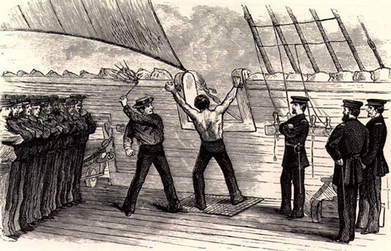

Easter is synonymous with bunnies, chocolate, marshmallow peeps, jelly beans and hunting for Easter eggs. But the religious holiday means so much more, especially in understanding the concept of true sacrifice, and receiving something back in return for that sacrifice. As the oldest and the most important Christian festival, Easter is the celebration of the death and coming to life again of Jesus Christ. For Christians, the dawn of Easter Sunday with its message of new life is the high point of the Christian year. This follows the period of Lent, a time to “give up” something that an individual adores because it’s a wonderful way to experience sacrifice. For kids, it should be something like candy, with the payoff being that basket overflowing with sugary treats on Easter morning. The word “Lent” traces back to Old Germanic words for “long” which seems appropriate for anyone anxiously awaiting warmer temperatures. Originally Lent was a time of discipline to prepare for Easter, 40 days dedicated to reflection, repentance, and anticipation for the hope of Salvation offered through Christ’s death and resurrection. In today’s world, many religious leaders are asking congregants to consider giving something in place of a sacrifice or “giving something up.” Here’s an opportunity to do something good for yourself and for others. “Taking up” good deeds and acts of kindness not only honors religious teachings of love and service, but also provides a nice distraction from the temptation to cheat on Lenten vows. Each workday, I’m reminded of the idiom: “You scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours.” And it’s not just because I work with very kind and passionate people here at Mount Olivet, something that is a necessity when working for a cemetery. No, it’s due to a grave monument I drive by at the end of each day on my way home. It reads “SCRATCH MY BACK” in large letters, a poignant and unorthodox message carved on the backside of a “tombstone” belonging to Nettie and Herbert Hartley.  Now before I tell you about the Hartleys and the curious command on their monument, I want to briefly explore the saying “You scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours.” Many say that this expression is best described by the Latin phrase quid pro quo, which means making a certain kind of deal or agreement, for example: you do this for me, and I'll do that for you. Online idiom dictionaries give similar definitions: *to return a favor for a favor *to take care of someone who is taking care of you *to work among equals by offering and getting favors The website www.idioms.com says that “You scratch my back…” is considered a corporate phrase from the modern day business world and is speculated to have originated in the 19th century. A more evocative explanation comes from www.grammar-monster.com and reads: This term has a nautical derivation. In the English Navy during the 17th Century, the punishments for being absent, drunk, or disobedient were severe. One punishment would see the offender tied to the ship’s mast and flogged with a lash (known as a cat o’ nine tails) by another crew member. Crew members struck deals between themselves that they would deliver only light lashes with the whip (i.e., just "scratching" the offender's back) to ensure they were treated the same should they ever found themselves on the receiving end at some time in the future.  This was all very interesting, another example of the amazing things to be learned from performing a GOOGLE search. I also found that Elvis Presley had a song entitled “Scratch my Back” which was featured in the 1966 film Paradise, Hawaiian Style. I’ve enclosed a link with this song for you viewing/listening pleasure: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3MjP59JsqQg The Hartley Monument After first time seeing the Hartley stone two years ago, I asked Mount Olivet superintendent Ron Pearcey about its meaning. He didn’t know, saying that the salesperson that sold the family the monument would possibly know, but he no longer worked for the cemetery. So that was that, but it was always in the back of my mind that I'd certainly like to find out the answer one day. That day would come in early November, 2017. It was a rainy Saturday evening, and I was about to give the final Mount Olivet candlelit walking tour of the fall season. As I huddled with participants in the covered information kiosks adjacent the Francis Scott Key monument, I met Sharon Rectanus and her brother David Hartley, the latter from Ocala, Florida up visiting his sister, a resident of Frederick. While waiting for additional tour-goers, I asked if they had been to the cemetery before? They told me yes, and that their parents were buried in the newer part of the cemetery near the mausoleum. Pointing to a large cemetery map on the wall, I asked in what area they were interred? They looked and pointed out the TJ (Thomas Johnson) area. They followed by saying, you can’t miss the stone because it says “Scratch my Back” on the monument. And, just like that, I had my answer! I asked Sharon and David about the rationale for such a curious command on a funerary monument. Here’s what Sharon told me, embellished a bit with a follow-up email set to me a few days later:

It is a terrific story, and the essence of cemetery memorialization in the form of grave monuments and plaques. Not only does it give a brief glimpse into the life, and more so the personality, of the decedent, but it will continue to be there for years (and generations) to come. I told Sharon and David about my “Stories in Stone” blog, and said that her mother’s story was perfect material for me to do as a feature in the future, but I needed some additional material. Sharon (Hartley) Rectanus was kind enough to provide me with photos and articles to help tell Nettie’s story. I guess you could say this is yet another example of reciprocal “back scratching.”  “The Back Scratchee” Nettie Hartley was born Nettie Rose Stephens on May 5, 1919 in Harriettsville, Ohio. She was the daughter of Wilbert and Ethel May (Rohrer) Stevens and grew up on the family’s farm. Her childhood consisted of milking cows, feeding chickens, washing dishes, and riding horses—her favorite was named Dan. Nettie attended Mountain State Business College in Parkersburg, West Virginia and afterwards worked as a secretary for the Imperial Ice Cream Company. During this time she corresponded with a friend’s brother named Herbert, a soldier in the US Army who was stationed overseas in World War II. When Herbert returned home from the war, they met and fell in love. Nettie married Herbert F. Hartley soon after, and the young couple moved to Washington DC. Herbert worked at the Pentagon, while Nettie stayed home and took care of David and Sharon.  The family relocated to Frederick in the 1960’s. Nettie became very active in her church (South End Baptist) where she played the piano and taught Sunday School. Herbert passed away in October, 1988 and Nettie would eventually take up residence at the Fiddler’s Green at Edenton. In an interview which appeared in an Edenton community newsletter, Nettie was purported to have taken a great interest in the wildflowers of Texas, and took great joy in telling fellow residents of her research findings. I venture to guess that she may have asked for “back scratchings” in return. Nettie Rose Hartley passed away on September 3rd, 2005 and was buried with, and next to, her two favorite “back scratchers” in Mount Olivet’s Thomas Johnson section in Lot 142. Rest in Peace Nettie, and we thank you, and your family, for bringing a smile to our faces each time we see the odd request etched upon your stone. (NOTE: Special thanks to Sharon Hartley Rectanus for invaluable contribution to this story!)

4 Comments

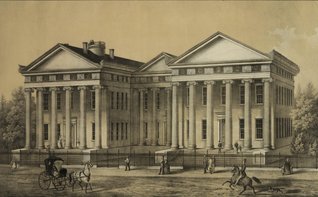

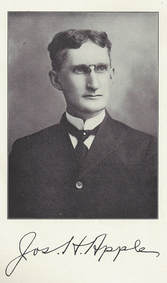

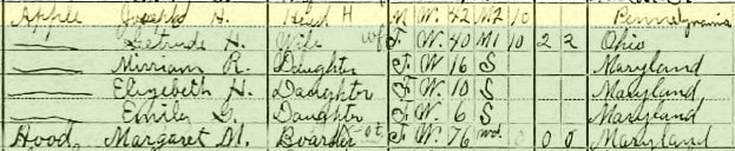

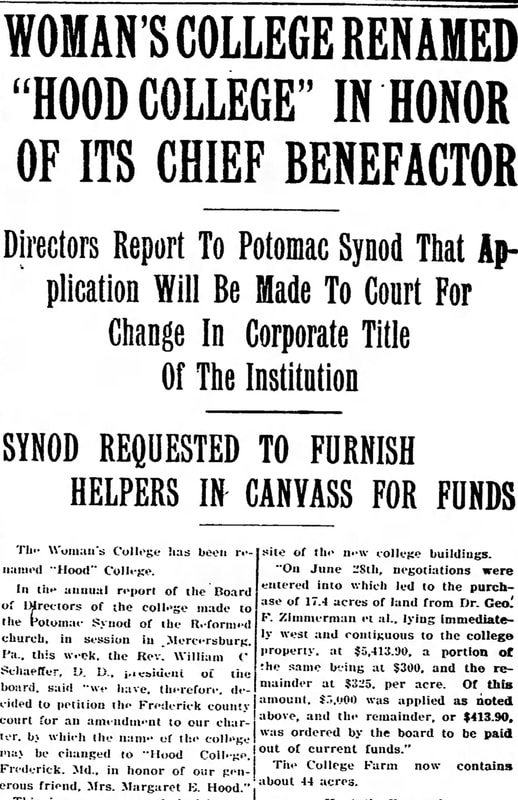

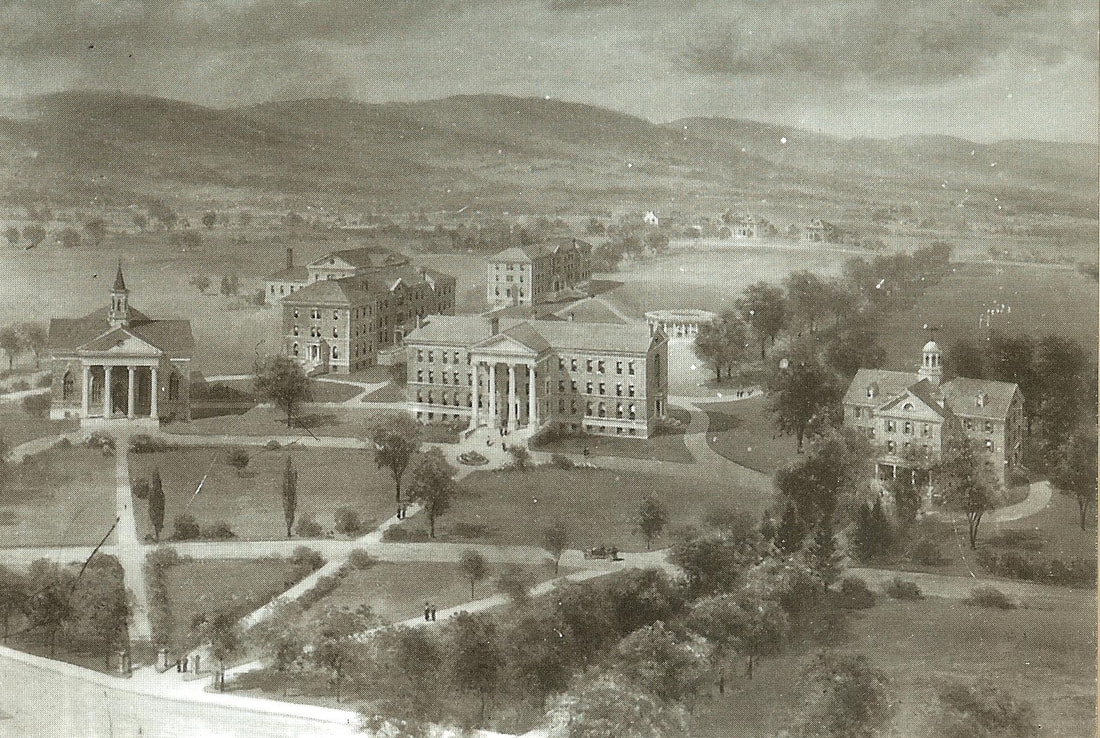

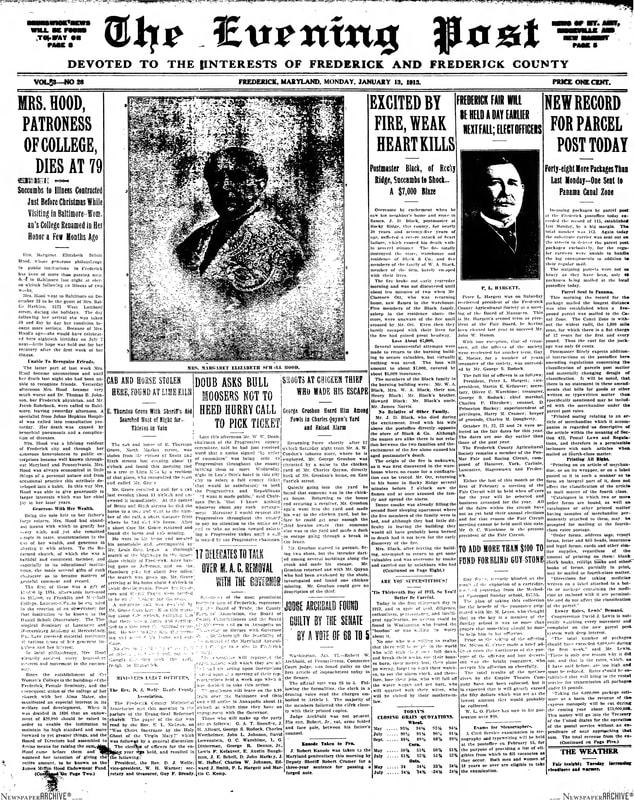

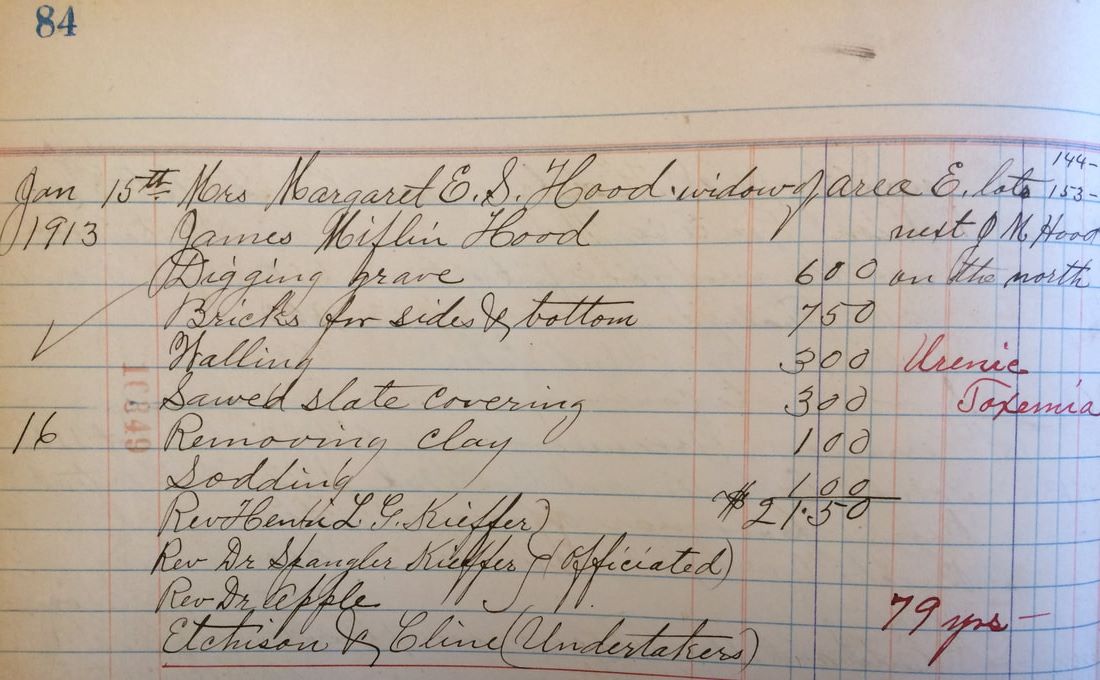

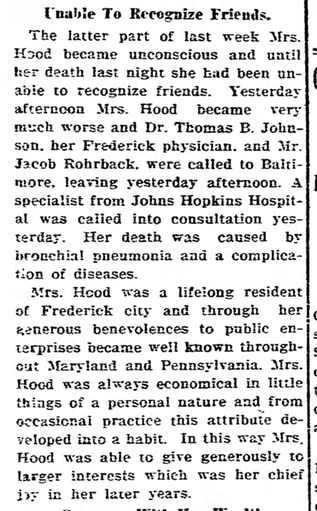

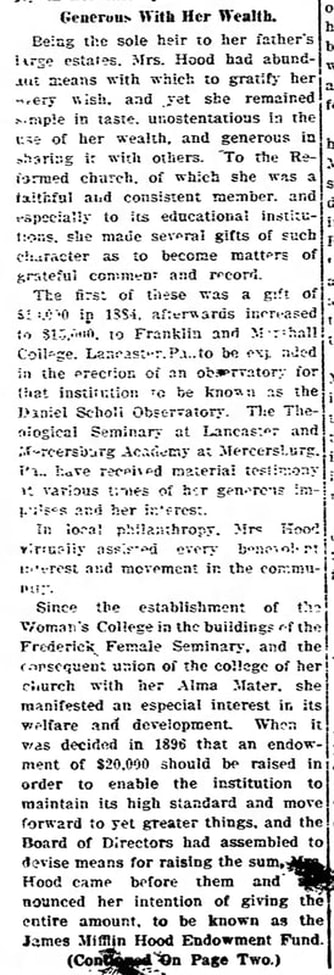

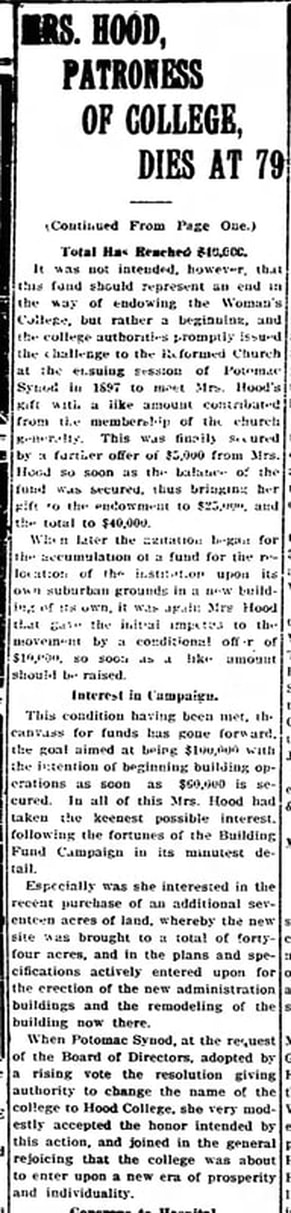

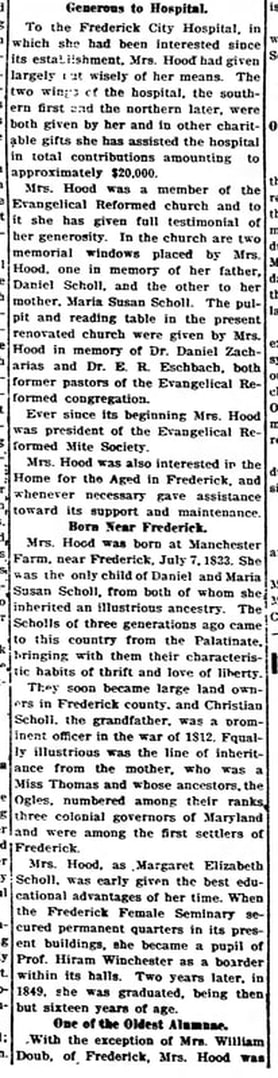

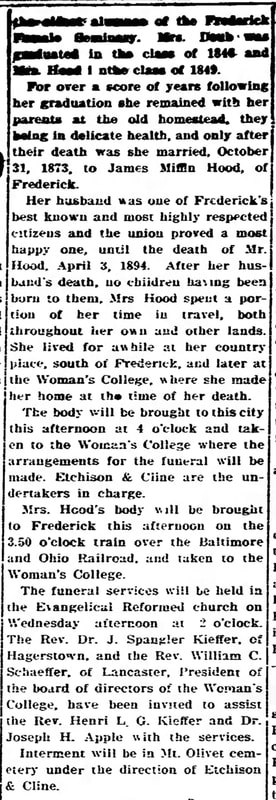

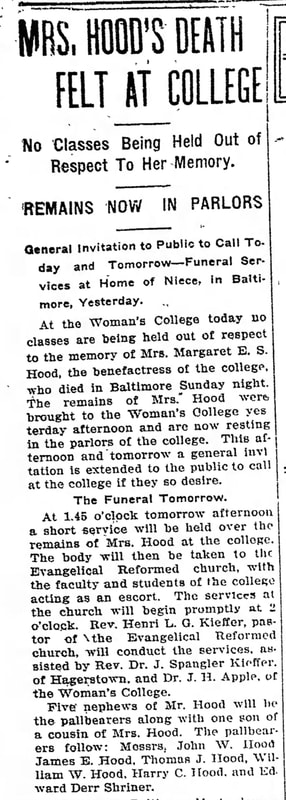

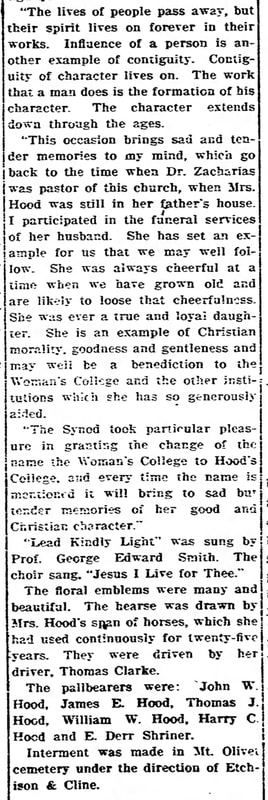

Students, staff and alumnae place red carnations on the grave of college namesake Margaret S. Hood (March 24, 2018) Students, staff and alumnae place red carnations on the grave of college namesake Margaret S. Hood (March 24, 2018) This weekend Mount Olivet hosted a special event organized by Hood College’s History Club, with help from the school’s Office of Alumni Relations and Special Events. It was a remembrance ceremony for the college’s namesake, and major benefactress, Margaret Elizabeth Scholl Hood. The event was part of a larger, year-long celebration of the school’s 125th anniversary. Students walked to the cemetery from Hood, as they were able, to Mrs. Hood’s final resting spot here in Mount Olivet. Once on site, they placed carnations on the gravesite. There was a brief graveside ceremony, and a small, informal reception followed in the cemetery’s Key Memorial Chapel. This event revived a bygone tradition intended to honor the college's namesake, one of Frederick's earliest philanthropists. Mrs. Hood was known for her thoughtful and discriminating generosity, along with an interest and concern for others. She was a called a “zealous supporter of good works,” and possessed a cheerful and lively nature. Mrs. Hood Many others have written fine pieces on the tremendous achievements and life contributions of Margaret S. Hood. I, however, will share some information on her death and burial here in Mount Olivet. But first, here’s a biographical sketch taken from Hood College’s website:  The Frederick Female Seminary (today's Winchester Hall, seat of Frederick County government) The Frederick Female Seminary (today's Winchester Hall, seat of Frederick County government) Margaret Elizabeth Scholl, the only child of Daniel and Maria Susan Thomas Scholl, was born at Manchester Farm in Frederick on July 7, 1833. In 1847, when Margaret was 14 years old, she enrolled as a boarding student at the Frederick Female Seminary, which was operated by Hiram Winchester on East Church Street. She graduated two years later; in 1849 this was considered a very adequate education for a young lady. Margaret returned to Manchester Farm to live with her parents. She traveled a great deal with them, helped with the management of the farm and cared for her parents until their deaths, after which, in 1873, she married James Mifflin Hood, a widower with several grown children. He was the owner of the successful firm Hane and Hood, which built and serviced carriages and wagons.  Margaret's alma mater, the struggling Frederick Female Seminary, closed in 1863 after serving as a hospital for wounded soldiers following the Battle of Antietam. The seminary was reopened in 1866 with Rev. Thomas M. Cann as its president. He introduced many innovations, including a library and a college newspaper. He helped with the formation of an alumnae association, known as the Pioneer's Club, which was one of the first women's clubs in the United States. In 1893, when the seminary could no longer afford to operate, the buildings and equipment were leased to the board of directors of the Woman's College of Frederick, operated by the Potomac Synod of the Reformed Church in the United States. The synod had decided to eliminate the women's part of Mercersburg College in Pennsylvania and instead establish a college for women below the Mason and Dixon Line. The synod commissioned Joseph Henry Apple, a 23-year old mathematics teacher from Central High School in Pittsburgh, to recommend measures for establishing such an institution. Professor Apple helped in its formation, and then accepted the presidency of the newly formed college. The Woman's College of Frederick was officially incorporated Jan. 12, 1897 and its first four-year class graduated in 1898. The seminary continued as a preparatory department of the College until 1920. Margaret was especially interested in the management and development of the newly founded College. In January 1897 she contributed $20,000 to what was to become the James Mifflin Hood Endowment Fund, which was established in October 1896 at the request of the Potomac Synod. In the following year, when the Potomac Synod issued a challenge from the Church to provide maintenance funds, Margaret contributed an additional $5,000. She also took a keen interest in raising funds for the establishment of additional buildings, purchasing new land and remodeling Brodbeck Music Hall. She contributed $10,000 toward the building fund on condition that the community contribute at least an equal amount.  The Daniel Scholl Observatory at Franklin & Marshall College in Lancaster, PA (1886-1966) The Daniel Scholl Observatory at Franklin & Marshall College in Lancaster, PA (1886-1966) In 1912, in recognition of Margaret's generous support, the Potomac Synod, at the request of its board of directors, adopted a resolution giving authority to change the name of the College to Hood College. The College's charter was amended in May 1913. Margaret passed away January 12, 1913. Her will provided an additional $30,000 for the College, which was the impetus for President Apple to begin building Shriner and Alumnae halls. Margaret's philanthropy and charitable efforts extended to many other causes in the Frederick community and beyond. She was a charter member of the Frederick Art Club; one of the organizers of the Historical Society of Frederick County; contributed to and served on many Reformed Church committees; and was one of the founding members of Frederick Memorial Hospital, eventually giving the James Mifflin Hood wing and later the Margaret Hood wing to the hospital. To Franklin and Marshall College she gave $15,000 for an observatory in memory of her father, she contributed to the seminary at Lancaster and to the academy at Mercersburg and was interested in the establishment of the C. Burr Artz Library by her relative, Margaret Catharine Thomas Artz. A few months back, I wrote a “Stories in Stone” article on Dr. Joseph Henry Apple, and was fascinated to study the relationship between the young educator (Apple) and the more mature patroness, Mrs. Hood. In his first year on the job, Dr. Apple properly, and professionally, built a relationship of trust with the former student of the Frederick Female Seminary. It was in 1893 that Mrs. Hood would put her faith (and money) in Dr. Apple’s leadership abilities by creating the $25,000 endowment in the name of her late husband, James Mifflin Hood. Years later, Margaret Hood would be invited by Dr. Apple to live at the school. He certainly made Mrs. Hood feel at home, becoming more than just an alumnus, but actually part of the institution itself. So much so, she would return the favor. In her will, Mrs. Hood made arrangements to donate property (formerly known as Groff Park) and give an additional $30,000, which would be the impetus for President Joseph Henry Apple to begin building Shriner Hall and Alumnae Hall. In light of Margaret Hood’s many contributions, Dr. Apple led the charge to have the school change its name from the Woman’s College of Frederick to Hood College. This occurred in October, 1912. A few months later, Mrs. Hood would travel to Baltimore to celebrate Christmas with widowed step-daughter Sallie A. (Hood) Harkins. It is said that she contracted pneumonia on Christmas Eve and was soon bedridden. Her personal physician, Dr. Thomas B. Johnson made trips to Baltimore to check on the 80 year-old patient. Newspaper accounts from early January claim that Mrs. Hood started had slowly been getting better the first week of January but took a downward turn thereafter becoming despondent, and unable to recognize friends and family. She would pass away at 11pm, Sunday, January 12th.

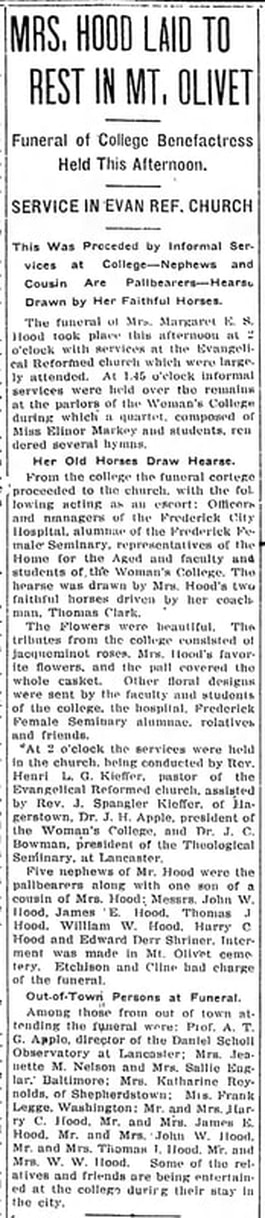

After a short memorial service at the college, Margaret Hood’s body was brought to her beloved Evangelical Reformed Church located less than two blocks to the west of the college on W. Church Street. The 2pm service was conducted by a host of clergyman, including college president Dr. Joseph Henry Apple. The church service was followed by an impressive procession to Mount Olivet, as Mrs. Hood’s hearse was pulled by two personal horses which she had owned for 25 years. Her personal coachman, Thomas Clarke, served as driver. A well-attended funeral culminated with her burial next to husband James and her parents (Daniel Scholl and Maria Susan (Thomas) Scholl) on the Scholl family lot located in Area E, Lot 155. Five months later, Hood College graduated its largest class to date. Diplomas were distributed during a ceremony held at the college on June 10, 1913. Dr. Apple concluded the ceremony with the following passage: “For a number of years past it has been customary to personally present at this time a bouquet of red flowers to our friend and benefactress, Mrs. Margaret Elizabeth Scholl Hood, the number of flowers commemorating her graduation from the Frederick Female Seminary. She is with us today in spirit, and we now lovingly institute the custom, which we trust may never fail of observance in the long years to come, of entrusting a bouquet of 49 red carnations to a committee composed of the Presidents of the four undergraduate classes, who will, at the close of these exercise, place the same upon Mrs. Hood’s grave. Will the audience stand as I entrust these flowers to the President of the incoming Senior class, and as we stand may we all think lovingly of all that Mrs. Hood has done for her community, for her church and for her college.”

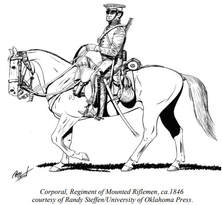

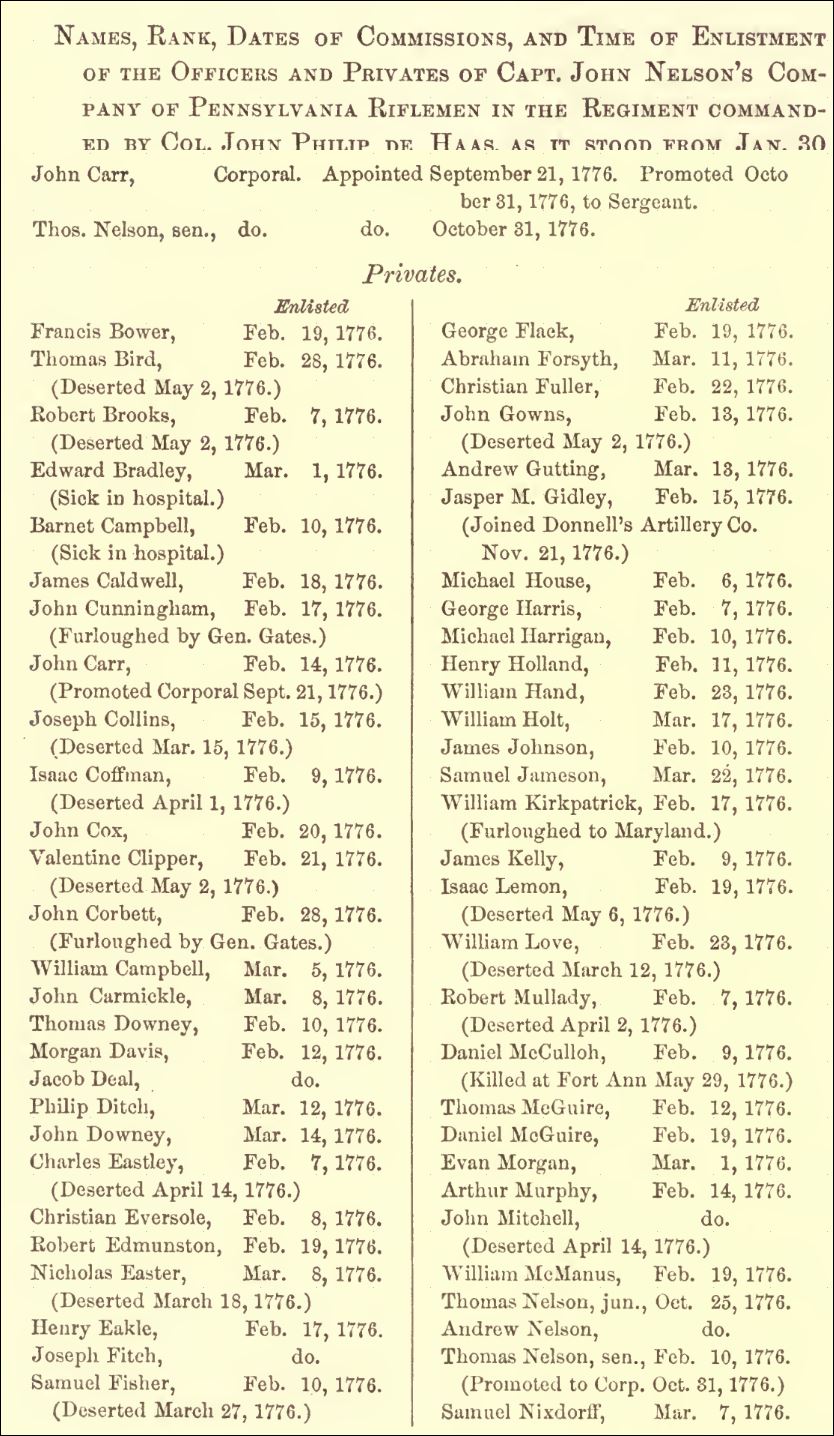

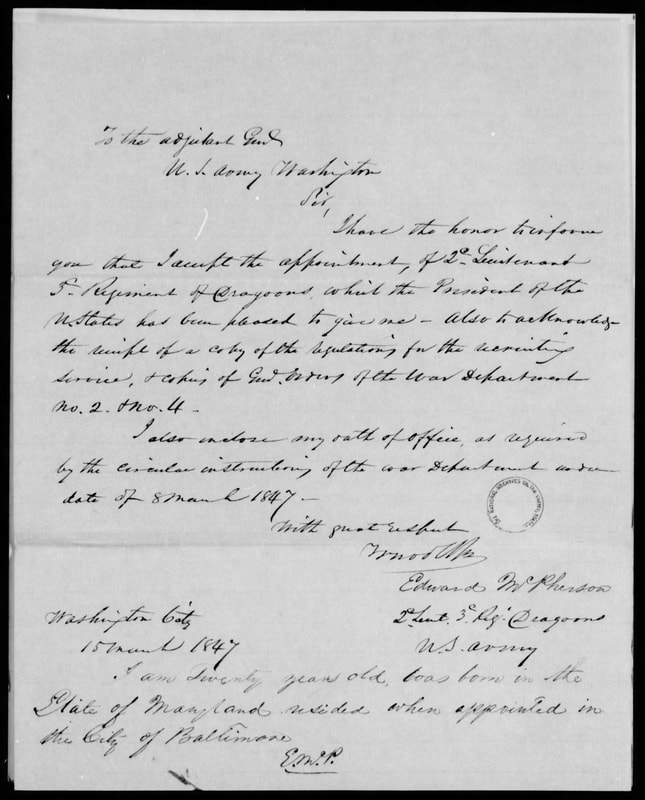

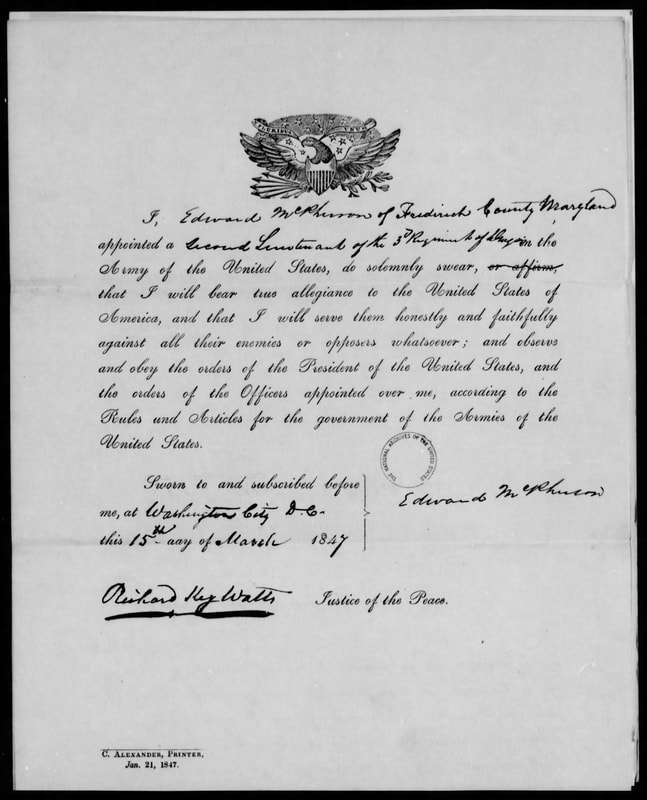

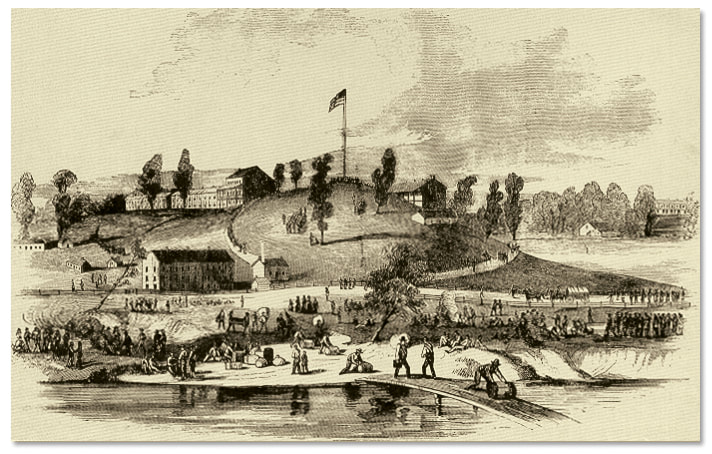

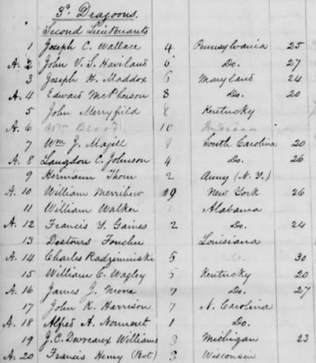

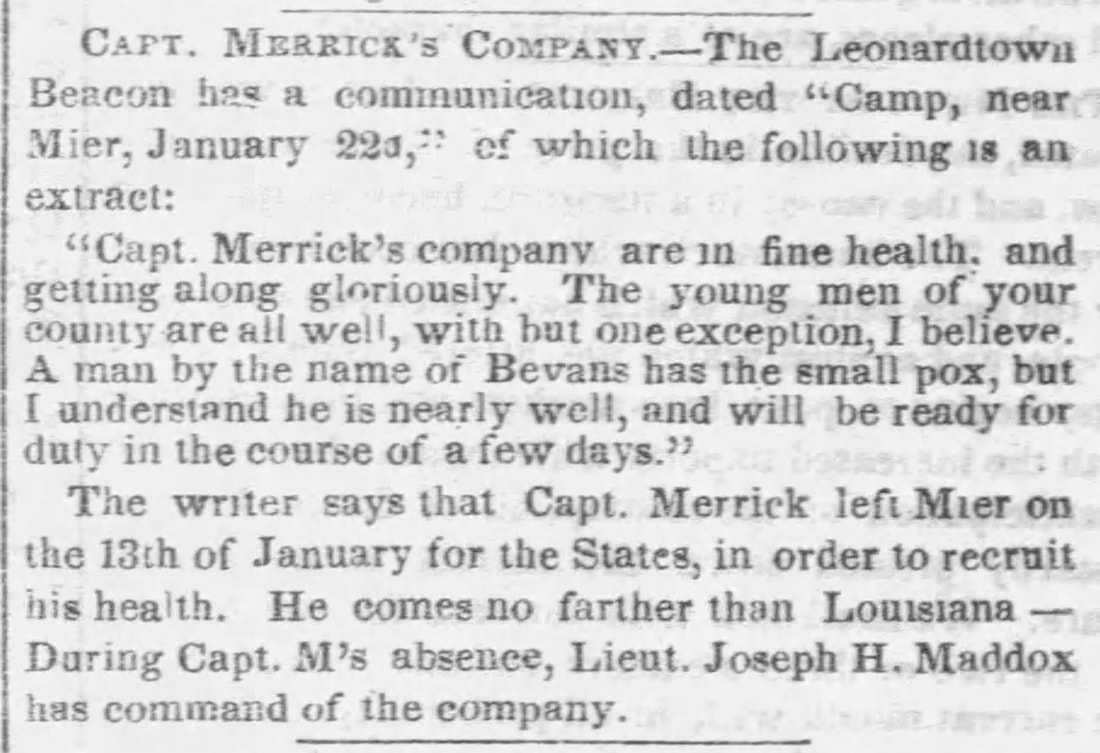

Last October, I referenced an enjoyable, local-flavored book by Alyce T. Weinberg entitled Spirits of Frederick County. From its pages comes the interesting tale of “Sir Edward,” the supposed ghost of Lt. Edward McPherson. He was alleged, for many years, to be a “spirit in residence” at Auburn mansion, located near Catoctin Furnace, a few miles south of Thurmont in northern Frederick County. Each night, the mysterious sounds of someone slowly climbing the back servants’ stairway of the 19-room, colonial home could be heard by descendants of the McPherson family of which Edward belonged. Auburn was built in 1808 by Col. Baker Johnson after purchasing the Catoctin Furnace iron enterprise. The stately home still stands today, and can be seen up on a slight bluff overlooking US15 from the west, near the intersection with Auburn Road and MD806/Catoctin Furnace Rd. Baker Johnson was born in Calvert County in 1747. He came to Frederick from his native Calvert County with brothers (Governor) Thomas, James and Roger. Baker immediately became a stalwart in the community, and lead troops in the American Revolution. One of his business ventures included ownership of the Catoctin Furnace, constructed decades prior by brothers Thomas and James. His involvement would be brief as he died in 1811 at the age of 63. The house and furnace operation would be sold, and eventually would come to be owned by Col. John McPherson and son-in-law, John Brien. These fellows had extensive real estate holdings in the area and were well-versed in operating iron furnaces. You may be familiar with some of their handiwork in downtown Frederick as they were responsible for building the elaborate “Ross and McPherson” homes on Counsel Street adjacent Frederick City Hall. These are owned by members of the Mathias family today.  Margaret McPherson (1892-1977) and husband Clement E. Gardiner, Jr. (1889-1931) on their wedding day in 1916 Margaret McPherson (1892-1977) and husband Clement E. Gardiner, Jr. (1889-1931) on their wedding day in 1916 So, who was this “Sir Edward,” and why was/is he at unrest, and stirring up trouble for Auburn? We’ll get to Lt. McPherson’s unfortunate death at the age of 21, but first let’s tackle the ghost tale. I consulted with my friend Chris Gardiner in an effort to gain additional context on the subject. Chris’ paternal grandmother, Margaret McPherson Gardiner, (later Donaldson with a second marriage), was kin to “Sir Edward” and a long-time resident of Auburn. Late at night, she regularly heard what she thought to be Edward’s melancholy, yet dutiful, ghost climbing the stairs and taking pause outside her bedroom door, as if to ceremonially guard it throughout the overnight. Chris’ father, (and Margaret’s son) Clement Gardner, III, dismissed the notion of a ghost as an “old wives’ tale.” He gave his mother, along with Chris and his siblings, a scientific explanation for the “haunting” sounds on the back stairway, saying that it was simply a function of pressure and its effect on elements found within an historic, old house. He told his mother that the sounds stopped at her door because she had a newly installed floor in there. Chris enjoyed both versions of the story, but most of all, marveled at his amazing lineage, linking him to family members of the past with interesting ties to the once-flourishing Catoctin Furnace. Chris, himself, has such a connection as he currently serves as president of the Catoctin Furnace Historical Society. I have had plenty of past workings with this fine organization, and also had the chance to spend an afternoon within Auburn back in the year 2000 as I was engaged in a video interview with Chris’ father for a documentary I was producing on Thurmont history. It was daytime, not night, and the only creaks and bumps I heard were those coming from my stomach as I had missed eating lunch because my morning interview with another individual had run long. In Alyce Weinberg’s book, an 80 year-old woman named Caroline McGill also gives an account of interactions with Edward McPherson’s ghost: “When I was a mere child,” she said, “I often visited Auburn, which was the home of the local minister, Reverend Ernest McGill, whose son I later married (William McPherson McGill). We children would be sent to nap in the afternoon in an upstair, back bedroom, but sleep was out of the question. We would bury ourselves in the canopied four-poster featherbed, completely hidden under the covers, and whisper and giggle while we listened for the sound of dragging feet limping up the back steps, a sword or something bumping all the way. I never saw “Sir Edward” because I was too afraid to look. But the others told me they did.” The sword in question was actually a sword's scabbard (holder), a prized family heirloom that resided in the house—the actual scabbard of Lt. Edward McPherson. Also on the premises, until a few years back, was a daguerreotype of McPherson in his military uniform, and holding the sidearm. Chris vouches for the authenticity of both of these items. “The scabbard and vintage photo went up for auction a few years back, and fetched a pretty penny,” he said. “The auctioneer had done his homework in researching Lt. McPherson’s military career.“ I, too, researched a bit of McPherson’s military career last spring in preparation for a course I was teaching for Frederick Community College’s Institute for Learning in Retirement. The class was entitled “Frederick County’s Ties to the Old, Wild West,” and I particularly zeroed in on Lt. Edward McPherson and his service in the Mexican War in the army of Gen. Winfield Scott. I had first learned of McPherson being buried here in Mount Olivet, but my initial intrigue for his story was linked to the fact that he met his final demise thanks to a gentlemen’s duel, rather than a noble showing on the battlefield. Edward Smith McPherson was born February 28th, 1827 in Frederick at his family’s estate of Prospect Hall, the grand home west of downtown built by his grandfather, Col. John McPherson. I have also found our subject listed as Edward B. McPherson, and I am wagering that the “B” stood for Brien. There was an older cousin living here that also held this name, so I’m guessing that is cause for multiple monikers. Apparently our Edward was not overly endeared by his father, Dr. William Smith McPherson, Sr. He was, however, favored by his brother, Dr. William Smith McPherson, Jr. and his McPherson nieces and nephews living at Auburn during his lifetime, and long after. The earlier mentioned Margaret McPherson Gardiner was Dr. W. S. McPherson, Jr’s granddaughter. It’s such a tangled web to keep straight, as the McPhersons and Johnsons have connections to so many early Frederick families. Regular readers of this blog may recall a story published last fall on the Fitzhugh family, also one-time owners of Auburn and Catoctin Furnace, who intermarried with the McPherson family. They were responsible for hiring Dr. W.S. McPherson, Jr. to provide medical care for furnace workers of the mid-19th century. “Sir Edward” Goes to War As one of the youngest sons in his immediate family, the “prospect” of land and other holdings, including Prospect Hall, coming into his inheritance were out of the question. Edward had studied law, but was reckoned to make a name for himself through military service. McPherson’s opportunity would come on Monday, March 1st, 1847. In his diary, Frederick resident Jacob Engelbrecht made an entry for the day in question: “Ho, for Mexico. Captain Richard T. Merrick of U.S. Dragoons is now in town recruiting a company for the Mexican War. The rendezvous is opposite our shop in Mrs. Rachel Steiner’s house. I am told he has 25 men enlisted already, among which are Sergeant Edward B. McPherson, Greenbury Froschauer, John Mulhorn, William L. Schley, 1st Sergeant, Frank Schelhausen, 2nd Sergeant & orderly, Allen Ezra, C. W. Burkhart, Allen Albaugh, John W. Burkhart, Thomas William Brightwell, Adam L. Eichelberger, Hy Jeff Favorite, Peter Galwith, Martin Hager, Alexander Hager, Amos Hall, Harritt, George W. Hussey, Martin larch, George Lawd, John H. McHenry, Basil P. Nelson, William H. Ott, John Phelps Shankley, Jacob Silvers, Ferdinand Schultz, John Jacob Snouffer, John A. Sweikeffer, South Frederick Vallo Warthen, William T. Taylor, Oliver P. Fowler, John Steel, Reuben B. Caxley, Charles W. Green, Thomas S. Smith, Hugh Barns. A few weeks later, Engelbrecht noted that the group left Frederick on March 17th, 1847 at 1 o’clock PM. Just over a week before leaving town, McPherson had been promoted to the rank of 2nd Lieutenant of the 3rd Regiment of Dragoons. This occurred on March 8th, as his appointment had been approved by the President of the United States, James K. Polk, and US Senate. The original documents, including his hand-written acceptance letter and signed “Oath of Allegiance to the United States,” still survive in the National Archives.  The "United States Regiment of Dragoons” was organized by an Act of Congress on March 2nd, 1833. This came after the disbandment of United States Mounted Rangers and Riflemen. It became the "First Regiment of Dragoons" when the Second Dragoons was raised in 1836. Years later in 1861, with the outbreak of the American Civil War, the War Department had a desire to re-designate and re-organize its mounted units. This which would lead to the name change of "First Regiment of Cavalry" by yet another Act of Congress. The First Dragoons headquarters were initially established at Jefferson Barracks in 1833, near St. Louis, Missouri. This is where I assume Lt. Edward McPherson and his Frederick comrades would be destined for a brief basic training. McPherson officially appears to take his place with the larger organized 3rd Regiment on April 9th, 1847. It is likely that this was the day he received that valued sword kept in the McPherson family at Auburn for all those years.  The regiment was originally formed to protect pioneers and others traveling on the Oregon Trail. When hostilities with Mexico broke out in the mid-1840’s, the regiment was re-routed southward. Tragically, these mounted rifleman lost most of their horses in a storm during the voyage across the Gulf of Mexico. They were forced to fight without mounts. The regiment landed at Veracruz (Mexico) on March 9th, 1847, and they would go on to serve in six campaigns of the Mexican War. For those interested in perusing the 3rd Dragoons’ regimental history (History, Customs and Traditions of the 3rd Cavalry Regiment Blood and Steel and thus gauge Edward’s experiences in the Mexican War, I have placed additional information at the end of our story.

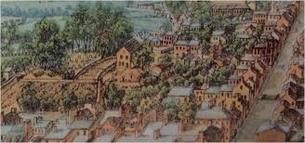

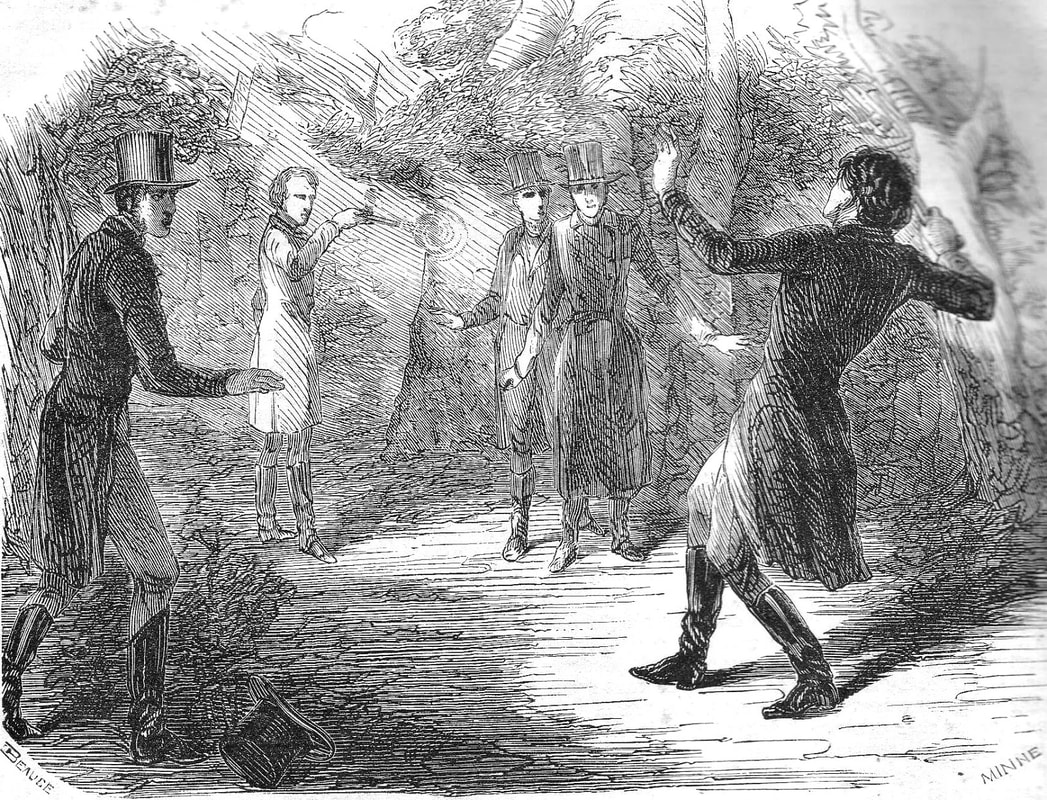

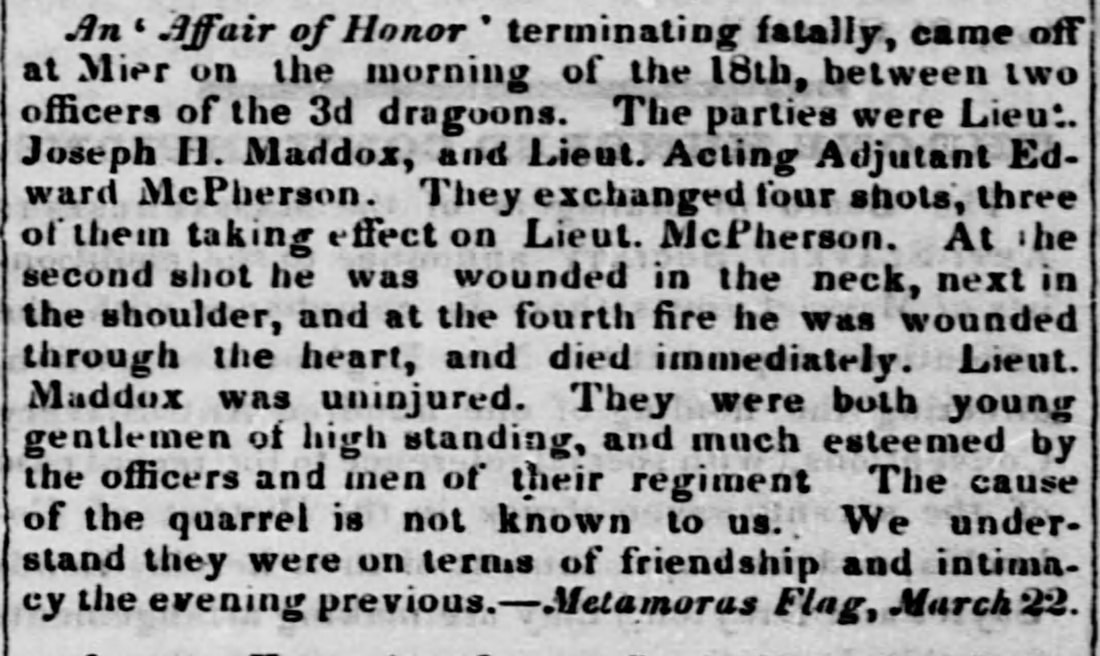

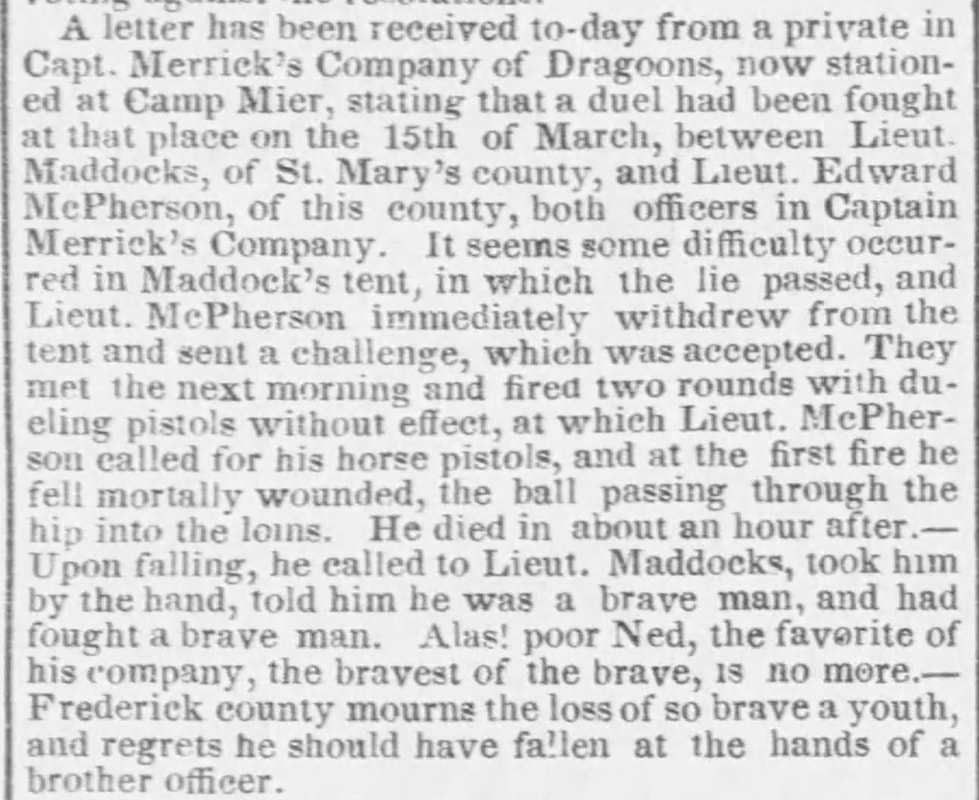

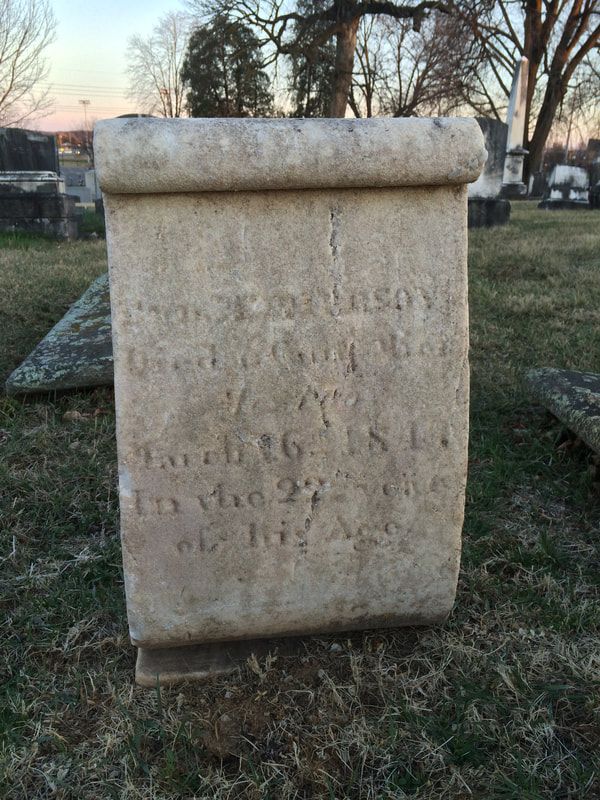

Parroquia de Ciudad Mier, Tamaulipas Parroquia de Ciudad Mier, Tamaulipas Newspaper accounts (some saying the 15th and others the 18th) varied to what actually had happened on March 16th, 1848, but the end result was the same. The fatal event took place in Mier, also known as El Paso del Cántaro, a city in Mier Municipality in Tamaulipas, located in northern Mexico near the Rio Grande, just south of Falcon Dam. (In case you were interested in making vacation plans to visit, this is 90 miles northeast of Monterrey on Mexican Federal Highway 2. Note: the town is a literal “ghost town,” pardon the pun, thanks to an exodus by most residents back in 2010 thanks to local drug cartels.) A widely shared account was from the Malamoras Flag newspaper (Malamoras, Mexico) dated March 22nd, 1848 which reported: “There was a duel fought at Mier yesterday, between Lt. Maddox and Lt. McPherson, both of the 3rd Dragoons. They had four rounds with cavalry pistols—they had fired 2 rounds, then went out and practiced for an hour, returned, and fired two rounds more, when McPherson was killed.” Another report conveyed: “They exchanged four shots, three of them taking effect on Lt. McPherson. At the second shot he was wounded in the neck, next in the shoulder, and the fourth fire was shot through the heart and he died immediately. Lt Maddox was uninjured. They were both gentlemen of high standing, and much esteemed by the officers and men of their regiment…Upon falling, he (Lt. McPherson) called to Lieutenant Maddox, took him by the hand, told him he was a brave man, and had fought a brave man.” The account goes on to say: “Alas! Poor Ned, the favorite of his company, the bravest of the brave, is no more.—Frederick County mourns the loss of so brave a youth, and regrets he should have fallen at the hands of a brother officer."  Frederick's All Saints' burying ground is to the right in this image from the 1854 Sachse lithograph Frederick's All Saints' burying ground is to the right in this image from the 1854 Sachse lithograph The remains of Lt. McPherson were returned to Frederick County in September for burial. I found another document that seems to imply that Edward’s brother, Dr. William Smith McPherson, Jr., went to Mexico to retrieve the lieutenant’s body and personal affects. Edward McPherson was originally buried in the Old All Saints burying ground adjacent Carroll Creek in downtown Frederick. This is where the McPhersons had a large underground crypt as well. Mount Olivet opened in 1854, and the All Saints Cemetery fell out of favor and into a state of disrepair and debauchery—no place for a respectable and noble ghost. On November 30th, 1867, the McPherson family would have Edward’s body re-interred to a family plot in Mount Olivet’s Area E/Lot 54. All I can say is that I hope the brave lieutenant is resting in peace, regardless of whether his spirit may still be residing at Auburn, keeping guard over that back stairway.

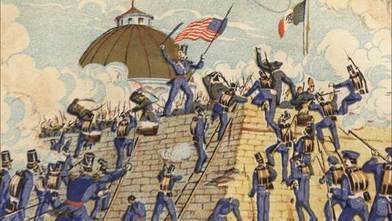

3rd Regiment of Dragoons (Mexican War Involvement) From History, Customs and Traditions of the 3rd Cavalry Regiment Blood and Steel On 17–18 April, 1847, the Regiment was engaged in fierce hand-to-hand fighting during the Battle of Cerro Gordo and were soon engaged again in the Battle of Contreras on 19 August. On 20 August 1847, General Winfield Scott, Commander of American Forces in Mexico, made a speech from which the first sixteen words have become important to the regiment. The regiment was bloodied and exhausted from the fierce fighting at Contreras, but even so, each man stood at attention as Scott approached. The General removed his hat, bowed low, and said: "Brave Rifles! Veterans! You have been baptized in fire and blood and have come out steel!" This accolade is emblazoned on the regimental coat of arms, and is the source of the regimental motto, "Blood and Steel" and nickname, "Brave Rifles." The Mounted Riflemen were soon after sent to engage in desperate fighting in the Battle of Churubusco later that day. Today, all enlisted personnel are required to loudly challenge all officers in the 3rd Cavalry Regiment with the portion of the regimental accolade given to the Regiment of Mounted Riflemen during the Mexican–American War. When an enlisted trooper is preparing to render military courtesy upon contact with an officer he will yell out "Brave Rifles" whereupon the officer will reply "Veterans."  On 8 September 1847, as US forces continued the drive to Mexico City, intelligence was received that a cannon foundry and a large supply of gunpowder was believed to be at Molino del Rey, 1,000 yards east of Chapultepec Castle. MAJ Edwin V. Sumner took 270 Riflemen to screen the American flank as the attack on Molino del Rey began. 4,000 Mexican cavalrymen were poised to attack the US flank, but Sumner's men navigated a deep ravine (considered impassable by the Mexican cavalry), charged, and defeated the vastly superior force. The climax to the regiment's participation in the Mexican War came on 13 September 1847when the brigade the regiment belonged to was ordered to support the assault on the fortress of Chapultepec, the site of the Mexican National Military Academy. A pair of hand-picked, 250-man storming parties were formed, including a large number of Mounted Riflemen under CPT Benjamin S. Roberts During the charge, a party of US Marines began to falter after their officers were lost, so Lt. Robert Morris of the regiment quickly took charge and led them to the top. While the fortress was being stormed, other elements of the regiment captured a Mexican artillery battery at the bottom of the castle. Leading the American forces, the regiment stormed into Mexico City at 1:20 pm. At 7:00 am on 14 September 1847, Sergeant James Manly of F Company and Captain Benjamin Roberts of C Company raised the National Colors over the National Palace while Captain Porter, commander of F Company, unfurled the regimental standard from the balcony. For the remainder of the regiment's tenure in Mexico, they would conduct police duty and chase stubborn guerrillas. However, they also took part in the battles of Matamoros on 23 November 1847, Galaxara on 24 November, and Santa Fe on 4 January 1848. The Regiment of Mounted Riflemen earned a reputation among Army leaders as a brave and tough unit; General Winfield Scott said “Where bloody work was to be done, ‘the Rifles’ was the cry, and there they were. All speak of them in terms of praise and admiration.” During the Mexican War, 11 troopers were commissioned from the ranks and 19 officers received brevet promotions for gallantry in action. Regimental losses in Mexico were approximately 4 officers and 40 men killed, 13 officers and 180 wounded (many of whom would eventually die), and 1 officer and 180 men who died of other causes. The Rifles finally departed Mexico on 7 July 1848 and arrived in New Orleans on the 17th. Their ship, the Aleck Scott, sailed them up the Mississippi River back to Jefferson Barracks, Missouri. Whatever happened to Lt. Joseph Harris Maddox, the man who killed Edward McPherson?

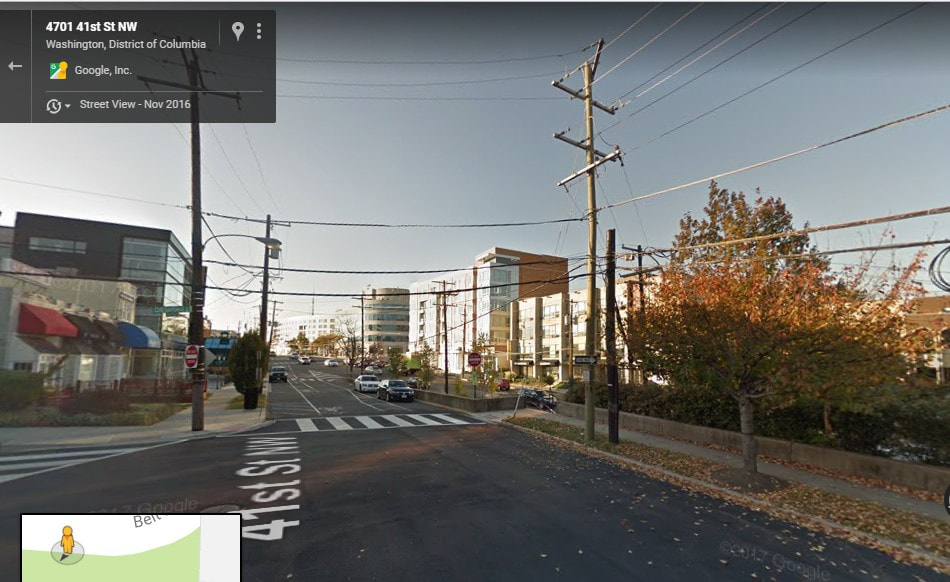

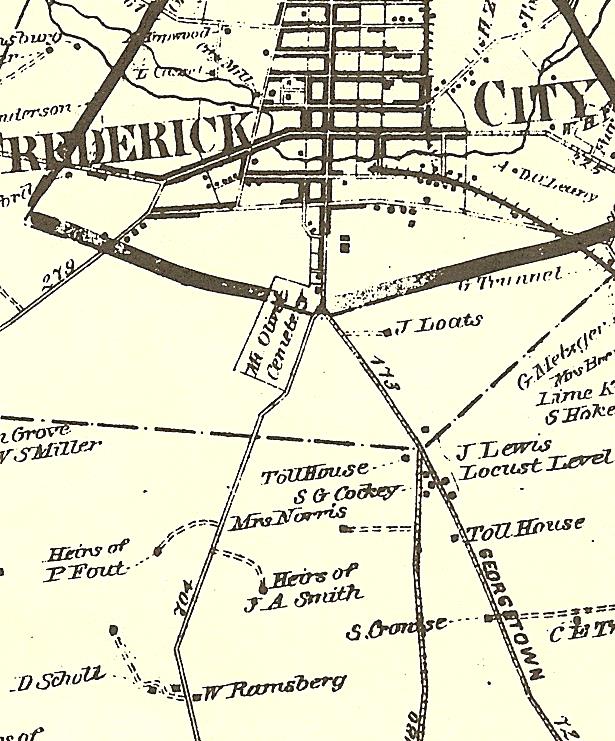

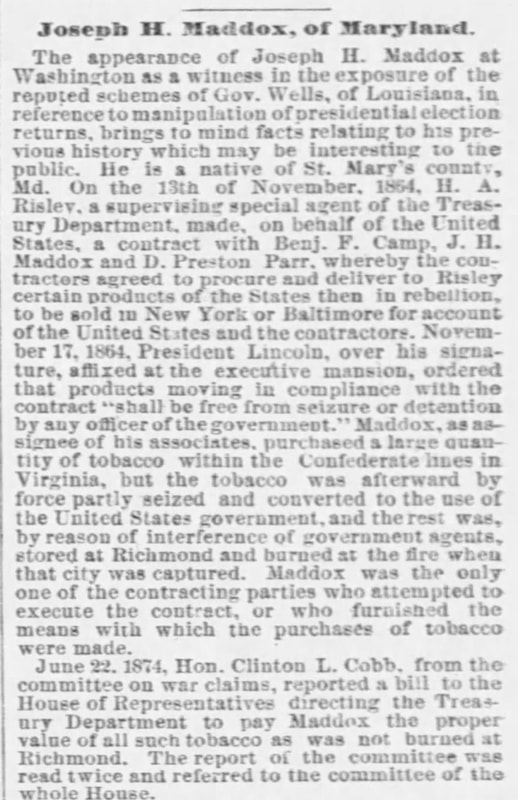

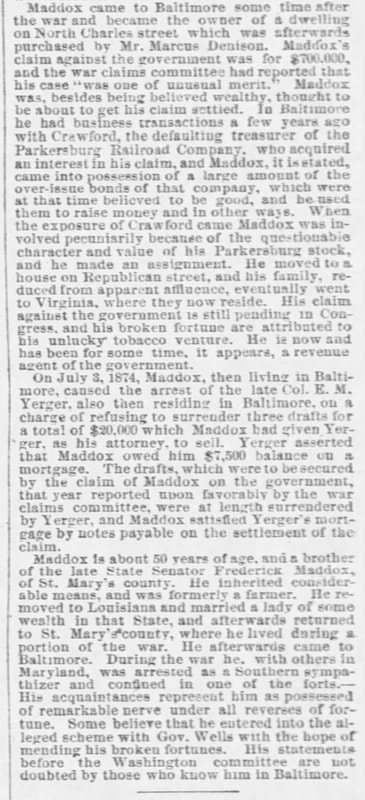

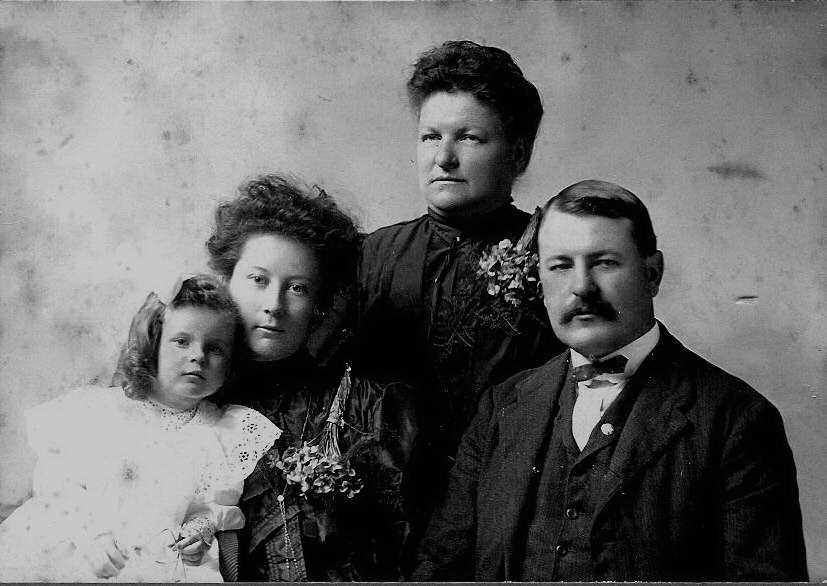

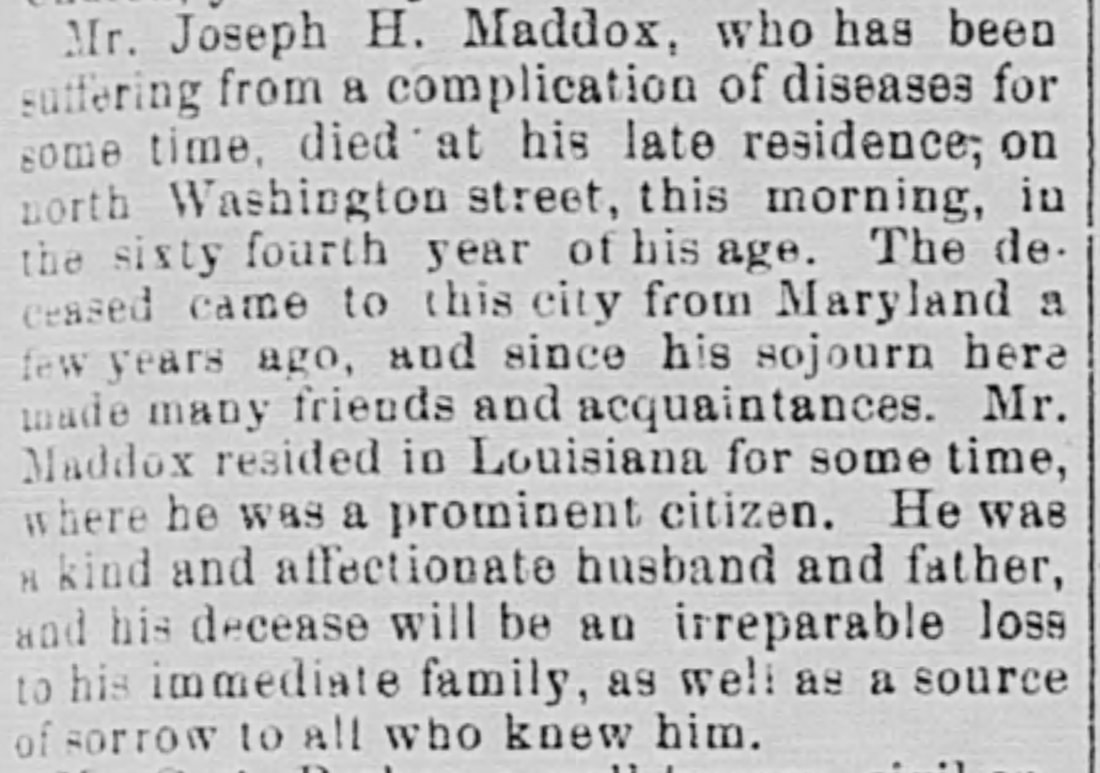

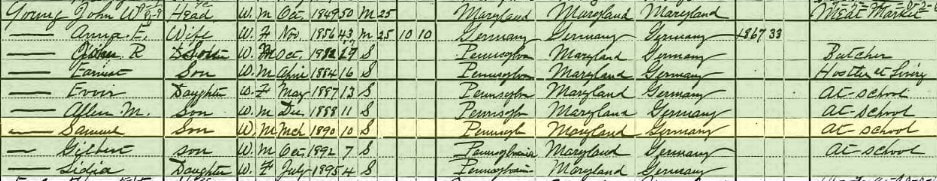

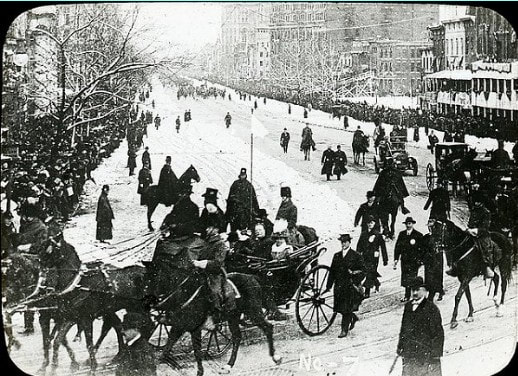

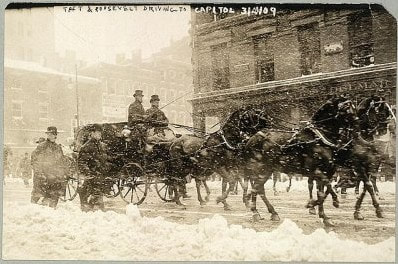

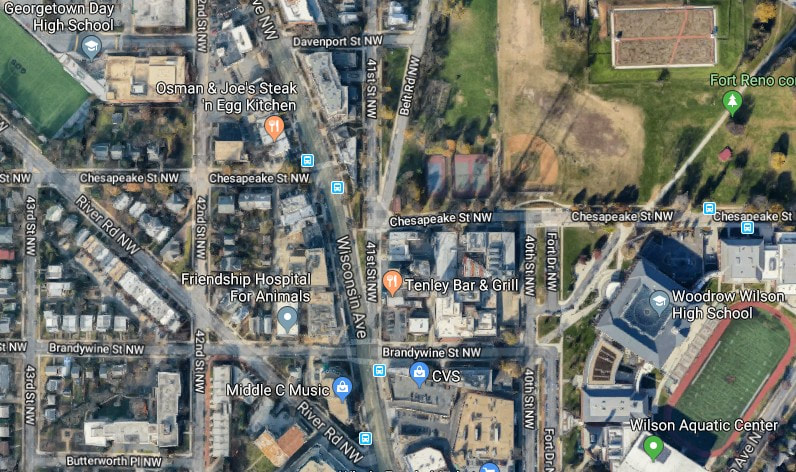

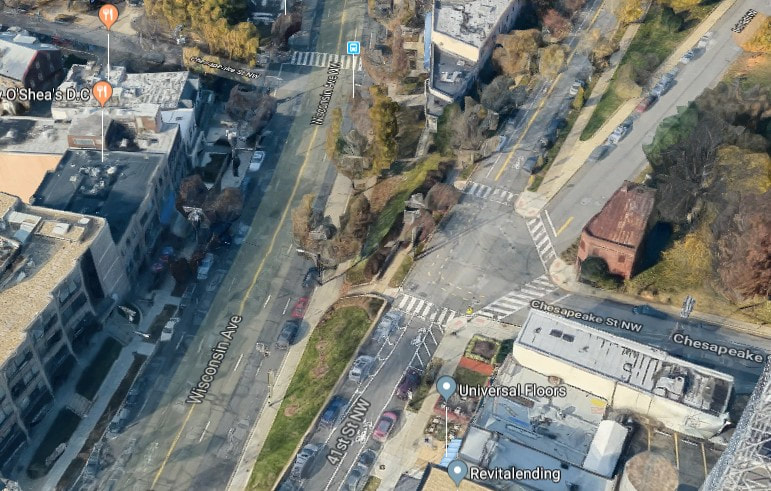

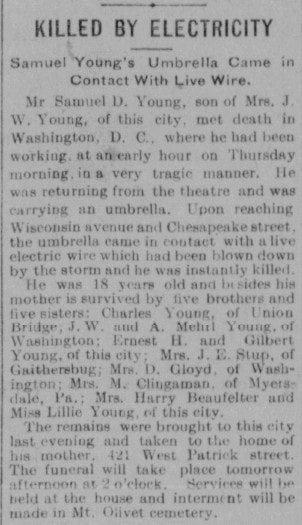

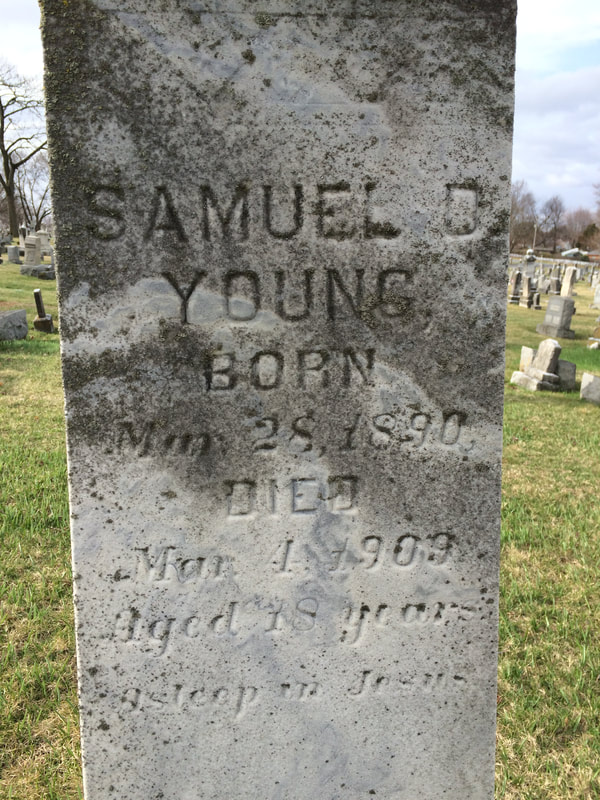

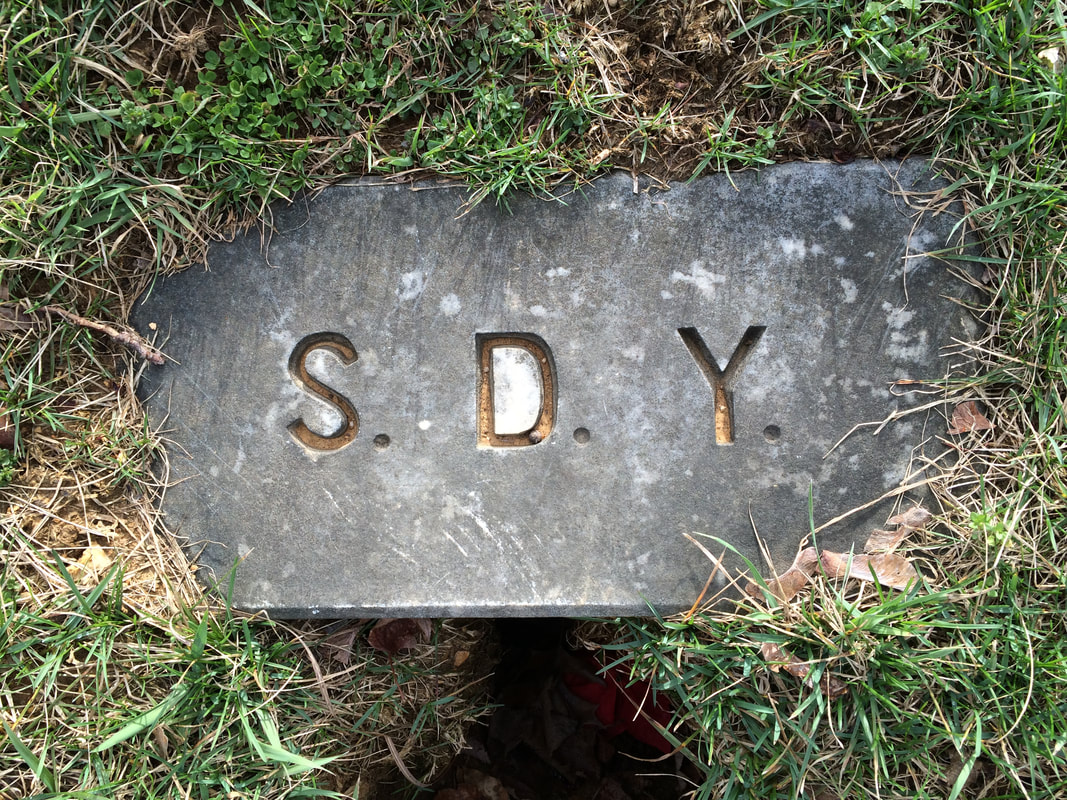

It appears that Lt. Maddox had a pretty adventurous life spent after the Mexican War. Here are a few clippings that tell the story. The weather folks correctly forecasted the recent bout of fierce weather for our area, the result of a March Nor’easter storm that morphed into a rare “bomb cyclone” in some parts of the Mid-Atlantic region. The whole of the eastern seaboard, from Maine to Georgia, was affected as many residents experienced heavy snow, intense rain and subsequent flooding depending on location. Here in the greater DC area, we had some rain during the overnight of March 2nd, 2018, but were spared the intense precipitations elsewhere, especially the snowfall. The area did, however, experience something equally dangerous and destructive from Mother Nature in the form of high winds with gusts blowing from 40-70 miles per hour. As a result, several school districts, including ours, closed for the day. In Washington DC, federal offices shut down as did museums and attractions such as the Smithsonian Institute. In the words of Yukon Cornelius (the loveable, Arctic-based mineral prospector of the 1964 Rankin/Bass “Rudolph the Red-nosed Reindeer” Christmas classic): “Isn’t a fit night out for man nor beast.” Back a few hundred years ago, the single worst part of windstorms was the threat of being struck by a tree, tree-limb, or any other projectile. It’s not hard to imagine the damage that could be inflicted on body, horse or home. As house-building methods, and weather forecasting improved, so did survival rates so to speak. However, a new problem arose with monumental innovations to come in the late 19th century, none better than electricity. Electrification was introduced to the United States in the 1880's, and was originally found in the large cities. Electricity needed to be carried from place to place by lines—and these were strung between homes and poles. Keep in mind the materials of the day, not to mention the common knowledge and expertise regarding the newfound energy source. Enter a windstorm, and you likely had electrical outages. Worst yet, wind toppled trees and limbs, which in turn downed power poles and lines, sometimes bringing damage in the form of fire—a harsh reality. Today, we frequently experience the inconvenience of outages, made the more impactful thanks to our increased dependence on lighting, appliances, computers, smartphones and other electronic gadgets. This recent storm was responsible for leaving many residents "in the dark," both figuratively and literally. However, the threat of fire is seldom worried about these days. Its rarity stems from various advances in electrical safety and technology over the years. A Shocking Discovery One of our “eternal residents” of Mount Olivet was a victim of high wind’s unfortunate effect on electricity in an earlier time. His name was Samuel D. Young, and the year was 1909. The 18 year-old, former Fredericktonian was living at the time in the Tenleytown vicinity of northwest Washington DC. Young was residing at a boarding house located at 4708 Wisconsin Ave. Interestingly, this was just a few blocks west of Fort Reno, one of a series of star-forts built to protect the Union capital city during the American Civil War. Samuel was here for work, apparently engaged in a long-term construction-related work assignment. He had grown up with a vast number of siblings in the 400 block of W. Patrick Street, an area once commonly referred to as "Battletown." The enclave of about 18 homes derived its name from a small encounter between Colonel Stephen Steiner & Stephen Klein, the first residents of the addition. And speaking of battles, this was a place traversed by the earlier mentioned namesake of Fort Reno, Major Gen. Jesse L. Reno. He passed through Battletown on the National Pike (W. Patrick St.) on September 12th, 1862 as he led his Union troops west toward Middletown. Just moments earlier he had encountered Barbara Fritchie waving her flag in support. This rising star in the Union Army would be killed by a sharpshooter's bullet just 48 hours later (September 14, 1862) at the Battle of South Mountain. Samuel Young's father, John William Young ran a meat market operation out of his home while also selling other groceries and provisions to neighbors on Frederick's west side. His son, also named John, did the butchering. Samuel's mother, Anna "Annie" Elizabeth (Otto) Young, was a German immigrant who had come to America when she was 11 years old.  William Howard Taft (1857-1930) William Howard Taft (1857-1930) Let's get back to talking about the weather, shall we? Residents in Frederick and Washington, DC awoke to miserable meteorological conditions on the morning of March 4th, 1909. It was a momentous occasion in Samuel's new home of the nation’s capital, as it would play host to the presidential inauguration of William Howard Taft. Just one day before, the head of what would eventually become the National Weather Service personally assured the President-elect that the overnight weather would only include rain and wet snow, giving way to ideal conditions for his big day. Taft later joked that he “knew it would be a cold day in hell when he became president.” Our 27th president was not far off, as the region had been hit by an overnight blizzard that produced ten inches of snow amidst destructive winds.  A variety of scenes around Washington DC on March 4, 1909. These range from snow-packed neighborhoods and downed telegraph/power lines to workers removing snow in front of reviewing stand for the Inaugural parade. Note images taken from the inaugural including a close-up of President and Mrs. Taft in an open carriage. The show must go on! "By the dawn's early light," crews of workmen began removing snow and slush along major thoroughfares and the US Capitol building. The Inaugural Parade, consisting of 20,000 marchers, would go on as scheduled, however the hallmark swearing-in ceremony had been moved indoors to the Senate chamber. Meanwhile, just a few miles away in the northwest part of the District, Samuel D. Young’s body lay dead in a tree-laden lot as Mr. Taft was taking his oath of office. The location of the deceased was less than a block from his apartment (4708 Wisconsin Avenue). Just after noon, a fellow boarder, named Henry Gearhart, set out looking for Samuel after the young man failed to return home the prior night after venturing out in the rain to take-in a show at a local theater. Around 2:00pm, Gearhart came across his chum lying in a blanket of snow. It wasn’t an ordinary, harmless “blanket of snow,” rather one riddled with downed electrical wires, apparently toppled by the storm. A physician was summoned, but it was too late as Young had died from electrocution. The body was removed to the Seventh Police Precinct, and later to the morgue by order of Coroner J. Ramsey Nevitt. An investigation showed that Samuel was carrying an umbrella at the time of his death. It was this umbrella that likely came into contact with downed power lines as the victim neared the intersection of Chesapeake Street and Brookeville Road (today's 41st St), just uphill from Wisconsin Avenue some 20 yards in the distance. Unable to see clearly in the dark, windy, and snowy conditions, Samuel D. Young unknowingly walked right into his demise.  I presume that Samuel D. Young died in this immediate vicinity showing a current day utility pole (to the right) located on the SW corner of the intersection between Chesapeake St (left) and Brookeville Ave (41st St). Wisconsin Ave is down a slight hill to the right, separated by a small, tree-covered parcel roughly 15 yards wide. There is a sidewalk with stairs that leads to Wisconsin Ave just beyond the pole as we are looking south in this photo. Perhaps this was a well used path at one point? Note the old/small pole located immediately next to the prominent pole in question. Is this a remnant of the original power line pole that witnessed the death of Samuel D. Young back in 1909?

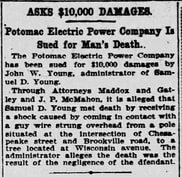

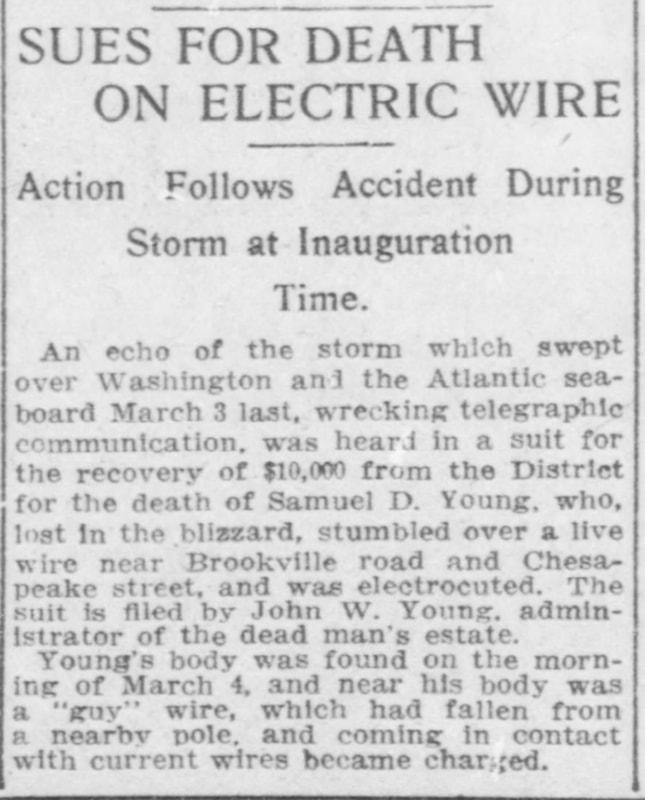

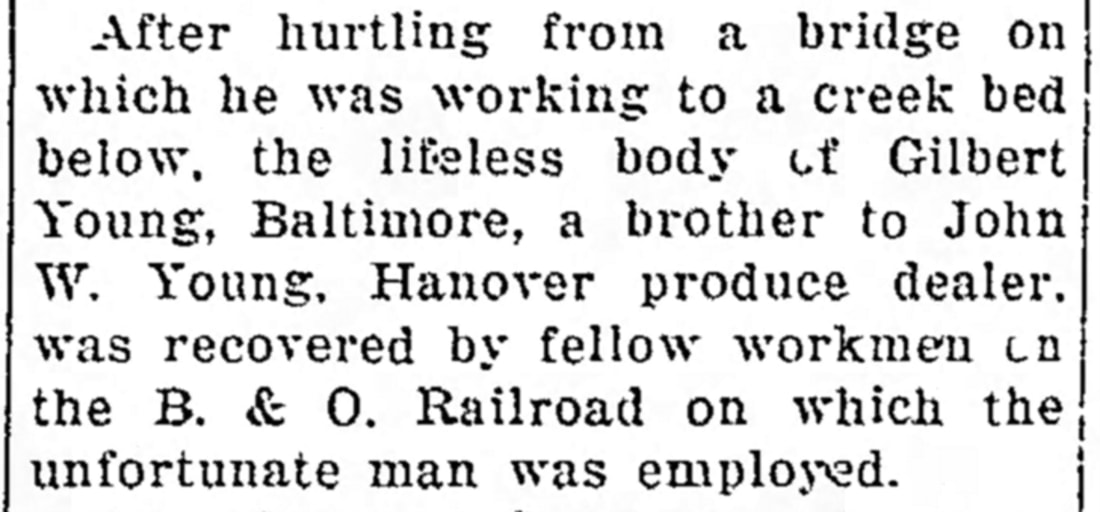

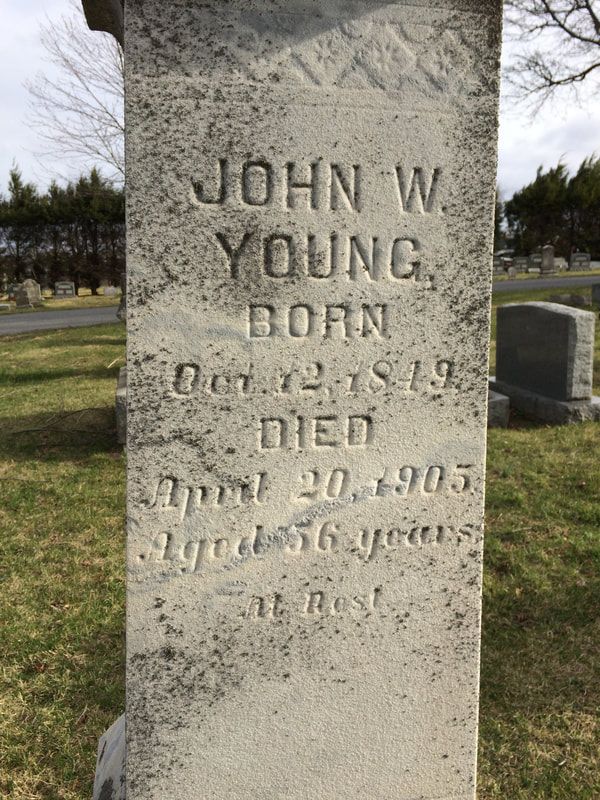

Nine months later, Samuel’s brother and estate administrator, John W. Young, Jr. (later a produce dealer living in Hanover, PA), filed a lawsuit in DC District Supreme Court for his sibling’s wrongful death. The plaintiff was the estate of Samuel D. Young, and the defendant was the District of Columbia.

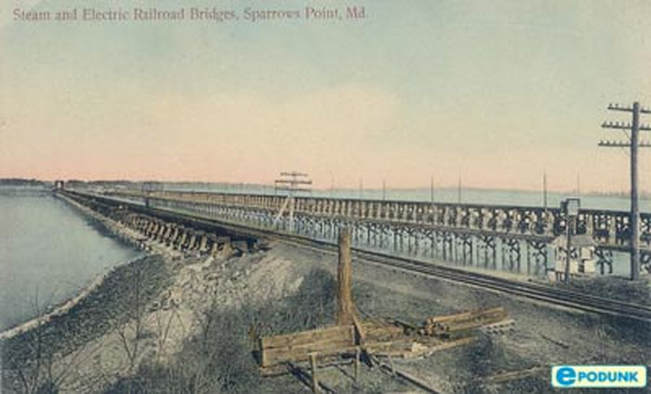

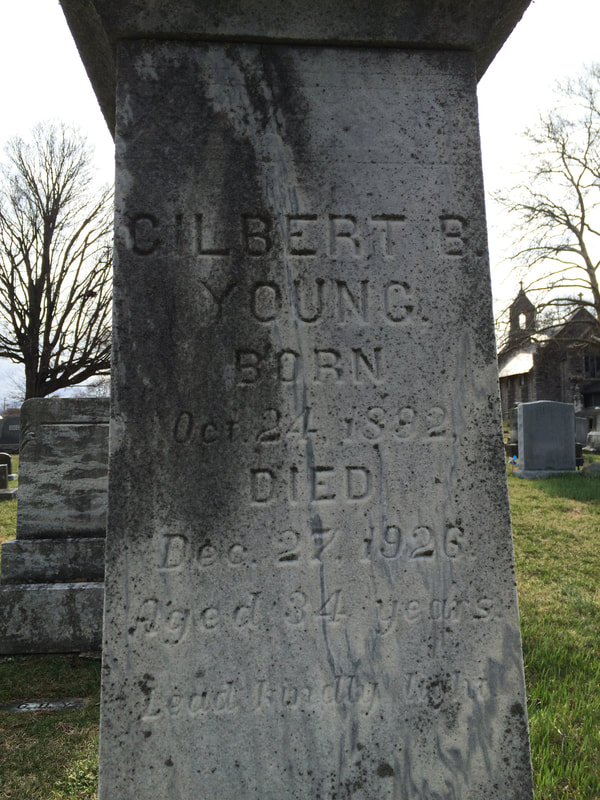

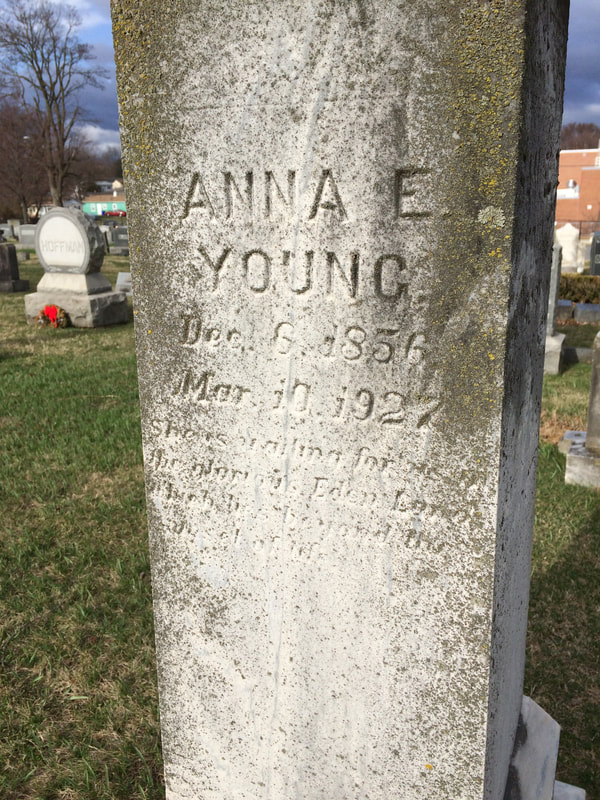

Washington Evening Star (March 4, 1910) Washington Evening Star (March 4, 1910) I couldn’t locate much more on how this suit played out, but it must have been dismissed, with a new defendant coming to the forefront—the Potomac Edison Power Company. Exactly one year after Samuel Young’s death, attorneys Maddox, Gatley and J.P. McMahon filed their suit for $10,000 against the electricity giant, and supplier of such to the nation’s capital and beyond. Again, I found no follow-up and assume that the matter was simply settled out of court. Solace in some form must have come to family members. Father and son were honored with an impressive 7–foot monument crafted in marble and topped with an ornamental urn. John W. Young, Sr.'s name adorned a panel on the west side, as Samuel’s was placed on the east. In mid-November of 1911, President Taft would come to Frederick to make a presentation on international trade. This took place on November 15th, 1911. Following the engagement, the presidential motorcade stopped briefly here at Mount Olivet on their way out of town and back to the District. President Taft placed a wreath on Francis Scott Key’s grave, a mere hundred yards down the lane from Samuel Young’s final resting place. Fifteen years into the future, another name would be carved on the memorial’s north face, but it would not be Mrs. Annie Young, Samuel's aged mother. Instead, it was that of Samuel’s older brother, Gilbert B. Young. He died at the age of 34 as a result of a unique accident, two days after Christmas of 1926. Gilbert Young was a veteran of World War I and a painter, currently employed by the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. On December 27th, 1926, he could be found painting atop a railroad bridge in the vicinity of Sparrows Point in southeast Baltimore, longtime home to Bethlehem Steel. Gilbert apparently slipped, or lost balance, and plunged into the water below. Mount Olivet Cemetery records state that he died due to an “accidental drowning due to a fall from a railroad bridge.” Like that of Samuel, Gilbert’s body would be brought to Frederick for final burial. This occurred on December 29th, 1926. The boys’ mother would pass less than three months later. She too would be buried under the shadow of the fine monument located on Area L/lot 41.

|

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed