|

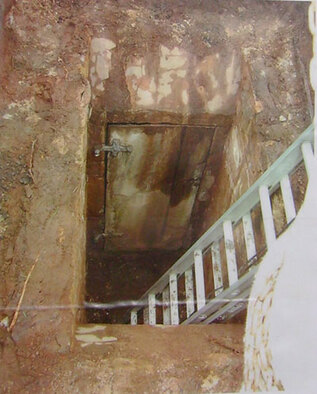

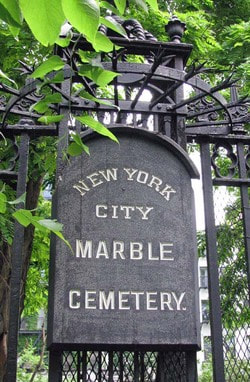

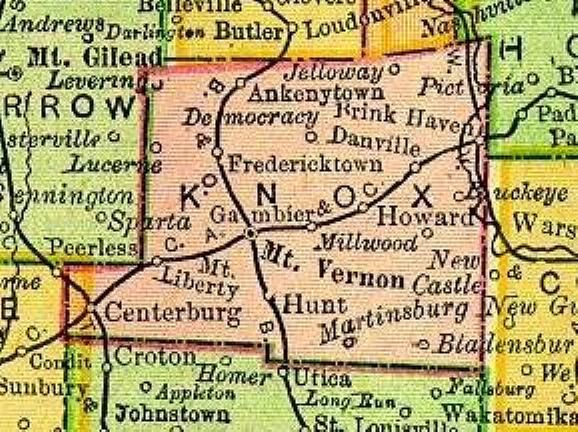

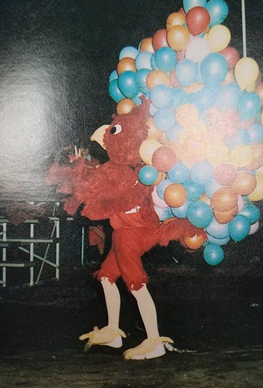

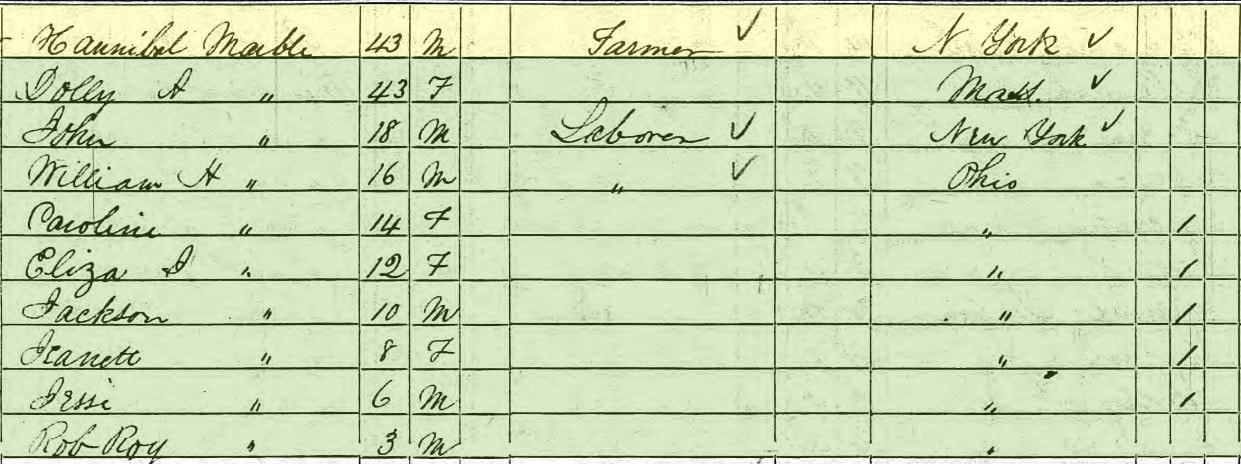

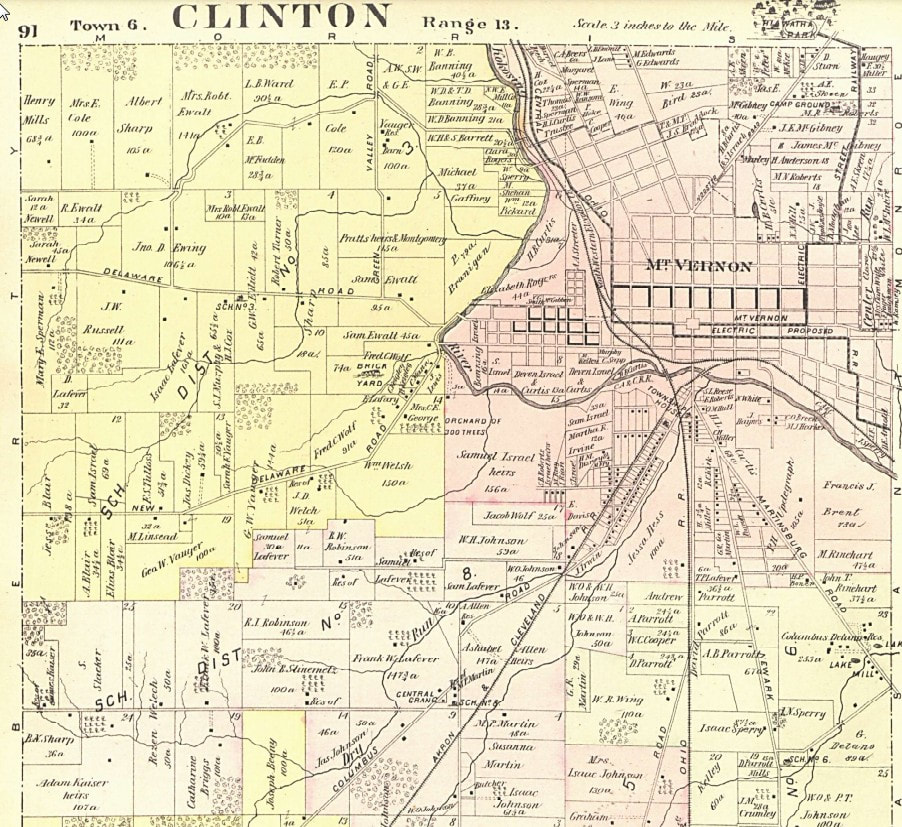

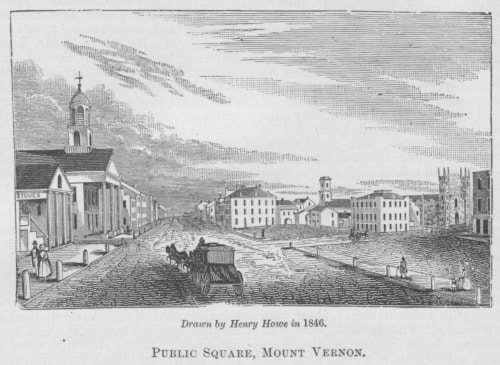

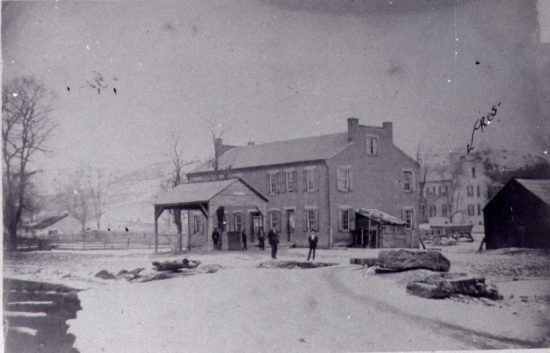

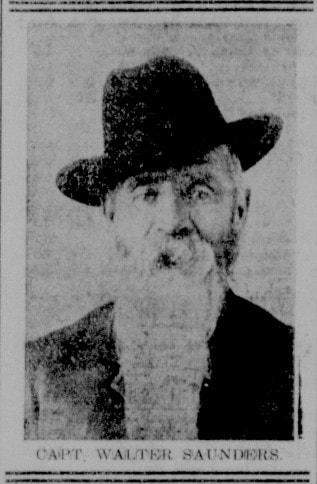

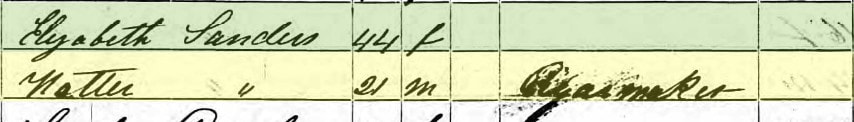

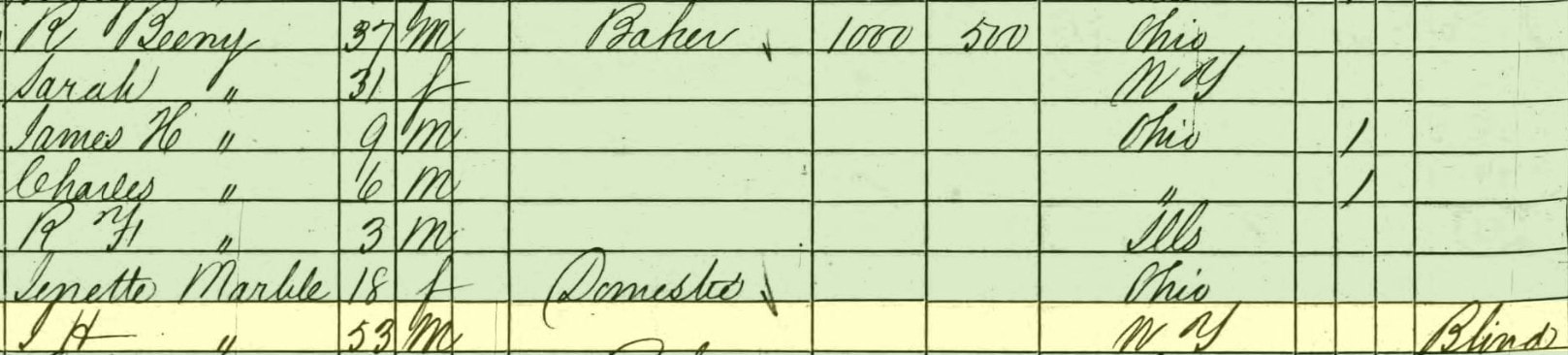

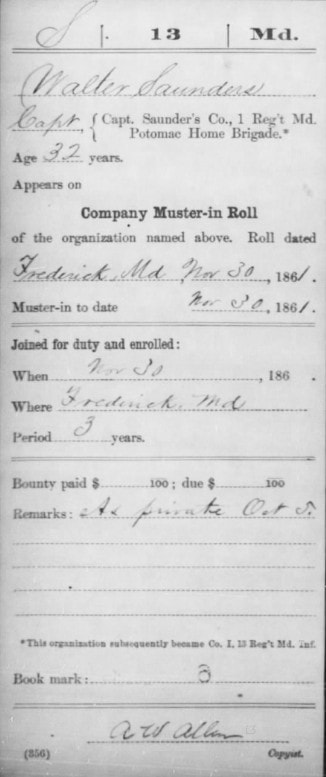

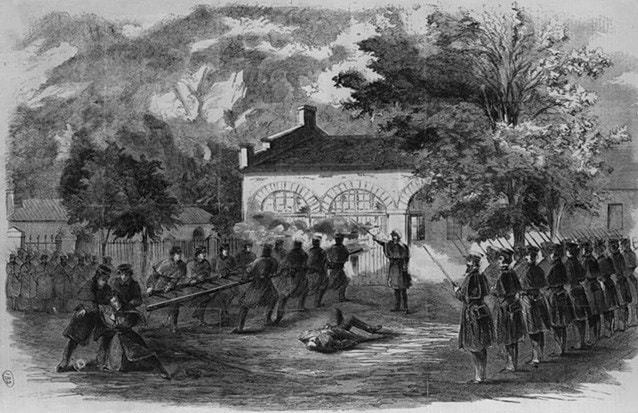

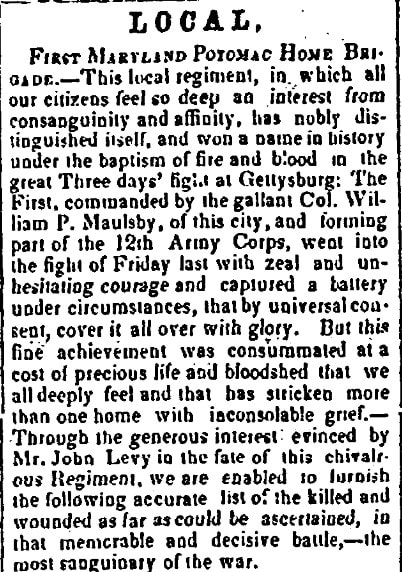

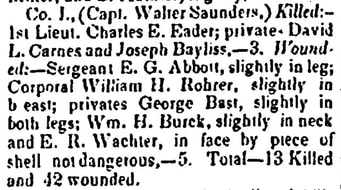

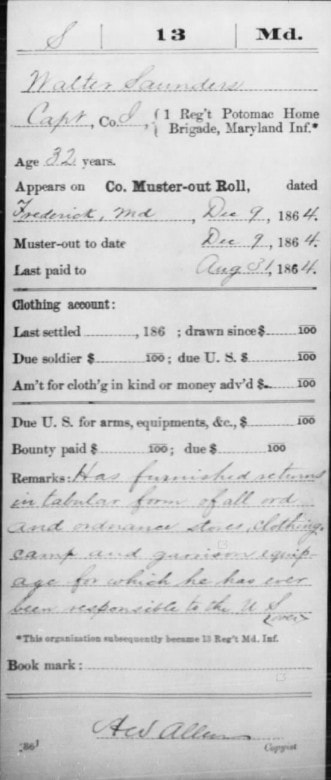

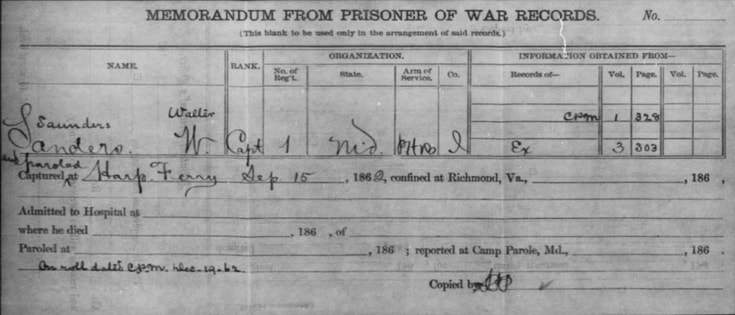

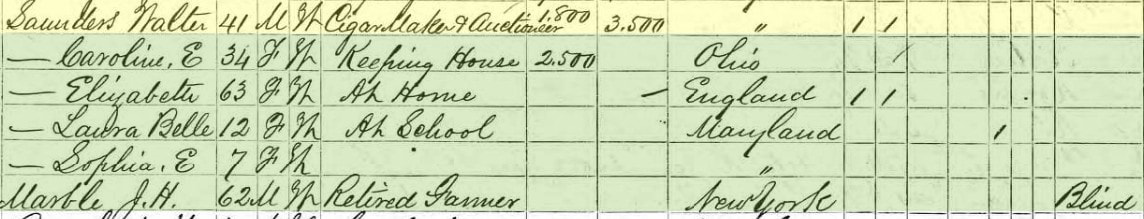

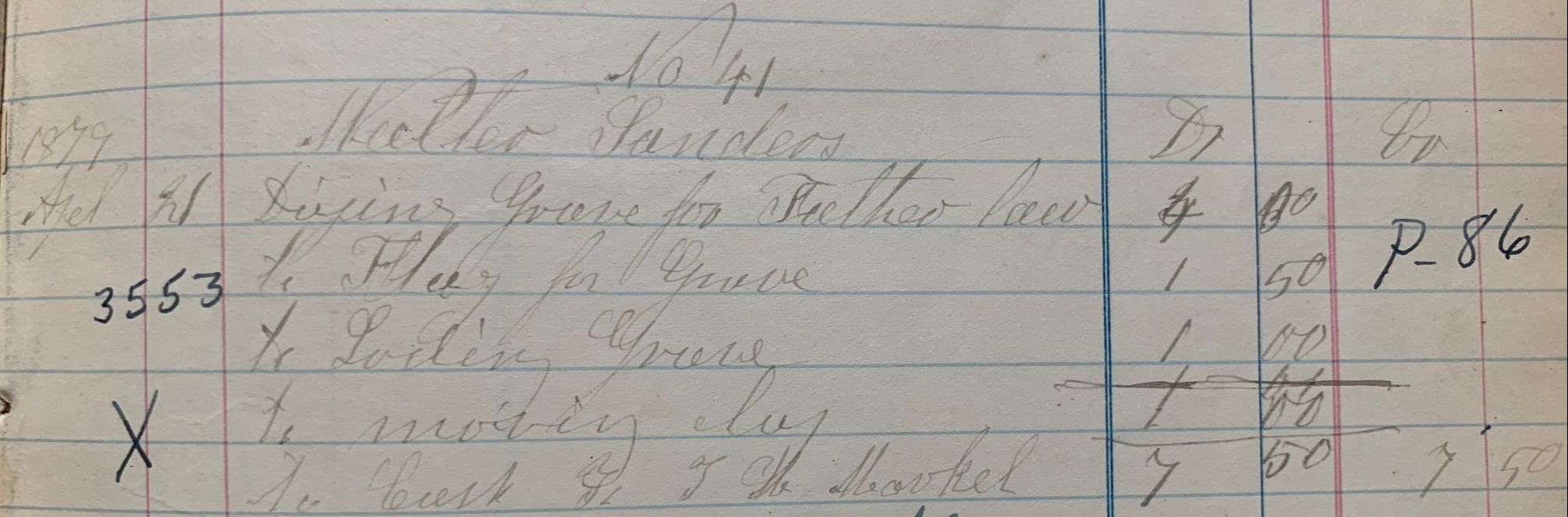

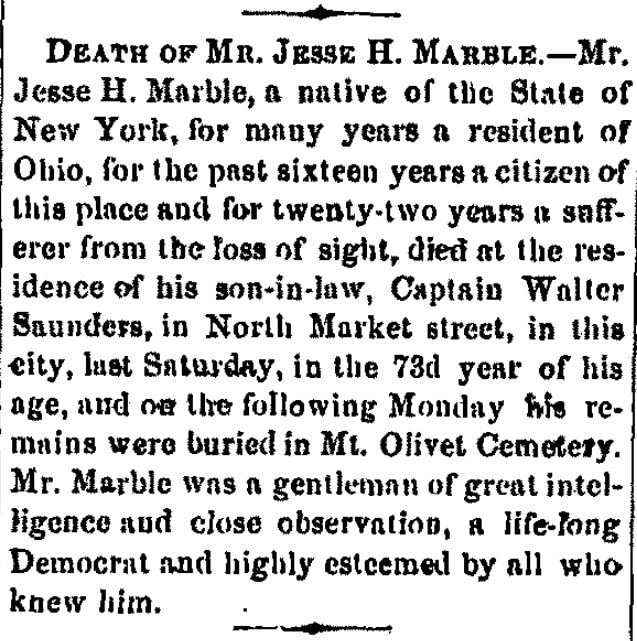

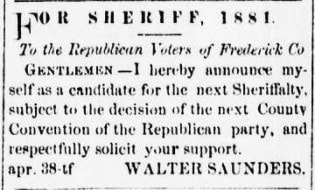

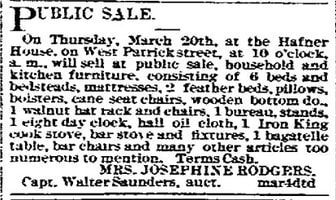

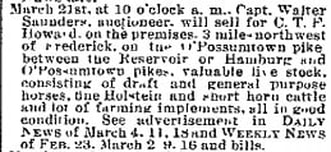

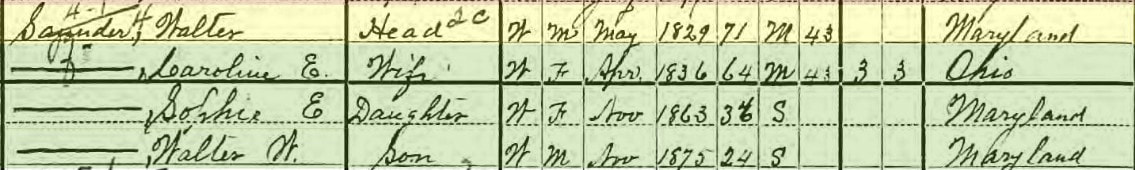

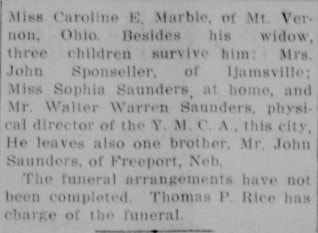

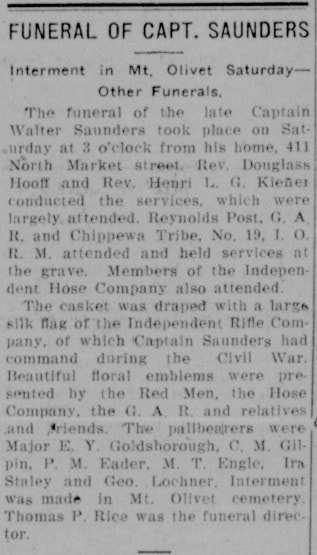

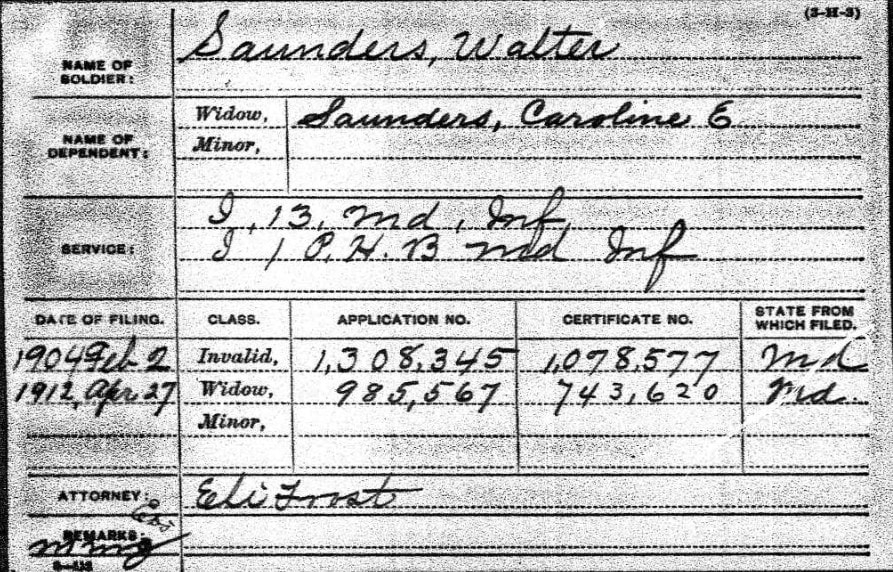

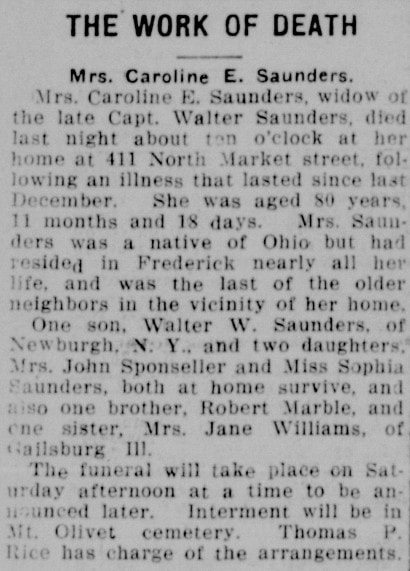

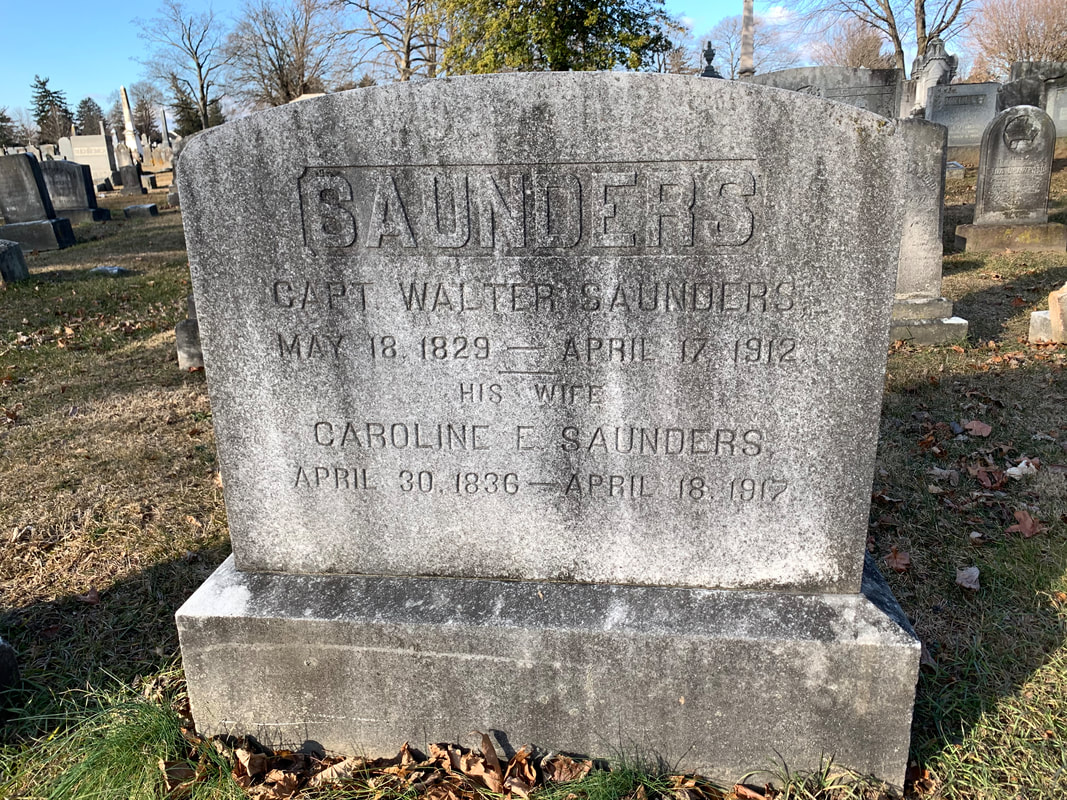

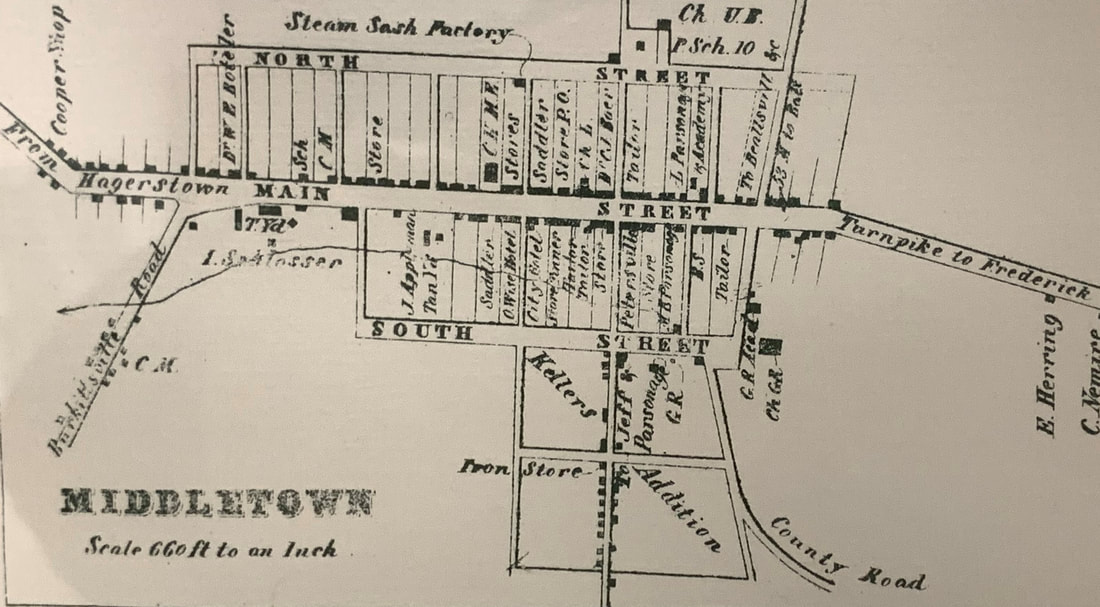

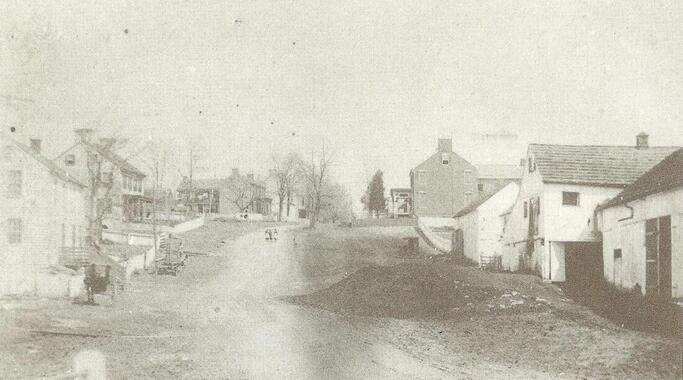

While on a trek through Mount Olivet a few weeks ago, my eye was caught by an interesting surname that I hadn’t seen before—Marble. Upon closer inspection, I noted that this was the grave marker of one Jesse H. Marble. I experienced a bit of difficulty attempting to read the vital information and other quotes found on the face of the “Marble” monument, and yes, I meant that to have a double meaning. Those who are regular readers of my articles know that I am all about connections: family connections, connections to events in history, and oddball/pop culture connections as well. I also love to have fun with puns, as well as idioms, sarcasm and satire. So, I have been searching the internet in an effort of finding marble/cemetery outside of the most common one referring to the frequently used tombstone material —metamorphic rock formed when limestone is exposed to high temperatures and pressures. For the most part, cemeteries all over can be described as “seas of marble and granite.” While I’m on the subject, I should share some of the differences between marble and granite. The following description comes from the website of one of our gravestone vendors: "Marble is made from limestone, which is a type of sediment rock and contains calcium carbonate which reacts to acids. Marble is soft enough to be scratched with a knife blade. In fact, a scratch test with a knife can determine marble from granite. If the stone can easily be scratched, then it is marble. Marble can also be detected by its various colorful swirls or veins in the pattern of the stone. Granite is an igneous rock, meaning that it is formed through the cooling and solidification of magma or lava. This creates a tough and durable rock, able to withstand climate changes, rain, sleet, snow, and salt. Granite will be difficult to scratch using a knife blade. This makes granite an excellent choice for headstones and monuments since it is heat and water resistant. Color variations usually appear as colorful flecks throughout the stone.” In addition to this impromptu Geology 101 lesson, I can give you a Geography 101 lesson as well as I found two interestingly named cemeteries in New York City: the New York Marble Cemetery and New York City Marble Cemetery. The New York Marble Cemetery holds the distinction of being New York City's first non-sectarian burial place, established in 1830 in what is now known as the “East Village” neighborhood of Manhattan, on the block bound by 2nd Street, 2nd Avenue, 3rd Street, and the famed Bowery. I learned that It can be entered through an alleyway with an iron gate at each end, located between 41 and 43 Second Avenue. About 2,100 burials are recorded in the cemetery's written registers, most from prominent professional and merchant families in New York City. To confuse matters, one can find the nearby New York City Marble Cemetery one block east, which is entirely separate, and was established one year later in 1831. Both cemeteries were designated New York City landmarks in 1969, and in 1980 both were added to the National Register of Historic Places. The former cemetery was fascinating to learn about from information found online. It also answered the question of why the word marble can be found within this burying ground’s unique name. “The cemetery was founded as a commercial undertaking of Perkins Nichols, who hired two lawyers, Anthony Dey and George W. Strong, to serve as organizing trustees. Recent outbreaks of yellow fever led city residents to fear burying their dead in coffins just a few feet below ground, and public health legislation had outlawed earthen burials. Nichols intended to appeal to this market by providing underground vaults for burial. Dey and Strong purchased the property on Nichols' behalf, on what was then the northern edge of residential development, on July 13, 1830, and Nichols had the 156 underground family vaults, each the size of a small room, constructed from Tuckahoe marble and laid out in a grid of six columns by 26 rows. He was then reimbursed from the sale of the vaults. Access to each pair of barrel vaults is by the removal of a stone slab set well below the grade of the lawn, which has no monuments or markers. Marble tablets mounted in the long north and south walls give the names of the original vault owners - though not the names of burials - and indicate the precise location of each corresponding underground vault. Nichols, Dey & Strong, and the subscribers applied to the New York State Legislature for a special act of incorporation, and this was granted on February 4, 1831. According to a historical plaque on the cemetery's entrance gate "Descendants of the 19th century owners may still be buried here." Located at 52-74 East 2nd Street (between First and Second avenues) in the East Village, the New York City Marble Cemetery is the city’s second non-sectarian burial ground on record, and has 258 underground burial vaults constructed of Tuckahoe marble. In addition, this cemetery has monuments and markers above ground, many made of, you guessed it, marble.  Outside of this thanatological find, I will guide you through a Cultural Studies or Sociology 101 breadth requirement, in trying to seek another parallel between marble and cemeteries. I fondly reflect upon the small, glass, spherical objects that I collected (and sometimes lost) in my youth. I know this is a true throwback, but I remember the many games that these colorful balls were used to play with my brothers and, more memorably, classmates at school. I distinctly remember days on the Yellow Springs Elementary School playground in which “marble matches” were held atop a circular pitch, and in my case we improvised with the tops of manhole covers boasting a labyrinth of perforated steel on each face. With that memory in mind, I have heard stories of further-back generations actually placing marbles on childrens’ gravesites as a gesture of letting a child’s spirit play with a popular toy from their youth. I’ve also seen evidence of this here in our cemetery on a few occasions.  Well, now it’s time to get back to Genealogy 101, and my fore-mentioned story trigger for this week’s blog. Jesse Hannibal Marble was born September 11th, 1806 in Jefferson County, New York, located in the north-central part of the state bordering Lake Ontario. His parents were Jonathan Marble, Jr. (1776-1860), a native of Petersham, Worcester County, Massachusetts, and Hannah Marsh (1783-1860) of Elizabeth, NJ. Both parents died in Saint Lawrence County, New York and are buried in Spragueville Cemetery in Antwerp (NY). Our subject appears to have spent most of his youth and young adult life in St. Lawrence. He married Lancaster, Massachusetts native Dolly Ann Littaye (b. May 16th, 1804) in 1829 in Oneida County, New York. Their first child, Sarah Ann, was born May 16th, 1830 in the town of Utica. Two additional sons, James Warren and John, were born before the family moved to Clinton Township in Knox County, Ohio by the summer of 1834. Here, eight more Marbles would be born to Jesse and Dolly over the next 12 years. One of these, Caroline Elizabeth, born in April, 1834, would be the impetus for Mr. Marble one day coming to Frederick, and eventually being interred here in Mount Olivet.  Jesse and his family lived about 40 miles northeast of Columbus, Ohio. Clinton is immediately west of Mount Vernon, Ohio. Located a few miles to the north, also within Knox County, Ohio, is the village of Fredericktown, Ohio. Located at the intersection of Ohio routes 13 and 95, Fredericktown was laid out by Marylander John Kerr around 1806. A year later, Kerr brought in his friend, William Yarnell Farquhar (1777-1854), to survey the village. This latter gentleman also built the first house here and is responsible for naming the place after his former hometown of Frederick, Maryland. If you are in the mood for another interesting pop culture aside, I learned that former actor Luke Perry (1966-2019), of Beverly Hills, 90210 television fame was raised here and attended Fredericktown High where one of his early acting roles was playing Freddie Bird, the school mascot. Back to Clinton, Ohio and nearby Mount Vernon, Jesse Marble and his large family operated a farm with all hands on deck. Meanwhile the area was fastly expanding, thanks in part to a growing Cooper Iron Foundry operation located here. I don’t know what exactly precipitated the move west by Jesse, but I did find a cousin, Jehiel Marble, would live with his family in Mount Vernon and was responsible for stone masonry for a great deal of the town’s buildings in the 1850s. It appears that Jesse and family led a relatively, quiet existence as farmers. Meanwhile, a collision course would soon occur between Frederick, Maryland and the Marbles, already well-traveled in life. Enter Captain Walter Saunders. Captain Walter Saunders Walter Saunders was born on May 18th, 1829 in Libertytown, Maryland. His parents are said to have immigrated from England, as Mr. Saunders, Sr. was a schoolteacher. Saunders spent most of his childhood in Woodsboro before coming to Frederick City. Walter apparently learned the trade of cigar-making in 1850 here locally in Frederick, but traveled west to further his career. After working at a few cigar factories in Ohio and Illinois, Saunders would wind up in Mount Vernon, Ohio in the year 1853, where he took charge as foreman of a cigar shop in town. One way or another, he met, and fell in love with, Jesse’s daughter, the fore-mentioned Caroline Marble. The couple were married on May 31st, 1855 and would return to Saunders’ native home the following year to raise a family of their own. Dolly Marble would die in 1856 and was buried in Mount Vernon’s Mound Cemetery. She was only 48. Her widower husband, now blind, eventually moved to Galesburg in Knox County, Illinois to live with his oldest daughter Sarah (Marble) Beeny and family. Jesse can be found in the 1860 census here, and had brought his younger children with him.  Grave of Jesse H. Marble, Jr in Nashville National Cemetery (Madison, TN) Grave of Jesse H. Marble, Jr in Nashville National Cemetery (Madison, TN) The American Civil War took hold of the country over the next half decade. Back in Jesse’s former home of Mount Vernon, a massive Unionist meeting was held in May, 1861 with Gen. Columbus Delano presiding over an afternoon crowd of 20,000 who heard from Gov. David Tod and other leaders making the case that Ohio stay loyal to the Union. Three of Jesse’s sons would enlist in the Union Army, however the war would claim his namesake son, Jesse, Jr. (b. 1844) who fought with Company D of the 102nd Illinois Infantry. (He died at Gallatin, Tennessee in January, 1863.) Meanwhile, back in Frederick, Maryland, Jesse’s son-in-law, Walter Saunders, had been a leading member of one of our three militia groups that also composed our local fire companies. He was a lieutenant /member of the Independent Rifles, and led men to Harpers Ferry in October 1859 to help quell John Brown’s legendary insurrection. At the beginning of the war, he became a Captain of the First Potomac Home Brigade’s Company I. Saunders saw heavy action throughout the war and took part in many key engagements. He was captured at the Battle of Harpers Ferry (September 12-15th, 1862, just days before the Battle of Antietam). He would be paroled and eventually returned to military duty, actually fighting at the Battle of Gettysburg in July, 1863. He would be transferred into Maryland’s 13th Infantry Regiment, Company I, and was honorably discharged in December, 1864. After the war, Captain Saunders returned to the business of cigars, and also began an auction firm that he would continue to oversee until his final years. For one reason or another, Jesse would move to Frederick to live with Caroline and his grandchildren during the war, likely 1863. Since Walter was off at war, perhaps that fact precipitated the move? Whatever the case, Jesse can be found in the 1870 census living on North Market Street. My research assistant Marilyn Veek found that the property where the Saunders family lived was located at 411 North Market Street, now a vacant lot. Capt. Saunders' mother Elizabeth Kiefer Saunders, had bought the property in 1850 that included both 409 and 411 North Market. I kind of see the life of Jesse Marble like the personification of a marble within a game of “old-fashioned marbles.” The goal of each shot is to hit one of the marbles in the center and knock it out of the playing circle. If the player knocks a marble out, then they get to keep the marble for the rest of the game, they also get to take another turn. If no marble is knocked out of the circle, the other player then gets a turn. It seems like poor Jesse just continually got “knocked” from place to place throughout his lifetime: Massachusetts to New York, New York to Ohio, Ohio to Illinois, and finally, Illinois to Frederick, Maryland. His final roll, so to speak, was to his eternal home in Mount Olivet’s Area P/Lot 86, where we got to keep him. Captain Saunders bought this lot upon Jesse’s death on April 19th, 1879 at the age of 72. Saunders was quite a mover and shaker in Frederick as he grew his reputation as one of the top auctioneers in the region, plus dabbled in the political realm as well. He was highly active in local civic and fraternal organizations and remained a guiding force within the Independent Fire Company. Captain Saunders would die on April 17th, 1912 and his lengthy obituary was a prime source of information for me to piece together how Jesse H. Marble came to be a Fredericktonian, at least one of the Maryland variety. I guess you could credit Walter as a “marble shooter” of sorts, and I was equally glad to learn his unique story as well. As for Caroline E. (Marble) Saunders, she would pass on April 18th, 1917, one day after the fifth anniversary of her husband’s death. In 1908, Capt. Saunders had sold his house to his children Laura Saunders Sponseller (1856-1932), Sophie Elizabeth Saunders (1861-1930) and Walter Warren Saunders (1875-1957). Walter, a physician and one of the early directors of the Frederick YMCA, sold it out of the family in 1935. All of these individuals can be found in the Saunders family plot in Mount Olivet.  Jesse Marble, Capt. Saunders and family lived at 411 N. Market St. (2nd house from right in above photograph found in the Library of Congress' Historic America Building (HABS) Survey conducted in 1933). A vacant lot marks the spot of the home today in the photo below taken of the same block. The family also once-owned the bookend house at 409 (3rd from left)

1 Comment

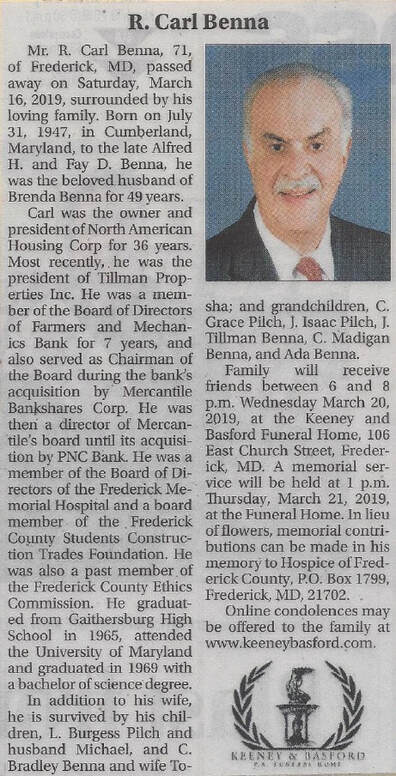

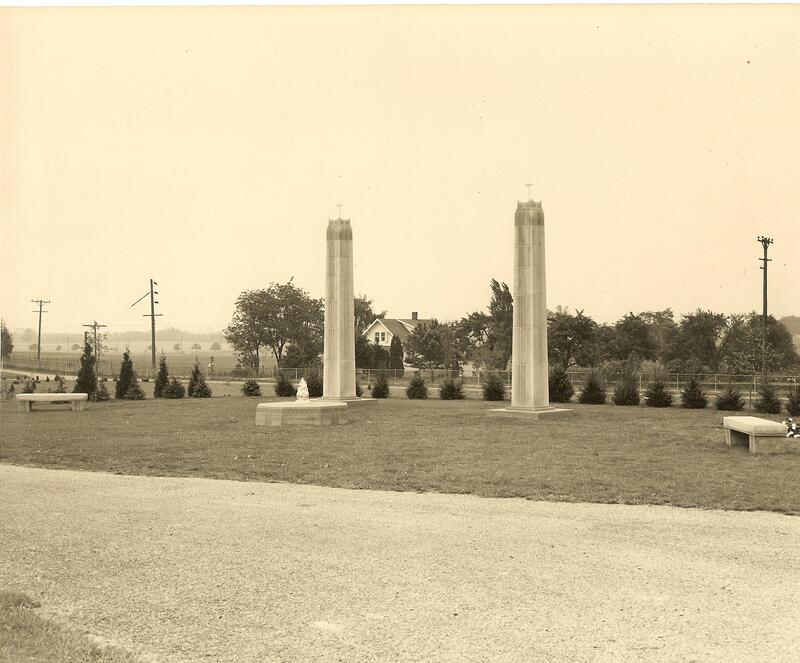

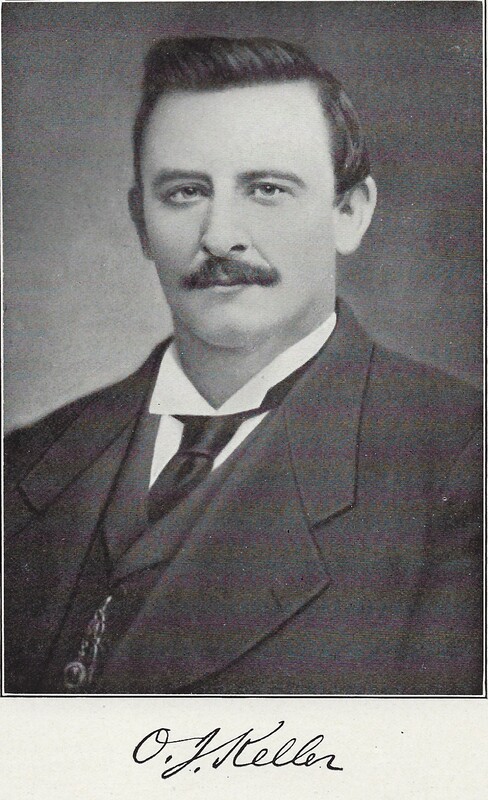

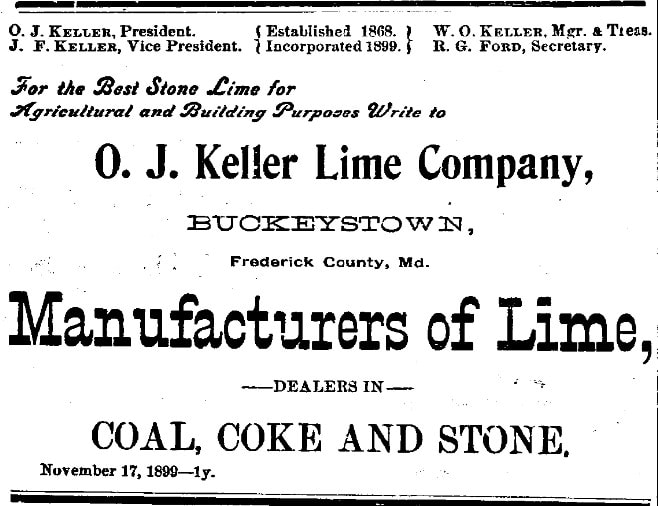

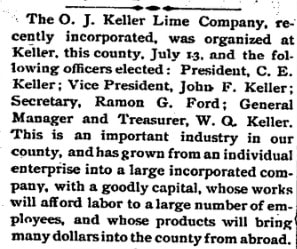

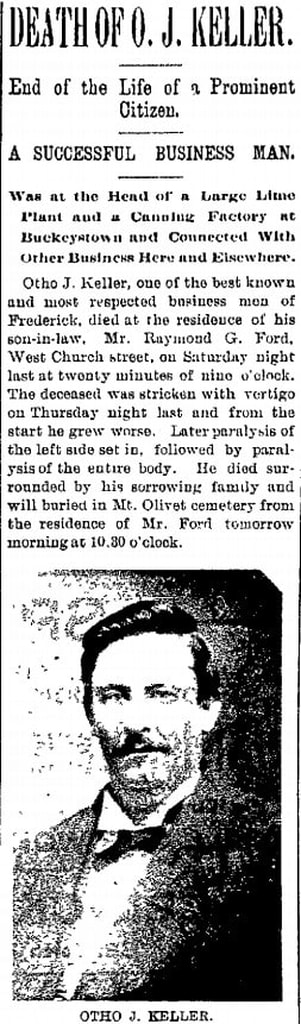

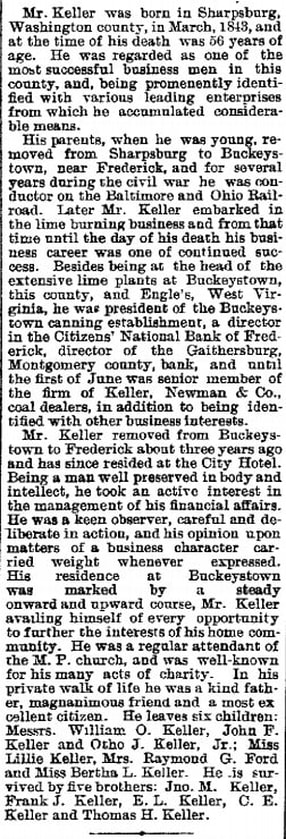

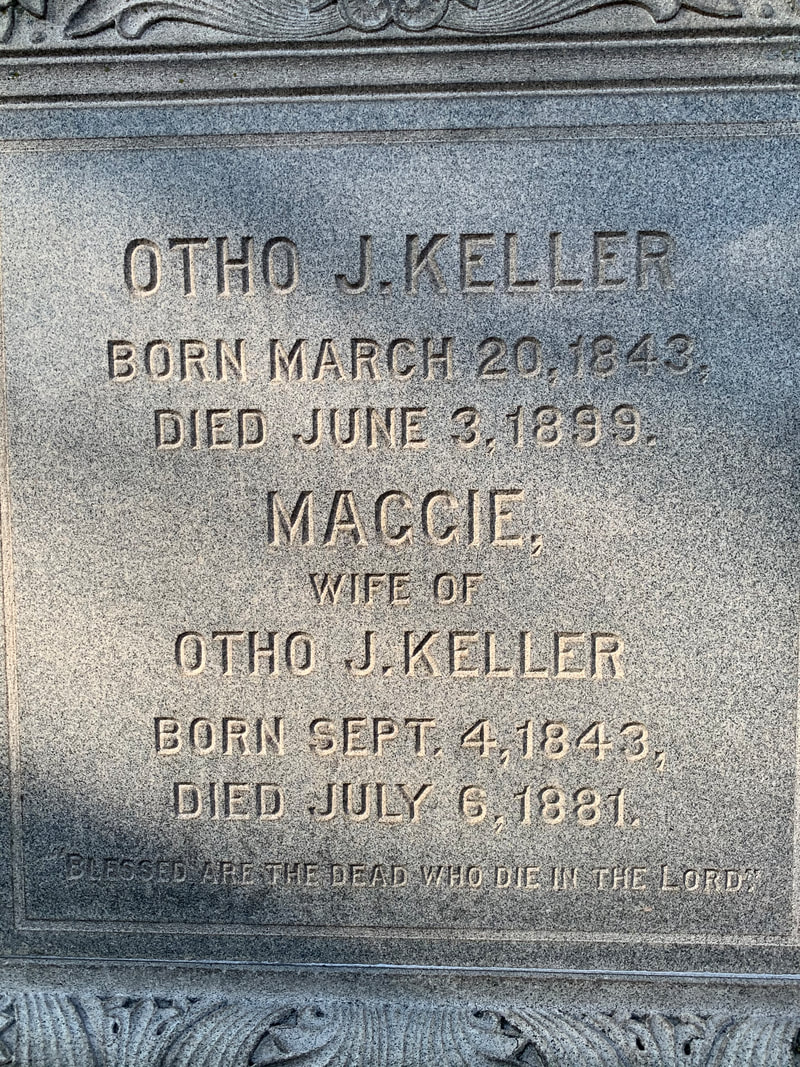

Well, we had an inaugural couple weeks of our own here at Mount Olivet Cemetery with the installation of some pretty awesome monuments. In fact, they represent some of the most impressive in my five year tenure, and surprisingly, one is the largest erected over the 55-year employment of our superintendent, J. Ronald Pearcey. Our administrative and sales offices are located in the central building of our mausoleum complex in the rear of the cemetery. This is close to the highways (I-70 and I-270) that pass by on the cemetery’s south side. I have an office here, and from my office window, I can see both of these impressive works of rock. If I look to the east and the FSK Area of the cemetery, I can spy a monument dedicated to the memory of R. Carl Benna, who passed away on March 16th, 2019 at the age of 71. The large headstone utilizes what is called the Apex style (as in apex roof) and features 7 inch raised lettering, also given in this particular case as 13 pennies high, a throwback measurement once common to the industry. This six-foot tall work was crafted by Star Granite of Elberton, Georgia, and was 3 months in the making utilizing Georgia Blue-Gray Granite with a “steeled,” or unpolished, finish. Mrs. Brenda Benna worked with our Assistant Superintendent/Sales Manager Rick Reeder in designing and executing this granite masterpiece with raised lettering. The gravestone’s placement is on the north driveway that leads visitors back to the mausoleum complex. As for the decedent, Mr. Benna, I have included his obituary below which documents an impressive business career in home building. This seems quite fitting as the monument atop his final resting place features an apex, a principal element in home architecture of course, not to mention the fact that this lasting memorial required a high degree of coordinated fabrication, transportation of major components, and on-site construction upon a sturdy foundation that required over 53 square feet of cement. As the Benna stone went up on January 5th, an equally impressive, and considerably taller, monument of the Cooper family was on its way to us from India, by way of Georgia and the forementioned firm of Star Granite. This 20-foot gravestone would be put in place earlier this past week on January 18th. Both markers required critical assistance from a crane. The Benna stone weighed roughly 21,000 lbs, while the Cooper obelisk, comprised of multiple parts, totaled a sum of 35,000 lbs of finely polished imported gray granite. This project came in six pieces and involved a great display of teamwork by our seasoned outdoor staff. These guys are certainly pros, and utilized the crane and a collection of trusty industrial-strength straps to get the job done to perfection. Two black granite benches were added to the base of the Cooper monument, and ornamental urns placed ion the four corners to delineate the boundaries of the lot. It is clearly "one for the ages." The location in Area SS allows for easy viewing by passing motorists, as well as being seen from several differing vantage points throughout the newer part of the cemetery, not to mention from my desk as well. The Cooper monument is a perfect example of pre-planning by a couple—in this case, Ottoway and Montcella Cooper of Fredericksburg, Virginia. We, here at Mount Olivet, are in no hurry to see either member of this fine couple as full-time resident anytime soon. I understand, that the family has other relatives buried here which prompted their choice for a final resting place. Saying that, it is expected that the couple will always be surrounded by family because they have truly made a familial plot harkening back to the days of old here in Mount Olivet. The Coopers own 24 grave spaces here for themselves and immediate kin, with the ability to provide for future generations for years to come. Talk about having the best centerpiece a family plot could have? I asked Superintendent Pearcey when he thought the last major monument of this caliber was installed in the cemetery. He told me that the Great Depression and World War II eras put to rest the Victorian era practice of grand monuments—a signature of our historic section. Not only was this based on economics, but perhaps, more so, on the growing popularity and affordability of the automobile and improved transportation through highways. Family members became more transient in nature, and left native hometowns that had hosted founding families for generations. People went west and all directions in search of fortune, work and a myriad of other opportunities. Some folks would still “come home” at the time of their death, but this is something that would change the dynamic of the stately garden cemeteries like ours (founded in 1852). Much like post-war suburbanization and housing development building on larger scales than ever before, we saw cookie-cutter style memorial cemeteries, boasting standardized size or style grave markers, come about in the 1950s and 1960s. This was also a departure in what could with rural church cemeteries throughout Frederick County, our state, and the nation. Some may recall a ”Story in Stone” I wrote a few months back in which I called out a large obelisk in Area G belonging to the Noah E. Cramer family (erected around 1930), and another erected recently in Area RR to the memory of Cleopatra Campbell in 2020. Mr. Pearcey told me he thought the World War II Memorial in Area EE was likely his best guess. This was constructed in 1948, and features two large pilasters bookending an eternal flame centerpiece. Fanned out here, are the gravesites of 30 servicemen who made the greatest sacrifice while in active service during that global conflict. Otho James Keller(s) I drove around the cemetery looking for another like-monument to the new Cooper gravestone, and my journey took me to Area P, and a 20-foot monument that faces Harry Grove Stadium, only a few dozen yards from Stadium Drive and our southeastern boundary. This granite masterpiece marks the grave of Otho James Keller and wife Margaret “Maggie” Burnett, formerly of Charles Town, West Virginia. The couple is surrounded by other members of their immediate Keller family, and generations that followed James and Maggie. Here you will find 20 members to date, the most recent being interred in 2020.

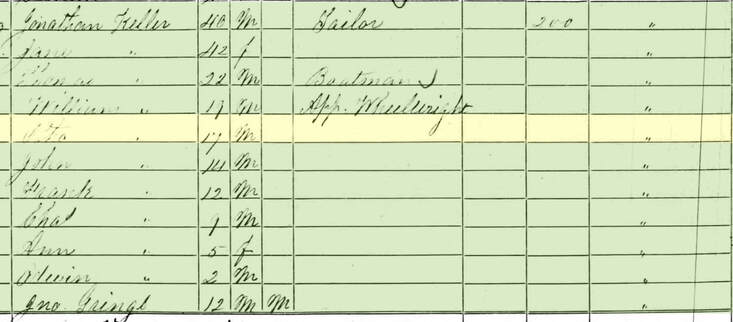

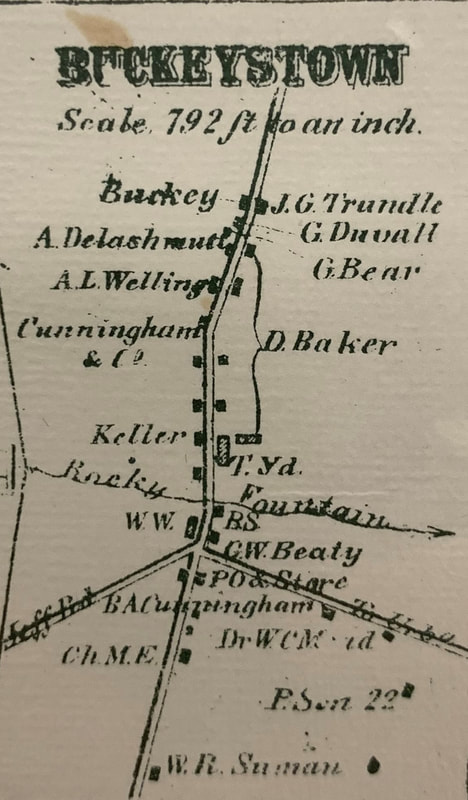

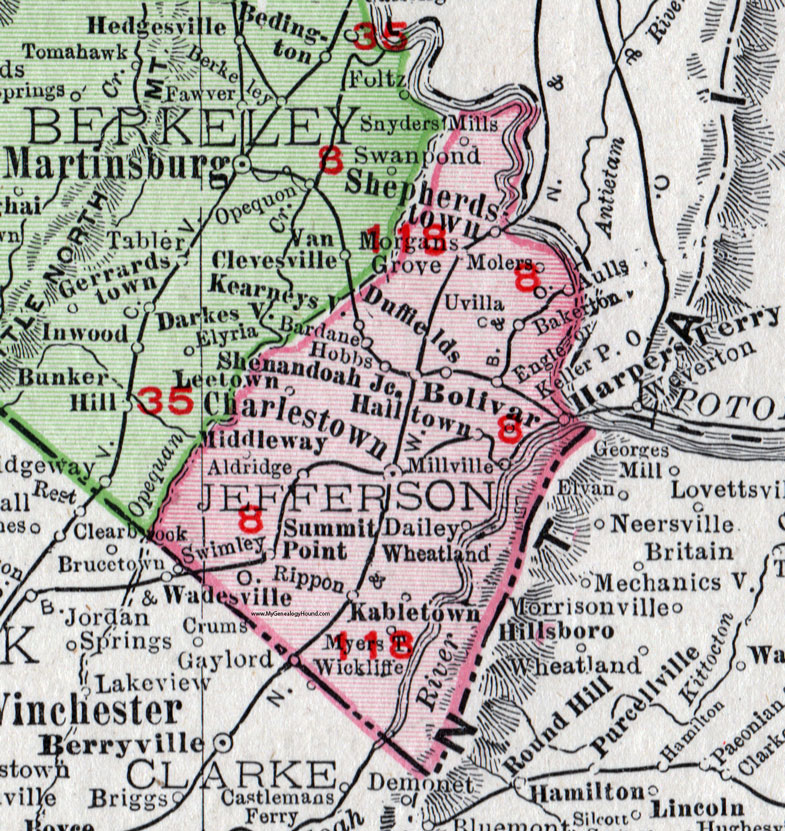

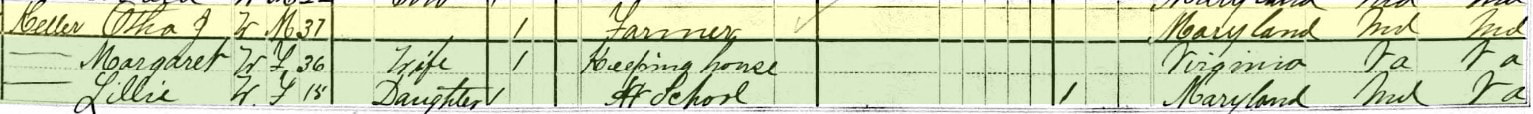

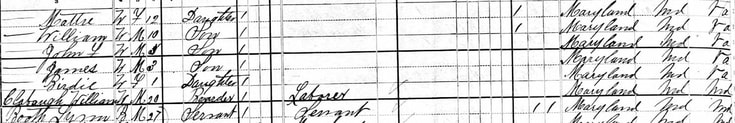

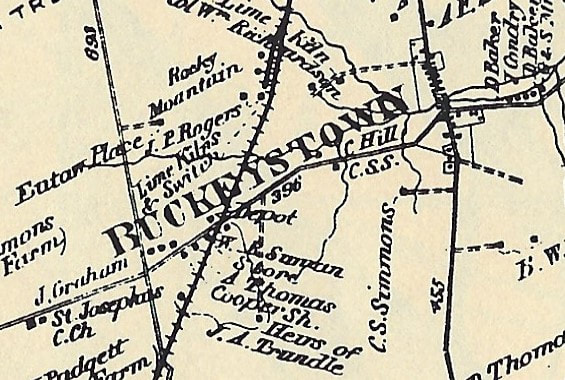

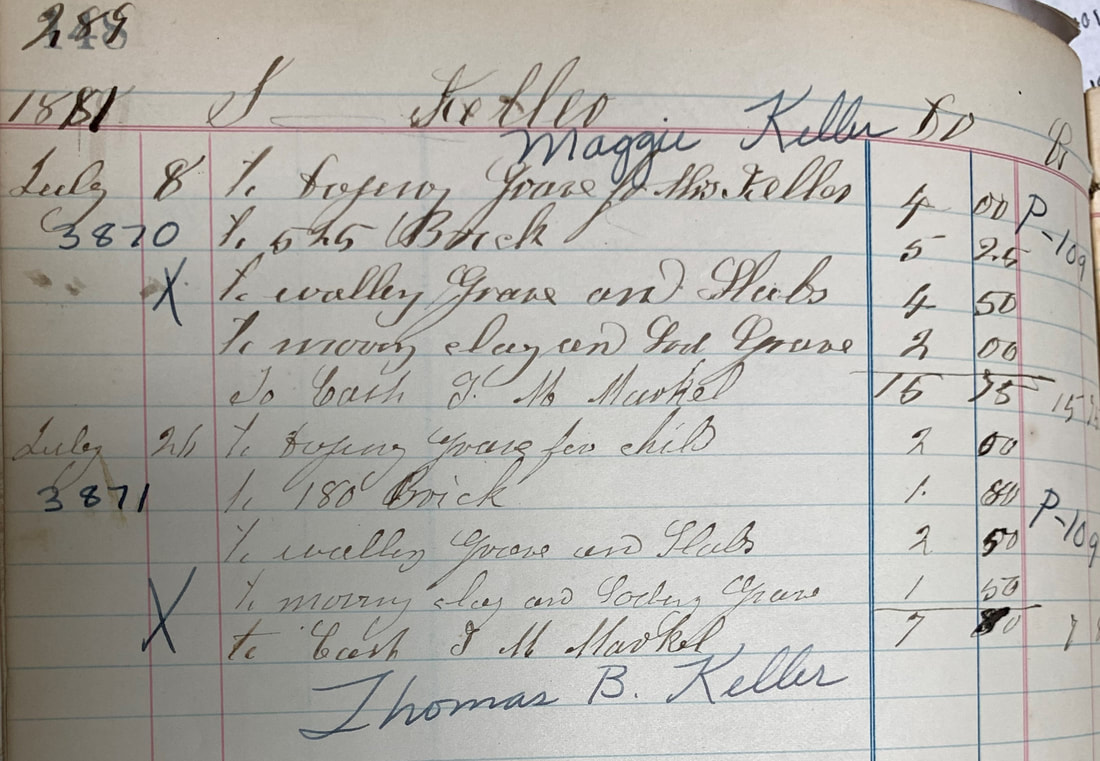

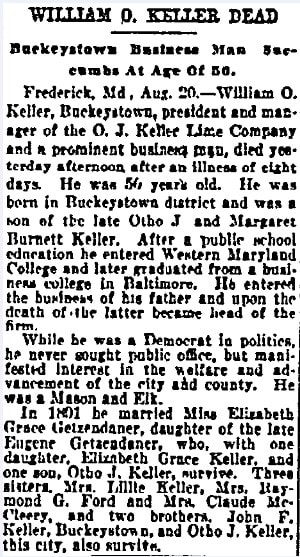

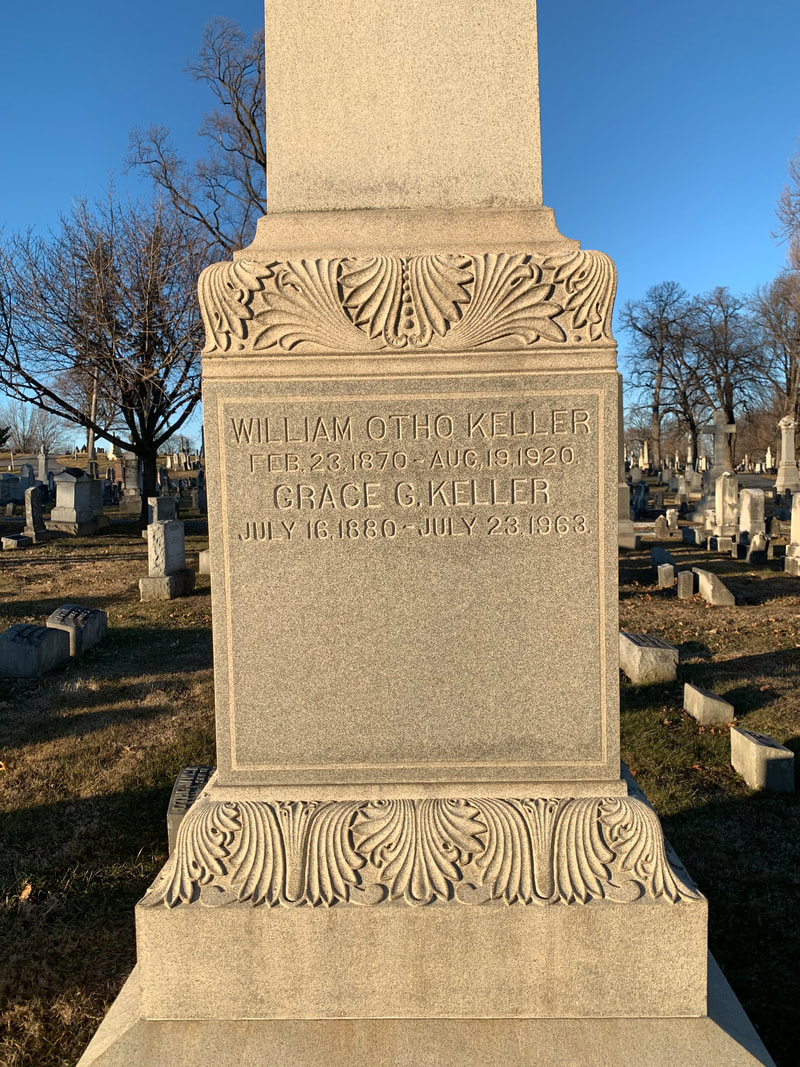

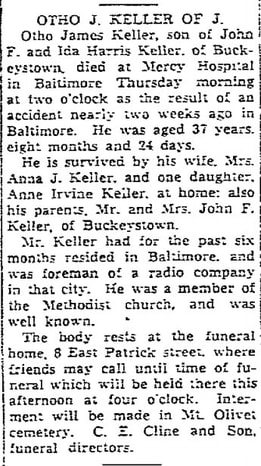

So I find this very ironic and fitting—why wouldn’t a family possessing a surname that means cellar desire a tall sky-reaching monument over a lowly ground-level ledger-style marker or common footstone marker. The Kellers here in lots 108 and 109 had a greater impact on the sleepy little village of Buckeystown, south of Frederick. Otho James Keller was the son of Jonathan Michael Keller (1823-1879) who is buried some 20 yards north of this fine obelisk. Jonathan (1814-1879) had familial roots in farming in his native Middletown, but moved to Buckeystown, and quickly became a well-known citizen here and also justice of the peace. Jonathan, a tailor by trade, married Jane Louisa Springer and the couple raised nine children, eight of whom reached maturity. There were said to have been nine boys and one lone girl. Mrs. Keller died in 1886 at the age of 67. In conducting research, I was interested to find that the former Miss Springer was a descendant of Swedish immigrant Christopher Springer, one of the original settlers of Wilmington, Delaware, hometown of our new US president, and more importantly for me, my mother, maternal grandparents and a set of great-grandparents. Our grave monument in question proudly displays the name of Otho James Keller and wife Maggie. T.J.C. Williams’ History of Frederick County, Maryland, Volume II (1910) includes a biography on Otho, and also contains his portrait. “Otho J. Keller, son of Jonathan and Jane Louisa (Springer) Keller, spent his early days in the neighborhood of Buckeystown, whither his father had removed at an early day, and received his education in the schools of the district. When quite a young man, he embarked in the lime business, in which he was very successful, having a plant at Buckeystown and also at Engles, West Virginia. His brother, C. E. Keller, was his partner in the West Virginia plant. In 1891, Mr. Keller removed to Frederick and became financially interested in a coal and wood business, in partnership with Jacob N. Newman, under the firm name of Keller, Newman & Company.” “Mr. Keller was one of the foremost business men of Frederick in his day. He was connected with various manufacturing establishments of Frederick and Montgomery Counties, and was a director of the Citizens’ National Bank of Frederick, and president of the Buckeystown Packing Company. Politically, Mr. Keller was a Democrat, and in religion, a Methodist.” Otho and Maggie were married in 1864, the final year of the American Civil War. The family lived on the noted estate named Rocky Fountain, and here also was the location of the Otho J. Keller Lime Company. Taking its name from the creek that bisects the property and crosses under Buckeystown Pike to the east, the former manor house was built in the mid 1700s by John Darnall, former Frederick County Clerk of the Court, famous in the annals of local history for his Stamp Act Repudiation Day (Nov. 23, 1765) fame. It no longer stands, but in doing my research I saw that an incredible million dollar mansion built in 2008 has taken its place! Otho and Maggie had ten children, however only six reached adulthood: Lillie M.; Mattie J. B. (Keller) Ford, William O., John F., Bertha L. (Keller) McCleery and Otho James Jr. In early July, Maggie gave birth to as son, named Thomas Burnett Keller. She would die in childbirth. To add insult to injury, the infant would die 20 days later. Mr. Keller would never remarry. Otho James Keller, in spite of being a widower, led a busy and successful life according to newspapers. However, it would be a life cut short as he died suddenly on June 3rd, 1899 at the age of 56. Otho James Keller would be buried in Mount Olivet’s Area P next to Maggie and young Thomas at a funeral that was largely attended on June 6th, 1899. Of particular note, five of his six other children are buried here in the plot. Bertha l. McCleery, the last of the immediate family, passed in 1964 and is buried in Area H. The O. J. Keller Lime Company continued operation with oldest son William O. Keller taking the helm. He ran the firm successfully until his death in 1920. His name, and that of his wife Grace, can be found carved on the side of the obelisk. The company sold its Jefferson County, West Virginia company in 1924 to the Potomac Stone & Lime Company. Afterwards the firm would become a casualty of the economic tumble and "Great Crash of 1929." Forty-six years after Otho James Keller had started his humble lime burning business in 1883, the firm's 140-acre Buckeystown property with equipment would be sold at public auction in October, 1929. Also here in this grave plot, one will find our subject’s other son, Otho James Keller, Jr. (1877-1921), who, like his father, died suddenly and earlier than one would expect. He died of a ruptured blood vessel in the brain. His son, Otho James III (1904-1969), is also buried here along with his son, Otho James Keller IV, whom I knew personally as we both served as board members of the Francis Scott Key Memorial Foundation. This gentleman, whom many called “Ody,” was the great-grandson of our subject, born in 1941 and died in 2017. I would remiss if I didn’t mention that there was a second grandson who held the name of Otho James Keller (1903-1941). This was the son of John Fletcher Keller, son of our main subject. This particular grandson had only been living in Baltimore for six months after taking a position as a clerk with a radio company. Apparently two weeks before his death, he suffered an accidental fall within a restaurant which contributed to his hospitalization and subsequent death at age 37. Let's get back to our talk of "heavy lifting" and monuments. Unfortunately, I was unable to find anything further on the actual installation date of the Keller obelisk. I’m assuming it occurred around the year 1900, but it could be anywhere from that year up through 1929 and the infamous Stock Market Crash. I can just imagine the scene, watching the Mount Olivet staff of the time erecting this monument. I saw the skill and expertise on display these past few weeks with the Benna and Cooper stones but with the advantage of today's equipment. I envision ropes, block & tackle and real horse-power with horses and men hoisting the base stone and obelisk needle into place—it must have been quite a sight.

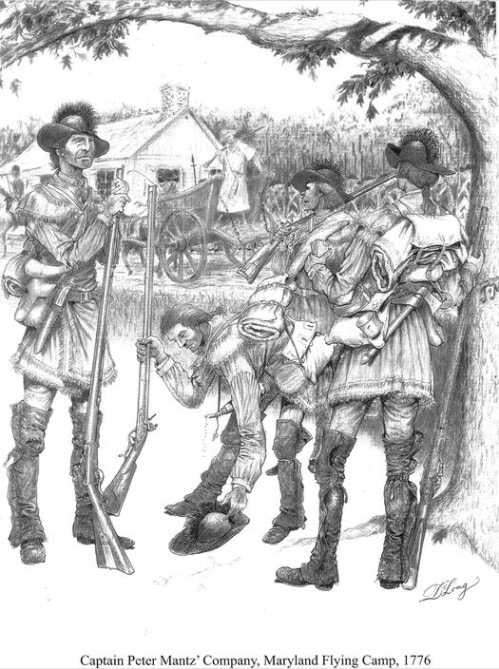

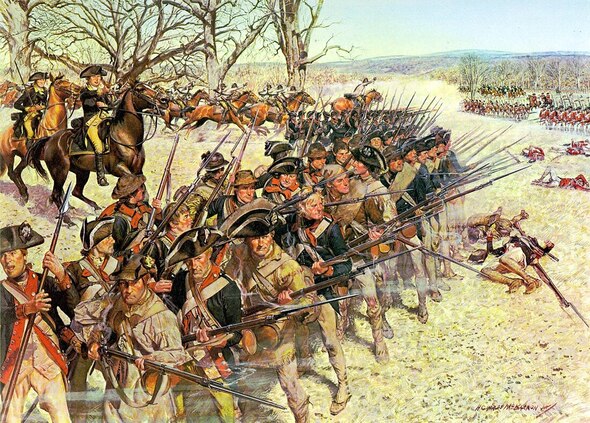

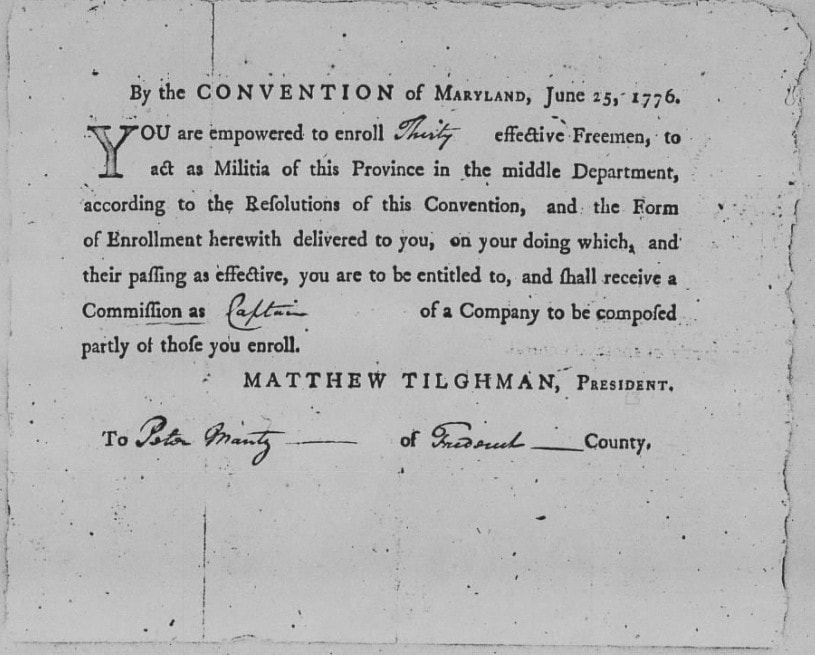

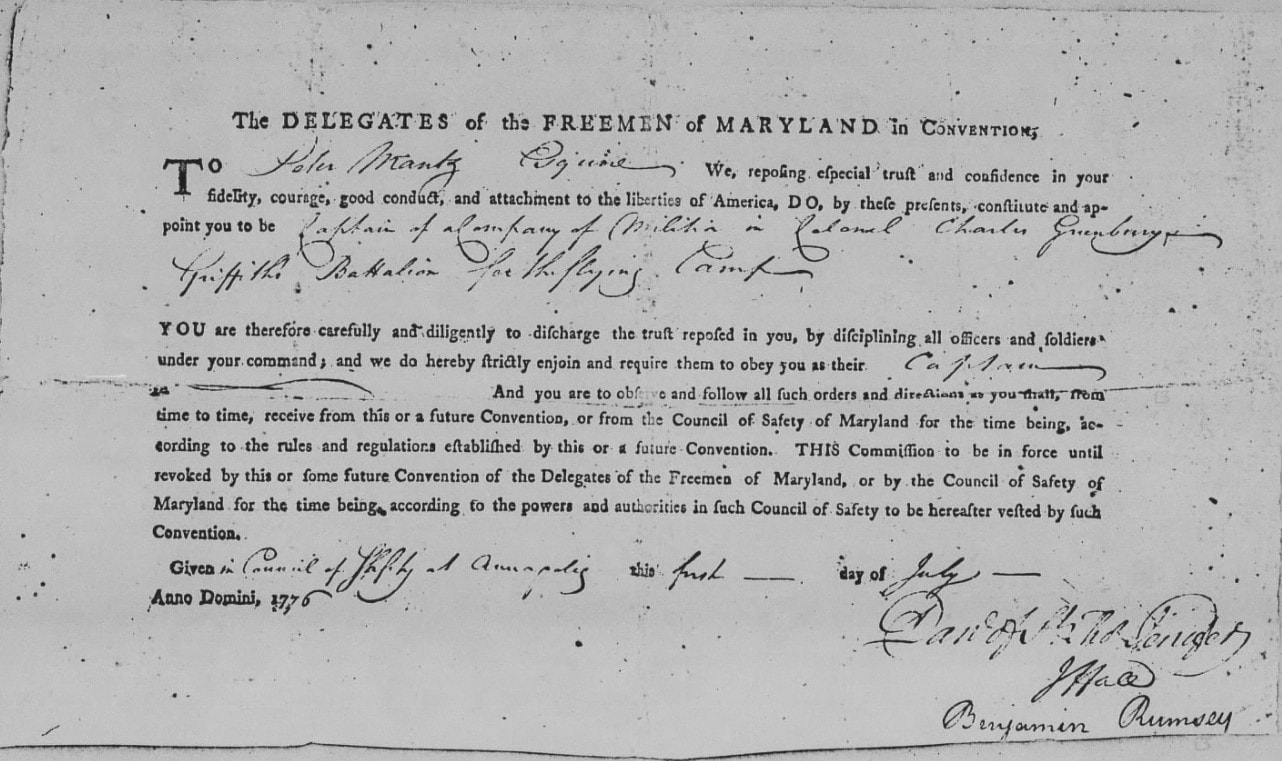

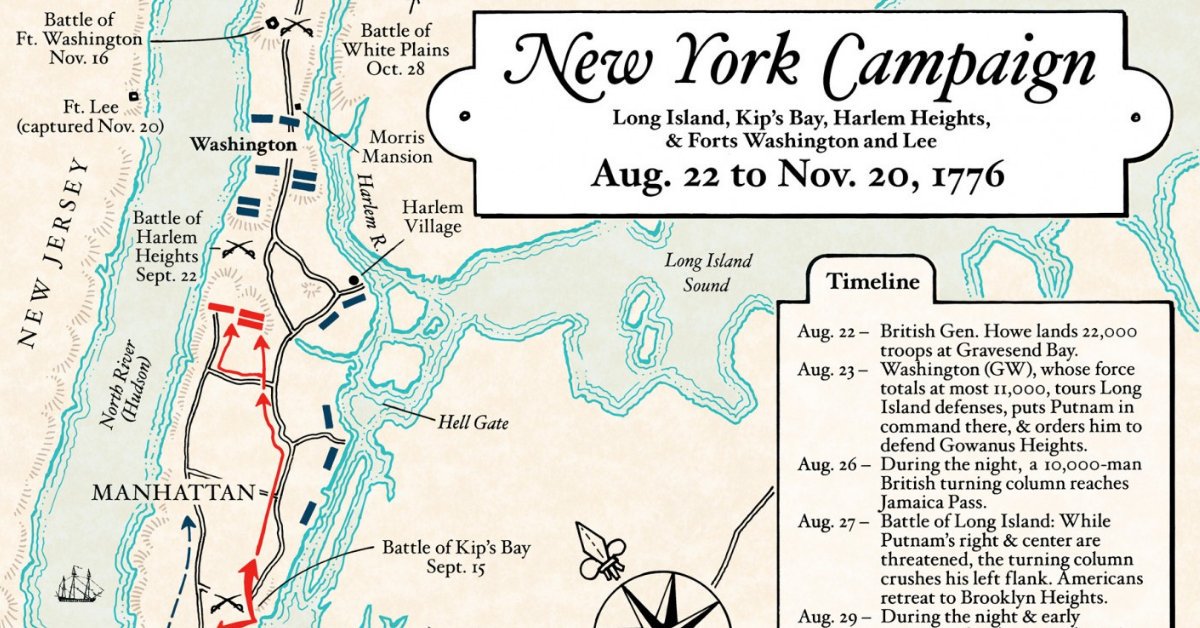

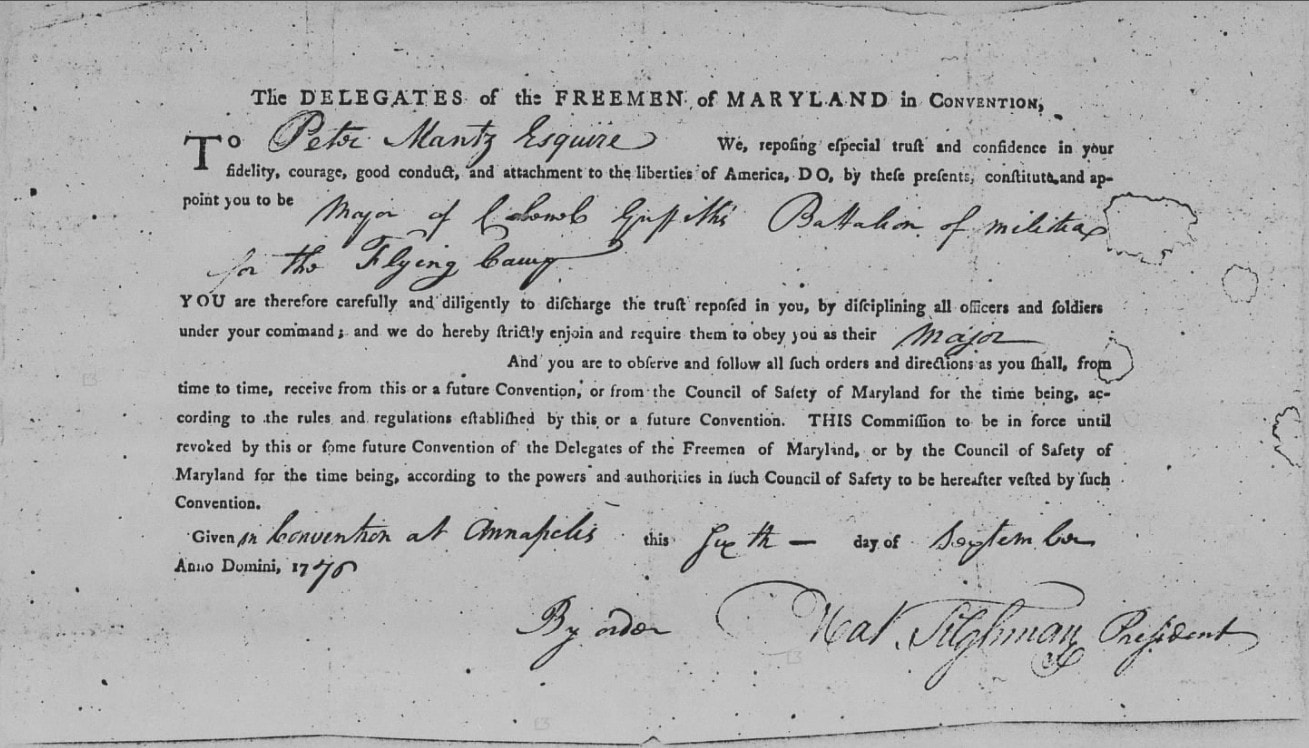

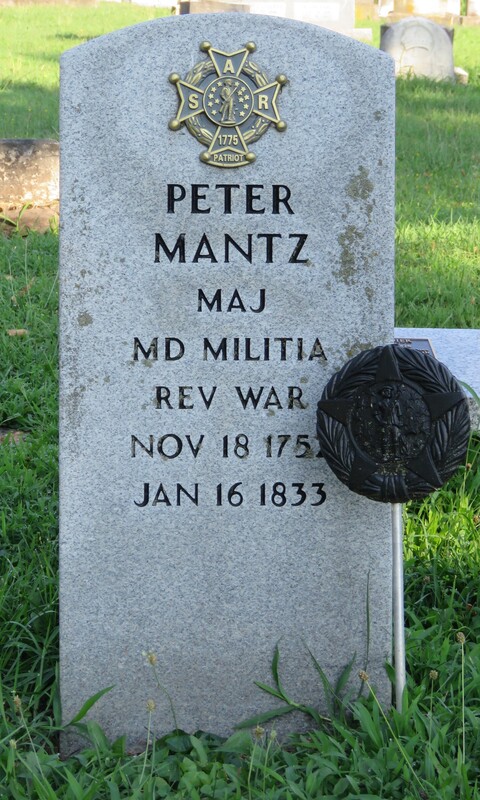

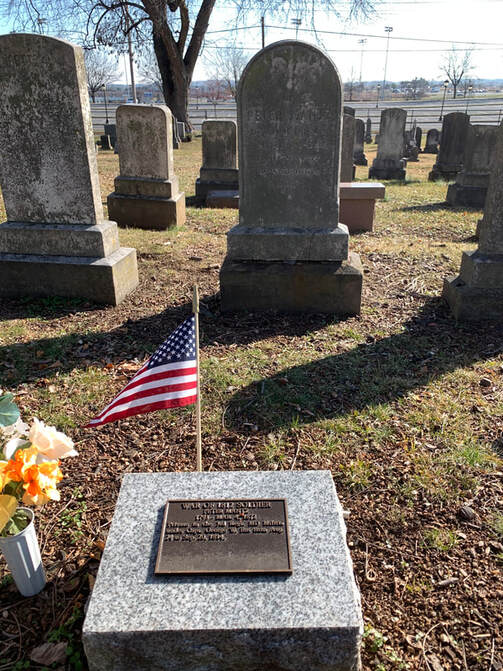

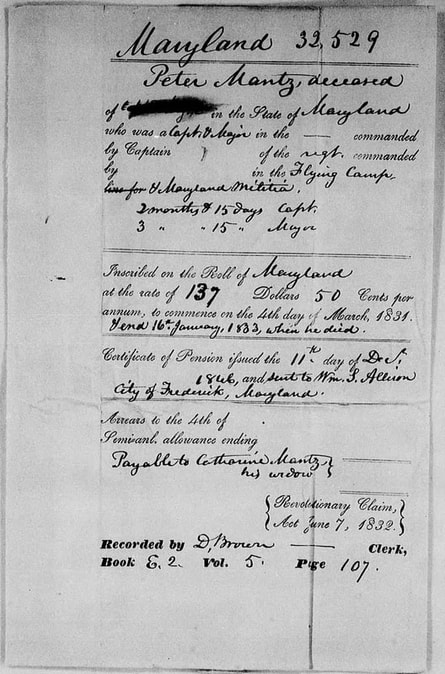

Oh the term, and name, “Patriot,” is being thrown around with reckless abandon this January, but not “thrown around” for the perennial reason with the New England Patriots making the NFL playoffs again—as they failed this year, after 17 appearances and five Super Bowls since 2000. I’m no fan of those Patriots, but I love the Boston-area patriots of 1775-1776 and forever beholden to my alma mater, the Gov. Thomas Johnson High School Patriots, a school that my wife and oldest son attended, while three more boys attend currently. Dictionaries offer the definition of the word patriot, as “a person who vigorously supports their country and is prepared to defend it against enemies or detractors.” Now, I know the media, politicians and some citizens (to themselves) are applying this term in respect to supposed “freedom fighters” involved in current (and past year) domestic events. I get the analogy, but I prefer seeing the lost fashion fad of tri-cornered hats at SAR functions and in Colonial Williamsburg. Call me old-school, but I prefer the age-old use learned in childhood that associates the term strictly with soldiers, militiamen and others who donated money, food, supplies and expertise to the Continental Army of the 13 Colonies in the War of Independence against Great Britain and King George III. An interesting side note, mentioned before in this blog series, is that the king’s father was the namesake of our fair town and county—Frederick Lewis, Prince of Wales. As a matter of fact, my parents gave me a bedroom with a patriot/American Revolution theme—no lie. My younger brothers had nautical and zoo themes respectively upon our move here to Frederick in 1974. I remember the Bicentennial year all too well, and my youngest brother and I even went as patriots for Halloween. I have to say, although some may think this was potential child abuse, (ie: a bedroom complete with Rev War-themed curtains, decoupage wall plaques of colonial soldiers, a Betsy Ross 13-star flag pinned on the wall, colonial drum bookends and piggy-bank and a 1776 bed comforter), it was definitely a factor playing a role in my career direction. I’ve said this before, TJ High School, and my time as a Patriot, was a prime influence on me as I had incredible teachers and the type of high school experience that you remember fondly for your lifetime.  Peter Mantz Dedication (June 2009) Peter Mantz Dedication (June 2009) In 2019, we had a nice little commemoration marking the 200th death of the fore-mentioned Thomas Johnson, a true patriot in the sense of the word who was a member of the Continental Congress, led Maryland troops in the American Revolution, helped draft Maryland’s state constitution and became it’s first elected governor. TJ served as one of the first Supreme Court justices and helped survey Washington DC as the new nation’s capital. Johnson was originally buried in the old All Saints’ Cemetery bordered by Carroll Creek and E. All Saints’ Street. He was re-interred in 1913, just one of many other patriots that were moved here from now gone downtown burying grounds. We have 40 confirmed patriots here in Mount Olivet today. Johnson’s brothers, James and Baker, are among these. Another well-represented, patriotic family went by the name of Mantz, and one of these actual patriots of ’76 has a birthday coming up at week’s end. January 16th, 2021 marks the 188th anniversary of the passing of former Frederick resident Peter Mantz. Now I know this is not a traditional anniversary year to commemorate one’s death date, but I didn’t want to wait until 2033, based on 2020, and the rate we are going in 2021 thus far. Peter Mantz is best known as one of Frederick County’s foremost soldiers in the Revolutionary War. A fitting celebration of this gentleman took place here at Mount Olivet back on June 28th, 2009. It was sponsored by The Sergeant Lawrence Everhart Chapter, Maryland Sons of the American Revolution, and featured an official dedication of Mantz’s gravesite by members of the MDSSAR Continental Color Guard and Rev. Frederick Pyne. The event was emceed by Chapter President Douglas and more than thirty folks were in attendance.  Captain Peter Mantz was born in Chester, Pennsylvania on November 18th, 1752 and moved early in his youth to Frederick County, Maryland. He was the son of German immigrants Johann Casper Mantz (1718-1791) and Anna Christina Heim (1728-1804), both hailing from Baden-Wurttemberg. Peter Mantz was among nine children belonging to an affluent family as the name of his father is readily found in the annals of our local history as a colonial-era “mover and shaker.” Our subject apparently received some form of organized education in the early days of Frederick, likely provided by the Evangelical Reformed Church of Frederick. He is said to have worked as a land surveyor and speculator. At the time of his death, he is reported to have owned 1,110 acres in Frederick and Allegany counties, plus five lots and ground rents on five more lots in Frederick Town by 1798. The winds of war blew strong in the mid-1770s and Peter and a few brothers answered the call to take up arms. Peter was part of the Toms Creek Gamecock Brigade. His father (Casper Mantz) also contributed money, food and supplies to the war effort.  “Captain Peter Mantz’ Company, Maryland Flying Camp, 1776”. On 3 June 1776, the Continental Congress resolved a ten-thousand-man flying camp be created to augment the Continental Army. This company was raised in Frederick County, Maryland. Company members are shown in their well-worn uniforms the morning of 16 September 1776 before fighting at Harlem Heights. Illustration by Don Long. Illustration from page 168 of Military Collector and Historian, Journal of the Company of Military Historians, Vol. 66, No. 2, Summer 2014. Peter eventually raised his own unit of soldiers from Frederick. He would serve with the 33rd Battalion of the Continental forces and was captain of the 1st Maryland Battalion of “the Flying Camp” during the Revolutionary War. What’s a “Flying Camp” you may ask? Well after the British evacuation of Boston in March 1776, Gen. George Washington met with members of the Continental Congress to determine future military strategy. Faced with defending a huge amount of territory from potential British operations, Washington recommended forming a "flying camp,” which in the military terminology of the day referred to a mobile, strategic reserve of troops. Congress agreed, and on June 3rd, 1776, passed a resolution "that a flying camp be immediately established in the middle colonies and that it consist of 10,000 men ...." The men recruited for the Flying Camp were to be militiamen from three colonies: 6000 from Pennsylvania, 3400 from Maryland, and 600 from Delaware. They were to serve until December 1st, 1776, unless discharged sooner by Congress, and to be paid and fed in the same manner as regular soldiers of the Continental Army. In July, 1776, Captain Mantz led his fellow Marylanders to the area of New Jersey to support Gen. George Washington's defense of New York City and the island of Manhattan in July. He and his part of the Flying Camp saw combat at the Battle of Harlem Heights, and nearby Fort Washington, where they took heavy losses. Afterwards, Mantz became a temporary major from September to December 2nd (1776) as the British overwhelmed the American forces in and around New York. His unit helped to cover the retreat of Washington's Army as it raced across New Jersey to the Delaware River. One of the officers in a different company in Mantz’s regiment, William Beatty, kept a diary of his time in the army. Their experiences would have been similar. You can read it online here within a 1906 edition of Maryland Historical Magazine: https://archive.org/details/marylandhistoric3190mary/page/104 Peter Mantz returned to Frederick in 1777 as he was appointed militia recruiting officer for Frederick County. After the war, Mantz served as tax commissioner in 1783, 1785, 1786 and a decade later in 1797. He served in legislative office by winning election for Maryland’s Lower House representing Frederick County in the 1782-83 General Assembly, however he did not attend and resigned in November, 1782. He would serve in this role, however, from 1786-1787. In that same year of 1787, he was made surveyor of Frederick County, and switched over to county sheriff from 1788-1791.

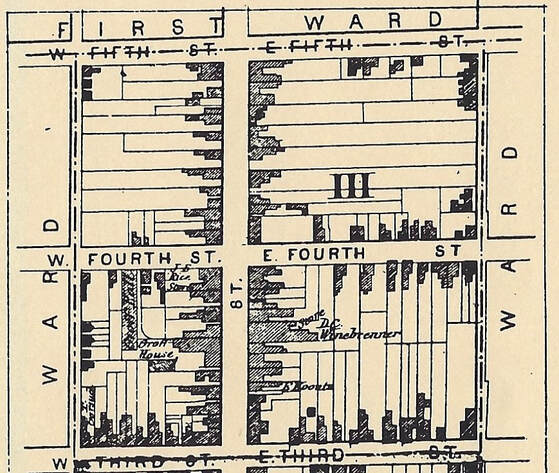

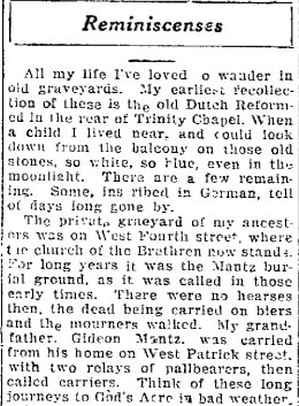

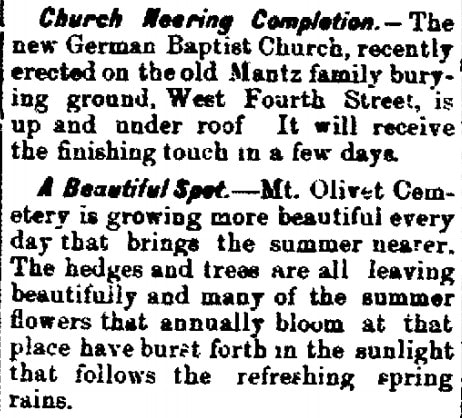

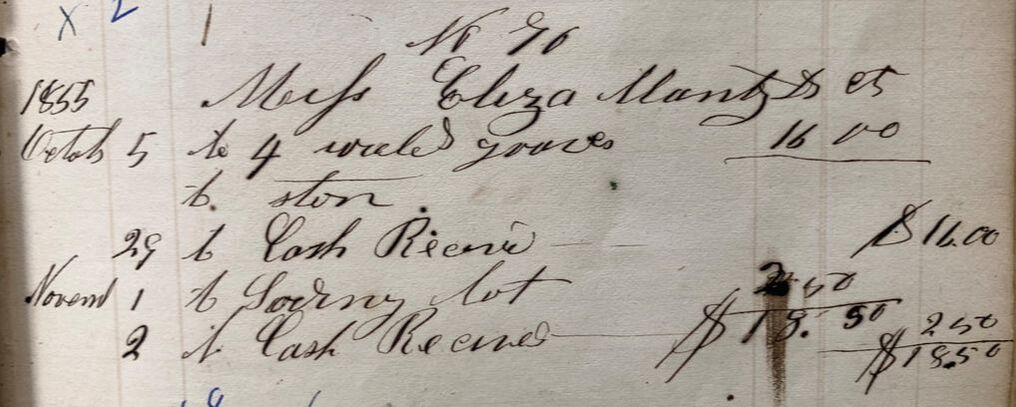

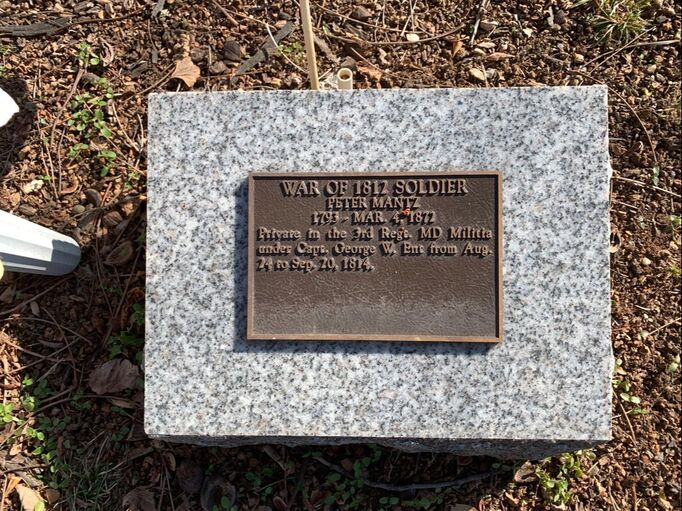

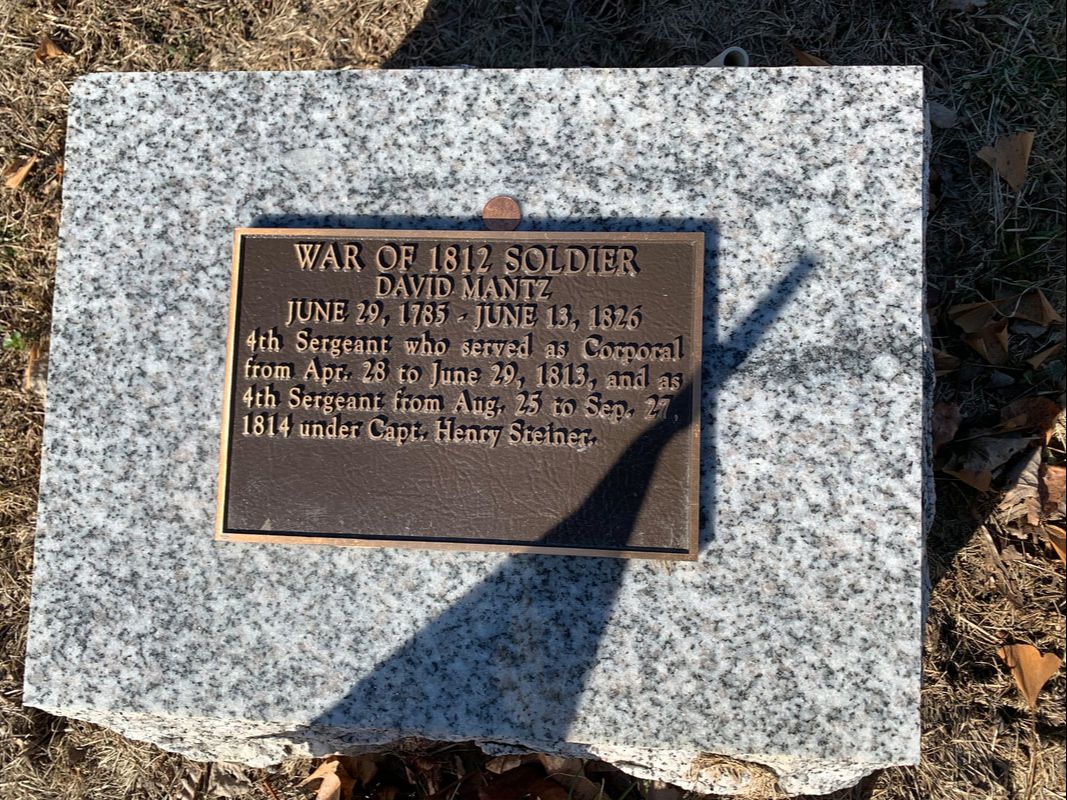

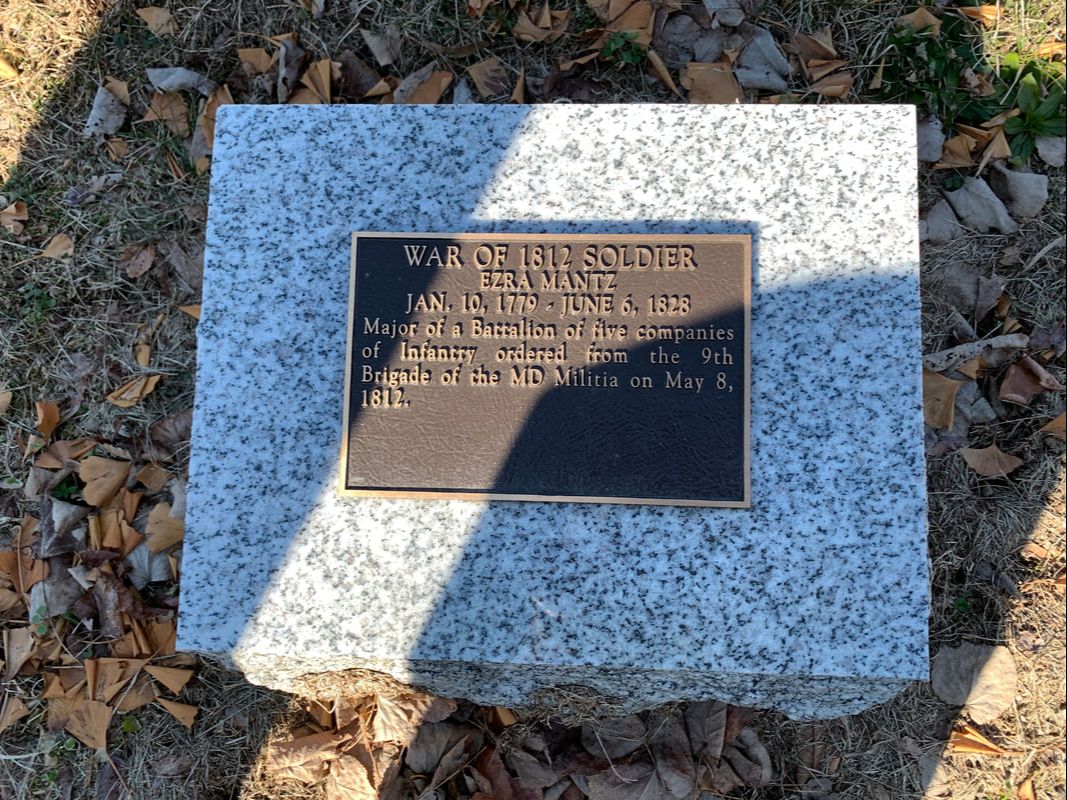

Engelbrecht’s diary entry makes mention that our "patriot of interest" was originally placed in a burying ground that no longer exists in downtown Frederick, known as the Mantz Graveyard. This property appears on old tax property maps on the north side of West Fourth Street and was more square than long and narrow like most city lots, so I researched it further. The Mantz burying ground was on the northeast corner of West Fourth and Klineharts Alley, running 110 feet along Fourth and 80 feet along the Alley. Today, the addresses are 21, 23 and 25 West Fourth. After an equity case in 1885 (William Mantz et al vs Charles Trail et al), the property was sold to the German Baptist Brethren to build a house of worship. The deed also specified that they were to "take proper care of the human remains buried in said lot of ground." The Brethren sold the property in 1955, and in 1962, it was sold to the Peoples Baptist Church. The property was sold by that church in 1973 to a private party, but the property was still "commonly known as Mantz Burying Ground" as late as a 1978 deed. From our records, Peter appears to have been re-interred here in Mount Olivet on October 5th, 1855. This was roughly a year-and-a half after our garden cemetery opened. Other family members are buried here too including his wife, parents, siblings, and multiple children. In his funeral plot located in Area E/Lot 138, one can find: A few lots away in Area E/Lot 147, rest three of Patriot Peter's sons who fought in the War of 1812: Peter Mantz, Jr. (1794-1872), Ezra Mantz (1779-1828), and David Mantz (1785-1826). In recent times, visitors and genealogists found the tombstone of Major Peter Mantz was eroded to the point that it was illegible. The Everhart SAR Chapter took the initiative to order a new military tombstone from the Veterans’ Administration. This would be unveiled at that commemorative event back in 2009. To learn more about Mount Olivet’s other patriots from the American Revolution, I invite you to visit our companion website, www.MountOlivetVets.com. Here, we are building memorial pages for over 4,000 veterans in Mount Olivet. The website, published in fall, 2017, can best be described as "a work in progress," and is being continually added to. We humbly ask for the assistance of descendants, historians and friends to provide us with photographs. portraits, documents and/or additional information of note to add. We also want to link to other sources of information regarding our vets, and the training and battles they participated in. As opposed to a finished publication like a book, we have the opportunity to add supplemental images and information at will, while also having the ability to correct errors and misnomers. We hope this site provides an educational and informational portal, one that sheds light on why Frederick, Maryland has always been linked to patriotism and the American flag.

"Little Christmas," also known as "Old Christmas," is one of the traditional names among Irish Christians and Amish Christians for January 6th, which is also known more widely as the Feast of the Epiphany, celebrated after the conclusion of the twelve days of “Christmastide.” It is the traditional end of the Christmas season and until 2013 was the last day of the Christmas holidays for both primary and secondary schools in Ireland. Christmastide (also known as Christmastime or the Christmas season) follows the better-known Advent and is a season of the liturgical year in most Christian church which begins on December 24th at sunset or Vespers, which is liturgically the beginning of Christmas Eve. Customs of the Christmas season include gift giving, attending Nativity plays, and church services, eating special food, such as Christmas cake, and singing Christmas carols. Today, it seems that Christmas music is shut down on December 26th, but this wasn’t the case when Little Christmas was more in vogue. Of course, one of the most fitting and familiar songs heard during this period in days of old was "The Twelve Days of Christmas."

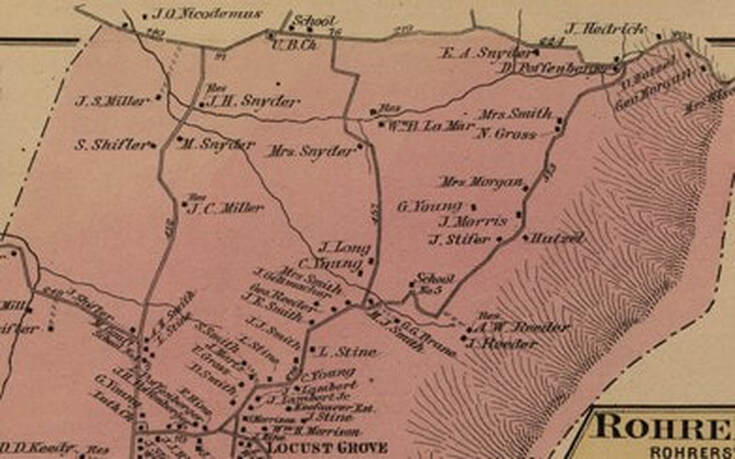

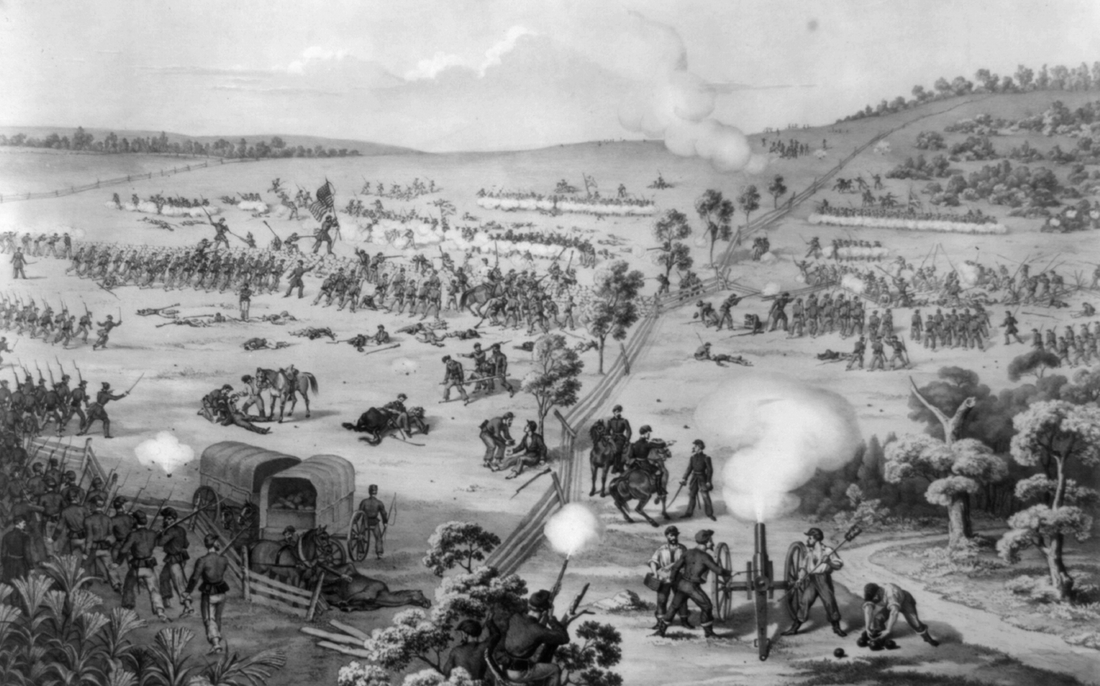

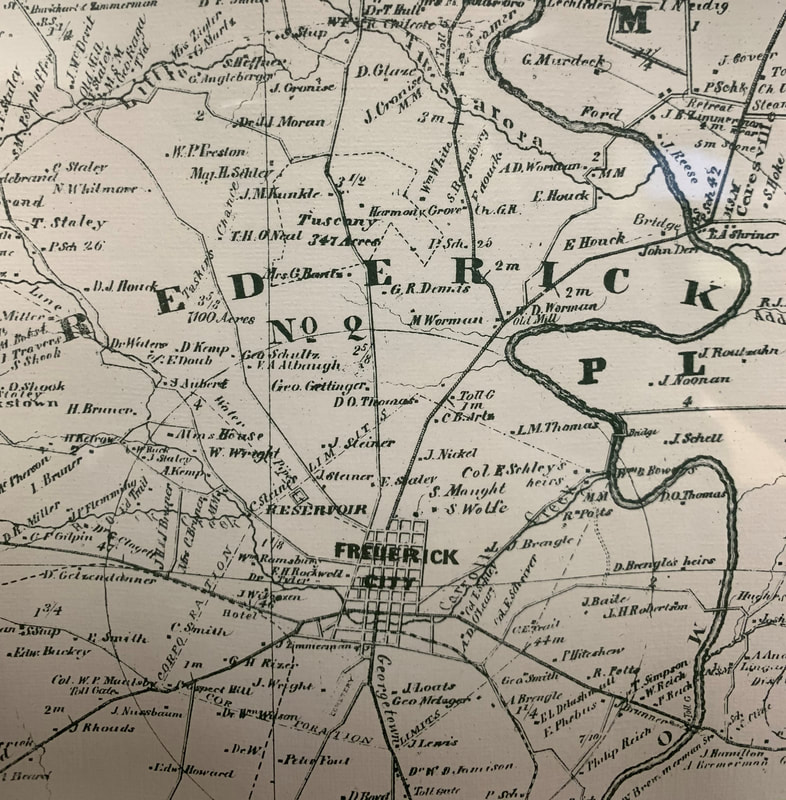

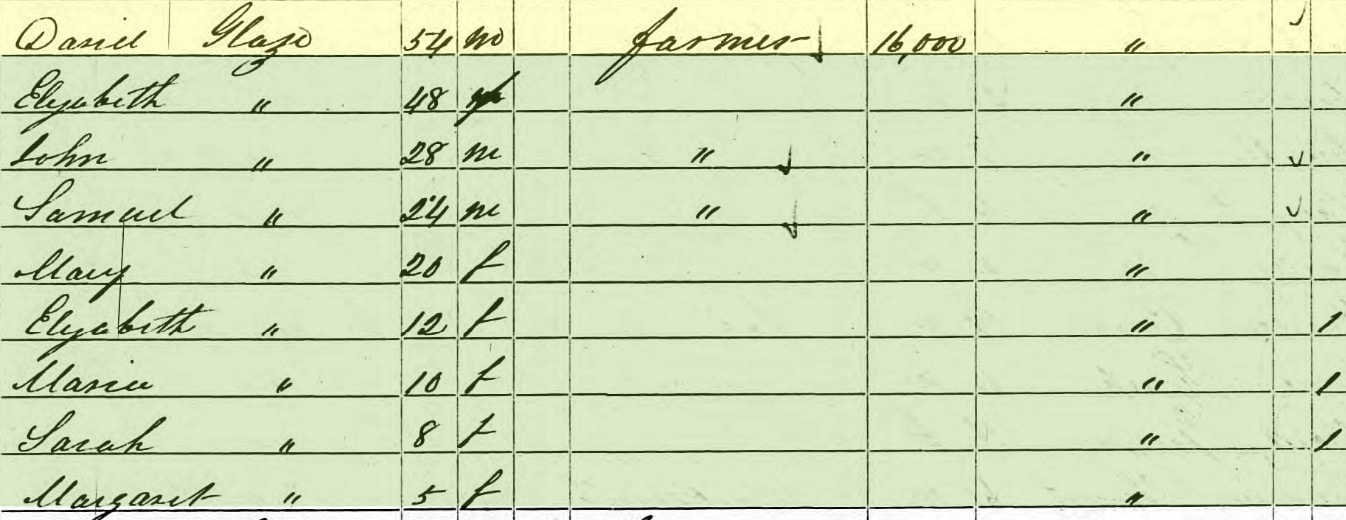

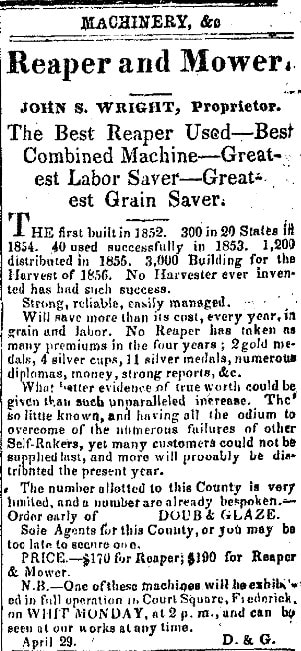

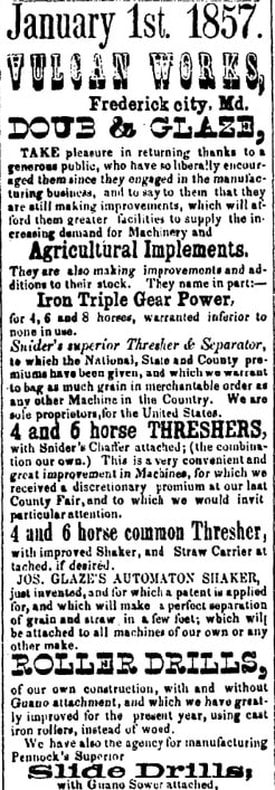

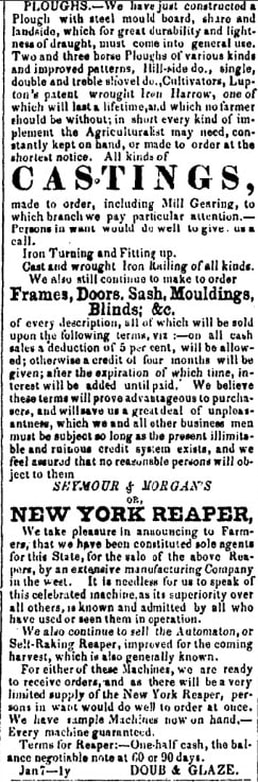

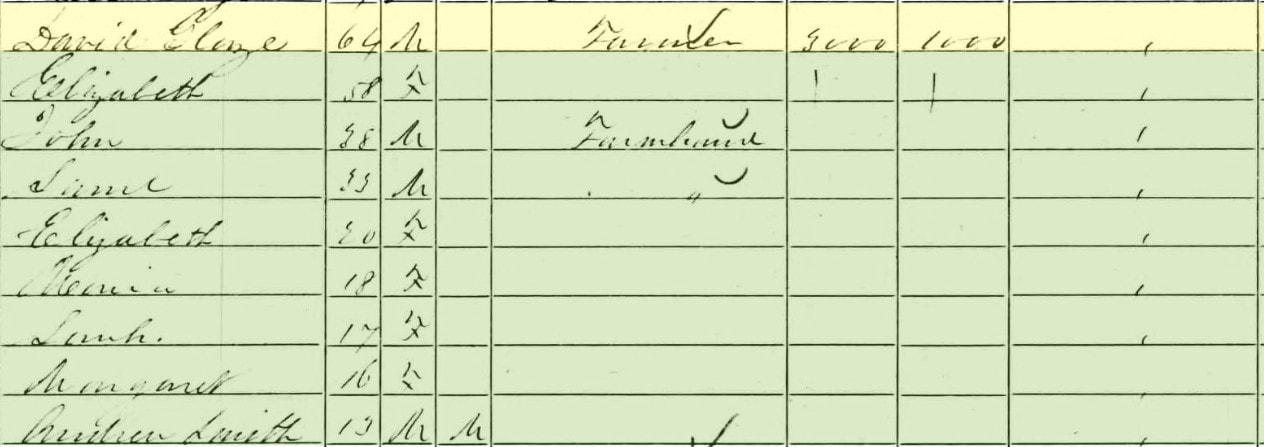

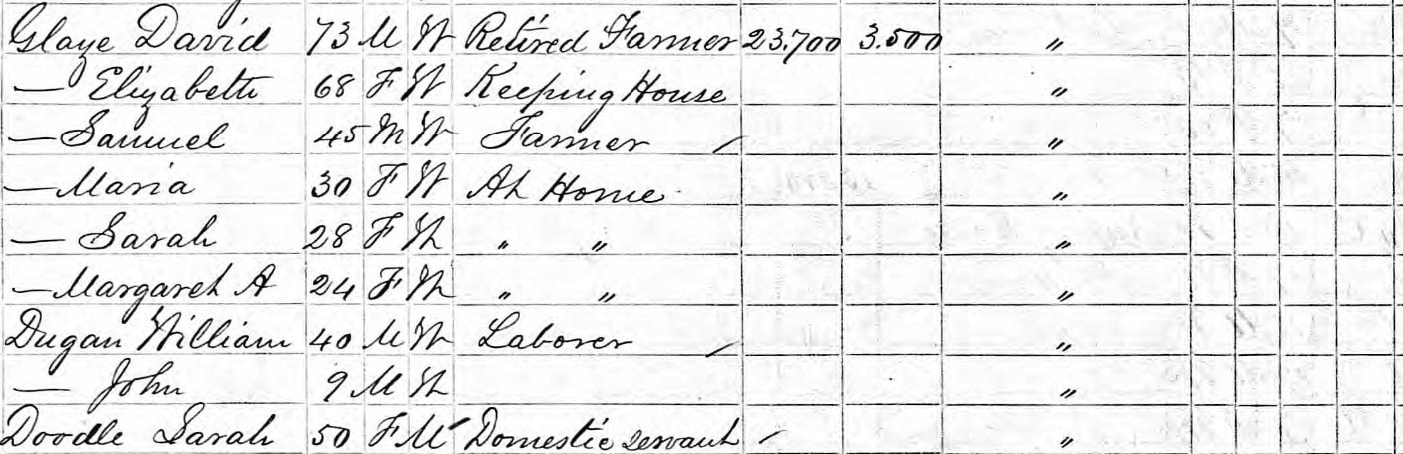

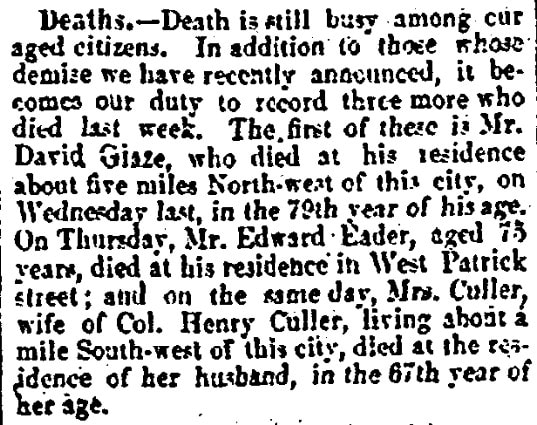

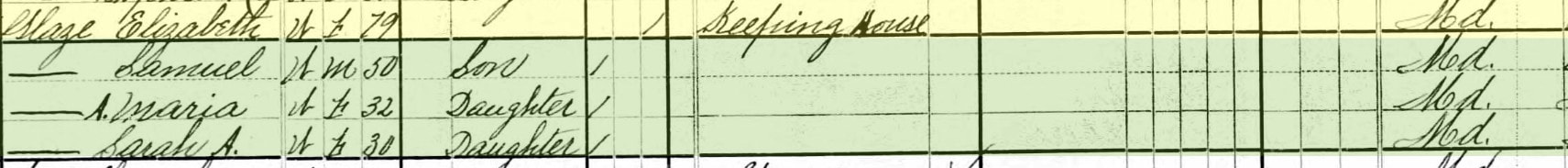

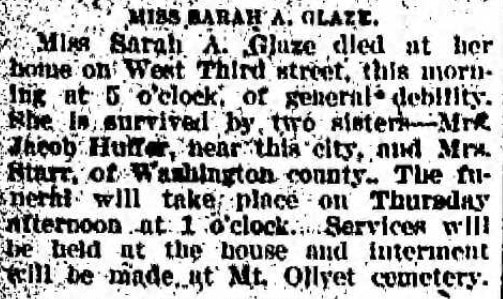

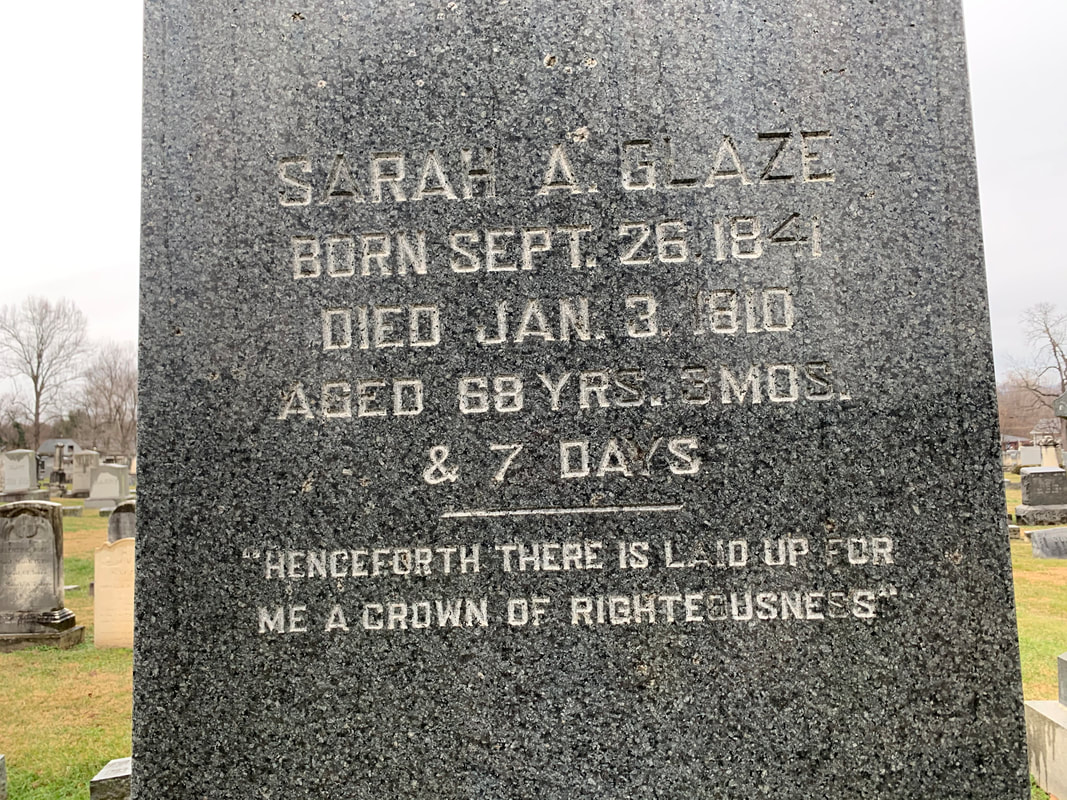

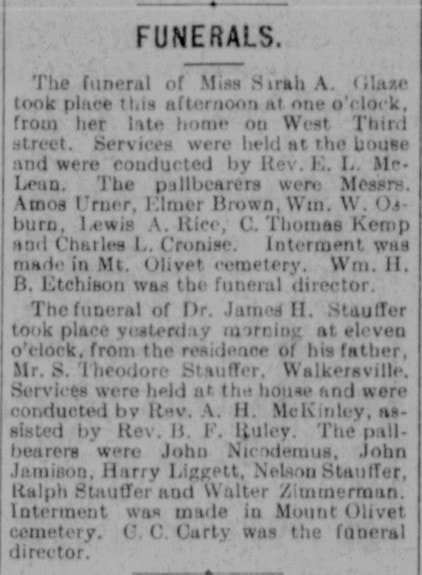

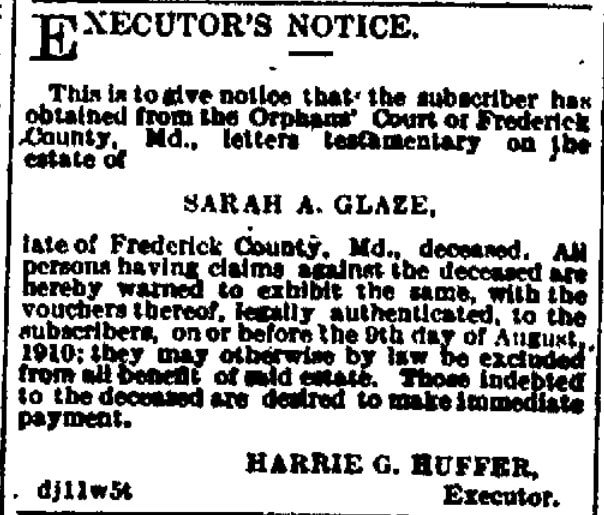

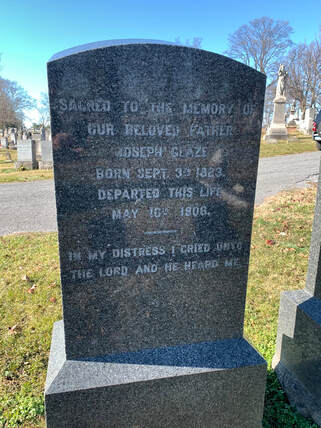

Outside of “drummers drumming,” “maids a-milking” and “lords a-leaping,” the song is half-comprised of aviary gift offerings ranging from partridges to turtle doves to French hens. Not in the market for “calling birds,” “swans a-swimming” or “geese a-laying,” especially this time of year, I can also confess that my “Christmas List” also doesn’t include the fore-mentioned “golden rings,” “dancing ladies” or “piping pipers.” But, hey, no complaints from me, as it’s been a nice twelve days regardless. In researching this piece, I learned that there are several celebrations comprising Christmastide, including Christmas Day, St. Stephen's Day (December 26th), Childermas (December28th), New Year's Eve, the Feast of the Circumcision of Christ or the Solemnity of Mary, Mother of God (January 1st), and the Feast of the Holy Family (date varies), and Epiphany Eve or Twelfth Night (the evening of January 5th). However, to my surprise, I found a brand-new celebration compartmentalized within the joyous “Twelve Days,” truly making it a Baker’s Dozen, both literally and figuratively. That’s right, “Four Days of Glaze!” from December 31st-January 3rd. Two dozen Krispy Kreme glazed doughnuts for $12! What a Christmastide delight for young and old, while crushing thousands of proposed weight loss New Year’s resolutions on a national scale. Only a temporary setback for the determined however, but made me think of a great lyric object if only the Twelve Days of Christmas Song was actually “Twenty-four Days of Christmas”--24 donuts a-glazin’. Yours truly certainly took advantage of this sugary celebration, but I admit that it was solely due to the arduous research work I was conducting on this week’s subject, a lady by the name of Sarah Glaze. In my introductory internet searches for “Glaze,” I was inundated by Krispy Kreme advertisements as you can imagine. Weeks ago, I was truly thinking that my lead-in segue for this blog would have been tied to a bout with freezing rain over donuts, but warmer temperatures simply delivered rain without a chance for “precipatory glaze.” Sarah A. Glaze. The possessor of one of the more magnificent monuments in the cemetery, I have marveled at the large monument dedicated to the memory of Sarah A. Glaze for the last few years. I wondered who this woman was, especially one who deserved such an amazing memorial? The name isn’t a Frederick moniker of local nobility. The woman never married and had no children. However, I have always been struck by the sleek, polished look of her massive grave in Area H, which must have been very expensive. It almost gives off the look of glaze, which is defined as a vitreous substance fused on to the surface of pottery to form an impervious decorative coating or, in the case with doughnuts and cake, a liquid such as milk or beaten egg which is used to form a smooth, shiny coating on food. After hours of study, I can’t say that Miss Glaze led a life becoming of such a name or grandiose monument. Instead, she seems more of the plain doughnut variety, perhaps a powdered doughnut, but that may be a reach. Sarah Ann Glaze was born on September 26th, 1841 in the Pleasant Valley district outside Keedysville in neighboring Washington County. She was one of eleven children born to David Glaze (1795-1873) and wife Elizabeth Furry (1799-1884). Previously, David Glaze had bought his Washington County farm in 1832 from his father Wendel Glaze (of whom a familysearch.org family tree gives the name as Johannes Wendel Glaze, born in Lancaster county, PA). Wendel came to America with his family as a young boy and his surname became Anglicized from the original “Kless.” The German word for “glaze” is “Die Glasur” in case you were curious. I learned that Kless translates to “the conquering people,” not quite glaze. Wendel, our subject Sarah’s grandfather, bought the Pleasant Valley property from one, Jacob Snyder Jr. It was located on the west side of the Rohrerstown Pike, MD67, and on the south side of what is now called Dogstreet Road, west of Mt. Carmel Road. On the 1877 Washington County Atlas (Lake, Griffing & Stevenson), the former Glaze property is owned by a J. S. Miller whose father had married into the Glaze family. Attached is a Google map - the property that shows as brown dirt with buildings in the middle is essentially the same property that Glaze owned. Across the street, to the east, sits a popular wedding venue by the name of "Whistling Wren Farm.” Three of Sarah’s siblings died on this farm and are buried in the small Snyder Farm Cemetery located about a half-mile south of their original home. (Note: the Snyder burying ground is located at 5513 Mt. Carmel Road). David Glaze sold his homeplace in 1850, when Sarah was nine years-old. She and her siblings (three brothers and three sisters) moved east to Frederick County. The former Glaze farm was certainly affected twelve years later as the Battle of South Mountain raged at nearby Fox’s Gap, a mile and a half to the east, on September 14th, 1862. The nearby Battle of Antietam raged a few days later to the west, but luckily about four miles distant. Most certainly soldiers of either, or both, armies trod the one-time Glaze Farm and at the very least, the surrounding roads. The Frederick-area farm that David Glaze moved his family was located a few miles north of Frederick City. There’s a possibility that Civil War soldiers could have walked this farmland as well, but luckily it was relatively far from the scene of the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863 and the Battle of Monocacy in 1864. The 237 acre parcel was located where the Willowbrook housing development stands now (roughly between US15 and Opossumtown Pike, south of Tuscarora Creek). “D. Glaze” is shown on the 1858 Bond map and again in the 1873 Titus map at this location.

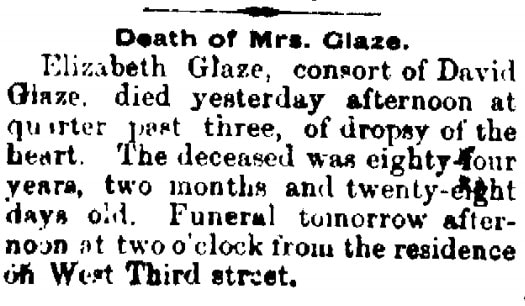

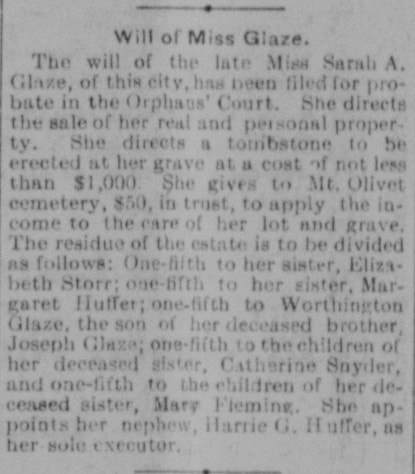

We have also talked about the colorful Captain Ezra Doub in a few past “Stories in Stone,” as his final resting place is here in Mount Olivet’s Area C/Lot 127. The Doub and Glaze Foundry and machine shop was listed in the 1860 census of manufactures in Frederick with $19,000 capital investment, 20 employees, and a 15hp steam engine. A great addition to this firm came with inventor extraordinaire McClintock Young. Annual output was 15 wheat drills and 200 plows ($8950). Look around Frederick, and you will still see cast iron grates and doors in sidewalks, along with coal chute covers on sides of dwellings that were produced by this firm. Now, I went into detail with this because Sarah, later in life, would live with her sister Maria in a house at 110 and 110A West Third Street purchased from Christian Bushey in 1884. The Glaze family may have been renting this house at least since 1870 based on the census record showing them on West Third Street. There is a link between this house and the Glaze’s Willowbrook farmstead as both had been owned by Benjamin Fitzhugh. The West Third Street house was owned previously by Christian Bushey's father, Jacob, bought by Fitzhugh in 1864, but reverted back to Christian as trustee. The farm, of course, conveyed to Sophia Fitzhugh in 1849. In addition, Jacob Bushey owned an early mill at the foundry site, and after a few owners (or leases) went to Fitzhugh. It’s my opinion here that it appears that everyone here may have had mortgage management and money issues. My research assistant Marilyn Veek conjectures that perhaps David Glaze couldn't afford to buy a town house, because he had a mortgage on the farm until 1864. Marilyn couldn’t find any deeds for David Glaze buying property on West Third. David Glaze died on January 21st, 1873 and was buried in Mount Olivet on Area H/Lot 305. David Glaze’s heirs, including Sarah, sold the family farm shortly thereafter. Mrs. Elizabeth Glaze headed the townhouse residence in the 1880 census at the Third Street property. She would pass just over 11 years after her husband and is buried at his side in Area H. Maria and Sarah took over the property at this point and I found that Maria died four years later in January, 1888. Sarah appears to have either rented or shared the home with other ladies over the next two decades. I was puzzled to not find any mentions of her in the local newspapers until her death on January 3rd, 1910 at the age of 68 years, 3 months and 8 days—a fact stated on her monument.  Scene from the Barre (VT) Quarry Scene from the Barre (VT) Quarry Was she just a good, ole-fashioned miser? I don’t know if Sarah A. Glaze belonged to clubs, attended church, traveled or celebrated holidays such as Christmastide. And if she did, she only made it through ten days of Christmas. All I know is that the month of January was not kind to the Glaze family, as it claimed Sarah, her live-in companion/sister and parents. You could say the month gave Mount Olivet “Four Graves of Glaze.” Our friend, cemetery restoration expert Jonathan Appell of Southington, Connecticut, pointed out to me how impressive this monument really is as it is crafted from Barre granite, a material much preferred for building projects and by sculpture artists for use in outdoor works. For tombstone and geology fans, Barre granite is a Devonian granite pluton found near the town of Barre in Washington County, Vermont. It is best described as “a fine granite, composed of quartz, feldspar, and mica. The mica is both muscovite and biotite.” The granite is mined at the E. L. Smith Quarry, the world's largest "deep hole" granite quarry, owned by the Rock of Ages Corporation. "Barre Gray" granite is sought after worldwide for its fine grain, even texture, and superior weather resistance. Jonathan also said it is quite expensive as well! They say you can’t take it with you, but it appears that a good chunk of Sarah’s money is close at hand. The monument is topped with arguably the most popular funerary symbol of the nineteenth century, a draped cinerary urn. The drape can be seen as either a reverential accessory or as a symbol of the veil between earth and the heavens. The urn was an ancient vessel used to hold human ashes and prevalent as an iconic symbol of the Victorian Age. An inscription carved on the monument's face is taken from the Bible’s Book of Timothy (The First Epistle of Paul to Timothy): “Henceforth there is laid up for me a crown of righteousness.” In addition to Maria, six more of Sarah's siblings are also buried within Mount Olivet: John H. Glaze (1822-1862), Joseph Glaze (1823-1906), Samuel F. Glaze (1825-1895), Mary A. (Glaze) Fleming (1829-1891), Elizabeth (Glaze) Storr (1837-1917), Margaret Ann (Glaze) Huffer (1846-1923). Fittingly, the Krispy Kreme promotion ended on the 110th anniversary of this lady’s death. I truly honored her by enjoying a glazed doughnut in her memory on January 3rd, 2021. I truly apologize if I offend, but the purpose of cemeteries is to bury the dead first, but more so, to remember them and their deeds (great, small or possibly non-existent to future researchers eyes) as fellow, and equal human brethren.

|

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed