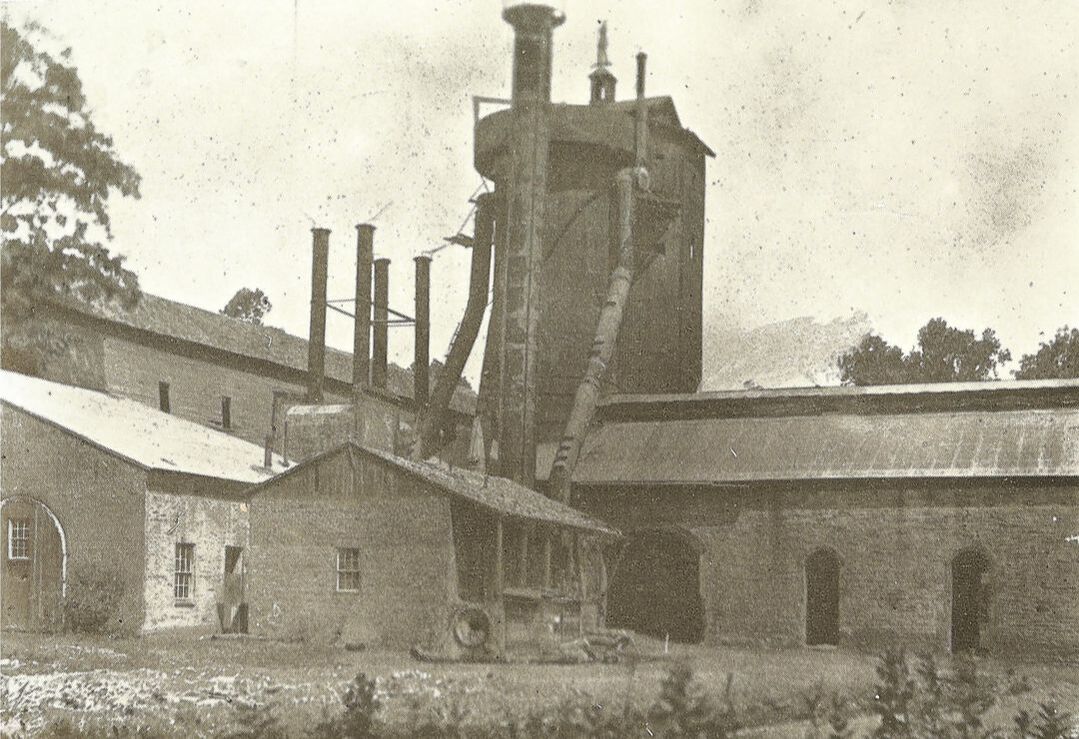

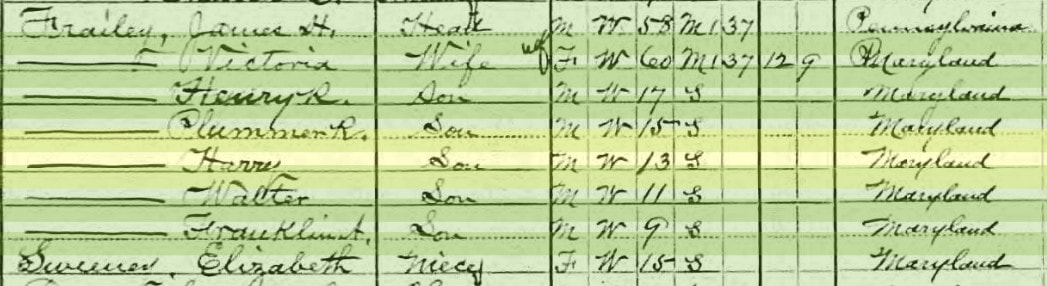

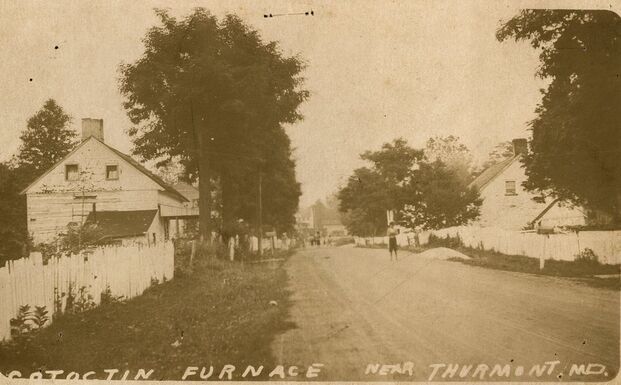

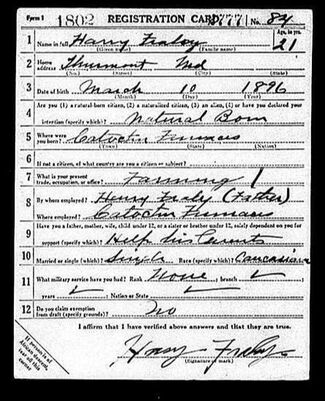

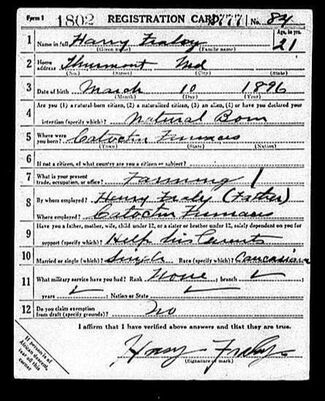

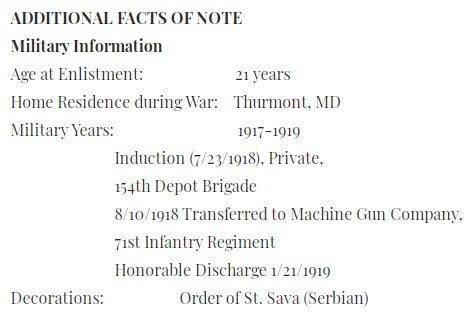

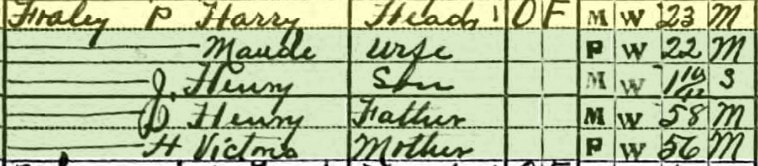

F. W. Fraley General Store in Catoctin Furnace F. W. Fraley General Store in Catoctin Furnace I guess you could say that Harry Payton Fraley spent the bulk of his life around furnaces and ovens—quite a “warm existence.” Born on March 10th, 1896, Harry was the son of James Henry Fraley and wife Victoria Isabelle Sweeney, farmers in the vicinity of Catoctin Furnace. The small northern Frederick County hamlet (below Thurmont) boasted a prosperous iron producing operation established by James and Thomas Johnson at the advent of the American Revolution. A bustling industrial and residential complex grew up here taking the name of Catoctin Furnace from the adjacent geologic structure of neighboring Catoctin Mountain. Harry’s cousins operated the company store for many years, so named with the family moniker—Fraley’s General Store. Harry P. Fraley’s great-great-grandfather, Johann Henry Frolich (anglicized to Fraley), was a drummer in the Hessian Army and apparently captured at the Battle of Yorktown in 1781 and brought to Frederick to be imprisoned. After the war ended, he, like many other Hessian soldiers, decided to stay in the fair county and the newly victorious United States of America. Johann would eventually gain employment at the Johnson Furnace and lived in the village until his death in 1830. His son, Solomon, and grandson, Jonathan S. Fraley, worked as laborers at the furnace in addition to farming. The latter (Harry P. Fraley’s grandfather) took employment at the local furnace, with the 1880 US Census showing that he drove a delivery team of mules for the operation. Harry grew up here at “The Furnace” and attended the local public school up through the 7th grade, which was customary as he assisted his father and siblings on the family farm. He would experience three major events in his childhood. In 1903, the Catoctin Furnace went out of blast, being quieted for good after a run of 128 years. In June, 1905, tragedy struck the residents as news reached town that a flat car loaded with railroad workers from Catoctin Furnace was being hauled up the line and as a result of an error in signals, a fast train crashed into it. Almost every family in the village was touched by a personal loss. Two years later in 1907, the Catoctin Iron Works went into the hands of receivership and was sold to a congressman from Bedford County, Pennsylvania and soon closed. All of the machinery was moved to a like plant near Pittsburgh. In February 1918, Harry married Maude Mahala Zimmerman. Five months later, the groom shipped out of the vicinity to participate in World War I. He was a private with the Machine Gun Company within the 71st Infantry Regiment. He is one of nearly 600 local veterans of the Great War featured with a memorial page on our sister website www.MountOlivetVets.com. Here is a brief overview of his war experience including his draft/enlistment papers. Harry would be honorably discharged in January, 1919 and came back to Catoctin Furnace unscathed. He got to first hold his son, Francis James Henry Fraley, who had been born in December, 1918. The couple can be found living here in the 1920 US census.  The exciting inner-workings of a vintage stave mill The exciting inner-workings of a vintage stave mill The furnace property had been used for a couple of different purposes, but the hamlet’s lifeblood was gone. One of these supplemental operations gave employment to Harry P. Fraley. In 1920, he took a job at the local stave mill here, housed within some of the old furnace operation buildings. Stave mills produce the narrow strips of wood that compose the sides of barrels, which were vital for the transportation of goods in the days before easily fabricated boxes and waterproof plastic containers. The Hickory Run Stave Mill was begun in 1914, and managed by a firm out of Lehigh, PA. It would operate for about 12 years. By 1930, Harry had moved to the Ballenger Creek Pike area southwest of Frederick, and was employed as a tenant farmer on a property owned by his father-in-law. Fraley also dabbled in trucking and hauling. He would live with his wife and son until 1938, at which time he separated from his wife. The 1940 census shows that he was a driver for an oil refining company. The couple was back living together again, but this would not last. In early 1946, Harry and Maude officially divorced, apparently due to Harry’s abandonment the previous year. Both had been put through immense strain in June, 1944 as they endured the news that son Francis had been wounded in France during World War II. In 1956, Harry remarried a divorcee named Lillian Anna Wachter. The two lived at 22 Hamilton Avenue in Frederick.

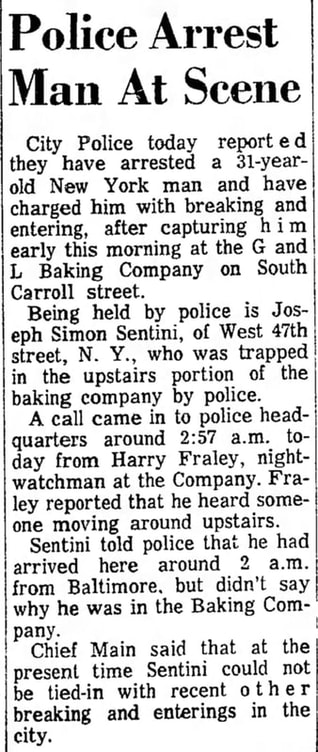

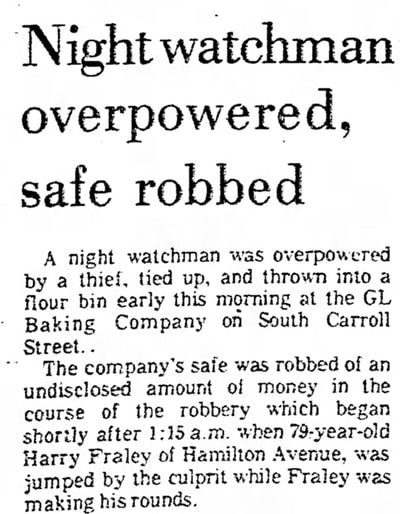

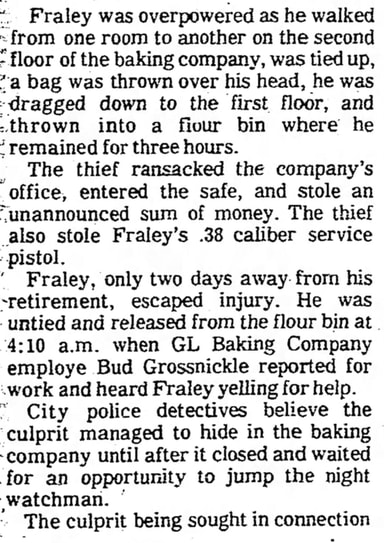

Oh What a Night Harry lived out his life working as a night watchman for the G&L Baking Company, also written out as G.L. Baking Company. It was a peaceful and drama-free job for the man from north county, at least until his very last week on the job before a well-deserved scheduled retirement in September, 1975. On that particular overnight of September 25th/26th, while making his rounds, the native of Catoctin Furnace suddenly found himself “floured and battered,” but not exactly in that particular order. Not a good showing for Harry as the bad guy made off with the dough, both literally and figuratively. So much for the gold retirement watch, I guess. I’m not sure if our subject had to work out his last two days or not, but he would retire from G.L. Baking with the dark-comedic story of a lifetime to tell, although not of the standard hero variety. Regardless, Harry P. Fraley was a child of the mighty furnace, a war vet, and faithful employee of the stave mill and bakery. I could not find anything further on the case, and am figuring they never caught the culprit. Harry would live to tell his harrowing tale for six anniversaries of the bakery burglary event. He died a few weeks prior to the 7th anniversary, succumbing on September 9th, 1982. He was laid to rest in Mount Olivet’s Area GG/Lot 55 by the side of wife Lillian, who had died nearly two decades earlier. I have to say, this simple story made quite an impact on me, so much so, I was inspired to place "flours" on Mr. Fraley's grave. It was only temporary though, and I had to settle for a brand other than G.L. --as it's been quite a while since that local product has been on the grocery store shelves!

(Author's Note: Special thanks to Thurmont mayor/historian John Kinnaird for the period images of Catoctin Furnace from the Robert S. Kinnaird Collection of Historic Thurmont Photographs.

2 Comments

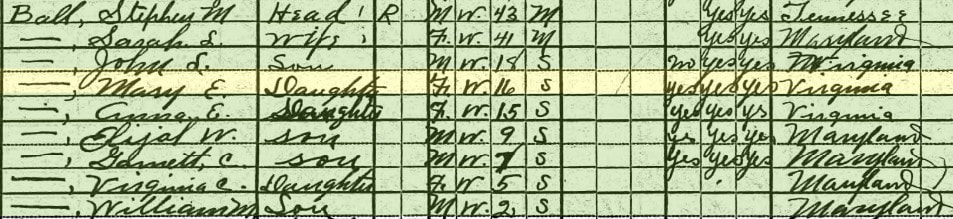

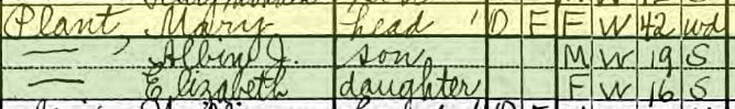

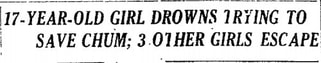

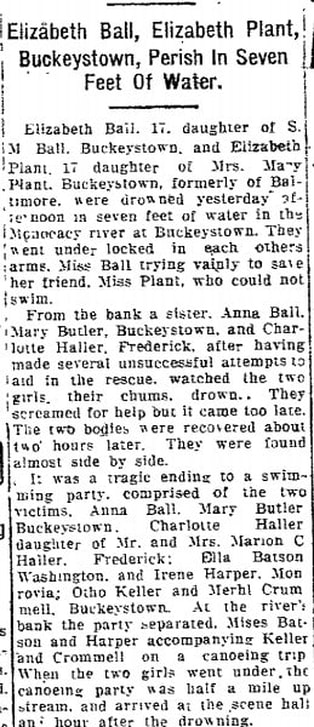

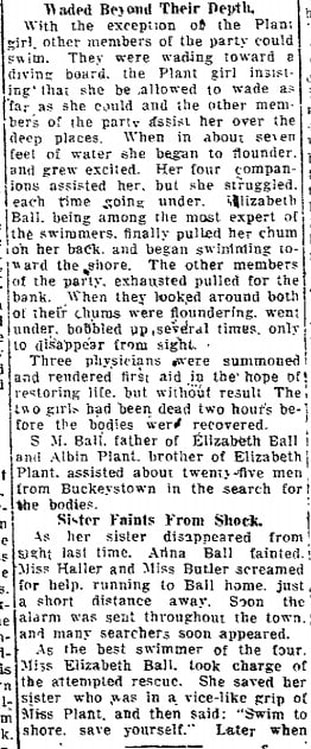

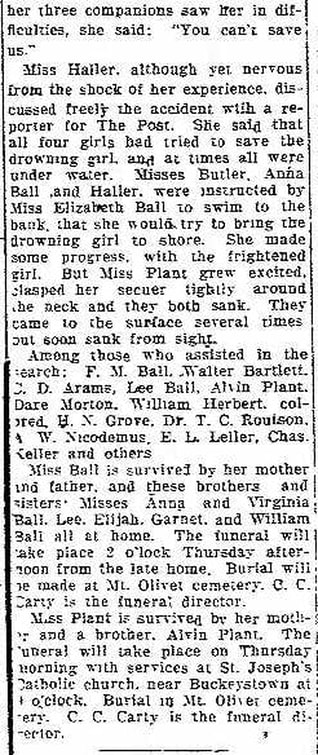

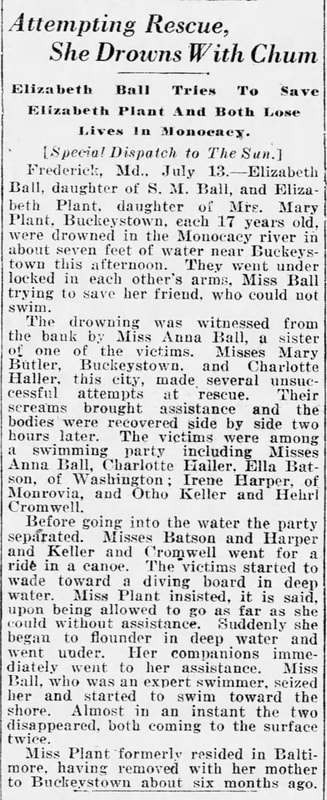

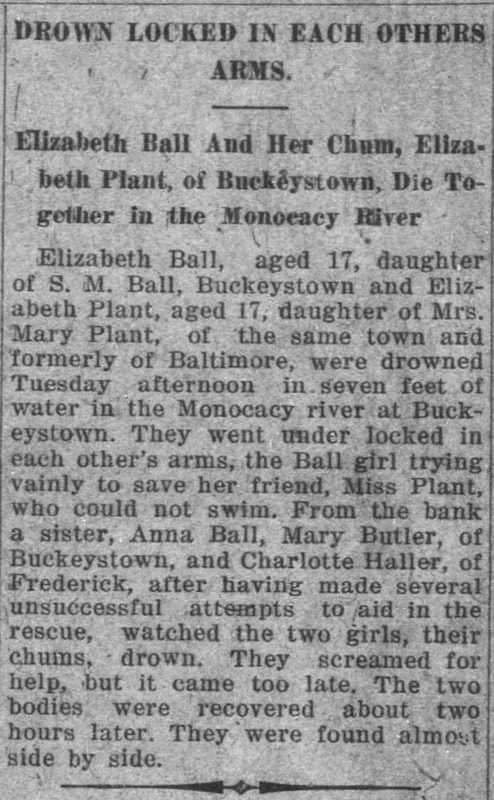

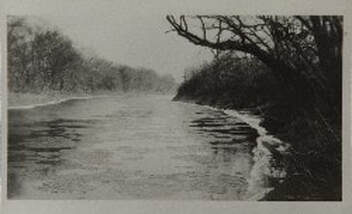

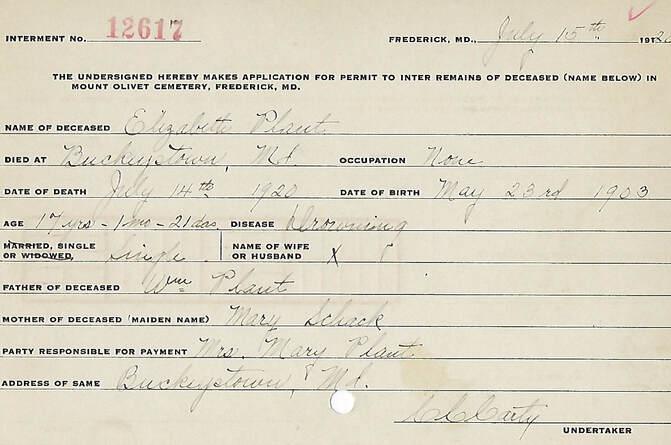

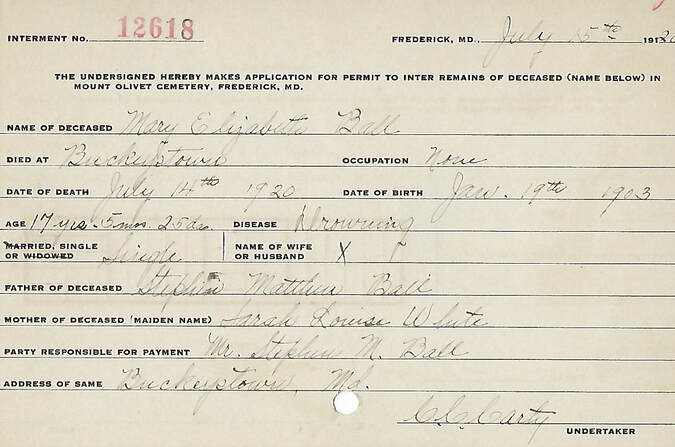

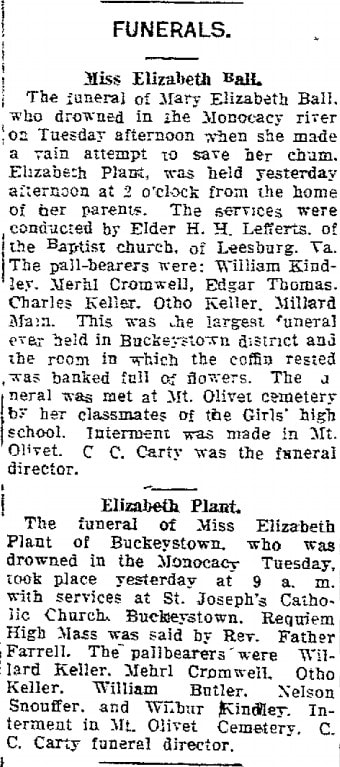

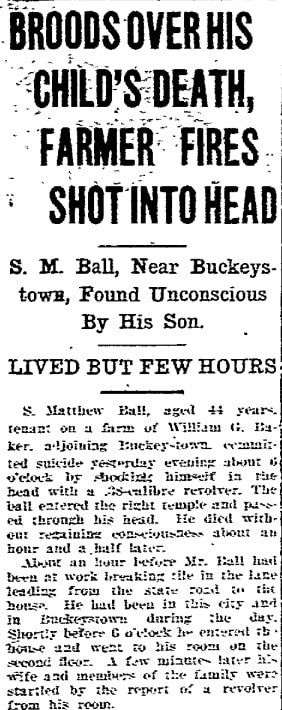

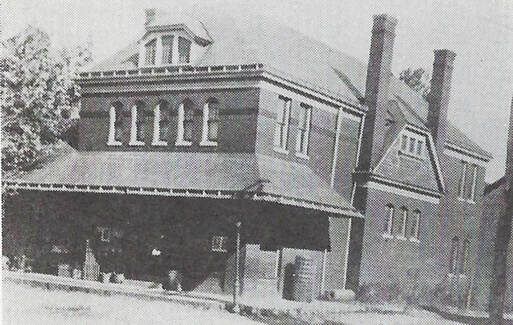

Grave of Bessie G. Jones in Area H/LOt 140 Grave of Bessie G. Jones in Area H/LOt 140 A few months ago, I wrote an article entitled “An Echo From the Past” which focused on a particular section of the cemetery’s Area T, which contains 40 victims of the Spanish Influenza pandemic of 1918. Most had died in the months of September and October. That time in our history featured mandated quarantines, event postponements and suggestions for social distancing. One also has to remember that there was a "world war" also going on at this time too! The war ended on November 11th, but celebration was tempered because a second, lesser, wave of the flu hit a few weeks later and stayed into the new year of 1919 before dissipating by late February/March of 1919. I'm sure many at the time replied, "Oh, 1918, what a crazy and depressing year." When things opened up there were no restaurant capacity limitations and mask requirements as we have been experiencing a century later, but one thing was certainly the same—people longed to return to normalcy after an eight-month period of unknown. Unlike Covid-19 which has targeted our older population today, the Spanish Flu skewed toward younger victims between 20-40, and included teens but not many children. Things eventually returned to normal. One particular place that needed a peaceful return was the sleepy hamlet of Buckeystown, located just a few short miles southeast of Frederick. It was here in late September, 1919, that Frederick County's first cases of Spanish Flu were occurred. Forty cases were reported there by September 26th, and our county’s first attributable death was that of resident Bessie G. Jones, a 33 year-old housewife. More "Buckeystownians" would perish in the weeks to come. In the summer of 1920, nearly two years later, the Buckeystown community would shaken when two local young ladies, both seventeen-year olds, would perish in a tragic accident, setting the stage for the largest attended funeral services in the town's history up to that time. Subsequently, the girls would be buried in Mount Olivet's Area T. Unlike their neighbors who had passed in 1918, their demise was certainly not caused by the flu, but by drowning. With the emergence of spring and summer, folks sought comfort in outdoor activities such as picnics, baseball games, the Braddock Heights amusement park, camping and swimming. The latter activity of water recreation can today be easily achieved with a multi-hour trip to the eastern shore and the beach or bay, or perhaps a trek westward to Deep Creek Lake. For most Frederick residents, the more common route to cool off in summertime included a jump in a nearby swimmin’ hole, be it pond, creek, or river. Sadly, our subjects of this week’s story would meet a tragic end in mid-July while on an innocent canoeing-swimming foray with a group of teenage friends in the Monocacy River just southeast of Buckeystown. Mary Elizabeth Ball was a native of Paeonian Springs, Virginia, located between Waterford and Leesburg. She was one of seven children, and went by her middle name. Her father, Stephen M. Ball was born in Tennessee, but had parental ties to Loudoun County. He married a Poolesville (MD) girl named Sarah Louise White. The Balls moved north of the Potomac River to Brunswick some years earlier but wound up in Buckeystown working as a tenant farmer on the farm of William G. Baker which was southeast of town on property now comprising Buckingham's Choice senior community and the Claggett Center. Elizabeth's paternal grandparents had a farm in Buckeystown as well. Elizabeth Plant had moved to Buckeystown just one month prior (June 1920) from her previous home at 2816 Alameda Street in downtown Baltimore. She was the daughter of William and Mary (Schuck) Plant. Her father was a successful builder and died in 1908 when she was five. Elizabeth and her brother Albin came with their mother from Baltimore and opened a small mercantile business. Although I didn't find one, I imagine that they must have had relatives or family friends here. On Tuesday, July 13th, 1920, both Elizabeths joined up with local friends for a day of fun and frolic on the Monocacy River (just east of town). Newspaper articles across the state would capture the terrible events of that ill-fated river excursion. As can be seen from the reports, Miss Ball was heroic in her attempt to save her new friend from Baltimore. Burial services were held at Mount Olivet a day later on July 15th, 1920. Interestingly, both girls are buried roughly ten yards apart in the northern section of Area T and have matching tombstones. As a matter of fact, Elizabeth Plant was buried in the Ball family lot. Mr. Stephen M. Ball, Elizabeth's father, took care of the arrangements for having Elizabeth Plant interred here. He, himself, would be laid to rest here just nine months later. The details of his death make the drowning story even sadder. All deaths come with a degree of sadness, but a century ago in 1920, there was no sadder place than Area T on account of those who died far before their prime. As a footnote to the story, my research efforts showed me that the Ball family were not the only ones trying to move forward from the tragic drowning of July, 1920. Elizabeth Plant’s grieving mother, Mary, was experiencing added stress and heartache. The daughter of German immigrants, she was raised in Baltimore and came to Buckeystown in 1920 to operate a general store a decade after the death of her husband. In November, 1920, the business would suffer destruction from a fire. After getting back and running again, her store fell prey to a burglary. Not a banner year for Mrs. Plant at all. One year later, exactly one week after the first anniversary of her daughter's death, Mary Plant would be named Buckeystown's postmaster. She would eventually return to Baltimore by 1930 and lived out her life in "the monumental city" until her death in 1963. I couldn't find her definitive burial site, learning that she wasn't buried here in Mount Olivet with her daughter. Her husband, William is buried in Dundalk's Sacred Heart of Jesus Cemetery in Baltimore. I would assume she is buried there alongside him. Her parents are interred there as well.

Author's Note: Special thanks go out to my friend Ron Angleberger who did some advance research and introduced me to this somber tale. Likewise, friend and Buckeystown historian Nancy Willmann Bodmer gave me additional info and photos. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed