|

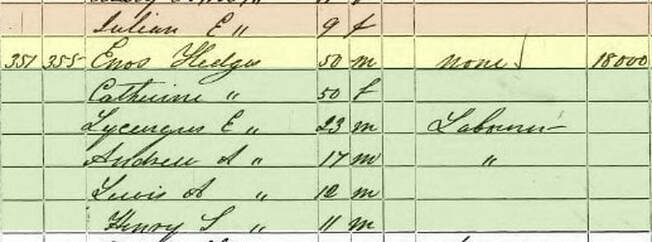

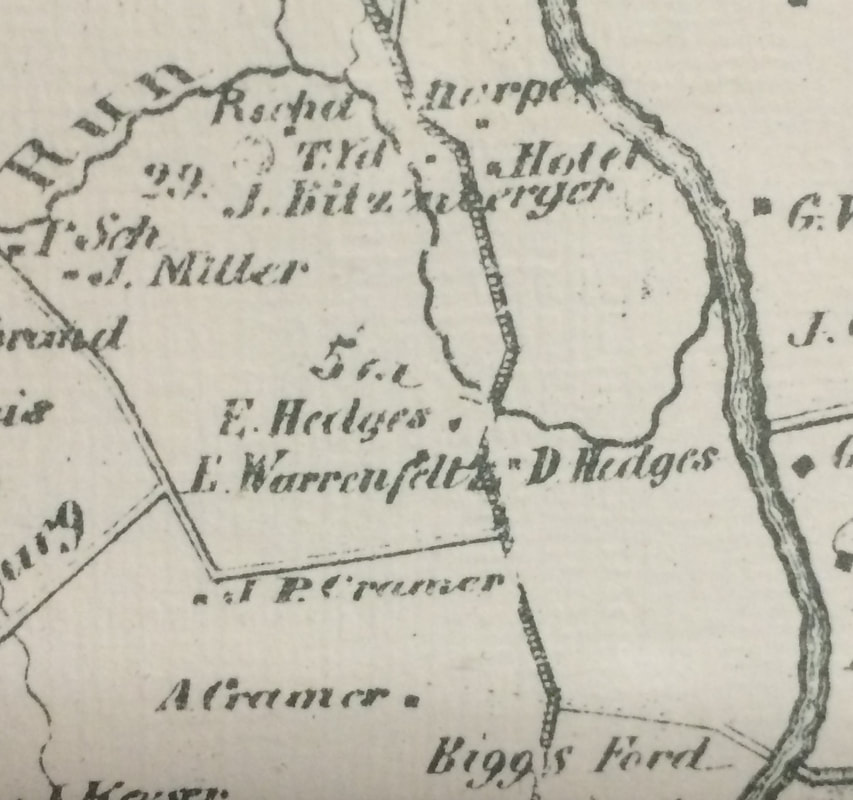

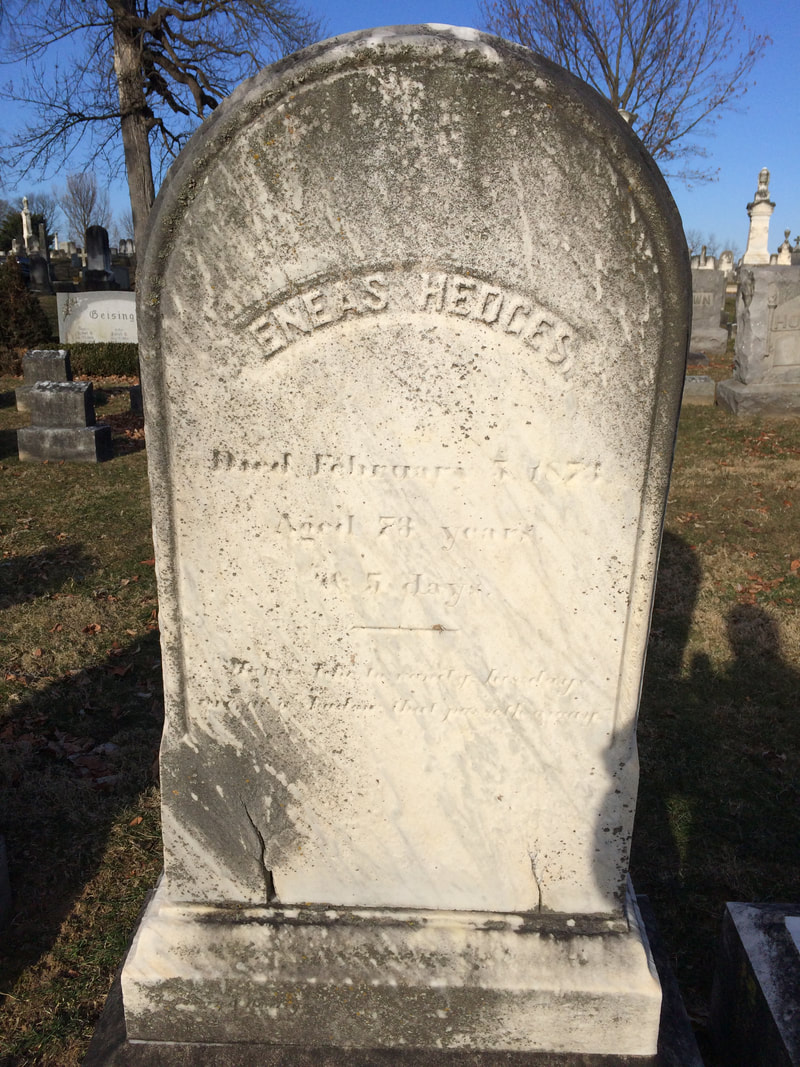

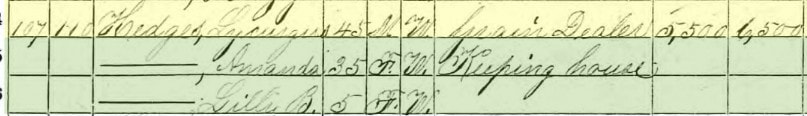

One of the most amazing monuments in Mount Olivet belongs to a gentleman whose name evokes an equal level of intrigue. Lycurgus Edward Hedges was a businessman who made a fine living engaged in the flour and grain business. He accumulated great wealth, but remained civic minded. One of his social accomplishments relates to having served as our cemetery's third president from 1889-1892. Lycurgus, a name you don’t run across every day, was born in Frederick County near Hansonville on February 14th, 1825. As the second child of Eneas and Catherine (Scholl) Hedges, he came into a family with roots dating back to before Frederick’s founding in the mid 1700’s. His ancestors settled a 258-acre parcel in the 1732 on Monocacy Manor which they gave the name “Hedge Hogg,” located roughly five miles north of Frederick City and west of the Monocacy River. Lycurgus childhood home was a family farmstead that straddled the old Frederick Turnpike (today’s US15) located south of Muddy Creek and north of Sundays Lane and Biggs Ford. The Hedges family would come to own other nearby parcels such as “Hedges Delight” to the southwest at Tuscarora Creek and my childhood stomping ground of “Yellow Springs.”  "Lycurgus of Sparta" by artist Jacques Louis David (1745-1825) "Lycurgus of Sparta" by artist Jacques Louis David (1745-1825) The Hedges are said to have originally come from Berkshire, England in the late 1600’s, first settling in the New Castle Delaware area, then Chester County, Pennsylvania. Lycurgus’ mother’s side was comprised of Scholls and Brunners, two early German families who came here in the mid eighteenth century. His maternal grandfather, Christian Scholl, Jr., was a War of 1812 veteran who married Maria Elizabeth Brunner of the family associated with Schifferstadt. So based on his family tree, how did he get a name like Lycurgus? Well, I can’t help to think of the old, downtrodden idiom “Its’ Greek to me,” because it is, Lycurgus is a name from ancient Greek history. Although it was faintly familiar to me, I looked it up immediately and found the following from “wunder-source” Wikipedia: Lycurgus (c. 820 BC) was the quasi-legendary lawgiver of Sparta who established the military-oriented reformation of Spartan society in accordance with the Oracle of Apollo at Delphi. All his reforms promoted the three Spartan virtues: equality (among citizens), military fitness, and austerity.

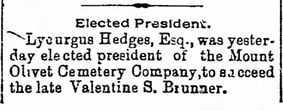

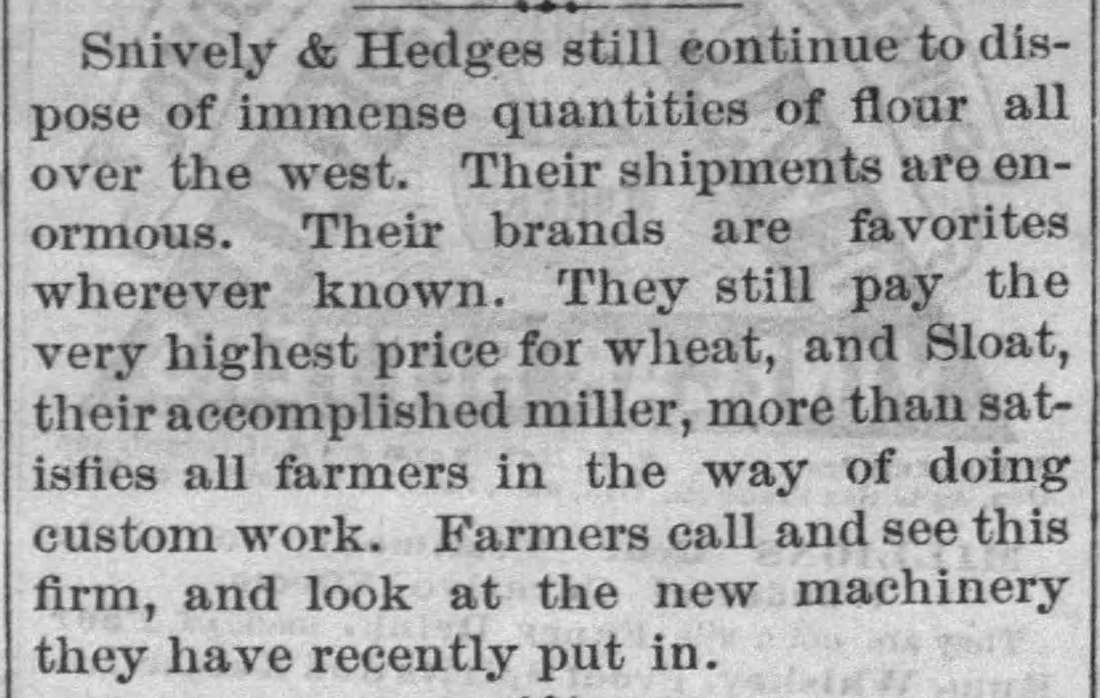

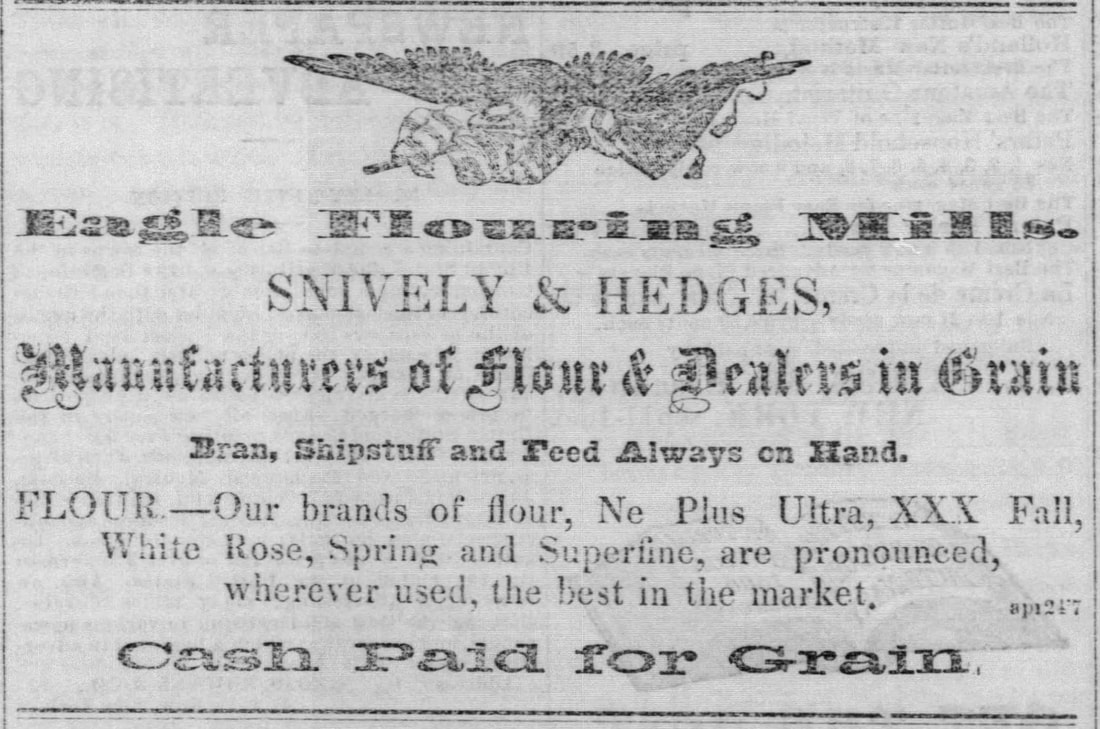

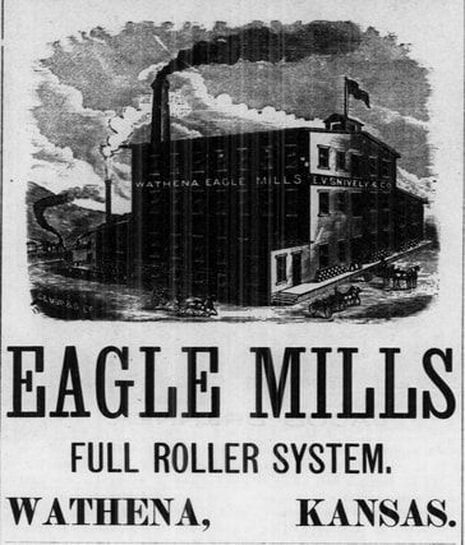

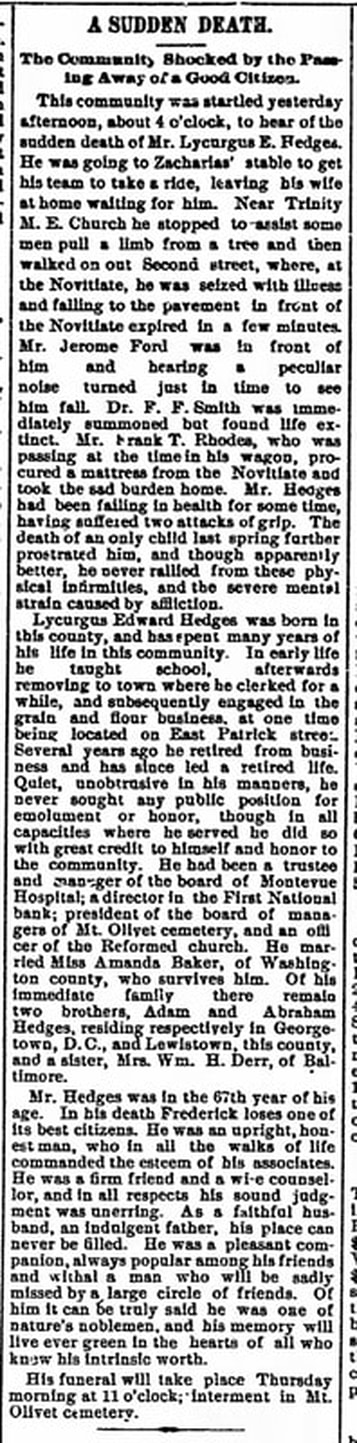

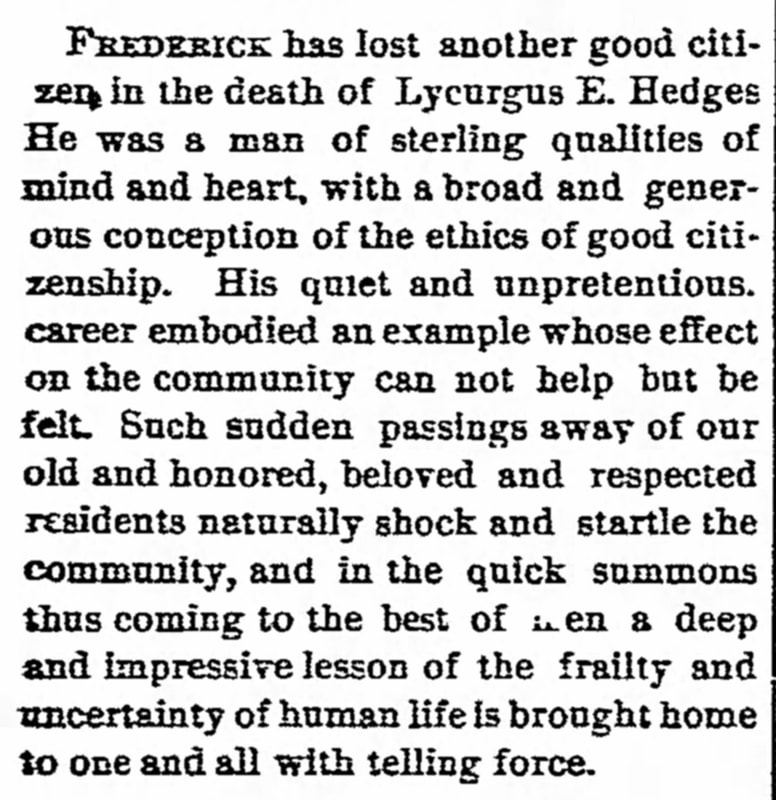

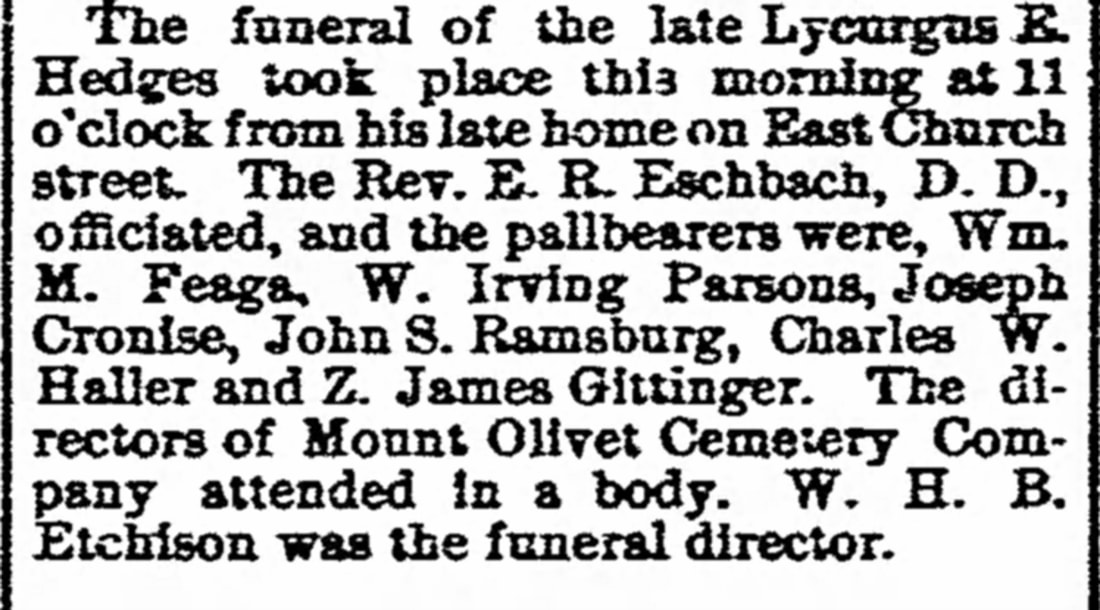

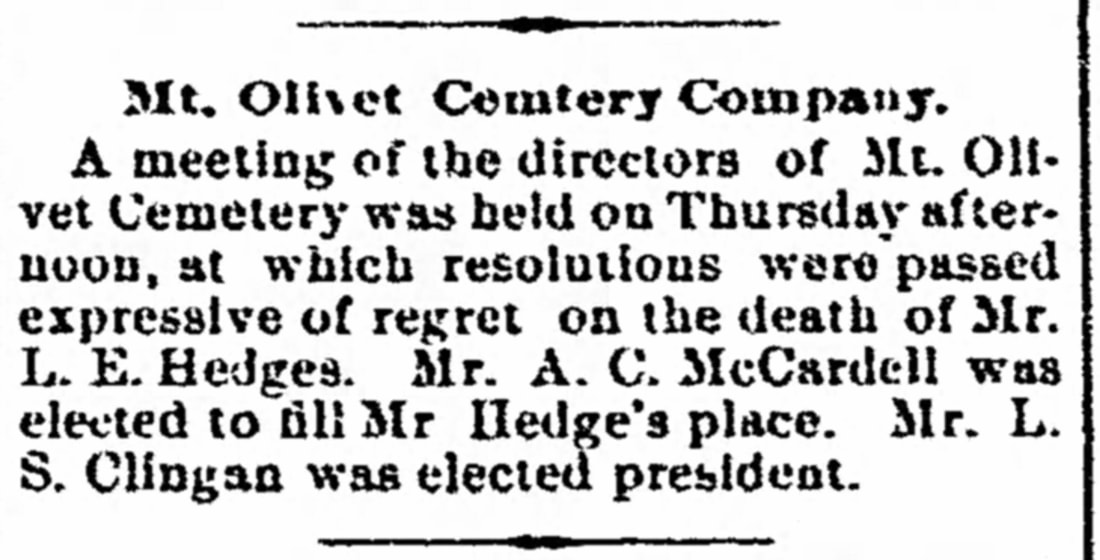

Lycurgus attended Marshall College in Mercersburg, Pennsylvania in the late 1740’s, just before it merged with Franklin College to become Franklin & Marshall. He actually worked as a teacher early in his career, but eventually moved to Frederick City and took a job as a clerk. His residence was on the north side of W. Third Street in the first block west of Market Street. Lycurgus’ big opportunity came when he entered into the flour and grain business, his firm having a location on E. Patrick Street. Somehow, he grew his efforts westward, going in business with a man named Joseph Snively. Around 1870, The tandem acquired a mill in Warthena, Kansas, a town in Doniphan County that bordered Missouri. This geographic location is just northwest of Kansas City, MO, and more importantly, is situated along the Missouri River, which provided a great opportunity for transport. The Eagle Flour Mill was a very successful operation, and one of the greatest suppliers of flour to the western territories, not to mention sending product north, south and eastward as well.  Frederick News (Dec 12, 1889) Frederick News (Dec 12, 1889) Mr. Hedges traveled to Kansas regularly, but his home was here in Frederick where he also busied himself with the growing needs of his community. Civic work included service as a trustee and board manager of the Montevue Hospital. Lycurgus also shared his talents as a director of the First National Bank. Best of all (for us), he also was a board member who rose to become the third president of the Mount Olivet Cemetery Company. He also belonged to the Evangelical Reformed Church, where he was both a member and an officer. Outside of that, I found a few newspaper articles that showed he enjoyed fishing at his favorite childhood spot on the Monocacy at Biggs Ford.

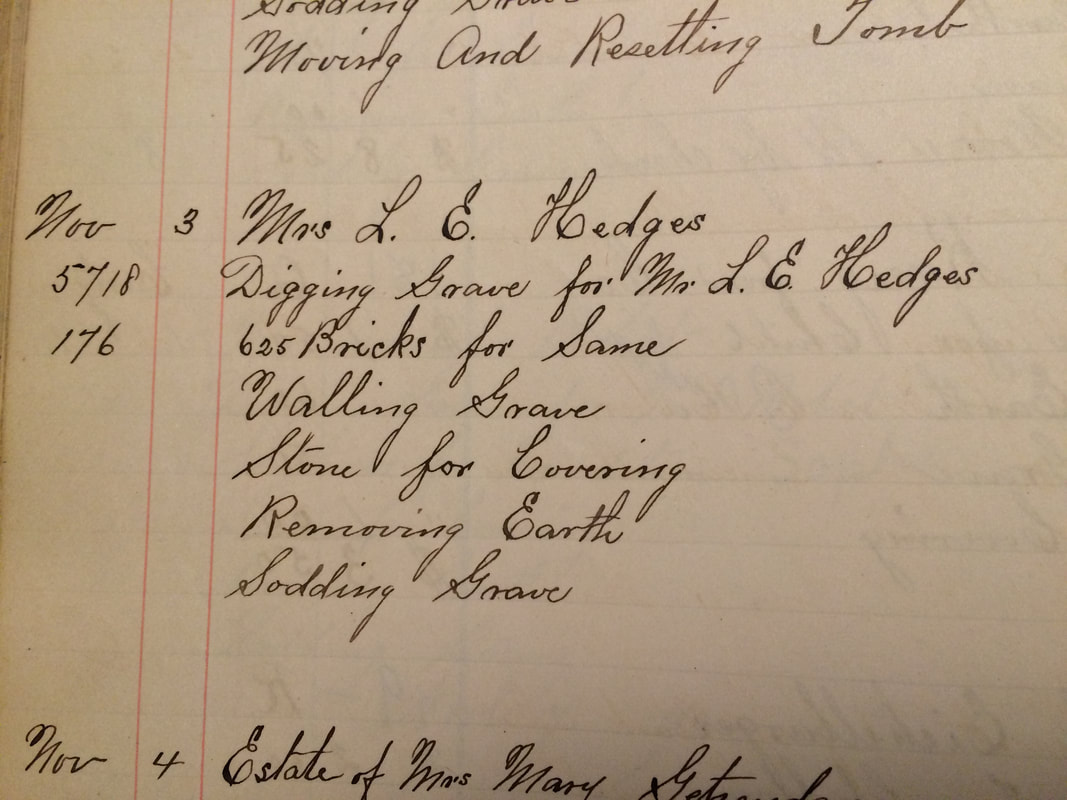

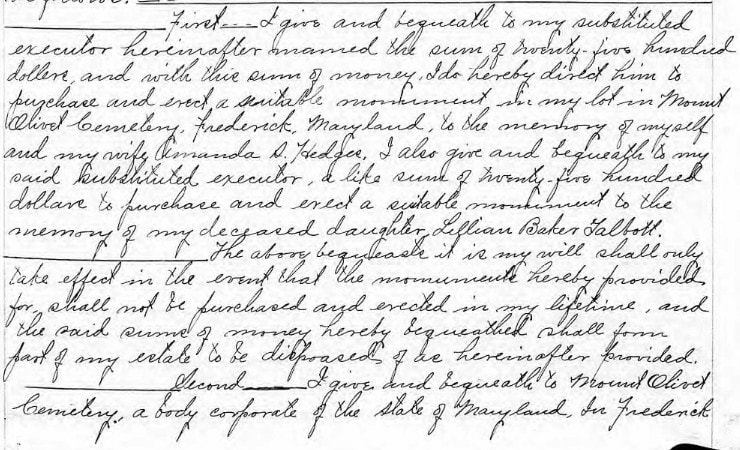

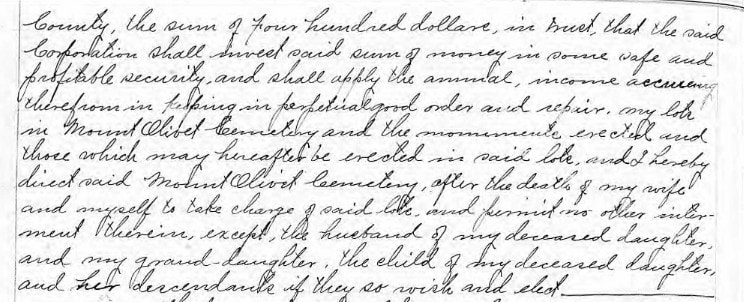

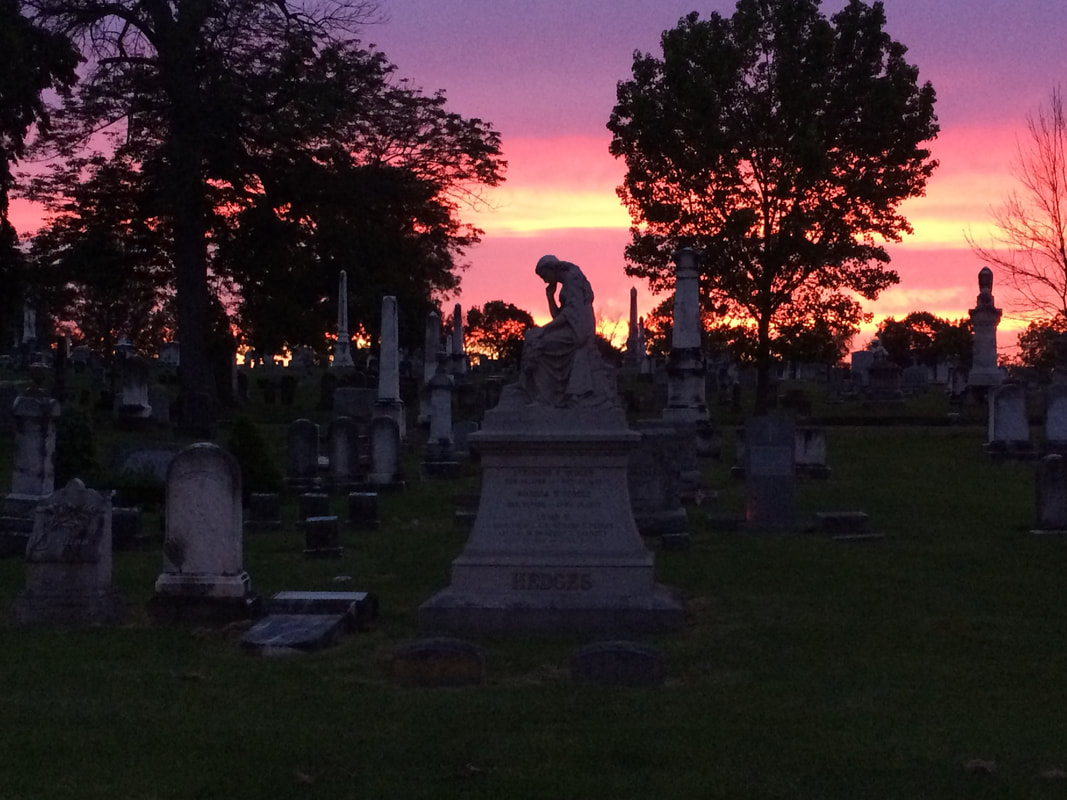

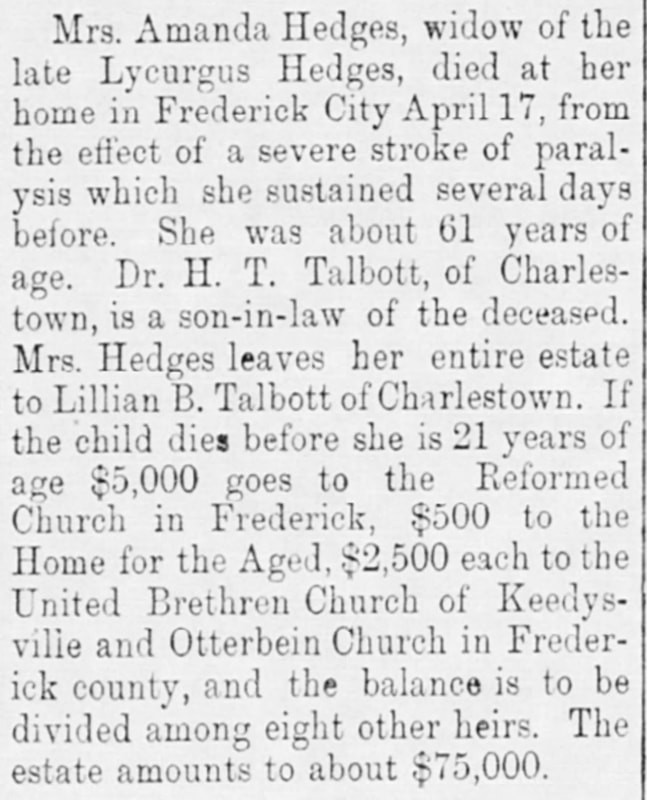

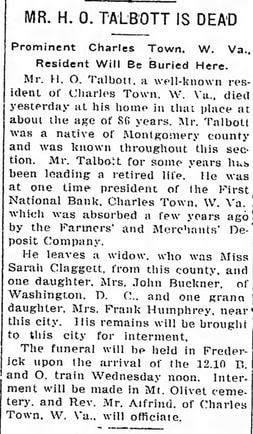

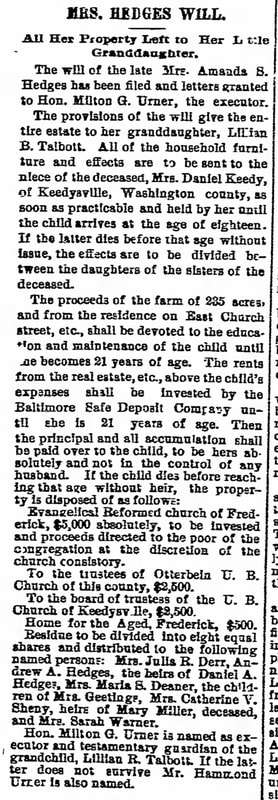

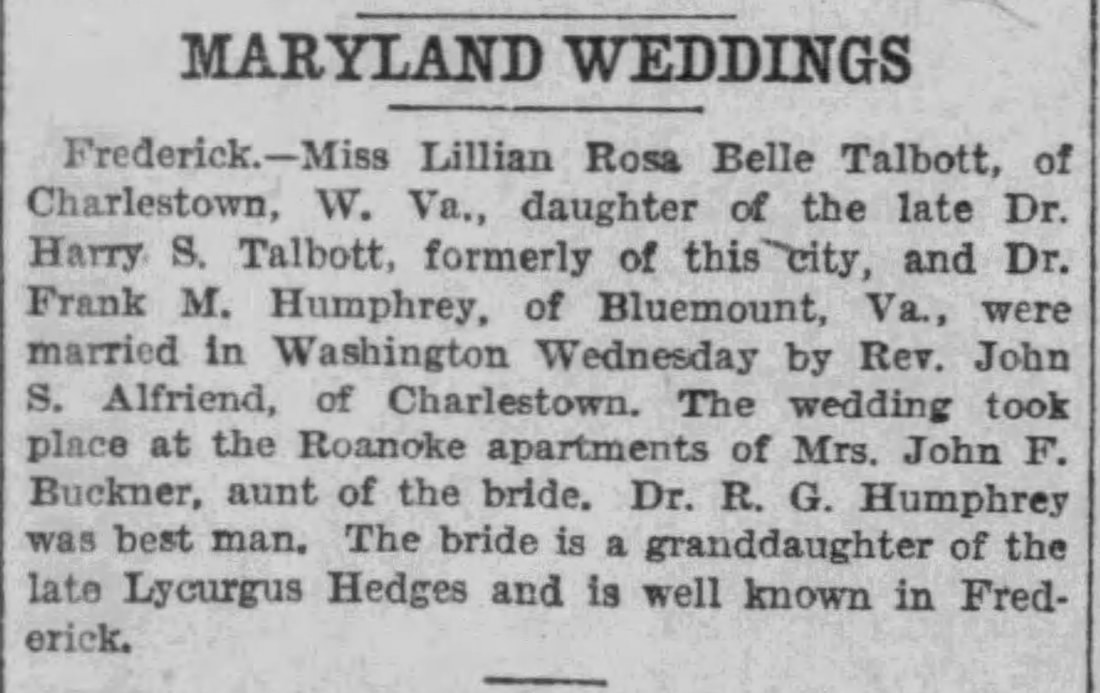

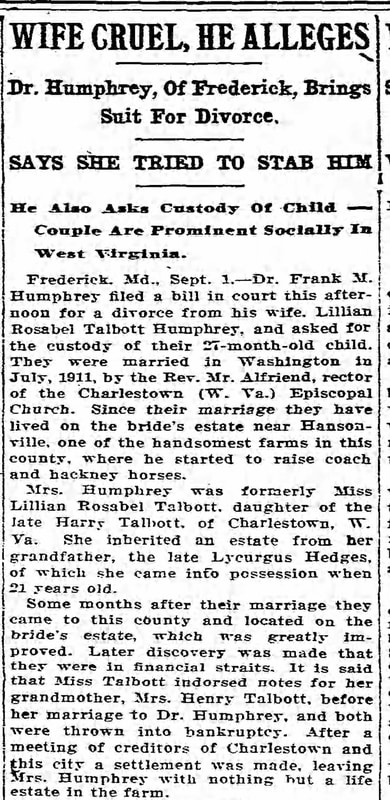

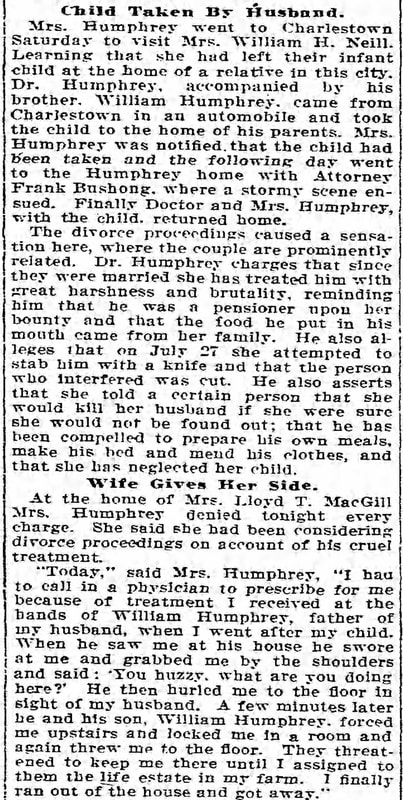

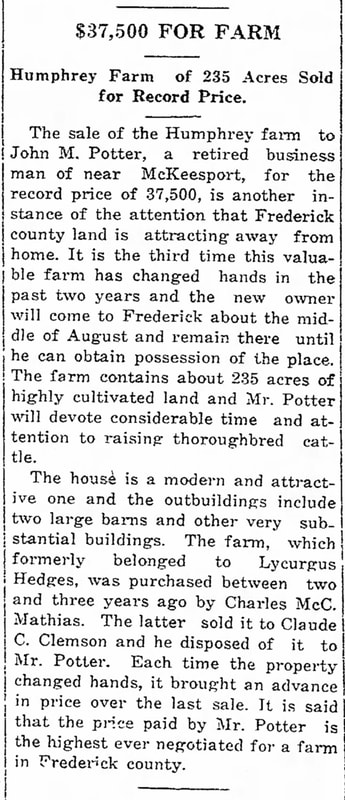

The ensuing summer and fall were very difficult for Mr. and Mrs. Hedges due to the loss of their only child. In addition, Lycurgus had been dealing with heart trouble. One day in late October (1892), Lycurgus was walking on E. Second Street, on his way to Zacharias’s stable where he boarded his horse team. He and his wife were planning to take a buggy ride to see friends. Having set out from his home, Lycurgus soon collapsed on the sidewalk and died in front of the Jesuit Novitiate.  Doniphan county Courthouse (Troy, KS) Doniphan county Courthouse (Troy, KS) Mr. Hedges was buried three days later on November 3rd. His body was placed in Area C/Lot 85, next to the grave of his beloved Lillian who had died eight months earlier. I found Lycurgus Hedges last will and testament on Ancestry.com, solely because it was also registered by Mrs. Hedges with the county courthouse of Donaphin County, located in the county seat of Troy—yet another serendipitous connection to Greek mythology. Mr. Hedges went to great lengths to spell out his intentions that his executor erect a "suitable" grave monument to the memory of himself and wife Amanda on his lot in Mount Olivet.  Learning all this information has certainly added to my fondness of the monument which features a weeping woman sitting atop, and holding a wreath in one hand with the other holding up her head. In the study of monument iconography, the grieving woman is self-explanatory, where the wreath symbolizes victory over death. Interestingly, the laurel wreath is associated with Greek attire and celebrations since ancient times, continuing a tradition to the modern day Olympic ceremonies. The weeping statue could be that of Niobe, another woman from ancient times. She appears a great deal in classical art and sculpture, especially in cemeteries. In Greek mythology, Niobe was a victim of hubris, and was turned to stone by Zeus after she mourned over her lost children. The story of Niobe, and especially her sorrows, is an ancient one. She is mentioned by Achilles to Priam in Homer's Iliad and is as a stock type for mourning. I can’t help but see Mrs. Amanda Hedges in the form of the grieving statue, having lost both her daughter and husband during that fateful year of 1892. She, herself, may have felt like Niobe, as if she had emotionally been suspended in stone. Mrs. Hedges would depart this life less than five years later on April 16th, 1897. Dr. Talbott would be buried here 16 years later. To the left of the monument are markers for Lycurgus’ parents, an individual stone for Lilly and another for husband Dr. Talbott. A final family member buried here is granddaughter Lillian Talbott Humphrey. From what could be gleaned from early newspapers, Ms. Humphrey was quite a colorful figure in her own right. Thanks to her grandparents, Lillian Talbott (Humphrey) incurred great wealth at age 21, as she inherited the Hedges fortune and farm property on Route15. It didn’t come without drama however as the article below attests to. The couple reconciled, but eventually sold the Hedges family farm as they had serious money problems. They moved to Baltimore but eventually divorced. Mrs. Humphrey would die in 1967 in Woodstock, VA, and represents the last of her family to be buried here. In retrospect, perhaps Lillian Talbott Humphrey should have been given the Athena or Pandora, or lesser known goddesses such as Dysnomia (associated with lawlessness) or Nemesis (goddess of retribution). *Note: Special thanks to Mary Mannix (C. Burr Artz Library Maryland Room) for deciphering the address of the Hedges home for me.

0 Comments

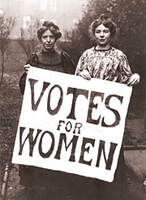

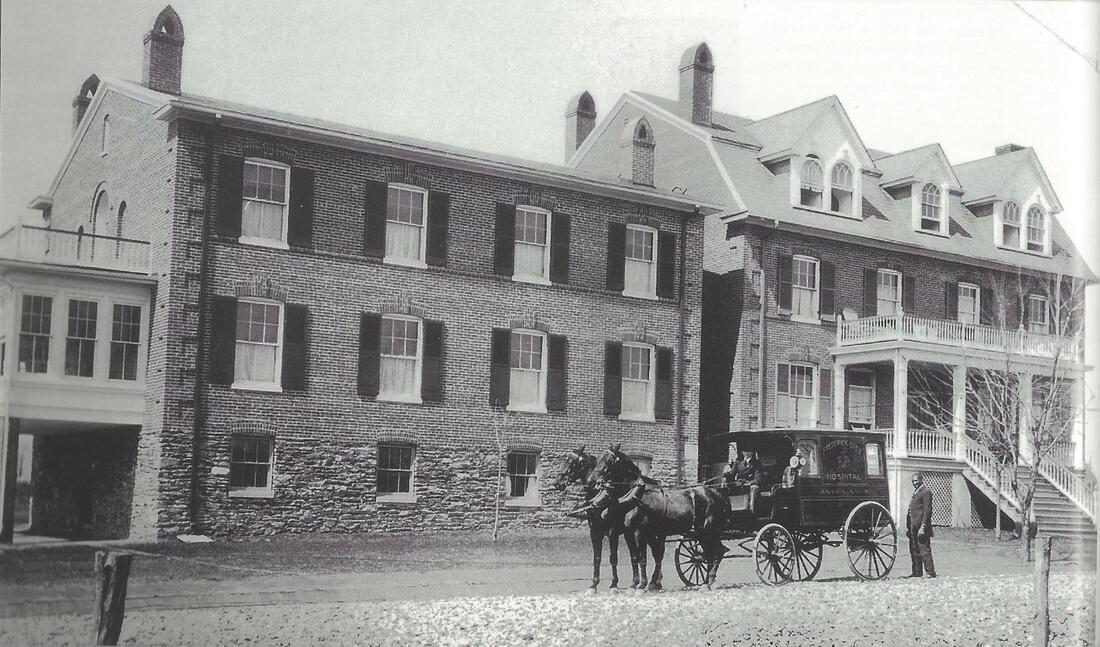

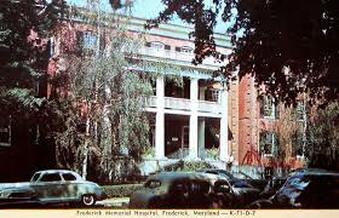

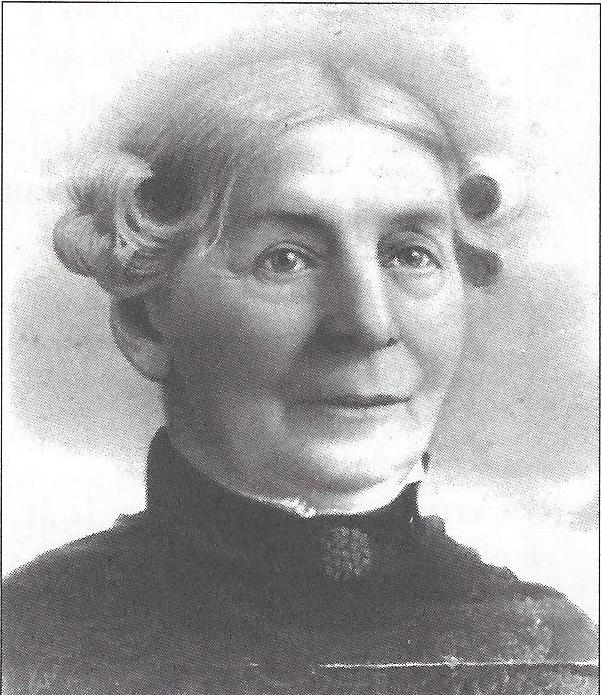

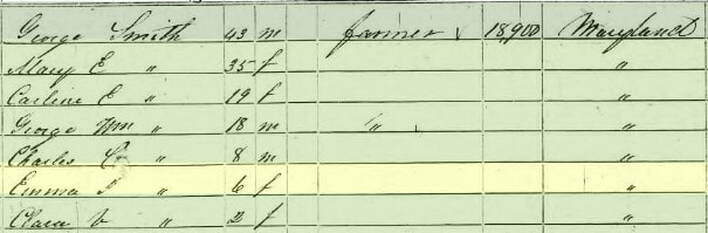

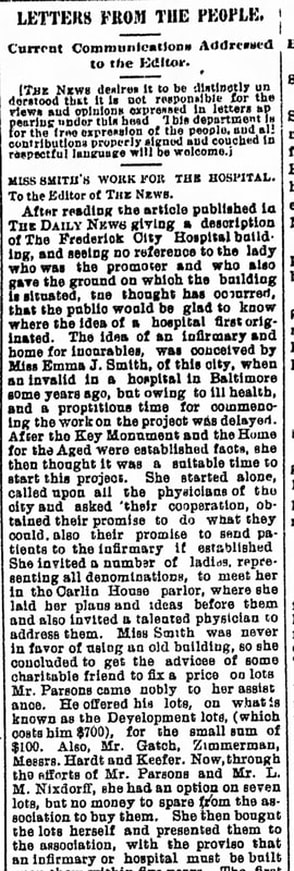

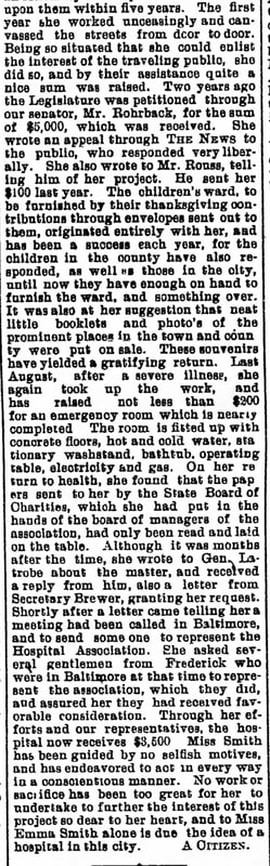

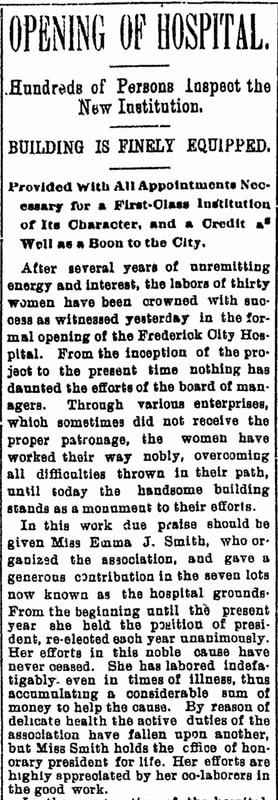

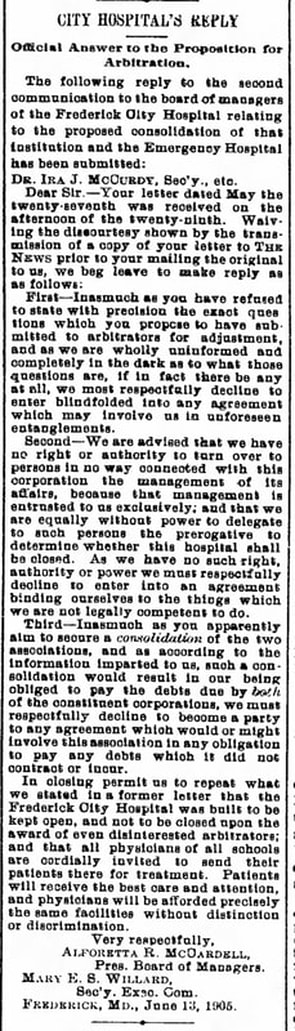

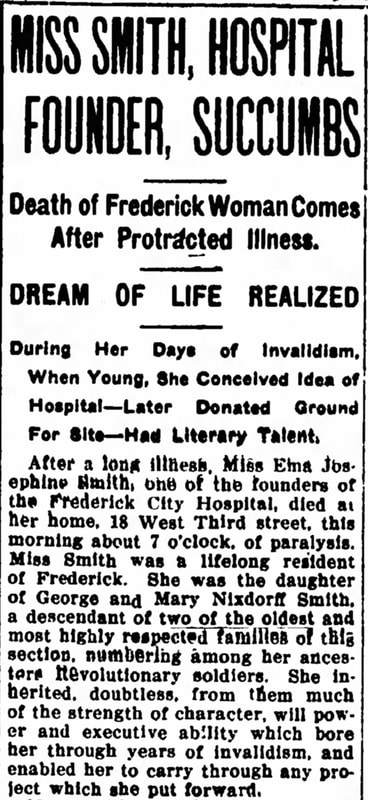

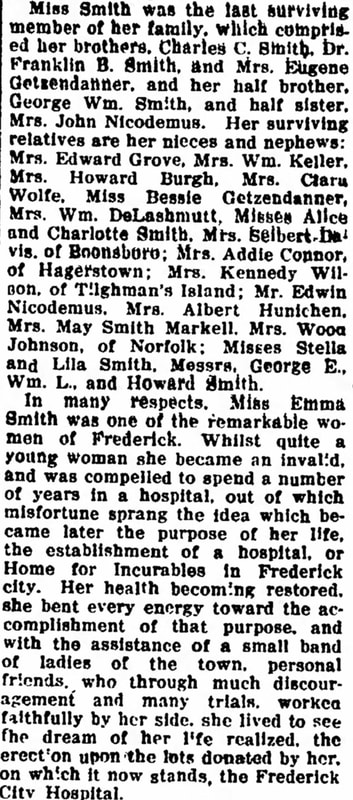

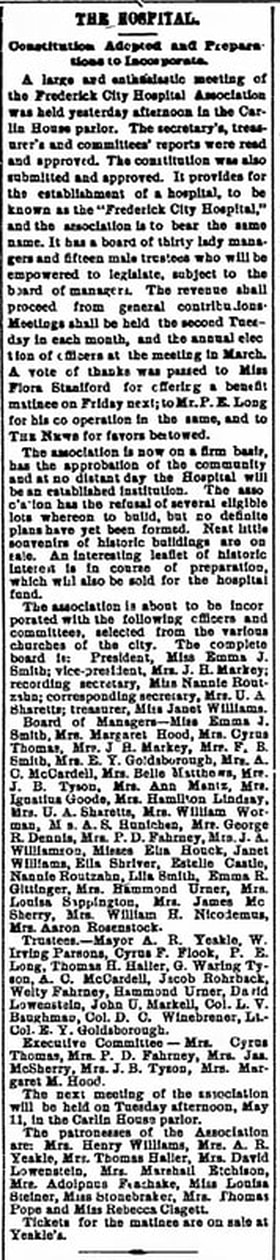

As we recently recognized Martin Luther King Day this year on January 21st, many were reminded that this holiday serves as a humble memorial to an extraordinary human being who dedicated his life to the Civil Rights Movement. Dr. King brought hope and healing to the America, and the memory of his sacrifice and tireless work continues to hold true for young and old. This same date of the 21st of January also is significant as the birthday of a Frederick woman who dedicated her later life for the literal construct of “hope and healing." In the 1890's, she would voice the importance of both (hope and healing) in our community's need for a healthcare facility in her hometown. Her name was Emma Josephine Smith, a tremendous leader in her own right, who spent the entirety of her 72 and-a-half years unable to vote, and oftentimes was viewed as an unequal to peers and colleagues. Emma was white, and came from an affluent family here in Frederick. Her father was an Orphan's Court judge, her brother a physician, and her half-brother was a well-known businessman credited with developing an inter-urban trolley system in 1896 known as the Hagerstown & Frederick Railway. Interestingly, Emma J. Smith is better known today (or should be) than all three of the above-mentioned immediate male family members for the impression she left on Frederick. While the county’s old “clanging” trolley line came and went, the innovation Emma helped bring to light is still in operation today, and ever-growing larger each year. In addition, this institution continues to serve as one of Frederick County's prime employers and has been a place that has given many a locals their start in life. For countless other fortunate residents, Emma’s creation has also been a true “life saver.” And then there are those that spent their last living days and hours here. We are of course talking about Frederick Memorial Hospital. Frederick Memorial started out under the name of Frederick City Hospital, a facility that grew considerably over a century. It began (and remains) at a location on the northwest outskirts of Frederick City on Montonqua Avenue, later to be named W. Seventh Street. For years, local residents have simply referred to this facility as FMH. Today, it is much larger in scope, and has expanded to a great extent over recent decades to keep up with the demands of a growing population. Today, “Frederick Memorial” is synonymous with the hospital on Seventh Street, yet the much larger Frederick Regional Health System (FRHS) includes the RoseHill facility and a dedicated cancer patient facility (off Opossumtown Pike), Hospice of Frederick County, Corporate Occupational Health Services and a myriad of other facilities featuring consultants, specialists and practitioners located throughout the area. While Emma could serve on a hospital board, and vote on early hospital matters, she would never in her lifetime have the right to vote for politicians, ranging from Frederick mayors to US presidents. Suffrage was the keystone of a larger women’s rights movement, a reform effort that evolved during the 19th century, but would not find its ultimate resolution until the 20th century. The women's movement initially emphasized a broad spectrum of goals before focusing solely on securing the franchise for women. Four years and five days after Emma J. Smith’s death, August 26th, 1920, the 19th Amendment to the Constitution was finally ratified, enfranchising all American women and declaring for the first time that they, like men, deserved all the rights and responsibilities of citizenship.  Seneca Convention of 1848 Seneca Convention of 1848 Emma Josephine Smith and a group of “fellow” women worked hard to give Frederick its first public hospital structure. She was born on January 21st, 1844, four years before the famed Seneca Falls Convention, the first women's rights convention. It advertised itself as "a convention to discuss the social, civil, and religious condition and rights of woman" and was held in Seneca Falls, New York (July 19-20, 1848). Here, some 300 women and men signed the Declaration of Sentiments, a plea for the end of discrimination against women in all spheres of society. Emma experienced the American Civil War while in her late teens. After the conflict, she would see the 14th Amendment passed by Congress in 1866 (ratified by the states in 1868), saying “Representatives shall be apportioned among the several States according to their respective members, counting the whole number of persons in each State, excluding Indians not taxed. . . .But when the right to vote . . .is denied to any of the male inhabitants of such State . . . the basis of representation therein shall be reduced in proportion.” It is the first time that “citizens” and “voters” are defined as “male” in the Constitution.  Three years later in 1869, the first woman suffrage law in the US was passed in the territory of Wyoming. The following year, the 15th Amendment received final ratification, saying, “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” By its text, women were not specifically excluded from the vote. Here are a few other highlights of the women’s movement over Emma’s lifetime, courtesy of the Virginia Commonwealth University’s Social Welfare History Project: *1870 The first sexually integrated grand jury hears cases in Cheyenne, Wyoming. The chief justice stops a motion to prohibit the integration of the jury, stating: “It seems to be eminently proper for women to sit upon Grand Juries, which will give them the best possible opportunities to aid in suppressing the dens of infamy which curse the country.” *1873 Bradwell v. Illinois, 83 U.S. 130 (1872): The U.S. Supreme Court rules that a state has the right to exclude a married woman (Myra Colby Bradwell) from practicing law. *1875 Minor v Happersett, 88 U.S. 162 (1875): The U.S. Supreme Court declares that despite the privileges and immunities clause, a state can prohibit a woman from voting. The court declares women as “persons,” but holds that they constitute a “special category of nonvoting citizens.” *1879 Through special Congressional legislation, Belva Lockwood becomes first woman admitted to try a case before the Supreme Court. *1890 The first state (Wyoming) grants women the right to vote in all elections. Emma’s privileged upbringing allowed her the advantage of travel. Her many sojourns brought the Frederick girl to towns and cities throughout the region and country. She noted how other places took proactive roles in securing healthcare facilities for their populations. The point was made even more personal when Miss Smith became incapacitated for a period of time in the late 1880’s due to illness. The episode made her an invalid, not being able to leave her current residence at the time of Frederick’s City Hotel, which once stood near the intersection of W. Patrick and Court streets. The Genesis of a Remarkable Lady Emma J. Smith never married. Her parents included the fore-mentioned George William Smith, Jr. (1807-1871) and Mary Ann Elizabeth Nixdorff (1815-1859), thus descending from some of Frederick's earliest settlers on both the Smith and Nixdorff sides. Emma's father was one of the founders of the Frederick County National Bank and served as a Judge of the Orphans Court. Mr. Smith is said to have "served with notable credit for many years as Judge of the Orphans' Court, in which capacity he displayed an ability and judgment that added materially to his repute. He was frequently called upon as a referee in the disputes that arose among his neighbors and it is worthy of mention in this connection that in many instances he proved an effective factor in the adjustment of such cases without the necessity of an appeal to the courts." Emma was one of nine children, only five of which would grow into maturity. She had two brothers (Charles Colvin Smith and Dr. Franklin Buchanon Smith) and two sisters (Mary Thomas Smith and Clara Virginia (Smith) Getzendanner), all of whom predeceased her. Emma had four additional half-siblings because her father had been married previously. One of these was the earlier mentioned George William Smith III (1832-1915) of trolley fame. Emma spent her early years on the family farm and received schooling. She attended the Evangelical Lutheran Church and had many friends. She learned business and political acumen from her father, and most likely, gained valuable medical knowledge from brother Dr. Franklin B. Smith (1856-1912), a local physician. Without kids to raise, the maiden lady had time, energy and money, to give. She busied herself with two fine projects in the mid-1890’s as a leading proponent and Charter Member of Frederick’s Home for the Aged on Record Street, and participated as a member of the Francis Scott Key Monument Association and was equally successful in helping Mount Olivet receive the grand memorial that greets visitors entering our S. Market Street entrance. From here, Emma set her sights on a new target.  The former Carlin Hotel (c. 1903) at the southeast corner of W. Church and N. Court streets The former Carlin Hotel (c. 1903) at the southeast corner of W. Church and N. Court streets In late 1896, and early 1897, Emma helped spearhead a series of meetings held at the Carlin House, a hotel once located at the southeast corner of W. Church and Court streets, today the parking lot for M&T Bank. The conversation centered on the need, and process to establish a hospital facility for Frederick. She was joined in these talks by a fine group of some of the leading women in town including Mrs. Ida N. Markey, Miss Nan E. Routzahn, Mrs. A. Gertrude Sharretts, and Miss Janet Williams. At another meeting held at the Carlin Hotel on March 26th, 1897, Miss Smith was elected president of the hospital venture. The four other women mentioned above rounded out the slate of elected officers for the inaugural board of directors. Unfortunately, Emma and the other ladies could not go further in forming a legitimate corporation. At this time, only men could perform this feat based on state law. Fourteen men were selected to accomplish this task and the Frederick City Hospital Association became a reality. The following year, a charter was received allowing the group to build a structure Meanwhile, Emma and a determined group of talented and resourceful women performed the arduous task of fundraising the fundraising. Many possible locations were discussed for the proposed hospital including Groff Park (future home of Hood College), the Groff Hotel lot atop W. 7th and Market streets which would become home to Frederick's first radio station), and the site of the old Stone Tavern at W. Patrick and Jefferson streets. Emma offered another option, donating seven acres of her own property, land positioned across from Park Avenue. This generous gift was duly accepted.  The original Frederick City Hospital as it looked in 1902 The original Frederick City Hospital as it looked in 1902 Emma and her lady Board of Managers worked earnestly to fund the hospital project. They went door-to-door, approached businesses and lobbied the state. In just five years, a new, "state of the art," two-story (and soon to be three-story) hospital building opened to the public. This was early May, 1902. The structure cost $8,000 to build, and featured 16 private rooms and would soon boast three wards. A school of nursing was also established in 1902 adjacent the Frederick City Hospital and named the Georgianna Simmons Nurses’ Home. Mrs. Simmons was the former Georgianna Houck (1832-1915) who contributed the bulk of the money needed to build this facility. Her gravesite is located in the same section of the cemetery as Emma and another major early benefactor of the hospital, Margaret S. Hood. Emma could not have been happier with making her dream a reality. Unfortunately though, there were many community medical professionals who were not. Trouble had been brewing for quite some time. Controversy soon followed between the new hospital and Frederick County Medical Society because the bulk of the doctors of town felt jilted that they had little to no say in the hospital's construction. Moreso, they were unwilling to take instruction from an all-female Board of Managers, headed by a woman administrator without medical training. Yes, they thought that these women were incapable of running a hospital. Another struggle with the Medical Society would ensue over a refusal by the Lady Board of Managers to hand over the hospital to allopathic (alternative medicine) physicians, a suggestion made by the Frederick County Homeopathic Physicians Society.

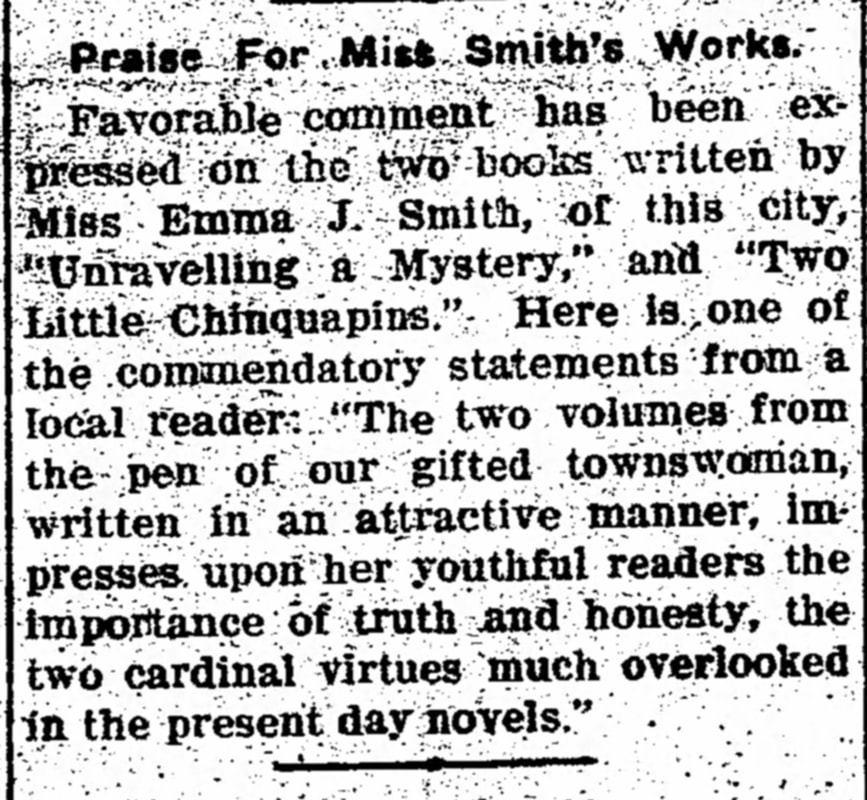

The Emergency Hospital closed its doors on October 31st, 1906 after a three-year stint. The doctors joined the Frederick City Hospital initiative and we have had one unified, community hospital ever since. This is certainly a testament to the tenacity of Miss Smith who would eventually step down from her position as president to take a lesser role in leadership due to health issues. She would now be given the title of Honorary President for Life of the Frederick City Hospital, one that was continuously upheld until her death. Emma spent her final decade of life continuing to give her energies to the hospital and the Record Street Home. She, herself, maintained a home at 18 W. Third Street, where she soon took to professional writing. In 1912, she published two novels, printed and distributed by Cosmopolitan Press of New York. These were entitled Unraveling a Mystery and a children’s book Two Little Chinquapin & Other Tales. Emma Josephine Smith died on August 21st, 1916 of a cerebral hemorrhage. Her obituary was given plenty of space in the local papers, one of which deemed her "one of the remarkable women of Frederick." She was buried under the shadow of a large monument erected in honor of her parents who had predeceased her. This is located in Mount Olivet’s Area E/Lot156). In the weeks to follow, several glowing tributes and memorials appeared in the newspapers.  Seven years after Emma’s death, the National Woman’s Party proposed the following Constitutional amendment in 1923: “Men and women shall have equal rights throughout the United States and in every place subject to its jurisdiction. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.” Things would not be firmly rooted until 41 years later in 1964, when Dr. King’s push for equality among races joined the women’s fight for equality with males. Title VII of the Civil Rights Act was passed, including a prohibition against employment discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, national origin, or sex. Miss Smith is still remembered by some in Frederick, and the hospital. Recently, Frederick Health honored Miss Smith by naming their westernmost entrance (off Seventh Street) Emma Smith Way. Thanks for the facility Miss Smith, Frederick couldn't live without it! *Bonus articles of note:

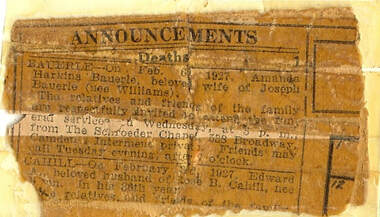

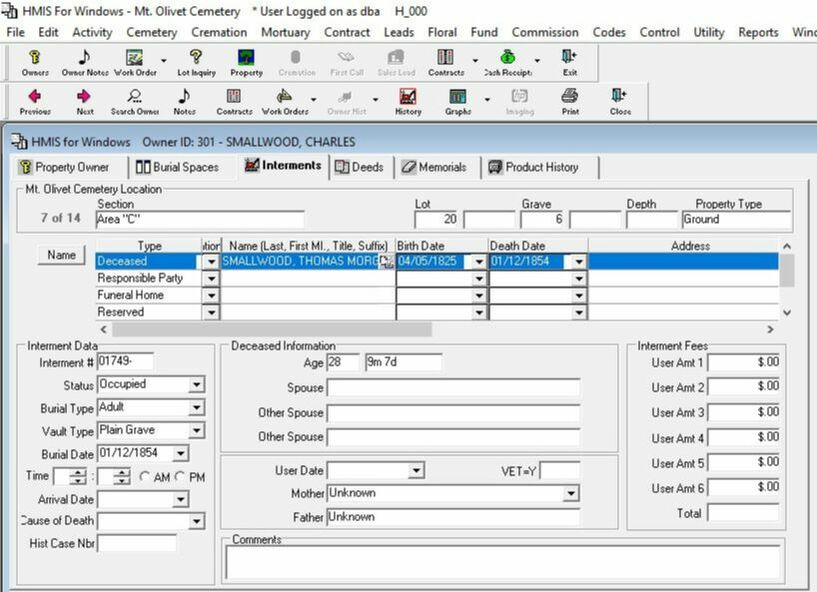

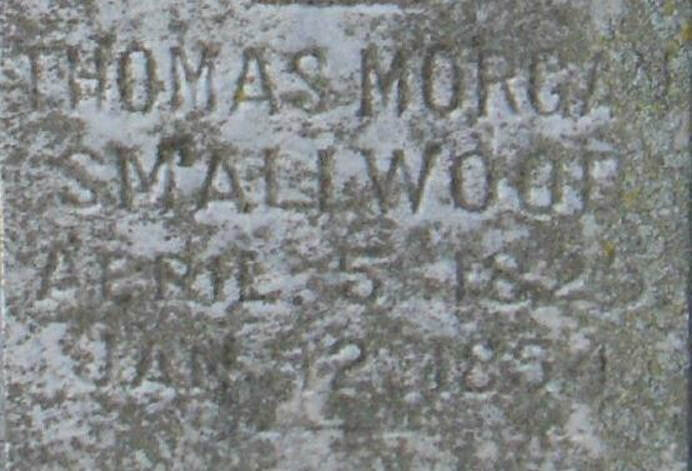

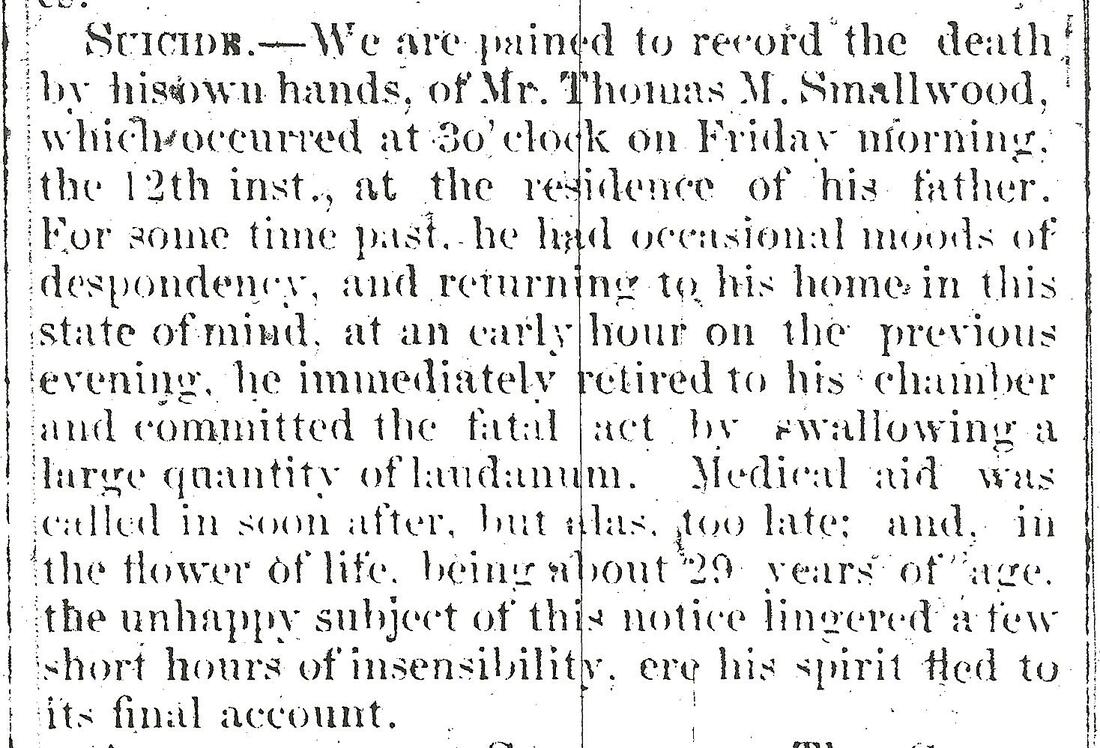

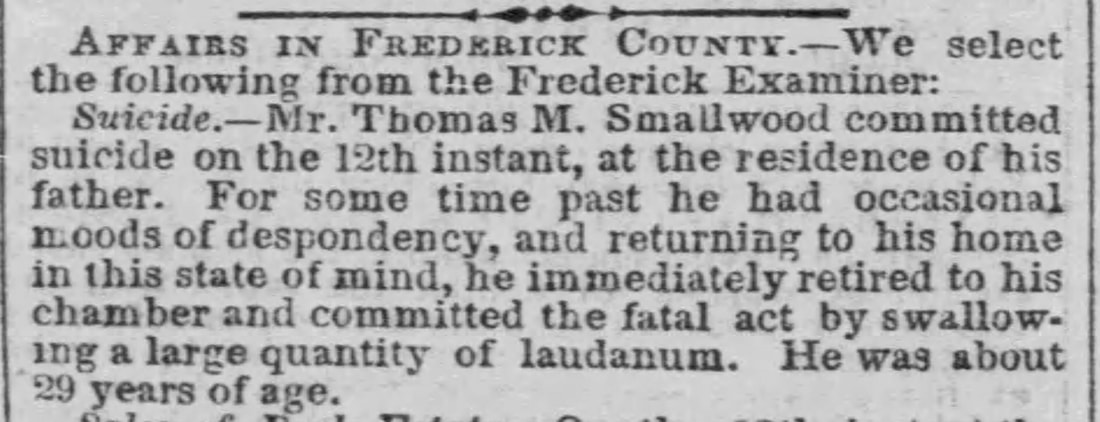

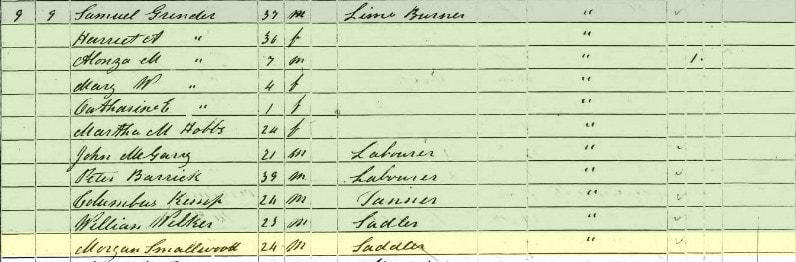

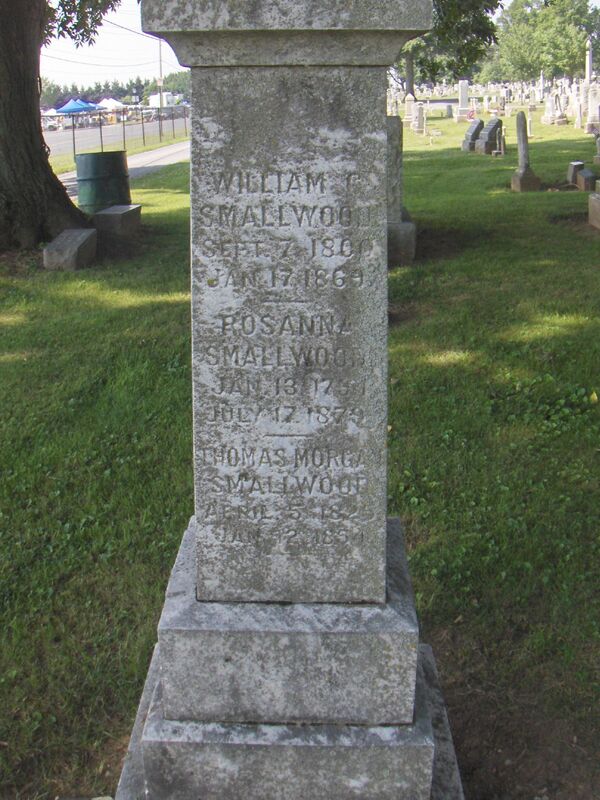

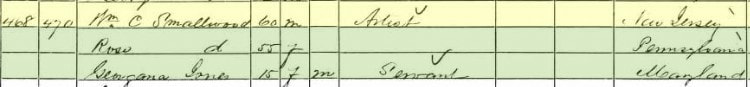

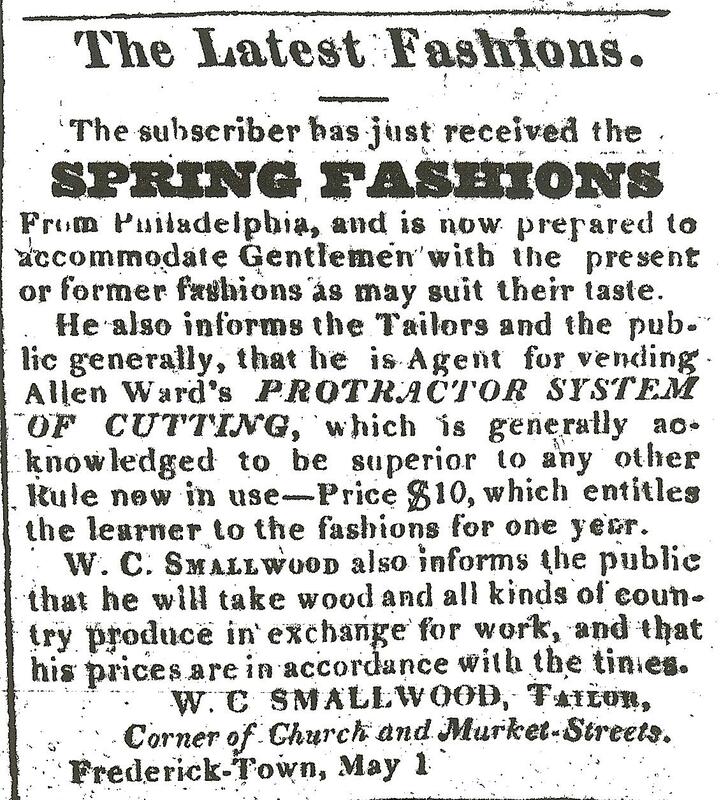

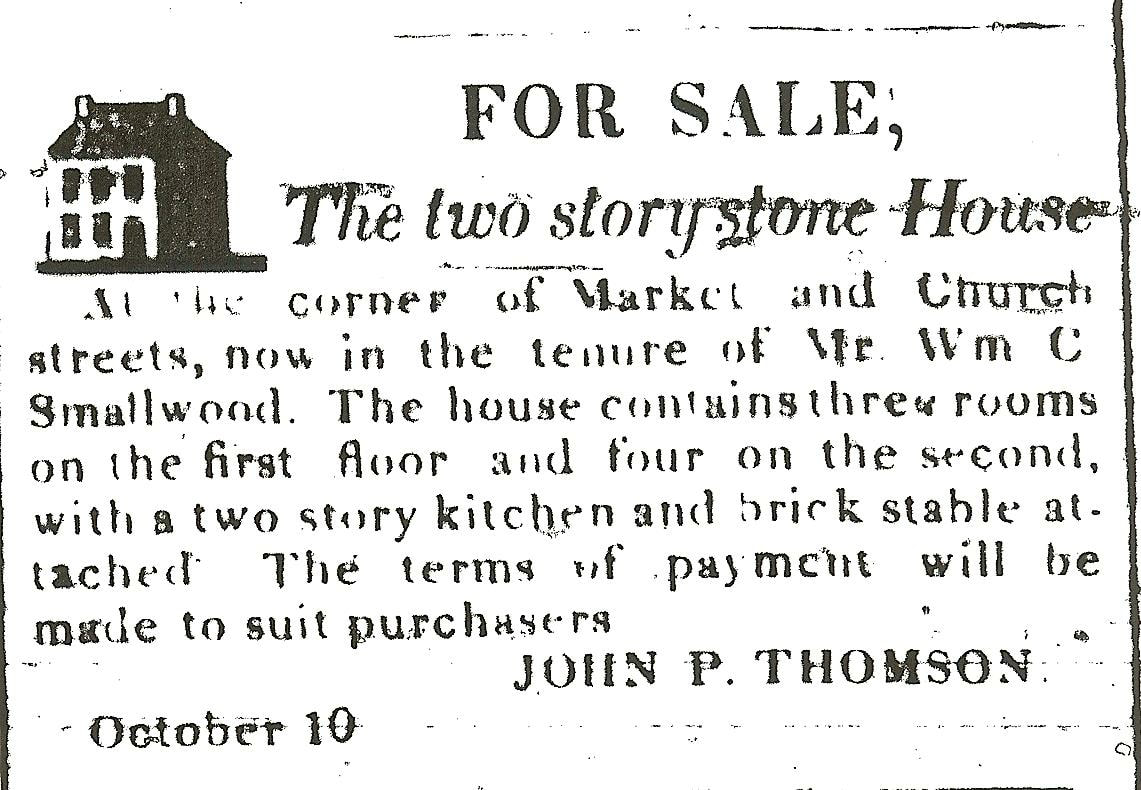

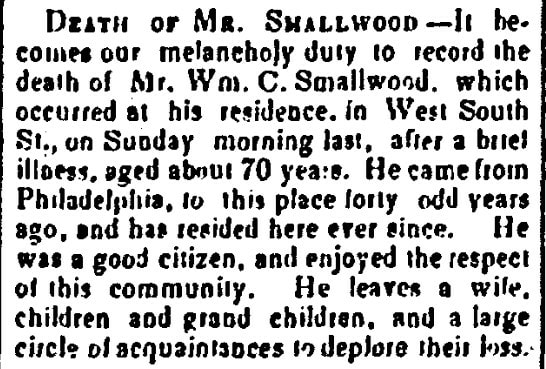

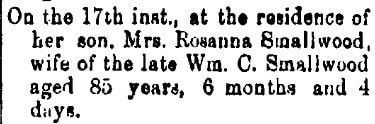

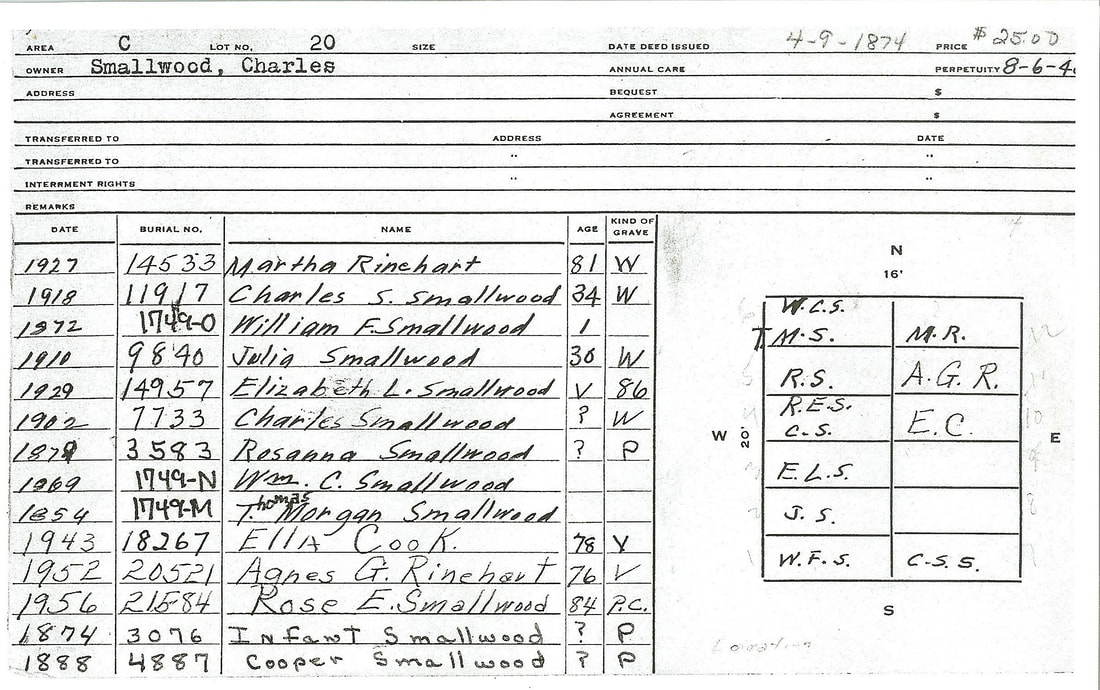

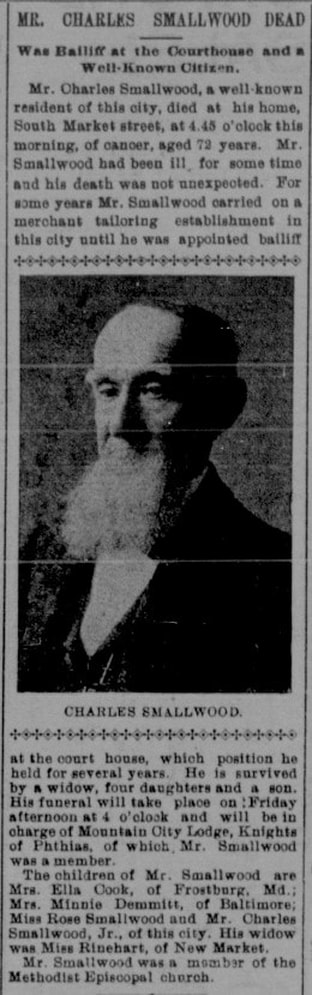

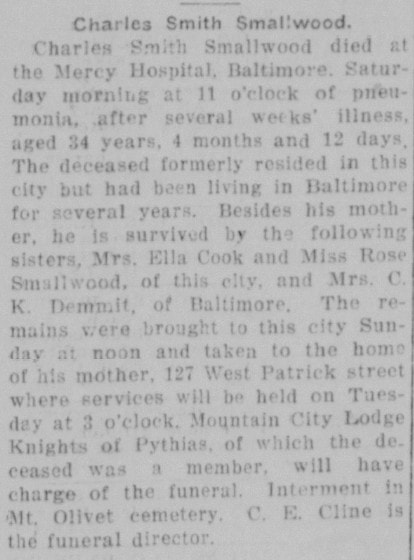

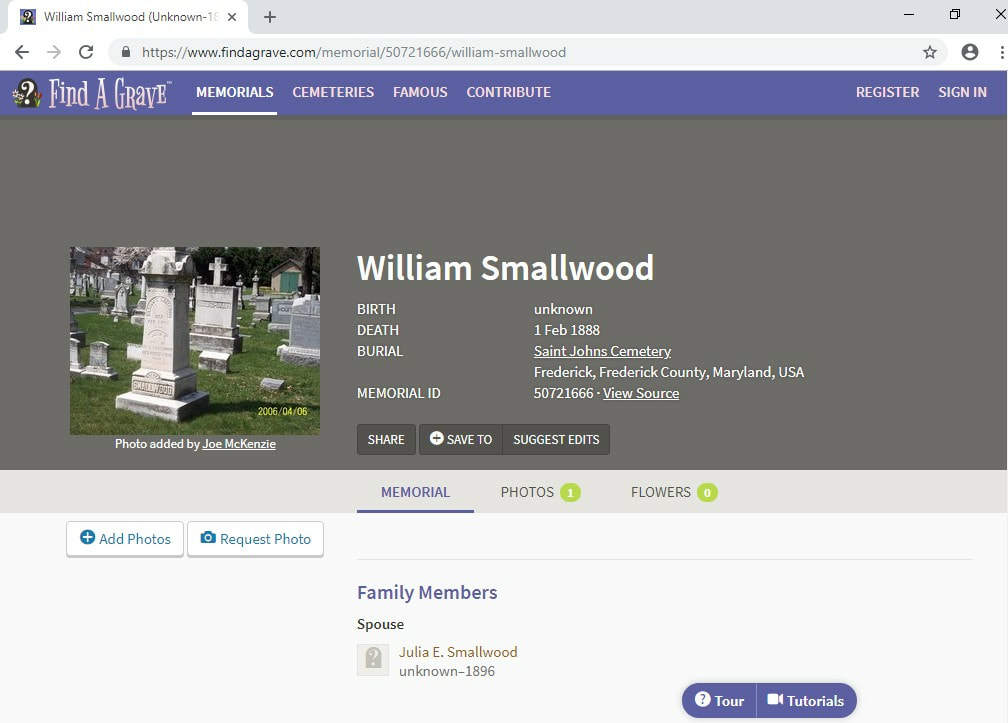

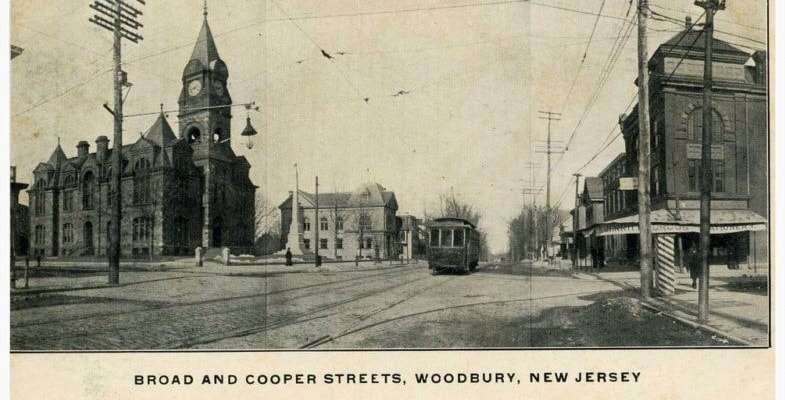

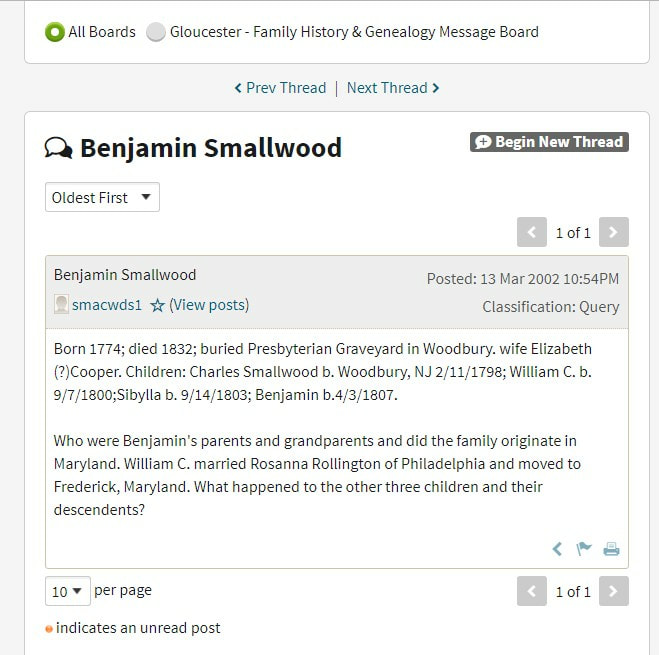

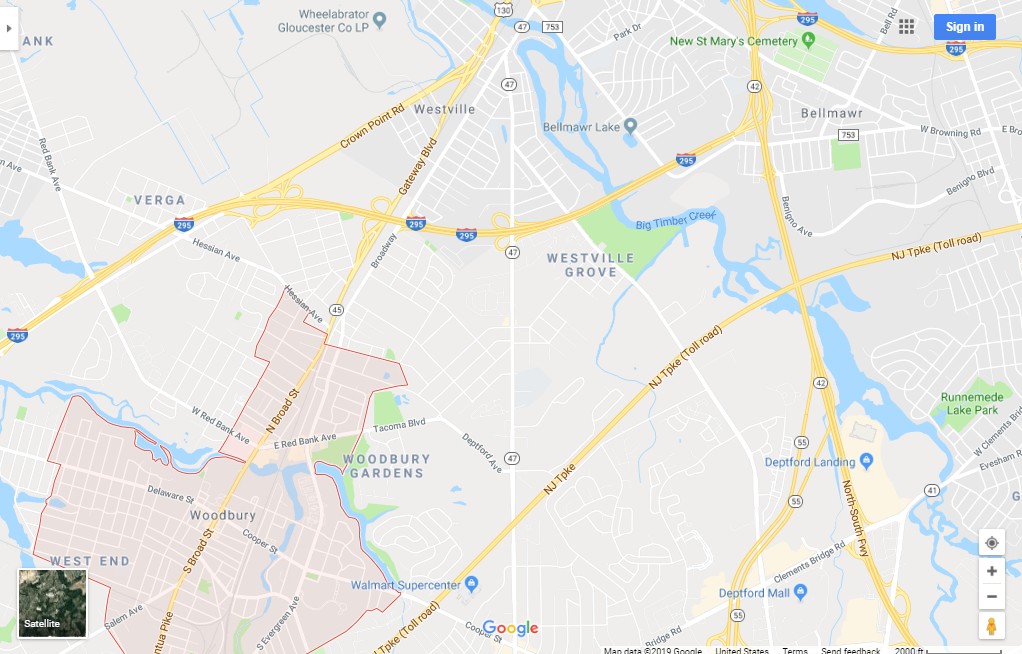

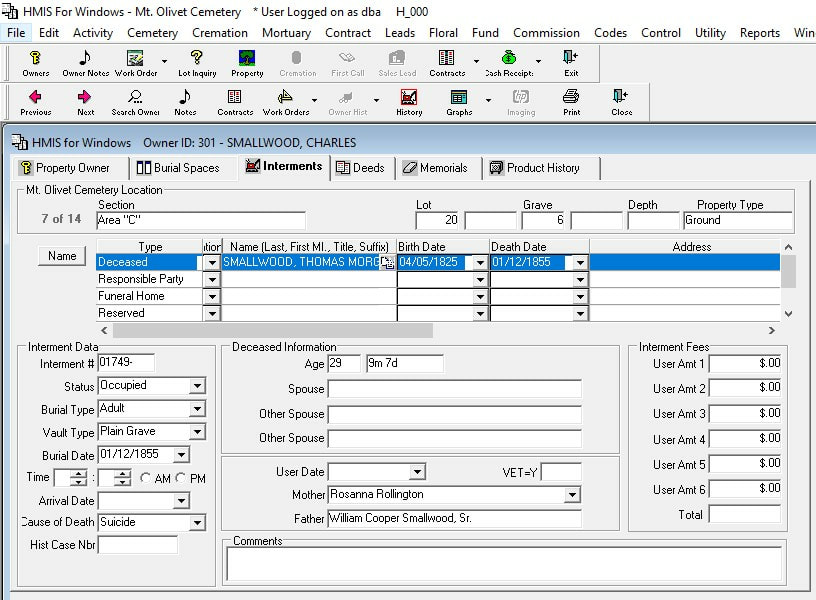

With the holidays behind us and winter weather finally setting in, many among us are newly armed with a Christmas gift subscription to an online genealogical site and/or recently received DNA results. This is the perfect time for conducting a search of your family history, however, I’m here to tell you from personal experience, beware the pitfalls that lie ahead! The theme of this week’s article is to preach the age-old advice of practicing persistence, be patient, keep an open and curious mind and most of all, seek multiple/credible sources. These are the keys to success. If we were contestants on the Family Feud television gameshow (hosted by either Richard Dawson or Steve Harvey), I would seriously hope to get the following question: "Top five answers on the board… Name a helpful source to find answers regarding your family tree." My top responses (not in any particular order) would include: *an online genealogy-based site (such as Ancestry.com, Newspapers.com) *a history research library or government record archives *a family bible/church records *older relatives *a cemetery I know I’m "preaching to the choir" to many of you who are well-versed in history research, but my aim is to share some personal experiences in hopes of serving as a helpful refresher to some, and valuable advice to beginners. Feel free to share your own tips and experiences in the comments column at the end.  Edwin A. Haugh, Jr. at the grave of ancestor Wilhelm Koch (Delaware City, DE) Edwin A. Haugh, Jr. at the grave of ancestor Wilhelm Koch (Delaware City, DE) A Fruitless Trip to a Cemetery Back in 2003, I was in the midst of conducting family research on my father’s “Haugh side.” There was a sense of urgency so to speak as my father had been diagnosed with cancer the previous year, and by summer of 2003 had finished his first round of chemotherapy. He was eager to occupy his mind with other things, and I was desirous of learning more about his life experience and genealogy. I especially needed to channel through him as my contextual advisor, knowing that time was limited and I could lose him in the near future. I supplemented my Dad’s “life story commentary” and tales of ancestors with the above-mentioned sources, especially utilizing online government and church records. In addition, I would take him on field trips to find former homes, schools and other landmarks from earlier eras. Among the most meaningful were cemeteries, finding and visiting tombstones of early relatives. Interestingly, one family branch that had always been lacking in information and stories was our Haugh side. I researched diligently in that period of my Dad’s sickness, and found out stuff that my Dad had never imagined, while also proving (and disproving) a few family myths and riddles handed down through the years. Like many folks I know, I think my quest at that time was similar to an adrenaline rush, something that subconsciously allowed me to counter the stress associated with Dad’s illness and my inability to take the pain and suffering away. This behavior is well-documented, as is the desire to start researching immediately after the loss of a parent or parents, as a source of keeping them near in heart and mind, or a desire to know them even better than ever before. I discovered priceless information regarding my immigrant Haugh relative (a great-great (GG)grandfather named Ambrose Jason Haugh) and found where he came from in Ireland. Much of my success can be credited to the internet, as I was literally working with the proverbial "needle in the haystack." Luckily I had a unique name to work with as opposed to my maternal great-great grandfather John Quill, also from Ireland. In Ambrose Jason’s case, I certainly found the proverbial " pot o’ gold" on the other side of the "family research rainbow." This man arrived in America in the 1870’s, married in Toronto and moved the family to Chicago. His wife (my GG grandmother) died as a complication of childbirth in 1887, leaving three children including my 3.5 year-old great-grandfather, Ambrose Albert Haugh. The boys were sent to Toronto to be raised by a maternal uncle and received schooling, vocational training and attained college educations. Ambrose "Al" Haugh eventually made his way to Philadelphia (via Buffalo), and eventually settled in Camden, New Jersey. He enjoyed a celebrated career as a newspaper writer and editor, and was said to have covered the Lindbergh Kidnapping Trial of 1932, but I haven’t confirmed this with surety as yet. Unfortunately, he didn’t have a "golden years" period of life, as he died in November, 1936 at the age 52. The irony strikes me as I just turned 52 last week, myself, "Al’s" birthday being January 17th, just ten days after mine.  Crazy Jennie (c. 1908) Crazy Jennie (c. 1908) My father never knew his grandfather as he was born in September of 1936. He did have a relationship with his paternal grandmother, Jennie Williams Haugh, a woman who would marry four times and go from "rags to riches" twice, and finally to "rags" again after she remarried a supposed shyster after my great-grandfather (husband #3). Jennie died in 1943, and my father didn’t recall attending her funeral held near Camden, New Jersey. Dad also couldn’t recall ever visiting Jennie’s grave, and assumed she had been buried with Al, but wasn’t sure. When it came to gravesite information (at the time I was conducting this research), Ancestry.Com and FindaGrave.com were nowhere as detail rich as they are today, with the latter website being in its infancy. I tried for months, but could not locate the final resting places of my GG grandparents (Jason Ambrose Haugh and wife Elizabeth Jane (Patterson) Haugh), scouring both the Chicago and Toronto areas for clues. I had an 80 year-old relative still living in Audubon, NJ, a suburb of Camden, NJ. He had grown up with my grandfather (Edwin Albert Haugh, Sr.) and had vivid memories of my great-grandparents "Al" and Jennie, or "Crazy Jennie" as he knew her. And yes, she was crazy from what I have been able to glean, but family is family, like it or not. We lovingly referred to this gentleman as Uncle Len, but he was actually a cousin to me—his mother being my great-grandmother Jennie’s sister. In his childhood, he lived next store to the Haughs in Audubon, and looked to my grandfather as the older brother he never had. Len supplied me with a slew of family pictures and stories from Jennie’s "Williams family," another branch I knew nothing about, originally coming from the Pottsville, Pennsylvania area to Philadelphia in the first decade of the 1900s. He also assured me that Al and Jennie were buried in New St. Mary’s Cemetery in nearby Bellmawr, NJ. It was an unusually pleasant Saturday in late May, 2003 when my Dad and I set out for Audubon, New Jersey and a visit to Uncle Len in anticipation of visiting the Haugh grave in New St. Mary’s Cemetery. Along the way, we picked up my Uncle Bob Haugh, my father’s only sibling, who shared equal interest in our family history quest. We arrived in Audubon in late morning and had lunch with Uncle Len and his wife. From there, we went to New St. Mary’s Cemetery and allowed Len to show us the way to the gravesite. The problem was, Len hadn’t been to the cemetery in quite a while, and the grave wasn’t where he thought it would be. Unfortunately the cemetery office had closed at noon, and we were on our own to find the location among a cemetery population of 18,000, located on 50 acres. To add insult to injury, there was one distinct older section of upright monuments, but the vast majority of gravestones here in this Catholic memorial ground cemetery made up neatly laid-out rows of uniform-shaped, low profile “hickey-style” markers that all looked the same. Well, after a few hours of walking aimlessly in different directions, we gave up our search—seemingly having exhausted all options. We came home disappointed, no one more so than my father. At 8:00 am on the following Monday morning, my father called the cemetery office to gather the information we should have gotten beforehand. The administration gave him the plot location, and agreed to take (and send out) a picture after my Dad told our hapless attempt to find the lost “Haugh family covenant of the lost arc.” An hour later, my father received a call from the superintendent of the cemetery with news that he had also had difficulty finding the gravesite because it was actually unmarked—never having had a gravestone atop the lot. Well that certainly explained our fruitless search, and hammered home the fact that we should have had some earlier correspondence to plan our visit. Regardless, we did receive some incredible information through the whole episode. The superintendent pulled the cemetery lot card, which listed those interred at this location which includes ages and burial dates. We found my great-grandparents (Jennie and Al) as hoped, but another person of paramount interest was buried here as well—my GG grandfather (Ambrose Jason Haugh) from Ireland. He had died in 1927, and I would later learn that he had been living at a nearby care facility in Camden.  Death announcement for Amanda Bauerle (Feb. 1927) Death announcement for Amanda Bauerle (Feb. 1927) Two other people were also here in this grave plot as well: a woman named Amanda Bauerle (1876-1927), and a man named Lloyd Emerson (1872-1937). Considerable research, coupled with a lucky internet find gave me an explanation as to who these folks were, and why they were buried here. I found that Emerson was an unmarried, 65-year old handyman that boarded with my great-grandparents at the time of his death. More interesting was Amanda’s story. Amanda Bauerle was actually the former Amanda Williams hailing from Pottsville, PA—a sister of the fore-mentioned "Crazy Jennie" and Cora Williams Jones (Len’s mother). Amanda had died in 1927, and I found a brief, yellowed obituary, which had been clipped from a newspaper and found hidden within a pocket of an old photo book of Williams family members (given to me by Len). I still didn’t know much, but soon stumbled upon a bulletin board inquiry about Amanda online. The message had been written a few years prior by a great-grandson of Amanda’s named Rob Hogan. He was living in a place called White House, Tennessee and was seeking information on his relative, above all wanting to learn the whereabouts of her burial site.  Amanda and Joseph Bauerle Amanda and Joseph Bauerle I had the answer, one that possibly would take him a lifetime to discover....like a needle in a haystack, of course. I duly emailed Rob of my find recent find in Bellmawr, New Jersey’s New St. Mary’s Cemetery. Suffice it to say that he was ecstatic, and called me that night. We stayed on the phone for nearly three hours, sharing notes, stories and even family photos I had never seen as we emailed each other scans from our respective computers while talking. Rob said that when he was a boy, his grandfather had told him the sad story of Amanda’s untimely and tragic death—a result of a freak accident. The story goes that Amanda was with her husband at the time (1927), enjoying a church sponsored Valentine Day social. The 51-year old, and her husband, took to the dance floor and unbeknownst to her, another party-goer would accidentally drop a drink behind her. This resulted in Amanda slipping on the spill, and on her way to the floor, her head hit a piano. She was rushed to the hospital in a comatose state. Amanda would never awake from the coma, dying a few days later. Her sister, Jennie Haugh, would purchase the grave plot in February, 1927. My great-grandmother had pre-planned wisely, as her own father-in-law (Ambrose Jason Haugh) would pass six months later, and was placed here too. Amanda Bauerle’s husband would eventually remarry and moved to the northern part of the state. Her 14 year-old son, Joseph Bauerle (1913-1983), soon developed a special relationship with his Aunt Cora and Uncle Elmer as his adopted parents in adulthood. These were Len’s parents, and Rob had heard his name before. Although Len didn’t remember Amanda, he fondly recalled her son Joseph as his parents accompanied Joe when he eloped in 1931 at Elkton, MD. Joe and his wife also took Len’s parents on trips to Florida and elsewhere. What a connection, and new friendship for me as I have learned a great deal from Rob, all the while garnering additional photos and having another expert to help identify relatives therein. A few years later, I made a trip to Pottsville in an effort to get a better handle on the Williams family. I visited old home addresses, cemeteries and also parlayed a tour of the Yuengling Beer brewery. Family lore has it that my grandfather often played with members of the Yuengling family while visiting relatives each summer in his youth. The best thing to come from this whole adventure of seeking the elusive Haugh gravesite was fulfilling a dying wish of my father, made in early summer 2004. He instructed me to place a grave monument on the Haugh site at St. Mary’s, with the names of each of the lot’s five inhabitants so future family researchers will have a much easier time finding them than we did. My father passed in June, 2004, and by the following spring, the Haugh gravesite was duly marked with a monument. I have made several visits since, as it’s a true touchstone of family, history and lineage to me. It represents the same to Rob, who can be credited with making several associated entries on Findagrave and Ancesty.com regarding his long-lost grandmother and her Williams kinfolk. Like pieces of granite and marble serve not only beacons and lasting monuments to former ancestors, but also play roles as important information portals. In the future these will continue to grow as virtual information resources as technologies such as GPS coordinates will connect gravestones to online information databases featuring genealogical information about the decedent, including stories, photographs, and videos. In fact its already a reality in some places. Thanks for your endurance as I truly love telling this personal "Story in Stone," one which links four out of six Haugh/generations in America. I’ve also gleaned much about my father through studying his ancestors, especially his parents. My grandfather, Edwin Albert Haugh, was a career Army and WWII veteran who died in 1970 when I was three. My Dad told me plenty of stories about his father, but I continue to learn about the man from various sources such as military records on Fold3, and online newspaper archives. He would give his name to my father, including that middle name of Albert taken from his own father. It’s this process of common name giving that can help aid, and sometimes confuse, the newfound family researcher at times. Good luck to my GG Grandson conducting genealogy in the distant future as I have the middle name of Edwin, and gave it as a first name to my son born in 2006, two years after the death of my Dad. The Haystack’s Needle of January 12th Now what does my long-winded tale have to do with Mount Olivet? Well, one of the greatest parts of my job is assisting family researchers on their history quests to our cemetery. Some just require a grave lot location, where others want to share their research and familial stories of a loved one buried here. I also know for a fact that we have had people come here thinking they know where a loved-ones grave is located, only to get lost. Thankfully, many come to our office, or look at the kiosk near the entrance of the cemetery, to find proper locations and map guides in both mounted and takeaway form. I have also noticed people wandering aimlessly, repeating again and again my experience at New St. Mary’s by thinking that it shouldn’t be that hard to find a distant relative’s name on a gravestone. Earlier I utilized the expression "needle in a haystack" because that best describes what it can be like trying to find a single burial amidst a collection of 40,000. The same can be said with finding a person in a written or internet database. Names can be similar and confusing. They can also be misspelled or inverted between first/middle. Dates (birth and death) can be a big problem as well. The key is starting any search with a legitimate handle on both name and date of the "sought-after" decedent. Again, I go to our opening Family Feud sequence to provide valuable advice. However, I also stress that the researcher beware, as there are definitive pitfalls with each method listed if you regard found kernels of information as "the God’s Honest Truth" as they say. Errors, and continuation of erroneous information, are around every bend. In my New Jersey story above, I shared a lack of guidance from available internet and archival sources at hand, or unavailability due of a closed cemetery office. I also referenced a confused relative to boot, but it wasn’t necessarily his fault because the grave was unmarked—it just would have saved us three hours of traipsing around a cemetery had he known, or remembered, that the site was unmarked. This whole lesson, and past related episodes, have come into my mind over the last few days as I researched the featured individual of this week’s blog. I have a full file drawer of potential "Stories in Stone." I decided to take a new approach to story choice for this week—I would simply pick a death date, enter into our Mount Olivet database, and discover someone altogether out of the blue. I figured I would write and likely publish this story on January 12th, so I sought an individual who passed on that date. A man named Thomas Morgan Smallwood was the first to pop up on my screen. He apparently died in 1854. My approach worked as I had no earthly idea who this was. I have known several African-American residents of Frederick holding the surname of Smallwood. However, I assumed Thomas Morgan Smallwood was white because Mount Olivet was segregated at the time of his death in 1854. I also was reminded of Gen. William Smallwood, a Revolutionary War patriot from Charles County in addition to serving as Maryland’s fourth elected governor. Could there be a connection to the southern Maryland Smallwoods? "What’s in a name?" you could say, as I had a full one now and I was determined to find out about this guy and his family. I soon looked at dates and began scratching my head on his given death of January 12th, 1854. How could this be right if Mount Olivet didn’t open its gates to the public until May, 1854? Our celebrated, first-known burial of Ann Crawford occurred on May 24th, 1854. I thought for a short moment that this could be a serendipitous find, perhaps a forgotten new first burial, several months before Crawford’s. I then thought, well I should check the gravestone, itself. Sure enough, it said 1854. What a quandary, but one I was determined to solve for the sole reason of "first burial bragging rights." In any other case, I would surely have believed the cemetery record which was confirmed by a death date etched in stone. The same held true for this death date as found in online records as well, not a surprise as these can be based on the two fore-mentioned cemetery records, not to mention Jacob Holdcraft’s Names in Stone. It was time to go to primary sources with more accuracy. I looked in the Frederick Examiner newspaper for an obituary. Finding nothing recording Thomas M. Smallwood’s death in mid-January, 1854, I wisely looked for something in mid-January, 1855. Sure enough I found an obituary in an edition dated January 17th, 1855. I also found the same story appearing in the Baltimore Sun of January 18th, 1855. Not only did I find, and confirm, a fixable error in our cemetery records, I also learned how Thomas Morgan Smallwood died on January 12th, 1855. He was only 29, and died as a result of suicide. I did not discover much more on Thomas, other than he appears by name in the 1850 census living in Buckeystown and working as a saddler. A decade earlier, he was listed among the members of Frederick’s Junior Tippecanoe Club. Without getting a fuller story on Thomas, I was now curious about his family, and found several Smallwood family members buried in his cemetery lot (Area C/Lot 20). This is located along the cemetery lane that parallels Stadium Drive, and is directly across from Harry Grove Stadium. From our cemetery record, I learned only that Thomas was born on April 5th, 1825, a fact also duplicated on his gravestone, but I was sure to confirm with other sources. Here I found several references to William C. Smallwood. In some of these references, I found William C. also referred to as William Cooper Smallwood. I did not, however, find a William Charles, so I deducted that William Cooper Smallwood and William Charles Smallwood were one in the same. Charles based on the middle initial "C" represents a common assumption made by a future generation, because William had a son named Charles. Now I searched for William Cooper Smallwood on Ancestry.com and found a match married to an Rosanna, but no mention of a maiden name. So I went back to Jacob Engelbrecht’s Diary and soon found the following passage dated May 7th, 1823: "Married last night by the Reverend P. Davidson, Mr. William C. Smallwood (Tailor) to Miss Roxena Rollington daughter of Mr. John Rollington all of this place." Bingo! This was definitive, giving me a maiden name for Mrs. Smallwood, mother of Thomas Morgan Smallwood. It also told me of William’s profession as a tailor. However, what’s up with the name Roxena? I assumed that this was just a case of Jacob not able to spell Rosanna correctly. I confirmed the marriage with another Engelbrecht diary entry on January 24th, 1826 featuring the death of Thomas’ maternal grandfather: "Died this morning at 1 o’clock, in the 50th year of his age Mr. John Rollington (barber) father-in-law to Thomas W. Morgan & William C. Smallwood, of this city. He lived nearly opposite my shop." Now I had learned something about Thomas M. Smallwood’s maternal grandfather, and was introduced to Thomas’ namesake Thomas W. Morgan, who I would later learn was a former county sheriff in the 1820’s and a longtime cashier for the Farmers & Mechanics National Bank. As for William Cooper Smallwood, a few notes found stated that he was an artist from Philadelphia. Another clue said that he was from New Jersey. I would follow this up later. Siblings, Nieces & Nephews In the meantime, I continued deciphering who we had in the burial lot with Thomas Morgan Smallwood and his parents. I found two brothers here. Now I knew who William Cooper Smallwood was, but what about two others holding similar names similar to that of dear old dad? A given was Thomas’ brother William Cooper Smallwood (1823-1888). I now could place "Jr." at the end of his name, and "Sr." after his father’s. I had seen references of the sort in Engelbrecht’s diary with entries referring to a Cooper Smallwood. The other brother was Charles Smith Smallwood (1830-1902)giving a possible explanation for the erroneous middle name of "Charles" found in our cemetery records for father William C. Smallwood, Sr. Jacob Engelbrecht made several entries in early July, 1864, a time when Frederick was invaded again by the Confederate Army and had a $200,000 ransom levied against by Gen. Jubal Early. The Battle of Monocacy would follow. Cooper Smallwood and Uncle Thomas W. Morgan were listed among the 29 "skedaddlers" from town on July 4th after hearing reports that the Rebel Army was heading toward Frederick. The entry was made on July 5th, 1864. They were Union men, as was William Cooper Smallwood, Sr., who was among the members of the Brengle Home Guard established to protect Frederick City in 1861. I also read in Engelbrecht’s diary that our subject (Thomas Morgan Smallwood) had two other brothers who died in childhood of Scarlet Fever. Henry (age one) died on Thomas’ 8th birthday (January 12th, 1833.) Just nine days later, six year-old Benjamin Smallwood died. Both boys were buried in Frederick’s Presbyterian Cemetery, one-time located behind the present church on W. Second Street and stretching to W. Third Street. Thomas Morgan Smallwood would come to be surrounded by nieces and nephews, all born after his death. William Cooper Smallwood married Julia E. Zeigler, however this was not the same Julia Smallwood I found in the Smallwood family plot. Rather this Julia Smallwood (1879-1910) was a niece, she being the daughter of Thomas’ brother, Charles Smith Smallwood. But wait a minute, there are two Charles Smith Smallwood’s here in this lot! Time again to delineate father and son with Sr. and Jr. Charles Smith, Sr. married Elizabeth Louise Rinehart and had seven known children, six of which are buried in this Smallwood lot. These include: *William F. Smallwood (1871-1872) likely a twin of daughter Rose *an unnamed infant of three months who died in 1874 *Julia Smallwood (1879-1910) a former teacher at the North Market Street School who died of tuberculosis *Charles Smith Smallwood, Jr. (1883-1918) a sales clerk who died from pneumonia while living in Baltimore *Ella (Smallwood) Cook (1865-1943) a housewife who had relocated to Frostburg, MD *Rose Elizabeth Smallwood (1871-1956) an accomplished dress-maker who lived out her final years at Frederick’s Home for the Aged on Record Street Two more individuals can be found in the Smallwood lot on Area C. This is Thomas’ sister-in-law, Elizabeth Louise Rinehart (1843-1929), the wife of Charles Smith Smallwood, Sr. and a former resident of New Market. Elizabeth’s maiden sister, Martha Ann Rinehart (1846-1927), of Baltimore rounds out the 14th individual in this plot. As an aside, I wondered what became of William Cooper Smallwood Jr.’s wife, the former Julia E. Zeigler? Well, she is buried in Frederick’s St. John’s Roman Catholic Cemetery, located between East Third and Fourth streets. I went to FindaGrave.com to seek out her memorial page. Low and behold, I found another page for her husband, stating that he is buried with Julia at St. John’s. Both names are also carved on a fine monument resting in St. John’s. This creates another snafu. I double-checked our Mount Olivet records, and he is said to have been buried here definitively. I also checked his newspaper obituary from 1888, which clarifies the fact that he was buried in Mount Olivet. However, there is no gravestone for him here. To compound matters, over at St. John's where William has his name in stone, his death date is erroneous as it should read February 4, 1888, instead of February 1, 1888. Good Grief as Charlie Brown would say. Julia would outlive her husband by eight years, dying in 1896. My guess is that her preference was to be buried in a Catholic cemetery, consecrated by a church bishop. M. Adelaide Smallwood (1858-1916), a daughter, is also buried with Julia at St. Johns. Her name appears on the side of the monument. Back to Jersey Well, I had completed my task at hand and identified everyone in this gravesite. Along the way, I was able to make valuable changes and additions to the cemetery records. Curiosity got the best of me and I set out to make the connection to other Smallwood’s in Maryland or Philadelphia. I was eventually brought to south western New Jersey. I went down several rabbit holes using online genealogical sites and digital newspaper collections. I was soon drawn closer and closer to a place called Gloucester County, New Jersey and a small township called Woodbury. This is located across the Delaware River from South Philadelphia in view of the sports complex home of the Eagles, Phillies, Flyers and 76ers. Here, I found a short municipal street called Smallwood Place, not far from a main thoroughfare of town—Cooper Street. I finally found a Sybilla Cooper (Smallwood) Rulon (1803-1883), who I hoped to be a sister of William Cooper Smallwood. I next discovered her brother, John Charles Smallwood (1798-1878), a noted civil servant and state legislator. Finally, I garnered another sibling named Benjamin Smallwood. A familiar name as William Cooper Smallwood had given this name to one of his sons who died of Scarlet Fever. This all set me up for the discovery of the three siblings’ parents, Benjamin Smallwood (1774-1832) and Elizabeth Cooper (1785-1830). Another reference in an early Gloucester County history from the late 19th century referred to their home as "the old Smallwood place" once located in the heart of Woodbury. The final confirmation of the puzzle came when I stumbled over a message Board post on Ancestry.com, dated March 13, 2002: Benjamin Smallwood’s father could well have been a William Smallwood from Maryland, whose father was Isaac Smallwood (born in England 1718), said to have moved from Charles County, Maryland to Gloucester County, New Jersey near the end of the Revolutionary War. He died in Gloucester County in 1792. This told me all I had to know! I had confirmed the hometown of our William Cooper Smallwood, Sr., the ancestral home of Thomas Morgan Smallwood’s family. I also connected the dots from New Jersey to southern Maryland but there are yet more "needles" to be found in this haystack to gain exact lineage. One other big thing jumped out at me with this trans New Jersey-Maryland ancestry synergy. Woodbury, New Jersey is less than five miles from Bellmawr, the final resting place of my Haugh great-grandparents and GG Grandfather, Ambrose Jason Haugh of Portlaw, Waterford County, Ireland. Their names are now preserved in stone for future generations of researchers to easily find within New St. Mary’s Cemetery in Bellmawr. Meanwhile, nearly 150 miles away, William Cooper Smallwood, Sr., wife Elizabeth Cooper Smallwood, son Thomas Morgan Smallwood and 11 kinfolk have their names preserved in Frederick, Maryland’s Mount Olivet Cemetery. As a guy with distant South Jersey roots, I guess I was guided to help in some way.

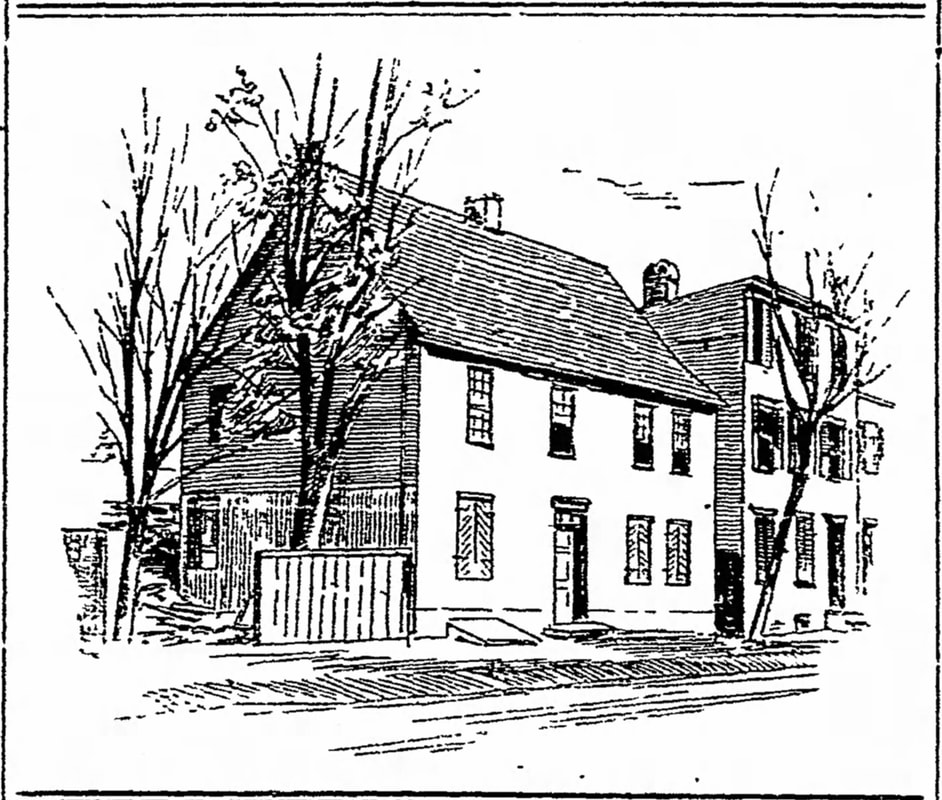

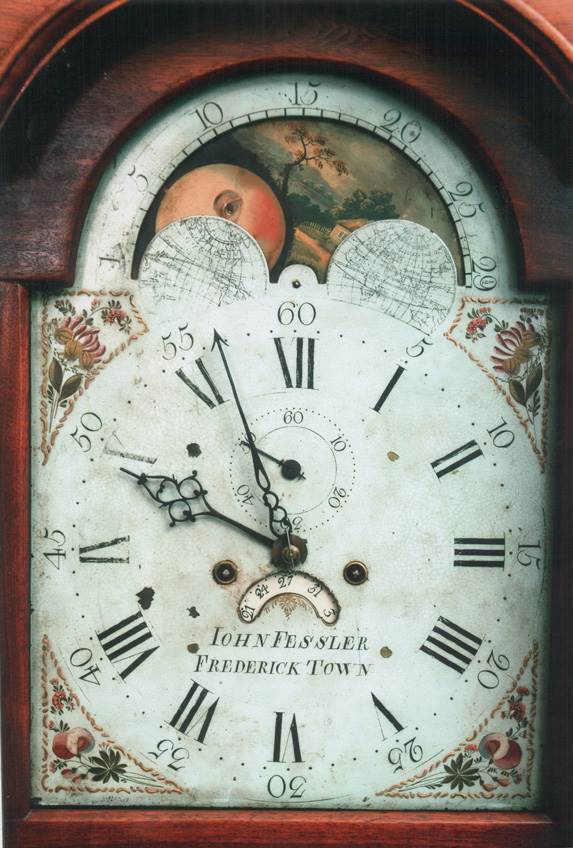

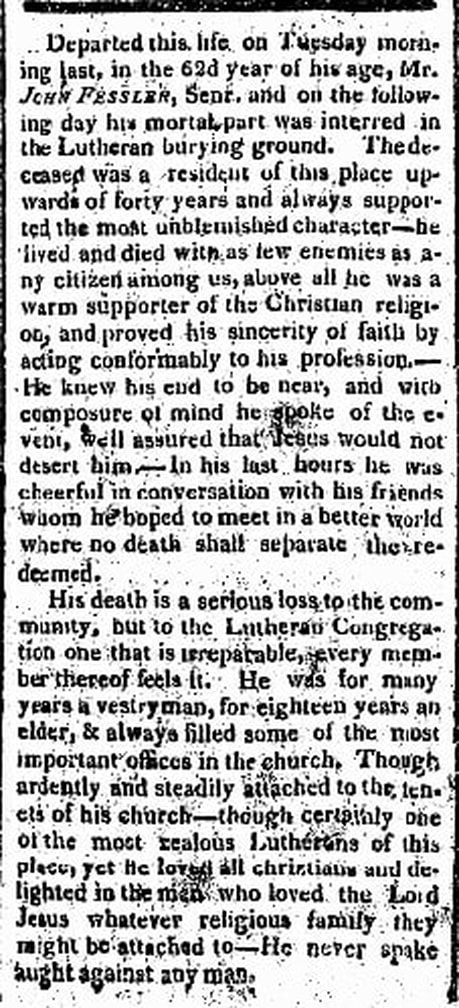

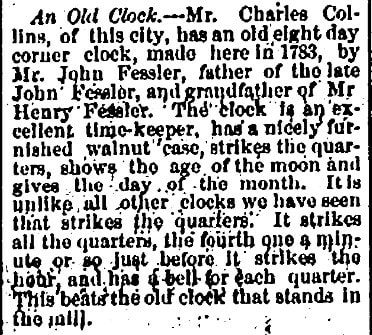

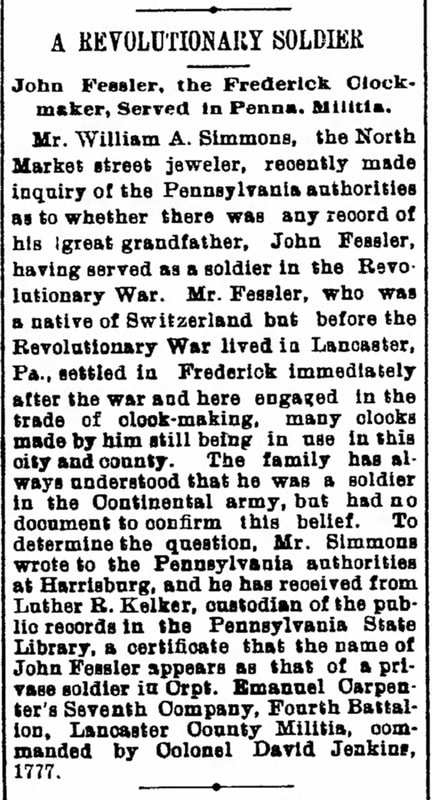

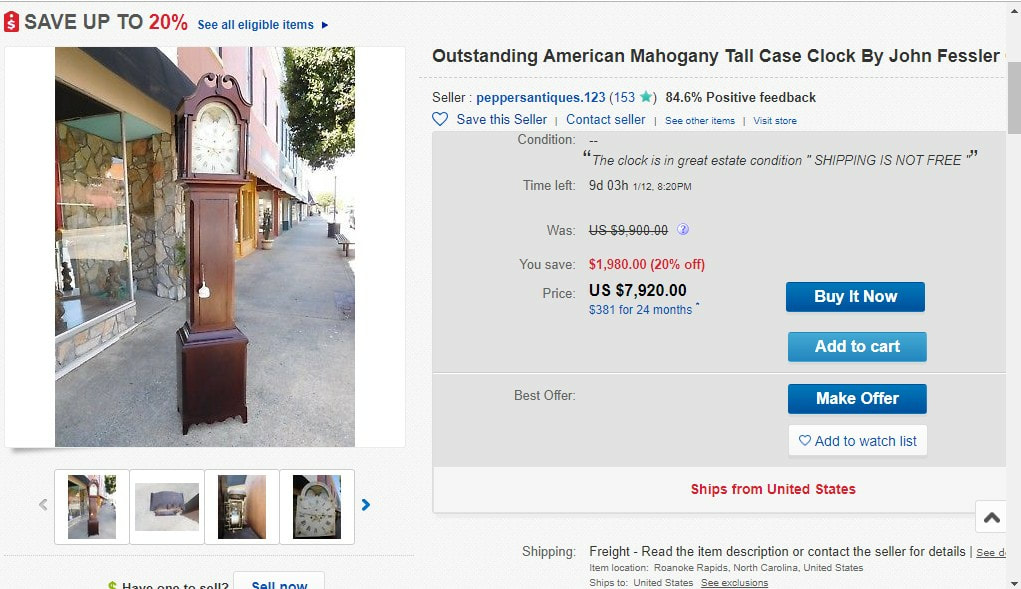

The clock is running. Make the most of today. Time waits for no man. Yesterday is history. Tomorrow is a mystery. Today is a gift. That's why it is called the present. Alice Morse Earle This is a quote that not only seems very fitting as we start a new year, but it’s also appropriate considering that this week’s featured “Story in Stone” recipient has a surname that is synonymous with time and clocks—John Fessler.  Alice Morse Earle (c. 1873) Alice Morse Earle (c. 1873) To go back to the quote for a minute, it first appeared in a 1902 book entitled “Sun Dials and Roses of Yesterday: Garden Delights Which Are Here Displayed in Every Truth and Are Moreover Regarded As Emblems.” The work’s author, Alice Morse Earle (1851-1911), was an historian and author from Worcester, Massachusetts. Her writings, beginning in 1890, focused on small, sociological details rather than grand facts, and are invaluable for modern social historians. Mrs. Earle wrote a number of books on Colonial America (with much concentration on the the New England region) such as Curious Punishments of Bygone Days. Alice Morse Earle could certainly appreciate her own quote regarding the inability to stop “the march of time” and enjoy “living in the moment,” thanks in part to a life-changing event that occurred in 1909. She nearly drowned off the coast of Nantucket while a passenger aboard the RMS Republic bound for Egypt. Shortly after departure and within a dense fog, her ship collided with the SS Florida. During the transfer of passengers, Alice fell into the water. This event impacted her health so severely that she died two years later. Tick-Tock Perhaps you are familiar with the fact that early Fredericktown was known for skilled craftspeople of many kinds ranging from furniture makers to glass artisans. The burgeoning Colonial era crossroads town on the western frontier was also known for its talented horologists. Now, like me, you may need a background in Latin and/or a small leap of imagination to see hour in horology, but if you do, you've pretty much deciphered the meaning of the profession based on the root “hora” (plural “horae”). Horology is the study of time and the art of making timepieces. Mount Olivet Cemetery is the final resting place to several horologists, but among the earliest is John Fessler, Jr. Mr. Fessler and his father are mentioned by name in an article written 80 years ago by D. W. Hering, the curator of the James Arthur Collection of Clocks and Watches at New York University, in which he discusses clockmaking in the 18th and 19th centuries, noting the rise and fall of the independent clockmaker, the movement away from quality items to clocks that could be sold cheaply, and the differences between public and domestic clocks. It originally appeared in the November 1937 issue of American Collector magazine, a publication which served antique collectors and dealers. Here is an excerpt from that article:  “To be a horologist, a man had to know both the science and the art of timekeeping; to be a clockmaker he had to be a skillful mechanic. From time to time a completely rounded man in science, art and handicraft appeared, such as Tompion, Graham, Harrison in England; LeRoy, Berthoud, Breguet in France; Ramsay, Reid, Smith in Scotland; Huygens in Holland; and Rittenhouse in America. In lesser degree there were many in America as well as elsewhere of measurable ability. In America we can cite examples that will show a wide distribution of such craftsmen and an interweaving of their output in a pattern that was spread over a broad territory. In clock lore as in that of furniture making and other industrial arts, certain names are so outstanding as to have become household words. Especially was this the case in the New England colonies where the fame of their clockmakers eventually rose to such a height as to produce the impression in later times that little ability or activity in that line was manifested anywhere else. But before the end of the 18th Century skillful clockmakers in other colonies had been producing their wares and acquiring a reputation. This was more marked in the Middle States and Maryland than in the colonies along the sea coast of the South. A clock was one of the few things not brought over in the Mayflower. If there was a clockmaker among the passengers he had no means of practicing his art except by importation of materials from Europe. Lack of mechanical facilities in America and high cost of materials for metal clocks, which had to be imported, drove would-be clockmakers of America to the production of wooden movements. These, however, were not attempted until the colonies had been growing for a hundred years and the compulsion under which they were made continued from about 1770 until about 1820. During this time these clocks were made almost entirely by hand and it is those only that can claim any attraction today as antiques. Toward the end of this period, with the aid of machinery that had then become available, wooden clocks were produced in such number and were so widely distributed that a wooden movement cannot now indicate either rarity or antiquity unless its date or maker is known. Handmade clocks, even those cheaper ones with wooden movements, were expensive and people who could afford to buy one could also afford to pay for an attractive case for it, and the long case or so-called “grandfather” clock became a prized piece of household furniture. Clockmaking as an industry related entirely to domestic clocks. Public clocks were installed by individual makers who, in many instances, carried on in a comparatively small way. Local makers of recognized ability constructed tower clocks to be installed in a town hall, a church steeple, or some public building in many of the thrifty New England cities, towns or villages, and also, though less commonly, in other sections of the country. Some of these clocks survive; others have been replaced by later ones. When an artisan built a public clock it was an important item in his own history and in the history of the place for which it was made. A clock of that nature was likely to be a chef d’oeuvre of its maker whose subsequent fame rested entirely upon that one work. A similar comment applies to an interesting public clock now in operation in the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D. C. Of this the Associate Director of the Smithsonian writes: ‘The clock movement was installed in the tower of Trinity Chapel, Evangelical Reformed Church, Frederick, Maryland in 1796-97. It was made there by Frederick Heisley. It was paid for by public subscription and was known as the Town Clock. It was removed about 1928 and replaced by an electric movement…It is a weight-driven, pin escapement, hour strike movement with a fourteen-feet pendulum with wooden rod and cast-iron bob. The frame is of hand-wrought iron, the wheels of brass, the drums of wood, and the weights cast-iron.’ Evidently this clock did duty faithfully on its original site for more than 100 years and, yet, so far as I know, no other clock by this maker is on record. “Willard,” “Terry,” and a good many other names suggest clocks to residents of the North Atlantic States who have no knowledge of clockmakers in other sections of the country, but there were makers in other sections, well known to residents there who knew nothing of the New England celebrities. Among such examples were the Fessler clocks in Maryland. John Fessler, Sr., learned the art of clockmaking in Germany or Switzerland and came to America sometime after 1750, settling in Lancaster, Pa. After serving in the Revolutionary War he moved to “Fredericktown” (now Frederick), Md., and established a business of making clocks. They are much in demand by collectors, especially in his local territory of Western Maryland. He died in 1820. One of the best authenticated and most fully recorded of early American clocks, with peregrinations and successive sojourns in three states is an example of a practice that was common with clocks of that kind and that period. The movement complete, without a case, would be placed on a shelf or bracket or could be hung up against the wall. As thus suspended it was, to all intents and purposes, a wag-on-the-wall but if the owner wanted a case for it he would have one made to suit his taste or his purse by a cabinetmaker in his own neighborhood. Our subject, John Fessler, Jr., learned the clock-making trade from his father, and would continue the family business upon the latter’s death in 1820. The Fessler story is atypical of the many German families that came to settle in early Frederick Town during the American Colonial period. To elaborate on Mr. Hering’s writing above, John Fessler was born in Switzerland in April, 1759 and immigrated with his parents and brothers to America in 1771, first living in Pennsylvania’s Philadelphia, then Germantown. He would move to Lancaster, where he likely apprenticed in the clock-making trade, although a few sources say that he came from a family of skilled craftsman of this ilk. Regardless, he took employment as a clock-maker there. From 1777-1782, John Fessler fought as a private in the Revolutionary Army. After the War, he relocated to Frederick Town, now a bustling crossroads, chock-full of skilled artisans including furniture and glass-makers. In the same year, John married a local girl, Anna Elizabeth Bach, and in 1783 opened a clock making and silversmithing business. The location is said to have been at the corner of W. Patrick and Publick (now Court) streets. The couple had four children, however, the first two (Heinrich and Elizabeth) would die in infancy. John, Jr. (also recorded as William John Fessler) was born July 2nd, 1787 and baptized in the town’s Evangelical Lutheran Church. Two years later, a sister Margaret would be born. I couldn’t find much on her aside from a marriage to George M. Conradt, Jr. in 1819. Mrs. Fessler, the former Anna Elizabeth Bach, was the daughter of German immigrants Balthasar and Rosina (Stump) Bach. Sadly, Mrs. Fessler would die prematurely in 1791, only in her 31st year. John Fessler, Sr. would remarry Elizabeth’s younger sister, Maria Barbara Bach. The couple would have three children, however two died as infants, and the third, a girl named Rosina, would die at age 13 in 1812. To compound the John’s pain, Maria Barbara would die in July 1801 at 30 years of age. Both marriages spanned only eight years each. Ironically, John Fessler, Sr. was dealt a hard lesson, over and over again, when considering Alice Morse Earle’s quotation regarding time when it comes to his loved ones. One can only assume that the bond between father and son (John, Sr. and John, Jr.) was exceptionally strong. Not only did John Jr. assist his dad in the family business, but he also stood as a steadfast family member throughout the entirety of John Fessler, Sr.’s adult life.

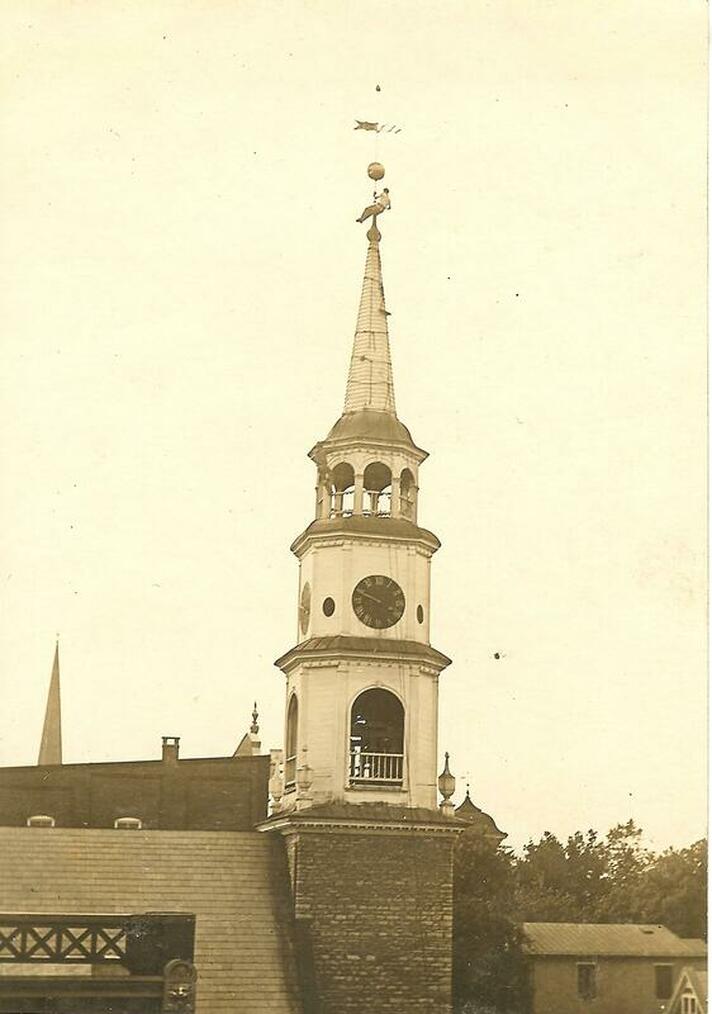

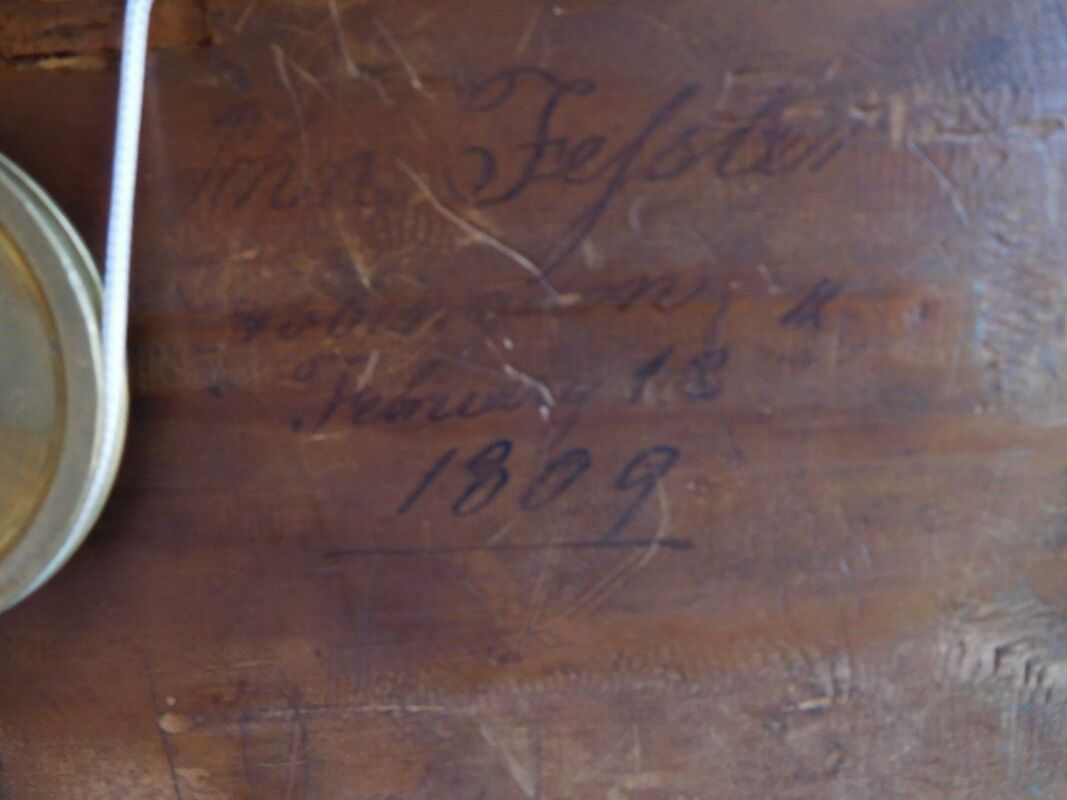

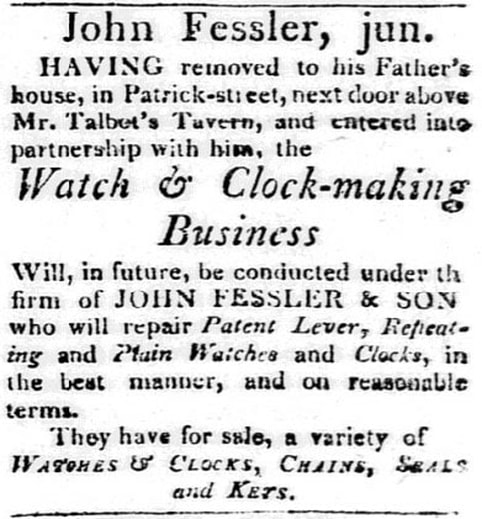

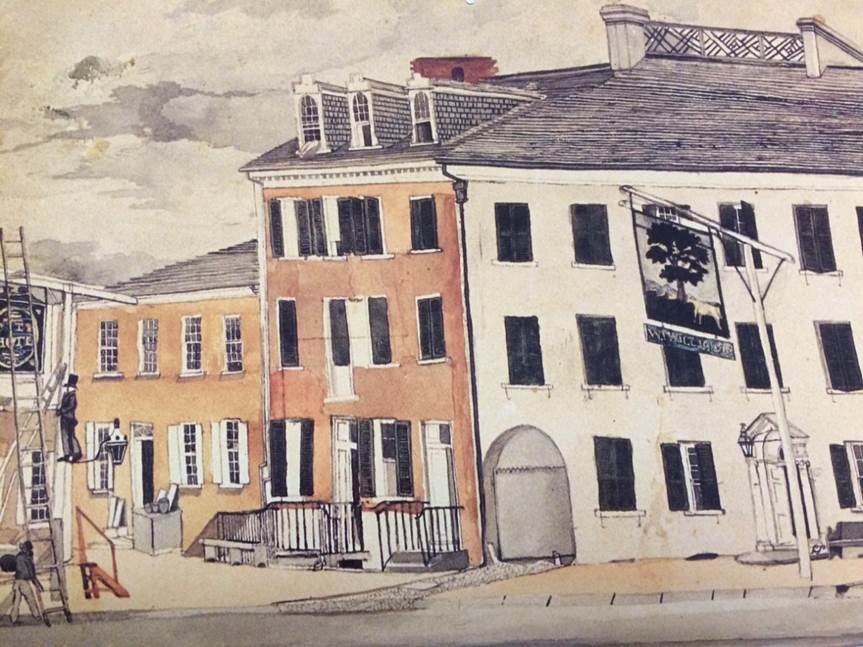

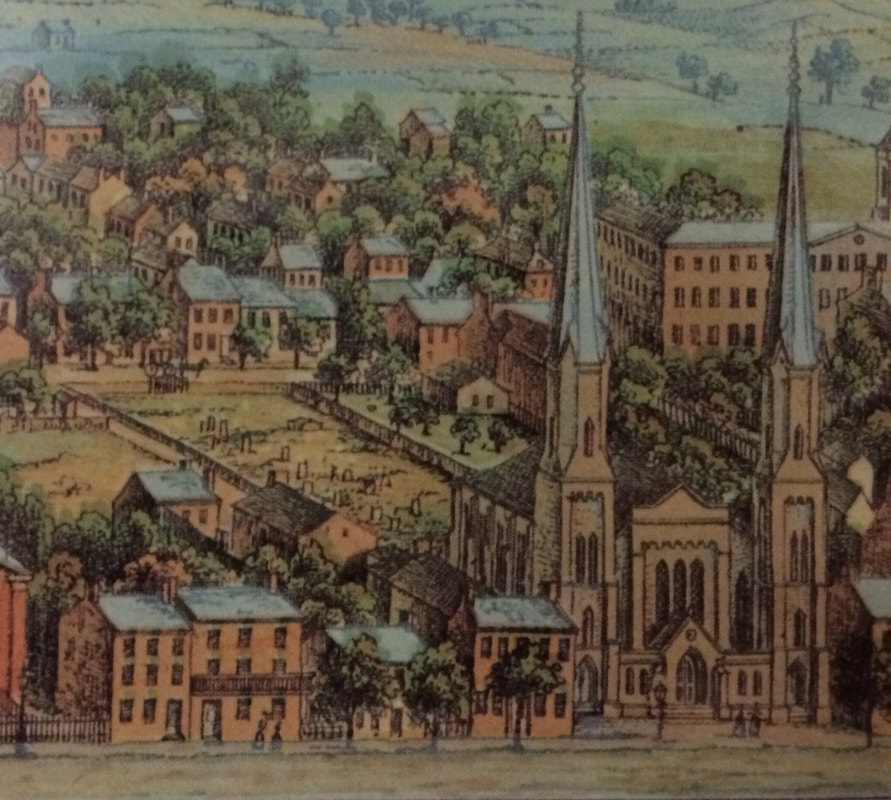

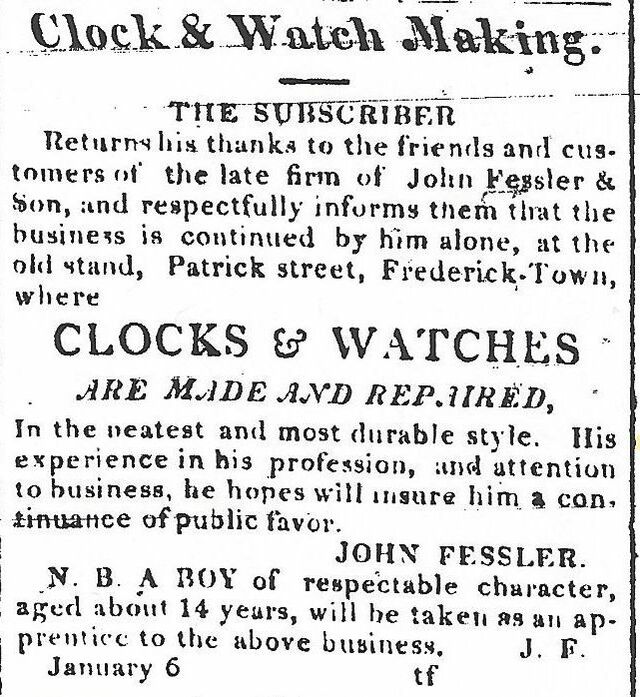

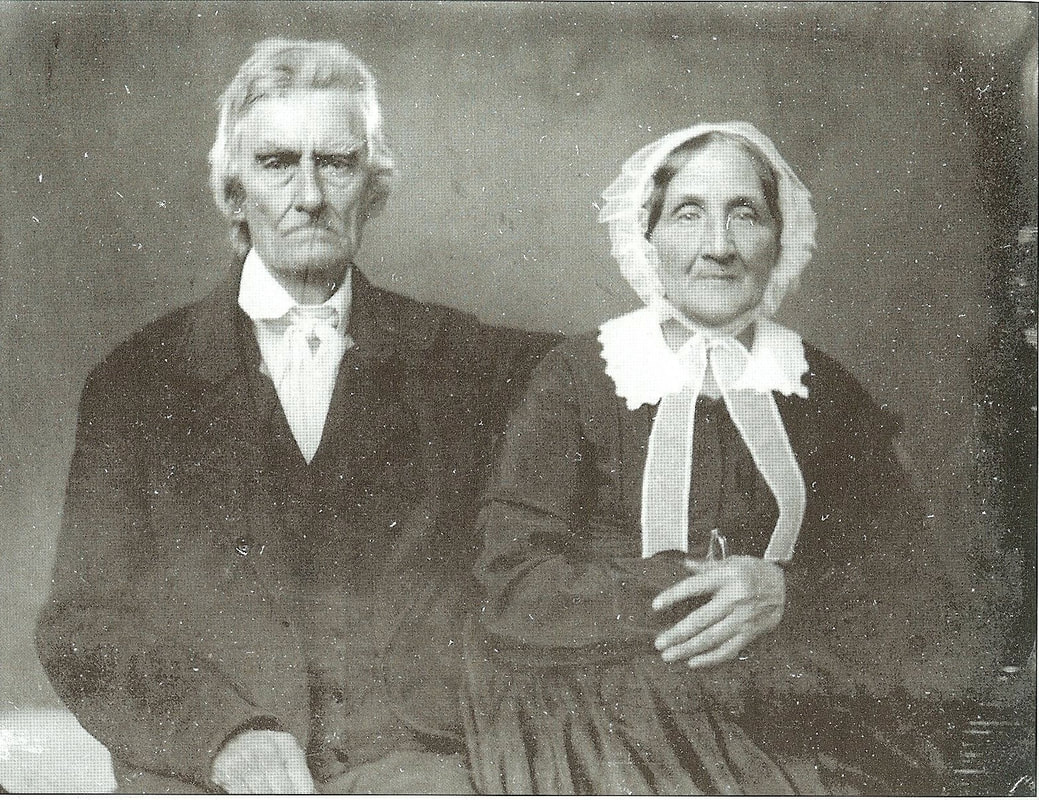

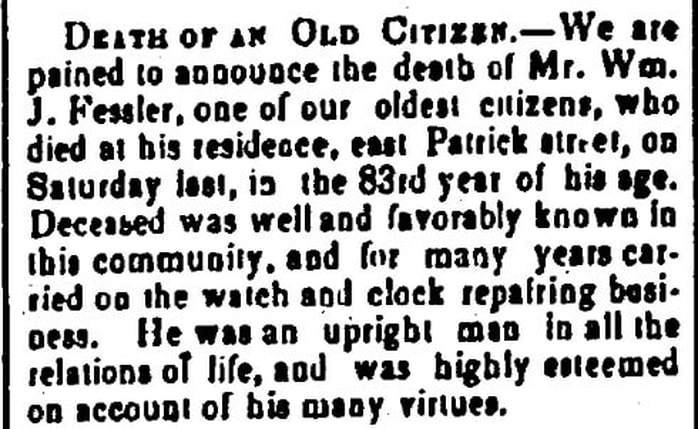

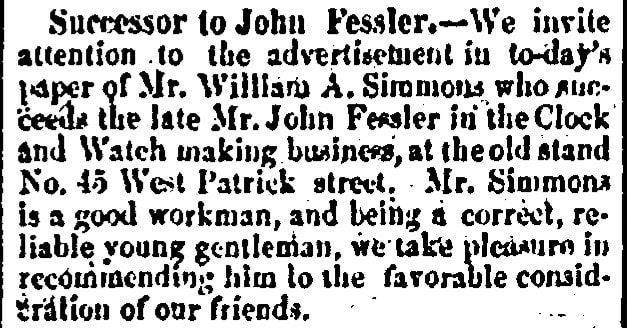

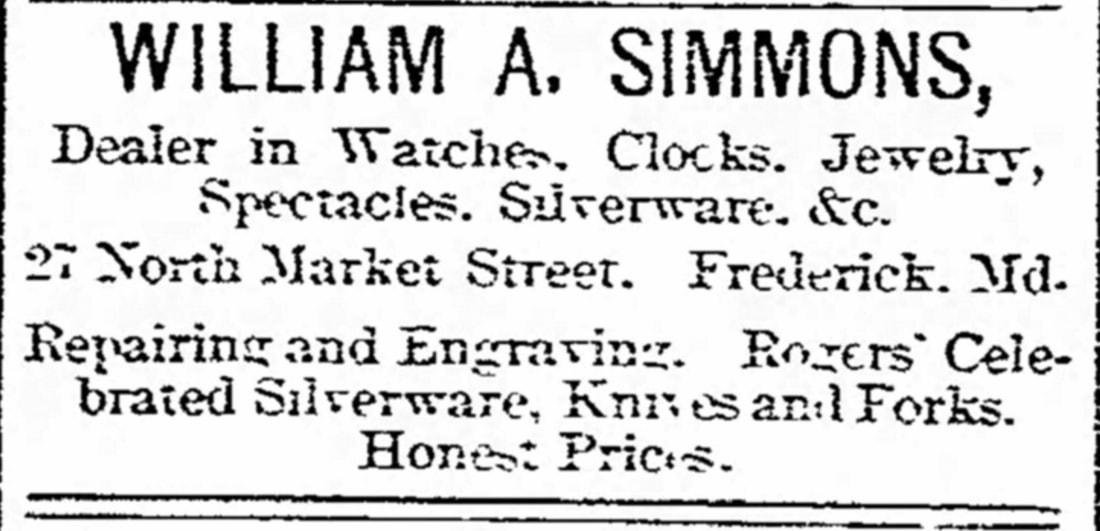

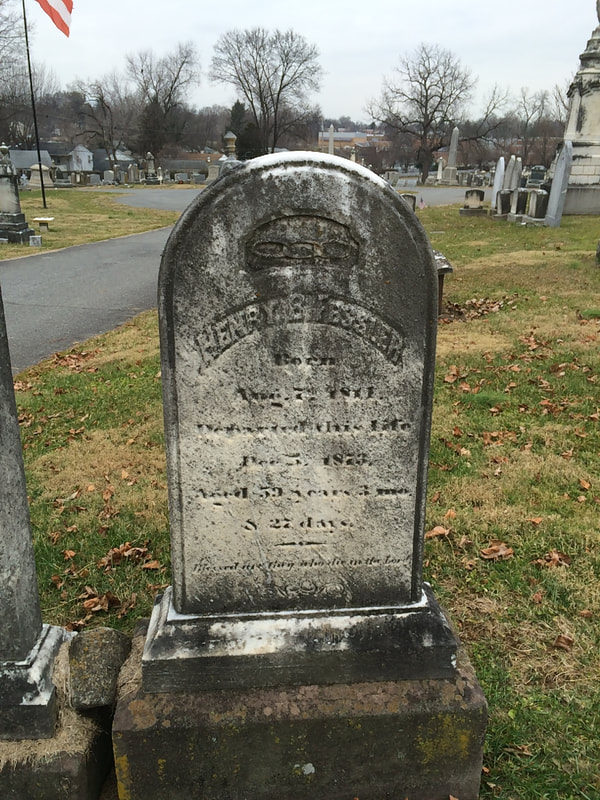

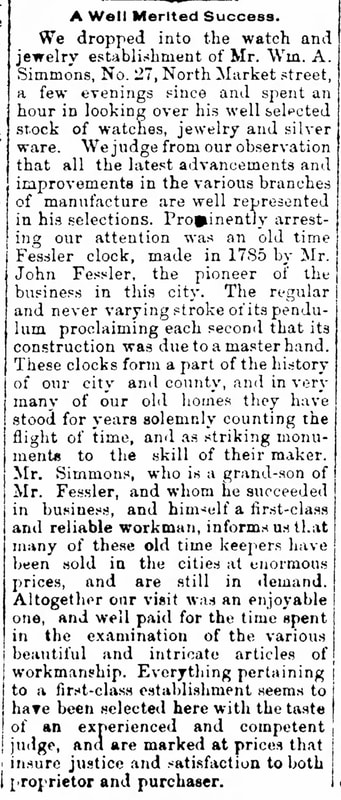

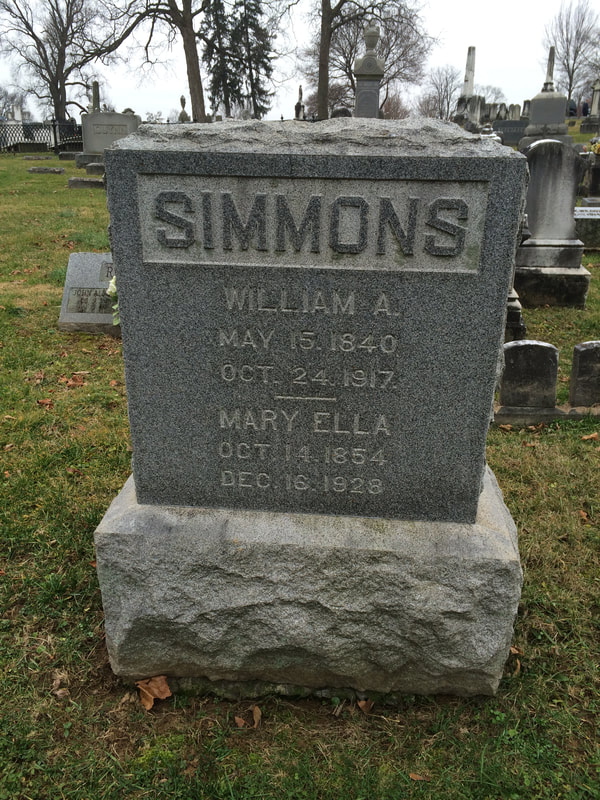

John, Jr. had assisted his father since childhood. One of his early responsibilities involved winding and oiling Frederick’s Town Clock, produced by fellow German and Revolutionary War vet, Frederick Heisley (1759-1843). This massive timepiece was placed within the spire of Trinity Chapel, located in the first block of West Church Street. To put things in context, I think I should give a brief overview of the fore-mentioned Mr. Heisely.  Compass made by Frederick Heisely Compass made by Frederick Heisely Frederick Heisely Frederick Heisely had also moved to Frederick in 1783 and set up a clock, watch, and mathematical instrument trade. He remained here about ten years, most of which spent located on South Market Street. Heisely’s prime offerings complimented the Fessler clocks as he specialized in surveyor compasses and other mathematical instruments, such as protractors, scales of different sorts, perch chains, pocket compasses, and sun dials. Around 1793, Heisely moved back to Lancaster, PA, and went into business with his father-in-law George Hoff. It is said that he returned to resume his own shop in Frederick in 1798, but this may be a bit fuzzy. Regardless, he was contracted by his own church congregation (German Reformed) to produce the clockworks to be placed in the spire of their church. Frederick Heisely may have bounced around as a journeyman, but would definitively move to Harrisburg, PA, in 1811, and worked with his two sons, George Jacob (1789-1880) and Frederick Augustus (1792-1875). Incidentally, we have a round-about connection with George J. Heisely as he is credited with putting the tune to Francis Scott Key’s “Star-Spangled Banner.” He was a soldier in Pennsylvania’s First Regiment during the War of 1812 and apparently shared his song book with fellow soldiers Ferdinand and Michael Durang. These two gentleman were amateur actors and the first to publicly perform singing the song with the accompaniment of the British drinking song “To Anacreon in Heaven”—and the rest is history (not to be confused with Heisely). In case you were curious as to the fate of Frederick Heisely, he would die in Harrisburg in 1843 and is buried in Harrisburg Cemetery. In early 1821, a register listing the Corporation of Frederick’s expenses for the previous year was printed in the Republican Gazette and showed that John Fessler and Son were paid $30.00 for winding and oiling the Town Clock. John, Jr. would continue to perform this task for years to come. Incidentally, the Heisely clockworks were eventually removed from Trinity Chapel in 1928 as mentioned in Mr. Hering’s article, and have been in the collection of the Smithsonian ever since. From that point forward, our Town Clock has been run by electricity. Fessler & Son On November 23rd, 1811, John Fessler, Jr. announced the opening of a shop in “the house of John Schley, opposite William and John Baer’s—a clock and watch making business.” This appeared in the Frederick Town Herald newspaper. Just over five years later, a formal business partnership with his famed father was publicized by way of an advertisement appearing in the Republican Gazette and General Advertiser in early 1817. The location given in this latter ad was that of a storefront on West Patrick Street, located to the west of Talbott’s Hotel, which in time would become known as the City Hotel. Today, the former Francis Scott Key Hotel sits on the site of both these former properties. The Fessler House, as it came to be known, was one of Frederick Town’s earliest domiciles, dating to the 1740’s. It served home to early surveyor, John Shelman, credited with assisting frontiersman Thomas Cresap in laying out the streets and lots for our oft-forgotten founder, Daniel Dulany of Annapolis. Through marriage, this house came into the Henry Baer family—John Fessler, Jr.’s in-laws as he had married Catharina Susanna Baer on January 28th, 1812. John Fessler, Sr. died on November 7th, 1820. His death was lamented in the local newspapers, and by noted Frederick diarist Jacob Engelbrecht in a passage written later that day: “Died this morning at 4 o’clock in the 61st year of his age Mr. John Fessler, one of the most respectable inhabitants of this town.” The old clockmaker was laid to rest in the burying ground of his beloved Evangelical Lutheran Church, amidst his “sister wives” and the five children that predeceased him. I wasn’t able to glean much about John, Jr.’s professional life, but he continued producing quality work, including addressing the need came for smaller mantel clocks and pocket watches as tastes and styles changed. He was very active in civic life, and was continually elected as a city councilman representing Ward 2, and served as City Commissioner several times. The Fesslers went on to have five children: Rosina/Rosanna Catharina (1818-1903), Henry Baer (1814-1873), Anna Elizabeth (1816-1898), Caroline Rebecca (1828-1901), John William (1830-1837), and another son whose name is not readily known (1835-1837). Jacob Engelbrecht mentioned John, Jr. often in his recounting of municipal elections. The diarist also made two melancholy entries in the winter of 1837, a downtrodden time in which John and Susanna lost two sons in a week’s time: “Died this morning a son (youngest) of Mr. John Fessler aged about 2 years. This is the second child of Mr. Fessler that died within two weeks. The other was in the 7th year of his age. Buried on the Lutheran graveyard.” (Thursday, March 9, 1837 2PM) John Fessler, Jr. had been down this road before, and likely channeled his heartbreak into his work as he had seen done by his father before him. Unlike his father though, he experienced 50 years of marriage with Susanna (Susan). We are very fortunate that a picture of the couple (in later years) taken around the year 1860 survives in the magnificent collection of Heritage Frederick (formerly known as the Historical Society of Frederick County). Better yet, the collection has several examples of the Fessler “horological handiwork!” The U. Mehrl Hooper tall clocks display is a must see, and has been a permanent fixture of the museum for years. Susanna (Susan) Fessler died on Christmas Eve, 1862. It had been a rough fall and “time of times” already with the Confederate invasion of town by Gen. Lee and his Confederate Army in early September, followed by the battles at nearby South Mountain and Antietam. John, Jr. lived to see the end of the war and a return to a new normalcy. Amazingly, he had been born four years after the end of the American Revolution, and would die four years after the surrender at Appomattox. The clock would sound its last chime in the life of John Fessler, Jr. on July 2nd, 1869, two days before Independence Day. He had lived for 82 years, three months and nine days, but who’s counting. Fessler would be buried next to his wife in the old Lutheran graveyard of town. On November 15th, 1891, their bodies would be moved to Mount Olivet and reburied in Area H/Lot 5. After John Fessler, Jr.'s death, the family business would in essence continue for several decades, as it eventually passed into the hands of grandson William Augustus Simmons, son of John, Jr.’s daughter Rosina (Rosanna) Catharina (Fessler) Simmons. Fessler’s only son to live into adulthood, Henry Baer Fessler, trained as a lawyer but proudly performed the municipality’s appointed, honorable role as “town clock winder” when his father reached an advanced age. Henry B. Fessler’s early death in 1873 culminated in the end of the Fessler family care of the Town Clock for three-quarters of a century. "Time marches on!" you could say, but thanks to the Fesslers, many Fredericktonians were able to measure it through the beautiful clocks and watches they produced over a tenure spanning three centuries.

|

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed