|

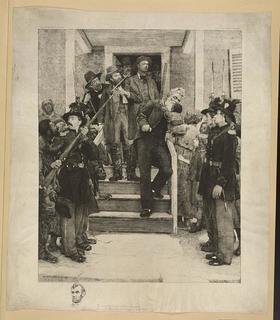

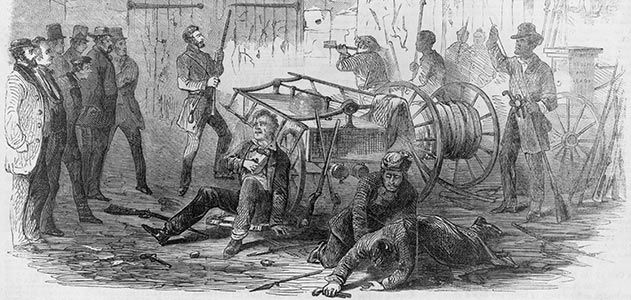

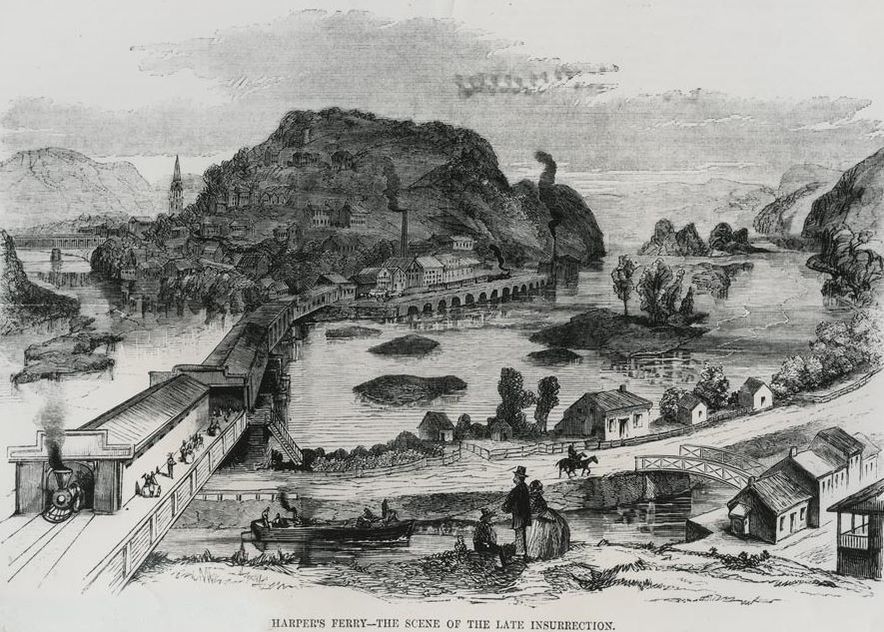

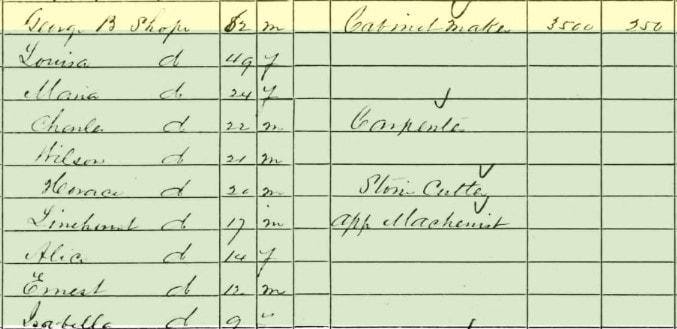

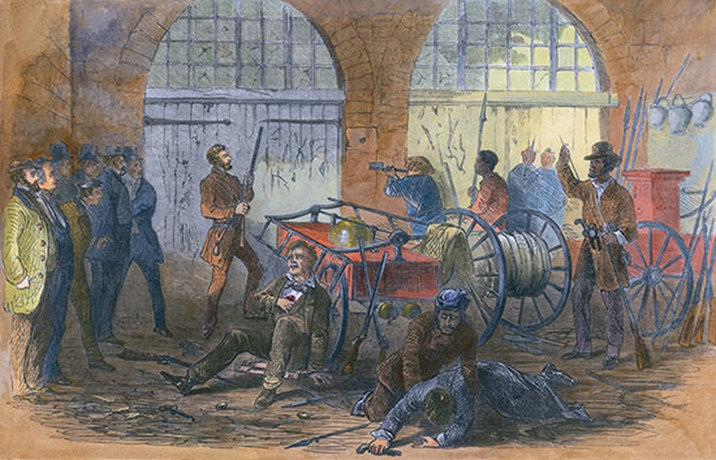

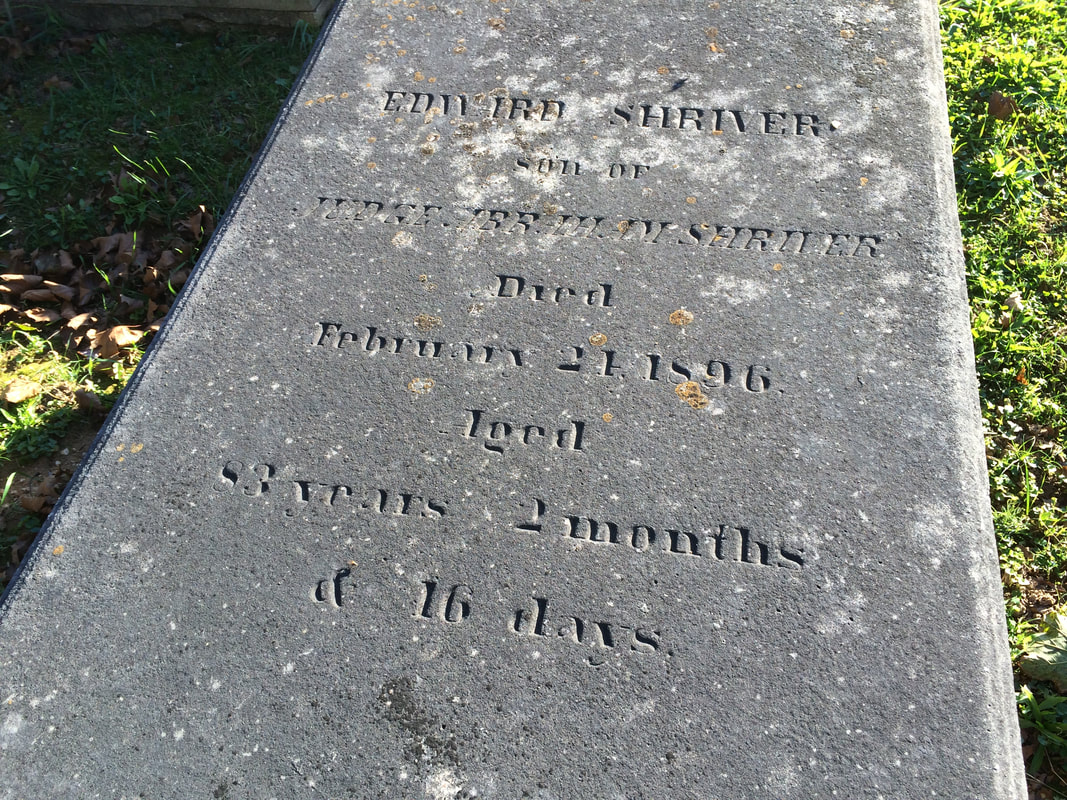

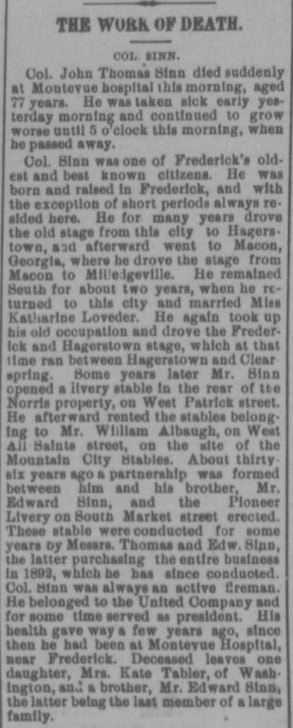

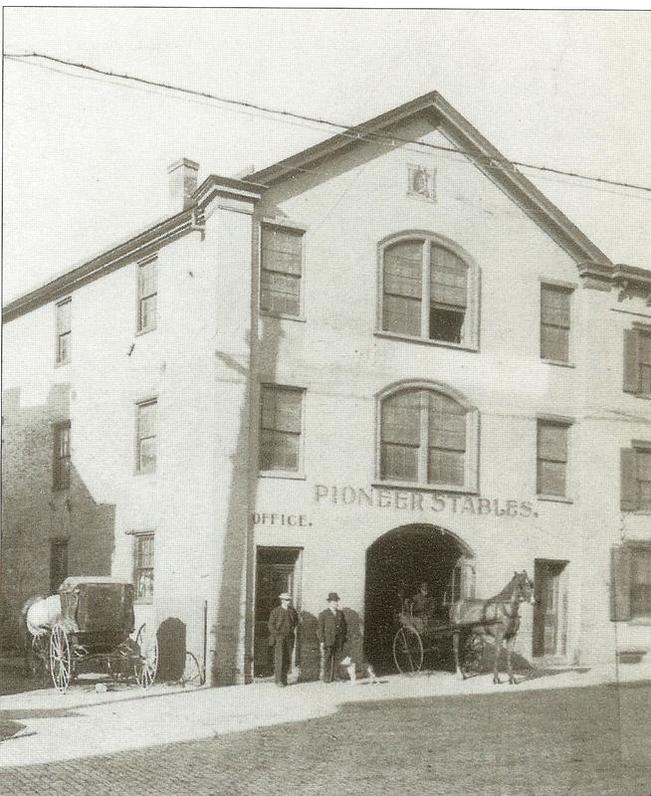

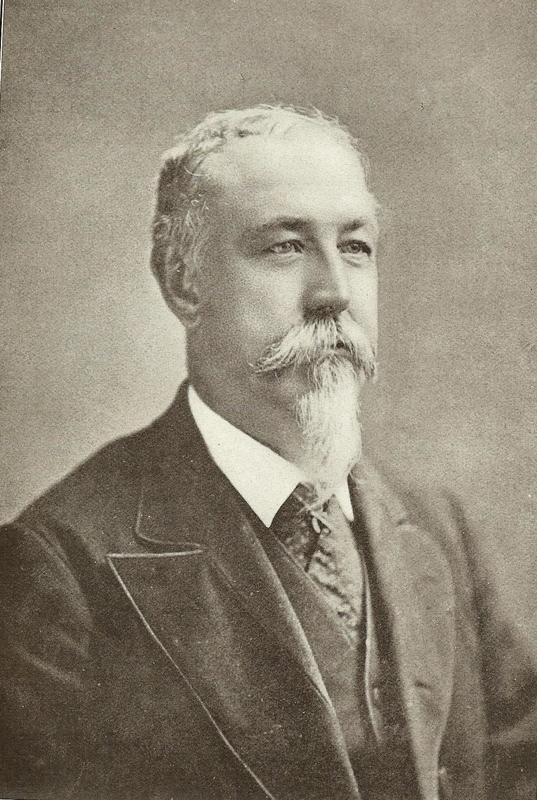

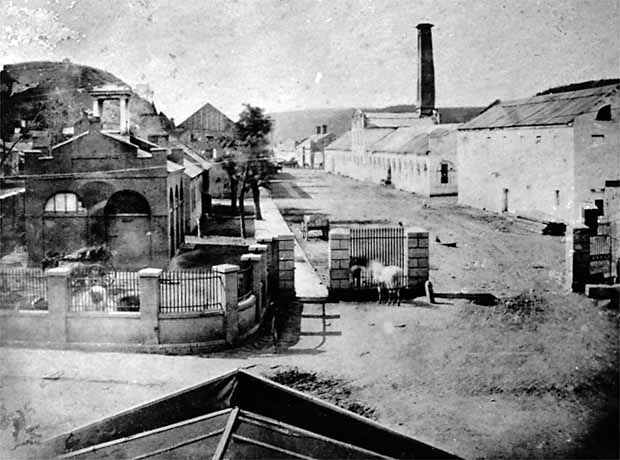

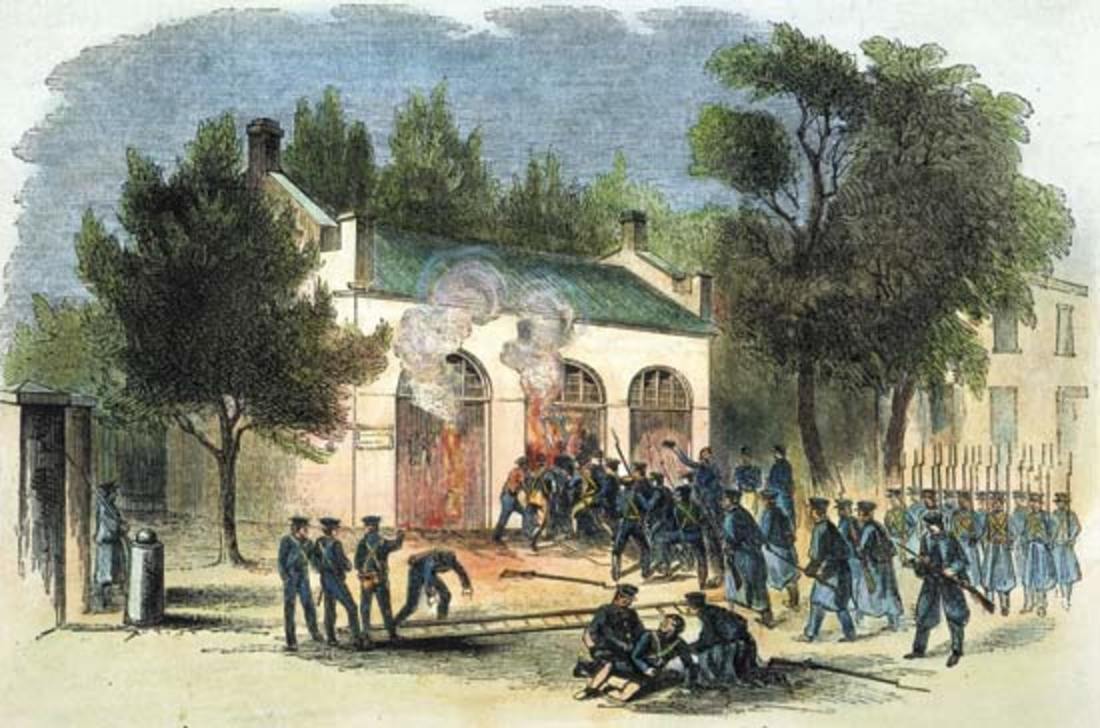

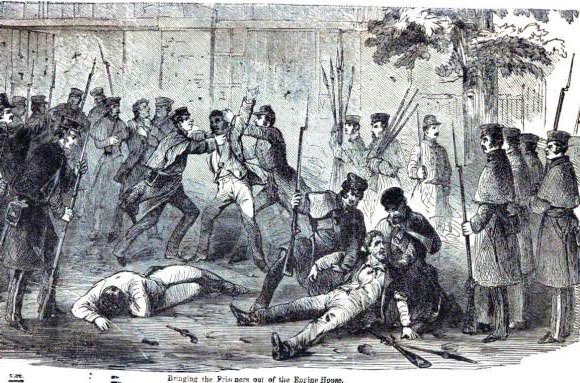

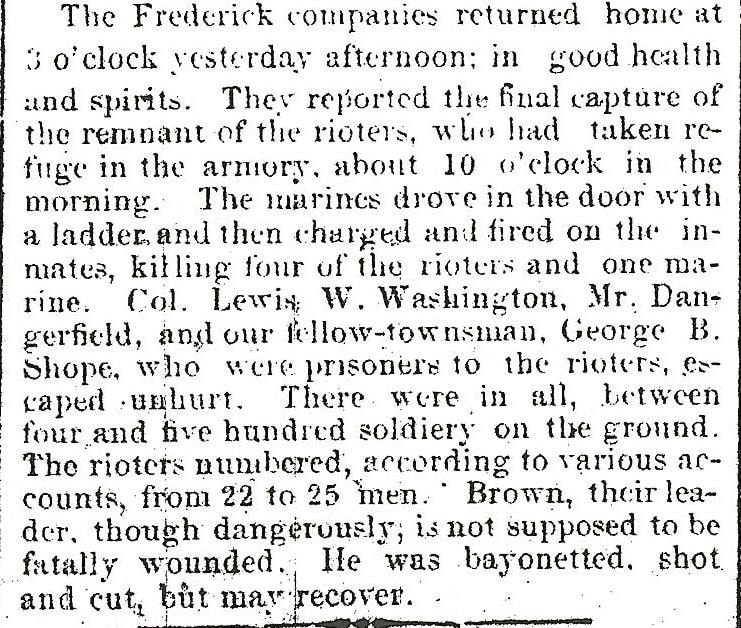

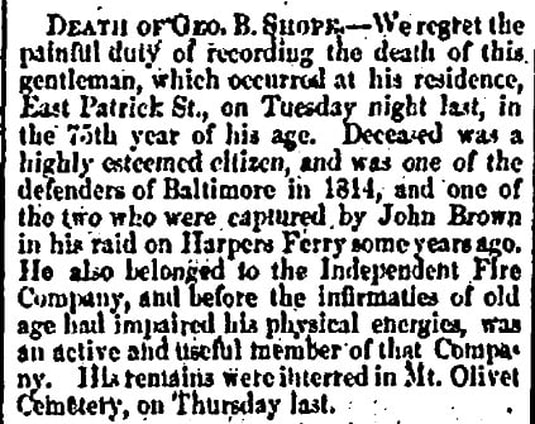

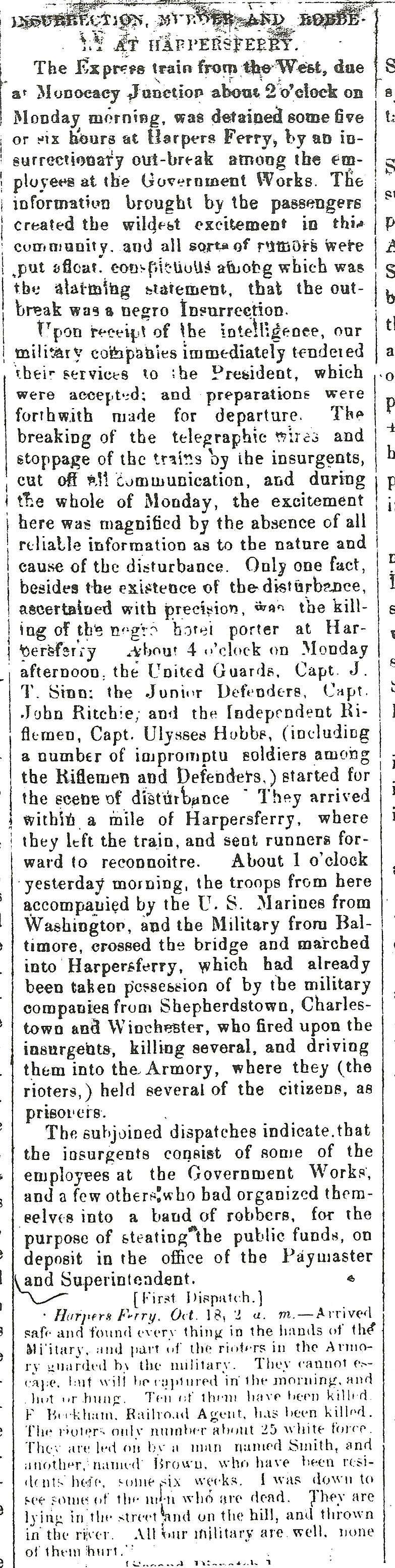

A lesser known gravesite in Mount Olivet (and its occupant) holds a definitive connection to one of the most famous events in US history. It was a long, frightening couple of days (and nights) for a Frederick man who found himself in the wrong place, at the wrong time—Harpers Ferry (VA) during the third week of October, 1859. On the night of Sunday, October 16th, 1859, a band of anti-slavery men under John Brown captured the US armory at Harpers Ferry. Earlier in the year, Brown had settled into the Kennedy Farmhouse, located just over South Mountain in Washington County’s Pleasant Valley. Here, he secretly trained his 18-man army in military tactics, and supplied them with pikes to be used as thrusting spears. John Brown’s goal was to seize weapons from the national armory at Harpers Ferry and arm slaves, who would then overthrow their masters. The raid quickly turned into a fiasco. Brown’s first victim at Harpers Ferry was a railroad night watchman, Hayward Shepherd—a free black man. Armory workers discovered Brown's men in control of the building on Monday morning, October 17th. Shortly after 7:00 am, a Harpers Ferry townsperson and armory employee, Thomas Boerly, was shot and killed near the corner of High and Shenandoah streets. During the day, two other citizens were killed, George W. Turner and Fontaine Beckham, Harpers Ferry’s mayor. When Brown realized he had no way to escape, he selected nine prisoners and moved them to the armory's small fire engine house, which later became known as John Brown's Fort. Infuriated—and mostly drunken—townspeople grabbed their rifles and trapped Brown’s men in the armory’s fire engine house. Shortly thereafter, local militia companies surrounded the armory, cutting off Brown's escape routes. One of the hostages inside was from Frederick. His name was George Brengle Shope.  Col. Lewis Washington Col. Lewis Washington The following excerpt is taken from THE OFFICIAL REPORT OF JOHN BROWN'S RAID UPON HARPER'S FERRY, VIRGINIA, OCTOBER 17-18, 1859. “About 11 a. m. the volunteer companies from Virginia began to arrive, and the Jefferson Guards and volunteers These companies, under the direction of Colonels R. W. Baylor and John T. Gibson, forced the insurgents to abandon their positions at the bridge and in the village, and to withdraw within the armory enclosure, where they fortified themselves in the fire-engine house, and carried ten of their prisoners for the purpose of insuring their safety and facilitating their escape, whom they termed hostages, and whose names are Colonel L. W. Washington, of Jefferson County, Virginia; Mr. J. H. Allstadt, of Jefferson County, Virginia; Mr. Israel Russell, Justice of the Peace, Harper's Ferry; Mr. John Donahue, clerk of Baltimore and Ohio Railroad; Mr. Terence Byrne, of Maryland; Mr. George B. Shope, of Frederick, Maryland; Mr. Benjamin Mills, master armorer, Harper's Ferry arsenal; Mr. A. M. Ball, master machinist, Harper's Ferry arsenal; Mr. J. E. P. Dangerfield, paymaster's clerk, Harper's Ferry arsenal; Mr. J. Burd, armorer, Harper's Ferry arsenal.” The hostages were lined up against the back wall of the engine house. The most prominent of these individuals was Col. Lewis Washington, the great-grand-nephew of President George Washington. His great-grandfather was Charles Washington, George’s younger brother. Charles Washington took up residence in this vicinity in 1780, and founded Charles Town, established in 1787. In 1794, President Washington selected Harpers Ferry, Virginia, and Springfield, Massachusetts, as the sites of the new national armories. In choosing Harpers Ferry, he noted the benefit of great waterpower provided by both the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers. Jefferson County was formed in 1801 as Charles Washington had anticipated, and the county court house stands on one of the lots he donated, as did the historic jail. In 1817, the federal government contracted with John H. Hall to manufacture his patented rifles at Harpers Ferry. That’s all well and good, but my interest, by George, is solely connected to another one of the luckless pedestrians kept hostage in the famed Harpers Ferry armory engine-house—George Brengle Shope.  Shope's 1812 soldier marker in Mount Olivet Shope's 1812 soldier marker in Mount Olivet George B. Shope George Brengle Shope was born on December 11th, 1796 to Jacob and Maria Elizabeth (Brengle) Shope/Schopp. He worked as a cabinet-maker by trade. Shope served as a private in the 1st Regiment of the Maryland Militia under Capt. John Brengle from August 25th to Sept. 29th, 1814. He would marry Elizabeth Dofler in February of 1818. The couple had two children (William Brengle Shope and George Dofler Shope) before Elizabeth’s untimely death in 1829 at the age of 27. George would soon-after marry a second time to Louisa Keller, and the couple went on to have eight additional children. Apparently, George considered, or made, a move to “Georgetown” in the District of Columbia as he was recorded as “having a sale of his personal property in late November, 1829.” Whether he followed through on the relocation at that time is not quite known, but records show he was back in Frederick by March, 1832 and serving as a Frederick City alderman. On July 4th, 1837, the Shope family did leave town for Ohio—but returned in 1838. The family appears in the 1850 US Census, living on N. Market Street, the site of George’s carpentry shop. The only other thing I could glean was that our future hostage was a member of Frederick’s Methodist Episcopal Church, and the Independent Fire Company. And now let’s get back to our insurrection and kidnapping in Harpers Ferry, already in progress.  Jacob Engelbrecht Jacob Engelbrecht Frederick diarist Jacob Engelbrecht (1797-1878) made poignant entries in his legendary diary the following morning: "Monday, October 17, 10 o'clock AM. — Harpers Ferry Riot — The Independent Bell & the United or Swamp Bell are both now ringing (Swamp first) calling together the military companies of our city." News of Brown’s Raid had reached Frederick before anywhere else, thanks to a train that Brown, himself, let pass out of Harpers Ferry. Frederick officials sent a telegram to President James Buchanan offering help. It was quickly accepted. The Frederick militia units, which doubled as the town’s fire companies, quickly grabbed their arms, ammunition and uniforms as they began the movement towards Harpers Ferry on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. All three were placed under the leadership of Col. Edward Shriver. Edward Shriver was born on December 8th, 1812, the second son of Judge Abraham and wife Ann Margaret Shriver. The colonel was a Frederick lawyer who in 1854 had provided the Agricultural Society of Frederick County with the land that has served home to the great Frederick Fair to this day. Col. Shriver quickly began assembling the three town companies of militia and went to Harpers Ferry by train to survey the chaotic scene for himself before bringing the larger militia contingent on the scene. Jacob Engelbrecht continued writing in his diary with another entry: "Monday October 17, ½ past 3 o'clock — Our three town companies, Captain Sinn, Captain Ritchie & Captain Hobbs just started for the cars at the Depot for the scene of War — Harpers Ferry." Interestingly, Col. Shriver and all three of his militia commanders are buried here at Mount Olivet. Here is a quick look at the group: Capt. Sinn Capt. John Thomas Sinn headed the United Home Guards (1817-1894). He was a stage coach driver earlier in life and operated livery stables in town including one named the Pioneer Stables located where LaPaz Restaurant sits today on the west side of S. Market St. at Carroll Creek. From spot accounts I have read, he was a beloved citizen but in his younger days seemed like a guy ready to pick fights with anyone who wanted a piece of him. Capt. Ritchie Capt. John Ritchie (1831-1887) had charge of the Junior Defenders. The Harvard graduate would have an illustrious career as a lawyer, rising to the position of Chief Judge of the Judicial Circuit and Court of Appeals of Maryland. He also would later serve as a representative in the US Congress. Ritchie grew up in a house that afforded a view of his future gravesite. Capt. Ritchie’s wife and daughter were featured prominently in two former stories written in September, 2017 about the founding of the Frederick Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution. Capt. Hobbs The Independent Rifleman were led by Capt. Ulysses Hobbs (1832-1911). Hobbs eventually rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel in the Maryland Militia. For years, he was one of the leading attorneys in Frederick County. Hobbs left for a while to practice in Howard County but returned to Frederick. He also served as a member of the Maryland Legislature. At the time of his death in 1911, Ulysses Hobbs was the oldest member of the Frederick Bar. He would die at the State Sanatorium in Sabillasville after a prolonged illness of several months. When Col. Shriver and the Frederick militia companies arrived at Harpers Ferry just after sunset, they experienced difficulty in getting across the Potomac River and into the town. The militiamen eventually came across the main railroad bridge into Harpers Ferry, where they were quickly put into position in an effort to help corner Brown’s surviving men holed up in his makeshift “fort,” the Armory’s guard and fire engine house. Ultimately they would surround John Brown, remaining until the US Marines under Col. Robert E. Lee would relieve them the next morning. Despite being fired on repeatedly by the raiders holed up in the engine house, Shriver’s men sustained no injuries during their night of guard duty. From their first arrival at the armory, his soldiers had “unanimously and warmly” favored storming the engine house, but Colonel Baylor from a Virginia militia outfit objected because the raiders had with them several prominent local citizens as hostages. A night assault would pose too great a risk, Baylor argued, so the Frederick troops settled in to their guard duties. Shortly before midnight (on Monday, October 17th), Capt. Sinn, while on guard in front of the engine house with some of his men, was hailed by one of the outlaws and asked to approach the building “for the purpose of conference in regard to the terms on which the Insurgents proposed to surrender.” Sinn spoke with a person who identified himself as “Captain Brown.” This of course was John Brown. Brown complained to Capt. Sinn that his men had been shot down like dogs in the street while carrying flags of truce. Sinn indignantly replied that men who take up arms in such a way must expect to be shot down like dogs. Brown replied that “he knew what he had to undergo before he came there, he had weighed the responsibility and should not shrink from it.” Brown said his terms deserved consideration for he had treated his captives well, refrained from massacring citizens when he had the power to do so, and that his men did not shoot any unarmed citizens. Captain Sinn informed Brown that Mayor Beckham was unarmed when killed. For this, Brown expressed deep regret. Brown mentioned the mortal wounds of his two sons and said that if he, his men, and their hostages were escorted to the Maryland shore, he would release the hostages unharmed and “the Insurgents would take their chance for their lives in an open fight.” Sinn relayed Brown’s proposal to Col. Shriver, who promptly went to the engine house where he personally “held a parly with Captain Brown and the gentlemen whom he held as prisoners.” John Brown repeated his offer to Col. Shriver, with one additional condition. He asked that after releasing the hostages he and his men should not be shot instantly, but rather be “allowed a brief period for preparing for fight.” Shriver told Brown that he was surrounded by an overwhelming force, and that his life was already “assuredly forfeited.” The Maryland colonel urged Brown to release the “innocent unoffending gentlemen” he was holding as hostages, but Brown retorted that “he had secured them as hostages for his own safety and the safety of his men and he should use them accordingly.” Shriver concluded there were no further grounds for discussion, and terminated the conference with Brown. The Maryland and Virginia field commanders met and decided to storm the engine house at dawn, using bayonets instead of gunfire to “secure as far as possible the safety of the prisoners.” On the morning of October 18th, Col. Lee and the US Marines sent from Washington, DC arrived at Harpers Ferry. Brown and his surviving eight men were quickly overwhelmed by the marines. In Shriver’s words, “in a very short time, all were killed, badly wounded or made prisoners.” Col. Shriver noted that the surgeons of each of the three Frederick militia companies were “at hand to render any service which might be required,” commending especially Dr. William Tyler, Jr., of Captain Ritchie’s Company, who “obtained a position inside of the yard, followed the Marines to the charge and was the first to receive and attend to the Marine who was mortally wounded.” US Marine Israel Greene is credited with being the leader of the group that captured Brown. Greene said afterwards of the captives that the eleven prisoners “were the sorriest lot of people I ever saw. They had been without food for over 60 hours, in constant dread of being shot, and were huddled up in the corner where lay the body of Brown’s son and one or two others of the insurgents who had been killed,” said Green. After the engine house was secured, effectively ending John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry, the Frederick militia were kept on guard duty inside the armory compound for a short time and then dismissed. During the early morning hours, Robert E. Lee supposedly had offered the honor of leading the attack to Colonel Shriver and the Frederick Militia. Shriver refused noting his men had families at home. He told Lee: “I will not expose them to such risks. You men are paid for doing this kind of work.” The Frederick militia returned to Frederick that afternoon, Tuesday, October 18th. Col. Shriver concluded his official written report by commending the “soldierly bearing, discipline, and readiness to discharge every duty assigned, displayed by each officer and private of the companies which formed the Battalion under my command.”  A wounded John Brown was taken to the Jefferson County jail and courthouse in Charles Town for trial. Documents also indicate the United Guard, and in particular Captain John Thomas Sinn, guarded John Brown and his men. In fact, Captain Sinn developed such a close relationship with John Brown that he was later asked to testify as a character witness for Brown at his trial in Charlestown. George B. Shope also gave testimony at the legendary trial which began on October 26th. Five days later, a jury found John Brown guilty of treason against the Commonwealth of Virginia. He would be hanged a short distance away on December 2nd, six weeks after the ill-fated attack on Harpers Ferry. I never found out why George B. Shope was in Harpers Ferry, or how exactly he got captured. The book The Strange Story of Harpers Ferry written by Joseph Barry in 1903 simply says this: “Of Mr. Schoppe (sp) little is known at Harpers Ferry. As before stated, he was a resident of Frederick City, Maryland, and his accidental presence at the scene of disturbance on the memorable 17th of October.” Elsewhere in the book, the author states that the Frederick resident happened to be on a business visit to Harpers Ferry at the time. In 1861, George B. Shope would join the newly-formed, Brengle Home Guards of Frederick City. On March 19th, 1866, he would be elected a Commissioner of Tax for Frederick City. George B. Shope died at his residence on E. Patrick St. on June 6th, 1871, at the age of 74. He would be laid to rest in the cemetery’s Area H/Lot 324. Below is the story of the John Brown Harpers Ferry Raid as it was reported in the Frederick Examiner newspaper on October 19th, 1859.

0 Comments

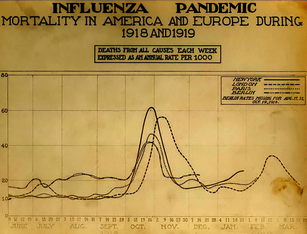

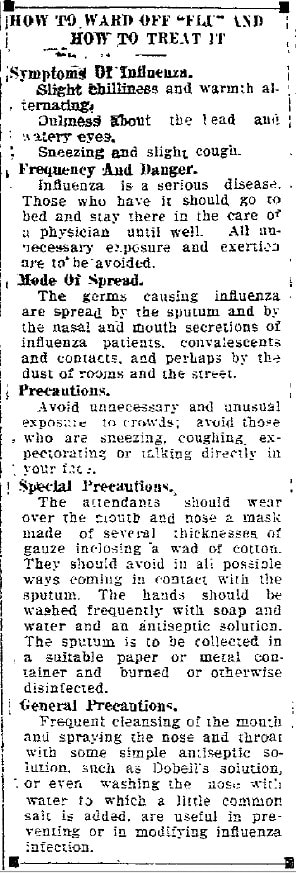

The fall of 1918 was not your ordinary “cold and flu season” here in Frederick. The same held true for the state, nation and world for that matter. It is estimated that about 500 million people, or one-third of the planet’s human population, became infected with this virus. The number of flu-related deaths was estimated to be at least 50 million worldwide with about 675,000 occurring in the United States. The pandemic, or widespread disease, was so severe that from 1917 to 1918, life expectancy in the United States fell by about 12 years, to 36.6 years for men and 42.2 years for women. Interestingly, there were high death rates in previously healthy people, including those between the ages of 20 and 40 years old, which was unusual because the flu typically hits the very young and the very old more than young adults.  “The Spanish Flu” The 1918 flu pandemic is often referred to as “The Spanish Flu.” It did not originate in the country of Spain at all, but this nation freely reported news of flu activity while remaining neutral during “The Great War”—World War I. The true cause can be traced to this international conflict, where soldiers of each side shared close quarters, and massive troop movements helped fuel the spread of disease. In the United States, unusual flu activity was first detected in military camps and some cities during the spring of 1918. For the US and other countries involved in the war, communications about the severity and spread of disease was kept quiet as officials were concerned about maintaining public morale, and not giving away information about illness among soldiers during wartime.

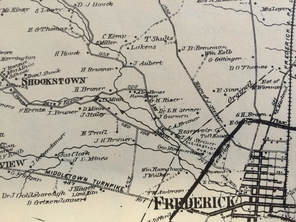

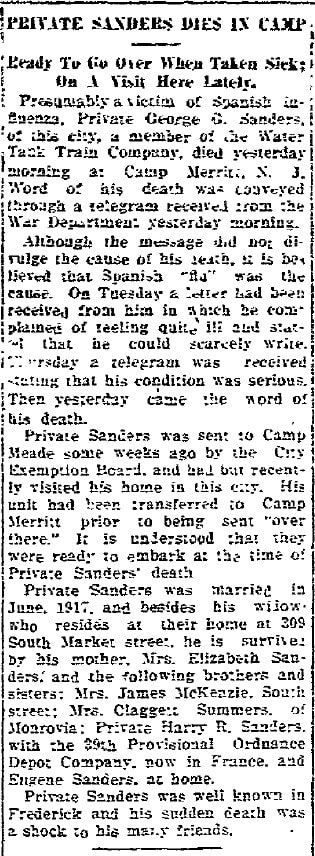

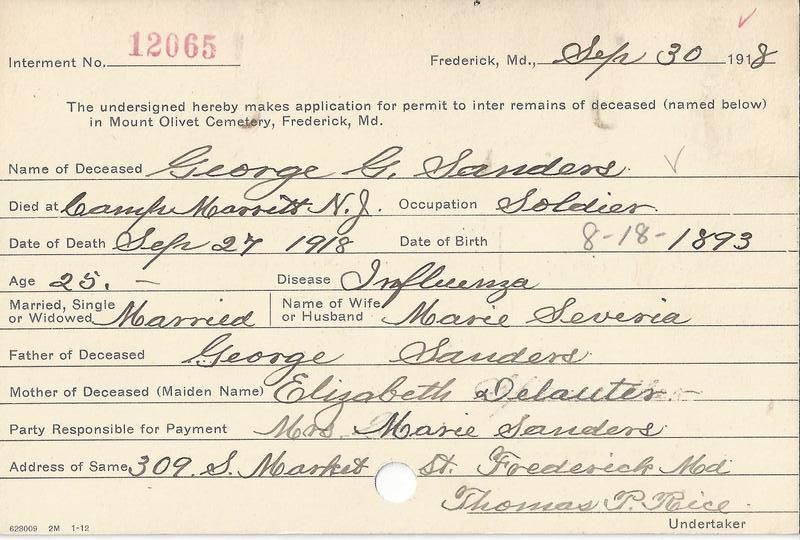

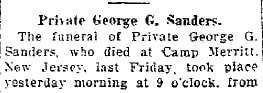

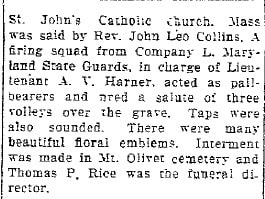

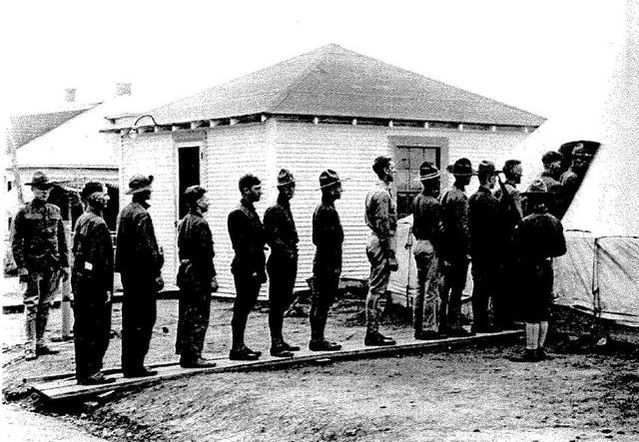

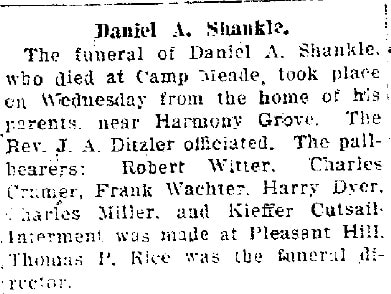

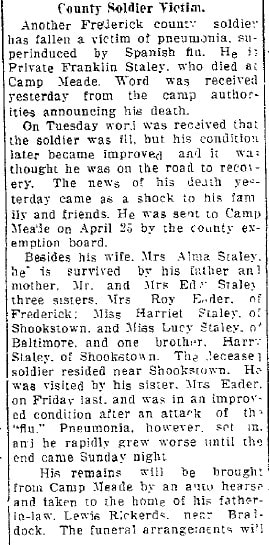

Private Sanders was serving with Company B of the 301st Water Tank Train. His unit was on the verge of heading to Europe, in late summer, however George became quite ill on Tuesday, September 24th. Sanders would be dead just three days later. News reached Frederick of Sanders’ untimely demise by telegram. The local newspaper reported his death the following day, presuming the cause to be the dreaded “Spanish Flu.” Sanders’ body was transported back home to Frederick by train, and given a funeral with military honors here at Mount Olivet on the morning of Tuesday, October 1st, 1918. He would be laid to rest in Area T/Lot 126. Unbeknownst to many townspeople, this would be a harbinger of doom for the community. This second wave of the flu was brutal, and peaked in the US from September through November. More than 100,000 Americans died during the month of October alone. In late September, a small number of flu cases had been reported at Maryland’s Camp Meade, the premiere training ground for local men in the US Army. This military installation, located 50 miles southeast of Frederick City in Anne Arundel County, was activated in 1917 as one of 16 cantonments built for troops drafted for the war with the Central Powers in Europe. The site was selected because of its close proximity to the railroad, the Port of Baltimore and Washington DC. The Post was originally named Camp Meade for Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade, the commanding Union officer during the Battle of Gettysburg of the American Civil War.  Daniel A. Shankle grave (Area LL/Lot 135) Daniel A. Shankle grave (Area LL/Lot 135) World War I During World War I, more than 400,000 Soldiers passed through Camp Meade, a training site for three infantry divisions, three training battalions and one depot brigade. During World War I, the Post remount station collected over 22,000 horses and mules. Hundreds of Frederick County's sons received their basic training here, and some would be permanently stationed in this vicinity. Like Private George G. Sanders, Jr., a few of these men would come down with the flu. As a matter of fact, by the start of October, 1900 soldiers were ill with the influenza. For many it would be a fatal affair. Two men with Mount Olivet Cemetery ties actually died there at Camp Meade during the first week of October. Both perished on Sunday, October 6th, 1918. These were Edwin W. Warfield, a native of Woodbine in Howard County (Co. D, 71st Infantry Regiment), and Franklin Luther Staley (154th Depot Brigade) of Shookstown, a small hamlet located on the east side of Catoctin Mountain, north east of Frederick City. Official records state that both individuals died of bronchio-pneumonia, shielding the terminology of “Spanish Flu,” or influenza. Two days later, Harmony Grove’s Daniel Austin Shankle (244th Ambulance Co., 11th Sanitary Train) succumbed to the same malady.

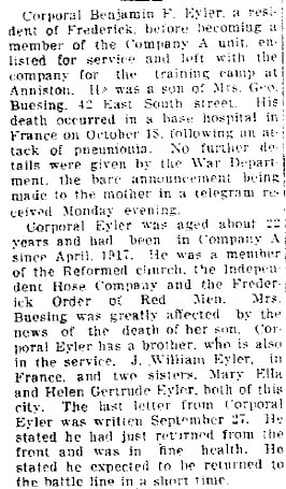

Leslie Franklin Selby gravesite (Area T/141) Leslie Franklin Selby gravesite (Area T/141) Two doughboys lost their lives on Friday, October 18th, 1918. Leslie Franklin Selby (Co. I, 17th Infantry Regiment) whose former home had been located at Frederick’s 14 W. 6th St., died at Camp Meade. On the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, Benjamin Franklin Eyler had been recuperating in a French hospital in Argonne, but lost his fight against the disease. Some loyal readers of this blog may recognize this latter, young man as the son of Frederick City’s first official dog-catcher. Benjamin F. Eyler originally joined the Maryland National Guard. He was promoted to the rank of corporal and shipped overseas to Europe in June, 1918 as part of Company A of the 115th Infantry Regiment. While on the front in France’s Center Sector, Corporal Eyler contracted pneumonia in the horrid conditions associated with trench warfare. He would be hospitalized on October 3rd and languished for two weeks before succumbing to the disease. The serviceman was originally buried overseas, but his body would be brought back home and re-interred in Mount Olivet’s Area Q/Lot 266. A well-attended memorial service was held on June 19th, 1921 in the mortuary chapel on the premises (Key Memorial Chapel).  Grave of Bessie Jones, first flu victim buried in Mount Olivet (Area H/Lot 140) Grave of Bessie Jones, first flu victim buried in Mount Olivet (Area H/Lot 140) Unwelcome Visitor The unwelcome visitor, in the form of the influenza, would wreak additional dismay and despair on Frederick. As far as Mount Olivet Cemetery is concerned, the first documented civilian fatality of the Spanish Flu was Mrs. Bessie G. Jones, a 33-year-old housewife from Buckeystown, MD. Mrs. Jones passed on September 28th, 1918. Two days later, a broom-maker named John H. F. Bender would be claimed as a victim and buried in Mount Olivet. Bender, age 60, was also from Buckeystown. Yet another resident from the same town of Buckeystown would help usher in funerals during the horrific month of October, 1918. Thirty-year-old Sallie Elizabeth Barber expired on October 2nd. The first Frederick City resident claimed by the flu, and buried in Mount Olivet, was a 21-year-old electrician named Marshall Howard Zepp, Jr. Zepp died on the fourth of October. By the 8th, flu cases had become so prevalent that the state health board ordered county health officer Dr. T. C. Routson to immediately close all schools, churches, theaters, pool halls and other places where the public may gather. Stress levels were also high for another Routzahn—Albert Routzahn, Mount Olivet’s superintendant. The chart below shows the incredible spike in burials in late 1918. A monthly average of 21 for the first 9 months of the year, skyrocketed to 77. Between September 27th and October 31st, related deaths by the influenza included five servicemen and 51 civilians, making a grand total of 56 individuals laid to rest. Remember that this was also a time where graves were still primarily dug by hand. Years ago, current Mount Olivet superintendent J. Ronald Pearcey was told by Melvin Engle, a former resident of S. Market St., that he vividly recalled the cemetery bell tolling almost non-stop (to signify funerals) that fateful October of 1918. The Year 1918 and Burials in Mount Olivet Cemetery Jan Feb Mar April May June July Aug Sept Oct Nov Dec 18 14 23 19 14 35 17 19 25 77 27 40 First 20 residents to die from Spanish Flu in Frederick’s Mount Olivet 9/28/1918 Mrs. Bessie G. Jones 33 Housewife Buckeystown Area H/140 9/30/1918 John H. F. Bender 60 Broommaker Buckeystown Area T/124 10/2/1918 Sallie Elizabeth Barber 30 Housewife Buckeystown Area OO/56 10/4/1918 Marshall Howard Zepp, Jr. 21 Electrician Frederick Area T/130 10/6/1918 Pearl Elizabeth Weaver 8 N/A Buckeystown Area OO/56 10/6/1918 Carl G. Wright 39 Laborer Baltimore Area G/209 10/6/1918 Edgar A Hollis 32 Jeweler Martinsburg Area OO/95 10/6/1918 Lee Ray Bentz 21 Machinist Baltimore Area M/5 10/8/1918 Mildred Jane Williams 23 Housewife Ijamsville Area T/81 10/9/1918 Jesse Franklin Knipple 18 Cannary Frederick Area M 10/8/1918 John Ridenour, Jr. 28 Baker Virginia Area T/131 10/10/1918 Anna E. Metz 5 N/A Frederick Area T/133 10/11/1918 Mary G. Metz 25 Housewife Frederick Area T/133 10/9/1918 Clarence E. Bentz 29 Linesman Baltimore Area M/5 10/10/1918 Harry N. Garrett 26 Munition Plant Baltimore Area T/132 10/10/1918 Jesse Francis House 44 Brushworks Frederick Area H 404 10/13/1918 George Frederick Strailman 27 Blacksmith Frederick Area T/T122 1014/1918 Marguerite E. Redmond 6 N/A Frederick Area T/120 10/14/1918 Lily Alma Shook 35 Housewife Frederick Area S/32 10/13/1918 William Henry Ogle 33 Adamstown Area T/118 Controlling the spread of an epidemic was a difficult task. Interestingly, children and senior citizens fared better against the Spanish Flu than those 20-40 years of age. Local industries such as Frederick Iron & Steel, Ox-Fibre Brush Company and the Union Knitting Mills were hard hit with many employees out on sick leave. Several store-keepers wisely kept their doors closed as well. The Frederick Agricultural Society called off the annual Great Frederick Fair in an effort to curb the spread of the disease, and save lives. Most interesting of all, Mayor Lewis H. Fraley and the Frederick Board of Alderman reinstated a ban on public spitting, referred to formally as “expectorating.” Violators would be fined $1.00 for each instance. Apparently, this just wasn’t restricted to spitting on city streets, as there had been a running problem with riders doing this on the floors of the local trolleys.

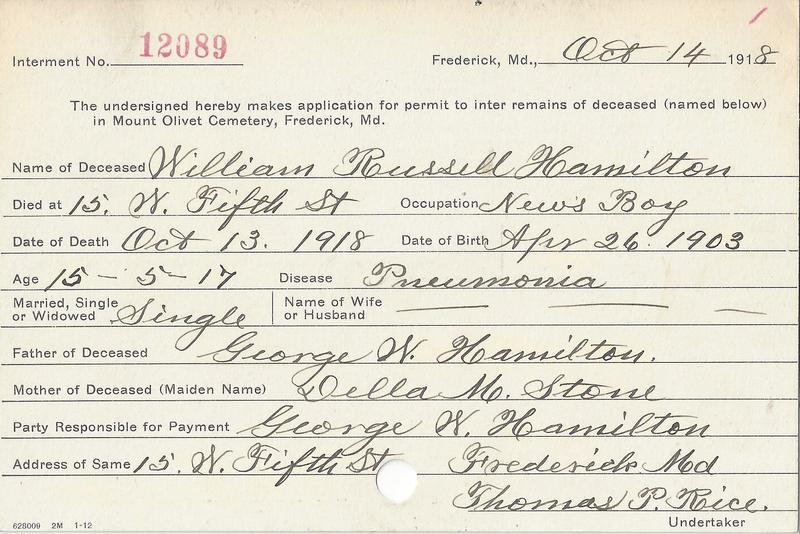

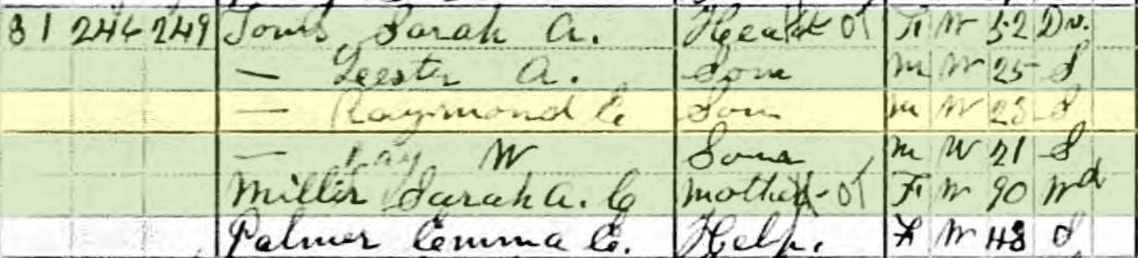

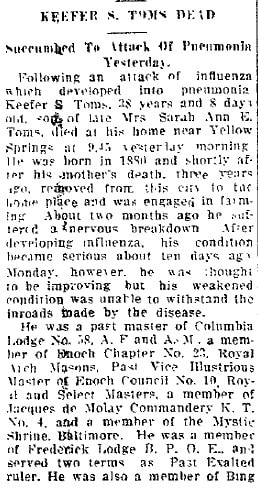

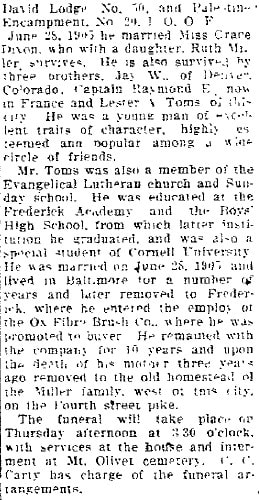

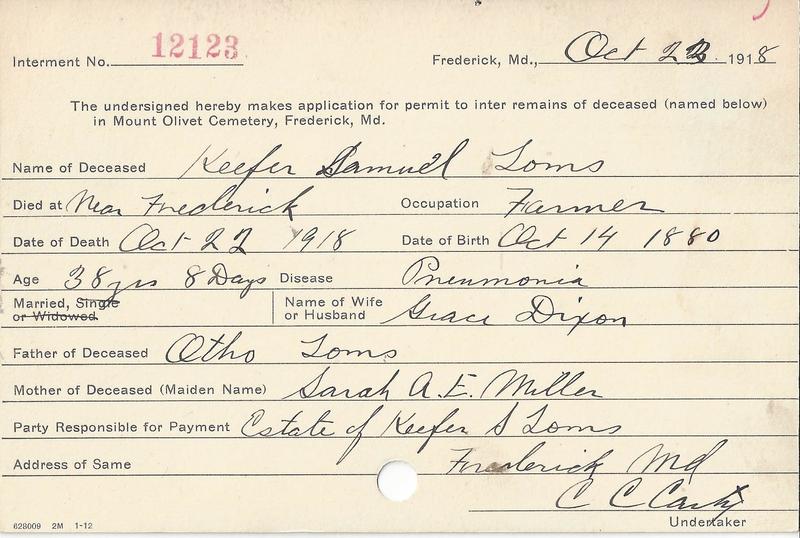

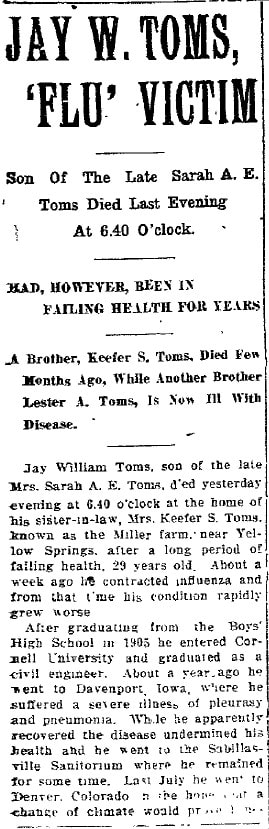

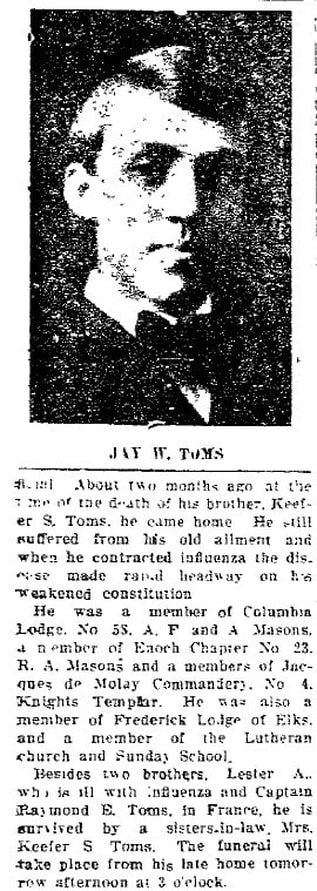

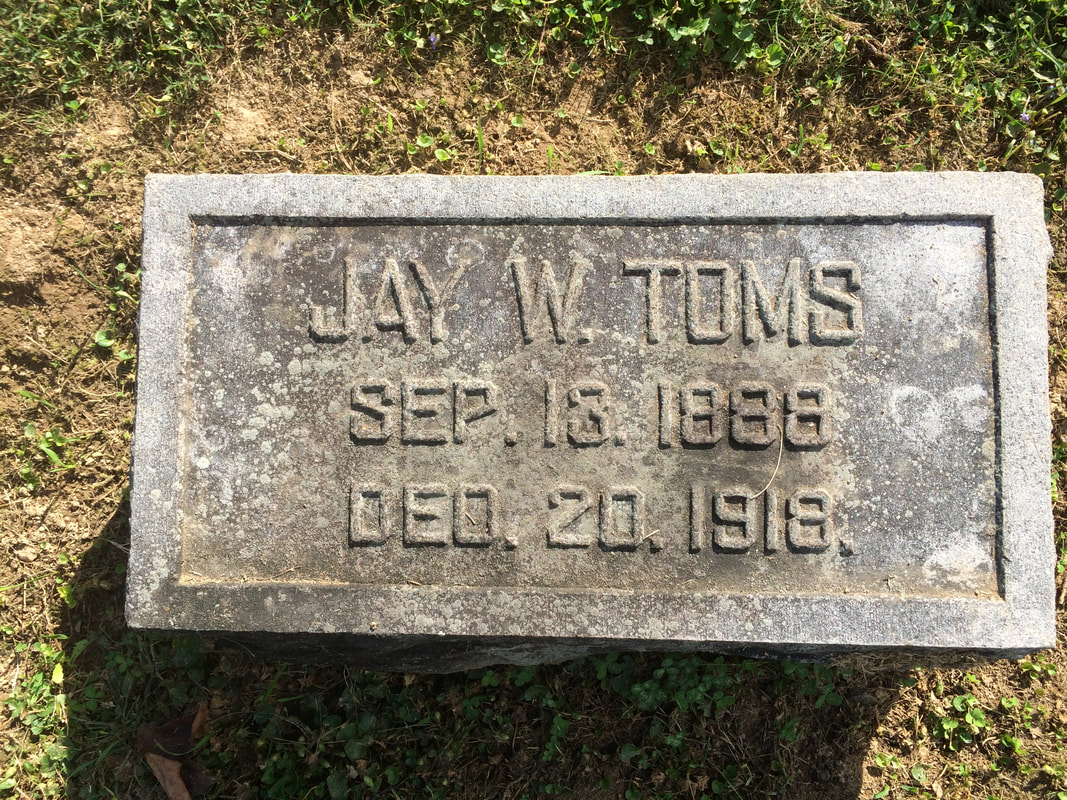

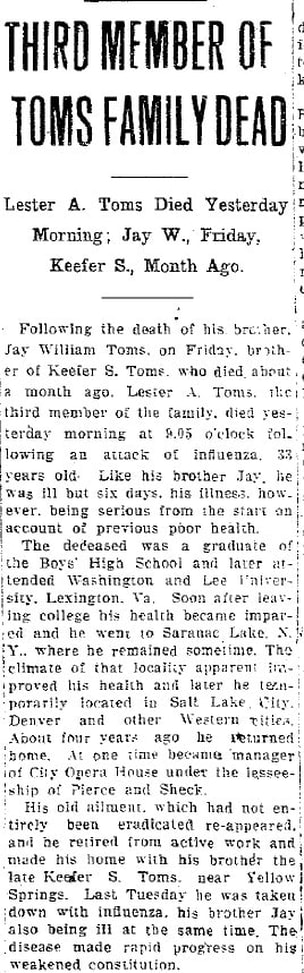

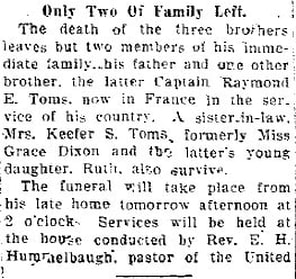

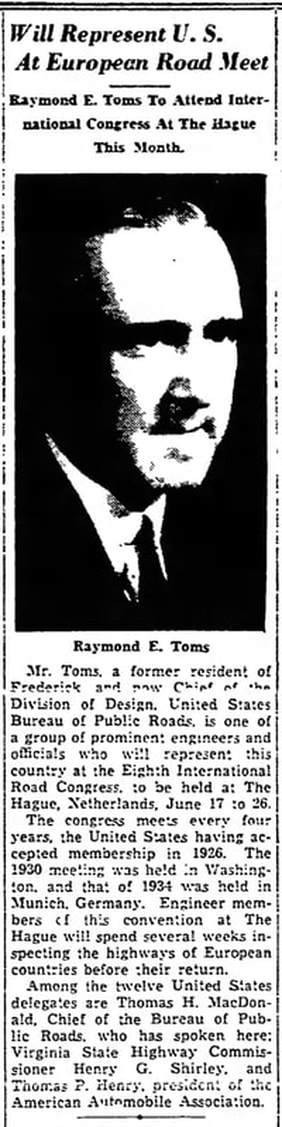

All in all, there would be roughly 2,000 cases of the deadly flu in Frederick County. Of these, 200 were fatal. During the remainder of the October, 48 other souls would go to early graves in Mount Olivet thanks to the Spanish Influenza outbreak. The high water mark having been reached by mid-month, cases waned by month’s end. Health Officer Routson even placed a temporary ban on church funeral services. Things slowly got back to normal in November. Ironically, Friday, November 11th called for celebration as the Allied Armistice was signed by the German powers, ending the war—but the battle still raged on stateside against the influenza. The citizenry had to slightly temper their enthusiasm as public celebration en-masse might not be the best activity to engage in. However, plenty joined in the revelry. It’s too bad Little “Willie” Hamilton didn’t have the chance to exclaim: “The Great War is Over! Read All About It!” In searching our Mount Olivet interment records, I found 22 more residents who died of the flu in November and December, 1918. Another 13 would succumb in January of 1919, before the influenza pandemic finally dissipated in our area. That makes a total of 93 folks laid to rest in Mount Olivet thanks to the Spanish Flu.  A Vanishing Family An interesting story of note was told to me in the summer of 2017, when I met some visitors to the cemetery in search of long lost relatives never met. Mrs. Anne Toms Richardson of Norfolk, Virginia was traveling with her husband back home after attending a medical conference in Chicago. The road brought them close to Frederick, so they decided to make a long anticipated visit to town, and more importantly, Mount Olivet. Mrs. Richardson shared with me the news that her father (Raymond Ezra Toms, Jr.) had recently passed, and she had taken up family genealogy in an effort to gain closure, and expand her horizons on knowing more about her roots. She told me that her paternal grandfather, Raymond Ezra Toms, had been born in Frederick and his immediate family lived at 31 E. 2nd Street. Sadly, Raymond’s father was a drunk and abandoned the family. However, his mother’s father, Samuel Miller, stepped in as an incredible mentor and male role model for Raymond and his three brothers: Keefer, Lester and Jay. Samuel A. Miller (1809-1894) was a prominent farmer in the vicinity of Rocky Springs, just a few miles north of old Frederick City. His farm would sit due north of the Rocky Springs Cemetery and was likely the same that was lived in by Dr. William Waters, subject of a recent blog. Mr. Miller provided for the college education of all four of his grandchildren. Three attended Cornell and the other, Washington & Lee.  The Toms brothers in 1913 (L-R Raymond, Lester, Keefer, and Jay) The Toms brothers in 1913 (L-R Raymond, Lester, Keefer, and Jay) Raymond graduated atop his class in 1903 from Frederick Boys’ High School. He chose Cornell for his higher learning institution and graduated in 1907, earning his Bachelor of Science with a degree in civil engineering. He eventually found employment with the United States Bureau of Public Roads (BPR) and was sent on assignments all over the country. It was an exciting time as he was a true “trailblazer,” with building the first major roads in many parts of rural America. He kept his home base in Frederick, and appears in the 1910 census living here. Raymond’s mother, Sarah Ann Elizabeth (Miller) Toms would pass in late July, 1915. Shortly thereafter, Raymond was sent to Kentucky to build a major road project to Sharpsburg in Bath County (KY). He made his project headquarters in Mt. Sterling, Kentucky. Unbeknownst to the young man at the time, this town would grow in great importance to him. With the US jumping into the World War in spring, 1917, Raymond E. Toms enlisted in the Army Reserves. He was chosen for the Benjamin Harrison Training School for Officers, where he received the commission of captain. He was then sent to Texas by the end of the year. He eventually became a member of Battery E, of the 127th Field Artillery. Capt. Toms would leave New York on a ship bound for the battlefields of France on September 25th, listing older brother Keefer Samuel Toms as his immediate next of kin. As Raymond may have pondered his own impending fate of not returning alive to his hometown again, he never could have imagined what would, in three months’ time, await him in the safe confines of home in Frederick, Maryland. Less than a month later, October 22nd, 1918, Keefer Samuel Toms died of pneumonia—brought on by the Spanish Flu. A farmer in charge of the old Miller homestead, Keefer had just celebrated his 38th birthday a week prior. His burial took place in Mount Olivet Cemetery on October 23rd, 1918. Brothers Jay and Lester lived with Keefer on the Rocky Springs Farm. A few weeks later, Capt. Toms would revel in the news of the war’s end with the signing of the Allied Armistice on November 11th, 1918. On Christmas Day (1918), he boarded a ship at Bordeaux, France bound for home with his 127th Field Artillery colleagues. I seem to think that he had not received word regarding Keefer’s death because he again listed him as his next of kin in the ship’s manifest. Sadly, his return to the states would be bittersweet as he had no family to come back to. Brother Jay William Toms, also trained as a civil engineer, had died from the influenza less than a week earlier on December 20th at the age of 29. As if that wasn’t cruel enough, Lester A. Toms (33 years-old) would pass on December 22nd of the flu. Both Jay and Lester were buried in Mount Olivet’s Area Q/Lot 72—a section that also contained their mother and Miller grandparents. Raymond’s triumphant return to Frederick, Maryland was empty, as he came to find all three brothers in their respective graves, along with his beloved mother and grandparents. He now found himself as the last surviving member of his immediate family. Devastated, Raymond E. Toms returned to Mount Sterling, Kentucky. Fate would lead him to Paulina Judy, whom he would marry in April of 1919 after a short courtship. He now had a new family in Paulina’s relatives. A year later in May, 1920, Raymond and Paulina had a daughter, Sarah, named for Raymond's mother. She would die a little over two years later. Son Raymond Ezra Toms, Jr. was born in 1924. The family would move about the country as Raymond excelled in his occupation as a road planner. They left Kentucky for Chicago and then Montgomery, Alabama. Raymond Toms came back to the Washington DC area, taking up residence in Chevy Chase, MD. Here he had garnered the position of Federal Bureau Chief of Roadway Design for the Department of Public Highways. Raymond supposedly developed the cloverleaf highway design while competing in a contest while in Chicago. He also was responsible for the highway design of the Mount Vernon Memorial Parkway, today more commonly known as the George Washington Memorial Parkway. Mrs. Richardson also shared with me a story that her grandfather was called to Germany and handed a medal for roadway engineering excellence by Adolph Hitler sometime in the 1930’s. It was likely the meeting referenced below, which took place in Munich. Thank goodness for the war in Raymond E. Toms’ unique case—who knows if he would have suffered the same fate as his three siblings in contracting the Spanish Flu? He lived a happy and very useful life, albeit dying at the age of 54 in November of 1942. Upon retirement, the road took him from Chevy Chase, bringing him once again to Mount Sterling, KY, his “new home.” He is buried in that town’s Machpelah Cemetery. I’m so thankful to have learned this bittersweet story from Capt. Toms’ granddaughter. Mrs. Sanders Speaking of Kentucky, I can only wonder if Raymond E. Toms ever crossed paths with Col. Sanders of fried chicken fame? Who knows, but the odds are that he likely knew fellow Fredericktonian George Grover Sanders, Jr. who I made mention at the onset of this story. That brings me to one final wrinkle in this sordid story of the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918. George Grover Sanders, Jr. died at Camp Merritt, NJ in late September, 1918. He left a wife, Marie, and a four-month old son, George Frances. Well, I found some good news and unfortunately, some bad news.  As for the positive, Marie Sanders would remarry another local boy who served in the Great War. This was Charles Smith Hobbs of New Market (1895-1963) Hobbs had entered the Regular Army at the end of 1917 and served overseas as a wagoner for the 335th Aero Squadron. He saw plenty of action in France within the Fismes Sector, Oise-Aisne, Clermont Sector, Meuse-Argonne Offensive and Thiaucourt Sector. He made it back home and had a career as a chauffeur and later a bus dispatcher for the old Blue Ridge Line. He and Marie would have two children of their own and would eventually move from Marie’s residence on S. Market St. to 501 Magnolia Avenue. Marie died in 1989 at the age of 93. The sad news is that George Frances Sanders only lived to 9 years of age, passing on May 4th, 1928, just 18 days shy of his tenth birthday. The cause of death—pneumonia.

|

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed