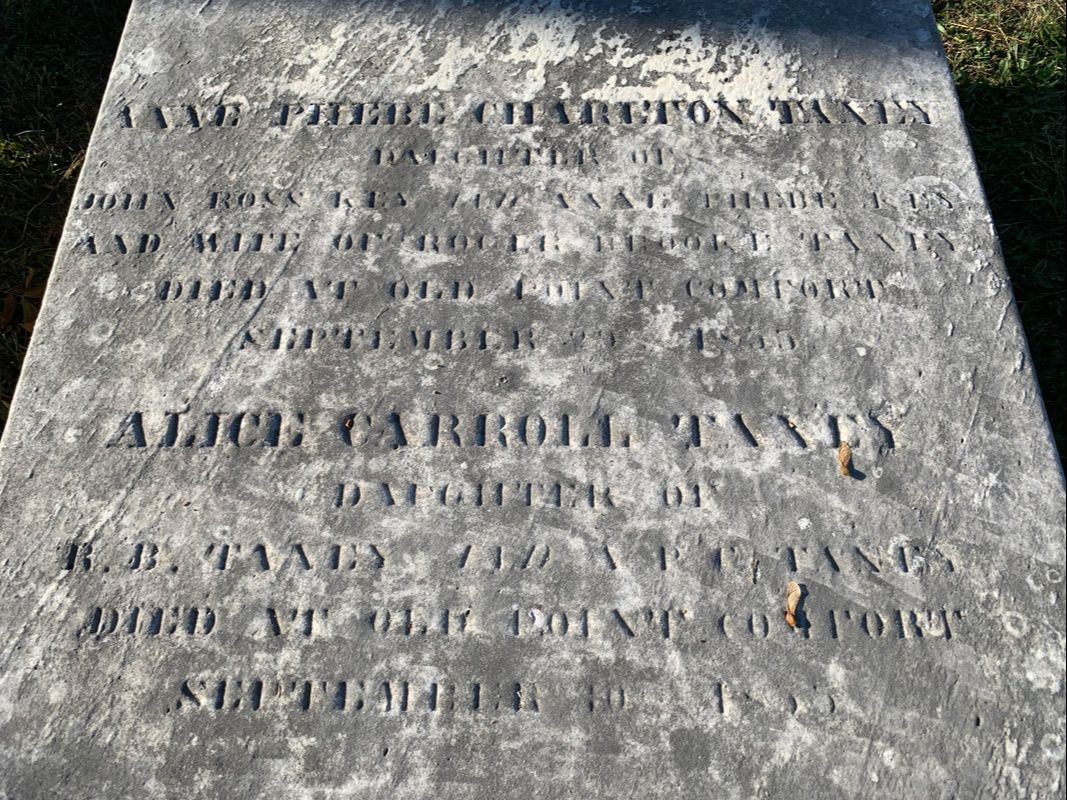

Without a doubt, the most famous resident in Frederick’s Mount Olivet Cemetery is Francis Scott Key (1779-1843). Marked by a grand monument, placed in 1898, his gravesite is basically the first thing visitors see as they enter through the “garden cemetery’s” front gates from Frederick’s South Market Street. Our native county son, a lawyer by profession, found himself in “quite the pickle” while being held captive aboard a British “Sloop of War” in Baltimore Harbor on September 13-14th, 1814. He had a front row seat to view the “perilous fight” between the “Defenders” of Baltimore and British military forces at Fort McHenry. FSK decided to take pen to paper, and wound up writing a catchy little song about the survival of United States flag above the fort throughout the attack—and the rest, as they say, is history. The patriotic, hometown hero has many ties to Mount Olivet. We have over 100 veterans of the War of 1812, some that were present in Baltimore on those fateful September days back in 1814. The cemetery also has dozens of colleagues and clients from Key’s law-practice days. Most important of all are, you will find a number of relatives of this man who gave us “The Star-Spangled Banner.”  Obviously Key’s wife, Mary Tayloe Lloyd Key (1784-1859), is buried beside him in a vault located under the impressive monument. In the couple's original burial lot (Area H/Lot 439), one can find FSK’s son, Francis Scott Key, Jr./ “Frank” (1806-1866). Two grandchildren are here in this gravesite as well: John Ross Key (III) (1837-1920), a prominent painter of national reputation and son of John Ross Key II, and Alice Key Blunt (1847-1927), a Baltimore socialite and daughter of Ellen Key. Fifty yards to the west of this spot is the location of Key’s parents—John Ross Key (1754-1821) and Anne Phoebe Charlton Dagsworthy Key (1756-1830). They are buried in what is called “the Potts lot,” located on Area G/Lot 47. It just so happens to be the only surviving "gated community" within Mount Olivet. Key’s younger sister is also buried in the cemetery, and located next to his parents. She is surrounded by three daughters, nieces of Francis Scott Key. Many are surprised to learn that this woman rests here, and not beside her famous (or infamous) husband in St. John’s Cemetery between Frederick’s East 3rd and 4th streets in Downtown Frederick. Her name was Anne Taney. Dearest Sister Anne Arnold Phoebe Charlton Key was born on June 13th, 1783 on the Key family plantation of Terra Rubra. Not far from the Monocacy River, and even closer to Double Pipe Creek, this locale was in Frederick County at the time of Anne’s birth, but would become part of Carroll County when the latter was established in 1837. Anne Key was described as beautiful, with a "bright mind and womanly graces." Sadly, I have not been able to find an image of her, however have read anecdotes that some do survive. Anne was the fourth of four children born to John Ross Key and wife Anne. Two of the Key children died in infancy, probably dictating the fact that Anne and brother Francis would have a close bond throughout childhood and adulthood. The little girl was a devoted playmate to her brother, and both received early schooling from their mother. Francis would be sent to St. John’s College of Annapolis in 1789. Meanwhile, young Anne would continue to experience her childhood on the family plantation, while making frequent trips to Annapolis to visit her brother and other relatives.

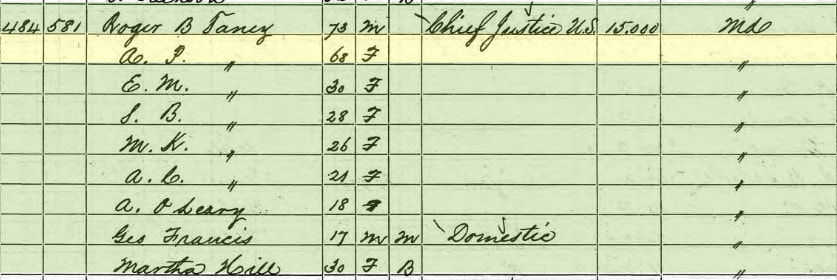

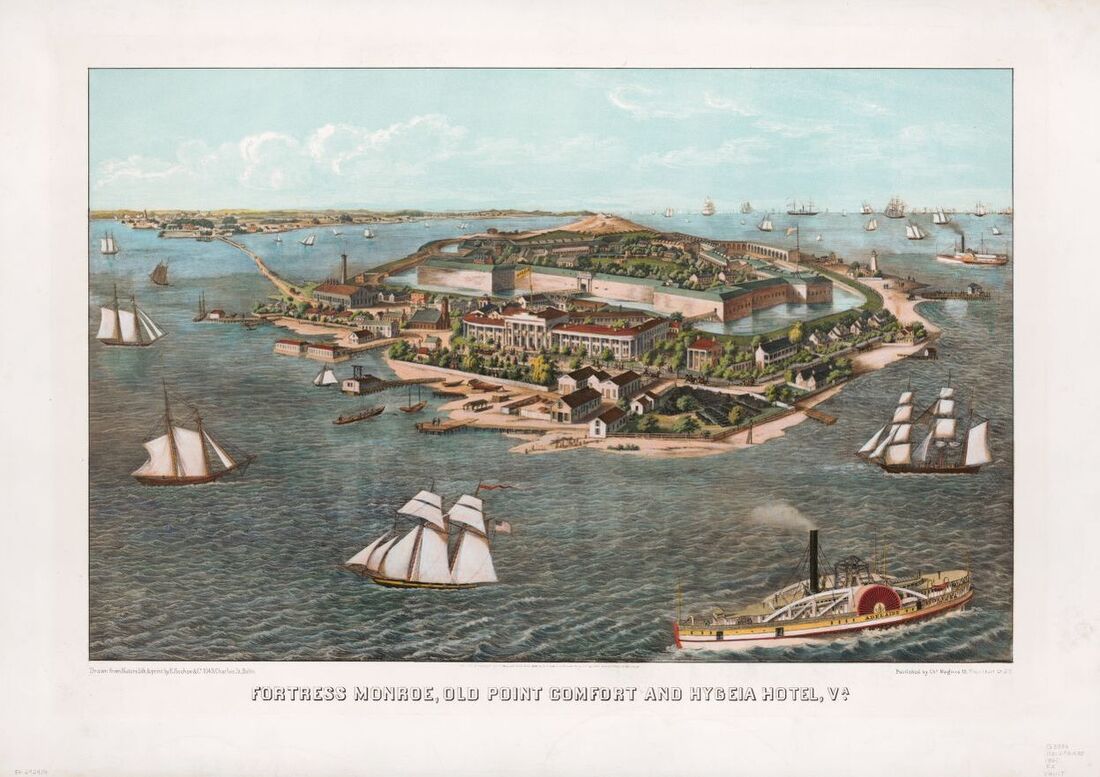

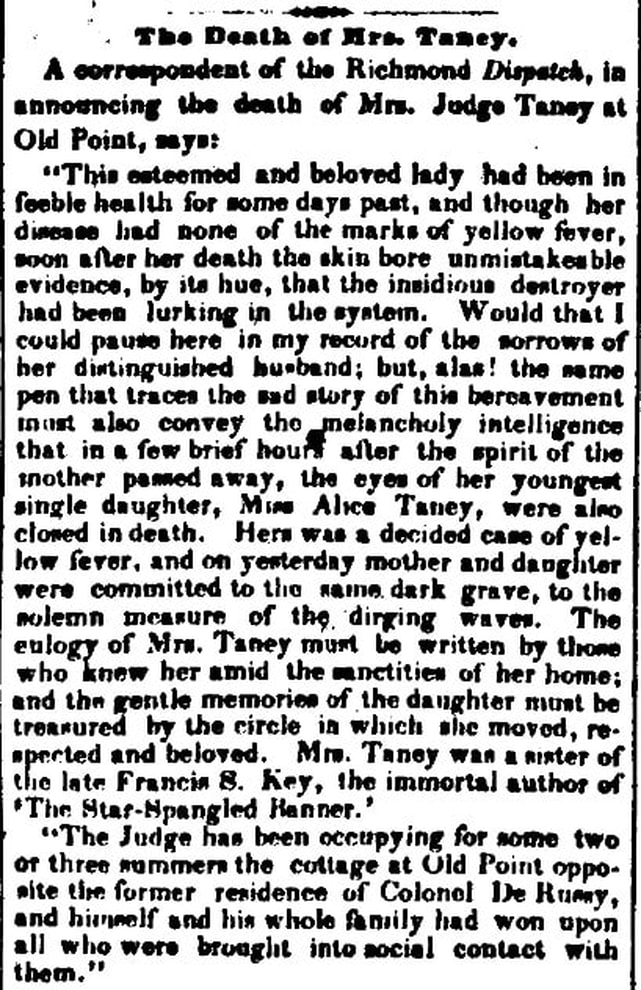

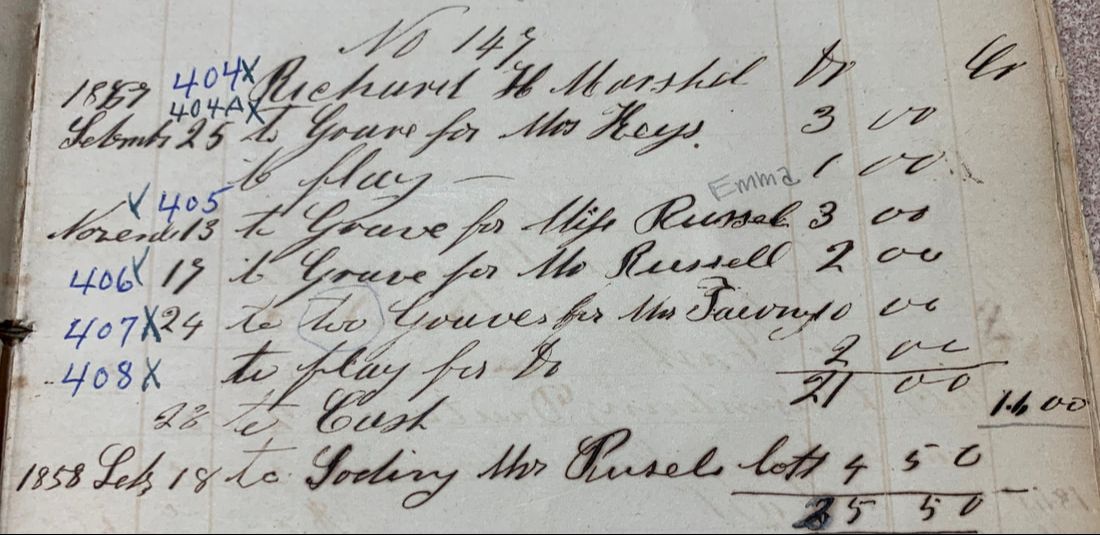

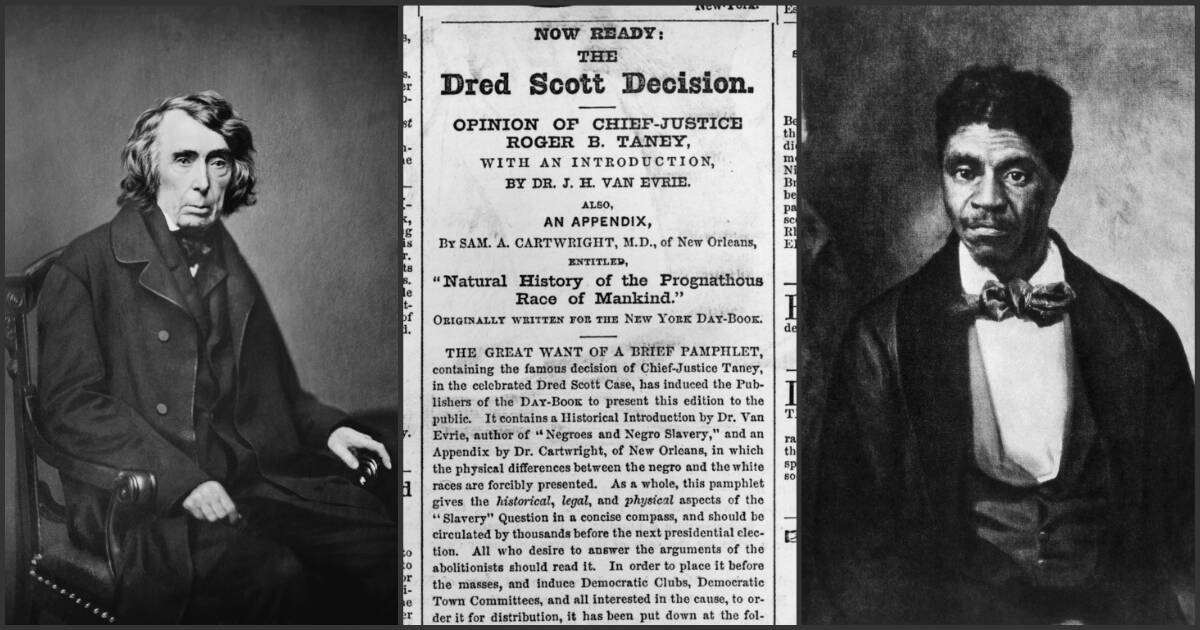

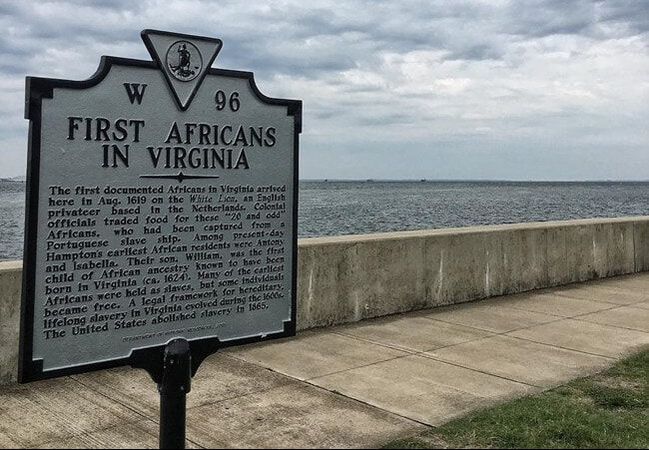

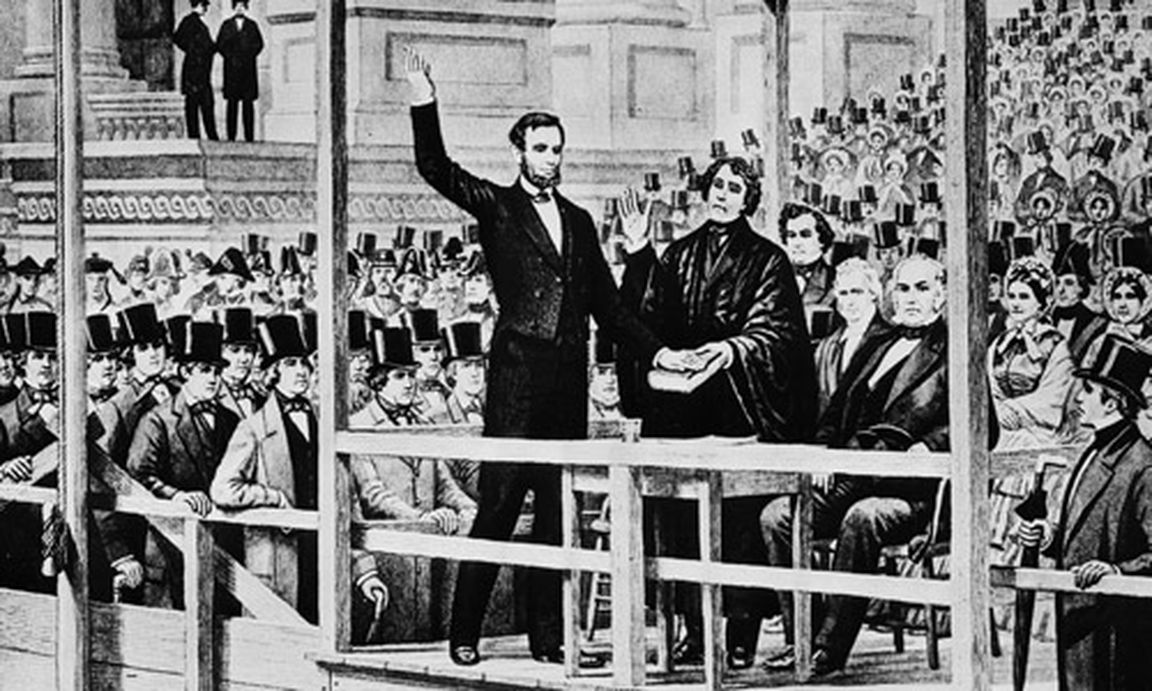

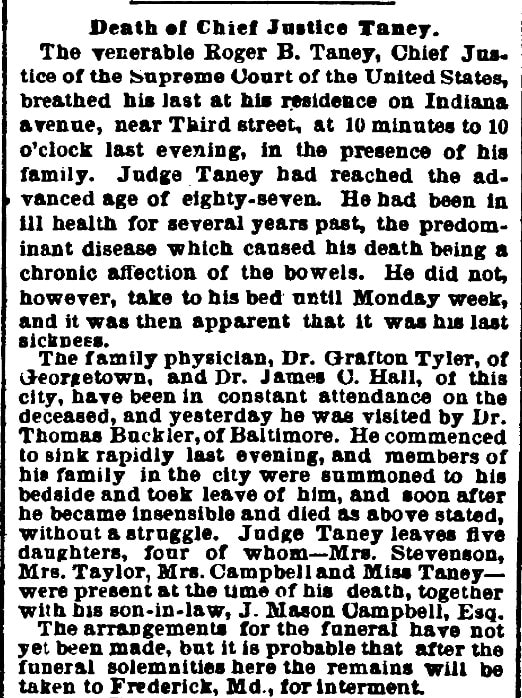

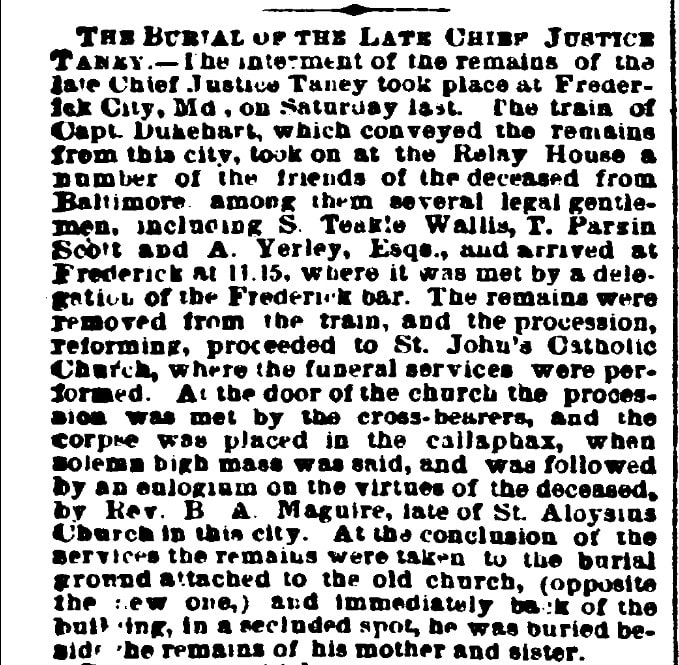

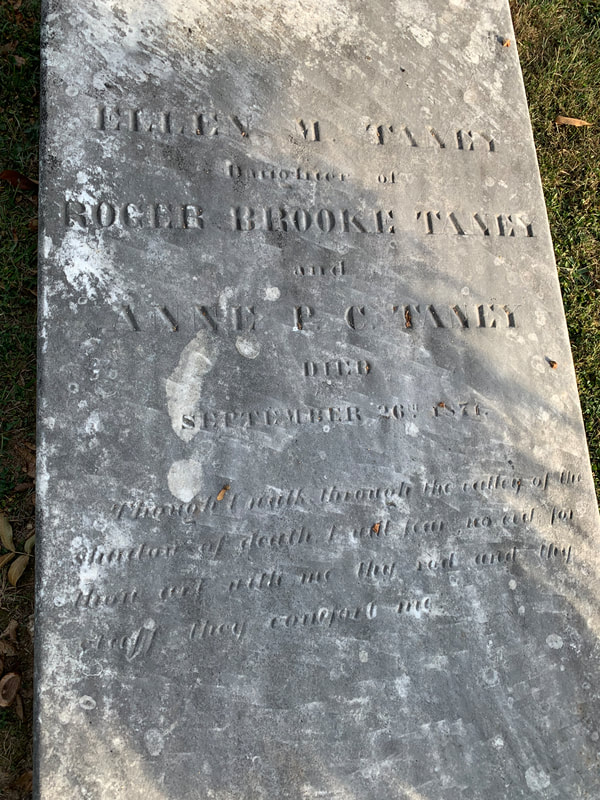

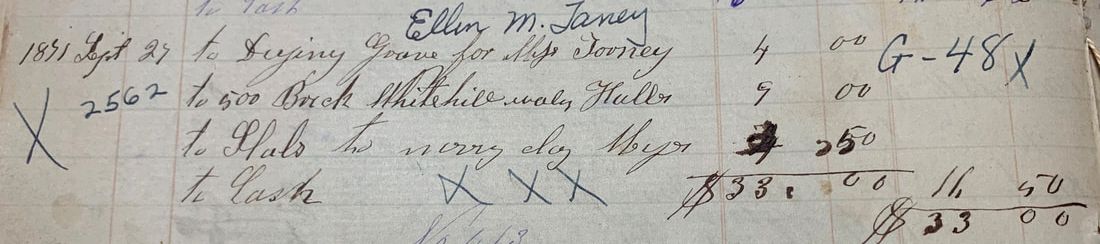

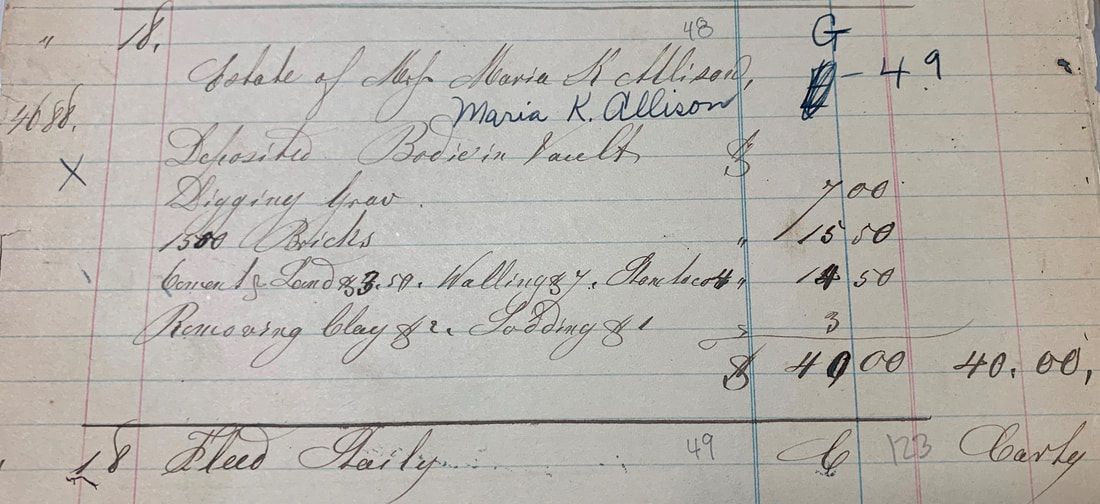

Judge Edward Delaplaine, in his work Francis Scott Key: Life and Times, wrote of Anne: “One of Key’s contemporaries recalled that Anne had the most cheerful face and the most pleasant smile that he had ever seen.” Delaplaine playfully relayed that their marriage “was likened to the union of a hawk and a sky-lark.” Anne and her brother would remain close throughout adulthood, and Francis would continue to call Anne’s husband one of his closest, lifelong friends. After the wedding, the Taneys resided in Frederick and went on to have the following six children: Ann Arnold Key Taney (1808-1834) married James Mason Campbell of Baltimore Elizabeth Maynadier Taney (1810-1873) m. William Stevenson of Baltimore Ellen Mary Taney (1813-1871) never married Augustus Brooke Taney (1815) died in infancy Sophia Brooke Taney (1817-1885) married Col. Francis Taylor Maria Key Taney (1819-1887) married Maj. Richard T. Allison Alice Carroll Key (1827-1853) No one is exactly sure of the location of the Taney family home in Frederick, because the site of the Roger Brooke Taney House on S. Bentz Street has been found to simply have been attributed to Taney as an investment holding, as it is doubtful that he ever lived there. Another theory I have heard is that Taney lived at a property that bordered the St. John the Evangelist Catholic Church property/compound. He was highly active in this church and could have lived on or adjacent to their grounds in some capacity. A lady, whose grandparents once lived at 113 E. Church St., told me that Taney was reputed to have lived at that location. This is the building to the immediate left of the former FCPS administration building on E. Church St., before one gets to Chapel Alley. Lastly, others have said that Taney’s law office was in the first block of N. Market St., on the east side of the street. The original townhouse is long gone, however the locale is today home to Cacique Restaurant.  R. B. Taney grave in St. John's Cemetery R. B. Taney grave in St. John's Cemetery Speaking of church, Anne and Roger Brooke Taney reconciled religious differences by agreeing that their sons would be raised as Catholics, and their daughters as Anglicans. This explains why Anne and three daughters are resting here in Mount Olivet, and Roger Brooke Taney is in St. John’s Cemetery in between East Third and Fourth streets in downtown Frederick. He is buried beside his beloved mother, Monica. Anne and Roger maintained close ties with Anne's family. They enjoyed frequent family reunions with her brother's family and also her parents, John Ross Key and Anna Charlton Key, at Terra Rubra. In the summer, the Taney family would sometimes retreat to the country to visit Anne's cousin, Arthur Shaaff. Mr. Shaaff was an interesting bachelor, who was a leader of the Frederick Bar. His plantation, named Arcadia, was a short distance south from Frederick. It still stands today, just below the Frederick Detention Center and immediately adjacent MD route 85. Shaaff helped mentor both Taney and his younger cousin, Francis Scott Key. The Taneys maintained close ties with Roger's family in Calvert County, as well. The lawyer's mother moved in with Roger and Anne during the War of 1812 period, and remained with them until she died in 1814. This particular year, Anne would also see her brother become an “American Idol” of sorts, thanks to his writing of “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Meanwhile, Taney’s reputation as a lawyer and politician was growing as well. Taney made influential friends earlier in life among fellow law students, and also classmates at St. John’s College, and the sons of prominent people who came to Annapolis for the season. Among them was William Potts, who planned to be a merchant in Baltimore. Young Potts was the son of Judge Richard Potts, of Frederick, who was to be one of the promoters of Taney’s professional and political career.  Anne and her husband would stay in Frederick until 1823, at which time Roger Brooke Taney received the job of circuit court judge after spending five years in the State senate. The couple moved to Baltimore, and another child would be borne to them here in 1827—Alice Carroll Taney. Additionally in the year 1827, Mr. Taney would be chosen as attorney general of Maryland. President Jackson appointed him Attorney General of the United States and he assumed office on July 20, 1831. He resigned the position on September 23, 1833. Taney was then appointed Secretary of the Treasury. In 1835 President Jackson nominated Taney to be Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. He was confirmed by the Senate and would hold the office for the rest of his life — October 12, 1864. “The twilight’s last gleaming” Anne and Roger had a very long and happy marriage. Roger wrote to her frequently when he was away from home on business. In his many letters, Taney shared with her the details of his public business, his belief in God, and his loneliness when away from her and his children. On their 46th wedding anniversary, Roger wrote Anne the following letter: Washington, January 7, 1852 I cannot, my dearest wife, suffer the 7th of January to pass without renewing to you the pledges of love which I made to you on the 7th of January forty-six years ago. And although I am sensible that in that long period I have done many things that I ought not to have done, yet in constant affection to you I have never wavered – never being insensible how much I owe to you – and now pledge to you again a love as true and sincere as I offered on the 7th of January, 1806, and ever shall be Your affectionate husband, R.B. Taney. Taney was a dedicated and loyal husband to Anne, and his love was unwavering for her. Health issues plagued the couple throughout their twilight years. A popular vacation and retreat spot for the family was Old Point Comfort in Virginia. Old Point Comfort is a point of land located in the independent city of Hampton, Virginia. Previously known as Point Comfort, it lies at the extreme tip of the Virginia Peninsula at the mouth of Hampton Roads in the United States. It was renamed Old Point Comfort to differentiate it from New Point Comfort, 21 miles up the Chesapeake Bay. In the 19th and first half of the 20th centuries Old Point Comfort served as the terminus and connection point for passenger and express freight ships connecting cities of Chesapeake Bay by both water and rail routes with Boston, New York and along the southeastern coast. Rail lines, for example the New York, Philadelphia and Norfolk Railroad, provided rail car through ferry service from Old Point Comfort to Cape Charles on the Eastern Shore of Virginia for land route connections to points north. For most of the 19th and 20th centuries, Old Point Comfort was a summer and winter resort in the town of Phoebus in Elizabeth City County. It appears that in 1952, the residents of both the town and county would vote to be consolidated with the independent city of Hampton. Old Point Comfort is the location of historic Fort Monroe, the Chamberlin Hotel, and the Old Point Comfort Light. I became intrigued with another work on Taney’s life, published in 1935 by Carl Brent Swisher. Entitled simply, Roger B. Taney, this book came out four years after a bust of the Supreme Court Justice was joyfully unveiled in front of Frederick County’s Courthouse. If you were unaware, the bust caused a bit of a “political correctness” –themed controversy a few years back. It now resides in Mount Olivet. As for Mr. Swisher’s biography, an in depth look at daughter Anne Key Taney’s final months can be inferred from letters included in the book from the hand of her husband, who was fixated on health epidemics and other contagious disease. The following passages come from Mr. Swisher’s book, and picks up in late spring, 1853: “I am out of health and soon fatigued,” Taney wrote from Richmond. “Perhaps Old Point may do something for me as I can get through the court here. But I am sensible of a sad falling off in my strength this spring.” The Campbells (Taney’s daughter Anne’s Family) were preparing to make their annual trip to Newport, Rhode Island. As Taney looked forward eagerly to his return to Old Point, his youngest daughter, Alice, begged to be permitted to go to Newport with the Campbells. Campbell broached the subject with Taney, and the latter replied with as close an approach to brusqueness as he seems ever to have used with his family: “I have not the slightest confidence in the superior health of Newport over Old Point, and look upon it as nothing more than that unfortunate feeling of inferiority in the South, which believes everything in the North to be superior to what we have. Yet I am willing that Alice shall go with you if she wishes it and her mother wishes it, and it will not cost more than $100. I would take that much from my increased salary but am unable to spare more without injustice to others. And it must be distinctly understood, that nothing additional must come from you. Until I see you have provided for your wife and children, I will accept nothing from you for mine.” Taney became so ill that he had to go to bed for three days before he finished his work at Richmond. He had been overworked, he wrote to Anne Campbell, and the fatigue of the journey to Old Point brought a relapse, so that he was in bed again for days. Yet he wrote about life at Old Point with no forebodings of disaster, no awareness that his attitude toward Alice’s desire to go to Newport, which had been such as to prevent her going, was to cost the life of one of those whom he dearly loved. Mrs. Taney was improving. Ellen and Maria were quite well. Alice, who had not yet joined them, had had a delightful visit with Elizabeth at some point outside Baltimore. Sophia was in Baltimore, shrinking from the disgrace which “that mean hypocrite,” her husband, had brought upon her. Taney hoped she would come to Old Point, “For I am afraid every day of hearing that the little boy is made sick by the summer heat of the town.” The weather had been cool at Old Point, and it had been necessary to close the doors and windows against the wind, “which was rather too strong for one who loves gentle breezes as much as I do.” It had been so cool as to keep the figs from ripening, but he was doing well, and last evening had walked around the fort on the outside without fatigue, a distance of a mile and a half. All of them enjoyed the sea bathing every day. Soon however, evidences of fearfulness became apparent in the letters. Rumors were drifting in concerning an epidemic of yellow fever. It had broken out in New Orleans, had been carried to Norfolk on ocean-going vessels, and was spreading back into the country. No one knew the cause. Taney attributed the disease to dirt. Bishop McGill, of the Roman Catholic church in Richmond, proclaimed that the Almighty had sent the yellow fever as punishment for the attacks of the Know-Nothings upon Catholics. It was of the irony of fate that the Taney family, wherein certainly no members of the Know Nothing party were to be found, even though the women were not Catholics, trembled alike with the heathen at the news of the spread of the menace. “The ravages of the pestilence in Norfolk and Portsmouth have not abated,” Taney wrote at the end of the month of August, “and the scene there must be awful….There has been no case at the Point. And the apprehensions and anxieties of Mrs. Taney and the girls is much abated….I have just returned from witnessing the grand parade of troops here. This being the last day of the month and inspection day, and of course there was a full turn out. And with the number now on the Point, the muster is quite an imposing spectacle. I left Ellen and Alice (who went with me)) with some friends as they wished to see the end of it.” “I have set about no work here, although I almost every day think of it. I have certainly a propensity to be idle and work hard only as a matter of duty, when the work can be no longer delayed. I excuse myself to myself on this occasion by the uneasiness and painful excitement which the state of things in Norfolk and Portsmouth produced in Mrs. Taney and the girls. Indeed apart from any apprehension of personal danger, it has been impossible not to feel saddened and depressed, when so many were suffering and dying near you and every day told of new victims to the disease. One’s thoughts must frequently be called away from matters of mere business, and he would be a hard man, and one whom I should neither love nor respect who could cooly fix his thoughts on any other subject for hours together, and feel no interruption from the agony and sufferings of the multitudes so near him.” Two weeks later Taney reported that the pestilence had given no signs of abatement. “But we hope the abundant rain and the sea breeze may operate favorably upon it. It has been a terrible and awful scourge without example in this country….We do not think that there is the least danger that the infected atmosphere can extend to this place…The place is perfectly healthy, and the weather is fine and pleasant, and we are all I think improving, notwithstanding the sad and depressing influence of the scenes around or near us.” Another week passed, and still no special cause for worry had appeared. Taney, voracious smoker that he was, realized that he would need cigars for the month or six weeks which he might yet spend at Old Point, and placed an order for a quarter-box of two hundred and fifty to last him through that period. The heat of the summer seemed to be over, and the weather was pleasant. “We all continue well here,” he wrote to Ann Campbell, “Mrs. Taney certainly much stronger, but I grieve to say that her difficulty in speech and defect of memory still remains, and I fear is not materially better. The constant uneasiness she unfortunately feels about the fever, and the sad amounts of suffering and death which she is continually hearing must be in some measure injurious to her health. Yet she has never wished to leave here, and indeed would be unwilling to go in any of the steam boats between this place and Baltimore or Richmond, as all of them have been filled with persons flying from the infected towns.” Three or four days later, Mrs. Taney, apparently already a victim of paralysis, suffered a severe stroke. In panic, Taney wrote to daughter Ann urging that medical aid be sent from Baltimore. Not trusting the mail service, he sent another note by private conveyance. “I wrote to you by mail today to tell you of the illness of my dear wife,” he said pitifully, “and to implore Doctor T. Buckler to come and see her. Fearing the letter may miscarry I write this note to give you this sad intelligence.” Mrs. Taney grew worse in spite of medical aid, and Alice suddenly fell seriously ill. On September 29th, Mrs. Taney died. It was believed at the time that paralysis was the cause, but it was reported later that after death the evidences of yellow fever were present in the body. A few hours later, on the morning of the following day, Alice also died, unquestionably the victim of the masquerading disease, leaving Taney crushed with another terrible blow. There was no possibility, at this time, of moving the bodies of victims of the dread contagion, to a cemetery at a distant place. Accordingly they were temporarily interred in a grave on Colonel Segar’s farm, near Old Point. Joseph Segar was a Hampton (VA) attorney and co-owner of the Hygeia Hotel which comprised the Point along with Fort Monroe. Some time later, at Taney’s request, his friend David M. Perine had the bodies moved to Frederick, where they were re-interred in the lot of the Potts family in Mount Olivet Cemetery, along with Mrs. Taney’s parents. Additional Burial Notes Unfortunately, here is where I take issue with Mr. Swisher’s account as it appears the bodies of Anne and Alice Taney underwent an additional burial to the two mentioned. Our Mount Olivet records say that both women were buried first at All Saints’ Episcopal Church burying ground, where I assume they were placed next to Anne’s mother and father, or within an underground family tomb. Richard H. Marshall, a prominent Frederick lawyer and founding member of the Board of Managers of Mount Olivet was listed as the responsible party for the move of the bodies here. The Marshall Lot today forms the eastern half of today's combined gated Potts-Marshall Lot within the cemetery. Marshall, a Charles County native, got his start as a lawyer under Roger Brooke Taney, whom he proclaimed his chief mentor. Marshall had made the arrangements for Anne Taney’s parents, John Ross Key and wife Anne, to be re-interred into Mount Olivet from All Saints’ on September 25th, 1857. Two months later, Anne and Alice Key were finally laid to rest in a shared grave to the immediate left of her father. This is in Area G/Lot 47. The broken-hearted family boarded a boat for Baltimore from Old Point Comfort. Taney was leaving this special place, the scene of many happy summers, countless memories and now, one terrible tragedy, never to return. While there on this trip, he had also been working on his memoirs, writing of the story of his life. This work was never to be resumed. So great had Roger Brooke Taney’s devotion to and dependence upon his wife that now, at seventy-eight years of age, there was a real danger that he would collapse completely when deprived of her companionship. It was here that his religion, an intimate spiritual reality rather than a mere commitment to creed, came to his aid. When a few days after his return to Baltimore a friend stopped at his house to take him for a drive he courteously refused to go. “The truth is, Father,” he said to the Catholic priest who happened to be with him at the time, “that I have resolved that my first visit should be to the Cathedral, to invoke strength and grace from God, to be resigned to His holy will, by approaching the altar and receiving holy communion.” Roger Brooke Taney sold his home in Baltimore in December (1855). Early in January, a month after the term of the Supreme Court had opened, Taney ventured in Ellen’s company to make the trip to Washington, and Maria whose husband was then at sea. In the nation’s capital, Taney took up quarters over a candy shop on Pennsylvania Avenue, between 4th and 5th streets. Taney’s office was partitioned off by a calico curtain from another apartment in which family cooking was done. He would eventually relocate to 23 Blagden’s Row on Indiana Avenue, near the Court House. Roger Brooke Taney was able to attend court only a small portion of the term during which he removed there, though within that portion he heard the first argument of the Dred Scott case. He described himself at this time in a letter to his sister Alice in August (1856): “At my time of life and broken constitution I have no right to expect again anything like the good health of earlier life.” Adding to his own health anxiety was the fact that his daughter Ellen was also experiencing health issues. The famed Dred Scott court case would begin arguments in February, 1856. Taney was still grieving for his wife and daughter who had only been gone less than five months. The case was argued from February 11 to 14, by Montgomery Blair of St. Louis, son of Francis P. Blair, for Dred Scott; and by Henry S. Geyer, formerly of Frederick County and at the time a US senator from Missouri, and Reverdy Johnson of Maryland for Sanford. The website Oyez, a multimedia judicial archive of the Supreme Court of the United States, says the following about the career of Roger Brooke Taney: Taney’s most infamous decision was the Dred Scott v. Sanford opinion. Ironically, Taney freed the slaves that he had inherited; however, he believed that the federal government had no right to limit slavery. He mistakenly thought he could save the Union when he ruled that the Framers of the Constitution believed slaves were so inferior that they possessed no legal rights. He held the Missouri compromise unconstitutional, claiming that as property, slaves were protected under Article V. In addition to this unpopular opinion, Taney became even more disliked when he challenged President Lincoln’s constitutional authority to apply certain emergency measures during the Civil War. Lincoln saw him as an enemy, and even defied one of Taney’s judicial decisions. Anyway, I could go on about the Dred Scott case and Taney’s accomplishments, but no need at this juncture as: 1.) I’m not trying to be a Taney apologist; and 2.) He’s not buried in Mount Olivet, its half of the rest of his immediate family, all of whom did not make decisions on behalf of the highest court in the land. I will say that his career was simply amazing, and he reached the zenith of his profession by becoming the fifth Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, along with involvement in thousands of cases over his lengthy career of roughly 64 years. His closest Maryland-born equal in the realm of law was the legendary Thurgood Marshall, who also served on the Supreme Court, and subsequently got more than a Frederick city street and apartment complex named for him. No Thurgood Marshall he got an international airport, and deservedly so. I would ask that people of today, especially those without a firm grasp on the history of this period, to frame their thoughts and opinions about the human being Roger Brooke Taney while using the lens and context of the time that the Dred Scott Case was heard (1850s). It's extremely complicated and major political ramifications were at stake. Go figure, the same is true today—hence the concern with the political and philosophical leanings of Supreme Court appointees, and the battles fought to either confirm or block confirmation. Compound this with health issues, the loss of a spouse and daughter less than a year earlier and you have a jurist who may not have an un-clouded mind. Again, not making excuses, just sayin'. To read more about the Dred Scott case, check out the links below: https://www.loc.gov/rr/program/bib/ourdocs/dredscott.html https://www.thirteen.org/wnet/supremecourt/antebellum/landmark_dred.html Ironically, since we are talking about slavery, and the history of slavery in our country as it is directly connected to Taney's most famous case, I would be remiss not to pass on the fact that the 400th anniversary of the first African slaves brought to the colonies occurred in August, 1619. The place, Old Point Comfort, Virginia, where Taney lost his spouse and youngest daughter. History can just be amazing, don't you think? As for the controversial fellow, himself, Roger Brooke Taney died on October 12th, 1864, at the age of 87. He had served as chief justice for 28 years, 198 days, the second longest tenure of any chief justice. Taney was nearly penniless by the time of his death, and he left behind only a $10,000 life insurance policy and worthless bonds from the state of Virginia. I found a news clipping that described the funeral procession in Washington, DC that accompanied Taney's corpse to the B & O Train depot for transport to Frederick and subsequent burial in the small burying ground on the campus of Frederick's Jesuit Novitiate. (His remains would later be removed to St. John's Cemetery in 1904.) President Lincoln attended the viewing at the Taney home and attended the body to the station. He would have likely attended the funeral, however we were still in the midst of the Civil War, and he was not to leave Washington for such a trip. An interesting show of respect from such a bitter rival. Sadly Lincoln would be destined to the grave just six months later. What I’d really love to know is how often Roger Brooke Taney visited the gravesite of his wife and daughter over his last nine years, if at all. In addition, in this same Potts Lot, he could find his in-laws, mentor Arthur Shaaff, and the man he mentored, Richard H. Marshall. As he took responsibility for the wildly unpopular Dred Scott Decision, I’m sure he firmly believed he was making the right call for the time, as six other justices agreed with his rationale, and only two dissented. However, Taney most likely despised and regretted full-heartedly his “decision” to stay at Old Point Comfort in the summer of 1855, not to mention the fact that he "guilted" young Alice into coming to Virginia instead of her intended plan of staying with sister Ann Campbell at Newport, Rhode island. These issues surely haunted him until his dying day nine years later. In time, two daughters would additionally be buried in the plot with their mother and younger sister. Ellen Mary Taney never married and died at the age of 58. This occurred on September 26th 1871, just days prior to the 18th anniversary of her mother’s death. She was buried on September 30th. Maria Key Allison would die on April 15th, 1887 and was buried three days later.

1 Comment

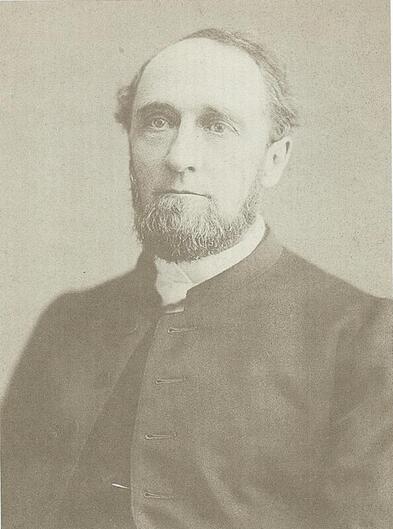

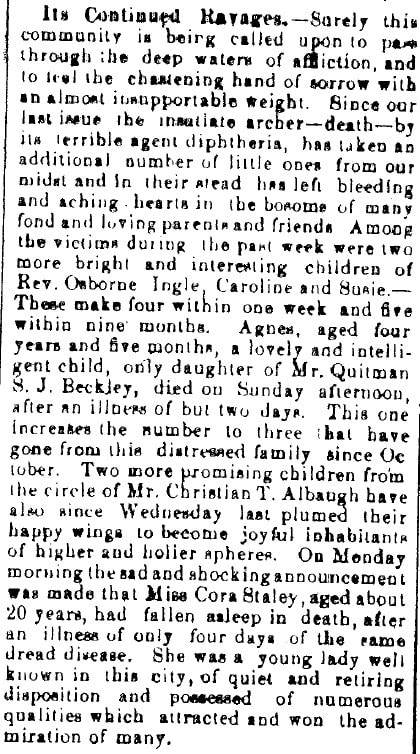

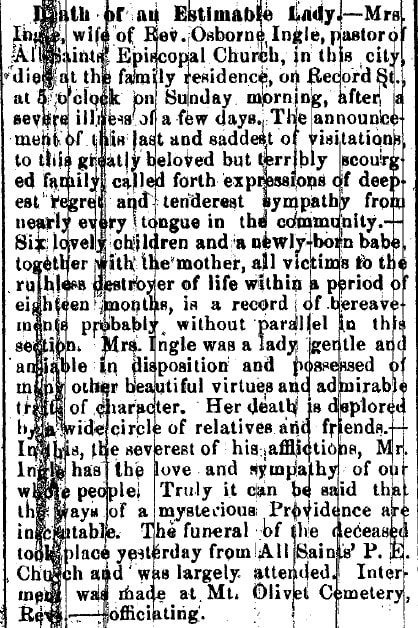

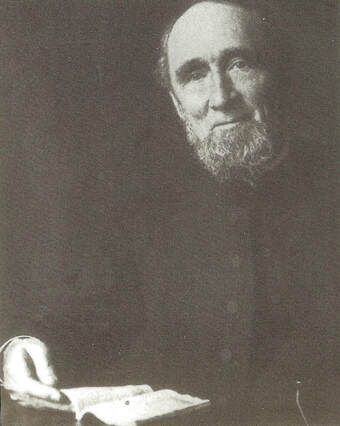

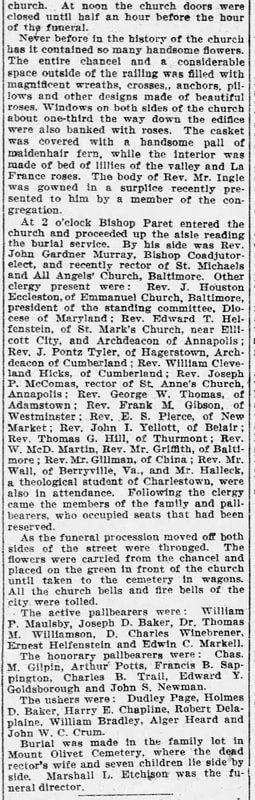

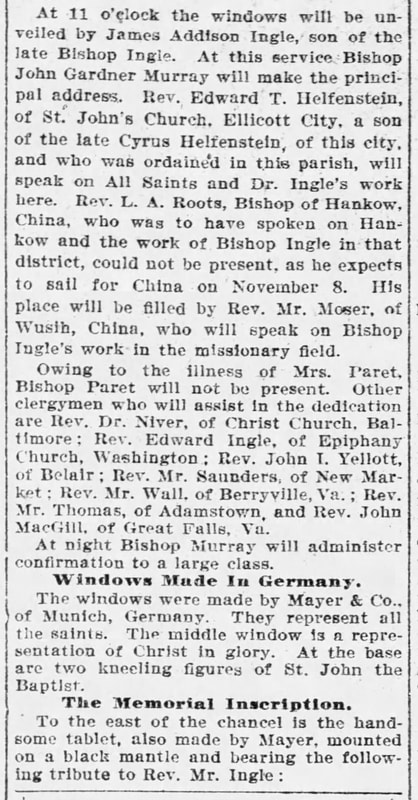

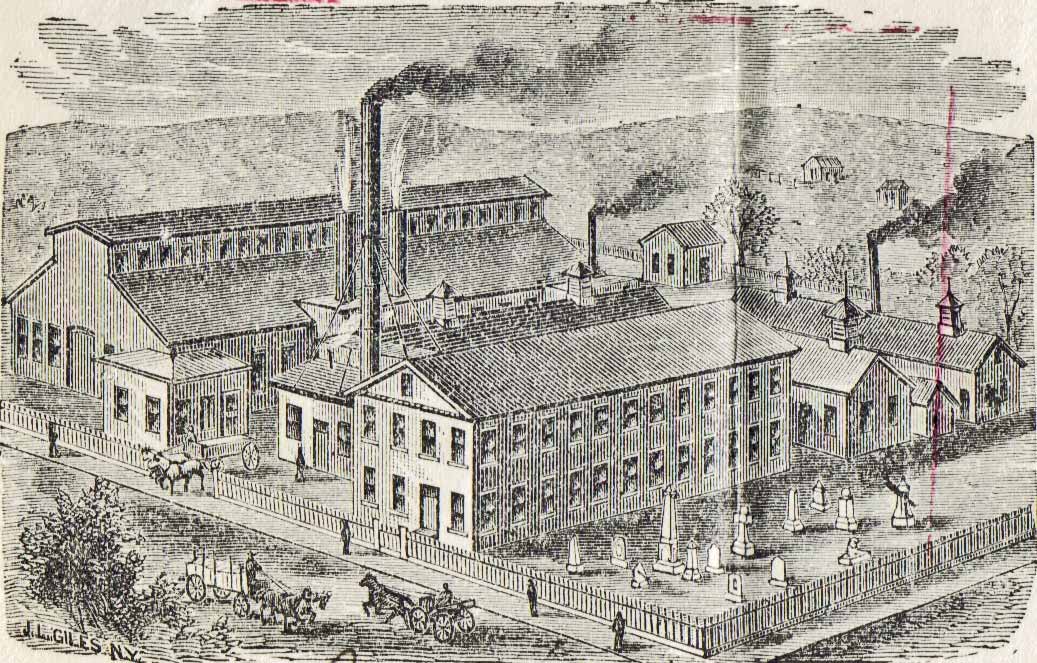

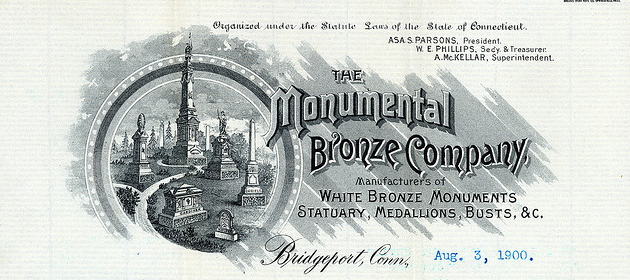

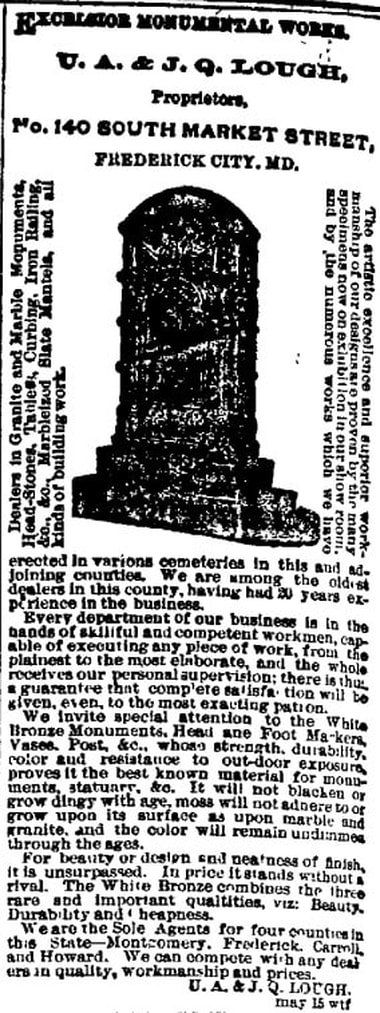

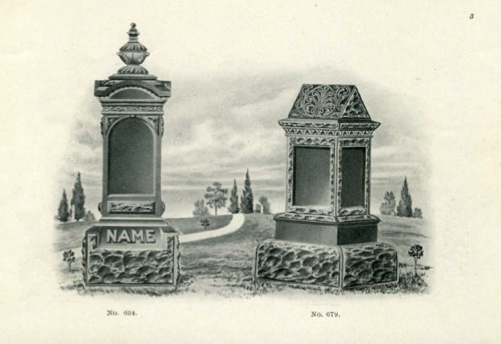

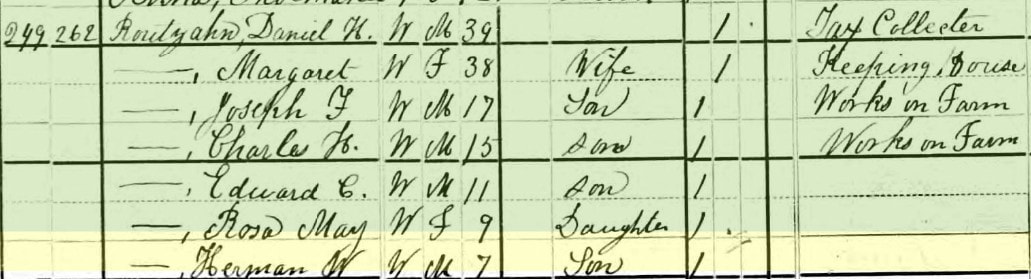

“The greatest man is he who chooses the right with the most invincible resolution; who resists the sorest temptation from within and without; who bears the heaviest burdens cheerfully; who is calmest in storms, and most fearless under menaces and frowns; whose reliance on truth, on virtue, and on God is most unfaltering.” -Seneca the Younger (c. 4 BC - AD 65) A couple years ago, I came across a few old postcards of the cemetery, and found one that I hadn’t seen before. It contained a view that featured a freshly “closed” gravesite, covered in flowers. And when I say “covered in flowers,” I mean, really covered in flowers. I thought about this particular card earlier this year, twice, as I wrote story on early Frederick postcards, and another on pioneering florists of town. In both cases, I wondered why this slightly depressing view of a flowered-grave would be considered for use as a postcard. And more so, who would send this as a jovial greeting to friends or relatives with a snappy salutation like: “Hi all, having a great time, wish you were here at Mount Olivet Cemetery!” I decided to go “in search of” this postcard's exact location. The card itself was labeled on its face as being in “Area G” which helped a great deal. I was quick to find an obvious, and highly recognizable, feature to the far right of the photo—gravestones that were part of our famed Confederate Row. Soon, I found myself on the actual scene of the postcard in Mount Olivet’s Area G. I tried my best to match the present- day landscape to an 8 x 11.5 printout copied from the original postcard image. I began to study nearby monuments in an effort to pinpoint the approximate location of the camera responsible for taking the particular picture. Of course, there are a lot more stones (in the vicinity now), than there were then. And when I say "then," I’m talking about the year 1909, a fact deduced thanks to a series of photographs that can be credited to that particular year by photographer Charles Byerly, Sr. (1874-1944). As an aside, Charles was the grandson of Jacob Byerly and son of J. Davis Byerly, both great early photographers of Frederick in their own rights. After about five minutes, I was joined in Area G by (Mount Olivet superintendent) Ron Pearcey. We eventually located what we thought to be the presumed (recently closed) grave site in the postcard's photo. After studying the various stones that were once covered in flowers, it became readily clear whose grave plot this was primarily due to a monument dating to 1909, and not seen in the photograph. It belonged to Rev. Osborne Ingle, whom both of us were already quite familiar with.

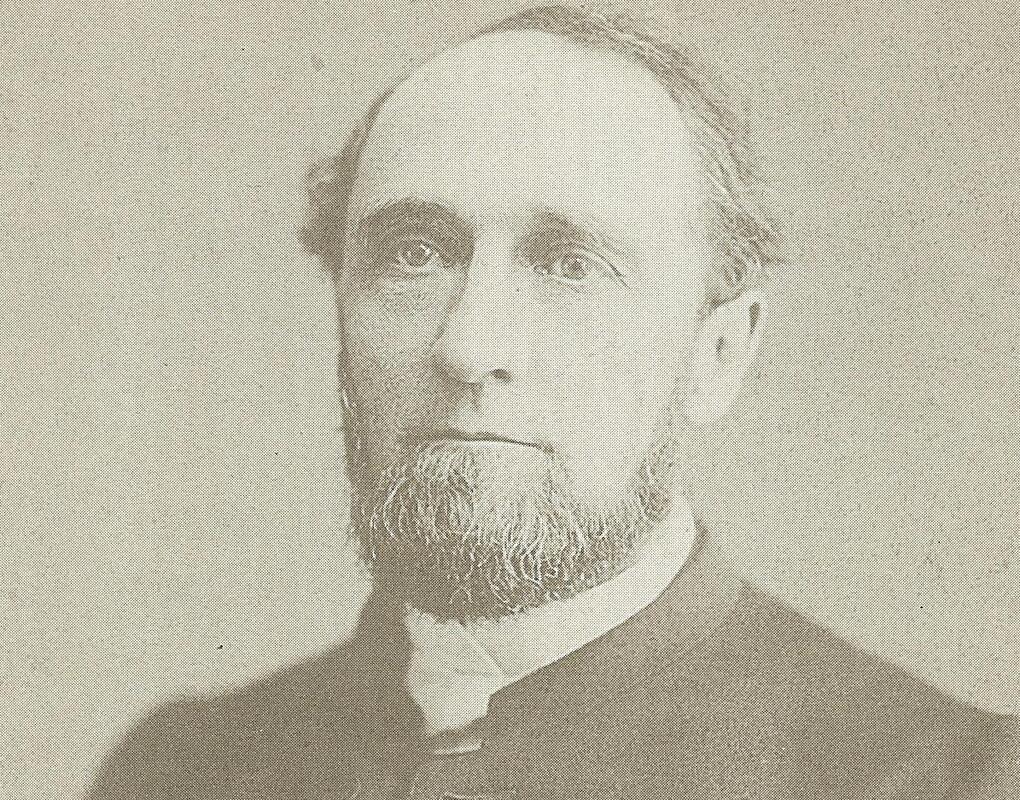

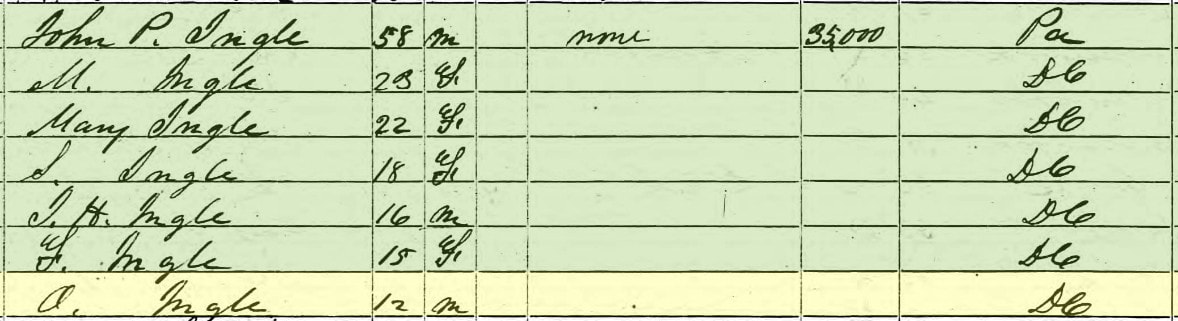

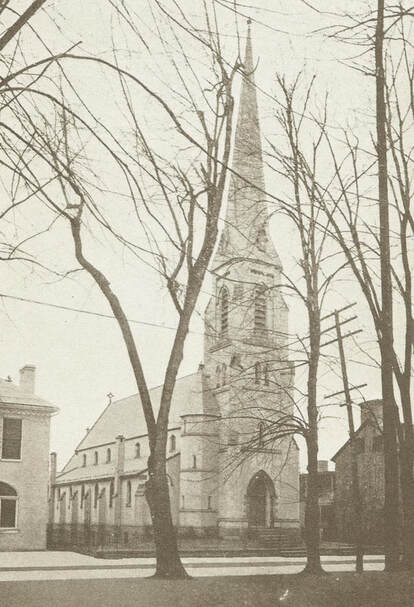

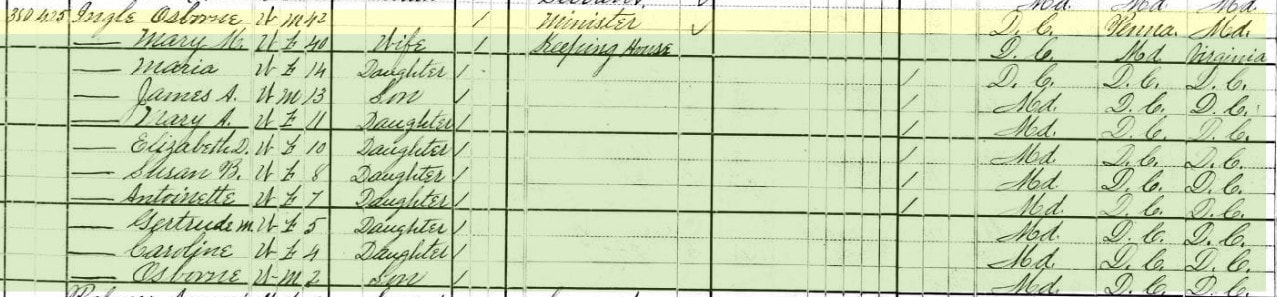

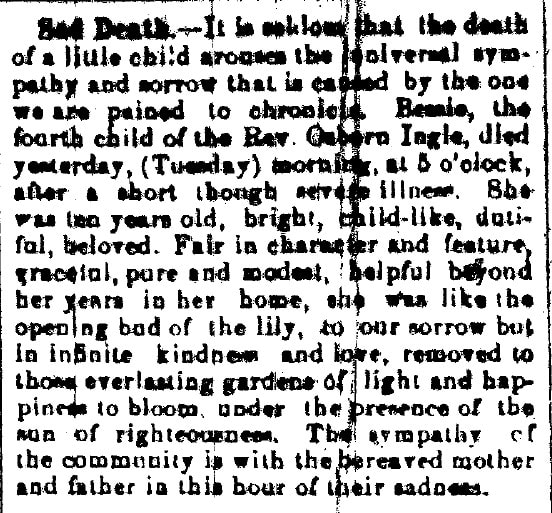

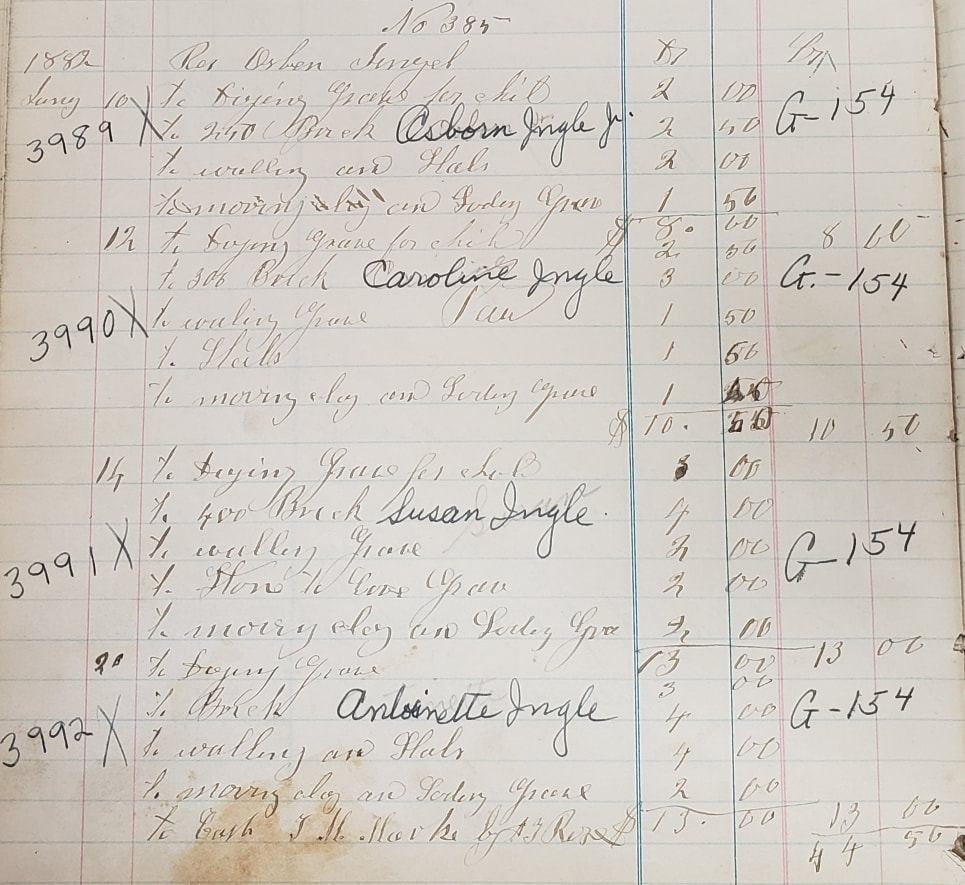

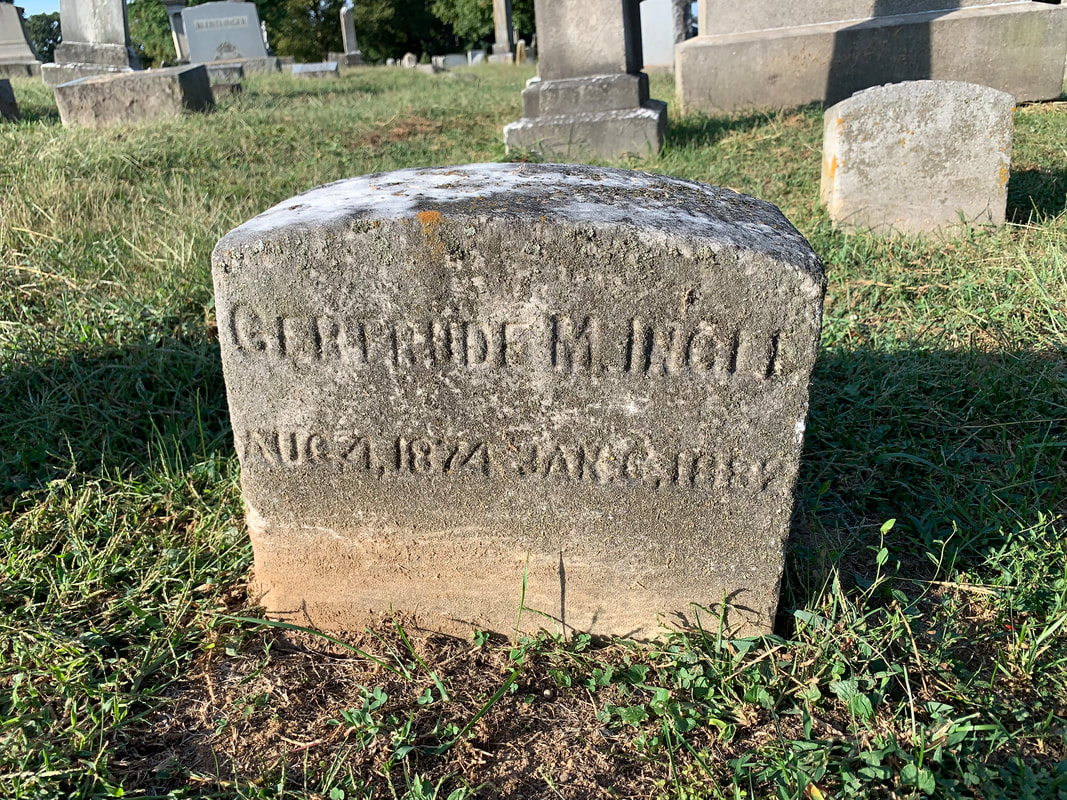

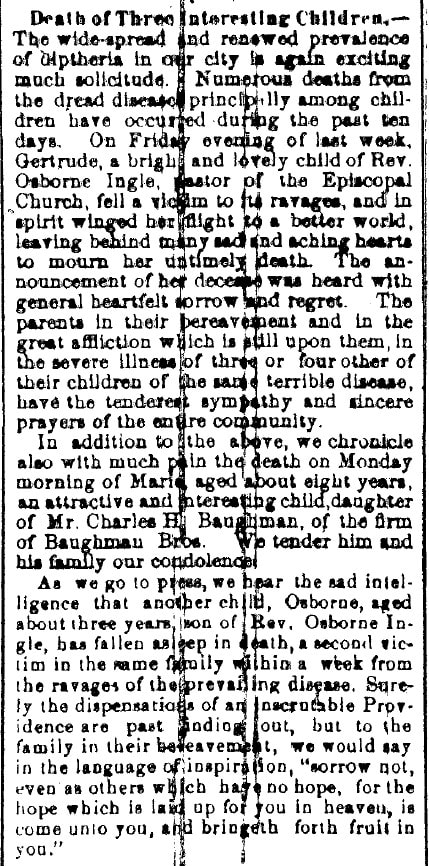

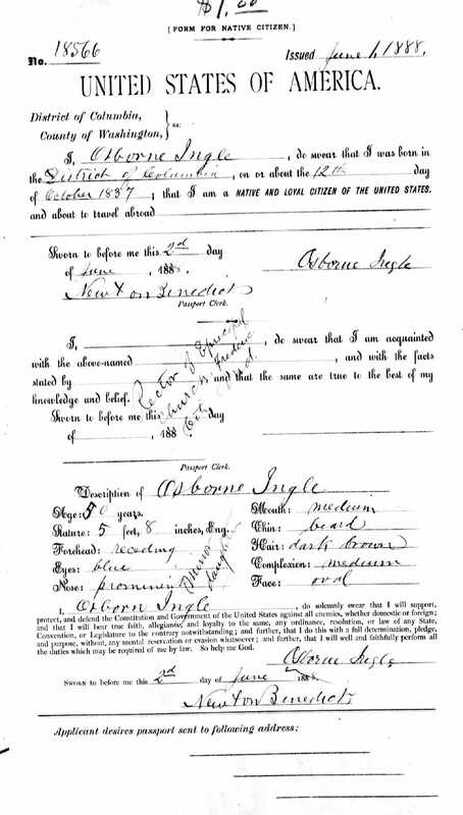

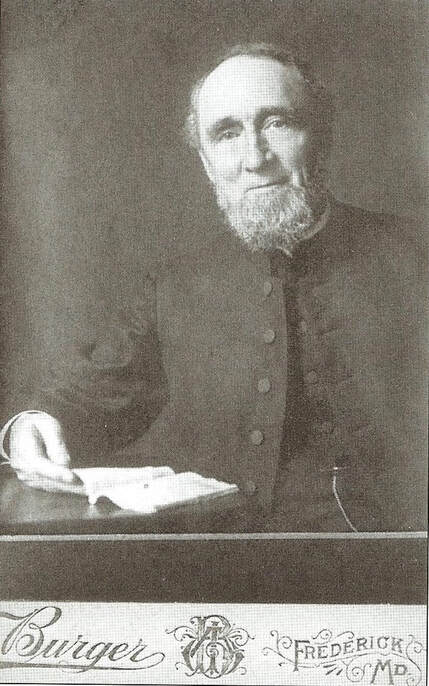

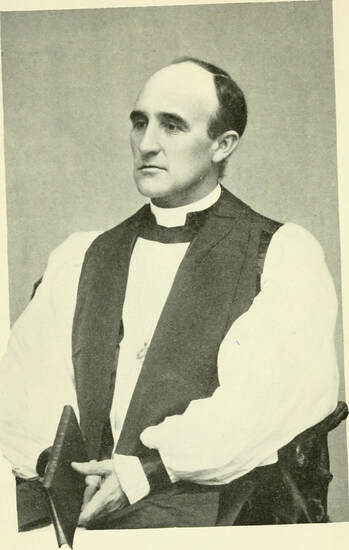

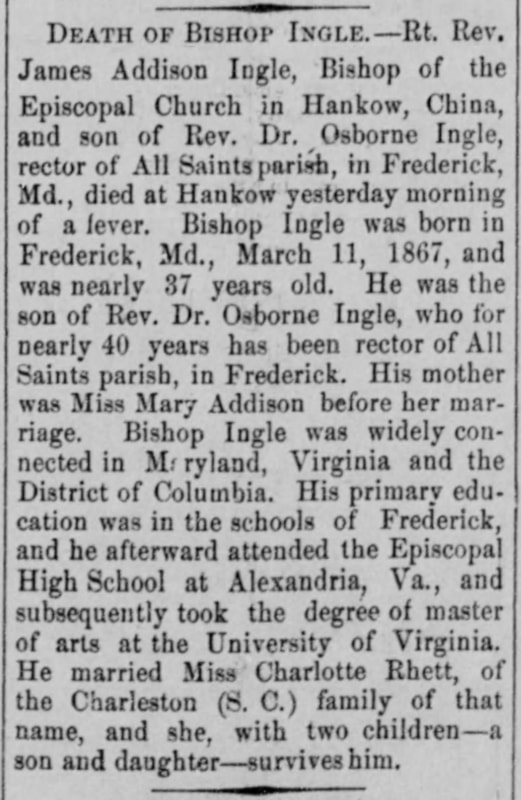

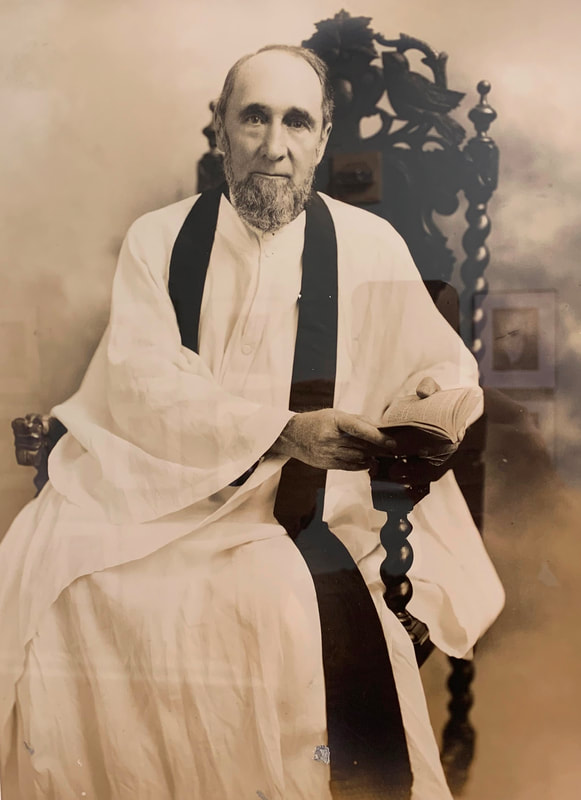

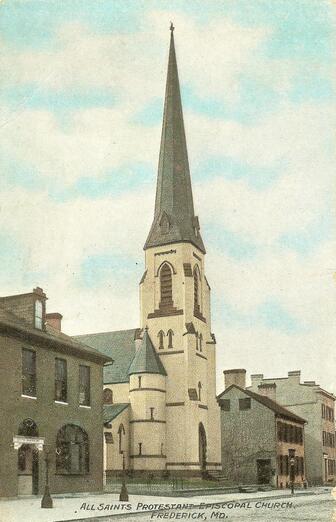

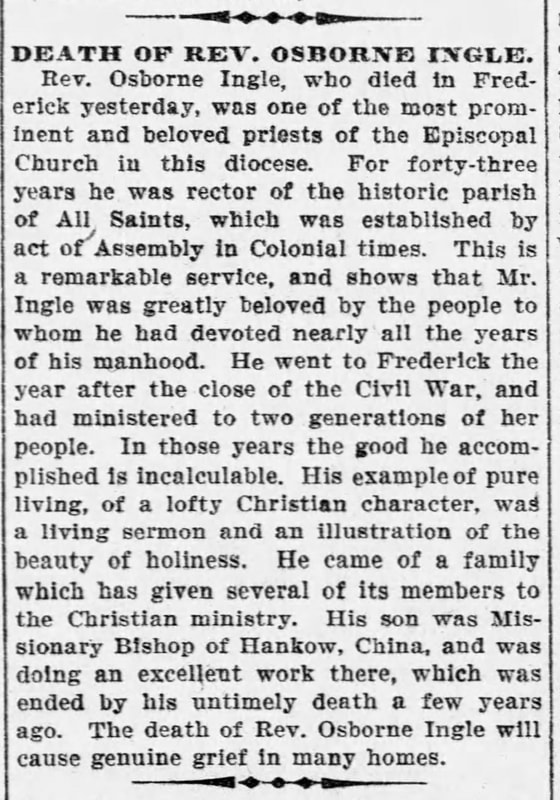

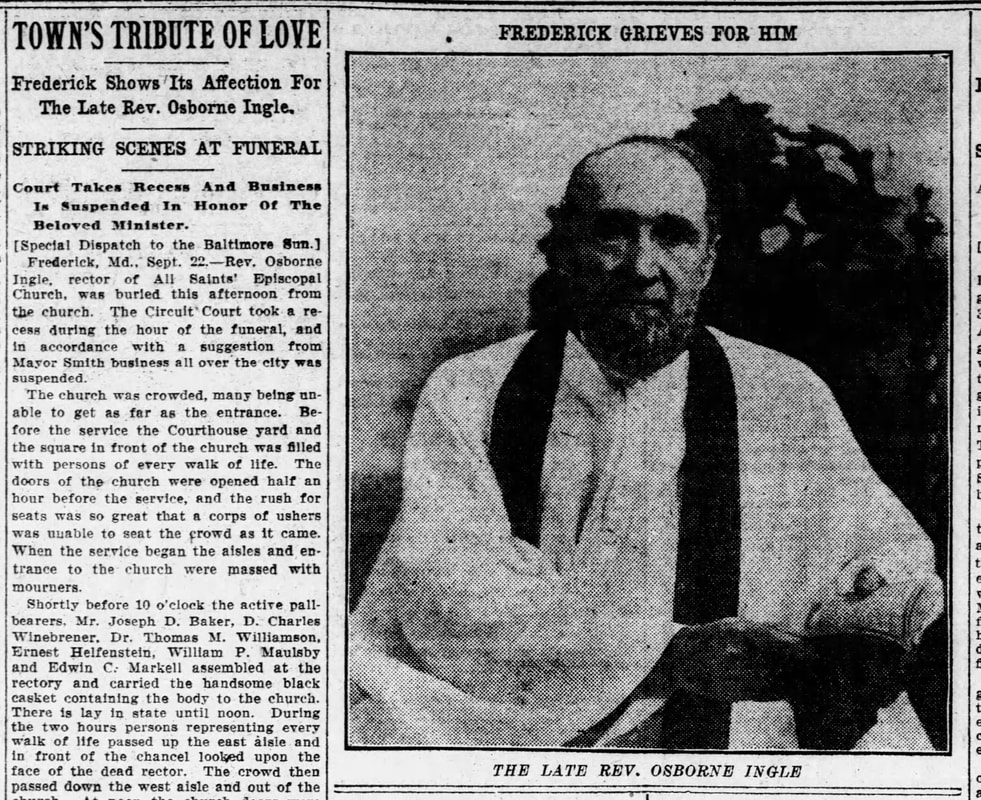

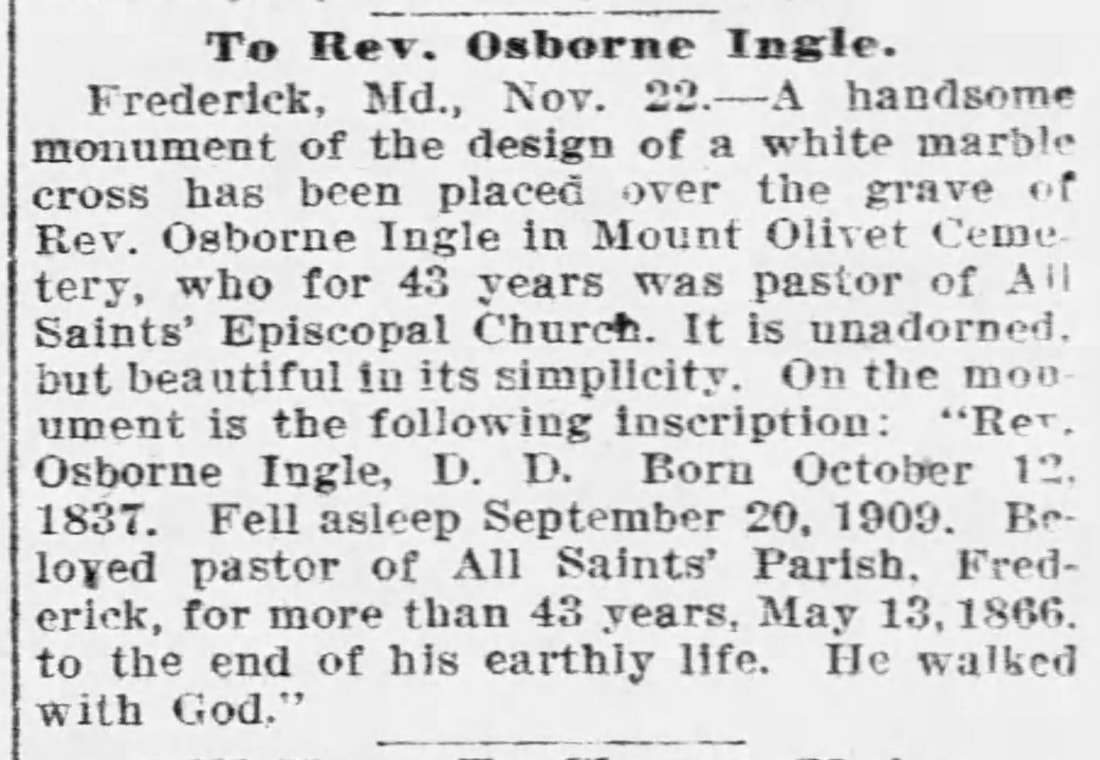

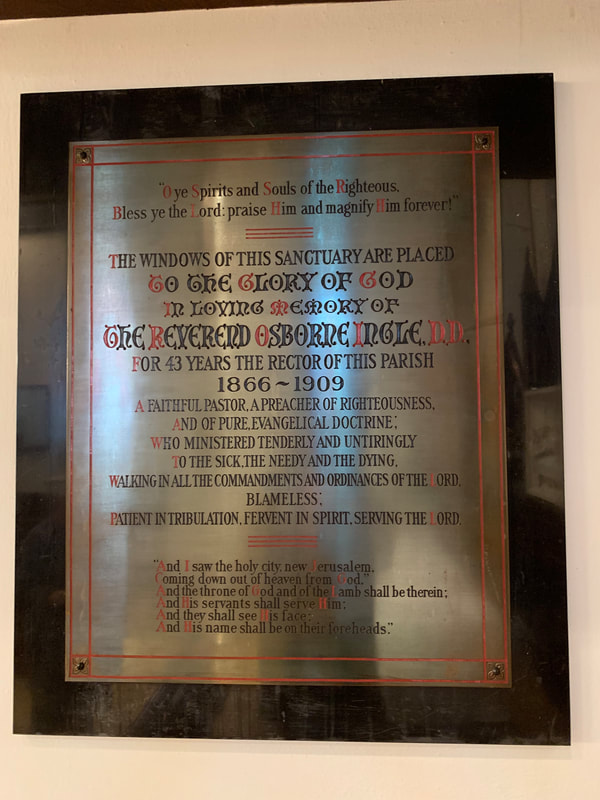

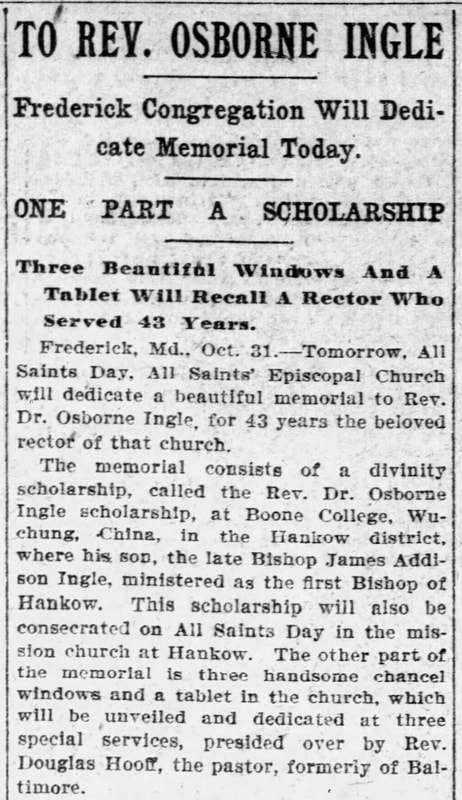

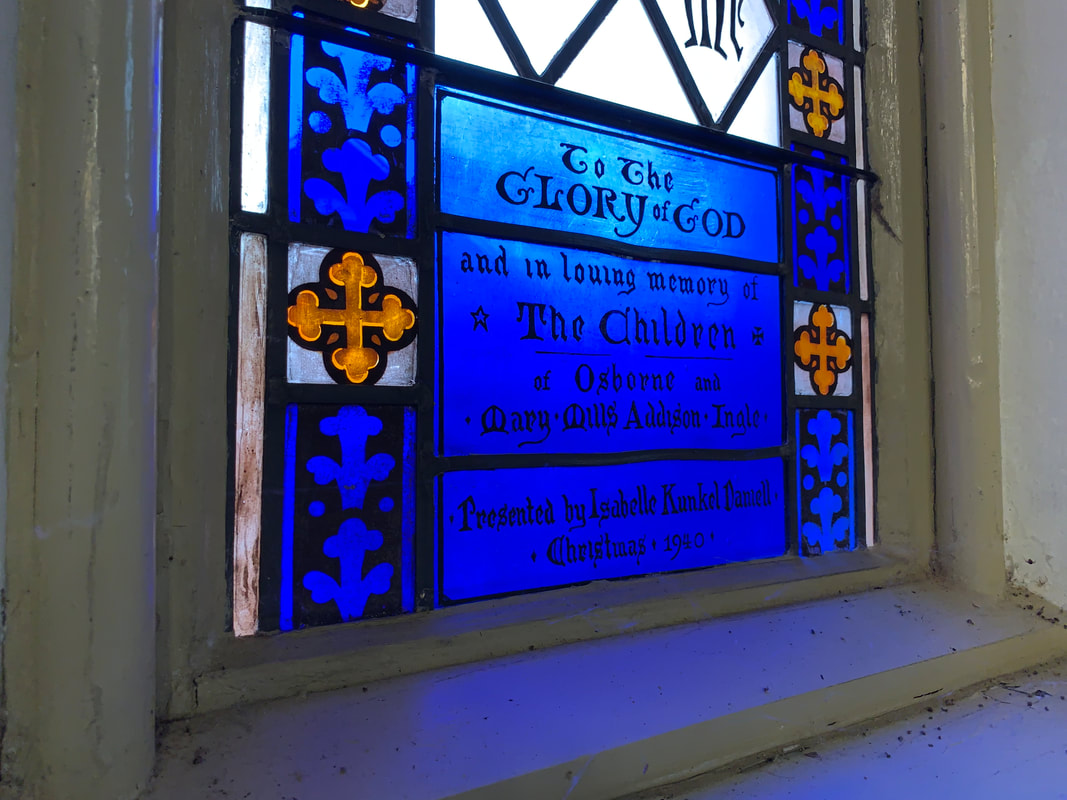

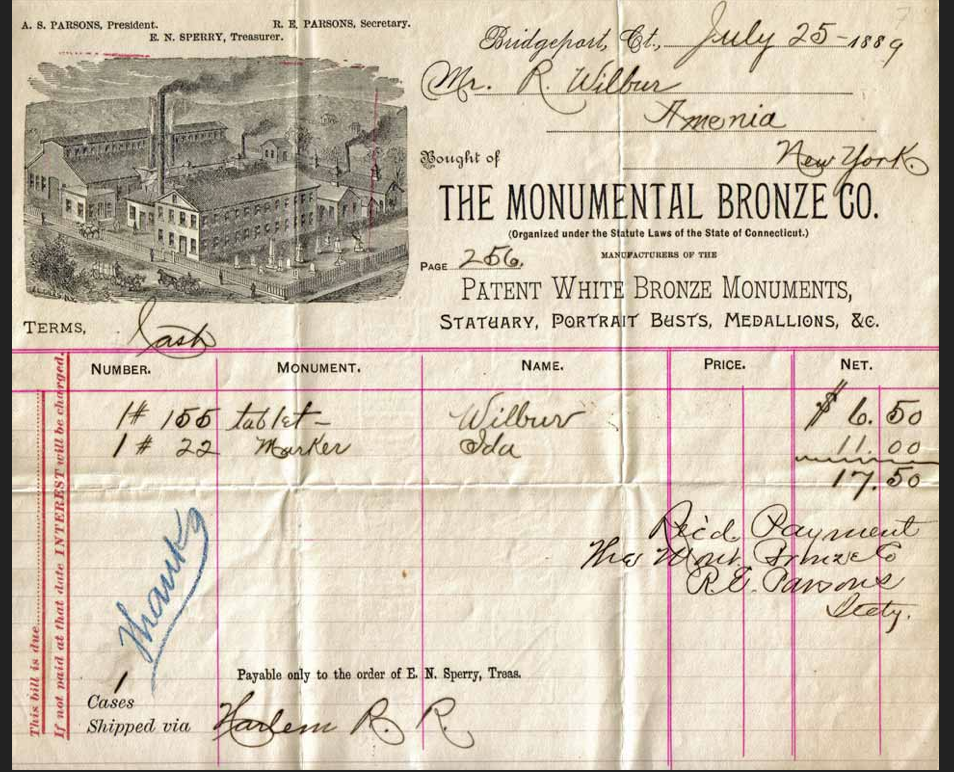

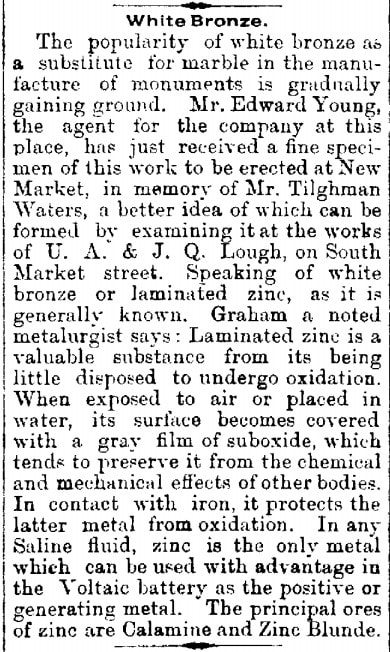

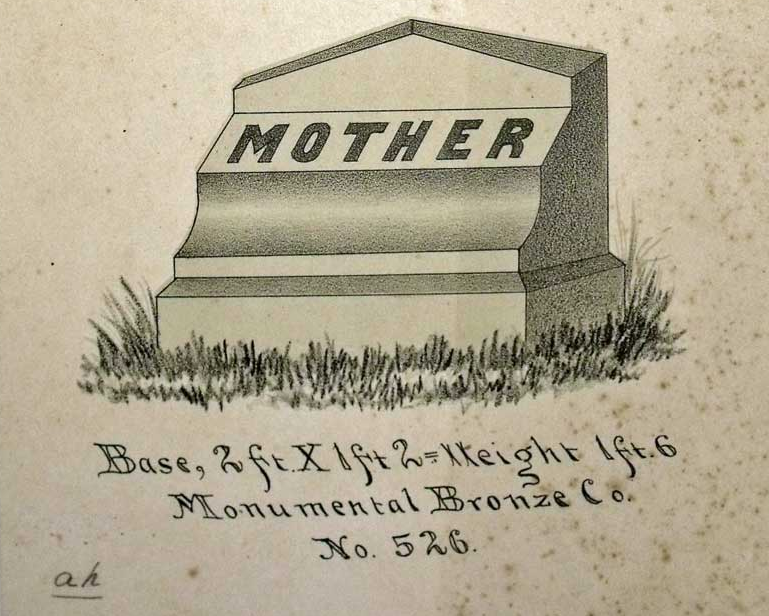

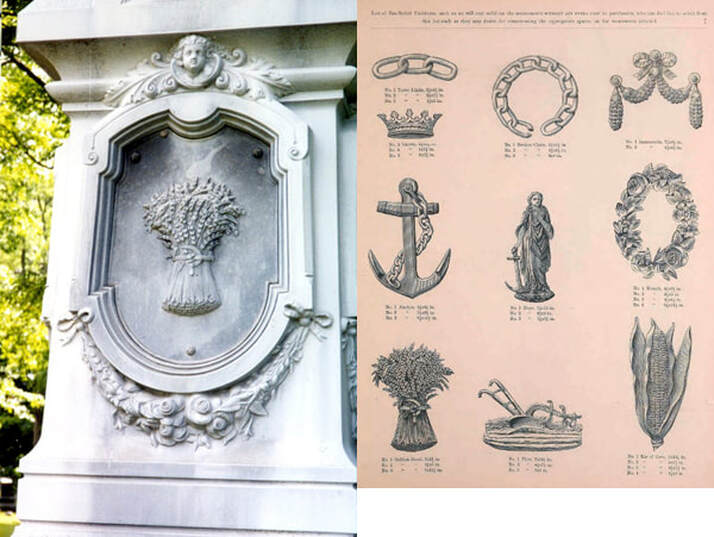

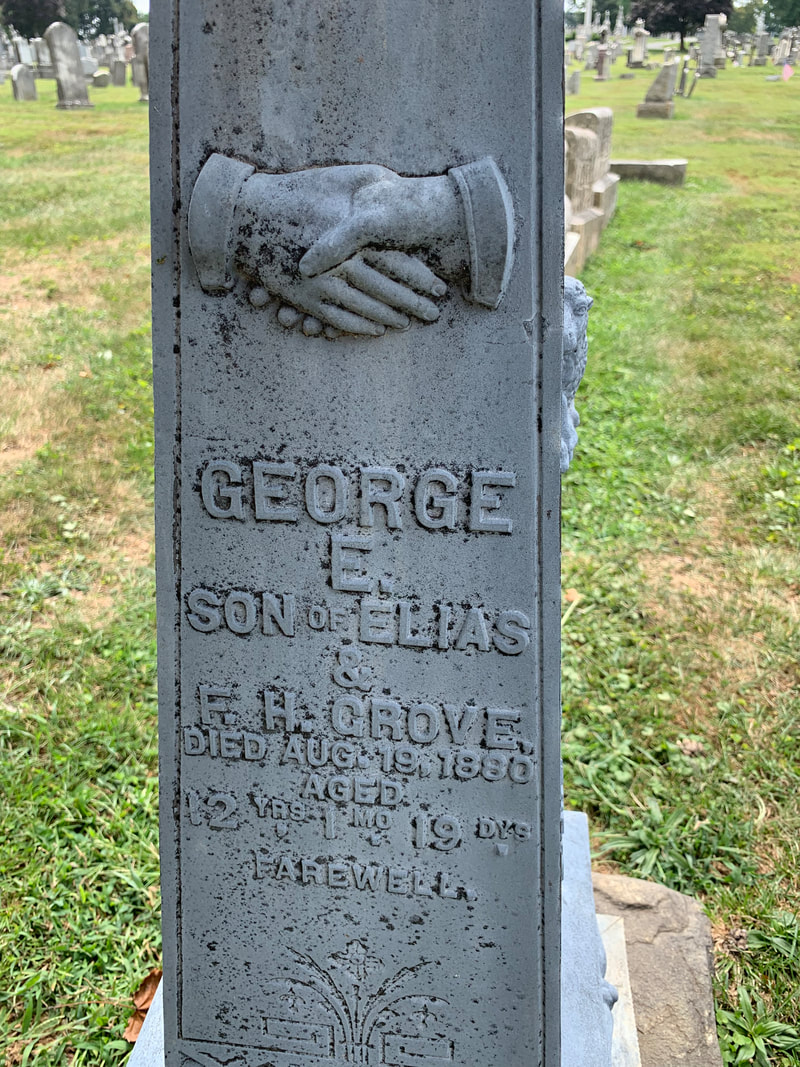

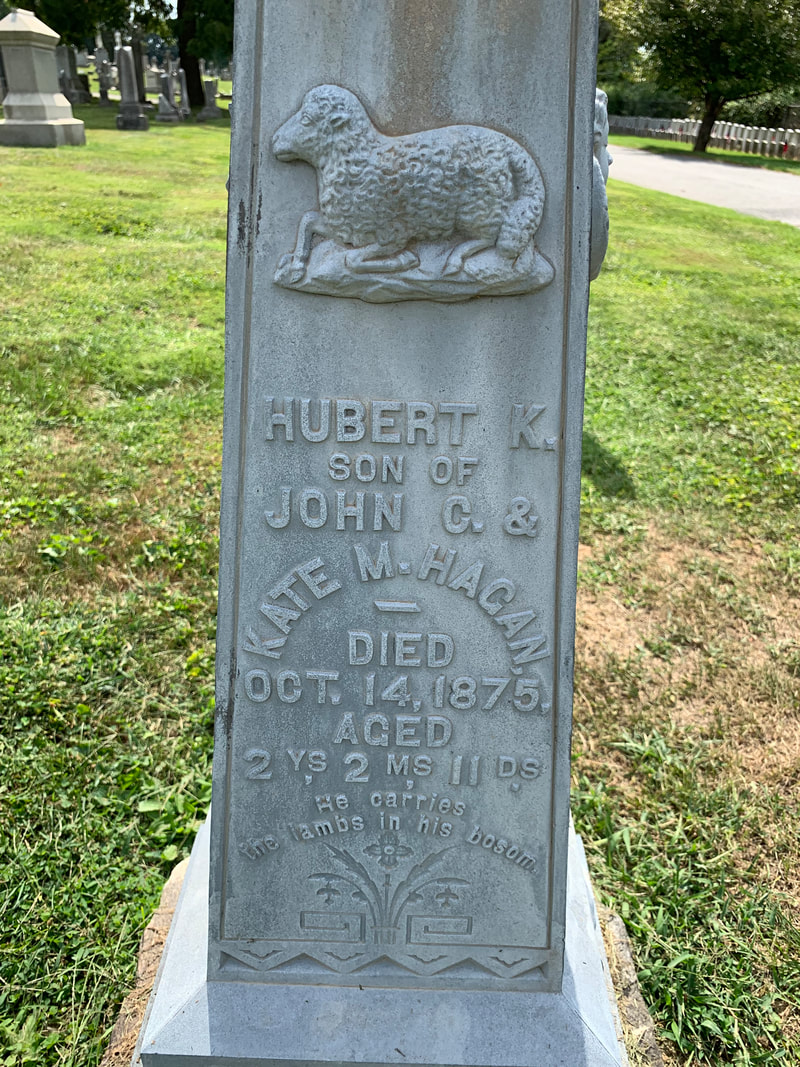

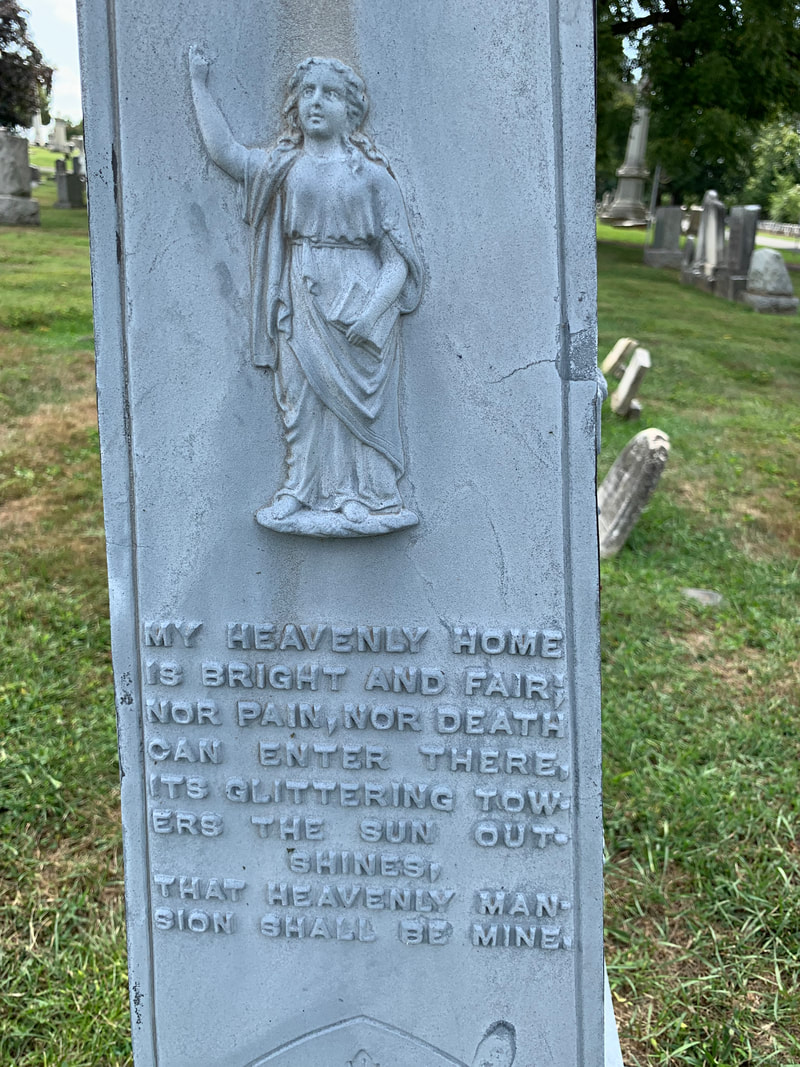

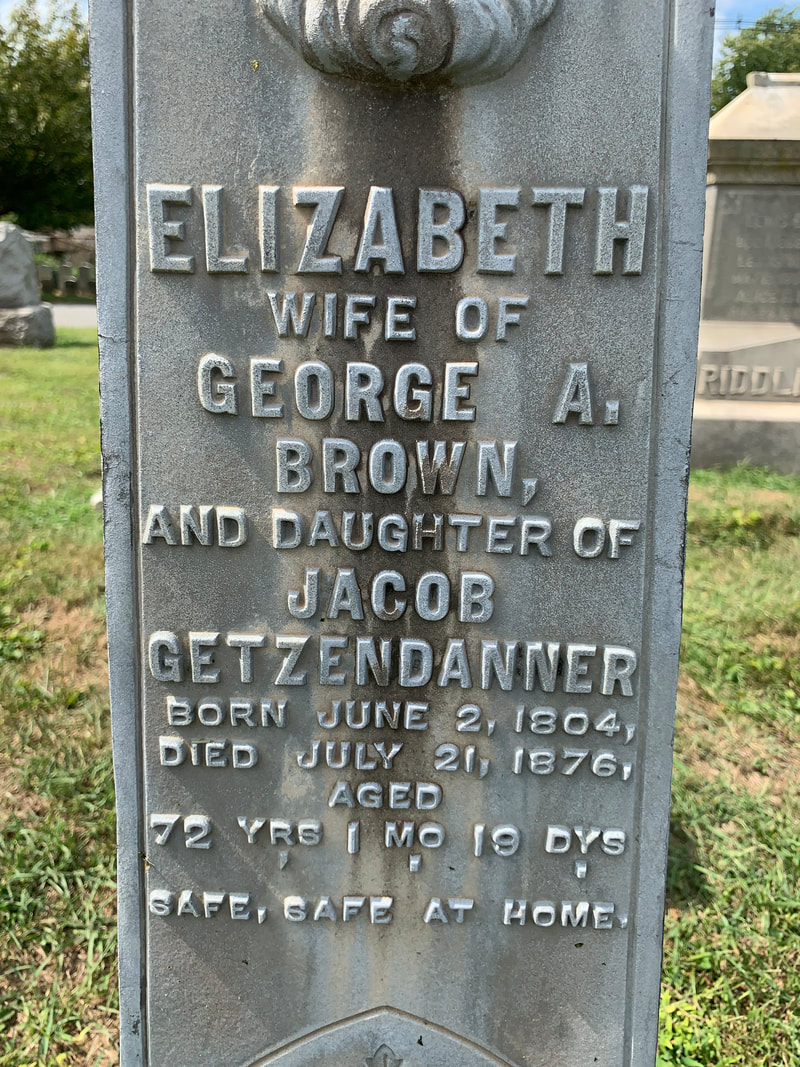

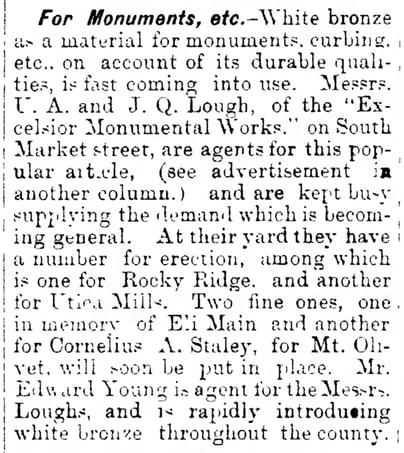

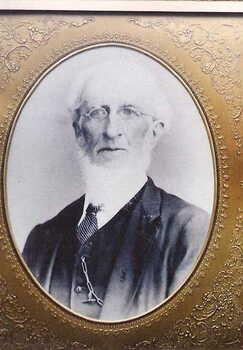

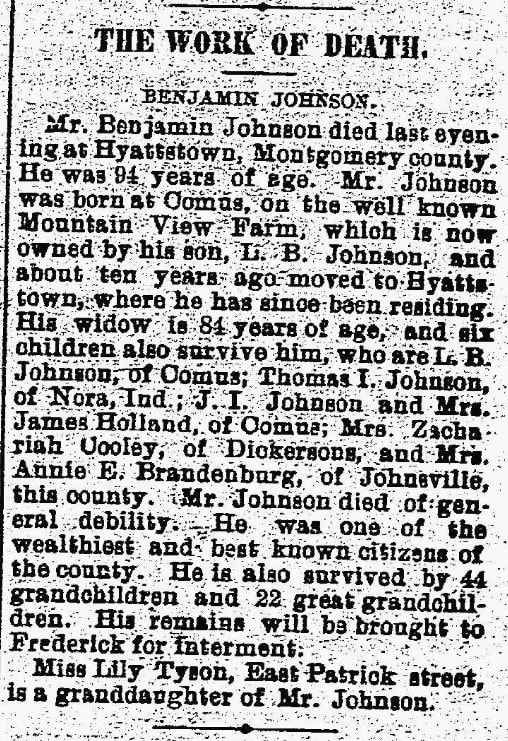

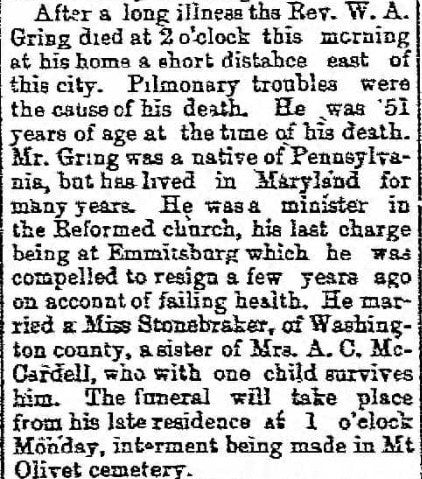

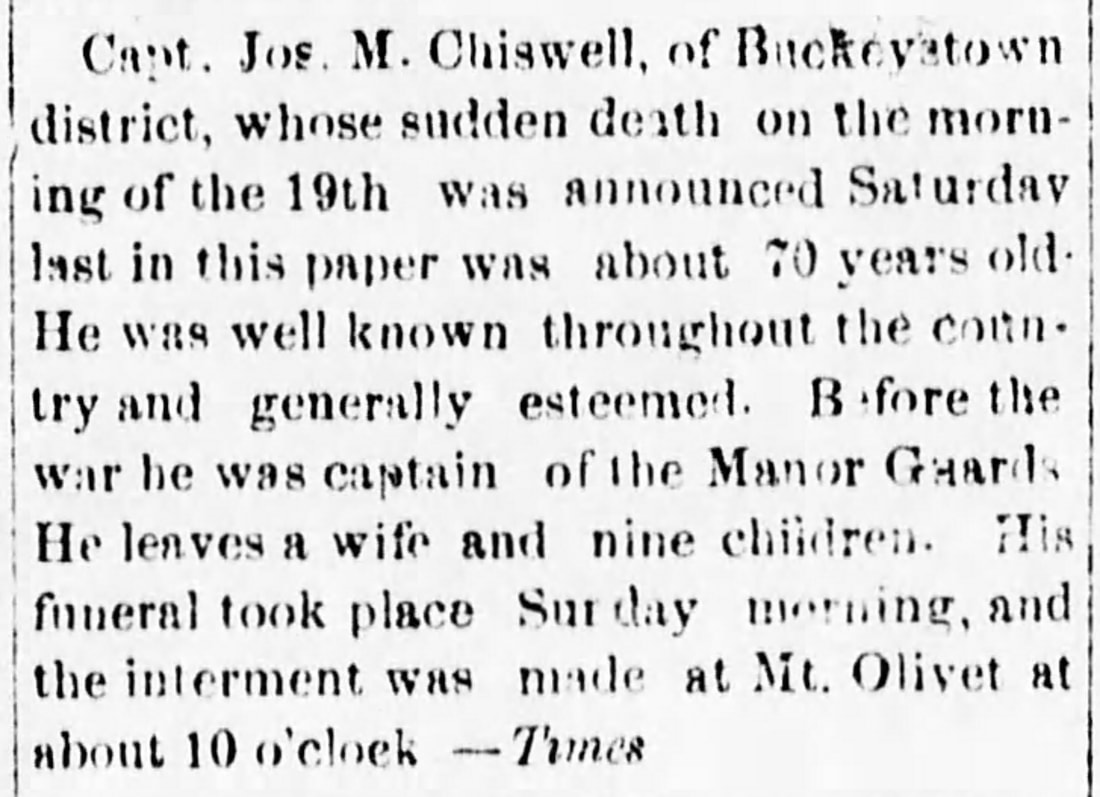

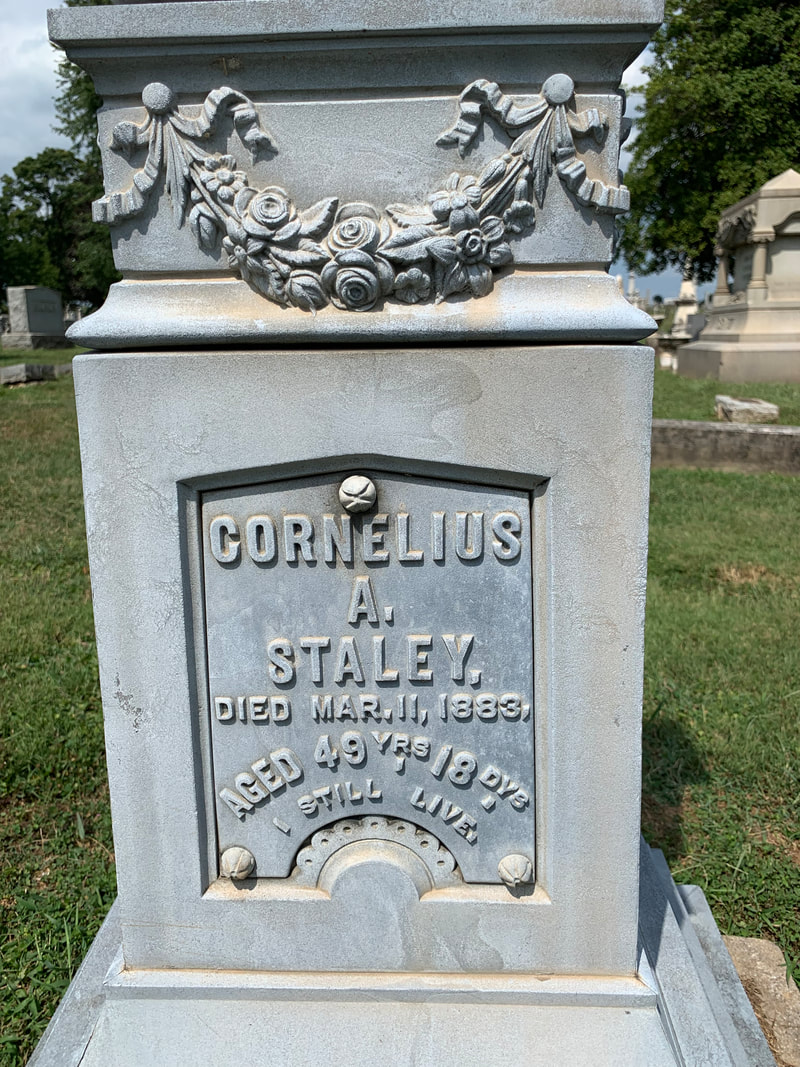

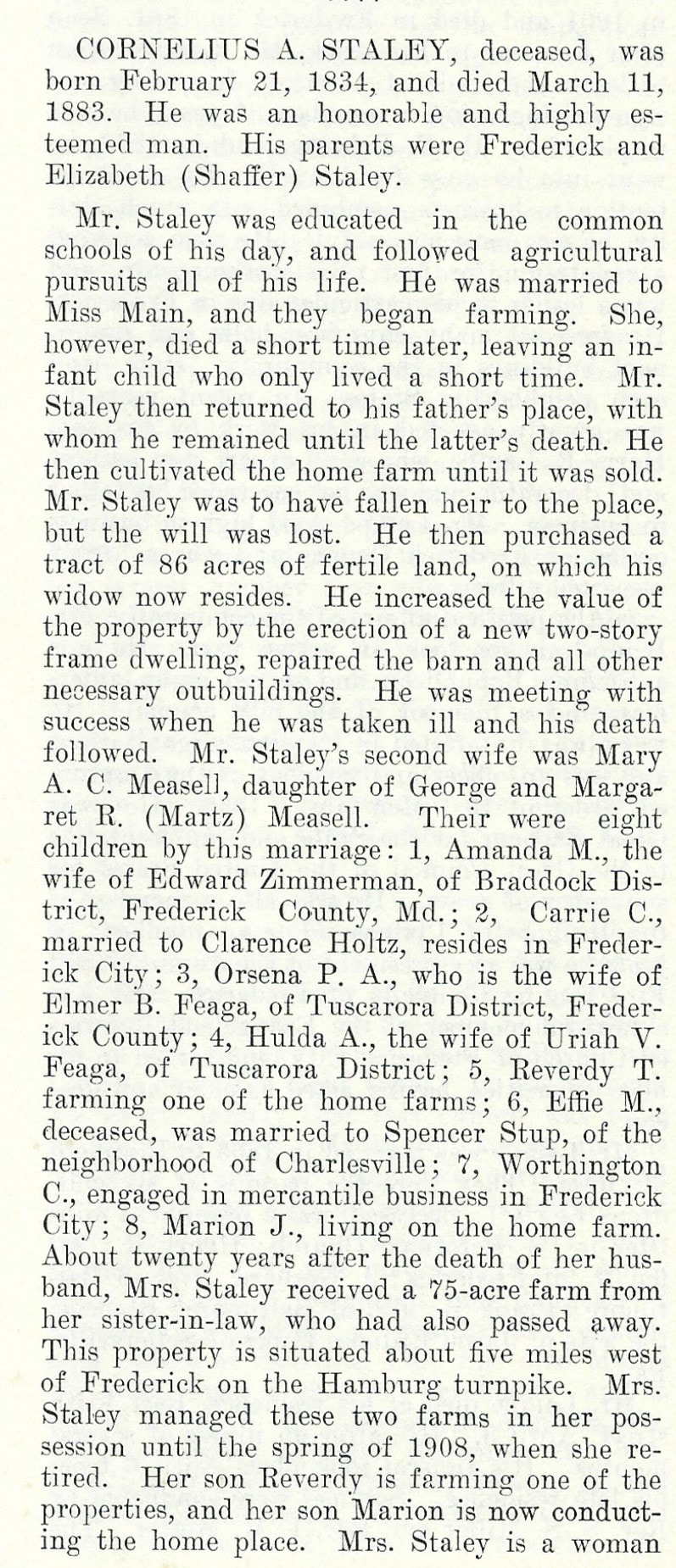

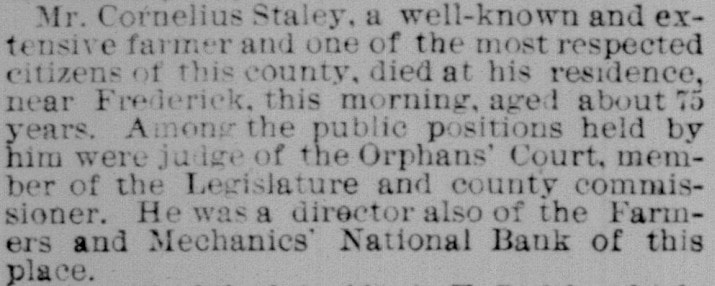

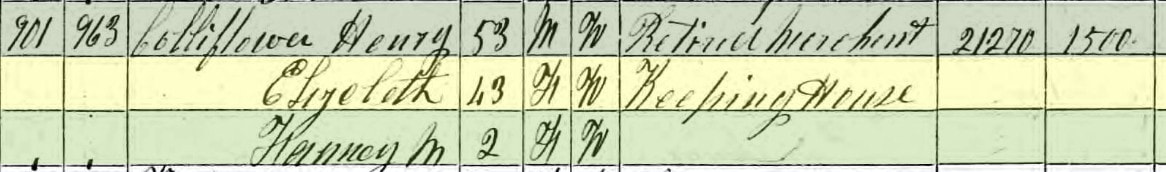

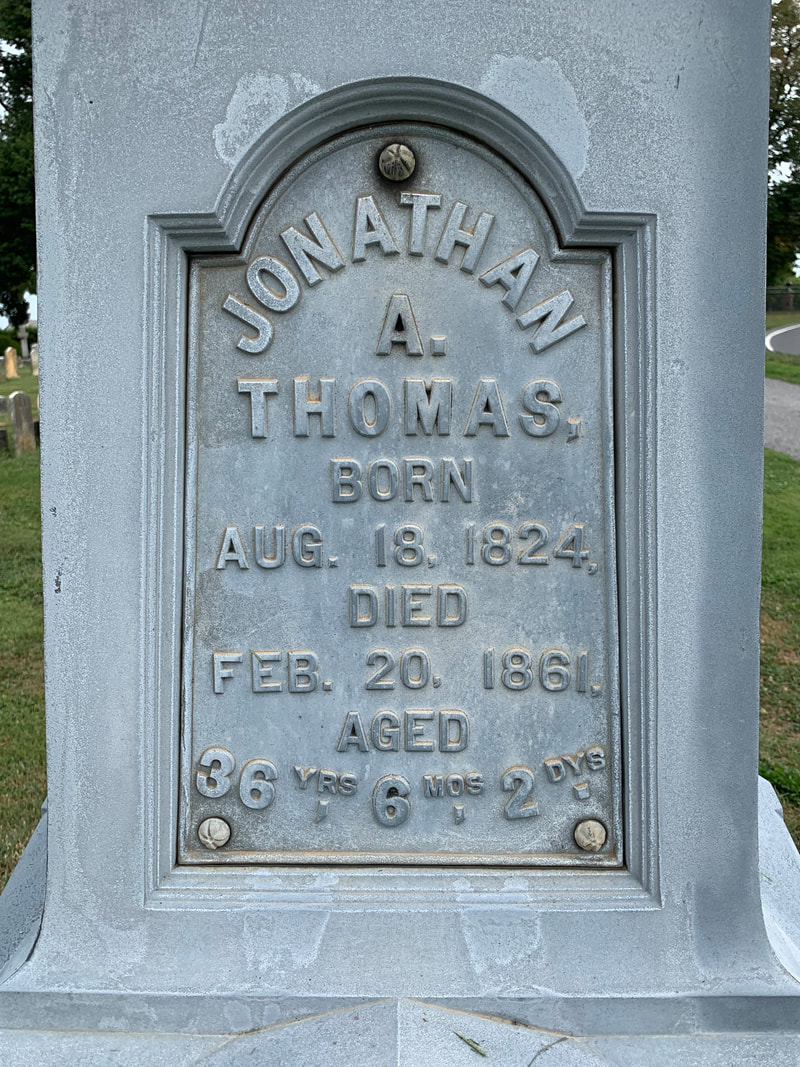

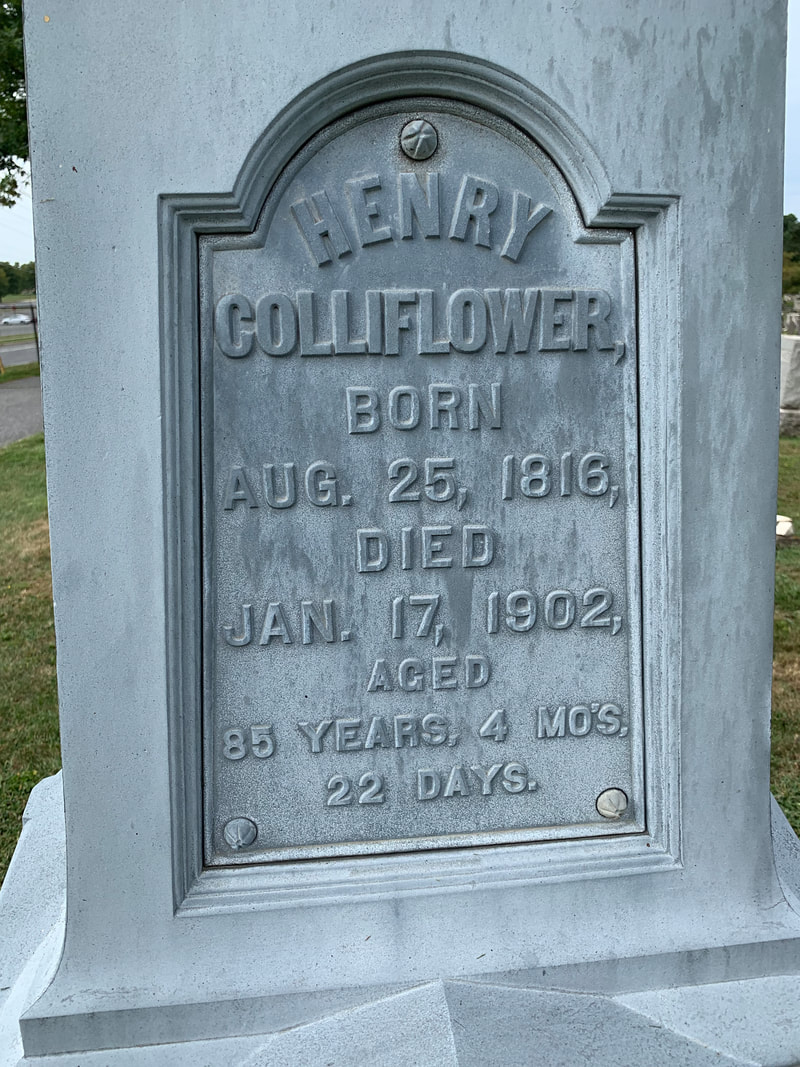

Interior view of the Philadelphia Divinity School Interior view of the Philadelphia Divinity School Young Osborne lost his mother when he was four years-old. He grew up in Washington, DC where he received his elementary education in private schools and later attended the Rittenhouse Academy. He would move on to Episcopal High School, near Alexandria, VA and subsequently graduated from the University of Virginia in 1860. In the fall of the same year, Osborne Ingle entered the Episcopal Theological Seminary of Virginia, where he remained until the spring of 1861. On account of the American Civil War, Ingle returned to the nation’s capital, and taught school for a short time. In January 1862, he entered the Philadelphia Divinity School, from which he graduated in the summer of 1863. Later that year, Osborne was ordained as a deacon of the Episcopal Church. Soon after his ordination, Mr. Ingle became assistant rector at old St. Peter’s Church in Baltimore where he remained until June, 1864, when he was ordained into the priesthood in Philadelphia. He then became rector of Memorial Protestant Episcopal Church, back in Baltimore. Here, Osborne stayed until the summer of 1865. On May 13th, of the following year, Mr. Ingle became rector of All Saints’ Episcopal Church here in Frederick. The City of Clustered Spires Mr. Ingle came to Frederick with “family in tow” after a turbulent time for the city. Just over four years earlier, Frederick had been the first major town that Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee would bring his Army of Northern Virginia. This occurred in September, 1862 and would include a multi-day occupation that eventually led to the nearby battles of South Mountain and Antietam. Less than a year later, the Union Army took over the town while en-route northward to Pennsylvania in hopes of intercepting Lee’s army who had crossed into Pennsylvania. Both North and South forces would clash at Gettysburg in early July, 1863. One year later, the Battle of Monocacy, was fought on July 9th, 1864. Town leaders had thwarted possible disaster by garnering funds to pay off a $200,000 ransom demanded (or suggested) by Confederate Gen. Jubal Early. Nearby fighting, south of Frederick, was fierce, and residents got to see the carnage of war up close and personal as corpses and wounded soldiers were regularly brought back into town. Many would be tended to in the All Saints’ church building itself, as it had been commandeered for use as a makeshift hospital. After the fighting had stopped in 1865, peace and reconciliation had to be made between southern supporters and northern supporters, This, in many instances, involved relatives, friends and neighbors. Rev. Ingle certainly had his work cut out for him as I’m sure many residents had "lost their religion" over the four-year duration of the conflict. Rev. Ingle was charged with pacifying a torn community with the “Word of God.” For this, he was offered a yearly starting salary of $1,200/year, plus use of the church rectory as his living quarters. Rev. Ingle’s first sermon resonated with his new congregation as he based his text on the bible passage of Acts 10:29 which reads: “Therefore came I unto you without gainsaying, as soon as I was sent for: I ask therefore for what intent ye have sent for me?” God’s purpose would certainly play out over time for the holy man. It’s also not an understatement to say that Rev. Ingle would come to know the confines of Mount Olivet Cemetery quite well over his 44-year tenure in Frederick. As his profession dictated frequent visits here, there would also be bittersweet personal tragedies that led the man once called “the Minister of Frederick” through the burying ground’s iron front gates. Right from the start, Rev. Ingle was called upon to officiate funeral services here in Mount Olivet. Interestingly, among the earliest, was the re-interment of Francis Scott Key who had been removed from Baltimore’s old St. Paul’s Cemetery and brought to Frederick’s relatively new “garden cemetery” in October, 1866. Thirty-two years later, Ingle would serve as officiating clergyman during the highly- attended unveiling of the Francis Scott Key monument. A passage from the second edition of Ernest Helfenstein’s History of All Saints’ Parish, published in 1991, states: “The parishioners were not slow in appreciating the personal qualities of their new rector and he soon won a place in their interest and affections which, with the passing of years, ripened into a devotion, unique in character and productive of incalculable good. The early days of Mr. Ingle’s administration were featured by his strong desire to broaden the influence and benefits of the parish.” Mr. Ingle received the degree of Doctor of Divinity from St. John’s College, Annapolis, Maryland. “the heaviest burdens” As for Osborne Ingle’s personal life, he had previously married Mary Mills Addison, daughter of Anthony Addison of Prince George’s County, on August 11th, 1864. The couple had been warmly welcomed to Frederick and four children were born in the first four years of residency, prompting the church to assist Rev. Ingle in finding larger living quarters than the original rectory in the first block of W. Church Street provided. The Ingles would soon relocate to a dwelling on West Patrick Street, but would eventually land at 113 Record Street in 1878. This was the former residence of Dr. William Tyler who had entertained Abraham Lincoln 16 years earlier while the president was on a brief visit to Frederick to check on the recuperation of an old friend, Maj. Gen. George L. Hartsuff. Soon, the Ingle family would consist of eight children in the 1880 US Census. The grim reaper would reverse the good fortune of Rev. Osborne Ingle over the next three years. To set the mood of the period, we can look as far as Jacob Engelbrecht's diary. At this point in time, the famed town diarist, tailor and former Frederick mayor had been dead since 1878. His son Phillip kept the diary going and made the following entry on October 26th, 1881. “Diptheria—This disease is making sad havoc among the children of our city, there having been about fifty deaths up to this writing & about them many more. The physicians have called on the City fathers to see in to the sanitary conditions of the city. We hope it will soon be driven from our town.” Rev. Ingle’s first born child, Elizabeth "Bessie" Dulany Ingle, died on April 5th, 1881 shortly before her 11th birthday. The child, nicknamed Bessie, died as part of the terrible diphtheria epidemic that would grow in destruction over the next several months, particularly August, 1881-February, 1882. During this period, Frederick lost 125 of her residents to the diseases. January, 1882 was particularly cruel to the Ingles as five children would be taken by the dreaded disease. These included: Gertrude Mills Ingle (Jan 6th, 1882 at the age of 7), Osborne Ingle, Jr. (Jan 10th, 1882 at the age of 3), Caroline Ingle (Jan 11th, 1882 at the age of 5), Susan B. Ingle (Jan 14th, 1882 at the age of 10), and Antoinette Addison Ingle (January 19, 1882 at the age of 6). This was a horrific happenstance that Rev. Ingle faced in a steadfast and strong manner. All of these children would be buried in Area G/Lot 154. The Ingles and their three surviving children counted their blessings and pledged to move forward. However, another tragic event would sting this pious family shortly thereafter. On January, 28th, 1883, Mrs. Mary Ingle would die in childbirth, along with her infant child. They would be buried together in the same space within the Ingle plot in Area G/Lot 154. After this heartbreaking event, Rev. Osborne Ingle found himself a single parent of three surviving children. He successfully raised these into adulthood. They included Maria, Mary Addison, and James Addison. An article found in the Frederick Post on April 9, 1976 by Judge Edward S. Delaplaine shares: “The grievous ordeals Osborne Ingle suffered while serving as rector of All Saints’ Church in Frederick, together with the lasting sympathy of the members of his flock, served to cement the bonds of affection.” This was exemplified five years later in 1888 when the congregation raised funds to send Rev. Ingle on a 3-month vacation to Europe with his daughter Mary as traveling companion. It was thought that this trip would help his grief and health. It was a smashing success. Rev. Ingle returned refreshed and rejuvenated. He would continue to lead All Saints’ in the last decade before the looming millennium. A joyous occasion occurred in June, 1890 when Ingle’s daughter, Maria, married Henry Randall Webb, of Washington, DC. “The last storm” Seven months after Maria’s wedding, Rev. Ingle presented his son, James Addison, as a candidate for deacon in the Episcopal Church. James had attended the local Frederick schools, then graduated from the Episcopal High School of Virginia at Alexandria, Virginia. He obtained his B.A. degree from the University of Virginia in 1885 and his M.A. from the same institution in 1888. After teaching at a private academy in Charlottesville (1886-1887), Ingle decided to study for the priesthood. He graduated from Virginia Theological Seminary in 1891, and was ordained deacon at his home parish of All Saints Church, January 29th, 1891 by Bishop William Paret. James Addison Ingle would be assigned to serve as a missionary to China. He left for the Far East by boat in October, 1891. James Addison Ingle served for ten years. He returned to the US on furlough in 1894, at which time he came back to Frederick to renew relations with friends and family. James Addison married Charlotte Rhett Thomson of Charlestown, SC. The wedding was presided over by the groom’s father, of course. Back in Frederick, James Addison used the break to refresh himself while sharing his stories of life in China to townspeople. He also co-officiated a Thomas Johnson, Jr. commemoration sponsored by the Frederick DAR Chapter. The younger Rev. Ingle gave the keynote speech at Johnson’s gravesite in the old Protestant Episcopal burying ground in between Carroll Creek and East All Saints Street. James Addison Ingle returned to China in 1895 and would eventually publish the Hankow Syllabary in Shanghai in 1899. Meanwhile, James’ father was continuing his efforts to lead the All Saints’ congregation, while making necessary improvements to the church building and related accoutrements and programs. Rev. Osborne Ingle was also very active in municipal affairs and served as chaplain to several organizations such as the Independent Hose Company, Frederick Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution and the Francis Scott Key Memorial Association. With this latter affiliation, Rev. Ingle was chosen to preside over the heavily-attended unveiling ceremony of the Francis Scott Key monument in August, 1898. Just thirty-two years earlier, Ingle had been on hand for the first burial of Francis Scott Key in Mount Olivet in the year 1866. In 1901, Osborne’s son was elected missionary bishop for the Missionary District of Hankow, China. In this, Rt. Rev. Ingle became the first bishop of the American Episcopal Church to be consecrated in China. The consecration service in both English and Chinese took place at St. Paul's Church, Hankow on February 24th, 1902. Sadly, at the age of 36, James Addison Ingle would die on December 7th, 1903 and was buried in the Old International Cemetery in Hankow. Meanwhile, the news was originally kept from Rev. Osborne Ingle as he lay ill in a Baltimore hospital, attempting to recuperate from a recent surgery. Apparently, his hospital room was said to be “banked with flowers” and Mary wanted to withhold the tragic loss as not to create a setback in her father’s recovery. James Addison left a wife and two children. Charlotte Rhett Thomson Ingle would survive her husband by four decades. When she passed and her body was interred at her family's gravesite in Magnolia Cemetery in Charleston, South Carolina, the couple’s joint cenotaph remembered Rt. Rev. Ingle. A memorial service was held in James Addison Ingle’s honor at Emmanuel Church, Baltimore, during which Rev. Arthur M. Sherman mentioned Rev. Ingle’s dedication to building a native church, and his efforts after the Boxer Rebellion. His Frederick, Maryland parish donated funds to establish a scholarship at the Boone Divinity School in China in his memory, which was mentioned at the All Saints' day services in both his parishes. A memorial to Osborne's son can be found in the form of a memorial pulpit at Frederick's All Saints' Church. Once again, Osborne Ingle had to endure another personal loss. His journey along these lines had started in youth with the untimely loss of his mother. Now the son who had followed in his footsteps was gone, a bright star in the Episcopal Church that was extinguished in a mere instant. Ingle made a full recovery, but he retained proverbial holes in both his heart and mind as he had lost more than a mortal man could ever imagine. He forged on, with his reliance on God. The year 1906 brought two very special and joyous occasions. In January, All Saints’ Episcopal would celebrate its 50th year in the present church structure fronting on W. Church Street. The opportunity was also taken at this time to properly consecrate the church as well. In May, the congregation celebrated once again. This wasn’t done for the church or structure, but solely for the man who had come to Frederick 40 years earlier to lead its members. In his Frederick Post article (April 9th, 1976), Judge Edward Delaplaine explained the actions of the church during this landmark occasion: The vestry on the 9th of May, 1906, adopted the following resolutions expressing the feeling of the parish that no man could have rendered “more blessed ministrations.” In the resolutions, Rev. ingle was praised for his life and his preaching amid the joys and the trials of 40 years, asserting that there had always been one figure—both in sunshine and in shadow—who had guided and comforted them all. They assured Mr. Ingle not only of their boundless confidence and love but also their prayers that his life would be “extended to the uttermost.” Rev. Ingle was also urged to take a summer vacation and was given a gift of $565 in gold, contributed by the members of the congregation. The 70 year-old minister was said to have been overcome with gratitude. Delaplaine commented: “He expressed his thanks and spoke feelingly of the many kindnesses which had been bestowed upon him during his 40 years in Frederick.” As for the vacation, Rev. Ingle and daughter Mary traveled out west and visited Yellowstone National park and returned home via Canada and the Great Lakes. Rev. Ingle’s physical strength and resolve would decline rapidly over the next few years. He would give his last sermon from the All Saints’ Church pulpit on August 15th, 1909. Just over a month later, he would be gone—dying on September 20th. Rev. Ingle’s death was felt strongly throughout the community he served for forty three years. His funeral service was held in his beloved church amidst the backdrop of a quiet City of Frederick with the exception of tolling bells in his honor. In tribute, the stores of town were closed, along with local manufacturers as nearly the whole town paid their respects to “the man who walked with God.” His mortal remains would be placed next to wife Mary in the now expanded family plot in Mount Olivet’s Area G as Lot 152 was purchased to adjoin existing lot 154 which held the remains of the six Ingle children lost to the terrible diphtheria epidemic of 1881-82 and the other lost in childbirth in 1883. Rev. Ingle would be further honored and memorialized by his congregation with stained glass windows and a memorial tablet in his church, and a white marble cross on his grave. Twelve years later, Maria Ingle Webb would be buried next to this cross in the Ingle plot following her death in 1921. The sympathetic members of Frederick’s All Saints’ congregation never forgot the ordeals through which the beloved rector had passed. Some 58 years after the deaths of Mrs. Ingle and her seven children, a stained glass window was installed in the church in memory of his children. This event took place in 1940 and was presided over by the remaining member of Rev. Osborne Ingle’s family—Mary. She would pass in 1955, and was buried beside her parents and siblings at Mount Olivet at that time. Have you ever wandered through Mount Olivet (or any other historic cemetery) and eyed a bluish-gray colored headstone or monument that appeared to be in stellar condition? Upon closer inspection, you likely noticed that it wasn’t derived from a rock material such as the traditional suspects of marble, granite or sandstone? Hopefully you went one step further and used a few other of your senses—that of touch, and that of hearing. It should feel like metal, and when knocked on with your hand or (gently) tapped with a metal object such as a key or screwdriver, you should hear a hollow “clang.” Chances are you found something very popular and stylish in the last few decades of the 19th century and known as “white bronze” markers. These standout funerary memorials were the brainchild of a man named Milo Amos Richardson (1820-1900) and business partner and brother-in-law, C. J. Willard. Mr. Richardson worked as a cemetery superintendent in Chautauqua County, New York, and had observed the need for a new and better material for cemetery monuments. He set out to develop a solution of creating a material for memorials that would repel moss, algae and lichen, invasive and unwelcome guests that takes up residence on traditional gravestones, especially monuments in shady locations within cemeteries characterized by abundant tree cover or dampness. Richardson and Willard’s formula centered on the use of zinc carbonate and found its home at a foundry in Bridgeport, Connecticut called the Monumental Bronze Company. Richardson, along with two business partners, tried to get a company off the ground but failed. In 1879, the rights were sold and a new company, the Monumental Bronze Company, was incorporated in Bridgeport, Connecticut. One more innovation (that white bronze made possible) resided in the opportunity for customers to employ a myriad of popular symbols and designs of the late Victorian period on these unique monuments. These beautifully ornate memorials became a high-selling novelty especially in the northeast, and the examples that have remained are well over a century old and look virtually new, so to speak! The name “white bronze” was given as it certainly sounded more elegant than zinc. Characteristics of a White Bronze Marker As already mentioned, the headstone will be a lovely bluish-gray, or dare I say “powder-blue” in color. The lettering on the marker will stand out as being made in a cast and put together in panels. The assured way to tell is to literally knock on the marker itself. Tombstone tourists have affectionately refer to these monuments by a nickname coined at the time of their popularity—“zincies.” In some cases, these specimens were often viewed as a status symbol for the deceased solely based on their uniqueness from the norm found in a burying ground. In other cases, they were frowned upon as cheap imitations as white bronze monuments offered a less expensive alternative for a custom designed and detailed gravestone as opposed to a solid granite stone. Some cemeteries even banned them, likely due to the urging of local granite and marble monument companies. Cost ranged anywhere from $10.00 to $5,000.00, depending on design. If attainable, there were often difficulties in finding a salesman in particular states, especially as you headed south and westward. Branches of the Monumental Bronze Company were established in Chicago (American White Bronze Company), Des Moines (Western White Bronze Company), New Orleans (New Orleans White Bronze Works), and St. Thomas, Ontario, Canada (St. Thomas White Bronze Monument Company). Here in Frederick, customers could go to Lough's Excelsior Monumental Works on S. Market St. to order a white bronze marker. The firm began their affiliation with Monumental around 1883-1884. White bronze markers came in all shapes, sizes and styles. They could receive additional customization in many ways including decedent(s) name, dates, epitaphs, and bible passages. Other designs were added as personal expression that can be found on stones today. Some represented religious, fraternal and popular Victorian iconography of the day such as particular flowers, leaves, or other objects often characterizing the personality of the deceased, or the hopes of those left behind. These could be “read” at a glance, part of the popular and material culture of the day. For example, a sheaf of wheat symbolizes a long and fruitful life and symbolizes immortality as part of the harvest cycle. “Rock of Ages” is the title of a hymn popular in the 19th century and still is today. The zinc monuments were made for only forty years, from 1874 to 1914. With the advent of World War I came the demise of the trade. Zinc was needed for the war effort and the Monumental Bronze Company of Connecticut was taken over by the government to manufacture gun mounts and munitions. Although the company continued to exist until 1939, they never produced another monument. Instead, they tried to maintain the industry by crafting panels for existing monuments. Some Romantic stories exist involving the use of white bronze monuments by bootleggers during the Prohibition Era that followed soon after the war. Alcohol was said to be stashed behind panels and inside the hollow portions of the White Bronze monuments, as they seemed to be the last place authorities would search for illegal spirits. In Frederick’s Mount Olivet Cemetery, I found 20 individual examples of white bronze funerary monuments. Some of these even carried the stamp of the Monumental Bronze Company near their base. To create a white bronze marker required several steps. An artist would begin the process by carving similar designs used on traditional granite and marble headstones into wax forms. Plaster would be poured into the wax forms and allowed to set, creating a plaster cast. A second, identical plaster cast would then be made. This would be the cast that the sand molds were made from and cast in zinc. The zinc castings were then assembled and fused together with molten zinc. Once assembled and fused, the monuments were sandblasted to create a stone-like finish. And the final step, a secret lacquer would be applied to chemically oxidize the monument, creating the bluish-gray patina – hence the name white bronze. Multiple designs and various sizes are represented in Mount Olivet. It’s hard to determine which one was the first, as some of the decedents memorialized predate the 1874 date given as the start of the “white bronze age.” Some families may have left graves unmarked at the actual death of their loved one until finding this cheaper alternative to a granite or marble marker. This particularly makes sense in connection to the death of a child, especially those of infant and toddler age. Other children and siblings are memorialized here as well. Let's take a look at our 20 markers, shall we? George Elias Grove (1868-1880) Hagan Children  Three children of John C. Hagan and Catherine Brining are listed on a small marker located across from Confederate Row in Area H/Lot 301: Marion Hampden Hagan (1879-1880) and two others that died of Scarlet Fever. These are Emma Claudine Hagan (1868-1875), Hubert Kemper Hagan (1873-1875) who died just 19 days after his older sister. The Olands The Mahoneys  Another brother and sister are located on Area E (Lot 116) Here, Edward Shriver Mahoney (1851-1857) has his own marker, and sister Sarah Kate Mahoney (1848-1872) has a larger memorial to the right of her brother who had died 15 years before her. Both are the children of Eleanor A. (Ervine) Mahoney and William Mahoney. Zimmerman Brothers  I did find it interesting, however, that the majority of the decedents appeared to have died from 1882-1884. Two such were young brothers, the sons of Milton Shuford Zimmerman and wife Alice Diehl Zimmerman. I found the graves of Murray D. Zimmerman (1881-1882) and Norman S. (1882-1884) in Area Q/Lot 98 as perhaps the most unique white bronze examples in our cemetery. Side by side, each is fashioned with a bird in flight. Burial here in Mount Olivet was made in early April, 1891 signifying that they were re-interred from another burial ground. German Roots Some white bronze monuments went to some folks with deep roots to early German families of town. The Staleys The Schmidts Mrs. Elizabeth Brown (1858-1883) Main Family Cousins Noteworthy "Stories in White Bronze" The Johnsons of Comus Benjamin Johnson IV (1813-1902) and wife Martha House Johnson (1819-1906) are located in Area P/Lot 152, not far from ancestor Gov. Thomas Johnson, Jr.’s large monument and memorial in Area MM. Benjamin’s great-grandfather was an older brother to Maryland’s first elected governor. The Johnsons lived in Comus, Maryland in Montgomery County, at the foot of Sugarloaf Mountain. Their daughter Louisa Catherine (1866-1883), named for the cousin who married John Quincy Adams, is honored by another white bronze monument. Rev. William A. Gring Another style that differs from the rest is that of Rev. William Augustus Gring (1838-1889). Rev. Gring was the son of Daniel Gring, a German Reformed Church minister in York County, PA. William Augustus was a native of Pennsylvania and at the time of his death had charge of the church in Emmitsburg from 1881-82. Rev. Gring's brother Ambrose was the German reformed Church's first missionary to Japan. The white bronze marker is crafted in the shape of a traditional cross upon a pedestal and contains the name of Rev. Gring’s ten year-old daughter, Vida Rebecca (1875-1885), and his wife, Emma Alice (Stonebraker) Gring (1838-1889). Emma appears to have been the last individual to have a name placed upon a white bronze marker because she died latest (of all decedents) in the year 1930. If you look closely, you can see that Emma’s panel seems out of place as it had to be specially crafted as the fad was long since over, the Monumental Bronze Company having closed years earlier. Hendry the Shoe Salesman Nathaniel Burwell Hendry (1831-1883) was a native of Urbana who worked as a successful shoe merchant who ran his business in places such as Staunton, VA and Baltimore in addition to Frederick. Hendry's widow, Candace E. C. Windsor ran a popular boarding house in Ijamsville after his death. It was called the Windsor Inn. She is buried beside him but has a traditional granite stone marker. Captain Joseph N. Chiswell Capt. Joseph Newton Chiswell (1812-1883) was a native of Poolesville, but spent most of his life as a farmer in Buckeystown for many years. At the time of his death, he was serving as the Treasurer of the Maryland State Grange. I found a reference online that he was a great nephew of Sir Isaac Newton which is sort of gravity defying. He is buried in his plot in Area H/Lot495 with wife Eleanor (White) Chiswell (1822-1864) and a second wife named Virginia Catherine White (1830-1903). Eleanor and Virginia were sisters. Captain Cornelius Staley Capt. Cornelius Augustus Staley (1834-1883) was an American Civil War veteran for the Union. He is joined by wife, Mary Ann Catherine E. (Measall) Staley (1838-1913). The Staleys lived north of Frederick City at a place called Charlesville. Colliflower and two other Sides The largest, and presumed, most expensive white bronze marker in Mount Olivet can be found near the front entrance in Area A/Lot 86. This is a stone likely erected shortly after the death of Elizabeth Ann (Long) Colliflower who died in late December, 1882 at the age of 57. Mrs. Colliflower was married twice and the names of both appear on opposite sides of her monument. Jonathan A. Thomas (1824-1861) was her first, and Henry Colliflower her second. Incidentally, Henry (1816-1902) outlived his late wife by just over 19 years. The Monumental Bronze Company always claimed that the white bronze monuments were superior to granite and marble gravestones. And after 100 years, this claim has proven true. The outstanding quality and durability of the white bronze monument has indeed survived, and become even more popular, right into another century. Routzahn Children The lamb is a widely used symbol in cemeteries used to signify innocence. It is frequently used to denote the grave of a child. This white bronze monument marks the final resting place of two young children belonging to Daniel Henry and Margaret Catherine (Fulton) Routzahn. The childrens names are Richard Henry (who died as an infant in 1877), and Herman W. (who died at the age of 8).

Mr. Routzahn owned a farm in Mount Pleasant and served as the Collector of State and County Taxes at the time of his sons' deaths. He would pass in 1898, but his grave would be marked with an upright granite marker which sits adjacent the white bronze lamb marker for the boys. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed