|

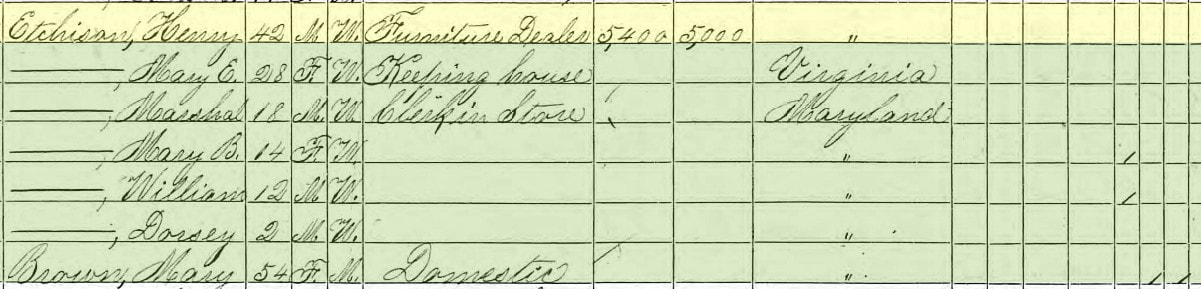

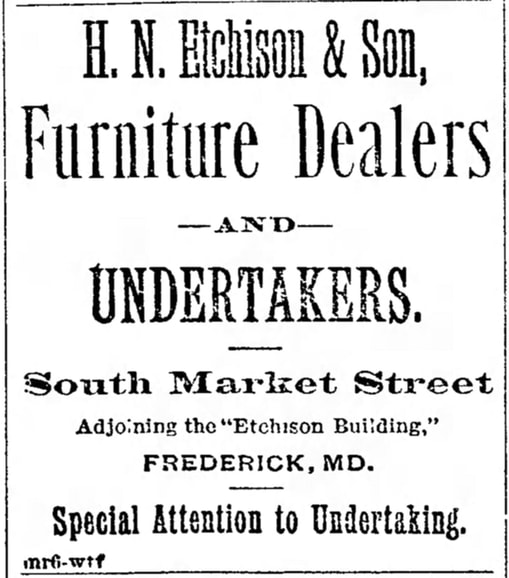

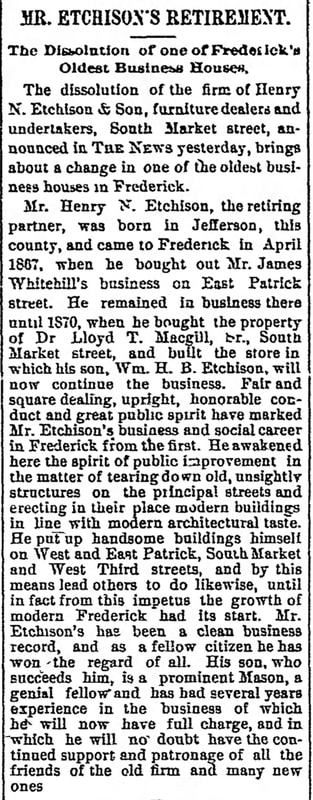

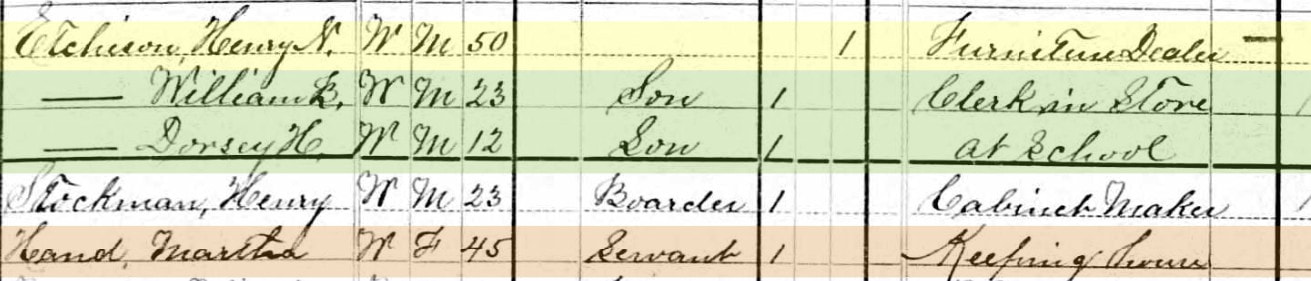

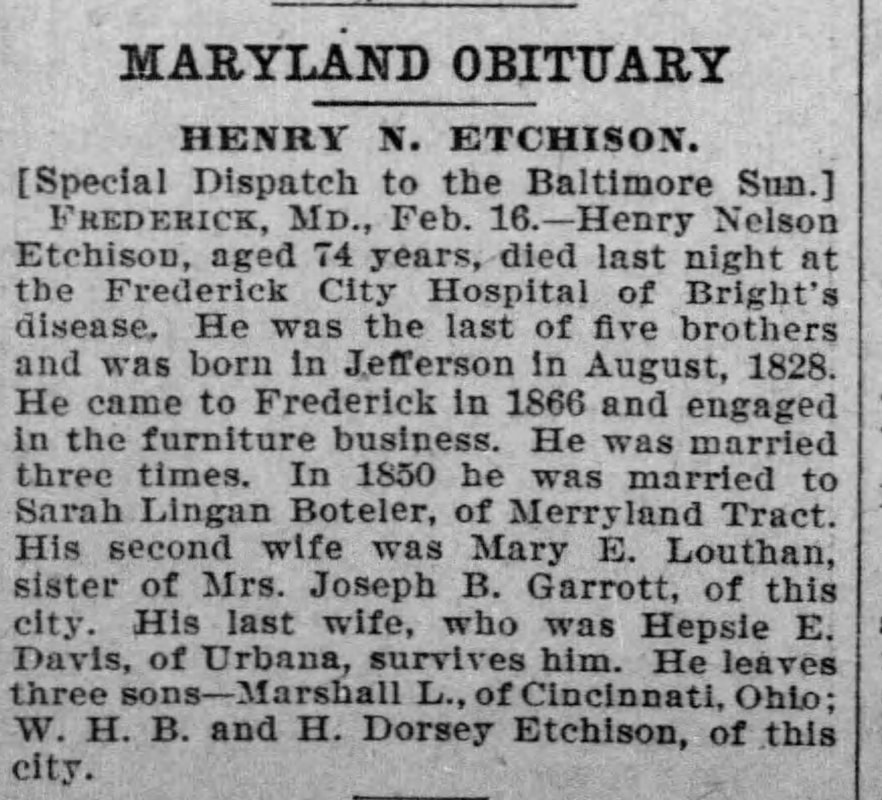

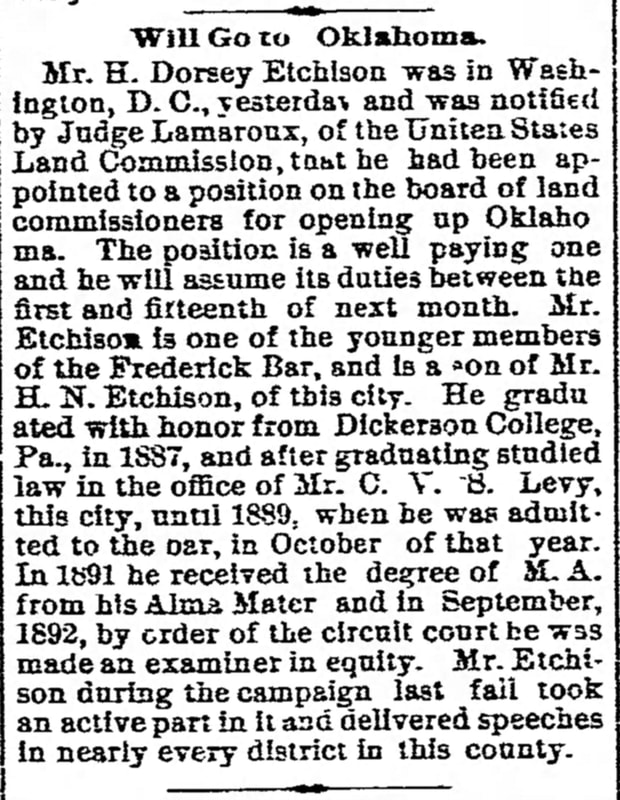

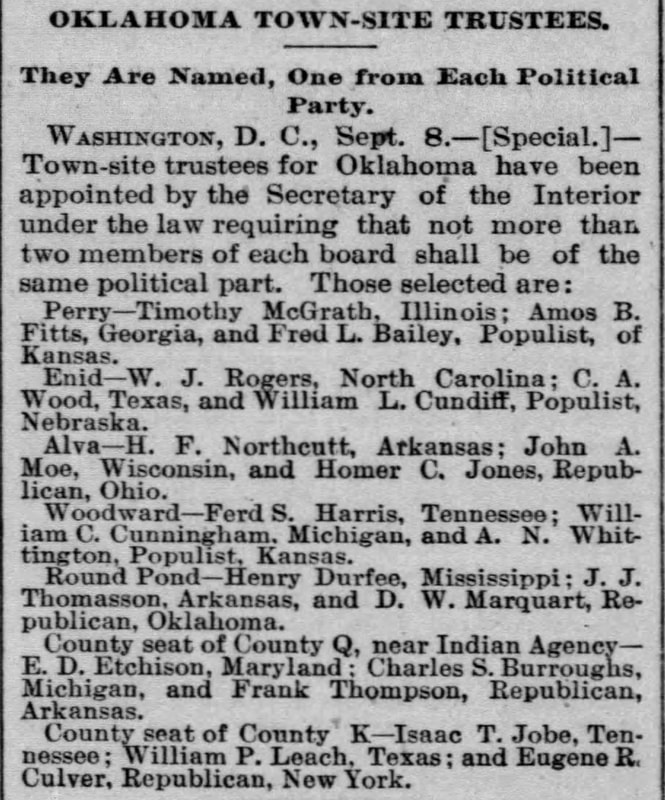

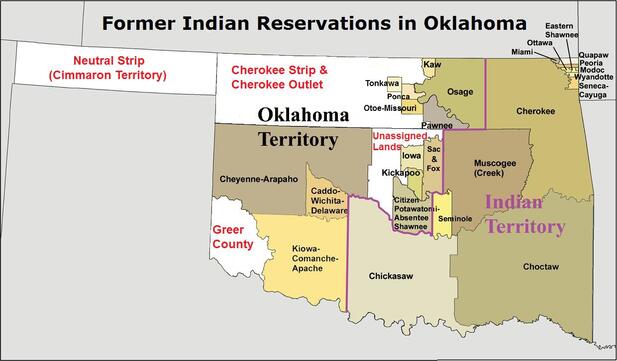

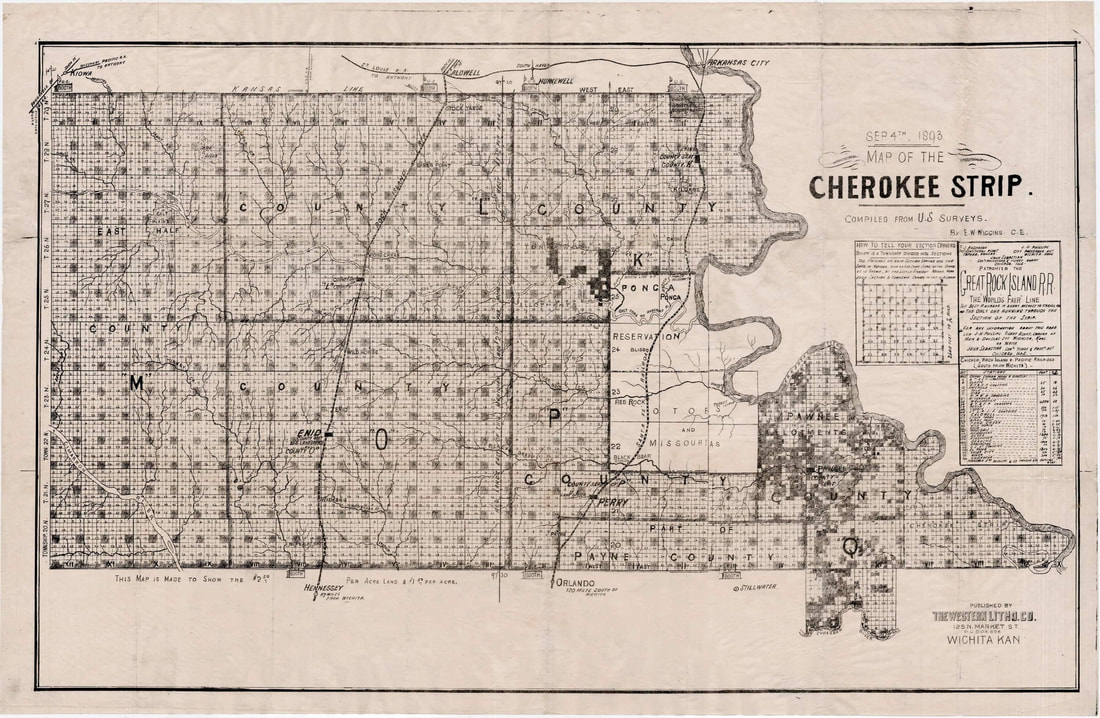

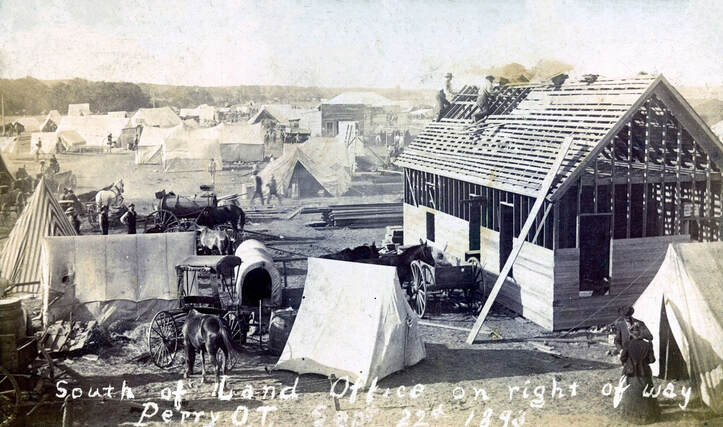

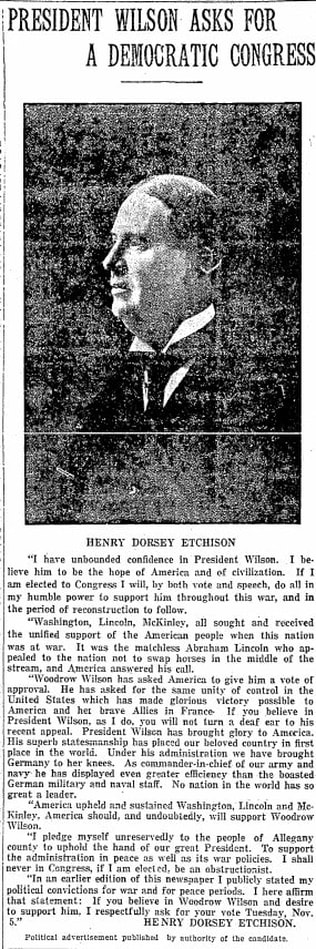

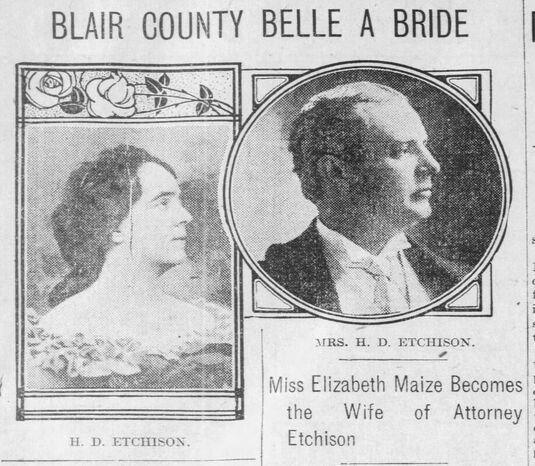

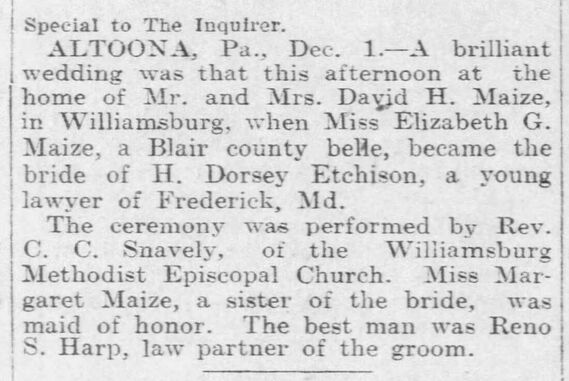

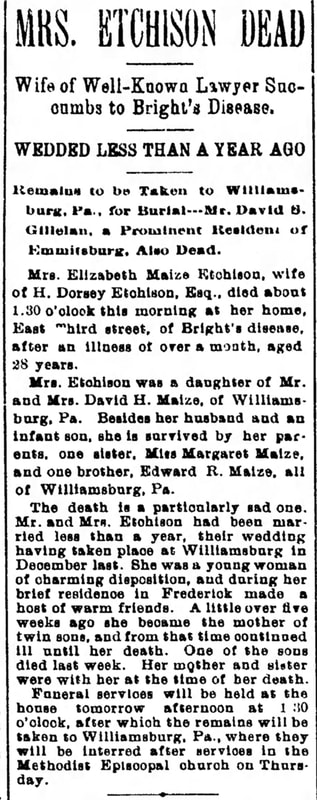

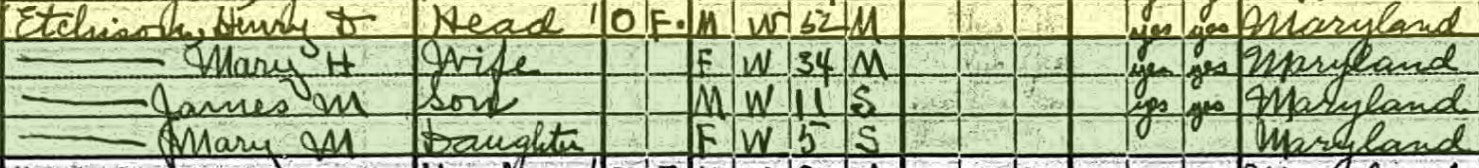

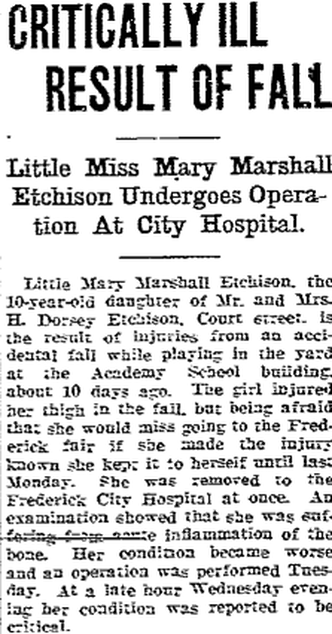

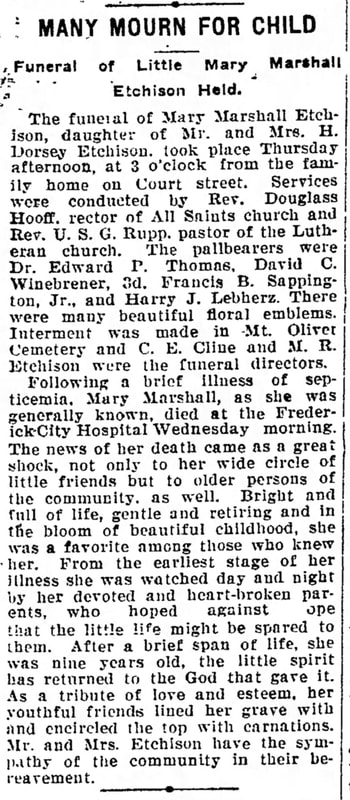

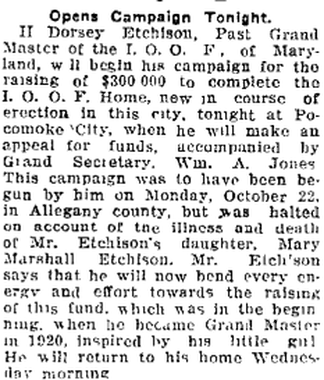

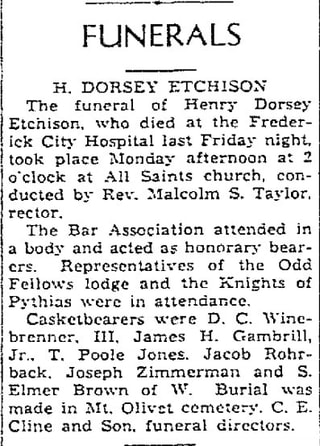

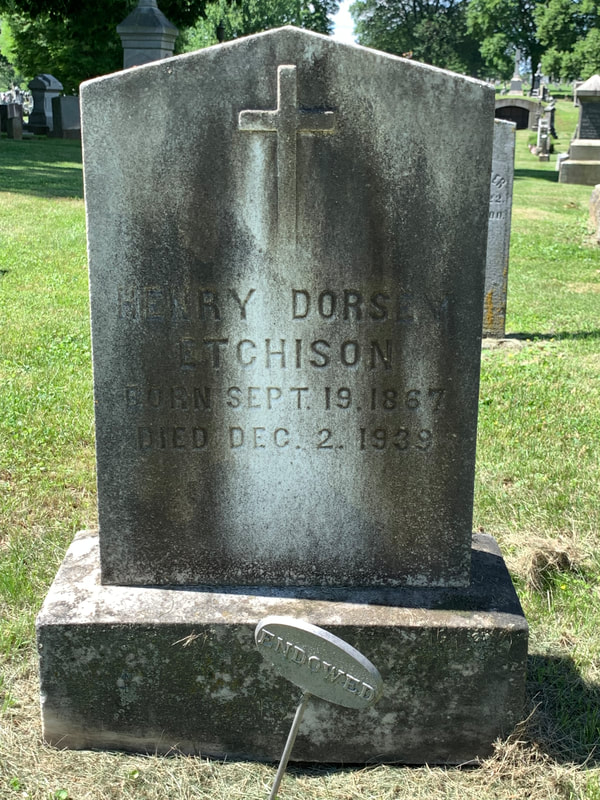

I’ve been wanting to write about Henry Dorsey Etchison since having the opportunity to introduce students to this former Fredericktonian in a class I taught for Frederick Community College’s ILR (Institute for Learning in Retirement) program. That was back in 2017, and the class was entitled “Frederick’s Ties to the Wild West.” Mr. Etchison’s gravesite can be found in a sizeable plot on Area R/Lot 31/32/33. I have been quite familiar with the family name in Frederick history, primarily being associated with a successful furniture and undertaking business that existed for years in the county. However, my subject, although directly related, had nothing to do with this endeavor. Over his lifetime, he would become one of the leading members of the Frederick Bar. Interestingly, he had a brief, yet historic, experience on the western frontier at the onset of his successful career. This adventure was connected to one of the chapters of our country’s history as it pertains to the concept of "Manifest Destiny." Henry Dorsey Etchison was born in Frederick City on September 19th, 1867 the son of Henry N. and Mary E. (Louthan) Etchison. Henry Nelson Etchison was a descendant of one of the old families of Frederick County, born in Jefferson (MD) on December 16th, 1825. He was a successful merchant in Frederick City for 40 years and described as “highly esteemed by the men of his generation.” I found his business location and family quarters at today's 10 S. Market Street, a unique townhome mentioned by Frederick diarist in June 1879 when Mr. Etchison had a fourth story added. Henry N. Etchison was married three times: first to Sarah Lingan (Boteler) who can be found in the family plot in Mount Olivet, having died in 1862 at only 31 years of age. Henry’s second wife (and mother of our subject), Mary E. (1840-1873), was the daughter of John Louthan (1804-1879), a descendant of one of the old Scotch families of Virginia, a slave holder, and prominent citizen of Clarke County, VA. A third wife would come in the personage of Hepzibah “Hepsie” Davis who long outlived her husband, dying in 1942. She is buried in Kemptown Methodist Church graveyard. Henry Dorsey Etchison had an older step-sister and two step-brothers: Mary V. Etchison (Mussetter), Marshall Lingan Etchison (1851-1919) and William Hezakiah Boteler Etchison (b.1857-1914). Like his siblings, Henry attended the public schools of Frederick, and completed his preparatory studies at the Frederick Academy. He would pursue his college degree in Carlisle, Pennsylvania at Dickinson College. An internet blog found back in 2017 on Dickinson College’s website offered the following narrative regarding the collegiate career of our subject: Etchison took a scholastic track including English grammar, United States and Ancient History, Ancient Geography, Arithmetic, Latin, Greek, the classical works, French, German, Natural Science, Religion, and Ethics; however, Etchison himself was far from a model student. The Dickinson faculty ranked Etchison second to last in his graduating class. The faculty also mentioned him twice in the faculty minutes for deserving reprimands. The most significant episode involved a serious case of hazing a fellow student, surname Pomele. The faculty decided to suspend others involved for a month, though Etchison received only a signed reprimand. Etchison still graduated in three years with the class of 1887 with his Bachelor of Arts degree. After graduation, H. Dorsey began his path to become a lawyer, and apprenticed under Charles Van Swearingen Levy (1844-1895), buried here in Mount Olivet in Area Q/Lot 133 only about 40 yards from his pupil’s final resting place in neighboring Area R. Etchison would pass the Maryland bar in the fall of 1889. His natural ability and knowledge made him a successful lawyer, and was fast-rising, prominent citizen of Frederick. However, his law career would not fully blossom immediately, as it was put on hold due to a very important assignment. In 1893, Mr. Etchison was appointed to a position in the land department under Hoke Smith, Secretary of the Interior during the administration of President Grover Cleveland. At the age of 26, Etchison became the land commissioner of the Cherokee Strip in Oklahoma. H. D. Etchison was stationed in Oklahoma, where he remained until January, 1895. The Cherokee Strip was originally owned by the Cherokee Indians. Because of their support of the Confederate Army, the Indians lost these lands to the Union at the end of the American Civil War. This strip of territory at the border of Oklahoma and Kansas was one of the last open pieces of land in the west. The territory was officially opened for settlement on September 16th, 1893. After only one day, prospective settlers had filed over 10,000 claims on the 42,000 tracts of land. The opening of the strip began the Oklahoma Land Rush and facilitated the ultimate settling and development of the state. For a year, Etchison helped to handle the numerous claims and homestead ownership disputes of the fledgling state. Many historians agree that the U.S. government’s procurement of the Cherokee Strip, and the selling of those lands, was another event within a long history of America’s abuse toward the Indians. Though the Cherokee Indians were paid some money for the Cherokee Strip, they were still largely forced to accept the Union’s terms of purchase. The tribe continued to pursue additional payment which was to come from the land rush’s land sale profits, however, the U.S. government responded that the Cherokee Indians had already been paid justly and thus refused to agree to any additional payment. The following letter was written to the Frederick newspaper by H. Dorsey Etchison in Oklahoma in which he describes his mission with the Cherokee Strip T. J. C. Williams’ History of Frederick County, Maryland (published in 1910) relays some more of Mr. Etchison’s life story in the biographical volume. We pick up after his work in Oklahoma. Returning to Frederick County, Mr. Etchison resumed the practice of his profession in Frederick, where he has a large and lucrative practice. He is one of the leading members of the bar. His legal acumen, vigorous diction, and splendid delivery give him great power in summing up evidence before a jury. He is noted for the zeal and care with which he safeguards the interests of his clients. He is well-informed on all such subjects. His private library is one of the best in Frederick. Mr. Etchison has never held an elective office. He was a candidate for nomination to Congress from the Sixth Congressional District of Maryland in 1910. From 1889 to 1897, he served as secretary of the Supervisors of Elections of Frederick County, and was a member of the Board for the reassessment of the property in Frederick City, in 1908. Mr. Etchison is a member of Mountain City Lodge, No. 29, Knights of Pythia, of Frederick City, and has occupied all the chairs of the Order; of Frederick City Lodge No. 100, International Order of Odd Fellows, and has filled all the chairs in the offices of this lodge; of Francis Scott Key Council, O. U. A. M., No. 48, and has held all the offices of this Order; of Camp No. 79, Patriotic Sons of America; Chippewa Tribe, No. 19, I. O. R. M.; Camp No. 7710, Modern Woodmen of America; and Braddock Lodge, No. 1834, of the Modern Brotherhood of America. You would assume that H. Dorsey Etchison was almost too busy for a private, home life. In the 1900 US census, he can be found living as a boarder in the Park Hotel once located at the SE corner of W. Church and Court streets. He took the plunge, however, marrying Miss Elizabeth Garvin Maize, of Williamsburg, PA on December 1st, 1903. Twin sons would be born the following year but then H. Dorsey's good-fortune changed drastically with the loss of one of the boys (Henry M.) and his wife in fall, 1904. Elizabeth died November 8th, 1904, five days after her son, leaving H. Dorsey a widower in care of surviving son, George Johnson Etchison. Mr. Etchison would marry again in 1908. This was to Miss Mary Helen Ward. They would welcome a son, James Milton, born in January, 1909. On May 25th, 1914, the Etchisons added a daughter, Mary Marshall to the family. Tragedy struck our subject again in 1923, as Mary died from a rare case of septicemia. I was curious to learn more so I looked up its definition according to Healthline.com: Septicemia is a serious bloodstream infection, also known as blood poisoning and occurs when a bacterial infection (elsewhere in the body, such as the lungs or skin) enters the bloodstream. This is dangerous because the bacteria and their toxins can be carried through the bloodstream to the entire body. Septicemia can quickly become life-threatening and must be treated in a hospital. If left untreated, septicemia can progress to sepsis. Septicemia and sepsis aren’t the same. Sepsis is a serious complication of septicemia which causes inflammation throughout the body. This inflammation can cause blood clots and block oxygen from reaching vital organs, resulting in organ failure. A visitor on one of my recent walking tours of the cemetery told me that she had learned that Mary’s illness was the result of falling into a rose bush while playing near her home on Court Street. I could not confirm this story with the articles that appeared in the newspaper at the time, but an interesting aside, nonetheless. H. Dorsey continued practicing law and was one of the most sought out men of the profession in town, usually involved in the leading cases of the day. All the while, Etchison stayed busy in church (Methodist), fraternal and civic activities. Two local projects of note in which he participated were the dedications of Memorial Park in 1924, and Baker Park in 1927. H. Dorsey Etchison was well-traveled and was one of the early promoters of Frederick tourism. I found an article in an edition of the Frederick News-Post of 1932 in which he talked of the importance of Frederick utilizing such assets as natural beauty and historical figures of national importance. Barbara Fritchie. He is quoted in response to the beautiful landscape and recalled a visit from a true wild west hero in 1916. In was then that he accompanied the legendary Buffalo Bill on a local visit, and hosted him atop Braddock Mountain. It made me wonder if he had met Mr. Cody while working in Oklahoma back in the early 1890s? In 1934, he lost a bid for Democratic state senator. He immediately took a break from his practice as he was appointed Frederick County’s Deputy Register of Wills. Following his four-year term with the county, he announced that he would resume his law practice in December, 1938. The following year would be his last. After a multi-week sickness in the fall of 1939, H. Dorsey Etchison would pass on the morning of December 1st. His funeral was very well-attended as he was laid to rest in the Etchison family lot (D32/33) alongside the graves of his parents, siblings, wife Helen and daughter, Mary. Son James Milton Etchison would be interred here in 2005, dying at the age of 96. His other son, the surviving twin, George, died in 1955 but is buried in Geeseytown Cemetery in Frankstown, Blair County, PA near Altoona.

0 Comments

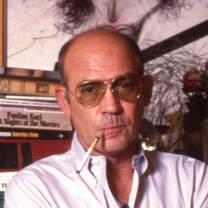

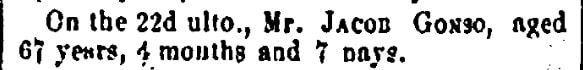

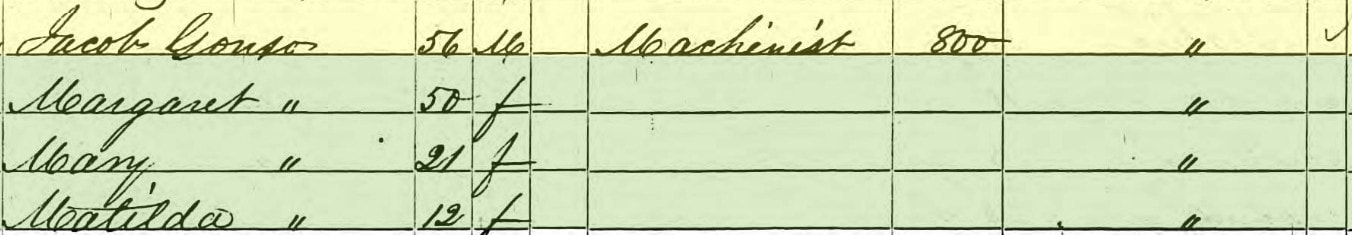

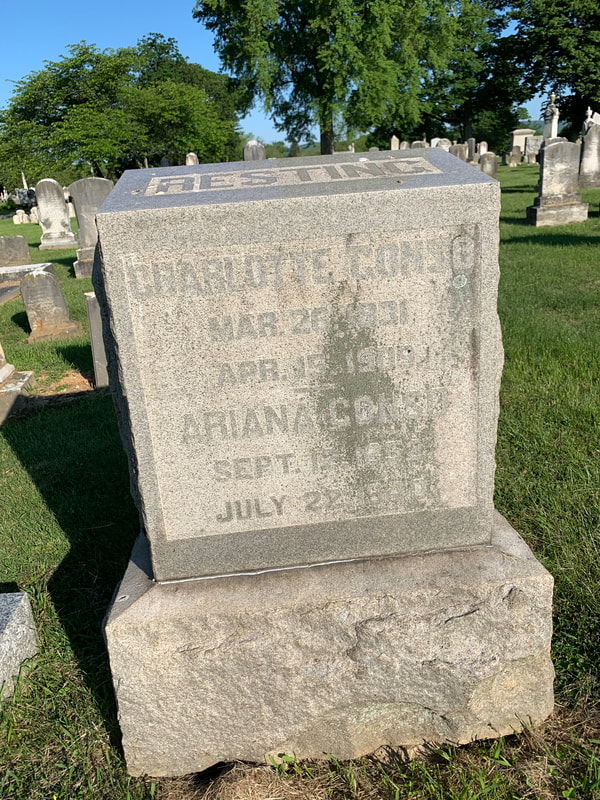

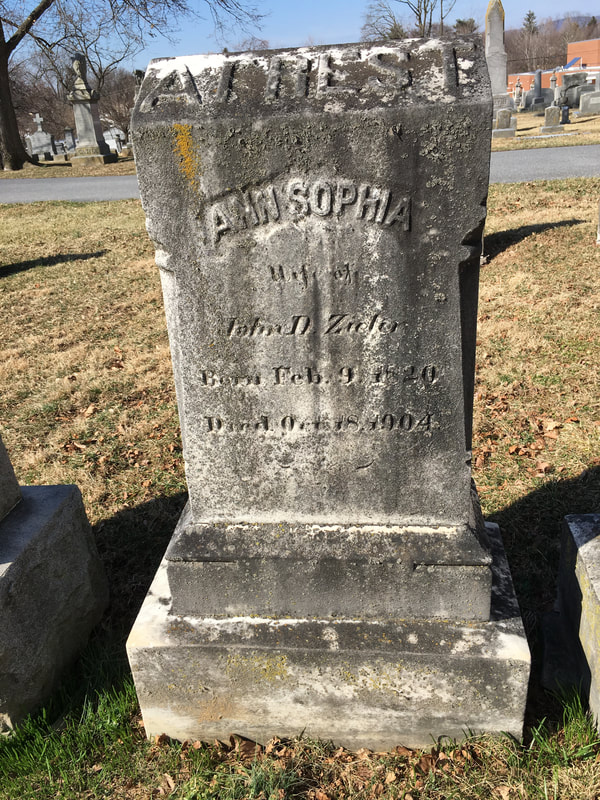

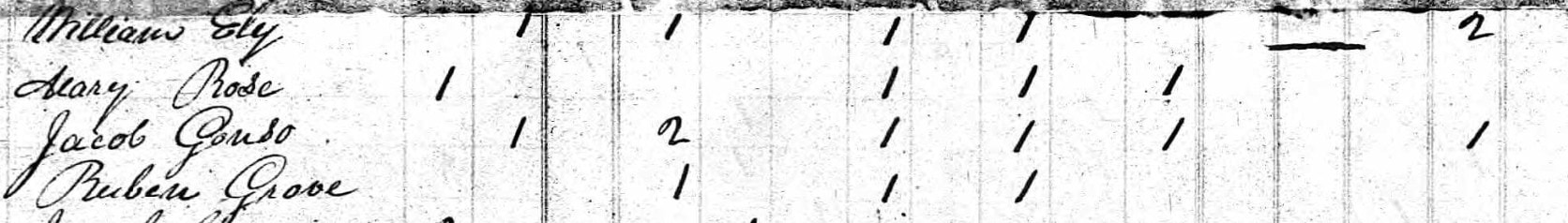

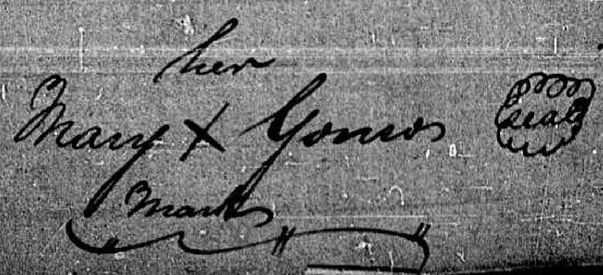

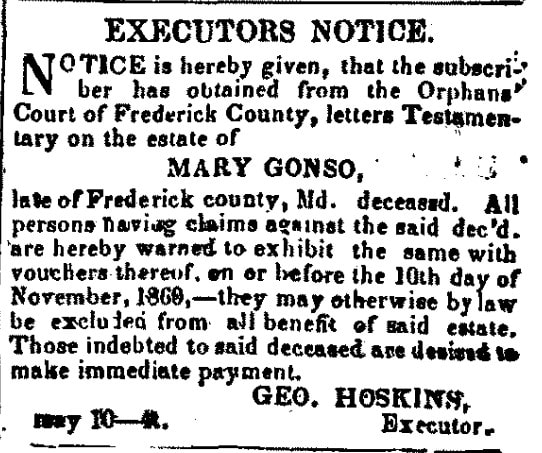

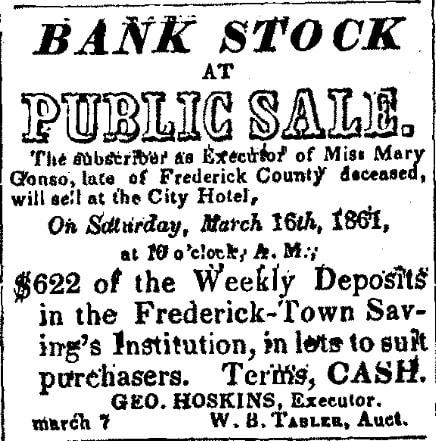

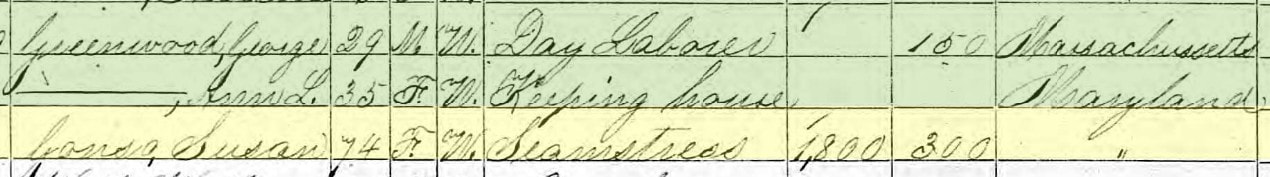

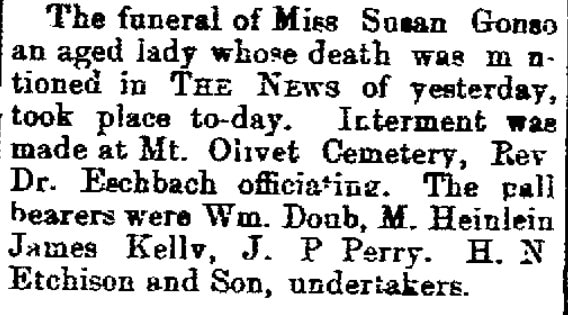

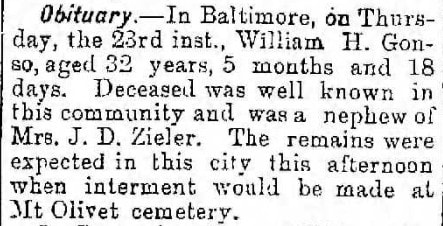

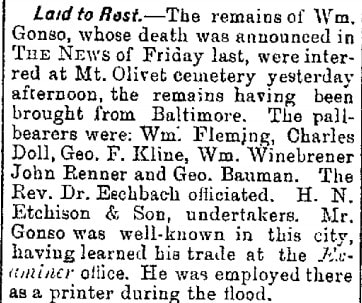

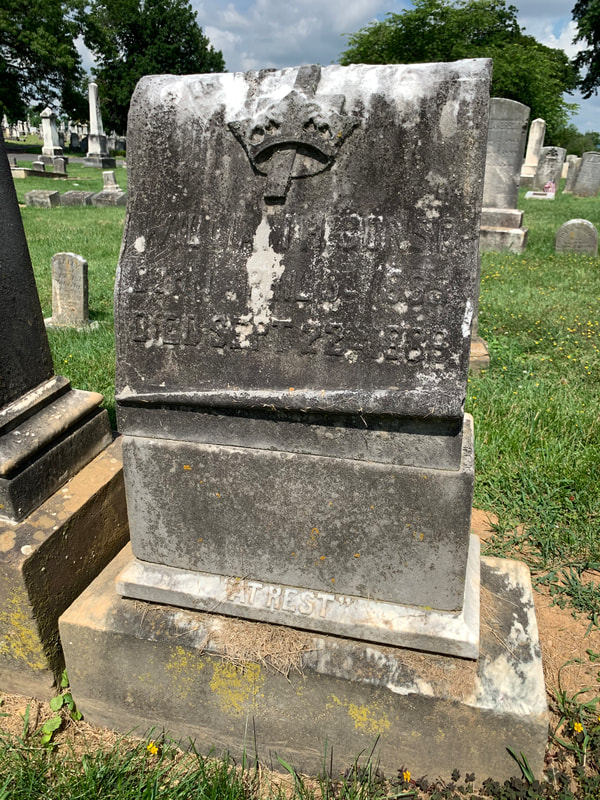

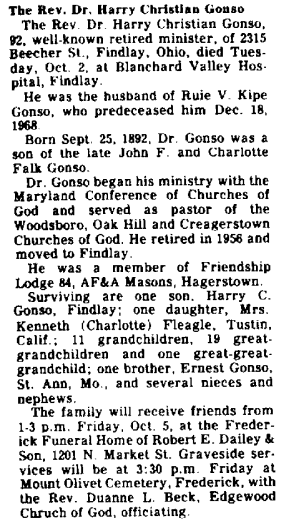

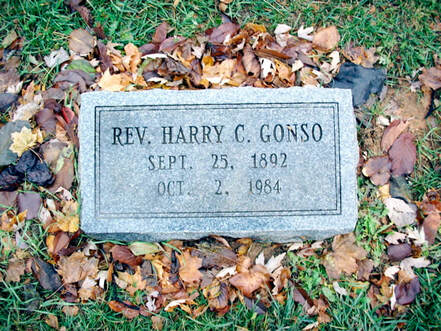

"Gonzo the Great" "Gonzo the Great" “Bizarre, unrestrained, or extravagant, usually used to describe a style of personal journalism.” That is what one will find when they seek the definition of the word “gonzo.” I can’t help but to have the image in mind of the famous cast member of Jim Henson’s Muppet Show—Gonzo, also known as "The Great Gonzo" or "Gonzo the Great," is known for his eccentric passion for stunt performance. Aside from his trademark enthusiasm for performance art, another defining trait of Gonzo the muppet is the ambiguity of his species, which has become a running gag in the franchise. Back to Gonzo journalism, this is a style that is written without claims of objectivity, often including the reporter/author as the story’s protagonist using a first-person narrative and it draws its power from a combination of social critique and self-satire. Gonzo journalism disregards the “strictly-edited” product favored by newspaper media and strives for a more personal approach commonly using sarcasm, humor, exaggeration, and profanity. The word "gonzo" is believed to have been first used in 1970 to describe an article about the Kentucky Derby by Hunter S. Thompson, who popularized the style. Mr. Thompson, a truly unique individual not all that different than Gonzo the muppet, may never have visited Frederick, Maryland during his lifetime (1937-2005), but certainly is linked through an affiliation with Flying Dog Beer, a popular craft offering brewed right here in the town of “clustered spires” since 2006. Author Hunter S. Thompson lived a few blocks from beer founder George Stranahan's Flying Dog Ranch in Woody Creek, Colorado. The two became good friends over common interests in drinking and firearms. In 1990, Thompson introduced Stranahan to Ralph Steadman, who went on to create original artwork for Flying Dog's beer labels in 1995. His first label artwork was for the Road Dog Porter, a beer inspired and blessed by Thompson who wrote a short essay about it titled "Ale According to Hunter.” In 2005, the brewery created a new beer in Thompson's honor, Gonzo Imperial Porter. One of the more peculiar surnames that I have seen in my exploration of Mount Olivet is Gonso, not quite Gonzo, but about as close as you can get. This piqued my curiosity, so I decided to explore the matter to find if this family could be described (according to the above-mentioned definition) as bizarre, unrestrained or perhaps extravagant? Although a long shot, could any of these folks be connected to journalism? I found 17 individuals holding this family surname buried here. I was most interested in exploring the earliest of these to hopefully find the origin of the name. I didn’t have to look far as I recalled a Jacob Gonso who served in the War of 1812. We had placed a special marker on this gentleman’s grave as part of our “Home of the Brave” project in which the burial sites of 108 like vets of this oft-misunderstood war were recognized with monuments, flags and a luminary ceremony that took place September 13th/14th, 2014. This was the 200th anniversary of the Battle of Fort McHenry, a momentous event that caused our most famous resident, Francis Scott Key, to write the “Star-Spangled Banner. Jacob Gonso served under Col. John Brengle in the 1st Regiment, Maryland Militia from August 25th to September 19th, 1814. He was among the 73 men hastily recruited by Brengle and Rev. David F. Schaeffer (1787-1837), then the acting minister of the town’s Evangelical Lutheran Church. We can get a feel for the mood of the day from an account from our esteemed resident/diarist Jacob Engelbrecht, merely a teenager at the time. Engelbrecht’s description would not be recorded until 42 years later (June of 1856), but still provides documented proof of a unique happenstance involving Rev. Schaeffer: “War of 1812. The following is the Muster Roll (copy) of Captain John Brengle’s Company of Volunteers, which Company was raised in four hours, by marching through the streets of Frederick, August 25, 1814, (the day after the Battle of Bladensburg, on which day we received the news) headed by Captain Brengle & by the side, with them, rode the Reverend David F. Schaeffer, encouraging the men to volunteer…” Engelbrecht proceeded to name all the men who joined up that day, including a John Gonso listed immediately before Jacob Gonso’s name. This is certainly a relation, but was John a brother, cousin or possibly a father? We will answer that in a minute.  Brengle’s Company, with Privates Jacob and John Gonso in tow, fought bravely at the entrenchments of the Battle of North Point. The Battle of North Point was fought on September 12th, 1814, between Gen. John Stricker's Maryland Militia and a British force led by Major Gen. Robert Ross. History accounts say of the battle: Although the Americans retreated, they were able to do so in good order having inflicted significant casualties on the British, killing one of the commanders of the invading force, significantly demoralizing the troops under his command and leaving some of his units lost among woods and swampy creeks, with others in confusion. This combination prompted British colonel Arthur Brooke to delay his advance against Baltimore, buying valuable time to properly prepare for the defense of the city as Stricker retreated back to the main defenses to bolster the existing force. The engagement was a part of the larger Battle of Baltimore, an American victory in the War of 1812. Jacob, John and colleagues would receive a hero’s welcome back in Frederick on September 21st, 1814. Two centuries later, Mount Olivet Cemetery pulled together a volunteer group of its own to conduct research on local 1812 vets in order to place the special, commemorative monuments. Biographies were researched and written by Larry Bishop and Ron Pearcey, and these appear in a book titled Frederick’s Other City: War of 1812 Veterans. On page 54, one will find the scant offering on Jacob Gonzo with information pointing to the name also appearing as Ganzau and Gonze in past written records. Jacob Gonso/Ganzau was born February 15th, 1795 in Maryland to parents who, at the time of the book's writing, were unknown to the authors. He was married at the age of 21 by Rev. David F. Schaeffer of the Lutheran Church in Frederick Town to Margaret Keller on September 5th, 1819. According to his obituary, Jacob Gonso died in Frederick on June 22nd, 1862 at the age of 67 years, 4 months and 7 days. Margaret was born about 1800 in Maryland, and died October 17th, 1867. She was laid to rest in Mount Olivet in Lot 52 of Area B. Jacob’s remains were removed from the Lutheran graveyard and placed beside her 27 days later. According to the 1850 Census, Jacob was a machinist with $800 in value of real estate owned. He can be found living with his wife and two children, Mary and Matilda. Research conducted shows he owned the property located between Market Street and Middle Alley at 17 East Fifth Street from 1839 until his heirs sold it in 1866. Jacob and Margaret Gonso had six known children: Ann Sophia Gonso (1820-1904) married John David Zieler; William Henry Gonso (1822-1865) married Louisa M. Stevens; Mary Elizabeth Gonso (1827-1893) married Isaac Philip Suman; Charlotte Keller Gonso (1831-1909) never married; Charles Jacob Gonso (1835-unknown); and Catherine Matilda Gonso (1839-1920) married William Amos Scott. Interestingly, Jacob, Margaret and some of their children ( Charlotte K. Gonso, Catherine M. (Gonso) Scott, and Charles J. Gonso (unmarked)) are buried in the Scott Family plot in Area B. Daughters Ann Sophia (Gonso) Zeiler and Mary Elizabeth (Gonso) Suman are buried nearby. A few other immediate family members can be found in Rocky Springs Graveyard, in the northern reaches of the city. I did locate Jacob in the census records dating back to 1820. The name was transcribed and spelled various ways which helped thwart easy efforts to obtain positive results via Ancestry.com. I didn’t find much in the local newspapers throughout his lifetime, save for a few mentions and his obituary appearing in 1862. As said earlier, Jacob Engelbrecht mentioned Jacob in his diary as being an active participant in the War of 1812. When searching real estate, my assistant Marilyn Veek didn't find any property owned by Jacob Gonzo before 1839. However, she did find that a George Gontzo owned the east half of lot 134 located between East 3rd and East 4th streets from 1798 until his heirs sold it in 1830. This turned out to be Jacob’s father, complete with a different variation on Gonso, but incorporating the “z” as discussed earlier. From this important find, the 1830 deed, George’s heirs are revealed as John Gontzo and Mary his wife, Eve (Gonso) Kieffer and husband Peter, Jacob Gontzo and Margaret his wife, Charlotte Keller, Mary Gontzo and Susannah Gontzo. Back to Engelbrecht’s diary, one can find a few early references to the name Gantsau/Ganzau which is one in the same with Gontzo and Gonso. In 1823, a three-month-old child of John Ganzau would be buried in the Evangelical German Reformed graveyard—today’s Memorial Park located at the intersection of North Bentz and West Second streets. On February 4th, 1828, Engelbrecht wrote: “Died this morning in the year of her age, Mrs. Ganzau (of East Third Street). Buried on the German Reformed graveyard.“ Mrs. Charlotte Keller, widow of Charles Keller and daughter of the late Mrs. Gantzau married Abijah Shepherd in 1835. Four years later, on February 17th, 1839, Engelbrecht penned the following: “Died yesterday in the 51st year of his age Mr. John Gantzau near Wormans Mill. Buried on the German Reformed graveyard today.” Using this information, I next went to Ancestry.com and began combing through user posted family trees. I eventually found that of George Gantzach (1754-unknown death after 1807), and also spelled "Gantzaug." Marilyn found his will (written in 1807) and filed under the name "George Gantzank." George is said to have been born in Hofgeismar, Kassel, Germany and arrived in America in 1775 as a Hessian mercenary soldier fighting for the British. He was supposedly captured at the Battle of Yorktown (VA), and was sent to Frederick and imprisoned at the Hessian Barracks that stand a few blocks north of Mount Olivet’s main gate. George Gantzach would marry a woman named Margaretha (b. 1772) and had the following children: John (1789-1839), George (1792-?); Charlotte (Gonso) Sheppard (1795-1838), Eve (Gonso) Kieffer (1795-1859), Jacob (1795-1862), Susannah/Susan (1798-1886) and Mary (1800-1860). I was very familiar with the gravestone of youngest daughter Mary Gonso as I drive directly past her stone every workday. It’s located on the main drive through the center of the cemetery and stands nearly five-foot tall. This white, marble stone in Area D reads “In Memory of Mary Gonso—Died May 2nd, 1860 Aged 59 Years, 7 Months and 15 Days.” I’ve often wondered about this woman as she has a substantial stone, but is the only person buried in this plot. I would soon learn that she was never married or have children of her own. I could not find her in any census records surprisingly. Once again, we had to glean info about her from land deeds of all things. In 1846, Mary Gonso bought the property that is now 237-239 East Church Street. She would leave it to her niece, Ann Cecelia (Gonso) Carlin, wife of hotel owner Frank B. Carlin, in her will of 1860. The property was still owned by Ann Carlin when she died in 1916, and it was sold to Gilmore Flautt in 1917. The tax records estimate a construction date of 1905, so Ann probably built the double house there. Outside of that, she remains somewhat of a mystery. She is buried in Area D/Lot 15. Mary Gonso's will includes the following language about her burial instructions: "I will and direct that my Executor purchase a Lot in Mount Olivet Cematary (sic) Company, and inter my body therein, and enclose the same, with Substantial Iron Railing and Erect Suitable Tomb Stones, such as I have directed him, at the charge of my Estate. I will and direct that One Hundred Dollars of my weekly deposits in the Fredericktown Savings Institution shall be reserved, and I do devise, & bequeath the dividends as they accrue, thereon, to be paid to the Mount Olivet Cematary (sic) Company, and such dividends be applied to keeping my lot which my Executor shall purchase, in good repair and properly attended to." In Mary's will, a provision was made for her estate to pay a surviving sibling a stipend of $18/year. I found an obituary and burial for this same woman, Jacob and Mary's older sister, Susan (Susannah) Gonso (1798-March 12th, 1886). Living until 1886, Susan would be the last surviving member from George Gantzach's immediate family. I could not find her, however, in our cemetery records. No tombstone exists either as no one stepped forward to do so, she having no children of her own. Susan would most likely have been buried in either Mary or Jacob's lots. Two other family members of note need to be brought up before we close out the article. William Henry Gonso, Jr. is buried in the Area B lot with his grandparents (Jacob and Margaret) and various aunts and uncles. He is the closest link to "Gonzo journalism" as he apparently worked for a short time at the Frederick Examiner newspaper. This is purely a stretch on my part because this man's talent was not in writing, but more blue-collar on the actual printing and fabrication side. He eventually moved to Baltimore, where he worked as a printer and also followed in the trade footsteps of his father (William Henry Gonso, Sr.) as a shoemaker. One other persons of note was Rev. Harry Christian Gonso, DDS (1892-1984). The great-great grandson of George Gantzach, great-grandson of Jacob Gonso, grandson of William Henry Gonso, Sr., and son of John Frederick Gonso can be found in Area L, Lot 132. His father worked as a blacksmith in the Yellow Springs area and lived at High Knob, now part of Gambrill State Park. The Rev. learned his father's trade at a young age, and used the images of "fire and brimstone" for saving souls on his future path as an evangelistic minister. It sure seems like something someone with a name close to gonzo should do. Well, one thing is for sure, the Gonsos, great or not, sure made a name for themselves in Frederick, Maryland dating back to George's incarceration here in the early 1780s. The anglicisation of names such as Gantzach is just one more thing that makes genealogy research so interesting, not to mention, bizarre, unrestrained, extravagant and just plain difficult at times.

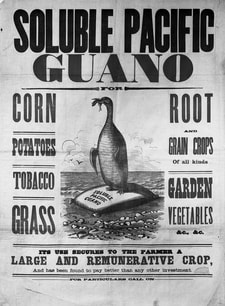

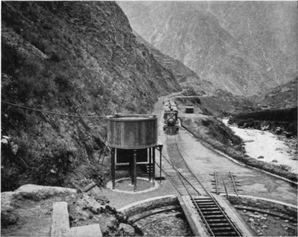

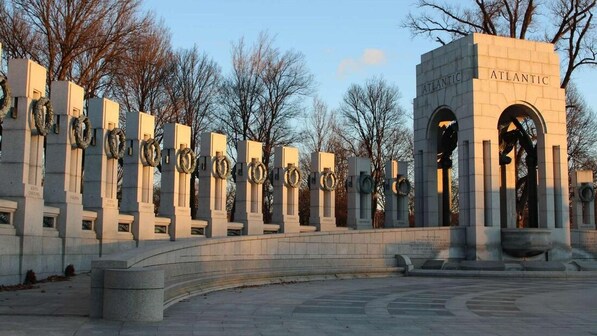

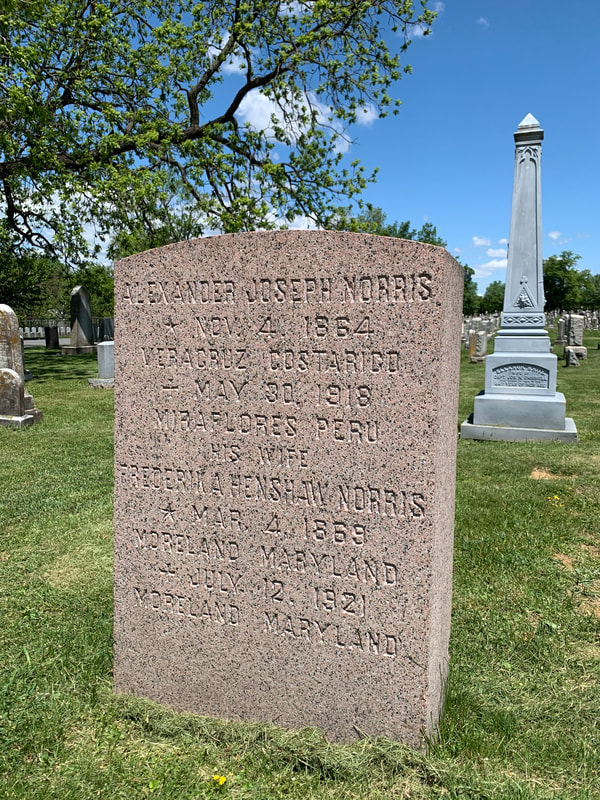

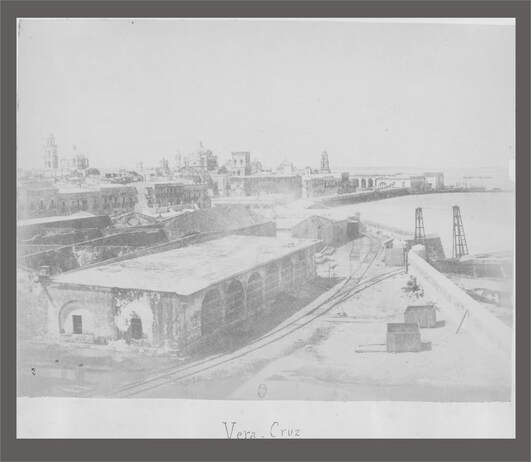

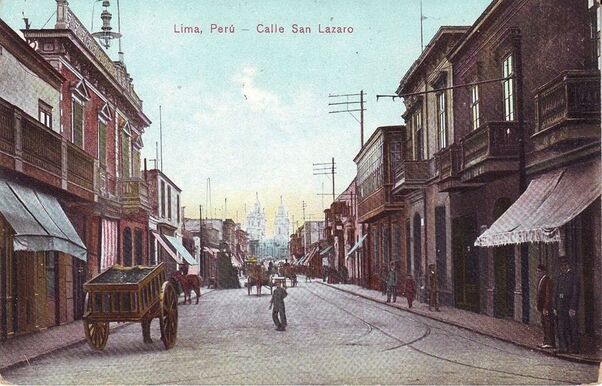

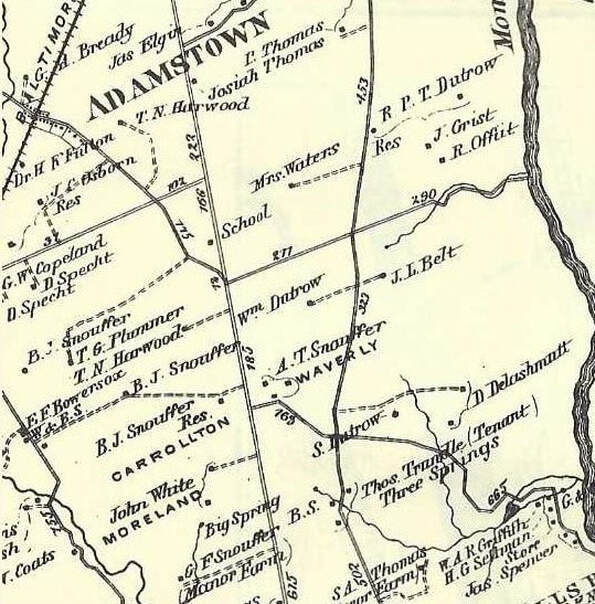

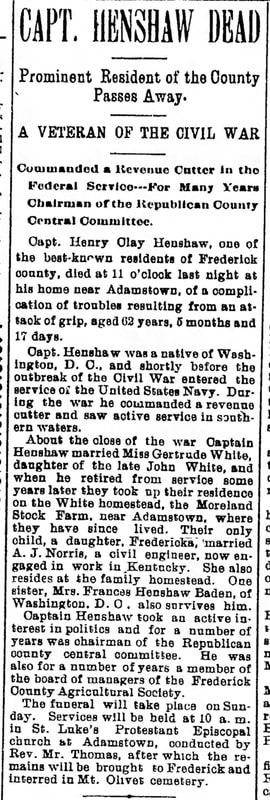

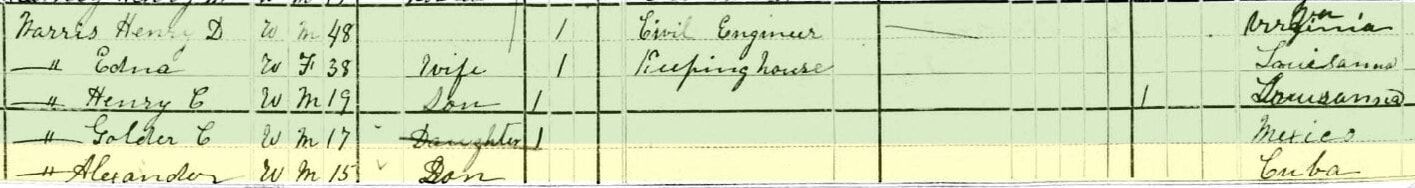

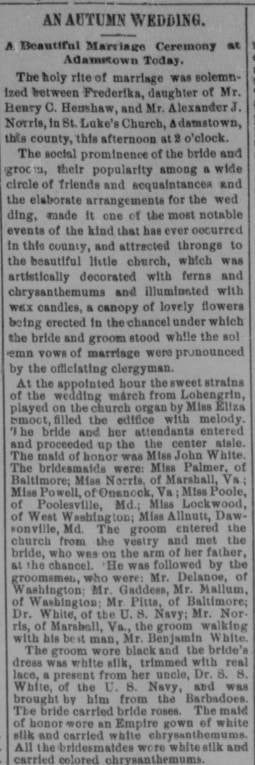

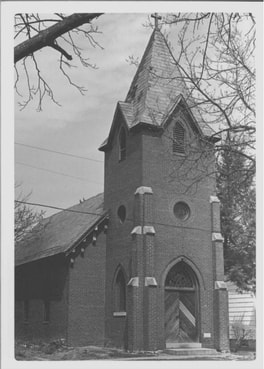

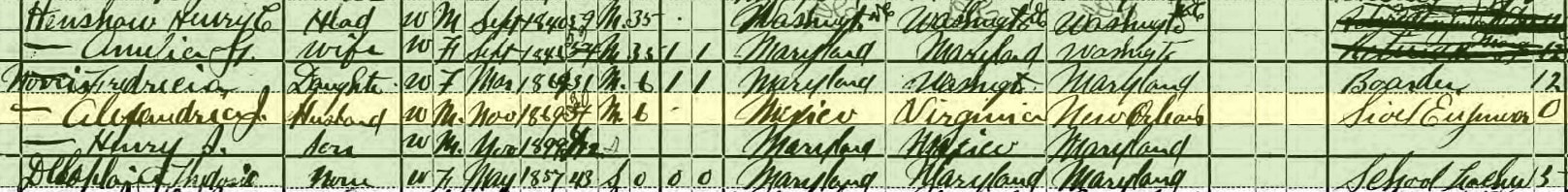

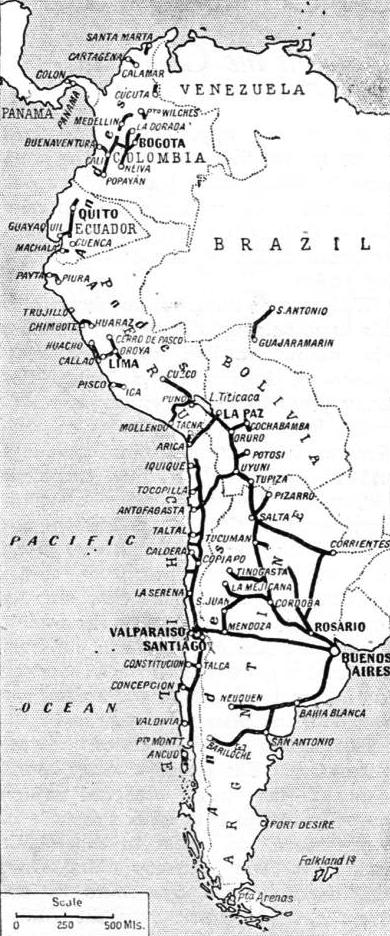

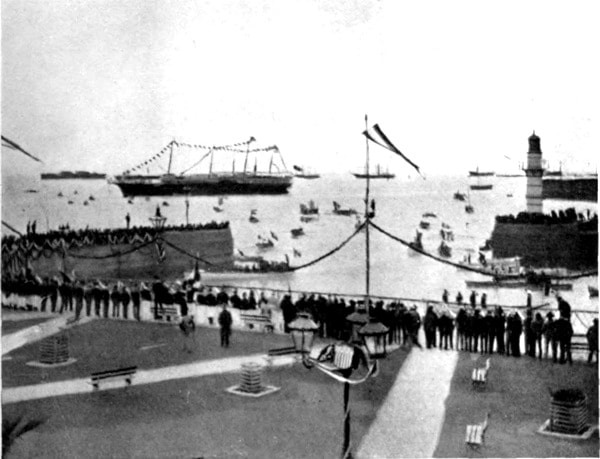

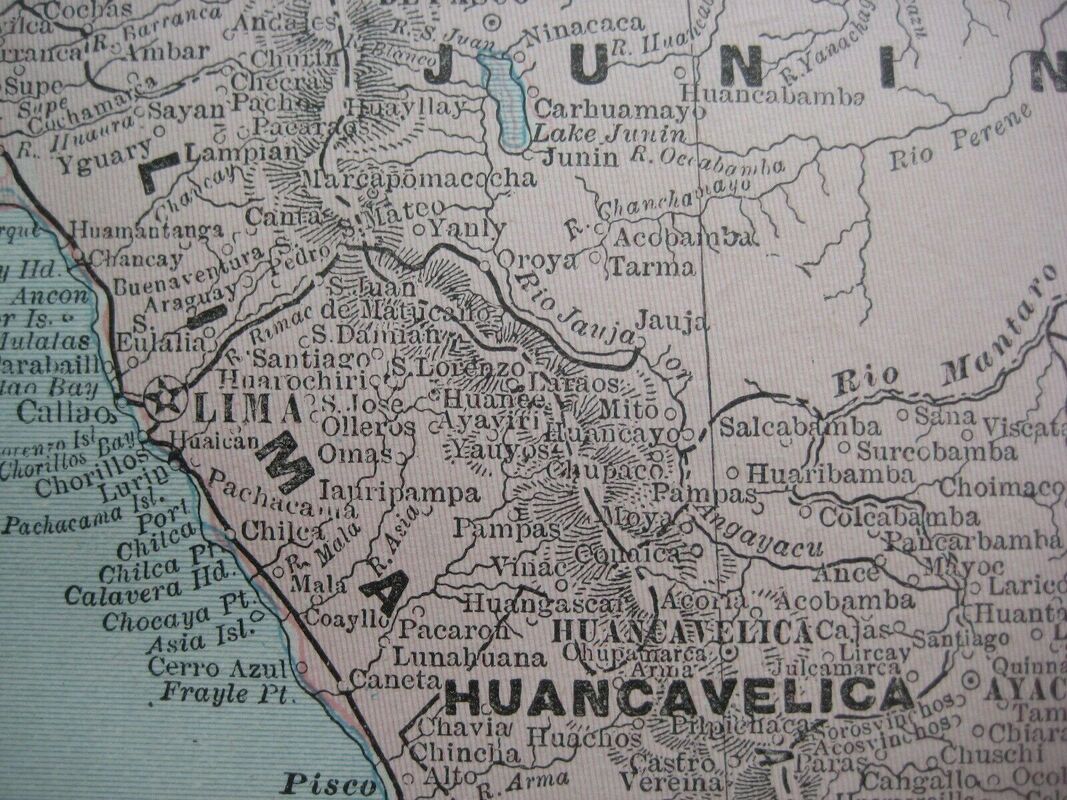

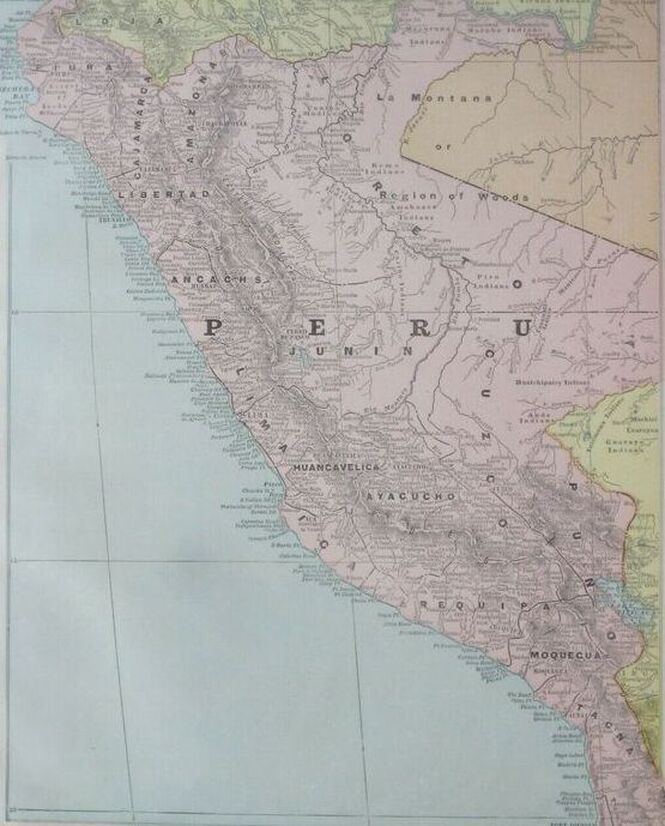

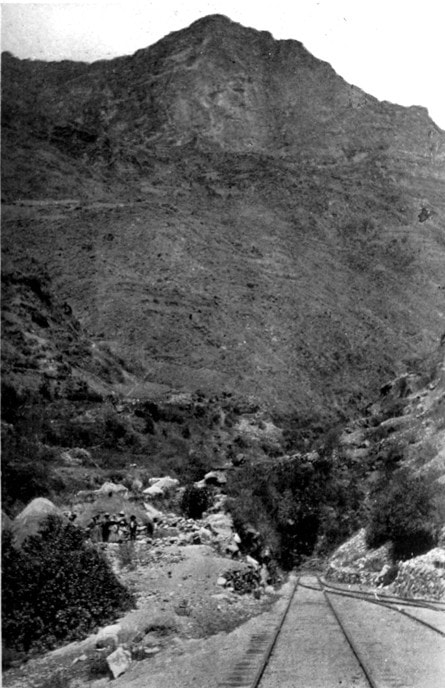

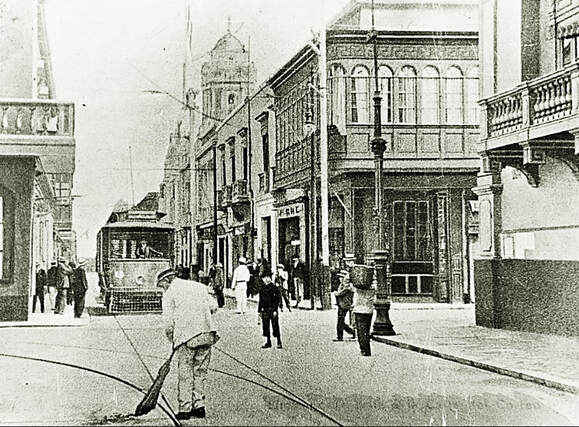

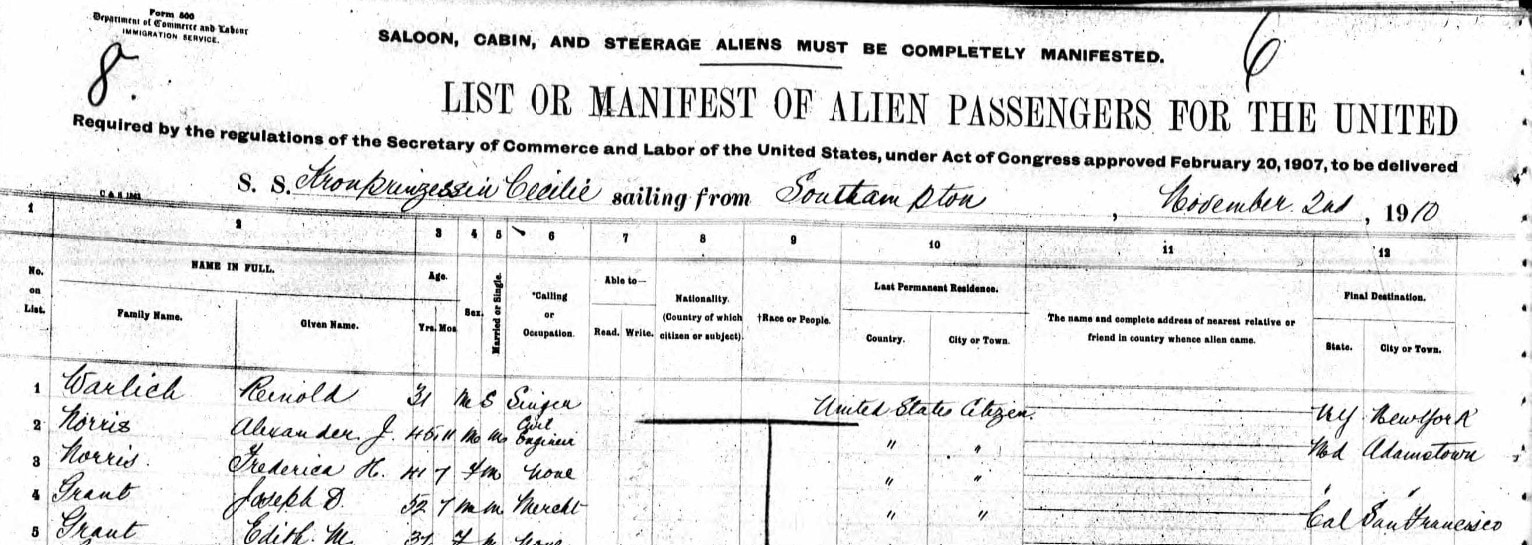

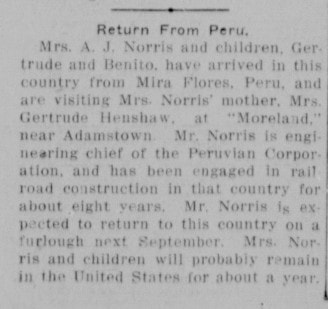

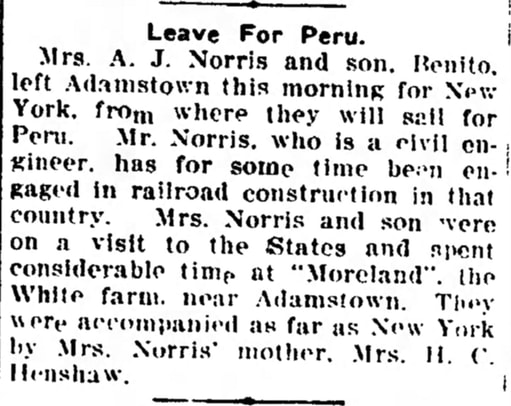

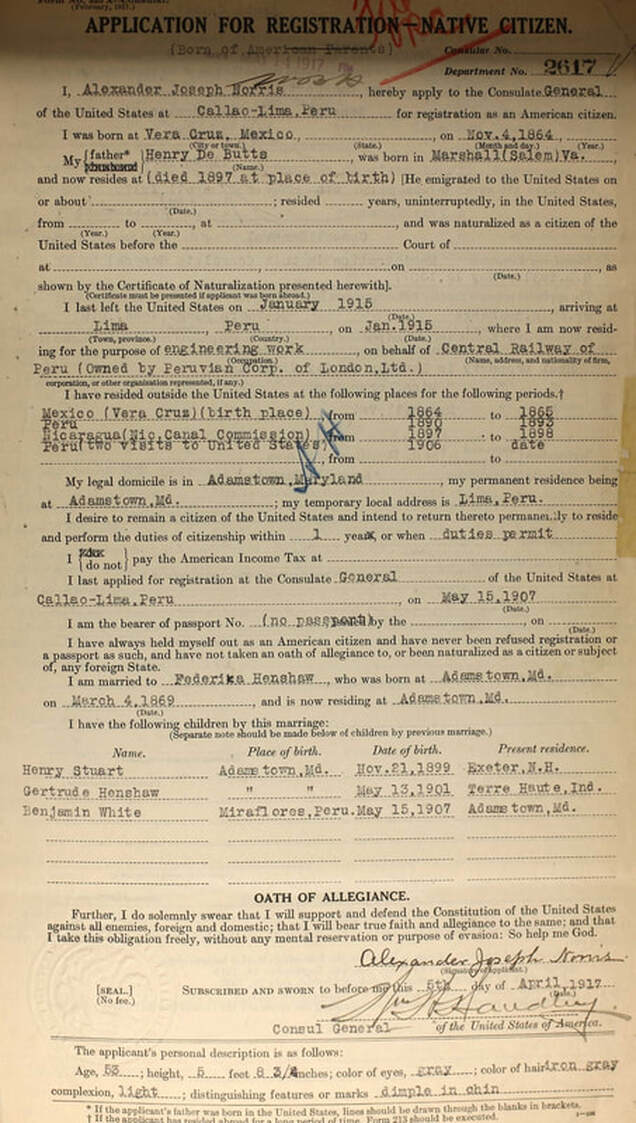

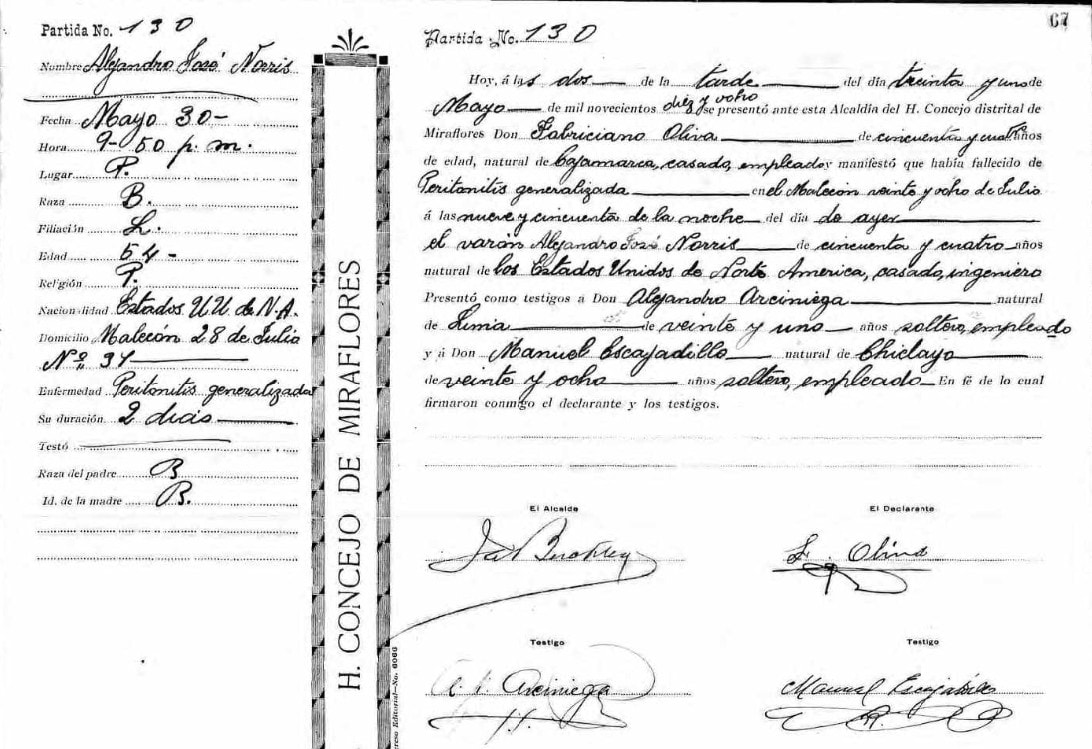

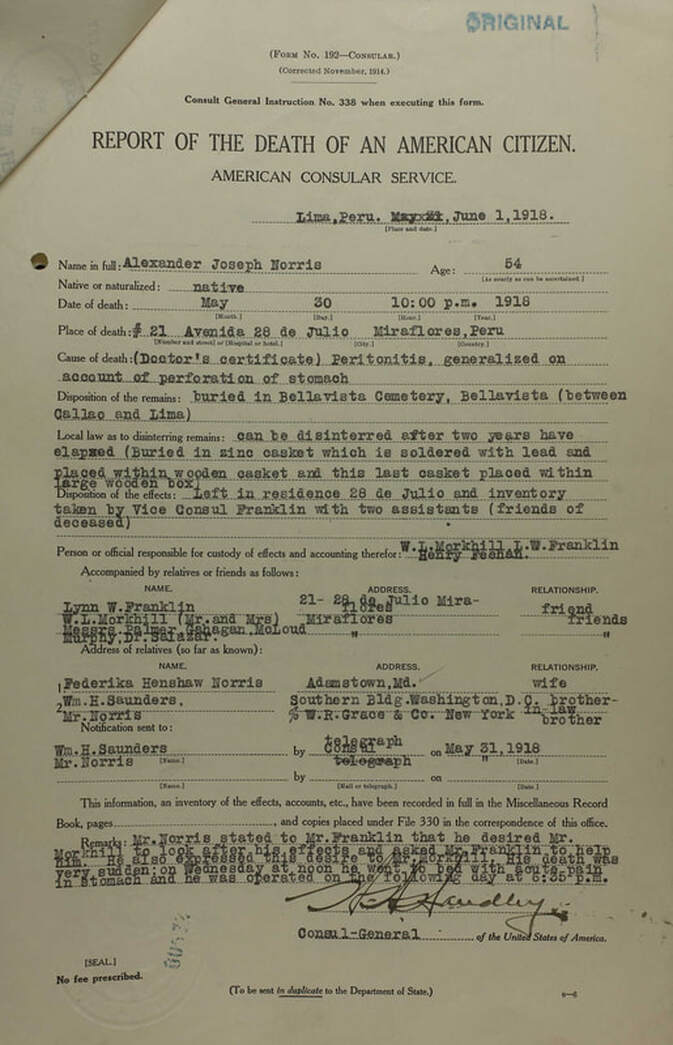

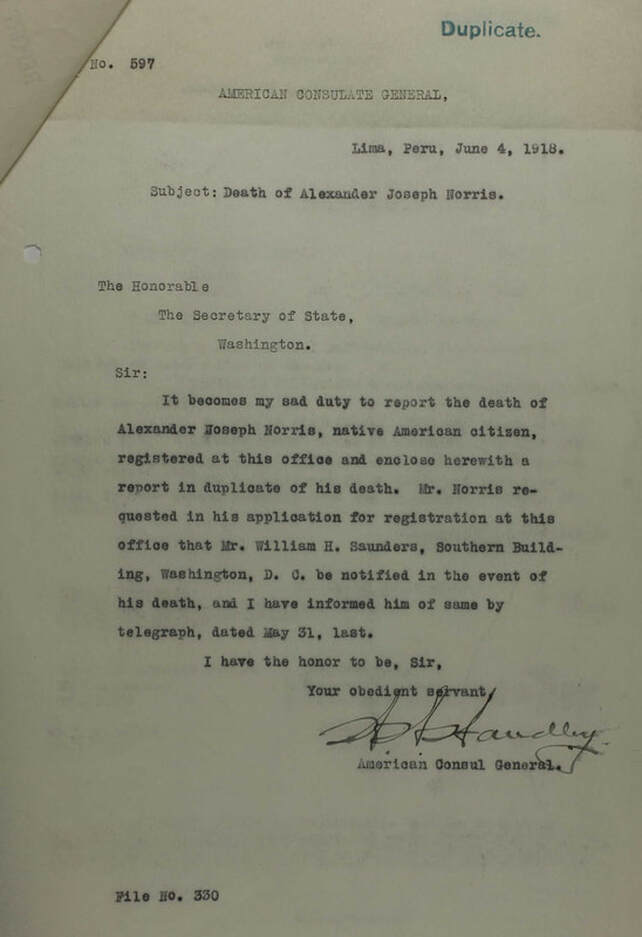

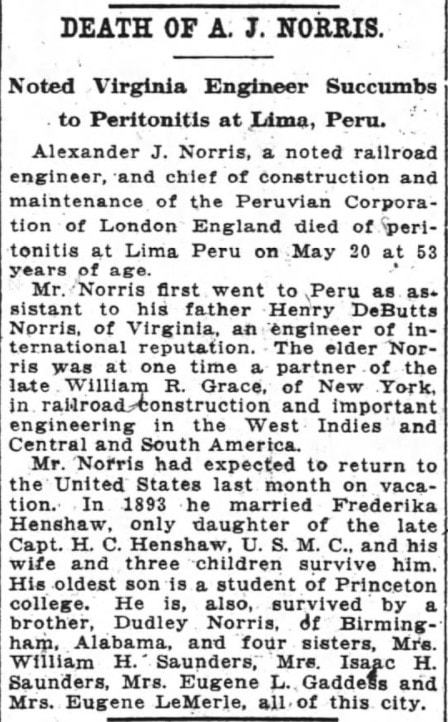

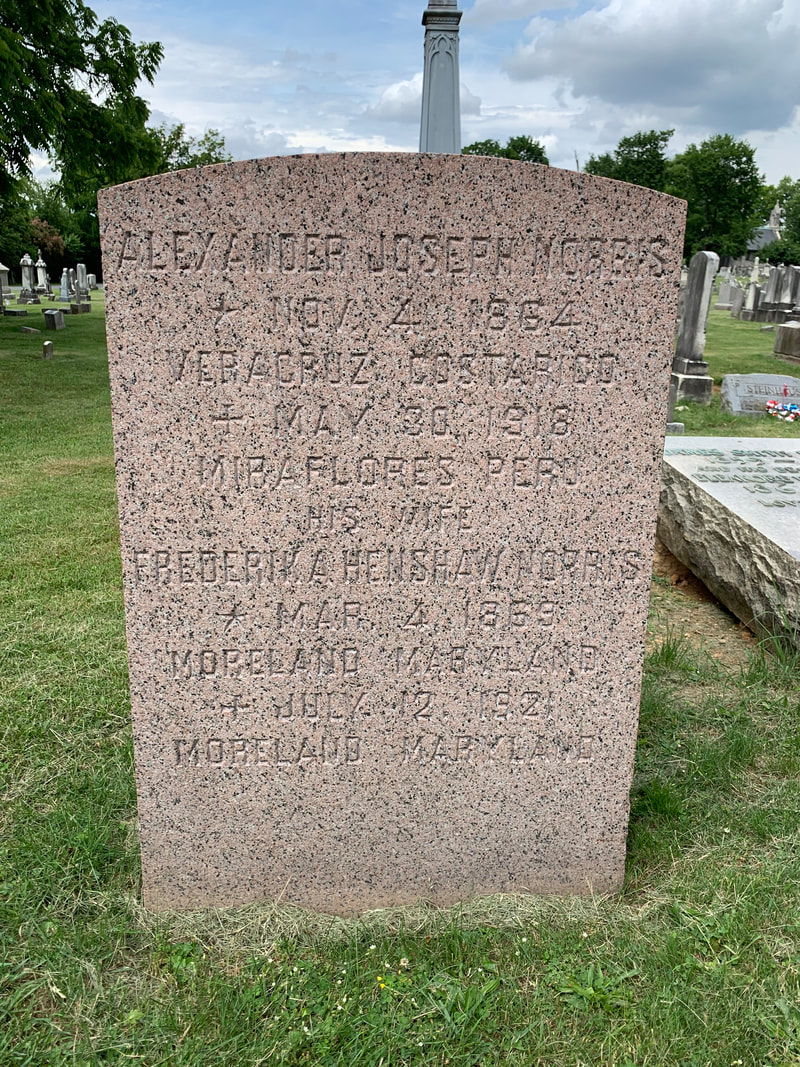

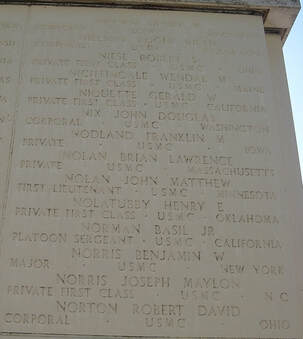

Well, you may think an author has run out of good topics when he or she turns to one that connects his subject’s success and demise to guano—the excrement of seabirds and bats. As a manure, guano is an effective fertilizer due to its exceptionally high content of nitrogen, phosphate, and potassium: all key nutrients for plant growth. My promise to you is this, please read on as this “Story in Stone” is certainly “worth a crap” as the old expression goes. Alexander Joseph Norris’ gravestone sits in Mount Olivet’s Area H, Lot 495 not far from the cemetery’s northwest boundary and Confederate Row. It certainly stands out from the majority of other gray and white monuments in this part of the cemetery, but not due to height or exquisite design or sculpture, but rather stone composition. The monument’s composition is known as Kershaw Pink Granite and the colorful hue gives this one away. It is one of a handful of its kind in Mount Olivet, quarried at Georgia Stone Industries at Kershaw Granite in Lancaster County, South Carolina. This is the same quarry that supplied about 50,000 tons of granite to form half the World War II Memorial in Washington DC, dedicated back in 2004. The Norris grave monument also features the name of Alexander’s wife, Frederika Henshaw Norris. A fascinating aspect of this stone is that not only are there vital dates given for both decedents, but there are birth and death locations. Mr. Norris was born in Veracruz, Costa Rico in 1864, or so says the tombstone. I would later see references to him being born in Veracruz, Mexico—not to mention the fact that it should be Costa Rica, not Rico if it was indeed in that location outside Mexico. The stone also says that he died in Miraflores, Peru, which is a district within Lima. With these worldly destinations, I bet you would be hard-pressed to find this combination of birth/death place for anywhere else. Meanwhile, Mrs. Frederika Norris’ hand-carved grave information boasts locations less exotic. As a matter of fact, her birth and death occurred at the same place—her family’s country estate of Moreland, located just east of Pleasant View/Doubs and south of Adamstown, a few miles south of Frederick City. The Maryland Trust’s architectural survey file says of this property: Moreland is an agricultural complex centered on a two-story brick house built between about 1856 and 1861 with Renaissance Revival trim, which was substantially altered in the 1950s. The house was built possibly by Benoni Lamar between 1856 and 1858 or by John White about 1861. Lamar was killed by lightning on the farm, perhaps on the porch of the brick house, in June 1858, leaving his family in debt. John White bought the farm as the result of the Lamar heirs' default and established a large plantation with many slaves and a well-to-do domestic lifestyle. Although a search for Mr. Lamar here in the cemetery turned up fruitless, I did find John Wailes White (b. June 5th, 1819 and d. April 4th, 1898) and wife Sarah Attillia White (b. February 7th, 1825-June 21st, 1909) are buried in Area H/Lot 497 just a few yards from their granddaughter, the fore-mentioned Frederika Norris. While I'm at it, I think this woman is possibly even named for our fair city and county as I have also seen her moniker spelled "Fredericka" in various records. Regardless, Frederika’s parents are also here: mother Amelia Gertrude White (daughter of John and Attillia), and father Capt. Henry Clay Henshaw. Gertrude was born September 28th, 1846 at Locust Hill in Baltimore. Her husband was a Washington, DC native who served in the American Civil War as Chief Engineer of the United States Revenue Cutter Service. (Decades later this would morph into the US Coast Guard).  EDEN Southworth EDEN Southworth Captain Henshaw was born on September 25th, 1840 and died March 13th, 1903. An interesting tidbit I gleaned while stumbling over this family member is that he had a stepsister who played a prominent role in Frederick’s history. I’m talking about a lady named E.D.E.N. Southworth, the top-selling female novelist of the 19th century. Miss Southworth lived in Georgetown and was an ardent abolitionist. In July, 1863, she wrote two known letters to a prominent, fellow abolitionist—the Quaker poet John Greenleaf Whittier of Amesbury, Massachusetts. In these letters, Ms. Southworth recounted a tale “meant for Whittier’s pen” about a feisty nonagenarian of Frederick, Maryland who defied Gen. Stonewall Jackson and the Confederate Army by proudly waving her flag out her second-story dormer window in September, 1862. You guessed it, Southworth was the principal source for our beloved Barbara Fritchie poem, a piece of prose that “literally” put Frederick, Maryland on the proverbial map. Capt. Henshaw seems to have lived an adventurous life which I learned from finding his obituary which appeared in local papers in March, 1903. I was also fortunate to have found a photograph of him and his wife via the www.FindaGrave.com website. So, by now you’re probably asking yourself, “That’s great Chris, but what’s the poop on this Alexander Norris guy.” Well, it has to do with Mr. Norris’ profession as a civil engineer, a job that took him to various places around the world. In fact, as a native of Veracruz, Mexico, he had already been well-traveled before reaching adulthood because of a transient childhood dictated by the profession of his father, Henry DeButts Norris (1831-1898), also a civil engineer, and highly respected. Henry was a Virginian of deep stock from Marshall in Fauquier County. Alexander’s mother, Edna Bach, was from New Orleans, Louisiana and became the mother of eight children, of which our subject was the third oldest. According to Ancestry.com family tree information, Henry’s family lived in Virginia, Havana, (Cuba), Veracruz (Mexico), Costa Rica, Louisiana and wound back up in Fauquier County, VA by 1880. In 1882, Alexander was attending the Shenandoah Valley Academy in Winchester, VA. Four years later, he would graduate from the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute located in Rensselaer, New York after entering in 1884. Without aid of the 1890 census, it can be assumed that Mr. Norris could have been anywhere. I found that he was in Peru from 1890-1893. We at least know his whereabouts on November 7th, 1893, because it was on this day that he married Frederika Henshaw at St. Luke’s Episcopal Church in Adamstown. By the space given in the local newspaper, it appears to have been the social event of the year around these parts. In 1897, Alexander was working in Central America, and more specifically Nicaragua, for the Nicaragua Canal Commission. The proposed canal here would never be built as plans were scrapped in favor of building a canal in Panama instead. This surely precipitated a return back home for the talented engineer and planner. The Norris family would expand rapidly over the next few years. Three children would be born to Alexander and Frederika, the first two of which at the familial home of Moreland in Adamstown. The 1900 census shows Alexander and Frederika here with son Henry Stuart Norris, born November 21st, 1899. Gertrude Henshaw Norris (b. May 13th, 1902) and Benjamin White Norris (b. April 15th, 1907) would follow. Gertrude was born in Adamstown, but Benjamin was born in Lima, Peru signaling that the family was living there at the time. They had indeed moved to the South American country in 1906.  This all makes complete sense to me now, especially due to what I discovered about Alexander’s employer, the Peruvian Corporation of London (England) A Wikipedia page for the firm states: The Peruvian Corporation of London was registered under the Companies Act in London in March, 1890. The company was formed with the purpose of canceling Peru's external debt and to release its government from loans it had taken out through bondholders at three times (in 1869, 1870, 1872), in order to finance the construction of railways. The main purpose of the incorporation included acquiring the rights and undertaking the liabilities of bondholders. After winning independence from Spain in 1826, Peru was financially strapped. Over the decades financial problems worsened, and Peru needed money. In 1865 then 1866, bonds were issued that were retired with new bonds in 1869. More bonds were issued in 1870 but the 1869 bonds were not addressed. New bonds were again issued in 1872 and again previous bonds were not addressed. A major problem, that would take many years to resolve, was that the rich guano deposits were used as security on all the bonds. Peru struggled to make bond interest payments but on December 18th, 1875, Peru defaulted. The War of the Pacific (1879–1883) made matters far worse for the country and its creditors, and by 1889 something had to be done about the situation. In London, a group formed the Peruvian Corporation (of London) to try to resolve the issues and recoup invested money. The objectives of the company were extensive. They included the acquisition of real or personal property in Peru or elsewhere, dealing in land, produce, and property of all kinds, constructing and managing railways, roads, and telegraphs, and carrying on the business usually carried on by railway companies, canal companies, and telegraph companies. It also was involved in constructing and managing docks and harbors, ships, mines, beds of nitrates, managing the State domains, and acting as agents of the Peruvian Government. The Peruvian Corporation took over the depreciated bonds of the Peruvian Government on the condition that the government-owned railroads and the guano exportation be under their control for a period of years. The bonds were exchanged for stock in the Peruvian Corporation. William Davies, of Argentina and Peru, ran the Peruvian Corporation for W.R. Grace and Company. The corporation later surrendered the bonds to the Peruvian Government in exchange for the following concessions: the use for 66 years of all the railroad properties of the Peruvian Government, most important of which were the Southern Railway of Peru and the Central Railway of Peru; assignment of the guano existing in Peruvian territory, especially on certain adjacent islands, up to the amount of 2,000,000 tons; certain other claims on guano deposits, especially in the Lobos and other islands; 33 annual payments by the Peruvian Government, each of $400,000. In 1907, this arrangement was modified by an extension of the leases of the railways from 1956 to 1973, by a reduction in the number of annual payments from 33 to 30, and by a further agreement on the part of the Peruvian Corporation to construct certain railroad extensions to Cusco and to Huancayo. I would later learn (through Alexander's obituary) that Henry DeButts Norris worked here for W. R. Grace so why wouldn't a son of the same profession be brought into the fold? Enter our Alexander Joseph Norris of Adamstown to help engineer, design and build said new railroad extensions, in part to move more guano and people, as part of the Central Railway of Peru. He would serve as a stationary engineer and hold the title of Chief of Construction. As if this wasn't impressive work unto itself, I would learn that this railroad would hold the distinction of being one of the highest elevation rail lines in the world. In 1910, it appears that the Norris’ traveled to London in what was likely a business meeting with his superiors. I found a record pertaining to his return trip through New York City’s Ellis Island. I found an article in the Frederick paper saying that Mrs. Norris sailed to London and met her husband there. After a brief stay, they planned to travel extensively together through Europe before making their way back home to the US. Over the next few years, there are only brief mentions of return visits to Frederick by Norris family members. Mr. Norris had returned to Peru in January, 1915 after spending the previous fall in Maryland in which he had the opportunity to see his family and friends and stay through the Christmas holidays. That abruptly, and sadly, brings us to the end of our story, or should I say Alexander’s tragic end? The year was 1918. Peru's trade opportunities with the outside world were severely hampered by the constant threat of shipping risk of exports to Europe against the backdrop of World War II. I was surprised to find government paperwork online that helped tell the story of Alexander’s demise. The guano didn't do him in, but the circumstances of building railroads in a South American country for our subjects to help transport the stuff was certainly an extenuating factor. Actually, our engineer suffered a sudden death due to Peritonitis, generalized after a perforation of the stomach. Since I’m no medical guy, I decided to learn more about this malady which is caused by the fore-mentioned perforation of the intestinal tract thanks to a variety of things including pancreatitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, a stomach ulcer, cirrhosis of the liver, or a ruptured appendix. As stated on the tombstone and death report, Alexander died in Miraflores, a district within Lima. Mr. Norris’ body was laid to rest at Bellavista, a British Cemetery of Callao, Peru—a cemetery used exclusively for burials of members of the British community in Peru. It has since been used for other expatriate nationalities. Due to health regulations, Alexander J. Norris’ body had to stay buried in Peru for at least two years before being exhumed and shipped back home stateside. It would eventually be brought back to Frederick and reburied in Mount Olivet’s Area H/Lot 495. Mrs. Frederika “Freddie” Norris would die a few years later and be laid at her husband’s side. I'm not quite sure when this monument was erected over the grave, but likely not until Frederika's death, and perhaps years later. As for the Norris’ children, Henry Stuart Norris went to Princeton and would make a career out of being an engineer of heating and boiler supplies and lived most of his working life in New York before retirement in Pennsylvania (d. 1977). Amelia Gertrude Norris Green lived most of her adult life in the vicinity of Washington, DC, dying in 1998 in Arlington, VA. Benjamin White Norris, the child born in Peru who lost his father at age eight, would die a hero’s death in World War II at the Battle of Midway. Military aviator Ben Norris was awarded a posthumous Navy Cross for his actions in the battle: The President of the United States takes pride in presenting the Navy Cross (Posthumously) to Benjamin White Norris (0-4382), Major, U.S. Marine Corps, for extraordinary heroism and distinguished service in the line of his profession while serving as Division Commander and a Pilot in Marine Scout-Bombing Squadron TWO HUNDRED FORTY-ONE (VMSB-241), Marine Air Group TWENTY-TWO (MAG-22), Naval Air Station, Midway, during operations of the U.S. Naval and Marine Forces against the invading Japanese Fleet during the Battle of Midway on 4 June 1942. Leading a determined attack against an enemy battleship, Major Norris, in the face of tremendous anti-aircraft fire and fierce fighter opposition, contributed to the infliction of severe damage upon the vessel. During the evening of the same day, despite exhaustive fatigue and unfavorable flying conditions, he led eleven planes from his squadron in a search-attack mission against a Japanese aircraft carrier reported burning about two hundred miles off Midway Islands. Since he failed to return with his squadron and is reported as missing in action, there can be no doubt, under conditions attendant to the Battle of Midway, that he gave up his life in the service of his country. His cool courage and inspiring devotion to duty were in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service. Benjamin White Norris’ remains were never found, but he is memorialized in “the Courts of the Missing” of the Honolulu Memorial is located within the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in an extinct volcano near the center of Honolulu, Hawaii. To read more, here is a link to Ben Norris’ Military Hall of fame webpage: https://militaryhallofhonor.com/honoree-record.php?id=98946

|

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed