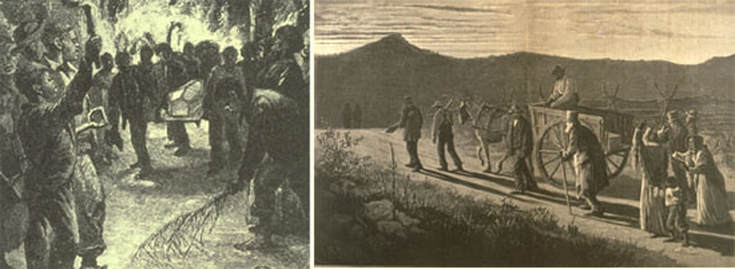

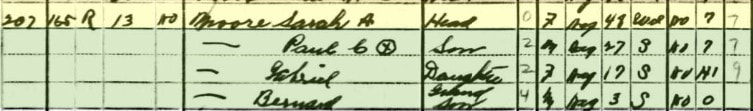

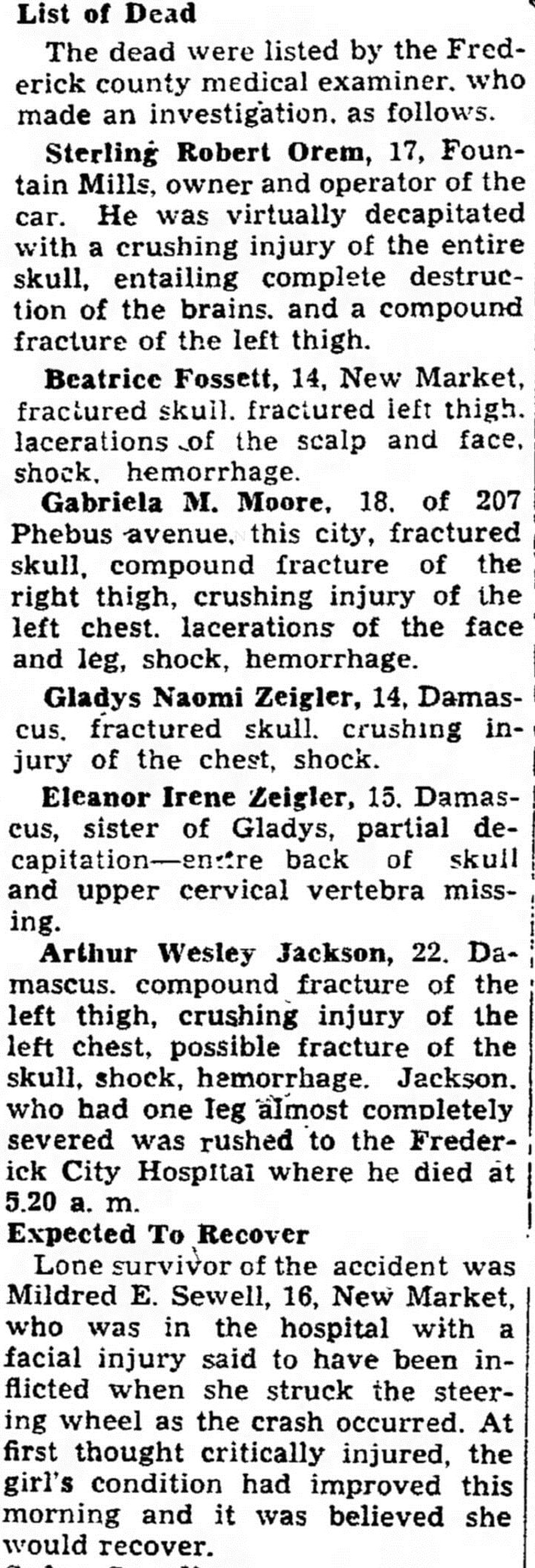

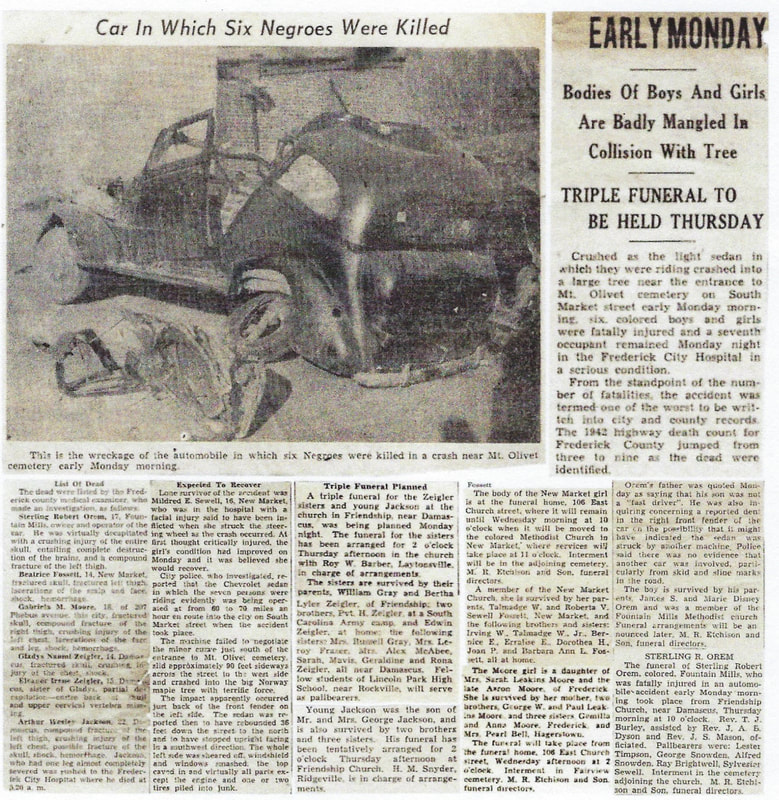

Grave of Dr. U.G. Bourne, Sr. in Fairview Cemetery Grave of Dr. U.G. Bourne, Sr. in Fairview Cemetery As February is quickly coming to a close, I was interested to see if I could tie-in topic relating to Black History Month. Some of you may recall the three-part series we featured (on this blog) last year at this time entitled: Sidestepping a Color Barrier: The first Black residents to be buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery. Yes, Mount Olivet, like so many institutions here in Frederick, was segregated up through the Civil Rights Movement. Although, I had a pretty good understanding of the genesis and evolution of Frederick’s “separate but equal” burying grounds, there is so much more to be gleaned by reading primary source materials of old to attempt to interpret or explain history. Of particular interest to me was the rise of Fairview Cemetery on Gas House Pike, which quickly filled the void left by the sale of W. 7th Street’s Greenmount Cemetery to the City Hospital (today’s Frederick Memorial Hospital) in the second decade of the 20th century. Fairview is the final resting place of Dr. U.G. Bourne, Sr., Frederick’s first Black physician and NAACP founder—a man who did so much over his lifetime to change mindsets and perceptions. Other Black history luminaries resting here include William O. Lee, Esther Grinage, John W. Bruner and Charles Brooks. As far as Greenmount, it was the predominant burying ground for Black residents of Frederick up until the time of its sale—if you will, it was “the Black Mount Olivet.” This sizeable cemetery was located on the ground now occupied by FMH’s west parking lot and garage. In reading last year’s series, you will also learn about the former All Saints’ Burying Ground (adjacent Carroll Creek) in the heart of Downtown, and the controversial story of Laboring Sons Cemetery. Much has been written about this latter location, sandwiched between E. 5th and E. 6th streets, employing a good measure of misinformation and embellishment which has caused media sensationalism and unique political posturing over the last two decades. Take it from someone who has thoroughly investigated the subject, the demise of Laboring Sons was self-inflicted by its trustees more than anything else. The most rewarding part of producing the 3-part series came as I tasked myself with finding the first individuals of color to be buried in Mount Olivet. I was pleasantly surprised with some of the revelations that came with discovering individuals such as Maria Harper, Laura Hill, Hester Houston, Abe Brighton, Martha Snowden and Bird Smith. All but Ms. Smith were former slaves, and death to them could have taken on the cultural mantra of “Homegoings.” As with other traditions, practices, customs and norms of Black culture, this ritual for dealing with death was shaped by the African-American experience. Author Sara J. Marsden, editor in chief for US Funerals Online, recently posted a feature on the topic entitled: “Homegoing Funerals: An African American Funeral Tradition.” Here’s an excerpt: The simplest explanation for the term “Homegoing” is that it represents the religious connotation of the deceased “going home,” to heaven and glory, and to be with the Lord. It is a Christian-based service, most commonly held in a chapel or church. The deceased is most commonly buried, after a very elaborate service, as the belief is held that their body will be resurrected. A homegoing funeral is often referred to as a “homegoing celebration” as it is considered to be an uplifting event celebrating the return of the soul to the eternal glory. The heritage of the homegoing funeral ritual has its origins back in Ancient Egypt. The ancient African Egyptian people had a rich culture of preparing for a funeral and preserving the deceased for their “after-life.” This could be noted as the origins of people of color demonstrating elaborate funeral practices. This rich Black heritage was brought to the United States during the era of slavery. During slavery the Black communities were not permitted to gather to conduct their funeral rituals for fear that they would conspire to revolt. Slaves that died were ordinarily just buried without any ceremony in un-marked graves in non-crop producing ground. However, at the same time slaves would be responsible for the preparation of the deceased plantation owner’s family following a death and preparing the elaborate family gatherings held to mourn the deceased. Controlling the repressed slaves and preventing an uprising was an ever-difficult task for the plantation owners, especially as the number of slaves on a plantation could begin to outnumber the plantation owner’s family and managers. So white Christian religion was introduced to the slaves to help pacify and subjugate. Many enslaved Blacks believed death meant their soul would return home to their native Africa. The Old Testament stories of God and Moses freeing a captive and enslaved race resonated with the slaves. The New Testament stories of Jesus and promises of glory in heaven and a far better after-life allowed slaves to forge through the turmoil of mortal life and look forward to the day when they would return home to the Lord. They fully embraced Christianity and death, for slaves, was viewed as freedom. Their death rituals were jubilant and it became one of the earliest forms of African American culture. Anyway, I invite you to partake in last year's 3-part story, you'll find links at the end of this article. Deaths occur within feet of FSK Monument While performing research work last year for the above-mentioned “Stories in Stone,” feature, I came across an especially traumatic and chilling event which occurred at Mount Olivet Cemetery 76 years ago. I found this article innocently enough while plugging word combinations into the search engine for the online Newspapers.com archival site. Among my searches, I eventually typed the words Mount Olivet Cemetery, Frederick, Negro, and death. Sadly I immediately found the following article headline, dated February 23rd, 1942. It appears that a horrific early morning car accident occurred just outside Mount Olivet’s picturesque front gate. Then superintendent Cyril Klein would be the first to see the grisly scene. The driver of a sedan entered town from the south on S. Market Street, going at a rate of 60-70 miles/hour. He lost control while attempting to negotiate the slight bend in the road. This was coupled with a wet road surface. The car subsequently slid 90 feet to the west until slamming into an aged Maple tree—one planted around the turn of the 20th century in front of the Superintendent's House and outside of the cemetery’s fence (fronting on S. Market Street). The reckless driving of an inexperienced driver was blamed for triggering the crash. Only one of the passengers was a Frederick City resident, hailing from nearby Phebus Avenue, roughly six blocks from the accident scene. This was 18 year-old Gabriela M. Moore. It was thought that the group was solely in town to bring Gabriela home. Unfortunately for the young lady and her friends, there would be six “homegoings” and only one homecoming. Six out of the seven occupants in the ill-fated sedan perished as a result of this tragic event—most expiring on impact. The driver was 17 and the others in the car ranged from 22-14 years of age. A lone survivor, Mildred E. Sewell of New Market, would spend the next month in the hospital, but would make a full recovery. I would eventually come across a better copy of the article from a scrapbook. This clearly shows the vehicle involved in this tragic accident. Up to that time, this was the single, deadliest automobile accident in Frederick County’s history. I venture to guess that it remains the worst in Frederick City history, and among the worst in county history. All in all, I was somewhat taken aback by the graphic level of reporting for this story, which also included a photo of the smashed-up automobile, but I couldn’t quite make it out clearly from the newspaper copy I had found. Nationwide, north and south, it was not uncommon in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s for newspapers to include reports of odd and awful accidents and deaths befalling Blacks and immigrants. I have included the initial report of this accident appearing in the February 23rd edition of the Frederick News. I still find the description of injuries a bit too much, especially in respect to an era with a backdrop of the Second World War. Frederick’s Gabriela Moore was laid to rest in Gas House Pike’s Fairview Cemetery on Wednesday, February 25th. A triple funeral would be held in Damascus, and others took place in New Market and Fountain Mills near Kemptown. Burying grounds are no strangers to victims of automobile accidents. Within Mount Olivet, there are hundreds. However, anyone would find it puzzling, and moreso ironic, to learn that a cemetery had played a contributing role in the deaths of six young people. So very sad.. Click any of the above icons to read more.

6 Comments

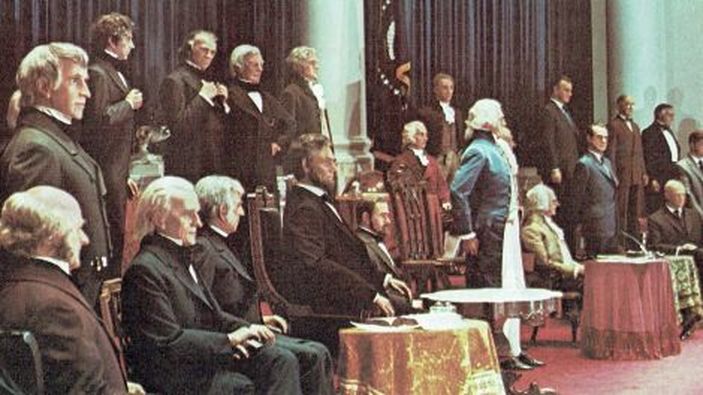

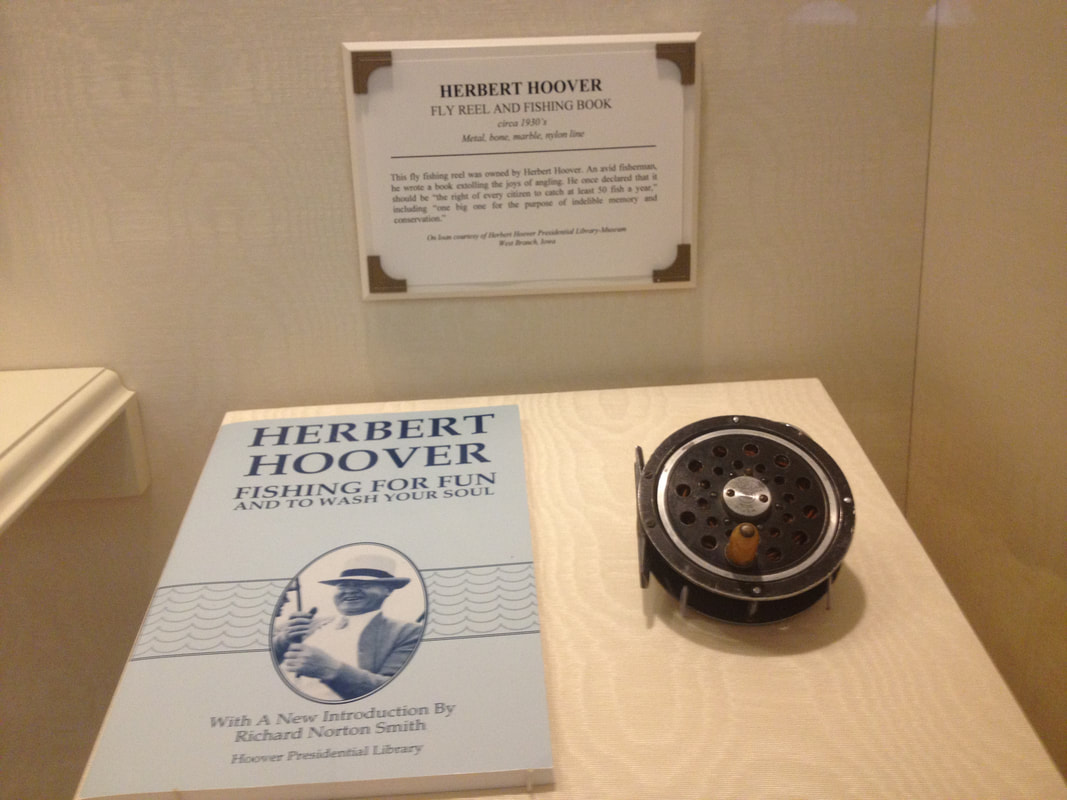

Happy President’s Day! .... once again. In commemoration, a year ago, I wrote a piece about Joshua Johnson (1742-1802), younger brother of Gov. Thomas Johnson, Jr. This Johnson brother was a London shipping merchant, US Consul to London (1790-1797), and US Collector of Stamps for Washington, DC. His greatest claim to fame, at least as it pertains to the history books, lies in the fact that his daughter, Louisa Catharine Johnson (1775-1852) would become a presidential First Lady when she married John Quincy Adams in July, 1797. This isn’t the only connection Frederick’s Mount Olivet Cemetery has to the US presidency, as we have a few other folks (interred here) that are blood-related to past “commanders in chief.” Just the other day, I came across an extended ”Johnson family” relative named William Monroe Johnson, Sr. (1895-1991), a World War I veteran. He was a great, great-grandson of President James Monroe, hence the catchy middle name. His mother, Ruth Monroe Gouverneur married Dr. William Crawford Johnson. All three individuals are buried here in the cemetery’s Area E. Ruth (Mrs. Johnson) was a founding member of Frederick’s Daughters of the American Revolution Chapter, and rightfully so. Nearby Ruth Gouverneur’s grave is that of another of Frederick DAR’s founding ladies—Millissent Washington (1824-1893). This Kentucky native was a daughter of William Temple Washington, a grandson of Samuel Washington, younger brother of George Washington—making Millissent the great-grandniece of our first US president. She married Robert G. McPherson of Frederick and took up residence here. In addition, Millissent McPherson was also a grandniece of Dolly Payne Todd Madison, wife of former president James Madison. I’m sure this is the tip of the iceberg as plenty more persons buried here in Mount Olivet could be linked genetically to US presidents and First Ladies. I kindly invite readers to add any special connections (that they may know about) to the Comments section immediately after this story. "It's a Small World After All" My son Eddie and I traveled to Orlando, Florida in late January for a mini-vacation spent visiting my brother Tim and his family. It really is a luxury having a family member living in Orlando, as there is always a free place to stay, and no shortage of great things to do. Atop that list is the varied experiences related to the Wonderful World of Disney, of course. Eddie, now 11, hadn’t visited the Magic Kingdom since age 3, and vaguely remembered any of the signature attractions. So it seemed like a good choice to have him experience Space Mountain, Pirates of the Caribbean, the Haunted Mansion, Jungle Cruise, and Big Thunder Mountain this time around with the benefit of lasting cognitive abilities. Saying this, I spared him the “It’s a Small World” ride experience, for the same reason. I did, however, pull him into the renown Hall of Presidents in Disney’s Liberty Square, built to resemble Philadelphia in 1776. The Hall of Presidents sometimes get passed by for rides and other more thrilling attractions, but not by a bona-fide “history-geek” Dad like me— Eddie Haugh is no stranger to US history. I have brought him to the real Philadelphia on several occasions, successfully slipping in visits to places like Independence Hall, the Liberty Bell and the Betsy Ross House, as preludes to seeing his favorite sports teams in the form of the Phillies and Eagles. For those of you who have not been to the Hall of Presidents before, this attraction is a multi-media presentation and stage show featuring Audio-Animatronic figures of all 44 individual United States Presidents, adorned in period attire of their respective era in the White House. The entire concept is based on Walt Disney’s Animatron of Abraham Lincoln, featured in an exhibit that first appeared at the 1964 World’s Fair in New York. The experience opened on October 1st, 1971, along with the rest of the Magic Kingdom and resort. Housed in a building resembling Philadelphia's Independence Hall, the current attraction features a short film depicting a historical account of several American presidencies, notably George Washington, Andrew Jackson, Abraham Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and John F. Kennedy. The film is followed by a stage presentation of all the presidents in Audio-Animatronic form and features speeches by Lincoln, Washington, and the most current incumbent President, Donald Trump.  President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Fala President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Fala As you are waiting to go into the theater for the 25-minute show, an ample-spaced indoor lobby serves home to a gallery of president-related portraits, murals and display cases holding historic artifacts and memorabilia. I spent our ten-minute wait engrossed with John Quincy Adams’ microscope, Gerald Ford’s tennis racquet, George Washington's beer stein, John Adams’ pocket watch and cowboy boots worn by George W. Bush at his inauguration. I also saw a plaster sculpture of Fala, the beloved Scottish Terrier of Franklin Delano Roosevelt. This item was made for the president, and kept atop his desk. I took particular interest in this because of a story involving Fala told to me by the late historian George W. Wireman of Thurmont. One day during World War II, FDR and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill were en-route to the presidential retreat at Shangri-La. The presidential motorcade made a stop for Thurmont’s only red light, located in the center of town. Apparently, Fala jumped out of the car and headed to the nearest fireplug to relieve himself. This public urination took place to the great chagrin of the world leaders in the car, and the secret service detail who tried to corral the presidential canine. Back at the Hall of Presidents, it was now our chance to go into the theater for the show. There was still time for me to see one last display case as we were being “herded-in” to our seats.

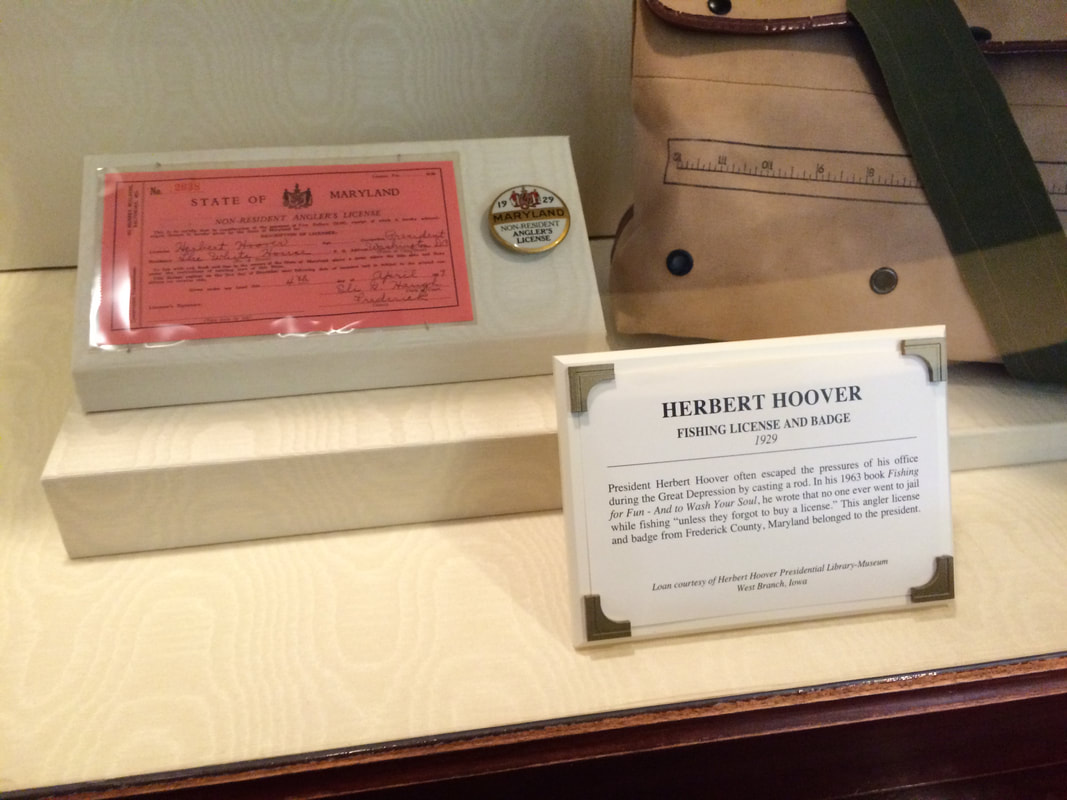

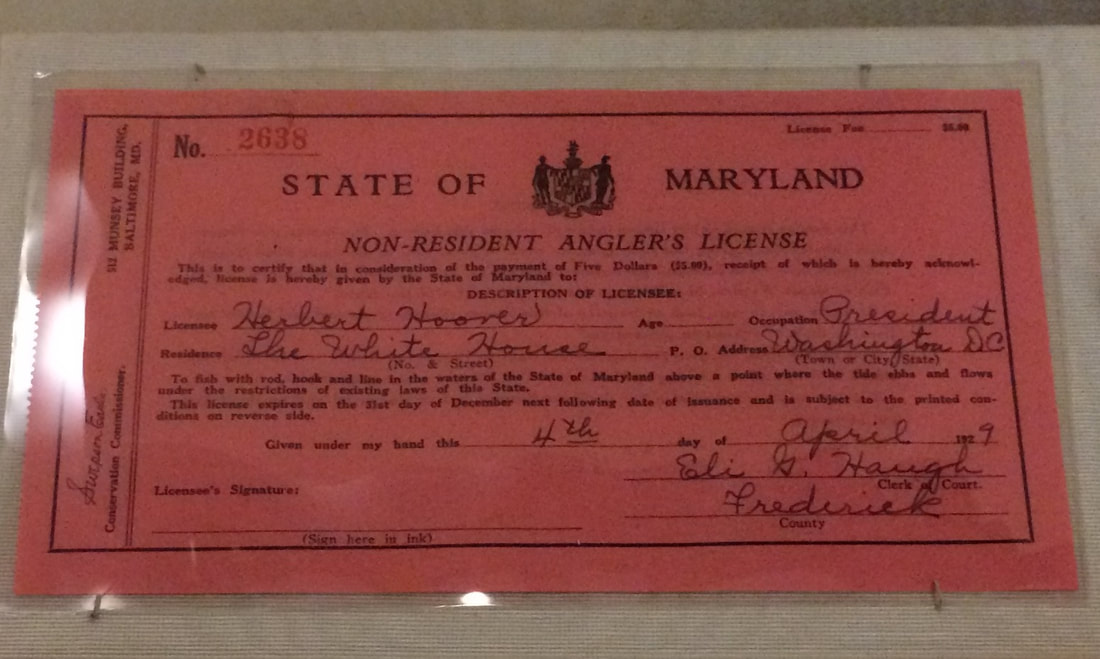

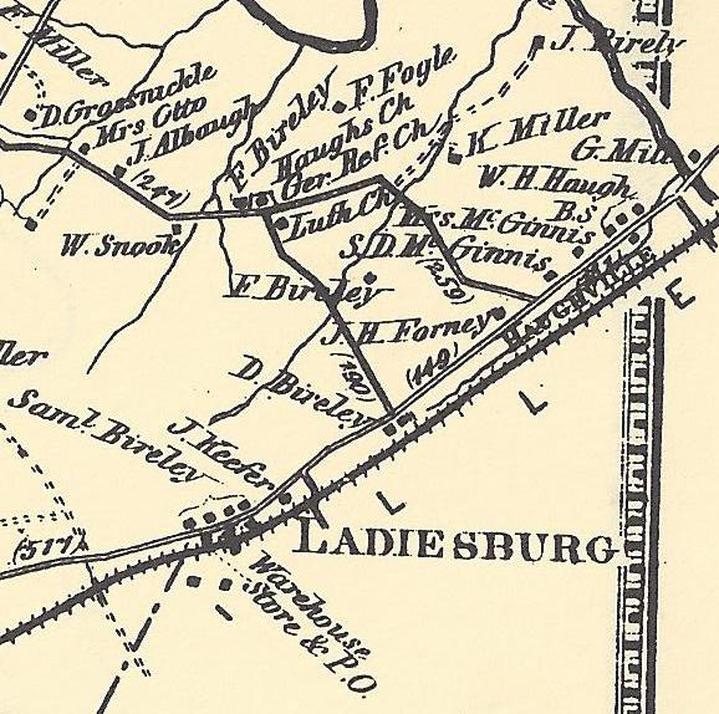

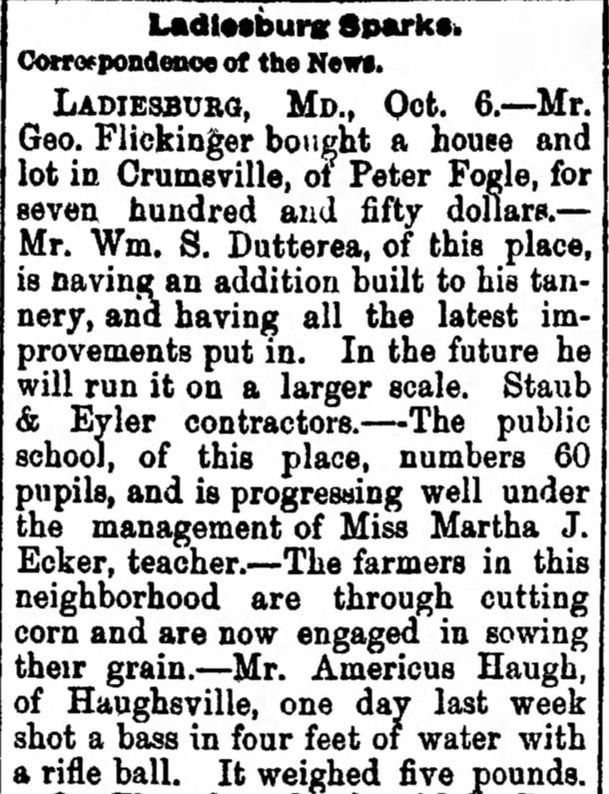

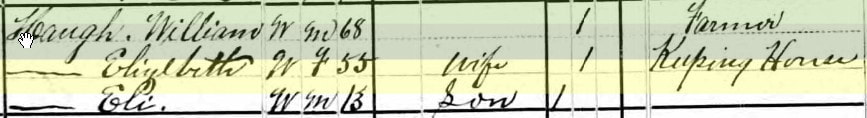

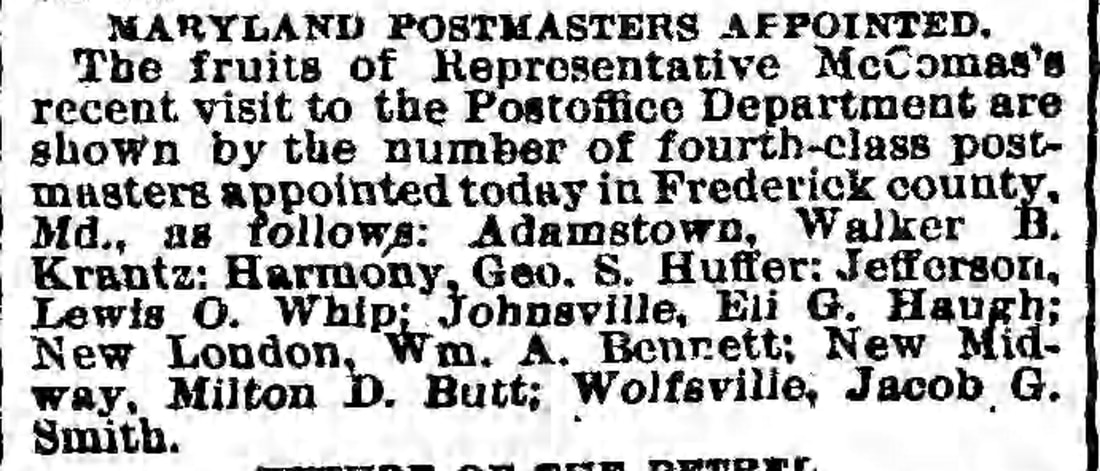

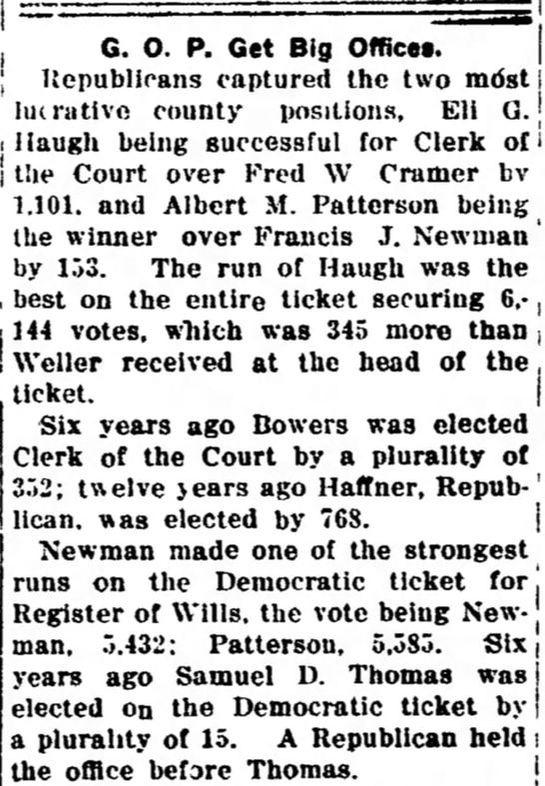

I have to admit that I was so excited to see someone from Frederick represented in the Hall of Presidents that I jokingly thought the attraction could be renamed “the Haugh of Presidents.” I could have easily overlooked the whole thing. Once back home, I set out to learn more about the former clerk of the court. Little did I know, that the day we visited Disney and saw this artifact, was actually Mr. Haugh’s birthday! Coincidence, or divine intervention? Eli G. Haugh Eli Grant Haugh was born on January 25th, 1866 to parents William Haugh, Jr. and wife Elizabeth Cramer. His middle name represents another connection to the presidency, but at the time of Eli’s birth, Ulysses S. Grant was better known for his keen leadership in the American Civil War, accepting Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Courthouse, VA just seven months earlier. The Haugh family lived near Ladiesburg in the Johnsville District of northeastern Frederick County. This vicinity is located off MD194, near Little Pipe Creek and Carroll County line. Lasting reminders of the once prominent family include Mount Zion/Haugh’s Church, Haugh's Cemetery and the aptly named rural road that goes by them up to Detour. In fact, on the 1873 Titus Atlas, one can see a plethora of Haugh properties in the area and an area between MD194 (Woodsboro/YorkPike) and the Frederick & Pennsylvania Railroad here is labeled as Haughville, also referred to occasionally as Haughsville. Again I claim no relation to this line, although I wish I did. And, I have been told that the family actually pronounced their name “Hawk” as in the flying bird of prey.

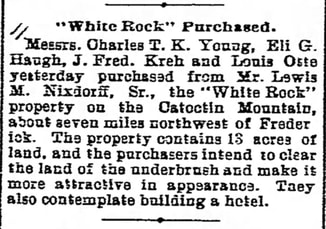

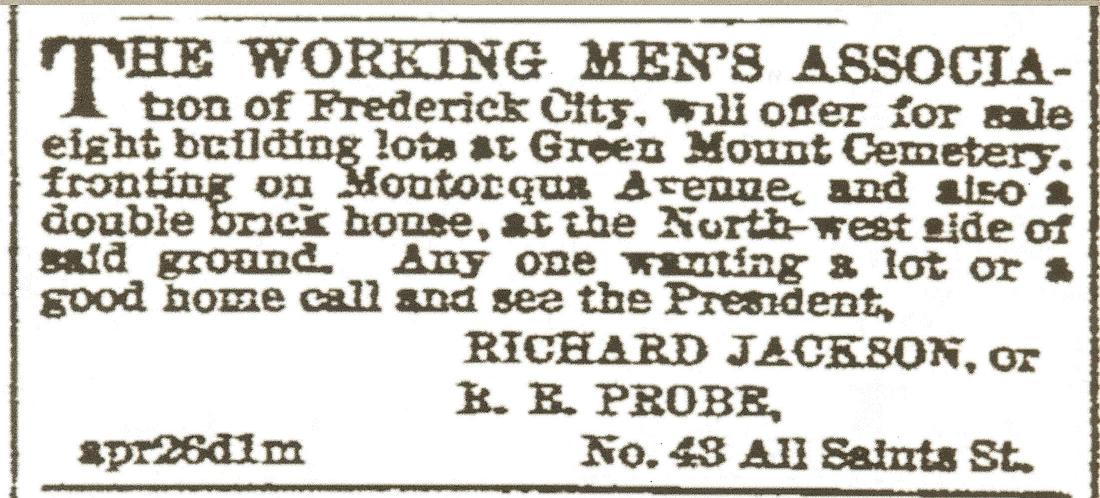

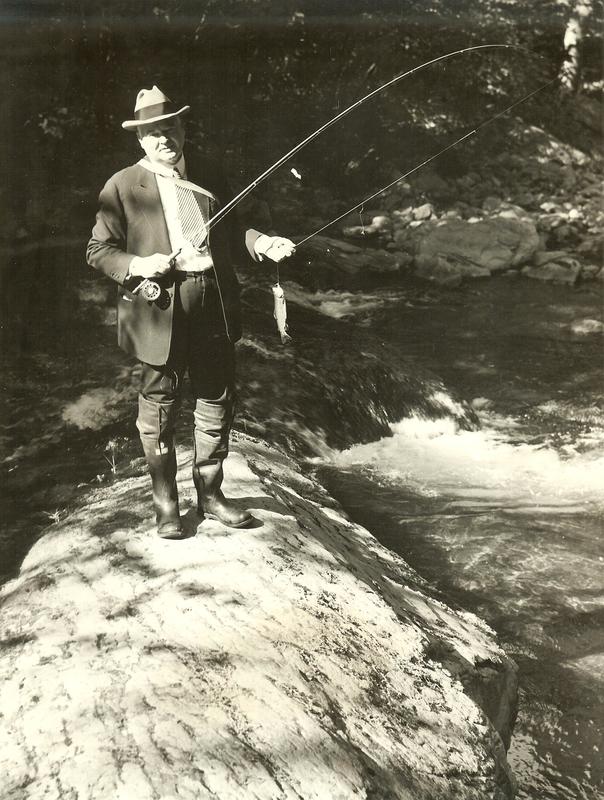

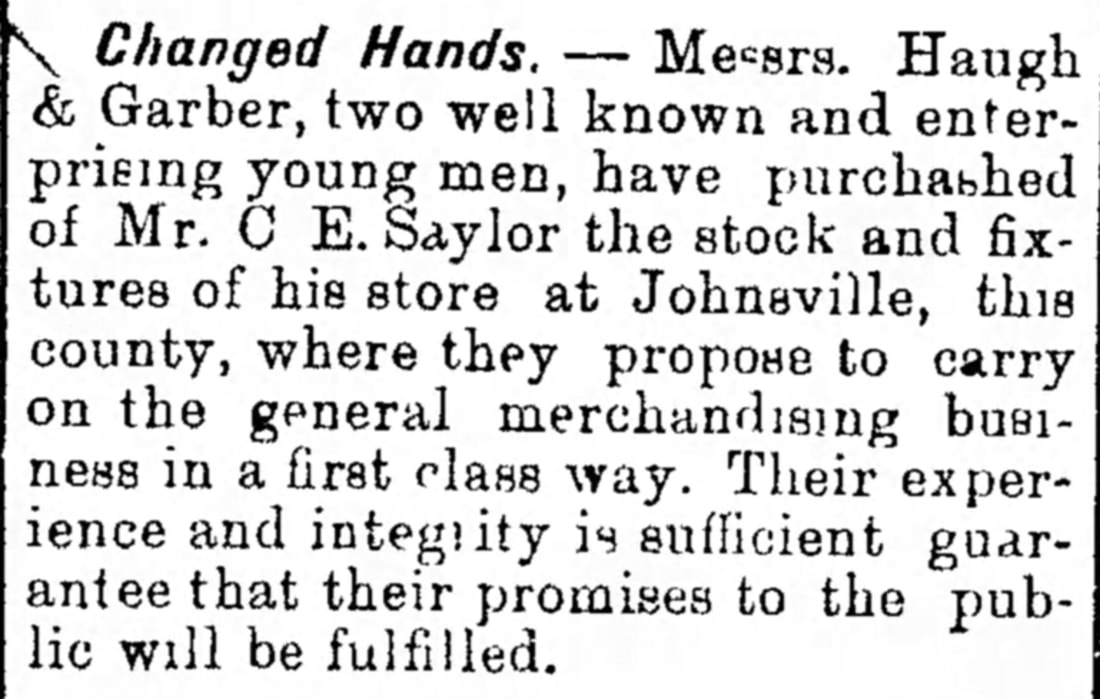

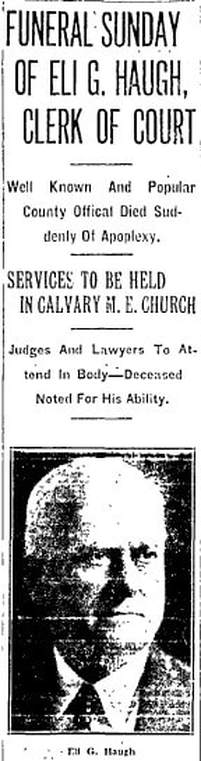

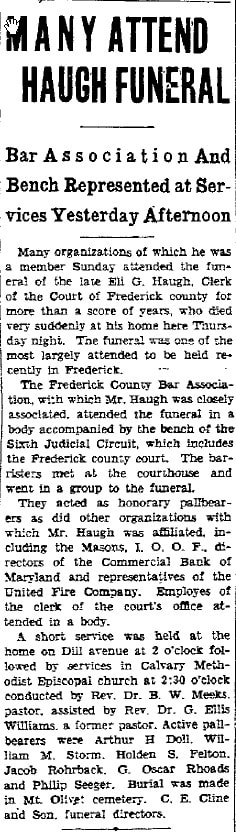

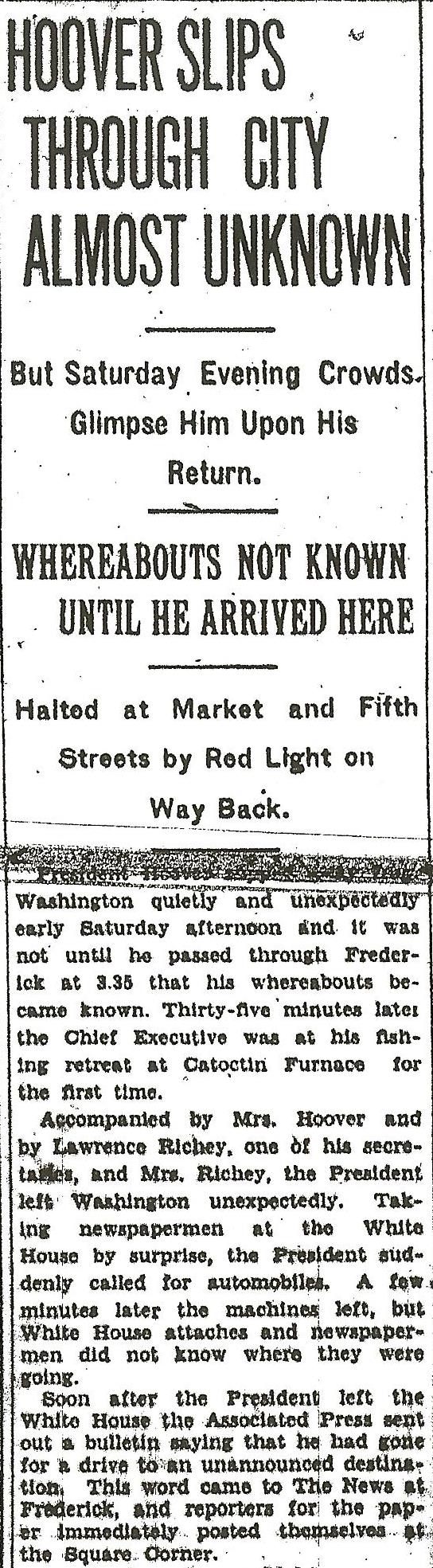

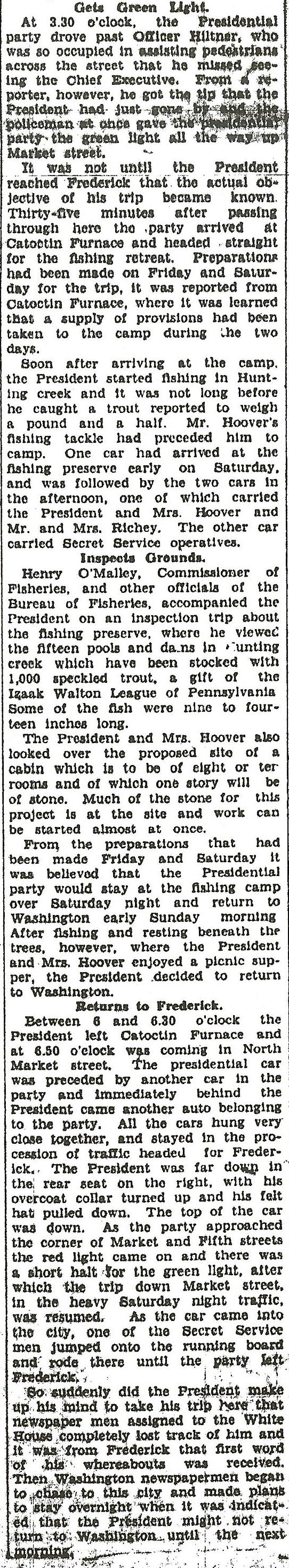

Eli’s great-grandfather, Paul Haugh (sometimes referred to as Powell), is said to have emigrated from Germany or Switzerland and settled here in late 1700’s, building a valuable farmstead at the location of Haugh’s Church. Paul Haugh gave the ground for the church, the first house of worship in the vicinity. A graveyard is associated with the church and holds the grave of this gentleman and generations of Haughs to follow. Eli’s grandfather, William Haugh, Sr., took up the occupation of village blacksmith. This gentleman’s son, William, Jr. (Eli’s father), grew up on the homestead, and received education in local public schools. He married and began farming, himself, quite successfully. Eli Haugh eventually accepted a position as superintendent of hauling teams with Peregrine Fitzhugh, owner/operator of Catoctin Furnace from 1843-1858. Interestingly, President Herbert Hoover would be linked to Catoctin Furnace and the Catoctin Manor, one-time home of Peregrine Fitzhugh. Hoover’s personal secretary, Lawrence Richey, would purchase the property in March, 1929, primarily to have a place at which the president could escape the White House and enjoy his favorite pastime of fishing in Little Hunting Creek (at Catoctin Furnace). The property was commonly referred to as Hoover’s Camp. And this, in turn, explains the fishing license issued by Clerk Eli Haugh to the president in April, 1929. Eli received his education in the public schools of the Johnsville District and remained at home until 15 years of age. He spent his youth working on his father’s farm and grew up in the German Reformed faith (practiced at Haugh’s Church). He soon went to work as a clerk in several stores in nearby Johnsville, eventually forming a partnership with a gentleman named Samuel Garber. The firm of Haugh & Garber lasted for four years, having bought the stock and trade of one Charles E. Saylor. The partnership would eventually dissolve, but Haugh would stay on as a clerk for new owner Samuel Furry for the next seven years. Haugh’s clerking skills also came into play as he served as Johnsville’s Postmaster in the early 1890’s. Along the way, Eli would marry a local girl from the Johnsville area named Annie M. “Mollie” Strasburg. This was in 1887. They would have two daughters: Hilda (b. 1889) and Nellie (b. 1891). Due to a career change, the family would soon take root in Frederick City, first living on E. Church Street. The year 1897 brought the opportunity of public civil service for the 31-year-old Haugh within Frederick County’s government sector. Eli’s hard work and determination as a clerk paid off, as he would be appointed deputy Register of Wills under his former business mentor Charles E. Saylor. He remained in this position for six years, at which time he was appointed Deputy Clerk of the County Court for Frederick County (1903). He served a full term in this role, and was reappointed in 1909 by newly-elected Clerk of the Court, Harry W. Bowers. T.J.C. Williams’ “History of Frederick County” reports: “During all these years he discharged the arduous duties of the office punctually and creditably giving entire satisfaction to his employer. Mr. Haugh is one of the leading citizens of Frederick, and is highly esteemed in the community.”  Frederick News (April 27, 1906) Frederick News (April 27, 1906) Eli Haugh was involved in several aspects of his community. He was a director of the Commercial Bank, served as secretary of the Frederick City Draft Board during World War I, and was a devoted member and steward of Calvary Methodist Church. I even found an article from 1906 where Eli was among a group of gentlemen who purchased "White Rock," in hopes of building a resort hotel. This never materialized to my knowledge. Haugh's involvement in fraternal organizations included the Masons, Independent Order of Odd Fellows, Knights of Pythias, Independent Order of Redmen, and Independent Order of Heptasophs. In the fall of 1936, Mr. Haugh, at the age of 70, had spent the majority of his life in the employ of Frederick County and her citizens. The community was stunned as he passed suddenly one week before Thanksgiving in the confines of his home located at 309 Dill Avenue. He had been engaged in his life’s work until his waning hours. Frederick historian John Ashbury, in his 1997 book entitled “And All our Yesterdays” chronicles the last hours of Eli G. Haugh’s life on November 19th, 1936: “After completing his day’s work at the courthouse on November 19, 1936, Mr. Haugh went home for supper. Shortly after he ate, he was called to the courthouse to issue a marriage license. When he returned home. He complained to his wife, Mollie, that he had indigestion. His daughter, Mrs. Edward M. Mantz, who was visiting, gave him his usual medication but to no avail. Mr. Haugh suddenly slumped in his chair, and a physician was called. He was pronounced dead of apoplexy.” Mr. Haugh’s death was front page news in the November 20th edition of the Frederick Post. Amongst the multi-column obituary provided, the paper said of the distinguished gentleman: “Among the law profession and others who came in constant contact with the clerk of the court’s office, Mr. Haugh was one of the most efficient public officials the county has had. His devotion to duty was reflected in his deputies and the office was conducted in an efficient manner. Lawyers relied upon him time and time again. The Circuit Court, itself had confidence in his judgment. He personally handled the ever-increasing business of the civil and criminal dockets of the court.” Eli Grant Haugh’s funeral in Mount Olivet occurred on November 22nd. It was performed by Dr. Benjamin Meeks under the charge of the deceased’s Masonic Lodge and before a large throng of onlookers and admirers. Mr. Haugh was laid to rest in Area S, Lot 130. Wife Mollie would soon be by his side, dying less than two months later on January 16th, 1937. Eli Haugh’s successor as Clerk of the Court for Frederick County was a man named Ellis G. Wachter, who would break his predecessor’s record of service—38 years. Ironically, Mr. Wachter’s replacement would be Charles E. Keller, born the same year that Eli G. Haugh passed away. Keller would serve 24 years until current Clerk of the Frederick Court (and fan of our blog) Sandra K. Dalton took office in 1998. One final point of interest to me was that my father (Edwin A. Haugh) was born in the fall of 1936, and my great-grandfather Albert A. Haugh died at that time—just two days after Eli Haugh on November 21st, 1936 in Camden, NJ.  As for the actual Hall of Presidents’ show, my son Eddie enjoyed it, especially seeing his favorite president, Harry S. Truman. He certainly liked the cavalcade of presidents more than hearing me blab on about seeing Eli G. Haugh’s signature on a fishing license for Herbert Hoover—my greatest takeaway from the exhibit. If you are heading to the Magic Kingdom anytime soon, please take note of this unique artifact as it truly is representative of Frederick’s Haugh of Presidents. In honor of President's Day, here are a few bonus articles pertaining to President Hoover and visits to our area.

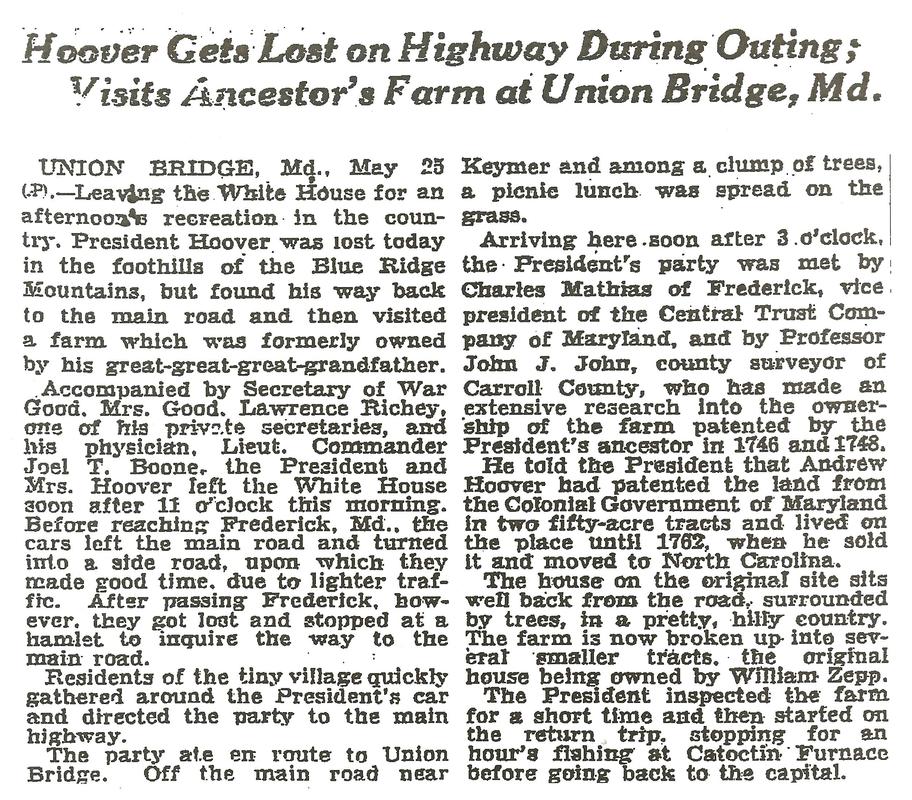

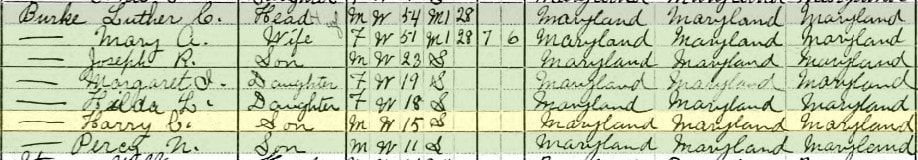

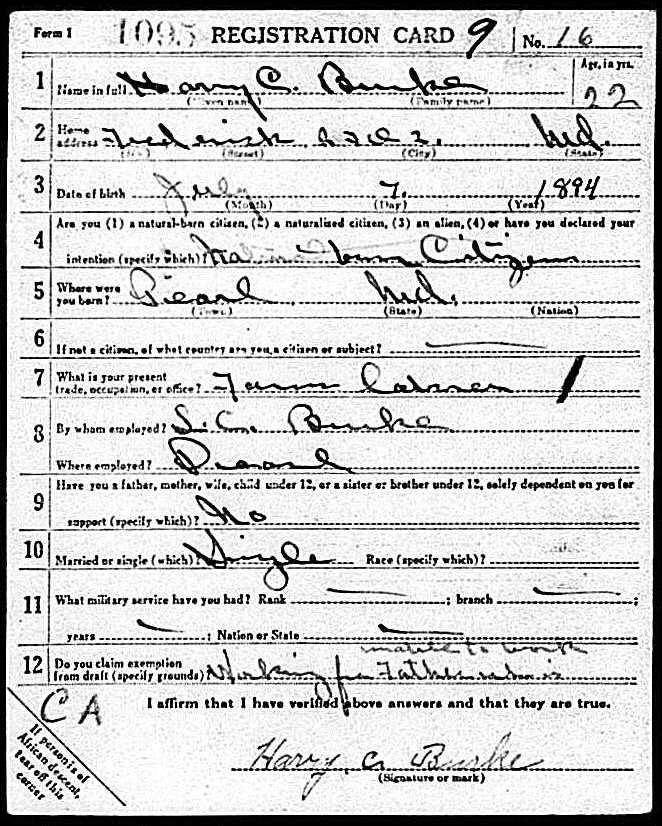

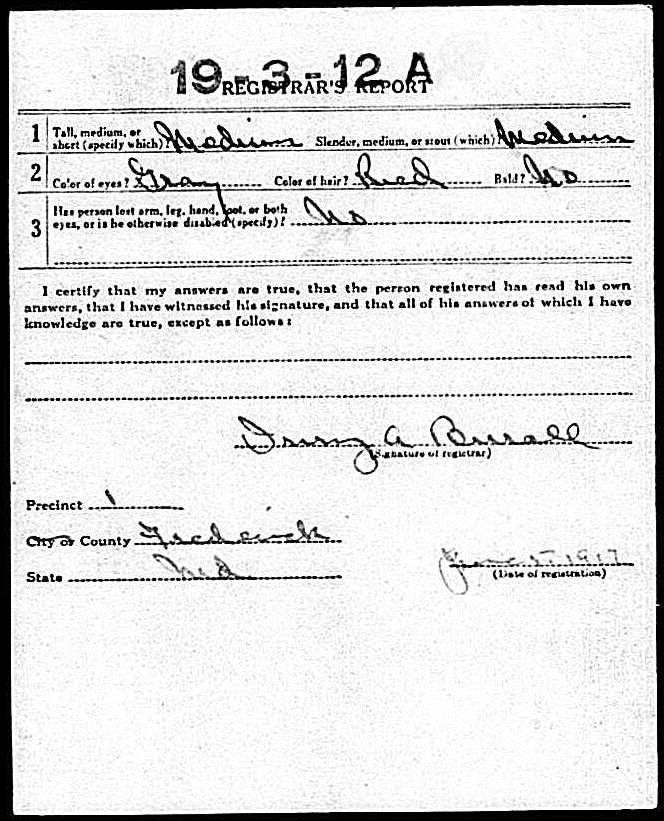

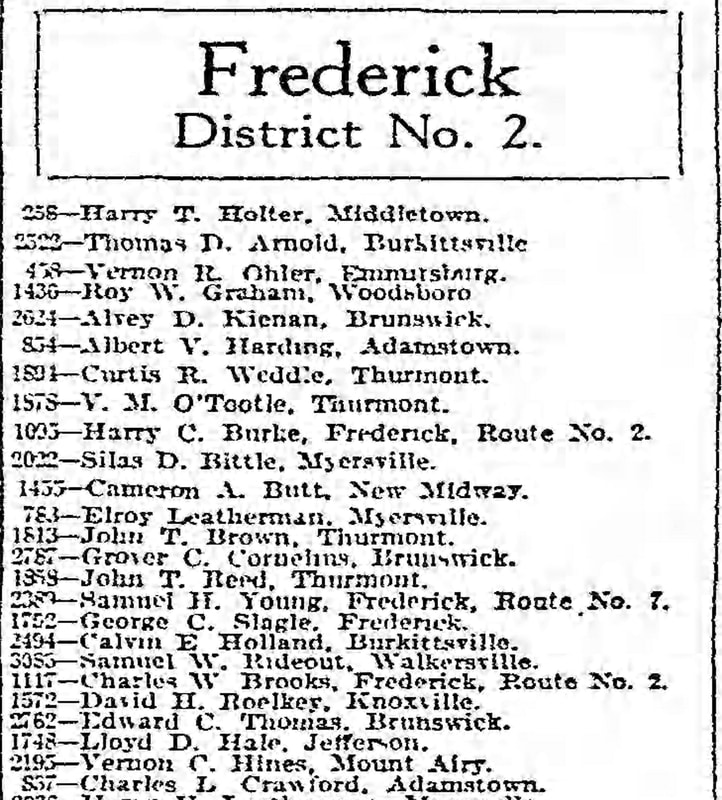

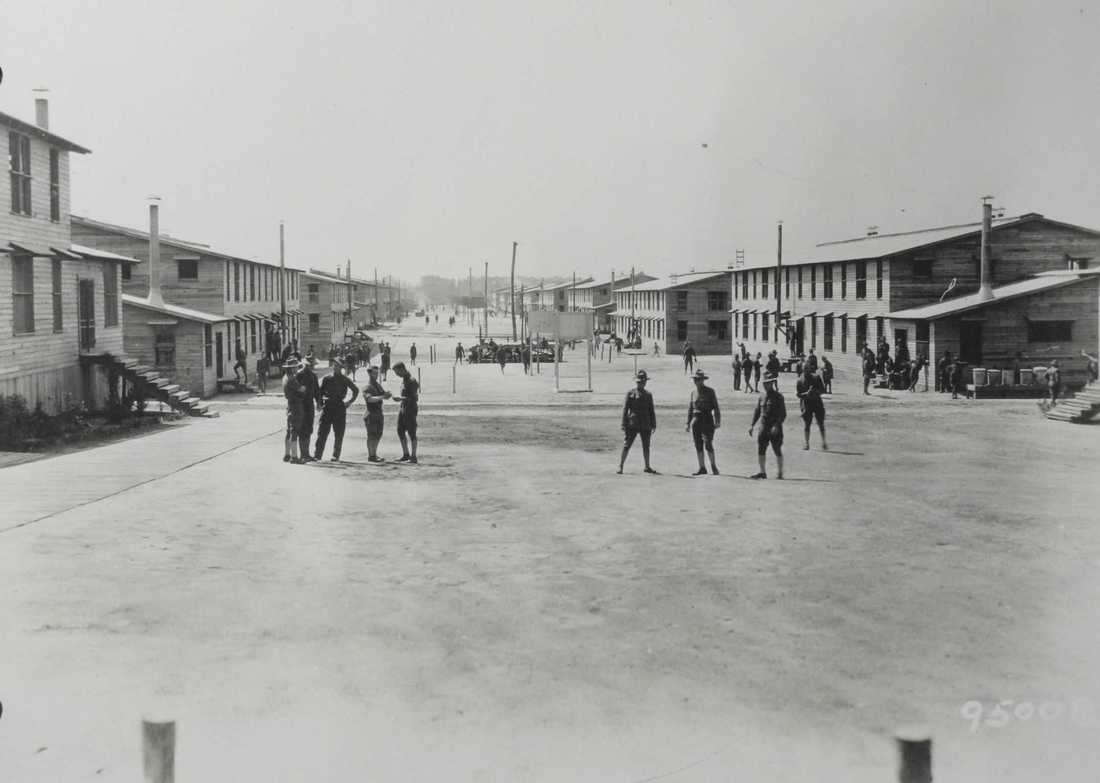

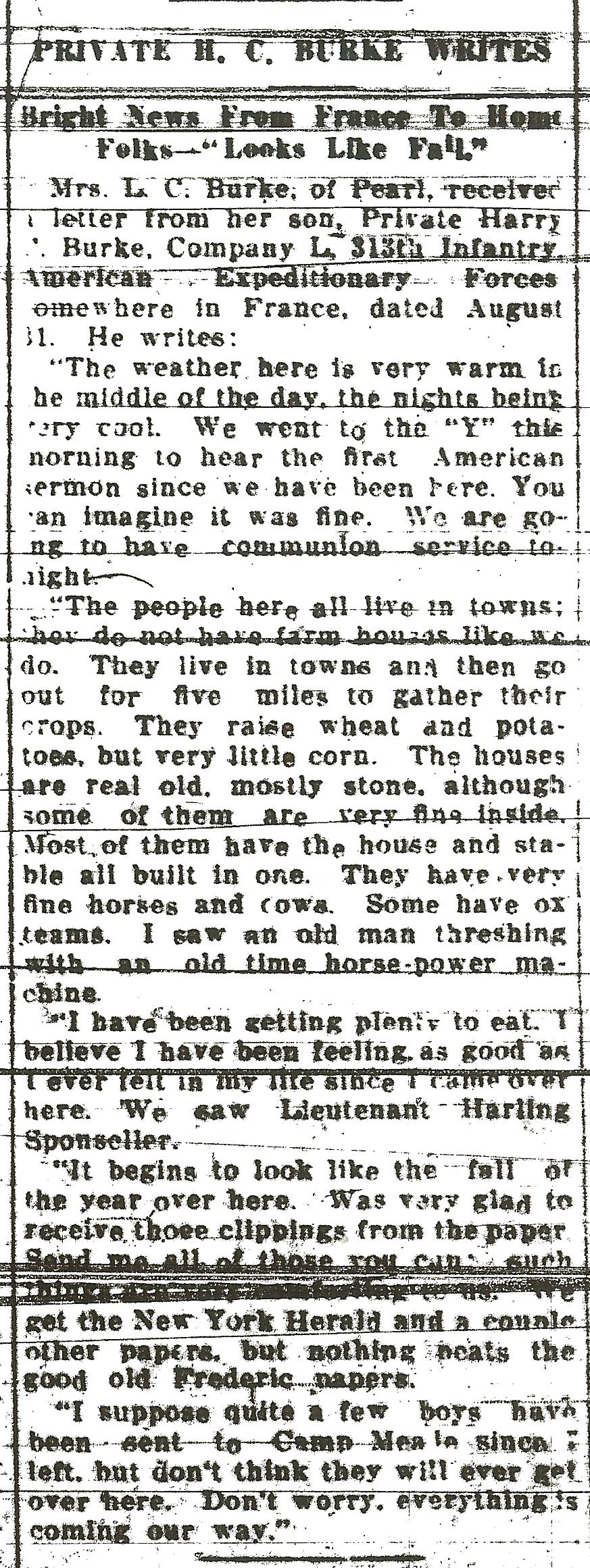

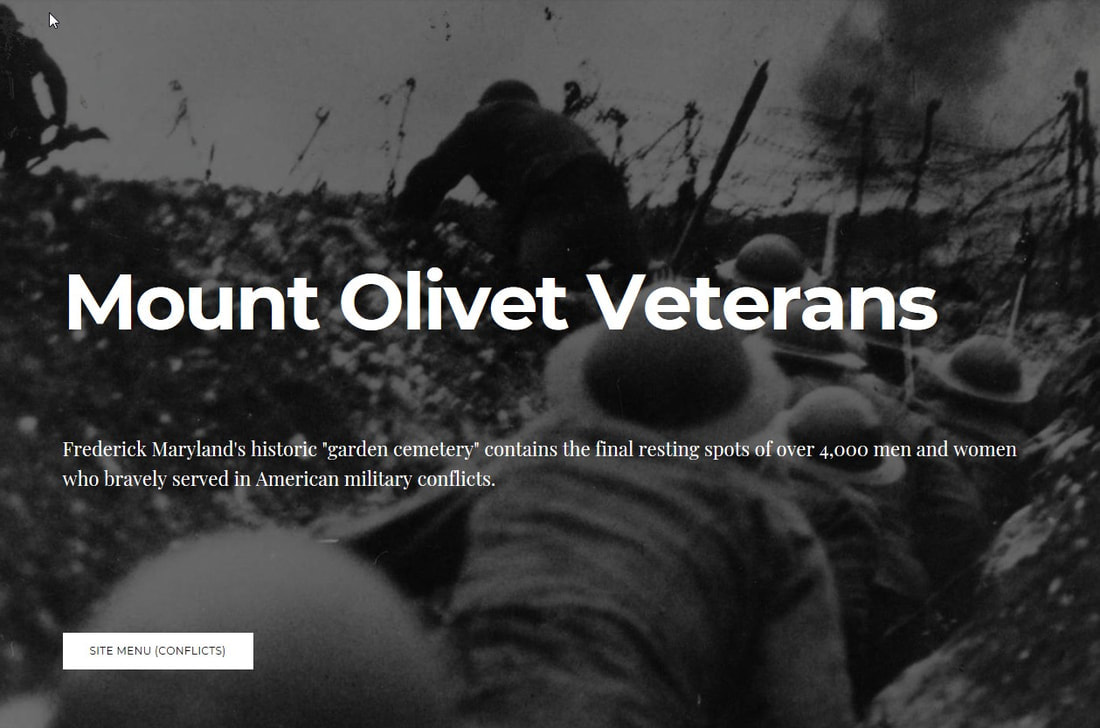

One hundred years ago this week, our country, state and county was in the throes of a first-ever “world war.” This year is marked with special commemorations and programming aimed at remembering “The Great War,” and those who served their country “to make the world safe for democracy.” Here at Mount Olivet Cemetery in Frederick, Maryland, we are currently researching local men and women who participated in the conflict and were subsequently interred here. Our historic, garden cemetery serves home to nearly 500 veterans of World War I. We have created a website entitled MountOlivetVets.com in which we are building online memorials for each of those veterans. Each page includes pictures of the gravesite, an obituary, vital and service-related information, draft registration documents and a few other facts such as name of parents and spouse, occupation and home address. In rare cases we have found photos of decedents. We are inviting help from users to supply us with (electronic) copies of photos or other documents of interest in an effort to preserve the history and memory of these important Americans.  As we have been compiling research, an interesting name came up in our cemetery database inventory. It was that of Harry C. Burke (1894-1918). I took particular interest in this 24-year old gentleman who died during the war. He is listed among 14 interments here at the cemetery constituting a “service connected” death. Upon further inspection, I ventured out to the grounds and found Burke’s gravestone but learned from our records that he is only here in name alone, his mortal remains repose in a military cemetery in eastern France. This inspired me to learn more. Area U, Lot 12 was purchased on September 6th, 1922 by Luther Columbus Burke, father of our subject Harry C. Burke. No one would be buried here until the elder Mr. Burke’s passing in late September, 1930. However, the cemetery lot had been adorned with a memorial monument dating back to at least November of 1923 as I uncovered an article in a local newspaper saying that this grave was among those decorated by a local contingent on Armistice Day (November 12, 1923). I’m assuming that the Burke family placed the existing granite monument here between the fall of 1922 and the fall of 1923. "Pansies and a new flag" would be placed on his grave on April 10th, 1925 by the American Legion Auxiliary. Harry C. Burke Harry C. Burke was born on July 7th, 1894 in Frederick. He grew up on his family’s farm, located in Pearl, a small hamlet east of the Monocacy River along the National Road (MD144). Today this general vicinity is better known as the southern part of the Spring Ridge community (around Avery's Maryland Grille/former site of Jug Bridge Seafood). In the days before the war, I gleaned little about Harry Burke. He attended Frederick High School and graduated @1912. Burke was mentioned from time to time as an attendee of a birthday party or family reunion. In 1915, he sang a duet for his church pageant (Mount Carmel Reformed Church), and in January 1916, Harry helped celebrate the marriage of his sister Margaret to Jesse E. Sponseller. Sadly Sponseller would die just three years later and is buried here in Mount Olivet—a story for another day. The national call was made for young men between the ages of 21 and 31 to register for the military draft. Maryland had a state quota of 15,000—7,500 from Baltimore City and 7,500 from Maryland’s counties. Harry C. Burke would register for the draft on June 5th, 1917 at the local county draft board’s first precinct here in Frederick . He would be the 1,095 man to do so in Maryland. On Friday, July 20th, 1917, young Harry Burke’s fate would be cast. His draft number, 1095, was chosen at random by the Frederick County Draft Board. He would be the 9th Frederick County man picked for military service for “the Great War.” The exemption board was said to have sent Harry C. Burke to Camp Meade in Anne Arundel County on November 6th, 1917. November 11th is given as the date Burke was inducted into military service. He initially served with the rank of Private in Company L of the 313th Infantry Regiment. The 313th would fall under the 157th Infantry Brigade of the 79th Division. The division was first activated at Camp Meade in August 1917, composed primarily of draftees from Maryland and Pennsylvania. The 313th Regiment was known as "Baltimore's Own" due to the large number of men from the city and was headed by Col. Claude B. Sweezey, a West Point graduate.  WWI troop transport ship WWI troop transport ship “Over There” After eight months of training, Harry C. Burke found himself on a transport ship on July 6th, 1918 preparing to cross the Atlantic Ocean. The next day he would celebrate his 24th birthday at sea, it would be his last. The 313th Regiment and its 3,667 men sailed to France to join the active front near Verdun, a scene of heavy fighting throughout 1916. Shortly after landing in Europe, Harry was given a promotion to Private First Class. Harry Burke would participate in early tough fights of the unit. Action for the Frederick boy over his first month in Europe was light, consisting mostly of travel (marching/train transport) to the Avocourt Sector of northeast France. He wrote the following letter “back home” at the end of August (1918). It would be published in the pages of the Frederick Post (nearly six weeks after its writing):

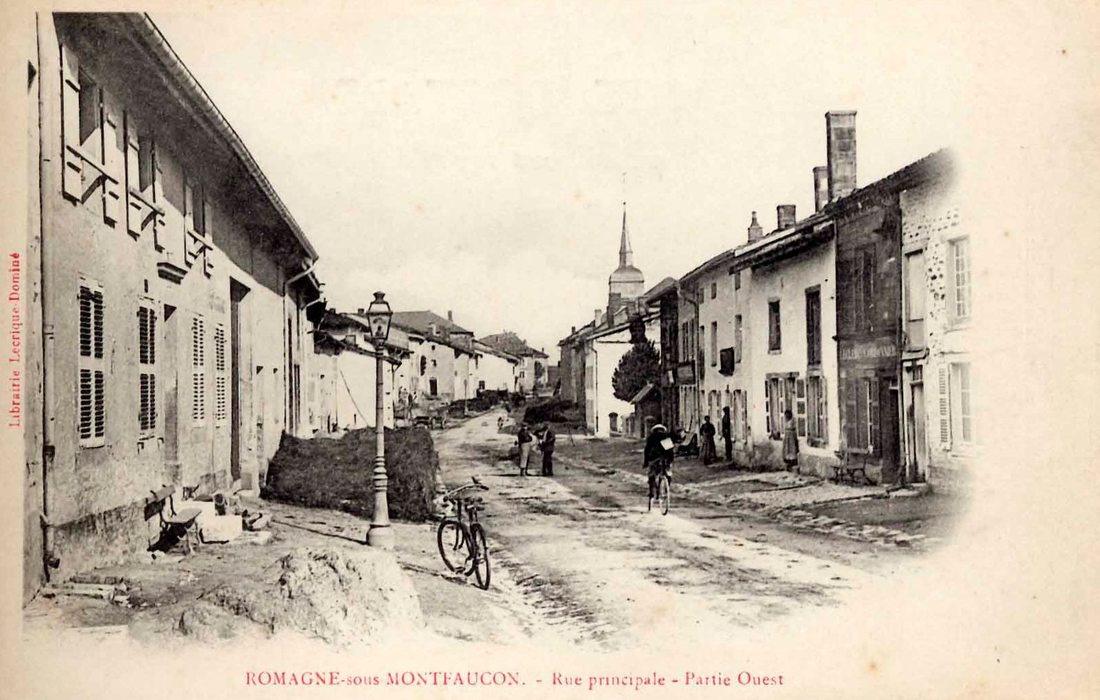

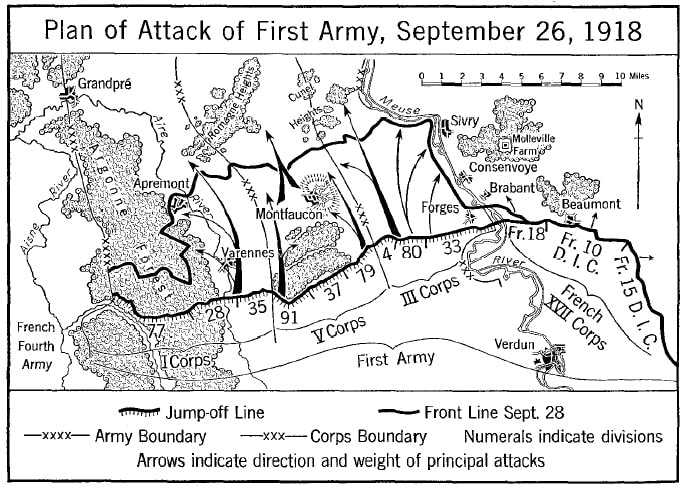

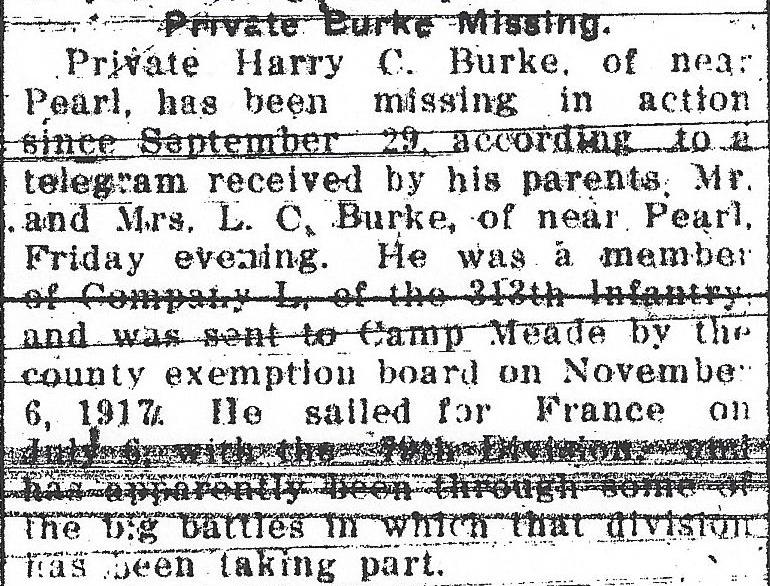

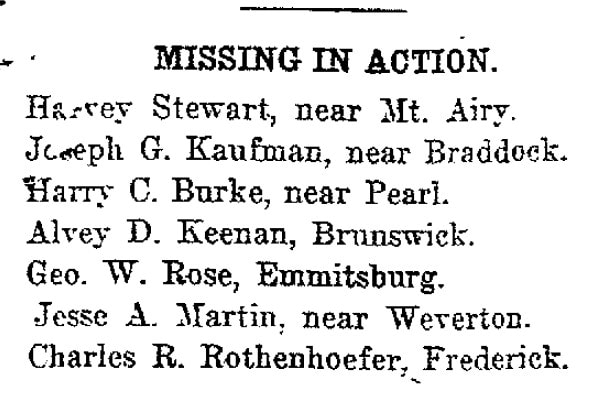

The optimism shown by PFC Burke would certainly play out for the American allies, but not for the Frederick resident himself. He would lose his life, likely before his parents read his charming letter of August 31st. At this time, the 313th was engaged in the principal engagement of the war—the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. The Meuse-Argonne Offensive was the largest of its kind in United States military history, involving 1.2 million American soldiers. Under the command of John J. Pershing, this was also the bloodiest operation of World War I for the American Expeditionary Force (AEF). The event was one of a series of Allied attacks known as “The Hundred Days Offensive,” which brought the war to an end. It would also serve as the second-deadliest battle in American history, behind World War II’s Battle of Normandy. American losses were heightened by the inexperience of many of the troops, and tactics used during the early phases of the operation. The battle cost 28,000 German lives, 26,277 American lives and an unknown number of French lives. Harry C. Burke was one of the casualties. The Frederick native participated in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive’s “First phase” which took place from September 26th to October 3rd, 1918. The 79th Division was assigned the deepest, first-day objective of any division of the Army even though it was facing some of the most difficult terrain in the Meuse-Argonne region. On September 25th, the 79th occupied Sector 304, which it had taken over from the 157th French Division on September 16th. With the 37th Division on its left flank and the 4th Division on its right, the 79th’s mission was to seize, in succession, Malancourt, Montfaucon, and Nantillois, which was some 5.5 miles beyond the German lines. Weeks spent confined in the Allied trenches would give rise to a foray into the famed “No Man’s Land” to the east. To give a glimpse of what PFC Burke experienced, I include this overview of the battle’s first phase, including information drawn from the Combat Studies Institute’s (Fort Leavenworth, KS) dissertation on the Battle of Montfaucon: By 4:30 a.m. on the morning of September 26th, 1918, the untested 79th Division’s 313th Infantry Regiment anxiously waited in trenches south of the ruined town of Avocourt. In one hour’s time, they would join 220,000 other American soldiers spread across a 26-mile line in the launch of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. Harry C. Burke and the soldiers of the 313th Regiment marched all night through heavy rain and darkness to reach this point. Traveling light, with only the necessities of war, they traversed thick brush, endless fields of barbed wire and terrain scarred with deep, mud-filled shell craters. As they moved forward, friendly artillery screamed overhead, climaxing in an intense barrage twenty minutes prior to their attack. An interesting footnote here resides in the fact that the Allies expended more ammunition than both sides managed to fire throughout the four years of the American Civil War. The cost was later calculated to have been $180 million, or $1 million per minute. Burke and his comrades hoped that each shell might help weaken the German forces soon to be encountered. The soldiers of the 313th Regiment were attached with a heavy burden on their shoulders. Their objective was the honor position of offensive’s first phase. By days’ end, they were expected to clear 4.3 miles of enemy territory and take the formidable heights of Montfaucon, on which the Germans observed the entire American sector from four to five positions. This same terrain claimed over 300,000 French casualties in 1916. The success of the entire campaign hinged on control of Montfaucon. It took the 79th Division only two days to capture Montfaucon, however, the cost to the 313th was high. The regiment lost 45 officers and 1,200 enlisted men. One soldier described the experience as a “hellish ordeal” in a letter home: “I’ve been on the firing line a week, and it was like a lifetime in hell. It was one of the worst and bloodiest battles of the war. Any why, or how, I came through it is more than I can tell.” In the days following Montfaucon, the 313th advanced little more than a mile and was halted. On September 29th, six additional German divisions were deployed to oppose the American attack. In the shadow of Montfaucon, and on this day, Harry C. Burke would lose his life—but it would be several months until his body was discovered. Over a month would pass until Burke’s family in Frederick would learn of his disappearance. A local newspaper shared the unfortunate news with the community.

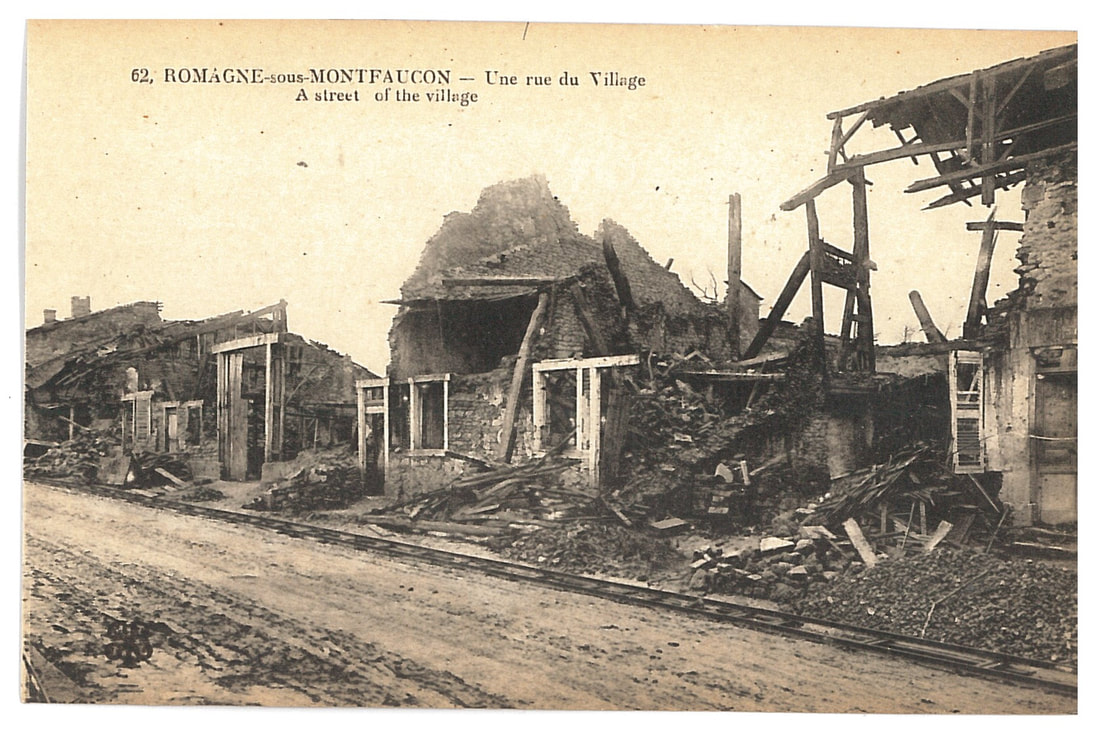

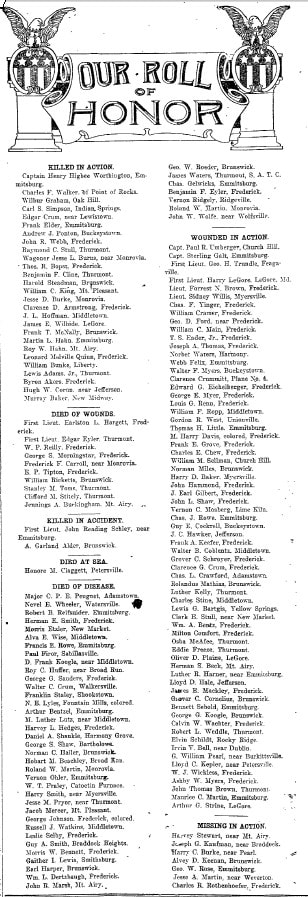

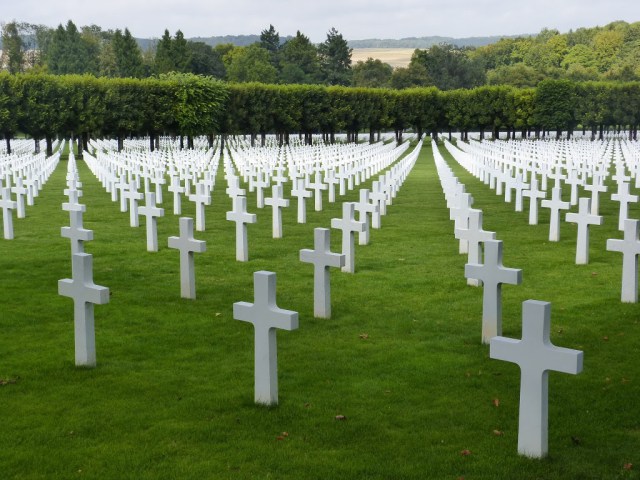

This chilling article appeared on November 11th, the day of the armistice which officially ended the war. A month later, the parents of Clarke Eugene Stull, a friend and fellow soldier of Burke’s, received a letter from their son giving brief hope to the Burke family. Stull was a former bunkmate of Burke, and was injured on September 29th. He claims that he saw Harry in “good health” earlier on the ill-fated day of September 29th, but had not heard from him up through the date of writing his letter (late November). By the end of what must have been an excruciating holiday season, the Burke family and friends must have been losing hope while others around them were rejoicing in the fact that their loved ones would soon be returning from Europe. The Frederick News began running large advertisements commemorating the efforts of Frederick County’s brave Doughboys, and entitled "Our Roll of Honor." Through the winter months, Burke’s name continued to run under a column headed “Soldiers Missing in Action.” On March 25th, 1919, The Baltimore Sun ran a story from the 313th Infantry Regimental Headquarters located in Conde, France. Sixty men of the regiment were listed, whose whereabouts were still unknown. The article stated that they could be buried in unmarked graves or graves marked simply as “unknown.” The piece also ventured to give optimism in saying that some of these men could be “lost in a hospital in France and may turn up later.” Throughout its entire World War I campaign, the 79th Division suffered 6,874 casualties with 1,151 killed and 5,723 wounded. Interestingly, a Maryland resident from east Baltimore, named Private Henry Gunther, was the last American soldier to be killed in action during World War I. Like Harry C. Burke, he served with the 313th Infantry Regiment of the 79th Division. I don’t know exactly when or where, but PFC Burke’s body was eventually discovered. His death was known at the time of Frederick's large Homecoming Parade and celebration which occurred on July 4th, 1919. Harry C. Burke would be given a proper burial in the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery located in Romagne, France, not far from where the Frederick soldier breathed his last breath. His gravesite is marked with a military-issue marble cross, sitting atop soil designated as Plot F/Row 39/Grave 24. I had the humbling experience of visiting this same cemetery while on a battlefield tour with my father back in 2001. Unfortunately at that time, I knew nothing of Harry C. Burke and his connection to Frederick. If I had, I certainly would have sought it out. I hope Harry’s parents had the opportunity to visit his actual European gravesite in an attempt to gain some semblance of closure. Whatever the case, the Burke family memorialized their son here at Mount Olivet with a fine monument, affording friends, family and others to pay tribute to a brave young man who “gave the last full measure of devotion.” |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed