|

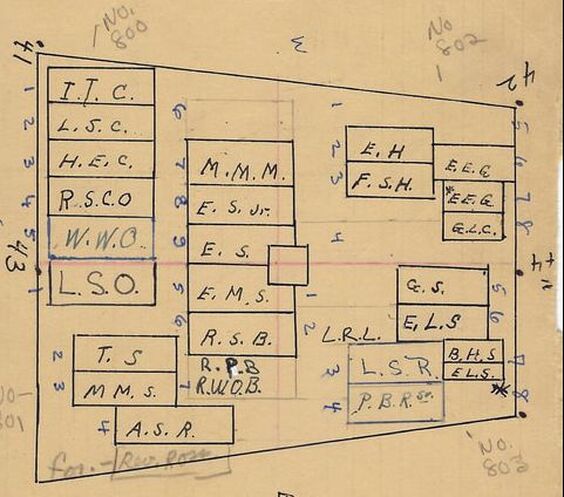

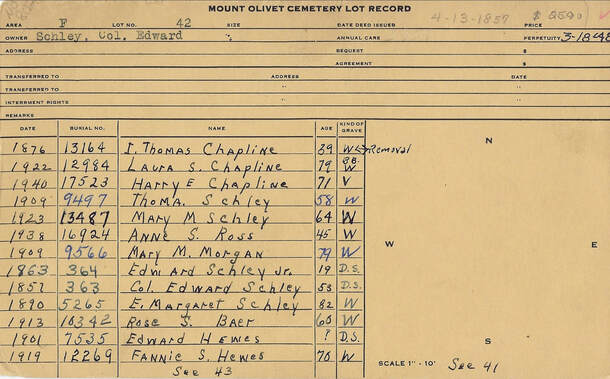

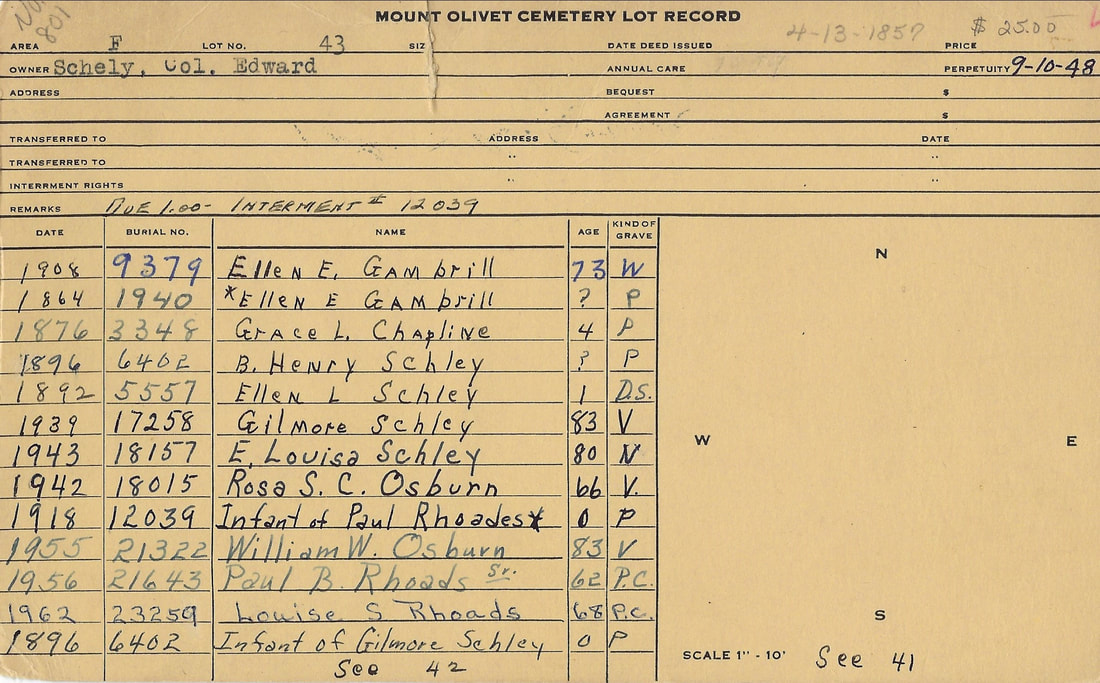

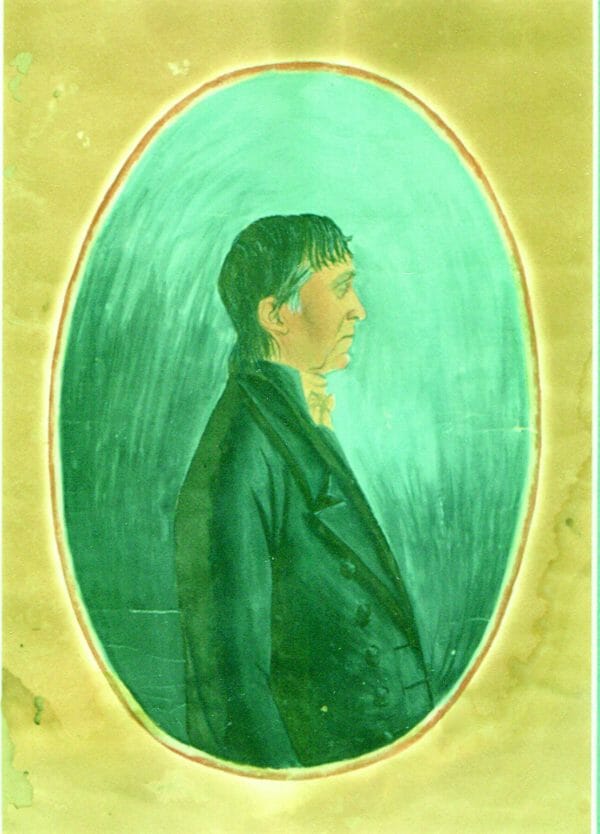

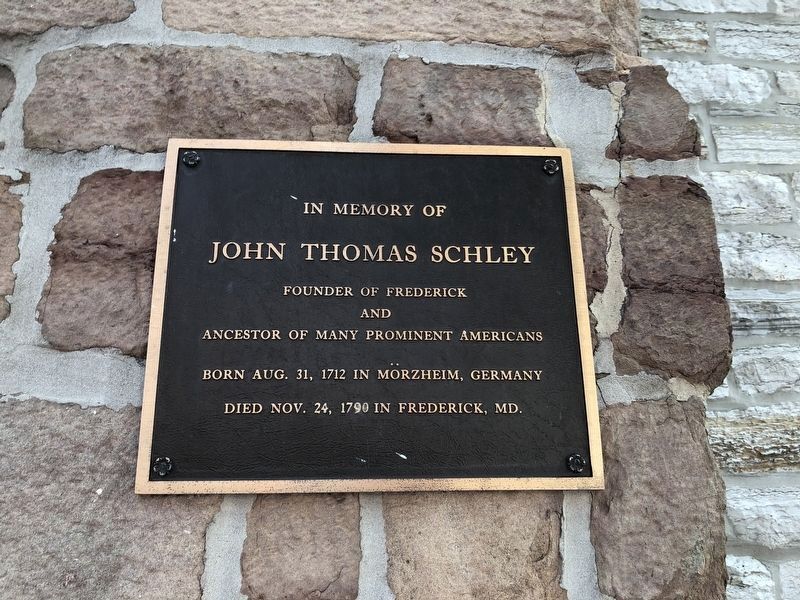

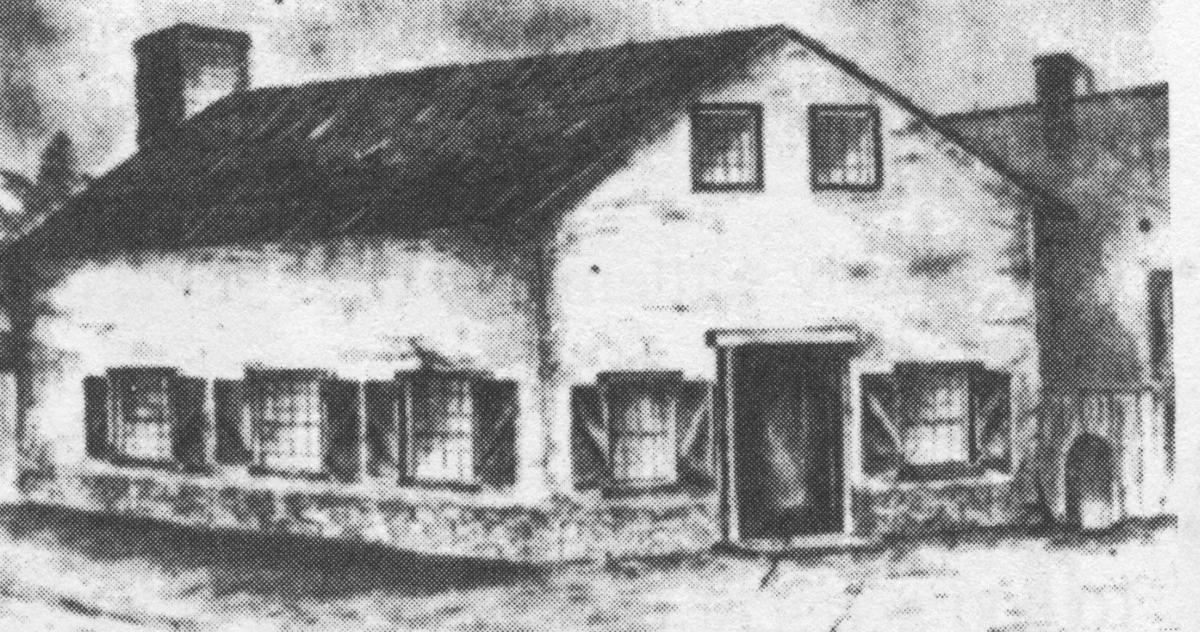

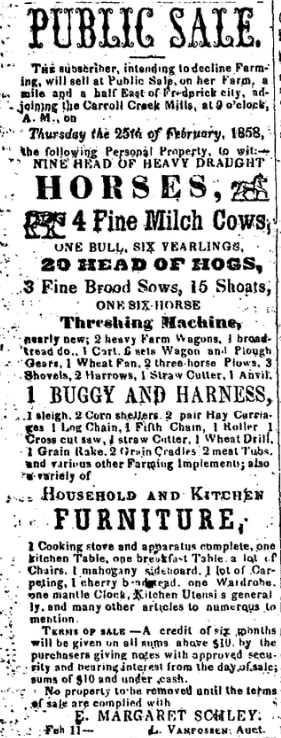

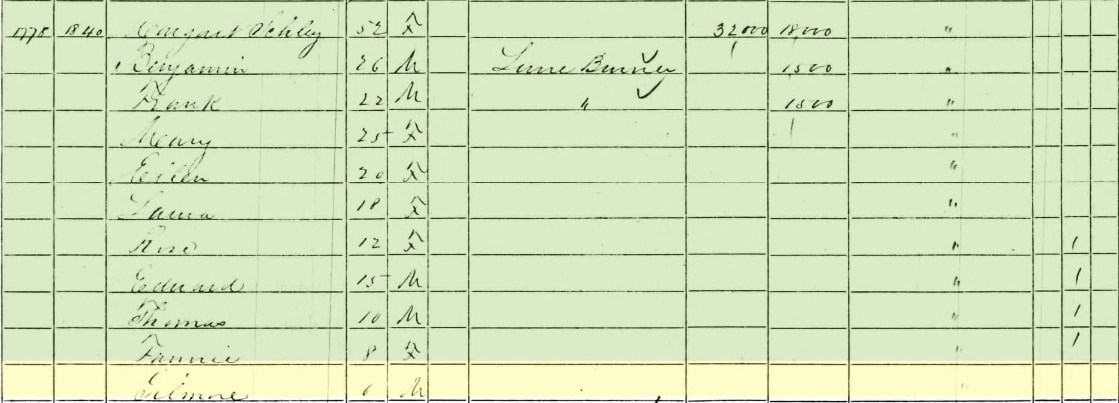

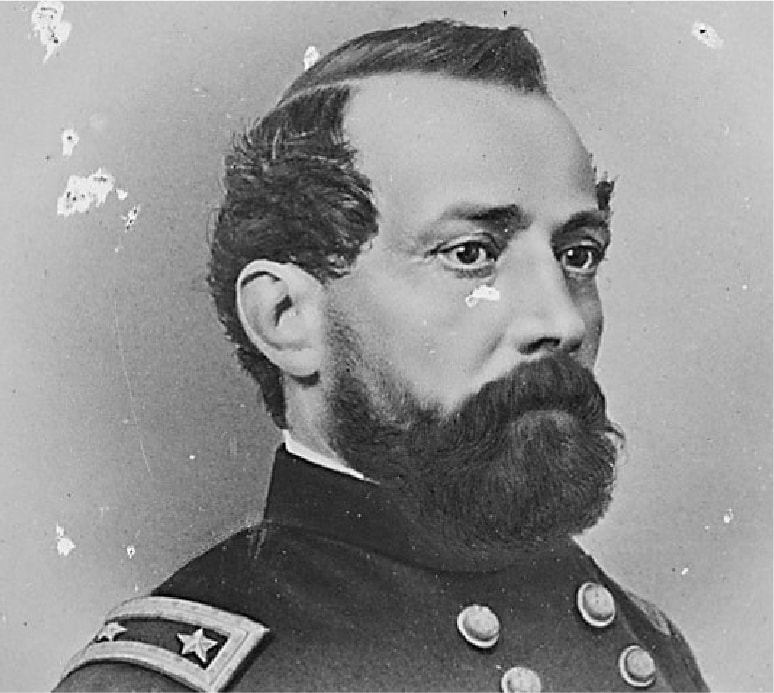

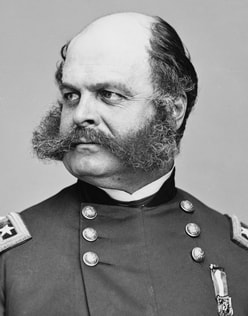

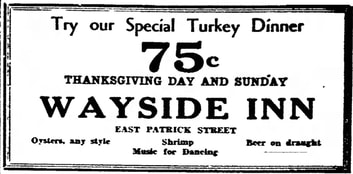

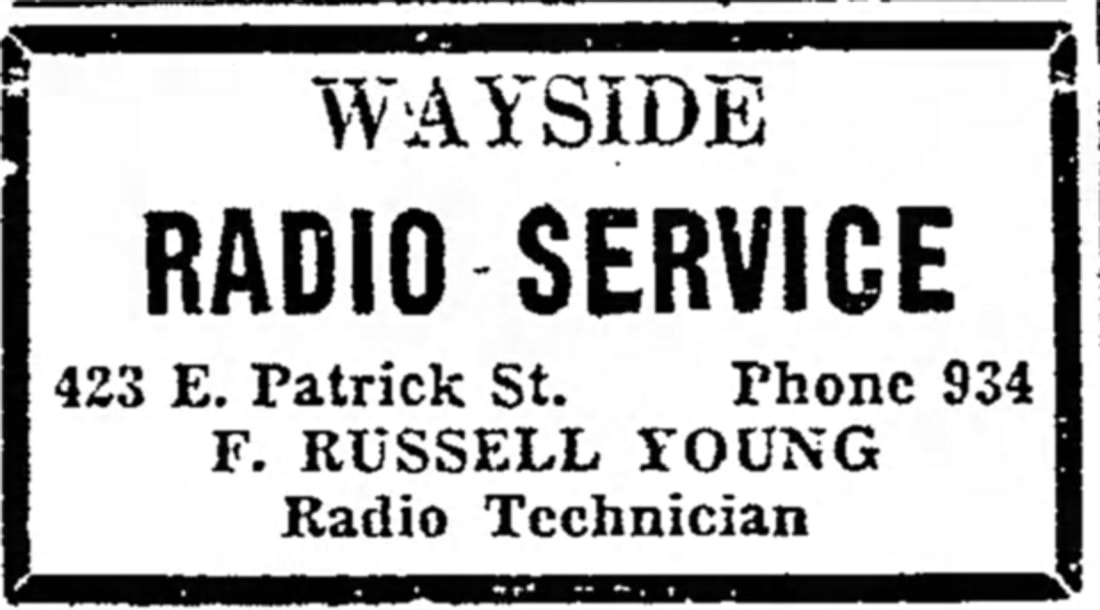

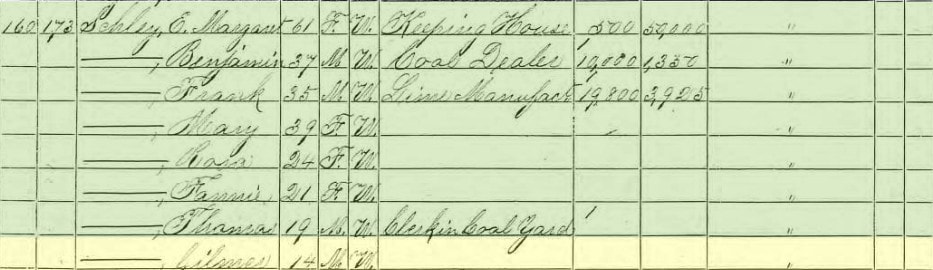

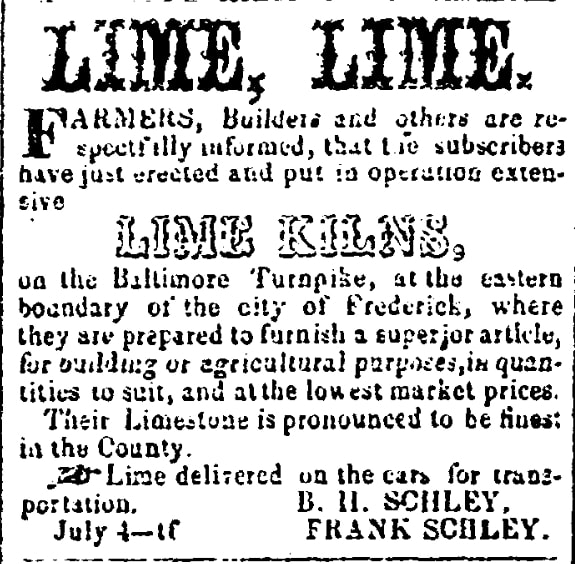

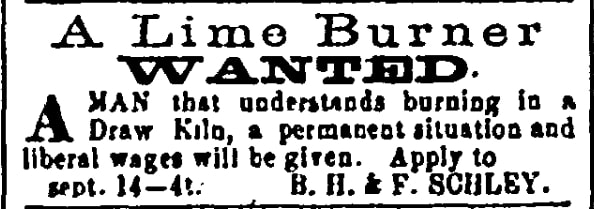

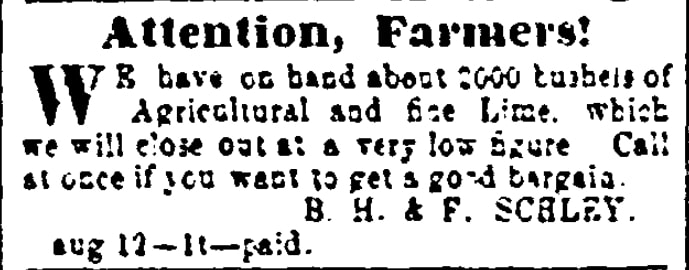

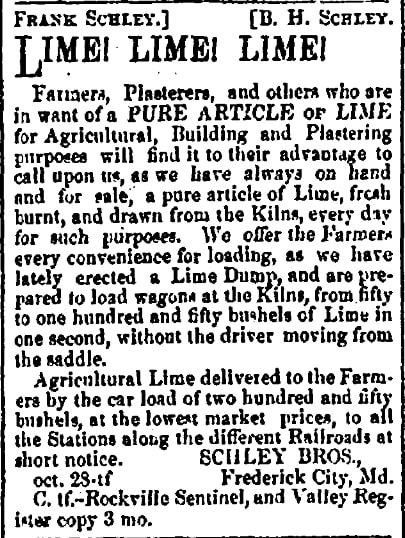

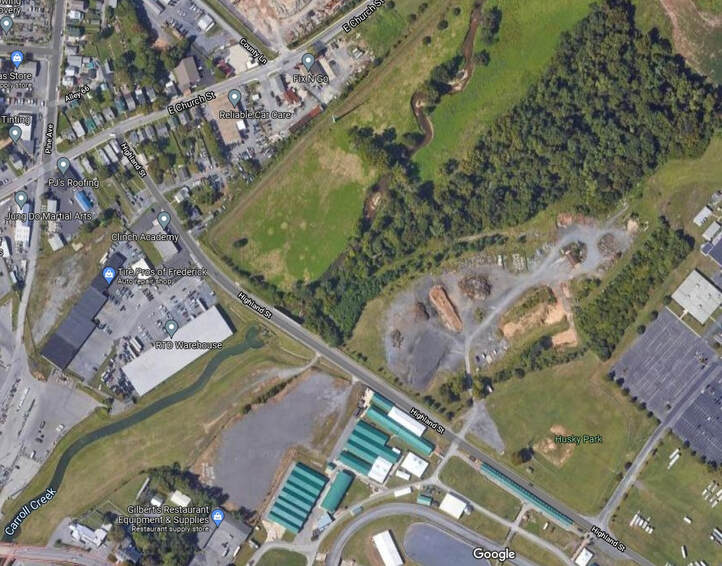

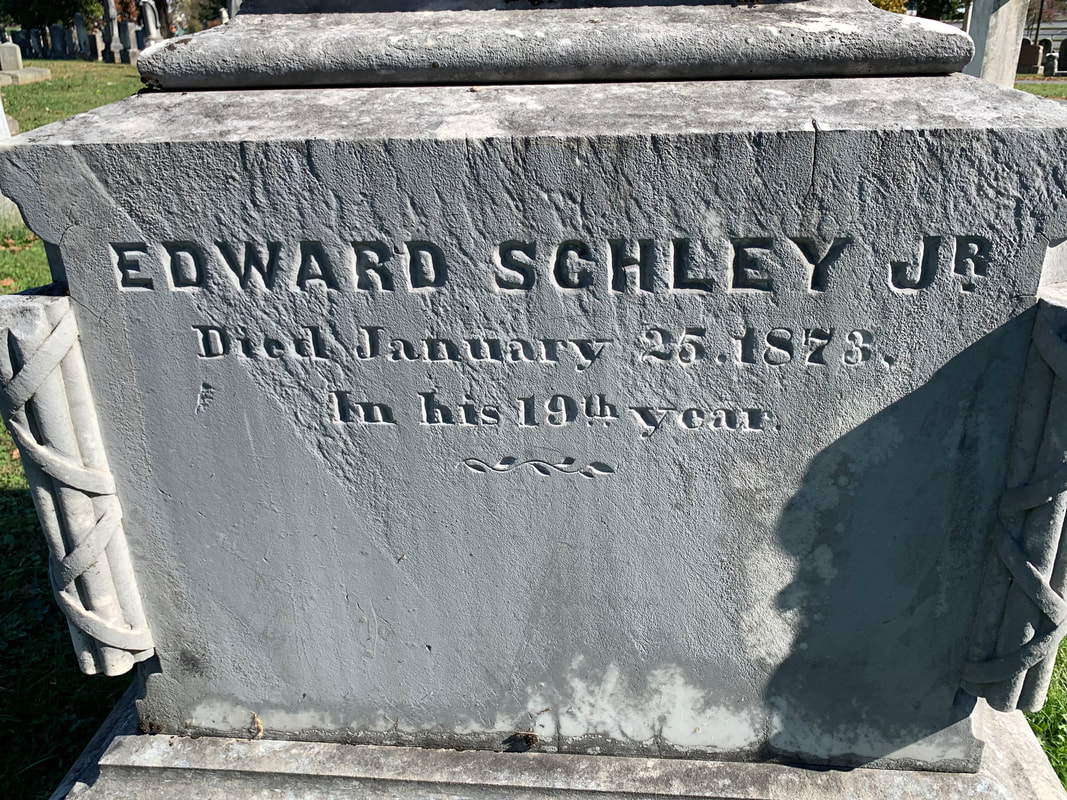

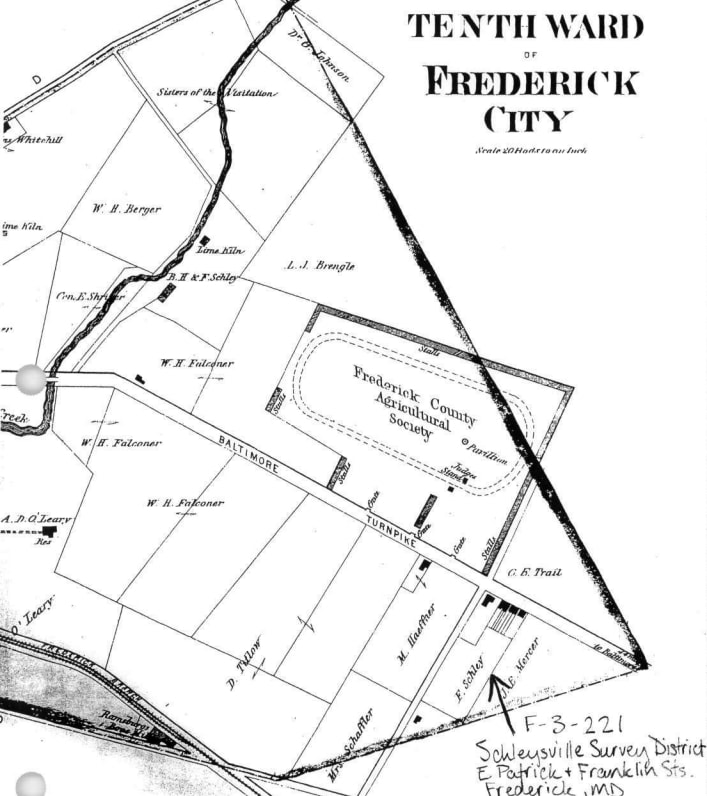

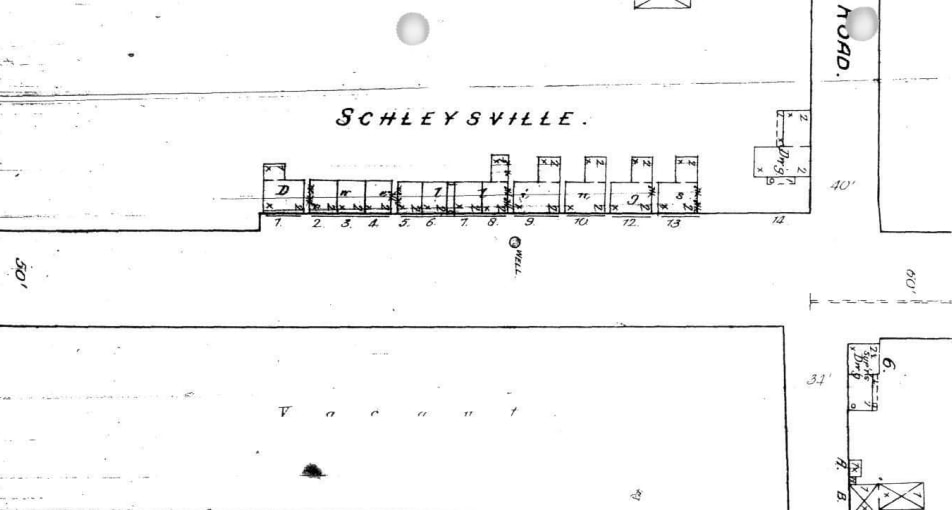

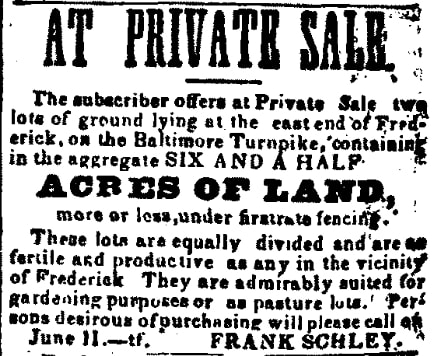

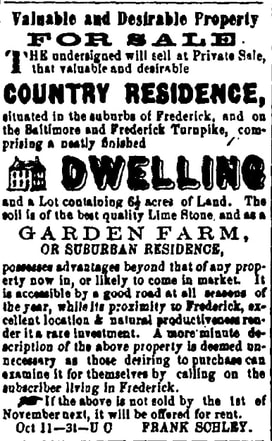

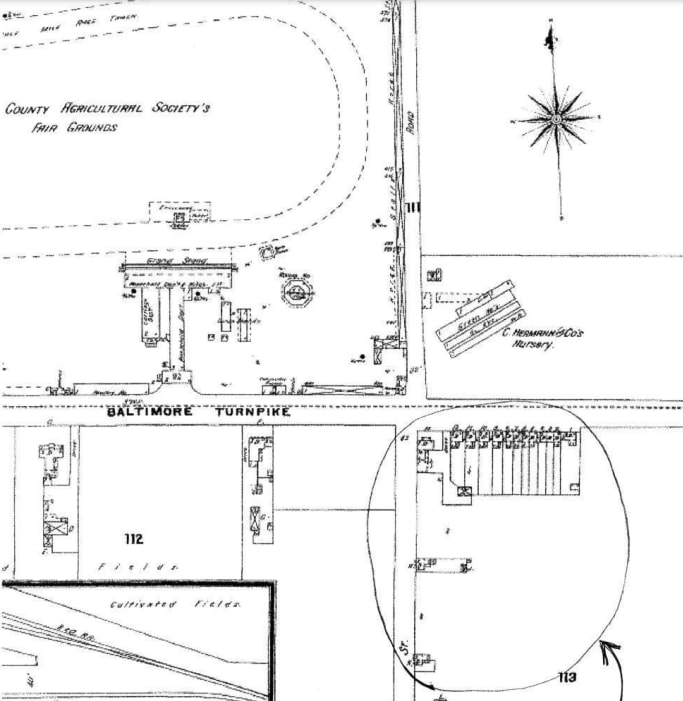

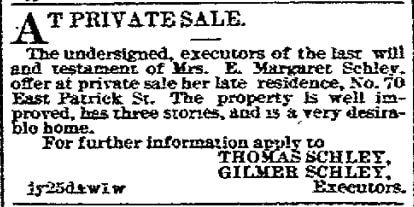

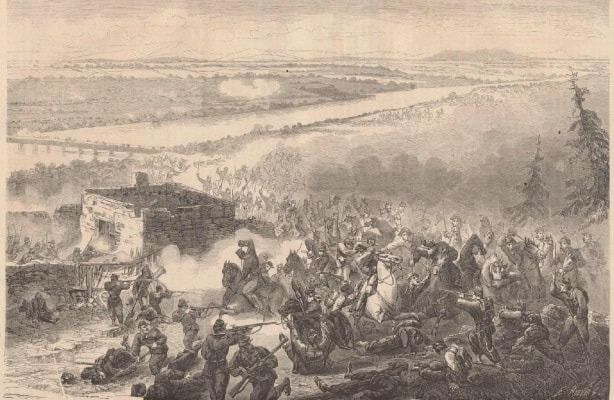

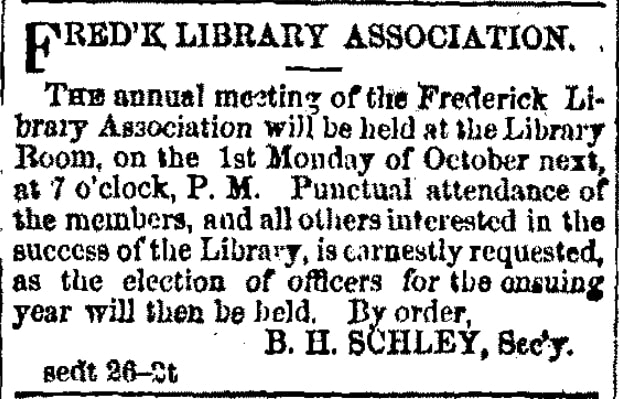

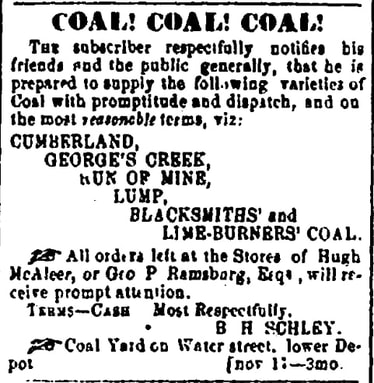

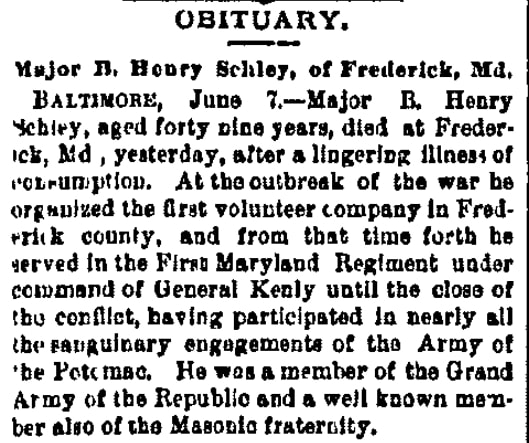

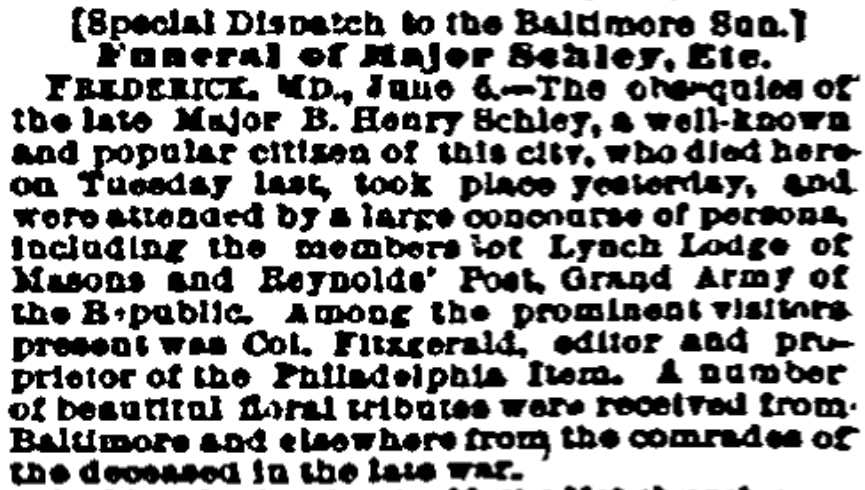

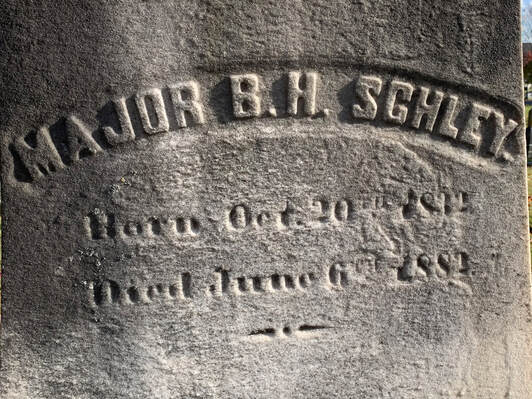

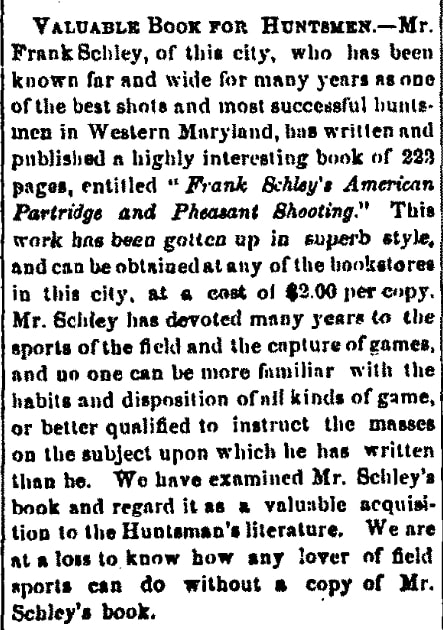

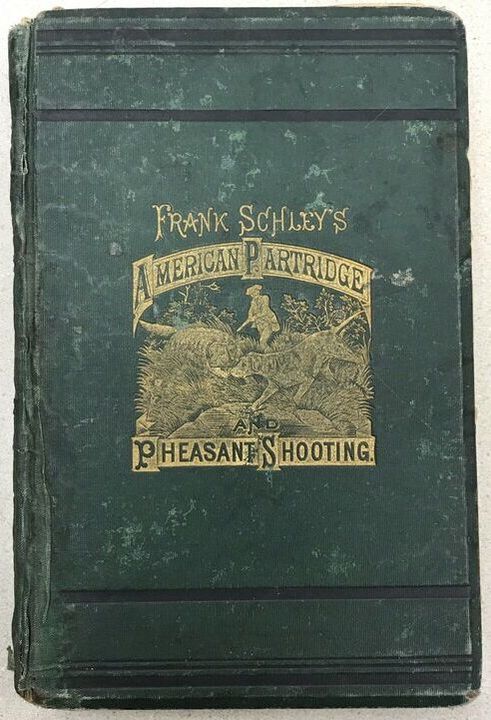

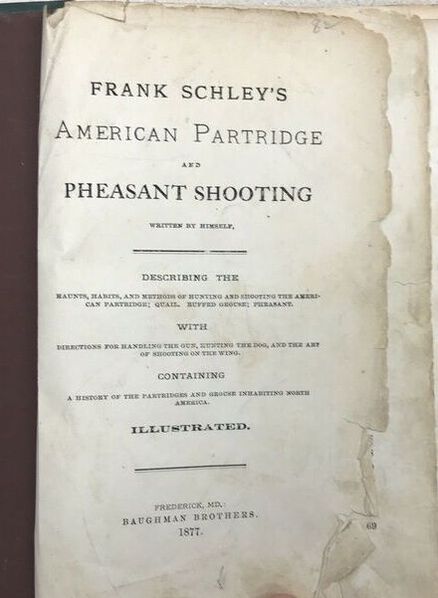

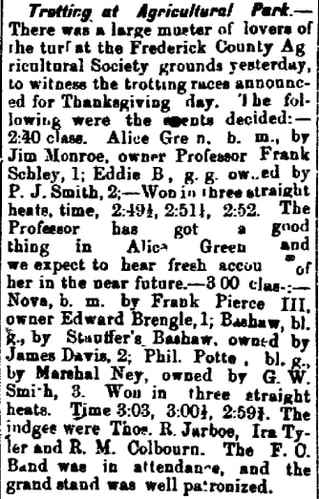

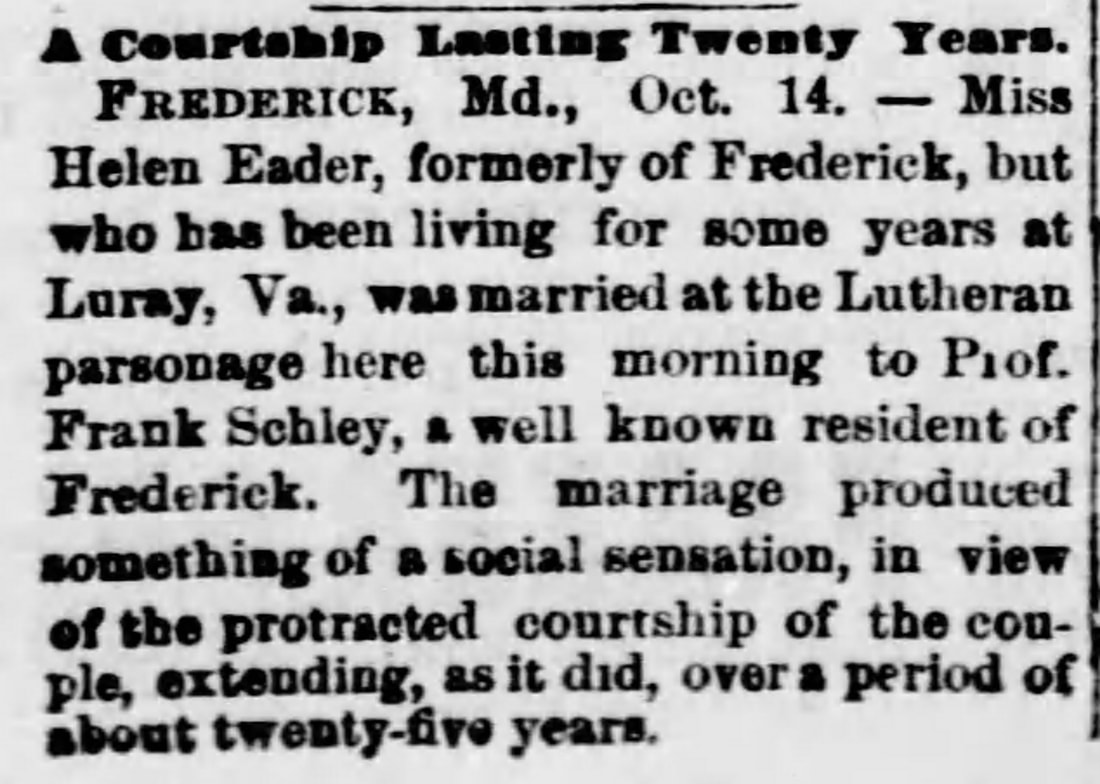

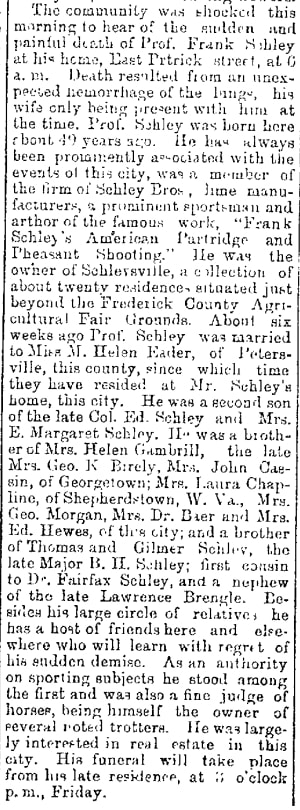

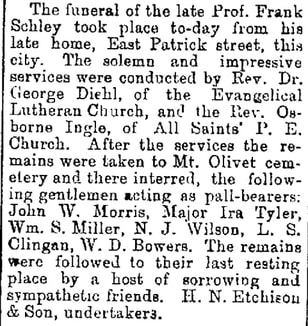

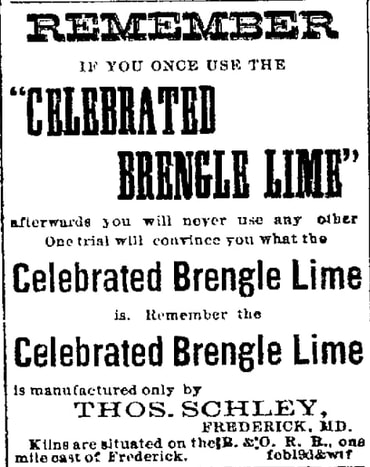

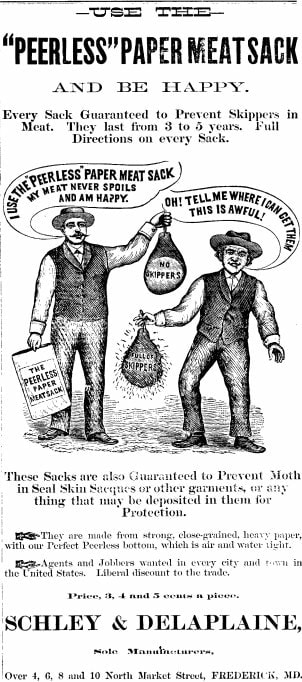

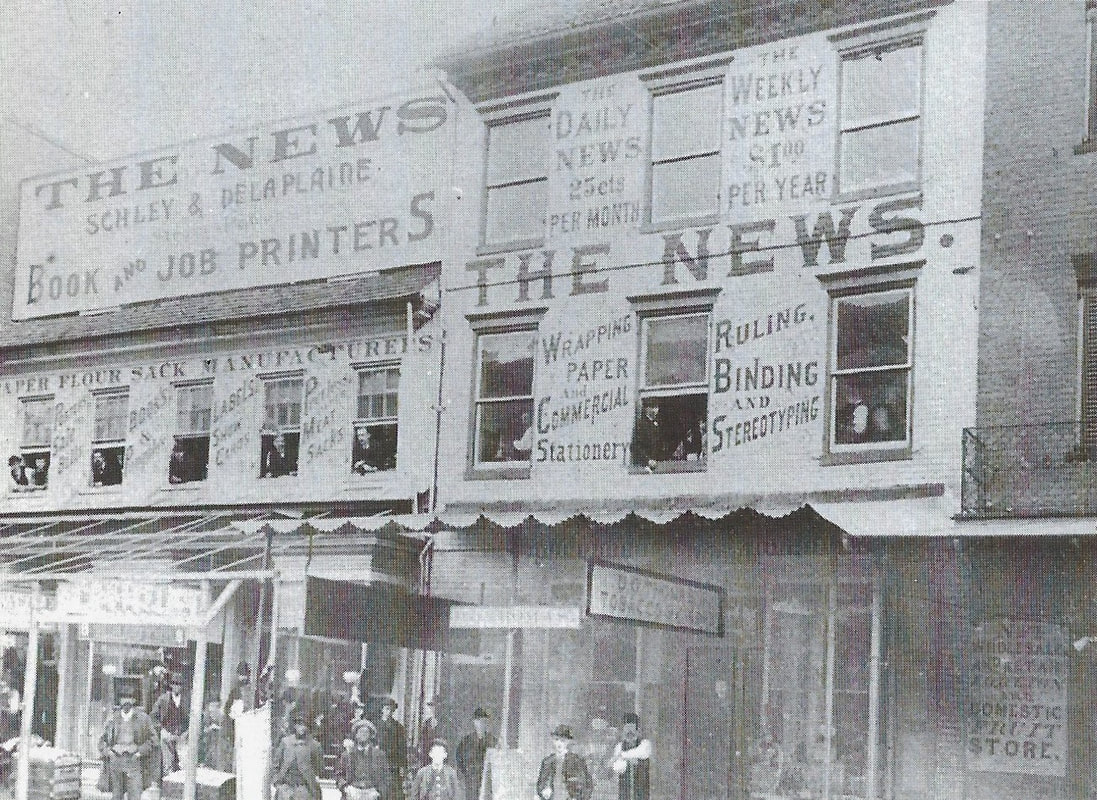

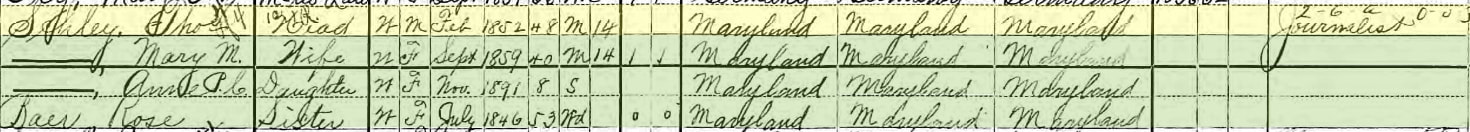

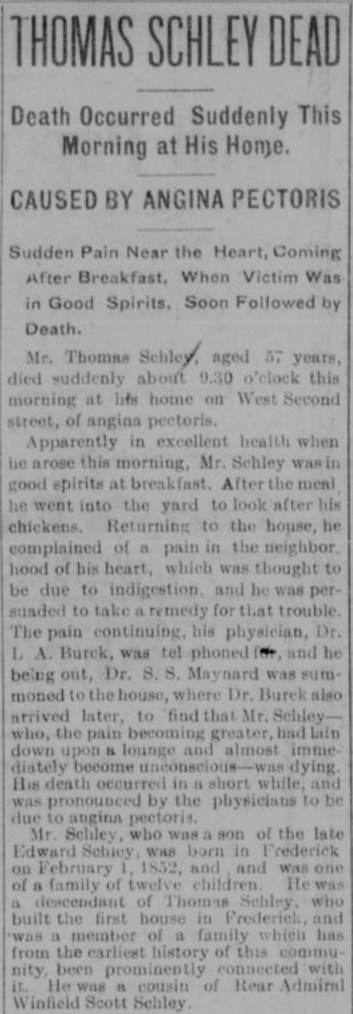

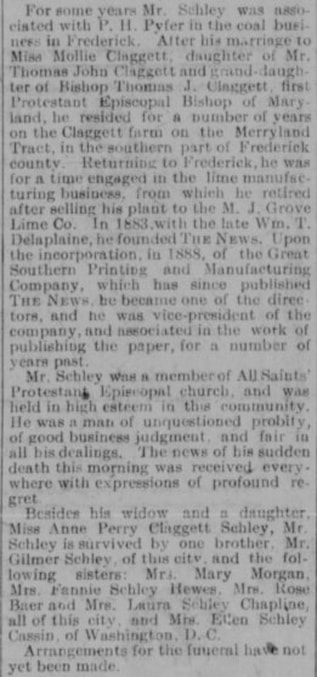

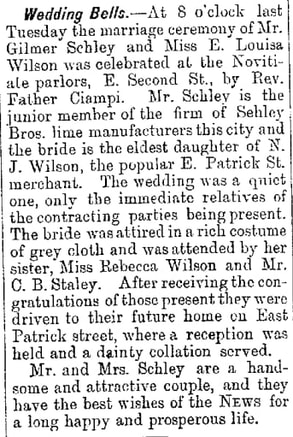

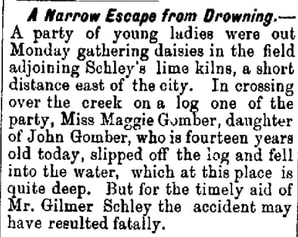

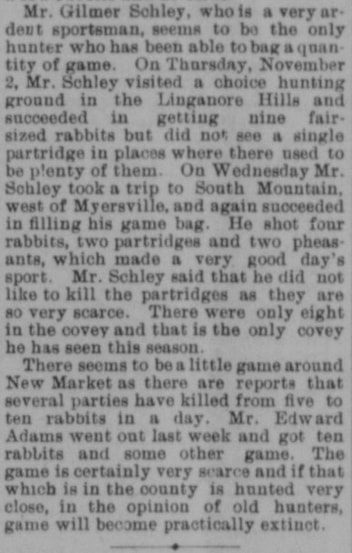

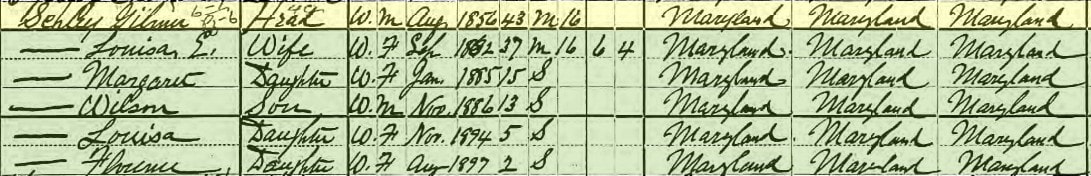

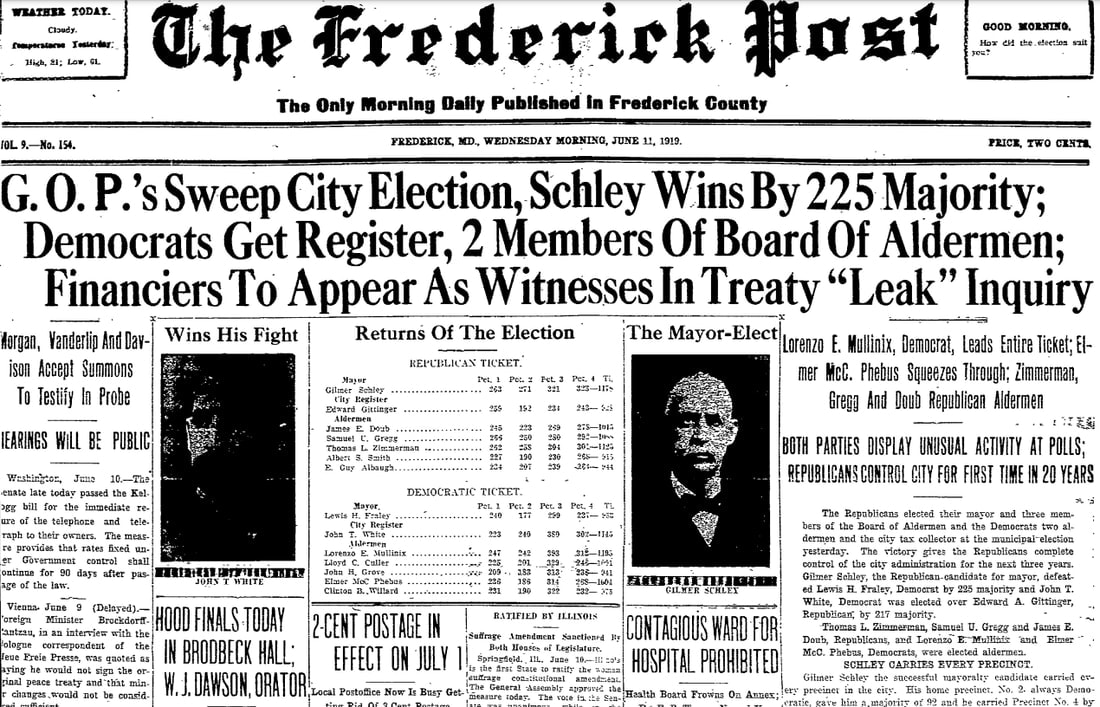

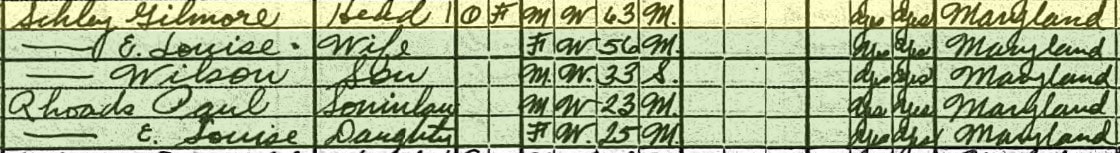

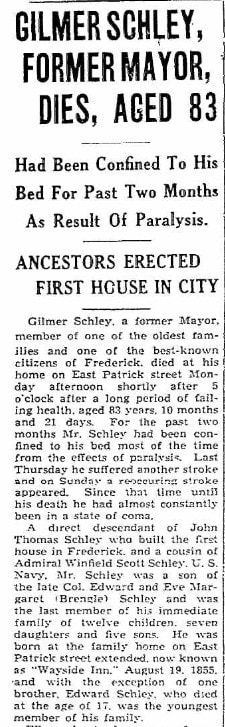

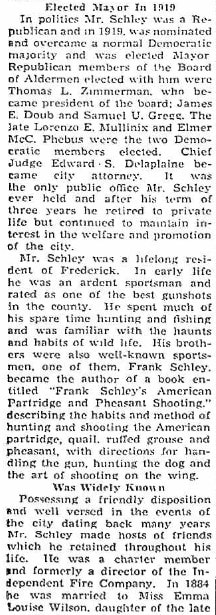

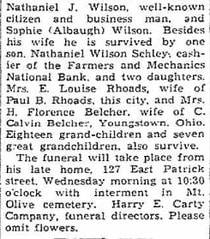

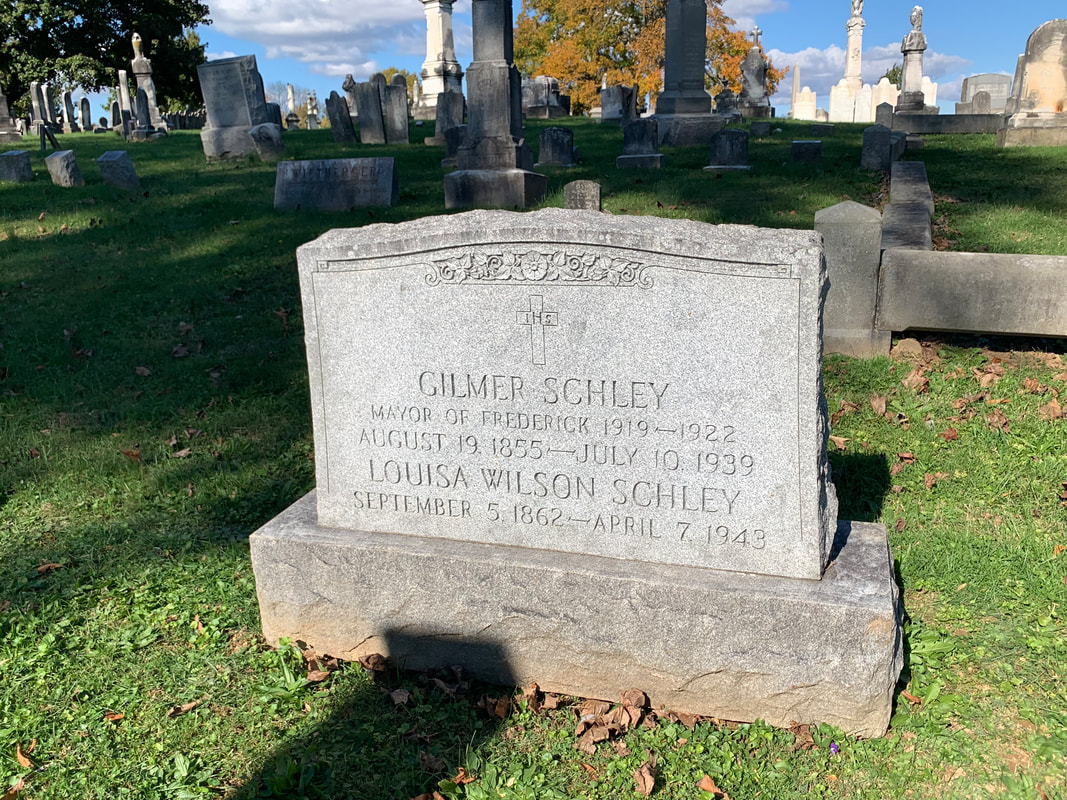

When one thinks of the month of November, three dates usually jump out at you as constants—Election Day, Veterans Day and Thanksgiving. Using that philosophy, I strived to find an individual or better yet family who I could “connect” to all three entities. I didn’t have to look far as I found this in a few generations of the Schley family, one of Frederick’s very first. I will use as my central pivot point the man buried beneath the beautiful monument photographed above—Col. Edward Schley. Col. Edward Schley is buried in Mount Olivet’s Area F/Lot 41. It is in the midst of a large family plot that contains the remains of 30 immediate family members and descendants of Col. Schley and wife Eve Margaret Schley. Nothing screams Thanksgiving like a large family gathering, right?!  A map of the Schley grave plots in Area F found on the back of an interment card. Col. Edward Schley's individual grave space (#6) is in the center and denoted with his initials E.S. His wife is below him in space #5 and labeled E.M.S. This map corresponds to the two lot cards below showing the majority of decedents here in the Col. Edward Schley family plot Col. Edward Schley, son of John Thomas Schley (1767-1835) and Anna Mary “Polly” Feree Shriver (1773-1855), was born in Frederick City on June 29th, 1804 and died in 1857. His father was a man all too familiar with Election Day as he served as judge of the Orphans Court from 1802 to 1813, was elected to the House of Delegates in 1809 and 1810, and held the position of Clerk of the Circuit Court from 1815 to 1835. In case you are curious, John T. Schley (Col. Schley’s dad) is buried a short distance away from his son in Area MM/Lot 43. Here also lies the colonel's mother as well, both originally buried in the Old Reformed Graveyard on Bentz and Second streets before being removed here to Mount Olivet in 1916. Col. Edward and his father were so named with a moniker that holds a special place in the Frederick history books. This was our subject’s great-grandfather, the famed John Thomas Schley, one of the earliest settlers in Frederick Town. The original John Thomas Schley (1712-1790) was the first schoolmaster of the German Reformed Church here in town, and as a matter of fact, is credited with building the very first house in town. He emigrated in 1737 from Morzheim, in the region of Rheinland-Pfalz some 328 miles southwest of Berlin. Like many early immigrants from the Palatinate of the Rhine, he first arrived in Philadelphia, and in 1745 removed to Frederick Town at the head of a colony of about one hundred families of Calvinists and Huguenots—natives of France, Switzerland and Germany. John Thomas Schley is credited with settling these immigrants here in the Monocacy Valley, and helped settle this town amidst a “howling wilderness.” He is noted as having been a talented musician and songwriter whose handwritten work can be found in the collection of Heritage Frederick. John Thomas Schley was also the father of Eva Catherine Schley, the first white European child born in this locality. He is said to have been a man of considerable means, and a leader among his people in the Province. Like his ancestor, Col. Edward Schley was active in the community, and is on record as raising money for a public school. He was admitted to the Frederick County Bar in 1833 and operated the Carroll Creek Flouring Mills in his early professional career. His legacy points to him being one of the leading citizens of the community in his day. Politically, he was an old-line Whig, and in religion, he was affiliated with the Episcopal Church. Schley was appointed the position of Captain of the Frederick Hussars on February 16th, 1850, and commissioned Lt. Colonel of the First Regiment in January 1851. This group was the equivalent of a local cavalry unit under the larger network of the Maryland state militia. The name, hussar, comes from those who earlier served as a member of a class of light cavalry, originating in Central Europe during the 15th and 16th centuries. The title and distinctive dress of these horsemen were subsequently widely adopted by light cavalry regiments in European armies in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. From several newspaper accounts I found in my research, the Frederick Hussar detachment under Col. Schley participated in ceremonial endeavors such as parades, funerals and special events both here in town, and abroad in places such as Hagerstown, Baltimore, Washington, DC and others. A number of armored or ceremonial mounted units in modern armies retain the designation of hussars. In Frederick, it appears that this group dissipated over the decade (1850s) into the formation of military units doubling as the towns leading fire departments (Junior Defenders, Independent Grays/Riflemen, and the United Guards (aka “Swampers"). Col. Edward Schley married Eve Margaret Brengle (b. 1809) on December 4th, 1827. The colonel’s bride was the daughter of an outstanding veteran of the War of 1812—Captain John Brengle, a co-subject of an earlier “Story in Stone” from August, 2019 and entitled: “A Patriot in the Pulpit.” http://www.mountolivethistory.com/stories-in-stone-blog/a-patriot-in-the-pulpit When it came to family building, Edward and Eve Margaret Schley had a lot to be thankful for as they were the parents of 13 children:. These included: Annie Elizabeth (Birely) (1828-1880), Mary Margaret (Morgan) (1830-1909), Benjamin Henry (1832-1882), Ellen E. (Gambrill) (1834-1908), Franklin (1837-1886), Alice Schley (Cassin) (1839-1911), Laura Louisa (Chapline) (1842-1922), Edward Jr. (1844-1863), Rose C. (Baer) (1846-1913), Fannie (Hewes) (1848-1919), Thomas Steiner (1851-1909) and Gilmer (1855-1939). The youngest of which, Gilmer Schley, would serve as Frederick’s mayor in the early 1920s. The Schley family would reside in an iconic mansion still standing on the east side of town on East Patrick Street, just east of Carroll Creek. Col. Schley purchased this property in 1852 for $7,724. This would later be more commonly known as the Wayside Inn. The Schleys operated a farm and a lime works operation on the eastern bank of Carroll Creek on the north part of their property. Col. Schley would die on another day typified by a gathering of family in one place. He passed on Easter Sunday night, April 14th, 1857 at the age of 52. Following Schley’s death, Eve Margaret and several children remained at the house on E. Patrick Street. An advertisement in the local papers in 1858 show that she intended on lightening her load by ceasing to operate her home as a farm operation. She duly sold many farming implements and livestock at auction. Her two oldest sons, Benjamin H. and Franklin “Frank” Schley, had taken over the operation of the agricultural lime works.  Christina Martinkosky of Frederick City’s Planning Department included some fantastic details regarding the Edward Schley family in her insightful Preservation Matters series with an article about Wayside. This appeared in the Frederick News-Post of April 8th, 2018, and Christina brought to light a great slice of local Civil War history: “Historic records show that the Schley family-owned slaves both before and after Col. Edward Schley’s death. However, when the Civil War erupted in the early 1860s, the two oldest sons served in the Union Army. During the summer of 1862, after the Union Army suffered crushing defeats at Richmond and at the Second Battle of Manassas, Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee sought to bring the war to Northern soil. On Sept. 5, 1862, Southern forces entered Frederick but moved westward the following day. As the Confederates withdrew, Union troops led by Gen. McClellan quickly maneuvered from Washington, D.C., into Frederick. On Sep. 12, the Union Army camped around the Schley House. However, according to Mrs. Schley’s daughter, Gen. Jesse L. Reno, a well-respected and beloved leader, and famed Gen. Ambrose Burnside were invited by Mrs. Schley to sleep in family home. The Union forces stayed only one night before moving westward to follow the Confederate Army. On Sept. 14, Reno was killed at Fox’s Gap by a Confederate sharpshooter. According to newspaper accounts, a flag given to Reno by Barbara Fritchie covered his casket at his burial in Boston. In 1864, two years after Reno and Burnside stayed at the house, Margaret Schley sold the property to William Falconer for $12,000. In 1906, Elmer and Amy Dixon purchased the old Schley House along with 50 acres of land. For several years, the couple farmed the property, which they called Lawnsdale. In 1917, however, the property was converted into an inn. Re-branded as the Wayside Inn, the site quickly became one of the city’s most popular restaurants. A large addition was soon added to accommodate a dance floor and nightclub.” It is used as apartments today. Mrs. Schley continued the job of raising her children into adulthood after Col. Schley’s death, but had the financial means to do so as her former husband left her in good financial standing. As said earlier, Benjamin H. and Franklin “Frank” Schley were running the agricultural lime works. This would be one more means of taking care of their mother and greater family. The Schley Brothers Lime Works was located on a parcel behind the main manor house, at a location on the northside of today's Highland Street and to the immediate west of Husky Park with its baseball field. The City of Frederick owns this parcel today and it is used as both a dump and storage-yard facility. This entity was originally begun by the boys' mother's family the Brengles. Entrance to the plant was via a dirt lane off East Church Street . This eventually became Highland Street, near what was at one time called Sister's Hill. There was a quarry from which the limestone was chipped by hand, which was a long and tedious process. The operation included several pot kilns where lime was burned and used as ground burnt lime, which farmers spread over their fields to enrich their soil. Benjamin H. and Frank Schley served in the American Civil War and escaped without injury or incident. They came back to the lime plant and would continue to operate the business through the 1880s. The brothers apparently retained the industrial parcel, with a right-of-way to the turnpike, even after their mother, Margaret Schley sold the manor house property to William Falconer in 1864. Margaret was likely still in mourning as she left Wayside because she had lost one of her children during the Civil War. This was Edward Schley, Jr. who died at the age of 19 of an undisclosed debility on January 25, 1863. The family would take up residence in town. Frank Schley purchased a nearby three-acre lot to Wayside in 1862, two years before his mother sold the family manor house. This was apparently purchased with the intention of building a new home for his family and perhaps his mother as well, the house (now 800 E. Patrick St.) must have been constructed by 1864 when the manor house was sold. In 1867, the Frederick County Agricultural Society purchased 30 acres of land east of the Schley’s Wayside property. The parcel in question was on the north side of East Patrick Street and formerly belonged to local attorney Gen. Edward Shriver. This would become the new home of the Frederick Fairgrounds, a move from the Frederick (Hessian) Barracks site on S. Market Street. By 1870/1873, Frank Schley had begun construction of a series of brick rowhouses, probably tenanted by his own lime works employees on lots fronting onto the turnpike. The 1887 Sanborn Insurance map shows the subdivision noted as "Schleysville," reinforcing its association with the Schley family and business. I learned more about this locale thanks to the Maryland Historical Trust’s Maryland Inventory of historic properties (No. F-3-221). “Today this constitutes a grouping of mid-19th century and early 20th century houses fronting on E. Patrick and Franklin Streets and centered on the Franklin Schley House on the corner. The subdivision of small, worker houses, some attached row houses and some single row-type houses, stands out along this part of E. Patrick St. where most of the houses are 20th century, large single family houses on large lots. In addition to the Franklin Schley House on the corner of E. Patrick and Franklin Streets, the survey district includes 4 brick free-standing rowhouses, a series of 4 attached brick rowhouses, a series of 3 attached brick rowhouses, and a frame free-standing house, all fronting on the south side of E. Patrick St.; and on the east side of Franklin St. are 2 brick free-standing rowhouses and 3 frame double rowhouses (6 units) set back from the street. The grouping of buildings is located on approximately 3 acres, historically one lot but since subdivided into individual parcels. There are 22 contributing buildings. Rear yards were not observed and so outbuildings that may exist are not included in the resource count. The Schleysville Survey District is a significant example of mid-19th century subdivision development for worker housing on the edge of Frederick City, Maryland (National Register Criterion A). Developed by Franklin Schley, owner of a nearby agricultural lime works, and adjoining his own elegant dwelling house, the brick rowhouses of Schleysville provided relatively substantial and convenient housing for Schley's employees. An early 20th century addition of three double rowhouses to the lots on Franklin St., probably associated with the ownership of the housing group by the M.J. Grove Lime Co., reveals the continued use of the dwellings as employee housing. The Schleysville worker houses and the Franklin Schley House are good examples of domestic design and construction in Frederick City during the mid 19th and early 20th centuries." Mrs. Schley could be found living at 70 E. Patrick Street in the 1880 census. She would live another decade before her death on July 13th, 1890. Margaret should be commended for the fine job she did in raising her children. I’m sure all 12, excluding Edward (who passed in 1863), had interesting adulthoods. I will briefly review the lives of her remaining four sons. Benjamin Henry Schley Benjamin and his brother Frank have already been mentioned in connection to the limestone business. Born October 20, 1832, Benjamin Henry Schley served proudly in the United Fire Company and militia unit and continued with involvement during the American Civil War. He helped form Frederick’s first volunteer company to fight on the side of the Union (1st MD Volunteer Infantry), and was said to have participated bravely in all the engagements of the 1st Maryland Regiment under the Army of the Potomac, eventually reaching the rank of major. B. H. Schley was captured in Front Royal, VA in late May of 1862, but would be exchanged at Aiken's Landing, VA in September of that same year. He is said to have also served as an aide on the staff of Gen. Lew Wallace at the Battle of Monocacy. After the war, Major Schley assisted with the lime business, but also headed up a coal business in Frederick. He married Martha Sophia Gaither(1834-1916) on January 9th, 1881. They would only have a year-and-a-half of wedded bliss. He was fraternally active in the local Grand Army of the Republic Post and also the Lynch Lodge of the Masons. On the civic level, he helped found the Frederick Library Association and served as secretary.Benjamin Henry Schley would die at the age of 49 from consumption. This occurred on June 6th, 1882. Franklin Schley Earlier, I discussed Franklin “Frank” Schley’s lasting legacy with the existing hamlet of “Schleysville” on E. Patrick Street. His first name also lives on through “Franklin Street” which runs between E. Patrick and E. South streets. Born July 31st, 1837, Frank would gain his early education at the Frederick Academy where he would excel at mathematics. Classmates included Alexander “Sandy” Pendleton of Civil War fame, and cousin Winfield Scott Schley of Spanish-American War fame. Frank would ironically only live to the age of 49 like his older brother B. Henry. He co-ran the Schley Brothers Lime operation with brothers Gilmer and Thomas after the death of Major B. H. Schley. Frank was particularly interested in real estate and our old Frederick newspapers are filled with advertisements pertaining to his listings, especially his 20-unit “Schleysville” community on E. Patrick Street. Frank was an avid sportsman especially in respect to hunting and fishing. He particularly excelled at partridge, pheasant and quail hunting. In doing so, he likely provided the main course for many a Thanksgiving dinner for the greater Schley family. Frank’s expertise led him to pen a book on the subject of game hunting entitled “Frank Schley’s American Partridge and Pheasant Shooting.” This was published in 1877 and resulted in Frank receiving the title of "Professor," and would be referred to as such Frank Schley also took interest in horses and owned several racing thoroughbreds. Having the Frederick Agricultural Society’s fairgrounds and track directly across the street from his home was surely a plus for this hobby. Thanksgiving races were even en vogue at one time. Mr. Schley carried on a courtship with Miss M. Helen Eader of Petersville for over two decades until finally tying the knot on October 14th, 1886. Sadly, six weeks later, Frank Schley would die from a sudden hemorrhage of the lungs at his home on Wednesday, November 26th, 1886. Ironically this was the day before Thanksgiving, so an incredibly somber time must have beset Mrs. Eve Margaret Schley and his several siblings, nephews and nieces. Not to mention the fact that the Schley family would now be without their resident fowl expert and provider to celebrate the special November holiday with from that day moving forward. “The Professor” was buried the day after Thanksgiving, but not in the family’s burial plot in Area F. Instead, Frank Schley would be placed in Area Q/Lot 74. His bride of one-and-a-half months would join him here in 1902. Like that of his father, Col. Edward Schley, a fine, large monument adorns this gravesite. Thomas Schley Thomas Schley came into the world on February 1st, 1851. He too, attended the Frederick Academy as did his brothers. While a young man, he became a bookkeeper for the late P. H. Pieffer, who was a large coal dealer of Frederick. He later engaged in the manufacture of all kinds of lime wih his own kilns situated a mile east of town on the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad line on E. South Street. This would be the vicinity of the Frederick Brick Works original location. He eventually sold this business to M. J. Grove and Company and took an early retirement for about five years. In 1880, Thomas Schley partnered with a gentleman named Victor M. Marken and another named William T. Delaplaine. The trio opened a printing firm on N. Market Street called Schley, Marken & Delaplaine. They performed various job printings and made the locally, renowned “Peerless Paper Meat Sack.” In 1883, the trio founded the Frederick Daily and Weekly News, and after some time the firm changed its name to W. T. Delaplaine & Company and eventually merged into the Great Southern Printing and Manufacturing Company with William T. Delaplaine serving as president, Thomas Schley as vice-president, and George Birely as treasurer. The latter man was Schley’s brother-in-law, married to his older sister, Annie. Thanks to Mr. Schley who is said to have “contributed his ability to the success achieved by this concern.” This paved the way for me, as I gained my first full-time position with this company, under the Frederick Cablevision/GS Communications division from 1989-2001 at which time it was sold to Adelphia Communications out of Coudersport, PA. Thomas Schley married Mary Martin Claggett in 1885 and the couple would have one daughter named Anne Perry. Mr. Schley would pass on March 11th, 1909. He would be buried in his father’s plot on Area F. Gilmer Schley The last of the Schley brothers I will talk about is Gilmer Schley. The youngest child of Col. Edward and Eve Margaret Schley, he was born August 14th, 1855 and would take sole charge of the Schley Brothers Lime Works upon the death of his older brother (Frank) and departure of Thomas to other pursuits. He would be credited with introducing a steam drill to the operation which greatly eased the extraction process. T.J.C. Williams History of Frederick County from 1910 gives some interesting biographical detail on Gilmer: “Gilmer Schley, son of Col. Edward and Eve Margaret (Brengle) Schley, was only one year old when his father died. He remained on the home farm until he reached his tenth year, when the family removed to Frederick, in which place he received his education in the Frederick Academy. At the age of sixteen, he began life for himself as a clerk in the grocery store of Johnson and Brosius, of Frederick, where he remained for two years. He was then in the employ of Julian Newahl as a clerk for about two years. His next position was with Birely Brothers, with whom he remained for four years. He then became a bookkeeper for Theodore Brookery, at the time conducting a tannery. In this position, Mr. Schley continued for four years. In 1881, he became associated with his brother Franklin in the lime business, and on the death of his brother in 1886, he assumed full control, purchasing his brother’s interest, in which business he has since continued. Mr. Schley is one of Frederick’s well-known and leading businessmen, and he is held in high esteem. In politics, Mr. Schley is a Republican supporter. Fraternally, he is a member of the Modern Woodmen of America. He is also a charter member and director of the Independent Fire Company of Frederick City. Mr. Schley was married, in 1884, to Emma Louisa Wilson, daughter of N. J. and Sophia (Albaugh) Wilson, a descendant of an old and well-known family of the county. The marriage had six children: Eve Margaret Schley (Remsburg), Nathaniel Wilson Schley (1886-1976, a veteran of WWI), Ellen Louisa Schley (1890-1892), Louise Schley (Rhodes) (1893-1962), and H. Florence Belcher, and an unnamed infant." Gilmer would sell the family lime business in 1912 to Shank & Etzler, and it eventually became the property of R. F. Kline. The quarry stood for many years as just a deep water hole and a dangerous swimming hole for the more daring young men of town. It was eventually filled in by the City. In 1919, Gilmer Schley ran for elected office in the mayoral race of Frederick City. He would be victorious in this, his only “Election Day” foray. After serving his term, he would officially retire and spent much time in outdoor recreations, primarily inspired by his older brother Frank.  Mayor-elect Gilmer Schley would take the new Board of Alderman for a retreat outing in the woods as captured in this photograph in the archives of Heritage Frederick. Schley is at the head of the table closest to the photographer, while Frederick city park namesake Lorenzo Mullinix is seated to his immediate right. Gilmer Schley died on July 10th, 1939. He would be buried a few feet from his parents and seven of his siblings: Edward, Mary M. Morgan, Ellen E. Gambrill, Laura Chapline, Rose Baer, Fannie Hewes, and Thomas Schley on Area F in Lot 45. As was my aim at the beginning with this story, I certainly found a November family with multiple ties to Election Day through former politicians, Veterans Day through military service, and Thanksgiving through the spirit of family and togetherness, not to mention, a fondness for Phasianidae—heavy ground-living birds.

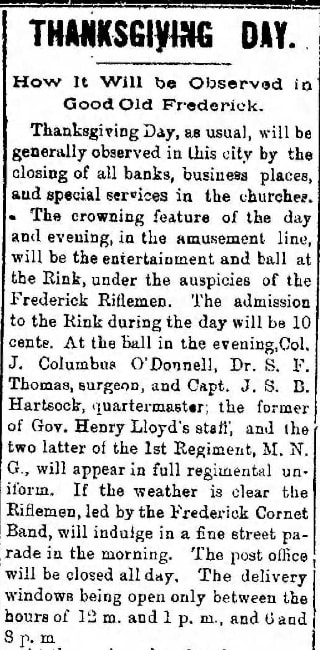

Happy Thanksgiving to all our readers, and thanks for your continued support of our mission of preserving the historic records, structures and gravestones of Mount Olivet Cemetery. These stories will keep the memories of our 40,000 inhabitants alive for future generations to learn from. In closing, here is an article from the same newspaper edition of November 24th, 1886 that featured the news of Frank Schley's untimely death. It certainly gives a little flavor of how the holiday was celebrated here in Frederick during the heyday of the Col. Edward and Eve Margaret Schley family.

1 Comment

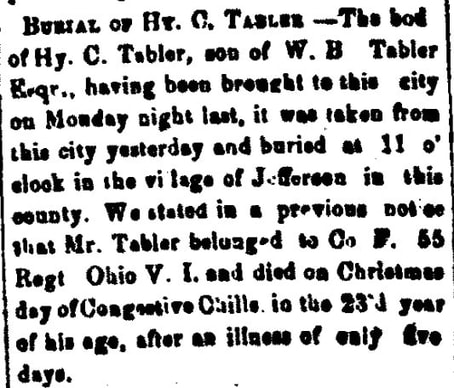

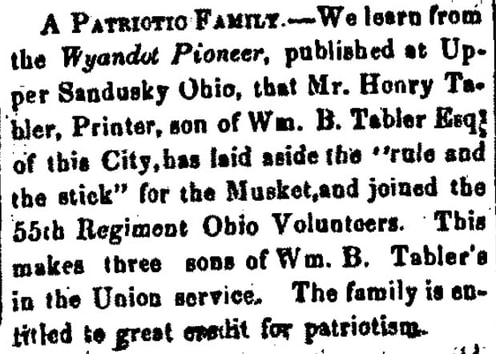

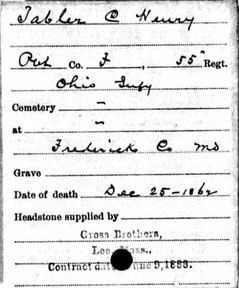

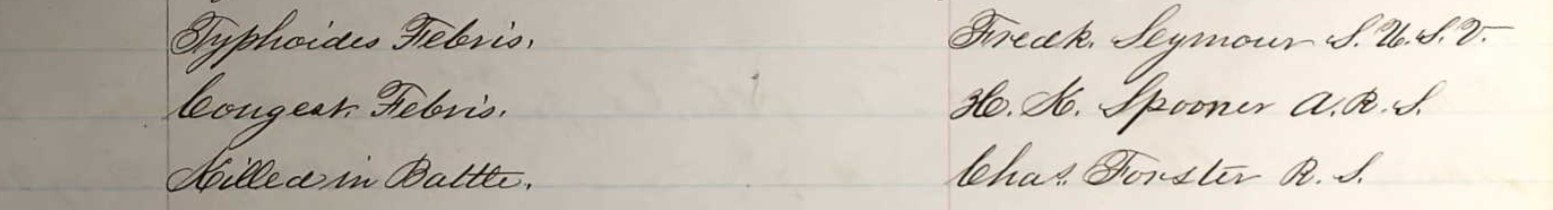

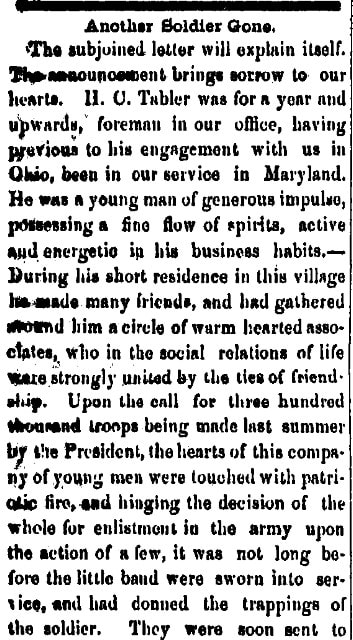

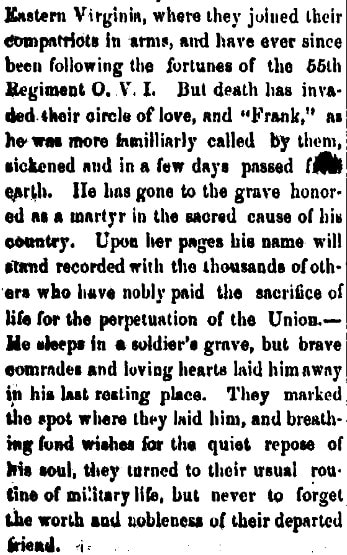

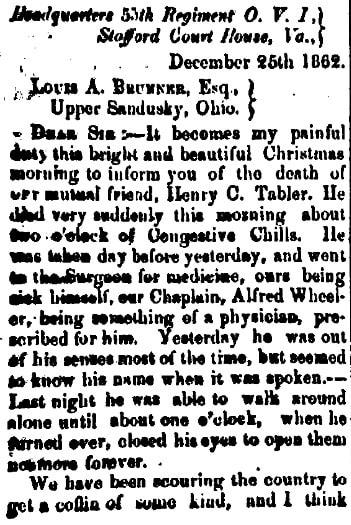

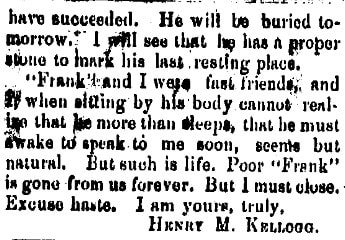

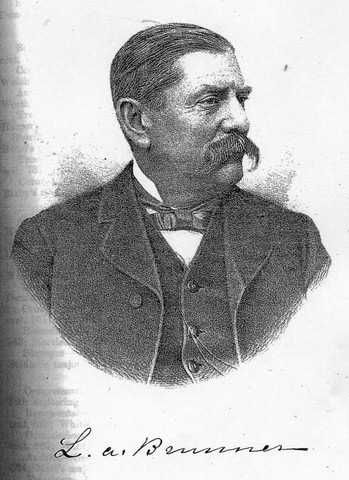

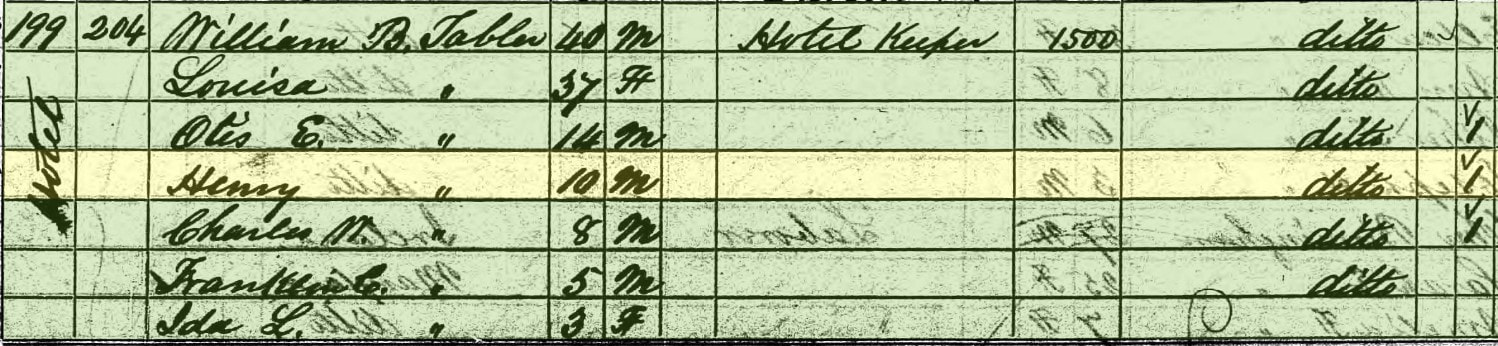

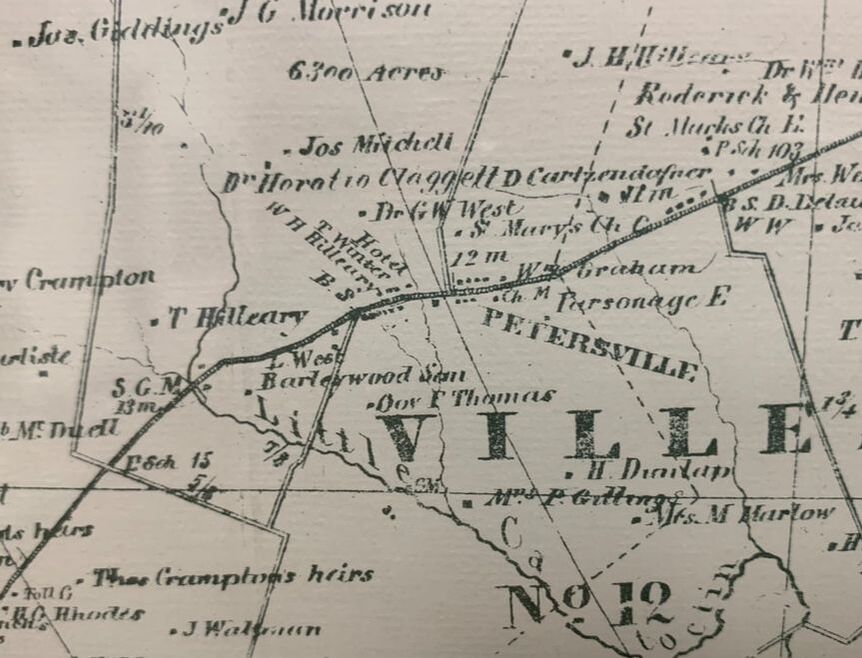

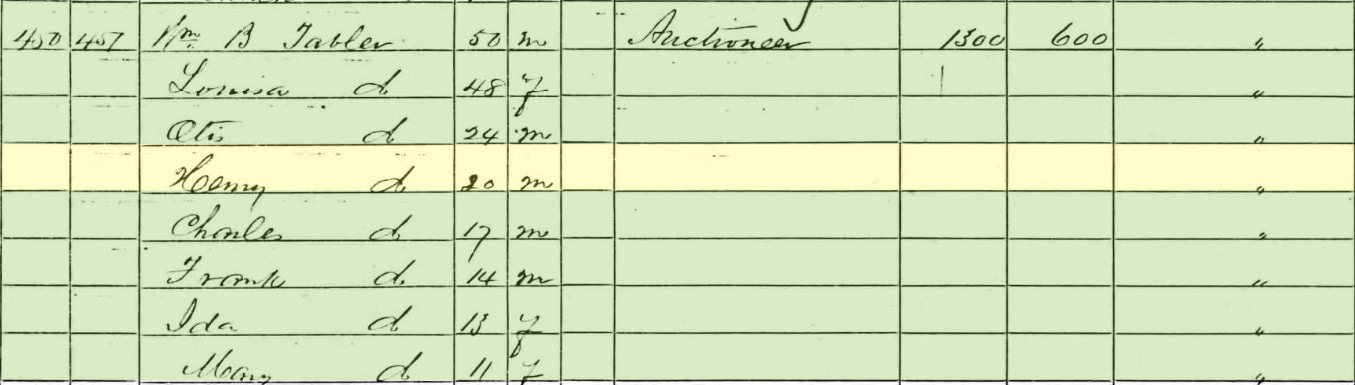

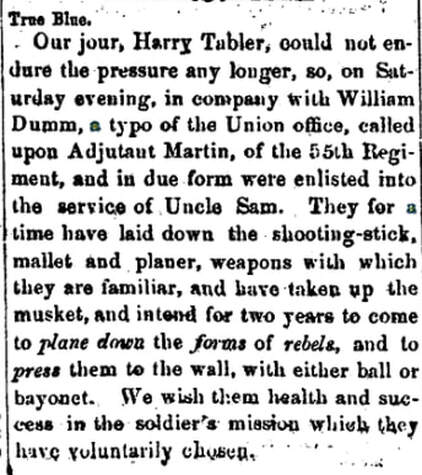

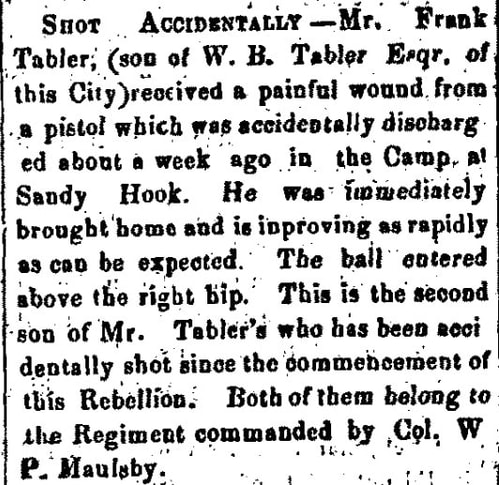

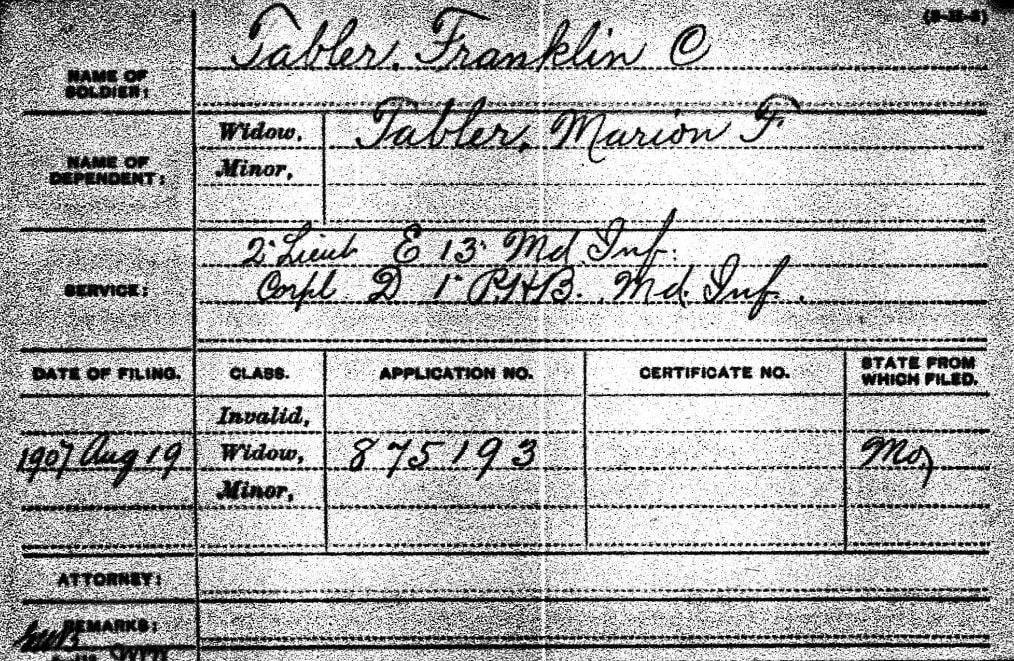

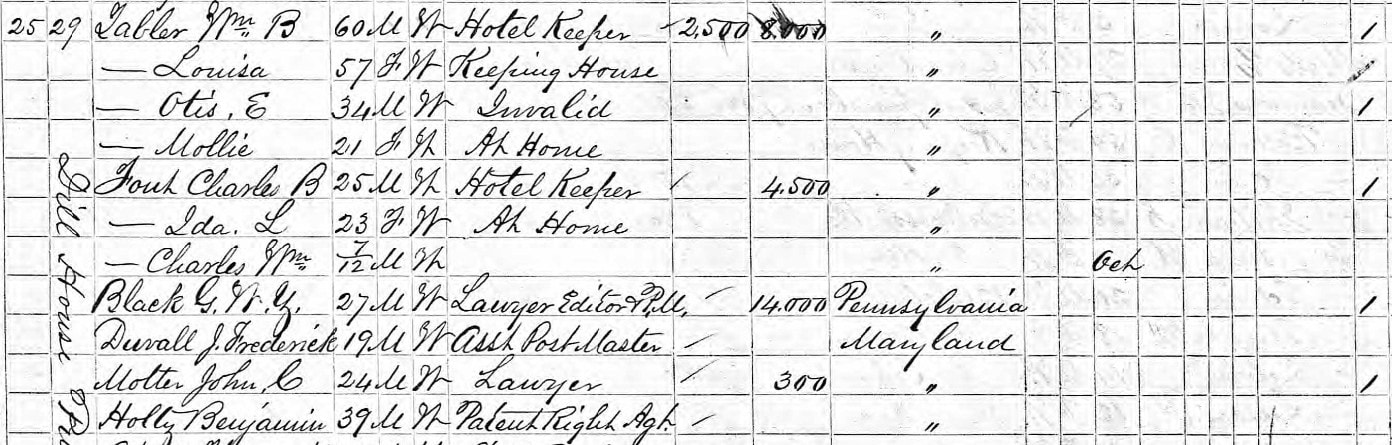

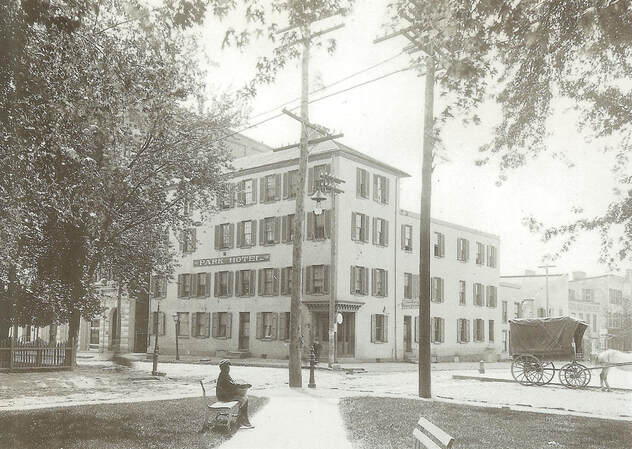

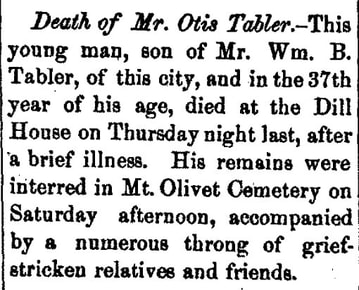

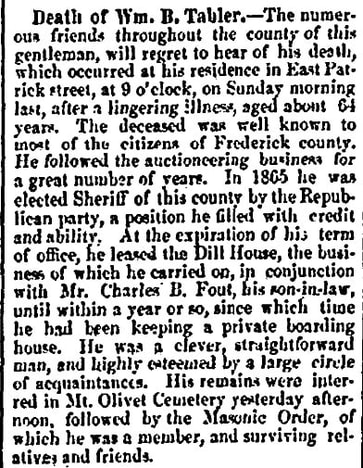

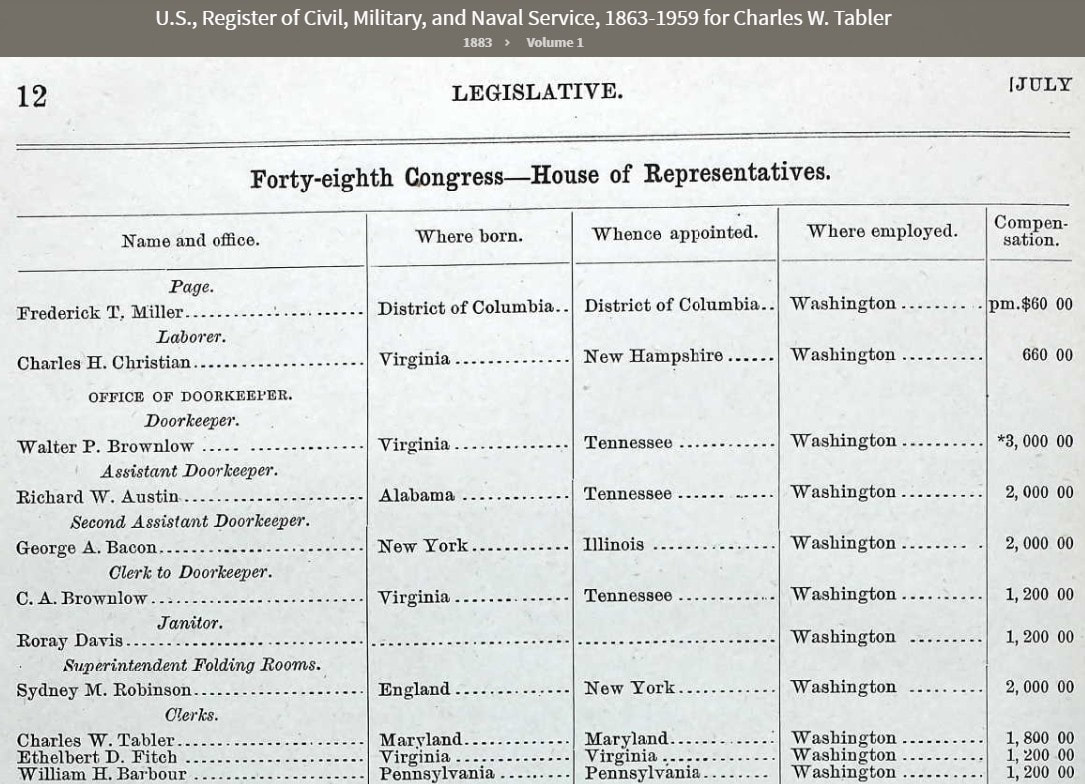

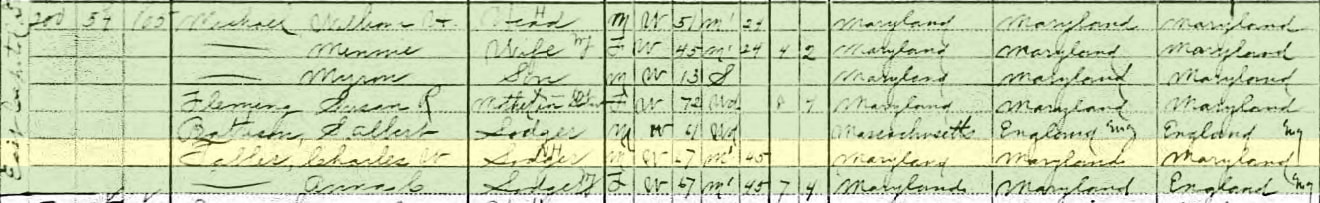

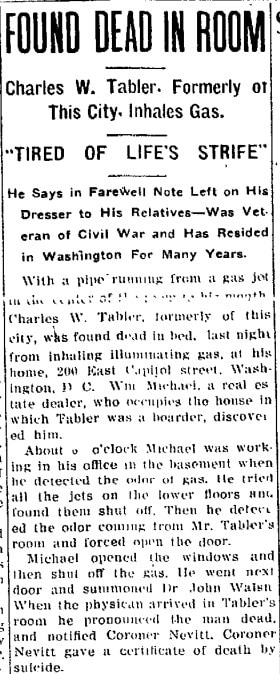

With the passing of Veterans Day, 2021, I had the opportunity to reflect on a personal and professional milestone this past week—one that had connections to Mount Olivet Cemetery, Veterans Day, the US flag and the pen (so to speak). It was five years ago, Veteran’s Day of 2016, when I published my very first edition of this “Stories in Stone” blog. My debut offering was entitled “Frederick Under the Flag” and featured the obvious overarching theme of patriotism evident here at Mount Olivet Cemetery. I shared, with readers, the well-known fact that this sacred, burial ground is the final resting place of over 4,000 military veterans. These men and women have connections to every conflict our country has taken part in. We have amazing luminaries buried here in the form of well-known former Fredericktonians like Francis Scott Key and Barbara Fritchie. As these two individuals are well-storied in the local history annals, they also became known on the national and international level through their respective patriotic deeds. Interestingly, in both cases of FSK and Dame Fritchie, we can thank “the almighty pen” for their immortality as both gained fame thanks to a song or poem written about the US flag under attack by the enemy, but ultimately our red, white and blue standard stood steadfast and strong through perilous fights.  Fred Schumacher starting Echo Taps outside the cemetery's front gate Fred Schumacher starting Echo Taps outside the cemetery's front gate In that inaugural “story in Stone,” I mentioned other patriotic characters of Frederick’s past such as Gov. Thomas Johnson, Winfield Scott Schley and Dr. Lewis H. Steiner. I wrapped the article up by heralding the cemetery’s role not only in burying the dead, but serving as an important touchstone on military holidays since its original opening in 1854. Since coming to work here in early 2016, I’ve been humbled by witnessing programming held here in conjunction with Memorial Day and Veterans Day. on Memorial Day, the American Legion has been performing a noontime ceremony at the FSK Memorial for over a century. For the last five years, our local Daughters of the American Revolution Chapters have organized another Memorial Day program that shines the spotlight on those vets residing in our spacious mausoleum complex toward the rear of the cemetery. On Veterans Day, local musicians perform Echo Taps, which begins by our front gate and concludes several blocks away at Frederick’s Memorial Park at W. Second and North Bentz streets. Amazingly, over this five-year span, I’ve seen Veterans Day programming take hold here in an all new way. We now have an annual history walking tour at noon, and this year we had a special-themed lecture in our FSK Chapel about the “Operation Whitecoat” program that occurred at nearby Fort Detrick from 1954-1973. Most memorable, however, has been the opportunity for partner groups and the general public to assist in decorating gravesites with flags. This had been done on Memorial Day for decades, but now is finally a staple for Veterans Day. On Saturday, November 6th, over 4,500 flaglets were planted in the ground at the site of veteran markers and stones across our 100-acre campus. These flags not only denote final resting places of “hometown heroes,” but also serve as important placeholders leading up to our Wreaths Across America Ceremony on the third Saturday in December. This year, the magic day is December 18th as we will mark as many of our 4,500 veteran graves (with as many sponsored wreaths) as we can. At present, we have nearly 2,100 wreaths, and are eagerly anticipating more over the next couple weeks (before the November 30th cutoff date) to up that total. Volunteer flag placers included groups representing the Homewood Auxiliary, the Friends of Mount Olivet membership group, Francis Scott Key Post #11 of the American Legion, the Frederick team of NaturaLawn of America, American Heritage Girls Troop MD3126, Tuscarora High Schools Rho Kappa and baseball team, and others, coupled with walk-up residents from Frederick and even some from neighboring counties. These folks traversed the grounds carrying lot maps, checklists, pens and screwdrivers in the effort to locate and identify our veteran gravesites to plant flags. You see, it’s not as easy as one might think because we are unlike Arlington and other US military cemeteries where it is a given that all these gravesites contains a veteran. In contrast, we have an eclectic assortment of gravestones belonging to our larger population of 40,000 interred here, and have plenty of lots where a veteran lies, but is not labeled or marked with a military insignia or plaque of any kind.  I have not only seen our interest in our cemetery and activity grow due to these military-based remembrances, but I’ve been humbled to see the popularity of our weekly blog grow as well. My top satisfaction in writing “Stories in Stone” centers on my ability and desire to connect decedents in our cemetery with places, other people, and events/happenstances tied to the past—most notably local, state and national history. I guess you could say I’m nothing more than a “conduit” in many ways. Best of all, is having the opportunity to connect you, the reader of the present, with the Frederick of the past. I do this through the context of gravestones that memorialize former residents whose lives “lived” helped gave us the Frederick we know and cherish today. The Tablers Earlier this week, I surveyed the cemetery grounds in preparation for giving our annual Veterans Day history walking tour. I introduce participants to a random collection of outstanding military men and women from different eras. I happened to be in Area A, among the oldest in Mount Olivet located closest to our front gate entrance off South Market Street. This locale has received great attention over the past year from our Friends of Mount Olivet group in terms of stone cleaning. Many gravestones formerly charcoal black in color due to age and pollution, are now gleaming white and reminiscent of the days these were first erected—some dating back to the 1850s. As is always the case, certain stones seem to jump out at me. Now my focus was somewhat skewed as I was especially taking note of graves decorated with flags as we had just performed that exercise last weekend. A small military stone of a Union Civil War veteran captured my imagination as I marveled of how clean and vibrant it was. I had not recalled ever seeing it before, and if I had, I surely wouldn’t have been able to decipher the writing on its face due to the aging these stones endure at the mercy of the elements. I snapped a few photos on my I-phone and decided I would look into the life of C. H. Tabler and figure out the cause of his early demise, not knowing whether he was a Frederick lad or a native of Ohio as his stone identified his particular regiment. Well the story began to take shape rather quickly as I checked our cemetery records on this individual buried in Lot 93 of Area A. It was clearly stated that C. Henry was a “removal” from Virginia who came to Mount Olivet on March 4th, 1871. The record said that “Henry” had died at Stafford Court House (Virginia) while serving in Company F of the 55th Ohio Infantry Regiment. In looking at his lot card, I realized that he had been buried in the family plot of William Benjamin Tabler, the decedent’s father. Unbeknownst to me when I first spied Henry’s grave the previous day, his parents and a few siblings were buried behind and within a few mere feet of his military-issue stone. I failed to take notice because they faced west instead of east as was the case with Henry’s stone. I searched for an obituary for Henry and found one in the January 22nd edition of the Maryland Union newspaper of Frederick. In this I learned that he died on Christmas Day of “Congestive chills.” I looked up this condition and found that this old disease name equated to Malaria with diarrhea. The article stated that he was buried at a graveyard in Jefferson at this time. This means that he was moved to Mount Olivet in 1871 from his former resting place in Jefferson. As I was searching for his obit, I had first come upon an article in the Maryland Union from the previous August (1862). This small article referenced The Wyandot Pioneer, a newspaper in Upper Sandusky, Wyandot County, Ohio, and the fact that our subject Mr. Tabler was an employee of this entity. The article talked about the Tabler family, and Henry’s recent enlistment in the Union Army following the patriotic spirit shown by his brothers Frank and Charles. This led me to find a couple reference records to his service including Ohio enlistment records and an order form for his subsequent military tombstone after his death. Best of all was the entrée into The Wyandot Pioneer in hopes that this publication to shed more information on the life and death of C. Henry Tabler. My wish was answered as I found a fuller obituary, and also a direct report to the newspaper’s publisher regarding Henry’s final days. Interestingly, Henry’s boss at the paper was a man named Louis Augustus Brunner (1823-1886), and yes he has definitive connections to the Brunner family of Frederick that gave us the famed Schifferstadt house at the end of West 2nd Street where it intersects with Rosemont Avenue. Mr. Brunner was the son of John (1792-1844) and Anna Maria Stickel Brunner (1794-1829), and a brother of Valentine Stickel Brunner, a former president of Mount Olivet. John was the son of Jacob Valentine Brunner (1760-1822) and served as an 1812 War veteran. The John Brunner family’s cemetery lot is located just a football field away from the final resting spot of L. A. Brunner’s former employee, G. Henry Tabler. I would find an additional article in the Frederick Examiner newspaper of March 4th, 1863 pertaining to Henry’s death, as it was attributed to the Wyandot Pioneer. This was a solemn poem to his memory written by an S. M. Boughton: Named for his paternal grandfather, Christian Henry Tabler was born in 1841 in the vicinity of Jefferson, Maryland. He first appears by name in the 1850 US Census living in Petersville. I took interest in the fact that Henry’s father, William Benjamin Tabler (b. 1810 in Martinsburg, West Virginia), served in the Brengle Home Guards unit in 1861, and would later be elected as Frederick County sheriff in 1865. He spent most of his working career as an auctioneer and also an innkeeper. In 1850, he was keeping a hotel in Petersville in the southwestern part of the county. I was fascinated to learn that Petersville was once a tourist destination, and this hotel, which no longer stands, was once located on the Jefferson Pike just west of Catholic Church Road. Of personal interest, this is only a stone’s throw from my son’s girlfriend’s house, but that’s neither here nor there as far as our subject is concerned. The Tablers would relocate to Frederick during the 1850s and can be found living on the south side of the first block of East South Street by 1859. In Williams’ Frederick Directory of 1859-1860, Henry is listed as having the occupation of printer, a fact not mentioned in the 1860 US Census. It is most likely that Henry went to Upper Sandusky, Ohio in mid-1861 and began his work with Mr. L. A. Brunner and The Wyandot Pioneer as a printing foreman I found the following article that gave a more complete picture of his desire to enlist in August of 1862, just a month before his former hometown of Frederick would be occupied for a week by Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia prior to the nearby battles of South Mountain and Antietam. Henry’s other brothers, Frank and Charles, were also serving in the Union Army as mentioned previously. I found an article in the Maryland Union that showed that Frank (Franklin Clay Tabler b. 1845) had suffered an unfortunate accident while in camp at nearby Sandy Hook on the Potomac and not far from the fore-mentioned hamlet of Petersville. Mrs. Louisa Tabler, the boy’s mother, was the former Louisa Crum, a native of Knoxville which is even closer to Sandy Hook. You can’t fault Frank as he had enlisted in the US Army in September, 1861 at the age of 16. Henry’s other brother Charles William Tabler (b. 1842) had the best military career of the three as he avoided a fatal illness and gunshot wounds of any kind. Based on later news accounts, he was commended for his bravery under fire during the war on numerous occasions. The 1870 US Census shows Henry’s parents and three other siblings living at the Dill House hotel on West Church Street. William B. Tabler was back in his familiar role as innkeeper at this famous hostelry once located on the southeast corner of West Church and Court streets. Today this is a parking lot that serves both M&T Bank and the Paul Mitchell Temple School. 1871 was the year that Mr. Tabler bought his burial plot in Mount Olivet. I surmised that Henry’s brother, Otis (b. 1836) had been afflicted with some sort of disability through life as the 1870 census lists him as an invalid. He may have been showing signs of imminent demise which could have prompted his father to purchase burial lots at this time. As I said earlier, Henry’s body was the first placed here in Area A’s Lot 93 in March of 1871. Otis would pass 14 months later in July of 1872. I found his brief obituary but could not find a gravestone for him. William Benjamin Tabler would die on May 3rd, 1874. He joined sons Henry and Otis here in grave lot today that is well shaded by a large oak tree that stands on the northwest corner of Area A. Wife Louisa died in 1878. Henry’s sisters Ida Louisa (Tabler) Fout (1847-1894) and Mary Katherine “Mollie” Tabler (1849-1931) would also be laid to rest here. To wrap up this Tabler family’s story here at Mount Olivet, originally inspired by me spotting the lonely, yet sparkling, grave of Union veteran C. Henry Tabler, I needed to find out what happened to the other two sibling-veterans. Frank married a young woman named Marion Farr in St. Louis in 1869 and worked as a clerk in some capacity. He died somewhere before 1900 and his body was not returned to Frederick for reburial. I assume he is buried in St. Louis but have been unable to find his final resting place. That brings us to Charles, who is buried in Mount Olivet up the hill from the rest of his family with his wife and in-laws in Area E/Lot 3. Charles worked as a clerk here in Frederick but re-located to Washington DC in the 1890s. He eventually gained a pension clerk job at the US Capitol but eventually became a real estate broker. He lived at 200 E. Capitol Street, which was known as the Manning House, but today serves as the Florida House, an embassy of sort for visiting Floridians. This is where he was living and working when he died in 1911 as a result of committing suicide. I found several front page articles in both the Frederick and Washington, DC newspapers of the time. These depicted in great detail how Mr. Tabler was depressed regarding a recent illness he was slow to recover from. They also discussed his assumed plans for burial in Arlington. Apparently, this final wish would not come to fruition.  "The Joiner" by an unknown artist from 1880 "The Joiner" by an unknown artist from 1880 So, in researching and writing this piece, I got to meet a new family, consisting of 3 of the 4,500 veterans in our midst in Mount Olivet. Fittingly I made more connections whether they be to patriotism, places, people and events. Best of all, I happened to be curious as to the meaning of the last name of "Tabler." You should have seen the look on my face when I learned that this family originally hailed from southwestern England in the county of Cornwall. The moniker derives from an ancient occupational name from Old French, tablier, which is better defined as “joiner.” Reminds me a lot of the related words “conduit” and “connector” if you asked me. What a special family name, and fitting subject for my 180th edition as I stop to give pause and reflect on my the five-year anniversary of writing “Stories in Stone.” Thanks for the continued support from all our readers and here’s to the next five years. Please help us mark the graves of veterans in Frederick's historic Mount Olivet by sponsoring a wreath!

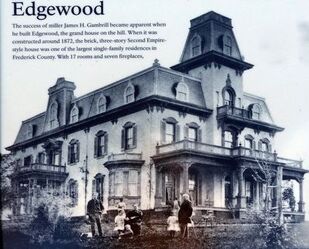

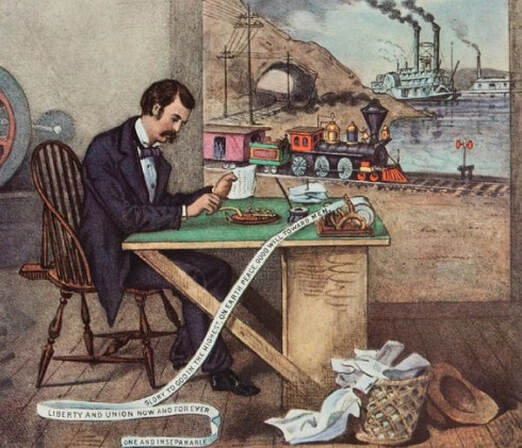

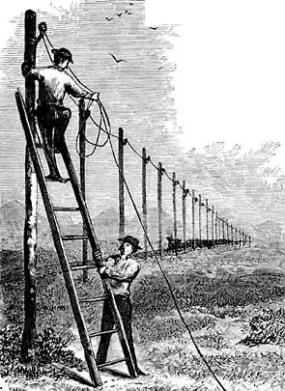

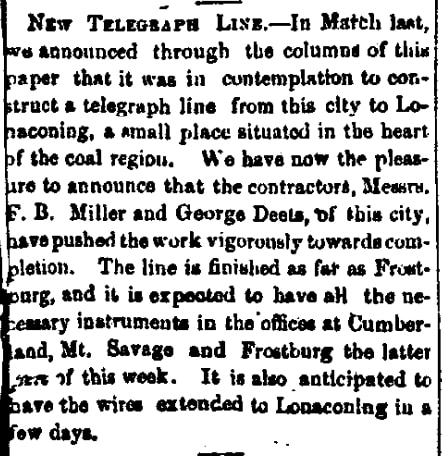

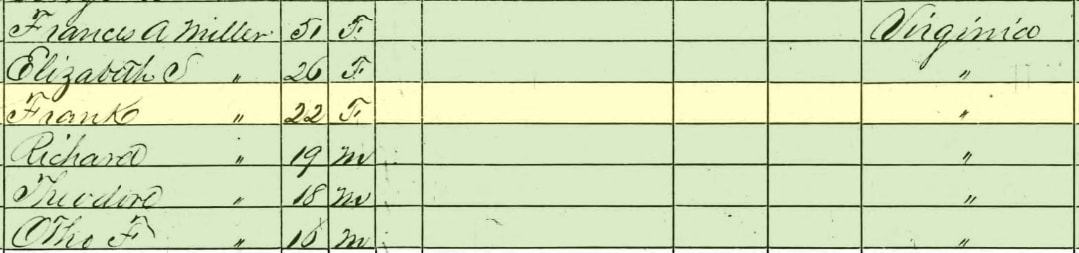

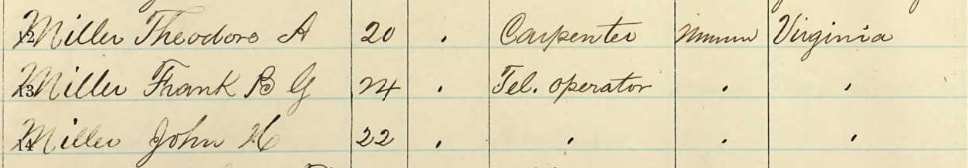

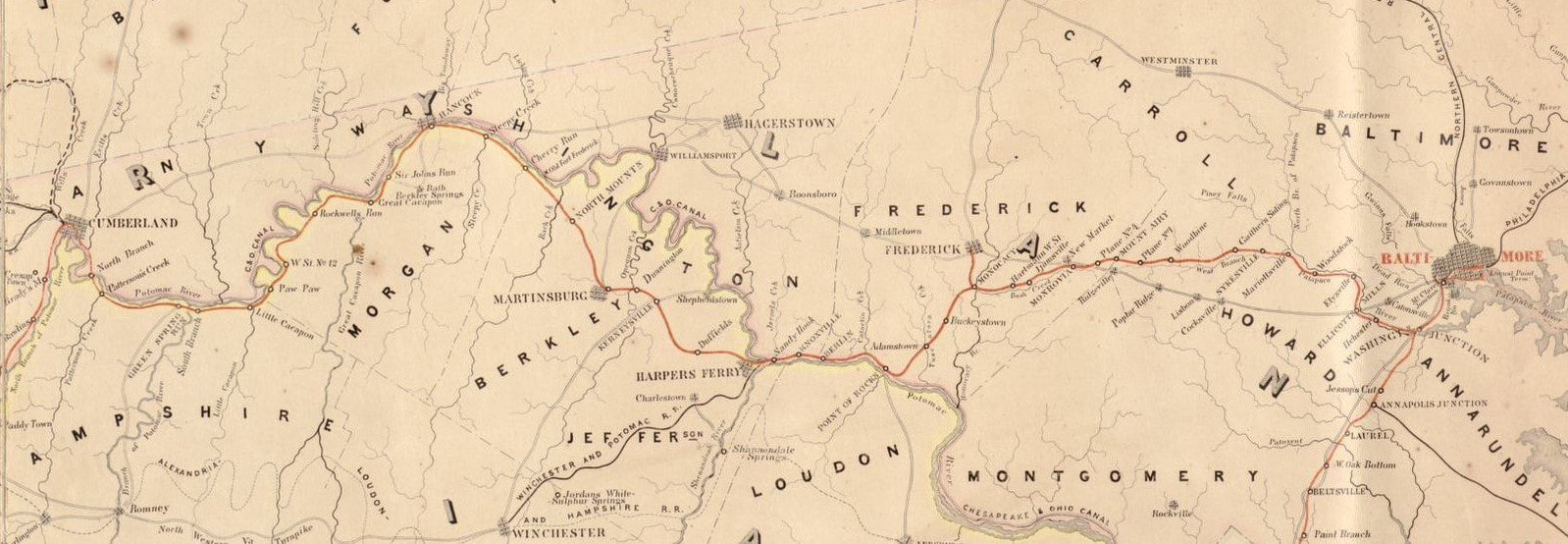

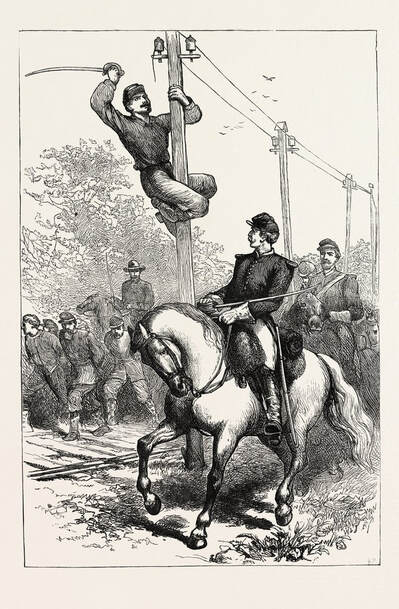

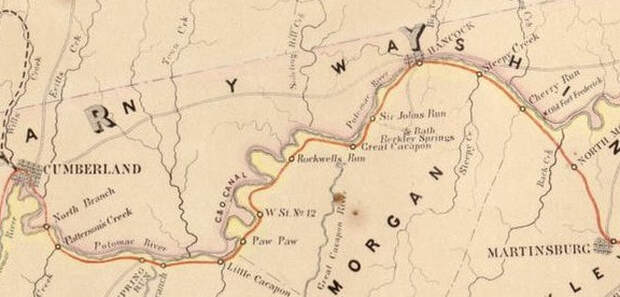

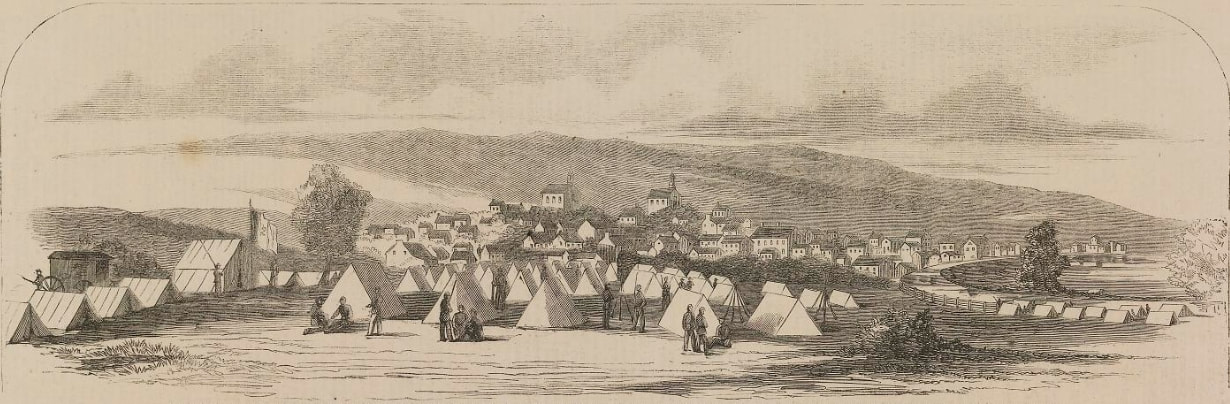

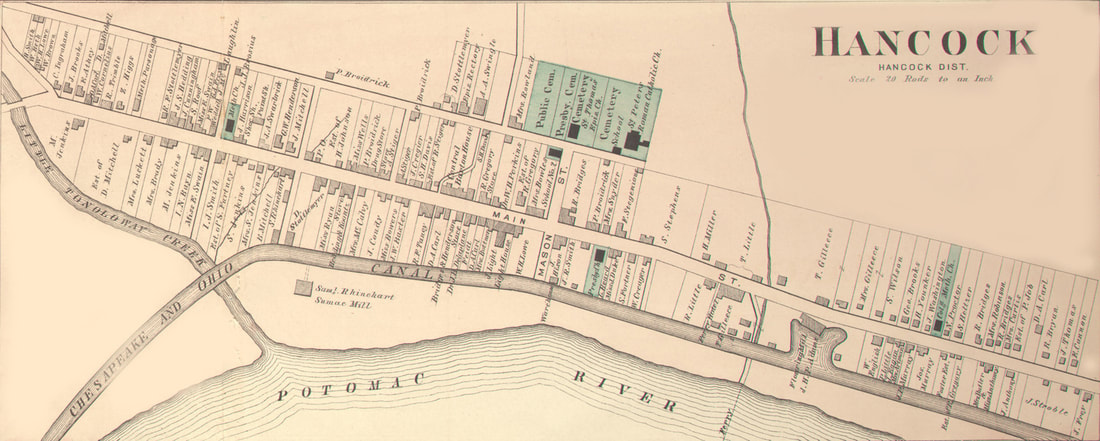

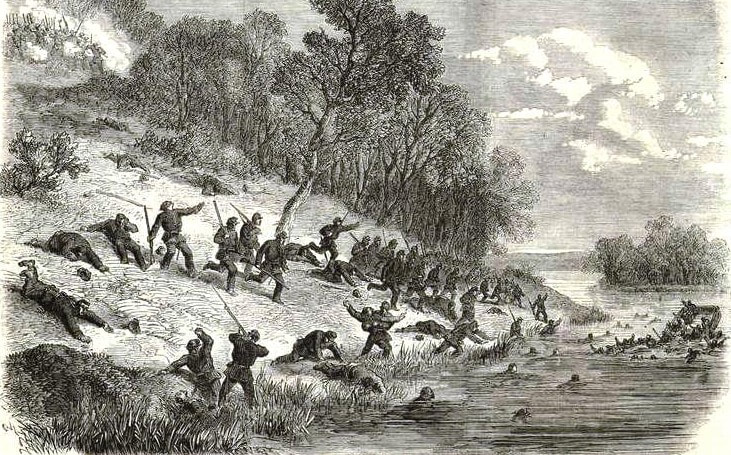

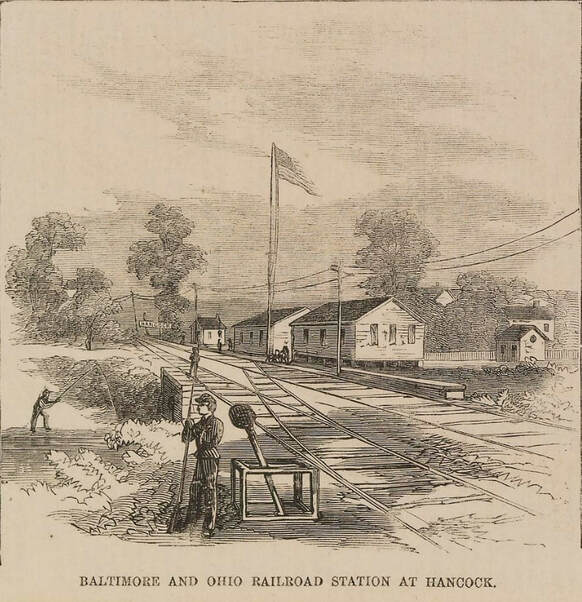

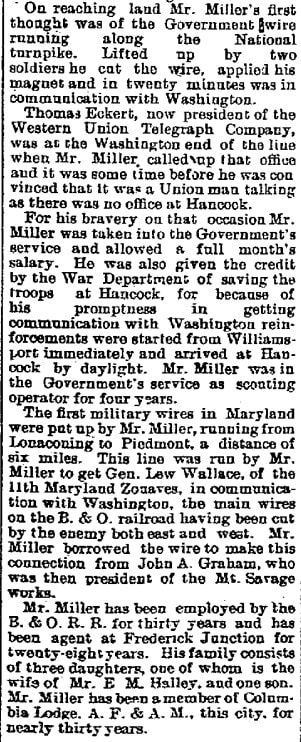

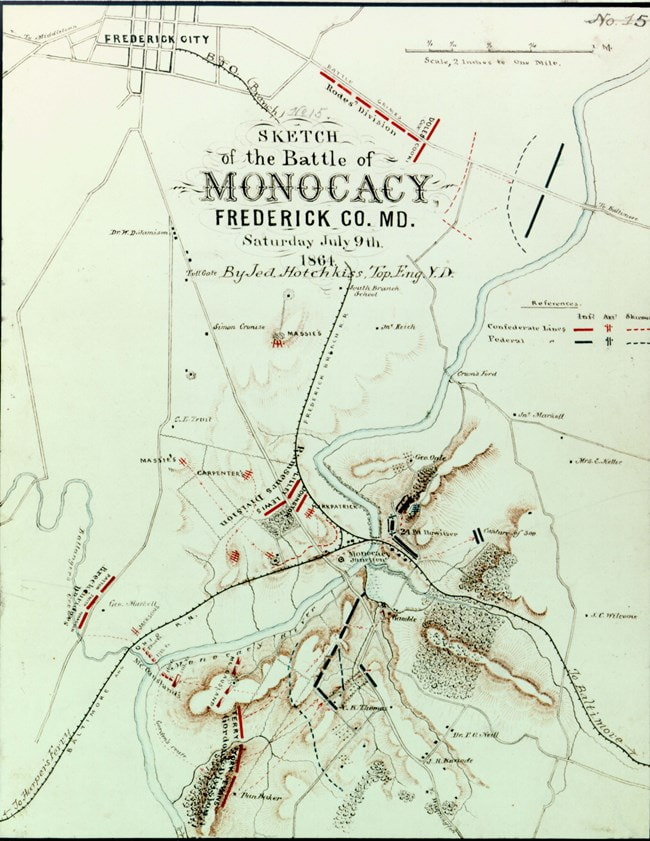

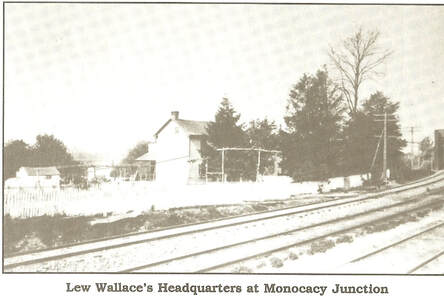

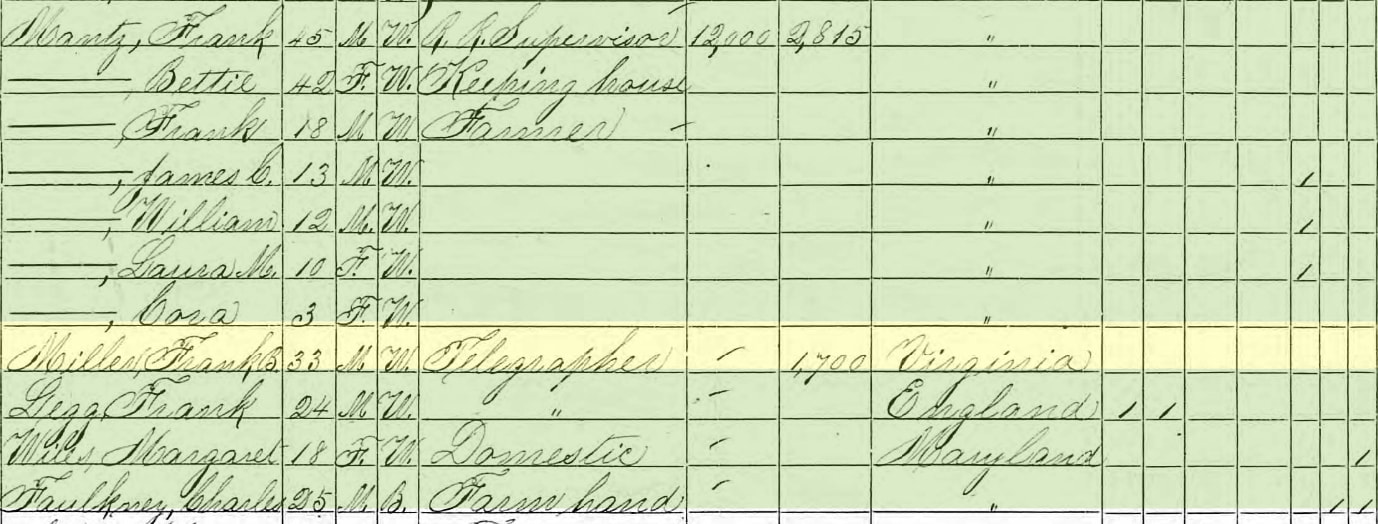

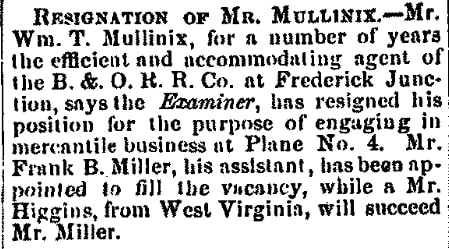

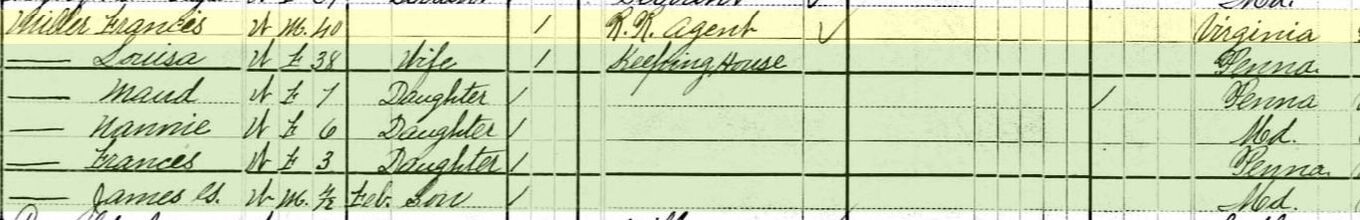

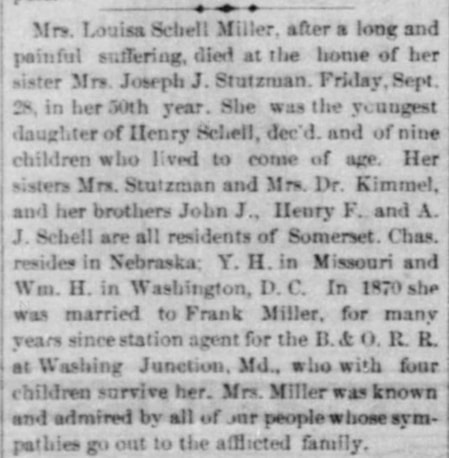

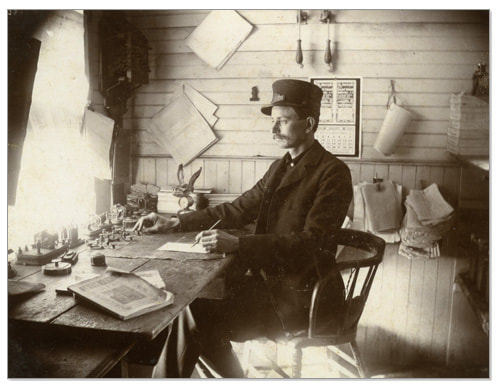

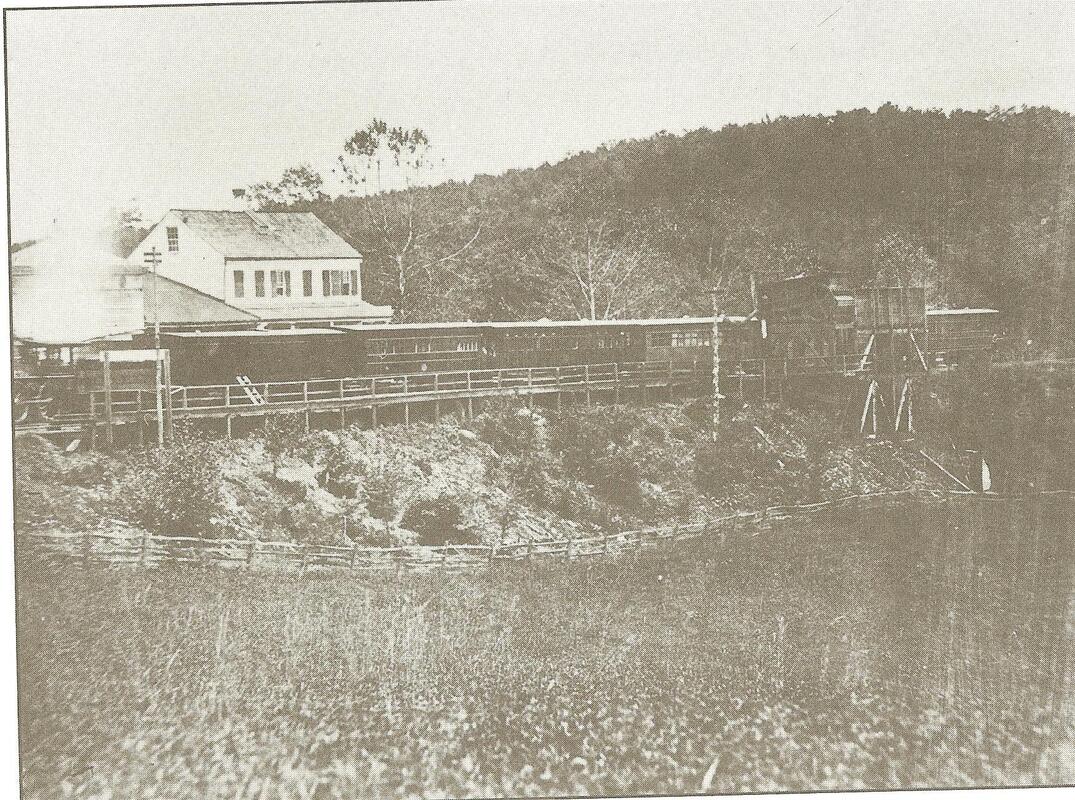

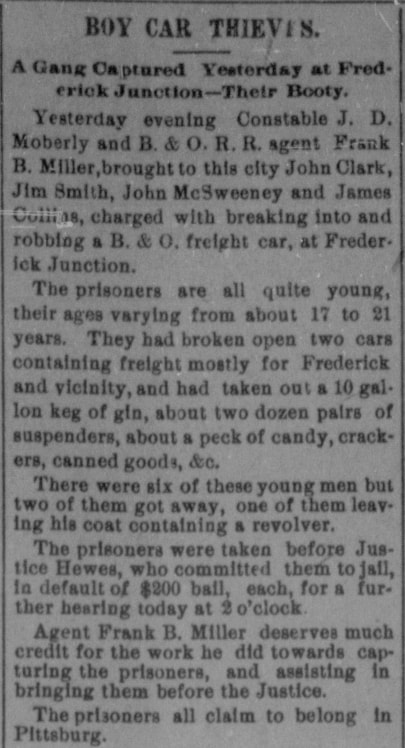

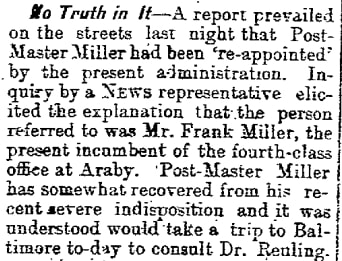

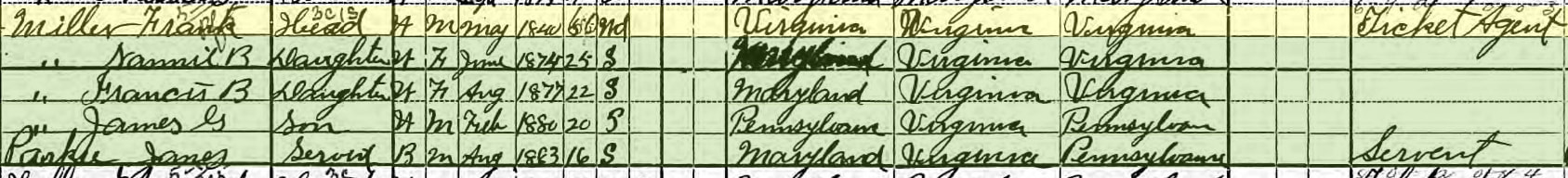

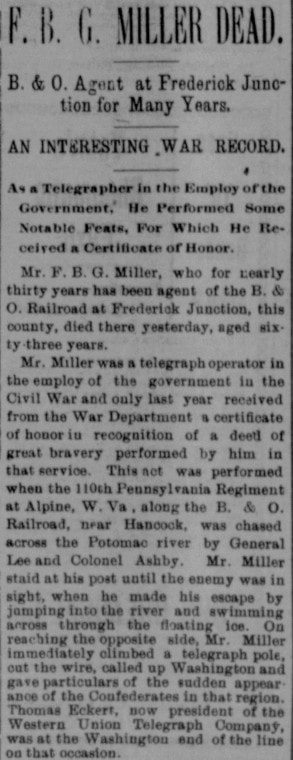

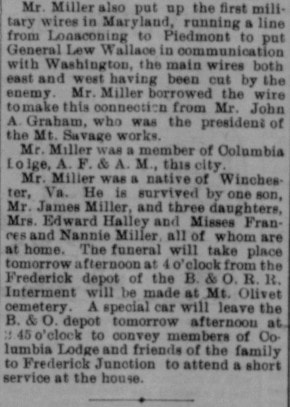

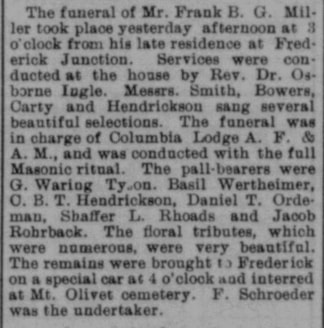

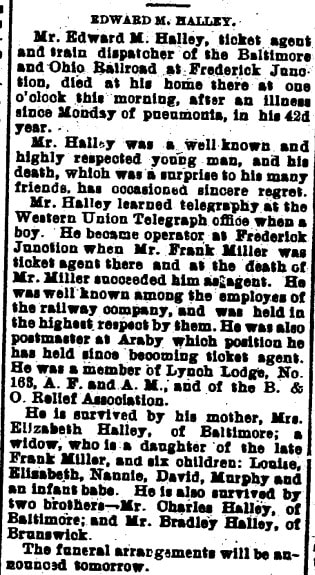

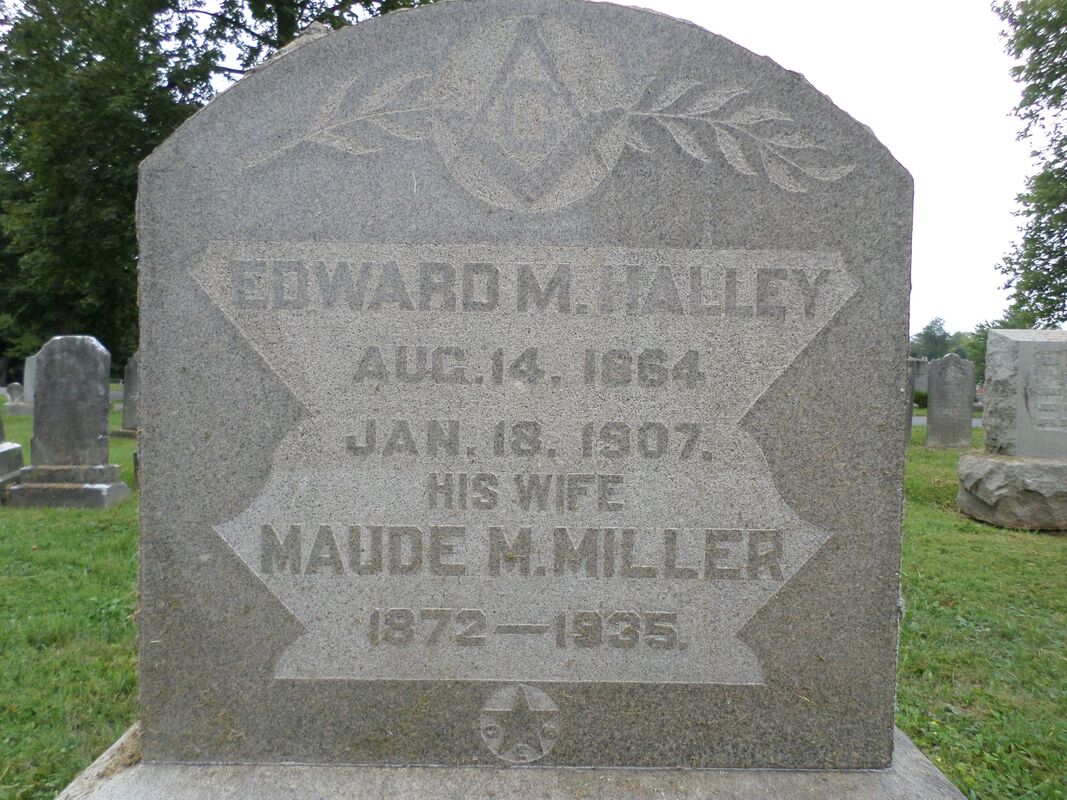

A few months back, an interesting visitor came to our Mount Olivet booth set-up at the Great Frederick Fair, (located under the West Grandstand). This kind lady approached me and told me she had been wanting to reach out to me in effort to share a tale of one of her ancestors buried in Mount Olivet. As historian of this amazing, historic garden cemetery, you can imagine that I’m always excited in learning more about our 40,000 plus inhabitants. This kind woman, Kristi Edens, even had gone to the trouble of putting some research together for me and printed a handful of newspaper articles, including an obituary for her GGG Grandfather—F. B. G. Miller. She also included a picture of Mr. Miller’s gravestone and a rough draft of a family tree pertaining to the subject, a long-time employee of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. So here I am a few months later to give you a brief glimpse into the life of Frances Bannister Gibson Miller, born in Winchester, Virginia on October 15th, 1838. He was the son of William Henry Miller (1808-?), a native of Pennsylvania, and wife Francis Ann Foster (1809-1866). Early life information is scarce, as I could not find the family in 1850 census, but they were indeed residing in Winchester in the 1840 US Census. I found my earliest account on this gentleman, better known as Frank, from an 1859 news article in a Cumberland, Maryland newspaper called the Maryland Civilian. It discusses young Frank’s amazing work ethic in running a telegraph line between Cumberland and Lycoming, Pennsylvania. Eventually he would make sure the line would reach Washington, Frederick and Carroll counties. This was the start of a lifelong profession. Frank’s father, William Henry Miller, had died somewhere before 1860, as he does not appear in the 1860 US Census with the family. We do not have either of his parents interred at Mount Olivet, so it’s been hard to piece info together aside from the semi-complete family tree Kristi shared with me. Frank’s mother, Frances Ann (Foster) Miller appears as head of household in the 1860 Census, in which he can be found living with his older sister Elizabeth and three younger brothers in Cumberland. I next found Frank Miller’s name in Allegany County’s Civil War draft registration roll books, which list his profession as a telegraph operator. He is listed as continuing to live in Cumberland. Here may be a good time to explain the once “state of the art” communication marvel of the telegraph and the profession of telegraphy that Frank had found himself engaged. A telegraph is a device for transmitting and receiving messages over long distances, i.e., for telegraphy. The word telegraph alone now generally refers to an electrical telegraph. Wireless telegraphy is transmission of messages over radio with telegraphic codes. A telegraph message sent by an electrical telegraph operator or telegrapher using Morse code (or a printing telegraph operator using plain text) was known as a telegram. The Baltimore & Ohio Railroad has a history intertwined with the first long-distance telegraph system set up to run overland in the United States.  The Baltimore & Ohio was the original telegraph line and was the right of way along which inventor Samuel F. B. Morse (1791-1872) constructed his experiment. Thereafter, many of the original expansion lines were built along the B&O. These lines were built through agreement between the original telegraph companies and the B&O. The telegraph companies were permitted to build the lines along the right of way, in exchange for providing service to the railroad. The lines might be the property of the railroads and operated by the telegraph company; or the lines might be owned by the telegraph companies, but at the end of the contract, if they did not remove the lines, they were surrendered to the railroad. The railroad controlled the most important thing for the networks—control of the right of ways. And the B&O controlled access to these right of ways in the mid-Atlantic, the most valuable market for the initial communications network. In 1861, when the Civil War broke out, the North/Union boasted a large network of telegraph lines, where the South had few lines. The North placed telegraph service under the War Department and used it to its strategic advantage. US President Lincoln and B&O president James B. Garrett (namesake of the Maryland county) developed a unique relationship in which the railroad and telegraph would assist the Union Army in communication and transport of troops and supply. In return, Mr. Garrett would receive protection from the army for his important investment consisting of trains, track, bridges and telegraph wires which had become regular targets for vandalism at the hands of Confederate raiders. The Civil War found Frank living to the east of Cumberland on the other side of Sideling Hill. He was in Hancock, Maryland, a town that grew up around the National Pike and later Chesapeake & Ohio Canal. The Baltimore & Ohio Railroad was a stone's throw away and across the Potomac River on the Virginia side. This settlement was called Alpine Station after the rail station positioned here, worksite for our subject Frank B. G. Miller. Hancock would see some of the first pitched action of the Civil War. The Battle of Hancock was fought during the Confederate Romney Expedition of the American Civil War on January 5th and 6th, 1862, near Hancock. Confederate commander Major General Stonewall Jackson began moving against Union Army forces in the Shenandoah Valley area on January 1st. After light fighting near Bath, Virginia (aka Berkeley Springs), Jackson's men reached the vicinity of Hancock late on January 4th and briefly fired on the town with artillery. Union Brigadier General Frederick W. Lander was in charge of Union forces here. The following passage comes from Peter Cozzens 2008 book entitled Shenandoah 1862: Stonewall Jackson's Valley Campaign: “By the morning of January 5, the temperature had fallen to 0 °F (−18 °C), where it would remain steady for the next three days. The Stonewall Brigade was brought up that morning, and Jackson aligned his men on Orrick's Hill across the flooded and ice-choked Potomac River from Hancock. At 09:30, Colonel Turner Ashby was sent across the river with a request for Lander to surrender; Jackson warned that he would shell and then capture the town if Lander refused. Upon meeting Lander, Ashby was instructed to tell Jackson to "bombard and be damned" and was given a written rejection of the offer. While Ashby returned to the Confederate lines, Lander ordered that civilians leave the town and assigned the 84th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment to serve as a fire brigade in case the coming bombardment started any fires. The 110th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment defended warehouses, and two pieces of artillery were positioned on a hill behind the town. The Confederate cannons opened fire at about 14:00, and a sporadic artillery duel which inflicted no casualties continued until dusk. A Confederate detachment under Colonel Albert Rust destroyed a bridge over the Big Cacapon River belonging to the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, while another detachment failed in an attempt to destroy a dam upriver from Hancock. While Jackson opened January 6 with a bombardment of Hancock by the Rockbridge Artillery, Lander still desired to take offensive action against Jackson. He asked Major General Nathaniel P. Banks to either cross the Potomac in Jackson's rear or to send him reinforcements, with which Lander would attack the Confederates directly. Banks had ordered Brigadier General Alpheus Williams's brigade to march towards Hancock on January 5, but sent the request for offensive action through Major General George B. McClellan, who viewed it as too risky and rejected it. Later that day, Jackson attempted to cross the Potomac at Sir Johns Run, but was repulsed. Having damaged the telegraph lines in the area, Jackson abandoned the attempt to take Hancock on January 7 and withdrew. The exchanges of artillery fire had caused little damage. The National Park Service estimates that the two sides combined suffered about 25 casualties during the fighting. Here is where two interesting connections to Frederick, Maryland come into play. First, the above mentioned Gen. Frederick Lander would eventually have his name grace a post office in southern Frederick County on Potomac River and on the west side of Catoctin Mountain. Of course this is Lander, a small hamlet that boasts a canal lockhouse at lock 29 near mile marker 50.8 Today, you can find a popular boat ramp here too. As for Gen. Lander (b. 1821), he was a transcontinental United States explorer, a prolific poet and had recently married a top stage actress from Great Britain. Likely due to the fatigue of the winter campaign of January and February, 1862, Gen. Lander contracted pneumonia and his gifted life would be cut short with his death on March 2nd, 1862. The second connection of note involved Frank B. G. Miller who was serving as the telegraph operator for Hancock at that time. The railroad station was located across the Potomac at Alpine Station. Here is an article from 1899 that explains the heroics he would employ during the Battle of Hancock in early January, 1862. Pretty cool stuff and the imagery of someone swimming across the Potomac in the dead of winter is one thing, but doing so amidst ice chunks in the water, and bullets whizzing by in the air above is awe-inspiring. And if that wasn’t enough, he didn’t even have time to dry off and change clothes, before climbing a telegraph pole to jerry-rig the communication line to Washington, DC. This seemed to be the most exciting action during the war for Frank Miller. Following the end of hostilities, he came to Frederick and served as the assistant telegraph operator at Monocacy Junction, another place that saw plenty of activity during the American Civil War. The pinnacle was the July 9th Battle which is known in history books as "the Battle that Saved Washington, DC." This conflict was mostly the result of telegraph and transportation lines of the B & O. Word was communicated via the telegraph to Baltimore that an unusual Confederate Army contingent had suddenly appeared in Martinsburg under Jubal Early in early July, 1864. This Rebel group headed east across to Potomac to Sharpsburg, and then Boonsboro crossing South Mountain to Middletown and eventually reached Frederick in July where they promptly requested a ransom of $200,000. Gen. Lew Wallace commanded Union troops here, hastily brought in from Baltimore to square off with Gen. Early's men. Interestingly, Miller had installed some of these same telegraph lines under Wallace earlier in the war in the western part of the state. A battle would rage at the Monocacy Junction, a few miles south of Frederick, on July 9th. The fighting could clearly be seen and heard from vantage points throughout town, including our fair cemetery, only in its 10th year of use at the time. One of the central areas of action of the battlefield area was the Monocacy Junction itself and associated buildings. Many fascinating things happened here during and after the battle, including action around the train station at the actual junction itself, Lew Wallace's command headquarters and the B& O Railroad Bridge across the river. A surprise visit from Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and Gen. Philip Sheridan occurred here on August 6th, 1864 for a secret planning meeting. One of the longest inhabitants though would become Frank Miller. Frank started as assistant telegraph operator, but would take the top job after his boss, William T. Mullinix (1849-1910), stepped down in 1880. It appears from other articles that he performed this top job as B & O Rail Agent with a high level of professionalism and creativity. On the personal side of life, Frank lived at the Junction but records show that he had purchased a 4-acre property between the railroad and Bush Creek on the east side of the Monocacy, but sold it in 1870 to Ann Johnson, wife of Worthington Johnson. Frank soon married Louisa Marie Schell (b. 1838 in Somerset, PA) around 1871. The couple would go on to have four children: Maude Mary Miller (1872-1935), Nan Boardman Miller (1875-1960), Frances B. Miller (b. 1877), and James H. G. Miller (b. 1880).  Frank's son, James, was named for neighbor and friend James Henry Gambrill who lived across the river from the junction in the large mansion once known as Boscobel House and Edgewood. The Gambrills owned the nearby Araby Mill and the Frederick City Mill (destined to become the Delaplaine Art Center). Now part of the Monocacy National Battlefield, the old Gambrill mansion houses employees of the National Park Service Historic Preservation Training Center. Sadly, the Miller family would undergo a great degree of sadness in the late 1880s as Louisa would become sick and required care from her sister in their hometown of Somerset, Pennsylvania. Here, Louisa succumbed to her illness on September 29th, 1888. She was laid to rest in Somerset's Husband Cemetery. Meanwhile, Mr. Miller took on the task of raising four children into adulthood. Mr. Miller threw himself into his job even more, one he already had great passion. He even foiled a robbery one night while on the job. In addition to his duties as a rail-road agent for the B & O, Miller would also be appointed the postmaster of the Araby Post Office. He would eventually be replaced in his Railroad agent position at Monocacy Junction by his son-in-law, Edward M. Halley, who had married his daughter Maude. Frank served as a ticket agent with the railroad in his final years. He would die on September 12th, 1900. He is buried in a small lot (#36) on Area F. This plot is owned by Columbia Lodge Number 58 of the Frederick Masonic Lodge. Frank was a member for nearly 30 years. Mr. Miller is one of four individuals actually buried within the Masons’ lot which was originally purchased in 1858. Staying true to form, he continued his streak of avoiding land property ownership. Frank G. B. Miller's obituary found in the Frederick paper included tales mentioned earlier of his early career in the telegraphy business, and his Civil War heroics and bravery under fire. His obit was carried in both the Baltimore and Washington newspapers where I'm sure many knew him from his connection to the B & O. Mr. Halley would be appointed as Araby's Postmaster just a few weeks after the passing of Frank Miller. Mr. Halley died just seven years after his father-in-law in 1907, thus ending the family's reign at "the Junction." Both Maude and Edward are buried in Mount Olivet’s Area H/Lot 29. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed