|

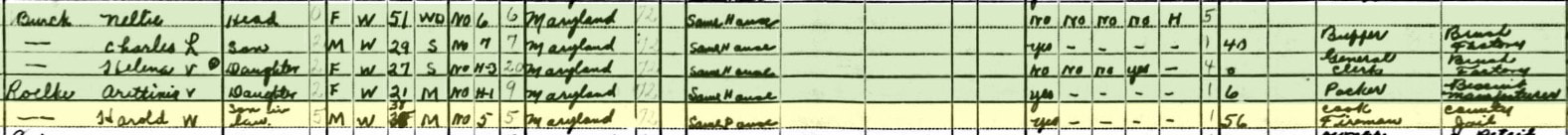

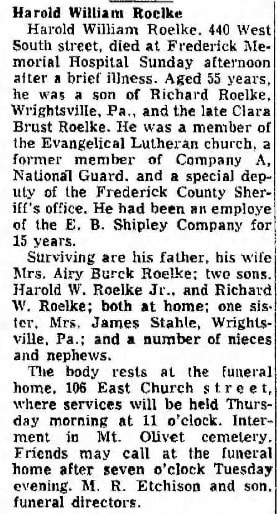

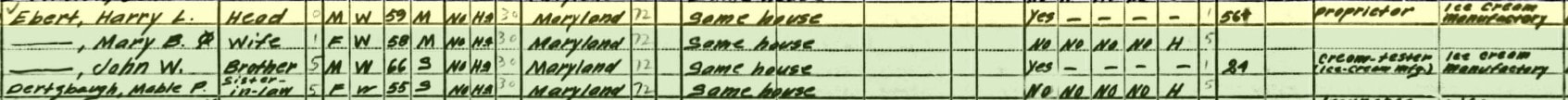

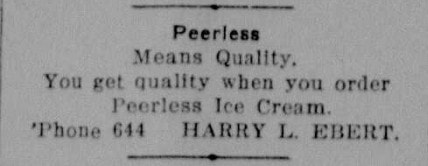

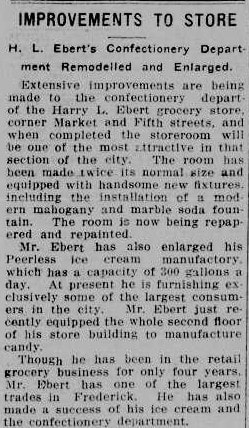

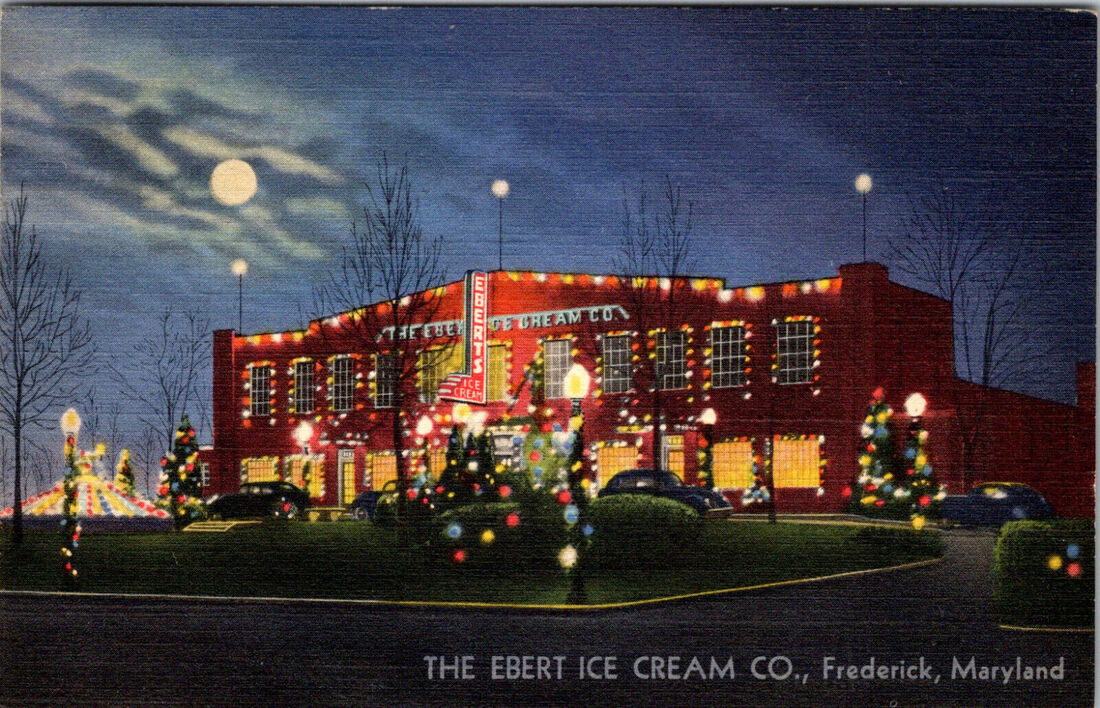

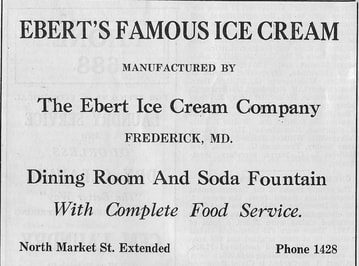

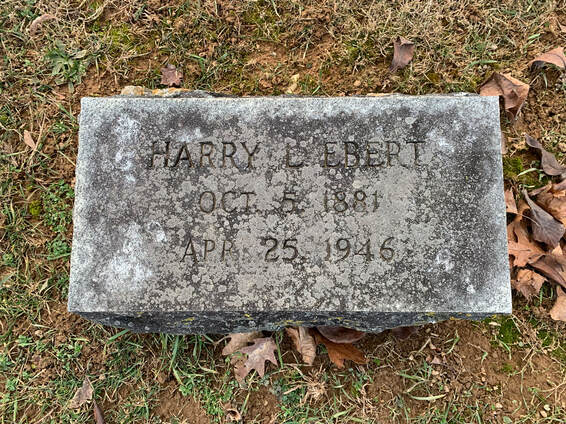

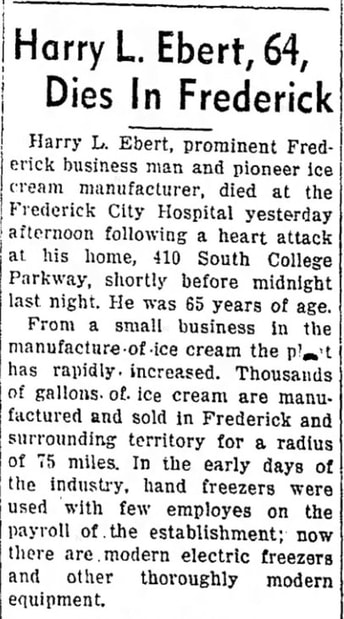

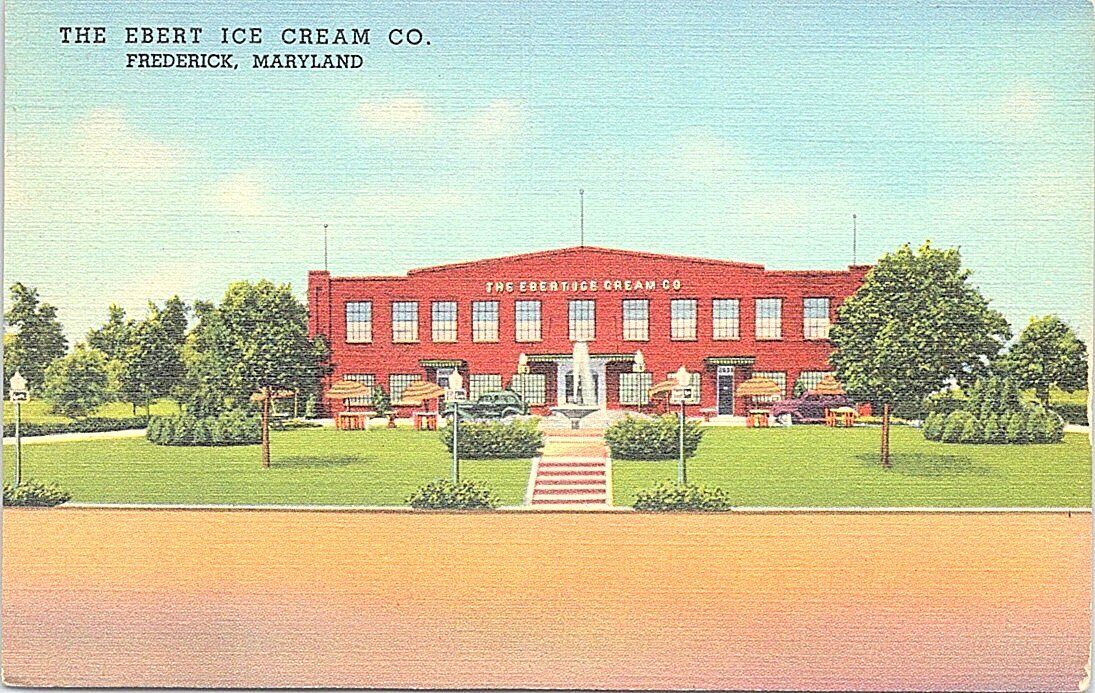

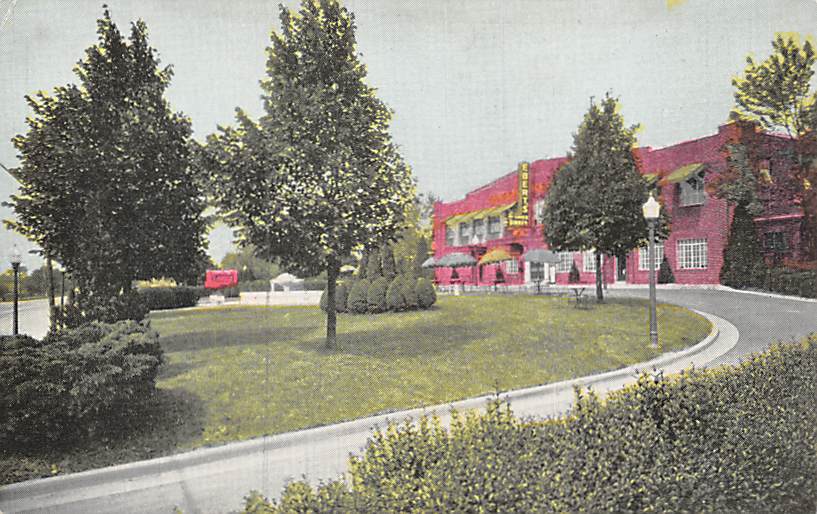

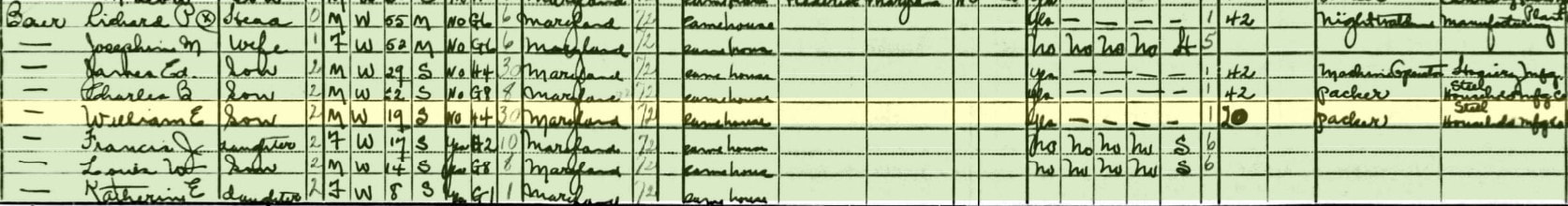

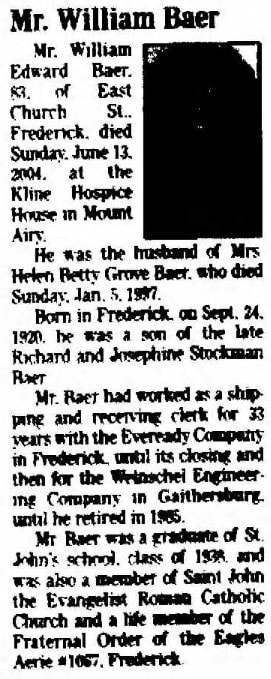

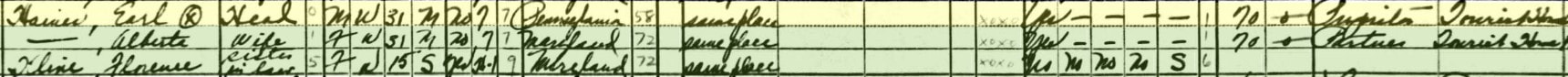

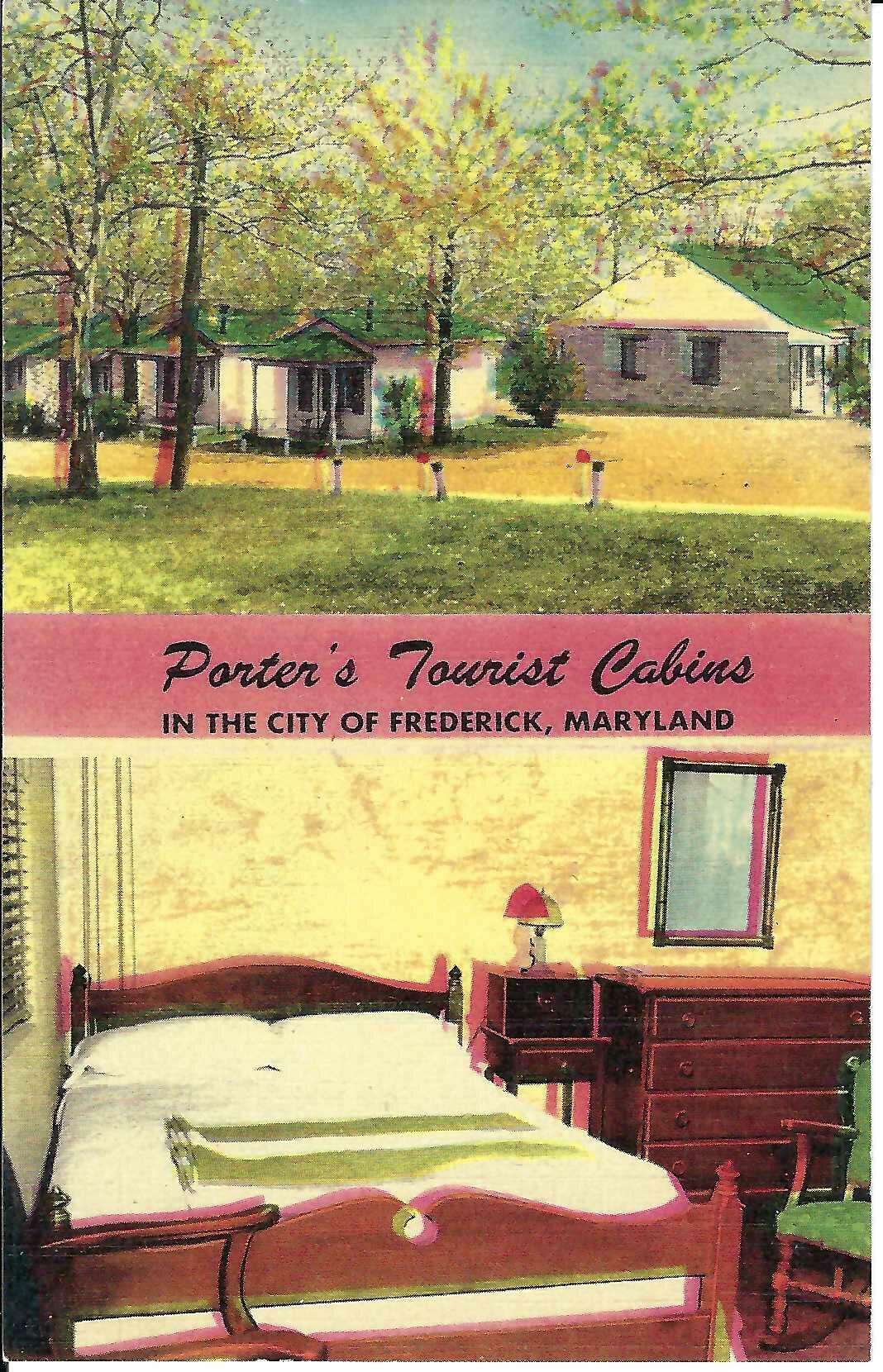

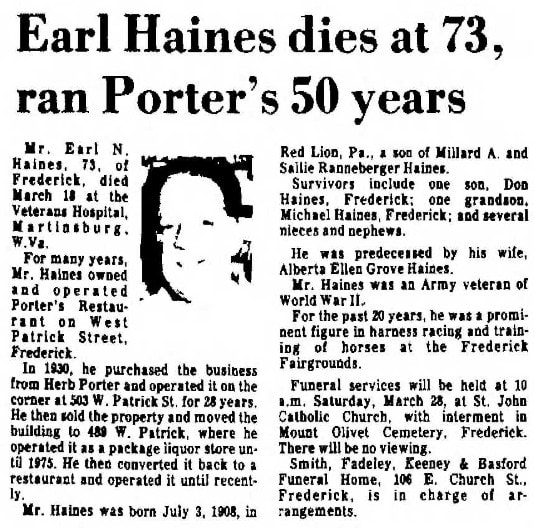

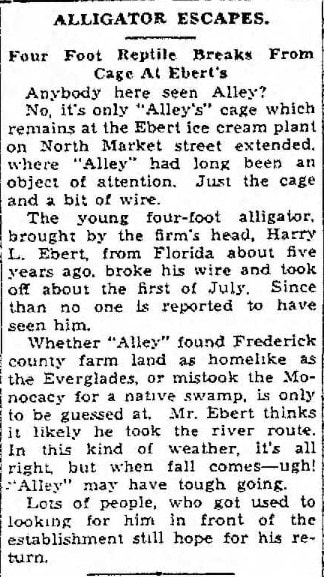

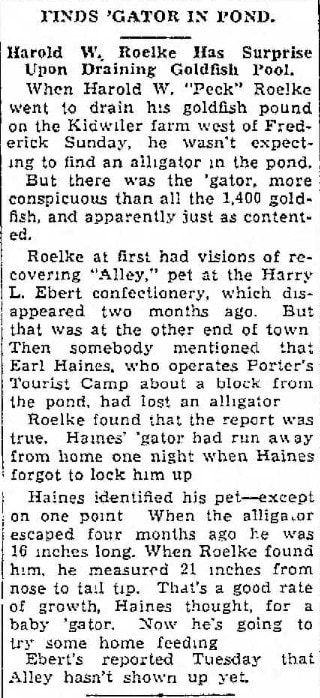

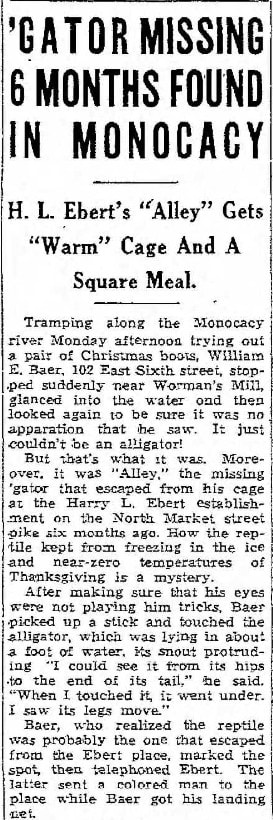

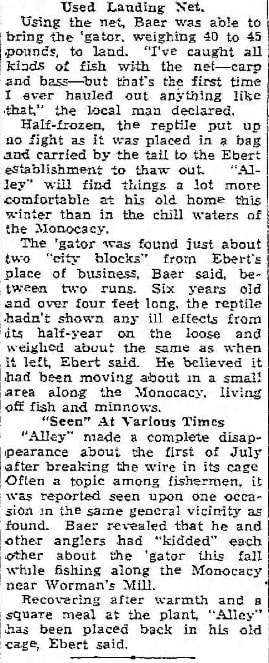

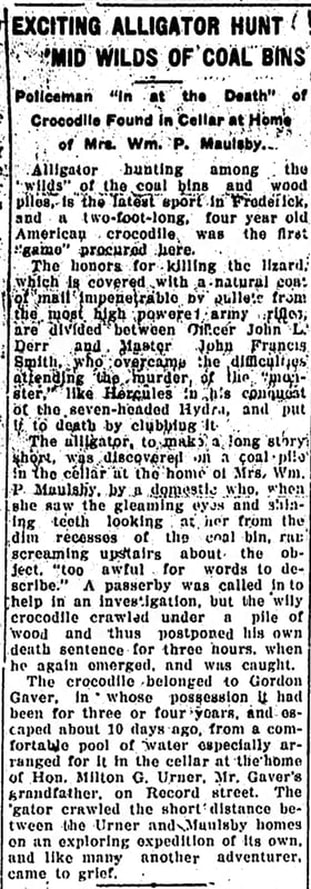

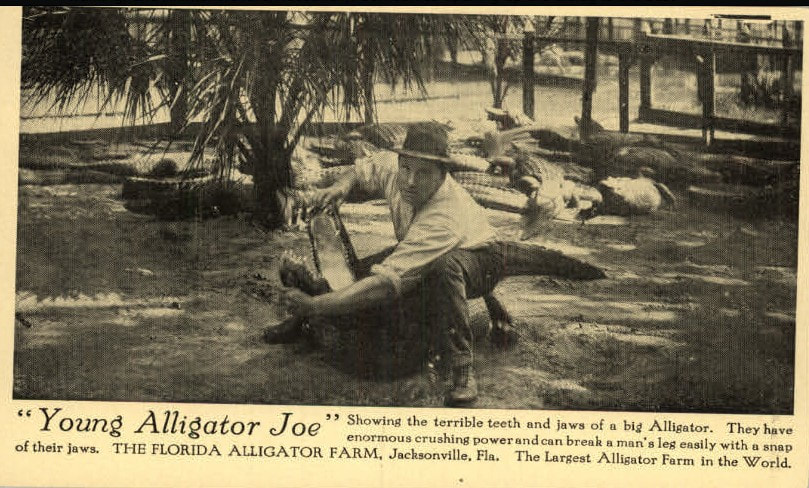

A few months ago, I stumbled across a tandem of interesting articles in the Frederick News-Post from the fall of 1938 while researching another Story in Stone. These finds featured a most unlikely topic for our “Clustered Spires” home—alligators. Within the clippings retrieved from the paper, I saw that Mount Olivet is the eternal resting place to four leading players in what can be deemed a gold ole-fashioned, reptilian drama. I will tell you about the gator, later. But before I do, I’d like to introduce a few former Fredericktonians to you. I will start with a gentleman, who at the time in question, was working as a fireman and cook at the county jail that once was located in the 400 block of West South Street. This is now the Frederick Rescue Mission. His name was Harold W. “Peck” Roelke, and he lived basically across the street from the old jail and just a few house to the east with his wife, Arittinia Virginia (Burck) Roelke. He was born in Frederick in 1901, the son of Richard and Clara (Brust) Roelke and died in 1956. "Peck" Roelke was a veteran of World War I, and recently received a wreath through the Wreaths Across America program. He is buried in Mount Olivet's Area CC/Lot 99A. You can read more about his life in the obituary below. Another player in this tale of yore was Harry Lucien Ebert. Mr. Ebert lived from 1881-1946, and his name may be recalled in relation to the fine dairy and ice cream establishment he was responsible for creating. He and his wife were laid to rest in Area T/Lot 11, not far from the grave of legendary patriot and Maryland’s first governor, Thomas Johnson, Jr. As a matter of fact, Harry Ebert’s dairy operation was constructed on land that was once part of Johnson’s vast plantation on the north side of the city. The Ebert Dairy and Ice Cream Parlor is long gone as a business, but the structure still stands at 1781 North Market Street, cata-corner from Gov. Thomas Johnson Middle School. Many may recall its use as Letterio’s Italian Restaurant for many years. Since 2011, it’s served as the home of both the Flying Barrel and Monocacy Brewing Company. As for Harry L. Ebert, he resided at 410 South College Parkway in Frederick. In the 1940 US Census, he is living with his wife Mary, brother John, and sister-in-law Mable Dertzbaugh. Since Mr. Ebert’s business plays a role in our story, I want to share a bit more on its history. I’ve been aware of it for quite some time, and have two postcards in my personal collection that illustrate it wonderfully. He started with grocery and confectionary, which became an ice cream parlor. This was located downtown on the corner of Fifth and Market, and later moved to the outskirts along the main road north before there was a US15. In her May 6th, 2018 edition of Preservation Matters for the Frederick News-Post, Christina Martinkosky wrote about the building that many longtime residents knew as the old Ebert’s Dairy Building. “Before the 20th century, farmers consumed much of the milk they produced, with only a portion sold to the nearby community. Ice cream was an inaccessible treat for most people until the mid-19th century, when Nancy Johnson invented the first hand-cranked freezer. By the turn of the 20th century, a new industry emerged, when ice cream production started to shift from the home to local businesses. But distribution was limited, given that the product had to stay frozen throughout its distribution cycle or risk destabilization. The creation of localized milk and ice cream markets in the first quarter of the 20th century coincides with Harry Ebert’s entrance into the industry in 1915. At that time, he was already running a profitable grocery and soda fountain. The new enterprise was branded Peerless Ice Cream and operated out of a 900-square-foot space on the second floor of 505 N. Market St. The business had one employee with an annual payroll of $750. Within the first year, 500 gallons of product were made. Within four years, Harry Ebert was distributing ice cream to some of the largest vendors in Frederick. By the end of the 1920s, the manufactory room at 505 N. Market St. had become inadequate to accommodate further growth. On Dec. 14, 1929, Ebert, along with his two brothers-in-law, Lewis R. Dertzbaugh and Frank M. Dertzbaugh, announced the formation of the Ebert Ice Cream Co. By 1931, Ebert opened the manufactory and dairy bar at 1781 N. Market St., which became one of the largest independently owned ice cream plants in the country. The company employed 45 people to run the plant, which was in operation day and night. When running at full capacity, the manufactory had the ability to produce up to 400 gallons of ice cream per hour. Much of the product was then transported by 10 large refrigerator trucks that delivered within a radius of nearly 60 miles, extending into Virginia, Baltimore and Washington, D.C. The manufactory and dairy bar was an impressive reflection of how significantly the ice cream business had changed since Harry Ebert began his production 15 years earlier. Technological advances and the rise of the automobile changed the way Americans got their ice cream, by taking them out of the ice cream parlors downtown and into roadside eateries on major thoroughfares." In April 1946, after 31 years in the ice cream business, Harry Ebert died at Frederick City Hospital of a heart attack. He is remembered as a founder and president of the Ebert Ice Cream Co. and a pioneer in the ice cream industry. The Ebert family retained ownership of this independent ice cream business until 1961, and the facility continued operations under the Ideal Dairy Co. until 1975, a time when prepackaged ice cream became available through supermarkets and independent manufactories were absorbed into larger businesses. The hero of this week's story was William E. Baer, a resident in the late 1930s of East Sixth Street, 102 to be exact. Mr. Baer is buried in Mount Olivet’s Area SS/Lot 37B. Born in 1920, he was only 18 when the event happened that would put his name in the papers for all the right reasons. In the 1940 census, he is living with his parents (Richard and Josephine Baer) and five siblings. He would pass in 2004 at the age of 84. Mr. Baer's death date of June 13 (2004) resonates with me as he died the day before my father and hero, and both from complications associated with cancer. Finally, I’d like to introduce you to Earl Haines (1908-1981). You can find him in Area LL/lot 65. I had come across Mr. Haines name before as the proprietor of Porter’s Tourist Camp once located on West Patrick Street, a block west of the intersection with Bentz Street. The native Pennsylvanian was assisted by his wife Alberta at their work-home at 503 West Patrick Street. Interestingly, I also have a postcard in my collection depicting Mr. Haines' former business that would be located on the west side of town at the familiar intersection of West Patrick Street and West College Terrace. The lodging for travelers here was started by a man named Herb Porter who sold Earl Haines the business in 1930. I presume the cabins were atop the hill but could have occupied some of the property that makes up Frederick High's football stadium complex. (Please let me know in the comments). Haines also ran a restaurant associated with his former employer (Porter) as well. Now having made proper introductions, I must confess that the true star of the show, once known around town as "Alley," is not buried here in Mount Olivet, but I'm sure you have a good idea for a reason why. I'm not quite sure where he wound up in the end, but I do know that he had quite the adventure in the late summer and fall of 1938. So it appears the newspaper had some fun with the daring escape. Alley was a well-known attraction at the ice cream parlor, not something usually seen in such a place. I have read that small alligators were popular as pets during the time. It was the Great Depression, folks needed an escape. How many Fredericktonians had the opportunity to travel south and see a gator with their own eyes? I found that alligators were living at the White House during the Depression, during Herbert Hoover’s presidency in the early 1930s. Hoover’s younger son, Allan, had two pet alligators that frequented the White House grounds, all the while, amazing and likely terrifying guests. The gators were said to have kept Hoover’s own German shepherd, named King Tut, on edge — not to mention the president’s Secret Service agents! In researching, I'm thinking that our scaly friend received his name because it was an easy play on alligator. However, I also saw that one of the leading newspaper comic strips was that of Alley Oop, a loveable caveman , created by cartoon artist V. T. Hamlin. The following comic appeared about the time of Mr. Ebert's introduction of the Florida native to Frederick. One month later in September (1938), an amazing find by the fore-mentioned "Peck" Roelke drew renewed interest and excitement in the case of the missing reptile. Mr. Ebert may have been happy for his fellow pet-owner Mr. Haines, but the search continued for Alley. As time passed and the seasons changed giving way to colder temperatures, it is likely Mr. Ebert's hopes were waning. Ebert Ice Cream Parlor was booming with the holidays, as was the Plant with its annual Christmas flavors and special "block" (of ice cream) sales. Two days after the day celebrating Jesus' birth, Mr. Ebert received a much unexpected present thanks to the acumen of William E. Baer. A happy ending as Alley was rescued and permitted to "thaw out" at an ice cream plant, which seems like a "just dessert" for the former escapee. As stated earlier, all these players, save the gator, are buried here at Mount Olivet. Some years back, I wrote a story about an alligator hunt thirty years previous. It involved another pet gone rogue in Frederick City's Courthouse Square neighborhood. The two-foot alligator of young Gordon Gaver escaped its domicile at the Urner household, eventually managing to gain entrance to a nearby property on W. Church Street—about fifty yards to the southwest, the home of Mrs. Henrietta Maulsby. A domestic servant got the surprise of a lifetime, finding the gator resting in a coal bin within Mrs. Maulsby’s basement. A police officer was summoned and aided by a young neighbor. The twosome successfully apprehended the sharp-toothed reptile after a three-hour standoff in which the said fugitive hid underneath a wood pile. Unfortunately, the alligator fell prey to vigilante justice as he was clubbed to death. Fifteen year old Gordon learned a tough lesson that night. However, Gordon Gaver (1904-1964) would make a career out of owing and displaying exotic pets as he later opened the Jungleland Serpentarium along US 15 below Thurmont. This would eventually become the Catoctin Mountain Zoo and Wildlife Preserve. Mr. Gaver is buried in Mount Olivet's Area Q/Lot 83. I wanted to wrap up the story with checking on any alligator-inspired gravestones. Although we can't claim any here in Mount Olivet, I did find a unique one in Jacksonville, Florida. It belonged to Joseph "Alligator Joe" Campbell (1872-1926), the originator of alligator farming in America and the owner of the former Florida Alligator Farm in Jacksonville. His unique grave marker can be found in Evergreen Cemetery in Jacksonville. A 2006 River City, FL News article provides the following information about "Alligator Joe:" "Joe's real name was Hubert and he was born in India in 1872, his father a decorated English officer. His passion was alligators and after his Wild West days and a stint of ostrich riding and training, he chose to live in Jacksonville, where, for all his showmanship, he was a well-respected naturalist. Due to the drainage of the Everglades and other state development, 2.5 million alligators were reportedly killed in the 1880s. Commercial hunters and gun-happy tourists helped decrease the population. There seemed to be no better fun than killing gators while cruising on a steamboat. Although Campbell also hunted alligators, because he feared their extinction he merged with Jacksonville's ostrich farm, the best in the country. By adding his gator collection to the lanky menagerie, he could study and breed both species. In 1912, when 200 ostriches strode into their new billet at Phoenix Park, Alligator Joe and his patient pod of gators were already awaiting the bubble-bottomed birds. This lively tourist destination, Florida's original theme park, percolated east of Jacksonville at Talleyrand Avenue, near Evergreen Cemetery and the river. Ostrich racing was a great sport of the era as contemporary ads and postcards indicate. So, to prevent hurt feelings and jealousy, Campbell likewise trained his gators to race and to carry riders. The alligators' education extended to climbing and to waltzing. While the reptiles and ostriches were not competitive, they spent little time together, promoting ostrich longevity. In 1907, the Dixieland Park exposition and resort opened at the ferry landing in South Jacksonville, where Alligator Joe, some ostriches and alligators, together with electric fountains, burros, bands and theater productions, were major attractions. The reptiles climbed ladders, slid down chutes and carted children on their broad, rough backs. Campbell was also becoming famous in the movies and newsreels for his alligator shenanigans and study of the creatures. In 1916, the Ostrich Farm and Alligator Farm, in some queer arc, shifted across the river to South Jacksonville on the site of the Aetna Insurance building, originally Prudential Insurance. Campbell and his wife, Sadie, lived on a houseboat near the southern end of the future Main Street Bridge." In later years, Campbell wrote a pamphlet about alligators, which included explanations of his life and work. His early gator farming was in Palm Beach, Arkansas and California. By the time he developed his Jacksonville enterprise, hoping to discourage their cannibalistic tendencies, he separated his alligators by size into pens of 200 head, numbering in the thousands. Alligator Joe died in 1926 at the age 53. His life story is certainly captured in stone.

1 Comment

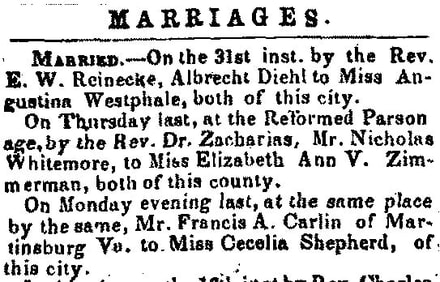

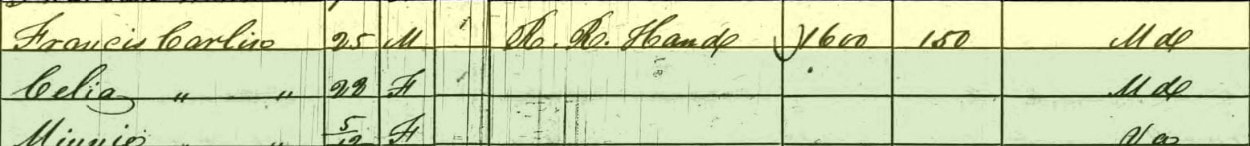

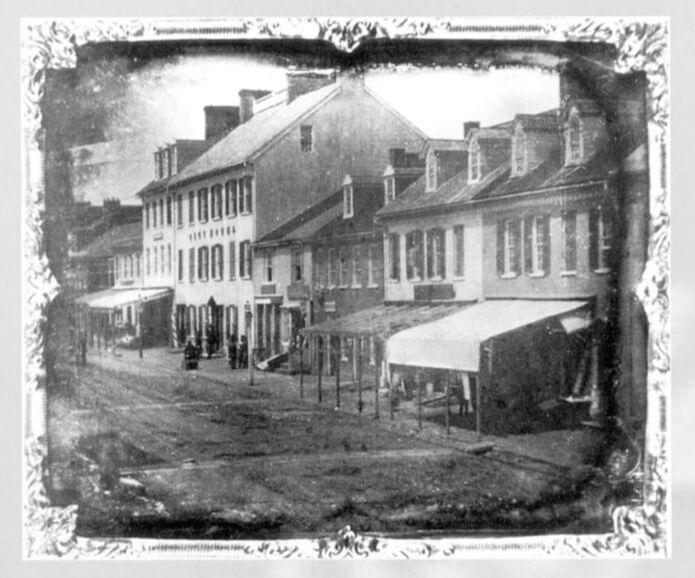

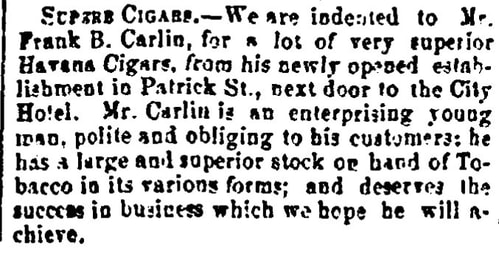

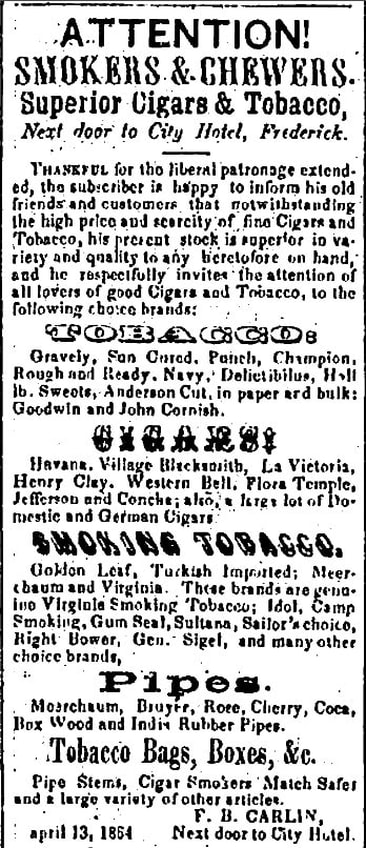

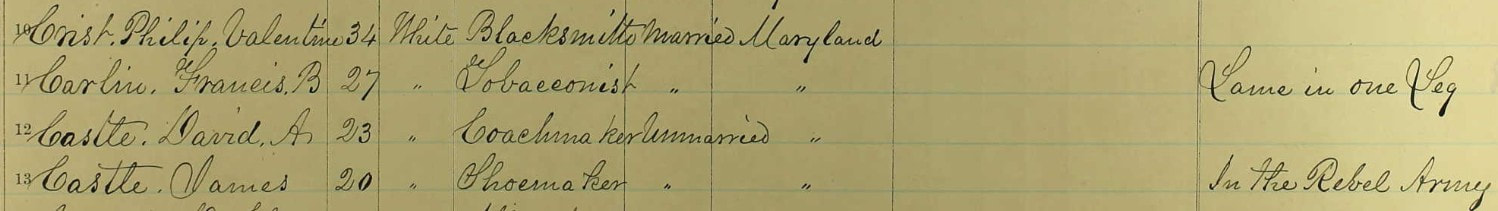

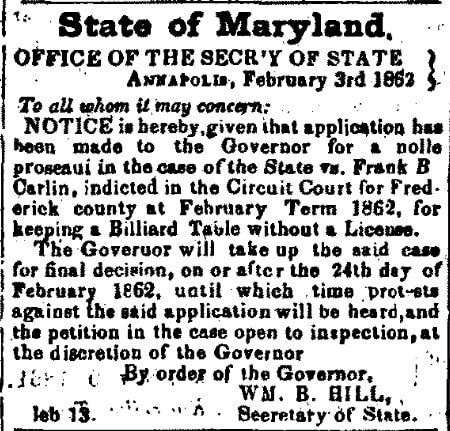

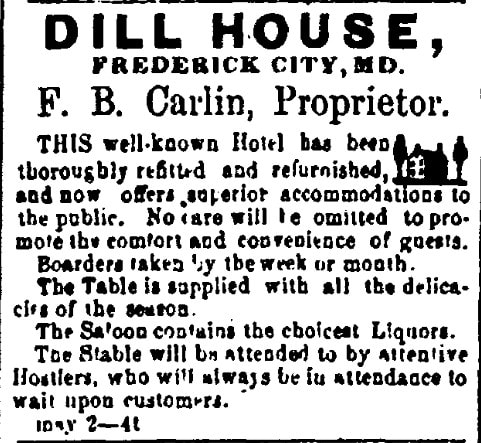

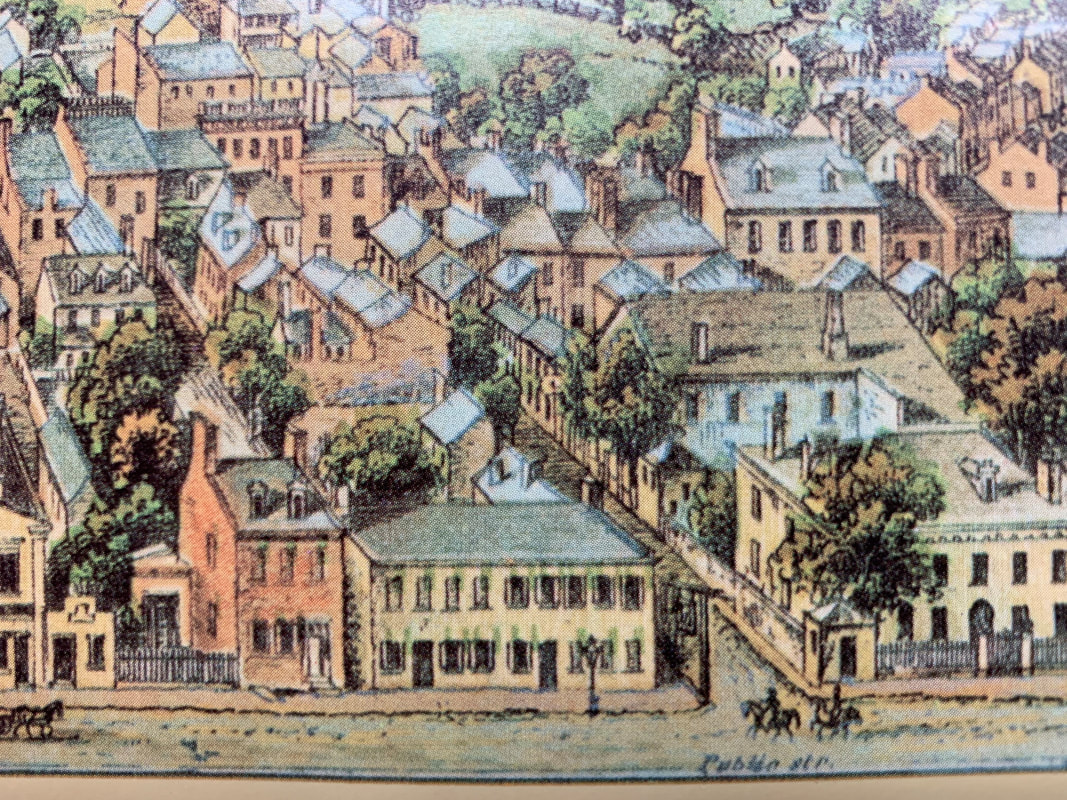

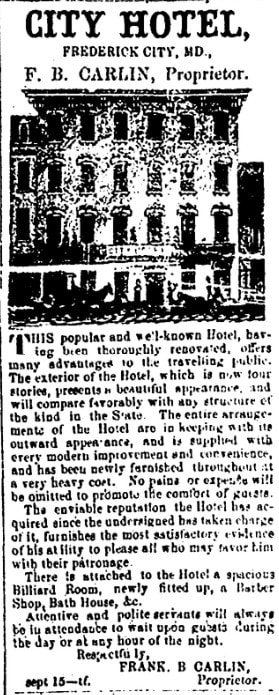

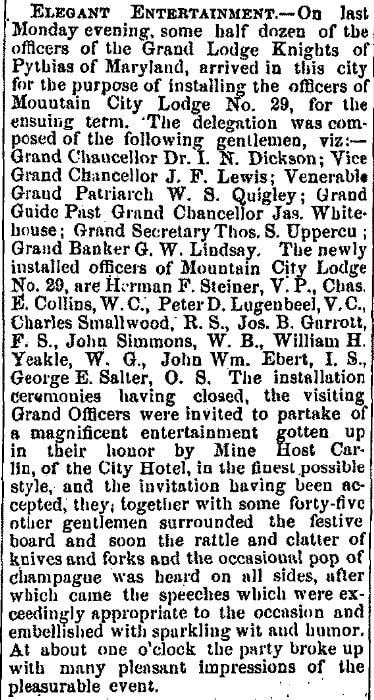

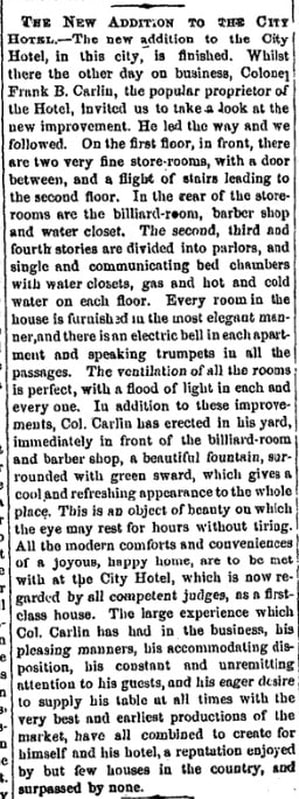

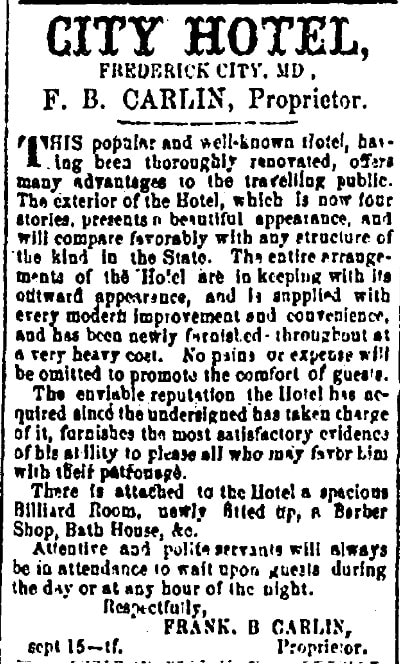

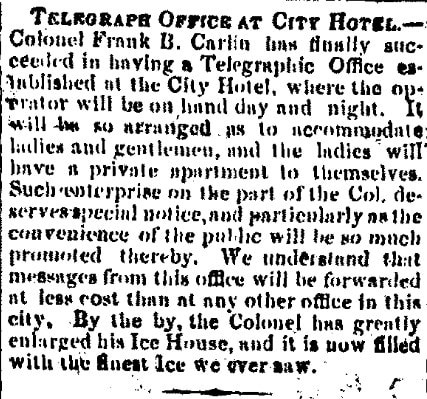

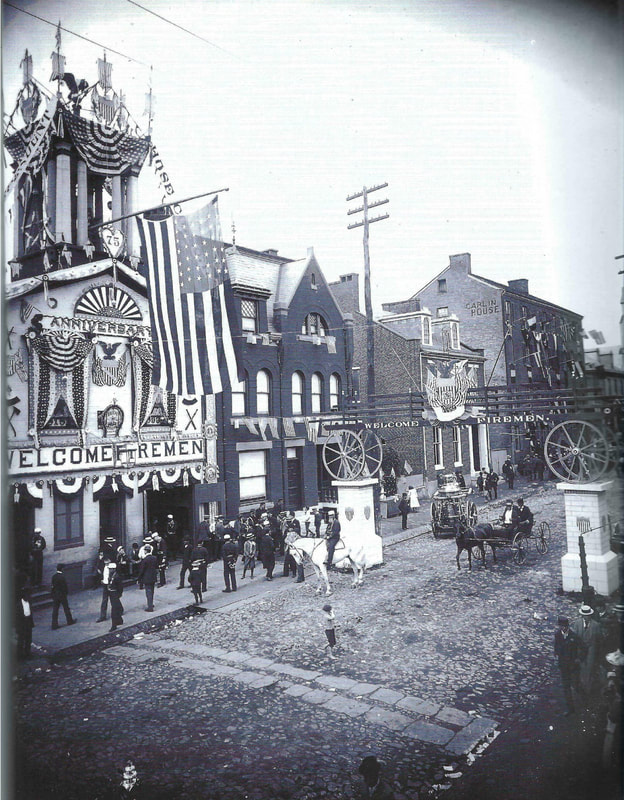

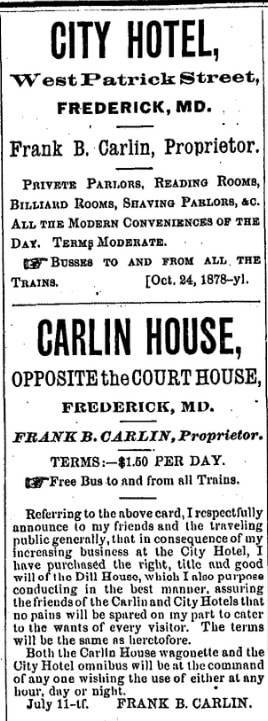

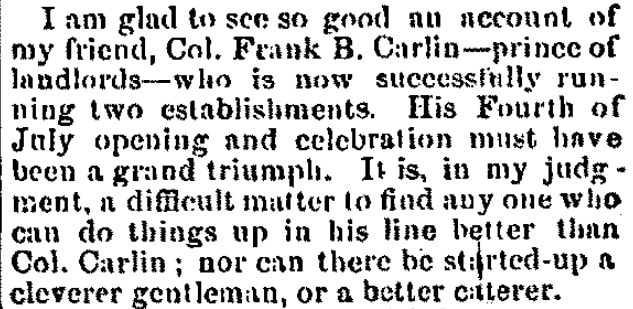

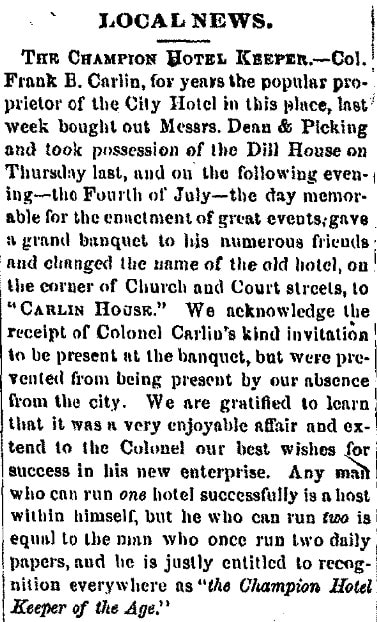

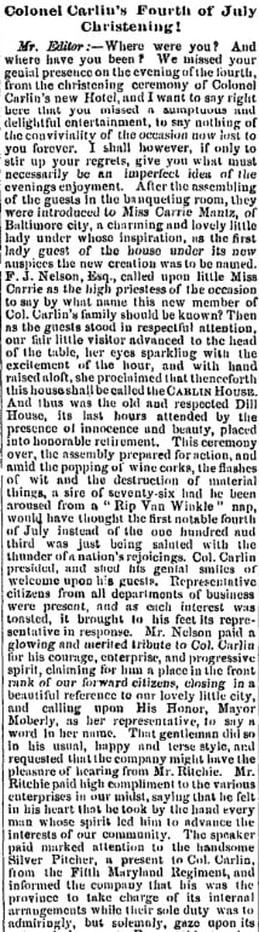

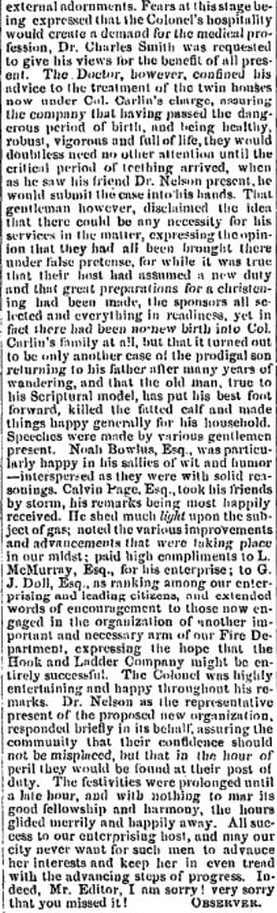

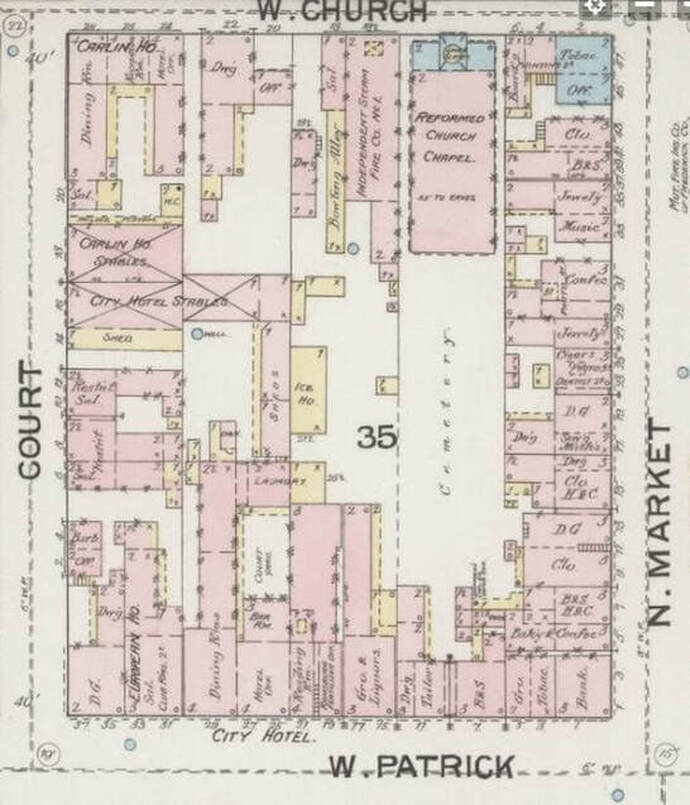

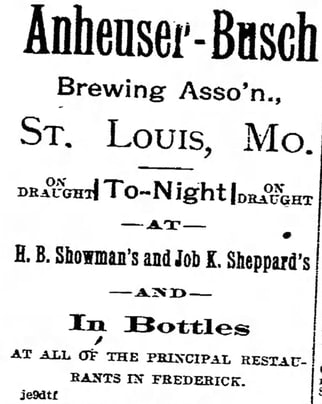

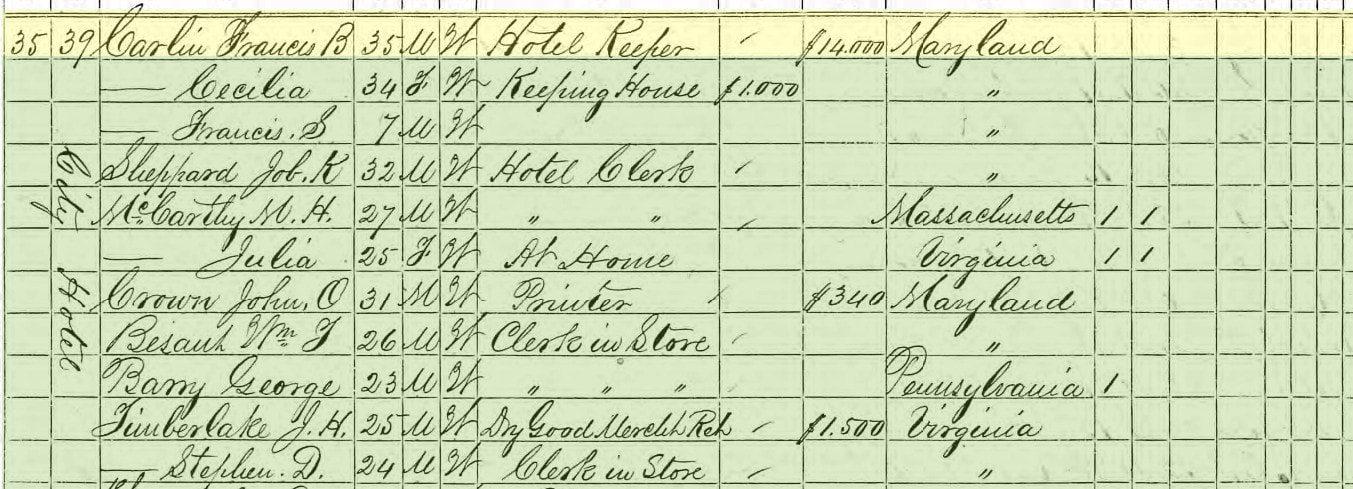

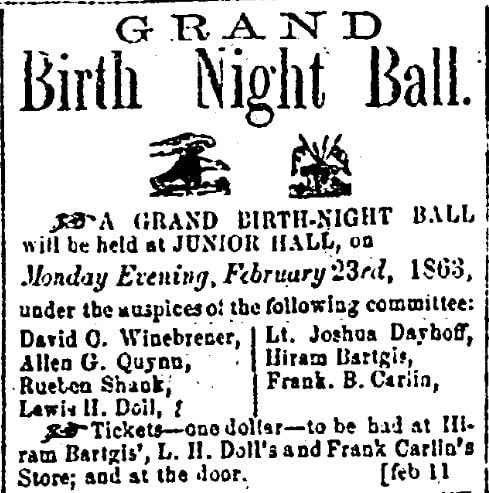

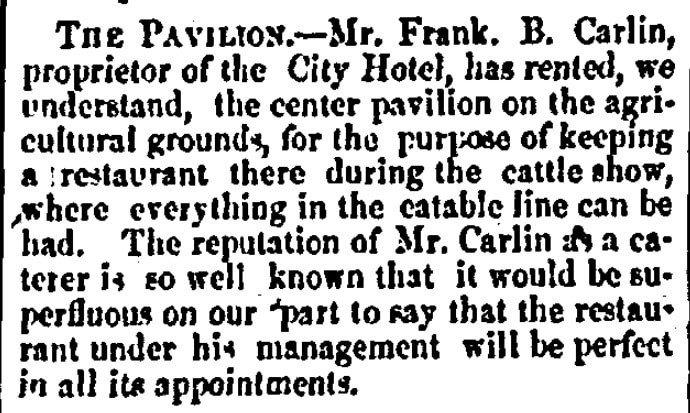

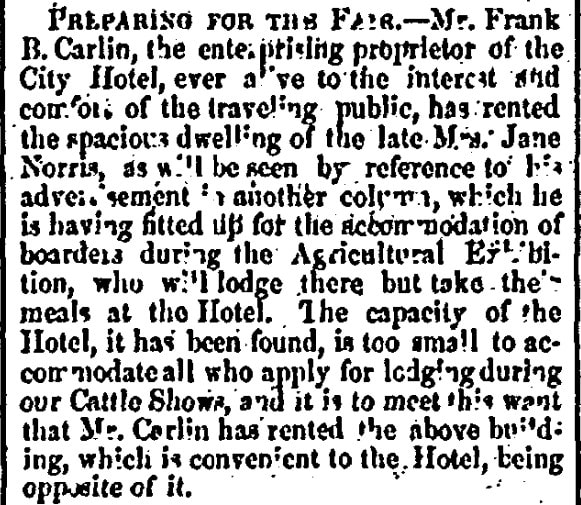

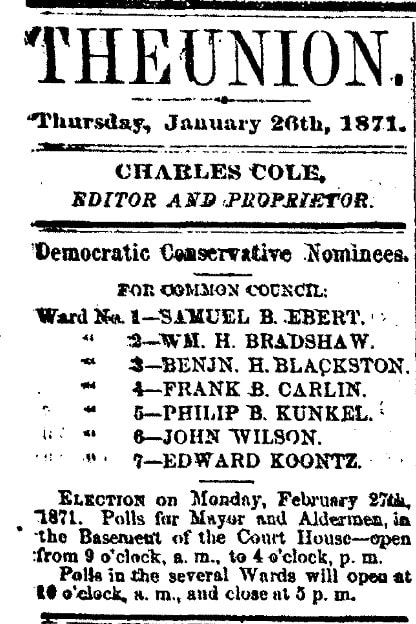

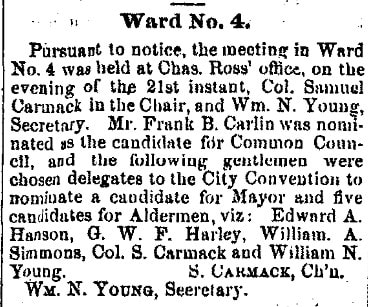

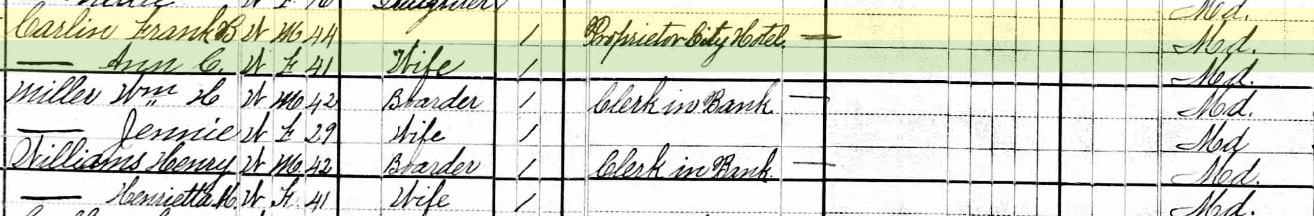

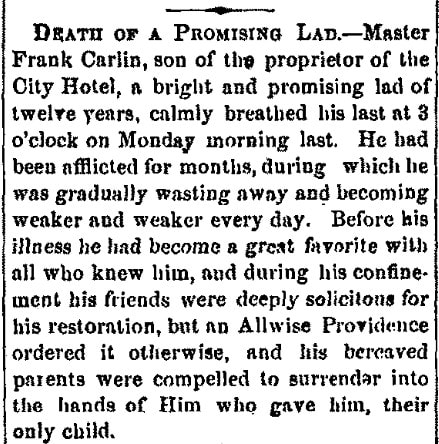

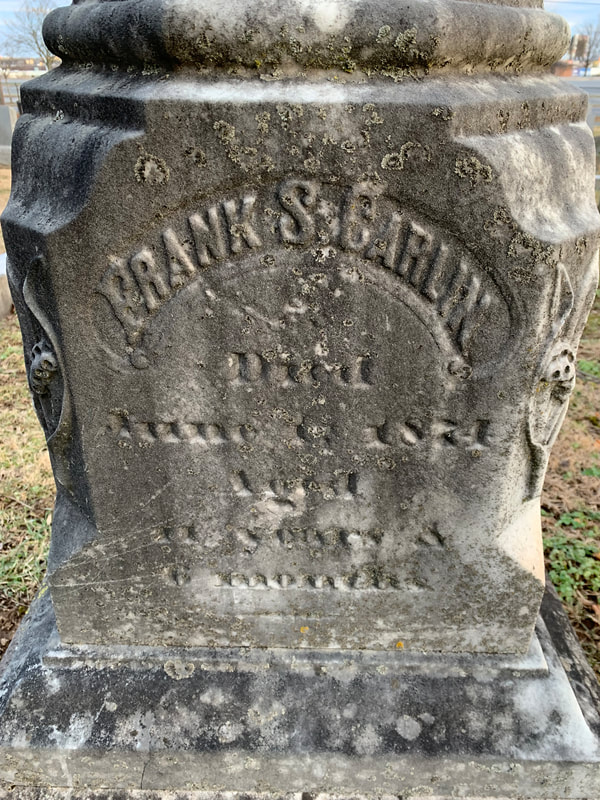

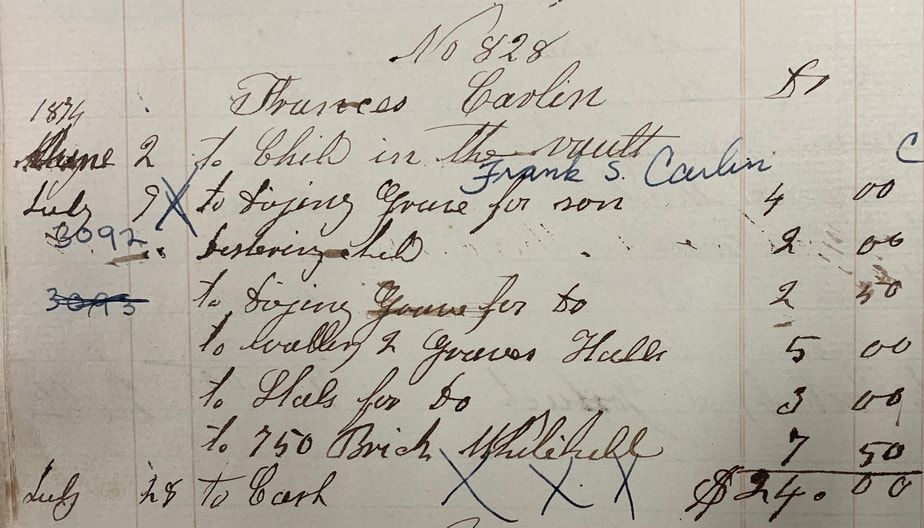

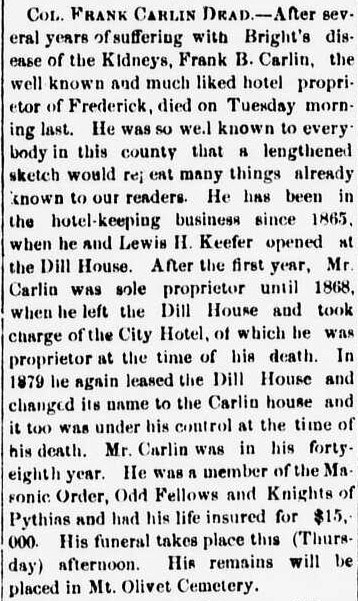

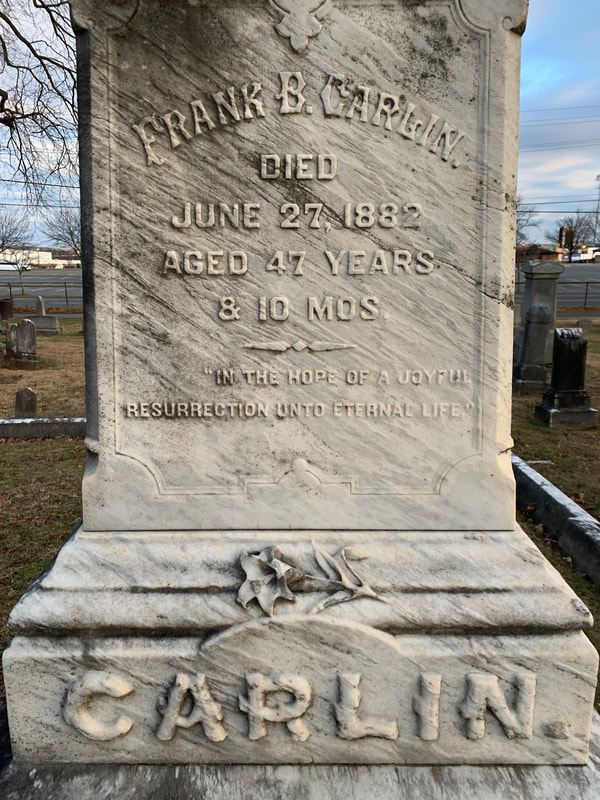

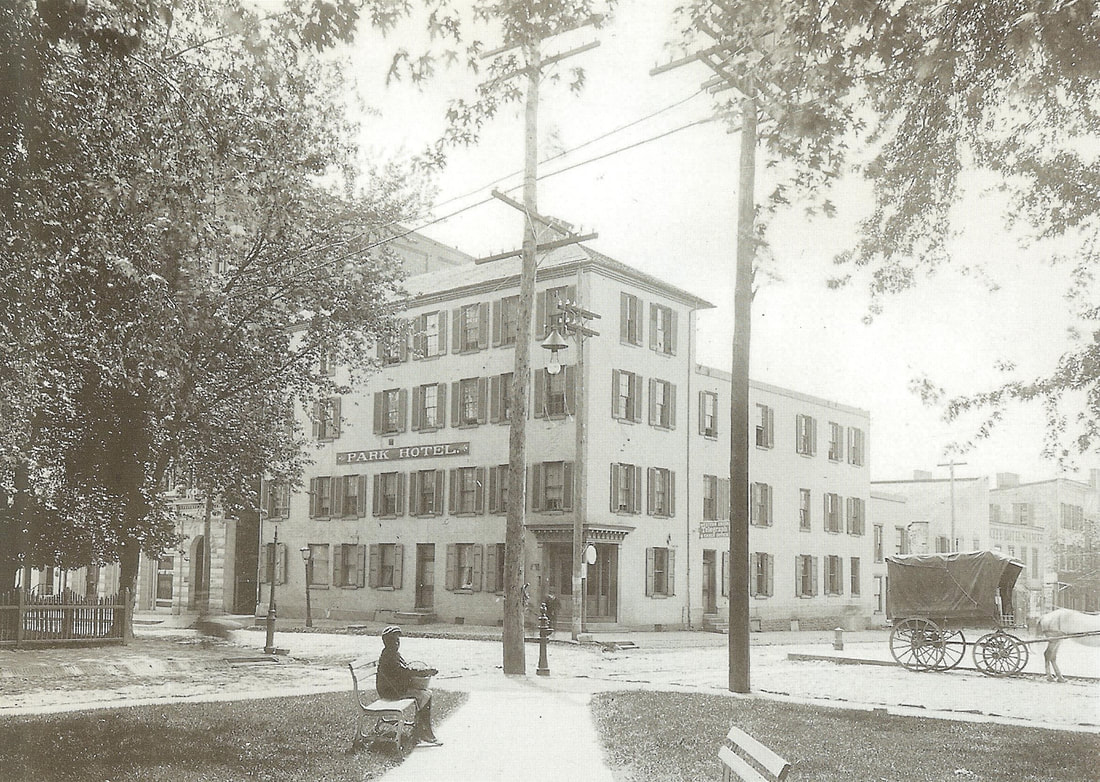

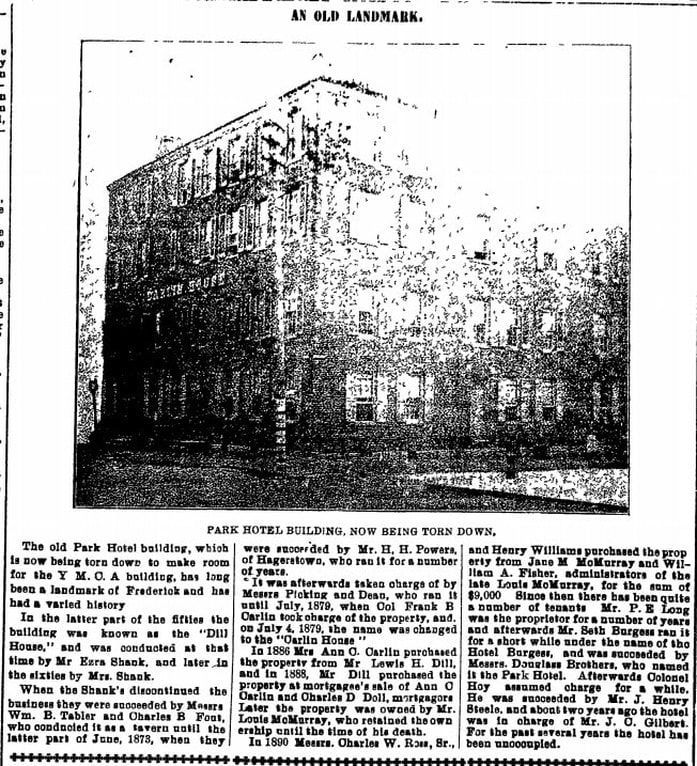

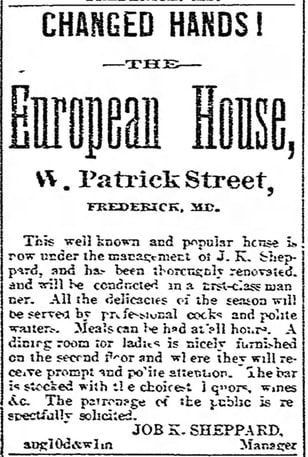

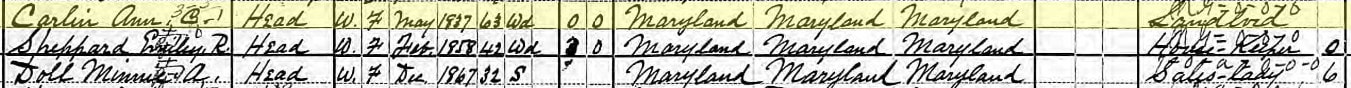

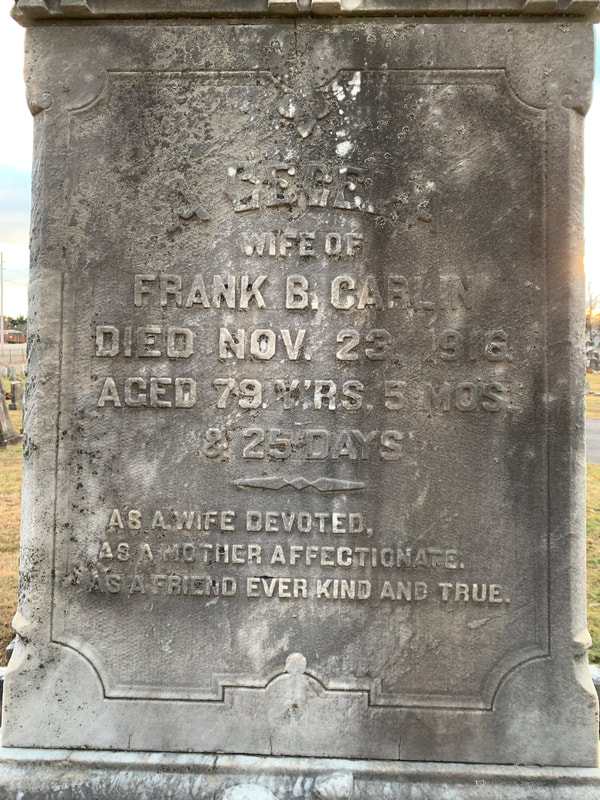

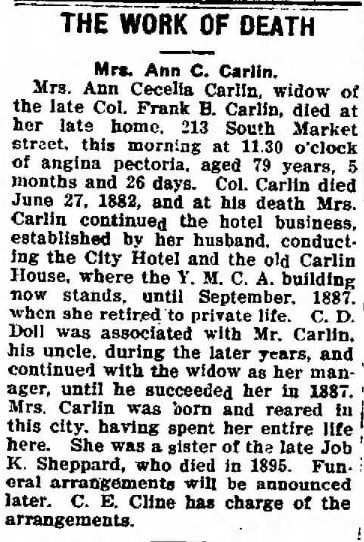

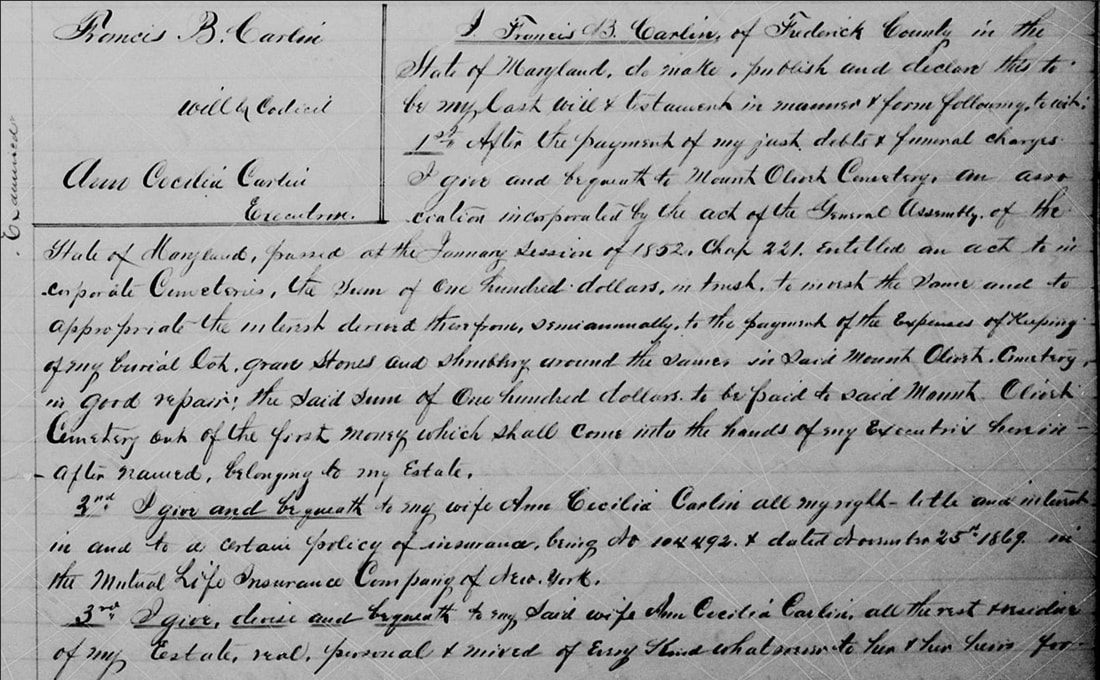

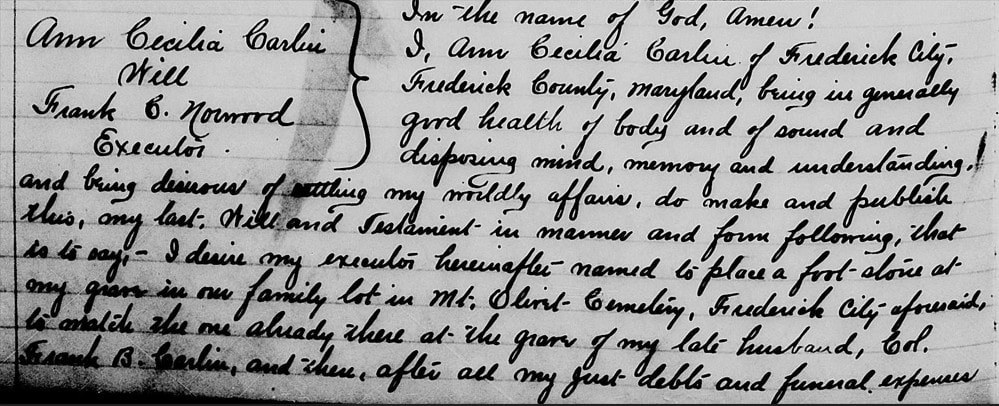

It’s hard to believe a man of such humble beginnings would be laid to rest and memorialized under one of the finest monuments in Mount Olivet Cemetery. He began his career as a rail hand for the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, working in Martinsburg, Virginia in the late 1850s (It wouldn’t become West Virginia until 1863). A decade later, he was one of Frederick’s most savvy businessmen and “hospitable” hosts. His name was Frank B. Carlin, and although his name isn’t remembered by many in the annals of town, the hotel businesses he helped grow are often referenced in context to Frederick of the late 19th century. These were exemplary of Frederick’s age-old role as a true travel crossroads and destination, and set the bar for our hostelry trade and an eventual successor—the Francis Scott Key Hotel. Born in Frederick in the year 1835, Francis “Frank” Brengle Carlin was the son of James Carlin and Eliza A. Hemsworth. James worked as a plasterer, but would be appointed one of the corporation’s town constables in 1826. He held that position for many years and worked closely with fellow constable (and later sheriff) Francis Brengle, after whom he would name his son. Young Frank Carlin eventually relocated to Virginia and worked for the railroad as earlier mentioned. He returned to Frederick often, including mid-February, 1858 when he married Ann Cecilia Sheppard (b. 1837) in Frederick’s Old German Reformed Church parsonage. Frank likely moved back to Frederick because his wife inherited a property (at what is now 237 and 239 East Church Street) from her aunt, Mary Gonso, in 1859. They relocated the following year. (As an aside, they would mortgage the property several times in the 1860s, and Ann Cecelia's executor finally sold it to early town realtor Gilmore Flautt in 1917.) The couple had their first child, Minnie, in 1860. Sadly, she died in infancy that same year. A second child named Francis Sheppard Carlin came in 1862. Frank entered into the tobacco business here in Frederick, operating a shop on the east side of the City Hotel and located in the first block of West Patrick Street. This famed hotel had been a principal place of lodging for nearly six decades, having been built in 1804 and originally operated by Mrs. Catharine Kimboll. It would be purchased by Col. John McPherson and John Need in 1861, and later by Allen G. Quynn and I. Alfred Ritter. The cost of the latter gentlemen’s purchase in 1867 was a whopping $19,000. Dating back to Mrs. Kimboll’s tavern, this locale continued to carry the reputation as serving as the principal inn of town, and was about to get better thanks to our subject. Being next door to the City Hotel was quite lucrative for Carlin’s tobacco emporium. He likely learned a great deal through his interactions with the City Hotel’s staff and ownership, as he regularly served its patrons with his cigars and other like products. This was the turbulent period of the American Civil War, and Frederick certainly experienced this conflict to the fullest. I have seen Frank referred to as Colonel Carlin and was curious as to whether our subject served in the war itself? This was not the case as I learned that he never was in the military, the colonel sobriquet was simply an honorary title. As for the Civil War, I discovered a draft register which showed a notation that Frank had a lame leg. Perhaps this was an old injury suffered on the railway? Regardless, Frank Carlin’s lame appendage did not hold him back in the employment realm as his upward trajectory was continuing at a fast pace. I found it very fitting that his surname of Irish origins translates to “little champion.” An interesting aside found in the old papers was an advertisement involving Frank Carlin in a bit of hot water with Maryland authorities. Apparently the state had brought suit against him for operating an illegal billiard table. The matter was to be decided by the governor, but I didn’t succeed in learning the final outcome. I'm guessing that the billiard table in question was located in a back room at the cigar store of Mr. Carlin. I next found his name associated with saloons and "the choicest liquors" in 1866. To my surprise, Frank Carlin was working with another hotel that was located around the corner from his shop. In fact, he was now the proprietor of the Dill House. This structure once stood on the southeast corner of North Court and West Church streets. In searching back through past Stories in Stone, I realized that I have referenced Frank B. Carlin several times in relation to these upscale eateries and also this hotel that would later take Frank’s name—the Carlin House. Soon, this experience would gain Carlin employment with the City Hotel, Frederick’s most famous “downtown hotel” of the 19th century. In September of 1867, Frank B. Carlin was given the job to manage the City Hotel as the fore-mentioned owners performed renovations, which primarily consisted of the addition of a fourth story in the fall of 1867. The old newspapers of Frederick included advertisements for this outstanding town traveler amenity in each and every edition. The proprietor, Carlin, penned many of these glowing testimonials himself. The newspapers also carried reports of special banquets, dinners and other notable occasions held at the hotel under the watchful eye of Mr. Carlin, who gained the moniker of “Mine Host,” which was most likely a play on the German “Mein Host” meaning “My Host.” The City Hotel’s restaurant would hold different names over the years. During Mr. Carlin’s association, the restaurant was known as “the Gem” and later, “the European House.” Carlin continued managing both hotels through the 1870s, making him without a doubt, Frederick’s “Champion Hotel Keeper” as an 1879 news clipping referred to him. I particularly took note of Mr. Carlin while researching a former article of mine written about the booming oyster saloons of Frederick. I stumbled upon the personage of Job K. Sheppard. This gentleman served as hotel clerk at the Dill House in the early 1870s and was Frank Carlin’s brother-in-law (Ann Cecilia Carlin’s brother). I assume Carlin hired (and mentored) Job Sheppard for this post. There was a very good relationship between these two men, and you could say at one time they practically controlled the hospitality district situated in the 100 block of North Court Street which was book-ended by the Dill House/Carlin House to the north, and the City Hotel to the south. In the middle of the street would eventually be a popular oyster bar/dining house managed by Job Sheppard in 1885. All can be seen to the left side of the map below. I also found that Mr. Sheppard was listed as a brewer in the 1880 census, and among the first restaurateurs in town to carry a familiar beer that is still with us today. The Carlins can be found living at the City Hotel in the 1870 US Census. Frank was involved in other local activities, notably the Junior Fire Company and the Great Frederick Fair. He would also throw his hat in the political arena. By 1880, Frank and Ann were residing at the Carlin House, a year after Frank took over management here. One notable name absent in the 1880 census record was that of little Frank S. Carlin. He had passed in 1874 and was buried with his infant sister in Mount Olivet’s Area C/Lot 163 & 112. (Minnie’s grave is unmarked). The Carlins bought, and sold, several properties in the 1880s. Notably, they purchased 5.8 acres along the south side of West Church St. in 1881 from the heirs of Gideon Bantz. (Based on the sale ad for Ann Carlin's properties after her death, she built houses on this property that are now 132-140 W. Church. Ann bought what is now 144 W. Church in 1895. These were all rental properties.) Frank was quite ill in the spring of 1882, as he had been diagnosed with Bright’s disease. This malady is an archaic term for what is now referred to as nephritis—an inflammation of the kidneys, caused by toxins, infection or autoimmune conditions. It is not strictly a single disease, rather a condition with a number of types and causes. Frank B. Carlin would finally succumb to this malady on June 27th, 1882. Ann Carlin took over his husband's duties of management for both hotel properties. Frank and Ann never owned the City Hotel property, as it was held by Allen Quynn and John Ritter. After Carlin's death, Ann bought a number of other properties. In 1884, she bought 620 N. Market Street (now a parking lot). She bought the Carlin House property in 1886 from Lewis H. Dill, and sold it in 1888 to canning factory proprietor Louis McMurray, who had been leasing it from her. In 1886, Ann Carlin also bought a store on the north side of West Patrick Street to the immediate west of the City Hotel. (This property was later sold to the Frederick Hotel Company which would eventually construct the Francis Scott Key Hotel in 1921-22.) As for the Carlin House, it later took the name of the Park Hotel and soon would disappear from the Frederick landscape, making room for a stately Y.M.C.A. building. Interestingly, in 1888, Job K. Sheppard was given the "job" as manager of the European House, the elegant dining hall associated with the City Hotel. Allen Quynn's heirs and I. John Ritter sold the City Hotel in 1890 to Tilghman Hersperger and Thomas Harwood. The hostelry would receive a makeover under its new ownership and would afterwards become known now as the New City Hotel. The European changed hands as well and would come to be known as "The Buffalo Hotel and Restaurant." Job Sheppard proudly served here until his untimely death (at the restaurant) in 1895. His sister, Mrs. Ann Cecilia Carlin, would have him buried in her family lot in Mount Olivet with her husband and two children. Ann Carlin apparently lived in the New City Hotel until buying a house at 213 S. Market St. in 1909. The savvy businesswoman died at this location seven years later in 1916. The Carlin Family plot and monument in Mount Olivet is certainly one to behold. It particularly looks majestic against a palette of spring or fall colors. I, however, decided to share recent photographs of it in its current attire in the heart of winter. My research assistant Marilyn Veek obtained both Frank and Ann's final will and testaments. Of particular interest to me, were directions pertaining to the Carlin’s final resting place. The first item in Frank Carlin's will is a bequest of $100 for Mount Olivet to invest and use the interest to keep his burial lot, grave stones and shrubbery in good repair. The first item in Ann Carlin's will directs her executor to place a footstone in Mount Olivet like the one already in place for Frank. She also left $500 to Mount Olivet to invest and apply the income for the upkeep of her monument, curbing and foot-stones and other parts of the family lot, replacing whatever needs to be replaced. She also left Emily Sheppard, widow of her brother Job Sheppard, the sum of $500. Ann Cecila Carlin’s properties were eventually sold at public sale. If anything else, the Carlin gravesite in Mount Olivet’s Area C is certainly that fit for “a little champion,” a man whose monument stands out among the surrounding landscape just as prominent and stately as did the old City Hotel and Carlin House in days of Frederick’s past.

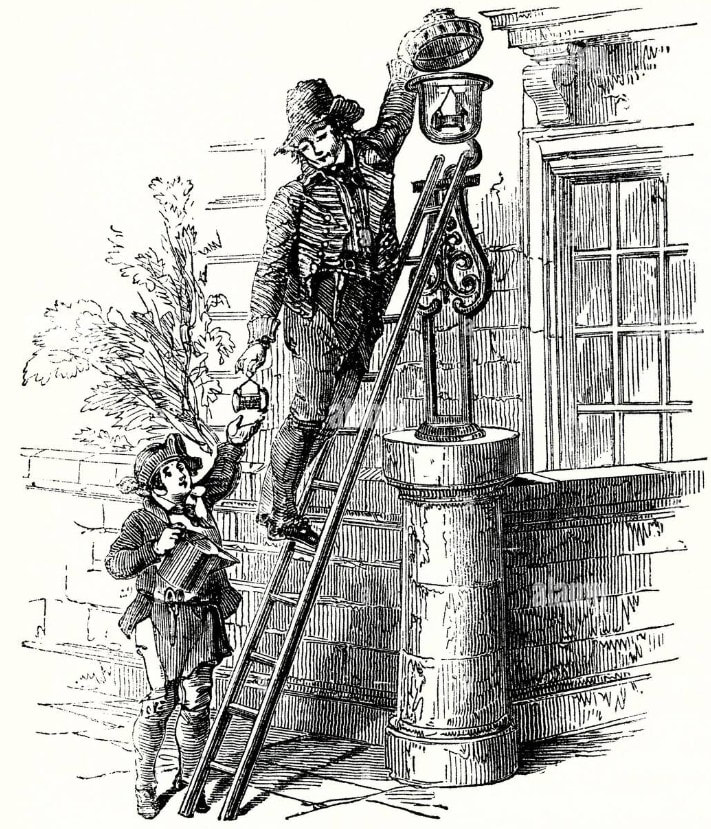

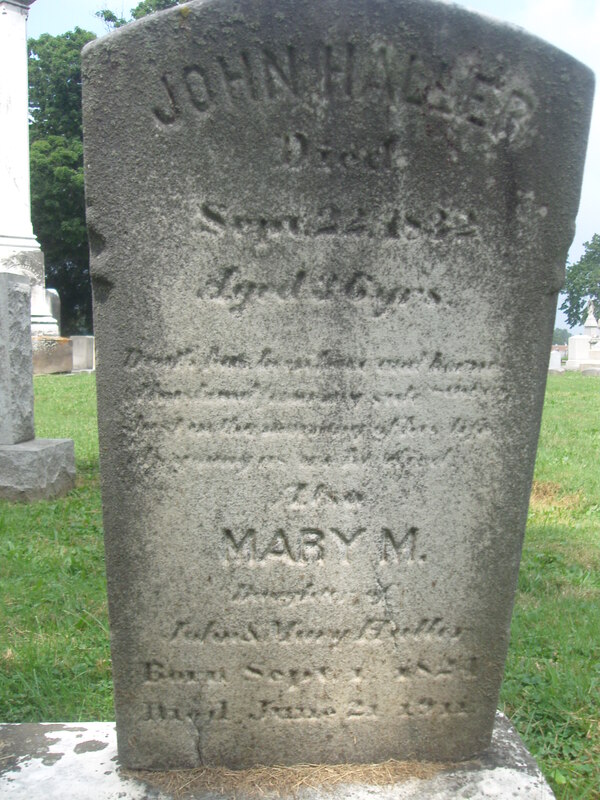

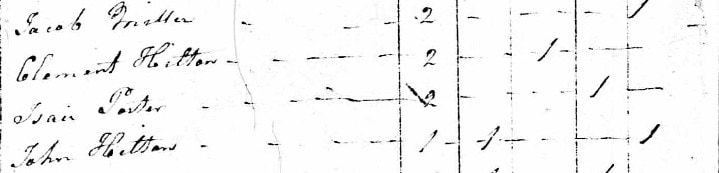

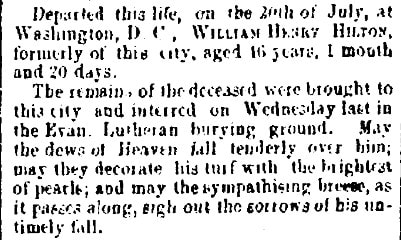

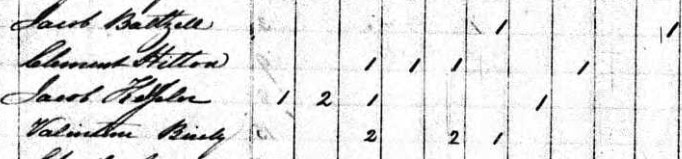

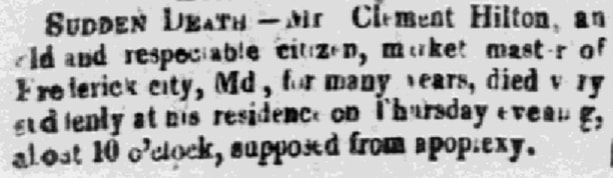

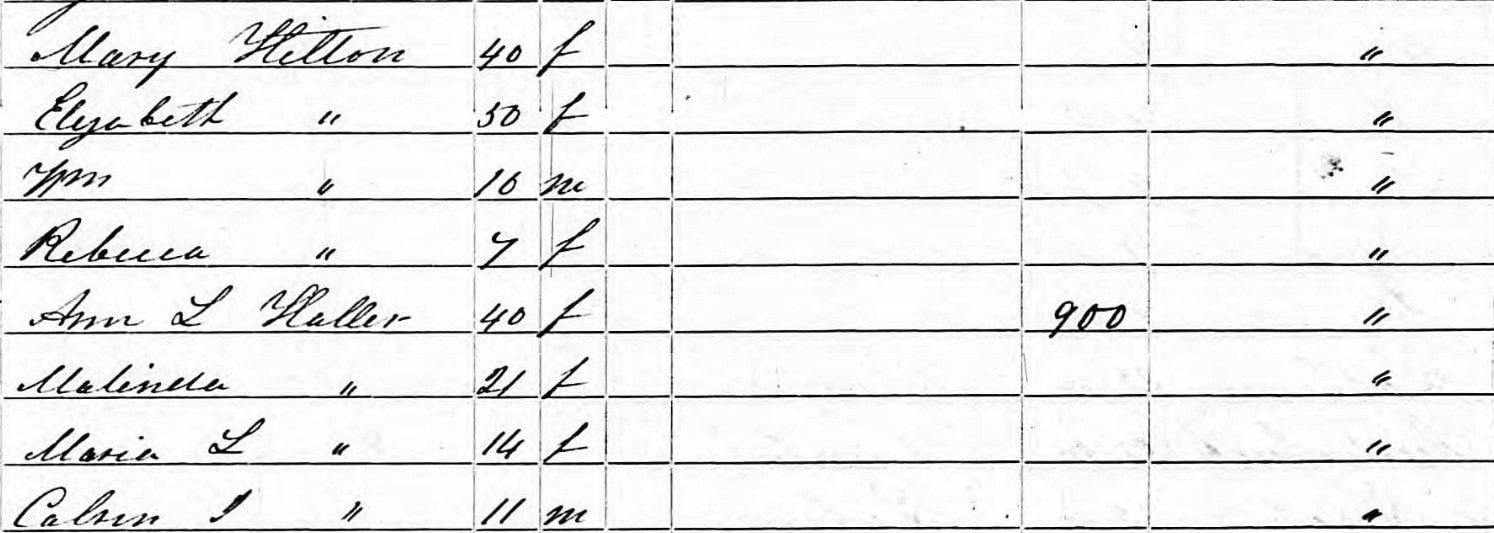

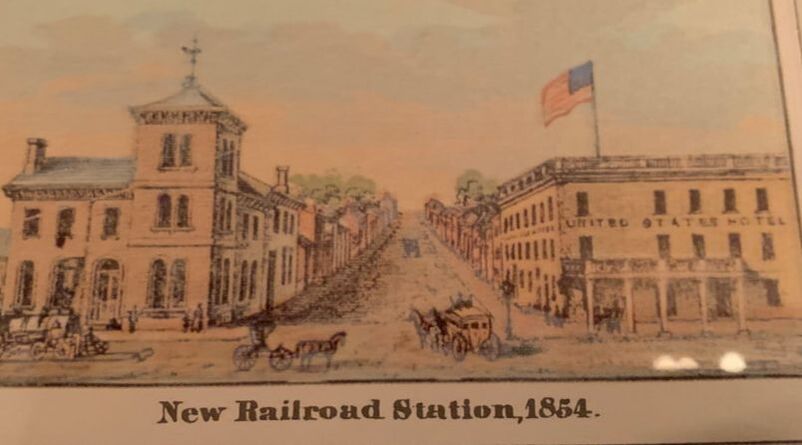

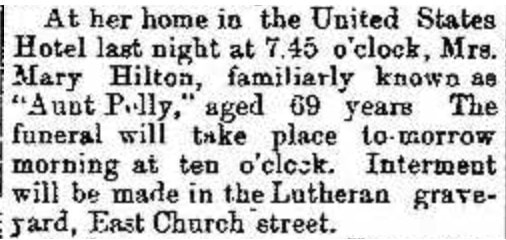

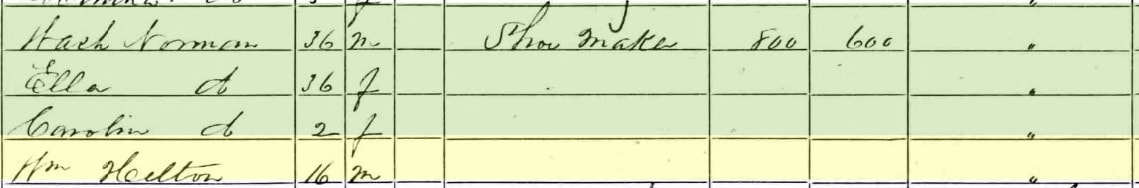

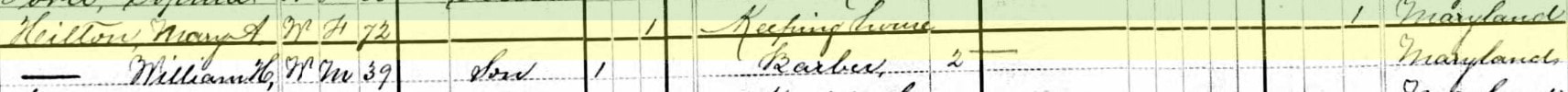

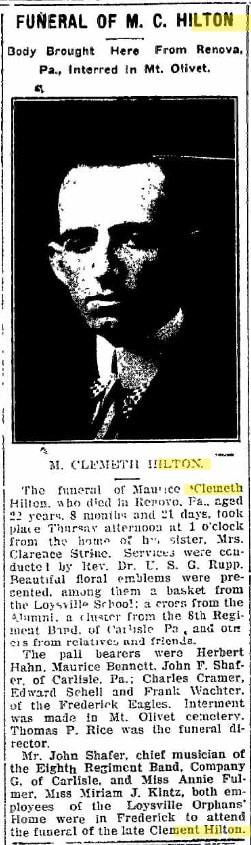

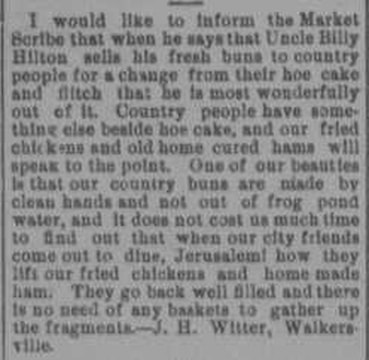

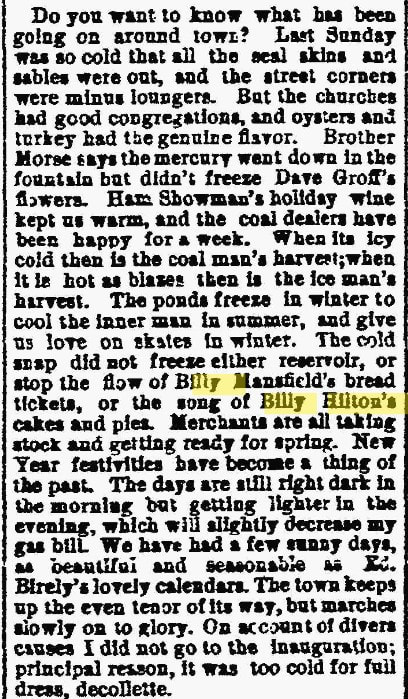

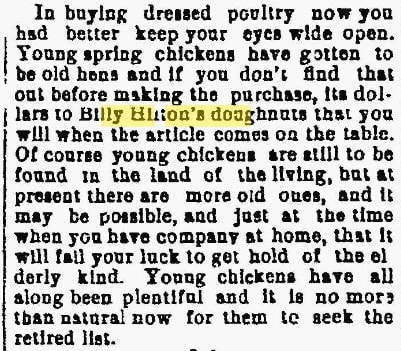

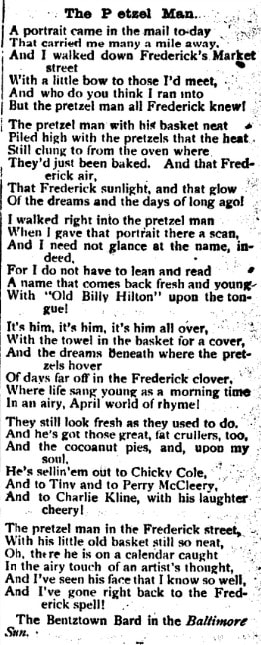

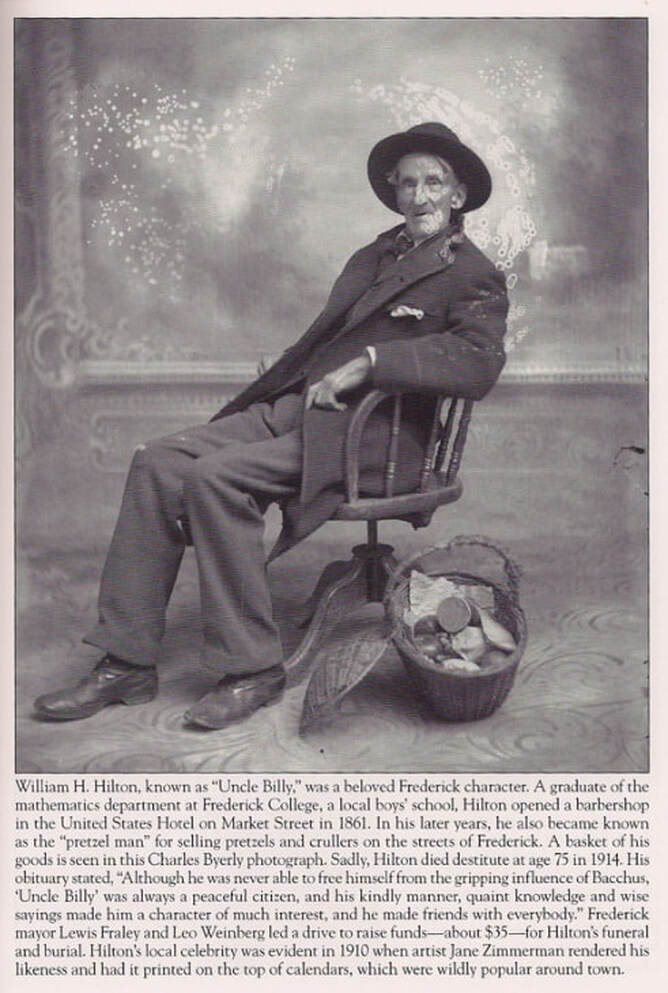

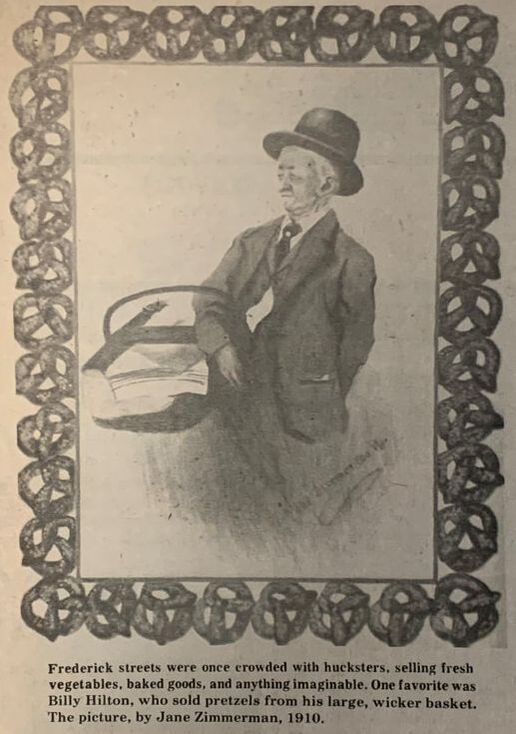

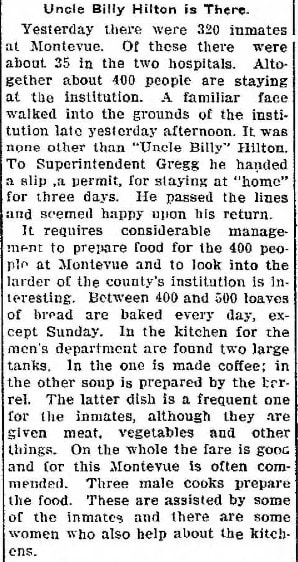

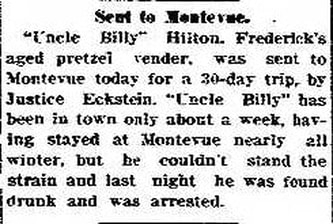

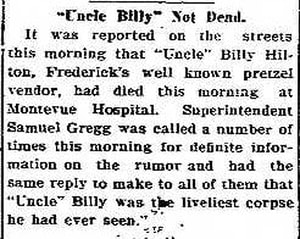

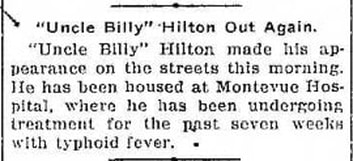

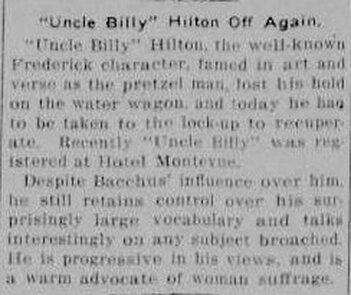

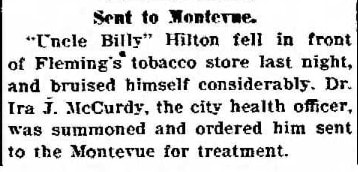

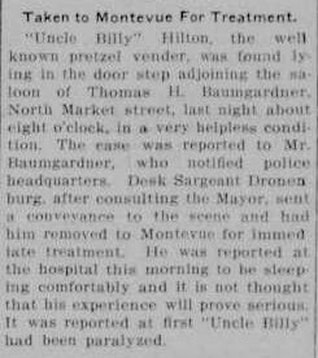

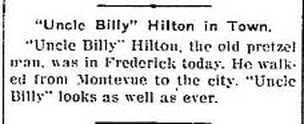

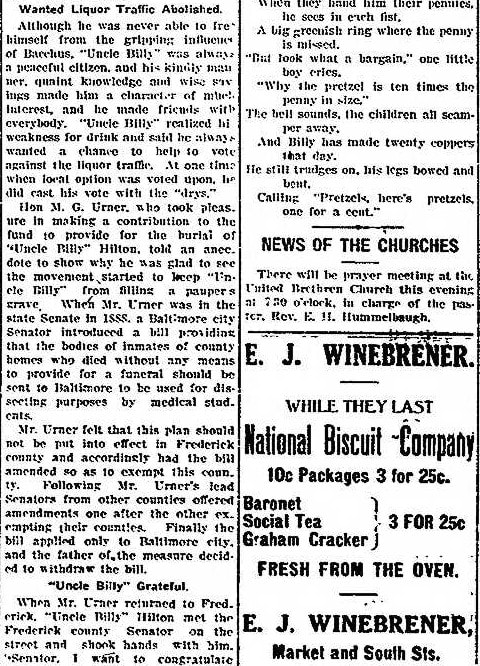

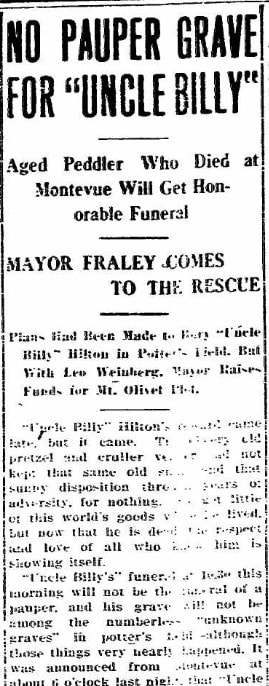

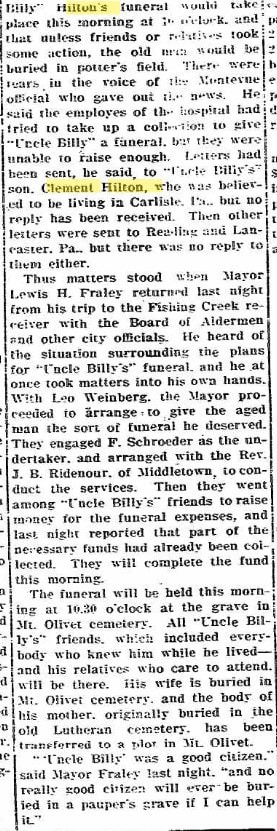

I’m going to try to tell you this “Story in Stone” at “the speed of light.” And speaking of light and dark, it’s hard to imagine Downtown Frederick without radiating brilliance unless, of course, you visit Mount Olivet Cemetery after sundown. With my old friend Ron Angleberger (owner/operator of Maryland Heritage Tours), we regularly guide people through the cemetery on candle-lit history sojourns in late fall (and certain other times of year). Ron is the true veteran, however, as he has been leading the Downtown Ghost Tours of Frederick for over two decades. The nocturnal ambiance is a little better for cemetery tours, but the side streets of the 50-block historic district make for a perfect backdrop for some pretty cool and chilling tales about people and events from the past. Another unique night-time feature of Frederick City is the fact that our beloved town mascots, the “clustered spires,” forever keep alive the legacy of Barbara Fritchie and the nonagenarian’s supposed interlude with Gen. Stonewall Jackson and his “Rebel horde” back in September of 1862. With the holiday season, our seats of city and county government are illuminated, as are the main thoroughfares of town (Market and Patrick streets) with annual decorating of trees with string lights. Frederick becomes a “festival of light” to use a well-worn cliché. Even the “old town creek” is lit, hosting the maritime players of “Sailing Through the Winter Solstice.”  Believe it or not, there once was a time when Frederick was “in the dark.” Certainly not figuratively or intellectually, but plain and simply devoid of light. People utilized candles by necessity, and it’s nice to see faux, electric candles these days in so many historic homes as part of holiday decorations. This gives us a glimpse, or should I dare say a “flicker” of what the scene may have resembled in the 1700s and early 1800s. Prior to the 1800s, lighting of streets was confined to only the most prosperous of communities, and was provided by torches or lamps which burned oils rendered from animal fat. While animal fat lamps were a blessing, they were also a curse, requiring daily scraping and cleaning to remove gummy deposits. With the exception of reflectors to diffuse (spread out) or concentrate the light, few improvements occurred in lamps until the late 1700s. In the 1780s, a Swiss chemist named Aime Argand invented a lamp with the wick bent into the shape of a hollow cylinder. Such a wick allowed air to reach the center of the flame. As a result, the Argand lamp produced a brighter light than other lamps did. Later, one of Argand's assistants discovered that a flame burns better inside a glass tube. His discovery led to the invention of the lamp chimney, a clear glass tube that surrounds the flame. During this period, whale oil, because it burned with less odor and smoke than most fuels, and colza oil, an oil from the rare plant, became important fuels for lamps. As a result, a thriving whaling industry developed to provide whale oil for lighting. In the United States alone, the whaling fleet swelled from 392 ships in 1833 to 735 by 1846. At the height of the industry in 1856, the United States was producing 4 to 5 million gallons of whale oil annually. Frederick finally “saw the light” in the spring of 1832. A town ordinance authorized the installation of 36 oil lamps. Up until this time, those venturing onto the unpaved muddy streets at night had to take lanterns with them, or rely on the lamps shining from store windows or taverns. Enter two former residents who were given the job to show others the way. Frederick diarist Jacob Engelbrecht introduces us to them with a journal entry dated May 21st, 1832: “City Lamps. The corporation of Frederick some months ago appropriated money for the erection of lamps at the different squares in this City. They are, I believe now completed and this might well be for the first time. Mr. Clement Hilton and Mr. John Haller have been appointed Superintendents or lighters.” Now again, these were strictly oil lamps at the beginning. The lamplighter was employed to light and maintain the candle, whale oil and, eventually, Kerosene, known in those days as "Coal Oil", which was much easier to produce, along with being cheaper and smelling better than animal-based fuels when burned. Kerosene also did not spoil on the shelf as whale oil did. Gas lighting would become a reality in the late 1840s, and that is a story for another day and was spurred on by another Mount Olivet resident. Lights were lit each evening, generally by means of a wick on a long pole. As depicted below, a lamplighter is climbing a ladder to replenish the oil in the light. At dawn, they would return to extinguish the light. Early streetlights were generally solid candles or oil (and similar liquids) with wicks. These methods would eventually give way to gas lighting. So, I went in search of our first lamplighters. I didn’t learn much about their lives, but I did find their final resting places here in Mount Olivet. John Haller is buried in Area D/Lot 52 with his wife Mary Magdalene (Brown). He was born in 1796 and the couple lived in Bentztown, the area of Frederick around the intersection of Bentz and Patrick streets. Haller died relatively young at age 36, a victim of a cholera epidemic that ravaged the city (and country). Unfortunately, John Haller's time on the job was relatively short as his death date is September 22nd, 1832. Originally buried in the town’s Lutheran graveyard on East Church Street extended, he would be re-interred here in Mount Olivet. Mr. Clement Hilton, on the other hand, had a bit more longevity to offer in terms of life story. Clement G. “Clem” Hilton was born May 31st, 1779. He was the son of Thomas Francis Hilton, who had connections to Washington County, Maryland. Clemm married Ann Maria Christina Herrlein (1772-1833) on September 12th, 1800. The couple are buried together in the unique Area NN of the cemetery. This is where three local congregations removed decedents from the former Presbyterian, Methodist and Lutheran graveyards of town for reburial here around the turn of the 20th century. The Hiltons were part of the Evangelical Lutheran congregation who had two cemeteries on East Church Street, the original behind the historic church and stretching to East Second Street. The one in question, however, was the second burying ground that once existed on the site of today’s Everedy Square. More specifically, this cemetery was located on the southeast corner of East Church Street (extended) and East Street, across from today’s Frederick Coffee Company. The bodies, and tombstones, of Clem and Ann Maria Hilton appear to have been moved here in 1907, and are placed tightly next to one another, along with other remains that hail from the ancient Lutheran burial ground. Outside of that, Clement can be found in the early census records of town, but it’s been hard to discern his occupation until that of town lamplighter in 1832. Through Ancestry.com, I found that the couple had seven known children mature to adulthood, four of which I definitively found buried here in Mount Olivet. These include Ann F. (Hilton) Cole (1803-1877) in Area R/Lot 98; Henry Konig Hilton (1805-1887) in Area B/Lot 104; Susan Columbia (Hilton) Young (1810-1849) in Area B/Lot 123; and Rosanna E. (Hilton) Boyer (1817-1847) in Area NN/Lot 124. The other three Hilton children are Elizabeth R. Hilton (1800-1856), Mary Polly Hilton (1815-1886) and William Herrlein Hilton (1811-1849). I’ve exhausted my search on Elizabeth, was frustrated with my attempt to find Mary Polly, and William Herrlein gave me three options within the cemetery, but the birthdates are from the next generation down (being in the 1840s and 1850s). One of these was a local celebrity of sorts, or at best a town character, who was the son of the fore-mentioned “missing Mary Polly Hilton.” As for Clem’s son William Herrlein (also referred to as William Henry Hilton), I learned that he married a Baltimore girl in Charm City, and actually died in Washington, DC. An obituary says he was brought home to Frederick to be buried in the Lutheran Graveyard. My research assistant, Marilyn Veek, found that in 1831, Clement Hilton was indebted to his son Henry for $105, so to secure that debt he sold Henry a cow, a desk, a ten plate stove, four bedsteads, four beds and the necessary bedclothes, three shoats (young pigs), eight chairs, two tables, one looking glass, one meat tub, one large iron pot, a kitchen cupboard, three washing tubs, and all his kitchen furniture. The sale would be void if Clement paid off the debt in two years. Although the deed is marked "paid", Henry sold essentially the same list of items in 1836 to his older sister Elizabeth, to secure his debt of $125 to her. That debt was also paid off. Ann Maria Hilton died in 1833 at the age of 62 and was buried in the fore-mentioned Lutheran graveyard on East Street. As for Clement, Jacob Engelbrecht makes mention of additional appointments as lamplighter over the next few years. In 1834, he would be given the additional honor as “market master.” This has nothing to do with stocks, but more with the town Market House constructed in 1769. He was the supervisor of the Market House, which once stood on the site of today’s Brewer’s Alley Restaurant. This structure (and Market Space behind) was the mall of its day, containing stalls that could rented for people to sell their products to the town citizenry. This primarily consisted of farmers and butchers selling their food products. Scales could normally be found here as well in order to measure crop items such as hay, wheat and barley for resale. The Market House was also the home of early offices for the town of Frederick, and I read recently that a school for girls was conducted here at one point in the late 1840s. By 1835, Clement Hilton’s sole job was that as Frederick’s market master. In time, he would be given an additional assignment as town messenger. The Corporation appointed him to both posts for consecutive years culminating in March, 1846, two months before his passing on May 21st of that year. Clement Hilton was well respected in Frederick, but must have earned a positive reputation outside of town, as I found his obituary in the Baltimore Sun newspaper. Clement Hilton’s son, Henry Konig Hilton, never owned property either, but daughters (with unknown gravesites) Mary and Elizabeth Hilton certainly did. In 1850, they bought a property at what is now 232 East Church Street, which Mary sold in 1871. Pictured below, it is within arms-reach of the Old Lutheran burying ground that would hold their parents—temporarily of course. After residing on Church Street, Mary apparently lived in the United States Hotel, where she died in 1886. This building was located on the southwest corner of All Saints and South Market streets, and still stands today. Mary should be here in Mount Olivet, but I can’t find her grave in our database system. We have a Mrs. Hilton in the mass grave in Area MM which includes re-interments from the All Saints Protestant Episcopal Cemetery brought here in 1913. However, the only bit of information captured from an ancient tombstone (which no longer exists) was that this woman died on November 11, 1821. This is not our Mary, but could it be Clem’s mother? Presumably born in 1732, I doubt it, but could be wrong. I’d love to be able to identify the woman therein. I strongly think Mary Polly Hilton was buried at the Lutheran Cemetery, but had no gravestone, and was unfortunately lost in the move. A gentleman named Bill Hilton created a FindaGrave.com memorial page for her connected to our cemetery back in 2012 (Mary Hilton (1815-1886) with appropriate links to other family members we have discussed here. Perhaps Bill Hilton had information, or family lore, that we don’t? Our main precursor for a burial is an interment card, which we don’t have for Mary Polly Hilton. In doing a little more genealogy in my search for Mary Polly Hilton’s gravesite, I came up with the fact that she had a son. However, this gentleman would continue the family name of Hilton and was named for his maternal uncle who I theorize lived, died and is buried in Baltimore or DC. I could not locate a father, who may, or may not, have married Miss Mary Polly Hilton. The child, William Herrlein Hilton, has also turned up as William Hugh Hilton in certain records. He was born on New Years Eve of 1841. In addition to being a “Baby New Year,” I soon realized that I had made a connection to a gentleman I had stumbled over before. He is prominently pictured in one of the Historical Society’s photo books, and was the subject of a Frederick Magazine article in 2004. He is best known as “Uncle Billy,” and pulling on the holiday theme, I don’t know if his was truly “a wonderful life.” This gentleman appears in the early census records as an apprentice shoemaker in 1860, and a barber in 1863 (Civil War Draft information) and 1880. I’m assuming he received an education in local schools, but can’t be sure, along with living with his mother and aunt on East Church Street. I also found that he married Miss Emma Melissa (Kimmell) Hilton (1851-1898) on January 3rd, 1888, and had a son. Maurice Clement Hilton was born in 1893 and moved to Pennsylvania where he spent the bulk of his life. Upon his death in 1916, he would be laid to rest in Mount Olivet next to his mother. Unfortunately, we don’t have the 1890 census to assist us with William H. “Uncle Billy” Hilton’s profession. I couldn’t find him in 1900 or 1910 either. I do know from several newspaper articles of the 1890s that he had given up his clipping shears for baker’s whisk and mixing bowl. He was known near and far for his flour-based creations. Uncle Billy Hilton was also captured in the poetry of Folger McKinsey, the Bentztown Bard who started his career in Frederick and transferred to the Baltimore Sun. We are lucky to have two photographs of Uncle Billy. The first is part of Heritage Frederick’s amazing collection and was taken by Charles Byerly. It is featured in Frederick County Revisited, published by the Historical Society of Frederick County (aka Heritage Frederick) in 2004 with the caption included. Another photo was included with the 1976 Bicentennial supplement of the Frederick Post. A story told of Uncle Billy’s unique operation of selling pretzels around town. He was certainly a town legend of yesteryear—maybe not holding the national prestige of Bryan Voltaggio, but in a time without radio, television and social media, he was pretty darn close on the local level. Uncle Billy also had flaws, and this was well known. He was frequently drunk and had mishaps that were covered in the paper. He continually made trips to the Montevue Hospital and home north of town. One such event led to a rumor reporting that Uncle Billy was dead. This was quickly debunked. Billy Hilton did get really sick in 1914 and passed on August 10th, 1914. He outlived his mother and wife, and apparently was estranged from son, Maurice Clement in Pennsylvania. It was thought that “Uncle Billy” would be buried in a pauper’s grave at Montevue. However, Frederick’s sitting mayor (Lewis Fraley) and a leading attorney (Leo Weinberg) could not let such a “shining light” as “Uncle Billy” not be buried in Mount Olivet. They would garner the amount necessary ($35) to bury Uncle Billy with dignity in proximity to other relatives. “Uncle Billy” Hilton is in Area M/Lot 26. This particular part of the cemetery, north of Confederate Row, was once called “Stranger’s Row.” This was a place for destitute individuals and unknown guests to town who unfortunately expired while here and far from family and native homes. He has never been given a gravestone, but his mortal remains are here among others of the same plight. As Hilton family member’s “life lights” were illuminated, they were also naturally extinguished in due time. The same fate will soon take the beautiful holiday lighting from our homes, city streets and creek. But don’t worry, there’s always next holiday season in 11 months, and it will be here in a flash.

|

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed