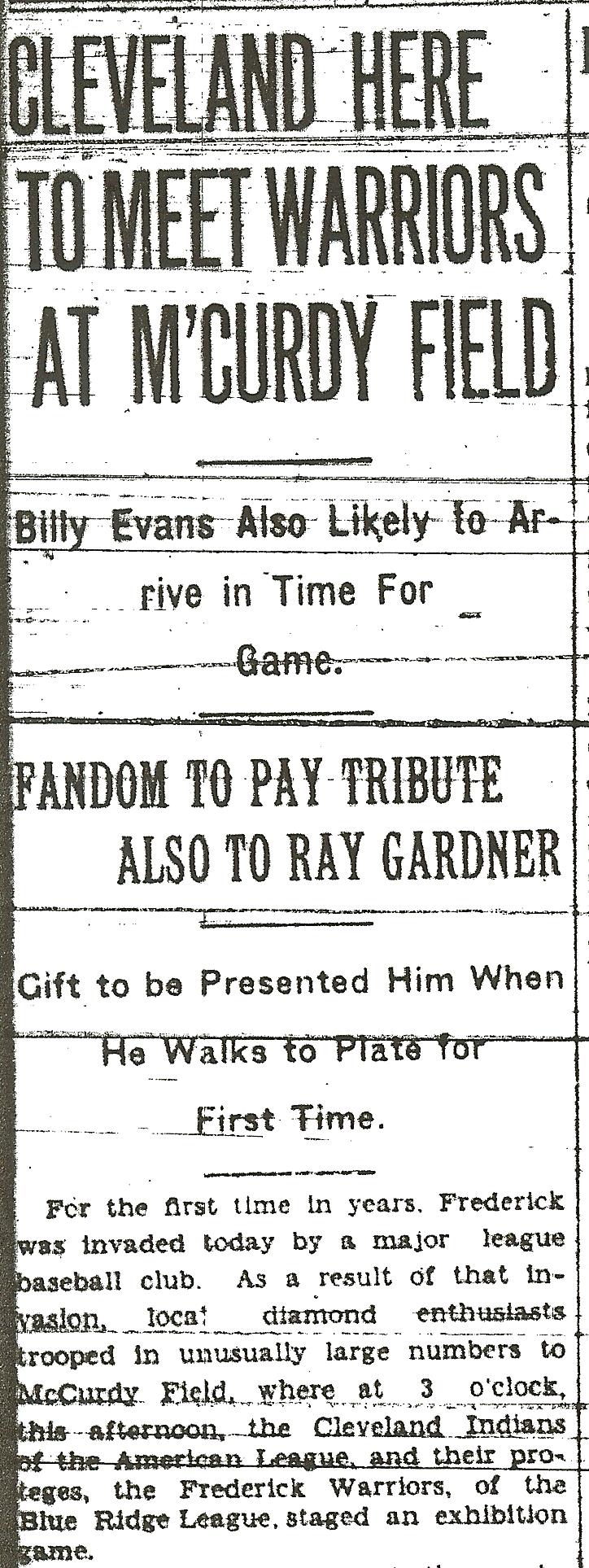

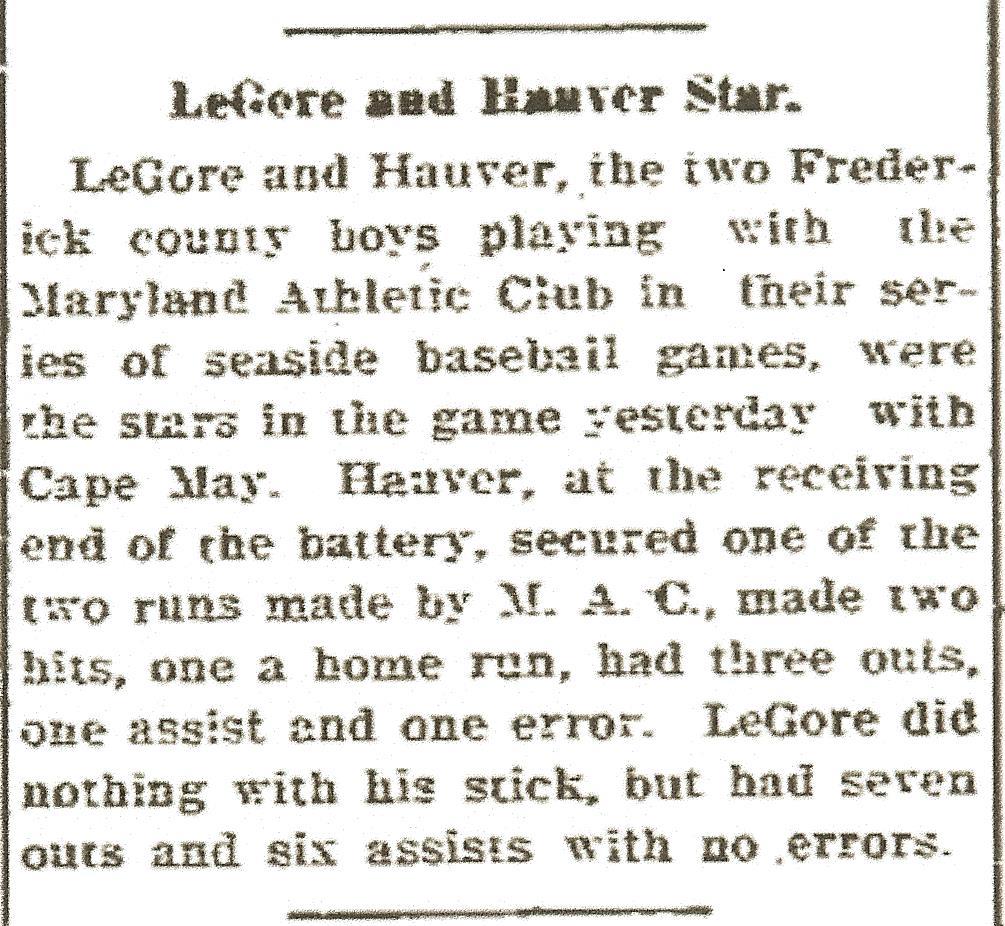

Clyde L. Hauver, Sr. Clyde L. Hauver, Sr. “White-lightning” did him in, without ingesting a drop. You could say he died from alcohol, but it’s not what you think.Blame it all on a remote mountain clearing known as Blue Blazes. Clyde Lester Hauver, Sr. was a pretty good local baseball pitcher. His gravesite is in clear view of Nymeo Park at Harry Grove Stadium. As a major promoter of the sport, I’d bet money that our Frederick Keys stadium namesake, James H. Grove, Sr., was well aware of the young phenom who once starred on diamonds around the county and state. Clyde Hauver’s name appeared in the Frederick Post newspaper on July 24th, 1929 when a local baseball aficionado was interviewed in respect to one of Hauver’s former fiercest rivals—Ray Gardner. A Frederick native, Raymond Vincent Gardner would soon be back in his hometown for a Major League exhibition game to be played at McCurdy Field. Just one decade earlier, both Hauver and Gardner squared off at this field in the Frederick City Twilight League, so named because games, in an era before stadium lights, would be played late in the day until sunset. This was a rare off-year for Frederick, not playing in the Blue Ridge League, which had added the Frederick Hustlers to their ranks in 1915.  Ray Gardner of the Cleveland Indians Ray Gardner of the Cleveland Indians Gardner played for the Hustlers and was recently elevated to the “Big Leagues,” playing shortstop for the Cleveland Indians. Earlier in 1929, the Cleveland Indians purchased the Hustlers and the new “farm” team changed its name to the Warriors to connect more with its parent team. Ray Gardner had been coveted by the organization a few years earlier as a top prospect, and the Indians were hoping to do the same with other local players. The gentleman interviewed in the Frederick Post article of July 24th (about Gardner) was not named, but I feel that he well could have been “Harry” Grove himself, the greatest early benefactor and promoter of professional baseball in Frederick. The purpose of the article was to reminisce about Gardner’s playing days in Frederick in an effort to generate additional interest in the upcoming exhibition game slated for Monday, July 29th between the Cleveland Indians and minor-league Warriors. The interviewee waxed of Gardner: “He was only a kid but he could hit, run bases, and sure scoop up everything around short. He was all over the infield and could go from second to third either as a baserunner or as a fielder so fast that it would make you dizzy to watch him. And the only reason he didn’t lead the league in hitting was because for some reason or another, he couldn’t hit Clyde Hauver. That was the real reason why his team (the Catholics) couldn’t lick Company L. They had no trouble with other teams. They simply cleaned everything up. Bet they could have licked the Blue Ridge League if there had been a Blue Ridge then but there wasn’t any Blue Ridge back in the summer of 1919. They didn’t play that year. It was in that league that Ray Gardner got his start. And we’ll all be on hand next Monday afternoon to see Ray play in a big league uniform.”

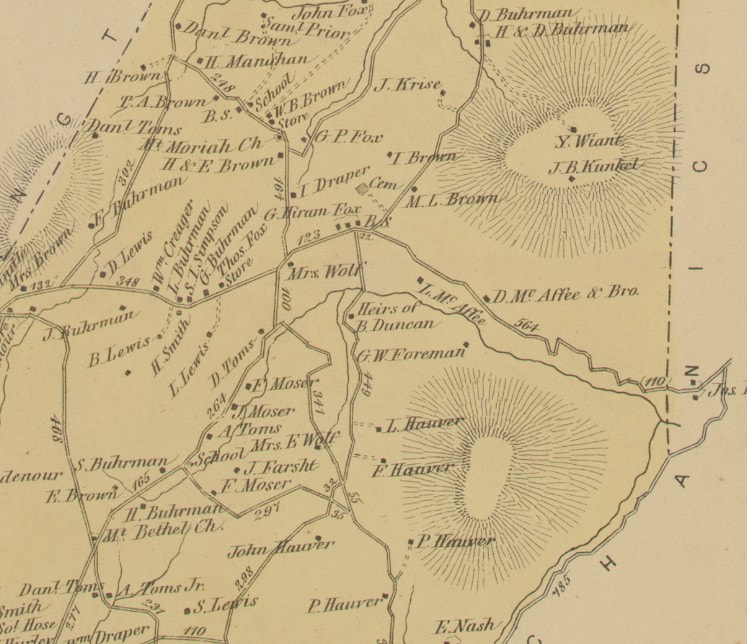

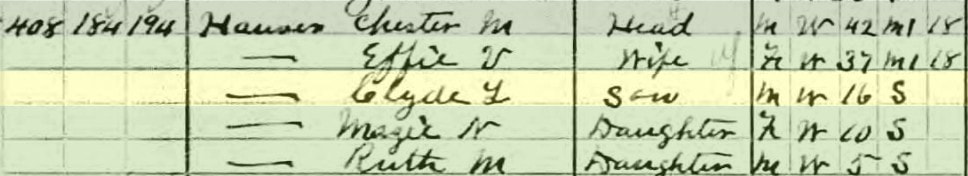

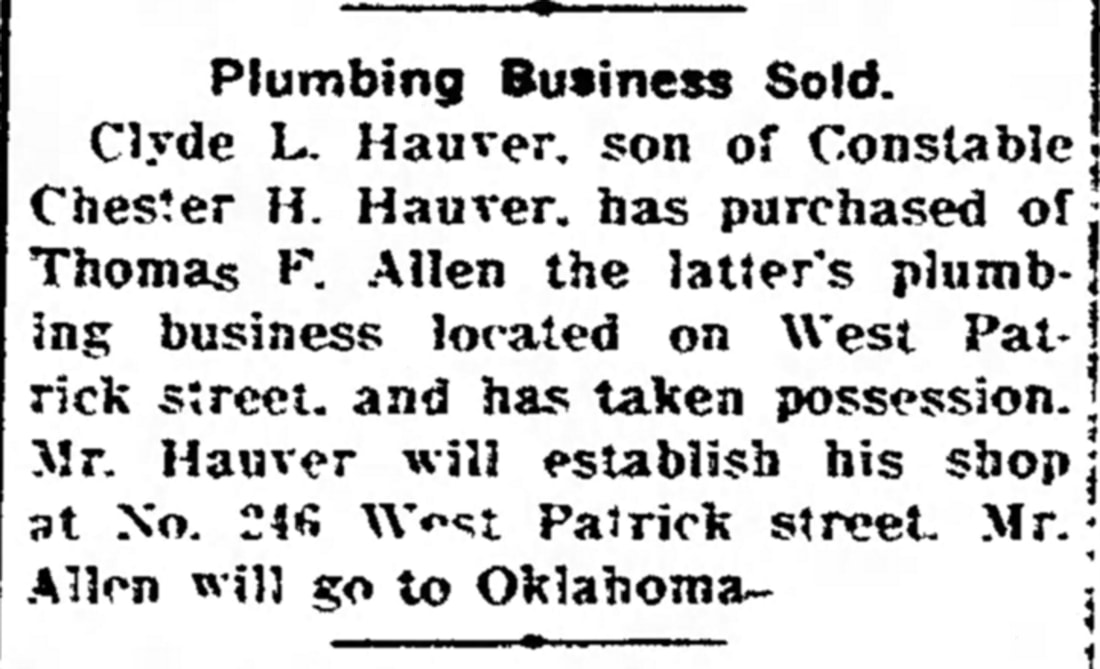

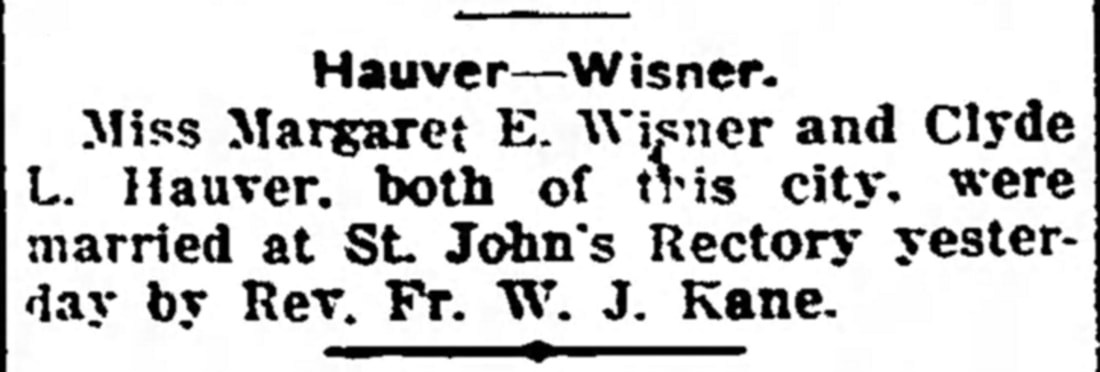

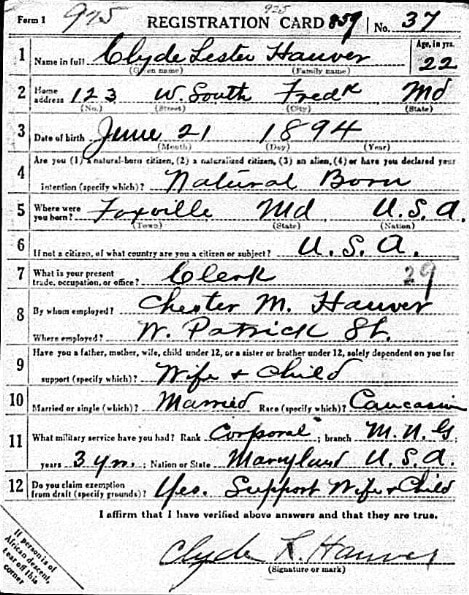

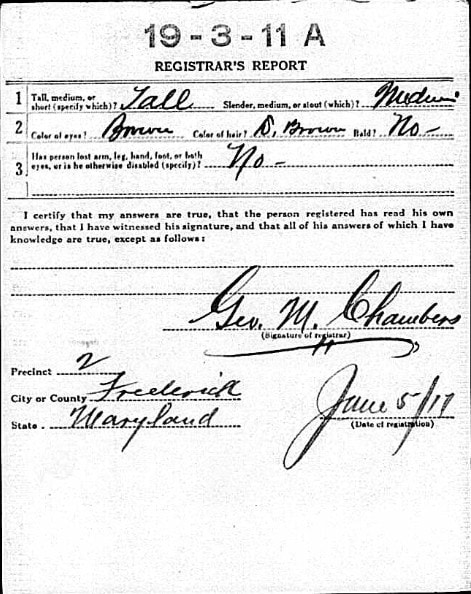

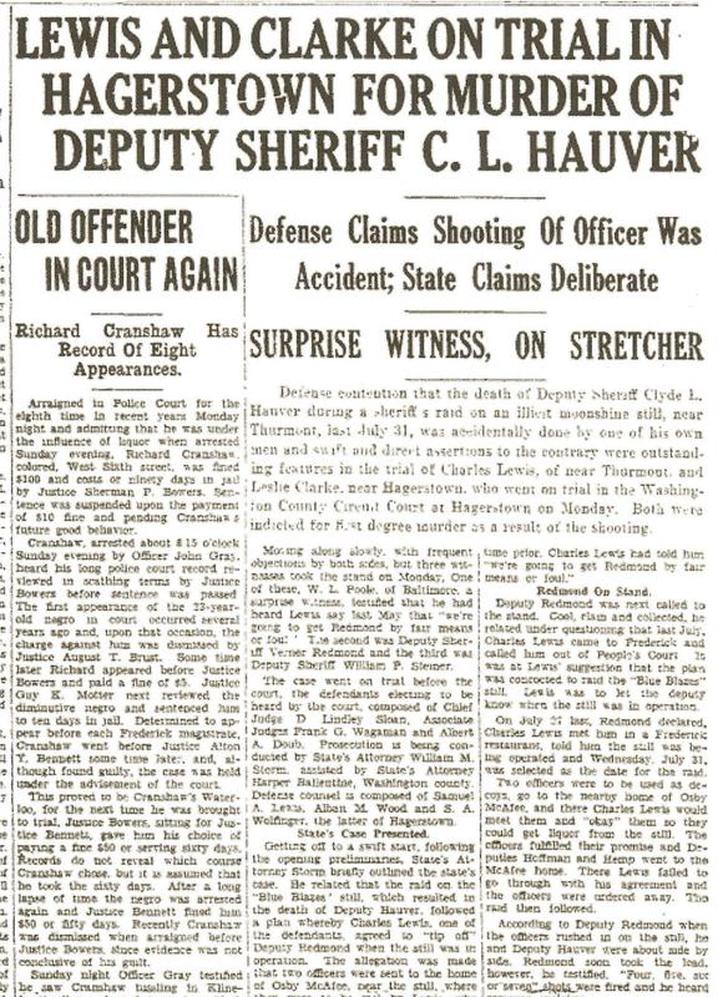

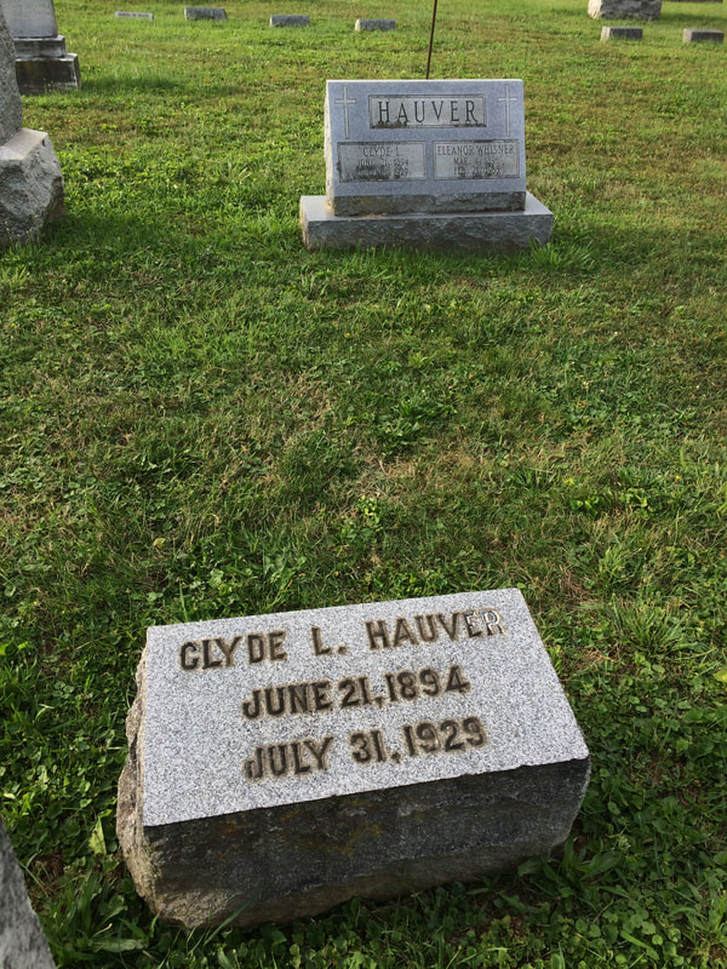

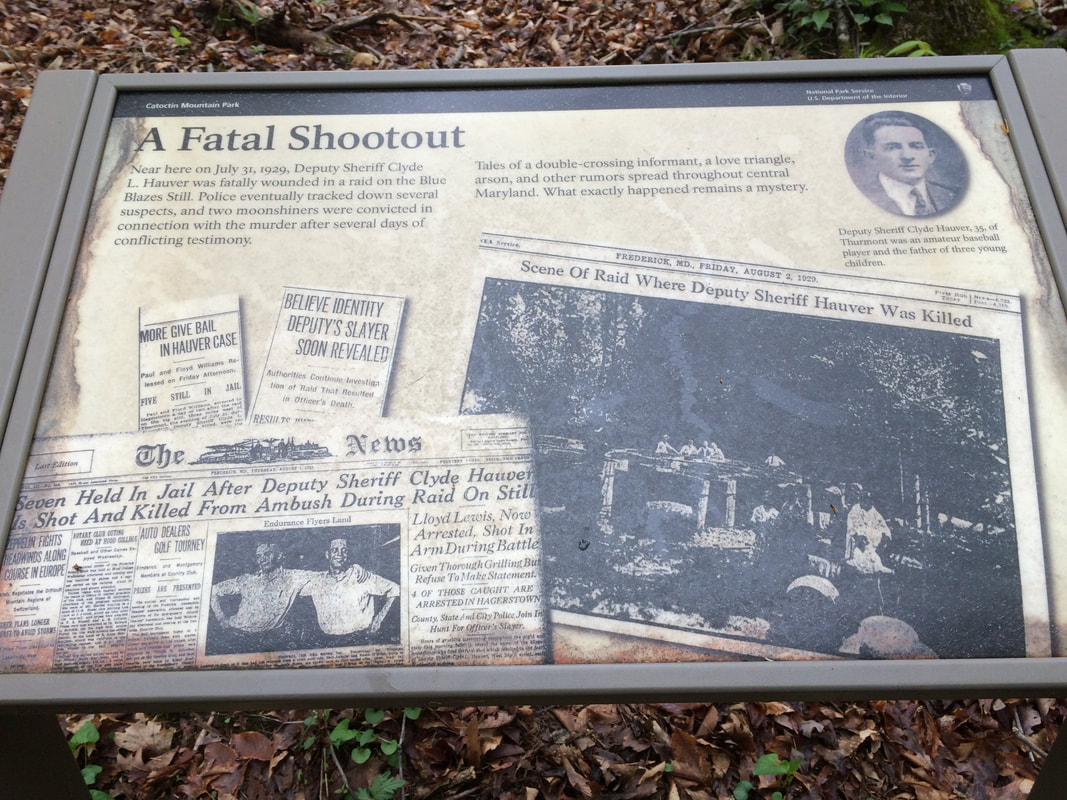

Meanwhile, in the woods of Catoctin Mountain outside Thurmont, Clyde L. Hauver would have his life snuffed out by a .30 caliber bullet. He was shot in the back of the head and died less than two hours later. In doing so, he became the first deputy sheriff in Frederick County history to be killed “in the line of duty.” Ironically this whole affair occurred not far from Clyde L. Hauver’s birthplace near Foxville. This locale was located in the aptly named Hauvers District, an area of northwest Frederick County originally settled by Clyde’s GGG Grandfather George Hauver (1730-1800), and wife Anna Susannah Hermann (1732-1800). George was a German immigrant who came by way of York, Pennsylvania in the mid 1700’s. His wife’s family were also among the first to settle in the greater Foxville area, roughly four miles west of today’s Thurmont , originally named Mechanicstown. Mechanicstown, itself, didn’t even come about until about 1803, a few years after the deaths of George and Anna Susannah Hauver in 1800. The area where they, and son Peter (Clyde’s GG Grandfather), settled was originally known as Hermann’s Gap, and a nearby cascading waterfall in the vicinity took the name of Hermanns’ Falls. Later, Hermann was Anglicized to Harman, and the picturesque falls took the name of later landowners named McAfee who married into the Hermann/Harman family in the mid 1800’s. To complicate things more, somehow this water form would be renamed Cunningham Falls in the early 20th century, but no one has been able to determine (with certainty) why, and, more so, who the namesake was. Anyway, it can be said that Clyde L. Hauver was murdered on his own home turf—although his assailants thought more of him as the unwelcome intruder on that eerie day of Wednesday, July 31st, 1929.  Insert from 1873 Titus Atlas of Hauvers District #10 (1873). Note the Hauver properties in the vicinity of today's Cunningham Falls State Park, just SW of Foxville. Also note the location of D. McAfee & Bro. as labeled on this map. This was the approximate site of the future Blue Blazes Still, today just a short distance west of the Catoctin Mountain Park Visitor Center adjacent the entrance of Park Central Road Clyde Lester Hauver Clyde Lester Hauver was born June 21, 1894 in Foxville. His father Chester was a farmer, as was his father before him, Melancthon Hauver. Both relatives married women who grew up “on the mountain,” like themselves. Young Clyde would spend his childhood here as well. He attended the local schools and graduated from Thurmont High. He was a natural athlete, and took a special liking to baseball, but also played basketball. His home life included a loving family that included mother Effie (Eccard) and two siblings, younger sisters Mazie and Ruth. Along the way, Clyde’s father switched professions to become a Frederick County Sheriff’s Deputy. He later would serve as a county constable. This likely prompted a move to Frederick City. The family could be found residing at 408 South Street in the 1910 US census. Clyde, 16 years of age, is listed as an employee of a brush factory—the Ox Fibre Brush Company located on E. Church Street extended. Clyde next tried his hand at plumbing. In June, 1914, he purchased a plumbing business from Thomas F. Allen who had relocated to Oklahoma. His shop was located at 246 W. Patrick St. His father made a business acquisition a short distance away just five months later. Chester Hauver purchased an interest in a local Frederick grocery store on W. Patrick Street in 1914. Known as Phleeger & Hauver, this entity partnered Mr. Hauver with John Edwin Phleeger, former Judge of the Orphans Court of Frederick County. Young Clyde promptly accepted a clerkship with the firm. Being the boss’ son also allowed Clyde the scheduling flexibility to continue playing baseball beyond his school days. He regularly participated in amateur leagues. Within two years, Clyde married Miss Margaret Eleanor Whisner of Frederick. Rev. W. J. Kane officiated the May 15th, 1916 ceremony at St. John’s Rectory. A child Eleanor was born in February, 1917, and a year and a half later, the family welcomed a second daughter named Margaret after her mother. Although Hauver did not serve overseas in World War I, he did serve in the Maryland State Guard, Company L. He attained the rank of 1st Lieutenant during 1918-1919. As if he wasn’t already busy enough, he continued to play amateur baseball on various county teams. In 1920, the family lived at 232 W. Patrick Street in a rowhouse next to Clyde’s parents. Clyde’s occupation listed in the January census of that year stated that he was an antique furniture collector. Heartbreak hit the family just before Christmas as Clyde’s father was killed in an automobile crash near Hansonville while en-route to a country butchering. He was 52. Clyde now gave extra assistance to his mother. He would experience the birth of another son a year later (October, 1921)—Clyde Lester Hauver, Jr.  Clyde L. Hauver, Sr. Clyde L. Hauver, Sr. By 1927, Clyde Sr. eventually followed in his father’s footsteps and joined the Frederick County Sheriff’s Department. As a Sheriff’s Deputy, he was charged with upholding law and order throughout the county. Not only did this pertain to the streets of Downtown Frederick, but his old stomping grounds of Foxville within the wooded environs of Catoctin Mountain. Local newspapers of the late 1920’s chronicle the challenges law enforcement officials had to endure during a time known as “the Roaring Twenties.” Alcohol prohibition set the stage for organized crime in the form on “moonshining.” Clyde L. Hauver was now 35 years old in July, 1929. The father of three left his wife with a kiss before going off to work on that morning of July 31st. He apparently told his nervous wife Margaret not to worry, saying "Your boy'll come back." The events of that day would forever link Clyde Hauver with the names “Blue Blazes” and “white lightning.” These could’ve easily been nicknames befitting a cunning baseball pitcher. Unfortunately, Hauver would not earn these on a baseball diamond, instead they would be the cause for Hauver’s premature death. Blue Blazes was the largest, and best equipped, moonshine still in Frederick County history. It was an illegal operation, and it was located within a mile of Deputy Hauver’s birthplace.  An informant named Charles Lewis had given a tip to Clyde Hauver’s co-worker, Deputy Verner Redmond, one week before. Lewis provided knowledge of the whiskey still’s location and proposed operating times. The department quickly mobilized and set up plans for a raid to take place on July 31st. Several newspaper accounts of the event and subsequent trials exists in archival repositories, as do stories written later on the subject. When conducting research and interviews for a history video documentary on Thurmont, I even had the opportunity to talk to several folks who remembered the great Blue Blazes Raid of 1929. Some had family members that had partook in and purchased the chief export of the famed still. Over the years, many talented writers have produced articles on the Raid and death of Clyde L. Hauver. Among my favorites are the following which will relay the story far better than I. Award-winning writer James Rada, Jr. wrote the following account for the Emmitsburg.net website and followed with a more recent article in the Catoctin Banner in 2016. Here is a portion of the former: ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------  Early 20th century view of MD route 77 through Harmans Gap Early 20th century view of MD route 77 through Harmans Gap “Even with the approach of evening, July 31, 1929, was still a warm day on Catoctin Mountain. Two cars drove up the mountain on Route 77, a dirt road leading from Thurmont to Hagerstown. Six men rode in the cars. Only five would be alive two hours later. The cars pulled off the side of the road. Frederick County Deputy John Hemp and Lester Hoffman climbed out of one of them. Although not a deputy, Hoffman was the only one in the group who knew his way through the forest to what an informant had described a week earlier as a "large liquor plant." This was the Prohibition era in the U.S. and although liquor was illegal, people still craved it. And so others made moonshine in stills hidden in mountains close to farms that supplied the grain needed for the fermentation process. The five deputies and Hoffman were headed to destroy just such a still, but first they needed to prove the Catoctin Mountain operation was making moonshine. The two men carried a jug as they headed up the winding mountain path. A man sitting atop a large rock alongside the path stood up and blocked their way. According to The Frederick Post, the exchange went like this: "Where are yuh goin'?" he asked. "We want to buy some liquor," Hemp said. "Yuh better git out of here if yuh don't want to git shot," the mountaineer retorted, according to the officers. Hemp and Hoffman turned around and walked back to the rest of their group. Then, joined by deputies Verner Redmond, William Wertenbaker, William Steiner and Clyde Hauver, they all started toward the still. "The officers, in attempting to creep up on the small vale in which the still was situated, ascended a winding mountain path, which led abruptly to the scene of the tragedy," reported the newspaper. Hauver and Redmond led the group. As they neared the still, shots rang out. Hauver fell and the deputies scattered for cover as the moonshiners fired on them, hidden by the underbrush. The deputies returned fire and the moonshiners retreated. "The sheriff's forces did not immediately realize that Hauver had been mortally wounded and, thinking he had merely tripped over a root, were intent only on the capture of the moonshiners. Counting up their forces after the fusillade of firing, Hauver was missing and, returning to the scene, he was found with his head in a pool of blood and his life was fast ebbing away," the newspaper reported. George Wireman wrote in a 1993 article, "From one of the statements gathered, it was learned that the bullet that struck Clyde Hauver was indeed intended for Deputy Redmond." Catoctin Mountain Park Ranger Debra Mills said, "Legend has it, he (Hauver) may have been involved in a love triangle and was shot in the back." Dr. Morris Birely from Thurmont treated Hauver while waiting for an ambulance. The ambulance took Hauver to the hospital in Frederick. "Although everything possible was done for Hauver he never had a chance. When he reached the hospital he had no pulse and was nearly bloodless, so great had been the loss of blood during his time he laid in the mountain trail and during the time necessary to bring him to Frederick," reported the newspaper. Once Hauver was on his way to Frederick, the remaining deputies used picks and axes to destroy the vats and boiler. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ The Frederick Post reported that Blue Blazes Still was "one of the largest and best equipped in Frederick County." It was said to have had a boiler from a steam locomotive, twenty 500-gallon-capacity wooden vats filled with corn mash, two condensing coils and a cooling box. Supposedly the still produced alcohol so fast that if a man took away a five-gallon bucket of alcohol and dumped it into a vat, by the time he returned to the still, another bucket would be filled and waiting to be removed. The authorities began an intense manhunt for the moonshiners. Word of the tragedy quickly spread throughout the county, eventually reaching Deputy Hauver’s family living at 407 W. South Street. Distilling the Case Another great account of the aftermath of the ill-fated raid comes from a historic resource study of Catoctin Mountain Park written by Dr. Edmund F. Wehrle in March, 2000. (https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/cato/hrs.htm) Here is a pertinent except from Chapter 4: ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Within a few hours police rounded up those responsible for the ambush. Paul Williams of Hagerstown surrendered along one of the roads leading from the still. He was shirtless and had several days growth of bread. Another moonshiner, Lloyd Lewis, stumbled into a doctor's office in Smithsburg, seeking treatment for a gunshot wound to the hand. The doctor quickly notified authorities. Police found yet another suspect, Lester Clark, drunk and hiding in the woods. In addition to Williams and Clark, police arrested Osby McAfee, William "Monk" Miller, Norris Clark, Charles Lewis, and Floyd Williams, the brother of Paul. McAfee owned a home on the Thurmont-Foxville Road, where the gang apparently stayed and took meals while working the still. Several of the moonshiners were locals. Charles Lewis was the son of prominent fruit grower Hooker Lewis from Thurmont. But the Williams brothers were from Hagerstown and hailed originally from North Carolina. Lester “Leslie” Clark was a Virginian. Authorities then had the difficult job of unraveling the events leading up to the botched raid. Police initially insisted that they had been double-crossed. Charles Lewis, they claimed, lured them into an ambush. But the day following the ambush, the sheriff's office released Lewis from custody. Frederick County Sheriff William C. Roderick, who strangely had been in Pittsburgh during the raid, returned and insisted that his officers had not been double-crossed. Likewise, not all local authorities seemed concerned with illegal moonshining in the mountains. Thurmont Constable Charles W. Smith, who had participated in several still raids, insisted that the "moonshiners appear to want to be let alone. They won't disturb anyone unless they are interfered with. To the man they are opposed to the prohibition law." Seeking to contain the confusion and suspicion surrounding the case, the Frederick Sheriff's Department arranged to have Special Detective Joseph F. Daugherty, from the Baltimore Police department, act as a special investigator in the case. Eventually State's Attorney William Strom sorted through the evidence and rearrested Charles Lewis. He then charged Lewis, McAfee, and Clark with the murder. The other moonshiners faced charges of manufacturing liquor for sale. A Grand Jury that convened on September 9, 1929 subsequently indicted Lewis and Clark for murder. An overflow crowd gathered for the trail, held in December in Hagerstown. A surprise witness from Baltimore, W.L. Poole testified that Lewis had threatened "to get [Deputy] Redmond by fair means or foul." Osby McAfee testified that Lewis wanted to use the McAfee house for a meeting at which to set up the police. McAfee insisted that he had refused. A few days after his testimony, McAffee's home burned to the ground. Authorities suspected arson. As the newspaper explained "firing property is a mode of revenge that has been practiced in some mountain sections." Attorneys for Lewis and Clark insisted that, while both men had fired shots, Hauver had been shot from the rear. Therefore, the killing was an accident. Facing the Christmas holiday, the presiding judge held night sessions to speed up the trail. After several days of confusing and conflicting testimony, the case went to the jury, who convicted both men. Three Maryland circuit judges then sentenced Clark to 15 years and Lewis to life. Both Lewis and Clark denied having fired the shots that killed Deputy Hauver. Given the confusion at the scene and the unresolved issue of who double-crossed whom, many in the local area long have wondered whether justice was served in the Blue Blazes case. Naturally, hearsay and rumors--all unsubstantiated--developed around the story. In 1972, the Youth Conservation Corps, a federal project to employ young people, sent forty youths into the community surrounding Catoctin Mountain Park to gather local folklore. When it came to the Blue Blazes story, some locals claimed that out-of-town "tar heels" had operated the still and that the tip-off to police came from local moonshiners upset about competition. The story has some validity since the Williams brothers were from North Carolina. Others insisted that the raid was the product of a revenge plot relating to a love triangle. According to the romance-gone-wrong story, Deputy Hauver was the innocent victim of a bullet meant for someone else. The fact that Charles Lewis was a locally-known figure, considered to be "a nice guy," and a member of a well-regarded family added to a sense that justice had not quite been served. Ultimately in 1950, Governor Theodore McKeldin commuted Lewis's life sentence. And the now-elderly inmate, suffering from tuberculosis was released from prison. Clark had been paroled in 1946. --------------------------------------------------------------- The exact circumstances surrounding the Blue Blazes raid and the murder of Clyde Hauver most likely will remain a mystery and a testament to the confusing times and effects of a law with little popular support.  And what happened to Clyde L. Hauver Sr.’s baseball rival, Ray Gardner? He played for the Cleveland Indians in 82 games during that 1929 season. He only managed 33 games during the 1930 Cleveland season. His major league career was over, but unlike Hauver, there was still life after baseball. He came back to Frederick and resided in Yellow Springs. He wasn’t through with baseball as he coached the Hustlers for a number of years. From 1952 until the time of his death in 1968, Gardner was employed at Fort Detrick. He lived until 1968 and is buried within St. Johns’ Catholic Cemetery in Downtown Frederick.  National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial In 1994, Clyde L. Hauver’s name was added to the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial in Washington, D.C. It was read during a candlelight vigil, attended by family members, Frederick County deputies and other County officials. This is located at 901 East Street NW (http://www.nleomf.org/memorial/) Today, the Blue Blazes Still is gone, but Catoctin Mountain Park has a 50-gallon pot still (captured in a Tennessee raid) on the same location along Harman’s Creek, renamed Blue Blazes Run. The National Park Service uses this to give context to the rich heritage of moonshining on Catoctin Mountain. Here the visitor will discover interpretive panels that tell the story of the still operation and death of Deputy Sheriff Clyde Hauver. And, by the way, if you're looking to find an alcoholic libation up in the area of Blue Blazes today, you'll have to look elsewhere as the Hauver's (voting) District remains one of five dry areas in Frederick County.

8 Comments

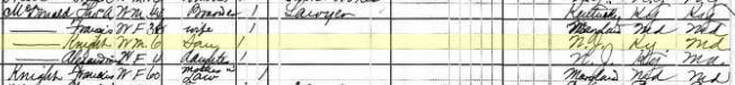

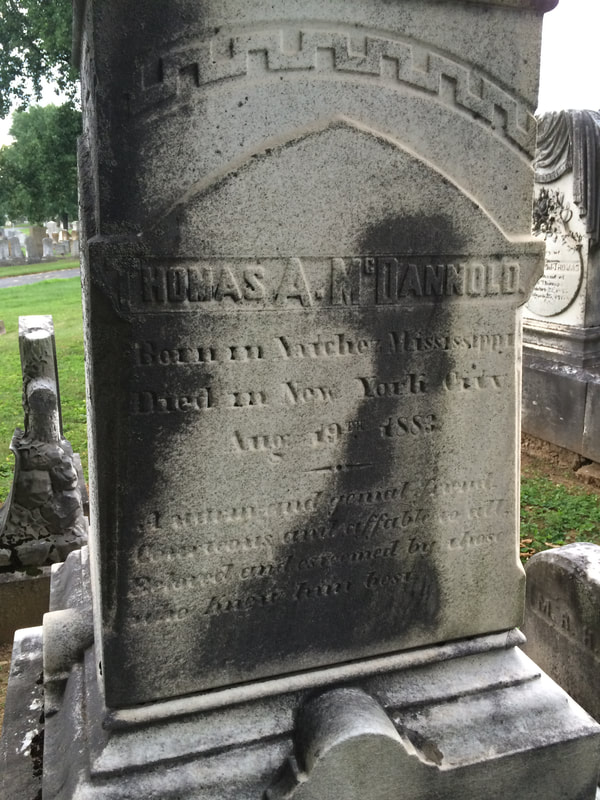

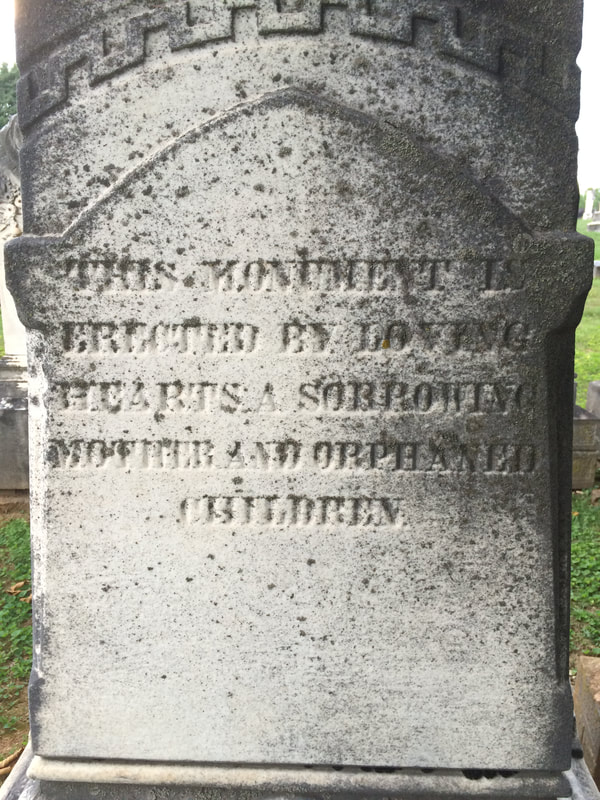

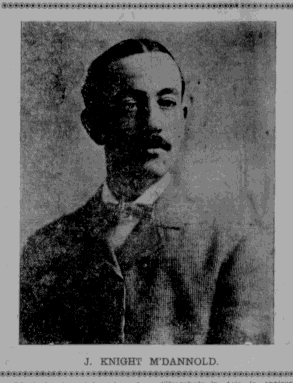

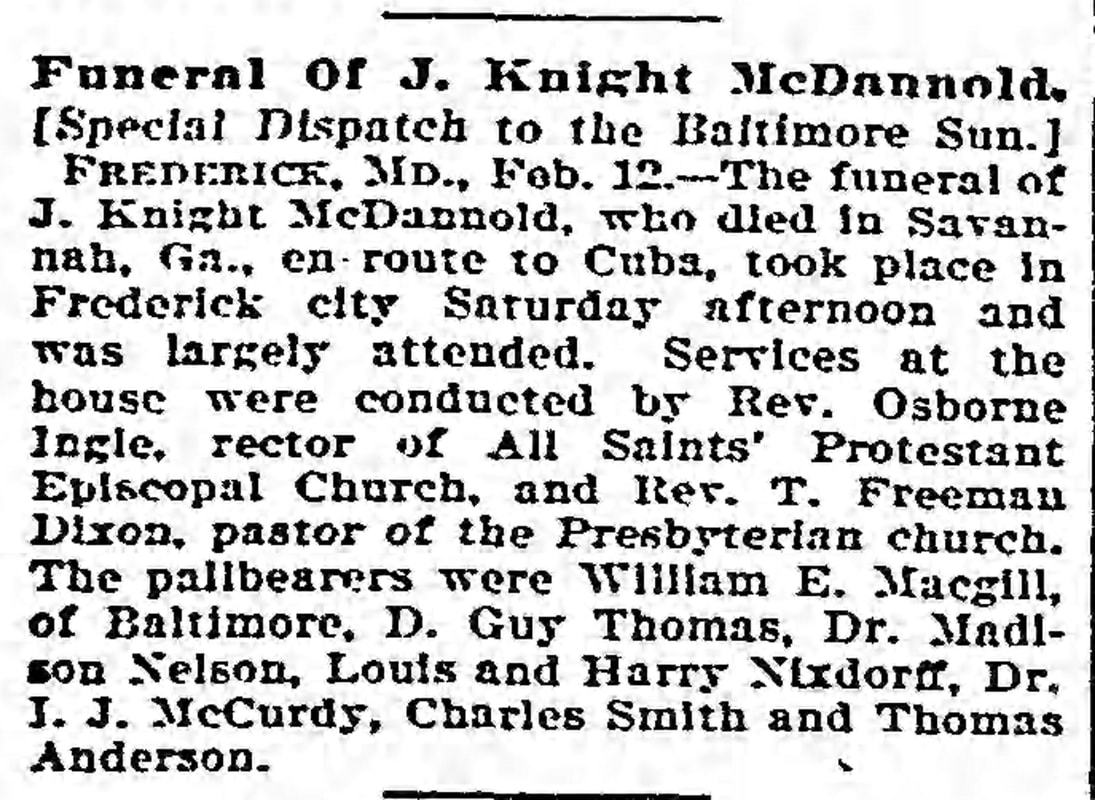

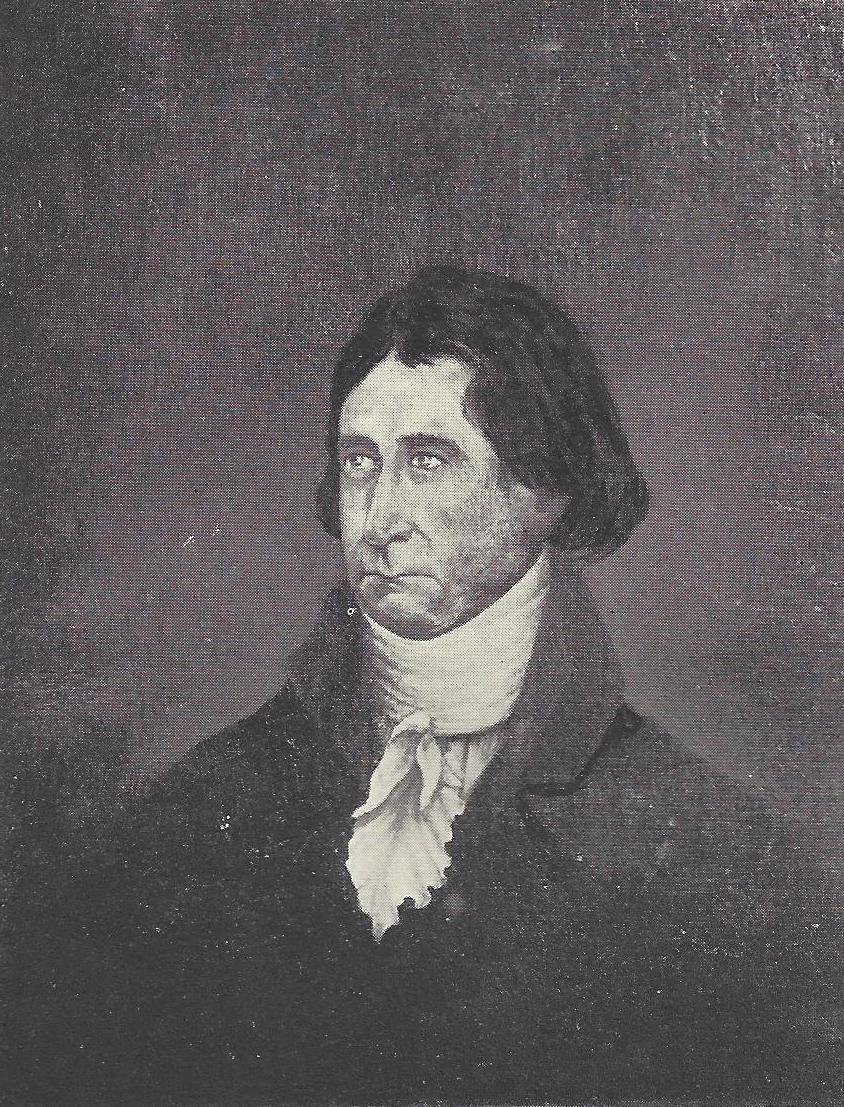

One of the most beautiful “stones” in Mount Olivet Cemetery was pointed out to me a few years back by my friend Theresa Mathias Michel. Over the years, Mrs. Michel has taught me a great deal about local history since our first meeting back in 1994. At that time, I was compiling a video documentary entitled Frederick Town for my employer GS Communications. More so, “Treta” Michel has been responsible for giving me several lessons on her own family members, and other notable figures in the rich annals of our town and county. Many of these folks reside in our fair cemetery, including Mrs. Michel’s brother, a former United States senator, the Hon. Charles “Mac” Mathias—a masterful local historian himself. A year-and-a-half ago, I found myself walking through Mount Olivet on a crisp autumn day, taking pictures of gravestones and the scenic grounds. My cell phone rang, and on the other line was Mrs. Michel’s personal assistant, Jennifer, asking if I would be available for an upcoming lunch date the next week. I replied in the affirmative and told her to pass on (to Mrs. Michel) that I was currently within yards of the burial spots of Mrs. Michel’s aforementioned brother, late husband Glenn, and parents. She abruptly directed me to stay where I was, and instructed her assistant to drive her out to the cemetery because she wanted to show me something special. Just fifteen minutes later, Jennifer pulled up to me in the cemetery, and Mrs. Michel told me to get in the car. I was driven to the southern tip of Area F, with a commanding view of the stadium entrance to Nymeo Field at Harry Grove Stadium. I helped my friend out of the back seat, and she proceeded to lead me up to a large, marble monument located not far from the car. It stood over eight feet tall and took the shape of an ornate Celtic cross. And when I say ornate, I mean master craftsmanship, designed with the inclusion of exquisite bas relief designs and portals. I asked, “So who is this John Knight McDannold?” (the name of the deceased individual lying under this monument). Mrs. Michel replied, “I have no idea, I just brought you here to show you this magnificent gravestone.” She then told me that her mother relayed to her the fact that this marble memorial was created by Tiffany’s of New York. I replied: “Thee Tiffany’s of jewelry and glass fame?” ”Yes, indeed!," she retorted.  Louis Comfort Tiffany Louis Comfort Tiffany I can’t do justice in describing the beauty and grandeur of this amazing art piece residing within Mount Olivet. However, a picture is worth a 1000 words, so I’ve included a few for this story. The Celtic cross is a form of Christian cross featuring a nimbus or ring that emerged in Ireland and Britain during the Early Middle Ages. A type of ringed cross, it became widespread through its use in the stone high crosses erected across the islands, especially in regions evangelized by Irish missionaries, from the 9th through the 12th centuries. In recent centuries, the Celtic cross became a popular design to incorporate into cemetery memorials. Through my research, I have failed to find any stories related to the creation of this particular monument, or a stamp or label saying Tiffany’s on the work itself (perhaps it’s on the bottom). I did find that other historic cemeteries in New York, Illinois and Kentucky have stones attributed to artist/designer Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848-1933). The example in Illinois provided me with important context for our “Tiffany” here in Mount Olivet. This was a commissioned work for Edmund Cummings, an officer who served in the Union Army during the American Civil War under Gen. Ulysses Grant and Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman. After the war, Cummings moved to Chicago and founded successful real estate company. Afterwards, he constructed an electric streetcar line called the Cicero & Proviso Street Railway Company. It should come as no surprise that the Cummings family had the necessary funds to approach the Tiffany Studios in New York. The testament to this prominent Chicago businessman resulted in a bas-relief angel carved into a soaring Celtic cross. It can be found in the Forest Home Cemetery at Forest Park, Illinois. Started as a stationery and fancy goods store in New York City in 1837, Tiffany’s became known for creating high-end silverware, glassware, and, of course, jewelry. Flash forward to the turn of the century (1900), still 60 years before Tiffany’s would surprisingly become known as a popular breakfast spot (at least for Audrey Hepburn in 1961). The firm, under the direction of Louis Comfort Tiffany, could be found designing and creating funerary monuments. I presume that our elaborate cross monument in question here in Mount Olivet was created in, or around, the year 1900 at Tiffany’s original studio located on Manhattan’s Fourth Avenue, between 24th and 25th streets. Unfortunately, I have not been able to find an exact delivery date to Frederick or project cost figure. I’m guessing like many “out of area” grave stones, and corpses, this was shipped via the railroad, and via cart or wagon to the cemetery from the freight station on South Carroll Street. Two other things are for sure: the monument was pricey, and likely did not arrive in one of those trademark Tiffany Blue Boxes. Mystery Person So back to the question I asked of Mrs. Michel back in October 2015, “Whose gravestone is this?” The answer—John Knight McDannold. At the time of his death, McDannold was arguably one of Frederick’s wealthiest residents. But why is he unknown? While we have plenty of McDonald’s Restaurants in the area, we lack a McDannold street, building or park. Who was this guy? I found John Knight McDannold to have an amazing pedigree. He seems to have lived a gilded life during the Gilded Age—one certainly deserving of a Tiffany headstone. Born in Orange, New Jersey on January 23rd, 1874, John Knight McDannold was the son of Capt. Thomas Alexander McDannold and Frances “Fanny” Beall (Knight) McDannold . Nearly a decade before John’s birth, Capt. McDannold was an unwelcome guest here in Frederick, the former hometown of his in-laws (John Knight and Frances Zeruiah S. Beall). It seems that the good captain (Thomas McDannold) was an officer in the Confederacy. More so, he was a member of Gen. Jubal Early’s staff. Of course, Gen. Early and staff are best remembered for inflicting a ransom of $200,000 on town back in July 1864. These Rebels threatened to burn the town to the ground at the time of the Battle of Monocacy. Luckily, the banking institutions came through with the necessary funds, and Frederick was spared…unlike Chambersburg, Pennsylvania a month later after failing to “ante up.” Ironically, it was Mrs. Michel’s brother, the aforementioned Sen. “Mac” Mathias, who in 1986 introduced legislation to Congress for the Federal government to repay Frederick for the money the municipality had to repay the banks for saving said hides. It was unsuccessful, but a noble attempt. After the war, Capt. McDannold, a native of Natchez, Mississippi took up residence in New York City and continued his pre-war occupation as a lawyer. In the 1880 census, six-year-old John was living with his family in the boarding house of Henrietta Knauff, located at 126 17th Avenue near the intersection with Irving Place. This is in the Gramercy Park neighborhood of east Manhattan. It is very likely that the McDannold family was no stranger to the many offerings of the Tiffany Company, located roughly 14 blocks away. John K. McDannold had a twin sister named Frances Celia, and another named Alexandra, born in 1876. Not much could be found on the McDannolds outside their fondness for traveling, which was said to have been done extensively. Perhaps all the jet-setting took its toll because the majority of the family was gone by the next census. Sister Frances Celia had passed in 1878 (age four). John’s mother, Frances, died in September of 1882. His father would follow his wife to the grave less than a year later in 1883.  Currier & Ives lithograph of a period cotton plantation in Natchez along the Mississippi River Currier & Ives lithograph of a period cotton plantation in Natchez along the Mississippi River The orphaned children (John and Alexandra) went to live with their maternal grandmother, Frances Zeruiah S. (Beall) Knight in Frederick, Maryland. Grandmother Knight was born in Frederick County in 1813, the daughter of William Murdoch Beall, a county sheriff hailing from the Urbana area. Mrs. Beall’s grandfather, Elisha Beall (1745-1831) was a veteran of the Revolutionary War—serving as a lieutenant in the Maryland battalion of the Flying Camp under Capt. Reazin Beall at the Battle of Long Island. His home, named Boxwood Lodge, still stands north of Urbana along MD355. Like her grandchildren, Mrs. Knight was supplied with a hefty inheritance left by her late husband John Knight, a successful merchant. Mr. Knight was originally from Frederick, but moved to Indiana with his family when he was ten. His father (Elijah) died that same year (around 1816), and his mother (Sarah Dix) followed suit three years later. He instantly became responsible for six little siblings. Knight soon hiked to Cincinnati on his own, and apprenticed in the printing trade. At 19, he went to Natchez, Mississippi and made a fortune as a cotton plantation owner and merchant. The young man came back to Frederick in 1833 and took Fanny Beall as his bride. Two sons were born to the couple in 1834 and 1835 respectively, but both died in the years following their birth. The Knights, likely devastated with grief, returned to Mississippi where their daughter Frances (Knight) McDannold (John’s mother) was born.  Enoch Pratt Enoch Pratt John Knight retired in the early 1850’s and took his wife and daughter to live in Europe. He shopped around and left his money and assets in the hands of a keen investor, a transplanted native from New England named Enoch Pratt (1808-1896). Pratt had moved to Baltimore and took an interest in civic affairs, later establishing a noted hospital and free library system. Mr. Knight had another notable philanthropist handling his monetary affairs in London—George Peabody (1795-1869). Letters found by a descendant in the 1950’s show that Enoch Pratt, an ardent Unionist, advised Knight to stay abroad during the turbulent years of the Civil War, thinking that his southern leanings could cause confiscation of his monetary holdings.  Biarritz, France Biarritz, France John Knight would not return to Maryland, and the US for that matter, during his own lifetime, dying in October 1864, just a few months after the Battle of Monocacy delayed Gen. Early (and his future son-in-law), allowing Gen. Grant to refortify Washington, DC against a Rebel attack. At the time of his death, the Knights were living in Biarritz, France, a resort town on the southwest coast of the country. Fanny Knight had the means in 1866 to have Mr. Knight’s body shipped across the Atlantic to be re-interred in Frederick’s new, “garden style cemetery,” originally opened in 1854. The two Knight children who died in the mid 1830’s had already been re-interred here in 1856, after being removed from the All Saints Episcopal graveyard. A large obelisk-style monument would be erected over his gravesite.

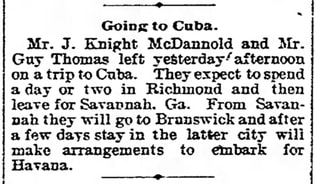

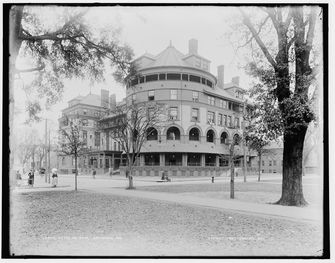

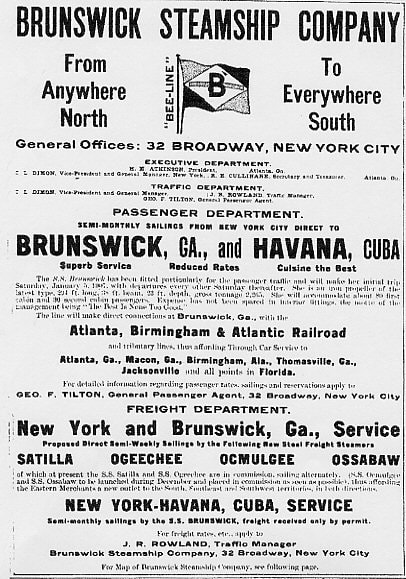

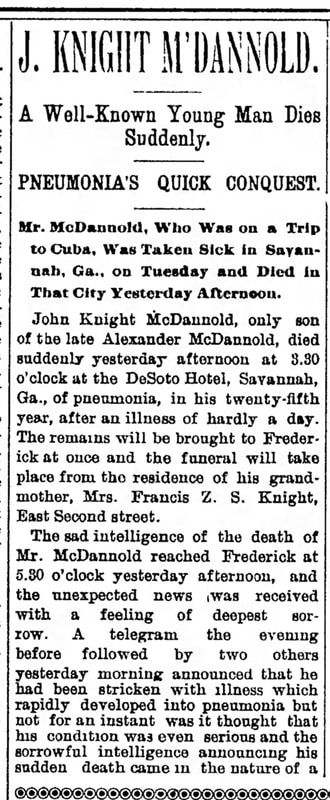

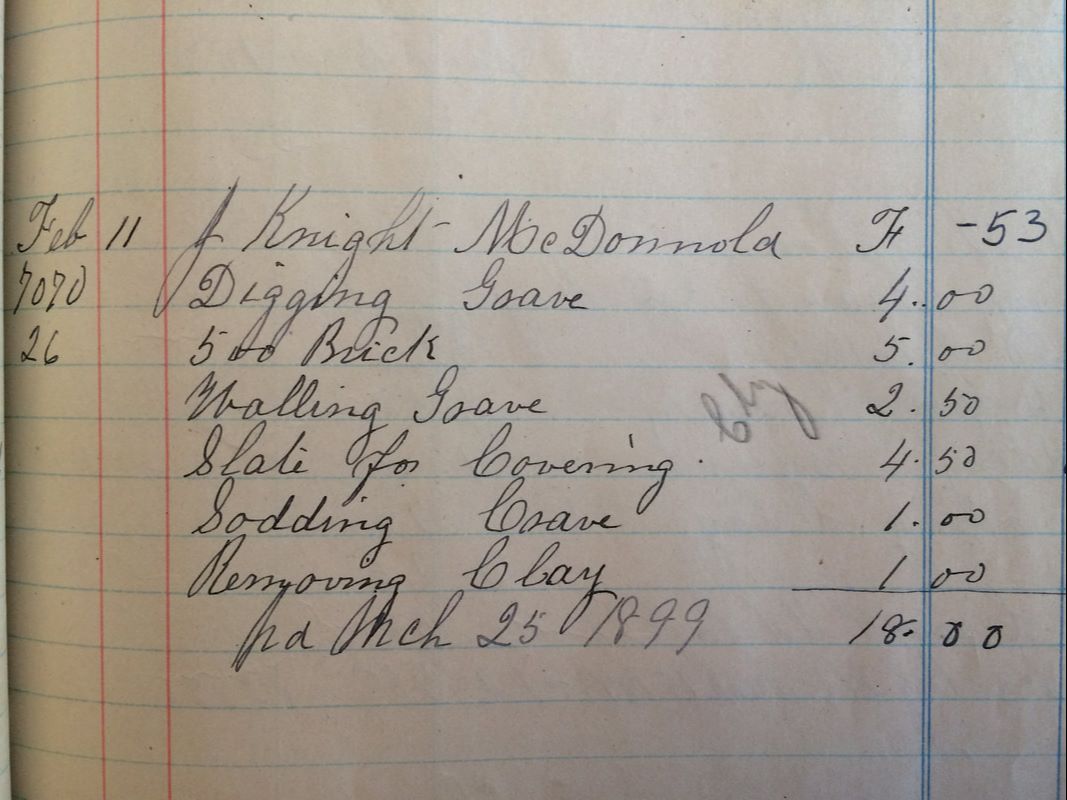

The Ill-Fated Mystery Trip In early February, 1899, John and friend Guy Clifton Thomas set out for a six-week sojourn with hopes of spending the remainder of winter in the warm sun of Cuba.  The Frederick Daily News (Feb 1, 1899) The Frederick Daily News (Feb 1, 1899) The departure of McDannold and Thomas from Frederick was a town event. It occurred on Tuesday, February 1st, 1899 and was even chronicled in the local newspaper. After spending a night in Richmond (VA), the duo next set out for Savannah (GA). The plan was to spend some time here visiting old friends before embarking for Brunswick (GA) where they would catch a boat for their tropical end destination. While in Savannah, McDannold and Thomas took up residence at the DeSoto Hotel.  DeSoto Hotel, Savannah (GA) DeSoto Hotel, Savannah (GA) John suddenly found himself hampered with an ailment which progressed into a heavy cold. Soon this inconvenience changed to pneumonia. Thomas telegrammed John’s grandmother and sister back in Frederick on February 7th, informing them of his companion’s malady. The next morning (February 8th) another telegram received in Frederick reported John’s condition having worsened overnight. Alexandra and her cousin Nannie Floyd quickly decided to make their way to John’s bedside in Georgia. The young women hastily packed bags and boarded the first train heading south. All the while, John K. McDannold’s condition continued spiraling downward. He would lose his fight at 3:30pm on February 8th. Word of John’s death was received in Frederick by telegram at 5:30pm. Alexandra would receive the heartbreaking news in Richmond while waiting to board a connecting train bound for Savannah. McDannold would never make it to his final destination of Cuba. Fate would instead carry his body back to Frederick, accompanied by devastated companion Guy Thomas. His death would make from page news, above the fold. John Knight McDannald would be laid to rest in the family plot (Area F/Lot 53) beside his deceased parents and grandfather. The funeral of John K. McDannold was very well-attended, and included friends with notable Frederick names remembered even today, such as Harry Grove, Ira J. McCurdy, Charles Doll and Harry Nixdorff. Alexandra and grandmother Fanny Knight likely placed the order in with the Tiffany Studio in New York for John’s elaborate grave monument. It may not have been in place for Mrs. Knight to see with her own eyes, as she would soon join her grandson in Mount Olivet, dying 17 months later (to the day) on July 8, 1900.  Miss Alexandra McDannold was now alone, but not for long. She kept up a life within social circles here and abroad, marrying in January, 1901. Her groom was Lawrence Rust Lee, a descendant of the famed Lees of Virginia, whose great-grandfather, Edmund Jennings Lee, was a first cousin to Gen. Robert E. Lee. The young couple made their home in Pittsburgh, where Alexandra’s husband worked for a large pump manufacturer. They would eventually have residences in nearby Leesburg and Washington, DC as well. Sadly, the Lees marriage would end in divorce in the 1930’s. Alexandra would die in the nation’s capital in April, 1955 at her Northwest residence at 3411 Newark Street. Alexandra McDannold Lee too would join her brother and extended family in Mount Olivet. This story certainly tested my genealogical skills, as I commend readers for keeping all the Knights, McDannolds, Bealls and lees straight. My biggest personal research surprise of all came in finding that Lawrence Rust Lee would marry again in 1956. He wed a lady named Louise Goldsborough (1888-1962)—an ancestral cousin of my wife, Ellen. Ellen’s middle name is Louise, and actually came from this woman, as she was a first cousin to Ellen’s grandfather. I guess it’s safe to assume, that when conducting history research of this time, one should always “GO LIGHTLY,” as you never know what you will find.  Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers Next weekend, I will be going to see one of my all-time music groups in concert in Baltimore. It’s a tour celebrating the 40th anniversary of Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers. So many hit songs from these Rock n’ Roll legends, with roots in the Gainesville, Florida area. This will be my seventh time seeing them, and I’m bringing three of my sons along. Their playlist of is lengthy and chock’ full of hit songs and memorable videos: Don’t Do Me Like, Breakdown, American Girls, Don’t Come Around Here No More, Runnin’ Down a Dream, Refugee and Freefallin’ to name a few. One song, however, gave me the impetus to write this week’s “Stories in Stone” piece. This is the Heartbreaker’s 1993 offering “Mary Jane's Last Dance.” The catchy chorus made this song a fan favorite, but a haunting video made it even more memorable and gave the group top honors for 1993’s MTV “Music Video of the Year.” The song, and accompanying video, conjures up plenty of abstract meanings and haunting images, although I want to single out a positive connection to a local “Mary Jane” for purposes of this article. This “Mary Jane” is buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery and was somewhat of a mirror who reflected Frederick, Maryland through her social and professional lives.

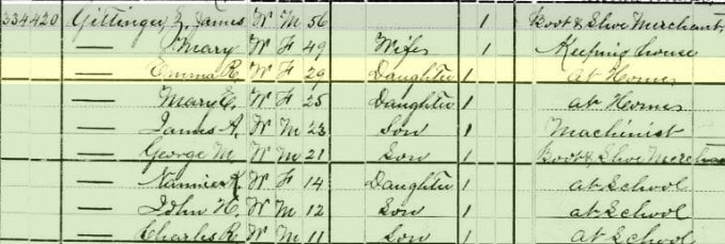

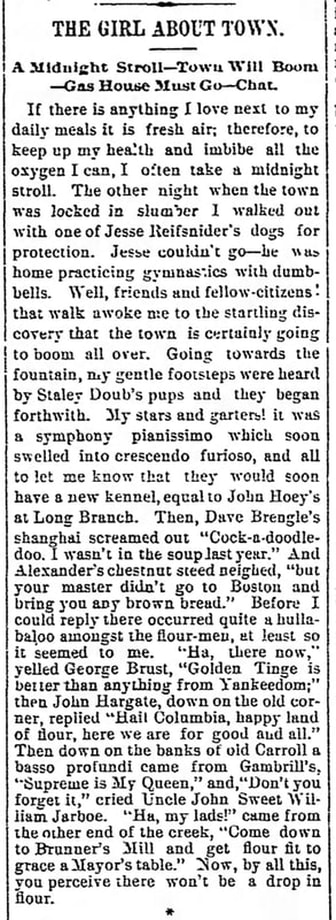

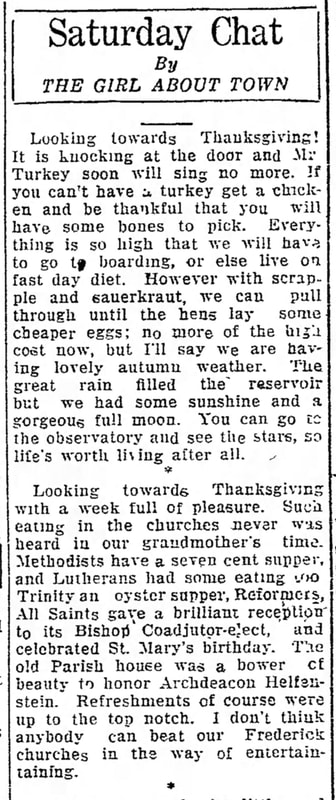

Frederick's Visitation Academy Frederick's Visitation Academy Emma’s childhood was a nice one, as she enjoyed a relatively peaceful rearing in a small town. She was the oldest of nine children, having four brothers and four sisters. Her father was a boot and shoe merchant. Turbulence would occur in her pre-teens with the American Civil War. Emma saw the wounded and dying first-hand. Her school, the Frederick Visitation Academy, had been commandeered for use as a makeshift hospital. Emma is also said to have assisted in carrying food and assisting with the care of soldiers at the General Hospital #1 site, located adjacent the Frederick Hessian Barracks (today’s site of the Maryland School for the Deaf). Emma would graduate with the Visitation Academy’s “Class of 1866.” Interestingly, her upbringing was not Catholic as could be imagined. I have found that she was baptized a few months after her birth in Frederick’s German Reformed Church. However, she appears to have jumped ship somewhere down the line as she had a strong lifetime affiliation with All Saints Protestant Episcopal Church of Frederick. A block separated both of these houses of worship located on W. Church Street—not too far of a hike from Emma’s home located on E. Patrick Street.  The former home of Emma Gittinger, located at 224 E. Patrick Street, is now a realty office (far left). Sadly, in Emma's time, the Frederick News was not located just a few short doors away to the west as could be imagined by this photo. The newspaper office was located on N. Market and later at the intersection of W. Patrick and Court streets before moving into the Old Hagerstown & Frederick Trolley Terminal building. Her commute would have been ideal.  Jacob Engelbrecht (1797-1878) Jacob Engelbrecht (1797-1878) Miss Gittinger came from good, patriotic stock—at least on her mother’s side. Emma was a great grand-daughter of Major Peter Mantz of Frederick, an aide-de-camp of George Washington in the Revolutionary War. Through this line, she was also a lineal relative of Barbara Fritchie, the famed nonagenarian that lived down the street. Interestingly, like her sampling of different religions, Emma’s family may have shown support to the Confederacy during the Civil War. Later in life, she became a charter member of the Fitzhugh Lee Chapter, Daughters of the Confederacy. She was the group’s treasurer and took active roles in Decoration Day ceremonies at Mount Olivet. Emma was equally active in the erection of the Francis Scott Key monument, and other civic and patriotic activities. Emma should be best remembered for her professional career—one that began with the Frederick News at the time of the paper’s founding in 1883. She would be faithful to the journalism industry, not to mention her family-based employer, for the next four decades. It all began with a column entitled "The Girl About Town" and later renamed "Saturday Chat with the Girl About Town," which continued weekly until 1927. Looking back from a historical perspective, Emma Gittinger was Frederick’s best documentarian/gossip, seemingly “picking up” where legendary diarist Jacob Engelbrecht left off five years earlier with his death in 1878. The column and its writer came to be known as “Mary Jane, the Girl about Town.” She knew all, and could talk with equal competence on topics ranging from local history to cutting edge social trends. “Mary Jane” was a straight shooter, sometimes brash, and other times crass. She was obstinate, outspoken, knowledgeable and funny. Her columns included sarcasm and tremendous wit, much like her predecessor Herr Engelbrecht. However, she differed greatly in the level in perceived social status—Miss Gittinger was part of the “in-crowd,” compared to the blue collar craftsman who was just part of the crowd. “Mary Jane’s” refined standing in Frederick Society boasted a magical panache—a cutting edge socialite living and partying in Frederick during the late 19th century! Gittinger’s writing has been described as “naturally cheerful and happy temperament, her column was witty and most re-readable. These traits reflected her personality. In later years she spoke of “the new Frederick,” contrasting the modern with a Frederick before the automobile, before the vogue of the telephone, the aeroplane. ”In time, her identity need not be disguised as she was a much sought after public speaker. A focus on World War captured the headlines of the Frederick News and Post of one hundred years ago. “Mary Jane” kindly provided a bit of levity at home, while many local men were fighting for our freedoms across the Atlantic. World War I would cease in 1918, giving way to the Prohibition amidst the Roaring 20’s. Oh what an amazing time to be a socialite. Unfortunately, Emma was slowing down. She was in the twilight of her years, both professionally and personally. Soon there would come the Stock Market Crash of 1929, plunging the country into the Great Depression. A decade later, the US would be engaged in a second, and greater, World War against Germany and Japan. “Mary Jane” would not have the opportunity to comment on either. At 76, Emma Gittinger was one of, if not, the oldest, female columnist in America in 1927. In early January of that year, she came down with a heavy cold, one she couldn’t kick. Her condition worsened, forcing her to vacate her home residence for the hospital in mid-January. One month later she became bedridden. Although she had many visitors, complications set in and she would become weaker. Emma died on April 6th, 1927 at the Frederick City Hospital. “Mary Jane” was gone. Her body gave final punctuation to an eventful life on a Wednesday evening at about 6:30pm. Death was given as due to a dropsical condition. Dropsy is an old term describing the swelling of soft tissues due to the accumulation of excess water. In years gone by, a person might have been said to have dropsy. Today, this condition would be more descriptive, while specifying a particular cause. For example, the person might have edema due to congestive heart failure. Emma’s body was taken to the home of brother George Gittinger living on E. 2nd Street. She would be laid to rest in Mount Olivet, a place she was very familiar with, having spent countless volunteer hours within, not to mention family visitations and picnics on weekends as was customary in the Victorian period. Emma Gittinger’s funeral was largely attended as the below article shows: I find it a bit ironic that Emma is unheralded in a town known for Francis Scott Key, Thomas Johnson, Jr. and Barbara Fritchie. All were patriotic and outspoken, but I’d certainly place money on the fact that none loved their hometown of Frederick more than Emma R. Gittinger. Virtually unknown by people today—she doesn’t even receive mention in the pantheon of local women’s heroes, a list boasting early settler Susanna Beatty, the abovementioned flag-waver Fritchie, collegiate benefactress Margaret Scholl Hood, Frederick City Hospital’s Emma Smith and fashion designer Claire McCardell. Perhaps my humble writing here will introduce local residents to one of the first women newspaper column writers in the United States.

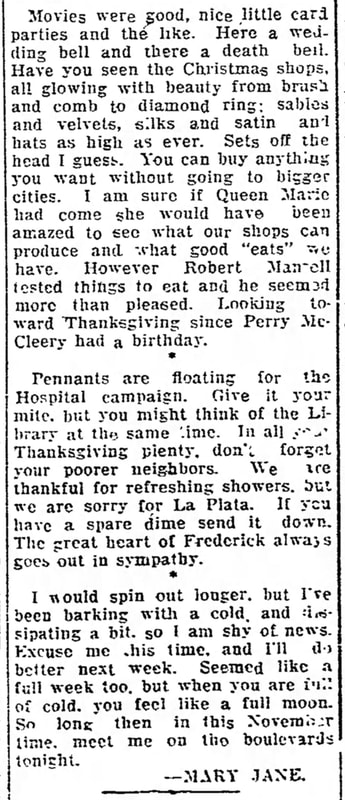

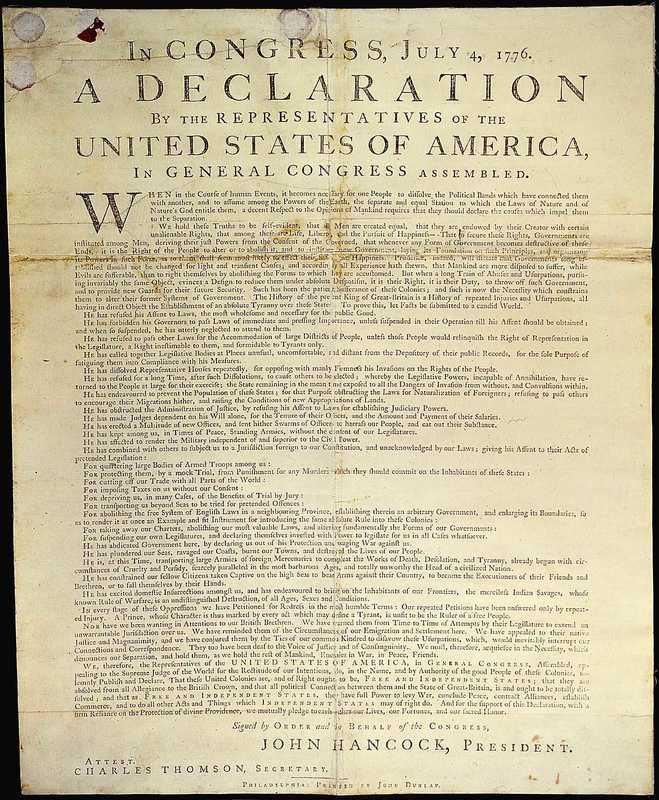

Goodbye Mary Jane—but thanks for all the “dancing” you did within the now yellowed pages of our town newspaper.  Trumbull's masterpiece "The Declaration of Independence, July 4th, 1776" Trumbull's masterpiece "The Declaration of Independence, July 4th, 1776" The town of New Castle, Delaware was bubbling over with nervous excitement in early July, 1776. Three weeks earlier on June 15th, the Assembly of the Lower Counties of Pennsylvania met here in the courthouse and declared itself independent of British and Pennsylvanian authority. This brash action thereby created the state of Delaware, as it hadn’t even existed as an independent colony under British rule. Since 1704, Pennsylvania had two colonial assemblies: one for the “Upper Counties,” (originally Bucks, Chester and Philadelphia), and one for the “Lower Counties on the Delaware” (New Castle, Kent and Sussex). All of the counties shared one governor. Now, New Castle was chosen the new capital of Delaware. Meanwhile just up the Delaware River in Philadelphia, the Second Continental Congress was convened and discussing a permanent break with Great Britain. On July 4th, the Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence, which proclaimed the independence of the United States of America from Great Britain and its king. Contrary to popular belief, the legendary convention of delegates adopted Richard Henry Lee’s resolution for independence from Great Britain on July 2nd, not July 4th. Furthermore, the document wasn’t signed by all delegates on July 4th as has been assumed, partially thanks to John Trumbull's iconic depiction. Most of the signatures were pledged and affixed one month later on August 4th, while some autographs wouldn’t be gotten until October and November. Two individuals did sign off on the corrected draft on July 4th, 1776 after edits were properly made. These were John Hancock, President of the 2nd Continental Congress, and lesser known Charles Thomson, Secretary to the Continental Congress. The day we celebrate each year is the day that these gentlemen signed the rough draft, and delivered to the official printer, a man named John Dunlap. Finished copies of the Declaration of Independence were brought to the Pennsylvania State House (later named “Independence Hall”) on July 8th. Philadelphia citizens were summoned for the first public reading of the document by the ringing of a very famous bell, one which had announced the battles of Lexington and Concord some fifteen months before.

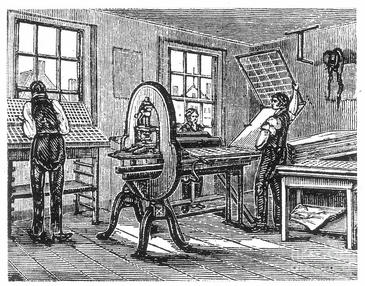

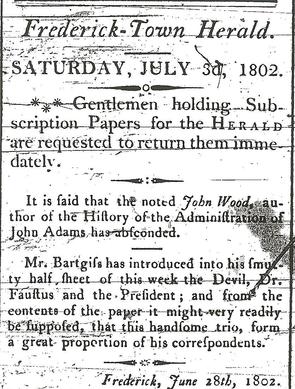

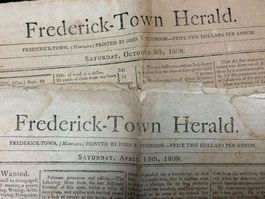

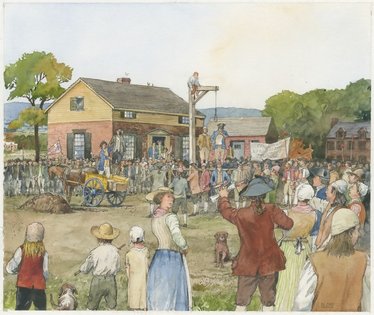

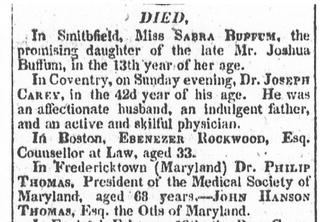

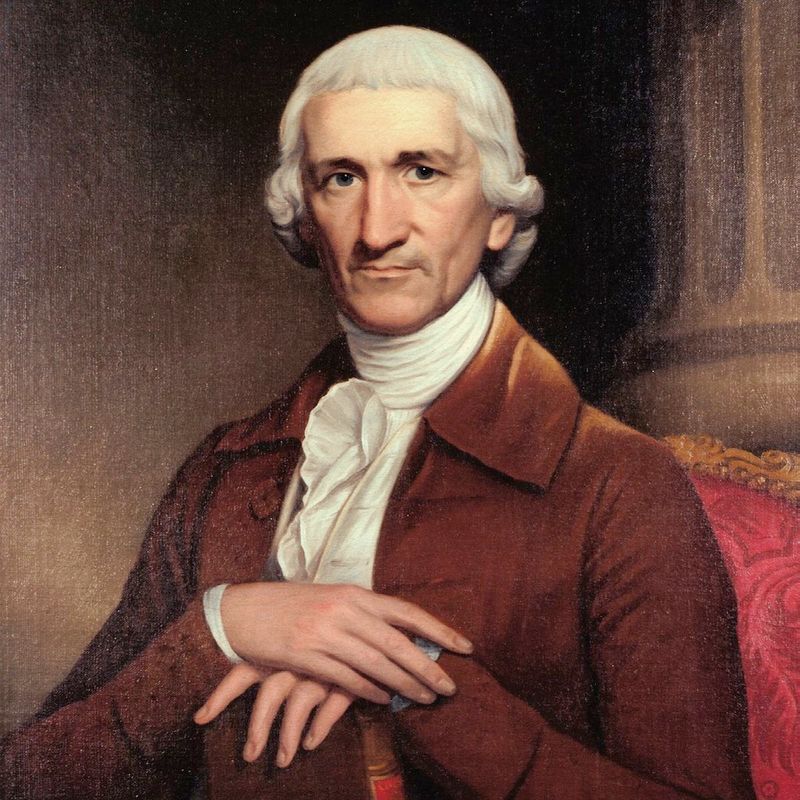

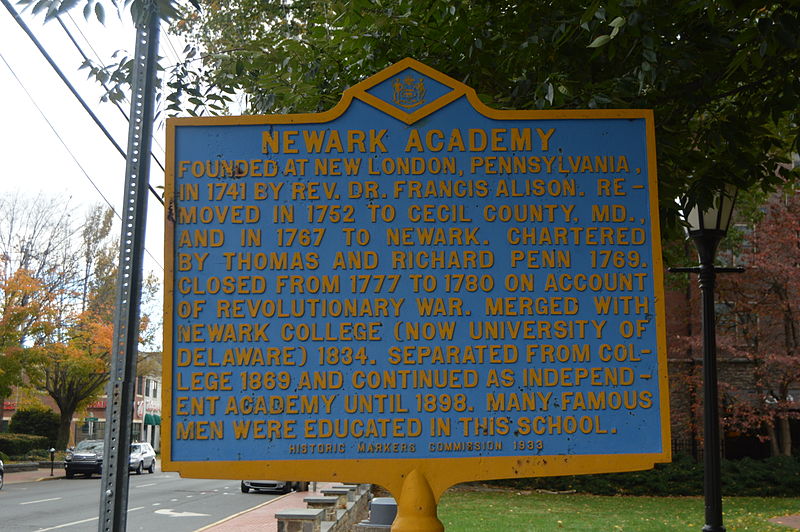

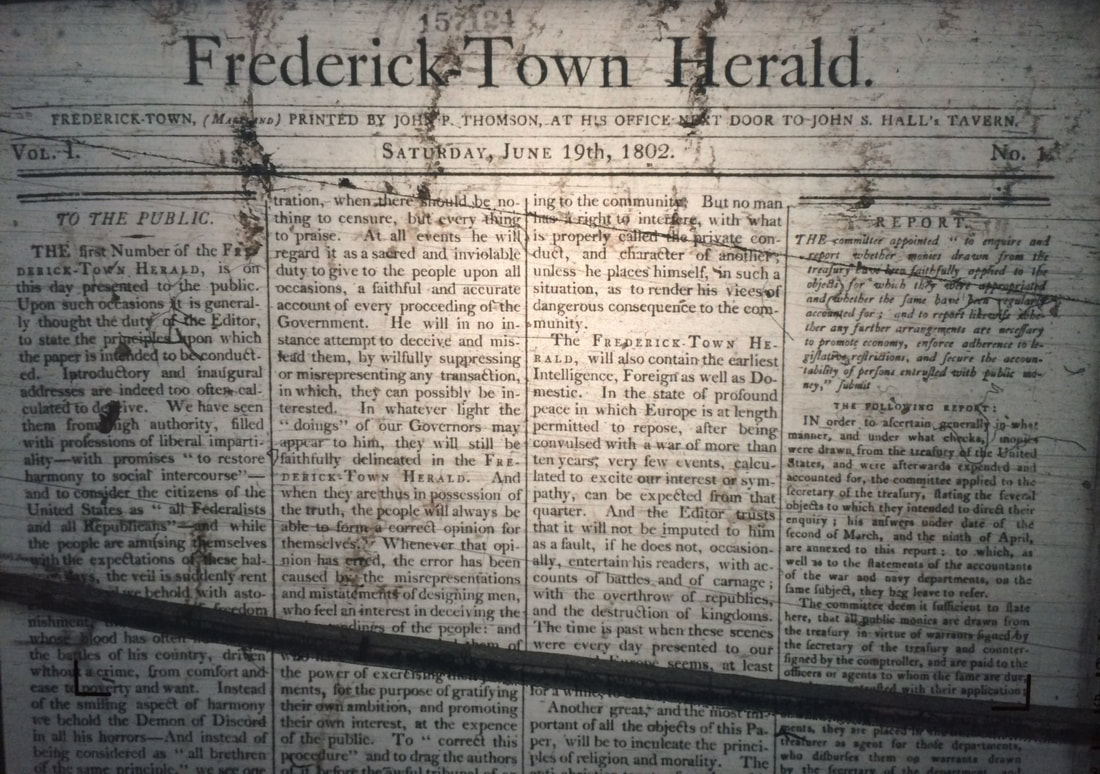

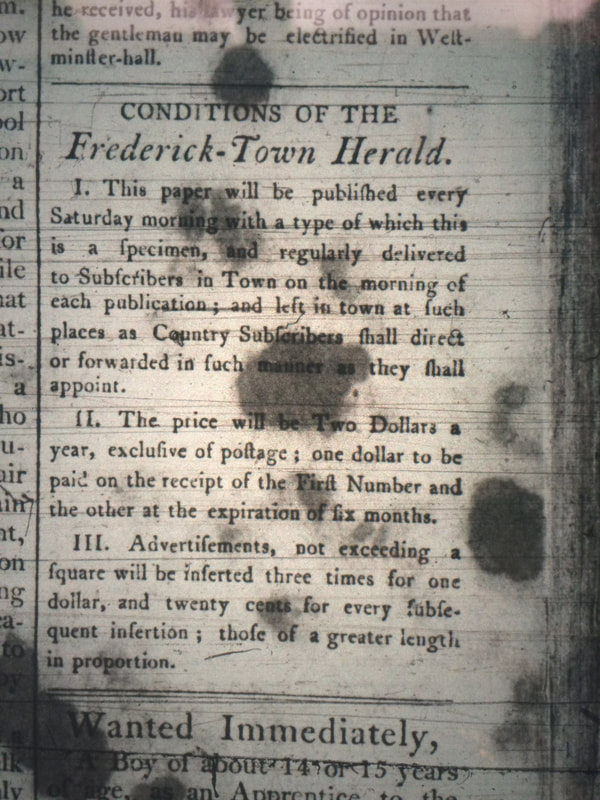

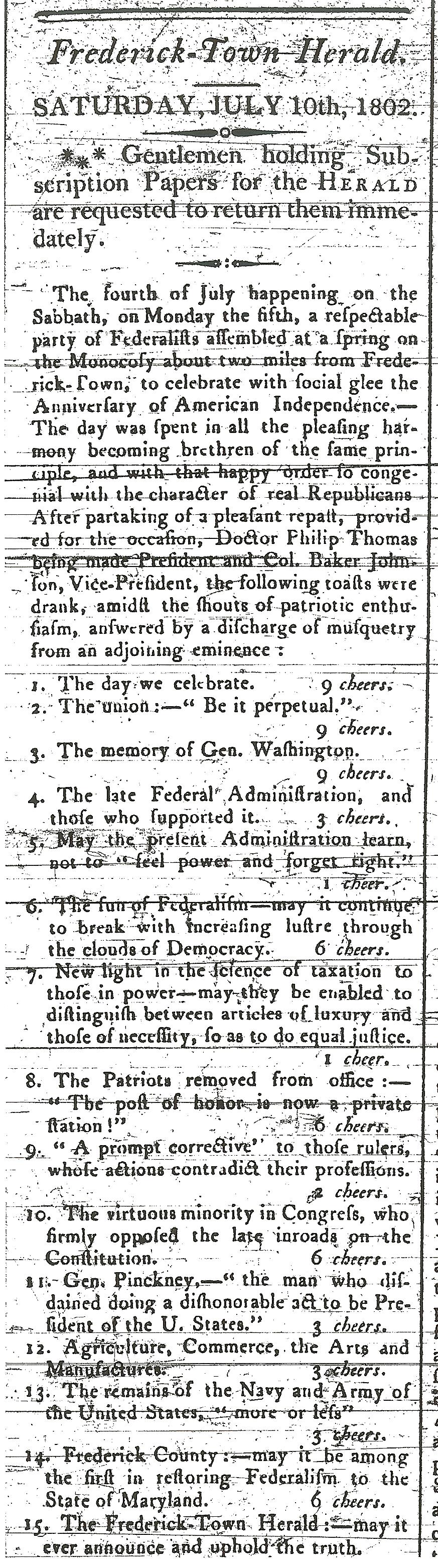

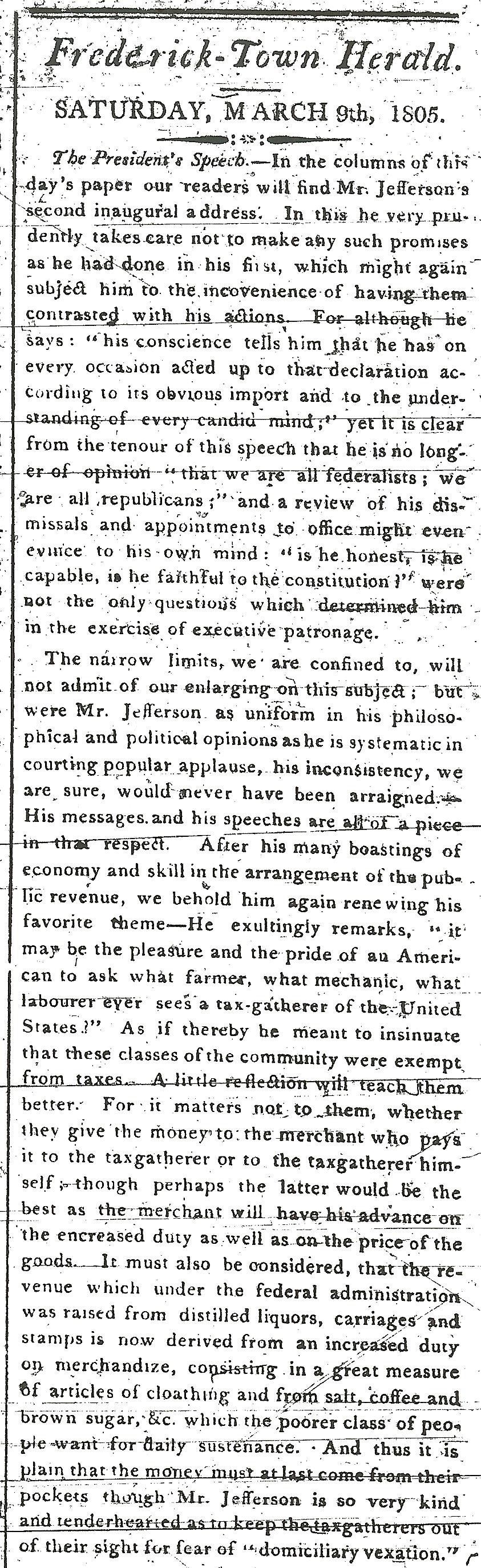

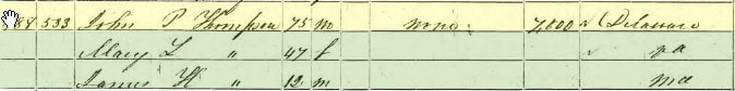

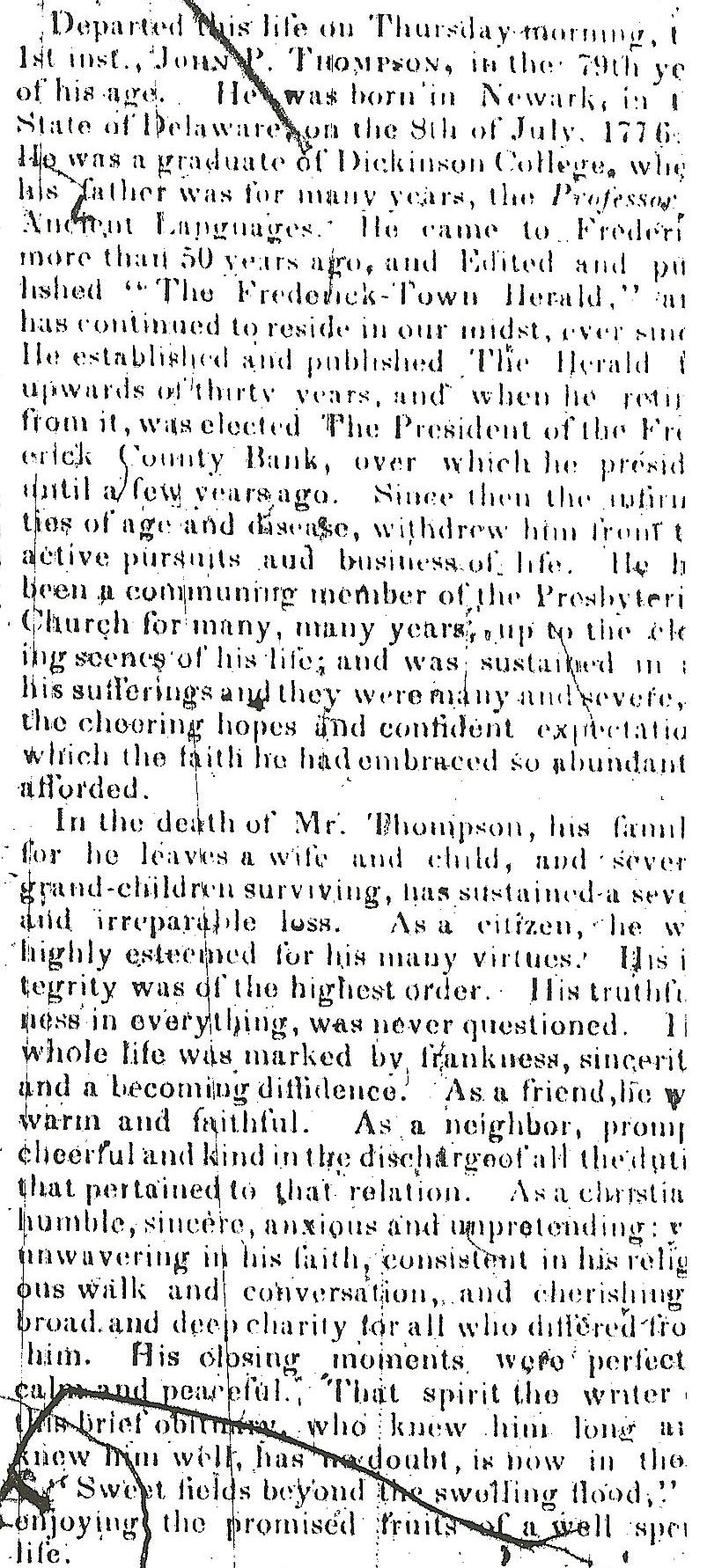

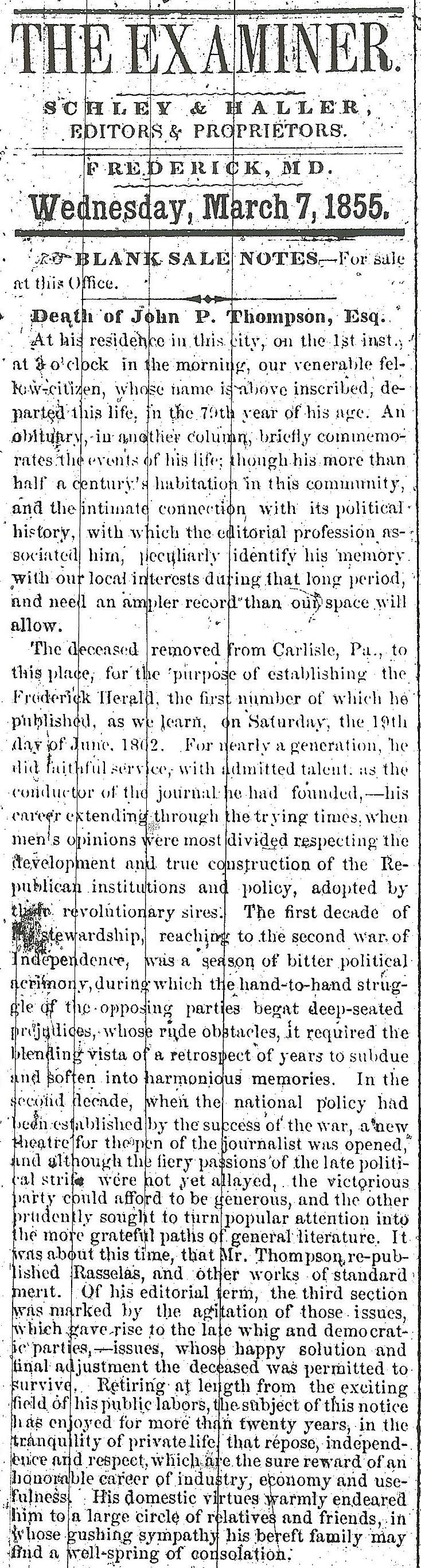

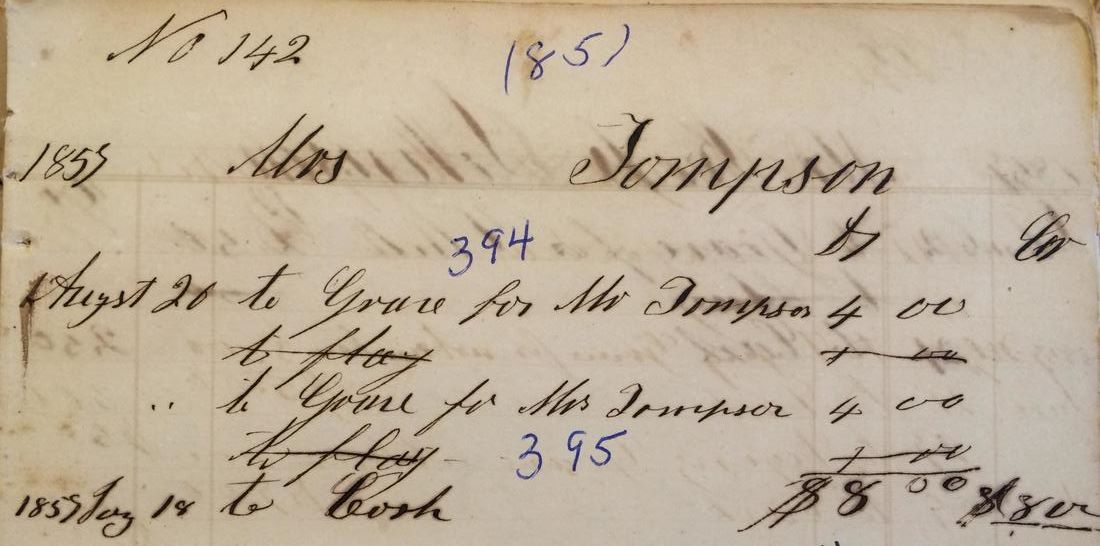

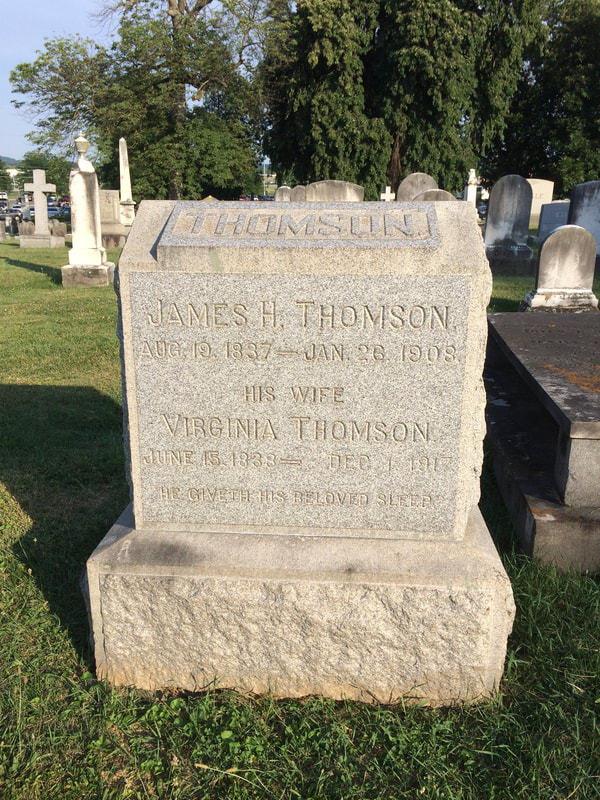

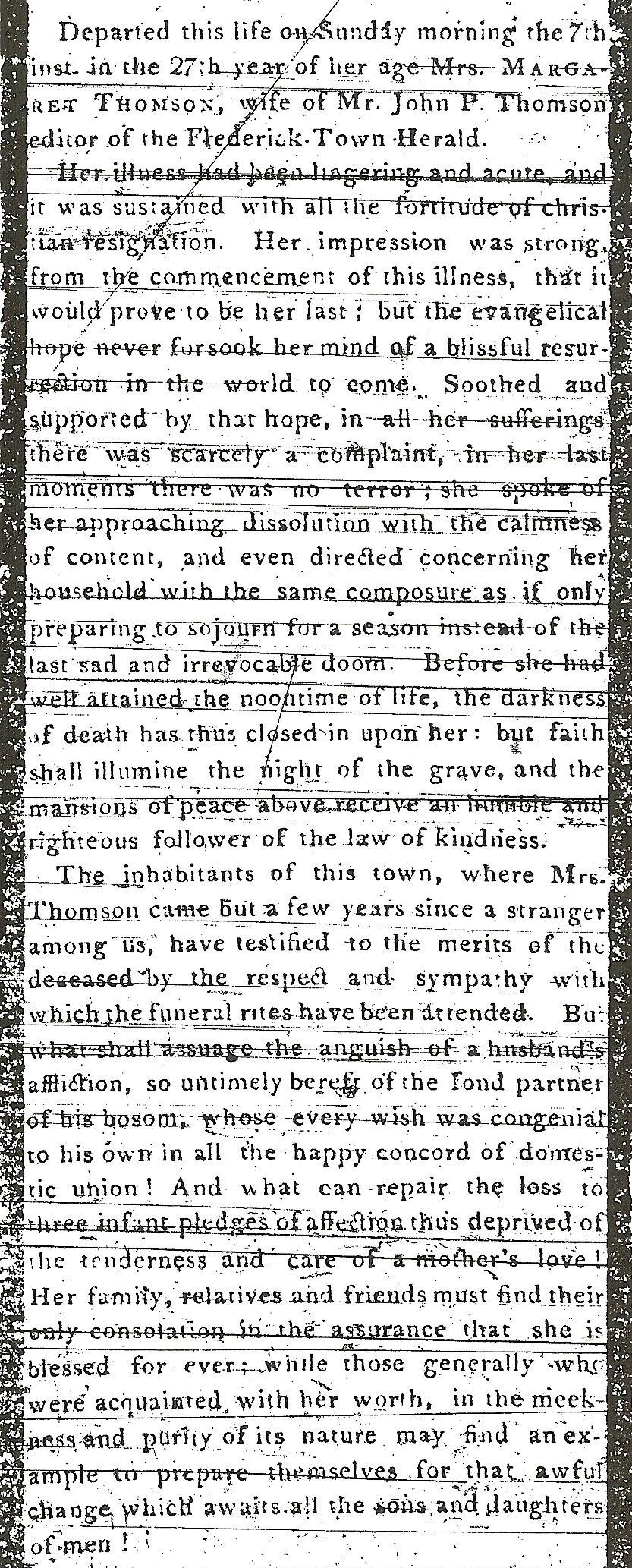

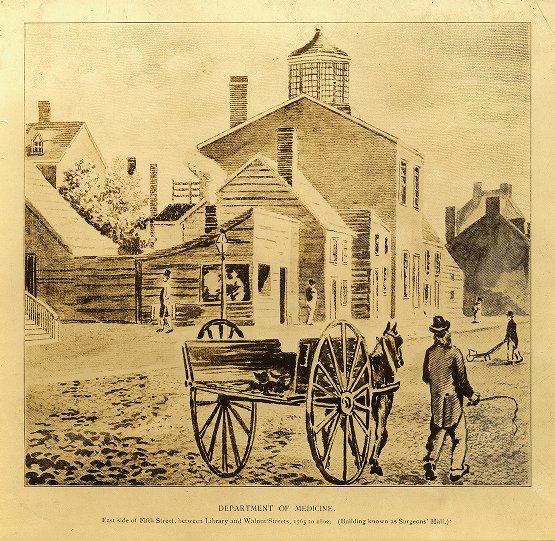

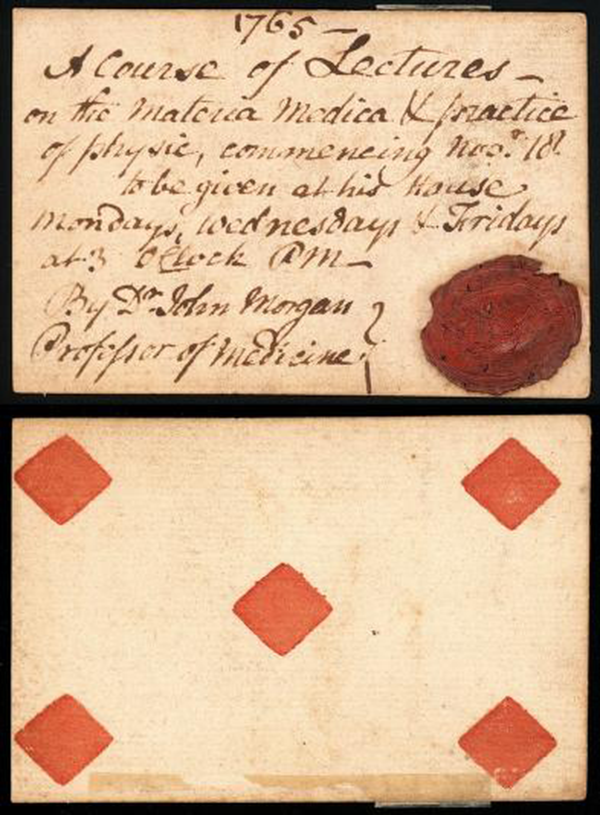

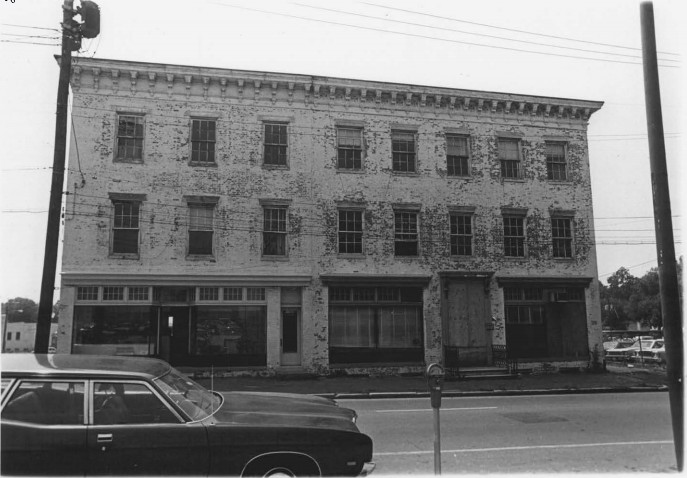

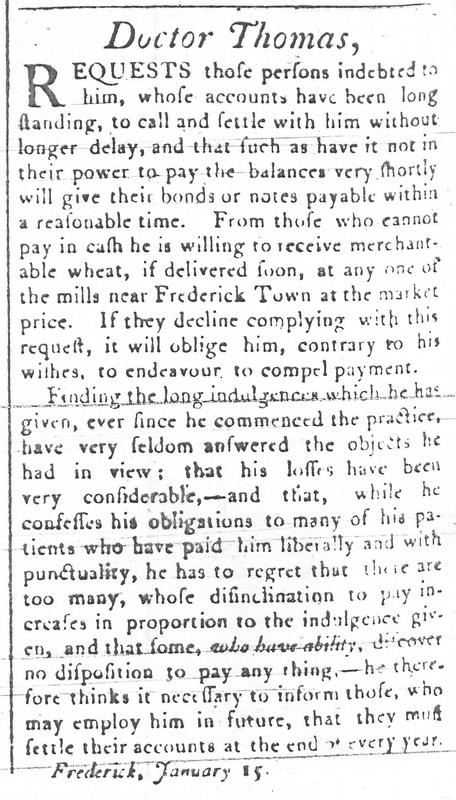

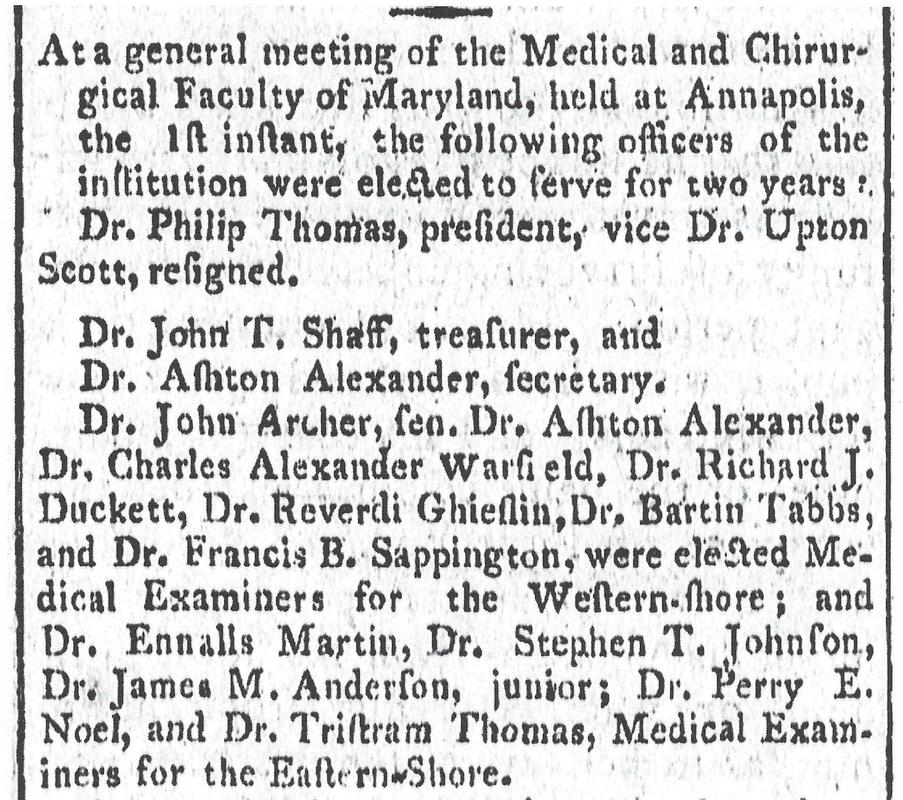

CharlesThomson's grandson would also declare his own independence of thought to the masses, criticizing some of the almighty 1776 signers in the process, especially the man who receives the majority of credit for authoring the Declaration— first presented to public audiences on the day of his birth. John Popham Thomson Future Frederick resident, John Popham Thomson was born to William and Margaret Thomson. William was the son of Continental Congress Secretary Charles Thomson. At the time of young John's entrance into this world, soldiers under Col. John Haslet’s Delaware Blue Hen Regiment came from Wilmington and “took out of the Court House all the insignias of the monarchy…all the baubles of royalty and made a pile of them before the Court house…set fire to them and burned them into ashes and a merry day we made of it.” John’s life was just as colorful as the events surrounding his birth. His first seven years were spent during the American Revolution. His father, William Thomson, was a 1772 graduate of the nearby Newark Academy, a continuation of Rev. Alison's New London endeavor. He married Miss Margaret Popham three years later. Mr. Thomson would become the principal of his alma-mater, having re-opened the school (because of a closure due to the war) in 1780. He remained here until 1794, at which time he and Margaret moved to Carlisle, Pennsylvania to take the post of Professor of Languages and librarian at Dickinson College. William Thomson would become the principal of his alma-mater, having re-opened the school (because of a closure due to the war) in 1780. He remained here until 1794, at which time he and Margaret moved to Carlisle, Pennsylvania to take the post of Professor of Languages and librarian at Dickinson College. This school had been founded by Declaration of Independence signer, Benjamin Rush, and named for another, John Dickinson. Things got off to a rocky start. In 1795, family friend Henry Ridgely wrote a telling letter home describing the state of the affairs for the Thomsons in their new home: "Mr. Thomson has been very sick since he has been at Carlisle, and kept his bed light on nine days, and Mrs. Thos. had the ague and fever, and James Thomson fell over a cellar door and broke 3 of his ribs.” Henry (Ridgely) and his brother George had been "under (the) care and tuition" of William Thomson at the Newark Academy in 1794 and had been sent by their mother to Dickinson to be under the same by the educator. As can be imagined, William’s son, John Popham Thomson, would experience a great educational upbringing. He would attend his father’s school, Dickinson College, and graduate with a law degree in 1797. Although well-versed in law and politics, John P. Thomson chose journalism and would soon embark on an illustrious, lifelong career as a newspaper publisher. The 23-year-old founded The Eagle or Carlisle Herald newspaper on October 3rd, 1799. It was mockingly labeled a “Tory paper” by critics for its Federalist stance and anti-Jeffersonian sentiment. John Thomson ran the paper while simultaneously performing duties as Carlisle, Pennsylvania’s postmaster. (John's grandfather Thomson had held the role of Postmaster General for the US under the Articles of Confederation.) Unfortunately, Thomson was soon fired from the postmaster gig, forcing him to give up the newspaper. The cause of dismissal resulted from his editorial attacks on President Thomas Jefferson (within the paper). A fellow publisher wrote in March of 1802 that Thomson: "proposed that the grand jury then sitting would present the election of Mr. Jefferson as a national curse." A competing newspaper in March ran the headline: "O Johnny Thomson, Johnny Thomson O!" upon hearing that John demanded to know why he was fired as town postmaster. The rival paper went on to call Thomson’s paper "slanderous." This was a major setback for the Delaware native, but John P. Thomson would not be unemployed for long. Several prominent citizens of Frederick asked the young publisher to move south and set up a Federalist paper. These included Judge Richard Potts and John Hanson Thomas, son of Dr. Philip Thomas and grandson of John Hanson. Thomson’s friend and former Dickinson classmate Roger Brooke Taney had come to Frederick a few years prior, launching his illustrious law career here. The new town newspaper would take the name of the Frederick-Town Herald.  John P. Thomson's printing office and headquarters was advertised as being next to John S. Hall’s tavern. I place this tavern on the northwest corner of N. Market and W. Church streets, location of today's Tasting Room restaurant. The next door (to the north) was the Frederick-Town Herald office, also serving as Thomson’s home address in the beginning. This would have sat on the footprint of present day Firestones restaurant. The first issue of the Frederick-Town Herald hit the streets on June 19th, 1802. The inaugural edition contained a long three-column preamble by Thomson explaining his political and editorial beliefs. He said that he supported Washington and Adams, but views "...with horror the late unpardonable attack of the Legislature on the independence of the Judiciary - an attack, that had proved but too successful, and which had effectually demolished one of the great pillars of the Constitution." John Thomson reassured readers that: "...he will in no instance attempt to deceive or mislead them, by willfully suppressing or misrepresenting any transaction." Maryland historian/writer Walter Arps labeled Thomson "...an unabashed polemicist” in an article that appeared in the spring, 1979 edition of the "Maryland Magazine of Genealogy” (vol. 2, #1, p. 30). Arps went on to say: “His (Thomson’s) chief target was Thomas Jefferson, whom Thomson said was embarked on a systematic campaign of subtle denigration of the achievements of Washington and Adams." Arps continued claiming that Thomson accused Jefferson of being in cahoots with Napoleon Bonaparte when the two leaders solidified the Louisiana Purchase: "Mr. Thomson was enflaming the political passions of the good burghers of Frederick County. With Bonaparte terrorizing Europe and the Barbary pirates plundering American shipping lanes, as well as Thomson's weekly multi-column tirades, there was relatively little page space left in the Herald for local news."  Thomson did not waste time taking shots at competing newspaper publisher Matthias Bartgis Thomson did not waste time taking shots at competing newspaper publisher Matthias Bartgis Thomson was partially recruited to do battle with Matthias Bartgis (1756-1825) an established Frederick publisher of several weekly papers under various different names in both German and English. These included The Hornet (1802-1814), Bartgis' Republican Gazette, The Independent American Volunteer or Der Americanische Voluntair (1807-1808), and the General Staatsbothe (1810-1813). The Hornet possessed strong Republican leanings and carried the motto: "To true Republicans I will sing, But aristocrats shall feel my sting" Bartgis' Republican Gazette (1800-1820) generally avoided politics and lasted much longer than The Hornet. In 1811 Bartgis took his son, Matthias E. Bartgis (1791-1849), in partnership. A great rivalry was born between Bartgis and Thomson.  As one of the leading citizens of Frederick, his paper gave additional glimpses into the personal life of Thomson and his family. Sadly, unfortunate personal events were displayed for readers to see such as the death of Thomson’s oldest daughter Margaret in February of 1823—only 17 years old at the time. The Frederick-Town Herald also shared the obituaries of his first two wives: Margaret (Holmes) in 1809 and Mary (Barnhold) in 1832. Wife Margaret's obituary is included at the end of story.  The Frederick-Town Herald truly made its mark on Frederick as it thrived for three decades, where many competing newspapers folded. The weekly newspaper published on Saturdays had become a mainstay in the community, especially beloved by Federalists. Thomson passed the reigns to William Ogden Niles when he sold the paper in late 1831, likely influenced by the sickness/eminent death of his second wife, Mary. In his last edition, of October 23, 1831, the seasoned publisher and printer graciously thanked his patrons and readers, and made no apology for his rhetoric and conduct over the past three decades. John P. Thomson's name would next appear in the Frederick-Town Herald a few months later in March (1832) an advertisement offering agricultural implements for sale. One week later, the Frederick-Herald would run the obituary announcing the death of Mary Thomson. The Frederick-Town Herald would survive another 30 years under various publishers until its abrupt end at the start of the American Civil War. The paper was suppressed in 1861 for its political stance, at this time, showing Southern sympathies. The Herald had supported presidential candidate John C. Breckinridge, former vice-president and Democrat, in the highly contested election of 1860. Abraham Lincoln won by the electoral vote as Maryland had overwhelmingly been in support of Breckinridge as he took 46% of the votes (42,482) compared to Lincoln’s 2% (2, 294 votes). From that point forward, the paper, under publisher John W. Heard, vehemently supported the Confederacy until its demise, caused ironically enough, by the federal government’s order of prohibiting the postmaster to send it through the mail. In a letter written in 1836 by Thomson’s niece, she describes her “Uncle John” as being a banker who had lived in Frederick for more than 30 years. She talks of his son Charles choosing to be a farmer, and that his daughter Elizabeth had died. Lastly, she mentioned that he had remarried– "...for the third time about a year ago." At the occasion of the marriage, John was on the verge of his 60th year, while his new bride, Mary Lucas Hamner (1802-1857) was nearly half his age—born in the year Thomson started the Herald. The union produced another son, who would be named James H. Thomson (1837-1908). Retirement was a busy time for John P. Thomson. He dabbled in politics, being named to the National Republican Central Committee in 1832. Thompson could now devote more time to his place of worship, the Frederick Presbyterian Church. He also served as the President of Frederick County Bank, being elected president in 1833 and serving the institution up through the early 1850’s in this capacity. In 1850, Thomson held real estate valued at $7,000. He lived with wife Mary and son James in downtown Frederick within the Court House Square area, but it could have well been the original N. Market Street location of his printing business. Thomson’s will was fittingly prepared and signed at the time of his 76th birthday, in July 1852. The man born within “the Spirit of ‘76,” possessing a childhood amidst the Revolution and experiencing a young adulthood framed by the experiment of self-government for a new nation, would pass three years later on March 1st, 1855. He would be buried in the old Presbyterian graveyard, once located near the intersection of Fourth and Bentz streets. Mary Hamner Thomson would die just two and a half years after her husband in August 1857. Son James would purchase lot 47/Area E within Mount Olivet at this time. Mary was placed here and the dutiful son would have his father reinterred and buried next to his mother. A large ledger or tablet monument marks their gravesite. James and his wife would be buried here in time. In 1907, the Presbyterian Church purchased lots in Mount Olivet’s Area NN in advance of a mass removal of the bodies from their downtown graveyard. This occurred in 1907, and brought the mortal remains of Thomson’s first and second wives, along with daughter Margaret and John’s brother James (1778-1847) who followed his older sibling to Frederick-Town and worked as a teacher.  Gov. Thomas Johnson, Jr. (1732-1819) Gov. Thomas Johnson, Jr. (1732-1819) It’s the July 4th holiday once again—a time-honored tradition marked best by vacations, baseball games, cookouts, parades, concerts and firework displays. Patriotism is certainly “a many-splendored thing.” Mount Olivet Cemetery is no stranger to the concept of patriotism as it includes thousands of military veterans and legendary figures oozing with the “right stuff” such as Francis Scott Key, Barbara Fritchie and Thomas Johnson, Jr. The latter was a member of the famed Continental Congress, which met in 1776 to discuss means to gain independence from Great Britain. He voted for the Declaration of Independence, however “old TJ” isn’t as well-known (as he should be) because he didn’t have the opportunity to affix his proverbial “John Hancock” on the “Declaration” parchment signed by his colleagues in early July, 1776. Nevertheless, Johnson made the history record for his leadership both on, and off, the battlefield during the American Revolution. He served as Maryland’s first elected governor and is remembered as one of Maryland’s finest statesmen and business entrepreneurs. He was, and always will be, viewed as Frederick County’s top “patriot.” But, of course, I’m biased as an alumnus from the high school that bears his name. Just a few yards away from Gov. Thomas Johnson’s grave (located in Mount Olivet’s Area MM), is the final resting place of another great Maryland patriot. In addition to his tireless work during the “fight for independence,” this gentleman holds the distinction of being one of Frederick’s first reputable doctors. Interestingly, he may have been referred to as Dr. Phil by a few former patients living in Frederick Town during the rustic 18th century. Philip Thomas was born on the 11th day of June, 1747, two years after Frederick Town was laid out by Annapolis businessman/politician Daniel Dulany. The son of James Thomas and Elizabeth Bellicum, Philip’s birthplace was Kent County’s Chestertown on Maryland’s upper Eastern Shore. The lad became fascinated with medicine and apprenticed with a local physician. He would go on to study in Philadelphia from 1768-1769 under Dr. Thomas Van Dyke and attended professional lectures by the most knowledgeable men in the profession this side of the Atlantic.  Pennsylvania Hospital Pennsylvania Hospital At this time, he attended Dr. William Smith’s lectures on Natural and Experimental Philosophy, and matriculated in the college that would one-day be known as the University of Pennsylvania, School of Medicine. This was the first, and only, medical school in the thirteen American colonies when, in the fall of 1765, students enrolled for "anatomical lectures" and a course on "the theory and practice of physik." By organizing a medical faculty separate and distinct from the collegiate faculty, Penn's trustees effectively created the first university in North America, though the corporate name continued as the College of Philadelphia until 1779. Philip Thomas spent time receiving valuable clinical practice by working at Pennsylvania Hospital, the oldest hospital in America (founded 1751) under professors Thomas Bond, William Shippen and John Morgan. Morgan, a young Philadelphia physician, was founder of the School of Medicine and like the school’s other early faculty, had earned his medical degree at the University of Edinburgh and supplemented Edinburgh's courses with further study in London, where advanced training was offered in anatomy by private schools owned by the field’s most successful practitioners.  Apparently, Thomas could not afford to pursue a medical degree, but completed his apprenticeship and obtained letters of recommendation from noted teachers. He relocated to Frederick in the summer of 1769 and “commenced the practice of Physic and Surgery.” In 1773, he married the “high-bred” Jane Contee Hanson, daughter of lawyer John Hanson. Like Thomas Johnson, John Hanson would also serve as a delegate to the Continental Congress and would one day become "President of the United States in Congress Assembled," and became the first president (third overall) to serve a one-year term under the provisions of the Articles of Confederation. Dr. Thomas built a townhouse at 110 W. Patrick Street, next door to his in-laws. He also owned a manor farm located west of town near the foot of Catoctin Mountain in which he bred horses. Thomas gave this endeavor his own name, calling it “Mount Philip”—this of course gave rise to the name of the adjoining road that still bears this name. Dr. Philip Thomas quickly became one of the most respected citizens of town, and his reputation spread throughout Maryland. This was solidified on the eve of the Revolution in 1774 when he was appointed by his county as a representative to attend the General Conference at Annapolis and later was one of the committee “to carry into execution the association agreed upon by the Continental Congress.”  Public protest and a mock funeral for the 1765 Stamp Act in the vicinity of Frederick County's first courthouse Public protest and a mock funeral for the 1765 Stamp Act in the vicinity of Frederick County's first courthouse Frederick had already earned the reputation as a highly "patriotic" (and rambunctious) place in November of 1765, when twelve county justices repudiated the Crown's order to utilize stamped paper. Under the leadership of his father-in-law (John Hanson), Dr. Thomas became a member of Frederick’s Committee of Safety comprised of the Committee of Observation and the Committee of Correspondence. During the American Revolution, committees of this sort included area “sons of liberty” and other die-hard patriots. They became a shadow government on the local level, slowly taking control of the Thirteen Colonies away from royal officials, rendering them helpless. Noted historian T. H. Breen of Northwestern University wrote that these committees were the first step in the creation of "a formal structure capable not only of policing the revolution on the ground but also of solidifying ties with other communities. The network of committees were also vital for reinforcing a shared sense of purpose, speaking to an imagined collectivity—a country of the mind of Americans.” Like the moniker states, these committees required oversight of local activities and allegiances, and precipitated correspondence and communication between towns and colonies. It was Homeland Security, long before the Homeland Security Department. Frederick Town’s committee was chaired by John Hanson and met regularly in the county courthouse structure that once stood on the site of present Frederick City Hall on W. Church Street. T.H. Breen went on to explain these early bodies: “For ordinary people, they were community forums where personal loyalties were revealed, tested, and occasionally punished. ... Serving on committees of safety ... was certainly not an activity for the faint of heart. The members of these groups exposed ideological dissenters, usually people well-known in the communities in which they lived. Although the committees attempted as best they could to avoid physical violence, they administered revolutionary justice as they alone defined it. They worked out their own investigative procedures, interrogated people suspected of undermining the American cause, and meted out punishments they deemed appropriate to the crimes. By mid-1775 the committees increasingly busied themselves with identifying, denouncing, and shunning political offenders. By demanding that enemies receive "civil excommunication" – the chilling words of a North Carolina committee – these groups silenced critics without sparking the kind of bloodbath that has characterized so many other insurgencies throughout the world.” At 28 years of age, the young physician sat as a member of the General Congress held at Annapolis on June 20th, 1774. Dr. Thomas is said to have rendered distinguished service until the close of the war, but not just as a statesman. He joined the local militia at the outset of war, but his leadership and master equestrian skills would be better utilized later. On February 3rd, 1781, he was commissioned as captain of the Frederick Light Dragoons, in which Francis Scott Key’s father, John Ross Key, was lieutenant. Thomas would be promoted to the position of lieutenant-colonel of Frederick County, which translated to the same position within the Continental Army. The entire Frederick County militia would come under his command and was subject to his call to action in the field at all times. Thomas also helped with the collection of revenue to purchase and acquire arms, ammunition and supplies as a member of a sub-committee authorized by the Provincial Convention. He had recruited a regiment of men to aid General Washington at Yorktown, and “forwarded to the jaded and hungry army 500 head of cattle and immense quantities of flour and provisions.”  Grave of Jane Contee (Hanson) Thomas in Mount Olivet (Area MM/Lot 19) Grave of Jane Contee (Hanson) Thomas in Mount Olivet (Area MM/Lot 19) At war’s end, Thomas would again lend his support to George Washington—this time as a presidential elector who proudly cast his vote for the Continental Army’s top commander to become the first President of the United States. With the birth of a new nation, Thomas could now turn his attention toward his medical craft, and more importantly, his own family. Wife Jane had died in June, 1781 at the age of 34, leaving the doctor with three young children to raise: Catherine Hanson Thomas (Alexander) (1775-1826), Rebecca Bellicum Thomas (Magruder) (1777-1814) and John Hanson Thomas (1779-1815) who followed in his father’s footsteps in public service to not only Frederick County and Maryland, but the country as he was elected as a United States Senator in 1815. In the late 1790’s, Dr. Phillip became active in a statewide organization of physicians. The group formed the Medical and Chirurgical Faculty, the first organization of its kind in Maryland, in January, 1799. This occurred at a meeting in Annapolis attended by 101 leaders of the medical profession. The physicians who started the organization represented most of Maryland's counties. The Maryland General Assembly approved a petition for a charter for an incorporated society of physicians in Maryland to be known as "The Medical and Chirurgical Faculty of the State of Maryland". ("Chirurgical" was the common spelling of surgical at the time of the 18th Century.) The society became the seventh of its kind established in the country. One of the founders was a prominent young physician of Baltimore named Dr. Ashton Alexander. Alexander served as the Faculty’s first secretary, treasurer, and last surviving charter member. Dr. Philip Thomas would become Alexander’s father-in law in December, 1799, when the young physician married his oldest daughter Catherine. Dr. Thomas would become the Faculty’s second president after inaugural president Dr. Upton Scott stepped down in 1801. He would hold this post for the next 14 years. The Medical College of Maryland was established in 1807, and because Thomas was president of the Faculty, he became chancellor of the school. In 1808, Thomas was elected as a Maryland State delegate.  Death announcements of Dr. Philip Thomas and John Hanson Thomas in the Rhode Island American (Providence, RI) May 12, 1815 Death announcements of Dr. Philip Thomas and John Hanson Thomas in the Rhode Island American (Providence, RI) May 12, 1815 In spring 1815, Dr. Philip Thomas found his town hit by a terrible disease epidemic. Typhus was causing several deaths of Frederick residents, usually passed by lice and other microscopic mites. Sadly, he contracted the disease himself. His 34-year-old son, John Hanson Thomas, newly elected to the US Senate, stood affectionately by his side until he drew his last breath on April 25th, 1815. Unfortunately, John Hanson Thomas would become a victim as well, said to have received it through his deep care of his dying father. John Hanson Thomas would die only six days later on May 2nd, 1815, cutting short a brilliant career that would have eclipsed that of his father. Both men were buried in Frederick’s old All Saints Church burying ground adjacent Carroll Creek. Their bodies would be re-interred in Mount Olivet in 1901 within Lot 19 of Area MM.  Inscription reads: Tenderly affectionate as a Husband and Father, sincere and ardent as a friend, a devoted patriot of '76. Great and humane as a physician, just and honorable in all his transactions — such was the character of the lamented deceased Inscription reads: Tenderly affectionate as a Husband and Father, sincere and ardent as a friend, a devoted patriot of '76. Great and humane as a physician, just and honorable in all his transactions — such was the character of the lamented deceased Dr. Philip Thomas’ obituary from the Frederick-Town Herald (April 3, 1815) Departed this life on Tuesday last, in the 67th year of his age, Doctor Philip Thomas. The various worthy and distinguished merits of this venerable and revered character, it cannot be expected, will be portrayed in an obituary notice. He was a native of Kent County, but removed to this place very early in life. Ardently attached to liberty and his country, he took a decided and active part in our revolutionary struggle, and was often elected by his fellow-citizens to represent them in the public councils. He was appointed by the great and good Washington to an office under the general government, which he held for a number of years, and shortly after the establishment of the Medical Society of Maryland, he was chosen its President, in which situation he continued until his death. These several trusts he discharged with the most strict fidelity and integrity. As a physician, no man was more highly and deservedly esteemed for his skill. No man was ever more beloved for his affectionate tenderness and unwearied attention to the sick. As a member of society, those who have been most intimately acquainted with his principles and motives of action, can attest their purity and correctness. As a man, and in all the relative duties of life, he was a bright model of excellence, a kind neighbor, a warm steadfast and immovable friend, an indulgent master, a most affectionate parent, and in all his dealings sternly and undeviatingly just. In him the poor had always a friend, the oppressed found a protector, and friendless merit, a patron and defender. As a Christian, his conviction of the truth was the result of careful and candid examination, and was deep and riveted. Fully persuaded that man was fallen, his nature corrupt, and that but for the salvation purchased for us by the merits and sufferings of a crucified redeemer, and the divine aid graciously afforded to the believing penitent in working out his salvation, his doom must have been eternal misery. His faith in all the distinguishing doctrines of the gospel was lively and sincere ; his hopes were founded on its promises, and his entire trust for salvation and happiness was in the mercy of God through the merits of Christ Jesus. He was, as his ancestors for ages had been, and as he has often been heard to express his hopes, that his posterity might remain to be members of the Protestant Episcopal Church, warmly attached to its doctrines, its government, its pure and evangelical services. He deeply lamented the many difficulties and disadvantages with which the religious denomination of which he was a member, had to struggle in this nation generally, and more especially in the place of his residence ; and after witnessing with joy, and it is fondly hoped with gratitude to the Author of all good, the success of many efforts for its revival, it was the happiness of his declining years to have contributed in no small degree, to- wards the erection and completion of a convenient and elegant building in which its worship maybe performed, and the ordinance of our holy religion administered. But although he gave a decided preference to his own church, and anxiously wished others to agree with him, yet he never presumed to dictate to any, but desired to live, and did live in peace and charity with all denominations of Christians. While he was very young he was deprived of his father, and to the more than parental care of a kind and affection- ate brother, he was indebted for his education and the means of his future usefulness. In the pursuit of his studies, and in qualifying himself for the exercise of his profession, he was obliged to exhaust the small patrimony which he received. Without friends, and in very delicate health, he left his native county, and with it the few valuable friends which remained to him, to settle among strangers. Of the kindness with which he was received and treated by many of them, it was his delight always to speak. His professional merit soon procured him an extensive practice, and although his constitution frequently appeared to be entirely broken, and his friends often feared that they would soon be deprived of him, yet, by a life of most rigid temperance and self-denial and care, he was enabled to persevere in the practice of his profession, and at the advanced age of sixty-six, was in the enjoyment of better health, than in early life. It has now pleased Almighty God to take him from us — to remove him from this world of affliction and trouble — to rest from his labors. But few around him have had more of the blessings and comforts of this life ; but few have partaken in a greater degree of its bitterest sufferings ; but few have been more greatful for the blessings which a gracious providence has been pleased to confer, or have submitted with a more pious and humble resignation to the severest chastisements. It will be the comfort and delight of his afflicted friends to remember, and it will be their duty to imitate his shining virtues. The separation, though painful, is but for a time. "In a moment, in the twinkling of an eye," those who followed the remains of the deceased, may, like him, be a lifeless corpse. And the voice of the preacher was a warning from Heaven, even to the most young and healthful, and sounded in their ears the awful words, " Be ye also ready." The remains of the deceased were, on Thursday evening, conveyed from his late dwelling to the new Episcopal Church, where the services of the Church were performed, and a very eloquent and most appropriate discourse was delivered by the Rev. Mr. Wyatt, of Baltimore. Afterwards the corpse was carried to the burying-ground, belonging to the congregation, attended by an unusually large concourse of friends and citizens. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020