|

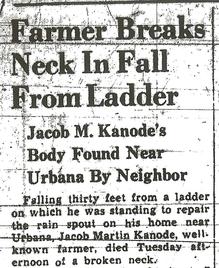

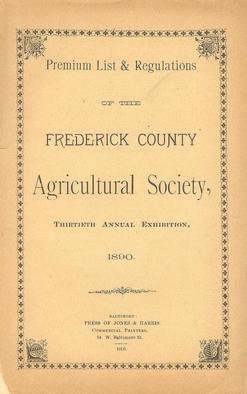

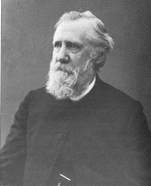

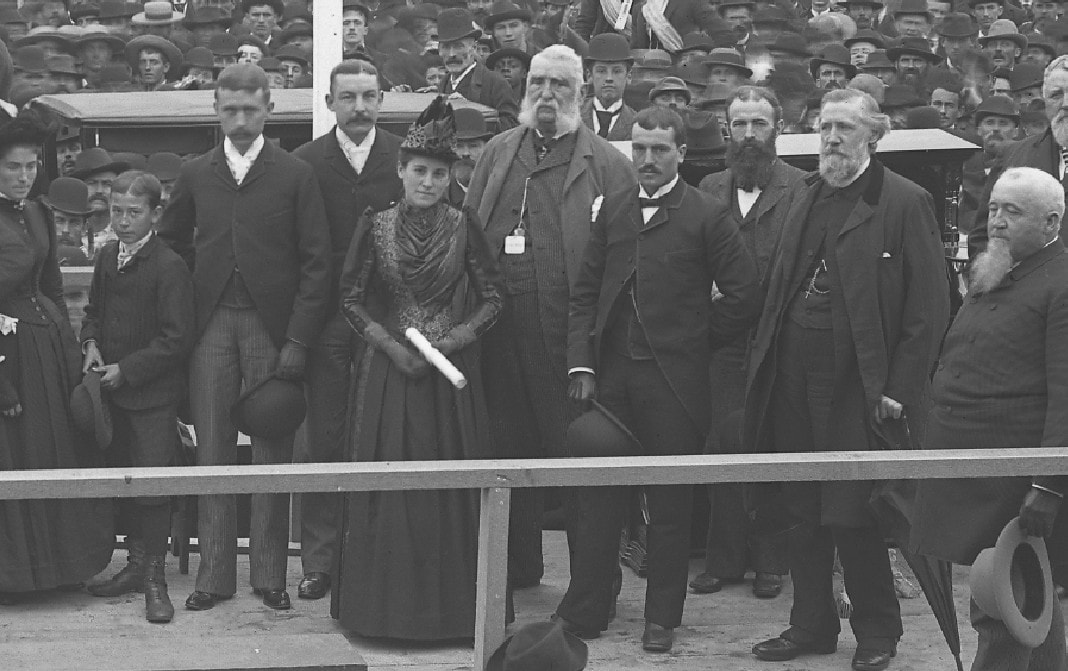

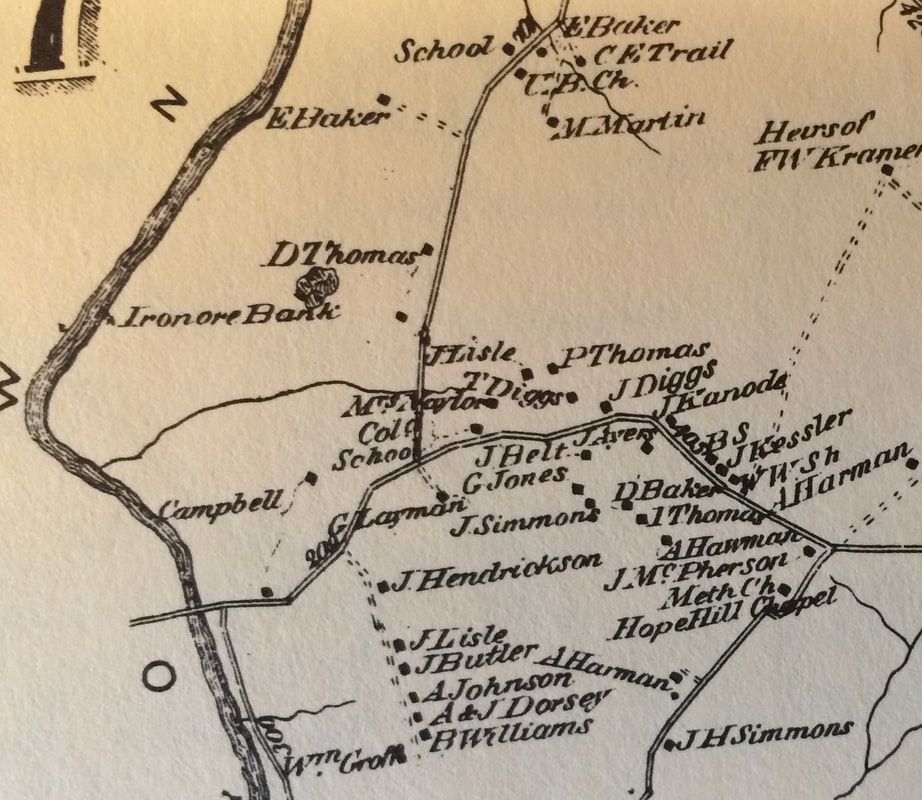

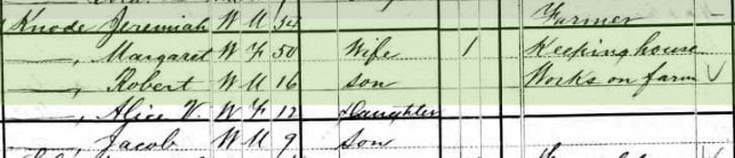

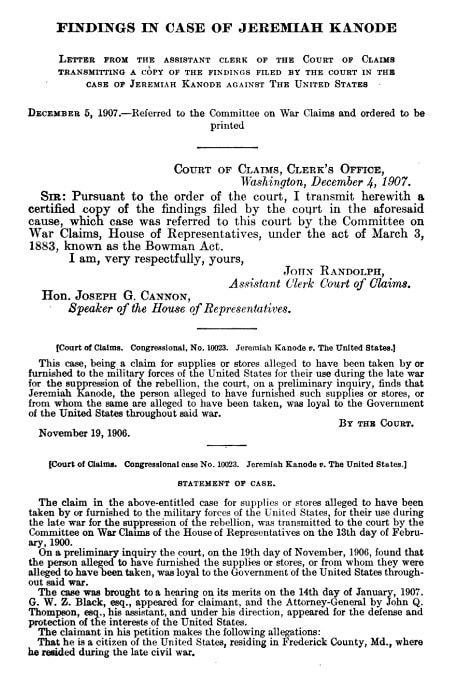

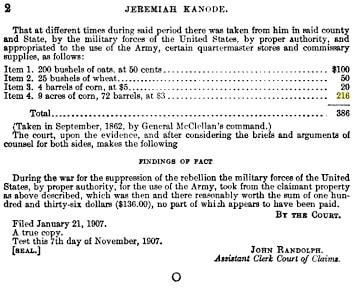

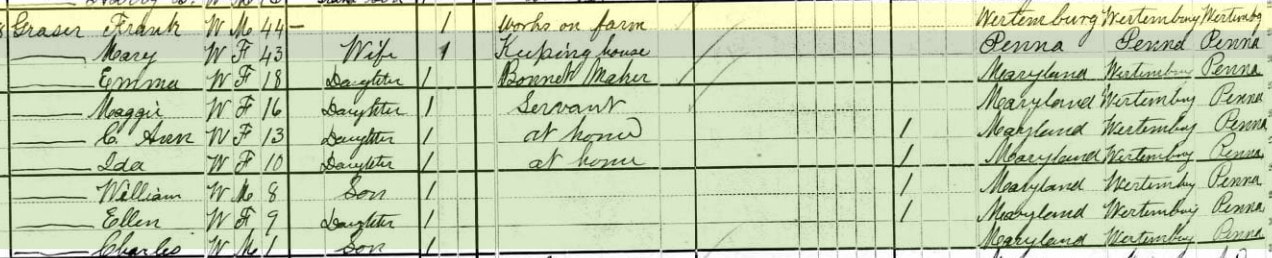

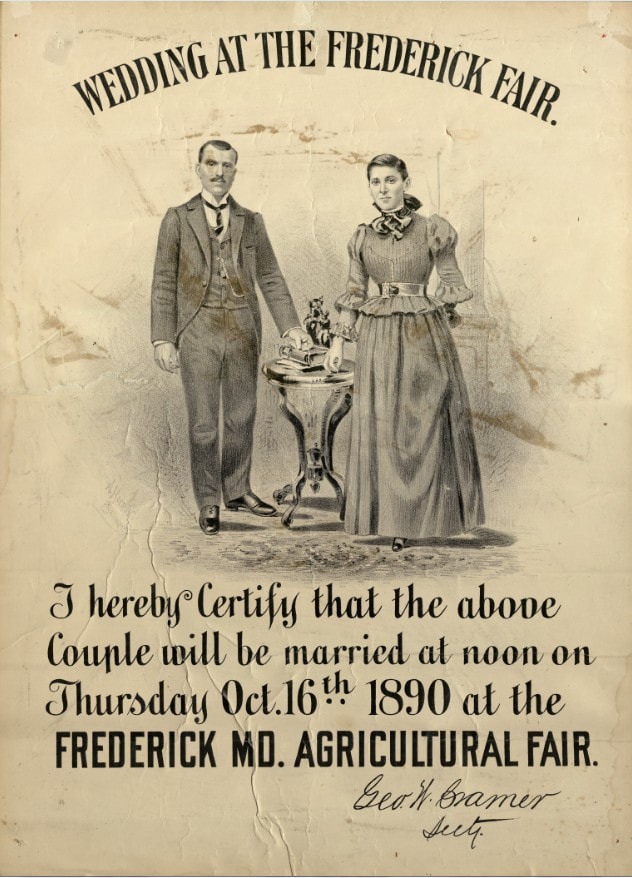

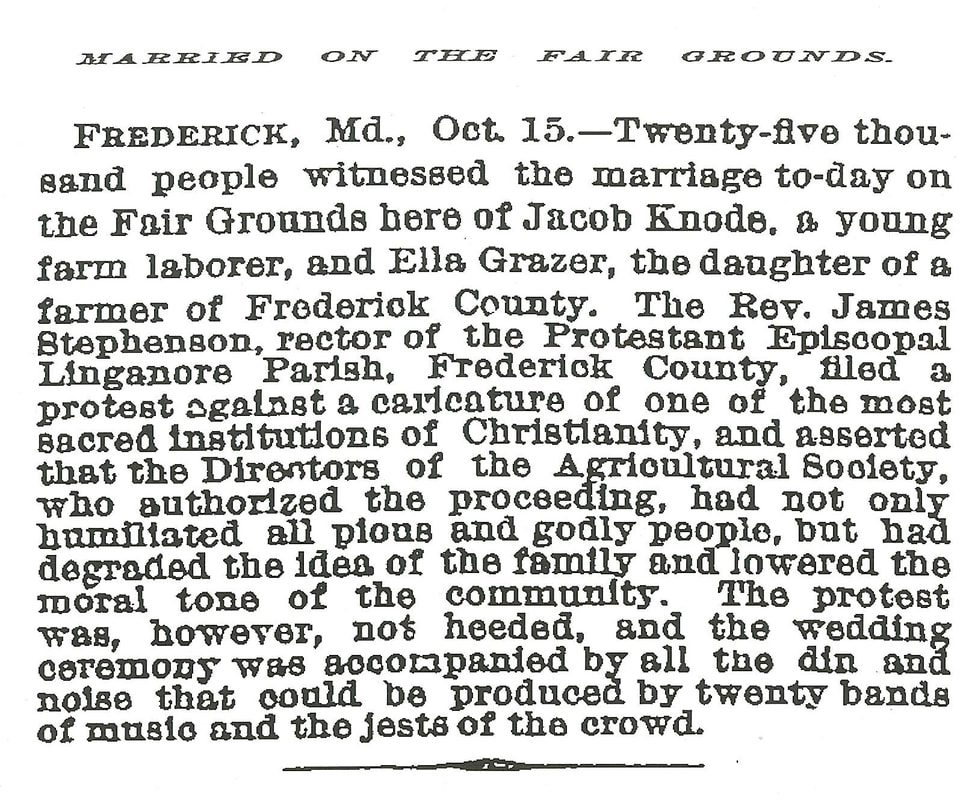

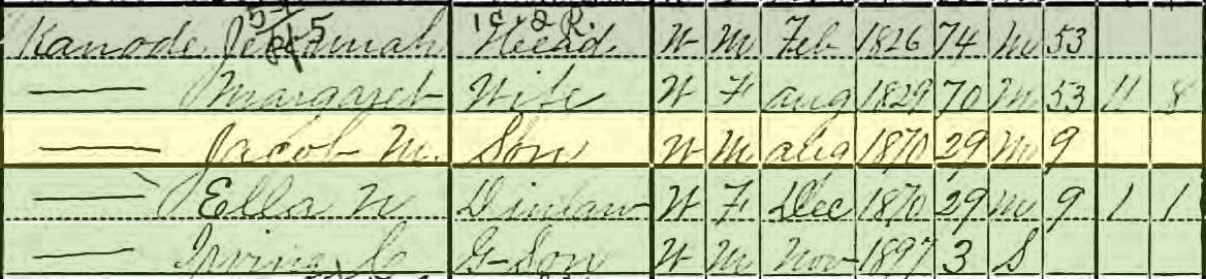

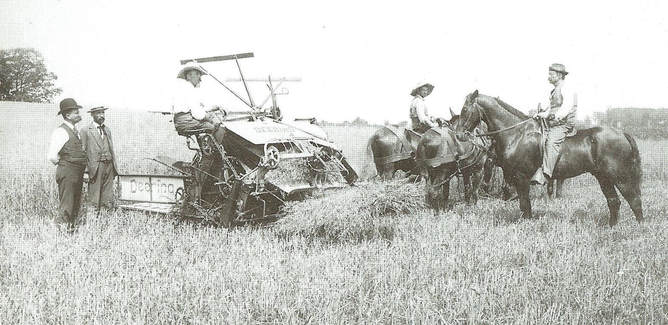

The zenith of any wedding ceremony is the presentation of wedding vows. These, of course, are the promises each partner makes to the other—at least as far as western Christians are concerned. Like any bonding agreement, groundwork and stipulations are determined to ensure that the two individuals know what they are entering into. One is required to make promises ranging from commitment during "good times and bad," along with caring for each other in varying economic conditions and stages of health. The closing line of typical marriage vows usually features a softening of the oft-used commercial slogan "all sales final." This is one that we are all familiar with: "Until death do us part." Nowadays, this specific line from the marriage liturgy (within the Book of Common Prayer) has been watered down to read "Until we are parted by death," and lighter yet, "through the final days of our lives." Divorces and annulments are much more commonplace today then they were half-a-century ago. There were far less 100 years ago, and fewer yet as you travel back in time from there. In the 18th and 19th centuries, divorce was a foreign concept for a variety of reasons. The 1970's saw a proliferation to nearly due to the acceptance for the "irreconcilable differences" claim. According to an article found on the website www.ahundredyearsago.com, "The divorce rate was 0.9 per thousand in 1913. It peaked at 4.6 in 1993; and decreased to 3.6 in 2013. So there's some encouraging news at least! Early on, most marriages ended because of the premature death of a spouse--a sad, yet common occurrence during a period in our history boasting rudimentary healthcare and fledgling medical knowledge (y today's standards). Back in the day, when you professed those wedding vows, you sure as heck meant it without hesitation. Now I'm not saying that this isn't the case today as all newlyweds "enter the ring" (both figuratively and literally) with the intent that their love and commitment will last a lifetime. I'm just interpreting the factual results. I always find it extremely heart-wrenching to see widows and widowers coming into Mount Olivet Cemetery on the funeral days of their husbands or wives. In many instances, I have been privy to see the photo shrines, slide shows and videos used for memorial services in our chapels. Most of these include pictures of a happy couple on their respective wedding day. This is an invaluable reminder of the day those legendary wedding vows were exchanged--including that promise, "Till death do we part." I can say with confidence that this phrase is usually the last thing on our minds as newlyweds, but comes to the forefront of our thoughts on the day of a spouse's death and/or funeral. On a cold, blustery day in late January, 1943, Mrs. Ella Kanode took her place in Mount Olivet Cemetery for the graveside service of her husband. The air was brisk amidst a snow-covered ground. Jacob Kanode's parents had predeceased him and were in Area L/Lot 148. This would be his final resting place as well. As his coffin was lowered into the grave, Ella likely thought back to a joyous day in the fall of 1890 when she and Jacob exchanged their marriage vows. The Backstory Just 24 hours earlier, Ella Kanode's husband was as vibrant, healthy and energetic as a 72 year-old could be. So much so, that Jacob willingly set out to perform a tedious home repair in the dead of winter. Apparently, there was some sort of problem with a downspout on the upper exterior of the Kanode's farm. Their home was located in Hopeland, a small community just east of the Monocacy River on Fingerboard Road (MD Rt80) near the intersection with Baker Valley Road. Jacob told Ella of his intention to fix the gutter problem in mid afternoon, as she would stay inside due to the weather and a health setback.  The Frederick News (Jan. 28, 1943) The Frederick News (Jan. 28, 1943) After a few hours, Ella, became concerned, likely annoyed, that Jacob hadn't returned from his chore. Darkness enveloped and concern soon turned to worry. She had been inside all afternoon and is reported to have called on a friend to whom she shared her worry. Next door neighbor Jesse L. Stup quickly responded around 7pm and found Mr. Kanode near the base of a ladder. He was dead, the result of a broken neck.. The sheriff was called for immediately. The cause of the fall was unknown, but the county medical examiner deducted that the death had happened around 4pm. It was most likely an accident, as the seasoned dairy farmer either mis-stepped, or over-reached, losing his balance atop the ladder or roof. Jacob Kanode would be the 18,100th person interred within Mount Olivet Cemetery, since its opening in 1854. Jacob Martin Kanode was born on the family farm on August 16th, 1870, as the son of Jeremiah R. Kanode (1825-1907) and Margaret Layman. His parents grew up on adjoining farms basically across the road from one another. The young couple endured the American Civil War. As a matter of fact, the Kanode's farm supplied, or was ravaged by, Union troops under Gen. George B. McClellan in September, 1862. I found that Jeremiah Kanode sued the federal government for a war claim reimbursement. The case was heard in the US House of Representatives in 1907, 45 years after the infractions in question. The Kanodes were awarded $136.00 in November of that year, nine months after Jeremiah's death. The Hopeland area was known as a haven for former slaves and free blacks after emancipation, and the American Civil War. Hope Hill Methodist Church and Hopeland Colored School catered to the local black community. Jacob went to a nearby school up through the sixth grade and tended to the obvious tasks farming life required. Along the way, he became intertwined with the annual county agricultural exposition-known more commonly as the Great Frederick Fair. From articles I found in 1888-1890, Jacob seems to have taken a strong interest in knight pageants and jousting tournaments around the state. Victors received premiums and the honor of selecting the Queen of Love and Beauty, and three Maids of Honor. It was sort of a medieval version of the "The Dating Game" television program of the 1970's. In one, he was labeled as the Knight of Redwood, another the Knight of New Market. Jacob appears to have been a popular eligible bachelor of the period. Mrs. Kanode was born Ella Nora Graser on December 10th, 1870. She was the fifth of seven children born to Francis "Frank" Graser and Margaret Musser. Mr. Graser came from Wurttemburg, Germany and worked as a farmhand. His wife, Mary Musser hailed from Pennsylvania.  I'm not exactly sure how the couple first met, but Jacob and Ella married under the strangest of circumstances. They were successfully recruited for a publicity and marketing stunt. Jacob was 20 years-old and working on the family farm in 1890. The 13th Annual Exhibition of the Frederick County Agricultural Society was held October 14-17th, 1890 and was billed as "A Mammoth Exhibition of Agricultural, Industrial, Natural and Artistic Products." The Agricultural Society was a clever marketer. Among the scheduled attractions used to lure fair-goers that year was a balloon ascension featuring a leap in the air by the pilot while traveling at a height of 5,000 foot from the ground. Other special events "on tap" were a Grand Bicycle Tournament, an equestrian Hurdle Racing and High Jumping Contest, and the most novel and unique attraction in Frederick Fair history up to that point--The Grand Wedding. An ad in a local newspaper announced: "The bride and groom have been secured, and the nuptial knot will be tied in the presence of the assembled multitude." Today, reality shows are commonplace, but in 1890, this prototype of The Bachelor or The Bachelorette was truly a must-see event. Posters were put up all over Frederick. The newspaper promoted the event, set for 12 noon on October 16th. The couple had been enticed by the Agricultural Society's offer of a free Honeymoon trip to Niagara Falls or any other point within 800 miles. James H. Gambrill, Fair Board president, met with the volunteer couple and their respective families. Everyone agreed to the Society's proposal, thanks to great legwork done by Secretary George W. Cramer. A committee was formed to plan and handle arrangements for the event. This included J. William Baughman, John W. Markell, and C. Stanley Gambrill. Things were not all "flowers and roses" as a local minister filed a formal protest of the public wedding. The Rev. James Stephenson, D.D. of the Protestant Episcopal Linganore Parish was livid. He felt the stunt was nothing more than a cheap farce, designed to "create a caricature of one of the most sacred institutions of Christianity." Rev. Stephenson threw his venom at the Fair Board, but to no avail as the show, I mean wedding, must go on. This complaint was not really surprising as pressure had been mounting toward the Agricultural Society to curb immoral sideshows, alcohol distribution and gambling. This would be addressed soon after with a re-focus on family values and intellectual culture.  Rev. Edmund Eschbach Rev. Edmund Eschbach The event was slated for noon on October 16th. The Frederick News reported that "by noon a few fights occurred among the rougher element and a number of women were insulted by the "toughs" from other cities, but not a single incident of purport occurred. The receipts were far in advance of any single day of the fair yet." It was a favorable omen, as it likely beckoned good luck to the bride and groom. The event attracted one of the largest crowds to date at the fairgrounds. One estimate put the crowd at 25,000 to hear the wedding vows. This number is especially poignant because the population of Frederick in 1890 was about 9,000 and the county was about 50,000. Dr. Edmund Eschbach of the Evangelical Reformed Church performed the ceremony. The Frederick News reported that Dr. Eschbach had married the couple in the presence of "thousands of our best people, and to the pleasure of a very happy couple." Mr. Gambrill reported that the beautiful ceremony impressed the respectable and orderly citizens who were present from Pennsylvania, Virginia and Maryland. Emma Gittinger, the pioneer female columnist of the Frederick News wrote of the spectacle in her weekly "The Girl About Town" column on October 18, 1890: "I occupied a cozy little nook on the grand stand during the wedding ceremony at the Fairgrounds Thursday and my dear girlish heart felt possessed by the Demon of Regret when I saw how beautifully the wedding passed off. It was a pretty wedding, I can tell you, and the bride looked just too sweet and lovely for anything. I felt sorry for her, poor thing, with all those people staring at her, but she didn't seem to mind it a bit, and indeed there was no reason to, for it was just as solemn and romantically impressive as something need well be. I don't believe in too much solemnity at a wedding. I think it must be the happiest moment in a person's life, and such an occasion ought to be as gay and happy as possible." "Not a single one of the vast throng of persons who witnessed the public wedding had any comment to make upon it except in the way of praise for the decency and decorum of the ceremony and the gentlemanly and lady-like conduct of the bride and groom. Even those who bitterly opposed the idea but went out of curiosity to witness the ceremony were convinced that they had been hasty in their judgment and too severe in their condemnation. As Governor Jackson arrived just too late for the ceremony he gave the bride away by proxy, his able substitute being Mr. R. Q. Taylor, of Baltimore. The bridal party were met at Monocacy Junction by the ushers, C. Staley Gambrill and John Usher Markell, and were driven first to the residence of Rev. Dr. Eschbach, who joined the party, occupying a seat in the coach with Mr. James H. Gambrill. The bride had been gotten in readiness by her friends at Araby and looked very beautiful. Her counterpart was a vision of manly glory and felt like a Prince. The couple didn't seem to mind the ordeal at all, taking a very casual and mature stance and accepting the crowd most favorably. They were met at the grounds by the bands and Grand Marshal and a partial circuit of the track was made. The ceremony then passed off. The ring service was used, and on the platform were the families of the contracting parties, the ushers, Mr. Taylor, Mr. Gambrill and Mr. George W. Cramer. During the impressive service an intense calm prevailed, but afterward the immense crowd cheered lustily, steam whistles blew and the small boy wasted the strength of his lungs on the inevitable tin horn. Dr. Eschbach was first to congratulate the bride, and he was followed by hundreds of others, all expressing their hearty hopes of a long and wedded life for the happy bride and groom. They re-entered their carriage , the top of which had been thrown open, and the party drove around the track, afterward going to the City Hotel, where the wedding breakfast was eaten. The bride and groom got off safely for Washington on the 8:30 train from Frederick Junction, amid the hearty good wishes of the friends who had gathered there to see them depart." Luck was certainly on the young couple's side! In other fair news later in the day, horse racing was hampered by rain. The balloon ascension was a failure as well, as the air-ship only ascended 25 feet, when it drifted over the cattle pens and collapsed. News of the successful public wedding was carried by newspapers throughout the country. I wasn't able to find a report of the Kanode's honeymoon, but I'm sure the couple reaped the spoils of their all-expense paid trip. Oh to be a fly on the wall and hear their thoughts and emotions as they reflected on the spectacle of the day. They must have felt like pseudo-celebrities while on vacation, due to media coverage. Once back in Frederick, the newlyweds took up residence at the Hopeland/Hope Hill family farm with Jacob's parents. They can be found living with them in the 1900 census. Jeremiah died in 1907, and was buried in Mount Olivet. Jacob, now 37-years old, took over the family dairy and creamery operation and would run it until the day of his death. Jacob and Ella had two sons—Charles and Ralph. At the time of Jacob's death, Charles E. Kanode (1896-1957) lived in Walkersville, while Ralph G. Kanode (1902-1957), resided near Monocacy Junction. Jacob and Ella possessed two grandsons and a granddaughter as well.  Ella would pass one year and two months after her husband on March 31st, 1944. The 73-year-old had been suffering from an illness for ten months. At the time of her passing, Ella's two grandsons, additional byproducts of the Frederick Fair publicity stunt of 1890, were serving in the US Military during World War II. These included Petty Officer Charles E. Kanode, Jr., in Norfolk (VA) and Corp. Ralph G. Kanode, Jr. in Fort Myers, FL. Ella Kanode was laid to rest in Mount Olivet on April 2nd, 1944. Beautiful marble footstones compliment a five foot pedestal-style monument commemorating Jacob's parents. To this day, the Kanode's nuptials at the fairgrounds back in 1890 still holds the undisputed record for best attended wedding in Frederick County's history!

Down on Fingerboard Road, the Kanode family farm is long gone, but part of it constitutes land that is today the site of the Maryland Sheriff's Boy's Ranch.

7 Comments

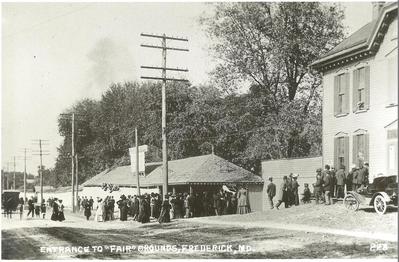

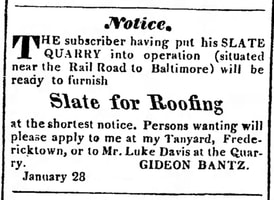

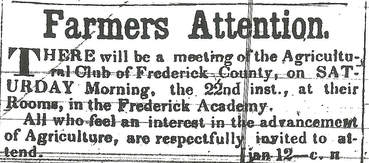

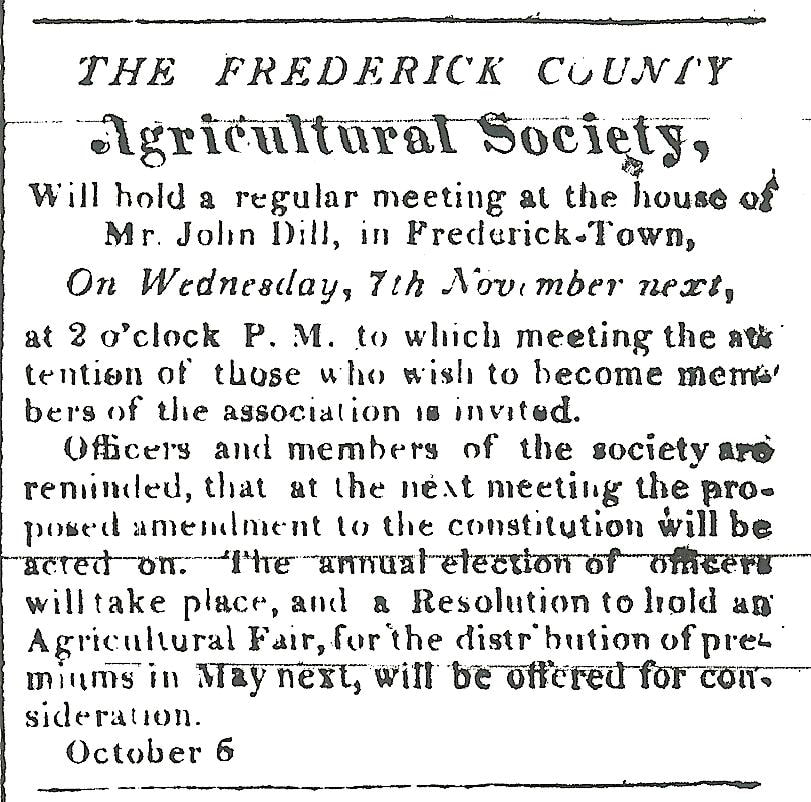

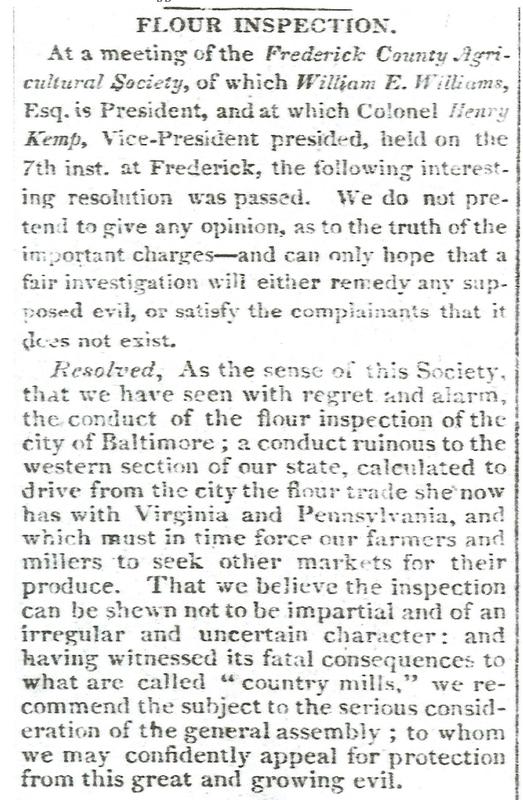

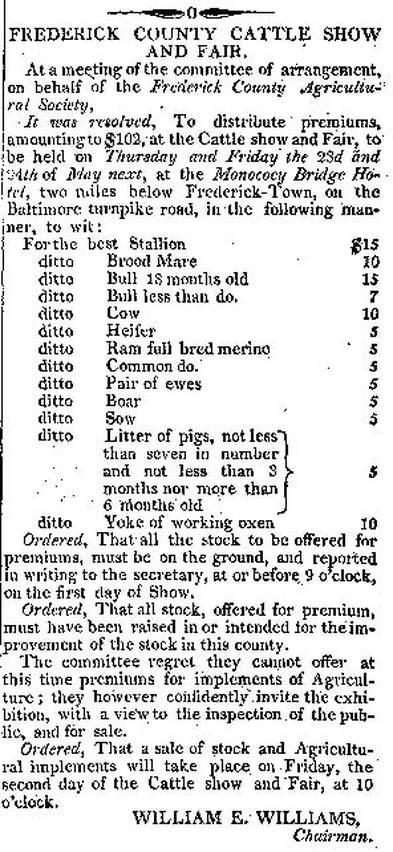

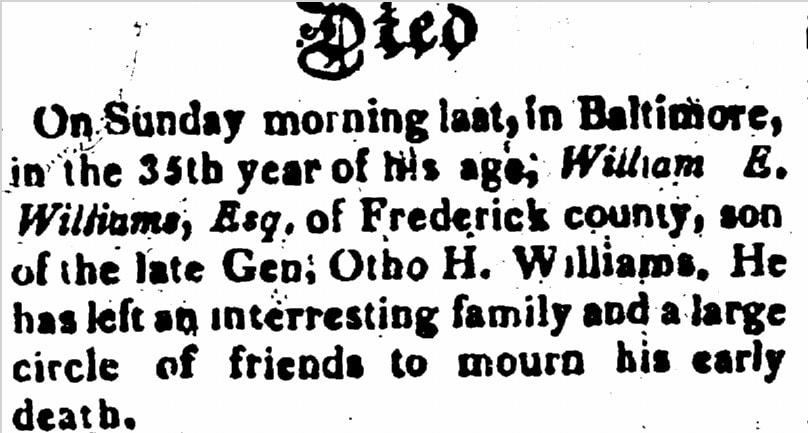

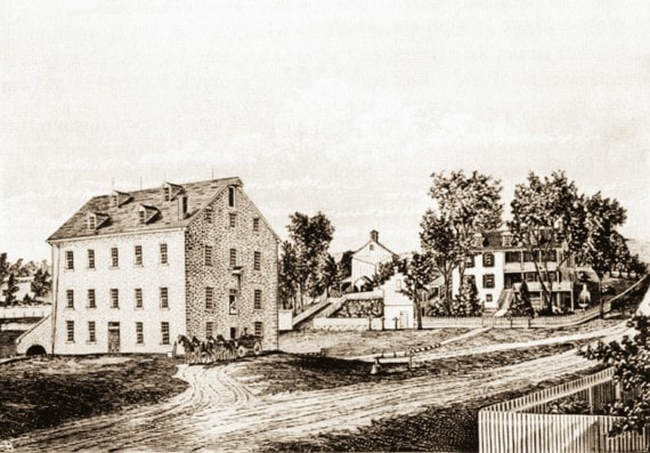

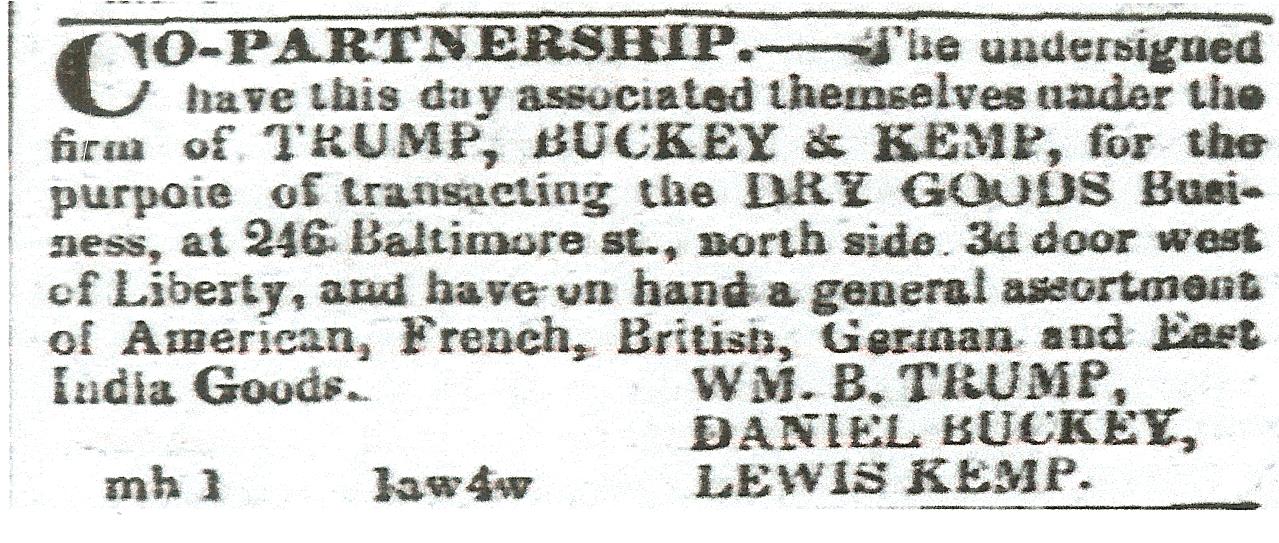

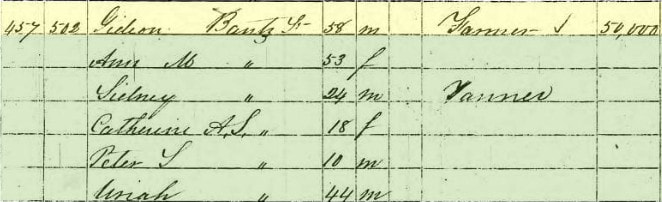

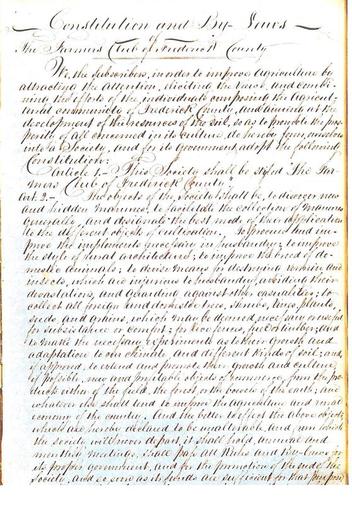

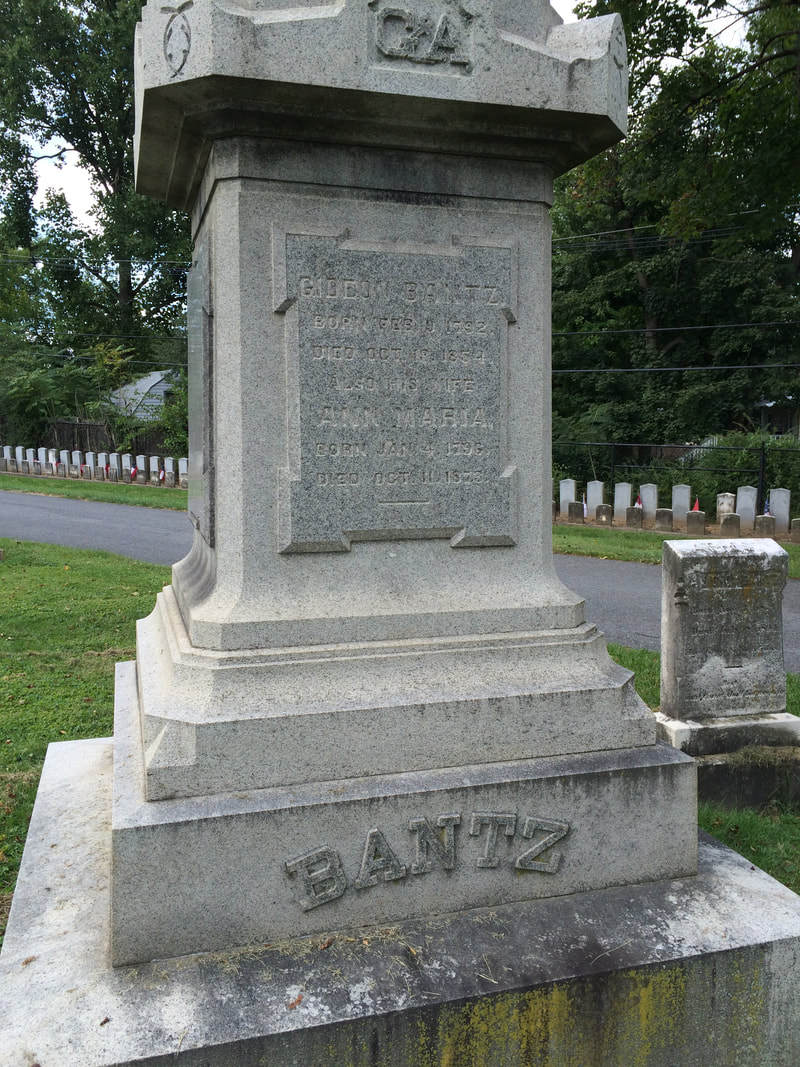

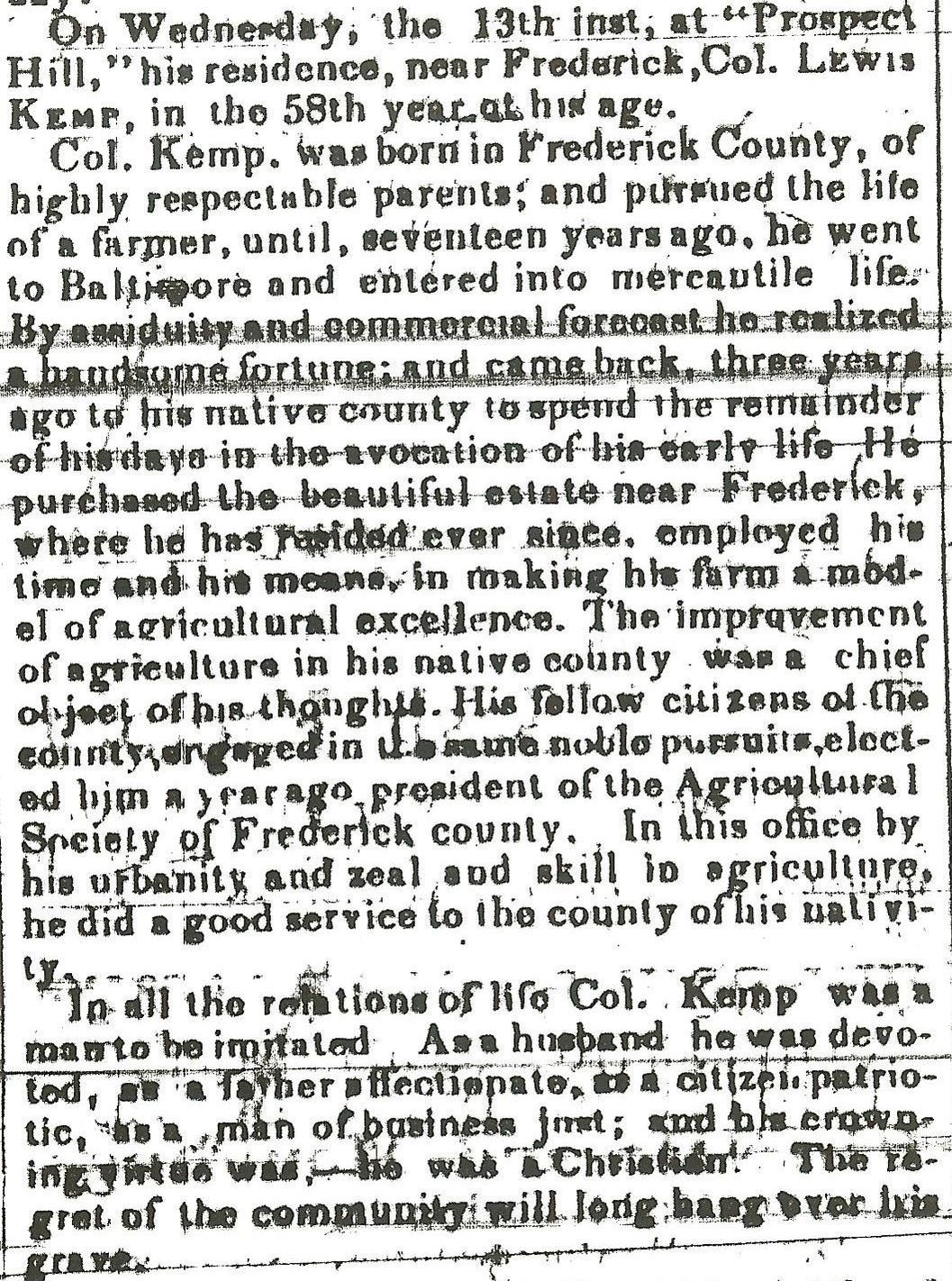

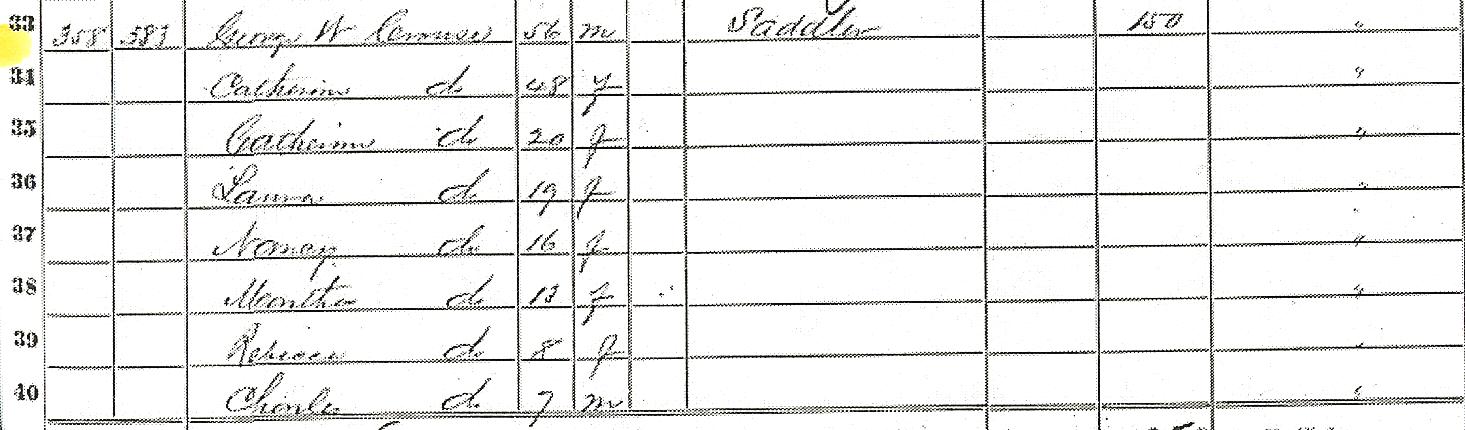

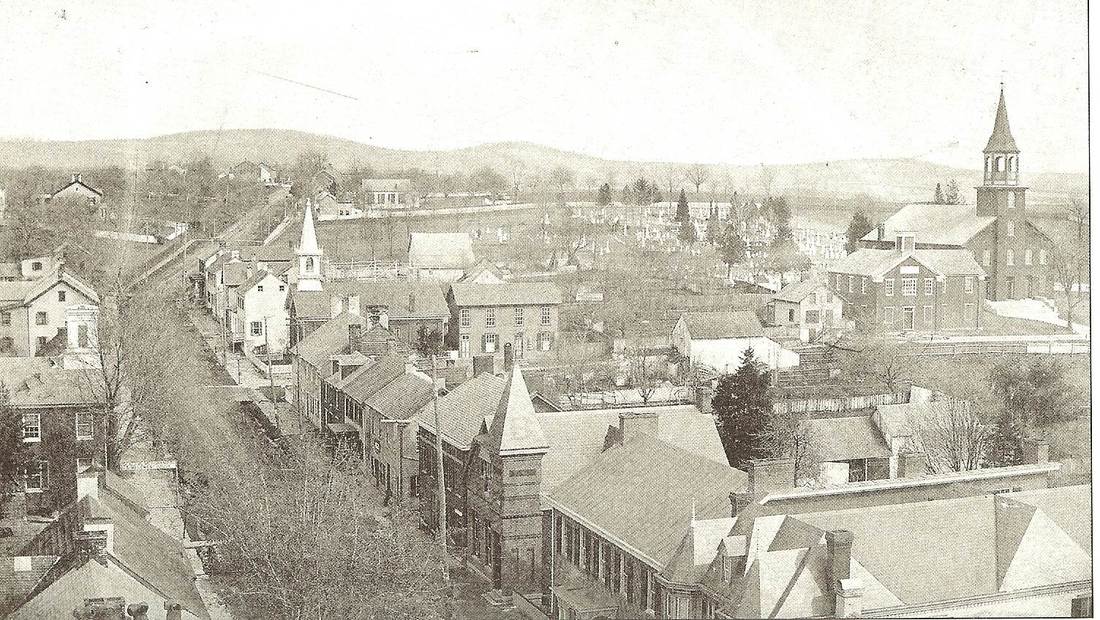

E. Patrick Street entrance to the Great Frederick Fair (c.1908) E. Patrick Street entrance to the Great Frederick Fair (c.1908) The Great Frederick Fair is once again in "full-swing." The largest county fair in Maryland has had an amazing run, revered by many as the best in the state. Be that as it may, Frederick's agricultural roots run deep, and our county has been blessed with amazing folks, both past and present, proudly wearing the moniker of farmer. The Frederick Fair continues to be a reflection of great "farm families," some dating back to the mid 1700's. Many of the brightest doubled as pioneering businessmen, while others served in politics. They were also leaders in their respective churches, social clubs and civic causes. From the gentleman planter to the tenant farmer, the knowledge and drive these individuals exhibited was, and still is, awe-inspiring. Just think of the countless Frederick agriculturalists who proved successful without the help of the internet and cable television. In this week's edition of "Stories in Stone," I have put the spotlight on three such individuals from Frederick's past. These men are seldom mentioned, or thought of, today. I'm sure that the vast majority of fair-goers entering through the "GFF" turnstiles have no earthly idea or context to who any of these gentlemen are. However, this trio helped pave the way for us to enjoy rides on the midway, experience entertainment in the grandstand, view the latest in agricultural implements and other home innovations and locally offered services, celebrate arts and crafts, and most importantly, understand the important and difficult tasks that farmers embrace each day by raising livestock, cultivating crops and ship food to market for our sole survival. William E. Williams The Frederick County Agricultural Society was "birthed" in November 1821. A group of the area's most distinguished planters and farm owners forged the organization’s bylaws and elected William Elie Williams as the society's first president. Williams was the builder and operator of the large stone grist mill on his plantation farmstead at "Ceresville," so named for the Roman goddess of agriculture and grain, Ceres. More than his contribution to farming, the leader of the county's first agricultural society was better known for being the son of celebrated Revolutionary War Brigadier Gen. Otho Holland Williams. This man (Otho H. Williams) once served as a county clerk for Frederick County, and was an intimate friend of George Washington. He is also the namesake of Williamsport, MD, where he persuaded Washington to place his capital city. Williams would serve as chairman of the society's greatest achievement, arranging and promoting the first-ever cattle show and fair in our county's history. Most local histories simply give credit to a mysterious man, and former sheriff, named George Creager, a one-time tavern keeper who supposedly hosted the first agricultural exhibition. Williams did so much more for Frederick's rich agricultural heritage. As the oldest son, William E. Williams obtained one of his father's treasured farmsteads in 1808 at the ripe age of 21. It was located just northeast of Frederick City on the eastern bank of the Monocacy River along the Liberty Road (current day MD26). Not much is known about Williams childhood, but it assumed he grew up in Baltimore and likely attended schools there as his father had been appointed as the port collector of that city by President Washington. Gen. Otho H. Williams passed in 1794 at the age of 45. William was born in 1787 and after his father's premature death was raised into adulthood by the family of his mother (Mary "Polly" Smith) family. He attended Princeton and received his Bachelors of Arts degree in October, 1806. He followed with service in the US Army Infantry, earning the rank of captain and eventually entered into the practice of law. Up until 1810, the Williams-owned farm at Ceresville had been run by overseers for the previous two decades. The property was described as "a farm of 300-500 acres, with a suitable number of hands, animals and implements; crops are wheat and other cereals, potatoes, hay and other food for stock; stock in horses, cows, sheep, pigs and poultry." William E. Williams ingratiated himself with the prospect of farming his father's Frederick-based plantation. Over the next five years, Williams would have the property surveyed and appraised. He contemplated adding Merino Sheep, searched for a mason to construct a home on the property, bought additional acreage, looked for a blacksmith and gardener among other slave hands, and got a sawmill up and running. The principal structure of his operation was a flour mill which he had built in 1813. It would be powered by water from nearby Israel's Creek. The Ceresville Mill, later to be known as Kelly's Mill, replaced a smaller mill on the property and was described as follows: “The new stone mill had six floors and two rows of dormer windows. The machinery from the mill came from nearby Catoctin. In 1826 the mill manufactured 30,000 bushels of wheat a year. The additional output was 5,000 bushes flour, 7 bushels rye, 132 tons meal and 180 tons of feed.” Williams also started a limestone quarry on the premises and operated a ferry to shuttle passengers and wagons across the Monocacy. Having a career, and home, William E. Williams moved with his wife, Susanna Frisby Cooke, to Frederick County. The couple married in April, 1812 and would have five children. In addition to agricultural pursuits, Williams was named one of the first directors of the Farmers & Mechanics Bank for Frederick County in 1818. He was also active in the local Republican Party, and ran for the state house of delegates in 1819. He was appointed a Justice of the Peace for Frederick County by Maryland's governor (1820/1821) and was active in All Saints Episcopal Protestant Church. William E. Williams and the other members of the Frederick Agricultural Society took seriously the charge of their organization to teach best practices and look after Frederick County farming interest in comparison to other locations and cities where local trade existed. An example of this came with a November, 1821 resolution involving flour inspection: William E. Williams and the Frederick County Agricultural Society quickly made plans for a Cattle Show and Fair on May 23rd and 24th, 1822 to immediately precede the Maryland State Show. This would be the second agricultural fair held in the state, and the rationale for the state’s date followed the planting of corn and was in advance of the tobacco planting season.  Representative view of an early Mid-Atlantic region Cattle Show in Pennsylvania Representative view of an early Mid-Atlantic region Cattle Show in Pennsylvania The first-ever Cattle Show and Fair in Frederick's history went off swimmingly, taking place at the Monocacy Bridge Tavern, on the western bank of the river along the National Pike (today's MD144). This was the site of the famed Jug Bridge. Williams wouldn't get his opportunity for an encore. Three months later, by mid-August 1822, the 35-year-old William E. Williams had relocated to Baltimore, taking up residence there once again due to illness. Williams was very sick, said to be suffering from a throat and respiratory ailment. His condition worsened as summer turned to fall. He would eventually succumb to this malady three on November 17th, 1822. I have not been able to find a burial record, but I am highly confident that our first president of the Frederick Agricultural Society was laid to rest in Baltimore's "Old St. Paul's" Protestant Episcopal Cemetery located at the corner of W. Redwood Street and Martin Luther King Boulevard. It is bordered by the University of Maryland Medical Center campus. Part of the cemetery was destroyed in the creation of MLK Boulevard, and this could hold the key for the lack of Williams' stone. Regardless, he is in good company as this burying ground contains the mortal remains of other leaders from Maryland's past such as Samuel Chase, John Eager Howard, George Armistead and Daniel Dulany, the Younger—son of Frederick's founder Daniel Dulany. This cemetery was also the first resting place of Mount Olivet's Francis Scott Key from 1843-1866. Spring 1823 didn't see a second Cattle Show & Fair in Frederick. One of the reasons was simply due to the sudden loss of William E. Williams. A related ag-related event would, however, be held at the Monocacy Bridge Hotel and tavern location by the Monocacy. This show was not officially sanctioned by all in the local Agricultural Club as it was more of a horse racing festival put on in conjunction with the Frederick County Jockey Club. Another factor contributing to this absence (of a follow-up Frederick cattle show) had to do with the previous scheduling of the Maryland Cattle Show and Fair by the state's Agricultural Society. This would be held in Easton, on the Eastern Shore, in November (1823). Things would follow suit with a failed attempt to have a cattle show in 1824 due to respectively not wanting to compete with the visit of Gen. Marquis de Lafayette's visit to Maryland. This hiatus allowed the Frederick County Agricultural Society to regroup, and reorganize, in December of 1824. William E. Williams would have made a far greater impact locally here in Frederick County if given the opportunity. His widow Susanna, and brother Henry Lee Williams, would take over the estate after his death. An ad appears in the Washington Intelligencer newspaper of December 31st, 1822 for a public auction of "Ceresville Farm" and the plethora of agricultural implements that Williams had acquired. A man named Cornelius Shriner would operate the mill afterwards, turning it into one of the most profitable of its kind in western Maryland. His son Edward A. Shriner would follow in his father's footsteps and flour would be continuously milled here until 1988.  Grave of Henry Kemp in Area NN/Lot 126 Grave of Henry Kemp in Area NN/Lot 126 Col. Lewis Kemp & Gideon Bantz The vice presidents of the Frederick Agricultural Society under first president William E. Williams included: Col. Henry Kemp, Col. John McPherson, Col. John Thomas, Mr. James Johnson, Col. G.M. Eichelberger, Mr. W.P. Farquhar, Mr. Jesse Slingluff, Mr. Joshua Delaplane and Mr. William Morsell. Of particular interest is Col. Henry Kemp (1863-1833), a veteran of the War of 1812 and successful mill owner. Kemp was influential in helping re-launch the Agricultural Society and another cattle show and fair in 1825. Like his friend William E. Williams, Col. Kemp dabbled in politics. He was appointed by the governor as a judge of the Frederick Orphan's court and would also be elected as a delegate to the Maryland General Assembly. Kemp was also a director of the Farmers & Mechanics Bank. Col. Henry Kemp and his colleagues would hold another cattle show, fair and exhibition in Frederick County in May, 1825. Two more would follow in 1826 and 1827, the latter taking place in Libertytown. For some unknown reason, the show went by the wayside, not to be re-visited until almost 25 years later. Henry Kemp's oldest son, Col. Lewis Kemp, assisted his father with the organization and served as the secretary for the county's Election District 1 subcommittee of the larger Frederick County Agricultural Society. Born January 22nd, 1797, Col. Lewis Kemp grew up on Carrollton Manor and eventually married Rebecca Charlotte Buckey, granddaughter of German immigrant Matthias Buckey. The couple wed on May 19, 1818. Rebecca's father, George Buckey, owned a large tannery in town. Two of Lewis' sisters married Rebecca's brothers, strengthening the bond between both families. Kemp was involved with the Buckey tannery operation, but eventually relocated to Baltimore around 1834 in an effort to conduct a dry goods store with his brother-in-law (twice-connected) Daniel Buckey. Col. Kemp retired and came back to Frederick in 1851. His great-grandfather had been Christian Kemp, builder of a large house and mill on Ballenger Creek. Lewis Kemp lived in the Carrollton Manor vicinity before his departure to Charm City, but upon returning moved to the Prospect Hill, taking up residence in the Prospect Hall manor house as a gentleman farmer.  Frederick Town Herald (Feb. 11, 1832) Frederick Town Herald (Feb. 11, 1832) In 1849, Col. Kemp found himself a member of the newly-formed Farmers Club of Frederick County. The Farmers Club was formed in November (1849) at a gathering in the Old Academy building on Council Street in downtown Frederick. A local businessman named Gideon Bantz would be named president. Gideon Bantz was born on February 9th, 1792, the son of Henry and Catherine Bantz. The 57 year-old owned farmland both inside and outside the town limits, plus a quarry east of Frederick on the National Pike. Bantz was best known for operating a tannery in downtown Frederick. It was positioned north of Carroll Creek along the west side of S. Court Street (between the creek and W. Patrick Street). Bantz's home fronted W. Patrick and took the form of a large three-story dwelling occupying a corner lot. Bantz was the husband of Ann Maria Sowers and had 12 children. Gideon Bantz served as a church elder (German Reformed Church), served on several board of directors and dabbled in politics earning him the title of the county's most popular Whig party politician. Many subsequent meetings would be held by the Farmers Club Of Frederick County, but no county-wide exhibition was planned, or held, during the next three years.

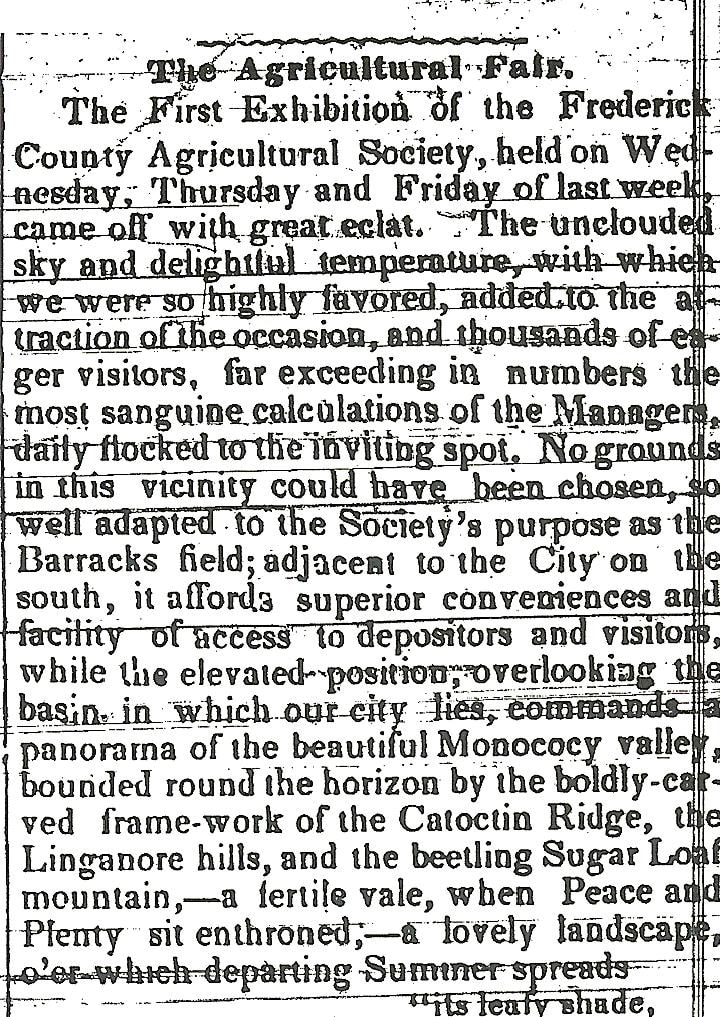

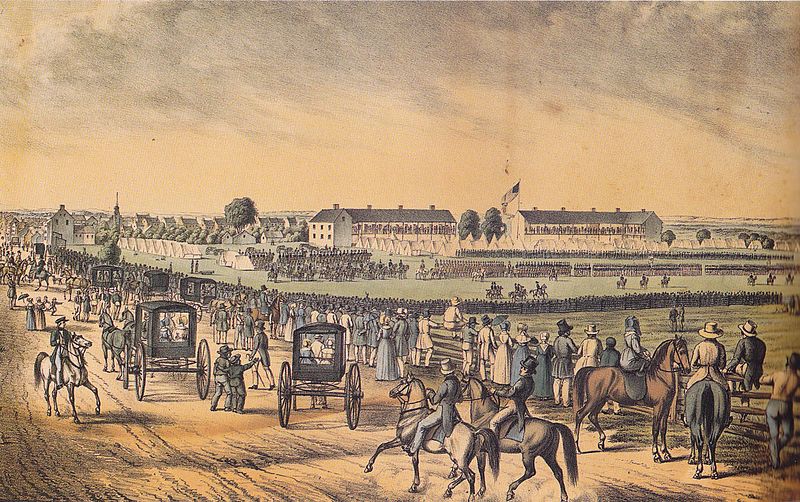

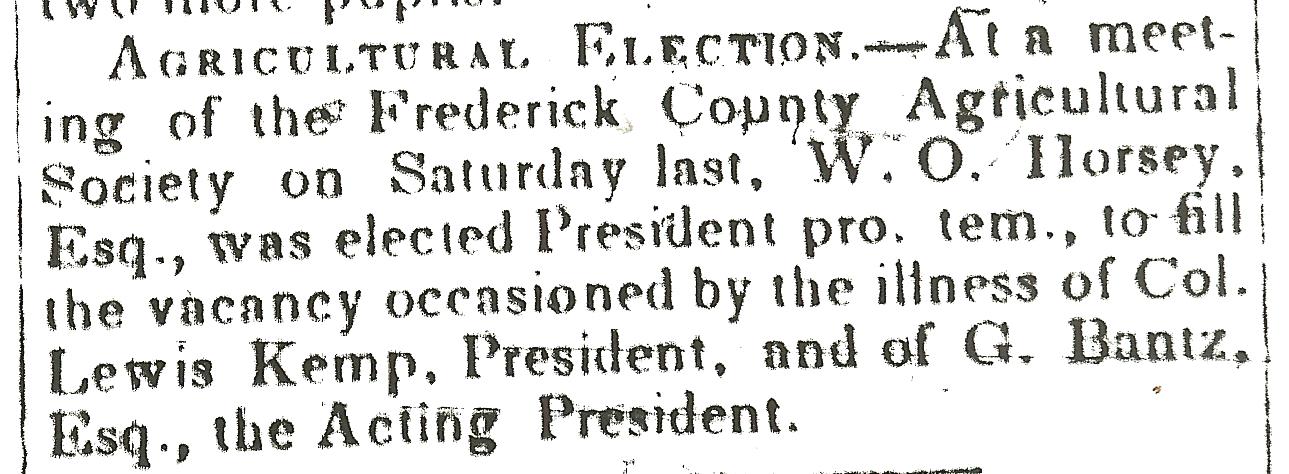

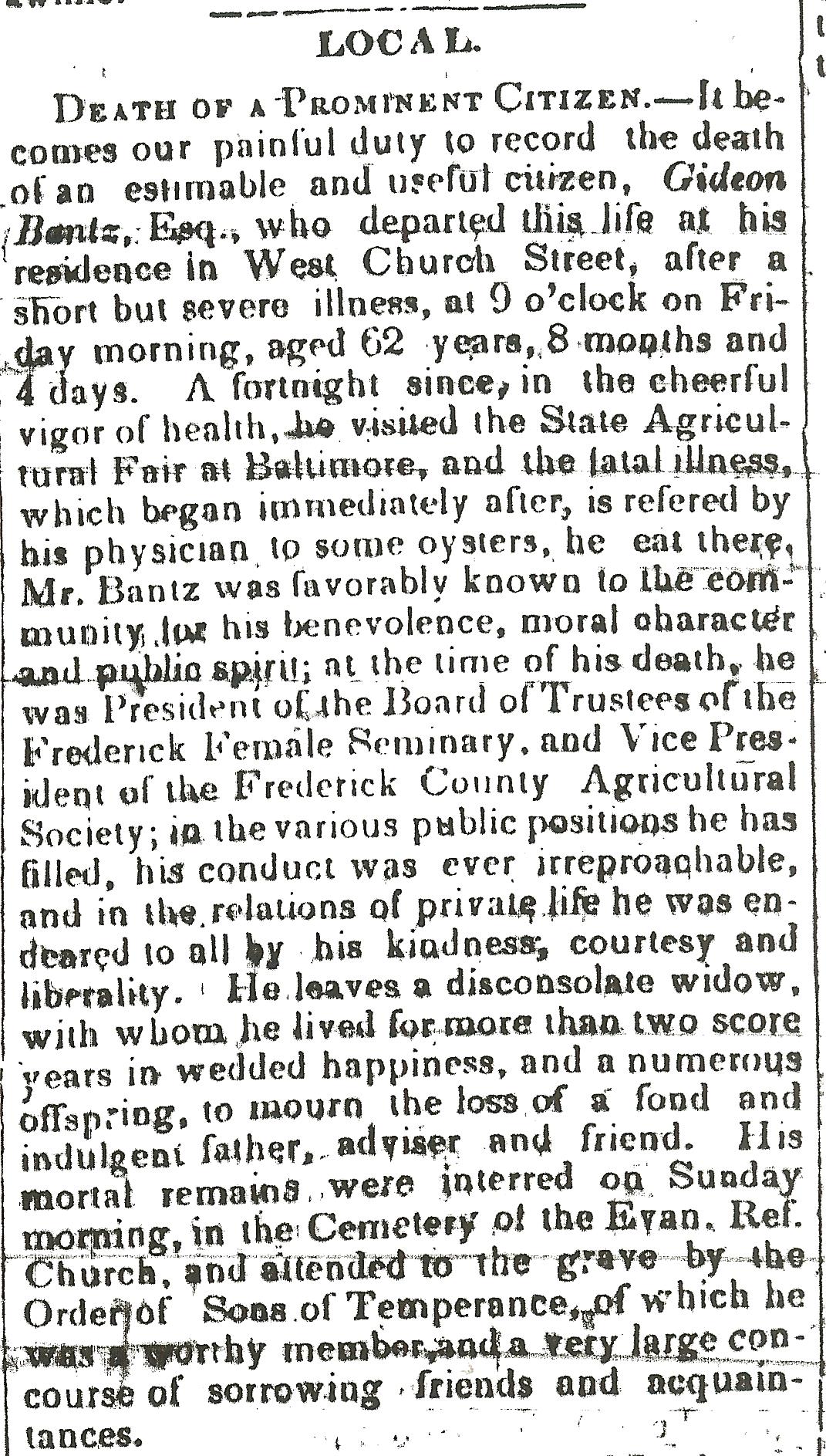

Although the new club seemed a little obsessed with poop, their overall constitution was rock solid. After four years under President Bantz' leadership, the Farmer's Club would make some alterations to itself.  On January 12th, 1853, the Frederick Examiner newspaper announced an upcoming meeting, which respectfully invited “all who feel an interest in the advancement of Agriculture” to attend. This ad was placed by members of the Farmers Club. In another part of the same paper, the Examiner’s editor pointed out the meeting as being “well worth the attention of farmers, millers, and all others interested in the development of the productive resources of our county. Its object is to revive and reorganize the Society, and it is to be hoped that a becoming interest and enterprise will be manifested in the important undertaking. “ This meeting took place on January 22nd, 1853 at the Frederick Academy building, where a large and highly respected group convened and organized an association under the title of the Agricultural Club of Frederick County and the Frederick County Agricultural Society. High spirit and enthusiasm abounded and another constitution and by-laws were adopted with amendments. An election for officers was held and Col. Lewis Kemp became the group's first president. The particular goal of the meeting was to make arrangements for holding a local agricultural fair for the following fall season. The first exhibition of the Frederick County Agricultural Society was held October 16-18th, 1853 and attended by thousands of eager visitors. This far exceeded the numbers imagined by the organizers. The home for the newly revived cattle show, fair and exhibition was the Frederick Barracks Grounds on Cannon Hill. One year later, the second annual Exhibition of the Frederick County Agricultural Society took place. The same support of the 1853 event was again demonstrated as it was estimated that 15,000 people attended the second day of the fair alone. The Great Frederick Fair, the way we know it today, was officially born. Sadly, two leading Frederick Countians, would experience their final fair opportunity in October, 1854. Gideon Bantz had been elected to serve as Acting President due to an illness that was pestering Col. Lewis Kemp. This occurred when the Agricultural Society's Board of Trustees met on October 7th, just prior to the opening of their Exhibition on Wednesday, October 11th. Gideon Bantz attended opening day, but would travel to Baltimore on Thursday to represent Frederick County by attending the Maryland State Fair. While there, he contracted a sudden illness, blamed on something he ate for dinner. He returned home, but would breathe his last breath just 24 hours later on Friday night. The community was stunned and deeply saddened. Gideon Bantz was buried in the German Reformed Burying Ground at the intersection of S. Bentz and W. Second streets. He would one day be reinterred in 1873 within Mount Olivet Cemetery. His mortal remains were placed in Area G/Lot 188. Bantz' obituary, (above), placed in the Frederick Examiner contains a wonderful sketch of Mr. Bantz' colorful achievements and standing in the community. Tributes of Respect also appeared in the newspaper. The following appeared in the October 18th edition of the Frederick Examiner:

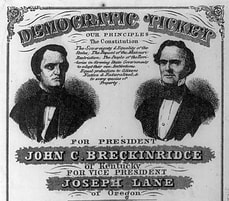

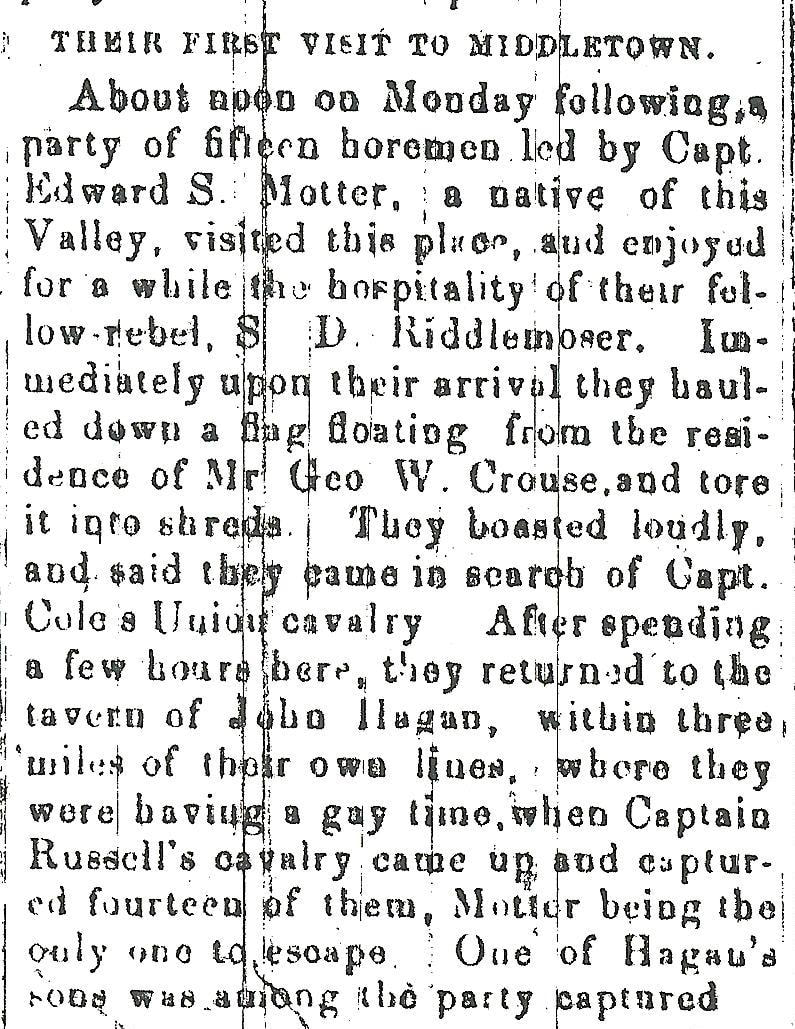

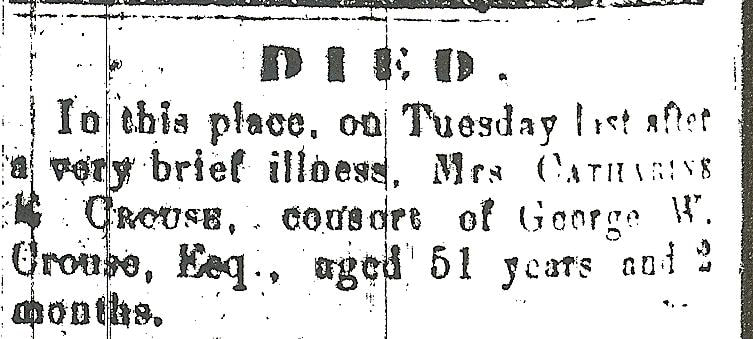

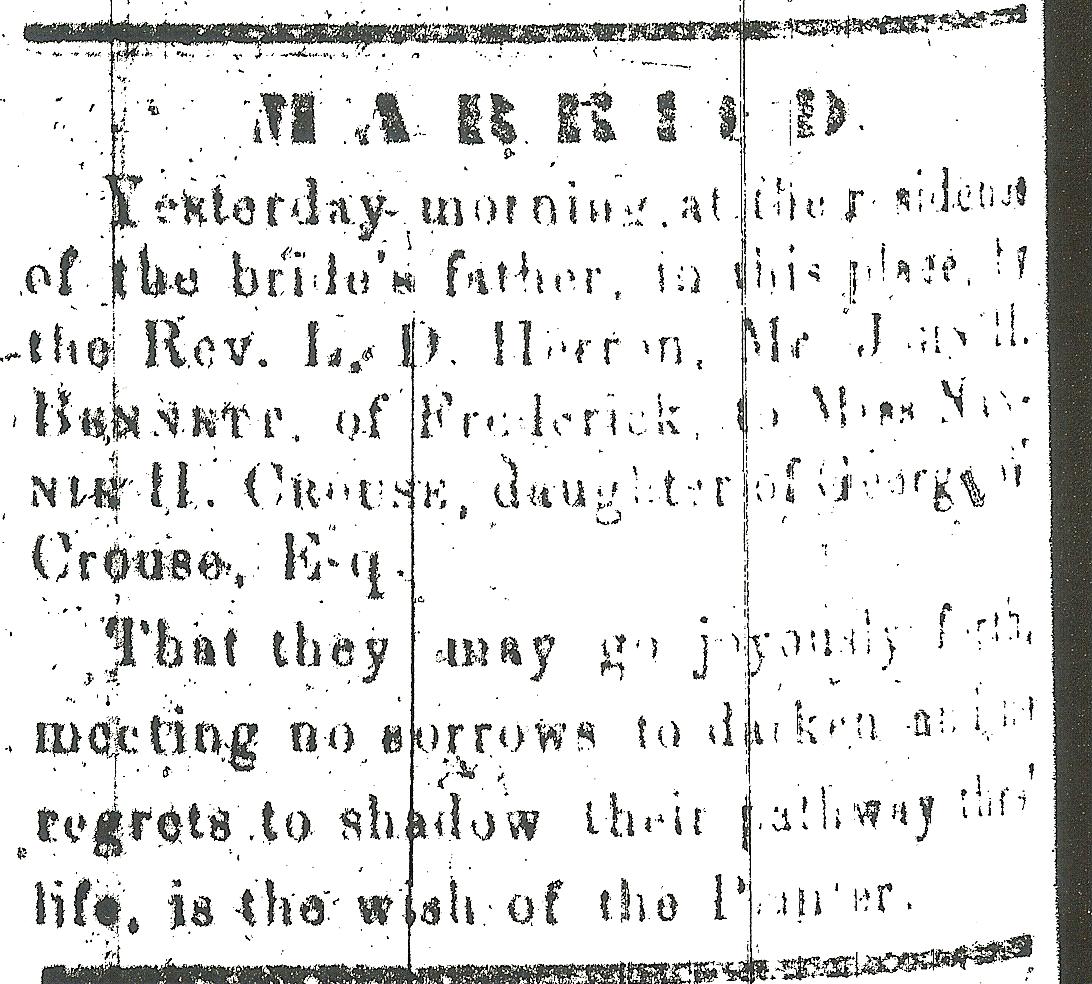

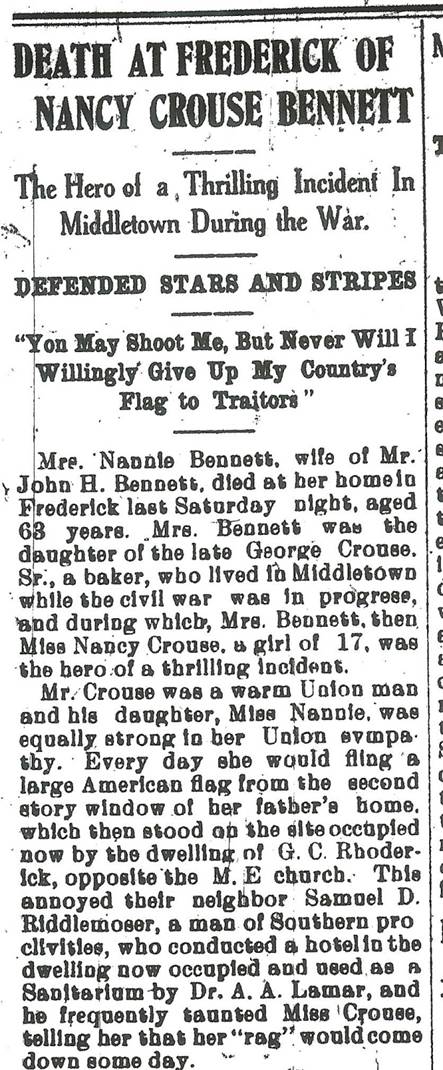

"Tribute of Respect At a meeting of the Frederick County Agricultural Society, held on Friday evening October 13th, the following proceedings were had: Whereas, It has pleased the Almighty to remove from our midst, within a few days of each other, two of our fellow citizens, F.A. Schley, Jr., and Gideon Bantz, Sr., the one young, ardent, energetic, full of all promise of usefulness, beloved by all who knew him; the other advanced in years and enjoying all that high respect and warm regard of his fellow citizens which a long life of irreproachable conduct had won for him; and whereas both the departed were valued members of the Association, Gideon Bantz being, at the time of his death, one of the Vice Presidents of the Society. Therefore Resolved, That we deeply deplore the loss of our fellow members, F. A. Schley, Jr., and Gideon Bantz Sr.; and that we sincerely sympathize with their afflicted relatives and friends. Resolved, That the Secretary of this Society communicate a copy of these resolutions to the respective families of the deceased. Resolved, That these proceedings be published in all the papers of the town; and be also entered upon the minutes of the Society. Outerbridge Horsey, President pro tem Oct. 18, 1854 One of the likeliest of pallbearers for Gideon Bantz' funeral was Col. Lewis Kemp. Whether he did, or not, Kemp would return to the German Reformed Cemetery just a few months later. Unfortunately, it wasn't to pay respects to his fellow farming brother. Instead, friends, family and neighbors were saying goodbye to him as he died on December 13th, 1854. Today, Kemp's gravesite is roughly 20 yards away from his old friend and colleague, Gideon Bantz. in Area G/Lot 177. Bantz had been brought to Mount Olivet and reburied on the 19th anniversary of his death (October 13th, 1873.) Col. Kemp would be re-interred on June 23rd, 1906.  Campaign poster for John C. Breckinridge (1821-1875) and Joseph Lane Campaign poster for John C. Breckinridge (1821-1875) and Joseph Lane It was 155 years ago, and Frederick County would find itself “invaded” by Gen. Robert E. Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia. Fresh after a victory at Second Manassas (VA), the Rebels had crossed the Potomac River and made their way to Frederick City where a large contingent would camp for nearly a week. In doing so, Frederick, was the first major town on northern soil they would visit. Some residents did not see the ragged boys in gray as the enemy. More so, many viewed these men, and their gallant generals (including Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson, James Longstreet and J.E.B. Stuart), as liberators of Maryland. Slaveholders or not, they saw their state being forced (against its free will) to stay with the Union. Southern-leaning legislators and newspaper publishers had been arrested and thrown in jail for speaking out. And this, thanks to a tyrannical president, certainly not put in office by Marylanders. No sir, John Breckinridge of Kentucky, former vice president under James Buchanan was the Old Line State’s POTUS choice in the famed election of 1860. He garnered all 8 electoral votes and 46% the popular vote. Abraham Lincoln only got 2, 294 votes statewide—2.5% of the popular vote. In Frederick County alone, 3,617 votes were placed in ballot boxes for Breckinridge. Lincoln only received 103. We will never know, but one of the 103 votes could have come from George Warner Crouse, a Frederick County resident who had moved with his family to Maryland in the late 1840s from “the Land of Lincoln”—Illinois. However, this family exemplified the complicated nuance of “border state living.” George Crouse was a native of Littlestown, Pennsylvania, and his wife, Ellen (Catherine Eleanor Smith), was a bona-fide Southerner originally from Leesburg, Virginia. Ironically, this “even-steven” family now lived, of all places, in Middletown, Maryland. This little hamlet lay in the heart, or better—the “middle” of the mountain valley which bears the same name. It is located roughly eight miles west of the county seat of Frederick. Middletown once prided itself as a trade center for surrounding farmers. Many of these possessed German roots dating to early settlers from the mid 18th century who had made their way from Pennsylvania. Mr. Crouse certainly assimilated nicely here thanks to his genealogical and geographical background. Most German derived residents threw their devotion and support behind President Lincoln. In September, 1862, these residents certainly saw the Confederates as unwelcome guests. But this was certainly not without exception as you will soon see. George and Ellen Crouse had eight children. They lived on the south side of W. Main Street, in a house located just west of the later constructed hospital and dwelling of Dr. A.A. Lamar. Mr. Crouse was listed as a saddler in the 1860 census, however other accounts have said that he was a baker and confectioner by 1862. This census shows five children living in the household. One noticeably absent was oldest son, George V. Crouse. Crouse had enlisted in the Union Army and was serving in Company G of the 7th MD Infantry. The middle child, living in the Crouse’s Middletown home, was Nancy, or Nannie, as she would become known later.  Current day view of the house rebuilt in place of the Crouse family's original structure demolished around the turn of the 20th century Current day view of the house rebuilt in place of the Crouse family's original structure demolished around the turn of the 20th century Nannie was born in Illinois on December 16th, 1844. She was 17 years old in September, 1862. Her courageous story defending the Union has always been a favorite of Middletown residents, earning her the title of the “Valley Maid.” Like Barbara Fritchie, the Frederick resident of German stock, Nannie too would have a poem written about her patriotic stand as it involved “the Stars and Stripes.” The major difference between heroines centered on the fact that Nannie was 68 years younger than Dame Fritchie on the alleged day of action—September 10th, 1862. In the December 11th, 1901 edition of the Frederick News, an article appeared which had recently been published in the Commercial Tribune newspaper of Cincinnati, Ohio. The writer claimed that Nannie’s story was the true basis of John Greenleaf Whittier’s poem entitled “Barbara Frietchie.” Here’s an excerpt of that article: Recently Mrs. Nancy Bennett was a guest of her brother, Mr. Charles M. Crouse, a prominent merchant of Cedarville, Ohio, and one day, in speaking of his sister he remarked that she was the real heroine of the poem. Said Mr. Crouse: I do not know how they got Barbara Fritchie’s name connected with the matter. She was a distant relative of our family and lived at Frederick, eight miles from Middletown, and at no time during the invasion of the Confederates was she able to leave her death bed at the time. It is known that Mrs. Southworth, the novelist, related to Whittier what she knew of the incident, but he garbled the facts to suit his fancy, or else he did not get the straight of it at all. At any rate, I can vouch for the truth of the matter, though I was only a boy of 10 years. My father was a red hot Union man, and of course, us children were demonstrative patriots; especially Nan, though a girl of few words. Her demonstrations were acts. We had a neighbor, a hotel keeper, who was as strong a sympathizer for the Southern cause as we were for the North, and he openly and daily taunted my sister whenever he saw her, particularly when she would fling to the breeze from the second story window of our house her big flag. One day on returning from the grist mill with a boyfriend, we met Jackson and his staff. He asked me several questions concerning Middletown and the roads thereabouts. He was a very pleasant, kindly spoken man, and his personality affected me pleasantly. On leaving us he asked if there were any Yankees about. “You’ll find plenty of them if you go far enough” I replied boldly, though with considerable trepidation for the consequence. He smiled and rode away. Charles M. Crouse then proceeded to tell of an even greater tale involving his older sister, and the flag she proudly flew at the Crouse family home in Middletown. He read an article written by a citizen of the town who observed an amazing drama scene play out while standing across the street from the Crouse home in September 1862, just a few short days before the nearby Battle of South Mountain. Unfortunately, the Rebels who would stop at the Crouse residence were far less chivalrous than General Jackson. The following account of the incident was published in the July 19th, 1906 edition of the Frederick News: Early in September a detachment of Confederate cavalry rode into Middletown and seeing the flag floating proudly in the breeze, halted in front of the house. A dozen of the cavalrymen quickly dismounted and were rushing up the steps of the porch to tear the flag down when Miss Crouse, who was a beautiful and superbly formed young lady, stepped out on the porch with her chum, Miss Effie Titlow, now Mrs. Effie Herron, of Washington, D. C. Miss Crouse demanded of the Confederates what they wanted. "That damned Yankee rag," said a big trooper, moving toward the door as if to enter the house and tear the flag down. Miss Crouse, anticipating the rebel's intention, with a taunt sprang past him, rushed up stairs, hauled down the flag and, draping it about her form, returned to the porch, looking the very impersonation of the Goddess of Liberty. Again the Confederate demanded "that damned Yankee rag." Again was his demand refused. Drawing a revolver, the brutal soldier placed the barrel at Miss Crouse's head and swore he would kill her if she did not surrender the flag. "You may shoot me, but never will I willingly give up my country's flag into the hands of traitors," boldly declared Miss Crouse. Again the demand was made with drawn revolver and, seeing that the odds were against her, Miss Crouse finally handed the flag to the captain, who tied it around his horse's head and rode away. A detachment of Union Cavalry was notified of the occurrence and they pursued and captured every man except the captain. The flag was secured and returned to Miss Crouse.  The former site of Motter's Tavern The former site of Motter's Tavern Later research has shown that the company consisted of about 20 Confederates (which made a dash out to Middletown) and had been assigned to camp in Frederick. These were native Virginians under the command of Captain Edward S. Motter, youngest son of the late John S. Motter. The Rebel captain formerly resided at Fountaindale Farm, two miles east of town. Motter’s father and grandfather kept a tavern here named Fountaindale Inn, fronting the Old National Pike (MD40Alt), at the intersection with current day Hollow Road. Although later histories recount Nannie’s rival hotel keeper as Samuel D. Riddlemoser, the census of 1860 shows the hotel was owned and operated by Riddlemoser’s son-in-law, Andrew Poffenberger. Two black servants are listed living with Poffenberger, as well.

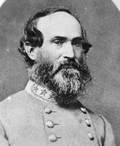

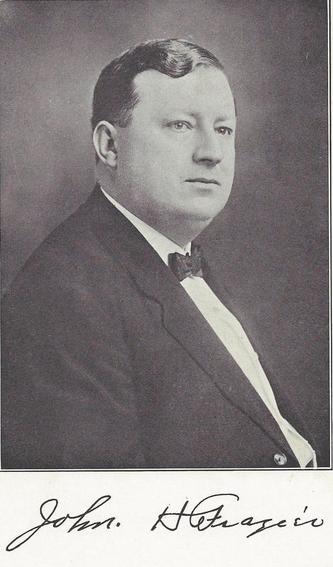

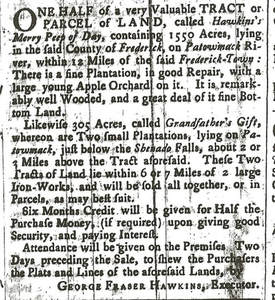

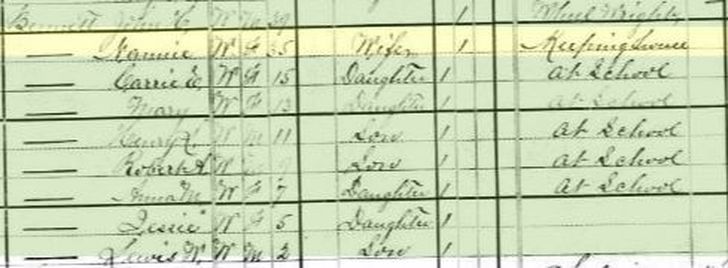

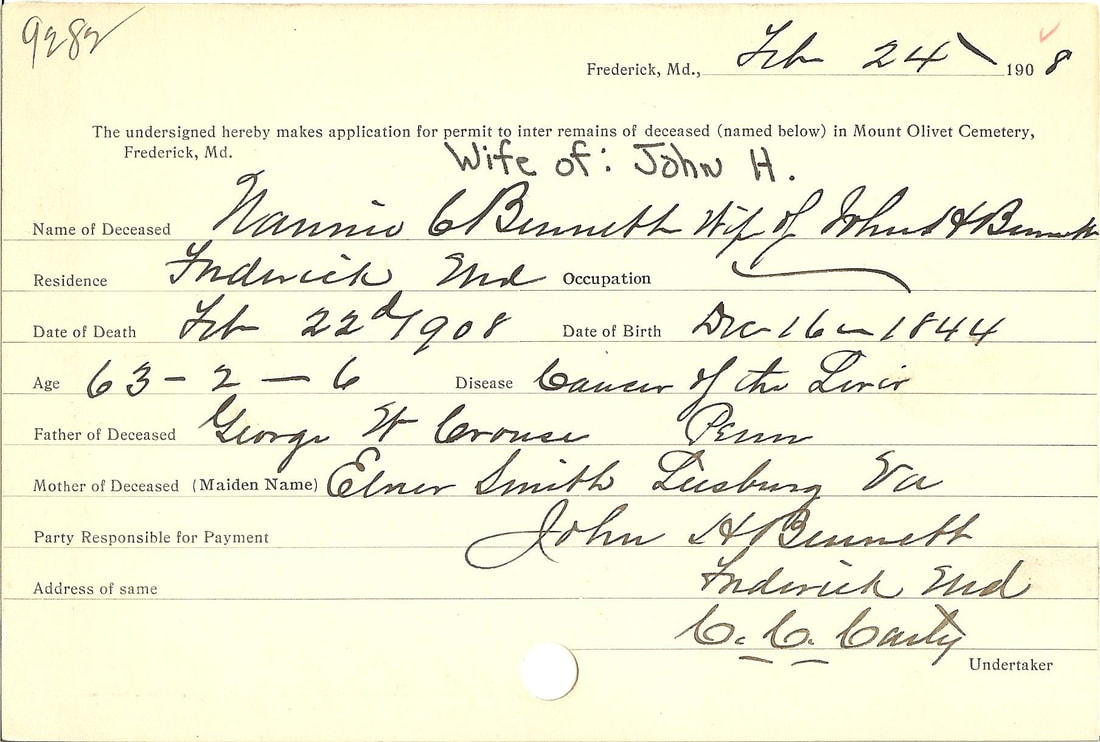

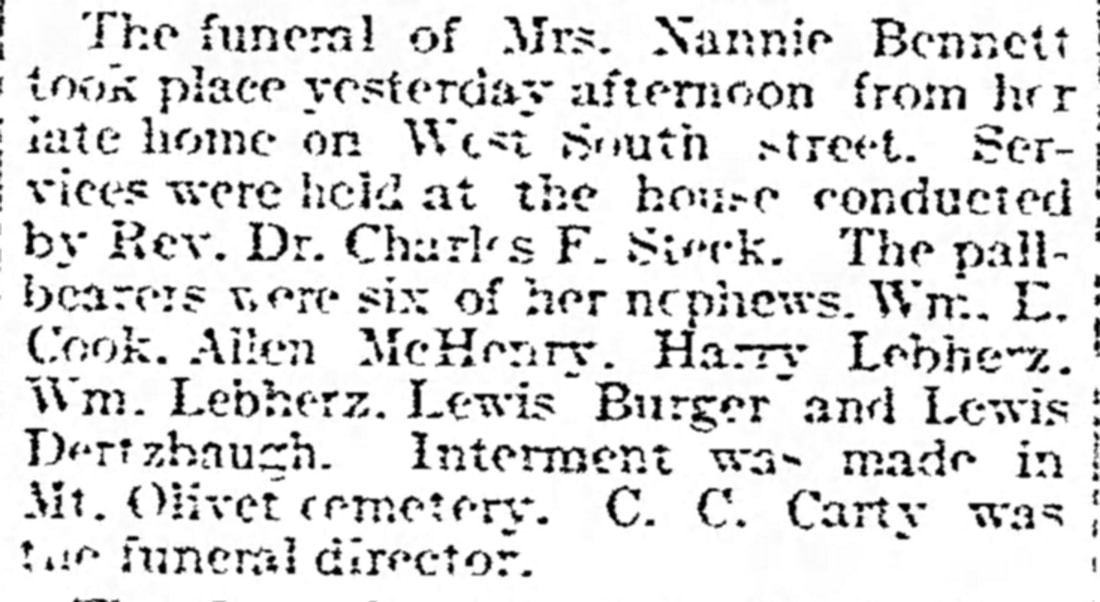

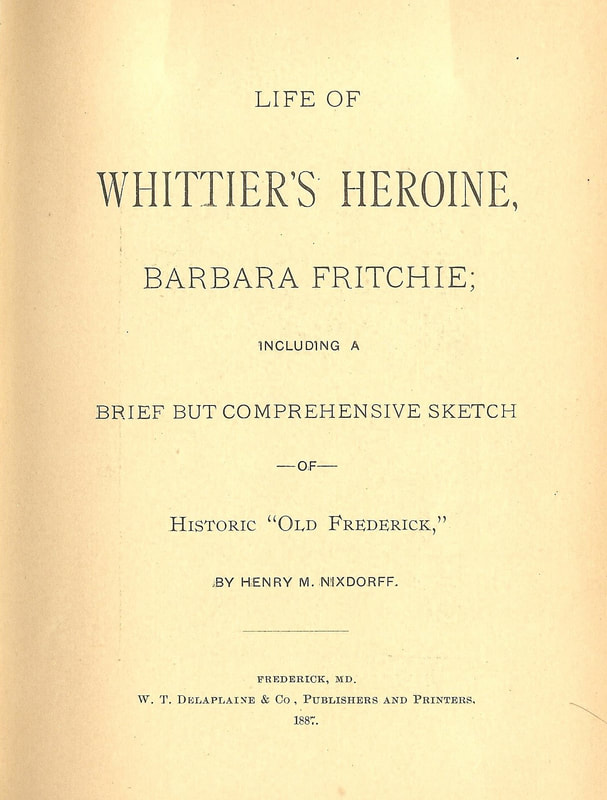

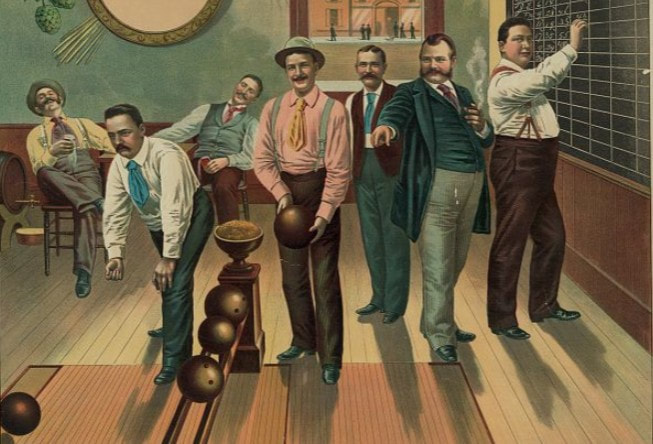

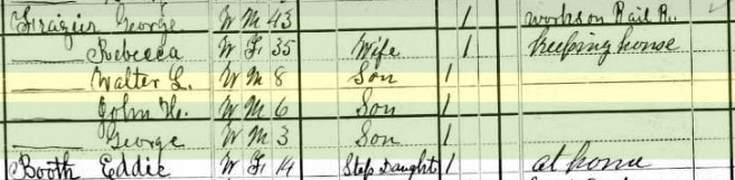

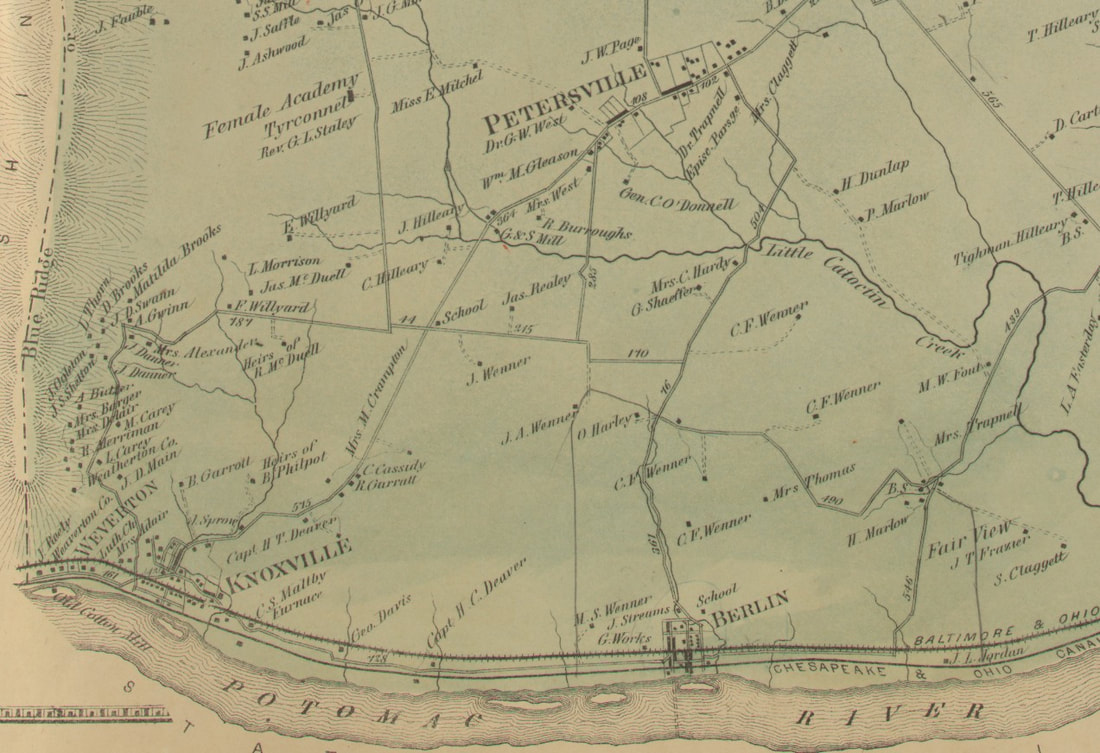

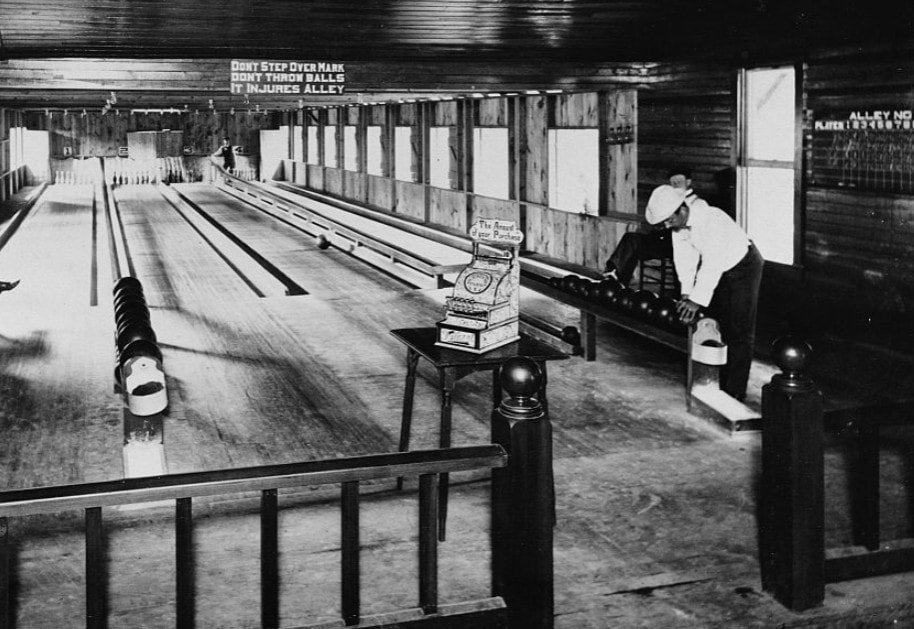

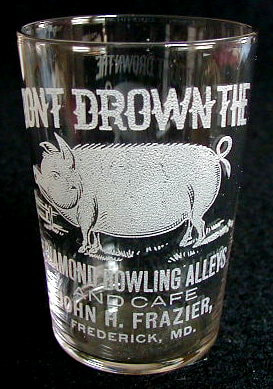

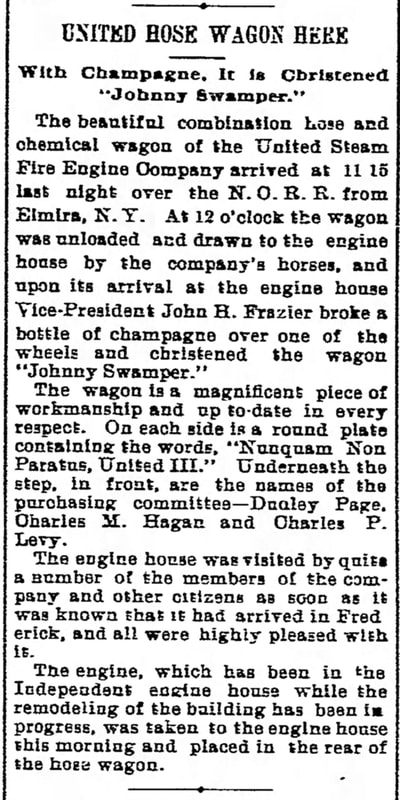

Confederate Gen. Jubal A. Early Confederate Gen. Jubal A. Early Well Nannie may have kept a low profile solely due to the fact that she was seven months pregnant. She would give birth to the couple’s first child, Carrie, on October 3rd, 1864. However, an apocryphal story exists about an employee of John Bennett’s who supposedly had a chance meeting with Gen. Early at the time. John Murdock, a free black, worked for Bennett’s wheel right business. As the story goes, Murdock was chosen by city authorities to carry the ransom to the grumpy Confederate general, who had placed a $200,000 bounty on Frederick, or he would destroy the town. When the delivery was made, Gen. Early supposedly told Murdock to spread the money on a blanket so that he might count it. He did so, but found that the payment was $2.35 short. At this, Murdock frantically turned out his pockets and found enough coins to make up the difference—thus saving Frederick from the Rebel torch. Whether true, or not, John Murdock would happily proclaim this accomplishment for years to come. Another interesting aside from this amazing time in our local history is that former US Vice President John Breckinridge, himself, led troops through Frederick and into the battle just south of town. I’m sure he was gracious to those 3,617 folks who voted for him back in 1860.  Julia Marlowe (1865-1950) Julia Marlowe (1865-1950) Nannie lived the humble life of a housewife, raising eight children in her home located, at 24 West South Street. The home still stands on the south side of the street within the first block. have never seen a photograph of Nannie Crouse Bennett, but I'm sure one survives based on the fact that she had so many children. Based on descriptions of her and my mind's eye, I like to think that she looked like early actress Julia Marlowe who played the role of Barbara Fritchie in Clyde Fitch's stage production of the same name. It opened in 1899, and Barbara would be portrayed as a young woman of Nannie's age, not to mention beauty. A poem, “The Ballad of Nancy Crouse” was written sometime around 1906, as it appears in the Valley Register and Frederick News that year. The author was poet/novelist Thomas Chalmers Harbaugh of Casstown, Ohio. Harbaugh was born in Middletown in 1849, but his family removed to Ohio just two years later in 1851. A nationally published author, Harbaugh could have been inspired to write the poem about his birthplace after seeing the Charles Crouse interview of 1901 in the Ohio newspapers. Sadly, he certainly didn’t receive the same public response as Whittier, with his “Barbara Frietchie” poem published in the Atlantic Monthly magazine in 1863. The Ballad of Nancy Crouse By Thomas Chalmers Harbaugh You’ve heard the story of Nancy Crouse, The Valley Maid who stood one day Beneath the porch of her humble house And boldly defied the men in gray; Over Catoctin’s lengthening ridge, Out from many a bosky glen, Down the pike and over the bridge, Booted and spurred, rode Stonewall’s men. Under the spires of Middletown Glinted many a rebel gun; The dear old flag, they said, must down, Nor flaunt its folds in Autumn’s sun; Mighty legions clad in gray Cursed the banner of the stars, And o’er the hills and far away Streamed the standards of the bars. Nancy Crouse looked out and saw The old flag floating on the breeze, Emblem fair of truth and law; Then as suddenly she sees Foam-flecked steed and rider stem Who the standard has espied; With an oath his hot lips burn, For the flag he turned aside. From the house the maiden springs, Grips the flag and round her form Wraps it while the cool air rings With the portent of the storm; With an oath the wretch in gray Tries away the flag to tear, Whilst the girl’s eyes seems to cry; Bold, defiant: “If you dare!” Closer to her form she claps The beauteous flag our fathers gave, And the rebel’s oaths and gasps Threaten her with early grave; “Not for you!” her words rang true, “Not for you this banner fair; You wear gray, its friends wear blue, It was blessed with many a pray’r.” With a final curse and threat Rides the rebel far away, And the flag once more is set Over the porch to taunt the gray; Smiling, Nancy sees the horde Vanish down the village street; Gleaming gun and swirling sword Once more in the distance meet. Honor to the Maryland maid Who the banner saved that day, When through autumn sun and shade Marched the legions of the Gray; Middletown remembers yet How the tide of war was stayed, And the years will not forget Nancy Crouse, the Valley Maid. Gone are Stonewall’s legions true Battle drums have ceased to beat, And the Banners of the Blue Wave not in the village street; But the years on Nancy brave Will of praise bestow the need; Time for her will honor crave, And the world will hail her deed!  Alton Young Bennett (1897-1976) Alton Young Bennett (1897-1976) The “Valley Maid” would pass away on February 22nd, 1908 at the age of 63Nannie Crouse was laid to rest in Mount Olivet Cemetery’s Area B/Lot 2. To the left of her grave is that of Henry M. Nixdorf, author of Life of Whittier’s Heroine of Barbara Fritchie and former neighbor of both Ms. Fritchie and Mary Quantrill, another forgotten flag-waver who actually confronted soldiers and a Confederate officer on September 10th, 1862. Another interesting irony has become evident involving the formerly mentioned patriotic females. Both Barbara Fritchie and Nannie Crouse had former relatives who were shown to be downright unpatriotic. It cost two men their lives. Interestingly, even though it was after the fact, Nannie Crouse’s mother in law (Mary Bennett) was born Mary Suman. This same Mary Ann Suman Bennett was a great-granddaughter of Peter Balthasar Suman–one of the seven men found guilty of treason in the 1781 Tory Conspiracy. He was also executed on August 17th, 1781 along with fellow conspirator (and Barbara’s father-in- law) Caspar Fritchie. On the flipside, Nannie’s grandson, Alton Y. Bennett would spend most of his life in the Frederick County Courthouse. He practiced law for 52 years, serving as trail magistrate for 17 years. Mr. Bennett, a Democrat, also served in the Maryland Legislature (starting in 1923) and devoted himself to countless local civic affairs. Good thing Nannie handed over that flag, as her most important legacy isn't patriotism, it is family and descendants.  What better story to have for Labor Day weekend than one featuring a former Frederick resident and businessman who seemed to derive a great deal of fun from everything he did. This gentleman surely didn’t look at his job as work, but more as a form of recreation and sport. I guess that’s because his work was directly related to amusements of sort. His name was John H. Frazier. Up until four days ago, I had no earthly idea about this gentleman—frankly I had never heard of him. After just a few days of reading and research, I now feel like I’ve known him for years! With several story ideas in the pipeline for upcoming weeks, I decided this past week that I would try something different in respect to my Labor Day topic—I didn’t want to put much “labor” into choosing my subject. I simply grabbed the second volume of T.J.C. Williams History of Frederick County. For those not familiar with this work, Williams published this two-volume classic, history work in 1910. Volume I is a chronicled history of the county, while Volume II contains biographies of past residents. This second volume was a sales gimmick on the part of Williams at the time, which still pays dividends to us history wonks and genealogists today. Williams sold subscriptions up-front to county residents for his history set. For those that bought into it, he offered the opportunity to have a biography/ personal family history included in Volume II. Anyway, for my labor day-based, “labor free” choice of subject, I just closed my eyes and opened up Williams’ History of Frederick County (volume II). My draw was page 1160, introducing me to the biography of John H. Frazier, complete with a photo.  Maryland Gazette ad from Aug. 1, 1765 Maryland Gazette ad from Aug. 1, 1765 Birth of a King Pin Born in the greater Knoxville area of south-western Frederick County on April 30th, 1874, John Henry Frazier has family roots in this area dating back to the Colonial era when George Frazier acquired lands originally patented by John Hawkins of Prince Georges County. One such was a portion of “Hawkin’s Merry-Peep-o-Day,” a 3,100-acre land grant from King George II of England. This original parcel comprised most of the area we today know as Brunswick, eastward to Catoctin Mountain, and received its unique name from the vantage point it gave each morning with the rising sun seen directly over Catoctin Mountain. Our subject was the son of George Washington Frazier and wife Rebecca Donaldson. George was employed by the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad as a laborer, as were two of his brothers. In addition to his parents, John H. Frazier’s family consisted of five children, three boys and two girls. John was in the middle. In the 1880 census, the family can be found living in the hamlet of Weverton along the Potomac, just west of Knoxville. The children attended school locally, but things would change drastically for them in the mid 1880’s when John’s mother died in 1885 at the age of 41. As was common with male widowers of the day, the children were dispersed to relatives due to George Frazier’s hard, blue-collar profession.  St. John's Literary Institution (c. 1890) St. John's Literary Institution (c. 1890) Now at 11 years of age, John was sent to Frederick City to live with his Uncle Edward Frazier, a railroad engineer. He took up residence in south east part of the city near the old B&O Train Depot (S. Market and All Saints streets). Sadly, John’s father would die less than two years later in 1887. Young John Frazier would attend St. John’s College on East Second Street. Originally opened in 1829, this school was positioned next to St. John’s Catholic Church and better known by its official name of St. John's Literary Institution for boys. He was taught by Jesuit priests in this academic rival to Georgetown College in Washington DC. Throughout these formative years, John worked as a message carrier for Edward Keefer, the depot telegraph operator for the B&O Railroad. This job introduced the former country boy to a great deal of city residents of all socio-economic levels. Frazier also learned business acumen from Mr. Harry E. Krise, working in the Krise & Dean grocery store once located at the southeast corner of S. Market and E. All Saints streets (directly across from the B&O passenger depot). This section of Frederick would serve as the center of his professional and personal life.  Frederick News (May 2nd, 1896) Frederick News (May 2nd, 1896) Break Point One decade after the death of his mother, John H. Frazier would be married on June 27, 1895. His bride was a Baltimore girl named Mary A. Finneran, daughter of a restaurant operator. Ten days later, according to Williams History of Frederick County, Frazier “embarked in the saloon business at the corner of Market and All Saints’ streets.” Perhaps he received additional guidance from his new father-in-law. I wasn’t able to ascertain the exact location, but it appears to be the former location of the old Krise & Dean corner grocery. As the 21 year-old was cutting his teeth as a young business owner, an incredible opportunity arose the following year, just a few doors up the street. Former Mayor Mathias E. Bartgis was looking for a buyer for his popular saloon and bowling alleys located next to the agricultural implements business of P.L. Hargett. The business was advertised in early April within the local newspaper as “one of the best paying saloons in Frederick, with stock and fixtures, comprising pool and billiard tables, a cash register, fire proof safe, 2 large ice boxes, and everything complete for a first class bar.” In Frazier’s eyes, it likely seemed the opportunity of a lifetime. He purchased the Bartgis’ business, (no. 58-60 S. Market Street ) on May 1st, 1896. He reopened as the Diamond Café and Bowling Alleys.

All the while, the saloon-keeper never lost sight of his family, and strove to give four children a happier, and richer childhood than he had experienced, solely due to the deaths of his parents at such a young age. The Frazier’s children included Marie, Estella, Louisa, and John H., Jr. Mr. Bartgis died in 1907, and John bought the latter’s fine, three-story brick, at 56 S. Market Street for $4,750. The next year, he made extensive improvements to this structure for his family home. It was located next to his café. At this time, He also took the opportunity to enlarge the bowling lanes, making this one of the best facilities in all of Western Maryland. Meanwhile, John H. Frazier kept his body strong as a member of the YMCA, and his mind and spirit sound as a faithful congregant of All Saints Episcopal Church. As his café and bowling alleys gave local residents much in the form of fun, Frazier took over another related amusement located on W. 4th Street. This was the former roller-skating rink located in a structure named Groff Hall. He did extensive renovations and renamed the business the Diamond Roller Rink, what else? He advertised skating accompaniment would be made by an orchestra. John H. Frazier promoted additional physical and athletic recreational endeavors in the years 1908-1910 in the form of semi-pro baseball and basketball in Frederick. In 1910, he even managed the Diamond Basket Ball team to a state championship.

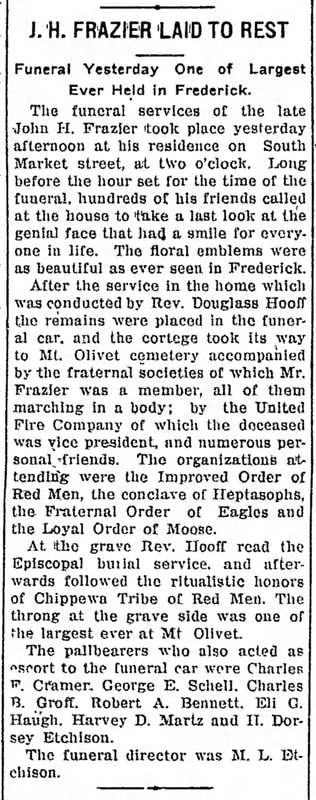

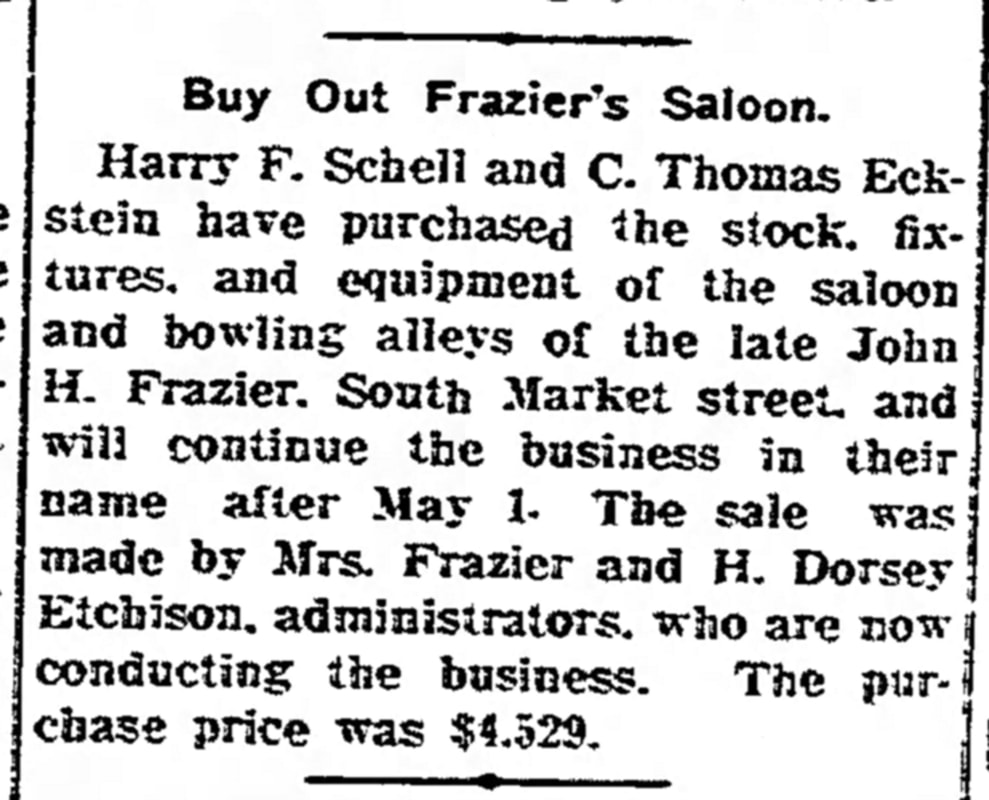

Frederick Post (March 13, 1913) Frederick Post (March 13, 1913) The Last Frame Unfortunately, Frazier suffered a major health setback in early March. He traveled to Washington with friends to participate in the presidential inauguration of Woodrow Wilson. While there, he suffered a double hernia and experienced tremendous pain difficulty in getting back home to Frederick. Not feeling better after a few days, the saloon-keeper extraordinaire made the decision to check himself into Frederick City Hospital. While there, he underwent surgery. Articles appearing in the Frederick News in subsequent days showed signs of improvement. However, all of that would change drastically on March 15th, when his condition reversed, and plunged quickly as the hours went on. John H. Frazier faded fast, as March 16th would be his last. He was only 38 years-old. A life dedicated to providing amusement and community service to his friends and neighbors was extinguished—gone was Frederick’s “Mr. Fun.” Touted as one of the largest attended funerals to date, John Frazier would be laid to rest in Mount Olivet Cemetery’s Area S (Lot 116) on March 19th, 1913. A fine monument bearing his surname would be placed here, along with a modest footstone including only his name and vital dates. Wife Rebecca would not join him here until 47 years later in 1960.

Demolition Day for the S. Market Street properties, March 7, 2016. (Photo courtesy of the Frederick News-Post) Demolition Day for the S. Market Street properties, March 7, 2016. (Photo courtesy of the Frederick News-Post) One-hundred and four years after Frazier’s death, a thunderous sound, reminiscent of a bowling ball crashing into a rack of pins, was heard echoing through S. Market Street and the surrounding neighborhood. This occurred on March, 7th, 2017 as the blighted façade of Frazier’s former home and Diamond Café and Bowling Lanes was demolished by order of the City of Frederick. I wonder if, somewhere out there, Mr. Frazier was watching intently, and yelled out, “Strike!” from wherever his spirit resides? |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed