|

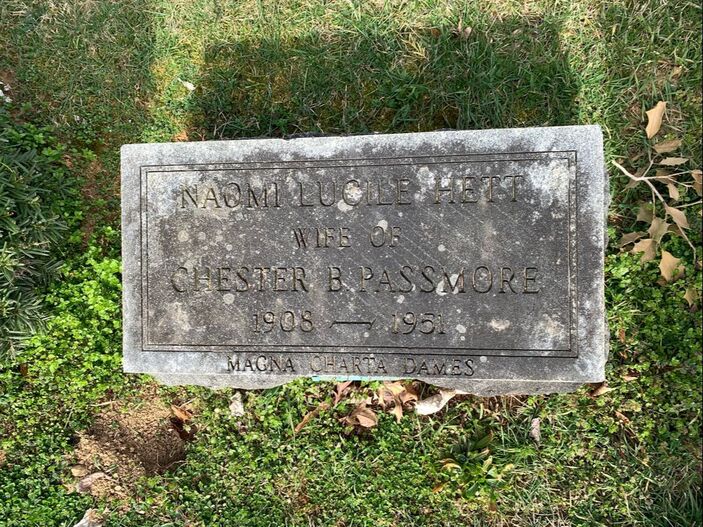

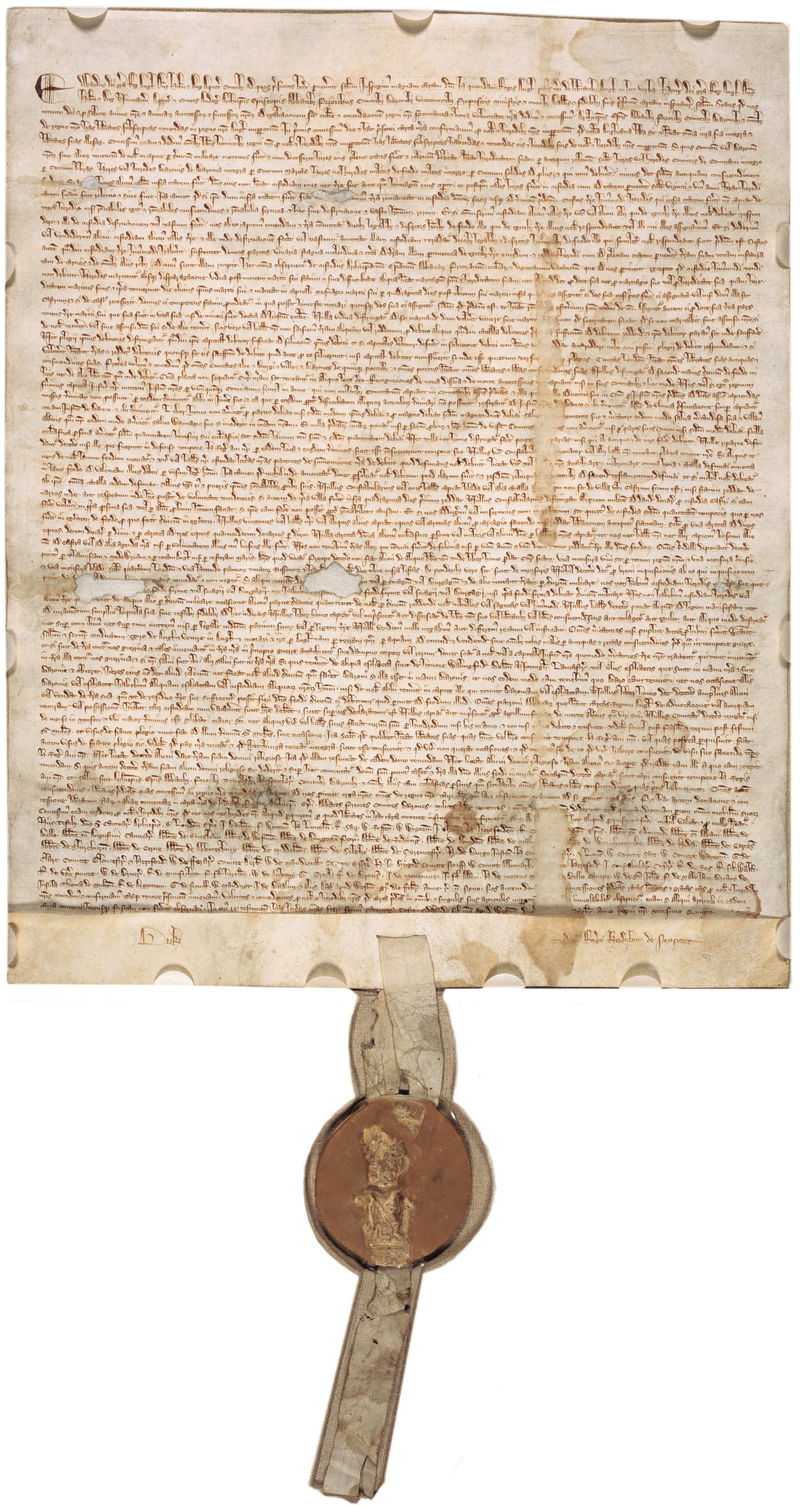

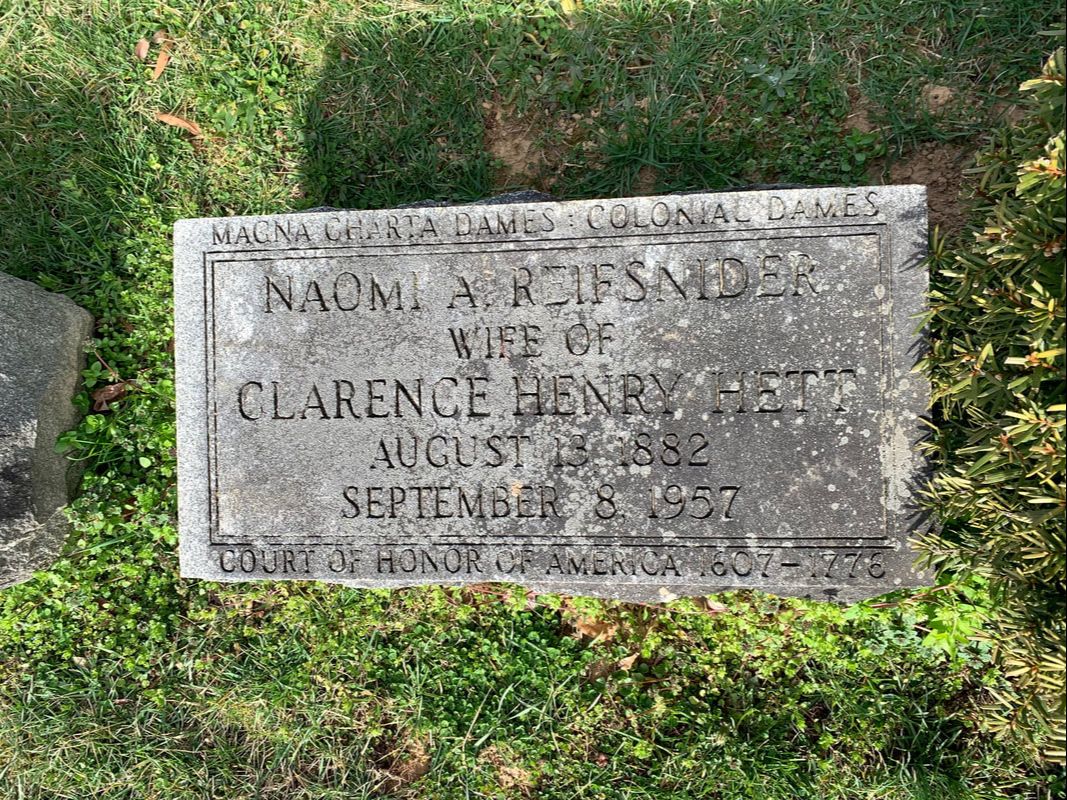

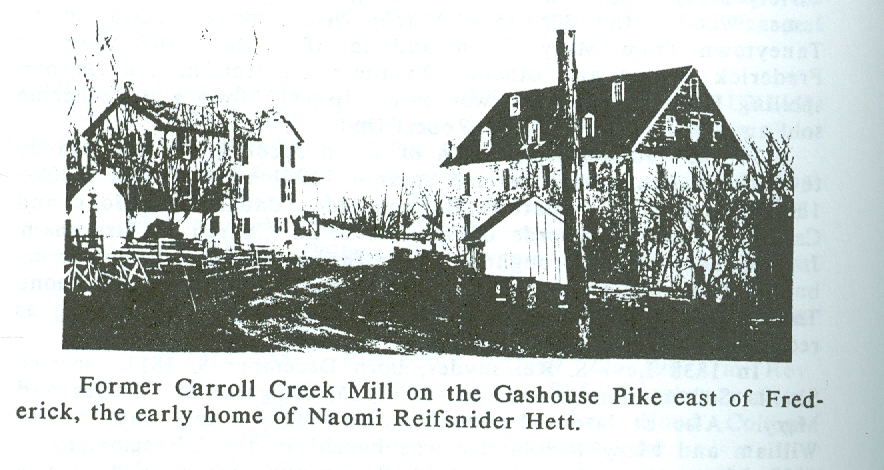

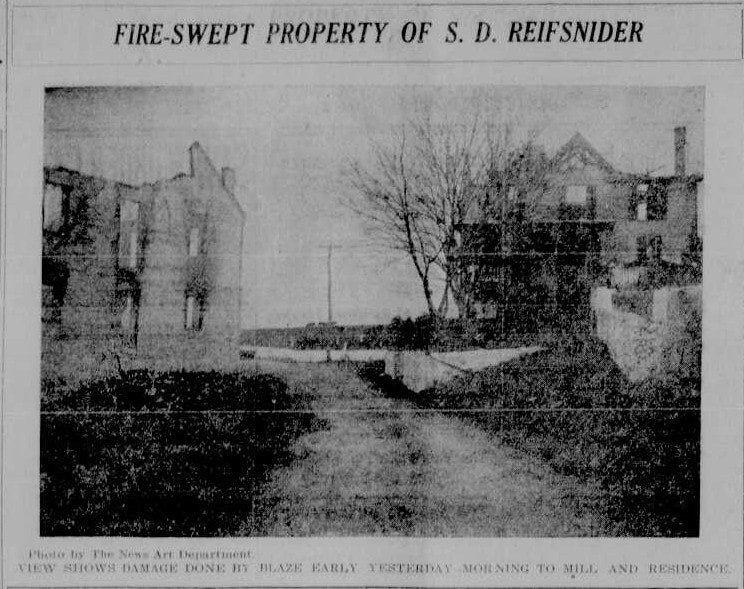

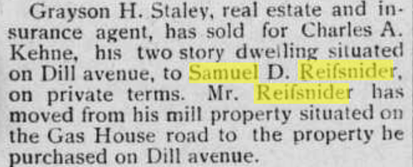

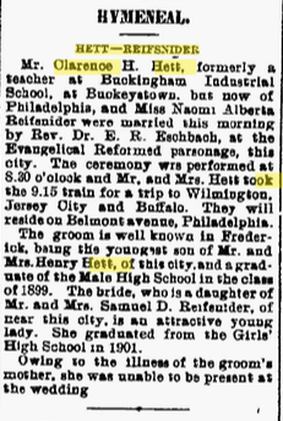

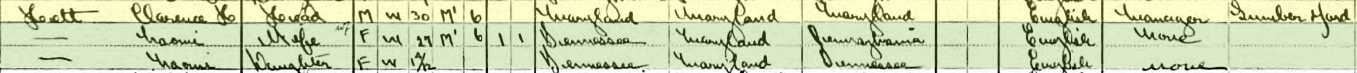

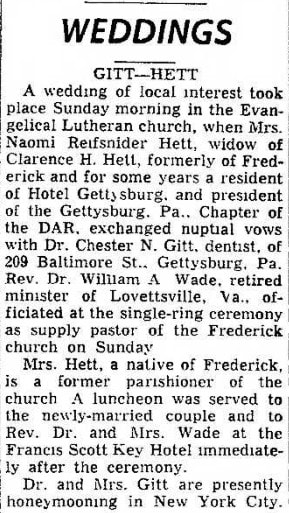

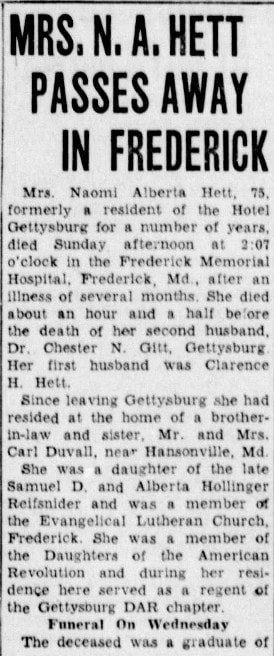

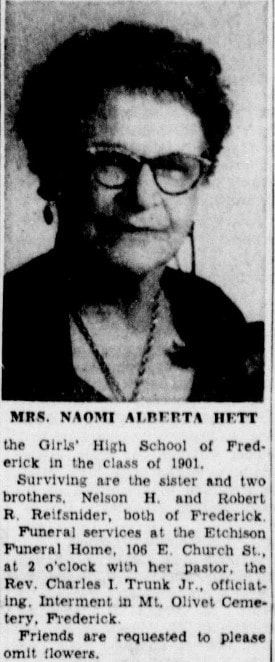

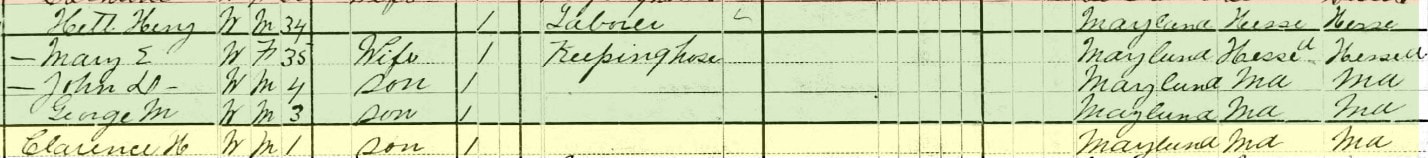

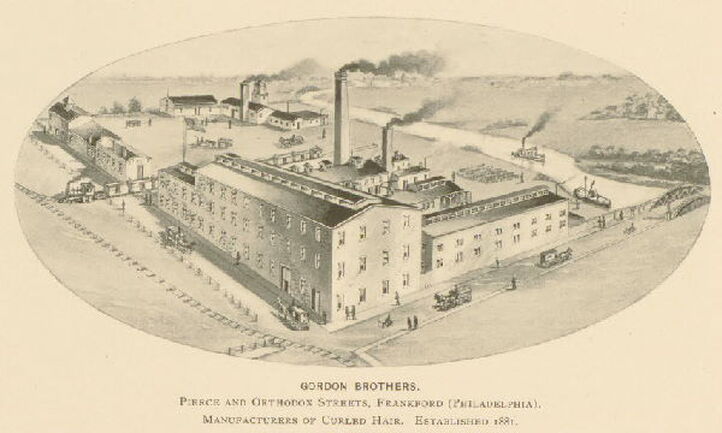

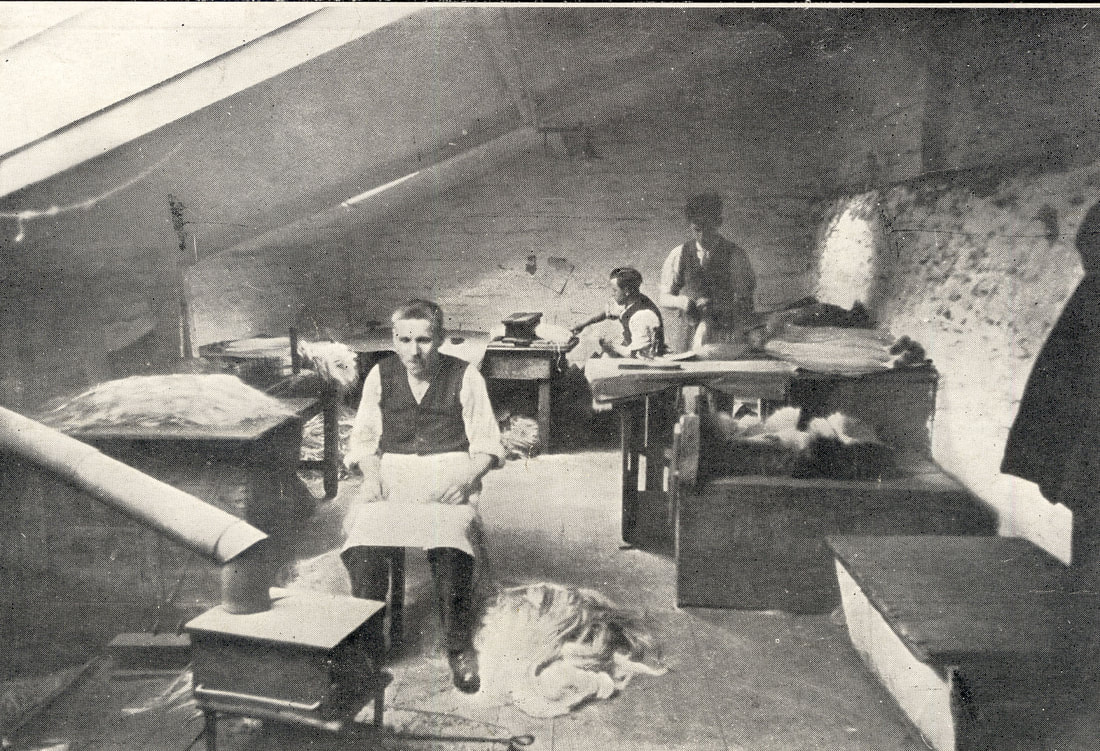

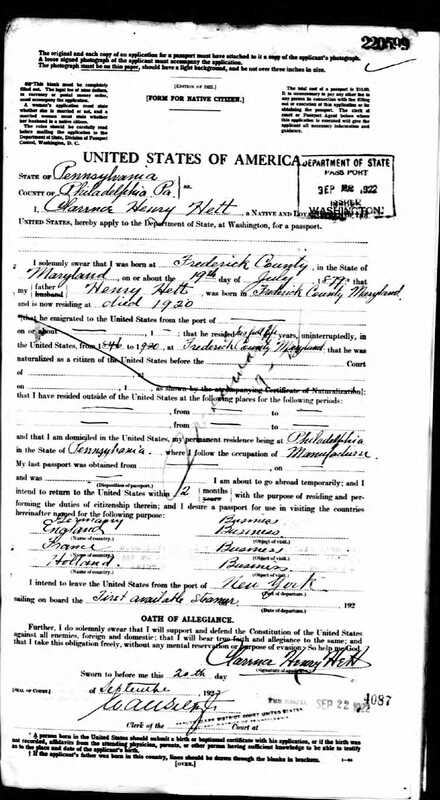

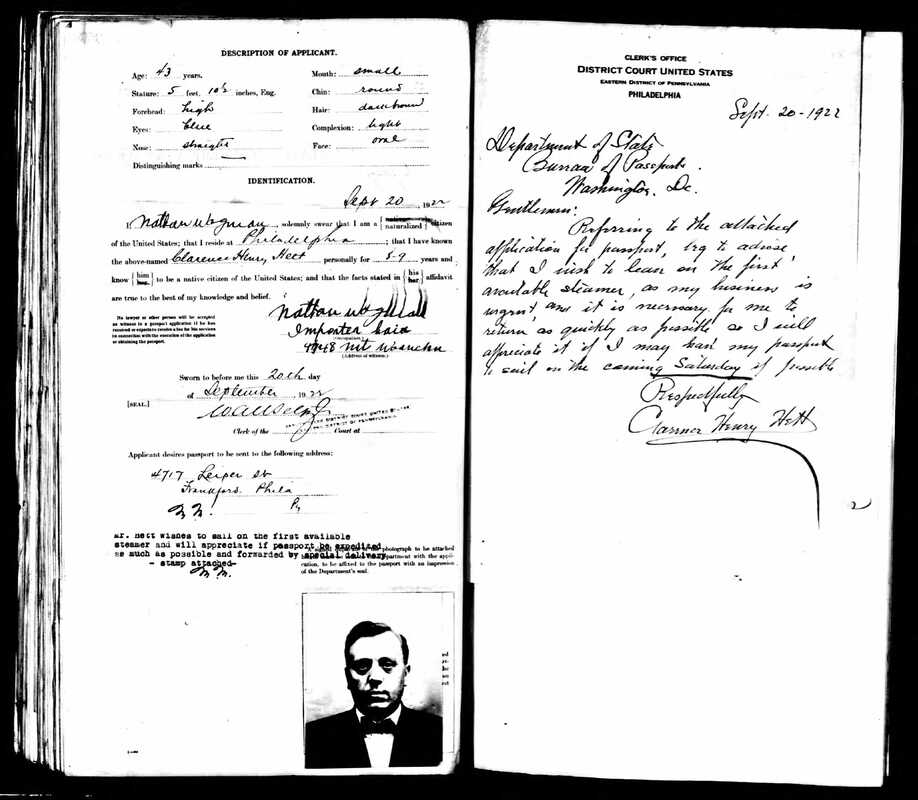

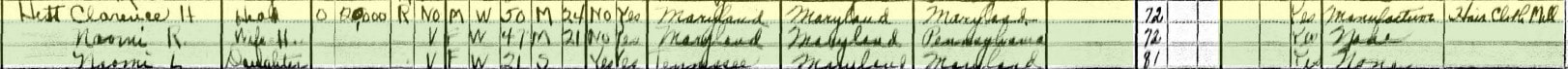

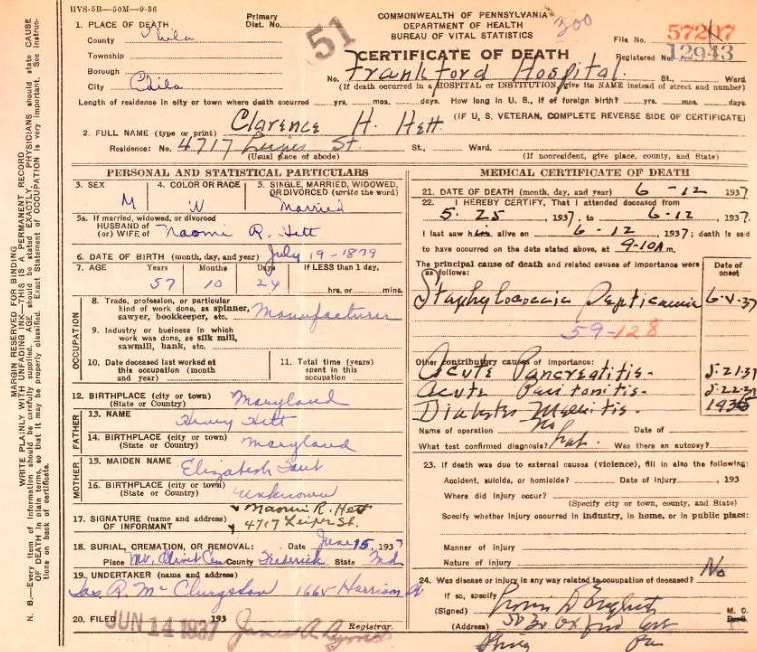

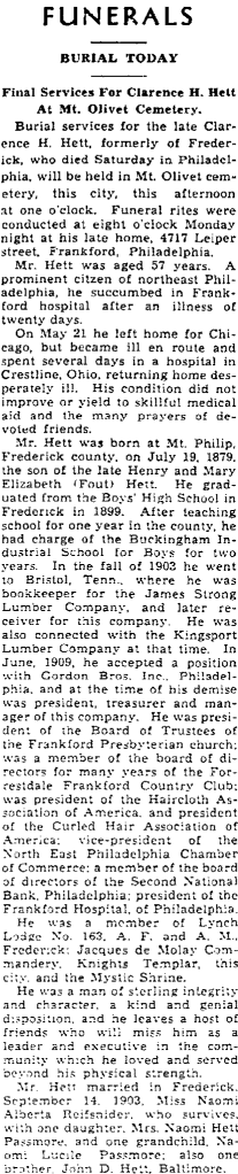

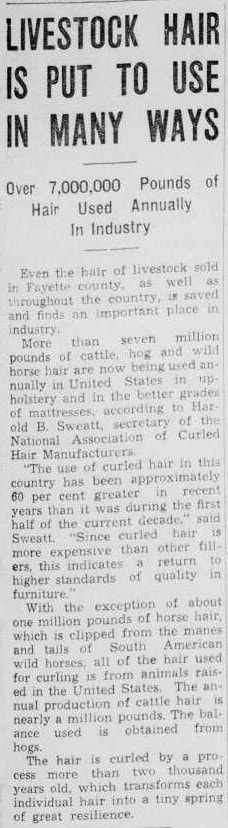

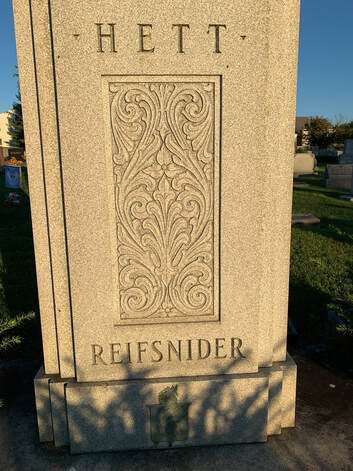

One of the most striking “newer era” monuments in Mount Olivet is located in Area AA on Lot 150. So I'm not a student of architecture, but I would classify it being in the category of Art Deco. The characteristics of this style should “reflect admiration for the modernity of the machine and for the design qualities of machine-made objects involving relative simplicity, planarity, symmetry, and unvaried repetition of elements.” One of the defining examples of Art Deco can be found in New York's most famous building, the one King Kong apparently climbed. The style is demonstrated both inside and out and the monument in question makes me think of the famed Manhattan landmark each and every time I pass by it. This is the Hett/Reifsnider Monument, likely erected around 1937/1938 and a distinguished member of our 2022 inductee class of our Mount Olivet Monument Hall of Fame. The family names are as unique as much as they are German. But there is something additionally interesting here in respect to the nine footstones that span out in two orderly rows in front of the tall, 14-foot, central marker boasting both surnames. The Hetts markers all carry some unique personal affiliations “in the margin,” if you will. Both the large family monument and the row of individual Hett family footstones in front of it are book-ended by bushes. In the center is Clarence Henry Hett (1879-1937). To the immediate right is Clarence’s wife of 33 years, Naomi A. (Reifsnider) Hett (1882-1957), and to Clarence’s left the couple’s only child, Naomi Lucille (Hett) Passmore (1908-1951). Let’s take a closer look at these individual footstone markers, shall we? Naomi Passmore’s stone naturally included the obvious vital dates and name of her husband who is buried in her lifelong home of Philadelphia. I immediately did the math in my head and found that she had outlived her father by 14 years, however she predeceased her mother. Mrs. Passmore’s marker includes the fact that she was a member of the “Magna Charta Dames.” This is an approved lineage organization in the Hereditary Society Community of the United States of America. Now what was that Magna Carta again, as it’s been a long time since learning about it in junior high history class. Plus it’s been a long time since there was such a thing as junior high—since the evolution of middle schools in the early 1980s, at least here in Frederick. The Magna Carta (“Great Charter”) is a document guaranteeing English political liberties that was drafted at Runnymede, a meadow by the River Thames, and signed by King John on June 15th, 1215, under pressure from his rebellious barons. As the first document to put into writing the principle that the king and his government were not above the law, it sought to prevent the king from exploiting his power, and placed limits of royal authority by establishing law as a power in itself. The Baronial Order of Magna Charta ("BOMC"), of which Naomi (Hett) Passmore found herself a member, is a scholarly, charitable, and lineage society founded in 1898.The BOMC was originally named the Baronial Order of Runnemede, but the name was subsequently changed to better reflect the organization's purposes relating to the Magna Charta and the promulgation of "freedom of man under the rule of law." The BOMC is a Pennsylvania 501(c)3 corporation with research, charitable, and educational purposes. Among other things, the BOMC, and the related Magna Charta Research Foundation, seek to "encourage the study and practice of the Magna Charta, within its historical context, and the evolution of its meaning as represented in the concepts of self-determination and the rule of law." Towards this end, the BOMC preserves documents and literature relating to the Magna Charta, sponsors scholarships and educational programs, and works with the Magna Charta Trust in the United Kingdom in furtherance of that organization's preservationist and educational goals. In finding Mrs. Passmore’s obituary in a local paper in 1951, there was surprisingly no mention of her affiliation with this group, however her obit does claim her membership in the Daughters of the American Revolution and the French Hueguenot Society. Go figure.  Next up is Naomi’s mother of the same name. The former Miss Naomi Alberta Reifsnider has a footstone that lists her connection with the aforementioned Magna Charta Dames, but also another group of “dames”—those of the Colonial variety. If that wasn’t enough, there is just enough room at the bottom to advertise her belonging to the “Court of Honor of America 1607-1776.” I think it’s safe to assume that we are dealing here with a lady of “blue blood,” and not “blue collar.” The Colonial Dames of America (CDA) is an American organization composed of women who are descended from an ancestor who lived in British America from 1607 to 1775, and was of service to the colonies by either holding public office, being in the military, or serving the Colonies in some other "eligible" way. A couple of interesting things I have recently learned about the former Mrs. Hett relate to her Reifsnider family here in Frederick, a prominent early mill on Carroll Creek, and a second marriage that would not last long. Naomi is buried within a few yards of her parents, Samuel David Reifsnider (1855-1921) and wife Sarah Alberta (Hollinger) Reifsnider (1854-1926). Two of her brothers are also here: Nelson Hollinger Reifsnider (1880-1958) with wife Nena Caroline (Knott) Reifsnider (1880-1947) and Robert Raymond Reifsnider (1886-1966) with wife Clytie Almeda (Baker) Reifsnider (1890-1961). Another sister, Edna Lucille (Reifsnider) Duvall and her husband Carl Duvall, are buried in Area GG, while two siblings who died as infants (Rea Halbold Reifsnider in 1888 and Samuel Miller Reifsnider in 1894) are buried in Area R. Samuel Reifsnider was a miller, who owned and operated Glissans Mill from 1877 to 1880, and Carroll Creek Mills, later known as Reifsniders Mill, from 1893-1913. The latter, originally built by Frederick’s founder Daniel Dulany about 1746, was later owned by Col. Edward Schley and most recently the Umberger family. The exact location is on the legendary S-curved portion of Gas House Pike near the current Frederick City Wastewater Treatment Plant at the mouth of Carroll Creek and the Monocacy River. The mill was flooded badly in August 1911, and struck by lightning and burned in July of 1912.  Looking west on Gas House Pike with much road reconstruction over the last few years with the Monocacy Boulevard project. The house on the right is part of the George Umberger Farm and represents the rebuild of the fire-damaged former Reifsnider home. The mill appears as if it stood where now the eastbound lanes exists today. Naomi’s father sold the family-owned mill and her adjacent childhood home between 1913-1914, and moved into Frederick City, buying a house at 236 Dill Avenue. The house associated with the mill is known as the George Umberger house in Maryland Historic Trust (MHT) documents found online, and of late the vicinity has seen a tremendous amount of development. Brother Nelson Reifsnider operated a feed and grain warehouse on North Bentz Street and lived at 608 Trail Avenue. Robert Reifsnider was a mechanic for the Baltimore Police Department, but retired in the Frederick area. Naomi had graduated from Frederick's Girls' High School in 1901 and married Clarence Henry Hett in 1903. She took up residence with her new husband in Philadelphia where Clarence performed accounting for a lumber yard. He would soon be needed by the James Strong lumber yard in Bristol, Tennessee and the couple would move and reside there until 1909. They would return to Philadelphia. Naomi would outlive her husband, and would live in Gettysburg at the Gettysburg Hotel. She would remarry a widowed dentist in Gettysburg in August 1954. Unfortunately, the couple would divorce the following year. What is more astounding, however is a novel connection in death between this former couple. Naomi’s life story is told in her obituary of September 9th, 1957, which appeared on the front page (and above the fold) of the Gettysburg Times. Three columns over, this same newspaper edition also carries news of the death of Dr. G. N. Gitt—Naomi’s short-term spouse. Naomi died at 2:07pm on Sunday, September 8th, 1957, and Dr. Gitt at 3:40pm the same day. That brings us to the aforementioned husband and father, Clarence Henry Hett. Clarence’s grandfather, John Hett (1804-1886), was a native of Hesse Cassel, Germany. A weaver by trade, John Hett came to America in 1841 and found employment at Harpers Ferry as a canal worker. He eventually relocated to the Mount Zion Road area south west of Frederick and established a successful farmstead. Now before we get into his bio, I’m sure you have noticed the distinguished, yet mysterious, resume accomplishment carved in the upper margin of the footstone. It reads: “President Curled Hair Association, USA.” Is this sarcasm, or inside joke? Is there a real “Hair Club for Men,” that elects officers? I have been blessed with naturally curly hair and am humbled by occasional compliments. But I promise you, that I will not request any mention of my “follicular blessings” on my headstone. And even if I did hold a position of authority in a “hair-related” secret society, I will stick with the basic names and vitals. For goodness sake, I also just found online that March 16th is National Curly-Hair Crush Day, there's a day for everything? This discovery, etched in stone for eternity, got me thinking. A Google search did not supply any answers, as I was hoping to find an active association for curled hair. I would eventually find my answer by researching Clarence’s professional life. Our subject Clarence Henry Hett was born July 19th, 1879 to John’s son Henry and wife Mary E. (Fout) Hett. He received a public school education and was raised on various farms owned by his father. His birthplace was at Mount Philip, whence the name of a local road just east of Catoctin Mountain and west of Frederick City. The plantation was the country estate of early Frederick physician and local leader in the fight for independence from Britain, Dr. Philip Thomas. Clarence’s father was also successful in farming and trucking, but would retire from the duties of agriculture in 1892. At this time, he moved his family to Frederick City and eventually opened a grocery store with Clarence’s older brother George. The firm was named H. Hett & Son. Clarence went in another career direction, that of teaching. He began a short career at the Shookstown Public School in 1900. He would soon find himself in charge of the Buckingham School for orphaned boys (south of Buckeystown). Clarence married Naomi in 1903 and changed careers, eventually settling on one that would have a distinct relation to the early weaving trade of his grandfather. He would take up employment as a bookkeeper at a lumber yard in Philadelphia, and would spend some time in Bristol, Tennessee. He would return to the City of Brotherly Love where he would live most of his life working for a cloth mill. But this was no ordinary mill, it was a “hair-cloth” mill. Bingo! I soon learned that horsehair fabrics are woven with the tail hair from live horses and cotton or silk warps. The last remaining manufacturer, John Boyd Fabrics of Castle Cary, England, still uses the original looms and techniques from 1870. Hair cloth was widely used by top end furniture designers, and is still used for a wide range of upholstered furniture. The fabric is known for its luster and is used by contemporary designers for its luxury and durability. Horsehair cloth became popular in the 1800s due to an abundant supply from live working horses whose tails were cropped. Today, the horsehair is sourced from countries such as Mongolia who still work horses with cropped tails. The Hett family lived in northeast Philadelphia in the Frankford neighborhood where the Gordon Brothers factory was located. The couple would just have one daughter in Naomi. The unique presidential achievement listed on Clarence Hett's footstone is duly mentioned in his 1937 obituary, along with his interesting employment history and many civic and social duties and activities. He fit a great deal of things in during his shortened life of 57 years. A final search of the Curled Hair Association in old newspapers only provided me with one result, but it showed me an article from 1939 that proved that there was actually a National Association of Curled Hair Manufacturers. And with this, I believe the semantics mean that the “curled hair” was processed by manufacturers, and not that the manufacturers, themselves, possessed curled hair. I will confess that there is a very minute chance that I could be wrong on this, however. The moral of the story and takeaway I guess, lies in the fact that cemetery plots may boast a breathtaking central monument or sculpture, but be sure not to miss small clues and details captured in stone on associated markers and plaques at ground level. But then again, I may just simply be “splitting hairs” here.

0 Comments

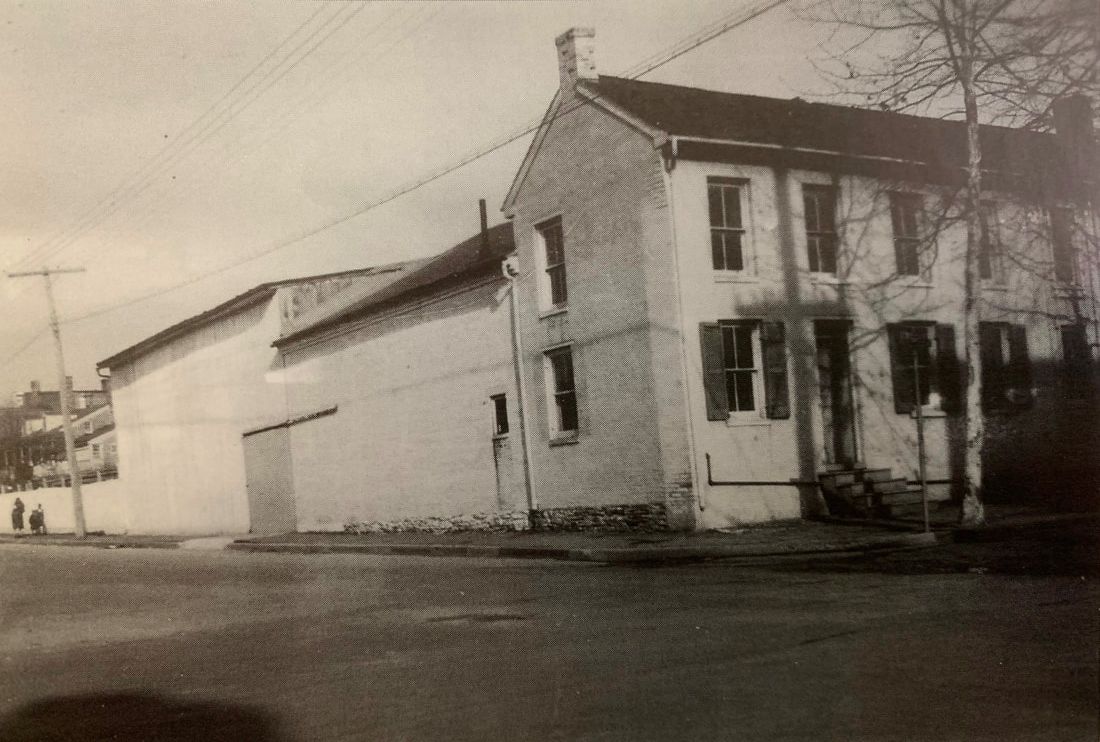

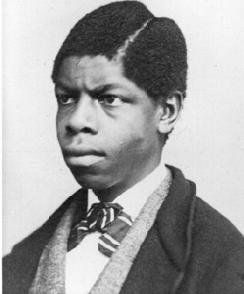

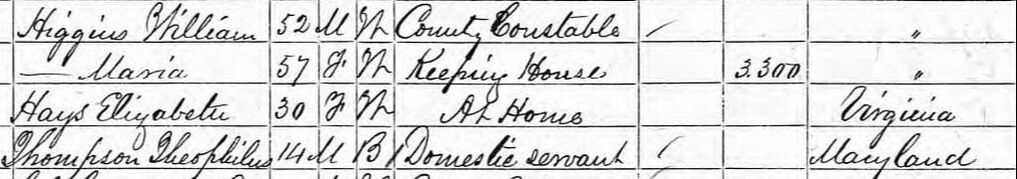

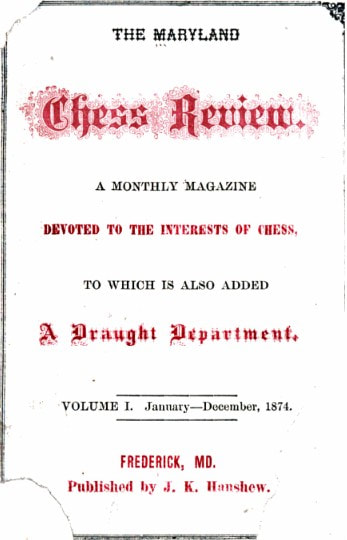

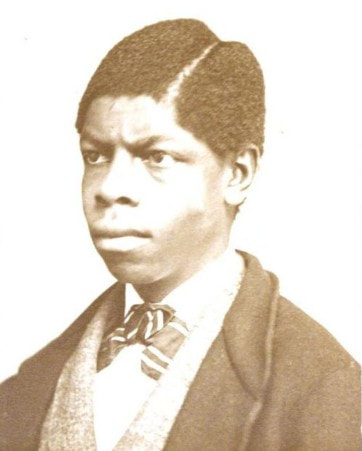

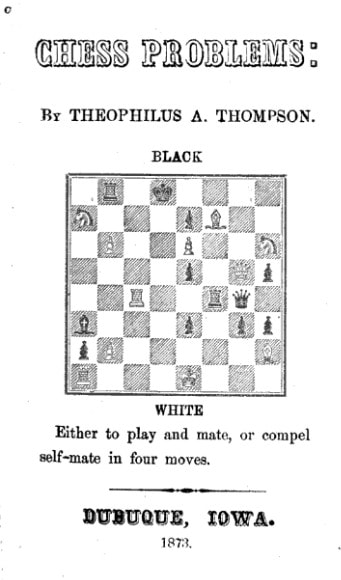

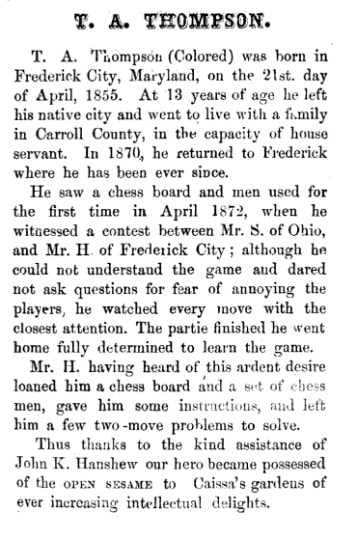

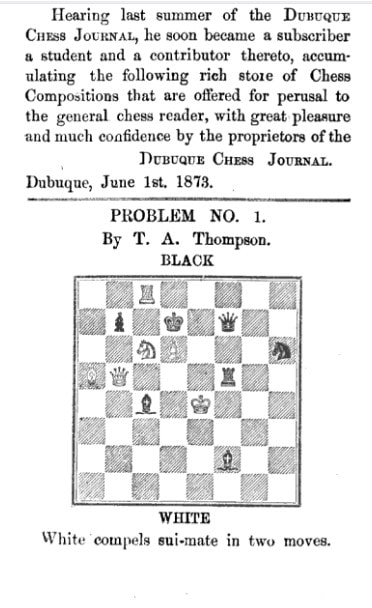

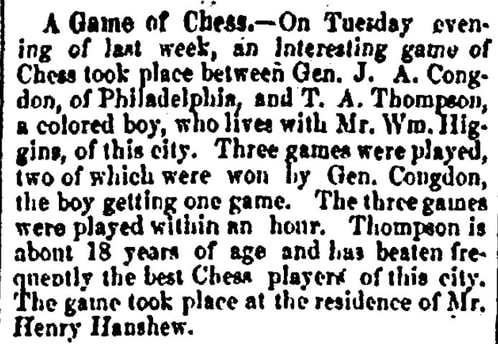

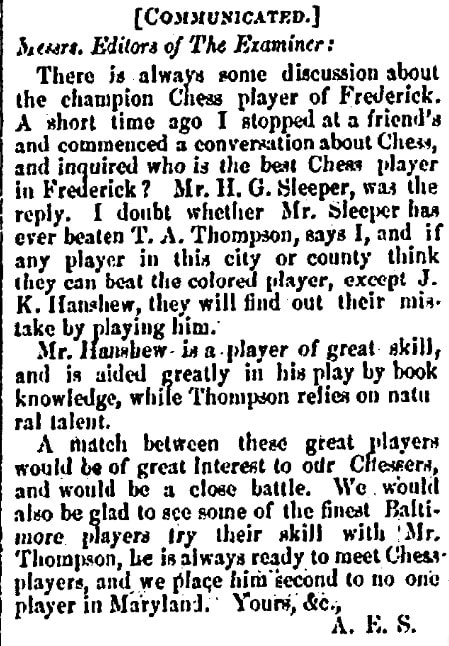

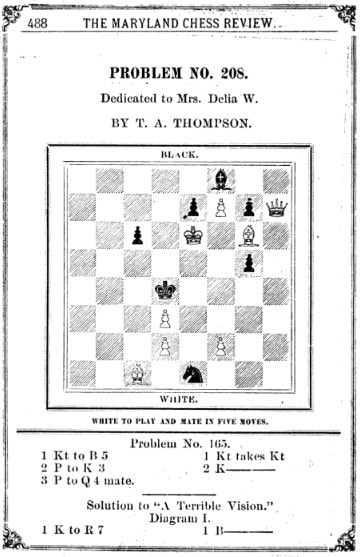

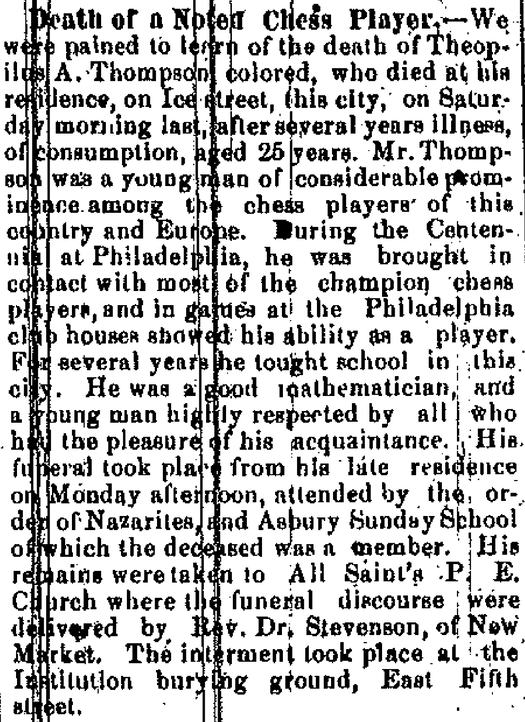

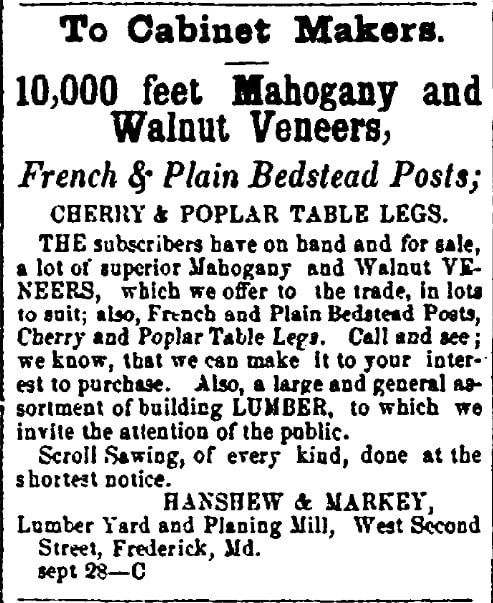

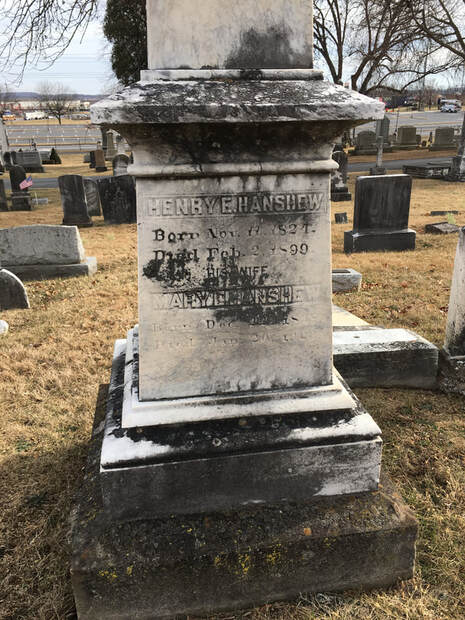

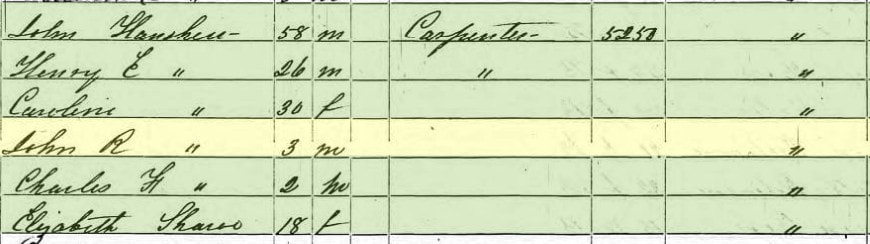

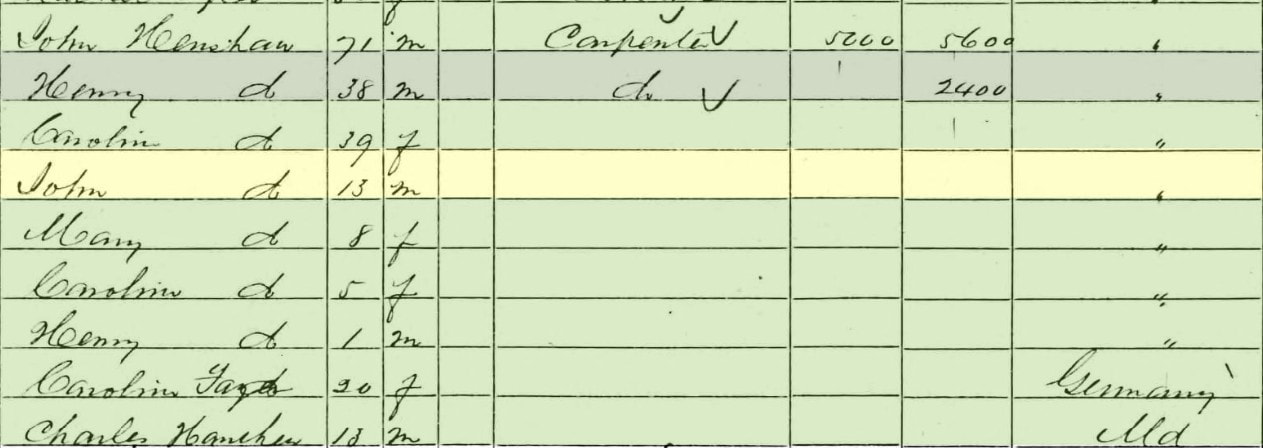

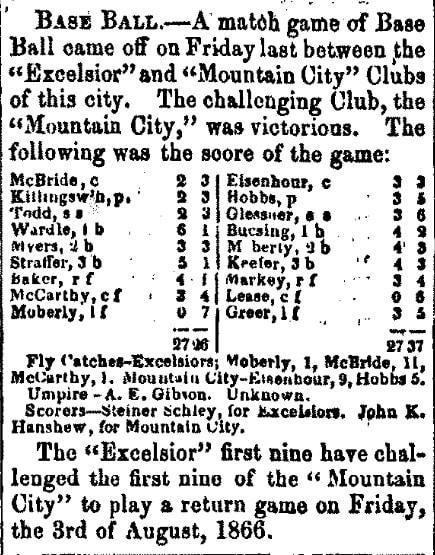

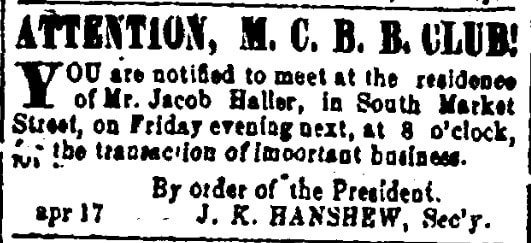

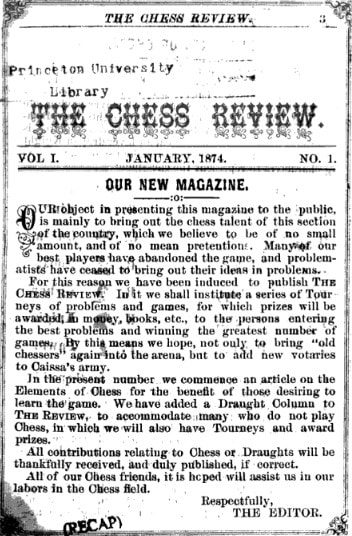

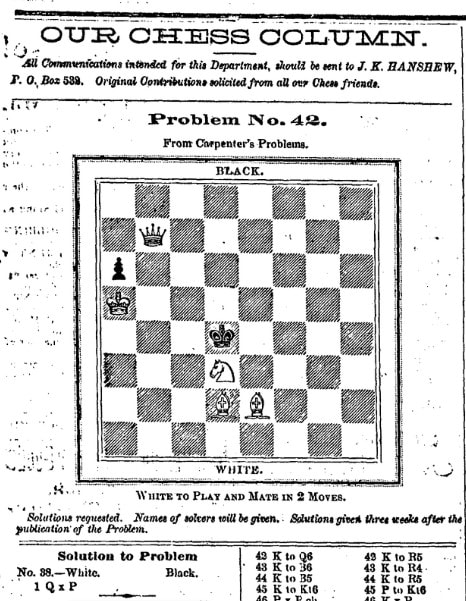

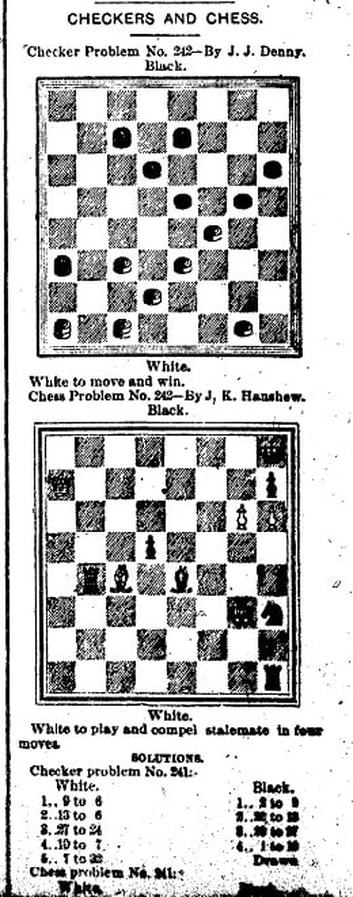

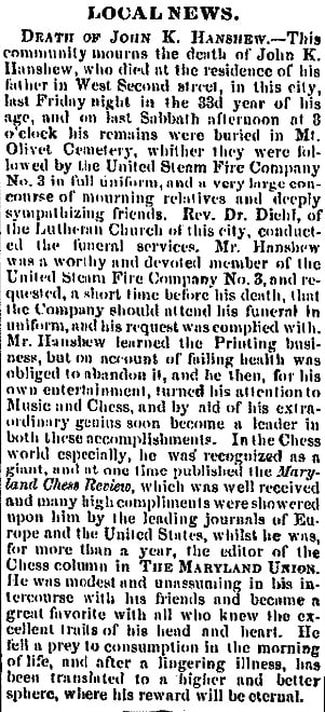

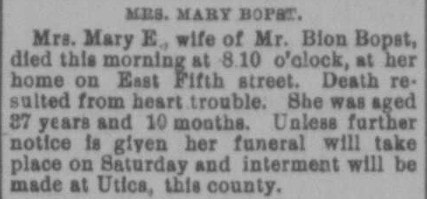

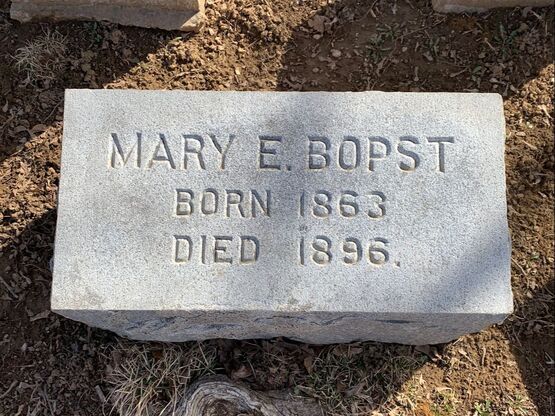

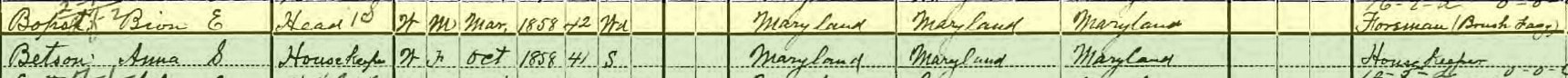

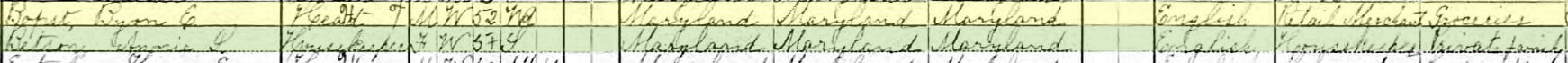

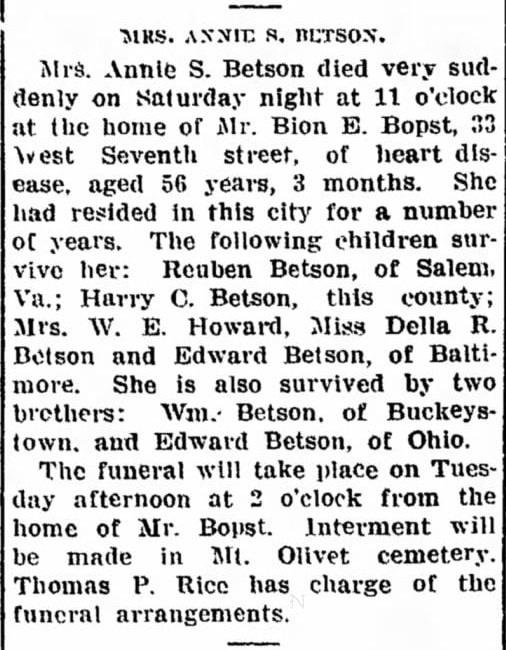

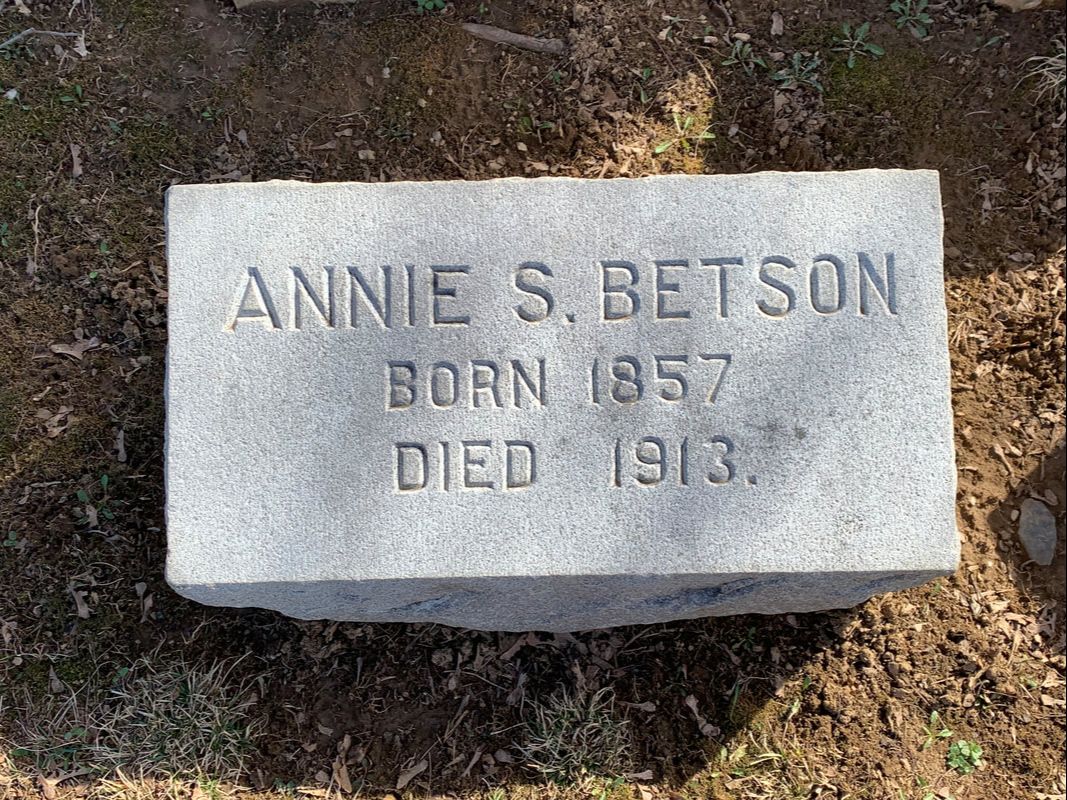

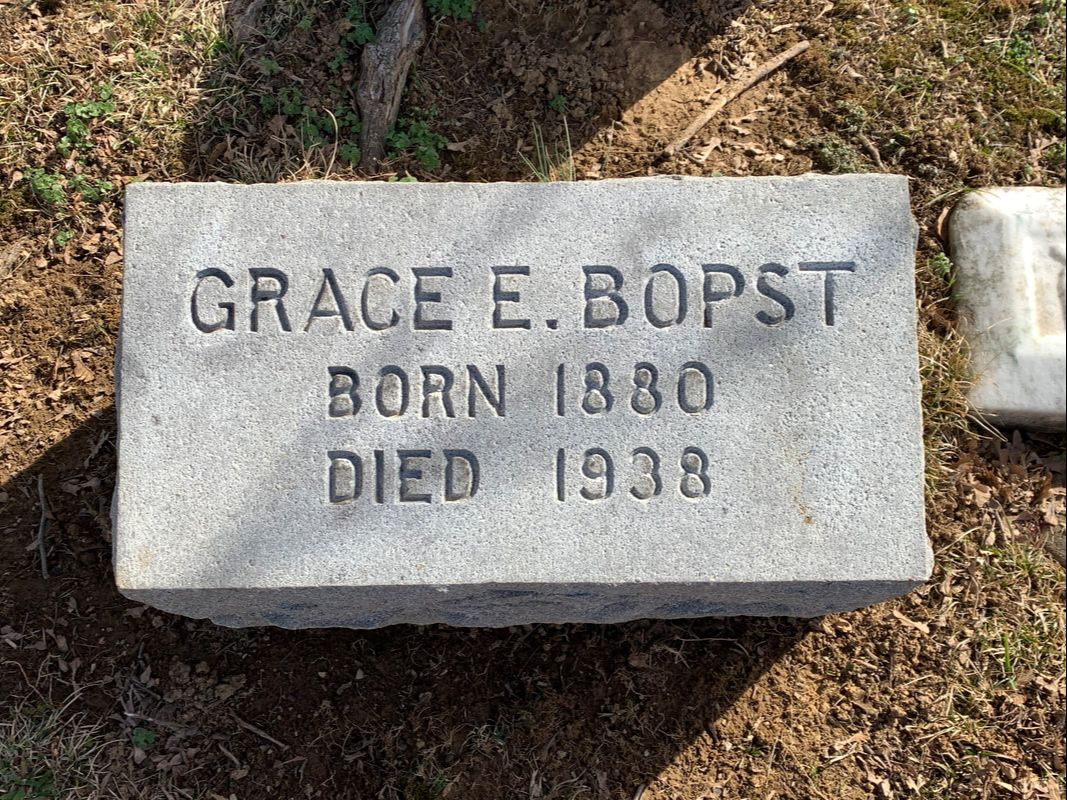

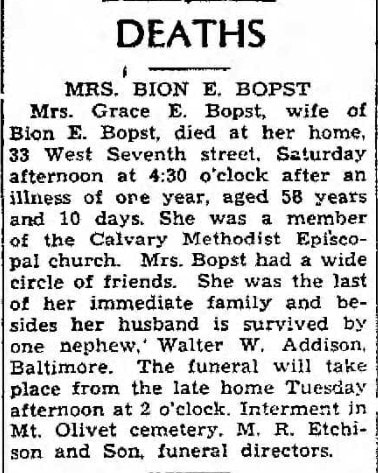

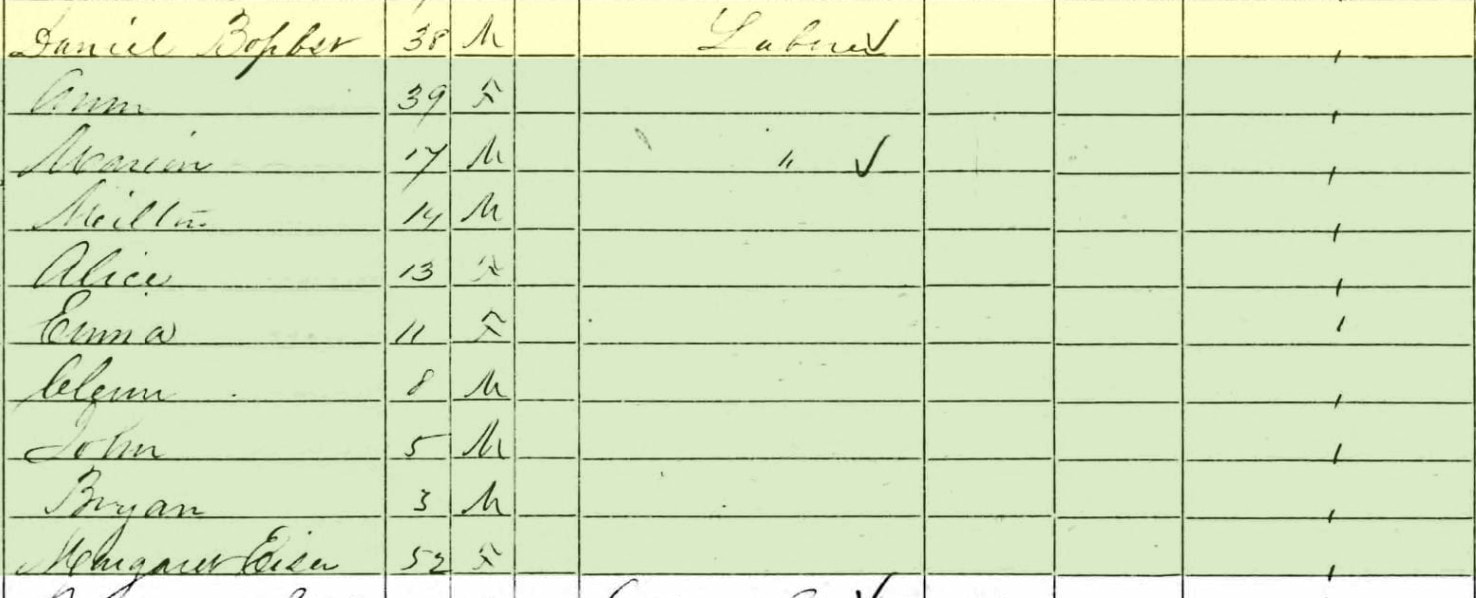

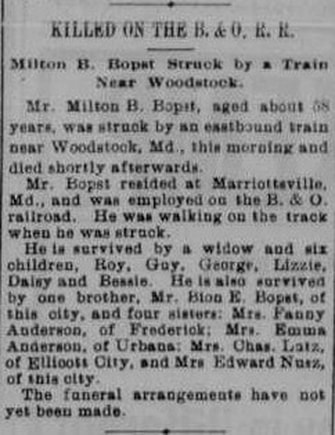

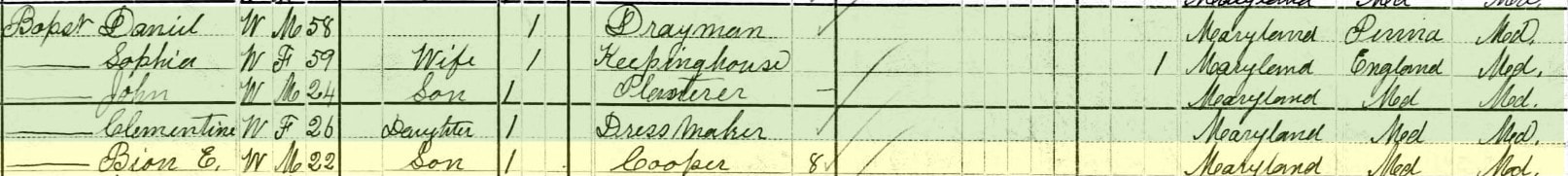

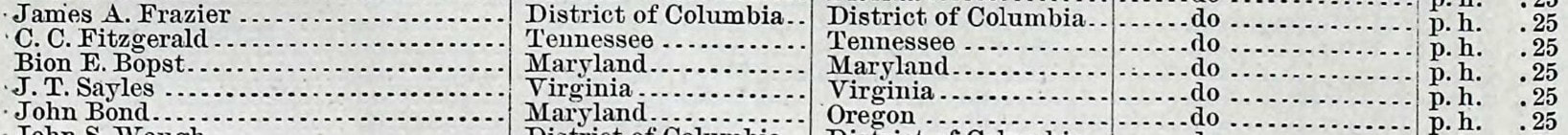

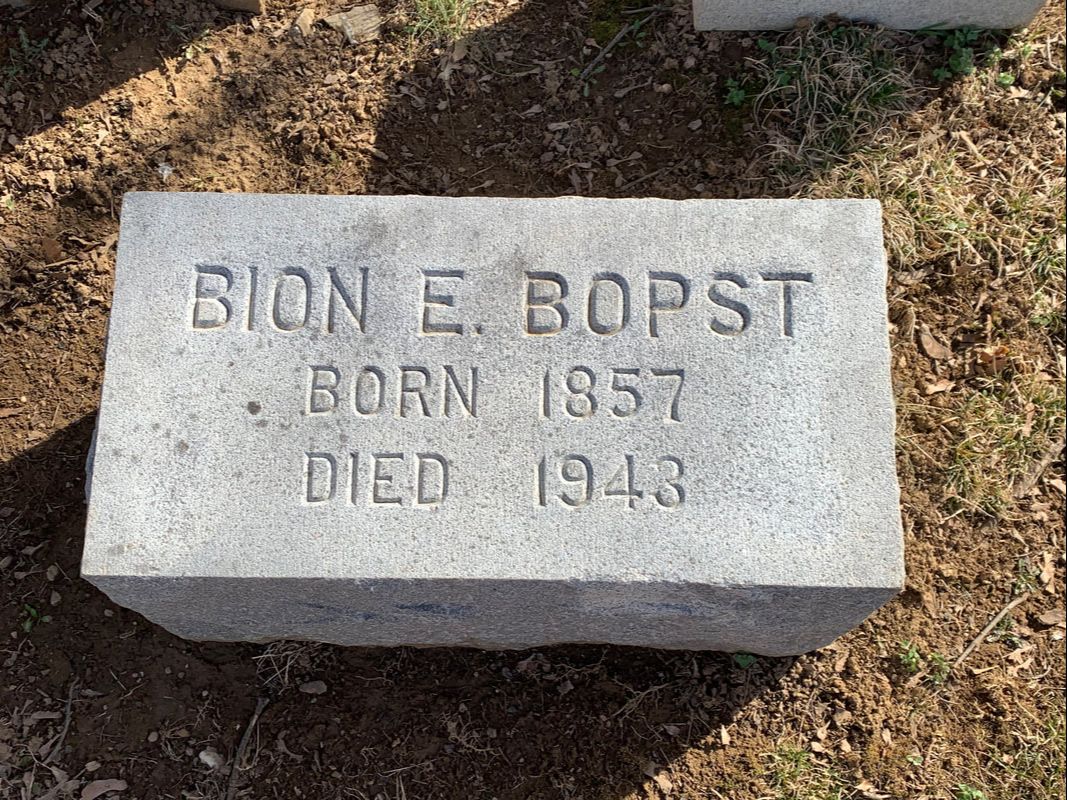

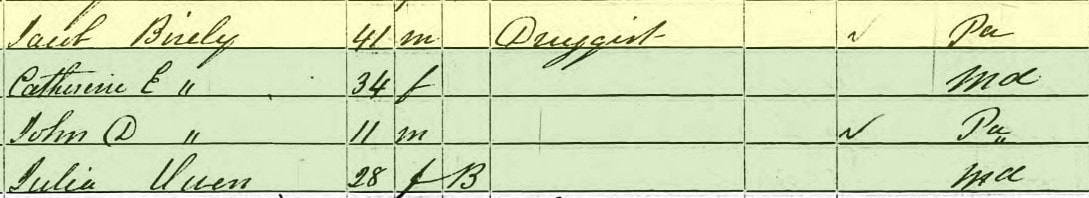

If you told me 30 years ago that I would one day be working full-time for a cemetery, I wouldn’t have believed you. More so, If you told me 30 years ago that I would not only be working full-time for a cemetery, but while there, would one day find myself intently perusing the website of the US Chess Center, I would have thought you were some sort of heretic. Well, by now, you know what I’ve been doing for the last hour—pretty odd for a guy who knows nothing about the game of chess, but could play checkers with the best of them back in his youth. The US Chess Center is located in nearby Silver Spring and promotes “self-confidence, social skills, and academic success for all” according to their webpage found at www.chessctr.org. “This group prides itself in providing students from throughout the Washington metropolitan area opportunities to meet as friends and equals over the chessboard at weekend classes, tournaments, and special events. The Center’s student programs have hosted World Champion Garry Kasparov, the national champions of Nigeria and Montenegro, and International Grandmasters including Maurice Ashley, the first African-American Grandmaster. Affiliated students have played Internet matches with students from China, the Czech Republic, Montenegro, Norway, Spain, Ukraine, and Zambia.” I was particularly interested in learning a bit more about Jamaican-born Maurice Ashley who, in 1999, was awarded this title of Grandmaster (GM) by the international chess governing body FIDE (Fédération Internationale des Échecs) for outstanding performance. In 2016, he was inducted into the US Chess Hall of Fame, located in St. Louis. In my limited knowledge on the sport, I could only name two chess players, popular icon and Grandmaster/Hall of Famer Bobby Fischer, subject of the movie Searching for Bobby Fischer, and Frederick’s own Theophilus Thompson. The latter gentleman recently had an art piece erected in his honor on Frederick’s Carroll Creek Park. The unique honor speaks to Theophilus Thompson’s standing as perhaps the first African-American chessplayer, a century before the forementioned Maurice Ashley began playing in his youth. A couple from Denver (Tsvetomir Naydenov and Marguerite de Messières) created “An Elusive Kinetic Portrait,” which has been displayed on Carroll Creek since 2020. The sculpture is part of the Carroll Creek Kinetic Art Promenade, a series of works positioned in the waterway that move with the wind. Born into slavery in Frederick on April 21st, 1855, Theophilus Augustus Thompson would eventually work as a domestic servant in Carroll County for a few years until moving back to his hometown in 1870 in the employ of siblings Maria and William Higgins, a county constable in Ward 6. Also listed in the Higgins household was a Virginian named Elizabeth Hays, but I failed to find her familial connection to the Maria and William Higgins, if one at all. In 1870, Theophilus Thompson and the Higgins family lived next door to the Henry Edward Hanshew family on West Church Street. An important member of the Hanshew member can be credited with Thompson’s eventual appearance on Carroll Creek. This was John Keller Hanshew, a 23-year old printer who published the Maryland Chess Review by his own volition. Hanshew began this publication in 1874, and just one year later, a mere five years after he had first learned the game, the young man was elected vice president of the American Chess Association. Theophilus Thompson's interest in chess was sparked while observing a chess match between John Hanshew and a "Mr. S. of Ohio." Thompson would later recall that this inspirational game occurred in April of 1872. He watched the men play, although he "dared not ask questions for fear of annoying the players." Hanshew noting his neighbor’s interest afterwards loaned Thompson a chess set and helped him learn the basics of the game. Theophilus quickly became a skilled player, practically teaching himself the game. Thompson would later write that the initial guidance and support from Hanshew was the "open sesame to Caissa's gardens of ever increasing intellectual delights." So one of the things that makes Mr. Thompson so intriguing (among many) is his name. I found several others across the country with this name in the 19th century and this led me to believe that there likely exists a famous namesake. Sure enough, I was correct, as there was a prominent London physician of the Victorian era that went by this name. Theophilus Thompson, M.D., F.R.S. (1807–1860) was known by American physicians for published clinical lectures and his writings on tuberculosis and influenza. Our chessmaster, Theophilus Thompson, competed against local players, both in person and via correspondence (in which the two players would send moves, one at a time, by mail). However, the young man would achieve his greatest acclaim as a composer of chess problems, himself. Thompson contributed individual checkmate puzzles to chess periodicals before publishing his own anthology entitled Chess Problems: Either to Play and Mate, in 1873, just one year after learning the rules of the game from John K. Hanshew. Interestingly, this was printed by a publisher in Dubuque, IA, instead of by Theophilus' friend and mentor, Mr. Hanshew, right here in Frederick. Theophilus Thompson’s accomplishments were remarkable, and not just because of the circumstances related to his birth and early youth as a slave. In the nineteenth century, there were very few players who made any significant mark in the chess world before turning twenty. Not only did Thompson win games against seasoned adult competition while still a teenager, but with the release of his book in 1873, he may have been the youngest published chess writer at the time. His talents attracted recognition as far away as London, where the City of London Chess Review Magazine praised a puzzle from his book as “one of the most beautiful compositions that ever came before our notice.” Not much was known about Thompson’s life after the publication of his book until a more recent discovery of his death notice in the archives of the Frederick Examiner. His obituary explains that he worked as a schoolteacher in the city of Frederick and is also said to have lived on Ice Street at the time of his passing. The fact that only a couple of Thompson’s problems, and none of his games, are dated after 1875 suggests that the tuberculosis affected his ability to fully apply himself to chess in the last few years of his life. Theophilis Thompson ironically died from the very disease his namesake was known for studying and writing about-- tuberculosis. His death occurred on October 8th, 1881. He was only 26. Theophilus' gravesite is unknown today, but his obituary states that he was buried at the Institution Cemetery on East Fifth Street which likely correlates to Laboring Sons Cemetery, today the site of a memorial park. I did count a number of Thompsons at Fairview Cemetery on Gas House Pike who could be relatives. Perhaps Theophilus Thompson's body was brought there as well when bodies were removed from Laboring Sons around 1949. Due to segregation, there was not an opportunity for Thompson to be buried here in Mount Olivet. However, his employer Maria Higgins (1811-1880) can be found in Area H/Lot 283, although unmarked with a gravestone. The fore-mentioned, Miss Hays, is in the same plot, but has a final stone that reads M. Elizzie Hays (c.1833-1871). More importantly, Thompson’s friend and mentor, John K. Hanshew, is here in Mount Olivet as well. Hanshaw had died of the same disease (tuberculosis) two years earlier and can be found in Area E. John Keller Hanshew was born January 5th, 1847 in Frederick, the son of Henry Edward Hanshew (1824-1899) and first wife Caroline Keller (1820 -1868). John was the oldest of five known children, and the family were regular members of the town’s Evangelical Lutheran Church. The Hanshews lived at what is now 127-129 West Second Street (129 is now part of the Calvary United Methodist Church property). It was also originally the site of a planing mill operated by John K.’s grandfather, John Frederick William Hanshew (1790-1863). The property had been acquired in 1821 according to land records.  The author believes this to be the Hanshew home that once stood at 129 W 2nd on the northeast corner of N Bentz and W 2nd. Note the adjoining planing building(s) that once fronted on Bentz Street. These were part of the family carpentry business until it was sold and later operated as the Wilcoxen & Brown Lumber Company for many years. The Hanshew home was demolished sometime before 1930 when the Calvary United Methodist Church opened here, moving from its previous location on East Church Street (where a parking deck now stands). The home pictured above (at 127 West Church) is said to have replaced an earlier structure. The Hanshews are the epitome of a classic early Frederick German family akin to the stories surrounding others such as the Schleys, Steiners and Bruners. Their surname, originally spelled Handschuh in the native language, points to an ancient profession as you can separate both words “hand”-“schuh” which translate to hand and shoe as we know them. If you were to request a “handschuh” in Germany, you would be offered a pair of gloves. Our subject’s great-great grandfather, Frederick William Handschuh (1714-1764), came from the village of Halle, in the (east) German state of Saxony-Anhalt. He emigrated to America, arriving in Philadelphia in 1748—the same year Frederick County was founded in Maryland. Handschuh would settle a short distance west of Philadelphia in Chester County’s Germantown, aptly named by design by the Penn family who were warmly welcoming these frugal, industrious and God-fearing people to his Pennsylvania colony. The immigrant’s son, Frederick William Handschuh (1760-1832), would change the spelling of the family name to Hanshew, for himself and later descendants. More importantly, he would relocate to Frederick Town sometime before marrying his wife Maria Whitehair in the year 1784. Frederick W. Hanshew would have a son John Frederick Hanshew (1789-1867) who later established a planing mill and lumber yard at the intersection of West Second Street and North Bentz Street. In the 1850 census, we find Henry E. Hanshew and family living on West Second Street, as earlier mentioned, with his widowed father for whom our chess enthusiast was named. Both Henry and his father (John), are naturally listed as carpenters in this census, and again in the 1860 census. John Keller Hanshew must have known his way around the family woodworking business, however he would be listed as a printer, and not a planer, a decade later in 1870. I don't know exactly what he was doing at this time period of life, as he was just too young to serve in the US Civil war. I did learn from old newspaper clippings that he was quite proficient of tracking more than chess moves. He was the official scorer of a local Frederick baseball team. He also served as the Mountain City Baseball Club's Board Secretary as well. Hanshew was a member of the United Fire Company too. As stated earlier, John began his chess publication in 1874, and he was aided by friend Theophilus Thompson in providing "chess puzzles/problems" for his readers to solve. Mr. Hanshew's chess problems would be utilized years later in various newspapers across the country. The first half of the 1870s decade saw John and his friend Theophilus engaged in a world of pawns, bishops, rooks, kings and queens—“checking and doublechecking” every move in life so to speak. Sadly, these two “checkmates” passed far too early. Both men can, and should, be remembered when visiting the Hanshew family lot at Area E/Lot 104. Mount Olivet’s “chessmen.” The neighbors of the Hanshews, with whom Theophilus was living in 1870, were Maria and William Higgins. These were the children of James Lee Higgins (1770-1837), the founder and first minister of the New Market United Methodist Church (formerly known as New Market’s Methodist Episcopal Church). Rev. Higgins would later become the first ordained bishop of the Methodist Church in the United States.  Rev. Higgins wife (Sarah Dorsey) came from a very large slaveholding family in our county’s history. Rev. Higgins and Sarah owned a large plantation in the area of New London, north east of New Market. There appears to be a connection between Theophilus and the greater Dorsey family of eastern Frederick County (and western Carroll County). At the time of Rev. Higgins’ death in 1837, it appears that son William inherited part of his property on Linganore Creek, as well as a number of enslaved persons. He manumitted four of them in 1840 and four more in 1842 (to take effect years later, as he mortgaged some of them in 1842 to pay off some debts. About the same time he mortgaged goods from a store he apparently had in nearby New London.) I wonder if any of those manumitted were the parents of Theophilus Thompson? William had two brothers-in-law who were slave owners in the 1850 and 1860 slave schedules: Perry Bennett and Ephraim Maynard. Bennett did live in Carroll County but also obtained the Higgins plantation which are both potential links to Theophilus having been a servant to someone during his youth in slavery and post- Emancipation in Carroll County from 1868 to 1870. This has yet to be proven however. The last hypothesis I will offer to Theophilus’ possible origins come in the form of the most influential early Thompson in Frederick’s history—John P. Thomson/Thompson, newspaper publisher of the Frederick Town Herald for many years . ( NOTE: See our earlier “Story in Stone” entitled “Heralding the 8th of July.” He was a nearby neighbor of Higgins in the Court Square Area during the 1850s. ) Could our chess champ been given this surname by this man? Rev. Higgins and wife Sarah are buried at Central Chapel near the intersection of MD 75 and Old Annapolis Road. As I said earlier, we have Maria Higgins interred at Mount Olivet in Area H/Lot 283, however her grave is unmarked like her father's and brother's to my knowledge.  As for William Higgins, he never bought any property in Frederick, instead he is indicated as living in Keefer's Hotel (later Carlin’s Hotel on the southwest corner of N. Court and W. Church streets) in 1850, a renter in 1860, living with sister Maria and Theophilus in the 1870 census. He is listed as a boarder in 1880 with the William Wright family on East Patrick Street. Mr. Higgins served various civic duties including county bailiff, acting coroner, Justice of the Peace, and city tax collector. I'm not sure whether he ever married, or what happened to him later in life. I presume that he may be buried in Central with his parents but am not sure. I guess you could say I’m at a "stalemate" when it comes to learning more about this fellow, not unlike my difficulty in discovering more on Theophilus Thompson and John K. Hanshew, I guess. The date was April 23rd, 2019 and it seems like a “lifetime” ago—something not to be taken lightly when said in a cemetery. We lost a prized and picturesque monument, or so we thought, due to an unkind act of nature. For an individual in charge of a preservation program aimed at caring for hundreds of previously downed and damaged gravestones and markers, it was certainly not an “uplifting” moment. This was nearly a full year before we would be panicked and quarantined due to a respiratory virus whose name, up to that point, was more commonly associated with a Mexican beer than an international pandemic. I’m noticing more and more how that period of 2020 was like a time warp, and certainly has thrown all of us off in remembering events and measuring/calculating time. A true speed bump for a historian with a great memory of past events. But I digress. It was particularly painful to see this lovely statue get damaged. A violent electrical storm brought with it strong winds and, we deducted, a lightning strike which felled a neighboring tree. There was a “silver lining,” however, in the fact that the tree fell in such a way that didn’t pulverize the statue with a direct hit. A limb was responsible for the principal damage as it sheared the figurine’s bowed head, which was attached to the right hand which snapped at the wrist. A stray finger was also a casualty, but I quickly gathered these pieces up for future repair. The toppled monument in question has its home in Area L, behind our Key Memorial Chapel. For over a century, the sculpture of this mourning woman has sat atop a large two part base, the centerpiece of a cemetery plot surrounded by smaller raised footstones. These belonged to the family of Bion E. Bopst—pronounced “bôw-pst” with a long “o.” Although this surname seems rare, we have 49 interments with this moniker buried throughout Mount Olivet. Plus, it’s fun to say Bopst, especially Bion Bopst! I did a search on the internet to see if I could find a name meaning for Bopst. Here is what I disovered on a site called www.4crests.com: “This surname of BOBST was a Russian and Jewish nickname from the word BOBR meaning 'beaver'. It related to the brownish colour of the owners hair and complexion. The name has numerous variant spellings which include BOBROFF, BOBROWSKY, BOBSTE and BOBZEN.” The Bopst monument, as I’ve referred to it for seven years now, is among the most beautiful in the cemetery. In my first year on the job here, I took several pictures for use in marketing materials for Mount Olivet such as brochures, our website and Facebook. Ironically, I also used a beautiful fall time photograph I had taken for a title page within a PowerPoint presentation I often give on the preservation mission we have here at the cemetery. Bopst Family Lot 192 was purchased by Mr. Bion Eugene Bopst in 1901 as a place to re-inter his first wife, Mary E. (Bruchey) Bopst. Mary had originally died five years earlier in November of 1896, at the tender age of 37. She was originally buried in Utica Cemetery in the quaint hamlet north of Frederick City and along Old Frederick Road that boasts one of the county’s oft-photographed covered bridges. Today, the adjoining church is known as St. Paul’s Evangelical Lutheran. I don’t know what prompted this move to Mount Olivet, but I deducted that her burial at Utica could have been precipitated by the presence of relatives tied to her mother's (Margaret Jackson Bruchey) Jackson family that had ties to the Woodsboro area. Regardless, Mary Elizabeth (Bruchey) Bopst was re-buried here in Mount Olivet on November 14th, 1901. I could not find any further information on the exact date of the memorial placement of our “mourning woman” on Area L, but I would surmise that it went in at the time of Mary’s re-interment, which would have generated a central “family” monument with her last name to give proper context to her individual, raised foot stone. However, it has Bion's name prominently displayed on it's base so maybe it did not appear until the 1940s? Maybe Mary's stone from Utica could have been re-purposed here originally, until a later time when the mourning woman monument and foot stone theme were employed. However, I immediately think of two like “mourning women” statues in Mount Olivet that I have written about in the past (John H. Williams Lot in Area R and the Lycurgus Hedges Lot in Area C) whose principal family members died in the decade of the 1890s. I just wish I had old photos of Area L that would definitively clarify its existence. The next individual to be placed here would be a woman named Anna “Annie” S. Betson (1857-1913). I could not find a true familial relationship to Annie with the Bopst family, but easily learned that she was a longtime housekeeper, and I’m sure served an important support and confidante role in assisting the widowed Mr. Bopst after the loss of his young wife. They can be found living together on West 7th Street in the 1900 and 1910 US Census records. Annie would be laid to rest here in Mount Olivet's Area L/Lot 192 upon her death in December 1914, just a few days prior to Christmas. Two years later, Bion would “quietly”(as stated in the local paper) marry Miss Grace Estelle Orem. This occurred in January, 1916. Mr. Bopst would outlive his second wife as well. She died at age 58, in the year 1938. That brings us to our lot-holder and main man in the lives of the three women buried in the shadow of our headless statue. The irony here is that it would have been more fitting to have a weeping man statue to symbolize the years of grief experienced by Bion Bopst with the loss of two wives and a dedicated friend/housekeeper in Annie Betson. Bion E. Bopst was born March 11th, 1858 in Shookstown, northwest of Frederick City on the eastern side of Catoctin Mountain. His name derives from Ancient Greece with a meaning of “life.” In science fiction, a bion is a robot or cyborg—hence the word bionic. Bion Bopst was the son of Mary and Daniel Bopst, farmers who are buried in Mount Olivet’s Area Q/Lot 63. While researching, I found that Bion’s brother, Milton and sister-in-law Rose Bopst are buried in the same lot as his parents. Sadly, Milton was killed in 1904 in a tragic railroad accident while working for the old B&O. The Bopst family moved in town and can be found on West 6th Street in the 1880 census. I found that first wife Mary Bruchey was a West 6th Street neighbor and this propelled the relationship. Bion is shown as being employed as a cooper, something his obituary 60+ years later would confirm. There being no 1890 census, I could not pinpoint when the couple married. I would later be notified by a relative that it was in 1889. Bion and Mary would have not have any children. I found a reference to Bion’s line of work around 1890 however. In 1891, he can be found as a laborer in the Public Printing Division of the US Government Printing Office in Washington, DC. Just weeks before Mary’s death, Bion opened a grocery store on East 5th Street, presumably at 100 East 5th Street. An advertisement in a 1907 newspaper states that Mr. Bopst was in the process of liquidating his stock and equipment at this location. I had my research assistant Marilyn Veek conduct some research on the home residences of Mr. Bopst. Apparently, he did a great deal of buying and selling throughout his life. Bion bought what is now 202 & 204 East 6th Street in 1893 and sold it in 1923. I would offer a guess that this could have been the home of his parents or in-laws. He bought what is now 206 & 208 East 6th in 1900 and sold 206 in 1923 and 208 in 1936. He also owned the following properties at various times: 34-40 West 6th from 1898 to 1923 13 West 6th from 1907 to 1936 14 & 16 West 6th from 1907 to 1938 18 West 6th from 1908 to 1938 2 properties on the N side of West 7th, one from 1889-1890 and another from 1895 to 1898 711 & 713 North Bentz Street from 1911 to 1923 another property on North Bentz from 1919 to 1922 part of the east side of Klinehardt's Alley between 5th and 6th from 1902 to 1909 part of the east side of Bentz Street between 5 1/2 and 6th Streets from 1906 to 1909 Bion Bopst bought his "Home Property" at what is now 33 West 7th Street (NE corner of 7th and Bentz) in 1902 and sold it in 1943. From the looks of all this real estate activity, it appears that Bion Bopst was doing well financially, working as a professional landlord after his grocery store ownership days. As I honed in closer in hopes to learn more about the store, I found a few articles that pointed to a down period for Bion, as he seems to have had some run-ins with the law. Bion appears with second-wife Grace in the 1920 and 1930 census. She is noticeably absent in 1940 because she had died in 1938 as mentioned earlier. Bion passed on July 8th, 1944, a fact that would be carved incorrectly on his foot stone in Mount Olivet. This is puzzling to me, but I guess no-one of note was there to supervise the work in the form of a widow or child. Perhaps, the stone was added much later? The Repair Last summer, our staff removed the entire sculpture after a restoration expert told us that it would require a series of repair phases that needed to be done at ground level. A backhoe was employed to lift the statue from its pedestal, and the headless marble body was brought to our maintenance shop area. Meanwhile, the base was duly cleaned with D2 solution by our Friends of Mount Olivet "Stoner" stone cleaning group as we’ve talked about before in previous blogs. At the end of September, our old friend, Jonathan Appel, returned to the cemetery from his New England home to continue a re-pointing and re-bronzing project involving the Francis Scott Key monument. Mr. Appel is one of the country's top experts in cemetery monument restoration and owns Atlas Preservation with a home base of Southington, Connecticut. He is no stranger to Mount Olivet as he has regularly presented cleaning and restoration workshops over the past six years. Jonathan Appell has well over 25 years of experience preserving, restoring, and repairing gravestones and monuments all over the country and has conducted a “48-state Tour” of preservation training workshops over the the last two years. A recent work project of note is “the Knight’s Tomb” in Jamestown, quite possibly the oldest existing gravestone in America, dating back to the 1630s. We feel fortunate to have had him repairing many of own here in Mount Olivet. The Bopst monument was a pretty complex fix, and we had the necessary expert to do the job. I marveled in watching him drill holes in the marble torso, head and appendages in an effort to rejoin these parts with metal pins and proper epoxy solutions. These are repair efforts requiring precise skill and confidence, certainly not for the meek as there are not second or third chances to re-drill at carefully calculated angles in which to compensate for precise placement of a bowed head as opposed to an upright head placed on level shoulders. Jonathan completed the job at hand, including the re-attachment of one (a hand). This finally got the statue back in one piece after nearly a three-and-a-half-year hiatus. The figure was then cleaned with D2 and brought back to the way the statue looked on the day it was originally brought into the cemetery. We had hoped to place the mourning woman back on her pedestal at the Bopst lot in fall but Jonathan’s busy schedule, coupled with the holidays and a few bad strokes of weather on our end (when we had opportunity of him traveling through the area) precluded us from making this happen. We did however complete the task on February 21st, 2023. I know it’s just a big piece of marble, but how gratifying it is to have her back up there on her base for all to enjoy. I truly love this monument. Besides, I was growing weary of explaining to curious visitors and lot-holders why we were displaying a headless statue in our cemetery. That’s something to be left to Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome. If you'd like to help us in our mission of repairing damaged historic gravestones in Mount Olivet, consider joining our Friends of Mount Olivet membership group, or feel free to make a tax deductible donation to the Mount Olivet Preservation and Enhancement Fund. (Click logo on the right for more info).

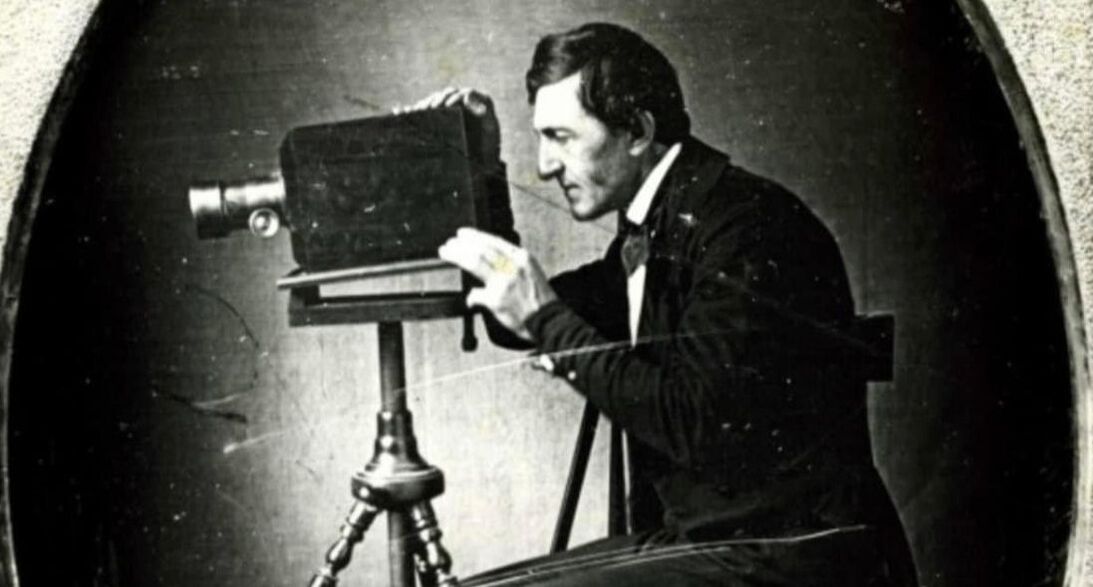

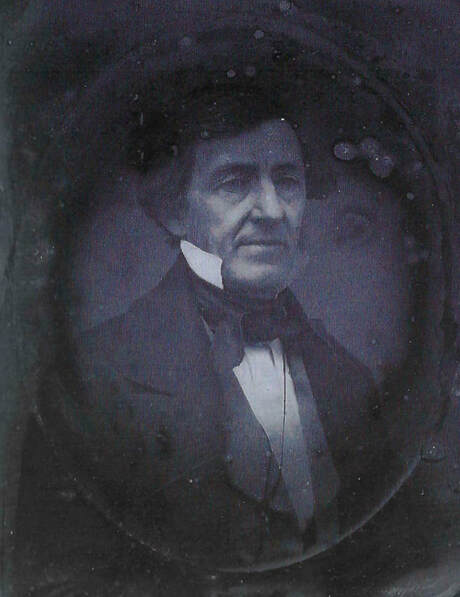

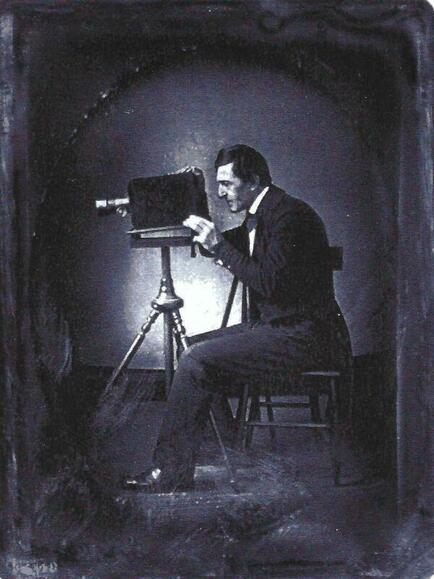

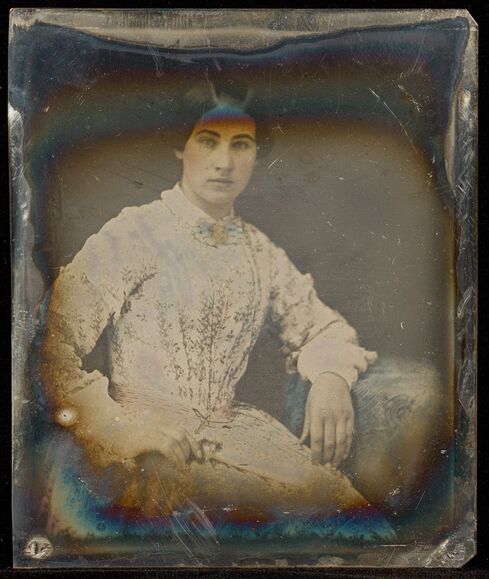

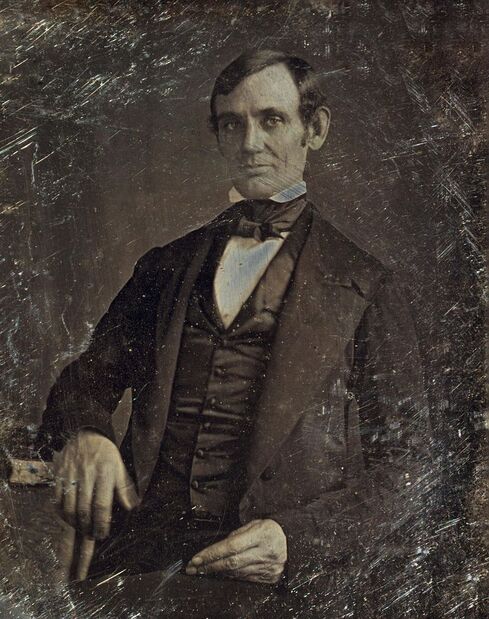

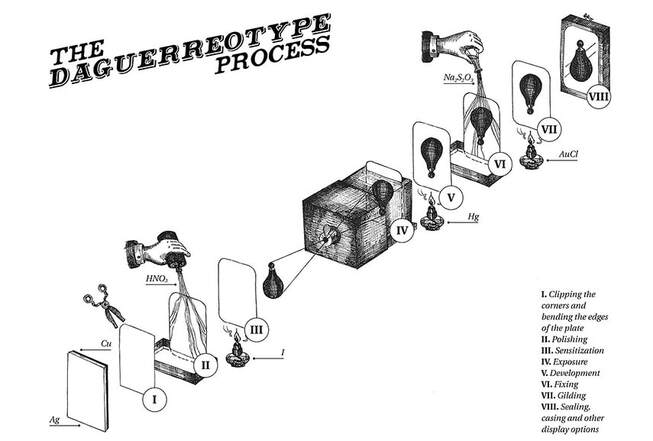

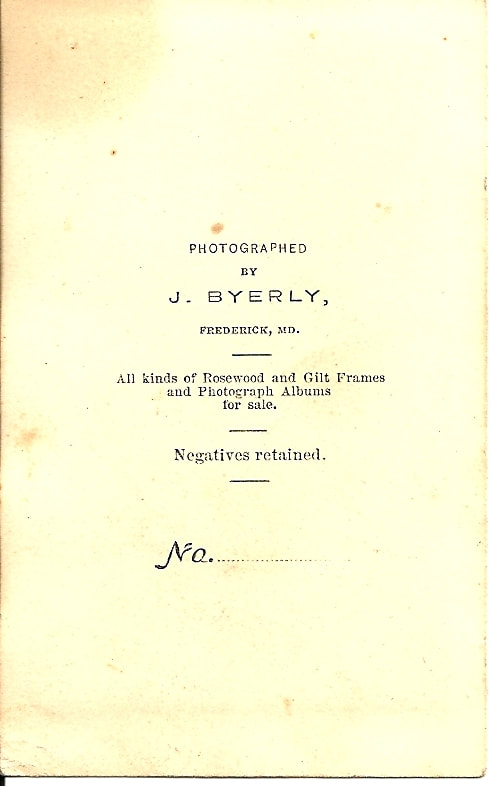

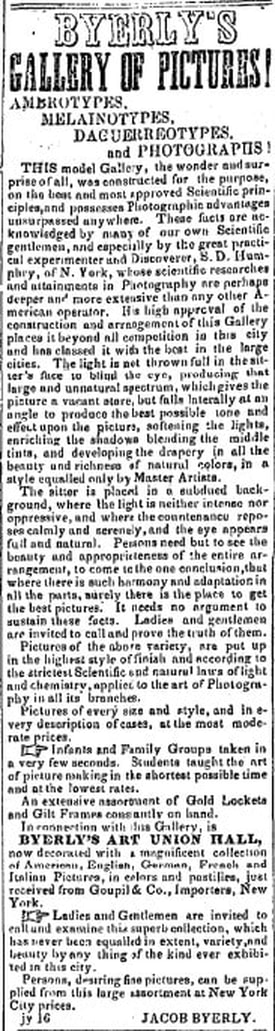

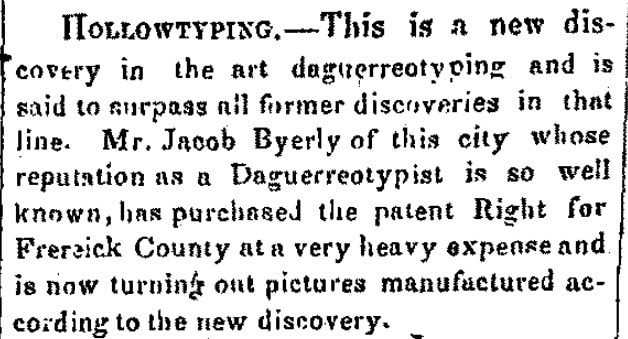

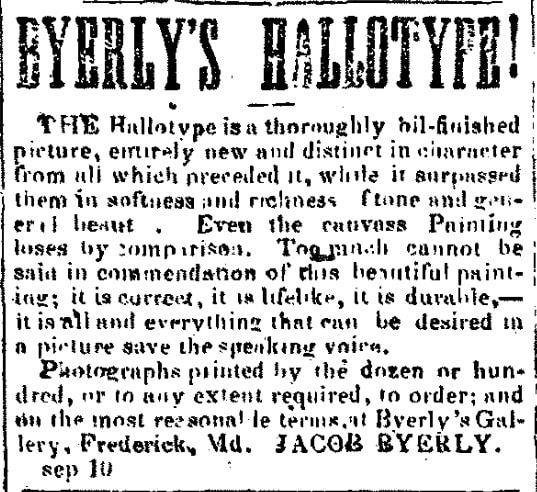

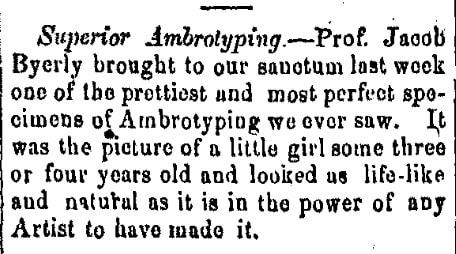

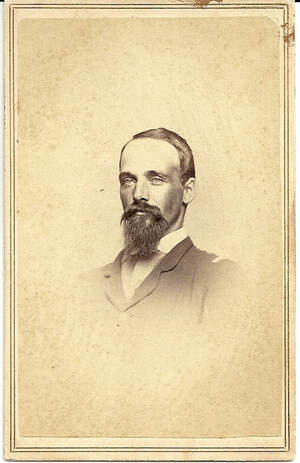

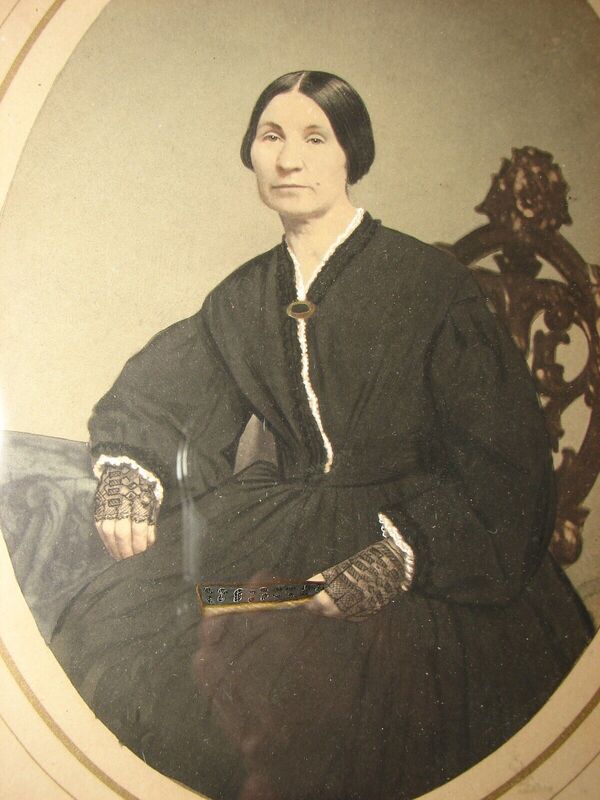

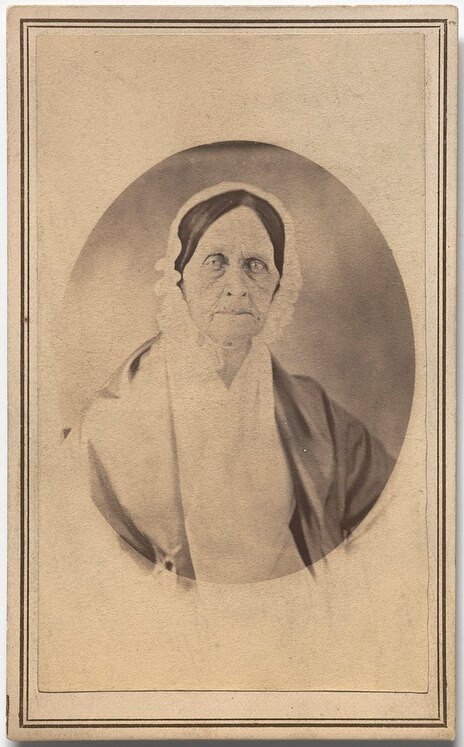

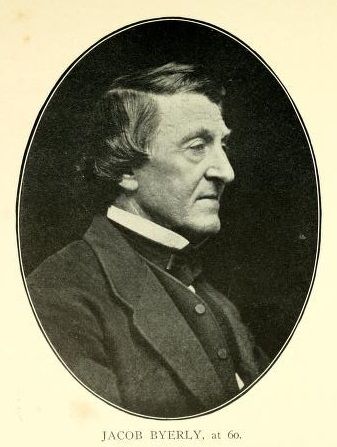

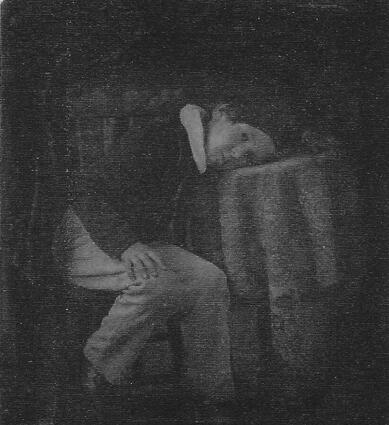

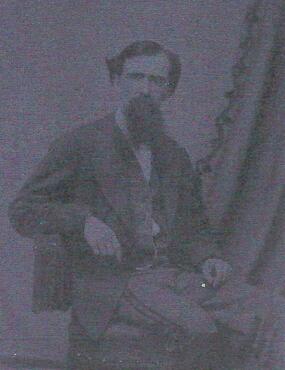

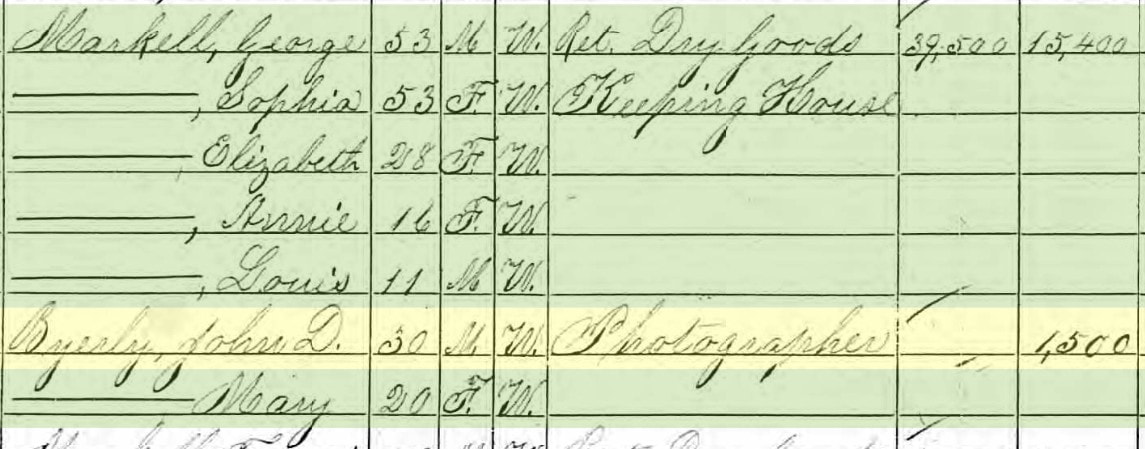

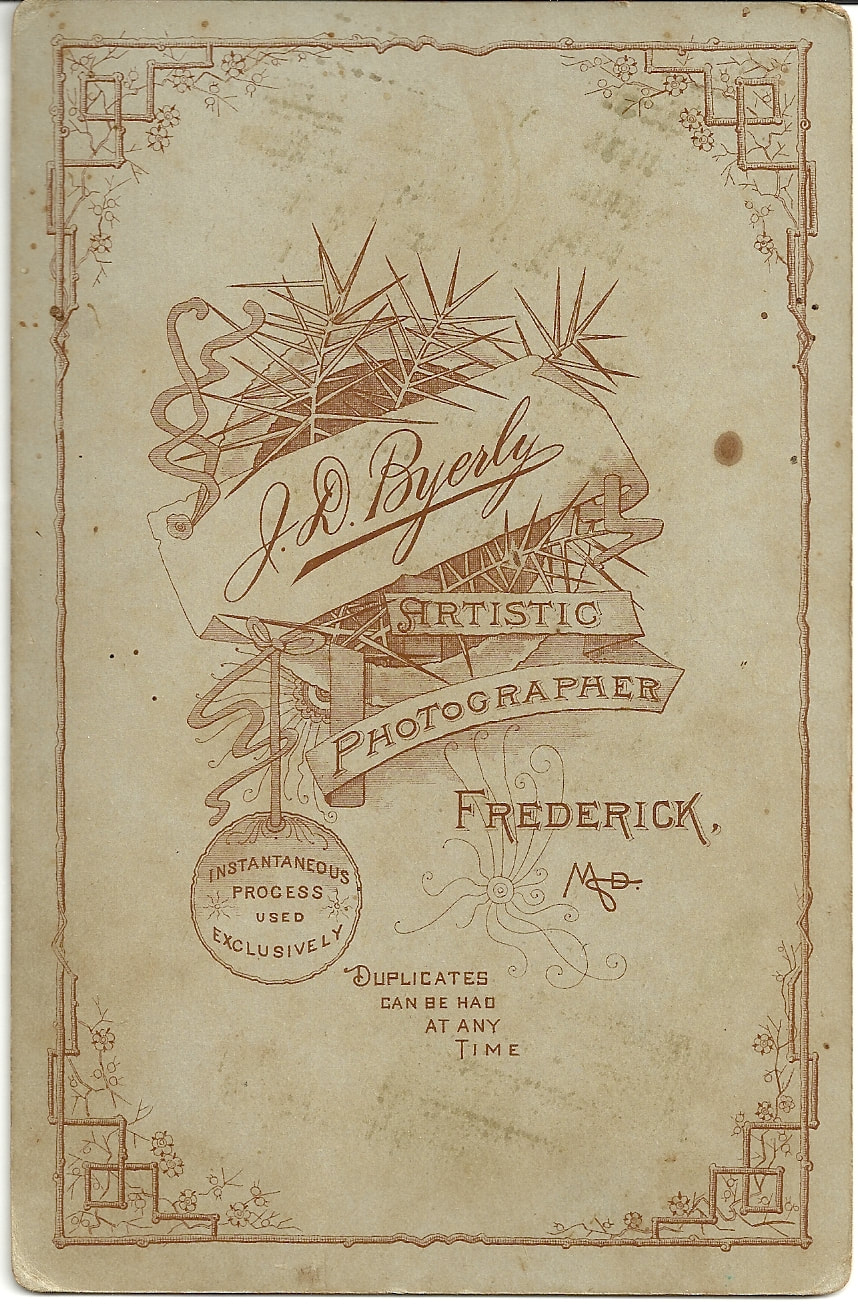

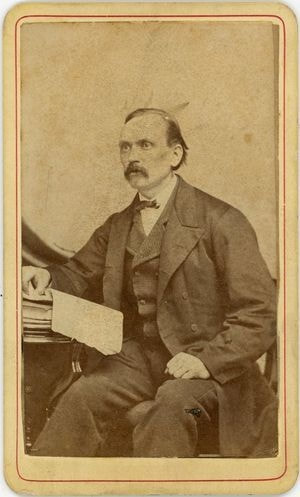

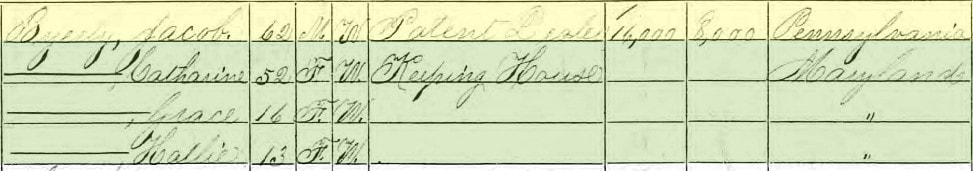

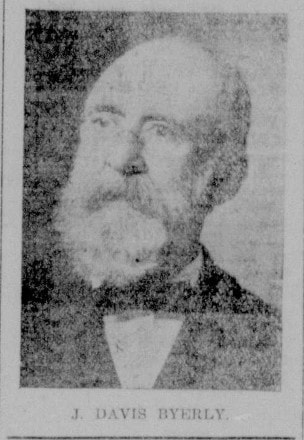

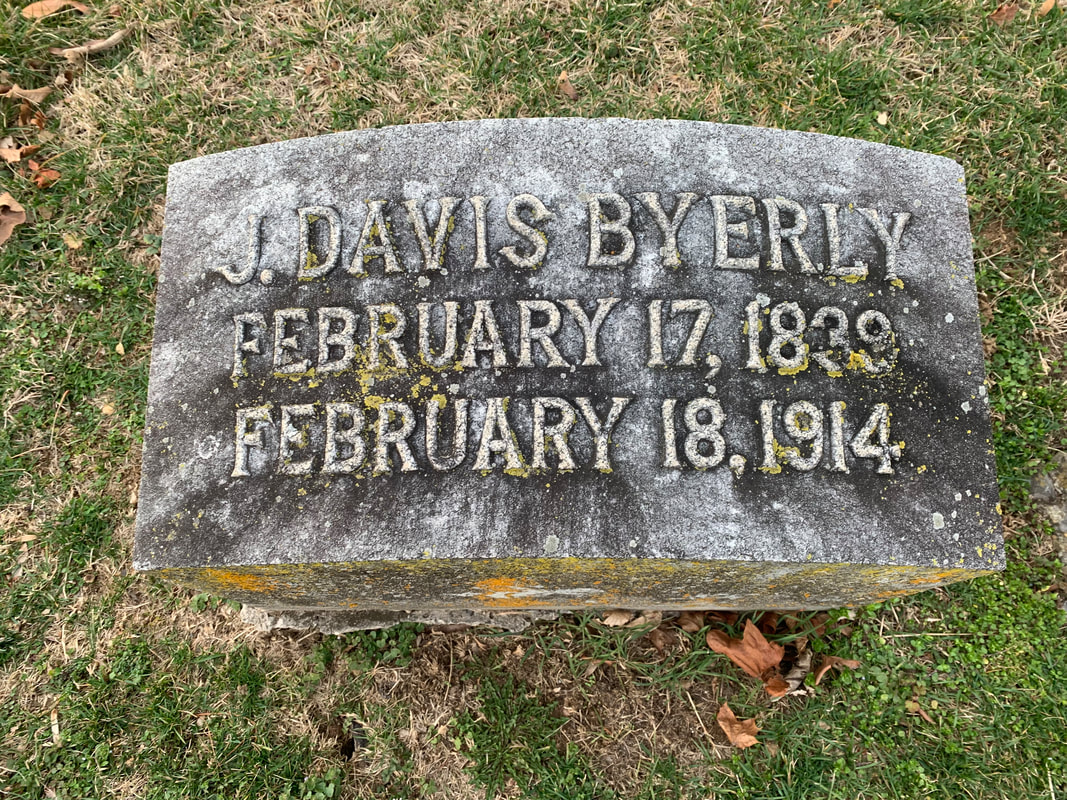

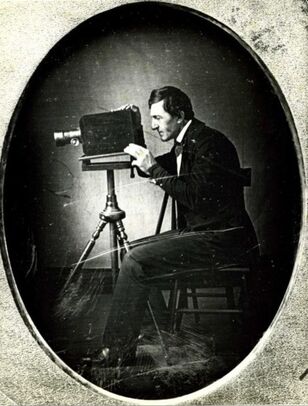

Next Prospective FOMO Member meeting is Wednesday, March 22nd at the Key Chapel with a lunchtime lecture presentation by author/historian Chris Haugh starting at 12 noon. (No obligation to join.) This is a continuation of a “Story in Stone” begun last week and features a proper chronicling of the famed Byerly family of photographers here in Frederick which spanned a century beginning in the 1840s. For those that read last week’s story entitled “Up From the Meadows,” you were introduced to a photograph featuring a former slave turned freeman named Luther Potts, holding a five year-old boy on his lap. There is a discrepancy as to whether the child in question is either John Davis Byerly (Jr.), or kid brother Charles Byerly. I surmised John D. (Jr.) and hedged my bet based on a Byerly family descendant’s unknowingly stating that the boy was John Francis Byerly. I proved the error, and deducted that John was the name of the pictured child regardless, as John Francis Byerly was a grandson of the photographer, not born until 25+ years after this photo was taken. This photograph, along with hundreds more that dominate local history books in the era mentioned, is part of a portfolio collection of antique images equivalent to Jacob Engelbrecht’s masterful diary. Each photo is reminiscent of one of Jacob’s colorful journal entries, magically documenting an earlier Frederick, with emphasis on the 19th century. We owe a great deal to both these men named Jacob.  CDV of Unknown young lady (c. 1860) CDV of Unknown young lady (c. 1860) As professional photographers, three generations of Byerlys took staged portraits in their studio once located in the first block of Frederick’s North Market Street. In addition, these talented artists captured unique town events and typical street scenes. In all cases, we have “photographic” proof of many former residents of both Frederick (and Mount Olivet), town happenings and Frederick structures—many still standing, and others long gone. Sadly for historians and genealogists, many Byerly portraits of individuals, couples and families have survived the test of time, but have no identification of who is pictured. A common practice in days of old involved writing names of those appearing in pictures in ink on the photo album page itself that once held and housed these photographs. Unfortunately, somewhere along the line, loose photographs became separated from their identification. Today these appear on eBay and in antique shops and thrift stores with a nearby label announcing “Instant Relatives.” We certainly commend those ancestors who wrote names on the back of portraits, or, in other cases, wrote on the photo themselves (at least) giving us an “inkling” of who was photographed, and/or where and when. I appreciate these old-time photographs so much, and in my personal family history collection have both marked, and unmarked, photos. My sleuthwork has been utilized as well in identifying several based on period dress, and facial features. In thinking of photography, I have to smile while reminiscing about the traditional 24 or 36 exposure rolls of film utilized in my younger days in the era before digital photography. Who would have imagined a handheld smart phone computer/camera/”Walkman” doo-hickey that you could carry with you at all times? Do you remember having to “ration” remaining film “exposures” on a limited film roll while on vacation or social events? One had to treat them like gold and be judicious in using up remaining pictures just in case something incredible happened like Bigfoot coming out of nowhere, a visit from a unicorn, or meeting Olivia Newton-John. Maybe I digress, as I am confusing my adolescent dreams with the possibilities of reality on that last one—as evidenced by my seeing the movie Grease multiple times at the theater by myself. I just shudder (or should I utilize the camera term, “shutter”) to think of the future where we will likely be overrun as a society by unidentified digital .jpg photograph files of people, places and events. Luckily, the Byerlys didn’t have any of these problems, but being pioneers in their field, brought several other challenges. It’s obvious that trying to get the right picture back in the 1800s was a hundred times harder than today with the equipment involved, and lack of automatic features to adjust lighting, filters and shutter speed. Jacob Byerly The most prolific photographer in Frederick County history was Jacob Byerly, born in Newville, Pennsylvania in 1807. Newville, near Chambersburg, was founded in 1790 and is located in Cumberland County, due west of Carlisle. The Byerlys (or Birelys before Jacob changed the spelling for himself) were a typical Pennsylvania German family, hailing from immigrant John Andrew Birely (1715-1774) who came to America and the Penn’s colony in the year 1738 from Rohrback, Heidelberg, Baden-Wurttemburg. This was Jacob’s great-grandfather who eventually settled and died in Lancaster. Named for his grandfather, Jacob Byerly (the photographer) was the son of John Henry Birely (1773-1813) and wife/cousin Rebecca Baer (1782-1851). Jacob Byerly was the oldest of four children and is said to have started as a teacher, but made the transition to the new field of photography at its introduction to this country. He possibly learned his future trade from a daguerreotypist in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, but information is not definitive. If you have never heard of the profession of daguerreotypist before, an individual in this line of work made daguerreotypes, the first publicly available photographic process and widely used during the 1840s and 1850s. Invented by Louis Daguerre and introduced worldwide in 1839, the daguerreotype was almost completely superseded by 1860 with new, less expensive processes, such as ambrotype (collodion process), that yield more readily viewable images. The first authenticated image of Abraham Lincoln, a daguerreotype of him as U.S. Congressman-elect in 1846, is attributed to Nicholas H. Shepard. Wikipedia does a nice job describing the process employed in making these early photographic images: “To make the image, a daguerreotypist polished a sheet of silver-plated copper to a mirror finish; treated it with fumes that made its surface light-sensitive; exposed it in a camera for as long as was judged to be necessary, which could be as little as a few seconds for brightly sunlit subjects or much longer with less intense lighting; made the resulting latent image on it visible by fuming it with mercury vapor; removed its sensitivity to light by liquid chemical treatment; rinsed and dried it; and then sealed the easily marred result behind glass in a protective enclosure. The image is on a mirror-like silver surface and will appear either positive or negative, depending on the angle at which it is viewed, how it is lit and whether a light or dark background is being reflected in the metal. The darkest areas of the image are simply bare silver; lighter areas have a microscopically fine light-scattering texture. The surface is very delicate, and even the lightest wiping can permanently scuff it. Some tarnish around the edges is normal.” I’m sure being a daguerrotypist was a highly rewarding job based on customer satisfaction and ego stroking. He was a true pioneer in this new field, one that fast rivaled portrait painters, and made the acquisition of family images possible for the less affluent. However, as the description above reads, it was tedious work that involved great patience, while exposing the technician to very dangerous chemicals without the necessary protections we expect today.

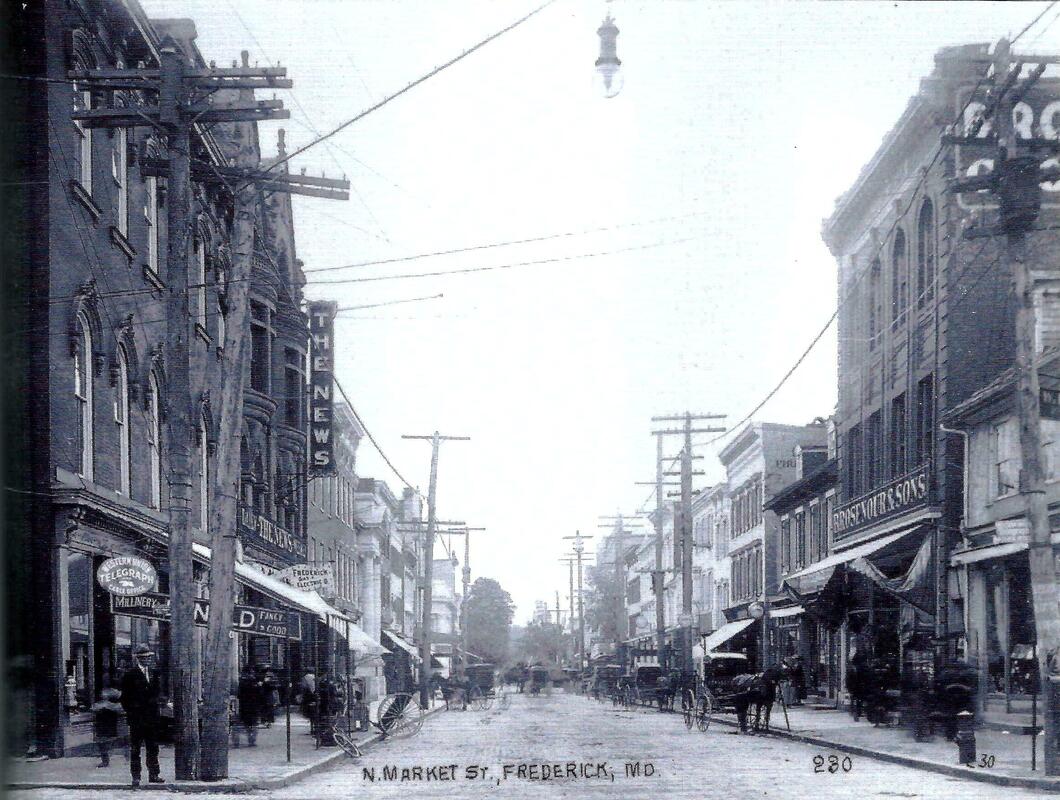

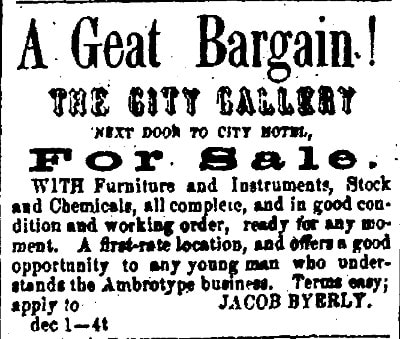

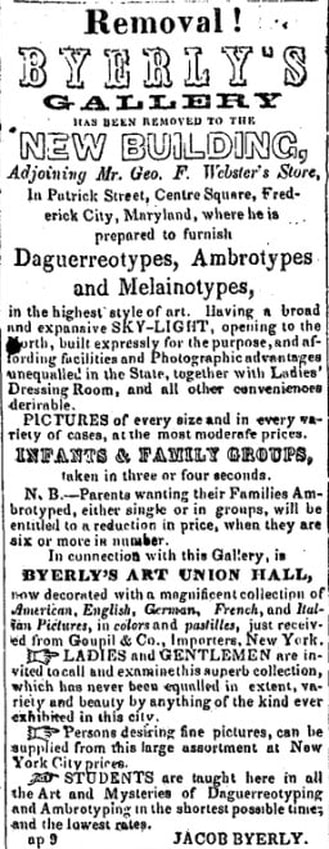

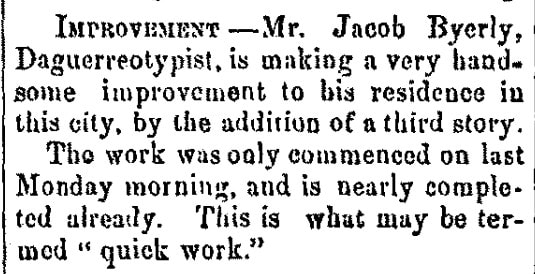

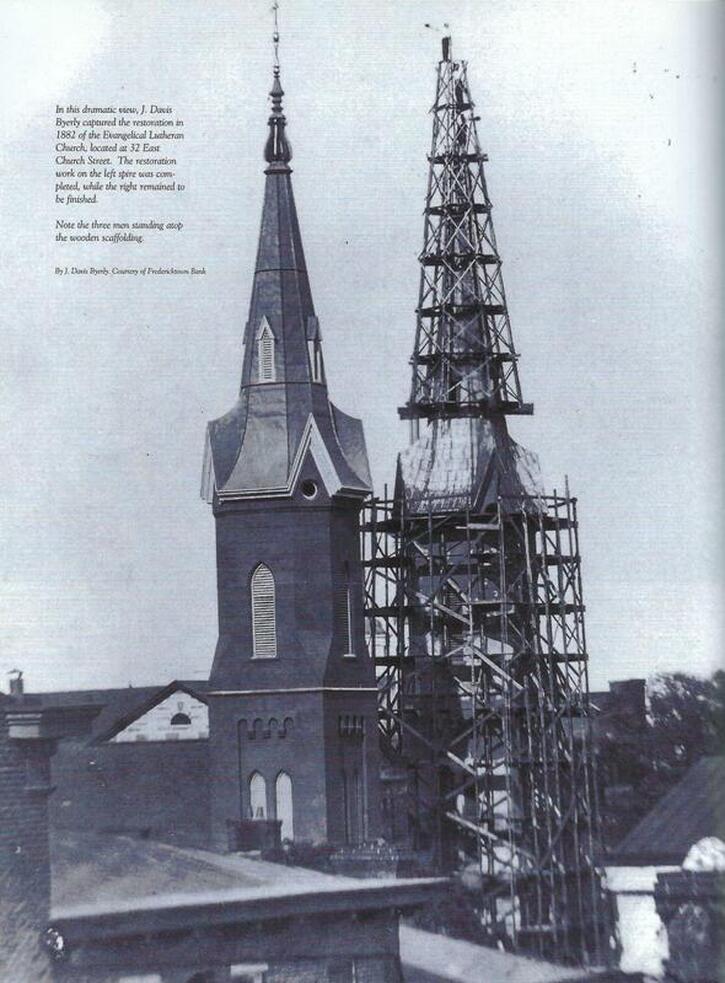

Jacob Byerly eventually set up shop as a daguerreotypist, one of the first people in Maryland to sell this new technology. He was originally located next to the City Hotel on West Patrick Street, and he named his business "The City Gallery." I feel that his first place of business doubled as his home as well. Jacob Byerly later established an artist studio at 29 North Market Street, which later became the Young Men's Shop and also served recently as Hunting Creek Outfitters and has recently re-opened as loulou, a store that will specialize in ladies accessories, gifts and fashion. He bought 29 North Market in 1851, and the structure, later to be named the Byerly Building, stayed in the family until its sale in 1965 by his great-grandson John Francis Byerly.  Looking south on N. Market St. from intersection with Church St. The Byerly Gallery is on the right (west side of street) and is the second building down (left) of the visible large brick store of Rosenour & Sons. In the magnified view below, see the letters "PHO" (the start of Photographer) on north side of building. The word Byerly was most likely stacked over the word Photographer(s) or Photo Gallery. The family lived on West Patrick Street in the 1850 Census, and earlier in the 1840s. I think this was in conjunction with Jacob's "City Gallery" next to the City Hotel. In 1853, Jacob purchased 108 West Patrick Street, and a few years later installed a third story. And if I’m not mistaken, this same West Patrick property was the earlier home of Revolutionary War era patriot John Hanson. Hanson’s statue stands in front of the Frederick County Courthouse, and he is best remembered for his tenure as president of Congress assembled under the Articles of Confederation. You may also here his name spoken by your car’s GPS if you happen to be traveling in the Annapolis Area on US Route 50—aka John Hanson Highway. The US-50 freeway from the District of Columbia to Annapolis was opened around 1957. Shortly after taking ownership of the house, the couple welcomed two children—Grace in 1855 and Harriet (aka Hallie) in 1857. I saw a few instances that pointed to another child who died in infancy but could find nothing definitive. Jacob's work earned him a mention in a book entitled The Camera about the history of photography published by Time Magazine in 1970. In this, he is hailed as a “trailblazer” in the photographic field, and held in the same company as the legendary Matthew Brady, who would open his studio in New York City in 1844—two years after Byerly opened his gallery in little old Frederick. An article written by a distant relative, Carol Zeigler claims that Jacob Byerly was personal friends with Matthew Brady, and for a short time may have photographed with him although there exists no real proof. At the onset of the Civil War, Jacob Byerly is said to have produced 1,500 images annually with the help of two male employees, one being son Charles. While Matthew Brady gained his fame with depictions of battlefield carnage, Byerly is credited with at least a few surviving documentations of his adopted hometown during the war. These photographs were taken from his upper-story studio while looking out the window onto North Market Street. He captured each of visiting armies at different times of the war. In fact, a few of the most famous civilian-related portraits dealing with the American Civil War came to light thanks to Jacob Byerly. These helped put Frederick on the map, so to speak, because they assisted in providing photographic proof of the existence of a particular resident “patriotic heroine” and the home from which she apparently waved a flag at Gen. Stonewall Jackson and his “invading Rebel horde” in early autumn of 1862. It is said that his portrait of Barbara was not done in his Market Street studio, but rather was taken at his “demonstration” booth which was set up at the Frederick Fair in 1860. The Agricultural Exposition was then held at the Hessian Barracks, the site that serves as home to the Maryland School for the Deaf today. Barbara was a Hauer family relative and great aunt of Jacob’s wife, Catherine, and this was probably the only reason the fabled nonagenarian allowed her image to be captured. I first encountered information about Jacob Byerly while researching the Fritchie images for a history of Frederick documentary back in 1994. A year later, I would learn so much more about Mr. Byerly from Tom Gorsline, former publisher of Diversions and Frederick Magazine. A huge fan of vintage photography, Tom has amassed a great collection of local imagery and regularly published many of his finds in his publications for all to enjoy. He was a great admirer of the Byerlys, so much so, he devoted an entire chapter of his 1995 Pictorial History of Frederick to educating readers about the incredible legacy left us by this legendary artist and his son and grandson. Tom’s book is packed with Byerly images, and naturally gives us an opportunity to see what the photographers, themselves, looked like. These were the first official “selfies” in Frederick history! Tom includes a few of Jacob's iconic town shots in his pictorial history, in which he was greatly assisted by talented history researchers/ writers Nancy Whitmore and Tim Cannon. One such image included the restoration of one of the famed “Clustered Spires” belonging to Evangelical Lutheran Church. If you look closely, you can see workmen waving to the camera from their scaffolding. Another shot features the disaster scene of Frederick’s first “Great Flood,” this one occurring in late July of 1868. His view of West Patrick Street (looking west) vividly shows the devastation. This scene was right outside his home and ironically, the legendary freshet was responsible for the destruction (and subsequent dismantling) of the earlier photographed Barbara Fritchie House. (Note: The replica house you see today was constructed around in the late 1920s). Text from the Pictorial History of Frederick states: “Jacob remained on the cutting edge of the technology of his day, switching to the glass-plate technique. Remarkably, at least a thousand glass-plate negatives from the three Byerly photographers have survived the decades. Jacob produced portraits, slides for the stereopticon (the TV of the time), and carte de viste, a popular form of calling cards with photographs on them. He sold the business for $2,000 to his son, John Davis, in 1868, but continued to take pictures until his death in 1883.” Years before, in 1852, Jacob is said to have written the following passage in a letter to his 14-year-old son, John Davis Byerly: "My son, remember the instructions of your Father; — trifle not away your time; reflect, and be careful, read your bible, neglect not its precepts, But take good heed to its instructions, and live accordingly; trample not upon the many good admonitions I have given you . . . “ Jacob was always the teacher, and looking back at the life of John Davis Byerly, it’s safe to assume “he knew the assignment” as the kids say today. Davis was brought in as a named partner to his father in 1863, as the firm became known as J. Byerly & Son. Davis apparently had a stormy relationship with his stepmother according to other letters. He received education both here in Frederick and abroad as a biographical sketch in the Maryland State Archives summarizes: “According to Williams and McKinsey's History of Frederick County, Davis received his education in the schools in Frederick; however, he was probably not at school in the city, because a letter from his father in November of 1853 or 1854 expresses his concern at the fact that Davis had to share a room with the three Fischer boys, who seem to have been disapproved of by the elder Byerly. Exhorting his son to 'be studious, make the most of your time you possibly can, recollect you are costing upwards of fifteen dollars a month,' Jacob continues later in his letter, 'Try to excel; and stand among the first in your school in the estimation of your Teachers. This will reward me, and be a plume in your Cap; I don't want you to be running home every few weeks, it looks badly. I don't expect you home until Christmas . . .' Due to the fact that Davis was far enough away to be boarding, and his parents to be sending him things rather than bringing them, but close enough to be 'running home every few weeks,' it is probable that he was at one of the private schools in Frederick County.”

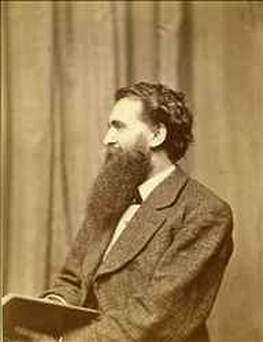

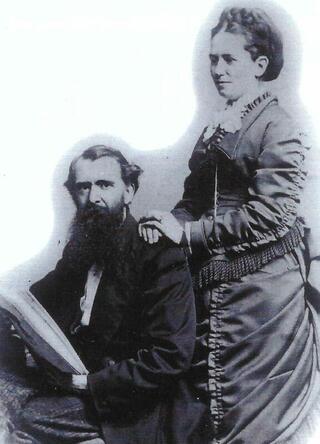

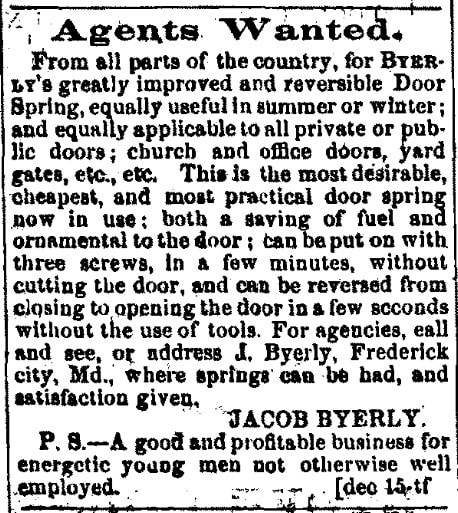

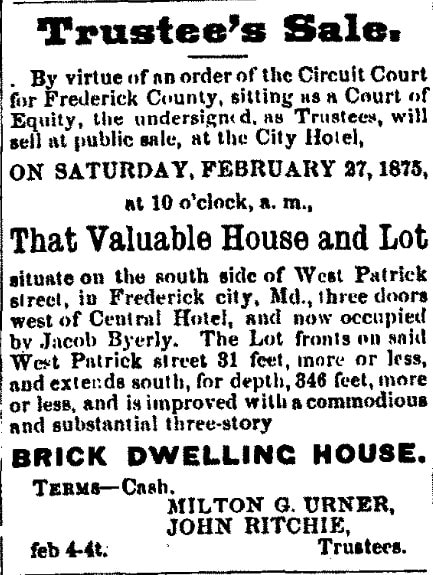

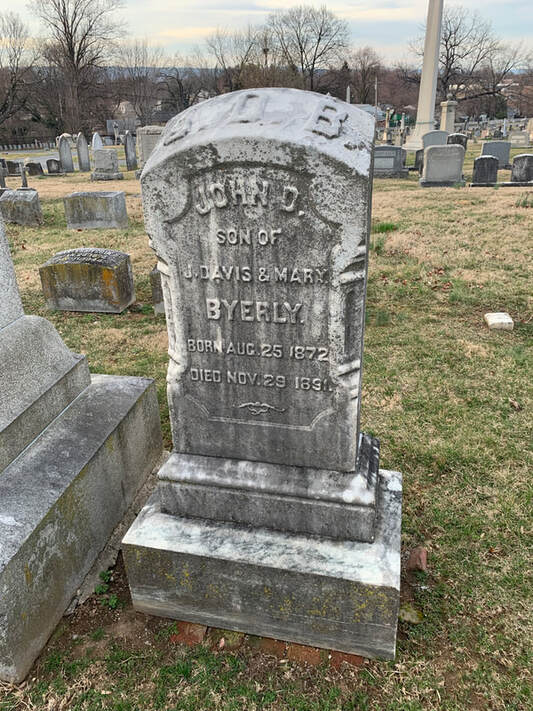

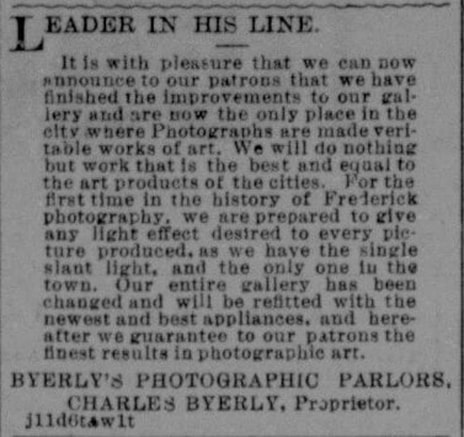

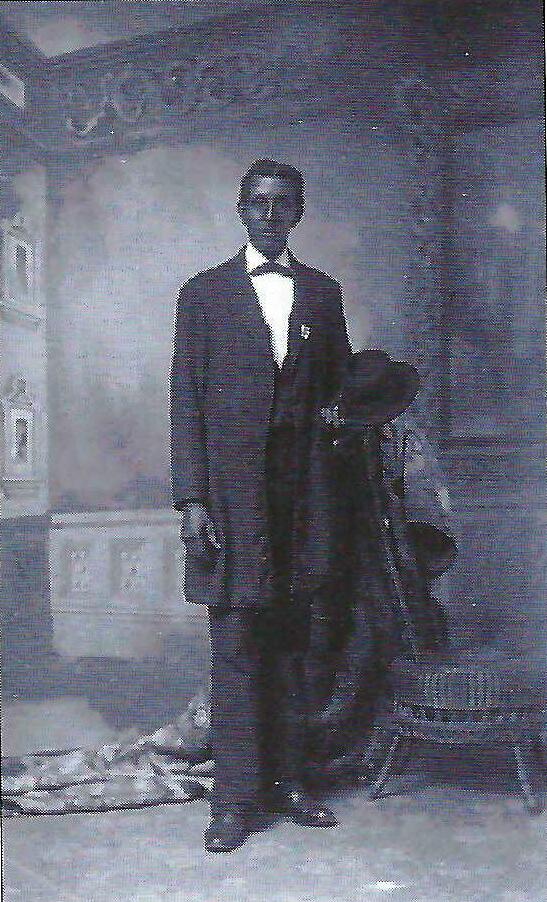

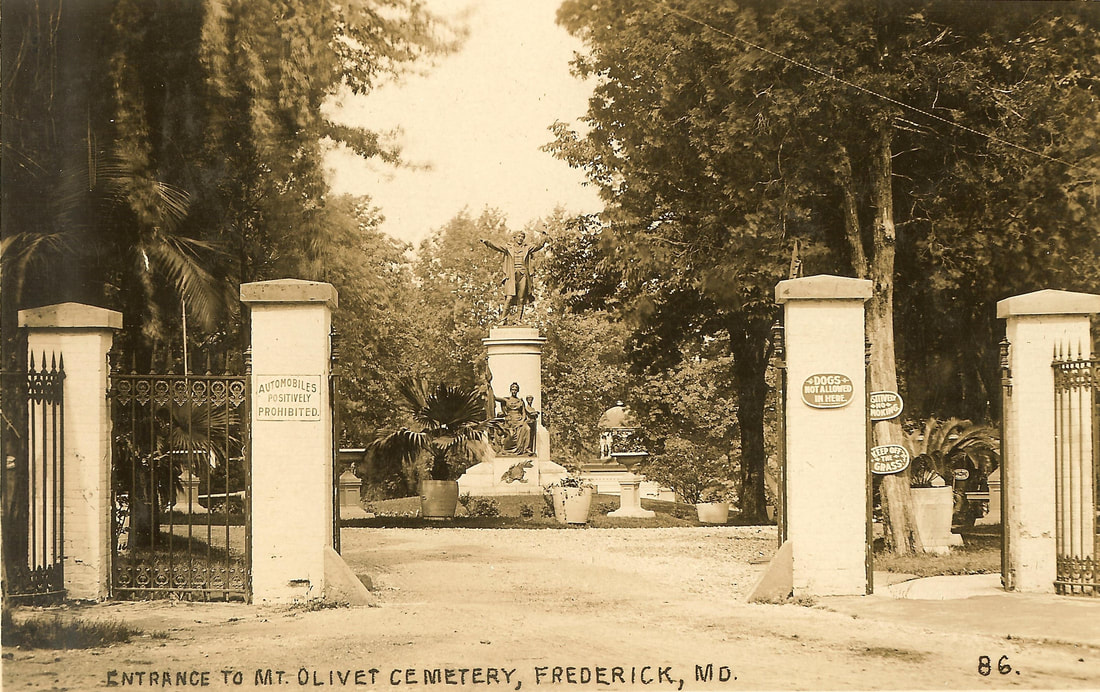

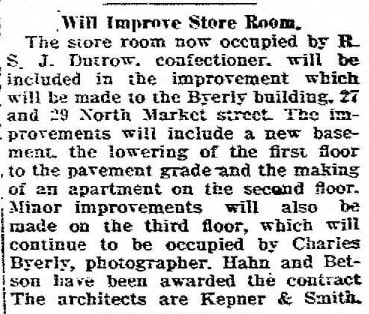

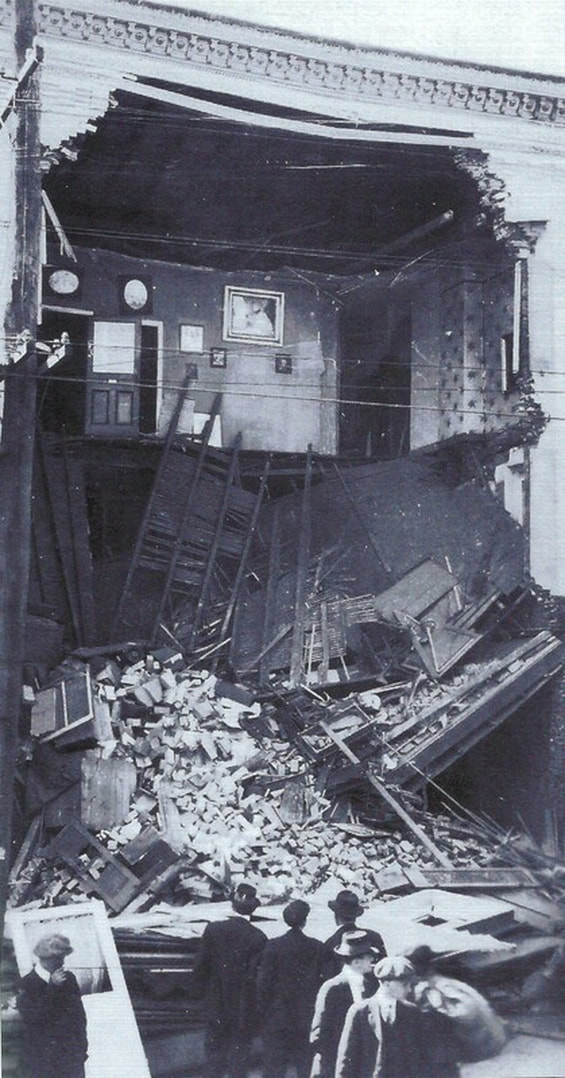

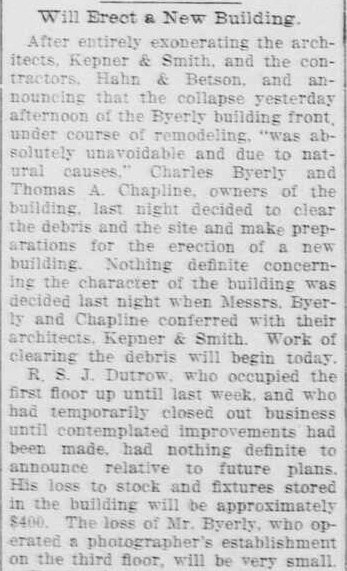

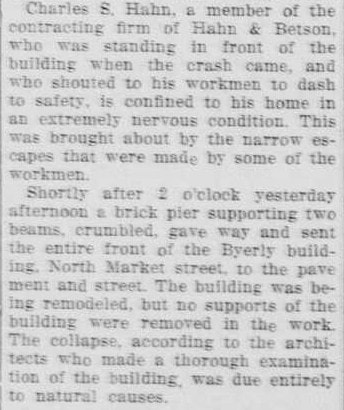

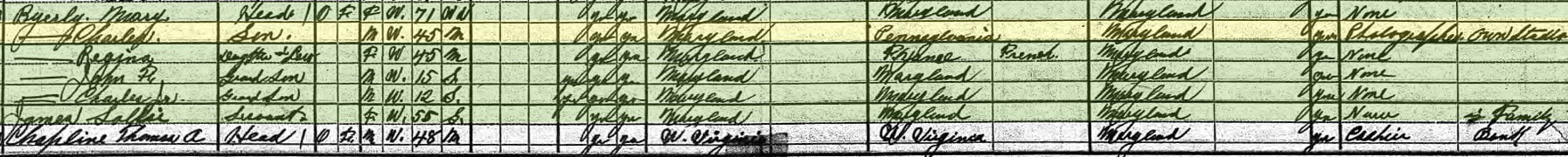

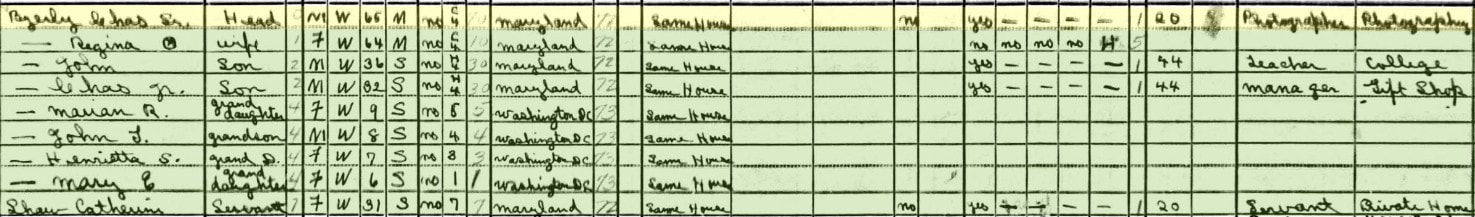

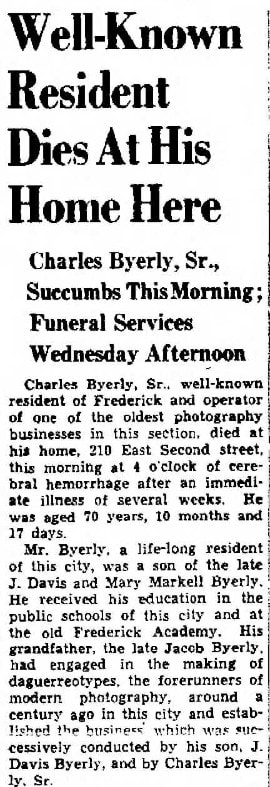

“Mame” Markell lived next door to the Byerlys in a connecting townhouse. Her father (George Markell) had bought 110 West Patrick (the other part of the former Hanson House) in 1852. J. Davis Byerly would wed his neighbor in late October of 1869 and they would soon become the parents of three children—Mary Catharine (1871-1937); John Davis (Jr.) (1872-1891); and Charles (b. 1874-1944). In addition to un-posed, event-driven pictures, Davis Byerly experienced great success as a portrait photographer as well. Heritage Frederick apparently has a copy of a booklet the Byerly photo studio gave out to patrons before they sat for a portrait. It reads: "Photography is not a branch of mechanics, whereby a quantity of material is thrown into a hopper and with the grinding of grim, greasy machinery, beautiful portraits may be turned out. The day when a daub of black and a patch of white pass for a photograph, you are well aware is ended; for you will not receive such abominations yourself as likenesses of those near and dear to you, and especially of the one dearer to you than anyone else, namely your own dear self." Hints are given to "never come in a hurry or a flurry" because a red face does not photograph well. "Ladies who have shopping and an engagement with the photographer on the same day, will please be careful to attend to the latter first." As to how to dress, the Byerlys rebuke those "who place upon their persons, when about to sit for a picture, all sorts of gew-gaws and haberdasheries which they never wear when at home or when mingling among their friends." Meanwhile, Davis’ father, Jacob, kept occupied with work as a patent dealer and advertisements in local papers showed him marketing door springs. He also busied himself with hobbies and activities of town, however had his own mortgage foreclosed upon in 1875, and the house at 108 West Patrick ended up being bought by Mary “Mame” (Markell) Byerly (wife of J. Davis Byerly). In her will, Mary would leave the house and lot to her daughter, Mary (Byerly) Chapline and it would stay in the family until 1971. The Byerly Picture Gallery flourished under Davis' direction as he was able to hire and train several assistants, two at least of whom later became competitors of his in Frederick in W. A. Burger and William F. Kreh. Business continued to be good for the Byerlys. In 1880, John Porter described the Byerly Picture Gallery in his book Maryland and its Industrial Developments: "It is situated in the best possible location in Frederick City, has large, well lighted rooms, and possesses every advantage which modern invention can suggest . . . Examination of his portraits shows a pleasing and agreeable variety -- the positions given have an ease and grace not often attained by photography, and in this, together with the admirable finish of his work, may be found the secret of Mr. B's great success. . . ." J. Davis' great success in the 1880s and 1890s was marred, however, by a series of personal tragedies. Jacob Byerly died March 21st, 1883, at the age of 76. He was originally buried in the German Reformed burial ground on North Bentz Street at the intersection with West 2nd Street. (This is Frederick’s Memorial Park today). Forty years later, Jacob’s body would be brought to Mount Olivet and laid to rest in Area G/Lot 182. Davis' stepmother, Catherine, died in 1885, and in 1890, his sister Grace, who had entreated him to return from his travels in the south in 1867, died at the age of 35 of paralysis. They are buried with Jacob in the same plot. Daughter Harriet "Hallie" (Byerly) Sweet and grand-daughter Catherine (Byerly) Chapline are buried in adjacent graves. Difficult as these deaths must have been for Davis, the next year brought a loss that must have been particularly hard for the photographer. Davis' eldest son, John Davis, died on November 29th, 1891 at the age of 19. The Frederick News' obituary column poetically titled "The Work of Death," began his obituary, "When death comes to the aged we look upon it as a visitation of the inevitable, but when it comes to one so young, so inestimable as a friend and companion, so thoughtful of the comfort and happiness of those about him, we feel to pang more keenly and sensibly.” A photo of John and his siblings, parents and extended family was taken shortly before his untimely passing. He would be buried in Area G/Lot 37.  My initial thought was “Who took this photo?” as all the professionals are within the shot. Interesting people of note here include J. Davis Byerly (Third Row extreme left with beard and moustache); Charles Byerly (Second Row extreme left); Mary Markell Byerly (second row to the immediate right of Charles); John Davis Byerly (Jr.) (second row extreme right); and Mary (Byerly) Chapline (front row, second from right in black and white dress and elbow on her grandfather George Markell’s knee). It can be assumed that John D. Byerly (Jr.) would have had a career in photography as well. His younger brother would play a greater role in assisting his father (Davis) throughout the 1890s leading to his eventual coronation by century’s end. In 1899, J. Davis Byerly retired from the photographic studio. He was 60 years old and had been running the studio for 30 years, surpassing his own father’s run of 27 years from 1842-1869. However, his retirement did not mean the end of the Byerly Picture Gallery, for like his father, Davis gave the business to his son Charles. Davis could now enjoy family and personal pursuits including his daughter Mary Catherine’s wedding that same year of 1899. She married Thomas Chapline, the son of a successful merchant family. J. Davis Byerly continued to be active in the community, in his church, the Republican Party, and his social club, the Order of Red Men. Just as his father before him, Davis was one of the most prominent men in Frederick, and was well liked and respected by the entire community. Charles married Regina Eisenhauer in 1903 and had two sons—(the previously mentioned ) John Francis Byerly (1904-1981) and Charles Byerly Jr. (1907-1983). He carried on the family business and continued the peerless brand that Frederick had come to expect. The Byerly Gallery was among the most prominent in western Maryland. Heritage Frederick has the works below by Charles Byerly in their extensive collection. The Black gentleman (lower right) is thought to be William Grinage, a former assistant of Charles Byerly and artist responsible for a portrait of Francis Scott Key that hung in the lobby of the FSK Hotel for several decades. We are very fortunate to have several images of Mount Olivet thanks to the lens of Charles Byerly. One such picture was taken of his brother John’s grave (at the photographer’s future burial spot) in Area G/Lot 37. This was taken in 1905. Charles took other images of Mount Olivet in the first decade of the 1900s, and we have several prints from the original glass negatives. I have incorporated one of these as the header, and logo, for this blog. J. Davis Byerly passed in 1914, February 19th to be exact, just one day following his 75th birthday. Wife Mary “Mame” (Markell) Byerly would die eight years later. Charles had shared his parent’s house on West Patrick until moving to 201 East Second Street in 1923 following his mother’s death. He continued running the family business up through 1915, at which time a terrible event beset the Byerly Studio. In spring of that year, the building was undergoing a major restoration. A month later, on April 14th, workmen hurriedly dashed for their lives as the front façade and floors of the building at 29 North Market Street collapsed. On the first floor of this building was located Dutrow’s Soda Fountain. Fortunately, patrons were not frequenting either business due to the construction work. No injuries were reported to the contracting crew, but Charles Byerly faced a total loss and the destruction of his 3rd floor studio with all its equipment and props. This event would promptly ended the business after a 73 year run. Many sources say that Charles would never pursue photography as a commercial venture again, but the census records of 1920, 1930, and 1940 continue to list his occupation as that of photographer. Perhaps it became a part-time or free-lance venture, instead? All the while, cameras were becoming more portable over time. Regardless, I can’t imagine a man surrounded by photography his entire life, would stop taking pictures. The 1940 US Census shows Charles’ sons and grandchildren living in the family home on Frederick’s East 2nd Street with their parents. John worked as a schoolteacher, and Charles as a gift shop manager who specialized in selling chinaware. Both appear to be single at time, however grandchildren are present. Like his father before him, Charles Byerly, Sr. kept busy with civic affairs. He would die on December 11th, 1944 and is buried directly behind his parent’s gravesite, and diagonally within a few yards of his older brother, whom he had photographed 39 years earlier. Charles, his father (J. Davis) and grandfather (Jacob) likely did not imagine the great importance of their work in their own lifetimes, as it was art, yes, but moreso a means to make an honest living. As mentioned earlier, it was also demanding work that took creativity, technical skill, patience and a toll on the respiratory system in working with all those chemicals.

I certainly can’t speak for all local historians, genealogists, and family historians, but what a tremendous legacy and gift the Byerlys have given all of us—worth billions of words, if the old adage is true about a picture’s worth? |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed