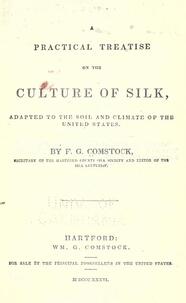

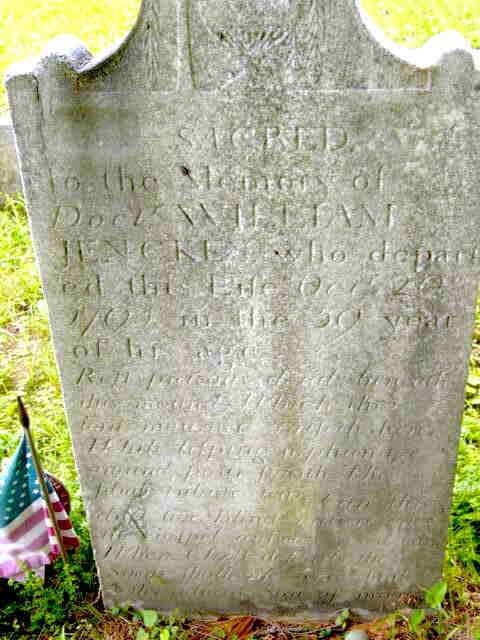

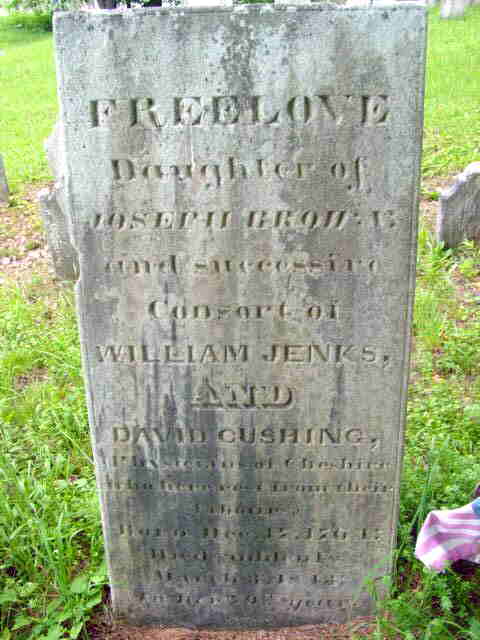

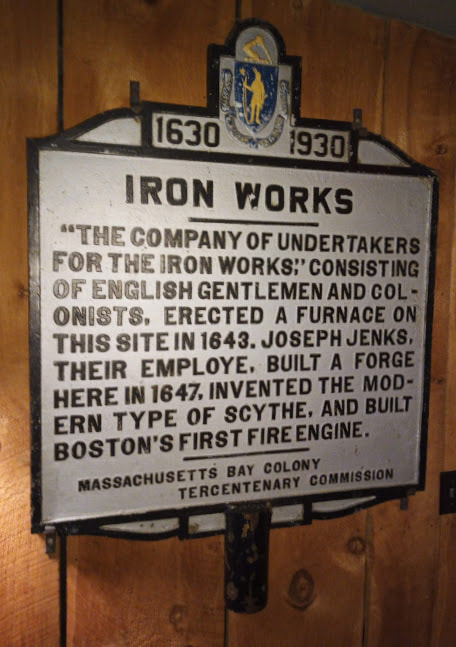

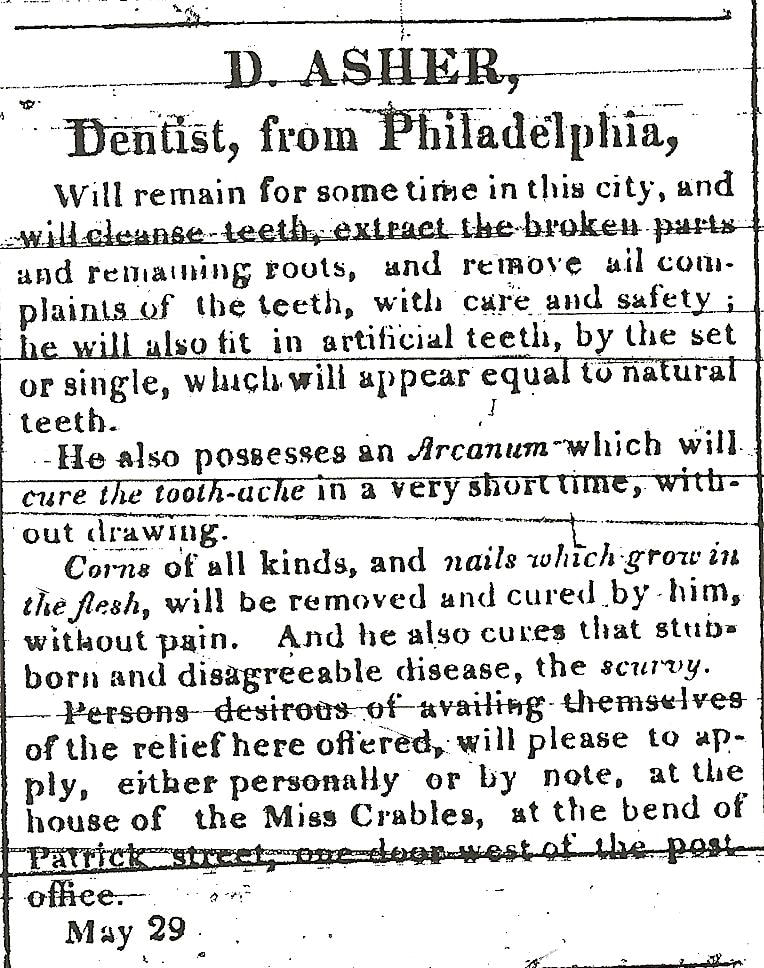

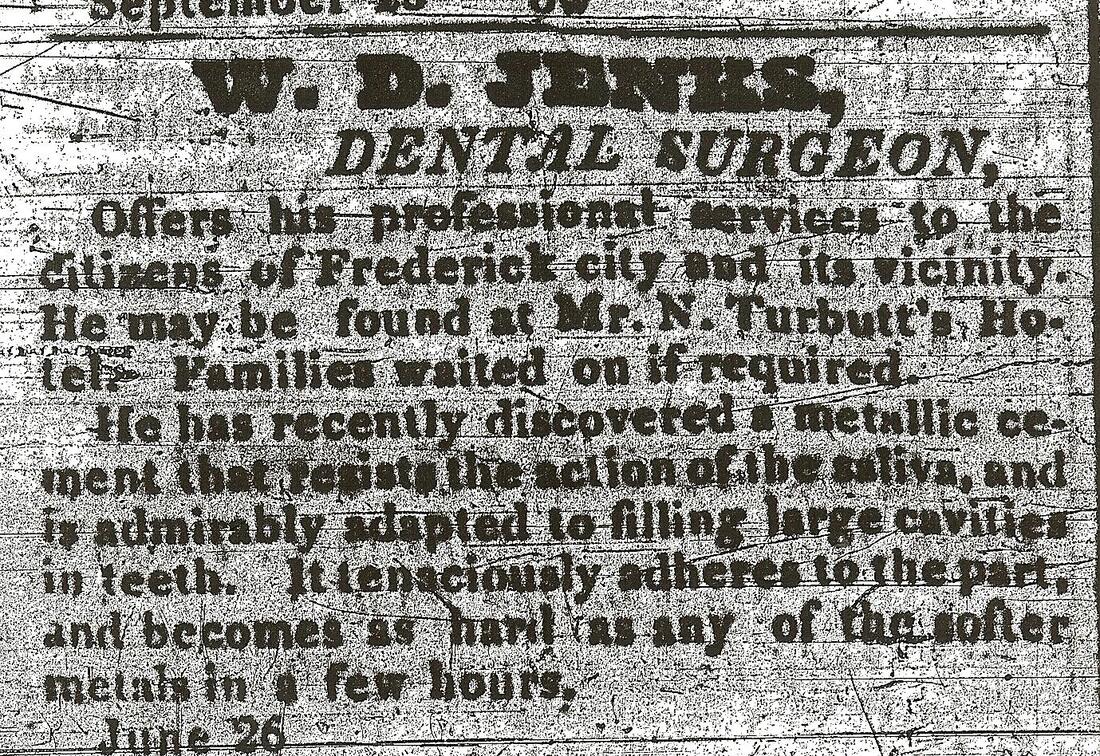

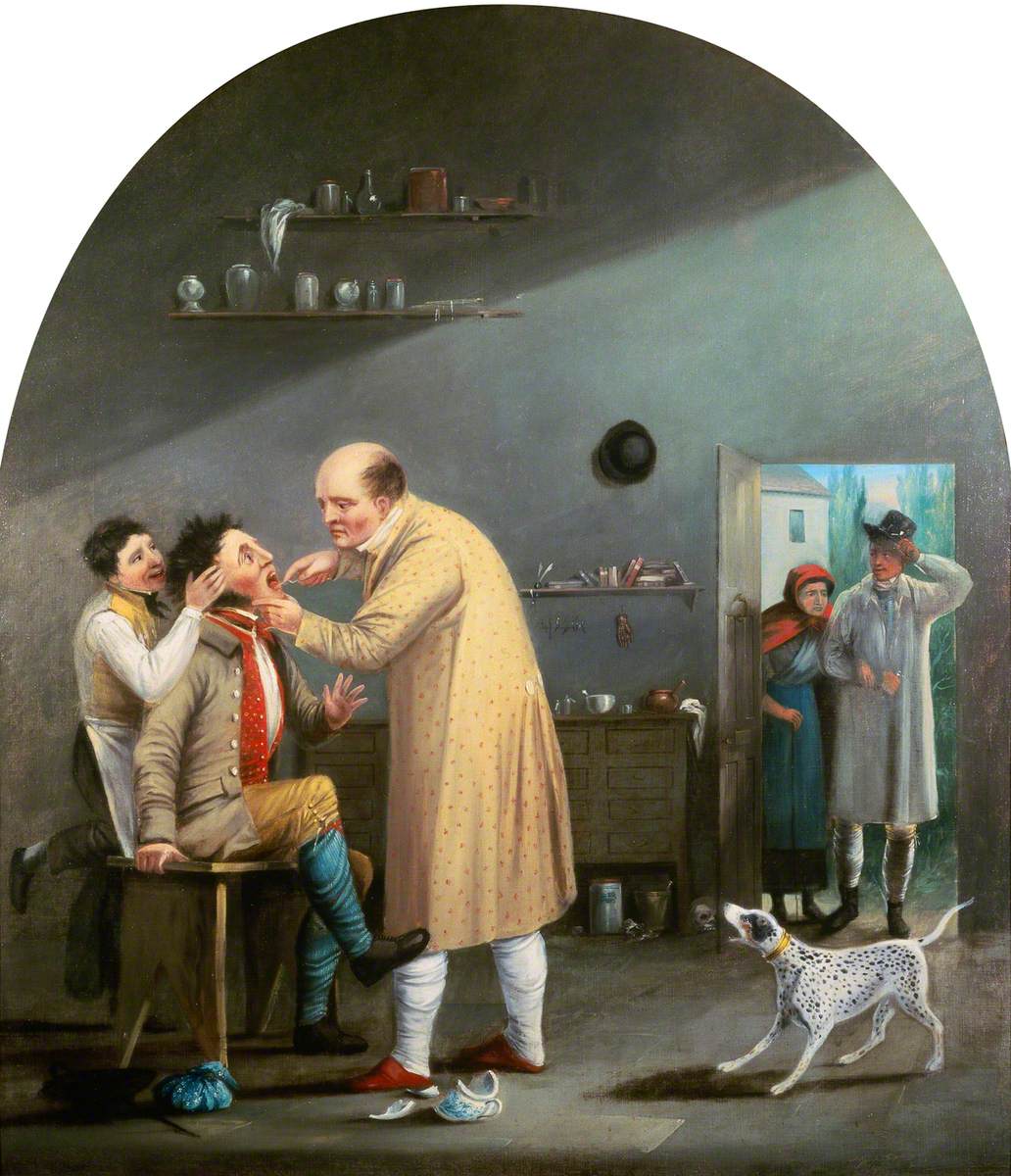

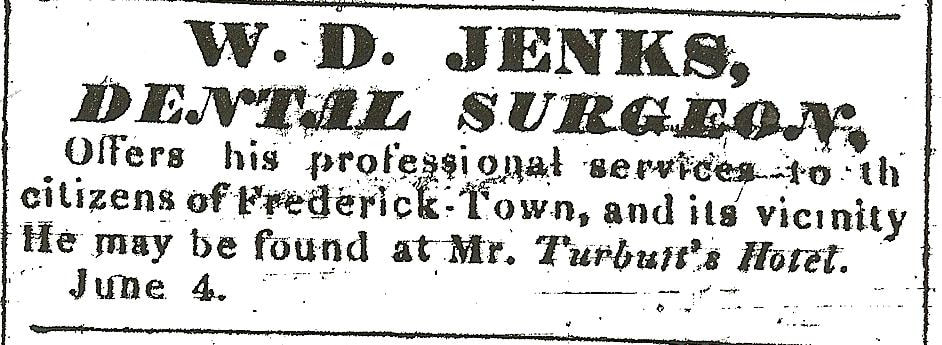

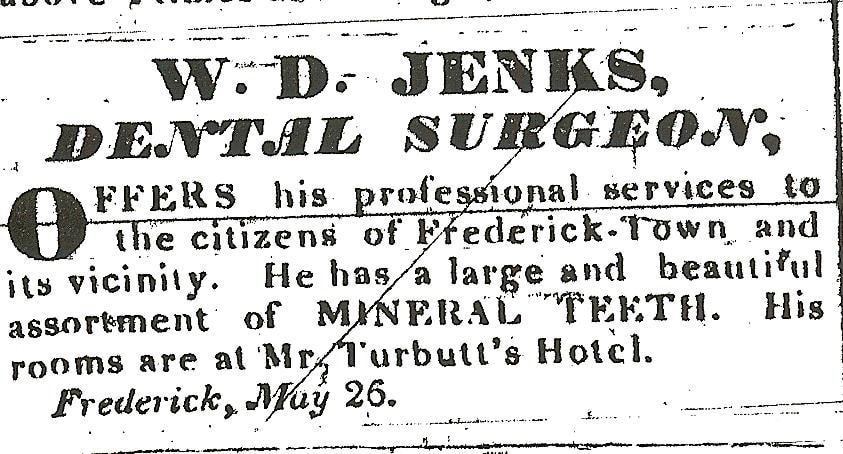

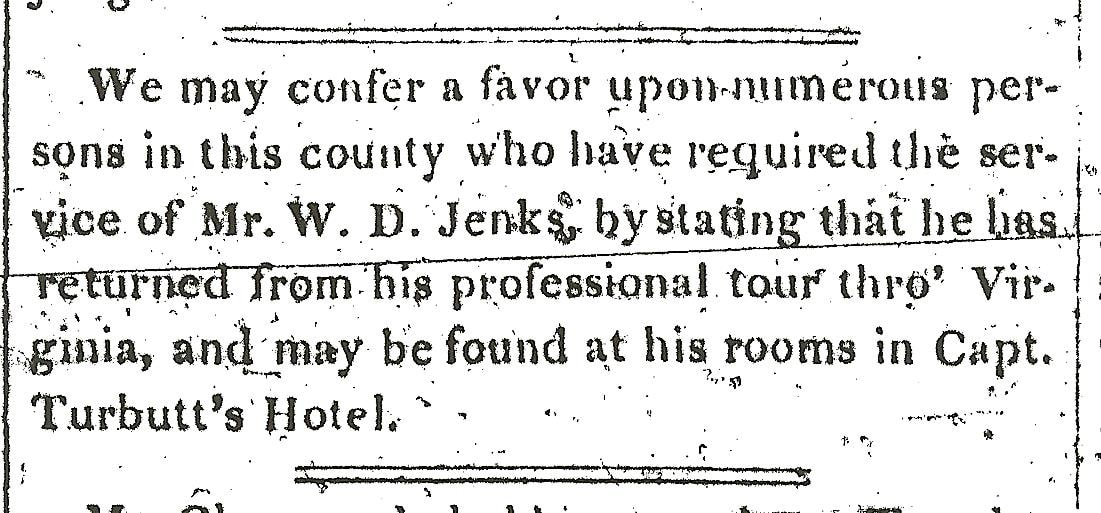

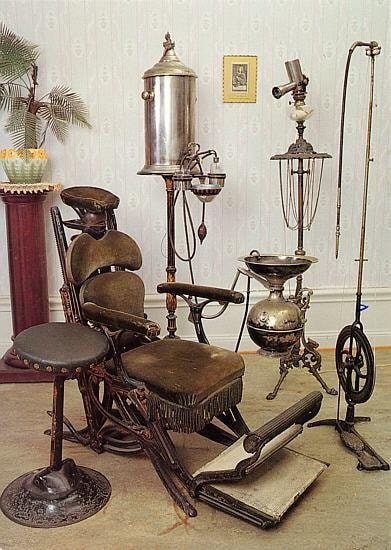

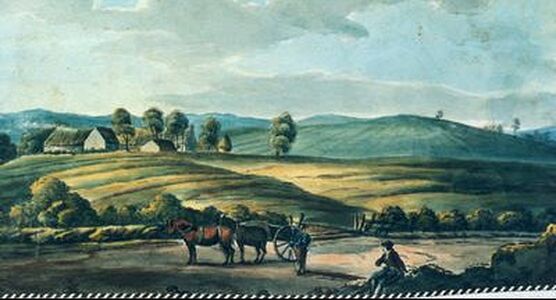

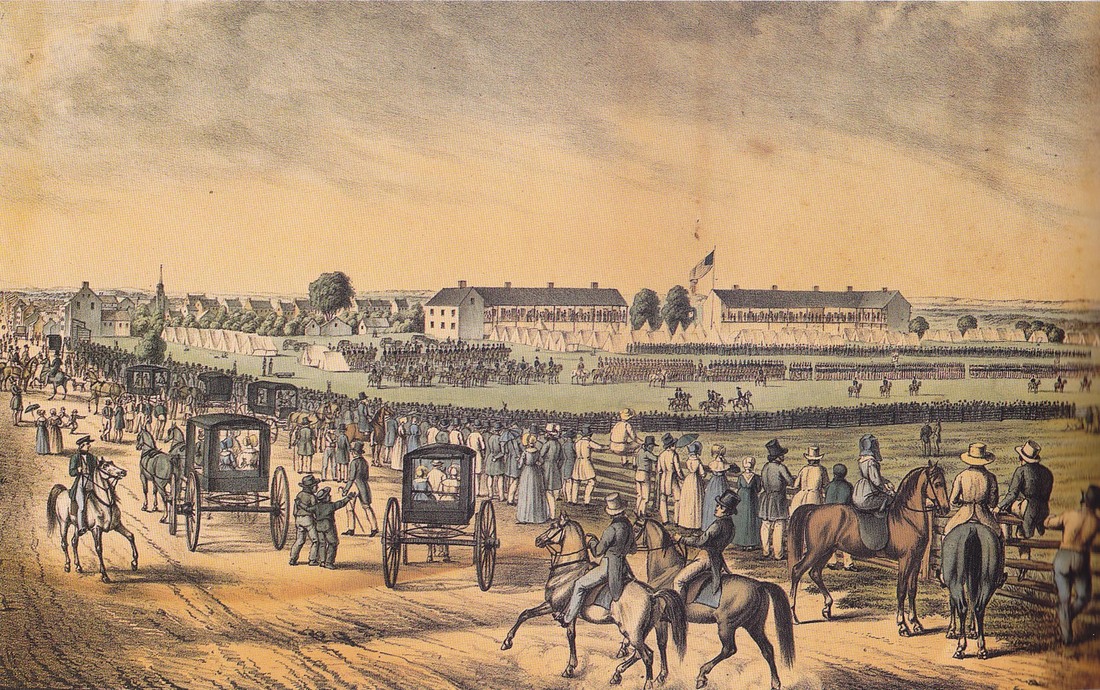

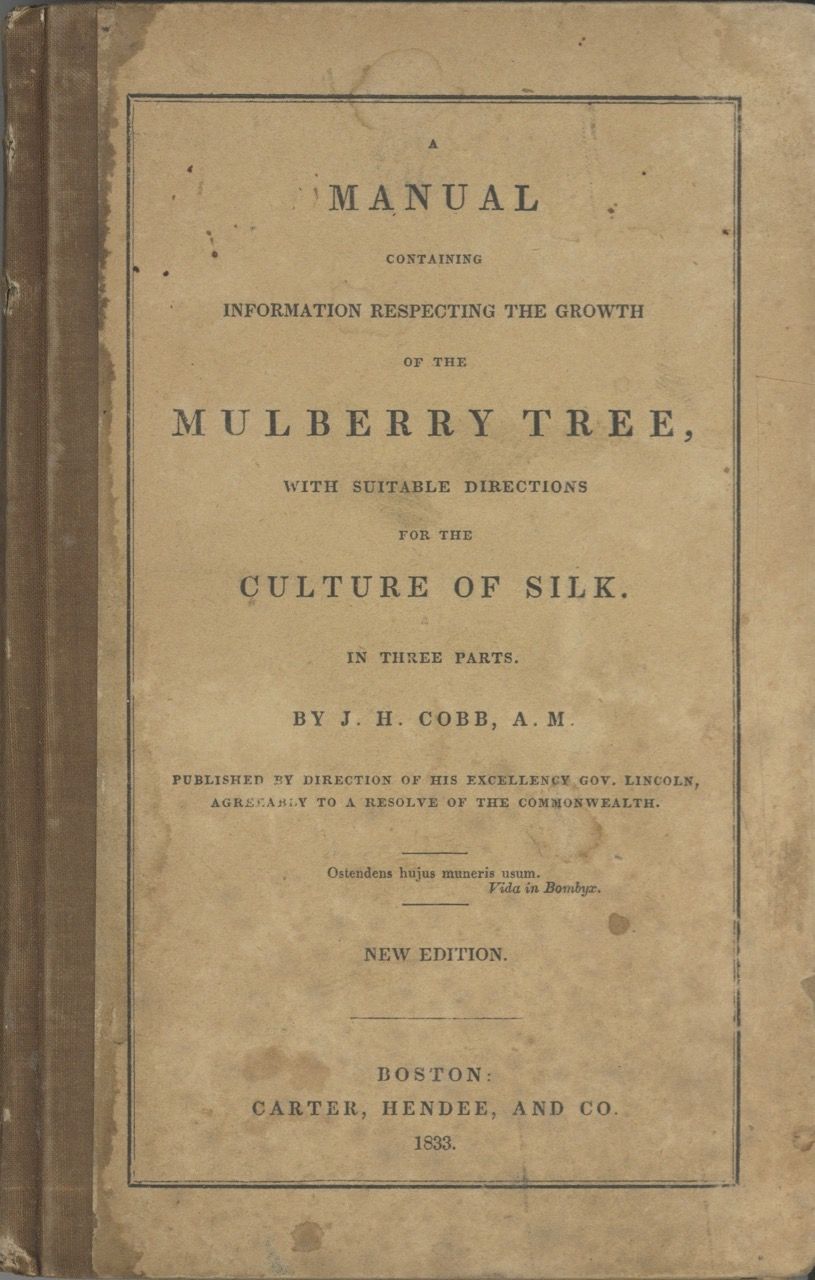

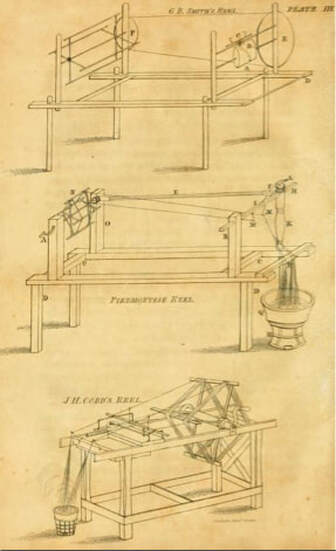

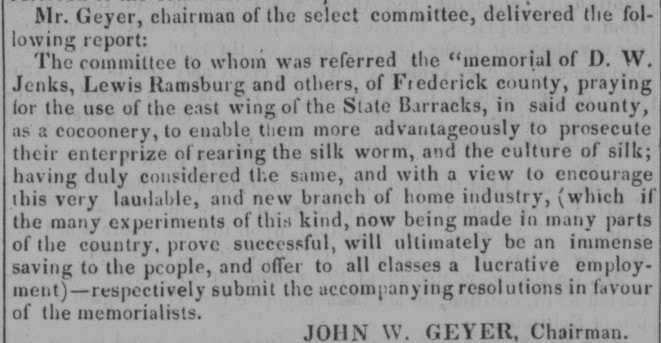

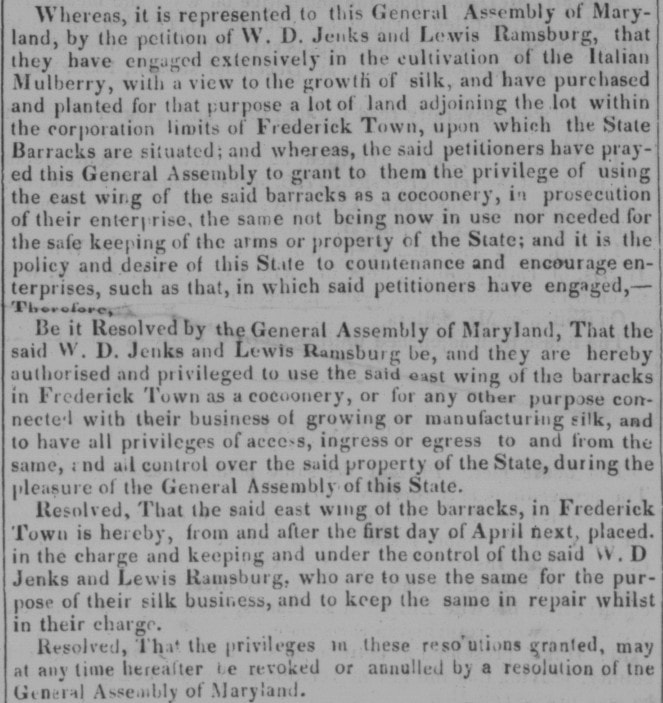

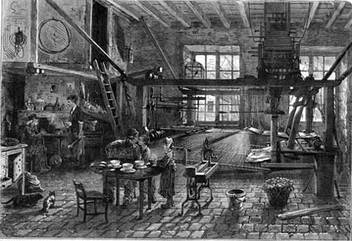

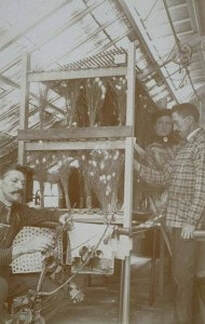

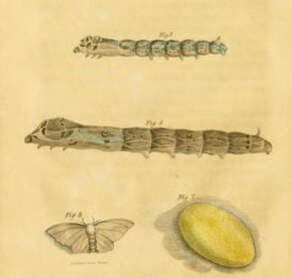

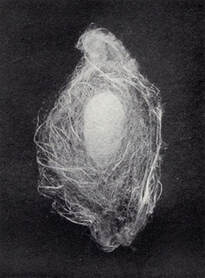

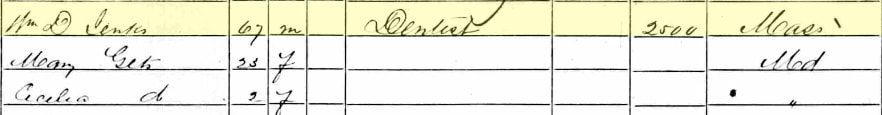

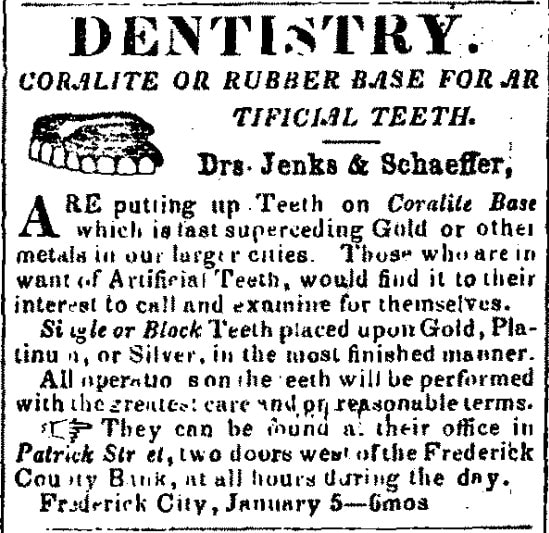

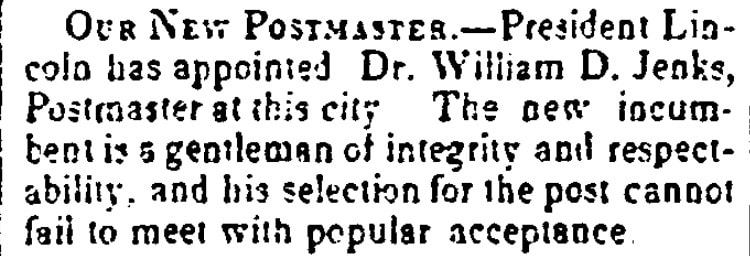

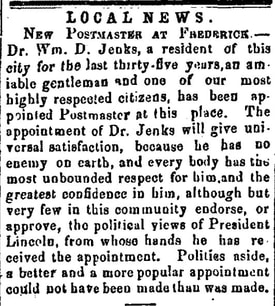

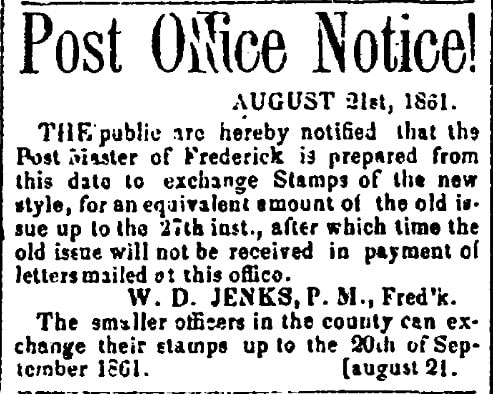

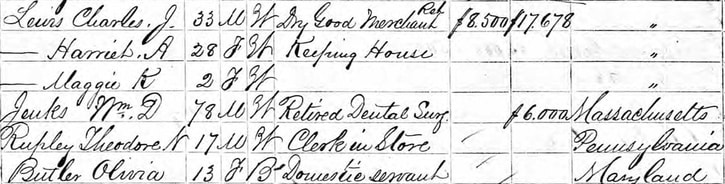

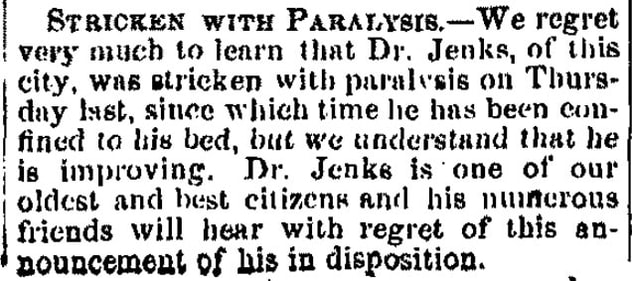

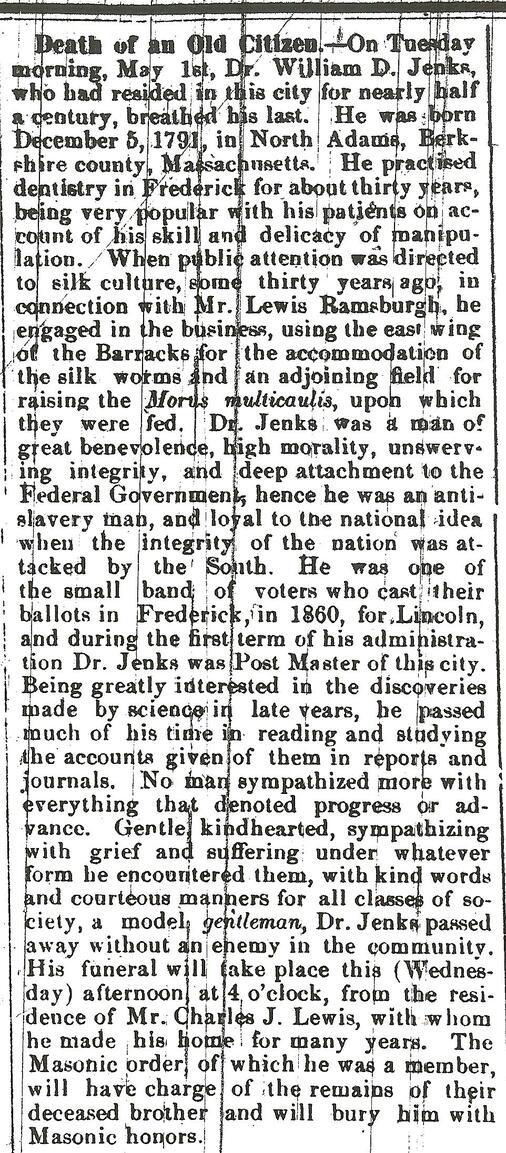

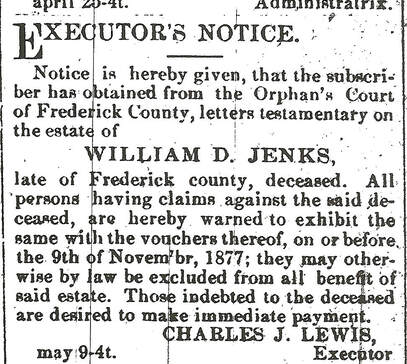

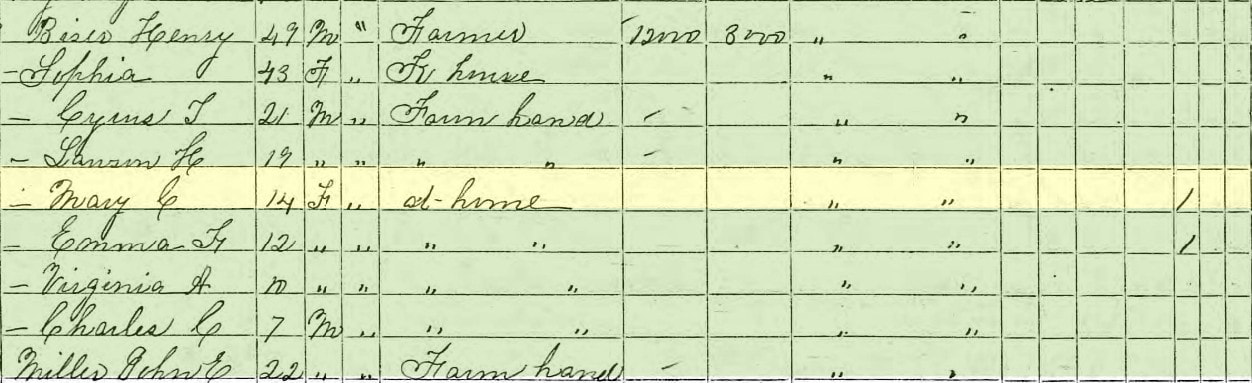

Once known by the name as Pumphouse Hill, a central area of Mount Olivet represents the highest elevation in Downtown Frederick. This was the one-time location of an actual pumphouse which fed water to all parts of the cemetery. Today, the pumphouse is long gone, but the area’s central facet is Founder’s Garden, a tribute to the seven church congregations that helped with the founding of this non-denominational burying ground which opened in 1854. A decade earlier, this was a farm field with a commanding view to the northeast that included the Frederick Barracks silhouetted against a large grove of mulberry trees. Today, at these "lofty heights," the view of the barracks is quite obstructed by buildings, but one can find some of the most prominent families and characters in Frederick history within a small radius. Just a few yards from Founder’s Garden, is the stand-alone grave monument of Dr. William D. Jenks (1791-1877), the man responsible for the previously mentioned Mulberry trees. I have been familiar with this gentleman, at least in name, for over 25 years now since my work on a video production called Frederick Town, a 10-hour documentary featuring a chronological telling of our town’s history from 1745-1995. Dr. Jenks was one of our earliest dentists. In addition, he, along with a business associate, was responsible for one of Frederick’s strangest, yet short-lived business endeavors, commencing in the late 1830’s. William Dexter Jenks was born on December 5th, 1791 in Cheshire, Berkshire County, Massachusetts. He was the youngest of four children born to Dr. William Jenckes (1757-1794), a private of the American Revolution who fought in a Rhode Island regiment and mother Freelove Brown (Jenckes) (1764-1843). Our Dr. Jenks received his middle name courtesy of his maternal grandmother, Hopestill Dexter (Brown). It was tough finding any early information on Dr. W. D. Jenks. His parents were natives of Rhode Island and moved their young family to Massachusetts prior to our subject’s birth. Dr. Jenks’ third great-grandfather (Joseph Jenckes, Sr.) emigrated from England to the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1643 and was involved with organizing and operating the first American iron works in the New England Colonies (1646). In 1953, this iron works was excavated and rebuilt to what is now the Saugus Iron Works National Historic Site in Saugus (MA) located about ten miles northeast of downtown Boston. Joseph Jenckes is credited with America’s first machine patent with his design of a waterwheel used at the forge. He would also be inventor of the first fire engine apparatus to appear on the continent in 1654. Joseph’s son, Joseph Jenckes, Jr., was also a native of Great Britain, having traveled across the Atlantic with his widowed father in the 1640s. An ironworker as well, Joseph Jenks, Jr. is credited as being the founder of Pawtucket, Rhode Island. Dr. Jenks’ father (Dr. William Jenckes) died a few months before the boy’s third birthday. His mother would remarry a gentleman named Dr. David Cushing and six additional step-siblings would come from this union. It comes as no surprise that our subject would enter into the medical profession like his father and step-father. I don’t know if they were dentists per se, but am assuming rather general practitioners. I also was not able to find anything on William Dexter Jenks’ professional schooling/training, or anything pertaining to his youth and young adulthood for that matter. A public family tree is posted on Ancestry.com which infers that Dr. Jenks married a woman named Julia A. Hamilton in the year 1806 in Hamilton, Butler County, Ohio. It goes on to show that the couple had three children: Judith (b. 1837), Freeman (b. 1839), and Harriet Ann (1841-1929). I have found nothing about any of these individuals in searching records galore. I feel somewhat confident in stating that the family historian that posted this either holds the only key, or is completely mistaken as Jenks’ obituary makes no mention of a former wife or children. I'm leaning towards the latter, especially after discovering that Jenks' brother, Stephen B. Jenks, moved to East Hamilton, NY, married a woman named Julia Ann, and had children named Judith and Freeman. I do know that W. D. Jenks came to Frederick in the late 1820’s, likely 1828, as his obituary dated 1877 says that he had spent nearly half a century in the western Maryland town of ours. I performed hours of additional research at the Maryland Room of C. Burr Artz Library hoping to discover his exact arrival. Sadly, the particular microfilm reel of the Frederick Town Herald newspaper facsimiles dating from summer 1827-mid fall 1830 is missing from the collection, and has been for years. Although this is conjecture, I feel that Dr. Jenks simply answered the call of local residents here looking for a dentist and moreso, a dental surgeon. In perusing earlier newspapers, I happened to find an advertisement dating from 1824 heralding the services being offered by an early dental physician named D. Asher of Philadelphia. It appears that Dr. Asher was simply an itinerant professional who set up “shop” during his stays at Frederick in the home of a Miss Crables (likely Miss Graybill) on W. Patrick Street. I saw no other dentist advertisements in local newspapers until I saw an immediate ad for Dr. Jenks on the front page of the first newspaper I scrolled to within the ensuing microfilm reel (after the missing reel). One year later, famed Frederick diarist Jacob Engelbrecht mentions our New England physician in an entry that dates to October 4th, 1831: “This day I had a jaw tooth extracted by Doctor W. D. Jenks. It was the 3rd from behind on the lower right jaw. It is the first I had extracted, except when I was a boy and then did it with thread & a sudden jerk. I had the next hind one plugged by Doctor Jenks on the 16 October & one filed.” I would see several other advertisements in the years to follow. Of particular interest was a small mention in the January 4th, 1834 edition of the Frederick Town Herald which sheds light on the fact that like the previously mentioned Dr. Asher of Philadelphia, Dr. Jenks apparently took his talents out on the road.  Dr. Jenks continued to serve the Frederick community throughout the 1830s, a decade that saw plenty of town growth and passers through as the National Pike was busier than ever with rushing stage coaches, settlers in large wagons heading westward, and travelers and livestock coming eastward along with valuable trade items and natural resources from the burgeoning Ohio River valley. The Baltimore & Ohio Railroad had arrived in town in 1831, changing the transportation landscape forever. Jenks continued to live and run his practice in hotels of town, Capt. Nicholas Turbott’s Tavern at first and later Talbott’s Tavern, operated by Joseph Talbott. This latter hostelry was located at the northeast corner of W. Patrick and Court streets, diagonally across from the Frederick County Courthouse of today. The site had hosted Gen. Lafayette back in 1824 and would gain later fame as the City Hotel before its removal in the early 20th century to make way for the Francis Scott Key Hotel. In my researching endeavors for this story, I found an article published in 1968 in which the managing staff of the Frederick News-Post became recipients of a booklet containing copies of several letters written by Dr. Jenks to relatives living in East Hamilton, New York, home to Dr. Jenks’ brother Stephen B. Jenks. In one of these letters, written in 1831, Jenks estimated that Frederick had a population of 5,000. He mentioned that the city had eight churches and that there was “an elegant and expensive iron railing” around the Court House. According to Jenks: “Frederick had a flourishing Academy for the education of boys, and also a Catholic Seminary and an Orphan Asylum operated under the direction of the Sisters of Charity.” In describing the citizenry, many of whom made up his customer base, Dr. Jenks reported: “A stranger on visiting Frederick County would discover little of that urbanity of manners so fascinating in the warm hearted Southerner; they are, however, sober, industrious and frugal; but the want of a system of general education is deeply felt.” Jenks said that he had never known business so dull, and he regarded the farmers as an unusually fortunate and happy class of people at that time. He went on to write: “The farmer, who is free from debt and can raise his own bread and meat is your most independent man after all, and must be the happiest.” Perhaps this last shared impression was the impetus for William D. Jenks to make a very interesting move in the late 1830s? In April, 1837, the local newspaper reveled in reporting to its readers: “Dr. Wm. D. Jenks has planted this Spring in the vicinity of this town, 20,000 white mulberry trees. On the growth of one year, for the purpose of feeding silk worms, and purpose of planting the same number next year." Jacob Engelbrecht would shed a bit more light on the progress of the enterprising tooth expert with an entry written into his diary on July 2nd, 1838: “Silk Worms—Messrs. William D. Jenks & Lewis Ramsburgh have a cocoonry at the barracks and their mulberry trees next to the barracks field. I saw them yesterday. Nearly mature they have about worms, this is the first year.” Of course, the barracks referred to the Frederick “Hessian” Barracks located today on the campus of Maryland School for the Deaf, just a stone’s throw from Mount Olivet’s front gate.  The process, as demonstrated by Dr. Jenks’ actions, begins with the mulberry tree and the silkworm, which is a type of caterpillar. The silkworm prefers a diet of mulberry leaves, and produces a cocoon which, when unraveled, can be spun into silk thread. In case you are curious, silk production is called sericulture. Historians trace the origins of what has been coined the “Mulberry Mania” or the “Multicaulis Craze” of the 1830s to an 1826 Congressional report. This stated that too much money was being spent on imported silk and that, to remedy this, the feasibility of domestic production should be explored. The result of this investigation was a 220-page illustrated manual published in 1828 by the U.S. Treasury Department. Following the federal lead, state legislatures took up the issue of silk production. Back in Dr. Jenks’ native state, the House of Representatives of Massachusetts actually passed a resolution in 1831 that a treatise be compiled that would contain “the best information respecting the growth of the mulberry tree, with suitable directions for the culture of silk.” The author of this work, Jonathan H. Cobb of Dedham, MA had experience in sericulture and claimed that he was able to produce $100 worth of silk a week year-round. Cobb’s promise enticed farmers with visions of silk production as the surest way to “acquire so much [income], with so little capital and labor.” Mr. Cobb also pitched silk production as a means of alleviating rural poverty. Cobb envisioned self-sustaining towns run silk farms, suggesting that “paupers” and students provide the labor. This manual also predicted ample funds would be available for public works and schools “if all the highways in the country towns were ornamented with a row of mulberry trees.” By the end of the decade, thousands of volumes had been printed and this wildly popular work had gone through four editions.  Similar works were published up and down the east coast. In 1836, F. G. Comstock, a Hartford, Connecticut seed dealer, published A Practical Treatise on the Culture of Silk, his own contribution to a growing body of work that sought to promote the planting of mulberries. With the fertile ground of imagined riches thus well prepared, the introduction of a new mulberry tree from China was the seed that allowed a bout of wild agricultural speculation to take root. Around 1830 a new variety of mulberry was introduced in America from France. It was known as Morus multicaulis, for its habit of sending up multiple sprouts from the base. This variety also had very large leaves and was said to be the secret behind the Chinese success at silk production. Nurserymen in several northeastern states began to grow the trees in great quantities. At the height of the bubble, young mulberry trees sold for up to $5 each, while the going rate for trees of other species was thirty to fifty cents apiece. Mulberries are fast growing, as well as easily cloned from both softwood and hardwood cuttings, so a skilled propagator was able to realize great profits. The dizzying heights which the speculation reached caused an insatiable demand for the multicaulis mulberry. In hindsight, it is clear that that market speculation drove the price of the mulberry trees well beyond the value of any silk which might be produced from the leaves. Indeed, none of the accounts from the period tell of any but theoretical profit made from silk farming, but instead of equal parts lucky and wily nurseryman who were able to capitalize on the craze. Dr. Jenks and Mr. Ramsburg also had the State of Maryland behind them as can be seen by proceedings in the Maryland General Assembly session of 1840. In January, the silkworm entrepreneurs received the permission necessary to utilize the Hessian Barracks for their endeavor.  John Thomas Scharf wrote in his History of Western Maryland (published in 1882): “From 1840 and for several years afterwards a portion of the Barracks (which belonged to the State) were used by special permission of the Legislature by Messrs. Jenks & Ramsburg as a cocoonery. They had a white mulberry orchard, consisting of ten acres, in an adjoining lot. The State granted them the use of the Barracks buildings to test the experiment of silk-culture, then creating so much discussion throughout the country. W. D. Jenks began operations and planted his trees in 1837. Feb. 28, 1840, the reels were put up. During the year sewing silk was made equal to that of foreign manufacture. After the flyer was in operation, gold-stripe vesting was manufactured in considerable quantities. With Jenks and Ramsburg leasing the Barracks, silk worms were being raised on the second floor. It has been said that results for this local endeavor were not commercially promising, although enough silk was produced in 1843 that a pair of silk stockings was woven by Buck, a prominent stocking weaver based on Patrick street. Supposedly, the following year featured silk being sent to the penitentiary, where a vest was woven, but this was the peak of the silk industry in Frederick County.  Another resident of town wrote on the subject of the Frederick cocoonery, present in her youth. This was Catherine Susanna Thomas Markell (1828-1900) who wrote an unpublished manuscript entitled "Short Stories of Life in Frederick in the 1830s." Mrs. Markell wrote in her memoir: "An orchard of thrifty white mulberry trees, covering ten acres, flourished on the sunny eastern slope. The greatest interest was manifested by citizens of all classes and for us children, the whole procedure possessed an inexpressable fascination. Imagination exhausted itself in varied speculations as to what new phase would be next developed. With unbounded admiration, we regarded the huge hampers of glistening, white, yellow and orange-colored cocoons, and when, after undergoing a heating process for the destruction of the grub, interminable lengths of soft gossamer fibre were wound smoothly off the great reels or flyers, our delight defied control.  In wonderment akin to awe, we watched the mysterious advent of the butterflies and the dainty things emerged, one after another, from their pretty oval prisons and hovered o'er the mulberry foliage strewn about on long plank tables. Upon these leaves the tiny eggs were deposited and upon them also the larvae subsequently fed. The moth, in its exit from the sheath, severed many strands of its fibre, thus rendering the cocoon in a measure worthless for reeling, though an uneven, lustre-less thread, known as "spun-silk" was often fabricated from these "cut" cocoons and used for knitting purposes."  Like all bubbles, the "Mulberry Mania" of the 1830s grew and grew until it popped. Precipitating events for the rapid deflation of the industry nationally can be blamed on a blight which wreaked havoc on newly-planted mulberry orchards in 1839, along with a particularly hard winter in 1844, to which many surviving trees succumbed. These two calamities offered a moment of clarity to farmers who had been swept up in the craze. This helped prove the point that silk production was not viable on a large scale in America. Too many factors, from climate, to the necessary labor and the knowledge of the production process were hurdles too large to surmount. By the time the market crashed, nurseries could not even sell a bundle of a hundred mulberry trees for a dollar. The operation at the barracks likely ceased by 1843, opening the opportunity for the grounds to be used easily with the large military encampment under Gen. Scott. Luckily, Dr. Jenks had a legitimate, and proven, career to fall back on. He continued to operate on teeth and create smiles here in Frederick. It’s just a shame he didn’t have the foresight to see the possibility of silk dental floss, embodied today by the product named Dental Lace. Dr. Jenks was a member of the Columbia (Masonic) Lodge #58, and served as a Methodist church trustee although he identified more closely with the Unitarian Universalist religion. He also busied himself with politics. In fact, Jenks’ obituary shares that he was among the small minority who supported (and voted for) Abraham Lincoln in the presidential election of 1860. He personally cast one of 2,294 votes for the future “Great Emancipator.” Many are surprised to learn that Lincoln only received 2.48% of the popular vote statewide, finishing last behind three other candidates: John Breckinridge (42,482 votes), John Bell (41,760 votes), and Stephen Douglas (5,966). Well, Dr. Jenks’ support did not go unnoticed as he was aptly rewarded after President Lincoln took office. This came in the form of an appointment as Frederick’s new Post Master. Dr. Jenks would conduct this job with great pride until having to step down for health reasons in 1865. I presume the assassination of his political icon that same year didn’t help matters either. Two years later, health setbacks forced a retirement from the dental business. Dr. Jenks soldiered on, living with a gentleman named Charles Lewis and family. According to the family tree I saw on Ancestry.com, Mr. Lewis would be Jenks' son-in-law, having married supposed daughter Harriet A. Jenks (b. 1842). I did find that Lewis was a merchant who owned a dry goods store on W. Patrick Street, and the family lived on the premises as this was Dr. Jenks' last home. The Lewis family would eventually move to Clarendon, TX in the late 1880s and be buried there. Charles would be appointed a Post Master of Clarendon years later, so I'm guessing the connection could be more along "postal" lines rather than familial. I'm thinking Jenks took Charles under his wing as a mentor of sorts. I still remain skeptical on this issue of Jenks being married with children, even though Charles and Harriet Lewis would name their first-born son William Jenks Lewis (1871-1960). Dr. Jenks would die on May 1st, 1877 at the age of 85. I’d really like to think that the good doctor breathed his last, with head lying comfortably on a silk-upholstered pillow from his earlier venture begun “two score” earlier. The former New Englander would be buried in Mount Olivet’s Area F/Lot 5. He had bought two adjoining plots when the cemetery was created in the early 1850s. With no family buried in the vicinity, his monument is surrounded by a nice green-space. It almost begs to ask a final, and befitting, question: “Is there room to plant a few mulberry trees?”

0 Comments

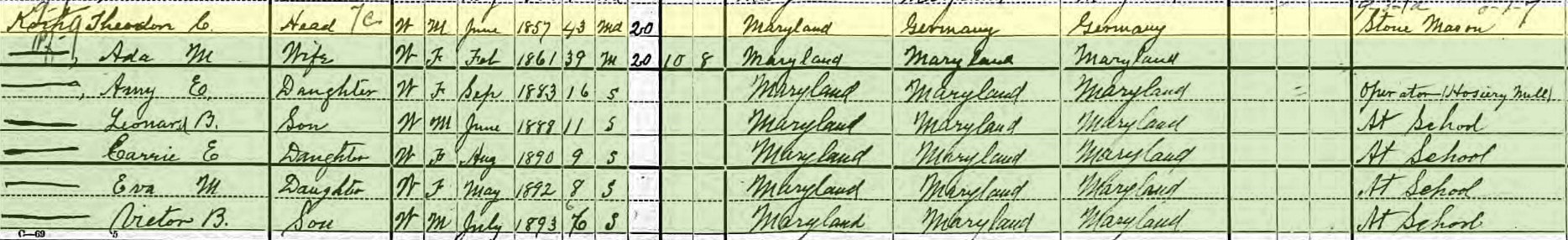

A scene from the motion picture 1917 A scene from the motion picture 1917 One of the hottest movies in theaters currently (at the time of this writing) is simply entitled 1917. We will continue to hear about this critically acclaimed work in coming months as it has already garnered Academy Award® consideration. The feature is an epic war film directed, co-written and produced by Sam Mendes and based in part on an account told to Mendes by his paternal grandfather, Alfred Mendes, a veteran of World War I. The movie chronicles the story of two young British soldiers during the war who are given a mission to deliver a message that warns of a suspected ambush during a skirmish, soon after the German retreat to the Hindenburg Line during Operation Alberich in 1917. The grave importance of message carrying in warfare cannot be understated. The common name applied to these brave souls was that of a “runner,” a soldier responsible for passing on messages between fronts during war. In the era before electronic communication innovations in warfare, battlefield administrators needed to share intelligence among one another in highly stressful, chaotic and rapidly changing situations. It was certainly a matter of life and death, as the lives of countless soldiers were at stake based on the safe transport of either questions or answers by the runner. Things could go horribly wrong with a lack of communication, a mistake, or an incorrect presumption made without the aid of military intelligence or observation. As can be easily imagined, this was a very dangerous job. The movie will certainly demonstrate this fact if you don’t believe me. World War I was dominated by trench warfare. With such, there was a tremendous need for runners. Passing messages between the trenches was not possible without climbing up to ground level and running towards the other trench. While on the ground, the soldier was hampered by weather conditions. The track was not ideal and full of obstacles, oftentimes forcing the soldier to sprint through smoke and chemical-weapon gasses, while on a muddy, or artillery riddled, track. Add to this the fact that runners were completely exposed to enemy sharpshooters, and it was commonplace for participants to die before reaching their destination. Officers could not be sure that a message had reached its recipient unless the runner managed to return. Last year was the anniversary of the end of the Great War, which prompted me to write stories on some of Mount Olivet Cemetery’s 500+ veterans of that conflict alone who are buried here. Many know that we have Charlotte Berry Winters here, who at the time of her death at age 109, was the last female veteran of the war to pass. We also have 13 soldiers who died during the war in active service. Some died in combat, and others due to the terrible Spanish Flu pandemic. One specific Frederick World War I vet, (today buried in our midst here in the cemetery) survived combat and the flu to return to the States and live a productive life. He was a bugler in the US Army’s Company A of the 115th Infantry Regiment, part of the famed 29th Division. Company A, started right here in Frederick. This gentleman’s name was William Theodore Kreh, Sr.—and he was a runner. Known by the nickname of “Whitey,” William Theodore Kreh Sr. was born on July 21st, 1897 in Frederick, the son of Theodore Christian Kreh and Ada Mae Stull. The family had 11 children and Mr. Kreh was an accomplished stone mason. The family lived at 239 W. 5th Street on Frederick’s south side at the time of William T.’s enlistment into service at the age of 20. He had joined the National Guard and was assigned to the 115th Regiment and Frederick’s Company A was based here in Frederick at the Armory located at the corner of Bentz and W. Second streets. As a matter of fact, the armory had been built in 1913, the third of a series of similar armories built for the Maryland National Guard in the early 20th century. Up until his time of deployment, he worked as a brushmaker at the Ox Fibre Brush Company.

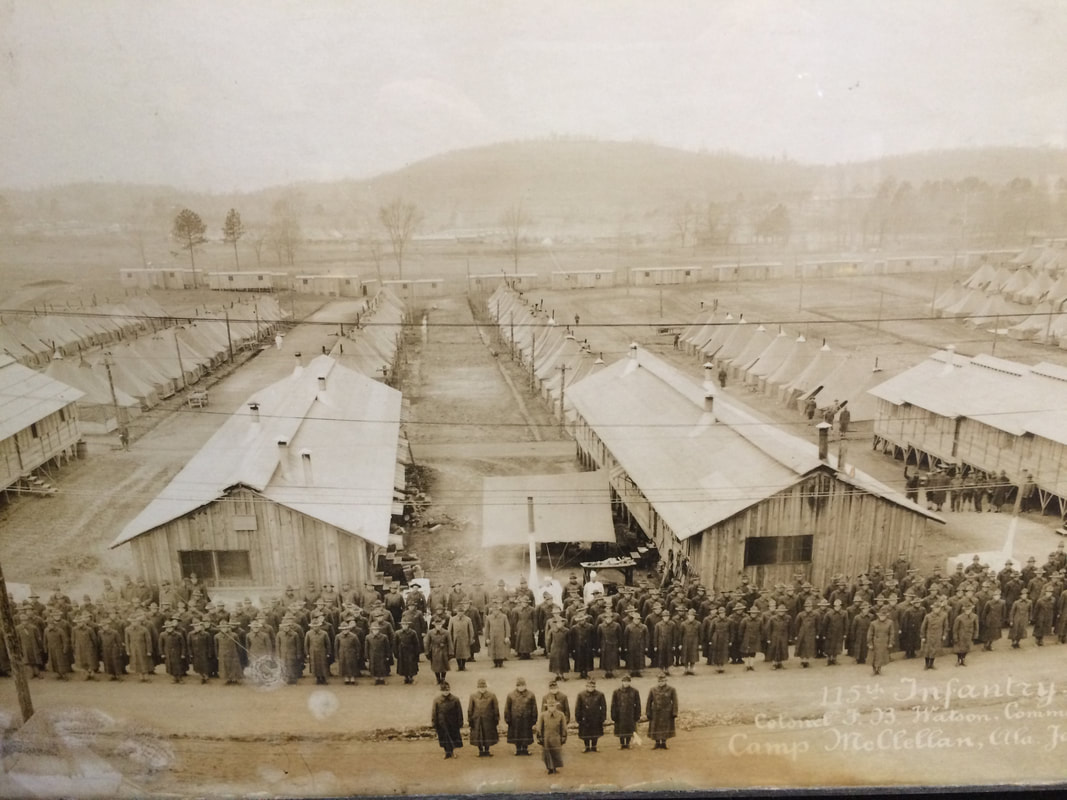

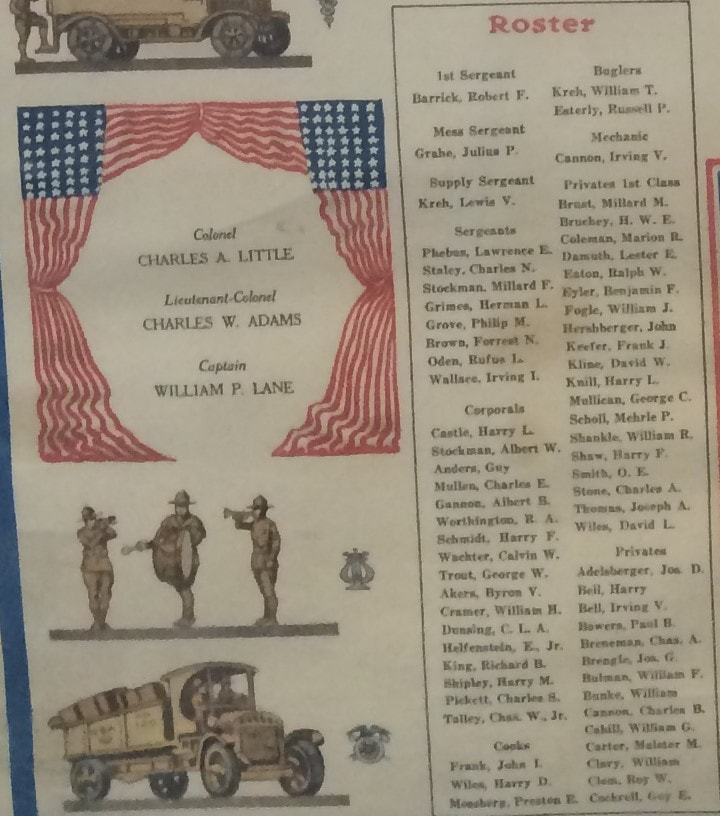

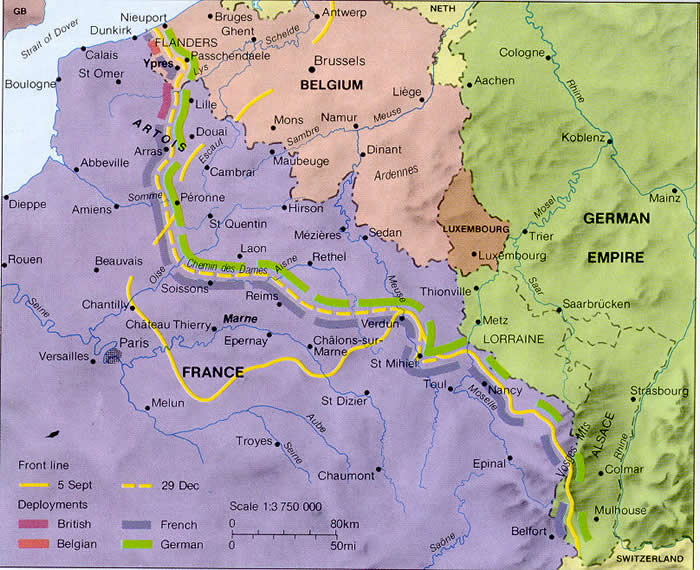

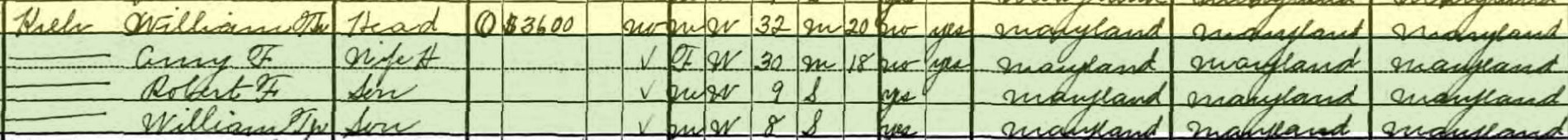

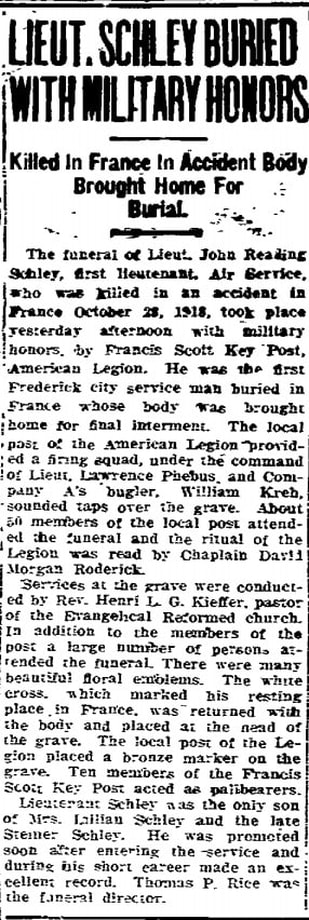

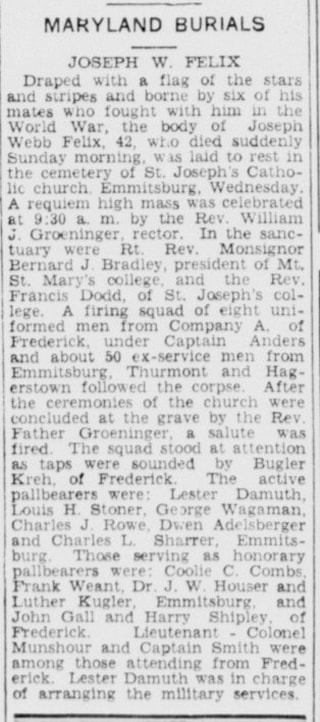

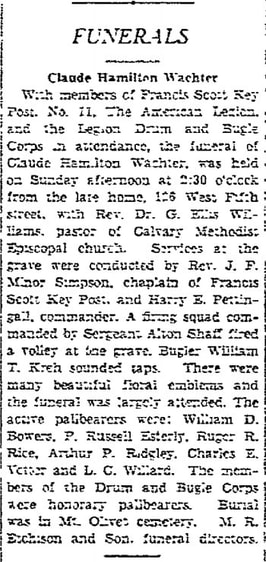

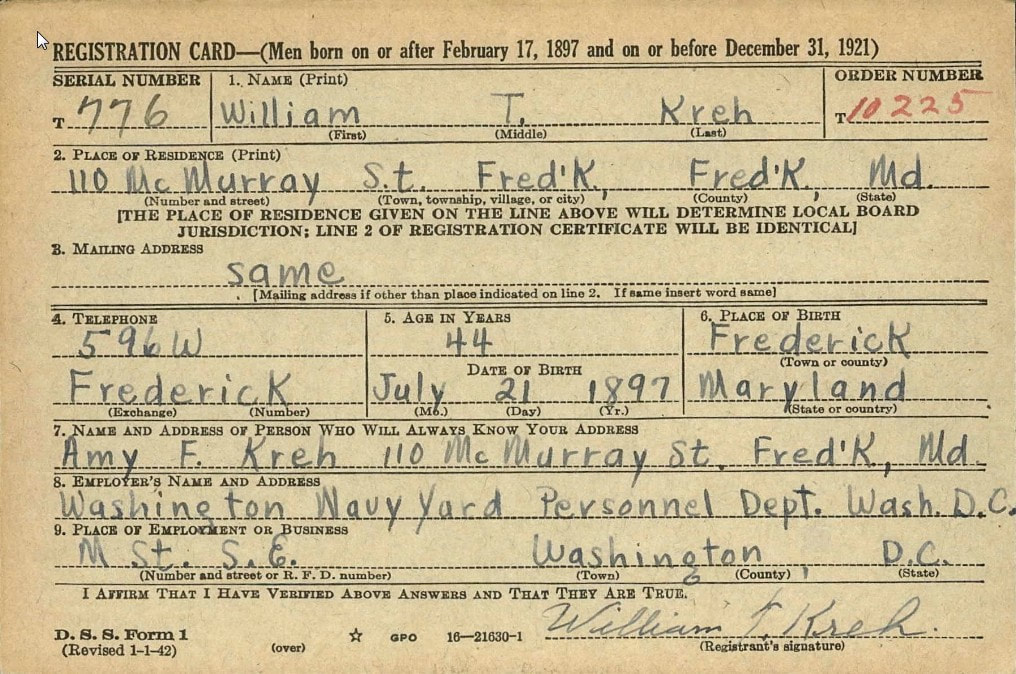

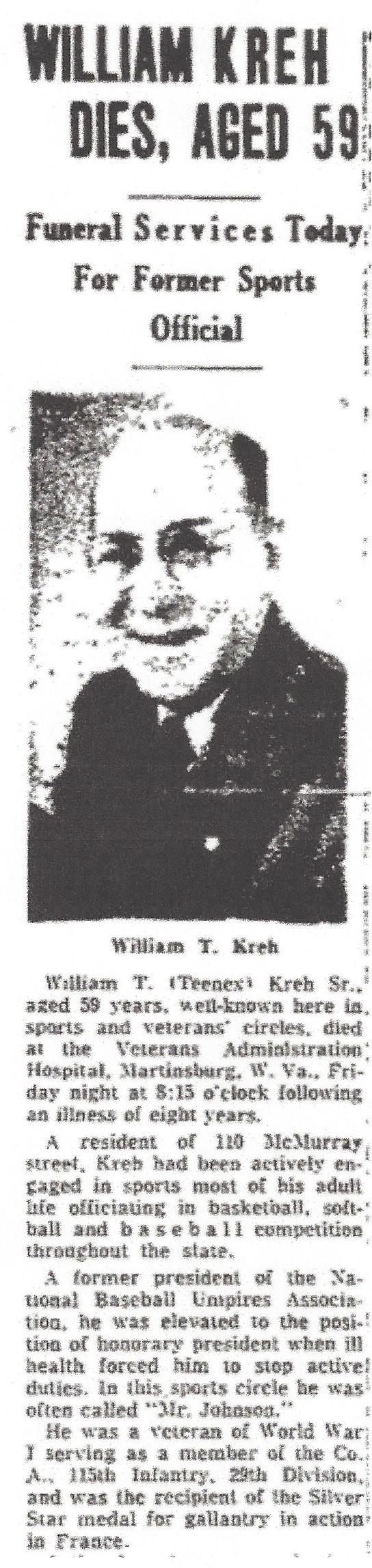

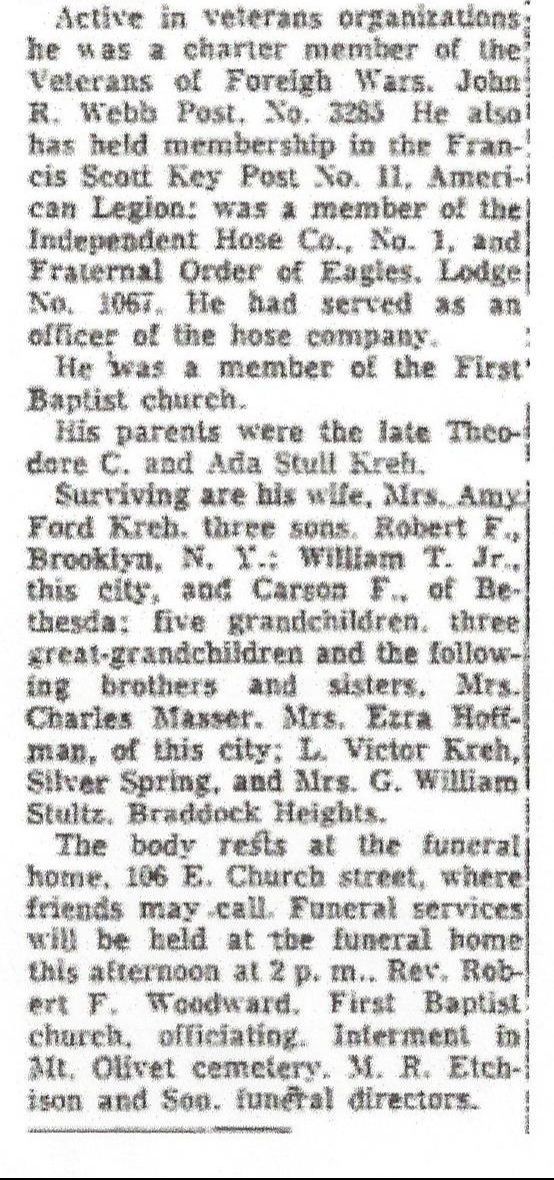

The following passage comes from the Regimental History of the 115th and paints a picture of what William T. Kreh experienced during his military service. Under command of Major General Charles G. Norton, the division was sent to Camp McClellan, near Anniston, Alabama, in August 1917. It spent ten months there in training before being shipped to France. On arrival at the front the division was given responsibility for a "quiet" sector on the German-Swiss border; its mission was to control the Belfort Gap. After two months in that position, the Blue and Gray division was sent north on September 22, 1918, to take part in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. The men of the division went "over the top" for the first time on October 8. In twenty-one consecutive days in the front line trenches they advanced six miles at a cost of 4,781 casualties, including 1,053 killed or died of wounds. The 29th sector was south of the Heights of the Meuse. The mission was to storm those heights attacking the entrenched positions of the Hindenberg Line with its pillboxes and machine gun nests. The division helped to take the Consenvoye Heights and the Borne de Cornouilles (Corned Willy Hill). On November 11, when the Armistice was declared, the 29th division was marching back to the line to join the Second (U.S.) Army's drive against the forts at Metz. William T. Kreh had recently married Amy Ford before making the trek to Alabama. Musical talents earned him a prestigious job as Company A’s bugler. This would put him in close proximity to the command element throughout the war. Like the runner, bugler was a hazardous position in any infantry unit—and often times one in the same. In addition to the standard Reveille and Taps calls, the bugler blurted out command signals for the troops during action. To do so required him to stand tall and play the instrument with great force so all could hear over the rattling of machine guns and the explosions of artillery shells. In doing this, he represented a perfect target for the enemy. Cutting off lines of communication in war was an essential objective for the enemy, and I’m sure William T. Kreh was well aware of this fact. On arrival at the front, the division was given responsibility for a "quiet" sector on the German-Swiss border with its mission to control the Belfort Gap. After two months in that position, the Blue and Gray Division was sent north to France on September 22nd, 1918, to relieve the soldiers on the frontlines northwest of Verdun taking part in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. The men of the division went "over the top" (of the trenches) for the first time on October 8th. In twenty-one consecutive days in the frontline trenches they advanced six miles at a cost of 4,781 casualties, including 1,053 killed or died of wounds. The 29th sector was south of the Heights of the Meuse. Up until the 8th of October, William T. Kreh and his colleagues of the 29th had been encamped in the Valley of the Meuse, waiting for orders to attack. Mustard gas created depression among the troops. Of all the death and destruction, the area of Molleville Farm would prove the bloodiest and fiercest. The locale was a key position in the German defenses during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. The farm was attacked on October 8th, by the 29th, who finally took the woods around the farm over a week later on October 16th at a cost of 3,936 casualties. Several Frederick doughboys fought in a fierce and decisive battle, as this action would become a deciding turning point in World War I. Going across this land, the soldiers not only fought the Germans but also the horrible conditions of the trenches located so close that one could hear their enemies talking to each other. Other inhabitants of the trenches were rats and vermin.  Major D. John Markey Major D. John Markey William T. Kreh would be given an assignment at the Molleville Farm, one that would receive great praise from a fellow Fredericktonian, Major D. John Markey (1872-1963), commander of the 112th Machine Gun Battalion of the 1st Maryland Infantry Regiment. He eventually took command of the 115th Regiment, and eventually rose to the rank of brigadier general, and served on the General Staff of the Army. In a letter written in January, 1919, Major Markey, an original founder of Frederick’s Company A, was quick to heap praise on the former unit he helped create. The letter was published in the February 21st, 1919 edition of the Frederick News: “Company A, 115th and the community can well be proud of the record they have made. One of their members, “Whitey” Kreh, a bugler of the company carried a message for me at the battle of Molleville Farm, an important message from the frontlines back to headquarters through an unusually heavy barrage.”  Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to find much more on Kreh’s heroics at Molleville Farm on October 15th, however his action under fire would not go unnoticed by the top brass as they say. On November 11th, when the Armistice was declared, the 29th Division was marching back to the line to join the Second (U.S.) Army's drive against the forts at Metz. The Armistice put an end to the war—the Allies were victorious. Kreh and the men of Company A would return home that spring, and Kreh officially wrapped up his service with the 115th on May 24th, 1919, receiving his honorable discharge. William T. Kreh would receive the AEF Citation for Gallantry in Action for his role in delivering important messages through an intense bombardment. This award is more commonly referred to as the Silver Star. His citation, dated June 3, 1919, reads as follows: “By direction of the President, under the provisions of the act of Congress approved July 9, 1918 (Bul. No. 43, W.D., 1918), Bugler William T. Kreh (ASN: 1283806), United States Army, is cited by the Commanding General, American Expeditionary Forces, for gallantry in action and a silver star may be placed upon the ribbon of the Victory Medals awarded him. Bugler Kreh distinguished himself by gallantry in action while serving with Company A, 115th Infantry Regiment, 29th Division, American Expeditionary Forces, in action in the Verdun Sector, France, 15 October 1918, in delivering important messages through an intense bombardment. In doing some more research, I found that the bugler’s mission in World War I would be replaced in the coming years by more advanced communication equipment and procedures. Once back home in Frederick, William T. Kreh took up residence with wife Amy at 110 W. 5th Street. They would have two sons: Robert and William T. Kreh, Jr. By 1930, the Kreh family can be found living at 110 McMurray Street and William was still employed as a machinist and Ox Fibre. I saw several articles that show Kreh’s involvement in the local American Legion Post and was a charter member of Veterans of Foreign Wars, John R. Webb Post, No. 3285. In addition, it seemed commonplace for him to be regularly given the honor of performing as bugler for military holiday events and on veteran funeral details here at Mount Olivet and other local churches. By the year 1941, America was heading into a Second World War. William T. Kreh, Sr. was involved in the war effort again, this time as an employee working at the Washington Navy Yard within the Personnel Department. His obituary says that he was actively involved in local athletics, primarily officiating games—a perfect hobby for a former bugler. He even served as a former president of the National Baseball Umpires Association. Kreh became ill in the late 1940’s and would slowly become debilitated by this malady. He spent his final months at the Newton D. Baker Veterans Hospital in Martinsburg, WV, dying of a heart attack on November 30th, 1956. His death and obituary made the front page of the local paper. William T. Kreh is buried in Mount Olivet’s Area P/Lot 198. His wife Amy would pass in 1968. Other family members reside here too.

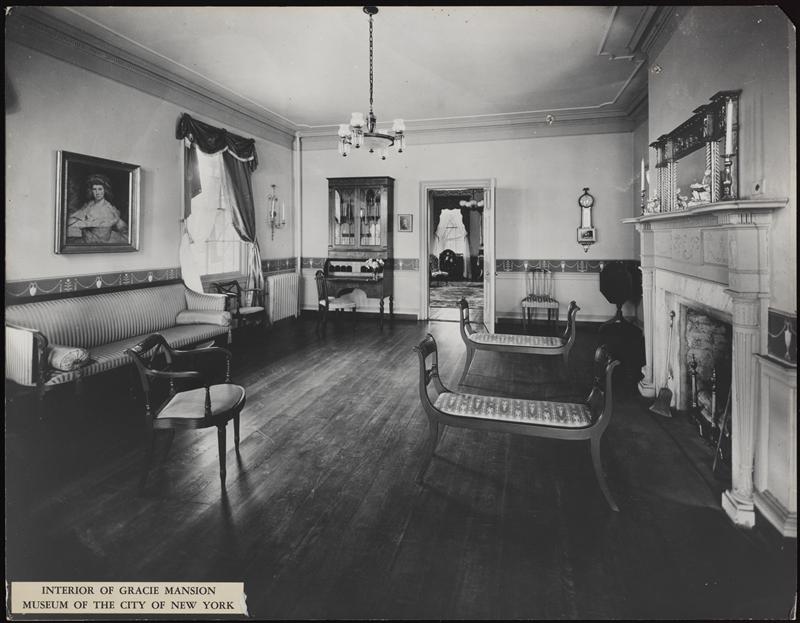

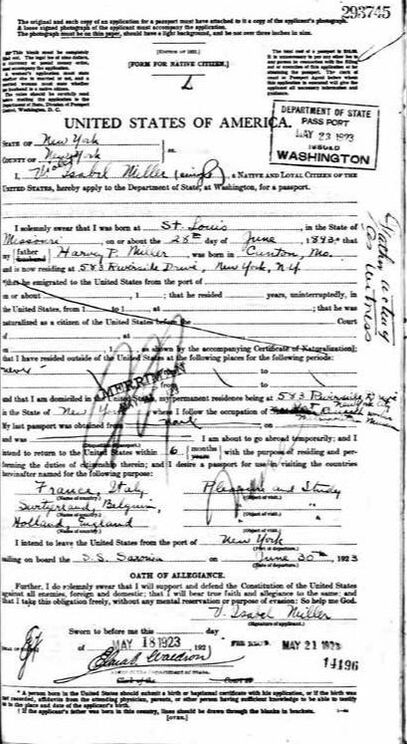

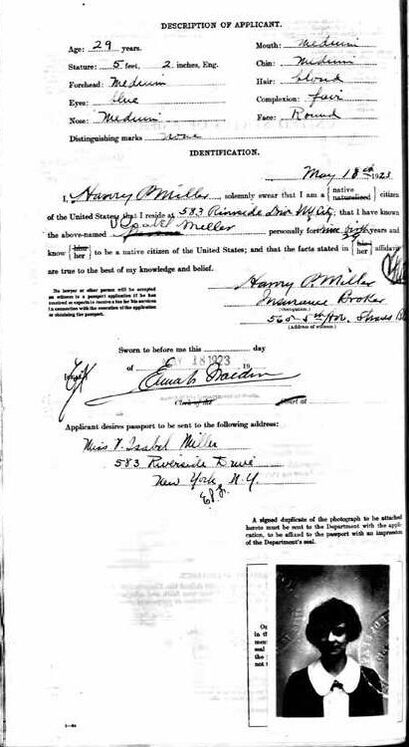

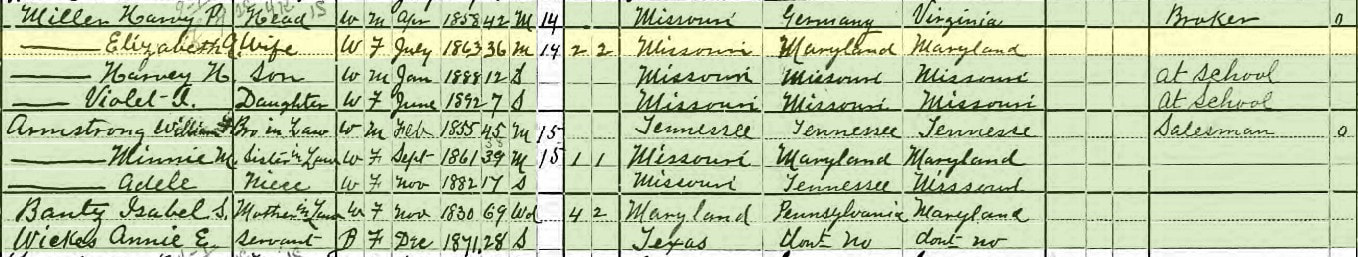

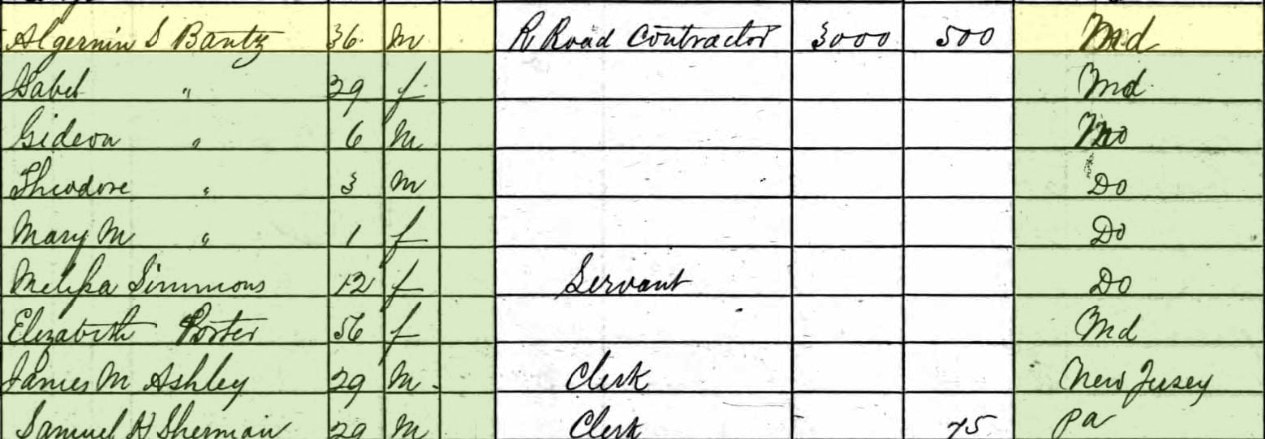

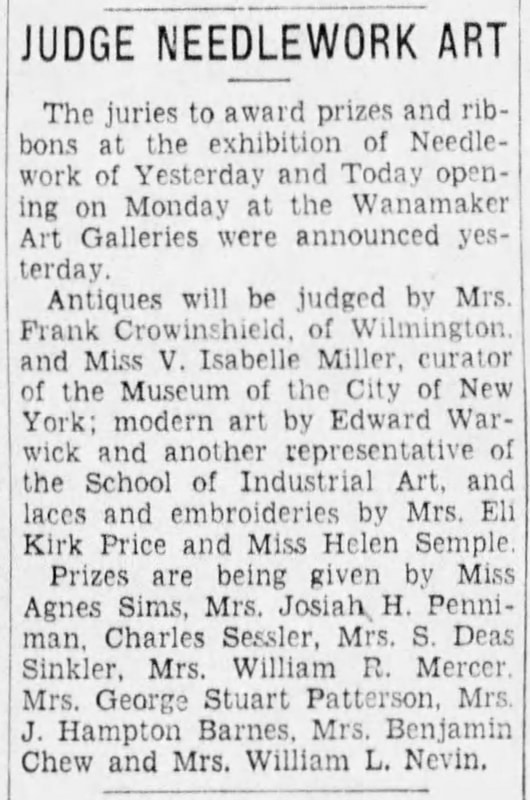

It's only fair to ponder the question: "Was Taps played at the former runner's funeral? And if so, who played the bugle?" ........................................................................It didn't take long to answer that question.  Claire McCardell Claire McCardell Early last year, I wrote an article about one of our most noteworthy residents of Mount Olivet—Claire McCardell. Born in 1905, McCardell revolutionized the fashion industry in the field of casual women’s wear with her work and designs in the 1930s, 40s and 50s. A monument of this Frederick native was commissioned by the Frederick Art Club in 2019 with the intent of being placed along Carroll Creek in 2021. Claire McCardell (Harris) was a New York City resident at the time of her death in 1958. She is fondly remembered by her alma maters, Frederick’s Hood College and the Parsons School of Design in New York City. A very nice collection of her garments is located at the Museum of the City of New York. Apparently, Ms. McCardell was also a keen consultant of historic costume within this same museum’s collections. She often gained inspiration here for her own work, along with items found in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute. Last February, I was contacted by a gentleman named William DeGregorio, a PhD Candidate of Bard Graduate Center in New York. Mr. DeGregorio was currently working on a dissertation involving the history of the Museum of the City of New York and sent me an email as part of his research quest. Interestingly, his query had nothing to do with Claire McCardell, but rather an interesting contemporary who was not a fellow designer, but like Claire, had distinct connections to Frederick, the fashion industry, and the NYC Museum. Best of all, both women are buried and memorialized here in Mount Olivet Cemetery. DeGregorio’s person of interest was a lady named V. Isabelle Miller. It is highly likely that Miss Miller knew Claire McCardell, because of her profession—as Miller was the Museum of the City of New York’s first curator of costume. She worked for the museum essentially from its inception in 1925 until her retirement in 1963. The extra novelty in this fact is that like McCardell, V. Isabelle Miller was a pioneering woman in a field and position traditionally held by men at the time. The museum was first founded in 1923 by Henry Collins Brown, a Scottish-born writer with a vision for a populist approach to telling New York City's rich story. The original home of the museum, and Ms. Miller's place of employment, was Gracie Mansion at 89th Street and East End Ave. The former estate is encompassed within Carl Schurz Park overlooking the East River. It would eventually become the future residence of the mayor of New York City, but at that time was a historic home owned by the Parks Department. The museum would move from this location in 1932, having outgrown its space. Mr. DeGregorio was looking for anything he could on V. Isabelle Miller, but encountered “road blocks” immediately as little archival information exists on her at the NYC Museum, combined with the fact that she essentially disappears from any records shortly after her retirement. However, the PhD candidate stumbled upon a clue when conducting a routine Google search. He found a V. Isabelle Miller buried in Frederick, Maryland’s Mount Olivet Cemetery on the immensely popular Find a Grave website. For those not familiar with this incredible internet offering and genealogical tool, Find a Grave is an American website that allows the public to search and add to an online database of cemetery records. It is owned by Ancestry.com. The site was created in 1995 by Salt Lake City resident Jim Tipton to support his hobby of visiting the burial sites of celebrities. He later added an online forum. Find a Grave was launched as a commercial entity in 1998, first as a trade name and then incorporated in 2000. The site later expanded to include graves of non-celebrities, in order to allow online visitors to pay respect to their deceased relatives or friends. Find a Grave receives and uploads digital photographs of headstones from burial sites, taken by unpaid volunteers at cemeteries. These volunteers then post the photos on its website, and add vital information taken from the stones themselves or cemetery records. In some cases, photos and obituaries of the deceased are added, along with links to family members in either the same, or different, cemeteries. As of October 2017, Find a Grave contained over 165 million burial records and 75 million photos. If you want to check out what Mr. DeGregorio found on his search, click the link below to view Miss Miller’s Find a Grave page: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/24391102/v-isabelle-miller I was able to confirm Miller’s interment here and supplied William with a few other tidbits in our scant records on the decedent. She is buried on Area G/Lot 201, directly across from Confederate Row, a prime landmark within our cemetery of 40,000+ interments. William then aided me with what he had been able to ascertain on this virtually unknown resident of Mount Olivet and forgotten to the local history annals of Frederick as well. Here is a passage from our email correspondence last February: “Chris, thank you for confirming that this is indeed our Miss Miller, who has so far eluded us. I am also grateful for the information on her family. My question now is how she ended up in NYC? She was briefly employed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in the early 1920s before being hired at MCNY in 1926 to oversee costumes, silver, and toys. She published a seminal catalogue on New York silversmiths in 1937, which is still widely consulted, and remained with the museum until 1963. There are a few mentions of her in the papers in 1964 but between that point and her death I am not sure where she was.” Her legacy at the museum can be seen in the incredible collection amassed today, something she began almost a century ago. Here is link to the costume collection alone on the museum’s website: https://www.mcny.org/collections/costume-textiles I painstakingly found two pictures of Ms. Miller. One featured her playing a piano and was within an old newspaper from the 1920s. The other was a passport photo from a document on Ancestry.com. I was able to glean a few more things now that William had sparked my interest in this individual. In our cemetery records, it says that Miss Miller died at Westwood, NJ and her occupation was museum curator. Her vital dates were 6/28/1892-1/05/1980. V. Isabelle’s mother, Elizabeth (Bantz) Miller, is also buried here in the same lot at Mount Olivet, along with her grandfather, Algernon Sydney Bantz. Elizabeth Miller died 9/12/1953 but we don't have a birth date on file. The record just says she died at age 90 in New York City. Our records say that Harvey P. Miller is buried in Westchester County, NY at Kensico Cemetery in Valhalla. V. Isabelle's brother, Haydock Harvey Miller (1888-1976), is also buried at Kensico with his father. I was interested to see that Algernon Sydney Bantz moved to Missouri, and that the Miller family was in St. Louis in the year 1900 according to the US census. This also told me that the "V" (V. Isabelle) stood for Violet, a fact that William DeGregorio did not have. The Bantz's had deep roots in Frederick going back to our founding in the mid 1700s. Violet Isabelle's great-grandfather was Gideon Bantz, a tanyard operator and huge proponent for farming and our early agricultural society which put on the first county fairs and expositions. I saw that Gideon's son, Algernon Sydney, worked as a tanner at his father’s operation until moving to Missouri. He had married Isabella Porter here in Frederick in 1853. The couple seemed to have left for the Midwest shortly after they wed, because their first child (Gideon) was born in 1854 in St. Louis, Missouri. Census records show Algernon Sydney holding the occupation of railroad contractor in 1860, and miner in 1870. He was actually in Sacramento, CA in 1868 for some reason, likely having to do with one of those two professions, I suppose. As cemetery historian and preservation manager for Mount Olivet, I had written an earlier "Stories in Stone" piece a while back that touches on Algernon’s father, Gideon Bantz. http://www.mountolivetcemeteryinc.com/stories-in-stone-blog/early-organizers-of-frederick-agriculture Gideon operated the Bantz Mill, which once stood on the north bank of Carroll Creek on the west side of Brewer’s Alley. This thoroughfare is known as Court Street today, and the former location in which Algernon Sydney worked as tanner is now the vicinity and home of the Citizens Truck Company, volunteer fire company. Heritage Frederick (former Historical Society of Frederick County) has a few photos of the early mill dating to the 1890’s at which time a fire had destroyed a warehouse. To review, Violet Isabelle Miller was the daughter of Harvey [Henry] P. Miller of St. Louis and Elizabeth Bantz (1862-1953). They married on September 28th, 1886 in Frederick, likely at Evangelical Lutheran Church. Elizabeth was the daughter of Algernon Sidney Bantz (1824-1894), a Frederick native who moved to St. Louis with wife Isabella (both also buried in Mount Olivet). I found the following mentions of V. Isabelle Miller in newspapers of the era. Violet Isabella Miller never married. She retired in 1963 as mentioned earlier. She lived her final years in Westwood, NJ, located in Bergen County. She died in 1980 and was buried here in Mount Olivet with her mother and grandparents in Area G. Her great-grandfather’s obelisk towers above the family plot. Sadly, I haven’t located an obituary for this woman as yet, truly ironic because you think a museum curator would want to leave a record of herself. Thanks again to Mr. DeGregorio, the PhD candidate who made me look differently at these family graves which I pass by each morning.

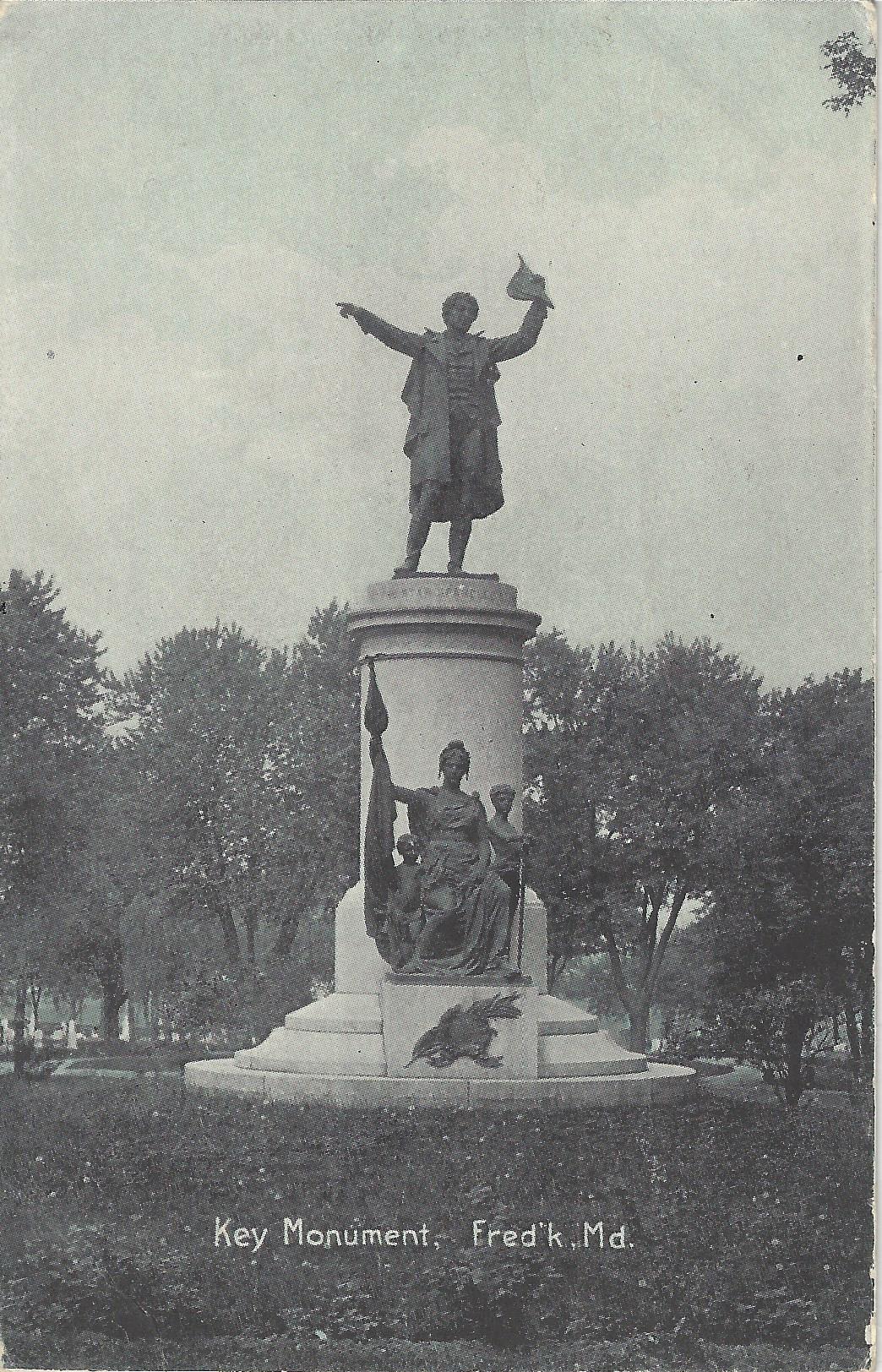

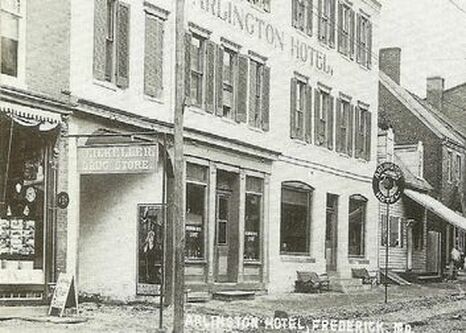

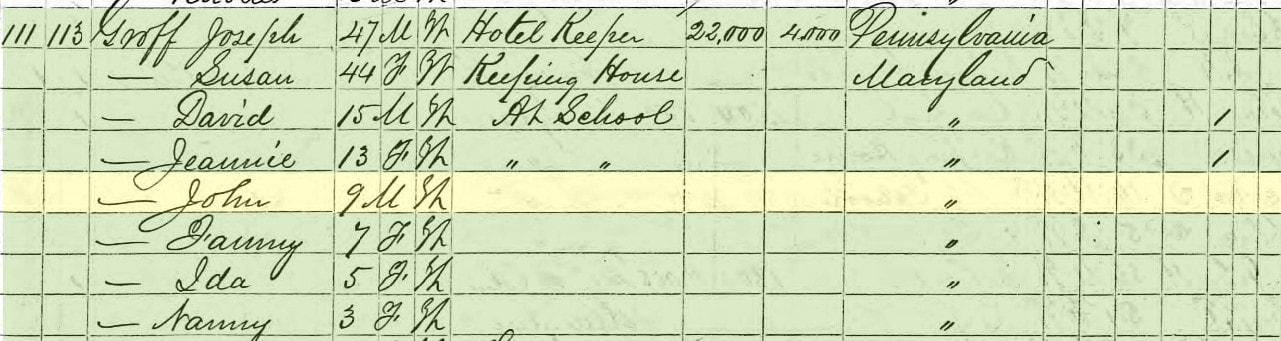

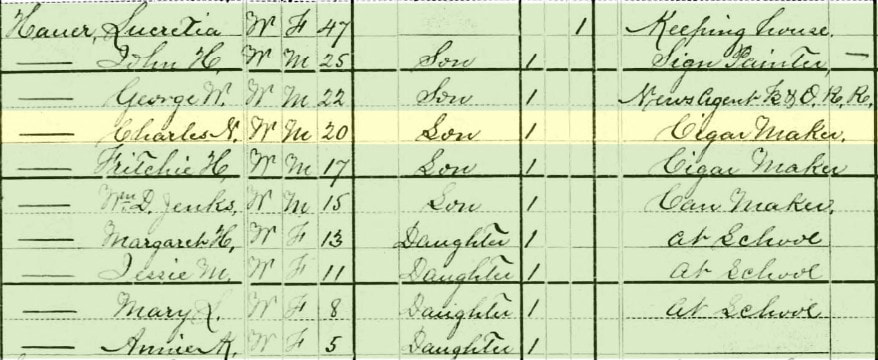

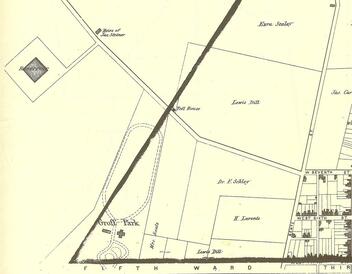

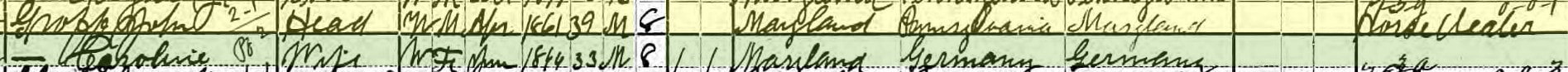

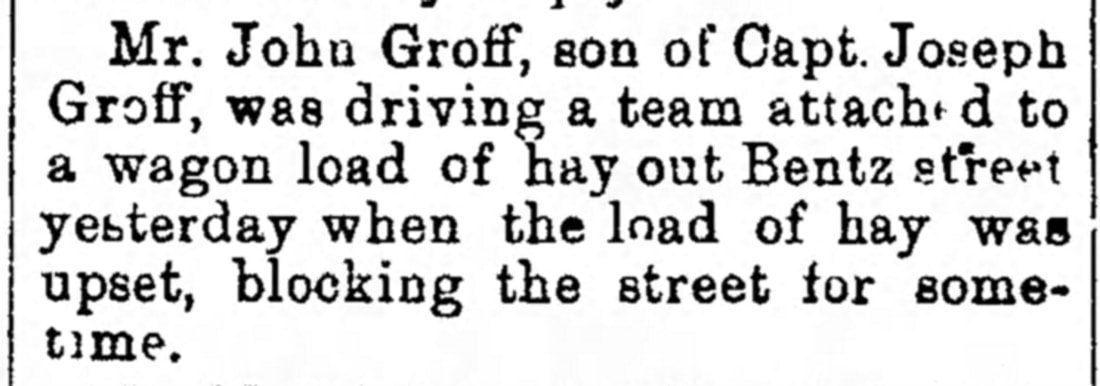

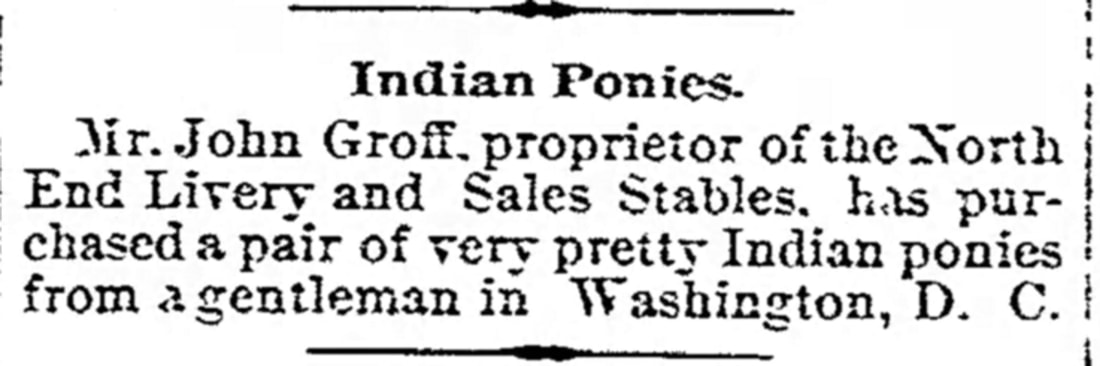

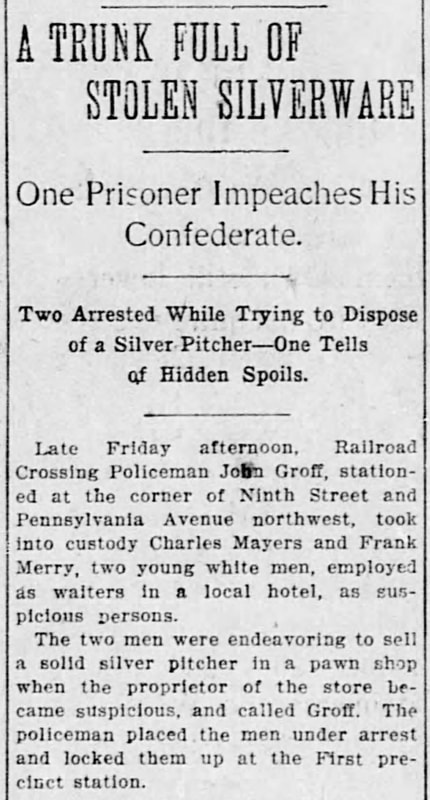

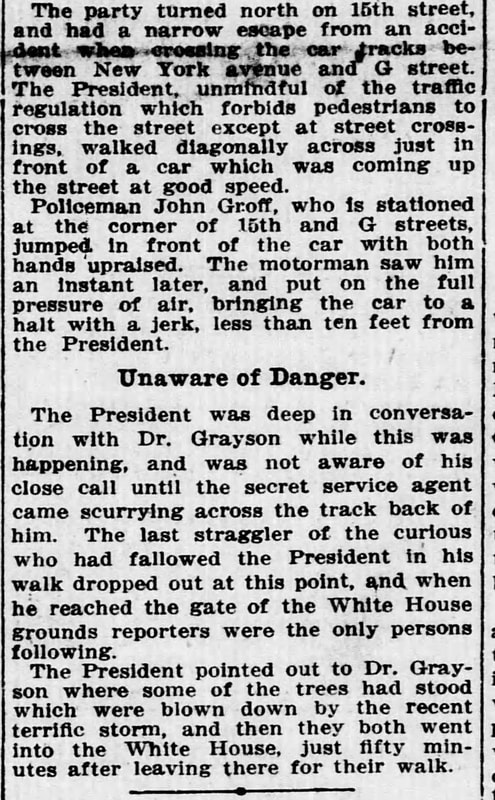

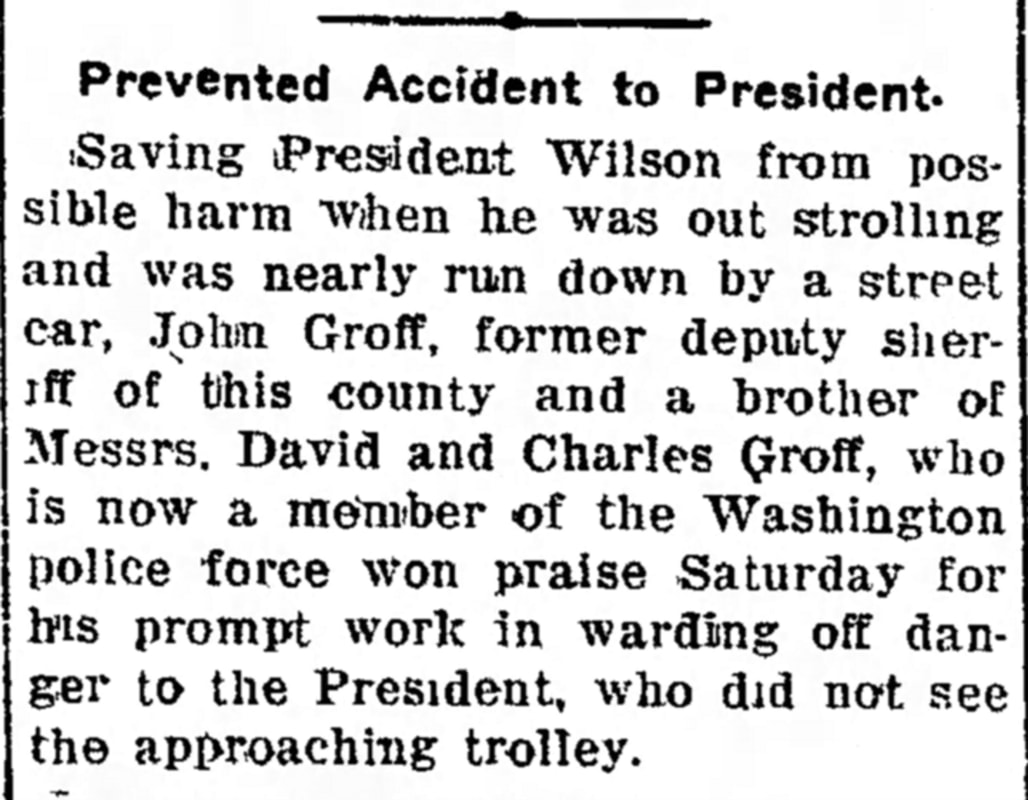

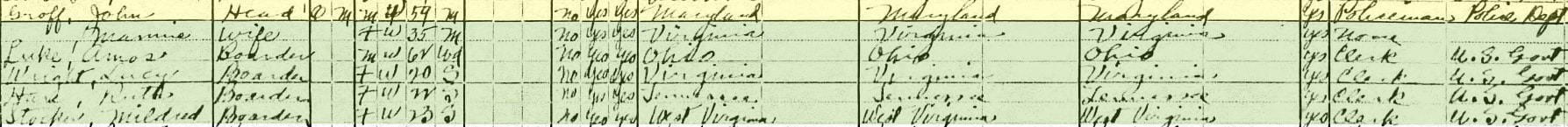

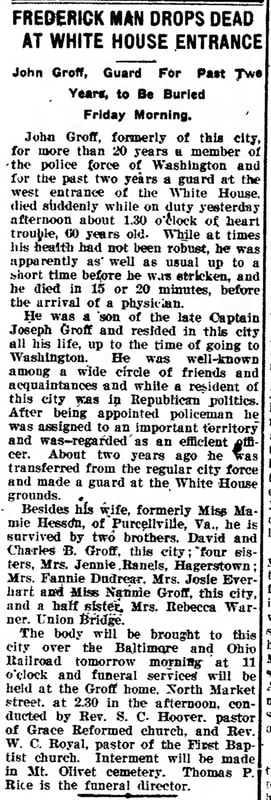

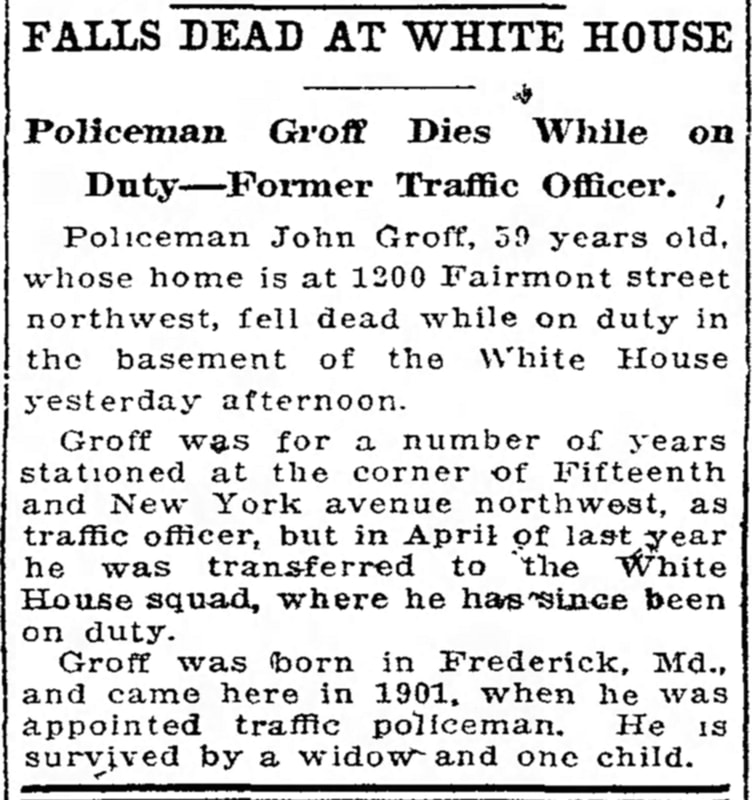

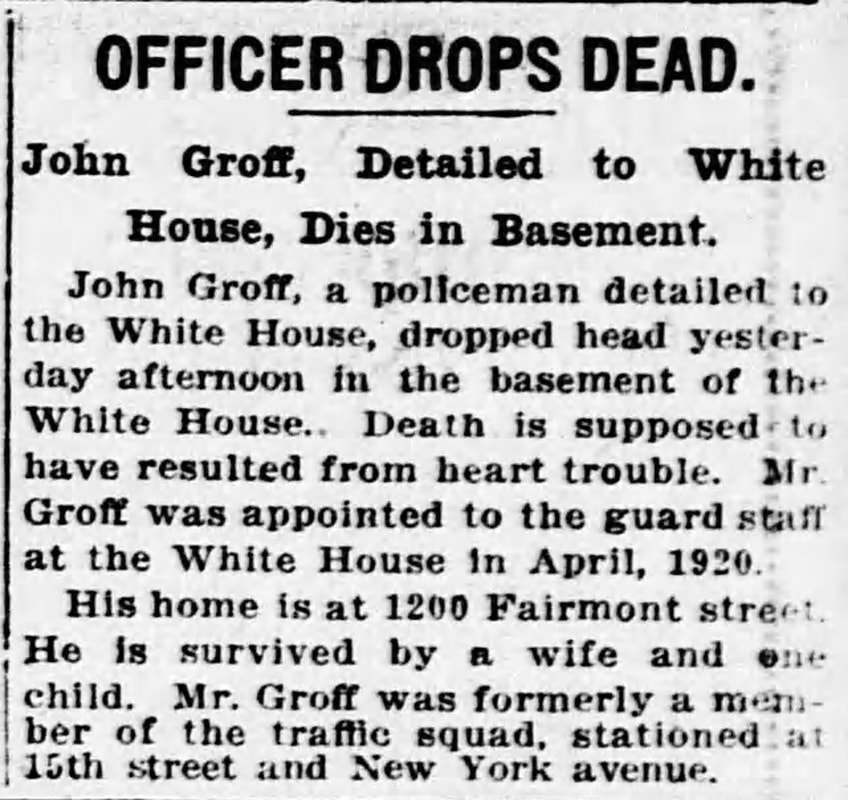

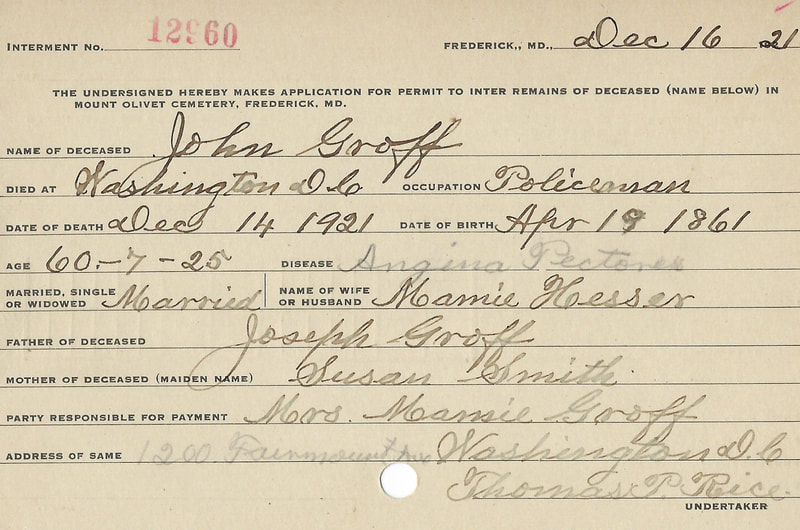

For longtime readers of this blog, many know that we have definitive proof that the cemetery was visited by at least one sitting US president, William Howard Taft. Others could have made unpublicized or after-hours visits, while several ranging from George Washington and Ulysses S. Grant to Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry S. Truman passed within feet of the front gate traveling the old Georgetown Pike. We at least know of President Taft’s trip here on November 15th, 1911. He was in Frederick to address the Maryland Boards of Trade at the old City Opera House, and his visit culminated by laying a wreath on Francis Scott Key’s gravesite, where the iconic monument had been placed just 13 years earlier. Of course, Key’s name is synonymous with our flag and it was none other than President Taft who signed an executive order in 1912 that officially standardized the American flag with thirteen stripes and 48 stars positioned into six horizontal rows of eights, with each star pointing upward. Of course, the design would later be altered with the additions of Alaska and Hawaii. An article in the Frederick paper the day prior talked at length about the security for the event. Specifically, it mentions a small force of detectives who arrived in town in advance of Taft’s visit, along with a contingent of nine mounted policeman from Baltimore to guard the President along with his additional secret service entourage. When conducting research, I was hoping to find the name of John Groff, a Frederick native who spent his career in law enforcement, and spent the last two and a half years as a member of the guard staff of the White House. One of events that may have elevated him to this great position lies in the fact that he is credited with possibly saving a former sitting president’s life thanks to his actions. John Groff was born on April 19th, 1861, the son of Captain Joseph Groff and wife Susan Christiana Smith. I explained a bit of this family’s illustrious story in an article published May 6th, 2019 and entitled “From Flowers to Fisticuffs.” John’s parents are known in the annals of Frederick history as prominent hoteliers and local heroes of the Civil War. The Groffs ran the Arlington House, located on N. Market Street during the turbulent era of the 1860’s. John’s father was a shrewd businessman who also ran a brickyard and dabbled in real estate acquisition. The Groffs would sell the Arlington House and operate the aptly named Groff House, a prime Frederick hostelry, at the site of the fountain atop N. Market Street where it intersected with 7th Street. A fine parking lot (sarcasm alert) adorns the former site of this grand structure that also served as the first home for WFMD radio station. Another such property that Joseph Groff had a hand in was the site of a former German social club called Scheutzen Park. This would soon come to be known as Groff Park and the former social group’s main club house would become the family’s new personal residence. In the next century, Groff Park would become the new site of the Frederick Woman’s College, renamed Hood College. The central facility of the property was a former drinking hall for the German club. Today this site survives and is associated with Hood College’s music department and holds the name of Brodbeck Hall. A brother, David Groff would go on to become one of Frederick’s most renown florists, and was assisted in business by another brother named Charles.  Old Frederick Jail (W. South St) Old Frederick Jail (W. South St) As for John, he was set on working in law enforcement, and his large frame suited him for the occupation. In the 1870 census, I found a gentleman named F. W. Schleigh, a police officer, who was a neighbor of the Groffs, living two doors down on N. Market Street. Perhaps he could have served as a role model and inspiration to John Groff in his youth. A family legend shared by genealogist Alice L. Luckhardt holds that John Groff was content to be Frederick’s jailer, looking after prisoners incarcerated in the town’s “pokey.” He married Caroline Miller in the early 1890’s and had a child, Charles J., who sadly died as an infant aged seven and a half months. John also split his time as a farmer. His property is said to have laid just outside Frederick City and he specialized in raising horses. This was likely the area in proximity to Groff Park, maybe the location of today’s Selwyn Farms development at W. 7th Street and Fairview Avenue. Groff would become a sheriff’s deputy here in Frederick but was destined to leave at the turn of the century, taking a job with the Washington D.C. police department on May 3rd, 1901. The 1900 census claims that Groff lived in Emmitsburg at the time of his hiring which prompted a relocation. John Groff was given many duties with the force in the nation’s capital. Among his first was that as a crossing guard at 9th street and Pennsylvania Avenue, NW. His residence was a farm on the outskirts of DC. Eventually he would move into a townhouse located at 1228 N Street (NW) and put the farm up for sale arounf 1919. I found some of his work exploits recorded for posterity in the local DC papers.  Woodrow Wilson (left) with William Taft Woodrow Wilson (left) with William Taft Nothing out of the ordinary really highlights the life of John Groff until the year 1913, just about two years after President Taft’s visit to Mount Olivet. Taft was no longer in office, having been defeated by Woodrow Wilson in the presidential election of 1912. The new commander-in-chief took the oath of office on March 4th and one of his most pressing issues was monitoring events in Europe as we would slowly be drawn into the First World War. Apparently, President Wilson liked to relieve stress by taking evening walks in the vicinity of the presidential mansion. The following passage comes from Alice Luckhardt’s family history entitled Legends Family Stories and Myths: How to Discover Fact from Fiction:  “It was a late summer evening on September 6, 1913, when the President headed out of the White House accompanied by Dr. Cary T. Grayson, the White House physician. The two gentlemen walked several blocks unnoticed. As they walked up F Street they started in a diagonal fashion across Fifteenth Street towards G Street. A streetcar (trolley) was driving at a safe speed on Fifteenth Street at the same moment. The driver did not see the two pedestrians and the two walkers did not see the streetcar which was coming up behind them. In a flash, DC police officer, John Groff, was on the scene to render assistance. He instantly stepped between the pedestrians and the vehicle and waived at the driver to immediately stop his vehicle. The driver reacted to the officer’s frantic motion and barely managed to halt the streetcar in time, just a few feet away from striking the President. If it had not been for the quick actions of Officer Groff, the new President could have been seriously injured or killed.” The incident had been eye-witnessed by several onlookers and stories appeared in both the Washington and Frederick papers. Although it’s not known whether Officer Groff was awarded anything at the time, the incident could have been fondly remembered at the time of his interview or selection for a post at the White House seven years later—or simply good karma paying him back. Another talent that probably played in Groff’s favor was his background in farming, and especially in dealing with livestock. This would prove valuable since the president had kept a flock of sheep at the presidential mansion. The sheep were brought here in the spring of 1918, at the height of our involvement in World War I, and grazed on the White House Lawn. After America entered World War I, the sheep helped to save manpower by keeping the grass trimmed. It’s not exactly known who came up with the idea, but Dr. Cary Grayson contacted his horse racing friend Wiliam Woodward about getting some sheep for the president. Woodward sent along a small flock from his farm in Maryland by wagon. Woodward understood that the idyllic appearance of sheep grazing on the lawn was part of the appeal of the project. Eventually, however, the flock was sheared, and two pounds of wool was given to each state. With governors acting as auctioneers, the wool was sold to the highest bidders and the proceeds donated to the Red Cross War Fund. In 1920, John and Mamie Groff can be found living at 1200 Fairmont Street in the northwest part of the district. Sadly, John Groff’s employ at the White House was short-lived. Earlier that year, President Wilson had left office after two terms. Warren G. Harding was Groff’s big boss now. In the early afternoon hours of December 14th, 1921, Officer Groff was in the location of the White House basement. Here he suffered what would be diagnosed as a heart attack. He would die within twenty minutes, surprisingly before the arrival of a physician. Groff, described by family members as a robust man, had known health and heart issues. He would die in his 60th year. John Groff’s body was brought back to his hometown by train on the 15th, and a viewing was held at the Groff House at N. Market and W. 7th streets. On the 16th of December, John Groff was buried in the Groff family plot in Mount Olivet’s Area L/Lot 247. People walk by his gravestone each and everyday, as I, myself, have several times in the past, having no idea that American history could have been altered had John Groff not done his part to keep Woodrow Wilson out of harm’s way on that September evening in 1913.

|

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed