You may not be aware of this, but April is Maryland Archeology Month. This has been the case since 1993 when Archeology Month was officially proclaimed by Governor William Donald Schaefer as “ a celebration of the remarkable archeological discoveries related to at least 12,000 years of human occupation here in “the Old-Line State.” Maryland Archeology Month has annually provided the public with opportunities to become involved and excited about archeology. With a variety of events offered statewide every April, including exhibits, lectures, site tours, and occasions to participate as volunteer archeologists, “Archeology Month elicits the gathering of interested Marylanders at various occasions to share their enthusiasm for scientific archeological discovery.” This according to the Maryland Archeological Trust, the chief sponsor of activities. Well, scheduled Maryland Archeology Month activities for 2020 were postponed because of the Covid-19 pandemic. These include featured lectures across the state, but most importantly the Field Schools, or Sessions, which are open to the general public. This year’s theme was Partners in Pursuit of the Past: 50 Field Sessions in Maryland Archeology. The Field Sessions are 11-day intensive archeological research investigations held every spring in partnership between the Archeological Society of Maryland, a State-wide organization of lay and professional archeologists, and the fore-mentioned Maryland Historical Trust, a part of the Maryland Department of Planning and home to the State’s Office of Archeology. While these two partners host the event every year, others are required to make the Field Sessions happen, including researchers/principal Investigators, archeological supervisory staff, property owners, and volunteers from the public.

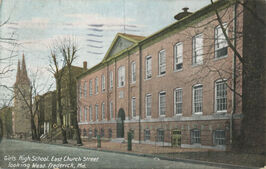

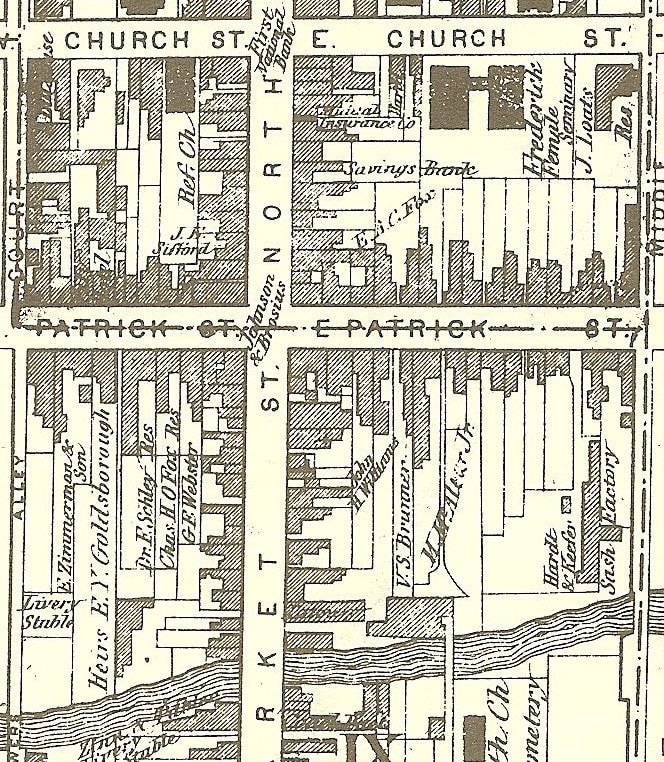

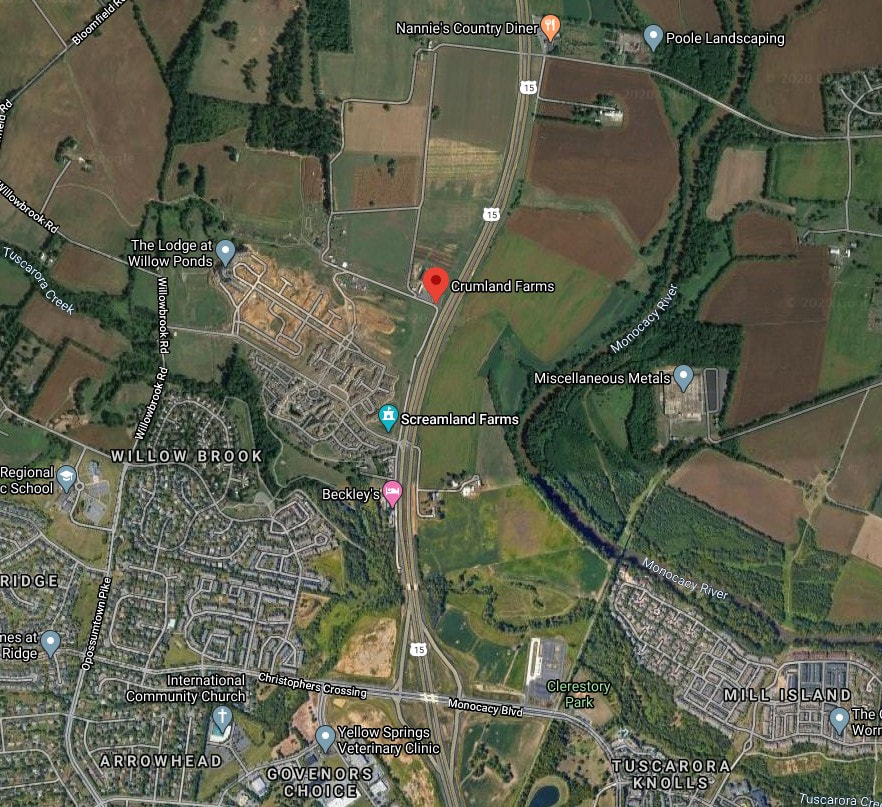

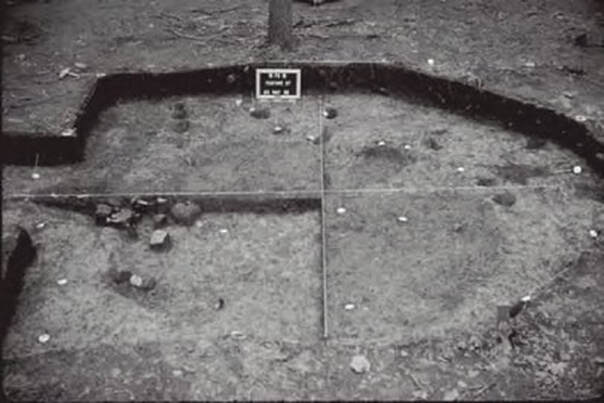

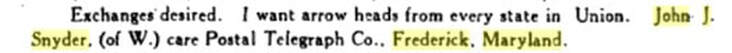

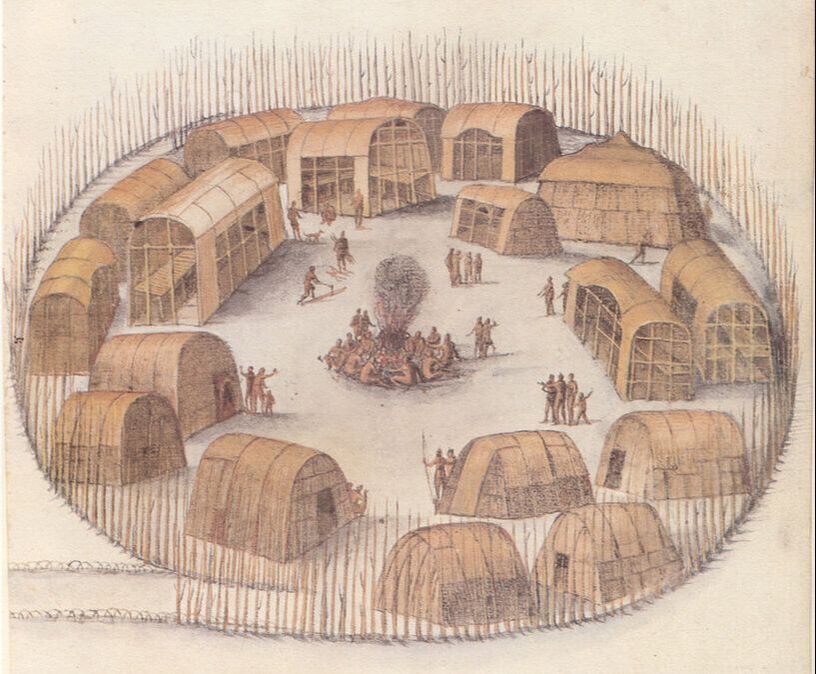

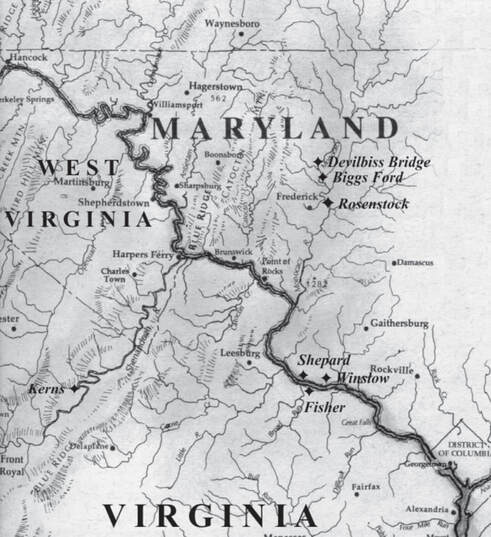

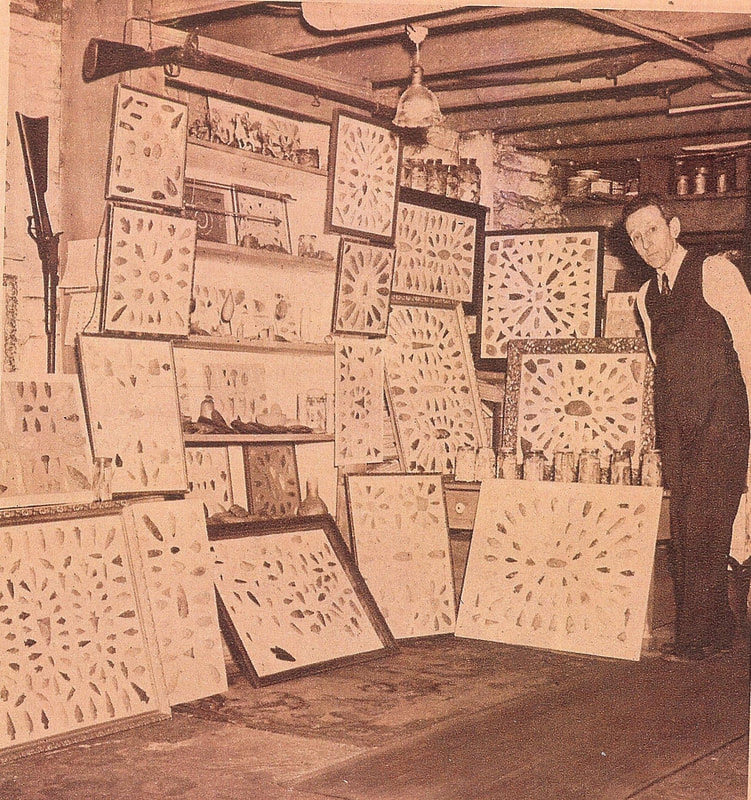

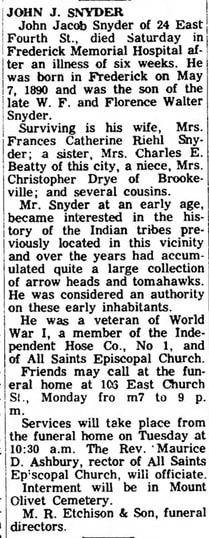

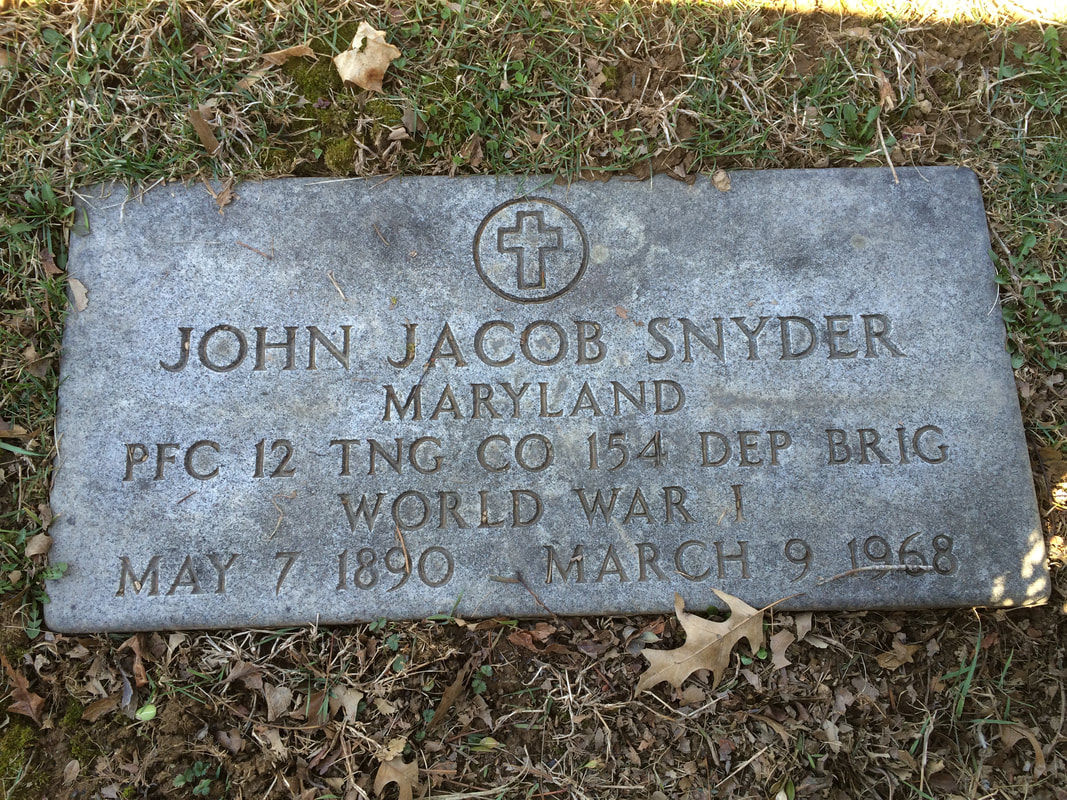

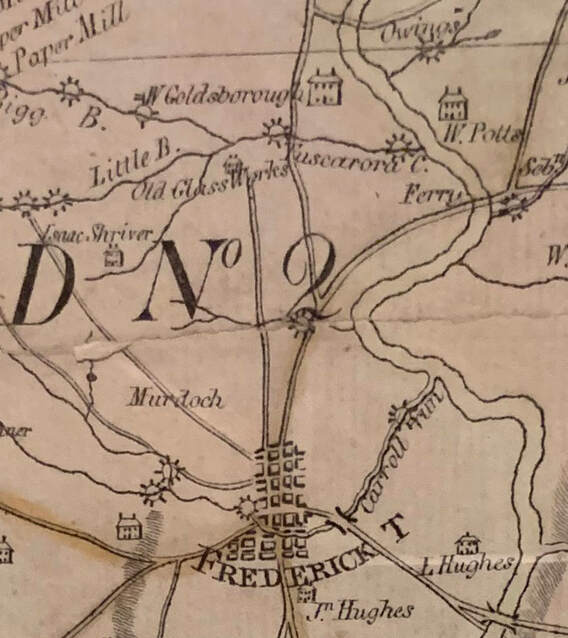

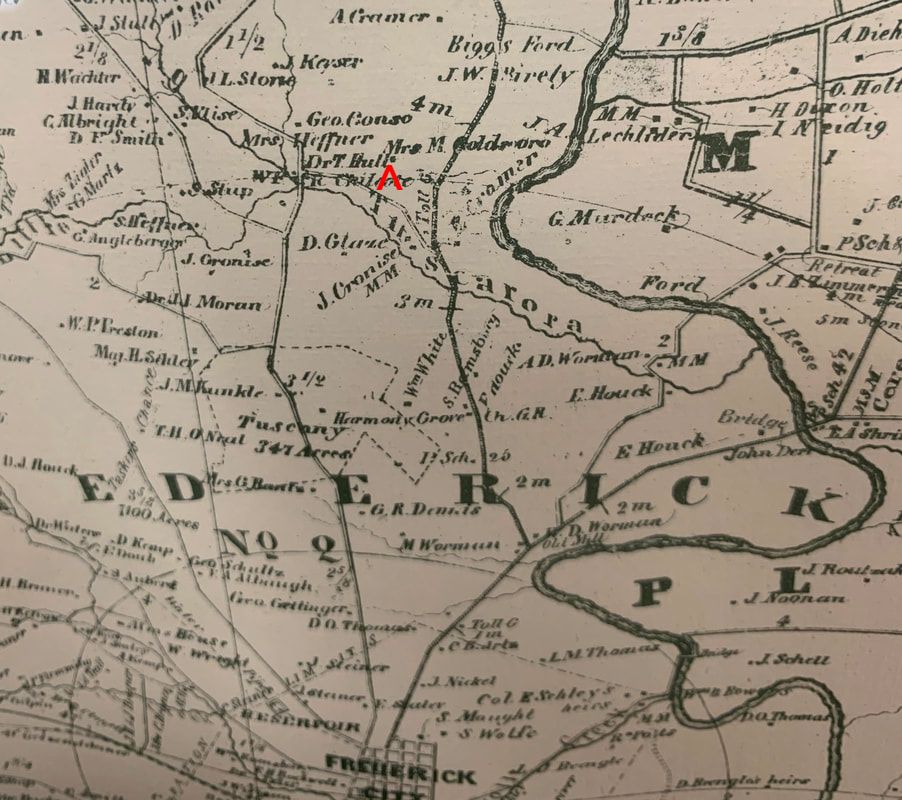

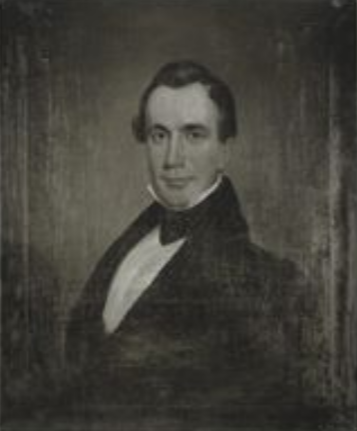

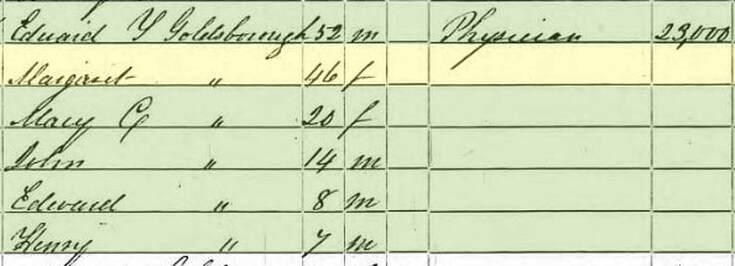

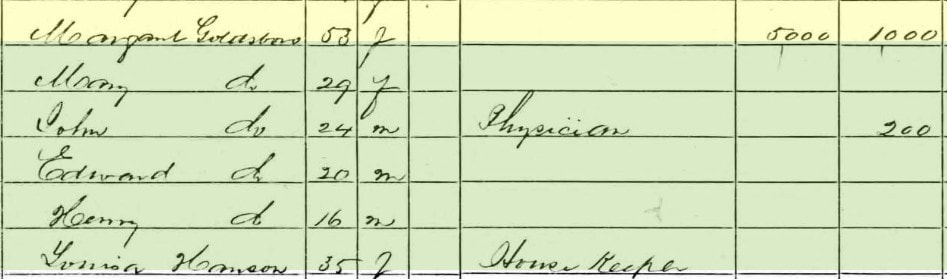

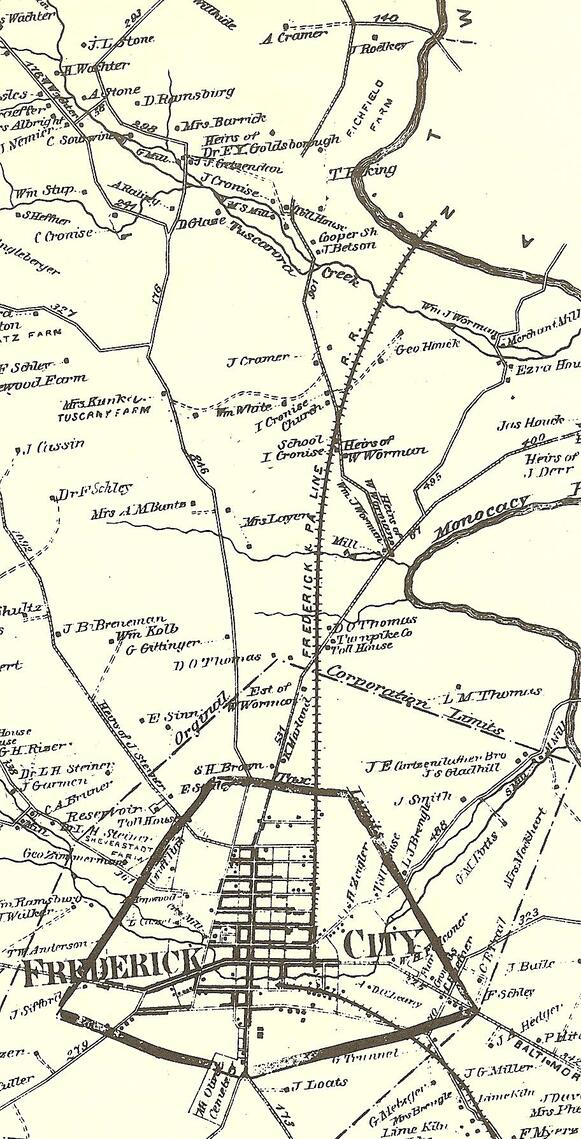

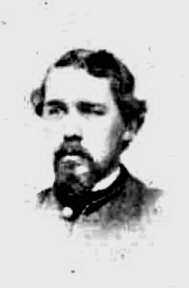

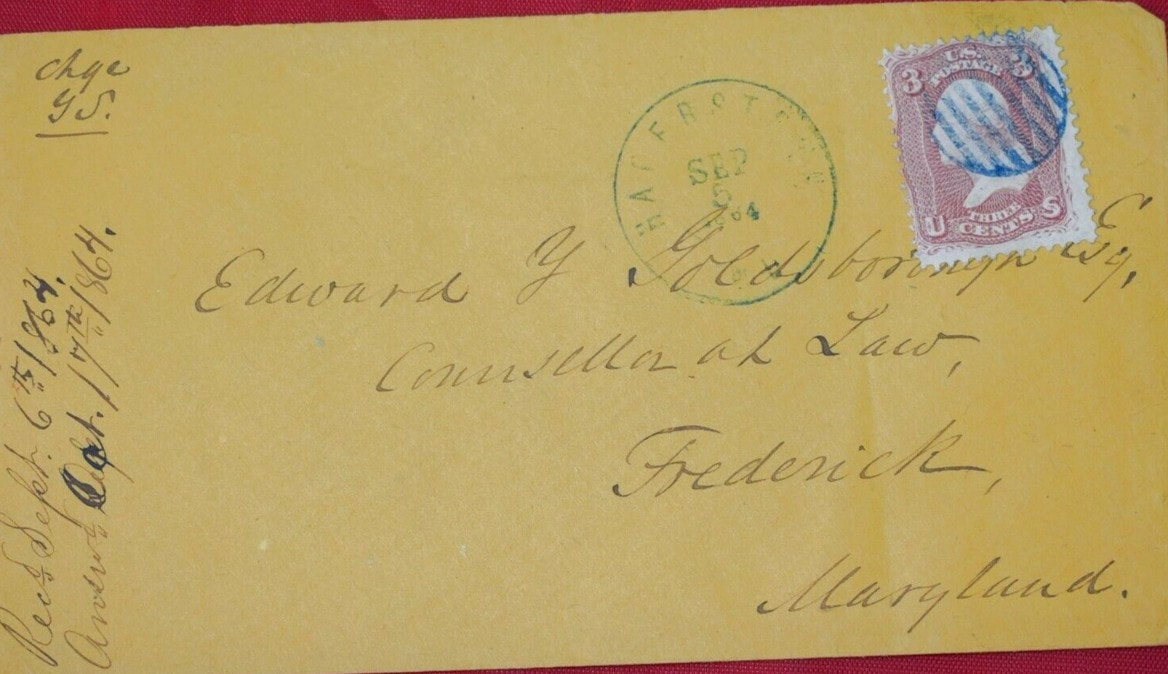

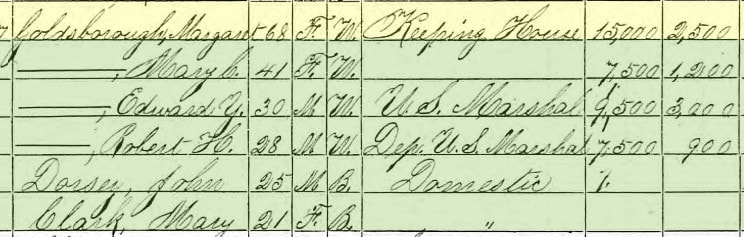

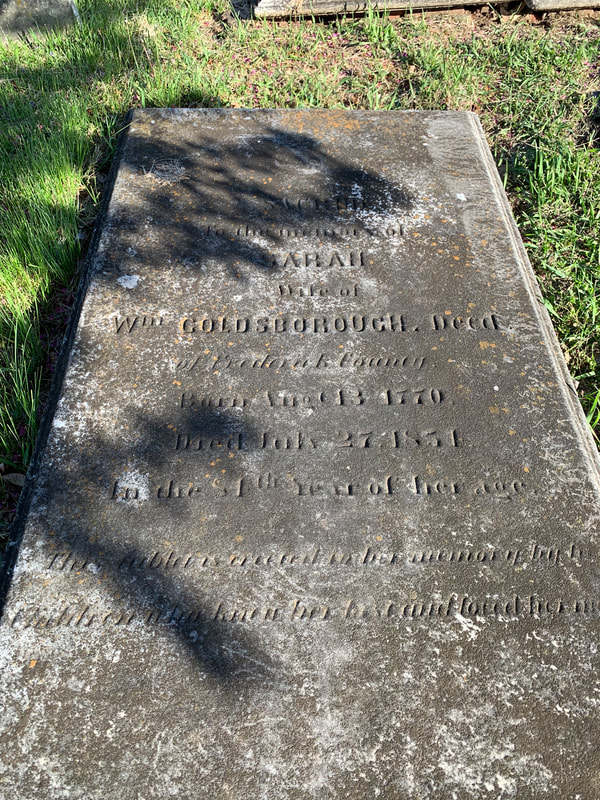

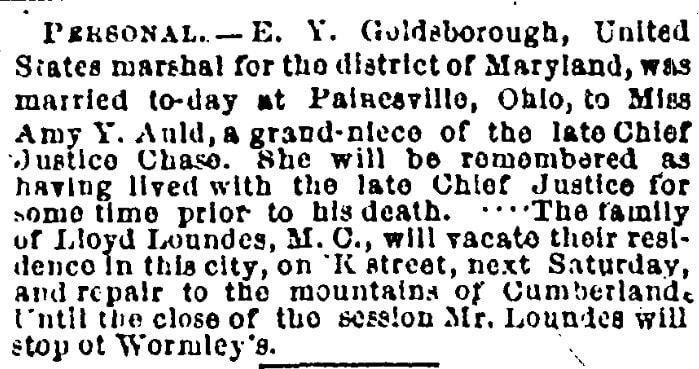

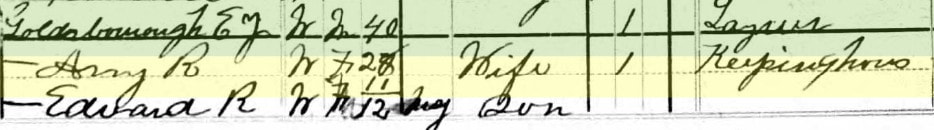

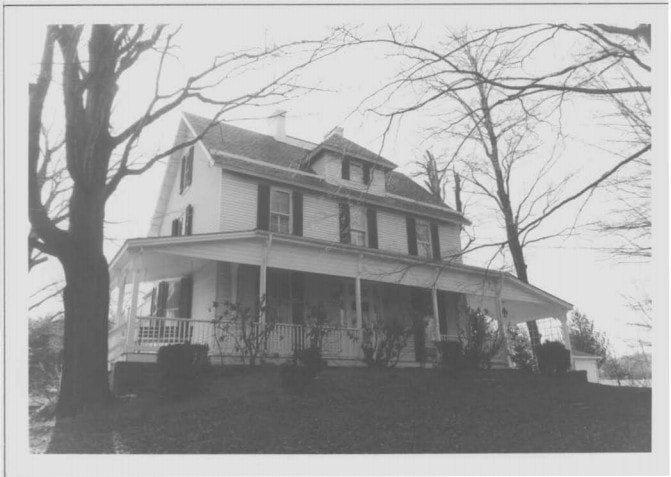

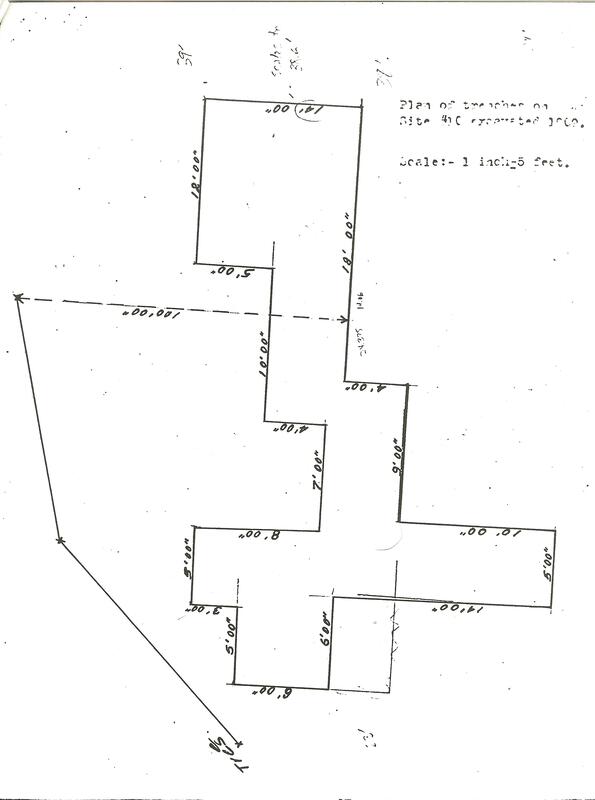

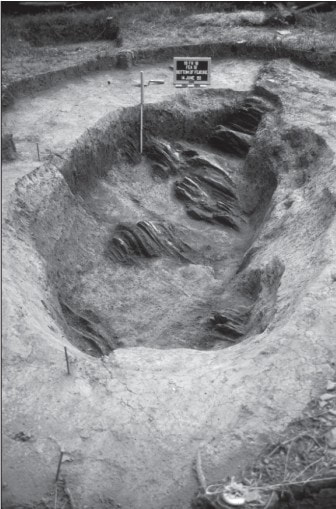

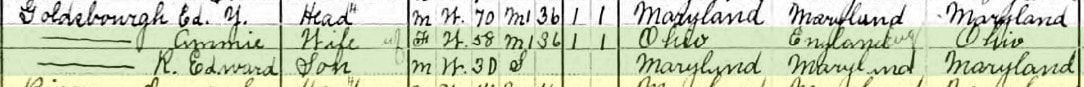

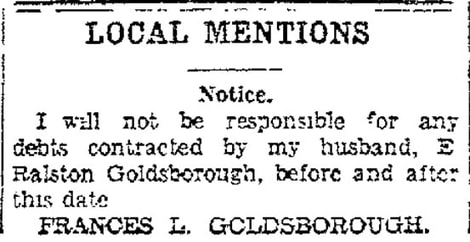

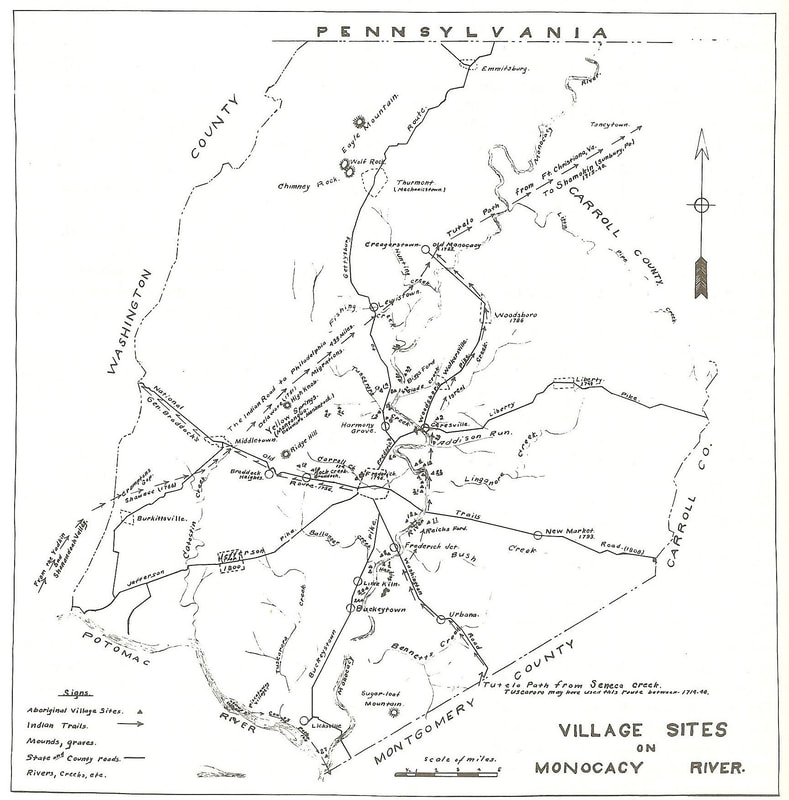

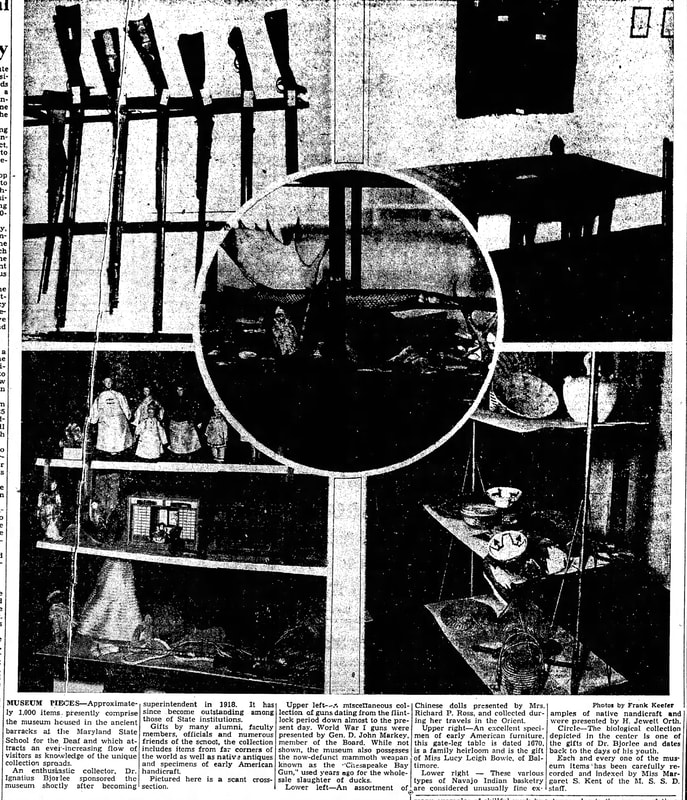

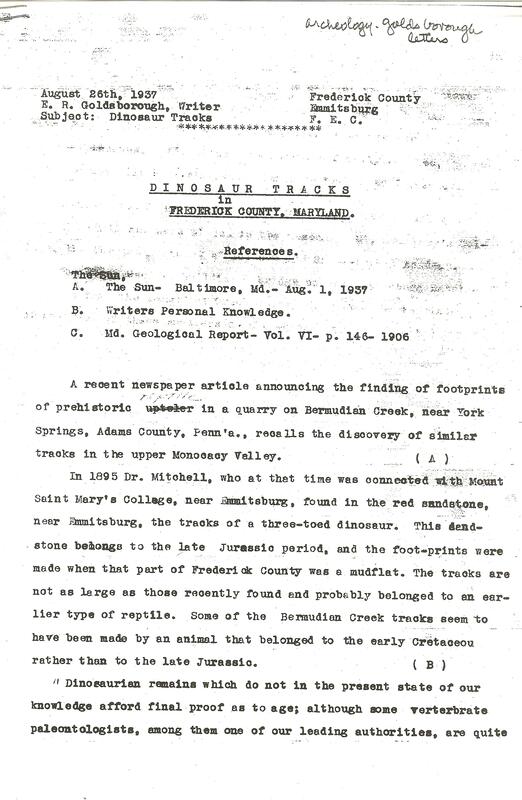

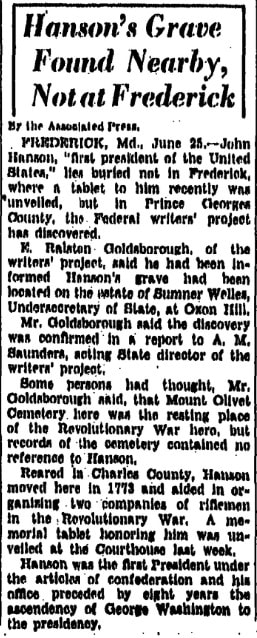

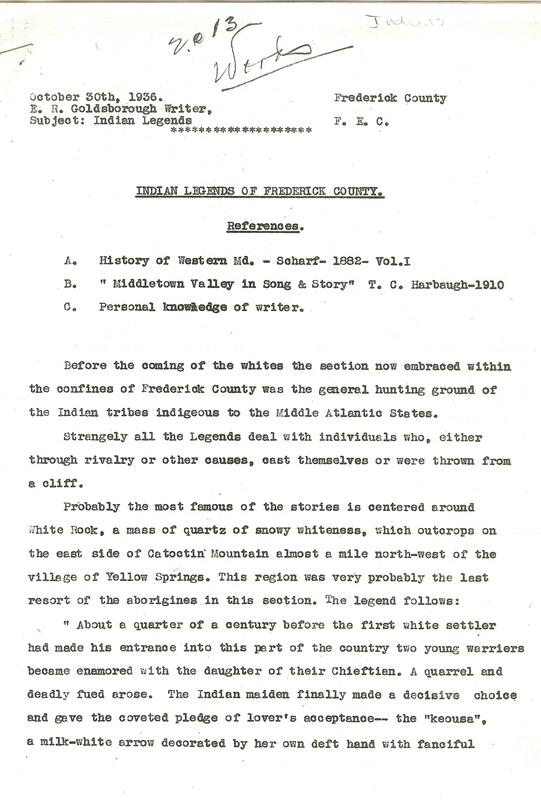

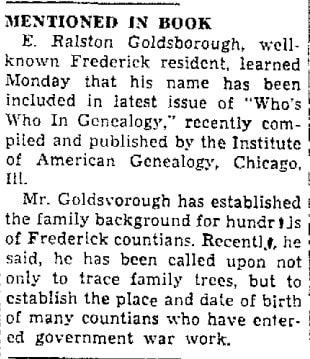

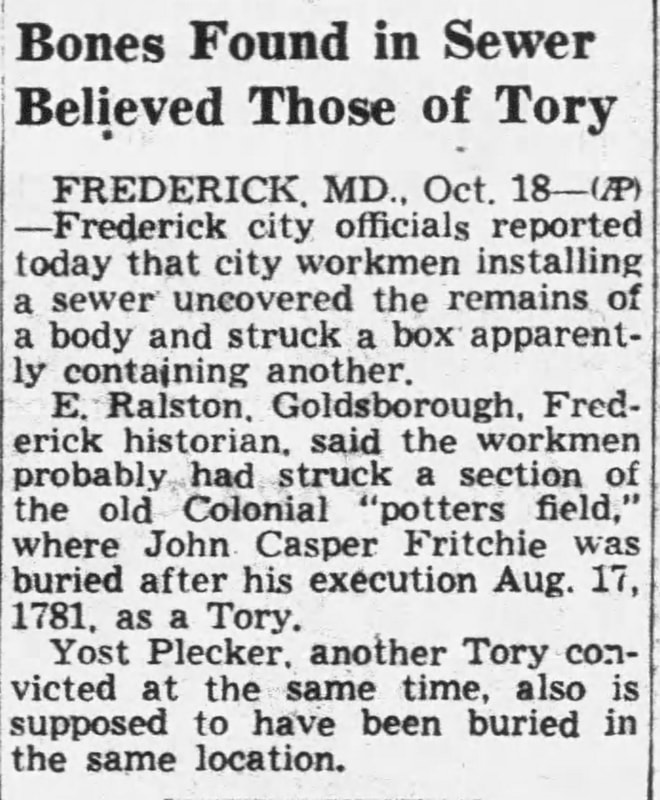

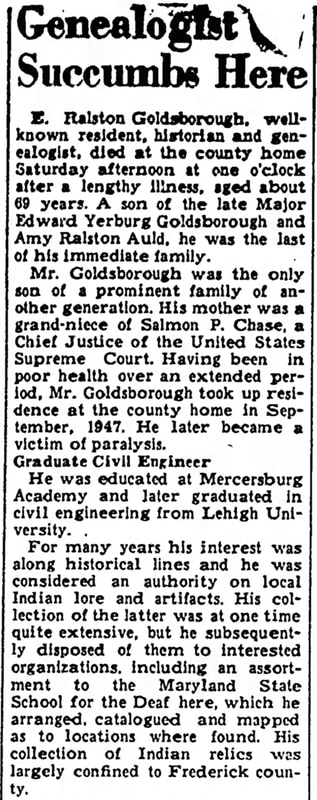

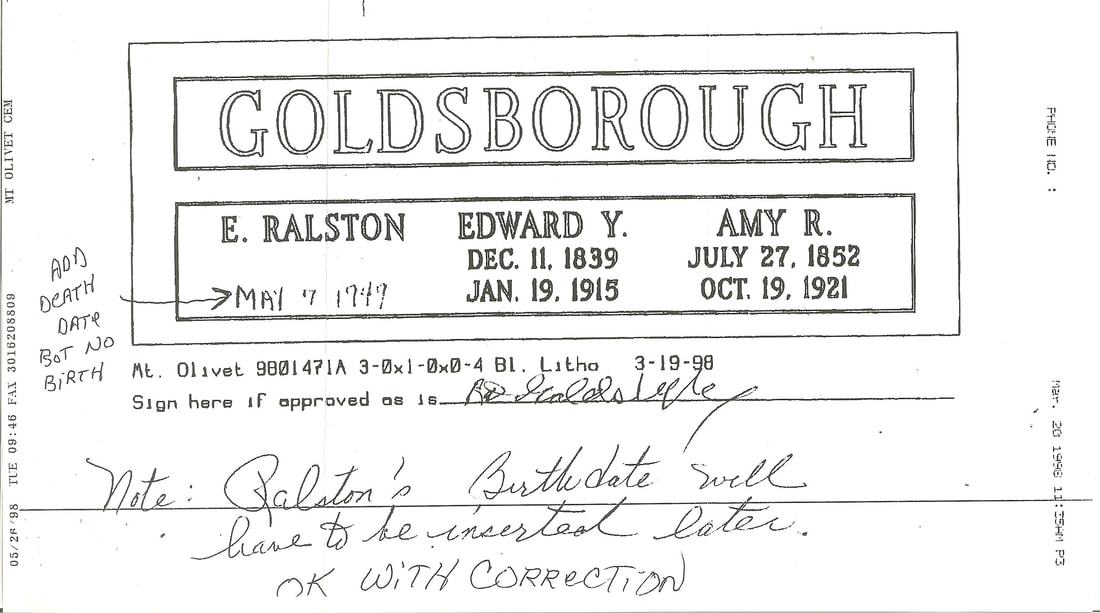

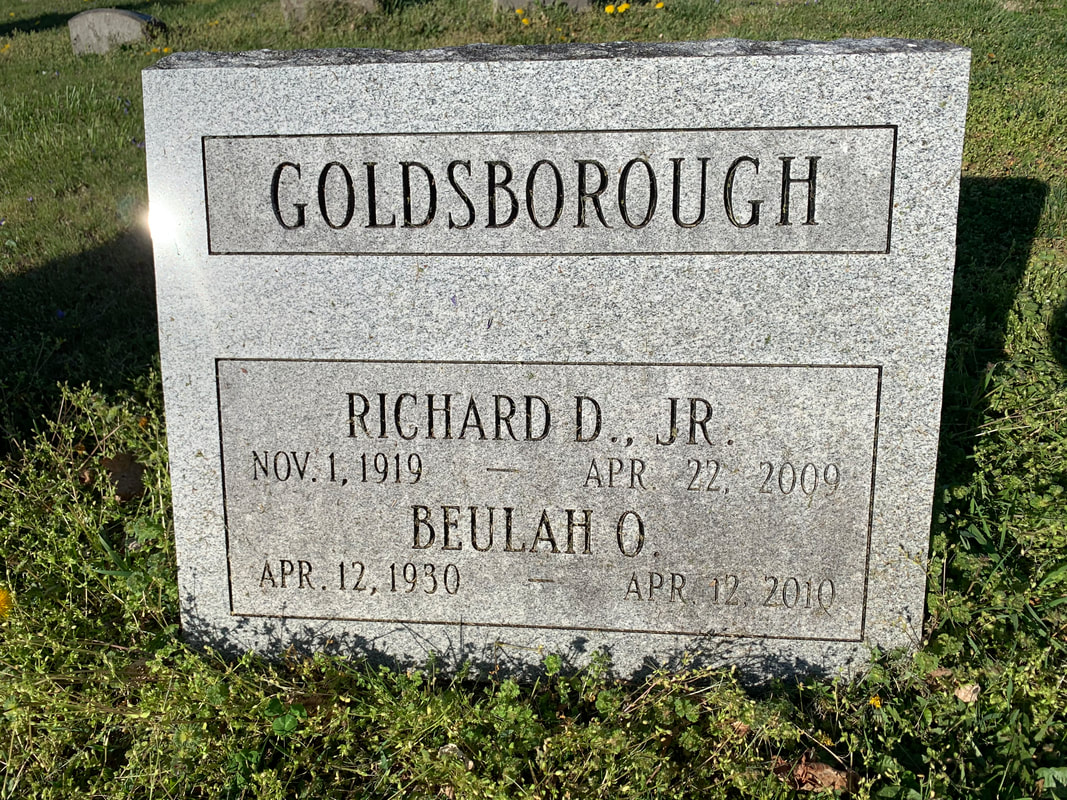

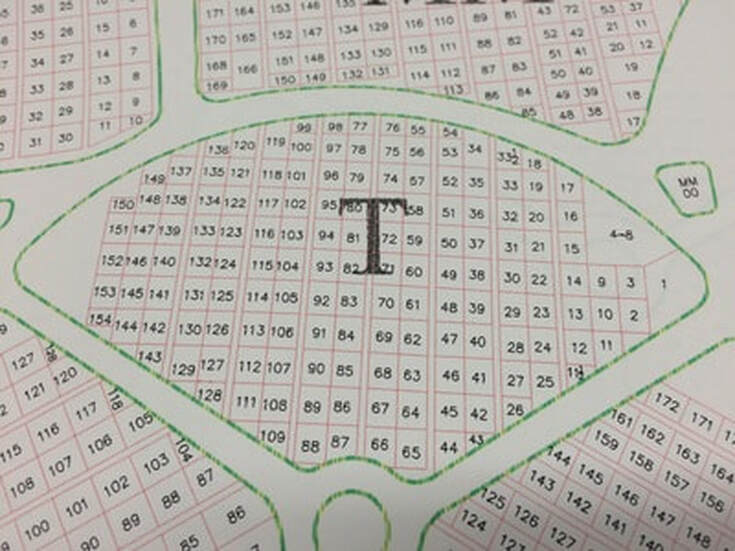

Spencer O. Geasey Spencer O. Geasey I had some prior knowledge and experience in the realm of archeology thanks to my work with a documentary produced in 1999 and entitled Monocacy: the Pre-history of Frederick County, Maryland. Here I got to learn first-hand from state archeologists and local/avocational lay people. One of these was my chief mentor for the project, Spenser O. Geasey (1925-2007). I would love to write a comprehensive “Story in Stone” on this New York native who spent the majority of his life in Frederick County, but he is buried in Mount Prospect Cemetery up in Lewistown (MD). This was close to his boyhood home of Mountaindale, which helped inspire his interest with arrowhead finds as a child. He always made it a point to tell me he was nothing more than an “avocational archeologist”—avocational translating to hobbyist without holding a degree in the field. Spencer was a World War II vet (304th Infantry/76th Division) who would make his living as Housing Manager at Fort Detrick. After retirement from the Army base, he worked as an archeological field assistant for the State Highway Administration. Although not formally trained in the field, his favorite hobby and passion would have him advising local, state and national professionals as he became an expert on Frederick’s native peoples through weekend exploration for fun. He walked the fields and carefully took notes which blossomed into extensive scientific reports for state archeological periodicals. Spencer regularly surface collected (with permission) and donated these artifacts (nearly 41,000) to the state collection housed at Jefferson-Patterson Park & Museum of Archeology in Prince Frederick in Calvert County. The MAC (Maryland Archeological Conservation) Laboratory has research space for working with the collections, a library of site reports and other material (such as field notes) and a variety of analytical equipment. Interestingly, this site along the Patuxent River in southern Calvert County is less than a stone’s throw from the birthplace of the famed Johnson brothers buried in Mount Olivet: Gov. Thomas Johnson, Jr., James Johnson, Baker Johnson, Joshua Johnson and perhaps Roger Johnson (but the latter is debatable). Spencer kept his proverbial “ear to the ground” and notified state officials when he felt that local sites were in danger of being disturbed. This most often happened with commercial or residential development and roadways. He helped organize the Maryland Archeological Society, regularly spoke to school children and civic groups about native peoples and was involved in the publication of several articles about the topic here locally in Frederick County and the State of Maryland. All of these “avocational“-archeological activities led to Spencer receiving the Calvert Prize in 1993, the highest award for preservation in Maryland. In fact, he was the first archeologist to win the coveted honor.  Spencer's gravestone in Mount Prospect Cemetery, Lewistown Spencer's gravestone in Mount Prospect Cemetery, Lewistown In my special time spent with Spencer, we built a great friendship. He showed me prehistoric rock shelters and fish wiers in the river. We walked several, freshly plowed farm fields in springtime. Best of all, he took me on personal tours of three of the state’s most studied and important sites: the previously mentioned Biggs Ford site (north of Frederick), the Rosenstock site (east of Frederick City) and the Noland’s Ferry site (in southern Frederick County along the Potomac). You could not have had a better guide than the one I had. I also gained the opportunity through Spencer to learn about Frederick’s early archeologists, and others who dabbled in collecting under a bit more unscrupulous title as “relic hunters.” The noble archeologist goes about his search of artifacts in the name of science and history exploration, taking careful notes and handling any and all human remains with the greatest of respect. The relic hunter is generally looking to cash in on his finds, raiding ancient gravesites and selling off local treasures to collectors throughout the country. I want to note here that some of these “relic hunters” did not have bad intentions as they simply participated in a hobby, and kept the prized finds for themselves and unselfishly shared their artifacts with the community in terms of education as their efforts were a labor of love and learning. Spencer introduced me to two of these men, that not only were Frederick County natives, but are buried within the confines of Mount Olivet Cemetery—John Jacob Snyder (1890-1968) and Edward Ralston Goldsborough (1879-1949). John Jacob Snyder I will start with a man that Spencer Geasey interacted with personally. John Jacob Snyder was reintroduced to me when I created a memorial page for him a few years back in building our MountOlivetVets.com website. Snyder was a Frederick native and military veteran of the First World War. He was born on May 7th, 1890, the son of William F. Snyder and wife, Florence Walter. He grew up in a house located at 127 N. Market Street and attended Frederick City public schools. On his MountOlivetVets.com memorial page, I included the following information regarding military service after his induction as a 27 year-old private on March 23rd, 1918: 5/14/1918, Headquarters School for Radio Mechanics (College Station, TX) 7/2/1918, C Squadron, Ellington Field (Texas) 8/10/1918, Field Artillery Training, Fort Sill (Oklahoma) 10/9/1918, Promoted to Private First Class, 328th Aero Squadron 1/11/1919 12th Company, 154th Depot Brigade Honorable Discharge 1/28/1919 I’m assuming that John J. Snyder had an opportunity to add to his interests and experiences with native cultures while serving with the US Army in the western states of Texas and Oklahoma. It seems to have been a love nurtured in his youth in Frederick. While conducting internet and newspaper searches on him, I came across a small classified ad in the Maryland Archeological Bulletin dated January 12th, 1912 on page 34: In a later Maryland archeology publication, I found a story in which Snyder caught the attention of the state’s professional community. John had discovered what is commonly called today, the Rosenstock site. This is a Late Woodland village located atop a 7-meter-high bluff overlooking the Monocacy River. First off, the Woodland period is a cultural classification roughly representing the time period of 1000BC to the time of European contact in the 1600 AD. The bluff location of the former native village is a narrow, level promontory bounded by a deep ravine on the north, the river on the west, and a small stream on the south. The site, known since just after the turn of the century, has remained uncultivated since 1913 and currently is wooded. Since an initial exploration in the early 1900s, the Rosenstock site lay largely forgotten until it was reported to the State Archeologist in 1970. Subsequently, the State Archeologist’s office, in cooperation with the Archeological Society of Maryland, Inc. (ASM), carried out systematic testing of the site in 1979, and more extensive excavations in 1990-1992. Each of these projects was undertaken as part of the ASM Annual Field Session in Maryland Archeology. John Jacob Snyder discovered the particular site on October 15th, 1907. Snyder, then a 17-year-old, was apparently “hunting for dogwood” on the Samuel Rosenstock farm, today making up Clustered Spires Municipal Golf Course. Snyder related at the time, “I was keeping to windward that was to the east on account of the Dogs [Russian Wolf Hounds], and hiding behind a shock of fodder saw 3 nice arrows about the shock so it was found by mere coincidence but I never got the dogwood.” At the time of discovery, the site—having been cleared of timber in 1884—was plowed. Snyder reported finding abundant pottery shards, triangular projectile points, clay, stone, and bone beads, discoidals, shale discs (about 3” in diameter with a hole drilled in the center), celts, and clay and steatite pipes at Rosenstock, which he considered the “most outstanding site” in the Monocacy Valley. The valuable location took the name Snyder’s “Site #1,” and farm cultivation would cease in 1913 in an effort to assist future researchers. John J. Snyder married Frances Catherine Riehl and raised his family at 24 E. Fourth Street in Frederick. In addition to his work as an avocational archaeologist, he spent his career as an electrical repairman and vulcanizer (skilled worker with rubber). He proudly displayed his Indian artifact collection to professionals and county residents for decades until his death on March 9th , 1968. He is buried in Mount Olivet’s Area GG/Lot 170. Edward Ralston Goldsborough Although Spencer Geasey could only talk about “Ralston” Goldsborough anecdotally through his past research and findings, I actually had the opportunity to meet one of his close relatives. I was particularly interested in this man (Ralston) who, like Spencer, made an incredible contribution through his research and work resulting in scholarly research by a non-professional. Edward Ralston Goldsborough was born on July 8th, 1879, the product of a very interesting pedigree which included Robert Goldsborough (1735-1788), a delegate to the Continental Congress, and Frederick Town’s supposed first settler, John Thomas Schley. Ralston was the only son of a prominent attorney and veteran of the American Civil War, Major Edward Yerbury Goldsborough. I need to tell you a bit about this Goldsborough family first as valuable context can be gleaned in respect to Ralston’s interest in archeology, genealogy and local/Maryland history. Ralston’s 5th great-grandfather, Nicholas Goldsborough, arrived from England (via Barbados) a few decades after Maryland’s founding and settled near Kent Island in the late 1660s. The next two Goldsborough generations would accumulate wealth and settle in the Eastern Shore areas of Easton in Talbot County and further south in Cambridge, Dorchester County along the Chesapeake Bay and Choptank River.  Robert Goldsborough and family by artist Charles Willson Peale Robert Goldsborough and family by artist Charles Willson Peale The fore-mentioned Robert Goldsborough would rise to the highest ranks of Maryland politics and play a substantial role as delegate to the Continental Congress and Maryland’s participation in the American Revolution. He narrowly missed his chance at eternal fame as being a Founding Father. Like Thomas Johnson, Jr., he was not present in Philadelphia on July 4th, 1776 for the signing of the Declaration of Independence, having withdrawn his position six weeks earlier to help frame Maryland’s first state constitution. Robert Goldsborough was friends with fellow patriot, Thomas Johnson, Jr., and this likely guided a future Goldsborough connection to Frederick County. Robert’s son, Dr. William Goldsborough (1763-1826), moved to Frederick and bought several properties from Thomas Johnson, including Johnson’s 138-acre plantation of Richfield. Johnson, whose health was frail at the time, had accepted an invitation to live with his daughter and son-in-law at Rose Hill Manor. He had built the latter for the couple as a wedding gift.  Dr. William and wife, Sarah Worthington Goldsborough, lived here at Richfield until moving in town shortly before his death in 1826. The location for a new domicile was another property acquired earlier from Gov. Johnson. It sat on 115-117 East Church Street, later destined to be Frederick’s first public Female High School and later the headquarters of Frederick County Public Schools. Dr. William Goldsborough died without a will, but with debts which seems to be a recurring theme for family members in the future. His wife, Sarah, sold the Richfield property with mansion house on the east side of the Frederick-Emmitsburg turnpike road to John Schley in 1829 and granted the property on the west side to son, Edward Yerbury Goldsborough, Sr. (1797-1850). Edward, Sr. was our subject Ralston’s paternal grandfather, and had married Margaret Schley (1802-1876) a descendant of John Thomas Schley, the German Reformed Church’s first choirmaster and builder of Frederick’s first house. The wedding occurred in 1826. Edward and Margaret Goldsborough would have five children: Mary Catherine (1827-1899); William (1830-1853); John (1835-1885); Edward Yerbury, Jr. (b. 1839) and Robert Henry (1842-1882). The family obtained a town-home in downtown Frederick in the first block of W. Patrick Street, where Dr. Goldsborough based his work office as well. William's History of Frederick County says the following about Dr. E. Y. Goldsborough, Sr. : He was educated for the medical profession, graduated from the medical department of the University of Maryland, and began to practice in Frederick City in 1826. His untiring energy, his skill, and his devotion to his profession, soon brought him a large practice. Dr. Goldsborough was a polished gentleman, and was not only respected for his skill as a physician, but was beloved and esteemed for his kindness to all of his patients, especially to the poor. He died while out on his visits to patients, November 4, 1850. After her husband's death, Margaret Goldsborough continued to raise her children into adulthood from the residence on West Patrick Street, while still holding the farm property north of the city purchased by her late husband's parents from Thomas Johnson.  The Titus Atlas map of 1873 shows the Goldsborough residence in the first block of W. Patrick Street on the south side with a back yard stretching to Carroll Creek. This is approximately the site of today's Weinberg Center. (c.1910) view of the first block of W. Patrick St. (looking east). In the photo below, the author believes the former Goldsborough residence is the three-story home with twin dormer windows (3rd structure from right) captured in this photograph taken around 1910 Two of Mrs. Goldsborough's sons became noted professionals in their fields and participated in the American Civil War. Both received their early education at the Frederick Academy just a few short blocks from their home. John Schley Goldsborough chose the medical profession and graduated from the University of Maryland. On the outbreak of the Civil War, he volunteered as a surgeon in the Union army and was actively engaged in hospital work at Harpers Ferry and in this city. When the war came to a close he had become somewhat disenchanted of his profession. The doctor devoted himself to agricultural pursuits, having ample means for the purpose and lived as a gentleman. Upon graduation from the Academy in 1859, John's younger brother, Edward Yerbury Goldsborough, Jr., became a law student in the office of Joseph M. Palmer and was accepted to the Frederick bar in October, 1861. He opened his own practice at this time as the winds of war were swirling. In August of 1862, he would receive a commission in the Union army as a second lieutenant in the Eighth Regiment, Maryland Volunteer Infantry. In 1863, he was nominated by Frederick County's Union party to serve as State's Attorney (for Frederick County). Another historical account says that Edward "served briefly in the Maryland Infantry of the U. S. Army in 1862-1863, but was mustered out due to illness. Still, he was a volunteer on General E. B. Tyler's staff during the Battle of the Monocacy in 1864, for which he earned the rank of Major. Beginning in 1869, he served as a United States Marshal for the district of Maryland, and he is often referred to by either ''Major" or ''Marshal" in historical accounts. He was known as a fine lecturer on the Civil War and his foreign travels and as an active Agricultural Society member. Margaret Schley Goldsborough died on Christmas day, 1876. A few years before her death, she took great pride in the fact that her son Edward had courted a young debutante from the Midwest with familial ties to one of the most famous politicians and legal minds in the country. The couple married in 1874. Margaret was laid to rest beside her oldest son William, who died in 1853 at the age of 23, in Mount Olivet's area E/Lot 15. Her husband is buried on the other side of William. A large obelisk and ledger stones mark these gravesites. Within a few yards are the graves of Margaret's in-laws, William and Sarah Worthington Goldsborough, and her husband's brothers: Nicholas W. Goldsborough (1795-1840), a War of 1812 veteran, and Dr. Charles H. Goldsborough (1800-1862). These monuments are exactly across from the Potts Lot, the only area remaining "gated" in the cemetery. Finally getting back on track with the biography of Edward Ralston Goldsborough, his parents married in June of 1874. Ralston’s mother, Amy Ralston Auld, was a grandniece of politician/jurist Salmon P. Chase (1808-1873) who served as the Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court, replacing Roger Brooke Taney. She was born in St. Louis, Missouri and I'm assuming they met in Washington, DC where she lived with her famous relatives. Ralston spent his childhood in Frederick City at a family home then located at 54 West Patrick Street, this would be 114 W. Patrick Street with today's numbering system. Ralston attended school in the city and took an interest local figures in Frederick's history, and those that came long before. More history of the Frederick County Goldsborough family can be found within a Maryland Historic Trust' State Historic Sites Inventory property summary for another residence of Edward Y. Goldsborough, Jr. The aptly named Edward Y. Goldsborough House is located at 6739 Clifton Road west of Frederick. This was a family summer home and farm located on the eastern slope of Catoctin Mountain below Braddock Heights. Edward Y. Goldsborough, Jr. bought the property in the 1860s and Ralston places this as his birth location in later records.  Richfield Richfield Continuing through his youth, Ralston Goldsborough took delight in finding Indian artifacts in the fields that surrounded his grandparent’s former plantation of Richfield, located a few short miles north of Frederick City. The plantation house of the Schley’s (named Richfield) exists today and was the birthplace of Admiral Winfield Scott Schley, a naval hero of the Spanish-American War. He was also a cousin of Ralston. The Richfield mansion was childhood home to Ralston's grandfather as I had earlier said it had been the site of Thomas Johnson's former mansion, with a house rebuilt by Ralston's grandfather William after a devastating fired destroyed the original Johnson dwelling in 1815. It sits between today’s US route 15 and the Monocacy River. Ralston's grandparents had kept the property to the west of the turnpike which is basically today's site of Crumland Farms and Homewood Retirement Community. Many of the artifacts found by young Ralston likely came from inhabitants of the neighboring Biggs Ford site on the east side of the Monocacy. This was their immediate hunting ground, a primeval forest before the European settlers cleared the land for farming. Ralston began hunting other local Indian sites, tracing Indian trails and collecting artifacts. His early interests were encouraged by his mother, who worked as an assistant in the office of the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institute. Ralston would graduate from Lehigh University and afterwards serve as a civil engineer in Frederick County, with an office at one time in Winchester Hall.  The modern-day aerial view captures the former Goldsborough properties north of Frederick City and on both sides of US15 below the intersection with Biggs ford Road and Sundays Lane. The Richfield House is located within the small cluster of buildings across the highway from Beckley's Motel marked on the map. Goldsborough was in contact with professional archeologists at the Smithsonian, but most were too busy with research in far-off parts of the world to study the nearby Indian locations which he pointed out in Monocacy Valley. He too ingratiated himself to Maryland’s earliest professionals in the field and became one of them. Sometime between the Rosenstock site discovery in 1907 and October 1909, John J. Snyder—who communicated closely with other artifact collectors in the Frederick area—revealed the site location to E. Ralston Goldsborough. Goldsborough visited the site on October 10th, 1909, and on October 26th received permission from Samuel Rosenstock to carry out excavations. Here is a summary of his notes written in 1911.  Goldsborough said that the village site was visible on the ground as a dark discolored area covering either 1.5 or 1.6 acres “by actual survey.” Between November 5th and December 8th of that year, Goldsborough spent eleven days excavating a series of trenches at Rosenstock, which was then planted in clover. With one exception, which is not specified, the depth of the trenches did not exceed 12 inches. The trenches—situated “one hundred and ten feet from the river, about the center of the site and parallel with it” —are depicted on a plan map, but there are no identifiable landmarks shown; discrepancies between written measurements and with the scale also detract from the map. From these excavations, estimated at 361 ft, Goldsborough recovered nearly 3,000 objects, including pottery, clay pipes, steatite beads, bone implements, and triangular arrow points. Several thousand animal bones included those of deer, raccoon, bird, dog, turtle, and beaver. This research was included in various editions of The Archaeological Bulletin in 1912. E. Ralston Goldsborough had truly arrived! In a report from 1912, Goldsborough notes that the pottery at Rosenstock, with its distinctive rim collar, is different from the pottery types found at other sites in the Monocacy valley, and speculates that it is the result of Iroquoian or Siouan influence. He also illustrates some of the decorative motifs used in a series of “restored” pots. Despite being taken out of cultivation in 1913, the Rosenstock site continued to attract artifact collectors. According to Snyder, around 1920 two collectors (Dudley Page and Alan Smith) had the site plowed; “it paid off well in broken pipes discoidals ceremonial & other material.” The subsequent decades-long unplowed condition of the site notwithstanding, Rosenstock’s location remained known and it was occasionally surface-collected by various individuals, including Spencer Geasey, who brought the site to the attention of then-State Archeologist Tyler Bastian in 1970. Nonetheless, the fallow and/or overgrown nature of the site since 1913 afforded a measure of protection not seen at most village sites in the region. Sadly, although the notes and writings of Snyder and Goldborough survive, the fate of the early artifact collections is less certain. Snyder’s collection from Rosenstock (which came to include the collections of Dudley Page, Allen Kemp, and some of Alan Smith’s material from the site) was owned by a Mr. Dennis Murphy as of 1979. A small sample of ceramic shards collected from Rosenstock by Dudley Page is curated by the Maryland Historical Trust. Spencer Geasey’s surface-collected material from Rosenstock is included in the extensive collections he donated to the Maryland Historical Trust in 1992. Ralston’s Personal Life Let's return to E. Ralston Goldsborough's home life, shall we? Ralston can be found living with his parents well into adulthood and his thirties. His father died in 1915, which came as somewhat of a shock. He would stay with his mother until her death in 1921. Not long after, he finally settled down, at least temporarily. Ralston married divorcee Frances Lillian Roger (nee Ashbaugh) on November 22nd, 1922. The bride was the daughter of William Ashbaugh and Rachel Dyer. She had divorced her husband two years prior and was teaching school in Emmitsburg. The couple was married in Gettysburg and took up residence at his family farm on Clifton Road on the mountain. He inherited the farm upon his parent’s death. It appears that he raised chickens as several newspaper articles point to fair and other competition entries under his name. He began selling off portions of his property in the late 1920s before parting with the whole in 1930. During this time, the house was rented as a summer residence by wealthy Fredericktonians and others attracted to the vicinity of nearby Braddock Heights, the mountaintop village developed by the Hagerstown & Frederick Railway alonq with its amusement park. According to Anne Hooper's Braddock Heights: A Glance Backward, the Goldsborough House during this period was an unofficial "Frederick Country Club,” with prestigious social events and parties. Oh, the "Roaring Twenties," but apparently not a great ending to the decade, or start to the first for our subject. I found a 1931 directory that shows the couple living at 29 Jefferson Street. Sadly I also found the following classified ad printed in the Frederick paper that year: I had heard that Ralston battled the demon of alcoholism during his life, and this perhaps contributed to a Sheriff’s sale of his property and a subsequent divorce in the early 1930s at the onset of the Great Depression. A story exists that at this time Ralston could regularly be found walking the streets of Frederick offering to produce family genealogies for the price of a dollar. Although the Stock Market Crash of 1929 could have cost him his home, fortune and marriage, the Depression did eventually provide Goldsborough employment with an opportunity to continue his dream as an archeologist. He would be tapped as the local director of WPA (Works Progress Administration) work relief in the field of archeology for Frederick County. Through US government funding, Ralston had as his official sponsor the Maryland School for the Deaf. He investigated a number of local American Indian sites, including a rock-shelter and a small village. Although he maintained a healthy correspondence with other archeologists in Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Washington, DC, Goldsborough does not seem to have completed a formal report on his WPA investigations. Virginia Commonwealth University alumnus Brenna McHenry Godsey assembled and examined the available archival record on Goldsborough’s work housed at the Historical Society of Frederick County, Maryland, while she was still a student. These records focused largely on Goldsborough’s pre-New Deal archaeological work. It remains unclear exactly what the nature of his relationship was with the Maryland School for the Deaf. Was the School simply a project sponsor, or did some of their charges participate in the WPA excavations? Regardless, Goldsborough produced a map showing numbered sites of special interest in Frederick County, and collected a vast array of artifacts which remain in the Bjorlee Archival Collection of the Maryland School of the Deaf. It is also thought that the Rosenstock material excavated by Goldsborough decades earlier may also be included in this same artifact collection prepared for the Maryland School for the Deaf during the WPA project. I had the opportunity to work with MSD back in 1997 in an effort to access and film Goldsborough’s map and hundreds of artifacts for my Monocacy documentary. I’m hoping Goldsborough’s treasures at the school will make their way out of storage again one-day, and go on display for local residents and visitors to behold.  Frederick's Pythian Castle (c. 1920) Frederick's Pythian Castle (c. 1920) Census records and directories show me that the couple apparently never formally divorced. Frances took up residence at 347 S. Market Street. in 1935 and can be found renting an apartment at 306 N. Market Street. in 1940. Ralston made his home during this time in Room 3 of the Pythian Castle, located in the middle of N. Court Street, a half block north of his childhood town home located near the corner of Court and W. Patrick streets—the site of today’s county courthouse. The files of the Frederick County Historical Society (Heritage Frederick) remain filled with Ralston’s research in the form of newspaper clippings and original manuscripts typed on onion skin paper. Many of those manuscripts and writings/research on Frederick history have the Pythian Castle address typed as their place of origin under Goldsborough’s hand. The last decade of his life saw him working as a top-tier genealogist. With his vast knowledge of Frederick's past, he was an easy choice to serve as Frederick City's official historian for the town's Bicentennial celebration in 1945. He wrote several articles and presented lectures on local topics and helped create a successful history pageant and other related events. Sadly, E. Ralston Goldsborough would suffer failing health in his final several years. This would not only throw him in poverty, but also led to a domicile change to the Frederick County Home at Montevue, northwest of town. Here he died on May 7th, 1949. He was buried at Mount Olivet Cemetery in Area G/Lot 162. His grave, in the shadow of a large obelisk erected to the memory of his paternal uncle, Dr. John Goldsborough (1835-1885), was unmarked until a marker stone was placed around here in 1998 by a relative. This was during the time I was doing my research on Ralston for my documentary. I vividly recall contacting Superintendent Ron Pearcey back in late 1997 for help in finding the grave of E. Ralston Goldsborough. He took me to the unmarked grave and let me know that he had been working with a family relative living in Delaware who was paying for a monument to be done. I hoped this gentleman may be able to provide me with a picture and more insight into the man few remembered, but was responsible for a tremendous body of work on the native peoples in our area.  Richard D Goldsborough, Jr Richard D Goldsborough, Jr Ron gave me the name and address of Richard Duvall Goldsborough, Jr. of Bayville, DE. I was excited in contacting Mr. Goldsborough and soon found that he lived just a mile from my family’s beach trailer located near the Fenwick Lighthouse in Fenwick Island (DE). Mr. Goldsborough graciously invited me to dinner to discuss his “archeological cousin” the next time I was “down the shore.” This visit eventually transpired in the summer of 1999. No pictures came about of E. Ralston (as I am still in search of one), but Richard shared the story of his remembrance of attending Ralston’s funeral with his parents. Richard lived in Baltimore, as did his folks, at the time and said that his father had kept a long-time correspondence with Ralston. He recalled childhood visits to Frederick with his dad to visit the peculiar man who told them rich stories of family history and local Indians on each trip. Upon learning of his failing health in spring of 1949, Richard and his father traveled to Frederick to make plans for Ralston’s burial as the archeologist had made none for himself, and had no immediate family. It would have been customary for Ralston to have been buried in Montevue’s potter’s field. As the next of kin, Richard’s father made arrangements for Ralston to be buried with his own parents in a lot adjoining the previously mentioned Dr. John Goldsborough. Dr. John was Richard Sr.’s grandfather and Richard Jr’s great-grandfather. Dr. John named his son Edward Yerbury Goldsborough as well, and he is buried in this lot. Of course this man is Richard Sr.’s father, and was named in honor of Ralston’s grandfather—Edward Yerbury Goldsborough. Dr. John’s father was William Goldsborough, the Confederate brother of Ralston’s father, Edward Yerbury, Jr. So to review the complicated family genealogy, my friend Richard’s great-grandfather (William), and Ralston’s father (Edward), were brothers. My dinner host shared with me the fact that Ralston had lost all his money through personal vices and never got around to putting a proper headstone on his own parent’s gravesite. Ralston’s father had passed suddenly in 1915 leaving wife Amy in dire straits. She would die in 1921 and things never really straightened out for Ralston financially speaking. Richard said that his father had always spoke of putting a stone on the graves of Ralston and his parents but never got around to it either. This was unfinished business, and Richard, Jr. never forgot his father’s intention. With medical issues of his own, Richard contacted Mount Olivet in the late 1990s to pre-plan burial arrangements for both himself and wife Beulah in a pair of grave-lots within Dr. John Goldsborough’s family plot. His parents were laid to rest here back in the 1970s. The new stone was finally completed in 1998 and placed over the grave of Ralston and his parents. Although I talked to Richard on the phone just once more after our dinner and shared a mail correspondence a few years later, we lost touch with each other. Not knowing his fate, I took solace in knowing that he is here buried in Mount Olivet, having died in 2010—a decade after our dinner meeting. His wife, Beulah, died the following year. That night at his house, I would learn that Beulah’s sister was married to an elderly third cousin of mine living in northern Delaware, the oldest member in a family line. Author's Note: I originally wrote this blog in April 2020 and have tried over 15 times to boost this post (marketing terminology) so a larger audience could see it. I found that Facebook was actually limiting the number of people who could see it. When I attempted to boost which puts it in people's newsfeeds for a fee, I kept getting rejected due to breaking Facebook's political and election policy. This had me perplexed because I had briefly mentioned the following regarding E. Ralston Goldsborough's ties to earlier Maryland governors in the 1830s and 1916. The first was Robert Goldsborough. You recall that it was Robert’s son William who came to Frederick around 1800. Robert had another son (William’s brother) named Dr. Richard Yerbury Goldsborough (1768-1815). He is buried at Christ Episcopal in Cambridge, MD along with plenty of other Goldsborough relatives including Phillips Lee Goldsborough (1865-1946). Phillips Lee was Maryland's 47th governor, serving from 1912-1916. He later was elected US Senator and held that seat from 1929-1935.

In either case, E. Ralston Goldsborough, could trace his amazing Maryland lineage back to Continental Congress delegate Robert Goldsborough, and original immigrant to America, Nicholas Goldsborough (1640-1670). History is complicated and tedious at times, but it's certainly worth the "dig!" Somehow, this was dangerous info? I even removed this from the story to no avail. I soon learned that bots and AI perform the screening of stories and the fact checking on this social media outlet. I desperately tried to reach Facebook for further discussion on the subject. First, its nearly impossible to make human contact with them, and second, the international team-member I spoke to in 2020 (and another again a year later) had no clue what I was talking about and kept reiterating/parroting corporate policy. My story on Gov. Thomas Johnson in October 2019 experienced a similar fate, and I was accused of electioneering. But I pleaded, "TJ was a politician in the 1700s!!!" They still rejected my boost attempts. All my research work and writing and basically I was censored from having a larger audience seeing it. So I've tried to run this Goldsborough story in April 2021, April 2022 and again in April 2023 to highlight Maryland Archeological Month, but to no avail. So here I am, in May, 2023, and trying to circumvent "The Powers That Be"....Facebook. Hope you enjoyed this special "Story in Stone." ;)

1 Comment

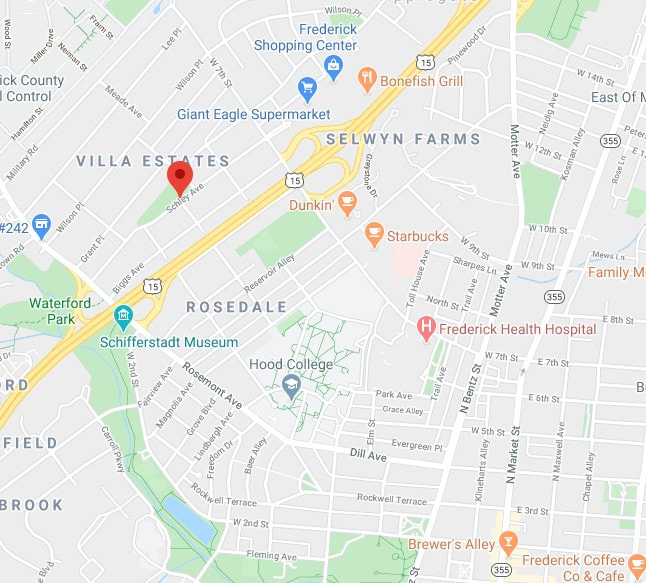

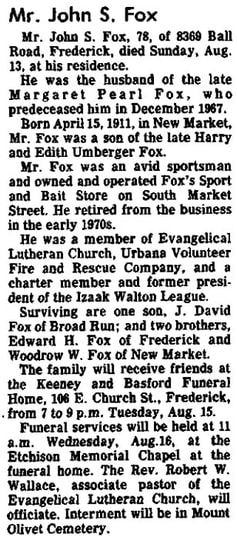

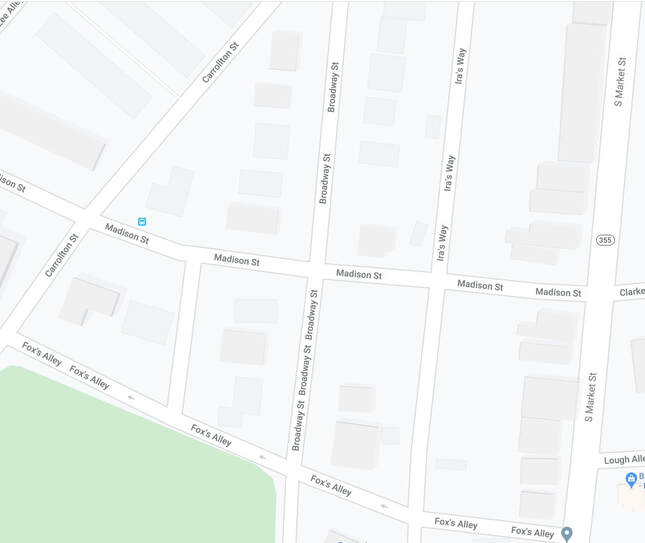

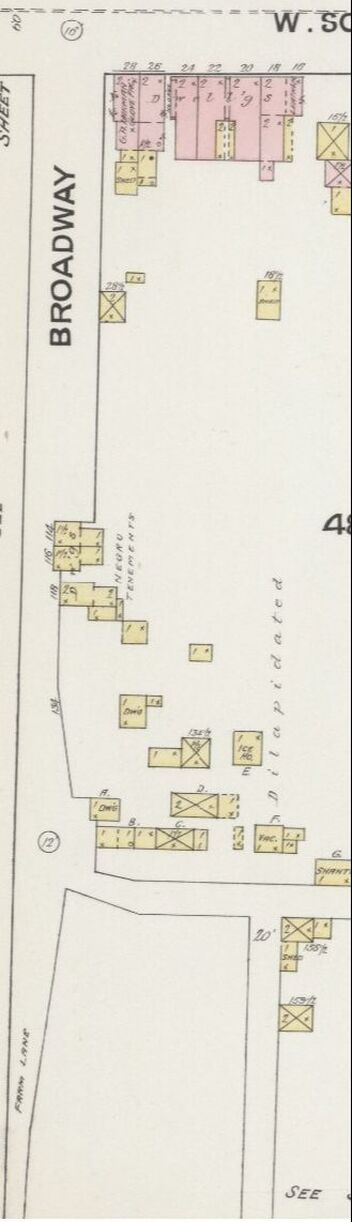

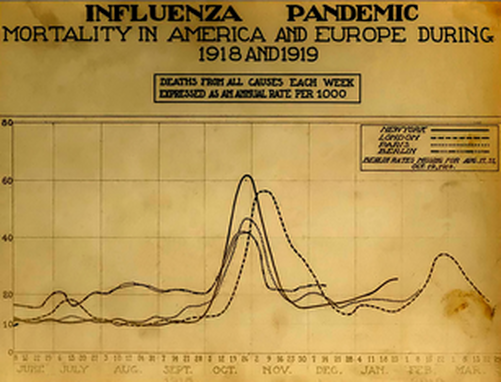

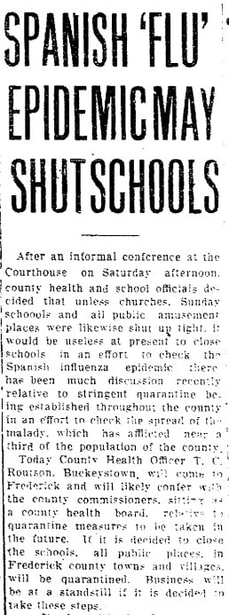

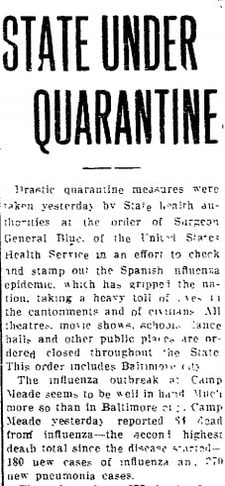

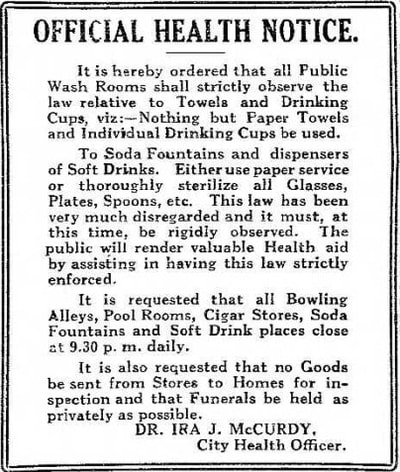

Of late, my commute home from Mount Olivet Cemetery to the Rosedale/Villa Estates neighborhood on the northwest side of Frederick has been as quiet as can be. Hey, I’m not complaining, and never have, since I have been so very fortunate to both work and reside here in Frederick for the last 30 years. I know darn well that I am one of the lucky ones having grown up seeing both of my parents commute to Bethesda each work day throughout my childhood. I can usually get to and from work in about ten minutes, and without the aid of major roads or a highway. In fact, I primarily use back streets and alleys, the names of a few may not even register with some readers. And on my way, I only have four turns to make once I leave the cemetery. So join me for my commute home, and I'll give you an impromptu, local-history tour/lesson along the way. Don't worry, we'll be properly "socially distanced," and I'm guessing that most of you have plenty of time to kill while in self-quarantine lockdown.  To begin, for those unfamiliar with the Rosedale/Villa Estates which I call home, it sits just north of Rosemont Avenue, sandwiched between US15 and Fort Detrick. Homes were primarily built here between 1930-1950, providing housing for many newcomers to Frederick employed at "Camp Detrick" during, and after, World War II. These included doctors and scientists from around the country and world, completely changing the cultural fabric of "small-town" Frederick which had been in existence for nearly 200 years up to that point. The neighborhood does have a nice park area and serves home to Frederick's current mayor—so we have that going for us! Fittingly, as you will soon see with this week’s story’s central theme, my neighborhood is best known today for its vehicular “cut-through” streets (linking Rosemont Avenue to West Seventh Street) probably more than anything else. Most of these roadways are named for leading historical figures: Schley Avenue (Admiral Winfield Scott Schley—Frederick boy turned naval commander and hero of the Spanish American War), Taney Avenue (Roger Brooke Taney--Frederick lawyer turned controversial Supreme Court justice), Grant Place (Ulysses S. Grant--Union general during the American Civil War and our 18th US president), Wilson Avenue (Woodrow Wilson--our 28th US president who served during WWI and the 1918 Spanish Influenza pandemic), and Lee Place (Robert E. Lee--Confederate general during American Civil War). Military Road (self-explanatory) runs along the northwestern perimeter of the Villa Estates and neighboring Fort Detrick and there is one more named Biggs Avenue, but that one seems to be a head scratcher. We'll pick that one up later. Speaking of streets, those belonging to the City of Frederick are far from bustling at the time of this writing (mid-April, 2020). This has been the case for multiple weeks now, thanks to the mandated state quarantine urging people to stay at home in an effort to curb the spread of the Coronavirus disease/Covid-19. If you are lucky enough to escape your house for a glimpse of life on the outside, you may spot a person or an occasional couple walking along the sidewalk--but I can’t even remember the last time I saw more than ten people gathered together in one place, let alone five. I smile in thinking that just two months earlier I found myself irate and stranded for ten minutes (no lie) trying to make a simple right turn while downtown. I had been doing some history research at C. Burr Artz Library and parked in the adjacent garage late that Saturday morning. I exited the garage okay but ignorantly decided to exit onto S. Market Street (by Wags restaurant). My error was forgetting that it was Downtown Frederick’s First Saturday, and not just any First Saturday, but February’s “Fire & Ice” First Saturday. The city was mobbed with people by the time I had left the library that afternoon! As I said a minute ago, these days, one sees but a few people out along the streets in late afternoon/early evening. They are usually engaged in a brief evening stroll or picking up carry-out from the multitude of busy restaurants and eateries offering "curb-side service." Some folks out walking are donning sneakers and shorts, while others have covered themselves from head to toe while wearing latex gloves and face masks. What puzzles me most is seeing other motorists with face-coverings, and they are the only ones in the car? How are they going to catch, or transmit any viruses while driving? "To each their own," I guess, especially during these anxious and curious times. Driving While “Stoned” I knew this sub- title would grab your attention, but it’s not what you think! When I was driving home one day last week, I contemplated upcoming topics for this blog. At the same time, I found myself taking extra notice of the thoroughfare names I utilize each and every workday. More so, I took specific interest in the names behind these streets traveled. It quickly dawned on me that this was somewhat like the “Stories in Stone” blog format itself, in which I research the names on gravestones and make connections to other elements of the community through people's life stories. I figured I could effectively “kill two birds with one stone” so to speak, and figure out for whom these streets are named, and then attempt to find these individuals in Mount Olivet, if they so happen to be buried here. So let's go! LEG 2 — "Frederick's Other City" Here’s an interesting piece of trivia to “wow” your friends and family with: Did you know that Mount Olivet Cemetery contains over eight miles of paved roadways? In addition to serving as a great place to work, visit, learn history and spend eternity, the cemetery is also a fabulous safe-haven for reverent recreationalists in the form of walkers, runners and cyclists. From my office, located within our administration office and mausoleum complex in the south end of the 100-acre burying ground, it’s a 1.3 mile-drive to the Key monument and cemetery's main/front gate positioned off S. Market Street. Call me a rebel, but I refuse to attempt a left turn in afternoon rush hour onto Market Street—doing so would double, or perhaps triple, my entire commute time! .....so says the idiot who wanted to drive on Market Street during "Fire & Ice First Saturday." I choose instead to use our side gate located off Fox’s Alley and Broadway Street. Those who use Stadium Drive each day to accomplish this daring feat (turning left onto S. Market) know exactly what I’m talking about. Interestingly, before I exit Mount Olivet, I've passed by the gravesites of at least four of the street namesakes involved in my commute. In addition, I passed another who isn't a true street namesake, but simply shares a moniker. I also passed a few more stones that have other connections to why things were named the way they are today. Now that I've likely either piqued your interest, or totally confused the heck out of you, let's pick up the second leg/part of my journey as I depart the "City of the Departed."  Fox's Alley (and former business) from S. Market St Fox's Alley (and former business) from S. Market St LEG 2 —"On Broadway” Albeit brief, I will include Fox's Alley in my story. I’m usually only on this for 1.7 seconds as I cross over to Broadway Street. Many commuters use this quiet lane (Fox's Alley) on their way home to bypass the stoplight at S. Market and Madison streets. This is a much better, and safer, alternative than those who insist on cutting through the cemetery, especially considering the safety and solitude of our visitors and recreationalists. Yes, we've had some near misses with people speeding on through which has prompted management to close this side gate now in late afternoon. Fox's Alley takes its name from John S. Fox, former proprietor of Fox’s Sport and Bait shop at 501 S. Market. This business just left us last year, but since around 1959 was an ideal place for one-stop-shopping, especially if your wife asked you to stop and pick-up a 6-pack of beer and pound of nightcrawlers on your way home. Mr. Fox (1911-1989) sold the establishment a few years before his death to Bill Offutt, son of local attorney Jerome Offutt. Mr. Offutt was assisted by daughter Lauralea over the years as it kept the Fox’s name for a little bit but changed to Offutt’s Sport and Bait. Recently this property was sold and received a true business makeover, opening as the Stanley Salon. Oh, if Mr. Fox could see it now! When I brought his name up to Superintendent Ron Pearcey, he immediately smiled. Ron knew Mr. Fox quite well and frequented his store regularly over the years, particularly for ice cream and purchasing miniatures for his boss, former cemetery superintendent Robert Kline. This practice, however, came to a halt once Mrs. Kline discovered the ruse of Mr. Kline having Ron make the secret purchases on his behalf. Ron hurriedly left my office for a second, saying, "Hold on Chris, I want to check on something." He returned a minute later and belted out, “February 26, 1964.” I asked, “What about it?” He said that this was the day Mr. Fox bought his burial lots and then proceeded to tell me his funniest remembrance of Mr. Fox, told to him by the previously mentioned, Mr. Kline. Ron said that Mr. Fox approached his old boss (Bob Kline) about buying a gravesite back in the mid 1960s, with the distinct caveat that the location must have a good view of Sugarloaf Mountain. Apparently, Mr. Fox had a decent view of the monadnock from his home on Ball Road south of town. Mr. Kline brought Fox to Area GG/Lot 28 and said, “Will this lot suit you?” At this point, Mr. Fox immediately proceeded to lie down on the ground, and from that vantage point looked to the southeast towards Sugarloaf Mountain. After about a minute, Fox sprang back to up his feet and said to Kline, “That’ll do, I’ll take it!” Mr. Fox’s wife passed in 1967 and was laid to rest here. Mr. Fox wouldn't join her here until August of 1989. Once on Broadway Street, I usually think about the famed thoroughfare in New York City which becomes the country’s epicenter every December 31st. I sometimes also get a tune instantly playing in my head—the song “On Broadway” of course, performed first by the Drifters in the 1960s, and later covered by George Benson a decade later. I will honestly say that I have never heard the song (“On Broadway”) while actually driving on Broadway Street, but that doesn’t mean that I will continue to suppress the urge sometime to do so in the near future! I wanted to see what Broadway looked like back on the 1873 Titus Atlas Map which I often reference with my "Stories in Stone" blog articles. Unfortunately, I couldn't find it, well at least all of it. As you can see in the image above, Mount Olivet appears with the cemetery superintendent's house shaded black, as well as a little gap depicting our front gate off S. Market Street. The side gate would be located above the "C" in cemetery at about the second black line (above) as you can see the alley that constitutes Fox's Alley coming off S. Market.

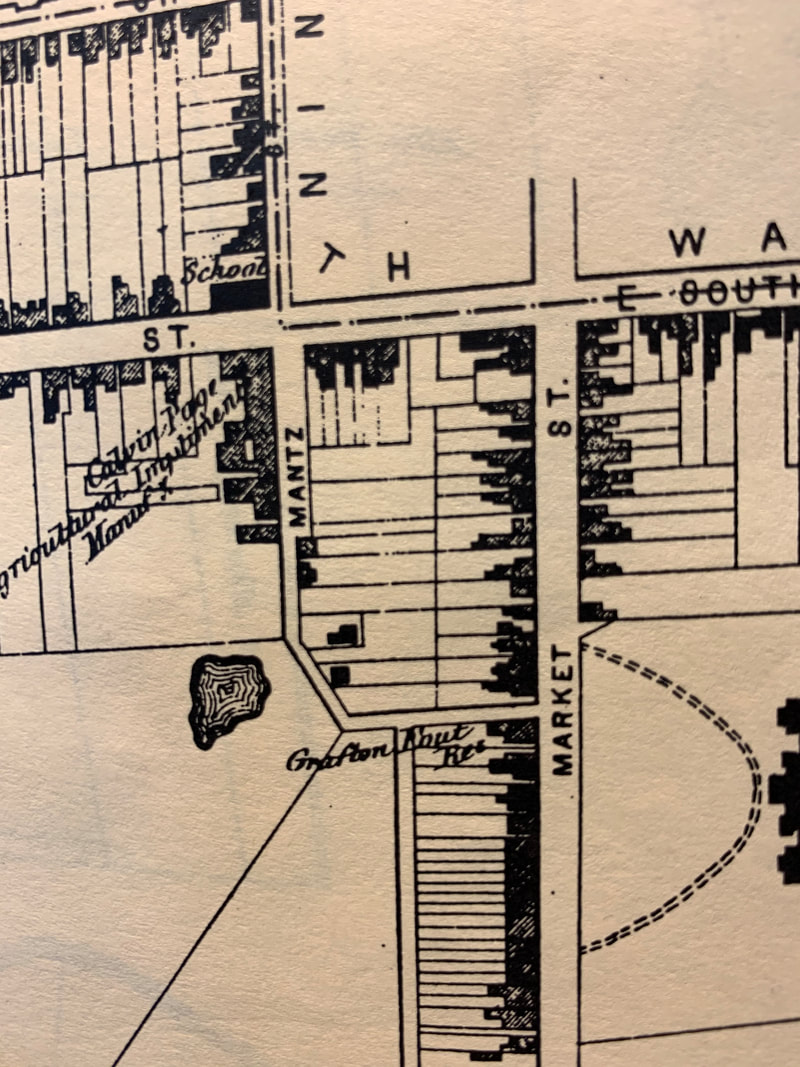

As I drive north, Broadway Street crosses over Madison Street (named for James Madison, our fourth US president) and continues on until it joins a much older portion of road near the intersection with today’s Getzendanner’s Alley (on the east). This was formerly known as Mantz Street in 1873, and this road came off S. Market Street in a westerly fashion and turned north to connect with W. South Street (see Titus Atlas inset below left).

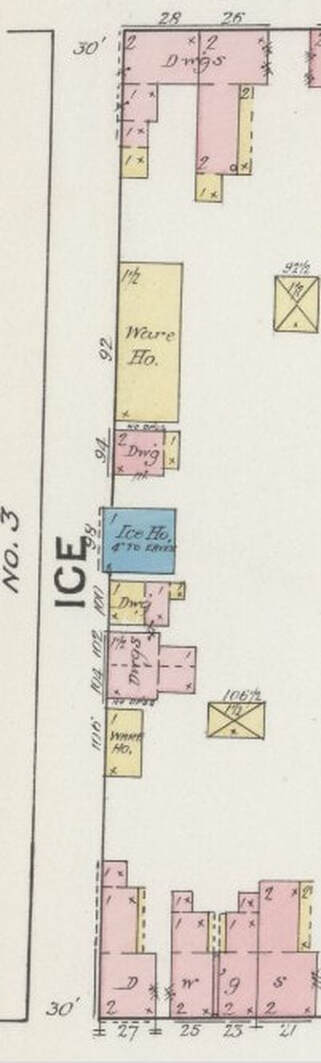

Broadway Street, itself, was not named for anyone in Frederick history, however, we do have a couple buried in Mount Olivet’s Area KK (Lots 51 and 52) by the name of Asia Cooper Broadway (1927-2010) and wife Hazel (Wells) Broadway. Even though Broadway Street does not honor Asia Broadway, I find it quite uncanny that Mr. Broadway was quite successful as a contractor in the paving and blacktop industry. This because of the sheer fact that streets and roadways are at the root, or should I say "route," of our conversation. LEG 3 —Ice Cold Beer Now, back to my ride home, and again, the title is alluding to nothing that I am doing behind the wheel on this ride home. As I depart Broadway, I cross over South Street (self-explanatory as this was once Frederick’s southernmost major thoroughfare) onto the coolest street in town--Ice Street. I learned that this narrow lane was originally called Tanner's Alley in an early newspaper article dating to 1832. It was so named for some tanneries located a few blocks north on Carroll Creek. Around the year 1840, an ice house was built by George J. Fischer (1809-1866) as he leased a lot from Elizabeth Hauer, a relative of Barbara Fritchie. The Hauers and Fritchie's were in the glove-making field which certainly was related to tanning. Fischer built his structure on the east side of Tanner's Alley, halfway between W. All Saints Street to the north and W. South Street to the south. Fischer sold his property, known as “Ice House Lot” in 1855, and has continued to be called called Ice Street ever since, although some old deeds still say Tanner's Alley and others say Brewer's Alley. Marilyn found a 1905 deed that refers to the corridor as both: “Ice Street or Brewers Alley.” As we know, the former name would primarily stick to the stretch from W. South to W. All Saints, and Brewer's Alley would adorn the road up until its intersection with W. Patrick Street for most of the 19th century and into the 20th (before becoming Court).

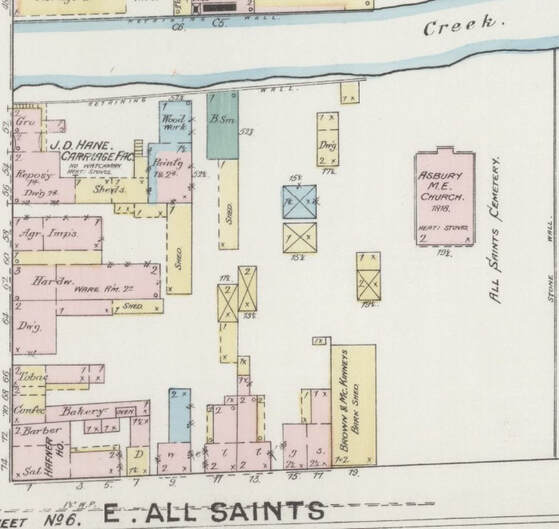

To backtrack, W. All Saints Street is so named for All Saints Protestant Episcopal Church, originally located adjacent E. All Saints Street. The church and graveyard stood atop a hill that was bounded on its north side by Carroll Creek. The Protestant Episcopal congregation moved to a new location closer to the Frederick Court House around 1814, and a new congregation of whites and blacks worshipped together and took over the former location and built what was known as Old Hill Church. This would morph into Asbury Methodist Episcopal and would remain here until about 1921, when it opened a new church structure on the southwest corner of W. All Saints and present-day Court Street. (Note: Today, the original site of the All Saints and original Asbury church locations is the home of a luxury condo development known as Maxwell Place on Carroll Creek. )

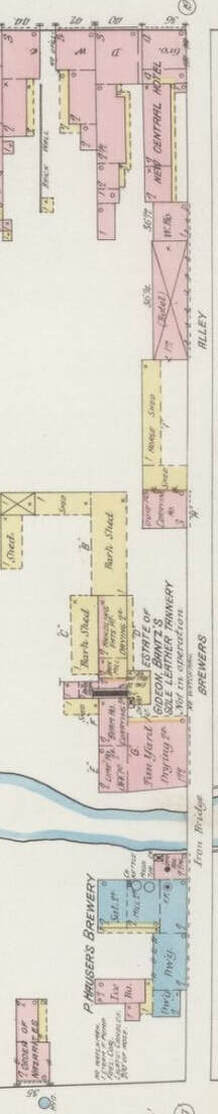

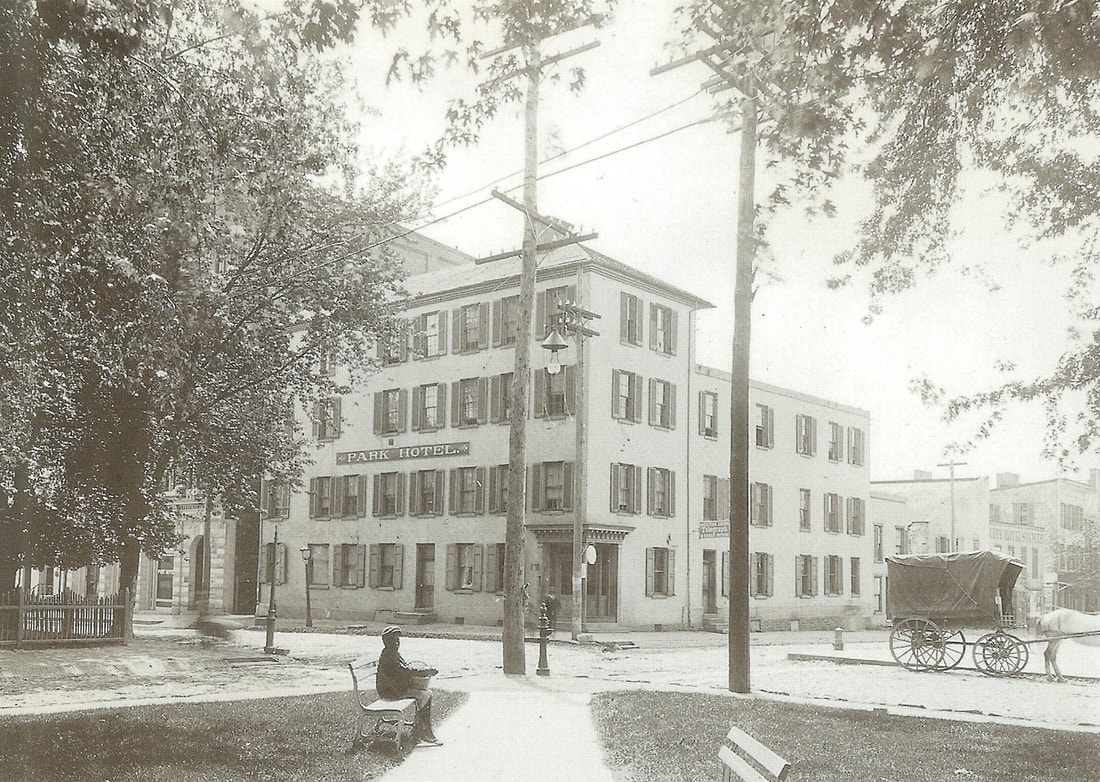

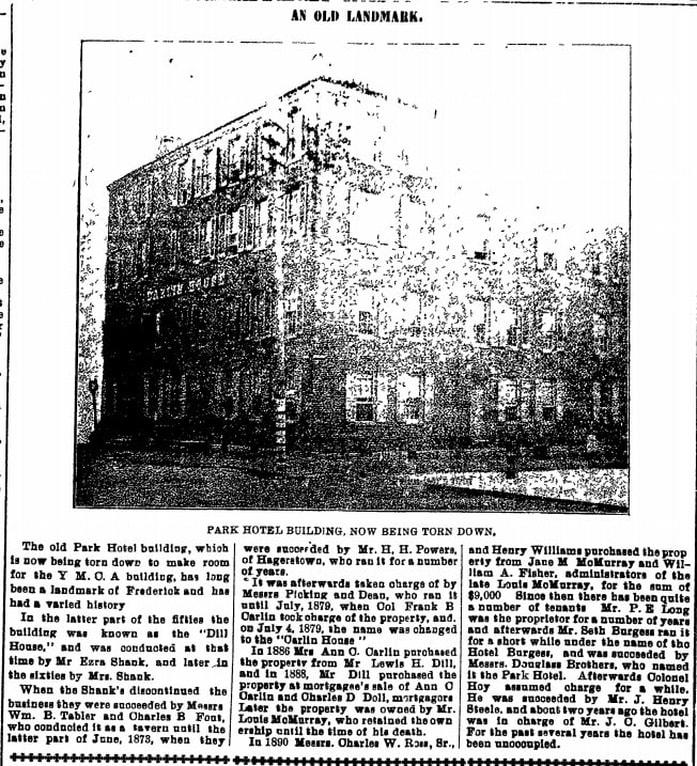

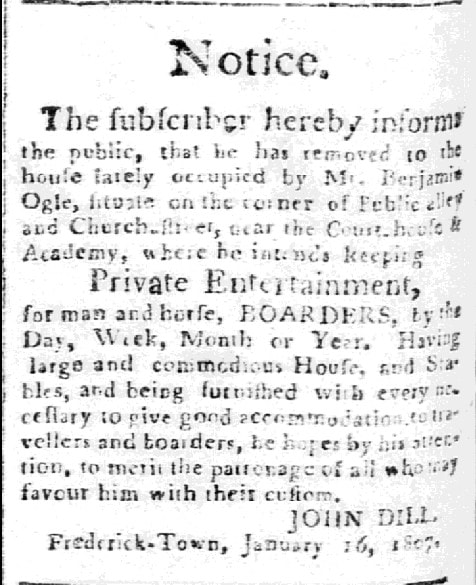

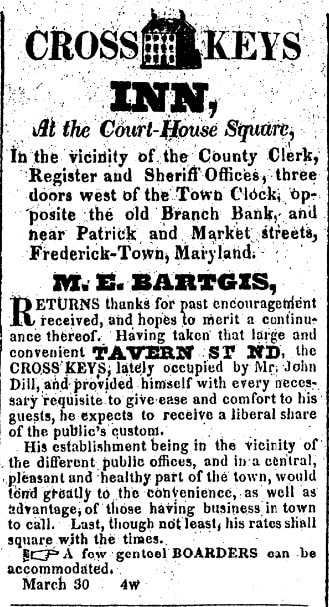

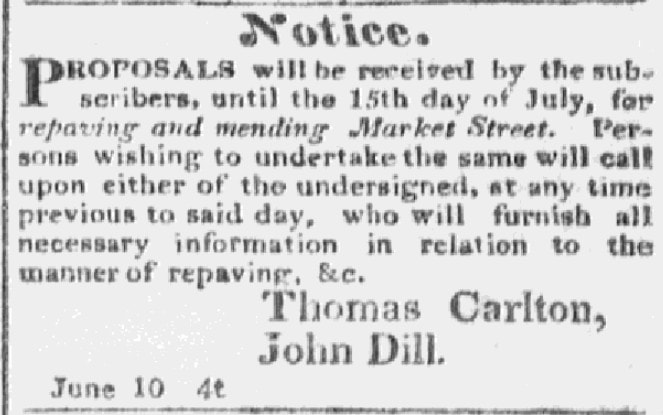

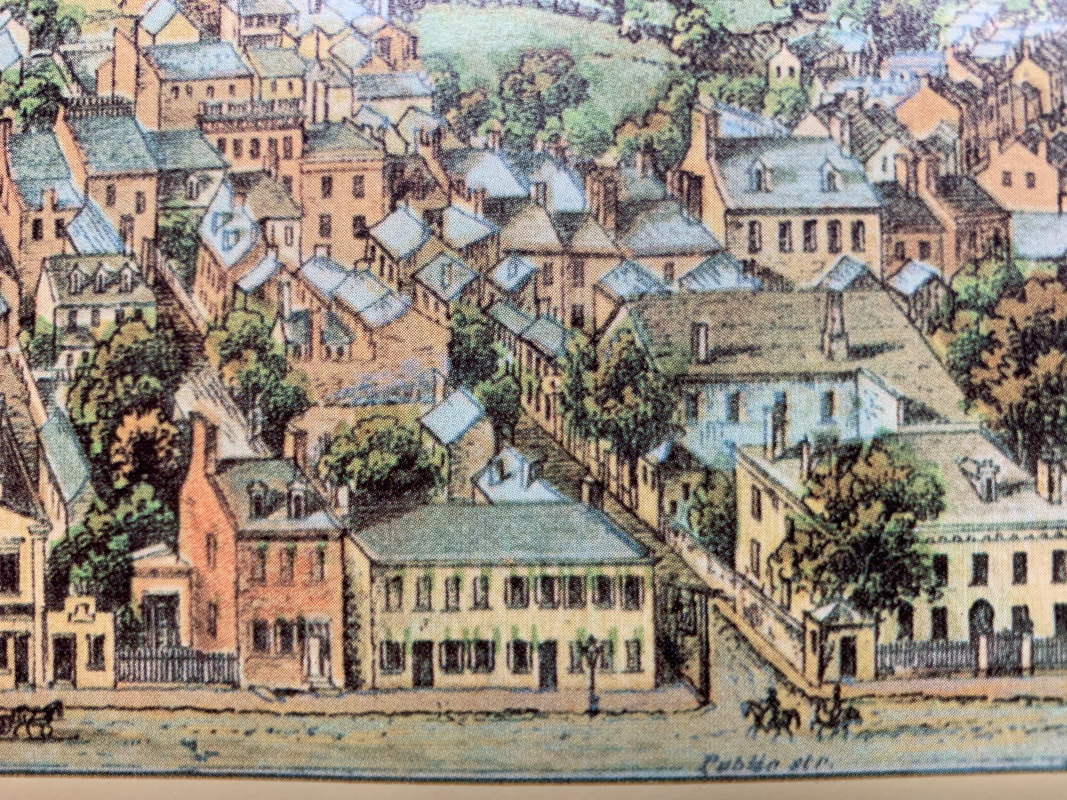

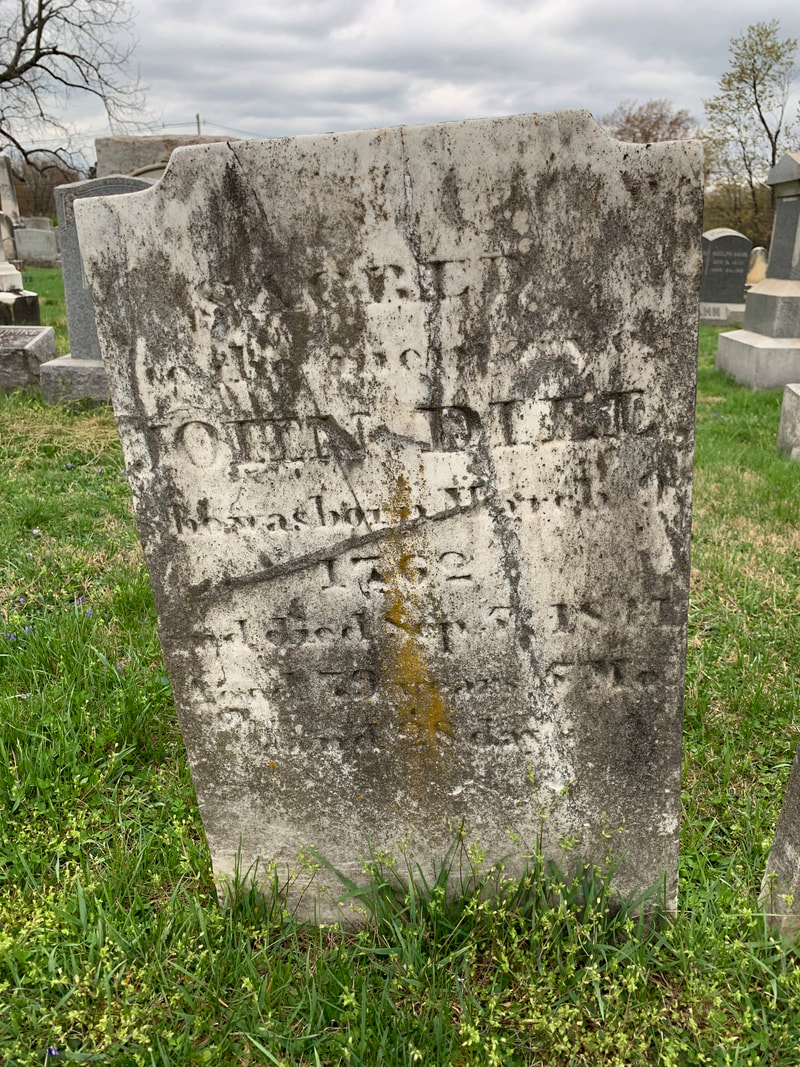

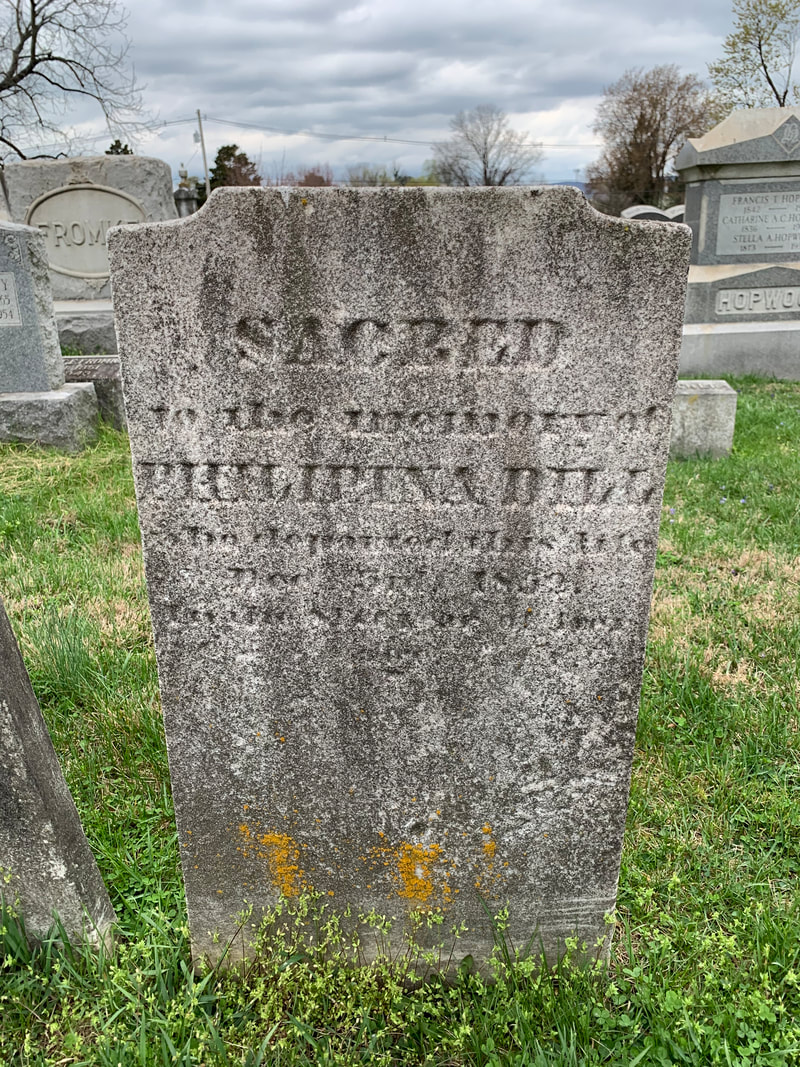

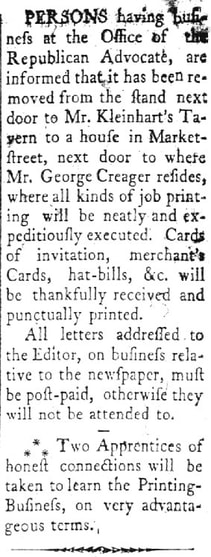

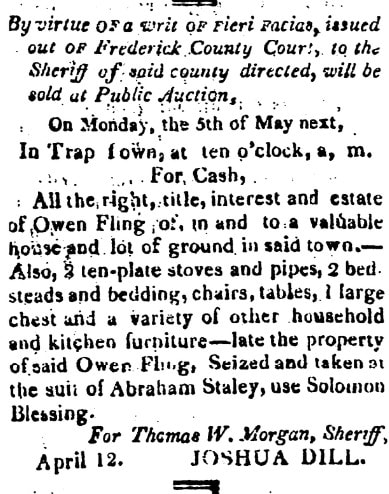

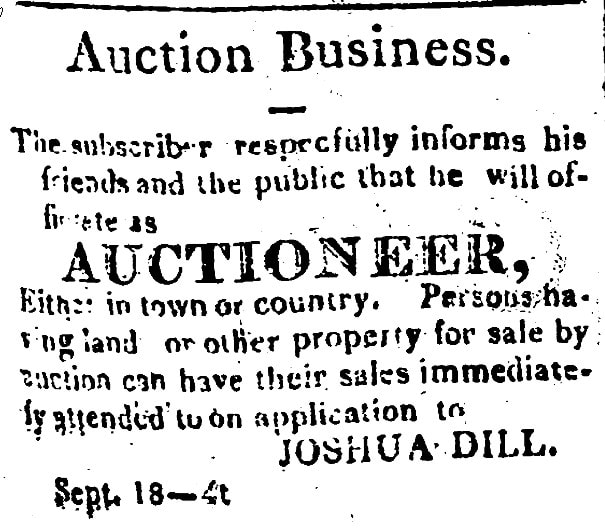

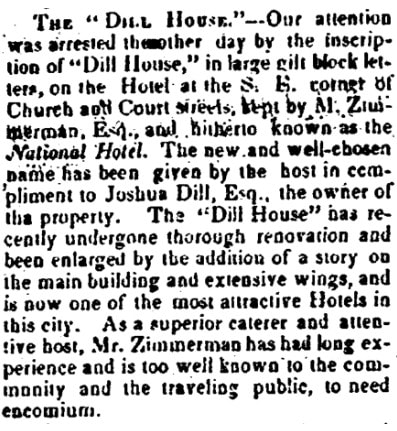

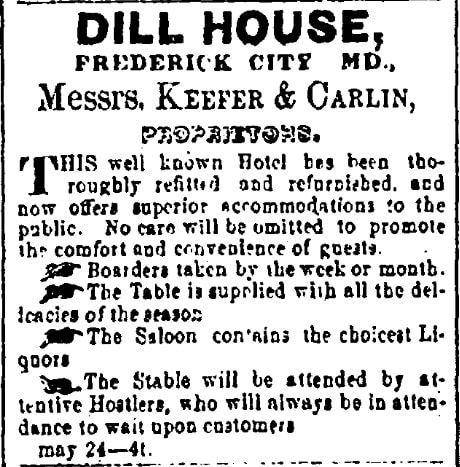

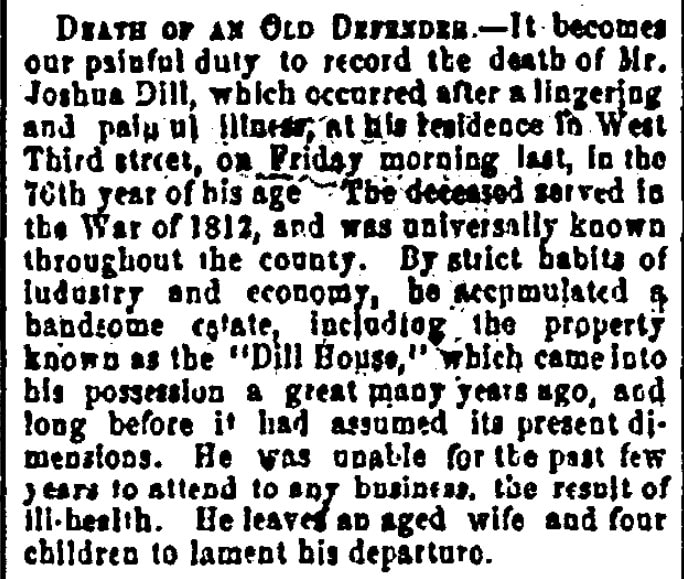

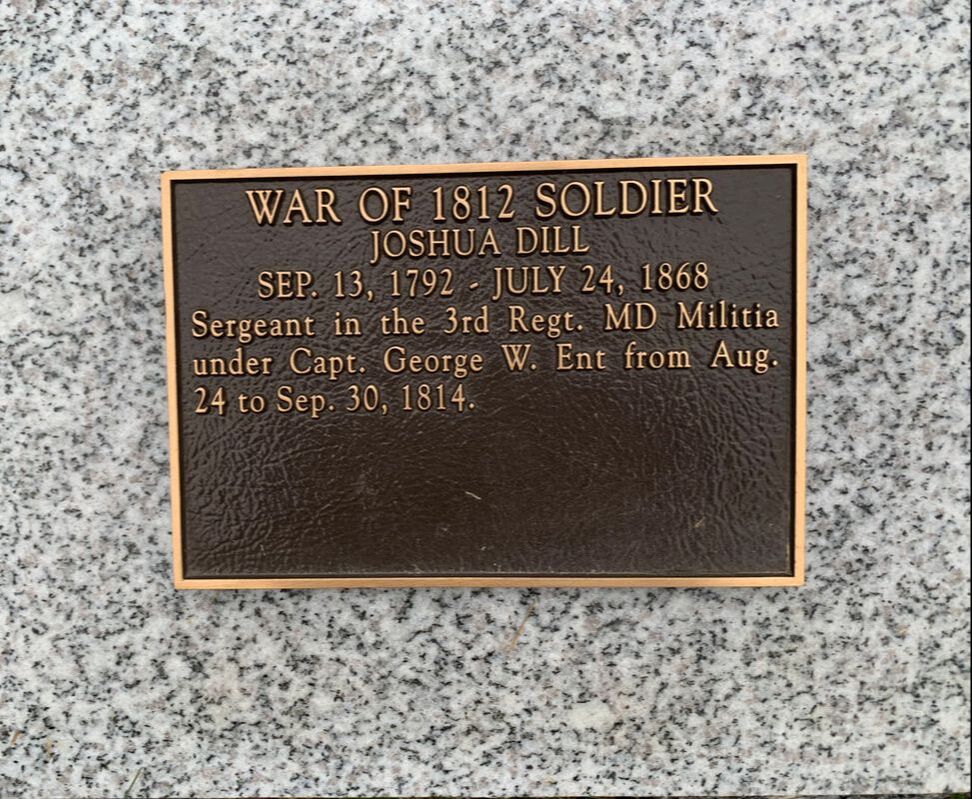

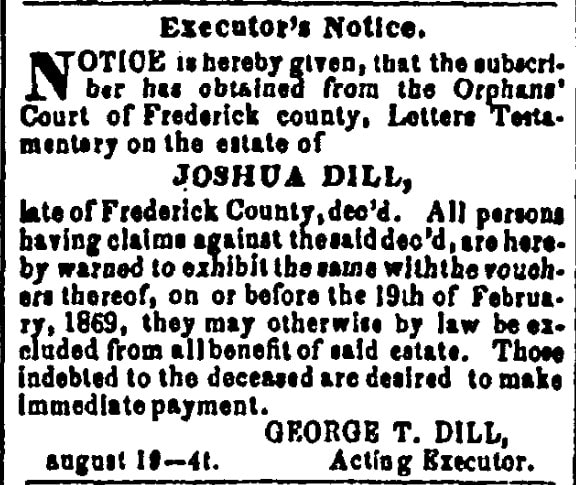

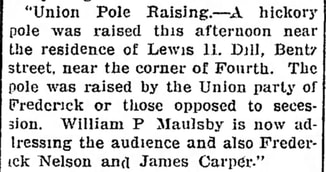

Patrick Dulany Patrick Dulany LEG 4 —The Public's Street I now cross over Frederick’s busiest, and oldest, roadway, Patrick Street, a part of the famed National Road which stretches from Baltimore to Vandalia, Illinois. This is said to have been named by Frederick’s founder, Daniel Dulany, after his cousin named Patrick Dulany (1686-1768), a noted theologian and clergyman of Dublin, Ireland noted as “an eloquent preacher, a man of wit and learning.”  The FSK Hotel in the 1950s The FSK Hotel in the 1950s Court Street continues for another few blocks but was originally known as Public(k) Street/Alley as it dates back to the time of the erection of Frederick County’s first courthouse, today’s Frederick City Hall. This occurred after Frederick became a county in 1748. Founder Daniel Dulany donated the lots for this purpose, and gladly, since his planned development of Frederick-Town would serve as county seat. Travelers on the National Road, and court business called for a profusion of inns and taverns here dating back to the 18th century. Hotels could be found on or near the east side corners of old Public Alley at intersections with W. Patrick and W. Church streets. I recently wrote about Mrs. Catherine Kimball who operated “The Golden Lamb” Tavern on the northeast corner of today’s Court and W. Patrick which eventually morphed into The City Hotel, and later the Francis Scott Key Hotel in 1922—now luxury apartments. Time out for a sidebar....Remember when I told you that the All Saints Protestant Episcopal congregation decided to abandon their former church structure down on E. All Saints Street to move closer to the courthouse? Well, here is where they went (on the left). This structure was used until the present church, fronting on W. Church Street and around the corner, was built in the 1855. There was another interesting hotel on the SE corner of the former Public and W. Church streets which once stood on the parking lot of today’s M&T Bank. I pull into this parking lot on occasion to use the ATM on my way home. Some residents may recall this as Frederick’s earlier YMCA location, up until the building’s destruction by fire in 1974. Before that, you have to go back to the year 1907, at which time stood the Park Hotel—the final moniker for a very popular lodging location that dated back to the 1700s. We are fortunate to have a beautiful old photograph dating from between 1903-1905, showing the hotel and adjacent area. The building would be demolished in 1907 to make room for the Young Men’s Christian Association which opened the following year. Preceding the Park Hotel, the structure took the name of the Carlin House, whose story will be told in a future article in context to proprietor Frank B. Carlin.  1765 Stamp Act Repudiation 1765 Stamp Act Repudiation The roots for inns and taverns run deep at this location, a funny thing to say considering that "The Temple," a Paul Mitchell Partner School for hair design, is located next door these days. The first apparent petition to the county court for a license to operate a tavern in Frederick was made by Cleburn Simms, who presented the following petition in March, 1749: "That your petitioner, having provided himself with accommodations fit for travelers and others, humbly prays that Your Worships would be pleased to grant him a license for ordinary keeping, he complying with the Act of Assembly in that case provided and he as in duty bound will pray." The petition was accepted by the county court justices, and the site of the Simm's tavern was built right here at this location of the M&T Bank and Temple parking lot. When Mr. Simms died, his widow Mary became the first female to hold an innkeeper's license. It is thought that this same location came into the ownership of a gentlemen named Samuel Swearingen who hosted the grand celebration dinner following the mock funeral of the 1765 Stamp Act in late November, 1765. The county court justices were all for taverns as we can see, but had little use for stamped paper from Great Britain. One way or another, the site of Swearingen's Inn at this location eventually became a private residence owned by a man named Benjamin Ogle. Later, another man named John Dill would come into the picture and be responsible for giving Frederick Town “The Dill House." This was purchased from Robert Miller of Baltimore on December 11th, 1806 for $2,450. John Dill (1762-1841) was of German heritage and could have come to Frederick by way of Pennsylvania. He operated his tavern stand here starting around 1807 and this would also come to be known as "the Cross Keys Tavern." From reading old newspapers, Dill’s Tavern seemed to be the premiere site for sheriff’s auctions, entertainment events, and organization meetings ranging from bank boards to the county’s Republican Committee to the Frederick Agricultural Club who put on the first cattle shows and fairs. This was even a site of special mayor & alderman meetings, as well as serving as a municipal election precinct. Mr. Dill eventually turned hotel management over to Mathias Bartgis in 1826. John Dill married twice. His first wife was Catherine Peltz, a widow and daughter of George Burkhart. The couple wed in 1790 and would have three known children to live to maturity: Joshua (b. 1792), Ezra (b. 1795), and Elizabeth (1800-1866), the latter marrying a man named Levin Thomas. After Catherine's death on October 4th, 1804, John Dill would eventually wed another widow, who had been married to a fellow named Henry Fout. Her name was Philipina, and her maiden name was Philipina Krieger, daughter of another tavern owner in town (George Krieger/Creager, Sr. (1752-1815). John Dill was civic-minded and served as a roads and street commissioner of town. He continued to own the tavern property throughout his lifetime, but leased it out to others to run. Upon his death in 1841, his will would convey the popular hostelry to his son, Joshua. Mr. Dill was originally buried in the Evangelical Lutheran burying ground behind the church within two blocks to the east of his tavern. His descendants would move his remains to Mount Olivet on September 20th, 1870. He was buried in Area H/Lot 327. His second wife, Philipina, would be reburied here as well on the same day. At 49 years of age, Joshua Dill had been involved in the hostelry business for a good part of his life. In fact, in addition to gaining experience from his father’s success in the trade, his father-in-law was also a prominent tavern keeper in town. This is a perfect segue to get back on Court Street and continue my ride home.

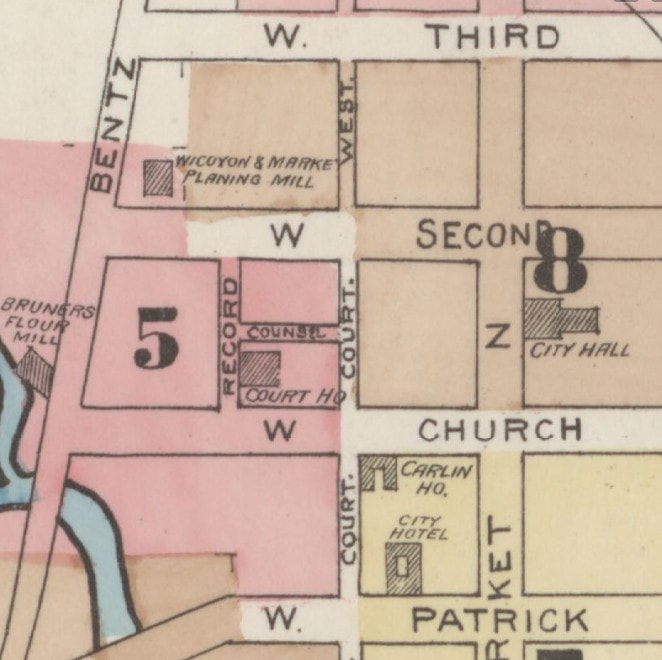

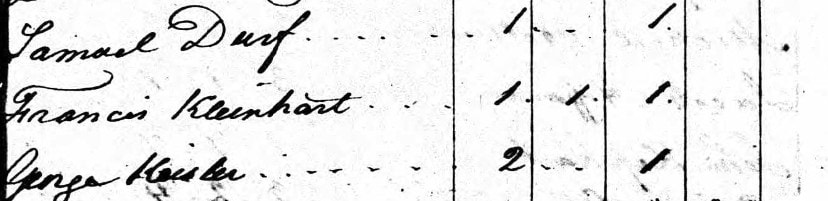

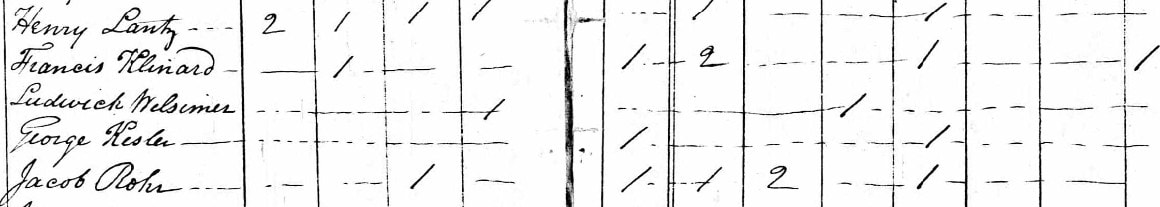

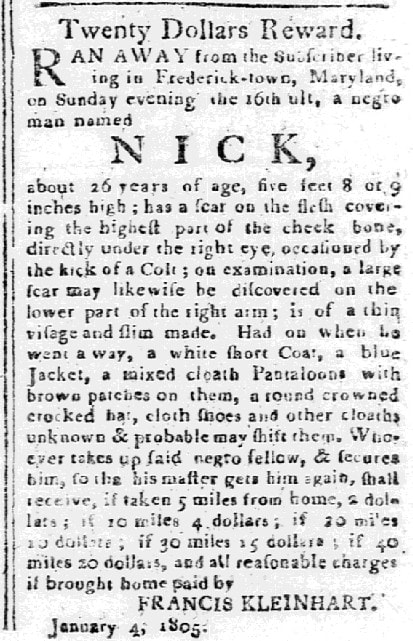

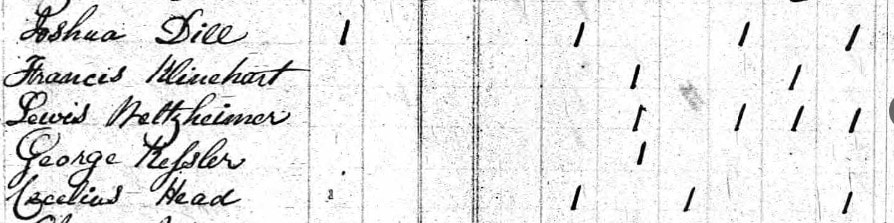

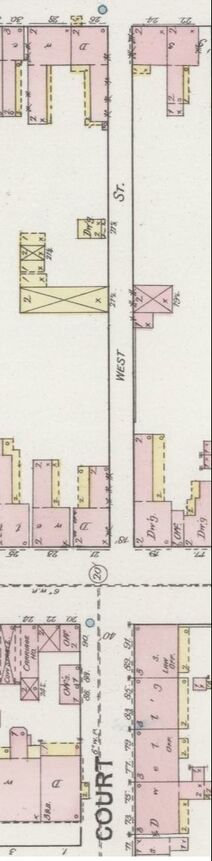

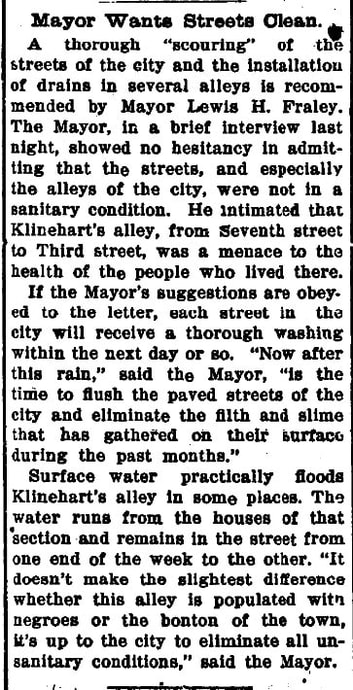

As I drive over W. Second Street, the street sign says that I’m still on Court Street. The road bed actually widens enough to allow for parking on both sides as I enter this new through-way. Up until the 1930's, this used to be called Kleinhart's Alley, a unique name that has a direct link with the fore-mentioned Dill family. You see, Joshua Dill (son of the previously mentioned innkeeper John) was married to Mary Kleinhart, the daughter of a Hessian mercenary soldier who was fighting under the British flag during the American Revolution. Johann Franz Kleinhart (born in 1751 in Hesse-Kassel) was likely captured in New Jersey at the Battle of Trenton. This small, but pivotol, battle took place on the morning of December 26th, 1776 in Trenton, New Jersey. After Gen. George Washington's crossing of the Delaware River north of Trenton the previous night, the iconic hero led the main body of the Continental army against Hessian auxiliaries garrisoned here. After a brief battle, almost two-thirds of the Hessian force (800-900) were captured, with only negligible losses to the Americans. The battle significantly boosted the Continental army's waning morale, and inspired re-enlistments. Kleinhart and other German soldiers were imprisoned at various sites. In his case, Franz Kleinhart would be brought to the Frederick-Town Barracks, a military installation located atop Cannon Hill, today’s site of the Maryland School for the Deaf. The concentration of these German mercenary soldiers led to it receiving the lasting nickname of Hessian Barracks. Kleinhart may have even been involved in constructing the barracks which seems fitting as I have seen a few references to him perhaps possessing talent as a stone mason. Like several other Hessians in captivity here during the war, Franz, or Francis (as his name would become Anglicized) decided to stay in Frederick once released at the end of the war in 1783. There were plenty of pretty German girls around and Kleinhart married a woman named Maria Salome Weltzheimer. The couple had a son named John Frederick in 1787, and two daughters: Mary Matilda in 1794 and another named Wilhemina in 1799. Herr Kleinhart operated a tavern on the southside of E. Second Street near the town's early gaol (jail) and later another on W. Third Street. In Rev. Frederick Weiser’s book Frederick Maryland Lutheran Marriages & Burials 1743-1811, I found references to a number of marriages performed at Kleinhart’s Tavern between 1803 and 1805.

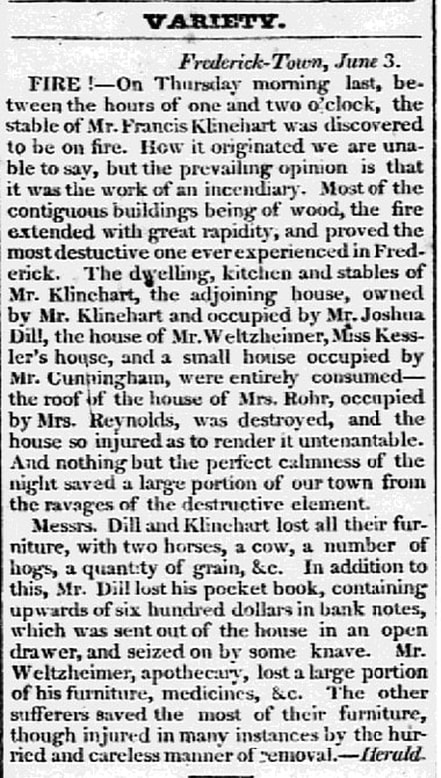

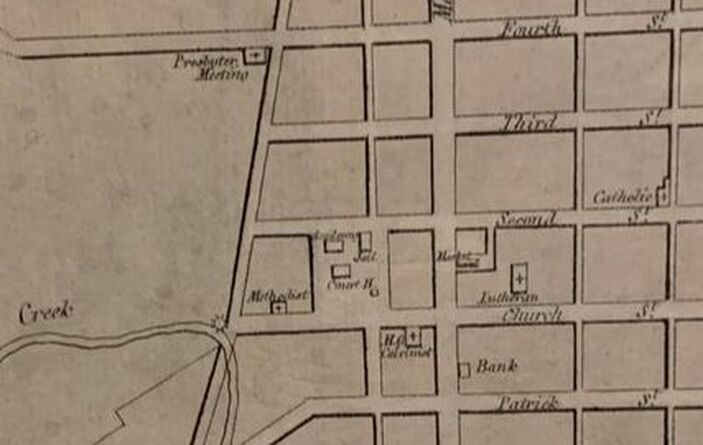

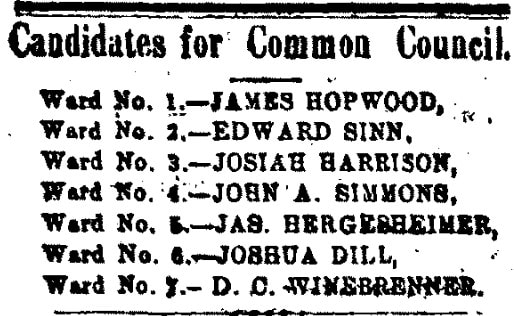

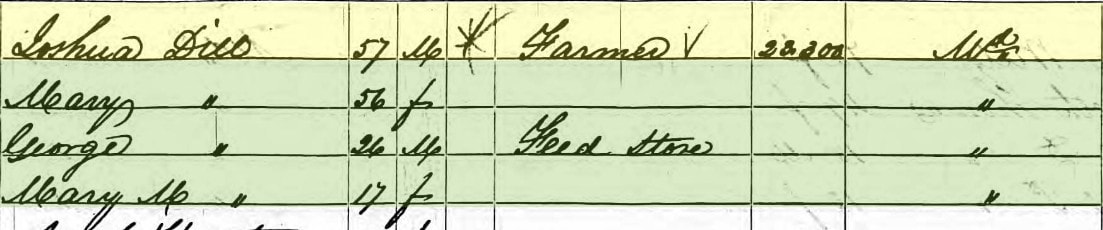

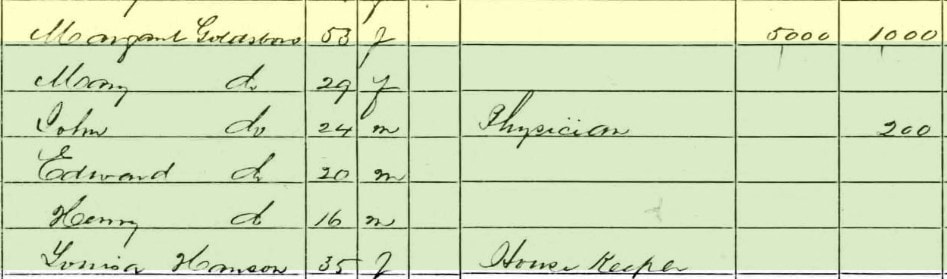

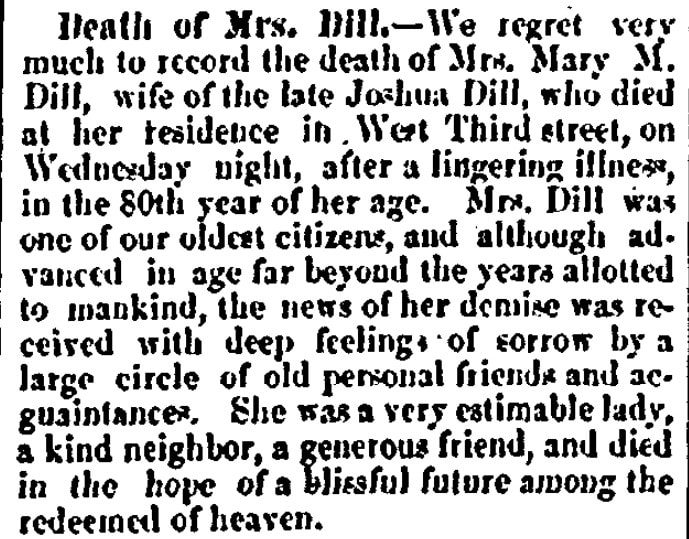

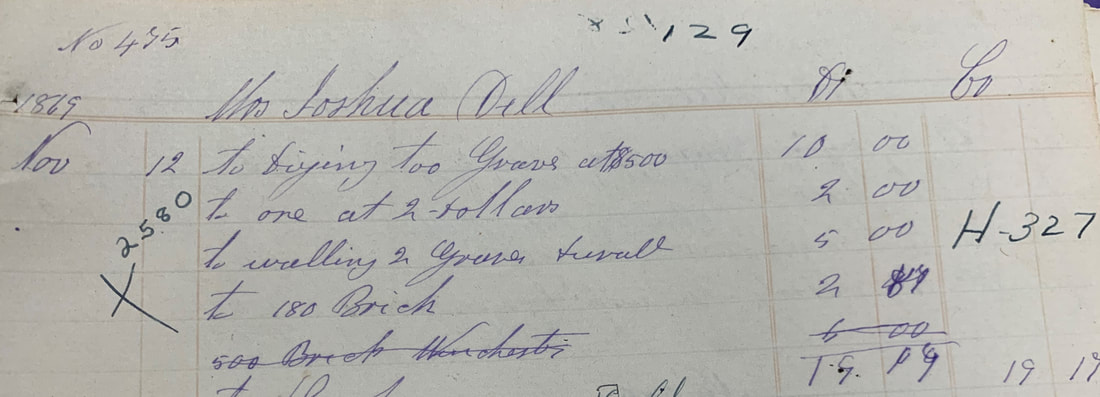

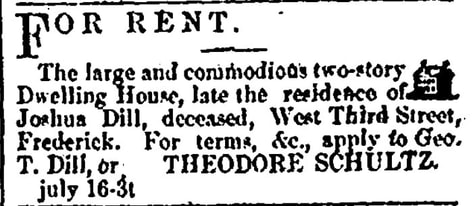

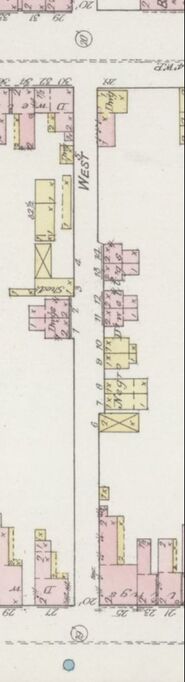

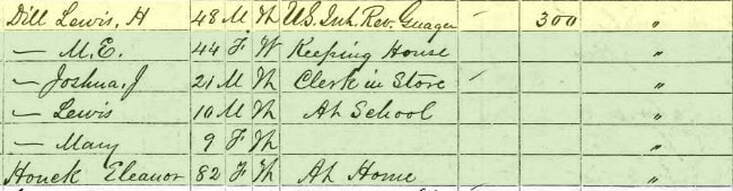

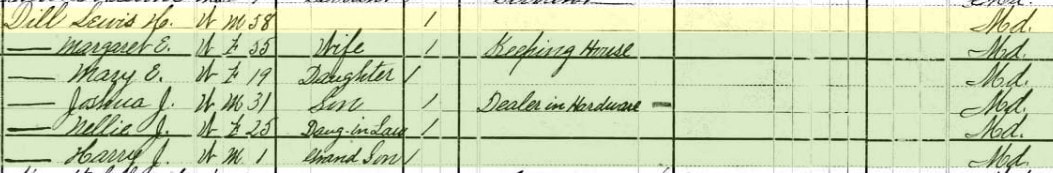

In 1827, Maryland newspapers carried the story of a terrible fire at Mr. Kleinhart’s residence in early June, 1826. Reported as the worst fire in Frederick Town up until that time, the blaze started mysteriously in Francis Kleinhart’s stables located along the alley between W. Second and W. Third streets. The fire spread to consume a number of nearby dwellings including that of Klinehart who was sharing his home with daughter Mary and her husband Joshua Dill. Kleinhart's brother-in-law, Dr. Lewis Weltzheimer, lived next door and his apothecary business fell prey to the flames as well.  News of the fire made newspapers all over Maryland including Baltimore and Easton. Frederick’s Jacob Engelbrecht wrote of the “dreadful fire” in his famous diary in an entry on June 1st, 1826. He would have known Mr. Kleinhart quite well as his own father, Conradt Engelbrecht, was also a Hessian soldier held captive at the Frederick Barracks during the Revolutionary War. I was, however, surprised to see the following written on June 3rd, 1826 by the man who seemingly had his finger on the pulse of Frederick: “Frederick Kleinert, son of Mr. Francis Kleinert was this day brought before the Mayor George Kolb & M. E. Bartgis & George Rohr Esquires on suspicion of being the incendiary of the fire of the 1st instant and after an investigation of 2 or 3 hours was committed to prison to stand his trial at the next County Court. It appeared in evidence that he had threatened to consume the whole fabric owing to some difference between himself and his father bye the bye Fred, is a very bad boy. PS. Clip & clear not indicted  I don’t know what became of Frederick Kleinhart, but assume that he eventually moved away from the area as I haven’t located a grave or obituary. He married Catherine Wiegle in 1813, and all I have been able to find relating to him is a marriage record and (Engelbrecht) diary notation for his daughter Susan Kleinhart (Faubel). He last appears here locally in the 1840 US Census, apparently living in Frederick. Francis Kleinhart, alley namesake, died the following year on September 14th, 1827 and was buried in or next to Frederick’s first Presbyterian Church cemetery. This sacred ground was once located by the congregation's meeting house on the southeast corner of N. Bentz and W. Fourth streets. Jacob Engelbrecht made note of his death and added that “he was buried in a vault made by himself for that purpose in his lot adjoining the English Presbyterian graveyard without a ceremony.”  The author imagines that the Presbyterian Meeting House looked similar to this one pictured here and built in the same era The author imagines that the Presbyterian Meeting House looked similar to this one pictured here and built in the same era Frederick's original English Presbyterian Church was constructed in 1780 and built of brick and boasted "high backed pews, a lofty pulpit, and a brick floor." A new house of worship was completed in 1825 on W. Second Street, but the original graveyard remained active until 1885, at which time the trustees decided to discontinue use. The old structure was utilized afterwards as part of an old factory until being sold, along with the cemetery ground, to the Salvation Army for $400 in 1887. Most of the bodies here were removed on May 10th, 1887 and transferred to Mount Olivet. These were originally placed in Area Q, but later moved to Area NN on December 12th, 1907. Among these was the old Hessian Kleinhart, who is said to rest in Lot 131/Grave 11. He doesn’t have a stone, as it likely disappeared along the way, not uncommon as broken or worn stones were seen as unsightly elements here in Frederick’s “Garden Cemetery” back in the day. Mary (Kleinhart) Dill and her husband, Joshua, repaired/rebuilt their home and lived on West Third Street until their respective deaths—the house still stands today at 102 W. Third Street. We are lucky to have a bit more info on Joshua thanks to a publication that the cemetery undertook in 2014 with the bicentennial of the War of 1812, entitled Frederick’s Other City: War of 1812 Veterans: Sergeant Joshua Dill served under Capt. George W. Ent, 3rd Regiment, Maryland Militia, from August 24 to September 30, 1814. Joshua Dill was born September 13, 1792 in Frederick to John (of “Dill House”) and Catherine Burkhardt. He was married to Mary M. Kleinhart on April 12th, 1817 in Frederick. Joshua died July 24, 1868 at the age of 75. He was laid to rest in Mount Olivet Cemetery in Area H/Lot 327. Mary was born March 24, 1794, and died May 14, 1873 at the age of 79. She too was buried in the same lot as her husband. Joshua held the following positions within Frederick City: A constable in December 1820, May 1825, and June 1833; Deputy Sheriff in October 1821; Lutheran Church warden in January 1824 and an Elder in January 1833, January 1841 and January 1844; a councilman for Ward #6 in February 1834, February 1862 and February 1863. He was the owner of the Cross Keys Hotel, which became known as the Dill House, located southeast of the Courthouse. Joshua and Mary Dill had six known children. First was John Francis Dill (1819-1891), Lewis Henry Dill (1821-1894), George Theodore Dill (1823-1888), Henrietta (Dill) Wisong (1826-1872), Hirame Dill (1828-1829) and Mary M. (Dill) Schultz (1830-1861). Here are census records showing Joshua and Mary Kleinhart Dill's family living on W. Third Street: Joshua Dill passed on his father’s tavern enterprise to his son, Lewis Henry Dill. As mentioned earlier, a gentleman named Frank B. Carlin entered the picture in the mid 1860s as he was hired to be the manager in 1867. Lewis Henry Dill would eventually sell the property to Mr. Carlin's widow, Ann Cecilia, in 1885, completing an 80-year ownership of this endeavor which had previously changed its name to the Carlin House in 1879. The Dills, primarily Joshua, did a great deal of buying and selling of land in and around Frederick City. He had ample opportunity during his terms as sheriff, as people regularly were put in the position of hastily unloading their holdings to pay outstanding debts. The lion’s share of these auctions occurred at the Dill House to boot. Joshua Dill and his children benefited greatly. In his later years, the former sheriff and innkeeper put his efforts toward farming, as he had plenty of parcels to care for. Joshua Dill died on July 24th, 1868 and wife Mary, daughter of the old Hessian, passed on May 14th, 1873. A notation in our cemetery records says the following: "REMOVAL from the Dill's Cemetery where he was originally buried on July 25, 1868." I haven't been able to find a reference to a "Dill's Cemetery" but have a theory that it could be a reference to a plot within or adjacent the Old Presbyterian graveyard where his father-in-law (Francis Kleinhart) was buried. Regardless, Joshua Dill was removed to Mount Olivet and reburied in the Dill family lot on November 24th, 1869. His parents would join him here a year later as previously stated. Unlike the hotel, the other "Dill House," the home of Joshua and Mary Dill, stayed among the family and descendants until 1979. I found an ad offering the dwelling for by son George and son-in-law Theodore Schultz. Cooler heads must have prevailed, or a relative stepped up with the cash to purchase. As I pass the old Kleinhart/Dill residence on my right, I cross over W. Third Street and find myself in a "tried and true" portion of virtually unaltered Klineharts Alley. I can’t travel the alley to its terminus at W. Sixth Street because I’m soon forced to take my first turn of the commute trip home—a left onto W. Fourth Street. In researching for a Frederick-based, Black history documentary project nearly 25 years ago, I learned that many African-American/Black residents lived along Klineharts Alley between W. Fourth and W. Seventh streets. A derogatory moniker of sorts once used as the name for a cluster of dilapidated shanties and shacks that once stood along the alley was Santa Domingo. I don't know if the Blacks here were actually of Haitian origin or not. The narrow roadway was usually in terrible shape and often flooded, prompting a former mayor's ire and municipal help. I could judge this from an article found in the Frederick News from 1914. LEG 4 —"Dilly, Dilly" Once on W. Fourth Street, I soon come to a stoplight at the next cross-street of N. Bentz Street. I won’t get into the name Bentz at this time, but here was another family with deep German roots in town and a namesake mill located at the southern portion of this intersecting roadway at Carroll Creek. A glance to my left toward the southwest corner of the intersection shows me a row of townhouses where the original English Presbyterian Meeting House once stood. Of course this was before the site became home for a number of years to the Salvation Army. The property sold again and was developed into townhomes on both corners. Francis Kleinhart, and perhaps son-in-law Joshua were once buried in the adjacent church graveyard as I remarked earlier. It all seems to come full circle as I cross Bentz Street and find myself heading west on Dill Avenue. Now where in the world did that name come from? You can guess by now...or you sure as heck better be able to!

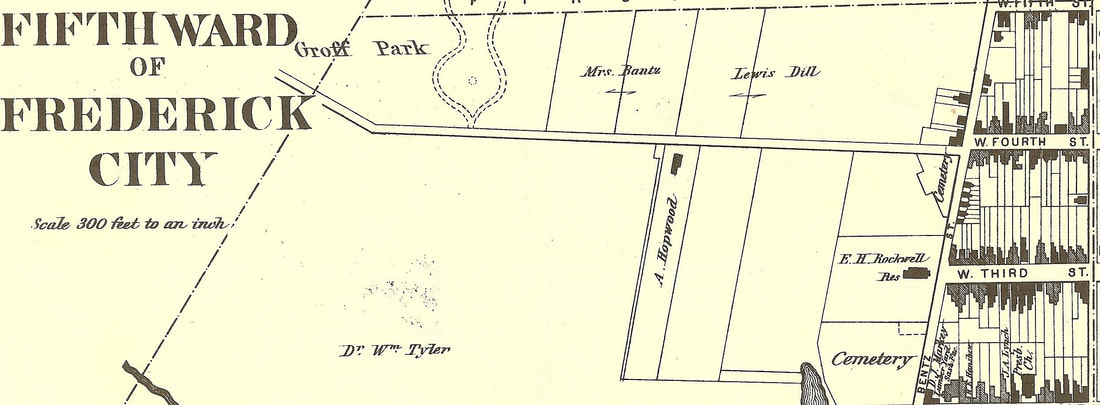

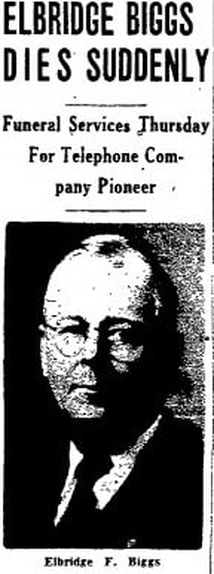

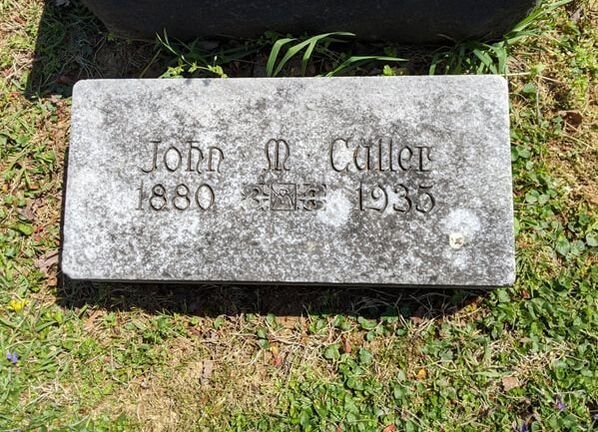

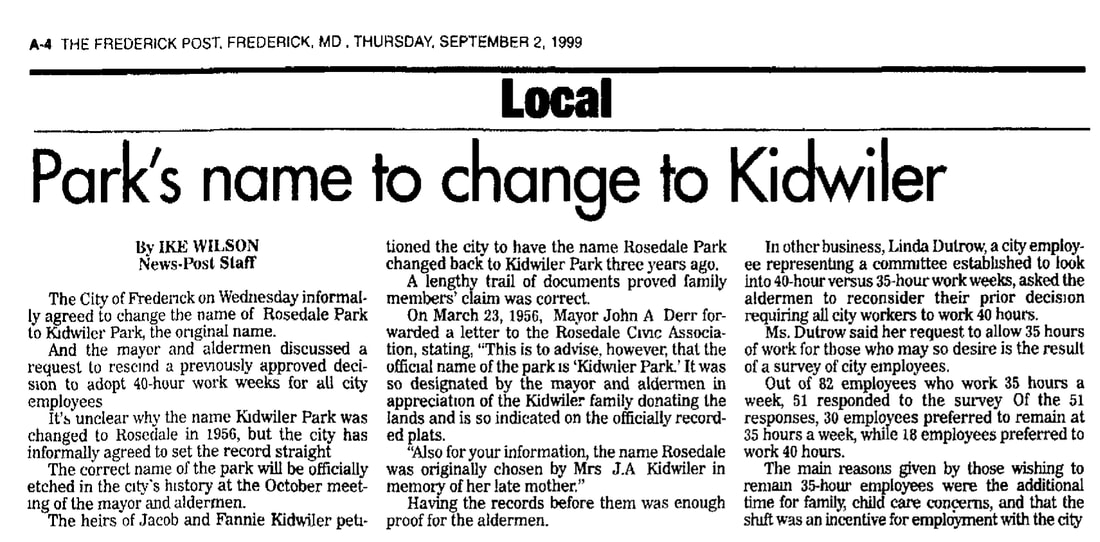

The 1873 Titus Atlas clearly shows land parcels owned by Dill. It wouldn’t be until August, 1901 when Frederick alderman John Baumgardner suggested the name of Dill Avenue to replace the W. Fourth Street Extended moniker. It was duly accepted, and the rest is history. As for Lewis Henry Dill, he made his living as a farmer and large landholder thanks to previous generations of “Dill”igent business persons. He is buried in Mount Olivet's Area G/Lot 32. Heading northwest out of town, Dill Avenue suddenly becomes Rosemont Avenue once you pass Hood College. The name Rosemont comes from a poultry farm, and later subdivision, of the same name. The neighborhood was laid out in 1913 by Eugene Sponseller and Harry Tritapoe, the latter being the poultry farmer. Two gentlemen of particular interest in the Rosemont story are Elbridge F. Biggs and John M. Culler, who jointly bought eight building lots here in 1913. Their purchase constituted the entire 1st block of Fairview Avenue, north of the newly named Rosemont Avenue which came with the development. John McCleary Culler (b.1880), was a grocery store proprietor, and Elbridge F. Biggs, Jr., the switchboard manager for Chesapeake & Potomac (C&P) Telephone Company. In addition to being successful businessmen and civic leaders, this tandem were brothers-in-law as Mr. Culler was married to Mary Ada Biggs, Elbridge’s sister. The Cullers lived on Elm Street and the Biggs took up residence on Fairview Avenue which was the principal street of the Rosemont development, which didn't go any further to the west. As far as Rosemont avenue, the road had been unofficially called the Montevue Turnpike, a crude translation to French of “Mountain View,” leading to the county almshouse of the same name as mentioned earlier. Rosemont Avenue became the new name as it ran past the new development. The transition between Dill and rosemont avenues occurs at a major bend in the roadway, exactly in front of Hood College's main gate. From a timeline perspective, the college campus here opened in 1913, moving from downtown's Winchester Hall. The cross streets here along Dill and Rosemont are mostly named for college connections (ie: College Avenue, College Terrace, College Parkway, Hood Alley), scenic vistas like the fore-mentioned Fairview, and trees/plants (ie: Elm Street, Ferndale, Magnolia Ave). A few more exist like Lindbergh and Grove. Lindbergh was named for the heroic aviator, but I don’t know if Grove paid homage to trees, or the local family of the same name. Scottish Alley is a story unto itself as well, and I will leave it alone for now. However, there is one additional street name that irks me more than any other--Dulaney Street. This is the only tribute we have to the founder of Frederick Town/City and Frederick County. It's more or less an alley, and should be spelled Dulany as this was the way the man spelled his name. The pathetic lane connects Dill Avenue to W. Second Street, running two measly blocks. For God's sake, I've done far less for Frederick over my lifetime, but have a prominent thoroughfare named for me in Christopher's Crossing. LEG 4 —"Bigg Deal" As I slowly approach the terminus of W. 2nd Street as it ends in front of Frederick’s oldest home, Schifferstadt, I quickly pass Culler Avenue to my right. I was particularly interested in this street name because my mother lived on this street for a decade back in the 1990s. I assumed Culler Avenue was named for Lloyd Culler, former mayor. I was mistaken as I have since learned (from my assistant Marilyn) that it was named in honor of John M. Culler, the grocery store owner/Rosemont lot buyer who lived on Elm Street. Sadly, Mr. Culler would die in a car accident in 1935 on MD 26 near Mount Pleasant while returning home from taking his son back to school at Western Maryland College. The street would be soon named in honor of the former businessman on a 1937 plat for a new subdivision called Rosedale, planned to encompass the Jacob A. Kidwiler property stretching from Fairview Avenue and the Rosemont subdivision, westward to existing Wilson Avenue in Villa Estates which had come about around 1930. The Rosedale property had been bought in 1931 from Henry Krantz, son of Edward Krantz who owned this property prior. You may remember Edward from another “Story in Stone” written just a few weeks back and entitles "A Statue of Hope". At the time, the purchase (Jacob A. Kidwiler) actually lived on the property where Frederick High School is now located before selling that to the Board of Education in 1938. Anyway, there was no US15 bypass as yet as this would come in the early 1950s. As I pass by Schifferstadt Architectural Museum and go under the US15 overpass, I soon make an immediate turn right off Rosemont Avenue onto Biggs Avenue. I failed to mention Biggs earlier in my dazzling overview of the roadways of Villa Estates/Rosedale. To tell the truth, I was very interested to learn who the famed namesake was myself. I ride this road nearly every day, and my boys had their elementary school bus stop here. Well, with help from Marilyn, I learned that Biggs Avenue was named for the other major Rosemont development investor, John M. Culler’s brother-in-law, Elbridge F. Biggs, Jr. It's certainly a further stretch than Mr. Culler by having his name remembered in the form of a street, but no big deal I guess. Or should I say, "No Bigg Dill" instead? As you can see, this commute, albeit short, has made me quite punchy! Although Mr. Biggs is entombed within the mausoleum at Clustered Spires Cemetery atop Linden Hills, John M. Culler and wife Ada Biggs Culler are buried in Mount Olivet’s Area AA/Lot 2. We also have buried here Mr. Kidwiler, "the former king of Rosedale" and a Spanish-American War veteran as well. His gravesite is in Area AA/Lot 84, not that far from that of Mr. Culler. I will write a more in-depth piece on him one day, but I learned that his name is the proper one for my neighborhood park as somewhere along the line it had wrongfully been changed to Rosedale Park.  Blue Ridge Ave with former O'Connor residence on the left Blue Ridge Ave with former O'Connor residence on the left I know this sounds anticlimactic, but my third turn is a left onto Blue Ridge Avenue. It’s a short thoroughfare of two blocks with few speaking points. However, to the left, at the intersection with Schley Avenue, one can gaze at the childhood home of Frederick’s current mayor, Michael O’ Connor. This property (on the southeastern corner of the intersection of Schley and Blue Ridge) was sold out of the family a few years back, after Michael’s dad passed away. Saying this, I’m assuming we won’t see any museum or "mayoral library" placed here in the near future.  Taney Ave (left) Taney Ave (left) I cross Schley and proceed to the next sleepy intersection, where I make my fourth, and final, turn-- a right, onto my home street of Taney Avenue. I won’t get into the story behind that guy, but those who may have read my September 19, 2019 "Stories in Stone" article, know that Roger’s wife, Anne, and three daughters are buried in Mount Olivet. Anne Taney's brother, Francis, also has a nice burial site, complete with an impressive monument up by our front gate. I hope this story was worth the read, as it surely took far longer to do so than it takes me to drive my daily commute home. Thanks for the company, take care and stay safe! "Stories in Stone" is made possible by: