|

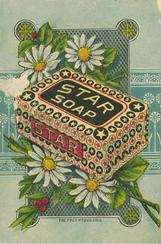

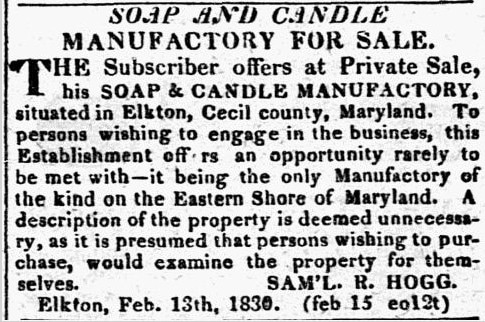

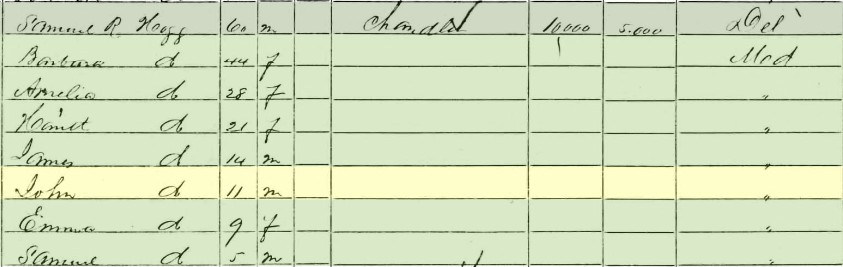

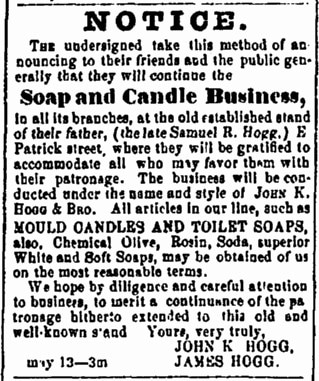

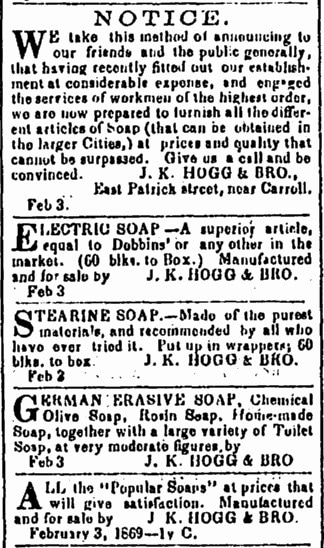

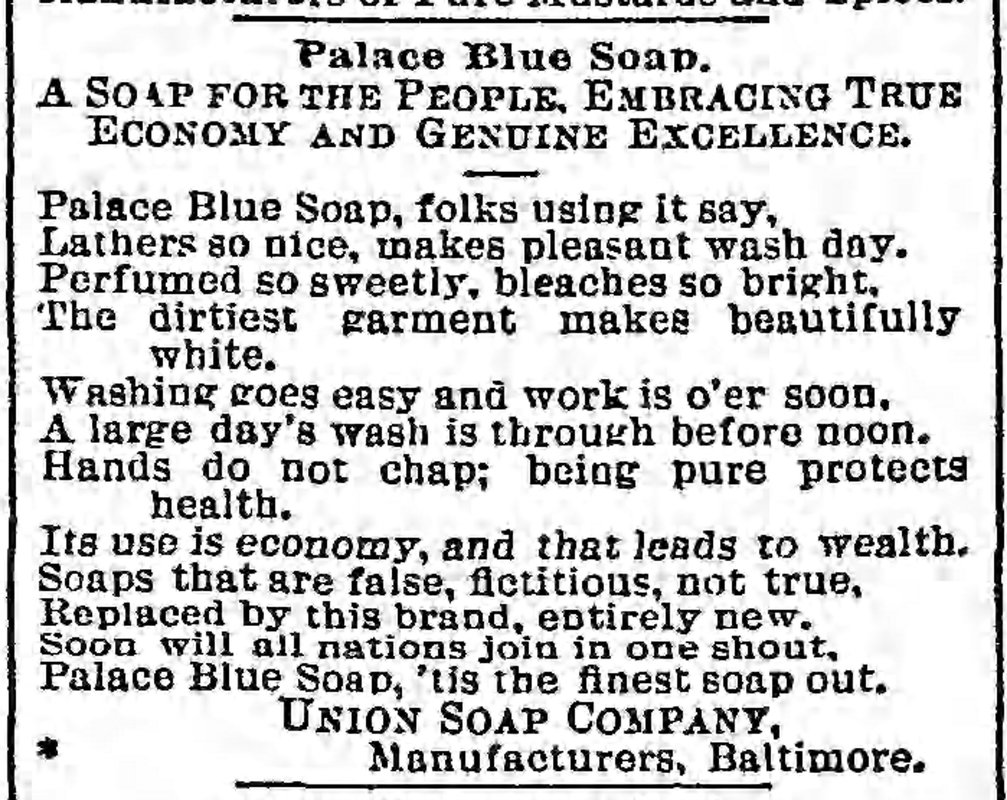

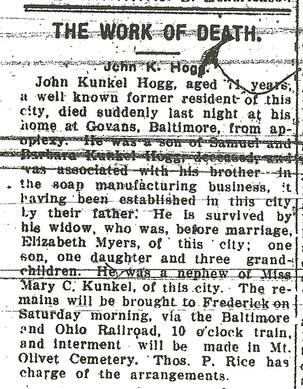

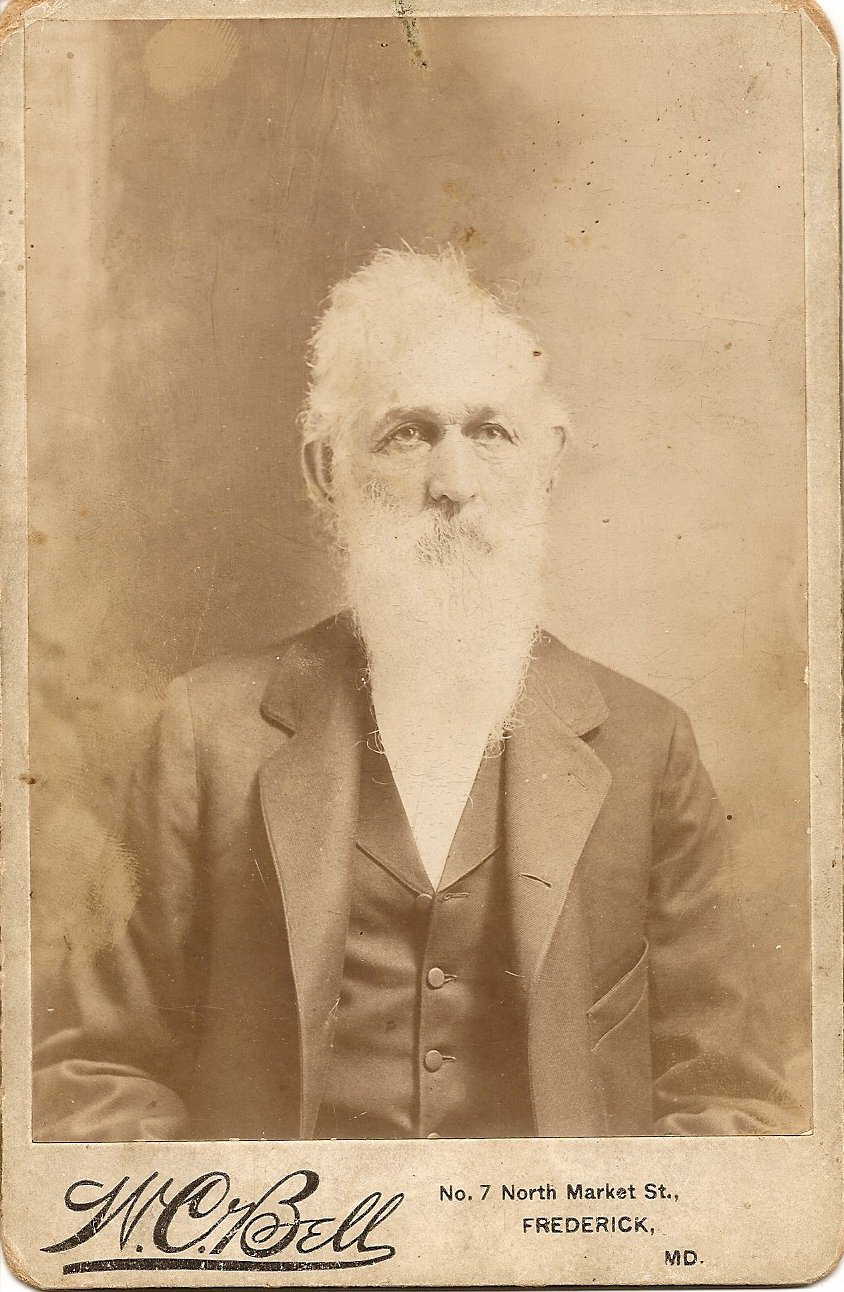

“As happy as a pig in mud” is an age-old idiom still used today. Along similar lines, another popular, pork-related phrase is “He is in hog heaven!” or “She went hog wild!” In all these cases, the subject seems to be enthralled, and satisfied, while engaged in some pleasurable act, all the while captivated within a desirable environment. Oftentimes, gluttony of some sort is implied. The basic underlying premise of the first phrase is that pigs are happy in mud. Not knowing the exact religious stance of most porcine-based creatures, I’m assuming that a mud-filled pen or trough is the closest thing to “heaven” that a pig, boar or hog will experience. Options are limited since it is generally known that they seldom make it off the ground, beings they aren’t known to fly. Interestingly, our human view of mud is totally congruent to that of swine. Unless involved in a social endurance event activity or spa treatment, we generally are very “unhappy” in mud. Even just the hint of mud on our shoes or clothes is repulsive, and we make extra efforts to avoid wet, soft earth as much as possible.  So what exactly is it about mud that makes pigs so gleeful? Researchers say that wallowing in the mud offers several practical benefits, like keeping swine cool. Reasons range from sun protection to parasite removal to temperature regulation. In April 2011, Researcher Marc Bracke of the Netherland’s Wageningen University and Research Center shared great insight after conducting a study for the Journal of Applied Animal Behavior Science. Bracke wrote: “Pigs have few sweat glands, high body fat and a barrel-shaped torso that stores heat. Wallowing can lower a pig's temperature by 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit, making it more efficient than sweating would be even if pigs had lots of sweat glands. A mud bath is more cooling than a dip in cold water because the water in mud evaporates off the pig's coated body more slowly, allowing the animal to reap the cooling benefits of evaporation for longer. But even in cool weather, pigs still wallow, suggesting that the magic of mud doesn't just lie in thermal regulation, Some wild pigs seem to use mud baths to scrape off parasites such as ticks and lice; they may also rub their scent glands around wallowing areas, possibly as a way of territory marking.” So there you have it, the secret behind “porcine mud bliss!” Now what does this have to do with Mount Olivet? Well I was recently triggered by a few tidbits picked up while researching the cemetery. First off, William T. Duvall (1813-1886), Mount Olivet’s first superintendent, actually raised hogs in a pen on the premises. I also stumbled across a few old prominent Frederick families having names that could be stretched to relate to swine terms, but certainly that is where the connections end. Mount Olivet has three graves associated with the Pigman family who were originally buried in the All Saints’ Church burying ground (once located downtown off E. All Saints Street). Meanwhile, the cemetery boasts 10 members of a family having the last name of Hogg. Both surnames were fairly new to me, however I recalled the latter from childhood with the fictional character of Jefferson Davis “J.D.” Hogg. Known more commonly as “Boss Hogg,” this was the unscrupulous county commissioner from the legendary Dukes of Hazzard television show. Tom Kohlhepp, an industry colleague and history lover, recently alerted me to one of the Hogg family being another unsung, and forgotten, individual buried within Mount Olivet’s gates. This was John K. Hogg, whose noteworthy achievement came in 1870, when he successfully registered U. S. Trademark No. 9 with the United States Trademark and Patent Office. That’s right, this was the 9th trademark in US history—and ironically Hogg’s entry was for soap. For quick review, a trademark is defined as a recognizable sign, design or expression which identifies products or services of a particular source from those of others. The trademark owner can be an individual, business organization, or any legal entity. A trademark may be located on a package, a label, a voucher, or on the product itself. We are surrounded by registered trademarks ranging from names/logos pertaining to soft drinks, candy bars, professional sports teams, car manufacturers, sneakers, and household cleaning agents. John Kunkel Hogg was born in Frederick on October 11, 1848. He was the son of Samuel Robinson Hogg, Sr., a native of Delaware who had come to town after living in Elkton (MD) in the 1830’s and opened his own business as a tallow chandler, a dealer in household items such as candles, wax, oil, soap, and paint. John’s mother was Mr. Hogg’s second wife, Barbara Ann Kunkel. Many of the Kunkels are also here in Mount Olivet, and of particular note are John’s grandfather John Kunkel II and uncles John B. Kunkel and Jacob Kunkel, a US congressman. These three gentlemen were onetime owners of the Catoctin Furnace (mid-19th century), and specialized in the production of what else—“pig iron.” John K. Hogg and brothers James and Samuel R. Hogg, Jr. learned and worked the family business with their father, who opened a small manufactory adjacent their home on the north side of East Patrick Street, near the intersection with Carroll Street. The home and lot once extended through to Church Street and boasted a two-story stone dwelling and a plentiful fruit orchard. Samuel Hogg purchased the property at auction in 1837. I have not claimed the exact address but strongly deduct that the Hogg home and store was located in the vicinity of the parking lot for downtown Frederick’s US Post Office, and along Chapel Alley.  A view looking north up Carroll Street and showing the old Frederick News-Post/Trolley Freight Terminal building (right) and the intersection with E. Patrick Street. The author believes the potential Samuel R. Hogg household to be at the NE corner of this intersection with the actual house immediately to the right of the trolley car pictured Samuel R. Hogg, Sr. was quite active in Frederick’s business and civic community. He was the father of 10 children, and said to have been an outspoken Unionist during the American Civil War. Hogg’s Soap was the chief product his small industry, and would be carried by merchants in other cities, including Baltimore. Mr. Hogg died in April 1868 at the age of 68, and was buried in Mount Olivet at a well-attended funeral by his many friends and neighbors. Ads began appearing one month later in the local Frederick Examiner newspaper announcing the fact that sons John K. and James Hogg would be carrying on the business their father had meticulously crafted over the balance of his life. One year later, the firm of J.K. Hogg and Bro. announced improvements to their store and works, and boasted a wide variety of soaps that could only be gotten by customers in larger cities. One year later, John would register for his trademark. In the meantime, John and James amicably dissolved their partnership, and John made a solo effort of it, apparently with help from kid brother Samuel R. Jr. In early 1870, an auction was held to sell off the old homestead and manufactory. The family appears together in the 1870 census, but soon they would depart Frederick, heading east to Baltimore and eventually bringing the family soap business with them.

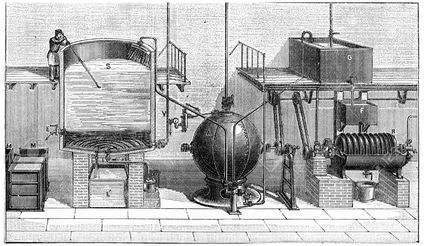

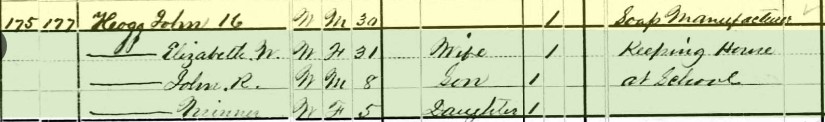

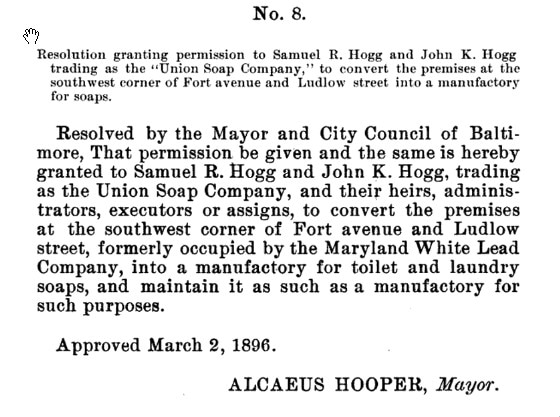

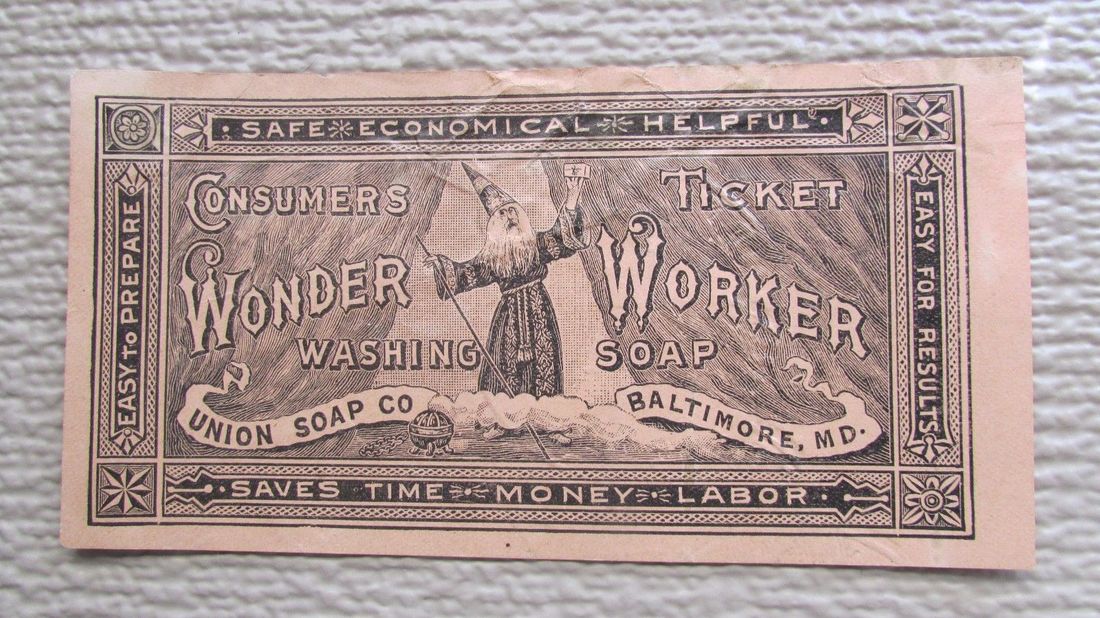

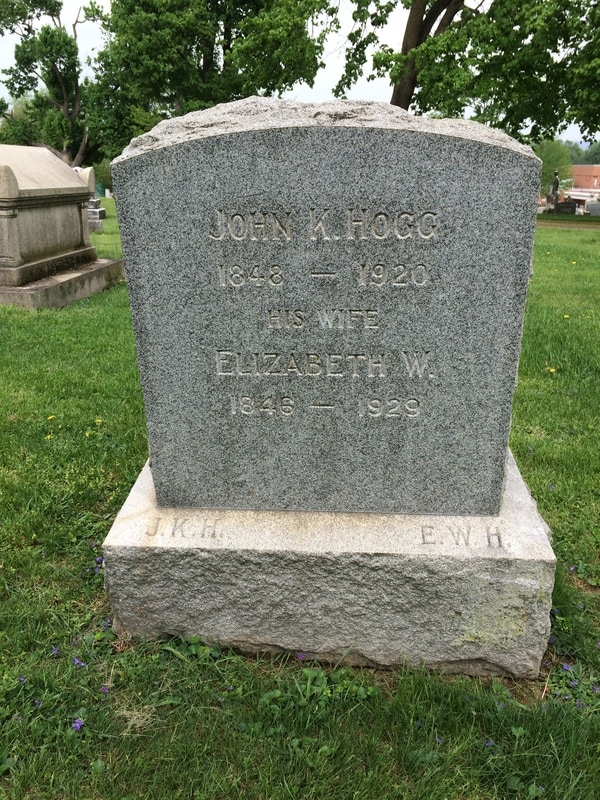

I wasn’t able to glean much of John K. Hogg’s personal life other than his marriage in 1870 to Elizabeth Wilson Myers (1846-1929), the daughter of German immigrants. The couple can be found living with John’s mother, Barbara, in Frederick in 1870 as newlyweds. A son, John Robert, would be born to them in October, 1871. By 1873, they had moved to Baltimore and were residing and working at 38 N. Paca Street, a few blocks south of the famed Lexington Market. John K. and teamed up with his brothers again to operate a grocery store under the name of J. Hogg and Bro. They also were manufacturing Diamond Yeast Powder. Today, this location is encompassed by the campus of the University of Maryland, Baltimore.  A daughter Minna would join the family in 1875. They appear to have moved around quite a bit, living in the downtown/west Baltimore area of the city at locations such as Mosher, Stricker and Arlington streets. Back to business, John and Samuel would start a soap-making firm under the name of the S. R. H and Co. in the Calverton section of town. Perhaps they did this to honor their father. The Brothers Hogg eventually changed this moniker to the Union Soap Company and advertisements appear in newspapers throughout the 1880’s and 1890’s. I don’t know what became of their production of Star Soap, as I have found another firm, under the ownership of the Schultz family, producing Star Soap out of Zanesville, Ohio in the 1880’s. The Schultz brothers would continue until 1903, when the Proctor & Gamble Company would purchase the endeavor and move it to Cincinnati, a city once known as “Porkopolis” because it was the one-time center of hog packing for the country. Proctor and Gamble were the makers of Ivorine Soap, which they smartly renamed Ivory Soap. In 1896, the Hogg brothers petitioned the Baltimore City Mayor and City Council for permission to convert the former Locust Point neighborhood property of the Maryland White Lead Company (located near Fort McHenry on the southwest corner of Fort Ave and Ludwell Street) into a manufactory for toilet and laundry soaps.  1875 illustration depicting soap-making in isolation, extraction with glycerin. 1875 illustration depicting soap-making in isolation, extraction with glycerin. I was curious as to what the soap production process consisted of—first having to explore the makeup of soap itself. Here’s what I missed while daydreaming in high school chemistry class (courtesy of Wikipedia): In chemistry, a soap is a salt of a fatty acid. Household uses for soaps include washing, bathing, and other types of housekeeping, where soaps act as surfactants, emulsifying oils to enable them to be carried away by water. In industry they are also used in textile spinning and are important components of some lubricants. Metal soaps are also included in modern artists' oil paints formulations as a rheology modifier. Soaps for cleaning are obtained by treating vegetable or animal oils and fats with a strong base, such as sodium hydroxide or potassium hydroxide in an aqueous solution. Fats and oils are composed of triglycerides; three molecules of fatty acids attach to a single molecule of glycerol. The alkaline solution, which is often called lye (although the term "lye soap" refers almost exclusively to soaps made with sodium hydroxide), induces saponification. In this reaction, the triglyceride fats first hydrolyze into free fatty acids, and then the latter combine with the alkali to form crude soap: an amalgam of various soap salts, excess fat or alkali, water, and liberated glycerol (glycerin). The glycerin, a useful byproduct, can remain in the soap product as a softening agent, or be isolated for other uses.

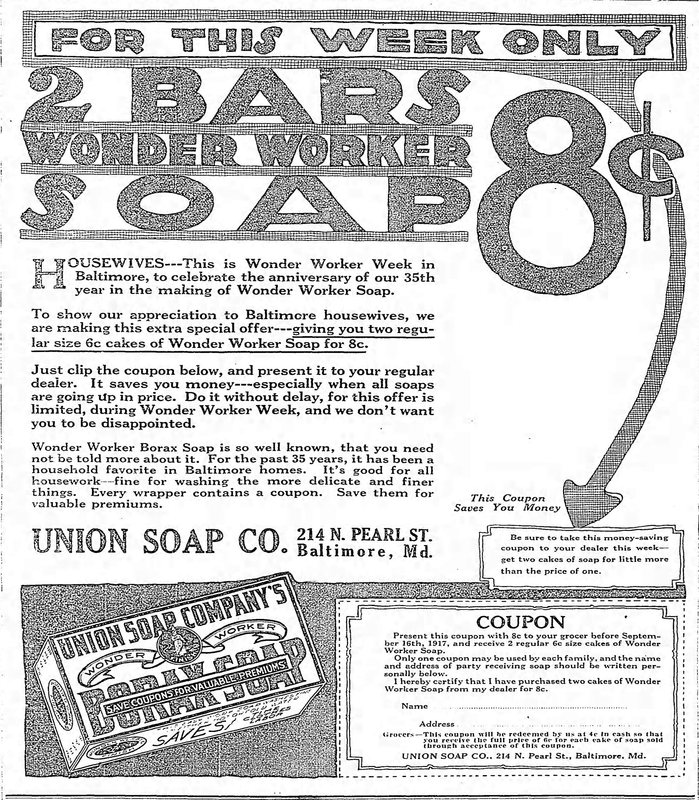

Into the 1900’s, the soap works would move back into downtown with locations on Arch Street and later Pearl Street. Newspaper and advertising cards can be found “barking” another signature product entitled “Wonder Worker Washing Soap.” The last citing I found of one of the company’s ads was in 1917.

3 Comments

Resurrection Sunday is Christianity’s most important day. Whether called Pascha in Greek (and Latin) or Easter, as its most commonly known in the western world, this is a festival and holiday celebrating the resurrection of Jesus from the dead as described in the New Testament. It is said to have occurred three days following Jesus "passion" and death by crucifixion at the hands of Roman soldiers. The place was Calvary, located immediately outside Jerusalem’s walls (c. 30 AD). In popular culture, Easter is connected to eggs, rabbits and candy. The custom of the “Easter egg” supposedly began with pagan rituals and festivals celebrating spring, and rebirth. Eggs were a key symbol of the latter (rebirth) and were given as gifts, oftentimes decorated. Another theory recalls a practice in Mesopotamia, where early Christians stained eggs red in memory of the blood of Christ, shed at his crucifixion. As such, the Easter egg is thought to be a symbol of the empty tomb for Christians.

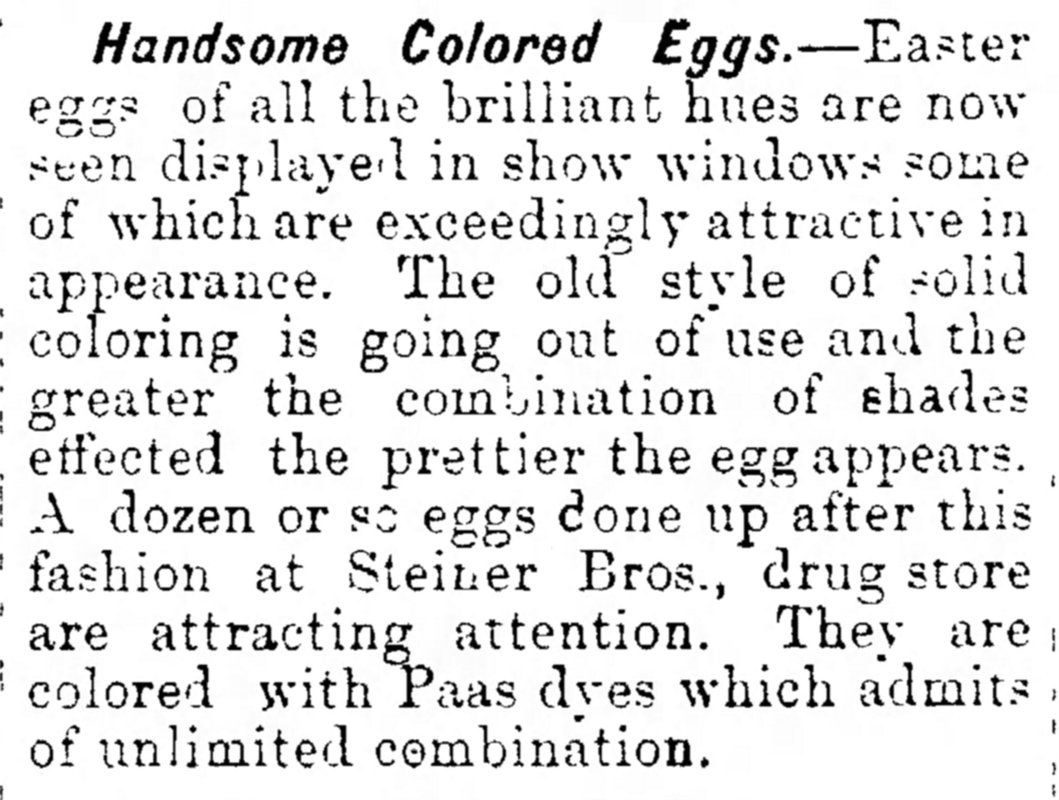

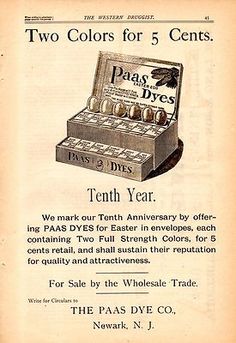

William M. Townley was the owner of a drug store in Newark, New Jersey, where he concocted recipes for home products. A holiday favorite was egg-coloring dye solutions, very popular this time of year, especially with German customers. One day, in 1879, Townley apparently ruined his shirt and marble counter while “spooning-out" dye for a customer. He immediately went to work on packaging a powder form of the dye to avoid further accidents to himself and customers at the point of purchase. Townley eventually figured out how to concentrate dye in tablet form, and the modern Easter egg dyeing kit was born. The original price of each tablet was five cents, and customers could make the dye by combining the tablets with water and vinegar. Townley eventually renamed his business the Paas Dye —the word borrowed from Pasen, another Dutch name for Easter.  I myself partook in coloring many an egg in my youth, and when my sons were smaller. I certainly think everyone should experience this “rite of passage,” not so much mixing dyes, but more so carefully balancing hard-boiled eggs on that crazy, wire dipper that came with the kit…but I digress. Over time, evolution has given us an egg substitute in modern times where real eggs have been replaced by artificial representations made from chocolate, or plastic—the latter filled with candy such as jellybeans, Hershey Kisses, or M&M’s. Back to the Easter Bunny, he is a folkloric figure and symbol of the Christian holiday, depicted as a rabbit bringing Easter eggs. Originating among German Lutherans, “the "Easter Hare" originally played the role of a judge, evaluating whether children were good or disobedient in behavior at the start of the season of Eastertide.” In legend, the creature carries colored eggs in his basket, candy, and sometimes also toys to the homes of children who were faithful and obedient during the 40-day Lenten period leading up to Easter Sunday. Apparently, the custom dates back to 1682, but I still haven’t figured out why the Bunny is depicted as wearing clothes. Truth be told, the symbolism of the rabbit has something to do with spring and fertility but that is taking me way off tangent for the aim of this article!  Depiction of Gamaliel addressing the Jewish Sanhedrin. Depiction of Gamaliel addressing the Jewish Sanhedrin. While brainstorming for an appropriate Holy Week-themed subject for “Stories in Stone,” I searched Mount Olivet’s database looking for any interred persons having the last name of Easter. While finding none, I did find 11 with the surname of Easterday. Of these, one jumped out to me—Gamaliel Easterday. I had never seen this first name before, so I immediately went in search of its origin. Gamaliel was a first-century Jewish rabbi and a leader in the Sanhedrin. He is mentioned a couple of times in Scripture as a famous and well-respected teacher and indirectly had a profound effect on the early church. Gamaliel was a Pharisee and a grandson of the famous Rabbi Hillel. Like his grandfather, Gamaliel was known for taking a rather lenient view of Old Testament law in contrast to contemporaries who held to a more stringent understanding of Jewish traditions. The first biblical reference to Gamaliel is found in Acts 5. The scene is a meeting of the Sanhedrin, where John and Peter are standing trial. The Sanhedrin was the equivalent of the Supreme Court of ancient Israel, comprised of 70 men and the high priest. This group met in the Temple of Jerusalem. After having warned the apostles to cease preaching in the name of Jesus, the Jewish council becomes infuriated when Simon Peter defiantly replies, “We must obey God rather than human beings!” (Acts 5:29). Peter’s statement enrages the council, who begin to seek the death penalty for both of these men. Into the fray steps Gamaliel, “who was honored by all the people” (Acts 5:34). Gamaliel first orders the apostles to be removed from the room, then encourages the council to be cautious in dealing with Jesus’ followers: “In the present case I advise you: Leave these men alone! Let them go! For if their purpose or activity is of human origin, it will fail. But if it is from God, you will not be able to stop these men; you will only find yourselves fighting against God” (Acts 5:38–39). The Sanhedrin is persuaded by Gamaliel’s words (verse 40).  Gamaliel, hailed as "the greatest teacher of his day" with students Gamaliel, hailed as "the greatest teacher of his day" with students Later rabbis praised Gamaliel for his knowledge, but he may be better known for his most famous pupil—another Pharisee named Saul of Tarsus (Acts 22:3). We know him better as the apostle Paul. It was under the tutelage of Rabbi Gamaliel that Paul developed an expert knowledge of the Hebrew Scriptures. Paul’s educational and professional credentials allowed him to preach in the synagogues wherever he traveled, and his grasp of Old Testament history and law aided his presentation of Jesus Christ as the One who had fulfilled the Law (Matthew 5:17). Later rabbis praised Gamaliel for his knowledge, but he may be better known for his most famous pupil—another Pharisee named Saul of Tarsus (Acts 22:3). We know him better as the apostle Paul. It was under the tutelage of Rabbi Gamaliel that Paul developed an expert knowledge of the Hebrew Scriptures. Paul’s educational and professional credentials allowed him to preach in the synagogues wherever he traveled, and his grasp of Old Testament history and law aided his presentation of Jesus Christ as the One who had fulfilled the Law (Matthew 5:17). So in conclusion, if you were to hold the name of Gamaliel, you should exude the qualities of wisdom and prudence. My hope was to find these same qualities in Gamaliel Easterday of Frederick County, Maryland. As for other “Gamaliels” of note, they are few and far between. I was surprised to find that one of our past presidents of the United States possessed Gamaliel for his middle name. I will save the answer for later in the article, but I’m sure you will agree that it doesn’t help prove my sought after “wise and prudent” hypothesis.

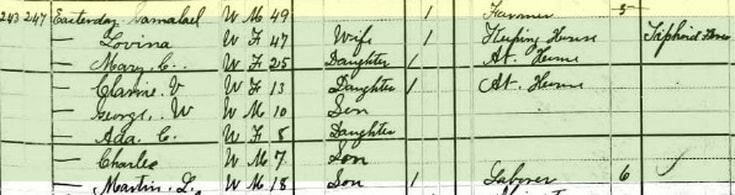

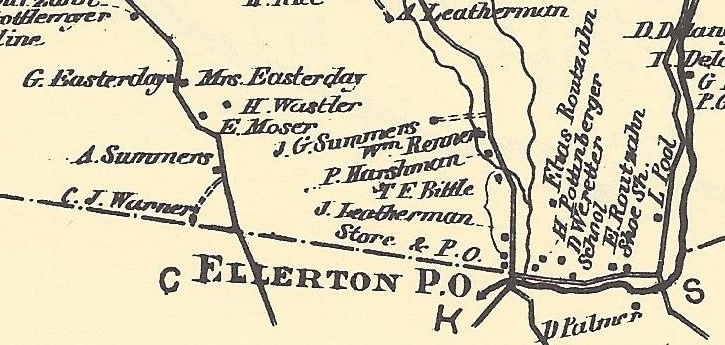

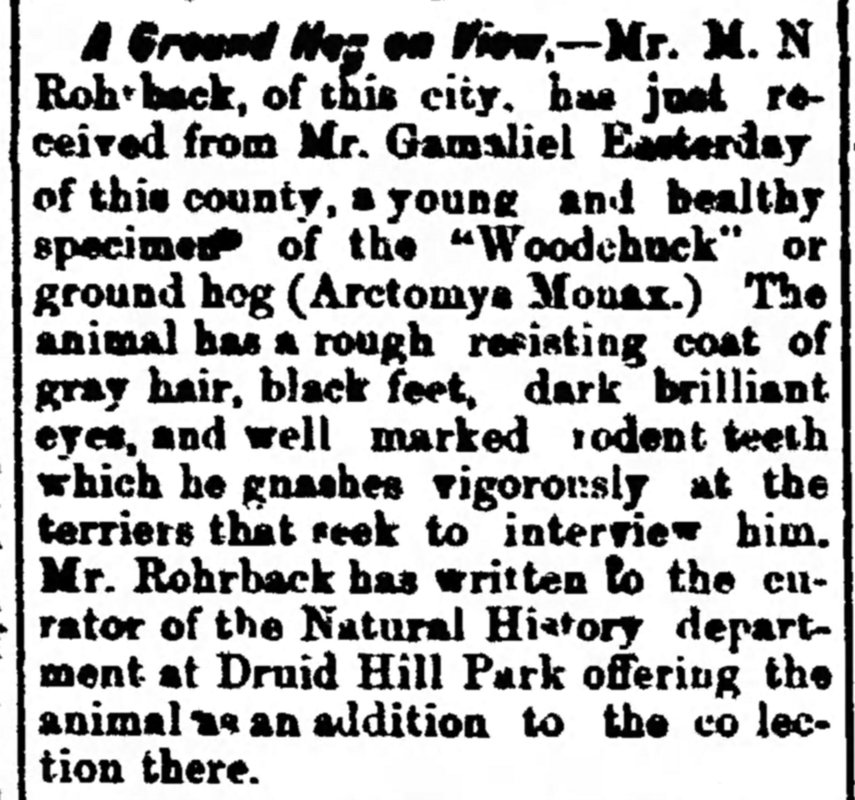

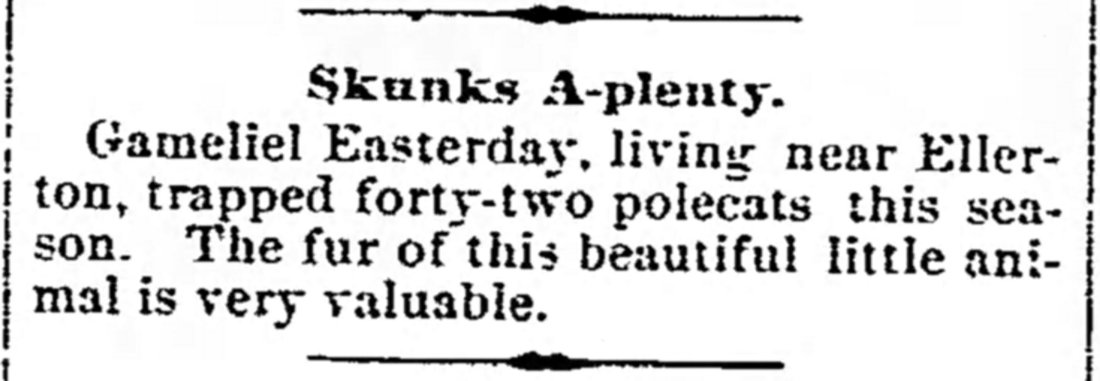

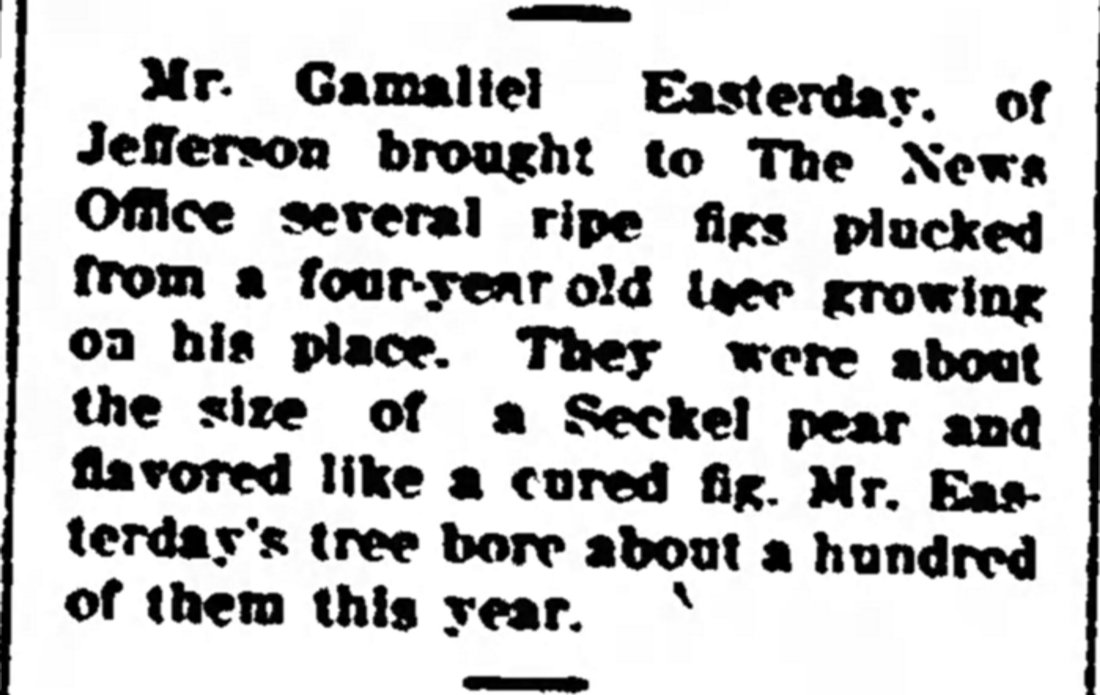

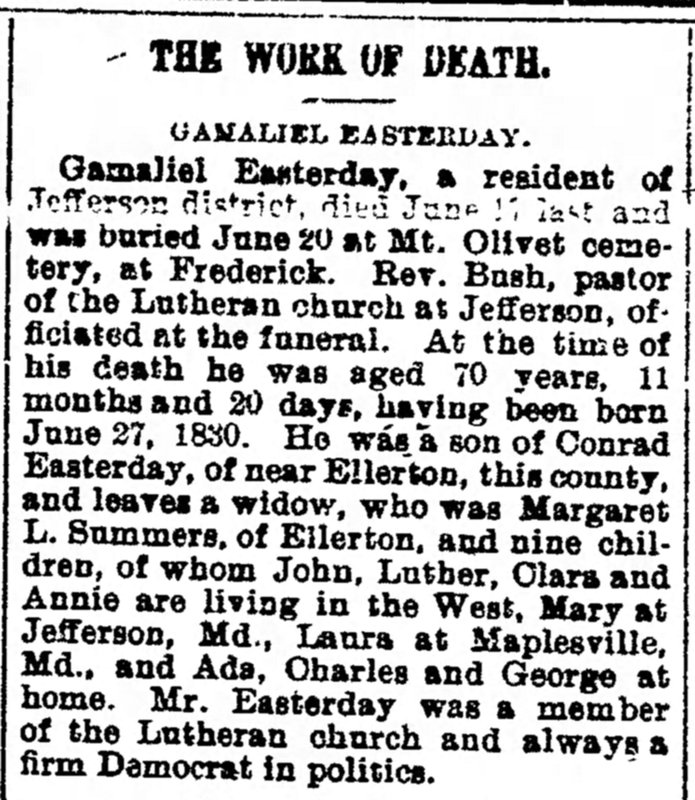

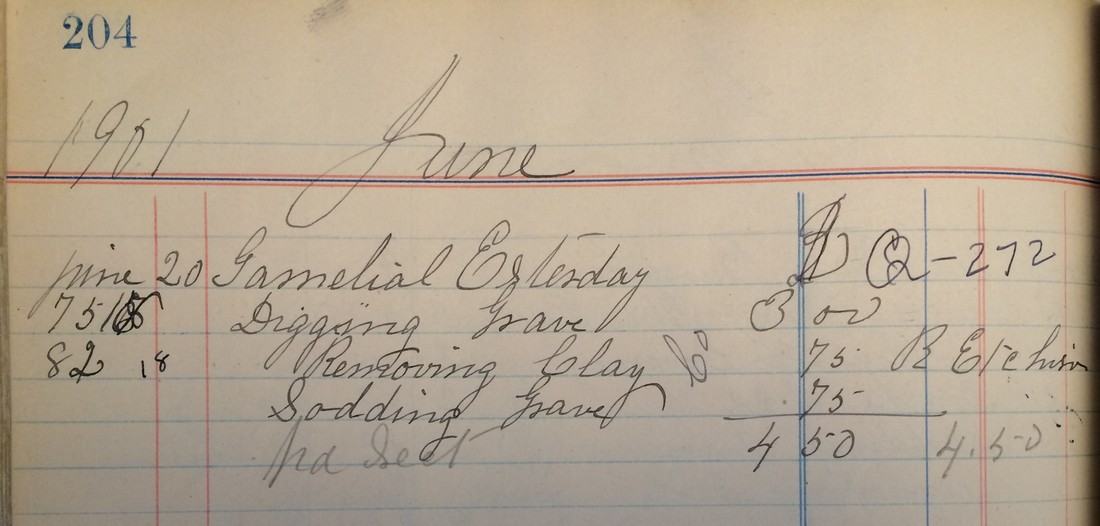

Although hailing from Saxony, within the Kingdom of Prussia, I would assume that the Ostertags who settled in Frederick County were not of the Jewish faith tradition. Gamaliel Easterday’s great- grandfather was Christian Ostertag (1730-1805), the first of his family to make his way to the Americas. He arrived in Philadelphia in 1749 having traveled across the Atlantic Ocean aboard a ship named “Christian.” First settling in the area of York (PA), Christian Ostertag would eventually come to Frederick County and established himself as a farmer and innkeeper near what is today Jefferson, Maryland. The Easterday ancestral farmstead still stands atop Steiner’s Hill, roughly a mile and a half west of Jefferson in the area where MD 180 crosses Catoctin Creek. Also making his home in Frederick County was a supposed brother to Christian named Martin Ostertag. Martin landed in Philadelphia in 1765, and would die by 1785. Last, but not least, many may be familiar with the story of Michael Ostertag, a former Hessian soldier who landed in New York in 1778 as a member of the Ansbach Regiment in the service of the British. He left the regiment at Yorktown and also made his way to Frederick County, moving to the Boonsboro area of Washington County, Maryland, where he died in 1837. Today’s Easterday Road and Ostertag Vistas, located near Myersville, are attributed to Michael’s descendants.  Rebecca (Raymer) Easterday (1801-1886) Rebecca (Raymer) Easterday (1801-1886) Gamaliel’s father and grandfather were both farmers, devout Christians, residents of the Middletown Valley and held the first name of Conrad. Ironically, Gamaliel’s roots would have additional ties to faith and religion as his paternal grandmother, Barbara Blessing had married Conrad Easterday. It seems as no surprise that Gamaliel would take up the wise and prudent occupation as farmer. His father died when he was twelve, leaving his mother to raise eight children on the family farm northeast of Myersville in Ellerton. Gamaliel was a member of St. John’s Lutheran Church in Ellerton, also known as “the Stone Church” and the namesake for Church Hill. This place of worship is a lineal descendant of the first church in Middletown Valley, once located at nearby Jerusalem, a few short miles to the west. St. John’s cemetery serves as the site of his parent’s burials. Gamaliel likely attended the nearby Church Hill School and married a local girl, Margaret Lavinia Summers, in 1851. Gamaliel and Margaret would have 9 children, all raised into adulthood on the Church Hill farmstead (located off Church Hill Road, just northwest of Ellerton). He would relocate around 1893 to another farm located about two miles east of Jefferson, on the north side of Jefferson Pike (MD180) at the eastern foot of Catoctin Mountain. Unfortunately I couldn’t glean much from archival resources. In 1879, Gamaliel made an unsuccessful bid to the government for running mail between Middletown and Ellerton. I found only a few local newspaper articles on him. The earliest in 1885 talked about him presenting a groundhog to a Mr. Rohrback in Frederick with hopes that it would become part of a museum collection at Druid Hill Park. Next, an 1890 clipping talks of a fascination with skunks. Finally, another article recounts him bringing figs (from his fig tree) into the Frederick Daily News office in Frederick (1894). Outside of that, I understand that half of his children moved westward, perhaps because of the skunks?

Warren Gamaliel Harding Warren Gamaliel Harding As for the US president who sported the middle name of Gamaliel? It was none other than our 29th president—Warren G. Harding (1865-1923). He usually is thought of as being among our worst president, but it has nothing to do with his unique middle name I’m sure. Harding died while in office, and was quite beloved at the time. However, after his death posthumous stories started emerging regarding scandals involving cabinet members, mistresses and even a bastard child fathered by William G. On the bright side, I’m pleased to close with this uplifting and appropriate little factoid as President Harding actually reinstituted a White House tradition started by predecessor Rutherford B. Hayes in 1878, but postponed for a few years due to World War I. March 28, 1921

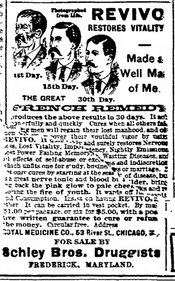

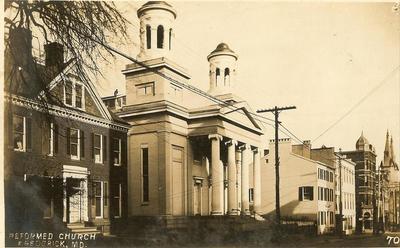

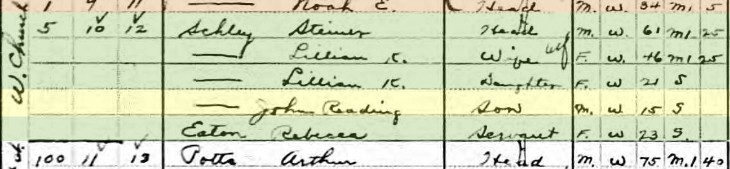

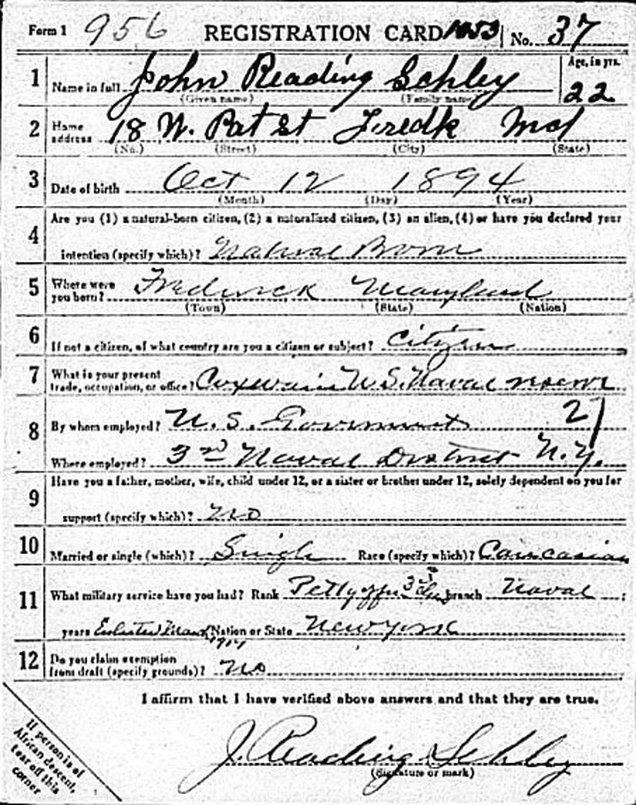

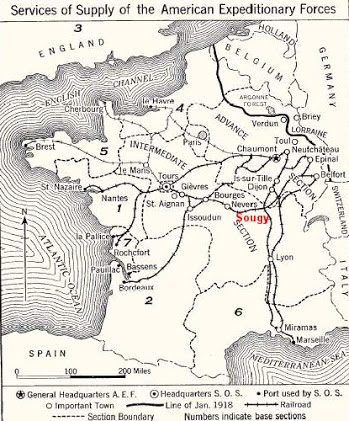

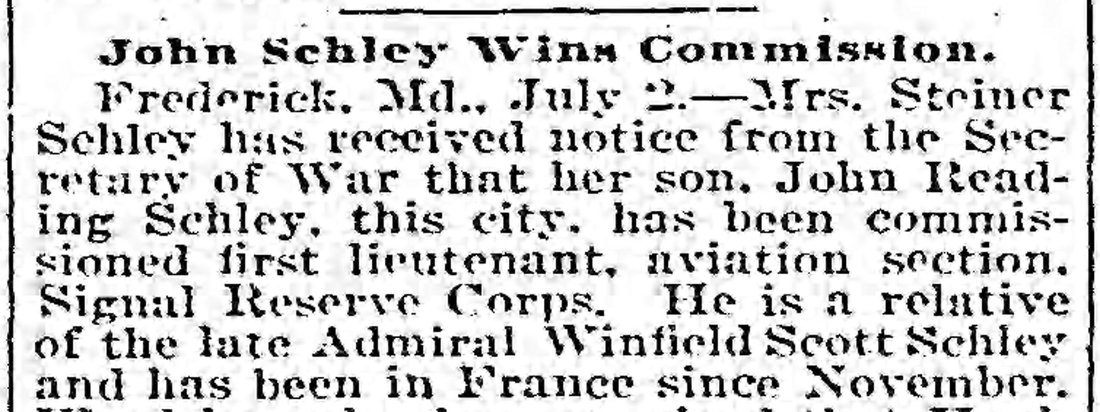

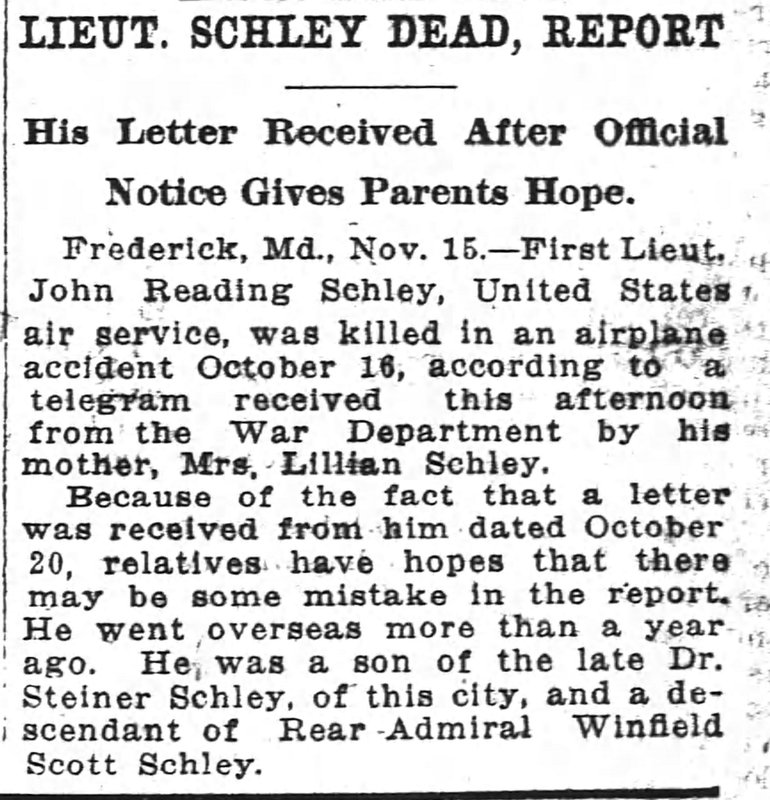

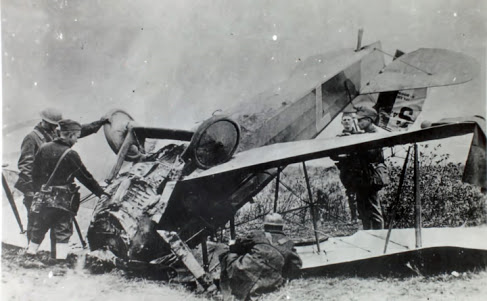

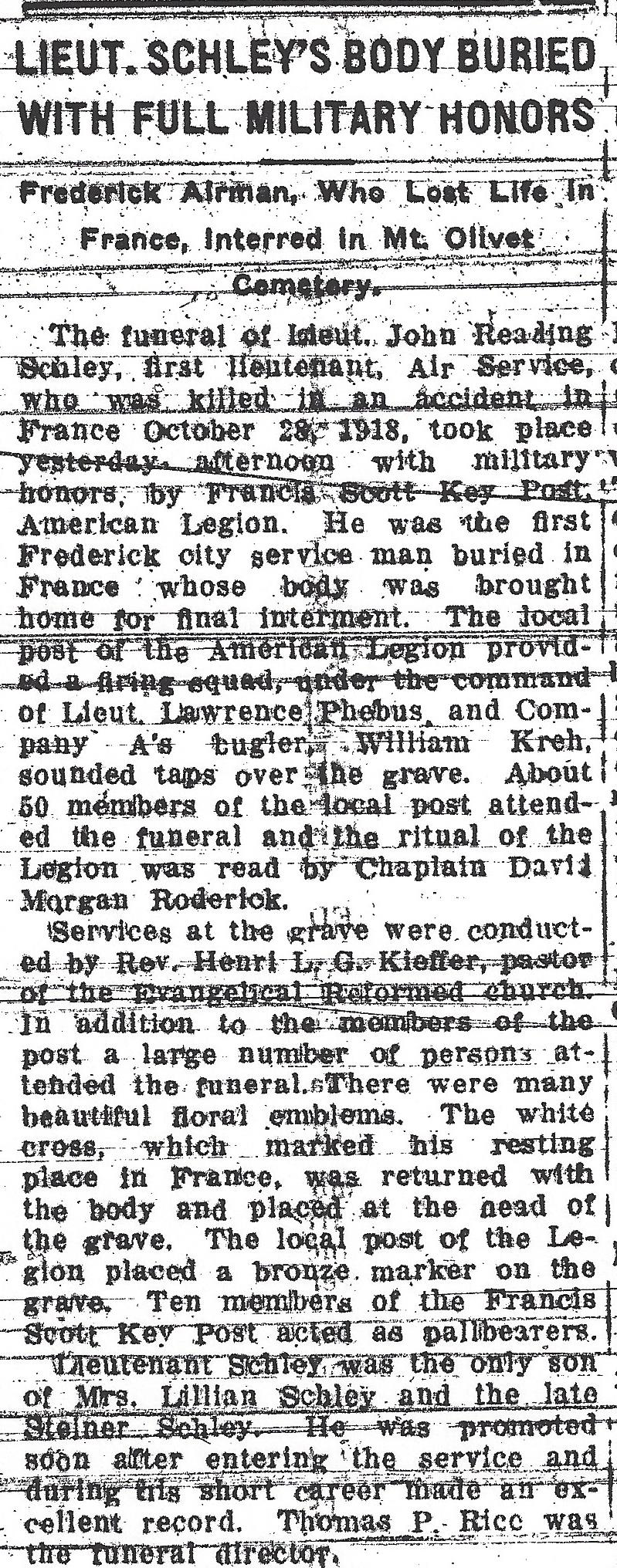

The White House Easter Egg Roll was held for the first time since 1916; between 50,000 and 60,000 children attended. President Warren G. Harding, First Lady Florence Harding and presidential pet Laddie Boy, an Airedale terrier, were on hand, along with characters from the childrens’ play “Alice and the White Rabbit,” then currently appearing in Washington. “Frohe Ostern!” (Happy Easter in German...of course) Frederick, Maryland has always taken great pride in its rich German roots. The area north of Frederick City is commonly known to genealogists and historians as the Upper German settlement. Frederick itself was named after a German prince from the House of Hanover. This was likely done as a “marketing ploy” to attract hard-working, frugal and God-fearing people—ones who soon showed that they were willing to escape the hardships of their homeland, for the opportunity to make a new life in the “New World.” Many of the earliest inhabitants of today’s Frederick County would come via Pennsylvania’s recently established Dutch country (Hanover, York, Lancaster areas). This first occurred in the mid 1700’s. Frederick Town, itself, was laid out in 1745 as a planned community on the western frontier of the Maryland colony. Founder Daniel Dulany sent circulars advertising the many benefits of settling here. These went to Germany (then a confederation of states) itself, and, naturally, had distribution and testimonials targeting those who had already migrated to William Penn’s colony. Two of the earliest German families to settle in Frederick were the Schleys and the Steiners. Both fill the local history books as pillars of the community through a multitude of endeavors, particularly civic leadership and the field of medicine. John Thomas Schley is reputed to have built Frederick Town’s first house, had the first native-born child and became the first schoolmaster (affiliated with the German Reformed church). Meanwhile, Jacob Steiner (Stoner) constructed the legendary Mill Pond house north of the town (proper) and built/operated the first principal inn at the southwest corner of the Square Corner (intersection of Market and Patrick streets).  Frederick Town Herald (October 1, 1814) Frederick Town Herald (October 1, 1814) In addition to being savvy business people, these two families are also known for their patriotic contributions. There was participation in the American Revolution. The grandsons of Jacob Steiner were Frederick's respective leaders of local militia units in the War of 1812: Stephen Steiner (infantry) and Henry Steiner (artillery). Both participated in the "Star-Spangled" defense of Baltimore. Henry’s grandson, Dr. Lewis H. Steiner, made a name for himself through his leadership of relief efforts put forth by the United States Sanitary Commission. He rose quickly through the ranks of the commission to become Chief Inspector for the Army of the Potomac.  Rear Admiral Winfield Scott Schley (1839-1911) Rear Admiral Winfield Scott Schley (1839-1911) Admiral Winfield Scott Schley was the GGG-grandson of John Thomas Schley, and enjoyed a much-decorated career in the United States Navy. After graduation from the Academy in Annapolis, he served during the Civil War. His greatest moment came more than three decades later in Santiago, Cuba during the Spanish-American War. Here, Schley commanded Admiral George Dewey’s flagship “the Brooklyn.” Ahead of the main squadron, “the Brooklyn” trapped the entirety of the Spanish fleet with Santiago Harbor, meanwhile exposing itself to a monstrous barrage of fire. Schley’s US comrades used this opportunity to successfully destroy the entire Spanish Fleet. This resulted in the cutting off of valuable aid and support to Spanish land troops who were currently doing battle with Teddy Roosevelt and his Roughriders.  Newspaper advertisement for Schley Bros. Druggists from Frederick News (April 10th, 1895) Newspaper advertisement for Schley Bros. Druggists from Frederick News (April 10th, 1895) Both families (Steiner and Schley) collided in 1847 with the wedding between local druggist Dr. Fairfax Schley and Anna Rebecca Steiner. The couple had four children—the oldest would be named Steiner Schley. Steiner Schley (1849-1911) would learn the trade of pharmacist and continued his father's successful drugstore business in town. He also tinkered in other endeavors, including his tenure as a longtime Board of Visitors member of the Maryland School for the Deaf, and is credited with building the Monocacy Valley Railroad, a four-mile track that connected the Western Maryland Railroad’s main line with Catoctin Furnace. He also served in the boards of the Central National Bank and the Mutual Fire & Insurance Company. Although Dr. Steiner Schley missed serving in active military duty over his lifetime, his son John would eagerly enlist in America’s first conflict against Germany—the country from which his Schley and Steiner ancestors hailed. This was certainly a conflicted time for some local residents boasting Dutch heritage, while others would recount the reason their families had originally left Germany, be it in the 1700’s or 1800’s. John Reading Schley holds the distinction of becoming the first Frederick Countian to become a military pilot. He joined the US Army air service in World War I, just 14 years after the Wright brothers had made their legendary first-powered flight of 1903. Born in Frederick City on October 12th, 1894, John Reading Schley was the son of Lillian F. (Kunkel) Schley-daughter of one-time Catoctin Furnace owner John Baker Kunkel. Through the Kunkels, young John could trace lineage to namesake John Reading, one of the Colonial-era governors of New Jersey and among the founders of Princeton University. Somehow along the way, John Reading earned the nickname of “Slip.”  The Steiner Schley family lived at 5 W. Church St, located immediately to the right of Evangelical Reformed Church The Steiner Schley family lived at 5 W. Church St, located immediately to the right of Evangelical Reformed Church As a boy, John Reading Schley became a member of Evangelical Reformed Church of Frederick, formerly known simply as German Reformed. The family lived directly next door to the east at 5 W. Church Street. John spent several summer vacations at a YMCA camp on Lake George, New York and conducted by one of the leading secretaries of the organization. Early education was attained at the Frederick Academy (Frederick College), from which Schley graduated in 1912 at the head of the class. He was known as a hard-working student and expert debater. Schley's father passed away at the age of 61 in 1911 after a six-month fight with pancreatic cancer. This prompted his mother to move with 17-year-old John and sister Lillian. They sold their fine townhouse and took up residence a block south in an apartment located at 18 W. Patrick Street. John eventually completed his preparatory course at Mercersburg (PA) Academy in 1915. Described as “strong, and well built,” he excelled in athletic sports, while being highly popular with classmates. Above all, his associates said “he was high-minded and honorable.” In the autumn of 1915, "Slip" Schley entered Lehigh University, expecting to take a four year-course track in electro-metallurgy. He soon was initiated into Sigma Phi fraternity. At the end of his freshman year, trouble with his eyes caused him to postpone studies, taking up work in one of the foundries in South Bethlehem, PA. One year later, he found another calling as the US Congress voted to enter what was then the largest, and bloodiest, war in history on April 6th, 1917.  John Reading Schley went to a recruiter’s office on April 12th (1917) and enlisted in the New York Naval Reserves as a coxswain on a submarine chaser. He apparently became weary waiting to be placed on active duty. At his request, he was transferred to the Aviation Signal Corps Service at Fort Myer, VA, on August 18th, 1917. From here, Schley was then sent to the United States School of Aeronautics at the Georgia Institute of Technology. He received his diploma as “flying cadet” from the Atlanta-based institution on October 19th, 1917. One week later, John Reading Schley was sent to France to be trained to fly. This was the war that boasted the early flying aces, using single seat biplanes such as France’s Nieuport models and Britain’s Sopwith Camel. This was also the era of the immortal Manfred von Richthofen, known more commonly as “the Red Baron.”

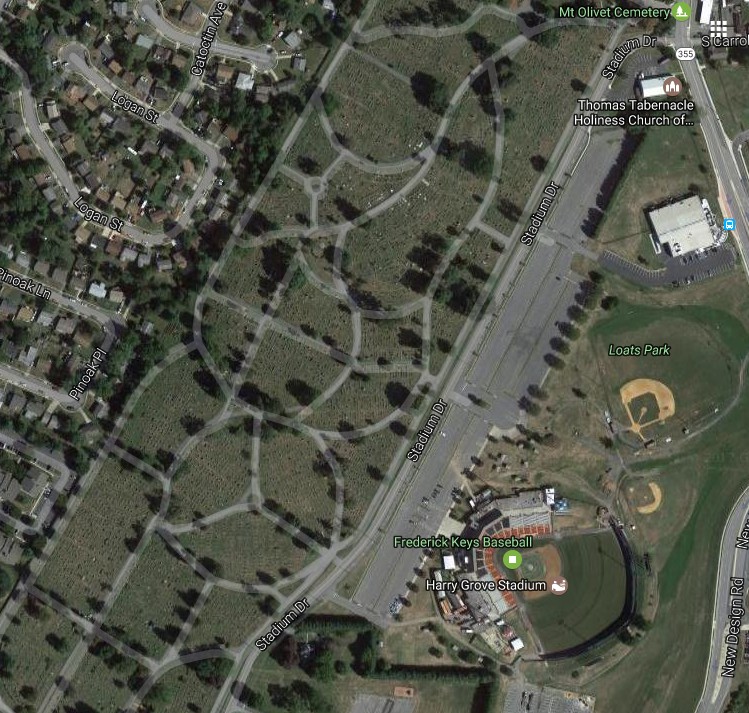

In mid-October (1918), Schley was granted leave to be spent on the Mediterranean in the luxurious French Riviera (southeast part of the country). He had been ill, and this furlough was thought to help him make a full recovery. Upon his return, he hastily resumed advanced training flights at Issoudun. He wrote a letter home on October 20th to his mother and sister. In hindsight, it is thought that he may not have been well-enough to resume the rigorous training schedule. Unfortunately, Schley would never get his chance to make the history books with wartime gallantry like so many of his ancestors. He would lose his life on a cross-country flight that commenced on October 22nd, 1918, 20 days before the war’s end. Lt. Schley was only 24 years old. A fellow-cadet, who originally befriended John Reading Schley at Mercersburg, wrote a letter home to friends of the Schley family. This gave further information to a scant and misleading telegram that reached Frederick and Schley's mother and sister with news of his death. The classmate's letter stated that “He (Schley) died a mighty clean and noble death. He was on his advanced training and was doing well, but on a cross-country flight something went wrong and he fell from a great height.” Military records report that Schley actually suffered a heart attack and lost control of his airplane on that fateful day. He was said to have drifted for a while, before hitting the ground. The young aviator was found unconscious and immediately taken to a hospital. He died and was buried in a military temporary cemetery on the grounds of the 3rd Aviation Center at Issoudun. Two years later, his body would be dis-interred and sent back home to his hometown of Frederick for reburial. Accompanying his remains, was the “military issue” marble cross that had marked his original gravesite. John Reading Schley would be laid to rest in Mount Olivet on November 20th, 1920 with full military honors. He holds the distinction of being the first military pilot from Frederick County. He is also the first Frederick serviceman buried in France whose body was brought home for final interment. Meanwhile, many of his Issoudun comrades were moved to the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery (France). For a number of years afterwards his grave would be decorated by the American Legion Auxiliary on Armistice Day (November 11). Across the Atlantic Ocean and "Over There," a monument was erected in the 1920’s near the Issoudun base, bearing the names of 171 Americans who died at the U.S. training facility during the war. Between 1917 and 1919, some 7,500 Americans were stationed at the 3rd Aviation Instruction Center of the United States—which included seven camps, 11 landing fields, and two field hospitals. Many of the fatalities resulted from flight training accidents. American participation in “the Great War” lasted only a year and a half, but in that time, an astounding 117,000 American soldiers were killed and 202,000 wounded. By the time of the Armistice, 766 pursuit pilots had completed their training at Issoudun, of whom 139 were retained as testers, staff pilots and instructors. The remaining 627 were sent to the Zone of Advance. 171 Americans died here in training accidents.

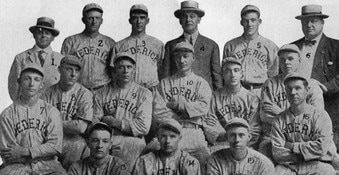

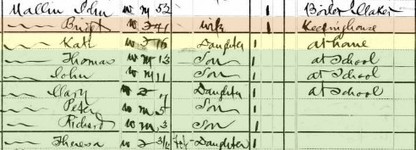

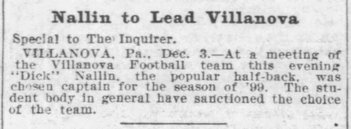

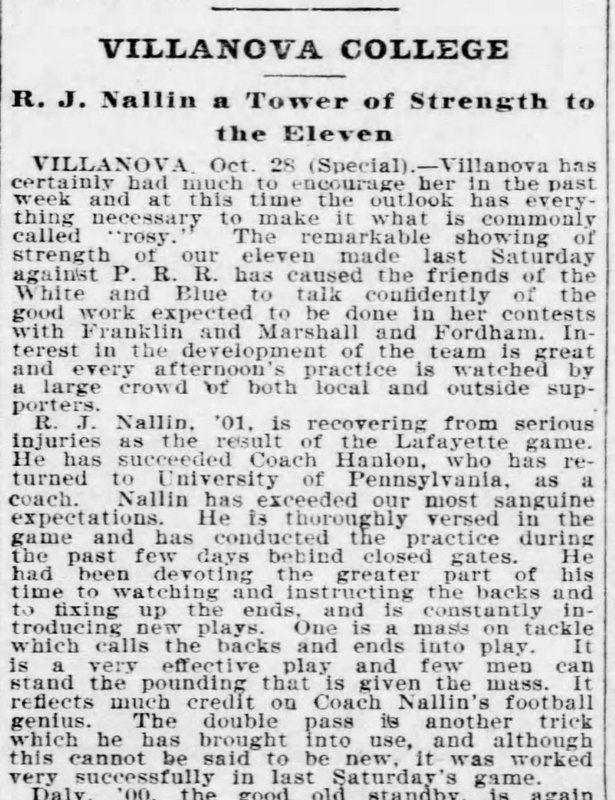

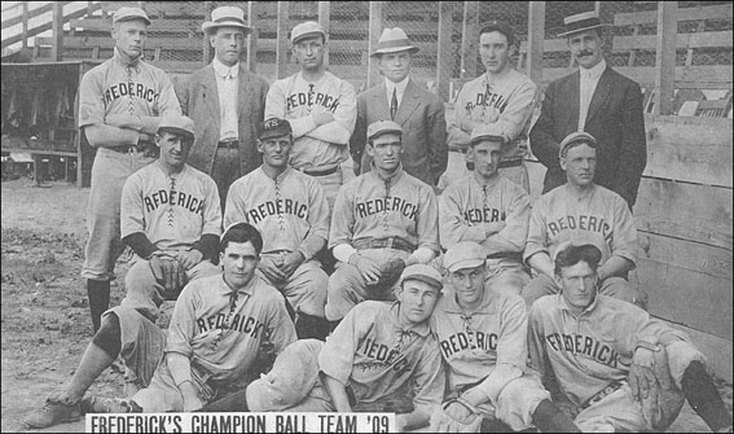

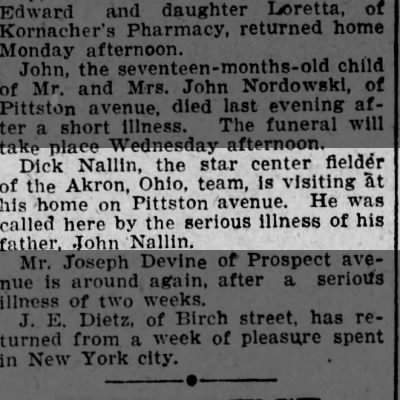

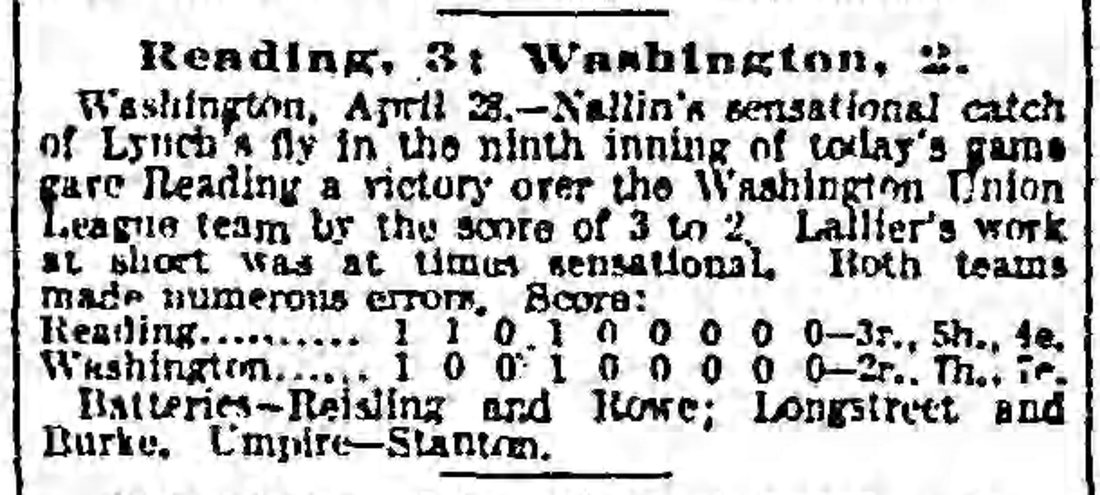

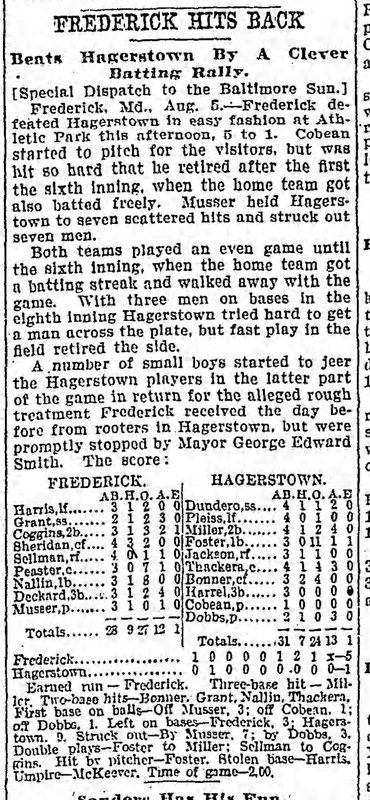

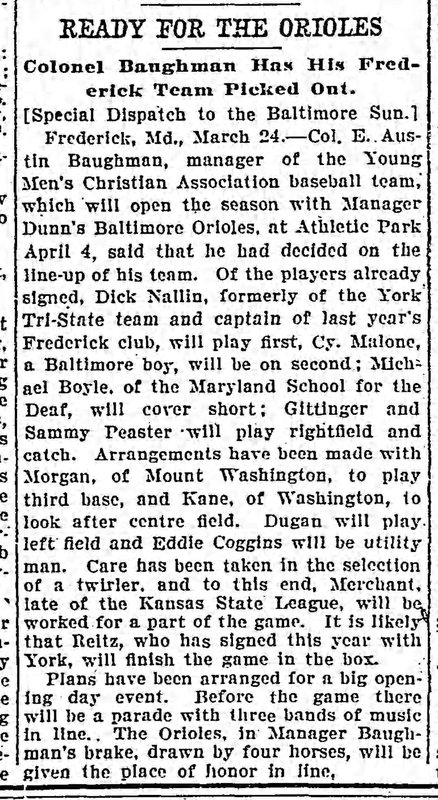

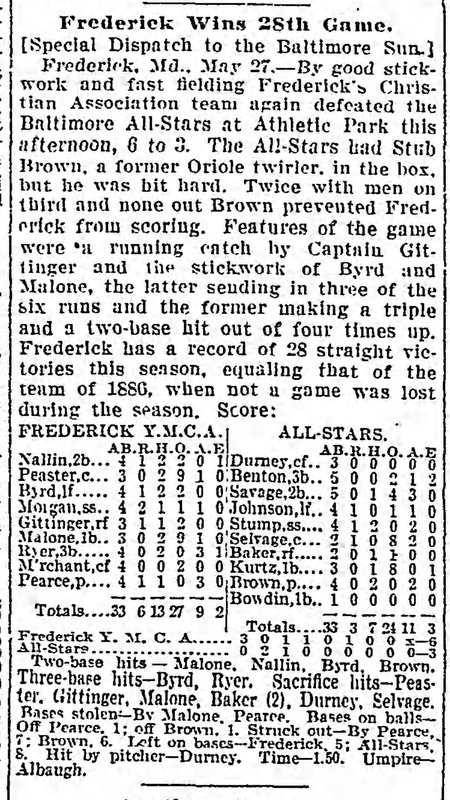

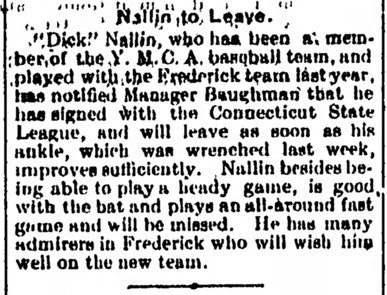

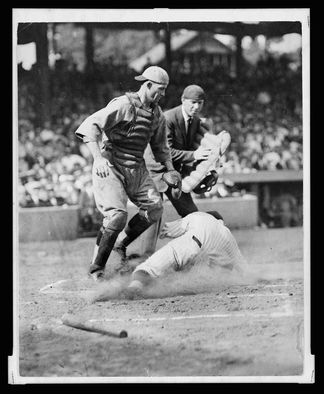

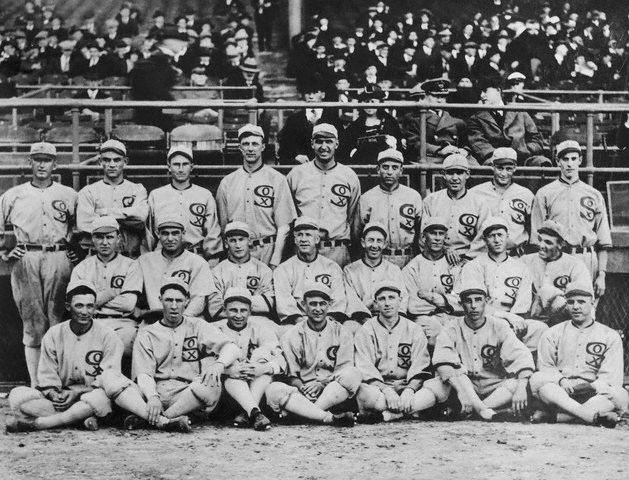

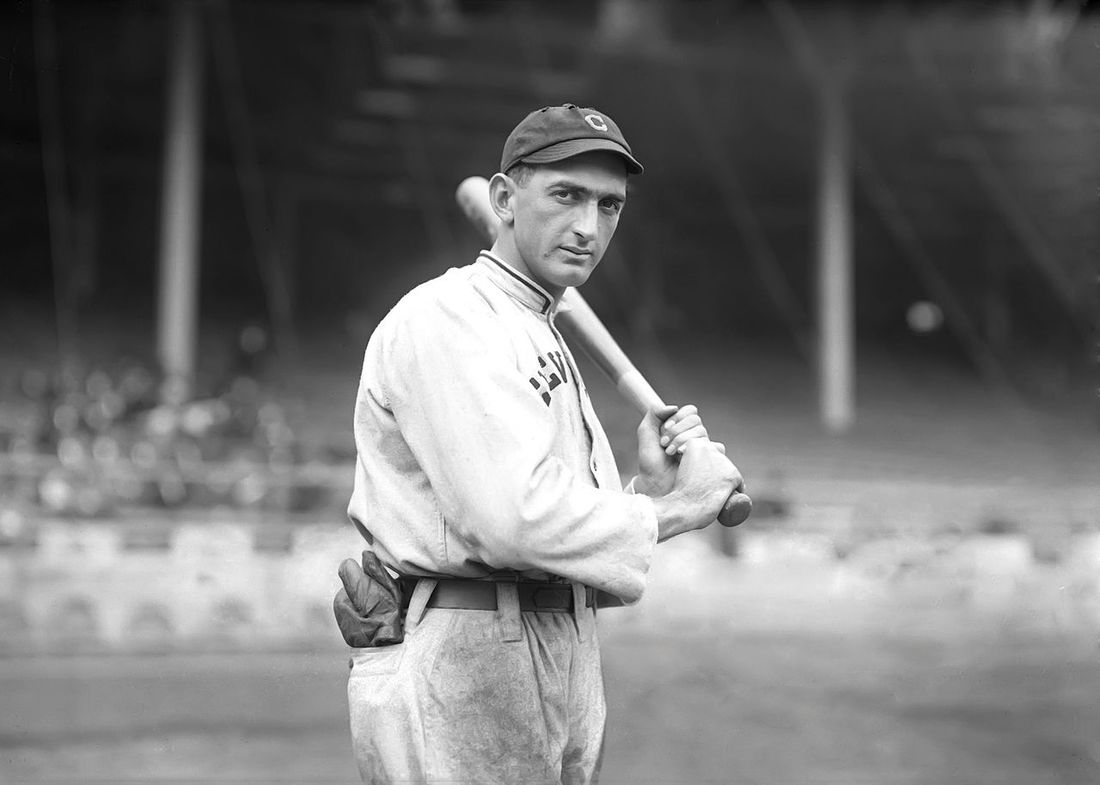

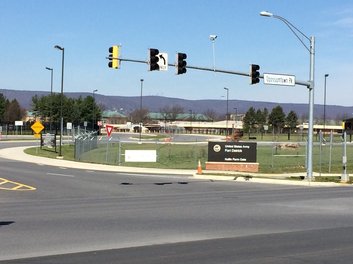

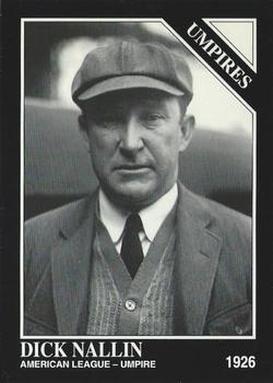

Mount Olivet Cemetery has true connections to "America's Pastime," baseball. Of course, the historic burial ground is the final resting place of Francis Scott Key—the guy who gave us “The Star-Spangled Banner.” This song is typically sung, or played, before baseball games of all levels, ranging from professional to little league. Along those same lines, the 160+year cemetery is located just next door to Nymeo Field at Harry Grove Stadium, home of the minor league Frederick Keys—so named for our fore-mentioned interred resident and patriotic hero of the War of 1812. Since the opening of Harry Grove Stadium in 1990, I’ve always thought that the national anthem being sung here is extra special, solely due to the fact that it is within earshot of the author. What other sporting venue can make this boast?  1915 Frederick Hustlers, the area's first professional baseball team 1915 Frederick Hustlers, the area's first professional baseball team Baseball is an incredible game, and one with deep roots here in Frederick going back to the 19th century. The town had a semi-professional ball team in the Sunset League dating to 1907. This league lasted until 1911. Three years later, another semi-pro collective would be formed, including teams from Frederick, Hagerstown and Martinsburg (WV). This was known as the aptly named Tri-City League. Plans would soon be underway to form a professional baseball league featuring these three teams, and three additional clubs (Chambersburg (PA), Gettysburg (PA) and Hanover (PA)) needed to gain official recognition by the National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues. Thus, in 1915, the Blue Ridge League was born. I could write more on the subject but will leave that to two experts I know: Mark Ziegler (www.blueridgeleague.com); and Robert P. Savitt, whose book is entitled The Blue Ridge League (Arcadia Publishing 2011). I will, however, take time to introduce readers to another one of the many ties between Mount Olivet and professional baseball.  1880 US Census showing John Nallin family in Scranton, PA 1880 US Census showing John Nallin family in Scranton, PA Although a player in his younger days, one gentleman interred in Mount Olivet claimed fame by calling balls and strikes behind the plate. In today’s Frederick, his last name is better known as an entryway and historic farm, than for his years spent on baseball diamonds and many personal acquaintances with “hall of fame” legends. February 26th, 1878 marks the birth date of Richard Francis Nallin, better known by his nickname “Dick.” He was one of seven children born to Irish immigrants John J. Nallin and wife Bridget McHale. Dick’s parents had immigrated to America in 1852, and soon after settled in Scranton, PA at the time of its incorporation in 1856. John J. Nallin served as the town’s first marshal, and worked most of his life as a boilermaker. Dick grew up in a house on Scranton’s Pittston Avenue, but increasingly seemed to be spending more time at the sandlots of town as years went by. He was an athletic standout in both football and baseball. Nallin first attended St. Michael’s College in Toronto, Canada and played first base for the college team. This would be short-lived as he transferred to his home state’s Villanova College where he played both football and baseball. The youngster especially made a name for himself in football, where he would play right halfback for the gridiron team.  Philadelphia Inquirer (Dec. 4, 1898) Philadelphia Inquirer (Dec. 4, 1898) Nallin quickly became a favorite of his teammates, as well as fans and classmates. This led to being named “team captain” for his junior season (1899). Unfortunately, Dick suffered a major injury in mid- October of that year in a game against Hill School in Pottstown (PA). The injury opened another door for the young man from Scranton. He would serve as a game referee the next week. The Villanova squad suffered another blow the following week with the sudden departure of their team manager to the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia). Now Dick Nallin found himself serving as coach of the football team, a role that lasted for the remainder of the season. Dick left college in 1900, having been offered a professional baseball contract. He would pitch and play first base for Harrisburg (PA) of the Tri-State League. This would commence a ten-year career in the minors which brought him to a variety of places: Southside Philadelphia, Norristown (PA), Minooka/Scranton (PA), Akron (OH), Youngstown (OH), Reading (PA), York (PA), and Frederick (MD). Dick played for Frederick in 1909. He performed admirably as first baseman plus served as team captain. In 1910, Nallin found himself on a highly competitive Frederick Y.M.C.A. independent team. This unit, managed by Col. E. Austin Baughman, opened its season on April 4, 1910 with an exhibition game against the Baltimore Orioles of the Eastern League. Col. Baughman’s team shut out the Orioles 2-0 at Frederick’s Athletic Field in front of a crowd of nearly 3,000 fans. While here in Frederick, Dick Nallin met, and became close friends with, a local girl from a prominent family. This was debutante Miss Alice E. Houck, daughter of Mr. and Mrs. James Houck. Mr. Houck was a bank president and agriculturist. Alice lived with her parents on the family farm, just northeast of town on the Frederick-Woodsboro Pike (MD26) near the western bank of the Monocacy River. Miss Houck was a good athlete herself, having successfully participated in equestrian-related competitions. In May, 1910, Dick suffered an injury to his ankle and was sidelined. He would soon notify Manager Baughman that he was leaving Frederick, as he had been offered a contract to play with the Connecticut State League. Nallin left Frederick in early June and became an outfielder for the Bridgeport (CT) team. His career was in its twilight, as injuries and age had taken a toll. The 32-year-old would be released by the team two months later. But as he had learned earlier in college, as one door closed, a window of opportunity opened. Nallin now took his turn as an umpire, earning a paycheck from the Connecticut League.  Frederick News (Oct. 3, 1912) Frederick News (Oct. 3, 1912) Dick worked the entire 1911 season in Connecticut. One major highlight came near the season’s end with a game between Hartford and New Britain. The New Britain coach heartily contested Nallin’s call on a play at first, which resulted in the coach’s ejection. A disgruntled New Britain fan proceeded to throw a rock at the umpire, narrowly missing him. The former ball player was really making a name for himself, especially with his athleticism, knowledge and confidence in upholding the rules of the game. This led to a promotion to the International League (formerly the Eastern League) for the 1912 season. One game during this campaign featured Nallin having to umpire a game between Newark and Baltimore all by himself. At the conclusion of the 1912 season, Nallin married Alice Houck. The October wedding was followed with a honeymoon in Atlantic City. The couple took up residence in Toronto, where Dick had an interesting offseason job as stage manager for the Belleville Opera House. The International League work brought Dick back to Ontario and Maryland quite regularly. Within this eight-team collective were baseball clubs from Toronto and Baltimore (Orioles). Other cities represented were Montreal, Newark, Jersey City, Providence and Buffalo. Nallin excelled at his newfound position behind the plate. After two seasons in the International League, he received the promotion of a lifetime—he would gain employment with the American League. Dick would go on to officiate games in the majors for the next 16 years, calling balls and strikes for, and against, some of the greatest to ever play the game—Babe Ruth, Walter Johnson, Lou Gehrig, Tris Speaker and Ty Cobb. Nallin rated Cobb the greatest player that he had ever seen, and had the distinct honor of serving as home plate umpire for Cobb’s final game in 1928. Among Dick Nallin’s many accomplishments is the claim that it was his idea to add more than two umpires to each officiating crew. He was the first to hold the position of third base umpire, which came in a game in 1916. Dick also called three “no-hit” games from behind the plate. Two of these were in successive games in 1917. His greatest career highlights included being picked to umpire four different World Series Championships. These included: the 1923 Series between the New York Yankees and New York Giants, the 1927 Series between the New York Yankees and Pittsburgh Pirates and the 1931 Series with the Philadelphia Athletics vs. St. Louis Cardinals. The most notable was his first in 1919, between the Cincinnati Reds and the Chicago White Sox. This latter series goes down as the most controversial in major league history, as it is known more commonly as the “Black Sox Scandal.” During the 1919 World Series, members of the Chicago White Sox (of the American League) intentionally lost the series to make money off of the Cincinnati Reds win. The fix was put on by the White Sox first baseman Chick Gandil with the help of professional gambler Joseph "Sport" Sullivan and gangster Arnold Rothstein. The situation stemmed from payment disagreements between the members of the team and its owner, Charles Comiskey. The affair led to eight members of the White Sox team being banned from baseball for life. One of these was the legendary “Shoeless” Joe Jackson, made popular to later generations through two motion pictures from the 1990’s: Eight Men Out and Field of Dreams. Nallin maintained that he and his colleagues “had no suspicion whatsoever” of any sellout in the series between the teams. After the series controversy of 1919 died down, the American League’s prominence grew in part to the celebrity attained by Babe Ruth, and the team success of the New York Yankees. Apocryphal local stories say that Nallin was off-field friends with Ruth and hosted the hall of famer in Frederick on more than one occasion. Supposedly Dick took “the Bambino” to lavish parties at the Ross Mansion on Courthouse Square.  Former Nallin residence located at 102 E. Patrick St., Frederick, MD Former Nallin residence located at 102 E. Patrick St., Frederick, MD Once Dick got to the majors, the Nallins appear to have made their full-time residence in Frederick. They first resided at 102 E. Patrick Street. A later residence was 111 W. Second Street, a large townhouse the couple constructed after purchasing land from the adjacent Presbyterian Church. Dick and Alice would eventually acquire “Rich Levels” for their home. Located between Montonqua Avenue (old 7th Street) and Opossumtown Pike, many know this property today as the Nallin Farm, home to Fort Detrick’s “Caretaker’s House.” The former ballplayer turned umpire couldn’t suppress his urge for competition. He could now devote more time to an offseason hobby—show dogs. Dick and Alice had their own thoroughbred kennel for English setters. After the 1932 baseball season, Dick stepped back to the International league, where he umpired two final seasons. He called it quits in fall 1934 and retired to his 255-acre farm north of Frederick. Here, he took up his new role as full-time gentleman farmer, and engaged in raising Guernsey cattle. As Camp Detrick continued to blossom after World War II, the couple decided to move back in town. The Nallins sold “Rich Levels” to the United States Army in 1952 for $144,800. The picturesque property included their historic home, along with an adjacent bank barn and spring house. All three structures are on the National Register. Since the late 1950’s, commandants of Fort Detrick have resided in the former Nallin residence. Dick Nallin quietly lived out the last decade of his life in Frederick before passing away at Frederick Memorial Hospital on September 7th, 1956. He was 78. After a service at St. John’s Catholic Church, Dick Nallin was laid to rest in the Houck Family lot in Mount Olivet. The young man from Scranton did not have a lifetime career as an athlete. However, he made a solid living out of working alongside career athletes in a very important support role. He would be inducted into the local Frederick “Quinn Hall of Fame” in 1979. Dick’s Irish last name has received new-found recognition as it adorns a recently constructed entryway into the Fort Detrick military installation off Opossumtown Pike—known as the Nallin Farm Gate. In a way, it’s sort of fitting, as baseball umpires are gatekeepers, themselves, so to speak.

Regardless, just as its comforting to know that Francis Scott Key’s final resting place in Mount Olivet is within earshot of national anthem renditions sung next door at Frederick’s Grove Stadium, come springtime, Dick Nallin’s gravesite is no stranger to the beloved sounds of the ball diamond—the crack of the bat, the ball hitting the glove, the cheer of crowd, and best of all, the reverberating echo of an umpire yelling "Safe!" or ringing up a batter with the proverbial “Strike three, you’re out!” |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed