|

Welcome to Halloween time and all is quiet in Mount Olivet Cemetery. Some people think that this is a big night for graveyard activity, but I can vouch for the same tranquil and peaceful atmosphere as the other days and nights throughout the year. It’s “the living creatures” that cause the mayhem and merriment—not the dead. Halloween is a contraction of All Hallows’ Evening. The word hallow is defined as a holy person or saint. The past tense, adjective means revered or respected, such as the popular expression “hallowed ground.” Battlefields and cemeteries are great examples of hallowed ground, where the living lost lives, or ground where the once living still reside. All Hallows’ Eve is a celebration observed on October 31st in a number of countries. This marks the eve of the Western Christian feast of All Hallows' Day, better known as All Saints Day, and also referred to as All Soul’s Day. Both days are part of a three-day period that comprises Allhallowtide, the time in the liturgical year dedicated to remembering the dead, including saints (hallows), martyrs, and all the faithful departed. It would not be wrong to refer to this time as “Allhallowmas,” just like the widely accepted term Christmas, but seldom do. And just like Christmas, popular culture and capitalism have claimed a greater share of attention than religious early origins and traditions such as attending church services and lighting candles on the graves of the dead. Commercial Halloween activities include “trick-or-treating,” attending costume parties, carving pumpkins, bobbing for apples, playing pranks, visiting haunted houses and corn maze attractions, telling scary stories and watching horror films. One of the most popular things to do at this time of year is “ghost hunting.”

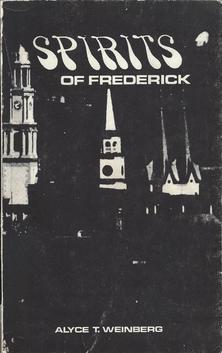

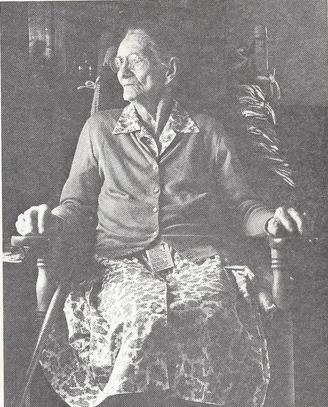

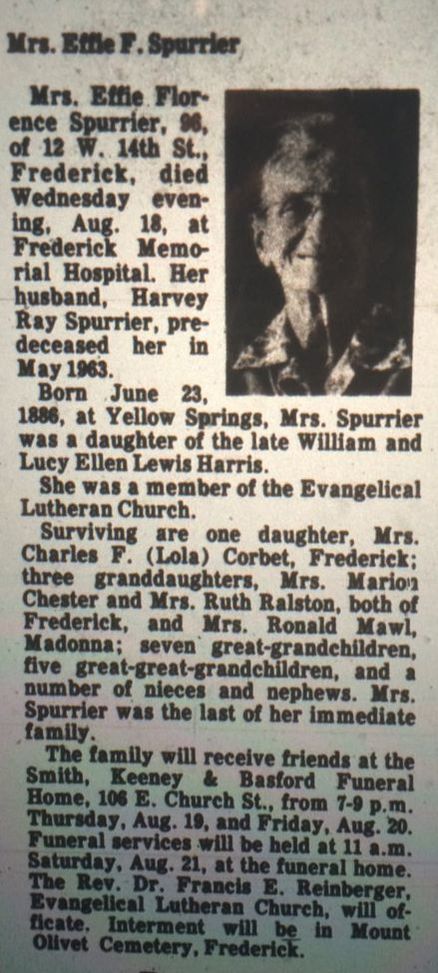

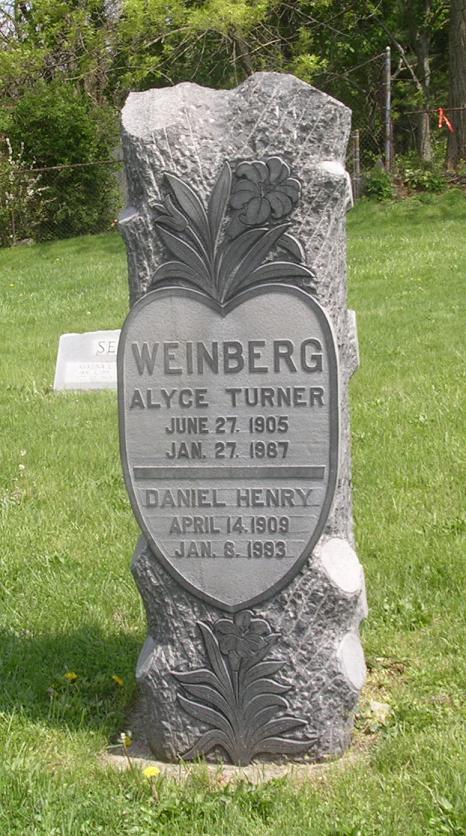

Although traditional science doesn’t support the existence or possibility of ghosts or spirits roaming or interacting with the living, there are plenty of people that do. As a matter of fact, we are in the midst of conducting our 6th year of the Mount Olivet cemetery Candlelight History Tour. I have had the pleasure of conducting these nocturnal walks each fall. I tell participants stories of the cemetery’s history, the evolution of the funerary business and best of all, tales of just a few of the 40,000 persons that have been interred here in this beautiful “garden-style” cemetery since it opened in 1854. A few weeks back I received a very kind, and thought-provoking email from a tour participant named Tera. She had just taken to tour the night before (October 14th) and attached a photo. Here is the content of her communication to me: “Hi there, I was on the walk on sat night and took this picture of you. On my I phone I took it in live mode and it comes down from the trees and surrounds you. I took many photos that night and this is the only one like this. Not sure how you feel about orbs? Anyway....Thought you would be interested. I can stop by sometime and show you on my phone so you can see how it moves. It was at our first stop on the tour. The first person buried there.” The grave site stop was that of Mrs. Ann Crawford, the cemetery’s first interment who I have been introducing tour participants to for years. She was laid to rest May 28th, 1854 and I featured her as the subject of a “Stories in Stone” last January, and entitled The First Burial. I don’t quite have a handle on the supernatural, as I’m just a humble historian, who occasionally loves to “mythbust.” At the same time, however, I love the challenge of proving myths true. I consulted with a few of my friends, more versed on the subject. From what I gleaned, my spirit encounter captured by Tera’s camera, seems to point to the fact that spirits are fond of me. More so they trust me, and are thankful that I’m doing these tours and writing these stories. So I’ve got that going for me.  Alyce T. Weinberg's article as it appeared in the August 27, 1982 edition of the Frederick News Alyce T. Weinberg's article as it appeared in the August 27, 1982 edition of the Frederick News I recently performed a diligent search of old Frederick newspapers for any published ghost stories attributed to Mount Olivet Cemetery. Unfortunately, I found none, but will continue to look. In my hunt for ghosts, I did stumble across a short feature piece from late August, 1982 in the Frederick News. It was written by Alyce T. Weinberg of Frederick. Mrs. Weinberg, and husband Dan, gave Frederick the majestic, historic downtown theater that bears the couple’s name. Mrs. Weinberg’s evocative column featured a remembrance of Frederick resident Effie Spurrier, coming just over a week after the latter’s death at the age of 96. Mrs. Weinberg had interviewed “Miss Effie,” as she called her, a few years prior for inclusion in a book entitled Spirits of Frederick, written in 1979 and published by Studio 20 of Frederick.

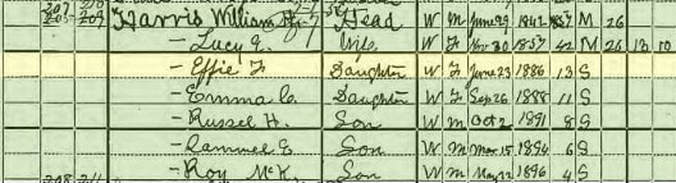

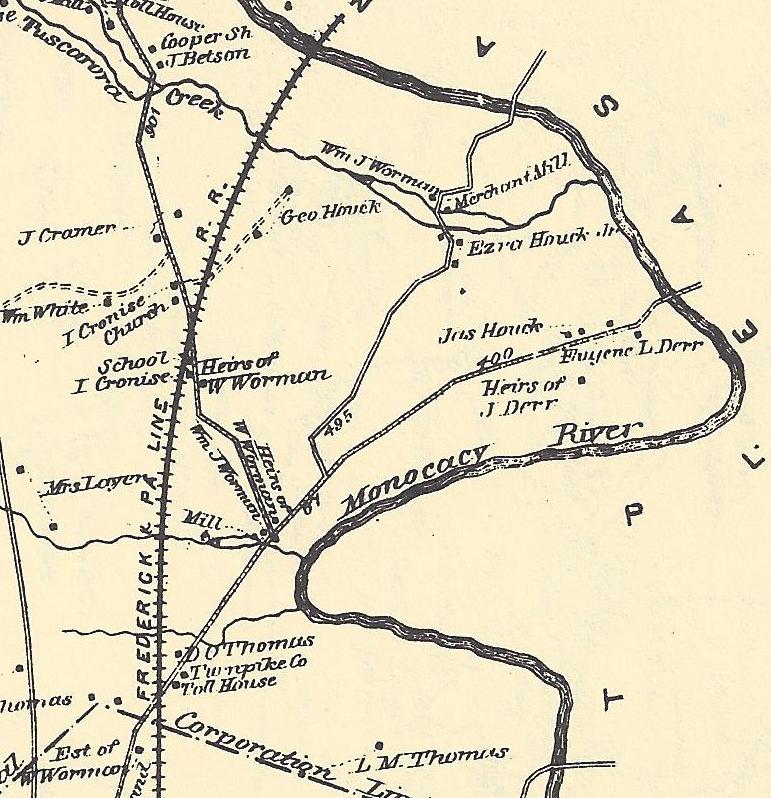

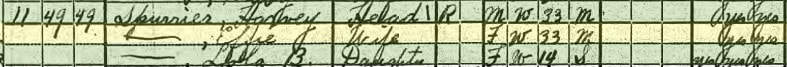

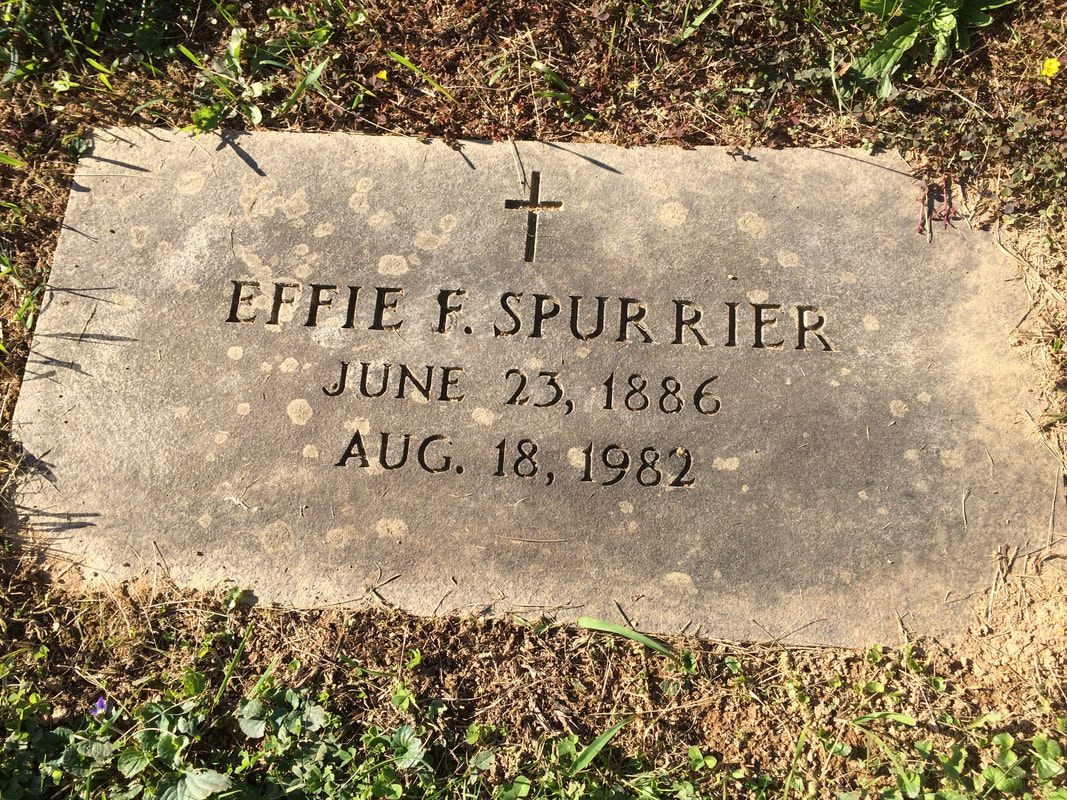

Grave of Lola May Harris (1877-1903) in Pleasant Hill Cemetery (located in Indian Springs off Yellow Springs Road) Grave of Lola May Harris (1877-1903) in Pleasant Hill Cemetery (located in Indian Springs off Yellow Springs Road) Another unexplained brush with the supernatural came after Effie’s mother claimed to have heard a noise outside the house after bedtime. Young Effie ran to a window, and to her amazement, witnessed “a woman in flowing white on a white horse, and her mother told her that was a bad omen.” Supposedly a daughter died a short time later. I looked into this and found that Effie’s older sister, Lola May Harris, died on October 30th, 1903. Ironically, this occurred on “Halloween Eve,” for those that want to look for more symbolism. Lola may was 26 years of age at the time of her death. I tried to find information on the cause, but found nothing. I did see articles in spring of 1897 where the young woman almost died of pneumonia, but made a phenomenal recovery. Effie would marry Jessie E. Bell in December, 1905. The couple would have a daughter, and named her Lola— either after Effie’s fore-mentioned late sister, or Lola V. Bell, a sister of Jessie. That alone is eerie, as Lola is not an overly common name. The family lived in Jessie’s birthplace of Harmony Grove, a small hamlet once comprised of a slew of houses along the Old Emmitsburg Pike north of Frederick. Nearby was the original Worman’s Mill, namesake of the large residential community that would come less than a century later. Many dwellings were lost in the 1960’s and 1970’s as the highway of US15 was dualized and designed to bypass sleepy Harmony Grove. Another interesting thing to mention here is that one of the original land patents comprising this particular area was Stephen Ramsburg's 473 -acre parcel carved from Daniel Dulany's Taskers Chance tract in 1746. Ramsburg named his property "Mortality."  Effie told Mrs. Weinberg that she lived with her husband’s family here when she first married. She inferred that the locale could have been watched over by the spirits of native Indian peoples that originally inhabited this higher ground in close proximity to the Monocacy River. The greater location has a rich Native American story with the famed Biggs Ford site to the north, and a tract named "Indian Fields" in colonial days, to the west. This latter location would become Rose Hill Manor. Traces of ancient life have been found by farmers, archeologists and relic hunters alike. These have come in the form of spear points, pipe and bowl fragments, found regularly in the nearby fields. “We heard something go upstairs anytime, opening and closing doors. Couldn’t keep the covers on the bed in one room, and the furniture rattled and moved around by itself. We weren’t afraid if we burnt the light all night, and the covers stayed on too.”  "Goodness, gracious... great ball of fire!" "Goodness, gracious... great ball of fire!" Interestingly enough, the Bells regularly heard mysterious “bell” sounds coming from their chimney. Her husband and male relatives would regularly experience this while engrossed in playing card games. They also would see lights in the Worman’s Woods “going round and round.” Effie topped her tale by telling Mrs. Weinberg that on one particular night, “a ball of fire traveled inside the room until it found an open window.” Was there an ancient Indian burial ground here that was disturbed by later growth and development leading up to the early 1900’s? Today, the Bell home is gone. What remains of Harmony Grove lingers in the shadow of Clemson Corner, the 37-acre shopping mecca and bookend Market Square, both conveniently located off MD route 26. When Effie lived here, it was a much quieter time, long before the modern-era defined by Wegmans, Lowes, Chipotle and a Super Wal-Mart. I venture to guess that the native spirits are beyond incensed at the sprawl here over their former tribal village site, but It’s simply much too congested for ghosts and spirits to even bother haunting today’s residents here, I suppose. Effie and Jessie Bell split sometime between 1910 and 1919. She would eventually remarry in 1919. This was to second husband, Harvey Ray Spurrier, a Mount Airy boy and World War I veteran. Harvey would work as a custodian of the Frederick Post Office for 27 years. The Spurriers moved into Frederick City and could be found living at 11 E. Fourth Street in the 1920 US Census. At this point in time, Effie was duly employed at the Ox Fibre Brush Company on East Church street extended (today the site of Goodwill Industries). Ten years later they would be living at 710 N. Market Street. They remained here until Harvey’s death on May 17th, 1963. He would be interred in Mount Olivet’s area AA/Lot 30. I give these addresses, as potential spots for supernatural activity, as Effie seemed to be followed throughout her days. Effie Spurrier lived 19 more years beyond Harvey. She had been living with her daughter when she passed at the age of 96 on August 18th, 1982. The ghost expert would be laid to rest at Harvey’s side in Mount Olivet on August 21st. Perhaps Effie is still visited by those old “haunts,” or maybe she takes her turn roaming our cemetery grounds or her past residences. Whatever the case, I hope to remain in her good graces, as it has been a pleasure getting to know a little about her through writing this article. I also owe a debt of gratitude to Mrs. Weinberg, who we lost in 1987. She wrote a great book, one of many gifts she (and her husband) gave to Frederick, Maryland. Oh yeah, and Happy Halloween to both of you!

3 Comments

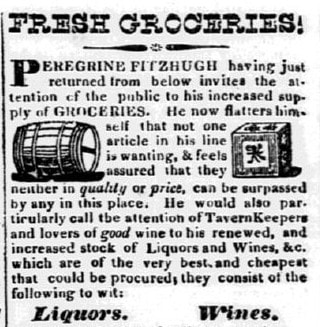

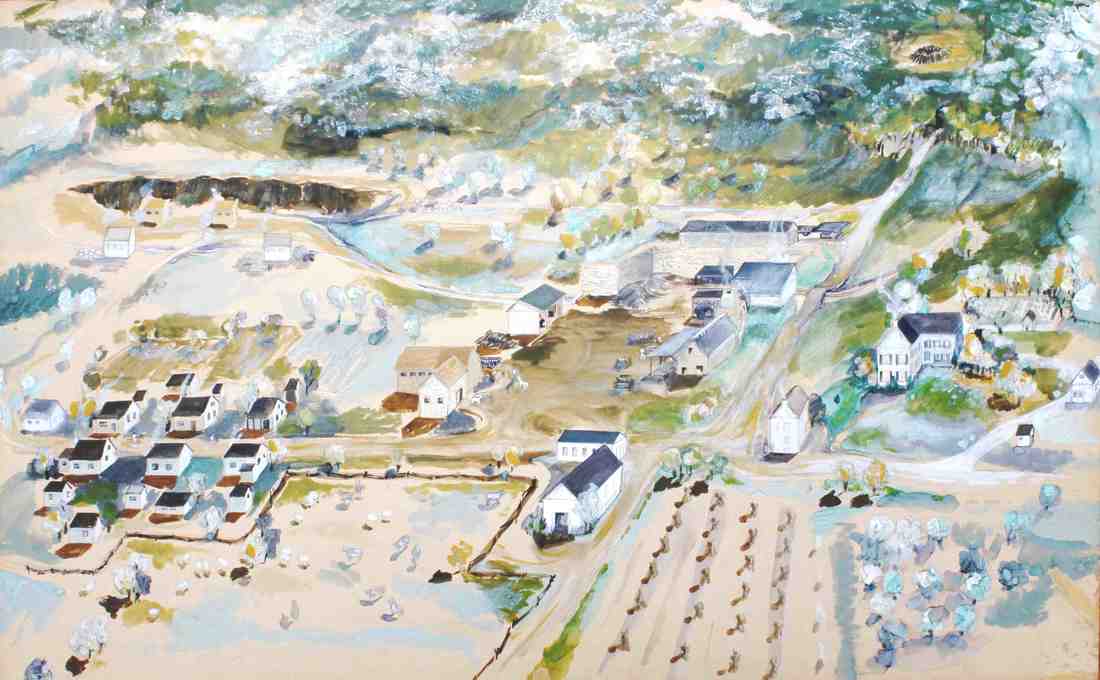

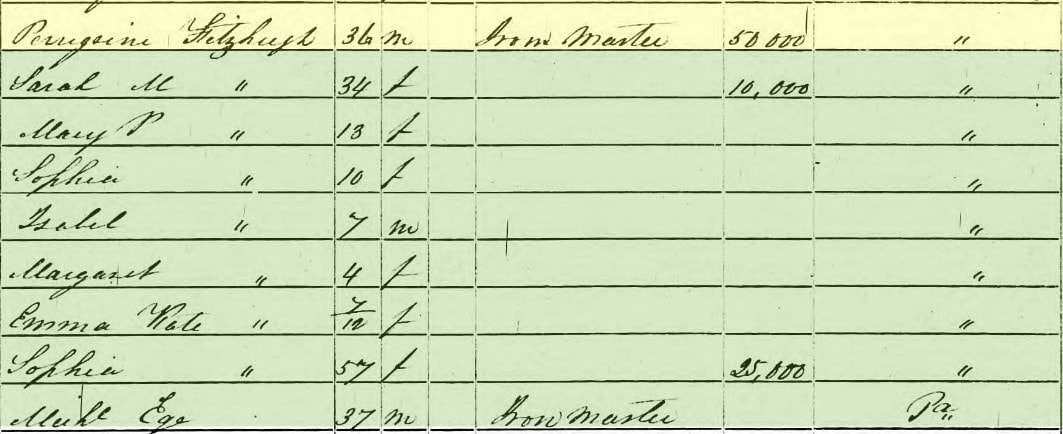

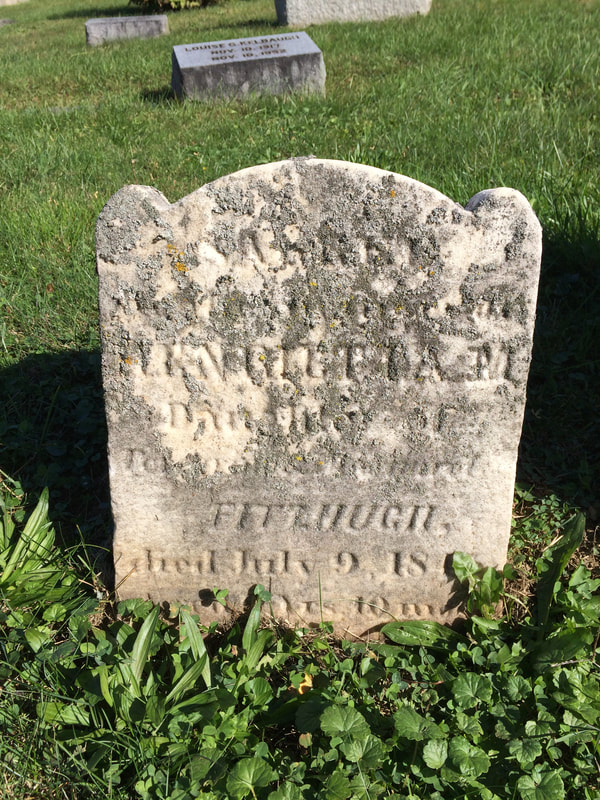

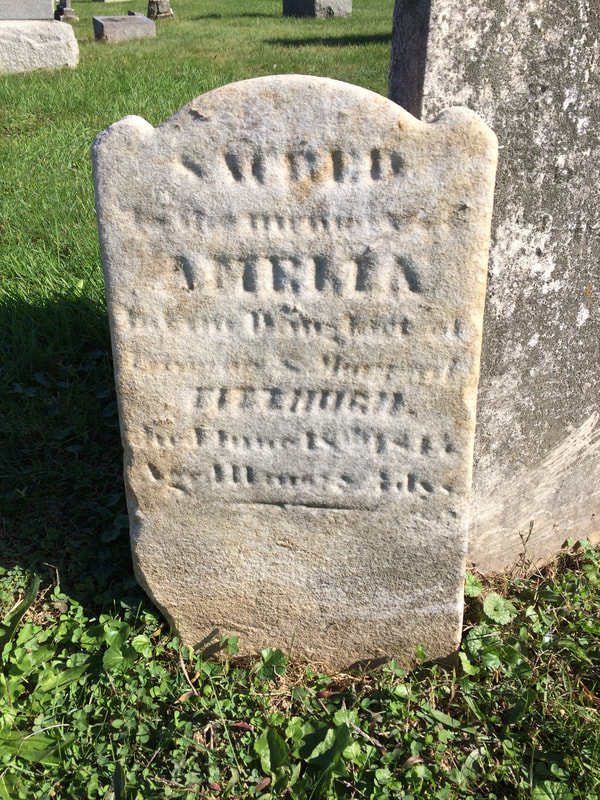

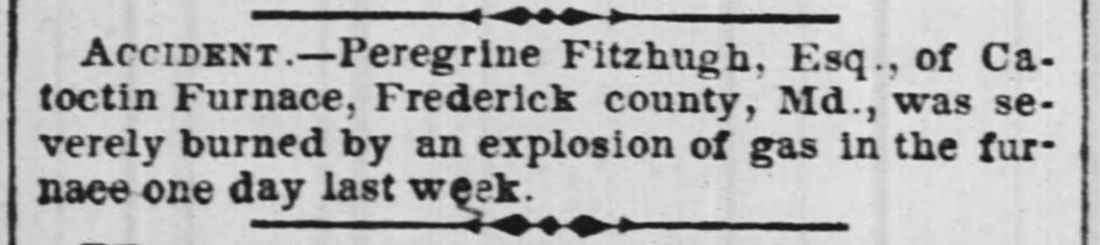

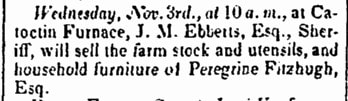

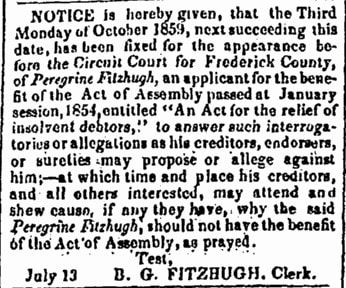

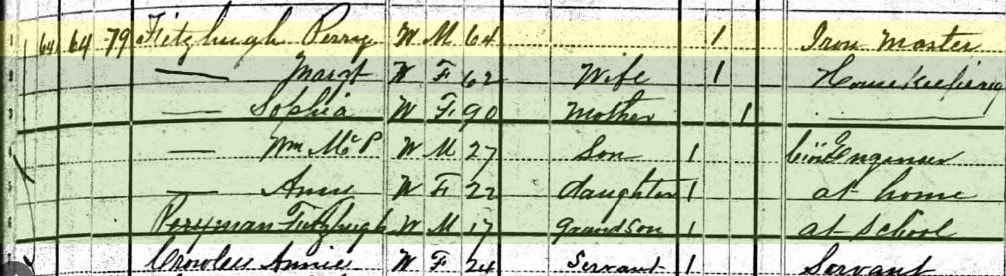

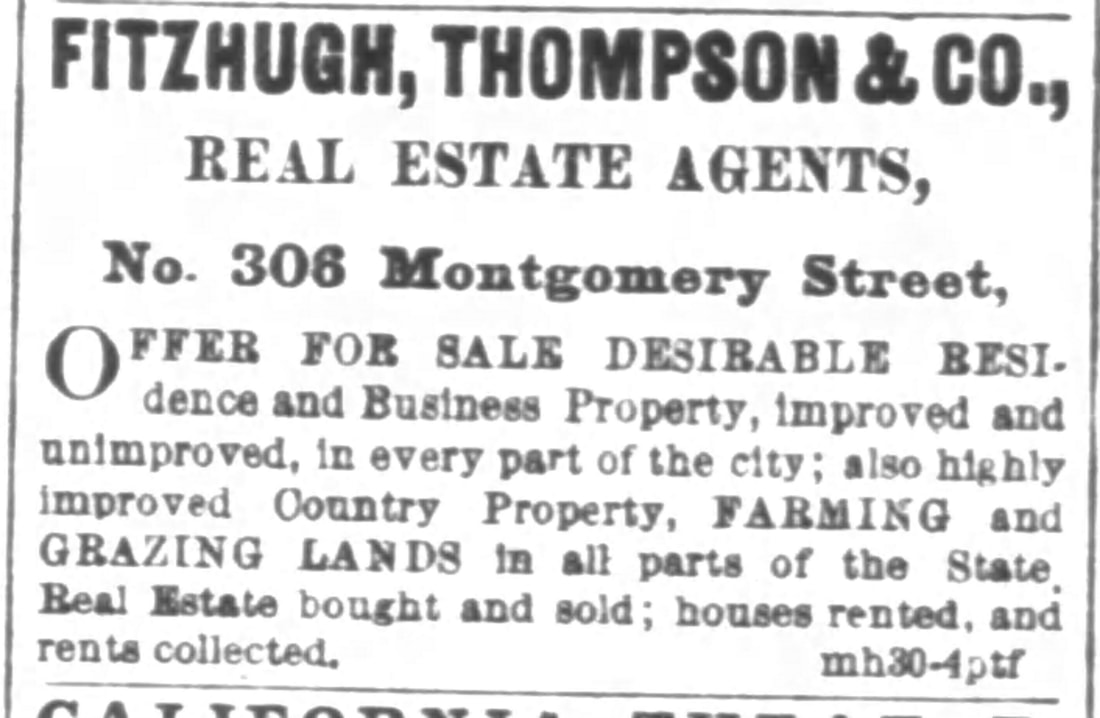

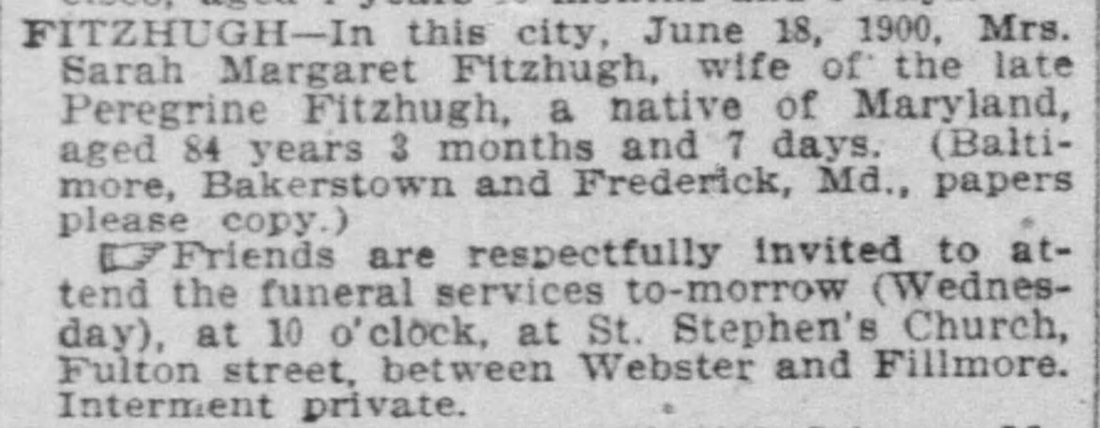

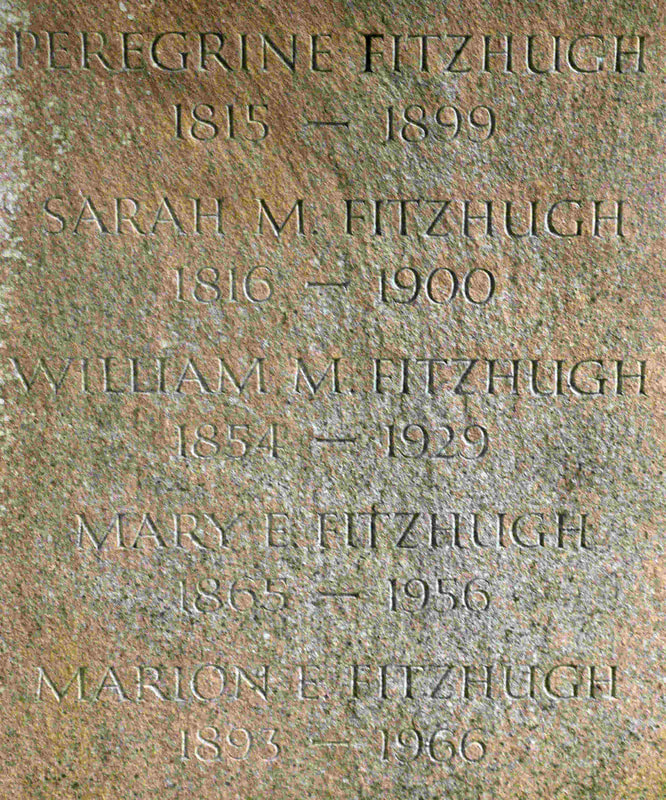

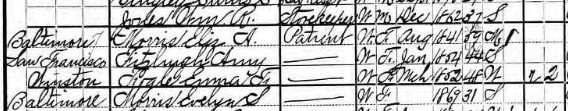

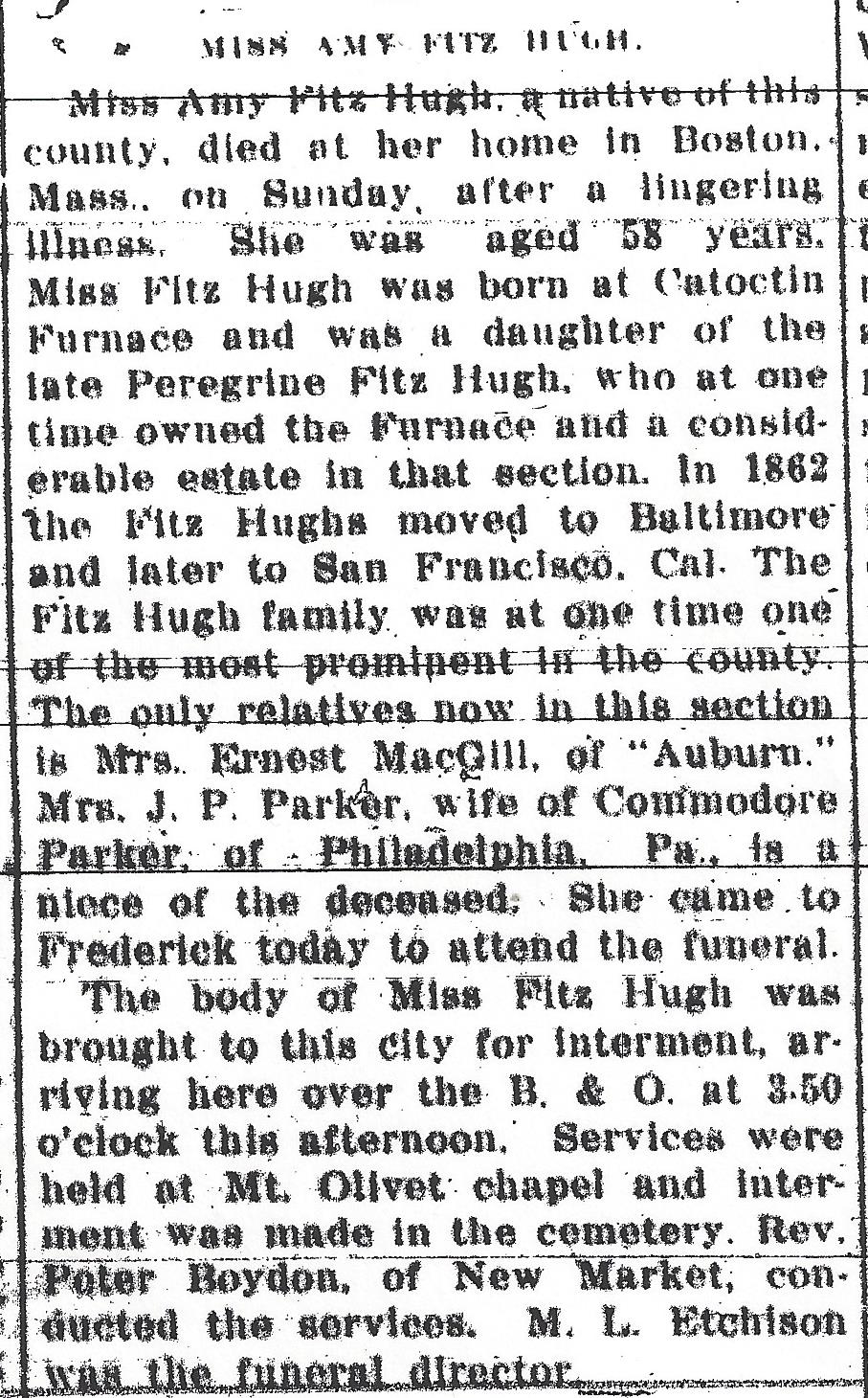

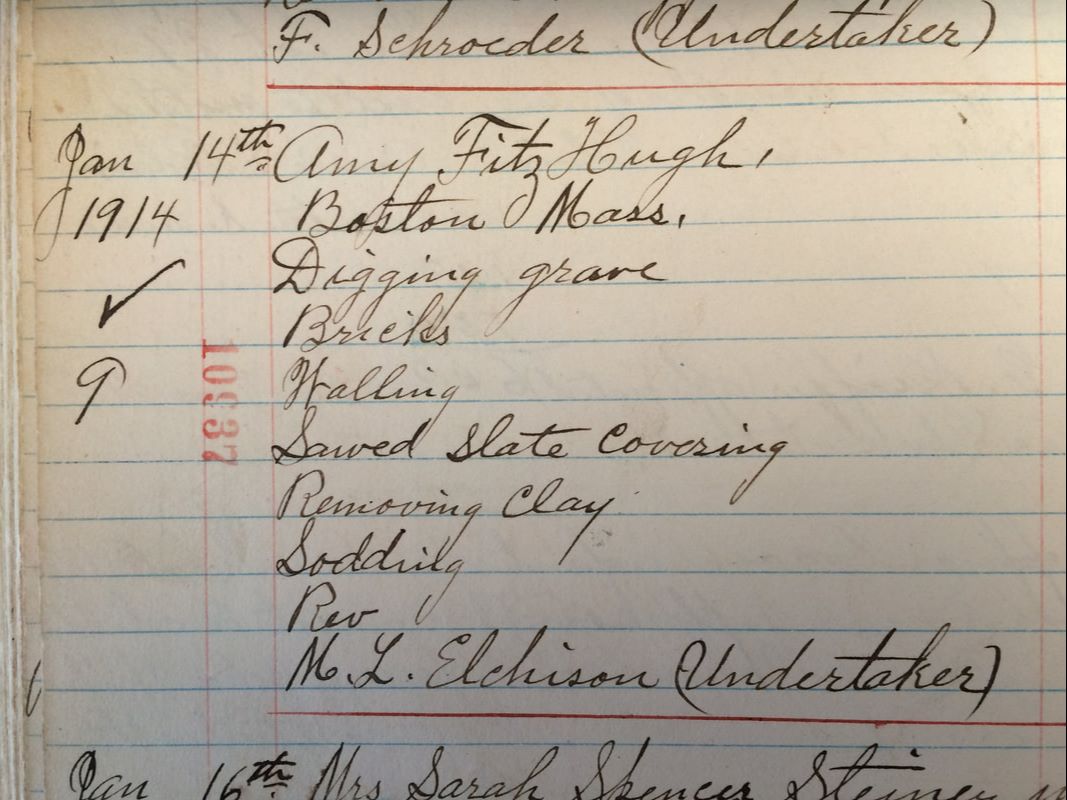

I borrow the title of this week’s article from a popular guided night hike that occurs this time of year up at the historic Catoctin Iron Furnace and surrounding village. Located just below Thurmont, this seasonal offering features tour stops at historic structures such as workers’ homes, an ancient slave cemetery, Harriet Chapel, the remains of the Ironmaster’s House, and best of all, “Isabella”—the iconic second stack structure of the once-booming pig-iron furnace operation. Here in Mount Olivet Cemetery, a trio of lonely looking gravestones can be found in the southernmost section of Area H. They have direct connections to the north county furnace industry and encompass a sort of transient spirit, one that can be traced to their removal here in the cemetery’s first year of existence. This was 1854, and two of the graves within Lot #416 were opened on October 24th of that year. Received were two young daughters of a prominent businessman named Peregrine Fitzhugh. Perhaps I perceive “loneliness” because these women are resting some 2,775 miles from their parents and siblings, interred on the other side of the continent.  The bust of Thomas Johnson, Jr. sculpted by local artist and architect Joseph Urner in 1926. The bust of Thomas Johnson, Jr. sculpted by local artist and architect Joseph Urner in 1926. To give some context, I want to bring into the story former Frederick resident Thomas Johnson , Jr. (1732-1819). TJ, as he is often referred to, has his name on a local high school (my alma-mater), a county park and children’s museum (Rose Hill Manor), and a roadway in town which contains a cornucopia of medical offices and offerings—Thomas Johnson Drive. More importantly, Mr. Johnson rests in peace in Mount Olivet. His grave monument lists his many accomplishments in life: lawyer, planter, Continental Congress member, Revolutionary War veteran, Maryland’s first elected governor, surveyor of the District of Columbia and US Supreme Court justice. Johnson was also a successful businessman, and we generally give him credit for creating, and operating, the famed Catoctin Furnace. The truth is that Thomas’ brother, James, (also buried here in Mount Olivet), was the true force behind the furnace’s first iteration, and was followed by a long list of subsequent operator/owners up through the early twentieth century. One of these “unsung heroes” was the gentleman mentioned above, Peregrine Fitzhugh. A Wandering Man For starters, I had never seen the name Peregrine before. So I looked it up in the online dictionary. It is defined as: “having a tendency to wander.” After looking into this man’s past, I can vouch that Peregrine Fitzhugh certainly did his share of “wandering” over his lifetime. Born on the 8th of February, 1815, Peregrine Fitzhugh was the son of William Fitzhugh (1784-1819) and Sophia Claggett (1792-1884). He was named for his grandfather, a wealthy planter of Virginia and officer in the American Revolution. Peregrine’s grandmother, Elizabeth Chew, was a native of early western Frederick County (today’s Washington County). These people came from Chewsville, located midway between Hagerstown and Smithsburg. The hamlet obviously took its name from the Chew family, but some old histories say the place name is derived from a shortened, slang version of Fitzhughsville—hence Chewsville. In the early 1840’s, the Catoctin Furnace was owned by John McPherson Brien (son of former Catoctin Furnace owner John Brien and grandson of another, Col. John McPherson). The young Brien had bought the operation from his late father’s estate in 1841, but he instantly encountered financial trouble and found himself in the position of having to sell the floundering operation. This occurred in April, 1843, a time of drastic change in the furnace industry based on the introduction of coke as a coal-based combustible agent over charcoal (created from bark and timber). Enter the “wanderer” from Chewsville, Peregrine Fitzhugh.  Hagerstown Torch Light (July 17, 1834) Hagerstown Torch Light (July 17, 1834) The Fitzhughs were connected through marriage to other “furnace-experienced” families of Maryland including the fore-mentioned McPhersons, and the Hughes. As for his own upbringing, Peregrine enjoyed the childhood that Washington County afforded. Family members were plentiful in the area. This was fitting because his grandfather had named his family plantation “the Hive,” because he saw it as the center of social, economic and familial life in its remote, rural setting. As for employment, Peregrine supposedly had some prior introduction and experience in the furnace and forge industry. I found an advertisement in an 1834 Hagerstown newspaper in which he was operating a general store. This operation offered groceries, wine and liquor. Peregrine Fitzhugh married Sarah Margaretta Pottinger (1816-1900) on September 24th, 1833. The couple welcomed their first child, a daughter, on September 6th, 1835 and named her Henrietta Maria. More daughters would follow: Mary Pottinger (b. 1837), and Sophia (b. 1840). The 1840 US census shows Peregrine Fitzhugh’s family living in Williamsford, known today as Williamsport.  All Saints' Cemetery in left center of lithograph in this view looking southeast from Square Corner (from 1854 Sachse lithograph) All Saints' Cemetery in left center of lithograph in this view looking southeast from Square Corner (from 1854 Sachse lithograph) Home and Hearth After purchasing the Catoctin Furnace in April, 1843, Peregrine took up residence at the Auburn mansion, formerly inhabited by distant ancestors and cousins, not to mention the stately home’s builder Baker Johnson, another brother of famous Thomas. As Peregrine dealt with the challenges associated with running a furnace operation, he would also be faced with familial triumphs and tragedies. A fourth daughter, Isabella Hudson, would be born in January, 1844. It’s interesting to note that this was nine months after the Fitzhughs took ownership of the furnace. This daughter was such a welcome addition and favorite of her father that her name would be used to grace a later built feature of the Catoctin operation. Another baby girl, Amelia, would follow, in 1845. Unfortunately, she would die shortly after on June 19th, 1845. While in the midst of mourning their infant daughter, the Fitzhugh’s oldest child, nine year-old Henrietta, would pass on July 9th. Just 20 days separated the deaths of these sisters. Both girls were laid to rest in the old burying ground of the All Saints Episcopal-Protestant Church congregation in Frederick City, located between Carroll Creek and East All Saints Street. Life at the furnace went on for the Fitzhughs. The family welcomed yet another little girl in 1846 and named for her mother, Sarah Margaretta. She would be given the nickname “Meta.” The next year, Peregrine received a financial boost when a wealthy great aunt died, leaving him a large chunk of money from her estate. This allowed Fitzhugh to make necessary improvements to his pig iron operation. He also took the opportunity to recruit some talented work associates with the mission of making the entity profitable again. This was exemplified by a man named Michael M. Ege. Another daughter, Emma Katherine (Kate), was born in 1848.  Stack #2, better known as "Isabella" Stack #2, better known as "Isabella" Hard Times Business success was short-lived, however, and a financial downfall would beset Peregrine Fitzhugh in the early 1850’s after the departure of Mr. Ege. Production was at a minimum, and little iron shipped out. The family would be forced to sell their spacious home of Auburn mansion, plus surrounding lands. With debts mounting, Peregrine borrowed heavily from relatives, namely his wife and mother. He would have to enter into a business partnership with Jacob M. Kunkel of Frederick. This occurred in 1856. Kunkel’s money allowed Fitzhugh to “right the ship” so to speak. Debts were paid and more improvements were made to the furnace. He installed a “mule powered” rail line to move ore from the banks to the furnace. He also built a second furnace stack next to the original. This steam-powered, hot-blast charcoal furnace was given the name Isabella, after Peregrine’s daughter. Peregrine was also a highly religious man and did his part to continue a close relationship between both his faith and furnace. He was a member of All Saints Parish in Frederick and was supportive of the previously built Harriet Chapel within the Catoctin Furnace hamlet. Fitzhugh deeded seven acres of land surrounding the small, stone chapel and went on to help build the Catoctin Parish Rectory. In 1854, a boy was born to Peregrine and Sarah Margaretta—William McPherson Fitzhugh. Another momentous thing happened within that year, Mount Olivet Cemetery opened in late May. Peregrine would invest money into the newly incorporated Mount Olivet Stock Company, buying five cemetery shares for a total outlay of $100. In return, these shares were surrendered for five burial plots in Area H. He would have his two deceased daughters removed from All Saints Cemetery and brought to the new non-denominational, “garden” cemetery for re-burial. Henrietta and Amelia would be re-interred into Mount Olivet on October 24th, 1854. While Jacob Kunkel now held the property mortgage, Peregrine continued the day-to-day management of the furnace, and his family lived in the Catoctin Manor house, also known as the Ironmaster’s home, located immediately north of the furnace operation. A few years went by and Peregrine worked diligently to pay off debts. Two more setbacks would hit the Fitzhughs in 1858. First off, Peregrine was severely burned by an explosion of gas at the furnace in January. Second, debtors brought suit against Fitzhugh and a local court actually appointed trustees culminating in a trustee’s sale. The furnace was bought by Jacob Kunkel’s father (John Kunkel) as an investment. After the sale of Catoctin Furnace, Peregrine left the area and headed west to find subsistence for his family. He went to Texas, and a few accounts say that he studied opportunities in the oil well business. Meanwhile, his name was constantly appearing in the newspapers back home, having lawsuits brought against him. This would continue in earnest over the next 3 years. Whatever the case may have been, Sarah Margaretta Fitzhugh and the children had been left behind at the Catoctin Furnace vicinity, still living within the Ironmaster’s House. Apparently, the records of the business were left in a drawer of Peregrine’s private desk. Mrs. Fitzhugh would soon be evicted when Jacob Kunkel’s brother (John Baker Kunkel) moved into the Ironmaster’s residence. From here Mrs. Fitzhugh migrated back to Auburn to live. Peregrine reappeared in spring of 1859, and immediately went about the process of relocating his family to the other side of the country. California Dreamin’ I guess you could say that their family wandered off. Thomas J. Scharf’s The History of Western Maryland (published in 1882) says this about the Fitzhugh family: Thomas J. Scharf’s The History of Maryland says this about the family: “This business catastrophe was promptly ascribed by the opposition papers to the effects of the Democratic tariff of 1846. Peregrine Fitzhugh left the county after the sale of his property in Washington and Frederick counties, including the Catoctin Furnace. In California there were a number of leading citizens including Major Richard P. Hammond, the surveyor of the Port of San Francisco during President Pierce’s administration, who had gone from Western Maryland and a few years after Mr. Fitzhugh left Catoctin Furnace he joined the Maryland Colony in California with his family consisting of his wife, a son and five daughters. Most articles say that the Fitzhughs actually left Maryland around 1862. Perhaps the American Civil War helped influence the family to vacate Maryland for the less chaotic environs of San Francisco. They likely sailed out of Baltimore to the West Coast. Once there, Peregrine found work as a land clerk, and later became a real estate mogul. He did very well for himself, as did his offspring. The California experience for beloved daughter Isabella Fitzhugh was short-lived, however. She would die in San Francisco not long after her marriage to Rev. Edward G. Perryman, at the age of 20. She had a child named Fitzhugh Perryman in 1863, who would be raised in part by his maternal grandparents. Isabella’s body would be shipped back to Frederick and Mount Olivet. She was placed next to her sisters Henrietta and Amelia, buried here a decade earlier.

Amy’s body would be transported back to Frederick by train from Boston. Three of her sisters were waiting for her in Mount Olivet Cemetery in the old Fitzhugh family lot. I’m glad to know that these four “Spirits of the Furnace” could be reunited here in Mount Olivet.

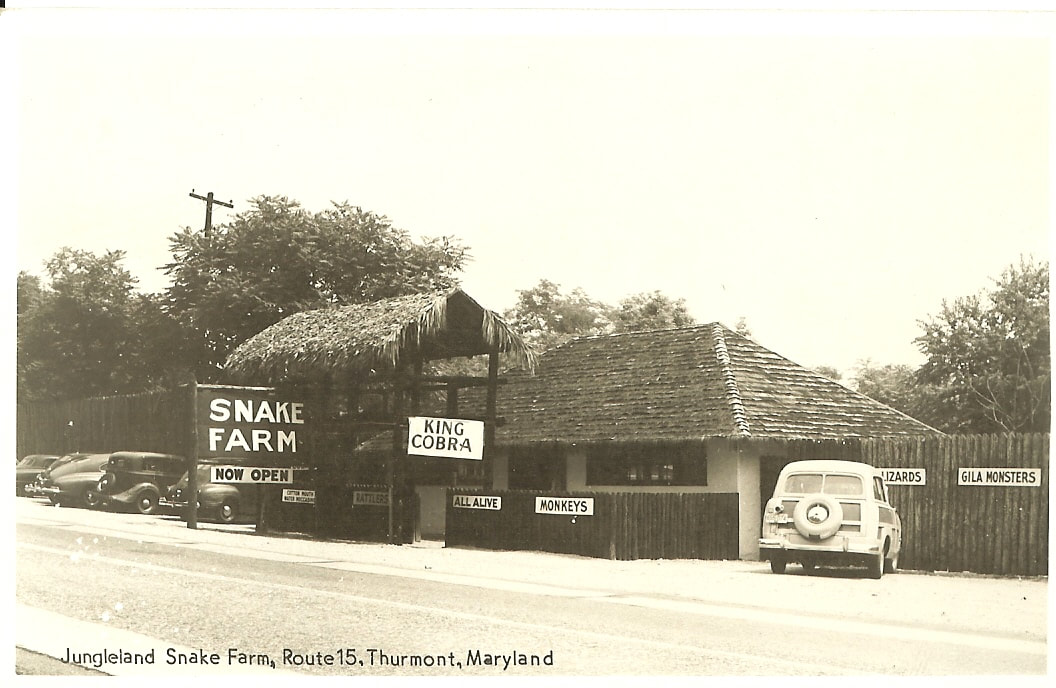

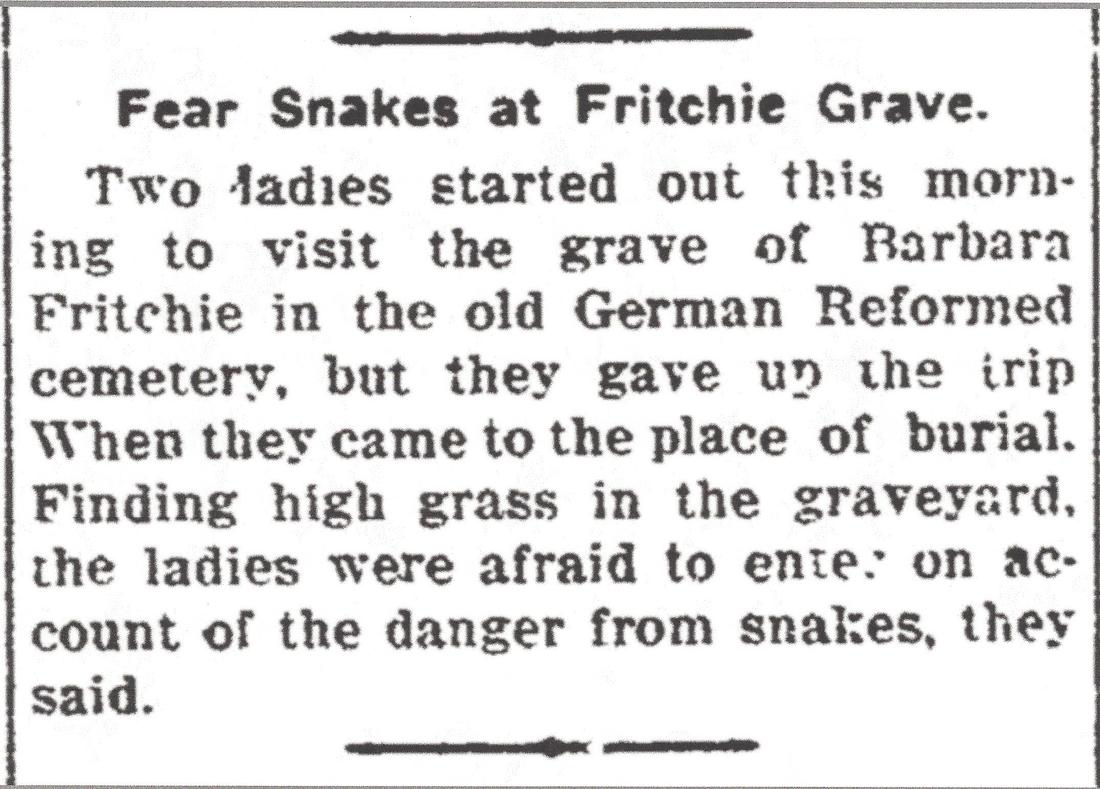

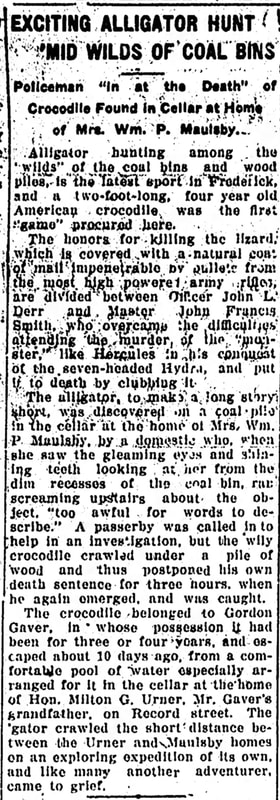

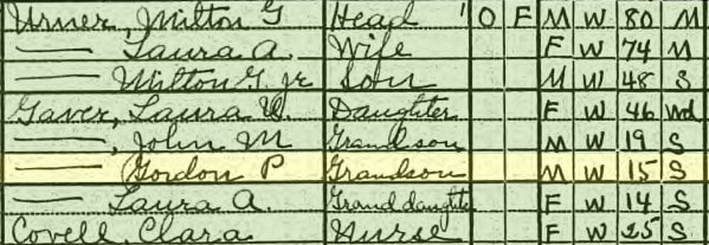

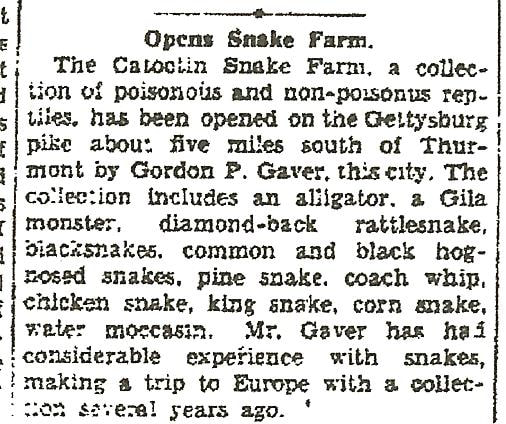

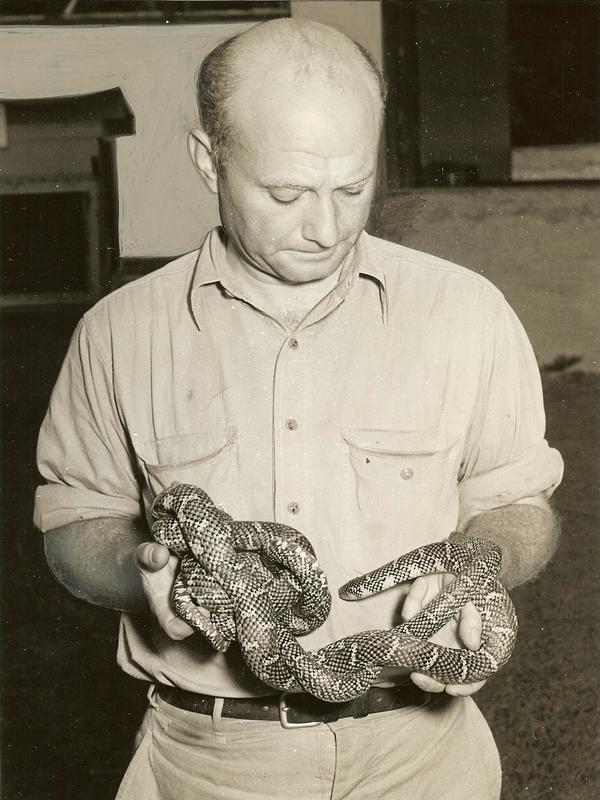

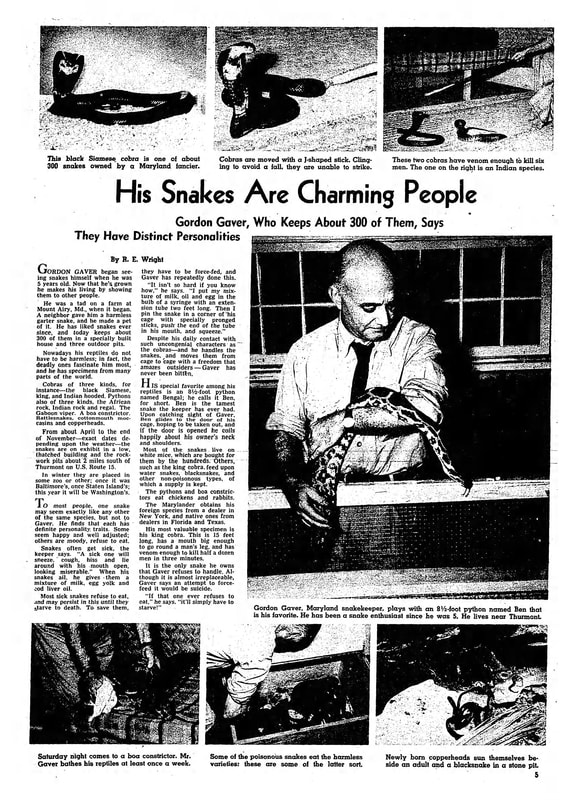

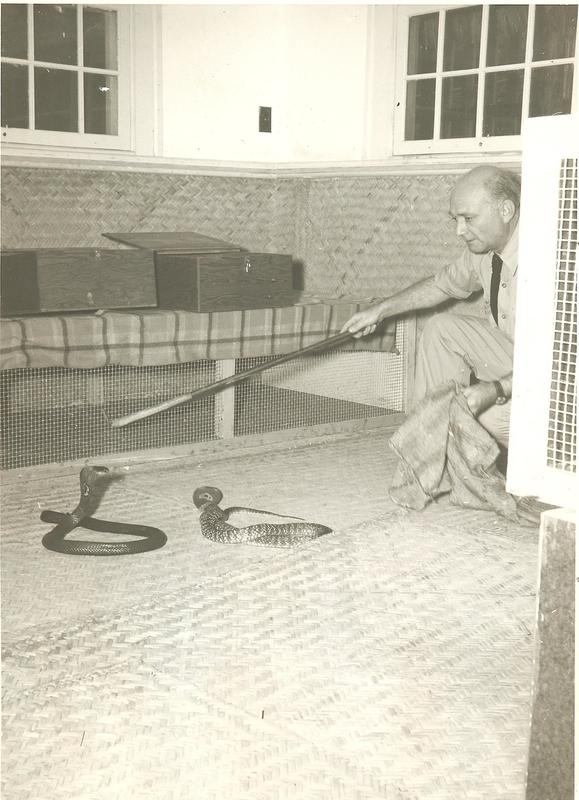

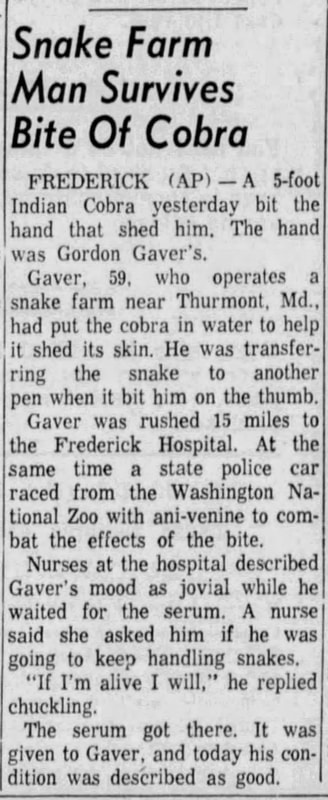

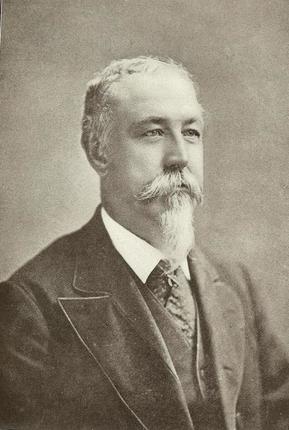

“Up from the meadows, rich with…snakes?” Last month, I stumbled across an interesting article appearing in the Frederick News, dated September 4th, 1912. Apparently there was a problem with hostile reptiles at the sacred gravesite of Frederick’s beloved flag-toting heroine, Barbara Fritchie. This occurrence took place in the old German Reformed Cemetery, once located at the corner of N. Bentz and W. 2nd streets. These days, this locale is more commonly known as Memorial Park. Of the many factors that would lead to Dame Fritchie’s re-interment to Mount Olivet Cemetery the following May (1913), I was quite surprised to learn that snakes may have played into the equation. Today, I can say with confidence, that you would have a better chance encountering “snakes on a plane” than encountering these creatures on, or around, Dame Fritchie’s grave. However, I find it quite ironic that just fifty yards east of Barbara’s grave, there lies a gentleman that made his reputation and livelihood on the limbless reptiles. His name was Gordon Gaver.  Milton G. Urner Milton G. Urner Gordon Paul Gaver was born February 2nd, 1904 on the Carroll County side of Mount Airy, Maryland. His father, William E. Gaver, was a local physician who originally hailed from Middletown. His mother, Laura Eugenia Urner came from one of the most prominent families in the county. Her father, Milton G. Urner was a local lawyer, who served Frederick County as State’s Attorney and two terms as a US Congressman. The Urners lived in downtown Frederick’s Court Square area behind the Frederick County Courthouse on Record Street. Gordon, brothers William and John, and sister, Laura Ann (Mrs. Richard Biggs), grew up on the family farm in Mount Airy. Like many kids of agricultural upbringings, the Gaver children developed affinities for animals. However, young Gordon would take an interest in a non-traditional member of farming life— one not found in the ever-popular “Ol’ McDonald” song. At the age of five, Gordon was presented with a peculiar new pet by a neighbor—a garter snake. From that point forward, the boy became fascinated with snakes and reptiles of all varieties. He would begin to obtain specimens from his family farm, and other areas throughout the county stretching from the Monocacy and Potomac River environs to the wooded elevations and rock outcroppings of Catoctin Mountain. Whether willingly, or not, his parents seemed to have supported his unusual hobby.

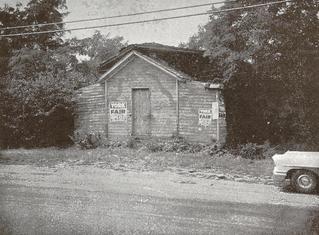

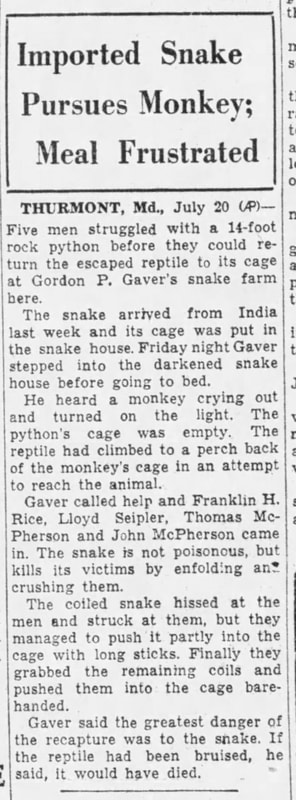

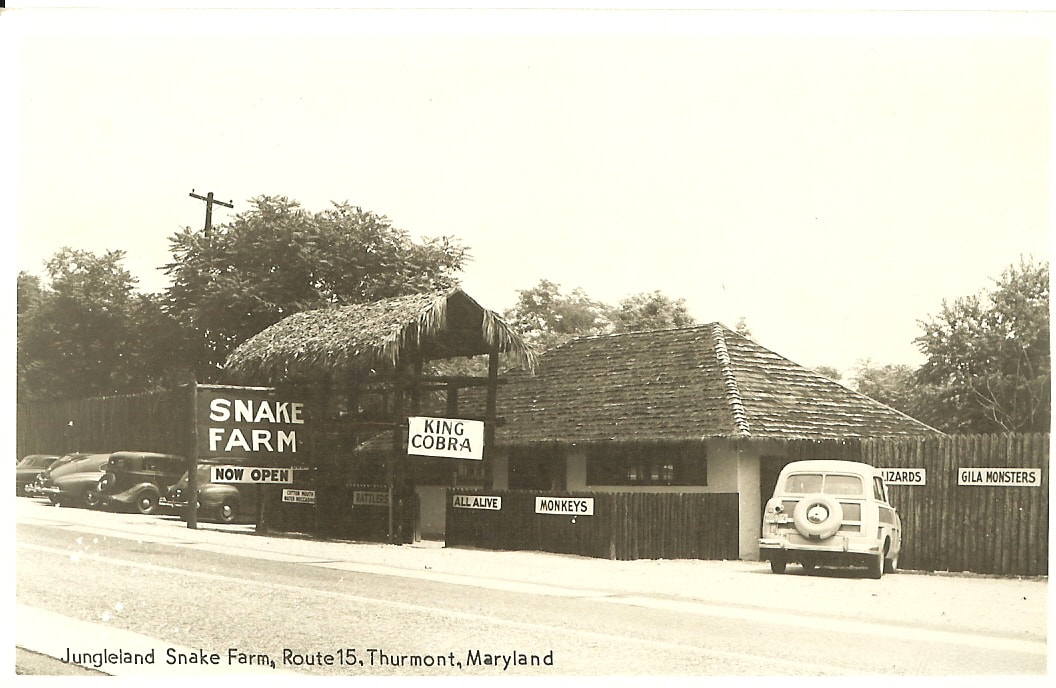

Gordon attended the Tome School for Boys, located in Port Deposit in Cecil County. At the time, this was a nonsectarian college preparatory school for boys. Interestingly, Gaver would not go on to college. It was said that his one ambition in life was to work for a large zoo, turning his hobby into a profession. He would acquire a great knowledge of snakes through self-induced reading, and contact with herpetologists. Throughout the Roaring Twenties, Gaver continued to capture and collect local species of reptiles, including poisonous snakes such as copperheads, rattle snakes and moccasins. He was contracted to supply specimens to zoos throughout the country. I haven’t found out to much else about Gordon’s personal life as it pertained to relationships. From an article found in a 1925 Frederick newspaper, Gordon’s thoughts about the perfect female were documented as he was briefly interviewed for a local “man on the street” article. Gaver told a reporter: “For myself, I like them to be quiet and sensible. I like those who are not fresh and those who you can depend upon not to lose their nerve and go back on you in anything.” He would eventually marry later in life, and it seems now as no surprise why. He appears to have enjoyed the same “quiet” and “sensibility” in his pet snakes. Apparently Gordon Gaver tried to obtain employment with the Washington National Zoo, but was unsuccessful. He then tried his luck at various other careers. In 1927, Gordon found employment on a ship’s crew out of Baltimore. He traveled to South America with visits to Buenos Aires, Montevideo and Sao Paulo. Unfortunately, he wasn’t cut out to be a sailor. From here, he experienced working the oil fields of Texas—not a strong fit either. Although temporary, these short-lived ventures provided the young Marylander the opportunity to see additional species of indigenous snakes and other critters in their natural environments. In 1930, Gordon could be found living in an apartment in Elizabeth, New Jersey, and working as an artist for an advertising firm. He had gone north in hopes to get hired by New York City’s Museum of Natural History. This never materialized either, and Gaver would relocate to Baltimore a year later. Throughout these moves, he was accompanied by many of his scaly pets. Gordon took opportunities to make a few extra bucks by exhibiting these to the public. In one such case, he was invited to show his small collection of American reptiles to groups in Europe. He did this in 1931. Gordon Gaver would return to Frederick with renewed optimism. He would forge ahead with his long-burning ambition to promote and educate others on his favorite topic—snakes. In 1933, Gaver set his dream in motion by opening a roadside attraction in the Old Catoctin Furnace schoolhouse. This dilapidated weatherboard structure was located a few short miles south of Thurmont along the newly designated US Route15 (1927), formerly the Frederick and Emmitsburg Turnpike. Gaver’s Catoctin Snake Farm became an interesting spot for local curiosity seekers and wayward motorists traveling between South Carolina and New York State. His first “star performer” was an 11-foot python, bought from a New York dealer. Also showcased, in the early exhibit, were 11 other specimens, less imposing than the large python. The enthusiasm of starting his new business must have gotten the best of Gordon, as he made the local newspaper for all the wrong reasons. On August 31st, 1933, Gaver was arrested by police authorities near the Square Corner in downtown Frederick. It was late in the day on a Thursday afternoon, and Gaver was heading southbound through Frederick on N. Market Street. This was a time of two-way traffic on the major north-south route through town, doubling as the city’s stretch of US 15, decades before a bypass. Gaver apparently crashed his automobile into the car of Augustus Boyne of 515 N. Market Street. This occurred near the 7th Street intersection, where the fountain is located. Gordon promptly left the scene of the accident in his Ford sedan, continuing southward on Market Street. He must have turned around somewhere along the route, and backtracked, because his next feat included an approach to the Square Corner coming from S. Market St. He swerved wide through the intersection onto W. Patrick Street, nearly hitting the posted traffic officer. Gaver became entangled in a traffic back-up and was duly pulled over at this point and arrested by special deputies Nusz and Redmond. Officers found an empty pint alcohol bottle, along with a full pint in Gaver’s possession. The deputies would soon find something even more disturbing. The Frederick News of September 16th, 1933 reported: “In the back of his machine was found a cotton bag containing two large rattlesnakes and a copperhead. Deciding discretion the better part of valor, police impounded the snakes with the car in a local garage.” Gaver admitted his guilt of driving under the influence when arraigned before Justice Alton Bennett. He was fined the minimum of $100, along with court and restitution costs. Officer J.R. Miller of the Maryland State Police, withdrew the charge of failing to stop after an accident when it was pointed out that Gaver was too drunk to know what he doing, and consequently could not be found guilty on the charge.

Gaver found himself partnering with the Washington National Zoo and others throughout the mid-Atlantic, as his animals needed suitable winter quarters.

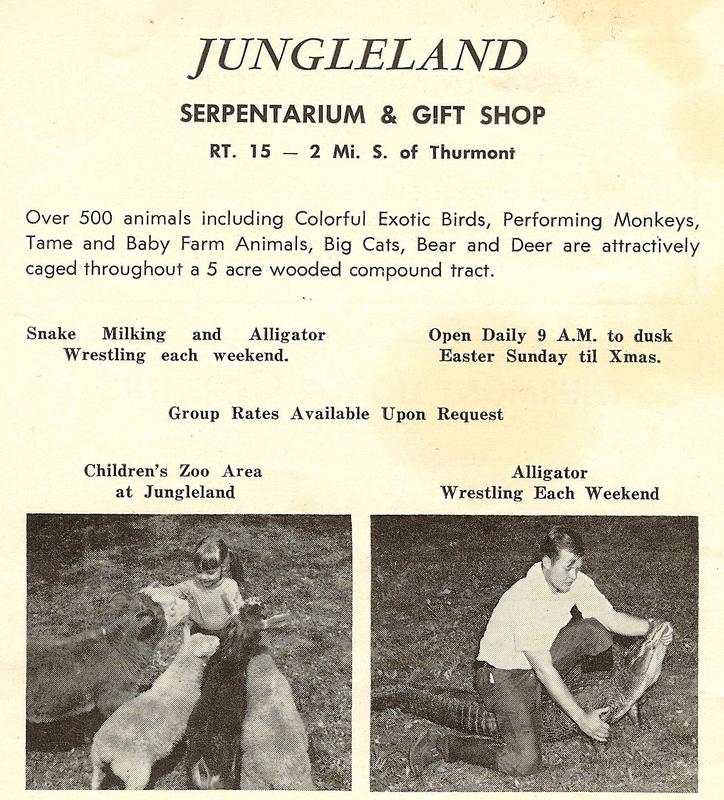

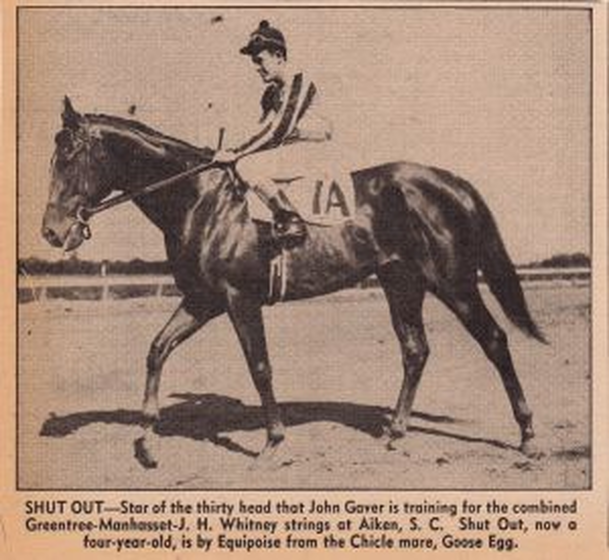

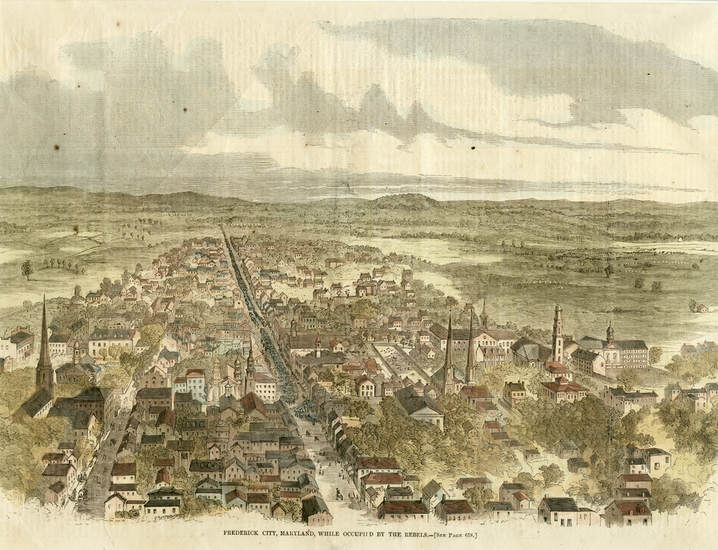

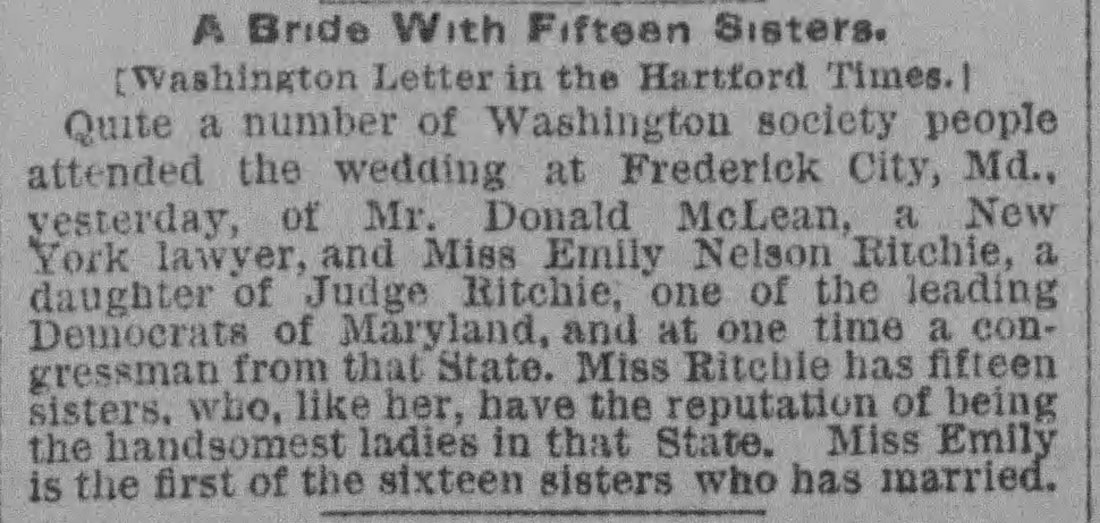

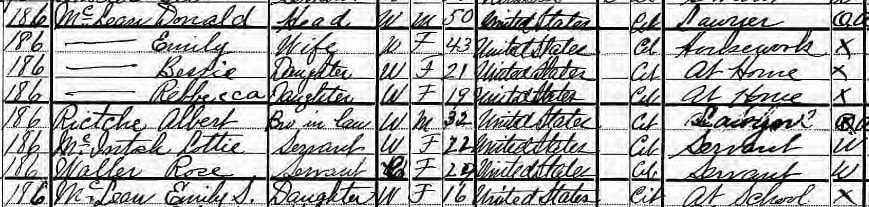

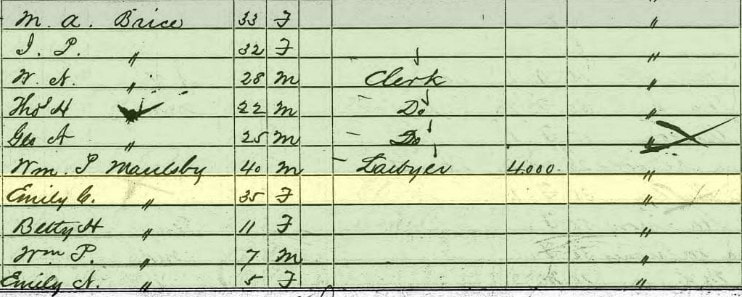

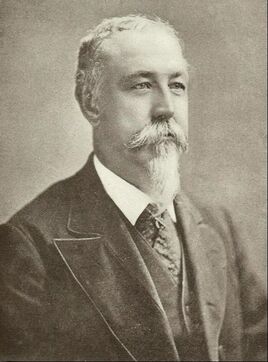

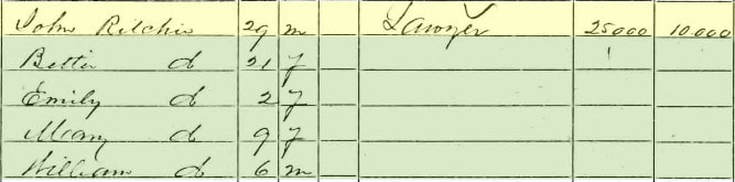

Less than a year later, Gordon P. Gaver would pass away at the age of 60, after suffering a heart attack in his Thurmont home on August 1, 1964. He had turned a hobby into a fulfilling career, spending three decades at the helm of his own serpentarium, preceded by a decade of chasing snakes and further learning. Gordon was buried beside his parents in Mount Olivet’s Area Q/Lot 83 on August 4th, 1964. Gordon Gaver’s legacy certainly lives on. Following the snake expert’s death, the Jungleland Snake Farm would be sold to Gaver’s employee Richard Hahn, who eventually changed the operation’s name to the Catoctin Mountain Zoo Park. The Hahn family continues to run this attraction to this day.  John M. Gaver, Sr. John M. Gaver, Sr. Famous Brother I’d like to add an additional note on one of Gordon Gaver’s siblings. As snakes encompassed Gordon’s world, brother John "Jack" Milton Gaver, Sr. loved horses. In fact, he was a lifelong trainer of thoroughbreds, and is a 1966 inductee to the National Museum of Racing Hall of Fame. Jack Gaver (1901-1982) would become associated with the fabled Greentree Stable of Red Bank, New Jersey. In 1939, he was appointed head trainer, a position he held for the next 38 years. During his time with Greentree, Gaver conditioned 73 stakes winners, including winners of five American classics, four champions, and two Horse of the Year honorees. Gaver won two legs of the Triple Crown twice. He conditioned Shut Out to victories in the 1942 Kentucky Derby and Preakness Stakes, and Capot won the 1949 Preakness and Belmont. He also won the 1968 Belmont with Stage Door Johnny. Gaver’s four champions were Devil Diver (1944 Champion Handicap Male), Capot (1949 Horse of the Year), Stage Door Johnny (1968 Champion 3-Year-Old Colt) and Tom Fool (1953 Horse of the Year). In the fall of 1905, the Gaspee Chapter of the National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution held its annual meeting in the rooms of the Rhode Island Historical Society, Providence, Rhode Island. Reports were read, officers for the ensuing year elected, and delegates chosen to attend the DAR’s Continental Congress for the ensuing year of 1906 elected. In addition, several minor matters of business were discussed. A special feature of the annual program was the presentation of a beautiful flag to the chapter on behalf of Chapter Regent Mrs. Eliza Harris Lawton Barker. This was a duplicate of one presented by her to the National Society DAR at a celebration in Continental Hall a few months earlier on July 4th. This was followed by another notable action— the sending of a telegram of greeting and congratulations to Mrs. Donald McLean, the new president general of the National Society. In the message, the ladies expressed the loyalty of the Gaspee Chapter. The feeling of many of the members was expressed by one woman, who said aptly: "Mrs. McLean is to the Daughters of the American Revolution what President Roosevelt is to the nation—a leader."  Prospect Hall Prospect Hall Mrs. Donald McLean was the seventh woman to hold the title of President General, the highest position in the National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution. The organization had only been founded 15 years earlier in 1890, for the purpose of promoting patriotism while preserving the shared heritage of women from throughout the United States. Small Town Girl Mrs. McLean was born Emily Nelson Ritchie on January 28th, 1859. She was born in the home of her maternal grandparents, the Prospect Hall mansion on the southwestern edge of Frederick, Maryland. Emily would be the first of 18 children born to lawyer John Ritchie and wife Betty (nee Maulsby)—a Frederick civic leader extraordinaire. The youngster came from good stock, boasting well-revered grandfathers (physician Dr. Albert Ritchie and lawyer Col. William P. Maulsby) and grandmothers with important ties to the American Revolution. They were Catharine Lackland (Davis) Ritchie, a daughter of James Lackland, commissioned by the Committee of Safety as a second lieutenant, 29th battalion of the Frederick County militia; and Mrs. McLean’s namesake, Emily Nelson, the daughter of Roger Nelson, a commissioned lieutenant in the Maryland Continental Line who was promoted to the rank of general for distinguished service.  Stamp Act "mock funeral" staged by the Sons of Liberty (Nov. 30, 1765) Stamp Act "mock funeral" staged by the Sons of Liberty (Nov. 30, 1765) Two more ancestors of Emily Nelson Ritchie McLean had taken part in the Stamp Act Repudiation of 1765. This defiant act by Thomas Beatty, David Lynn and 10 other justices of the Frederick County Court occurred seven years prior to the legendary Boston Tea Party, and has been called by some historians “the verbal shot heard around the world.” As a youth, Emily developed her love of history, thanks in great measure to familial and geographic connections her hometown of Frederick had to the American Revolution, War of 1812 and the American Civil War. In fact, Emily’s earliest memories dated back to the turbulent Civil War era. Frederick played witness to the major military campaigns in 1862 (South Mountain-Antietam), 1863 (Gettysburg) and 1864 (Monocacy). In between, the town served briefly as the state capital where secession was discussed (Summer 1861), and more so played the pivotal role as “one vast medical hospital” throughout the war. The Ritchie family first resided on the north side of W. Patrick Street, just east of Carroll Creek. Neighbors included noted diarist Jacob Engelbrecht and the legendary Barbara Fritchie. They would eventually move a block north to the Court Square area of downtown Frederick. They lived in the large home originally built in 1821 by Emily’s great uncle (grandmother Emily Nelson Maulsby’s brother), John Nelson. The “gracious white house,” as described by former Sen. Charles “Mac” Mathias, Jr., was located at 114 W. Church Street. In 1933, The News Citizen paper described the house in the time of the Ritchie’s ownership:  Nelson Mansion on W. Church Street, later home of the John Ritchie family Nelson Mansion on W. Church Street, later home of the John Ritchie family “Behind those gorgeous twin horse-chestnut trees stood the beautiful home of Chief Judge and Mrs. John Ritchie, those remarkable parents of eighteen children. ‘Ritchie’s wall’ was a Frederick institution over which we ran, jumped and raced up and down. Years ago the wing of the house, the old flagstone driveway with its large iron gates, and the Judge’s fascinating little white brick office with green door and shutters gave way to modern buildings. The yard, where every kind of fruit tree grew, with its circle of old English boxwood and abundance of old fashioned flowers was a veritable Eden when the trees were in bloom.”  John Nelson (1791-1860) John Nelson (1791-1860) John Nelson was a highly distinguished citizen, and held several important offices. He served in the United States House of Representatives (1821-1823), and was the Charge’ d’ Affaires to the Two Sicilies, (1831-1832). In case you were wondering what a Charge’ d’ Affaires is, it’s a French term for a diplomat who heads an embassy in the absence of the ambassador. The Two Sicilies (1815-1860) was the largest of the states of Italy before Italian unification and was formed as a union of the Kingdom of Sicily and the Kingdom of Naples. John Nelson also held positions of US Attorney General (1843-1845) and interim Secretary of State in the cabinet of President John Tyler in 1844.  The Frederick Female Seminary, later to become the Woman's College. Today this is Winchester Hall The Frederick Female Seminary, later to become the Woman's College. Today this is Winchester Hall Emily attended local schools, punctuated by the Frederick Female Seminary, eventually called the Frederick Woman’s College. She graduated at the age of 14, but would continue her study of history, languages and mathematics by taking post graduate courses. Emily also is said to have traveled extensively with her father in his business and political dealings. This added to her breadth of knowledge. A few years after the Civil War, Emily’s father was elected State’s Attorney for Frederick County. Before his term was over, he would be elected to Congress’ House of Representatives where he served in the 42nd Congress (1871-1873). In 1881, he was elected to serve a 15-year term as Chief Justice of the Sixth Judicial Circuit and Judge of the Court of Appeals of Maryland. One of the greatest gifts Emily received from her father was his great talent as an orator. From her mother, she received a love of American history, along with the management skills to get things done. These traits would one day propel the young lady into one of the highest positions a female could find one’s self in during the end of the 19th century. Women rarely held leadership roles of any kind outside of being business holders. Social celebrity came only to wives of politicians, military officers and industrialists. Of course, a few female artists, stage actresses and writers made names for themselves as well. On April 24th, 1883, Emily Nelson Ritchie was married at age 24. Her choice was a Rahway, New Jersey native turned New York City lawyer named Donald McLean. Mr. McLean’s mother was a Marylander, and he received his education at the Bel Air Academy (Harford County). He was admitted to the New York bar in 1872. Emily didn’t have to go far as the wedding ceremony took place at Frederick’s All Saints’ Episcopal Church, three doors west of her family home. Rev. Osborn Ingle and Rev. William Pinkney, Bishop of Maryland performed the service. Once married, the new Mrs. McLean left Frederick and Maryland to take up residence in New York City. Mr. McLean made his fortune on his legal abilities, but his reputation was solidified through distinctions in office conferred upon him by the President of the United States and the Mayor of the City of New York. He was elected alderman of New York City in 1881. In time, Donald McLean would be appointed by the US Congress to hold the position of General Appraiser of Merchandise for the Port of New York City. This position was under the US Treasury Department. Of unique interest is the fact that he was a director of the Guanajuato Consolidated Mining and Milling Company (located near Chihuahua, Mexico), along with the British Guyana Gold and Railroad Company. Emily spent the last half of the decade of the 1880’s involved in childbirth. The couple produced three daughters: Elizabeth Maulsby McLean (1852), Rebecca McCormick McLean (1887) and Emily Nelson Ritchie McLean (1889). The family resided in a four-story town house in Upper Manhattan, part of the neighborhood of Central Harlem. The McLeans lived at 186 Lenox Avenue (renamed Malcolm X Boulevard). Thanks to Mr. McLean’s profession, along with several business and political associations, Emily had the opportunity to mix in New York City’s upper class social circles. She was a gifted conversationalist who loved talking and writing about US history. Mrs. McLean’s essays and letters began being printed in the New York papers. Even as a southerner from Maryland, she was readily being accepted in her new home, and started taking responsibilities in "Gotham City's" service organizations and civic groups. Like Emily, Donald seems to have loved history, geography and was proud of his family heritage. His father was Col. George Washington McLean, a Civil War participant and the son of John McLean, a Revolutionary War veteran who served as 2nd Lieutenant in the New York Troops. Mr. McLean had memberships in the Sons of the American Revolution, the Veteran Corps of Artillery, the Society of the War of 1812, the New York Historical Society, and the National Geographic Society. It was a match made in heaven. In 1890, Emily learned of the potential for a new organization for women, dedicated to preserving heritage and enhancing patriotism through education and service. One year before, a group calling itself the Sons of the American Revolution (SAR) had been formed. The SAR traced its roots to the founding of the Sons of the Revolution, a New York Society which was organized in 1883 as an aristocratic social and hereditary organization along the lines of the Society of the Cincinnati.

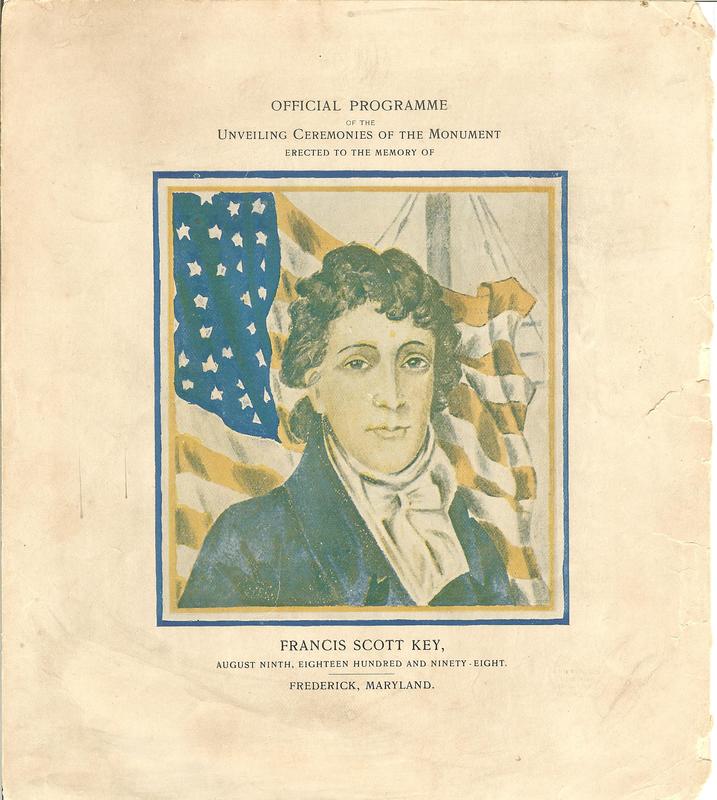

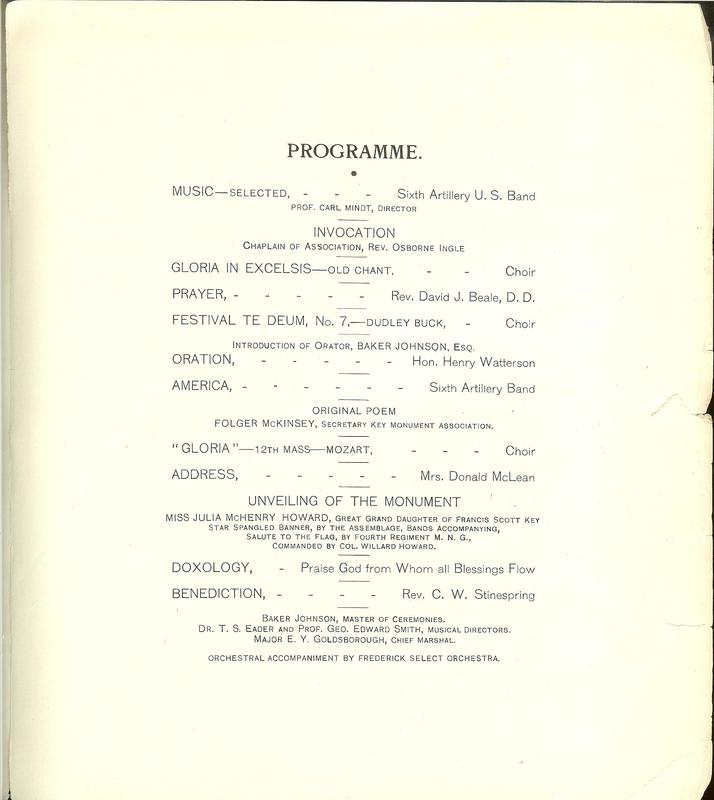

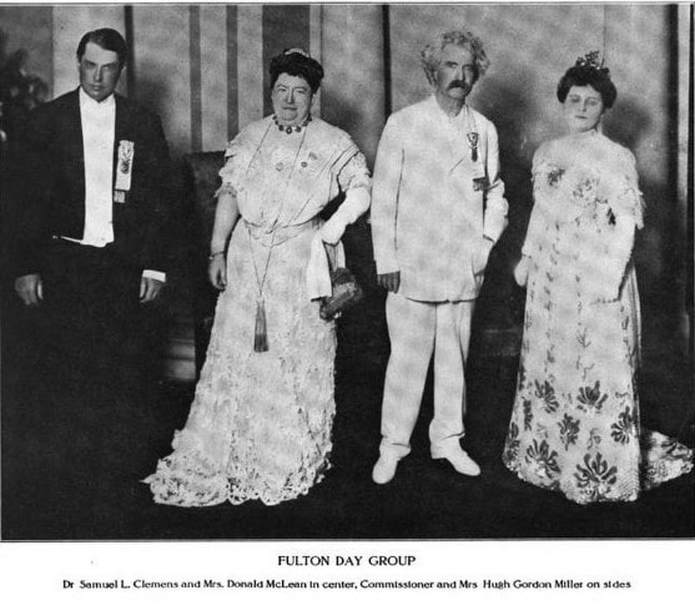

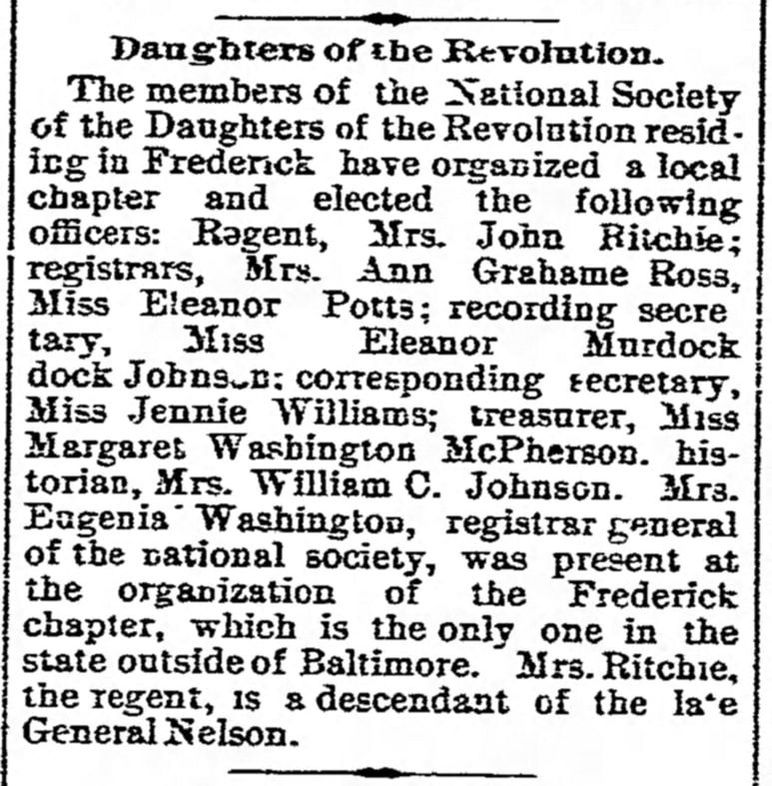

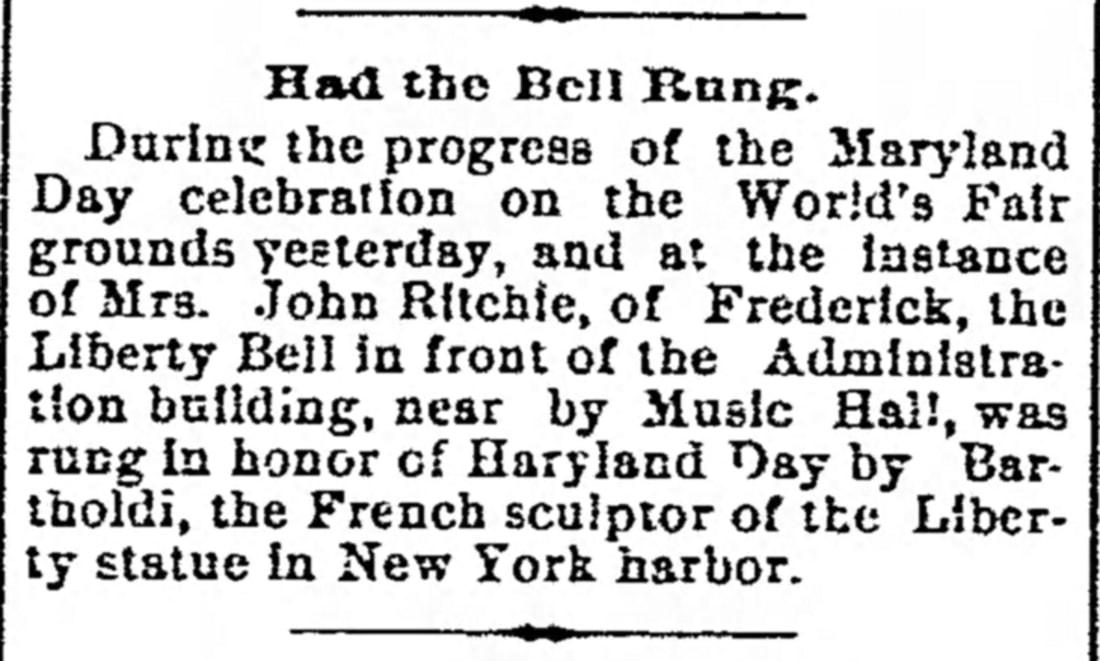

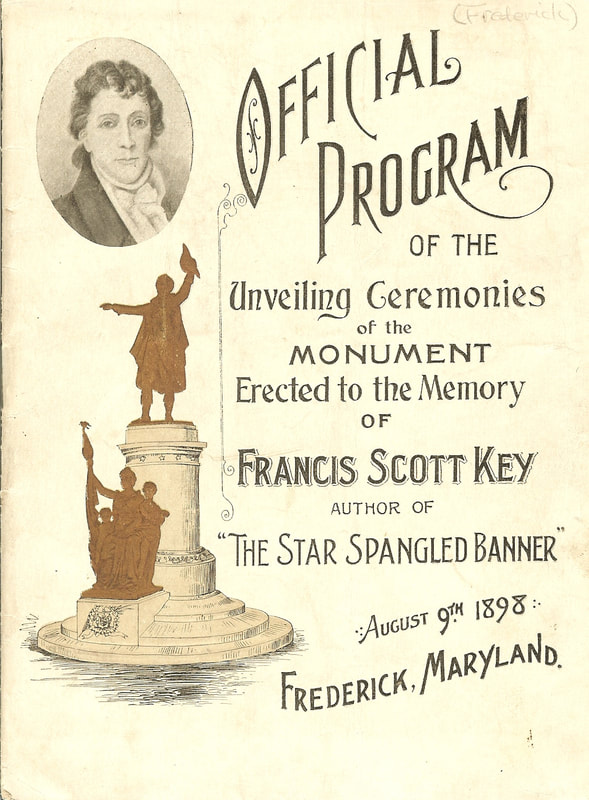

During that time Emily saw her mother and sisters (Eleanor, Anna and Willie) start a DAR chapter in her old hometown. Emily’s mother served as the first Regent of the Frederick Chapter, and then played roles on the national level as Vice President General and Maryland State Regent. Meanwhile, Mrs. McLean was harboring larger aspirations of her own to serve at the organization’s national level. The Daughters of the American Revolution elected officers at their annual congress event, held in spring at Washington DC. In 1895, Mrs. McLean ran unsuccessfully as a minority candidate for DAR’s top spot in the nation—the position of President General. The national officers of the NSDAR (National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution) carry the title “General” to indicate that they are responsible to the general organization, not to indicate rank. The local, and state, chapter “Regents” govern vicariously for the one presiding president—the “President General.”  Dedication ceremonies of the FSK Monument in Frederick's Mount Olivet Cemetery Dedication ceremonies of the FSK Monument in Frederick's Mount Olivet Cemetery Although the DAR was established as a non-political entity, politics surely entered into officer elections, because it had plenty of marital and blood connections to prominent politicians. This played out in the NSDAR election as part of the annual congress of 1897. Newcomer Emily had to run up against ladies connected to Washington DC’s social elite, usually peppered with wives of the nation’s leading politicians. It was a tall task, but Mrs. McLean’s New York City Chapter consisted of the largest single “voting bloc” in the country, the base of her operations. She also had tremendous lobbying going on from her friends and family within the Frederick and Maryland chapters of DAR. Sadly, Mrs. McLean lost again, but would receive a hero’s welcome when she returned to her old hometown in August of 1898, as she had been invited to give a patriotic address at the unveiling ceremonies of the Francis Scott Key Monument in Mount Olivet Cemetery. This took place on August 9th, 1898.  Cornelia Cole Fairbanks Cornelia Cole Fairbanks In spite of ”strenuous efforts,” the President Generalship went to Mrs. Charles Fairbanks—the young wife of a Republican Senator from Indiana, who later would become President Teddy Roosevelt’s vice presidential running mate. Driven "not to go quietly," Emily Nelson Ritchie McLean would run again at the organization’s annual congress of 1905. She was pitted against the Washington political establishment, as administration wives represented a power clique destined to keep the DAR's top spot. To combat this, Mrs. McLean appealed to the "grass roots" level of the organization. She “campaigned” hard, with chapter visits and lobbying forays in an effort to become elected. One-such happened in St. Louis at the 1903-1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition, where she made a concerted effort to represent the varying interests of women, education and the DAR.  Mrs. McLean addressing the annual DAR Congress in Memorial Continental Hall Mrs. McLean addressing the annual DAR Congress in Memorial Continental Hall Two years later, the NSDAR Congress was held for the first time in the auditorium of the society’s own building—Memorial Continental Hall. On April 20th, 1905, two ballots were taken. On the second ballot, 684 votes were cast. Emily received 362 votes and won the election for President General of the National Society DAR, becoming the seventh individual to hold this position. She now represented the whole country while wielding a high degree of power and celebrity. Emily Nelson Ritchie McLean's first order of business after giving her acceptance speech and greeting her constituents and fellow officers was to make the short trip from the stage of Memorial Continental Hall to the White House. Here she would receive congratulations and support from the President of the United States. The sitting president at this time was a fellow New Yorker—Theodore Roosevelt.  Crypt of John Paul Jones, US Naval Academy Chapel, Annapolis (MD) Crypt of John Paul Jones, US Naval Academy Chapel, Annapolis (MD) The 15th Continental Congress in 1906 received a special invitation from Secretary of the Navy Charles Bonaparte, former United States Ambassador to France General Horace Porter and Maryland Governor Edwin Warfield. President General Emily R. McLean announced with great pleasure that an invitation was extended to every member attending Continental Congress to be present at the ceremonies related to the final interment of John Paul Jones at Annapolis, Md. The American naval hero was to be placed in “his rightful tomb,” after Ambassador Porter located and identified his remains, which had been buried in Paris in an unmarked coffin. Jones’ remains traveled to the United States aboard the cruiser Brooklyn, the vessel that made Frederick native Winfield Scott Schley a star just eight years earlier. According to an issue of American Monthly Magazine, Jones' coffin was “draped in colors lovingly presented by the Daughters of the American Revolution, through their honored chief, Mrs. Donald McLean." She is said to have remarked, “This invitation I consider a great honor to this Congress, not only because we should all wish to be present at such an historic occasion, but because it is an unusual courtesy shown to us …”  Emily Nelson Ritchie McLean would serve two consecutive terms as President General (1905-1909) and is often considered to be the first President General chosen solely for her work within the Society, and not because of her husband’s status. In her words, she was “the only President General who has ever known what it was to sit under the Gallery,” according to a NSDAR historian. Another author wrote: "Mrs. McLean has traveled several hundred thousand miles throughout the states, visiting innumerable cities and towns, making addresses upon patriotic subjects, not only in furthering the work of the Daughters of the American Revolution, but in participation in civic and national patriotic celebrations. She is deeply interested in the work of patriotic education, both for immigrants and Southern mountaineers, as well as in keeping alive a patriotic spirit in all classes of American citizens, and is widely and internationally known as a speaker in patriotic and educational gatherings, and in her interest in the movement for peace by arbitration.'' Emily shared stages with political heavyweights and other celebrities of the day such as humorist Samuel Clemons, better known as Mark Twain. Her greatest accomplishment would encompass completing the interior work on Memorial Continental Hall in Washington. The 300th anniversary commemoration of the founding of Jamestown, Virginia took place in 1907. The DAR built a small house at the historic site and donated it to the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities as a “rest house.” Mrs. McLean was a vice-president, and the only woman member, of the commission from New York to the Jamestown Exposition. She was the perfect ambassador for New York. Emily was held in high esteem by commission colleagues, as well as history and political leaders of the state of New York.

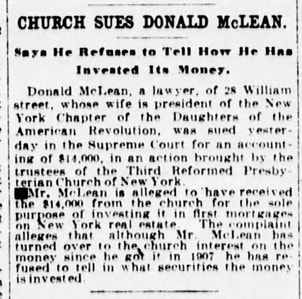

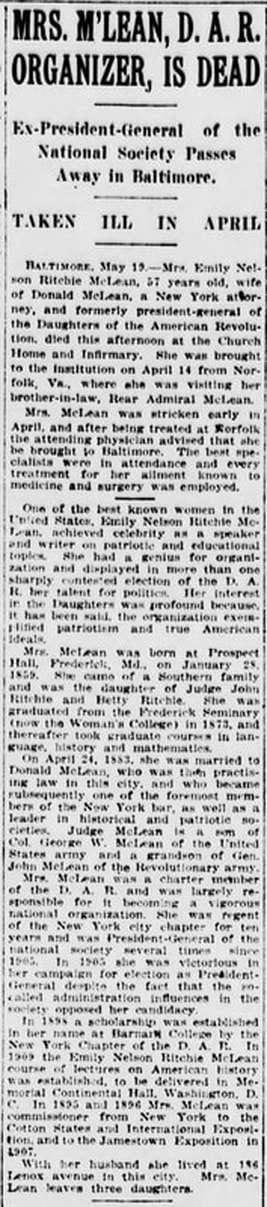

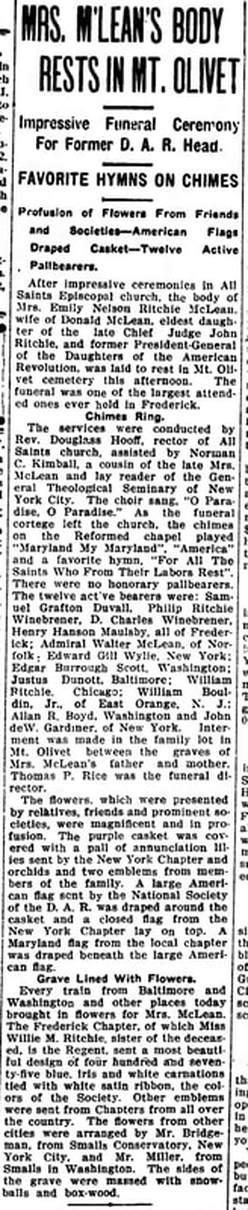

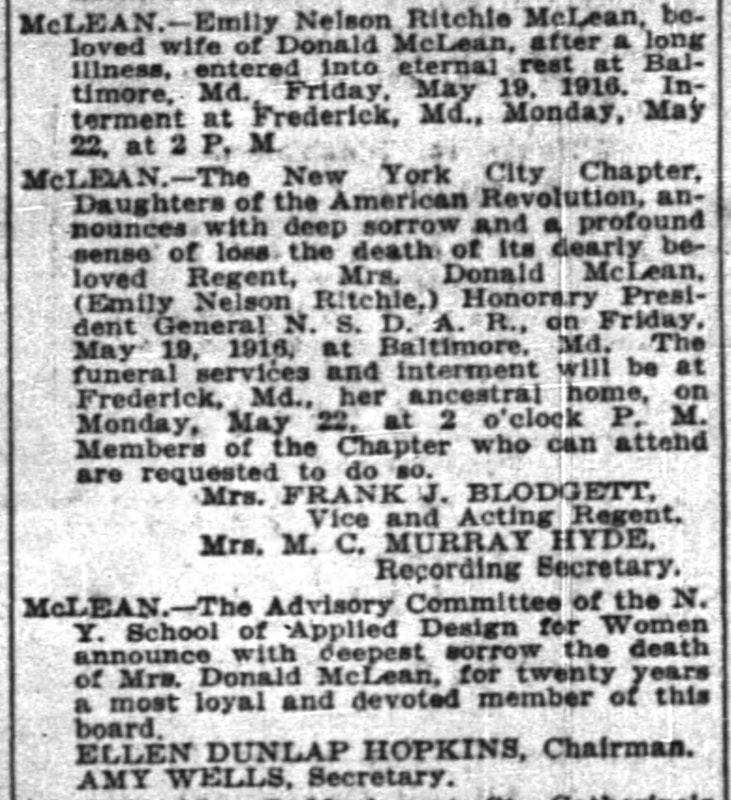

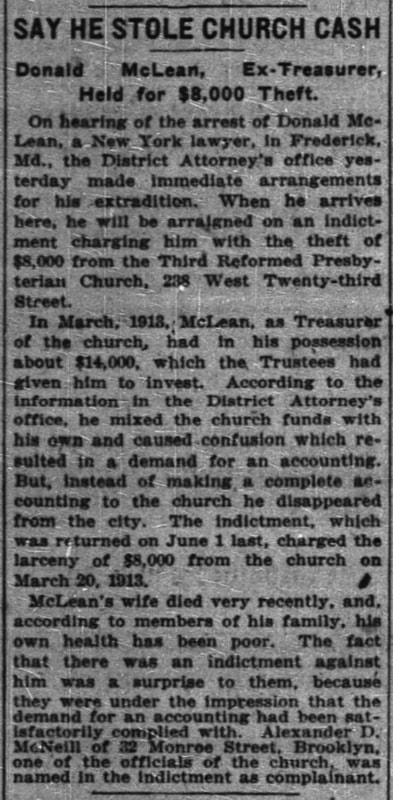

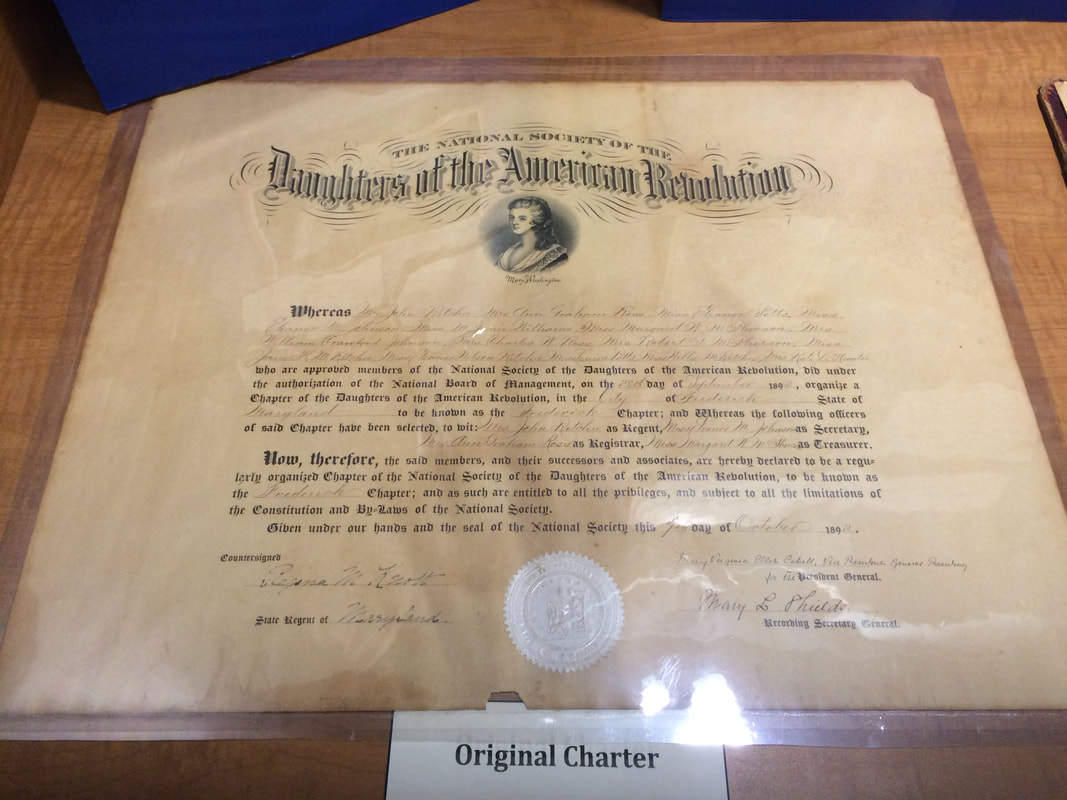

The following can be found within the 1912 book, The Part Taken by Women in American History, by Mrs. John A. Logan, (Published by The Perry-Nalle Publishing Company, Wilmington, Delaware, 1912): “It has been the editor's valued privilege to have known Mrs. McLean since the beginning of the twentieth century, and she takes pleasure in adding that among the thousands of gifted women she has met during these years Mrs. McLean is second to none in largeness of heart, brilliancy of mind, quickness of perception, eloquence of speech, marvelous executive ability, genial disposition, sturdiness of purpose, and charming personality. As president general of the Daughters of the American Revolution she lifted the society out of the chaos into which contentious rivals had dragged it, and placed it in the line of progression and achievement. She made the dream of Continental Hall a possible reality by her skillful financial management No other woman has received greater honors or worn them more gracefully than has Mrs. Donald McLean, who is among the most faithful of wives, tenderest of mothers, loyal of daughters, truest of patriots, most generous and loyal of friends.” After serving the maximum of two terms as President General, the Continental Congress of 1909 named Mrs. McLean an Honorary President General. Upon her return to New York City, her home chapter named her “regent for life.” She continued to stay active in her home chapter and would continue to be sought out for advice and guidance at the state and national level. Her daughters were grown and married with families of their own. The Marylander turned New Yorker settled into life as a doting grandmother. She would also spend her time traveling and enjoying the fruits of her celebrity with hundreds of new friends and acquaintances made thanks to NSDAR.  New York Sun (March 25, 1913) New York Sun (March 25, 1913) In 1910, scandal surrounded the McLean household as Donald was accused of embezzling money given him to invest on the part of Third Reformed Presbyterian Church of New York City. Other accusations of money mismanagement would follow in 1913 and 1914, as well as lawsuits. These stories were carried in New York City’s leading newspapers, along with getting picked up by papers across the country. Sadly, Mrs. McLean’s good name and reputation were slowly being tarnished in the process. In my conjecture, I feel that this caused incredible concern, embarrassment and consternation within Emily. It may have caused her to seek solace in alcohol. The newspaper coverage eventually waned, but the McLeans had experienced a change in fortune along the way as Donald’s associates stepped in to pay restitution and legal fees. By 1915, the family felt they had “weathered the storm,” as Donald and his legal counsel had paid monies owed and shown sufficient accounting evidence in regard to investments, particularly in the Third Reformed Presbyterian Church case which reached the New York Supreme Court. But it wasn’t over yet.  Admiral McLean Admiral McLean In April of 1916, Mrs. McLean was vacationing in the Norfolk, VA area with her brother-in-law, Rear Admiral Walter McLean, commandant of the Norfolk Navy Yards. Emily had experienced stress and nagging health issues for the last two years, but suddenly became gravely ill while here in Virginia. She would be removed for advanced care in her home state. She was sent to Baltimore’s Church Home and Infirmary. Unfortunately, Mrs. McLean would die three weeks later on May 19th, 1916, succumbing to complications associated with cirrhosis of the liver. She was only 57 years old. Emily Nelson Ritchie McLean would return once again to Mount Olivet Cemetery, the scene of patriotic triumph 18 years earlier as she spoke at the legendary Key Monument dedication and ascending to the national stage. Now, her incredible voice had been silenced. She would be laid to rest next to her namesake grandmother, Emily Nelson. Mrs. McLean’s sister, Willie Maulsby Ritchie, was Frederick Chapter Regent at this time, and played a leading role in making sure an appropriate funeral was conducted. The May 22nd church service at All Saints' Church and burial took place amidst the large attendance of several friends, relatives, and endeared compatriots from the Daughters of the American Revolution. In April 1972, 56 years later, members of the Frederick and New York City DAR Chapters, along with representatives and officers from the NSDAR paid homage to their legendary former colleague. A new footstone style monument was placed on Emily’s grave, listing the DAR related accomplishments of this legendary pillar of leadership. Memorial Continental Hall, DAR, the greatest memorial building ever erected by women in the world, was completed during Mrs. McLean’s administration and dedicated with beautiful and interesting ceremonies in Washington DC on April 19th, 1909. This monument to the heroes and heroines of Liberty, 1776, is a stately marble building erected at a cost of half a million dollars. In it hangs a portrait of Mrs. McLean, painted by artist Irving Wiles, and presented to the Hall by members of the NSDAR as a token of appreciation for the great work accomplished by Emily Nelson Ritchie McLean as President General in financing and bringing to successful completion this unrivaled building project. For many years, a course of lectures on American History was presented regularly and known as the Emily Nelson Ritchie McLean Lecture Course, established and endowed by members of the DAR, as a tribute to Mrs. McLean’s interest in patriotic endeavors.  Portrait of Mrs. McLean currently hanging in the Frederick County Historical Society Portrait of Mrs. McLean currently hanging in the Frederick County Historical Society Back in New York, a scholarship in perpetuity was founded at Barnard College for $3000. This was established by the New York City Chapter and named the “Mrs. Donald McLean Scholarship.” One of the most prominent women in the country was gone. Although forgotten to time by many, her name deserves to be included within the ranks of the immortal patriots from Frederick, Maryland who made lasting contributions to patriotism and the promotion/preservation of the American ideal of freedom and faith in the flag. This list includes past residents such as Thomas Johnson, Jr., Lawrence Everhart, Francis Scott Key, Barbara Fritchie, Admiral Winfield Scott Schley and William Tyler Page. Like the rest, Emily was human and had flaws. So did her husband Donald, who, less than a month after burying his wife, would be extradited from Frederick back to New York City on June 16th, 1916. Once there, Mr. McLean was indicted on the charge of grand larceny connected to faulty accounting of funds and stealing $8,000 from the New York City’s Third Reformed Presbyterian Church.  Eugenia Washington (1840-1900) Eugenia Washington (1840-1900) On Tuesday, September 20th, 1892, 14 local women met in the Frederick home of Mrs. Betty Harrison Maulsby Ritchie located at 116-118 West Church Street. The guest of honor was Miss Eugenia Washington, a sister of Millissent Washington McPherson, one of the meeting’s participants. Miss Washington was one of the original four co-founders of the National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution. She had reportedly been inspired by experiences during the American Civil War to found an organization for preserving the shared heritage of women from both the North and South of the United States. Eugenia Washington and sister Millissent were natives of nearby Charles Town (West Virginia) and the daughters of William Temple Washington, a grandson of Samuel Washington, younger brother of George Washington. This made both ladies the great-grandnieces of the first president. In addition, both women were grandnieces of Dolly Payne Todd Madison, wife of former president James Madison. The purpose of the meeting at Mrs. Ritchie’s home related to the organizing of a local chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution—the National Society (DAR) had been formed in part by Miss Washington two years earlier in October, 1890. The Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) is a lineage-based membership service organization for women who are directly descended from a person involved in the United States' struggle for independence. The organization was founded as a non-profit group, whose charge is to promote historic preservation, education, and patriotism. The local chapter was formally organized (according to charter) on September 28th, although a record at the national headquarters from 1911 gives the organization date of September 20th, 1892. Regardless, the chapter was duly approved and accepted by the National Society on October 7th, 1892. This was the second chapter to form in Maryland, behind Baltimore. It was named “Frederick” in honor of the record made by Frederick County in the struggle for national independence. Betty Harrison Maulsby Ritchie was named Organizing Regent for the Frederick Chapter. The elected national officers of the NSDAR (National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution) carry the title “General” to indicate that they are responsible to the general organization, not to indicate rank. The head of each local chapter or state is called “Regent” because she governs vicariously for the one presiding president -- the President General.

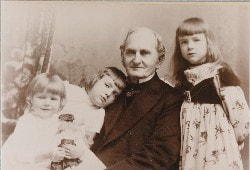

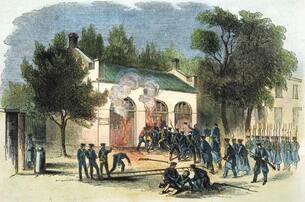

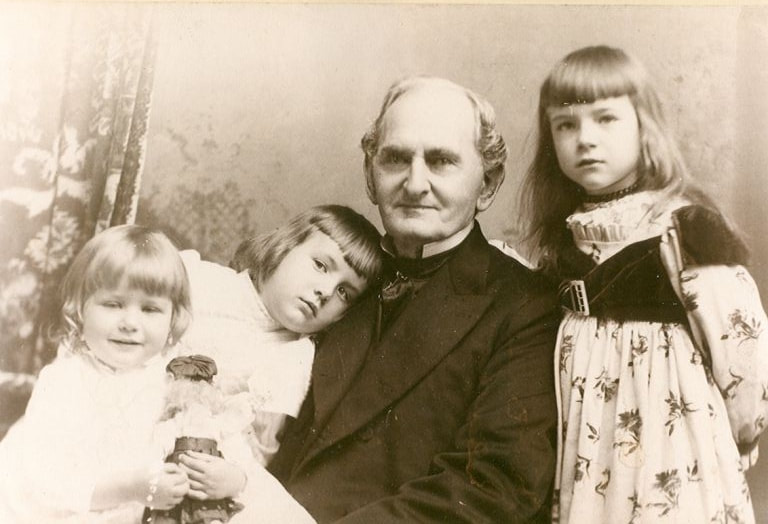

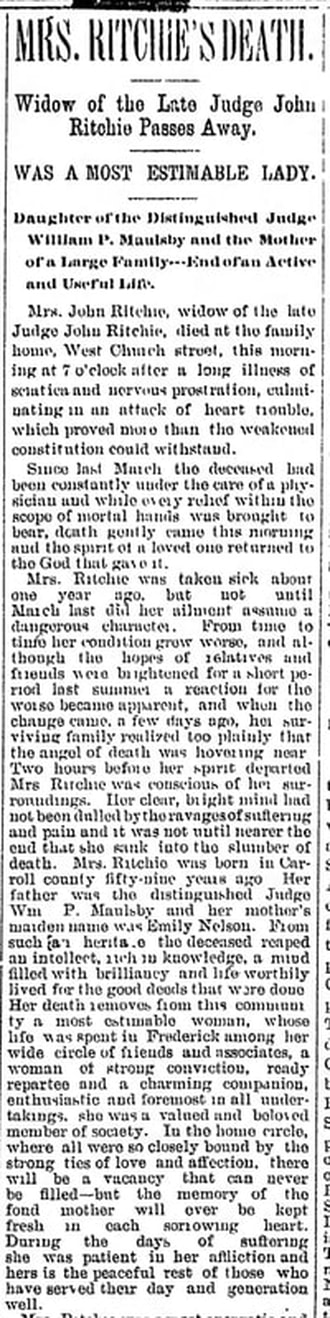

Regent Betty Ritchie certainly knew something about “daughters,” in more ways than one. She had given birth to 18 children, an accomplishment etched on her tombstone. Fifteen of her biological offspring were girls. Three of these ladies were founding members of the Frederick Chapter—Eleanor Nelson Ritchie, Jane Hall Maulsby Ritchie Boyd and Willie Maulsby. Ritchie’s eldest child, Emily Nelson Ritchie McLean, lived in New York City, and was one of the founding members of the New York City DAR Chapter. She likely provided additional influence to her mother and three sisters. In time, Mrs. McLean would eventually hold the NSDAR’s highest office.  William P. Maulsby with three grandchildren William P. Maulsby with three grandchildren Betty Maulby Ritchie Elizabeth “Betty” Harrison Maulsby Ritchie was born June 24th, 1839 in Westminster, Maryland. Her parents were Col. William Pinkney Maulsby (1815-1894) and Emily Contee Nelson (1815-1867). Betty’s father was originally from Bel Air, Maryland (Harford County) but began an illustrious law career here in Frederick, where he met, and married, his wife in 1835. He would take his practice to Westminster, followed by Baltimore during Betty’s youth, eventually returning to Frederick in 1851.  Col. Maulsby headed up the local Frederick militia outfits that arrived first on the scene to help quell John Brown's ill-fated insurrection attempt at Harpers Ferry in October 1859 Col. Maulsby headed up the local Frederick militia outfits that arrived first on the scene to help quell John Brown's ill-fated insurrection attempt at Harpers Ferry in October 1859 Mr. Maulsby played an active role in civic affairs, but none greater than his service in the American Civil War. William P. Maulsby served as colonel of the First Maryland Regiment of the Potomac Home Brigade, and took part in several local battles including action at Charles Town, Harper’s Ferry, Martinsburg, Monocacy and Gettysburg. Before and during the Civil War (1858-1864), the Maulsby family resided at the stately mansion of Prospect Hall, located on the Jefferson turnpike west of downtown Frederick. Here, in June 1863, military command of the Union’s Army of the Potomac passed from Gen. Joseph Hooker to George G. Meade just days before the Battle of Gettysburg. After the war, Mr. Maulsby resumed his law practice, but would soon receive an important appointment in 1870 from Maryland’s governor, Oden Bowie. Upon the death of Maulsby’s brother-in-law, Madison Nelson, he would assume the position of Chief Judge of the 6th Judicial Circuit.  Brig. Gen. Roger Nelson (1759-1815) Brig. Gen. Roger Nelson (1759-1815) Betty’s mother had died in 1867. Emily C. Maulsby was described as a woman of fine education and exceptional talent as an author, having written many articles for leading magazines of the day. It is this “estimable lady” who played a pivotal role mode and provided Betty with her patriotic pedigree. Emily Maulsby was the daughter of Roger Nelson (1858-1815), descendant of one of the first-settled landowners in Frederick County. Roger Nelson ran away from William & Mary College to enlist as a private in the Continental Army during the American Revolution. In 1780, he was commissioned lieutenant as part of the Maryland Line. At the August, 1780 Battle of Camden (South Carolina), Nelson was left for dead on the field, only to be taken prisoner by the enemy and eventually exchanged toward the end of the war. He was promoted for distinguished service, and gained post-war celebrity as a judge and member of the United States Congress, from 1804-1810, representing Maryland’s Fourth District. Betty Harrison Maulsby also claimed descendancy from David Lynn, one of Frederick County’s “Immortal Justices,” who repudiated the Stamp Act on November 23rd, 1765. Under her regency, Frederick Chapter members would choose as their motto “No Taxation without Representation,” referring to the Frederick Court’s direct defiance to the British Crown back in 1765. This event occurred 127 years before the Frederick DAR’s founding, but would remain a prime concern for the local chapter to champion up through to this day. Betty enjoyed a happy childhood and was educated both in Frederick and at St. Mary’s Hall in Burlington, New Jersey. She would marry a local attorney, John Ritchie, on May 5th, 1858 in Baltimore. Ritchie was born in Frederick on August 16th, 1831 on his father’s farm, land that would one day become a portion of Mount Olivet Cemetery. John’s father, Albert Ritchie, was a local physician who had graduated from the University of Pennsylvania in 1826 and practiced here until early 1857, a year prior to his death. Young John Ritchie attended the Frederick Academy, and afterwards studied medicine. However, he changed direction towards the study of law, which was taken up under the instruction of Judge William P. Maulsby. Ritchie subsequently entered the law department of Harvard. After his graduation, he came back to practice in Frederick and married his mentor’s daughter. A year later, while serving with the Junior Fire Company’s Defenders militia outfit, John Ritchie was among the first responders to Harpers Ferry, sent to suppress John Brown’s ill-fated insurrection attempt of October 16th, 1859. In 1867, Betty’s husband was elected State’s Attorney for Frederick County, and before his term was over, would be elected to Congress’ House of Representatives where he served in the 42ndCongress (1871-1873). Mr. Ritchie resumed his law practice in town. In 1881, he was elected to serve a 15-year term as Chief Justice of the Sixth Judicial Circuit and Judge of the Court of Appeals of Maryland.  Birmingham Farm, the childhood home of John Ritchie Birmingham Farm, the childhood home of John Ritchie The Ritchie family resided near the Court Square area of downtown Frederick, living in the large home originally built by Emily Nelson Maulsby’s uncle, John Nelson, located at 114 W. Church Street. Betty remained here with some of her children until John Ritchie's death on October 27th, 1887. She then moved next door to 116-118. Betty was heartbroken, but dedicated herself to carrying on her husband’s legacy, trailblazing her own in the process. A story recounted in Williams’ History of Frederick County says that when John Ritchie died, the exact ground that comprised his gravesite had been clearly viewed from the window of the childhood home room in which he was born. This was the longstanding home that stood on Birmingham Farm, which survived until its demolition in the late 1970's (now surrounded by the Carrollton subdivision. Much of the land that comprises Mount Olivet was part of this farm once owned by families such as the Ritchies, the Mullinixes and the Trouts in the 20th century.

Maryland Monument Maryland Monument Betty Harrison Maulsby Ritchie served as the Frederick Chapter’s Regent from 1892-1894. During her first term, the Chapter honored Revolutionary War patriots by contributing toward a monument that the Maryland Sons of the American Revolution was erecting in Brooklyn, New York—a tribute to the Maryland Line’s valiant efforts in the Battle of Long Island. The chapter also arranged for the remains of Thomas Beatty, a 1765 Stamp Act Repudiation judge, to be re-interred in Frederick’s Mount Olivet Cemetery. Mrs. Ritchie showed her dedication to the organization by serving at the national level. She served as Vice President General (1894-95), and then as Maryland State Regent (1895-96). She returned to her original role as Chapter Regent for a second term (1896-98). During this stint, Betty helped organize the movement to bring about the Francis Scott Key Monument in Mount Olivet Cemetery. Betty Ritchie was on hand for the momentous unveiling ceremony for her “pet project”—the Key monument, on August 9th, 1898. It was a proud day for Frederick, Maryland, but an equally proud day for Betty as she had both her Chapter and biological daughters by her side. In fact, Betty’s daughter Emily Nelson Ritchie McLean did a great deal from her post in New York City. McLean’s DAR Chapter was the largest in the country, and did much to promote, and raise funds, for the FSK monument project in Mrs. McLean’s old hometown. For her efforts, Emily Ritchie McLean was afforded an opportunity to speak at the Key Monument dedication in the summer of 1898.

Betty’s daughter, Emily Nelson Ritchie McLean, would ascend to President General, NSDAR (1905-1909), while another, Willie Maulsby Ritchie, would serve as Chapter regent for two terms (1903-1906) and (1915-1917). This past week, the Frederick Chapter, NSDAR celebrated its 125th anniversary. A luncheon gala was held to recount the chapter’s many projects and contribution’s since that 1892 founding by Mrs. Ritchie and 13 other local women. Mount Olivet Cemetery is the final resting place for not only Betty Maulsby Ritchie, but all 14 of the founding Charter members of the Frederick DAR Chapter. The NSDAR is still headquartered in Washington, D.C., and serves as a non-profit, non-political volunteer women's service organization dedicated to promoting patriotism, preserving American history, and securing America's future through better education for children. It currently has approximately 185,000 members in the United States and in several other countries. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed