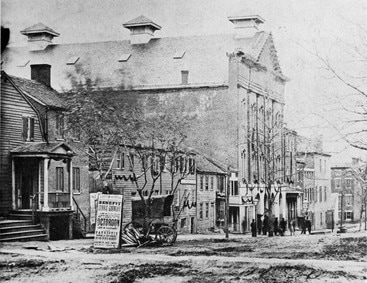

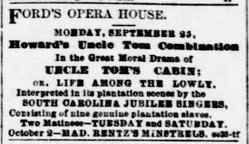

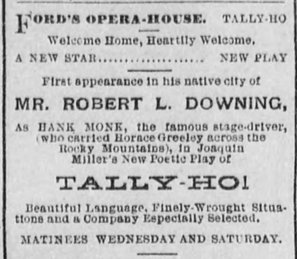

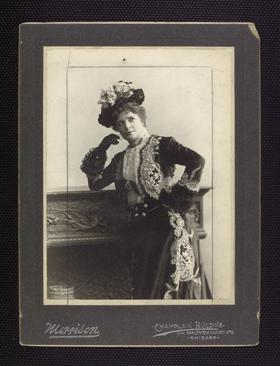

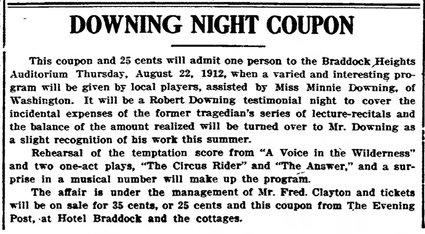

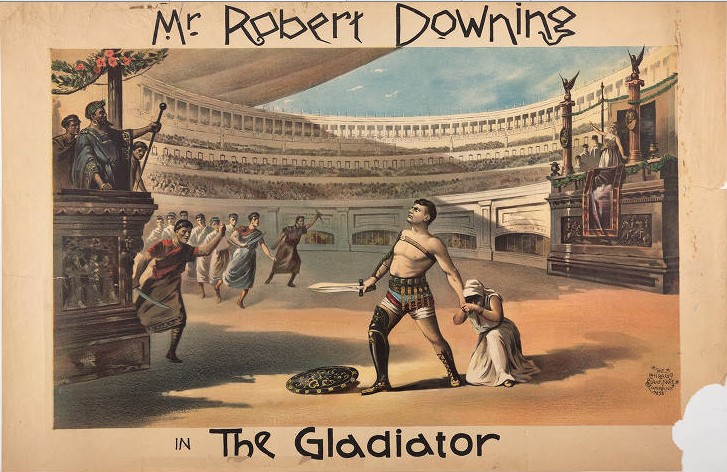

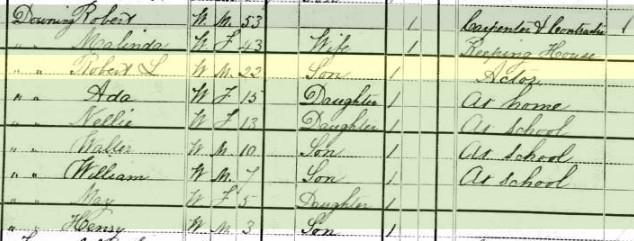

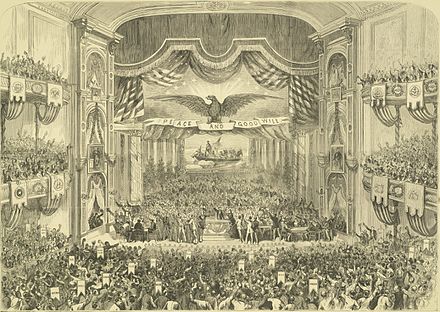

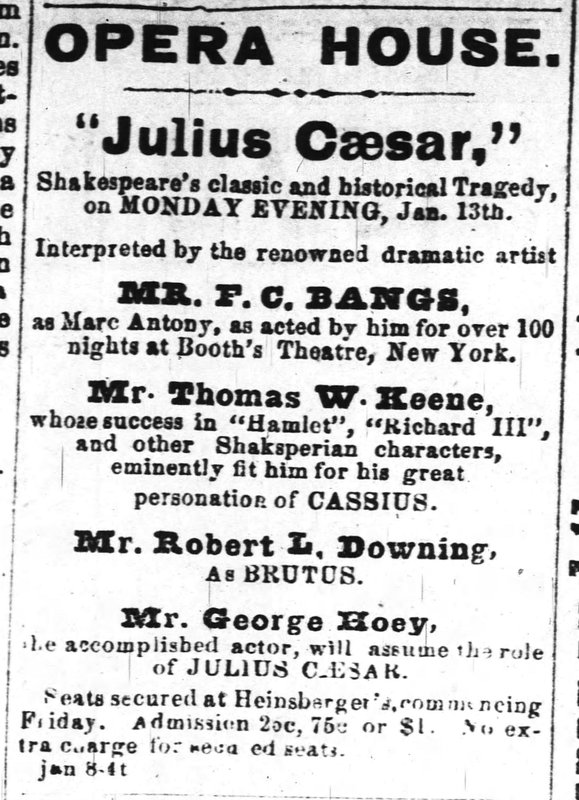

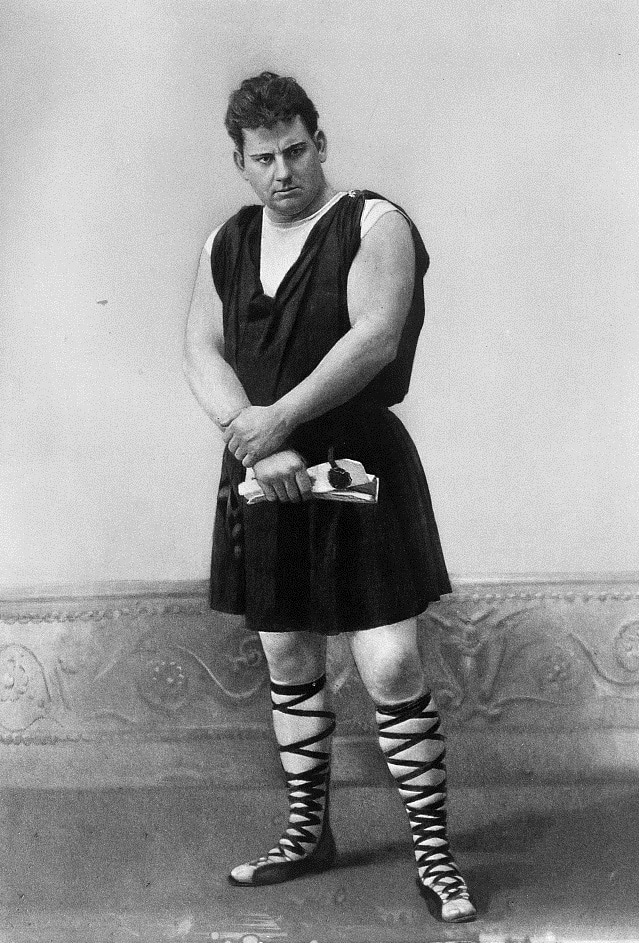

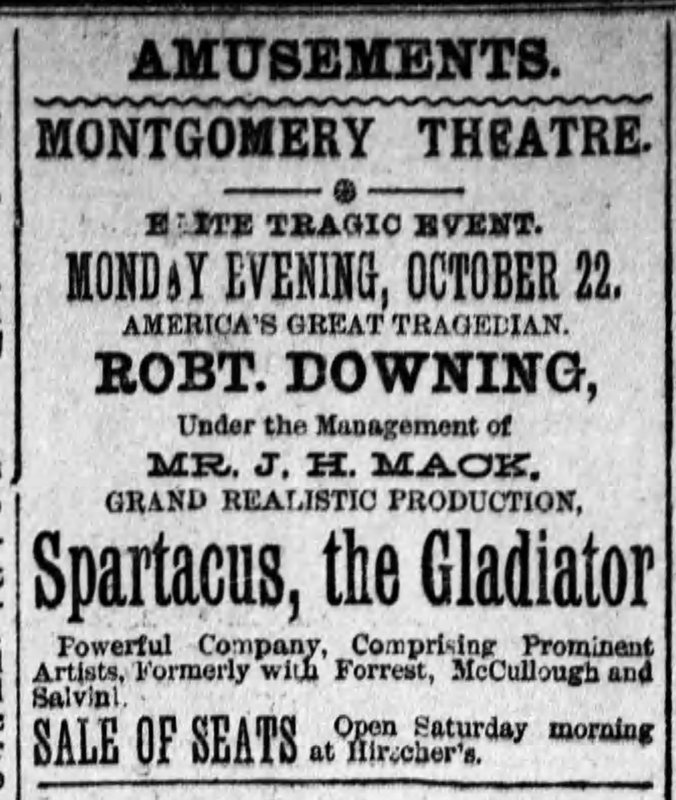

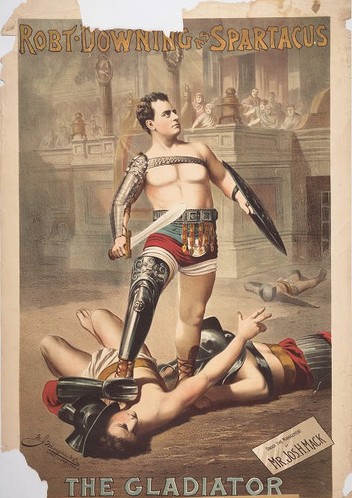

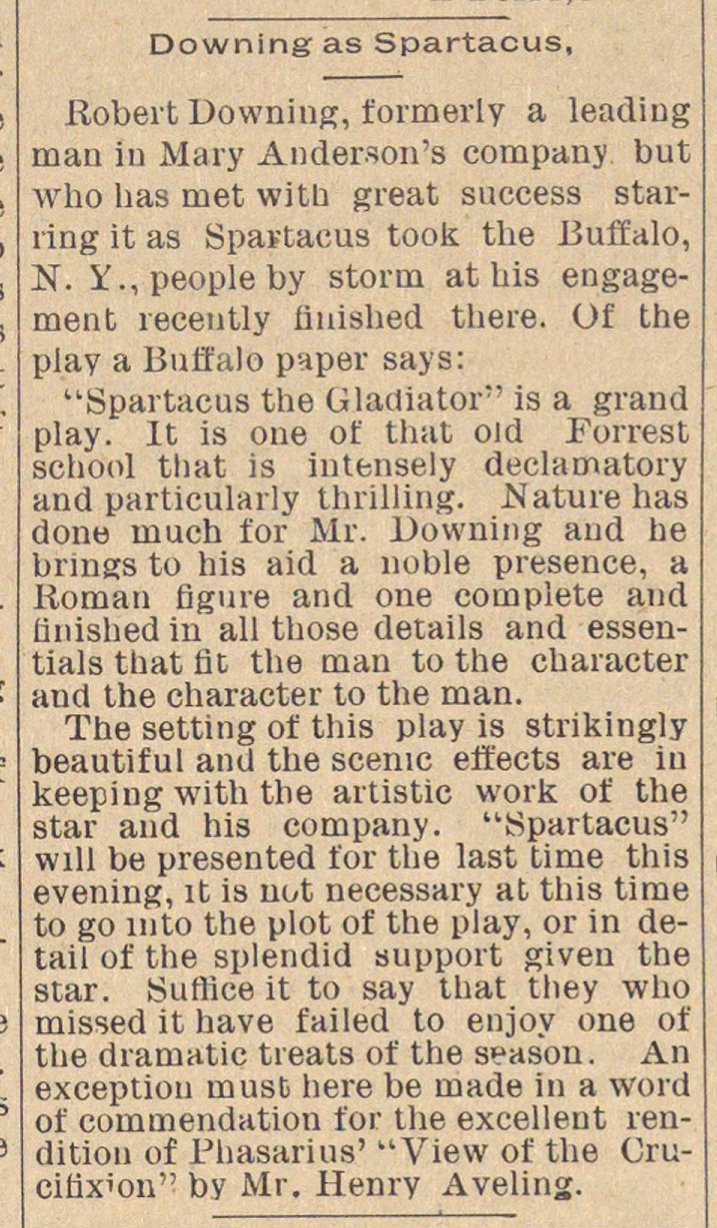

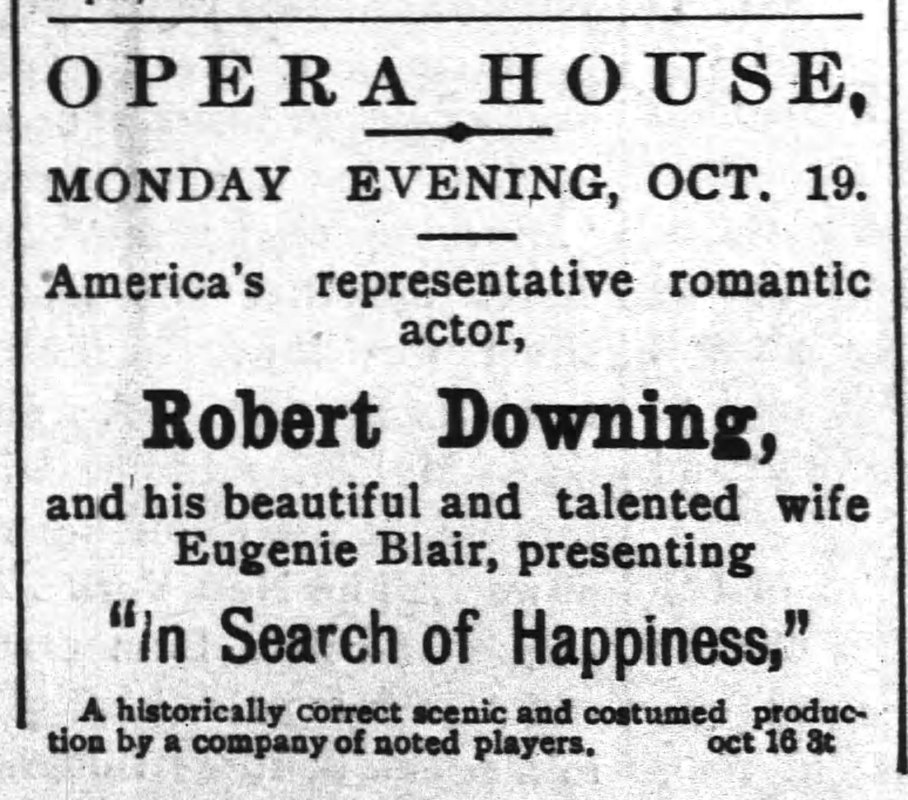

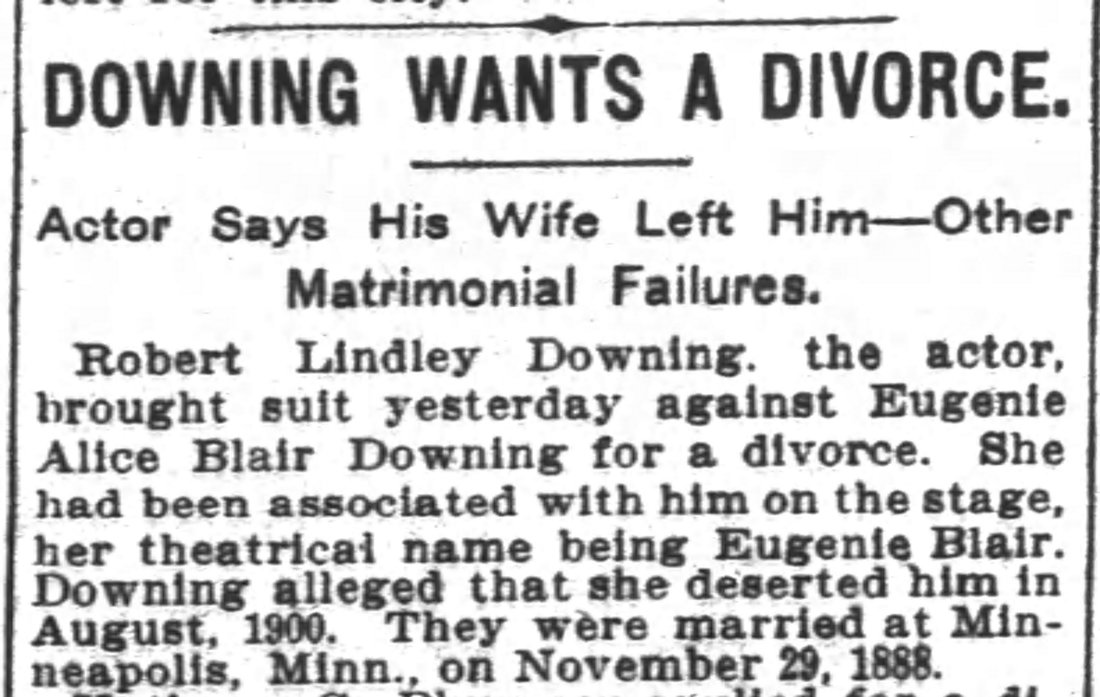

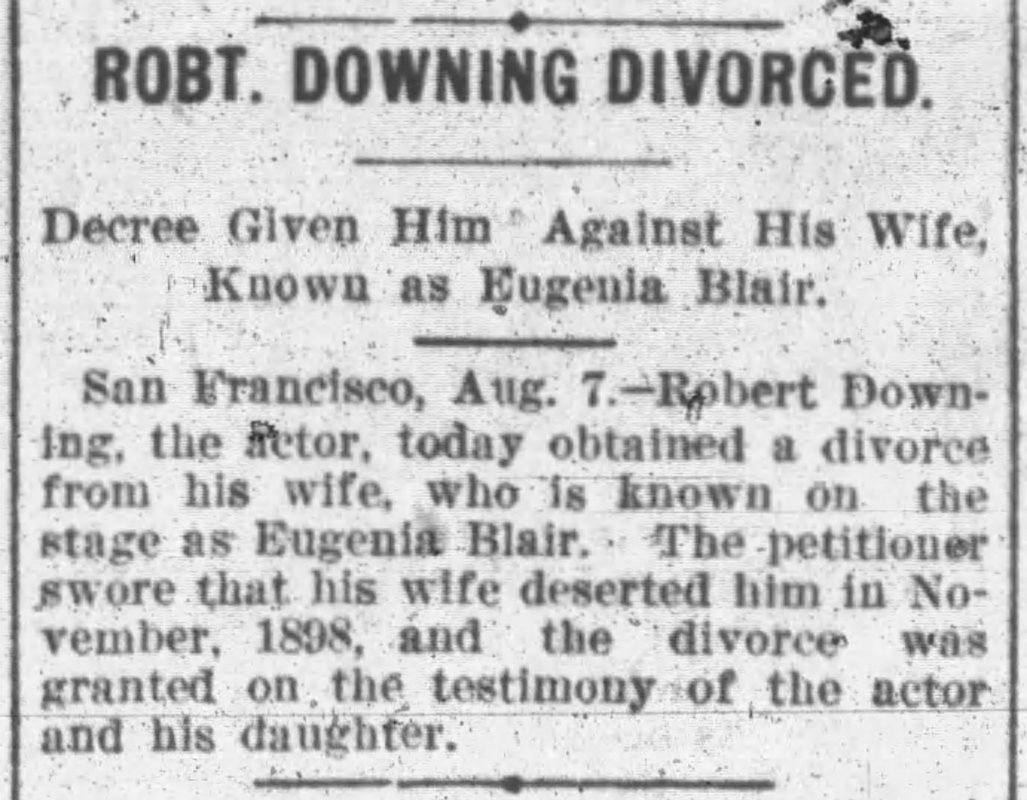

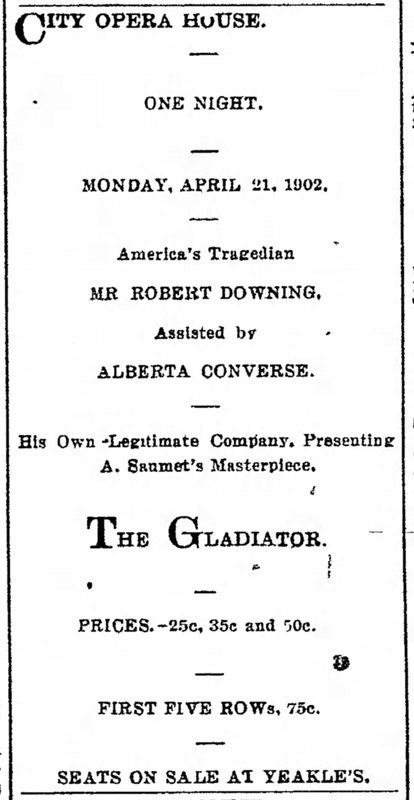

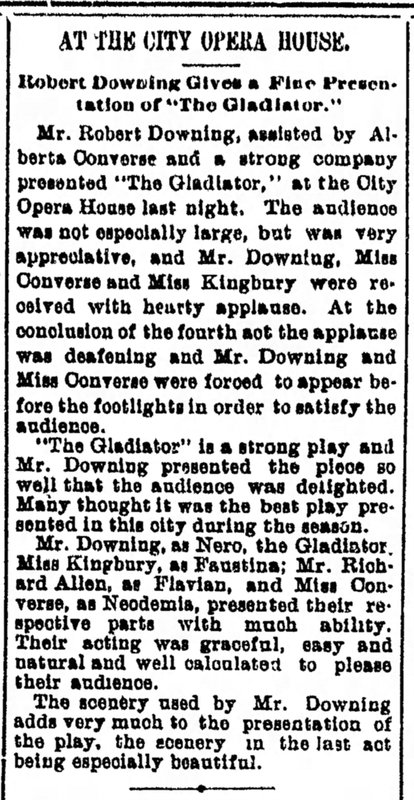

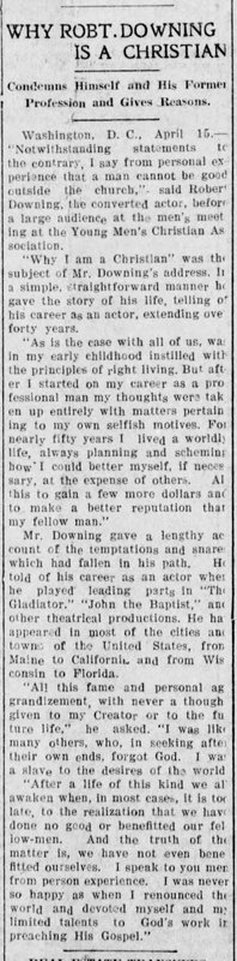

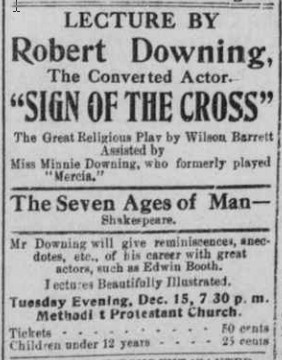

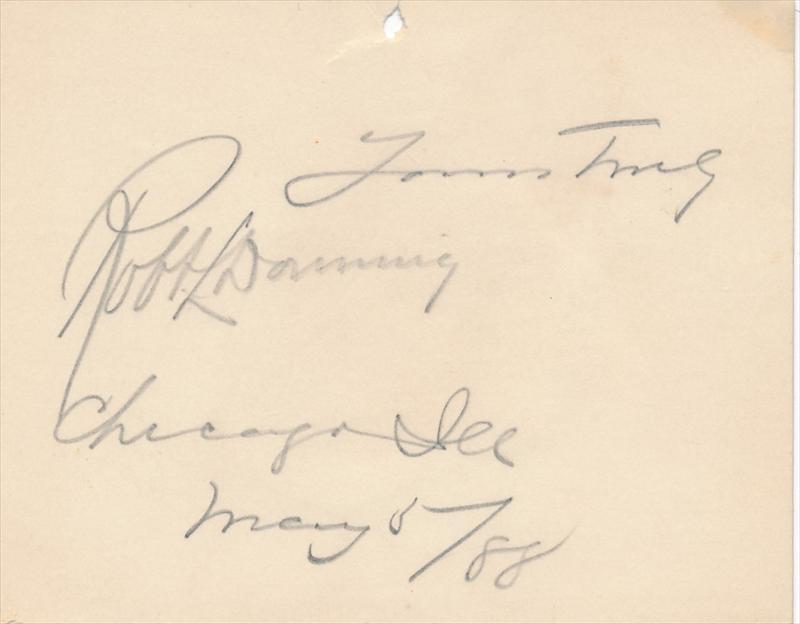

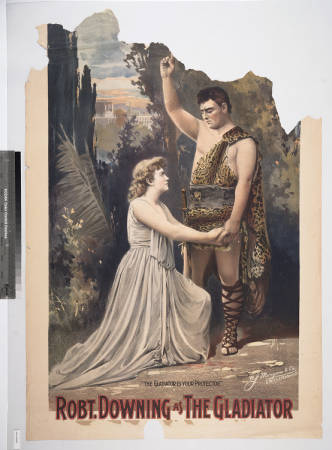

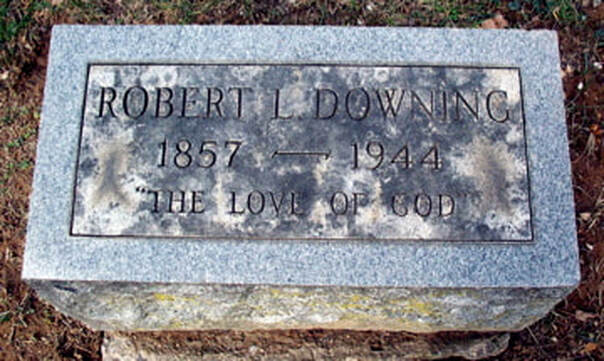

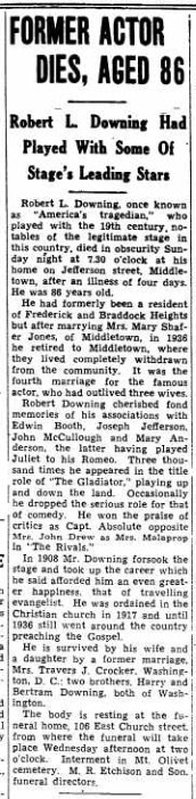

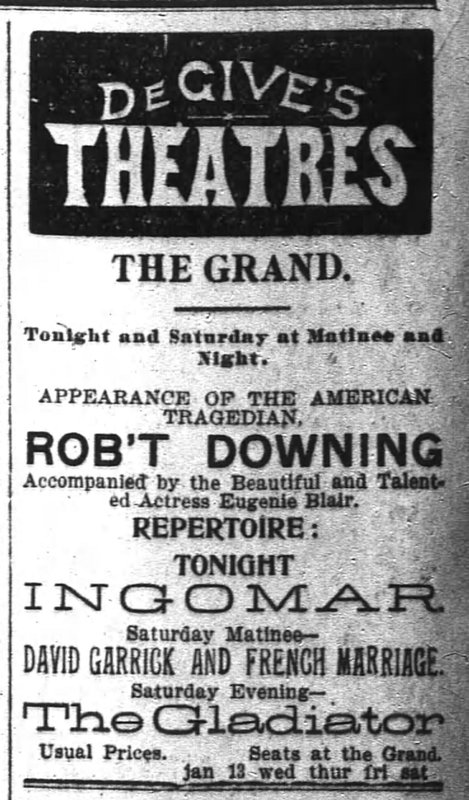

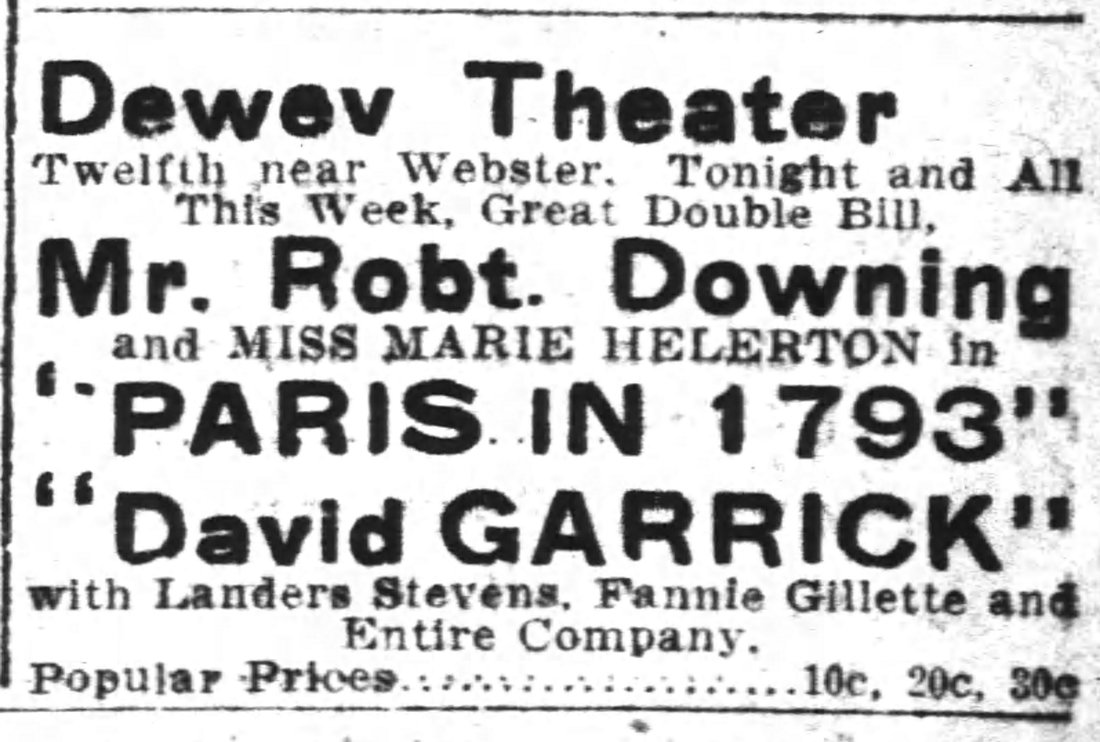

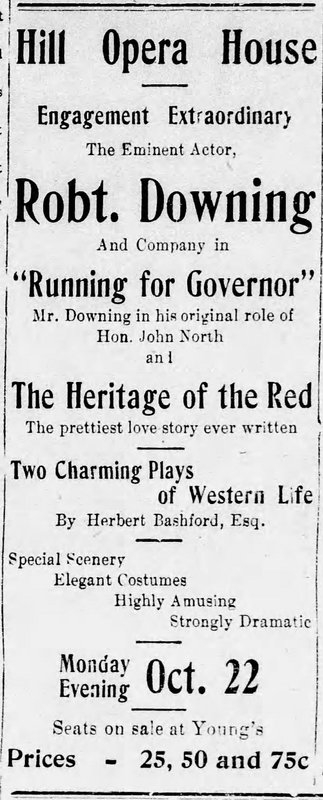

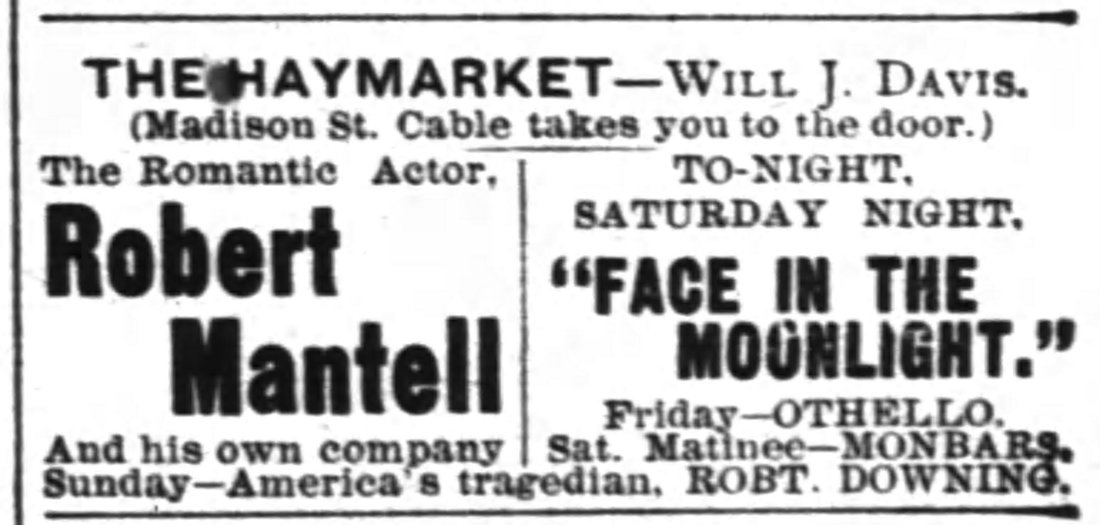

Robert L. Downing (1894) Robert L. Downing (1894) Mount Olivet Cemetery serves home to thousands of interred people. They have come from all walks of life and socio-economic backgrounds. And certainly not all are native Frederick Countians. I was surprised to find out last fall that we have an outstanding former actor in our midst. This gentleman was not the recipient of an Oscar, Emmy or Tony award, but in his defense, his “acting” days predated 1929—the inaugural Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences awards ceremony at the Hotel Roosevelt in Los Angeles. Newspapers of early October, 1944 announced the death Robert L. Downing, sparking recollections of a bona-fide superstar of stage productions several decades earlier. Once the object of standing ovations from audience-packed theaters throughout the country, Mr. Downing would pass quietly in his home located on S. Jefferson Street in Middletown, Maryland. The once famous actor, commonly known as “America’s Tragedian,” had moved here in 1936 upon the occasion of his fourth marriage to Mary Shafer Jones. His life on-stage and off, can be succinctly described by one word—"dramatic."  Ford's Theater, Washington, DC (c. 1865) Ford's Theater, Washington, DC (c. 1865) Early Life Robert Lindley Downing came into this world on October 28th, 1857 in Washington, DC. He was the son of Robert, Sr. and Malinda Downing. His father was a master carpenter, and operated one of the leading architectural and building firms in the city. He would also serve as vice president of the District of Columbia Building and Loan Association in the 1870’s. Son Robert was the oldest of seven children, all of whom enjoyed a privileged and cultured upbringing, while attending fine schools. Robert’s earliest childhood memories were painted with news and scenes associated with the American Civil War. Washington, DC was an important backdrop and potential target throughout the four-year conflict. It suddenly became “center-stage,” literally and figuratively, as the site of one of the worst tragedies in our country’s history in April, 1865. President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated by an actor, while watching a performance at Ford’s Theater. Robert Downing was seven years-old at the time. Interestingly, dramatic moments at this location, along with a relationship with proprietor John T. Ford would have a profound effect on his life. At 18 years-old, young Robert sidestepped a career in the family building business, for the chance to act on a stage. His parents supposedly were adverse to this decision at first, but eased in seeing his true passion for the trade. Downing worked hard, took advantage of family contacts and regularly commuted between the nation’s capital and nearby Baltimore to work for prominent theater manager John T. Ford. He became a member of the stock company at Ford’s Grand Opera House, Baltimore—one of several locations now managed by Ford.  Advertisement from the Washington Evening Star (September 27, 1876) Advertisement from the Washington Evening Star (September 27, 1876) A Star is Born Robert L. Downing’s first performance of consequence was the stage adaptation of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, in which he played the role of George Harris, the young white man who befriends Uncle Tom. What followed this endeavor was five years of stock company playing. He then began associations with the top actors of the day including Charles Fechter and John McCullough. Downing would find himself traveling the country and cast for additional strong supporting roles in Shakespearian masterpieces. He worked alongside Edwin Booth, Maryland native and considered by many theatrical historians to be the greatest actor of the 19th century, a fact often overshadowed by his brother ( John Wilkes Booth) being the assassin of Abraham Lincoln. Robert L. Downing played the role of Brutus, (and later, Marc Anthony) in “Julius Caesar." He would follow by portraying Romeo opposite English-born Mary Anderson, one of the most popular actresses of the age in “Romeo and Juliet.” In 1881, Downing made his New York debut with Miss Anderson as Claude Melnotte in the melodrama “Lady of Lyons” performed for a six-week engagement at the Fifth Avenue Theater. He was on the rise and would continue spending the next few years with Anderson, followed by a stint with Joseph Jefferson(1829-1905), considered one of the leading comedic actors of the 1800’s.  A time for both Comedy/Tragedy masks The year 1884 was an eventful year for Robert L. Downing, both personally and professionally. He married Mary Emma Millspaugh of Vermont, and the couple soon found themselves expecting a child, with a due date expected in March the following year. At the same time, author Joaquin Miller was completing a three-act play specifically designed for Downing to play his first-ever lead role. Entitled “Tally-Ho,” this was the story of Horace Greeley’s trip west across the Sierra Mountains with the production’s hero embodied in stage coach driver “Hank Monk,” played by Downing. The premiere of “Tally-Ho” would take place in Downing’s hometown of Washington, DC on March 16th, 1885. The engagement was promoted heavily in local papers and friends, near and far, came to see their native son take center stage at legendary Ford’s Theater. It was also a slight departure for Downing to try his hand at comedy in this melodrama. What an amazing time for Robert as he became a father earlier in the month with the birth of a daughter who would be named Minnie Roberta. Sadly the successes of March and the launch of “Tally-Ho” would be eclipsed by the death of Mary Emma Downing on April 1st, most likely from complications related to childbirth just weeks before. This adversity certainly challenged “America’s Tragedian,” but he seemed to use it to further strengthen his drive to succeed. During this time, his career was being carefully watched by some of the most successful producers of the day. One of these was Joseph H. Mack, who at first took a friendly interest in the young actor. He soon came up with the idea of recruiting Robert Downing for the starring role for an elaborate production of “Spartacus, the Gladiator.” Mack’s production debuted in New York at the Star Theater in 1886. The ancient Roman themed-stage play would become an audience favorite across America, propelling Downing to new heights. Over his career, he would perform the role of Spartacus over 3,000 times. For the next two decades, Downing would remain one of the kings of Broadway, starring under his own management and playing roles such as Virginius, Othello, Marc Anthony, Ingomar, Damon and other heroic roles. An entertainment magazine of the day exclaimed: “He (Downing) has become a popular favorite, and a worthy successor to the great exemplars who have immortalized themselves in the portrayal of these forceful characters.”  Eugenie Blair (1864-1922) Eugenie Blair (1864-1922) Robert L. Downing found love again in 1888 as he married a co-star—the celebrated actress Eugenie Blair. The couple wed, but the marriage would last only a decade. In time they would live more apart than together, both balancing the rigors of professional schedule and daughters from respective previous marriages. Typical of many celebrity relationships of today, things went south and scandal and public intrigue soon followed. Downing claimed that Blair had deserted him in 1898, and sued for divorce in August 1901. It came to fruition later that year. At this time, he was spending a great deal of his time residing on the West Coast, and in particular, San Francisco. He opened an acting school and was attempting to further the career of daughter Minnie with an entrée into show business. “Head East, Middle-Aged Man” Robert would return back east and focused his efforts on growing his drama school in his old hometown. On April, 21st, 1902, Downing made his first theatrical appearance in Frederick. This was a performance of his legendary “Spartacus, the Gladiator” stage play, which would be performed at the City Opera House on N. Market Street. While in DC, Downing found love once again—this time with a divorced socialite named Helene Kirkpatrick. Kirkpatrick was a noted musician who hailed from Louisiana. They married in late March, 1904. The Downings split their time together in Washington and at a newly purchased country home located just east of Frederick, Maryland’s downtown area. They had acquired the historic Boteler mansion/farmstead named “Park Hall.” (Located at 1100 E. Patrick St., this fine structure and spectacular barn stood up until its demolition by current owners in 2014. It was wedged between the site of a McDonald’s and the Eastgate Shopping Center. The tree-lined driveway still exists and the property stretches from E. Patrick Street to I-70).  Frederick News (August 19th, 1912) Frederick News (August 19th, 1912) Not having far to travel, Robert L. Downing once again performed at the City Opera House on Thanksgiving night, 1905. They continued spending time at Park Hall, in addition to other places around the country. The couple actually sold the estate to Professor Amon Burgee in 1907, but would continue holding residency in Frederick as they would be found living at 217 E. Patrick Street in the 1910 census. The Downings also appear to have spent time living, and socializing, in Frederick’s new posh mountain resort of Braddock Heights, atop Catoctin Mountain. Robert apparently lectured and performed here in the summer of 1912. In 1908, Robert L. Downing walked away from the popular theatrical stage to play another role that seemed his calling. He became an evangelist preacher to the shock and surprise of fans and actor friends alike. He was ordained as a minister in 1907 and now toured the country preaching the Gospel. He used his life experiences, both triumphant and tragic, to inspire others in choosing God over fame and success. Over the next few decades, he would continue to lecture, dabble in smaller theatrical productions and occasionally work with daughter Minnie, now married to Travers J. Crocker and living in Washington, DC. He won praise from critics as Captain Absolute in a production entitled “The Rivals.” In 1918, he would make a return to the stage with 300 performances of “Ten Nights in a Bar Room,” a play adaptation of a temperance novel written in 1857. One of the greatest Shakespearean actors of all time kept true to his evangelistic mission. He would preach in churches and on street corners, all the while refusing to place the title reverend before his name. The Downings usually settled in coastal resort towns including Providence, Rhode Island and Norfolk, Virginia for the summer months. After 26 years of happy marriage, Downing would find himself alone again. Helene died in 1930. He had survived all three of his former wives, including Eugenie Blair who died back in 1922. She collapsed backstage immediately following a performance in Chicago. By this point, Robert L. Downing was virtually forgotten by the public. The great stage actors of the 19th century were long gone as new stars of the silver screen had taken their place. Westerns and modern warfare offerings had won over popular interest in the Shakespearean classics. However, Robert L. Downing would make one last “dramatic” splash in 1936. Newspapers across the country soon carried a heartwarming story connected to “America’s lost tragedian.” Curtain Call The third time was a charm, but Robert wasn't finished yet, marrying once again at the age of 78. His bride was a former Washington DC sweetheart and career schoolteacher with familial roots in Middletown (MD). Her name was Mary (Shafer) Jones. At 65 years-old, the former “Mrs. Jones” had been widowed since losing her physician husband. She split her time between homes in the nation’s capital and Middletown. Once remarried, the couple made the decision to retire to the country. Robert L. Downing had lived a dramatic life, and excelled in his chosen field. His name was regularly in lights on big city marquees, and his image adorned advertising posters plastered around towns in which his touring schedule delivered him. Now it was time for quiet and solitude—all curtain calls complete. “America’s tragedian” would die on October 1st, 1944 in relative obscurity at the age of 86. A quote from Shakespeare’s “As You Like It” seems a fitting epitaph for the man who followed his dream, and walked away from the stage to pursue other convictions and the fruits of his success:

“All the world’s a stage, And all the men and women merely players; They have their exits and their entrances, And one man in his time plays many parts, His acts being seven ages.”

3 Comments

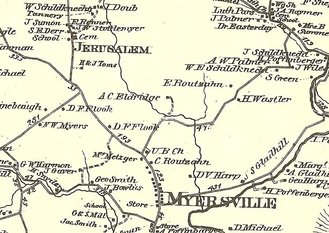

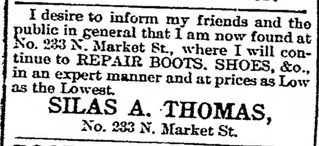

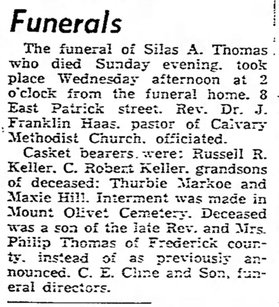

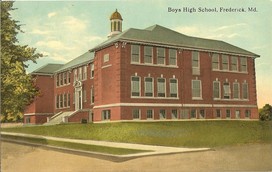

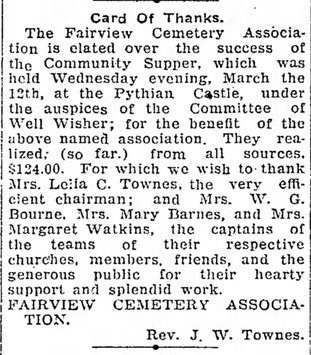

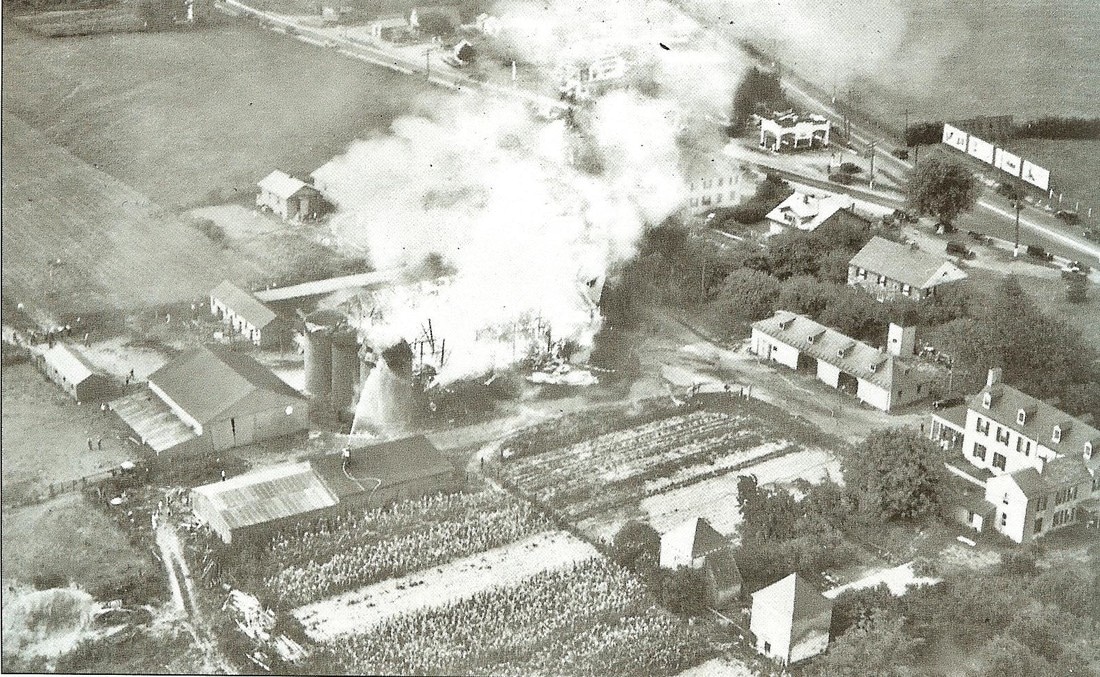

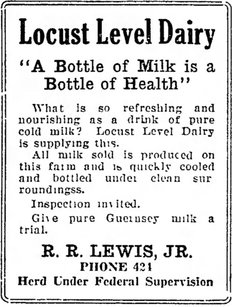

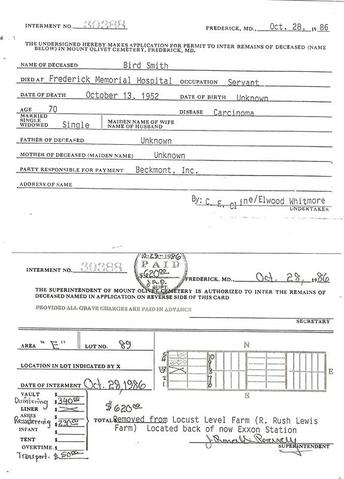

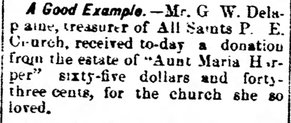

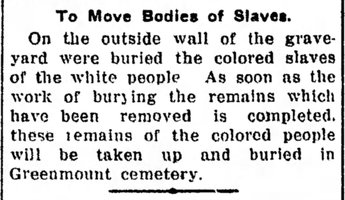

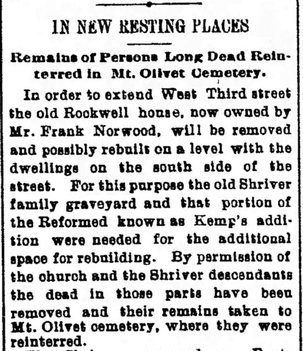

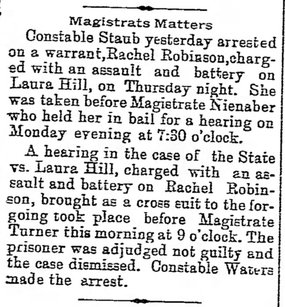

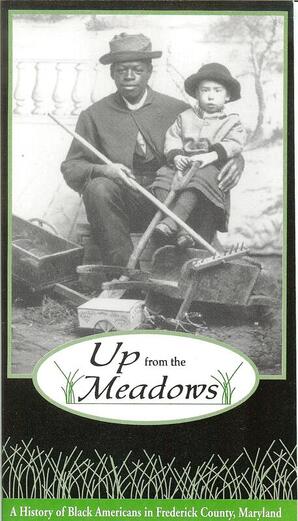

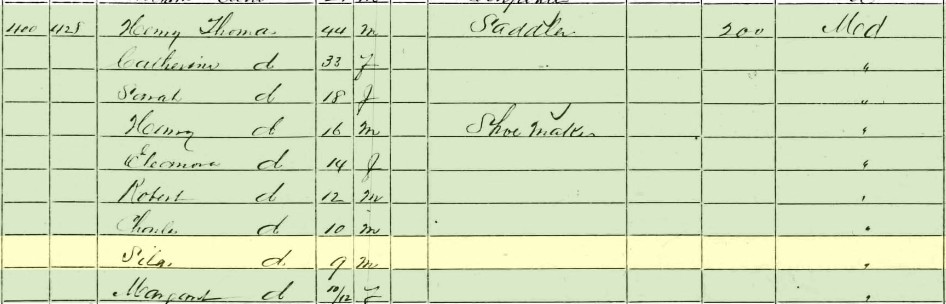

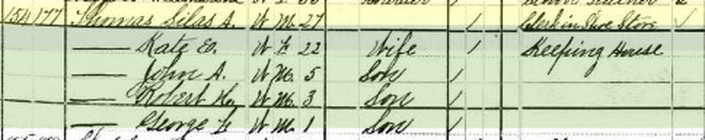

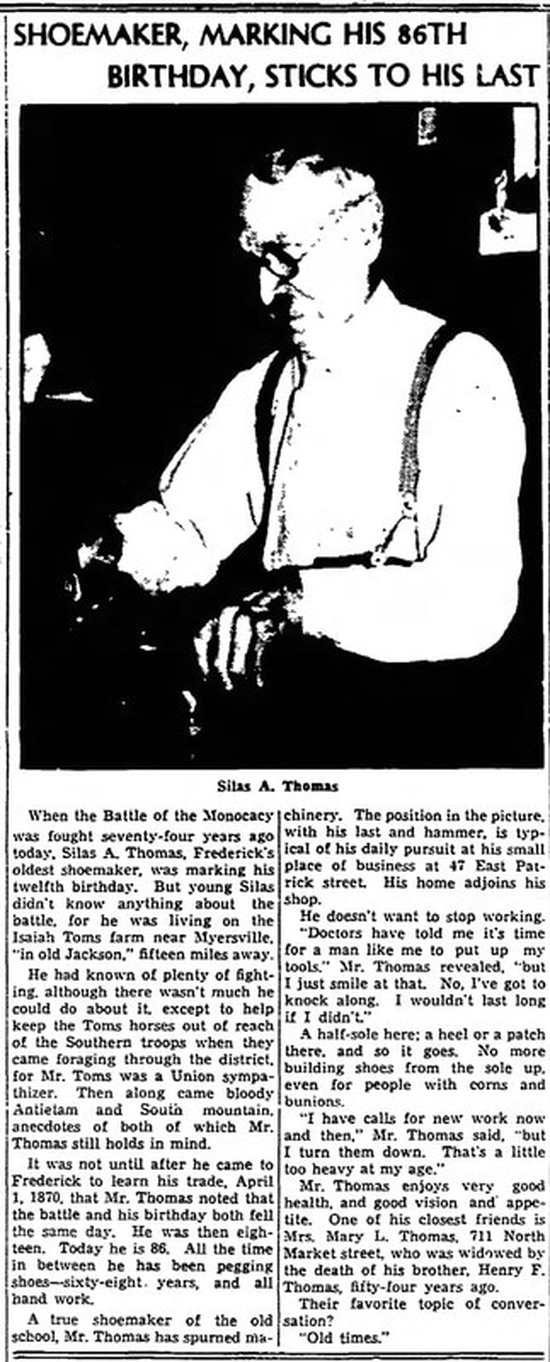

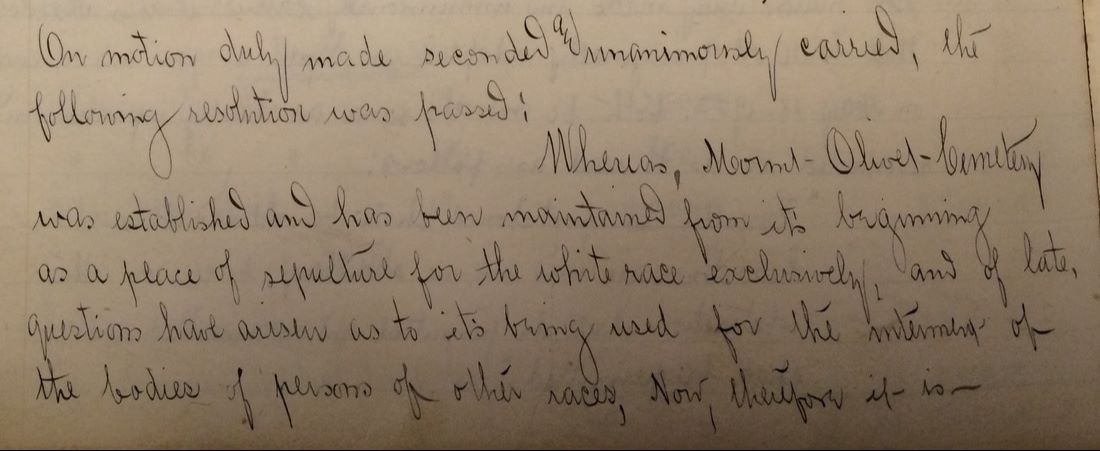

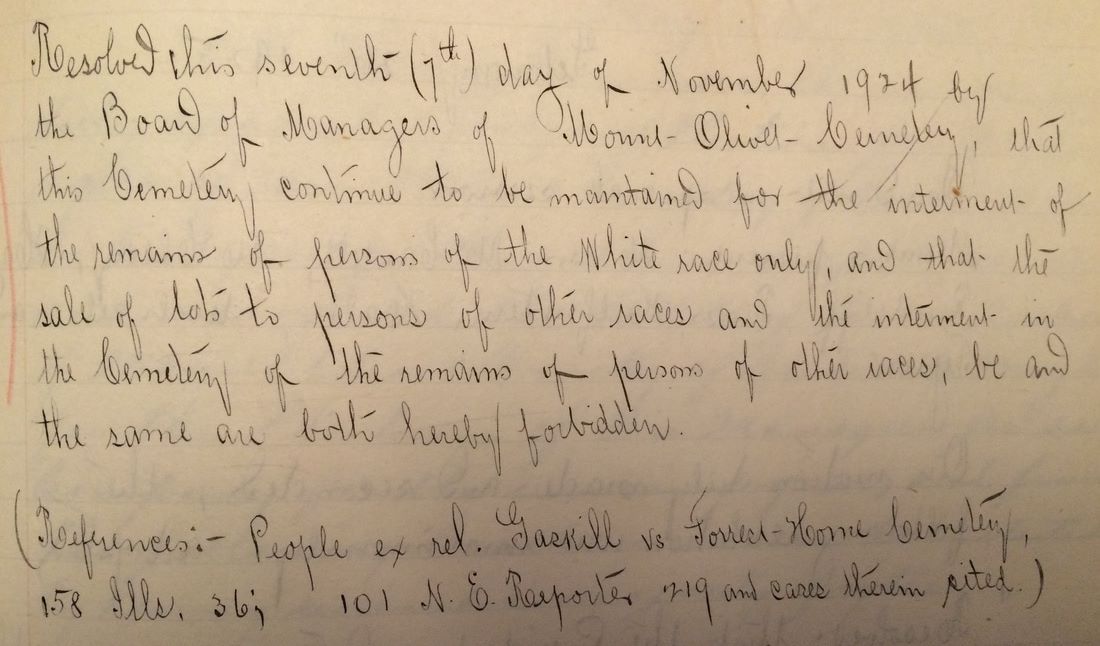

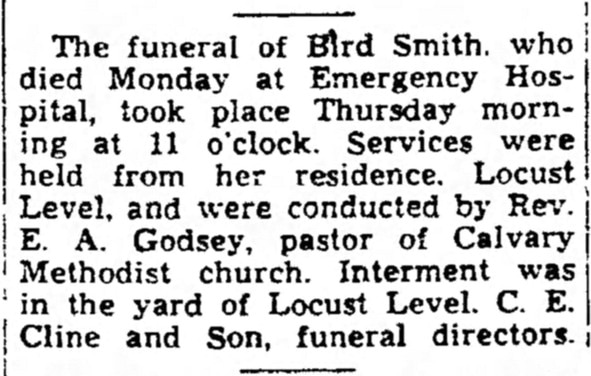

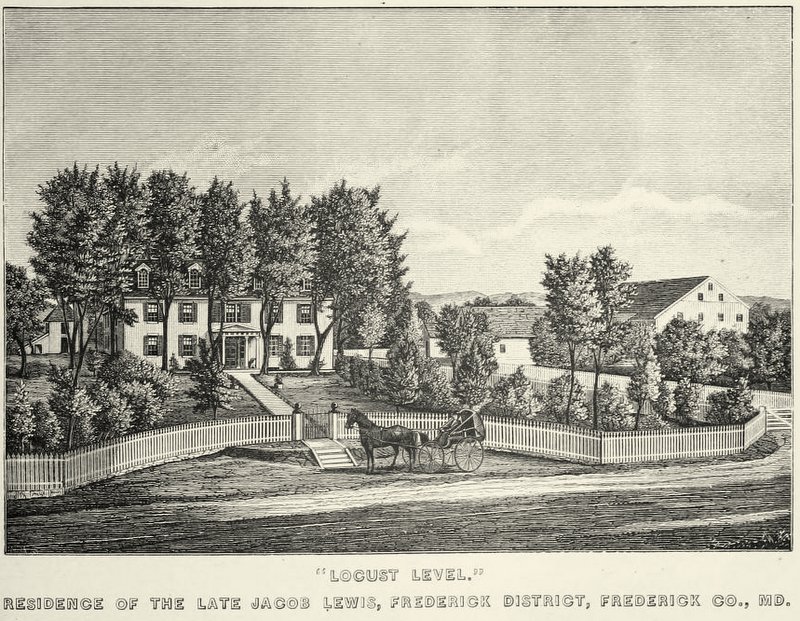

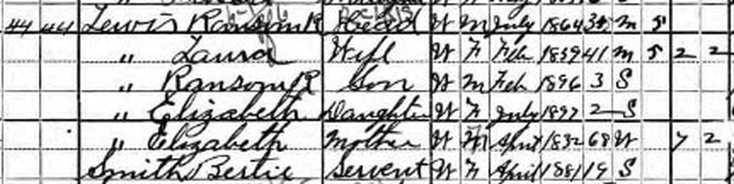

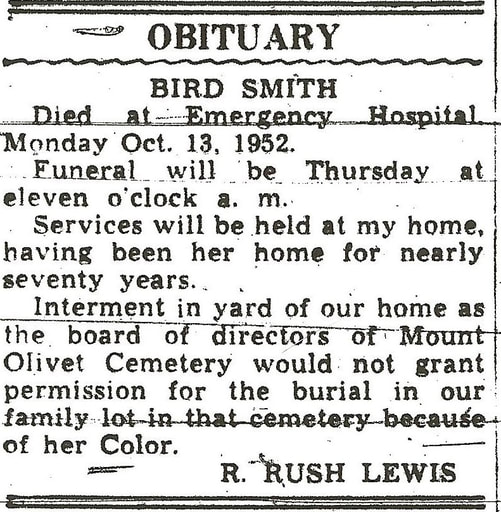

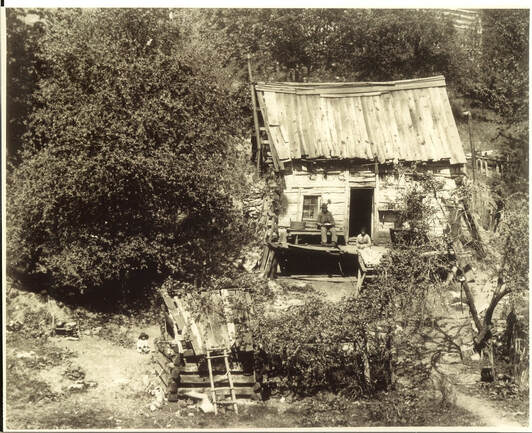

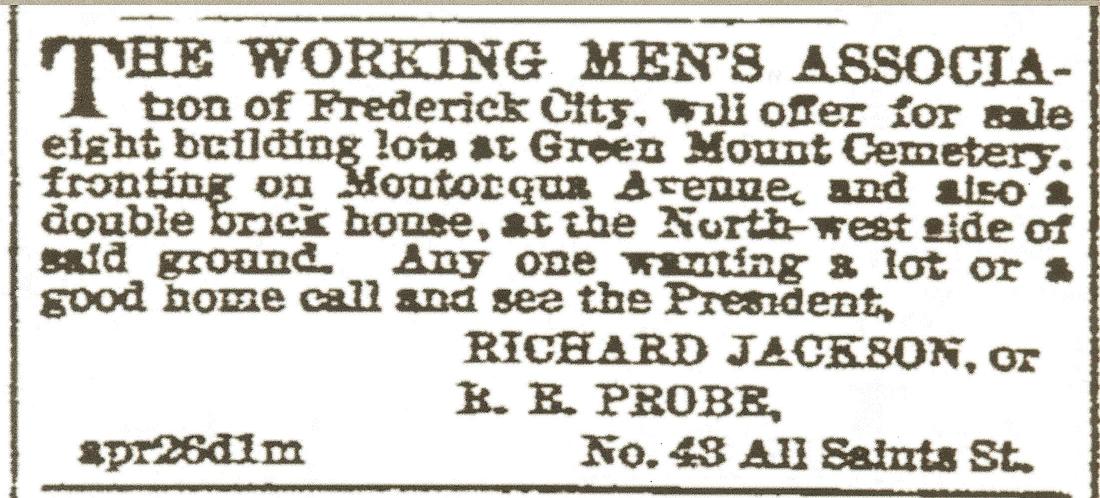

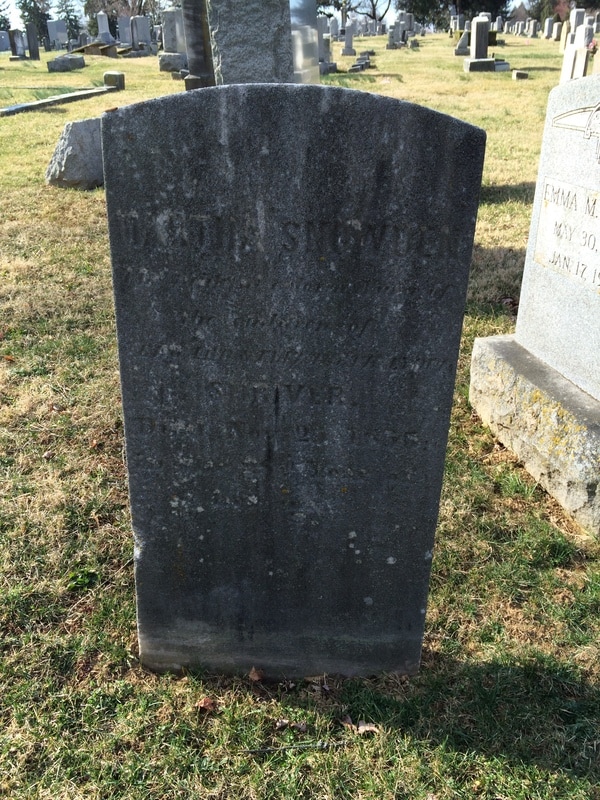

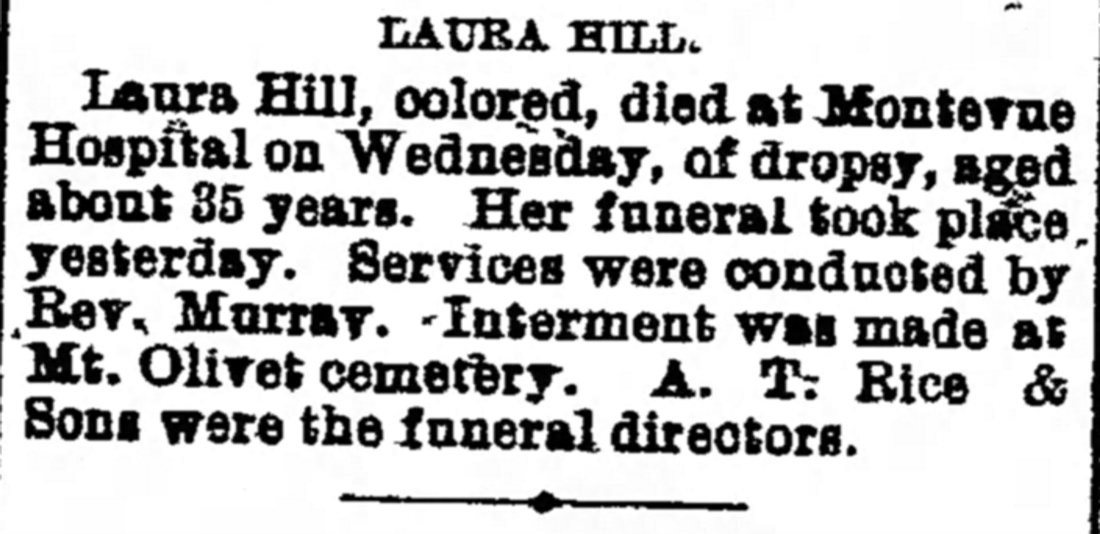

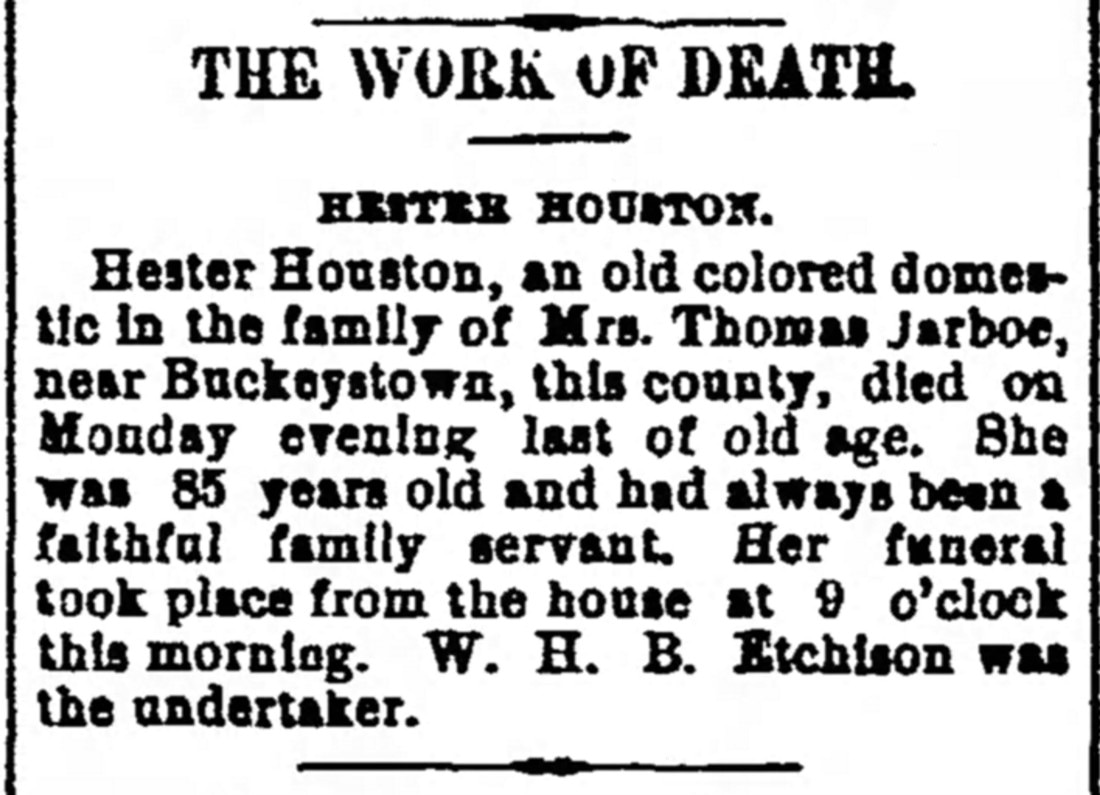

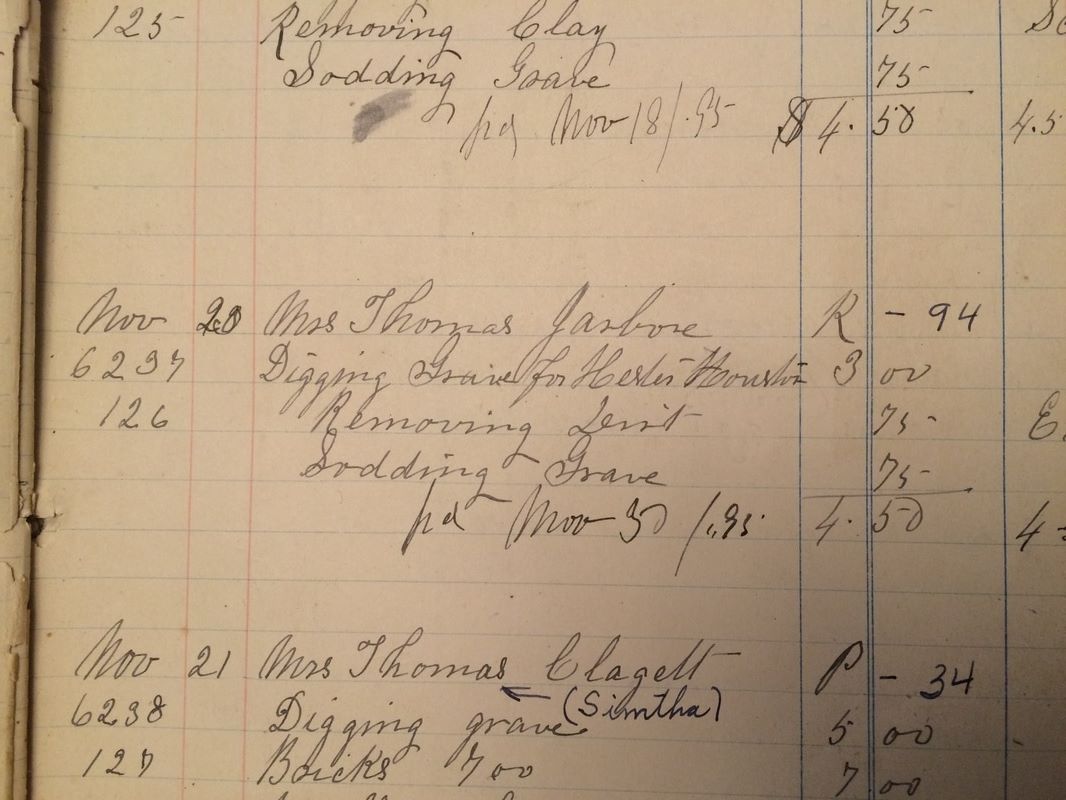

,A “throwback” name for a man who devoted himself to a “throwback” occupation. This week’s subject was a humble gentleman who lived what I assume must have been “an oft quiet life of solitude.” He worked alone, as was generally the case with early cobblers—menders and makers of shoes. In Silas’ case, he would endure incredible voids made in his own life by the repeated loss of dear family members, taken in the prime of life. Silas, on the other hand, would live to the “well-worn” age of 96 years, 5 months and seven days. There is an old Irish rhyme that seems fitting for this particular life story of a Mount Olivet resident. It appears that the wear and tear of shoes has a bit of symbolic superstition behind them: “Worn at tip of toe, wearer sees woe, Worn out at the side, wearer meets his bride, Worn on the ball, best not to buy at all, Worn at the heel, wearer makes a wise deal.” While we are on the subject of superstition, I found the typical “good news/bad news” when it comes to foot apparel, with a quick internet search. Supposedly placing shoes diagonally upright in your doorway is a good way to outsmart devils and monsters from entering your door. “Place one shoe with toes facing out the door, and the other shoe with toes facing in. This is said to confuse little demons and keep your home evil-free.” On the flipside, it appears that placing shoes on top of a table is symbolic of death. This seems to make sense, because my wife doesn’t even like shoes to be worn in our house. If I was to put my shoes on the kitchen table, I would certainly be “taking my life into my own hands,” so to speak, but I digress. The origin of “the shoes on the table superstition” comes from the days of public hangings in which convicted prisoners were executed with their shoes still on. “Upon letting loose of the noose, their shoes would tap on the surface – the association was translated to table tops.” It may be a stretch to link our featured subject to superstition and the melancholy effects of shoes, but he worked daily with having shoes atop his cobbler’s bench. And he did this for nearly seven decades! Silas Alvan Thomas, Sr. was born in Middletown on July 9th, 1852. He never knew his mother, Ann Rebecca (Wise) Thomas, as she died less than a month after his birth—most likely a complication associated with childbirth. She was only 38 years-old. Silas’ father, Philip Henry Thomas, now faced the common occurrence of raising the infant, along with six other children.  Jerusalem and Toms' farm are depicted on this 1873 Titus Atlas inset of the Jackson District Jerusalem and Toms' farm are depicted on this 1873 Titus Atlas inset of the Jackson District Philip H. Thomas continued laboring hard in order to keep a roof over his children’s heads, food for their bellies and shoes on their feet. He was a saddler by trade, which probably sparked an interest in son Silas for working with leather. In the 1860 US Census, Silas Thomas can be found living with his family in Middletown. Of particular interest is the presence of a stepmother, Catherine, and a new infant step-sibling. Silas’ older brother Henry is listed here as a shoemaker. It must have been about this time that Silas’ father changed jobs himself. He switched from “bridling horses” to “saving souls,” becoming a minister in the United Brethren religion. Silas was then shipped off to live, and work, in the home of Isaiah Toms and his extensive farm located in Jerusalem, a small hamlet northwest of Myersville in Frederick County’s Jackson District.  The Battle of Monocacy, July 9, 1864 (courtesy NPS) The Battle of Monocacy, July 9, 1864 (courtesy NPS) All I can conclude is that Silas was sent here to assist in the farming operation. With a busy ministering schedule, new wife and baby, Rev. Philip H. Thomas may not have had the time or resources to care for Silas. We may never know, but I’m sure the void left with the passing of his biological mother, grew larger with the loss now of his father who would subsequently move to West Virginia in due time. He would also marry for a third time and settle in Hedgesville (WV). On July 9, 1864, Silas turned twelve. It was a particularly memorable day for Frederick Countians as Gen. Jubal Early and his Confederates battled a much smaller force of Union defenders under Gen. Lew Wallace at Monocacy Junction, a few miles south of Frederick City. Silas was well-distant of the fight, but some Rebels had come through the Myersville area days earlier looking to take whatever they could find. This same “tattered” army had levied ransoms on Hagerstown, Frederick and Silas’ native Middletown in the days leading up to “the battle that saved Washington DC.”  Advertisement appearing in the Frederick News (June 5th, 1897) Advertisement appearing in the Frederick News (June 5th, 1897) In 1870, Silas A. Thomas came to Frederick to learn the trade of “shoemaking.” He soon married and began a family of his own. They usually resided in rented properties that would provide not only a home, but ample room for Silas’ shoemaking business. This took place usually in a front parlor. A search of archival materials shows the Thomas family on W. Third Street, N. Market, East Fifth and finally E. Patrick Street. In addition to keeping the community in shoes, he and wife Kate (Conrad) did an admirable job in raising eleven children. Kate, however, would soon die after a fatal bout of pneumonia in 1895—she was only 38. Sadly, Silas could appreciate the death of a mother as this family tragedy likely hit the Thomas’ youngest son, Silas Jr., the hardest. The seven year-old boy now found himself with more in common with his father than just his name. Did they console each other as kindred spirits, both suffering the loss of mothers at such a young age? Keep in mind, that Silas, Sr. had not only lost his own mother, and mother of his children, but this time it was his wife and best friend. Silas, Jr. would leave Frederick for Philadelphia, where he worked as a printer. He had married a Pennsylvania girl in 1907 and took up residence in Philadelphia. A sister lived in nearby Camden, NJ across the Delaware River. Two more siblings lived across the state in Pittsburgh. His father was still back in Frederick, living alone. But Silas, Sr. had his work to keep him company. In addition to a career in "feets," Silas had a career in "beets," credited for growing some of Frederick County's largest in 1909. Silas A. Thomas, Sr. would once again feel the pain of loneliness in 1925. Young Silas died after a prolonged illness. He was only 38, a familiar death age that haunted Silas, Sr. He met his son’s body at Frederick’s Pennsylvania Railway Station as it traveled back home by train. The shoemaker carefully had his son’s body brought to Mount Olivet where it would be laid next to the boy’s mother who had passed three decades earlier.  Last known address of Silas A. Thomas, 47 E. Patrick St. This is the number/address posted on the gate between both buildings (Beans & Bagels to the right). I'm not sure as to whether the shop was in the courtyard behind or was a narrow structure that once existed in this alley between both buildings.  Silas A. Thomas, Sr. funeral report (above) from the January 20th, 1949 edition of the Frederick News and (below) family lot in Mount Olivet Cemetery (Area H Lot 381) Silas A. Thomas, Sr. funeral report (above) from the January 20th, 1949 edition of the Frederick News and (below) family lot in Mount Olivet Cemetery (Area H Lot 381) Silas would continue to occupy his days with work. He held the title of “Frederick’s oldest shoemaker” when a reporter wrote a feature story on the occasion of his 86th birthday—July 9, 1938. I find it ironic, of course, that this was back in ’38, or better, the 38th year of the 20th century. Mr. Thomas had been a shoemaker for 68 years. He would live another decade, joining Kate and Silas, Jr. here in Mount Olivet in mid January 16th, 1949. As for superstition, I think it’s best to say that “the shoe was on the other foot” in this case. For Silas A. Thomas, the repair and mending of shoes was therapeutic—an outlet to overcome the pain of loss, and realize his life’s calling. He couldn’t restore health and life to his mother, wife and son…but he could perform miracles for his many patrons through the art and craftsmanship of shoe repair. (Part III) Sidestepping a Color Barrier: The first Black Residents buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery3/11/2017  Frederick City Hospital (ca. 1906) Frederick City Hospital (ca. 1906) The year was 1913. As the defunct All Saints’ Cemetery of Frederick was being eyed as an eminent site for business and industry along Carroll Creek, the Greenmount Cemetery property on the northwest side of town was becoming increasingly more important and attractive—especially to people not looking to purchase a burial plot. Although major real estate development was being planned for this suburb of downtown, Greenmount also represented a strategic opportunity for a burgeoning young medical facility. The Frederick City Hospital organization had been formed in 1897 with the aim of establishing, and maintaining, a central place of care for the surrounding community. This became a reality on May 1st, 1902, when a 16-room structure opened on Park Place, a long-gone, house-lined street that once paralleled Trail Avenue. Miss Emma J. Smith, first president of the Frederick City Hospital, graciously gave seven acres of land—land that bordered Greenmount Cemetery. The hospital grew rapidly over its first decade of existence. Wings were added, boasting the name of Hood, a tribute to James Mifflin Hood and wife Margaret Scholl Hood, Frederick’s “benefactress extraordinaire.” A nurses’ school and home would be built in 1911-1912 on a neighboring site in close proximity to both the hospital and cemetery. The Frederick Boy’s School would simultaneously be constructed as a public secondary school for boys. This structure served as such until 1938 when it would be converted into a junior high school which would carry the moniker as the Elm Street School. The Building backed up to the south edge of Greenmount.  Greenmount Cemetery (center of picture) located on the south side of W. 7th St. ca. 1899 Greenmount Cemetery (center of picture) located on the south side of W. 7th St. ca. 1899 Unfortunately, or fortunately, Greenmount had much more land than possibly needed. Developers knew this, and so did the hospital. This could also be the reason to explain why the Working Men’s group changed from a beneficial order to a stock company. Whether an offensive maneuver, or a defensive stand to stave off other uses, the Frederick City Hospital made the Greenmount trustees a purchase offer for their unused parcel—roughly half of their property. This happened in 1913, for $3,000. The Greenmount land sale did nothing to deter plans for the willing acceptance of bodies from the “Old Hill” colored burying ground in early 1914. I’m assuming the Vestry of All Saints’ Church was required to purchase re-interment lots, as they had done the year before with Mount Olivet. All in all, 380 bodies were moved to Greenmount in April, 1914. Seven years after the Working Men’s Stock Company sold half of Greenmount’s Cemetery land to the Frederick City Hospital, an offer was made by the hospital to purchase the entirety of the largest black cemetery in Frederick’s history. Expansion was of key importance, but there was also a psychological component—most of the hospital's patients were happy to look out their window and see a beautiful green mountain, but not a cemetery. Forty years in business had netted nearly 1,000 burials, not to mention the bodies re-interred from the All Saint’s colored burying ground in 1913. Many of the families related to burials at Greenmount are said to have moved away from Frederick in order to find to work in metropolitan areas such as Washington, DC, Baltimore, Philadelphia and Pittsburgh. Other families, pardon the pun, simply “died out.”  Boys High School of Frederick Boys High School of Frederick The talk by many in both the black and white communities back in 1913 forecasted the future of both Greenmount and Laboring Sons as one day becoming abandoned cemeteries. Articles in the local newspapers shared the demoralizing view. But Frederick had seen earlier white cemeteries fade in time, their land used for other purposes like that of the All Saints’ Cemetery. In 1920, the Working Men’s group sold their burial ground to the hospital, described as 146' and 6" along the south side of W. Seventh St. and 689' back, adjoining the Boys High School lot (later Elm Street School). I strongly believe that the subject of openly allowing blacks the opportunity to be buried in Mount Olivet had to be broached in 1922-23. Although I have yet to see a published account, it’s hard to imagine the question not being asked in light of the climate of growth taking place. The City of Frederick, Frederick City Hospital and real estate developers likely thought about the potential need to relocate the deceased residents of Greenmount, not to mention the urgent need of finding a new burial ground. Laboring Sons Cemetery was not an option. It had been in freefall for years. Articles of Laboring Sons unkempt and deteriorating condition, peppered with occasional brush fires and trash dumpings did not make this “burial ground” an ideal choice at this time. It would languish for another 25 years until something was done with/to it. Couple the need of a suitable new location for blacks to be buried with William Jarboe Grove’s folksy local history book (The History of Carrollton Manor) which must have been read by many in town upon its release in 1923. The importance here was that Mr. Grove had let the proverbial “cat out of the bag” so to speak, by publishing the fact that Mount Olivet allowed a black person in Hester Houston, be buried within the cemetery’s gates in 1896. This wasn’t a reburial or charity case, but a one-time slave/domestic with an at-need burial. Whatever the case, something prompted the Mount Olivet Board of Managers to issue the following resolution during one of their quarterly meetings, held November 7th, 1924:  The resolution plainly stated that Mount Olivet was a place for white burials only. As I said earlier in Part One of this article, the original bylaws of the cemetery did not contain any written restrictions based on the race of the deceased. I also could not find anything in the cemetery’s Board meeting minutes book as well—these dating back to 1852. The cemetery was simply set up as a non-denominational, community (of shareholders) owned cemetery. I believe there was a silent push to allow blacks, or possibly reinter blacks (from Greenmount) at hand. The resolution of November 7th firmly set out to put that talk to rest—or better yet, “bury it.” At the same time, perhaps this language was designed to send a firm message to the cemetery’s superintendent and lot-holders thinking they could freely dictate what could be done with funerary property. Keep in mind that the time period between 1915 and 1925 was especially turbulent for black-white relations. The D.W. Griffith film “Birth of a Nation” came out in 1915 and played to sold-out crowds across the country, including a multi-night engagement at Frederick’s City Opera House. Local theaters were segregated, having separated entrances and seating areas for black patrons, if indeed, they were allowed entry at all. “Colored” soldiers returning from Europe and military duty after World War I found newfound hostilities back home, as many whites refused to acknowledge their equivalent role in protecting the country. This began with the “red summer” of 1919, in which racism and brutality against blacks soared all over the country, both north and south. Incredible riots broke out in Washington DC during the summer of that same year. Frederick had not been immune to lynchings and Klan activity, it happened here, and not just rural settings out in the county. Jim Crow was real, and the climate of Frederick was not ready to abolish the “separate but equal” policies that were a way of life. Schools, hospitals, stores, restaurants, and municipal parks were all segregated here in Frederick—even places like the YMCA. This was only 50-60 years removed from the mixed emotions and sympathies portrayed here through the white citizenry during the American Civil War.  Fundraiser activity for Fairview Cemetery (Frederick News, March 15, 1924) Fundraiser activity for Fairview Cemetery (Frederick News, March 15, 1924) Back to the Frederick burying ground dilemma, a formidable solution was gained by a group of active and progressive religious, business and social leaders of town. A new cemetery association was formed, and its name borrowed from a nearby thoroughfare within a stone’s throw of Greenmount Cemetery was utilized. This was Fairview Cemetery. The Fairview Cemetery Association of Frederick County, Inc. was established in 1923. A committee of Rev. John W. Townes, M. E. Jenkins, and Dr. Charles E. Brooks was assembled to find and purchase an appropriate lot of ground. Another committee, comprised of William R. Diggs, Dr. U. G. Bourne, Dr. Charles Brooks, Thomas Clark, Albert Dixon, George Norris, M. E. Jenkins and Rev. Townes, was tasked with raising the funds to purchase the lot. On October 12th, 1923 the Association paid $500 as down payment on their $5,500 purchase from L. Edgar Betson and his wife Dora. The 6-acre property was located on the eastern approach to town on E. Church Street extended, better known as Gas House Pike.  Present day site of Greenmount Cemetery (1880-1926). This is a parking lot for Frederick Memorial Hospital, located directly south of intersection of W. 7th Street and Toll House Avenue. (photo taken from atop the hospital's parking deck facility) Present day site of Greenmount Cemetery (1880-1926). This is a parking lot for Frederick Memorial Hospital, located directly south of intersection of W. 7th Street and Toll House Avenue. (photo taken from atop the hospital's parking deck facility) The land deal would be completed in 1924, interments began in late 1924. Burials in Greenmount would continue through 1926, however the hospital had decided the previous year that no more burials would be allowed here. With Greenmount’s closing, people of color looked at their new cemetery with hope and adoration— filling rapidly in those infant years thanks to as many as 284 Greenmount burials moved to the Fairview Cemetery in 1927. One of which was Greenmount cemetery founder Richard Jackson (died 1910) and his wife Emily (died 1899). Interestingly, twenty years later (1945), the family of the last official president of the Laboring Sons Cemetery Association, John Makel, would choose Fairview over his own cemetery to serve as his final resting place. Through all of this, the trustees of Laboring Sons would fail to move any of their cemetery inhabitants to Fairview. As Mount Olivet represents the sum of the city’s earliest burying grounds, Fairview has carried the “tongue in cheek” moniker of being "the Mount Olivet of the black community. " Historic monuments, pleasant looking grounds and “a who’s who of Frederick” go far to prove that point, while black residents of Frederick have continued to make Fairview the largest and leading black burial ground for 90+ years. “A Bird in Hand” In 1952, a 70-year-old black woman named Bird Smith breathed her last. Uterine cancer would take her life, one that had mostly been spent working as a life-long domestic/maid for a local farm family living just south of town near the local landmark of Evergreen Point.  Today's view of the once-glorious "Locust Level" estate and manor house. (looking south across US I-70 from the Costco parking lot) Today's view of the once-glorious "Locust Level" estate and manor house. (looking south across US I-70 from the Costco parking lot) Ms. Smith actually served multiple generations of the Ransom Rush Lewis family on their 200-acre farm, named Locust Level. This property is only a short distance south of Mount Olivet. In fact Mr. Lewis, Sr. delighted in purchasing lots for his family that were in clear view of his farm. We know this location today by commercial landmarks replacing the former manor farm first established in the 1700’s. Here one can find Costco, Interstate 70, plus properties located off Francis Scott Key Drive: the Econo Lodge, Enterprise Rent-a-Car and Sheetz.  Aerial view of the Lewis family's Locust Level manor estate from August, 1934. A fire had engulfed the main barn on the property. Note the location of Evergreen Point in the upper right of the photo. This is the intersection of MD355 and MD85, today a major interchange located roughly a quarter mile south of Mount Olivet on S. Market Street.  Advertisement in the Frederick News (June 30th, 1923) Advertisement in the Frederick News (June 30th, 1923) Before we get to the few details known about this woman of color boasting an interesting name, let’s talk about her employer. Mr. R. Rush Lewis had a successful career as a leading farmer and prominent businessman. His father, Jacob Lewis had originally moved to Frederick from Chester County, Pennsylvania and purchased Locust Level in 1854. Born in 1864, R. Rush Lewis spent his youth on the family farm and stayed active in agricultural pursuits, particularly dairy farming. In addition, he was chosen president of the First National Bank of Frederick in 1909, and served as president of the G. & L. (Garber & Lewis) Baking Company, vice president of the Borough Peoples Fire Insurance Company, and a director in the Central National Bank. I haven’t found anything substantial on Ms. Smith other than the fact that she was a Maryland native, born in April 1881, and never married. Her unusual name was written as Bertie in an early census, perhaps giving a hint that her real name was possibly Bertha or Roberta. Bird Smith faithfully served three generations of the Lewis family. She was a true part of the family, playing a “nannie” type role to Rush and Laura Lewis’ two children—Ransom Rush, Jr. (b. 1896) and Elizabeth (b.1897). Unfortunately, Bird Smith would not leave the nest of Locust Level farm site after her passing. Ransom Rush Lewis had gone to Mount Olivet, in order to make burial arrangements for Bird within his pre-purchased family plot (Area E Lot 89). His request would be rejected by the cemetery’s Board of Managers. They referenced the minutes of the November 7th, 1924 resolution upholding “white only” burials. The policy was again written, verbatim, within the Mount Olivet minutes book in early November, 1952, nearly 30 years after it s first writing. The Lewis family was deeply upset in seeing their lifelong friend and family member denied access for burial. The cemetery was literally a next door neighbor to the Lewis farm. R. Rush Lewis had already buried two wives here, first wife Laura Yerkes Lewis in 1924, and Margaret Duvall Lewis (second wife) in 1947. Lots had been purchased for R. Rush’s children and faithful Bird.  R. Rush Lewis R. Rush Lewis R. Rush Lewis didn’t settle for help and memorialization in Fairview Cemetery, as you would expect. Instead, he had Bird Smith buried in the yard of Locust Level Farm. It must have been extremely frustrating for Mr. Lewis, a man of considerable wealth and influence in Frederick, but powerless in this particular situation involving race discrimination. All the while, Mr. Lewis took out a scathing classified ad in the Frederick News, made to look like an obituary. In doing this, he directly called out Mount Olivet’s Board of Managers, chastising them for not allowing the burial of Bird Smith based solely on the color of her skin. It was a bold and historic move. I’ve heard that he started a litigation process against the cemetery, but did not follow through because the cemetery had the right to enforce its own rules because it was a private cemetery.  Lewis family plot in Mount Olivet Lewis family plot in Mount Olivet R. Rush Lewis died in 1958. Years passed as Bird Smith would eventually be the last reminder of the Lewis family on the property. The farm had been deeded to the Frederick Home for the Aged and City of Frederick in 1858 before Mr. Lewis’ death. However, it was subsequently sold by the Home for the Aged to developers in 1964. The property became bisected by a superhighway (US70) in the late 1950’s. The proud Locust Level Farm had traded in its dairy parlors for gas pumps— the Pure Oil Truck Stop was opened on the north side of the former Lewis property in December, 1965. The grand manor house of the 1700’s was demolished, to make room for an Exxon gas station. Evergreen Point and MD routes 355 and 85 sprouted into a major commercial cluster of car dealerships, fast food restaurants shopping venues anchored by the Francis Scott Key Mall, opened in the late 1970’s. Bird Smith’s “cemetery of one” remained, about 30 yards from the highway to the rear of the gas station, next to an asphalt parking lot. Her gravesite, outlined with bricks, was buttressed by stanchions to safeguard it from being hit by lawnmowers. A small 2’x1’ granite monument stood at the head of the grave and boasted a Bible passage from Revelations 2:10. It read: “In loving memory of Bird Smith who has served on this farm for seventy years. Be thou faithful unto death and I will give thee a crown of life.” In 1986, a representative for a company called Beckmont, Inc. out of California visited cemetery superintendent J. Ronald Pearcey at his office. Beckmont was the development company that owned the present property that once belonged to the Lewis family. The representative explained to superintendent a quandary he had on his hands. There was an opportunity to build a motel on the former farm site on the parcel immediately behind the gas station, and along the highway. However, there was one small problem, Bird’s gravesite. It had to go. Superintendent Pearcey was in his fourth year at the helm of Mount Olivet, but had originally started back in 1966. He immediately recalled hearing the story of Bird Smith from his predecessor Robert Kline. Mr. Kline was not the superintendent in 1952, but was on the cemetery staff. He explained to Pearcey that he felt very guilty with the stand made by the cemetery’s board against the Lewis family’s wish to bury Bird Smith in the family lot. Mr. Kline reiterated that there were sympathetic members on the board, as well as staff members like himself. However, there were also strong lot holders who helped in pressuring the board to hold firm to a “white only” policy. On a personal level, Mr. Kline grew up in an environment in which he had many black friends and a cerebral approach to "separate but equal." Kline’s father once ran a canning factory in town, boasting many black employees, many of which became close friends and confidantes of the Kline family. There were now no obstacles in place as there had been three decades earlier. Pearcey shared Bird’s story with the Beckmont representative, and suggested that he would attempt to make contact with Elizabeth Lewis Peters, daughter of R. Rush Lewis. Pearcey thought to himself that this could be an opportunity to make things right after all these years. He subsequently met with Mrs. Peters, who lived on the corner of Record and W. Church streets in downtown Frederick. The 88-year-old woman immediately supported the idea with Pearcey’s assurance that the job could be handled correctly and with dignity. Tuesday, October 28th, 1986 began as a somewhat pleasant day with showers forecasted for the afternoon. The gravesite in Mount Olivet had been opened and sat ready to receive its long overdue decedent. The special day was October 28th, 1986. Superintendent Pearcey, current-day foreman Tyrone Hurley and other staff members journeyed the quarter-mile to the Locust-level site and Bird Smith’s grave with necessary tools needed for rare occasion of grave removal, not placement. The team carefully exhumed the burial vault that had been placed within the ground of the old Lewis home place. They placed this within a van for transfer up the Georgetown Pike to the cemetery.  Bird Smith's interment card at Mount Olivet (dated October 28, 1986) Bird Smith's interment card at Mount Olivet (dated October 28, 1986) Thirty-four years, and fifteen days after her death at Frederick Memorial Hospital, site of the former Greenmount Cemetery, Bird Smith’s body made its way through the large iron-gated entry of Mount Olivet Cemetery. The lifelong black servant was finally placed where she was supposed to be, amidst her extended Lewis family, in plain view of her former home of Locust Level. Over this duration, the Civil Rights movement had conquered “separate but equal,” opening the gates for equality. The staff placed Bird Smith in her new resting place and it came time to close the grave. The gravestone from Locust Level was brought as well and awaited its final placement atop the head of the grave. There was just one final step left, which involved a promise made by Superintendent Pearcey to Mrs. Peters. She wanted to inspect the grave before. It was afternoon, and the skies had opened-up, drenching the area with steady rain. Pearcey ventured downtown to the Court Square area of Frederick to pick up the widowed octogenarian. He recalls she was particularly quiet and somewhat pensive. The superintendent drove her to the nearest spot that the grave could be seen from a cemetery lane. The rain continued to fall, and Mrs. Lewis was familiar with the location as she had been attendance for other funerals here including her parents and brother who had died in 1972. Pearcey was taken aback when Mrs. Peters asked if she could inspect the grave from up-close. He gladly obliged, grabbing an umbrella from under the seat then rushed around to open Mrs. Peters door. Holding the umbrella over the diminutive woman, Superintendent Pearcey escorted Mrs. Peters to Bird’s open gravesite. Once there, Mrs. Peters stared intently down the hole, saying nothing. Ron says that a sense of great relief seemed to be-fell the senior, perhaps releasing the weight and emotional pain associated with the initial burial rejection, her family’s disappointment/anger and a 34-year time passage before Bird’s mortal remains could reunite with the rest of her former family members here at Mount Olivet. After about a minute, Ms. Peters told Pearcey that she was satisfied and it was time to head back home. Less than three years later, Elizabeth Peters would take her place beside Bird and the others. She had witnessed the “righting of a wrong” in today’s context. Segregation was a practice that was a known part of life, and in this story’s case—death, in earlier times. The story of Bird Smith is a fascinating one. It is also a painful and embarrassing moment in the cemetery’s rich story. But such is the history of any person, place or thing—a collection of trials and tribulations, successes and failures. The cemetery is richer to have Bird Smith, Hester Houston, Maria Harper, Martha Snowden, Abe Brighton and Julia Hill among its interred population. These individuals somehow triumphed the institution of “separate but equal,” to be laid to rest in Mount Olivet, either by accident or design. This is especially important when viewed in context to cemeteries and burial places—distinct places where the journey of life is complete, and our God judges us not by the color of our skin, but simply by our earthly good deeds and charity toward others. We gladly invite any further information and, or, photographs pertaining to Bird Smith.  History Shark Productions Presents: "UP FROM THE MEADOWS: The Class" Are you interested in learning more about the incredible African-American heritage story of Frederick City and Frederick County, Maryland? Check out this author's latest, in-person, course offering: Chris Haugh's "Up From the Meadows: The Class" as a 4-part/week course on Tuesday evenings starting March 12th, 2024 (March 12, 19, 26 and April 2). These will take place from 6-8:00pm at Mount Olivet Cemetery's Key Chapel. Cost is $79 (includes all 4 classes). For more info and course registration, click the button below. (Part II) Sidestepping a Color Barrier: The first Black Residents buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery3/5/2017  Grave of Dr. Ulysses G. Bourne, Sr. (1873-1956) in Fairview Cemetery Grave of Dr. Ulysses G. Bourne, Sr. (1873-1956) in Fairview Cemetery In part one of this story, I explained the preface of searching for the earliest Frederick residents of color to be buried in Frederick’s Mount Olivet Cemetery. The rural cemetery opened in 1854 and specifically catered to Frederick’s white community, an unspoken and understood practice not only here and the Deep South, but in many places in the North as well. Separate burying grounds, or sections within established graveyards, had been set up by churches or beneficial societies for the black populace. This was no different with how churches had evolved, marking a color divide with religion (ie: the Methodist Episcopal Church vs the African Methodist Episcopal Church). The same was true here in Frederick as well. From before the time of the Civil War up through to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, many cemeteries would remain segregated with “unwritten” and, in some cases, “written” rules to back the claim. Today, Mount Olivet is the largest cemetery in Frederick County, open for over half a century operating without discrimination in burying people regardless of color, creed, religion, sex and national origin. At the same time, Fairview Cemetery, located on E. Church Street extended/Gas House Pike continues a proud tradition of service as the predominant “black cemetery” of town. This is more of a historical and cultural precept in the time following the civil rights movement. The cemetery continues to cater to black citizens, especially those with long family ties to the community. Within its gates, the visitor can find outstanding leaders of our past such as Dr. Ulysses G. Bourne (Frederick’s first doctor), John W. Bruner (Frederick’s first Superintendent of Colored Schools), Rev. J. W. Townes (Faith and Community leader/First Baptist Missionary Church), Esther E. Grinage (Educator and Kindergarten Foundress), William O. Lee (Frederick’s First Alderman) and Albert V. Dixon (Frederick’s First Black Undertaker). Although Fairview’s monuments may not be as grand as many found in Mount Olivet, the ”life’s work” of what each of these gentlemen did for our Frederick community certainly rivals, if not surpasses, that done by some of our gilded heroes—particularly the big three—Francis Scott Key, Gov. Thomas Johnson, Jr. and Barbara Fritchie. And speaking of the Thomas Johnson, in the last article I talked at length about Mrs. Maria Harper, associated with the extended family of Maryland’s first governor and Frederick’s All Saint’s Church congregation. In 1913, the mortal remains of Gov. Thomas Johnson, Maria Harper and over 300 others were removed from the colonial-era All Saint’s Cemetery in downtown Frederick, and reburied in Mount Olivet. This was certainly a historic occasion as Maria gained entrance into Mount Olivet Cemetery and became one with thousands of white residents resting in peace since the cemetery first opened its gates nearly sixty years earlier.  Frederick News (May 13, 1885) Frederick News (May 13, 1885) And speaking of the Thomas Johnson, in the last article I talked at length about Mrs. Maria Harper, associated with the extended family of Maryland’s first governor and Frederick’s All Saint’s Church congregation. In 1913, the mortal remains of Gov. Thomas Johnson, Maria Harper and over 300 others were removed from the colonial-era All Saint’s Cemetery in downtown Frederick, and reburied in Mount Olivet. This was certainly a historic occasion as Maria gained entrance into Mount Olivet Cemetery and became one with thousands of white residents resting in peace since the cemetery first opened its gates nearly sixty years earlier. Maria Harper may have been the earliest-born black female resident to be buried in Mount Olivet, but she was not the first. To seek out whom that distinction belongs to, I have had to dig deep (no pun intended). Due to many factors such as lost or missing records, we may never have the true answer to this question. But we also may be sidetracked due to a record that was deliberately lost, or deliberately “unwritten.” I will explain this statement further into our discussion. No matter the situation, I am pleased to report that my total findings of known early black residents in Mount Olivet has doubled over my last few weeks of research—from three to six definitive cases bearing proof. Because of this increase, I have decided to turn a two-part article into a three-part article. I seek not to overwhelm you the reader, as I regularly push internet blog and etiquette norms with regard to article length.  Frederick News (11/26/1913) Frederick News (11/26/1913) Backstory First off, I want to give a little more context into the history of black burial as it pertains to Frederick City. In part one of this article, I discussed the myriad of slave and family cemeteries which could be found across the county. I also presented information regarding isolated burials of blacks in the older “white church congregation” graveyards of town—places such as St. John’s Cemetery and the fore- mentioned All Saints Cemetery, with adjoining “Old Hill” Burying Ground. Re-interment of bodies that were originally buried in the latter “Old Hill” ground (also referred to as the “colored people’s graveyard”) followed that of the whites once buried in All Saints. While the whites, plus one black (Maria Harper), headed south of town to Mount Olivet in fall of 1913, the black bodies were transferred “uptown” to a new home—Greenmount Cemetery. Greenmount Cemetery was incorporated for the purpose of aiding Frederick's black residents under the leadership of The Working Men's Association of Frederick. This occurred in 1880, as the black beneficial society purchased a "lot of ground for burial purposes" from Gideon and Julia Bantz, situated on the south side of Montonqua Avenue, today’s W. Seventh Street. A gentleman named Richard Jackson signed the deed as the association’s president. In the 1880 census, Jackson is listed as a black shoemaker, born in Virginia, and living with his wife and three daughters on W. All Saints Street.  Greenmount Cemetery as captured in this zoom from an 1899 photo taken from the atop Trinity Chapel, looking nw across Court Square. The white house to the immediate right of center was the cemetery keeper's house that once sat on the south side of W. 7th Street (which bisects the photo left to right heading nw.) Greenmount Cemetery and its monuments can be seen below and to the left of the house as the property stretches to the southwest from this particular angle. Note the hedgerow separating the cemetery property from Groff Park to the west (future Hood College) and Emma Smith's purchased parcel to the east (future City Hospital site). In 1898, The Working Men’s Association changed its name to The Working Men's Stock Company. The Greenmount Cemetery quickly overtook another beneficial society-formed “colored cemetery” located roughly six blocks to the east, between E. Sixth and E. Fifth Street, on Chapel Alley. This was the Laboring Sons Cemetery, formed in 1837 by a group of free black laborers and craftsmen residing in and around Frederick. This group had purchased their cemetery property in 1851, and burials soon commenced after. A schism of some sort occurred in the early 1860’s within the Beneficial Society of Laboring Sons, apparently causing two-thirds of the members to defect. In turn, many of these folks were responsible for establishing the Working Men’s Association and subsequent rival cemetery. All the while, Maria Harper had been buried in All Saints Cemetery in 1884, and would make her way into Mount Olivet less than 30 years later in 1913. However, there are at least three other documented cases involving black women being buried in Mount Olivet before this time (1913). In addition, a fourth incident involves the first burial of a black male.  German Reformed Cemetery (located at the corner of Bentz and W. 2nd streets) German Reformed Cemetery (located at the corner of Bentz and W. 2nd streets) Martha and Abe An entertaining article in the May 19th, 1904 edition of the Frederick News announced that the remains of the Shriver family had recently been successfully reinterred within Mount Olivet cemetery. A family plot belonging to Judge Abraham Shriver (1771-1848) and son Gen. Edward Shriver (1812-1896) was located along N. Bentz Street, specifically on the west side, just south of today’s Rockwell Terrace thoroughfare. The Shriver family graveyard was an addition to the existing German Reformed Burying Ground, and was said to have been “a quiet, pretty plot, enclosed with an iron railing, and shaded with tall pine trees.” Gen. Shriver was associated with a local militia unit and the Union Army’s Potomac Home Brigade during the Civil War. His home was only a block and a half away in Courthouse Square. Another family member buried here was Charles Edward Shriver. Charles fought with the Confederacy, falling in battle in August, 1863 at the tender age of 18.  Frederick News (May 19, 1904) Frederick News (May 19, 1904) At the time of the article’s writing, a plan was in effect to extend W. Third Street to the west from Bentz Street (today’s Rockwell Terrace). The namesake home of Elihu Rockwell was originally positioned on the west side of Bentz in the street bed that exists today—it had to be moved to the south of its present location. Thus came the need for the Shriver family and others to be moved. Since these bodies had to be re-located anyway, why not re-bury the inhabitants in the newer, prime cemetery location of town in Mount Olivet? Ever since the new cemetery's opening, the traditionally white city cemeteries (with the exception of St. John's) had been slowly falling out of favor for burial. The German Reformed Burying Ground would become Memorial Park by the mid 1920's. The Shriver family cemetery plot consisted of Judge Shriver’s children and grandchildren. Along with these, were included two interesting extended family members that served as slaves and servants for this wealthy family. The article mentions both of these individuals, Martha Snowden and Abe Brighton. Martha Snowden, along with her ancient tombstone, was moved into the cemetery on May 11, 1904. Her marble stone reads: “Martha Snowden/faithful colored nurse of children of Edward and Elizabeth Shriver/died 25 Nov. age 28.” The same story holds true for Abe Brighton who died in 1847. His grave marker states: “Abe Brighton/1847 age 60/a faithful servant of the Shriver family”  The Shriver Family Plot in Mount Olivet (Section MM) The Shriver Family Plot in Mount Olivet (Section MM) Sadly, I could not find anything further on these individuals, except for a brief reference in Jacob Engelbrecht’s diary, dated December 5, 1820, in which he recorded a list “of the different Negroes” in Fredericktown.” Engelbrecht simply mentions the “Shriver’s Abraham Brightwell” among his tally. I wonder if the name could have been confused by Engelbrecht—Brightwell instead of Brighton? Or was it possibly changed by the family over time? (NOTE: A Daphne Brighton (d.1893 age 75) can be found among those buried in Greenmount, but there are also multiple burials of Brattons. Two other Brightons are among the burial record of Laboring Sons Memorial Ground—Francis Brighton (b.@1833-d. 1874 age 41) and Harriet Brighton (b. @1814-d.1894 age 80). These individuals can be found in the 1850 census living in the same household with a Margaret Brighton (b. @1830). If Abe’s name was indeed Brightwell, a likely relative named Hannah Brightwell is also in Laboring Sons Memorial Ground. Hannah Brighton died in November 1907 at the age of 100.) The new Shriver lot in Mount Olivet is located in Area MM, placing Martha and Abe within twenty yards of the Johnson family vault holding the remains of Maria Harper. Other nearby friends include Jane Hanson (wife of John) and Dr. Philip Thomas, noted upper class residents and former slaveholders in their own right. Again, these two burials predate Maria Harper by nine years. Maria is the oldest known/earliest born woman of color in Mount Olivet, but Abe Brighton now holds the title for being the oldest known black individual resting here. Interestingly, the names of both Martha Snowden and Abe Brighton could not be found in the cemetery’s database and record books of Mount Olivet. The database is understandable as this system relies on the written record at the time, in this case 1907. Was this done deliberately, to hide the fact that people of color had knowingly been transferred into the cemetery? The white Shrivers can be found on their corresponding lot card for Area MM Lots 22 & 23, but not Martha and Abe. I assure you that I will duly add this info, albeit 110 years later. The Strange Story of a “Stranger” On the flipside of the situation with Martha Snowden and Abe Brighton, our Mount Olivet computer database shows the burial of a “colored” individual on July 24th, 1902. There is scarcely any detail in the official records, however, the information was likely added in recent years based on the finding of an obituary for the deceased. The burial card simply says that a female named Laura Hill was buried in lot 136 within the Stranger’s Row area of the cemetery. Stranger’s Row was a potter’s field area of Mount Olivet, reserved for early visitors to town, unknowns and indigent persons. This was the charity card for the cemetery, a norm in the old days of the funerary business. Dated July 25th (1902), a brief newspaper article mentions the death of Laura Hill, colored, who died at the Montevue Hospital and was buried at Mount Olivet. The actual space of Ms. Hill’s final resting place is lost to time, unmarked and unknown. But we have reason to believe this was no mistake by the paper. We also haven’t found her in other cemetery records.  Montevue Hospital (c. 1909) Montevue Hospital (c. 1909) While we are here, I’d like to explain another burial option of the time that relates to “strangers to town,” tramps, elderly residents and the indigent. The Montevue Hospital was the treatment place of record for Frederick’s black population, even for decades after the establishment of the Frederick City Hospital at the turn of the 20th century. The “hospital building” and later Montevue Home structures replaced the original Frederick Almshouse, where the indigent and insane were housed. Usually, when these full-time residents (black and white) died, they were buried in a “potter’s field” located on the property. Some of those who expired at the Montevue Hospital from sickness, wounds or surgery were buried here as well, but most having means were buried at the city’s established white and black cemeteries including Greenmount and Laboring Sons. The case of Laura Hill is quite puzzling. I’m really not quite sure how, or why, she ended up here in Mount Olivet.  Laura Hill...ultimate fighter? (Frederick News/Aug 3, 1889) Laura Hill...ultimate fighter? (Frederick News/Aug 3, 1889) I found one lone reference to “Laura Hill” in the census records. In 1880, she was listed as an 18-year-old mulatto working as a wash woman, and living on East Third Street, apparently in an apartment. A number of newspaper incidents of the late 1800’s mention Laura Hill. These were generally related to fighting and disturbing the peace. I can’t prove that our Laura Hill was a “rough and tumble” wash-woman, but there certainly is a possibility. No Laura Hill could be found in the 1900 census, but a Martha Hill was the closest match. This 36-year-old woman was living in the infamous tenement complex of Shab Row on East Street, with an 18-year-old daughter named Mary. Martha’s birthdate is listed as January, 1864, and profession given as a cook with daughter Mary as a wash woman. Looking back further, Martha Hill can be found in the 1870 census, but not that of 1880 where I found Laura. Martha in 1870 is shown as the daughter of Henry and Maria Hill. Could these be the same lady? Regardless, it still doesn’t answer the question of how she got to Mount Olivet. The cemetery records fail to show a burial on this date as well. Perhaps this was another stealth burial of a person of color.  Grave of Hester Houston (Area R/Lot 94), "first known black person buried in Mount Olivet" (Nov 20, 1895) Grave of Hester Houston (Area R/Lot 94), "first known black person buried in Mount Olivet" (Nov 20, 1895) "Houston—We have our First Burial" That brings us back to the year 1896, and a definitive first-time burial of a black female, in a documented lot site within the cemetery, and, best of all, capped with a monument. She was Mount Olivet's 6,237th burial on record. But most importantly, the name of this woman, who I believe to be the first black individual buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery, is Hester Houston. I have been familiar with this individual for roughly 25 years, all due to a book entitled The History of Carrollton Manor by William Jarboe Grove. I mentioned Mr. Grove’s magnificent narrative of southern Frederick County in an earlier piece written about Clara McAbee, a young resident of Lime Kiln (near Buckeystown) who was named “Maryland Prettiest Girl” in 1915. William Jarboe Grove was onetime president and treasurer of the M. J. Grove Lime Company. The noted philanthropist grew up on Carrollton Manor and published his memoir laced history book in 1922. On page 48, Mr. Grove speaks of Hester Houston (whom he misnames Easter Houston) a slave once-owned by his aunt Margaret Lauretta Jarboe(1838-1900): “It was not unusual that some respected colored slave was buried beside her master. I will mention one, Easter Houston, who was owned by William Eagle, she was given to his daughter, Lauretta, the wife of Thomas R. Jarboe, who is buried by their side in Mt. Olivet Cemetery.”  Manor House at Gayfield Manor House at Gayfield My curiosity with this woman has been piqued ever since. Hester lived with the Thomas R. Jarboe family on their spacious Gayfield Manor estate at Lime Kiln, having the Monocacy River as its eastern border, and the Buckeystown Pike as a western border. More recently, Gayfield was the 145-acre home of US Congressman Roscoe Bartlett. It was a fine plantation during its heyday, full of social entertaining which surely kept Hester on her toes. That’s all that can be gleaned about Hester Houston in this book, however 19 pages later, Grove tells a story about another one of William Eagle’s slaves with the last name of Houston—perhaps a husband or brother to Hester? Grove writes: “Jonah Houston, who I remember well, large and a powerful man who was looked upon as being the champion fighter in the neighborhood. He was quite an athlete, fond of dancing and fond of liquor, for a drink he would sing and dance the following which usually brought down the house. “This way buzzard and where you ‘gwine crow, I am ‘gwine up the river to jump just so, First upon my heel tap, then upon my toe, Every time I jump around, I jump Jim Crow.” The routine performed by Houston was "Jump Jim Crow", a song-and-dance caricature of blacks originally made famous by white actor Thomas D. Rice in blackface. It first appeared in 1832 and was used to satirize President Andrew Jackson's populist policies. As a result of Rice's fame, "Jim Crow" had become a derogatory expression meaning "Negro” by 1838. When southern legislatures passed laws of racial segregation directed against blacks at the end of the 19th century, these statutes became known as Jim Crow laws. We also know these as the “separate but equal” status of blacks up through 1965, following the monumental Civil Rights movement and legislation passed the previous year. I could not find anything further on Jonah, but in Hester Houston, we have definite proof of a major color boundary “having been jumped.” Hester Houston was buried in the Jarboe family lot in Area R, lot 94. The record book is well over 121 years old and yellowed from age. Mrs. Jarboe met with the cemetery Superintendent (or Secretary) on November 20th, 1895. Hester’s name appears in the log book as the decedent, however there is no notation signifying Houston as being black, mulatto, colored, or Negro. I find this odd, especially for the times, as it seemed common practice to differentiate people of color. As for the public written record, Hester Houston’s obituary/funeral report appears in the Frederick News on November 20, 1895, however it does not mention place of burial. The bulk of the arrangements in those days were handled by the undertaker. Mr. Marshal R. Etchison was that undertaker, and a known friend to the black community. No one from the cemetery would have had a need to open the casket, so they wouldn’t know.  Mount Olivet Superintendent D. J. Michael Mount Olivet Superintendent D. J. Michael I became curious after seeing this allowance of four blacks into the cemetery over a nine-year span between 1895-1904. I checked to see who the cemetery superintendents were during this time and was fascinated to learn that it was only one, Daniel Jerome Michael (1840-1908). Mr. Michael served as the third superintendent of Mount Olivet. It was only a nine-year term which began in 1893 and lasted until late 1907. Michael was forced to resign due to health reasons, and died eight months later. Daniel J. Michael knew two things very well: 1.) the Buckeystown/Carrollton Manor Area of which he grew up; and 2.) the institution of slavery. However, he understood the latter by never being a slaveholder himself, and the same held true with his father Henry S. Michael as far as I can find. The irony lies in the fact that his paternal grandfather and uncles were known slaveholders, as were many of the neighbors that lived around him. Is it possible that he had been raised with abolitionist ideologies?—or simply an admiration for the bond existing between some white families and beloved former slaves and employees of color? Did he, or someone else on the cemetery’s Board of Managers, purposely look the other way, allowing Jim Crow to trip and fall? We’ll never know, but I have a weird hunch that Superintendent Michael may have played a part in these burials, and the surreptitious manner in which each took place, or were recorded. If anything else is telling, Daniel J. Michael’s grave is only 20 yards distant from that of Hester Houston. Stay tuned for next week’s final part 3. It’s a sad story that relates to segregation and Mount Olivet, but offers a positive ending tied indirectly to the Civil Rights Movement. If you have any information, corrections or photographs to add to our stories, we are greatly interested. Please comment or contact me via this website's contact page. Many thanks in advance!  History Shark Productions Presents: "UP FROM THE MEADOWS: The Class" Are you interested in learning more about the incredible African-American heritage story of Frederick City and Frederick County, Maryland? Check out this author's latest, in-person, course offering: Chris Haugh's "Up From the Meadows: The Class" as a 4-part/week course on Tuesday evenings starting March 12th, 2024 (March 12, 19, 26 and April 2). These will take place from 6-8:00pm at Mount Olivet Cemetery's Key Chapel. Cost is $79 (includes all 4 classes). For more info and course registration, click the button below. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed