|

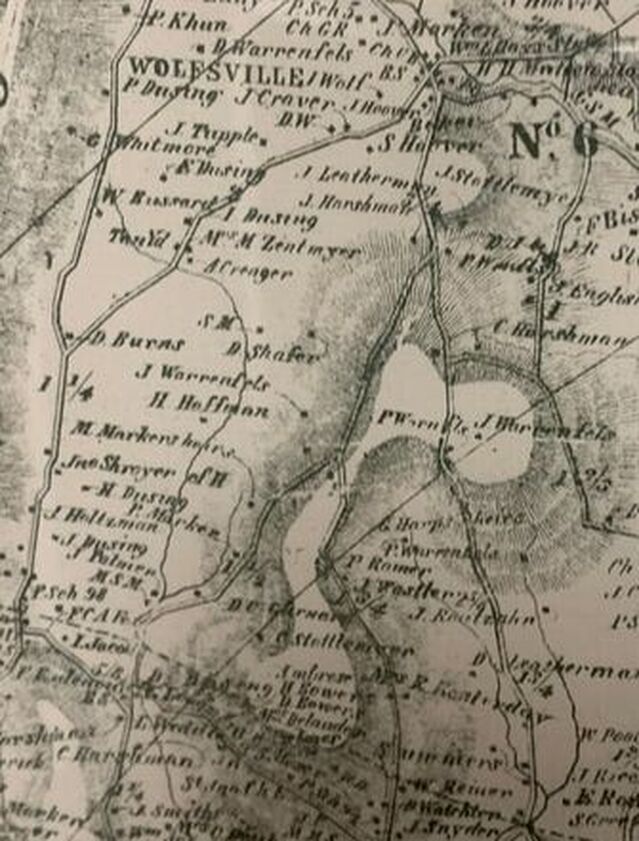

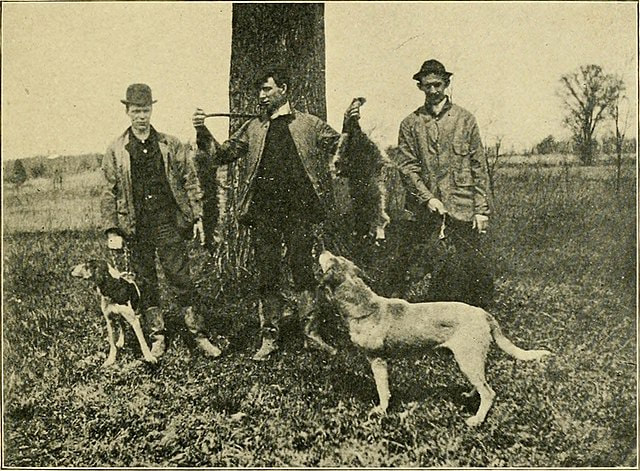

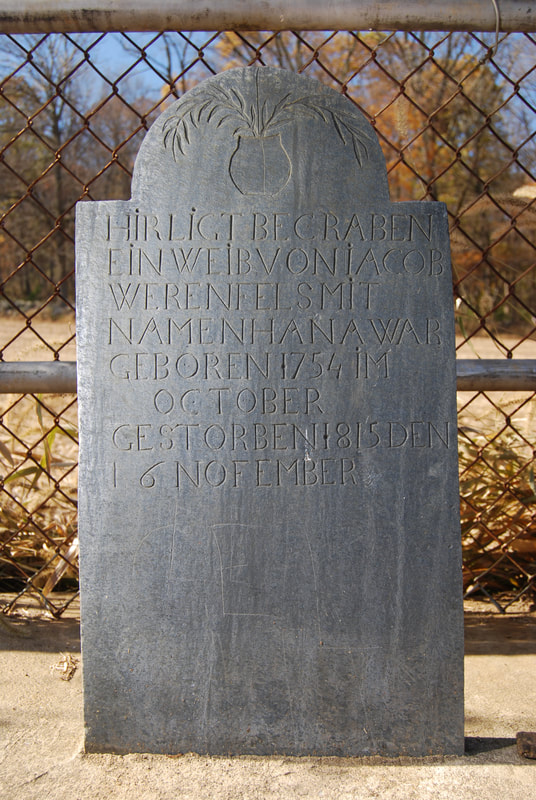

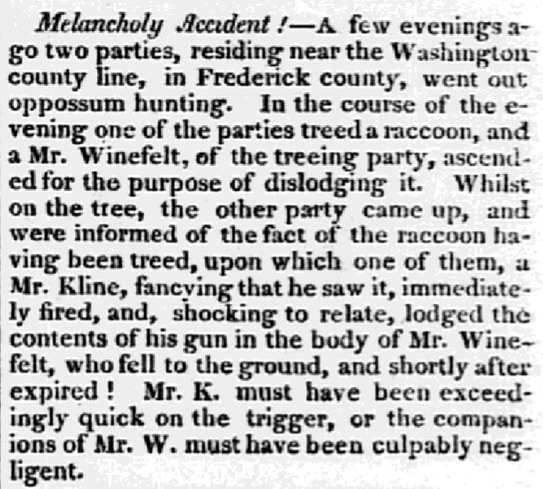

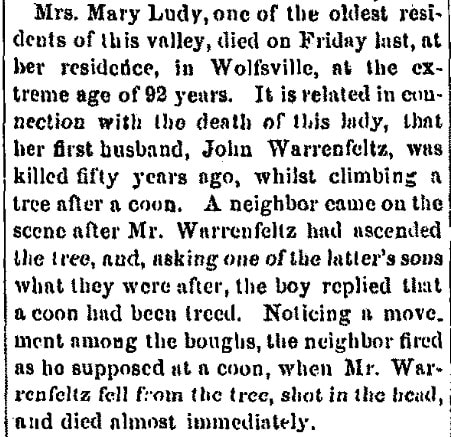

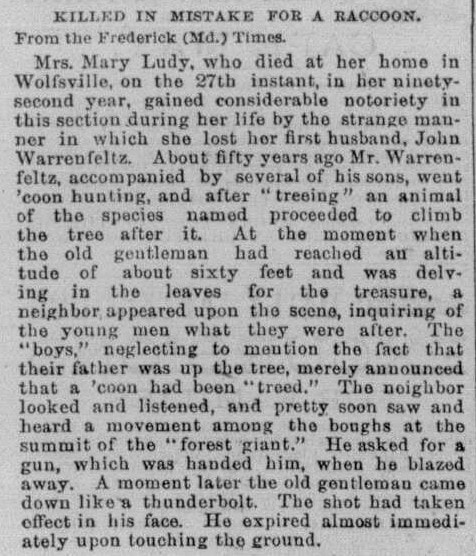

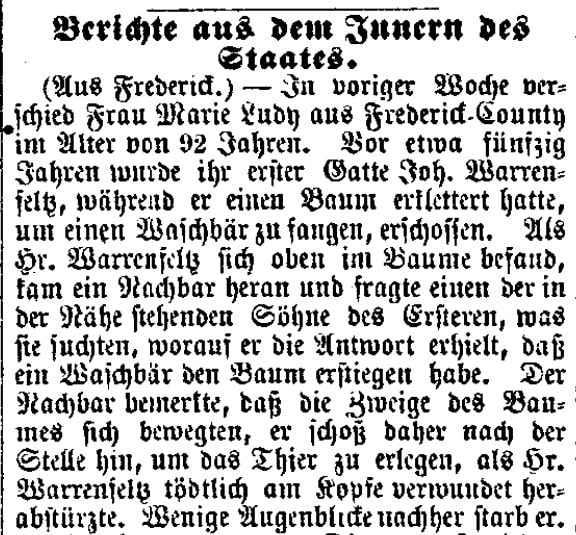

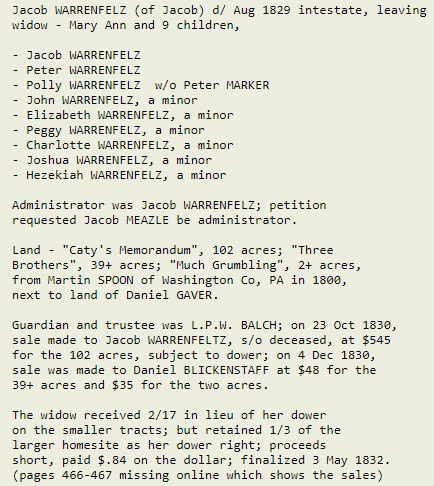

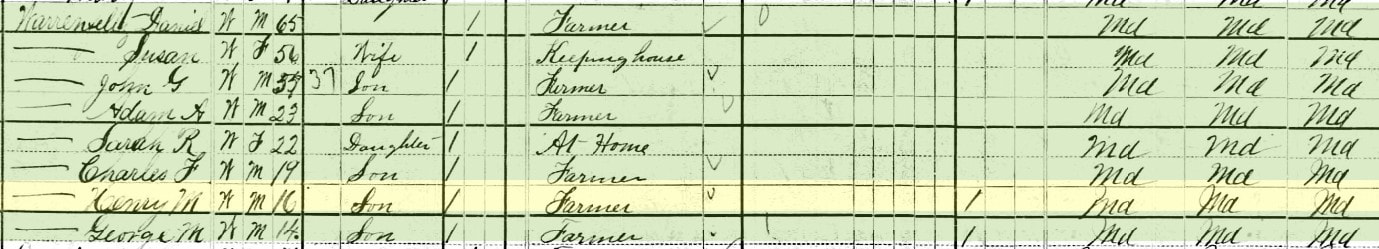

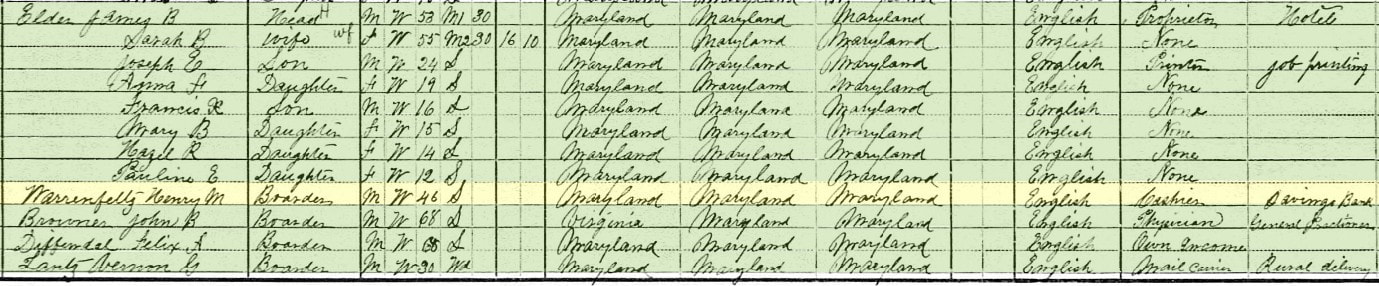

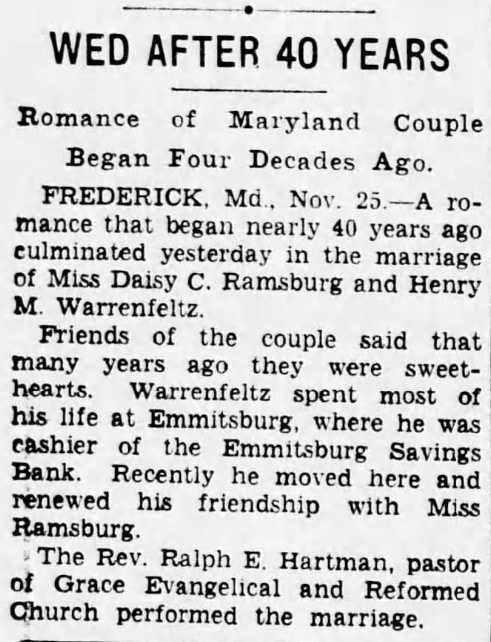

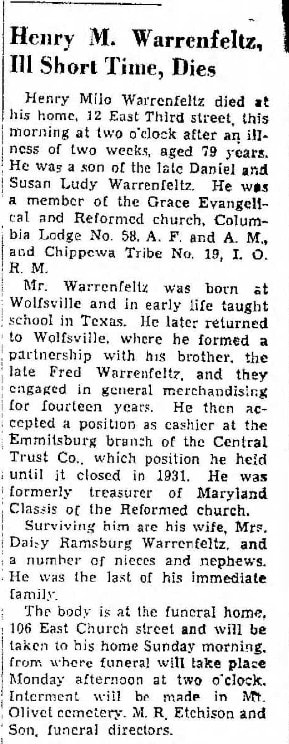

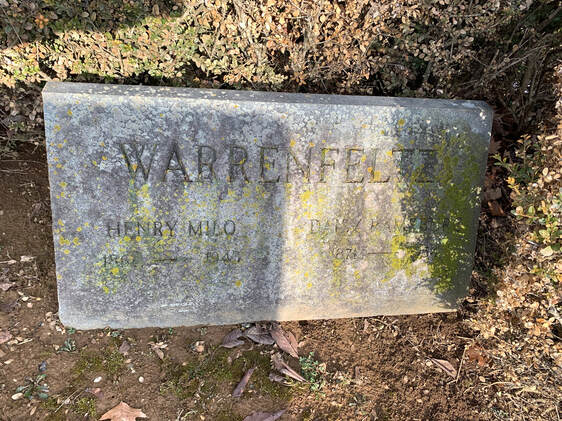

Perhaps the following short story is certainly more suitable for early October instead of late February. I recently learned that October 1st is International Raccoon Appreciation Day. This find came simultaneously with an interesting and bizarre obituary I saw in a vintage newspaper while researching a completely different story. International Raccoon Appreciation Day (IRAD) is a day meant to celebrate all animals, specifically raccoons, that, while being an important part of their ecosystem, are misunderstood. Often these "bandit-looking" creatures are commonly associated with thefts from garbage cans and dumpsters, but moreso rabies. It's fair that most of us consider these woodland creatures as “pests” or “nuisance animals," like foxes, wolves and coyotes. The raccoon is a nocturnal mammal characterized by its bushy ringed tail. It is native to North America and can be found in many parts of the U.S., Canada, Mexico, and the northern part of South America. There are also raccoons in Germany, Russia, and Japan. IRAD was started in 2002 by a young girl in California. It was meant at first to show that some folks liked and respected raccoons, as evidenced by a plethora of raccoon items from stuffed animals to t-shirts. There are also some people who have misguidedly tried to keep raccoons as pets. As word spread of the young lady's campaign (mainly to the girl’s relatives in various world countries), the name was changed to International Raccoon Appreciation Day in 2003. The day also encourages people to protect the raccoon’s natural habitat. I have yet to see a raccoon here in Mount Olivet, but I would bet that we've had some of these visitors in the past as I've seen coyotes, foxes, deer, and even a bear. A few weeks ago I was drawn to the Mount Olivet gravesite of Henry Milo Warrenfeltz, born January 15th, 1864. He wasn't my prime search on that particular day as I found him solely by stumbling upon the obituary of his paternal grandmother while working on another story about quilting. I soon after sought out his grave in Mount Olivet's Area T, and found him a literal hop, skip, and a "shoot if you must this old grey head" from the final resting spot of Barbara Fritchie. Remember that I said "shoot" here as that plays a paramount role in our story. Henry would be my Mount Olivet connection to an interesting early immigrant family that descends from Switzerland. They have the prototypical story of Frederick County with early German and Swiss immigrants settling in the northern reaches. The apocryphal tale says that our mountainous terrain at the eastern edge of the Maryland Piedmont reminded these people of their former homes in Europe, thus inspiring them to clear forests for family farms. In this particular case, it is said that Johann Jacob Werenfels (1730-1807) came to America around 1749 from his native town of Basel. The surname would eventually be anglicized to Warrenfeltz in time, and it would become one of the well-known names of the area up to the present-day. This gentleman apparently acquired 999 acres of land between Wolfsville and Ellerton on the western foot of Catoctin Mountain, north of Myersville. In the late 1770s, he married Hannah Ann Hartman (1754-1818) and raised 11 children on his large farm. Johann Jacob is also said to have made buckskin breeches and gloves. His neighbor, Godfrey Lederman (later Leatherman), was a Revolutionary War veteran, and owned a like amount of property to the north of his, which was considered to be in Wolfsville. Three of Mr. Lederman's children would marry three of Mr. Warrenfeltz' children.  Close-up view of Wolfsville-Ellerton vicinity on this 1858 Isaac Bond Map showing Warrenfels family properties as labeled on map. The original property is to the center/right along the Harmony-Wolfsville Road and marked with heirs "P Warrenfels" and "J Warrenfels." Henry Milo Warrenfeltz grew up on the farm of his father, Daniel Warrenfeltz, which is located upper left and marked as "D. Warrenfels." One of these pairings would be Johann Jacob Warrenfeltz, Jr., born September 21st, 1785 and Mary Ann Lederman (1788-1879). The couple married in 1809 and built a nice stone house on a 30-acre parcel that "John" bought from his father-in-law. By 1828, the couple had ten children with one of these being Daniel Warrenfeltz (1814-1901), the father of Henry Milo Warrenfeltz —the gentleman who started our impromptu "roots quest" here, and buried in Mount Olivet within Area T. Henry Milo is somewhat of a "Burial Black Sheep" of the family in terms of resting place, as his parents and most of his siblings were interred in Wolfsville Reformed Cemetery. Here is where our story gets a little interesting in regard to "wildlife fun," just not so much for the aforementioned grandfather of Henry Milo Warrenfeltz —Johann "John" Jacob Warrenfeltz, Jr. We must slip back to the 1820s to tell the story of his unfortunate death. And yes, this is where this week's colorful story title comes in. The history of raccoon hunting in our time can be traced to Native Americans, who hunted them for food and pelts. The practice was adopted by European settlers, who introduced raccoon hunting dogs to the equation in Colonial times. George Washington was credited with owning some of the best raccoon hounds. Early dogs had trouble tracking the raccoons when they climbed trees, so breeders developed varieties that learned how to follow treed raccoons. In the mid-to-late 1800s, raccoons were hunted primarily for their pelts. A fair price for a pelt, half a century later in 1885, was 25 cents.  On the 9th of October, 1828, John and a few of his teenage sons (likely including Daniel aged 14) went on a night-time hunting excursion in the darkened woods by their home. Descendant Virginia Kuhn Draper wrote in her book The Smoke Still Rises (published in 1996) that this party was not the only one in the vicinity on this particular, moonlit evening. Apparently a neighbor, a Mr. Kline, had gone out in search of squirrels for his supper that night. It seems that Mr. Kline had instant success in bagging his prey and was on his way back home when his dog started to bark wildly ahead. When he caught up to his hunting companion, he found that his dog had "treed" a raccoon, as it had taken refuge in the top of a tall arboreal specimen. Mr. Kline discharged his firearm a few times with no luck of shooting the "interloper." Feeling he did not have the right ammunition, he quickly returned to his nearby home in hopes to return shortly and finish off the business at hand. Meanwhile, while Kline was on his way for greater firepower to fell the raccoon, John Warrenfeltz and his boys came on to the scene as their dogs "re-treed" the raccoon, who I am assuming was a little late in trying to make a great escape (after Kline stepped away for the moment). Mr. Warrenfeltz had been successful in killing the rogue animal on his first shot, however it was lodged between tree branches. John laid down his gun and proceeded to climb the tree in an effort to retrieve the masked-beast. Just then, Mr. Kline returned to the area with a silver bullet in his gun's chamber. Unfortunately, this is when a major breakdown in communication between all parties occurred. What a tragedy, and one that would later be recounted in newspapers throughout the country in 1879 upon the death of John's widow, Mary Ann, who would die on June 27th, 1879 at the age of 90. She had remarried in 1831, but would raise her children (including Henry Milo's father Daniel) into adulthood. Her obituary told the melancholy story of her first husband being mistaken for a raccoon, 61 years earlier. Although well known in the upper Middletown Valley, the former Mrs. Warrenfeltz would become "almost-famous" posthumously the country over as her obit (carrying this sensational story of her first husband's death) would be carried everywhere. I found newspapers presenting the disturbing last moments of life for John Warrenfeltz all over the country. I even found it published in German! As with many stories, it became a bit embellished along the way. Nonetheless, this sensational tale from Ellerton, MD made publications all over the country including the Westminster (MD) Democratic Advocate, the Baltimore Sun, the Philadelphia Times, Bridgeton (NJ) West Jersey Pioneer, Winnemucca (NV) Silver State, Ironton (MO) Iron County Register, Austin-Mower County (MN) Transcript, Superior (WI) Times, Decatur (IL) Daily Review, Sterling (IL) Gazette and the Jeffersonville (IN) National Democrat to name a few. As for the gravesite for John Warrenfeltz (aka Johann Jacob Warrenfels, Jr.), I could not find one. Jacob Holdcraft's Names in Stone didn't help me in this arena either. I hypothesize that he would have been buried with his parents in the Warrenfeltz Family Cemetery shown earlier, or in the Wolfsville Reformed Burying Ground. His gravestone was either lost to time, or never placed. He did leave Mary Ann, his wife, with multiple children and a large farm to run. She remarried soon after as I've stated. Williams' History of Frederick County states that John's son, Daniel, would become a prominent member of the community and Catoctin District. He would eventually purchase property from the heirs which included 130 acres of farm and timber land, and spent his life cultivating and improving it. He was also engaged in sawing out timber for buildings of all kinds. Daniel married Susan Ludy, daughter of another local and prominent farmer of the area, and had 13 children, raising 11 to maturity, Henry Milo being the second youngest. Daniel eventually operated a farm west of Wolfsville which can be found on the Bond Map of 1858, and again on the Titus Map of 1873. This is where Henry Milo Warrenfeltz spent his childhood. The boy would attend local area schools and had a successful professional career engaged in teaching, running a commercial business, and lastly, banking. He was also one of the incorporators of the Catoctin and Pen Mar Railway Company. He can be found in census records living as a boarder in Elder Hotel on East Main Street in Emmitsburg. Henry Milo married late in life a local woman named Daisy Ramsburg, and the couple lived in her family home (with a sister) at 12 East Third Street in Frederick. Henry Milo Warrenfeltz' life story is represented in his obituary of November 27th, 1943. His death made the front page of a Frederick News edition which included up to date information about the second World War raging in Europe and the South Pacific. However, there was absolutely no mention of his grandfather's untimely death. The great-grandson of the supposed "Ellerton (supposed) Raccoon" was laid to rest in Mount Olivet Area T/Lot 3. Henry's wife Daisy (Ramsburg) would join him here in March, 1954. One particular rabbit hole, or should I say "Raccoon Hole," that I explored with no luck was finding out where that nifty middle name of "Milo" came from. Although, I couldn't make this familial connection, I did make another to a stuffed animal that relates nicely to the wonderful world of raccoons. Along the way of research, I also found this interesting aside on the magical internet. The unsung heroes, or instigators in our story are the four-legged hunting companions of John Warrenfeltz and Mr. Kline. You could call them "coon dogs," a popular name for such well-trained beasts. Well, I learned that there exist a Coon Dog Memorial and its located in a special graveyard in Colbert County, Alabama. It's called the Key Underwood Coon Dog Memorial Graveyard. This is a specialized and restricted pet cemetery and memorial, reserved specifically for the burials of coon dogs. The cemetery was established by a man named Key Underwood on September 4th, 1937. Underwood buried his own dog there, choosing the spot, previously a popular hunting camp where "Troop" did 15 years of service. More than 300 dogs are buried here.

4 Comments

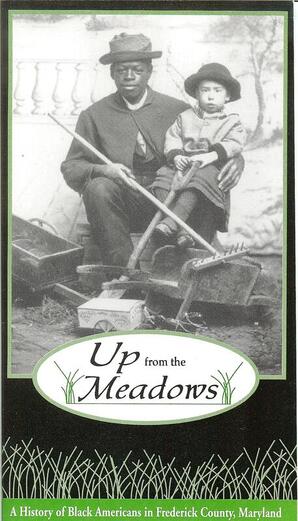

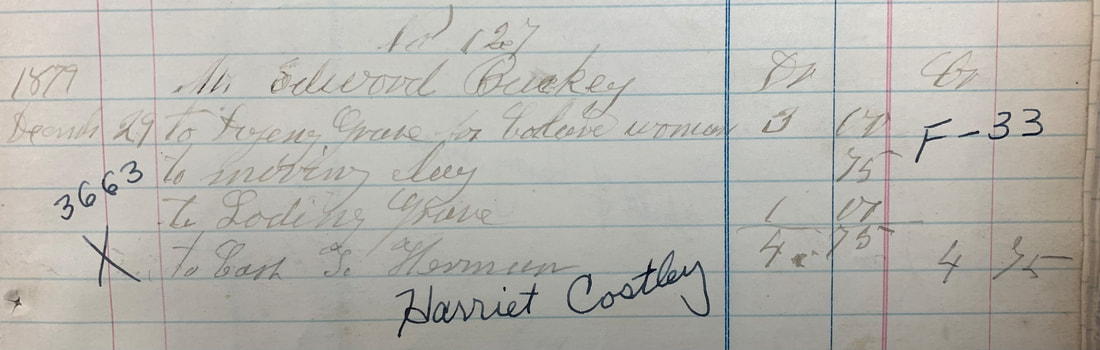

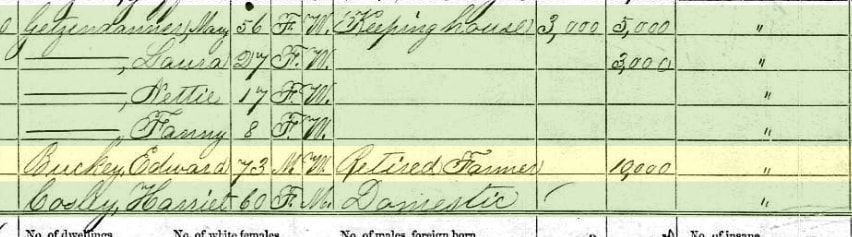

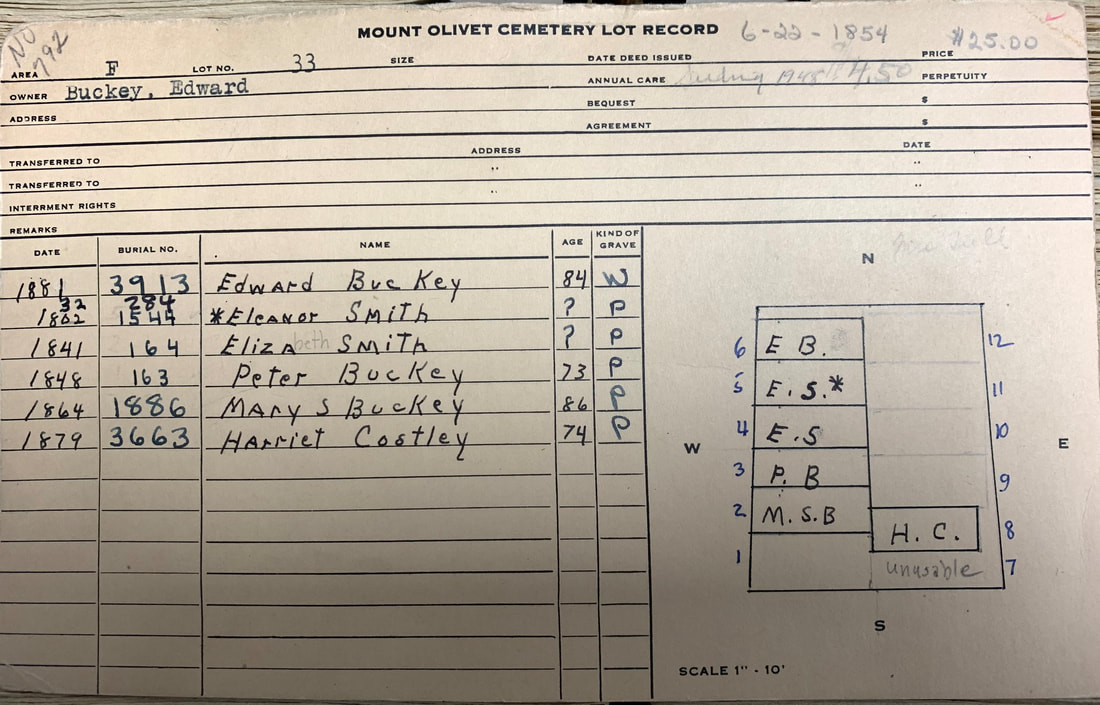

With Black History Month here once again, I can't help but think about the research I was conducting seven years ago at this time with a special three-part story exploring the first people of color buried here within Mount Olivet Cemetery. This cemetery opened in 1854 and was segregated for its first century of operation. This was no different to Frederick having separate schools for black and white residents, and the same could be true for parks, restaurants and shops. Special entrances were employed for races at places of entertainment like our several theaters, while the Great Frederick Fair had restrooms and water fountains for white patrons and black patrons. It was a different time, and this history is not meant as a shaming lesson, but one of understanding and moving forward as we are all Fredericktonians, Frederick Countians, Marylanders, Americans, humans before we should start separating off into skin, hair or eye color and matters of faith, politics or what sports team or musical stylings one follows. The "Stories in Stone" blog was just months old in February 2017, as I had just started it in November 2016. As a matter of fact, I was still a new employee with Frederick's historic garden cemetery, having begun work as community relations and historic preservation manager in February 2016. I called (what I had thought would originally only be a two-part story) "Sidestepping the Color Barrier: The First Blacks Resident Buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery." This was not my first foray into this subject as I had developed, produced, researched, wrote, shot and edited a 5.5 hour documentary focusing on the Black history of Frederick County, Maryland back in 1996-97 when working for GS Communications' Cable Channel 10. To me, it was soon revealed that Frederick's African-American heritage is a tremendous and dynamic case study of "a border county within a border state." The award-winning video documentary explores the achievements and struggles of local Blacks since the inception of Frederick County in 1745 up through Emancipation in 1864 and the Civil Rights movement 100 years later. The magic of the program was certainly due to the incredible on-camera commentators who shared their research, experiences and stories. I was so lucky to have had so many great mentors and teachers for this, a truly humbling experience.  So, I had a pretty good contextual background to guide me going in search of the very first African-Americans buried here in Mount Olivet. As its been 30 years now since I first had the idea to produce that project with my very supportive employers (the Delaplaine and Randall families), I have put together an adult-learning class to act as a companion to the video. In that same manner, I have continued doing some new research as I truly watch in awe the fine work being done with the local AARCH (African American Resources Cultural and Heritage Society) Group and their work towards opening a research center and museum here in town. Since 2017 and my "Sidestepping" series, I have done a few other subjects connecting to our local Black History and have made connections to some interesting national figures and events. In the process I am putting together a Cemetery walking tour that will help tell a very interesting cultural story, of course employing various gravestones to represent the lives of subjects whose mortal remains lie below. Coming full circle, I began my "Up From the Meadows" documentary with a montage of gravestones in Black cemeteries throughout the county, and posed the question: "If these stones could tell the stories of those they represent." This would eventually become the premise for my blog here. Last September, I stumbled upon a discovery that changes one of the major claims of my 2017 "Sidestepping" article in which I claimed that the first Black individual buried here in Mount Olivet was a woman named Hester Houston in the year 1896. As I said back then, I had been familiar with this individual for roughly 25 years, all due to a book entitled The History of Carrollton Manor by William Jarboe Grove, onetime president and treasurer of the M. J. Grove Lime Company. The noted philanthropist grew up on Carrollton Manor and published his memoir laced history book in 1922. On page 48, Mr. Grove speaks of Hester Houston (whom he misnames Easter Houston) a slave once-owned by his aunt Margaret Lauretta Jarboe(1838-1900): “It was not unusual that some respected colored slave was buried beside her master. I will mention one, Easter Houston, who was owned by William Eagle, she was given to his daughter, Lauretta, the wife of Thomas R. Jarboe, who is buried by their side in Mt. Olivet Cemetery.” Anyway, there is more to the story, and you can read about it for yourself as I am including the links to the three-part story at the end of this blog. I feel that I may have found an individual and person of color who may have been buried 17 years earlier in 1879. With the approaching Frederick Fair at hand, I decided to write a like-themed story on one of the early Fair Board presidents buried here by the name of Edward Buckey (1797-1881). Edward was the man in charge during the Civil War period, one of only three times in which the Fair was canceled, the other two being times of health pandemics in 1918 and 2020. Born in Libertytown, Edward Buckey was the son of Peter Buckey (1775-1848) and Mary Salmon (1778-1864). His father was one of eight siblings born to Matthias Buckey and wife Mary (Hoffman). Two of these were John and George Buckey who would be responsible for helping to create the crossroads town south of Frederick that bears the family name-Buckeystown. John was a tavern-keeper and blacksmith and George was a tanner. Edward Buckey was a longtime farmer who never married. After settling his deceased mother's estate, his family farmstead was sold, and he moved in with his widowed sister, Mary (Buckey) Getzendanner and his three nieces in a townhouse located on Frederick's East Church Street. Mr. Buckey would pass on October 7th, 1881 at the age of 84. His body would be buried in the same burial plot containing his parents in Area F/Lot 33. In looking at our cemetery records, I became especially interested in this grave plot. Edward's father died in 1848, six years before the cemetery opened in May of 1854. He would be the 163rd interment as he would be reburied here in the "new" family plot in early June (1854). At this same time, Edward's sister was removed here as well, having died in 1841, the wife of Daniel Grove Smith. Mr. Smith would remarry first former wife's sister Eleanor. This woman is buried in this lot as well, dying in December, 1855. Edward would eventually lay his mother to rest beside her husband and two daughters in March of 1864, four months before the Battle of Monocacy. Jubal Early and his soldiers passed somewhat near the family farm located south of Butterfly Lane. There is one more person in this lot, and this was the most surprising find of all. She was a woman named Harriet Costly, who had died in 1879. I was familiar with this surname from my "Up From the Meadows" research and immediately recalled this name's association with the greater Libertytown and Mount Pleasant area. Our records state that she was 74 years old when she passed the day after Christmas, December 26th, 1879. Harriet would be buried here three days later. I immediately sought out her obituary without luck, but I already had a transcript of it written in our records but without a source. It reads as follows: "Harriet Costly, an old colored servant in the family of Mr. E. Buckey, East Church Street, died suddenly on Sunday morning last in the 74th year of her age. She was raised in Mr. Buckey's family and was held in high esteem by everyone who knew her as an honest and faithful servant. Her funeral took place Tuesday afternoon. The interment was made in Mr. Buckey's family lot in Mount Olivet Cemetery. Rev. Martin Spiddle officiating." I next went to find her in the census records, and low and behold, found her living with Edward Costly in the 1870 US Census. This was the residence on East Church Street, and the census offered that she was working as a domestic. Amazingly, I would later learn that the townhouse in which Harriet and Mr. Buckey lived (and died) was my home back from 1995 to 1998, the exact time I produced "Up From the Meadows." Perhaps I was channeling her energy? Sadly, I didn't get much further in my research, however, the discovery places her here in Mount Olivet before Hester Houston, making her the first person of African blood here that I know about. However, there is also that situation with another Harriet —that of Harriet Heckman. The downside to the story is that I couldn't find Harriet's gravestone. I searched the Buckey plot for it with no luck, and then had to actually look at the individual grave spots as they are mapped out by way of our cemetery lot card collection. Harriet again is verified as being buried here, but I was perplexed that there was not a gravestone. That's when I called in my volunteer preservation/repair experts, lovingly known as "the Fixers." They carefully excavated the site and found only a base buried beneath the ground's surface. Where was the dye, the upright part of the stone? All they could find was a partial piece of marble with no writing whatsoever. Is this the stone of Harriet Costly? More research needs to be done. Then again, maybe she was buried here "quietly," as well? Was there pushback of any sort after she was buried which would cause the stone to be taken down or hidden? Again, as is the case with Hester Houston, not a lot of fanfare or attention was brought to the burial here of these ladies as to cause "issues." It was a a time when this was "a whites only cemetery." The preservation team just used a piece of buried marble fragment found at the site to mark her grave for now. As I just stated, additional work needs to be done, and a tasteful monument or memorial to Harriet's memory is certainly in order. Perhaps by next February, 2025, I will find myself writing an addendum to this story with news of a marker for Harriet, and hopefully more information about her time among the living.

If you haven't read the 2017 three-part "Sidestepping a Color Barrier: The First Blacks Buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery" series, here are links.

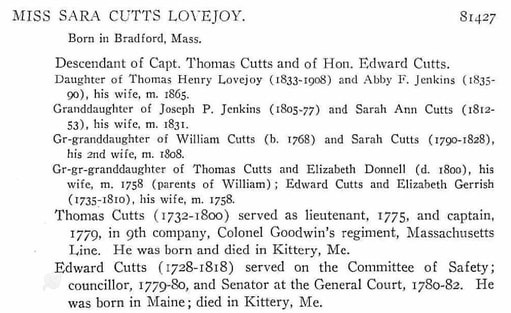

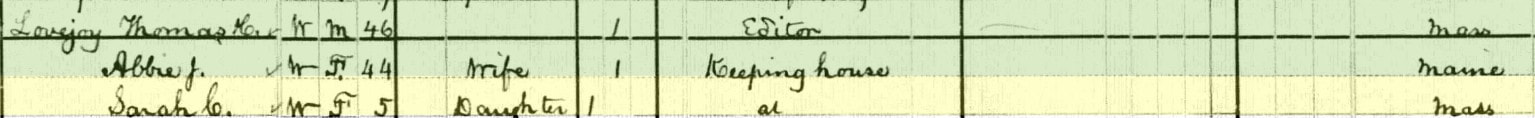

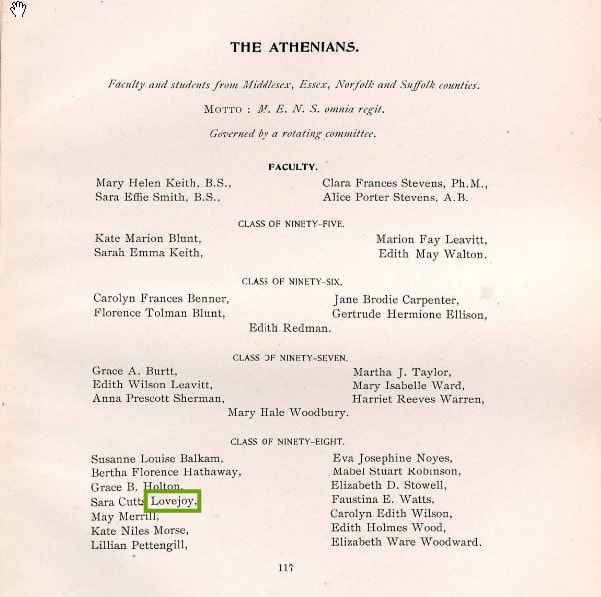

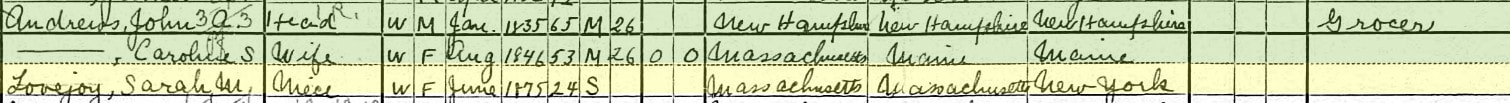

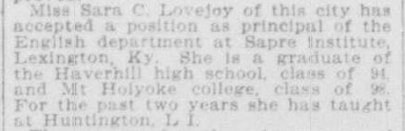

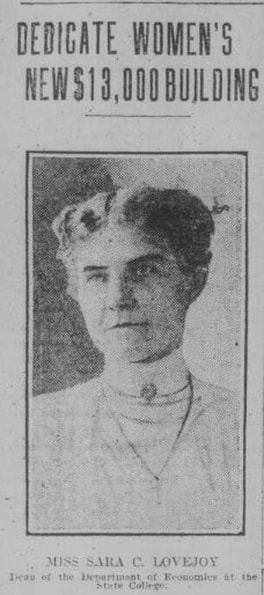

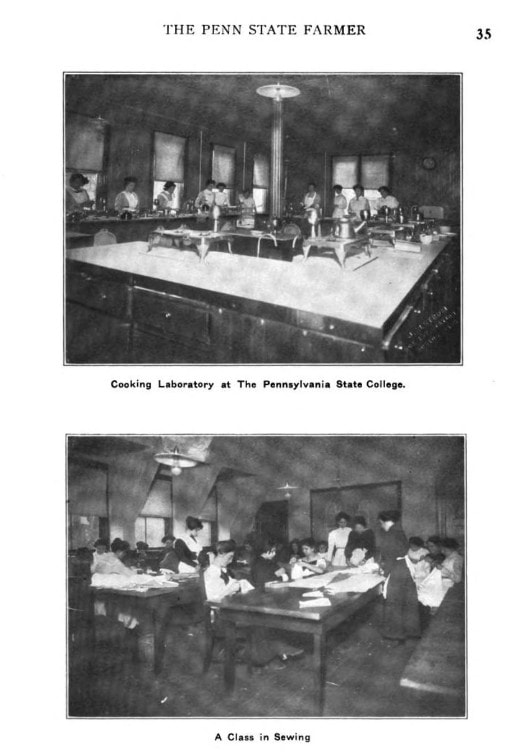

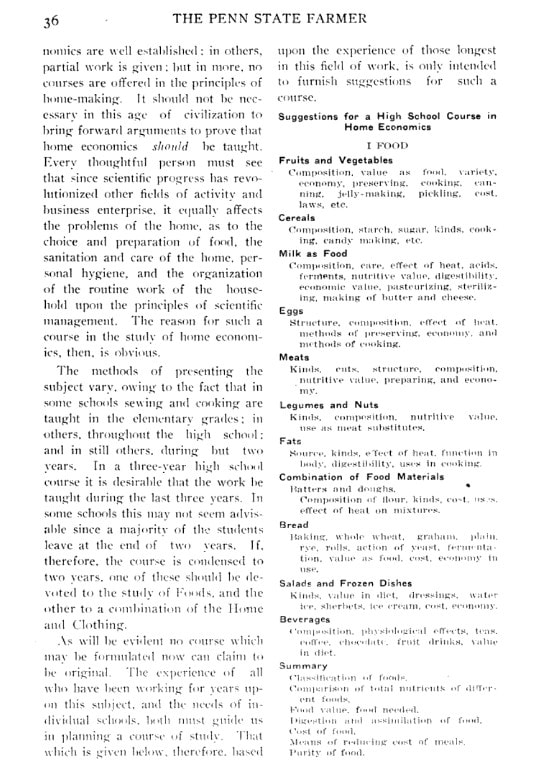

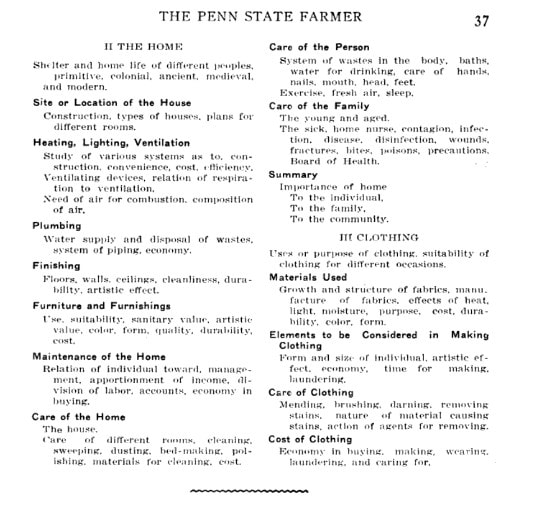

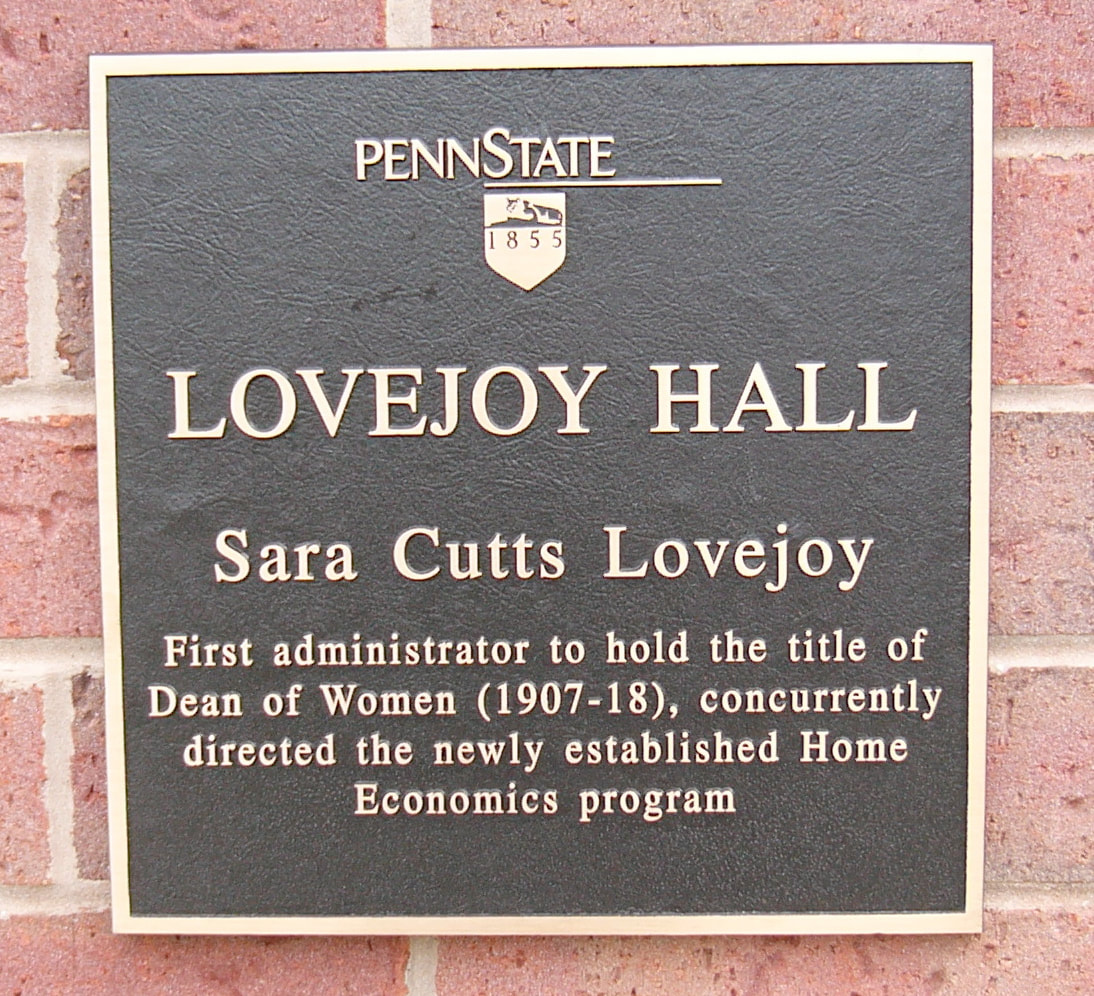

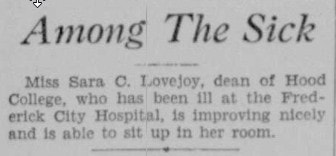

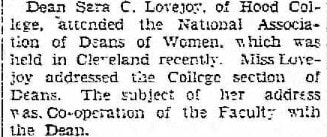

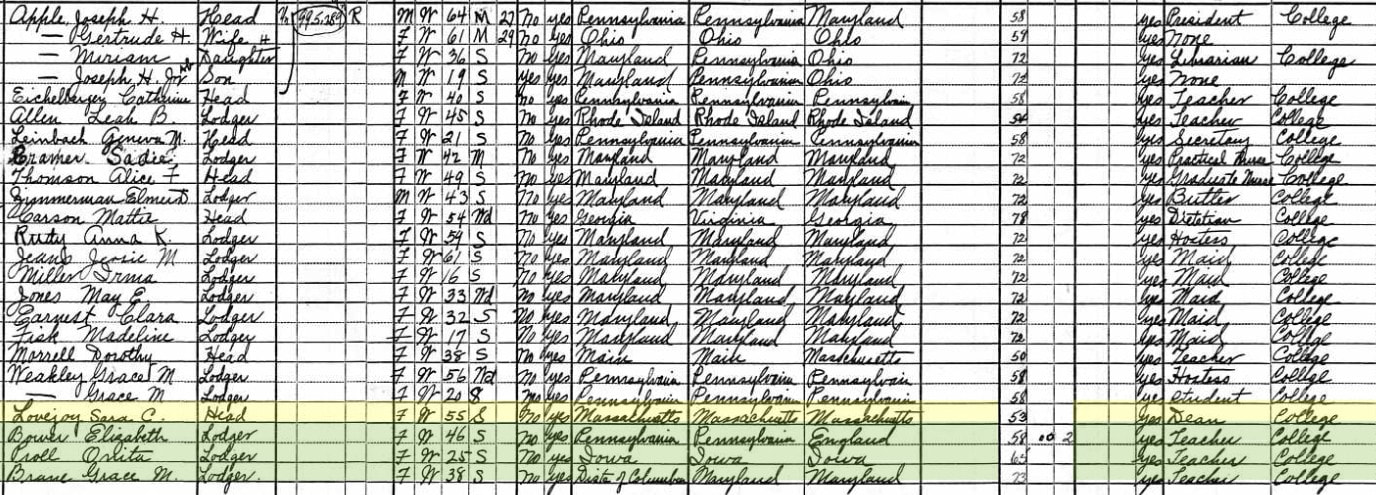

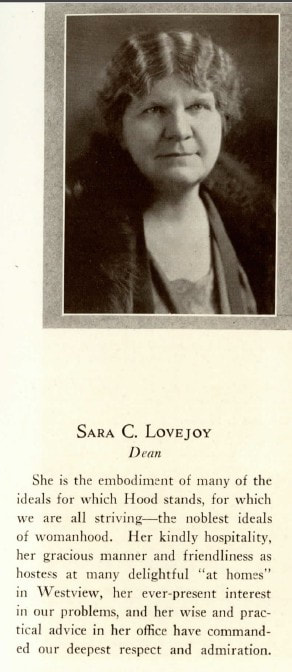

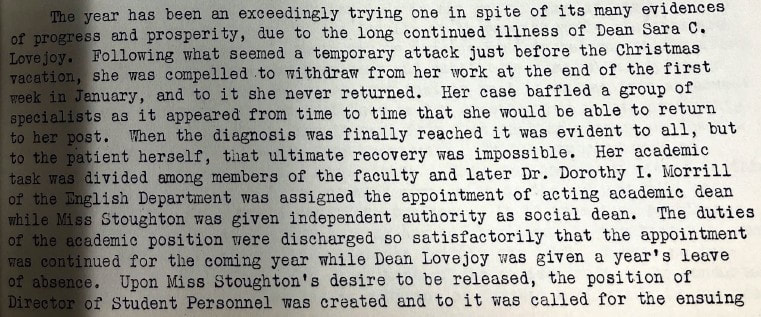

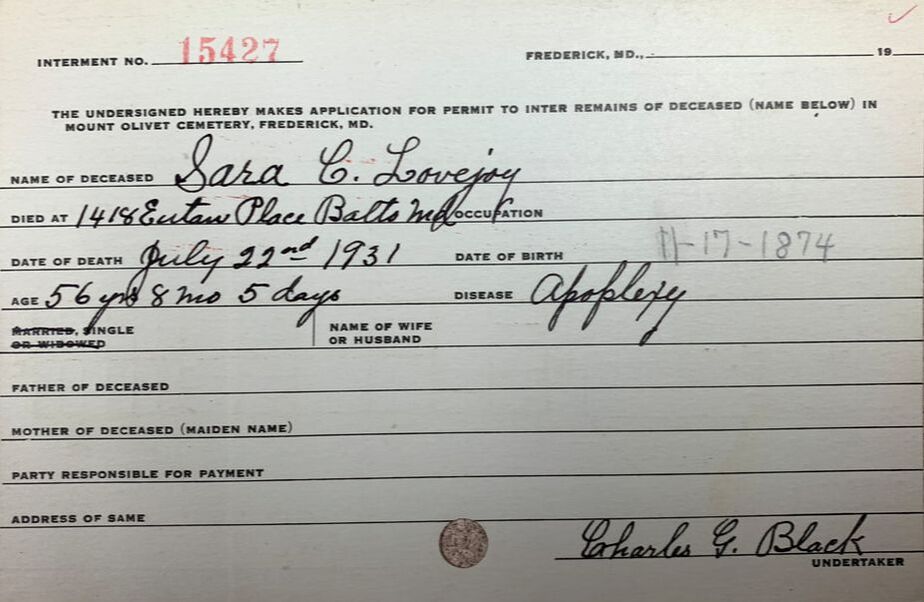

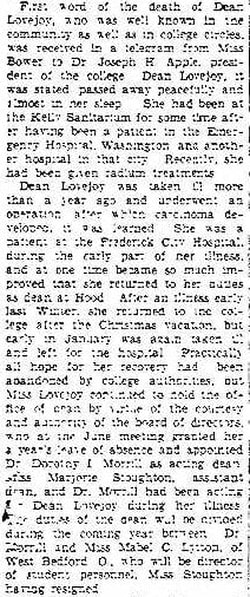

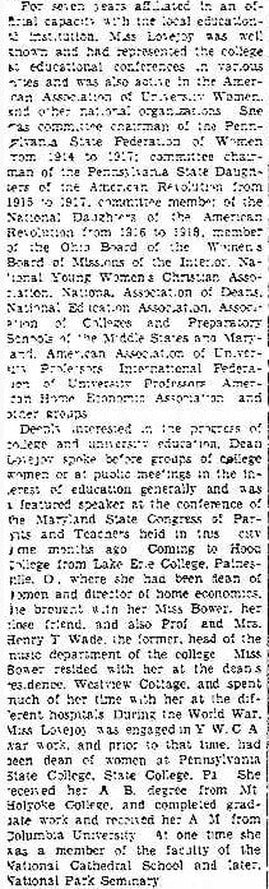

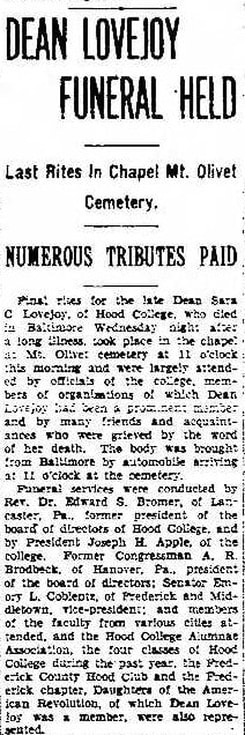

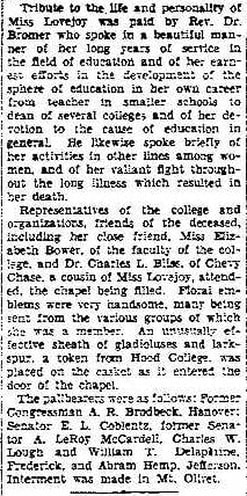

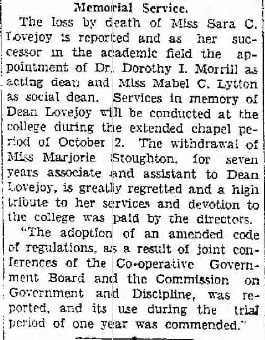

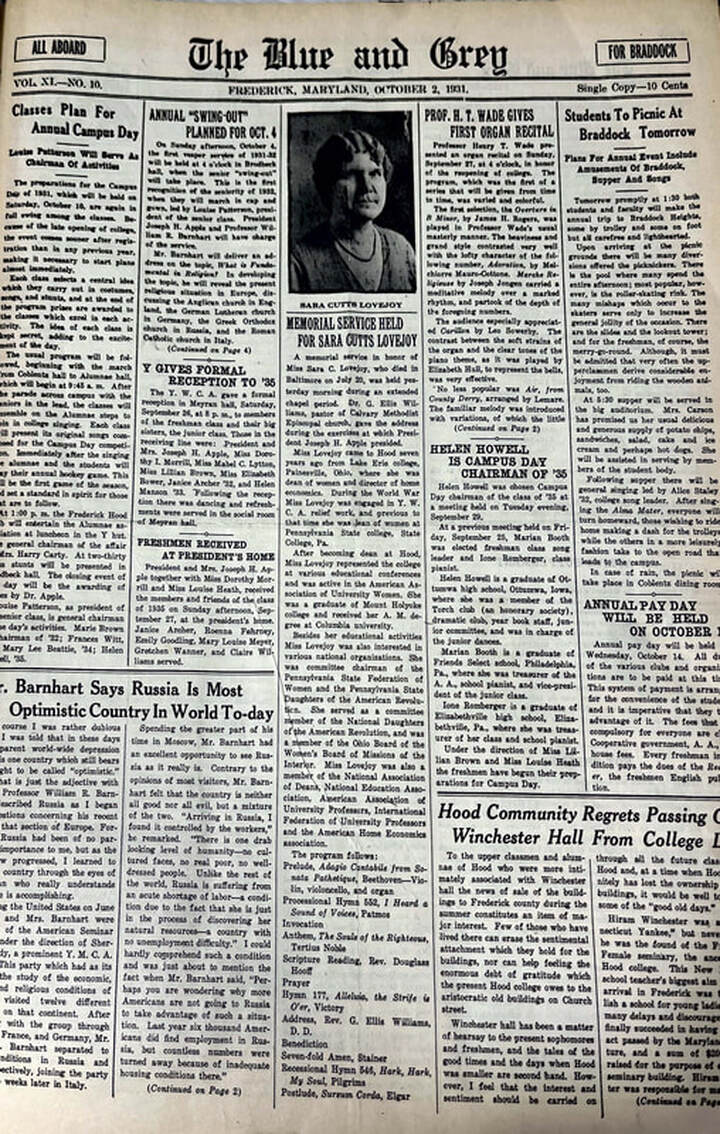

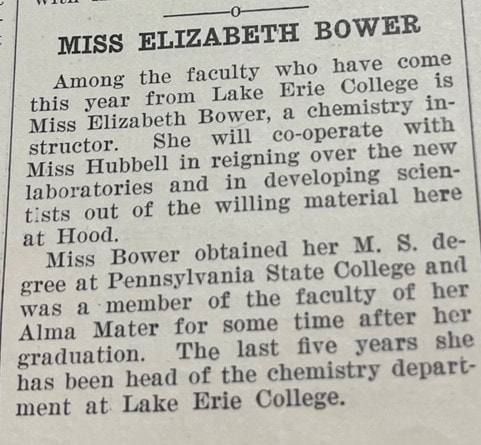

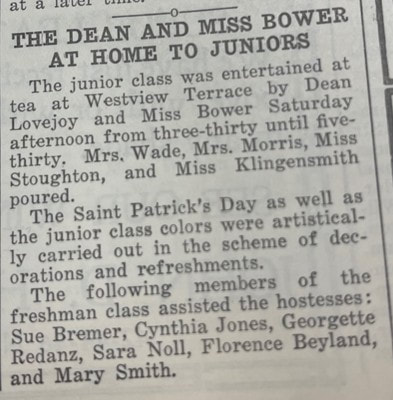

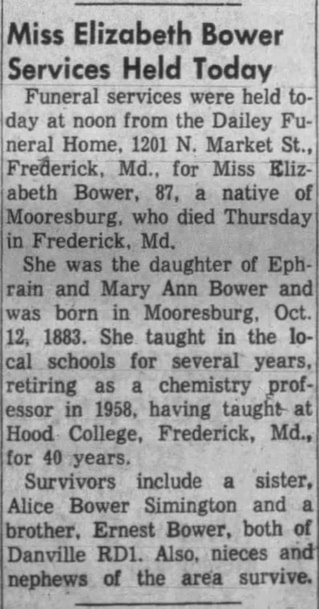

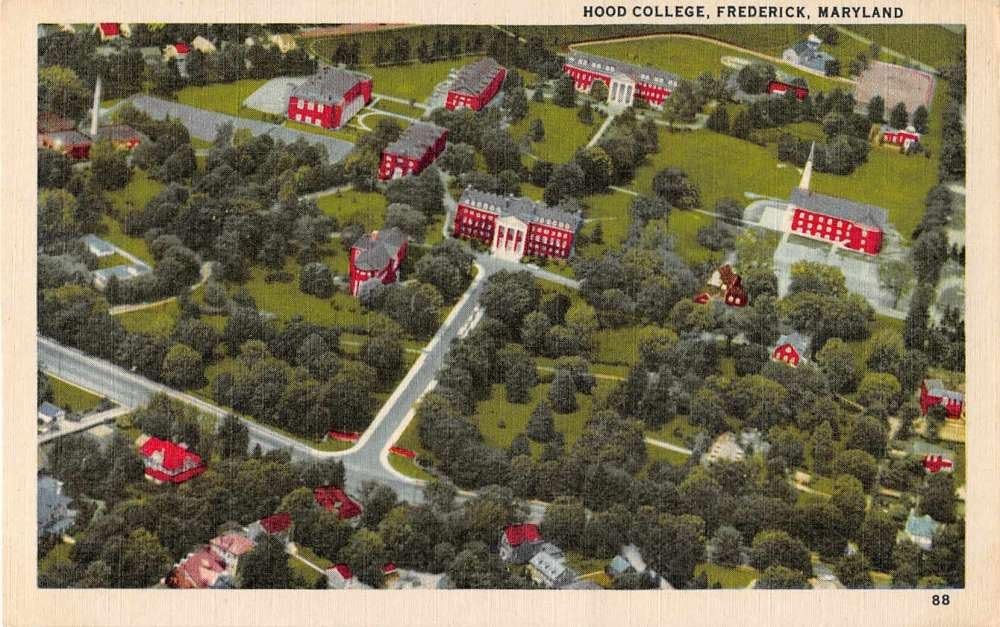

Love is certainly in the air as Valentines Day is coming up once again. We’ve featured “Stories in Stones” in the past exploiting this romantic holiday theme. One of my favorites included a 2022 inventory of people named “Valentine” and entitled “Mount Olivet Valentines,” while another was about a "love quadrangle" in the early 20th century called “Maryland’s Prettiest Girl stars in Too Many Valentines.” So, I thought I’d try my hand again at playing up the Valentines Day theme. Now all I needed was a willing participant from our cemetery population of 41,000 to write about. I consulted my trusted assistant Marilyn Veek, and we sat down at our computer database and starting looking at names that have possible connections to Valentines Day and what it represents, not simply a vital date that includes February 14th. We began looking for names such as “Rose,” of which we have 16 individuals by that name here in Mount Olivet. Next, we searched “Flowers” in which we have two. This was followed by two strikeouts with "Candy" and "Chocolate." The late comedian John Candy proves that the former last name is indeed a real thing, while, low and behold, I learned that Chocolat is actually a surname that can be found in Argentina and the Congo according to the website: www.Forebears.io and is the 4,532,898th most common surname in the world. Nothing was truly captivating us, so we looked up the name "Heart." There were no entries of decedents having that name, however, we hit the motherlode by tweaking the spelling to “Hart.” Here is a rundown of those with “Hart” as a surname and the number of interments in Mount Olivet: I still wasn’t feeling it. I needed a name that conveyed the essence of Valentine’s Day—the unbridled “joy of love.” That’s when Marilyn suggested we look to see if we have anyone by the name of "Love" in our cemetery. We soon discovered four folks with the name of “Love,” and four others whose surname had the root of “Love.” These latter examples include: an infant Elizabeth Loveder (1834), Allene I. Lovelace (1908-1979), and Susan R. Loveless (1950-2001) and one more, which would be our overwhelming choice to research. Ladies and gentlemen, I’d like to introduce you to Sara C. Lovejoy—a sweet and sugary surname that says it all! I’m well aware of the term “killjoy,” and this is its polar opposite or antithesis. As for our proposed subject, I would quickly learn that she was a career educator who served as the Dean of Students for Hood College during the second half of the “Roaring 20s” up through her premature death in 1931. Sara C. Lovejoy Sara Cutts Lovejoy was born November 17th, 1874 in 1910 in Bradford, Essex County, Massachusetts. She was the daughter of Thomas H. Lovejoy (1833-1908) and wife Abigail F. Jenkins (1835-1890). Her father worked as an editor and Sara came from a family with deep roots going back to the Revolutionary War and early Massachusetts and Maine on her mother's side. She was named for her maternal grandmother. Sara experienced childhood in Haverhill, Massachusetts and grew up in a “learned” household, gaining a fine, early primary education. She attended college in Hadley, Massachusetts at Mount Holyoke, and would be a graduate of the Class of 1898. In the summer of 1900, Sara can be found living with an uncle and aunt (John and Caroline Andrews) in Newton City, Massachusetts. She had just performed two years of instructional teaching in Huntington, Long Island while earning her masters from Columbia University in New York City. Miss Lovejoy received her first administrative position at this time, which would call for a move to Kentucky. I found that the spelling of the school’s name was off in the first article I had found, as it should read the Sayre Institute in Lexington, Kentucky. This school was founded in 1854 by David Austin Sayre for the education of young women. Sayre believed that women deserved an “education of the widest range and highest order.” Originally named Transylvania Female Institute, the school was renamed in honor of Sayre in 1885. The school’s original curriculum included French, Latin, German language and literature, and vocal and instrumental music, which were typical courses of study for women in that era. But, true to Sayre’s educational philosophy, other classes offered by the school included algebra, geometry, trigonometry, geology, chemistry, astronomy, history, English literature, and philosophy. These courses were somewhat of a departure from the traditional female academies which primarily focused on music and languages. The institution still exists today and is known as the Sayre School. Sara C. Lovejoy served here until 1906, at which time she moved to State College, Pennsylvania to take the job as Director of the Household/Home Economics Department. While here at Pennsylvania State College (aka Penn State), she would be named Acting Dean of the school's Woman’s Department. In 1908, Miss Lovejoy was promoted to Dean of Women. I had my memory refreshed by reading about Home Economics and wondered, to myself, why this class isn’t taught today in public schools as was the case in my youth? I soon came across an article Sara had written for the February, 1912 edition of an agricultural journal published by the school and called The Penn State Farmer. I think I have a good handle on the job duties associated with a school principal, and also those of a collegiate president. I thought it would be good to revisit the job duties of a college dean, and in particular, a “Dean of Women.” I consulted Wikipedia and here is what I found: “The dean of women at a college or university in the United States is the dean with responsibility for student affairs for female students. In early years, the position was also known by other names, including preceptress, lady principal, and adviser of women. Deans of women were widespread in American institutions of higher education from the 1890s to the 1960s, sometimes paired with a "Dean of Men", and usually reporting directly to the president of the institution. In the later 20th century, however, most Dean of Women positions were merged into the position of dean of students. The Dean of Women position had its origins in the anxiety of the first generations of administrators of coeducational universities, who had themselves been educated in male-only schools, with the realities of coeducation. The earliest precursor was the position of matron, a woman charged with overseeing a female dormitory in the early years of coeducation in the 1870s and 1880s. As the number of women in higher education rose dramatically in the late 19th century, a more comprehensive administrative response was called for. The Deans of Women served both to maintain a protective separation between the male and female student populations and to ensure that the academic offerings for women and academic work done by women were kept at a sufficiently high standard. In the initial years, the responsibilities of the dean of women were not standardized, but in the early 20th century it quickly took on the trappings of a profession. The first professional conference of deans and advisers of women was held in 1903. In 1915, the first book dedicated to the profession was published, Lois Rosenberry's The Dean of Women. In 1916, the National Association of Deans of Women was formed at Teachers College. By 1925, there were at least 302 deans of women at American colleges and universities.” This background on the title speaks volumes, and demonstrates that Sara C. Lovejoy was not just one of many women to serve in this role within the educational profession, but was a pioneer and trailblazer. This woman destined to be the very first “Blazer” Dean to serve at our local Hood College helped shape and mold this position, and attended the National Association of Educators Conference in New York City in early July, 1916 where a special session was held for Deans of Women. I also found that Sara had attended the 13th Annual Convention of the Association of American Agricultural Colleges and Experiment Stations, held in Washington, DC in November of 1916. She was quite an ambassador for her employers. One more find of mine in conducting Google searches on Dean Lovejoy showed that our subject was a stickler for holding students to a high standard as she is quoted as saying that too many female students "show a lack of previous training that hinders their rapid progress." Sara C. Lovejoy is remembered on the Penn State campus by having a dorm, Lovejoy Hall, named in her honor. It provides on campus hous ing for graduate students. By 1919, Sara found herself in the position of Dean of Women at Lake Erie College in Painesville, Ohio. Over her five years here, she continued her shaping of young women’s minds and I found a clipping where she spoke on the benefits of recreation for females as exemplified by the Y.W.C.A. (Young Women’s Christian Association). Miss Lovejoy would make her way to Frederick, Maryland in 1924 as she would be appointed to the position of "Academic Dean" and "Dean of Women" for Hood College. She worked under Dr. Joseph Henry Apple, first president of the institution, and lived on the new campus which had only opened less than a decade earlier. In 1925, Sara would travel to Indianapolis to take part in the American Association University Women Conference bringing together some of the brightest women educators across the globe. She would go on to serve as president of Frederick’s local chapter of the AAUW from 1927-1929. To illustrate the experience and insight that Sara C. Lovejoy brought to Hood College, we can look at President Apple's yearly reports. Hood College archivist Mary Atwell shared with me a few pages from Dr. Apple's 1925 Annual Report on the College which shows that Dean Lovejoy was a force to be reckoned with, even in her first year on the job here in Frederick. The local newspapers are filled with mentions of Dean Lovejoy hosting school functions and events and presenting talks and lectures both here and abroad. She was certainly at the pinnacle of her career and had worked hard at her craft. However, I find it interesting that she never married or had children. An expert on teaching women how to properly conduct households, she would never quite be in that position herself. Instead, she worked in high-end academic positions. As this article is supposed to be about the “joy of love,” I presume that her career in education was the “love of her life,” without rival. In the summer of 1928, Miss Lovejoy spent the months abroad in Europe. She would return to Frederick and her duties in mid-September prior to the start of the fall semester but had to be hospitalized at Frederick City Hospital due to contraction of Typhoid Fever. She would make a recovery after a month’s hospitalization. By November, she would be performing her regular duties in earnest, including the hosting of the annual Thanksgiving banquet. In March of the following year, she traveled to Cleveland to participate in a Deans of Women conference. The 1930 US Census shows Sara C. Lovejoy living in Frederick on the Hood campus in a building once named Westview, which sat behind the President's original home. In the 1930 census, Dean Lovejoy is residing here with three other women teachers: Elizabeth Bower, Onita Prall and Grace Brane. The only building on the Hood College campus named for a faculty member is the Onica Prall Child Development Laboratory. This is the former Westview. Built in 1921 by the College’s workmen, it was a residence for the vice president, Charles Wehler. The building was renovated as a child development laboratory school after Miss Prall’s arrival at Hood and was further renovated in 1966. Miss Prall’s life was devoted to improving the quality of early childhood education and in 1971 the building was named in honor of her pioneering work. (Today this is shown on the current Hood map as Georgetown Hill Lab School). For the next few years, Dean Lovejoy continued with performing her regular duties until she became ill again in January, 1931 after her return from Christmas break. There would be no full recovery this time as Sara was suffering from cancer. Dr. Apple and Sara's co-workers sadly saw that this was a dire situation and began making succession plans. Dr. Apple's Annual Report of 1931 shows his concern. Sara Cutts Lovejoy succumbed to her illness six months later on July 22nd, 1931 in Baltimore. Her death certificate states that she died of apoplexy at the Kelly Clinic, a private hospital operated by noted physician Dr. Howard A. Kelly (1858-1943) at 1418 Eutaw Place in Baltimore. Dr. Kelly was one of the founding “Big 4” professors of Johns Hopkins University and is credited with establishing gynecology as a specialty by developing new surgical approaches to gynecological diseases and pathological research. Miss Lovejoy’s funeral service was held in our Key Chapel here at Mount Olivet with services conducted by Dr. Joseph Henry Apple, himself. Her body would be laid to rest in Area LL/Lot 132. A special memorial service for Dean Lovejoy would be held at Hood a few months later when school was back in session. This would be for the benefit of the students who had been on summer break at the time of her death. I found it interesting that Sara would be buried here in Frederick, a place she had only lived for barely seven years. Her half grave plot contains six spaces but only one other individual is buried here. This woman’s name is Elizabeth Bower, and she died in November of 1970. In looking a bit closer, I learned that Miss Bower had a very special relationship with Dean Lovejoy. At the very least, she was a teaching colleague, housemate, and “close friend.” She is even listed as such in Miss Lovejoy’s obituary. I also found that Elizabeth Bower would serve in the role of Sara C. Lovejoy’s Executrix, and it seems she assumed much of Miss Lovejoy’s estate including the grave plot here at Mount Olivet. Miss Elizabeth Bertha Bower was born on October 12th, 1883 in Mooresburg, Montour County, Pennsylvania. She was the daughter of a Union Civil War soldier and had attended Pennsylvania State College where she would receive her Bachelor of Sciences degree in 1909, and her Masters in 1912. She most definitely met Miss Lovejoy at the college while the latter was serving as Dean of Women. Elizabeth Bower was a professor of chemistry, and from what I’ve read, was called for by Miss Lovejoy to take a position at Hood in 1925. I went back and searched the ship log of the SS Minnekahda which sailed from London to New York in August of 1928. This was the ill-fated journey that would precede Sara’s bout with Typhoid fever. Low and behold, I found Miss Bower as Sara’s travel companion to Europe. Whatever the relationship these two women had, and considering neither married, I take heart in knowing that they were the closest things to Valentines for each other, and hopefully found joy in their close friendship on many "February 14ths" up to Dean Lovejoy’s last in early 1931. Miss Bower stayed in Hood College’s employ until her retirement in 1958. Miss Bower’s legacy lives on at the college through the Elizabeth B. Bower Prize, awarded annually to an outstanding student in chemistry. The prize was established in 1956 by the late Rebecca Ann Eversole Parker '55, who was inspired by Professor Bower to make chemistry her career. At the time of her untimely death, Rebecca was studying for her doctorate in chemistry at Oxford University. In 1962, the Eversole family endowed the prize as a memorial to Rebecca. Elizabeth Bower kept herself busy in retirement by traveling and taking part in various civic groups. She gave many presentations as historian for the local Daughters of the American Revolution chapter. Elizabeth Bertha Bowers died in November 1970, and at that time was placed in the gravesite next to her old friend Sara who had preceded her in death nearly forty years earlier. A woman by the name of Beatrice Malone of Lutherville, MD took care of Elizabeth's burial plans and was the Personal Representative for her estate. She was a student of Dean Lovejoy at Lake Erie College and again in the Hood class of 1926. She would become a supervisor for the Children's Aid Society of Maryland. Sara C. Lovejoy and Elizabeth Bower helped build the great tradition of Hood College, one that continues on. Think of them with both love and joy as you cherish loved ones, past and present, this coming Valentine’s Day. AUTHOR'S NOTE: Very special thanks to Mary Atwell, Archivist and Collections Department Librarian at Hood College, for her assistance with visuals and additional information for this story.

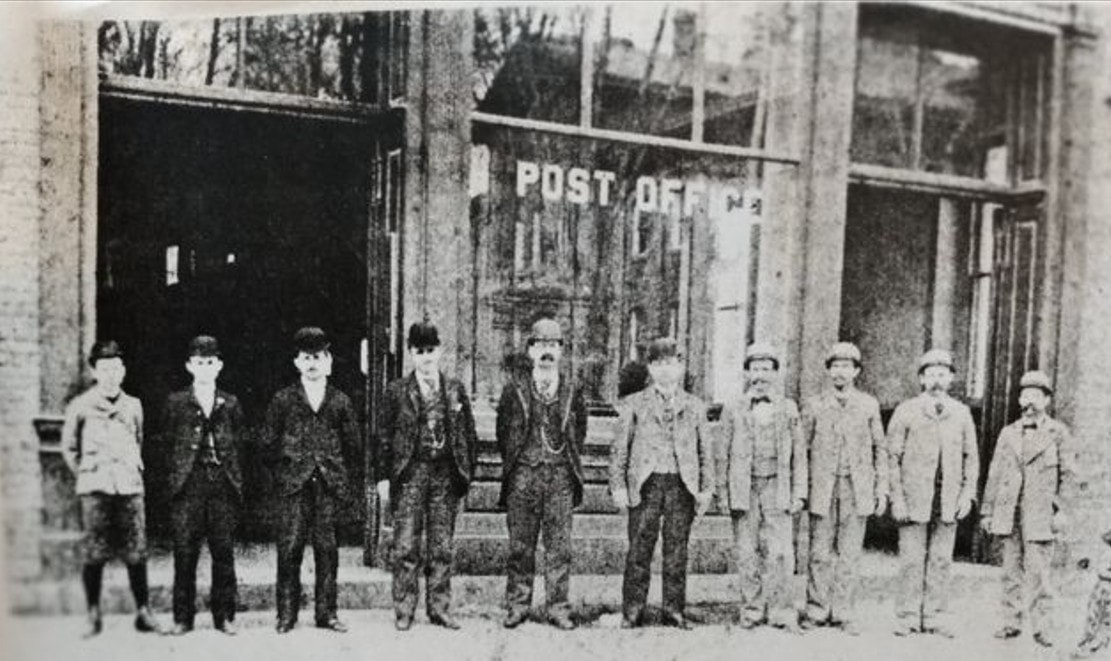

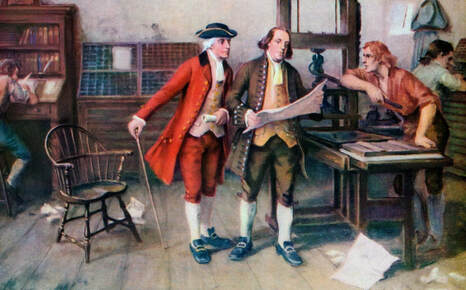

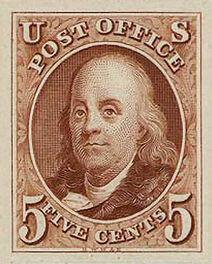

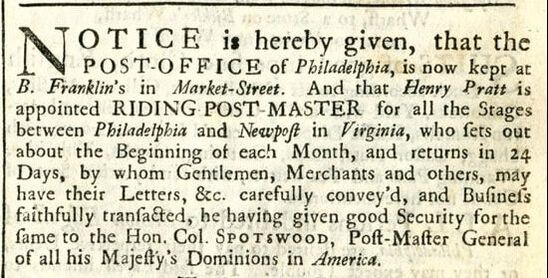

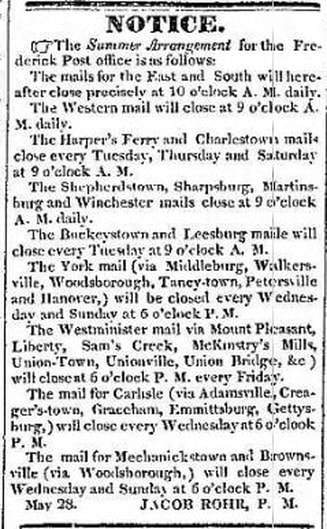

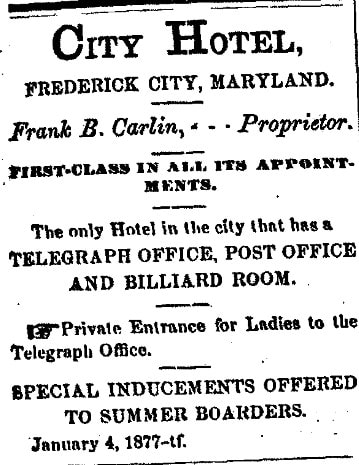

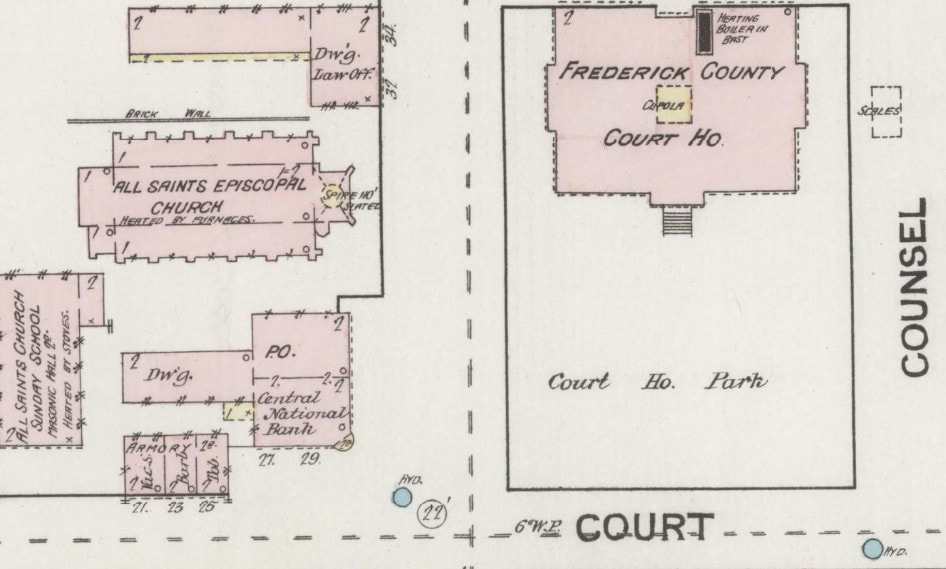

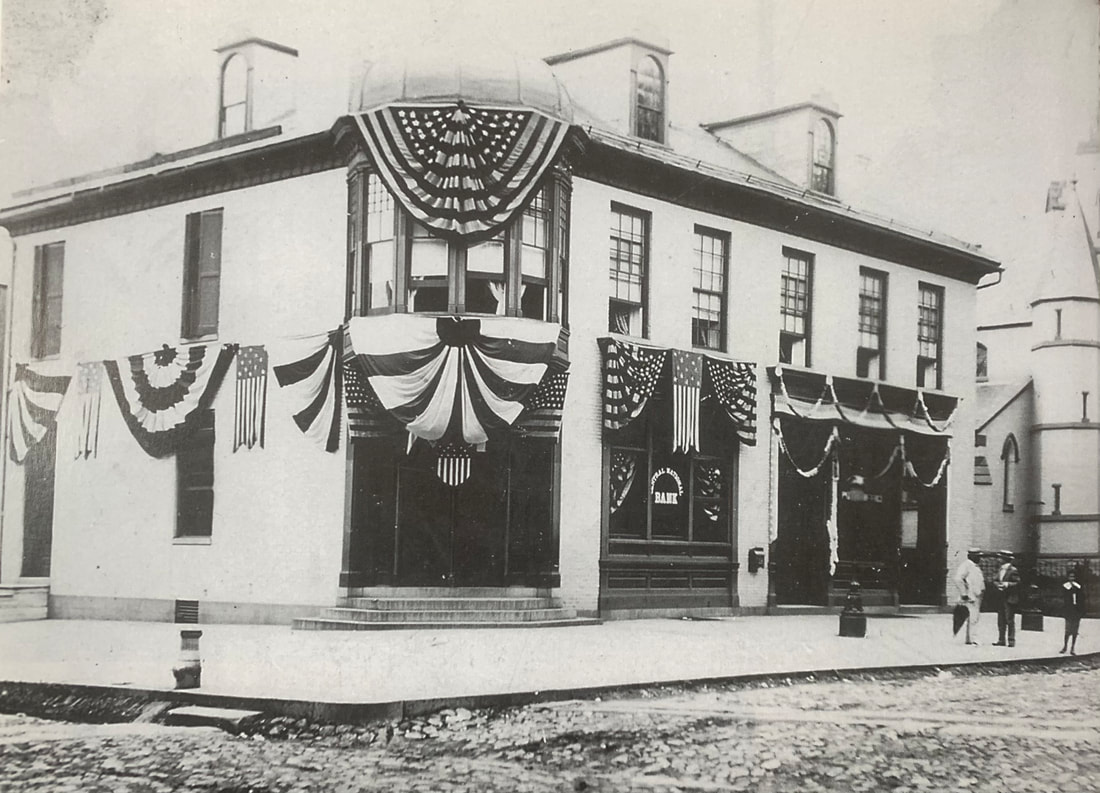

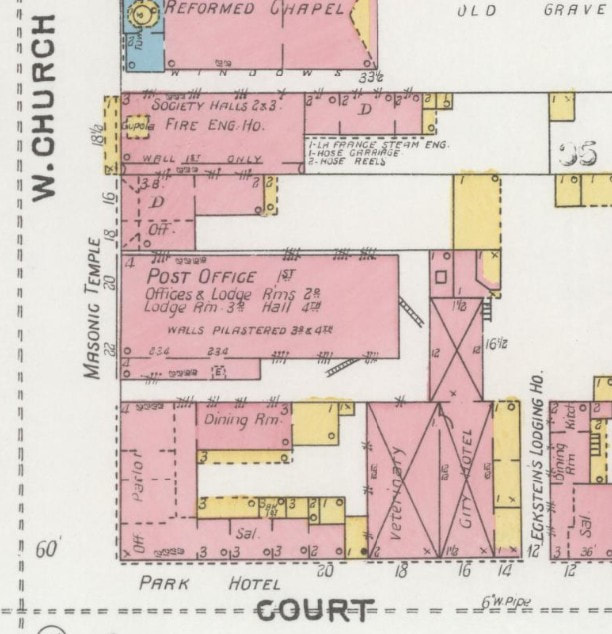

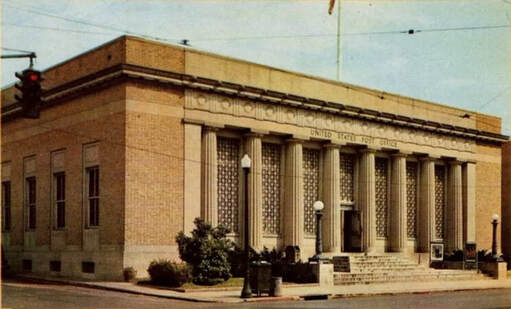

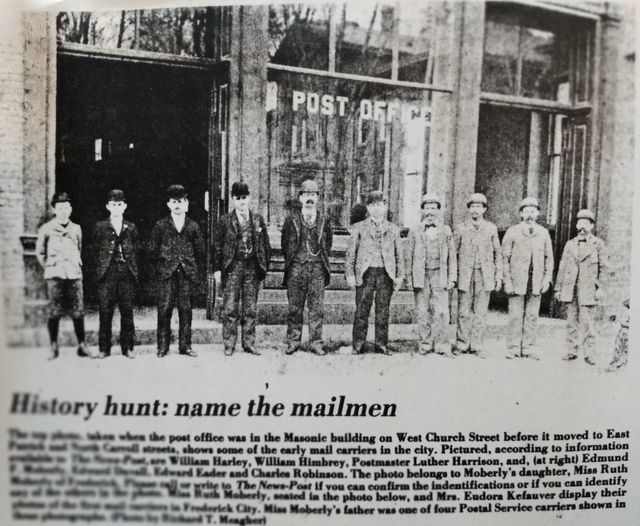

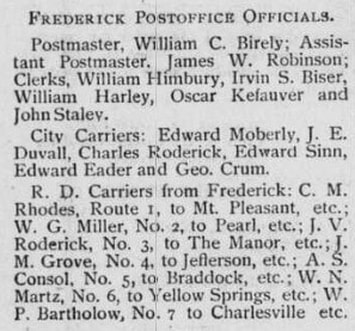

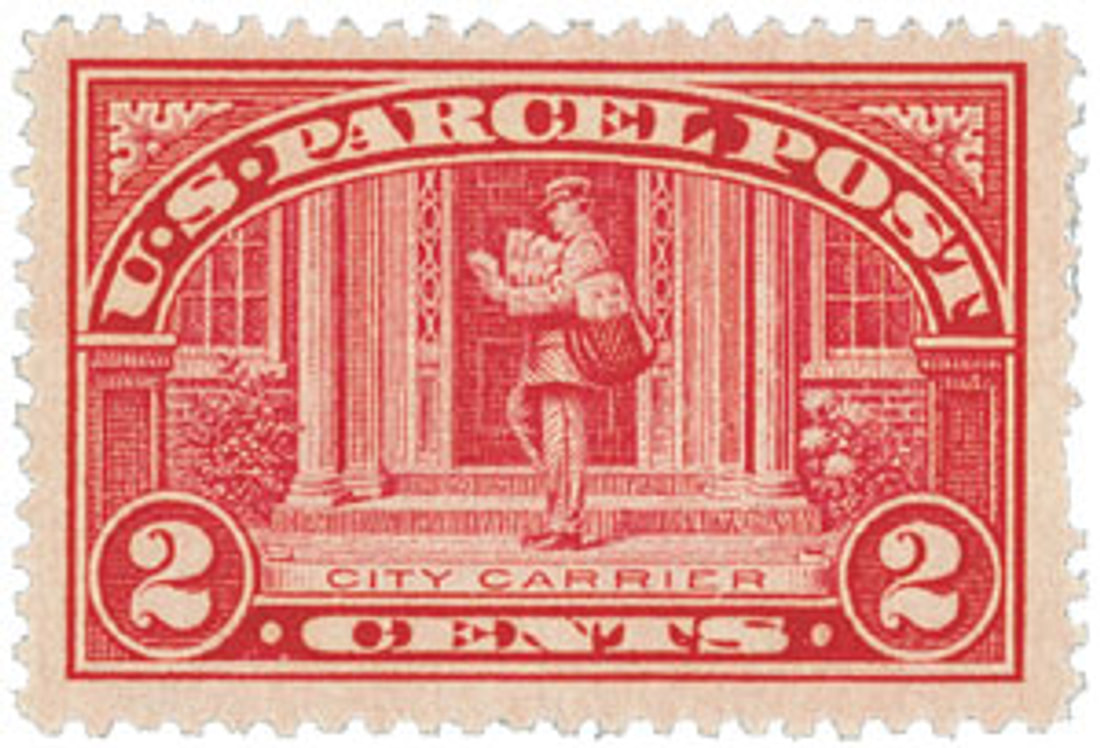

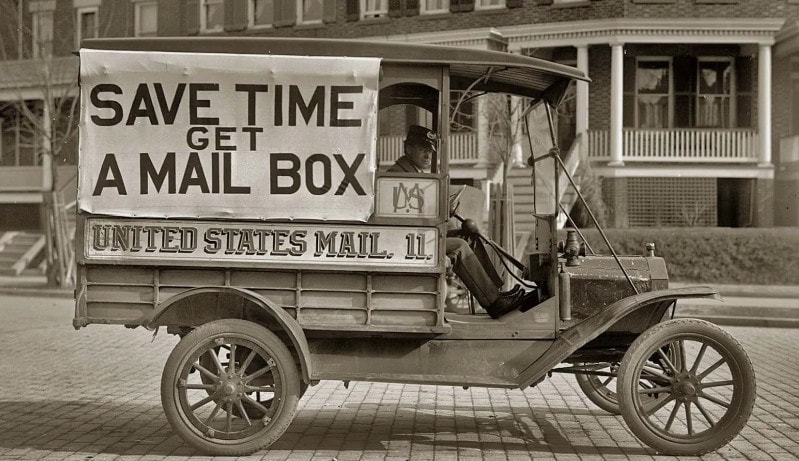

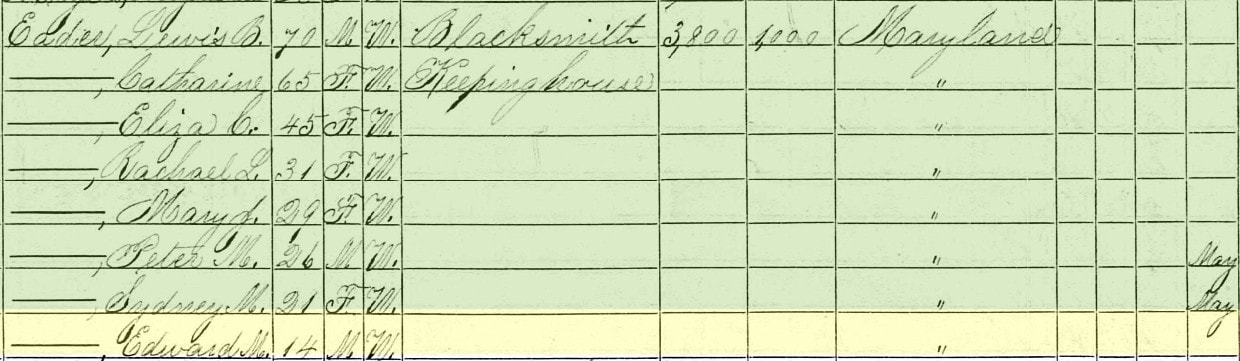

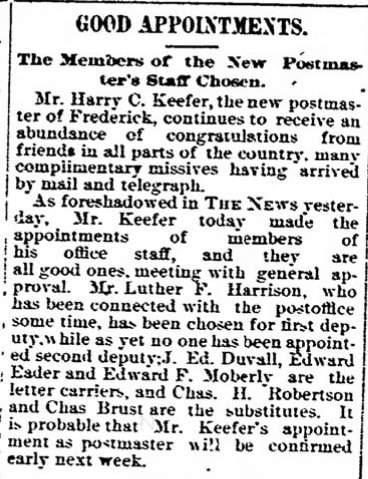

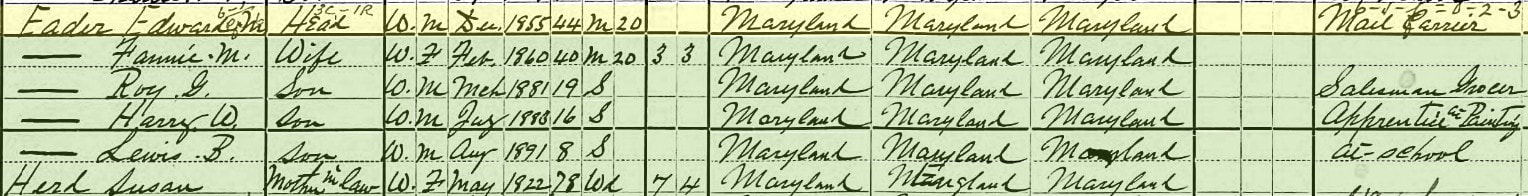

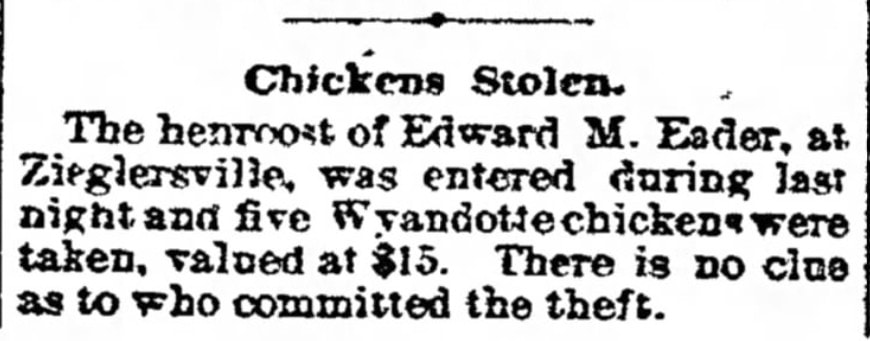

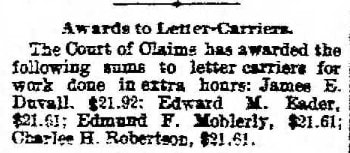

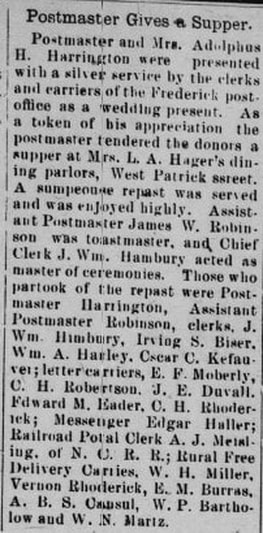

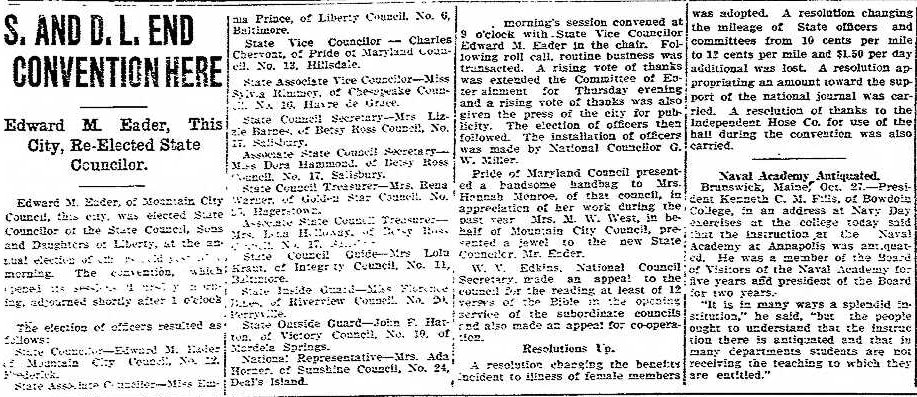

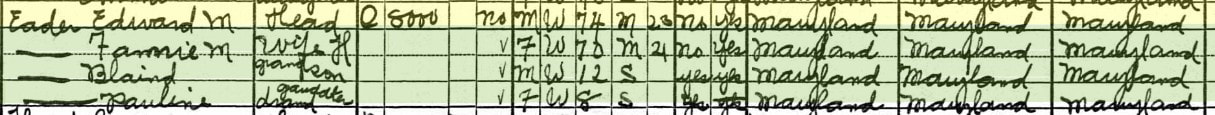

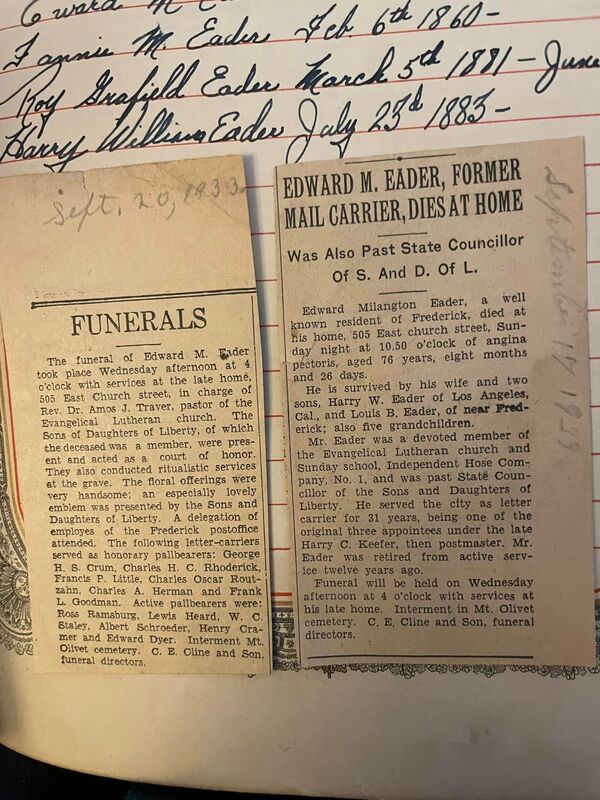

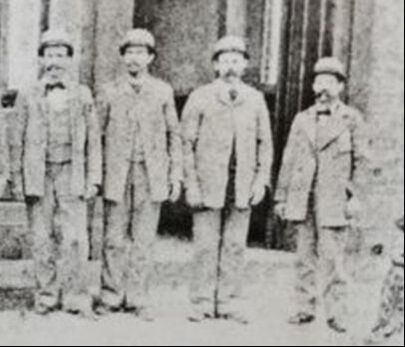

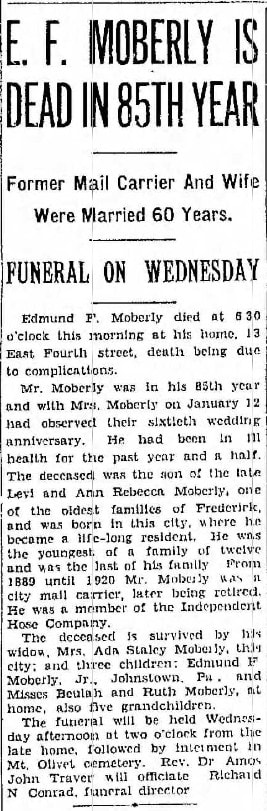

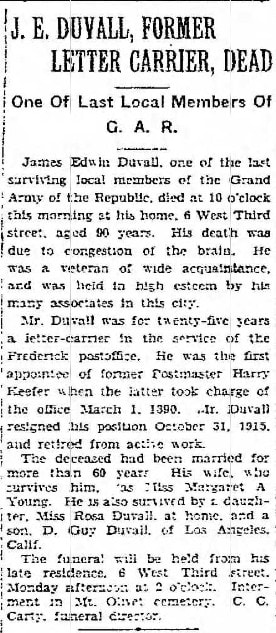

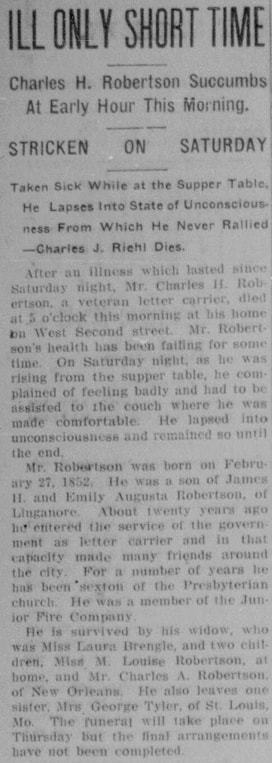

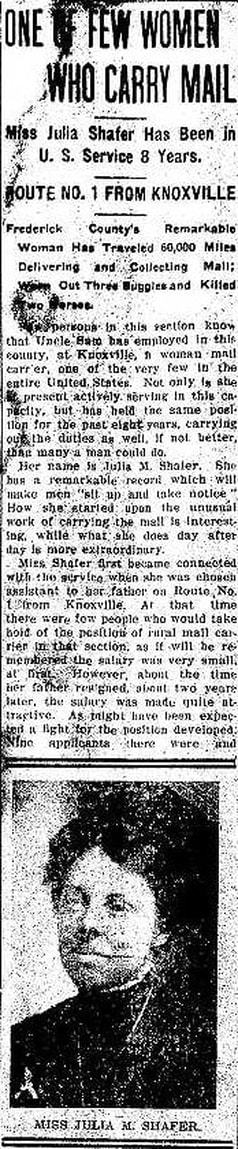

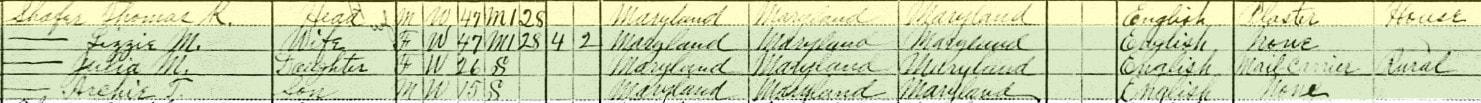

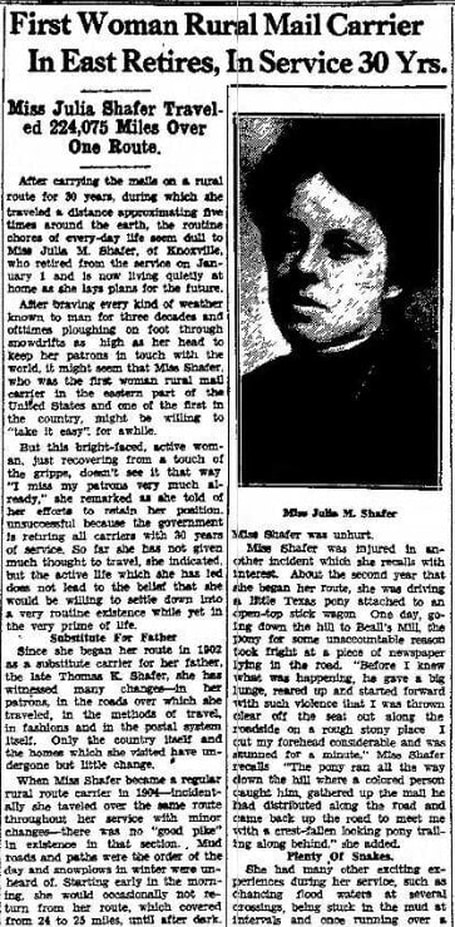

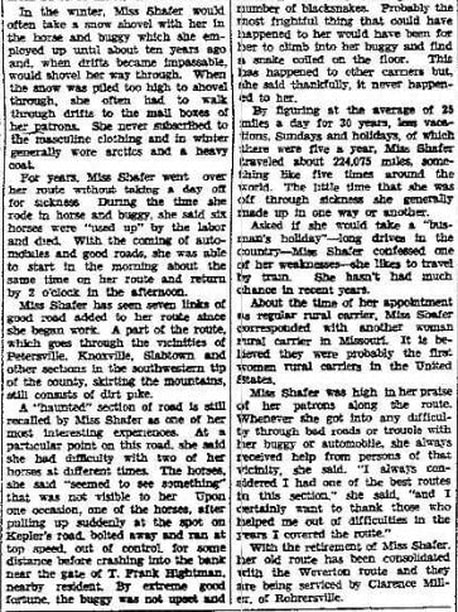

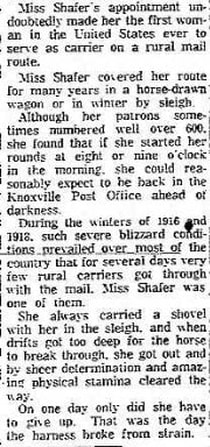

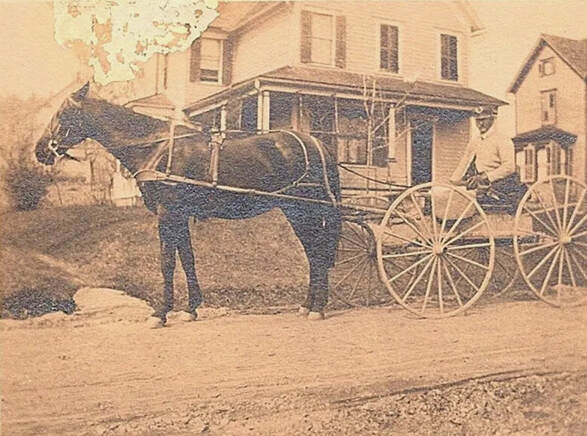

So, tell me one thing: ”Are you ready for the big day?” It’s early February, and I am in no way referring to the Super Bowl, or sport of football. There’s certainly no need for goalposts, however specific “goals” are critically important in what I’m referring to, while any and all connections to “post” is just plain paramount. I guess you could say, “It’s all about the delivery.” —theirs, not mine. February 4th is National Thank a Mail Carrier Day! It’s a time when “going postal” is actually a good thing, but please don’t get this event confused with National Postal Worker Day. The latter is observed every year on July 1st. Keeping track of all these newfound “national days” is quite confusing, I know. The folks in this profession brave the elements and work hard to get us our letters, packages, magazines and campaign mailers in a timely manner. Our nation’s letter carriers “serve with great fidelity” in the faithful execution of their work as public servants. The American Community Survey, in conjunction with the US Census Bureau, estimates that there are about 302,000 mail carriers currently working in the United States. The profession can thank the ratification of the United States Constitution in 1788 which gave Congress the power “To establish Post Offices and Post Roads” in Article I, Section 8. One year later, the Act of September 22nd, 1789, continued the Post Office and made the Postmaster General subject to the direction of the President. Four days later, President Washington appointed a gentleman named Samuel Osgood as the first Postmaster General (under the Constitution). At that time, almost four million residents would be served by 75 Post Offices and nearly 2,400 miles of post roads. Carved in stone over the entrance to the old New York City Post Office building on 8th Avenue, one can find the quote, “Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds.” According to the United States Postal Service, the quote often mistaken as the US Post Office motto comes from “The Persian Wars” written by the ancient Greek historian Herodotus around 445 BC and refers to the Persian system of mounted postal couriers who “served with great fidelity” during the wars between the Greeks and Persians (500-449 BC). Frederick is no stranger to the postal service. In fact, the most famous postal professional of all-time visited Frederick in the spring of 1755. This was Benjamin Franklin who had been sent by the leaders of the Pennsylvania colony to assist British Gen. Edward Braddock in his expedition into the interior of the country to battle the French & Indians. Communication to and from the unsettled wilderness with the colonial capitals would be "a necessity" for Braddock and governors like ours in Horatio Sharpe and Virginia's Alexander Spotswood.  Franklin started as postmaster of Philadelphia in 1737, and eventually was elevated to serve as postmaster general of the Colonies. This would last until 1774, at which time the British authorities finally figured out that Ben Franklin was a revolutionary who could not be trusted. Not good to have a man of his stature wielding power of the principle communication delivery system of the day. Christina Martinkosky of Frederick City’s Planning Department wrote a fantastic article last April on the subject of Frederick's early post office and subsequent homes in the Frederick News-Post newspaper as part of her heralded “Preservation Matters” series. She wrote: “In the early years of Frederick, there was an absence of post offices and mail routes. Correspondences were deposited in public-houses and messages were transported to their intended destination through ad hoc methods. Benjamin Franklin was appointed the first postmaster general in 1775. By 1815, there was a daily mail service to Washington, DC, Baltimore, Hagerstown, and Wheeling. The mail was carried by hired riders in some cases, who, it has been said, frequently changed horses in Frederick as a major connection hub to other regional destinations. Stagecoaches then played a role as the earliest thru-roads and turnpikes came into existence." The town's inns and taverns were the first mail centers in places like Frederick and eventually surrounding towns. In 1825, the post office of Frederick was situated on North Market Street next to the town’s Market House. Today, this is the site of Brewer’s Alley restaurant. Fourteen years later, town diarist Jacob Engelbrecht made an interesting entry in his famous journal on January 4th, 1839: “Post Office—John Rigney Esquire the new Post master of this town, entered on his official station on Tuesday last 1 instant. The office is now kept in Bentz’s old house near the Market Street Bridge, opposite the residence of Mr. Rigney.” The Post Office would bounce around a bit, sometimes associated with established business sites, and at other times, private homes. The deciding factor in most cases resided with the Post Master himself as it had to be in close proximity to his regular workspace or home domicile. Nearly 20 years later in late March, 1858, Engelbrecht states that the Post Office of Postmaster J. J. Smith, Esquire moved from its home on West Patrick Street adjacent the City Hotel, to the house of Basil Norris on Court Street. Norris conducted a grocery store of sorts. The town Post Office would be back on West Patrick within 20 years as it is mentioned within the City Hotel in advertisements in the late 1870s. Ms. Martinkosky, in her article, adds: “By 1887, the post office was at the southwest corner of the intersection between Court and Church streets. This property, known as the Court Square Building, was originally constructed in 1782 as one of the fine homes that circled the original courthouse. The unique “top hat” dormers are likely an original feature. For many years the property served as headquarters for several long-lasting institutions, including the Central National Bank and Annapolis Bank. Sanborn Maps show that the western half of the building was used as a post office between 1887 and 1902.” In 1902, the Masonic Temple Association purchased the property at 22 W. Church St. and constructed an impressive four-story building. Between 1902 and 1917, the post office operated from the first floor. Frederick’s first post office, specifically constructed for that purpose, was located on the corner of East Patrick and North Carroll streets. The cornerstone was laid in 1917. The Greek Revival styled building was built of white brick and Indiana limestone. The former structure once stood where the current parking lot of the Downtown Frederick USPS Office is located.  Parts of the old Frederick Post Office were thought to be re-used locally, but seemed to disappear. Some sections of the beautiful Doric columns of the old Post Office's front entrance were employed for a while as earlier window-dressing for the Carroll Creek Promenade. Many referred to these as "Tinkertoys" after the famed childhood building toy playset of yesteryear. The loss of the post office entails a very sordid and sad story. I will leave that for another day because I want to talk about a few of Frederick’s earliest mail carriers—also referred to as “letter carriers." A friend of mine, Caroline Eader, provided me with the following image of mail carriers and other postal staff in front of Frederick’s Post Office of June, 1914. This would be the site of the Post Office when it was located on West Church Street within the former Masonic Lodge, today the home of The Temple Cosmetology School. Caroline had a particular interest in the photograph because of an ancestor named Edward M. Eader. This gentleman is buried in Mount Olivet and is Caroline’s great grandfather. I trust my friend's family lineage because her mother, Edie Eader (1944-2022), was one of the best genealogists in the area for over 30 years. More importantly for Frederick, Mr. Eader was one of our town’s very first mail carriers. Edward was not alone as the picture attests. As a matter of fact, the four gentlemen to the right of the line (and likely dressed in light gray) within this old 1914 photograph were our mail delivery pioneers. This includes the following who served Frederick City: (Left to right) Edmund F. Moberly, James Edwin Duvall, Edward M. Eader and Charles Robertson. All four of these fellows are actually buried in Mount Olivet, along with other letter carriers that would subsequently take their place in delivering our city (and county's) mail up through the present day. In doing research for this story, I found that mail carriers of yesteryear, both city carriers and rural deliverers, were pseudo celebrities. Everyone knew these individuals, and they were usually associated with bringing joy in the form of vital communication, especially in those early days before widespread telephone use, television and radio broadcasting, and the email and texts of today that have been the postal service's biggest competitor in modern times. People anxiously awaited letters from loved ones, friends, personalized correspondence from businesses and government entities and magazines in the form of subscriptions. It was an endorphin rush to receive a letter in my youth. Now, not so much. Today, the mail carrier is tasked with delivery of bulk mail circulars, bills, and (to some) dreaded election campaign marketing pieces. With a high school senior in the household, I’m shocked to see the number of colleges that have sent parcels to my home. So back to the vintage photograph and our mail carriers. On September 18th, 1914, an article published in the Frederick News stated: “The Post Office Department invites your attention to the benefits to be derived from the use of private mail receptacles. Such receptacles in the form of a box or a slot in the door obviate the necessity of patrons responding to the carrier’s call at inconvenient moments, permit the safe delivery of mail at all times, and contribute materially to the efficiency of the service.” Mailboxes for both delivery and reception were quite helpful to resident and letter carrier alike. Many of our historic homes still boast original mail receptacles in the form of interior boxes and mail slots in front doors. Let's take a closer look at those four early mail carriers captured in the photograph. Edward M. Eader Edward Melancthon Eader is buried in Mount Olivet's Area L/Lot 189 not far from the rear of Key Memorial Chapel. He was born December 22nd, 1855. He was the son of Anna Mary Eader (1832-1876), however his biological father is said to be unknown. His mother remarried a man name Joseph Talbott and moved to Howard County without Edward from what I can tell. In 1860, he can be found living on the farm of a maternal uncle (Charles Ezra Eader) who would die at Gettysburg three years later during the American Civil War. In 1870, Edward would be living with his maternal grandparents here in Frederick. Edward M. Eader can be found living on East Street with his widowed grandmother in the 1880 census where his occupation is simply listed as a laborer. Edward married Fannie M. Heard (b. 1860) in late 1880 and the couple raised three sons: Roy, Harry and Lewis (Caroline's grandfather). Soon, he would be one of the three inaugural appointees for the job of "city-carrier" with Frederick’s Post Office. Mr. Eader would be chosen in February 1890 by Frederick's new Post Master, Harry Clay Keefer, and would serve faithfully for 31 years. I found only a couple of articles of note in local newspapers on Edward M. Eader, as most others mentioned him in connection with involvement in the Independent Hose Company and the Sons & Daughters of Liberty Organization. Edward would serve as State Councilor for the organization. Edward M. Eader spent most of his adult life living at 505 East Church Street extended. The 1930 census shows two grandchildren living with he and wife Fannie. He would pass three years later on September 17th, 1933. Great-grandaughter Caroline Eader supplied me with an image showing clippings pertaining to Edward's obituary and funeral announcement. Note that fellow letter-carriers served as pall-bearers. I found like articles in the local newspapers saying much the same. I was impressed that this made front page news. Mr. Eader would be laid to rest in Mount Olivet's Area L/Lot 189 as I mentioned earlier. I thought it would be interesting to search the cemetery for the other three "letter-carriers" in the vintage photograph taken on West Patrick street nearly 110 years ago. Following are their obituaries and gravestones. Edmund F. Moberly (1850-1935) James Edward Duvall (1839-1929) Charles Robertson (1852-1911) One of the most interesting finds along the way was this little article which appeared in the March 17th, 1915 edition of the Frederick Post. This led me to search further, and I would learn a great deal about Julia M. Shafer of Knoxville in the southwestern part of Frederick County. As the article states, Miss Shafer (b. Sept. 1885) was one of the first female rural mail carriers in the Eastern U.S. Being a rural mail carrier was regarded a rougher challenge than city-carrier based on the roads of the time, weather issues and wild animals occasionally making the job a bit more difficult. She unofficially began in this endeavor by assisting her father (Thomas K. Shafer) in 1896. The family lived off of Petersville Road, just southeast of the village of Burkittville and on the greater Needwood estate of the earlier Lee family. A feature article appeared in the Frederick News in December, 1911 stating she had been in the U.S. Service for eight years. Miss Julia May Shafer never married but served her employers with "great fidelity." She would retire after 30 years under the United States Postal Service, and it is said that she traveled over 234,000 miles in her goal of delivering mail to the masses. Another feature article appeared shortly after her retirement in January, 1934 and states that adding her work-based travel miles together would equate to circling the globe five times. It's an amazing feat regardless of sex, however her story is one for the ages. Julia M. Shafer died in January, 1961 at the age of 75. She is not buried here in Mount Olivet, however her mortal remains are reposing with her family in Burkittsville Union Cemetery. For well over 30 years, Miss Shafer would dutifully pass this burying ground, in the shadow of South Mountain, almost daily as part of her established rural postal route. I hope this article gave you a little more appreciation for our mail-carriers, both past and present. Even though National Thank a Mail Carrier Day (February 4th) falls on a Sunday this year, please give them a thank you on Monday if you see them — better yet, leave them a note or letter.

|

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed