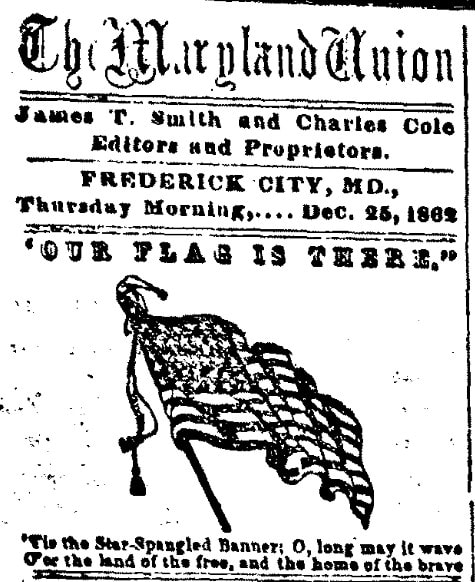

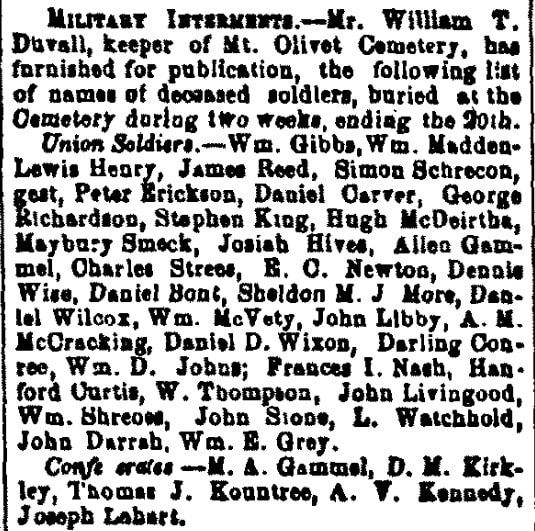

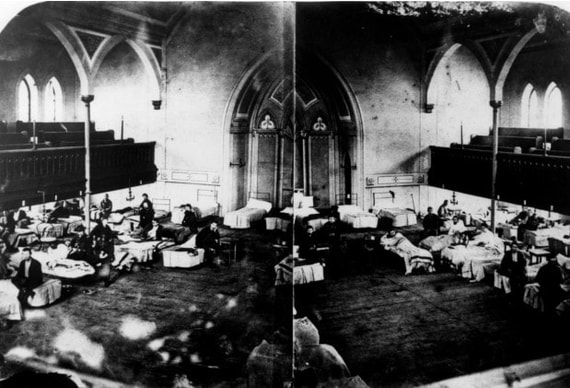

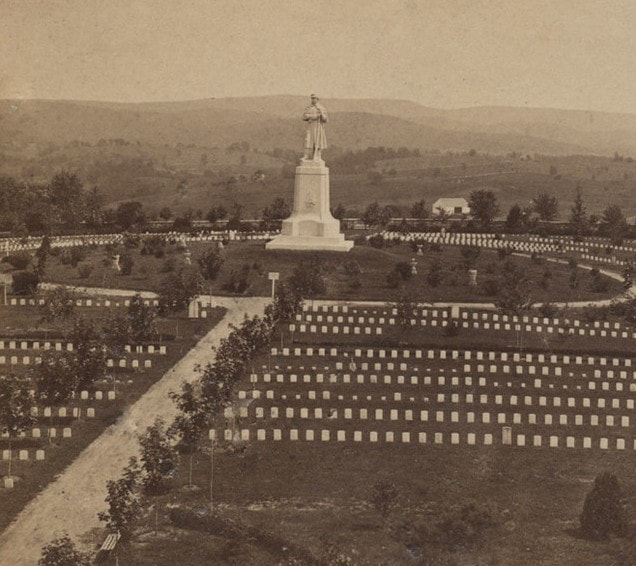

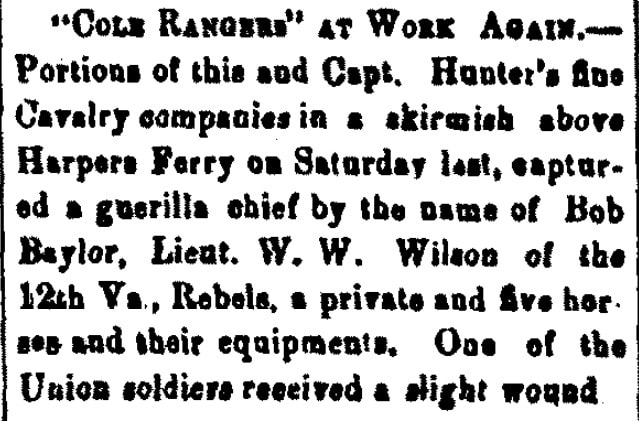

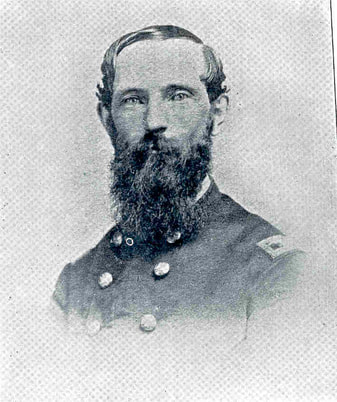

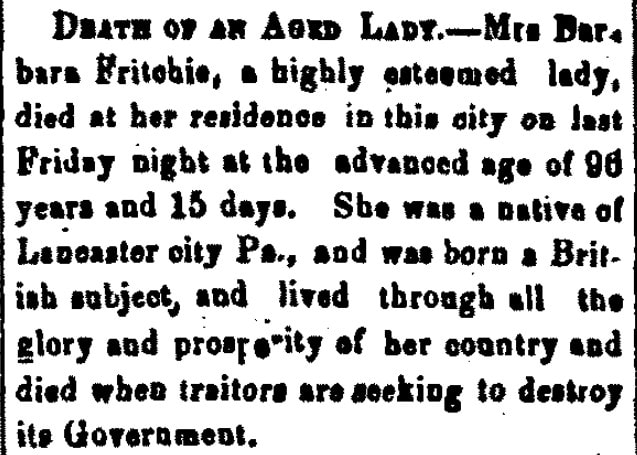

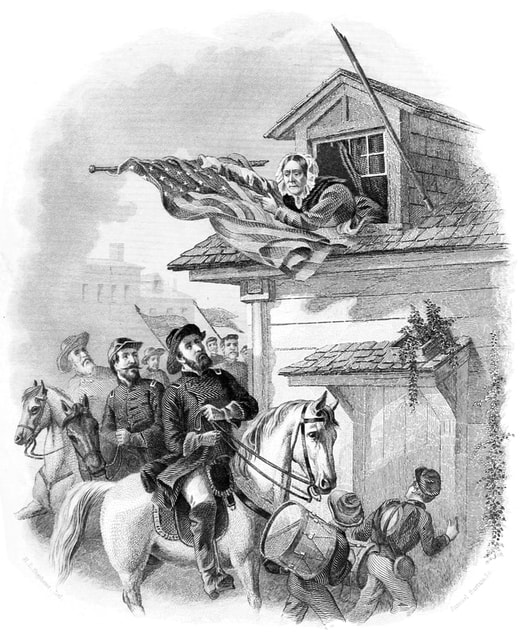

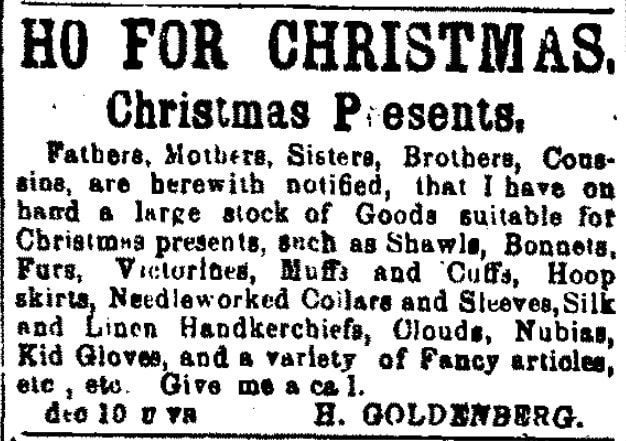

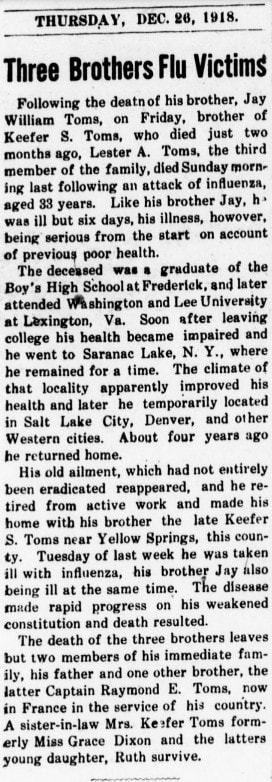

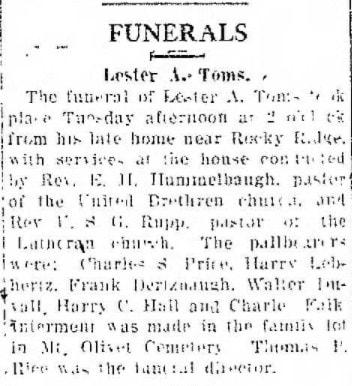

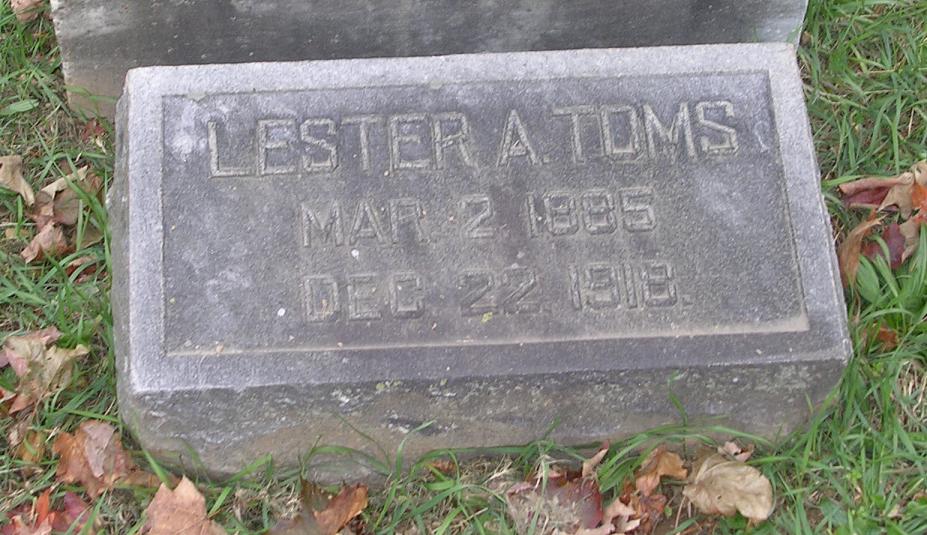

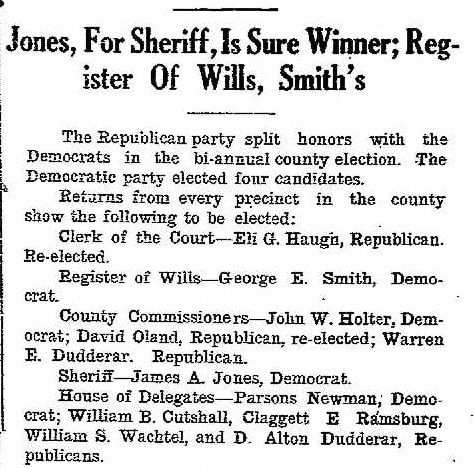

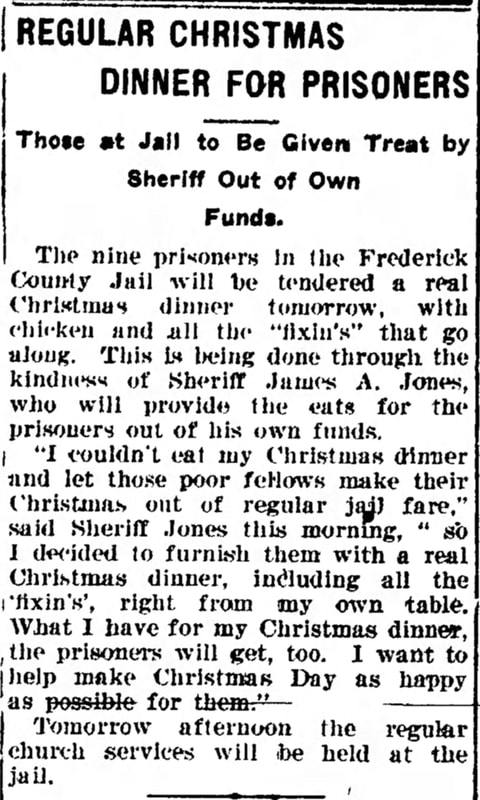

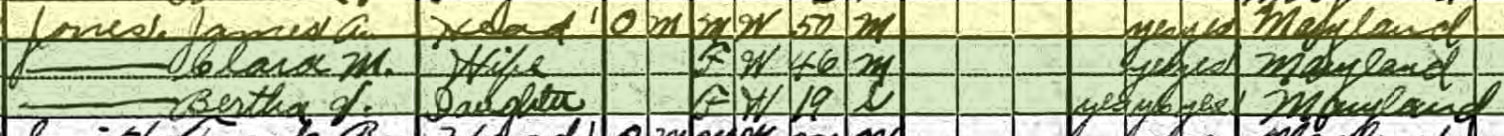

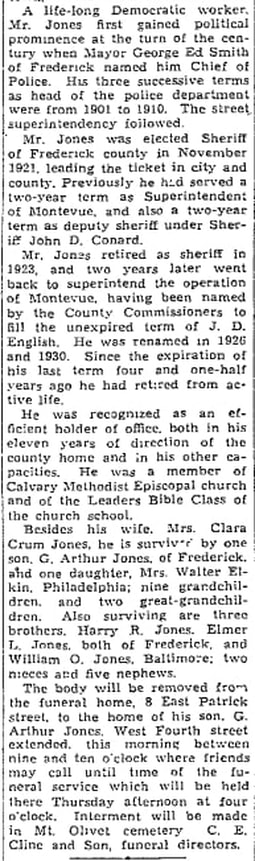

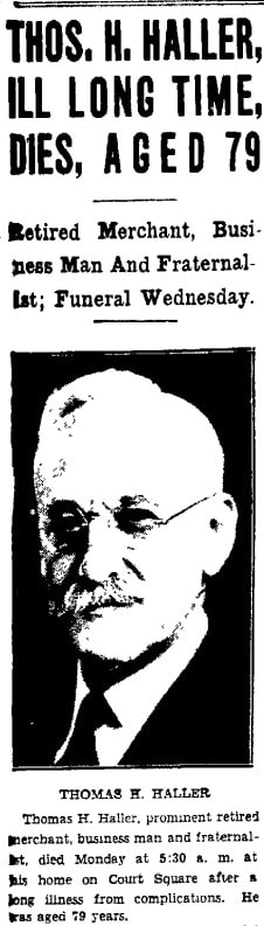

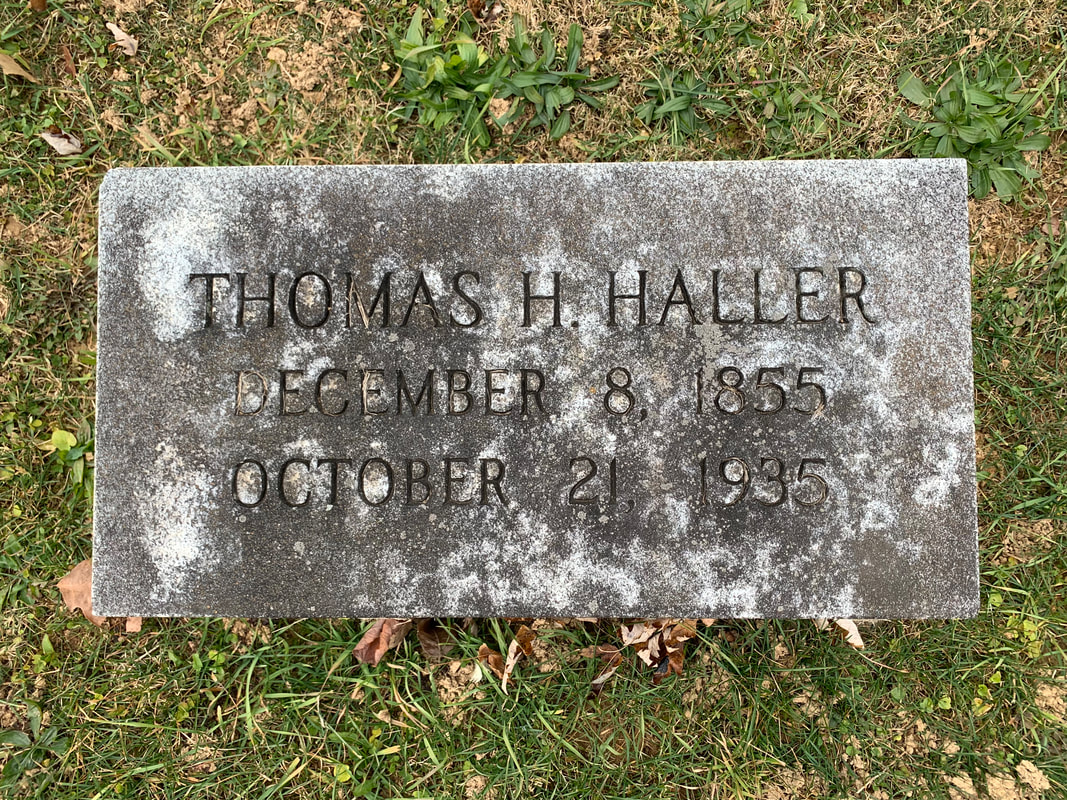

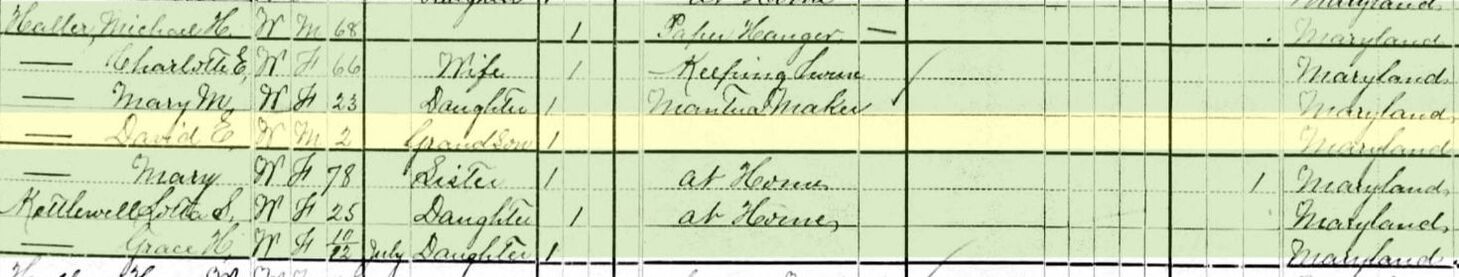

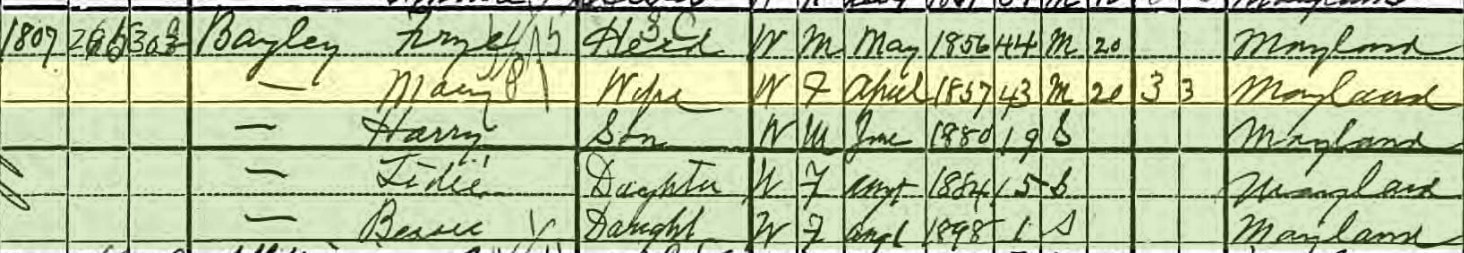

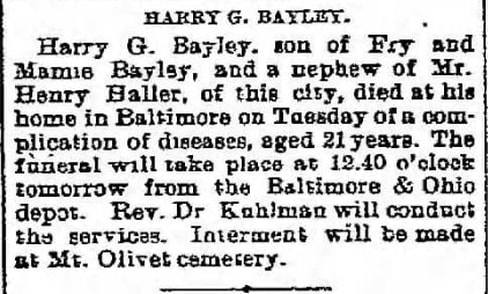

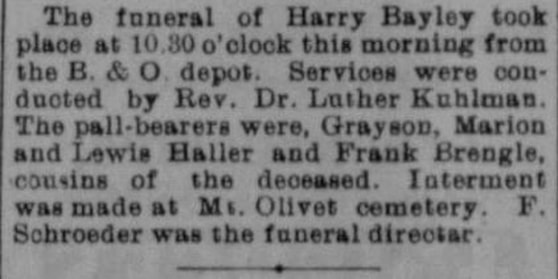

Opening ceremony of Wreaths Across America Day (Dec 18, 2021) Opening ceremony of Wreaths Across America Day (Dec 18, 2021) Christmastime is here—literally and figuratively, of course. I decided to look for a few interesting connections to Christmas at Mount Olivet, employing, of course, my keen senses, research skills and an uncanny curiosity to find relations between those interred in our cemetery and local, state and national history. I also enjoy linkages to pop culture, past and present. As a result, we have gathered a few yuletide tidbits pertaining to three specific individuals to share with you. But before I get to that, I’d like to share some intriguing items found in a local newspaper edition from Christmas 1862. Since I’m still running on fumes from our recent “Wreaths Across America” Day and program here at Mount Olivet last weekend, I still have military veterans firmly on my mind—and how could I not? One location (in the cemetery) that received a good number of wreaths last week was a quiet corner located on the southernmost tip of Area C. This is where 17 former Union soldiers are buried in a 3-lot parcel. It was originally bought, and owned, by the local Frederick Chapter of the Grand Army of the Republic. After the American Civil War, this veteran's group was commonly referred to as the G.A.R., founded on April 6th, 1866, in Decatur, Illinois. It was a benevolent organization that helped with health and burial needs of Union veterans. One can find G.A.R. symbolism and monuments throughout American cemeteries marking the graves of men and women who served during the war. This spring, I plan to tackle a lengthier discussion on this particular lot and those in it with a specifically aimed “Story in Stone.” As for this “holiday edition” of our blog, I’d like you, the reader, to put yourself in the shoes of a Frederick soldier or civilian resident experiencing Christmas, 1862 with the country at war. To give context, the attack on Fort Sumter took place in April, 1861, and the First Battle of Bull Run occurred on July 21st, of 1861 in Manassas, Virginia. Just over a year later, the Second Battle of Bull Run was fought in late August and resulted in a decisive Confederate victory. This prompted Gen. Robert E. Lee to cross the Potomac River and bring the war to the North (or Union) for the first time. The first major, northern (or Union) town that he would bring his Army of Northern Virginia would be Frederick. This was in early September. The Rebels entered on September 4th and 5th and stayed until the 10th. The rest of the story, as they say, is history. These soldiers were mostly seen as unwelcome guests, and they departed heading west out of town toward the Middletown Valley, and points on the other side of South Mountain. Two high-pitched battles would follow: The Battle of South Mountain occurred at three mountain gaps west of Middletown and Burkittsville on September 14th, and was followed by the Battle of Antietam just three days later. These conflicts brought two major armies through our area as Gen. George McClellan and the Union Army of the Potomac pursued the Confederates coming up from Washington, DC and through Frederick city and county. The result of both battles made “one vast hospital” out of Frederick as all public buildings, schools, churches and private homes were commandeered in an effort to take care of the large number of wounded and sick men of both armies. Sufficed to say, it was a troubling fall and winter. Certainly not to downplay our last two holiday seasons with Covid-19 at the forefront, but this was a true time of turmoil where people were dying at the hands of fellow Americans. The Union was under siege, and no end or compromise was clearly in sight. I found it interesting that a newspaper edition of the Maryland Union was published and distributed on Thursday, December 25th of that year. I’m thinking that the thirst for knowledge and information at this particular time certainly outweighed the opportunity to take the day off from continued critical thinking amidst the hostile environment of the country at that time. In that newspaper of Christmas Day, our cemetery’s first superintendent, William T. Duvall provided the newspaper with a bi-weekly report of the Civil War dead that had been buried in Mount Olivet from December 6th through 20th. To give some context, Mount Olivet had an agreement in place with the federal government to bury the dead from both armies, but did so in two distinct rows along the cemetery’s northern and western perimeters. Note that there were many more Union soldiers than Confederate? Today, those Confederate soldiers listed are still resting here, but as for the Union boys, most that perished during wartime (and subsequently buried here) like those listed in the article above were moved to Sharpsburg and the national cemetery there dedicated on September 17th, 1867. This was the fifth anniversary of “the bloodiest one-day battle in US history.“ Back to that newspaper of December 25th, 1862. The war naturally dominated the news of the day, just like the Omicron variant, mask mandates and vaccine debates of today. I found another prominent newspaper article talking about Col. Henry Cole and his cavalry outfit. Cole was commander of this group originally organized as the 1st Potomac Home Brigade Cavalry, and better known as Cole's Cavalry of Maryland Volunteers (1861-1865). Again, this gentleman will be the recipient of a future story. I will say that he was living in Baltimore at the time of his death in 1909 at age 70, and would be buried here in Mount Olivet’s Area R/Lot 98. His grave also received a wreath last week as part of our Wreaths Across America program. Further down the newspaper column, I found another treat—the obituary of our legendary heroine of the Civil War, the incomparable Barbara Fritchie. Barbara had actually died the previous Thursday on December 18th at the age of 96, having had a birthday just weeks before on December 8th, 1862. You may be surprised that there was absolutely no mention of Barbara’s flag-waving heroics at all in this obituary, something you would certainly expect to see mention of. Based on her fame as a folk hero, I think a headline announcing her death on the front page would have been warranted, but alas, this was simply page 2 news! There is a reason this did not happen, and the simple explanation is that John Greenleaf Whittier would not write his famous poem until the following year of 1863. It was published in the Atlantic Monthly magazine in October 1863. And that’s when the name of Barbara Fritchie became a household name in the North, and a “propagandic strike” at Confederate chivalry in the South. Barbara Fritchie became famous, as did her hometown. The Barbara Fritchie we know today can be somewhat contradicted by this humble obituary, and lack of news coverage throughout the fall of 1862 for this sacred event and the validity of her supposed actions on September 10th, 1862 at her home on West Patrick Street by Carroll Creek. You may recall that Frederick diarist Jacob Engelbrecht commented on the incident in his diary, remarking that the article in the magazine constituted the first he had heard of the whole (flag-waving) affair, as he lived directly across the street and noticed nothing of the sort occurring throughout that particular day and involving the feeble, nonagenarian. A final thing in this particular newspaper caught my eye. It was a Christmas-themed advertisement for Henry Goldenberg’s millinery business on Market Street. Interestingly, I researched this gentleman a few years back, but he is not buried in Mount Olivet. Mr. Goldenberg ran his business out of a shop a few doors north of the Market House (today’s location of Brewers Alley). This location was formerly the site of the above-mentioned Jacob Engebrecht’s tailoring shop, a business whom the diarist partnered with his brother Michael for some time, before moving to a new location across the street from the Fritchie home on West Patrick Street. A Baltimore native, Mr. Goldenberg, would continue to be prosperous here in Frederick until making a fateful decision to re-locate to Johnstown, Pennsylvania in March, 1884. Five years later, Henry Goldenberg would be a victim of our country’s most infamous flood on May 31st, 1889. To read more, click on the button below to read a story I wrote about Mr. Goldenberg back in May, 2020 for my HSP History Blog. 1921 We have left 1862 and now I have you time traveling to a century ago to look at Christmas, 1921. Life around these parts had truly returned to normal, especially considering the situation and mood in town three years previously. Perhaps you could say it was reminiscent of Christmas 1862 in a way? In 1918, our troops had just experienced victory on the battlefields of France on November 11th with the armistice to end the First World War. Celebration was tempered here at home, however, because we were still battling a formidable foe in the form of the Great Spanish Flu pandemic which had killed 50,000,000 worldwide and created 500 million cases. One hundred of these victims are buried here in Mount Olivet, including three brothers of the Toms family. The third of these, Lester A. Toms, died on December 22nd and was buried here on Christmas Eve.  John Luther "Casey" Jones in 1898 John Luther "Casey" Jones in 1898 Aside from this depressing news, I was happy to find two articles that made me smile. Both featured individuals buried here in Mount Olivet, James Alonza Jones and Thomas Henry Haller. Mr. Jones was mentioned in one of my earlier “Stories in Stone” entitled “Casey Jones you Better, Watch your Speed” from August, 2017. In this foray, I found two Frederick men with the nickname of “Casey” Jones like the famed John Luther “Casey” Jones of Tennessee immortalized as an American folk hero thanks to an original song by Wallace Saunders. Some may be more familiar with the later song of the same name by the Grateful Dead, which puts a more psychedelic spin on the old legend. Our two Mount Olivet “Casey Jones” include Charles Edwin Jones (1871-1950) in Area OO/Lot 132 and George Arthur Jones (1895-1971). This latter gentleman's father, James Alonza Jones (1870-1939), headed Frederick City’s police department from 1901-1910 and was elected Frederick County Sheriff in 1921. He also served as superintendent for the Montevue Home for the Aged before, and after, his term as sheriff. James A. Jones’ name made the paper quite a bit, including early November of 1921 when he was victorious in the Sheriff’s race for county elections that year. However, just over a month on the job, Jones did something on Christmas that would surely endure him to me. James A. Jones made a strong statement through this kind gesture on this day. He passed in 1939 and is buried in Area P/Lot 188 next to wife Clara Margaret (Crum) Jones. In this same edition of The Frederick News, I found a curious little message in the form of a print ad and attributed to one, Thomas H. Haller. It was entitled A Christmas Song. His message was an age old one. Thomas Henry Haller was born in the vicinity of South Market Street on December 8th, 1855, the son of Thomas Henry Haller, Sr. and Caroline Rebecca Fessler. His obituary is crammed with amazing achievements in regard to Frederick’s history. The prominent businessman headed up his own dry goods store for decades, along with taking the helm as a director for other amazing companies and endeavors such as the Union Knitting Mills, the Frederick and Hagerstown Railway and the Economy Silo Factory. Linkages with the Citizens Bank and Frederick Building Company also come as no surprise. Mr. Haller would pass on October 21st, 1935 at the time living at 101 Council Street adjacent the former county courthouse. He is buried in Area MM/Lot 84, not far from Gov. Thomas Johnson. His obituary paints quite a life story—one that explains his mantra and message of Peace on Earth and Good Will to Men as he was heavily involved in Frederick’s charitable and benevolent activity throughout his adult life. I also found these memorials in the newspaper in the days following his death as they pertained to Mr. Haller and two financial oriented Boards he participated on through the “Roaring 20s,“ followed by “the Stock Market Crash of 1929” and “Great Depression Era” to follow. When I read about the Frederick Building Company, I couldn't help but think of the Christmastime classic movie that revolves around a small-town building and loan company of this same era. Of course, I'm talking about the fictional Bailey Building & Loan of Bedford Falls (NY) from the 1946 Frank Capra film It’s a Wonderful Life. The firm in question was started by Peter Bailey in 1903, and was later turned over to his son, the film’s central character, George Bailey, played by actor Jimmy Stewart. George Bailey was born in 1907, and the film opens with a children’s group sledding scene taking place around the time of Christmas, 1918. Multiple kids are sledding (by use of a shovel) on a frozen pond, including 12-year-old George and his kid brother, Harry (b. 1911). Unfortunately, Harry was too young to control his sled away from a weak spot on the ice, and soon plunged into the frigid water below. Without hesitation, George heroically saves the life of his younger brother by unselfishly jumping into the water and pulling his brother to safety. In the process, George loses the hearing in his left ear as a result.  The movie eventually flashes forward to 1929, and the death of George’s father, saddling him with running the family business (Bailey Building and Loan) and squelching his dream since childhood of traveling the world. George would begrudgingly sacrifice his utmost desire in order to serve his fellow citizens and neighbors in Bedford Falls, a decision he would continue to regret. A lot happens along the way including George starting a family, but a confrontation against the villainous town scrooge, Mr. Henry F. Potter, and a series of missteps and trials puts George Bailey on the brink of committing suicide. George says he wishes he hadn’t been born at all, thinking his life was a waste and the world is a better place without him. An angel named Clarence is sent to intercede and shows George just how many lives he touched along the way. If George Bailey hadn’t been born, a chain reaction of terrible things would have beset many characters already introduced in the movie, not to mention the town of Bedford Falls would be a far different place. One of the worst of these “losses” would have surely resulted in the death of George’s brother, Harry, who would grow up to be a decorated pilot in World War II. Harry’s bravery saved multiple lives of serviceman aboard a transport ship through his heroics in battle. George’s little brother later became a successful businessman. George demonstrated jealousy towards his younger brother’s successes earlier in the film, but later would see the light that his selfless acts and sacrifices allowed people like his brother to live and succeed, thus he could share in these amazing triumphs and accomplishments as well. Well that long description brings me to my last person of interest to tell you about here who connects to Christmas. We do not have a George Bailey here at Mount Olivet, but we do have a Harry George Bayley! He is buried in Area B/Lot 144. Now finding info on this individual was quite difficult. He was born in Frederick in June, 1880, the son of Frye Bayley and Mary Margaret Rosanna Haller (1857-1952). Once again, to show that Frederick was still a small town in the big picture, Mary (aka Mamie) Haller was a first cousin of our fore-mentioned Christmas poet—merchant/building and loan man Thomas Henry Haller. Mary’s father, Michael Henry Haller (1811-1889) and Thomas’ father, John Thomas Haller (1816-1882), were brothers and sons of Tobias Haller (1775-1818) and wife Matilda Elizabeth Heichler (1772-1863). Frye W. Bayley worked as an auditor for the B&O Railroad. Mary Bayley was listed as a mantua maker in the 1880 census. In the 1900 census, the family can be found living at 972 Riggs Avenue near the intersection with North Fulton Avenue in northwest Baltimore. Up the street on the right corner is Mount Pisgah Christian Methodist Episcopal Church. Harry was the oldest of three children, having two younger sisters in Lidie and Bessie. Details of Harry Bayley’s life are scarce as already stated. Our subject’s life was cut drastically short of experiencing “a wonderful life,” dying at the age of 21. Our records simply say that Harry died of complications of disease on June 2nd, 1902 in his hometown of Baltimore. His body would be delivered to Frederick by train, and he was buried in a plot on Area B/Lot 144 . This was a cemetery lot where his grandparents were buried, and today includes several aunts, uncles and a few maiden great aunts from his mother’s Haller family. Harry G. Bayley’s parents lived for decades after. They are not buried here at Mount Olivet, but rather Lorraine Park Cemetery in Baltimore. His father died in 1933, and his Frederick native mother in 1952. I thought about poor Harry George Bayley the other night as I enjoyed my annual viewing of It’s a Wonderful Life. I read that Frank Capra once affirmed the movie’s purpose in an interview. He said: “The importance of the individual is the theme that it tells: that no man is a failure and that every man has something to do with his life. If he’s born, he’s born to do something.” George Bailey’s biography shows us that every life holds infinite possibilities, sending ripples out into the farthest reaches of the world. I like to apply that to all who are buried in Frederick’s Mount Olivet Cemetery, and burying grounds everywhere. What a nice thought when strolling through a cemetery, and thinking about the countless “lives once lived.” So many connections when I ponder how many peoples’ lives here were affected, shaped, and molded, (hopefully for the better), by others who may well lie in close proximity in our garden cemetery. Regardless of the stresses, strains and challenges of life be it 1862, 1918, 1921 or 2021, we all have the ability to see the wonders and good in life, and how we may affect family, friends and aquaintances in the process of living from day to day. Merry Christmas, Happy Holidays and thanks for the support of Mount Olivet’s preservation of history over the past year. With 2024 on the doorstep, consider a membership in the Friends of Mount Olivet where our mission is to preserve the historic records, structures and stones of the cemetery. In addition to those wanting to do volunteer history research and stone cleaning, we also have a calendar of special social events ranging from lectures and walking tours to other special events and get-togethers.

0 Comments

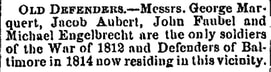

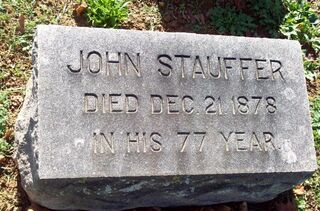

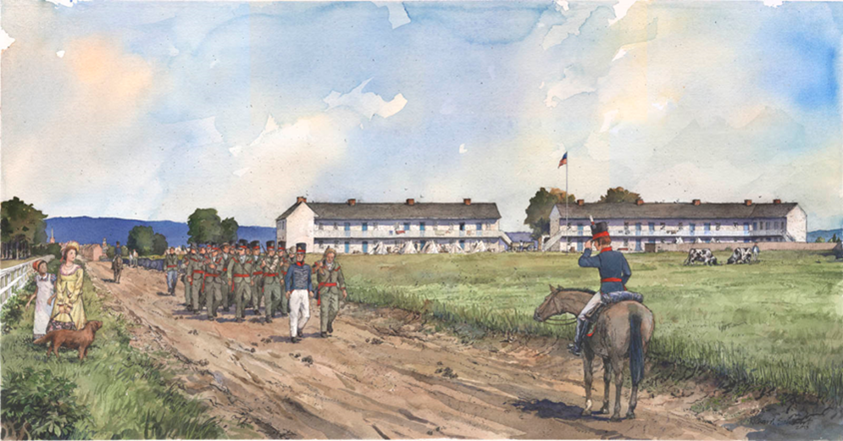

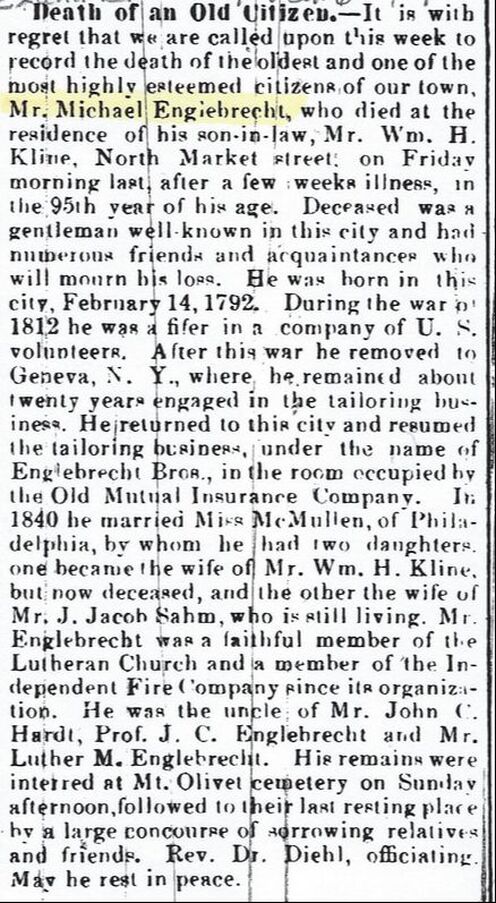

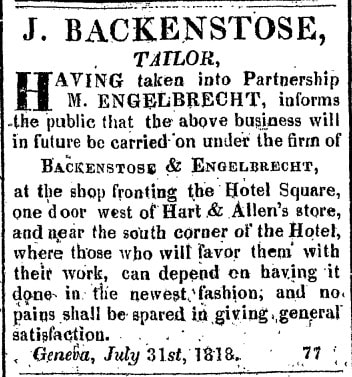

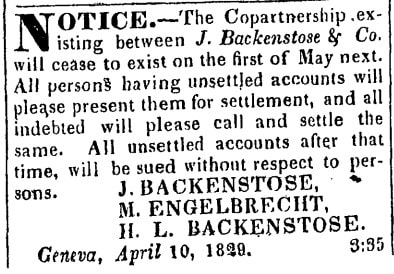

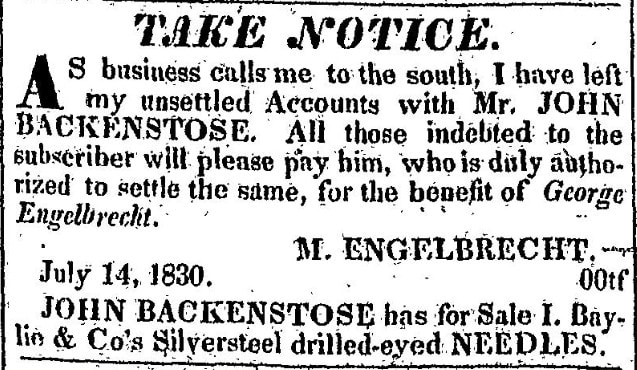

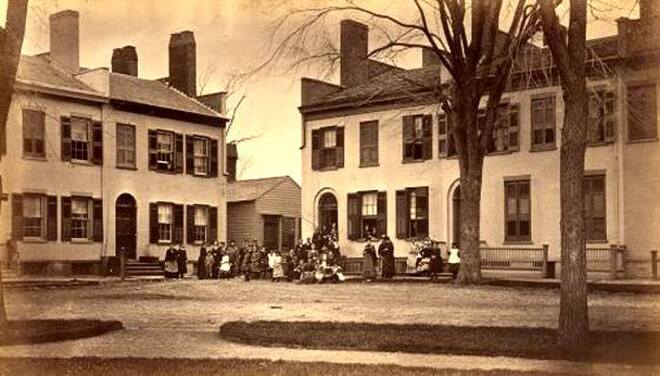

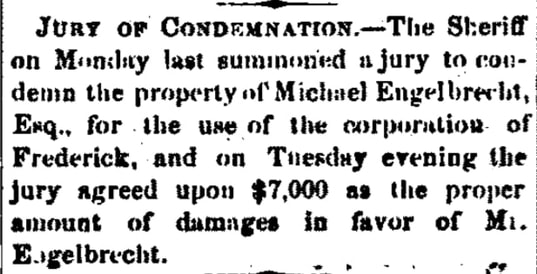

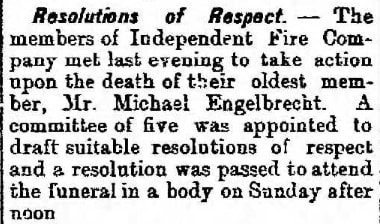

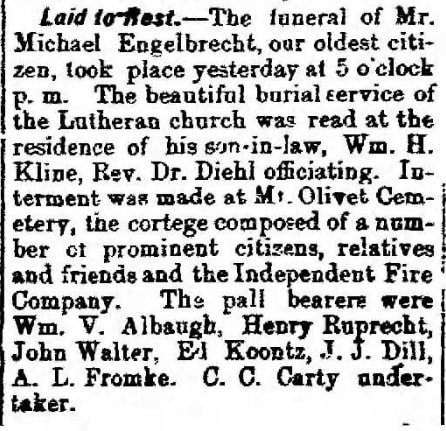

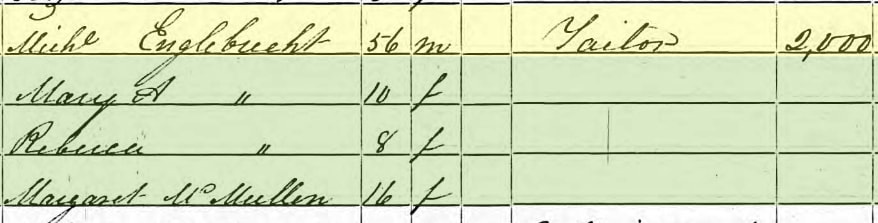

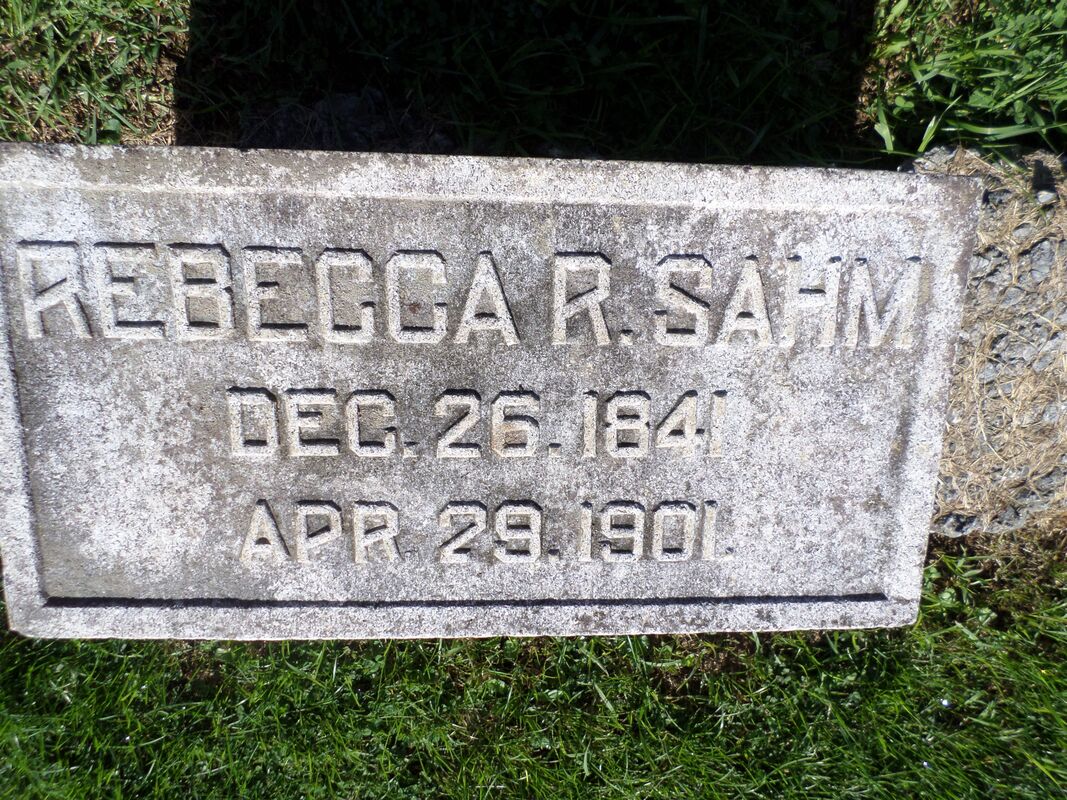

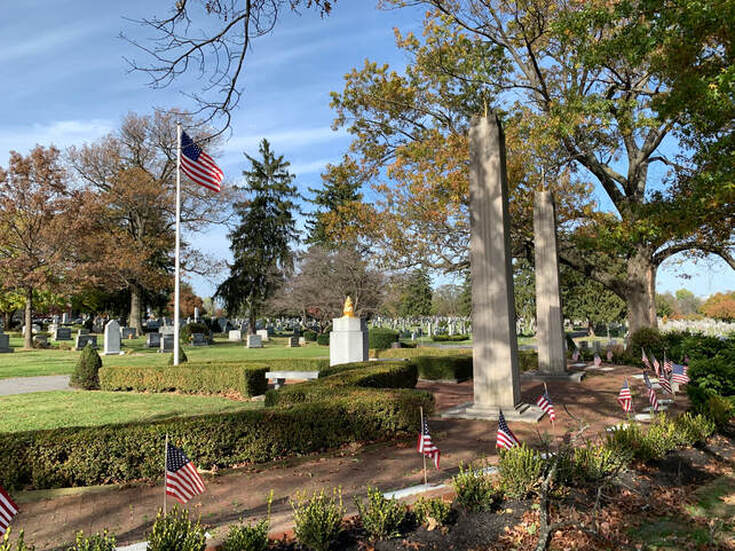

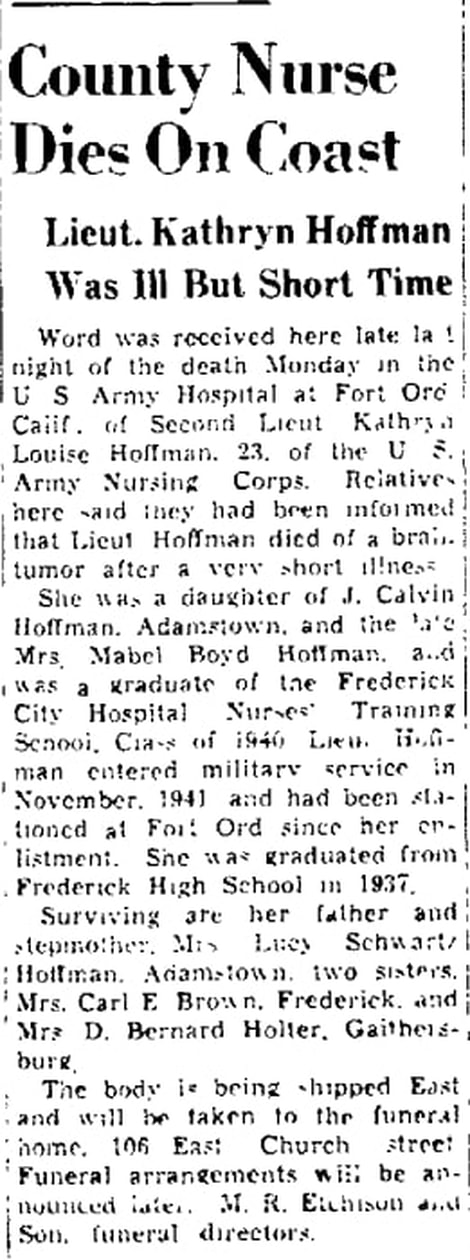

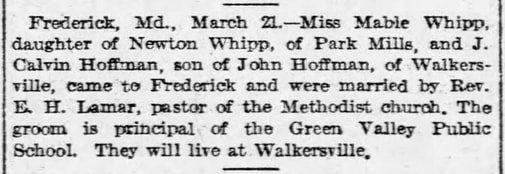

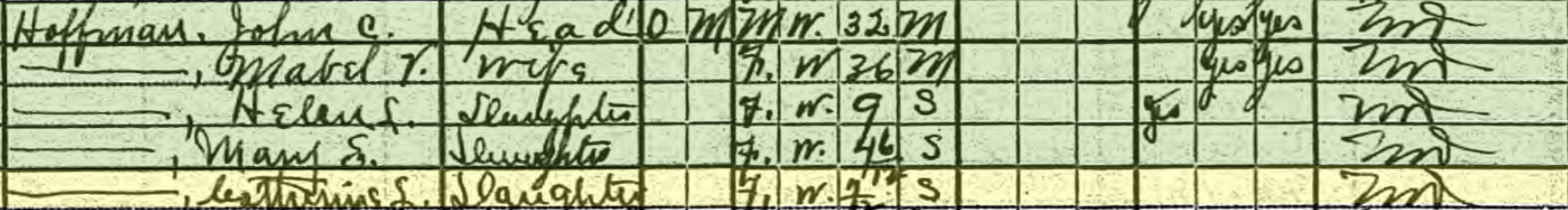

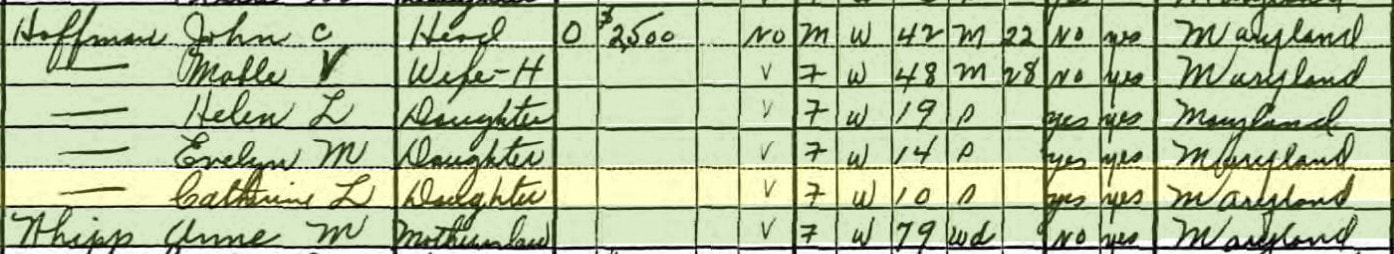

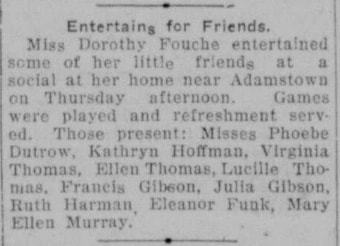

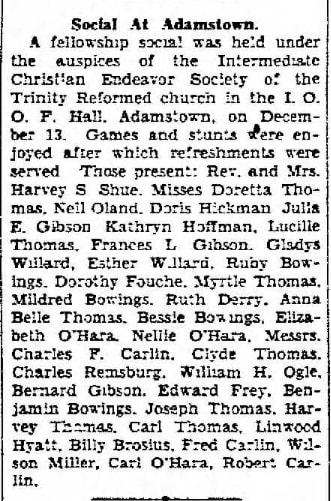

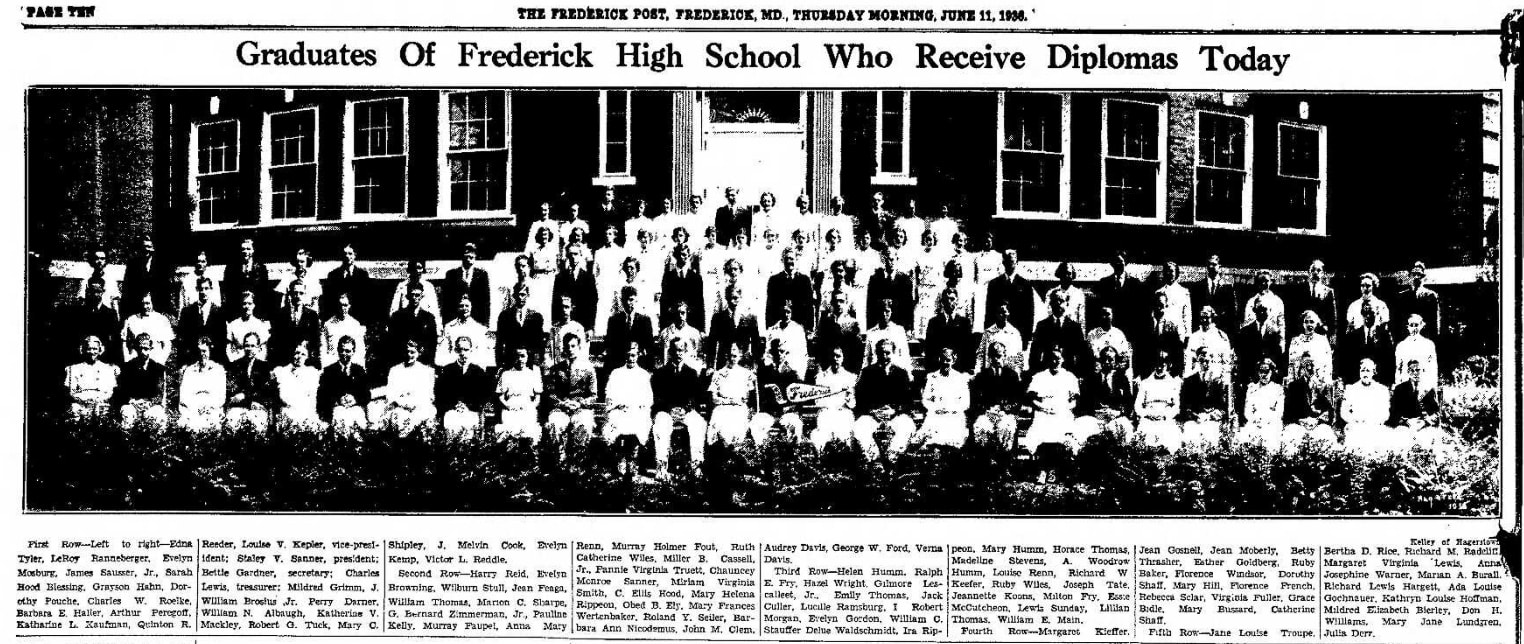

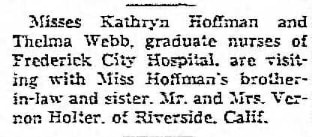

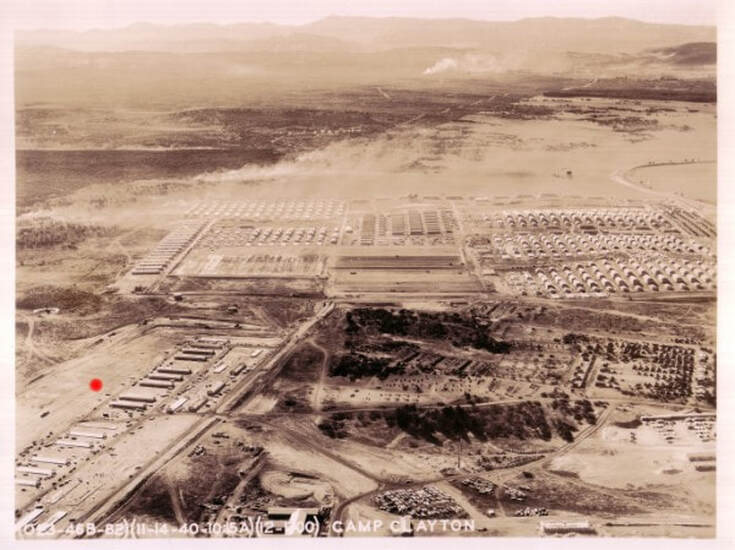

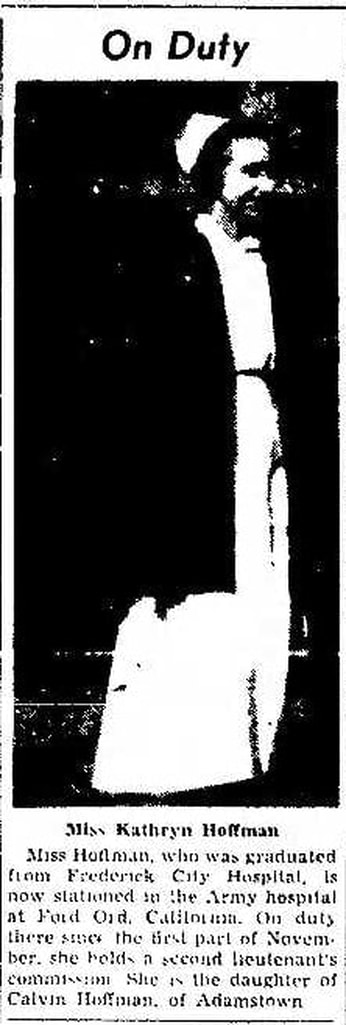

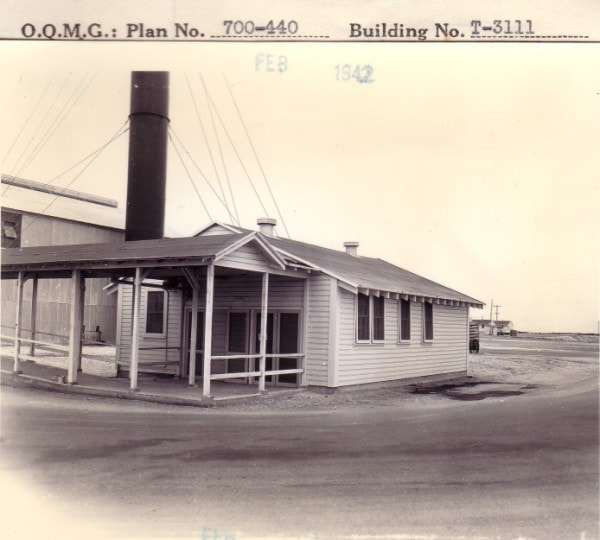

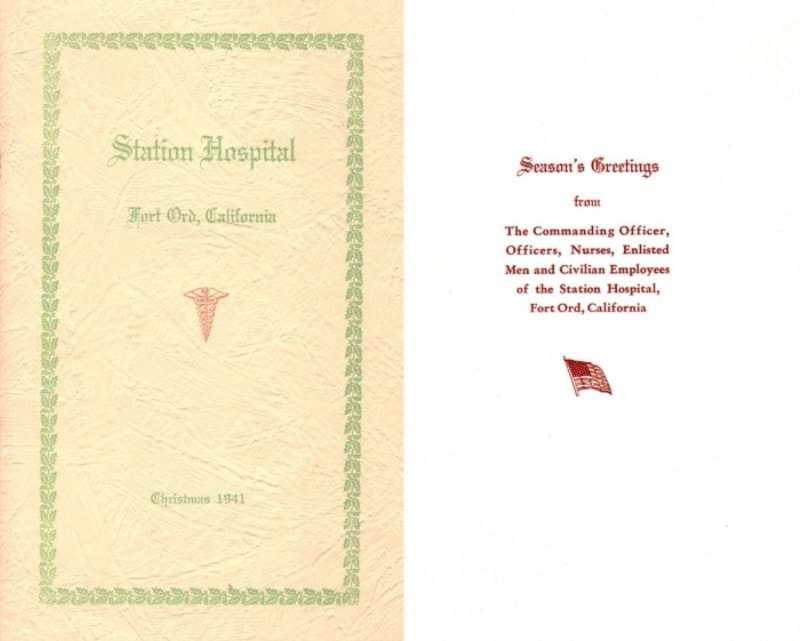

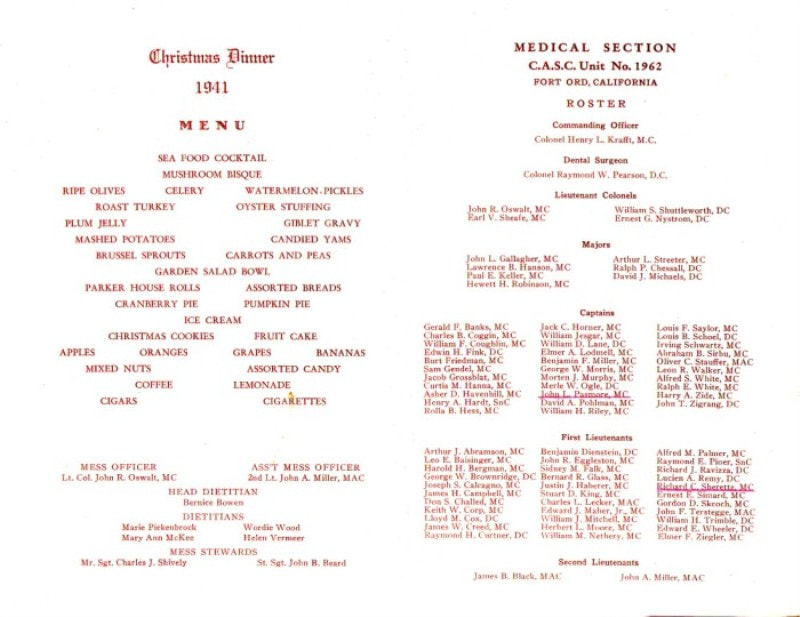

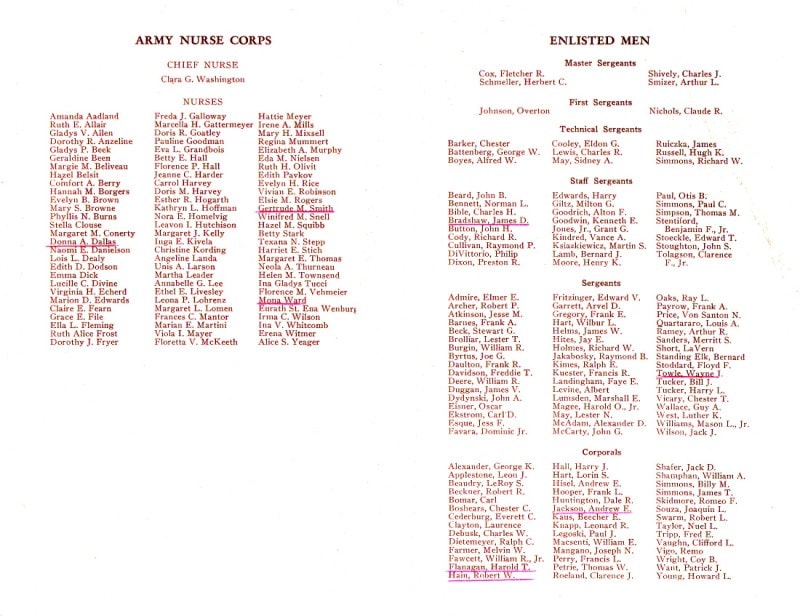

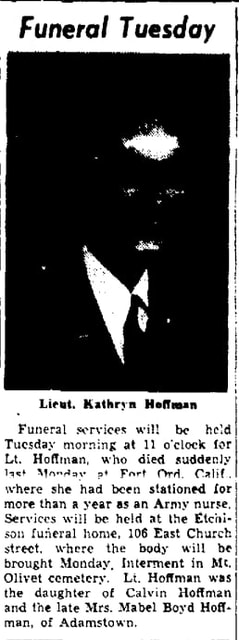

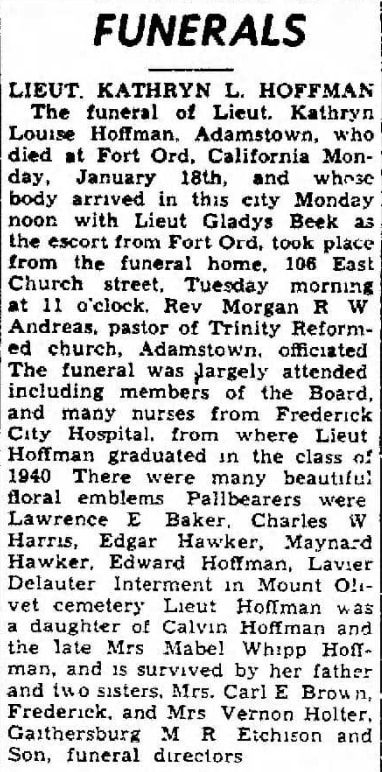

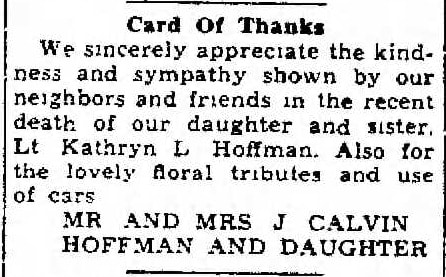

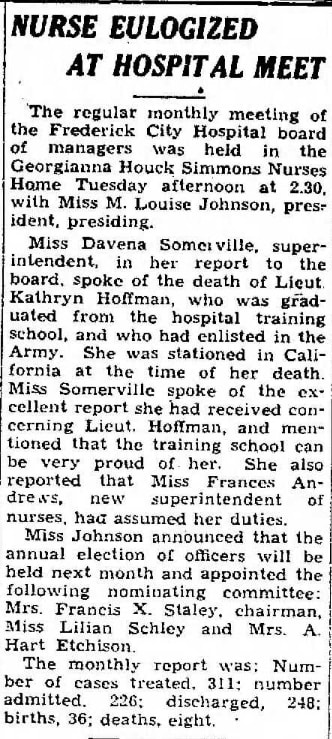

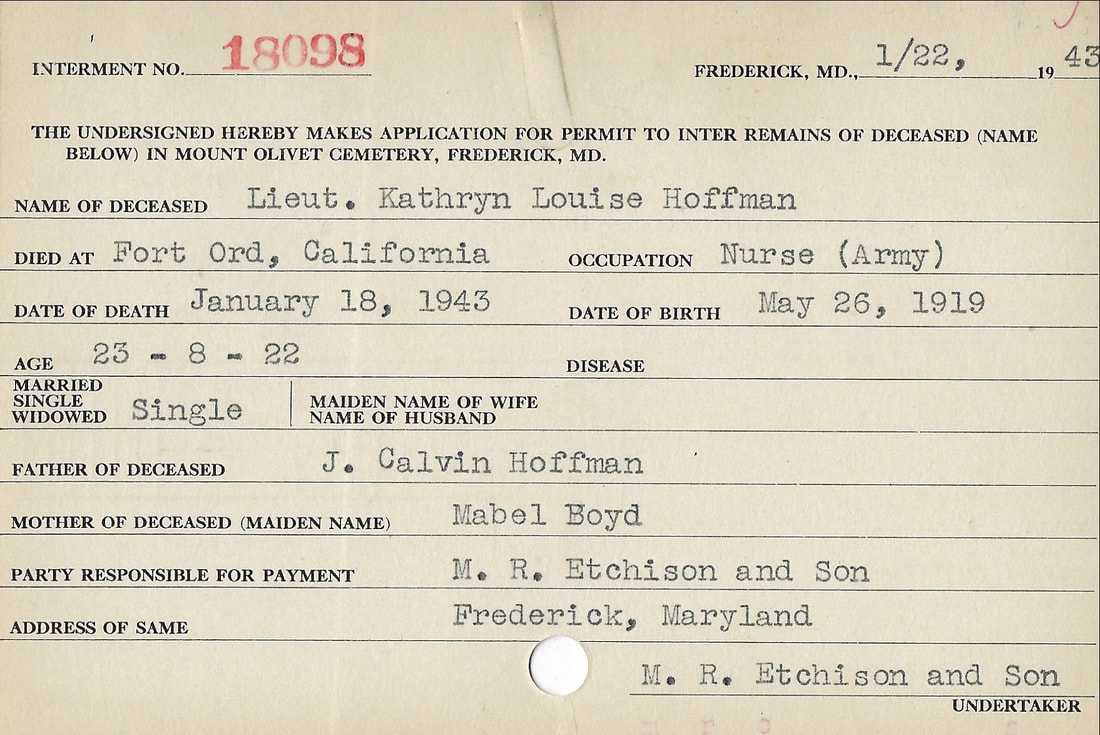

Well, it’s that special time of year once again here at Mount Olivet, and no, I’m not talking about Christmas. While the cemetery looks great with many grave monuments decorated for the holiday season, I’m instead referring to the third of Mount Olivet’s commemorative military trifecta--Wreaths Across America. The others include Memorial and Veteran days. We have over 4,000 men and women buried here who served in the US military. Many participated in active combat in conflicts including the American Revolution, War of 1812, the Mexican War, American Civil War, Spanish-American War, the World Wars, Korea, Vietnam, the Persian Gulf War and Afghanistan. As more and more research is done, we seem to find our total number of vets here growing. Unlike Arlington or other veteran cemeteries, we have military men and women representing 10% of our cemetery grave population. (40,000+). This makes identifying veterans buried here without military markers a tough task. This is especially true if the individual in question moved here from elsewhere after completing their service. This Saturday, December the 18th, 2021, we will be hosting our fourth annual Wreaths Across America (WAA) Day. We won’t be alone, of course, but joined simultaneously by the fore-mentioned Arlington National Cemetery down the road, and over 1,600 additional locations throughout the United States, and at sea and abroad. Each site will include a host of volunteers and sponsors celebrating WAA’s mission of Remembering, Honoring and Teaching through the placement of special wreaths on veteran graves. This year, we came ever closer to our ultimate goal of covering all 4,000 graves with wreaths. Our final tally was 3,411, and again we sincerely thank all of our partners and sponsors for making this possible. On the other hand, we may not be thanking the “weather gods” as rain is in the forecast. This has been the case each year, however last December we were spared rain, but had eight inches of snow dumped on us three days before the event. This presented a challenge in uncovering graves to lay the wreaths, but we thankfully had our Veteran's Day flags on graves to help guide us. All in all, the weather isn’t important, but remembering the magnitude of the sacrifices made by these men and women in uniform for our freedom and liberty is all that counts. This is why we are involved in this important program, and will continue to hold it here in a patriotic cemetery where the grave of the guy who wrote our national anthem is just inside our front gate. In this installment of "Stories in Stone," I want to briefly call out two veterans whose grave sites will be adorned with wreaths this upcoming weekend. Other than having German lineage, they could not be more different. Each participated in conflicts separated by 130 years, however their lives were only separated by 57 years. They were both non-combatant members of infantry-based units, and played different roles than typical ground soldiers. One was a musician, and the other a nurse. Our subjects this week are Pvt. Michael Engelbrecht in Area Q, and 2LT Kathryn Hoffman in Area LL.  Maryland Union (Sept 16, 1880) Maryland Union (Sept 16, 1880) Michael Engelbrecht Private Michael Engelbrecht served as a principal musician in the Frederick County militia in the War of 1812. He served under Capt. James F. Huston and then Capt. Joseph Green from July 23rd to October 13th, 1814. Engelbrecht was born in Frederick Town on February 14th, 1792. His father was Johann Conrad Engelbrecht of Germany. His father fought as a mercenary soldier under the British throne during the American Revolution. Michael’s father had been captured at Yorktown and he and his his “colleagues” were transported to our very own Frederick Hessian Barracks, located a few short blocks down from Francis Scott Key and our cemetery front gate. These men were loosely guarded and found work at many local farms, owned by German immigrants who had migrated here in the decades predating the war. Several of these men decided to stay here after the war, not returning to Germany. Can you blame them? There was a great deal of strife happening back home in Western Europe, and Frederick Town was appealing for several reasons. These included: the German language was generally spoken more commonly than English here at this time; there was opportunity in the form of farming and working the trades including having a market for gifted immigrant craftsman. Best of all, there were plenty of cute and talented German females living in town and county who would make perfect marriage partners. Johannes Conrad Engelbrecht (1758-1819) settled here and worked as a tailor, and married Anna Margareth Houx. His family home was in the first block of E. Church St., on the south side of the street, between the corner of Market Street and the alley that runs between Church and Patrick immediately west of Winchester Hall . This is where Michael grew up, surrounded by six siblings, as he was the third of seven children. These included Frederick (b. 1786-1843), John Conrad (1790-1847), George (1795-1874), Jacob (1798-1878) and Catherine (Engelbrecht) Hardt (1805-1885). You may be familiar with Michael's little brother Jacob Engelbrecht, as he had quite a way with his pen, keeping a diary from 1817 until his death. He wrote about everything and every person. Michael attended school here and was a devout member of the Evangelical Lutheran Church, practically just across the street from his home. Two of the Engelbrecht boys answered the call of the "Second War for Independence" against our old foe, Great Britain. Michael was 22 years-old in 1814, and held the position of "fifer" in the militia company led by Capt. James Huston and others. Michael's brother, William, served as well but under Capt. Nicholas Turbott and in the role of an infantry private. I was curious as to the importance of fifers in warfare. A few years back. I marveled at the role of buglers in World War I as they were used as message "runners" for high command. This was the specific case with another veteran here at Mount Olivet named William Theodore Kreh. A fifer is a non-combatant military occupation of a foot soldier who originally played this instrument during combat. The practice was instituted during the period of Early Modern warfare to sound signals during changes in formation, such as the line, and were also members of the regiment's military band during marches. These soldiers, often boys too young to fight or sons of NCOs, were used to help infantry battalions to keep marching pace from the right of the formation in coordination with the drummers positioned at the center and relayed orders in the form of sequences of musical signals. The fife was particularly useful because of its high-pitched sound, which could be heard over the sounds of battle. Fifers were present in numerous wars of note, as Armies of the 18th and 19th centuries "depended on company fifers and drummers for communicating orders during battle, regulating camp formations and duties, and providing music for marching, ceremonies, and moral."  All I can share with you about Michael Engelbrecht's military experience is what I can glean from Sallie A. Mallick and F. Edward Wright's Frederick County Maryland Militia in the War of 1812 (2008). The Company of Captain Lewis (Emmitsburg Area) served from July 23, 1814 until January 10, 1815. They served at Bladensburg, Annapolis and Baltimore. According to one veteran, Captain Lewis Weaver commanded the company at the Battle of Bladensburg and after the engagement took his company to Baltimore. They arrived at camp outside of Baltimore on September 4, 1814. At some point he was cashiered and succeeded by Captain James Huston who in turn was succeeded by Captain Joseph Green of Emmitsburg who remained in command until the company was discharged on January 10, 1815 at Annapolis. Sergeant Martin Shultz stated that when Captain Huston was taken sick he returned to Frederick and never rejoined the regiment. From that point the company remained under the command of Lieutenant Thomas W. Morgan until Captain Green took command and retained it until the company was discharged. A reference is made in the Frederick-town Herald to the departure of a company under the command of Captain James Huston during the last week of July of 1814. From this item it can be concluded that Huston first commanded the company followed by Weaver, perhaps Morgan, and finally Green. On December 31, 1814, a reward was posted in the Frederick-town Herald for deserters from this company. Fifty had deserted in Baltimore, three deserted at Annapolis and two had deserted at Bladensburg. Captain Green offered $550.00 for the return of the men at his headquarters at Annapolis. Mallick and Wright included a roll list from that period of July-October, 1814 that included the major activity in our region including the Battle of Bladensburg and the Battle of Baltimore at which Francis Scott Key put pen to paper and came up with that catchy song about the US flag. The roll includes the names all the non-commissioned militia members numbering 90 and 14 commissioned officers including the name of Capt. James Huston and another interesting find, George W. Hoffman. Hoffman was an ensign who was promoted to 2nd lieutenant on September 20th, 1814. (Note: Keep this nugget for later on in this story.) Lastly, this company had three musicians: Michael Engelbrecht, George Shade and John Stauffer. Stauffer (1802-1878) was the drummer and apparently deserted on September 25th, 1814. Perhaps we need to cut this volunteer veteran some slack as he was only 12 years-old during the time of his military service. He lived out his life as a farmer in Woodsboro and would be re-buried here in Mount Olivet in 1924 from his original resting place of the Shiloh Methodist Protestant Churchyard in Walkersville. His gravesite is in Area U/Lot 78. Michael’s obituary appeared in the Frederick Examiner newspaper in July of 1886. Here we can get a better image of this man and the life he experienced. Two important notes to point out regarding this article. First, Engelbrecht was spelled incorrectly throughout the article, and I’m sure Jacob told the newspapers editor about it too. Secondly, Michael went into business with brothers Jacob and William on May 7th, 1841 at a location on N. Market Street between Church and Patrick streets. This was after his hiatus of a couple of decades where he had re-located to Geneva, Ontario County, NY. Michael moved to upstate New York in 1814 and lived at the northern tip of Seneca Lake until 1830. I learned that he was employed in the tailoring business of Jacob and Sarah Backenstose, and eventually became a partner of this firm. Jacob Backenstose (1769-1813) was the first tailor in western New York and well-reputed among the elite. I assume that Mr. Backenstose' death prompted Michael's re-location as they could have been earlier associates or perhaps relatives of some degree. Michael returned to Frederick in 1830 and would spend the next 56 years working and living in his native home. The tailoring shop operated by him and brother Jacob is said to have been located just a few doors north of the Market House (today's Brewer's Alley) in the 1859/1860 William's Frederick Directory City Guide. To reiterate another part of the obituary in respect to Michael’s personal life and connections to Mount Olivet, I want to mention his wife and daughters. In 1838, on August 28th, Michael married Rebecca Reed McMullin in Philadelphia. Michael’s bride was born in 1802 in Port Penn, Delaware which today neighbors Delaware City, Delaware to its north—the hometown (and final resting spot) of my father, grandparents, great-grandparents and two earlier generations dating back to the early 19th century. Sadly, Rebecca and Michael’s time would be cut short at less than a decade with her death on January 28th, 1847. She was only 45 years old. Rebecca was buried in the churchyard of Frederick’s Evangelical Lutheran Church. Michael would continue to raise their two known children into adulthood: Mary Ann Engelbrecht (1839-1880) and married William Henry Kline in 1860; and Rebecca Reed Engelbrecht (1841-1901) and married John Jacob Sahm, Jr. in 1864. Mary Ann is buried here in Area C/Lot 51 and Rebecca is in Area B/Lot 60. Michael Engelbrecht was Frederick’s oldest resident at the time of his death. We already know the gift of a diary that Jacob left as his legacy, just imagine the stories told by Michael whose life spanned an amazing time in our country. Fittingly, he is buried close by our town’s most famous nonagenarian who achieved the same age of 96—Barbara Fritchie. A few months after his death, Rebecca Engelbrecht’s body was unearthed from its resting spot in the Lutheran churchyard and re-interred here with that of her husband. Kathryn L. Hoffman The front page of the Frederick News edition of January 19th, 1943 carried the sad news of the untimely death of a local woman serving the war effort on the opposite coast of the country. 2LT Kathryn L. Hoffman was a nurse serving at Fort Ord in Monterey, California. Additional details would pepper the newspaper over the next several days as the young Adamstown resident would be fondly remembered as her body would make its way back home for burial. Kathryn was born May 26th, 1919 in Adamstown, the daughter of schoolteacher John Calvin Hoffman and wife, Mabel Viola (Whipp) Hoffman. Kathryn’s mother would die on July 28th, 1930 at the age of 48. She would be buried on Area LL/Lot 162. Mr. Hoffman would raise his three daughters into adulthood in the same manner as the fore-mentioned Michael Engelbrecht. He had help as he would re-marry, and this woman was named Lucy Schwartz. The girls would all do their mother proud. Helen Lenore (1910-2006) graduated from Hood College, and Mary Evelyn (1915-2001) Brown's husband, Carl E. Brown, was a familiar face at the C. Burr Artz Library Maryland Room for many years when I began my local history pursuits in the 1990s. Kathryn Hoffman was a 1936 graduate of Frederick High School and 1940 graduate of the Frederick City Nursing School, part of the Georgianna Simmons Nurses Home located in conjunction with the former Frederick City Hospital, known until recently as Frederick Memorial Hospital. Kathryn was no stranger to California as her older sister Helen (Hoffman) Holter had moved out there in the late 1930s. A newspaper article mentions a visit the young nurse had in 1940. It appears that Kathryn was part of the Army’s Third Corps and stationed in Baltimore when she received her next assignment in mid-fall, 1941, just a few months before the infamous attack on Pearl Harbor. Kathryn would be sent to Fort Ord, located on Monterey Bay. This installation was named for Edward Otho Cresap Ord (1818 – 1883) an American engineer and United States Army officer who saw action in the Seminole War, the Indian Wars, and the American Civil War. He commanded an army during the final days of the Civil War, and was instrumental in forcing the surrender of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee. Most interesting to me was the fact that Gen. Ord was a native of Cumberland, MD and descended from the legendary Cresaps of Oldtown, masters of the colonial Maryland frontier. Today Fort Ord is no longer a US Army base having closed in 1994. Instead, in 2012 a 14,651-acre portion of the former post was designated a national monument which helps to interpret the installation’s history dating back to World War I. An online history of the fort states: “After the American entry into World War I, land was purchased just north of the city of Monterey along Monterey Bay for use as an artillery training field for the United States Army by the U.S. Department of War. The area was known as the Gigling Reservation, U.S. Field Artillery Area, Presidio of Monterey and Gigling Field Artillery Range. Although military development and construction was just beginning, the War only lasted for another year and a half until the armistice in November 11, 1918. Despite a great demobilization of the U.S. Armed Forces during the inter-war years of the 1920s and 1930s, by 1933, the artillery field became Camp Ord, named in honor of Union Army Maj. Gen. Edward Otho Cresap Ord, (1818–1883). Primarily, horse cavalry units trained on the camp until the military began to mechanize and train mobile combat units such as tanks, armored personnel carriers and movable artillery. By 1940, the 23-year-old Camp Ord was expanded to 2,000 acres, with the realization that the two-year-old conflict of World War II could soon cross the Atlantic Ocean to involve America. In August 1940, it was re-designated Fort Ord and the 7th Infantry Division was reactivated, becoming the first major unit to occupy the post. Sub camps were built around the Fort to support the new training of Troops, Camp Clayton. Camp Clayton was built near CA Highway 1, the South Dakota National Guard 147th Artillery were the first unit to train at the new camp. In 1941, Camp Ord became Fort Ord. But soon the first threat came from the west as the Imperial Japanese Navy struck the island of Oahu, Hawaii at Pearl Harbor near Honolulu in an unannounced air attack, Sunday, December 7, 1941. In a few days the other Axis powers, such as Adolf Hitler's Nazi Germany, along with Fascist Italy of Benito Mussolini, declared and spread their war in Europe against Great Britain and France and the Low Countries to the U.S.” LT. Hoffman spent the holidays at her new, and final, home of Fort Ord. This program of Christmas Day festivities was found online. LT. Hoffman's name appears on page 4. Please note that cigars and cigarettes were on the menu as part of the dinner, especially interesting for a hospital, right? It was a different era, all-together. I became quite interested in the role and responsibilities associated with the Army Nurse Corps of World War II. I learned plenty from a brochure prepared in the U.S. Army Center of Military History by Judith A. Bellafaire. Here is a segment from Ms. Bellafaire’s publication (https://history.army.mil/books/wwii/72-14/72-14.htm): “More than 59,000 American nurses served in the Army Nurse Corps during World War II. Nurses worked closer to the front lines than they ever had before. Within the "chain of evacuation" established by the Army Medical Department during the war, nurses served under fire in field hospitals and evacuation hospitals, on hospital trains and hospital ships, and as flight nurses on medical transport planes. The skill and dedication of these nurses contributed to the extremely low post-injury mortality rate among American military forces in every theater of the war. Overall, fewer than 4 percent of the American soldiers who received medical care in the field or underwent evacuation died from wounds or disease. The tremendous manpower needs faced by the United States during World War II created numerous new social and economic opportunities for American women. Both society as a whole and the United States military found an increasing number of roles for women. As large numbers of women entered industry and many of the professions for the first time, the need for nurses clarified the status of the nursing profession. The Army reflected this changing attitude in June 1944 when it granted its nurses officers' commissions and full retirement privileges, dependents' allowances, and equal pay. Moreover, the government provided free education to nursing students between 1943 and 1948. Military service took men and women from small towns and large cities across America and transported them around the world. Their wartime experiences broadened their lives as well as their expectations. After the war, many veterans, including nurses, took advantage of the increased educational opportunities provided for them by the government. World War II changed American society irrevocably and redefined the status and opportunities of the professional nurse. Early Operations in the Pacific The Army Nurse Corps listed fewer than 1,000 nurses on its rolls on 7 December 1941, the day of the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. Eighty-two Army nurses were stationed in Hawaii serving at three Army medical facilities that infamous morning. Tripler Army Hospital was overwhelmed with hundreds of casualties suffering from severe burns and shock. The blood-spattered entrance stairs led to hallways where wounded men lay on the floor awaiting surgery. Army and Navy nurses and medics (enlisted men trained as orderlies) worked side by side with civilian nurses and doctors. As a steady stream of seriously wounded servicemen continued to arrive through the early afternoon, appalling shortages of medical supplies became apparent. Army doctrine kept medical supplies under lock and key, and bureaucratic delays prevented the immediate replacement of quickly used up stocks. Working under tremendous pressure, medical personnel faced shortages of instruments, suture material, and sterile supplies. Doctors performing major surgery passed scissors back and forth from one table to another. Doctors and nurses used cleaning rags as face masks and operated without gloves. Throughout 1941 the United States had responded to the increasing tensions in the Far East by deploying more troops in the Philippines. The number of Army nurses stationed on the islands grew proportionately to more than one hundred.” I am still very curious as to LT. Hoffman’s daily activity throughout 1942. Even though she was on the American mainland throughout, I’m sure it was a stressful yet gratifying work, the fruits of her education, study and training. An amazing young life taken far too young, but such was the case with so many involved with World War II and all conflicts for that matter. One of the other unique findings seen while researching articles of LT. Hoffman’s funeral lies in the fact that her body was escorted back to Frederick by a LT. Gladys Beek. I wondered how the rest of her war experience played out? I started to go into that rabbit hole, but quickly jumped out and back on task. LT Hoffman was buried on January 26th, 1943 in Area LL/Lot 162 next to her mother. Eight months later, her sisters would have the body moved to a spot roughly ten yards to the south in Lot 143. This would eventually be the resting place of Kathryn’s two sisters and their respective husbands. This move also facilitated the opportunity for their father to be buried alongside his first wife. In case you were concerned, Mrs. Lucy Hoffman is buried with Schwartz family members in Mount Olivet’s Area P. Stories of 2LT Kathryn Hoffman and countless others laid to rest in Mount Olivet are priceless. I will never get tired of hearing about the people they call "the greatest generation." Those that put themselves in harm’s way, some making the greatest sacrifice, are the greatest of each generation in our country’s rich history. That’s why we must never minimize or forget the deeds of our veterans, long passed like Michael Engelbrecht and more recently with 2LT Hoffman. And don't forget those veterans who still live amongst us too.

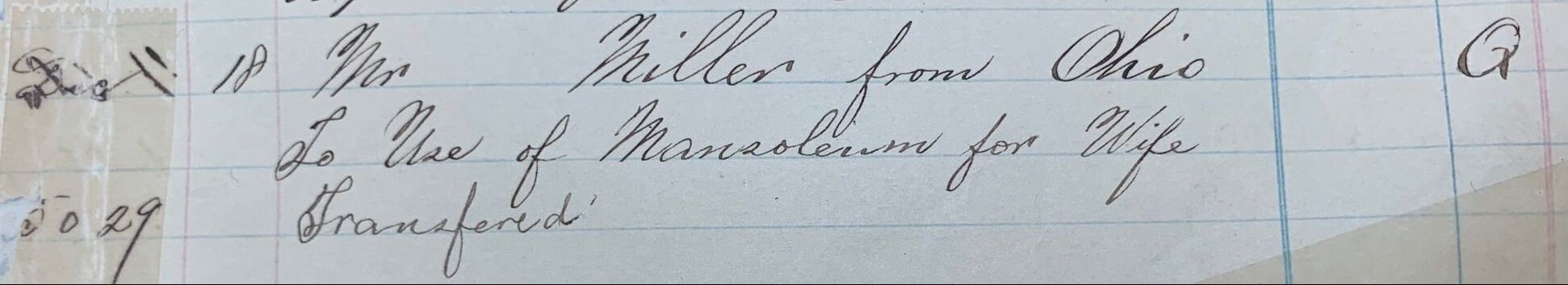

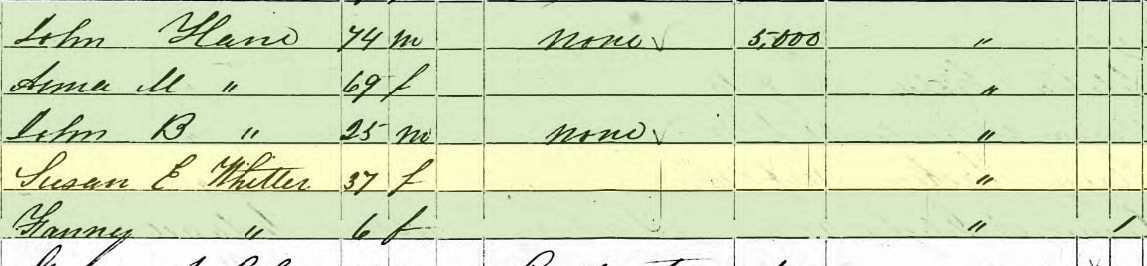

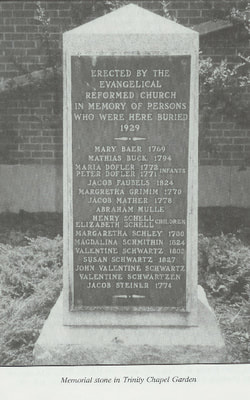

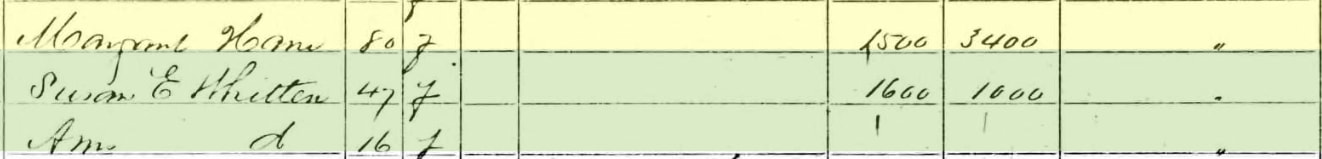

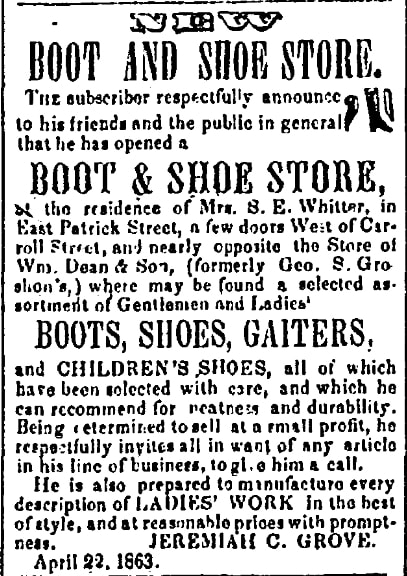

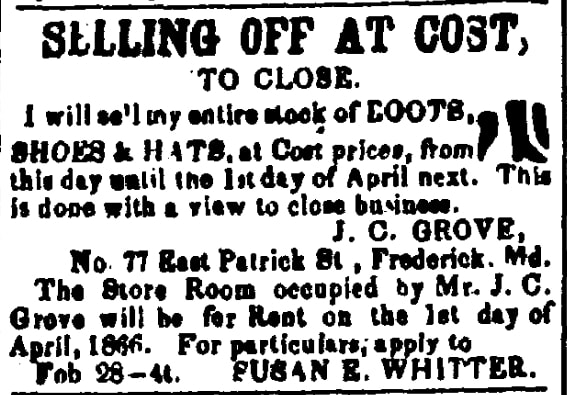

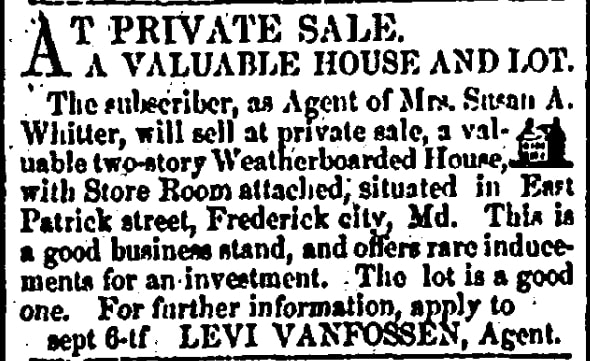

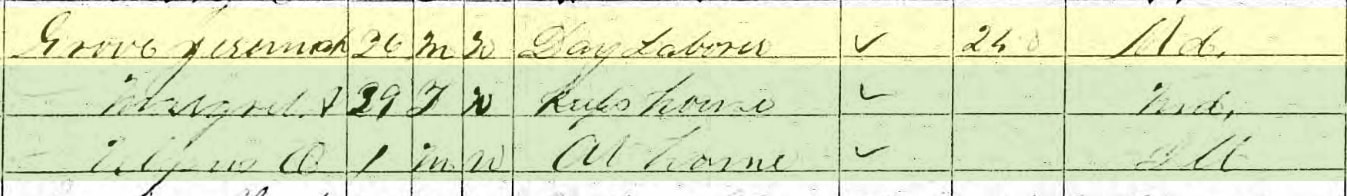

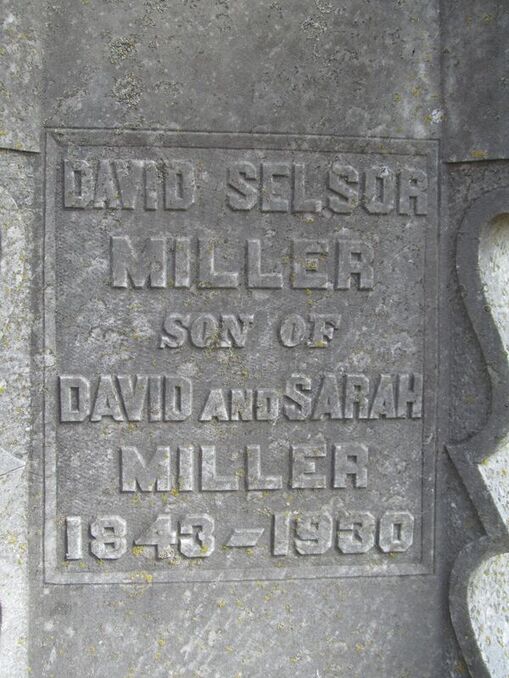

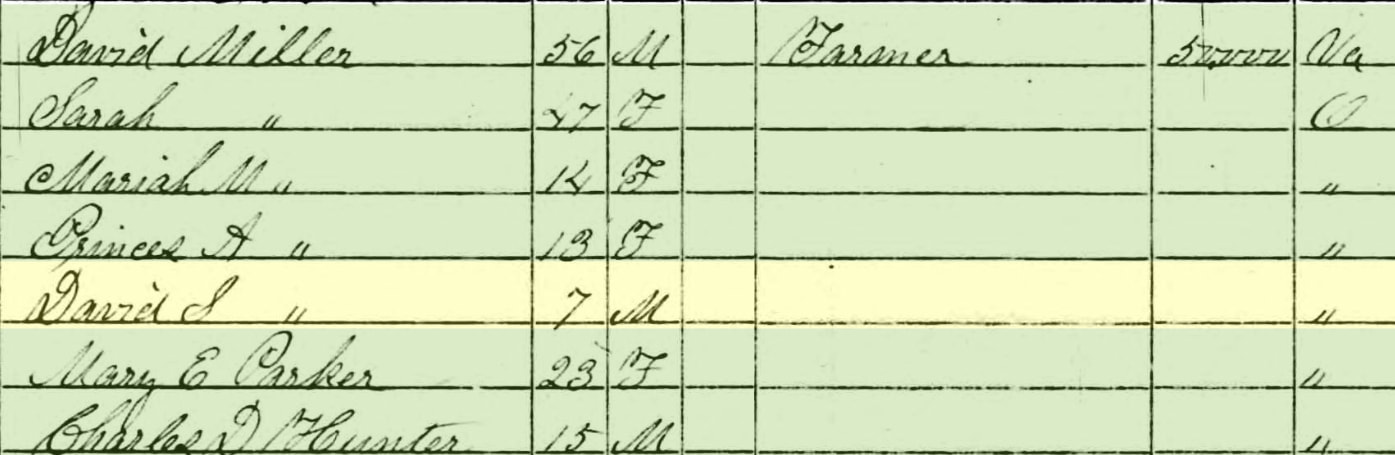

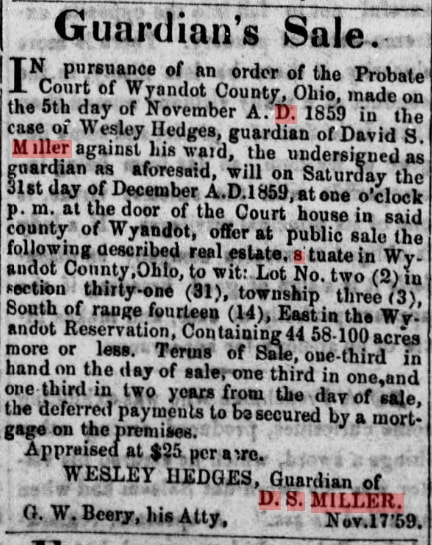

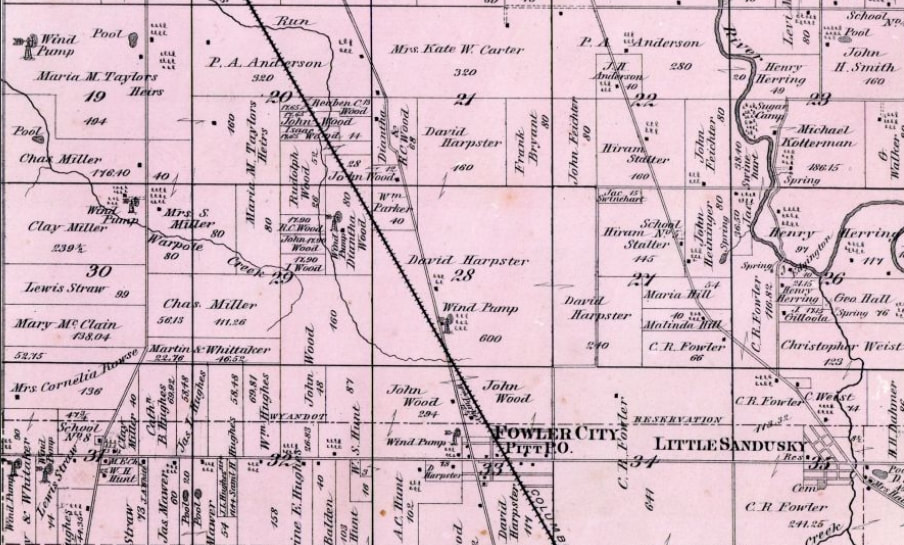

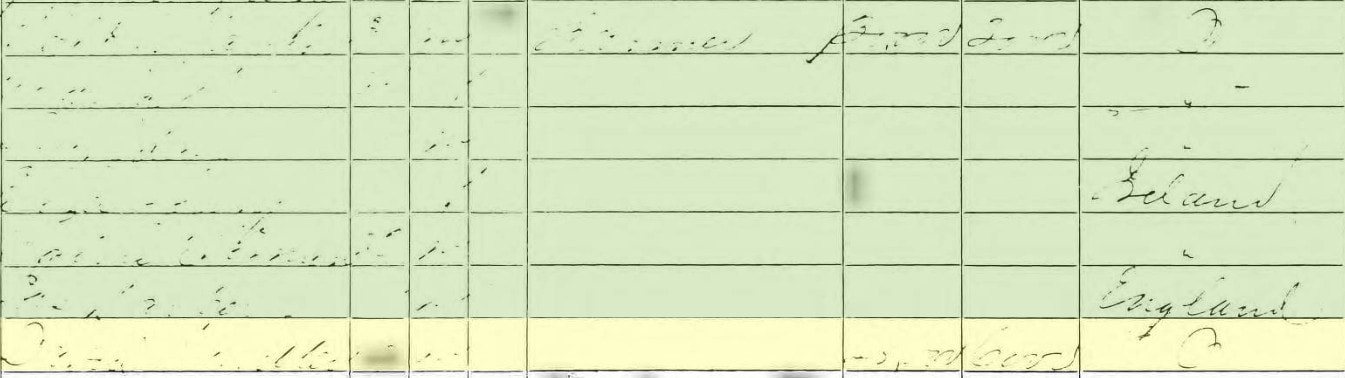

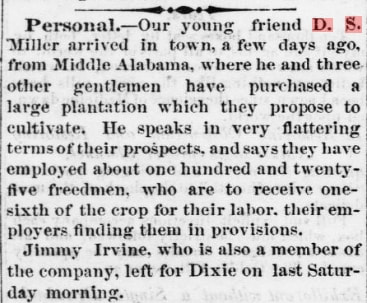

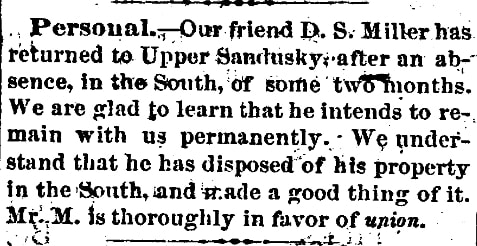

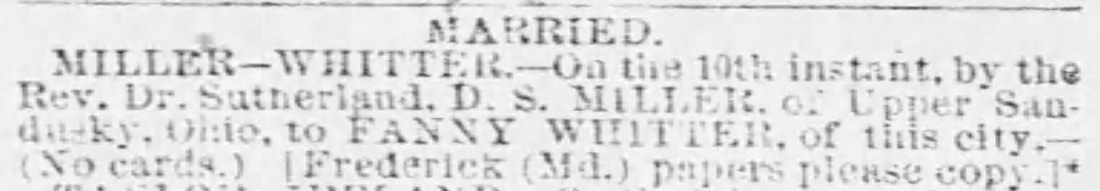

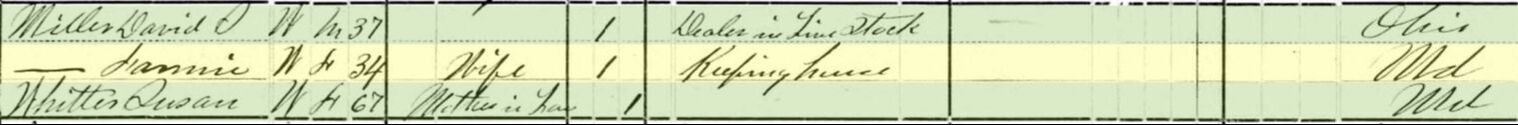

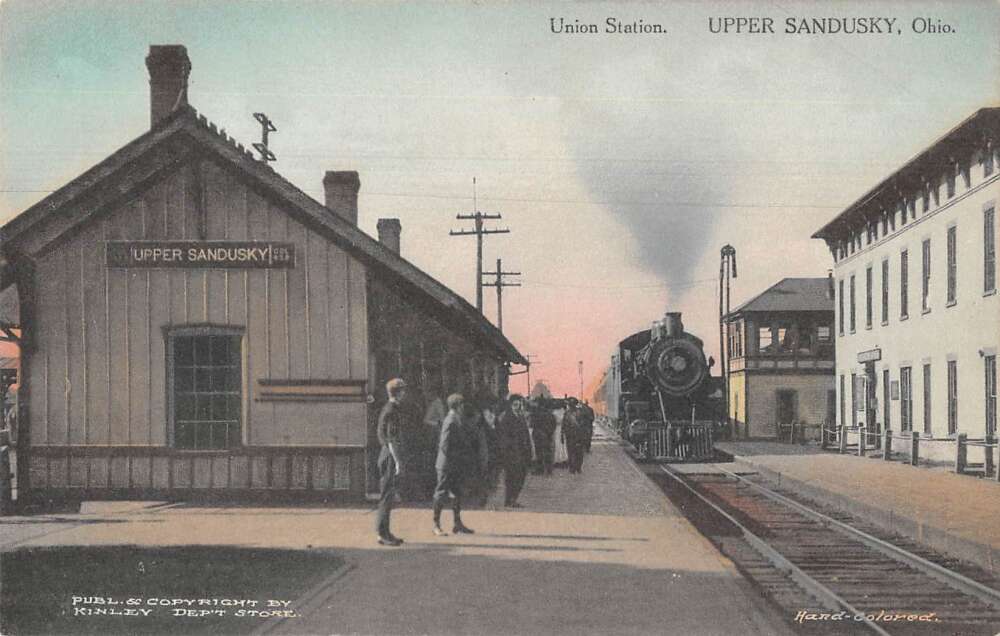

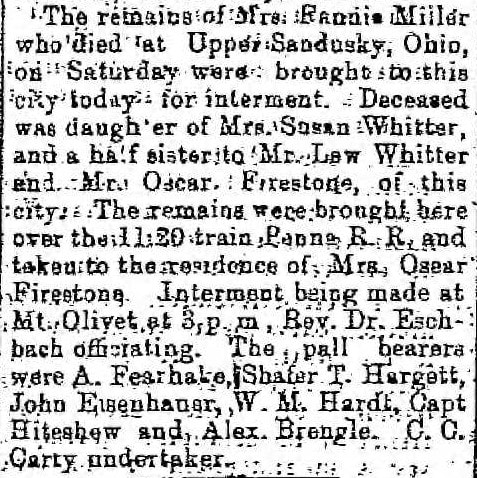

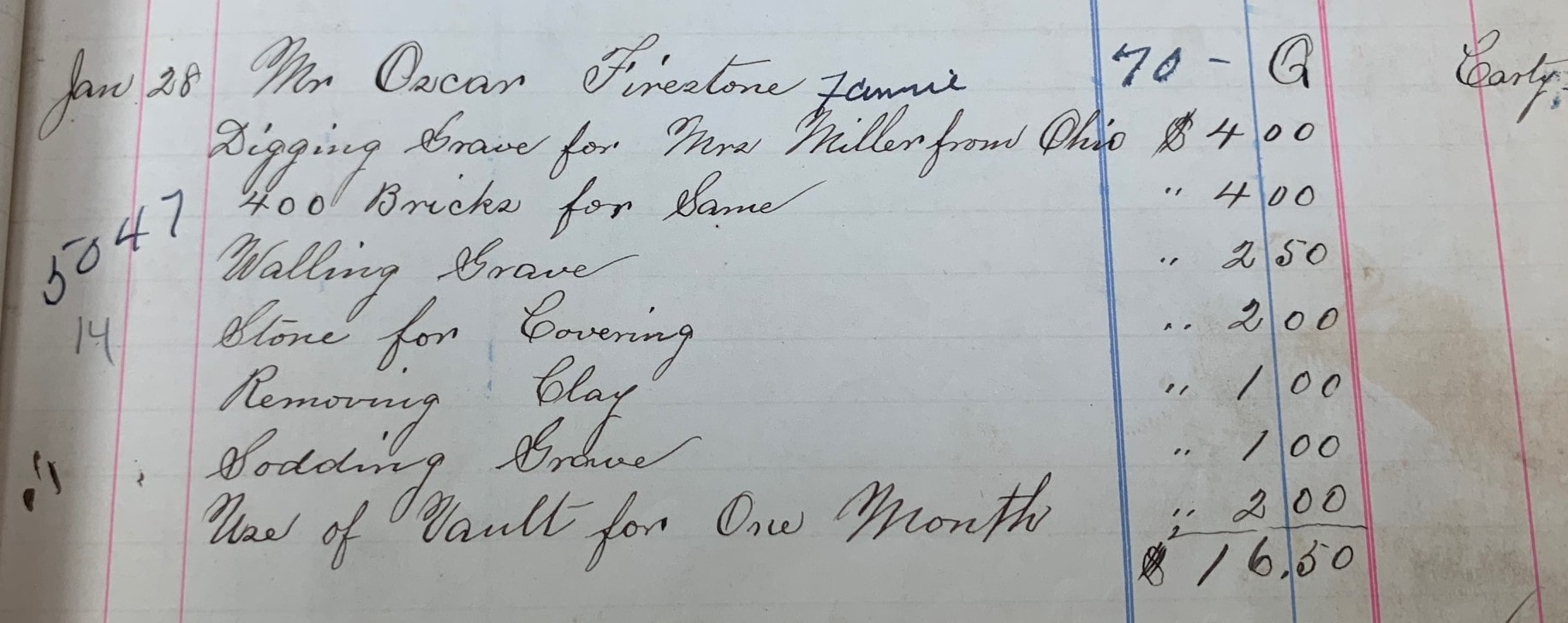

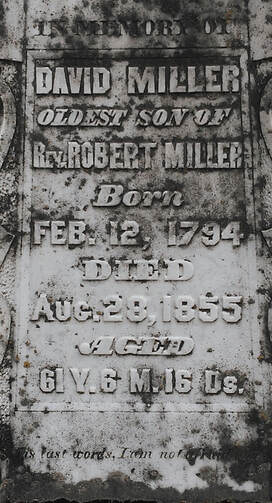

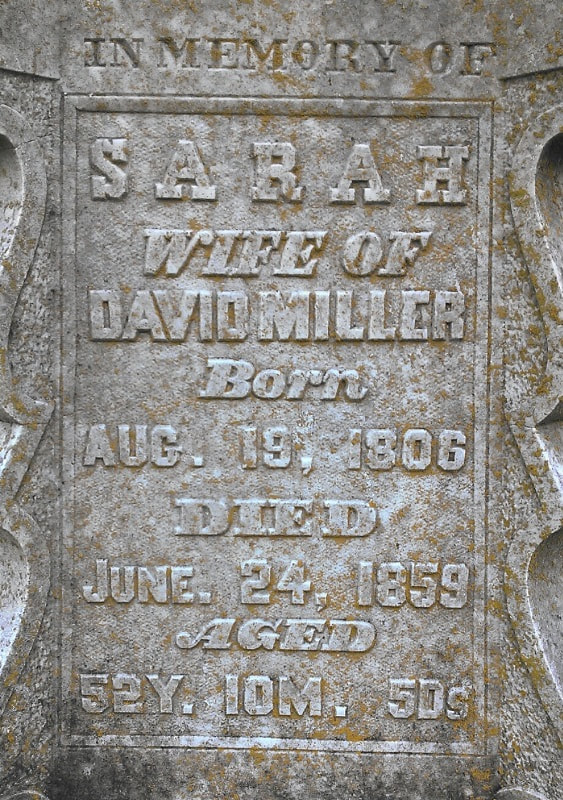

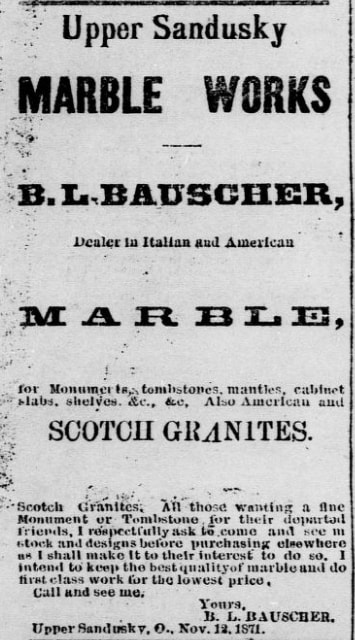

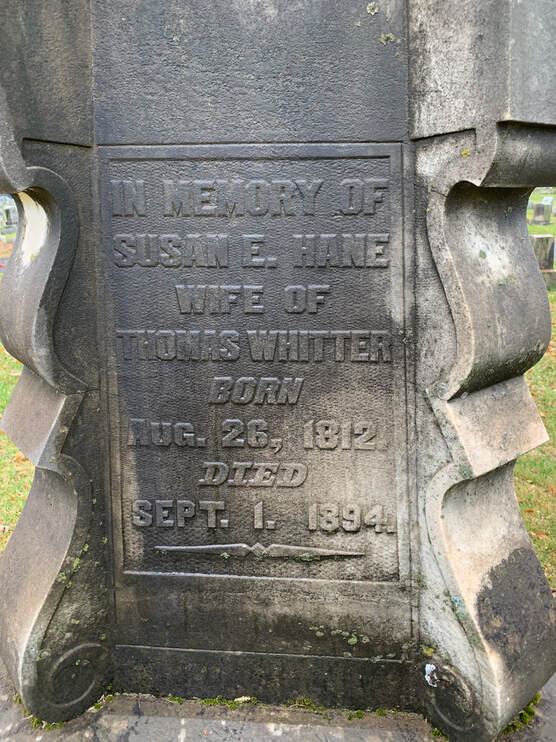

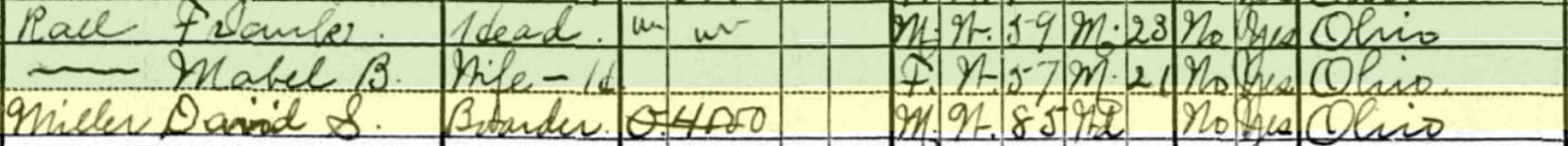

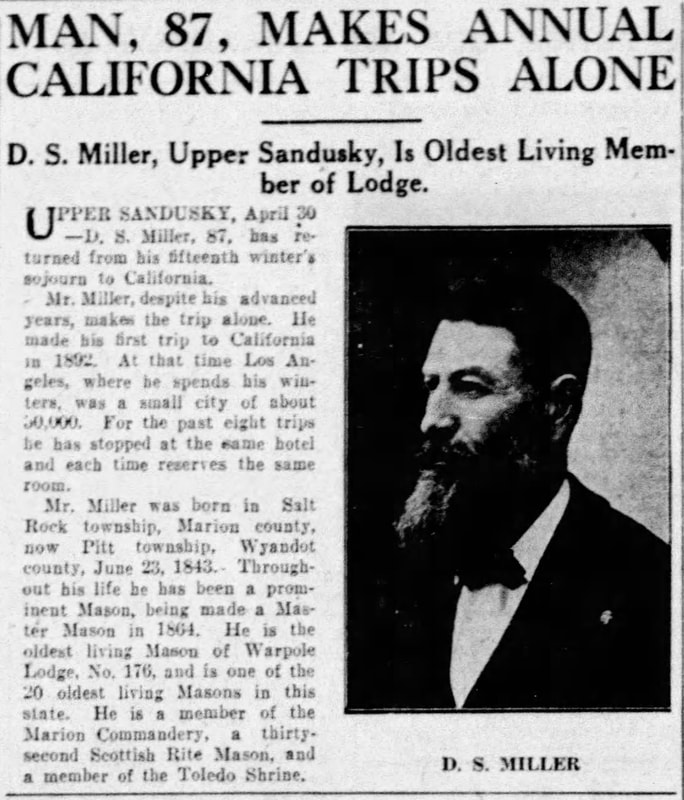

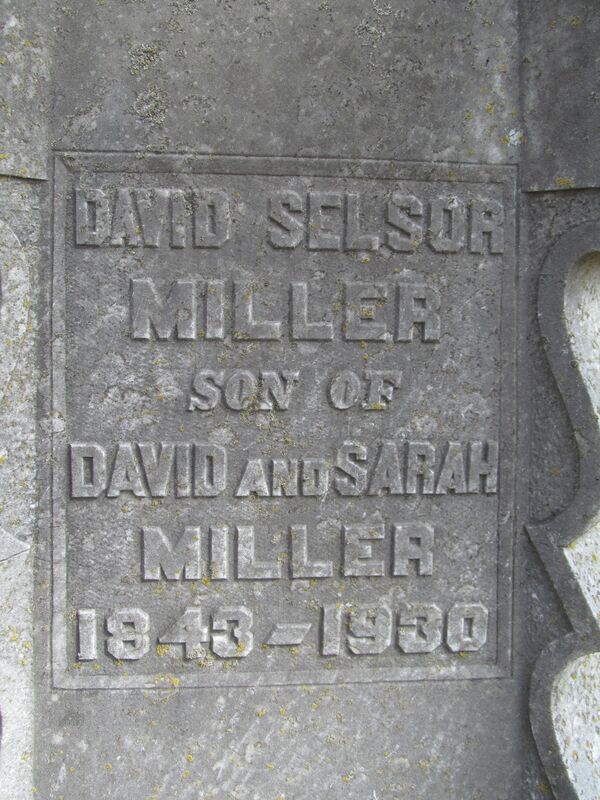

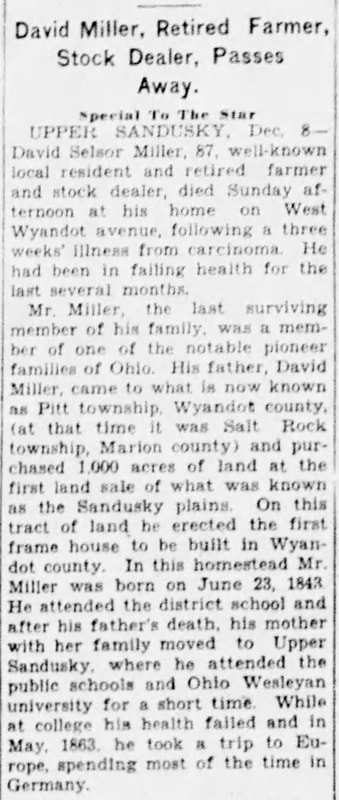

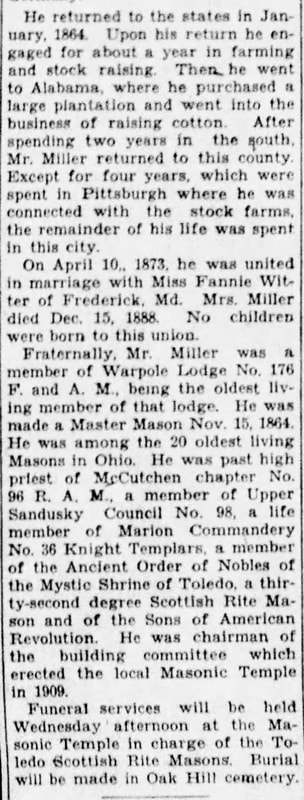

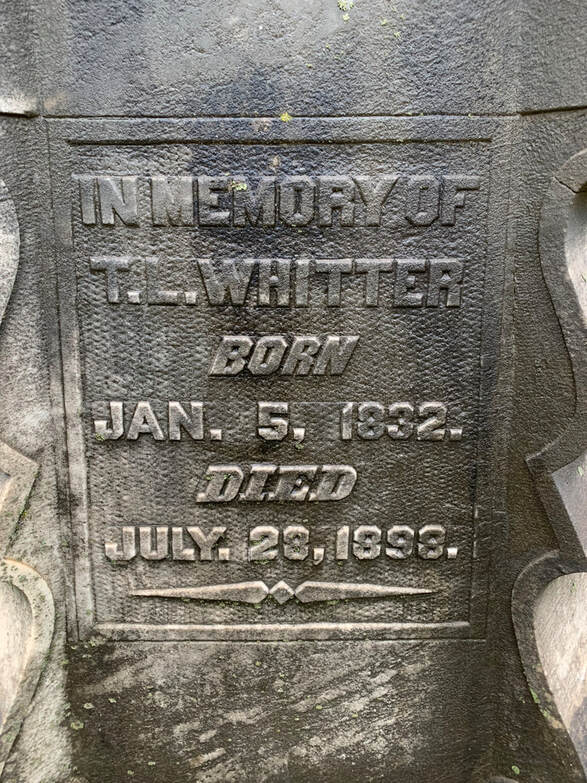

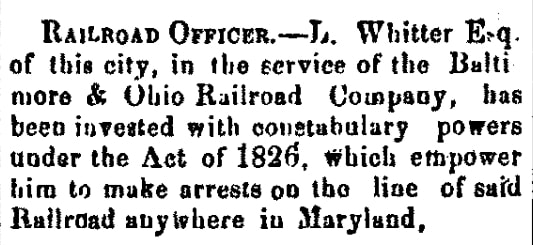

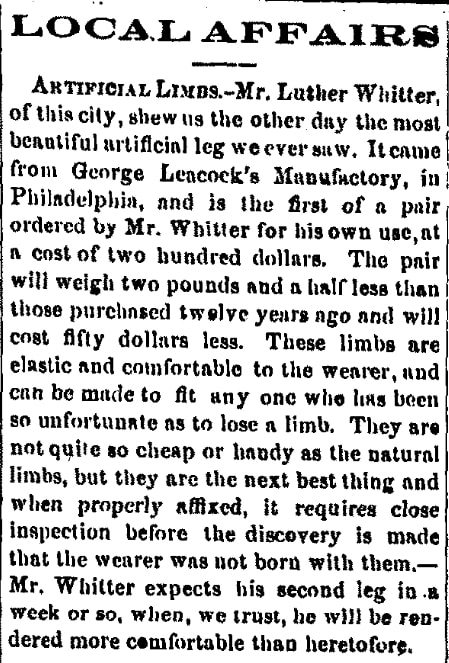

Wreaths represent a circle of eternal life, symbolism dating back to Ancient Greece. This weekend they will be placed with care on over 3,400 graves. Thank you for your support in help making this happen each year.  Sometimes I’m simply inspired to write some of these “Stories in Stone” by the shape, size or uniqueness of a particular monument that catches my eye. This week’s blog follows that approach. When I first saw the grave memorial to Fanny Miller, I was intrigued by the design from a distance. As I approached to inspect closer, I learned that the decedent had passed on December 15th in the year 1888. On top of that, a unique piece of information came from the stone stating that Mrs. Miller had not died here locally in Frederick County, rather she had “breathed her last breath” in Upper Sandusky, Ohio. Information was scarce regarding Fanny Miller, although I quickly learned from our cemetery records that she was the wife of a Mr. D. S. Miller, and her cause of death was due to cancer. Her maiden name was Whitter, which I learned is also an intransitive verb which means “to chatter or babble pointlessly or at unnecessary length.” I may well follow suit here, as this article is not one that definitively tells the life story of a person, or family for that matter. Regardless, the cultural origin of the surname “Whitter” seems to derive from the United Kingdom. One of the defining figures of this monument is that it is designed as an elaborate stand for an urn. This vessel is crafted atop the work, and is covered by a cloth. You will see many draped objects in the cemetery as the shroud is a general symbol of mourning, but it may also symbolize a parting of the veil between this world and the next. Drapery was also an outward expression of mourning in the Victorian era (1837-1901), as heavy black fabric would be draped throughout the homes of those in mourning. A few of Fanny’s family members are buried under this monument in Area Q/Lot 70, and their names appear on two of the other three remaining “faceplates” on this memorial. These include her mother, Susan E. (Hane) Whitter, and half-brother Thomas Luther Whitter. Fanny Miller Fanny was born with the given name Ann in 1843 in Frederick, the daughter of Thomas W. Whitter and Susan (Hane) Whitter. She wouldn’t really know her father that well as he died in 1846. As a matter of fact, Fanny’s mother’s time with Mr. Whitter was somewhat brief as well as she had only married him on October 8th, 1842. Susan was Thomas’ second wife as his first, Mary W., had died on December 17th, 1840 according to diarist Jacob Engelbrecht. Mary was originally laid to rest in the town’s Methodist burying ground on the east side of town along Middle Alley between Third and Fourth streets. As for Susan Whitter, she was born August 26th, 1812 in Frederick as the daughter of John Hane, Sr. (1776-1855) and Ann Margaret Bartgis (1780-1862). Both Fanny and her mom are found living with the Hanes in the 1850 census. The Hanes were faithful members of Frederick’s German Reformed Church, today known as the United Church of Christ and located in the first block of W. Church Street. The elder Hanes likely worshipped at both iterations of the church which began in the footprint of Trinity Chapel with the stone tower dating to 1763 and steeple of 1807 on the south side of the street, before building a new, larger structure on the north side of Church Street in 1848. It’s always worth talking about the religious roots of Frederick because these congregations were the glue that held the community together back in the early days when Frederick Town was literally on the western frontier of Maryland. Within this howling wilderness, when attacks by hostile Indian tribes were a real possibility, these religious institutions not only represented the spiritual hearts of the fledgling community, but also served as the educational and social centers for our residents. In addition, it’s also where the dead were laid to rest. I’ve talked before about the two previously established German Reformed graveyards once located in downtown Frederick. Well I guess, I should rephrase, as the second of these simply left in name only. The second Evangelical Reformed Church graveyard began around 1802, and was abandoned in operation in 1924. In that year, this former burying ground would receive an above ground makeover, and became the site of the Memorial Grounds Park, on the corner of W. Second and N. Bentz streets. A bronze plaque was erected to remember the existing burials of hundreds of Frederick’s earliest setters and their descendants. Today, these individuals still reside below the many war monuments that create the viewscape above ground. A number of these internments were originally at the Trinity Chapel churchyard, before being moved here. Fronting on N. Bentz Street, a plaque in Memorial Grounds Park contains 366 inscriptions from the two cemeteries. Two of these are the fore-mentioned John Hane, Sr. and Anne Margaret Hane, grandparents and parents, respectfully, of Fannie (Whitter) Miller, and her mother (Susan (Hane) Whitter). The Frederick Directory City Guide and Business Mirror of 1859-60 includes the names of Mrs. Anna Margaret Hane and daughter Susan, both widowed, living on the southside of E. Patrick Street between Middle Alley and Chapel Alley. The census of 1860 shows Fanny living with her mother and grandmother here. Just a few years later, on August 16th, 1862, it appears that Fanny was married, but not to the fore-mentioned Mr. D. S. Miller. On this date, she wed Jeremiah C. Grove. I found little on this gentleman outside the strong possibility that he was the same Jeremiah C. Grove who was born in Hagerstown around 1845, and enlisted in the Union Army in 1864. I found a few advertisements in the Frederick papers as Mr. Grove was the proprietor of a shoe business on the first floor of Mrs. Whitter’s home of E. Patrick. The first of these ads appears in 1863. However, in 1866, I found another newspaper notice signed by Susan E. Whitter that the business was closing in May, 1866. I couldn’t discover exactly what happened but it seems that Jeremiah re-located to Illinois and was remarried in November, 1868 and lived out his life in Ogle, Illinois. So I’m thinking there was either a divorce or desertion at play here for our subject Fanny. I got this notion before seeing the shoe store ads, as I desperately searched for Jeremiah and Fanny in the 1870 census. I still never located Fanny, but I found a Jeremiah C. Grove married to a Margaret Neff, who spent her youth in Washington County and her father was born in Frederick. Maybe the rekindling of a childhood romance caused divorce or abandonment in the case of Fanny Whitter? Or maybe Fanny went out to Illinois with him and things fizzled out for the couple? David Selsor Miller As for another person living in the Midwest for the 1870 census, I did find David Selsor Miller working on a farm in Brookfield, Iowa in 1870. His father (David Selsor Miller, Sr.), was a wealthy man from Virginia with Miller grandparents who had emigrated from Scotland to Maryland's Prince Georges County in the 1600s. David, Sr. had died in 1855. David's mother, Sarah Bent Miller, passed in 1859. I would find that his legal guardian would advertise a land sale on his behalf in 1859. In 1860, David was living in his native home of Pitt Township in Wyandot County, Ohio with his sister Maria’s (Mrs. Robert Taylor) family who owned a farm, quite possibly the Miller family farm. Interestingly, the census shows that David had $5,000 in real estate to his name, perhaps from that sale the previous year? In the 1860s, Mr. Miller apparently did some other land speculating down south, while selling off some of his holdings in northwest Ohio. So how did Fanny and David meet? There was no Match.com back in the day so it makes you wonder. Did Fanny venture to Iowa or Ohio or Alabama? Did David travel to Maryland? The answer could be the latter as the couple were married on April 10th, 1873 in Baltimore where the bride was apparently living at the time. They would eventually re-locate to Ohio and can be found living in Upper Sandusky, Ohio by 1880 as that fact is established by the US Census of that year. On top of that, I took notice that the couple had a boarder living with them in the person of Susan (Hane) Whitter—Fanny’s mother. I could not find anything on Fanny’s life in Ohio, just a few newspaper articles on her husband, a successful livestock and hay dealer who seemed to be financially sound with his real estate holdings. As stated earlier, Fanny died in Upper Sandusky on December 15th, 1888. David and Susan would send her body back home to Frederick, Maryland via train, where she would be delivered to Mount Olivet on December 17th. Fanny Miller's burial would not be immediate. Whether the delay was based on transportation of other family members (from Ohio) or simply weather, our records show her burial date as January 28th, 1889. My first inclination for a six-week delay seems to be predicated on the weather at the time being perhaps too cold. Mount Olivet once had a structure called the public vault that stood on the site of today’s Key Memorial Chapel, a mortuary chapel built in 1911. The public vault was used to store corpses during periods in which the ground could not be dug by hand until warmer temperatures prevailed.  Two entries from Mount Olivet's interment books showing that the Public Vault was used as a temporary mausoleum to store Fanny Miller's body before burial. Interesting that a Firestone (a name synonymous with Ohio) would help take care of burial arrangements as he was husband to Fanny's half-sister, Rebecca (Whitter) Firestone. Now, I am not sure if this was the case, as it may have just been a function of storing the body until the responsible parties of Fanny’s husband and mother could get to Frederick and make appropriate plans. Regardless, she would be laid to rest before the end of January, 1889. Although having help from Fanny's local relatives here, I’m assuming that David took charge of the final funeral/burial arrangements for his wife, including placing the unique monument for his departed wife in our Area Q. Interestingly, this memorial depicting a shrouded urn on a large stand would be an exact duplicate, or bookend, of a monument in Upper Sandusky’s Oak Hill Cemetery on Lot D/Section 3. This exact style is marking the gravesite of David’s parents, with the names of his father on one of the four panels, and that of his mother on another. I could not find a maker’s mark on our monument here in Mount Olivet, but I have reason to believe that it was made by the same craftsman/company that made the Millers monument in Oak Hill. When researching the cemetery, I also found Mr. Miller to be one of the founders. The Miller monument was most likely crafted by a firm in Ohio, and my gut tells me in Upper Sandusky. A little research led me to the Upper Sandusky Marble Works run by B. L. Bauscher. I truly think it was here, where our monument for Fanny was crafted as well. Susan Whitter would move to Columbus, Ohio and would die of a hemorrhage just six days after her 82nd birthday on September 1st, 1894. Her body was sent back to Frederick by train like her daughter’s six years earlier, however, she would be laid to rest immediately upon reaching Mount Olivet on September 2nd. As for husband David, I found him continuing his work and living with various family members over the next four decades after Fanny’s death. In the 1930 US census, he is living with his niece’s family. Her name was Mabel Bent (Taylor) Rall. David S. Miller would still lead an active life in his final year on Earth. I was very pleased to find a news article of him making the final of many self-pilgrimages to California. David Selsor Miller would die on December 7th, 1930. This was one week shy of the 42nd anniversary of Fanny's death. While he had an available plot here in Mount Olivet next to his wife and former mother-in-law, he would be buried in Oak Hill with his parents. His name adorns one of the four panels on the grave monument. Like the bookend version in Frederick, only three panels would be used. I mentioned Fanny’s half-brother, Thomas Luther Whitter, being buried in Area Q/Lot 70. He was from the union of Fannie’s father, Thomas W. Whitter and first wife, Mary. I found that Fanny and Thomas’ father (Thomas) is buried in Mount Olivet’s Area A, along with the fore-mentioned Mary. As both had died before Mount Olivet was established, it gave me cause to check their re-interment dates here. I found that they were originally buried in Frederick’s Evangelical Lutheran burying ground at the southwest corner of E. Church and East streets. This re-location was performed on October 12th, 1863, by the direction of Rebecca (Whitter) Firestone, another half-sister of our subject, Fanny. Born January 5th, 1832, Thomas Luther Whitter went by "Thomas," "Thomas Luther," "Thomas Lewis" and "Lewis." He spent a good amount of his working career in the employ of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad as a watchman. Mr. Whitter had both legs amputated as a result of an accident prior to 1863. In addition, I found that he also was the proprietor of a cigar shop in town on W. All Saints Street in the mid-1880s. He died of paralysis on July 28th, 1898 and was laid to rest by his mother and half sister on the 29th. His name adorns the third of four panels on the monument that gave rise to this story. So, there you have it! I successfully provided a whole lot of chatter (Whitter) about two, unique grave monuments symbolizing large urn holders. More so, they represent symbolic bookends memorializing a couple buried 400 miles apart. Oddly, the old expression, “’Til death do you part” seems to be more than appropriate in this case.

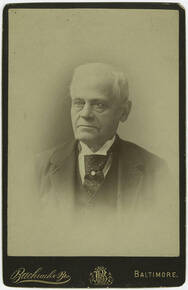

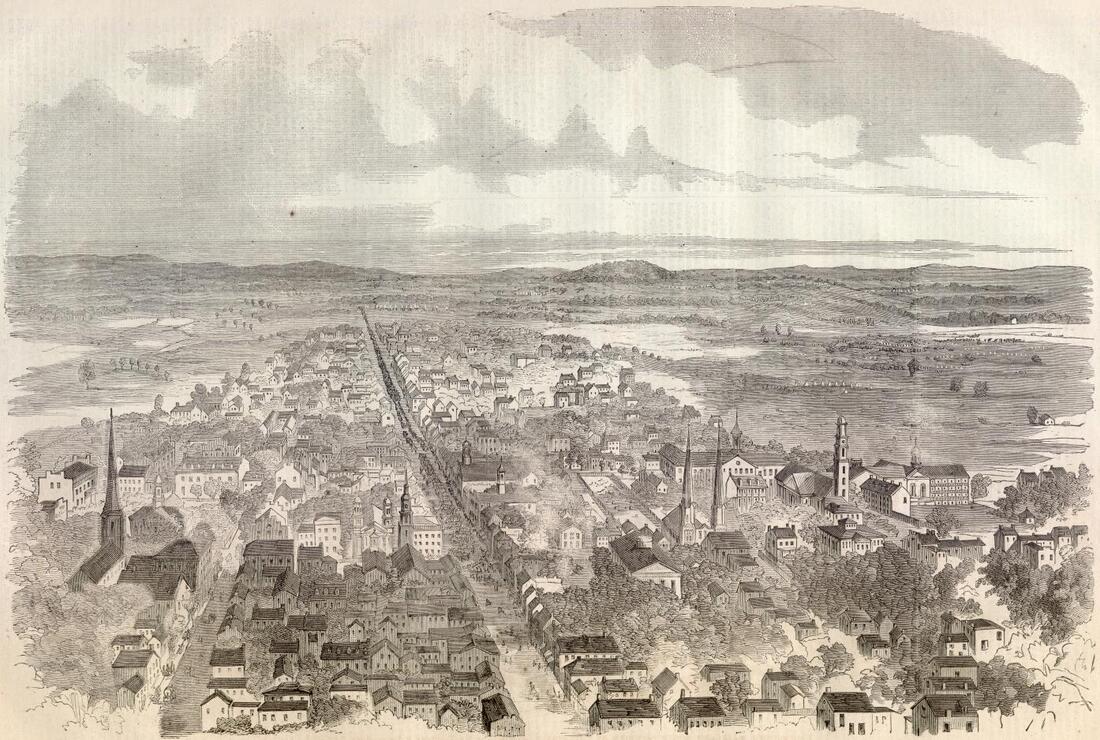

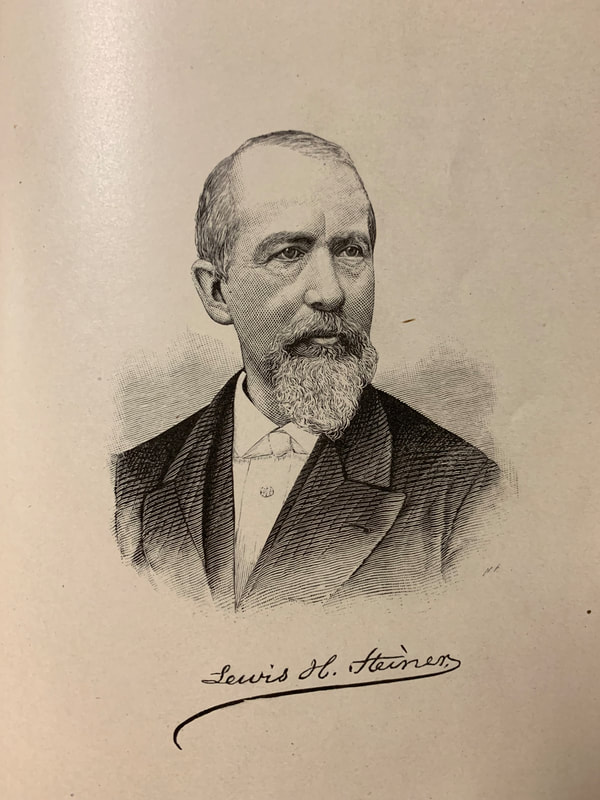

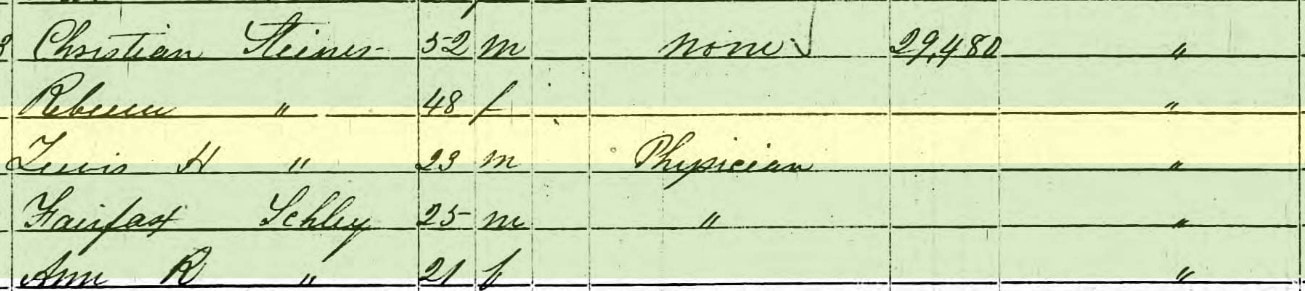

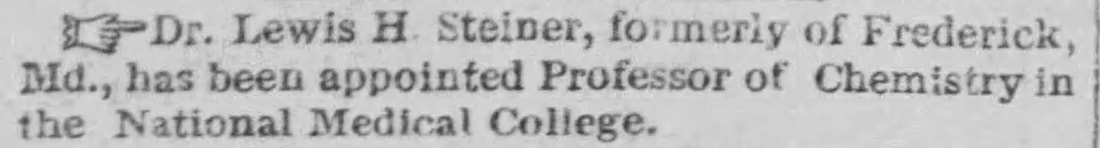

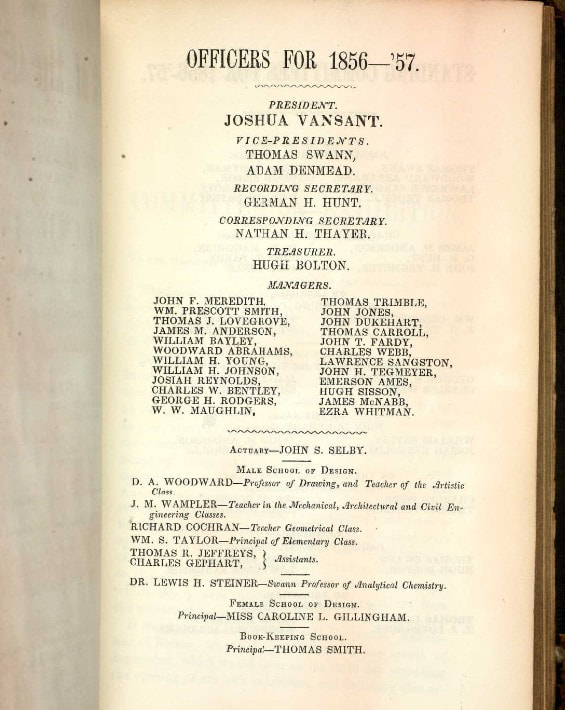

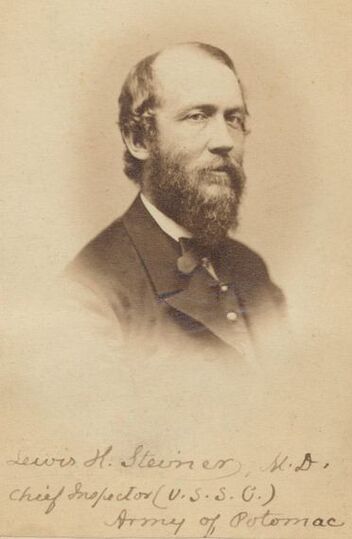

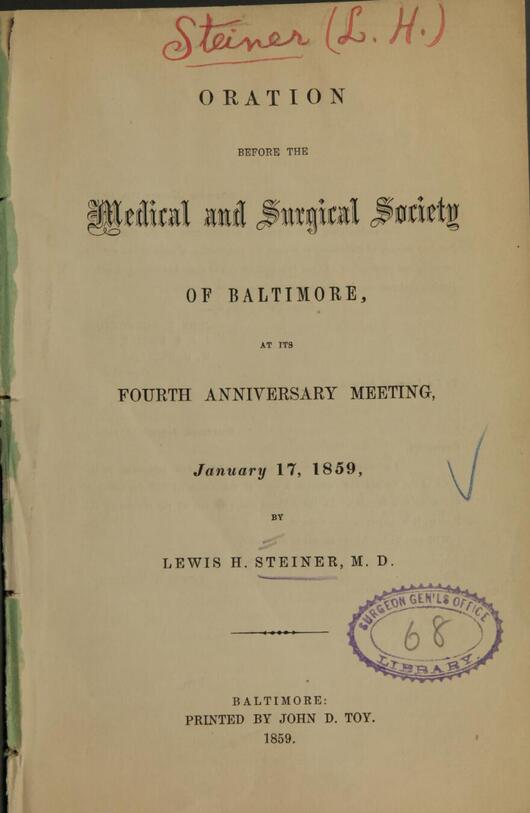

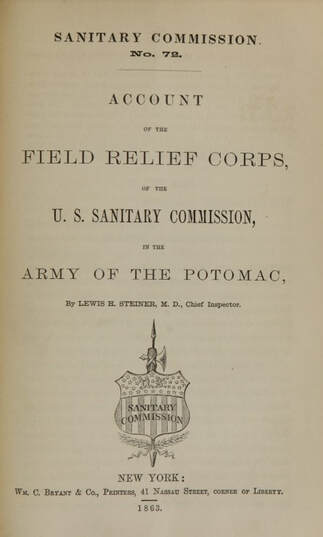

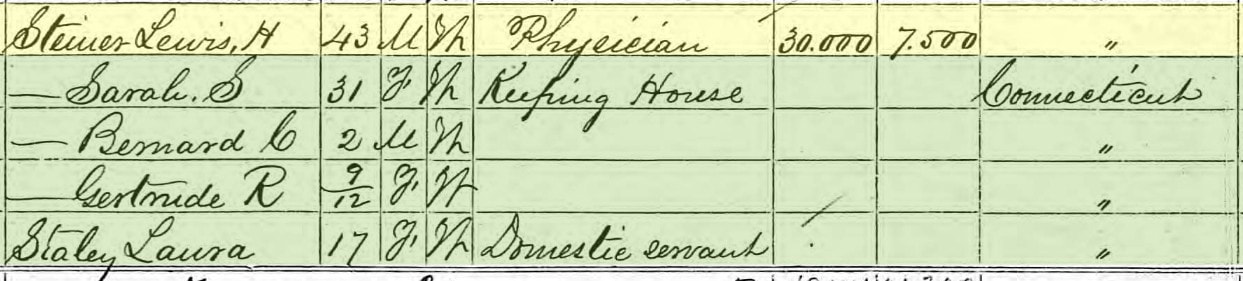

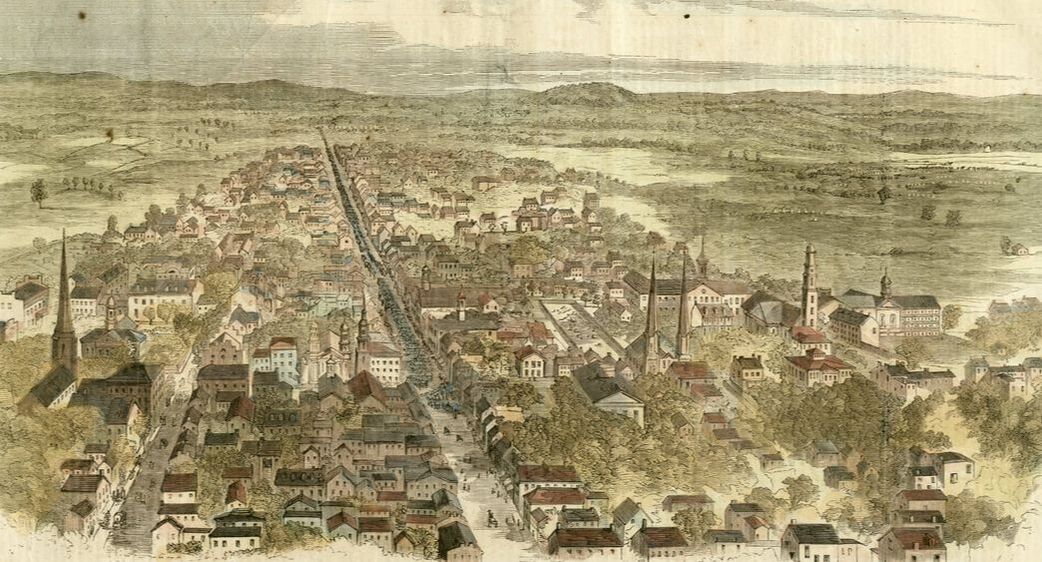

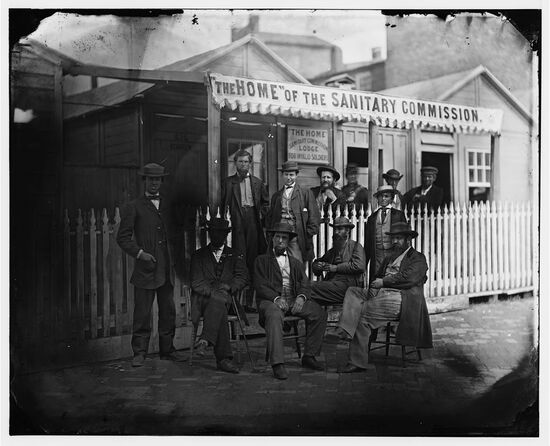

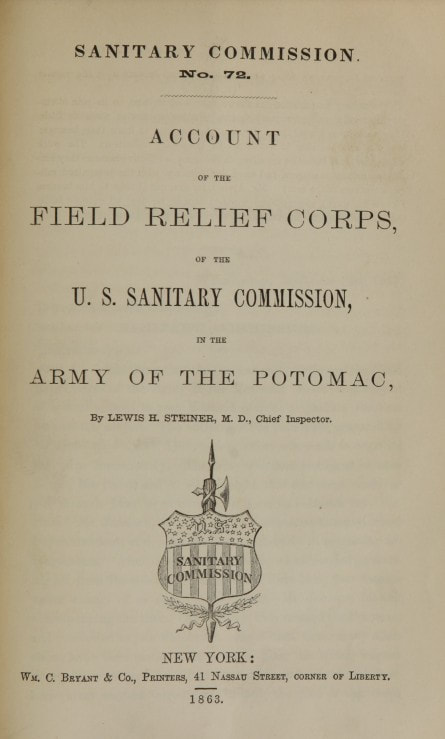

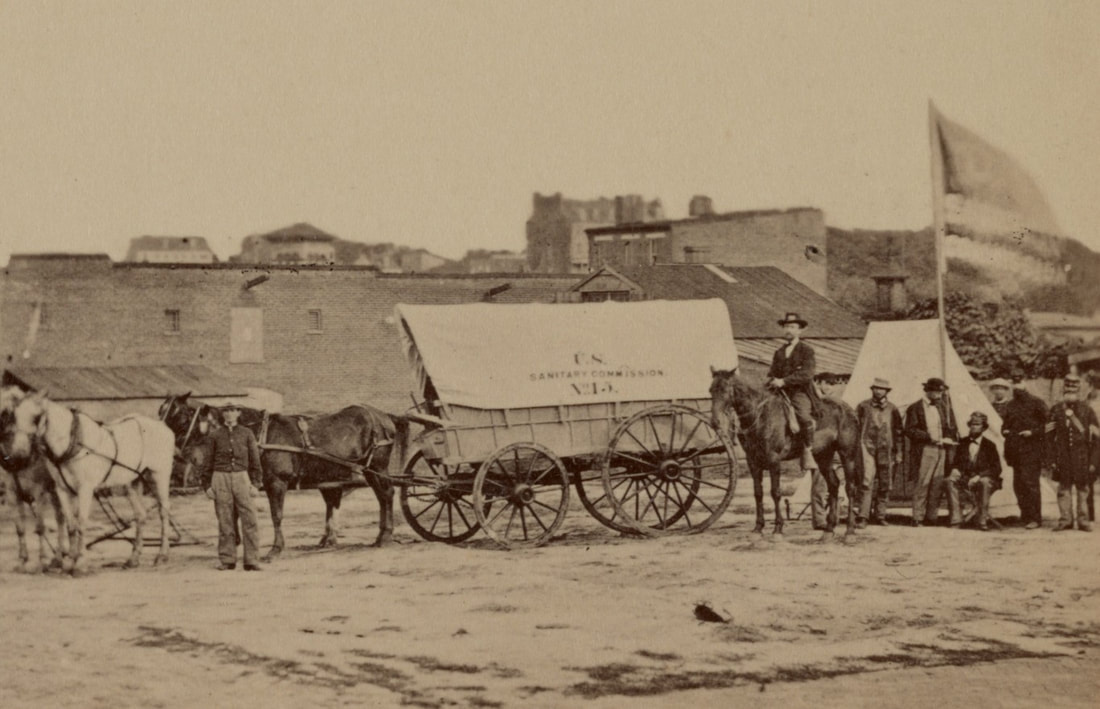

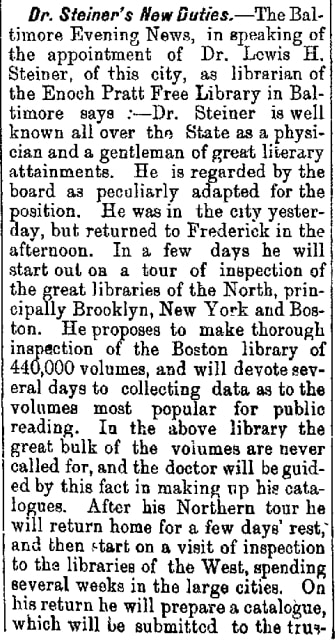

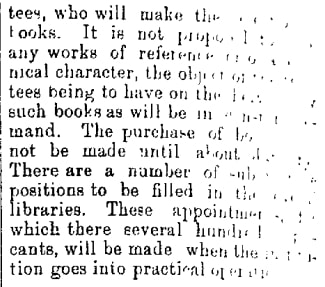

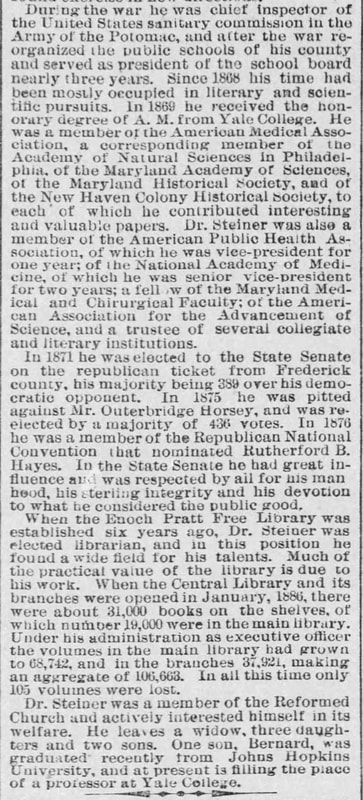

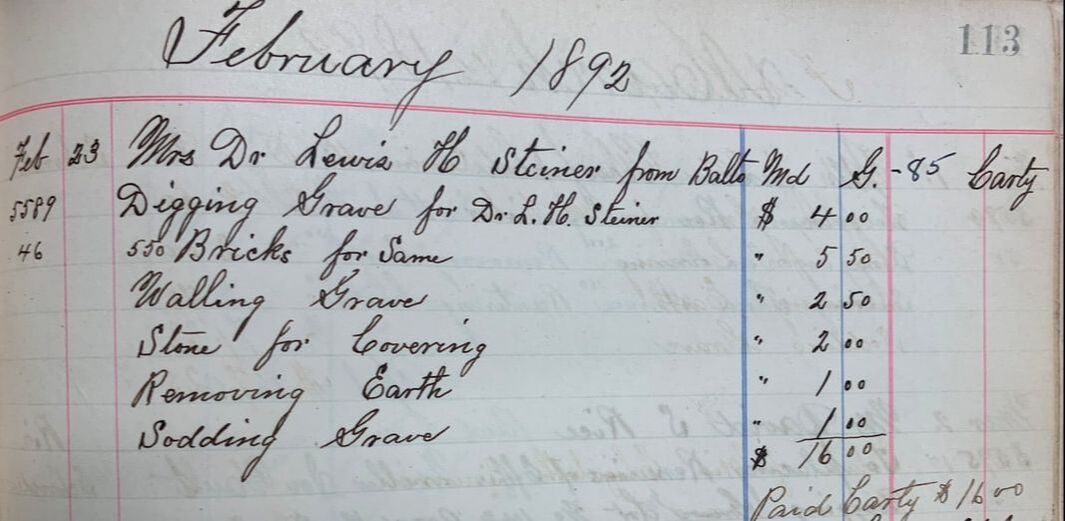

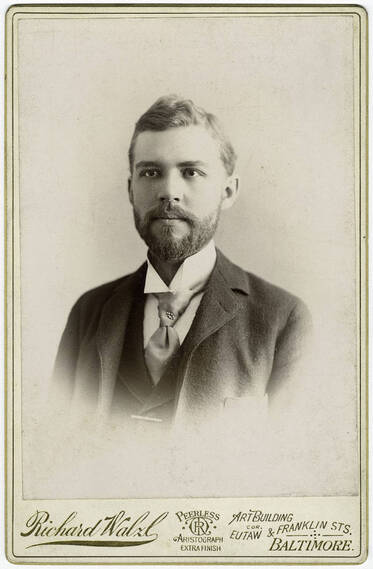

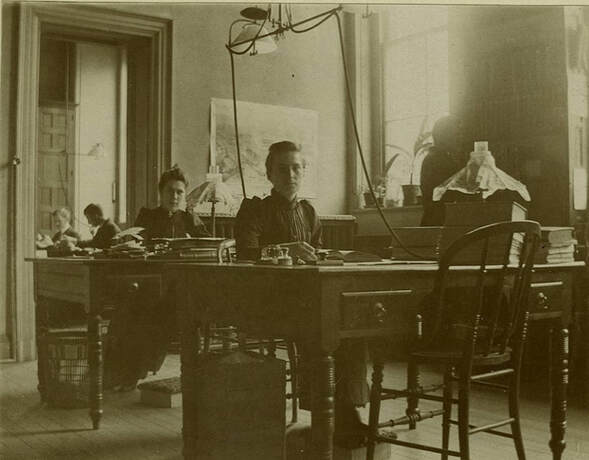

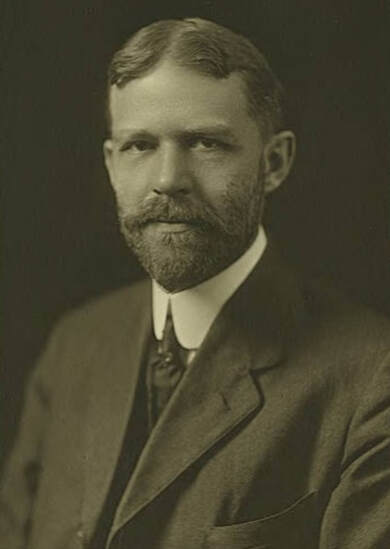

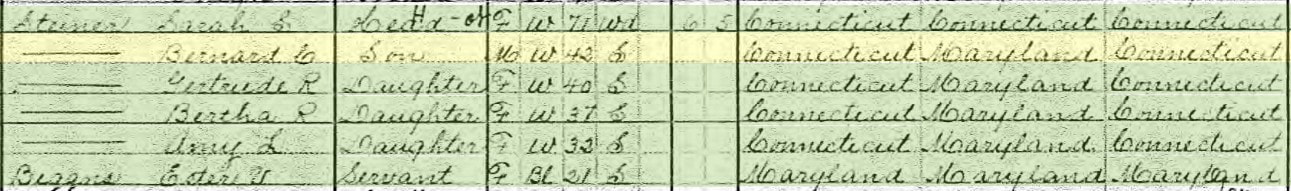

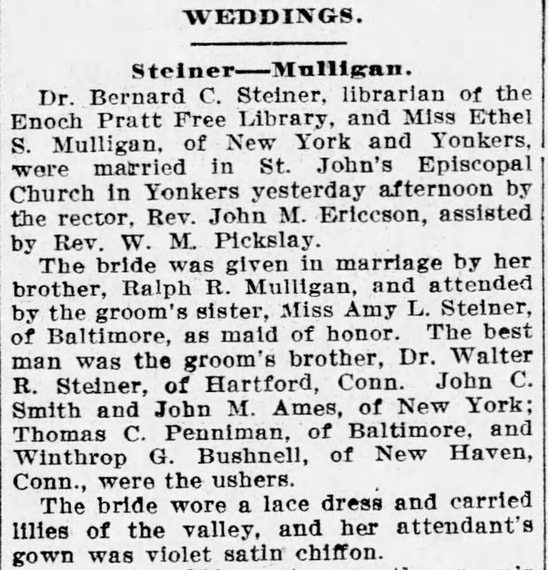

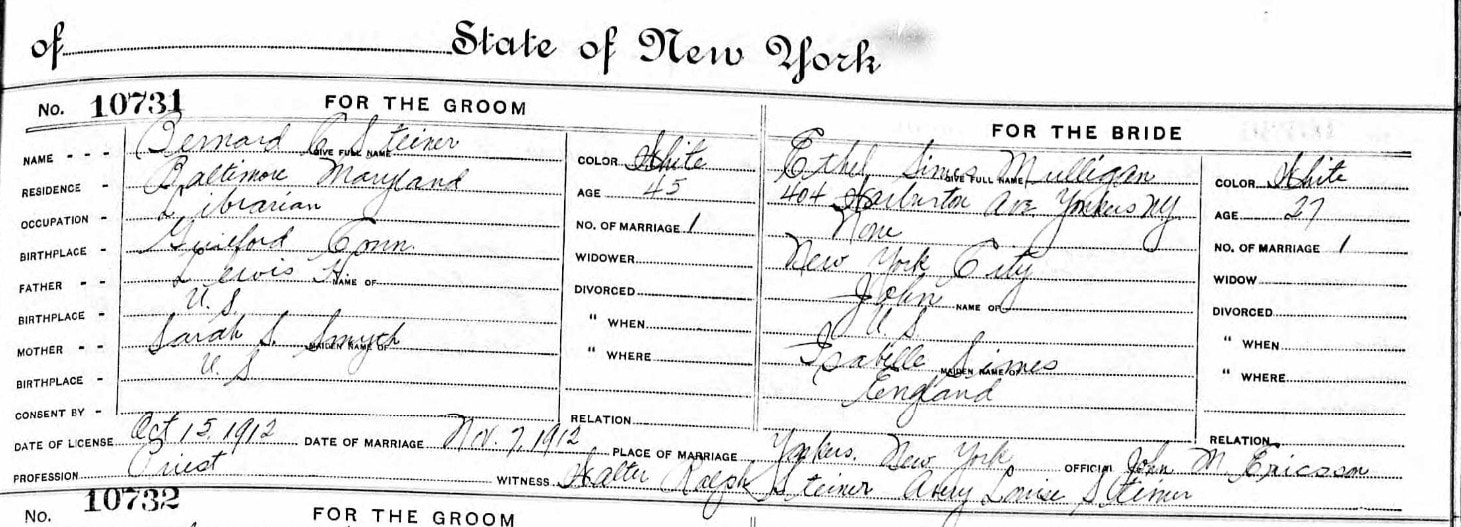

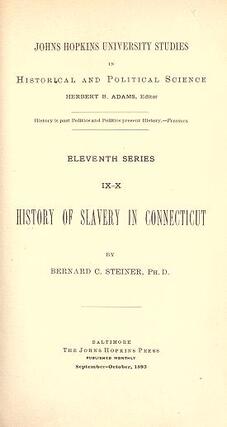

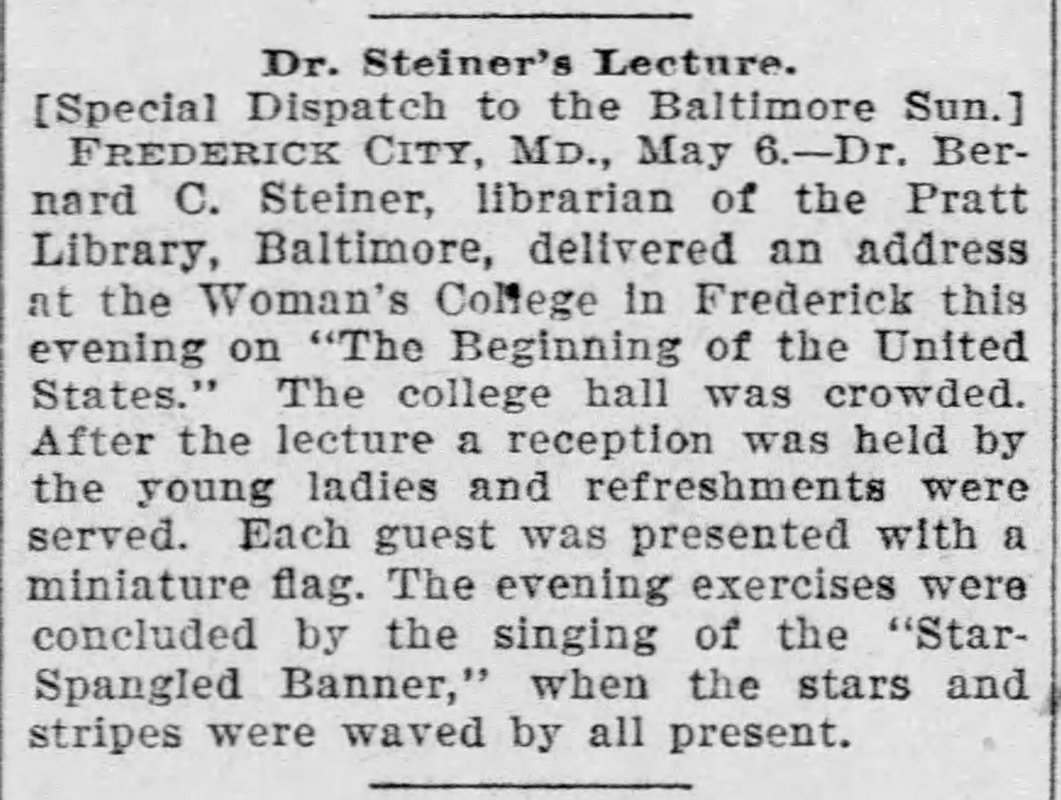

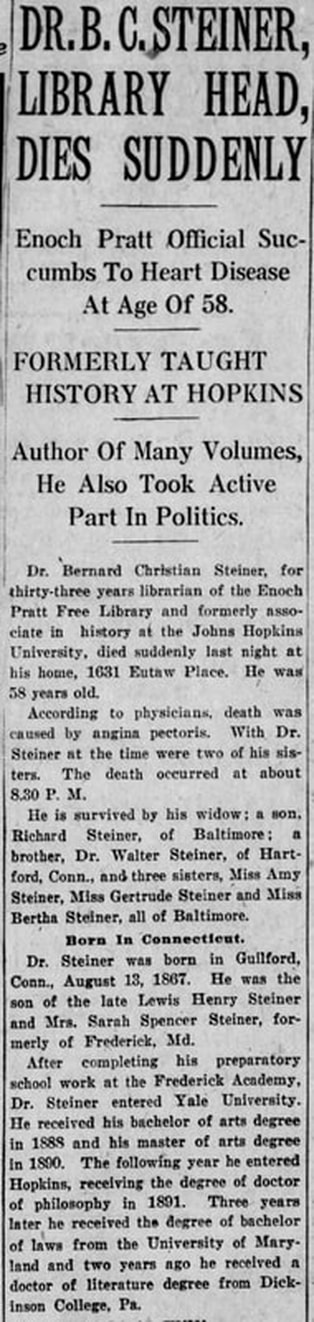

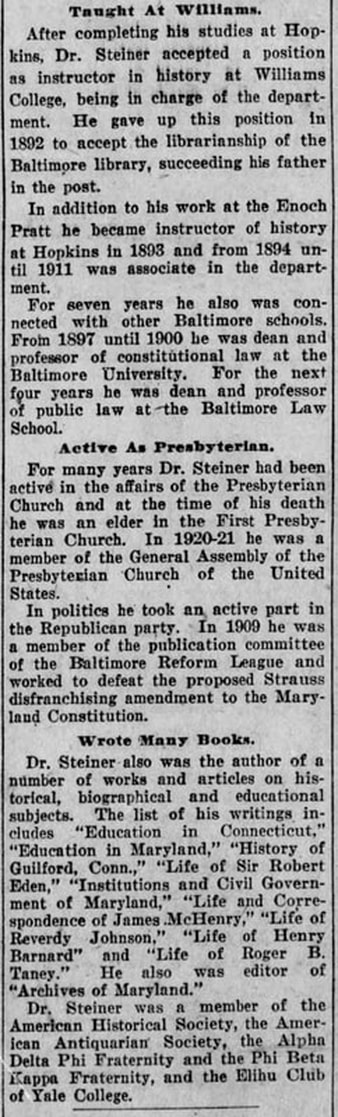

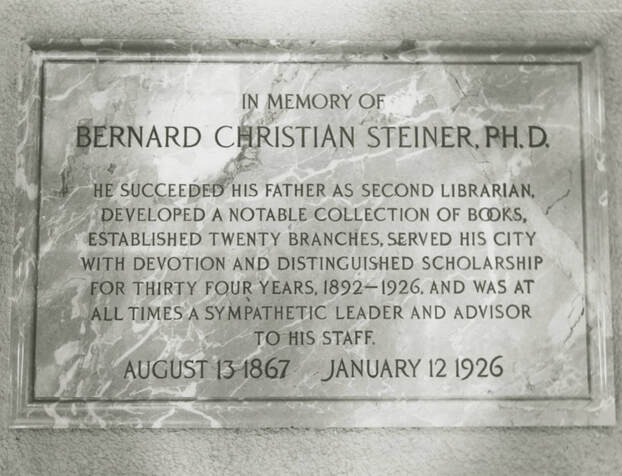

So, yours truly has a big lecture gig coming up next week in which I will once again be sharing the history of Mount Olivet and discussing the lives of some of those individuals buried within it. My host is Baltimore’s legendary Enoch Pratt Free Library and my presentation will be part of their monthly Lunch and Learn Series sponsored by the Maryland Four Centuries Project, a grassroots, non-profit, independent program, laying the foundation for the commemoration of Maryland’s 400 years as a colony and state. Unfortunately, I won’t be “performing” in person in “Charm City” due to Covid-19 restrictions, but rather this will be a virtual event in which I will be presenting via the Zoom video conferencing platform (over the internet) from the cozy, confines of my desk within our Mount Olivet administration offices located in the mausoleum chapel complex.  Enoch Pratt Enoch Pratt In preparing my program, I naturally sought out connections between Mount Olivet and my host site (and its founder), Enoch Pratt (1808-1896). I found interesting links to both the library and the man, himself, whose philanthropic gesture made this library system possible back in 1882. Interestingly, I found my connectors “etched in stone,” both literally and figuratively. Two past “Stories in Stone” feature cemetery residents with definitive ties to this American businessman, born and raised in Massachusetts. Mr. Pratt would later move south to the Chesapeake Bay area and became devoted to the civic interests of the city of Baltimore. Beginning in the 1830s, he earned his fortune as an owner of several business interests, starting out as a hardware wholesaler. This later expanded into railroads, banking and finance, iron works, steamship lines and other transportation companies. Back in July, 2017, I wrote a story titled Breakfast at Tiffany’s…or McDannolds. It was about a wealthy, young man named John Knight McDannold (b. 1874), who died on his way to Cuba for a pleasure trip in the winter of 1899. McDannold’s maternal grandfather, John Knight (1806-1864), is buried in the same plot, and had accrued a large fortune due to his successful operation of mercantile businesses and cotton plantations in Natchez, Mississippi before the Civil War. Mr. Knight eventually moved to coastal southern France for health reasons, and while abroad, had Enoch Pratt oversee his financial holdings here stateside, while Pratt’s close friend, George Peabody, minded Mr. more of Knight’s money during Knight's stay in Europe. John Knight died in 1864 In France, but he had amassed a fortune which allowed his family to have his body brought back to the US and, in particular, Frederick, for burial. Area F/Lot 53 contains some stately monuments for not only Mr. Knight and his wife (Frances Z. S. (Beall) Knight), but also his daughter (Fanny K. (Knight) McDannold) and playboy grandson John Knight McDannold, whose grave stone was crafted by Tiffanys of New York. Thank you Mr. Pratt and Mr. Peabody—talk about a financial “dream team?” Although not direct, another past “Story in Stone” which would have “future” Enoch Pratt implications was entitled “The Steiner Stone.” This blog was about the gravestone of Jacob Stoner (1713-1748), one of Frederick’s first German/Swiss settlers. He came here in the 1730s and built the famed Mill Pond House (no longer standing) and owned much of the lands that now comprise the Worman’s Mill development north of Frederick City, located off MD route 26. Stoner would also build one of Frederick Town’s first hotels on the southwest corner of Frederick’s Square Corner (Market and Patrick streets). This is the site of Colonial Jewelers today. Stoner’s gravestone, like that of the Knights and McDannolds, is pretty remarkable as I venture to say that I believe it to be the oldest, formal surviving gravestone in western Maryland as it dates to 1748, the year our county was founded. Okay, so how does this connect to Enoch Pratt or his library? Well, Jacob Stoner’s premature death at age at 35 left a widow and children. One of these was Capt. John Stoner(1735-1792), or as this family would revert back to the German spelling of the name—Steiner. Capt. John had a son Henry (1764-1831) who in turn had a son named Christian (1797-1862) who is buried in Mount Olivet’s Area C/Lot165. One of this Christian’s sons is our main person of interest for this week’s story. His name was Lewis Henry Steiner, and he would serve as the first librarian of the Enoch Pratt Free Library. Lewis’ son, Bernard, would follow in his father’s footsteps at the Baltimore-based bibliotheque. These two "book-worthy" gentlemen are buried in Area G/Lot85 and make for fascinating “Stories in Stone.” Lewis Henry Steiner Talk about a great backstory. Lewis Henry Steiner was clearly a man of his times—well-educated, well-traveled, and well-accomplished. John T. Scharf’s History of Western Maryland, published in 1882, features an illustration (above) and character sketch of Lewis Henry Steiner which I will include here: “Hon. Lewis Henry Steiner, M.D., was born in Frederick City on the 4th of May, 1827. His father, Christian Steiner, born Jan. 14, 1797, and his mother, Rebecca Weltzheimer, born April 20, 1802 were both natives of Frederick. Dr. Steiner is a great-great-grandson of Jacob Steiner, who emigrated from Germany to Frederick County, and a great-grandson of John Steiner, who was born about 1735, in Frederick County, about three miles from the present residence of Dr. Steiner; commanded a company of militia against the Indians in 1775, and was a member of the Committee of Observation for Frederick County during the Revolutionary War. Dr. Steiner was prepared for college at Frederick Academy, and entered the sophomore class of Marshall College, Mercersburg, Pa., in 1843, receiving in 1846 the degree of A.B., and in 1849 that of A.M. He studied medicine with Dr. William Tyler, of Frederick, and graduated from the University of Pennsylvania in 1849 with a degree of M.D., commencing the practice of his profession in his native city in 1850. In 1852, he removed to Baltimore, where he associated with Dr. J.R.W. Dunbar for several years in the conduct of an institution for medical instruction. In 1853, he was appointed Professor of Chemistry and Natural History at Columbia College, Washington, and Professor of Chemistry and Pharmacy at the National Medical College of the same city; in 1854, Lecturer on Chemistry and Physics at the College of St. James, Maryland; in 1855, Lecturer on Applied Chemistry at the Maryland Institute; and in 1856, Professor of Chemistry at the Maryland College of Pharmacy. In 1852 he was elected a member of the American Medical Association; in 1853, Fellow of Medical and Chirurgical Faculty of Maryland, and in the same year member, and in 1874, Fellow, of the American Association for Advancement of Science; in 1855 he was elected correspondent of the Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia; in 1869, corresponding member of the Maryland Academy of Sciences; in 1872, member , and in 1876, Vice-President , of the American Public Health Association; and in the latter year member of the International Medical Congress (Philadelphia); in 1876, Fellow, in 1876 and 1877, Vice-President, and in 1878, President, of the American Academy of Medicine. In 1861, Dr. Steiner returned to Frederick, where he has since resided. At the outbreak of the Civil War, he took an active interest in the Union cause, assisted in raising troops, and when the Sanitary Commission was organized, in 1861, he was appointed inspector, and in 1863 chief inspector, and assigned to the Army of the Potomac. In this service, he labored indefatigably until the close of the war, and distinguished himself so greatly by his zeal and skill that in 1868, in recognition of his services, he was elected by the New York Commandery companion (third class) of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States. After the close of the war, he took great interest in adapting the system of public education to the changed condition of affairs, and as president of the school board of Frederick County from 1865-1868 reorganized all the schools of the county. Dr. Steiner’s contributions to literature and science have been constant since 1851, and have given him a high place both in and out of his profession. Dr. Steiner has been a frequent contributor to reviews, medical and literary journals, and was for several years assistant editor of the American Medical Monthly, published in New York. The honorary degree of A.M. was conferred upon Dr. Steiner by the College of St. James in 1854, and by Yale College in 1869. He is corresponding member of the Maryland Historical Society and the New Haven Colony Historical Society, trustee of the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute at Hampton, Va., and honorary member of the Harrisburg Pathological Society. Before the war, Dr. Steiner was a member of the Whig party, but became a Republican when that organization passed away. Since 1871, he has represented Frederick County in the State Senate, having been elected three successive terms over strong Democrat opponents. In 1876, he was a member of the Cincinnati Republican Convention which nominated Mr. Hayes for the Presidency. Dr. Steiner’s scientific and professional attainments have won for him a national reputation, and given him a high place among the most distinguished names known to medical science in this country. Although he has been frequently honored in the political confidence of the people of Frederick County, he is not a politician in the ordinary acceptation of that term, and stands high above the petty arts and devious methods which too often characterize the politics of the day. In the Senate, Dr. Steiner is the recognized leader of the Republican Party; but while loyal to the political principals of that organization, he never forgets the superior fealty due his constituents and the State at large, and his services in the General Assembly have gained him an enviable place in the estimation of the people of all sections of Maryland, and of every political complexion. An elegant scholar, an able physician, a man of high scientific attainments, of the purest personal character, a refined and genial gentleman, Dr. Steiner is a representative whom western Maryland at large is happy to count among her sons. Dr. Steiner was married on the 3rd of October, 1866, to Sarah Spencer, daughter of Hon. R. D. Smyth, a distinguished lawyer and genealogist of Guilford, Conn, and his five children, two sons and three daughters. photo As I said at the onset, what a unique individual, and this biography only takes us up to 1882, and does not include the last decade of Dr. Steiner’s life story. I want to backtrack back to the American Civil War, when the Frederick native was actively employed as an inspector by the United States Sanitary Commission (USSC) in September 1862, and for a period would head its operations in the Army of the Potomac as chief inspector. The Sanitary Commission was in charge of ensuring the cleanliness of hospitals, coordinating medicine transports and related duties during the Civil War. Immediately before the Maryland Campaign, he was at the battlefield of 2nd Bull Run in Manassas, Virginia following the combat there and Gen. Lee’s victory which eventually spurred him to cross the Potomac and take his Army of Northern Virginia into Maryland and Union territory. Frederick would be the first major northern town that Gen. Lee would visit during the war. Dr. Steiner returned to Frederick from Washington, DC on September 5th, immediately ahead of the Confederate Army, and reported on the character and conduct of that army and the response of the residents here as the army passed by Mount Olivet’s front gate on South Market Street and came into town via Market Street from the south. Steiner kept a diary and wrote of the experience: “The citizens were in the greatest trepidation. Invasion by the Southern Army was considered equivalent to destruction. Impressment into the ranks as common soldiers; or immurement in a Southern prison—these were not attractive prospects for quiet, Union-loving citizens.” Shortly afterward, Dr. Steiner published his observations as “Report containing a Diary kept during the Rebel Occupation of Frederick, Md., etc.” (New York, 1862). (Note: For an additional passage from this work, click on the button below for a quote read by Steiner’s great-grandson Roland Steiner of Howard County.) In July 1863, Dr. Steiner would oversee the Field Relief Corps, which would grow out of the USSC’s inspection, field relief and battlefield relief practices dating from the beginning of the war. U.S. Sanitary Commission workers known as relief agents, under the direction of the inspectors, followed the troops while they were on campaign. They were expected to familiarize themselves with the wants and needs of the soldiers and medical officers, so that the USSC could provide the right supplementary goods and services. As the Battle of Monocacy raged just outside Frederick in July 1864, Dr. Steiner was with the Union Army of the Potomac on its way to besiege the Confederate capital at Richmond, Virginia. The inspector for the Sanitary Commission learned of the battle and made his way back to see about the safety of his family. He owned the famed Schifferstadt farmstead northwest of town at this time. Steiner’s diary would contain additional information about the state of affairs here in Frederick: "This battle of the Monocacy was one of the sharpest little fights of the war. It is possible that it saved the city of Washington," Steiner wrote July 19th, 1864. He began his writings on this part of the war by mentioning the difficulty in securing transportation out of Baltimore to his native Frederick which is to be understood. Steiner wrote of crossing the heavily damaged bridge at Monocacy Junction by train, but noted that the Rebels had pillaged little in the city because they received a $200,000 ransom. The author related seeing the Thomas House, the restored home now part of the Monocacy National Battlefield, with abundant evidence of a terrible fight and how some Confederate soldiers had been buried in the field adjacent, the whole located in the crossroads location of Araby off the old right of way of the Frederick-Georgetown Pike. Steiner went on to say: "There is a terrible state of depression pervading this community. Three of the prominent stores are about closing and men are disposed to sell their farms and leave the land of their nativity." Later he adds two other entries: "Really this war has produced so much that is heart rending in the way of separation of families that one's heart bleeds over it,” and “God help us and free us from our troubles right soon." Lewis Henry Steiner published a brief history of the Commission in 1866. The year prior, he became president of the Frederick County School Board where he expressed a major interest in developing school facilities for African-American children. A decade later, his efforts were chiefly responsible for the Maryland General Assembly adopting the 1876 Great Seal of Maryland, which remains the State's Seal to this day. He was later assistant editor of The American Medical Monthly. Quite a resume of jobs and experiences and that brings us up to the last I will share. In 1884, Dr. Steiner was appointed the first librarian of the Enoch Pratt Free Library. An incredible holding in the Pratt Library archives is a vintage photograph of Dr. Steiner sitting at a table within the library with a group of gentleman including the library’s founder, Enoch Pratt. The Steiner family lived in Baltimore on Eutaw Place, only a few blocks away from the library on Cathedral Street across from the Baltimore Basilica. Dr. Steiner remained active in his church as an elder and played his part in civic activities as his health allowed in his waning years. He would remain in this post until his death on February 18th, 1892. He was 64. His body would be brought back home to Frederick where he was buried in Mount Olivet’s Area G/Lot 85 on February 23rd. I found that the grave-lot was originally purchased in 1877 as Dr. Steiner’s three-year old son, Ralph Dunning Steiner, had been laid to rest here. Dr. Steiner’s successor would be a familiar figure in his life, son Bernard Christian Steiner. Born in Guilford, Connecticut on August 13th, 1867, Dr. Bernard C. Steiner’s career can be described as that of an educator, librarian and jurist. Bernard prepared for college at the Academy of Frederick before attending Yale, where he graduated with an Bachelor of Arts degree in 1888, and Masters Degree in 1890. He was a Fellow in history at Johns Hopkins, 1890–91 and received a PhD there in 1891. From 1891 to 1892, he was an instructor in history at Williams College, a private liberal arts school located in Williamstown, Massachusetts. In 1892, Bernard took over his father’s former post at the Enoch Pratt Free Library. He occupied this position for the rest of his life, and to it he devoted his primary attention, his motto being “The Library is the continuation school of the people,” which motto however did not always ring true with his patrons, and was the source of some friction. He vigorously spread the influence of the library, increasing the number of branch libraries from six to 25 during his years of service. In addition to his work at the library, Bernard C. Steiner continued as an educator. In 1893, he was instructor of history at Johns Hopkins, and served as an associate there from 1894 to 1911. Steiner graduated from the University of Maryland with a Bachelor of Law degree in 1894. He was dean and professor of constitutional law at the short-lived Baltimore University from 1897 to 1900, and was dean and professor of public law at Baltimore Law School from 1900 to 1904. Bernard Steiner married Ethel Simes Mulligan of Yonkers, New York in 1912 and had two children: Richard and Gilbert. The family resided at 1631 Eutaw Place in Baltimore.

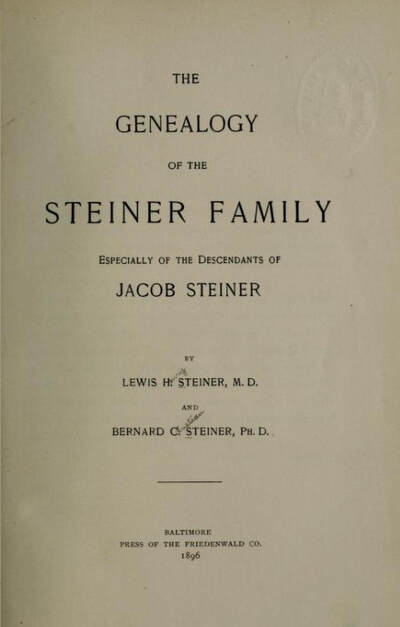

Fifteen years later, Mr. Steiner would be called upon once again to lead Fredericktonians in the reinterment of another legendary history figure—Barbara Fritchie. This occurred on May 30th, 1913 I’m sure there were other visits to Mount Olivet to visit his father’s gravesite. Bernard C. Steiner lived out his life in Baltimore before his death on January 12th, 1926. Bernard C. Steiner would be buried next to his father in Area G. Other family members are here including his mother, Sarah (Spencer) Steiner (1841-1914), brother Dr. Walter Ralph Steiner (1870-1942) an accomplished physician and medical librarian, and sisters Bertha R. Steiner (1872-1944), Gertrude Rebecca Steiner (1869-1949) and Amy Louise Steiner (1877-1966). His son Richard Lewis Steiner (1913-1989) is also here and served as a city planner for Baltimore for many years. Bernard’s other son, Gilbert Simes Steiner (1915-1922) had originally been buried in Baltimore’s Greenmount Cemetery, but was reinterred in Mount Olivet at the time of Richard’s burial. Bernard's wife, Ethel (Mulligan) Steiner, is not here however. The last I could see was that she was living in the New Market area at the Riggs Asylum in both the 1930 and 1940 census. I surmise that she was buried in a family lot in her native New York. And when I took recent pictures of this sacred gravesite of Enoch Pratts first two head librarians, I did not get shushed, but I made sure I was quiet and respectful as they would have wanted. Of all the accomplishments both men celebrated, perhaps their most important achievement or legacy on the local level came through a posthumous collaboration utilizing both men's talent in the field of research and record/information organization in book form. The Steiner family genealogy is a tricky mistress, and this humble book not only has helped me, but many generations, historians and genealogists since 1896. Author's Note: Special thanks to Mr. Roland Steiner, Enoch Pratt Free Library and the Library of Congress for various vintage photographs of both Lewis Henry Steiner and Bernard Christian Steiner.

|

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed