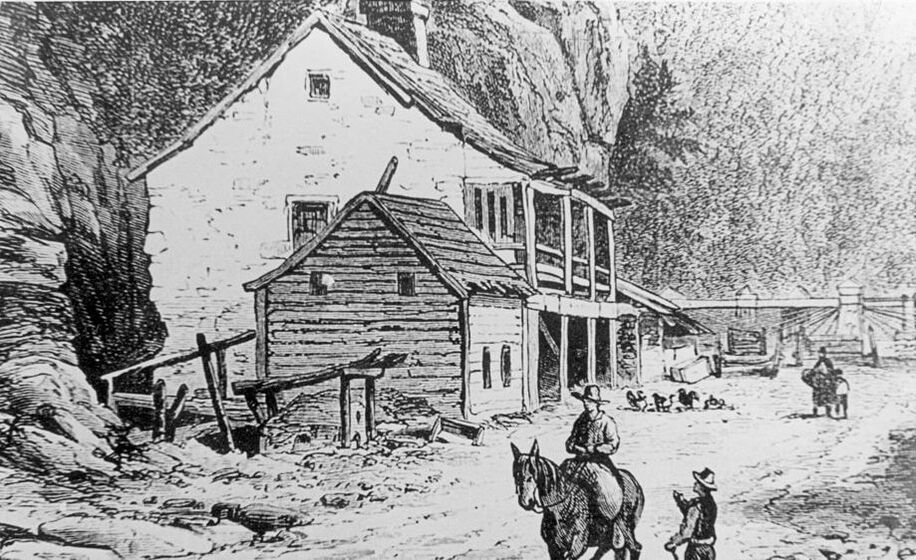

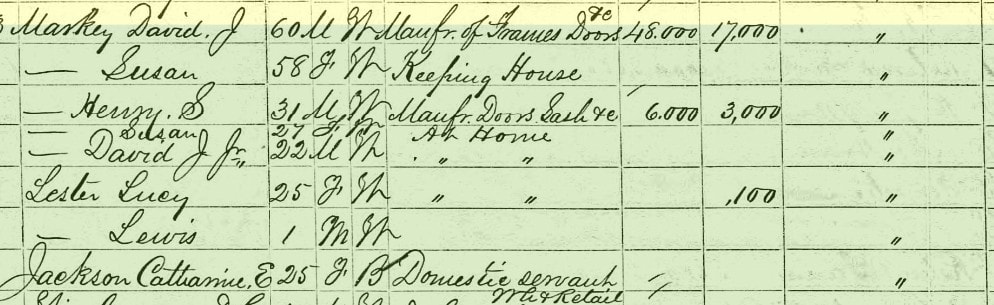

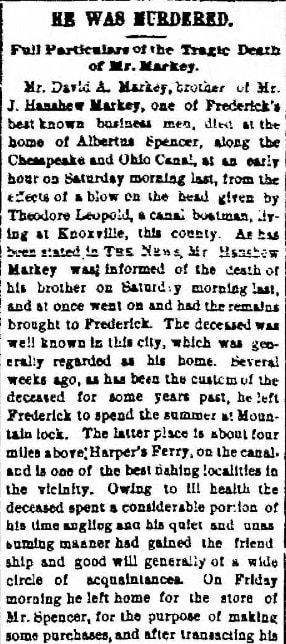

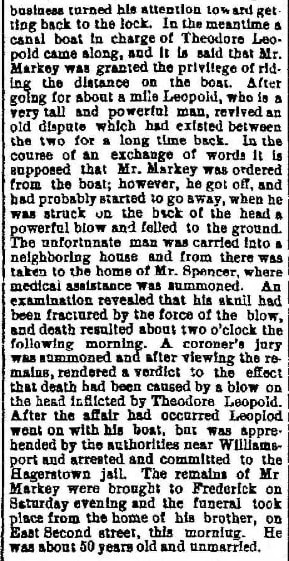

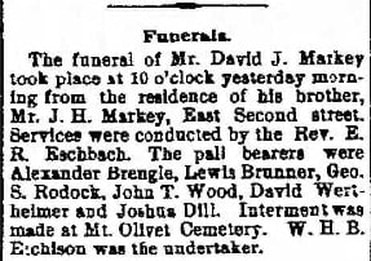

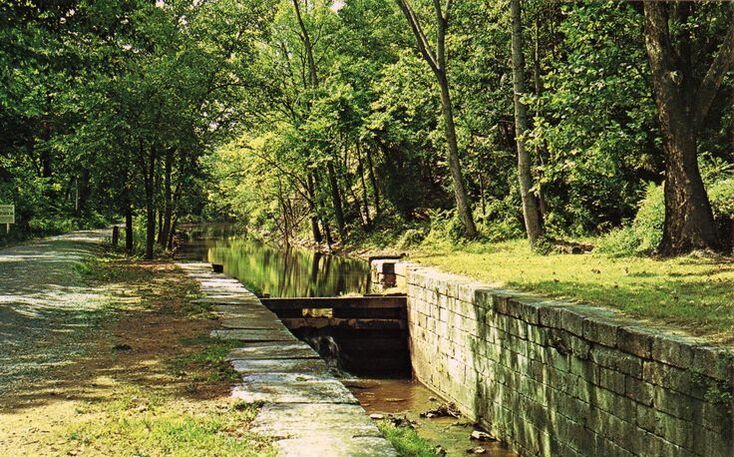

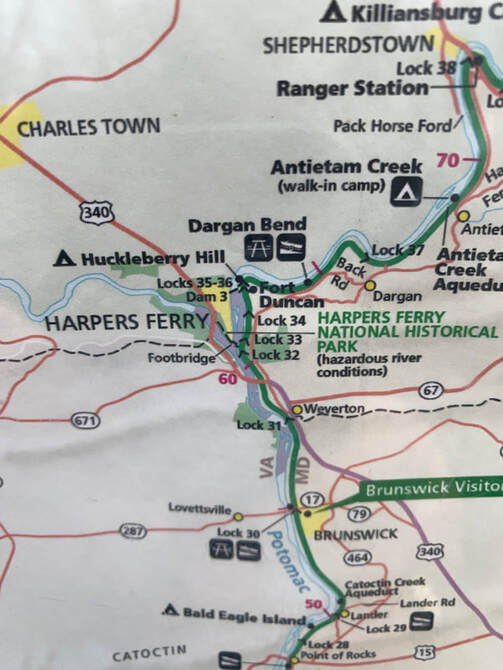

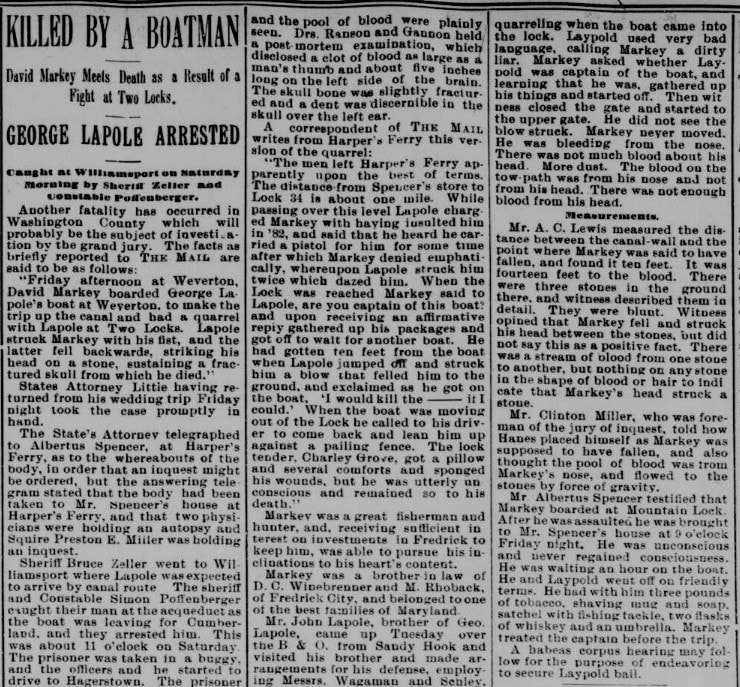

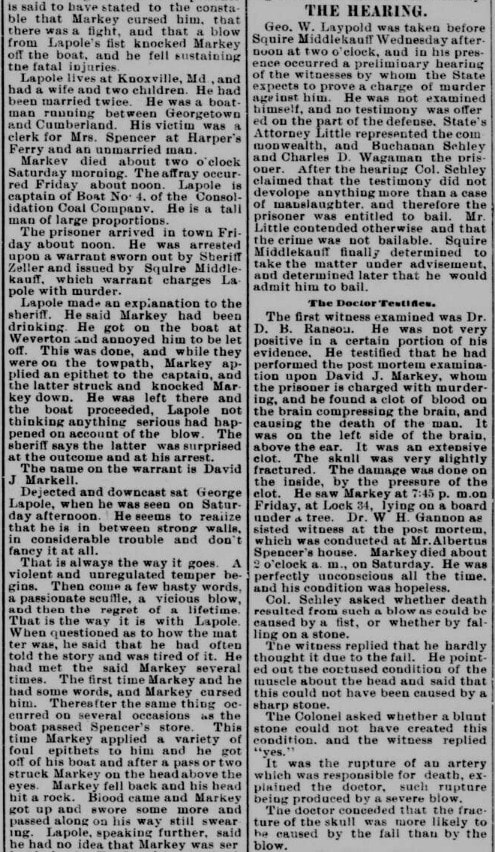

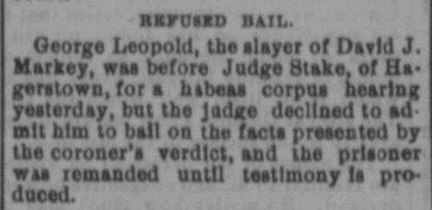

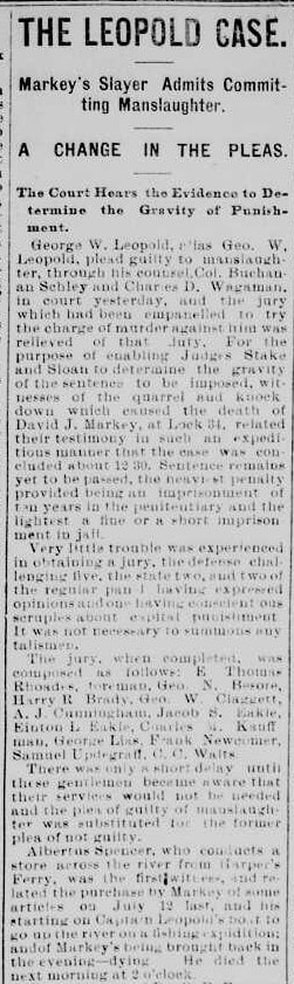

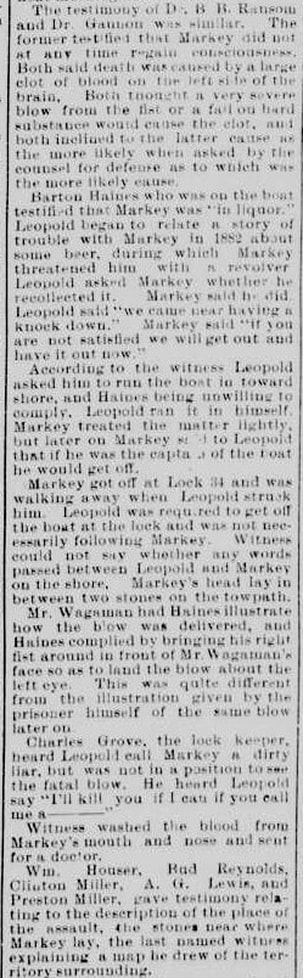

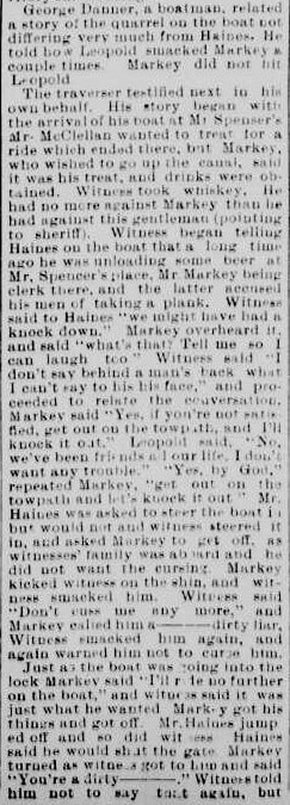

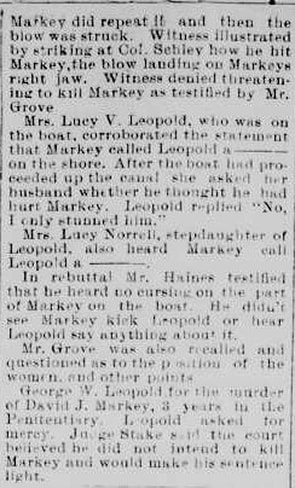

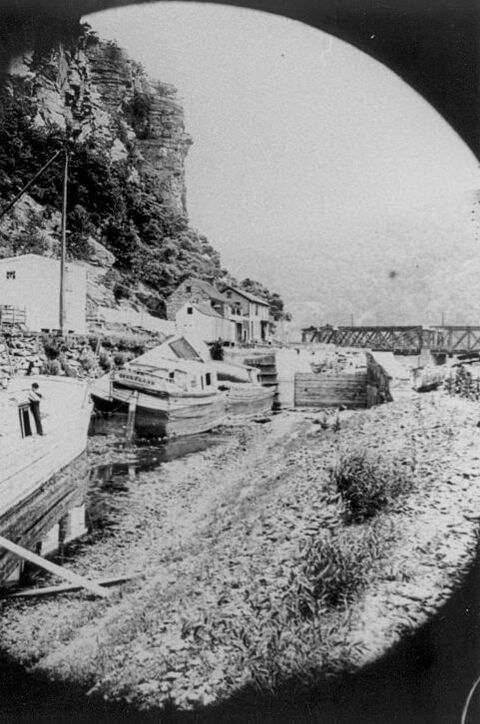

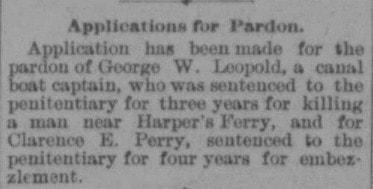

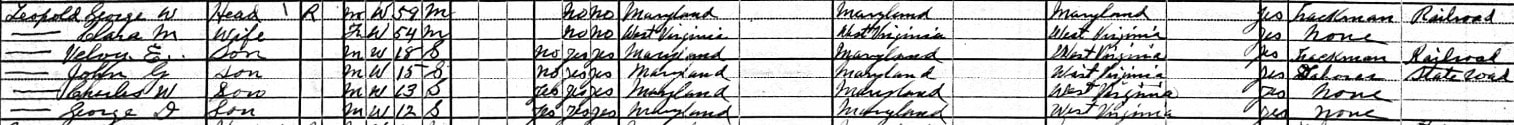

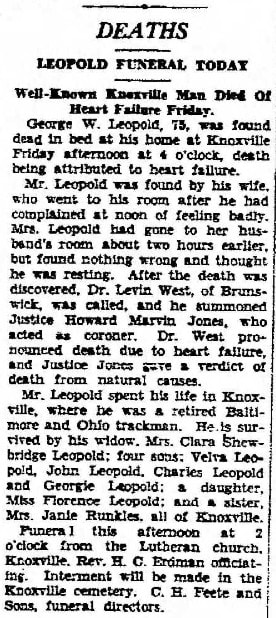

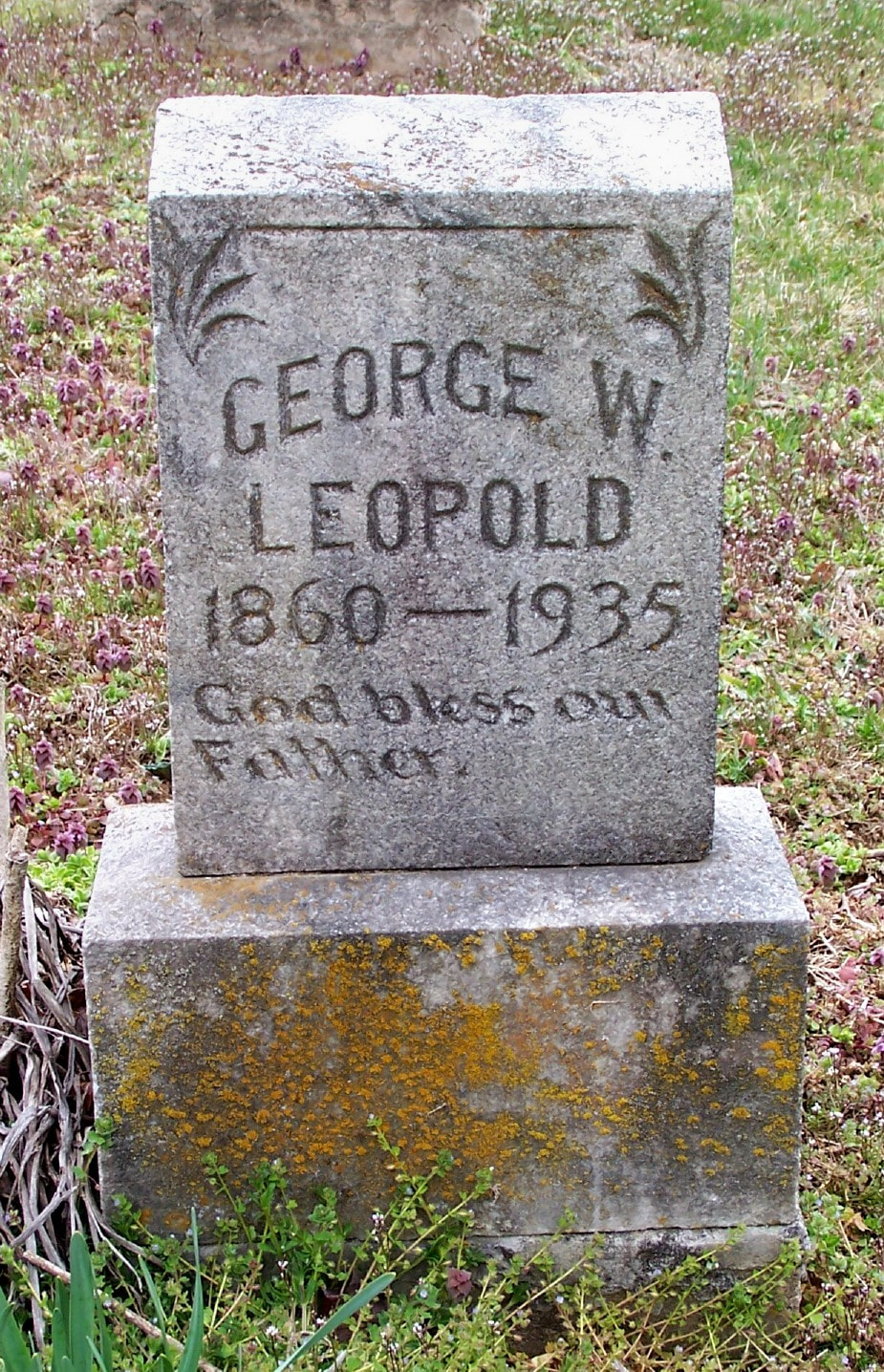

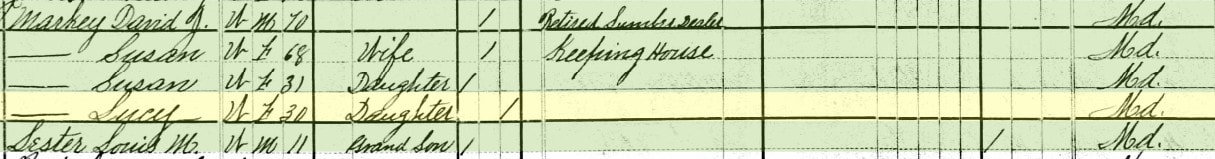

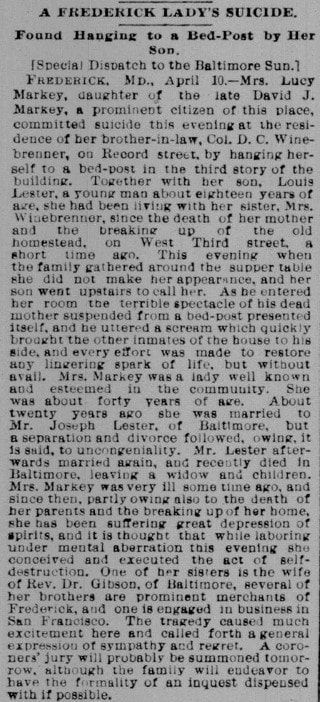

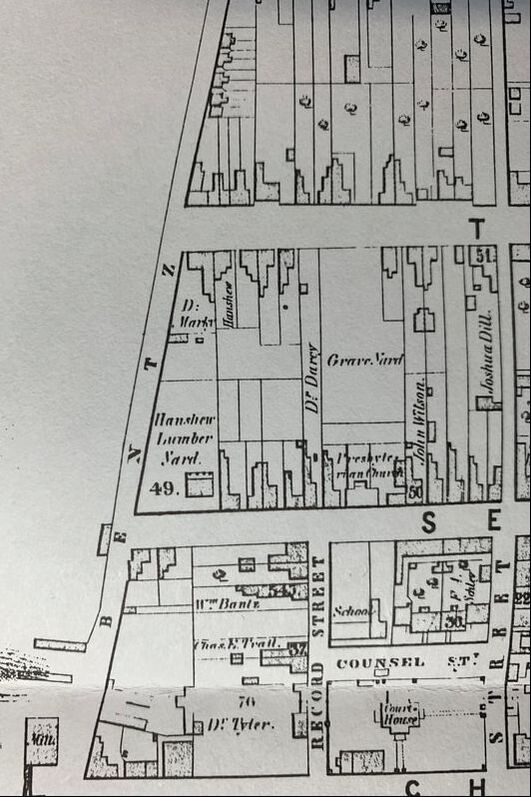

Anna Garnhart Anna Garnhart A couple weeks back, I had the great opportunity once again to spend time on the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal towpath. It was a beautiful, and unseasonably warm, Sunday in early March and I wasn’t the only one out there as you could imagine. The week prior, I had found myself thinking intently about the canal while researching one of these “Story in Stone” blog recipients. However, my reading, as opposed to my glorious walk, dealt with a dark day along the Potomac River back in July, 1895. On the day of July 12th of that year, a former resident from a prominent Frederick family would meet an early demise over an old argument regarding stolen beer. This altercation would send the Fredericktonian to an early grave in Mount Olivet. My interest in the death of David Jacob Markey was piqued while writing about a talented quilt-maker named Anna Catharine (Hummel) Markey Garnhart. I became amazingly struck (perhaps not the best word choice) by the demise of her reclusive grandson in 1895. David Jacob's sister, Lucy, another grandchild of “the quilt-maker,” died seven years earlier by suicide. This may have added to his desire for peace and solitude along the shores of the Upper Potomac. With a murder and a suicide, you can imagine my hesitance to hold out these "Stories" as not to take away from positive vibes generated by my exploration into Grandmother Anna’s sweet life and talent as an early craftswoman and lasting recognition by museum curators and other experts in the field of textiles. Somehow, I was reminded of the ironic expression involving "a wet blanket" in this particular case. David Jacob Markey Born October 27th, 1847, David Jacob Markey was one of eight children born to David John Markey (1809-1885) and wife Susan Bentz (1810-1887). He was a native of Frederick, and his family was of German descent. David Jacob grew up on the southwest corner of N. Bentz and W. Third Street. Our subject's father’s lumber mill was directly behind (and next door) his home and located where Calvary Methodist Church sits today on the corner of N. Bentz and W. Second streets. David would never marry and eventually moved out of Frederick City later in his life, but didn't go that far. He could be found living in Tomahawk, Berkeley County, WV and Keep Tryst near Sandy Hook, MD in Washington County adjacent the Potomac (in the vicinity of Harpers Ferry). On the occasion of his unfortunate death on July 13th, 1895, the victim was not far from his home in Washington County when he received the injury that led to death. He was just across the Potomac River and north of Harper’s Ferry near Lock #34 of the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal. Our cemetery records make mention of Sandy Hook as his place of death which is a mile downriver. I would soon find that both statements were correct and this was a complex story requiring both a careful coroner’s inquest, and a court trial five months later. The following article is one of several appearing in regional newspapers to describe the unfortunate experience that would befall the 48-year-old David Jacob Markey on July 12th, 1895. Details, such as the assailant’s true name, would be refined over the days following the tragic altercation between two men who had known one another for years and we’re supposed friends. The victim's middle initial, however, would not be corrected. David Jacob Markey’s corpse would be brought back to Frederick where he would be buried in the Markey family plot in Mount Olivet’s Area F/Lot 86. This was within feet of a quilting grandmother and his parents who had died in the previous decade. As this was a case involving a leading local family, the papers were abuzz with news of Markey’s supposed assailant, Theodore Leopold. However, it would be quickly discovered that Point of Rocks’ resident Theodore Leopold was wrongly accused, for the person of interest was George William Leopold of Knoxville. Sources corrected the first name, but a few printed “Lapole” instead of Leopold. If anything else, it would eventually be straightened out. The story made it into the Baltimore Sun as well. I too, got caught up in the hoopla, and wanted to better understand what seemed to me at first glance either an accidental, or senseless killing. I soon learned that it was a combination of both. But, how would justice be served? To summarize the story, former Frederick resident David J. Markey went to Sandy Hook, MD at Lock #33, immediately across from Harpers Ferry. This is accessed by the railroad bridge over the river of today, and sits at the base of Maryland Heights along the old Sandy Hook Road road that parallels the C & O Canal. Our subject was said to be stocking up on additional fishing provisions in town. On his return journey from Harpers Ferry via the river crossing by the railroad bridge, Markey would run into an old acquaintance named George W. Leopold. Leopold was piloting his own canal boat. Apparently, David Jacob invited Leopold to have a libation or two with him at the Sandy Hook saloon/store of Albertus Spencer. A bit inebriated after a few drinks, Markey receives transportation from Leopold to his home a few miles upriver. They would not make it that far because a heightened quarrel between both men erupted over the lonely mile trip from Sandy Hook and Lock #33 to Lock #34. Mr. Markey was apparently in the act of berating boatman Leopold over a theft of beer that occurred three years earlier when Markey worked as a store clerk in Sandy Hook. This resulted in Mr. Markey receiving repeated blows from Leopold, prompting Markey to request being taken ashore to leave Leopold's company. This would be done near Lock #34. Our Mount Olivet records say that Mr. Leopold followed Markey off the boat and retaliated one last time by striking his "verbal aggressor" in the back of the head. The inquest would find that Markey was sucker-punched from behind, basically knocking him out. David Jacob Markey hit the ground, which most likely occurred on the rocky tow-path itself, or an adjacent trail that had some large stones scattered about. The victim's head hit something on the way down which fractured his skull. David Jacob Markey would not regain consciousness from Leopold's ill-fated strike. Meanwhile, Leopold had left the scene of the crime as he continued his boat run with family members "in tow" upriver. Markey showed signs of trauma, and onlookers jumped into action, albeit a slow action. David Jacob Markey would be brought back downriver to "the Stone House" of Mr. Spencer at Lock#33. This is the location where our subject would perish around 2:00 in the morning of July 13th. Leopold would continue his canal boat run up the Potomac as mentioned, but would be arrested by authorities at the Williamsport Aqueduct. He replied that he thought Markey was just drunk, so he continued making his canal boat run. As can be seen below, the jury of inquest did their job quickly and efficiently. George W. Leopold would continue to profess his innocence, but was denied bail in mid-August, one month after the incident occurred. His day in court would be scheduled for the following December. In a change of events, George W. Leopold would eventually plead guilty in the court case. This would result in a three year jail sentence. In May of 1898, application would be made for Leopold to be pardoned by the governor. This would occur a month and a half later. Leopold was now a free man again. George W. Leopold lived out the rest of his life in the Petersville/Knoxville area of southwestern Frederick County. He worked jobs as a farm laborer, a B & O railroad employee and a river guide before dying in spring, 1935. This was nearly 40 years after the unfortunate altercation at Lock #34 which cost himself three years of freedom, and rival David Jacob Markey, his life. Leopold is buried in Knoxville Reformed Church Cemetery. I mentioned earlier that David Jacob Markey's sister would die seven years before him in 1888. This too would be a shock to the community. Her name was Lucy Emma Russell and she was only 38 at the time of her death. Lucy, like brother David Jacob Markey, had endured the death of her father in 1886, and her mother in 1887. Not much is out there on Lucy outside her birth in 1846. I also found that she was an 1864 graduate of the Baltimore Female College. Master genealogist Margaret Myers added info to our cemetery database stating that Lucy had been married, but was buried under her maiden name. She had wed Joseph R. Lester of Baltimore on May 5th, 1868. In the 1870 US Census (shown earlier in this story), Lucy is listed as "Lucy Lester" but not living with a husband, but rather her parents. She also is living with a a one year-old son named Louis. Lucy reverted back to her maiden name in the 1880 Census and her status is listed as a widow. It is this census that shows that son Louis M. Lester continues to live with her at her parents family home on W. Third Street in Frederick. It is not known what haunted Lucy's mind. Did her husband die, or was there an unfortunate split of some kind that lead to separation of divorce? We may never know. What we do know instead are horrific details of her suicide. These appeared in newspapers throughout the country. A very tragic situation, and perhaps something that weighed on her bother David Jacob's mind, causing him to seek the serenity (and isolation) with the Potomac River. Lucy would be buried in Area F/Lot 86 at the foot of her grandmother's grave and within a few feet of her parents. In time, David Jacob Markey would join her here, but not of his own design as we have seen. I guess the takeaway in this week's "Story in Stone" is the same as all those I have written for the past eight years in that they all end the same way... the subject dies. However, that is not all we are doing here with this series. Instead, we are trying to better understand the human existence, using those who have come (and gone) before us as a lens in which to view life and the way others lived their lives. We also see the varied ways others have lost those lives.

Again, you can walk through any cemetery in the world and pass a row of gravestones and related monuments, never knowing the triumphs and struggles experienced by those individuals buried beneath the surface. Ask yourself, "How did their existence compare to mine? or How did their experience differ?" That's why I feel that conducting research and writing of this nature for the enlightenment of the reader is so worth while to me. We can all learn something from those who have have come before, especially those who had to endure hardships, and learned from mistakes and decisions made throughout their lives. We can also glean so much from the response and conduct of friends and families of the deceased themselves. Any opportunity to witness and/or practice resiliency can be a sacred experience. Now, with the weather improving for outdoor activity, consider soothing mind and soul with a leisurely hike on the C&O Canal Towpath, or a contemplative walk through Mount Olivet.

0 Comments

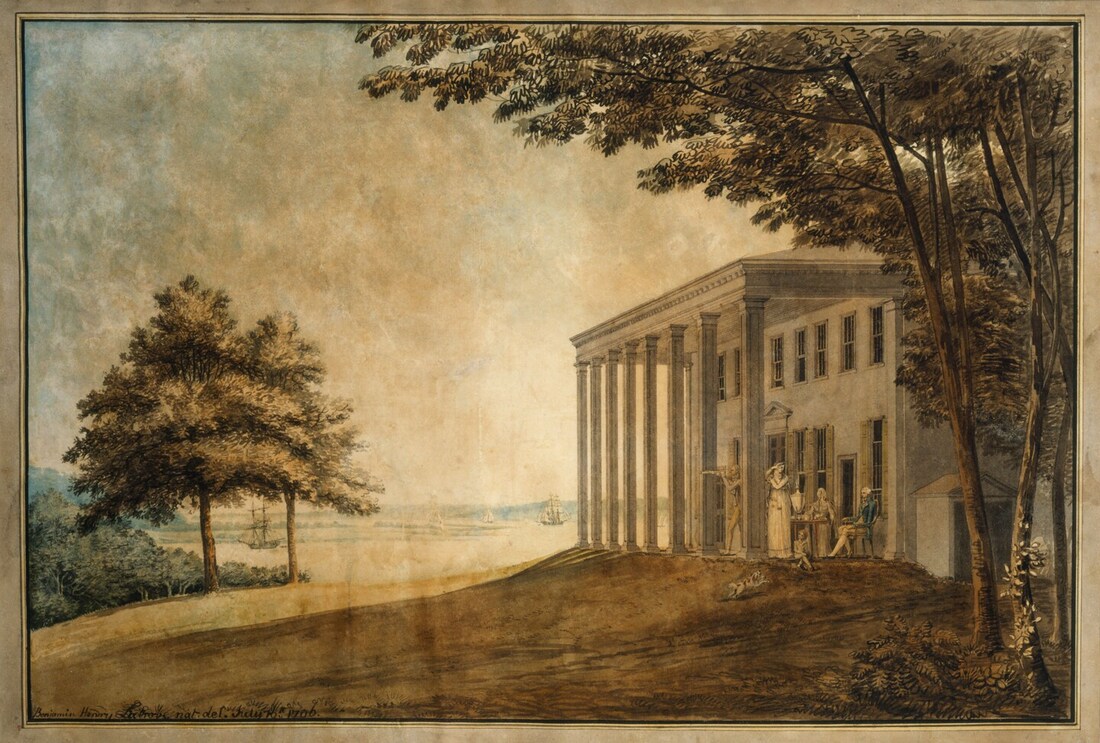

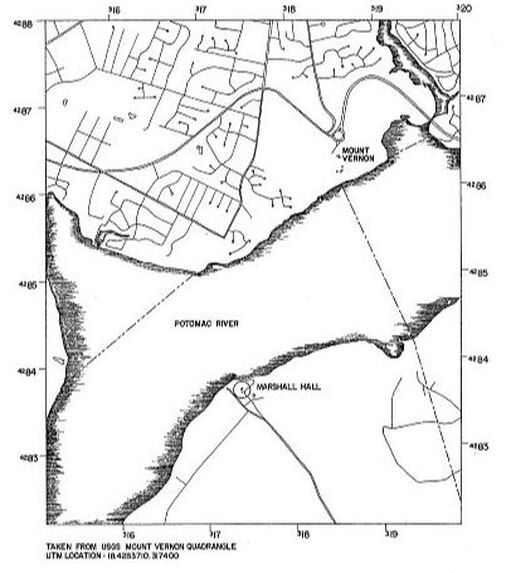

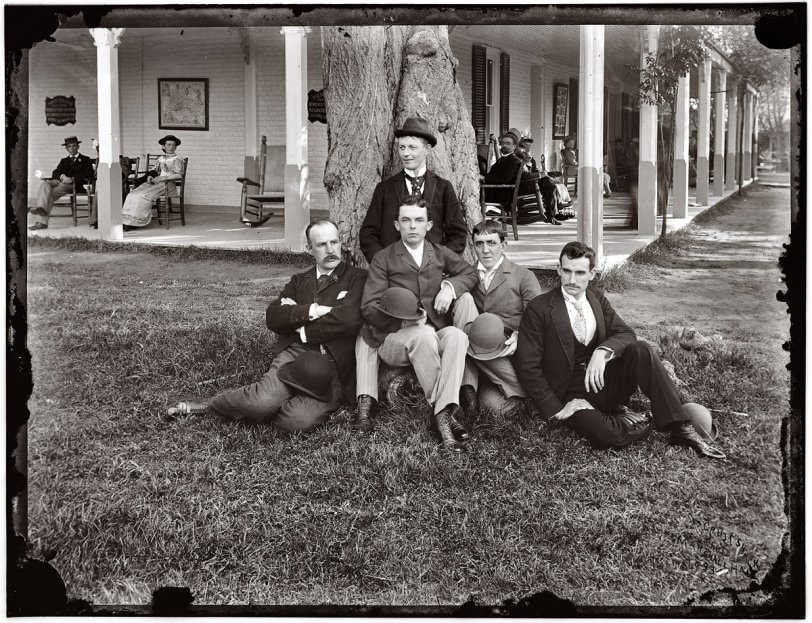

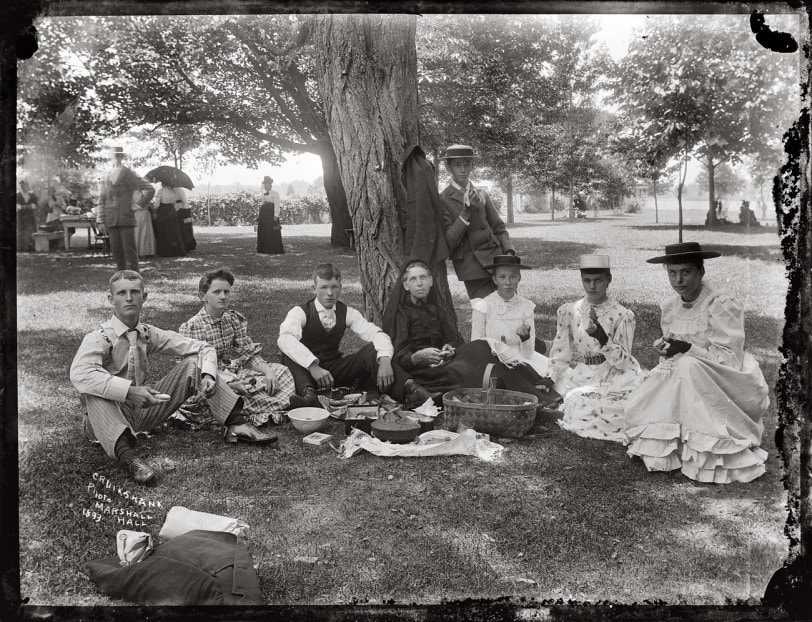

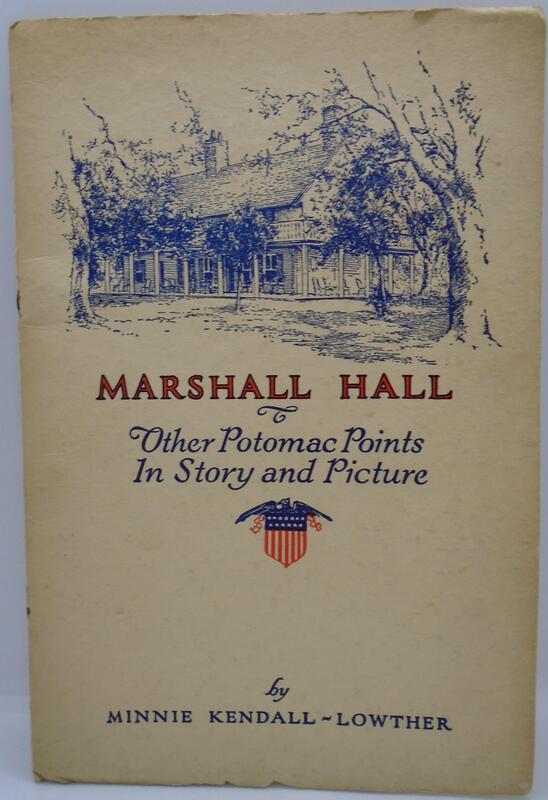

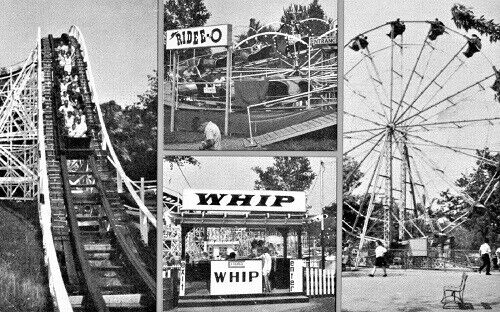

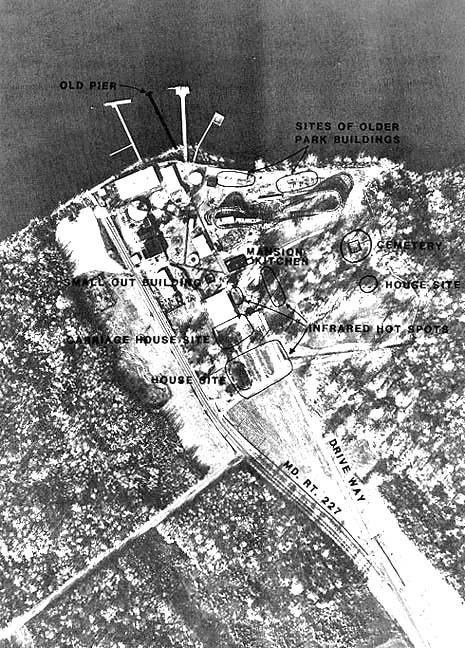

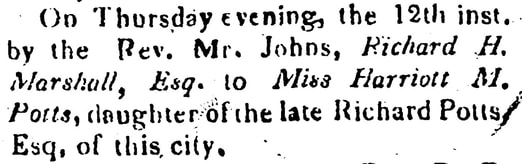

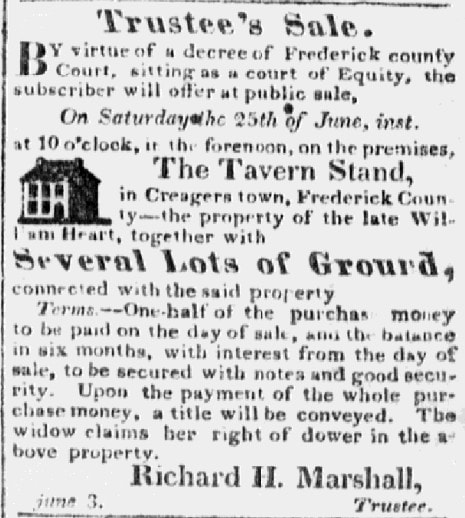

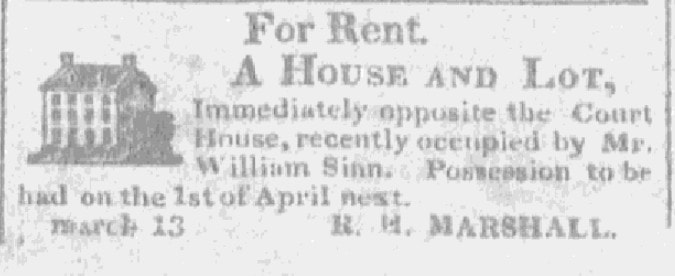

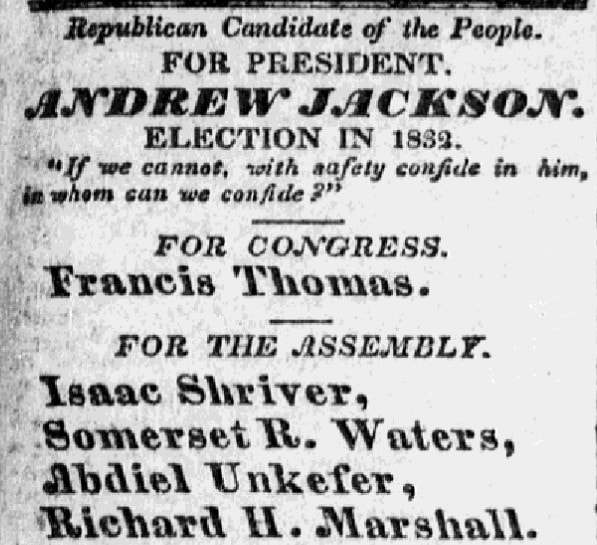

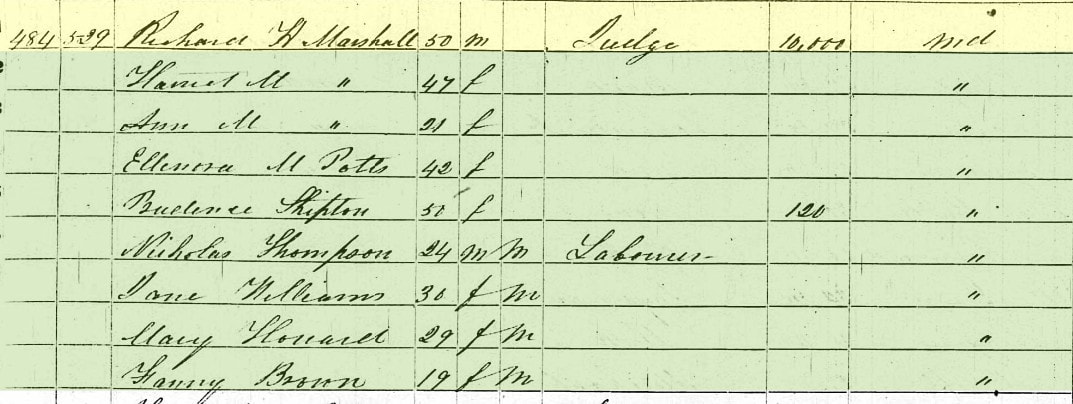

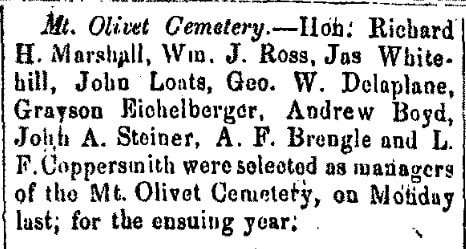

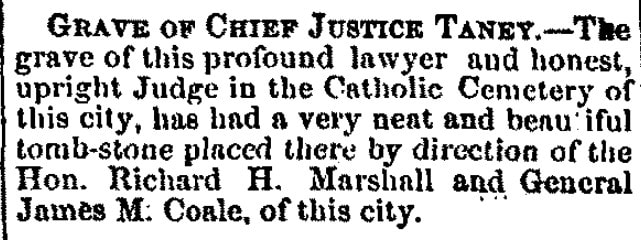

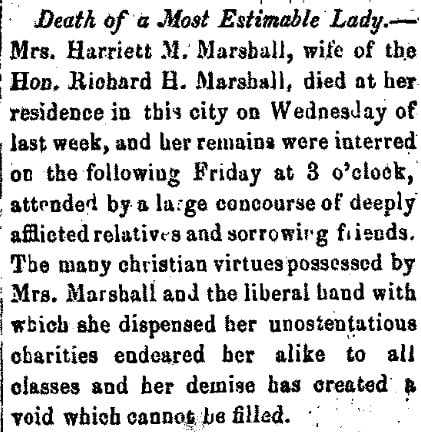

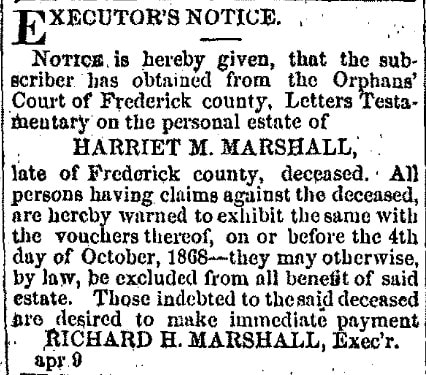

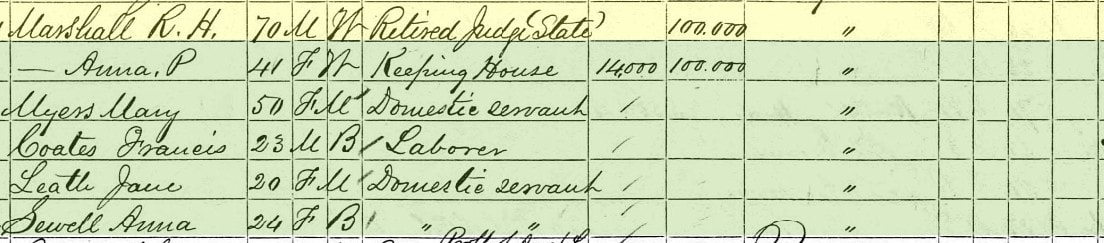

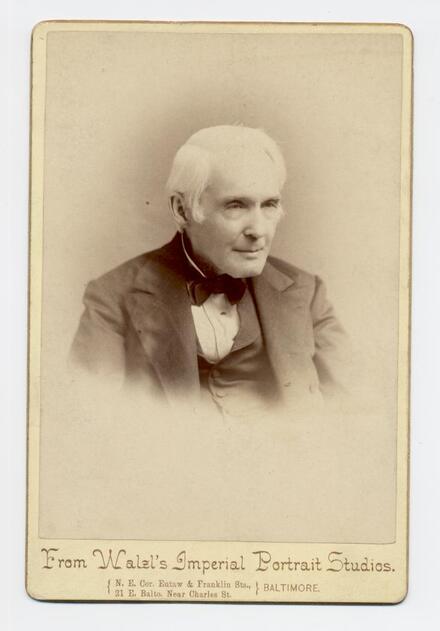

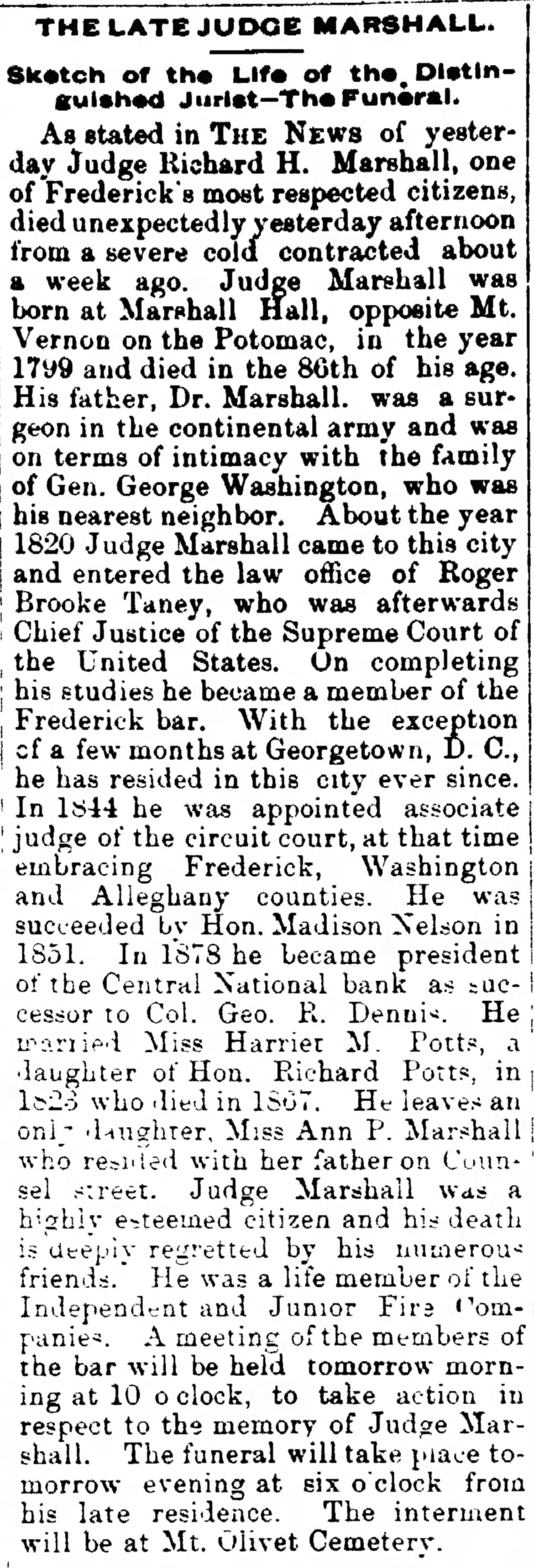

While conducting walking tours, I usually joke with visitors that the Potts Lot in Area G is Mount Olivet’s only “gated community.” This is an area on the northeastern approach of Cemetery Hill that includes a large, multi-plot collection of a few of Frederick’s most prominent families—primarily hailing from the Courthouse Square neighborhood of Frederick. The Potts Lot is surrounded with decorative, iron railing—a delineation barrier that dates from the cemetery’s earliest days in the 1850s, when it was not uncommon to see many family lots “fenced-in” so to speak. The practice was both practical and decorative. Iron railings and fences, complete with closeable gates like the one here at the Potts Lot, started with a simple purpose in mind—keeping unwanted animals out. We are not just talking simply about woodland creatures here, but more also cattle, pigs, sheep and large wild animals. As far as cemeteries are concerned, fencing has also served as a sign of respect to buried loved ones and added a degree of attractiveness and panache to family lots. This practice was also accomplished by the construction of stone and brick walls around church yards and cemeteries. Based on the early burials (and reburials) found within the Potts lot, it’s not hard to see that the graves here date primarily from the early to mid-1800s. The surrounding fence is authentic and shows the talent and work of craftsmen of a time before pre-fabricated shapes and mouldings. The Potts Lot fence is hand-hammered with evident grooves and dents. No one is quite sure when this fencing was added, but it is thought that it was done within the first few years of the cemetery which opened in spring of 1854. I once had a brief conversation about the fence with my friend, Elizabeth Comer, longtime professional archaeologist and president of the Catoctin Furnace Historical Society. We both agree that there is an possibility that this particular railing could have been forged at the Catoctin Furnace due to connections to this Potts family of decedents, and relatives of another that has been forgotten here to time—the Marshall family. Liz and I promised one day to make a study of the Potts Lot's fencing to see if it matches other known exports of Catoctin Furnace. One particular example of fencing from Frederick history seems like a good starting point to this exercise. I’m talking about Courthouse Square, a place where many of the decedents buried here in the Potts Lot once resided. As a matter of fact, I broached the subject exactly five years ago back in March 2019 when I wrote a story about Gen. James C. Clarke, a transportation captain of industry and namesake of Frederick’s Clarke Place who helped add to the beauty of our town’s Courthouse Square. Frederick became incorporated as a city in 1817 by an act of the state assembly. Prompted by animals grazing on the courthouse lawn, an ordinance issued that same year ordered that all hogs and geese found wandering in the streets be impounded. Notice of their arrest was made by public outcry at the Market. To prevent animals from using the courtyard as a pasture, residents and officials decided to enclose the Courthouse grounds with iron railings and ornamental iron gates much like a London square. Authorities were stunned by the expense of the proposed project, however a leading citizen and neighbor in Col. John McPherson agreed to donate the railings. Beginning in 1818, Courthouse Square resident, Col. John McPherson began installing iron railings around the Frederick County Courthouse and subsequent public lawn. This material was forged at McPherson’s Catoctin Furnace operation located in the north sector of the county between Lewistown and Mechanicstown, destined to become Thurmont. Apparently, the neighbors of “the Square,” consisting of the town’s “upper crust,” were annoyed with the recent phenomena of rogue animals grazing on the prestigious courthouse lawn that once boasted legal luminaries such as Francis Scott Key, Roger Brooke Taney and Reverdy Johnson. What seemed like a philanthropic venture by McPherson soon angered the general citizenry as they saw this “fencing” symbolizing an obtrusive wall to a public place and access to courthouse amenities and officials. It also seemed an extension of the adjacent affluent neighbors hoping to keep all others out of their prestigious neighborhood unless they had official court business to perform. The squabble would last for many decades. Seventy years later, the railings were finally removed in 1888. To help pacify the masses, Gen. James C. Clarke found it necessary to offer an olive branch to all citizens by providing a perfect centerpiece to the courthouse green—an ornamental fountain. The Clarke fountain was duly dedicated to all people of Frederick. That’s all well and good, but doesn’t exactly connect dots to Mount Olivet and our Potts Lot. Or does it?There are several unique connections among this cemetery, the Potts Lot and the history of Catoctin Furnace. It has more to do with former residents and entrepreneurs than the actual manufacture of iron. Outside of the Potts Lot, one can find the graves of the Fitzhugh girls about 30 yards to the north. These were daughters of one-time Catoctin Furnace owner Perigrine Fitzhugh who later moved to California. In Area H/Lot 416 sits the gravestone of Isabella Hudson (Fitzhugh) Perryman (1844-1864) and three sisters: Amy, Amelia and Henrietta Fitzhugh. Isabella was the namesake for the existing iconic second stack structure of the once booming pig-iron furnace operation. I wrote a "Story in Stone" about this family of Fitzhughs in October, 2017. To the east, about 20 yards from the Potts Lot, we have the graves of the fore-mentioned Col. John M. McPherson (1760-1829) and his son in law John Brien (1766-1834). These two gentlemen were partners in ownership of Catoctin Furnace in the early 19th century (before the Fitzhughs), and were also next door neighbors in “Court Square.” For it was these gentlemen who built impressive twin mansions at 103 and 105 Counsel Street, now spelled Council Street. These structures date to 1817, and Col. McPherson is best remembered for his role in helping to bring the Marquis de Lafayette to town in late 1824. The French hero of the American Revolution was wined and dined by Col. McPherson, himself, at that time in the home that still stands today. Today these homes are known by the names of later owners as the Ross and Mathias mansions. A mother and daughter tandem, part of the same local Mathias family that produced Sen. (and noted statesman) Charles McCurdy “Mac” Mathias, are the current residents. The elder Theresa Mathias Michel owns the house formerly owned by her parents (Charles McCurdy Mathias, Sr. and Theresa McElfresh Mathias) and grandparents (Charles B. and Grace Trail). Daughter Tee Michel owns the former Ross Mansion next door. However, this house (originally known as the McPherson Mansion) could also go by the name of the Potts Mansion, or Marshall Mansion as it did during other ownerships. I’ve had the good fortune to dine within and explore the interiors and gardens of both houses over the years. To do this though, I had to gain entry through the heavy wrought iron front gates that are reminiscent of those found in places like Charleston, South Carolina and New Orleans. Since the original builders of these houses owned the furnace, it’s no wonder how they got here. The iron railing in front of these homes on Council Street also provides a tangible example of the quality of the former fence that once surrounded Court Square. To think that Gen. Lafayette gained entry to the Ross/McPherson home by use of this same front entryway. Another individual of major patriotic fame to do so was more of a frequent visitor to the Ross Mansion in the early 19th century—Francis Scott Key. Key’s supposed law office was a stone’s throw away on North Court Street. The “Star-Spangled Banner” author regularly looked in on his first cousin, Eleanor Murdoch Potts (1773-1842), who resided here in the house after McPherson’s ownership. Eleanor Potts is one of 42 family members holding that surname and buried within Mount Olivet’s Potts’ Lot. She and husband Judge Richard Potts (1753-1808) are more than worthy of having their own “Story in Stone” written, which I will surely do on another day. Eleanor and Judge Potts died long before the opening of Mount Olivet, and originally reposed at the All Saints’ Protestant Episcopal burying ground along Carroll Creek. Our records don’t specifically say the exact date, but it is safe to assume that they were among the first two individuals placed in the Potts Lot around the time of Mount Olivet’s opening.  Upon closer inspection of the entrance of the Ross home, one will notice a polished, brass “doorbell pull” at the top of the front door landing. Etched directly below this entry accoutrement is the name “R. H. Marshall.” "Who is this gentleman, you may ask?" Well, his full name is Richard Henry Marshall, and he would be the one I’d love to have had the opportunity to ask about the Potts Lot fence here in Mount Olivet. Mr. Marshall, a lawyer, was not only one of our original cemetery founders, but was a member of Mount Olivet's first Board of Directors from 1852-1865. In looking at old "minute books," I saw that Richard Marshall actually proposed the location for the superintendent’s house to be built in the northeast corner of the property and directly adjacent the entrance off South Market Street. It was also Mr. Marshall who is responsible for establishing this large, fenced plot area known as the Potts Lot, in which he would have re-interred his wife Hariett's family members from All Saints’ Protestant Episcopal Cemetery. I soon learned that Richard H. Marshall purchased lots in which to move Francis Scott Key’s parents (John Ross and Ann Phoebe Key) and the Taneys including Ann (Key) Taney (1783-1851) and daughter Alice on behalf of his old friend and legal studies mentor, Roger Brooke Taney. They occupy the Potts Lot as does another interesting individual Marshall moved from All Saints’ by the name of Arthur Shaaf. Mr. Shaaf was a cousin of Francis Scott Key and local lawyer who served as a mentor to both Key and Taney. The Marshalls actually have the largest grave monument within the Potts Lot. I also have noted that the surname can be found upon the fore-mentioned Potts Lot fencing. So, this is why I have always wondered why this area is not referred to as the Marshall Lot? My question was answered when I found that Richard Marshall married Miss Harriet Murdoch Potts, a daughter of Hon. Richard Potts and wife Eleanor, in 1823. Mrs. Marshall died in 1867, just 13 years after the cemetery opened. In conversations with a few friends of mine with a commanding knowledge of Court Square lore and history, I learned that Mr. Marshall certainly helped his own standing, both professional and personal, by marrying into one of Frederick’s wealthiest and most respected families. This led to his eventual place of residence becoming the later known Ross mansion on Council Street, originally built by Col. John McPherson and once the home to Marshall’s in-laws—Richard and Eleanor Potts. So, just who was this Mr. Marshall? Richard Henry Marshall Richard Henry Marshall was born March 8th, 1799 at Marshall Hall, a former plantation located diagonally south and across the Potomac River from George Washington’s Mount Vernon. Marshall Hall is near Bryans Road in Charles County, and sits on the majestic banks of the lower Potomac River. I had the opportunity to visit this place last June after my son’s participation in a nearby baseball tournament. It was certainly worth the look. Although only ruins remain today, it's not too hard to imagine that Richard H. Marshall’s upbringing here was “not too shabby” to say the least. Multiple generations are contained within a “Marshall Lot” here on the old grounds within a fenced-in burial space. This includes Richard H. Marshall’s parents, Dr. Thomas Marshall II (1757-1829) and Anne Claggett Marshall (1778-1805). In this private family plot are Richard’s two brothers in Thomas Hanson Marshall (1796-1843) and George Dent Marshall (1802-1820); and grandparents Capt. Thomas Hanson Marshall I (1731-1801) and wife Rebecca Hanson Dent Marshall (1737-1770). For good measure, one will also find our subject’s great-grandparents here as well: Thomas Marshall I (1694-1759)and Elizabeth Bishop Marshall (1693-1750), first owners of Marshall Hall. With his whole family tree within one family lot, it’s not hard to imagine why Richard saw the importance in keeping the Potts family of his wife together, along with having a place for his own offspring to be buried with himself and his spouse. In its heyday, the Marshall family retreat was a classic colonial-era mansion, and what remains of it is now part of Piscataway Park operated by the National Park Service. The home is said to have been “one of the finest built on the Maryland shore of the Potomac in the early 18th century” as the Marshall family were minor gentry and owned as many as 80 slaves by the early 19th century. Marshall Hall, patented as “Mistake” in 1728 by Thomas Marshall, was the home to this family from sometime after 1728 until 1857. The mansion house dates from the earliest period and was erected as a one and one-half story brick house and enlarged c. 1760. Soon after the Civil War, the site became a highly frequented picnic ground because of its proximity to Mount Vernon. Steamship lines, originally established to ferry tourists from Washington DC and Alexandria to/from Mount Vernon, discovered a new source of revenue in the park across from the historic estate. In the 1880s, the Mount Vernon and Marshall Hall Steamboat Company ran large ships between Washington, Alexandria, Mount Vernon and Marshall Hall: the round-trip fare at that time was $1, and included admission to Mount Vernon. Washingtonians fled the summer heat of the city for all sorts of events at the picnic grounds, from exclusive catered events to popular cultural events such as a swimming exhibition given by the daredevil Robert Emmet Odlum in the summer of 1878, seven years before his death at the Brooklyn Bridge. Marshall Hall later became one of the first amusement parks in the Washington, DC area in the 1890s, offering numerous "appliances of entertainment" for visitors who wanted to do more than picnic, many of them arriving by river boat. Starting in the 1870s, annual jousting tournaments took place at the site. In the last century, the site of Richard H. Marshall’s childhood home and family estate was known as a small amusement park opened in the early 1920s, and included a small wooden roller coaster. It was a favorite of Washington, DC residents who continued to arrive via an excursion boat. New attractions were added throughout the 20th century, and gambling became a major draw for a while after World War II. Between 1949 and 1968, the Southern Maryland area offered the only legal slot machines in the United States outside of Nevada. A larger wooden roller coaster was built in 1950, but would be destroyed by tornado force winds in July 1977. This was the beginning of the end for the amusement park which officially closed in 1980. The National Park Service gained control of the park after Congress, acting upon a request from the Mount Vernon Ladies' Association, mandated that the views from Mt. Vernon had to be protected and returned to something resembling the days when George Washington sat on his colonnaded porch and looked across the Potomac. The term "historic viewshed" was coined for this act of preservation and the Park Service tore down all vestiges of the amusement park in 1980, whose popularity had declined due to competition by much larger, newer parks. A fire destroyed much of the colonial house soon after in 1981. In January 2003, a truck driver slammed his rig through the remaining hulk. The damage done to the brick shell was repaired the following year. Getting back to Richard H. Marshall, he was the son of Dr. Thomas Hanson Marshall I, a surgeon in the continental army during the American Revolution. He is said to have been “on terms of intimacy with the family of Gen. George Washington, who was his nearest neighbor.” I couldn't find anything on Richard Marshall's childhood, but I'm sure he was provided with an education which would prepare him for the study of law, and the mentoring he received from Roger Brooke Taney in Frederick around the year 1820. On completing his studies, he became a member of the Frederick bar. With the exception of a few months at Georgetown, DC, he would reside in our fair city. As stated earlier, he married Harriet Potts on June 12th, 1823. The couple would have multiple children, however only one lived to maturity in Miss Ann Potts Marshall (1827-1890). The others included Eleanor Ann Marshall (1824-1827), Harriet Potts Marshall (1826-1826) and Mary Elizabeth Marshall (1831-1833). The family resided at 101 Council Street. Mr. Marshall certainly involved himself in town activities including delivering a patriotic address on July 4th, 1825 in conjunction with a parade culminating in a public celebration held at the Frederick Courthouse. In 1844 Marshall was appointed associate judge of the circuit court, at that time embracing Frederick, Washington and Allegany counties. He was succeeded by Hon. Madison Nelson in 1851. In 1878, he became president of the Central National Bank as successor to Col. George R. Dennis. Judge Marshall appears in the early newspapers quite often in conjunction with legal handlings, trustee sales and the many boards he served on. Harriet Marshall died a week before Christmas in 1867. This too would cause his name to appear in our local weekly papers, including an executor's notice which was rare to see for a woman at this period of history, but not in Mrs. Marshall's case. Richard H. Marshall died on September 3rd, 1884 at the age of 85. He would be laid to rest next to his wife who had predeceased him nearly 17 years earlier. Here, Marshall had erected a large monument to her memory. A few yards behind this grave marker, one can find three small monuments marking the reburials of the couples young children who died in the 1830s and were originally buried in the All Saints’ burying ground. The last member of the immediate Marshall family here in Frederick died in 1890 at the age of 62. This was only six years after her father's death. Ann Potts Marshall never married and the surname of this mighty Maryland family ceased with her. This, more than anything else, explains why the Potts name has stuck to this unique gated lot within Mount Olivet’s Area G.

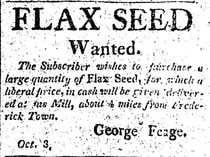

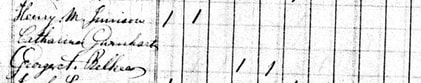

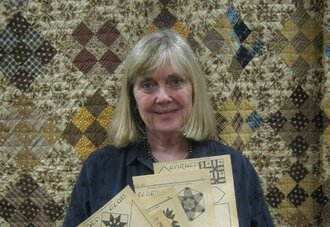

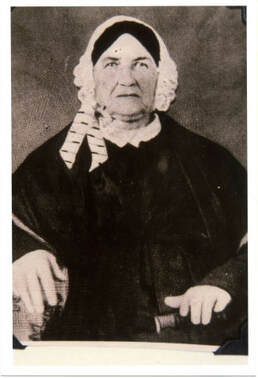

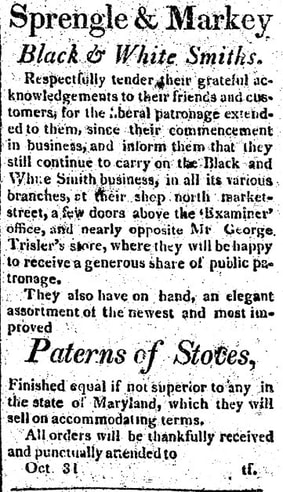

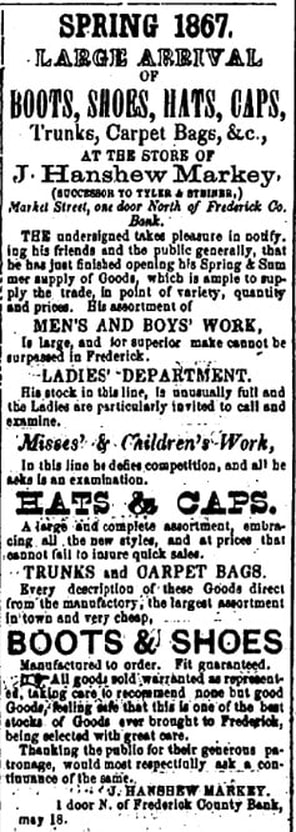

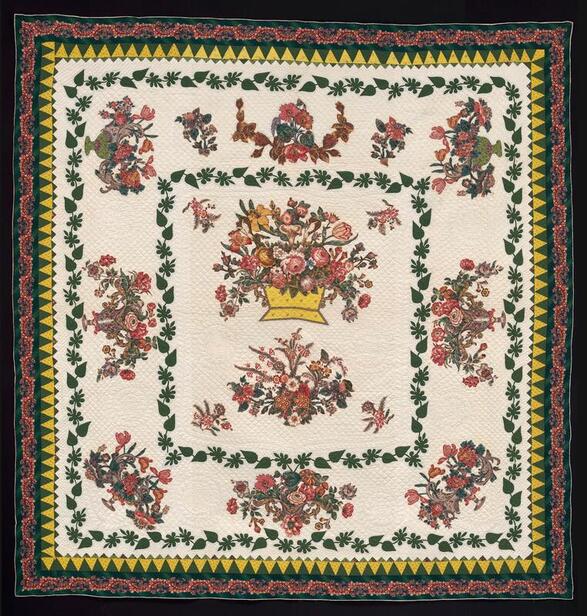

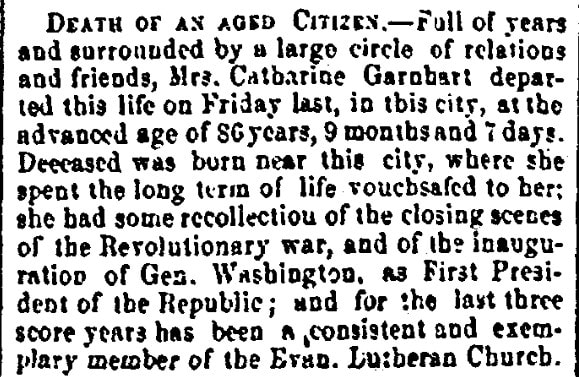

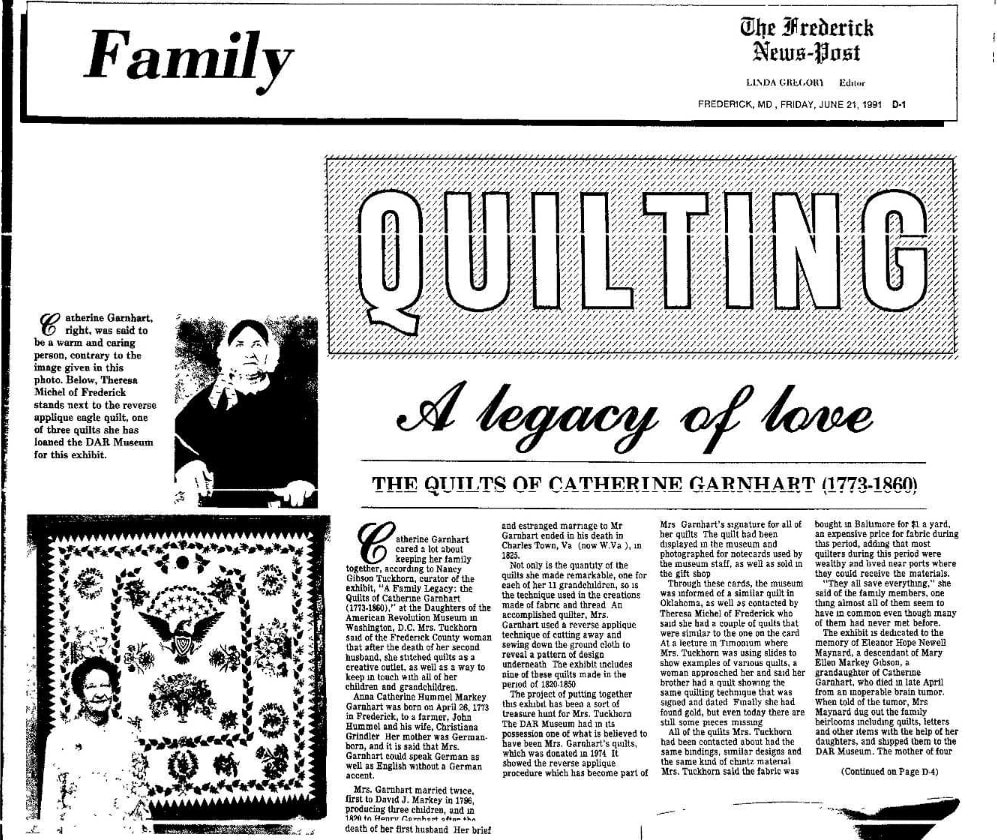

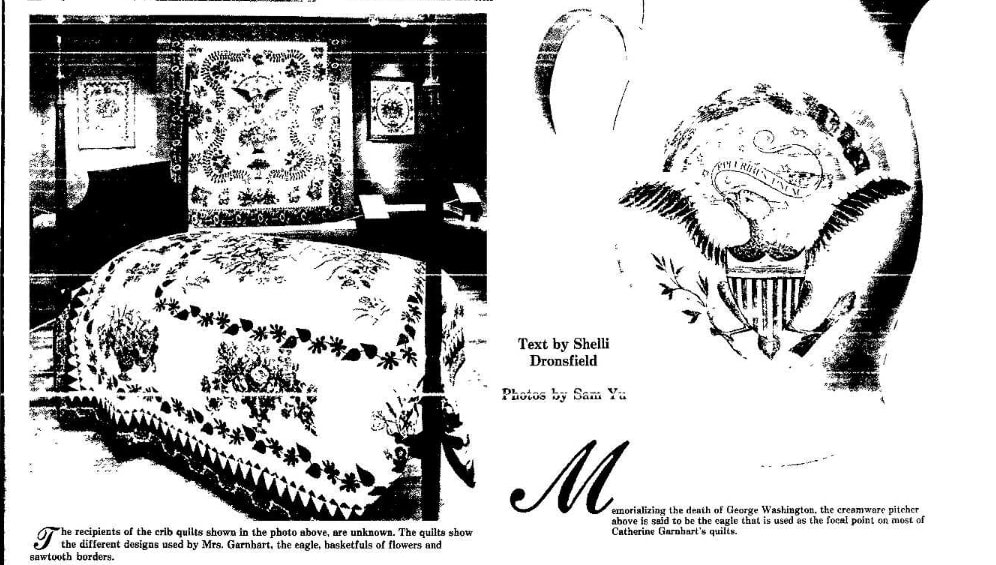

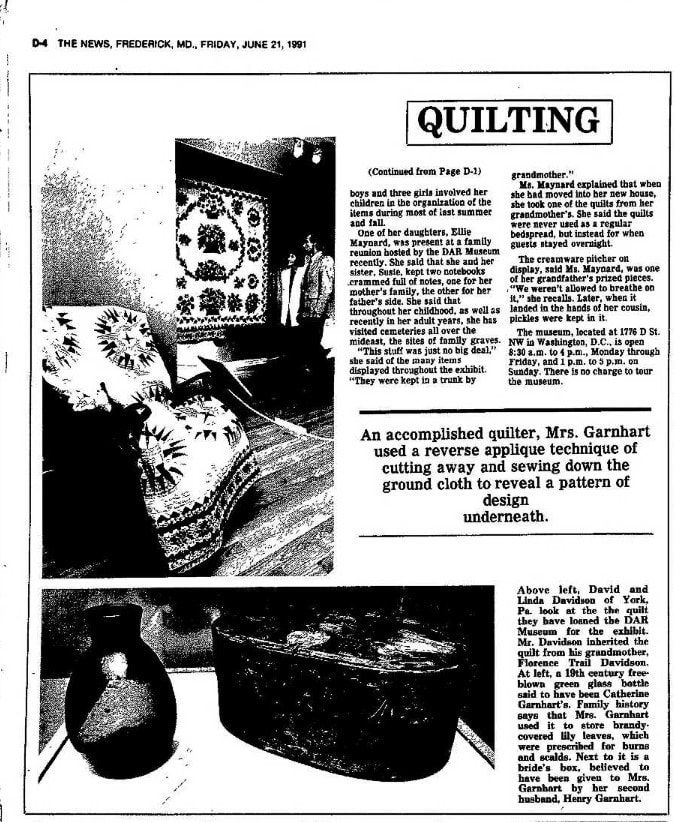

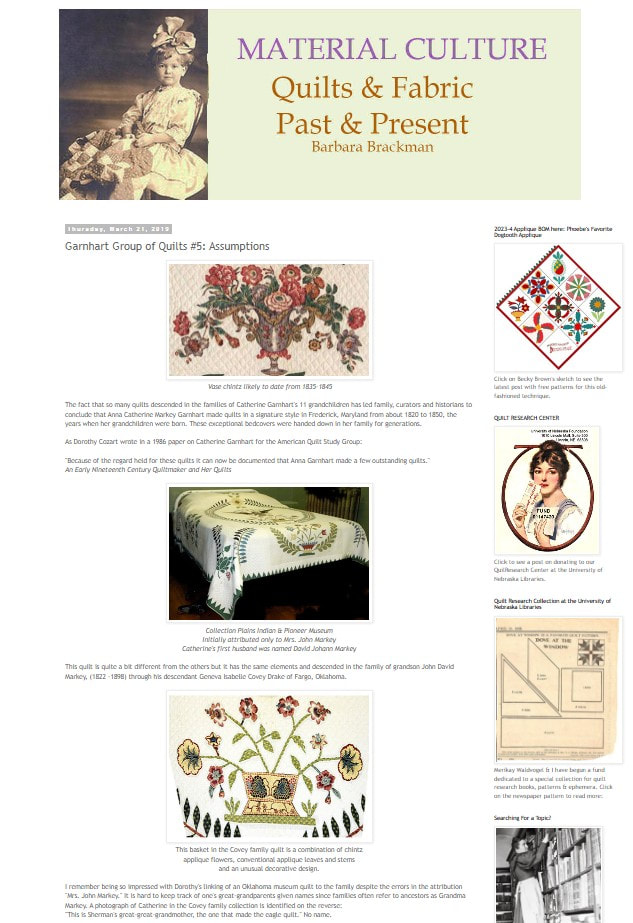

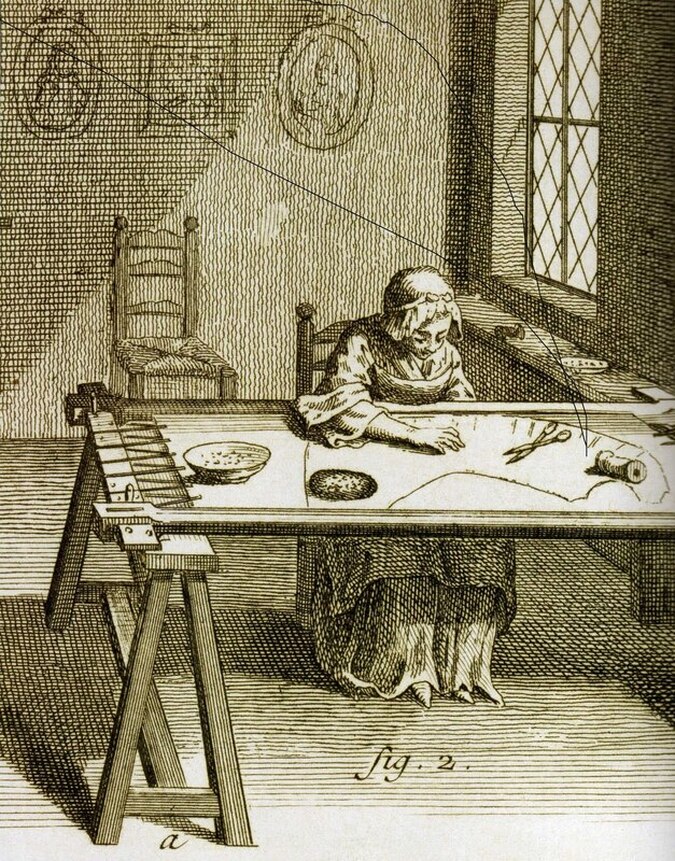

Richard H. Marshall's grave lot in Mount Olivet, and former home in Frederick, don't carry his family name, but there exist subtle reminders, etched and forged, in metal. At least an old rollercoaster and amusement park once carried the mighty name of Richard's prominent colonial family—but that too is slowly becoming a faded memory of yesteryear. “In your life, the people become like a patchwork quilt. Some leave with you a piece that is bigger than you wanted and others smaller than you thought you needed. Some are that annoying itchy square in the corner, and others that piece of worn flannel. You leave pieces with some and they leave their pieces with you. All the while each and every square makes up a part of what is you. Be okay with the squares people leave you. For life is too short to expect from people what they do not have to give, or were not called to give you.” -Anna M. Aquino Nobody knew this concept better than Anna Catherine (Hummel) Markey Garnhart. Not only is her name a “stitched-together masterpiece” unto itself, but her life and family relationships seem to have been so as well. Add to this the fact that her chief hobby in life appears to have centered on the craft of quilting. Works of hers are well-known by applique quilt and coverlet experts as well as collectors around the country. Examples of her craftsmanship can be found in both private and museum collections. One such repository includes the DAR (Daughters of the American Revolution) Museum in Washington, DC, where one of Garnhart's signature quilts, "the Eagle Quilt," is displayed and bears as its central object an eagle. A corresponding label states that: "Eagles were a hot design trend in the decorative arts, throughout the United States and not only in quilts, from the early years of the republic through our semicentennial in 1826. Garnhart made four eagle quilts, probably all before about 1830, and all with her extensive use of reverse appliqué. The sawtooth borders are typical of this region." Catharine Garnhart's prime contribution to the trade comes in the form of applique quilting. Applique is a needlework technique in which one or more pieces of fabric are attached to a larger background fabric to create pictures or patterns. The fabric can be attached by hand, machine or fused. The word comes from the French meaning "applied or laid on another material." Catharine is said to have shopped in Baltimore, paying up to a dollar per yard for her chintzes - a lot of money back then. Over fifty small prints appear throughout Garnhart’s quilts, and over twenty large-scale chintzes. Many prints appear in several quilts. Many of this Catharine's quilts can be seen online including a site called the Quilt Index (www.quiltindex.org) and various other websites.  Evangelical Lutheran Church and Graveyard (c. 1854) Evangelical Lutheran Church and Graveyard (c. 1854) Catharine Garnhart Anna Catharine (Hummel) Markey Garnhart was born on April 16th, 1773 on the eve of the American Revolution. Her parents were immigrants including father John Hummel (1743-1781), whose mother brought him to America in 1749 from Wurttemberg, Germany, and twice-married Christiana Catharine (Grundler) Hummel Feaga (1747-1849), who emigrated to the New World (from Germany) in 1754. John Hummel would take part in the American Revolution and died in battle as a result. He served as a corporal in Capt. Jacob Baldy’s company of the 6th Battalion of Berks County (PA) militia commanded by Col. Joseph Hiester (this stated by Sons of the American Revolution records). Corp. Hummel’s grave is said to be located beneath the Frederick Evangelical Lutheran Church and cannot be seen or photographed. Anna, better known as “Catharine,” was a life-long resident of Frederick. Her mother, the fore-mentioned Christiana Grundler, immigrated to America as a young girl with her mother, father and four older sisters. During the passage, Christiana’s mother died and was buried at sea. After arriving in America, Christiana's father placed her with "adoptive" parents Friedrich and Catharina Wittmann, who needed the help of another child, and raised her in Frederick. These were (her future husband) Johann Hummel’s mother and step-father. Christiana was married for the first time in 1771 to husband Johann Hummel, a farmer, mill owner, and land investor. She gave birth to five Hummel children (including our subject “Catharine”) before losing her husband, Johann Hummel, in 1781. He was only 38 at the time. I couldn’t find the final resting place of this gentleman, but his namesake son, John Hummel (1777-1826) is buried in Mount Olivet’s Area NN. After struggling with Mr. Hummel's estate, Catharine’s mother married again in 1782. Her new spouse was a Hessian soldier and prisoner of war named Johann Philip Fiege (1750-1829). This former mercenary soldier came to America to fight under the British flag. He would be captured at the Battle of Yorktown and would be imprisoned in Frederick. Like many Hessian soldiers kept here in Frederick, they were loosely guarded at the aptly named barracks located a block from our cemetery’s front gate.  Political Intelligencer (Feb 6, 1819) Political Intelligencer (Feb 6, 1819) Upon war’s end, Philip Fiege and his comrades were welcomed wholeheartedly by Frederick’s German community, and decided to stay in this new country instead of going back to Germany where their leaders sold them out to Great Britain in most cases. Mr. Fiege had experience with mills in Germany, and soon made a successful business from the mill on Johann Hummel's property. He would eventually change the spelling of his name to Feaga and his sons would continue to prosper with the milling operation. In time, the hamlet where the family lived and work would take the family name of the former prisoner of war and principal landowner—Feagaville. This is located about four miles southwest of Frederick City on MD route 180. In this marriage, Christiana Feaga would have four more children. Philip Feaga died in 1829 and was originally buried in the Evangelical Lutheran Churchyard. He would be re-interred in Mount Olivet’s Area F/Lot 78 in 1860. Christiana died in January of 1849, and was moved here to Mount Olivet from Evangelical Lutheran as well. According to a great, great-grandson's family history, Christiana was a devout member of the Evangelical Lutheran Church and a financial supporter. She enjoyed good health and spoke English with a German accent while living to be over 101 years of age. Christiana outlived all but four of her nine children and remained financially independent throughout her 22 years as a widow. The young Catharine (Hummel) experienced the loss of her father at age eight, and the trials and tribulations of her mother’s life, but with the accompaniment of many siblings it appears. For a girl of her times, she would have been well-versed in cooking and home-keeping tasks, but it’s likely that her well-rounded mother taught her things such as writing, music and needlework. The latter being a given! Catharine married David Johann Markey (1771-1820) in 1796. They had three known children: Frederick Markey (1796-1827), David John Philip Markey (1809-1885) and Christina Catharine Markey, b. 1812 , about whom nothing is known as she likely died in infancy. David Markey worked as a wheelwright and served at least one term as Constable and was later Clerk of the Sheriff's office. Catharine’s husband, like her father, fought for independence against the British but in the second go-round with the War of 1812. Markey was one of the townspeople recruited by Capt. John Brengle and Rev. David Schaeffer on August 25th, 1814. He served in Brengle's company and is believed to have been engaged in the defense of Baltimore which helped win Francis Scott Key immortal fame thanks to a catchy song. David Markey died in 1820 and was originally buried in the All Saints’ Protestant Episcopal burying ground before being re-located to the Markey Family Lot in Area E/Lot 86 in 1868. The Markey family lived in Frederick Town and, in 1818, Catharine Markey is on record having bought what is now 218-220 N. Market Street from Jacob Gonzo. Following David Markey's death, Catharine would remarry. This gentleman was a widower with deep ties to neighboring Jefferson County, Virginia (at the time). His name was Henry Garnhart (b. 1754), and from what I could find was a tavern operator earlier in life before coming to Frederick. Sadly, Catharine would endure the loss of her adult son Frederick in 1827. Frederick Markey was formerly a partner on a blacksmithing/white-smithing business in town. He was married to Elizabeth Dill (1800-1866) and left three children.  Catherine Garnhart as head of household in 1840 US Census Catherine Garnhart as head of household in 1840 US Census Catharine’s second husband, Henry, would die the following year in 1828. He was buried in a small, family cemetery near Hall Town (today's WV), but would later be moved to Edge Hill Cemetery in nearby Charles Town (WV). I’m theorizing that our subject, Catharine, worked out her grief from both of these great losses by keeping busy with making her appliqués, once again defined as "ornamental needlework in which pieces of fabric are sewn onto a large piece of fabric to form pictures or patterns.” Catharine Garnhart still had her son David John Philip Markey at arm's reach, and "Jack" (as he was commonly called) was one to be extremely proud of. While still in his twenties, Catharine’s son perceived the need for a planing mill to produce window sashing, doors and moulding in the city. Trained as a carpenter and familiar with lumber milling thanks to his mother’s family, David John Philip "Jack" Markey partnered with John Hanshew to build and operate a highly successful planing mill at the northeast corner of North Bentz and West Second Street. Today this is the site of Calvary Methodist Church. The firm also acted as a building contractor with projects ranging from housing to the parsonage of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Frederick where Markey also served terms as elder and alderman. He was a prominent citizen of the community, co-founder and board member of the Mutual Insurance Company of Frederick and city councilman, alderman and Tax Commissioner. The home residence of David J. P. Markey and family was built near the mill around 1839 at the southeast corner of North Bentz and West Third Street (134 W Third). His marriage of over 52 years to Susan Bentz produced eight children, including Frederick shoe merchant John Hanshew Markey (1835-1895), father of David John Markey (1882-1963) who would be responsible for forming Company A of the Maryland National Guard, and this unit’s original home, the Frederick Armory, located cata-corner from the site of the family planing mill.  A memorial stone for David John Markey, great-grandson of Catharine Garnhart. This gentleman was quite impressive as he served as a politician, career Army officer, businessman, and college football coach. He served as a Major in the United States Army during the Spanish-American War, World War I and World War II. He was a candidate for United States Senator from Maryland in 1946. Although buried in Arlington National Cemetery, this memorial cenotaph can be found in the Markey family plot in Mount Olivet’s area E Anna Catharine (Hummel) Markey Garnhart was blessed with eleven grandchildren. She would make a quilt for each (including nine large quilts and three crib-size quilts which survive today). In addition to the previously mentioned John Hanshew Markey, most of these grandchildren are buried here in Mount Olivet. Out of David J. P. Markey’s eight children, all but one, Daniel Scholl Markey, are here. (D.S. Markey moved to San Francisco).  Appliquéd Chintzwork Quilt, by Catharine Garnhart. Two grandchildren’s quilts ended up in the same branch of the family, so it’s unclear whether this was made (ca. 1845) for Rebecca Markey or her sister Susan, both children of David Markey. Part of an exhibit in Colonial Williamsburg called "Art of the Quilter" in the Foster and Muriel McCarl Gallery (Gift of David and Linda Davidson)  Barbara Fritchie (1766-1862) Barbara Fritchie (1766-1862) As for Catharine, she had died at the age of 86 on February 3rd, 1860. She would be spared the stress and strain of the American Civil War, having lived herself through the two wars for independence. It's also safe to assume that she knew Barbara Fritchie, ten years her senior, but I'm sure they were both "cut from the same cloth." These ladies have the same bonnet and beautiful smile as evidenced by the fortunate fact that we have surviving photographs of both women. (Note: I'm being very sarcastic about the smiles.) Two days after her death, the body of Anna Catharine (Hummel) Markey Garnhart would be the first to be buried in the Markey family lot in Area E. As already mentioned, first-husband David Markey, and son Frederick, would be removed from Evangelical Lutheran to be buried on each side of her. Decades later, David J. P. "Jack" Markey and wife Susan would be placed here, and their children (Catherine's grandchildren) Lucy Emma Russel Markey and David Jacob Markey. Other family members, and generations, would surely follow to more recent times. Anna Catharine (Hummel) Markey Garnhart was so much more than I could find recorded about her. In writing and researching this story, its not hard to see the similarities between a patchwork quilt, and a family tree. That's something that will stick with me, as will my memories of my own loving grandmothers, and their role in "enveloping" families with love, tradition, support and kindness. When done correctly, it's kind of like that warm and euphoric feeling you experience on a cold winter day or night, when you wrap yourself in the cocoon of a heavy blanket or duvet. All this hits home as my grandmother Haugh even knitted me an Afghan when I was a kid, and it continues to be a prized possession. How many of you have a quilt or homemade textile made by your grandmother or great-grandmother? I originally learned about this woman from my good friend Theresa Mathias Michel of Frederick’s Council Street. She showed me a picture of one of Catherine's quilts that she actually owned, and had told me of Mrs. Garnhart’s fame in quilting circles. I soon learned that a collection of her quilts is being displayed at the DAR headquarters in Washington as I relayed at the start of this "Story in Stone." While digging through online newspaper archives, I was pleased to discover an article showcasing Mrs. Garnhart’s quilting work in the Frederick News-Post in 1991. Mrs. Michel and her quilt were featured as the article promoted the fact that a special exhibit of Garnhart's quilts was occurring that summer at the DAR Museum in Washington, DC. I soon learned a bit more about Catharine's handiwork by consulting the internet, specifically the website and blog of Barbara Brackman, a quilter, quilt historian and author. I would soon learn that Ms. Brackman was not just an enthusiast, but one of the country’s leading authorities on the subject, not to mention being a “Hall of Famer.” She was inducted into the Quilters Hall of Fame of Marion, Indiana in 2001.  Barbara Brackman Barbara Brackman Barbara has written numerous books on quilting during the Civil War including: Facts & Fabrications: Unraveling the History of Quilts and Slavery, Barbara Brackman's Civil War Sampler, Barbara Brackman's Encyclopedia of Appliqué, America's Printed Fabrics 1770-1890, Civil War Women, Clues in the Calico, Emporia Rose Appliqué Quilts, Making History–Quilts & Fabric from 1890-1970, and Quilts from the Civil War, all published by C&T Publishing. Her Encyclopedia of Pieced Quilt Patterns contains more than 4000 pieced quilt patterns, derived from printed sources published between 1830 and 1970. In 2019, Barbara Brackman conducted a deep dive of research on our subject Catharine Garnhart. She wanted to see if the Frederick woman was truly an originator and innovator of designs which would be later copied and found around the country. Ms. Brackman theorized that the Garnhart group of quilts are products of Maryland's commercial quilt-making workshops, seeing these as a parallel style to the more abundant Baltimore album-style quilts. She had her doubts, thinking that Catherine Garnhart was just a customer who purchased similar quilts—a generous grandmother who could afford to buy some fashionable luxury gifts for her family. Brackman carefully studied existing specimens and conducted intensive detective work, publishing her findings in the six posts below: Barbara Brackman concludes: "Catharine Garnhart bought her family quilts, possibly as gifts for grandchildren, probably purchased in the Baltimore vicinity where a group of seamstresses were selling basted and/or finished blocks and quilts in the kind of workshop I was looking for in Frederick. This group of designers and seamstresses making the Garnhart group may predate the high-style Baltimore album group which dates from about 1845 to 1855, but it seems likely that the two types of quilts overlapped in the late 1840s." I can’t say I know much, or, honestly anything substantial, about the textile trade, but Ms. Brackman certainly does. Read the blogs for yourselves, and feel free to post your own theories and conclusions in the comments after the story. Regardless of the authenticity of Catharine Garnhart’s quilts and talents, the greater family of Ms. Garnhart is quite a tapestry itself, one which certainly typifies the quote featured at the outset of this article, especially the following three lines:

“You leave pieces with some and they leave their pieces with you. All the while each and every square makes up a part of what is you. Be okay with the squares people leave you.” |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed