|

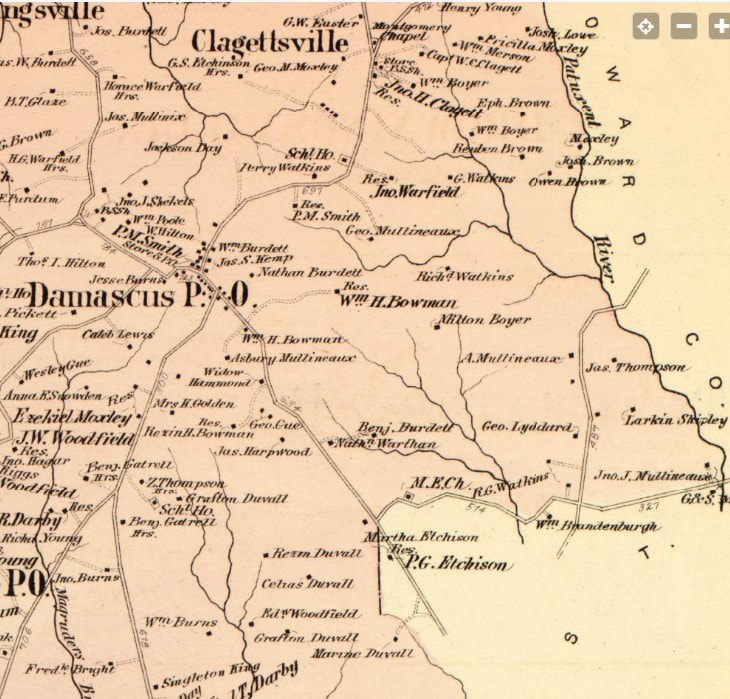

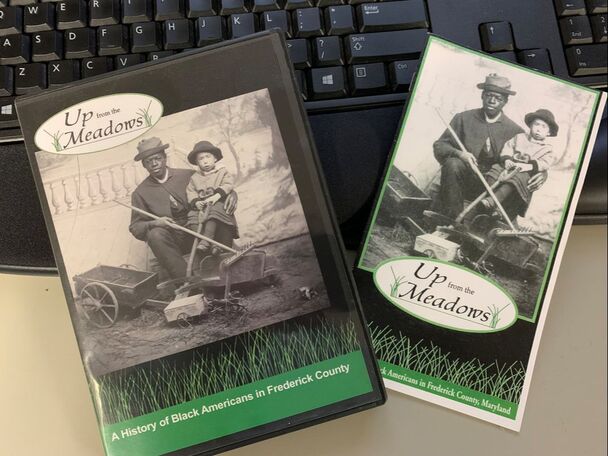

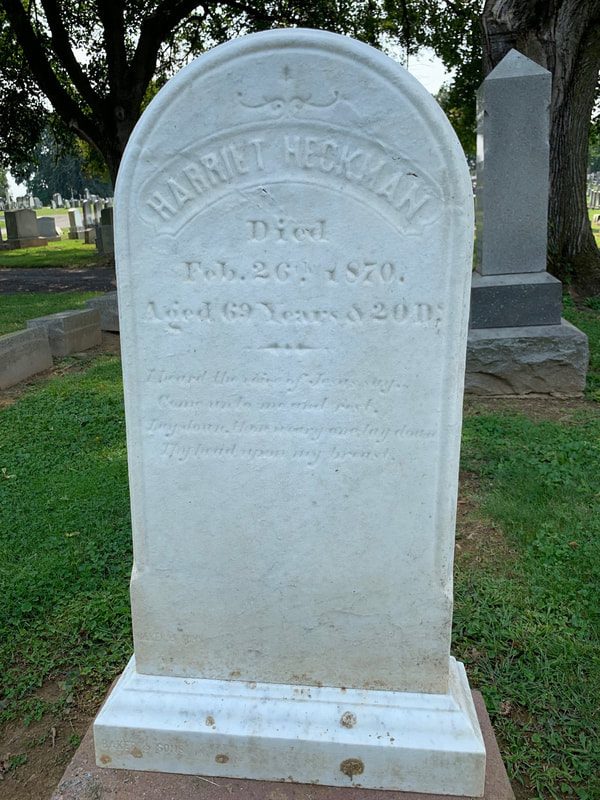

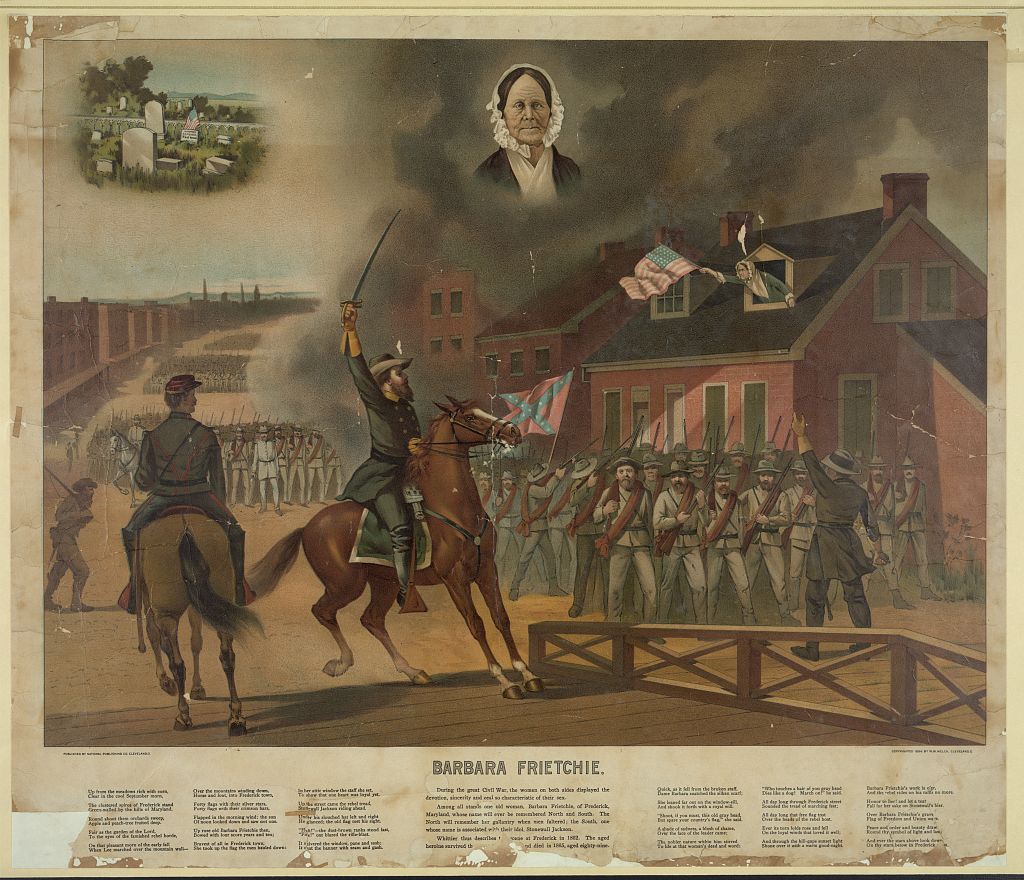

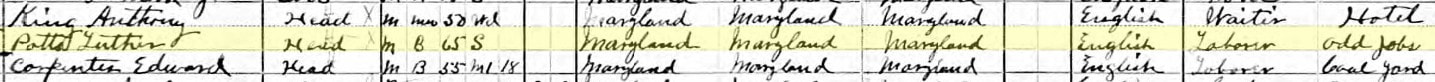

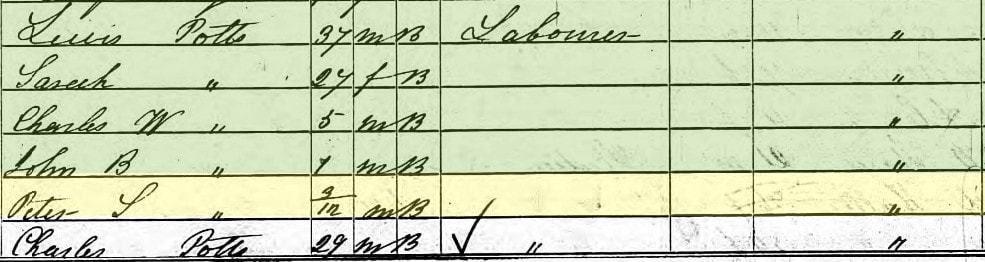

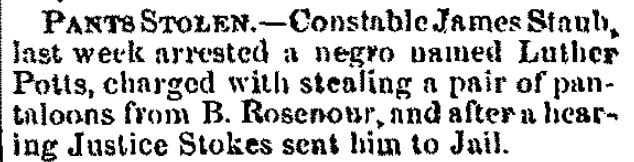

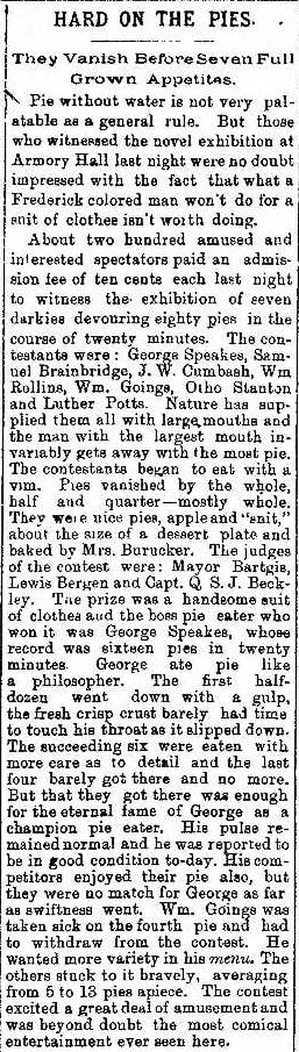

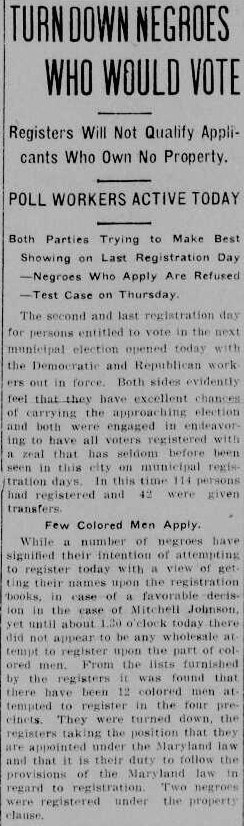

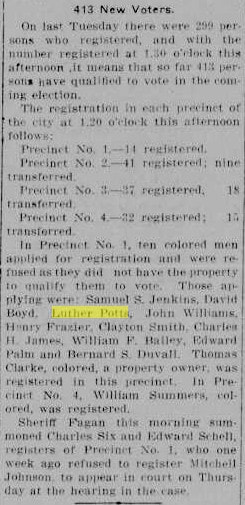

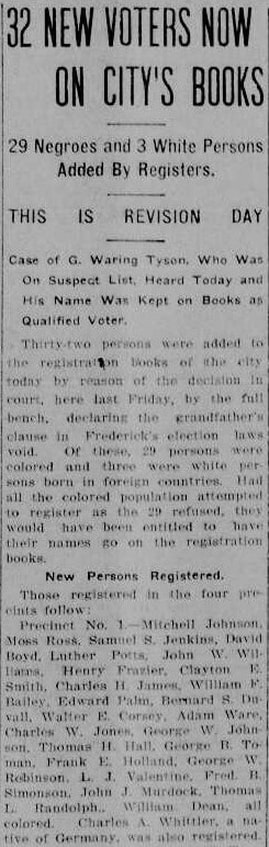

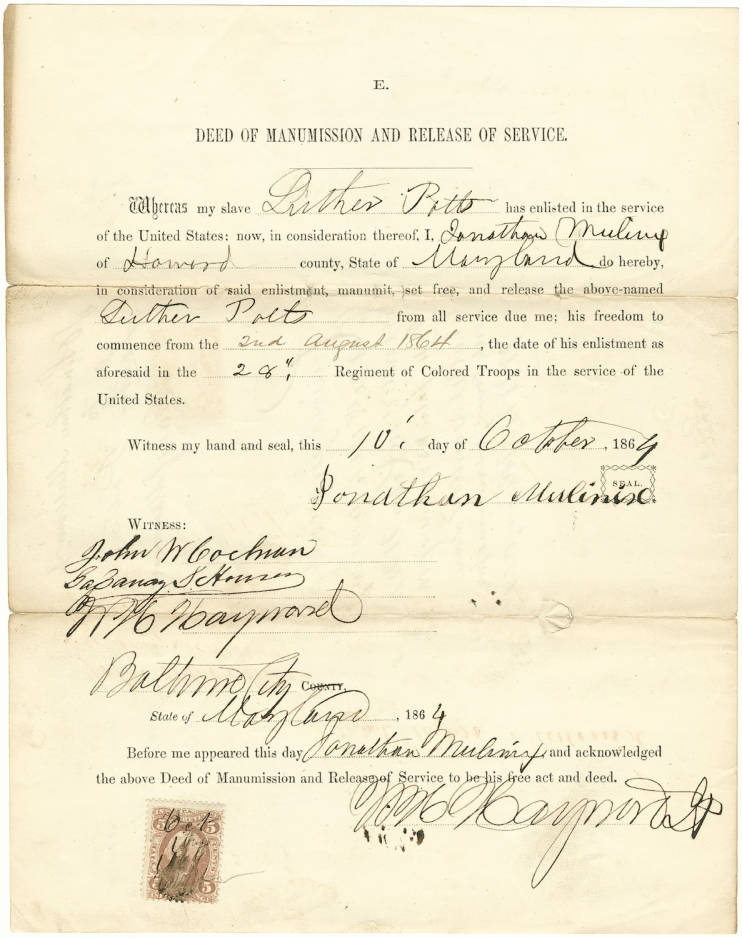

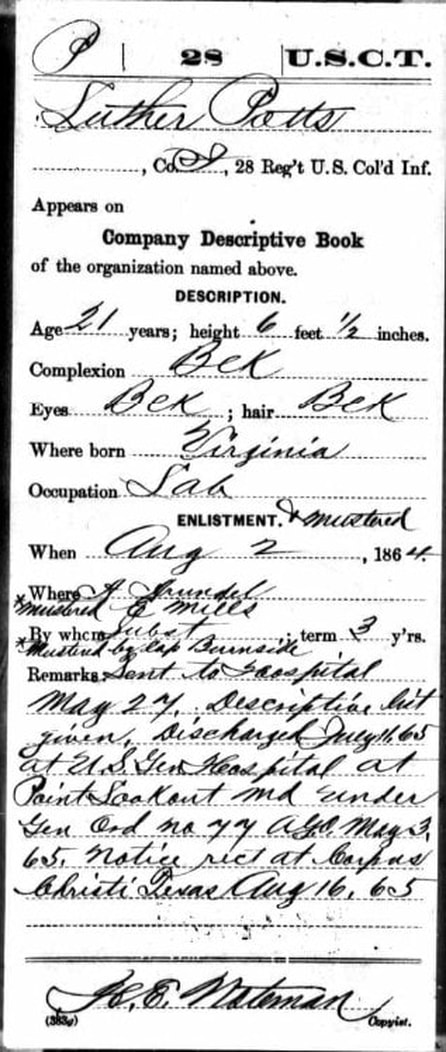

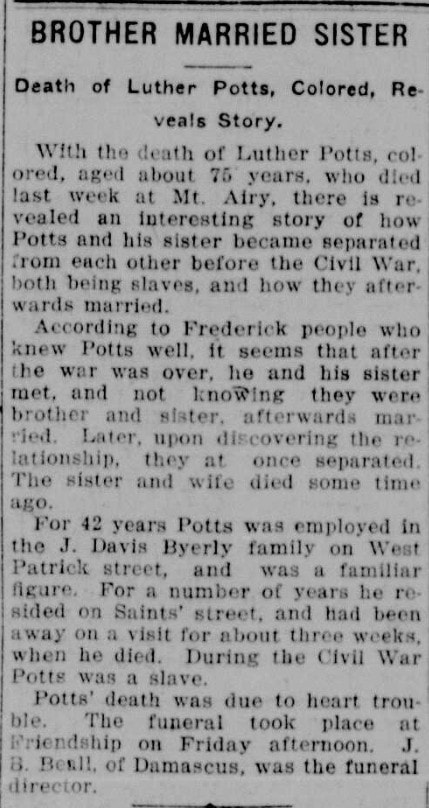

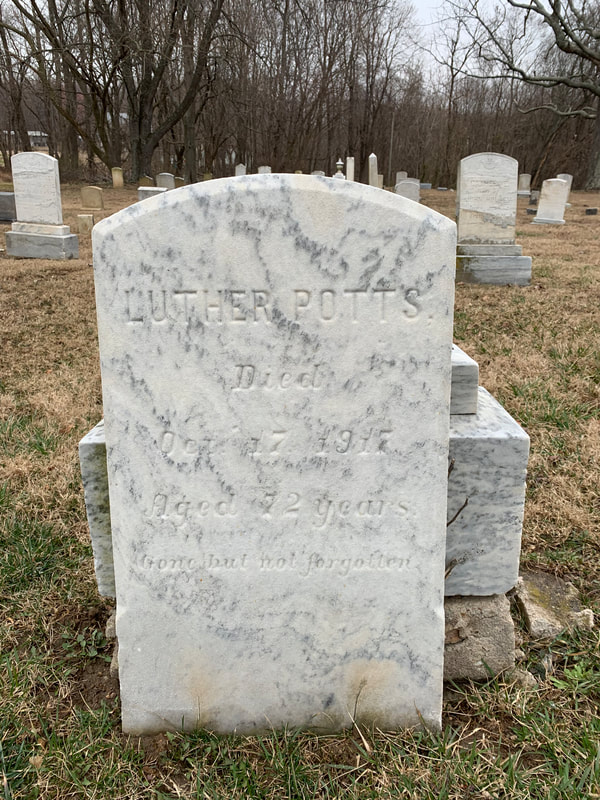

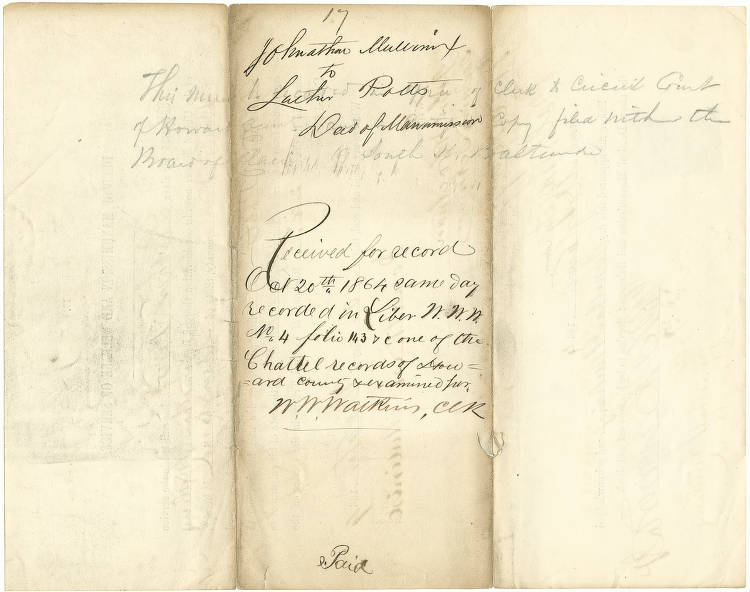

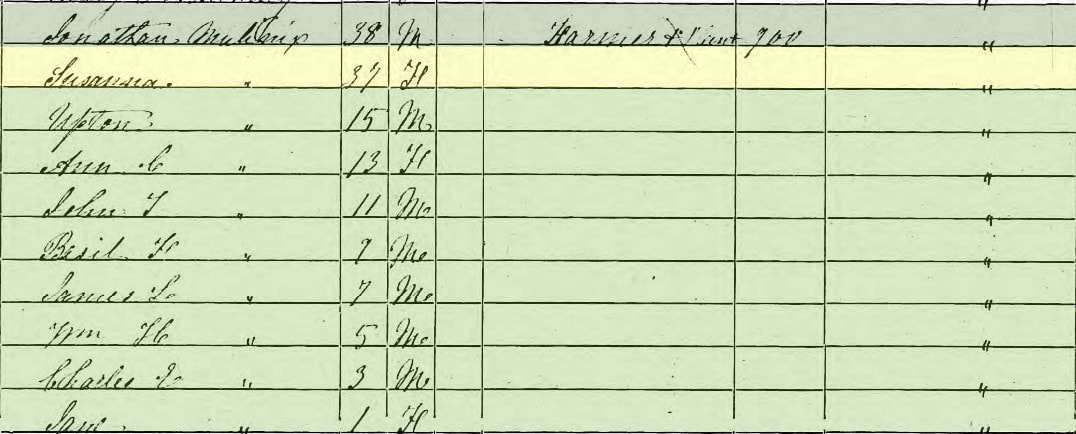

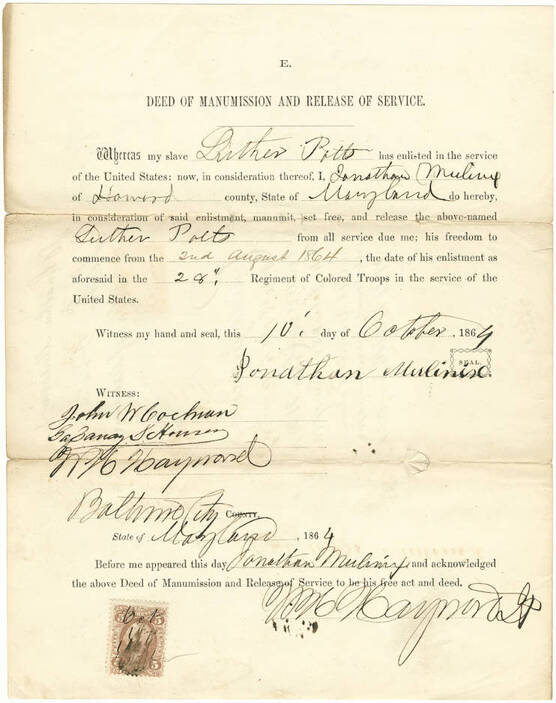

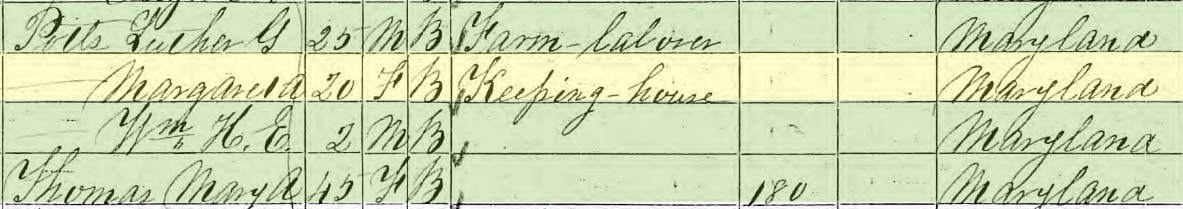

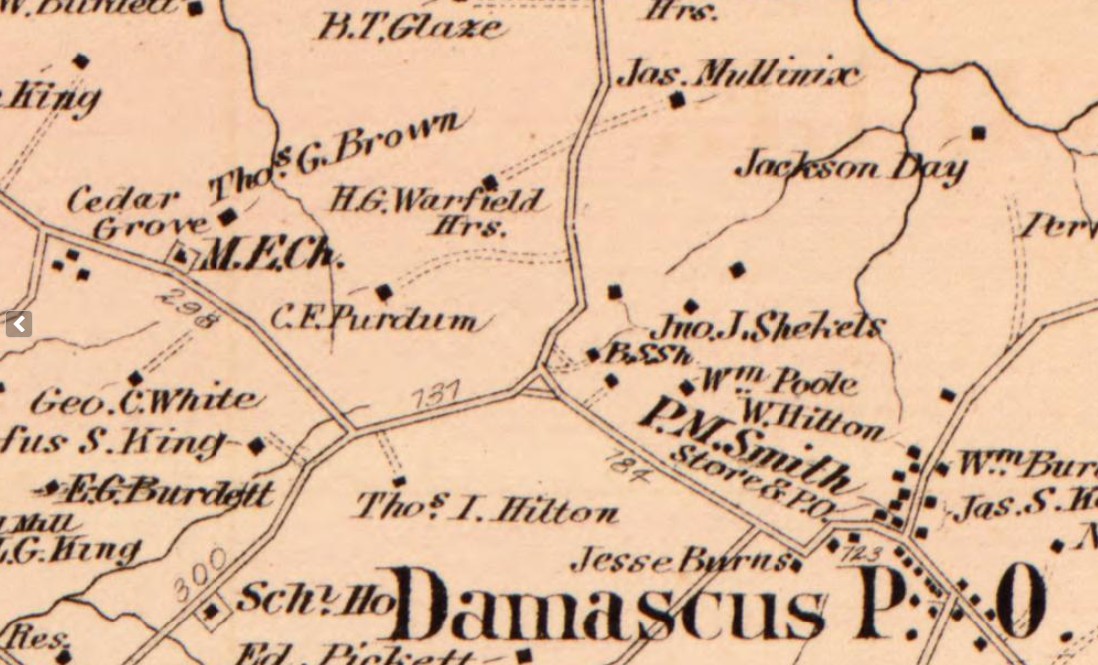

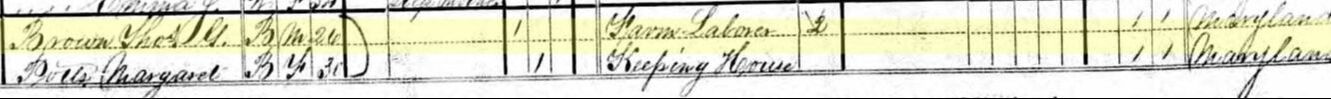

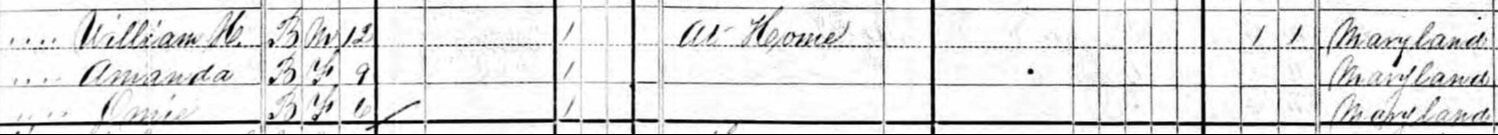

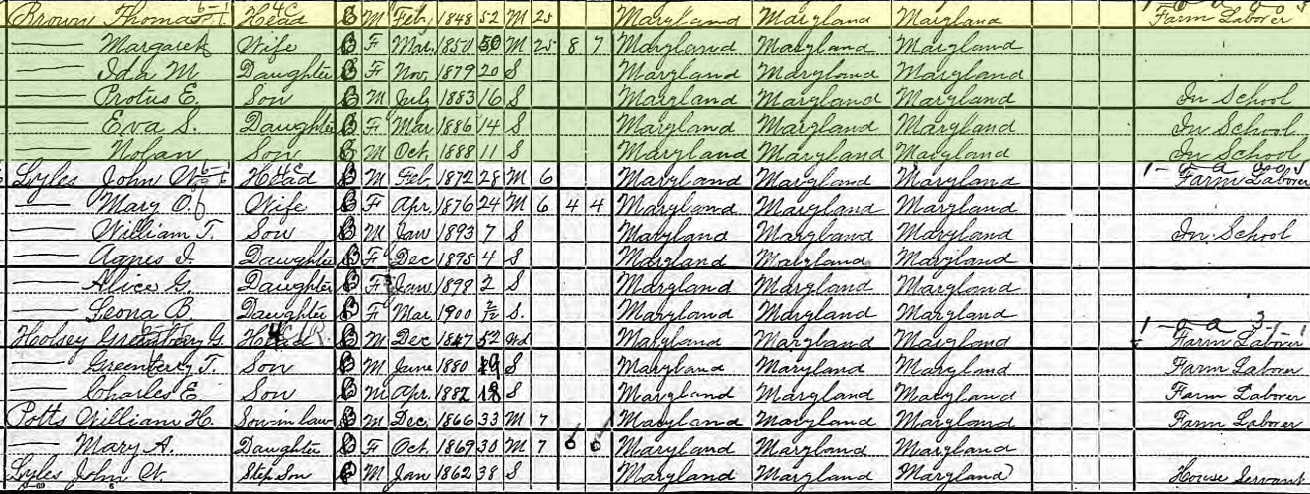

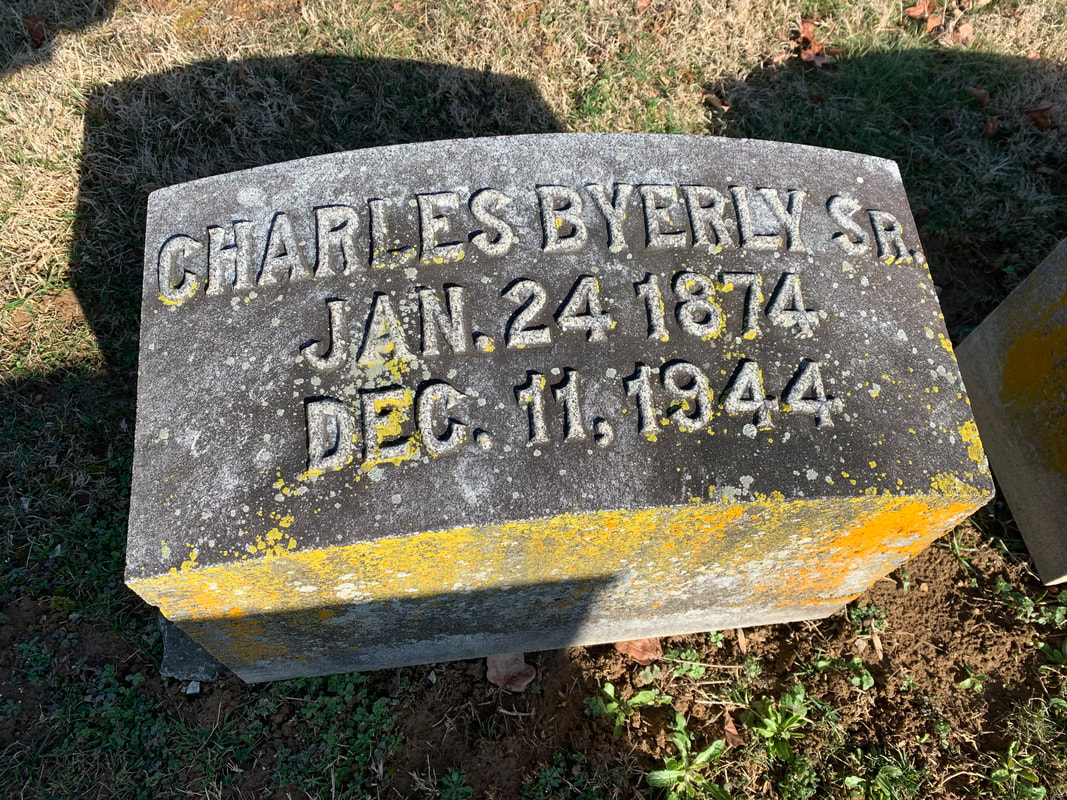

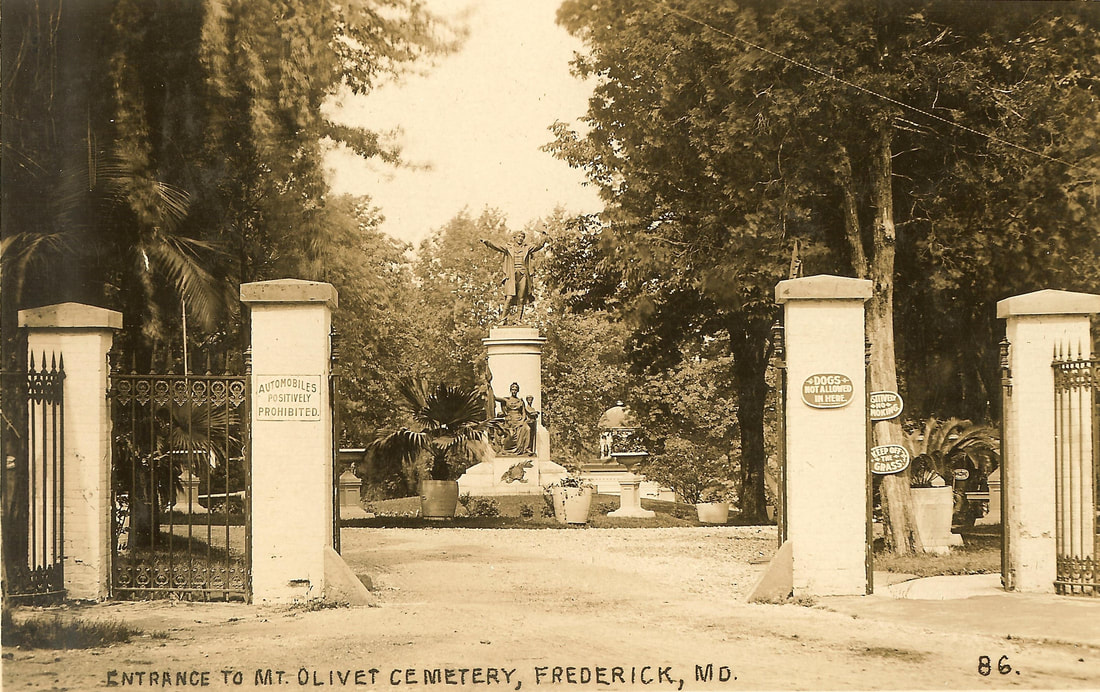

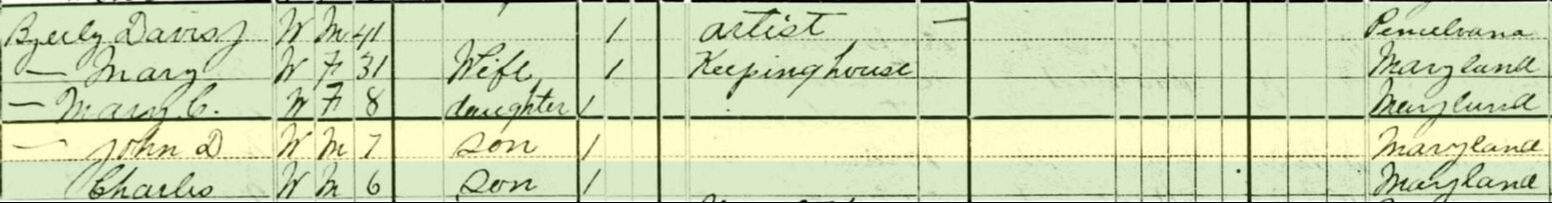

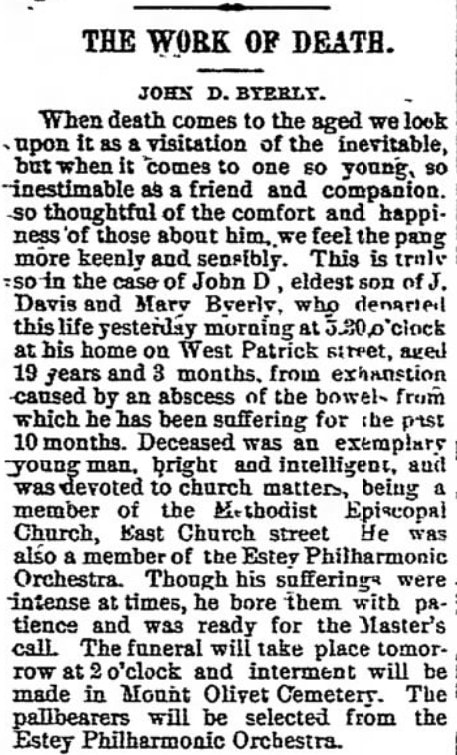

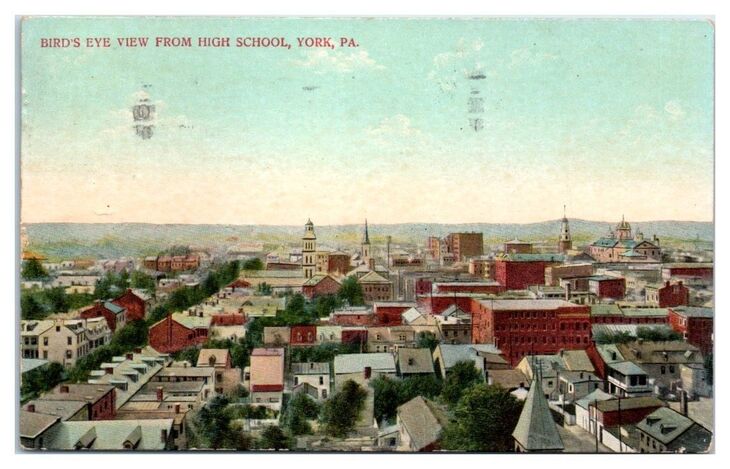

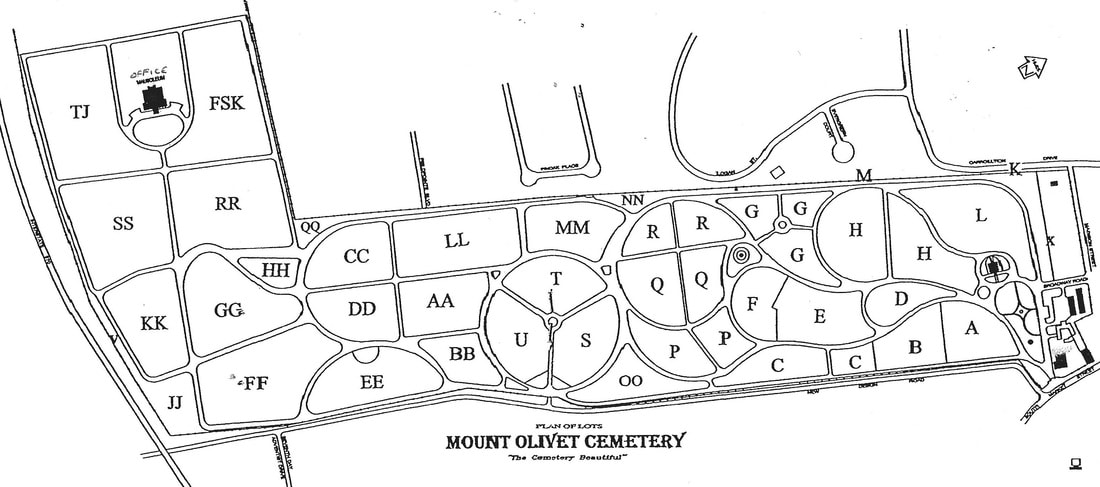

I truly can’t believe it’s been 25 years. Late February of 1998 was a very exciting time in my professional life as it marked the culmination of a documentary project that not only taught my local community a great deal about itself, but it had the same effect on me. The recipient of several local and national awards, this film afforded me the chance to travel to San Diego, California as the film had been nominated for a best documentary in the telecommunications industry. Subsequently, this work, which I titled Up From the Meadows: A History of Black Americans in Frederick County, Maryland won the Beacon Award of Excellence from CTAM—the Cable & Telecommunications Association for Marketing. The 5.5 hour video documentary originally aired the previous March (1996) on Cable Channel 10 of our local cable company of the era, GS Communications, which was co-owned with the Frederick News-Post by the Delaplaine and Randall families. While Cable 10 and GS Communications are memories now from Frederick’s past as well, the documentary (which was originally available on an equally ancient format called VHS) was remastered to dvd in 2014. It can still be purchased at the Frederick Visitor Center, and from time to time I am delighted to hear from new viewers who have stumbled upon it and learned from its rich content as I did while researching and writing it. The true magic comes from the the film’s amazing array of on-camera commentators and local historians. None of these people are still with us today, but their stories and words remain. As the title suggests, this program includes a comprehensive study of Blacks in Maryland’s largest county through the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries. Established in 1748, our north-central environ of the state serves as an amazing case study to explore cultural history through the past 275 years, although I only covered 250 of it. The story continues. My central premise with this project was that Frederick represented “a border county within a border state” during the American Civil War. As a coincidence of geography, we were situated below the Mason-Dixon Line and Pennsylvania, loyal stalwart of the North, while being positioned directly above the Potomac River, the only thing dividing us from Virginia—home to Richmond, the former capital of the South. Of course, European settlement patterns dating from the mid-1700s helped dictate Frederick’s situation in regard to slavery (and non-slavery) up through the Civil War, and later would have a definitive influence on segregation until its abolishment with the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. As many know, German historically settled north and west of Frederick City, while many English and Scots-Irish settled south and east of our county seat. Of course there are plenty of anomalies, but the Germans followed a model of family farms, while many English and Scots-Irish employed the slave plantation model. In Frederick’s case, we had early French families who brought slave labor to the area as well. Again this is very generalized, as I invite you to watch the film if you have continued interest. This unique backstory helped me understand and explain events occurring here in Frederick throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. We had “brother vs brother/neighbor vs neighbor “ confrontations during the Civil War, and Frederick was a place of supposed “separate but equal” policies up through the 1960s which included restaurants, shops, theaters, and even Mount Olivet Cemetery as I wrote about in a three-part “Story in Stone” blog back in February-March of 2017. As I said at the time, I was very humbled to be in the position of making this film. As a 30-year-old white guy at the time of its debut, I served as nothing more than a conduit for several talented historians, researchers and former citizens who allowed me to share their stories and information. In 1997, the internet certainly did not afford the dissemination opportunities it does today, and the chance to make this documentary available to tens of thousands of people through our cable channel and VHS tape sales was more than worth the incredible amount of work and effort put into the project which boasted a shoestring budget and less than a handful of video production specialists. As I drive each day through the fore-mentioned Mount Olivet, I think of the Black residents of Frederick who have been buried within our gates today over the last five+ decades, and a small collection of folks I chronicled that died before the Civil Rights Movement and were interred or re-interred here anyway. One such could even be the long-lost daughter of President Thomas Jefferson and slave Sally Hemmings. I also think of the cemetery serving as the eternal resting place for Civil War soldiers from both sides, along with former slaveholders and local abolitionists. Along the lines of the latter group mentioned, we have two abolitionists to thank for the fame of our beloved Barbara Fritchie—author John Greenleaf Whittier of Massachusetts and E.D.E.N Southworth of Georgetown. Miss Southworth was the top-selling female novelist of the 1800s, and is credited with sending the “alleged” story of Dame Fritchie’s flag-waving heroics to Mr. Whittier. I could give you another history lesson here, but I will save it for another time. What I will say defiantly, is that this poem put Frederick “on the map” as they say, and filled readers’ heads worldwide with the vision of a sleepy little town characterized by its “clustered spires” framed against “the green-walled mountains of Maryland.” As many have already noticed, I borrowed my documentary title from the opening lines of Whittier’s Ballad of Barbara Fritchie: “Up from the meadows , rich with corn, Clear in the cool September morn.” I just thought it fit for so many reasons, as I recall explaining to Lord D. Nickens, one of my central mentors for the project. We were driving around the countryside near his former home in Flint Hill, southeast of Buckeystown, and he asked me what I planned calling this thing. He smiled, and said “I like it.” Now that I had a title, I needed to incorporate a brand which included a logo, color scheme and central image. The talented staff at the Frederick News-Post art department came up with a great logo and I had in hand what I thought to be the perfect vintage photo to use. When I started the project in late 1995, I relied heavily on the amazing collection of Frederick’s past, both housed and interpreted at the Frederick County Historical Society, today known as Heritage Frederick. The photograph and manuscript collection was not filled with a plethora of Black artifacts, but there were a few standout items. Among these was a vintage photograph that instantly struck me upon first sight. It was the photo of a young Black gentleman with a young child on his knee. The photograph dates from the late 1870s, and was taken by a local professional in his studio once located in the heart of downtown Frederick. Many have seen this image as it has appeared in other publications since my usage in the late 90s. Last fall, David J. Maloney, Jr. posted it on the Frederick Maryland Old Photos Facebook page. David is an expert when it comes to antique assessment and all things curatorial, and mentioned in his accompanying post that his offering was a glass plate scan from his own collection courtesy of Heritage Frederick. He described this image as “Portrait of a Black Man, Luther Potts, and John Francis Byerly (son of the photographer).” David pointed out the prominent presence of agricultural implements in the hands of both subjects and went further to include a close-up view of the bottom of the photo pointing out that Luther’s clothing shows evidence of wear. At their feet is an assortment of props including a child’s wagon and wheelbarrow. There is also a horse drawn toy wagon marked “HARD & SOFT COAL/COKE AND KINDLINGS/COAL.” Upon my first viewing of this photograph at the Historical Society back in 1996, I was unsure of the race of the child, thinking perhaps it could be a mixed-race child. I soon read the description attached to the Society’s collection which confirmed for me the young boy as being white as I was already familiar with the Byerly family of photographers. In 2007, Mark Hudson, former director of the Historical Society of Frederick County, worked with staff and volunteers to produce a few brown-book pictorial histories under the title of Frederick County and Frederick County Revisited under Arcadia Publishing’s Images of America series. On page 113 of the second book, one can find the photograph in question, with a more detailed caption: "John Francis Byerly took this photograph of his son, Charles, and Luther Potts, the family’s handyman, about 1880. Potts was an organizer against Frederick’s registration law in the 1913 municipal election. The law required that only those males who owned more than $500 worth of property and were eligible to vote, or were male descendants of someone who was eligible to vote, in a state election before January 1, 1869, could register. The law was aimed directly at the local Black community. It was challenged in court, and pending a decision, Potts and about 30 others tried to register but were refused because of the “grandfather clause.” They believed that the law was in conflict with the 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution; city attorneys claimed that the amendment regarded only federal elections. On May 16, county judges disagreed and declared both clauses unconstitutional." I wanted to learn a bit more about these two photograph subjects, and readily assumed that I would likely not find Luther Potts here in Mount Olivet due to our past history of burial. Interestingly, we have many people of that surname interred here and even a special gated lot in Area G, which holds the relatives of former early congressman Richard Potts. In contrast to Luther, I easily located the final resting place of the younger subject, and his photographer father, just 20 yards to the south of the Potts Family Lot, and along the central drive that passes by both. I will start with just a few things I could find through Ancestry.com and local papers on Luther Potts. He appears in the 1910 US Census living in Frederick at 65 years of age. This dictates that he was born roughly 1845, which would make him around 35 in the Byerly photograph. In the 1910 census, his listed occupation was that of odd jobs which seems to match that of having served as a handyman for the Byerly family at that 1880 time period. I could not find Luther Potts in another local census at first, however I did locate a Lewis Potts in the 1850 census. Lewis and Sarah Potts lived in Frederick City at the time and had children, one under the named Charles who was listed as being five years old at the time. This matches our Luther's approximate 1845 birthdate, however the name is nowhere close. Back to the drawing board, but maybe these folks are relatives of some sort? I found a couple of newspaper articles mentioning Luther from the 1879 and 1887, but these do not showcase Luther in a positive light. On the other hand, I did find some articles from 1913 to back up the claims of Luther’s role as an organizer against Frederick’s unjust voter registration law. The last two remaining tidbits, I uncovered through my quick research, may provide clues to Luther’s whereabouts during (and before) the American Civil War. I found an interesting document for a Luther Potts of Howard County who was released from bondage to join the Union Army’s 28th Regiment of Colored Troops. Could this be our Luther? Although, I could not locate a traditional obituary for Luther Potts, I did learn of his death in the fall of 1917 courtesy of an odd news story which appeared in both Frederick and Westminster newspapers. It claimed that Luther was a former slave, and confirmed Luther’s employment relationship with the Byerly family. His home was also addressed as having been on All Saints Street, however he had some sort of connection to Mount Airy, and also the Damascus area of Montgomery County, as his final resting place would be in a small hamlet called Friendship (about two miles north of Damascus on MD 27). I found Luther’s gravestone in the Friendship Methodist Church Cemetery along Ridge Road (MD27) with a death date of October 17th, 1917 (age 72). I was inspired this past weekend to visit the gravesite of the man who has graced my documentary cover for the last 25 years. Unfortunately, his tombstone needs to be placed back up on its pedestal, but it looked as if it had been recently been cleaned. While at the graveyard, I also found other folks holding the last name of Potts as well: Potts, Amelia, d. Mar 11 1917, age 65yr 3mo Potts, Caleb G., d. Dec 10 1922, age 46yr 8mo 15da Potts, Caleb, d. Jul 21 1916, age 77yr John Henry Potts (1870-1946) unmarked grave Joseph Washington Potts (1883-1959) unmarked grave Potts, Lillian M., b. Jun 4 1892, d. Dec 24 1940, age 58 years Potts, Margaret, d. Oct 25 1906, age 60 years Potts, Mary E., b. 1872, d. 1947 Potts, William E., b. 1867, d. 1945 In doing a little more sleuthing, I learned more about Friendship, and a nearby slave plantation that likely held the answer to Luther’s days as a slave, and also his manumission. Jonathan Mullinix (1811-1899) was very wealthy man who owned an enormous amount of property and slaves in northeastern Montgomery County near the county line with Howard County. Friendship is located to the south of Clagettsville (where Kemptown Road (MD80) and Ridge Road (MD27) converge. Named for Friendship, the farm to the north, it had its origins as a Black community. One of its earliest dwellings, perhaps with roots dating to the 1830s, is the Inez Zeigler McAbee House on Holsey Road. Tradition holds that this dwelling was built on land conveyed in 1835 to John Holsey, a Black farmer, by the Mullinix family, The Holseys and other Black families who settled in the vicinity were former slaves on the Mullinix plantation named Long Corner, among other Mullinix properties in the area.  Section of the 1879 Bond Atlas Map of Montgomery County showing plenty of Mullinix farms (Mullineaux) in the vicinity east of Damascus. Friendship Cemetery is on the road between Damascus and Clagettsville and below the Jno. H. Clagett residence on this atlas but not in existence at the time of this map. I immediately flashed back to the Civil War record for Luther I had found. The witness who had signed it was Jonathan Mullinix. This explains why Luther enlisted in Howard County. As a matter of fact, Luther was manumitted so he could serve. Another military record shows that Luther was listed as a substitute. I think it is highly likely that he took the place of one of Mr. Mullinix’ sons. Speaking of the Civil War, I found that Luther’s brother, Caleb Potts, Sr. served in the USCT as well. He lived in the Mount Airy-Woodville area. Luther was likely visiting Caleb’s son at the time of his death, his brother having died the previous year. He is buried only a few yards behind Luther at Friendship. Most interesting was the discovery of Margaret Potts. Her final resting place was positioned in the northwest extreme of the small burying ground that extends to the side of route 27. Her stone seems as if it were not in the right place as it faced east while most other stones here faced west. It was oddly placed away from the pack as well. Had it been moved? So just who was Margaret you may ask? Well, I searched for her on Ancestry.com and made an incredible discovery. In the 1870 US Census, she can be found living in Friendship. More interesting is that she was living with Luther as his wife. The couple had a 2-year-old son also listed , William H. E. Potts. If we are to believe the article that appeared in local papers at the time of Luther’s death in 1917, Margaret was Luther’s sister and also his wife. I found Margaret again in the 1880 Census, but Luther was not living with her. However, housemates included son William and two other children—Amanda and Omie. The head of household listed was a Thomas G. Brown. I found his name, and the location of this dwelling a mile west of the cemetery, on the Bond Atlas of 1879. That little graveyard at Friendship held the graves of a few of Luther's children and I just kept thinking of Luther holding each on his knee, as he had done with the Byerly child in the famous photograph. The Byerlys This is a family that I have been planning to write a “Story in Stone” on since this blog’s inception in fall of 2016. I will go in-depth with a “part II” of sorts next week. For now, I’d like to stick with our Black History focus and the image of Luther Potts captured by the camera of long-time Frederick photographer John Davis Byerly (1839-1914). I will give a brief prelude by saying that John Davis Byerly was the son of Jacob Byerly (1807-1885), founder of Frederick’s first photographic studio in 1842. J. “Davis” Byerly took over the family business upon his father’s retirement in 1869, and is credited with so many well-known vintage images in, and around, Frederick during the late 1800s, before turning over the firm to his son Charles. The latter continued making incredible photographs of Frederick’s people and places, including several iconic photographs of Mount Olivet Cemetery in the early 1900s. So, is Charles the young boy in the photograph with Luther Potts as reported in the Frederick County Revisited book of 2007? Or is it John Francis Byerly as David Maloney added to his Facebook post this past fall of 2022 on the Old Frederick Photos Facebook page? Either way, both gentlemen are buried in the Byerly family lot in our cemetery in Area G/Lot 36 and 37, along with father J. Davis Byerly. There is one glaring problem however. John Francis Byerly is definitively not the name of the child in this photograph that has been dated to c. 1880. That’s because John Francis Byerly was the name of a son of Charles Byerly, and would not even be born until 1904. This was not a typo or error by Mr. Maloney, as it simply goes back to an error that is attached to the record of the photograph in the files of the old Historical Society of Frederick County. And here is that record from Heritage Frederick’s extensive archive: Black Man (Luther Potts) and Child (John Francis Byerly) Photo taken in studio of young black man and child in his lap. Farming tools and toys. [Mrs. Howard Kelly, in an interview at the Historical Society in 1998, identified the little boy as John Francis Byerly, son of Charles Byerly (b. 1874). She further identifies the man in the picture as Luther Potts who was a gardener or handy man who worked for the Byerlys. She did not know anything else about Luther.] And there you have it, all is fine until some meddling, cemetery historian comes along and spoils the party. I have to say, that I see now that I, myself, could have been the cause of the problem solely by my interest and use of this photo for my documentary in 1997. Perhaps that curiosity led to the 1998 interview with Mary Elizabeth Kelly who passed away in 2006 at the age of 94. She was the daughter of Mary Catherine Byerly (1871-1937), a daughter of photographer J. “Davis” Byerly, and sister to Charles. This would make John Francis Byerly a first cousin to Mrs. Kelly. That leads me back to the family of John Davis Byerly. Since the photo at hand was said to have been taken in 1880, let’s simply look at the 1880 US census for guidance, shall we. Davis and Mary have three children, the aforementioned Charles, Mary Catherine and one more, John Davis Byerly, (Jr.). That’s it, error solved, did Mrs. Kelly mean to say John Davis Byerly instead of John Francis Byerly? She was 86 when the interview was conducted, and certainly a forgivable mistake—more impressive was her identification of Luther Potts. John Davis Byerly (Jr.). was born on August 25th, 1872. He was the middle child of Davis’ children, but just a year and a half older than brother Charles. This photo was likely taken a few years before 1880, because the young boy seems to be about four or five in my estimation. So now we have a conundrum on our hands—W as it John Davis (Jr.) or Charles sitting on Luther’s knee? We may never know, but for Mrs. Kelly to bring up John’s name instead of Charles, I would go with the old expression, “Where there’s smoke, there’s fire.” I’m leaning toward John Davis Byerly (Jr.). Now I have one more opportunity for those among you who want to employ a facial analysis study. Mrs. Kelly provided several family photos for Gorsline, Whitmore and Cannon’s Pictorial History of Frederick—a must have for every Frederick history lover. One such photograph within this work (first published in 1995) is a family group photo including the Byerly and Markell families taken in the courtyard of the Byerly residence at 110 West Patrick Street. It was “snapped” in the year 1891 at the stately town home that sadly no longer exists, as it is now the site of the Frederick County Courthouse outside plaza area. My initial thought was “Who took this photo?” as all the professionals are within the shot. Interesting people of note here include J. Davis Byerly (Third Row extreme left with beard and moustache); Charles Byerly (Second Row extreme left); Mary Markell Byerly (second row to the immediate right of Charles); John Davis Byerly (Jr.) (second row extreme right); and Mary (Byerly) Chapline (front row, second from right in black and white dress and elbow on her grandfather George Markell’s knee). Take a look at the faces of both brothers, Charles and John Davis, and compare to the kid in the photo with Luther, and tell me what you think. As I said earlier, they are buried next to their parents on Area G/Lot 36-37, only a few yards south of the Potts Lot along our central driveway through the cemetery. I will talk more about Charles in our next installment, however, I want to bring up the fact that John Davis Byerly (Jr.) would pass not long after the family photo above was taken. He spent most of the year battling a painful malady, requiring frequent treatments in Baltimore. His death occurred on November 29th, 1891.

I will wrap this up this “Story in Stone” with another fascinating Byerly photograph from the archives of Heritage Frederick. This was also featured in the Frederick County Revisited publication with a caption that reads as follows:

“This photograph was taken by Charles Byerly about 1905 at his brother’s Mount Olivet Cemetery grave site. John D. Byerly died in 1891, at ager 19. While the photograph today may seem a bit odd, it would not have been when it was produced. At the time, public cemeteries, with their mixture of natural and monumental, were considered pleasant and respectable places for picnics and and other informal gatherings.”

2 Comments

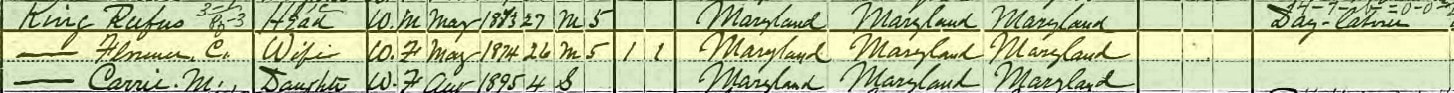

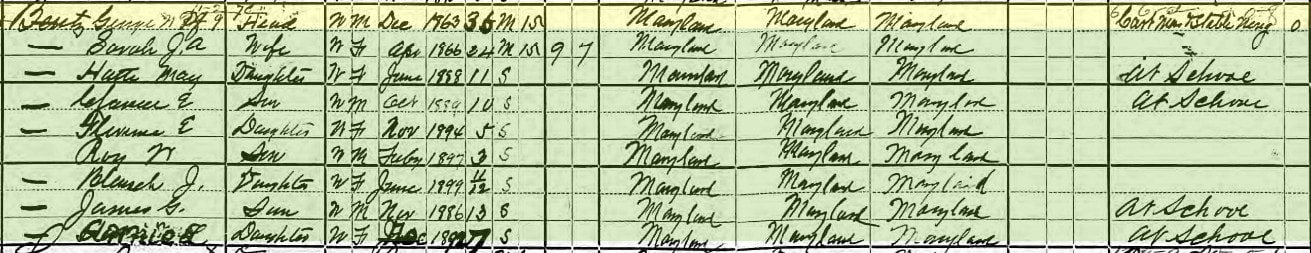

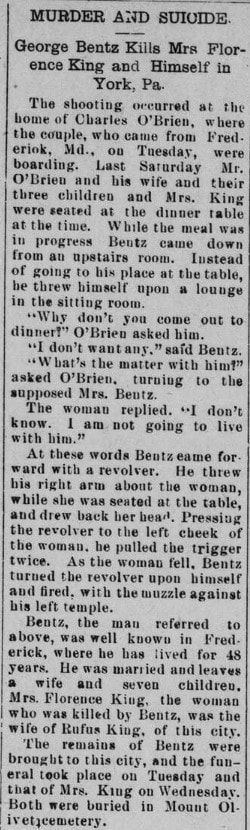

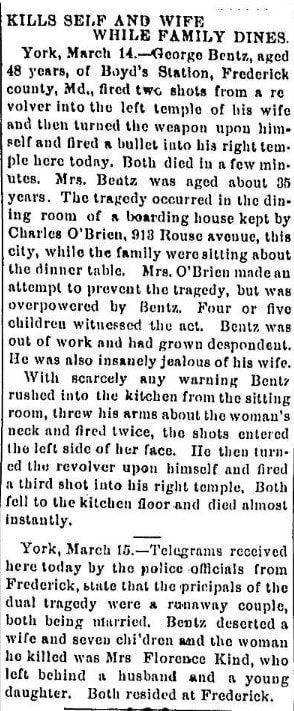

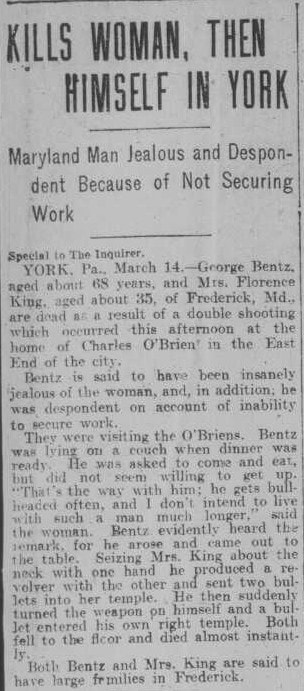

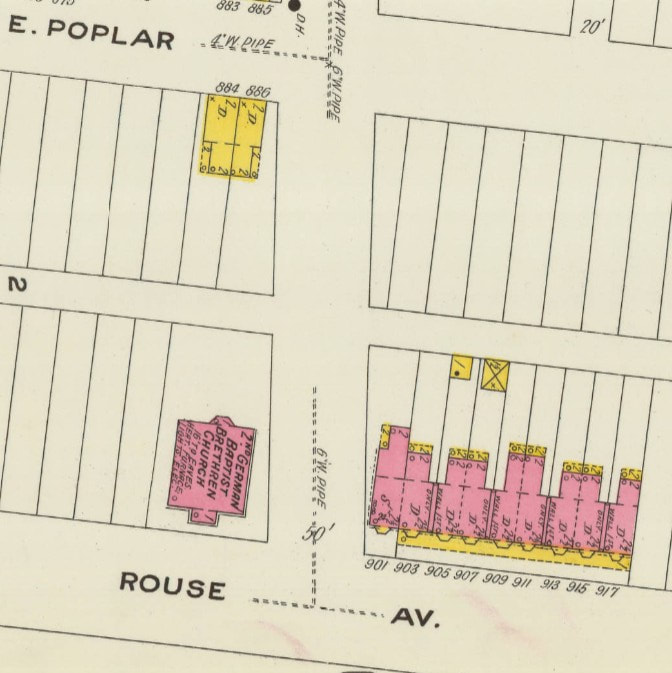

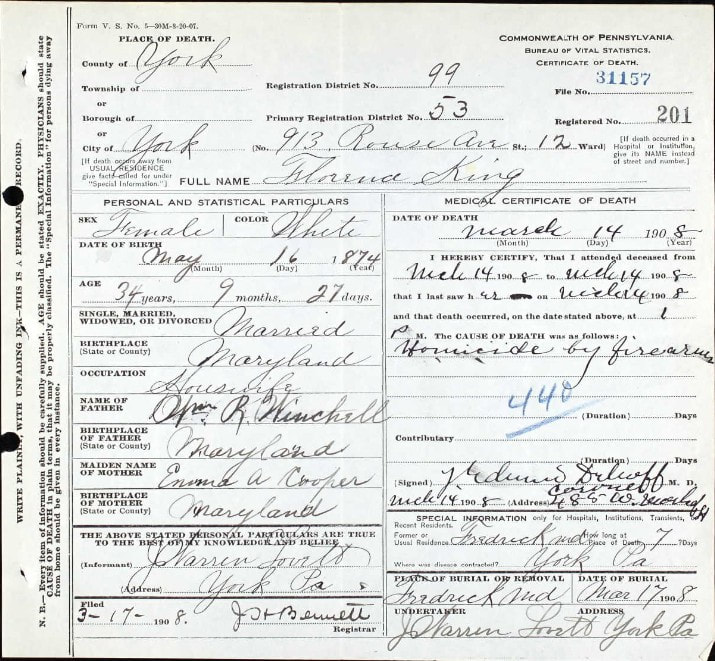

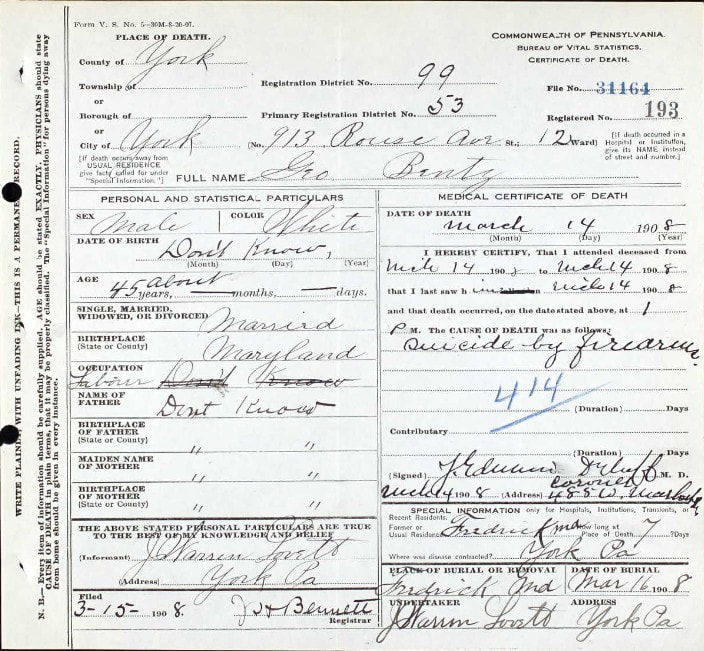

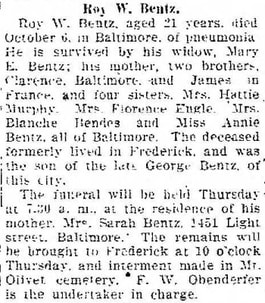

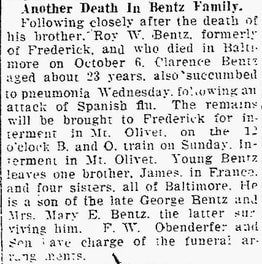

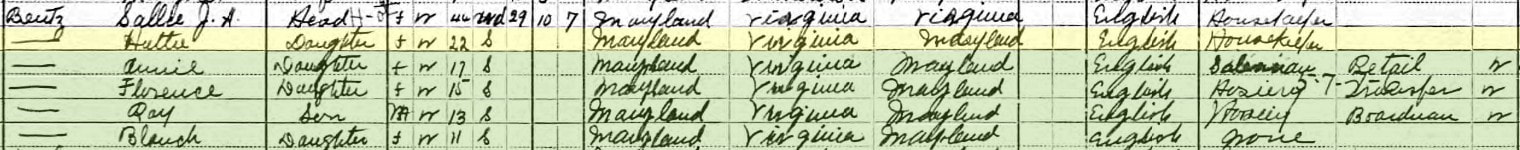

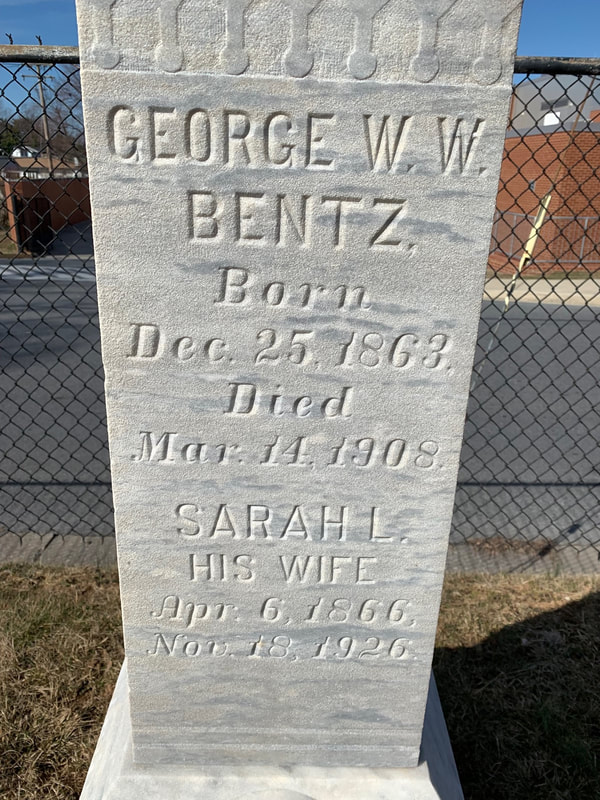

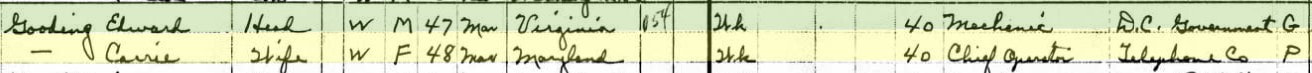

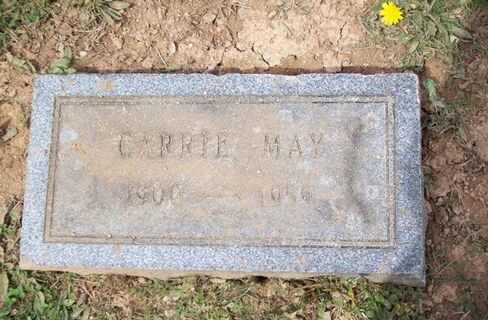

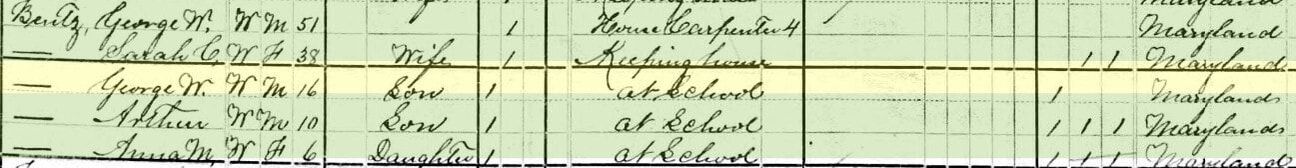

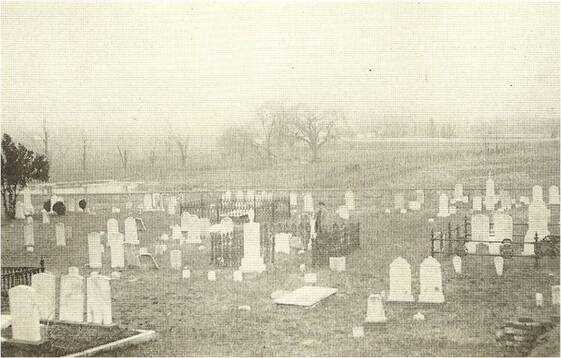

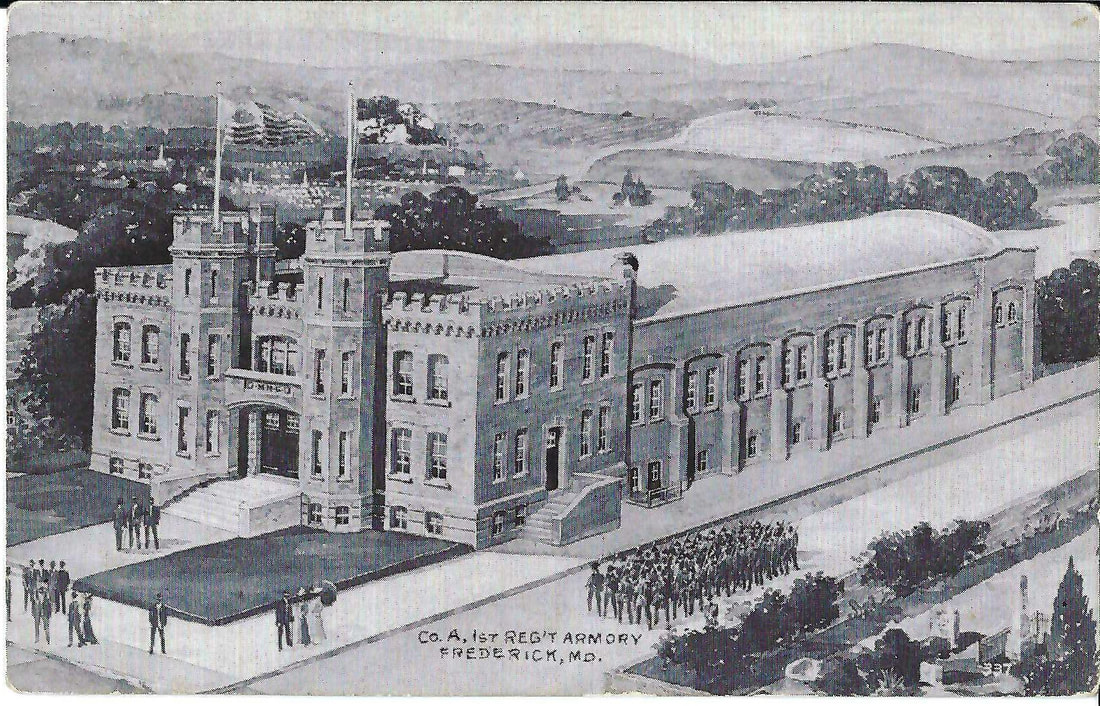

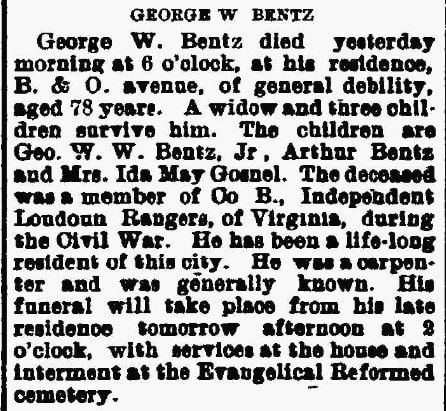

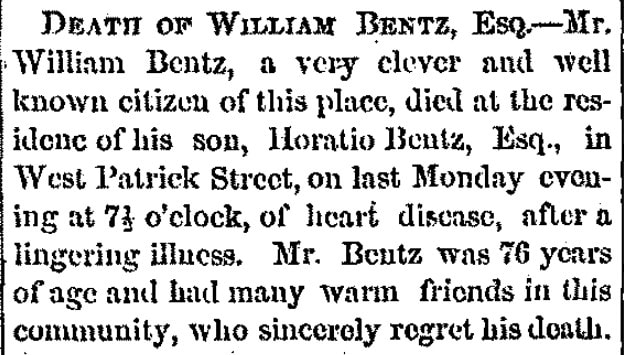

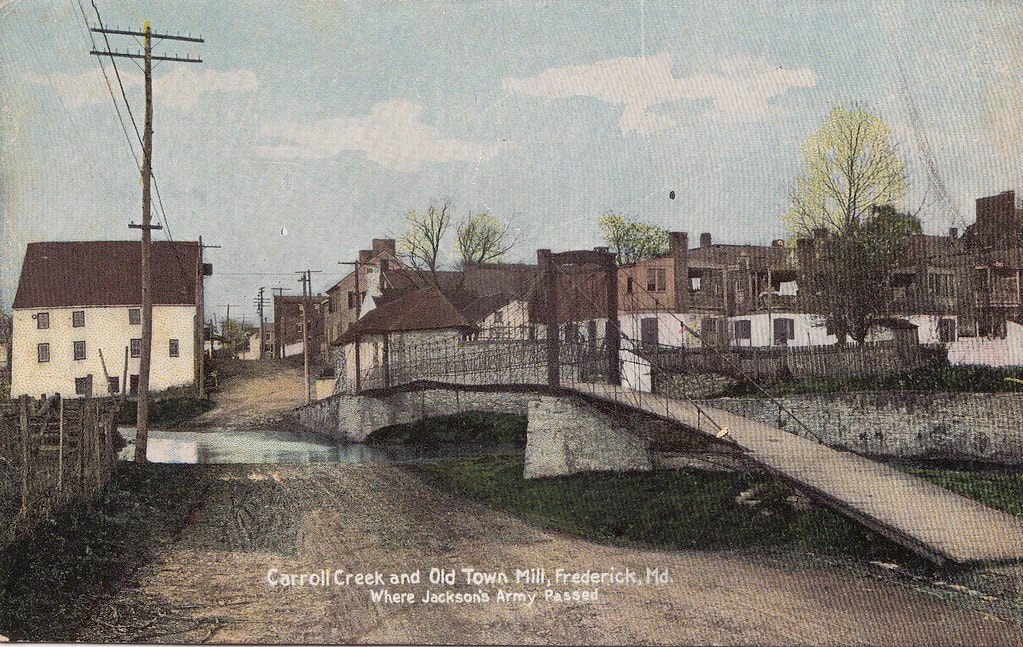

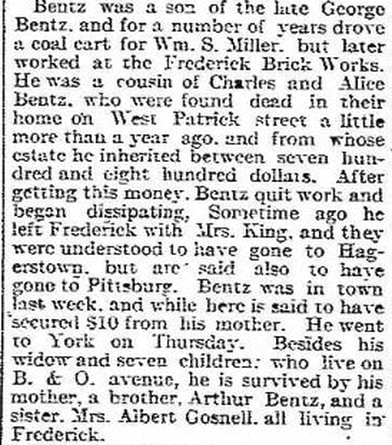

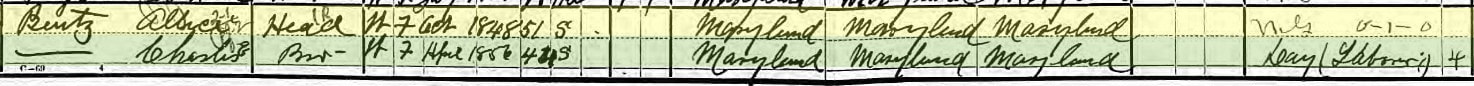

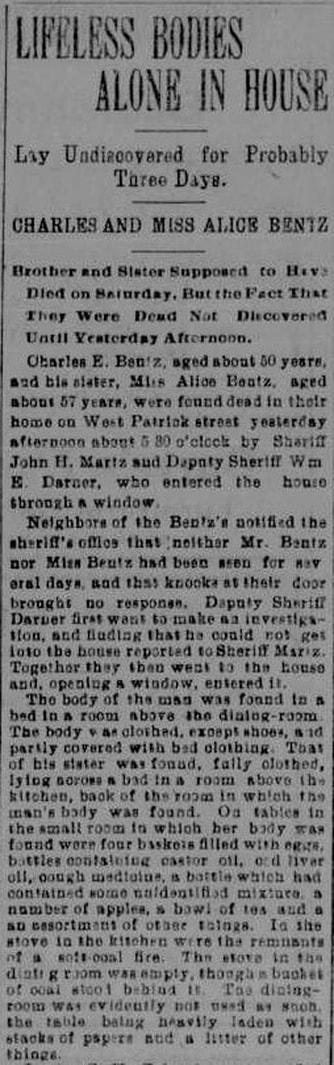

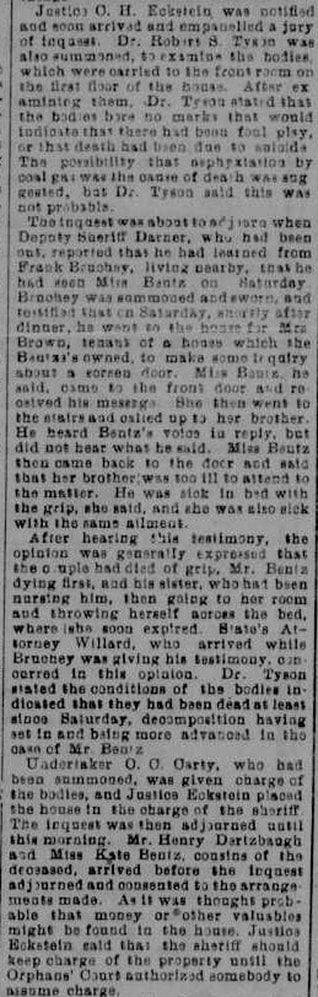

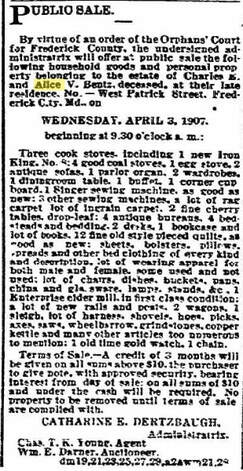

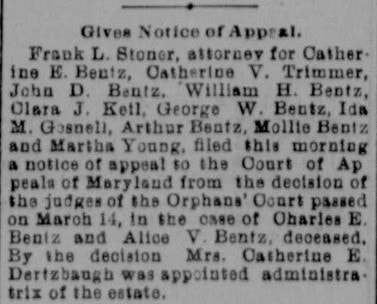

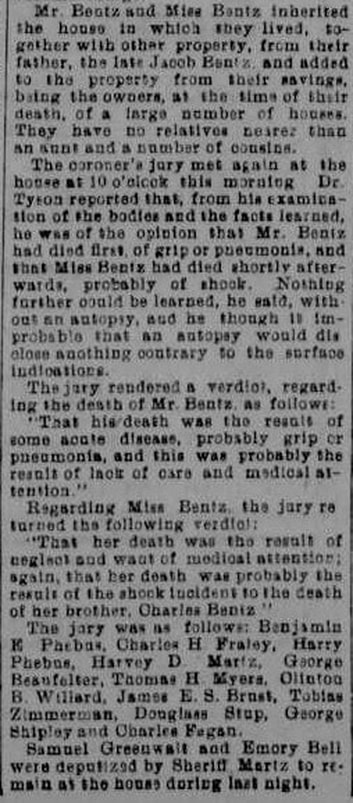

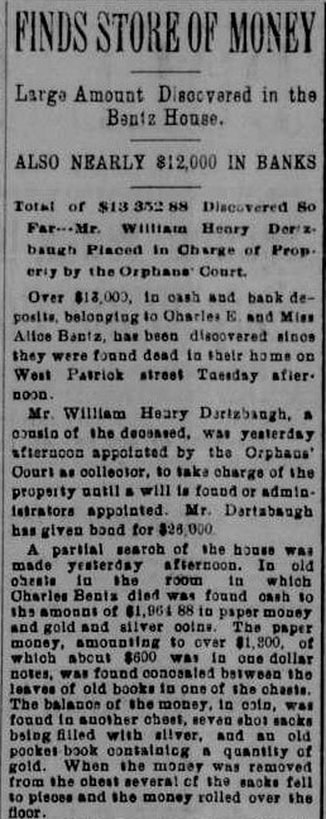

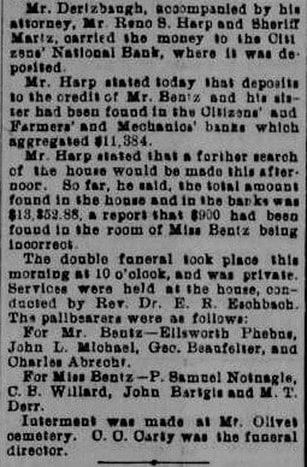

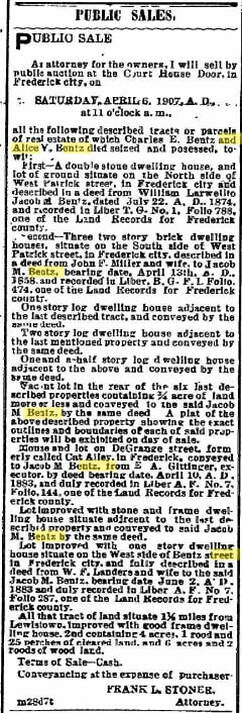

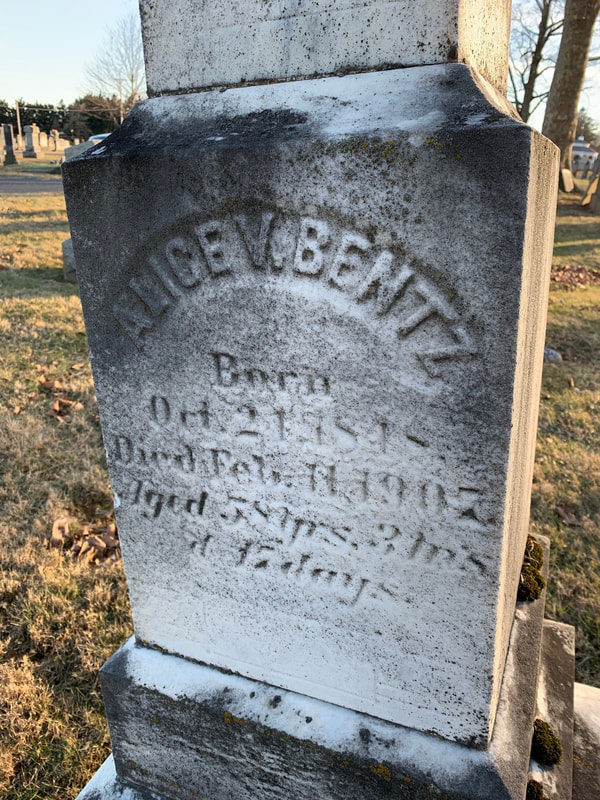

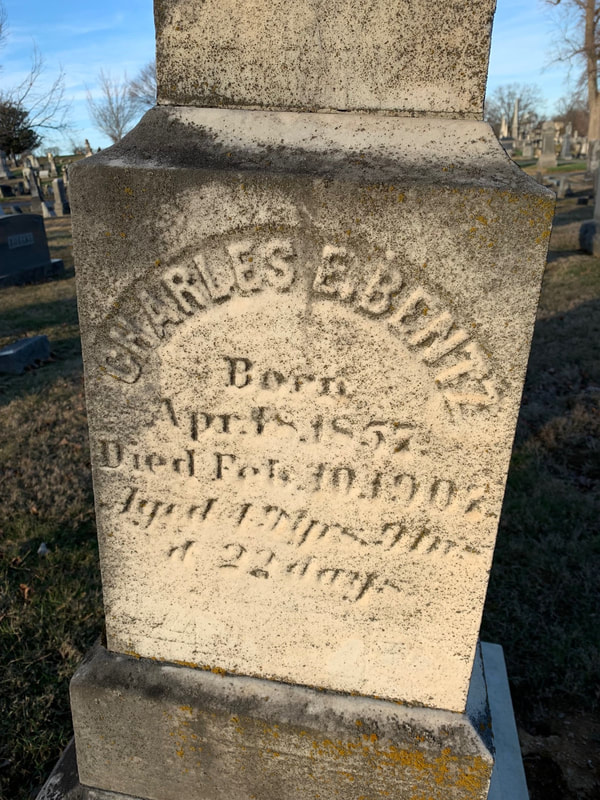

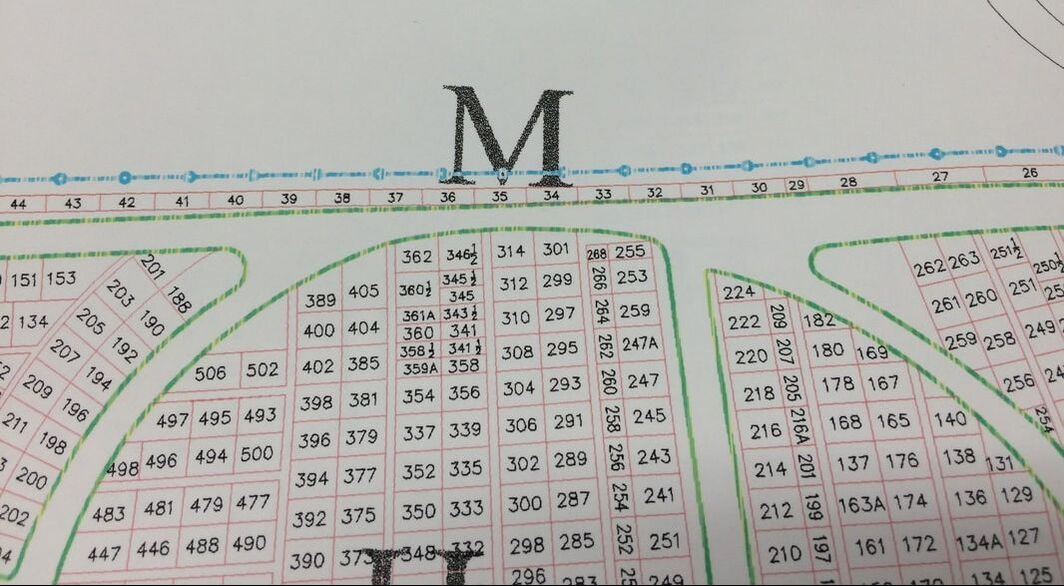

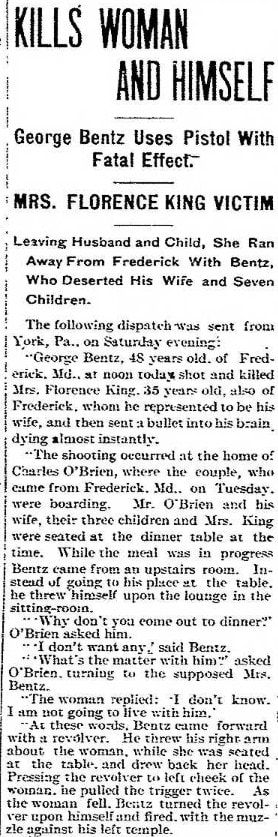

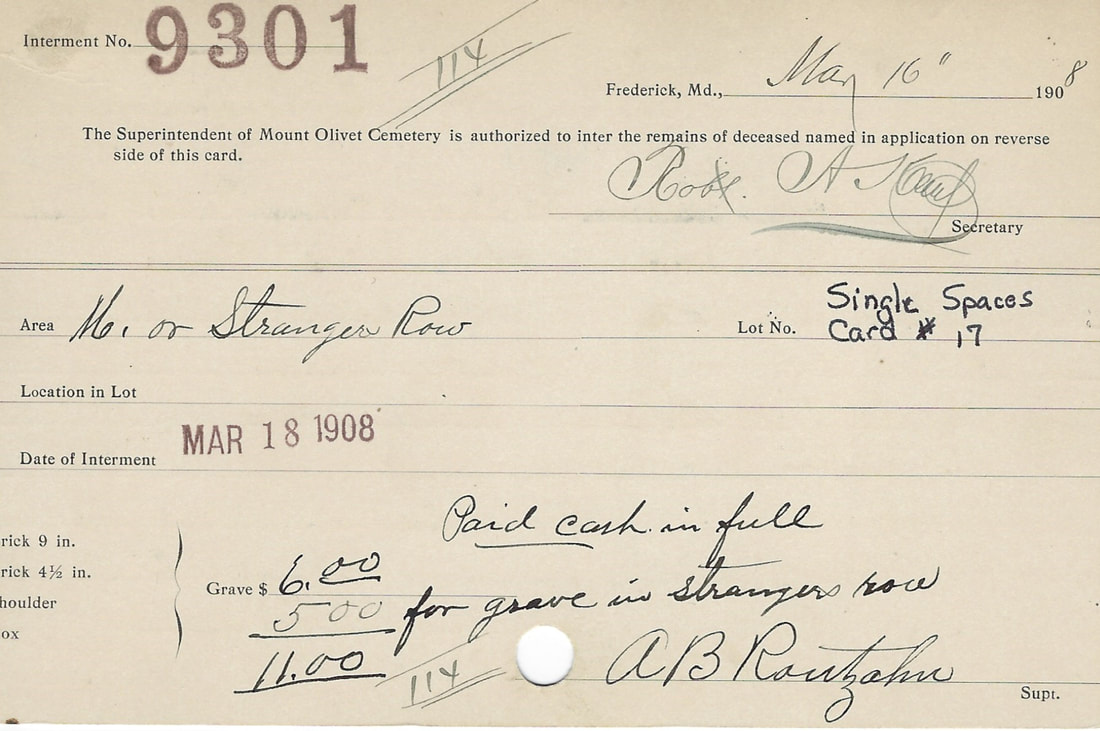

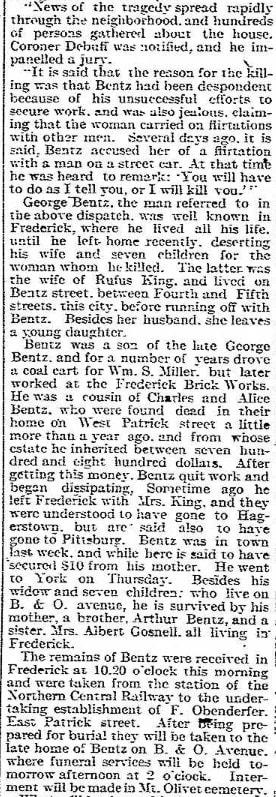

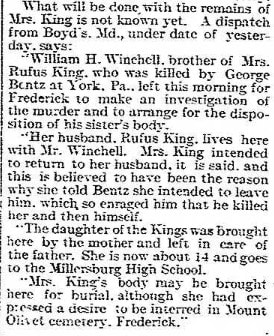

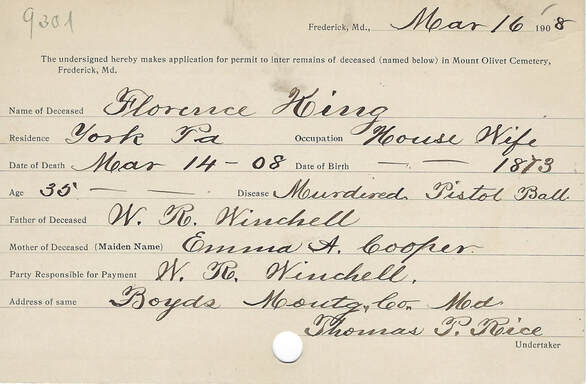

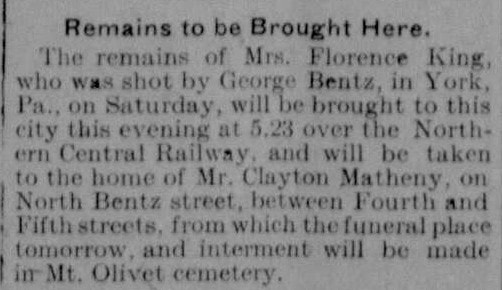

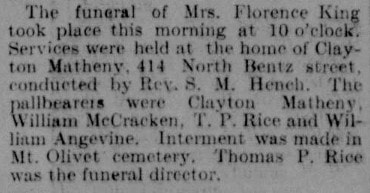

Last week’s “Story in Stone” centered on a unique patch of green grass in the cemetery in the heart of winter. I took readers to Area M/Lot 27, within a section at one time known as “Stranger’s Row.” This week’s story will be a brief continuation of an episode relayed last week involving one of the decedents buried here in this plot. I realized that I needed to complete a bit more “detective work” to tell that story a little more fully. Specifically, it is the tragic tale of Florence (Winchell) King, whose life abruptly ended at age 35 in York, Pennsylvania on March 14th, 1908. She had married Rufus King around 1894/95, and the couple had one daughter named Carrie, born in 1895. They resided on Bentz Street, between 4th and 5th streets. Mrs. King would abandon Rufus and Carrie in 1907, running off with a married man named George William Wallace Bentz. Mr. Bentz had lived on the southeast part of town on B & O Avenue with his wife, Sarah J. A. “Sallie” (Lowe) originally from Buckeystown, and the couple’s seven children. Florence and George were said to have first gone to Hagerstown, and then Pittsburgh before ultimately heading to their last destination of York. A primary issue that had the fugitive couple “on the run” was George’s desperate attempt to secure employment. With funds running low and jealousy (on behalf of Mr. Bentz) running high, George could best be described as very tense, if not a ticking time-bomb. Unfortunately, Florence did not fully comprehend the state George was in, and what he was capable of doing. Apparently these factors were perceived by Florence and she communicated to George her intent to return to Frederick to reunite with her husband and daughter. As you can imagine, this “change of heart” by Mrs. King did not go over very well. Instead, it cost the former Florence Winchell, her life. She was only 35. In last week's story, I shared the dramatic newspaper story which appeared in the Frederick Post's March 16th edition. Here is another Frederick newspaper account and a few from Pennsylvania: I found the death certificates for both individuals in Pennsylvania records. Their bodies were brought back to Frederick and subsequently buried. Apparently, Mrs. King had expressed (during life) that she desired to be buried in Mount Olivet. Sadly, she received her wish too early and is buried in a currently unmarked grave in Area M/Lot 27. Through our Friends of Mount Olivet membership group, we hope to start a program in the near future to mark all decedents in the cemetery through fundraising efforts. As for George W. W. Bentz, his grave is roughy 40 yards away from his lover/victim Florence as he is buried in Area M/Lot 5, directly across Carrollton Street from Lincoln Elementary School along our cemetery fence. A fine monument sits here atop this burial plot that includes Bentz former spouse “Sallie,” a grandson named James M. Bentz, and two (grown) sons— Clarence and Roy. Interestingly, I learned that both Clarence and Roy died in 1918—victims of the Great Spanish Flu Pandemic. Sallie Bentz moved with her children to Baltimore after her husband’s death, and would remain in "Charm City" until her own passing on November 18th, 1926. On the flipside, I found it interesting that Mrs. King’s widower, Rufus King (1876-1936), is buried in a plot in Mount Olivet’s Area U/Lot 22, owned by Florence’s brother, William Winchell, and sister-in-law, Ida May Winchell. He was living with them at the time of Florence’s murder, and seemingly continued a close relationship up through his death in late March, 1936. Here, is also located the King’s daughter, Carrie Mae, who was 12 at the time of her mother’s murder. She would go on to marry Edward T. Gooding, and spent much of her adult life in Montgomery County. In the 1950 US Census, she can be found working for the telephone company as “chief operator." She passed away in 1959, and is buried just a few grave spaces away from her father and next to her husband. George W. W. Bentz Something in the newspaper clipping about the murder-suicide made me want to look into the life of George Bentz a little closer. George W. W. Bentz was the son of George W. Bentz. The father was born in Frederick in 1828 and was a carpenter by occupation. He was married to Sarah Catherine Beall. Our subject’s father was a Civil War veteran. On August 30th, 1863, George’s father enrolled in the Independent Loudoun Virginia Rangers of the Union Army, at Harpers Ferry. He was mustered in on January 26th, 1864 at Point of Rocks. With other Loudoun Rangers opposed to their proposed transfer to West Virginia, Mr. Bentz enlisted in Co. L of Cole's Cavalry on April 6th, 1864, but then he rejoined the Loudoun Rangers in September. He was mustered out with the rest of his unit on May 31st, 1865, at Bolivar, WV. George W. Bentz died in 1903, but is not buried in Mount Olivet. Instead, he is with his parents (William (1792-1868) and Elizabeth (1793-1868)) among the remains that are in Frederick’s Memorial Park on the corner of West 2nd Street, and fittingly, North Bentz. As regular readers of this blog know, the former Evangelical Reformed Church Cemetery was abandoned in 1924. No tombstones exist because they were re-interred with their respective decedents in 1923 as part of the new park project. Above the surface of this hallowed ground are a number of war monuments today. A bronze plaque fronting on Bentz Street has a list of those buried here. It is said in an old News article that the Bentz family referred to here were along a southern wall of the burying ground across from the old armory (today’s Talley Recreation Center). Bentz Street takes its name from the family which at one time owned several parcels near the intersection of West Patrick Street and today’s namesake thoroughfare. This can be credited to our subject’s relative Jacob Bentz (1760-1815), and the plethora of such-named people (including grandfather William)in this vicinity giving rise to the area being called Bentztown for many years. Of course, many are familiar with Jacob’s stone mill (Bentz Mill) built along Carroll Creek by 1778 on his tract named Long Acre. It would later be known as the Brunner Mill and would survive into the early 20th century and is documented in several photographs and postcards. The Frederick Post article about the deaths of Florence and George appeared in the March 16th, 1908 edition. Therein was a richer biography on George W. W. Bentz. But there was also something mentioned about money coming George’s way due to inheritance gifts. I perked up when I read that an aunt and uncle had given him money. However, both had been mysteriously found dead in their home in February of 1907. I wondered to myself, was George’s “flight” with Florence King bankrolled by this inheritance from his Aunt Alice V. Bentz and Uncle Charles Bentz? And if it was, did George perhaps have a hand in the deaths occurring in the same house, and seemingly the same day as both were found at the same time by authorities called to the scene after neighbors became curious in not seeing Alice or Charles for a number of days. These two were not a couple, but rather siblings, who were living together on West Patrick Street in a dwelling that had served as their family home. The following article from the local paper gave me the information I needed to know. I felt better about George, but still think he blew that inheritance on Florence. As the money ran out, one can sense his desperation as the earlier article noted that he had made a special trip to Frederick to secure $10 from his mother, just days before his own death. Alice and Charles E. Bentz are buried under a monument similar to their nephews. It stands in a Bentz family plot in Area Q/Lot 183. Neither had children, and their sudden deaths without wills would be fodder for family squabbling and court cases over inheritances for years to come. I would find a news article about a case in Frederick court as late as 1915, in which a key witness was called in the form of George and Sallies’ son James G. Bentz, a World War 1 veteran. James had to testify to the mental condition of his Great Aunt Catherine Dertzbaugh, named administrator of the Bentz estate. So that concludes my investigation. The murder of Florence King and suicide of George W. Bentz is a very sad story on so many levels. Of course, two lives were cut far too short. The greater tragedy was the hurt done to the former spouses and several children left behind by the senseless, impulsive act that occurred at the O’Brien’s boarding house in York 113 years ago in March, 1908. I’m sure it was difficult, but kudos to Sallie Bentz and Rufus King for raising their respective kids into adulthood.

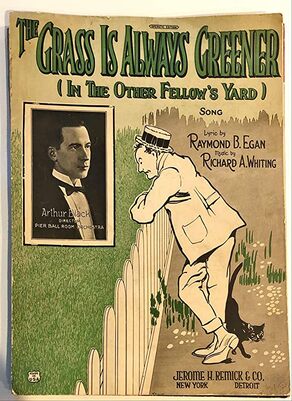

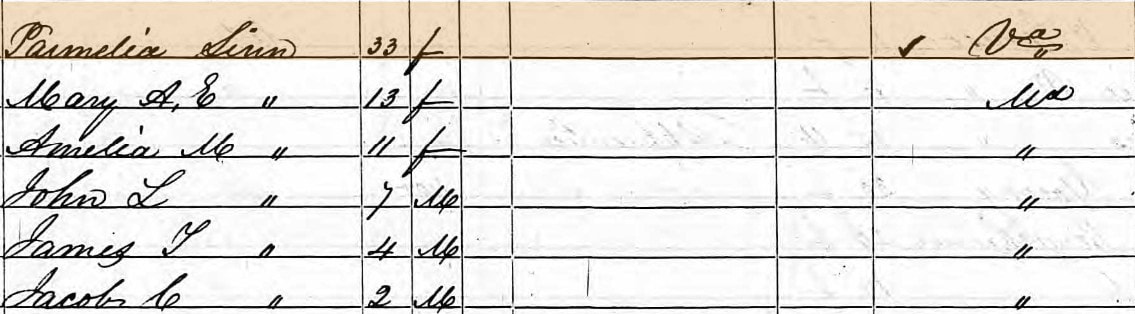

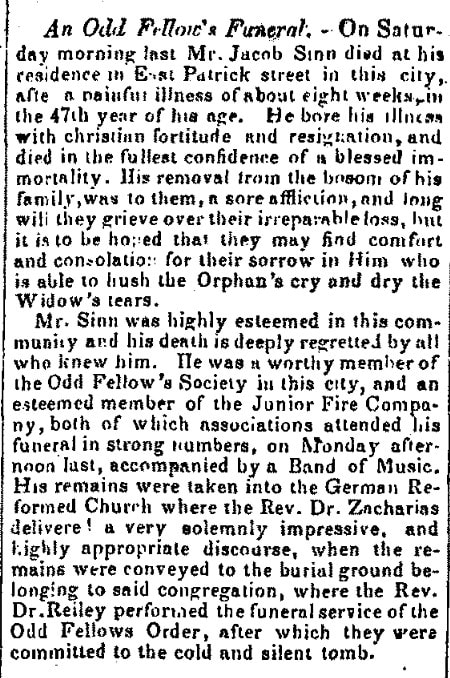

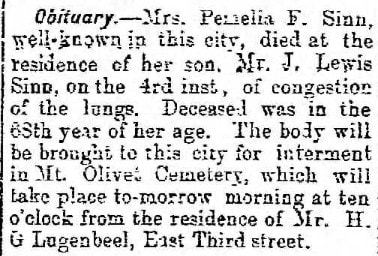

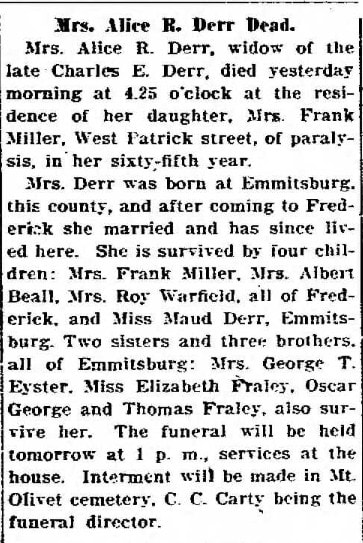

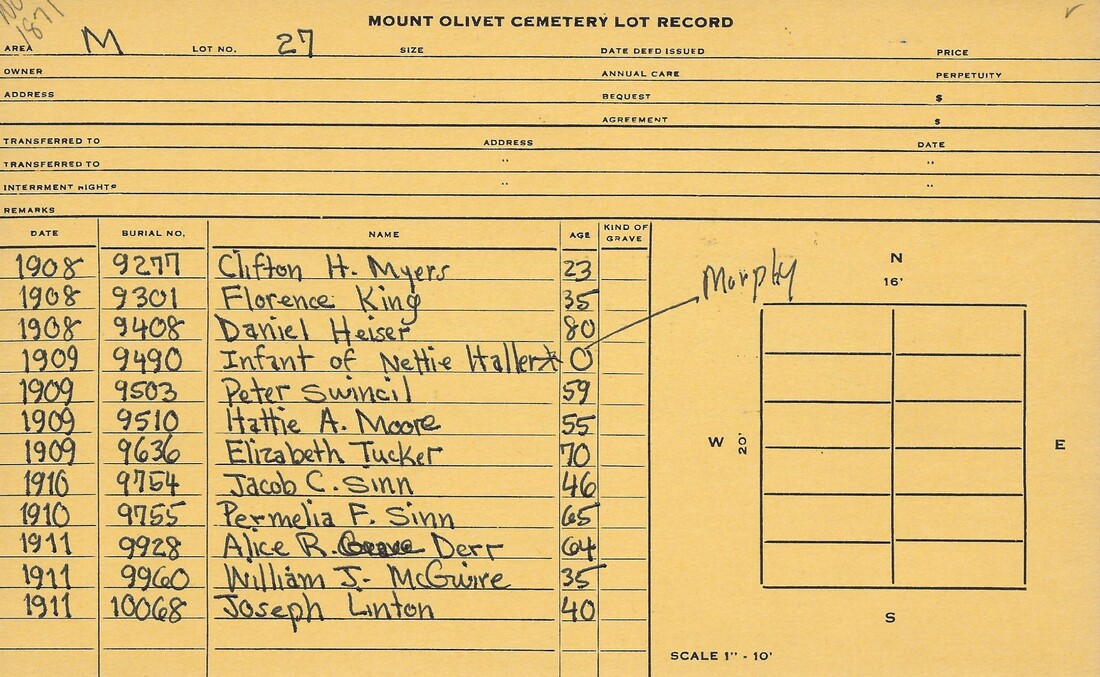

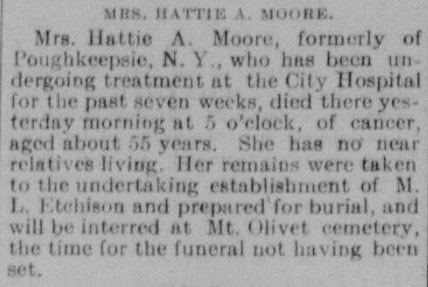

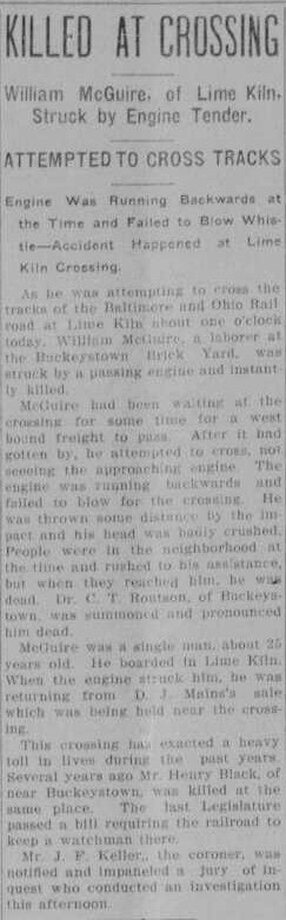

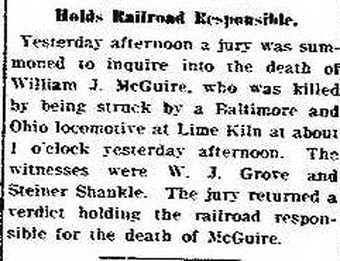

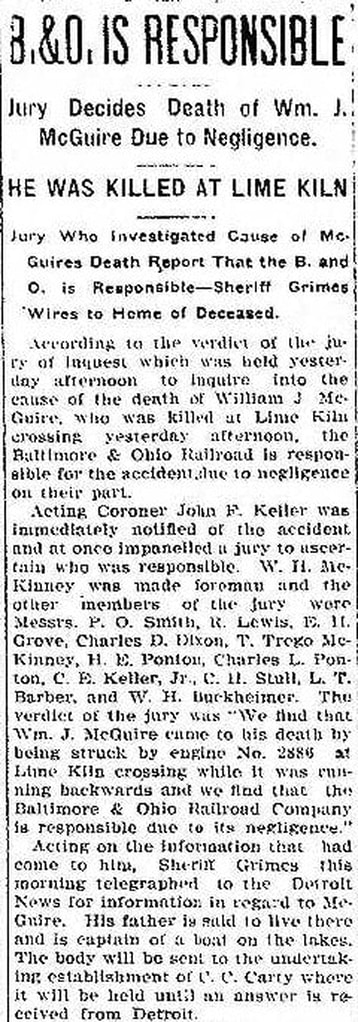

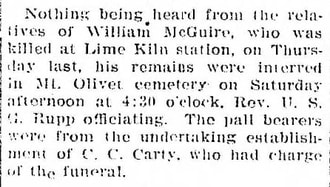

And let’s not forget the O’Brien family who had a front row seat to an event that surely stayed with each family member until their own dying day. It’s early February, pre-Valentine’s Day Weekend, to boot. The sun is shining and the weather is uncharacteristically spectacular. No snow, no sleet, no blustery winds. As I took a late-night walk after midnight, much earlier this morning, the temperature was 61 degrees, and the ground was glistening with moisture because the difference in ground and air temperature. I enjoyed much of the same state of affairs again, with a morning run taken at 7:30am. Not long after, a funny thing happened to me on the way to the mausoleum, where my work office is located here within Mount Olivet Cemetery. My eye was caught by something other than a gravestone, or monument this time. I had taken the driveway that runs adjacent to our western perimeter of the cemetery and appearing out of nowhere, I saw the most beautiful oasis of green. I casually breezed by this colorful spot in lonely old Area M, located in a plot not far from the northern beginning of “Confederate Row,” where nearly 700 soldiers from southern states repose—their lives cut short thanks to the American Civil War. The particular part of Area M that I am referring to with my morning optical surprise was actually commonly called “Strangers Row,” the topic of a “Story in Stone” I wrote in early January, 2023 about town lamplighter William “Uncle Billy” Hilton. Over a century ago, this was a place designated for burials of destitute individuals and unknown guests to town who unfortunately expired while here and far from family and native homes. Most laid to rest here have never been given a gravestone, simply because family was not here locally, or individuals that were such as a widowed spouse, orphaned children, a sibling or parent had no means to do so. I felt the immediate urge to turn back and reinvestigate this “strange” observance in “Stranger’s Row.” I navigated my trusty Jeep Liberty around at the first opportunity of a side lane. As I reached my “former” position, I knew for sure that my weary eyes had not deceived me. It was as bright and eye-opening as I can recall the foundation of a delightfully-filled basket of candy on Easter Sunday morning in my childhood. This was a true spring-like experience. My brain, the strange machine it is, also immediately conjured up the very first time I saw Astroturf while attending a game at Philadelphia’s Veteran Stadium in the late 1970s. Now this was a Phillies baseball game, and not an Eagles game, which I would see on plenty of occasions later as well. Seems fitting, as many will think of that old sports venue late this weekend as the Eagles play the Chiefs in the Super Bowl. Could my green, here in Mount Olivet, be a sign that the Eagles may be victorious on Sunday? I walked closer to the few gravestones among the lush green grass I’m talking about. I would eventually learn from our interment database that this location is Area M/Lot 27. I was familiar with this terra-firma, albeit a little softer than I recall it being five weeks earlier when visiting Lot 26 next door in subfreezing, windy conditions (while compiling my research for the William Hilton story referenced earlier). The age-old idiom naturally came to mind instantly: The grass is always greener on the other side. I tried to find special symbolism here on this interesting winter day that feels anything but. I also thought about the mystique attached to many in this section of Area M, including all our Rebel soldiers who I’m sure never would have guessed that their final resting places would be in a town named Frederick, Maryland.  As I started writing this piece, I felt the need to check the idiom and proverb again, because I seem to be guided to this location by divine intervention this morning, within a week where I have done a lot of self-reflection and soul-searching myself. No need to get into any of that here, but I will say that the proverb at hand comes with a great deal of irony. Upon deeper investigation, I learned that the expression has actually been shortened in modern usage, as it began as “the grass is always greener on the other side of the fence.” We have also created a well-used “variant,” with “the grass isn’t always greener on the other side,” and/or “the grass may not be greener on the other side.” Whatever the iteration, the message is the same as it is used to say that the things a person does not have or desires always seem more appealing than the things he or she does have, or the opposite of thinking that what you desire may not be better than what you already have. Oh desire, temptation and envy, why must you prod? In other words, we are always tempted by and envious of what other people have. This whole exercise has now made me understand another old saying, “green with envy.” The phrase dates back to the Greek poet Ovid, who lived in the first century B.C. The original saying was, “The harvest is always richer in another man’s field.” The proverb as we know it comes from an American folk song titled: “The Grass Is Always Greener in the Other Fellow’s Yard.” This was written by Raymond B. Egan and Richard A. Whiting in the year 1924. The chorus reveals our answer: The grass is always greener In the other fellow’s yard. The little row We have to hoe, Oh boy that’s hard. But if we all could wear Green glasses now, It wouldn’t be so hard To see how green the grass i In our own backyard. I only found four stones in Lot #27 of Area M, within the center of what appeared to be “the sea of bright green” that I’ve been gushing about. Now, I will be very careful bringing humorist writer Erma Bombeck into our story, because she hinted to the “green grass” proverb with her 1976 classic The Grass is Always Greener Over the Septic Tank. While this funny take provides a great deal of truth, I can say with certainty that there are no septic systems here beneath the cemetery proper, instead just people from our past—12 to be exact in this particular grave lot. I would later learn that one of these was an interloper, in gravestone only. The marble tombstone leans against the chain-link, cemetery fence and shouldn’t even be at this location. It reads Thomas J. Bell. Mr. Bell was a gentleman who died at 62 years of age and lived at 161 B & O Avenue at the time of his death. His stone belongs over his (body) which is in Lot 26, just to the south. The prominent monuments of Lot 27 are few, as mentioned earlier. There are only three here representing a group of 12 individual grave spots. The centerpiece includes a tandem of marble offerings, mounted on the same base. Here, we find husband and wife, Jacob C. Sinn (1813-1860) and Permelia F. (Cole) Sinn (1820-1885), who I learned were married on March 19th, 1836. Our cemetery database provided a few tidbits on each of these decedents who were originally buried in the German Reformed Graveyard on the northwest corner of the intersection of North Bentz and West Second streets. I purposely didn’t say “former graveyard,” as many of the Sinn’s Reformed brethren (nearly 300) are still buried at the familiar site we know as Memorial Park. Decedents still lie underneath the various monuments dedicated to local residents who participated in 20th century wars. I guess you could say that the Sinns were reinterred to the “greener pastures” of Mount Olivet and Area M/Lot 27 on April 21st, 1910. That also seems like a date more fitting of having such a colorful array of ground cover than February 10th. Our records show that the Thomas P. Rice undertaking business of town performed the honors. A son of Phillip Henry Sinn and wife Mary Elizabeth (Lare), Jacob Sinn was born on May 8th, 1813. He had a career as a cabinet-maker and served as a member of the Order of Odd Fellows fraternal organization. He also was the Sexton of Frederick’s German Reformed Church, a position that entailed the holder to look after the church and churchyard, sometimes acting as bell-ringer and formerly as a gravedigger as a common description cites. Speaking of gravedigging, Mr. Sinn would be the recipient of two. The first came when our subject died on January 14th, 1860 and was spared having to witness the carnage of the American Civil War, some of which is laid out in a long row just a few yards to the south as I explained earlier. As for Permelia, her name alone deserves some exploration. Do you know anyone having this moniker? It is of Greek origin and translates to “all sweetness.” A variant form of this name found today is Pamela. Other records associated with Frederick’s German Reformed Church also show this woman’s name as Emily Ann. Regardless, our records say that Permelia was the daughter of James Cole and a mother with the maiden name of McNally. All I can tell you about this woman is that she passed on July 3rd, 1885 from congestion of the lungs. Next to the Sinns (buried in grave spots #8 and 9), one will find a dwarf stone that simply reads Alice R. Derr as it pokes above the green, green grass. She was the wife of Charles E. Derr and died on February 5th, 1911 at the age of 64. She is thought to be a native of Emmitsburg, the daughter of residents Thomas Fraley and Mary Rodenger (or Rodenhiser). Just three gravestones (and one that doesn’t belong here) upon a beautiful emerald tablecloth. But what of the other nine souls buried below? Here are their names and vitals: Space 1 Clifton H. Myers (1884-1908) Space 2 Florence (Winchell) King (1873-1908) Space 3 Daniel Heiser (1828-1908) Space 4 Six-month- old Infant of the William and Annie (Haller) Murphy (1909) Space 5 Peter Swintzell (1850-1909) Space 6 Hattie A. Moore (1854-1909) Space 7 Elizabeth Tucker (1839-1909) Space 8 Jacob C. Sinn (1830-1860) Space 9 Permelia F. Sinn (1820-1885) Space 10 Alice R. Derr (1847-1911) Space 11 William J. McGuire (1876-1911) Space 12 Joseph Linton (1871-1911) Some of these folks were just people who worked low-paying jobs and simply did not have money for a burial plot, let alone the opportunity to place a custom grave monument above. Clifton Myers was a painter, Peter Swintzell a junk dealer (in our records he is also called a “rag man”), and Joseph Linton was a laborer. Daniel Heiser was a stone mason, so one would expect him to at least have thought ahead about a tombstone, or wouldn’t his employer or co-workers have stepped in? Unmarried Elizabeth Tucker appears to have died at age 70 of tuberculosis. Hattie A. Moore was a nurse at the Frederick City Hospital and from Poughkeepsie, NY. I would assume the hospital would have taken care of one of their own, especially so far from home. I took special note with the information in our database surrounding the violent deaths of the two remaining individuals here in Area M/Lot 27, both in unmarked graves for well over a century plus a decade— William J. McGuire and Florence W. King. William J. McGuire was a casualty of the ill-fated “Ides of March,” dying March 15th, 1911. The 55-year-old was killed as a result of being struck by a train at the industrial village Lime Kiln, located along the Buckeystown Pike, south of Frederick. Sadly, McGuire’s supposed relatives from Detroit never responded. A trial of inquest was held and found that the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad was at fault. You would think at the very least that the railroad would provide some sort of marker for the man they literally, and figuratively, put in the grave. Florence (Winchell) King has a complex story which culminated in her being the unfortunate victim of a deadly lovers quarrel in York, Pennsylvania on March 14th, 1908 ("Ides of March" Eve). Apparently, Mrs. King had expressed during life that she desired to be buried in Mount Olivet. Sadly, she received her wish too early, as she was only 35 years of age. As for Mrs. King’s murderer, he is buried in Area M/Lot 5, but more on him in our next “Story in Stone"" I found it interesting that Mrs. King’s widower, Rufus King (1876-1936), is buried in a plot in Mount Olivet’s Area U/Lot 22 with Florence’s brother, William Winchell, and sister-in-law, Ida May Winchell. I had to smile thinking while he had a small, modest marker, the grass atop his grave is nothing like that of Florence’s grave. Sadly, for each of the 12 individuals in this lot, the grass was certainly “greener” elsewhere from where they once stood (or laid) on their respective last days in each personal circumstance—some more than others. Take note of what you have today, and be thankful for it.

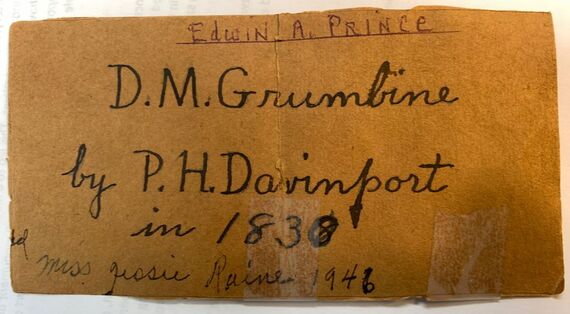

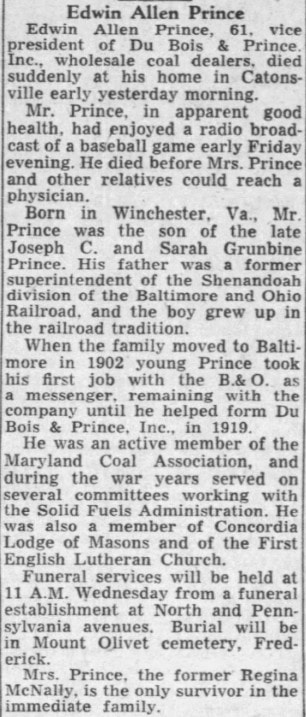

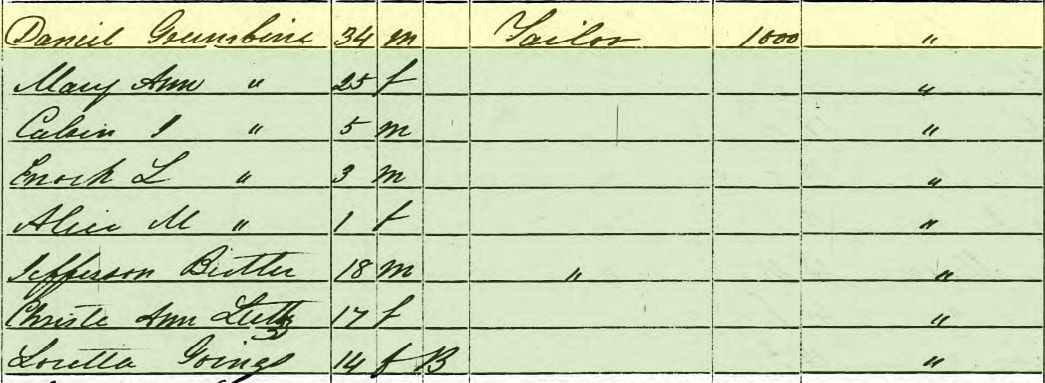

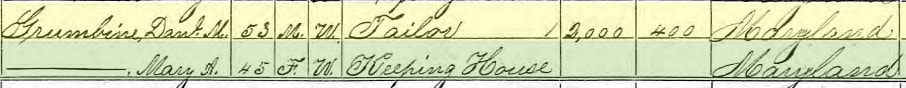

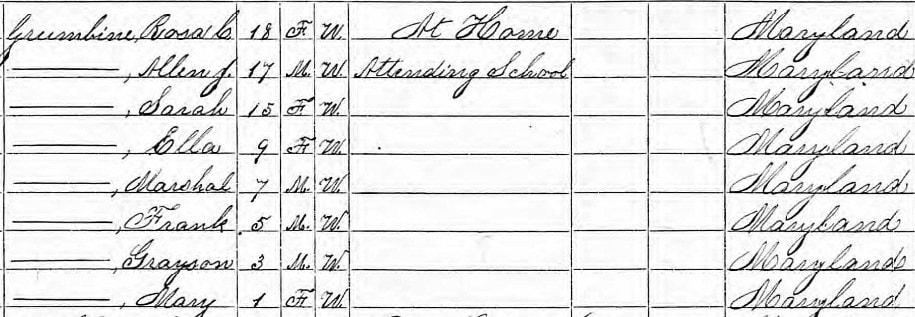

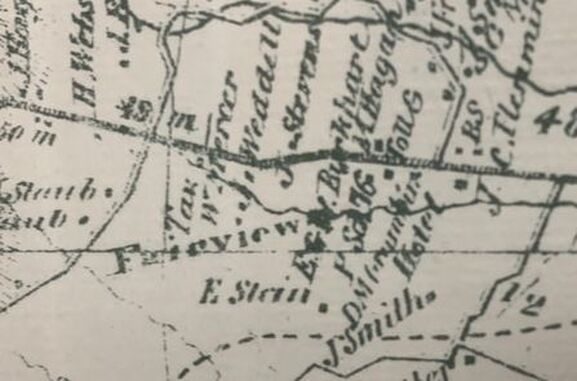

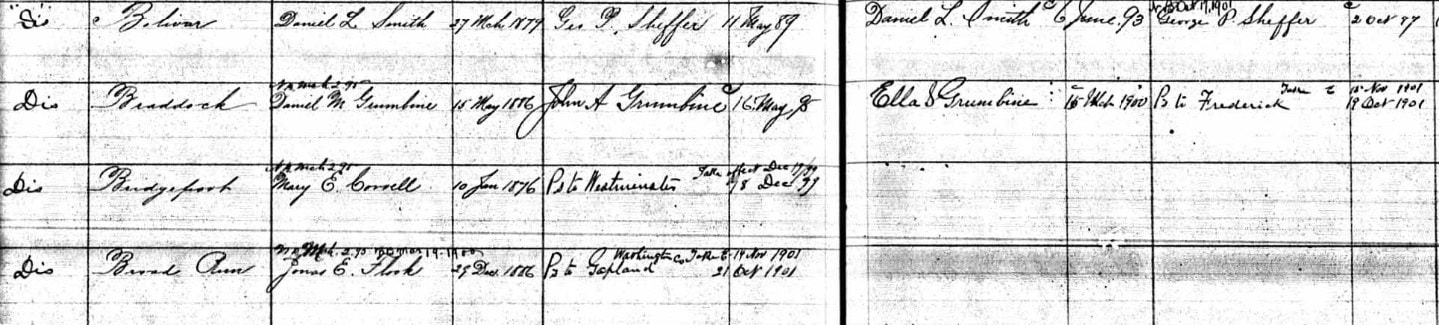

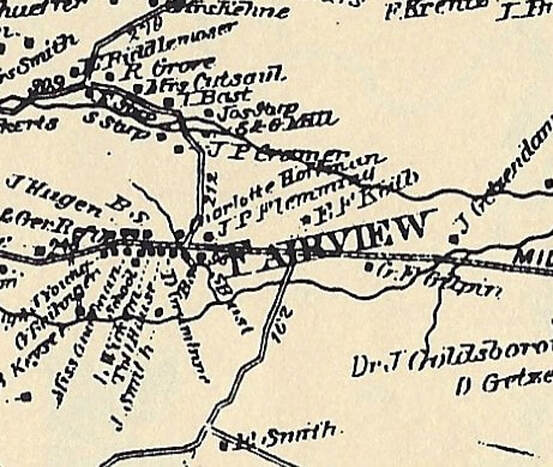

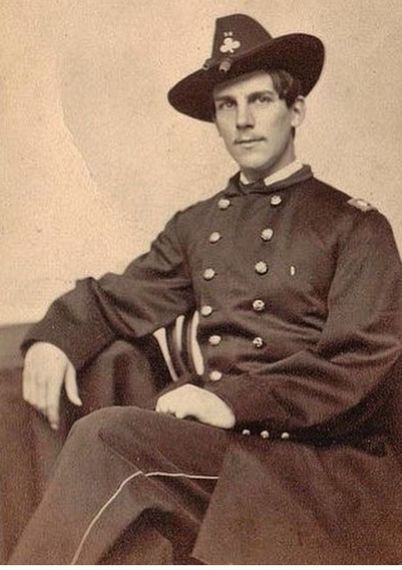

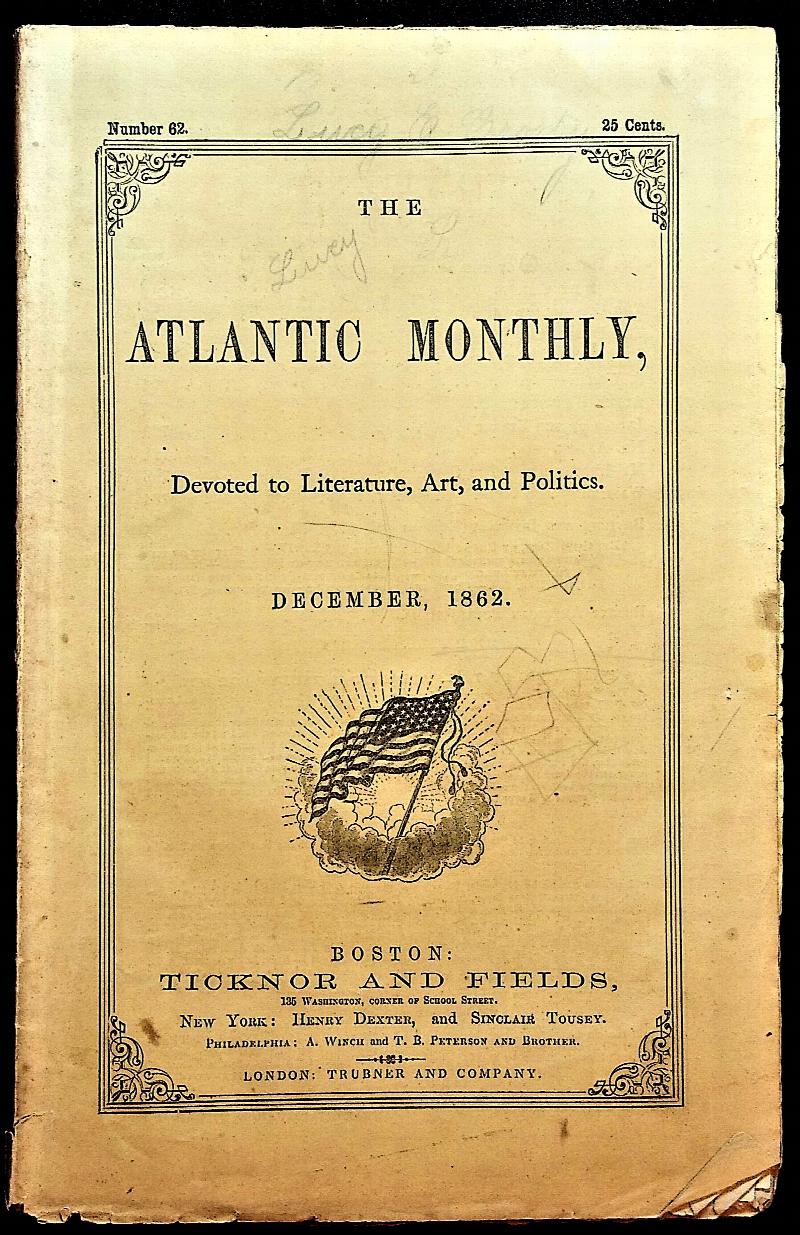

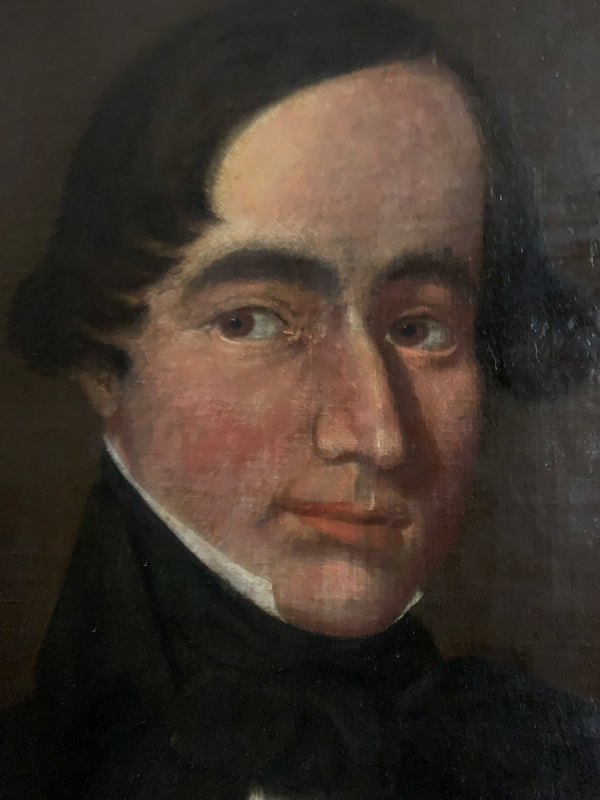

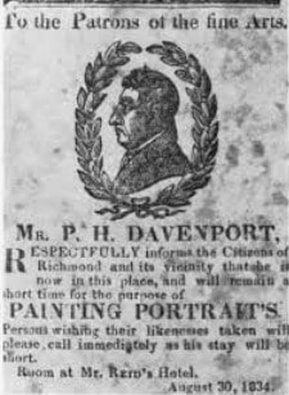

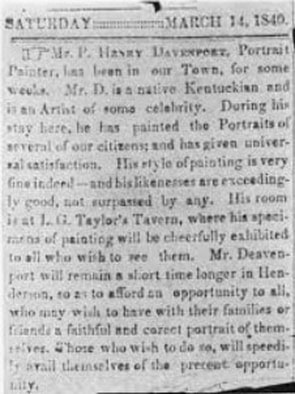

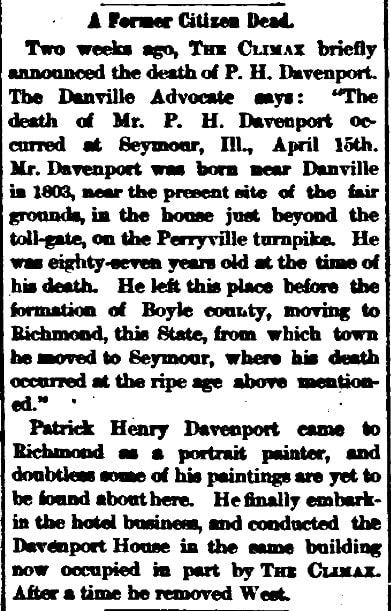

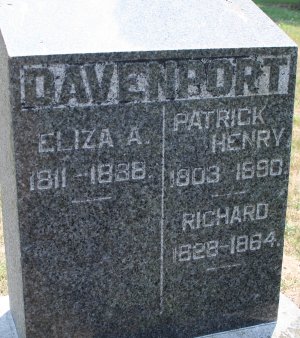

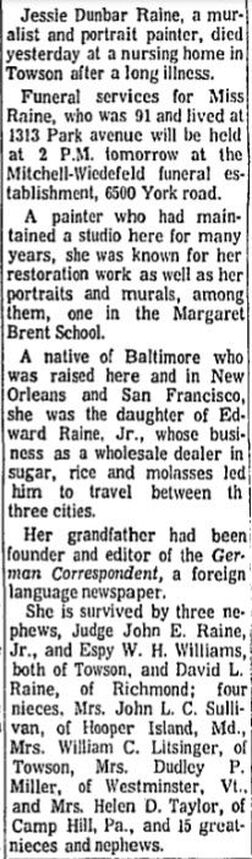

While everything is brown and drab elsewhere around the cemetery and Frederick community, these “strangers” deserve to have the most stunning/vibrant grass in town on this random February day. “Grandpa Snazzy,” there you are—up on my wall, Keeping tabs on this historian named Chris Haugh. Are you staring in judgment—is that what you do? Oft’ thinking in jest, "I look so much more dapper than you?” Well, I’m sure that is not the case. You have been very respectful, and equally quiet. However, the expression on your face never changes, and that’s a little bit strange. Sometimes, I forget your near—but you are always there in all your steadfast glory. What’s your story? And more so, how did you get to be on my wall? Who made this likeness of you, and when? What’s your connection, if any, to Frederick, and our beautiful “garden cemetery?” These are some of the random questions I wish could be answered by the gentleman being referring to here. He cannot answer for good reason, as a matter of fact, two primary reasons. First, he’s been dead for over 127 years, and second, oil paintings cannot speak—or can they? A few years back, I received a phone call from Mary Ellen Marsalek of Ellicott City. Ms. Marsalek, a former banking professional, explained that she and her husband (Dennis) were in the process of downsizing and planning to move out of state. Mary Ellen possessed a unique, and mysterious, family heirloom that she had no real attachment to, but it had been a familiar fixture throughout her life. It was now time to part ways, and she thought it might best come to us here at Mount Olivet. This is where “Grandpa Snazzy” enters the story. In 1993, the Marsaleks bought Mary Ellen’s family home in Ellicott City from her mom and dad. “Grandpa Snazzy” came with the house, as he had been hanging in the living room for decades. Mary Ellen’s father, Hugh Royal Williams, Jr., died July 6th, 2013. He had inherited the portrait in question in 1968 upon the passing of his aunt, Alice Regina Prince. Mrs. Prince was married to Edwin S. “Eddie” Prince (1889-1950), a grandson of the man in the portrait. Both Alice Regina and Eddie are buried in Mount Olivet’s Area G/Lot 189. Mary Ellen’s great Aunt Regina, also known as “Aunt Geege,” is responsible for providing the moniker of “Grandpa Snazzy” to her husband’s family heirloom. Mary Ellen told me that the portrait was a focal point in the formal living room of her childhood home for many, many years. Not a big genealogy fan, Mrs. Marsalek was relatively unaware of Grandpa Snazzy’s past, as he was simply a distant relative through marriage. Regardless, she decided not to break with tradition and left our subject hanging on the living room wall witnessing countless holiday and special gatherings over the years. One thing is certain, he was always “dressed for the occasion” with his stylish appearance. A small piece of brown backing paper accompanying the painting reveals the subject’s name of D. M. Grumbine. Not much else was known, but it was common knowledge that he was buried in Mount Olivet in Frederick. That same brown backing paper gave the assumed artist’s name as P. H. Davinport, and the year 1838. No one is certain when this information was written in ancient ink pen, but, interestingly it appears that someone attempted to draw a zero around the “8” in 1838, signifying that the portrait was produced in 1830. As I conducted my research, I trust the original 1838 date, and not the attempted revision. A final line at the bottom is written with a distinctively different pen and includes the name Miss Jessie Raine 1946, who may have been the responsible party for the edit. The fore-mentioned name of Edwin A. Prince is written in purple ink, and is certainly a more modern addition to the small parchment title plate. I now used this simple piece of surviving paper as my makeshift “Rosetta Stone” for attempting to learn more about my dapper, yet humble, officemate—"Grandpa Snazzy.” It was now time to “connect the dots." To review, Mary Ellen’s father’s aunt, Alice Regina (McNally) Prince (1895-1967) of Baltimore was married to Edwin Allan Prince (b. June 18th, 1889). Mr. Prince is our pivot point, as grandson of D. M. Grumbine, aka “Grandpa Snazzy.” Eddie Prince was the son of Thomas Cole Prince (1846-1904) and wife, Sarah “Sallie” Jenette (Grumbine). You guessed it, Sarah was the daughter of D. M. Grumbine. She was born on May 26th, 1855 and died on November 5th, 1941. The Princes are buried in Mount Olivet’s Area G/Lot 189 in the same lot with son, Edwin and Regina. As a matter of fact, mother and son (along with respective spouses) share the same exact gravestone, with names on opposing sides. I couldn’t find a great deal about Sarah (Grumbine) Prince, but her husband held an important position with the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad as evidenced by his obituary. As for son Eddie, he began his working days with the railroad, influenced by his father, and later had a sales career in the coal industry. Mr. Prince died suddenly at his home in Catonsville on October 1st, 1950.  From our database, I learned that Sarah J. Prince, was the daughter of Daniel M. Grumbine and wife Mary Ann R. (Schaefer). I now had a first name and a spouse to go with my mystery man. Sarah was the caretaker of our heirloom portrait, and passed it on to her only son Edwin. Going back in the census records, I began to see a bit more unfold on the Prince and Marsalek family’s “Grandpa Snazzy.” I got the whole picture thanks to a biography/family history sketch of Jacob Allen Grumbine, one of Daniel M. Grumbine’s sons. This important family history review can be found in T.J.C. Williams’ History of Frederick County (Volume II). This book was published in 1910, years after Daniel’s death, but was a Godsend like so many other family histories found in this work. The biography states that Daniel was born on May 15th, 1815, a fact that corresponds to our cemetery records. I learned, however, that his place of birth was Hanover, Pennsylvania. Daniel was the son of Jacob and Margaret Grumbine. Jacob emigrated from the Palatinate area of Germany as a young man and settled in York County, PA where he was engaged in the manufacture of jacks for heavy lifting. He eventually removed to Frederick City where he is said to have started in business “on the site of the present Frederick and Middletown Electric Railroad carbarn.” This site was located on the east side of Carroll Street, north of Carroll Creek. Our subject, Daniel M., apparently had the advantage of a private school education and grew up in the Lutheran religion. He learned the trade of a tailor, and upon the completion of his apprenticeship engaged in the merchant tailoring business in Frederick City in what had once been known as the old Woodward building (of Milton Woodward) eventually owned by C. Thomas Kemp. The biographical sketch says that Daniel occupied this site for a number of years and prospered. Daniel married Mary Ann R. Schaeffer, daughter of Jacob and Susan Schaeffer, on June 10th, 1841. The couple went on to have 11 children, many of whom are buried here in Mount Olivet. Grandpa Snazzy’s children included three buried in his own gravelot here in Mount Olivet, with two others nearby. (1.) Calvin J. Grumbine, (1843-1905) married Mary Burucker (2.) Alice V. Grumbine, the wife of Lewis Burucker, of Baltimore City. (3.) Enoch L. Grumbine, (1847-1924) lived in Baltimore, MD (buried in lot with parents) (4.) Rose C. Grumbine, (1851-1925) lived at Braddock (buried in lot with parents) (5.) Jacob Allen Grumbine (1853-1928) (buried in lot with parents) (6.) Sarah J. Grumbine, (1855-1941) married Thomas C. Prince, of Baltimore (MOC Area G/Lot 189) (7.) Marshal S. Grumbine (1863-1948) of Frederick and buried in MOC’s Area L/Lot 17 (8.) Charles F. Grumbine, (1865-1947) removed to Cleburne TX and buried in Clarksburg, WV (9.) Daniel G. Grumbine, a resident of Baltimore. (10.) Mary M. Grumbine, who is the wife of James McFarland, of Baltimore. (11.) Ella N. Grumbine, married Charles Kehn, of Buckeytown. Williams’ History of Frederick County offers the following passage on Daniel M. Grumbine: “Owing to ill health, he was compelled to remove to the country. He bought a small truck farm from Mr. Schaeffer about three miles west of Frederick on the National pike, at Fairview, now called Braddock. The present owner (in 1910) of this property in J. Allen Grumbine. In 1845, Mr. Daniel Grumbine was appointed gatekeeper by the National Turnpike Company at Braddock, and served in that capacity until his death, May 1st, 1895. When he died , he was one of the oldest employees of the company, having been fifty years in the service.” I found Daniel in the 1850 US Census and found his home in the 1858 Isaac Bond Atlas and the 1873 C. O. Titus Atlas along the National Pike just west of the intersection with today’s Blentlinger Road. In addition to his job of controlling the tollgate, Daniel Grumbine was also appointed a postmaster for the original “Braddock” in the 1880s. As an aside, Mr. Grumbine was a member of the Mason’s Columbia Lodge during his lifetime, and today that same fraternal organization is headquartered on Blentlinger Road, just a short distance away from his one-time home. Our subject died in the spring of 1895 as mentioned earlier. He would be laid to rest in Mount Olivet’s Area H/Lot 354, and is surrounded by the graves of his wife, three children (Jacob, Enoch and Rose) and seven grandchildren. Confederate Row provides a dramatic backdrop looking west, but making it even more picturesque and worthy of a portrait, is the rising Catoctin Mountain which served as Mr. Grumbine’s home for half a century. Daniel M. Grumbine’s life was lengthy, especially for a man of his times. I think about his experiences as a civilian during the American Civil War, and eye-witnessing cavalry and troop movements, both Union and Confederate, ascending and descending Braddock Heights in much the same fashion the locale’s namesake general (Edward Braddock) did over a century earlier. I wonder if “Grandpa Snazzy” encountered the father of famed American jurist Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. who, in 1862, wrote the book, My Hunt After the Captain? Captain Holmes, a Union officer with the 20th Massachusetts Regiment, had been wounded at the Battle of Antietam and went missing, at least to his family. This prompted a father’s desperate search for his son, and gave rise for the following quote from Oliver Wendall Holmes, Sr. as he gazed upon Frederick for the first time from the vantage point of Daniel Grumbine’s neighborhood: "In approaching Frederick, the singular beauty of its clustered spires struck me very much, so that I was not surprised to find 'Fair View' laid down at this point on a railroad map. I wish some wandering photographer would take a picture of the place, a stereoscopic one, if possible, to show how gracefully, how charmingly, its group of steeples nestles among the Maryland hills. 'The town has a poetical look from a distance, as if seers and dreamers might dwell there." Various writers over the past 150 years have theorized that Holmes's use of the phrase "clustered spires" was the inspiration for John Greenleaf Whittier's opening lines in his 1863 poem "Barbara Fritchie," This was published shortly after Holmes's account initially appeared in the Atlantic Monthly in December 1862. Whittier’s poem was written nine months later and appeared in the same magazine in print in October, 1863. Here's where I see two more interesting connections based on the location of Fairview. The real-life Barbara Fritchie is said to have lived here in close proximity to the toll gate in the early 1800s before moving to her famed home along Carroll Creek in Frederick City. Secondly, it is a pity that we don’t have a photograph or painted portrait of Frederick with its “clustered spires” from this vantage point at the time of the mid 19th century as Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. had wished. Keeping with our art theme for this story, noted Frederick painter Helen Smith (1894-1997) lived in the former home of the Fritchies at Fairview, and gave us plenty of “fair” views of Frederick from this locale. More so, I have a portrait of a Fairview resident in my office, but no view of Fairview, or of Frederick, dating from the 1800s. As I repeatedly say on this blog, it is so valuable to have images of those folks here at Mount Olivet, resting under our countless stones and monuments. This is quite a treat to have this gentleman as well. What an interesting life, as he encountered so many others in his work professions as a tailor and turnpike keep. Daniel Grumbine would also see many changes in our country and technology, especially in respect to transportation. More fitting, he experienced numerous trends and shifts in clothing fashion, and this is what he is famous for with that hip nickname of his. It almost makes one ponder how “Grandpa Snazzy” was dressed for his funeral service on May 4th, 1895, three days after his initial death? Well, maybe few, if any, would actually ponder that question. Speaking of pictures and portraits, that brings my curiousity back to the man truly responsible for this “Story in Stone”--artist P. H. Davinport (1803-1890). I found his biography online, published by the Kentucky Historical Society: “Patrick Henry Davenport, who became a noted portrait painter from the 1820s into the last quarter of the 19th century, was born in Danville, Kentucky at the Indian Queen Tavern, which was operated by his parents. Later his father became a brigadier general in the War of 1812. The parents were committed to educational excellence, and the father was a trustee of Danville Academy which the children attended. Patrick began portrait painting in Kentucky on his own at age fifteen, and his art training was not formal, although he may have had some lessons from Matthew Jouett, Kentucky portrait painter. It has also been written that Asa Park, who did a portrait of one of Patrick's brothers, was also an inspiration. As a very young man, Davenport assisted Oliver Frazer in painting the full-length portrait of George Washington at the Old Capitol building in Frankfort. In 1827, he was married at Vicksburg, Mississippi, to Eliza Ann Bohannon, a native of Georgia, and they returned to Danville where they lived with Patrick's widowed mother. Subsequently they had eight children. By that time, his career was already successful because the year of his marriage he had a commission to paint the wife of Kentucky governor Isaac Shelby. To support his growing family, he was, until 1853, the popular proprietor of the fashionable Crab Orchard Springs spa, a fashionable watering place in Lincoln County, Kentucky. However, much of his activity was traveling around to small towns, doing portraits of prominent persons. He worked in Indiana from 1850 to 1870, and then moved to Lawrence County Illinois, near Evansville, where he and his wife purchased a 200 acre farm and lived there the remainder of his life. One of his biographers, Edna Whitley, believed that his work of that period showed declining skill in that it was more anatomically correct but lacking in emotional commitment. From that time, most of his sitters were residents of southern Illinois, many of them neighbors, and he did a number of child portraits. Patrick Davenport died at age 88 at Sumner, Illinois, and was active almost to the time of death. He signed his paintings in various ways: Henry Davenport, P. Henry Davenport, and P.H. Davenport.” Of course, I can add one more variation to that list—P. H. Davinport. I found the grave of our artist in southeastern Illinois in Sumner Cemetery located in the town of Sumner in Lawrence County, Illinois. I also took the opportunity to search for Miss Jessie Raine, the woman I mentioned earlier whose name was written on that brown paper that initially provided the names of the portrait subject (Mr. Grumbine), and its painter (Mr. Davenport). I quickly learned that Jessie Dunbar Raine (1888-1974) was not a relative of Edwin A. Prince and the Grumbines as I had imagined, but instead an artist herself. I found her as a resident of Baltimore living at 1313 Park Avenue in the mid 20th century. I now presume that Jessie was hired to restore the work done by P. H. Davenport over a century before. This was likely performed in 1946, as the reason for the date written at the bottom of the paper placard. I found Ms. Raine’s obituary in the Baltimore Sun, and her body was laid to rest in her family’s plot in Charm City’s Loudon Park Cemetery.  1970 edition of Dapper Dan by Playskool 1970 edition of Dapper Dan by Playskool Finally, I’d like to report that Mary Ellen and Dennis Marsalek are living in “Lower, Slower Delaware” these days, and enjoying their retirement in the same exact state where both my “grandpas” lived and are buried. I recall both these gentlemen, but lost them in my youth. I have to laugh recalling that also in my youth, I had one of those Dapper Dan dolls. My parents got me that in 1970. Who would of thought I’d have another “Dapper Dan” (Daniel Grumbine) on my wall all these years later? I just feeling fortunate to be the latest caretaker of this old National Pike gatekeeper of “Braddock Mountain”—but, I certainly won’t be the last. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed