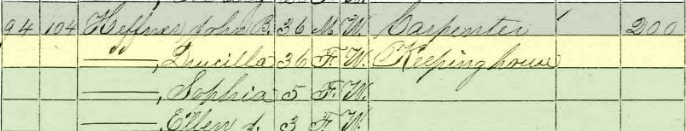

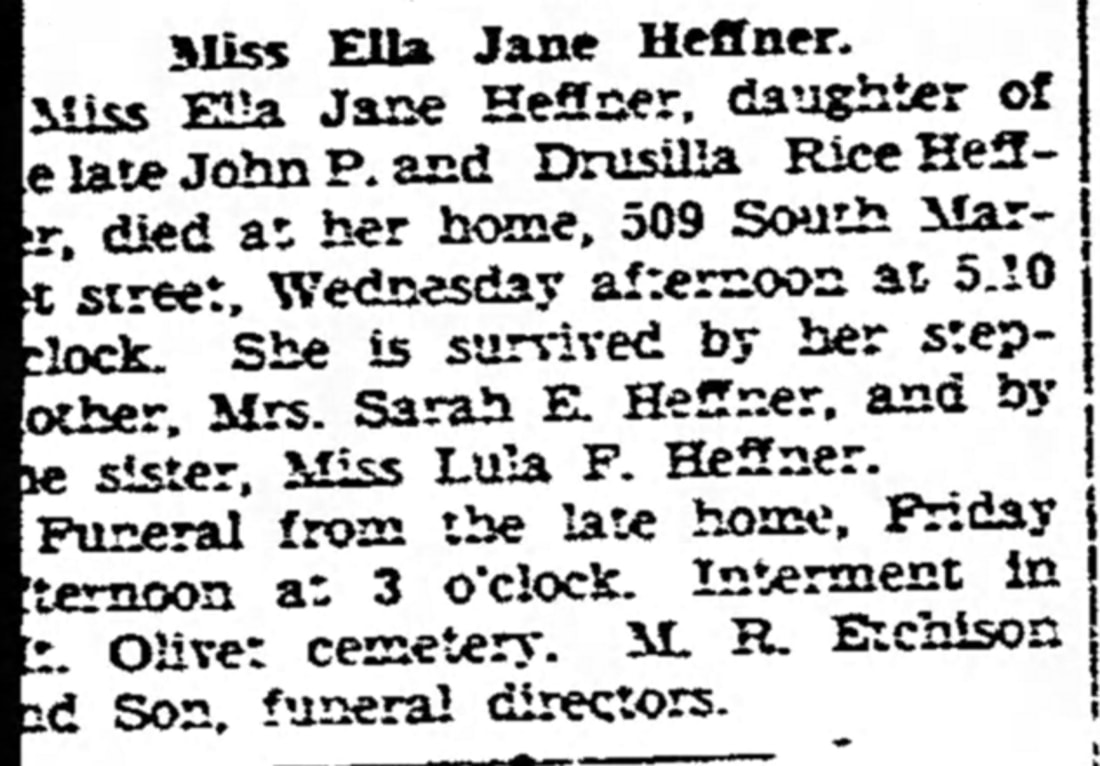

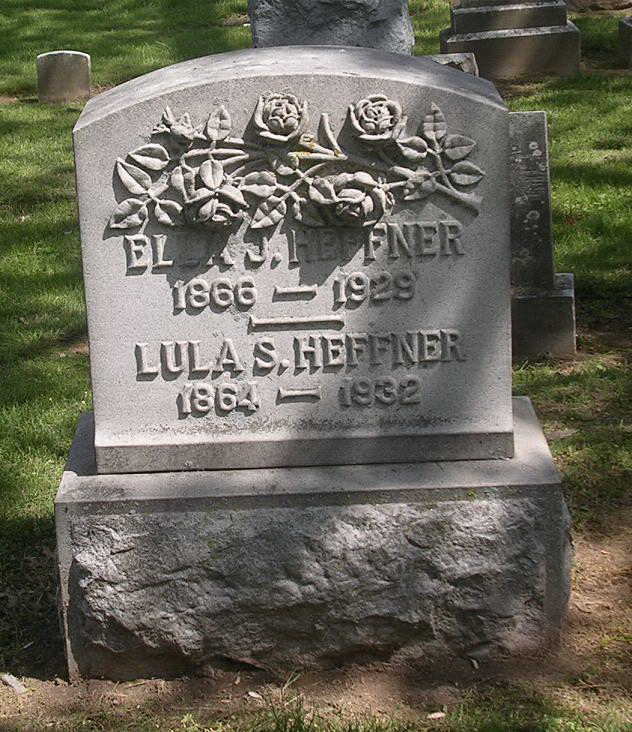

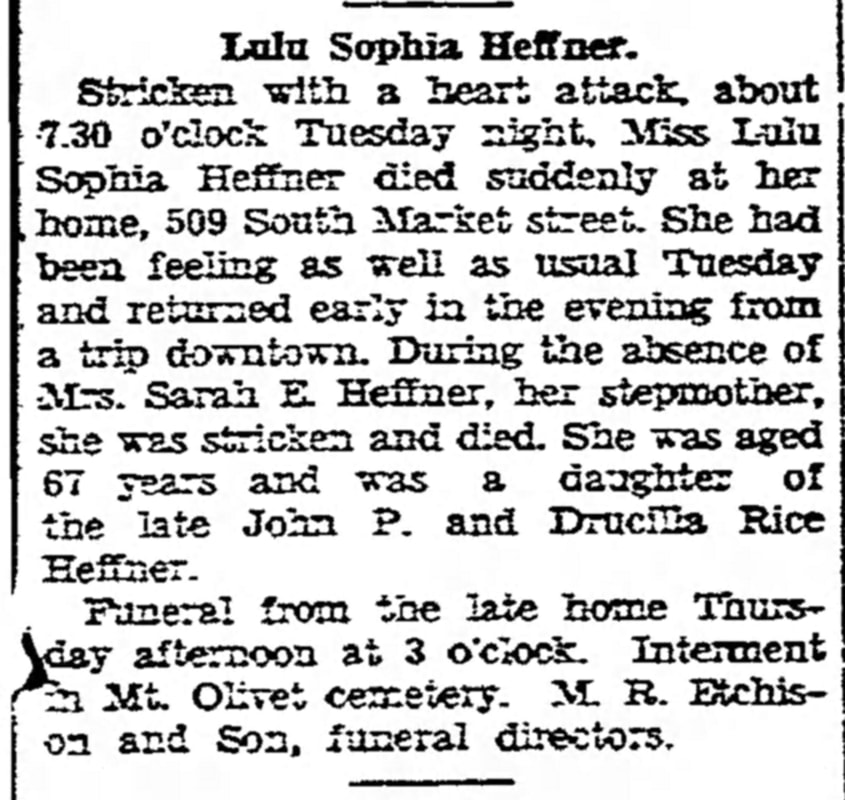

Grave of Howard J. Baker (1935-2001) in Area FSK Grave of Howard J. Baker (1935-2001) in Area FSK It’s no surprise to see flowers in a cemetery, especially a “garden cemetery” like Mount Olivet. Yes, graveside ceremonies are commonly marked with floral arrangements, and plenty more are placed during holidays such as Mothers Day and Fathers Day. Many stones are annually decorated “to the nines” by family members with beautiful care each spring, giving way to the artificial variety (of flowers) in cold weather months. And then there are the occasional flower pots and special plantings located next to specially endowed lots. Some of the most fascinating flowers of all in Mount Olivet actually appear on gravestones themselves, not just adjacent them. Symbols have been used for centuries, however common people could first employ statues and elaborate carvings of tombstones in the mid-nineteenth century. This was the time of Queen Victoria of England, hence giving rise to the moniker of the “Victorian Era,” an age best defined by peoples’ love of ornate designs. Gravestones were no exception, as stone carvers were often commissioned to produce small works of art. “Garden cemeteries” such as Frederick’s Mount Olivet became the local art gallery, so to speak, as everyday people got to view intricate carvings, majestic statues, and iconic shapes used to embellish grave markers.  Victorian-era funeral flowers Victorian-era funeral flowers People of the era were enamored with floral themes. Plants and flowers were held up to remind others of the beauty and brevity of life. Flowers have served as symbols of remembrance since the beginning of memorialization in cemeteries. The Victorians took great pains to offer special flower attributes, adapting many ancient myths to Christian symbolism. The Victorians thought flowers had their own language. Red roses signify love, yellow roses indicate friendship, and a white rose meant innocence, or secrecy. It’s no wonder they carried this silent language on to the grave.  Roses on a tombstone can have several meanings, depending on the number shown, and if the rose is in bud or bloom. A rose symbolizes love, hope and beauty. Two roses joined together signified a strong bond, as on a couple’s stone. A wreath of roses stands for beauty and virtue. Age could also be noted with a rose bud indicating the grave of a child. A partial bloom was used to show someone who had died in his or her teens or early adult life. And a full bloom signified someone in the prime of life. A broken blossom, whether a rose or another flower, indicated that someone had died too young. Another flower that is abundant in the cemetery is the lily, which reverberates innocence and purity. There are several various types of lilies used on gravestones, each with a slightly different meaning. The most popular is the Easter Lily, which represents resurrection and the innocence of the soul being restored at death. Calla Lilies represent marriage and fidelity. A Lily of the Valley signifies innocence, humility and renewal. The Fleur de Lis is actually a stylized lily that represents the Holy Trinity. The daffodil, also part of the lily family, indicates grace, beauty and a deep regard. Usually, live daffodils are abundant in older cemeteries during the spring. Other flowers used on gravestones include the daisy, which means gentleness and innocence, and the morning glory, which suggests mourning, mortality and farewell. Greenery is also used to convey unspoken thoughts. Many stones are covered in Ivy to imply faithfulness, undying affection and eternal life. The fern was very popular in Victorian times as an indicator of sincerity and solitude. And the palm, another plant associated with Easter, signified triumph over death, and a forthcoming resurrection. Several stones in Mount Olivet have flowers carved into their faces. I recently decided to take a stroll in the cemetery’s historic section, and see what I could find in reference to flowers. Here are three that I found to fulfill my quest, all maiden females who would never marry by choice, accident or God’s will. I have tried to find out as much as I can about each of these ladies to perhaps find some context to their floral themed grave monuments.  Of Rice and Roses Two maiden sisters reside in Mount Olivet’s Area C/Lot 69. Here is the floral engraved gravestone of 62-year-old Ella Jane Heffner (b. 12/15/1866) and 67-year-old Lulu Sophia Heffner (b. 10/12/1864). As for their stone, one can find what appears as three, fully blossomed roses on the monument’s face. Both women were the daughters of John P. Heffner (b. 1834) and Drucilla Rice (b. 1834), a couple who married here in Frederick during the height of the American Civil War in 1863. In the 1870 census, the young family could be found living just a few doors down from Mount Olivet at 109 S. Market St. The girls’ mother (Drucilla) died in 1873 at the age of 39, and Mr. Heffner remarried a woman named Sarah Miller Rice in 1879. The interesting thing about Sarah (b. 1849) is that she was also the girls’ maternal aunt, as she had married Levin Tyler R. Rice, Drucilla’s brother. Sadly, Levin died in early 1872, three years after his marriage to Sarah. She was left to raise a son, Walter Levin Rice (b. 1869). As was often done in those days, in-laws such as John P. Heffner and Sarah Miller Rice simply turned to each other for companionship as both had lost their respective spouses and had children in need of parenting. Lulu and Ella Mae were nine and seven respectively at the time of their mother’s death. Sarah helped raise them into adulthood, as John did the same for Walter Levin. The blended family would continue living in the home on S. Market St. John P. Heffner died in 1901, and the girls continued to live in their childhood home along with stepmother Sarah Miller Heffner. As was stated at the onset, the two girls would never marry. They remained by each other’s side for the duration of life. Ella Jane Heffner died on September 11th, 1929. Lulu would succumb on January 5th, 1932.

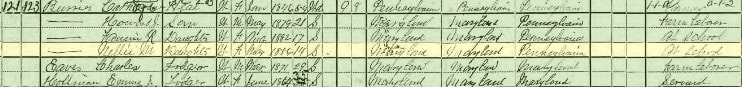

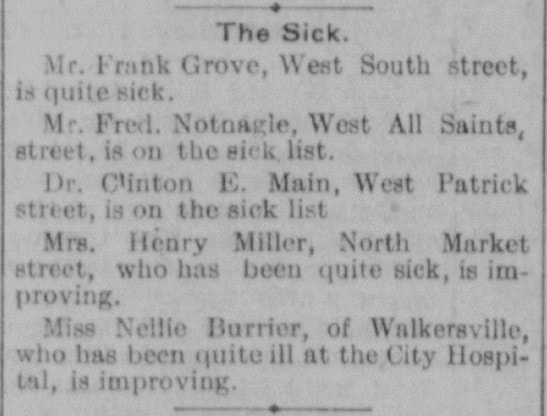

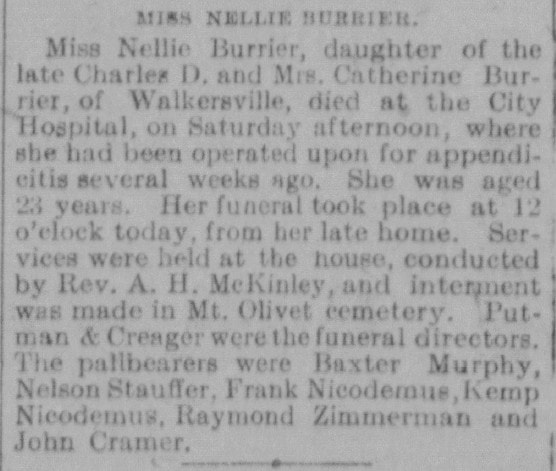

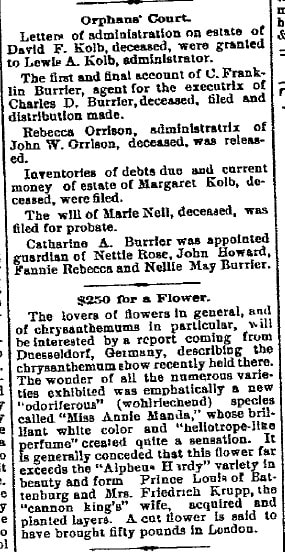

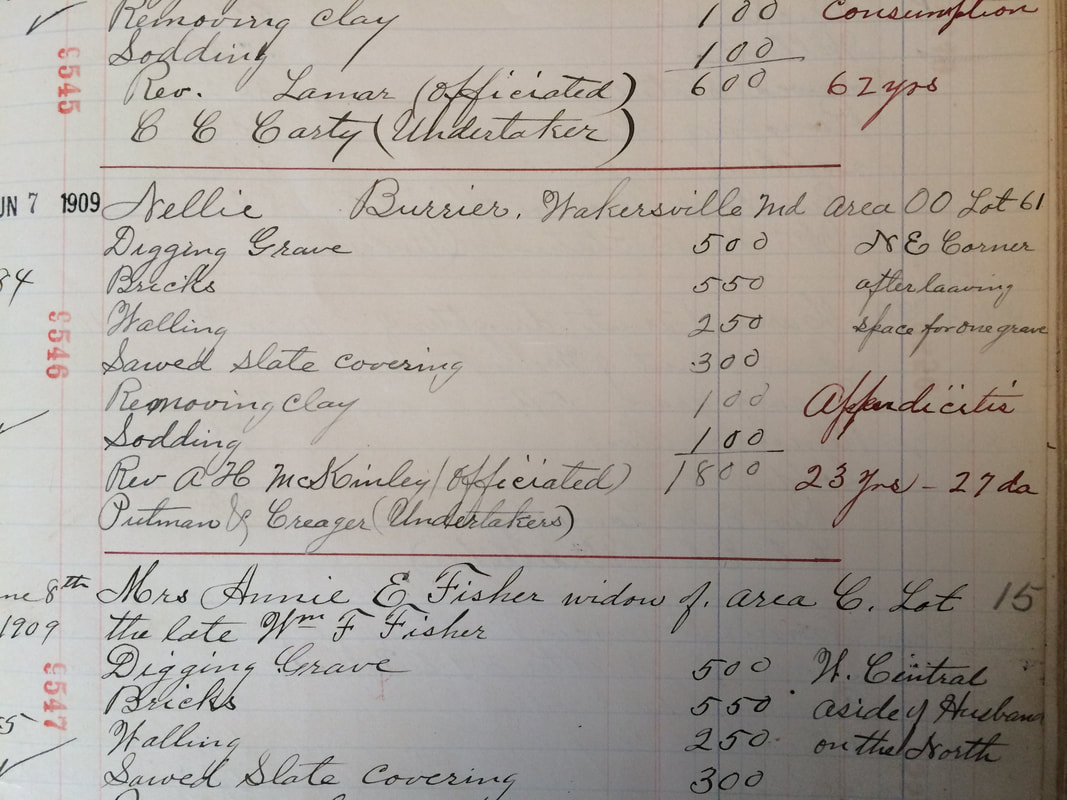

The Maiden of Mount Pleasant A few years ago, assistant cemetery superintendent Rick Reeder pointed out the beautiful grave monument belonging to one, Nellie Burrier. This can be found on Area OO/Lot 61, with a backdrop of Harry Grove Stadium. Miss Burrier was born on May 9th, 1886, the daughter of Charles D. Burrier (1841-1892) and wife Catherine Hoke Burrier (1846-1935). Catherine Hoke Burrier was the daughter of Samuel Hoke, who possessed a sizeable series of farmsteads in the vicinity of Ceresville, with a home dwelling across from the famed Ceresville Mill. Nellie was the youngest of eight siblings and raised on her family’s farm located in Mount Pleasant, just east of Ceresville and northeast of Frederick City. Just as the Hefner girls lost their biological mother as youngsters, Nellie’s father passed away when she was five.

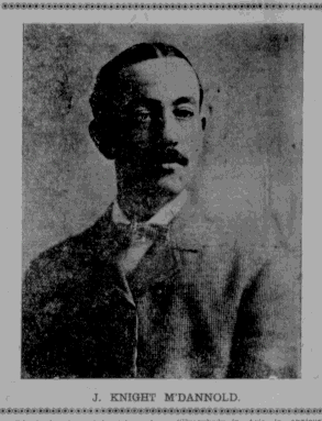

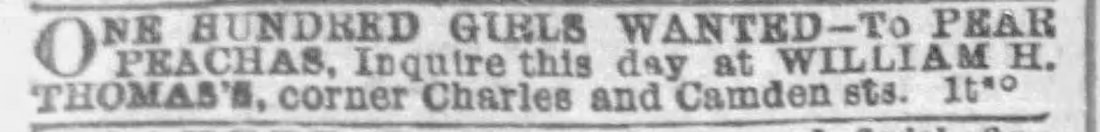

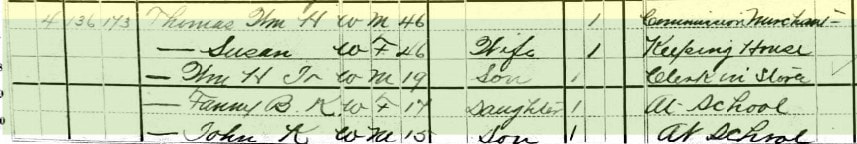

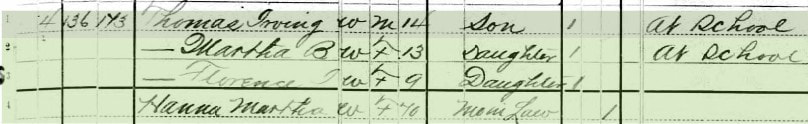

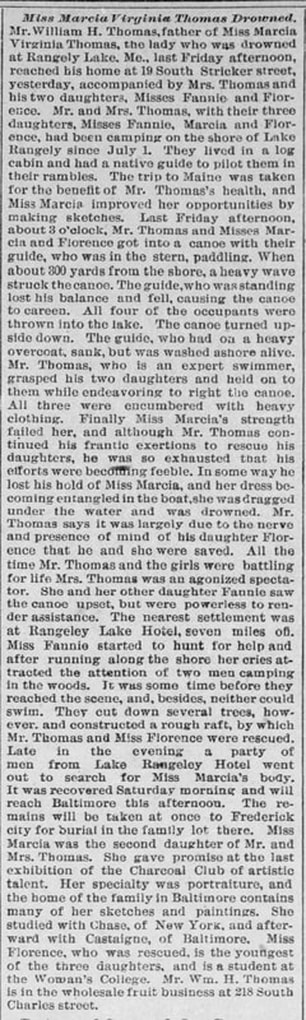

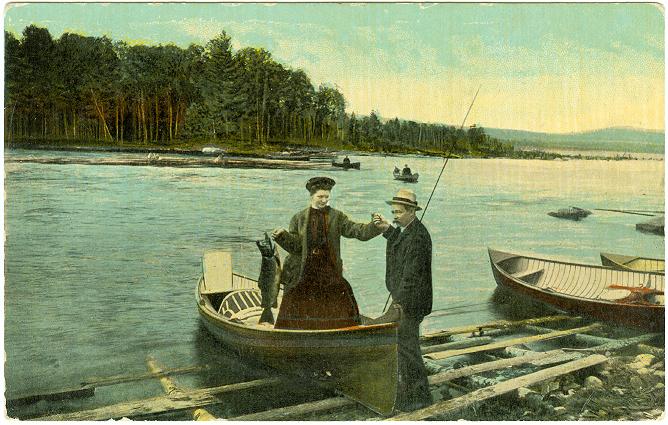

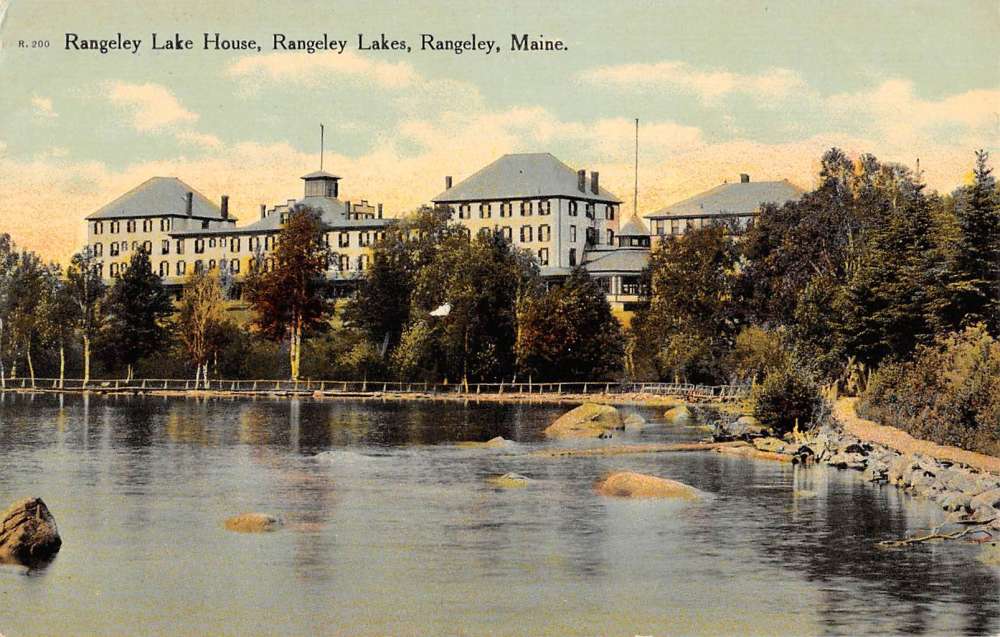

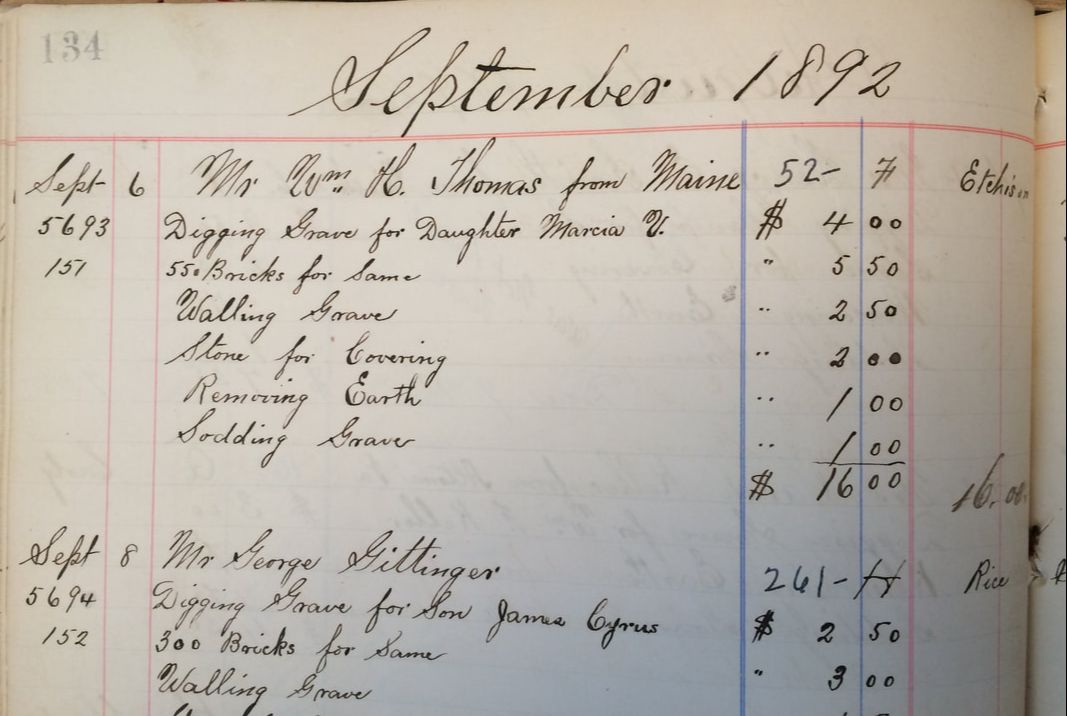

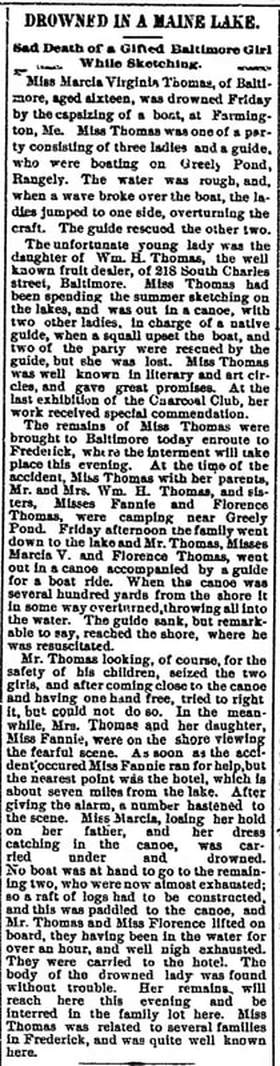

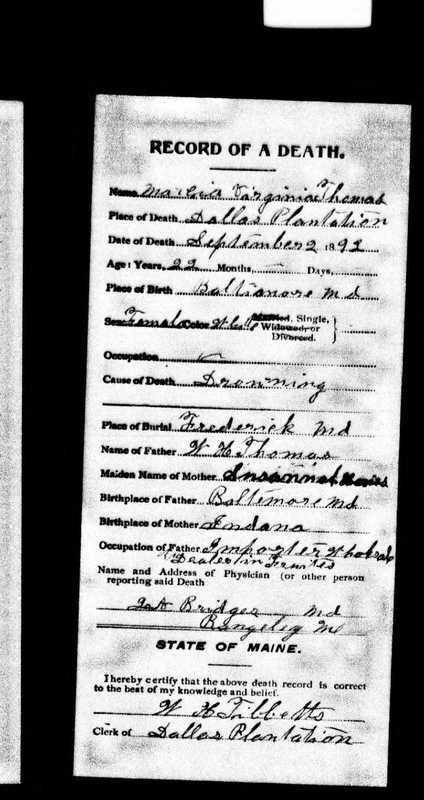

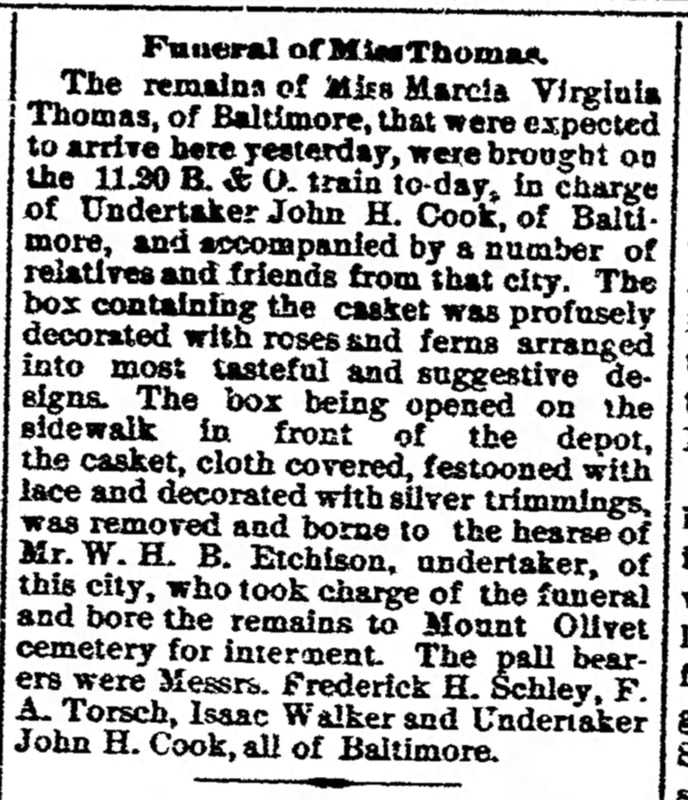

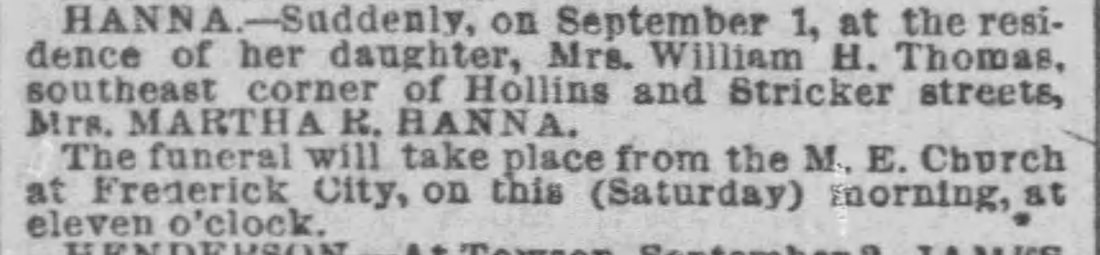

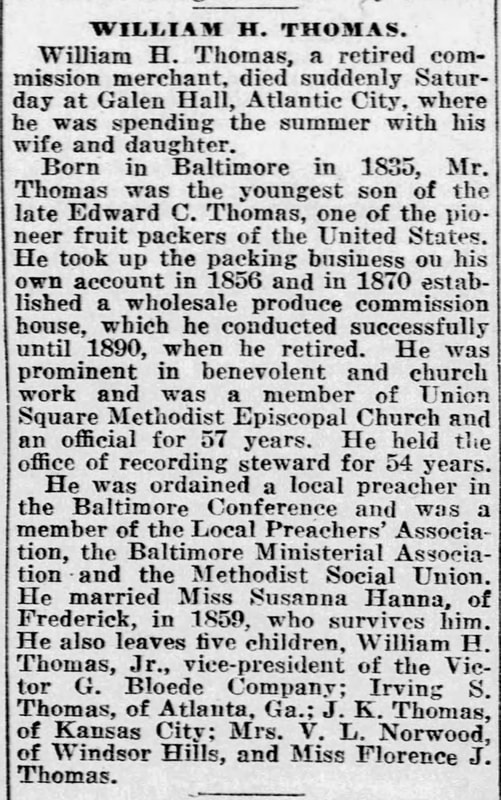

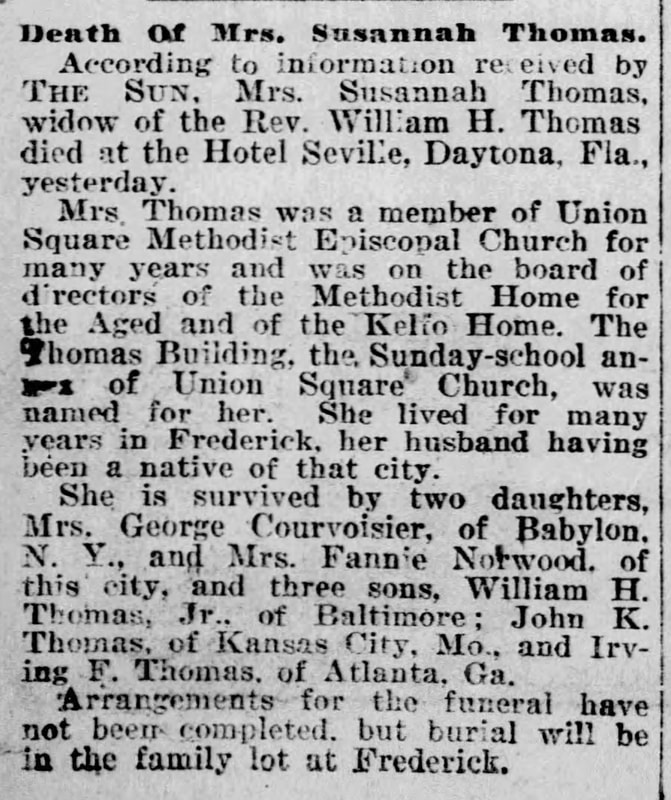

Marcia A mixture of different flowers rises from a sculptured scroll, unrolled, and perfectly balancing on a “half-column,” generally used to denote a life cut short. Indeed, this was the case of Marcia Virginia Thomas. The 22-year-old from Baltimore was innocently vacationing with her family at Rangeley Lakes, Maine in the summer of 1892. Mr. William Hamilton Thomas (1835-1917) had roots in Frederick, as did his wife, and had done very well for himself going into his father Edward C. Thomas’s oyster and fruit packing business, started several decades before in Charm City. Success and hard work did take a noted toll on Mr. Thomas’ health and well-being, however he would combat the unfortunate fate suffered by the Heffner sisters and Nellie Burrier by the family had embarked on this trip in hopes that health would be fully restored to Mr. Thomas, an escape from the hustle and bustle of work responsibilities and big-city living. The mountainous environs of northwestern Maine seemed to be “just what the doctor ordered.” Marcia’s family unit in 1892 consisted of two other sisters, Florence and Fannie, and mother Susannah Hanna Thomas (1835-1920). The Thomas’s were staying in a cabin adjacent Greeley Pond, and had the services of a local resident to serve as a guide for nature and social activities with the intended design of aiding the family enjoy their “rustic” stay. Marcia spent much of her stay improving her skills as a sketch artist. Unfortunately, this talent would be a contributing factor toward her early demise on the morning of Friday, September 2nd, 1892. A chilling account would appear in the Baltimore Sun the following Monday, September 5th. The Frederick News also carried the tragic story of Marcia’s death on Monday, September 5th. Also added was information pertaining to Marcia’s body arriving at the Frederick B & O Railroad Depot from Maine by way of Baltimore. The elaborate casket was brought to Mount Olivet, and a funeral service took place on Tuesday the 6th. Her gravesite is located in Area F/Lot 52.  In my research, I was very interested to find that Marcia Thomas’ maternal grandmother, Martha Ritchie (Knight) Hanna, had a direct link to one of my past “Story in Stone” entry written about young John Knight McDannold. She was McDannold’s maternal aunt, and a longtime resident of Frederick, although a native of Indiana. As for John Knight McDannold, he was a popular, 25-year-old socialite who had big plans for spending the winter of 1899 in Cuba. Unfortunately, John would succumb to pneumonia in February, 1899 while en-route to the Caribbean destination. His gravesite in Area F/Lot 53, is within ten feet of his Aunt Martha (who passed in 1887) and is marked by a Celtic cross made by the Tiffany’s Company of New York. It is highly likely that Marcia, herself, and the Thomas family attended John Knight McDannold’s funeral, heralded as one of the largest in the cemetery’s history up to that time. Marcia’s unique monument, not unlike that of cousin John’s, a few yards away are two of the finest in the cemetery. William H. Thomas died in late August, 1917, a few days shy of the 25th anniversary of Marcia’s drowning. He would be buried next to his mother-in-law and soon joined by his wife Susannah less than three years later in February, 1920. All three grave monuments include the same sculpted floral design. Expressionism “From my body, flowers shall grow and I am in them and that is eternity.” In closing, I leave you with the above quote from Norwegian Symbolist painter and printmaker Edvard Munch. He was an important figure in art history, best known for his 1893 oil painting entitled “The Scream.” Another one of Munch's highly acclaimed paintings titled The Sick Child is said to have helped inspire the Expressionistic art movement, a style of painting, in which the artist seeks to express emotional experience rather than impressions of the external world.  A fitting Munch considered The Sick Child, his first “soul painting,” a break from impressionism. “As for The Sick Child,” Munch wrote, “it was the period I think of as the age of the pillow.” Many artists did pictures of children on their pillows. Since hailed as the first expressionist masterpiece, the painting shows his sister Sophie, on her deathbed, turned toward a dejected figure nearby. The Sick Child portrays a dying adolescent, her physical and spiritual attractiveness heightened, as was believed, by her very illness. Therefore, beauty, joy, and life are valuable because they are transitory and eventually become their very opposites. Flowers are perfect representations of this concept as well—vibrant, colorful and beautiful today, but soon to be brown and withering. However, when flowers are depicted in sculpture on gravestones, these floral displays have eternal beauty, and will not fade—not unlike the happy memories and appearances we wish to remember about those who have gone before.

0 Comments

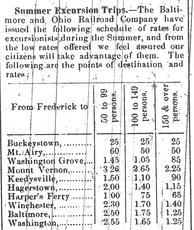

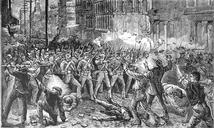

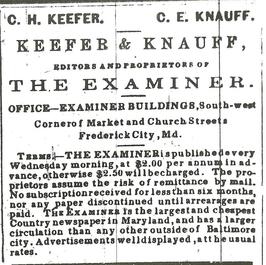

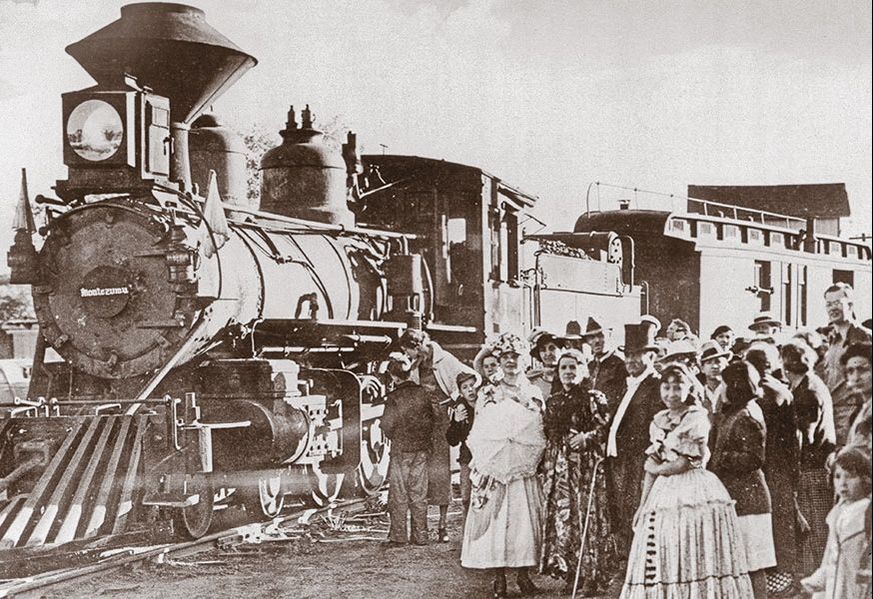

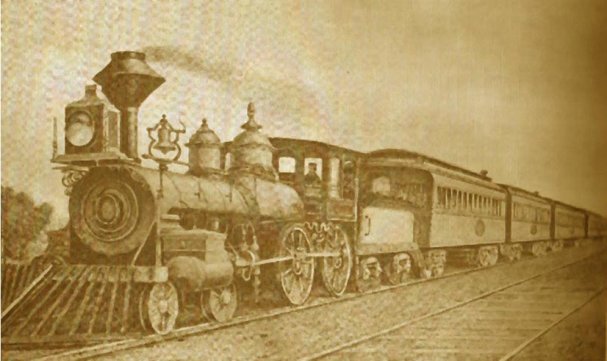

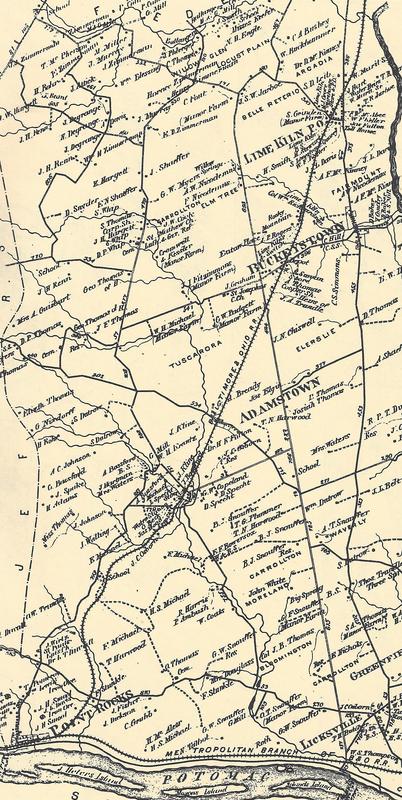

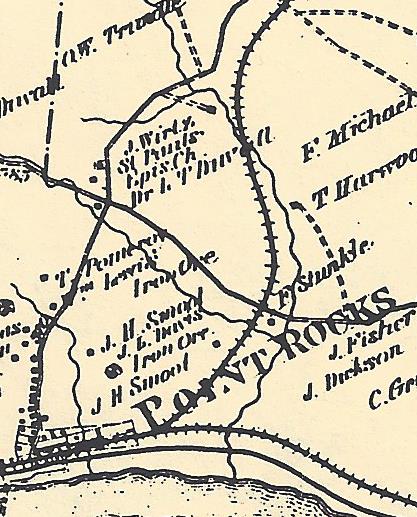

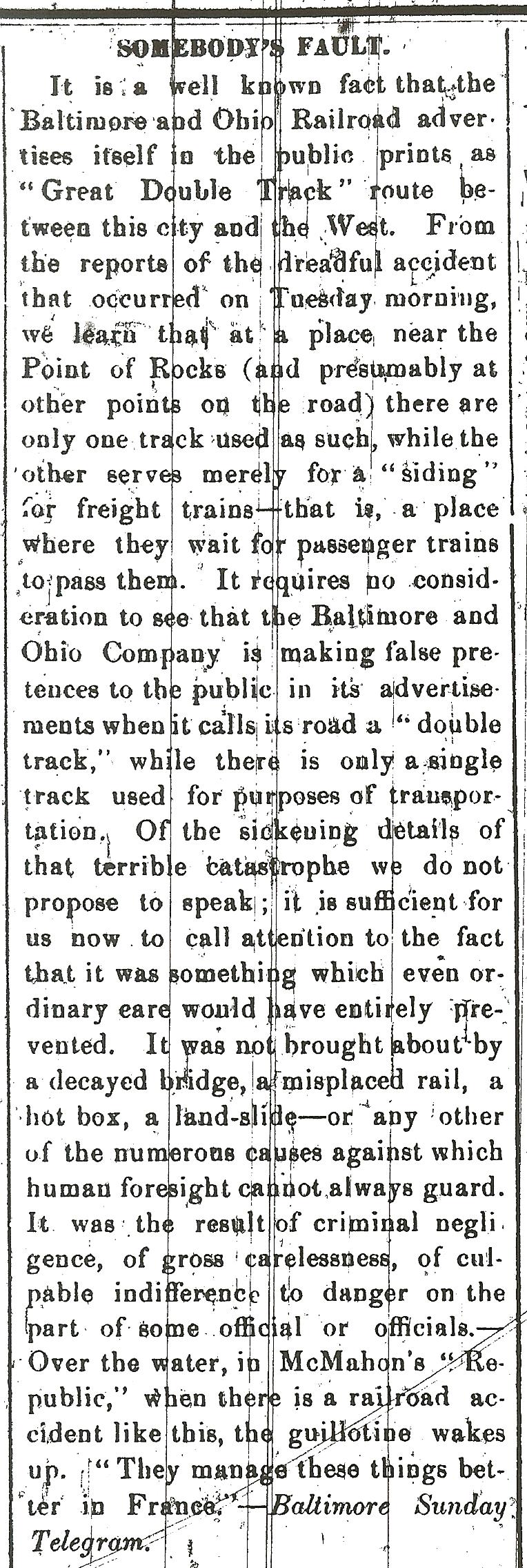

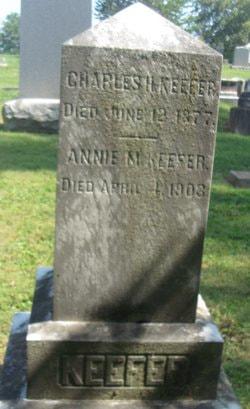

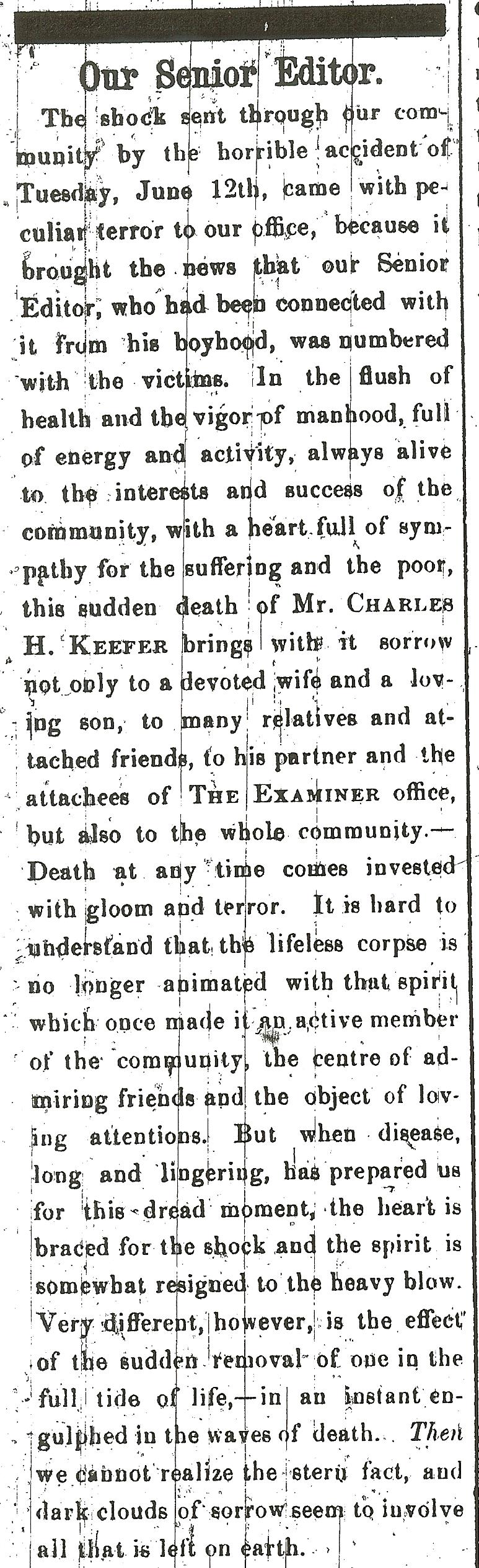

Examiner (June 6, 1877) Examiner (June 6, 1877) The June 6th, 1877 edition of the Frederick Examiner newspaper includes an advertisement announcing summertime railroad excursions provided by the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. Destinations naturally included Washington, DC and Baltimore but also included places such as Hagerstown and Winchester. Special jaunts for history enthusiasts included Harpers Ferry and George Washington’s Mount Vernon. The incentive here was to promote the daily treks with the incentive to attract large groups to ride the “iron horse”—the bigger the better, with patrons garnering a modest discount in fare. It’s often said that “the early bird gets the worm,” and this was certainly the case with the B&O’s excursions that particular summer. What nobody knew was the fact that the railroad would be coming to a screeching halt over a month later in mid-July. This was due to a work stoppage by employees coupled with violence, part of an unprecedented labor dispute centered at the railroad’s home base in Baltimore. This was preceded by one in nearby Martinsburg, West Virginia a few days before (July 14th, 1877). At that time, Martinsburg was the site of the B&O’s railroad “classification yard” which was used for switching cars to different lines. As an aside, the railroad would relocate its yard from Martinsburg to Brunswick in 1890.  The 6th Maryland Regiment quells rioters in Baltimore The 6th Maryland Regiment quells rioters in Baltimore The unfortunate activity at Baltimore and Martinsburg was clearly associated with the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, during which widespread civil unrest spread nationwide following the global depression and economic downturns of the mid-1870s. Strikes broke out along the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad on July 16th, the same day that 10% wage reductions for employees were scheduled. This was the third such salary cut employees had experienced within the year. Violence erupted in Baltimore on July 20th, with police and soldiers of the Maryland National Guard clashing with crowds of thousands gathered throughout the city. In response, President Rutherford B. Hayes ordered federal troops to Baltimore, local officials recruited 500 additional police, and two new National Guard regiments were formed. Peace would be restored on July 22nd, but not after a dozen people were killed, 150 injured, and many more arrested. Negotiations between strikers and the B&O were unsuccessful, and most strikers quit rather than return to work at the newly reduced wages. Thanks to an influx of immigrants readily at hand, the company easily found enough workers to replace the strikers, and under the protection of the military and police, traffic resumed on July 29th. The company promised minor concessions at the time, and eventually enacted select reforms later that year.  If Only… “If only” is an expression used just as much as “the early bird gets the worm.” In our context here, I’d like to bring in “the early bird” reference to say that those who acted before the rail strike got to experience the excursion opportunity and discounted fares. However, I have to come back to “if only,” as in “If only the B&O Strike would have happened just one month and a few days earlier.” Excursion fever was alive and well in Frederick, Maryland on Tuesday, the 12th of June as nearly 600 folks, from all over Frederick County, were heading to Mount Vernon. Among those assembled was a small delegation headed by Charles H. Keefer, publisher of the Frederick Examiner newspaper. Mr. Keefer was also serving as current secretary for the Frederick Agricultural Society, and chairman of a committee who were traveling to Washington for the sole purpose of delivering an invitation to President Hayes to attend the upcoming Great Frederick Fair scheduled for the upcoming October.

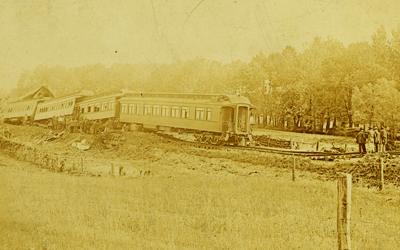

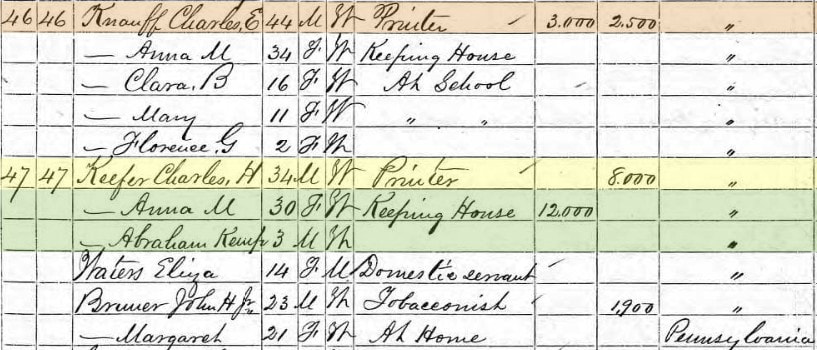

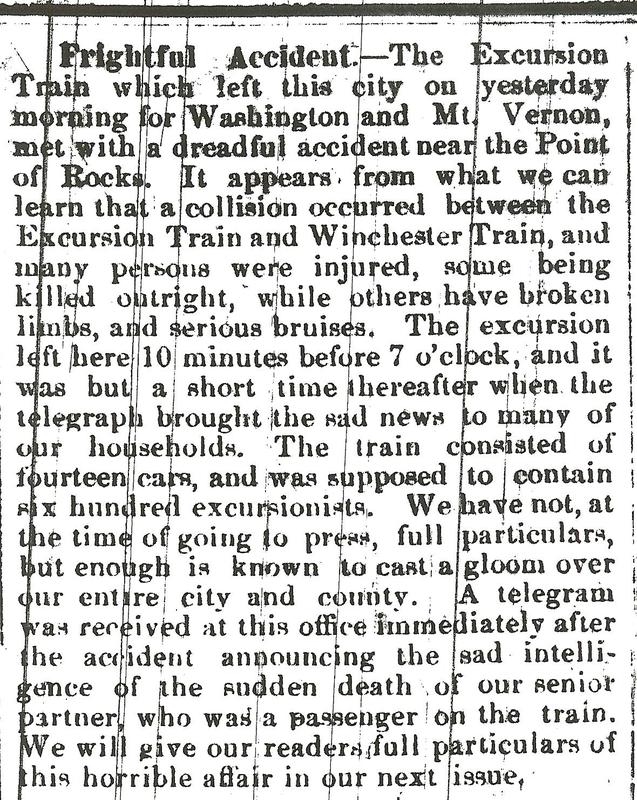

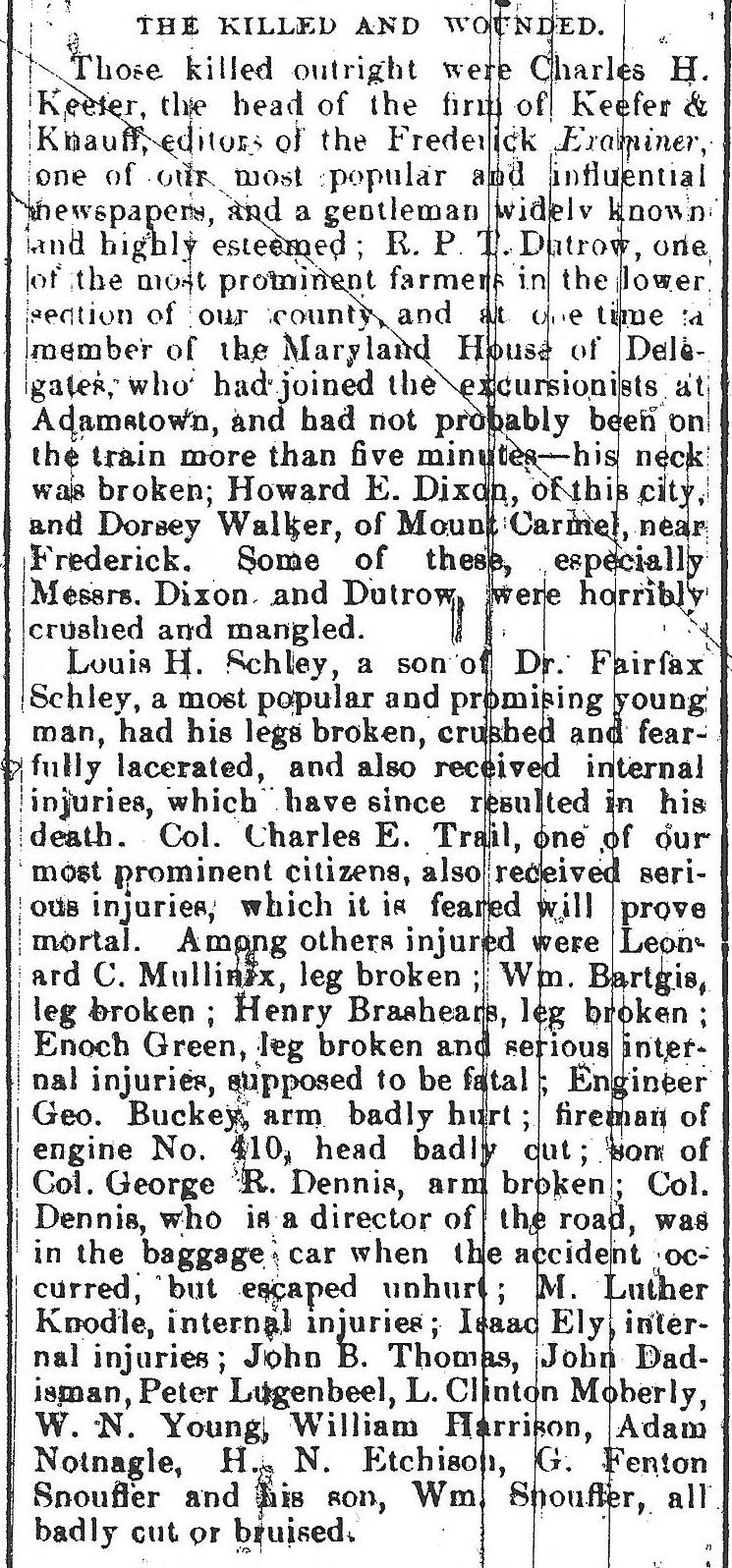

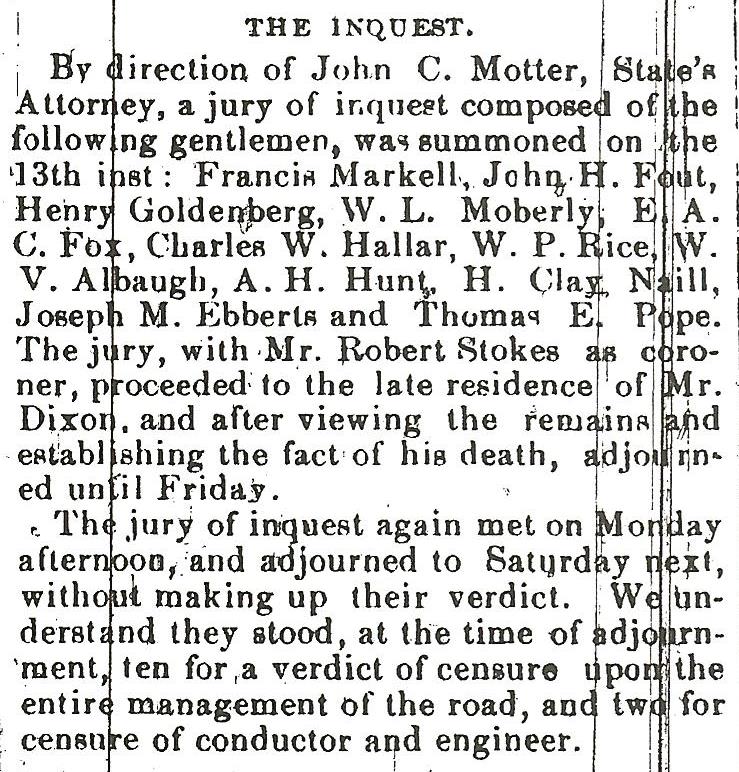

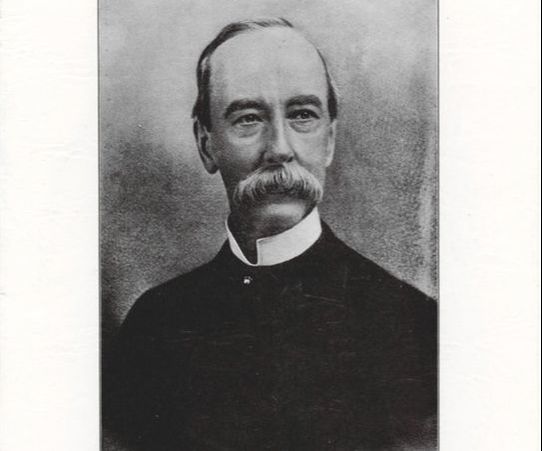

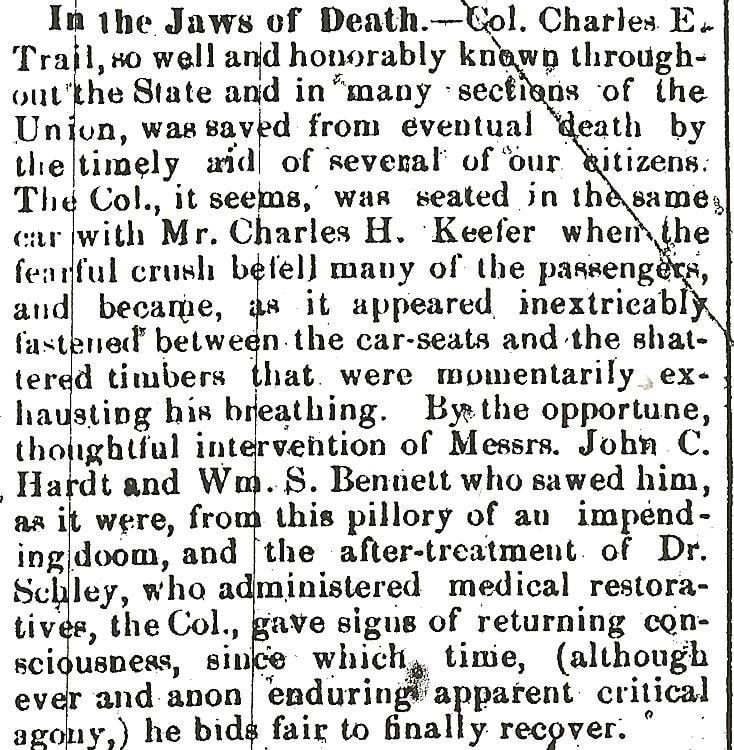

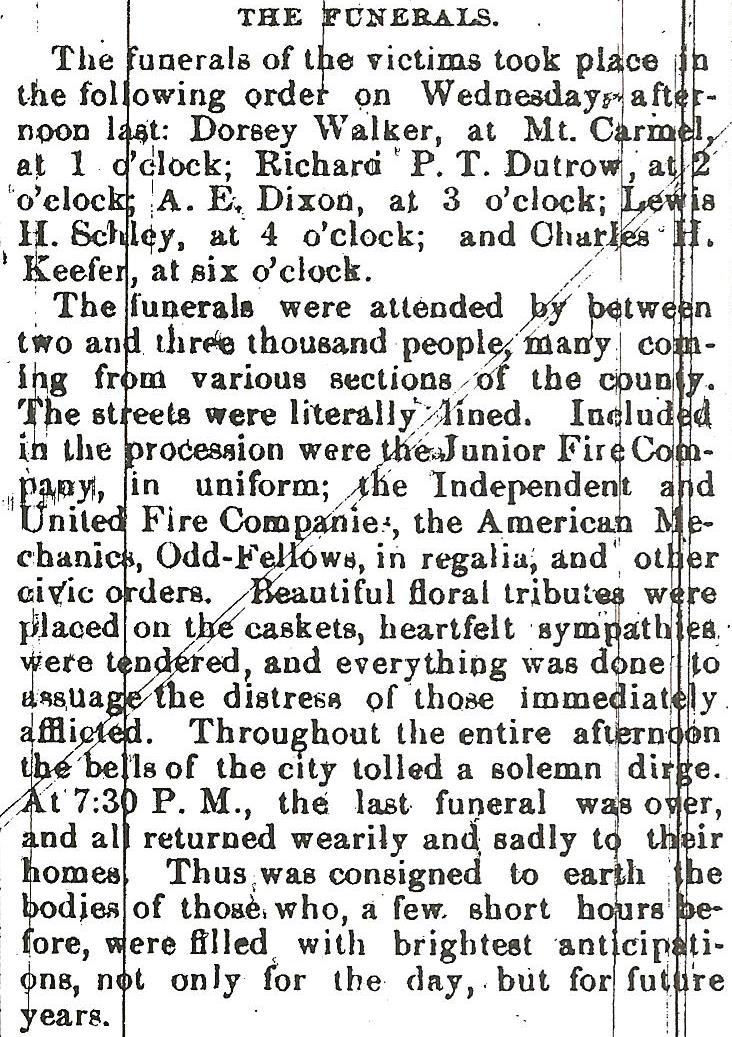

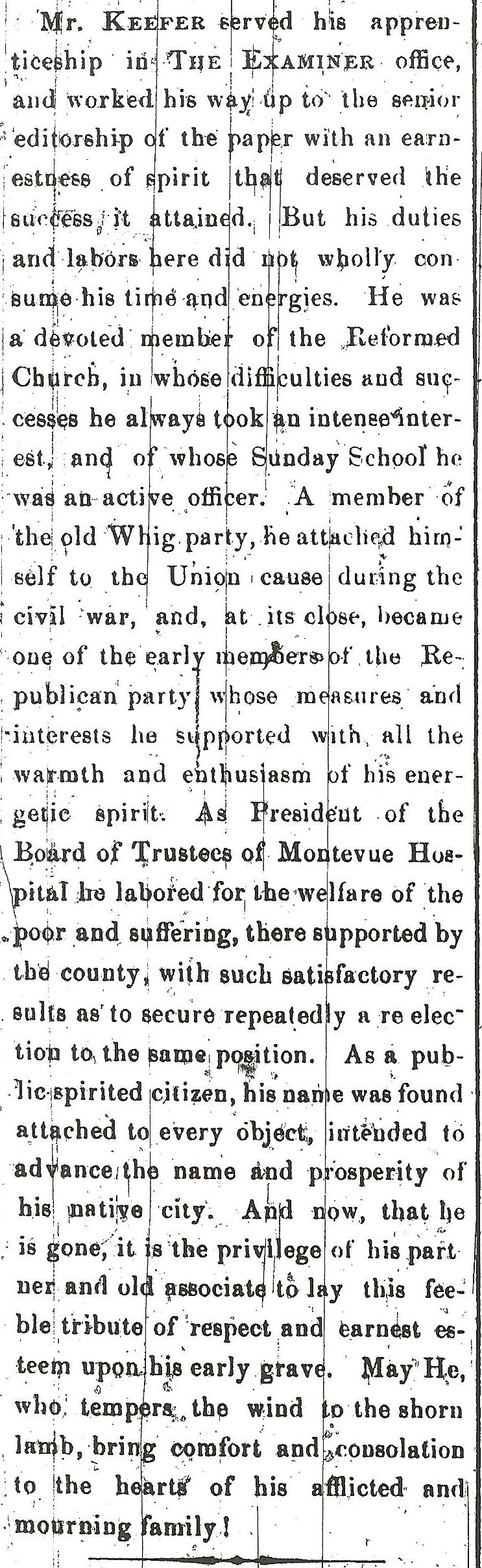

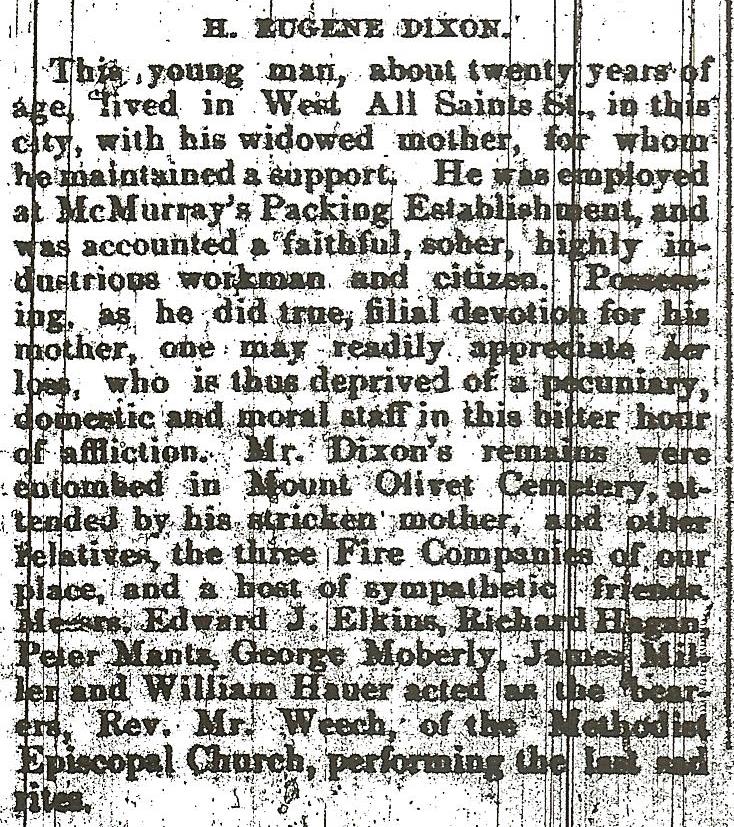

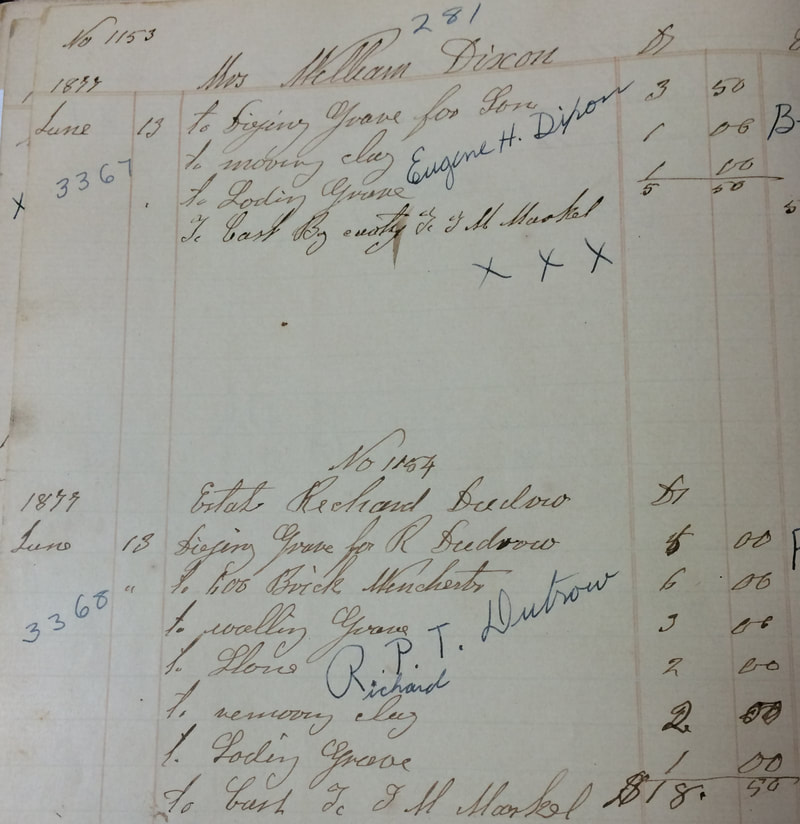

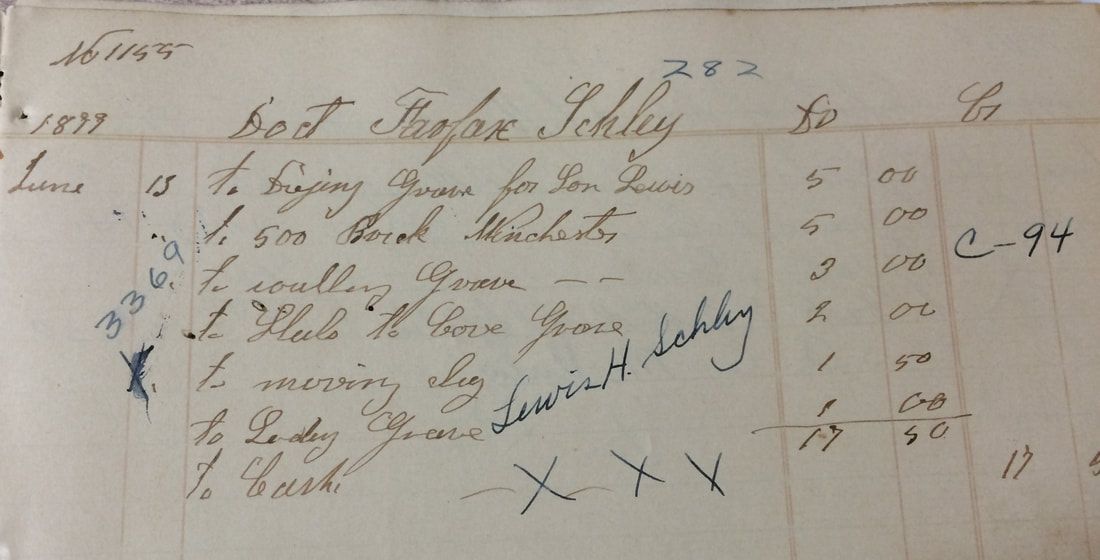

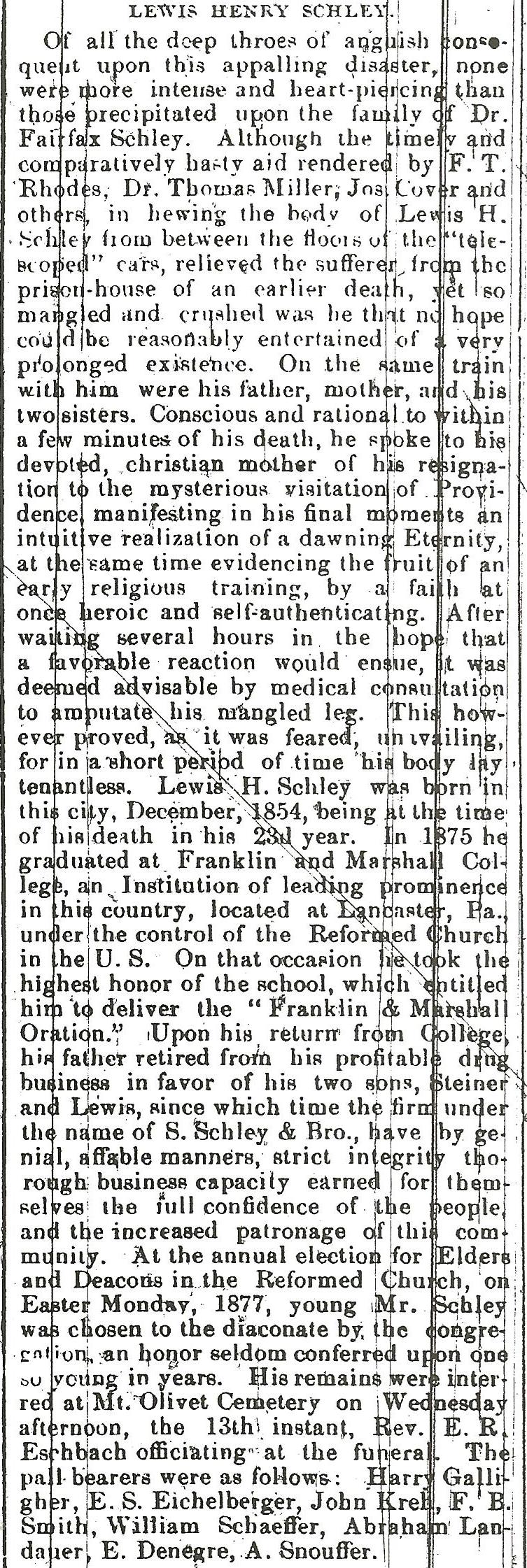

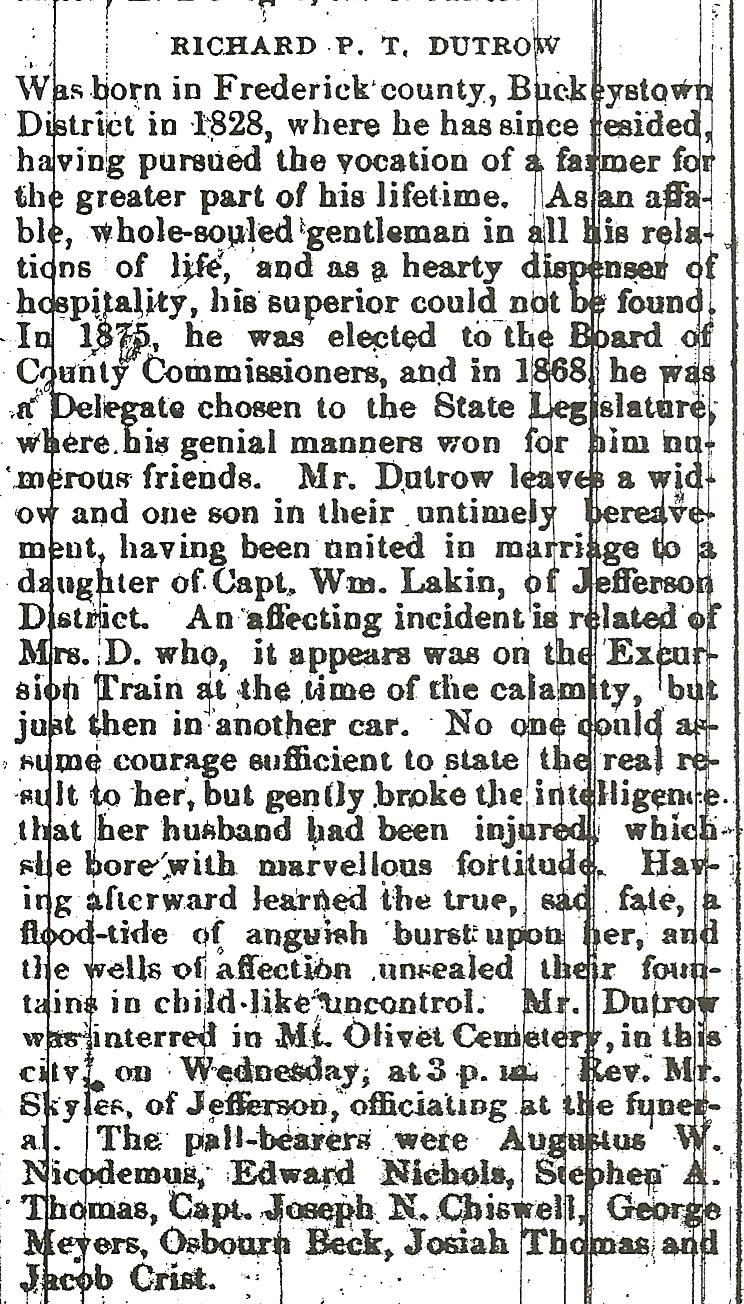

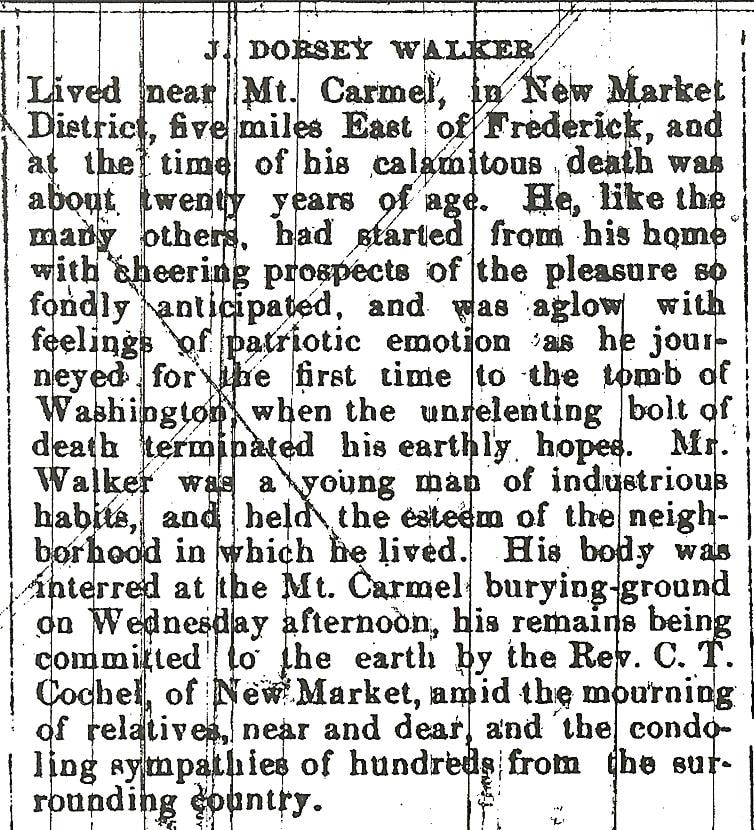

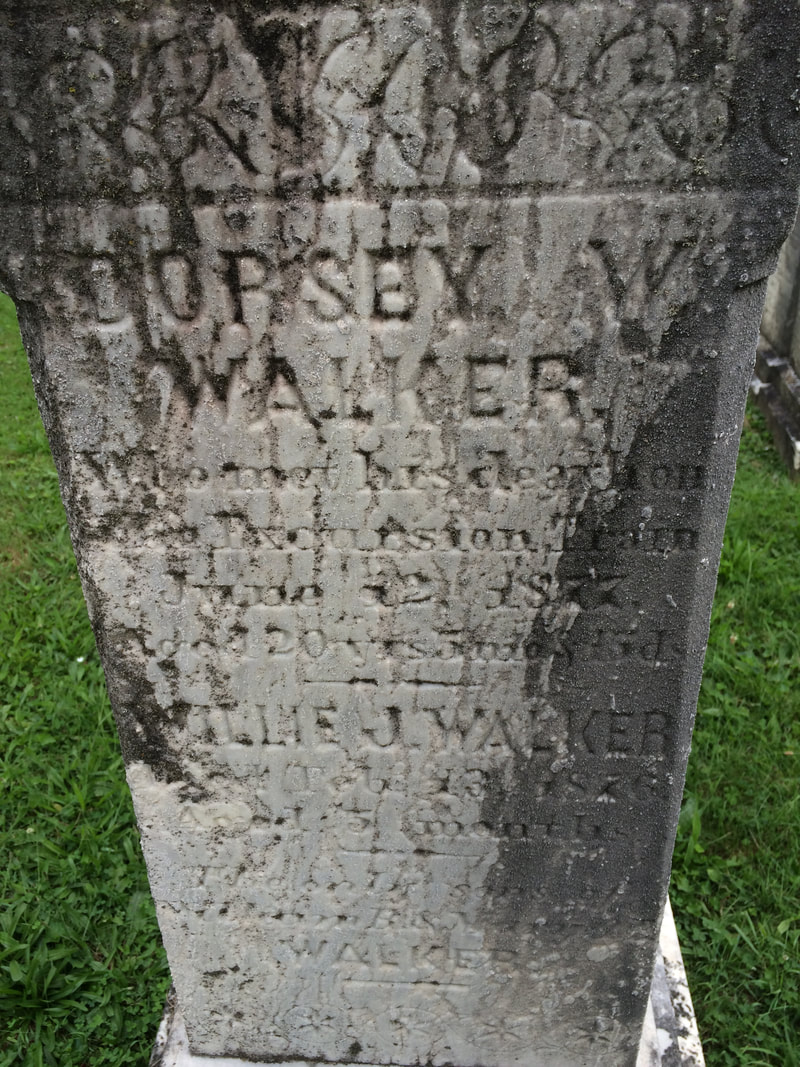

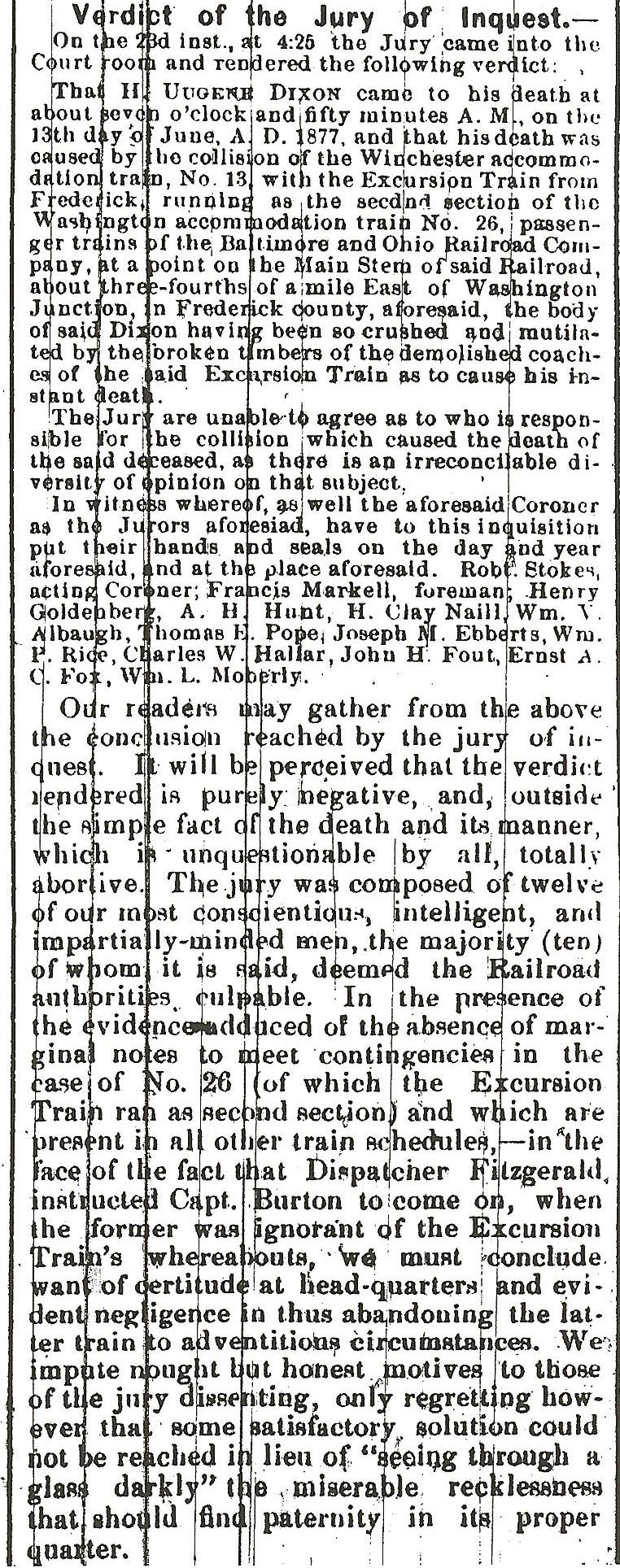

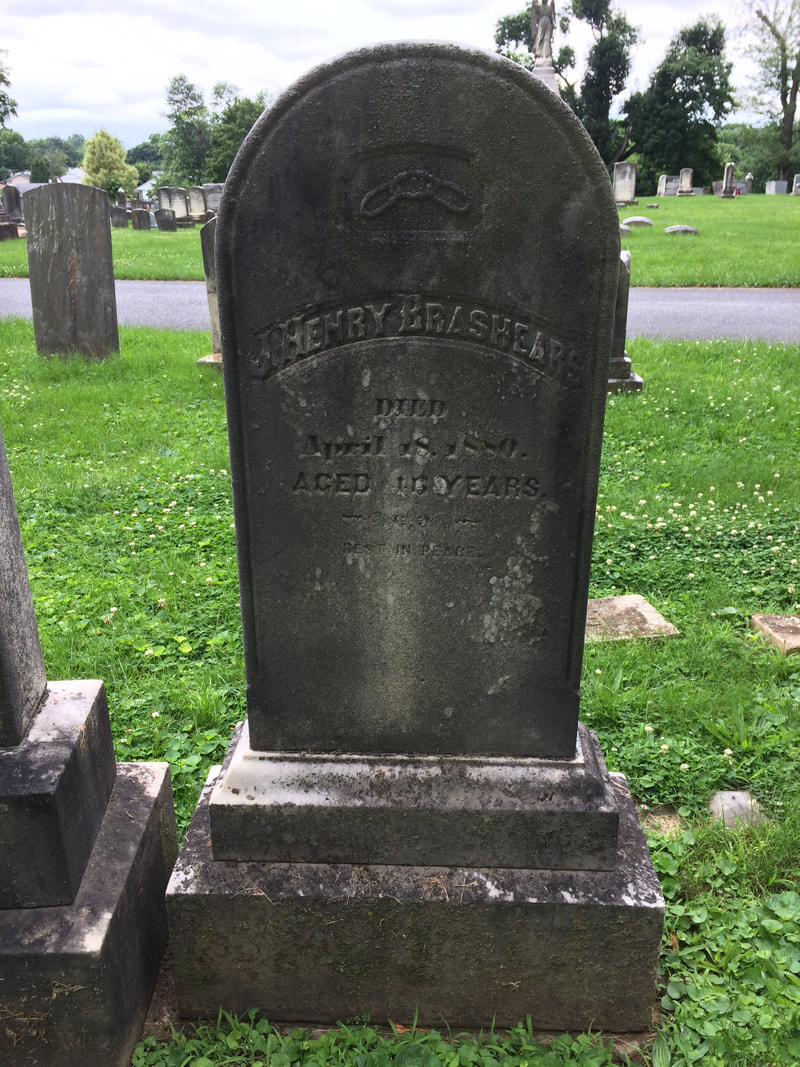

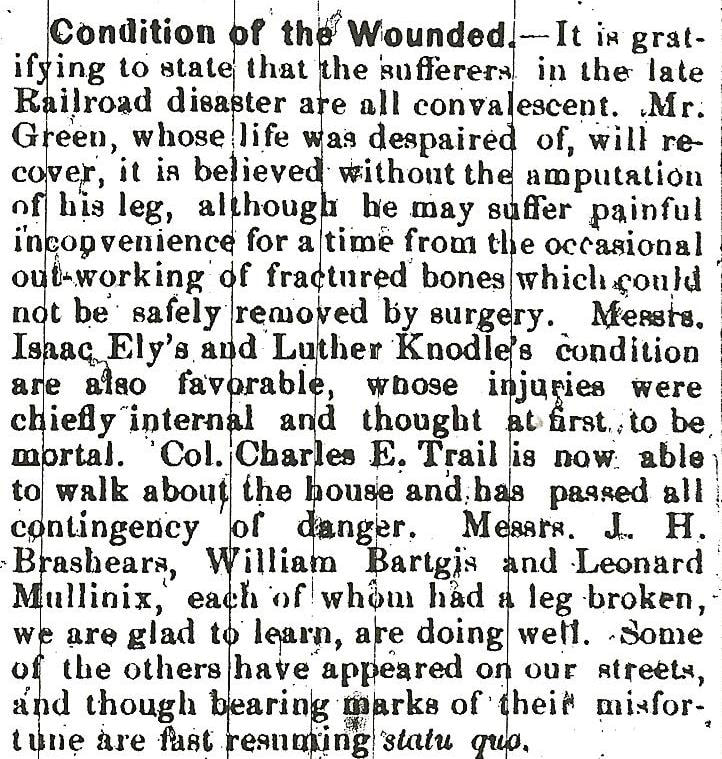

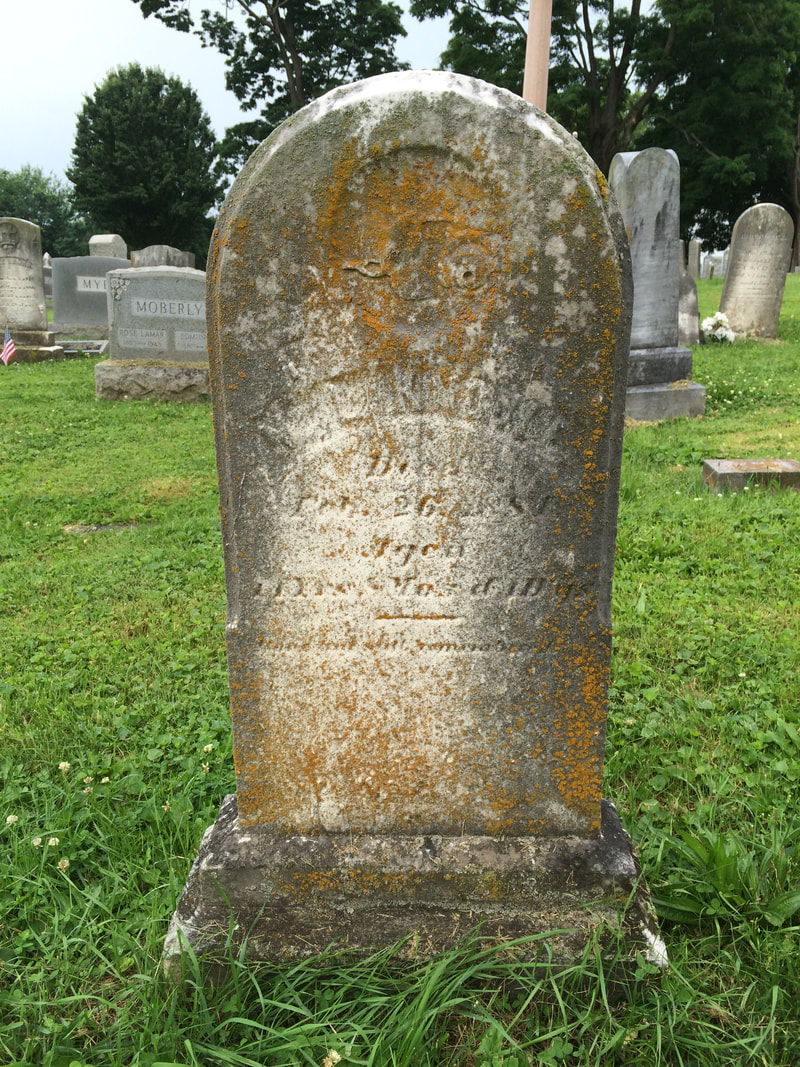

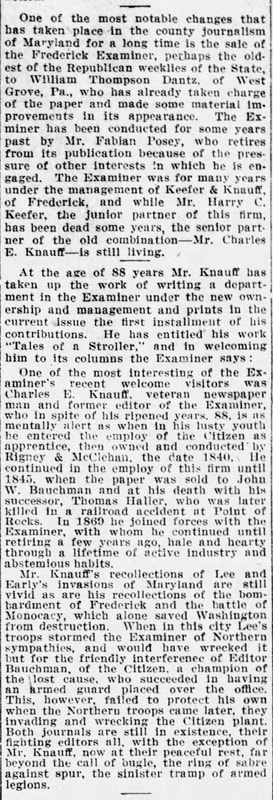

Charles E. Knauff Charles E. Knauff The lead cars of the excursion train derailed, including but thankfully those toward the rear did not. Unscathed passengers in the back of the train came to the immediate aid of their unfortunate brethren. A day that started with such joy and frivolity, now had turned into a scene of tragic proportions. Five Fredericktonians lost their life that day, including Charles H. Keefer of the Frederick Examiner. Numerous others were injured, some almost fatally. You can imagine the media attention this accident received as Mr. Keefer’s newspaper included a reporter who was among the passengers that survived that day. Stories filled the Examiner’s columns in the ensuing weeks of June. As it was a weekly offering, published on Wednesdays, the suddenness of Keefer’s demise left the staff in shock, barely able to collect thoughts to announce news of the disaster, along with the death of their colleague and leader on June 13th, 1877. I now will turn things over to the Frederick Examiner and its staff—bonafide eyewitnesses to history. I surmise that Charles E. Knauff provided the editorial, as he was Mr. Keefer's partner in the newspaper and printing business. Now with a week under their belt, Editor Knauff and staff had the opportunity to share with readers the particulars of the train accident. These articles appeared in the June 20th edition of the Examiner. The Examiner of June 20th, 1877 also included a pointed editorial on who was to blame for this tragedy. A Coroner's Inquest would be launched, using victim Eugene Dixon as the pivot point. An update was also given on Col. Charles E. Trail. the most revered Frederick citizen aboard the train. Col. Trail narrowly escaped "the jaws of death." In that June 20th edition, The Examiner gave a poignant report of the scene at Frederick's Mount Olivet Cemetery on Wednesday, June 13th, the day following the wreck at Point of Rocks. Beginning with Dorsey Walker at 1:00pm, the garden burying ground hosted successive funerals for all five victims. The last ended at 7:30pm. The paper would also include obituaries for each. The June 27th Examiner brought with it news of the Coroner's Inquest case, and an update status on a few of the badly injured from the wreck . Thankfully, no further fatalities occurred, possibly adding to the number of residents calling Mount Olivet Cemetery home. However, in due time, some of these individuals would join their colleagues originally lost on June 12th, 1877. These would include five others who could have easily died in the wreck: Col. Charles E. Trail, Enoch Lewis Green, Martin Luther Knodle, Isaac H. Ely and John Henry Brashears. An article found in the Frederick News on June 12th, 1884 marked the seventh anniversary of the accident, and claimed that Knodle and Brashears had since died, with their early deaths being indirectly tied to injuries suffered on that fateful day at Point of Rocks. Charles E. Knauff would continue operating the Frederick Examiner newspaper long after the death of partner, and friend, Charles H. Keefer. He would contribute writings up to his death in 1915. Knauff would be buried as well in Mount Olivet, however his name never made the headstone erected at the time of his wife Mary's death in 1900. Ironic that a man who devoted his life to print, would have his "by-line" omitted.

|

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed