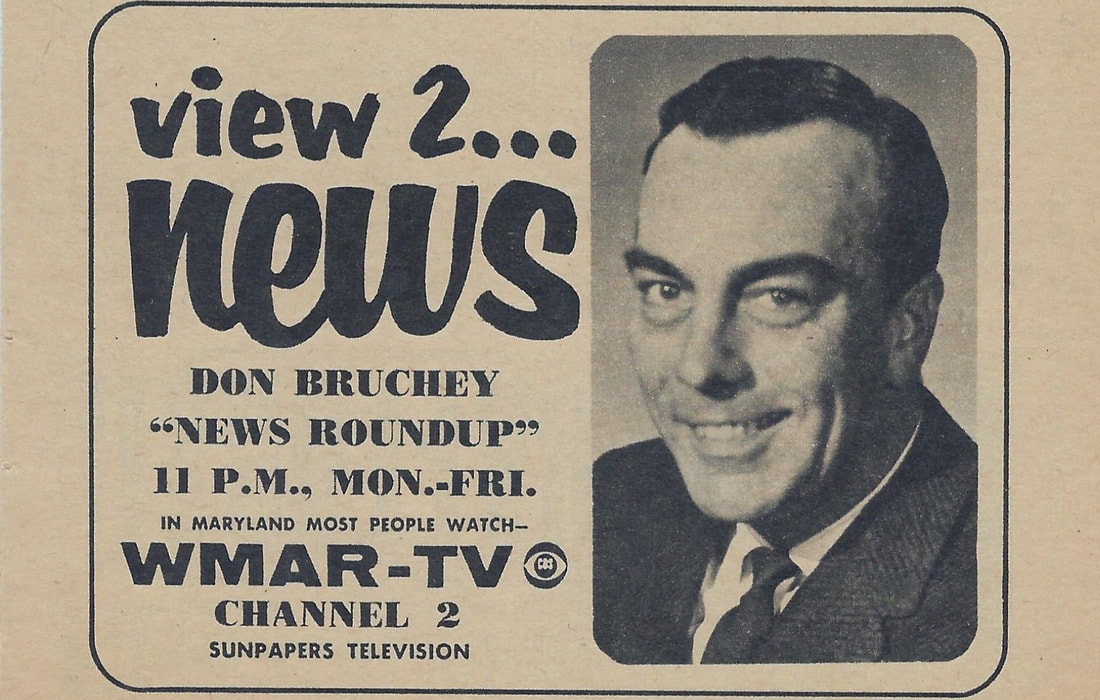

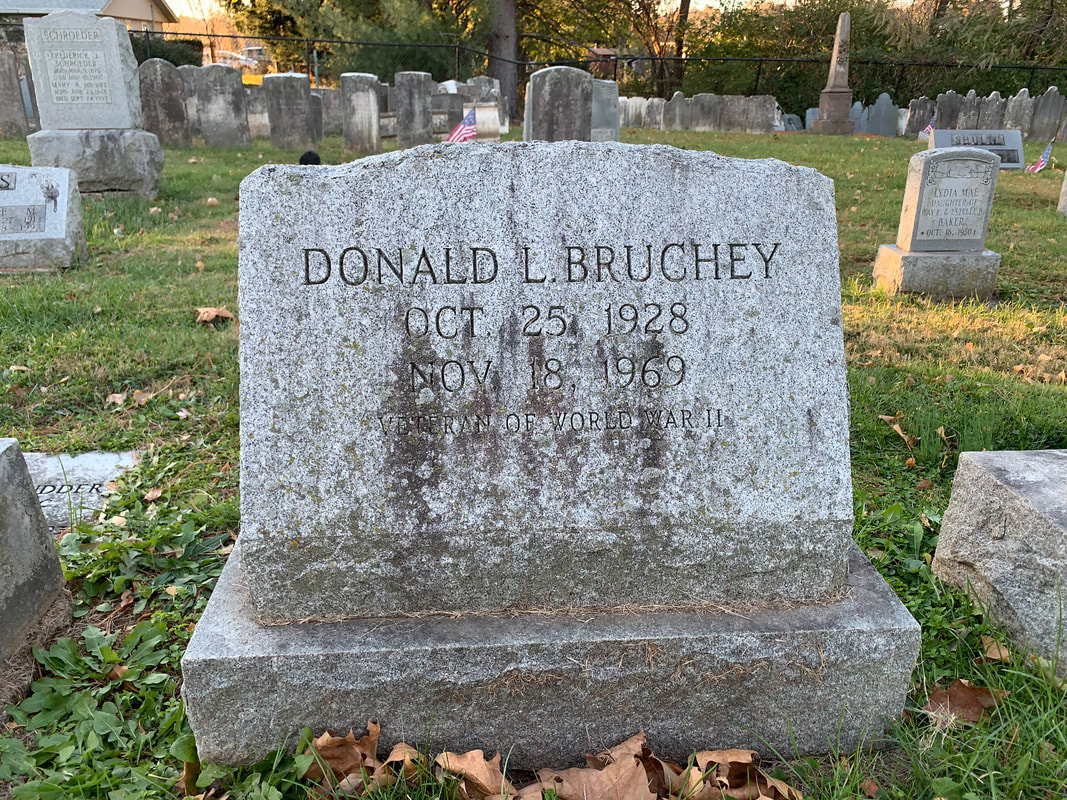

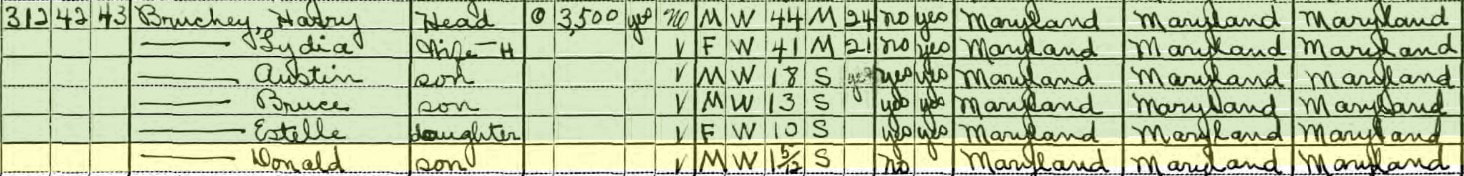

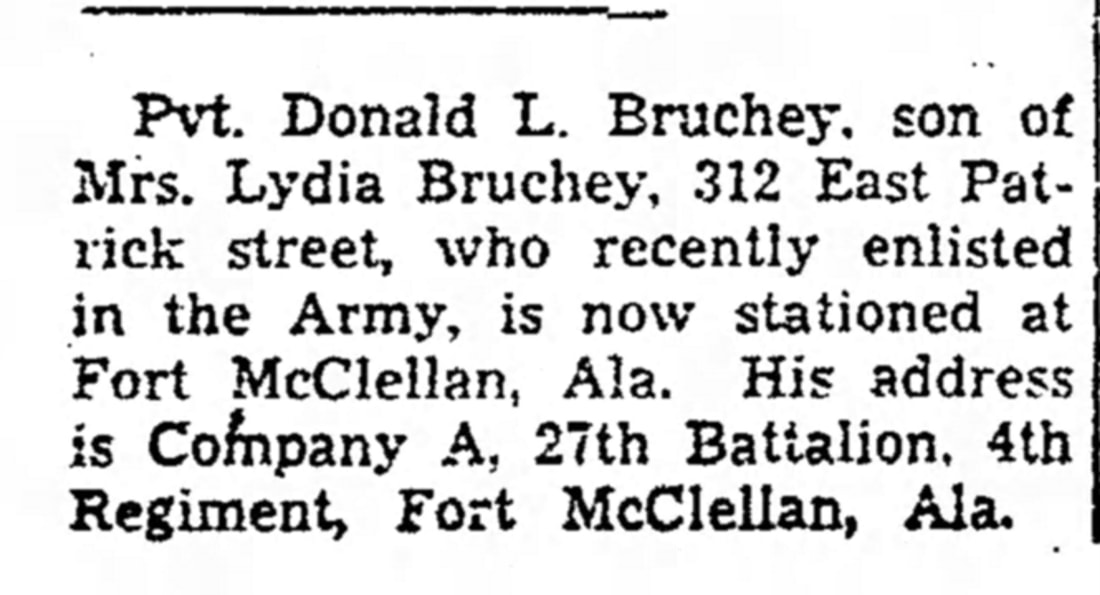

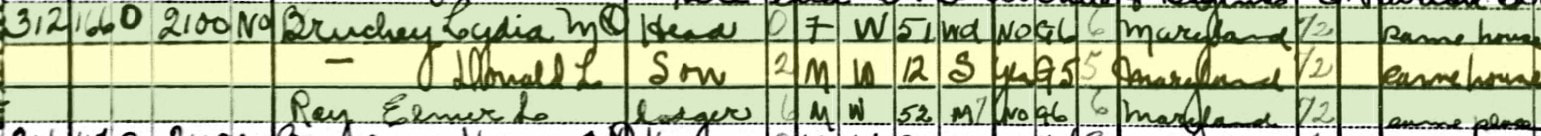

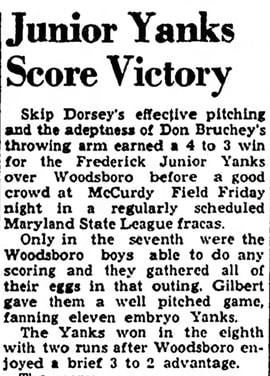

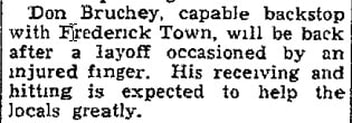

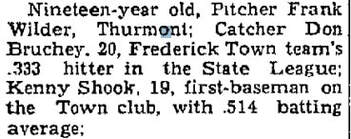

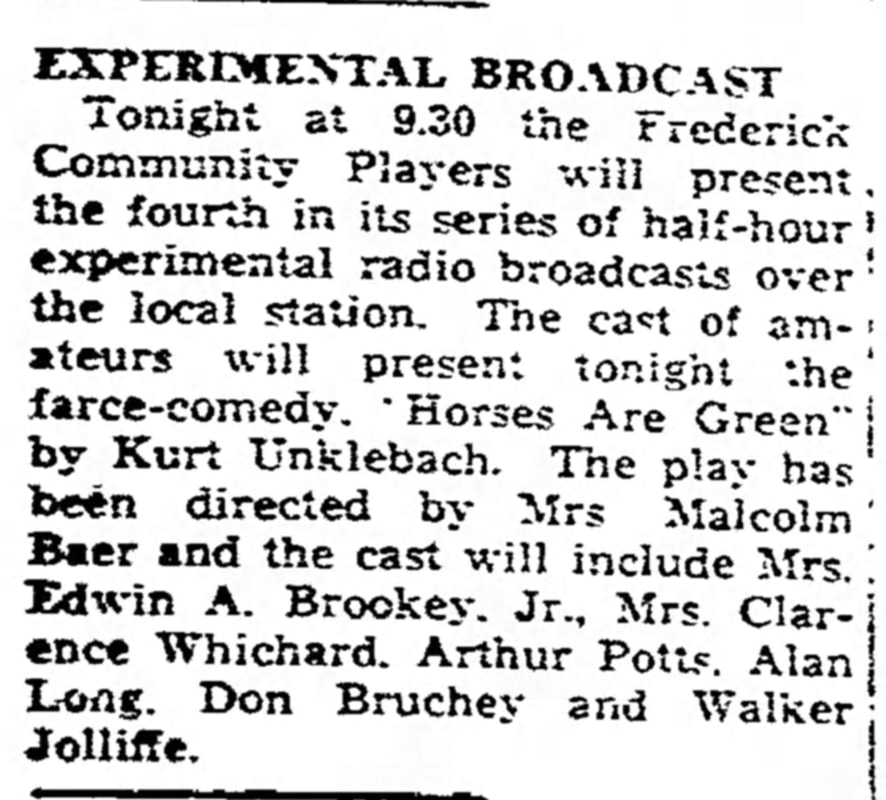

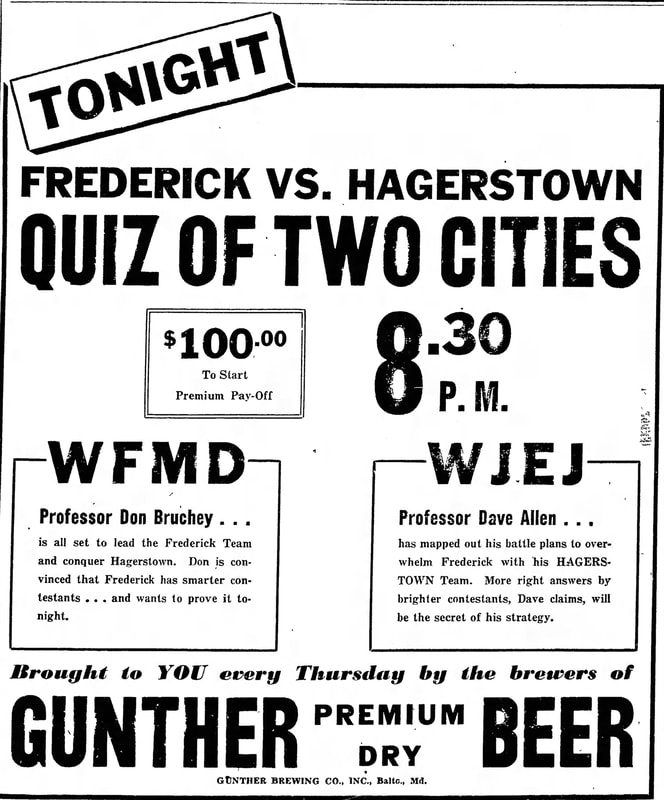

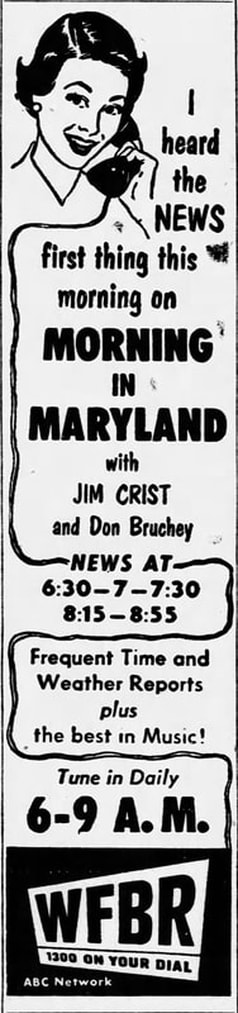

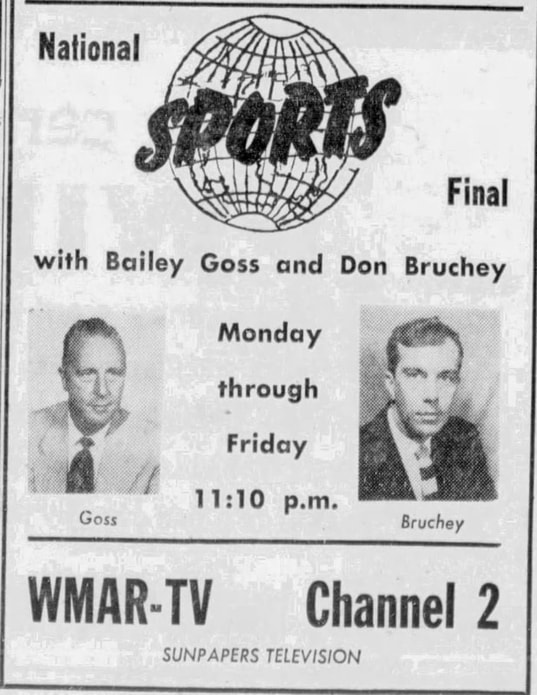

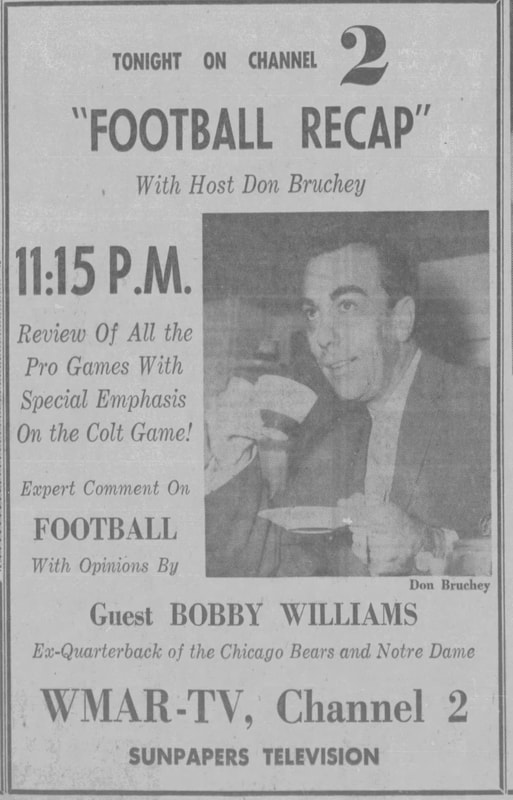

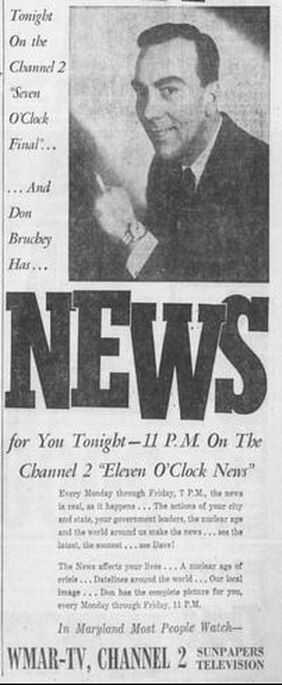

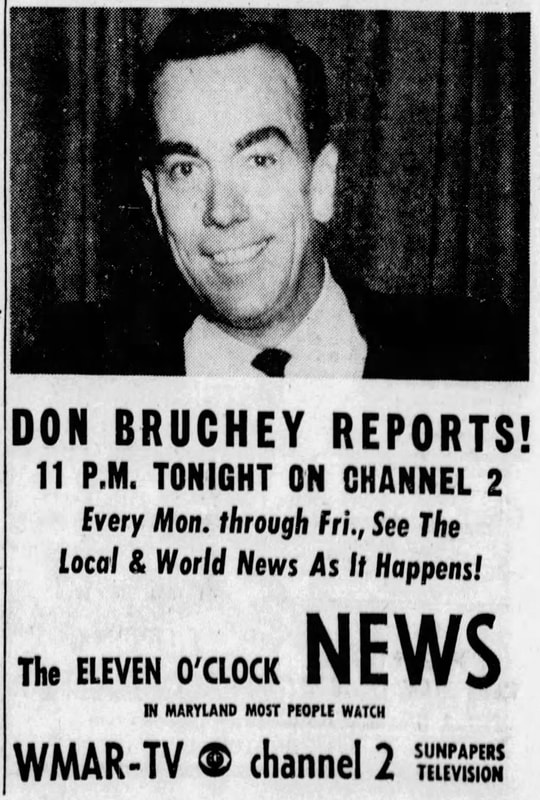

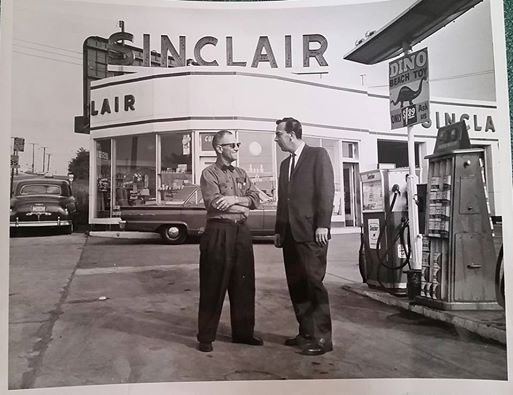

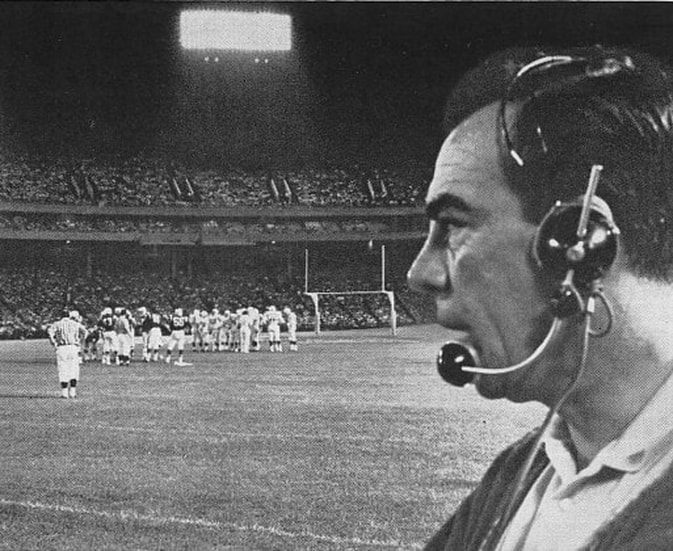

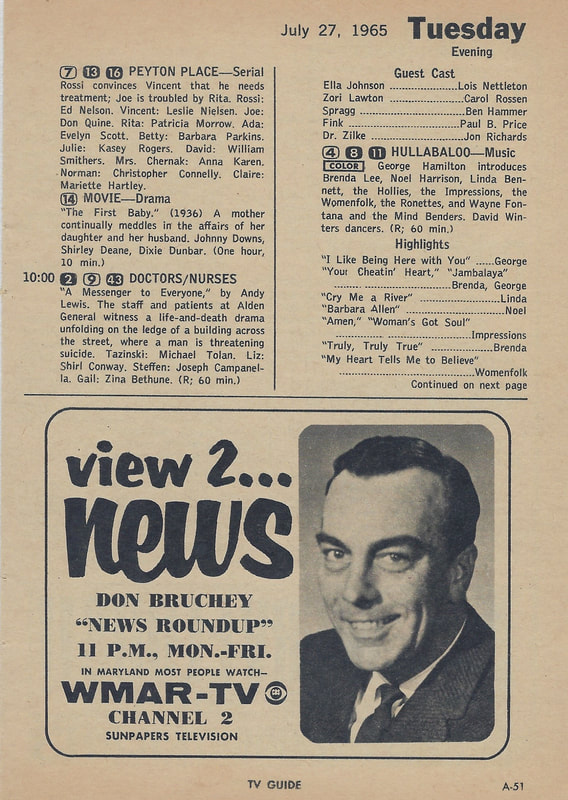

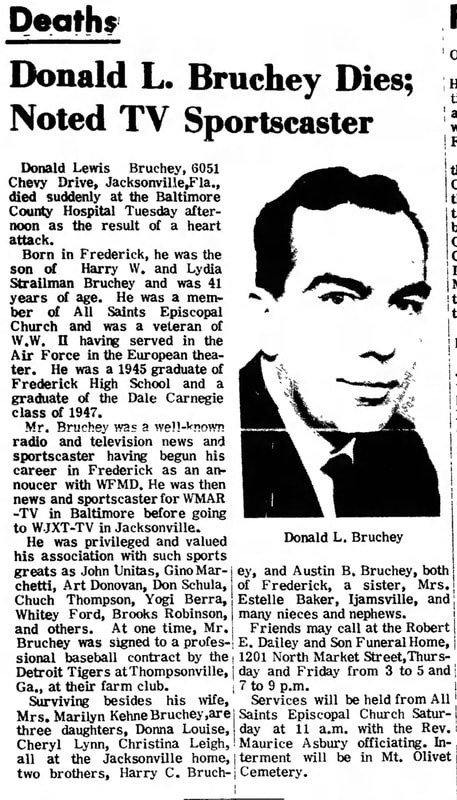

Area NN is an interesting one here in Mount Olivet. It’s shape is somewhat triangular as it sits against the western boundary of the cemetery, not far from the Barbara Fritchie and Thomas Johnson gravesites. The section often raises curiosity among visitors as the stones within are somewhat positioned very closely together—almost too close together, but there is a reason. Most of those people interred here today, came from other burial grounds that once graced downtown Frederick. Some of these gravestones have death dates that predate the cemetery’s opening in 1854, and there are several examples written in German. The Colonial architecture is clearly evident and the rationale for these stones placed so close together lies in the fact that these comprise church group reburials dictated by the trustees of local congregations. Three different churches bought the bulk of the lots on NN to be exact— the Presbyterian, Evangelical Lutheran and Methodist Episcopal. These churches once had their own designated burying grounds downtown, but elected to transfer bodies via mass removal to Mount Olivet, allowing for reuse or resale of the former graveyard properties. This option took the congregations out of the graveyard business and deferred the job to an entity that solely was suited to handle the assignment. This was certainly not an uncommon practice for the time, and in the case of Area NN, most of this reburial activity occurred in 1907-1908. As for the makeup of the property, the Methodist are to the left, Lutherans in the middle and Presbyterians to the right. I plan to write future articles about all three congregations in context to their earlier burying grounds, but not here. I have only brought all this up because I found that there are several other burials on Area NN that are not affiliated with the three church re-interment projects. I discovered one recently by researching the final resting place of this week’s person of interest. He died 50 years ago this past week. Donald Lewis Bruchey The grave of Donald Lewis Bruchey sits prominently in the foreground of the designated “church lots.” His gravestone type is called a slant face marker. To the immediate right is a larger stone for his parents: Harry W. (1885-1934) and Lydia Mae Strailman (1889-1963). On November 18th, 1969, Don Bruchey found himself visiting at the home of friends living in Pikesville, northwest of Baltimore. He had just been seen by thousands of television viewers days before, while performing his full-time job as a news anchor on WJXT-TV in Jacksonville, Florida. No one could have predicted the terrible circumstance that would soon beset this charismatic, 41 year-old who had returned to his native Maryland in advance of celebrating the Thanksgiving holiday. Don would suffer a heart attack and would die a short time later at Baltimore County General Hospital in Randallstown.  Frederick High yearbook photo of Don (c. 1945) Frederick High yearbook photo of Don (c. 1945) The Frederick native had worked in the broadcasting business for more than half his life—21 years. Don Bruchey had started as an on-air announcer at Frederick’s WFMD radio station in 1948. This came three years after graduating from Frederick High School in 1945 where he was a theater standout and an outstanding baseball player who was signed to a professional contract by the Detroit Tigers. He would play catcher for their minor league affiliate in Thomasville, GA—the Thomasville Tigers. Baseball had to wait however, as Bruchey served his country in the Army in Europe during the waning months of World War II. The 1940 US census shows Don living with his mother Lydia at 312 E. Patrick Street in downtown Frederick. His father, a barber by profession, had passed away back in 1934 when he was six. He was the youngest of four children. Don's professional baseball dreams were short-lived. He would play for local teams such as the Frederick Hustlers and the Junior Yanks for a few years. Don set his sights on a career. Interestingly his true passions for sports and acting would pave his path. The young man took a pivotol Dale Carnegie Public Speaking Course in 1947. His penchant for acting beyond high school had him playing leads in several local stage productions here in Frederick and at the storied playhouse venue that once stood in Braddock Heights under the direction of James Decker. He performed regularly with Frederick's Community Players ensemble and with a like group in Hagerstown known as the Potomac Playmakers. It appears, the actor was introduced to the world of radio through the broadcast of some of the Community Players' productions in 1948. Don's talents led him to be asked to do narration work for recordings and emcee duties for local events. Don would leave Frederick and WFMD in 1950, taking a job at Brunswick, Georgia's WGIG where he hosted his own show titled "Spinner Sanctum." After a year he came back to Frederick and WFMD. It is most likely he came back for the love of his life, Miss Marilyn S. Kehne of Yellow Springs area of Frederick. He took on employment at Baltimore's WFBR in 1952. Don took up residence on N. Calvert Street in Baltimore. The couple would marry on March 14, the following year. Bruchey eventually headed south again, going to Greenville, South Carolina and WGVL in late 1953 where he hosted a studio-based music program called "Club 23." I assume this could have been similar to Dick Clark's "American Bandstand." The former Fredericktonian returned to Maryland, and Baltimore, in late 1954 and worked at radio station WWIN. Don also got his chance to work in television with sports on Baltimore's WMAR, Channel 2. He would host a sports program called "Football Scoreboard" in 1955. He was also asked to present weather from time to time. Don’s impressive reputation as a former athlete sportscaster served him well. His theater background also allowed for him to bring dramatics to the events he was covering. Bruchey’s obituary states that he had valued associations with several star athletes including Johnny Unitas, Gino Marchetti, Art Donovan, Don Shula, Chuck Thompson, Yogi Berra, Whitey Ford, and Brooks Robinson. Within a few years, he would transition to covering news. Don successfully transitioned into news from sports and served as a reporter and finally a news anchor for Channel 2 (WMAR). On eBay last year, I found an ad featuring Don Bruchey in an old TV Guide dated July 27th, 1965. It was an intriguing find which led me to write this blog. He anchored the 11PM edition, the prime newscast of the station. In 1968, Don jumped at the opportunity for a change of venue, and more importantly, the chance to serve as lead news anchor for a station in Florida. After 13 years in “Charm City,” he relocated to Jacksonville in January, 1968, taking with him wife Marilyn and three daughters: Donna, Cheryl and Christine. An eitor's note in the Baltimore Sun in 1968 remarked that Don was homesick for Maryland.  As I said at the outset, Don and family traveled back home to Maryland 50 years ago this week for Thanksgiving in 1969. He would suffer a heart attack while visiting friends in Pikesville. Interestingly, his father had also died of a heart attack in his forties. Don Bruchey’s body would return to Frederick for burial. Services were held at All Saints’ Episcopal Church on W. Patrick Street on Saturday, November 22nd. Graveside service followed here at Mount Olivet within the historic backdrop of Area NN as he was placed to the side of his father and mother, Lydia, who had died earlier in 1963. As could be imagined, the service was largely attended and including relatives, friends, former teammates, former acting partners, and news colleagues. I was excited to see that one of his pallbearers was Stu Kerr, a legendary Baltimore television star I remember from my youth. He was a weatherman, afterschool movie host, played Bozo the Clown, emceed "Dialing for Dollars" and was the star of local show "Professor Kool's Fun Skool."

3 Comments

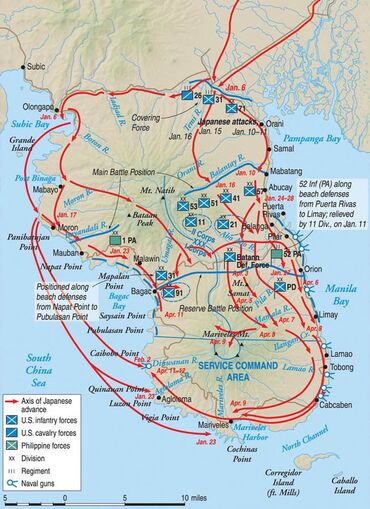

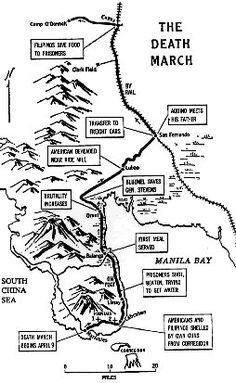

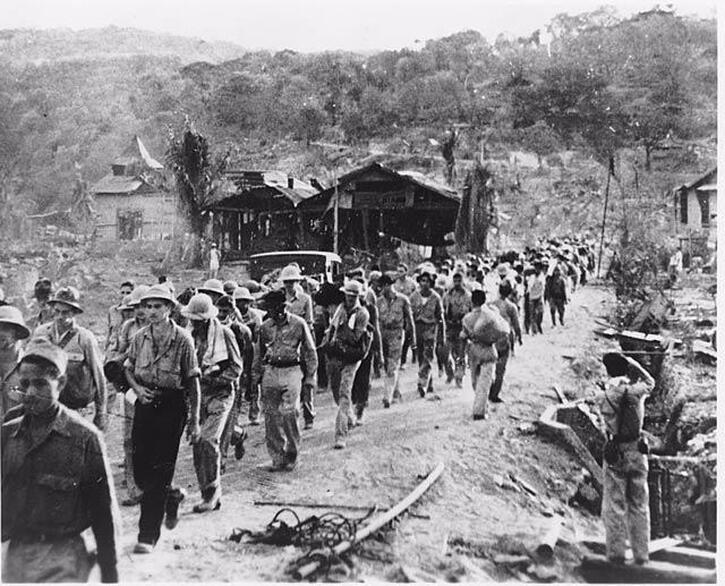

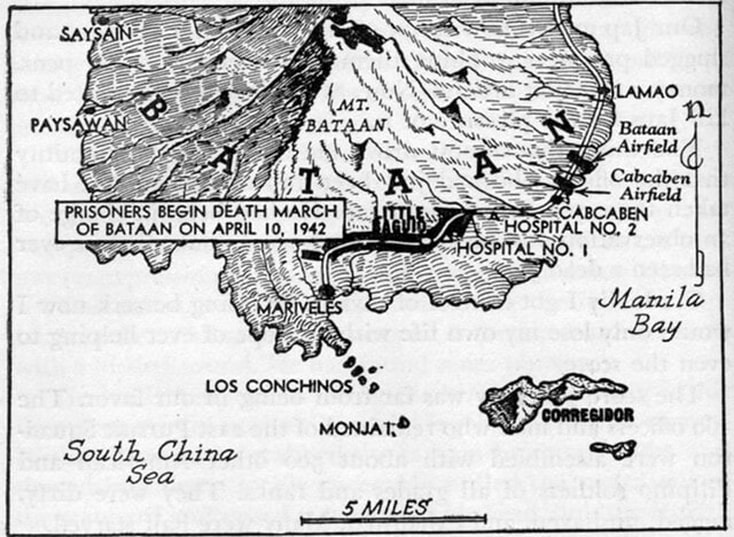

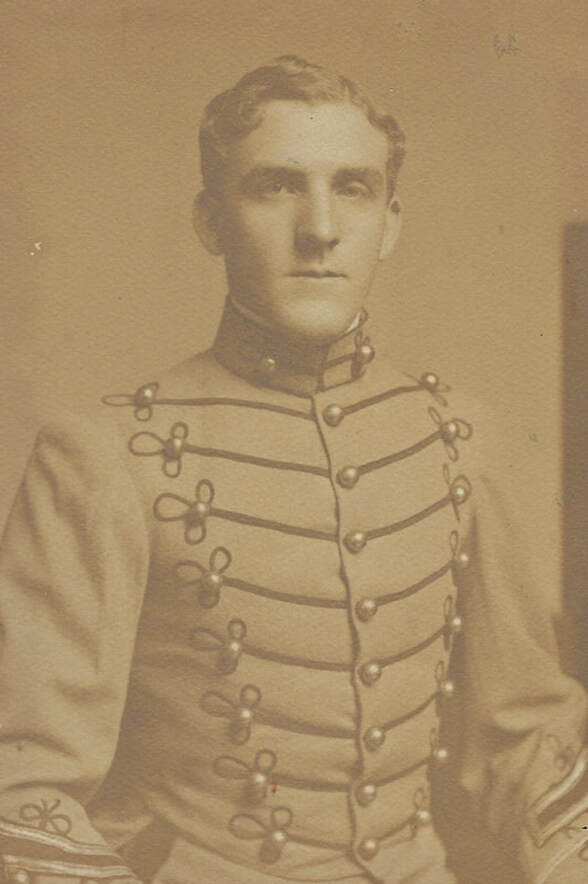

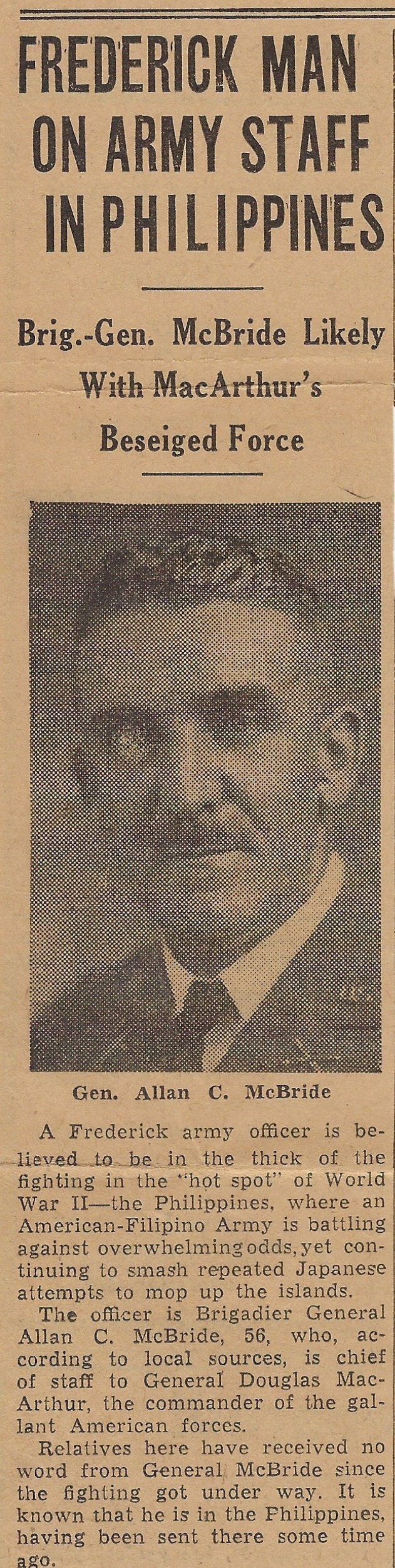

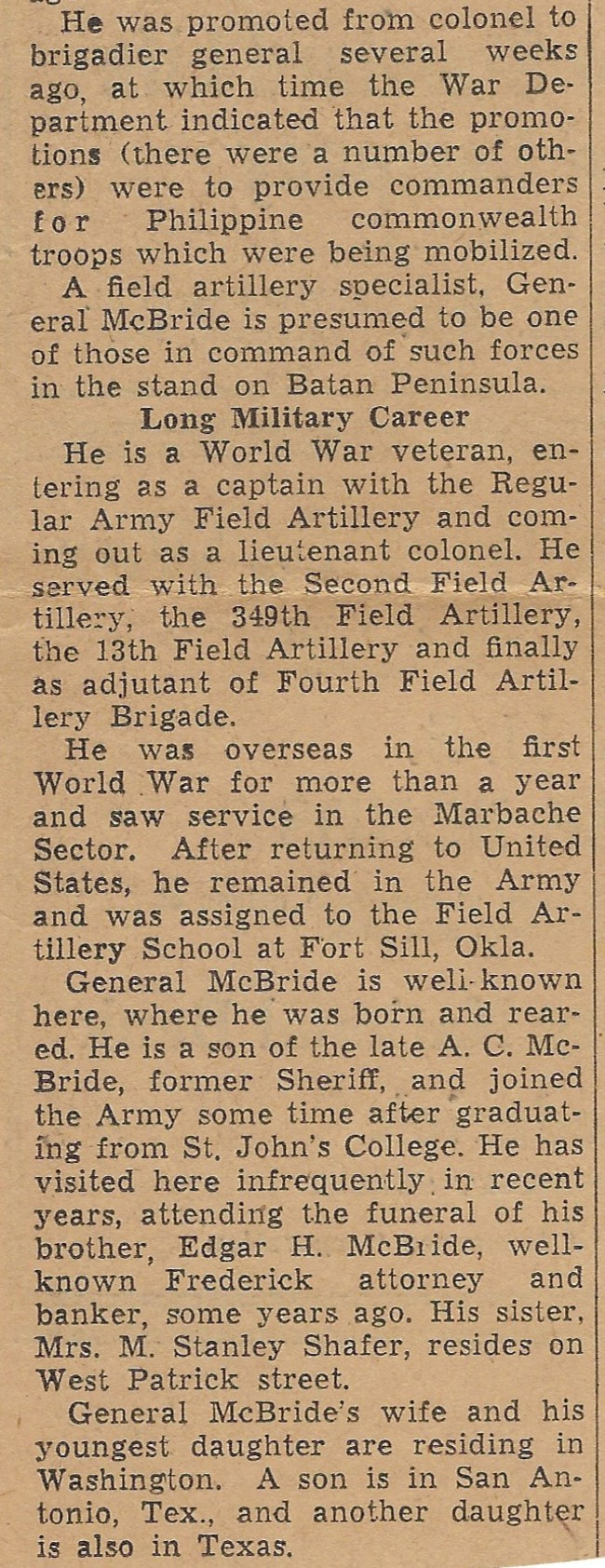

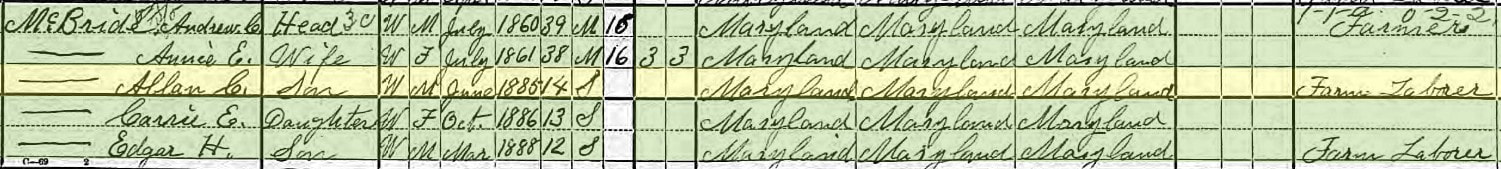

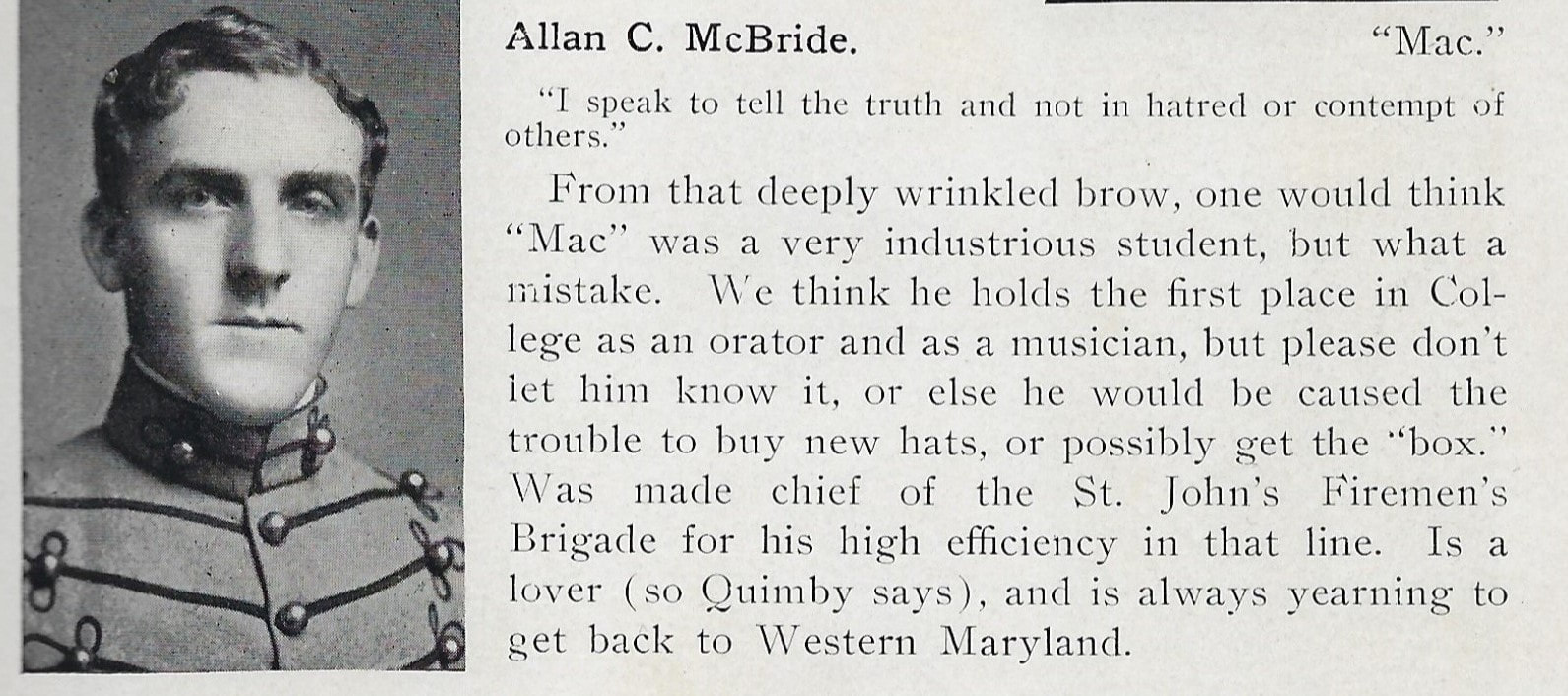

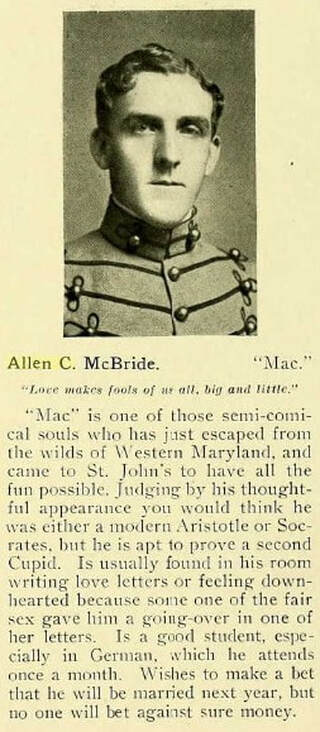

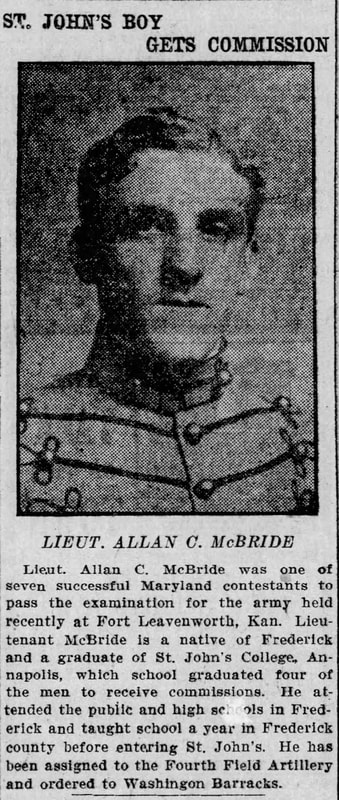

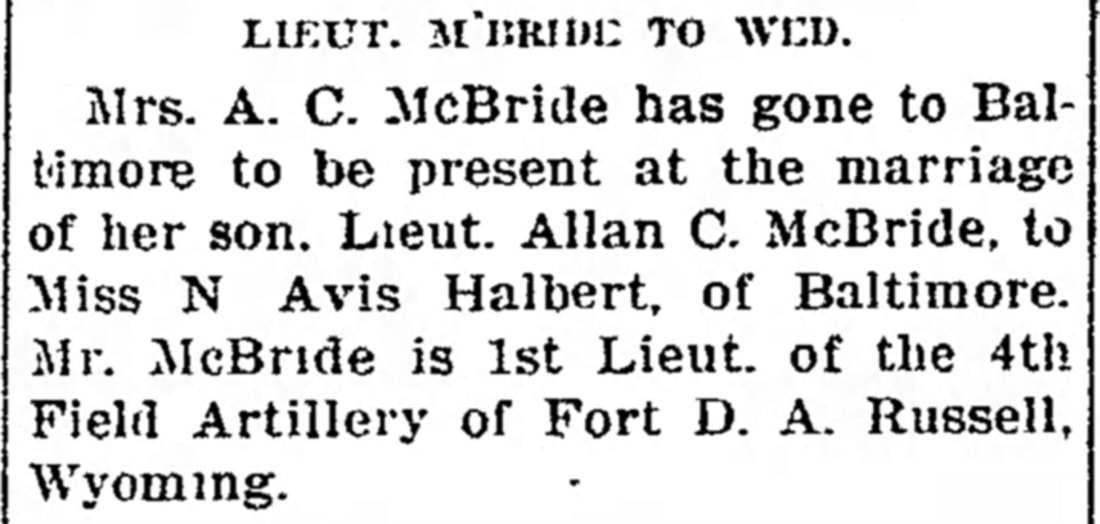

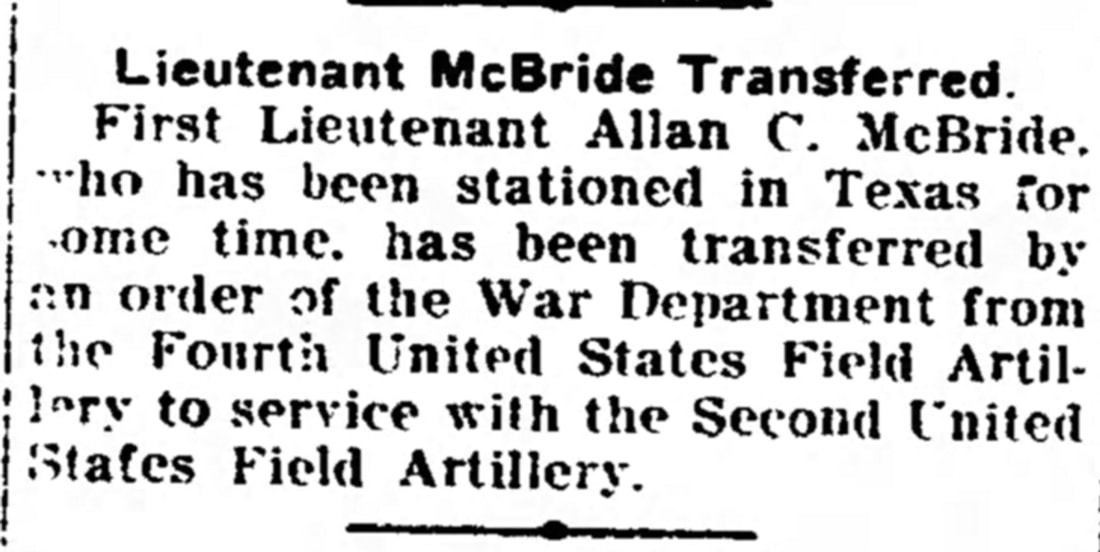

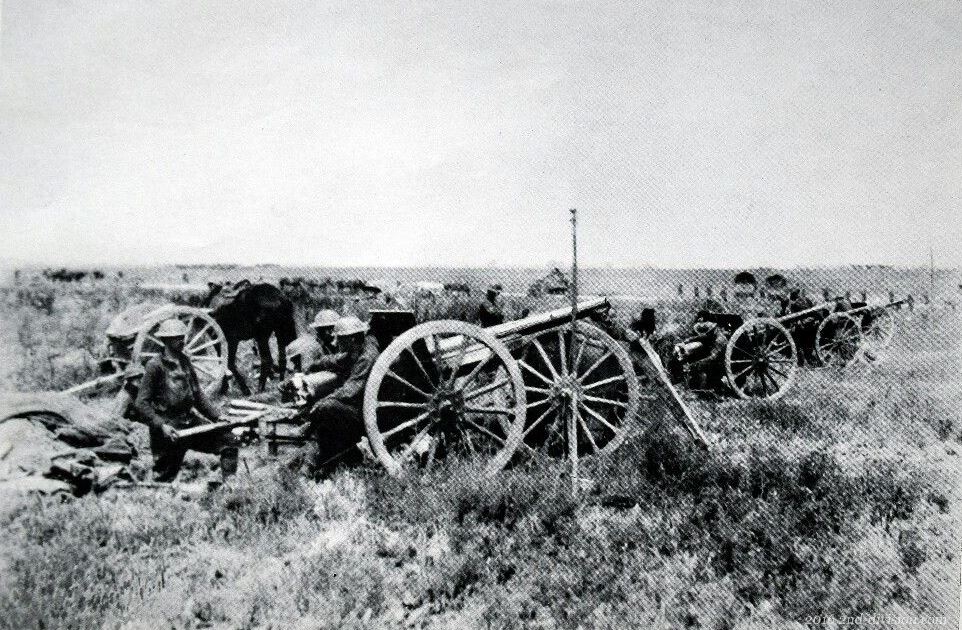

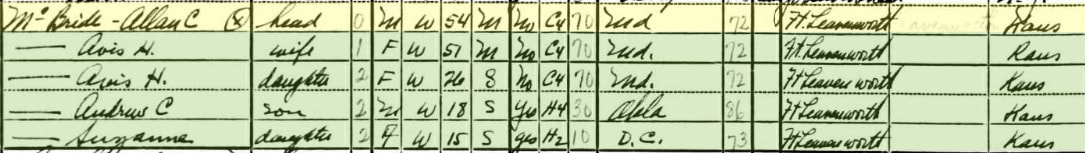

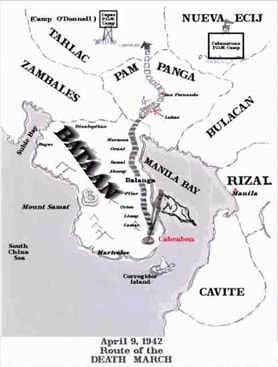

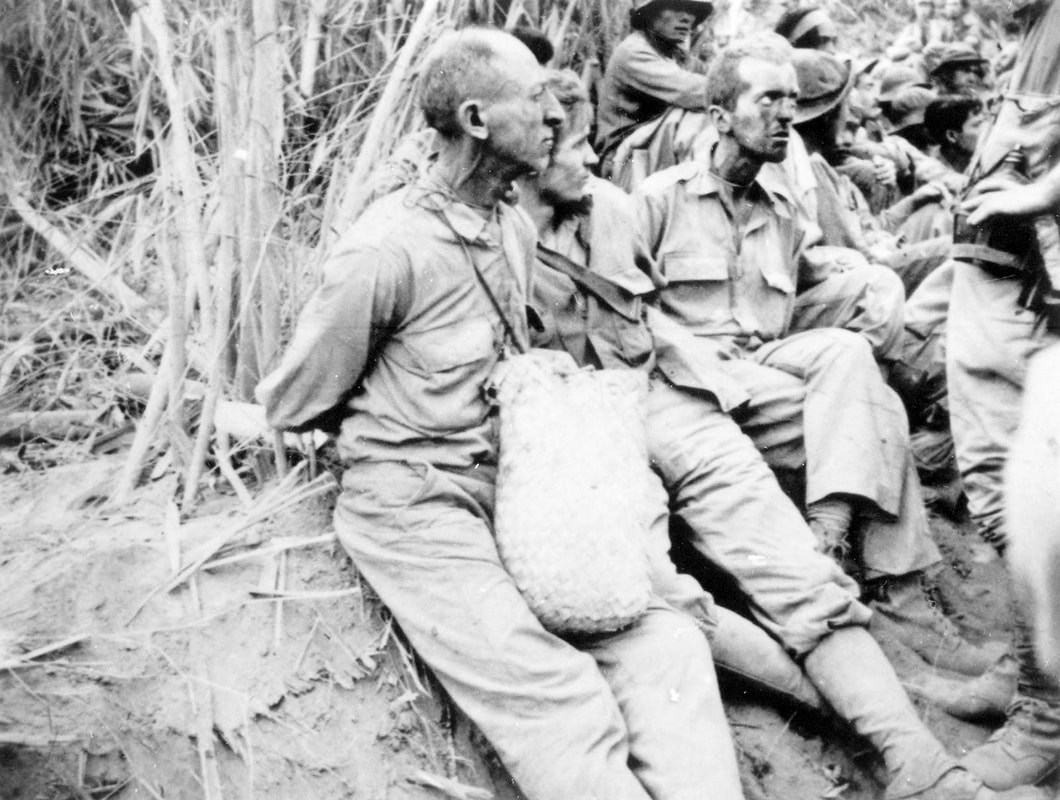

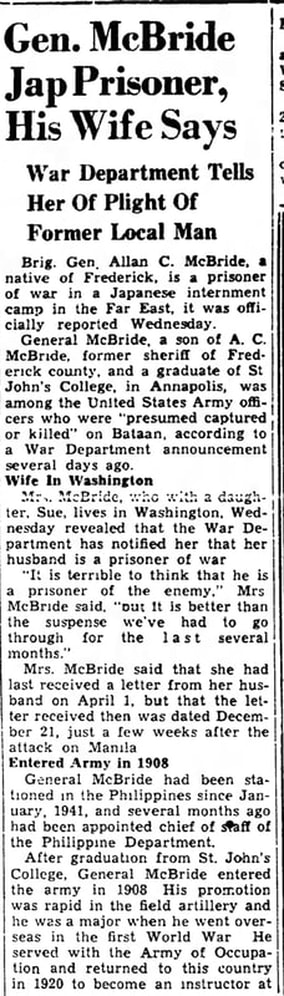

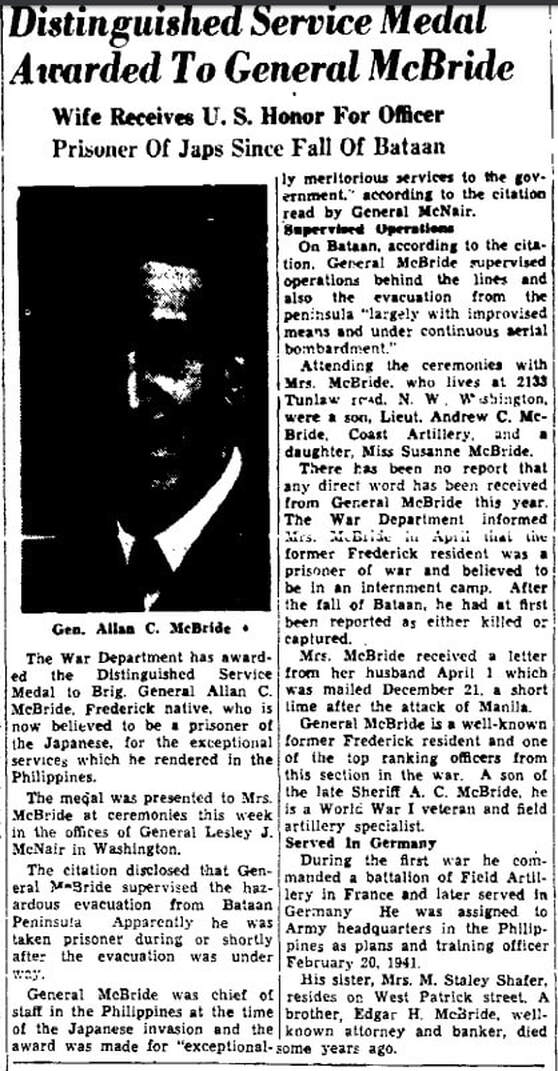

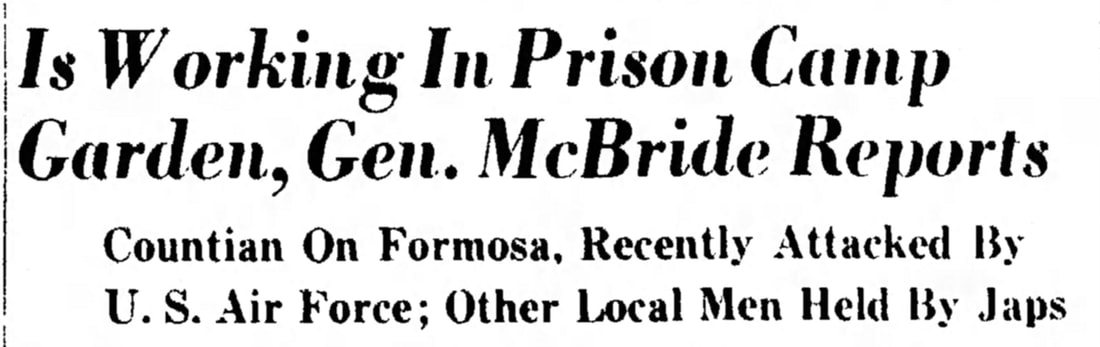

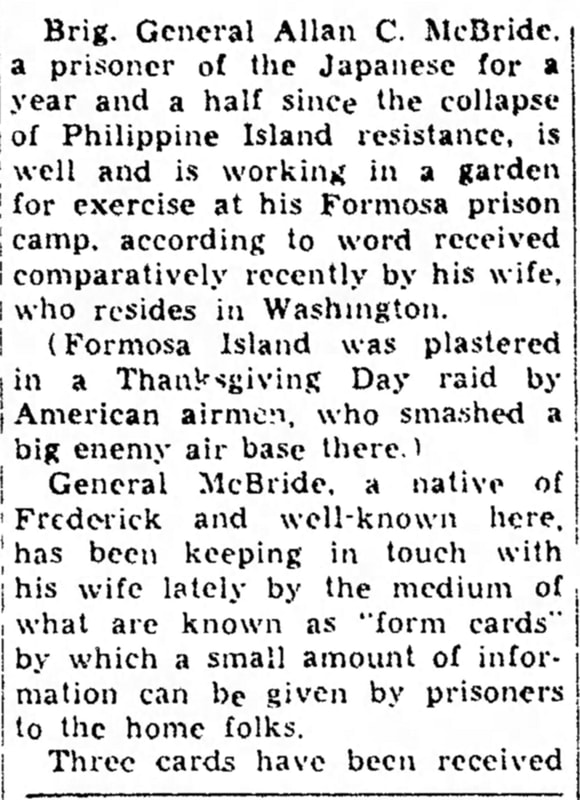

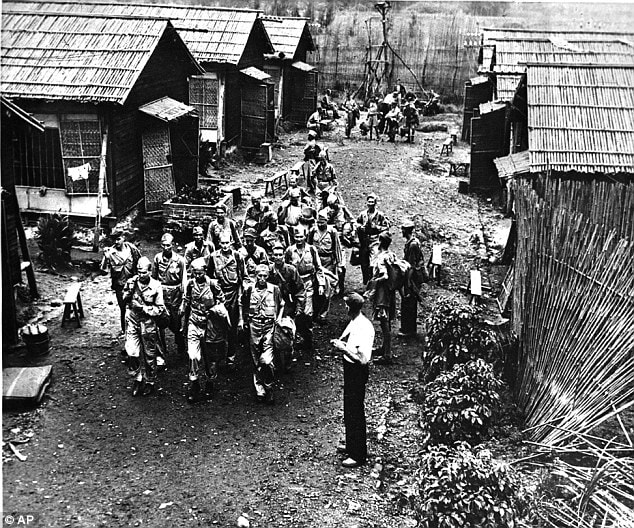

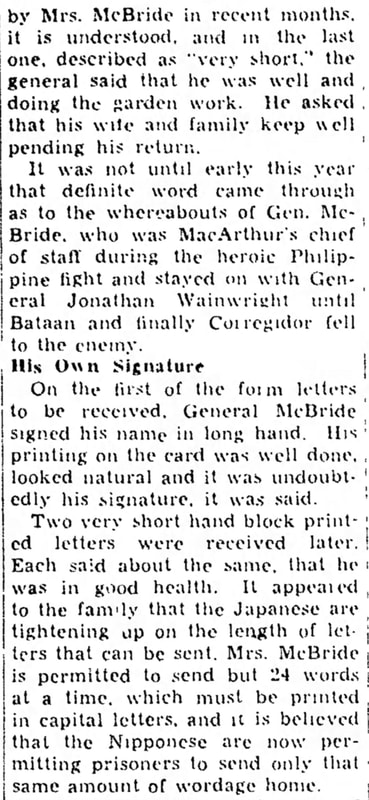

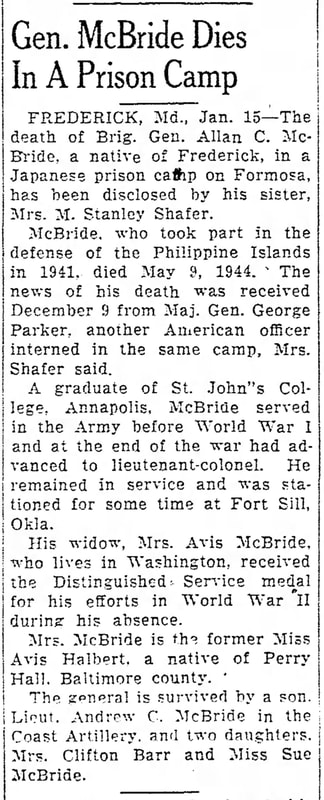

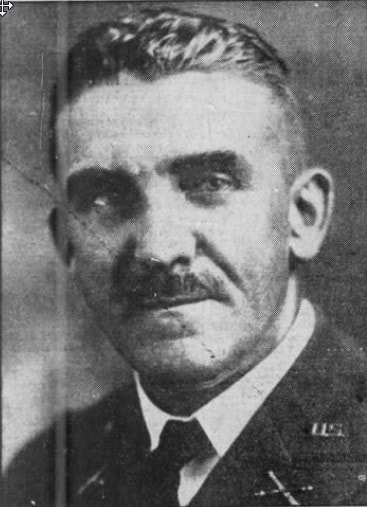

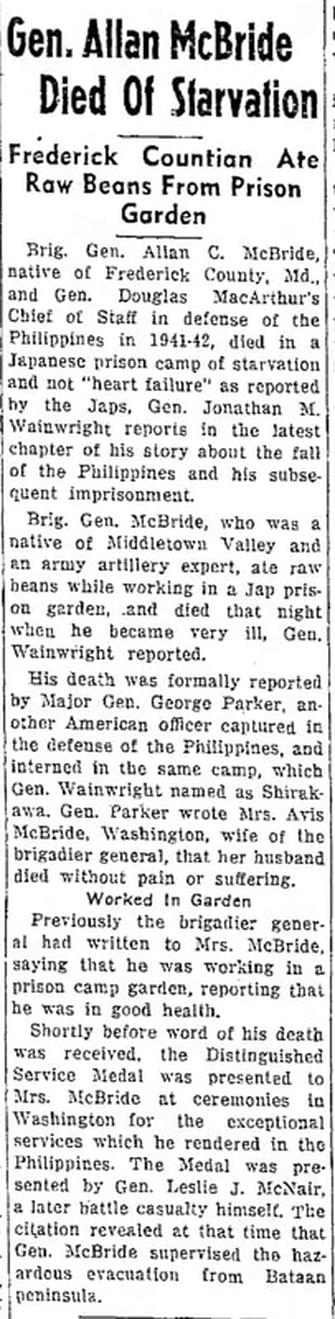

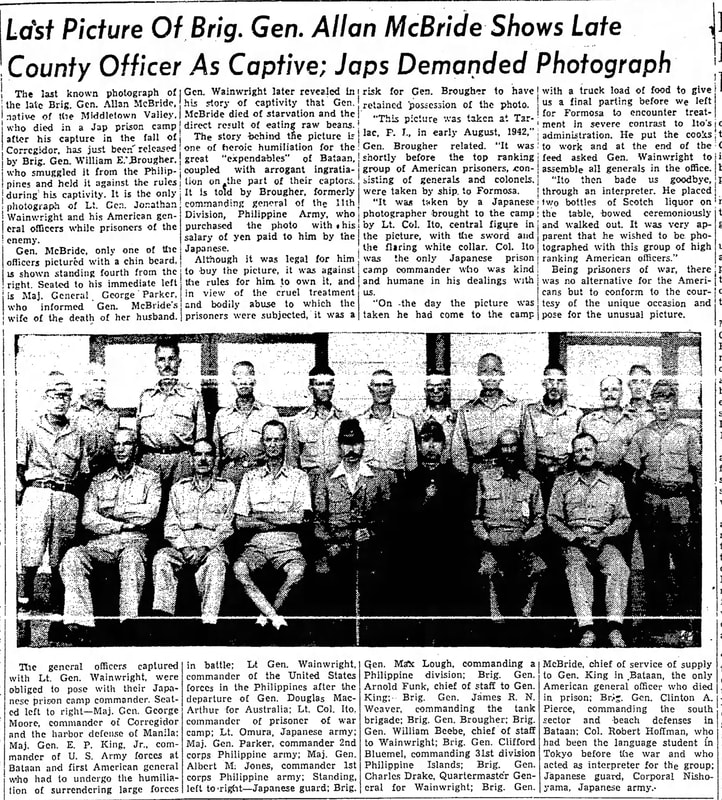

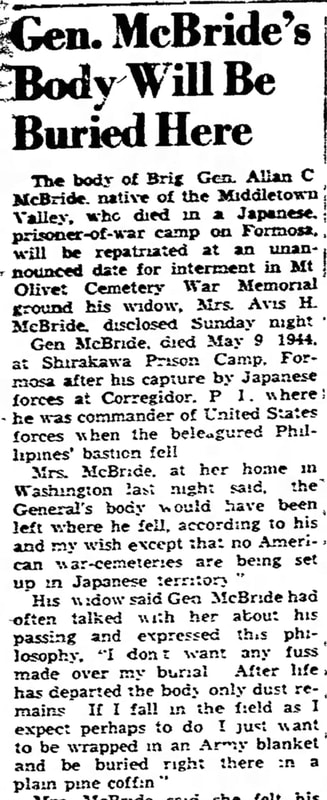

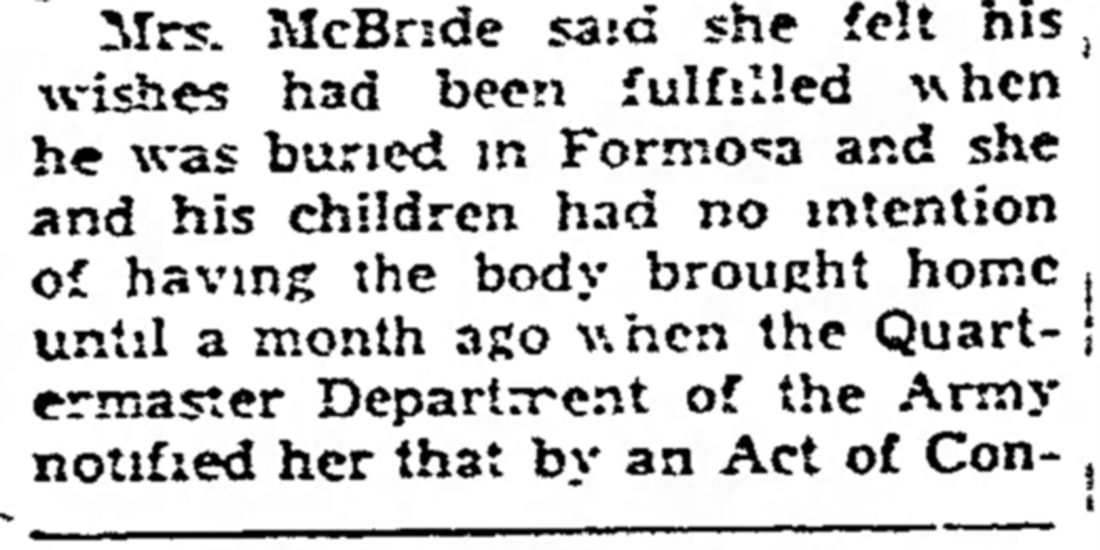

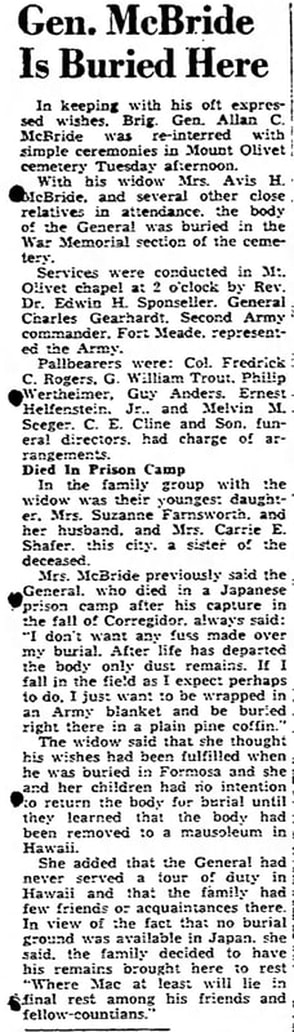

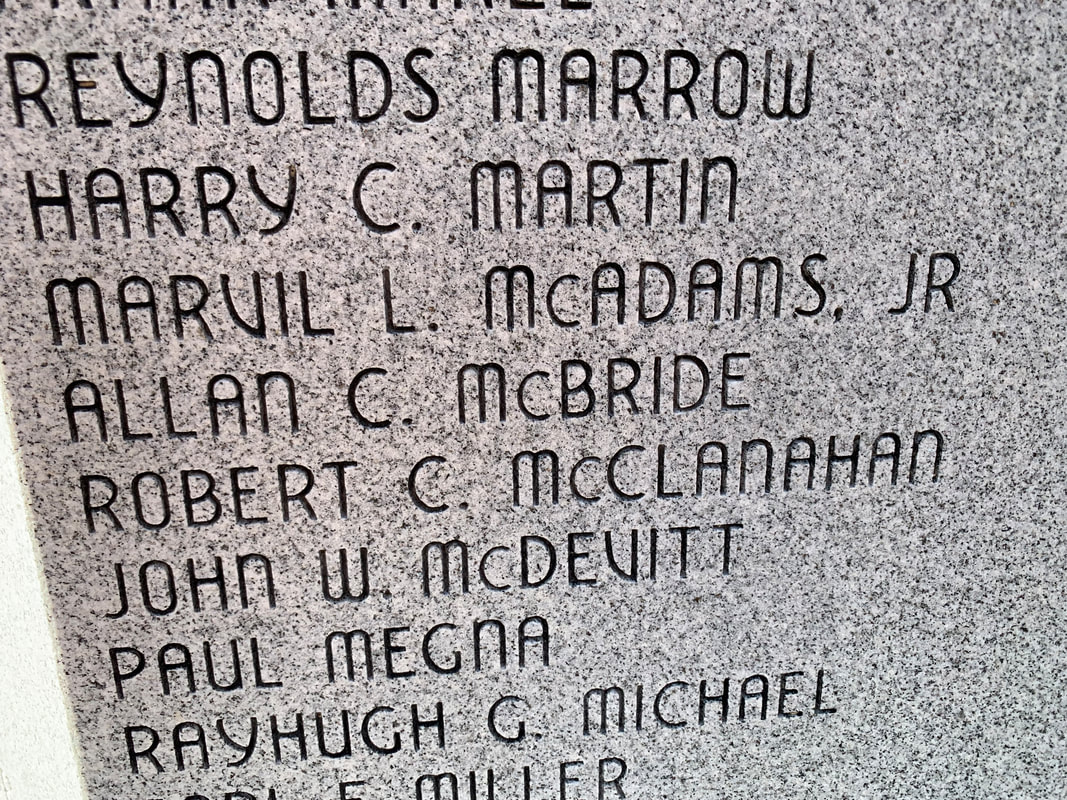

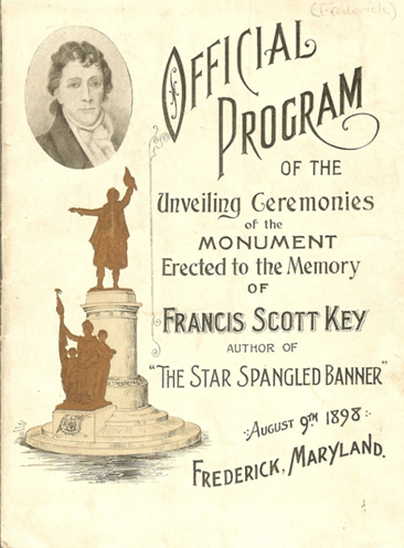

A point I often make to cemetery visitors and tourists here to Mount Olivet is that we have an over-arching theme of “patriotism.” Our two most famous interments include the guy who wrote our national anthem and a nonagenarian who became an overnight heroine thanks to a New England poet who glorified her supposed defiance in front Confederate general Stonewall Jackson and his troops during the American Civil War. Two phrases, attributed to this tandem, speak volumes: “O’ Say Can you See, by the Dawn’s early light?” and “Shoot if you must this old gray head, but spare your country’s flag, she said.” A third “history celebrity” is buried here as well, an actual patriot himself. Thomas Johnson, Jr., best remembered as Maryland’s first-elected governor, but also served as a business entrepreneur, member of Continental Congress and brigadier general during the turbulent time of the American Revolution. The above trio is surrounded by nearly 4,000 other men and women (laid to rest here) who performed active military duty—many participated in national and world conflicts. We have individuals who connect to conflicts ranging from the French & Indian War to Vietnam. In a few cases, we have particular decedents who took part in multiple wars over the course of their lives. This is often true of professional military men. One such is buried here in Mount Olivet, and his story is as amazing as it is heartbreaking. A veteran of both “World Wars,” it can easily be said that he gave his “last full measure of devotion” to the country Thomas Johnson helped create, and the flag Francis Scott Key championed with in song, and Barbara Fritchie protected with her life. Bataan Many recall, or have heard about, one of the most unsettling events in the history of warfare. It is known as the Bataan Death March. This atrocity took place in the Philippines during World War II and included 76,000 prisoners of war (66,000 Filipinos, 10,000 Americans) forced at gunpoint to walk some 66 miles at the mercy of the Japanese military captors. It occurred in April 1942, during the early stages of World War II. The name Bataan comes from the province situated in the Central Luzon region of the Philippines-Luzon being the northernmost island (of the Phillipines). Occupying the entire Bataan Peninsula on Luzon, Bataan is bordered by the provinces of Zambales and Pampanga to the north. The peninsula faces the South China Sea to the west and Subic Bay to the north-west, and encloses Manila Bay to the east. It’s complicated to give the backstory of this event to those unfamiliar, but it plays a very important role in understanding this week’s “Story in Stone” subject. Our “Story” also involves the famed US Army General Douglas MacArthur as well—the impetuous five-star general and Field Marshal of the Philippine Army, who had previously been a participant in World War I and served as Chief of Staff of the United States Army during the 1930s. He had even retired from the US Army in 1937. MacArthur played a prominent role in the Pacific theater during World War II after being recalled to active duty in 1941 as commander of United States Army Forces in the Far East. This move would reunite Philippine and US forces under one command. Unfortunately, a series of disasters soon beset Douglas MacArthur, starting with the destruction of his air forces at Pearl Harbor in December, 1941. Immediately after, the Japanese would set their sights on invading the US held Philippines. The Philippines had become an American possession in 1898, a result of the Spanish-American War. After being ceded by Spain, an era of American colonization commenced, lasting nearly four decades. When the Commonwealth of the Philippines achieved semi-independent status in 1935, Philippines President Manuel Quezon asked MacArthur to supervise the creation of a Philippine Army. The two men had been personal friends since the latter's father had been Governor-General of the Philippines, 35 years earlier. With President Franklin D. Roosevelt's approval, MacArthur accepted the assignment. It was agreed that MacArthur would receive the rank of field marshal, in addition to his major general's salary as Military Advisor to the Commonwealth Government of the Philippines.  Japanese troops in Bataan Japanese troops in Bataan The following summary can be found in Encyclopedia Britannica, written by Elizabeth N. Norman and Michael Norman: Within hours of their December 7, 1941, attack on the American naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, the Japanese military began its assault on the Philippines, bombing airfields and bases, harbors and shipyards. Manila, the capital of the Philippines, sits on Manila Bay, one of the best deep water ports in the Pacific Ocean, and it was, for the Japanese, a perfect resupply point for their planned conquest of the southern Pacific. After the initial air attacks, 43,000 men of the Imperial Japanese 14th Army went ashore on December 22 at two points on the main Philippine island of Luzon. Gen. Douglas MacArthur, the supreme commander of all Allied forces in the Pacific, cabled Washington, D.C., that he was ready to repel this main invasion force with 130,000 troops of his own. MacArthur’s claim was a fiction. In fact, his force consisted of tens of thousands of ill-trained and ill-equipped Filipino reservists and some 22,000 American troops who were, in effect, an amalgam of “spit-and-polish” garrison soldiers with no combat experience, artillerymen, a small group of planeless pilots and ground crews, and sailors whose ships happened to be in port when Japanese forces bombed Manila and its naval yards. At the landing beaches, the Japanese soldiers quickly overcame these defenders and pushed them back and back again until MacArthur was forced to execute a planned withdrawal to the jungle redoubt of the Bataan Peninsula. This thumblike piece of land on the west-central coast of Luzon, across the bay from Manila, measured some 30 miles long and 15 miles wide, with a range of mountains down the middle. In early January, 1942, the Japanese made their next major move on the Philippines. Altogether the Japanese landed at three separate places, each a finger of land jutting out from the rocky coast line of western Bataan into the South China Sea. The first landings came on January 23rd, as an overconfident MacArthur gave orders for the American and Filipino troops to begin falling back to a reserve battle position. The Japanese employed multiple assaults and an end run, amphibious style, with its objectives far to the south, in the Service Command Area. By March, the Japanese invasion had compelled MacArthur to withdraw his forces on Luzon to Bataan, while his headquarters and his family moved to Corregidor. The doomed defense of Bataan captured the imagination of the American public. At a time when the news from all fronts was uniformly bad, MacArthur became a living symbol of Allied resistance to the Japanese.  Fearing that Corregidor would soon fall, and MacArthur would be taken prisoner, President Roosevelt ordered MacArthur to go to Australia. A submarine was made available, but MacArthur elected to break through the Japanese blockade in PT boats. Upon his arrival, MacArthur gave a speech in which he famously promised "I shall return" to the Philippines. The staff MacArthur brought with him became known as the "Bataan Gang". They would become the nucleus of his General Headquarters, Southwest Pacific Area. One senior member of MacArthur’s leadership team, however, would be left behind. He was a Frederick native who is buried right here in Mount Olivet.  The Service Command Area When the American line was first established on Bataan on January 7th (1942), defense of the southern tip of the Bataan peninsula was designated by the name: the Service Command Area. This task had been assigned to Brig. Gen. Allan C. McBride, MacArthur's deputy for the Philippine Department. McBride's command included, roughly, all of Bataan south of the Mariveles Mountains, and was divided into an East and West Sector by the Paniguian River which flows southward into Mariveles Bay. The Service Command Area covered over 100 square miles. The distance around the tip of Bataan along the East and West Roads, from Mamala River on the Manila Bay side to the Paysawan River on the South China Sea coast, is at least forty miles. Inland, the country is extremely rugged and hilly, with numerous streams and rivers flowing rapidly through steep gullies into the surrounding waters. The coast line facing Manila Bay is fairly regular but the west coast, where the Japanese landings came, is heavily indented with tiny bays and inlets. The ground on this side of the peninsula is thickly forested almost to the shoreline where the foothills of the central range end in abrupt cliffs. Sharp points of land extend from the "solid curved dark shoreline" to form small bays. An adequate defense of this long and ragged coastline would have been difficult under the best of circumstances. With the miscellany of troops assigned to him, the task was an almost impossible one for General McBride. Things were extremely tough for both American and Filipino forces over the next few months, and even worse after MacArthur and his staff pulled out in late March. By early April, McBride and tens of thousands of soldiers would surrender to their foes. Back to the summary by Elizabeth N. Norman and Michael Norman: MacArthur had planned badly for the withdrawal and had left tons of rice, ammunition, and other stores behind him. The Battle of Bataan began on January 1, 1942, and almost immediately the defenders were on half rations. Sick with malaria, dengue fever, and other diseases, living on monkey meat and a few grains of rice, and without air cover or naval support, the Allied force of Filipinos and Americans held out for 99 days. Though they ultimately surrendered, their stubborn defense of the peninsula was a significant propaganda victory for the United States and proved that the Imperial Japanese Army was not the invincible force that had rolled over so many other colonial possessions in the Pacific. It was against this backdrop that the Bataan Death March—a name conferred upon it by the men who had endured it—began. The forced march took place over some two weeks after Gen. Edward (“Ned”) King, US commander of all ground troops on Bataan, surrendered his thousands of sick, enervated, and starving troops on April 9, 1942. The siege of Bataan was the first major land battle for the Americans in World War II and one of the most-devastating military defeats in American history. The force on Bataan, numbering some 76,000 Filipino and American troops, is the largest army under American command ever to surrender.  Beginning on April 9th (1942) in Mariveles, a village on the southern tip of the Bataan Peninsula, the prisoners, including Frederick’s own Allan C. McBride, were force-marched north to San Fernando and then taken by rail in cramped and unsanitary boxcars farther north to Capas. From there, the men walked an additional seven miles to Camp O’Donnell, a former Philippine army training center used by the Japanese military to intern Filipino and American prisoners. During the main march—which lasted five to ten days, depending on where a prisoner joined it—the captives were beaten, shot, bayoneted, and, in many cases, beheaded. A large number of those who made it to the camp later died of starvation and disease. Only 54,000 prisoners reached the camp, though exact numbers are unknown. It is believed that some 2,500 Filipinos and 500 Americans may have died during the march, and an additional 26,000 Filipinos and 1,500 Americans died at Camp O’Donnell. The Life of Allan C. McBride As America gasped at the news reports coming from the South Pacific, relatives and former friends of Allan C. McBride pondered his fate at the hands of the Japanese. He had been assigned to Army headquarters in the Philippines as plans and training officer over a year earlier on February 20th, 1941. His wife, Avis, was living in northwest Washington, DC at the time, and had only received a belated Christmas card from her husband in late January (1942), having been written a few days before Christmas when the Japanese initial invasion on the Philippines occurred. At the time, he said he was doing well on the protected confines of Corregidor. Gen. McBride was well known here, even though his military career took him all over the world. He was the son of Andrew Clay McBride (1860-1910), a former Frederick County sheriff, and Annie Estelle Routzahn (1861-1927). Allan Clay McBride was born June 30th, 1885 in Frederick’s Middletown Valley and attended public schools. The family lived on a farm in Jefferson, and consisted of younger brother Edgar and sister, Carrie (Shafer). The McBrides would eventually move into Frederick City as Mr. McBride served as principal of the N. Market Street School for some time and also was one-time manager of the Washington, Frederick and Gettysburg Railroad. The family could be found living at 221 S. Market Street. Allan would attend St. John’s Military College in Annapolis, graduating with the Class of 1908. He would join the Regular US Army on September 9th, 1908 and was given the rank of captain in 2nd Field Artillery unit. He would be assigned to the 4th Field Artillery and promoted to 2nd lieutenant by September. He was stationed at Fort Vancouver in Vancouver, Washington. By 1910, he was reassigned to Fort D. A. Russell in Laramie, Wyoming. Allan would marry Mary Avis Halbert of Baltimore on October 23, 1911. The couple welcomed a baby daughter in July, 1913, and she was named Avis Halbert McBride in honor of her mother. A few years later, McBride was promoted to major of field artillery with the National Army in World War I. Soon after, he was transferred to Headquarters of the 349th Field Artillery and gained the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. He spent time overseas in the Great War from mid-June, 1918 until July, 1919. While in France, he took part in fighting within the Marbache sector and received multiple battlefield promotions as he spent time with the Headquarters unit of the 2nd Field Artillery and 13th Field Artillery. He commanded a battalion. McBride would be promoted to Adjutant General on January 11st, 1919 with the 4th Field Artillery Brigade. Upon his arrival back in the States, he was assigned to Fort Sill, Lawton, Oklahoma where he served as an instructor of Field Artillery. A son, Andrew would be born here in 1921. The McBride family moved back east and can be found living on N. Calvert St. in Baltimore in 1924. A daughter, Susanne was born in 1925. The family relocated to Washington, DC when Allan was accepted into the US Army War College in 1926. He next attended General Staff School and also Chemical Warfare School, Field Officers’ Course. Maj. McBride and family were back at Fort Sill and Lawton, Oklahoma by 1930. In 1935, they were in Fort Leavenworth, Kansas and by 1940, Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas. His last assignment came in 1941. Allan C. McBride was assigned to Army headquarters in the Philippines as plans and training officer February 20th, 1941. As news of the Bataan Death March unfolded, relatives and friends in Frederick received scant information about Gen. McBride in the local papers. His sister, Mrs. Carrie Shafer, resided on West Patrick Street. The family of his deceased brother, Edgar H. McBride, a well-known attorney and banker, also was also very concerned and eager for details. I will let old newspaper articles tell the rest of his story.  Upon his arrival in Australia in March, 1942, Douglas MacArthur gave a speech in which he famously promised "I shall return" to the Philippines. After more than two years of fighting in the Pacific, he fulfilled that promise. For his defense of the Philippines, MacArthur was awarded the Medal of Honor. He officially accepted the Surrender of Japan on September 2nd, 1945 aboard the USS Missouri, which was anchored in Tokyo Bay, and he oversaw the occupation of Japan from 1945 to 1951. As the effective ruler of Japan, he oversaw sweeping economic, political and social changes. General McBride is one of 4,000 veterans whom we plan to honor on Veterans Day. We also look forward to adorning his gravesite with a wreath on Saturday, December 14th during our 2nd annual Wreaths Across America event. The WAA kickoff ceremony will begin at 11am only feet from Allan C. McBride's final resting place at our World War II Memorial, erected in 1947 and dedicated on May 30th, 1948. Gen. McBride's mortal remains are joined by those of 29 other servicemen of World War II who died in active duty. Their military issue stones are placed in a semi-circle surrounding two large pillars and an eternal flame monument which reads:

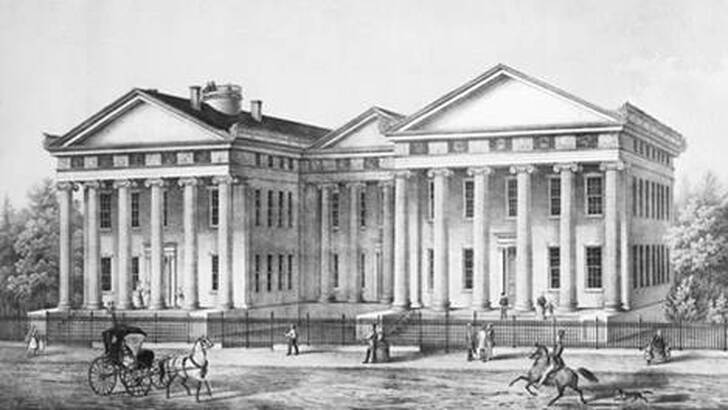

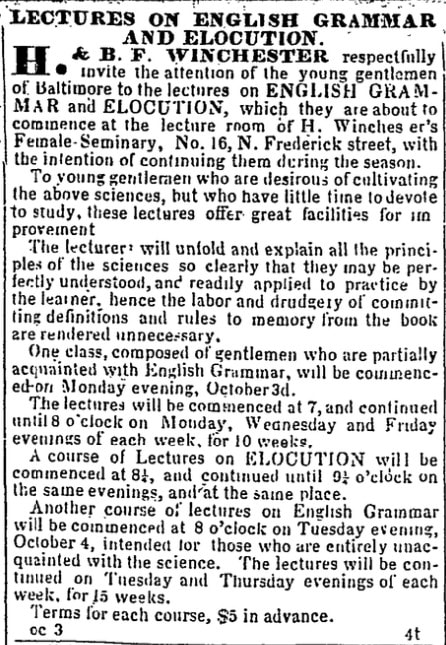

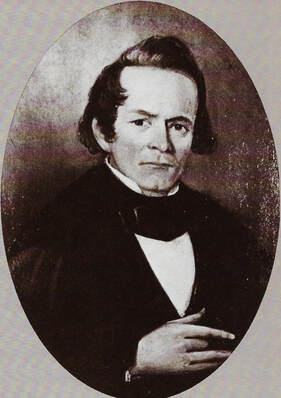

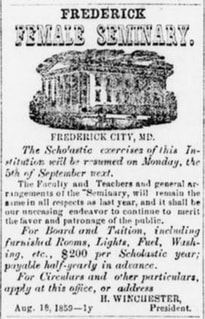

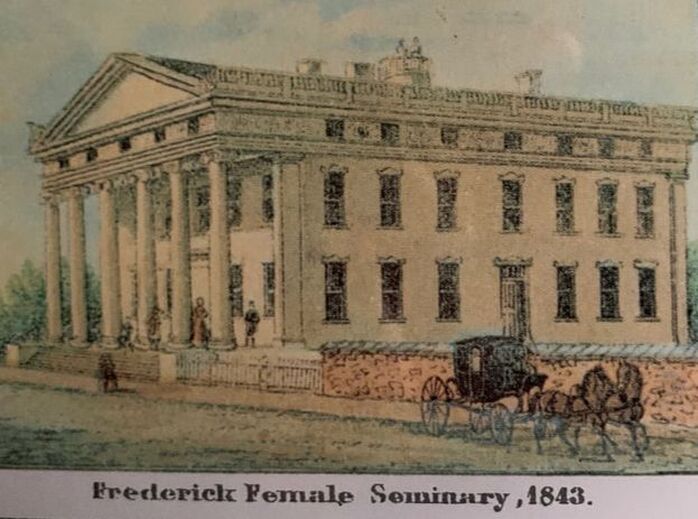

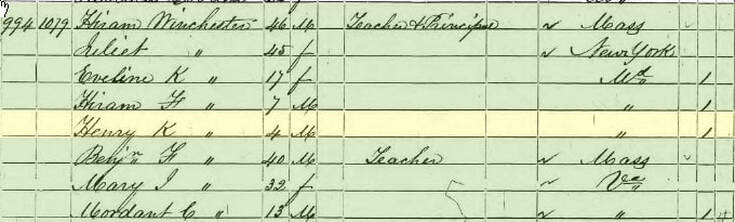

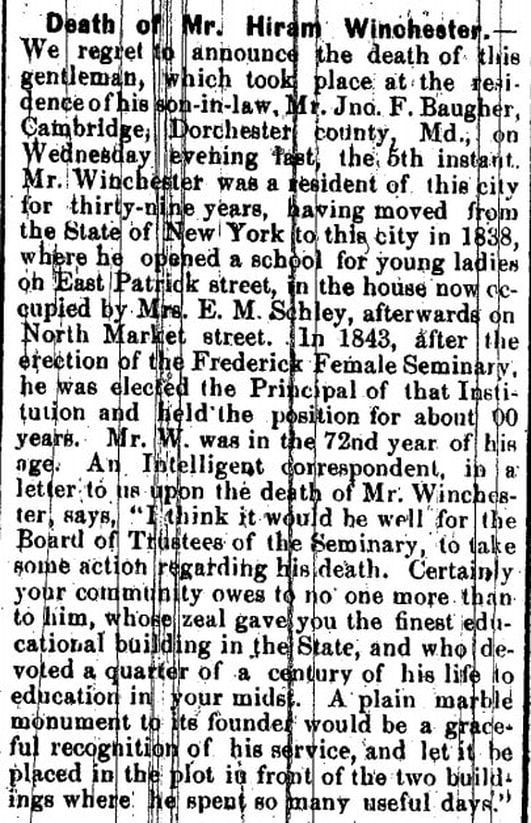

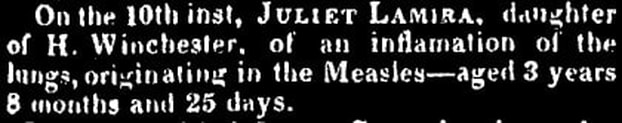

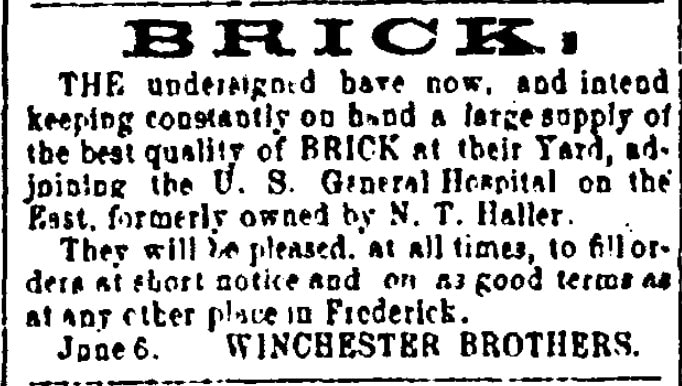

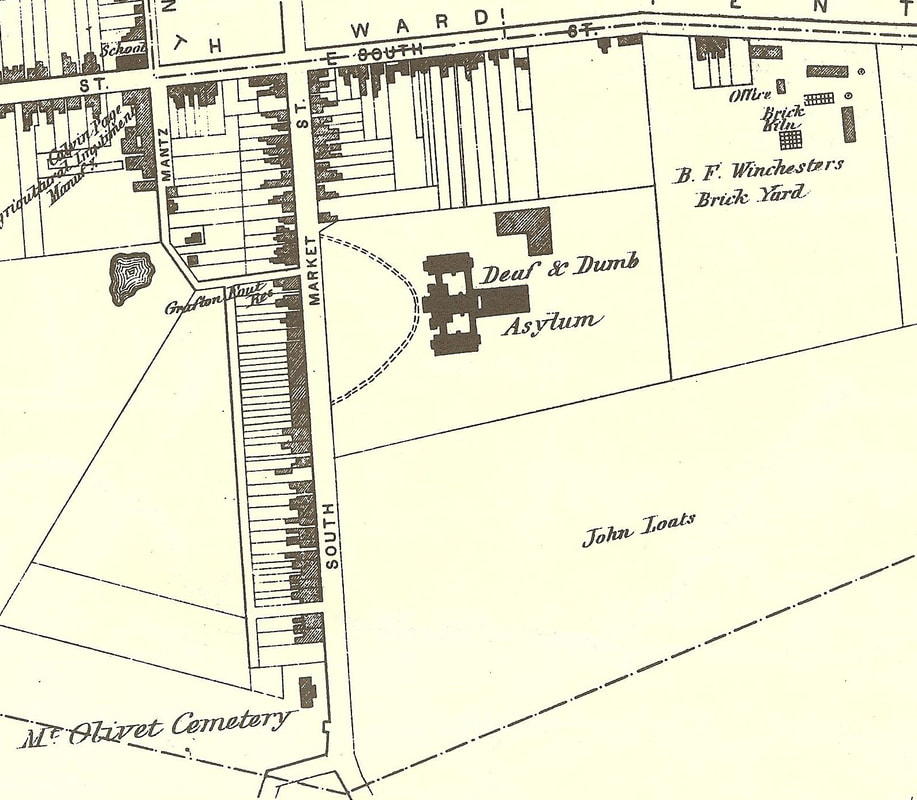

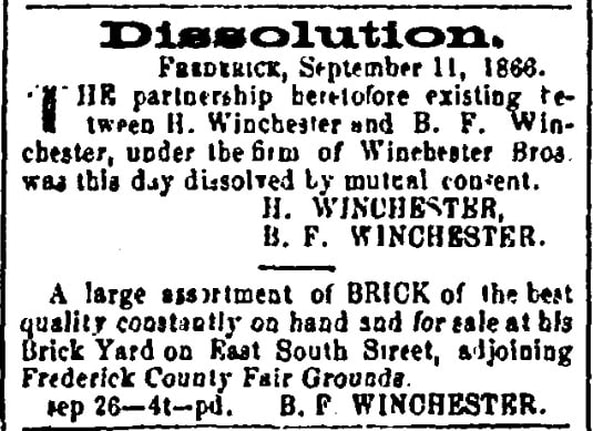

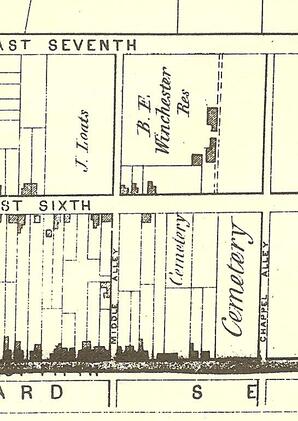

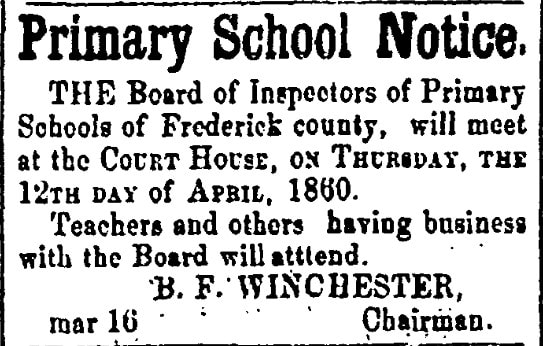

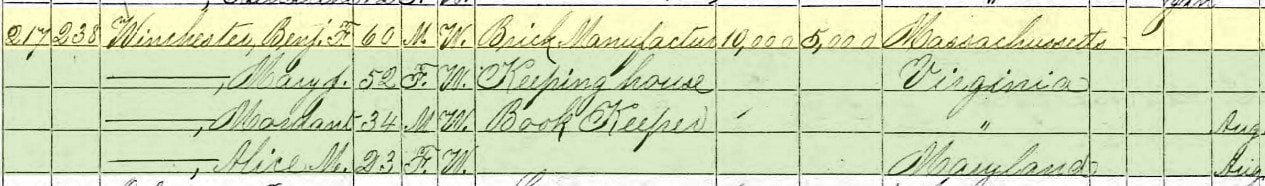

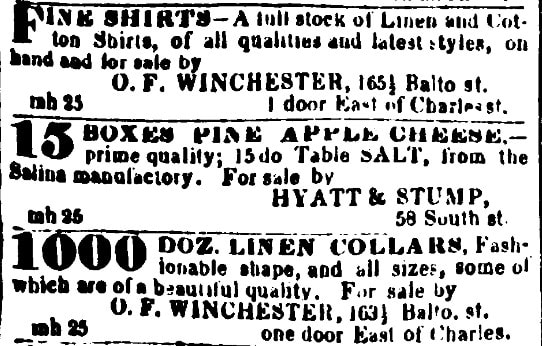

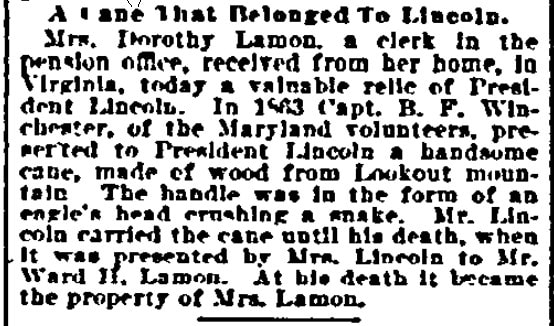

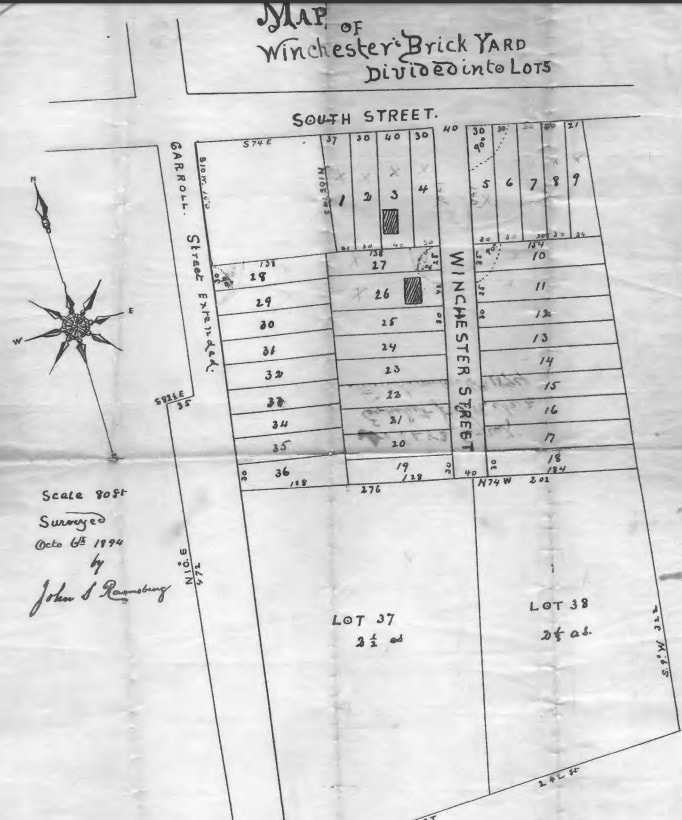

"Dedicated to the Men and Women of Frederick County, who by their unselfish devotion to duty, have advanced the American ideals of liberty and the universal brotherhood of man." It also reads, "The flame of love shall burn into our hearts the memory of our noble dead."  Like many others, the Winchester family lot in Mount Olivet is particularly pretty this time of year, shrouded in fall foliage. It sits in Area C/Lot 53 near the original southeast boundary of the cemetery just as it stood at the turn of the 19th century. To the immediate east, one once saw the spacious John Loats farm on the other side of the Newly Designed Road (as it was first called). Today, this thoroughfare has been renamed Stadium Drive and offers a viewshed of the main concourse area in front of the entrance to Harry Grove Stadium at Nymeo Park. Buried here in the Winchester family lot are Henry Kirkham Winchester, Benjamin Winchester, Mary Jane Winchester, Mary Winchester, and Mordaunt C. Winchester. The family has a lasting connection to Frederick as we named our seat of county government for them. Well, the actual namesake for the building located on E. Church St., Hiram Winchester, is buried in Cambridge, Maryland. But the name has stayed with us since Mr. Winchester lent his regal sounding moniker to the building he planned and built on E. Church Street between 1843-1844. More importantly, Hiram and brother Benjamin Franklin, made a profound impact on our community in the realm of education, and construction. These teachers were good for students, contrary to the Pink Floyd anthem, and it is fitting that they crafted their female pupils to be important building blocks for our community. The son of Benjamin Winchester III and Rebecca (Wing) Winchester, Hiram (b. 1803 in Hardwick, MA) was one of five children. He had come to Frederick in the late 1830’s after teaching school in Connecticut and serving as a lecturer at a seminary in Baltimore located at 16 N. Frederick Street, this according to the 1835 and 1837 Matchett's city directories of Baltimore. He is said to have come to Frederick in 1839. It was this year that he would open the Frederick Literary Society located on Frederick’s N. Market Street in the old Bartgis Hotel, a space he had rented for the purpose of the school. This would evolve into what would become known as the Frederick Female Seminary, and Winchester knew he needed a larger space to work within. This school was established by an Act of the Maryland Legislature. A lottery was raised providing an amount of $50,000 for the initial construction and endowment. The cornerstone was laid (for the current East Wing) in 1843. This was the year that Mr. Winchester was named principal. Charter and privileges were granted in 1845 and the first school catalog issued in 1846. A primary target demographic for school enrollment included wealthy children from southern states. A second wing would be built onto Winchester Hall in 1856. Seven years later in 1863, the school closed due to the American Civil War as student numbers were down as many southern families cut back due to wartime activity. Union soldiers had occupied the West Wing the previous year. Meanwhile, Hiram Winchester had been forced to retire due to poor health. He would move to Cambridge, Maryland and took up residence with his oldest daughter (Eveline Kirkham Baugher) and son-in-law there. Hiram would die on July 5th, 1876 and was buried in the Cambridge Cemetery, joining his wife, Juliet Kirkham Winchester (b. 1806) who had been laid to rest there in 1868.  Margaret Hood (1833-1913 ) Margaret Hood (1833-1913 ) In 1893, the Potomac Synod of the Reformed Church would buy the property and opened the Woman’s College of Frederick and came under the purview of Dr. Joseph Henry Apple. A former student of Mr. Winchester was invited to live at the school with the school president and his family. This was newly widowed Margaret E. (Scholl) Hood, an 1849 graduate of the Frederick Female Seminary. Hood would leave the Woman’s College $30,000 upon her death in 1913 and a new campus was made possible on the northwest suburb of town because of her generosity. The school was soon renamed after the benefactress. As for the old school building constructed by Mr. Winchester, the structure would be bought in 1931 by the Board of County Commissioners for $35,000. Since that time it has served as Frederick’s seat of county government. Which Winchester? You may ask: “If Hiram Winchester is buried in Cambridge, MD, then why are you writing a “Story in Stone” article on him?” Well, I am and I’m not. My premise though is the fact that I think Hiram, and wife Juliet, should have been laid to rest here in Area C/Lot 53, if not for their departure from Frederick and relocation to Dorchester County. I surmise this based on multiple facts, foremost the 12-plot lot was purchased by Benjamin Franklin Winchester, Hiram’s kid-brother who was born in 1810. Only four decedents are definitively marked on the central monument here, along with our interment lot card. However, our card shows that probing the lot nearly 70 years ago found the possibility of three others buried here. Later research clarified that one of these burials is the gravesite of Hiram and Juliet’s youngest child, Henry Kirkham Winchester, who died a child at age six (1845-1851). He was originally buried in Frederick’s Presbyterian Cemetery, but was removed to Mount Olivet in 1887. His name was never added to the monument. We also have reason to believe that two infant children of the Winchesters are also buried here, although they don’t appear by name in our records. Again, we see that there are two additional spaces that appear to be occupied here in the Winchester lot. The hypothesis is that this grave site could have two youngsters within, also moved from the Presbyterian Church. The children in question are Caroline (1838-1839) and Juliet (1838-1842). Lastly, the large monument placed upon the lot has two major faces on its south and west sides that have stayed blank after all these years. Benjamin's family names are on the east and north faces. I bet the other two were reserved for Hiram's decedents, but never placed on there, likely because Hiram and Juliet Winchester wound up being buried in Cambridge, Maryland. As for some backstory on the buyer/owner of this lot, we must examine the life of Benjamin Franklin Winchester. Earlier mentioned Hiram, appears to have pulled a few strings in getting his brother a teaching job at the Frederick Female Seminary in the school’s first decade in operation. B. F. would follow is brother’s educational footsteps to Frederick as he taught Mathematics to the students. He was also a native of Hardwick, MA, and taught with his brother previously in Baltimore. He would find a greater career for himself after leaving the Frederick Female Seminary when Hiram decided to call it quits. B.F. Winchester owned a brickyard, located on the southeast part of town on E. South Street today. It appears both Hiram and Benjamin started the venture together in the 1860s, perhaps in response to the school's closure during the Civil War. You would have found this venture near the intersection of E. South and the aptly named Winchester Street. Begun in the 1860’s, the Winchester Brick Works would be family-run up through the 1890s at which time it would take the new name of the Frederick Brick Works. The Winchester firm's bricks are still the prime building blocks used in a substantial number of buildings throughout the Frederick region. One such example was the original home of the Maryland School for the Deaf, located on the former grounds of the Frederick “Hessian” Barracks on South Market Street. Keep in mind that the Barracks grounds were also the first home of the Great Frederick Fair as well up through 1867. This locale was located just a few hundred yards west of the brick-works itself. We can get a glimpse of the scope of Mr. Winchester’s profitable venture through a passage recorded on July 3rd, 1875 within (Frederick diarist) Jacob Engelbrecht’s storied diary: The State of Maryland Asylum for the Deaf & Dumb—The north wing of this asylum is nearly finished. It was commenced in summer of 1874 (the north wing). I inquired from Mr. B. F. Winchester, who furnished the brick, how many brick there were in the whole building. He said, nearly or quite 2 and a half million. He also said the new jail (now nearly up) will take about 800,000. Mr. Winchester furnished brick for both buildings. The bricks were made in the brickyard in East South Street adjoining the ground on the east side of the Deaf and Dumb Asylum. The cornerstone of the D. & D. Asylum was laid “May 31, 1871.”

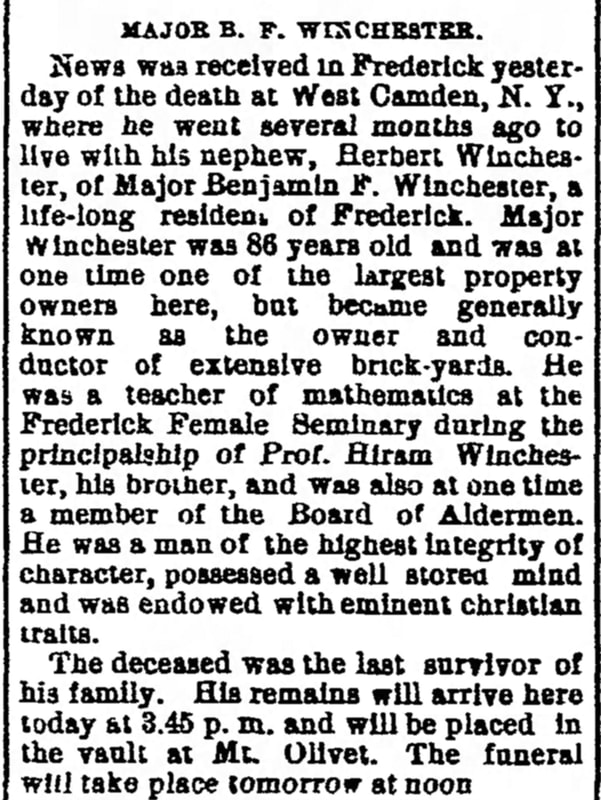

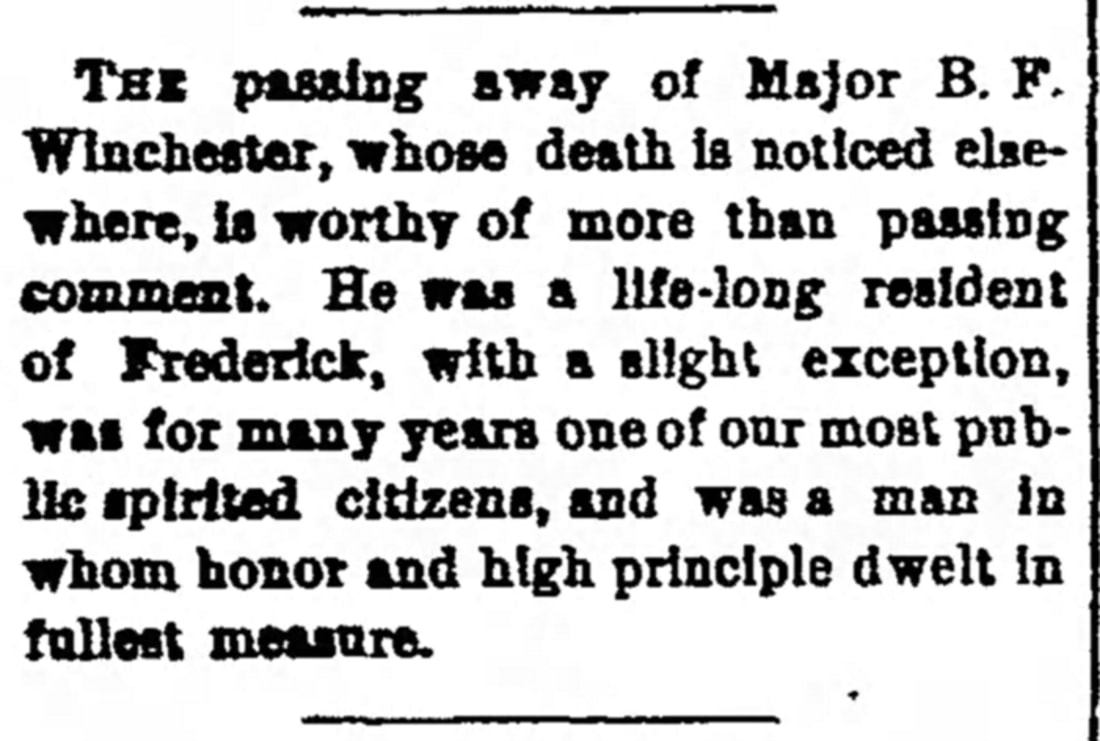

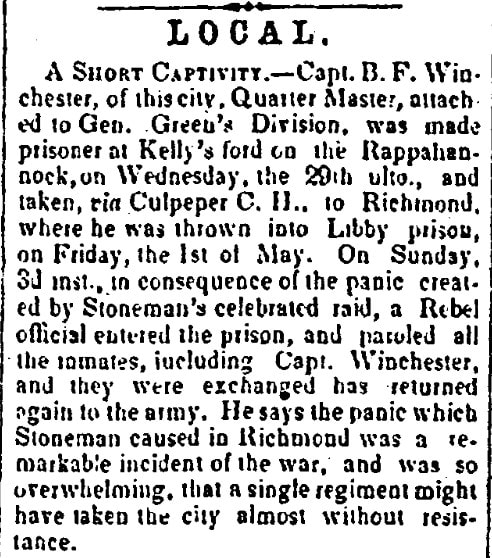

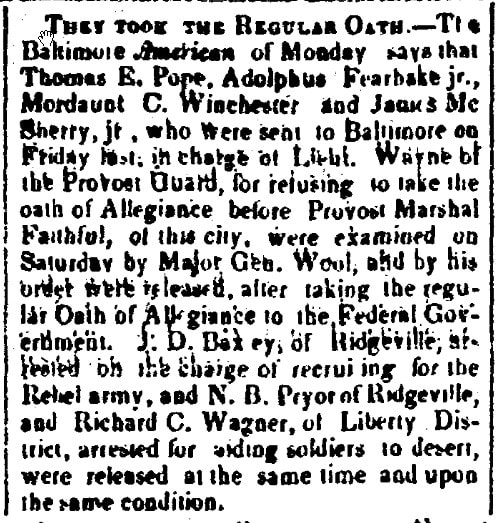

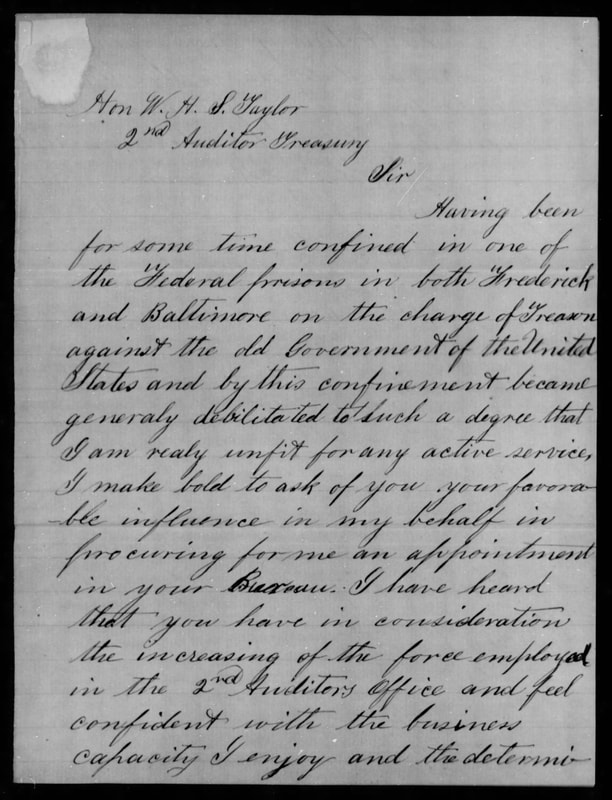

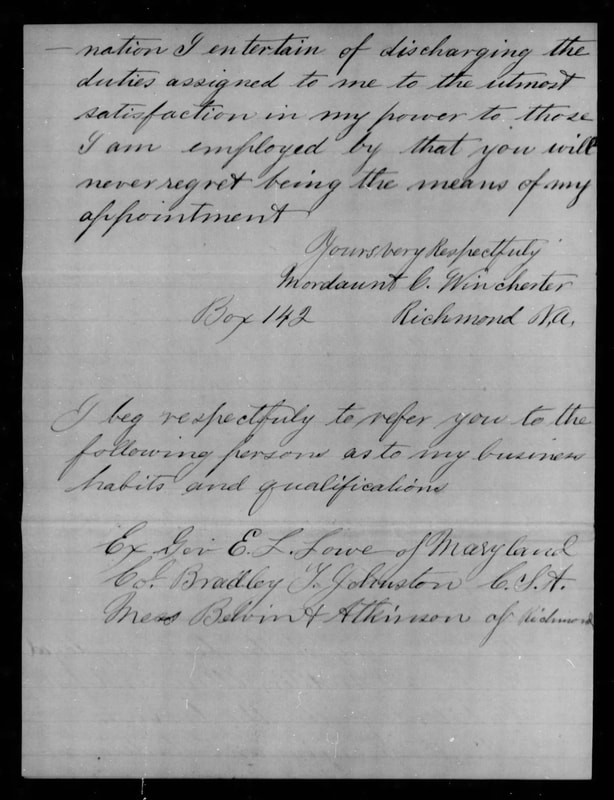

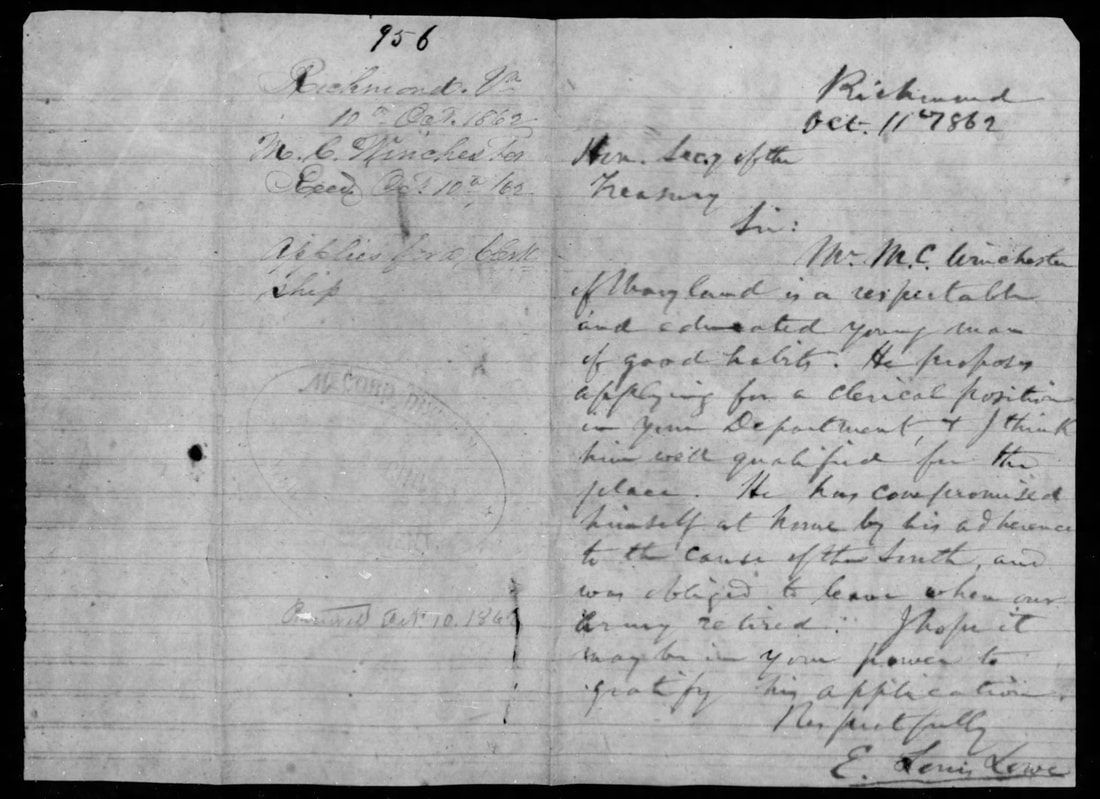

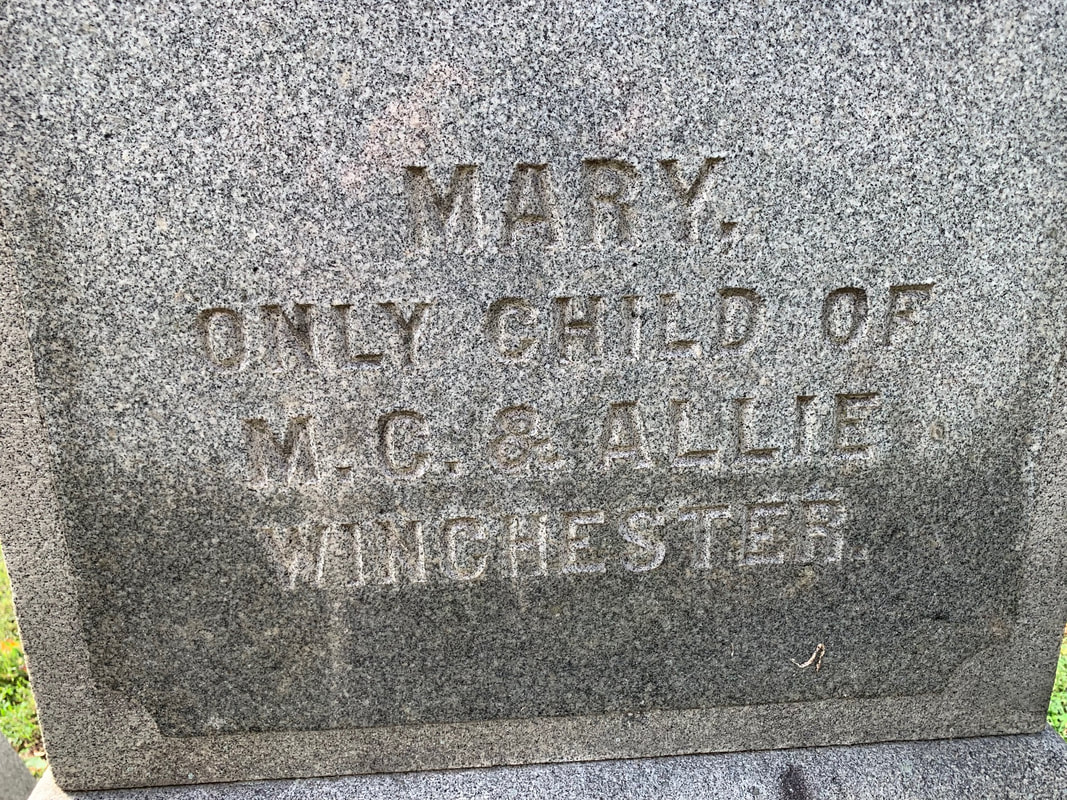

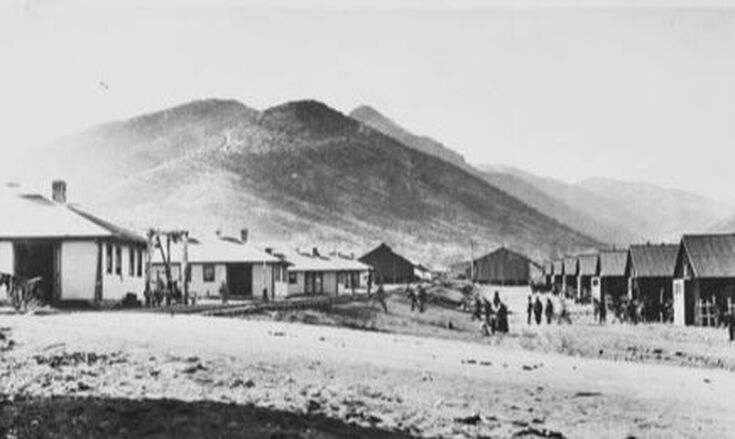

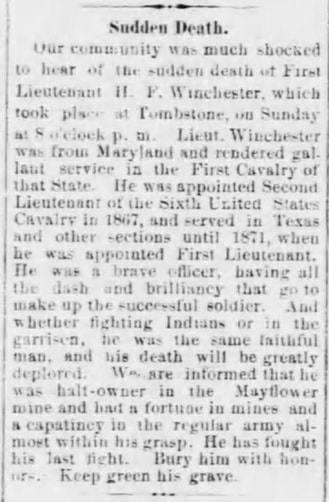

B. F. Winchester died in 1895 and buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery. Wife Mary Jane had passed five years earlier in 1890. Sadly the elderly couple had to endure the death of their only son (Mordaunt) in 1878 and sole granddaughter, Mary, who died in 1874. Benjamin’s obituary of May, 1895 labeled him as “a man of the highest integrity of character, possessing a well-storied mind and was endowed with eminent Christian traits.” He died at the age of 86 at the home of his nephew, whom he had been living with in West Camden, NY. Patriotic Zeal The Frederick Winchesters will be of special interest to those fans of the American Civil War. When President Lincoln called for recruits in 1861, B.F. Winchester volunteered and served under Benjamin Henry Schley and the Union Army. He is also listed as 1st Lt. Quartermaster, 1st Potomac Home Brigade Cavalry, and took part in the Battle of Monocacy in 1864. Benjamin ultimately attained the rank of Major. B.F. Winchester’s son, Mordaunt, however, would side with the Southern Cause. We have no way of knowing how or why things went down in the family home, but Benjamin was likely outnumbered because his wife was a southern belle, herself, hailing from Richmond. Mordaunt is thought to have been a Confederate spy. He was arrested on a number of occasions, these recorded by Jacob Engelbrecht in his diary with the first infraction occurring on August 1st, 1862. Mordaunt was arrested a day later after taking an oath to the Union. However, just three weeks later, he would be arrested again and this time sent to Baltimore.  Speaking of the Civil War and arrest, our old friend Hiram Winchester’s son of similar name had quite a life journey, only making it to his 38th birthday. More interesting is the fact that he died in the infamous frontier town of Tombstone, Arizona territory in 1881. Hiram Franklin Winchester (b. 1843) served in the Civil War under the Union flag. He was a 1st Lieutenant/Quartermaster for the 1st Potomac Home Brigade Cavalry from 1864-1865 under Col. Henry Cole. After the war, he would remain in military service, becoming a part of Maryland’s 6th US Cavalry and would be stationed at places such as Fort Richardson, TX, forts Riley, Hayes and Dodge (all in Kansas) and finally forts Huachuca, Lowell and Thomas (all in Arizona). Apparently, the trouble for young Hiram Franklin began when a new postmaster showed up at Fort Huachuca: A post office was constructed in November and Huachuca received its first postmaster, Fredrick L. Austin. By the beginning of 1880 Huachuca had telegraph communications, daily stagecoach runs from Benson, and the Southern Pacific Railroad now stopped at Tucson near Fort Lowell, just forty-seven miles distant. One of the unexpected difficulties that coincided with the arrival of a new postmaster was the sale of liquor on the camp. In addition to serving as the postmaster, Austin also ran a sutler’s store from which he sold whiskey. Whitside was sternly against intoxicants on the camp and attempted to curb, if not shut down, Austin’s business. Unaffected by the post commander’s protestations, Austin had the audacity to complain to Whitside that his troopers were slow in paying for spirits bought on credit. Whitside summoned his senior noncommissioned officer and told him to “take care of it . . . and let the la dies of the post know about it also.” The ploy worked, and Austin left the post all but penniless seven months after arriving. One of the troopers who imbibed of Austin’s whiskey was Captain Whitside’s second in command, First Lieutenant Hiram F. Winchester. In addition to obtaining liquor at the sutler’s store, Winchester could also be seen drunk in the saloons of Tombstone, located twenty miles east of Camp Huachuca. The lieutenant’s intemperance caught up to him in the summer of 1880 when he was court-martialed for being absent without leave displaying “loud and indecent behavior . . . in company with a prostitute.” Winchester was incarcerated at Fort Yuma, California, for nine months. Apparently after completing his sentence in May 1881 and prior to reporting to his unit, Winchester returned to Tombstone where he turned up dead on 29 May of a “disease unknown.” The following obituary reports the mysterious and untimely death of 1st Lt. Winchester as it appeared in the Arizona Weekly Citizen of June 5th, 1881.

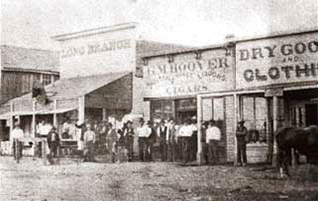

The younger Hiram Winchester died on May 29th, 1881. Interestingly, the village he had come to, Tombstone, had only been founded two years before in 1879. The boom town was only 30 miles from the U.S.–Mexico border and was an open market for stolen cattle from ranches in Sonora, Mexico. This feat was regularly accomplished by a loosely organized band of outlaws known as “the Cowboys.” Meanwhile, the legendary Earp brothers—Wyatt, Virgil and Morgan—as well as Doc Holliday, arrived in Tombstone in December 1879 and mid-1880. The Earps had ongoing conflicts with Cowboys Ike and Billy Clanton, Frank and Tom McLaury, and Billy Claiborne. The Cowboys repeatedly threatened the Earps over many months until the conflict escalated into a shootout on October 26th, 1881. The historic gunfight is often portrayed as occurring at the O.K. Corral. It’s fascinating to think that the son of the namesake of our Winchester Hall, a native of Frederick and young man who regularly walked the streets of downtown, may have had interactions with the Earps and Doc Holliday while he was there in Tombstone. If so, I sure hope they were positive encounters. We’ll likely never know. Following the death of Hiram Franklin Winchester, his corpse would be brought cross-country and eventually be re-buried in the family plot at Cambridge Cemetery on Maryland’s Eastern Shore in Dorchester County. He left a wife and daughter. (NOTE: For more on this provocative story, click this link: And speaking of guns and shootouts, Hiram Winchester, the school principal and namesake of Winchester Hall, was distantly related to Oliver Fisher Winchester, a one-time shirt-maker who became incredibly wealthy as the inventor and manufacturer of “the gun that won the west.” This innovation is also known as the Winchester repeating rifle. Both Winchester men (Hiram 1803-1876 and Oliver 1810-1880) were Massachusetts natives who migrated to Baltimore as young men in the 1830s. Most important here is the fact that these men were cousins who shared the same GGG Grandfather— a man named John Winchester, Jr. (1644-1719) of Hingham, Plymouth County, Massachusetts. John’s father, John Winchester, Sr. (1611-1694) was the family progenitor who immigrated to Massachusetts from England in 1635.

Now, how's that for finishing with a bang? I'm sure I've given you plenty to think about, next time you visit, or drive by, Frederick's Winchester Hall! |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed