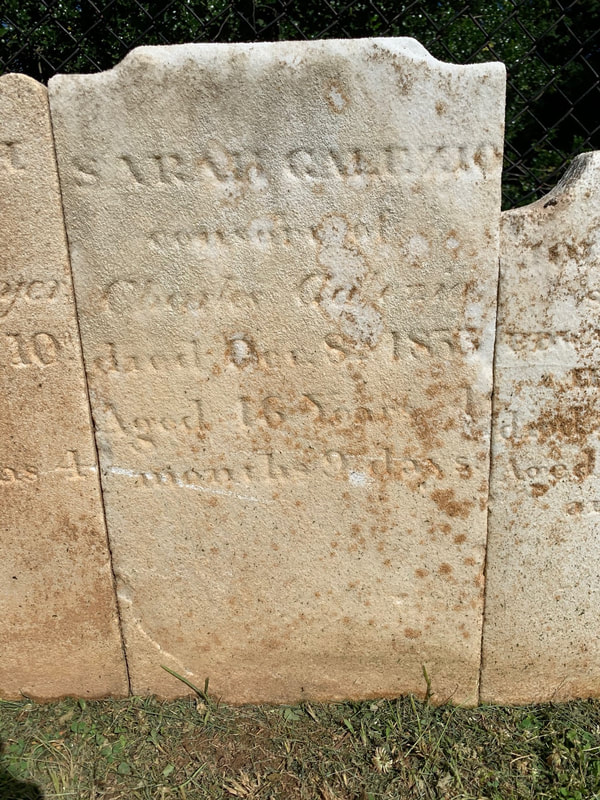

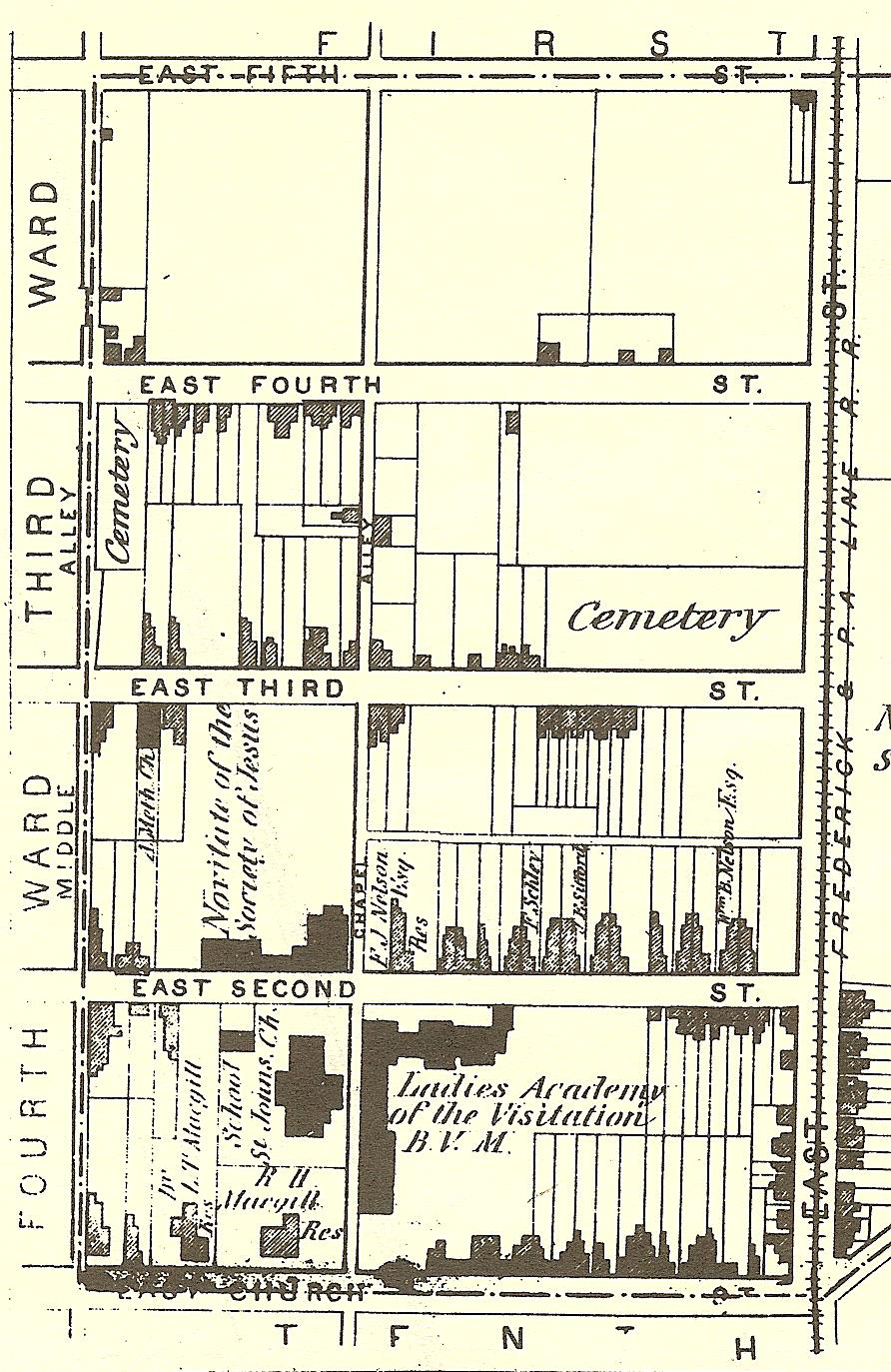

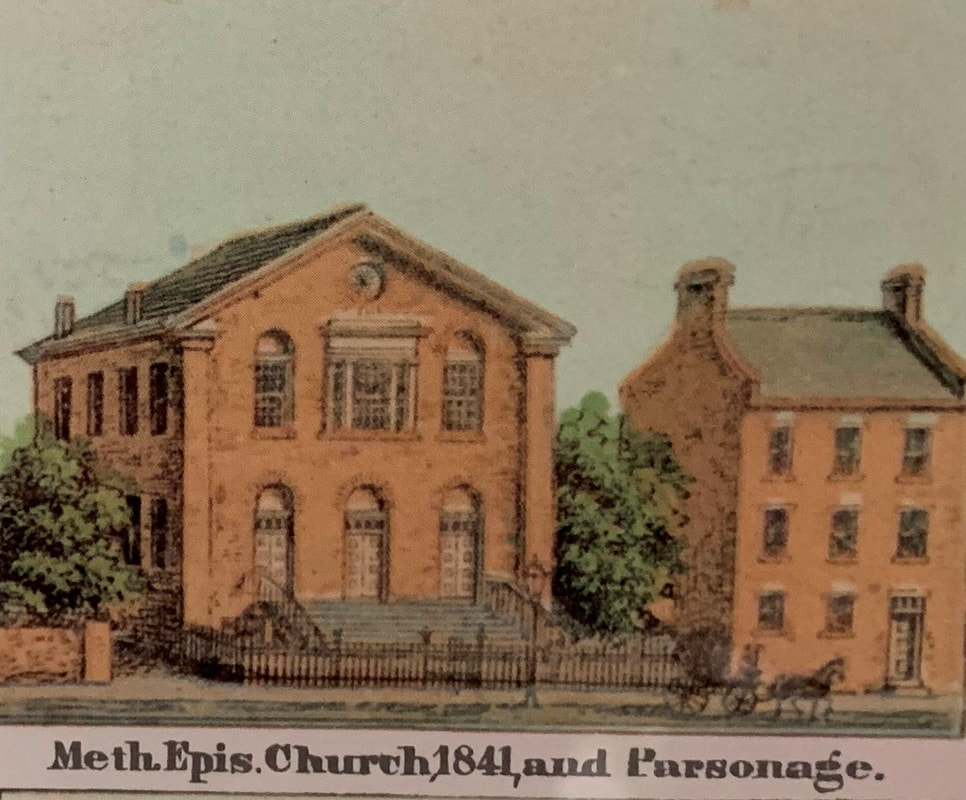

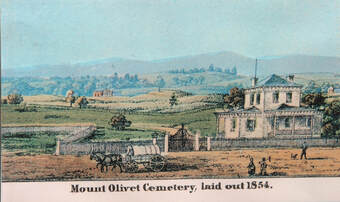

One of the most interesting areas within Mount Olivet Cemetery is labeled as NN. Here, stones are tightly packed together, many of which marking the graves of folks born before 1854—the year our cemetery opened for burials. Three local churches would buy lots in this small section that once marked the northwest extent of Mount Olivet before additional ground to the west were opened around 1910. In 1908, bodies originally interred in Frederick’s Methodist Episcopal church graveyard were placed here, along with decedents brought from Evangelical Lutheran’s former burying ground (at today’s Everedy Square corner of E. Church and East streets) and others formerly resting in the Presbyterian burial ground on the northwest corner of N. Bentz and Dill Ave. I have written stories on others buried within Area NN, which was neatly laid out in rows with the inhabitants of each of the three fore-mentioned cemeteries in distinct sectors according to congregation—from left to right, Methodist, Lutheran, Presbyterian. Adjacent our boundary fence, a non-Frederick name on a stone jumped out at me. It is in the back row, right side, of the “Methodist section.” The decedent is Sarah Galezio. The brief “story on the stone” says that Sarah was the consort of one, Charles Galezio, and that she died on October 8th, 1833 aged 46 years, 4 months and 9 days. Now Galezio is my focus for this story, but while I’m here, I want to mention the funerary phenomenon of the word “consort.” One can find that many women buried in our cemetery bear a descriptor on their stones in an effort to give context to a man of note she is related to. Now, I’m not trying to “stir the proverbial sexist pot” here, but “stations in life” carved into marble and granite grave markers are abundant. These include “wife of,” “daughter of,” “grandmother of,” “aunt of,” and “widow of.” On much older stones, the term consort or relict was used to describe the woman’s marital status. From the 17th through 19th centuries, consort was usually used on the graves of women, although a man could also be a consort. The word consort was normally used in this manner: ‘Sarah--consort of Charles Galezio,’ in which consort meant that Sarah was Charles’s spouse and died before her husband did. There is no other information listed. The fact that she was married to Charles is all that’s left as a reminder of her life and identity. Oh, and our cemetery database report that she was the mother of Charles and Mrs. Margaret Hobbs. Again, this was a name I was not familiar with in the annals of Frederick history—so what better reason than to go “in search of,” right? Well, I didn’t expect to find much, but would be pleasantry surprised with what I did “uncover”—however, maybe not the best word use when referring to cemetery-based research of this kind.

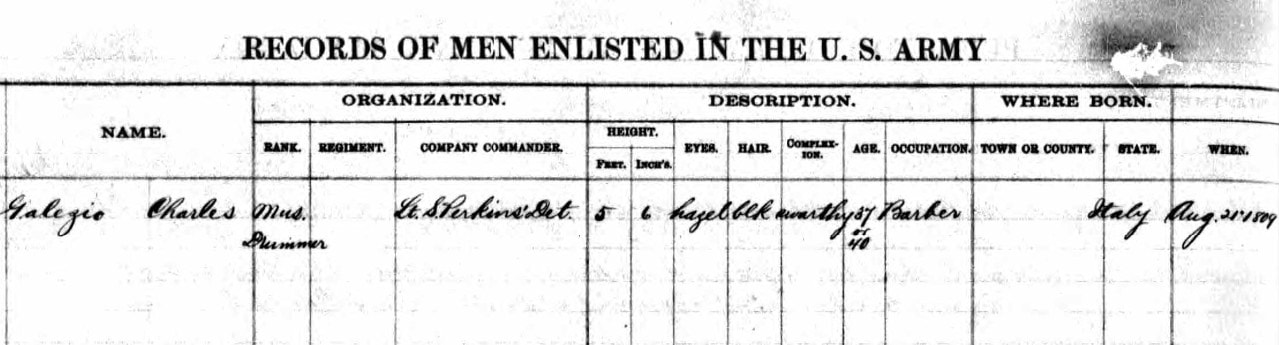

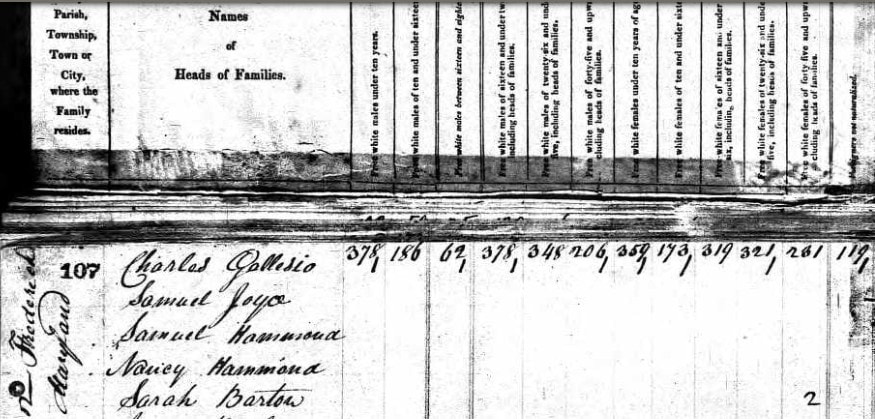

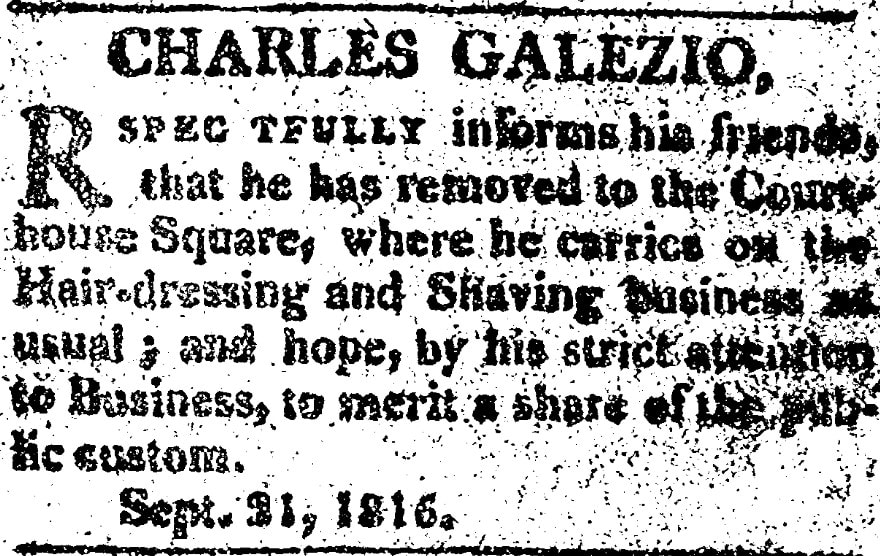

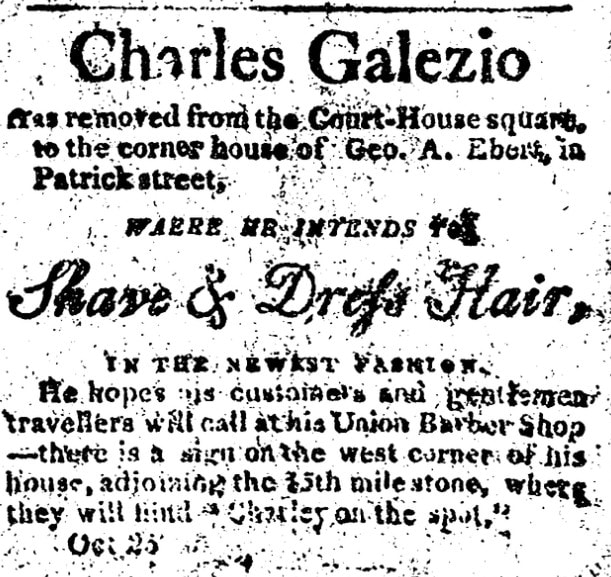

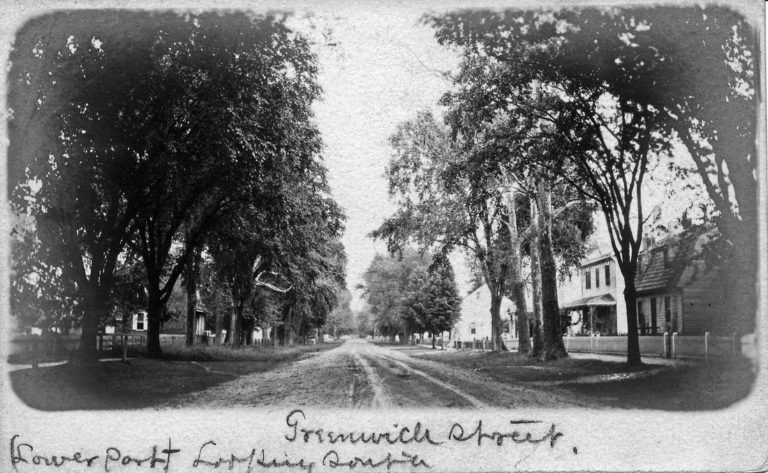

Our records record Sarah’s birthdate as May 30th, 1787, but no parents named, and a burial date in Mount Olivet of June 4th, 1895. She actually was buried three times as the 1895 date marks her removal from the Methodist Episcopal Church’s graveyard to Area Q, Lots 252-253. In January, 1908, the Methodist churchyard burials were removed to her present resting spot in Area NN, Lot 123. Thank God once again for the internet! I mean, it would have also been quite possible to find a short biography on my subject of this week’s blog (Sarah Galezio) had I been researching, in person, within the New York Public Library, specifically the stacks within the Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations. I’m sure that a work titled Ancestry and posterity (in part) of Gottfried Frey, 1605-1913 would have easily fallen in my hands. This book is a family genealogy written by Samuel Clarence Frey and published by Dispatch-Daily Print of York, Pennsylvania in 1914. Of course, the world wide web led me to an online version after a few short word/name searches utilizing the Google search engine. I have since found that Frey’s book can be found in college libraries across the country, and also a hardcover reprint can be purchased on Amazon.com for $28.95, and if you have a Prime account, shipping is free and you could have in two days time! But, I digress. Here is what Samuel Clarence Frey had to say about his distant cousin buried in our fair cemetery: “SARAH ANN CATHARINE FREY, the fourth child of Godfrey, was born in Montgomery County, Md., May I, 1789. Somewhat to the surprise, if not annoyance, of her conservative German father, when she was but sixteen years old she married an Italian music teacher, Charles Antonio Cazemere Galezio, born at Turin, Italy, March 4, 1773. He was a highly educated man, having been fitted for the priesthood; but left Rome and came to America, where he secured a position of some sort in the Navy, serving under Commodore Decatur. He spoke seven languages, and acted as interpreter for some of the foreign Legations. Two years after marriage, he was ordered on a naval cruise, and their first child was born at Sandy Springs, Montgomery County, Md (presumably Godfrey's home) during the father's absence, and was three years old before she saw him. The other children were born at Frederick. Md., where, after a little over fifteen years of married life, Charles died, in 1821. His widow survived him until October 9, 1833. From this union sprang the following descendants : MARGARET GALEZIO, b. Aug. 5. 1810; d. May 22, 1882. Married Jan. 3, 1833, Rezin Hobbs, Farmer, Frederick. Md. ANNIE VIRGINIA HOBBS. b. Oct. 17. 1835. Married Oct. 7, 1856, Richard Linthicum Waters, b. Feb. 18, 1834; d. Sept. 6, 1884, Farmer, Howard County, Md. (*granddaughter of Sarah) SARAH MARGARET WATERS, b. July 22. 1857. Married, May 31, 1887, Thomas Edward Denoe. b. Apr. 25. 1846. Retired Grocer, Baltimore.” (*Great granddaughter of Sarah) Another child is mentioned a little later in Mr. Frey’s family history. This was Sarah (Frey) Galezio’s only son, named Charles after his father: “CHARLES GODFREY GALEZIO, b. Aug. 27, 1815, at Frederick, Md.; removed to Athens County, Ohio when a young man, living first at Chauncey and later at Wapatoneka. He was the first Recorder of the county, and a prominent Mason. At the outbreak of the Civil War he went to La Porte. Indiana, and enlisted, becoming a Lieutenant. At the expiration of his term he re-enlisted as a private and served until the end of the war, under Sherman, participating in the March to the Sea and the Grand Review at Washington. Died, Oct. 9. 1882, at the home of one of his daughters at La Porte. Ind. Married Sept. 16. 1838, Joanna S. Herrold, b. Mar. 21, 1822; d. Aug. 19. 1848. ALEXANDER HARPER GALEZIO. b. June 20. 1839; d. Aug. 16, 1846. ADELAIDE LOUISE (GALEZIO, b. Nov. 28. 1841. Sister M. Aloysia, in Convent at Glandorf, Ohio. MARY VIRGINIA GALEZIO. b. May 15, 1844. Married Apr. II, 1867. Charles R. Baird, b. Apr. 1832, Farmer, La Porte, Ind.” Wow, again, you can learn so much about a person in a cemetery when you start digging. Again, maybe not the best word use, but you catch my drift. Sarah Galezio was now coming more into view for me. Now unfortunately, the problem with genealogy, especially when researching women in earlier times, is that most available information primarily focuses on those contextual others such as parents, husbands, children, cousins as they seldom held occupation titles of note, ran businesses or performed military service. Thus, these incredible ladies are simply a reflection of the deeds/professions of their husbands, fathers and sons. This in addition to the incredible work done in keeping homes, birthing/rearing children, and supporting husbands—some of which were true “pains in the ass!” Sad but true, and more so frustrating. We get lucky sometimes in finding personal letters or accounts of these women. Diaries can also be helpful in shedding light on one’s family and friends, or can paint an incredible picture of the personality of a diary keeper, be him man or woman. And you can’t talk about Frederick, Maryland and diaries without a mention of Jacob Engelbrecht who kept a chronicle of life in Frederick from 1818 through to his death in 1878. This quickly became my next research destination. I found a handful of references to the Galezio family in Engelbrecht’s diary. Best of all, Sarah Galezio was mentioned by name in an entry penned by Jacob on October 9th, 1833 at 11am on a Wednesday morning: “Died this morning in the year of her age Mrs. Galezio (widow), mother of Charles Galezio (at Smallwoods) & Mrs. Margaret Hobbs. Buried on the Methodist Episcopal graveyard, of which church she was a faithful member.” Engelbrecht doesn’t give us much, but at least Sarah Galezio’s death was noteworthy enough for him to document. In looking deeper into the diary, I explored a few more entries. Earlier that same year (1833), Engelbrecht mentions the marriage of daughter Margaret to Rezin Hobbs, and two years later, another marriage, that of daughter Sarah to Jacob Yeakle.  Jacob Engelbrecht Jacob Engelbrecht I did revel in two additional posts made by Engelbrecht in the previous decade, as he recorded the death of Sarah’s husband, or should I say—consort? “Died yesterday (at the Almshouse) in this town, Charles Galezio (barber) a native of Italy and a citizen of this town about six years. Whisky principally occasioned his death. He used to say “if a rich man dies, he died with the consumption but if a poor man dies, then whiskey killed him.” So report says.” Sunday, March 11th, 1821 Jacob Engelbrecht, a tailor by trade and son of a German Hessian mercenary soldier captured and brought to Frederick during the Revolutionary War, recalled one of Frederick’s earliest southern Europeans four years later in 1825: “There was a barber living in this town, 4 or 5 years ago named Charles Galezio (an Italian) who once advertised, for employment, and at the end of the advertisement he had, ‘Call when you will, there’s Charley on the spot with razors keen, and water boiling hot.’ He used to say too, during his lifetime (recollect, he’s now dead). “When a rich man dies, (they say) he died with the consumption, but when a poor man dies, why then whiskey killed him. The latter of which, Charley was tolerable fond of; but there are many more in the world who are fond of the “creature.” March 25th, 1825.  Theodoric of York skit on SNL with Steve Martin, John Belushi and Bill Murray Theodoric of York skit on SNL with Steve Martin, John Belushi and Bill Murray We all know what a barber is, but men of this profession were once called Tonsorial experts. These individuals have an occupation with responsibilities to cut, dress, groom, style and shave men's and boys' hair or beard. Barbering was introduced to Charles Galezio's native home's capital city of Rome by the Greek colonies in Sicily in 296 BC. Barbershops quickly became very popular centers for daily news and gossip. A morning visit to the tonsor became a part of the daily routine, as important as the visit to the public baths, and a young man's first shave (tonsura) was considered an essential part of his coming of age ceremony. A few Roman tonsores became wealthy and influential, running shops that were favorite public locations of high society, however, most were simple tradesmen, who owned small storefronts or worked in the streets for low prices. Starting in the Middle Ages, barbers often served as surgeons and dentists. Some readers, of a certain age, may remember the popular early Saturday Night Live skit featuring comedian Steve Martin as "Theodoric of York, Medieval Barber." In addition to hair-cutting, hairdressing, and shaving, barbers performed surgery, bloodletting and leeching, fire cupping, enemas, and the extraction of teeth; earning them the name "barber surgeons". Barber-surgeons began to form powerful guilds and received higher pay than surgeons until surgeons were entered into British warships during naval wars. Some of the duties of the barber included neck manipulation, cleansing of ears and scalp, draining of boils, fistula and lancing of cysts with wicks. Well, the varying descriptions of Sarah’s consort paint Mr. Galezio as a bilingual music scholar who could quote scripture while giving you a shave and haircut. But a word to the wise, it sounds as if scheduling an appointment with the tonsorial expert would be better before he hits the booze, because he was well- armed with a sharp blade and boiling water. I have no idea what became of Charles Galezio (burial-wise) as he is not accounted for in our records. The old Methodist burying ground was located between East Third and Fourth streets in Frederick, off Maxwell Alley as photographed earlier in the story. I would assume that Sarah would have been buried by her husband's side if he was laid to rest there. The two would have been re-interred together here. If anything else, perhaps he didn’t have a stone, or it was in bad shape and rejected by cemetery authorities which did happen with some of these removals. In any case, he would still be here. My theory is that he was buried at the old Frederick Almshouse, the predecessor to the Montevue Home. This facility was located on the north side of West Patrick Street, just beyond Bentz Street. An old burial ground for the indigent inmates of this asylum was located behind the structure. I don’t know the exact whereabouts of those buried there as the area eventually became the place of residential housing and small businesses like automotive garages. This seems like it could be the most logical answer. Sarah Galezio is here in Mount Olivet, and so are her daughter and two granddaughters. Margaret (Galezio) Hobbs (1810-1881) is buried in Area H/Lot 139, and so is Annie Virginia (Hobbs) Waters (1836-1913). (NOTE: Annie even had a brush with greatness during the Civil War by hosting Robert Gould Shaw in her home. Shaw took command of the 54th Massachusetts "colored regiment" that was heralded in the movie "Glory.")

A five month-old namesake granddaughter, Sarah E. Hobbs, died in December, 1834 and was buried at the Methodist Church originally. She resides a few yards from Sarah Galezio in Mount Olivet's Area NN. Sarah’s son is buried in LaPorte, Indiana. The Civil War veteran attained the rank of 2nd lieutenant with Indiana’s 35th Volunteer Regiment.

0 Comments

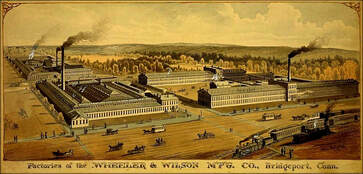

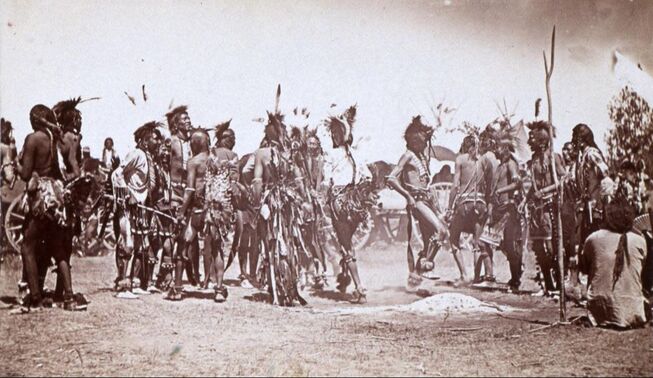

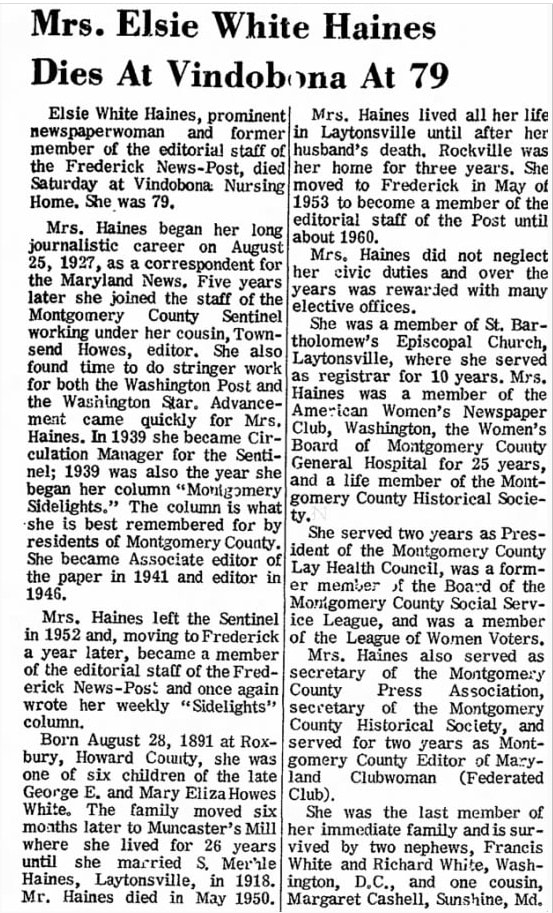

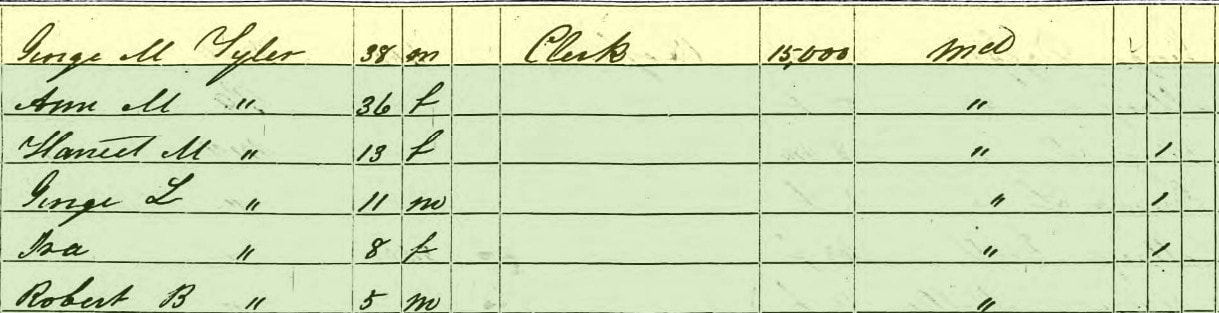

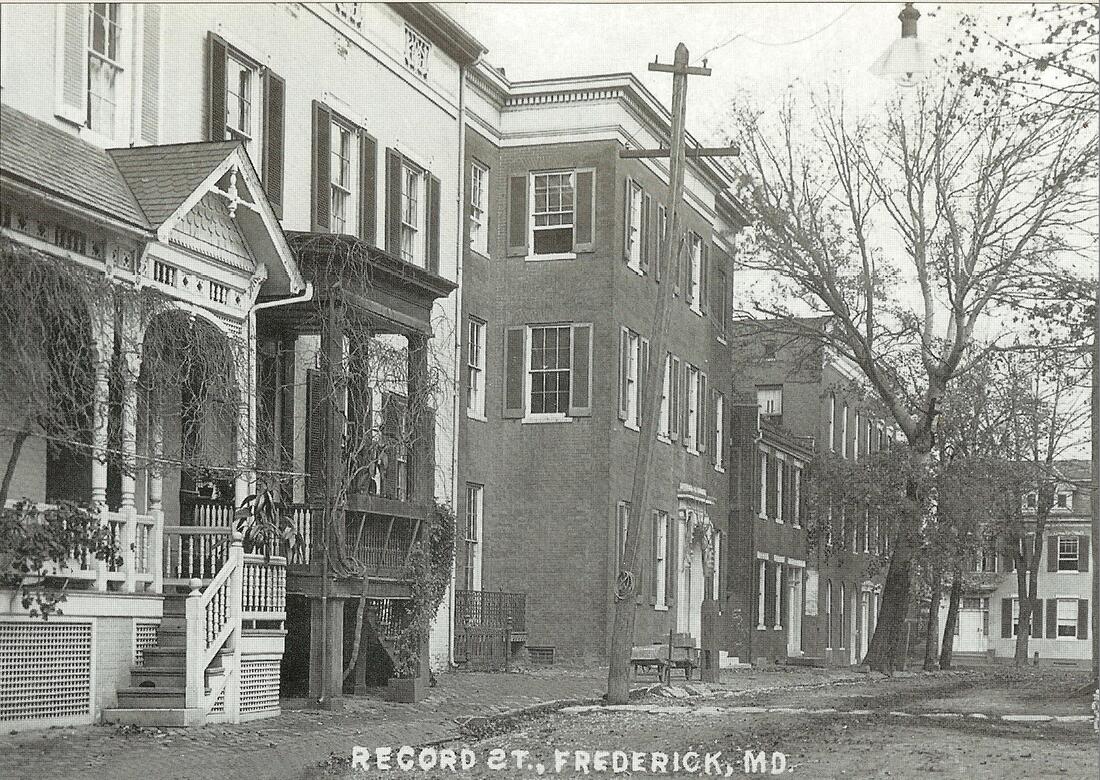

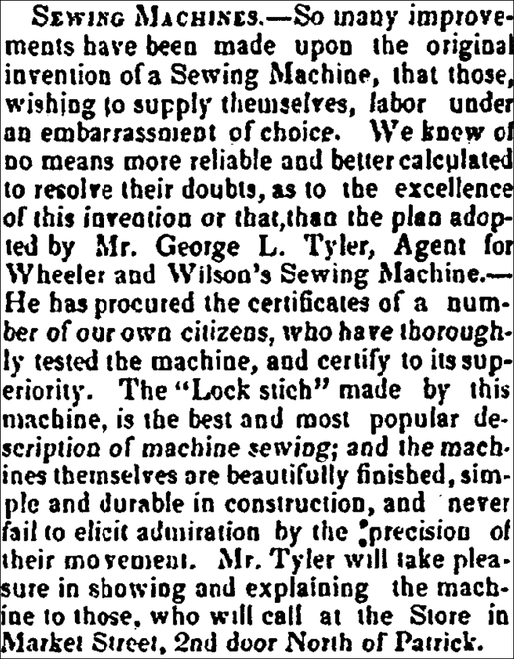

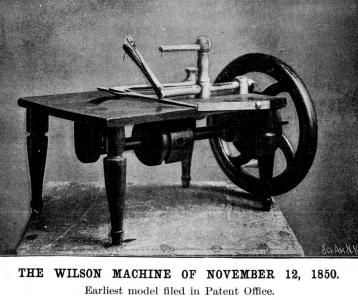

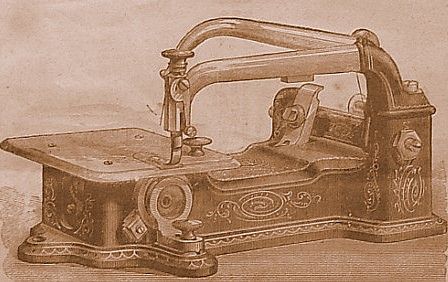

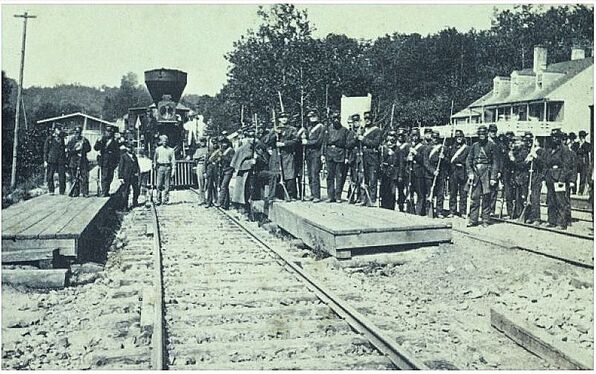

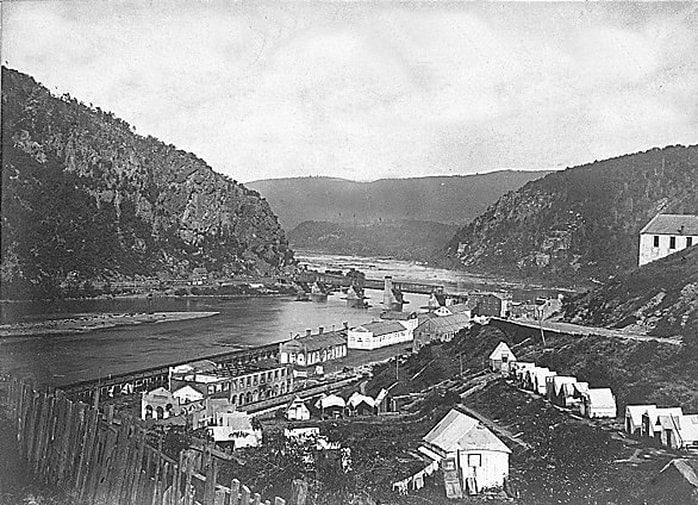

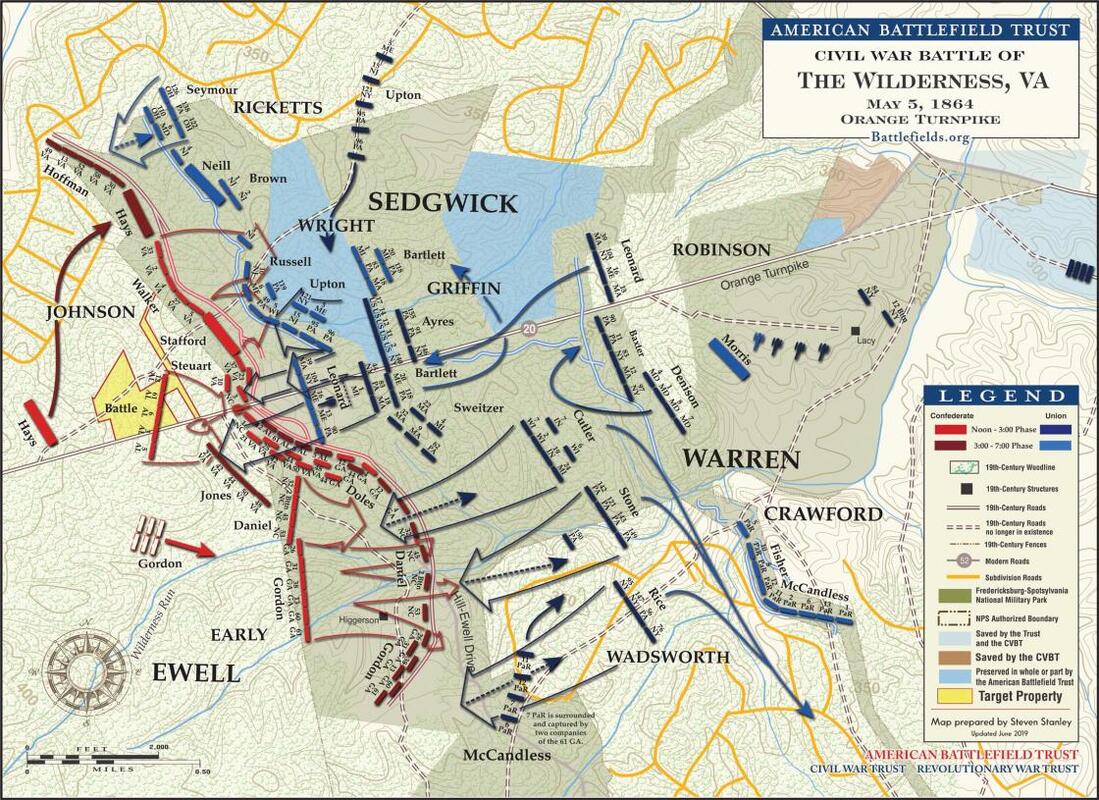

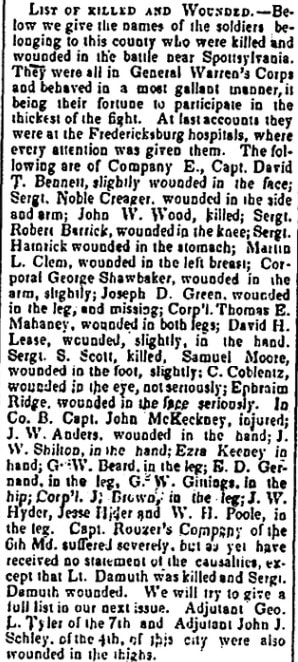

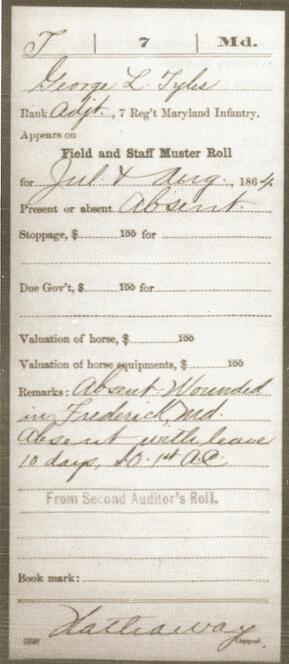

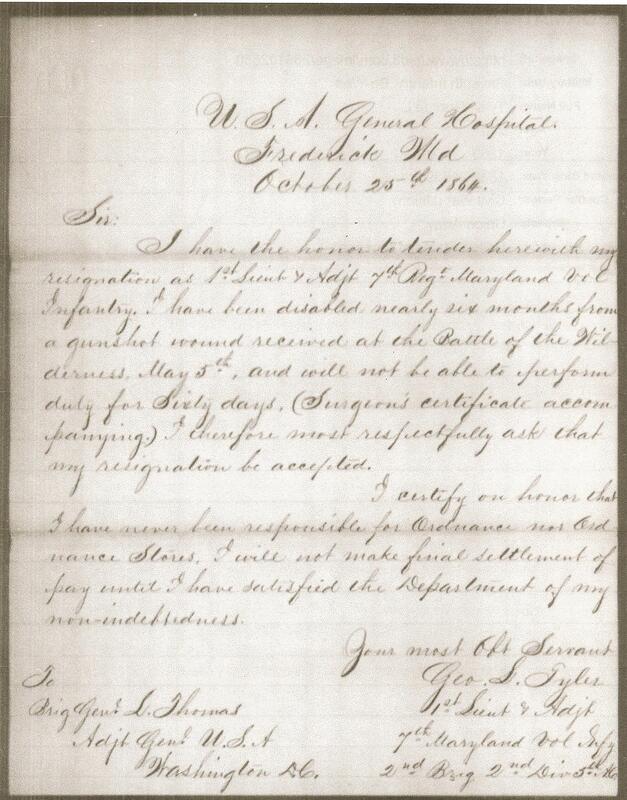

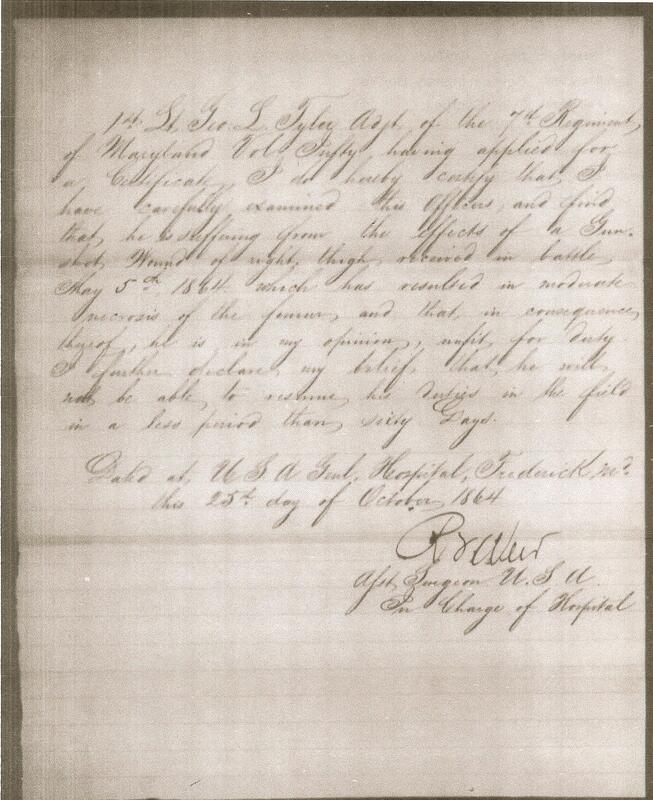

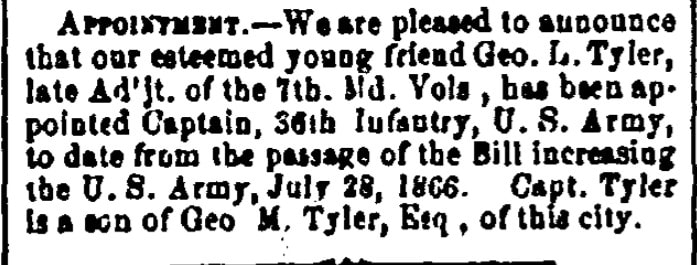

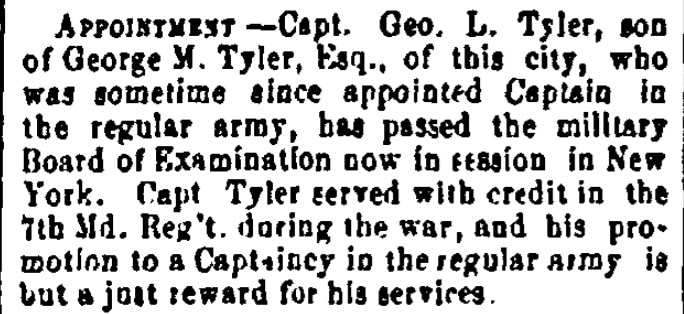

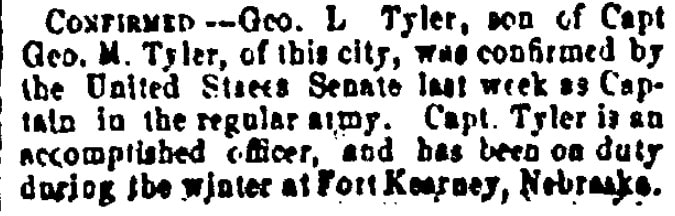

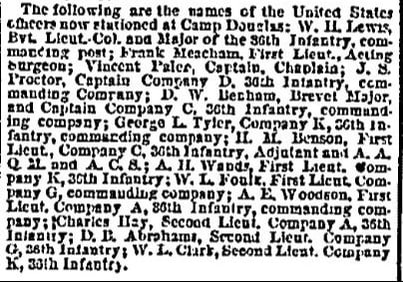

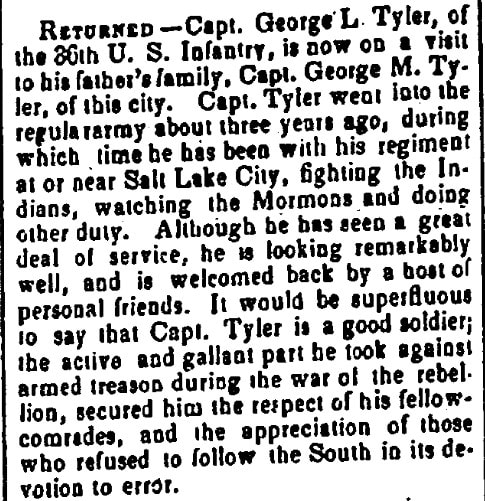

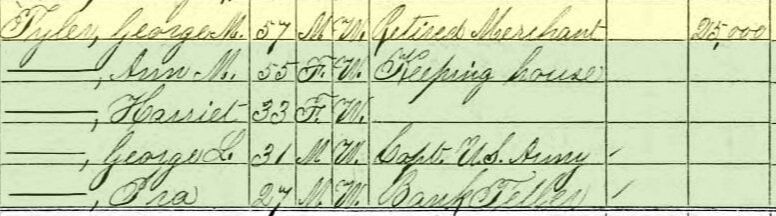

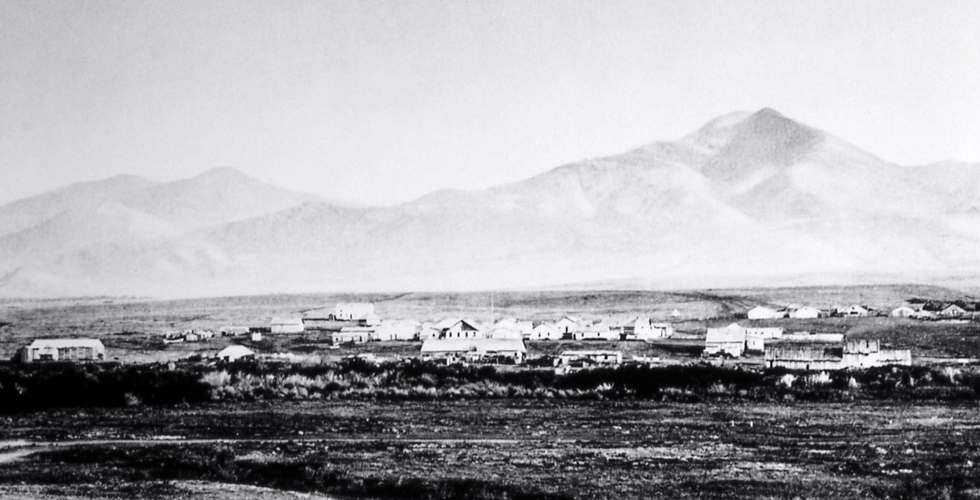

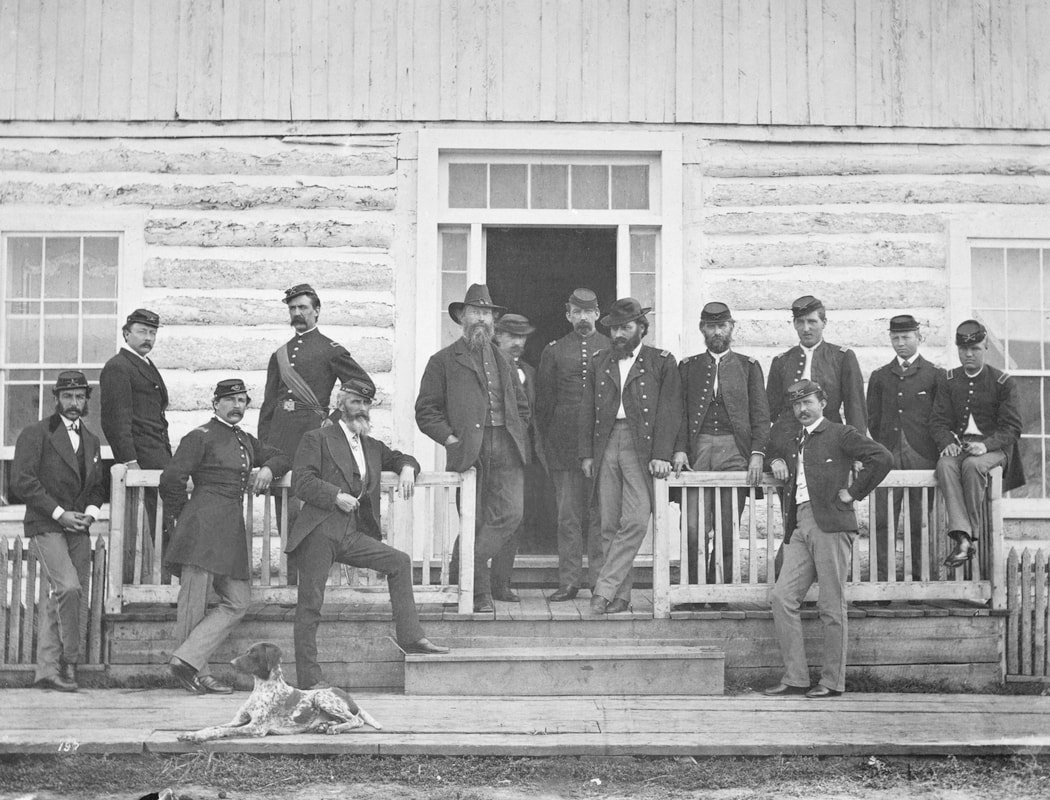

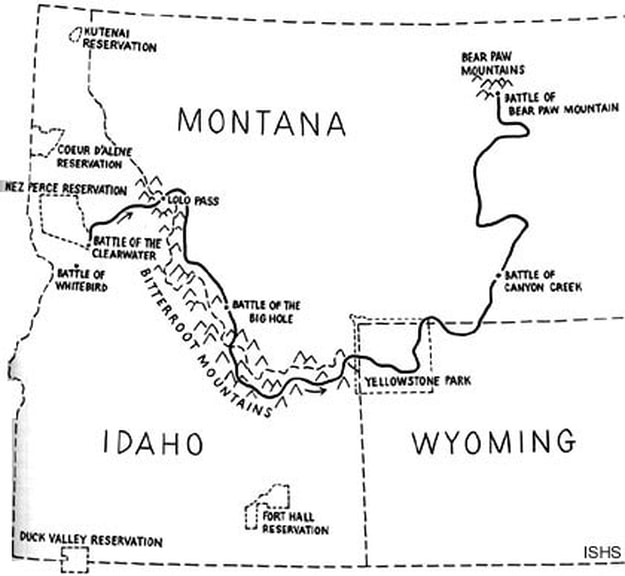

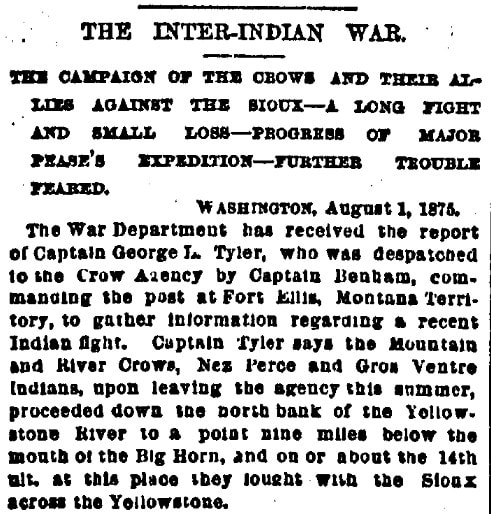

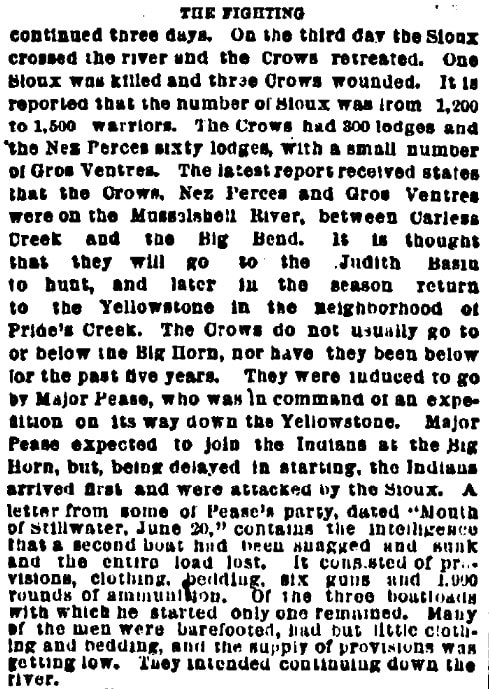

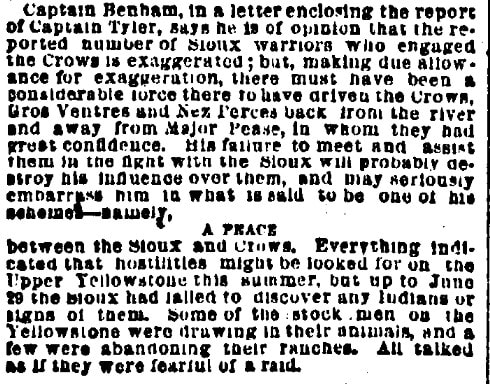

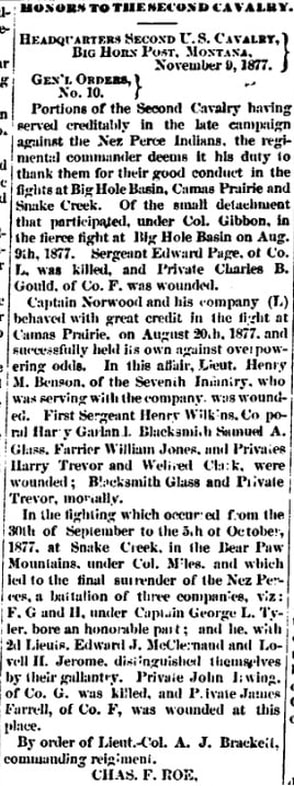

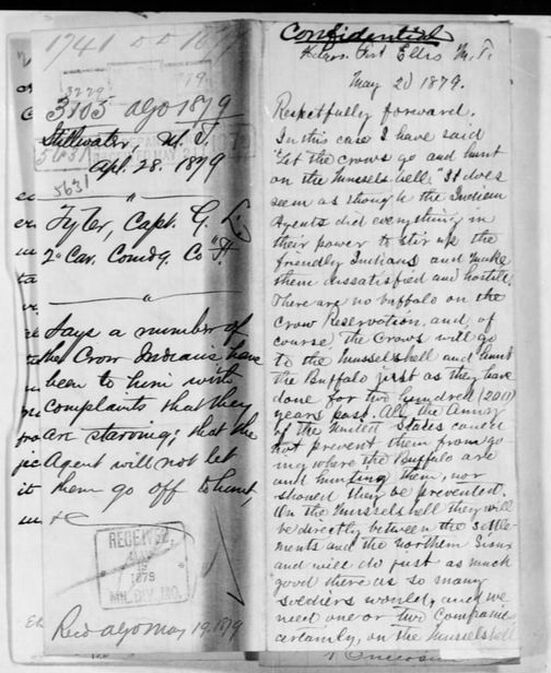

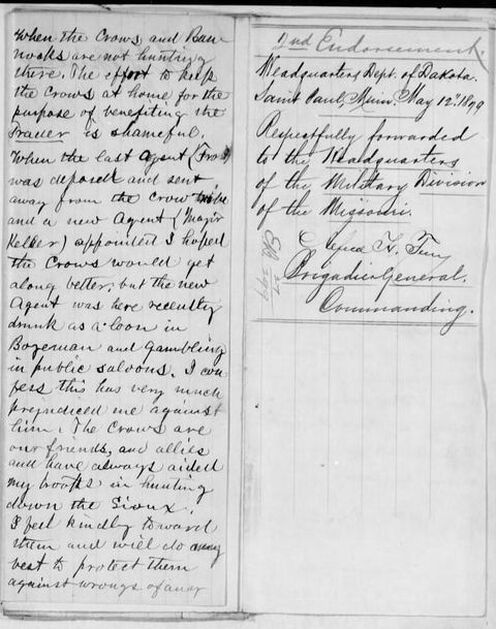

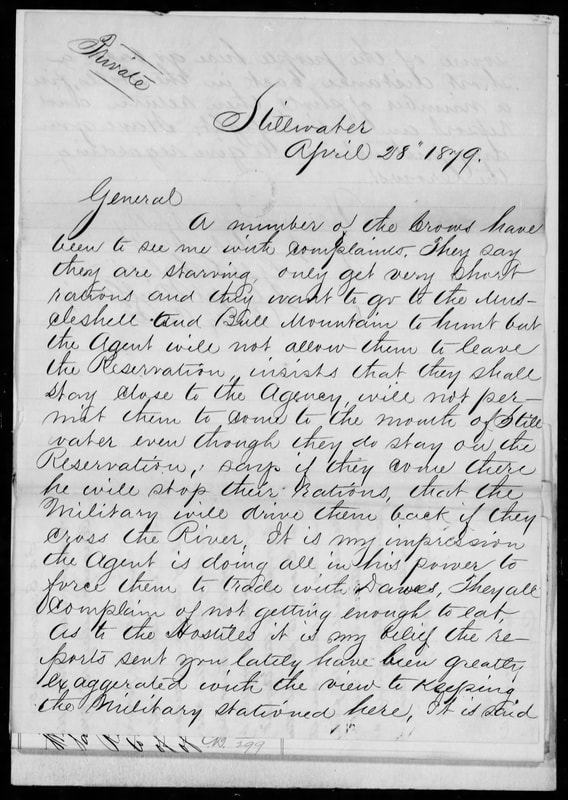

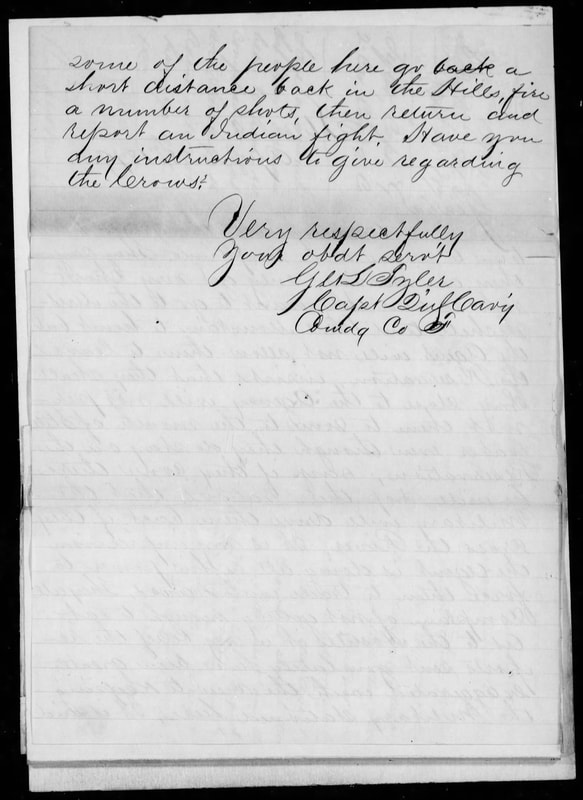

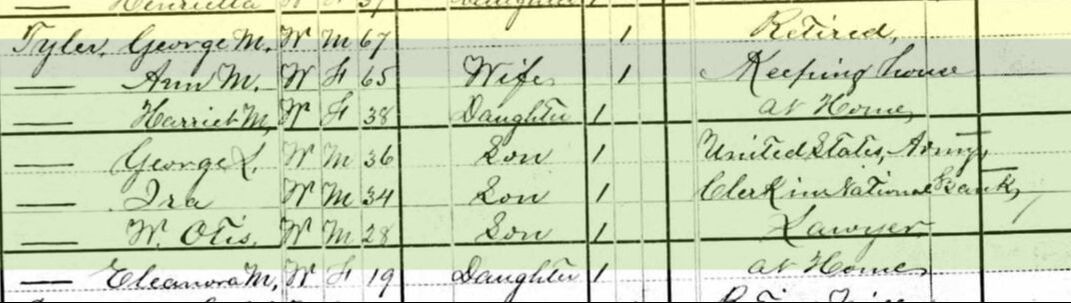

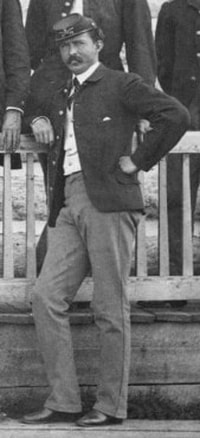

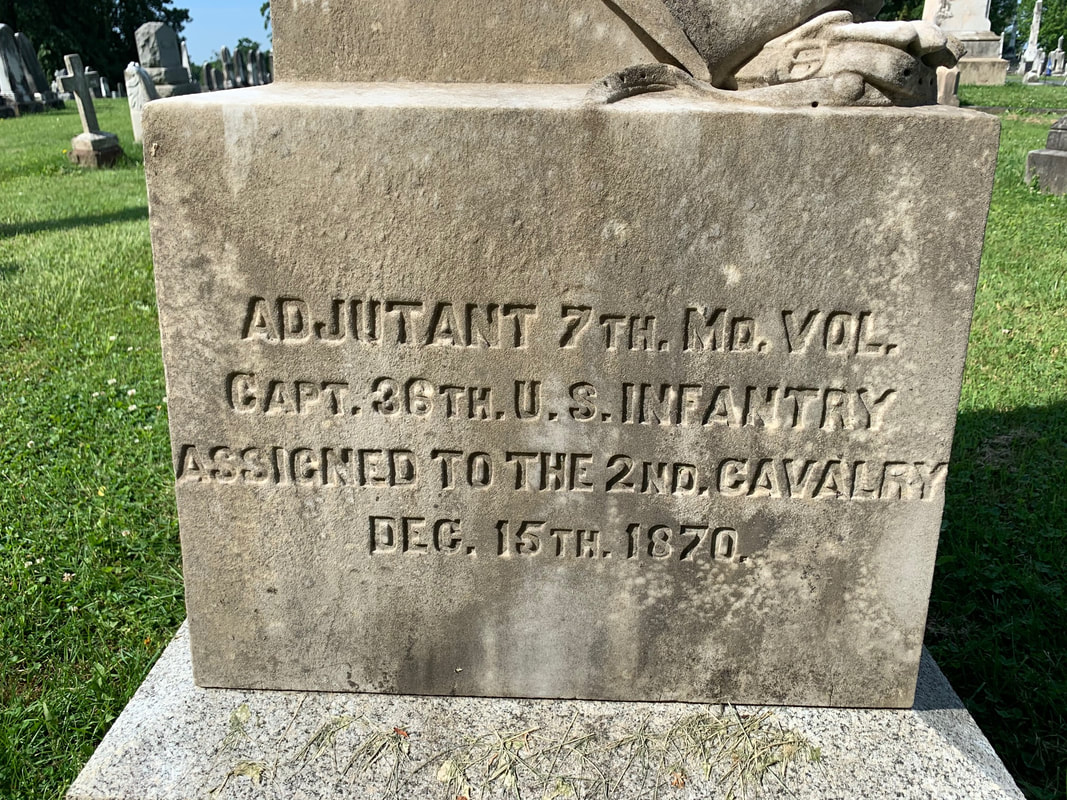

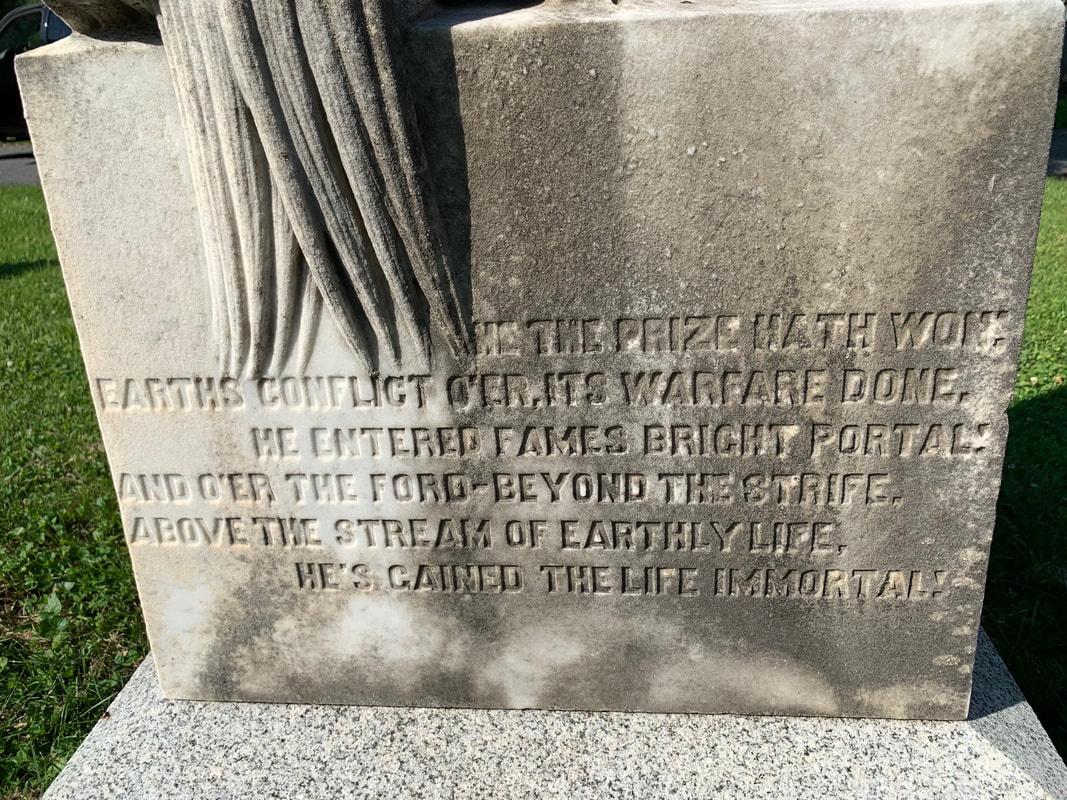

Although it has been on my own personal, radar for years now, I was pleased to find a vintage newspaper article with a mention of a particular, outstanding burial monument here at Mount Olivet, often overlooked. The anecdote can be found within the Sidelights column from the Frederick Post’s edition of August 7th, 1962. The weekly feature highlighted local history and culture with a strong bend toward preservation. “An interesting memorial to Capt. George Late Tyler, 2nd Cavalry USA who died October, 1881, aged 48, has a stone with a column from which is suspended a sword and belt, above the helmet, gloves and spurs.”  The author was reporter Elsie White Haines, a seasoned journalist who started with the Frederick newspaper in the early 1950s. Soon, Ms. Haines had a recurring column on Fridays. She did a great job in bringing historic preservation to the forefront at a time when many old structures here in the city (and county) were being demolished. Her past experience hailed from a similar column written for a newspaper in her native home of Montgomery County. After my impromptu introduction to Ms. Haines (1891-1970) and her artfully-penned writings, I experienced an immediate connection, and also a tinge of guilt and embarrassment because I hadn’t know her name earlier. In addition, I felt regret that Ms. Haines died in 1970, not having the chance to see incredible strides toward preserving so many structures within Frederick's 40-block historic district, not to mention the efforts of the Frederick County Landmarks Foundation in saving buildings such as Schifferstadt and Rose Hill Manor in the immediate decade following her death. If she could see the adaptive re-use mentality in play with local shops, restaurants, and even government and non-profit entities like my old stomping grounds of the Frederick Visitor Center, she would be very proud.  Elsie White Haines (1966) Elsie White Haines (1966) What resonated most with me was a poignant quote that Ms. Haines used to start off a Sidelights column dated June 4th, 1965. This line was attributed to a gentleman named Fred Gebhardt who wrote an article the previous year in DAR Magazine: “Tomorrow is built upon yesterday, Therefore let us save America’s yesterday—today. Let us not wait for tomorrow, For tomorrow might be too late.” Oh, how important and powerful this quote is today, looking back at the activity that saved much in our little town, while the county seat of Ms. Haines home county, Rockville, lost so much of its heritage through historic structures. Ever since I’ve lived here in Frederick (1974), I’ve always heard the expression: “Don’t let happen to Frederick, what happened to Rockville.” I use this brief parlay into Ms. Haines’ life as a grand introduction into my main subject of this week’s “Story in Stone.” This is the decedent buried under the fine monument Ms. Haines described in the above-mentioned passage from 1962--George Late Tyler, a man from a prominent Frederick family who would transition in life from selling sewing machines in 1860, to receiving commendations for gallantry in the Battle of the Wilderness four years later, to fighting Indian tribes in the wild west over the next 17 years until his untimely death in 1881 at the age of 42. George Late Tyler Born February 12th, 1839 in Frederick City, George Late Tyler was one of five children of the marriage union between George Murdoch Tyler and Ann Maria “Mary” Late. George Late Tyler’s grandfather was Dr. William Bradley Tyler (1788-1863), a prominent physician. Dr. Tyler, the son of an English immigrant, made his way to Frederick in 1814 from his native Prince Georges County after stints in Baltimore and Leesburg, VA . In addition to medicine, he served as clerk of the county court and would serve in politics on the local and state level including a run for governor in 1825. George’s namesake father was a merchant of shoes and boots here in town, with a shop located at in the first block of North Market Street on the west side of the street. The family lived next door his father, Dr. Tyler, on Record Street. Our subject attended local school for his early education. He didn’t have far to go, as he attended the Old Frederick Academy located across Record Street from his home. A few of his classmates included future military men who would make names for themselves in the coming American Civil War. Two of these were Alexander Swift “Sandie” Pendleton, son of All Saints Church rector William N. Pendleton who would serve as the youngest officer on Confederate General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s staff; and Winfield Scott Schley, who went on to the Naval Academy in Annapolis and participated in the Vicksburg Campaign. George, himself, and brother Ira, would serve in the Civil War under the Union flag. The Tyler family, however, was one of those families that was split in allegiance. George’s paternal uncle, local lawyer Bradley Tyler Johnson, would serve as Maryland’s highest-ranking Rebel, promoted to brigadier general and responsible for commanding the 1st Maryland Infantry, CSA. Frederick history buffs in the know may recall that Dr. William B. Tyler owned slaves, but was also a major Union supporter who hosted President Abraham Lincoln for a meal in his home on Lincoln’s brief visit to town on October 4th, 1862. More confusion from the war that featured Southerners (including many Confederate soldiers) that didn’t believe in slavery and thought their rights were being trampled by a “collusion of northern states,” and die-hard Unionists in the north who maintained slaves, somehow convinced that it was their right within the Union, which it was in border states. So complicated, even for seasoned historians like myself to attempt to comprehend. George Late Tyler’s life would be defined by the United States military, hence the gravestone depicting this fact. Before I get to that history, let me “sew” some seeds of what his life may have been had the American Civil War not come about. As would be expected, George worked as a clerk in his father’s store, with the intent of taking over the business one day, or at the least breaking off with his own. In 1860, an article in the Frederick Examiner newspaper talks of 21-year old George as Frederick’s agent for a newfangled invention that would help define the industrial revolution. The first sewing machine to combine all the disparate elements of the previous half-century of innovation into the modern sewing machine was the device built by English inventor John Fisher in 1844, a little earlier than the very similar machines built by Isaac Merritt Singer in 1851, and the lesser known Elias Howe, in 1845. However, due to the botched filing of Fisher's patent at the Patent Office, he did not receive due recognition for the modern sewing machine in the legal disputations of priority with Singer, and Singer reaped the benefits of the patent. Meanwhile, a man named Allen B. Wilson developed a shuttle that reciprocated in a short arc, which was an improvement over the sewing machines of Singer and Howe. However, John Bradshaw had patented a similar device and threatened to sue, so Wilson decided to try a new method. He went into partnership with Nathaniel Wheeler to produce a machine with a rotary hook instead of a shuttle. This was far quieter and smoother than other methods, with the result that the Wheeler & Wilson Company produced more machines in the 1850s and 1860s than any other manufacturer. Wilson also invented the four-motion feed mechanism that is still used on every sewing machine today. This had a forward, down, back and up motion, which drew the cloth through in an even and smooth motion.  George Late Tyler was on the cutting edge and likely the apple of local seamstresses’ eyes—sales were booming. But there was an ugly side to the business. Throughout the 1850s, more and more companies were being formed, each trying to sue the others for patent infringement. This triggered something known as “the Sewing Machine War.” A former law student at George Mason School of Law wrote the following in a 2009 research paper: “The invention and incredible commercial success of the sewing machine is a striking account of early American technological, commercial, and legal ingenuity, which heralds important empirical lessons for how patent thicket theory is understood and applied today.” In 1856, the Sewing Machine Combination was formed, consisting of Singer, Howe, Wheeler, Wilson, and Grover and Baker. These four companies pooled their patents, with the result that all other manufacturers had to obtain a license for $15 per machine. This lasted until 1877 when the last patent expired. The winds of another war swept up George. He joined the ranks of the 4th regiment of the Potomac Home Brigade. An effort had been made to raise this outfit during the winter of 1861-62. Only three companies (A, B & C) were organized for a term of enlistment for three years. Company “A” was raised in Hagerstown, Company “B” in Baltimore, and Company “C” in Frederick County. Initially these three companies were assigned to guard duty along the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, between Harper's Ferry and Martinsburg.  A S Pendleton A S Pendleton On August 11th, 1862 George L. Tyler’s company was incorporated into the ranks of the 3rd Potomac Home Brigade. This infantry outfit was also assigned to duty as railroad guard on Upper Potomac in Maryland and Virginia. Less than a month later, the war came to Frederick as Gen. Robert E. Lee and his Confederate troops camped in and around Frederick City from September 5-10th. The invaders (or liberators for some families) headed west and were eventually engaged by the Union Army at South Mountain and Sharpsburg (Battle of Antietam). George L. Tyler participated in the Rebel siege of nearby Harper's Ferry with the Battle for Maryland Heights (September 12th-15th) led by Gen. Stonewall Jackson with help from Tyler’s old schoolmate, Sandie Pendleton. The Potomac Home Brigade’s 3rd Regiment surrendered on September 15th. They were paroled September 16th and sent to Annapolis. George would be transferred into Company F of Maryland’s 7th Volunteer Infantry unit and was promoted to the rank of adjutant. For those not familiar with this rank, an “adjutant” is a military appointment given to an officer who assists the commanding officer with unit administration, mostly the management of human resources in army unit. I’m thinking there was some “family pull” somewhere that got these guys into higher-end duties. Meanwhile, around this same time, George’s younger brother, Ira, would be commissioned a 1st lieutenant in the 6th Maryland Volunteer Infantry. As for the 7th Maryland, who had served guard duty in the defenses of Washington, the regiment was sent to the Shenandoah Valley for operations. Their first combat came on March 13, 1863, when they repulsed a charge by the 5th Virginia Infantry regiment. They were sent to V Corps, Army of the Potomac. At the Battle of Gettysburg, they were forced to withdraw from the Peach Orchard early on the second day. They were among the units who repelled Pickett's charge. The unit was stationed for garrison duty in southern Pennsylvania and was involved in skirmishes against some of Confederate Gen. Jubal Early's infantry units. George Tyler would participate in the Battle of the Wilderness, fought May 5th–7th, 1864, the first battle of Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant's 1864 Virginia Overland Campaign against Gen. Robert E. Lee and the Confederate Army. Both armies suffered heavy casualties, around 5,000 men killed in total, a harbinger of a bloody war of attrition by Grant against Lee's army and, eventually, the Confederate capital, Richmond, Virginia. The battle was tactically inconclusive, as Grant disengaged and continued his offensive. Tyler would suffer a gunshot wound that would severely injure his right hip while in combat at the Battle of the Wilderness. He would later be breveted captain for gallantry and meritorious service. Tyler would return home to Frederick to recuperate from his injury immediately after it occurred in May, 1864. Some muster rolls report him at the at the General Hospital created here, but I assume he was nursed back to health in the comfort of his home. Tyler was here that summer, particularly in early July, 1864, the time of Jubal Early’s infamous raid and ransom on Frederick, culminating with the nearby Battle of Monocacy. In November of 1864, Tyler was still hospitalized as a result of his wounds from Wilderness. He was suffering from necrosis of his right femur and obtained a Surgeon's Certificate from famed Union Army physician Robert F. Weir saying he was unfit for further duty during the war. Less than two years after leaving the ranks of the military, George L. Tyler would accept a commission as captain in the 36th US Infantry. Tyler would go unassigned during reorganization of the army in 1869. Late in 1870, he was appointed to the Second Cavalry, and was a member of F Troop. He would soon make his way west to the Montana Territory and Fort Ellis located at today's Bozeman, Montana. The story of the US Cavalry in the west is not a pretty history in hindsight, however, it is our unblemished history, nonetheless. Here are some highlights of the unit’s major activity during the decade: On 23 January 1870, elements of Companies F, G, H, and L participated in the Marias Massacre in the Montana Territory, where 200 Piegan Blackfeet Indians were killed. After this massacre, Federal Indian policy changed under President Grant, and more peaceful solutions were sought. On 15 May 1870, SGT Patrick James Leonard was leading a party of 4 other troopers from C Company along the Little Blue River in Nebraska attempting to locate stray horses. A band of 50 Indians surrounded this detachment and the men raced for cover and made a fortified position with their two dead horses. One trooper, PVT Thomas Hubbard, was wounded, but they managed to hold the Indians at bay and inflicted several casualties. When the hostile band retreated after an hour of fighting, the troopers left, took a settler family under their charge and returned safely. All 5 men were awarded the Medal of Honor (SGT Patrick J. Leonard, and PVTs Heth Canfield, Michael Himmelsback, Thomas Hubbard, and George W. Thompson). Today, junior NCOs in the 2nd Cavalry Regiment compete for the Sergeant Patrick James Leonard award. On 17 March 1876, troopers from Companies E, I, and K (156 men) joined the 3rd US Cavalry Regiment under COL Joseph J. Reynolds to combat the Cheyenne and Lakota in the ill-fated Big Horn Expedition. During the Battle of Powder River, the cavalrymen attacked, but were repulsed, and the 2nd Cavalry lost 1 man killed and 5 wounded. 66 men also suffered from frostbite. The 2nd Cavalry was once again repulsed by the Cheyenne and Lakota at the Battle of the Rosebud on 17 June 1876, and only a few days later, Custer's 7th Cavalry were defeated at the Battle of Little Bighorn. By April 1877, most of the US cavalry was in the west, fighting against bands of hostile Indians. The Cheyenne surrendered in December, Sitting Bull escaped to Canada, and Crazy Horse, the victorious chief in the Battles of the Rosebud and Little Bighorn, surrendered in April 1878. Chief Lame Deer was one of the last Lakota war-chiefs left resisting the US Government. The "Montana Battalion" of the 2nd Cavalry Regiment eventually caught up with his band near the Little Muddy Creek, Montana on 6 May 1878. After a midnight march, the troopers surprised Lame Deer's warriors at dawn on 7 May. H Company charged the village and scattered the enemy horses, while the remaining troopers charged and routed the band of Lakota. During the intense battle, PVT William Leonard of L Company became isolated, and defended his position behind a large rock for two hours before he was rescued by his comrades. He, and PVT Samuel D. Phillips of H Company both earned the Medal of Honor for their gallantry in this battle. While searching the ruined village, the troopers found many uniforms, guidons, and weapons from the 7th Cavalry Regiment, and they left knowing that they had avenged those fallen at Little Bighorn  At the 10-year memorial of the Battle of Little Bighorn, unidentified Lakota Sioux dance in commemoration of their victory over the United States 7th Cavalry Regiment (under General George Custer), Montana, 1886. The photograph was taken by S.T. Fansler, at the battlefield’s dedication ceremony as a national monument. On 20 August 1877, elements of the 2nd Cavalry which had been pursuing Chief Joseph's band of Nez Perce Indians through Idaho reported that their quarry had turned on them, stole their pack train, and began attempting to escape to Canada. Despite being low on supplies, L Troop and two additional Troops of the 1st Cavalry were dispatched to retrieve the pack train. After a hard ride, the Indians were overtaken and a fierce battle ensued. CPL Harry Garland, wounded and unable to stand, continued to direct his men in the battle until the Indians withdrew. For his actions, he would receive the Medal of Honor along with three other men from L Troop; 1SG Henry Wilkens, PVT Clark, and Farrier William H. Jones. Today, the annual award for the most outstanding trooper in the 2nd Cavalry is called the Farrier Jones Award. On 18 September, a force of 600 men under General Oliver Otis Howard and Colonel Nelson A. Miles, including Troops F, G, and H of the 2nd Cavalry, marched to stop Chief Joseph's band from reaching Canada. L Troop was sent back to Fort Ellis to gather supplies but would join the expedition later. On 30 September 1877, the Battle of Bear Paw Mountain began. The three Troops of 2nd Cavalry were dispatched to drive away the Indians' ponies by attacking their rear. G Troop, under LT Edward John McClernand, caught up with Chief White Bird as he and his band tried to escape to Canada. The ensuing engagement was brief, but violent, and resulted in the capture of the Indians and their mounts. Lt McClernand was awarded the Medal of Honor for his gallantry. After a four-day siege, Chief Joseph surrendered his band to General Howard on 4 October 1877. The following newspaper article praises Capt. George L. Tyler "who bore an honorable part." In the fall of 1878, the 2nd Cavalry was posted in two forts in Montana; Fort Custer and Fort Keogh with the mission of preventing Chief Sitting Bull from returning to US territory after escaping to Canada. In early winter, Chiefs Dull Knife and Little Wolf left their reservations in Oklahoma and began moving northwards. Dull Knife was intercepted and surrendered at Fort Robinson, Nebraska, but Little Wolf sought shelter in the Sand Hills of Wyoming. Elements of E and I Troop under LT William P. Clark (who had earned a special rapport with the Indians) were sent to negotiate with these stalwarts. The band was located near Box Elder Creek, Montana on 25 March 1879, and was persuaded to accompany the troopers back to Fort Keogh. During the march back, on 5 April, several Indians escaped and attacked the soldiers. SGT T.B. Glover took 10 men of B Troop and charged the numerically superior enemy, forcing them to surrender, and SGT Glover received the Medal of Honor for this action. Chief Little Wolf eventually surrendered his band when the party returned to Fort Keogh. (NOTE: The above info came from editor Chris Golden’s "History, Customs, and Traditions of the "Second Dragoons" (2011). On the Fold3 website, I was lucky enough to find several military records on George Late Tyler. Specifically, I was fascinated with source documents held by the National Archives in the form of letter correspondence between Capt. Tyler and the commandant of Fort Ellis (Montana) in April, 1879. The content of these materials consisted of complaints made by the Crow Indians and "sundry charges" against their assigned Indian Agent liaison (assigned by the federal government). It seems Capt. Tyler worked to assist this tribe by writing a confidential letter to his superior, calling out said agent. These concerns, as presented by Capt. Tyler, would be forwarded to the Department of the Interior's Office of Indian Affairs and the War Department. Tyler would be commended for this action. Below are pages from Tyler's personal notebook from his interview with the Crow tribe, and the letter he penned to Washington, DC: The summer of 1880 featured another trip home to Frederick by George L. Tyler. I don't know how his military leave worked, or whether his trips back home were add-ons to visits to superiors in Washington. Regardless, he can be found in Frederick within the 1880 US Census.

George Late Tyler died in town on October 20th, 1881. He was buried in the Tyler family lot in Area E/Lot 184. A remarkable monument was erected in his honor--a true masterpiece.

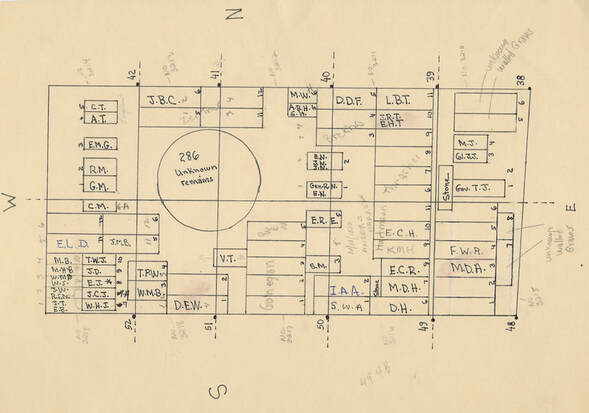

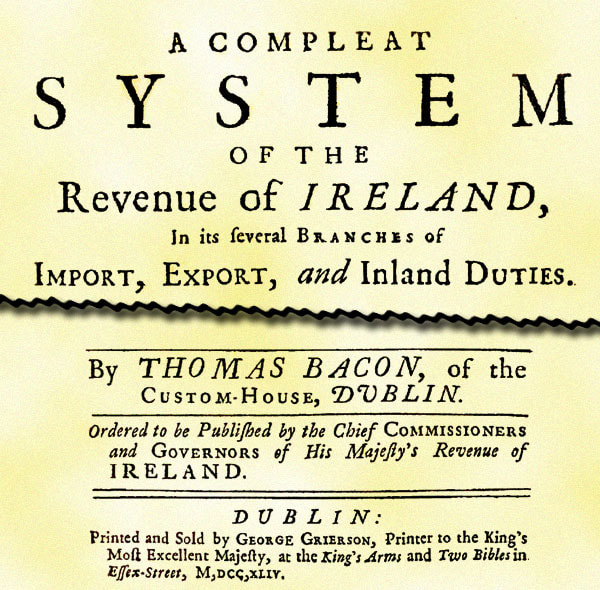

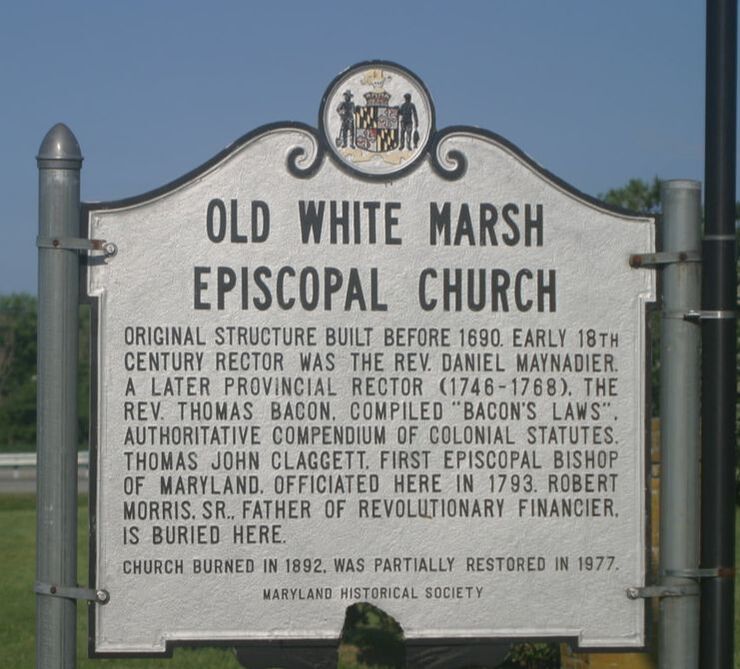

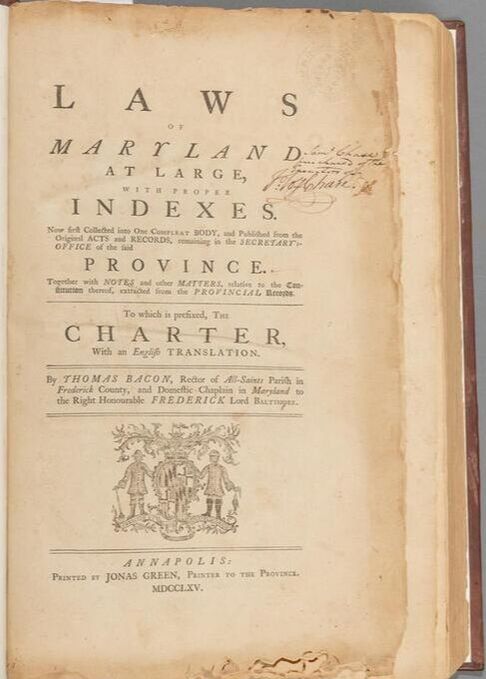

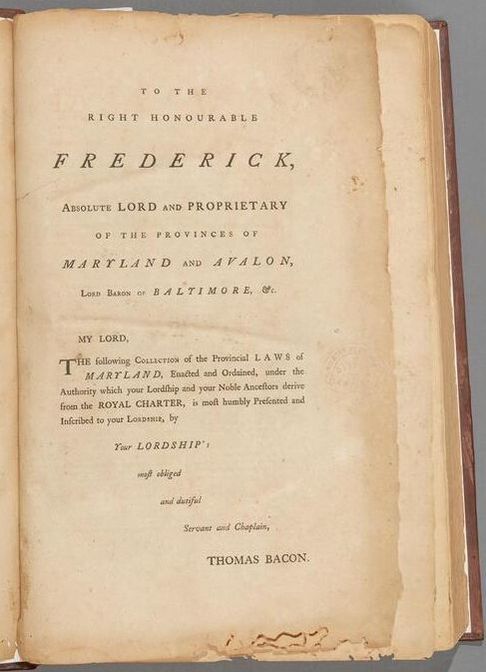

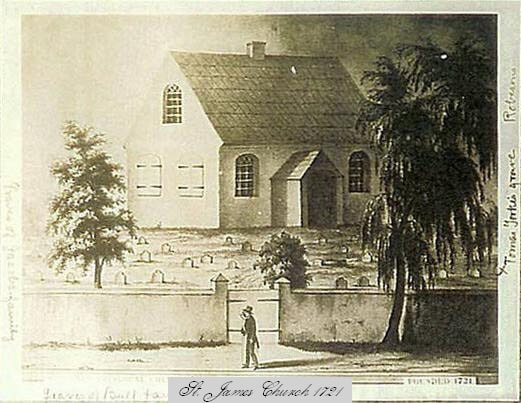

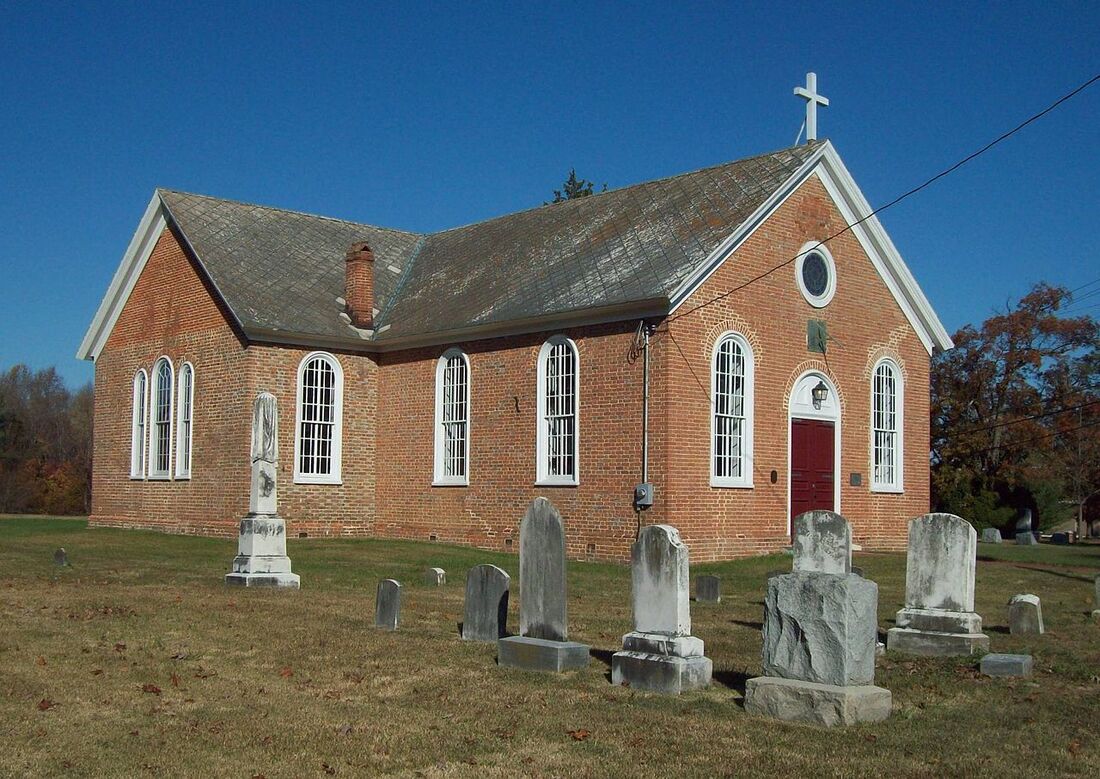

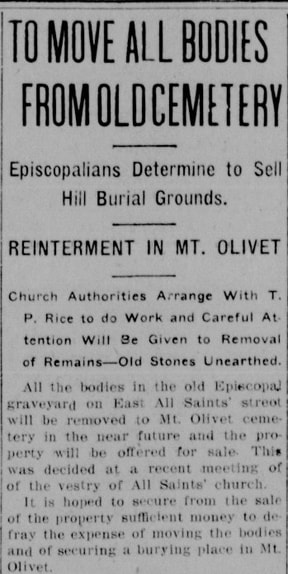

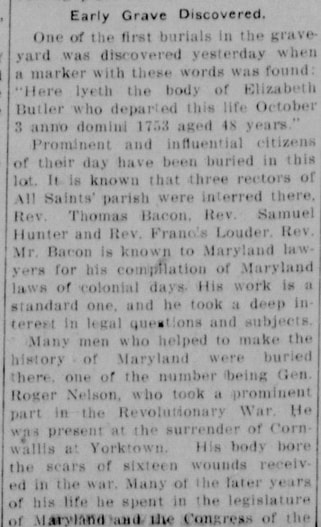

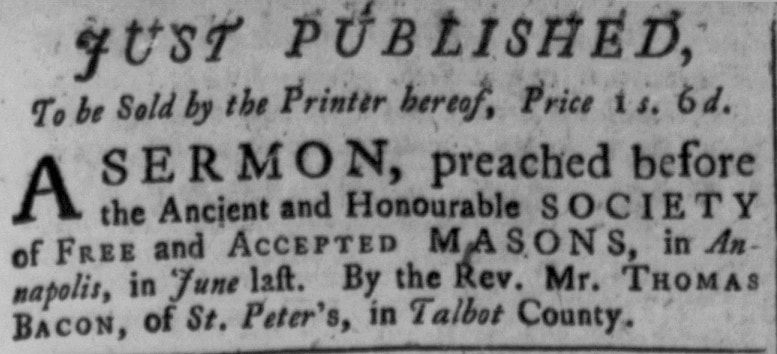

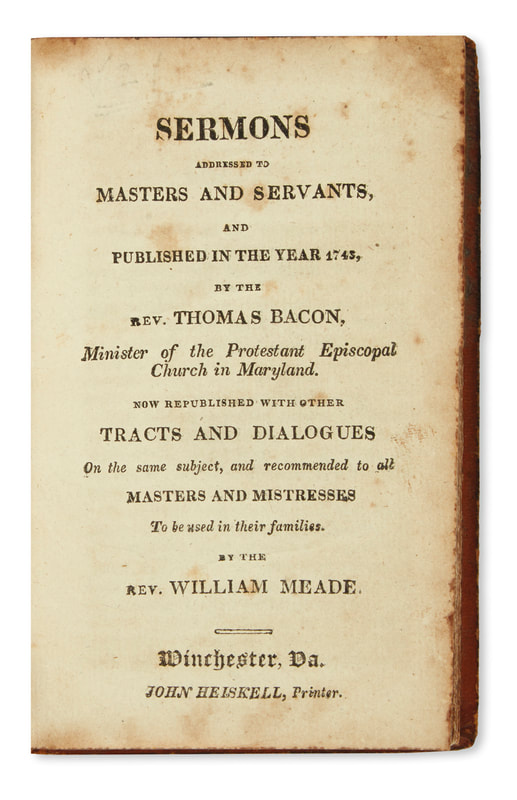

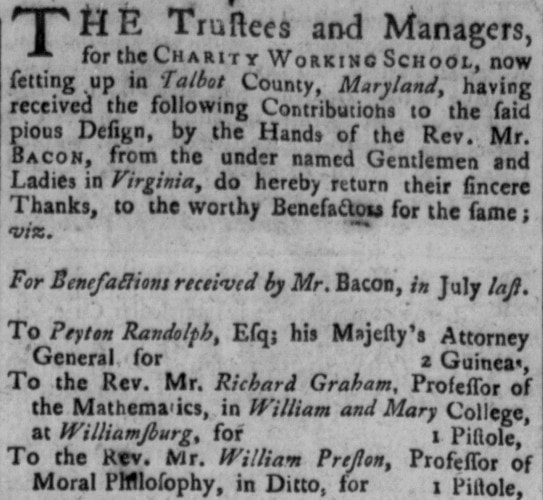

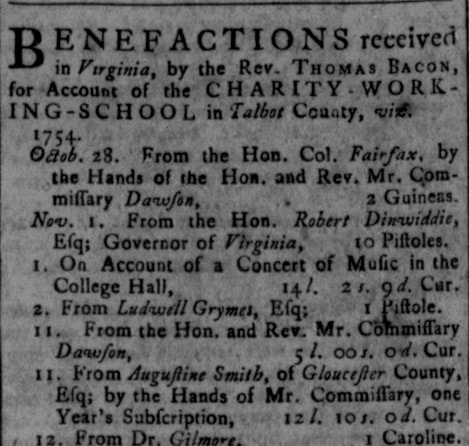

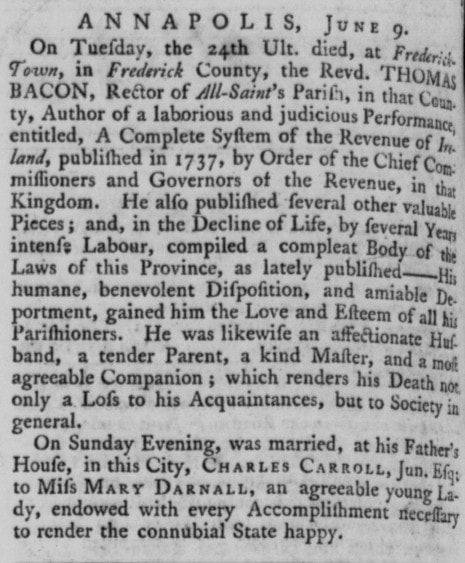

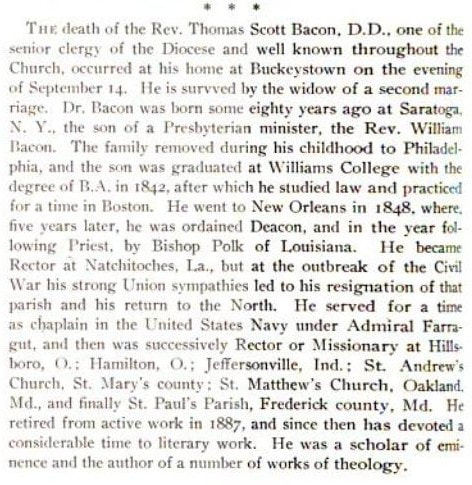

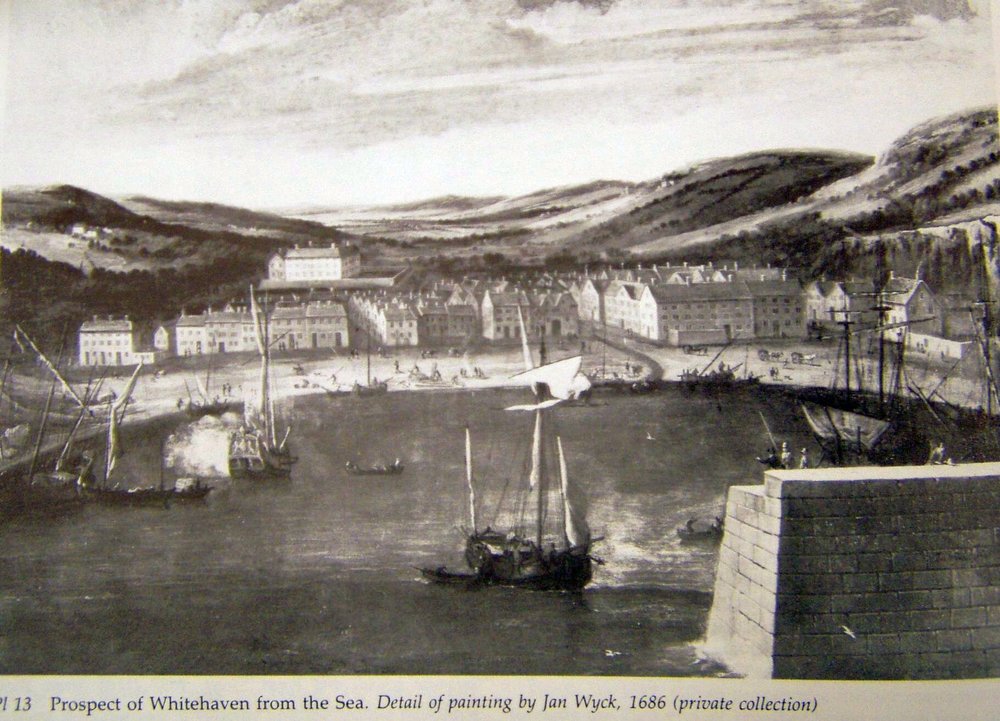

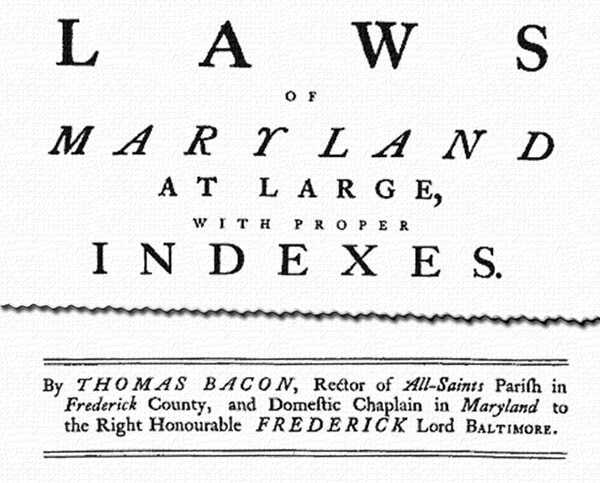

Some years ago, I stumbled upon a grave in Mount Olivet’s Area H/Lot R. It was that of Rev. Thomas Scott Bacon. I paused for the second as the name resonated with me. Not because of the savory, pork-related surname, but for history's sake. I searched my brain, full of infinite Frederick-oriented history, names, dates, sordid trivia, and random tidbits to make the connection. The light bulb went off as I eventually associated with the early days of All Saints Episcopal Church. The incident did little more to embed a potential idea in my brain for a future story. Back last summer, I was talking with a friend (and member of the All Saints congregation) about a beloved later minister of the same church, Rev. Osborne Ingle, who lost his wife and six children between 1881-1883. We somehow got talking about other faith leaders in the church’s illustrious history, inspired by a gallery of photos that exists in a hallway outside the church office within their worship center complex between West Church, North Court and West Patrick streets. I pronounced to said friend that some of these ministers on the wall were buried in Mount Olivet, and somehow mentioned Rev. Thomas Bacon being in the mix. My friend reprimanded me saying, “Well that’s a different Rev. Thomas Bacon you have there, perhaps a relative, but not the legendary man who lived during Maryland’s Colonial Period, led our church and was responsible for a compilation work commonly referred to as “Bacon’s Laws.” I was certainly taken aback but when I came back to the cemetery that afternoon. I stopped by the Rev. Bacon grave and realized my "grave mistake" because this Rev. Thomas Scott Bacon was born in 1825 and died in 1904. This was in no way my famous Rev. guy—case closed. The other day, my boss (Ron Pearcey) was researching individuals within an unmarked mass grave here in Mount Olivet that belongs to the All Saints Episcopal Church within Area MM. In our records, this particular parcel is labeled as sub Area N/Lot 71—one of ten lots bought by the church in the early 20th century. This mass burial holds the unknown remains of 286 people brought here in 1913, and formerly buried in the All Saints Burying Ground, once located between East All Saints Street and Carroll Creek. As Ron was rattling off names, my ears perked up on one that was eerily familiar—Rev. Thomas Bacon. I did a doubletake and asked Ron again about this, saying that I was told “the famed reverend” was not here, but we only had another, later Thomas Bacon. How was I, or anyone else of today, aware of this fact because we don’t have a tombstone with appropriate birth and/or death dates? So, we have two Rev. Thomas Bacons here in Mount Olivet. My quest here with this story is equally two-fold: 1.) Who were these guys; and, 2.) How many degrees of separation are either Rev. Bacons to each other, and more importantly, Kevin Bacon. Rev. Thomas Bacon (1711-1768) The first of the Thomas Bacons we will cover is the more famous of the two. Much has been written about this Episcopal clergyman, musician, poet, publisher and author. Rev. Bacon was considered “the most learned man in Maryland of his day,” and is still known as the first compiler of Maryland statutes. His career path was much different than his father and grandfather who were ship captains in the coal trade bringing the resource between England and Ireland. Rev. Bacon and his brother would come to Maryland after the death of their parents and lived on the Eastern Shore with maternal uncles Thomas and Anthony Richardson who were tobacco plantation shipping magnates back to England. Young Anthony Bacon would captain a ship at a young age, return to England at age 22 and become one of the greatest merchants and industrialists of the 18th century in that country coming from humble beginnings to becoming a Member of Parliament and one of the richest commoners in England. His brother Thomas, our subject, didn’t do all that bad either in his own chosen vocation. I found the following information regarding him from a biography found on the Maryland State Archives website (msa.maryland.gov) and Geneaology.com: The eldest child of mariner William Bacon and his second wife, Elizabeth Richardson, Thomas was probably born a year or so after their 1710 marriage. He had an elder half-brother William and a younger brother Anthony (baptised in 1716). Thomas Bacon was either born on the Isle of Man, or at his parents' earlier home in Whitehaven, a port town in Cumberland, after which they moved to the island. He probably received a very good education for his time, because by the mid-1730s, Bacon lived in Dublin and worked in the royal customs service. He had previously managed vessels in the coal trade between Whitehaven and Dublin. In 1737, Bacon published his first book, A Compleat System of the Revenue of Ireland, in its Branches of Import, Export, and Inland Duties. This earned an invitation for him to become a free citizen of Dublin, with associated privileges.  By 1741, Bacon had married and was publishing the biweekly Dublin Mercury, possibly with the help of his wife or his elder half-brother William, as well as auctioning goods and operating a coffeehouse. In addition to private pamphlets and handbills, Bacon also published the official Irish newspaper, the Dublin Gazette in 1642 and 1643, but abruptly ceased publication in July, after which Augustus Long resumed publication on August 23, 1743. In the interim, a copyright dispute between author Samuel Richardson and other Irish publishers of his controversial novel Pamela, may have caused problems for Bacon, as some characterized him as an agent for the English publisher for selling imported copies after an Irish publisher had printed the first page required under Irish copyright law at the time (which changed as a result of the dispute). Rather than continue his various businesses or pursue a civil service career, Bacon decided to study for the ministry. He returned to the Isle of Man and studied under Thomas Wilson, Bishop of Sodor and Man. At Kirk Michael, Wilson ordained Bacon as a deacon on 23 September 1744, and on 10 March 1745 as a priest "in order to go into the Plantations." Bacon's brother Anthony had moved to Maryland by 1733, and was working for his uncle, merchant Anthony Richardson until the latter's death in 1741, after which he continued in Maryland for a while, but circa 1749 moved to London to continue his mercantile career, which included the transatlantic slave trade. A 1744 letter mentioned Thomas's prospective missionary career in the colony. The new priest sailed for the colony shortly after his ordination, arriving in Talbot County and assisting the aging priest of St. Peter's parish, Daniel Maynadier, until the latter's death in 1746, when the vestry selected Bacon his successor and he accepted Governor Thomas Bladen's appointment. Thomas Bacon became well known in the local area and in the colonial capital, Annapolis, for his musical abilities (as member of the Tuesday Club in the capital and the Eastern Shore Triumvirate), as well as his learning. Back in 1753 he had started to compile an Abridged compilation of the Laws of Maryland in alphabetical order which he had essentially completed by 1758. He had then approached the Legislative Assembly to permit and fund him to have published and printed the Laws of Maryland. Apart from the literary difficulty of collating all the separate statutes into one volume this was beset with problems. There was the difficulty of raising money for such an ambitious undertaking, the fact that new laws would be passed during the long process but not least of all the political disputes between the elected lower house seeking to rebel against the appointed upper house and the proprietor, Lord Baltimore, in the early rumblings of the revolution. He refused to leave out two laws disputed by a political group known as the Patriots and they did everything they could to block the publication. Eventually the bill to publish was passed and funding was found to the estimated £1000 required in the form of subscription and this included from Lord Baltimore himself the sum of £100 which on completion he turned into a gift for Bacon along with a gold snuff box. Many other subscribers had been members of the Tuesday club. Frederick Town was established in 1745, then part of Prince Georges County. Frederick County would come three years later in 1748. Early English settlers called for the establishment of a second parish in the northern reaches of Prince Georges County. This would become a reality in 1742 with the establishment of the All Saints’ Parish. Rev. Joseph Jennings would be the first to serve the parish, which became seen as the most lucrative and extensive parish in the colony which included most of Western Maryland and today’s area of Montgomery County. Records are scarce but Jennings was replaced at his post by Rev. Samuel Hunter, formerly of Christ Church, Kent Island. In 1748, an Act of Assembly directed the erection of the parish church at Frederick Town. Justices of the Peace of Frederick County would levy a tax to raise 100 pounds in 1750 to complete a worship structure to be placed in Frederick Town. They built a stone and brick structure as the area’s first Anglican Church. It was located atop a hill between Carroll Creek and the aptly-named All Saints Street. The specific location has long-since been redeveloped as it was atop the hill that hosts the Live at Five concerts on the creek, between East All Saints and the amphitheater adjacent the creek and across from the C. Burr Artz Public Library The brick was allegedly imported from England. An old description of the structure says: “It was approached by a paved walk leading from the gateway. It was built east to west. One arm, pointing north where it joined the main aisle held the pulpit so that the rector could face all the congregation. There was a brick floor and high back pews. There was no fire. People carried their foot warmers—wooden boxes lined with tin, some with an iron drawer which held about a tin cup of coals; these to keep the feet warm. We suppose the body was comfortably clad.” The first minister to preside here was the fore-mentioned Rev. Hunter. Not much more is known about Hunter, however he is mentioned in parish histories as being a driving force in completing the church and two other chapels in the vast county of the day. He would die in October of 1758 and was laid to rest in the burying ground next to the church. In checking the records associated with our All Saints’ mass gravesite, I found Rev. Hunter here in Mount Olivet as well in the mass grave with his church successor, Rev. Thomas Bacon. Rev. Bacon came to Frederick from Talbot County. The History of All Saints’ Church states: “Although Mr. Bacon was in impaired health at the time of his arrival in Frederick, his administration showed marked activity, not only in his ministerial duties but along philanthropic lines. During his entire ministry he labored untiringly for the cause of education and for improving the condition of the poor.” Rev. Bacon’s reputation in regard to personal life had preceded him, having been twice married. He sailed from England with his first wife and son John, probably born in the early 1730s. After her death, in the mid-1750s, the widower clergyman was involved in a scandal, with a spinster mulatto woman named Beck, who accused him of being the father of her child. That was not proven, and he filed a defamation suit, which plodded through the courts. In 1756, Bacon remarried Elizabeth Bozman, the daughter of Col. Thomas Bozman, a prominent Talbot County resident. However, that too caused scandal, for Rev. Bacon had earlier married this woman to Rev. John Belchier, and after the couple moved to Philadelphia, Elizabeth learned that her husband was an adventurer and bigamist (having left a wife in England) so she returned home to Maryland and married the widower Bacon. Bacon would be fined for not properly reading the marriage bans beforehand, but could not pay, so this would be another legal situation that would follow him for years. Thomas Bacon’s only son, John, served as a lieutenant in the French & Indian War who commanded troops hailing from Annapolis. He was killed and scalped near Fort Cumberland. The talented music composer and flautist used his time at All Saints in Frederick “to finish his great work chronicling all Maryland's laws since the first in 1638.” He would also include the Maryland Charter and other useful appendices. It was 1762 before the manuscript had been verified with the original statutes and was ready to print although printing was apparently delayed by lack of suitable paper and the quality type, incidentally being supplied by his brother Sir Anthony from England. It was 1765 before “The Bacon Laws” was printed by the Maryland Gazette’s publisher, Jonas Green, in Annapolis. Bound copies would be available the following year, and in finished form consisted of 1000 pages on the largest paper and was of a quality unsurpassed in America at that time. Bacon’s creation, entitled Compilation, would become a very important historical document of the formation of Maryland. The close connection between Church and State, and the influence of many laws upon the rights and relations of the clergy, had influenced Bacon in undertaking this work. At the same time, the endeavor also required his presence at Annapolis a great part of the time which required the need for an assistant to help him in the discharge of his parochial duties. Bacon's abridgement of the Laws of Maryland became celebrated. The Lord Proprietor of Maryland, Frederick Calvert, who originally subscribed to 100 pounds, gave Rev. Bacon a gold snuff box, which was later noted in the inventory of his estate. I learned that Bacon also penned Maryland’s response to Benjamin Franklin’s complaint on behalf of Pennsylvania regarding an ongoing border dispute with its southern neighbor. These writings appeared in London and helped bring resolution through the marking of the Mason-Dixon line by English surveyors of the same name. The above-mentioned internet sources also shared more about Bacon and his work with the church in connection to the institution of slavery: “Rev. Bacon also became known for his concerns with the education of children in his parish, and especially the religious education of African Americans. Himself a slaveowner, beginning in 1749, Bacon published several sermons lecturing masters about the benefits of extending religion to their slaves, and grave consequences should they fail to fulfill their duties. Like Alexander Garden and George Whitefield, Bacon reassured slaveowners that religious principles upheld their earthly authority over their slaves. Bacon started a school to instruct African Americans, and received books from the Anglican organization of Dr. Thomas Bray. Two collections of his sermons were republished in London: Two Sermons Preached to a Congregation of Black Slaves at the Parish of S.P. In the Province of Maryland, By an American Pastor (London, 1749), and Four Sermons upon the Great and Indispensable Duty of All Christian Masters and Mistresses to Bring up Their Negro Slaves in the Knowledge and Fear of God (London, Society for the Propagation of the Gospel 1750). In 1750, Bacon published a pamphlet and began a subscription to provide a school for free, manual training for children without regard to race, sex, or status. He solicited subscribers from other colonies, giving several concerts in Maryland and Delaware and even traveling to Williamsburg, Virginia the following year to raise funds. The Charity Working School was built in 1755 and operated for a time, including under Rev. Bacon's successor as rector, but Talbot County officials ultimately converted it into a poorhouse. Rev. Thomas Bacon died in Frederick on May 24th, 1768 at the age of 57, leaving his widow Elizabeth and three daughters (Rachel, Elizabeth, and Mary). His daughter Elizabeth moved to England to become a servant to his brother Anthony's wife, and both Rachel and Mary ultimately married and remained in the colony. The reverend was buried in the All Saints’ churchyard. As for Frederick’s All Saints’ Church, Bacon’s clerical successor, Bennet Allen of Annapolis, was the subject of scandal. Allen’s “wanton” reputation led him to be met by resistance by Frederick parishoners upon his arrival in town on the day of Rev. Bacon’s funeral. A petition had been signed renouncing Allen’s ascension to the parish post here, and he was actually locked out of the church. He immediately complained to Gov. Horatio Sharpe about this happenstance, and needed to hire a curate to handle spiritual duties in the huge parish, one that would eventually be divided after the American Revolutionary War thanks to the creation of Montgomery and Washington counties (out of the larger Frederick.)

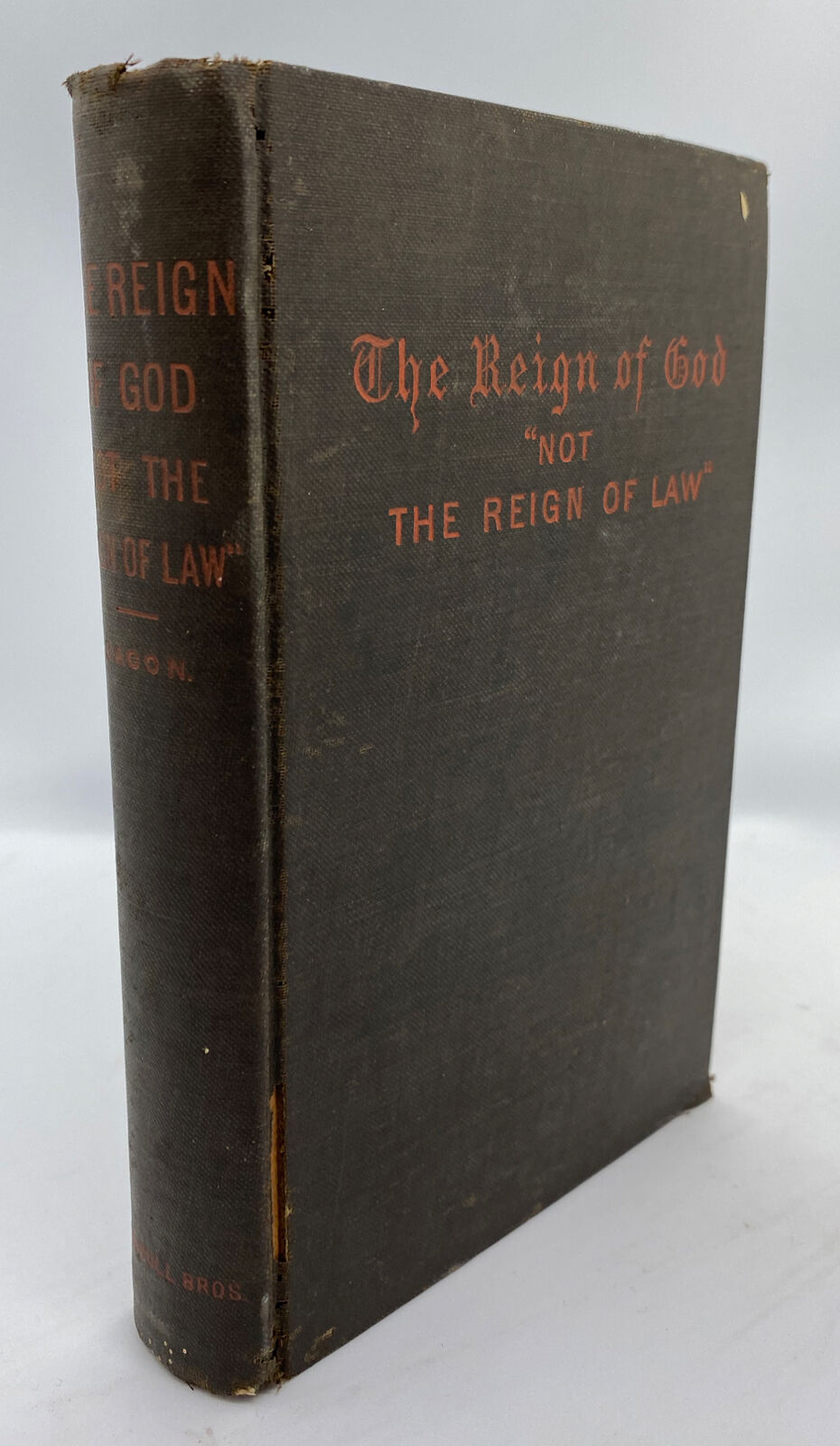

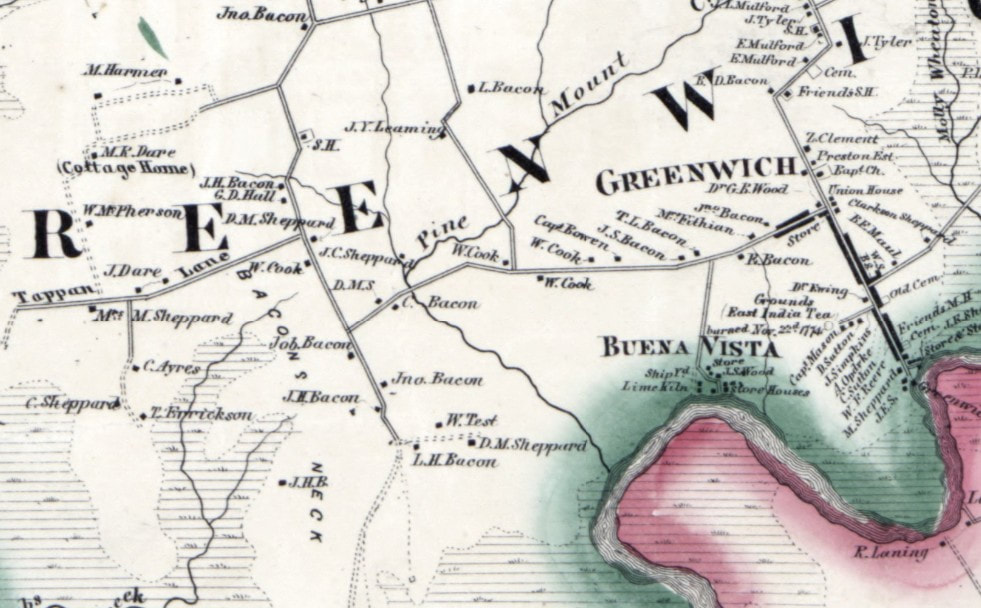

THE LATE REV. THOMAS SCOTT BACON, D. D., who resided in Buckeystown, Md., son of the Rev. William Bacon and his wife, Abbie (Price) Bacon, was born in Saratoga, N. Y. in 1825. Mr. Bacon’s paternal grandfather, Captain David Bacon, served under General Selton of the Continental Army, during the Revolutionary War. He was a farmer of the state of New York, and was a descendant of some of the earliest settlers in the vicinity of Boston, Mass. The Rev. William Bacon, father of Thomas Scott Bacon, was a most saintly man, whose power for good was far-reaching, and had a noticeable effect upon all who came under its influence. He was a life-long member of the Presbyterian Church, and was one of its most efficient pastors. For a few years, he had a charge in Philadelphia, Pa., but most of his life was spent in New York State, where he graduated from the Union Theological Seminary. The Rev. William Bacon was married to Abbie Price, whose only brother was a distinguished member of the New York bar. Their children are: 1, A. B., a lawyer and editor of note, a member of the Senate of New York, sympathized strongly with the South during the Civil War, died in New Orleans, La.; 2, the Rev. Henry M., a minister of the Presbyterian Church, served as a chaplain in the Union Army all through the Civil War; 3,---------- died in youth; 4, Thomas Scott; 5, Maria (Mrs. L. P. Brewster), of Oswego, N. Y. Mrs. Bacon died, aged fifty. The Rev. William Bacon died in 1862, aged sixty-eight. For some time previous to his death, he had retired from active ministerial work The childhood of the late Rev. T. S. Bacon was spent, mainly, in Philadelphia, where he received his elementary education. He matriculated at Williams College (the Alma Mater of General Garfield, Justice Field, and many other notable men) and was graduated at seventeen. He was, at the time of his death, the youngest surviving graduate of the college. Mr. Bacon studied law and was admitted to, the bar in Boston, Mass. In 1848, he went to New Orleans, where he was, soon afterwards ordained a minister in the Episcopal Church by Bishop Polk. He was given a charge which he filled until the beginning of the Civil War when he returned to the north. After having been stationed in a pastorate in western Ohio, for a few years, lie settled in St. Mary’s County, Md., and later went to Oakland, on the crest of the Alleganies. For five years he was pastor of St. Paul’s parish, in Frederick County, but since 1886 he had been practically retired. After a very busy and useful life devoted to the service of the Master, the Rev. Dr. Bacon retired to his beautiful home in Buckeystown, where he spent the remainder of his life. At last he gave himself up almost exclusively to study and research finding his chief pleasure in “seeking for the deep and hidden things of God.” He had for a long time desired to devote himself to this field and was, by nature and experience, well calculated to lead others in the “paths of righteousness.” His tastes were distinctly literary and lie had already published several valuable additions to religious literature. The comprehensive and scholarly work of his first publication, “The Beginnings of Religion,” shows great study and research, as well as unusual knowledge of the motives of the human heart which is always, in all times and lands, reaching out after God. That he might do justice to his subject, the author went to England, where he had access to the old manuscripts, inscriptions, etc., narrating the early efforts of the human race in expressing their ideas of the creator. The work was published in England. His next publication was entitled, “The Reign of God not the Reign of Law,” and then came his great work, “The First and Great Commandment of God,” which was published in New York. All of his publications were well received. The Rev. Dr. Bacon was married, in 1856, to Miss Kelsoe, of Baltimore City, who died in 1882. His second wife was Sophia T., daughter of William and Anna (Brown) Graff, both deceased, whose parents were prominent in the southern part of the County. Mrs. Bacon is a granddaughter of the late Mathew and Elizabeth Frick Brown, editor of the Federal Gazette, the first daily newspaper of Baltimore City. He afterwards removed to Frederick County where he bought 1000 acres of land called “Montevino,” situated eight miles south of Frederick, at what is known as Park Mills. He was one of the prominent businessmen of the county. The Rev. Thomas Scott Bacon, D. D., died at his home in Buckeystown, September 13, 1904, and is buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery. Mrs. Bacon resides in her beautiful home in Buckeystown I found an interesting anecdote regarding Rev. Bacon in my friend Nancy Bodmer's "Buckey's Town: A Village Remembered" published in 1984. The definitive history on the southern Frederick hamlet contains a series of diary entries by former resident William H. Thomas (1878-1938) towards the end of the book. The particular passage is dated January 15th, 1890: "This afternoon after school, a bunch of us were coasting down the big hill trying to see who could coast the farthest. All had come down but John Dutrow who was waiting for a sleigh to cross over the bridge so he could have a clear road. Just as John's sleigh whizzed over the bridge, old Dr. Bacon who was walking to the store, stepped in front of the sled. He landed on top of John and John's sled in the deep snow alongside the road. Dr. Bacon was furious and gave him a scolding and told him how terrible it was to knock people down on a public highway."  Actor Kevin Bacon Actor Kevin Bacon Six Degrees So there you have it, two slabs of heavenly bacon for you. But I did promise one more quest….the connection, if any, of our Mount Olivet subjects to actor Kevin Bacon. I went back nine generations on the star of “Footloose,” and found the commonality of recent generations living in Kevin’s hometown of Philadelphia, and being Quakers in faith. Going back to early Colonial times, immigrant Samuel Bacon (1636-1695), Kevin’s seventh great-grandfather, hailed from the village of Stretton in Rutland County, England, located in the East Midlands of the country. It is thought that he came to America with his parents William and Ann, and siblings including a brother Nathaniel. The Bacons settled in Barnstable, Massachusetts (Cape Cod) not long after the year of Samuel’s birth. He would relocate to Woodbridge, New Jersey in the late 1660s and further south to the area of Greenwich, New Jersey in Cumberland County by 1682. His property, Bacon’s Neck is still known by that name today. As for Rev. Thomas Scott Bacon, his immigrant ancestor was Michael Bacon (1579-1648), a native of Winston in Suffolk County, England. Like Kevin Bacon’s ancestor (Samuel Bacon), Michael Bacon came to Massachusetts during the Great Puritan Migration (1620-1640). He arrived somewhere around 1636 as well, but settled in Dedham, Massachusetts, a town southwest of Boston and located in Suffolk County. The family stayed in Dedham through several generations before our subject Thomas Scott Bacon’s grandfather, Capt. Abner Bacon (erroneously called David in the earlier bio) relocated to Oneida, New York in the early 1800s. In fact, Capt. Abner (1758-1832) participated in the American Revolution and was among the combatants who fought in the famed Battle of Bunker Hill. Rev. T. S. Bacon’s father William (1789-1863), as mentioned earlier, was a man of the cloth as well, however he served as a Presbyterian minister. Finally, Rev. Thomas Bacon of All Saints Church came from Whitehaven, Cumberland County, England on the northwest coast of England. He arrived in Maryland in 1745. I could only get back as far as the reverend’s grandfather, Thomas Bacon.  Francis Bacon Francis Bacon I didn’t find any true relative connections between the three gentlemen in question. I also tried desperately to find a common thread to the famous English philosopher and statesman Sir Francis Bacon (1561-1626), and Nathaniel Bacon (1646-1676) who led Bacon’s Rebellion in 1676-1677 against Virginia’s governor, William Berkeley. Now if I had the time and resources available, I’m sure that there is likely kindred blood as you go back further in time. Family tradition between all three individuals above has surely conjured up thoughts that the Bacons were descendants of a Norman invader, Grimbald, who settled near Holt, Norfolk (England) soon after the 1066 invasion. Either he brought the Bacon name with him, or he took it from old English (perhaps from the Saxon word for beech tree, "buccen" or "baccen"), or perhaps Grimbald took it on as an existing local placename: Beaconsthorpe or Baconsthorpe (which means Bacon's village). The ancient manor home is in the village of Baconsthorpe (Baconsthorpe Castle).

In this whole exercise, I did discover an interesting, personal connection, afterall. I am related to Kevin Bacon through my father's great-grandmother, Emma (Hall) Cook whose own grandfather hailed from Cumberland County, New Jersey and was descended from the Bacons. I never thought I’d be tired of bacon/Bacon, but at this point, I'm getting fried. I will leave you with two last thoughts: 1.) "It is a reverend thing to see an ancient castle not in decay, but how much more is it to behold an ancient noble family which has stood against the waves and weathers of time." -Sir Francis Bacon 2.) see below |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed