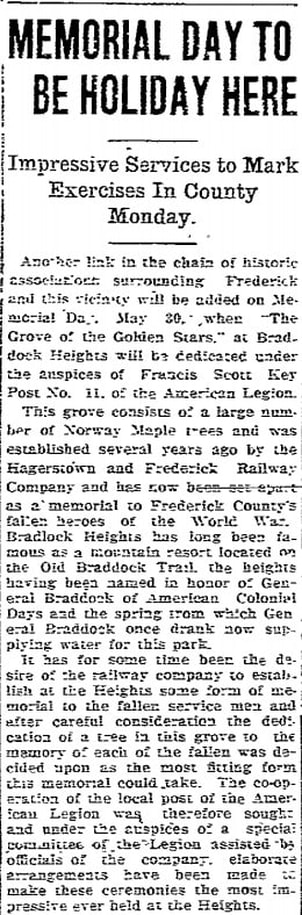

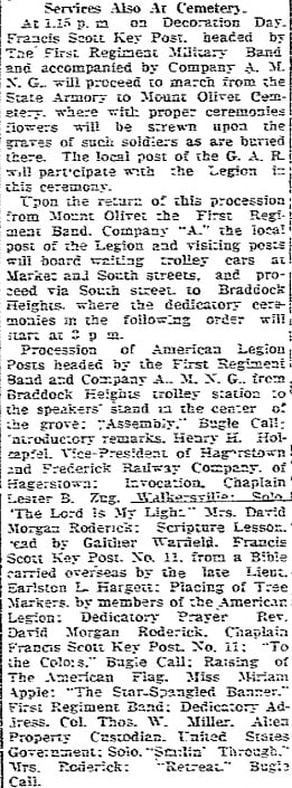

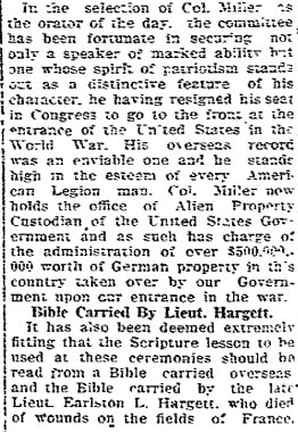

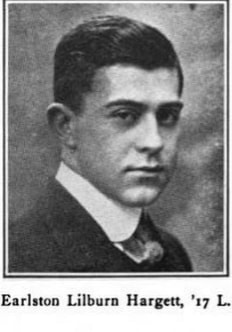

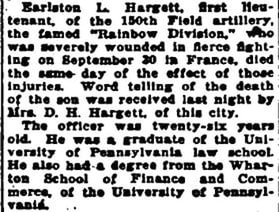

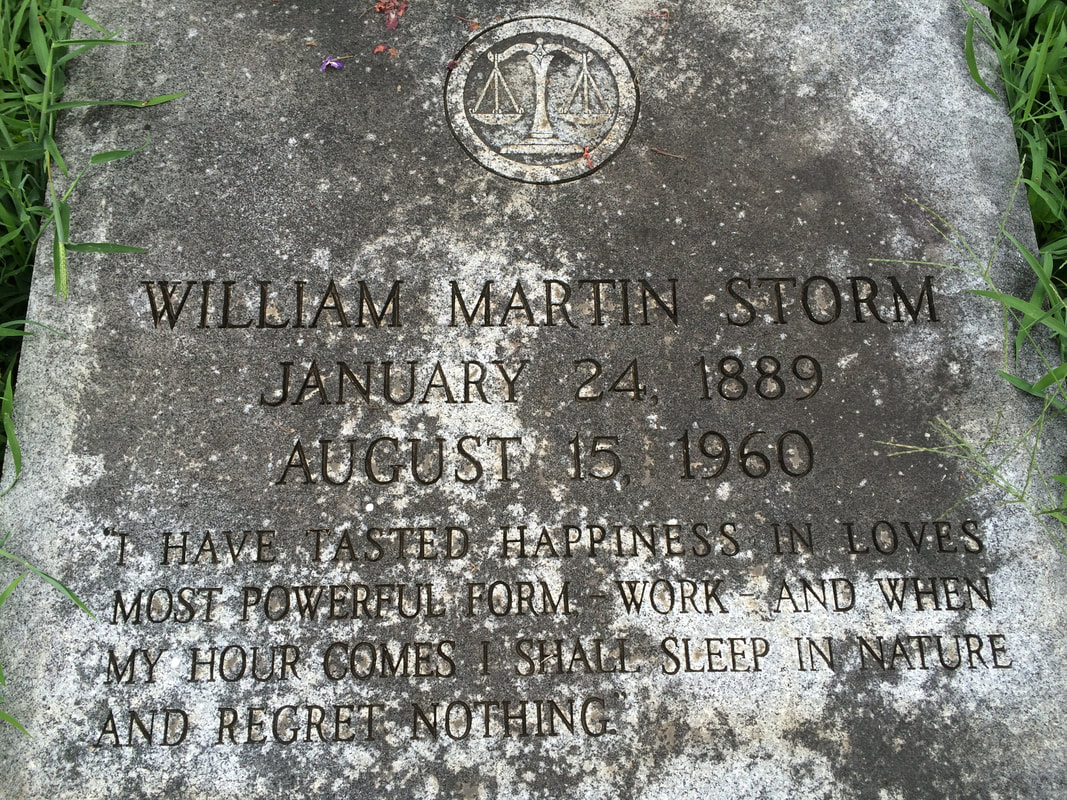

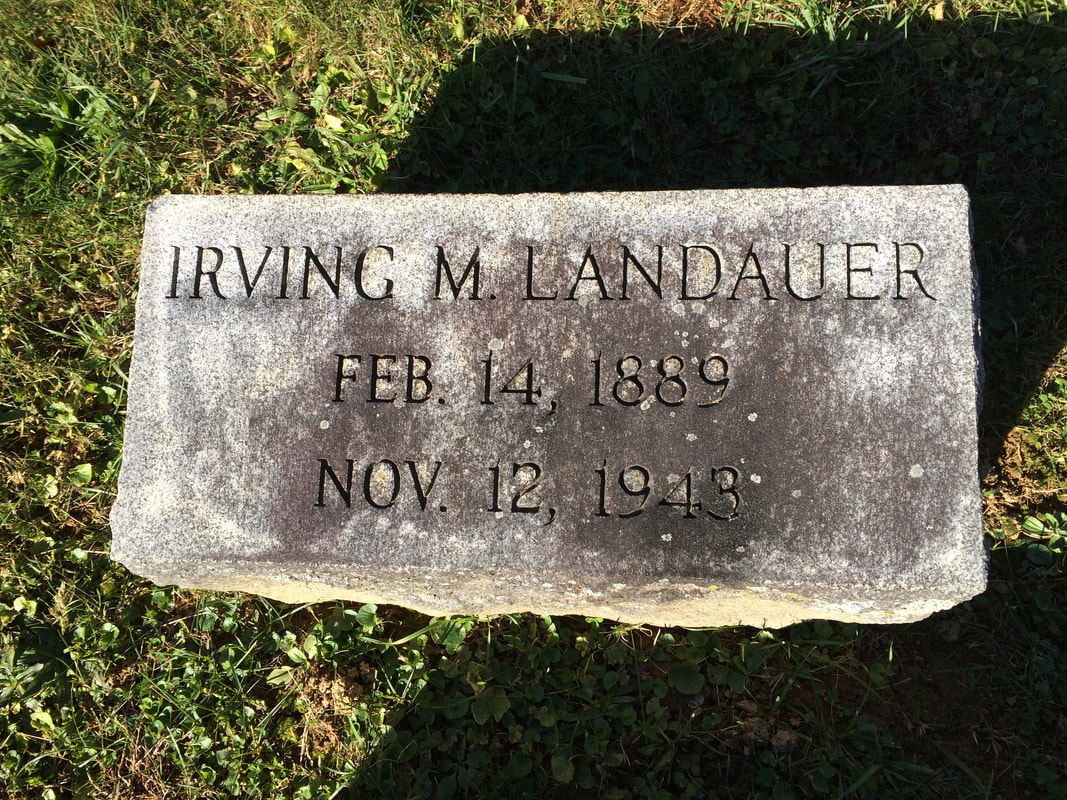

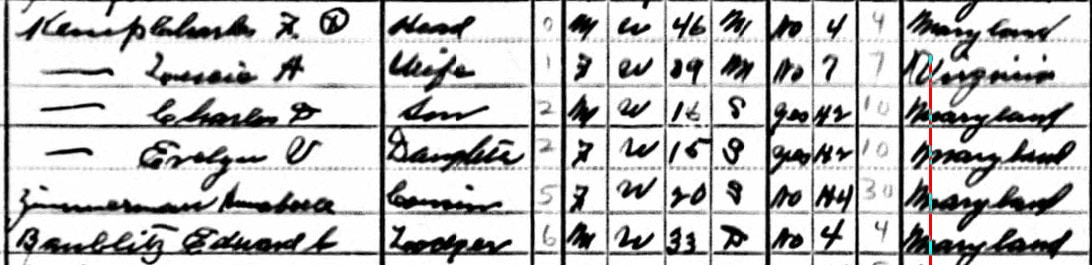

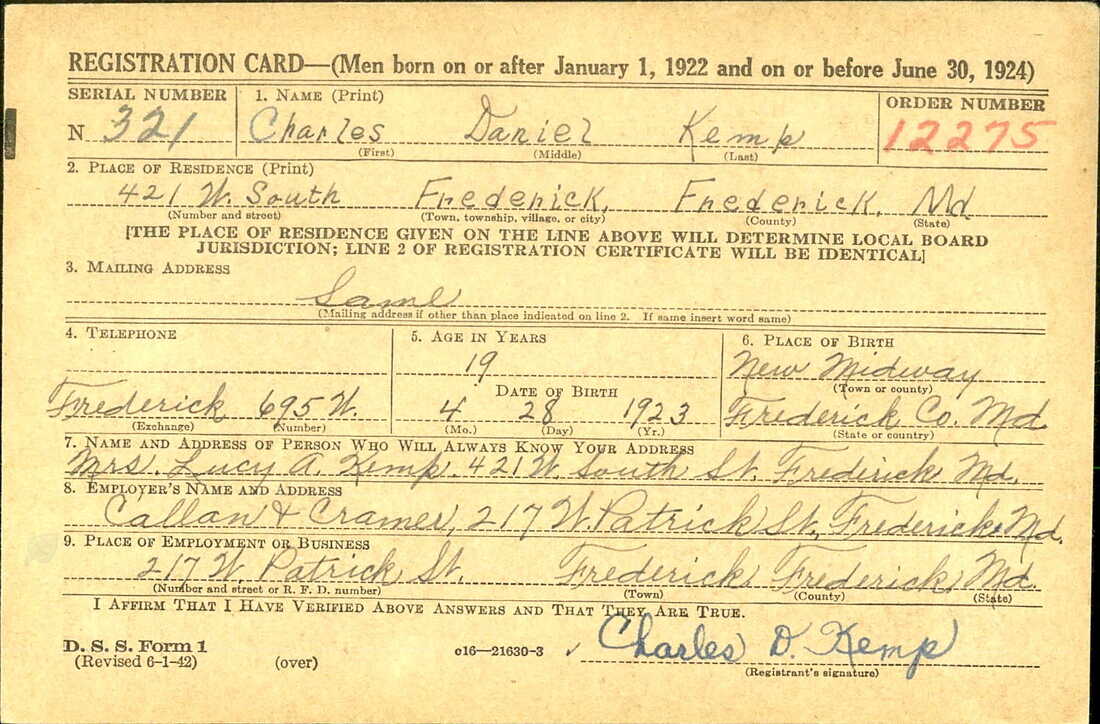

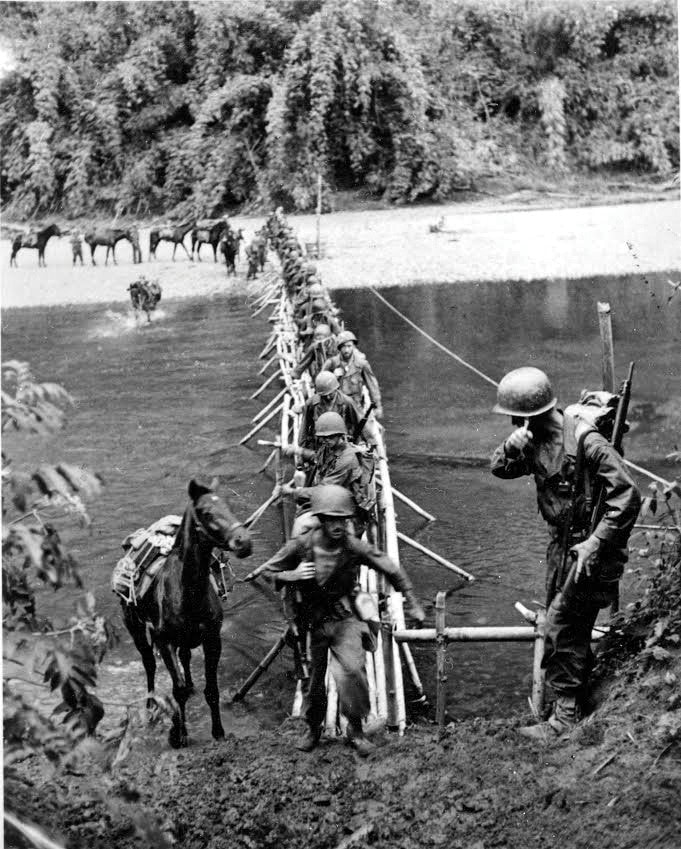

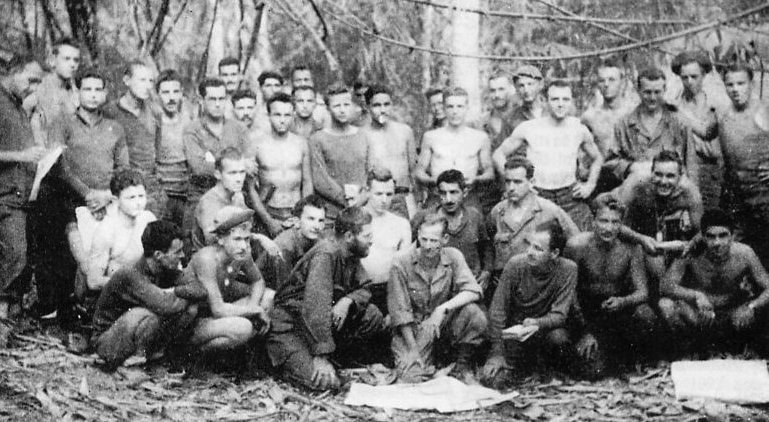

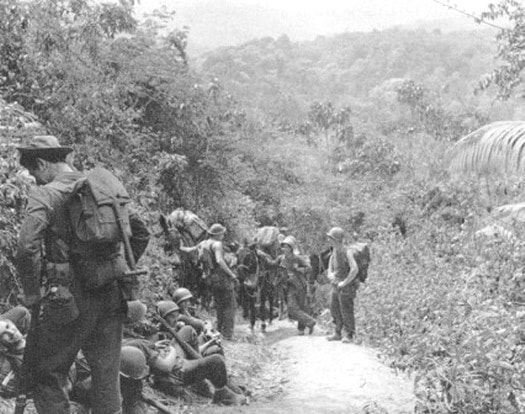

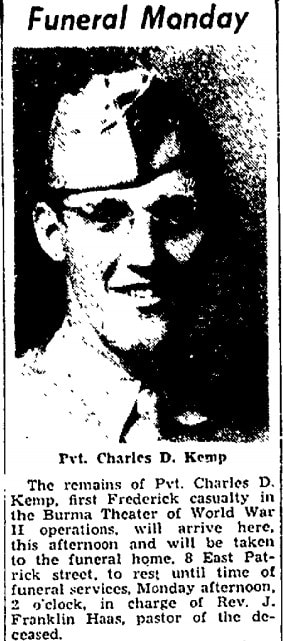

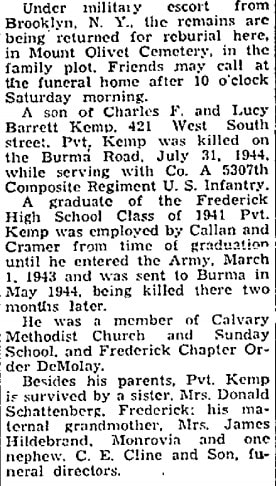

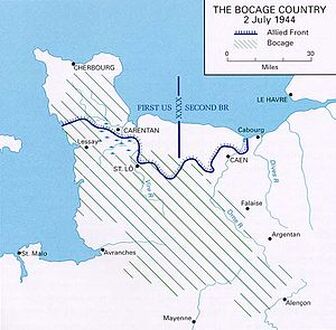

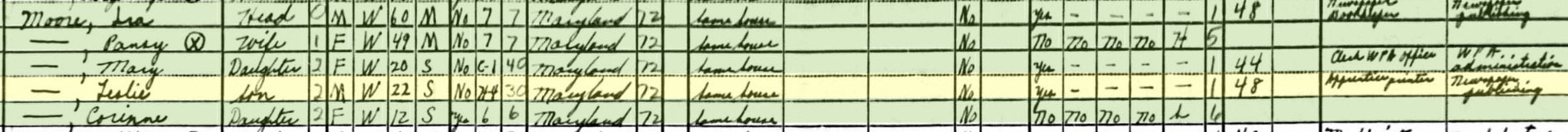

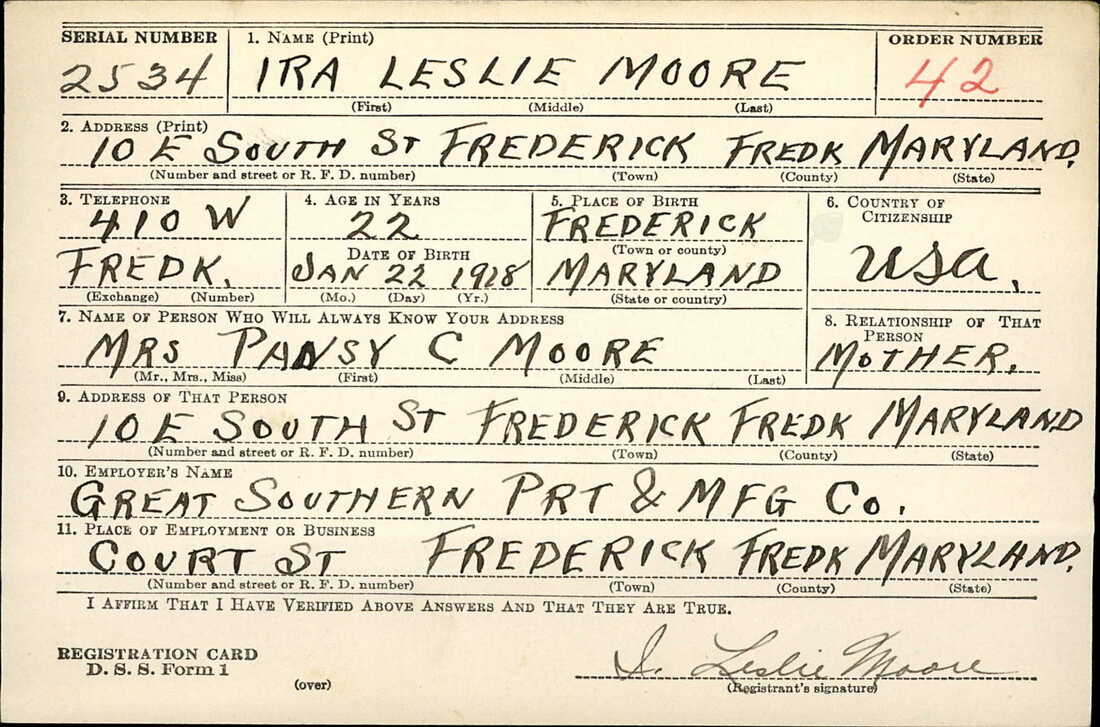

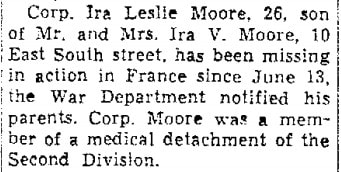

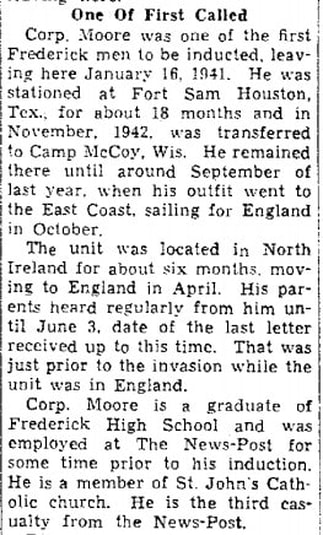

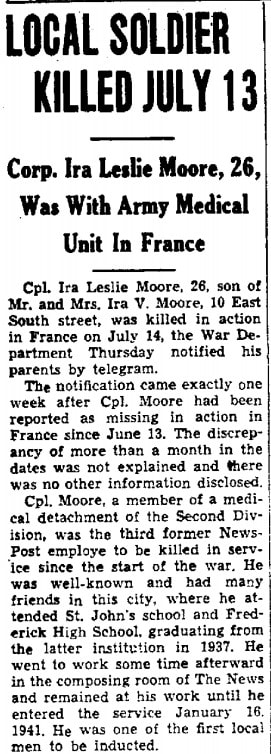

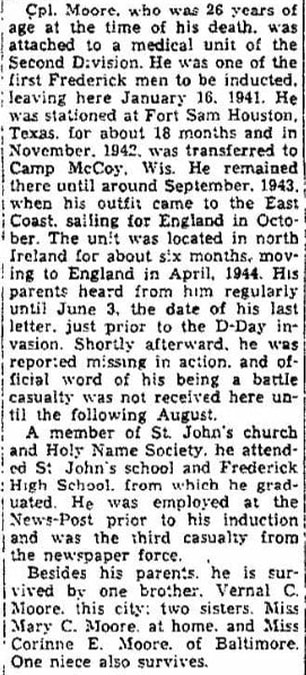

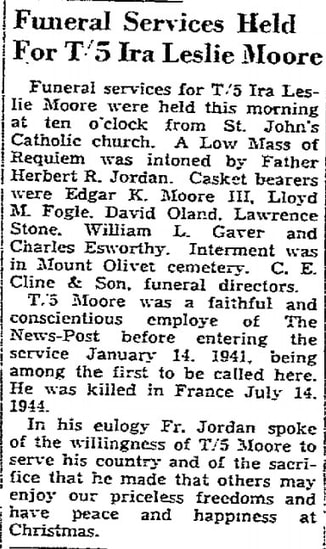

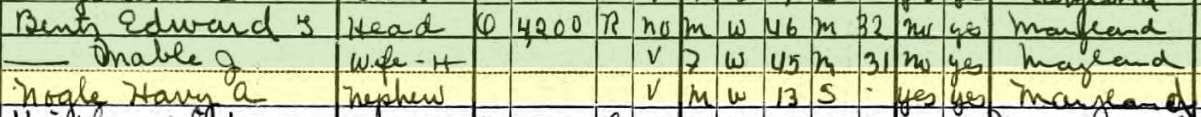

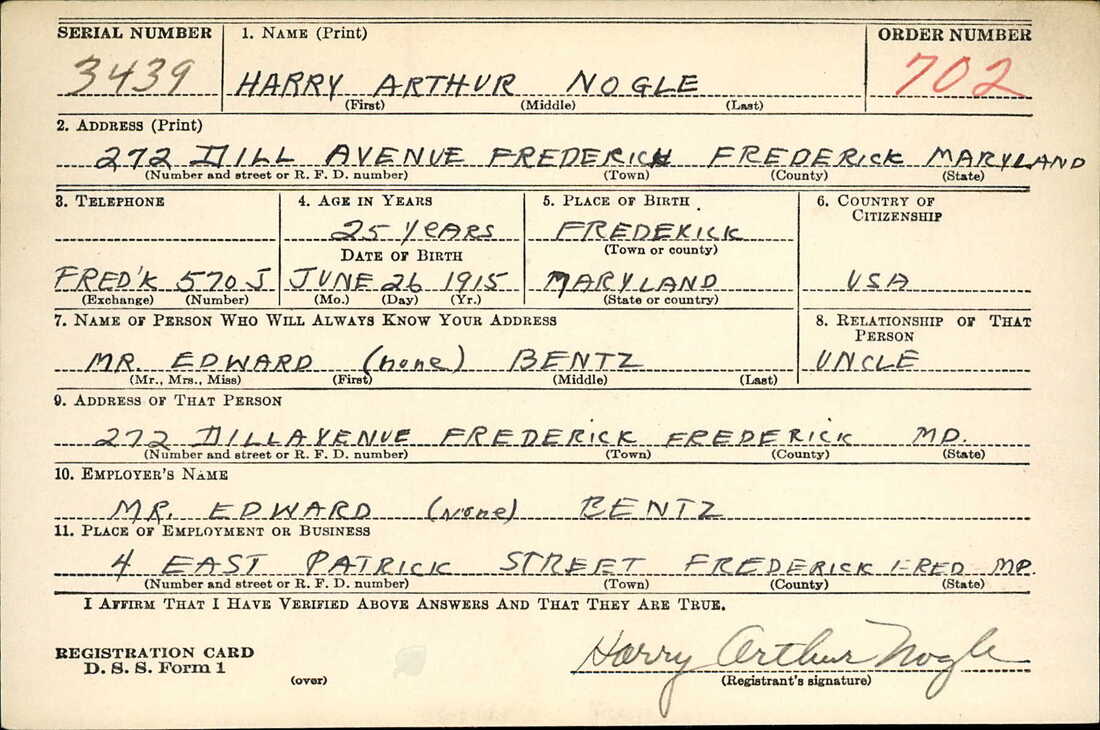

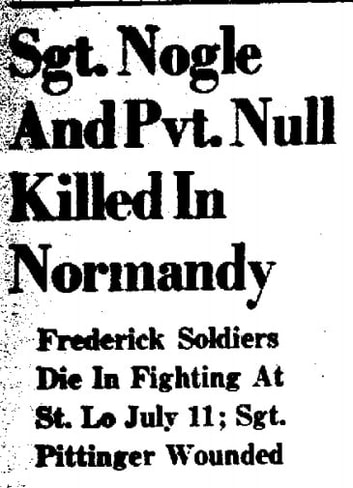

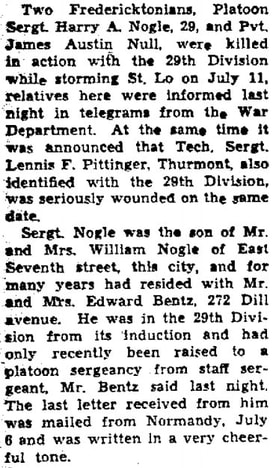

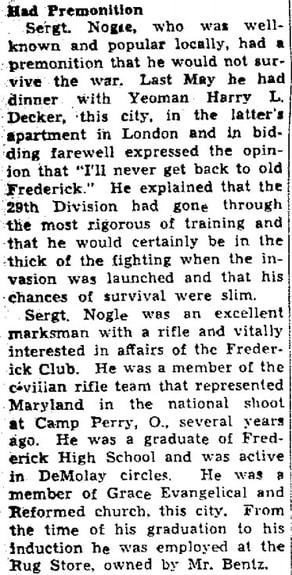

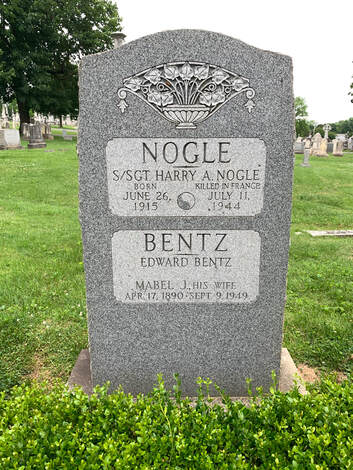

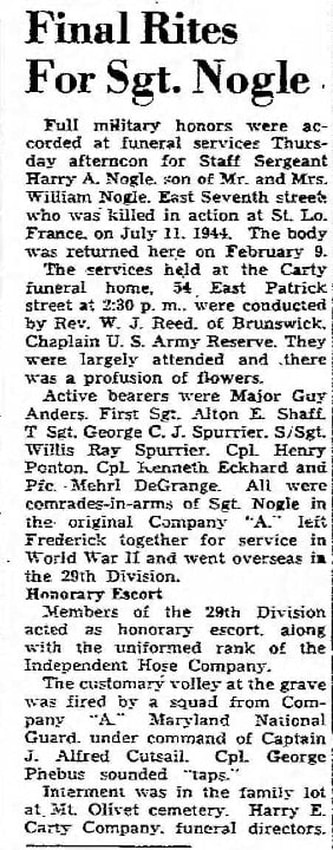

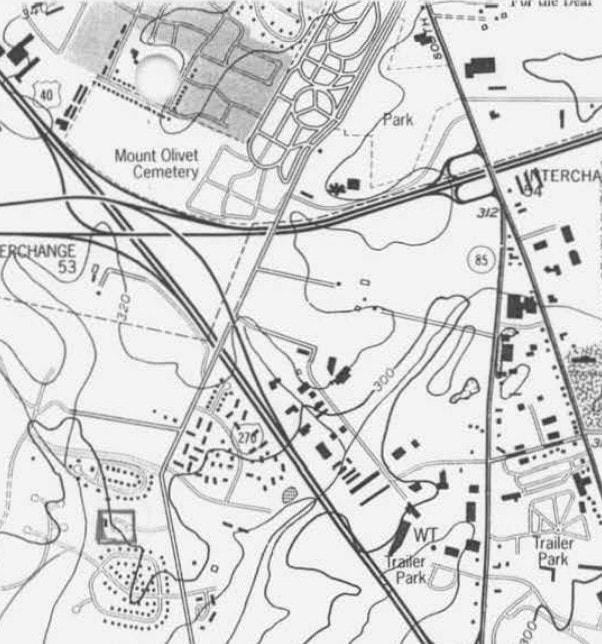

It’s Memorial Day once again—a very special day for Mount Olivet Cemetery not unlike national, state and private memorial grounds throughout the country and world that are the silent keepers of men and women who gave their lives in protecting us and our United States of America. The same holds true for small town graveyards and ancient rural churchyards that may hold only one, or a handful of former veterans who died as a result of warfare or military duty. The American holiday, originally called “Decoration Day,” originated in the years following the Civil War and would not become an official federal holiday until 1971. It is observed on the last Monday of May, and its purpose is to honor the men and women who died while serving in the US military. In the chaotic and commercial world in which we live today, many simply see Memorial Day as the unofficial kickoff to summer, paving the way for much-anticipated outdoor activities such as picnics, swimming, games, camping and beach and Disney vacations. Thankfully, commemorative activities such as flag-plantings on veteran graves, wreath-layings on war monuments, military-themed parades and veteran recognition programming keep reminding us of the real reason we have Memorial Day. Regardless of where your mind and heart are at this Memorial Day, the adoration for those lost in past service-related situations, and the annual seasonal “rite-of-passage” both take on heightened purpose and meaning this year as we emerge from local, state and federal restrictions regarding the Covid-19 pandemic. Last year, most related Memorial Day activities were canceled and scrapped. Among these was the annual program by our local Francis Scott Key Post 11 of the American Legion. Although the group faithfully planted flags in advance, this was the first time their service at Mount Olivet was missed since its very first held a century earlier on May 29th, 1920. The 100th anniversary of that very event was missed of course in May, 2020, but I was fortunate to have been invited to participate as a program speaker in Post 11’s centenary ceremony held on Memorial Day, 2019. It was a beautiful day, and I had the unique opportunity to call out veterans buried here who were connected to nearly every major military conflict our country has participated in. As we see things getting “back to normal,” we can look fondly toward next Monday, May 31st at 12 noon, as the Legion will return to Mount Olivet to hold their annual observance ceremony at the base of the Francis Scott Key Monument, located just within our front gate off Frederick’s South Market Street. I have a pretty good idea of how Memorial Day 2021 will shape up, and I must say, it doesn’t have far to go to easily out-perform last year’s Memorial Day chock-full of cancellations, safety restrictions, and social justice protests and rioting on both mainstream and social media. However, the sentiment for our fallen heroes should be the same, pandemic or not. That said, I became curious as to the mood here locally back a century ago, in 1921, for the second “official” Memorial Day observance here in Frederick in respect to a “renewed” focus on Memorial Day, mostly driven by newly-formed veterans groups such as our local Legion Post. These came about as a result of World War I which had ended on November 11th, 1918, better known as Armistice Day, and in time this date would serve as Veterans Day. Fredericktonians and countians had recognized Decoration/Memorial Day since the 1860s in originally commemorating Civil War dead. Groups such as the Grand Army of the Republic and the United Daughters of the Confederacy kept the spirit alive. However, in the late teens and early 1920s, newspapers advocated for commemorations of those killed in The Great War (World War I). By Memorial Day 1921, the tradition was solidly on its way, and would embrace service men and women who had perished in the line of duty. I went back to the Frederick newspapers of late May, 1921, and here is what I found on the Memorial Day docket. Memorial Day, 1921 took place on May 30th under the leadership of Post Commander William M. Storm and Adjutant Irving M. Landauer. Both these gentleman were veterans of World War I, and have Mount Olivet as their final resting place along with over 4,000 service men and women. Landauer would serve as Post Commander a decade later from 1931-1932. We have done a great deal of research work in the last few years regarding our World War I veterans buried in the cemetery, numbering over 600. If you haven’t done so already, please check out the memorial pages for these men and women on www.MountOlivetVets.com . As said earlier, the veneration paid to the WWI vets back in the years immediately following “the Great War” would continue to swell. It grew exponentially with the occurrence of World War II and 20th century conflicts thereafter. Speaking of World War II, I’ve written several articles on some of the fallen soldiers, sailors and airmen that can be found buried beneath our World War II monument in Area EE. This lasting tribute was dedicated on Memorial Day 1948. Instead of rehashing that history lesson, I thought I would briefly talk about three other individuals who lost their lives in active duty during World War II, but were laid to rest in other areas of Mount Olivet. Charles D. Kemp Private Charles Daniel Kemp was born in New Midway in northeastern Frederick County on April 28th, 1922. He is buried on Area MM/Lot 119. Our records show that he served with Company A of the 5307th Composite Regiment of the US Infantry and was the first Frederick resident to be reported killed in the Burma Theater of World War II. The son of Charles Franklin Washington Kemp and Lucy Alice Barrett (Hildebrand) was known also by the name of “Buttercup.” I wasn’t familiar with this part of the war, so I consulted some online resources to learn more. The Burma campaign was a series of battles fought in the British colony of Burma. It was part of the South-East Asian theatre of World War II and primarily involved forces of the Allies; the British Empire and the Republic of China, with support from the United States. They faced against the invading forces of Imperial Japan, who were supported by the Thai Phayap Army, as well as two collaborationist independence movements and armies, the first being the Burma Independence Army, which spearheaded the initial attacks against the country. Puppet states were established in the conquered areas and territories were annexed, while the international Allied force in British India launched several failed offensives. During the later 1944 offensive into India and subsequent Allied recapture of Burma, the Indian National Army, led by revolutionary Subhas C. Bose and his "Free India", were also fighting together with Japan. British Empire forces peaked at around 1,000,000 land and air forces, and were drawn primarily from British India, with British Army forces (equivalent to eight regular infantry divisions and six tank regiments), 100,000 East and West African colonial troops, and smaller numbers of land and air forces from several other Dominions and Colonies.  The campaign had a number of notable features. The geographical characteristics of the region meant that weather, disease and terrain had a major effect on operations. The lack of transport infrastructure placed an emphasis on military engineering and air transport to move and supply troops, and evacuate wounded. The campaign was also politically complex, with the British, the United States and the Chinese all having different strategic priorities. Charles was a member of the 5307th Composite Unit (Provisional Army), also known as Merrill's Marauders. Merrill’s Marauders (named after Frank Merrill) or Unit Galahad was a United States Army long range penetration special operations jungle warfare unit, which fought in the South-East Asian Theater of World War II, or China-Burma-India Theater. The unit became famous for its deep-penetration missions behind Japanese lines, often engaging Japanese forces superior in number. Private Kemp lost his life on July 30th, 1944. He was only 22. His obituary soon appeared in the local newspaper. Moore and Nogle We have two other veterans who perished in the European Theater of war in the same town of Saint-Lô, France. I am familiar with this town as I had visited back in 2001 as part of a World War II Battlefield tour of Normandy with my father. (My grandfather was in the war and we went with many members of his division). The action in Saint-Lô between Allied forces and the Germans occurred in July (1944), roughly a month after D-Day, June 6th. The Battle of Saint-Lô is one of the three conflicts in "the battle of the hedgerows," which took place between July 7th and 19th, 1944, just before Operation Cobra. Saint-Lô had fallen to Germany in 1940, and, after the Invasion of Normandy, the Americans targeted the city, as it served as a strategic crossroads. American bombardments caused heavy damage (up to 95% of the city was destroyed) and a high number of casualties. The first of these two casualties of Saint-Lô is buried in Mount Olivet's Area Q/Lot 246, only steps from two immortal Frederick patriots in Civil War heroine Barbara Fritchie and Revolutionary War hero, Gov. Thomas Johnson, Jr. His name is Ira Leslie Moore. Moore was born on January 22nd, 1918, in Frederick, the son of Ira Vernal Moore and Pansy Cecelia Carlin, Mr. Moore’s second wife. He lived on East South Street, only a few blocks from Charles Daniel Kemp. He worked for the Frederick News-Post as a printer at the time of his enlistment. Ira eventually held the rank of T/5 in the Army and was part of a medical detachment. For a little background on this curious designation, I did a some additional research: Technician fifth grade (abbreviated as T/5, TEC5 or TEC-5) was a United States Army technician rank during World War II. The grades of Technician in the third, fourth and fifth grades were added by War Department on the 8th of January 1942 per Army Regulation 600-35. An update issued on the 4th September 1942, added a letter "T" to the rank insignia. Those who held this rank were addressed as corporal, though were often called a "tech corporal". Technicians possessed specialized skills that were rewarded with a higher pay grade, but had no command authority. The pay grade number corresponded with the technician's rank. T/5 was under the pay grade 5, along with corporal. Technicians were easily distinguished by the "T" imprinted on the standard chevron design for that pay grade. The technician ranks were removed from the U.S. Army rank system in 1948, though the concept was brought back with the specialist ranks in 1955. T/5 was as high as our subject would rise by early summer 1944. Ira Leslie Moore would first be reported missing in action. A week later, newspaper reports confirmed that he had died on July 11th, 1944. A second victim of the action at Saint-Lô, France was Staff Sergeant Harry Arthur Nogle, son of William Arthur Nogle and Pauline Elizabeth Kline. Nogle was born on June 26th, 1915. I could not find him living with his parents in the 1920, 1930 or 1940 US Census records. Harry was instead living with an uncle and aunt and I'm guessing that they actually raised him into adulthood. In the years leading up to the war, Harry was employed by his uncle, Edward Bentz, as a clerk in Mr. Bentz's rug store. This was located on E. Patrick Street in downtown Frederick. Nogle would become a member of one of the war's most celebrated units, the 29th Division.  The 29th Infantry Division, also known as the "Blue and Gray Division," is an infantry division of the United States Army based in Fort Belvoir, Virginia. It is currently a formation of the US Army National Guard and contains units from Virginia, Maryland, Kentucky, North Carolina, South Carolina and West Virginia. Formed in 1917, the division deployed to France as a part of the American Expeditionary Force during World War I. Called up for service again in World War II, the division's 116th Regiment, attached to the First Infantry Division, was in the first wave of troops ashore during Operation Neptune, the landings in Normandy, France. It supported a special Ranger unit tasked with clearing strong points at Omaha Beach. The rest of the 29th Infantry Division came ashore later, then advanced to Saint-Lô, and eventually through France and into Germany. S/Sgt Nogle would make it as far as Saint-Lô, but thus ended his war experience and life. As I have said again and again with these “Stories in Stone” articles, the typical visitors to Frederick’s Mount Olivet Cemetery are awestruck to see the vast sea of grave monuments present here on our 90-acre footprint. This collection of former Frederick Countians and others is comprised of over 40,000 interments joined by eight miles of roadway. One generally sees nothing but names, numbers and dashes carved into the faces of granite and marble. The first two elements (names and dates) are pretty straight-forward. However, the dashes represent what is most important, yet are usually often shrouded in mystery unless you make the effort to “dig deeper.” It’s probably not the best expression to use when talking about a cemetery, but think about all the stones that fail to get recognized by the visitor on a typical sojourn? On days like Memorial Day, Veterans Day and now, Wreaths Across America Day in mid-December, one just needs to look for the flaglets marking the graves of over 4,000 service men and women buried within our special “museum without walls” to garner a small part of “the dash.” If you have the interest and time, please go further in discovering more of the dash. Find out who these individuals were, where they lived, what their occupation was, and what constituted their military experience. If you are a relative or family friend and already know the answers to these questions, please make the effort to reach out to me and the staff of Mount Olivet, because we want to learn more about those we are tasked to keep care over. Our goal is to have this important vital information as part of our cemetery’s archival repository. The same goes for photographs as well, as it is always great to “put a face with a name,” and more so, “to put a face with a monument.”

So with Memorial Day, 2021, let’s appreciate the opportunity to experience it fully once again, and keep sacred the thoughts of those who made the greatest sacrifice to preserve our freedoms. The three servicemen highlighted here in this story may have participated in those early Frederick Memorial Day exercises of the Roaring 20s, and “Great Depression” years of the 1930s. They had the opportunity to think about the concept and construct of Memorial Day up through its occurrence in late May 1944. However, all three would die two months later, thus ending their ability to do so ever again. We must carry the torch for them, as we have the chance to do so, one that was abruptly taken from them as they became part of the greater Memorial of "Memorial Day," themselves. Many thanks to groups such as the Legion, VFW, Amvets, Daughters of the American Revolution and others for their continued commemorative efforts.

0 Comments

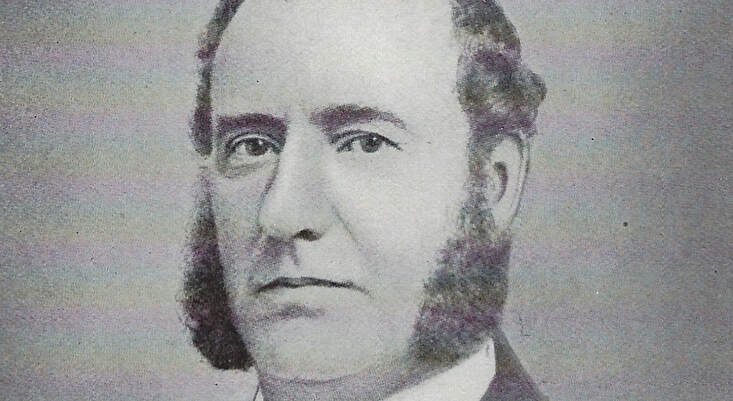

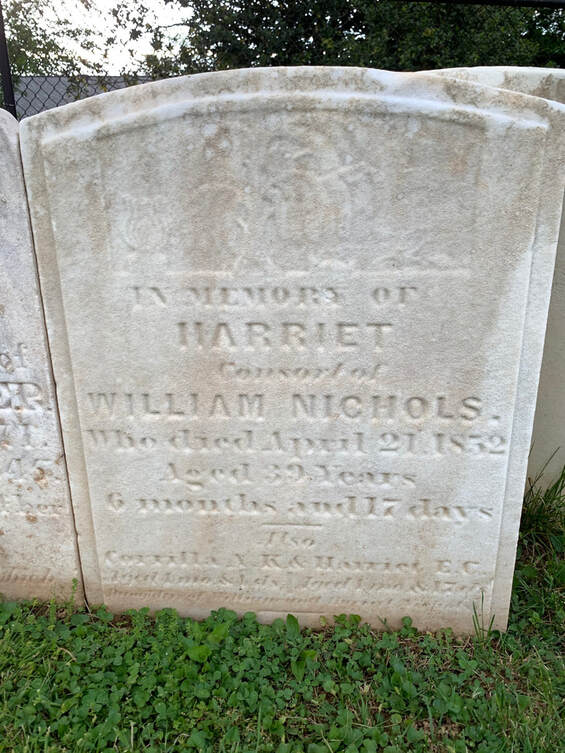

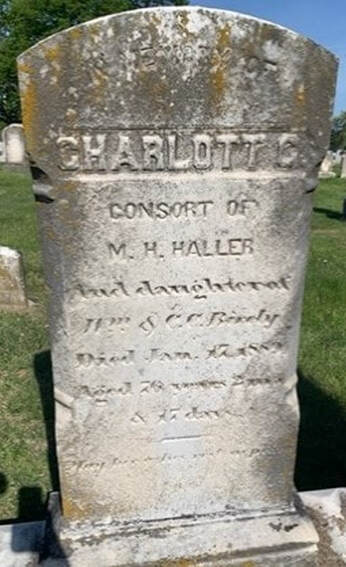

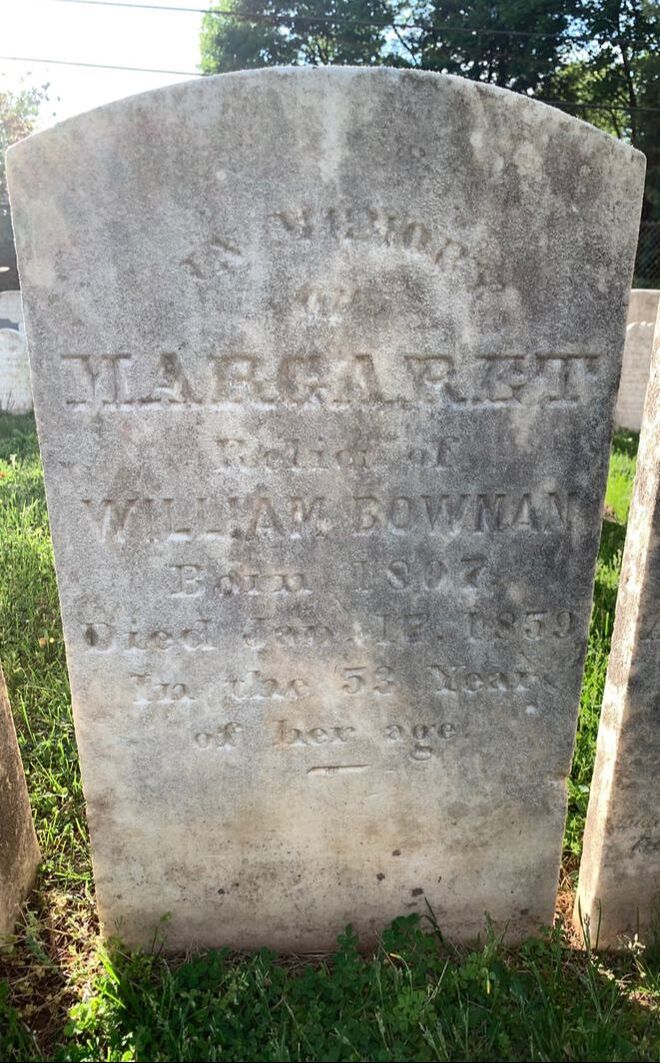

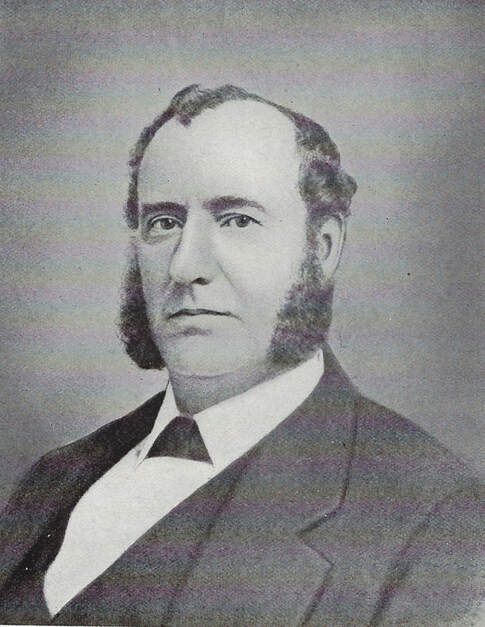

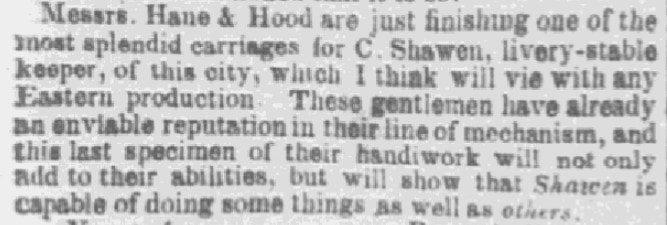

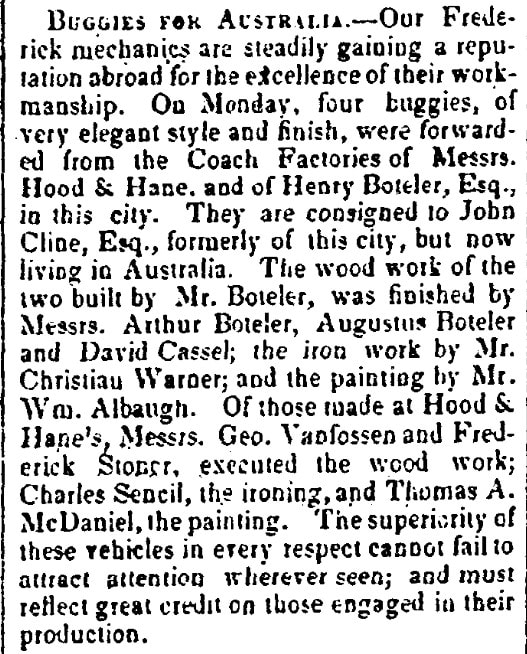

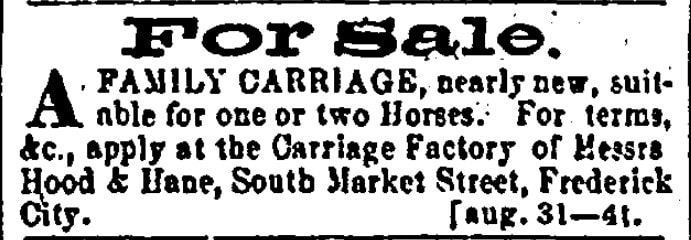

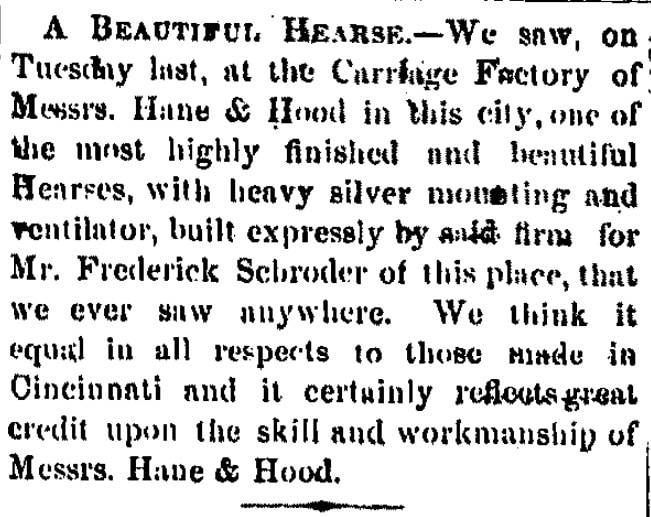

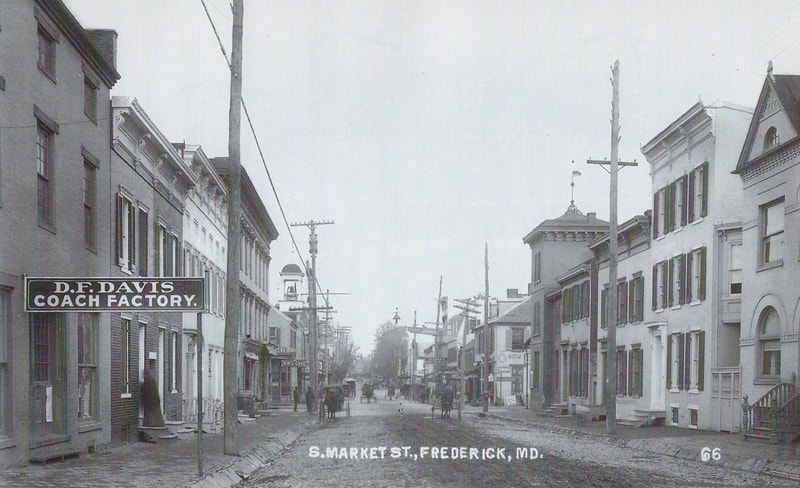

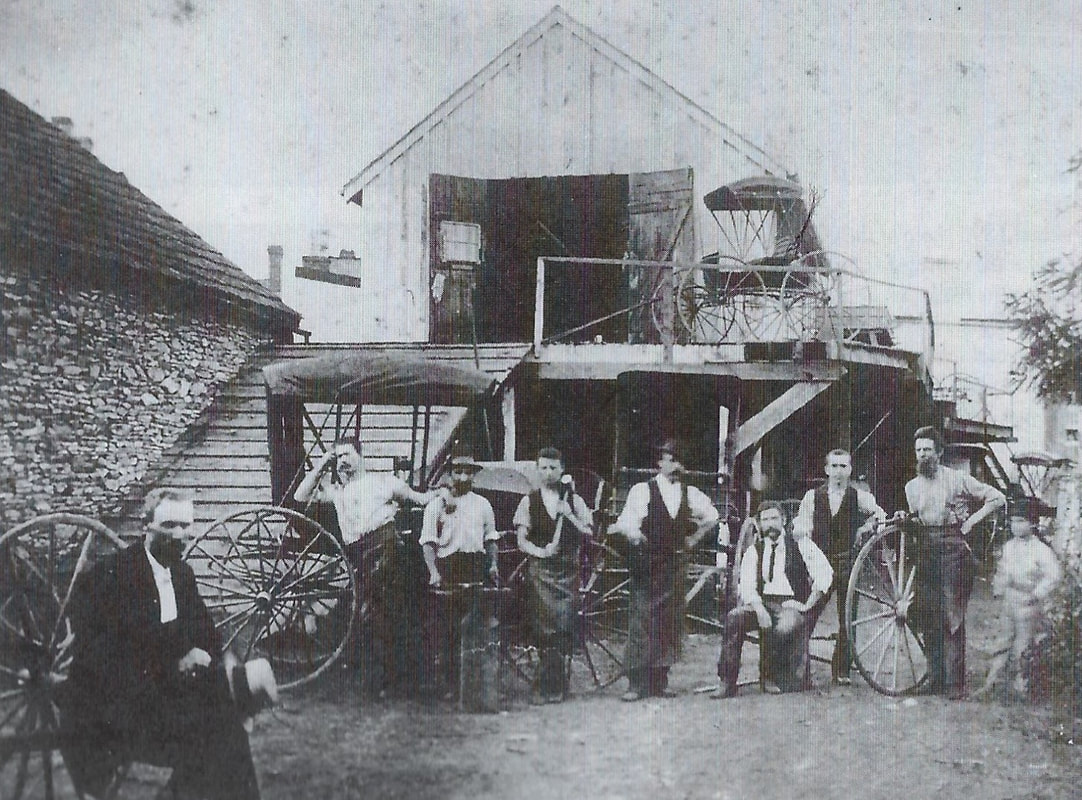

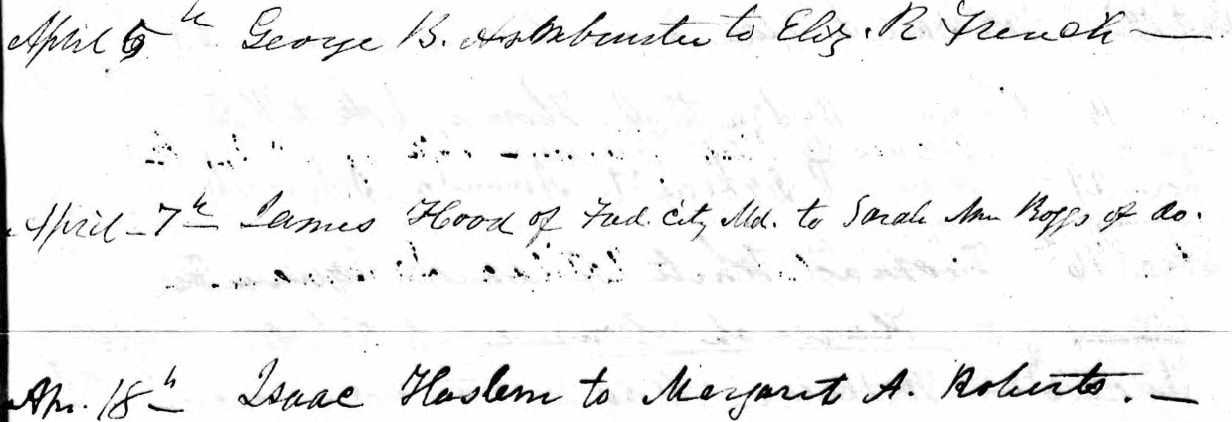

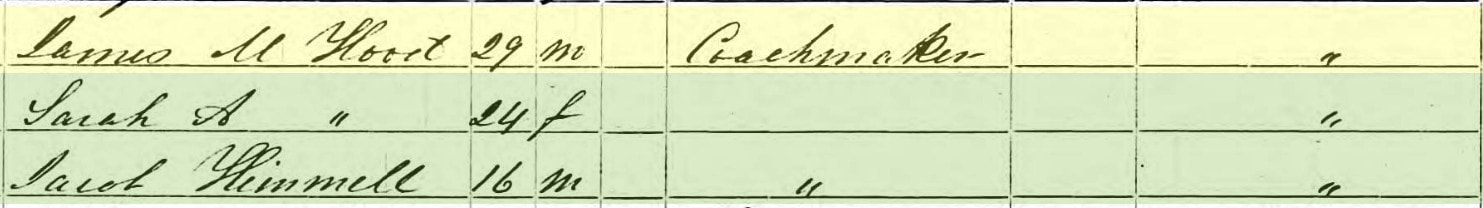

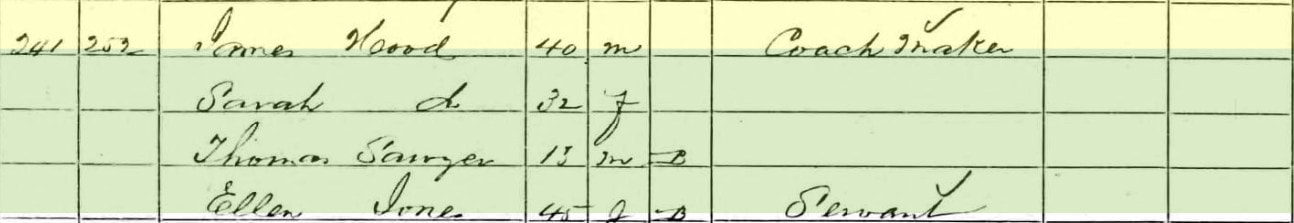

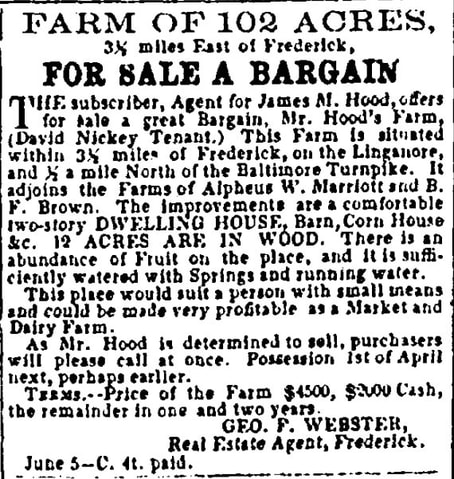

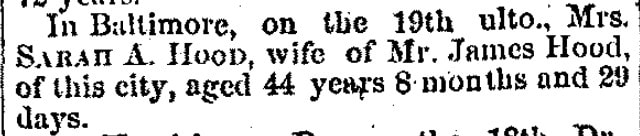

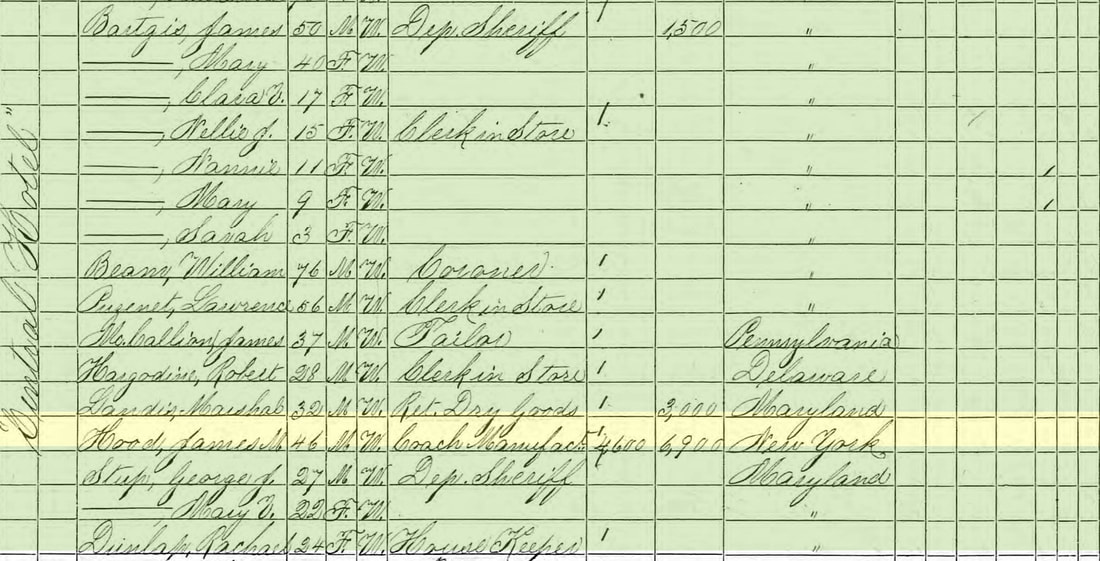

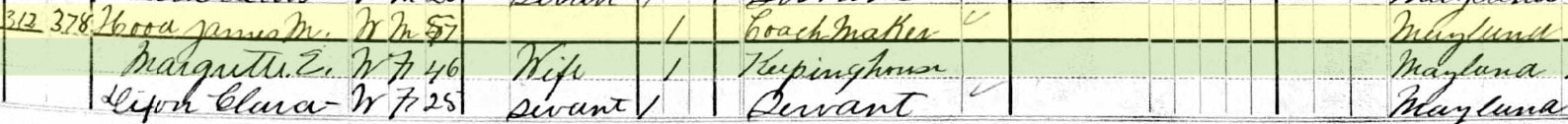

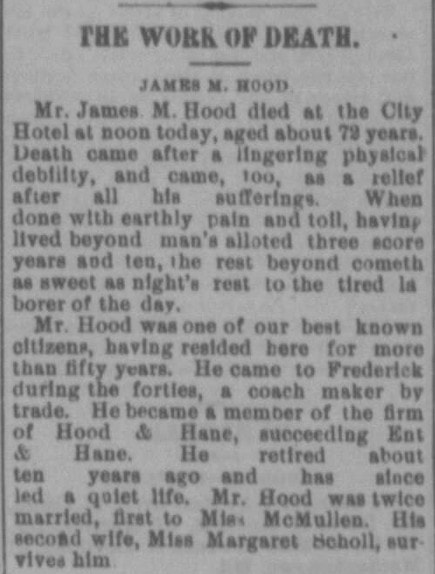

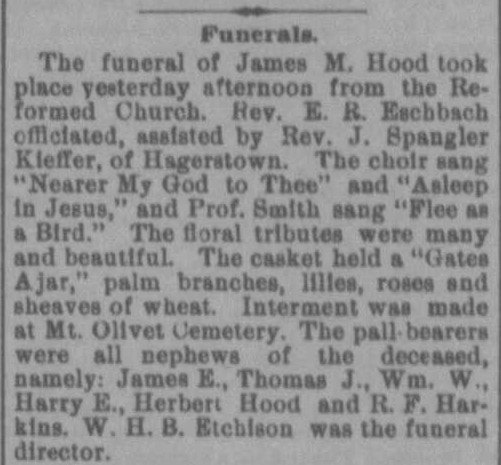

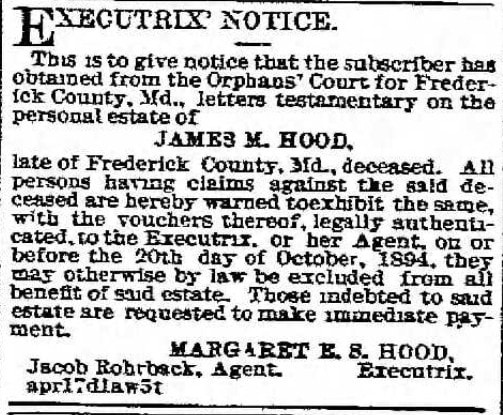

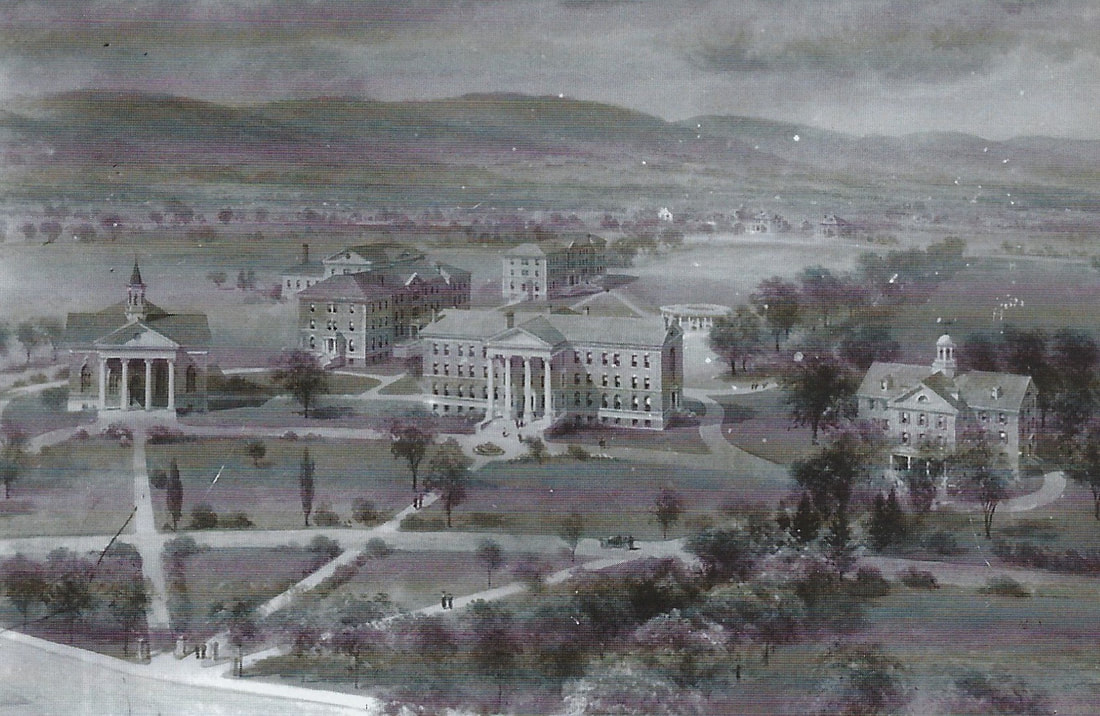

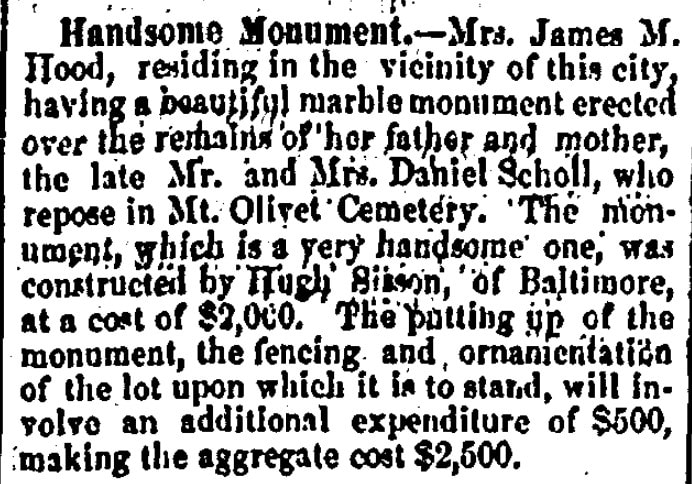

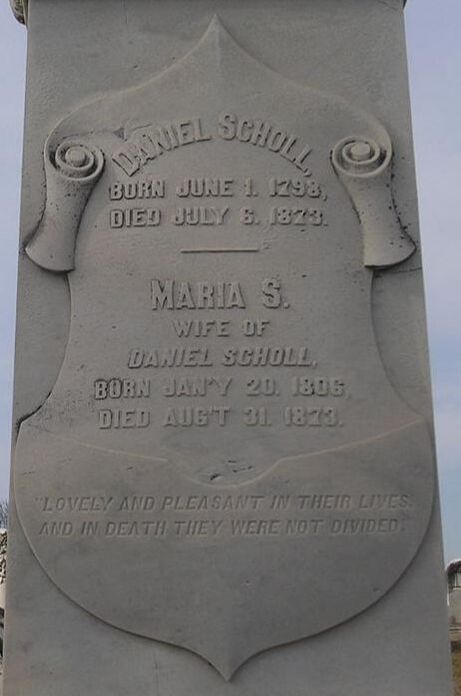

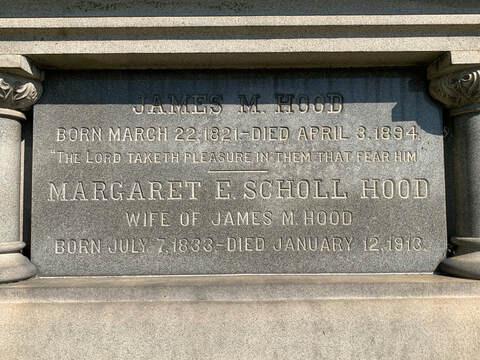

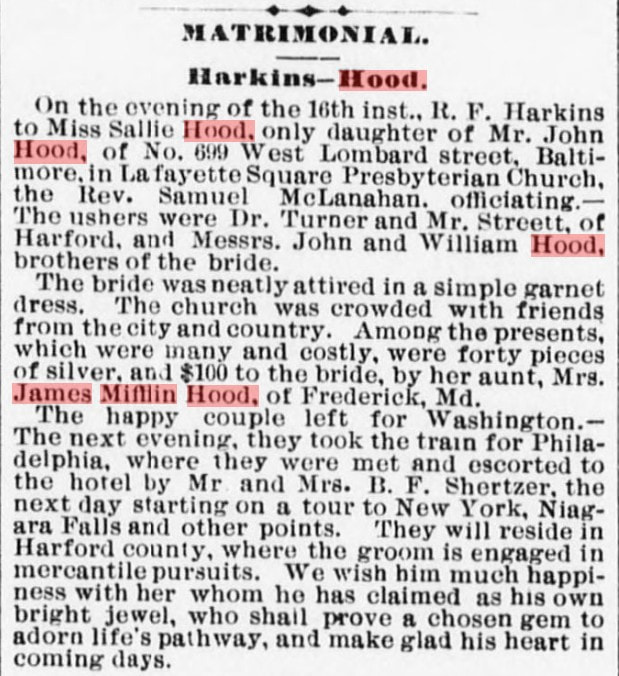

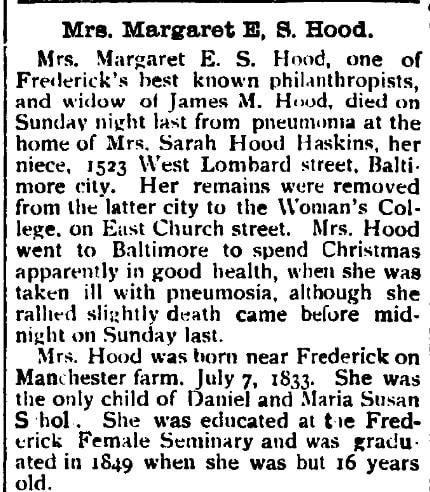

Margaret S. Hood (1833-1913) Margaret S. Hood (1833-1913) From my time here at Mount Olivet, I’ve had the pleasure of meeting some of the loyal "Stories in Stone" readers through the Friends of Mount Olivet membership group or from interactions in the office. For those of you who have not met me yet, my name is Katelyn Klukosky, and I am currently a senior studying History and Nonprofit and Civic Engagement at Hood College. For my major, I decided to fulfill the internship requirement by spending my time here at Mount Olivet Cemetery this semester, and I have enjoyed every part of it. Fortunately, I will be continuing my learning experience at Mount Olivet next fall semester. What a great way to complete my undergraduate degree! If you are a Frederick native, or have heard of Hood College, there is a good chance that you know a thing or two about Margaret Scholl Hood. A couple years ago, Chris (Haugh) wrote about this woman in one of these “Stories in Stone,” so we thought that it would be interesting to find out more about her immediate family, specifically her husband and who provided her with the money (and a four-letter surname) to fuel her philanthropic ventures. We thought that this would be a great story for me write as a guest writer since I am connected to the college as well as Mount Olivet at this time. In most history books and articles referring to Margaret, James Mifflin Hood is primarily mentioned as her husband and nothing more. This is truly ironic because, at the time of their lives and decades afterwards, it was more common for women to be defined by their husbands. From the 17th through 19th centuries, many cemeteries exhibit this standard through gravestones in which wives were commonly labeled as either a “consort” or “relict” to their husbands. A consort refers to a spouse that dies before the other. Although a man could be labeled a consort as well, a woman was more likely to receive such a label due to cultural norms assigning a lesser status to females in respect to males. According to Webster’s Dictionary, a relict refers to "a widow or a spouse that outlives the other and does not remarry." In this case, Margaret would be the relict of James after his death. Regardless of the term, women were often defined by their marital status instead of individual identities. In the case of Margaret S. Hood, she was able to turn this "patriarchal standard" of spouses on its head—so fitting for the namesake of one of the country’s first institutions for higher learning/education for women. Margaret was a successful and prominent woman who, instead, posthumously defines her husband’s legacy. That being said, I hope to bring to light the life of James Mifflin Hood, and to redefine his label as “consort” to his wife. Since Margaret Hood is more well-known than James Hood, there are relatively very few accounts that go into vast detail about this individual's life. Fortunately for us, and him, Margaret had a hand in adding her husband's life story to the local biographical record as she paid to have James Mifflin Hood included with the areas other leading “men of mark” in T.J.C. Williams’ History of Frederick County, published in 1910. The following is basically what we know of him due to that publication, specifically pages 1400-1401: "James Mifflin Hood, deceased, for many years one of the most enterprising and progressive businessmen of Frederick County, was a native of Baltimore, Md., where he was born March 22, 1821, and died April 3, 1894. He was a son of James and Elizabeth (Mifflin) Hood. James Hood was a native of England, and after coming to this country resided in Baltimore, Md. He was married to Elizabeth Mifflin, a descendant of General Thomas Mifflin, president of the Supreme Executive Council and Governor of Pennsylvania. James Mifflin Hood spent his boyhood on the shores of Chesapeake Bay. He received his education in the public schools, and was an apt scholar, his taste for literature becoming even more pronounced in after life. Early in life he removed to Frederick, where he became interested in the manufacture of vehicles, and was for many years the head of the firm of Hane & Hood, located in South Market street. This firm met with success and won a foremost position in its own special branch of trade, ranking for years as one of the leading houses of its kind in the East. Mr. Hood during the time that he was at the head of this enterprise directed its affairs with an ability, foresight and sagacity that stamped him as a man of huge executive capacity. To his forceful personality was due much of the prosperity and prestige attained by his firm, and he became widely prominent in manufacturing circles as one of the ablest and most representative men identified with that branch of industry. Honorable in all his dealings and a man whose business methods were characterized by the highest principles, he commanded the respect and confidence of business and financial circles generally. Mr. Hood, however, did not confine his energies to the vehicle trade, but was always ready to render whatever assistance he could in promoting any new industry or enterprise that would be of good to the community. The firm of Hane & Hood employed a large number of men and possessed an excellent trade. In 1885, Mr. Hood retired from active business life. He was the owner of a fine farm, situated one and a half miles from Frederick City, where he was accustomed to spend the summer months. In the winter he and his family resided in Frederick.” “Mr. Hood in politics was a supporter of Democratic principles. Although often urged by his friends to allow his name to be used for some candidacy, he steadfastly refused, as he was never desirous of holding public office. During the Civil War he was in sympathy with the Union. He was devoted to his home, never cared to belong to secret societies, and found his chief happiness with his family and books. He was allied in a religious way with the Reformed Church of Frederick, and he was liberal in his charities, doing whatever he could for every one and aiding every worthy purpose that appealed to his sympathies. He was a gentleman of high mental qualities of charming personality, endowed with moral worth of an unusual order, his life proving one of untarnished honor and his memory remaining fragrant in the minds and hearts of those who knew him best.” When one thinks about James’ married life, they visualize Margaret as his sole wife. However, this is not the case. Chances are that a good number of people had no prior knowledge of a former marriage involving Mr. Hood. We learn more as T.J.C. Williams’ biography continues: “In early manhood, Mr. Hood was married first to Sarah Ann Boggs, of Philadelphia [on April 7, 1846]. She was a Quaker lady, and the daughter of a wealthy and prominent merchant, who was the owner of several ships. He was also an importer of china and kindred wares, and was the possessor of a large and remunerative trade.” The only other information that I could find from Miss Bogg’s “early” life is that she was born on 1824 and living with James on West Patrick Street in Frederick in the 1860 census. In 1869 at the young age of 41, Sarah Boggs unexpectedly died from unknown causes. "After the death of his first wife, Mr. Hood was married second, October 21, 1873, to Margaret Elizabeth Scholl, daughter of Daniel and Maria Susan (Thomas) Scholl. Mrs. James Mifflin Hood was born on July 7,1833 and grew to womanhood in Frederick County. She received many educational advantages, and attended the Frederick Female Seminary, now known as the Women's College. She is a lady of thorough education and culture. She has traveled extensively, both in this and various countries of Europe. She is a liberal benefactor to all benevolent and charitable organizations and a liberal but unostentatious helper of many deserving persons. In honor of her revered father, Mrs. Hood endowed an observatory for Franklin and Marshall College, Lancaster, Pa., at a cost of $10,000. In 1897, she gave to the Women's College, her alma mater, the sum of $20,000 as an endowment fund in memory of her husband, James Mifflin Hood, and in addition to the above generous gift has contributed in various ways for the benefit of the college $5,000 since. Recently she has contributed liberally to the Frederick City Hospital, and erected both wings of the institution. In all of the above bodies, Mrs. Hood exercises a potent influence and is a predominating spirit. From the number and size of her contributions, it is easily seen that she is a sincere friend of education and the needy and unfortunate. Mrs. Hood is an active and consistent member of the Reformed Church, to which she is also a liberal contributor.” It is clear to see that Mrs. Hood took the opportunity here to "toot her own horn" in this biography attempting to memorialize her consort. James life story ends in 1894, a victim of paralysis, but this is where his connection with Mount Olivet begins, although it seems to have happened earlier with the burial of first wife, Sarah, here at the time of her death. The biography in Williams' history concludes as follows: “His useful and active life was brought to a close, April 3, 1894, his demise evoking genuine regret among all who knew and admired him. He was laid to rest in beautiful Mount Olivet Cemetery.“ Margaret became James' relict and widower. She inherited her late husband's assets which fueled her philanthropic mission to give back to the city she knew and loved all her life. A year after Margaret’s passing on January 12th, 1913, the Women’s College changed their official name to Hood College to celebrate her contributions to the college. Located in Area E/Lots 144 & 155, the Scholl-Hood family plot is one of the many grand masterpieces here at Mount Olivet Cemetery. Just in passing, one can tell of the prominence held by this family here in Frederick. The original owner of this plot was Margaret’s father, Daniel Scholl. Beside him is buried his wife Maria, and behind lies James and wives Sarah and Margaret. These are modest, individual stones, however there is also a large memorial monument to James and Margaret styled in the fashion of an ancient sarcophagus. It is very interesting that the Scholl family decided to bury Sarah right next to James in this grave plot. Sarah had died in 1869, three years before James had married Margaret (in 1872). Typically, first wives and second wives are not found in the same grave plot—particularly one owned by the second wife’s family. According to the cemetery lot card, this was not the case as James was buried in proximity to both women. Interestingly, Margaret’s father, Daniel, also played a pivotal role. Mr. Scholl arranged for Sarah to be buried at Mount Olivet with the Scholl family. There must have been a prior connection between the Scholls and Hoods (James and Sarah) before the death of Sarah. One possible explanation is that they were related, or somehow knew each other due to their status or business dealings in Frederick. Unfortunately, Chris and I were not able to find concrete evidence of their interactions. It is unfortunate that Sarah’s life is defined solely as being James Hood’s first wife, which made her fall under the purest definition of a consort. She was quickly overshadowed by James’ second marriage to the seemingly more prominent Margaret Scholl. This may be a mere case of "chicken or the egg" because Sarah's family seems to have been as successful or more so than the Scholls. Interestingly, Margaret developed a special relationship with the children of James' brother, John Hood, living in Baltimore. These were John, James, Thomas, William, Harry and Sallie Hood. The latter, Sallie would appear to be the daughter that Margaret never had. The college benefactress is mentioned in Sallies' wedding announcement in the local papers and years later, it would be Sallie who would be Margaret's caretaker in her final days. Her five Hood nephews would serve as pallbearers at Mrs. Hood's funeral in Mount Olivet on January 15, 1913. And then there is James. Although not as well-known as Margaret today, he did live a significant life, one that impacted the city of Frederick and the people around him. From the “tongue in cheek” words of Chris Haugh, "Isn't it interesting to keep in mind that it is actually James’ family name that honors the college? If not for him, we’d have no Hood College." If so, would my diploma read Scholl College at the top, instead of Hood? It's a great school regardless, thanks to both of you, James and Margaret! (Author's Note: the earlier referenced "Story in Stone" about Margaret S. Hood can be found by clicking the link below:

Three years ago this week, we (unknowingly) hosted a very interesting visitor here at Mount Olivet Cemetery. It led to arguably my favorite FaceBook post yet on our company site—one which garnered well over 300 likes! I was lucky to have been tipped off by a friend with news of “the burly intruder” on that particular night of May 1st (2018). She sent me a few photos (above and below) that had been posted by one of her friends on an Instagram account. Apparently, this "Instagrammer" had simply come to the cemetery earlier that night to make a casual visit to her father’s grave here. To her great surprise, she spotted our four-legged “tombstone-tourist” not far from the graves of Frederick luminaries Thomas Johnson and Barbara Fritchie. I, myself, had just missed seeing the bear as I had left work for the evening and passed by this very spot about 20 minutes earlier. Looking back, I marvel at the fact that more folks didn’t encounter “said bear” considering all the walkers, runners and cyclists we have in here each evening. Regardless the story of our special friend did not end here. For those who remember this episode, the baby black bear captivated both mainstream and social media, not to mention the hearts and minds of Fredericktonians. Facebook included constant reports of appearances our fugitive was making throughout Downtown Frederick, eventually winding up near the West 7th Street ramps to US15, then over to Selwyn Farms apartments near Fairview Avenue and N. 9th Street. This is the vicinity of North Frederick Elementary School, where the building would be actually placed on Lockdown Mode because of a bear.

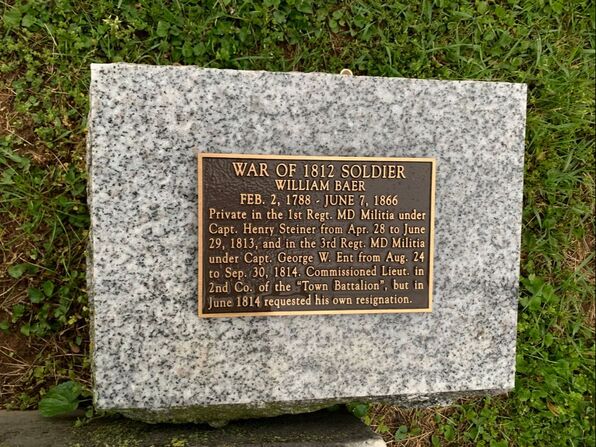

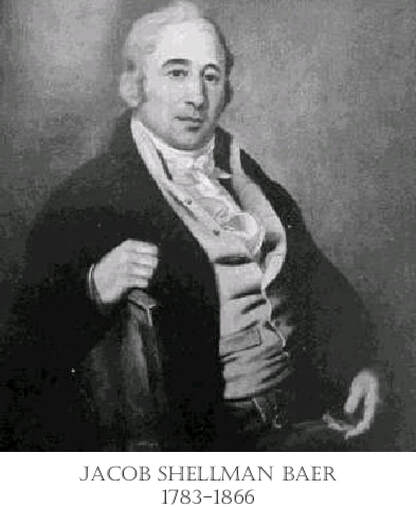

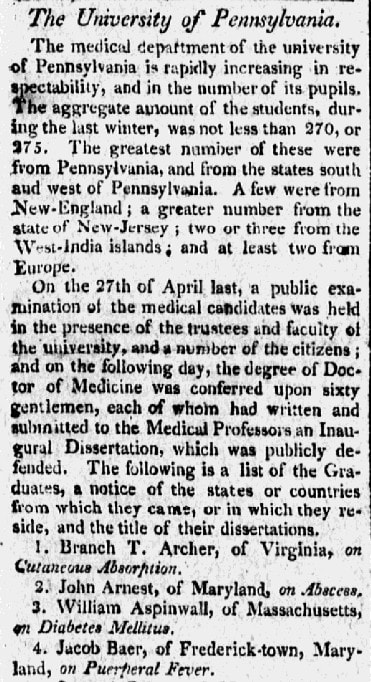

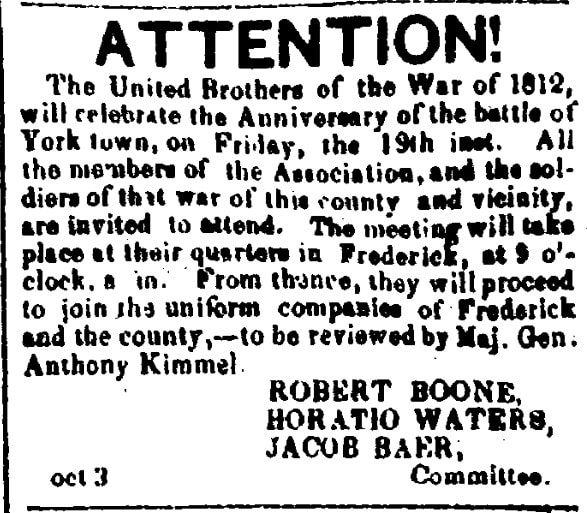

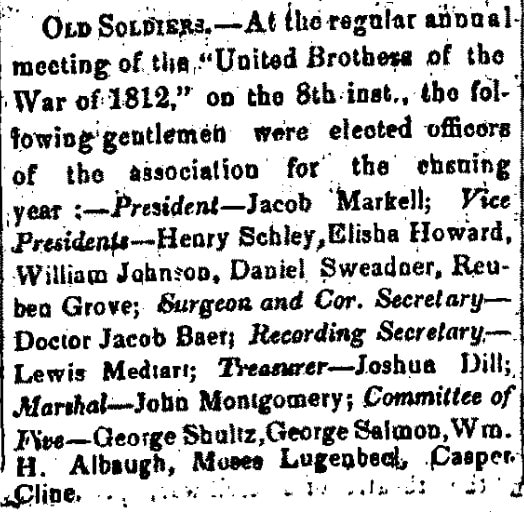

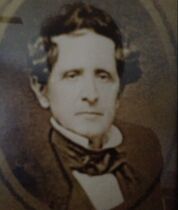

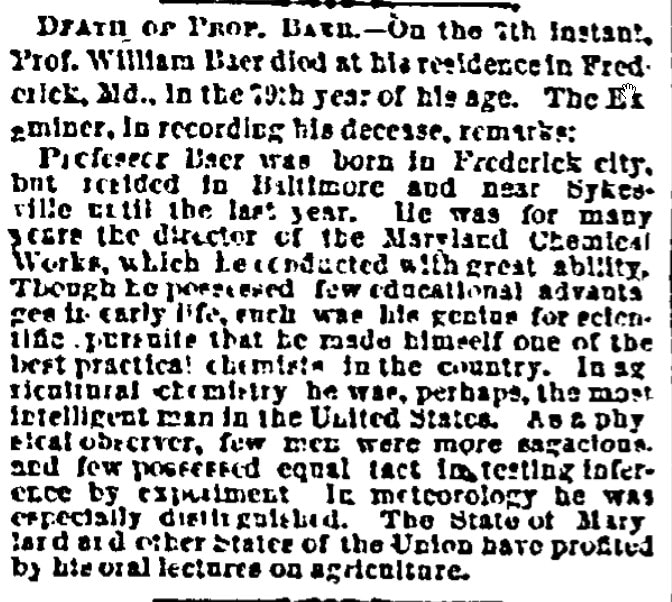

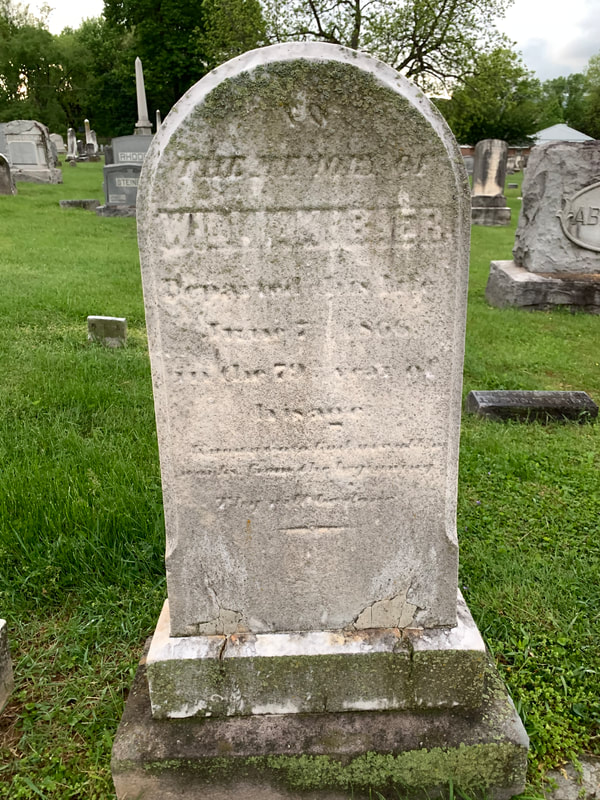

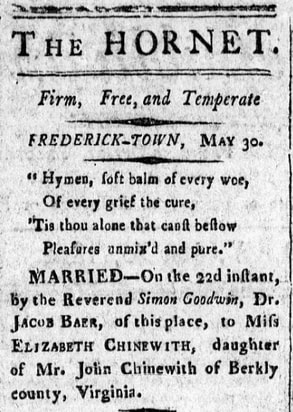

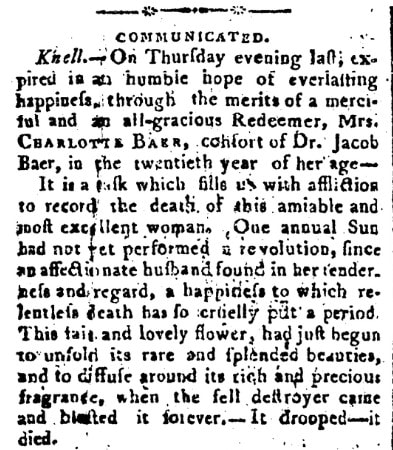

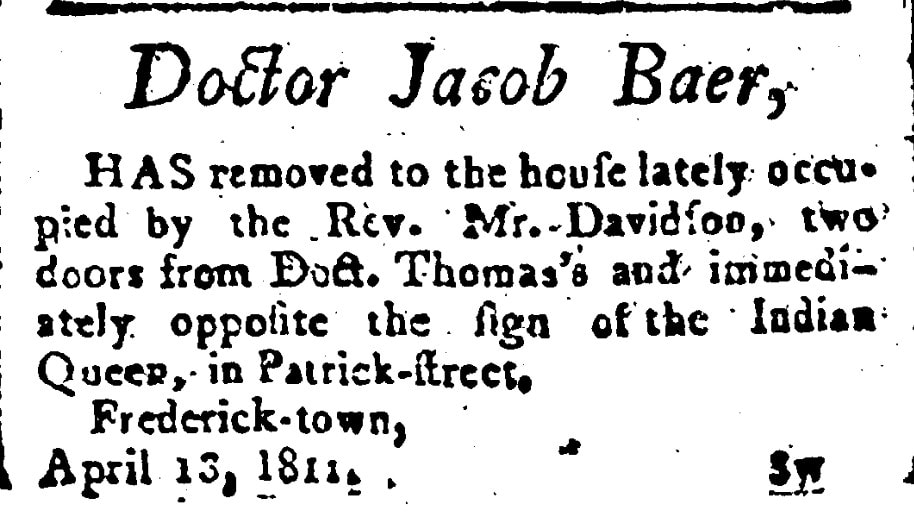

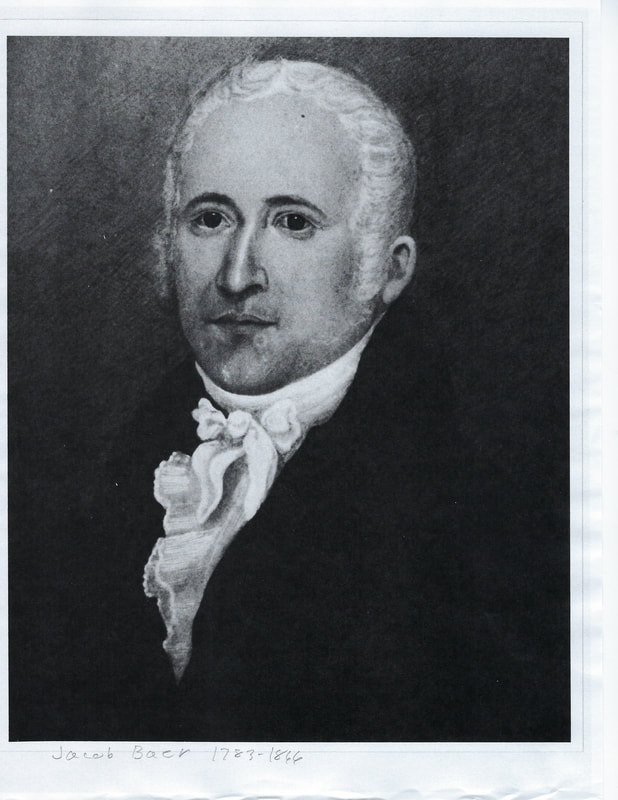

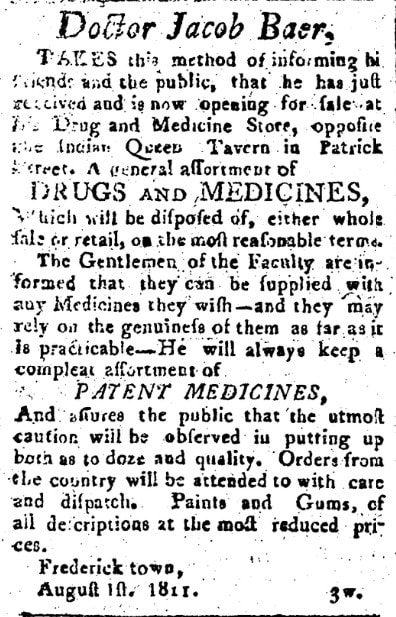

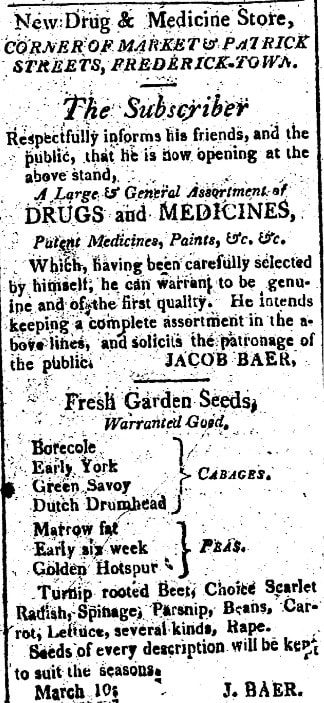

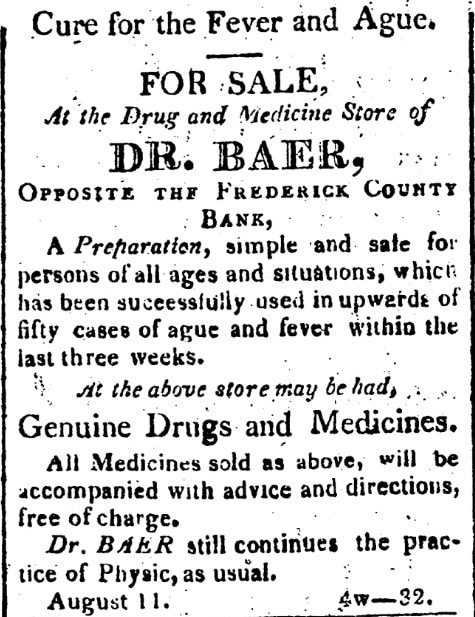

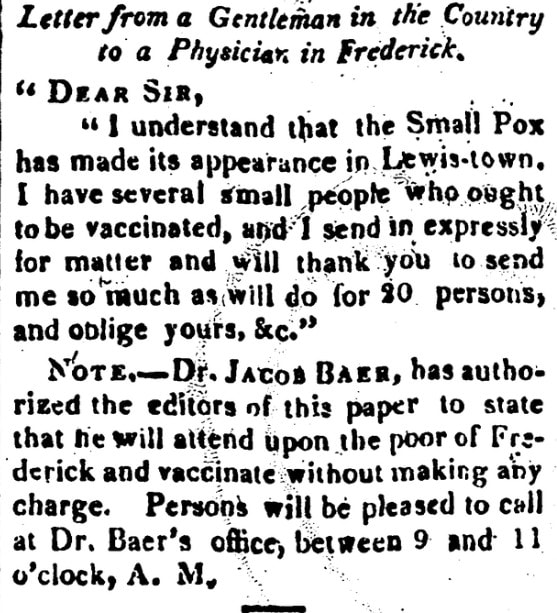

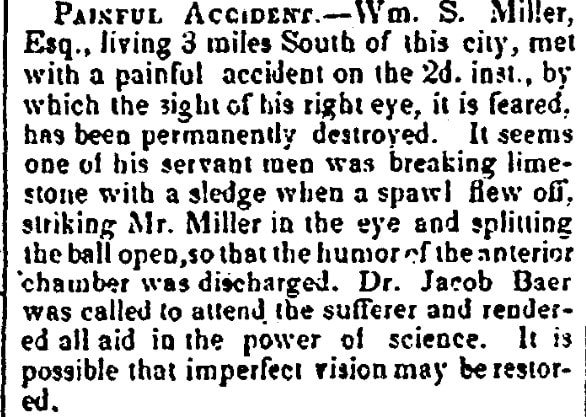

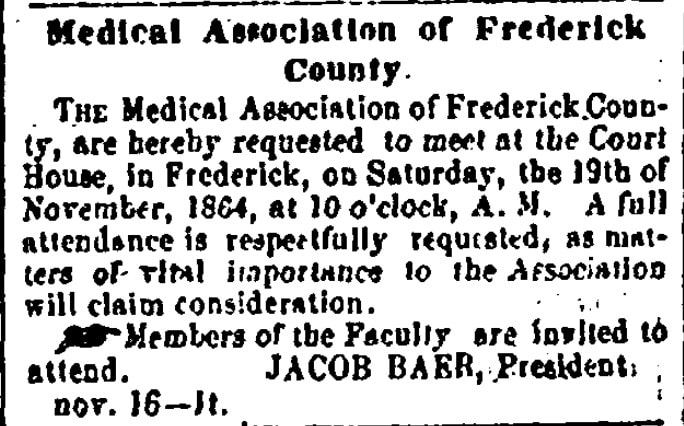

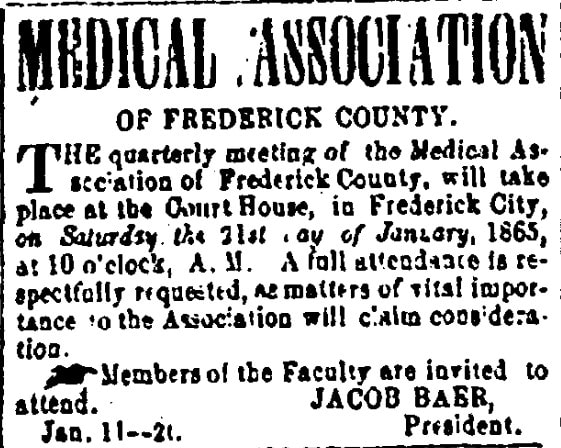

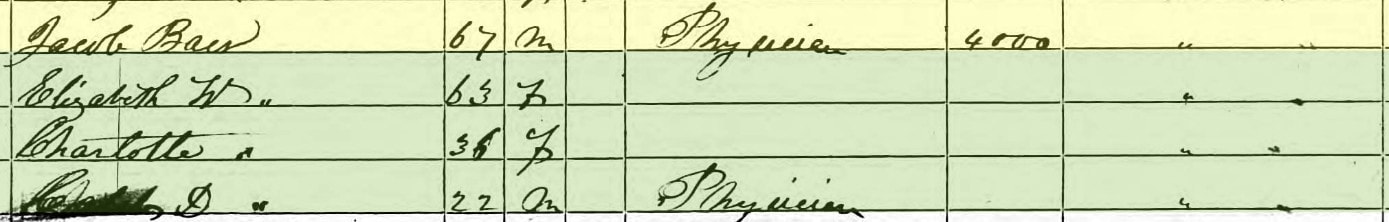

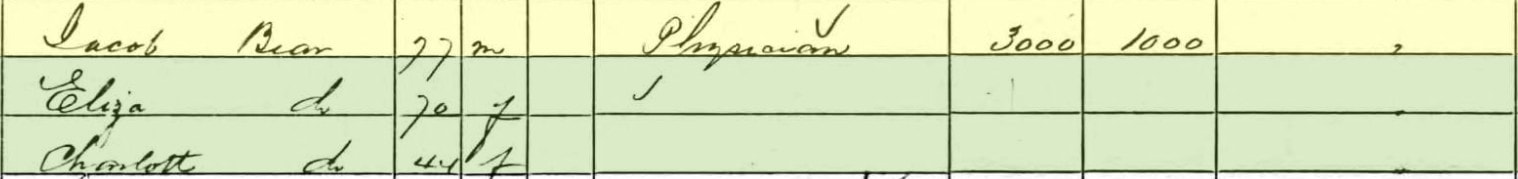

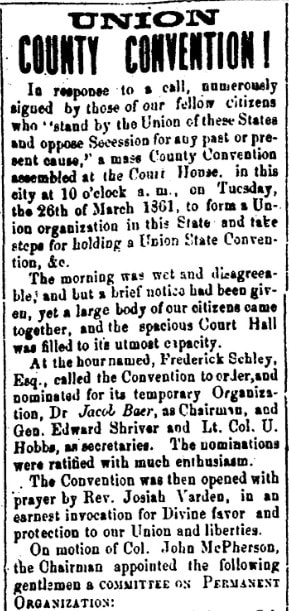

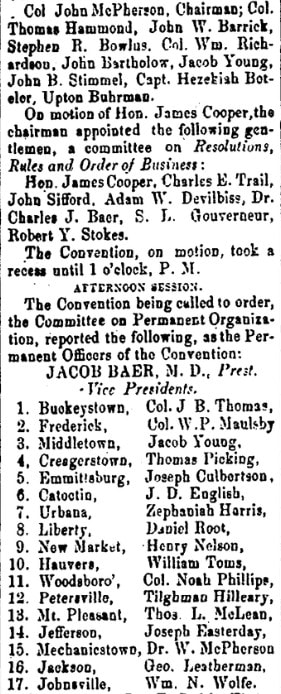

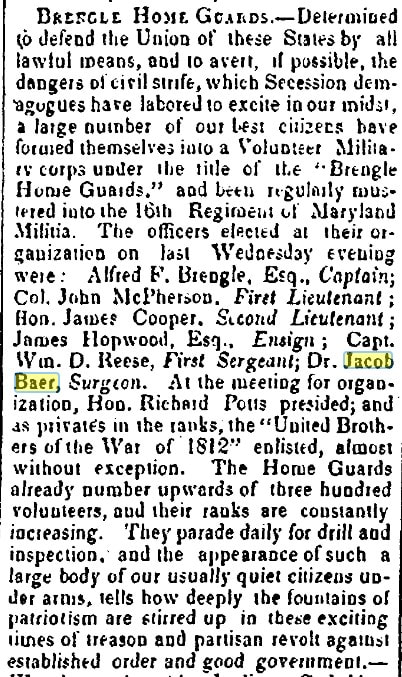

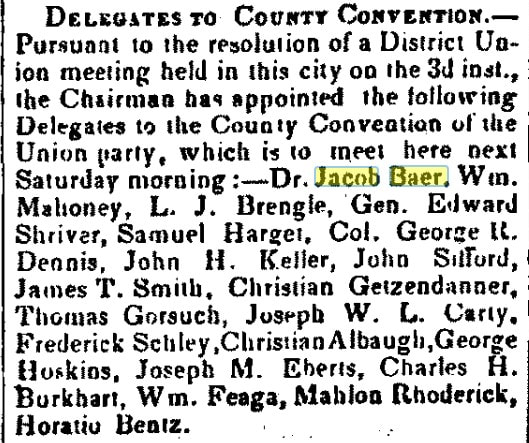

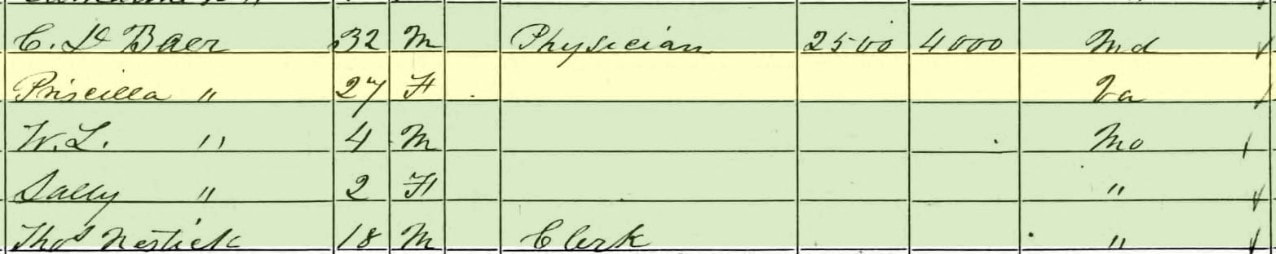

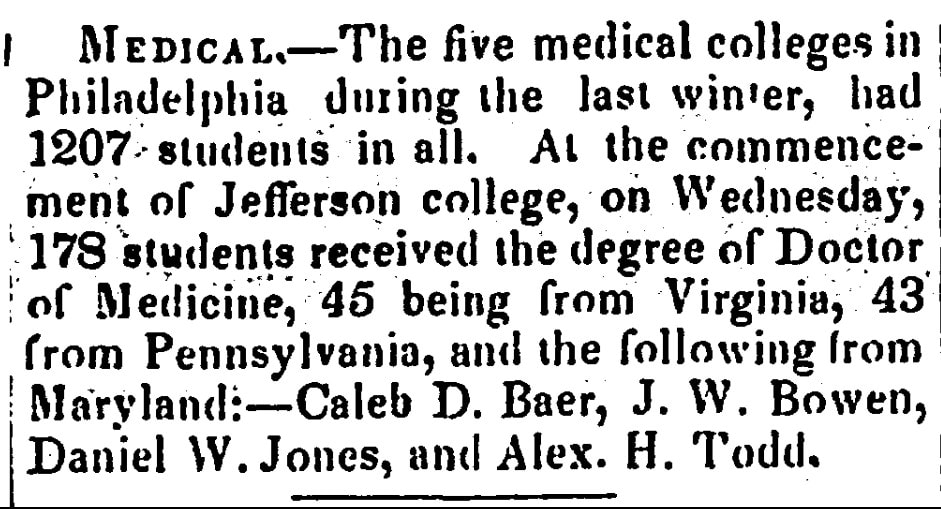

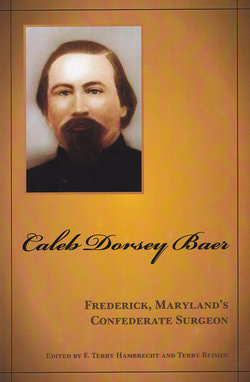

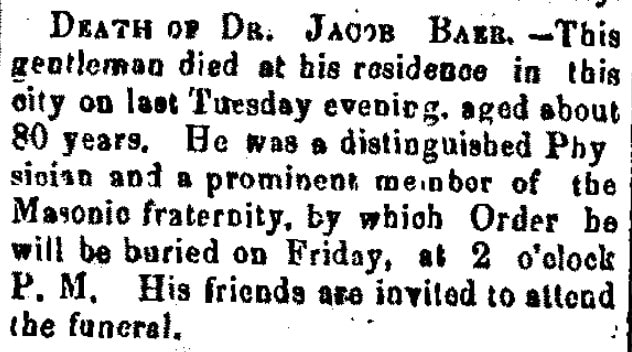

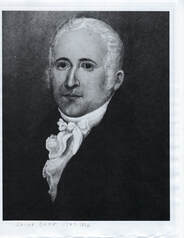

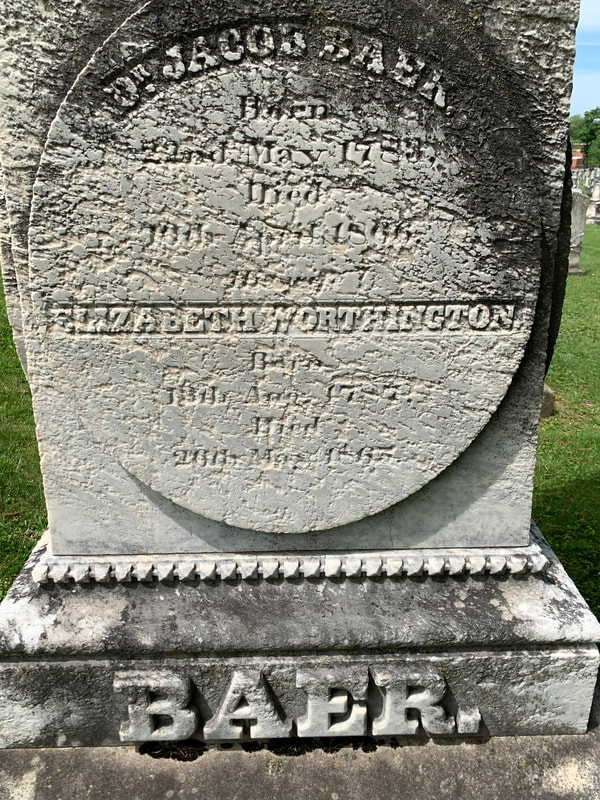

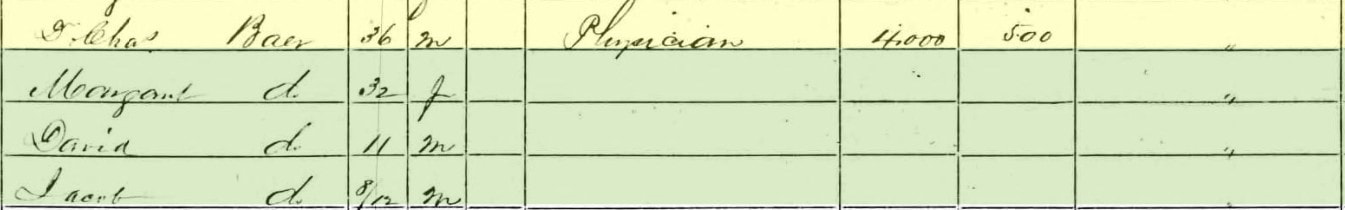

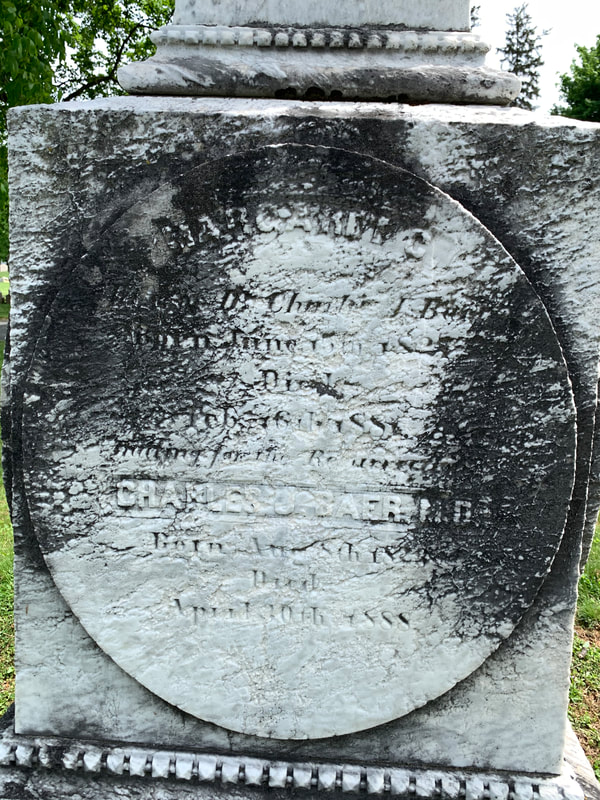

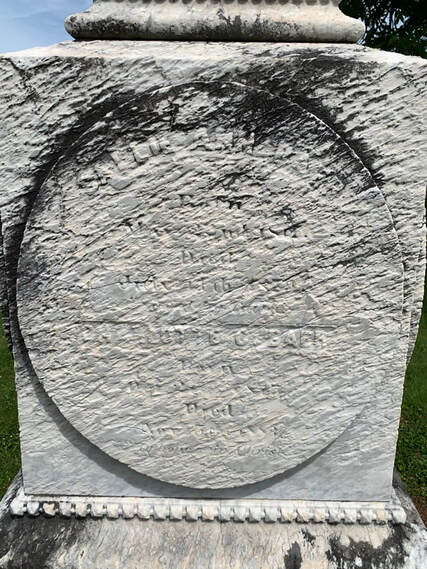

Back to my Facebook post for a second, I quipped about there being others with the name Bear, Bare and Baer being buried here. Most common is the name Baer, of which I reported that we have 96 interments with this certain moniker here in Mount Olivet. Of these 96, a very impressive monument belongs to Jacob Shellman Baer in Area G/Lot 40. Here in this plot atop Cemetery Hill, one can find 16 Baers.  Dr Henry Baer Dr Henry Baer Jacob Shellman Baer was born on May 22nd, 1783 in Frederick County, a son of Dr. Henry David Baer (1758-1848) and wife Elizabeth Shellman (1759-1829). His great-grandfather (Heinrich Baer) came to this country from Hausen near Zurich, Switzerland and settled in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Jacob’s grandfather (George) came to Maryland and settled in the Middletown area shortly before Jacob’s birth. Jacob followed in the footsteps of his father, a physician, who is buried down the hill from his grave in Area H/Lot 5. Jacob’s mother is also buried here as both were buried elsewhere and re-interred here in Mount Olivet in 1877. Our subject attended the University of Pennsylvania where he received his medical degree in 1808. He became a surgeon’s mate to the 16th Regiment of Western Maryland Troops at the Battle of North Point in September of 1814. I was disappointed to find that we overlooked him in honoring our collective group of over 100 veterans of the War of 1812 found here in Mount Olivet, and among those that gave inspiration to Francis Scott Key in their brave defense of Baltimore in September, 1814. He appears to have been active in veteran affairs throughout his life. That said, we do have a special 1812 veteran marker on the grave of Jacob’s brother, Professor William Baer (1788-1866), who is also buried in Area H down the hill from his brother. This gentleman has an interesting story as he was a noted chemist and lecturer, who was declared in his obituary in 1866 as having been “one of the best practical chemists in the country. In Agricultural Chemistry he was, perhaps, the most intelligent man in the United States.”  I was able to find newspaper advertisements for Dr. Baer offering his services to the Frederick community as early as 1811 at in the first block of W. Patrick street in Frederick Town as it was still known back then. This would be a time of great time of personal strife for the young physician as he would lose his young bride, Charlotte Elizabeth Chenowith, not even having the opportunity to celebrate his first wedding anniversary. She and the couple's infant died in childbirth. Charlotte was only 19. Dr. Baer would marry again in early January 1813. This was Elizabeth Worthington (1787-1865), the daughter of Caleb Dorsey, Esq. of Anne Arundel County. Two years later, the couple would name their first daughter Charlotte in honor of his first wife.  For more than 57 years, Dr. Jacob Baer practiced medicine in the city of Frederick and in his hometown of Middletown. Dr. Baer was a vice president of the Medical & Chirurgical Faculty of Maryland from 1848 to 1851. He served as president of this organization from 1855 to 1856. The Medical Annals of Maryland 1799-1899 includes a biography on Dr. Jacob Baer. The entire work was prepared for the centennial of the Medical and Chirurgical Faculty by a gentleman named Eugene Fauntleroy Cordell, M.D. (Baltimore, 1903). A passage found on page 132 states: “Dr. Jacob S. Baer, of Frederick (on whose motion the semi-annual meeting at Easton in November, 1853, had been held, in order to rouse the profession of the State to stand up for its rights), again came forward as the champion of justice by moving that the committee be instructed to proceed to institute such proceedings to recover the chartered rights of the Faculty as should be deemed necessary and that an assessment should be made for the necessary expenses. This motion was carried on a division vote, showing that there was strong opposition. The election of Dr. Baer a day or two later, however, indicates that the part he took in the matter had not estranged from him a majority of the Society.”  Dr Michael S Baer Dr Michael S Baer Jacob’s younger brother, Michael Shellman Baer, also practiced medicine and rose to great heights in his profession as well. Born in 1795, Michael graduated from the University of Maryland in 1818. He was an “Attending Physician of the Baltimore General Dispensary,” 1822-1826, and also was a “Vaccine Physician” in 1824 and a member of the Baltimore City Council from 1830-31. Michael would also serve as President of the Medical and Chirurgical Faculty of Maryland from 1852-53. He died in Baltimore on June 8th, 1854, and I assume is buried there as well, because he is not here in Mount Olivet.  Grave of Libby Musser in Area P Grave of Libby Musser in Area P A Divided Den Back in 1994, I was working for Frederick Cablevision/GS Communications and busily writing and producing a documentary on Frederick City’s history in advance of the town’s 250th anniversary celebration. This project would eventually air on our local Cable Channel 10 in September of 1995. In my endeavors, I was fortunate to make the friendship of a charming lady of “the old school of manner and grace.” Her name was Elizabeth Tyson Musser (1911-2000), or “Libby” as most knew her. Mrs. Musser was kind enough to share many stories of her life and friends in Frederick, and that of her ancestors as she lived in the historic home of her great grandparents, Jacob Baer Tyson (1842-1926) and wife Amelia Mann (1846-1913). This Jacob (1842-1926) was named for our subject as his mother, Elizabeth Worthington Dorsey Baer (1814-1886), was the daughter of our Dr. Jacob Baer. He was a successful fertilizer merchant in a firm founded by his father Jonathan Tyson back in 1842, with headquarters on S. Carroll Street. Jacob Tyson also served as a member of Mount Olivet’s Board of Directors. The Tysons lasting legacy is the iconic, Italianate-style house that can be found at 101 E. Church Street just beyond Maxwell Alley. It was built in 1854 and shares many design qualities with its twin directly across the street which was built for Col. Charles E. Trail (now home to Keeney and Basford Funeral Home.)  Mrs. Musser shared with me some amazing family letters that were in her possession that pertained to Dr. Jacob Baer. She introduced me to this family of doctors, saying that all three shared a joint practice at one point in town, and I believe this to have been near the bend in W. Patrick Street. I first learned about the Baers in connection with an interesting episode pertaining to Civil War history from a pair of my history mentors, Paul and Rita Gordon, who helped me incredibly with my Frederick Town documentary project. It involved a prime example of the pitting of “brother vs. brother” during the four-year conflict which almost tore our country apart. The Gordons would write about this in their 1994 book entitled Frederick County Maryland Playground of the Civil War. In the chapter A House Divided, (pgs. 206-208), one will find the following story: The father (Jacob) and his son, Caleb, disagreed over the right of states to withdraw from the Union and form a confederacy. Politics sharply divided the family with a third son, Charles Jacob, siding with his father. When duty called, (father) Jacob became a surgeon in the Potomac Home Brigade, USA, while Caleb became a surgeon in the 4th Brigade of Forrest’s Division, CSA. Dr. Jacob Baer was influential in the local war effort as he achieved leadership positions for conventions representing his cohorts in Frederick city and county. As mentioned earlier, Jacob was made surgeon of the Brengle Home Guards, which melded into the Potomac Home Brigade. Caleb helped to establish a number of military hospitals, including Polk Hospital, near Helena, Arkansas. On July 28, 1863, he wrote his wife Priscilla, about a battle that had occurred, and described his unit’s casualties: 150 killed and 400 wounded. He wrote about the withering rifle shot and artillery shells “cutting off trees and limbs, tearing holes in the ground large enough to bury a horse.” He wrote about the wounded he treated: “what stoicism, the men saw the knife pass through their flesh or stood the wrench and forces of the bullet forceps.”

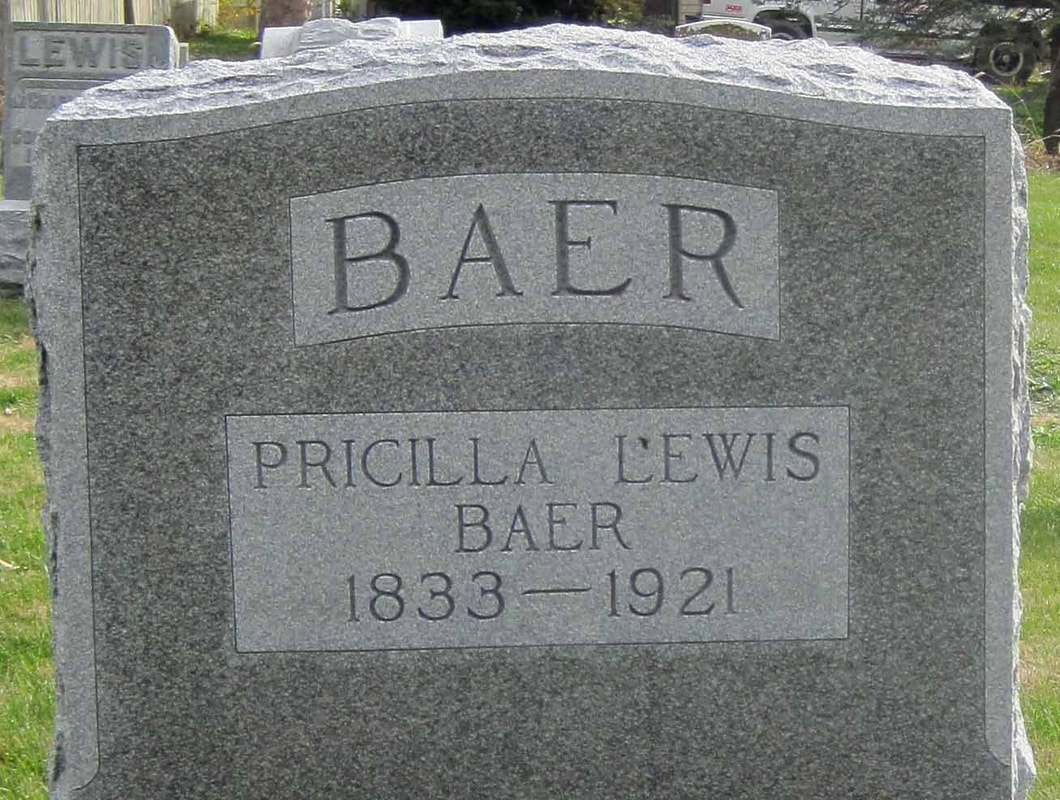

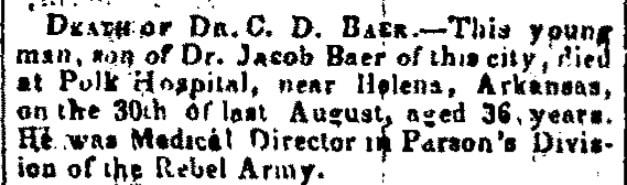

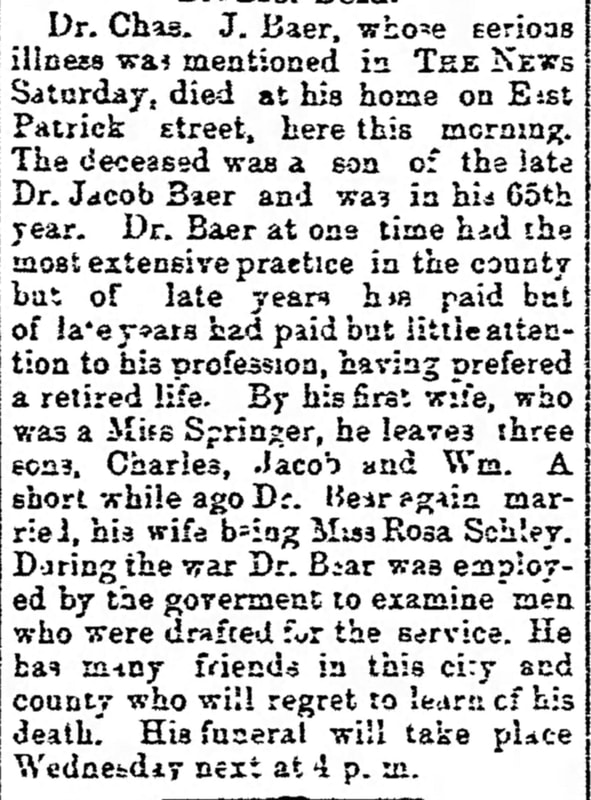

Caleb had written to a sister living in Baltimore, three weeks previously, that he lamented the division between himself and his father. He noted that he had received only two letters from his family in two years. He wrote: “…but the differences between my father and myself prevented correspondence before hostilities commenced…father would never blush for his son as a surgeon tho’ he may for his rebel proclivities…Truly I am tired of blood, for two years, my knife has scarcely been idle and altho’ when I took pleasure in surgery, I have had my fill.” Caleb told his sister to thank his mother for sending clothing and other items to his wife, noting she was badly in need of the items. He indicated his wife “struggles on against poverty and privation with the spirit of a woman of whom I am, proud.” A letter dated August 31, 1863, from Dr. Andrew N. Kincannon, who served with Caleb, was addressed to Priscilla. It informed her of the death of her husband on August 30th at 4 PM, after a painful illness of two weeks. His death was due to the illness and “a disease of the heart.” Apparently, Dr. Baer had known about his heart condition. Kincannon, who also operated on Baer at the end, wrote: “He had many warm and true friends in the army who will very much regret his loss.” At the bottom of the letter was penned a note that a lock of Caleb’s hair was enclosed. His body would not be returned home and buried until 1866. Our cemetery records shed light on the reason: Caleb Dorsey Worthington Baer: Confederate soldier with Field & Staff of 2nd Missouri Inf., 8th Div. Died at Polk Hospital, Helena, Arkansas, while serving as senior surgeon in the 4th Brig Forrest Div. He was originally buried in Missouri, and according to the Frederick paper dated Feb. 6, 1866, he was reinterred here early Feb. 1866. While his Soldier History states he enlisted as a surgeon and served in Field & Staff of the 2nd Missouri Infantry. His Detailed Soldier History states he enlisted as a surgeon, served in 2nd Reg't. Inf., 8th Division, Missouri State Guard. The chasm between father and son existed unto the grave. Yet Jacob Baer and his two sons are buried in the same plot in Mount Olivet Cemetery in Frederick. Furthermore, Priscilla must have been taken into the family’s fold. The tea set was not sold and remains in Mrs. Musser’s possession. As for Caleb’s father, Dr. Jacob Baer, he would die a year after the war’s end on April 10th, 1866. He would join his wife and son, along with other children who had not reached maturity up on Cemetery Hill. As for Dr. Baer's other son, Charles Jacob Baer, he was a native of Frederick City, born on August 8th, 1823. He received his education at the Frederick Academy and followed this with studies at Baltimore City College and St. John’s College. He received his medical doctorate from the University of Maryland in 1845 and served as a Vaccine Physician at Middletown. During the Civil War, Charles served as the Examining Surgeon of his Congressional District. In fact, he participated in action at the nearby Battle of South Mountain and attended to a downed colonel from Ohio who had been shot just south of Fox’s Gap on September 14th, 1862. He saved this man’s life, allowing the lucky patient to reach greater heights after a lengthy recovery begun in Middletown. This was none other than future US President, Rutherford B. Hayes. Dr. Charles J. Baer continued to practice for 27 years and later spent his retirement in agriculture in Roanoake County, VA, where he eventually died of spine paralysis on April 30th, 1888. He was buried here in Mount Olivet on May 2nd. It is certainly worth noting that the earlier mentioned daughter Charlotte, along with Dr. Jacob Baer's second daughter, Sallie Ann, are buried in this plot along with two other children who died in infancy. Our records state that Sallie Ann Baer was unmarried at the time of her death in 1879, and had amassed a great estate estimated between $50-$60,000. Well that's enough for now, as their are still other family members of note that I will tell you about on another day. Thanks for sticking with me to the end, as I know this particular story was a lot to bare, after I lured you into my history trap with a few alluring photos at the onset!

|

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed