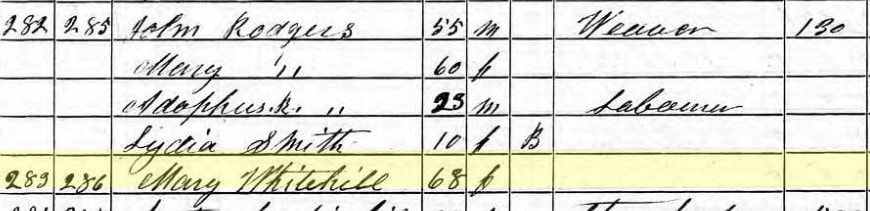

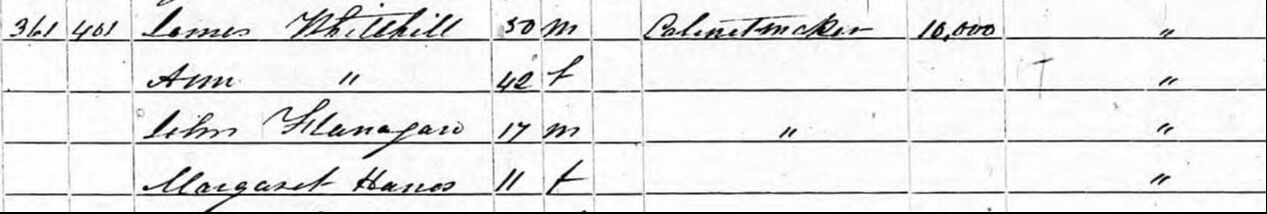

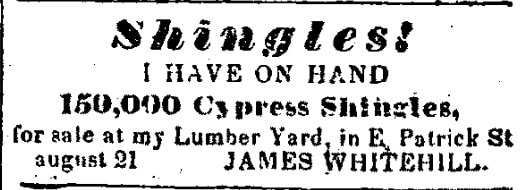

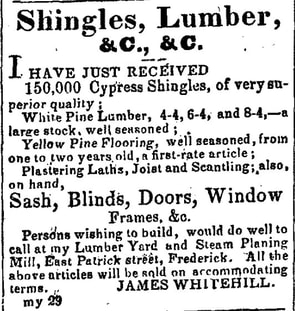

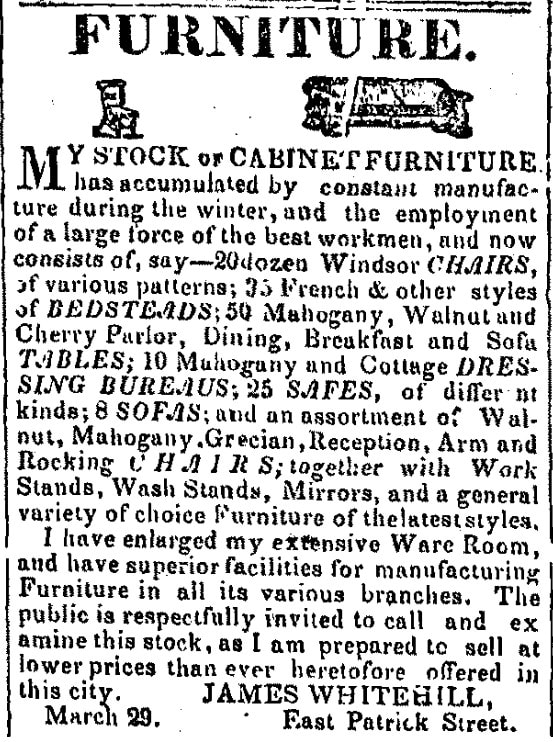

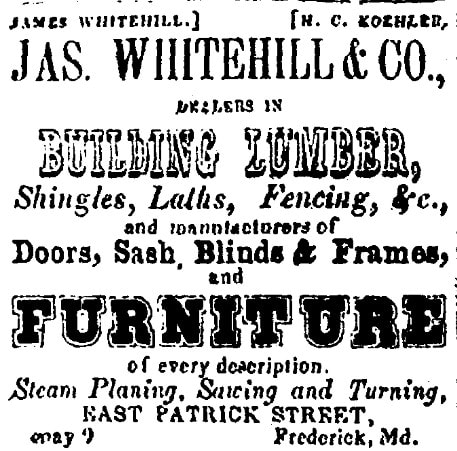

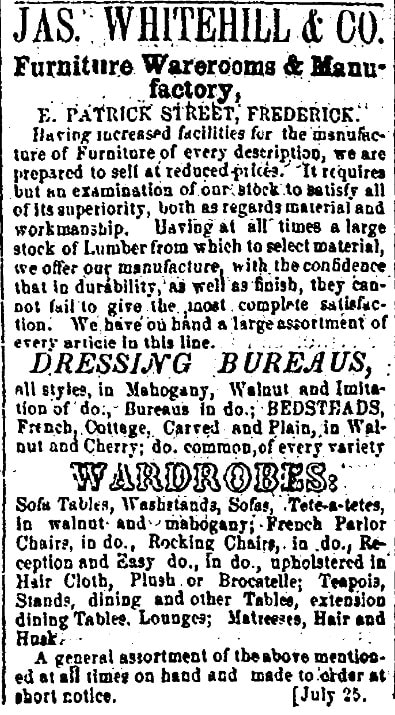

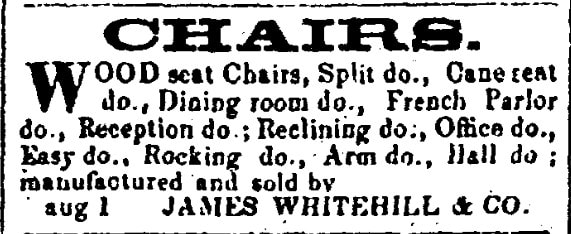

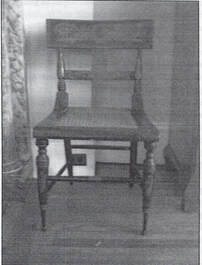

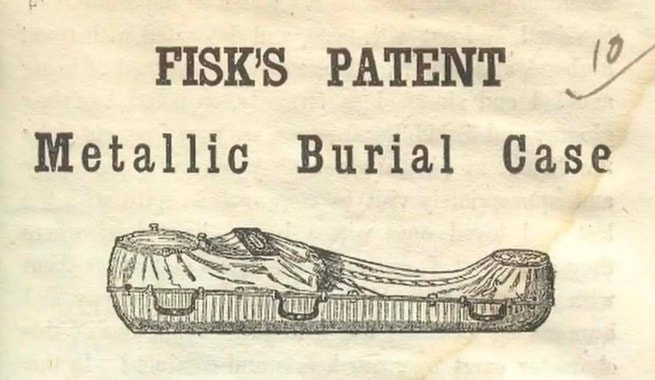

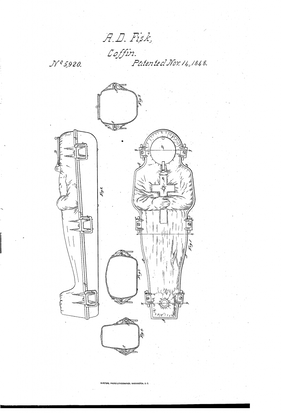

Halloween (a contraction of "All Hallows' evening") aka Allhalloween, is a celebration observed in many countries on October 31st, the eve of the Western Christian feast of All Hallows' Day. It begins the observance of Allhallowtide, the time in the liturgical year dedicated to remembering the dead, including saints (hallows), martyrs, and all the faithful departed. Well then, that completely explains the iconic symbols associated with the day (Halloween), at least in terms to pop culture. Fittingly, graveyards have played an important role in the real commemoration of the dead, obviously. But this also holds true in the commercially-based, candy and costume-riddled version because one could hypothetically find many iconic Halloween-oriented objects within a burial ground, or cemetery. Take ours for example. We have a few jack-o-lanterns, and I’m sure a random bat or two, but I am pleased to report that I have not encountered a ghost, witch, warlock, vampire or werewolf in my five years of working at Mount Olivet. However, I must confess that we are not short on tombstones, coffins, skeletons and skulls. Well, we are short on one of the latter, but I will get to that later. A friend, and former work colleague of mine, Ron Angleberger, and myself, have been conducting candlelight walking tours of Mount Olivet since 2013. The majority of these nocturnal sojourns have occurred in advance of Halloween, and for good reason. Ron certainly has more experience in the “macabre” tour game as he is the brains behind the popular Downtown Frederick Ghost Tours. I’m no slouch either, as I can certainly ”carry my water” as the historian and preservation manager of this historic garden cemetery and love conducting these tours as well. That said, we continue to both try our best to reverently “wow” visitors with the amazing history and stories of those buried here in Mount Olivet’s past. Over the years, the cavalcade of tour patrons has ranged from kids to teens, young couples to middle-agers up to seniors. This fall, I decided to step back from conducting the general public tour, allowing Ron to take the lead. I, instead, have concentrated on developing/delivering tours to our Friends of Mount Olivet membership group, not to mention students associated with Frederick Community College’s Institute for Learning in Retirement (ILR) program. One common stopping place, on all of these sojourns, has been a particular hillside gravesite in Area F. Lot 25 to be exact. It belongs to one of the cemetery’s founding members, while the site itself, represents only one of two built-in, ornamental crypt tombs in our cemetery. His story and final “resting” place has Halloween written all over it. The gravesite of James and Ann Whitehill is one to behold, even though it took on a more prominent air in olden days. Today, it just seems a bit more subdued in contrast to its former reputation as representing the prominent, strong-willed resident that it would hold for eternity. This has been the case for the past 15 years, dating back to some unfortunate events which occurred here in early 2005. More about that later, as I think I should start by telling you a bit about the “souls” encrypted here, but they were anything from poor!  Thanks to talented, professional photographer Van Corey, we have this photograph of the Whitehill crypt from 2003 Thanks to talented, professional photographer Van Corey, we have this photograph of the Whitehill crypt from 2003 The Whitehills Instead of re-inventing the wheel, I have gladly turned to an old friend of mine, Joyce Cooper, for expertise on our prime subject this week as she wrote a comprehensive biography on this gentleman and his family for the Fall 2002 edition of the Journal of the Historical Society of Frederick County, Maryland. Joyce relocated to Walton, Kentucky years ago with her family. Thanks to FaceBook, I have her secured as a friend, only a simple “Messenger” message away these days. I fondly recall the assistance, support and expertise received in my early research and documentary endeavors from the article’s author, Joyce Cooper, a former teacher and longtime staff member of the Historical Society. In respect to James Whitehill, she performed exhaustive research in an effort to glean more about this man because of his connection to many of the items residing in the Society’s archival and artifact collection. Whitehill was a prominent businessman in town and had his hand in all kinds of endeavors, the greatest of which was furniture making, primarily from a location that is very much known today by locals and visitors alike—the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. Joyce did an amazing job in capturing the vivid events of a difficult childhood for Mr. Whitehill caused by an abusive father. However haunted his early life seems, James seemed to keep his head on straight and would rise to become one of Frederick’s leading citizens in his adult life—a true testament to human resiliency. Sadly, he did not have much opportunity to reverse the cycle of fathering to his own son, as a lone child would die as an infant at six months of age. James C. Whitehill by Joyce C. Cooper James Whitehill’s ancestral roots were firmly anchored in the British Isles. While his maternal great-great-great grandparents emigrated from England, his paternal great-grandparents, James and Rachel Cresswell Whitehill, arrived in America from Renfrewshire, Scotland. They married in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, where they spent the rest of their lives. Their son David Whitehill, born May 24, 1743, married Rachel Clemson in Salisbury Township, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. The children born to David and Rachel exhibited the wanderlust typical of the period, most of them spreading into central and western Pennsylvania. Their son John, however, moved to Maryland where he married his fifteen year old first cousin, Mary Clemson, a daughter of John and Elizabeth Haines Clemson. Following their marriage in August of 1795, John and Mary set up housekeeping on a farm near Libertytown, Maryland, owned by Mary’s father. Mr. Clemson allowed them to live rent-free for two years, and provided them with “two horses, some other valuable stock, and household and kitchen furniture.” The young couple may have had a difficult time financially, for Mr. Clemson rented the farm to them for several more years at a “moderate rent much below the real value.” Three children were born to John and Mary Whitehill during their first five years of marriage, with three more surviving children being born by 1815. James Clemson Whitehill, their second child and first son, was born August 12th, 1798. Unfortunately, young James and his siblings must have known times of great unhappiness during their childhood years, based on evidence found in court records. A “Bill of Complaint of Mary Whitehill” addressed to “the Honorable Judges of Frederick County sitting as a court of Chancery,” dated April 20, 1815 and presented by John Clemson, Mary’s father and “next friend,” details a life of spousal abuse. Mary’s complaint paints a graphic picture of a hard-working woman struggling with a husband who “day after day...was rioting in taverns or wasting their mutual gains in the most criminal debauchery.” Somewhat balancing the aggrieved wife’s statement was the testimony of Leonard Six, taken October 16, 1818 by the court. The abstract of his testimony says that “Whitehill, when in a state of intoxication was a high tempered man, but not apt to get out of humor unless he is brought to it. That when sober, he was as good a tempered man and sociable neighbor as he would wish to live beside.” Good neighbor that he might have appeared to be to outsiders, John’s wife alleged that she had suffered John Whitehill’s abuse in silence for most of her nearly twenty years of marriage, hoping to “at least ward off his unkindness” by being a loving and good wife. Rather than showing her respect, if not love, he beat her severely and repeatedly. Finally, one April evening he threatened to kill her if she did not leave their home in one minute. Their oldest daughter, Rebecca, described to the court the horrible scene played out before the children: I was present at the time of the separation of John Whitehill and Mary Whitehill. He said if she did not go he would murder her. She begged for God’s sake that he would spare her life. That she wanted to live with her children. The more she begged, the more he swore. He said he had sworn the hardest oath that a man could swear. That she would go and would give her but one minute to clear herself or he would murder her. These threats were made in the house. Mary Whitehill was suddenly driven off without any clothing more than those she was wearing. A horse was brought for her to ride away on by order of John Whitehill who helped her on. ‘Twas near sunset. She went alone except having her infant child with her. Certain court records indicate that Mary returned to her father’s home. On March 9, 1826, over ten years after Mary’s initial bill of complaint, the court annulled John Whitehill’s parental control and gave Mary custody of her minor children. Hopefully, the court also ruled in Mary’s favor on her request that John Whitehill make “adequate and valuable provisions” for her financially. Her case was pressing, for her husband had “lately given out that he will speedily leave this state and go into some one of the Western states to reside,” a move that would endanger Mary’s claim and make it “difficult for the complainant to recover the same.” John Whitehill died in 1829, but Mary lived until March of 1862. At the time of the 1850 Federal Census, she lived in her own home near Libertytown a few doors from the homes of her brother John Clemson and her nephew Dennis Clemson. By the time Mary won her custody case, her two older daughters had married, and her son James had embarked on his career as a furniture maker. He announced his business in the December 14, 1822 issue of the Frederick Herald. James Whitehill Cabinet-Maker Respectfully informs his friends and the public generally, that he has commenced business in Liberty-Town, and is now prepared to execute any kind of work in his line, in the most fashionable and substantial manner, and on very accommodating terms. He also intends to keep on hand a Supply of furniture neatly finished, and by his diligence and industry hopes to be liberally patronised [sic] by the public Seven years later he announced the opening of his business on East Patrick Street in Frederick in the April 25, 1829 issue of the Frederick’s newspaper, The Examiner. Furniture The subscriber would notify the citizens of Frederick-town and county that he has removed to Frederick, and purposes carrying on the Cabinet and Chair Making Business extensively. His shop is in Patrick-street, nearly opposite the store of Mr. Stuart Gaither, where he can supply all kinds of furniture either of mahogany, walnut or cherry; also plain and elegant chairs. All orders promptly attended to, and the Work executed in the best manner. Two Journeymen Cabinet-makers who are sober, industrious, good workmen, will find immediate employment. James Whitehill His move to Frederick was not the only major change in James Whitehill’s life that transpired in 1829. On February 9, 1829 he married nineteen-year-old Ann Campbell, daughter of Bennett and Catherine Devilbiss Campbell. In addition to the Devilbiss family, Ann’s ancestral lines included such early Frederick families as the Barricks (Bergs), Herzogs, and Stulls. Just where the newlyweds lived is unknown, but the 1850 Census lists them on East Patrick Street, probably living over his shop. According to the 1850 census information, James owned some $10,000 in real estate. He had $3000 invested in the business, with an inventory of wood valued at $1200, hardware valued at $500, and finished furniture worth $500. The manufactory, employing seven men whose salaries totaled $175 monthly, relied on hand power. His household included James himself, his wife Ann, John Flanagan (age 17) and Margaret Hanes (age 11). John Flanagan may have been an employee, and Margaret Hanes was likely a relative of Ann Whitehill. No children are listed, for the only known child of the Whitehills, a son named James Campbell Whitehill, would not be born until 1852 and lived only six months. James Whitehill and his employees conducted several branches of business at the East Patrick Street location for nearly four decades. Foremost was the manufacture and sale of furniture and an associated activity—coffin making. In addition to coffins, Whitehill offered for sale the “Fisk Metallic Burial Case” with a rosewood finish in his January 9, 1856 advertisement in the Frederick Examiner. Whitehill’s third branch of business was selling lumber and other building materials. The Examiner of January 4, 1854 contains his advertisement for shingles, lathe and lumber. In March of 1856, a Maryland Union advertisement announced to the public that he had “just received 150,000 Cypress Shingles, of very superior quality” as well as lumber, lathe, sash, blinds, doors, windows, and frames. A detailed advertisement found in the Maryland Union newspaper ran for several weeks in the spring of 1856:

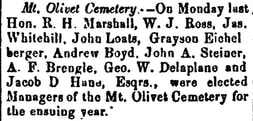

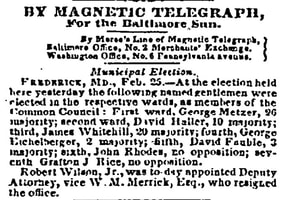

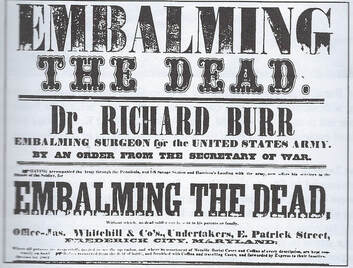

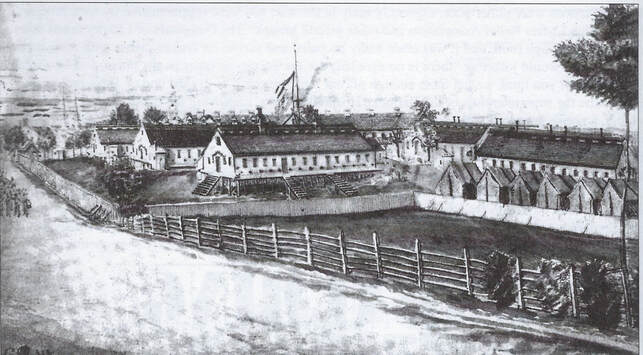

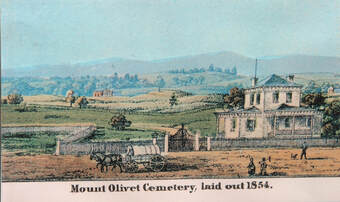

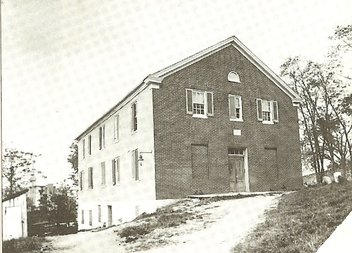

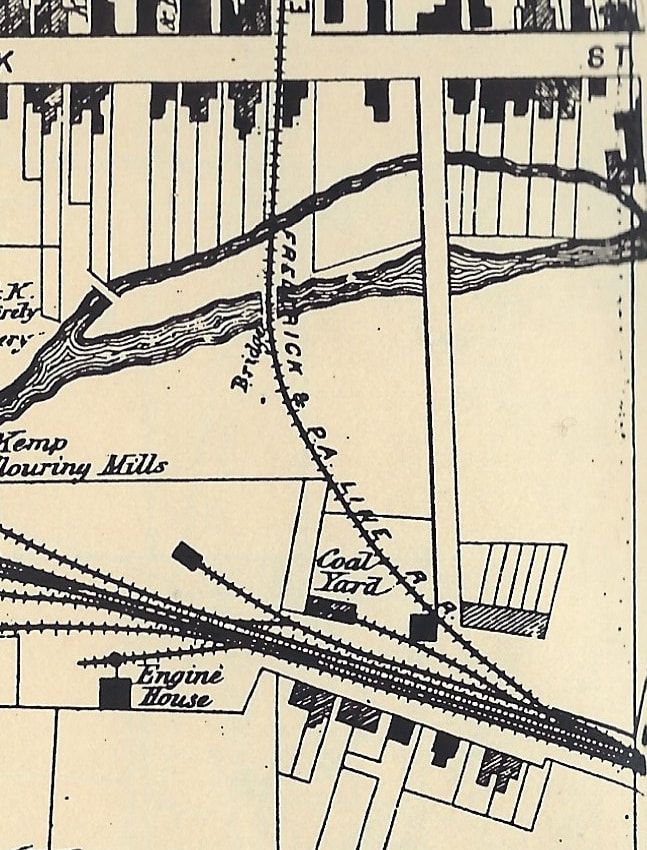

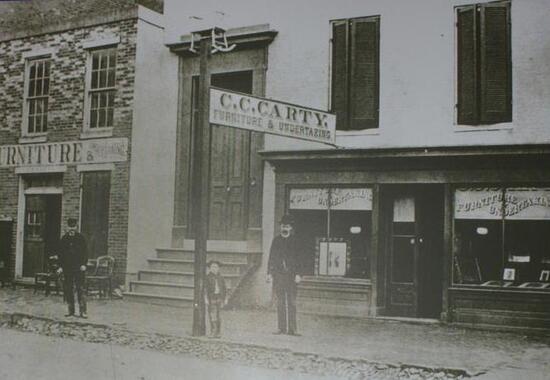

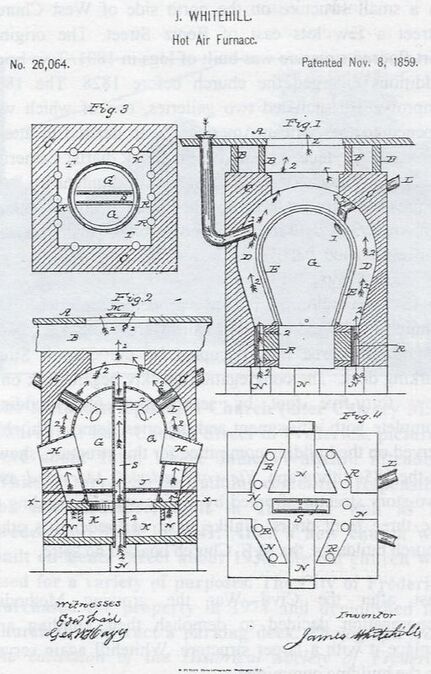

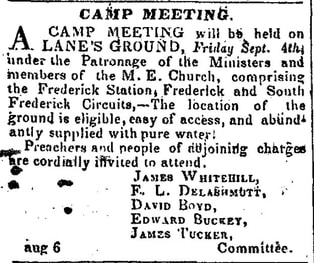

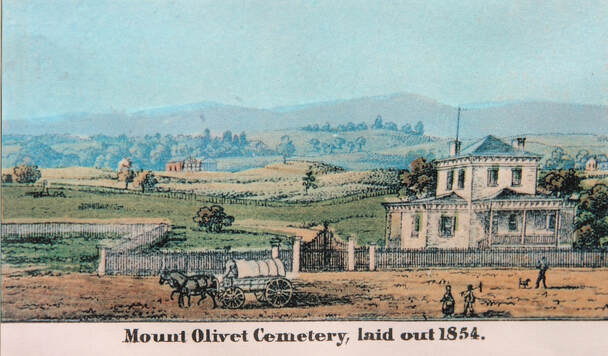

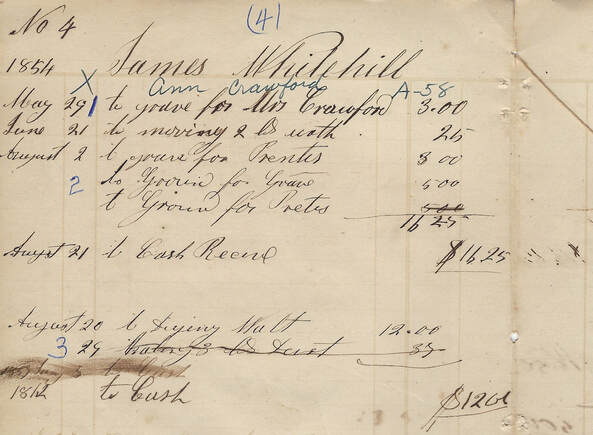

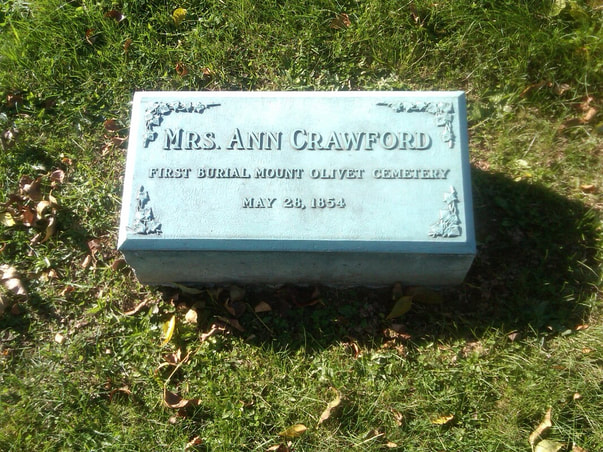

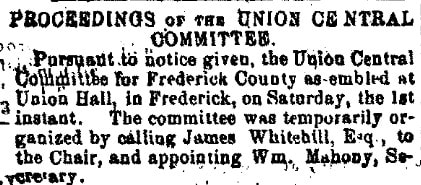

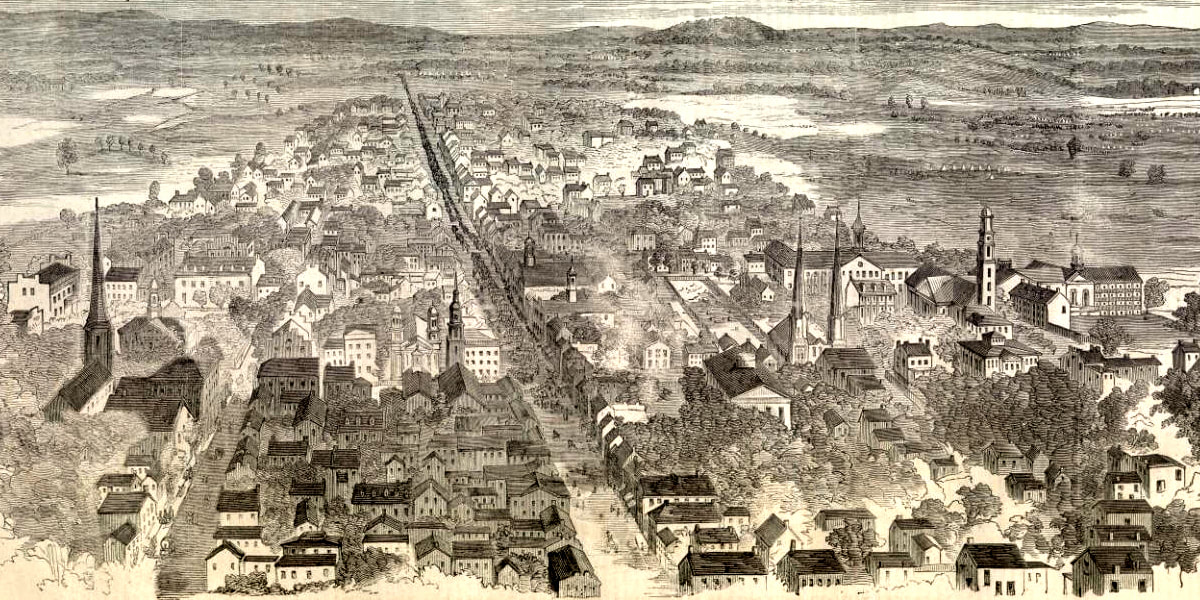

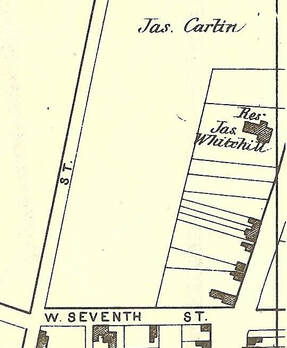

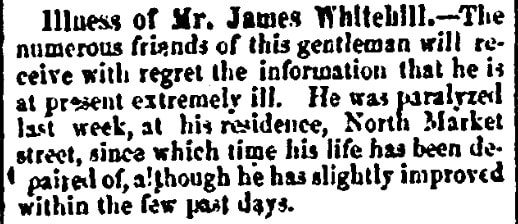

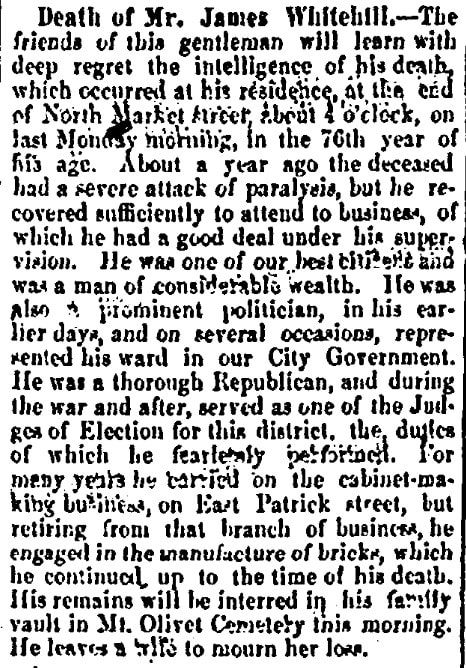

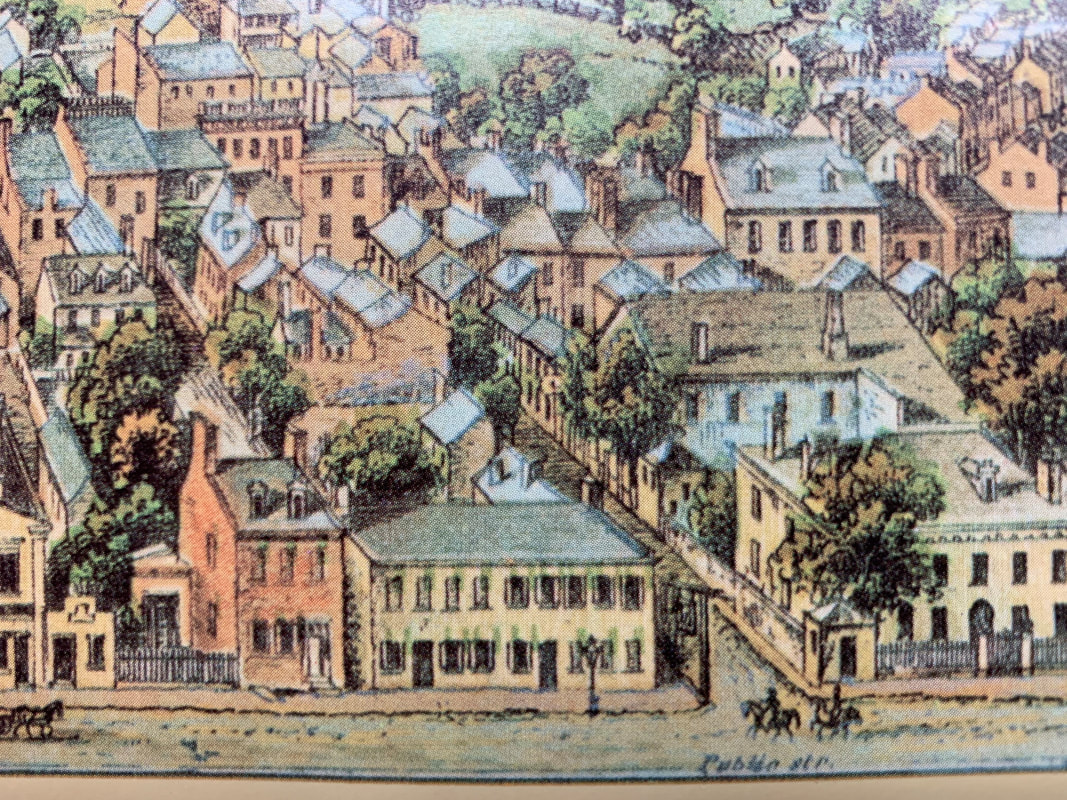

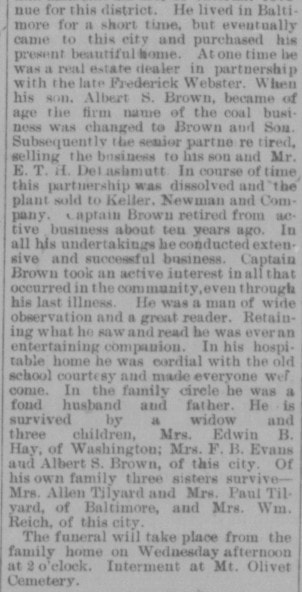

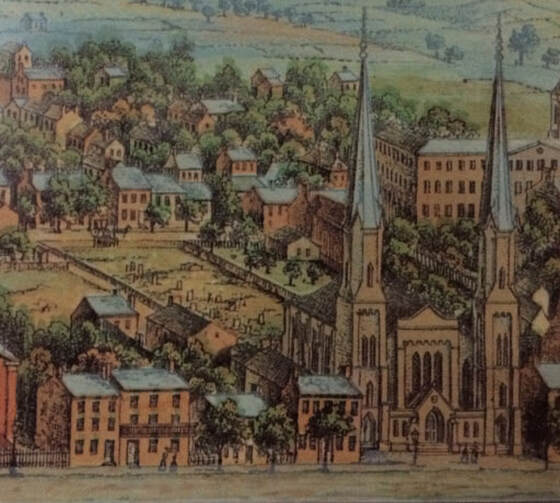

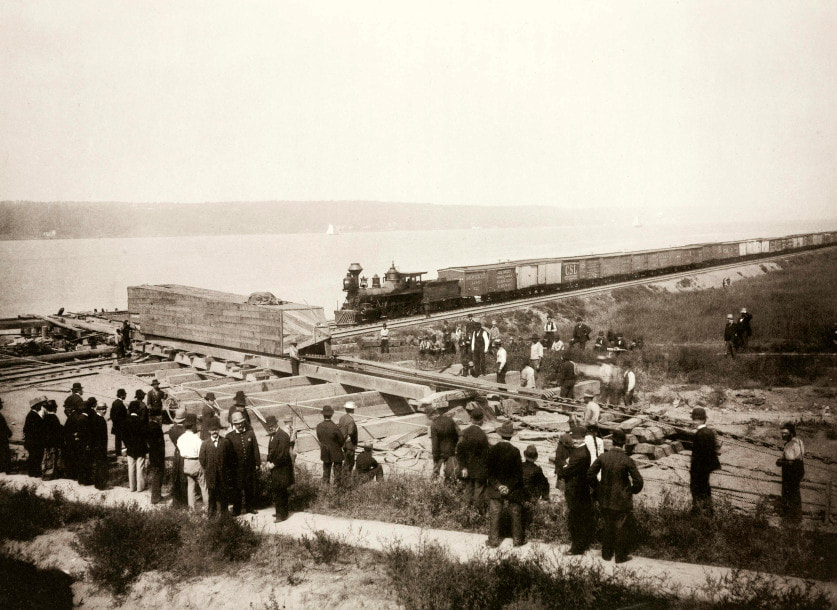

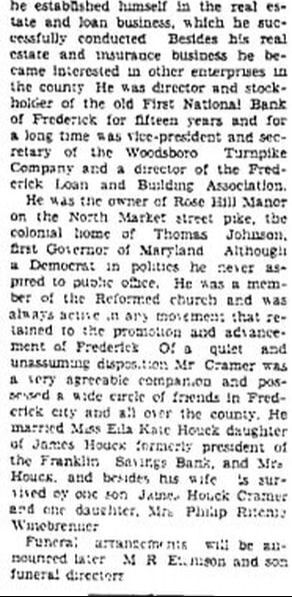

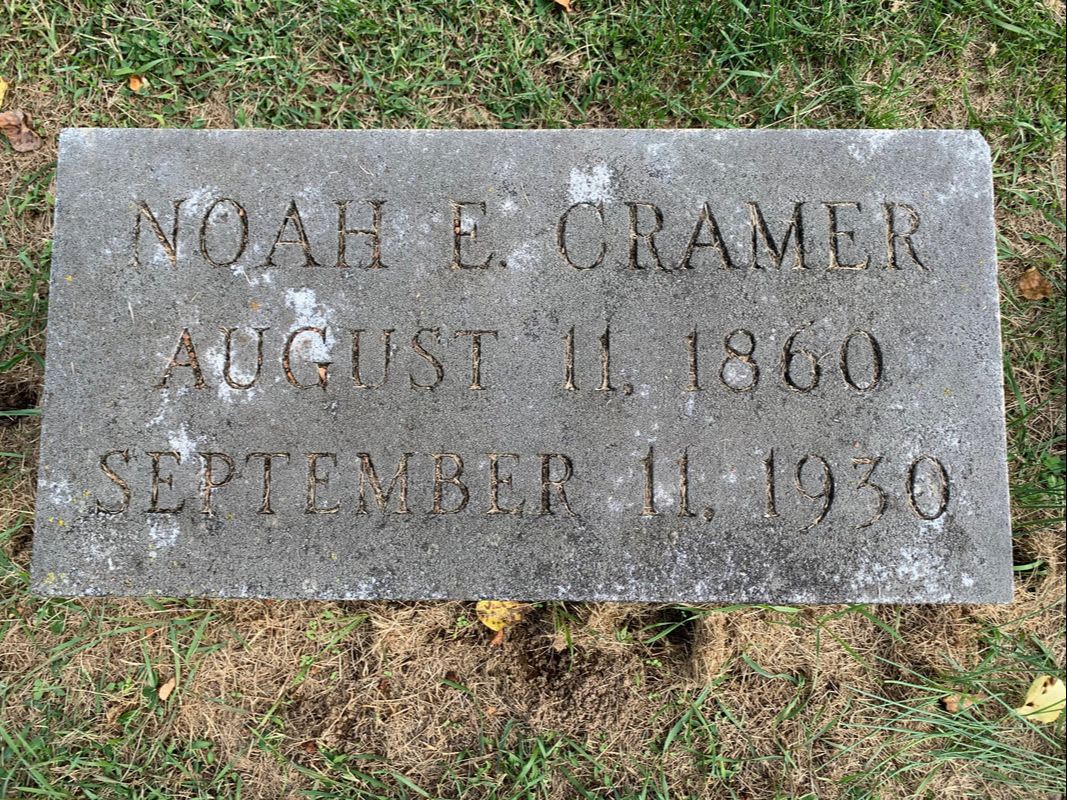

Engelbrecht identified another construction project when he wrote, “Nearly the whole winter and at this time Mr. James Whitehill is putting up three small brick buildings at the depot. Remarkable mild season this. Friday January 22, 1858.” In his will, Whitehill seemed to refer to this completed project, describing it as “six brick houses known as ‘Whitehill’s Row’ near the lower depot of the B & O Railroad.” Jacob Engelbrecht provided further information on Whitehill’s changing business activities in his Wednesday, November 7, 1866 entry: “’Lumber yard’ –John C. Hardt and Hiram M. Keefer bought from James Whitehill his lumberyard in East Patrick Street. They took possession on Monday morning last.” This sale involved only a portion of Whitehill’s complete property. In 1870 Whitehill retired from the furniture business, which was purchased and carried on by Clarence C. Carty and his descendants for many years. Though retired, Whitehill launched another business venture, purchasing the “brick yard, lime kiln and dwelling out Church Street below and South of the Gas House for $7000 from John A. Steiner,” according to Engelbrecht’s diary entry for April 13, 1870. He operated this business until his death. Perhaps his involvement in the construction business stimulated his inventiveness. The United States Patent Office holds Whitehill’s application for Patent No. 26,061, dated November 8, 1859. The letter that accompanies his detailed drawings begins: To all whom it may concern: Be it known that I, James Whitehill, of Frederick, in the county of Frederick and State of Maryland, have invented a new and usefull (sic) improvement in Hot Air Furnaces; and I do hereby declare that the following is a full, clear, and exact description of the same, reference being had to in the accompanying drawings, forming a part of this specification…” Whitehill’s design involved a double firebox, allowing for the use of one or both parts to heat the air in the chamber between them. Thus, the temperature of the air in the chamber could be somewhat regulated to accommodate the needs of the homeowner as the weather fluctuated. But James Whitehill was not solely a man of business; he took an active part in community affairs—religious, civic, and political. He was an active member of the Methodist Episcopal Church, being one of the trustees named when an act of the General Assembly of Maryland incorporated the Frederick Methodist Episcopal Church in 1840. In 1841 the church purchased a property fronting on East Church Street and extending northward to Market Space, roughly the area now occupied by the Church Street parking deck. The congregation quickly began work on a new 45’ x 75’ building, complete with a basement and galleries. James Whitehill served on the building committee for this structure, shown in the 1854 lithograph View of Frederick, Maryland as a two-story structure fronted by a wide stairway leading to the three front doors. Unlike most of Frederick’s other church buildings, the Methodist Episcopal Church boasted no spire.  Frederick Examiner (May 10, 1860) Frederick Examiner (May 10, 1860) Another area of Whitehill’s sphere of community involvement was the establishment of Mt. Olivet Cemetery. Churches and cemeteries were closely related in Frederick during the first hundred years of its history, when several congregations maintained their own graveyards, often behind their buildings. By the middle of the nineteenth century, however, these cemeteries were nearly full. The community urgently needed a new burial ground. Therefore, the Judges of the Circuit Court incorporated a sizeable group of men—including James Whitehill, William J. Ross, Richard Potts and John Loats—as the Mt. Olivet Cemetery Company in October of 1852. The next year lots and driveways were laid out on the thirty-two acre cemetery property. In May of 1854 the cemetery received its first burial. Jacob Engelbrecht reported: The first corpse buried on the New Cemetery—Mrs. Ann Crawford, who died at the house of Mr. James Whitehill on Sunday evening, May 28, 1854 was buried on “Mount Olivet Cemetery.” This was the first burial on the cemetery since they dedicated it—there had been several bones removed the week or two before. Old Mr. Baltzell and wife (father and mother of Doctor Baltzell & several others. Reverend Alexander E. Gibson officiating Minister (of Methodist Episcopal Church). Tuesday May 30, 1854. 7 o’clock A.M.  Baltimore Sun (Feb 26, 1851) Baltimore Sun (Feb 26, 1851) Yet another of Whitehill’s avocations made its way into Engelbrecht’s detailed diary entries. The diarist often recorded details of political affairs at all levels of government. As early as the 1830s, James Whitehill appears as a frequent candidate and sometimes winner in Frederick’s elections for Board of Alderman and Common Council. Perhaps politics ran in the Whitehill blood, for several of his Pennsylvania relatives were politicians; at least three served terms in Congress during the first quarter of the nineteenth century. Jacob Engelbrecht chronicled Whitehill’s political career, starting with his unsuccessful run for a seat on Frederick’s Common Council in 1835. He met with success in the 1836 election, and was chosen to fill the seat of a deceased Council member in 1850. In each of the next five years, Whitehill was re-elected to the Council. In the 1862 election for Aldermen, he—and all the other Union Party candidates—won easily, for they ran unopposed, there being no “Rebel” party candidates. Talk of disunion disturbed Frederick citizens, inspiring a group of them to form a Union Club on February 11, 1860. They chose James Whitehill as their president. Soon every district within the county had its Union Club. Members of these clubs raised Union flags, sang patriotic songs, and pledged their loyalty to the Union.  The war years made normal civilian life difficult, if not impossible. Frederick endured the movements of and occupations by thousands of Federal and Confederate troops, especially during September of 1862, July of 1863, and July of 1864. Following the 1862 battles of South Mountain and Antietam, Frederick played a major role in caring for sick and wounded soldiers of both armies. Research shows that nearly all public buildings, including most churches, were converted into hospital wards, and James Whitehill’s Methodist Episcopal Church was not exempted. It, with the nearby Lutheran Church and Winchester Seminary (Frederick Female Seminary, now Winchester Hall), formed General Hospital #4. Between September 17, 1862 and January 17, 1863 over 900 men were treated in this hospital complex. In addition to seeing his church used for war purposes, Whitehill saw his primary business change from the furniture manufacture and sale to the undertaking trade, with the establishment of an embalming station in his store. A broadside advertised an embalming station operated by Dr. Richard Burr, embalming surgeon for the United States Army, with its office located at “Jas. Whitehill and Co.’s, Undertakers, E. Patrick Street.” In addition to undertaking, James Whitehill provided coffins, wooden headboards, and hospital furnishings to General Hospital #1 located in and around the Hessian Barracks on the south side of town.  Union Hospital #1 on the Barracks Grounds on South Market Street (today the site of Maryland School for the Deaf). Below is a depiction by local artist Richard Schlecht of burial at Mount Olivet Cemetery during the Civil War. Many of Mr. Whitehill's coffins made during the Civil War are in the ground here in Confederate Row. Again, thanks to the Historical Society of Frederick County and in particular, Joyce Cooper and her incredible research, allowing me to tell you the rest of the Whitehill story and how it pertains to Mount Olivet Cemetery, and Halloween. In 1867, the Whitehills moved from their East Patrick Street home to a large house on the west side of North Market Street at Eighth Street. The home is located at 731 N. Market Street and was originally built by Hiram Winchester, female seminary principal and namesake of Winchester Hall (Frederick County's seat of government). Winchester sold this to Whitehill for $4,550, a hefty price for the time. The house became the Frederick City police station and jail in the mid-fifties and remained so until 1982. In December, 2016, this building was opened as the Frederick Rescue Mission’s “Faith House,” a temporary shelter for homeless women and children. James Whitehill experienced poor health in his final years. An article from February, 1874 gives us a glimpse of the condition he found himself in. His health further declined in the ensuing months. James Clemson Whitehill died on July 13th, 1874. He was buried in a fine funerary crypt In Mount Olivet built into the southeast side of Cemetery Hill (also once referred to as Pumphouse Hill). His funeral occurred on July 15th and it can be assumed that it was well-attended.

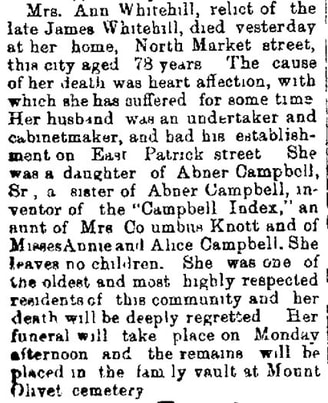

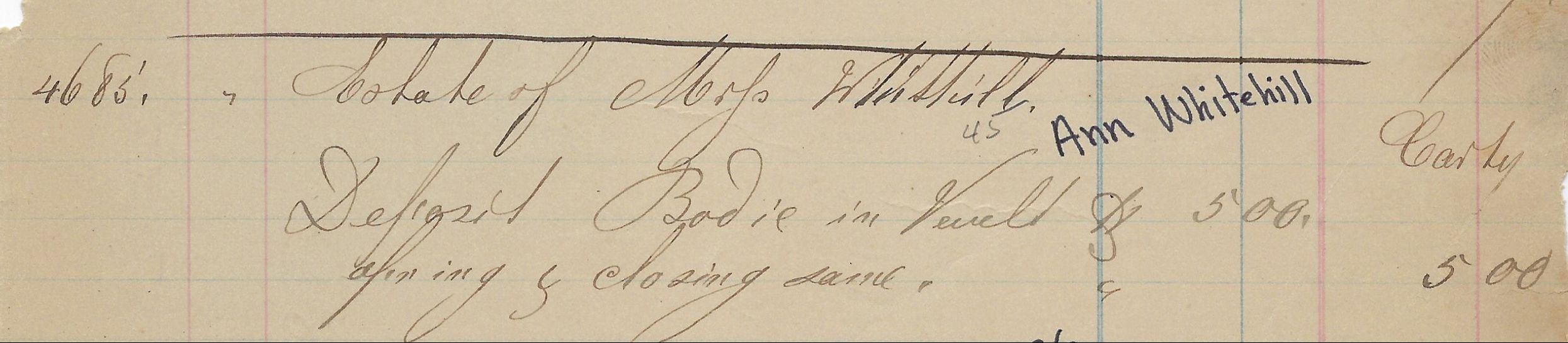

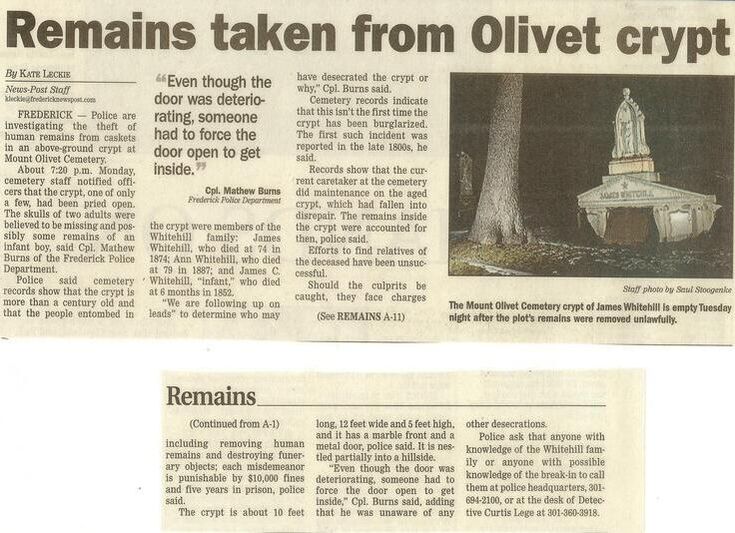

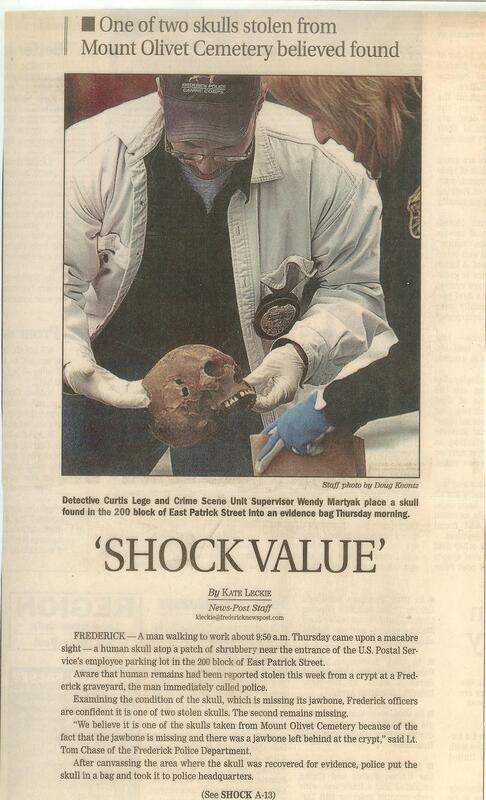

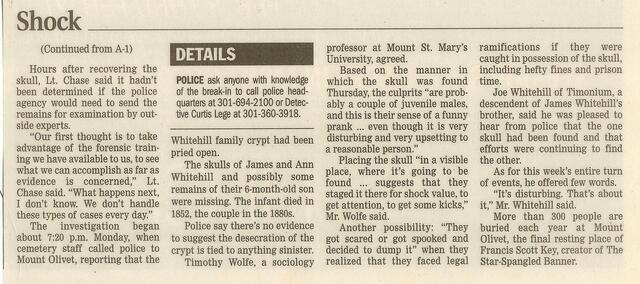

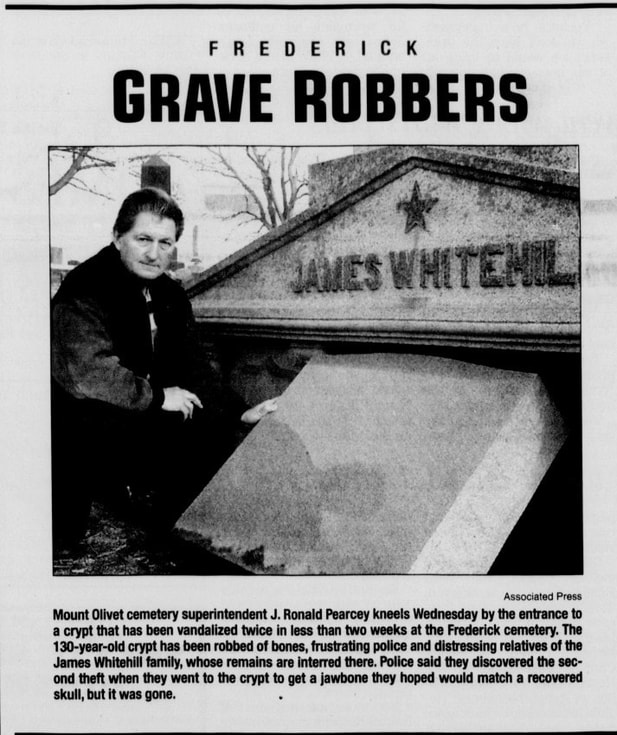

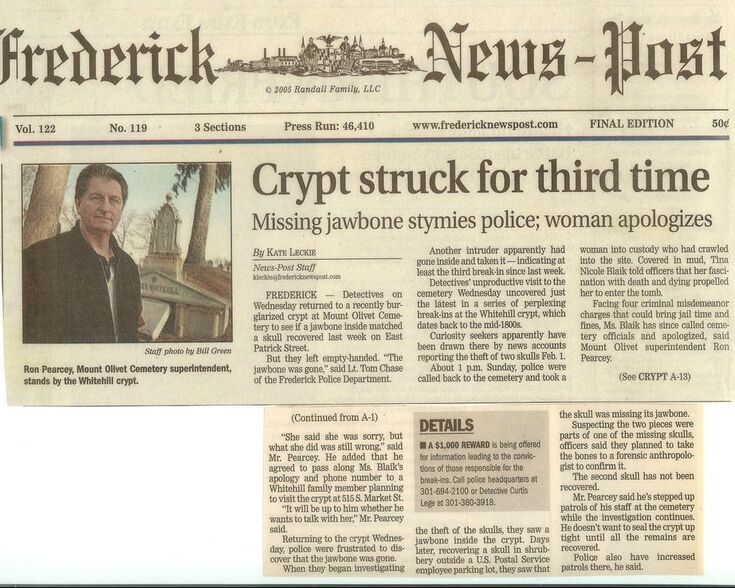

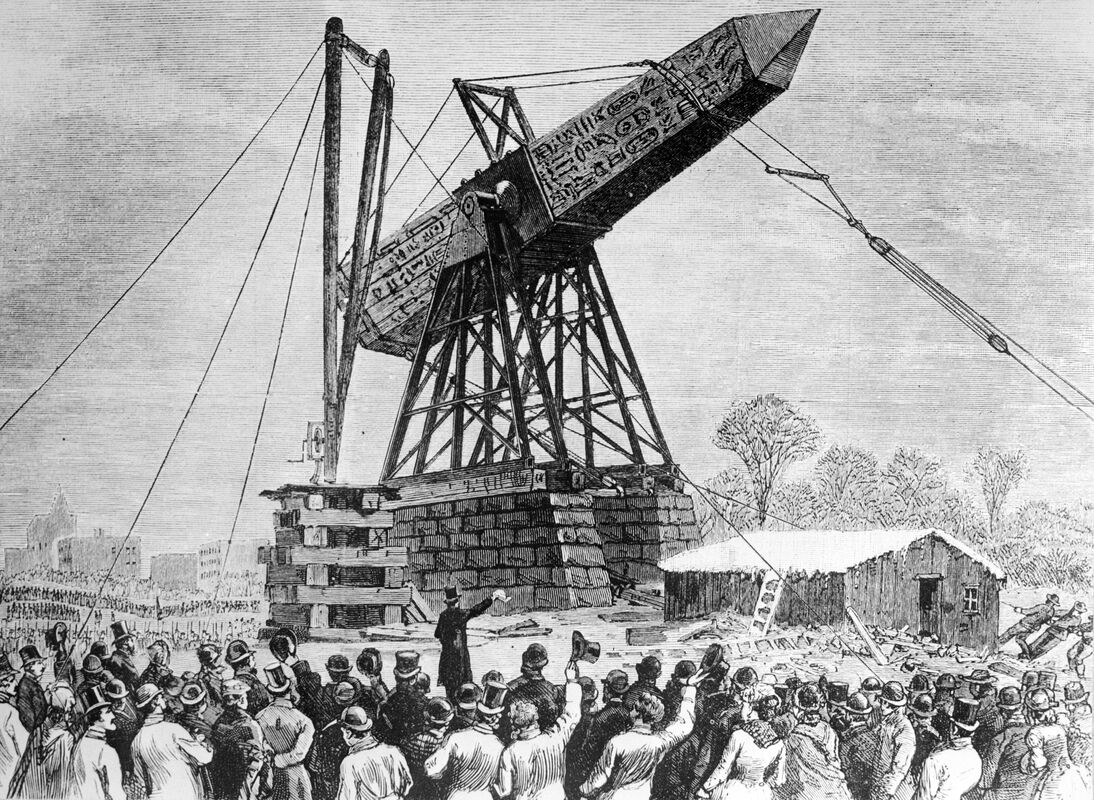

Ann Whitehill would pass on April 8th, 1887. The cause of death was the same given as her late husband-—heart disease. So that was that, the Whitehill family was resting in peace—but even this age-old cemetery-centric cliché could be deemed “debatable.” There is a strong suspicion that the crypt was a victim of “grave-robbing” in the late 1890s or early 1900s. Although we have no official records of this occurring in Mount Olivet, these criminals were stealth-like in their attempt to steal jewelry off corpses in cemeteries around the country and world. Crypts (like the Whitehills) were appealing because there was no digging to be done, and you didn’t have to go “subterranean” for the heist.  While I’m on the unpleasant subject, another type of graveyard crime in “days of old” was “body snatching.” This was an even more despicable situation as thugs actually took bodies from their intended grave lots. Why, you may ask? Well, for educational purposes of course. Early medical schools were in desperate need of cadavers. They paid quite well, and didn’t ask questions. I can practically guarantee that we never had a case of “body snatching” in Mount Olivet’s history, but I can’t give the same surety for the other early burying grounds in downtown Frederick or surrounding countryside. I guess we will never know. (NOTE: add here devilish laugh sound effect followed with “ ba ha ha”). Grave robbery on the other hand could have occurred in earlier days, and actually would in 2005. And yes, our friends the Whitehills and their crypt in Area F were the victims of such a dastardly thing, perhaps more than once. Our superintendent of 53 years, J. Ronald Pearcey, says that he recalls the iron door on the Whitehill crypt never seemed 100% secure since the time of his own arrival on staff back in the 1960s. The top hinge had been jarred from its setting in marble, and the upper part of the door near this junction seemed to have been somewhat bent, as if having been pried open at some time by use of a crow bar or like instrument. Ron said that he tried to fix the hinge back in 1997. The opportunity came about as Ron was performing intensive research in updating cemetery records. Apparently, he had no record of Mrs. Whitehill’s actual burial here in our cemetery record books. He decided to visit the crypt and take a glimpse inside to survey the contents. In our possession at that time was a “skeleton key” (pardon the pun) that opened the Whitehill crypt door lock. Ron made multiple discoveries that particular day as he found the lead coffin of infant James Campbell at the foot of the crypt, just behind the entry door. In front of him, he saw two metal coffins on the concrete base floor, placed longways, from left to right, in front of him. He assumed that Mr. Whitehill, who died first, was placed in the back/rear and that the matching coffin in front was that of Mrs. Whitehill. The couple possessed metallic Fisk-brand coffins, which Whitehill had advertised in the newspaper back when he owned his funerary business. These were unique caskets, made of metal and featuring a glass “porthole” in which one could view the decedent’s face. Fisk metallic burial cases were patented in 1848 by Almond Dunbar Fisk and manufactured in Providence, Rhode Island. The cast iron coffins or burial cases were popular in the mid–1800s among wealthier families. While pine coffins in the 1850s would have cost around $2, a Fisk coffin could command a price upwards of $100. Nonetheless, the metallic coffins were highly desirable by more affluent individuals and families for their potential to deter grave robbers. Ron commented that the coffins were in a stage of deterioration, rusting and the lids somewhat collapsed. He said that his brief observation showed that the bones of these bodies had been somewhat disturbed, not truly matching up to how they should be if left alone. A fourth coffin was also in this crypt, off to the right, and placed lengthwise across the foot of the Whitehill coffins. It was a wooden coffin in a far worse deteriorating condition. Research in our records showed this to be the body of Elizabeth (nee Schade or Schaed) Tice, a former tenant of Mr. Whitehill who died on October 25th, 1863. Mrs. Tice was born on May 27th, 1780, and was the wife of George Tice, a tailor, who had died in December, 1831. Mrs. Tice’s husband, son Henry (d. 1839) and a four-year-old grandson are buried in the old German Reformed graveyard, currently under the various war monuments of today’s Frederick Memorial Park. A check of 1850 and 1860 census records shows Elizabeth Tice as a next-door neighbor to the Whitehills when they lived on East Patrick Street and ran their furniture business. This finding was an extra bonus for Ron in his record research. Upon completion, he and staff members did what they could to further secure the door when they closed the crypt back up. Obviously, this would not be enough, however. Ron told me that, at the time, he sensed there had been a prior disturbance of some kind as the caskets didn’t seem to be neat and orderly as he thought they ought to be. This led staff to believe that the crypt had fallen prey to an earlier break-in, but it had not been thoroughly ransacked, rather carefully combed through. I have searched early newspapers and cemetery records, but came up empty in my search for documentation of any early events (19th or 20th century) relating to grave intrusion here at Mount Olivet involving the Whitehill crypt. I could see a situation of this nature downplayed and not reported to authorities in an effort to keep the peace with relatives and lot-holders. As we learn with incidents of vandalism in cemeteries, there is a strong feeling of violation felt by not only staff but all who have a loved one in a particular burying ground, even if just one gravesite has been tampered with or defaced. Twice Bitten Early Monday morning of January 31st, 2005, Ellie Summers and Liz Claggett, regular walkers in our cemetery, made a horrible discovery. They found bones strewn about on the small knoll in front of the Whitehill crypt. It had snowed during the overnight, and the ladies also saw the door to the crypt was wide open. They immediately made their way back to the front of the cemetery and notified Superintendent Pearcey. Pearcey immediately went to the site with another staff member, our current cemetery foreman, Tyrone Hurley, and saw what had been reported to them—the crypt door had been fully pried open, and the display of bones had indeed come from the Whitehill crypt. Ron then notified the authorities who came out to make a report and investigate. The group saw nearby car tracks and footprints in the snow outside the cemetery’s only other crypt belonging to the Roelkey family. It appeared that someone had been pulling on the outer gate of this funerary repository, but were frustrated in their vain attempt. The thought prevailed that the culprits hit the Whitehall crypt before the snow had started falling, and then attempted to raid the Roelkey crypt as the precipitation had started accumulating. Because of the snow forecast, Superintendent Pearcey left the gates open so that staff could enter early in an effort for snow removal. Back at the Whitehill crypt, Tyrone was sent into the structure to assess the damage. He reported that the glass portal on each coffin appeared to have been smashed, and the boxes themselves had been raided of some of their human contents. Tyrone and Ron carefully retrieved the remains and placed them back in the broken deteriorating coffins within the crypt. Unfortunately, they realized that both skulls and a jawbone were missing from the scene. Ron and Tyrone closed the door the best they could, with hopes of doing more the following morning as they had to put their energies toward plowing the 3-4 inches of snow covering the cemetery lanes and roadways. The next day word got out through the initial police report, and a media-circus ensued with news entities from Baltimore and Washington wanting to cover the unfortunate Whitehill crypt break-in. Superintendent Pearcey was interviewed by newspaper and television reporters throughout the day. The crypt entrance way was now blocked by the placement of an extra piece of granite found in one of our storage areas. News Channel 5 (out of Washington) did a live remote report from the cemetery that Tuesday night, and CNN had a team up here as well to do the same. On Wednesday, February 2nd, the Frederick News-Post would run the following story: While the Frederick City Police were conducting their investigation, a unique find occurred near downtown Frederick’s Post Office. The story would make front page news in the February 4th edition of the Frederick News-Post. The Whitehill break-in made other newspapers across the area including Baltimore, Annapolis, Hagerstown and Cumberland. The Associated Press picked up the story and it ran in various publications throughout the country. The Washington-Post would also interview Ron about the unfortunate vandalism, now thought to be the work of juveniles. The following Sunday, February 7th, brought a new and equally unsettling wrinkle to the story. Late in the afternoon, Superintendent’s Pearcey's son was driving through the cemetery in late afternoon and noticed a lady entering the Whitehill crypt. He immediately notified his father. Here is the newspaper story related to this aspect: And just when you thought it was safe to go back in the water....this was the front page of the February 10th Frederick News-Post: The following day, Ron and his grounds staff worked to fully secure the Whitehill crypt. The Police were still searching for the lone missing skull and jawbone, as the other had been returned to the crypt. Meanwhile, no remains of the Whitehill infant had been removed as erroneously reported in the papers. Fill dirt was utilized to further build up the ground around the crypt’s door, and the granite slab was turned on its side and packed-in tight against the door. The 600-pound marble slab was remains intact since that day. The good news, there have been zero instances of vandalism here at the Whitehill crypt, a true positive. On the downside, however, the missing skull has never been located and returned to its rightful burial tomb. Ironic in a way, as many residents of Mr. Whitehill’s day described the prominent businessman and politician as progressive, stubborn and headstrong. Maybe it’s time to remove the last adjective?

1 Comment

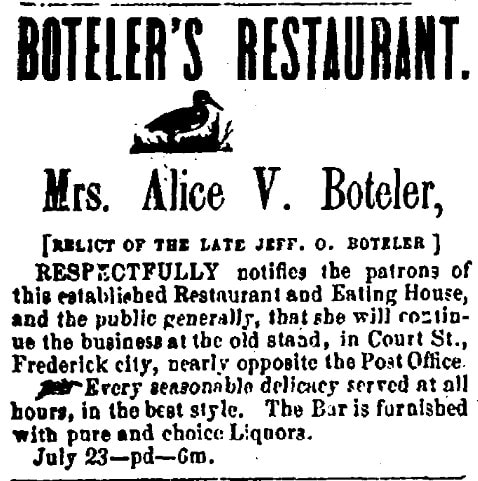

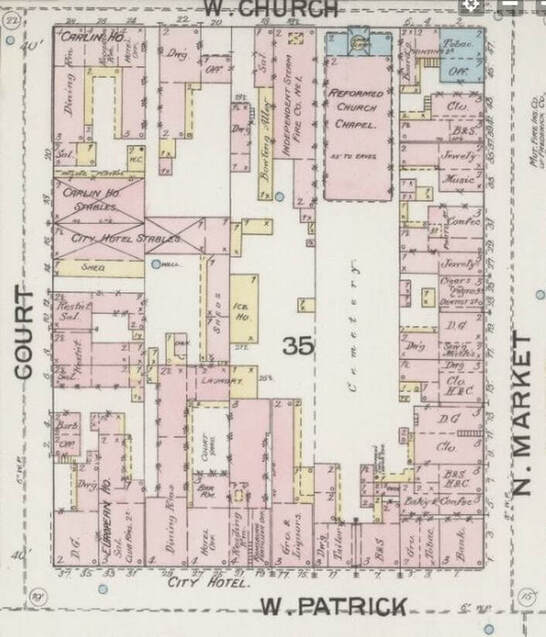

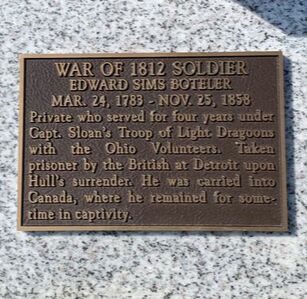

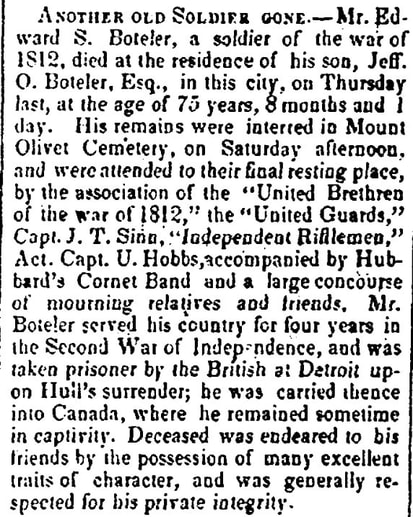

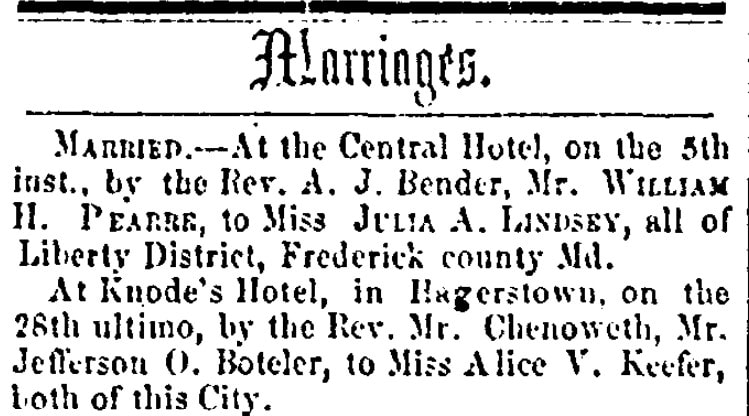

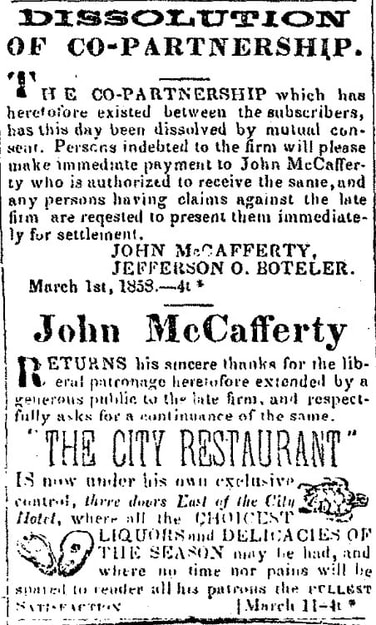

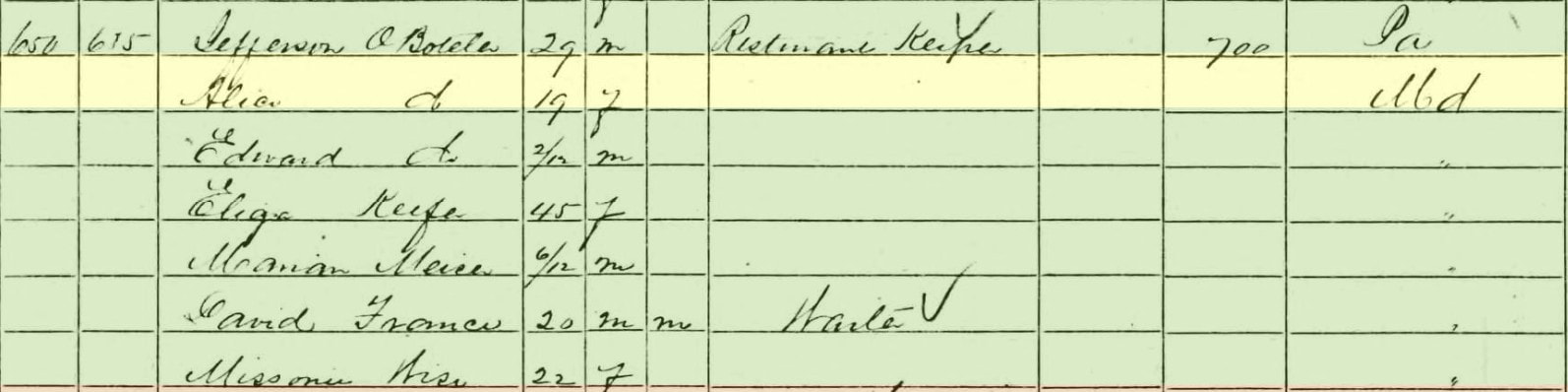

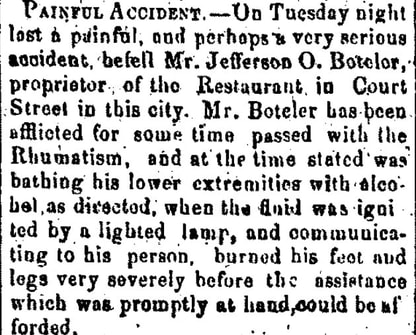

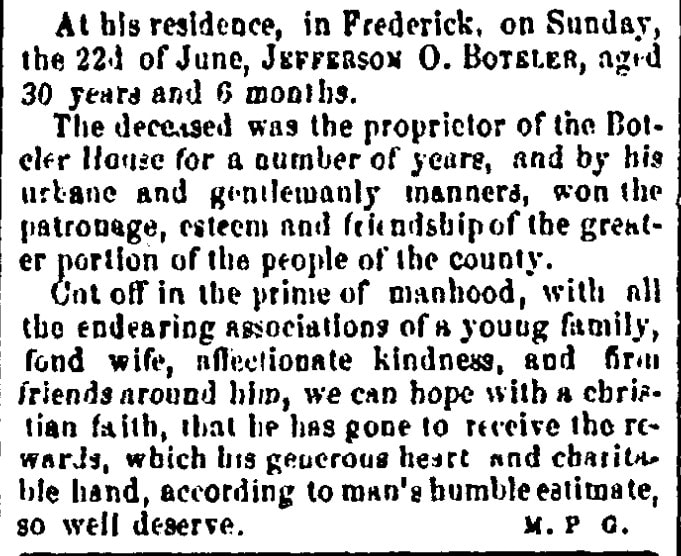

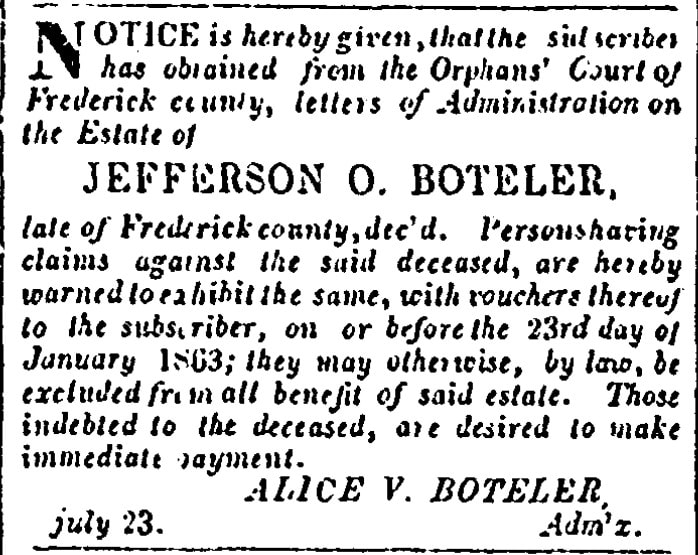

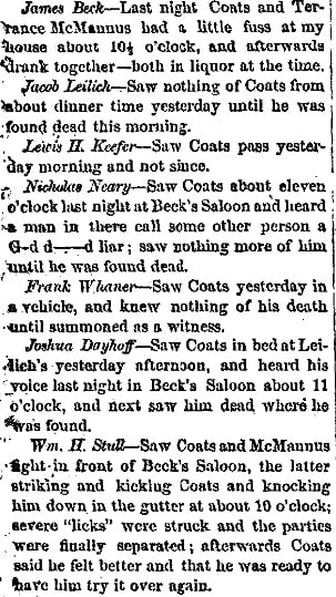

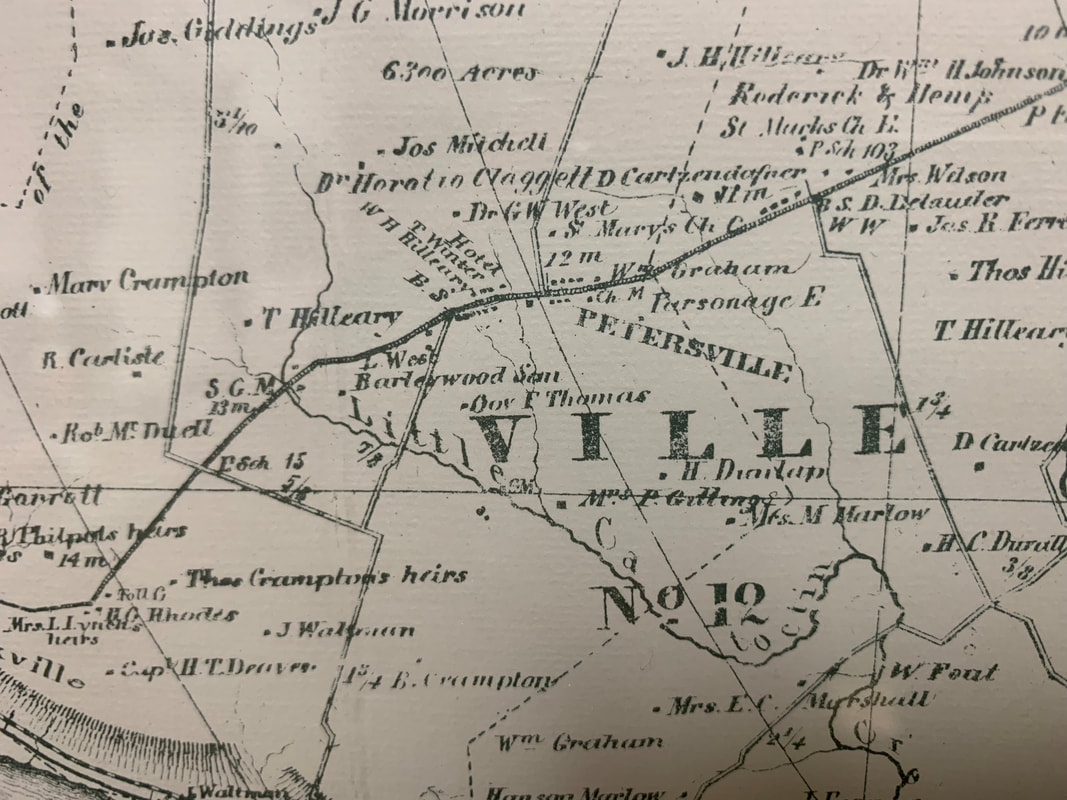

I stumbled upon an interesting wife and husband last spring while researching Frederick’s early oyster saloons from the 1800s. It occurred while I was trying to find more on who I imagined to be a spunky, former female business owner at the time of the American Civil War. The woman’s name was Alice Beck, and she is buried in Mount Olivet. Sadly, she isn’t readily remembered today because she has no gravestone, yet her first husband and father-in-law (who predeceased her) do. All three reside in the same grave lot in Mount Olivet’s Area A, a stone’s throw from Francis Scott Key’s final resting place. Miss Alice Virginia Keefer was the daughter of John Henry “Harry” Keefer and Elizabeth Titlow. Born on June 27th, 1840, she grew up here in Frederick City and was a member of the town’s German Reformed Church. Alice would be twice married, her first nuptials having taken place in late October, 1857. Her groom was a gentleman named Jefferson O. Boteler. The Botelers were soon the operators of a restaurant-saloon located at 12 N. Court Street, the stretch that goes between W. Patrick and W. Church Streets. At the time, this thoroughfare was known as Public Street because of its proximity to the county courthouse. The Boteler’ saloon location was sandwiched between the largest hotels in the city (the City Hotel and the Dill House, later to be renamed the Carlin Hotel). Actually the Boteler’s tavern was bounded by the livery stables connected to each of the aforementioned hospitality venues. Today, the Pythian Castle building sits on the old site of the old watering hole. Although I wasn’t familiar with Jefferson O. Boteler, I soon learned that his father was someone I did know through earlier research going back nearly seven years. This gent’s name was Edward Sims Boteler, one of 110 War of 1812 veterans interred here at Mount Olivet. His story was a bit different from the norm as he served in a Dragoon Troop in Ohio. He was captured at the Battle of Detroit and spent time as a captive in Canada. I specifically singled out Private Boteler’s grave (Area A/Lot 126) for a newspaper photo and article back in 2014. I was working for the Tourism Council of Frederick County then, and had partnered with the cemetery in a grant project in which we received money from the state’s War of 1812 Bicentennial Anniversary Commission to place marble and bronze markers on the graves of all our 1812 vets.  "Home of the Brave" event on Sept 13, 2014 "Home of the Brave" event on Sept 13, 2014 A special ceremony was held in September 2014 to mark the 200th anniversary of the Battle of Fort McHenry and writing of “the Star-Spangled Banner.” We had an evening ceremony adjacent the FSK monument with the purpose of unveiling these markers. Participants were led on a candlelight history tour of 1812 veteran graves. As the master of ceremonies, I went one step further in recognizing Edward Sims Boteler and read his bio in which I shared with the audience a few scant particulars about Boteler’s military service. I also reveled in presenting a poignant inscription found on his gravestone. It reads as follows: “Each soldier’s name Shall shine untarnished on the roll of fame. And stand the example of each distant age. And add new luster to the historic age."  Graves of Edward L. and Elizabeth Boteler Graves of Edward L. and Elizabeth Boteler Edward Sims Boteler was born on March 24th, 1783 in the vicinity of New Town, later known as Trappe, and today recognized by the name of Jefferson, Maryland. Edward’s parents were Edward Lingan Boteler and Elizabeth (Delashmutt) Boteler. Both father and son fought for independence from Britain. Edward’s father (Edward Lingan Boteler) was recognized by the Carrollton Manor DAR Chapter as a Revolutionary Patriot with a DAR plaque. In 1812, Edward’s apparent first wife was a Sarah Elizabeth Norris (b. 1783). The couple had one known child, Henry E. Boteler (1812-1843). I’ve read that Edward would be married a second time to a woman whose name is only known as Elizabeth. The offspring of this union was the afore-mentioned Jefferson Orestes Boteler (b. 1832 in Pennsylvania). Interestingly, this same year of 1832 was the one in which “Jefferson” was duly incorporated and given its patriotic name after our third US president. Edward Sims Boteler appears to have been engaged in farming and lived in the area of Jefferson, and Petersville to the southwest. He died on November 25th, 1858 at the age of 75. Around this same time, Jefferson was operating the saloon on Court Street with business partner, John McCafferty. One year later an advertisement would appear in the local paper announcing a dissolution of this business, as McCafferty left to take a job running the restaurant associated with the City Hotel, Frederick’s leading lodging place of the time. This was likely when Mr. Boteler had his new bride serve as his business partner, however she could have assisted with the saloon prior. Apparently, Jefferson had been going through life with health problems. In January of 1862, he would experience quite a further setback to his medical maladies. Jefferson O. Boteler’s health continued to decline as the year went on. He would die on June 22nd, 1862 and was buried in Mount Olivet the following day, next to his father. Meanwhile the American Civil War was in full effect. Union soldiers had been plentiful in town for over a year. That number would grow exponentially over the next two. In her husband’s absence, Alice Boteler took over sole operation of the oyster saloon, while also raising a son, Edward, two-and-a-half years old at the time. I can just imagine the often bawdy scenes in the saloon establishment now frequented by imbibing Union soldiers from out of town. The following September (after Jefferson’s death) the town would receive a week-long visit from the Confederate Army under Gen. Robert E. Lee. They wouldn’t stay long, but certainly left their mark on town before heading westward where the engagements of South Mountain and Antietam would take place on September 14th and 17th respectively. Again, I can’t help to wonder what Alice’s state of mind could have been like through those troubling times, not to mention losing her husband, raising a child and running a business.

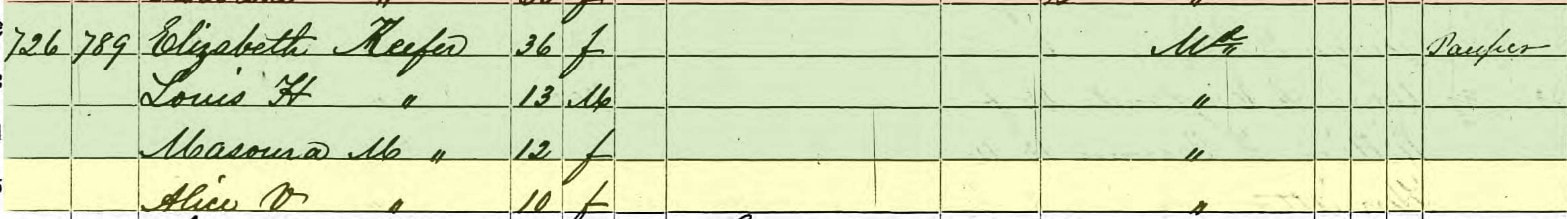

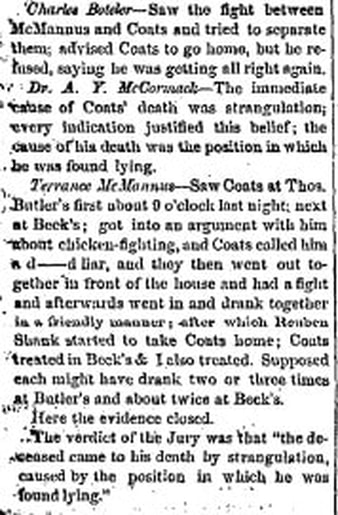

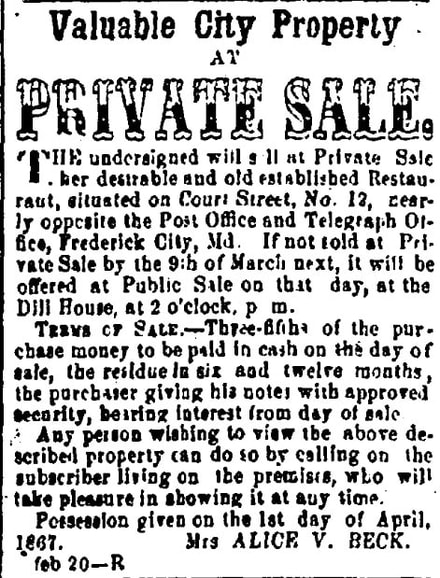

Well, the above story just goes to show that you never know what can happen in life. It also echoes the old sentiment: ”What happens in rowdy oyster saloons, should stay in rowdy oyster saloons.” I found an advertisement in the local paper announcing a private sale of Mrs. Alice V. Beck’s oyster saloon in February 1867. For one reason or another, it doesn’t appear that she sold at that time, or perhaps she did sell, but kept a lease agreement with a new owner in an effort to continue running her popular establishment. The Botelers had rented the building up until Jefferson's death, at which time Alice purchased the property. The 1870 US census shows the Beck family living above the restaurant as was quite common in that day. I found out that Mrs. Alice V. Beck had $4,000 of real estate in her name in the form of her restaurant building. I also found that husband James Beck was listed as a restaurant keeper, but Alice was simply keeping house. Alice's son, Edward was now ten-years-old and the census mentions that he was attending school at the time. Advertisements in Frederick’s Maryland Union in the fall of 1871 announced that a gentleman named J. William Brubaker was now the new owner of the former saloon operated by Alice V. (Keefer) Boteler Beck. Brubaker would eventually sell fourteen years later to Lewis A. Hager in 1885. During that run by Mr. Brubaker, Alice busied herself with legitimate matters of home, first and foremost relating to the fact that she had given birth to three additional children between 1871-1874: Nellie Virginia (b. 1872), Mollie Adele (b. 1873), and Willie Justus (b. 1874). Alice died of pneumonia at her home residence on W. Patrick Street on April 8, 1876. Only 36 years of the age, she would be buried alongside her first husband, Jefferson O. Boteler, and father-in-law, 1812 veteran Edward Simms Boteler. As I began the article saying, her gravesite has no monument or marker whatsoever. I found that there are five others in this plot who have suffered the same fate and are blood relatives of Alice from the Keefer family. They include: Death Year *an infant child of Alice and Jefferson 1859 *Elizabeth Titlow Keefer 1888 (Alice’s mother) *Missouri M. (Keefer) Meese 1860 (Alice’s sister) *Hiram Bartgis Keefer 1878 (4 year-old nephew of Alice/son of L. H. Keefer) *unnamed Keefer nephew 1869 (infant son of brother Lewis Henry Keefer)

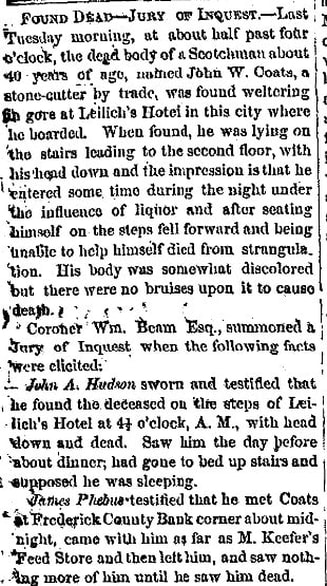

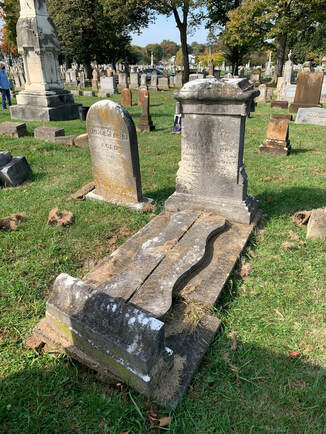

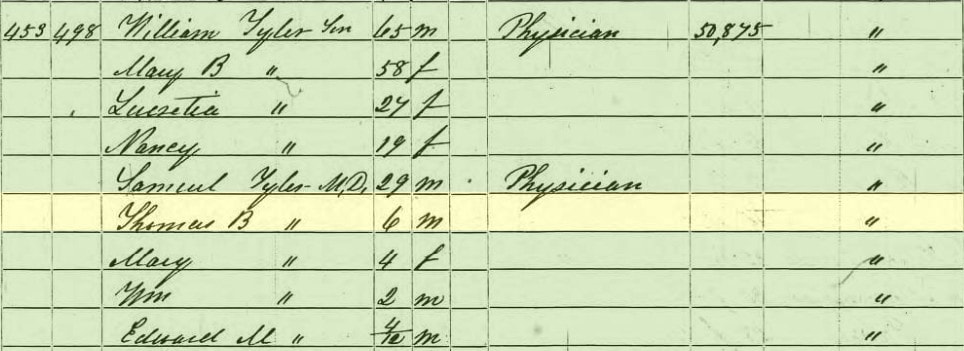

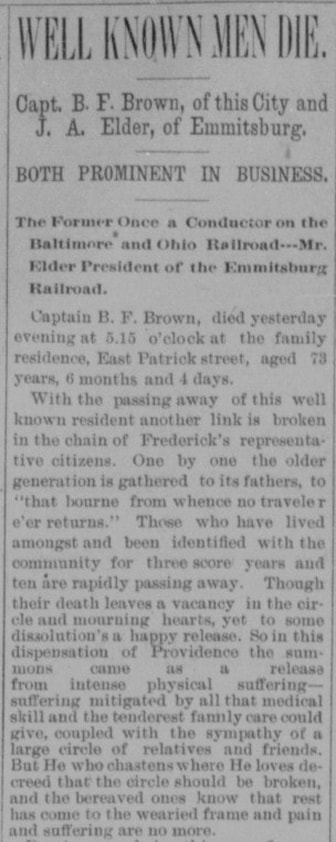

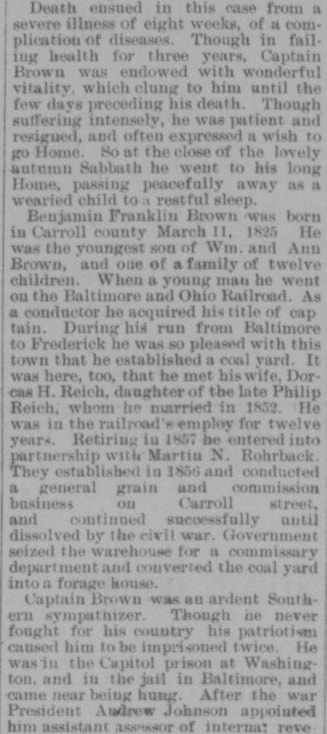

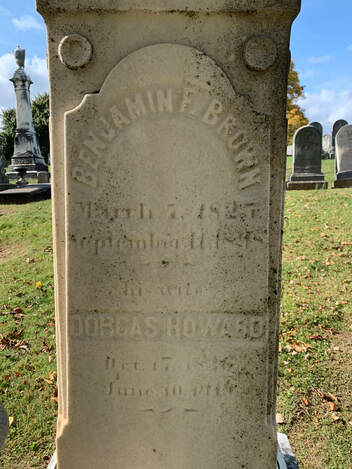

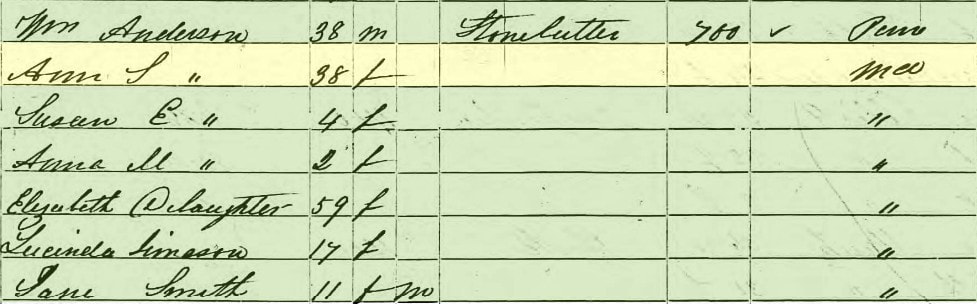

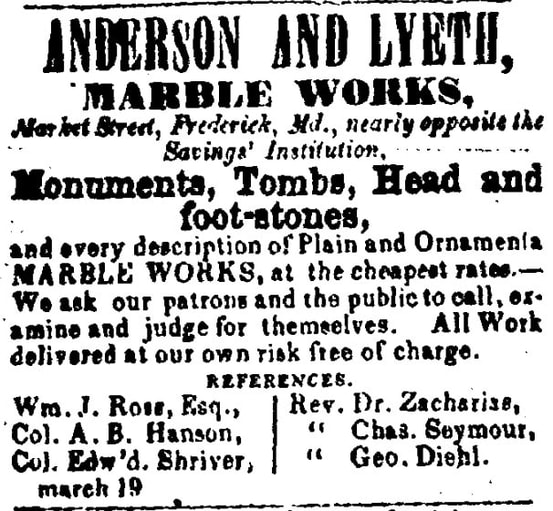

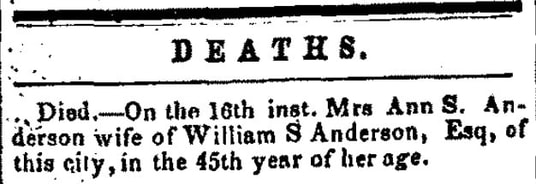

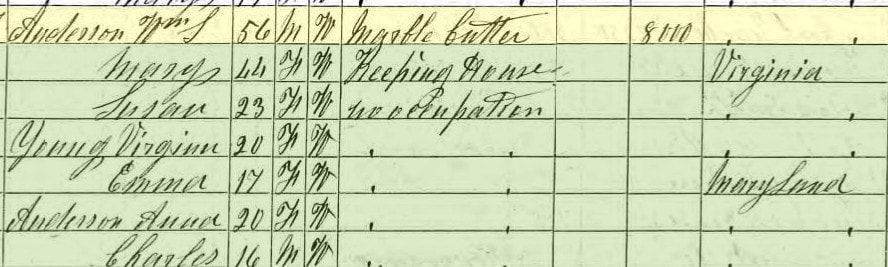

As was common in those days, the children were unfortunately split up. I learned there whereabouts from the the 1880 census. Here, I found husband James M. Beck living in his native Woodsboro with his sister and working as a painter. He had daughter Nellie living with him. Mollie was sent to live with her Uncle Charles Beck in Hagerstown and Willie was adopted by a paternal aunt living in Woodsboro. The latter would move to Brooklyn, NY as an adult and worked as a telegraph operator. As for Alice's oldest son, Edward O. Boteler, he went to live with his Meese cousins in Wetmore, McKean County, Pennsylvania. He worked for F. W. Meese who operated a hotel there and was married in the 1880 census at the age of 21. James M. Beck died in 1905 and is buried in Woodsboro's Mount Hope Cemetery.  As I walk through the cemetery on a crisp, autumn day, I’m suddenly reminded of an idiom found often in British literature—“From the Cradle to the Grave.” It seems so fitting for a stroll through this hallowed place, as I look from gravestone to gravestone and contemplate the lives of the local tenants. Defined, the idiom beckons “From birth to death; the entire period of one’s life; throughout one’s life.” Simply put, this is what the hyphen stands represents on each and every monument, strategically sandwiched between birth and death dates of the decedent. The “Cradle to Grave” expression is usually used as an adjective, and has been around since the year 1709 when it appeared in author Richard Steele’s British literary and society journal entitled The Tatler. Steele used the idiom as follows: “In a word, to speak the characteristical difference between a modest man and a modest fellow; a modest man is in doubt in all his actions; a modest fellow never has a doubt from his cradle to his grave.” I thought this expression ("Cradle to Grave") would serve as a nice title for this week’s edition of “Stories in Stone” in which we could explore another unique style of cemetery markers referred to as “cradle graves.” These are also known as “bedstead monuments,” and were very popular in the 19th century, around the time of the American Civil War. A cradle or bedstead is composed of a headstone, footstone, and cradling. These elements represent the headboard, footboard, and bed rails on a bedframe. In 2016, preservation specialist Ashley Shales of Oakland Cemetery (Atlanta, Georgia) wrote that cradle grave monuments portrayed a particular style that appealed to Victorian-era sentiments for three reasons: “First, heaven was likened to “returning home,” which was comforting to loved ones left behind because they could hope for a future where they were eternally reunited. A bed is a natural symbol of home. Second, the 19th century witnessed a phenomenon referred to by historians as the “feminization of death.” Public displays of mourning became fashionable, as did more beautiful, peaceful, and pleasant monuments and iconography. The bed is not only a symbol of the home, but of femininity and domesticity. The third — and the most frequently cited — reason for the bedstead’s popularity is that it likens death to sleep, a notion that undoubtedly eased the sorrows of many mourners.” Bedsteads come in several forms and are made from a variety of materials, depending usually on the purchaser’s economic means, available stone, and current fashions. Headstones may be quite elaborate, often featuring iconography such as lambs or lilies, symbolizing purity and innocence. Most bedsteads are made of marble. Headboard and Footboard On some cradle graves, the top is designed to resemble the headboard of a bed and the bottom looks like the footboard. Plain or decorative curbing (or molding) can also be used to outline a single grave in the shape of a bed; hence these graves are also known as bed graves. A perfect example of this survives in the final resting place for Thomas Baltzell Tyler in Area B/Lot 113. Hailing from the prominent Tyler family of Frederick City, Thomas died at age 13 after an illness of three weeks. He was the son of Samuel Tyler (1820-1856) and Lucretia Josephine Baltzell Tyler (1823-1901) and was born on August 9th, 1843. The oldest of four children, he was a grandchild of the prominent Dr. William Tyler, a physician who served as the first president of the Farmers & Mechanics Bank, a post he would hold for 55 years from 1817 until his death in 1872. Young Thomas Tyler passed less than a week before Christmas in the year 1856. His obituary says the 19th, however his stone says December 20th. Child's Cradle Grave Although they can be found throughout the country, cradle graves were more popular in the South and Midwest regions. William Raymond Brown died of pneumonia at the age of one year and three months. He was born at the advent of the American Civil War on November 26th, 1861. The beautiful example of this grave style can be found near the drive on the east side of Area E, where Lot 126 holds several members of the deceased' immediate family. William’s father, Benjamin Franklin Brown, has the most auspicious monument of the group. He was an ardent Southern sympathizer during the war who was arrested on more than one occasion for his sentiments. Mr. Brown ran a successful warehouse business at the lower train depot on Carroll Street. He specialized in providing coal for his patrons, but bought and sold several other commodities. Although little is known about young William, his father’s life story is well-told through his obituary which appeared in the local papers in mid-1898. Adult Cradle Grave Despite the name, cradle graves were not just for children. Adult graves were also marked in this manner. One such is just up the hill from young William Raymond Brown within Area E. In lot 34, one lone soul exists in a space capable of holding several other family members. Ann Savilla (Delauter) Anderson is the only one here as I surmise her husband and two daughters left the Frederick area a few years after Mrs. Anderson’s untimely death at age 44. Ann was born on April 11th, 1813. Little is known about this parishioner of the Evangelical Church. Interestingly, however, she was married in Frederick’s German Reformed congregation on February 5th, 1845 to William S. Anderson of Pennsylvania. The couple would have two little girls, Susan Elizabeth and Anna Mary and a boy, Charles, born in 1855. It is thought that the family lived on E. Church Street near the intersection with Chapel Alley. Mr. Anderson was a stone cutter and monument maker who specialized in marble works. It appears he commenced his business in the late 1840s as is mentioned by Frederick diarist Jacob Engelbrecht with an entry dated July 24th, 1851: “Mr. William S. Anderson, Stone Cutter of our town has eleven tomb-stones to make for the Catholic Priests of our town. They are all buried in the graveyard just at the north end of the old church.” Sadly, William S. Anderson’s wife Ann, would die on March 16th, 1858 and he was saddled with the responsibility of carving her gravestone. For one reason or another, he felt compelled to mark her gravesite with a bedstead design. He would include an inset relief carving of a woman with an anchor, symbolizing hope. At this time, his business was located in the first block of N. Market Street.

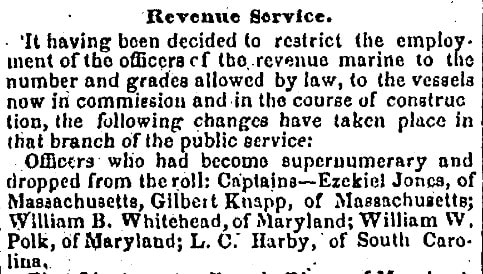

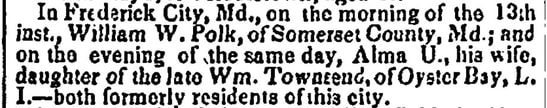

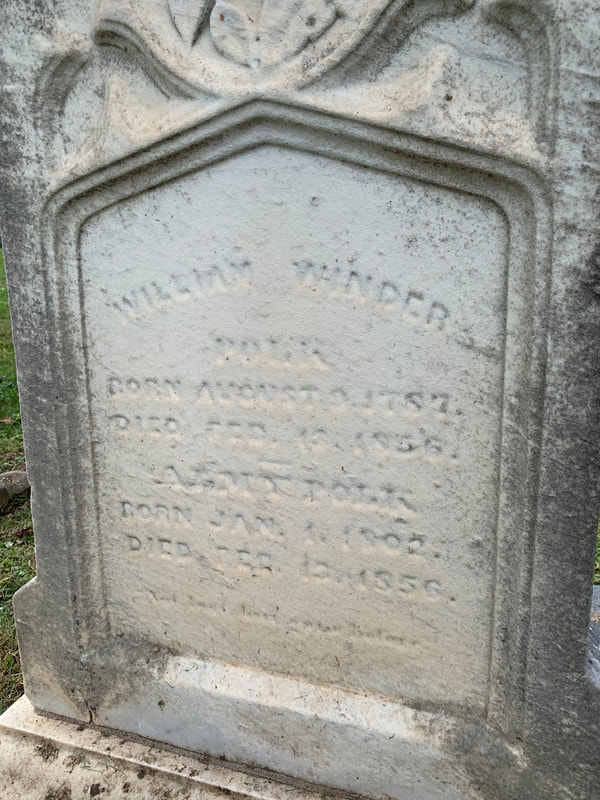

Leaves and Grass on Cradle Grave The empty space between the curbed sides was usually filled with “blanket plantings” – flowers, grasses, or bushes that filled up the inside of the cradle grave, giving it the full and lush appearance of a bedspread, from spring through fall. In the winter, snow would take on the appearance of a blanket drifting over the grave. A short distance from the Key Memorial chapel towards the front of the cemetery, lies a bedstead dedicated to the memory of a well-traveled couple, neither hailing from Frederick originally—William Winder Polk and wife Almy. Mr. Polk was a native of Coventry parish, Somerset County on the eastern shore. He was the son of Wesley William Polk (1752-1814) and first wife, the widow Esther Polk Handy. The youngest of eight children, he was born on August 3rd, 1787. Mrs. Polk was the former Almy U. Townsend of Oyster Bay, Long Island and born on January 1st, 1802. She was married in a double ceremony involving her sister Phoebe on November 27th, 1817. Both girls married Navy officers. Shortly after marriage, the couple could be found in New Haven, Connecticut. Mr. Polk was a member of the US Marines. William and Almy had seven children, but raised five into adulthood. New Haven marked the birthplace of daughter of Mary Townsend Polk, born September 8th, 1822. She married a Victor Monroe of Kentucky, a cousin of former president, James Monroe. Their son, Francis Adair Monroe (1844-1927) became a judge in the court system of Louisiana. Mary would live a majority of her later life in Milledgeville, Georgia where she passed. Capt. William Winder Polk’s career in the US Navy and Marine Service, as it was called back then, does not seem to fit the fact and story-line of most sailors. It seems to be a career he began while in high school. Details are slim, but it appears he worked in various positions including Hawaii, the northern central states, and New England and the long Island Sound. Eventually, Capt. Polk would be one of four Maryland officers who actually received petty cash, while working for the revenue service. An article found in a vintage newspaper announced that he was dismissed from duty in February, 1856. I haven't been able to figure out why this couple came to Frederick, most likely after living for years in Annapolis. I am also searching for a fuller obituary in the local Frederick newspaper archives, but don't have access to microfilm of the specific year which I need. Interestingly, both husband and wife are said to have died on the same day. William died on the morning of February 13th, 1856. Wife Almy was said to have died that very evening of the 13th. The Polks would be buried on February 14th (Valentine's Day), 1856 in a lot located on Mount Olivet's Area H/Lot 26. To this day, they remain the only tenants in this lot which contains several more grave spaces. Although we can replace the expression "Cradle to the Grave" with synonyms such as lifetime and existence, the bed analogy brought about by Victorian era is surely something to behold, especially as can be evidenced by these unique grave monuments.

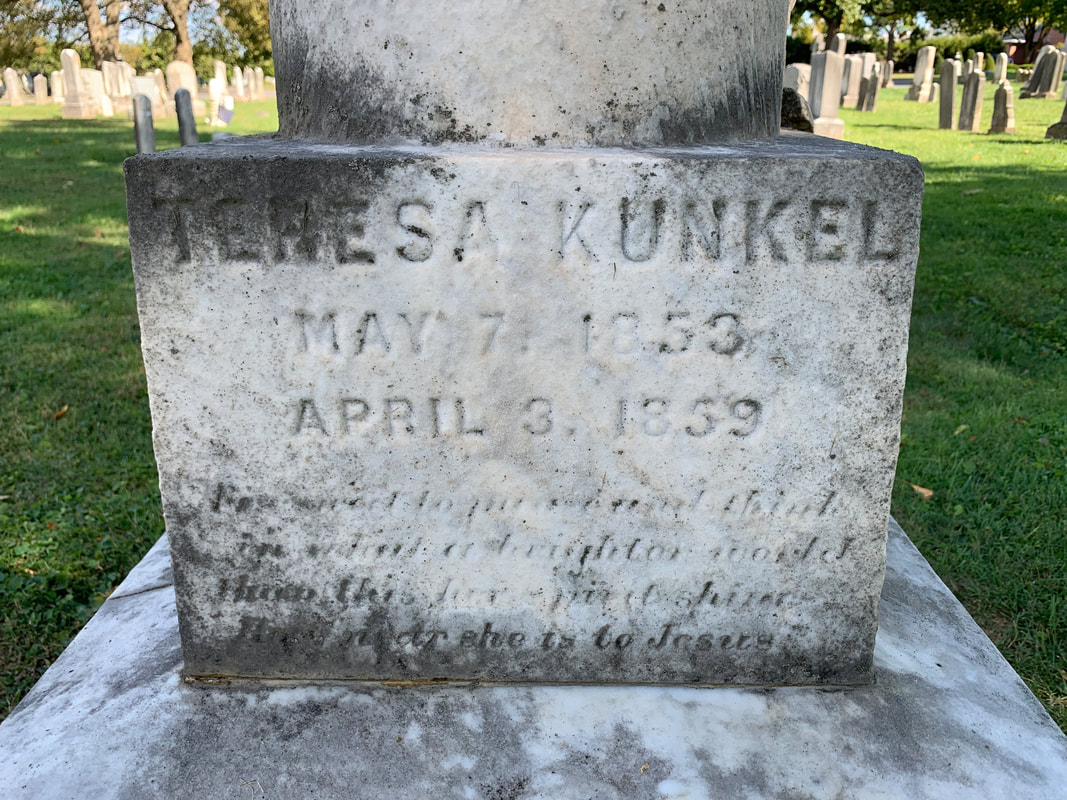

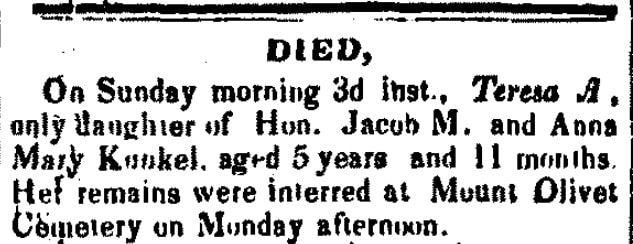

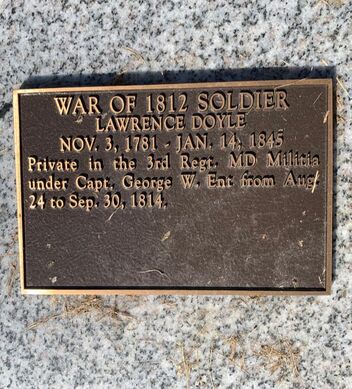

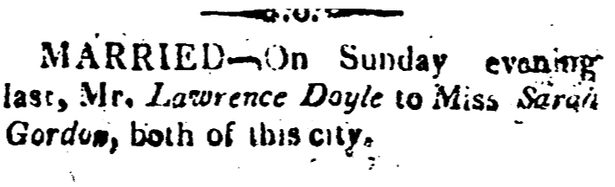

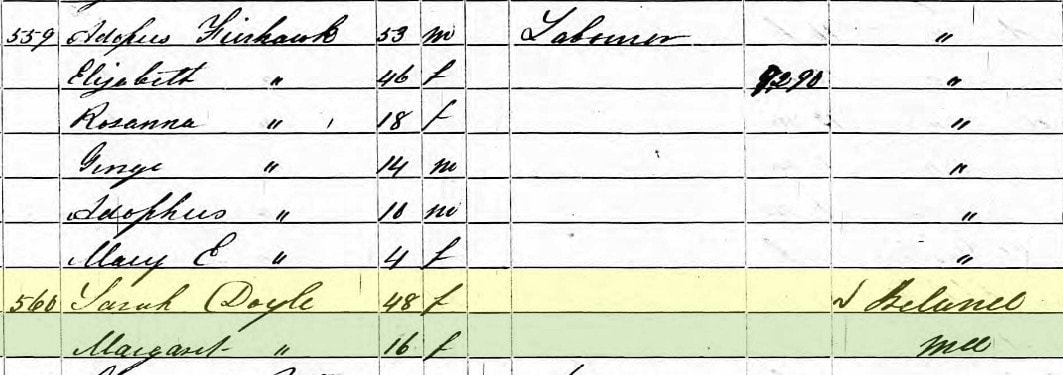

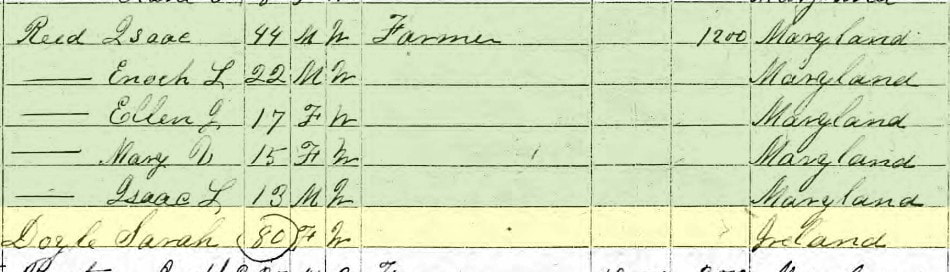

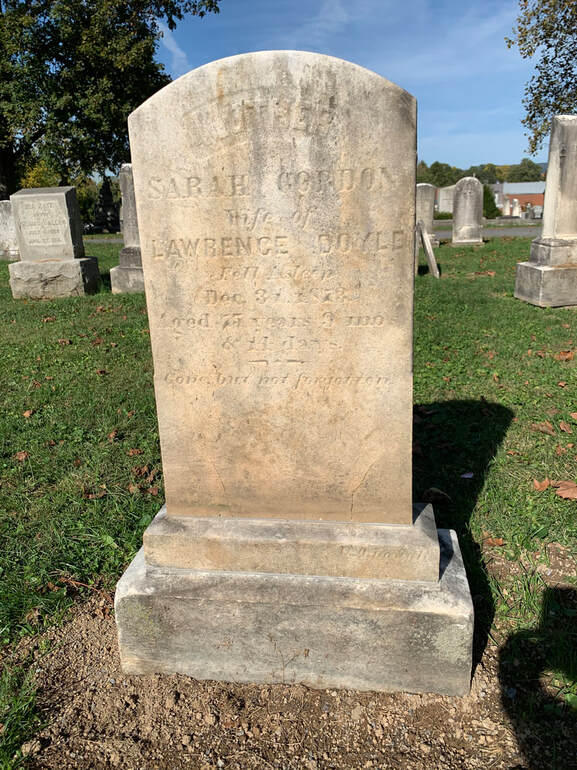

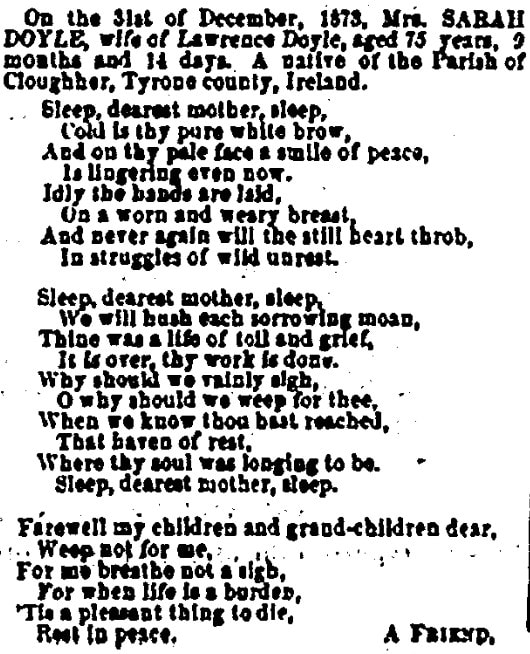

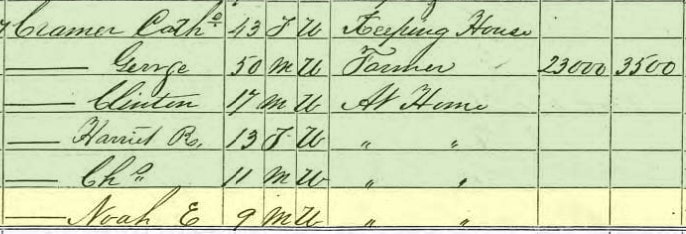

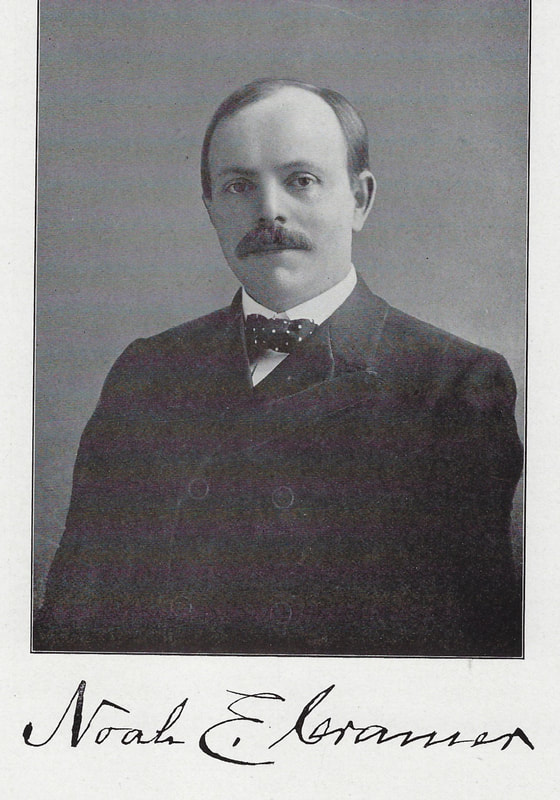

For over a decade, the Mount Olivet Board of Directors entertained the idea of establishing a preservation fund. The plan was first pitched, and championed, by the late Colleen Remsberg, longtime Board member and immediate past president. Ms. Remsberg left us in May, 2018, but not before she saw the Mount Olivet Preservation and Enhancement Fund become an IRS accredited 501(c)(3) public charity. The mission reads as follows: The mission of the Mount Olivet Cemetery Preservation and Enhancement Fund is to assist in the conservation of the natural beauty and historic integrity of Mount Olivet Cemetery and to increase public knowledge and appreciation of its unique, cultural, historic, and natural resources through charitable and educational programs. Putting this in layman’s terms, we continue taking steps to preserve the history of this great “garden cemetery,” a community institution since the 1850s. In doing so, we are safeguarding the cemetery’s historic records, structures and grave monuments. We began nearly four years ago with the launch of this “Stories in Stone” weekly blog, combined with additional education opportunities through our websites (MountOlivetCemeteryInc.com and MountOlivetVets.com), along with public lectures and commemorative events. In February 2020, we officially launched our Friends of Mount Olivet group, allowing us to expand upon special activities and product development which includes cemetery walking tours, visitor assistance with genealogy and family history research, special events and anniversaries, educational partnerships with local schools, and interpretive historic wayside displays and unique commemorative plantings. Best of all, we now have volunteers and patrons to help in documenting, cleaning and helping to raise financial support to restore, repair and preserve broken and illegible gravestones/monuments in the cemetery’s historic section. Evidence of this latter task made the front page of our local newspaper last week, and let me tell you how gratifying it was to see positive publicity associated with Mount Olivet. It’s not hard to fathom that we’d rather see monuments going up, as opposed to three months ago (in July) when we saw some coming down. In particular headlines were made with vandals destroying our 140-year-old Confederate sentinel monument made from Italian Carrera monument. It symbolically kept peaceful watch over 700+ known, and unknown, dead soldiers who sided with the South during the American Civil War. Speaking of history, the Friends of Mount Olivet public workshop on stone restoration last week was simply fantastic! We were the very last stop for Jonathan Appell of Atlas Preservation, Inc. (Southington, Connecticut) who had been conducting a unique restoration tour involving 48 cemeteries in 48 states—performed in 48 days. Mr. Appell is one of the country’s leading experts in this field. He, boasts an impressive resume of work projects and experience that have spanned decades. The workshop began with an hour-and-a-half walking tour of the grounds in which Jonathan was joined by friend and colleague, Moss Rudley, longtime exhibit specialist and Superintendent of the National Historic Preservation Training Center based here in Frederick. The seasoned duo explained styles, trends, and even pitfalls of grave ornamentation of the 18th and 19th centuries.  Work on the Knight's Tomb in Jamestown in Spring, 2019 Work on the Knight's Tomb in Jamestown in Spring, 2019 I first met Jonathan and Moss two years back in October of 2018. At that time, Mount Olivet became an outdoor classroom for a two-day session on gravestone restoration—part of the 22nd annual International Preservation Trades Workshop. We brought Jonathan back to Frederick in October, 2019 to conduct a free, public workshop on our grounds. This would also generate interest in our 2020 launch of our friends group as well. Last year, Jonathan was given the opportunity to explain to participants various projects that he has worked on around the country over his career. This included 17th century burying grounds in his native New England, jobs with the National Park Service, and a recent collaboration with Preservation Virginia involving the mysterious Knight’s tomb in Jamestown Church, historic Jamestown settlement. This gravestone is thought to be the oldest known grave of a European settler in North America. (Note: For more info on these gentlemen, I have added a link to the Frederick News-Post story at the end of my article along with a few others). As for our event on October 7th, 2020, the talented craftsmen chose a random grave monument of interest to conduct an introduction on cleaning gravestones. Jonathan and Moss went on to explain contributing factors to stone discoloration and staining. They followed by demonstrating to participants methods of properly cleaning these stones, using tools and materials that will bring many of these stones back to their original condition, if done correctly. With knowledge and know-how at hand, our instructors encouraged participants to take their hand of cleaning stones for themselves. This lively actively, fitting for a cemetery in so many ways, was followed by a lunch break. After lunch, Jonathan and Moss picked three stones in Area H to repair, and one more in neighboring Area L. Both sections flank the historic Key Chapel and their eastern halves contain several interments dating from the mid-1850s and 1860s—the time of the cemetery’s opening decades. A beautiful day afforded attendees a relaxing atmosphere in which to experience this free portal in which to watch these experts at work. Moreso, they were also breathing new life into stones that had experienced toppling by way of old-age, weathering and ground shift over the years. While engaged in the session first-hand, I suddenly thought beyond the tombstones themselves as I usually do. I asked myself, “Who were the recipients of these “mortuary makeovers?” And just remember, if this ever becomes a program on TLC, you heard the potential program title here first! I decided to come full circle. I would purposely seek out anything I could about the people (beneath the scenes) who unknowingly volunteered their grave markers for our workshop. By the way, I thought I’d share the fact that although we regularly throw around the term “6 feet under,” our cemetery uses the industry standard of 4.5 feet underground for burial. Not counting ground erosion or build up, the cemetery aims for the lid to be at least 18 inches below the surface. And there’s a social distancing update for you. Anyway, four years ago, in November, 2016, I began "cyber-preservation” by publishing weekly features that can be stored on the Mount Olivet website, while new features (like this) make their premieres on the cemetery's FaceBook page. However, none of this would be possible without a gravestone, and even more, an upright and legible gravestone. Markers, monuments, and tombstones are tributes to, and representations of, past lives. Each provides that tangible connection to the deceased. Repairing a stone is no different than penning a biography, the common thread is remembering a life once lived—a lasting footprint. The Kunkel Children The monument featured on the front page news story last week was within Area H/Lot 57 and was erected by a prominent politician, lawyer and businessman named Jacob Michael Kunkel. On the morning tour, Kunkel’s fine monument was called-out by our lecturers for its grand style, but it was another unique funerary offering that was targeted for the cleaning demonstration. This was a seven-foot Greek-style column which appears broken at the top. This latter issue was not done by vandalism or a tree, but rather by design as a popular style of the mid-nineteenth century. Because of its visual impact, the broken-column has remained one of the most popular symbols in cemetery iconography. It represents “a life cut short,” and that is indeed what we have with this particular gravesite containing two children: Henry and Teresa.  I want to start by giving context on the Kunkel name and family. To date, we have 22 folks with the name “Kunkel” interred within our gates. This unique surname is derived from the Middle High German word "kunkel," which means "spindle." It is thus supposed that the first bearers of this surname were spindle makers by occupation. The forementioned Jacob M. Kunkel did more than make spindles as his “Story in Stone,” could weave quite a yarn. I have seen his name in the local papers and history books quite often, and knew he had a connection to the Catoctin Furnace, as an owner in partnership with Peregrine Fitzhugh in the 1850s. Kunkel’s brother (John Baker Kunkel) would run the north county operation throughout the American Civil War, as it would stay in blast without interruption throughout the conflict as armies marched by going to and from the battlefield at Gettysburg in the summer of 1863. The Biographical Directory of the United States Congress 1774 – Present gives the following summary on Mr. Kunkel: KUNKEL, Jacob Michael, a Representative from Maryland; born in Frederick, Frederick County, Md., July 13, 1822; attended the Frederick Academy for Boys and was graduated from the University of Virginia at Charlottesville in 1843; studied law; was admitted to the bar and commenced practice in Frederick in 1846; served in the State senate 1850-1856; elected as a Democrat to the Thirty-fifth and Thirty-sixth Congresses (March 4, 1857-March 3, 1861); resumed the practice of law in his native city; delegate to the Loyalist Convention in Philadelphia in 1866; died in Frederick, Md., April 7, 1870.  You may be interested in the fact that the Kunkel family residence during Jacob M. Kunkel’s life between 1848-1870 was 112 W. Church Street—the famed Tyler-Spite House. This grand mansion would remain in family hands until 1892. The Kunkels have two of the largest, and beautifully ornate, monuments in all of Mount Olivet. Our hosts talked at length about the craftmanship and construction of each before taking us a few short yards away to focus on the grave of two of Jacob’s children. There are seven individuals buried within Area H’s Lot 55. They include the forementioned Jacob Michael Kunkel and wife, Anna Mary McElfresh Kunkel (1821-1879). The Kunkel’s three children are buried here, only one reaching adulthood—John Jacob Kunkel (b. 1849). This family would re-locate to New York City, the site of John’s death, in 1888. John Jacob’s wife, Mary Elizabeth McGill (Kunkel) (1852-1909) is buried beside him, as is one of the couple’s sons, John Harold Kunkel (1878-1912), who died at age 33 of Typhoid fever. The remaining tenants are Jacob Michael Kunkel’s two other children. Henry Kunkel was born August 8th, 1851 and only lived 16 months. He died on April 30th, 1853 and was originally buried in Frederick’s All Saints’ Protestant Episcopal graveyard, once located between E. All Saints Street and Carroll Creek. The family had Henry’s body exhumed and reburied here in Mount Olivet on April 4th, 1859. This was a somber date as it marks the burial of the Kunkel’s only daughter, Teresa. Teresa was born on May 7th, 1853 but would not have the opportunity to celebrate her sixth birthday as she died April 3rd, 1859. Of course, a fair question to ask would be, “Why wasn’t Henry buried here to begin with?” The answer: Because Mount Olivet wasn’t open for burial business until May, 1854. Rest in peace little ones. Sarah G. Doyle Thanks to Jonathan and Moss, this straightforward marble gravestone, white in color, and boasting bold carving, now sits back on its original base in Area H’s Lot 14. Ground shift caused the two base stones to shift, allowing water to rust out the two iron pins holding up the die, or main part of the headstone. Today, it once again stands boldly in memory of Sarah G. Doyle, not far from the grave of her husband, one of 109 veterans in Mount Olivet who served in the War of 1812. Luckily, I was able to glean a bit about this lady who lived 76 years, 9 months and 16 days. I’ve brought up the concept and conundrum of being “a consort” in earlier stories. Sadly, we don’t know a great deal about most women of olden days outside of being “dutiful wives” and “doting mothers”—except, of course, in those rare cases when they actually killed their husbands, and I will leave it at that. And, if you were concerned, I can assure you that Sarah had nothing to do with her husband’s death in 1745. Sarah Gordon was born March 15th, 1797 in Clogher Parish, Tyrone County, in Northern Ireland. I don’t know when she came to the United States, but she married a man named Lawrence Doyle on January 26th, 1822 here in Frederick.

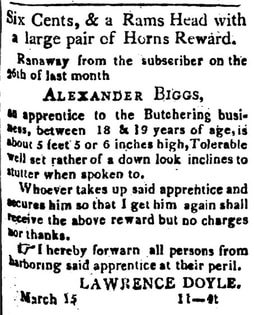

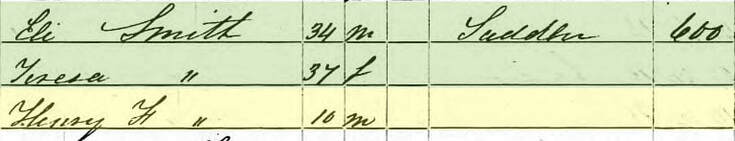

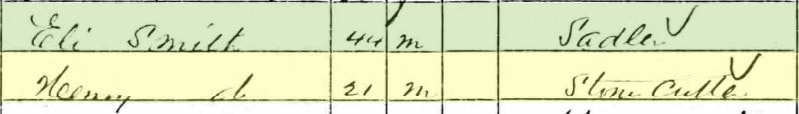

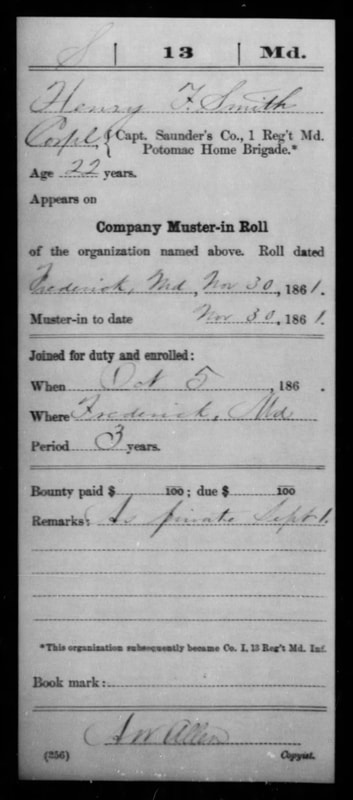

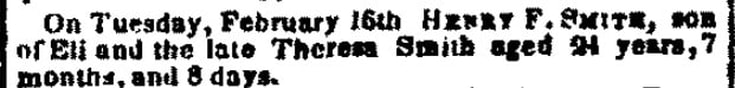

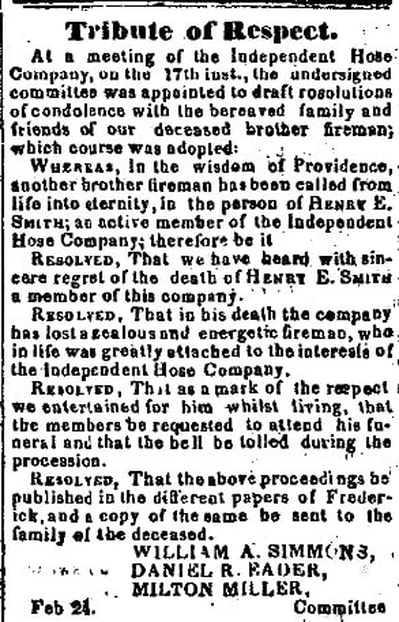

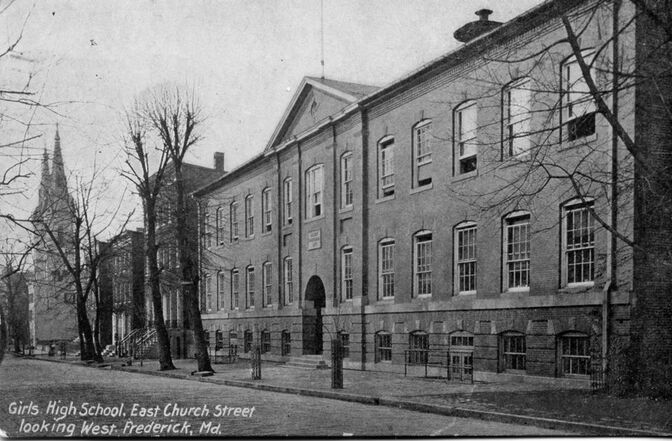

Lawrence Doyle died in January, 1845 and was laid to rest in the Lutheran Cemetery between E. Church and E. 2nd streets. The couple had 23 years together, and five children came from this union: Mary Magdalene Doyle (b. 1822-1825); Elizabeth Margaret Doyle (Feb. 5th, 1825-Feb 16th, 1825); Mary Jane (Doyle) Reed (1827-1858); and Margaret (Doyle) Crum (1838-1905). A son was also born by 1830, either named Lawrence or Henry, but I had difficulty finding more information. In 1850, Sarah was living with daughter Margaret in a home owned by local lawyer Adolphus Fearhake in Court House Square, likely Court Street. I have a strong hunch that Mrs. Doyle was working for the Fearhake family in some capacity. It’s also possible she came into contact with the Kunkels, neighbors living less than half a block away during this period. In 1870, I found Sarah living with daughter Mary Jane Reed’s family in Mount Pleasant. Mary Jane had died in 1858. The native of Ireland passed on December 31st, 1873 and was buried in Mount Olivet on New Years Day, 1874. Lawrence would join her here after a re-interment in 1907, 33 years after Sarah’s death. Henry F. Smith After repairing Sarah Doyle’s grave, we only moved ten yards to our next “mortuary makeover.” It would be in Area H/Lot 25, the grave of Henry Frederick Smith (1839-1864). Talk about a life cut short, perhaps Henry should have had his grave marked by a broken column, instead he had a broken gravestone. Smith’s slim-style upright, tombstone was actually severed in two, the fracture having occurred near the base. This was certainly a more difficult repair than the previous re-setting of the Doyle monument. Our professionals were tasked with re-attaching this piece, while making certain that the base was stabilized—something that was located below the ground surface. The son of Eli and Theresa Smith, Henry Frederick Smith was born on July 8th, 1839 in Frederick. He was baptized in the town’s Lutheran Church and lived in the vicinity, likely on E. Church Street. Henry’s father was a saddler, and according to the 1860 census, Henry worked as a stone cutter. His mother died in 1856, at which time the plot in Mount Olivet was purchased by his father. With hostilities growing in 1861, the winds of war were blowing. Henry joined the Union Army in late November of that year and became a member of Company I of the 1st Maryland Infantry Regiment, Potomac Home Brigade under Captain Walter Saunders. For a glimpse of what he experienced, we can look at the regimental history: During the winter of 1861-62 it served with Gen. Banks and in the following spring marched with that commander up the Shenandoah Valley as far as Winchester, when it was assigned to the duty of guarding the line of the Baltimore & Ohio railroad. When Banks was driven out of the valley the regiment was concentrated at Harper's Ferry, where it remained until the Union troops again the valley, when it resumed the work of guarding the railroad. After Gen. Pope's defeat at the second battle of Bull Run the regiment opposed the passage of the Potomac river at the several fords and ferries near the mouth of the Monocacy, and was then concentrated at Harper’s Ferry, where it was surrendered with the garrison on Sept. 15, 1862.The men were paroled and after being exchanged the regiment was assigned to duty along the Potomac in the southern part of the state. The surrender in question here was associated with the Battle of Maryland Heights, which happened a day after the Battle of South Mountain, and a few days prior to Antietam. Corporal Smith would not return to regular duty as he had experienced a debility supposedly stemming from a cold caught the previous winter. His illness developed into phthisis, known today as pulmonary tuberculosis. Henry would remain at the US General Hospital located in Parole, Maryland, just outside Annapolis. And yes, this is how the current vicinity gained its name. Corporal Henry F. Smith would never see active duty again as he was honorably discharged from duty in February, 1863 due to his disability. He would die of consumption (tuberculosis) one year later on February 16th, 1864. A scant obituary for Henry appeared in the local paper, along with a memoriam from fellow members of Henry’s fire company. Eli Smith, Henry’s father, would die four years after his son in 1868. Since Mr. Smith was the last of his family, this likely explains why he has no grave marker over his final resting place. Eleanor “Ella” O. Keller The final resident renovation of the day in Mount Olivet required some special tools of the trade in the form of a tripod. This tombstone had simply fallen backwards off its base due to its base sinking downward. Thankfully there was no visible damage whatsoever. The solution involved leveling the foundation under the base. An additional challenge was presented with a large, and extremely heavy, gravestone which could not simply be lifted and put back in place by one or likely two workers. Enter a tripod to lift and hold the weight of the die, readying it for placement. In addition, an adhesive compound and lead strips was necessary to help attach the die to the base below. The monument in this demo belonged to Miss Eleanor “Ella” O. Keller, born October 11th, 1851 in Frederick. Miss Keller was the daughter of Charles Frederick Keller and his second wife, Caroline E. Hunt. Ella spent all of her life on E. Church Street. She lived here at what was lot #63, which is the townhouse on the southeast corner of Church and Chapel Alley. She attended school at the Frederick Female Seminary (located at Winchester Hall) and graduated in June of 1868. A professional career saw Miss Keller as a teacher, and she worked at the Frederick Girls’ High School. The former school structure still stands at 115 E. Church and was the former headquarters of Frederick County Public Schools. More recently, it was the home of Artomatic, an artists’ showcase brought to Frederick by the Ausherman Family Foundation. Ella died at age 52, after what her obituary called a brief illness. She is buried to the right of the Key Chapel in Area L/Lot 5. Her two brothers are buried in this plot, along with her mother, Caroline, who is positioned to the immediate left of Ella. Jonathan and Moss took the liberty of re-setting and straightening Caroline's monument while here. According to our cemetery records, Ella’s father is buried in Williamsburg, Perry County, Pennsylvania. It was a great day of information and repairs. Thanks again to Jonathan Appell and Moss Rudley. I know they only made a physical impact on just four monuments in a cemetery containing tens of thousands. However, these are not just any markers, they are above-ground reminders and extensions of the deceased themselves. As if that isn’t enough, now you know a little bit more about the individuals linked with the stones we repaired last week. Banksy is an anonymous England-based street artist, political activist, and film director whose been active since the 1990s. He has left his graffiti art all over the world. A much-repeated quote , poignant for any discussion regarding the importance of tombstones, is attributed to this mysterious man: “I mean, they say you die twice. One time when you stop breathing and a second time, a bit later on, when somebody says your name for the last time.” In respect to restoration and preservation, we’ve got plenty more work to do at Mount Olivet Cemetery. Doing so may positively resuscitate countless victims of an unfortunate second death, one not explained by science, but by forgetting those who have already passed.

ADDITIONAL LINKS to news stories relating to Jonathan Appell and Moss Rudley: