|

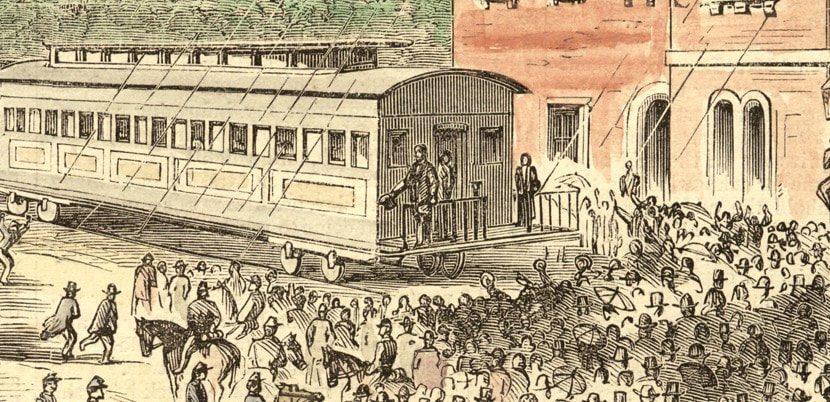

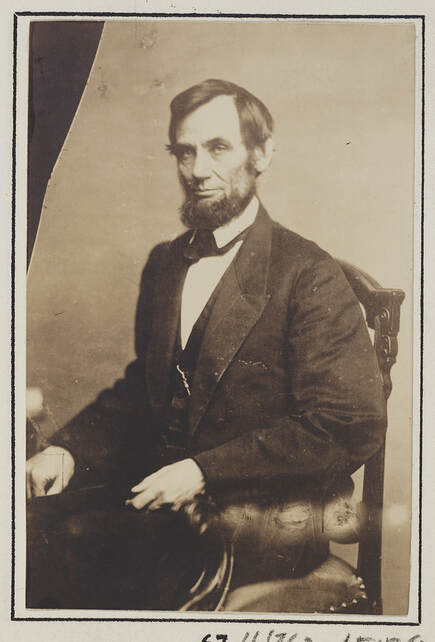

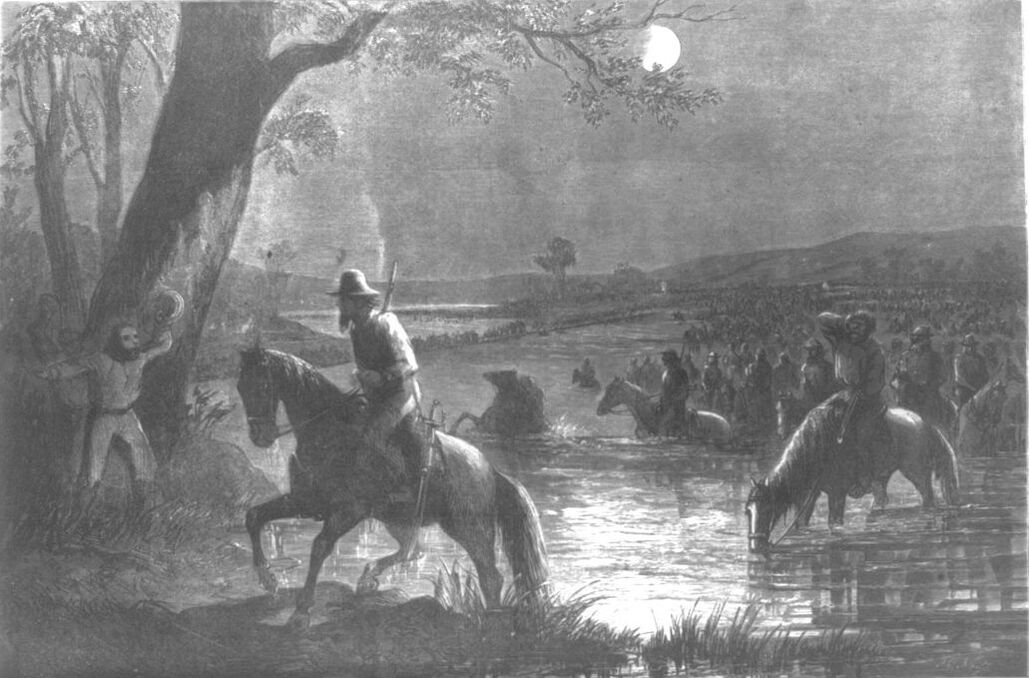

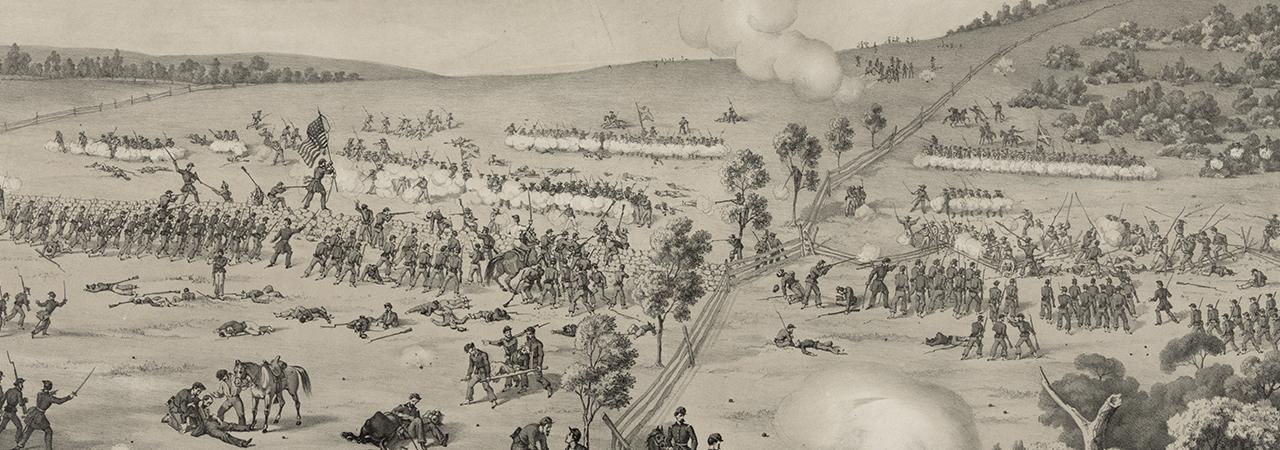

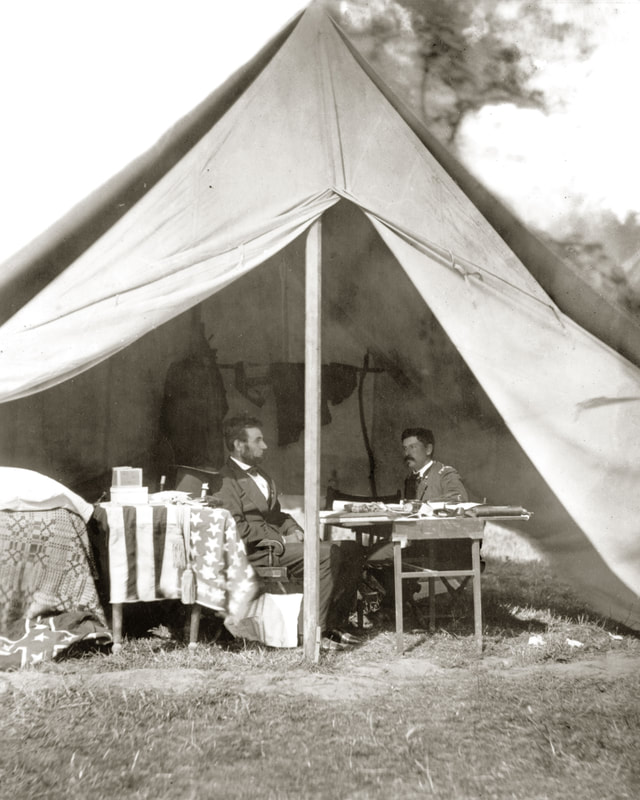

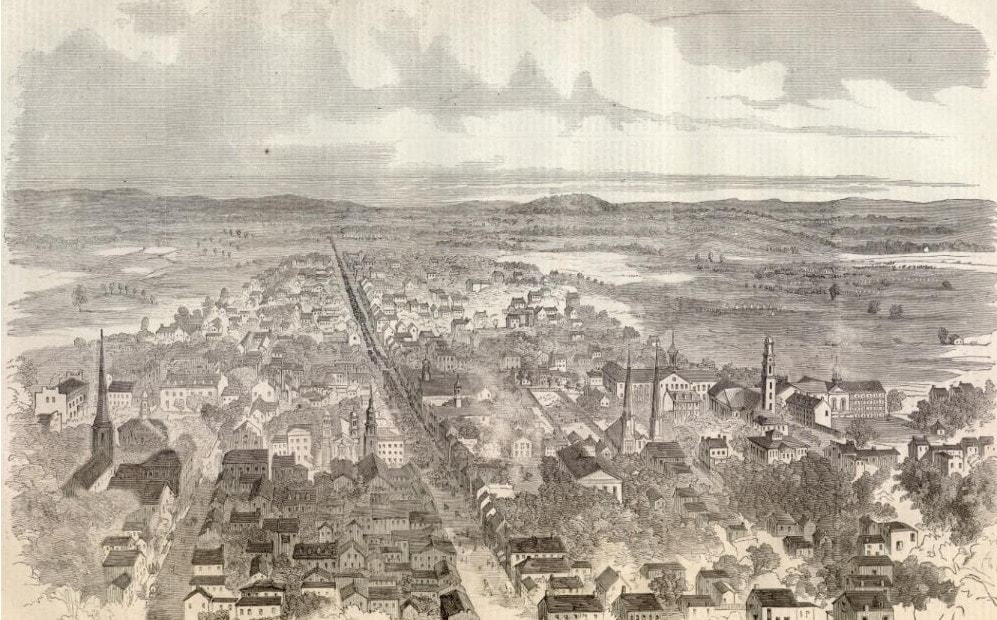

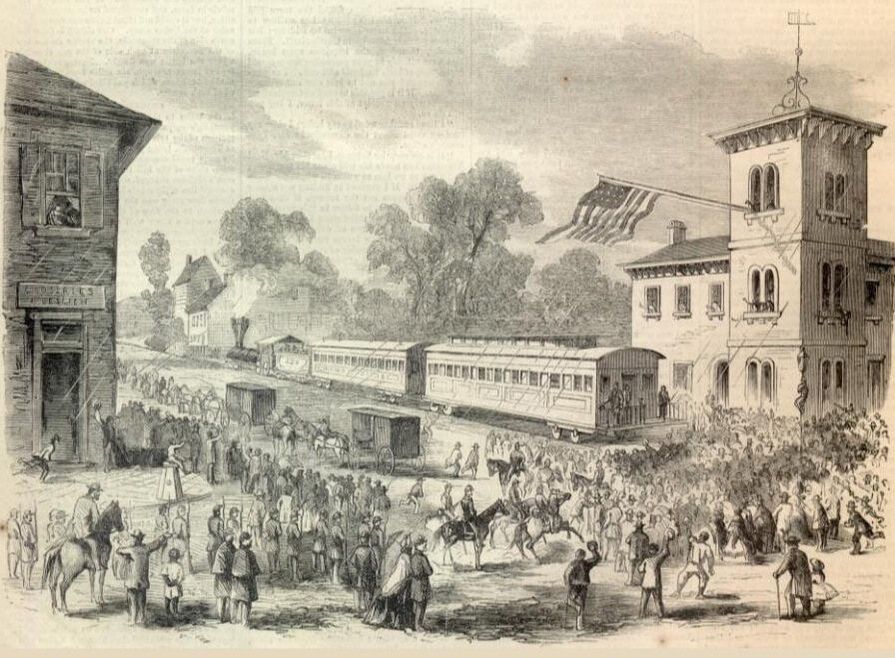

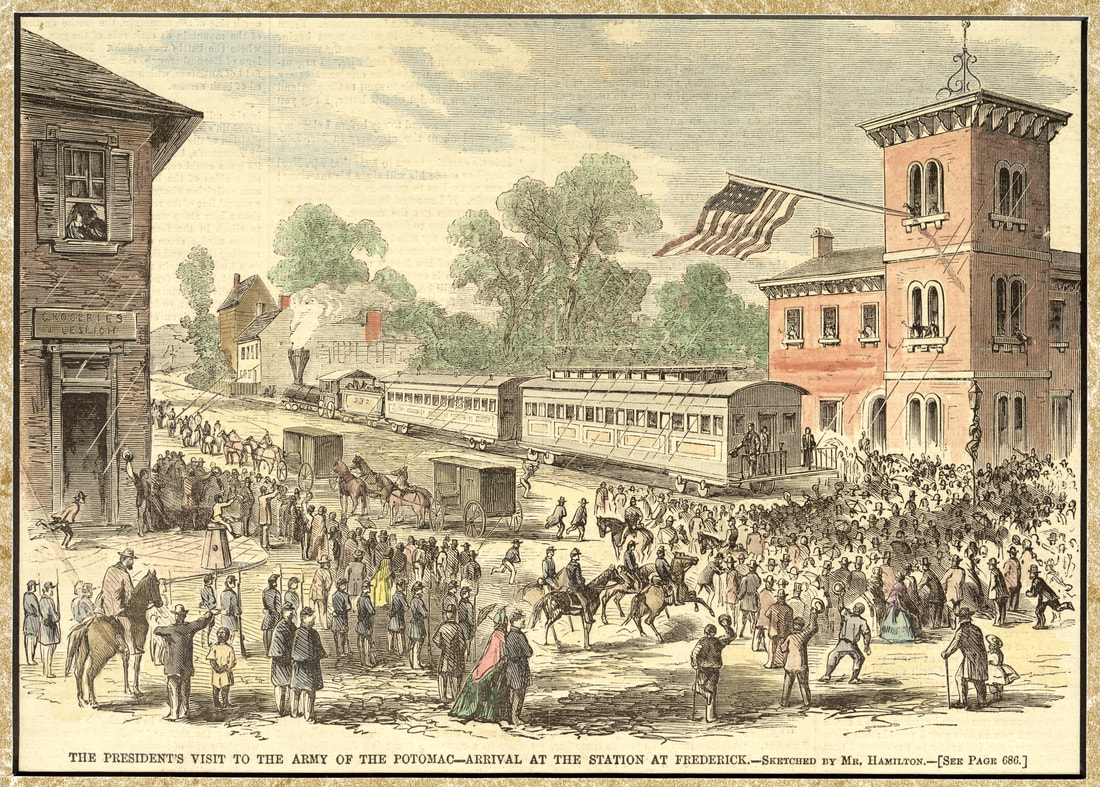

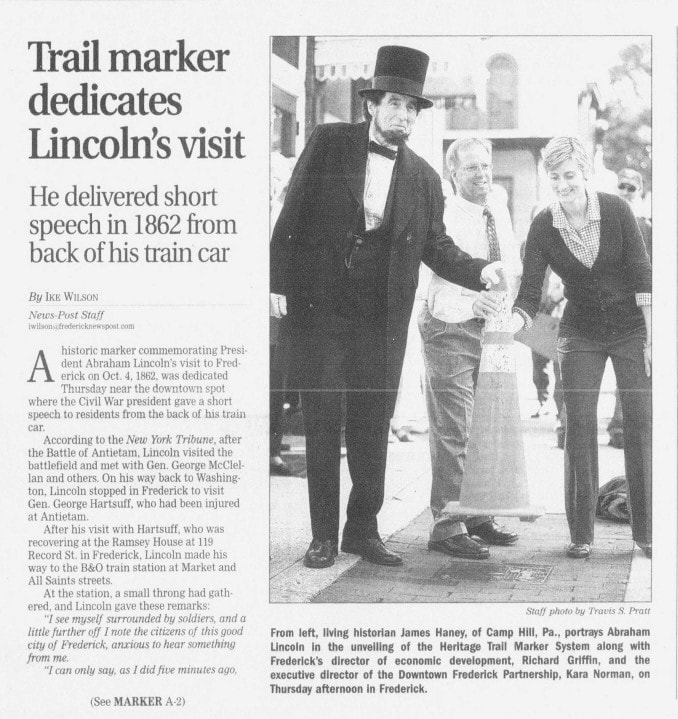

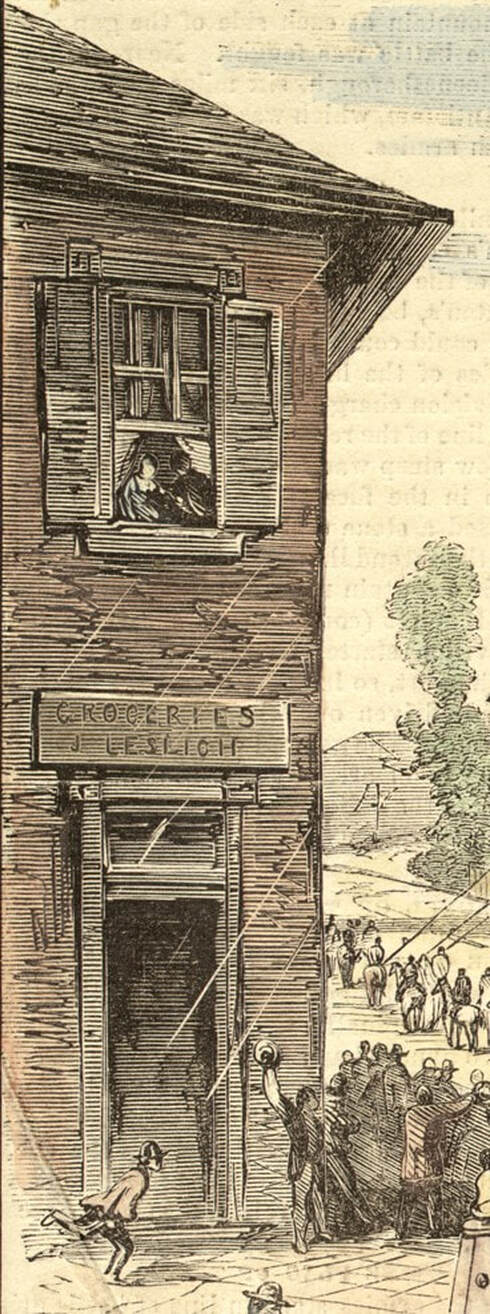

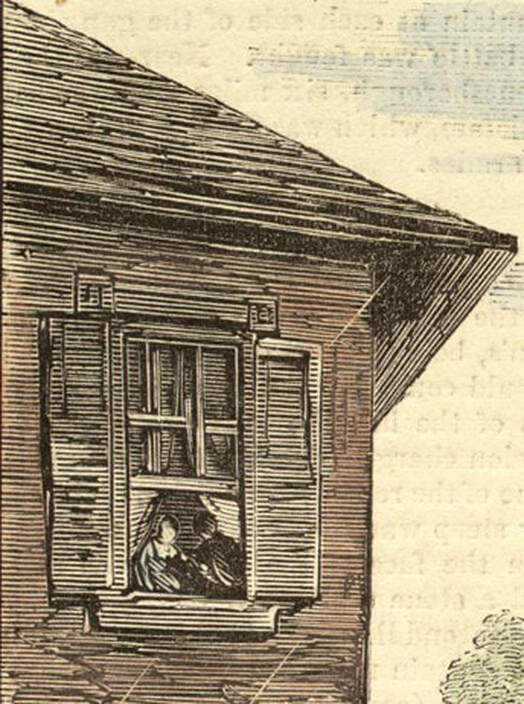

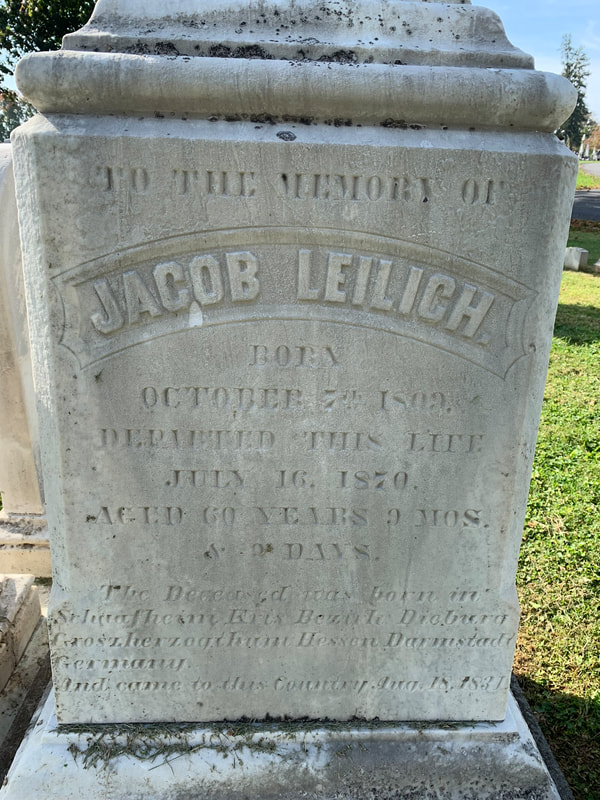

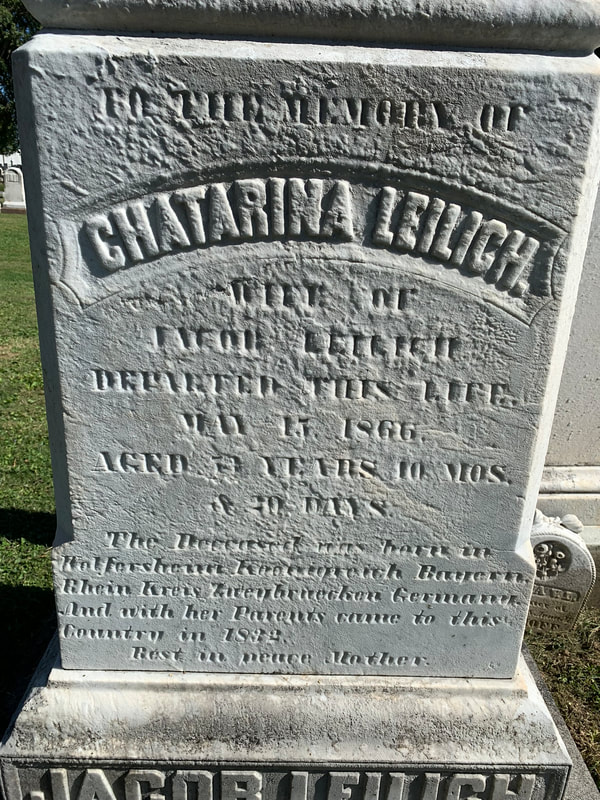

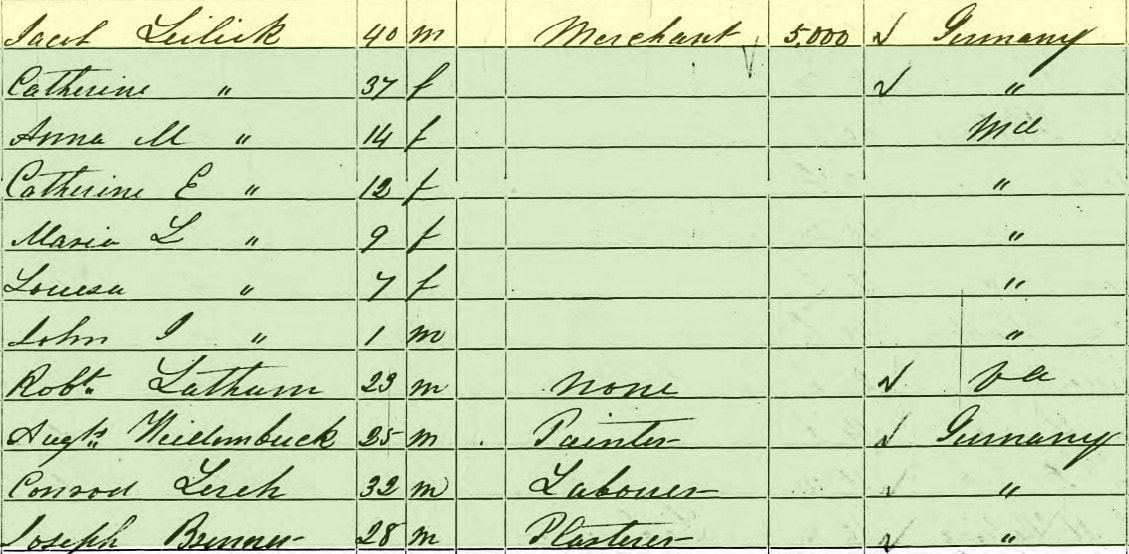

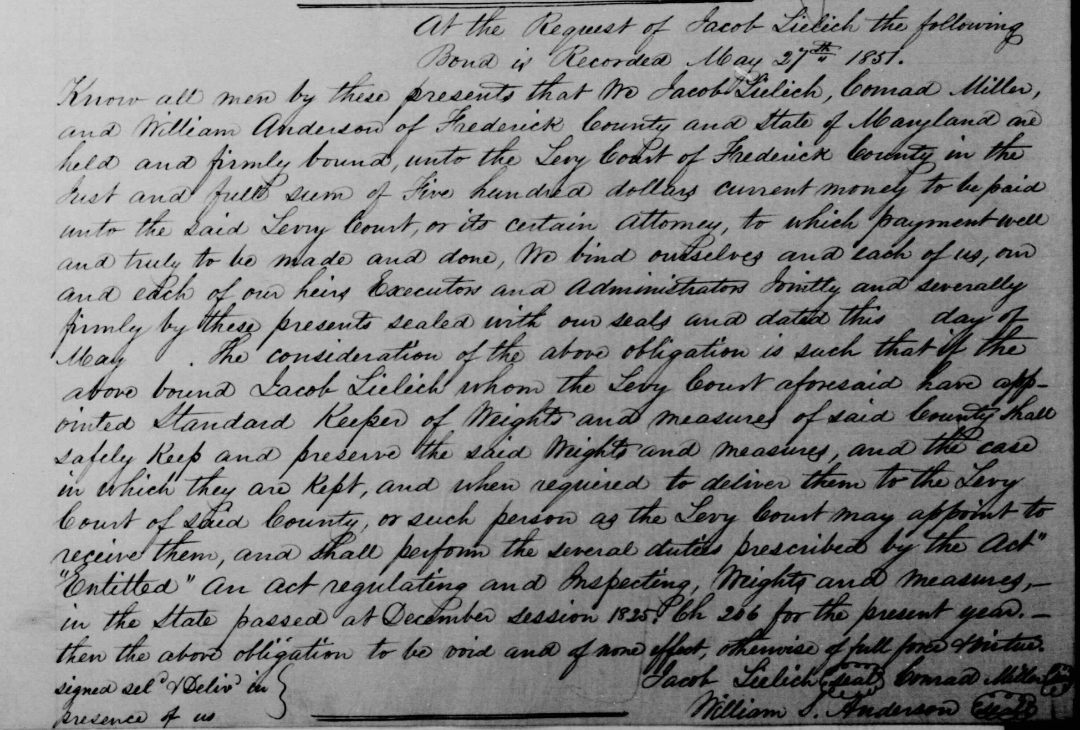

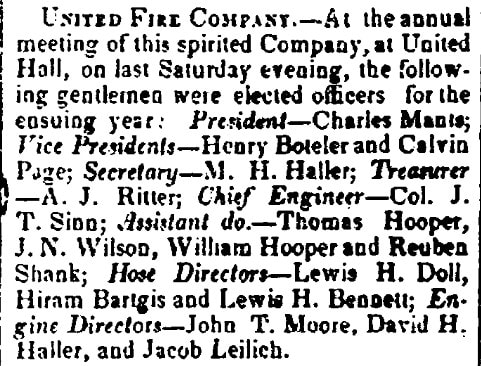

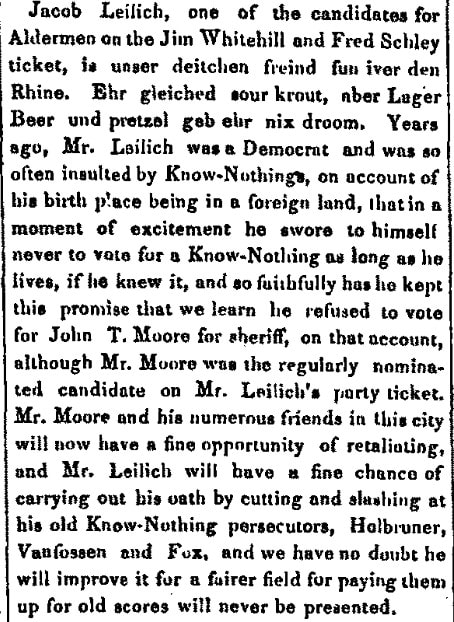

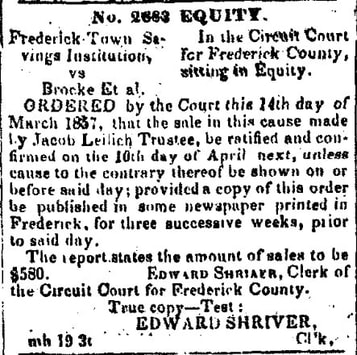

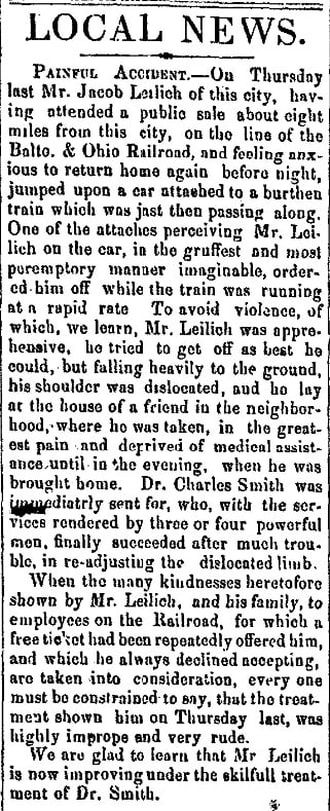

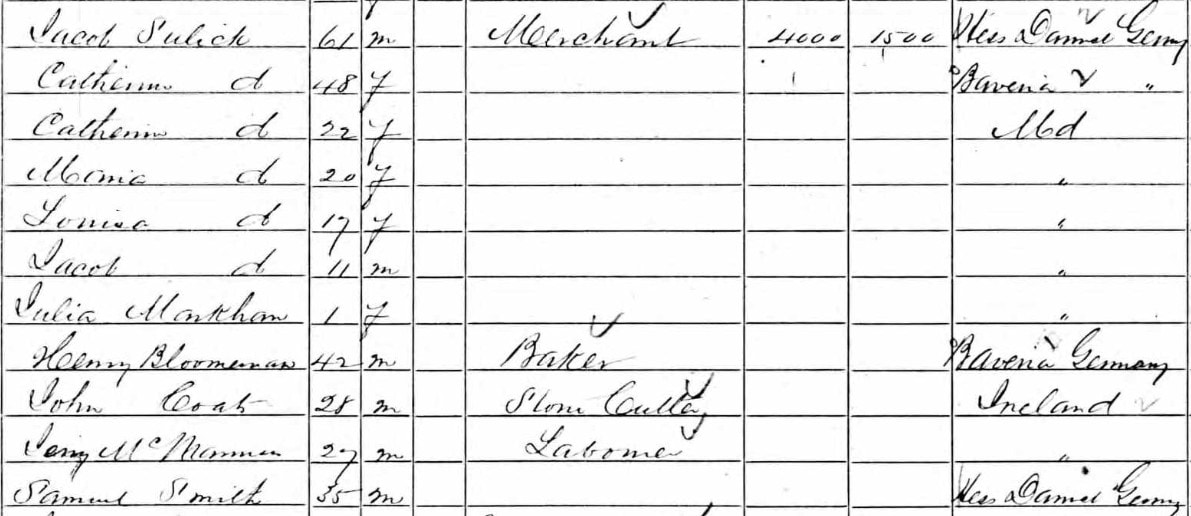

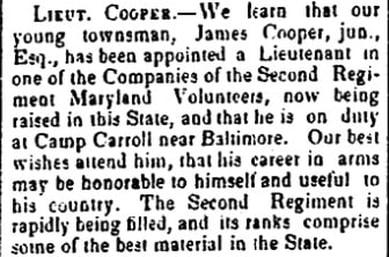

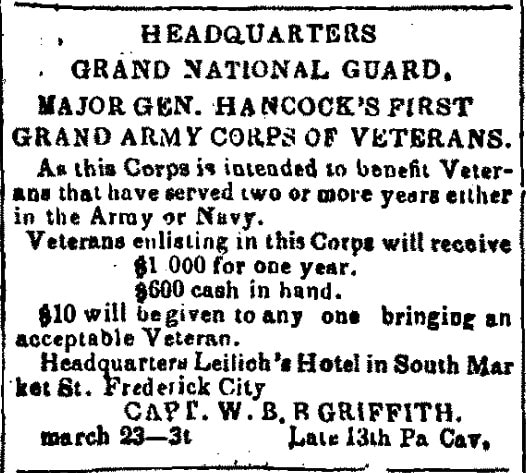

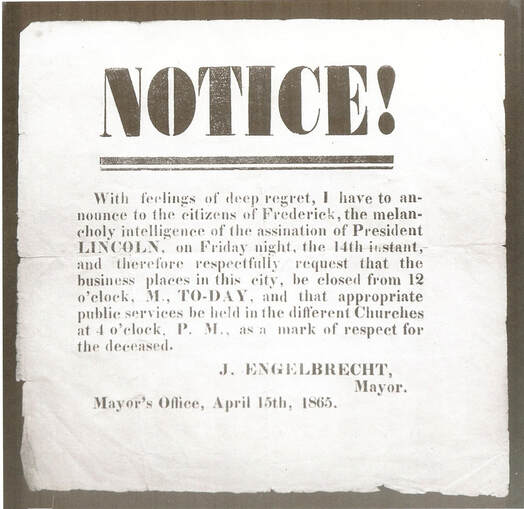

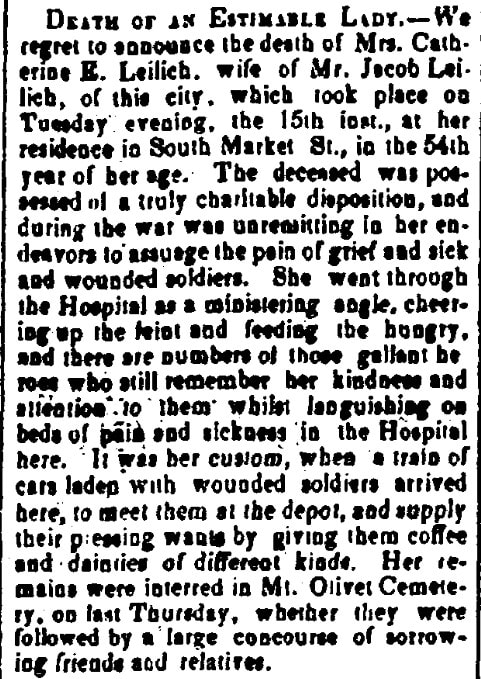

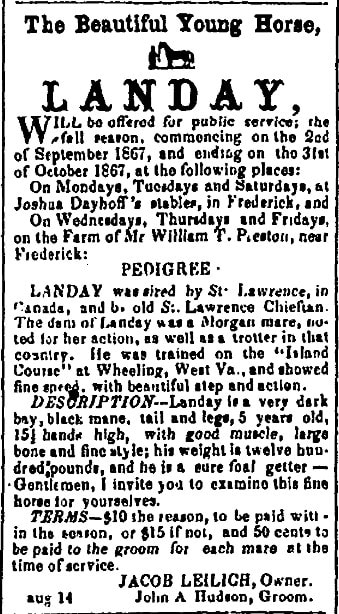

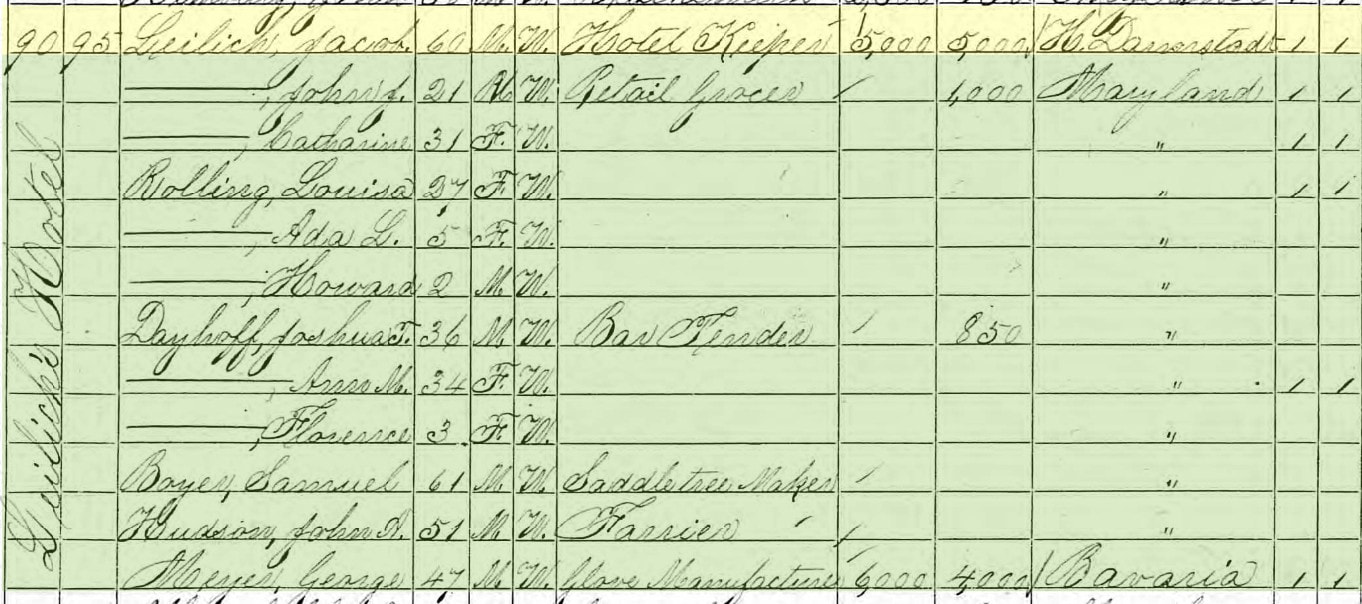

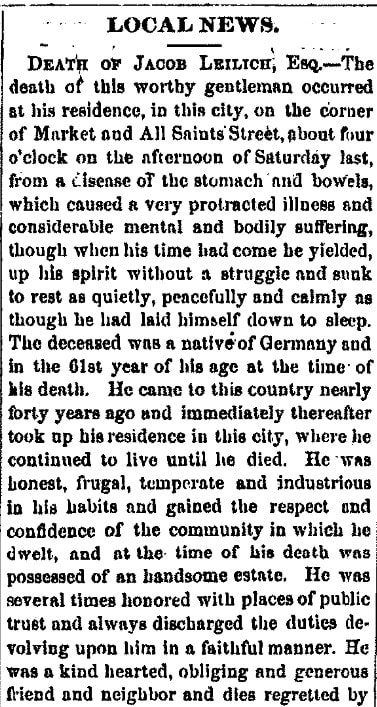

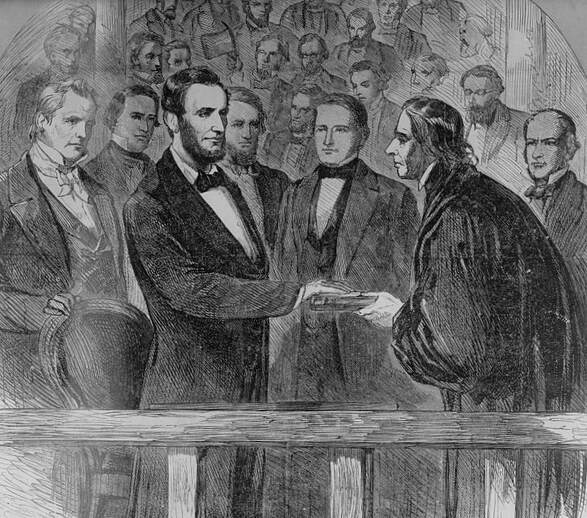

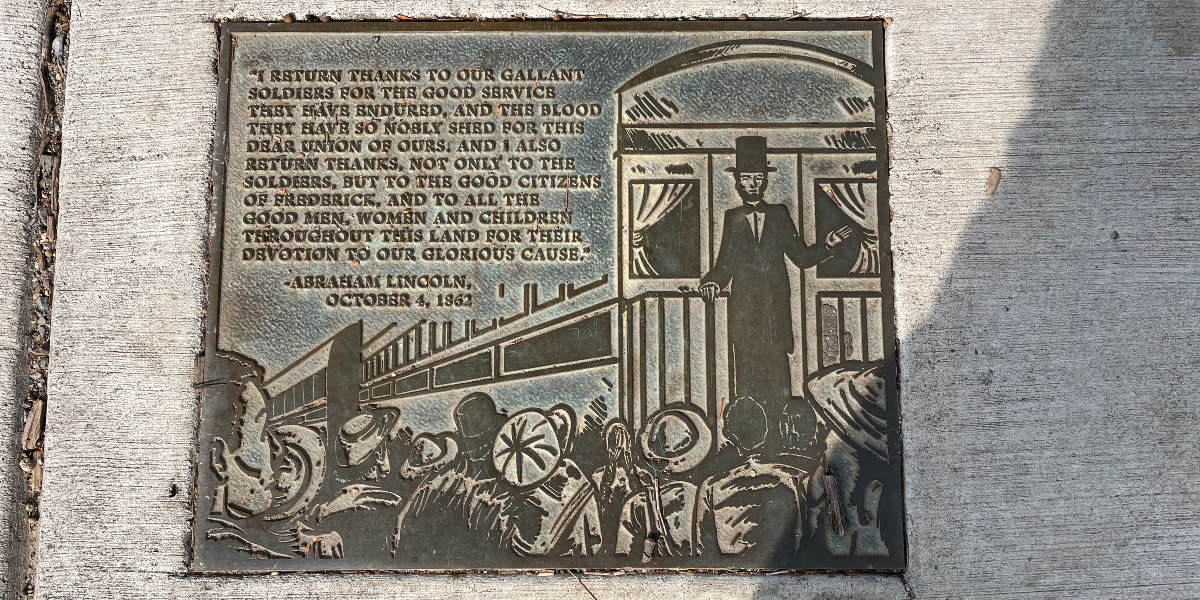

There is a fine, large monument in Mount Olivet’s Area D whose owner can certainly be considered an eyewitness to history. As a matter of fact, he and his family had, what you would call, “a front row seat” (or at worst, balcony seats) to a major moment in Frederick, Maryland’s magnificent history. His name was Jacob Leilich, and his resting spot is along the east side of the cemetery’s central driveway where he is buried with his wife Chatarina. The Leilichs were not alone in their memorable observance on the late afternoon of Saturday, October 4th, 1862. Several members of the town’s citizenry were also on hand for an impromptu speech given at the old Baltimore & Ohio Railroad’s passenger station at the corner of East All Saints and South Market streets. The oratory was made by our legendary 16th President of the United States—Abraham Lincoln. One of the most interesting aspects of this experience for Mr. Leilich (and his family) comes in the fact that he never had to leave his home—the oratory came from the back of a train car that was parked right outside his window. The Leilichs lived in the building directly across East All Saints Street from the train station, today the home of Downtown Piano Works (74 South Market Street). The former train station is better known as the Frederick Community Action Agency, home of the Frederick City Food Bank. The Leilichs operated a hotel and grocery store as part of their spacious home which stretched down East All Saints Street. I know from researching/writing other stories that the neighboring house to the north on South Market was home to Jacob Haller’s Tavern, a popular oyster saloon for many years, conveniently located across from the United Fire Company (which still operates to this day.) First off, I’d like to talk about President Lincoln’s speech and what brought him to Frederick in early October of 1862. We will conclude with a look at Jacob Leilich and his family. President Lincoln Exactly one month earlier, Frederick County found itself at the hands of what many townspeople thought were invaders. Others, however, saw these men as liberators. Either way, the soldiers of Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia had crossed the Potomac into Maryland after a successful late August victory in the Second Battle of Manassas, also known as the Second Battle of Bull Run. Frederick would be the first, major northern (or Union) town that Lee would bring his Confederate Army. Those students of Civil War history (among you) know that the occupation of Frederick lasted almost a week until Lee made a move west. The Union Army of the Potomac, under Gen. George B. McClellan, headed north toward Frederick out of Washington, DC in pursuit of the Rebels. After the supposed flag-waving episode of Barbara Fritchie (September 10th, 1862), the Confederate Army continued west on the old National Pike, making use of today’s Alternate US 40 over Braddock Mountain, through Middletown and across South Mountain. Here the armies would engage one another on September 14th in the Battle of South Mountain. Three days later on September 17th, both sides squared off outside the small town of Sharpsburg in the Battle of Antietam, the bloodiest one-day battle in American history. This conflict was deemed a Union victory and helped set the stage for President Lincoln to issue the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. My friend, and fellow historian, Dennis Frye gives great context to this episode in American Civil War history in Maryland’s Heart of the Civil War: A Collection of Commentaries. (The written transcript is below) (DENNIS FRYE) Abraham Lincoln had a great victory given to him by the Army of Potomac; keep in mind that when September begins the Confederate Army is invading Maryland. Lee's compass is pointed towards the Mason-Dixon Line and he has every intention of crossing it and moving towards the Susquehanna River. Now, here we are the 1st of October, the Confederate Army has been defeated, Maryland is safe, Pennsylvania is secure, Lincoln has issued his Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, it was one of the most extraordinary months, turnarounds of the war for the Lincoln administration. So the president wanted to come out and congratulate the men that gave him and the United States this great victory. So on the 1st of October, he gets on the B&O train, first comes to Harpers Ferry, meets the troops, greets the troops, inspects the troops at Harpers Ferry and then comes to Sharpsburg. He establishes his home with McClellan at McClellan's headquarters at the Showman home just south of Burnside Bridge and there he will meet with McClellan, he will talk about what the Army had accomplished, what the future should be, and even had his own ideas for the campaign. Lincoln always had his own ideas, and he and McClellan talk about what the next step will be. Well, as so often was the case, Lincoln and McClellan did not agree. McClellan intended to utilize the Shenandoah Valley as the base of operations. The president said, no, we're going to go east to the Blue Ridge and move back towards Richmond, huge debate, complete disagreement. But in the meantime, the president would go out, review the troops, complement them, praise them and really feel that this army had matured into an army that could truly give him victory and he had proven it on the banks of the Antietam Creek. Well, after the meetings were completed, and they never did come to an agreement on what their future would be, the president would leave via Keedysville, Boonsboro, South Mountain. He would actually cross the mountain and see part of the South Mountain battlefield. So he didn't just visit Antietam, but he actually visited three battlefields on this trip, Harpers Ferry where his forces did not succeed, of course there at Antietam where he visited famous landmarks like the Burnside Bridge, and then on his way back he went via Boonsboro and South Mountain and then Middletown and ultimately to Frederick. And when he arrived at Frederick there was a train there awaiting to take him back to Washington. And there was a throng, a huge crowd there to greet the president. And the president didn't really like to give “just off-the-top” speeches but the demand was great, they wanted to hear from the president. And so there at the train station at Frederick, he stood on the back of his car, the presidential car, and made a little speech to the citizens of Frederick. They were happy with it. The speech didn't say much, but it was a very nice little speech, the president of the United States in Frederick speaking to those Union citizens who in their mind had stood up against the tyranny of the rebels. And with that off he went back towards Washington. From Sharpsburg, President Lincoln would travel to Frederick City where he received an enthusiastic welcome complete with “signal guns and a parade.” Arriving around 5:00pm, Lincoln visited Brig. Gen. George L. Hartsuff of Michigan, who was injured in the morning phase of the battle at Antietam. Hartsuff was recuperating in the home of Mrs. Eleanor Tyler Ramsey, a short distance from the town’s courthouse square. After visiting the general, Lincoln gave a brief impromptu speech to a group assembled outside the Ramsey House, then made his way to Frederick’s B&O train station for the return trip to Washington. When he arrived at the station, the president found himself surrounded by a large crowd of citizens, soldiers and free blacks. We are very lucky to have a depiction of this event from the exact period. It was sketched by Mr. Hamilton, a Civil War sketch artist for the newspapers of the day. The lithograph appeared in the October 25th, 1862 edition of Harper’s Weekly newspaper. The newspaper also provided the following text to describe the image, along with a transcript of the president’s speech: THE PRESIDENT'S VISIT TO McCLELLAN'S ARMY. We publish on page 684 an illustration of the President's visit to Frederick. His journey through Maryland was one continuous and triumphant ovation, and will have the effect not only of teaching the rebels how little they gained by their last raid upon the affections of "My Maryland," but of convincing Northern traitors that henceforth we may count her as irrevocably fixed to the Union. A vast concourse of people had assembled at the railway station at Frederick; and the President had no sooner got away from those who rushed to shake hands with him, and reached the train, than loud cries brought him to the platform of the rear carriage, to show himself and speak to his friends. This is the moment seized upon and illustrated by our artist. The President, in a clear voice, and with that honest, good-natured manner for which he is so noted, spoke as follows: (Written transcript included below) “Fellow Citizens: I see myself surrounded by soldiers, and a little further off I note the citizens of this good city of Frederick, anxious to hear something from me. I can only say, as I did five minutes ago, it is not proper for me to make speeches in my present position. I return thanks to our soldiers for the good service they have rendered, for the energies they have shown, the hardships they have endured, and the blood they have so nobly shed for this dear Union of ours; and I also return thanks not only to the soldiers, but to the good citizens of Maryland, and to all the good men and women in this land, for their devotion to our glorious cause. I say this without any malice in my heart to those who have done otherwise. May our children and our children's children to a thousand generations, continue to enjoy the benefits conferred upon us by a united country, and have cause yet to rejoice under those glorious institutions bequeathed us by Washington and his compeers. Now, my friends, soldiers and citizens, I can only say once more, farewell.” Abraham Lincoln October 4, 1862 I have a framed, original copy of this lithograph from an old Harper’s Weekly edition. Mine is even hand-colored and I have hanging in my office. The Lincoln speech event of 1862 is especially near and dear to my heart because I helped organize a re-enactment of it back on October 4th, 2012. This was the 150th anniversary of Lincoln’s legendary visit to Frederick. Our Lincoln portrayer that day was James Hayney of Camp Hill, PA. The day culminated with the official unveiling of the Downtown Frederick Heritage Trail Marker System. One marker commemorates Lincoln's 1862 visit and was placed in front of the Leilich former home. As an aside, before our downtown event at the old train station, Mr. Hayney (as Lincoln) entertained schoolchildren at Lincoln Elementary School a few blocks to the south. Interestingly, the Leilich gravesite affords a view of this school. One day, I looked at the lithograph very closely, scouring the individuals depicted in Lincoln’s audience. My eye wandered over to the building sketched on the far left and saw that the artist had included a sign over the door fronting on South Market Street. It reads: Groceries J. Leslich. It should read Leilich, but it was either misspelled by accident, or by design. From there I did my research, and here we are a few years later. One more thing, I will kindly draw your attention to in respect to this particular art piece, is the presence of individuals by the Leilich’s front door and, moreso, people visible in the upstairs window. Were any of these folks Jacob, Chatarina or, more likely, the Leilich children? We may never know, but I guarantee that you will never look at this particular lithograph quite the same when you see it again! Jacob Leilich First off, you may be interested to know that the name Leilich is German in origin, and constitutes the 1,052,587th most common surname in the world at the time of our publishing. I couldn’t find a meaning for the name. The Leilich monument in Area D is pretty impressive and among the largest of the section. It is also educational, including brief biographies on both Jacob, and wife Chatarina (Blumenauer) Leilich. “To the memory of Jacob Leilich Born October 5th, 1809 Departed this life July 16, 1870. Aged 60 years 9 mos. & 9 days. The deceased was born in Schaafheim, Kris Bezirk Dieburg Broszherzogthum Hessen Darmstadt Germany and came to this Country Aug. 18, 1831." "To the memory of Chatarina Leilich Wife of Jacob Leilich Departed this life May 15, 1866 Aged 53 years 10 mos. & 20 days. The deceased was born in Wolfersheim Koenigsreich Bayern, Rhein Kreis Zweybruecken Germany and with her parents came to this country in 1837. Rest in peace, Mother." I’m not certain as to the exact year Jacob Leilich came to Frederick, but it was between 1831-1834 because he married Chatarina here on April 19th, 1834. From 1835-1859, Leilich owned the property on the west side of South Market Street that is now 75-77 South Market. He had a blacksmith shop there. Leilich bought the 72-76 South Market property in 1845 from Capt. Henry Jefferson Walling, a popular passenger train conductor for the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. You may recall the surname as Henry’s son, “Uncle Joe” Walling was a subject of an earlier “Story in Stone.” Let’s just say that unlike his father who preferred train travel, Joe preferred walking. Jacob Leilich was bonded to the Levy Court as the "Standard Keeper of Weights and Measures" for the county in 1851. In addition to being a businessman, I found newspaper articles showing his connections to civic activities. He was an active parishioner of Evangelical Lutheran Church and a member of the United Fire Company. Perhaps he could have been with the Uniteds (militia) unit in October 1859 when they were among the first responders to Harpers Ferry for John Brown’s ill-fated insurrection attempt? I saw mention that Jacob also catered big events for his fire company, among others. Mr. Leilich indulged himself in local politics as a proud Democrat, and I saw many ads in local newspapers which had him running for various city offices such as town council and the Board of Aldermen. One of the articles talked about his dislike of the Know-Nothing (aka American) Party who were certainly not fond of immigrants. Leilich was slandered for his German heritage. (NOTE: The sentences in German translate roughly to "our German friend from over the Rhine. He likes sauerkraut but not lager beer and pretzels.") As with the hotel-based taverns of the day, these places were often locations of public auctions as they had the accommodations to hold larger public gatherings. Hoteliers, like Jacob Leilich, frequently appeared as trustees for many of these. The most detailed article I uncovered regarding Mr. Leilich chronicled a terrible accident involving train travel and a daring escape in which injuries were sustained. This occurred in August, 1858. The Civil War came to Frederick in so many ways, and it also came to the Leilich’s home—literally and figuratively. Jacob made a recovery at home, but he wasn’t the only one who convalesced at the one-time hotel located on the northeast corner of South Market and East All Saints streets. A unique news article comes from July 1861 when a Union soldier from Easton, Pennsylvania attempted to recover from an illness at the Leilich hotel. I’m assuming that Jacob was a Union supporter, which I’m sure would have been comforting to Private Lerch. Apparently, the hotel had a reputation as a hangout for Union officers and soldiers. This fact could have also led to the location being chosen as the headquarters for the Grand National Guard, Major Gen. Hancock’s First Grand Army Corps of Veterans. As proxies of history for us living today, I wonder how the Leilich family took the news of President Lincoln’s assassination in April, 1865? A candlelight procession of respect was conducted by Mayor (and famed diarist) Jacob Engelbrecht. I’m sure the Leilichs participated. Two significant things happened to Mr. Leilich after the war. His wife of 32 years passed in 1866. A year later, he was offering "stud services" via his horse "Landay." Here is newspaper proof to both of these things. Jacob Leilich continued the hotel as can be witnessed by a newspaper advertisement placed in the local newspaper by a sewing machine salesman who had taken temporary residence in 1867. He also continued his work on behalf of local politics. The 1870 US Census shows “Leilich’s Hotel” still serving home to now widower Jacob Leilich, and four out of five of his children and extended family. In addition, there are three other boarders listed. Three of the Leilich girls would marry. Two of which Anna M. (Leilich) Dayhoff (1836-1888) and Maria L. (Leilich) Burke (1841-1880) are buried here in this plot, along with unmarried Catharine “Kitty” Elizabeth Leilich (1837-1920). The remaining sister, Louisa L. (Leilich) Rollins (1843-?) married a Union soldier from Wisconsin during the Civil War and eventually moved west to Iowa. The Leilichs’ only son, John Jacob, is also buried here (1849-1873) and his name adorns the southside of the large monument. Jacob Lielich died on July 16th, 1870. His robust obituary appeared in the Maryland Union newspaper a day later. He would be laid to rest in the family plot next to his wife. As for the old “Leilich Hotel,” it was sold to Robert Lease in 1874. The property had been advertised for public sale several times following Leilich's death, but one of the executors died and authorization for the other executor was revoked so a new executor had to be appointed by the Orphans Court, hence the delay. Looking at the bigger picture, Frederick County and City remain an incredible case study in Black history. Along with an audience which included freeman and slaves, Jacob Leilich watched as Abraham Lincoln, known later as “The Great Emancipator,” gave a brief speech on East All Saints Street on October 4th, 1862. This neighborhood would become the hub of Frederick’s Black community in the decades and century to come. Interestingly, Roger Brooke Taney, Lincoln’s greatest political rival, would be attributed to a house close to the western end of All Saints Street. This is near the intersection with Bentz Street. This dwelling would eventually become a museum that would interpret the life of Taney, the former Frederick resident and Chief Justice of the Supreme Court who is remembered for writing the majority opinion in the Dred Scott Case. It was also Taney who twice administered the presidential oath of office to Abraham Lincoln. History is simply amazing when you really think of all the intricate connections between events, places and people. Best of all, Frederick and her citizens are part of so many chapters of our great country’s story. As can be found each and every week through this blog, we can learn so much from examination of the lives in those residing in not only our cemetery, but any burial ground.

0 Comments

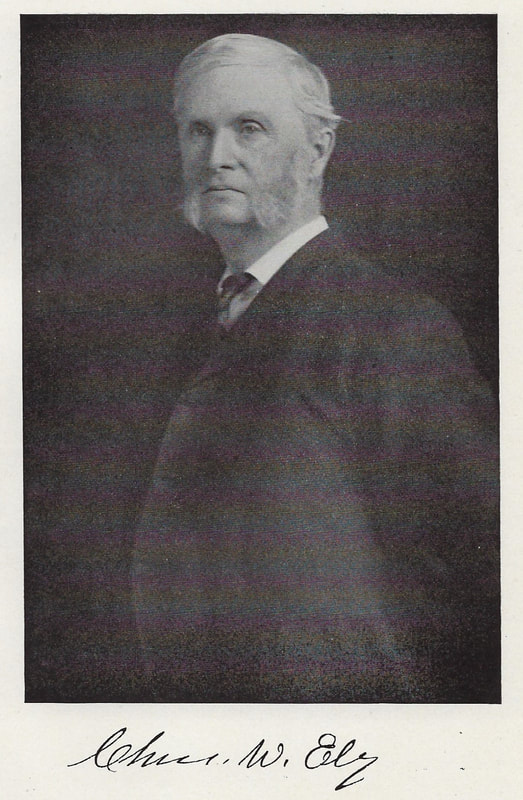

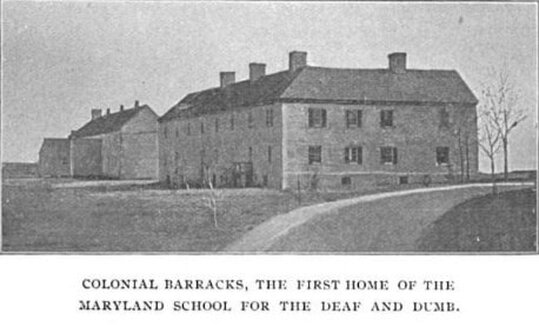

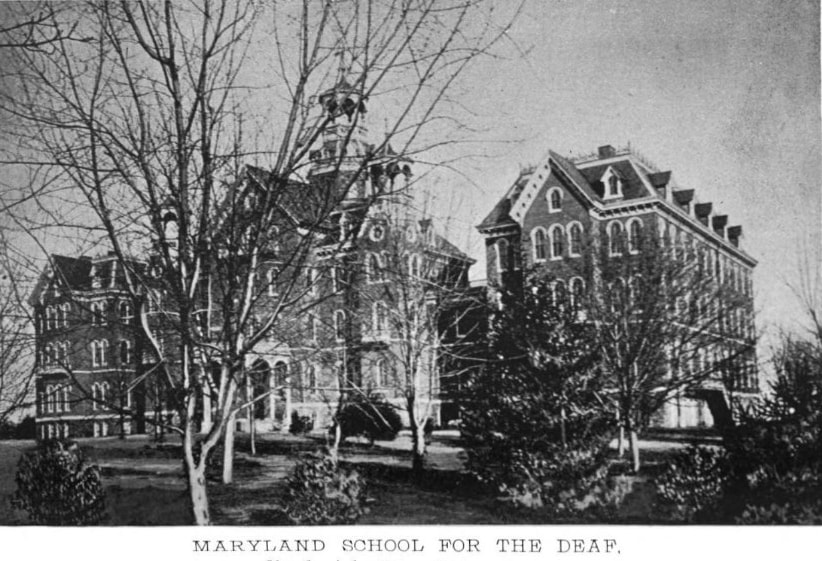

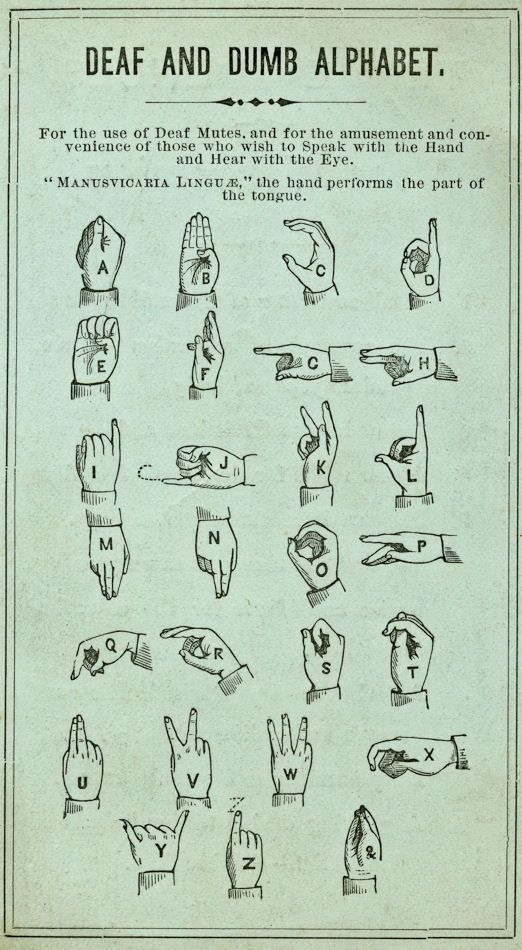

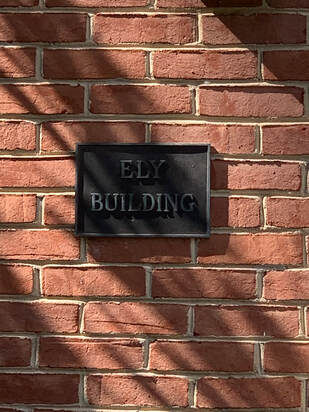

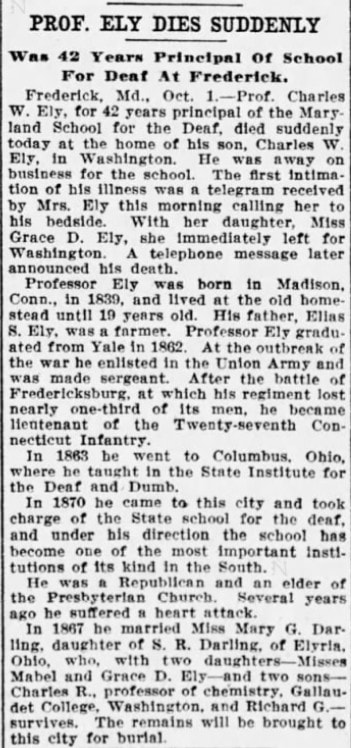

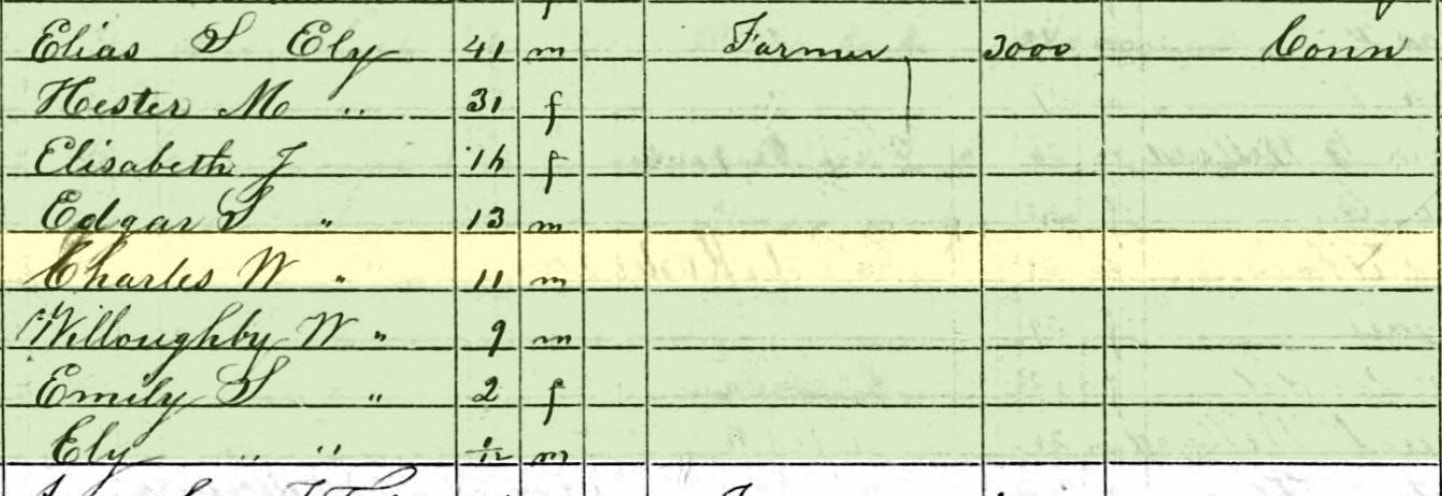

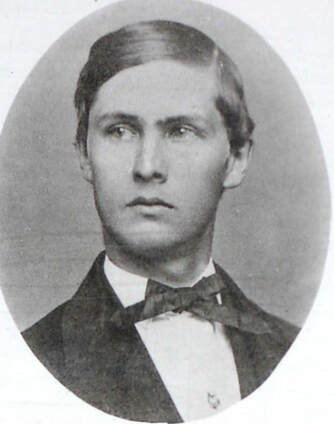

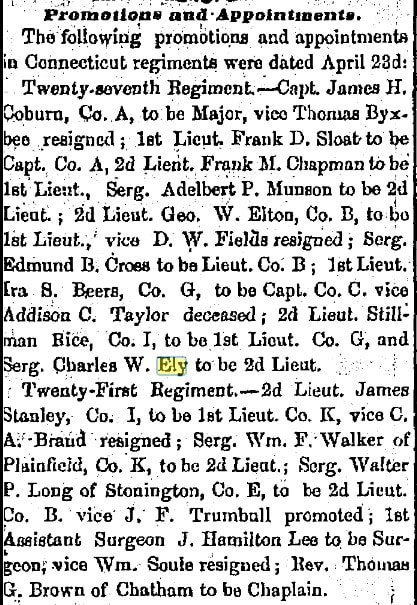

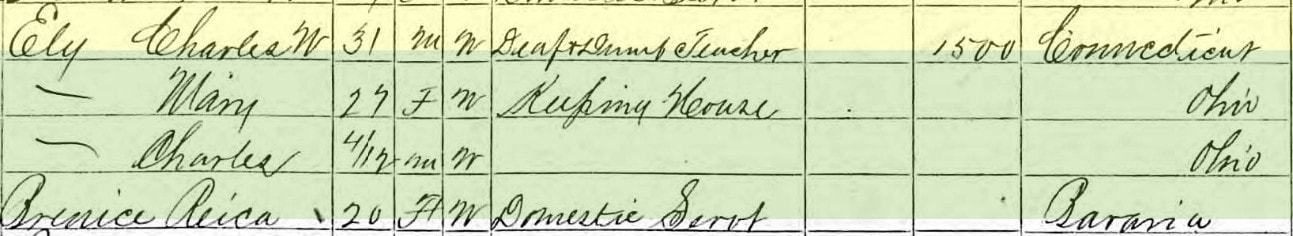

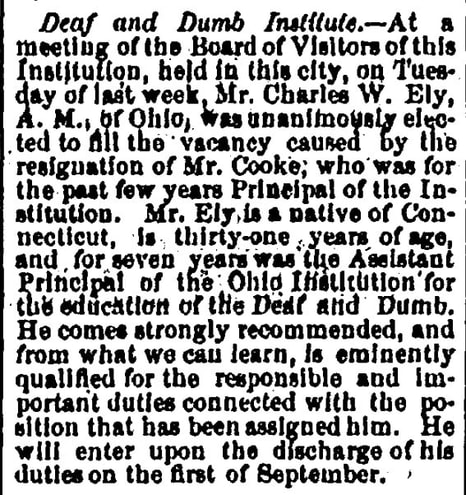

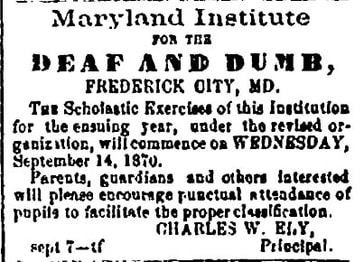

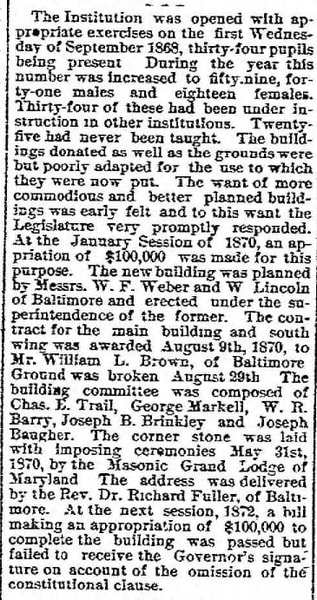

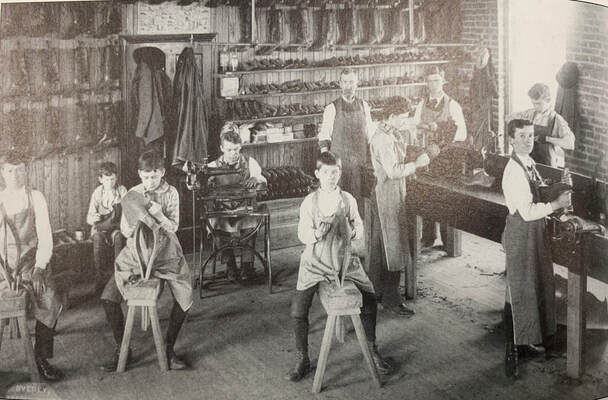

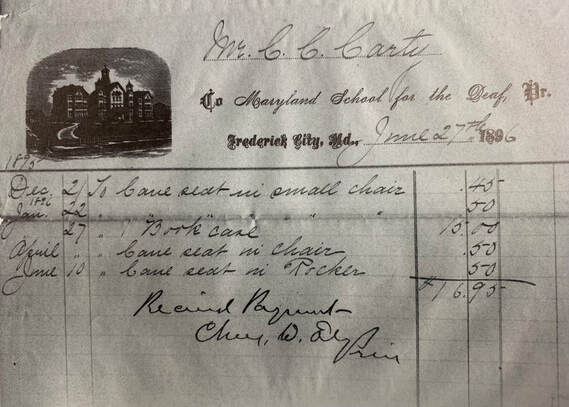

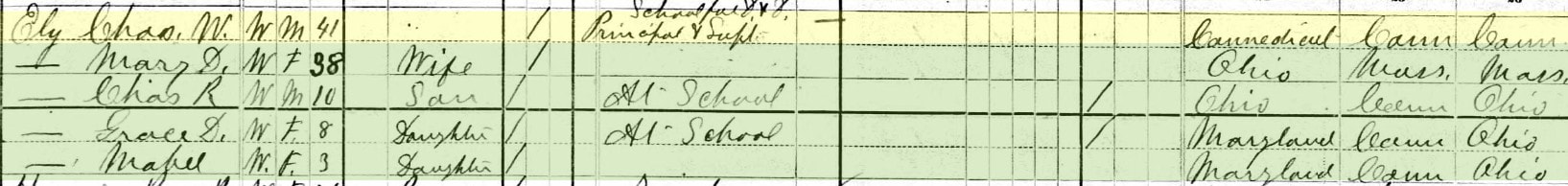

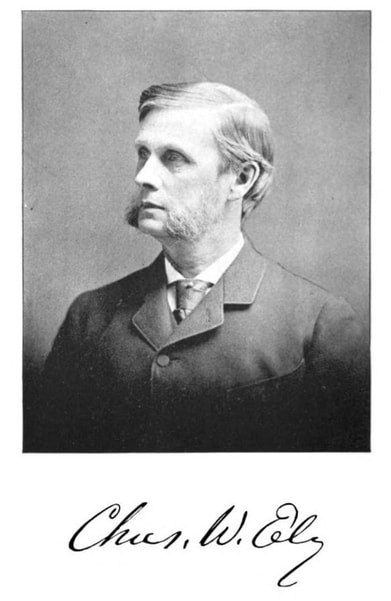

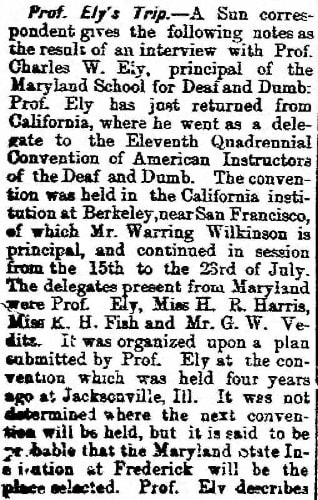

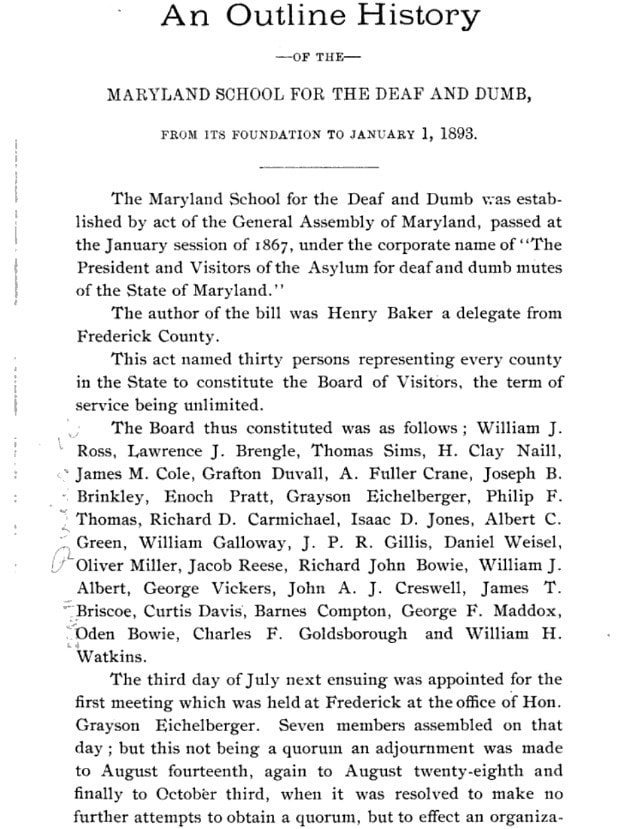

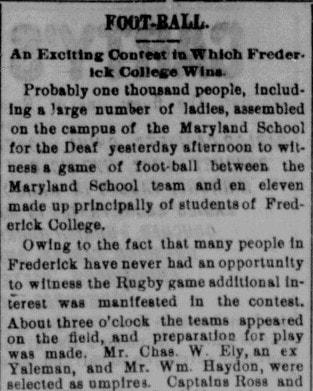

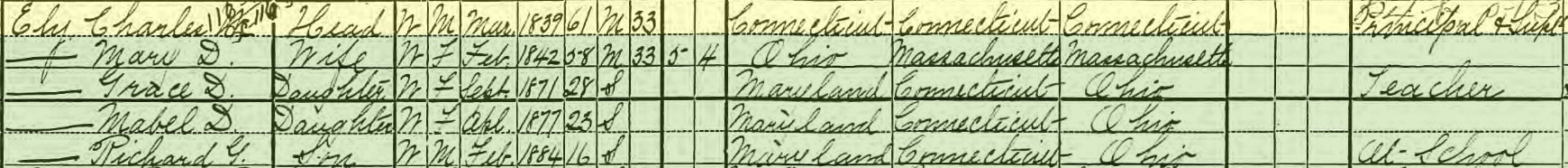

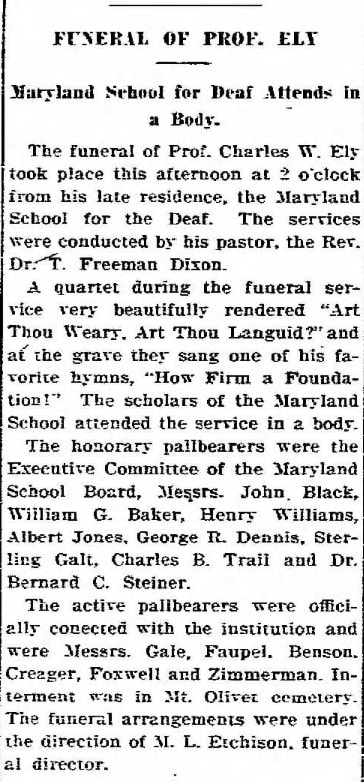

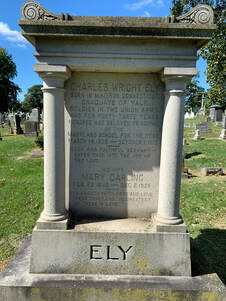

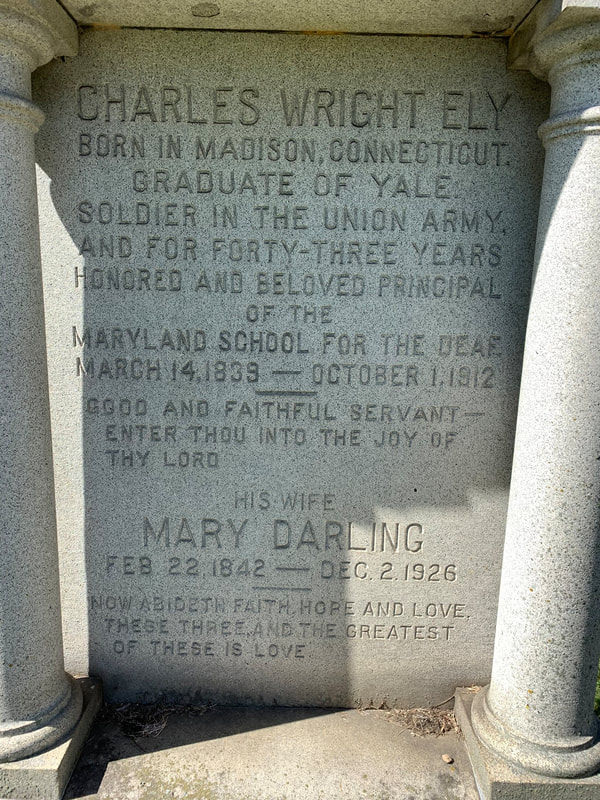

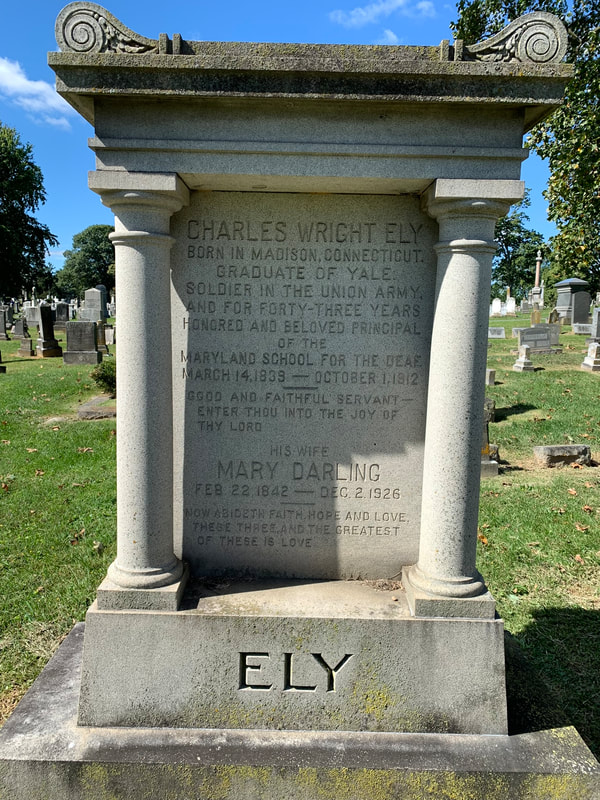

“Art Thou Weary, Art Thou Languid?” This hymn, written for quartet, rang out in the early afternoon 110 years ago on this very day (October 3rd, 1912). The occasion, a funeral of course, featured hundreds of people in the form of friends, family members, neighbors, education colleagues and former students. They had come to Mount Olivet to pay their last respects in the cemetery’s Area P at the southeastern base of what we call Cemetery Hill. The decedent was a man who did a great deal for his community, state, nation and fellow man. I’m not trying to be facetious here, but I can say with conviction that this man’s greatest achievements fell on deaf ears—and he wouldn’t have had it any other way. Charles Wright Ely was not a native of Frederick or Maryland, as he hailed from the northeast. Ely came to Frederick in 1870 after accepting an administration position for a newly formed educational facility established here just two years earlier in 1868 in the form of the Maryland School for the Deaf. Interestingly, Professor Ely’s old school is located half the distance to Mount Olivet’s front gate as his gravesite is to the same gate near the statue of Francis Scott Key. This Ely family plot is adorned with a central monument for Charles and wife Mary, with the graves of four of his five children on both sides. I opened up this blog with the mention of a particular religious hymn from Professor Ely’s Funeral, as it is also mentioned in his obituary. The hymn’s lyrics were written by an English minister named John Mason Neale in 1882, and based on music composed 12 years earlier by Henry W. Baker in 1868. Coincidentally, that was the year of Maryland School for the Deaf’s founding. The hymn "Art thou weary? Art thou languid? " is a translation from the Greek of St. Stephen the Sabaite, who was a monk who lived near Bethlehem, overlooking the Dead Sea. Born in 725 AD, this poor fellow was placed in a solitary monastery at the age of ten by his uncle, and left there for fifty years. He died in 796. I found it interesting that he, like Professor Ely, spent a large part of his life amidst a backdrop of silence. Regardless, here is a rendition of the beautiful hymn that Neale wrote: From the research I’ve done, the subject of our “Story in Stone” was anything but “weary and languid.” He was a guiding force for the institution we Frederick residents refer to simply as “MSD.” He even sported a mean pair of "muttonchops"..... Charles W. Ely certainly meant business! When taking the position as principal in 1870, no one could have known that Professor Ely would work tirelessly for the next four decades on behalf of students, staff and a board of directors headed by the famed Enoch Pratt of Baltimore. Maryland School for the Deaf is located on South Market Street. At one time, this was considered far south of Frederick Town. The Frederick “Hessian” Barracks had served home to a Revolutionary War prison facility, a drilling camp for militia soldiers of the War of 1812, a cocoonery for making silk, and was the first permanent home of the Frederick Agricultural Society’s annual exposition and fair. This event came to an abrupt halt during the American Civil War, as the barracks property was transformed into a major military hospital center labeled Union Hospital #1. Here, soldiers of both armies received care from a talented group of physicians, nurses and benevolent townspeople doing their part to help. At war’s end, the Agricultural Society found a new home for their “fair” and the locale was destined to serve home for an educational use. Within a few years, this would become home to the Maryland Deaf and Dumb Asylum, specifically chartered by the State to care for children in need of special instruction means to assist with the challenges that deafness brings. The mission of today’s MSD is to provide ASL (American Sign language) and English language models for early language acquisition, and to provide linguistically-enriched ASL and English environments for the attainment of fluency in both languages. This mission is accomplished when all MSD students become fluent in both ASL and written English upon graduation. The name of Charles Wright Ely adorns the Academic Building and Auditorium at Maryland School for the Deaf. He is remembered fondly, and with good reason. This building and others like it were built in the late 1960s after the demolition of the original institution structure, one of the former architectural masterpieces of our famed town. It was constructed under Professor Ely’s careful management. In my research, I wanted to check on the origins of American Sign Language and here I found another irony involving Professor Ely, and in particular, his home state of Connecticut. ASL is thought to have originated in the American School for the Deaf (ASD), founded in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1817. Originally known as The American Asylum, At Hartford, For The Education And Instruction Of The Deaf And Dumb, the school was founded by the Yale graduate and divinity student Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet. Inspired by his success in demonstrating the learning abilities of a young deaf girl Alice Cogswell, Gallaudet traveled to Europe in order to learn deaf pedagogy from European institutions. Ultimately, Gallaudet chose to adopt the methods of the French Institut National de Jeunes Sourds de Paris, and convinced Laurent Clerc, an assistant to the school's founder Charles-Michel de l'Épée, to accompany him back to the United States. Upon his return, Gallaudet founded the ASD on April 15th, 1817. Thomas H. Gallaudet’s legacy is honored by the naming of the famed educational institution bearing his name in Washington, DC—Gallaudet University. Originally known as the Columbia Institution for the Instruction of the Deaf and Dumb and Blind (from 1864-1894), T. H. Gallaudet’s son Edward Miner Gallaudet served as its first president from 1864-1910. This gentleman and our subject, both Connecticuters, were intimate colleagues as well as friends. The Ely family name can be found here on this campus as well as on our own MSD campus in downtown Frederick. Charles Wright Ely gave assistance to Gallaudet from his seat to the north in Frederick, but one of his sons would have a lasting impact. Charles Russell Ely would serve as a teacher here from 1892-1912 and from 1913-1939, the year of his death. Charles Russell only left the school for a brief period immediately following his father's death, during which he served as MSD's principal from 1912-1913. Later, he served as vice-president of Galluadet from 1920-1939). The old student center building at Gallaudet was named for Charles Russell Ely. Back to our subject, Charles Wright Ely, he died in 1912 while visiting his son at Gallaudet. It came as quite a surprise because as he was only 73 and in relatively good health in both mind and body. To give a backstory on this interesting man, I share here the biography of Professor Ely found in T.J.C. Williams’ History of Frederick County, published in 1910, two years before his death. “Charles Wright Ely, for nearly forty years the efficient and able superintendent of the Maryland School for the Deaf and Dumb, at Frederick, Md., was born in Madison, Conn., in 1839. He is a son of Elias Sanford and Hester (Wright) Ely. The Ely family is one of the oldest of the New England families, the American ancestor settling in Connecticut in 1660. Elias S. Ely, the father of Charles W. Ely, was a native of Madison, Conn., where he was born in 1809, and died in 1888. By occupation, he was a farmer. He was one of the leading and most prominent citizens of his neighborhood, and there was scarcely a local office that he did not fill at one time or another. In politics he was an ardent supporter of the old line Whig party, and served for one term in the State Legislature. He was a man of sterling worth and strict integrity. In religion he was a consistent member of the Congregational Church. Elias S. Ely was married to Hester Wright, a daughter of Jedediah Wright, who in early life was a sea captain. The Wrights, also an old Connecticut family, located there in 1660-’70. Mrs. Wright lived to the age of three score and nine. Elias S. and Hester (Wright) Ely had eight children, three of whom are living: 1, Elias H., merchant of Columbus, Ohio; 2, Cornelia M., wife of the Rev. W. T. Sutherland, of Oxford, N.Y.; 3, Charles W. Charles W. Ely grew up on the homestead, where he remained until he was nineteen years of age. After leaving the public schools of his native State, he entered Yale College, from which he graduated in 1862. He then entered the Union army as a private, became a sergeant and participated in the battle of Fredericksburg, in which engagement his regiment lost one-third of their men. After this, sanguinary battle, he was promoted to be a lieutenant in the Twenty-seventh Connecticut Infantry. At the expiration of his term of nine months, he was mustered out, and, in 1863, went to Columbus, Ohio, where he engaged in teaching in the State Institute for the Deaf and Dumb. In 1870, Mr. Ely was induced to come to Frederick in order that he might take charge of the Institute for the Deaf and Dumb. For the first three years after his coming, the institution was located on the Old Soldiers’ Barracks, but that has been supplanted by the present fine structure, which now accommodates one hundred pupils, and could easily care for half as many more. All modern facilities and conveniences are to be found in the buildings, and the grounds comprise about twelve acres. Here, for nearly forty years, Mr. Ely has labored hard, and it is due to him that the institution has attained the high rank which it occupies among educational schools of this kind in the country today. He has always had interests of the school at heart, and he has devoted all his energies of mind and body to perfecting the system now in use there. The evidences of his labors are apparent to the most casual observer, and to him is due the most unstinted praise for the high plane to which he has brought the school. In politics, Mr. Ely has always adhered to the Republican party, although he has never sought public office. For many years he has been an active member of the Presbyterian Church in Frederick, in which he has served as an elder for a long time, and of which he is ever a liberal supporter. Charles E. Ely married Mary G. Darling, daughter of S. R. Darling, of Elyria, Ohio. They are the parents of four children: 1, Dr. Charles R., professor of Natural Science, Gallaudet College, Washington, D.C.; 2, Grace Darling, a teacher in the institution of which her father is the head; 3. Mabel D. ; and 4. Richard Grenville, both engaged in teaching. Mr. Ely is a member of the G. A. R., of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion and of the Sons of the American Revolution. Not "weary and languid," but rather "polite and able" (according to another article), I found countless articles regarding Professor Ely and his professional accomplishments and work around the country as a leader in the field of deaf education. The basis of many lectures as a case study in early deaf educational models, Ely took time in the early 1880s to pen MSD’s early history. I was fascinated to see an article in which Ely served as an umpire for an MSD football game in the year1894. His name often made the papers for his church and community work, and I learned that he regularly spent summers in his native Connecticut with family. Professor Ely continued his mission to serve students and the Deaf educational community at large up through his last moments. His final activity was a work engagement in Baltimore, followed by an impromptu stop on the way back home to Frederick at Washington, DC to see his son Charles. Sadly, his wife would not get the chance to say goodbye as his demise came quick with Mary and a daughter in transit, getting to his bedside too late. Charles Wright Ely was finally silenced, as he said a great deal in life through his professional and personal deeds and integrity. Ely's obituary, and reports of his funeral, appeared in multiple newspapers as his reputation was held in high esteem on a national scale. Monument inscription: "Born in Madison, Connecticut. Graduate of Yale. Soldier in the Union Army and for forty-three years honored and beloved principal of the Maryland School for the Deaf." Charles W. Ely was not the first to be buried on this grave plot. An infant son, Robert, was buried here upon his death in 1873. Wife Mary Ely would die in 1926, and children Grace, Mabel and Richard would follow in future decades. As an aside, daughter Grace Darling Ely (1871-1960) also served as a teacher at MSD. I will leave you with a contemporary arrangement of our opening hymn which has been Anglicized to “Are You Weary, Are You Languid? by a musician named Nathan C. George. I can’t get the song out of my head, and the thought of it makes me thankful for the art of music, and the ability to hear its peaceful melodies and harmonies in all forms. Of course, Deaf individuals can, and do, enjoy music too contrary to some beliefs. It's just that they experience it in a different way than hearing people. Regardless, it can still be enjoyed, as I'm sure it was by the students who attended Professor Ely's funeral back in October of 1912. While researching, I learned that the legendary guitarist and music artist Prince performed a surprise, free concert for Gallaudet students back in 1984 at the pinnacle of his success with the "Purple Rain" Tour. Prince was a legendary pioneer in music, and Professor Charles W. Ely was a pioneer in deaf education. Wow, who saw that comparison coming? Ely worked diligently to make the lives of students as full and ready as possible so they could get the most out of the lives they had waiting in front of them. That's why I like that the word "uplift" was used to describe his contributions on the 1931 plaque found on MSD's Ely Academic Building. Professor Ely's legacy lives as the school he helped build continues "uplifting" lives today, 110 years after his sudden passing. I. King Jordan, the first deaf president of Gallaudet University and for whom the new student and academic center is named, offered this poignant quote in 1988:

“Deaf people can do anything hearing people can do except hear.” |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed