|

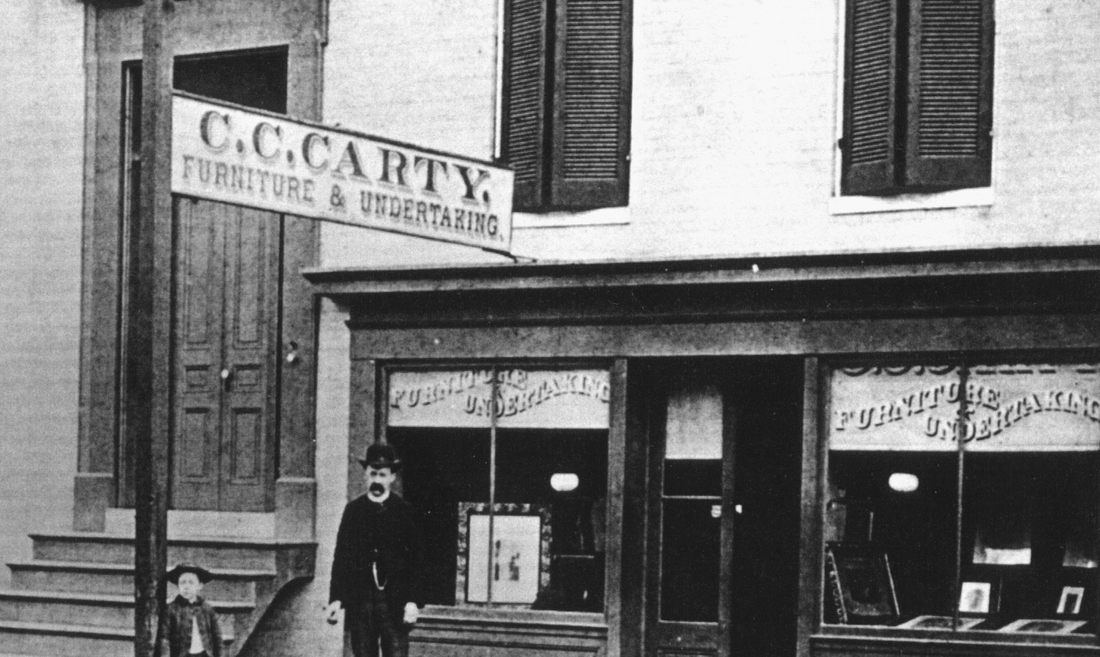

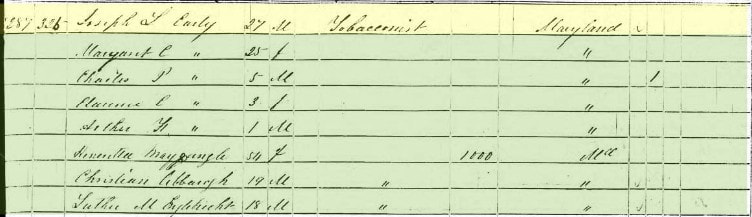

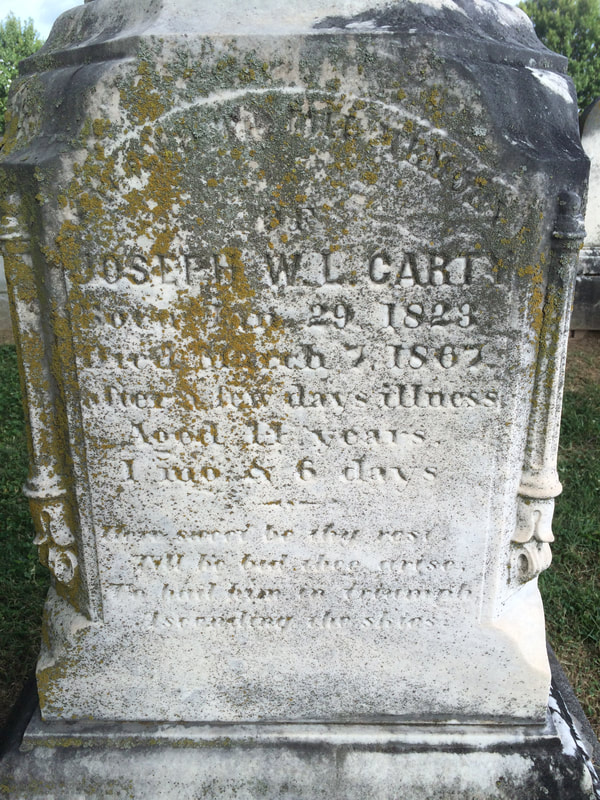

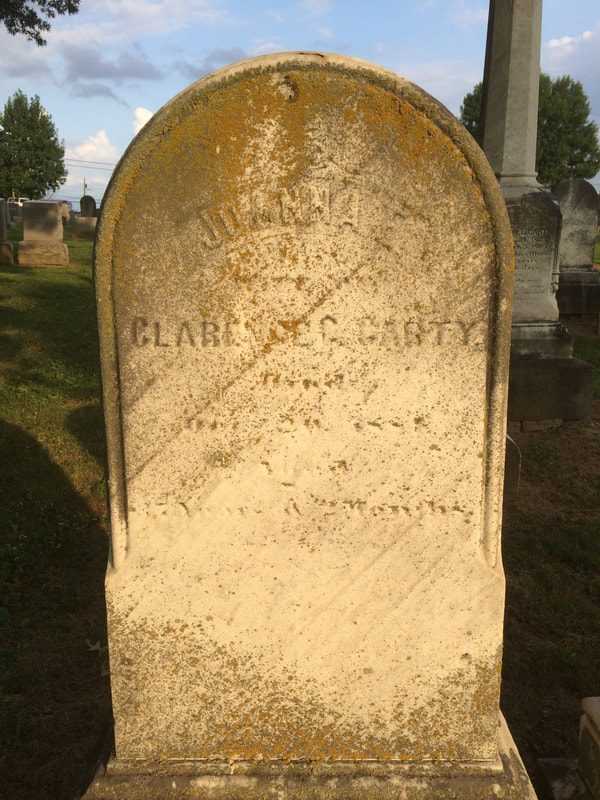

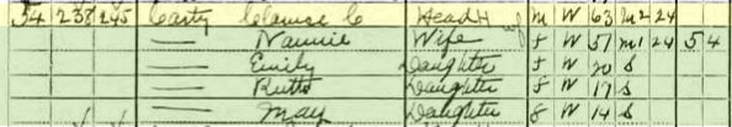

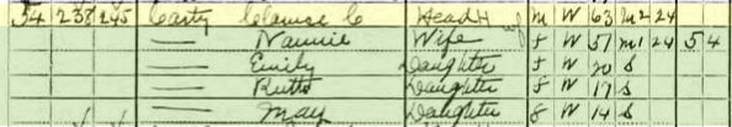

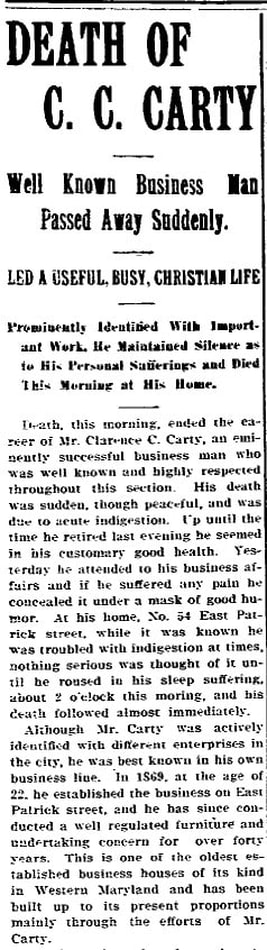

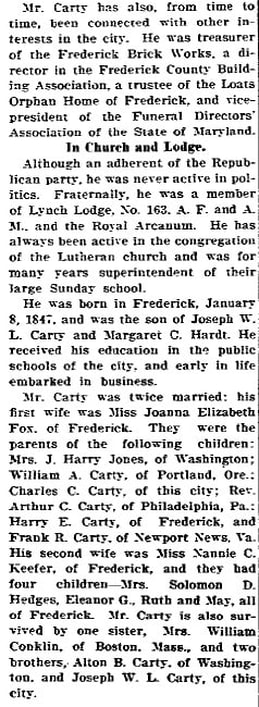

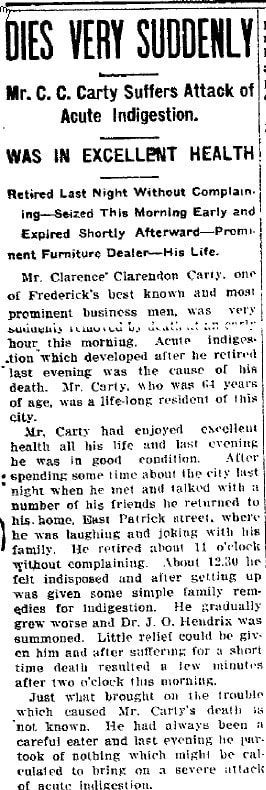

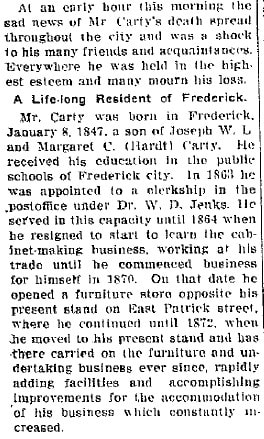

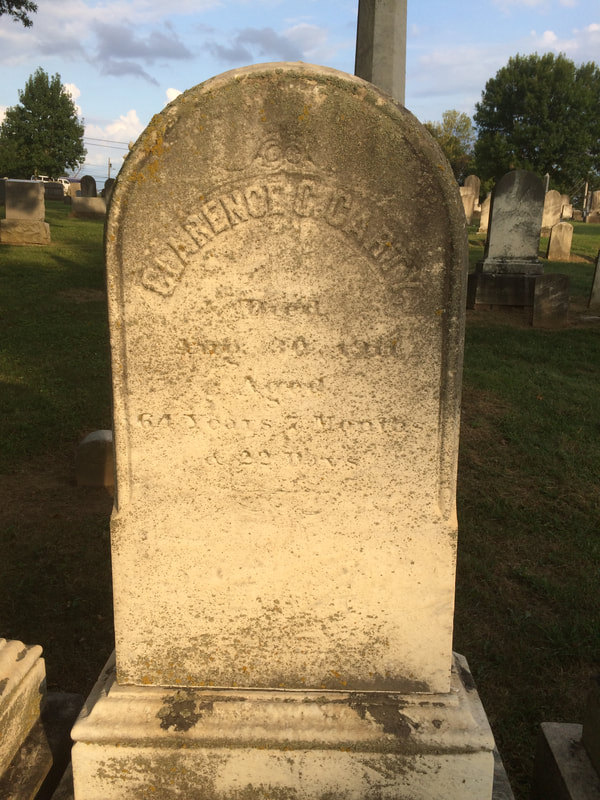

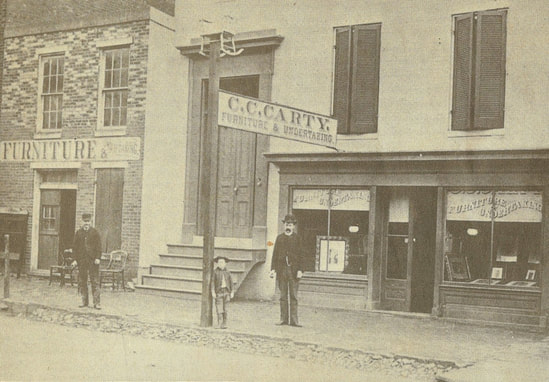

A very interesting figure in Frederick's past had a virtual run on the letter "C" as he boasted the initials C.C.C. His name was Clarence Clarendon Carty, and he lived in a time long before the Civilian Conservation Corps of the 1930’s. This gentleman was never in need of government employment as his life's work (and that of his future descendants) had an incredible connection to death and local cemeteries, especially Mount Olivet. I thought of C.C. Carty the other day as I walked past his gravestone in the cemetery’s Area A, located directly across the road from the Key Chapel and large obelisk of Gen. James C. Clarke. It just so happened to be the 107th anniversary of Mr. Carty’s death on August 30th, 1911. I had first heard of Clarence C. Carty nearly three decades ago when I worked for Frederick Cablevision. Mr. Carty was the maternal grandfather of my employers George B. Delaplaine, Jr. and sister Frances “Franny” (Delaplaine) Randall. Many know that George and Frannie’s paternal grandfather, William T. Delaplaine, founded the Frederick News in 1883—a business that was handed down multiple generations before being sold in 2017 to Ogden Newspapers, Inc. Likewise, C. C. Carty started a business in the late 19th century that would be continuously operated by his descendants well into the next century. I knew Mr. Carty started a highly successful furniture and undertaking business on E. Patrick Street. His son, Charles Clarendon Carty, would take the reins, eventually turning this over to his son, James Walker Carty. For the last several years, I have taken participants of our annual, fall-time Candlelight Cemetery Tours to Mr. Carty’s grave, pointing out that this former resident had started in business at a relatively young age, and is buried between both his first and second wives. I usually spellbind my audiences by stating the fact that due to his profession as a local undertaker, C.C. Carty passed his future eternal resting place on a daily basis—hundreds of times. I then ask the question: “How do you think he felt about his own impending death? Did he know too much?” A Family Tradition The son of Joseph William Leonard Carty and Margaret Catherine Hardt, Clarence Clarendon Carty was born in Frederick on January 8th, 1847. His father was a tobacconist and later served as clerk of the Frederick County Circuit Court in the waning years of the American Civil War. The elder Mr. Carty was also credited as an organizer and director of the Lincoln Building Association and a director of the Farmers & Mechanics Bank. William’s History of Frederick County refers to him as “a public-spirited” citizen and consistent member of Frederick’s Evangelical Lutheran Church.” By 1850, three-year-old Clarence Clarendon was the second of three young brothers which also included Charles Proctor (b. 1844), and Arthur Alexander (b.1849). He would soon have to deal with death with the tragic losses of immediate family members. His mother, a niece of famous Frederick diarist Jacob Engelbrecht, died in October, 1850 at the age of 25. Two months later, C.C.’s baby brother (aged 2) would pass. (Both mother and son were originally laid to rest in the Lutheran cemetery of town, but would be removed to Mount Olivet in November 1886). Clarence Clarendon’s father eventually re-married (Mary M. Lugenbeel) and three step-siblings would come from this union. C.C. Carty grew up on S. Market St. and would receive his education from the public schools of Frederick City. In 1863, he was awarded a clerkship at the Post Office, but clerical work was not his thing as he resigned a year later to pursue an interest in becoming a professional cabinet-maker.

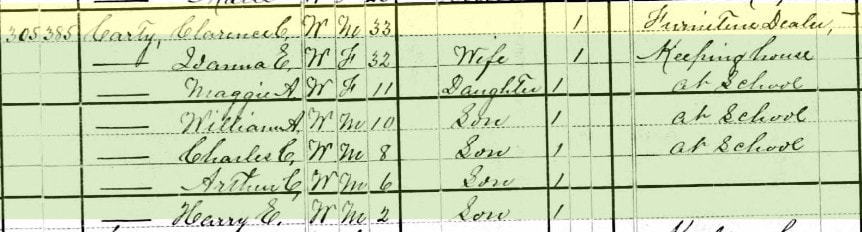

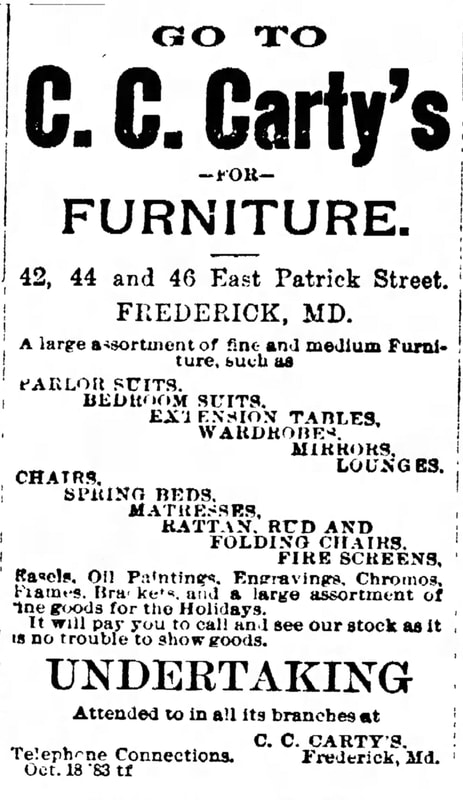

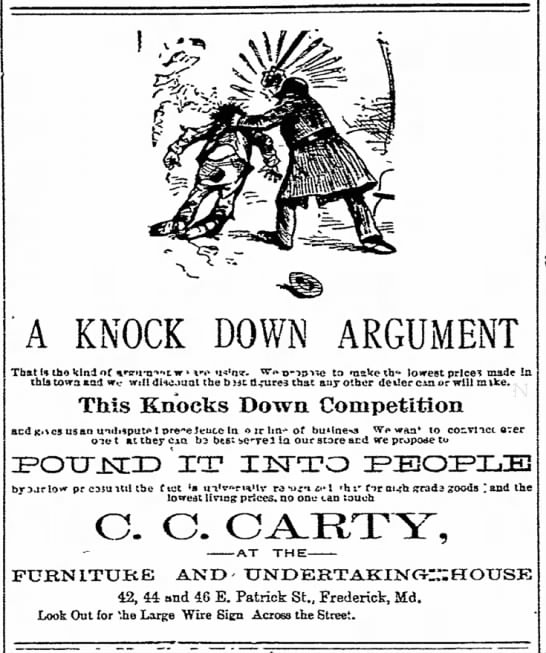

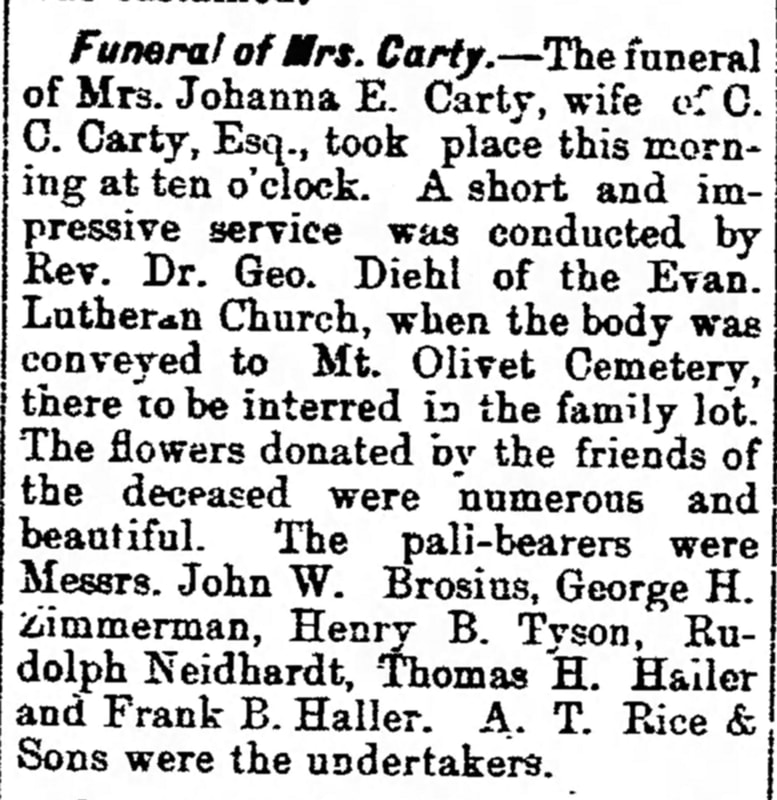

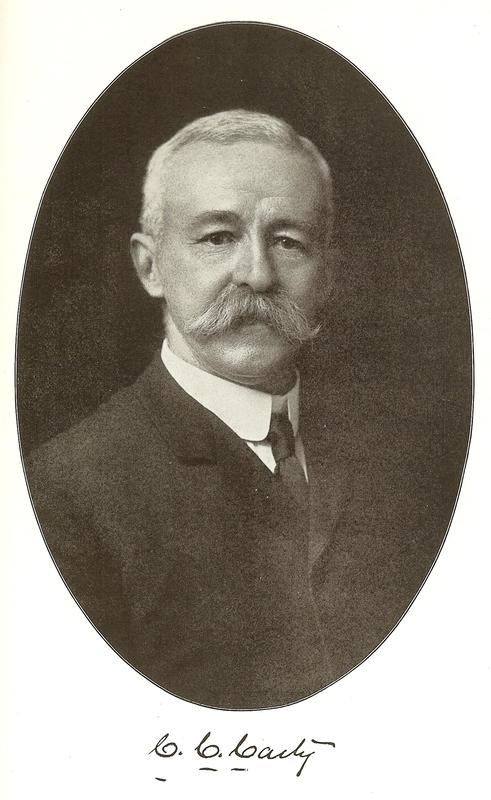

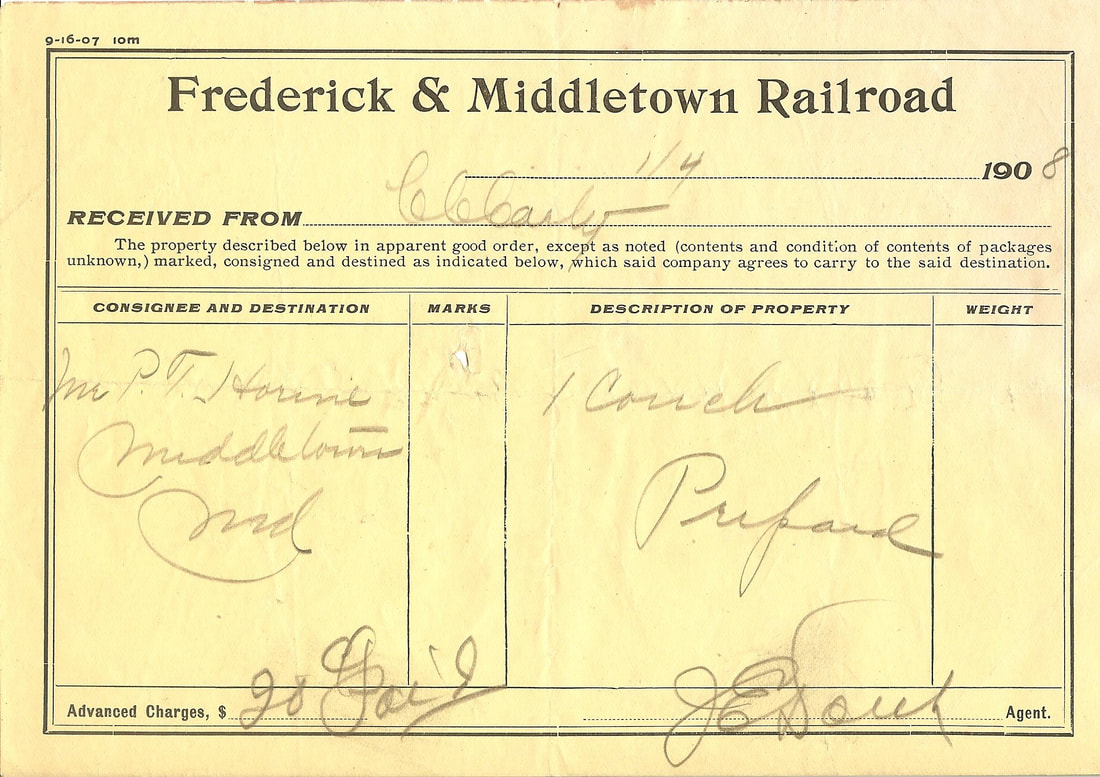

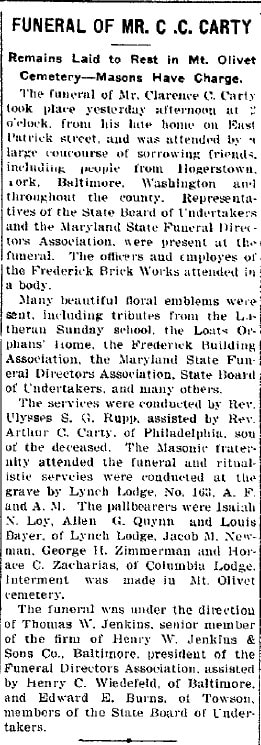

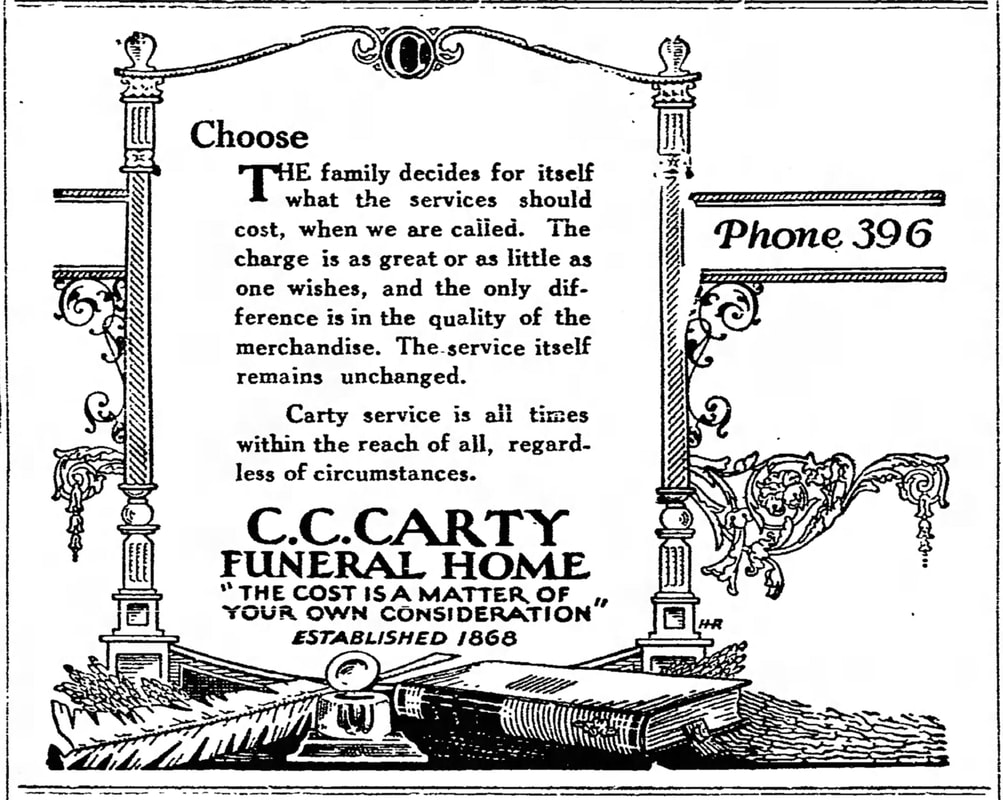

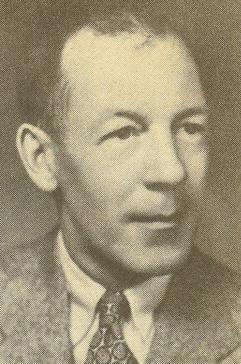

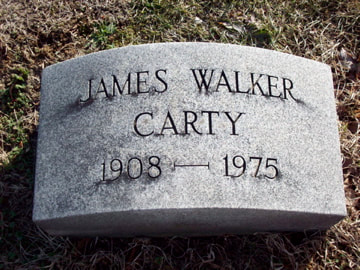

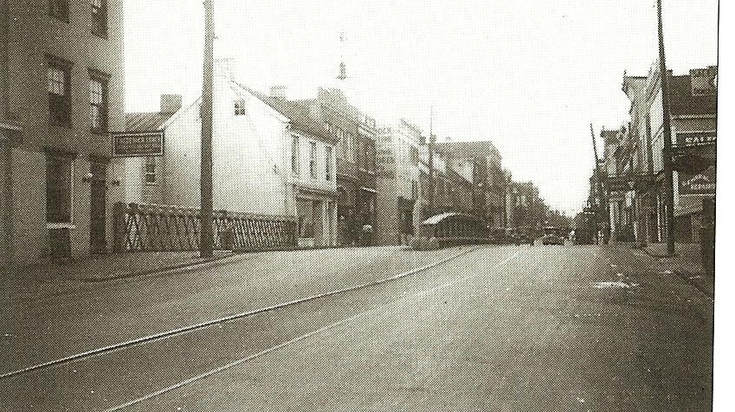

I guess you could say that Mr. Whitehill “made a killing” during the Civil War with this product focus. He hired a controversial embalmer as a necessary “value add” for his customers, especially those desiring to transport their fallen military loved-ones back to hometown cemeteries. Mr. Whitehill, himself, was also no stranger to Mount Olivet as he was one of the original founders of the town’s new burial ground back in the early 1850’s. Apparently, James Whitehill served as a mentor of sorts to young Carty. The local lore says that Carty asked Mr. Whitehill to consider him as a successor for the prosperous E. Patrick Street furniture and undertaking establishment when it came time for retirement. C.C. Carty’s big break eventually came in 1869 when Mr. Whitehill granted his request. Joseph W. L. Carty had died in March 1867. Perhaps, C.C. received some inheritance money which allowed him to enter into such a venture? Regardless, at 22 years of age, C.C. Carty became owner of his own business, one that originally opened on the north side of East Patrick near Middle Alley. On the personal life level, I find it interesting that both of Joseph W. L. and Margaret Carty’s sons married in late October, 1867. Charles married Lucy C. Keneaster of Indianapolis on October 29, 1867. The very next day, Clarence Clarendon married Joanna Fox, daughter of C. F. Adolphus Fox, a noted watchmaker from Germany. Charles and Lucy moved to the Midwest. Of the latter pairing, C.C. and Joanna would go on to have five children: Margaret A. (b.1868), William A. (b. 1870), Charles Clarendon (b. 1872), Arthur Clarence (b. 1876), Harry Edwin (b.1878) and Frank (1884). Over the first decade of his business ownership, Charles Clarendon Carty manufactured most of the fine furniture sold at his shop. He also built on Whitehill’s acumen as an undertaker. A humble cabinet shop eventually morphed into C.C. Carty’s Furniture Store and necessitated a move across the street to a larger warehouse facility. Soon Carty’s became the largest outlet of its kind in Maryland, outside Baltimore. The term “undertaker” refers to the person who “under took” responsibility for funeral arrangements. Many of the early undertakers were furniture makers because building coffins, and later caskets, was a logical extension of their business. For them, undertaking was a second business rather than a primary profession. C.C. Carty soon became widely prominent in furniture circles and the undertaking business “as one of the ablest and most representative men identified with that branch of the industry.” C.C.’s family lived above the business establishment on the upper floors of his building. The furniture showroom was towards the front of the first floor, and the funeral operations occupied the rear of the ground level floor. Not as much room was needed for the latter as compared to today’s more extensive funeral home operations. Funerals, or more so wake services, were held in the decedent’s home. Bodies were either picked up by the undertaker, or brought to him by horse and wagon. The body would be embalmed here, and then returned to the home or church for “viewings” and memorial services. In other cases, undertakers delivered the body directly to the cemetery for burial. Mr. Carty suffered another major blow in October of 1884 as his wife Joanna died in her 37th year. With five children and a flourishing business, C.C. was quick to remarry a year later as he took Ann “Nannie” Catherine Keefer as his second wife on November 4th, 1885. He would go on to father four more children: Cora (b.1888), Eleanor (b.1890) and Ruth (b.1892 and future mother of George B. Delaplaine, Jr. and Franny Randall) and May (b. 1895). Williams’ History of Frederick County (1910) says of Mr. Carty: “He is recognized as one of the foremost and most prominent merchants of Frederick, and is held in high esteem by all with whom he has come in contact. Mr. Carty has directed the affairs of his establishment with a foresight and sagacity that stamp him as a man of superior executive ability. To his forceful personality is due much of the prosperity and prestige attained by him.” Ch-Ch-Changes In 1895, the existing buildings comprising the furniture store and undertaking business were demolished to make way for a new home for the downtown operation. At this point, the family moved their living quarters to 54 E. Patrick St., a few doors to the east on the corner of Middle Alley. This is one of the oldest structures in Frederick City dating to the mid 1700’s. Some say it is one of the oldest brick built structures in town. It would eventually be utilized as one of the first funeral homes in town, owned by the Carty’s. Today this is the home of Brainstorm Comics.  Charles C. Carty Charles C. Carty In 1905, sons Charles and Harry became involved in the family business as the boys inherited the establishment from their father upon his semi-retirement. Charles headed up the furniture endeavor, while Harry took the undertaking side. Meanwhile, C.C. had become an officer with the Frederick Brick Company, and took on extra responsibilities of representing the firm in Baltimore and other cities. C.C. Carty enjoyed a few years of retirement before his death on September 1st, 1911. He would be buried next to first wife Joanna, and in the morning shadow of his parents’ beautiful monument, capped with a hand with a finger pointing toward heaven. His second wife, Nannie would be buried to the right of C.C. Carty upon her death in 1931. Throughout the years, many changes were instituted to keep the business location of 48-52 E. Patrick St. modern and up to date. The building was expanded once again in 1922. For decades Carty’s served as the largest retail store in Frederick. In 1930, the partnership between the brothers was dissolved as Charles took over the furniture business as sole owner, and Harry received the undertaking and funeral home operation. Once again, the furniture business sole owner had the initials C.C. Carty. However, this would be short-lived as Charles Clarendon Carty would die suddenly at the age of 60 from Angina on March 4th, 1932. This came as a shock and surprise to the entire community. The family must have found some degree of solace as the Carty Furniture Store would now be run by grandson James Walker Carty (1908-1975), son of Charles Clarendon Carty. “Walker” Carty was attending college at Princeton at the time. He returned home to Frederick and provided leadership until his own retirement in 1975. Walker’s wife, Janice, had taken an active role in the business by creating an interior design service sector. Harry E. Carty died in 1934 and was succeeded by his son, Clarence Clarendon Carty, Jr. Another grandson of the founder ran the funeral home business until his retirement in 1964, at which point he went to St. Petersburg, Florida, while is cousin (Walker) continued with the furniture operation for well over another decade. After 109 years, the business closed its doors for good on July 19th, 1978. It was a great run, and truly “a family affair.” A builder from the beginning, C.C. Carty had certainly “undertaken” an endeavor that not only served his neighbors, but certainly established his place in the annals of Frederick history. Each year, thousands of visitors continue to explore the site of the former Carty business location, as one can see antique furniture from the 1800’s and actual coffins, all the while learning about early embalming practices. It was the Carty family, in the early 1990’s, who were kind enough to donate their former commercial building to serve as the home to the National Museum of Civil War Medicine.

7 Comments

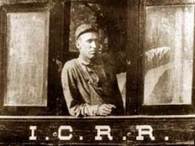

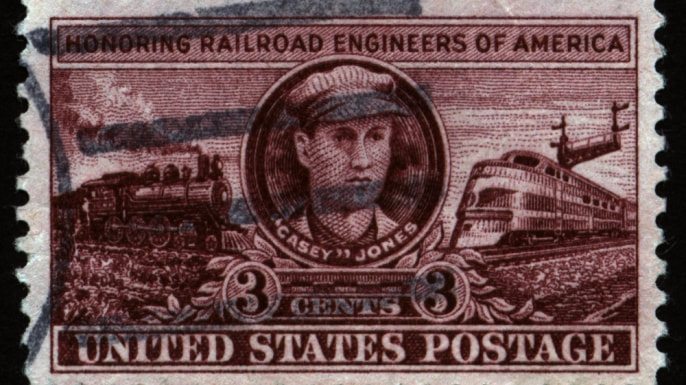

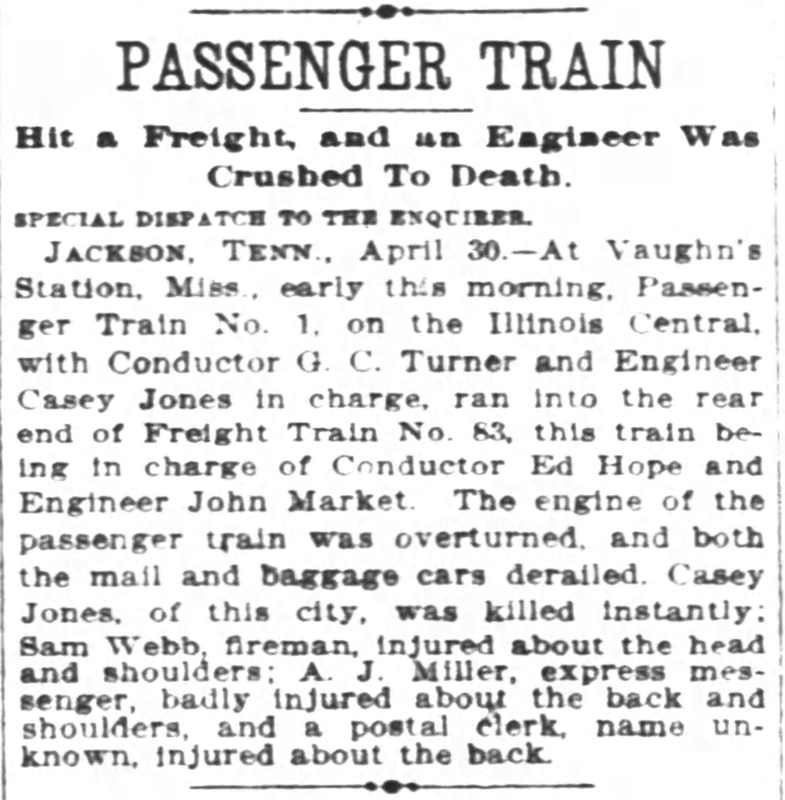

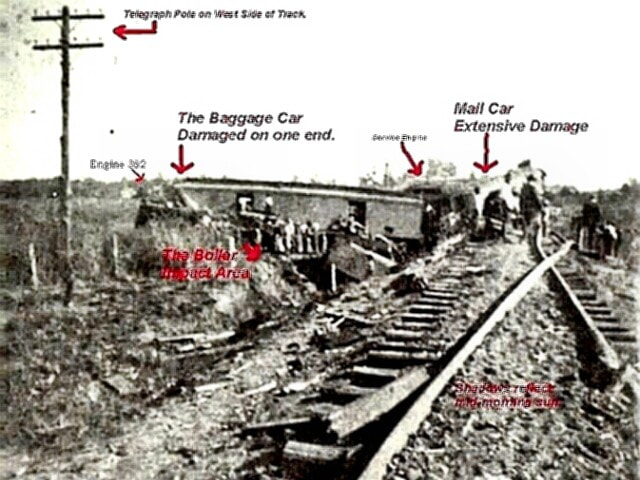

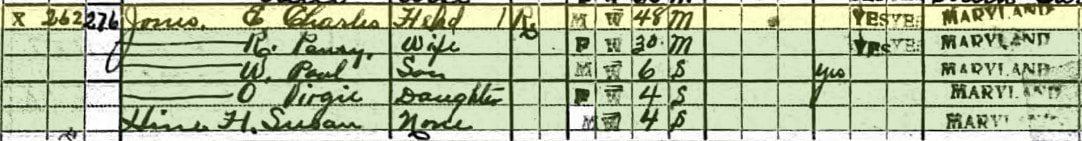

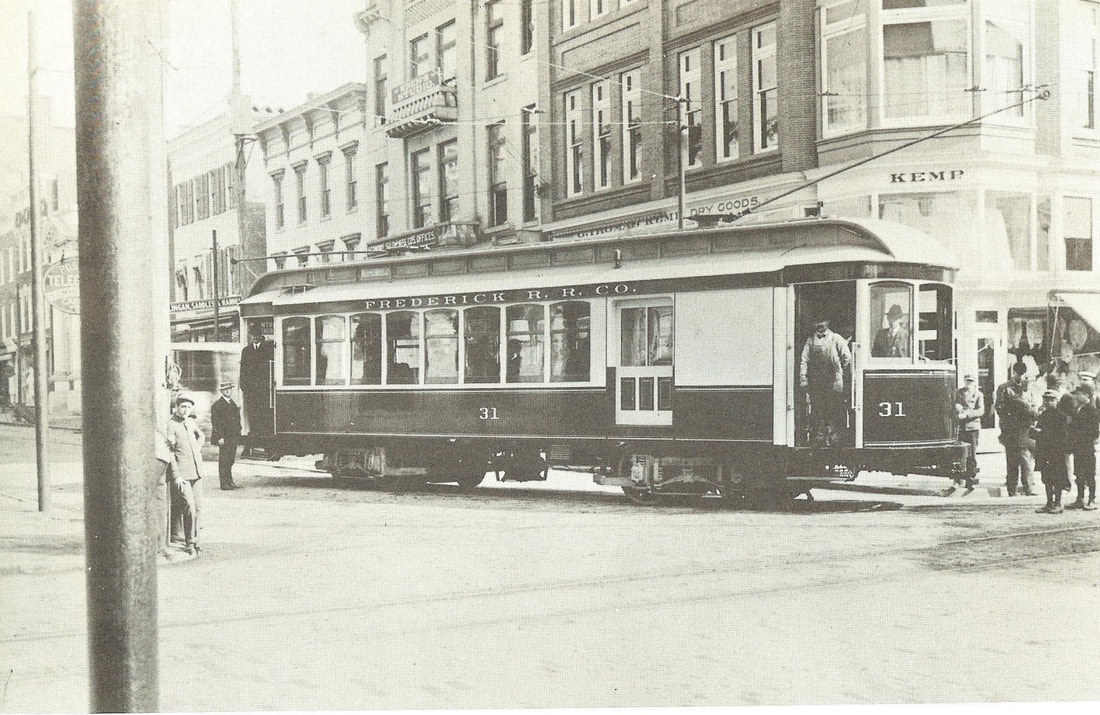

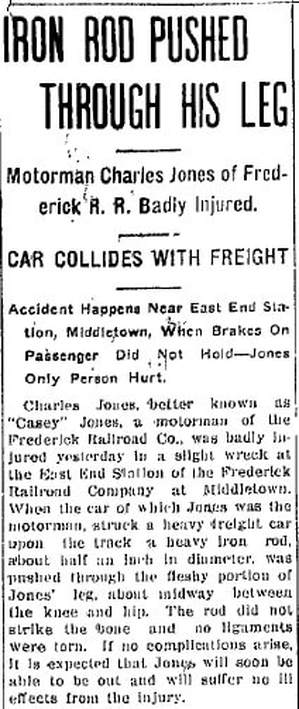

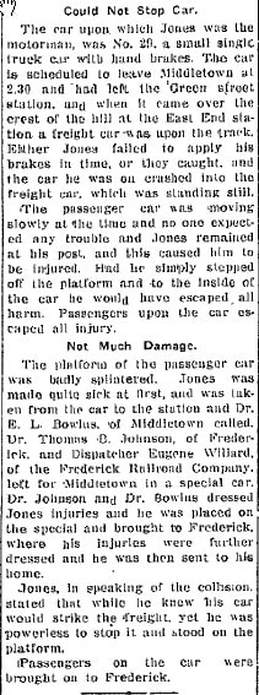

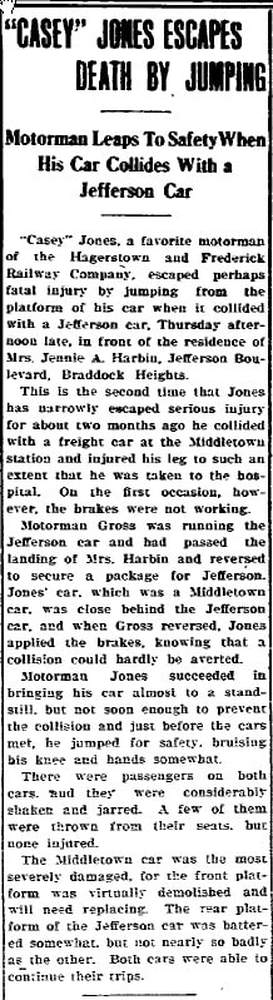

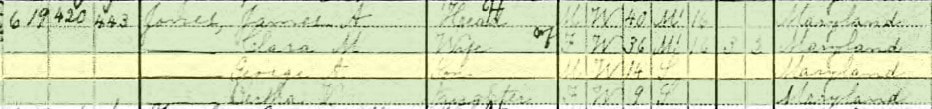

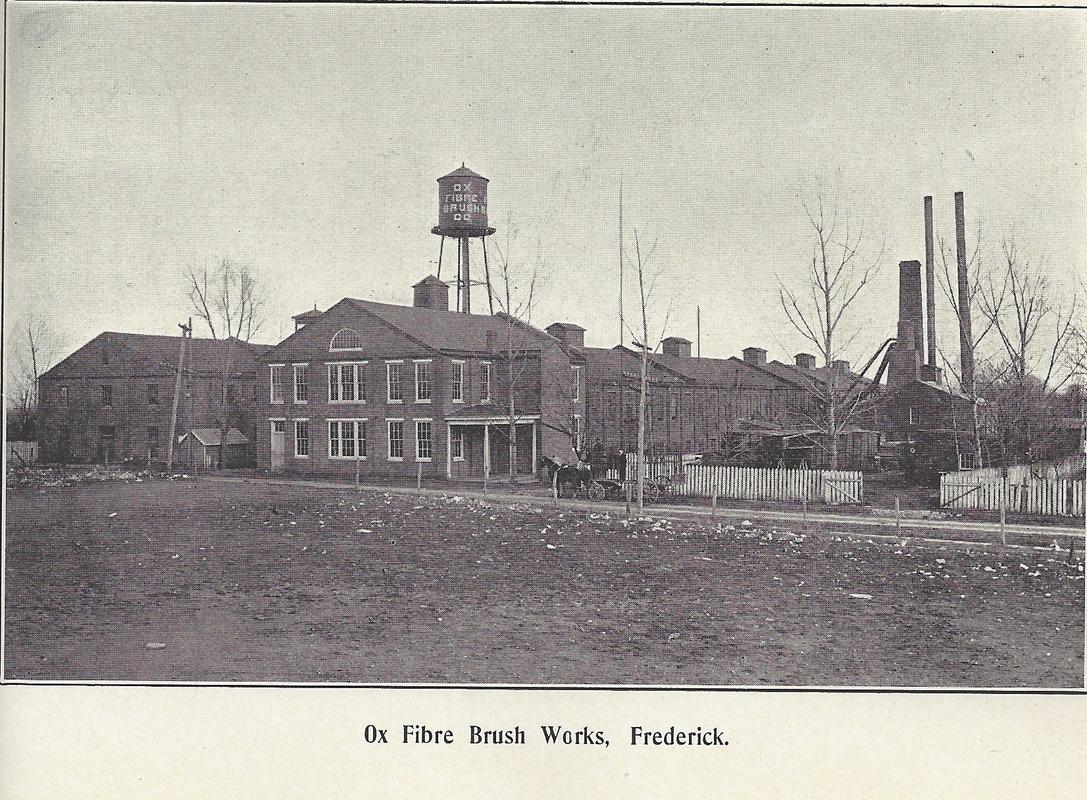

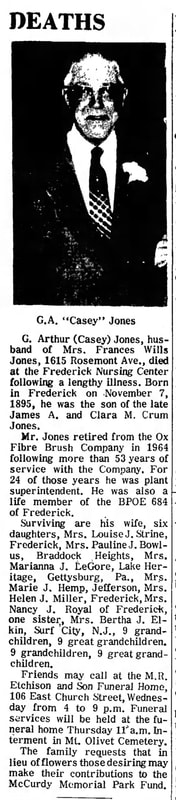

Mount Olivet is home to a few heroes whose names have appeared in the national history books. We have Francis Scott Key, Barbara Fritchie, Thomas Johnson, Jr. and “Casey” Jones. Now, anyone who knows their local history should have flinched on the last offering in that list—“Casey” Jones. The real “Casey” Jones is actually buried in his hometown of Jackson, Tennessee, but Mount Olivet contains at least two gentlemen known by the same moniker. First things first, many folks may not be familiar with “Casey” Jones in the first place. I will start by saying that he wasn’t a baseball player (as some may mistakenly think), a mighty player who struck out for the third out in Mudville’s ninth inning. That “Casey” was the star of a poem written in 1888 by Ernest Thayer.  No sir, we are talking about a real human being who sadly "struck out" in the game of life 12 years later in 1900. Born John Luther Jones on March 14th, 1864, in Missouri, “Casey” Jones was an engineer during the heyday of the American railroad and is considered an American folk hero. "Casey" Jones is best known for his tenacity in keeping trains on schedule, but more so for courage shown as he sacrificed his own life in a terrible accident. He died tragically in the early morning hours of April 30th, 1900 in Vaughan, Mississippi, when he collided with another train. Just before impact, Jones kept one hand on the brake to slow the train and his other on the whistle to warn others who might be near the train. A ballad written by Wallace Saunders entitled "The Ballad of Casey Jones" made Jones a permanent figure in American folklore. The song became a vaudeville favorite in the early 20th century, inspiring American rock’s legendary band the Grateful Dead to write the song “Casey Jones,” which appeared on their 1970 album Workingman’s Dead. (NOTE: In connection with the Dead song, I will add that cocaine had nothing to do with the 1900 accident... but it is a "notion" that commonly crossed the minds of these latter song artists, of course). Now I have to come clean in saying that the actual John Luther “Casey” Jones is buried in Mount Cavalry Cemetery in Jackson, Tennessee and not Frederick, Maryland’s Mount Olivet. We do, however, have buried here two individuals who held the nickname of “Casey” Jones and another who quite possibly could have been professionally acquainted with John Luther Jones.  James C. Clarke (1824-1902) James C. Clarke (1824-1902) James C. Clarke He’s definitely a story for another day, but Frederick resident James C. Clarke could have met or known “Casey” Jones, perhaps just missing a chance to serve as the famed engineer’s big boss earlier in his career. Clarke served as president of several railroads during the late 19th century, including the Illinois-Central from 1883-1887. In 1888, Clarke went to the Mobile & Ohio Railroad and served as its Vice President and General Manager. Ironically, “Casey” Jones began his railroading career with the Mobile & Ohio, but switched to the Illinois-Central in March, 1888 for the promotional opportunity to fulfill his lifelong dream of becoming an engineer. This occurred in 1891. Two of Clarke’s legacies are still evident today in the form of an ornate fountain in front of Frederick's City Hall, and his namesake street located a block from Mount Olivet’s front gate—Clarke Place. Charles Edwin Jones Charles Edwin “Casey” Jones was born in Middletown (MD) in 1871, the son of Charles and Isabelle Clay Jones. Around the year 1910, he got a job with the interurban, electrified trolley system of the old Frederick Railroad Company, an offshoot of the Potomac Edison Company. This endeavor went into business in the late 1890’s and eventually connected Frederick City with Hagerstown and a slew of municipalities and other local spots—primarily Braddock Heights, Middletown and Thurmont. The company would come to be known as the Hagerstown & Frederick Railway. Mr. Jones served as a motorman, and like the legendary “Casey,” our local resident was known for making up lost time on the rails caused by delays caused with earlier trolley runs. He would eventually take the Thurmont run by 1920, and can be found living on Carroll Street extended in the 1920 US Census. Frederick’s Charles E. “Casey” Jones retired from the railway in 1943. Shortly thereafter he took on a job as janitor for the C. Burr Artz Library. A few months back, I stumbled upon two specific newspaper articles which shed light on this man Fredericktonians called “Casey” Jones. I’d like to refer to these articles as “Strike1” and “Strike2” to return back to a baseball theme. Thankfully, our “Casey” never struck out! Charles Edwin “Casey” Jones passed away on May 24th, 1950 at the age of 79. He was laid to rest in Mount Olivet’s Area OO/lot 132. G. Arthur Jones While I was researching information in old newspapers and our cemetery archives about Charles E. Jones, I came upon yet another "Casey" Jones in Frederick. This was the person of George Arthur Jones. G. Arthur Jones was born in the city on November 7th, 1895. His father, James Alonza Jones (1870-1939), headed Frederick City’s police department from 1901-1910 and was elected Frederick County Sheriff in 1921. He also served as superintendent for the Montevue Home for the Aged before, and after, his term as sheriff. From what I could glean, George Arthur grew up in a house located at 619 Park Place. When he grew up, he married Mary Esther Rothenhoefer and his new family lived next door to his parents on Park Place. Miss Rothenhoefer was the daughter of Charles A. Rothenhoefer, longtime proprietor of the Excelsior Sanitary Dairy on East 7th Street. Both home dwellings, as well as several others that comprised the block of Park Place, would eventually be demolished to make room for an expanding Frederick City Hospital. G. Arthur would spend his entire working career at the Ox-Fibre Brush Company, starting in 1911. He began as a machinist, eventually becoming the supervisor of the machine shop. He served as Plant Superintendent for 24 years and would retire in 1964. All in all, he spent 53 years with Ox-Fibre. On a personal level, the Jones' lived at 1615 Rosemont Avenue. Mary Esther died in November of 1953. Mr. Jones was married a second time to Frances Wills.

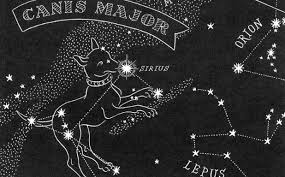

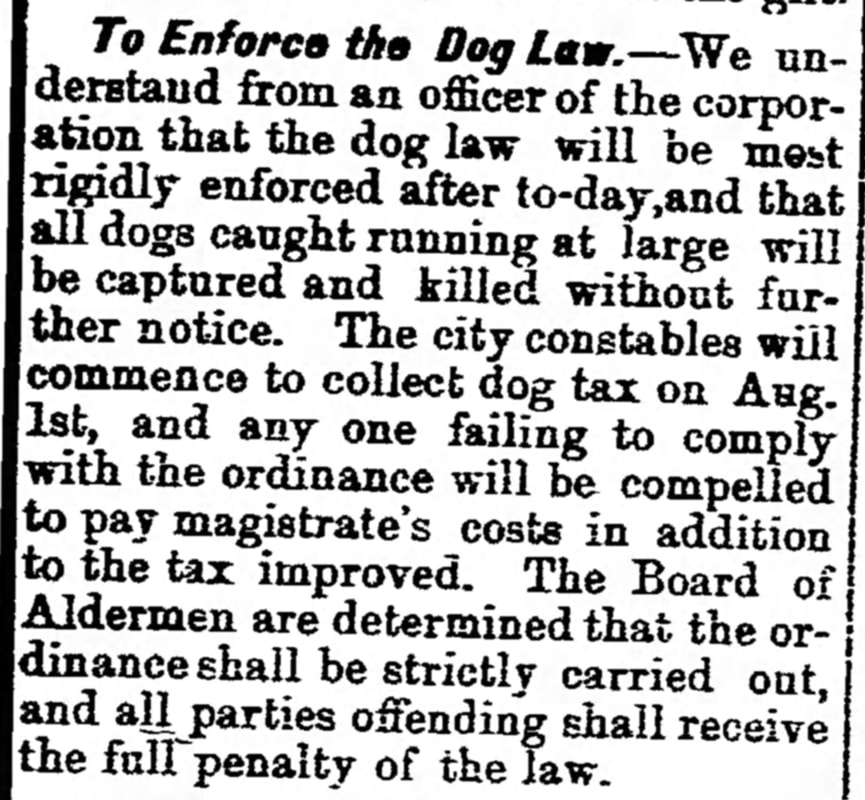

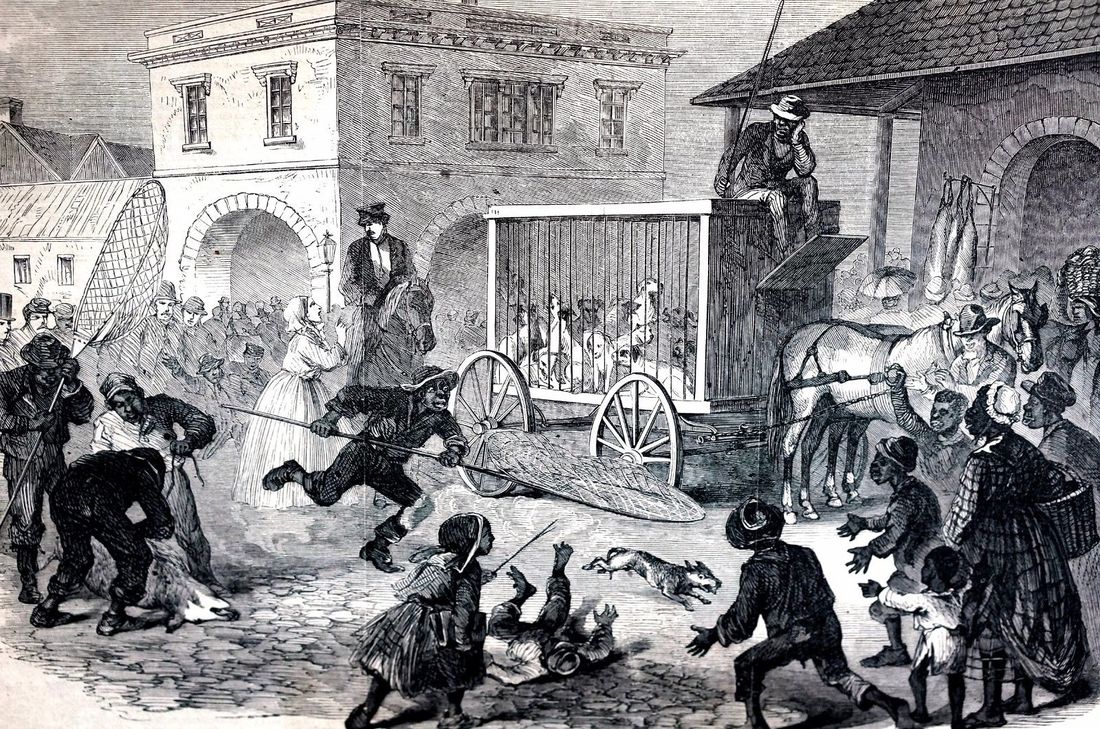

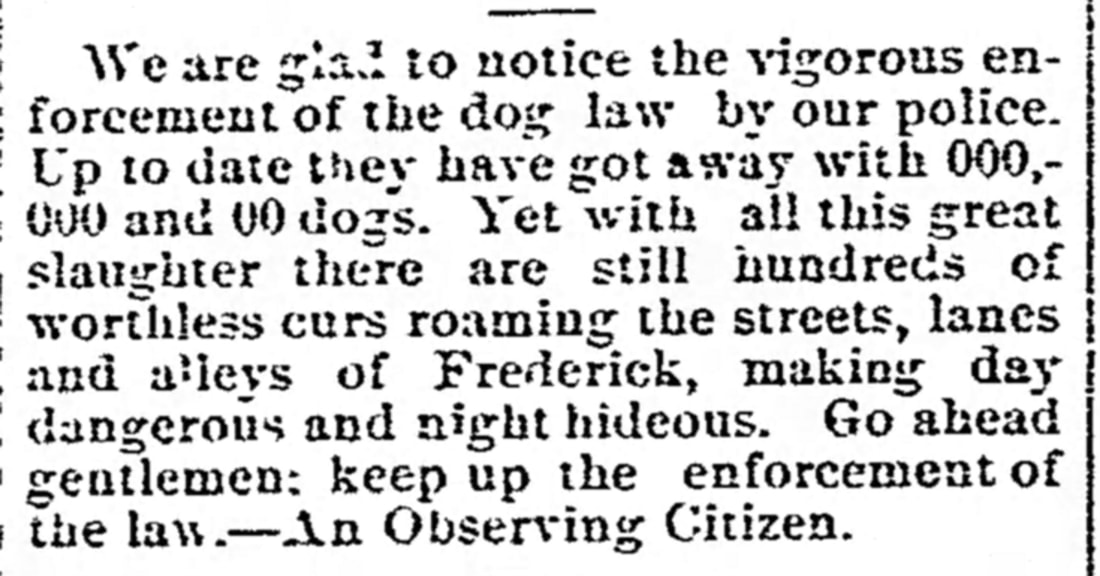

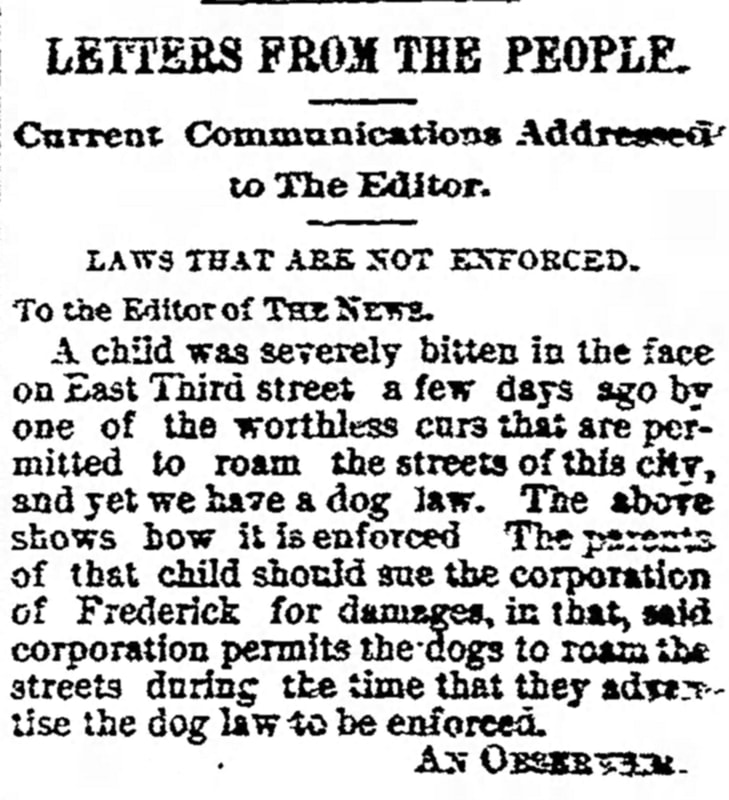

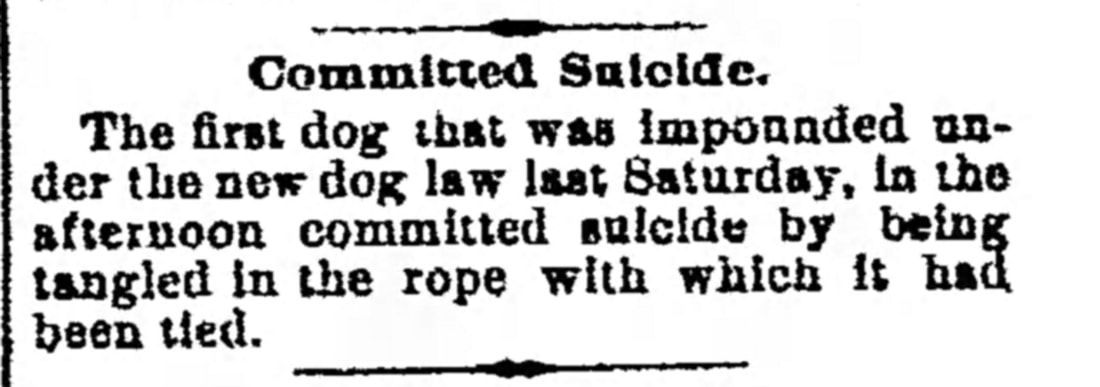

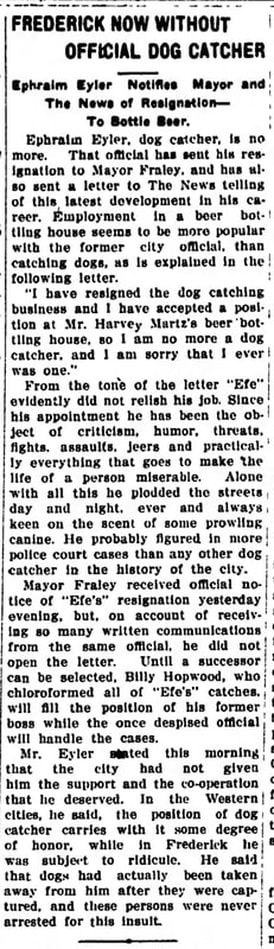

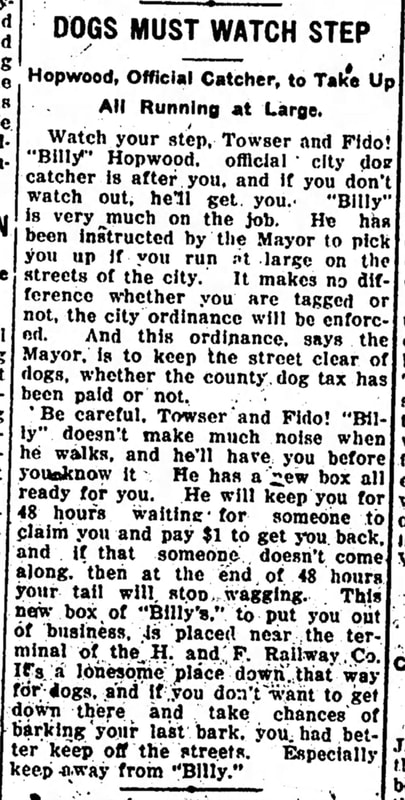

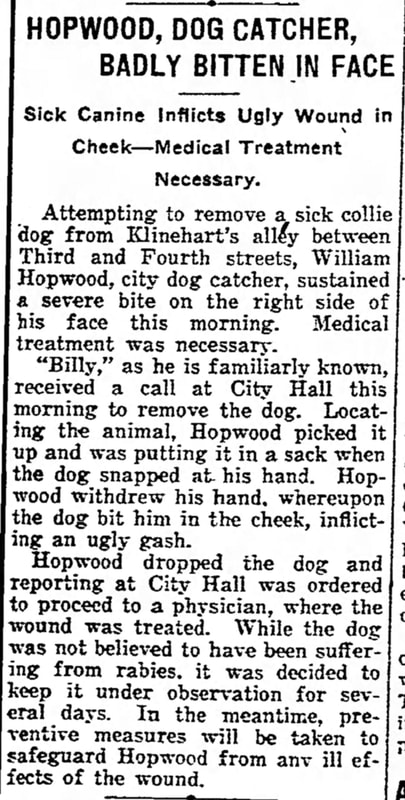

George Arthur “Casey” Jones died on April 20th, 1971. He may not have engineered a train or trolley, but he was as loyal and hard-working to his company as John Luther Jones was to the Illinois-Central Railroad. He certainly deserved the nickname of “Casey” for sure. He was buried in the cemetery’s OO Area in Lot 136. Ironically, both Mount Olivet’s “Casey” Jones are located just six yards apart! A pretty amazing circumstance, especially since I could not find any relation between both gentlemen and families.  The “dog days of summer” are upon us—those devastatingly hot ones that cause dogs to lie around and pant. The phrase itself has been used for centuries, however, the apparent original meaning has nothing to do with canines being overheated or experiencing “the warmest season of them all.” The “dog days” phrase goes back to the times of the ancient Greeks and Romans and their celestial worship of the star Sirius, also known as the “dog star.” The usage pertained to its position in the sky. The specific time in question is late July and early August, the period when Sirius appears to rise just before the sun. The ancients also knew these days to be the hottest of the year, a time that could bring fever-related illness and other catastrophes. “Dog days” was translated from Latin to English about 500 years ago. Since then, it has taken on new meanings such as a time when our four-legged friends “go crazy” from the heat, and the same could be said from our two-legged brethren as well. In doing some research a few weeks back, I stumbled upon a forgotten period in Frederick’s history when the town had literally, and figuratively, “gone to the dogs.” Fittingly it was this same hot and humid time of year. I take you back to the turn of the 20th century and am pleased to introduce William Henry Hopwood, better known around town as “Billy” Hopwood. Saying Billy Hopwood was a colorful character is certainly an understatement! He had plenty of personality, and one of the worst jobs in town. Beloved by some, hated my many, his job was dangerous and depressing—but somebody had to do it.  The Dogcatcher There have been dogcatchers in the United States since the 18th century, perhaps even earlier. One of their job duties was to pick up dogs that appeared to be rabid or vicious. The public greatly appreciated this service, but it was a difficult and often dangerous profession. As the 20th century neared, and the United States became more urban, it became less accepted for dogs to have free run of cities and towns alike. Frederick, Maryland was no exception. On July 1st, 1886, a “Dog Law” went into effect for the first time here. Apparently, the new law was strictly enforced those first few years, however things went south by the end of the decade. Several articles and letters to the editor appeared in the local paper in the early 1890’s challenging (then) Frederick’s Mayor Derr and the Board of Alderman for non-enforcement of the “Dog Law.” July 1st, 1893 involved a reinvigorated effort by the municipality to tackle its stray pet problem. At this point, a somewhat softer approach (as opposed to outright capture and killing) was employed. Dogcatchers began picking up stray and “non-registered” dogs that were on the loose. These were taken to the local repository (dog pound) where they were euthanized if not picked up within a prescribed number of days. Unfortunately, the first captured animal of the season suffered an accidental death which led to more unwanted media coverage. As more and more pets were picked up and taken to the pound, dogcatchers became less popular.

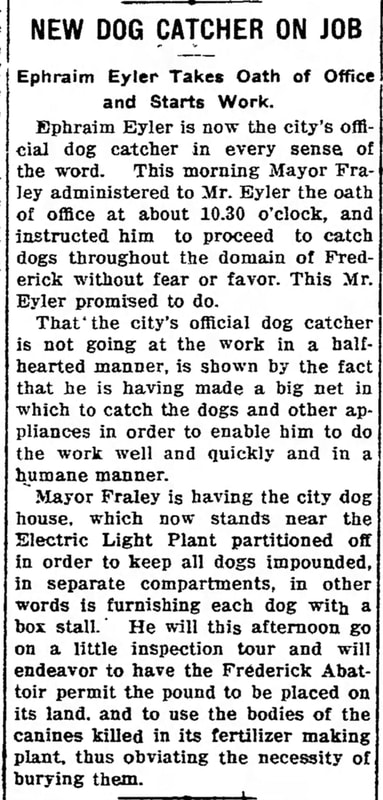

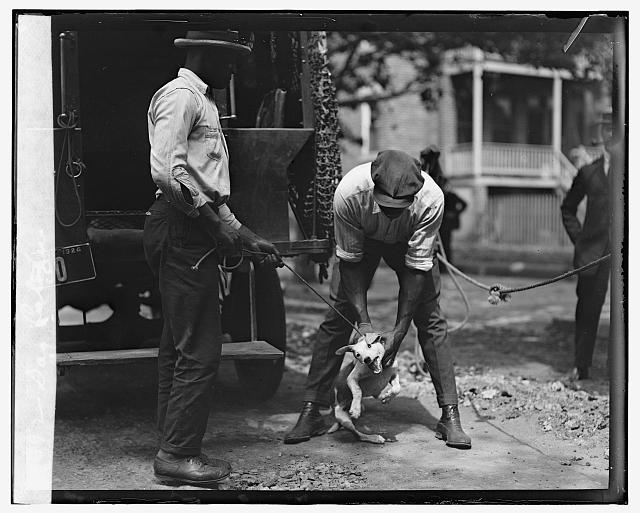

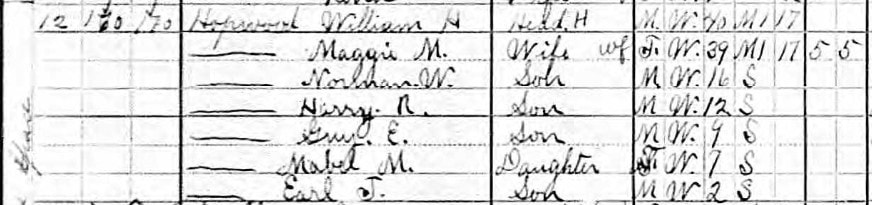

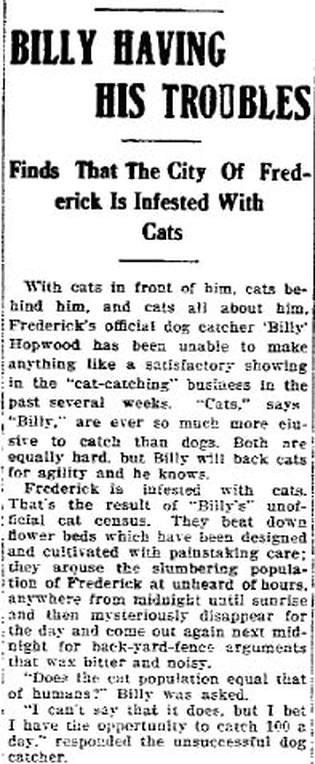

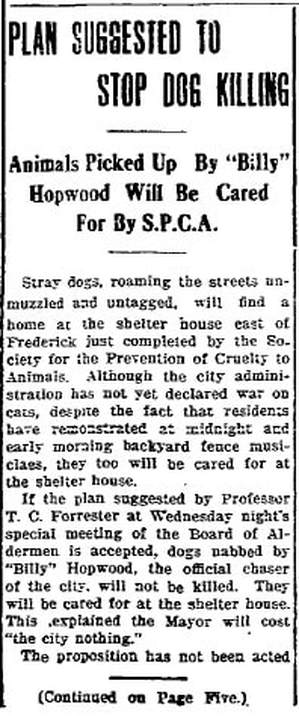

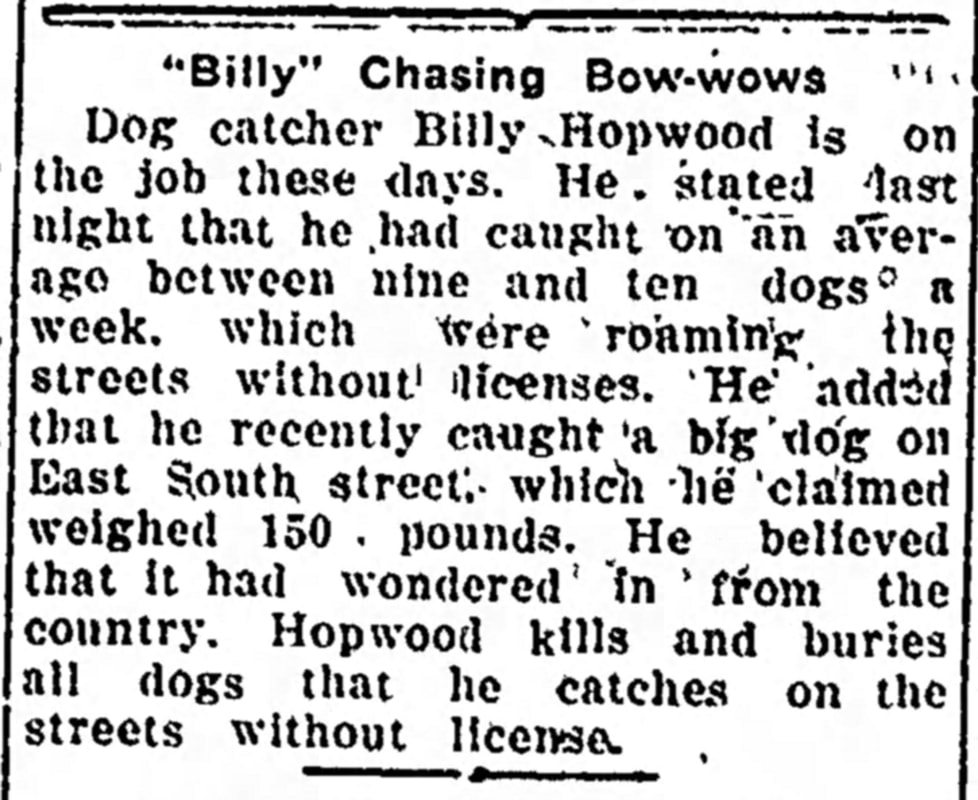

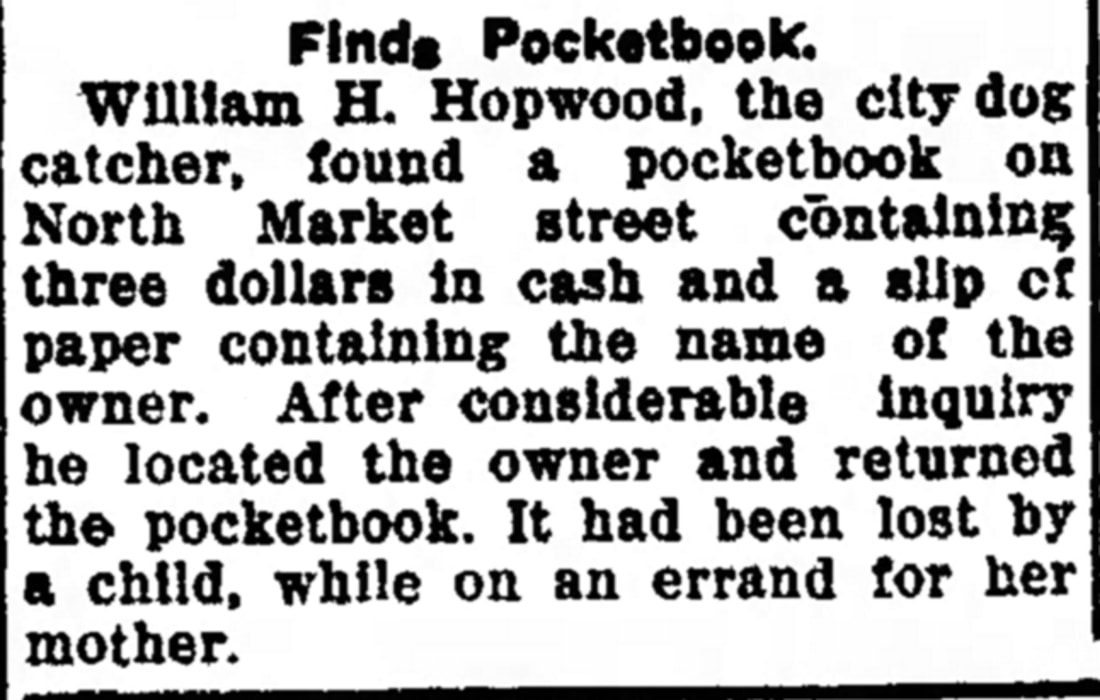

Library Of Congress photo of a Washington DC dogcatcher at work (1932) Library Of Congress photo of a Washington DC dogcatcher at work (1932) Economics was surely at play as dogcatchers were poorly paid. This led to some of these men acting in unscrupulous ways, such as taking dogs from the stoops of their own homes. Sometimes they lifted them from open windows. This type of behavior led to the satirical portrayals often played out in cartoons and movies over the last century. Today, it’s a completely different story. The people who perform this function now have a much more descriptive, and honorable title: Animal Control Officers. These are the fine folks who rescue abandoned, lost, abused, and neglected animals. They work in shelters that provide care, rehabilitate, and find homes for the animals brought in. 1914 When it came to pets being “on the lam,” 1913 was quite eventful here in Frederick, prompting action for the following summer. A new “Dog Law” ordinance went into effect in June, 1914 to help curb a rash of hydrophobia cases—better known as rabies. The action was deemed as necessary by some, and controversial by others. Regardless, at 10:30am, on June 19th, 1914, 67 year-old Ephraim Eyler was sworn into duty as Frederick’s first official dog catcher. Prior to this, a myriad of municipal police officers performed the task, along with hired hands. Mr. Eyler grew up on a Woodsboro farm. He eventually moved to Frederick and took up residence on Carroll Street. In addition to agricultural pursuits, he had formerly worked at the bottling company of J. C. Lipps on W. Patrick Street. It was here in 1894, that Eyler was severely injured by a bolt of lightning that apparently struck outside the workplace and reached the washing trough through open windows. He rebounded from that injury with no problems. The year 1912, however, would bring Ephraim some major challenges. In August, he was almost crushed by falling milk cans at his job at the White Cross Milk Company. A month later, he received a “severe thrashing” from a crook trying to break into his house. In October, Ephraim sued for divorce from first wife, Mattie. After surviving all that, why not take on the job of Frederick’s dogcatcher, right? How could life get any worse? Well...it did. Talk about a comedy of errors, the next three months would be agonizing for Mr. Eyler to say the least. Newspaper articles paint a colorful picture of what Frederick’s new dogcatcher encountered. It’s no surprise that Ephraim Eyler quit his post in late September, 1914. He made it past the traditional 90-day probationary period, but not with flying colors. Ephraim went back to his old profession at a bottling plant, a much safer choice even if you have to occasionally dodge kegs or suffer the "after effects" from lightning strikes. Eyler's "right hand man" was City Hall janitor William Henry “Billy” Hopwood, who resided in Market Place, located directly behind the old municipal headquarters. Mayor Lewis Fraley quickly awarded Hopwood the job. Billy Hopwood was “tailor-made” for the local papers, even better than Ephraim Eyler. The father of five was born in Frederick on May 19th, 1870, the son of James Warner Hopwood and Christiana Baltzey. Before landing his janitorial job at City Hall, Billy did odd jobs around town. One such included distributing pharmaceutical samples to local businesses back in 1903. In December, 1913, Billy lost his wife Maggie (Long) to heart disease. Her obituary states that her husband was a former desk sergeant for the Frederick City police. This was a temporary position held in late summer of that year, but one that must have left a favorable impression with Frederick's town fathers of the time. Billy Hopwood had to provide for his family. He relished his new position as dogcatcher and local pet owners and their beasts were soon put on notice. He could be viewed as a maverick of sorts, at least in the "pet-wrangling" arena. Cats presented a new challenge. Hopwood was perfect fodder for the local papers. The dog catcher stereotype, combined with Ephraim Eyler’s former performance, set Billy up for immediate ridicule. He seemed to take it in stride however, and rolled with any and all hard knocks encountered. Like a true, "love/hate" relationship, Hopwood usually took heat from the mayor. Billy waged war on stray cats and built a homemade dog pound adjacent the town’s light/power facility, then located on East Street. Best of all, Billy Hopwood seemed to bask in the limelight, he had fast become a local celebrity of sorts. I marveled at the countless stories found in local newspapers of the day. Every Dog has its Day Billy Hopwood’s reign of terror lasted for nearly a decade. He was briefly fired in 1917 after appearing for work drunk and bleeding profusely from his face after a fall down the steps. All this while he refused to leave the scene of a public meeting of the mayor and Board of Alderman. City Hall Janitor Charles J. Riddlemoser was apparently given the dog catcher job, but didn’t last long. Hopwood would eventually be re-instated. Everything seemed to be going well for Billy, business was good. The "Roaring Twenties" seemed to be going smoothly, and Billy now had better equipment to work with, the support of his bosses and an improved new pound facility. A local chapter of the Society for Protection Against Cruelty to Animals was established. This group was responsible for creating clean water receptacles for pets at different points in the city. They now took charge of the animals captured by Billy Hopwood at a shelter located on E. Patrick Street extended. Best of all, the prevalence of rabid or stray dogs severely decreased. Life was relatively good for our friend, Mr. Hopwood. That is until the morning of April 5th, 1928. It would not be a nice one for the city dogcatcher. Chalk one up for man’s best friend.

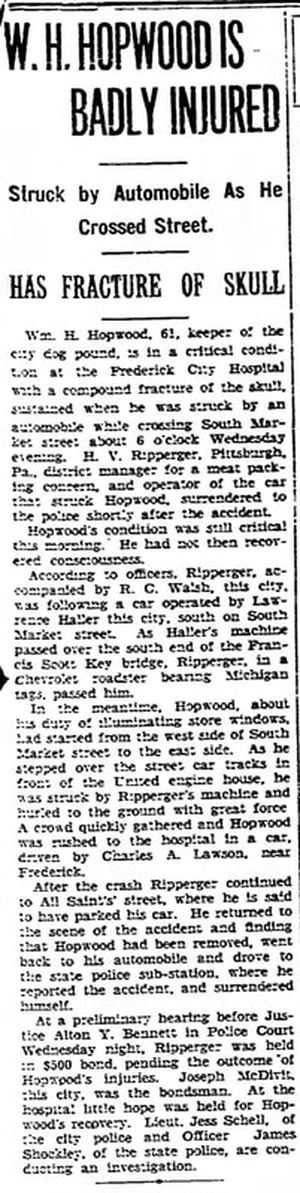

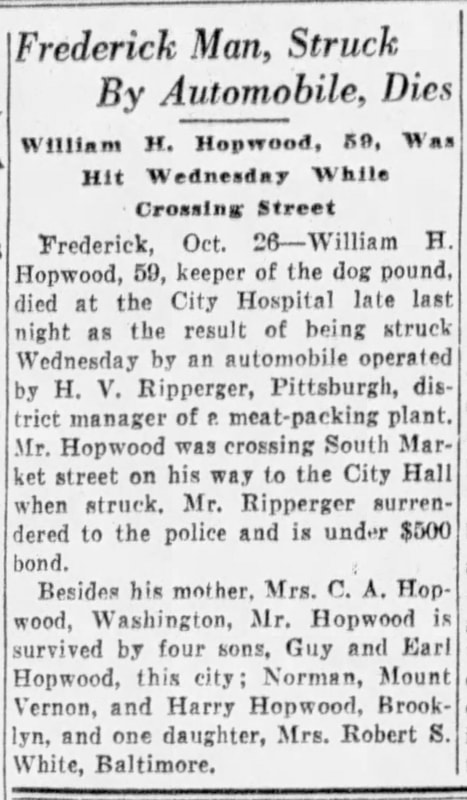

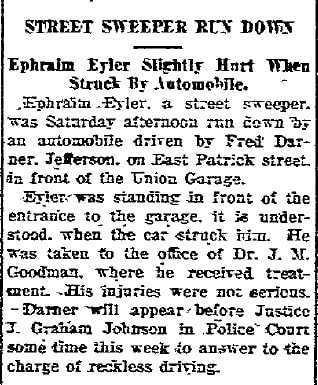

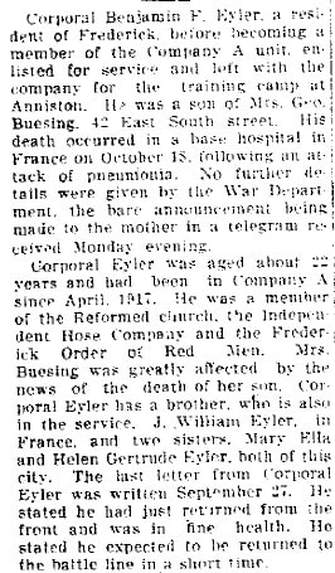

On Friday, October 25th, 1929, Billy Hopwood was in his daily act of walking to work from his home located at 109 W. South Street. As the dogcatcher crossed S. Market Street at the aptly named Francis Scott Key Bridge over Carroll Creek, he, himself was struck by a speeding motorist named Harry V. Ripperger. Mr. Ripperger was visiting Frederick from his home in Michigan, possibly scoping out opening one of his popular chain of Regal Sandwich Shoppes, made famous in western Ohio. I guess one could call that day "Black Friday" as it was within the terrible week of the Great Stock Market Crash of 1929 which began on October 24th ("Black Thursday") and concluded on October 29th ("Black Tuesday"). The tragic story was even picked up by the Baltimore Sun newspaper. William “Billy” Hopwood was buried the next day (October 26th) in Mount Olivet’s Area L/Lot 237. Today, dogs, tagged and on leashes, pass within feet of Billy Hopwood’s grave each and every day. in Mount Olivet also features a special burial-ground section known as the Faithful Friends Pet Cemetery. This was opened in 2015 and is located in the rear of the cemetery, behind the mausoleum complex. An interesting connection, and aside, relating to Mount Olivet can be made to Hopwood’s predecessor, Ephraim Eyler. After his tumultuous tenure as dog catcher, Eyler went to work for a local beer bottling plant but returned to work for the City of Frederick in the official capacity of "City Street Sweeper." In August, 1918, Eyler was hit by a car…perhaps he was hexed by a local canine. Mr. Eyler, however, received only minor injuries from the accident. Ephraim Eyler died in late May, 1932 at Frederick’s Montevue Home for the Aged. He was buried in the potter’s field adjacent the long-gone facility. Eyler’s ex-wife, Mattie Mae Wiles (1874-1956), remarried a gentleman named George E. Buesing and is buried here at Mount Olivet, along with the couple’s daughter Mary Ellen Eyler (1891-1973). Mattie married Mr. Buesing in March, 1916. Within two months, she had been widowed as her new husband committed suicide by cutting his throat while in the act of shaving. Mattie's gravesite is located in Area X /Lot 118. From Dogs to Doughboys Also of interest, one can find the final resting spot of Ephraim and Mattie’s son Benjamin Franklin Eyler (b. 7/17/1896) here in Mount Olivet. Benjamin joined the Maryland National Guard and would take part in World War I. He was promoted to the rank of corporal and shipped overseas to Europe in June, 1918 as part of the famed Company A of the 115th Infantry Regiment. While on the front in France’s Center Sector, Benjamin F. Eyler contracted pneumonia in the horrid conditions associated with trench warfare. He would be hospitalized on October 3rd and languished for two weeks before succumbing to the disease on October 18th, 1918. Eyler was originally buried overseas, but was brought back home and re-interred in Mount Olivet Area Q/Lot 266 on June 19th, 1921. To learn more about the nearly 500 World War I veterans buried in Mount Olivet, go to our companion website: www.MountOlivetVets.com

|

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed