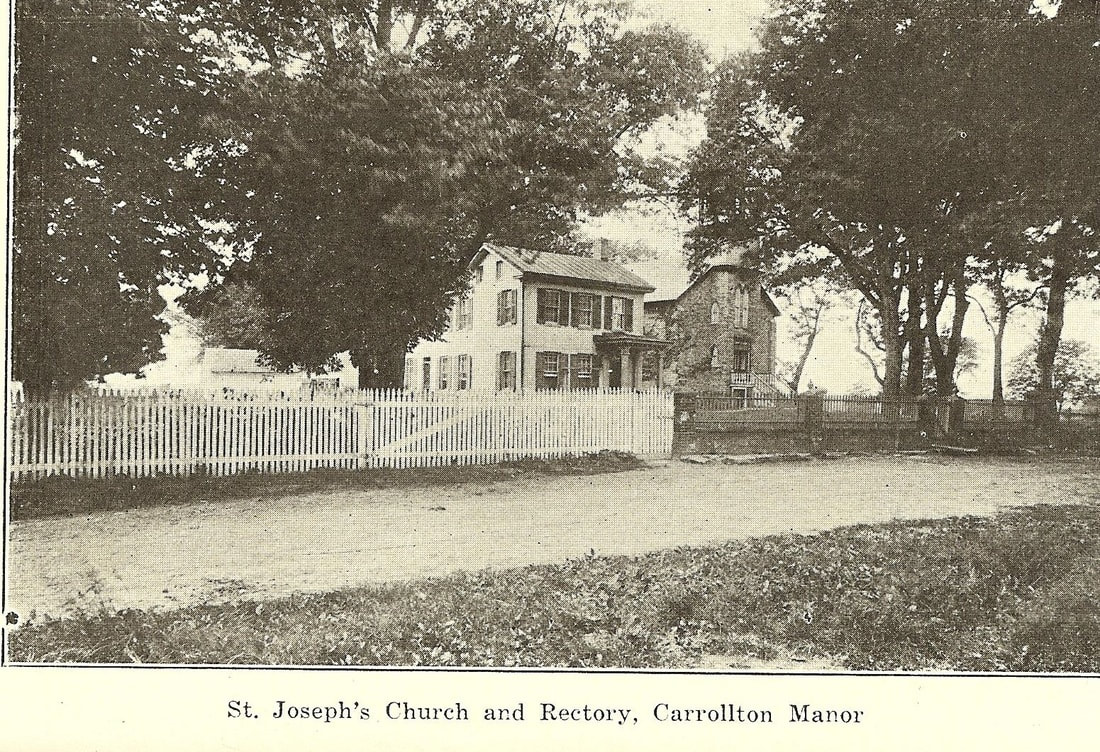

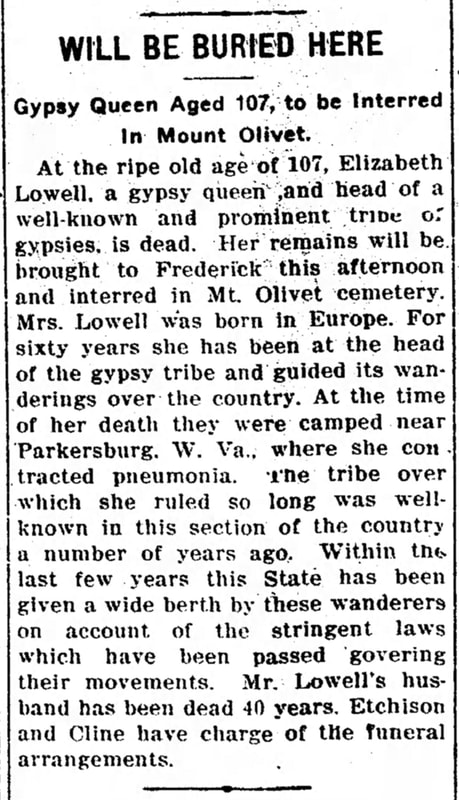

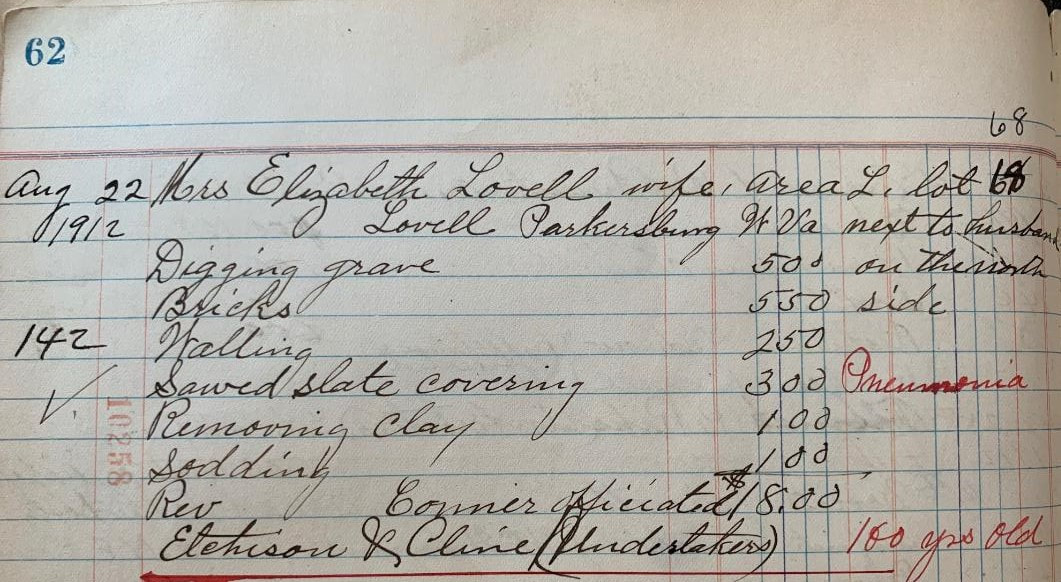

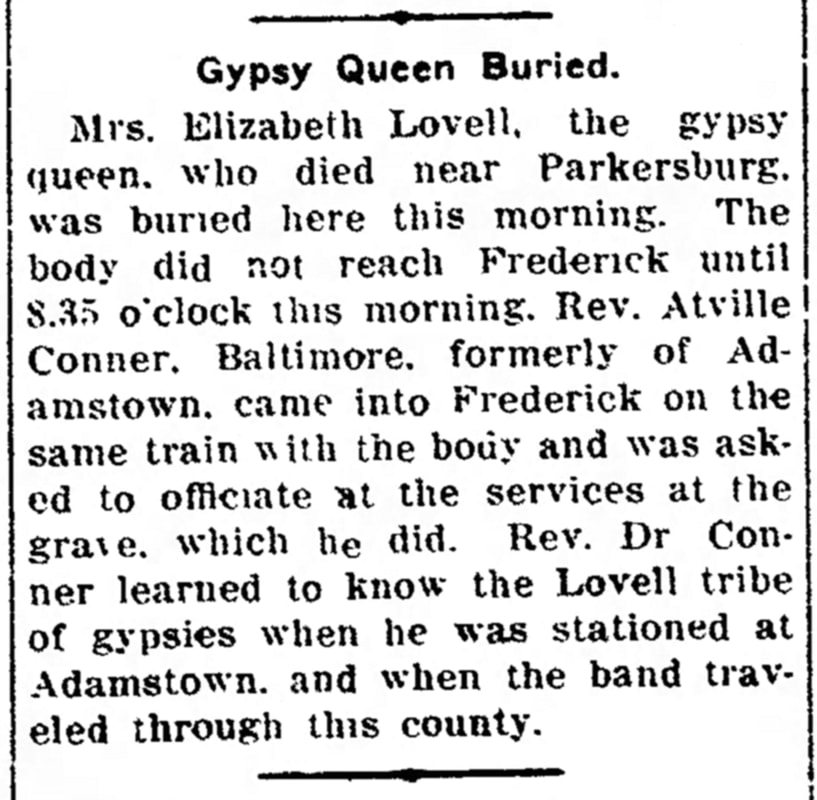

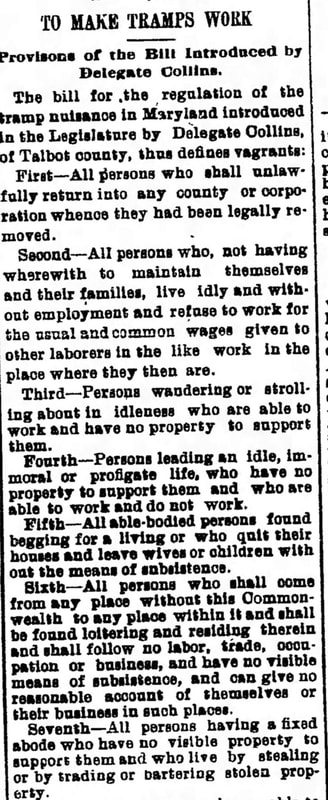

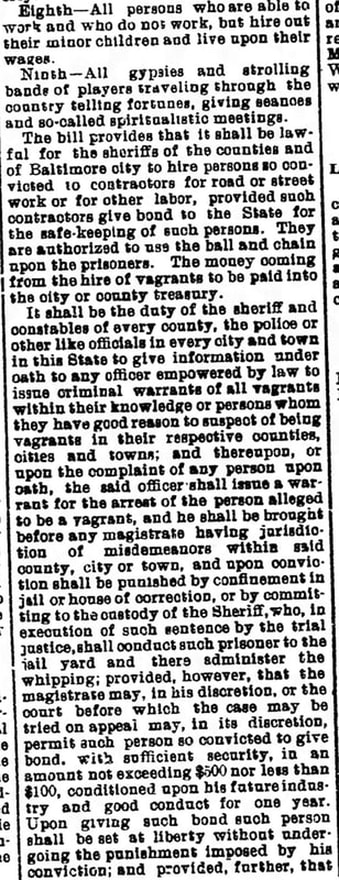

Who would have thought that we have actual royalty here within the historic confines of Frederick’s Mount Olivet Cemetery. A mention of this fact came back in fall of 2015 when cemetery superintendent Ron Pearcey actually published an elongated post on FaceBook under the heading: Interesting and Unknown Residents of Mount Olivet Cemetery. The focal point of the story was a gentleman named Frank Lovell, who was referred to in local newspapers as "King of The Gypsies." Superintendent Pearcey began his article from November 18th, 2015 as follows: “Among the lesser known people buried at Mount Olivet Cemetery is one whose notoriety at one time made him a major person of interest during the mid-1800s up through the early 1900s. He could often be found among a traveling band of gypsies that would camp regularly in, and around, Frederick County. Although there were similar groups throughout the United States, those that came from England were among those who would frequent Frederick County the most. Their culture and heritage has all but disappeared, but gypsies’ life as wanderers goes back very far, and has often been depicted in ancient books and vintage movies.” On April 18th, 1904, the Cumberland (MD) Evening Times included an article that not only reported the passing of Mr. Frank Lovell, but boasted the fact that this same Mr. Lovell was, at the time of his death, the King of his tribe. The Frederick News carried a like obituary in its April 18th issue: Frank Lovell, king of the tribe of Romany gypsies encamped across the Potomac river from Cumberland, MD in West Virginia for several months, died Sunday, April 17 from an illness of only a few days. He was 80 years of age and was well and healthy up to last Friday. He was an unusually large man and presented a fine appearance in his camp. He was born in England and came to this country about 28 years ago. His ancestors, as far back is known, led the wandering life so peculiar to the gypsy. He leaves a widow and 10 children, 8 of whom are with other tribes. A brother Chizadine (Hezekiah) Lovell, chief of a large tribe located near Chicago, also survives him. He has been notified. A daughter of the family is very low with pneumonia at the camp and is not expected to live. One of the most pitiful survivors is the old wife of Lovell, to whom he was married in England when both were quite young. She is about 76 years of age. The remains will be taken to Frederick for interment, where the tribe buries its dead. Lovell was a member of the Protestant Episcopal Church in England and funeral services will be conducted from the Protestant Episcopal Church in Frederick. He will be buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery. The camp of the tribe in West Virginia is mourning on account of the death of their king. A piece of black rope hangs at the entrance of the tent in which the body rest on a black couch, clad in the finery so peculiar to the gypsy. Levi Lovell, the gypsy who was murdered by Frank Moro, an Italian in Frostburg, about three years ago, was a member of the same tribe. And in case you were curious as to the death of Levi Lovell, a man also known to Frederick residents... This killing of cousin Levi was one of many life incidents that Frank Lovell had to navigate his family through. The Frederick newspaper carried the same story about Frank's death as did the Cumberland paper, on April 18th. I found the story in other papers around the country, with the novelty being Lovell's "royal" status over a misunderstood people that were generally mistrusted and "shared" (or Cher-ed) the labeled as tramps and thieves. One day later, April 19th, 1904, the Frederick News included the following announcement: The Romani Now, before we get into the life and burial of Frank Lovell, I’d like to explain the term “gypsy,” and the term “gypsy king” in context to the time period we are talking about. Gypsy, as it was used at the time of Frank Lovell’s death, was a slang term used to describe people of Romani heritage (also spelled Romany). They traveled in packs, and were nomadic, in a way we see carnival workers of today. These newcomers to town were known for fortune telling, taking on all sorts of odd jobs, but also were thought by some as hucksters and pickpockets. It is estimated that there are one million Romani people in the United States today, though this population has assimilated into American society with the largest known concentrations being found in Southern California, the Pacific Northwest, Texas and the Northeast as well as in cities such as Chicago and St. Louis. The Romani were different from other Europeans ethnically and genealogically, and began settling in America in the mid-19th century.  The largest wave of Romani immigrants came after the abolition of Romani slavery in Romania in 1864. Romani immigration to the United States has continued at a steady rate ever since. The size of the Romani American population and the absence of a historical and cultural presence, such as the Romani have in Europe, make Americans largely unaware of the existence of the Romani as a people. The term's lack of significance within the United States prevents many Romani from using the term around non-Romani: identifying themselves by nationality rather than heritage. The U.S. Census does not distinguish Romani as a group since it is neither a nationality nor a religion. The Romani people originate from Northern India, presumably from the northwestern Indian states of Rajasthan and Punjab. Linguistic evidence has indisputably shown that roots of Romani language lie in India. Genetic findings in 2012 suggest the Romani originated in northwestern India and migrated as a group. According to a genetic study in 2012, the ancestors of present scheduled tribes and scheduled caste populations of northern India, traditionally referred to collectively as the Ḍoma, are the likely ancestral populations of modern European Roma. Romani slaves were first shipped to the Americas with Columbus in 1492. Spain sent Romani slaves to their Louisiana colony between 1762 and 1800. The Romanichal, the first Romani group to arrive in North America in large numbers, moved to America from Britain around 1850. Eastern European Romani, the ancestors of most of the Romani population in the United States today, began immigrating to the United States on a large scale over the latter half of the 19th century, following their liberation from slavery in Romania mentioned earlier. In the case of the Lovell family, or tribe, they hailed from Wales and came here to America in June, 1874. Well, every family can have a leader or patriarch. In the case of the Romani people, this “leadership” position was serious business, resulting in the exultation of said leaders as a kings and queens. I found that Wikipedia has a page description for this:  Library of Congress photo taken in 1924 and titled John Lovell, King of the Gypsies. This could be the son of our Frank Lovell who would have been around 58 years old in 1924. Library of Congress photo taken in 1924 and titled John Lovell, King of the Gypsies. This could be the son of our Frank Lovell who would have been around 58 years old in 1924. The title King of the Gypsies has been claimed or given over the centuries to many different people. It is both culturally and geographically specific. It may be inherited, acquired by acclamation or action, or simply claimed. The extent of the power associated with the title varied; it might be limited to a small group in a specific place, or many people over large areas. In some cases the claim was clearly a public-relations exercise. As the term Gypsy is also used in many different ways, the King of the Gypsies may be someone with no connection with the Romani people. In the early 1970s, it was decided, at the First Annual Romani Meeting that the term Gypsy would no-longer be used to describe themselves. It has also been suggested that in places where they were persecuted by local authorities the "King of the Gypsies" is an individual, usually of low standing, who places himself in the risky position of an ad hoc liaison between the Romani and the gadje (non-Romani). The arrest of such a "King" limited the harm to the Romani people. Reviewing old newspapers, I found instances of “Bands of traveling Gypsies” encamped in Carroll and Washington counties, and here in Frederick in the areas of Thurmont and Libertytown and different times. Two articles from the mid to late 1880s mention their presence outside Frederick. As for Frank Lovell, we can glean valuable insight from his 1904 obituary. Lovell and his band were well known in the neighborhood of Adamstown, located southwest of Buckeystown in the Carrollton Manor area of Frederick County. As the above article states, King Frank’s tribe camped for almost two decades in the Manor Woods area in close proximity to St. Josephs-on-Carrollton Manor Catholic Church. In Nancy Bodmer's Buckey's Town: A Village Remembered, one can find the following passage from the diary of local resident William H. Thomas (1878-1938): June 14, 1890- "The gypsies are up in the Manor woods again this summer. The men travel through the country trading horses, while the women go from house to house begging and telling fortunes. The boys learn the art of trading at an early age. They start by trading various playthings with the local boys. Some of our fellows go up to trade knives. Sam was badly beaten in a trade last week., so yesterday he decided to make another try at it. He took a knife having only one blade and came home with one having no blade and no handle!" From the newspaper article above, I see that Daniel Z. Padgett made arrangements for Lovell’s funeral. Mr. Padgett (1848-1917) took over the operation of his family farm, part of the original manor farm of Charles Carroll of Carrollton, a signer of the Declaration of Independence. By the aid of the Titus Atlas of Frederick County published in 1873, I found the location, then owned by Daniel’s father, George Washington Padgett. I’m presuming that the Padgett’s allowed the Romani tribe to set up camp on their property, which would come to be owned by the Eastalcoa Aluminum Company several decades later. This is also the vicinity of several Emancipation icnics by Frederick’s African-American population dating back to the late 19th century. Interestingly, I also saw another unique connection thanks to the 1873 Frederick County Titus atlas. To the immediate west of the Padgett farm, was one owned by William Henry Michael (1833-1904). Mr. Michael’s brother was Daniel Jerome Michael (1840-1908) who served as Mount Olivet’s third superintendent. His term stretched from 1893-1907, encompassing the 1904 burial of King Frank Lovell. I presume that the Lovell tribe was also friendly and trusting of the Michael family, whether having a direct relationship or appreciating that between the Padgetts and Michaels. This likely answers the question of why the Lovells chose Mount Olivet as the final resting place to bury their King and patriarch. Frank Lovell would be buried in Area L/Lot 68, about 40 yards behind the Key Memorial Chapel. Another story appeared in the Frederick News the following November as Lovell’s gravesite was marked with a magnificent monument. The Lovell Tribe continued on under the leadership of “the Gypsy Queen,” Elizabeth Lovell, Frank’s wife. The group made the papers in the summer of 1905 when an affray occurred with a rival group of Romani people, a family named Hedges. At the time, I thought it was interesting to see that the Hedges had taken over the old stomping ground of the Manor Woods, while the Lovells were said to be living further east in the Hopeland/Hope Hill area near the intersection of MD85 and Baker Valley Road. Elizabeth Lovell passed seven years later in August, 1912. She would be buried at Frank’s side here in Mount Olivet, and the occasion of her death in Parkersburg, WV, and subsequent burial in Frederick was reported in several newspapers of the day. Although Elizabeth’s obituary states her age as 108, I find the math to be a bit fuzzy as she was 76 years of age at the time of Frank’s death just eight years earlier. Perhaps this can be chalked up to Gypsy magic I suppose. Unfortunately, Elizabeth's name and birth/death dates were never carved into the Lovell monument, so many researchers, Find-a-Gravers and "tombstone tourists" haven't a clue that she is even buried here.

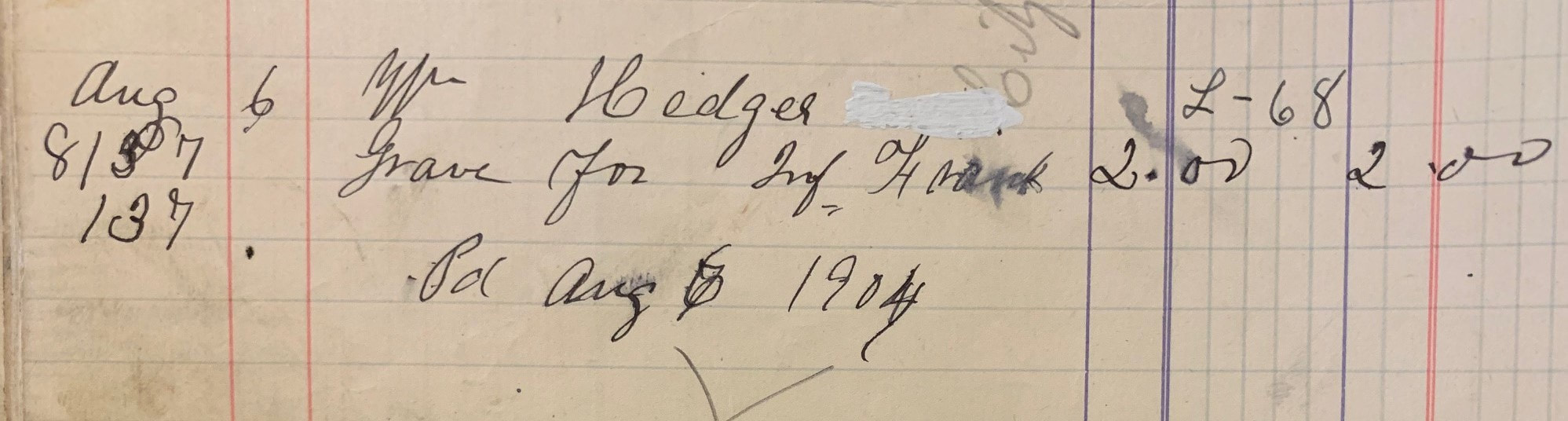

The funerary article also states that “it was said to be the custom of the tribe to bury prominent members of their band in Frederick,” although their king and queen and an infant are the only decedents known to have been placed in the burying ground at that time. This child was named Frank Hedges. Our cemetery records show that this child, with a very familiar first name, died on August 4th, 1904 at the tender age of six months and one day. The death occurred in Strasburg, VA. The baby’s father was a William Hedges, and his mother was Harriet Lovell, a daughter of King Frank and Elizabeth. I find it interestingly that we have a joining of the Lovells and Hedges, combatants one year later on Carrollton Manor. It’s an amazing story, and one that certainly sheds an interesting light on the Romani culture. Sadly, Maryland began turning the proverbial screws on these nomadic folks beginning in the early decades of the 20th century as seen in this Maryland General Assembly proposal for legislation. Maryland virtually outlawed Gypsies in the 1920s. Baltimore followed suit a decade later. Gypsies were described during a public meeting as unsanitary, a menace to organized labor and undesirable to the police. An interesting article by reporter Peter Hermann in the November 22nd, 1994 edition of the Baltimore Sun wrote:

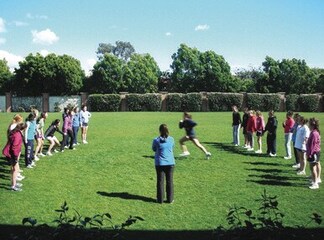

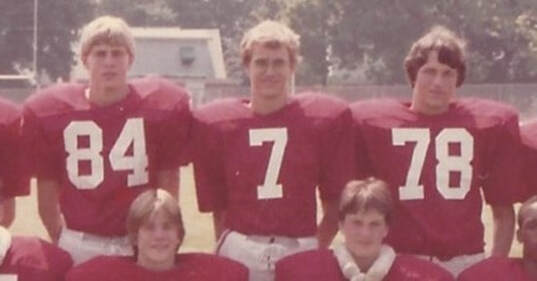

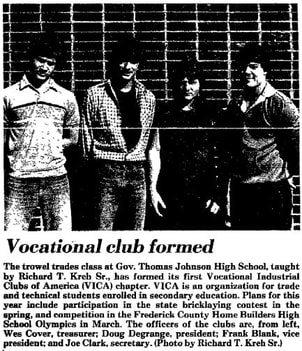

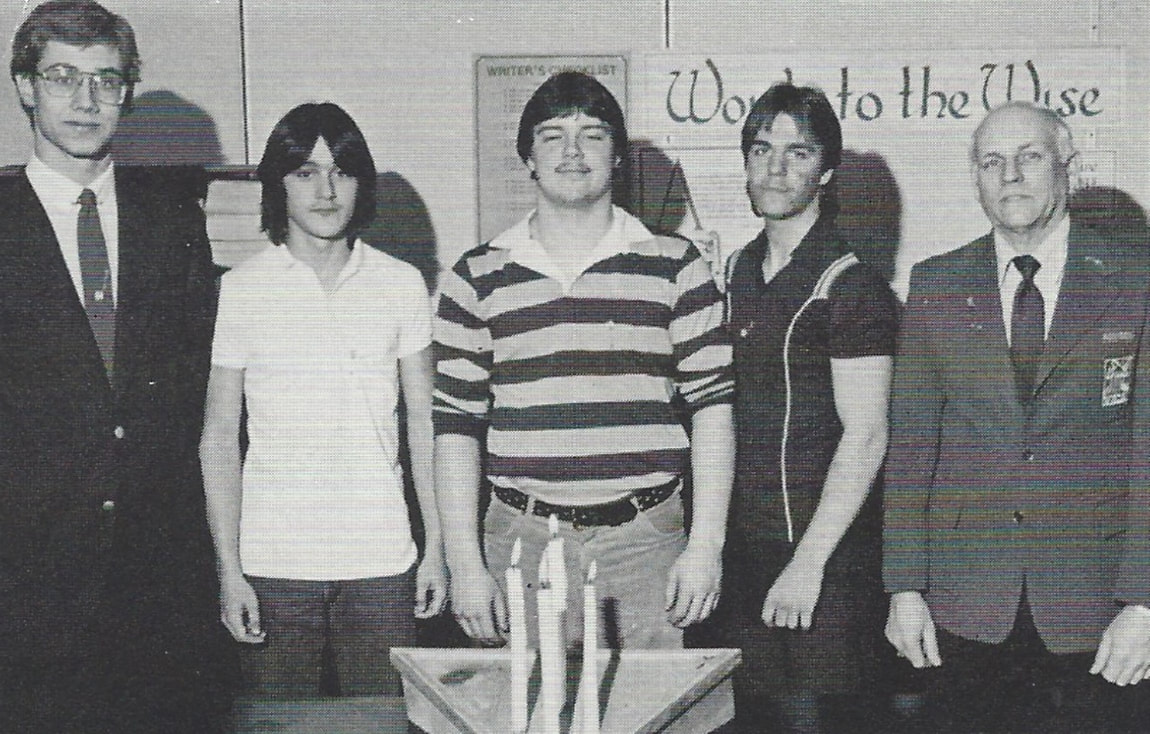

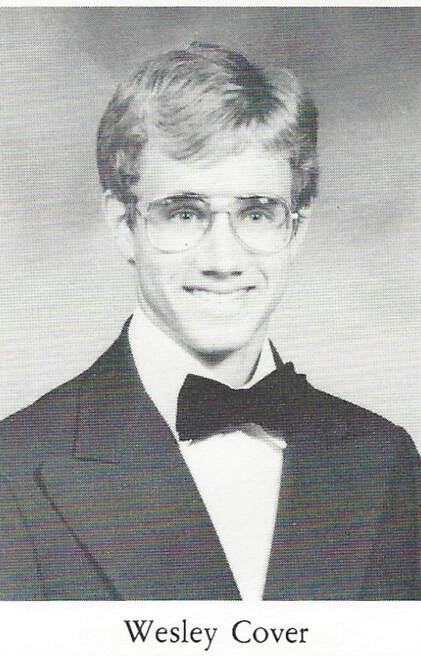

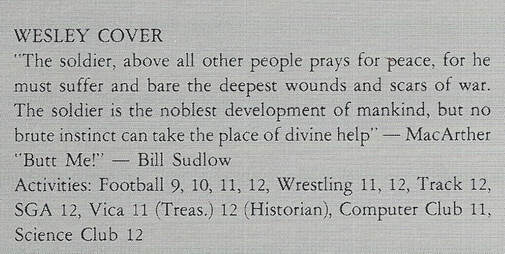

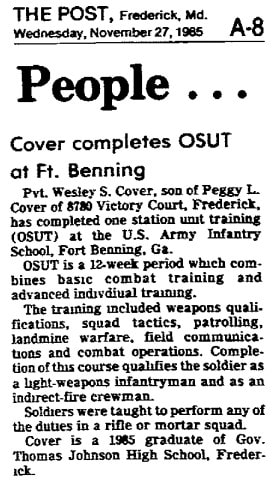

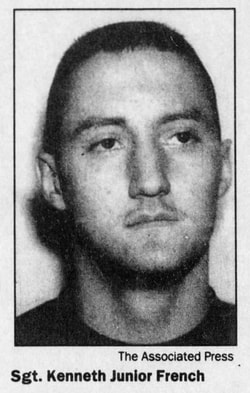

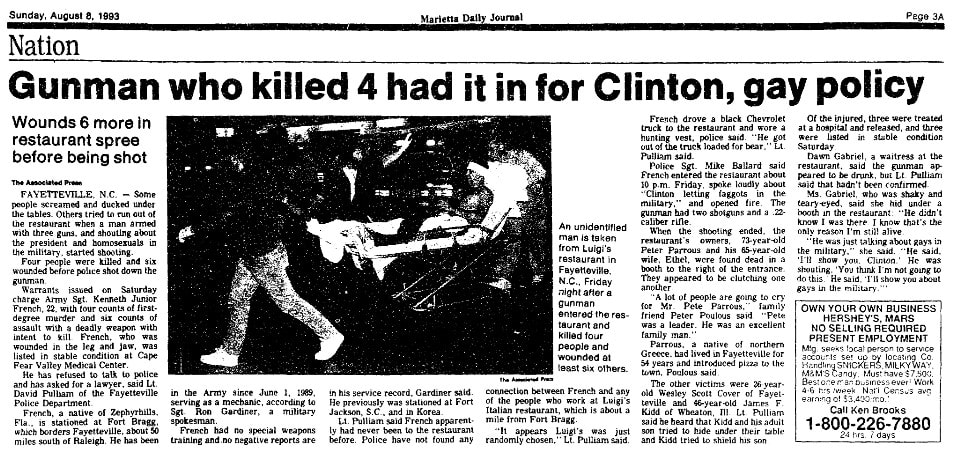

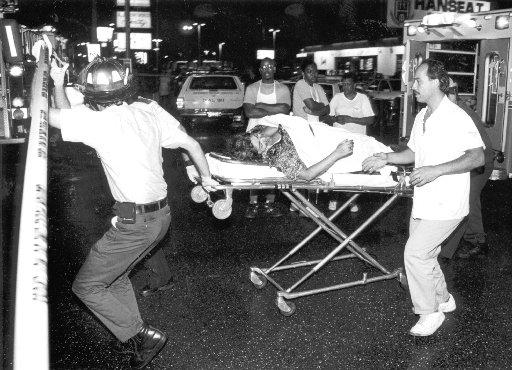

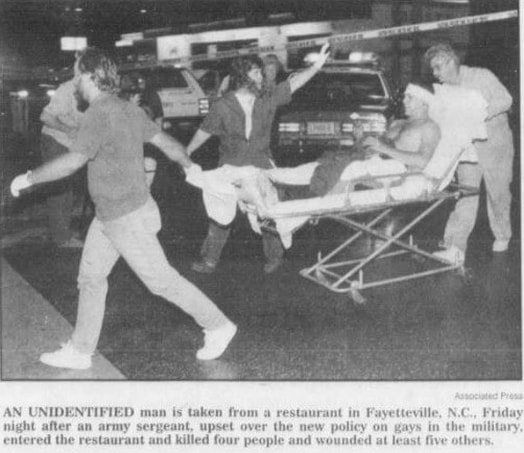

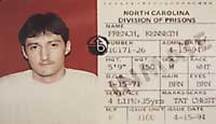

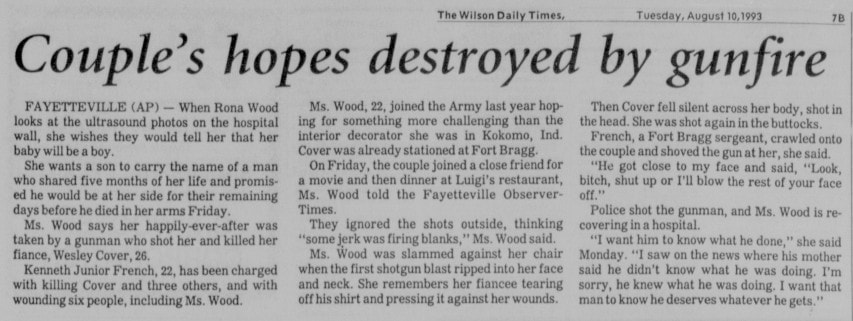

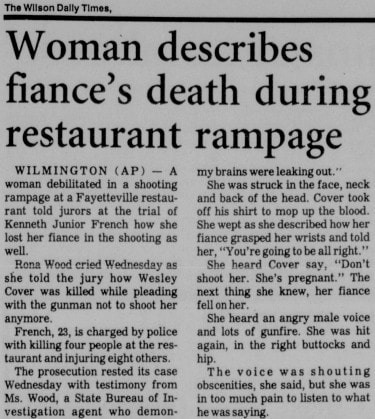

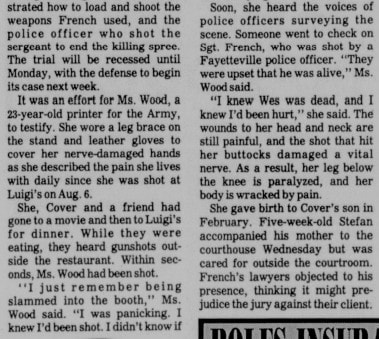

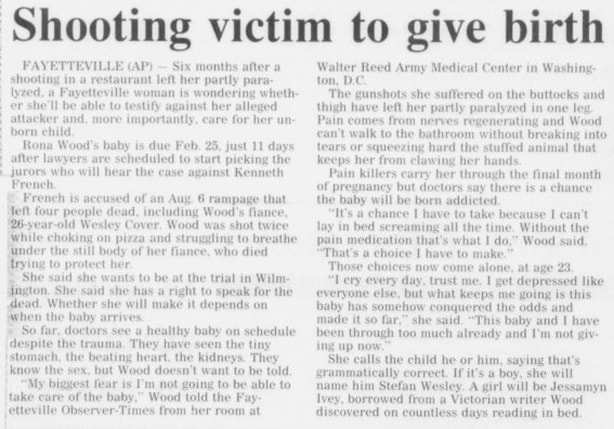

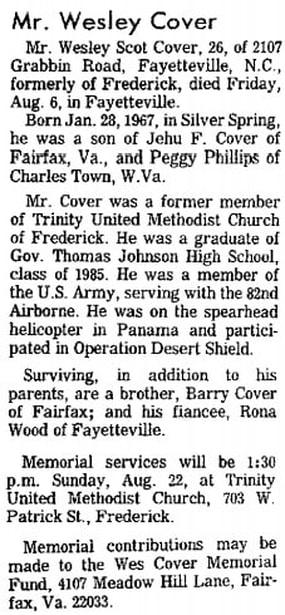

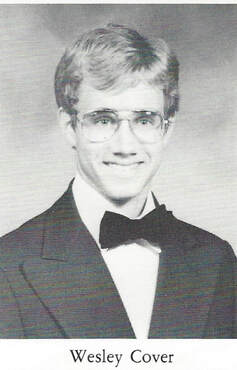

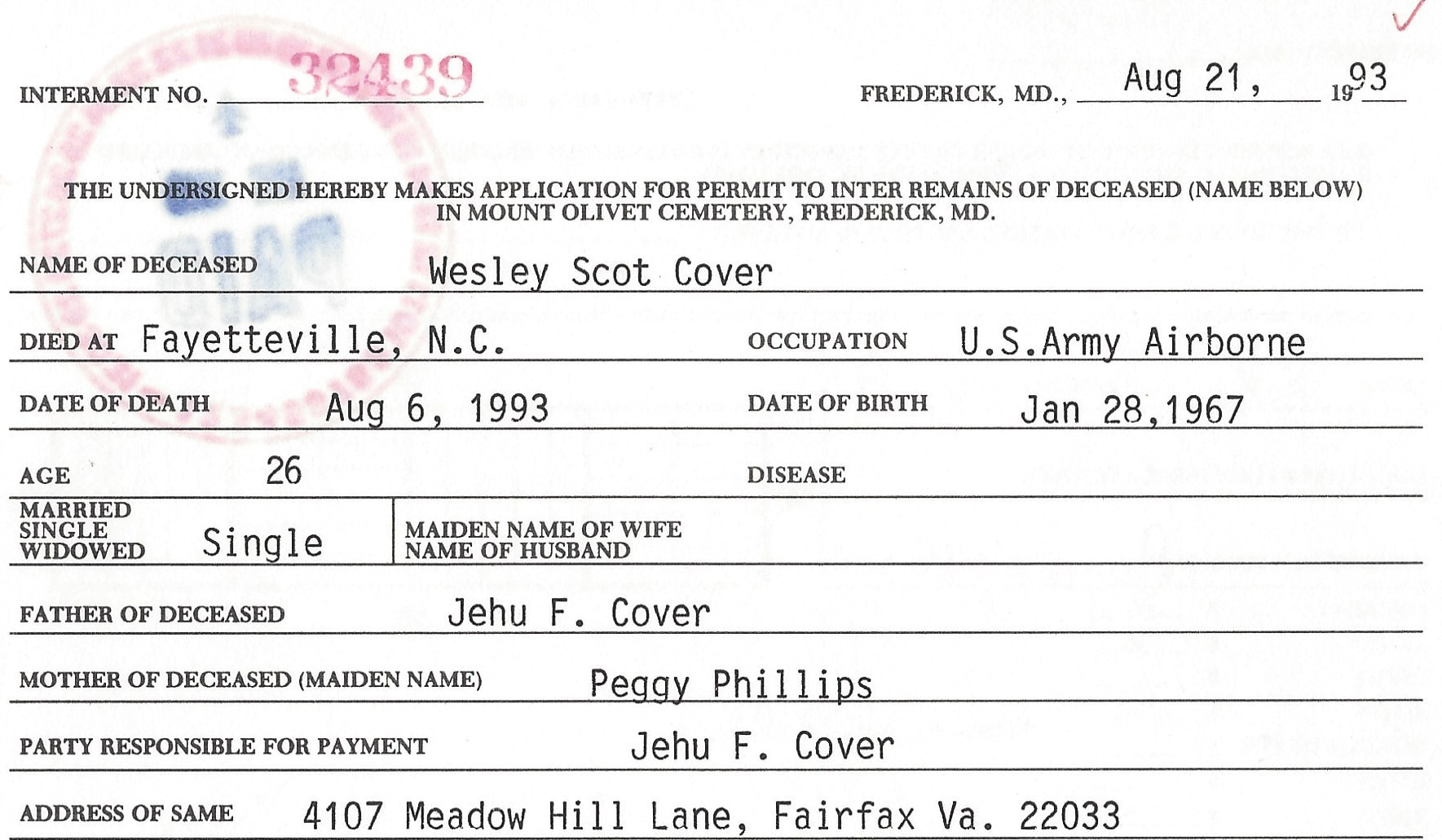

“Gypsies of Romanian descent have made Baltimore their home for more than a century -- six generations are buried at Western Cemetery -- yet members say they still are not accepted. About 200 Gypsies live in the city, engaged in a struggle to preserve Middle Eastern and Asian traditions that date back to the ninth century as members of the younger generation start to break away.” Mr. Hermann went on to say: “Gypsies came to Baltimore because it was a central location on the carnival circuit, and camped in Cherry Hill because it was undeveloped and on the city's outskirts. A series of laws enacted in the 1920s and 1930s, outlawing fortune-telling for profit and requiring nomads to pay a $1,000 entry fee each time they came into Baltimore, prompted this headline in an edition of The Sun: 'Gypsy horde leaves Maryland for good.' The law appeared to have been rarely enforced, and the Gypsies returned to the city two years later.The 1950s and 1960s brought newspaper stories on Gypsy arrests and trials -- on charges of swindling, theft and fortune telling -- and tales of elaborate weddings and funerals.” All of my “Stories in Stone” end the same, the subject of the written piece dies—thus making it possible for them to be interred here in Frederick, Maryland’s historic Mount Olivet Cemetery. Some of these online biographical essays are uplifting, as we frequently recount the life achievements of many of the lives that have shaped Frederick’s past. Other features are quirky and informative, utilizing individuals to give context to local traditions, civic organizations, public/private structures and even explaining why some of Frederick’s streets are named as they are. Occasionally, I will also throw in a melancholy story about a freak accident or happenstance that lead to a premature grave for one of our interred. Two years ago, I was surprised to learn that one of my childhood classmates was buried here in Mount Olivet. I had heard of his death back in 1993 when it occurred, and have again been reminded on the occasion of high school reunions every five years. I truly had no idea his final resting spot was just a few hundred yards out my office window. A “Story in Stone” write-up for this gentleman, Wesley Scot Cover, was contemplated a few years ago, but I decided to wait until August, 2018. This date would mark the 25th anniversary of his passing. When the time came to write the story, I had a difficult time actually putting “pen to paper,” or in today’s updated terms—"fingers to keyboard.” I got particularly emotional in researching, and reading, old newspaper accounts. You see, Wes’ death was no accident, rather it was a horrific situation that found him, and his fiancée, Rona Coomers -Wood, “at the wrong place, and the wrong time.” I decided to table the story then and there, and pick it up one day when I felt more comfortable with the subject matter.  When coming to work on Monday morning, I quickly noticed the flags at half-staff. The events of this past weekend featured troubled gunmen responsible for mass killings in El Paso, Texas on Saturday, August 3rd, and Dayton, Ohio on August 4th. Both shooters were in their early 20's. These senseless massacres have occurred so frequently over the last few years, that we can’t say we are truly shocked and dumbfounded anymore. This is yet another problem. Usually these episodes end with the death, or capture, of the assailant at the hands of the police. Many investigators, including the media, law enforcement, and researchers of human behavior, look for clues as to why a lone killer goes on these shooting sprees. The hope is to find something that will help us in trying to curb these events in the future of course. For the rest of us, we are left questioning our own good-fortune and safety, and that of our family members. Some folks take time to reflect on their own mortality, while others engage in the political debate over gun ownership and background checks. The only thing we truly have control over is the ability to pray for the victim(s) and his/her family. And those not religious, or inclined to pray, should simply demonstrate empathy toward said victims and the immense pain endured by loved ones, friends, co-workers and all other acquaintances. Those who don’t pray, or others incapable of showing empathy, should perhaps be watched carefully. “Red Rover” I can immediately be brought back to a portal of my mind that stores memories from Yellow Springs Elementary School and the mid-1970’s. The Six-Million Dollar Man and M*A*S*H were on the television; Kiss, E.L.O., and KC & the Sunshine Band were on the radio; Jimmy Carter was in the White House; many local kids became bandwagon fans of the Vikings and Steelers; our parents had Bicentennial Fever; and you could occasionally catch a glance of the Concorde flying over Frederick. As for my old school, it was a great place for primary learning. We had a fine group of teachers, a modern school structure (for the time), and surprisingly an American Indian for a mascot (back in the days when you could do that sort of thing). “Chief Montonqua” was a fitting representative for our school because the neighboring community was named for the Sulphur-laden “Yellow Springs” which bordered our school property. This particular location was known to native peoples as Montonqua, roughly translating to “medicine waters,” and was something that not only healed ills, but aided the mind, body and spirit in battle. As a matter of fact, 7th Street leading northwesterly out of Frederick toward this area was once named Montonqua Avenue before being bisected by Camp Detrick in the 1930’s. The further north portion of the route still retains the Anglicized version of the name today—Yellow Springs Road.  Like a lot of boys, I seem to recall gym class and sports activity in elementary school more so than particulars regarding the three R’s. I also remember the fascination with group activities and exercises such as Greek dodge ball, bouncing volleyballs into the air from outstretched parachutes in the cafeteria, climbing cargo nets and performing three-point tip ups (a gymnastic maneuver) in order to achieve the President’s Physical Fitness badge. In 1976, none of us at Yellow Springs Elementary would sense that change was in the air as a new physical education teacher in 5th grade would turn gym class upside down by introducing us to disco dancing instead of the regular beloved fare of softball, football and basketball. I certainly have digressed with my story, I apologize. One of the best sports moments from elementary school was the school’s annual Field Day, boasting individual and group sport activities ranging from relay races to tug-o-war. A prime memory of this day was the playing of “Red Rover.” The game was wildly popular at one time, but is thought to be taboo these days because of the risk of injury and you'd be hard-pressed to find it played at any elementary school today. For those not familiar, the game is defined by Wikipedia as such: “The game is played between two lines of players (usually called the "East" or "West" team, although this does not relate to the actual relative location of the teams), usually positioned approximately thirty feet apart with hands or arms linked together. The game starts when the first team, in this example the "East" team, calls a player out, by saying or singing a line like "Red rover, red rover, send [player on opposite team] right over", or "Red rover, red rover, let [player on opposite team] come over", or even "Red rover, red rover, I call [player on opposite team] over." The immediate goal for the person called is to run to the other line and break the "East" team's chain (formed by the linking of hands). If the player called fails to break the chain, they join the "East" team. However, if the player successfully breaks the chain, they may select either of the two "links" broken by the successful run, and take them to join the "West" team. The "West" team then calls out "Red rover" for a player on the "East" team, and play continues. The game needs five people to play at least, although this would be a very short game. When only one player is left on a team, they also must try and break through a link. If they do not succeed, then the opposing team wins. Otherwise, they are able to get a player back for their team.” Well, when you have a name that rhymes with "Rover," perhaps trouble can innocently arise thanks to smart-alec/sarcastic juveniles like yours truly. My victim was the above-mentioned Wesley Cover. Wes was a transplant to Yellow Springs, now a resident of Clover Hill, having originally started his elementary career at Waverly Elementary. I immediately coined the phrase: “Red rover, Red rover, send Wesley Cover on over.” I had my teammates in hysterics by boldly pronouncing this at our third-grade field day back in 1976. Seconds later, I suddenly looked up to see young, Master Cover running directly at me with a full head of steam. The chain broke thanks to my foolish conjuring up of Wes’ athletic prowess. He had the last laugh of course, and anyone who knew Wesley Cover knew that he had no malice at all, and was truly a kind and laid-back guy. This same episode would play out again and again whenever Red Rover was played—Wes knew what was coming from me and others. Wes and I were friends and also participated in Cub Scouts together, however I recall Wes showed interest in Boy Scouts and higher level scouting experiences. He was an average athlete and played Little League in his youth. If anything else, Wes Cover was one of those guys prone to crazy miscues or accidents. I recall him coming into school with a black eye and broken nose because he slipped in the bathtub due to his brother leaving the floor wet. When we made the jump to Gov. Thomas Johnson Junior High in 1980, Wes would continue with Babe Ruth Ball and Midget League Football. In high school, Wes joined the wrestling team and we both played football together for the Patriots. I remember Wes being a great sport on the football practice field, and often taking a friendly ribbing from upper-classmen and those of us that had known him since elementary days. Every play involved a ferocity much worse than Red Rover. Wes was such an honest, wholesome and innocent individual, that he set himself up occasionally for pranks and the role of a human punchline. I wouldn’t call his athletic career stellar, as mine wasn’t either, but he was stable and sturdy like a brick wall—a fitting trait since he was very active in our school’s VICA masonry program. In fact, I found an old article saying that he participated in the 1984 Frederick Homebuilder’s High School Olympic contest. Wes also regularly participated in high school blood drives, donating in order to help others in need. By senior year, we all saw Wes Cover’s interests turn towards a potential career in the US military after high school. His senior quote, taken from Gen. Douglas MacArthur, lays testament to this. We both graduated on a warm night in early June, 1985. Our paths wouldn’t cross too many times thereafter. That fall of ’85 found me away at college for my freshman year at the University of Delaware. My Dad had known Wes dating back to our Cub Scout days. He thoughtfully clipped, and sent a newspaper article regarding Wes completing a phase of his basic training. I recall seeing him shortly after at the TJ Homecoming (Nov. 1985) game and dance, and he looked every bit the part of a US Army Airborne Ranger, complete with the stylish beret. We reminisced and laughed about old times, including the ridiculous “Red Rover” tradition I had started back in 3rd grade. I was lucky enough to run into him over Christmas break as well and would see him one more time in the summer of 1986. These would be my last interactions with Wes Cover. I was busy with school over the next three years, and Wes was compiling the fine military career he had contemplated back in high school. I also heard that he had participated in the Gulf War in 1990-91, and came out fine.  Time marched on in the early 1990s, as I now was in the midst of starting my post-college working career. Even though I worked at Frederick Cablevision, the sister company of our local newspaper, and was involved in local public affairs, I had no idea that Wes’ life would meet a tragic end in the summer of 1993. A former classmate told me of his death, a week after it happened. My immediate thought was that Wes had died heroically somewhere on a battlefield or on a complex training mission. He was a Ranger, and those guys are among the toughest—talk about impenetrable if lined up as a chain for a game of Red Rover. I knew Wes was strong, smart, and thoughtful, but I recalled that he was also unfortunate at times. Imagine my surprise when I learned the full story of his death at the hands of a fellow soldier, within the confines of an Italian restaurant in Fayetteville, NC. He was only a mile off base from his home at Fort Bragg Military Installation. Nonetheless, he would die a hero. The Massacre at Luigi’s On Friday, August 6th, 1993, Kenneth Junior French, a US Army master sergeant from Fort Bragg, became enraged with President Bill Clinton and the pending institution of the military’s new "Don't ask, don't tell" (DADT) policy involving service by gays, bisexuals, and lesbians. The policy prohibited military personnel from discriminating against or harassing closeted homosexual or bisexual service members or applicants, while barring openly gay, lesbian, or bisexual persons from military service. After a long afternoon of drinking whiskey while watching Clint Eastwood's The Unforgiven, which concludes with a violent massacre at a saloon, the 22-year old French grabbed two 12-gauge shotguns and sought to display his displeasure in downtown Fayetteville. Unfortunately for Wes Cover and other patrons, French chose the popular Luigi’s Restaurant, operated by an earlier US Army and war veteran named Pete Parrous and his wife Ethel. French pulled up to the restaurant, shouting about President Clinton and homosexuals in the military. He began shooting his weapon outside the establishment and soon made his way inside through a back door to the kitchen. From here, he made his way into the main dining room and shot people at random, killing four and wounding six before being shot and captured by local authorities. The gunman killed Peter and Ethel Parrous, who were 73 and 65 years old. Mr. Parrous had lived in Fayetteville for 54 years and had introduced pizza to the town. Apparently, he pleaded with French not to hurt anyone, when the gunman ruthlessly shot him in the face at point blank range. This prompted Ethel to stand up and scream, which resulted in French next taking her life. The Parrous’ daughter, Connie, would also become a shooting victim, but would recover from her injuries.  Interior view of Luigi's dining room Interior view of Luigi's dining room The other fatalities were 46-year-old James F. Kidd of Wheaton, IL and the former resident of Frederick, Wesley Scott Cover. Mr. Kidd was a lawyer with the Internal Revenue Service and simply in town to visit his 20-year old son Patrick who was stationed at Fort Bragg. At the time of his death, Wes was only 26 years of age and living in Fayetteville. He was currently engaged to be married, and was eating at Luigi’s with his fiancée Rona Wood, after the two had just enjoyed a movie with a good friend. Both were also connected to Fort Bragg. The stories of bravery and selflessness demonstrated by Mr. Kidd, and of my old classmate are heart-wrenching. With mere seconds to act, both men sacrificed themselves in covering their respective dining partners. Not just two, but three lives were directly saved as a result of their “duck and cover” maneuvers as both ultimate victims used their bodies to shield the other (Mr. Kidd’s son and Wes’ fiancée Rona) from French’s deadly fire. Patrick Kidd was physically unhurt as his father draped himself across the young man in the booth in which they were sitting. Wesley and Rona dropped to the floor below the table after the latter had been shot initially. Wes would cover Rona with his body after having ripped his shirt off to help compress the blood seeping from Rona’s open wound. The gunman proceeded to their table and stooped down with his firearm pointed at Wes’ head. Wes asked French not to shoot Rona because she was pregnant. At this point, Wes was callously shot in the head, and slumped further on top of his wounded fiancée. It was at this time that the gunman would be felled by an off-duty police officer, who shot from outside the restaurant’s front plate glass window. Other police arrived moments later and successfully captured French. Here is a link to a short, television news story from 1995 that recounts the incident two years prior: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sVQ3zZ658DE Three of those injured were treated at a hospital and released, and three others would be listed in stable condition but recovered. Rona would suffer being shot but survived, albeit with lasting complications including paralysis in her right leg. The miracle of the situation was the protection given by Wes in saving Rona’s life, and that of the unborn son she was carrying. The baby would be born the following February without complications—Rona would name him Stefan Wesley Wood. The shooter, Kenneth Junior French, was wounded in the leg and jaw, and apparently asked responding emergency personnel to let him die. He would make a full recovery but was charged with four counts of first-degree murder and six counts of assault with a deadly weapon with intent to kill. The highly anticipated court case occurred in February, 1994 in Wilmington, NC. French claimed to not remember the events of the murders, stating he had gotten excessively drunk prior to the occurrence at Luigi’s. He said that he had been deeply depressed with President Bill Clinton’s policy allowing homosexuals and bisexuals to serve in the military, under the condition they not divulge their sexual orientation. Defense attorneys for French argued that this decision had struck a nerve with their client and his rage, combined with alcohol, l had him out of sorts. They also cited a lifetime of childhood abuse at the hands of French’s late father as a key factor. They went as far as trying to make the case that French’s actions were not premeditated, rather that he was acting out his aggressions as his father on that deadly night. After a colorful court case, lasting over a week, French was found guilty and sentenced to four consecutive life terms plus 35 years. Since 1998, he has been imprisoned at the Marion Correctional Institute. Luigi’s Restaurant is still open today. It naturally was closed for several months after the tragedy. Pete and Ethel’s son Nicholas Parrous, daughter Linda Parrous Higgins, and son-in-law, Tony Kotsopoulos, did not want to let their parent’s legacy to end with the massacre of August 6th, 1993. They decided to reopen the restaurant later that year and were received with great community support. As I have looked back in old newspapers, I’m a bit surprised to see that the Fayetteville shooting doesn’t seem to have made our local papers. Wes Cover’s obituary appeared here however on August 19th, 1993. He would be buried two days later on August 21st in the cemetery’s KK/Lot 23. As I approached Wes’ gravesite to take a few photographs for this story, I felt a special calm and noticed the peace and tranquility of the surrounding area. Things got very quiet and I swear I heard a faint echo from over forty years ago calling:

“Red rover, red rover….send Wesley Cover on over." |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed