|

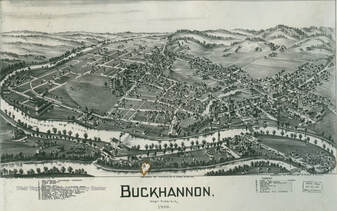

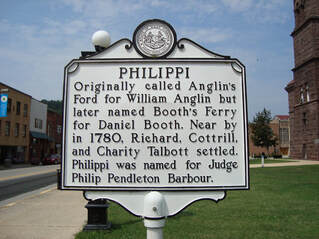

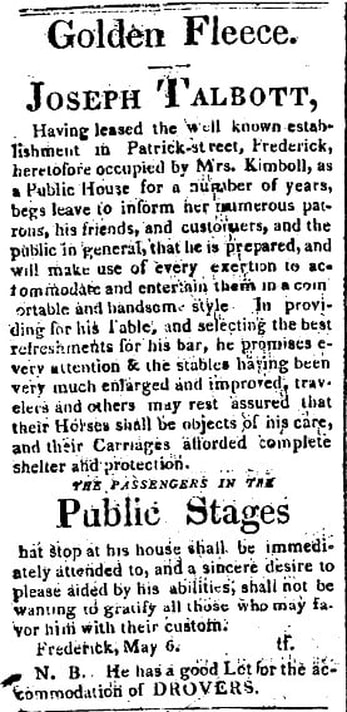

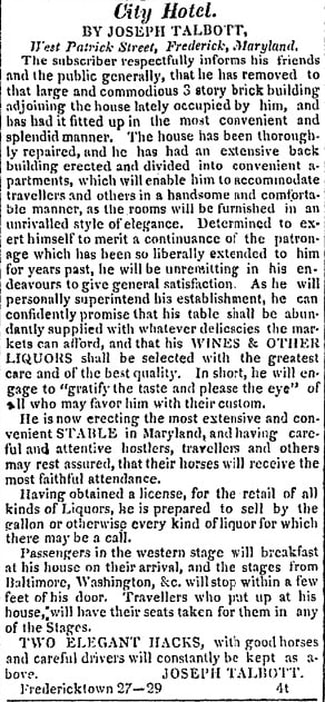

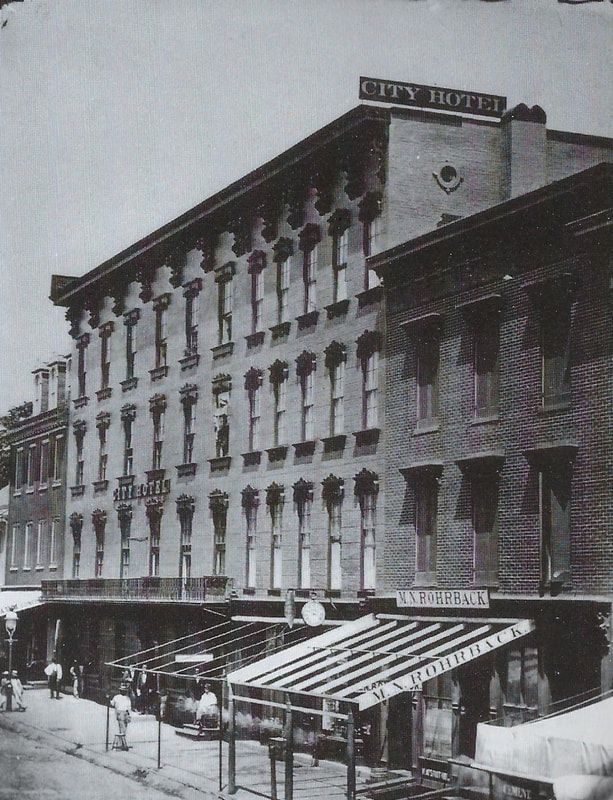

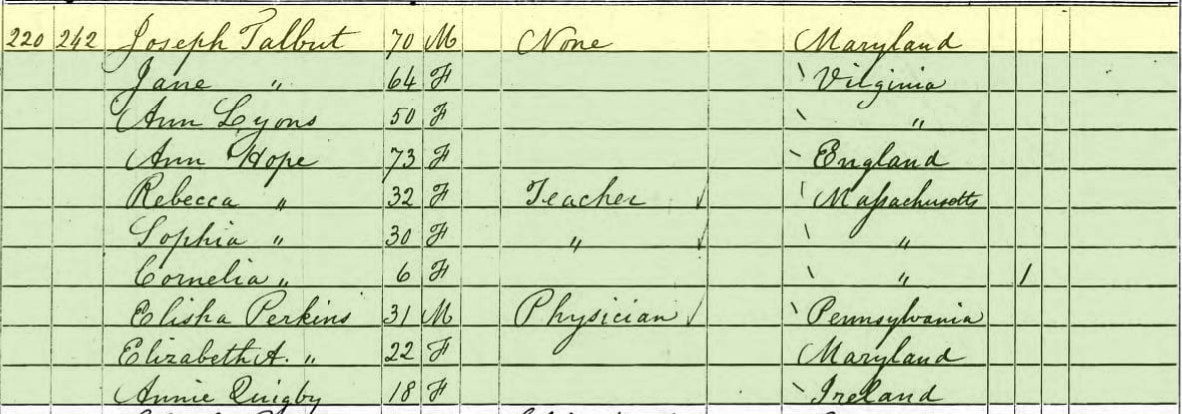

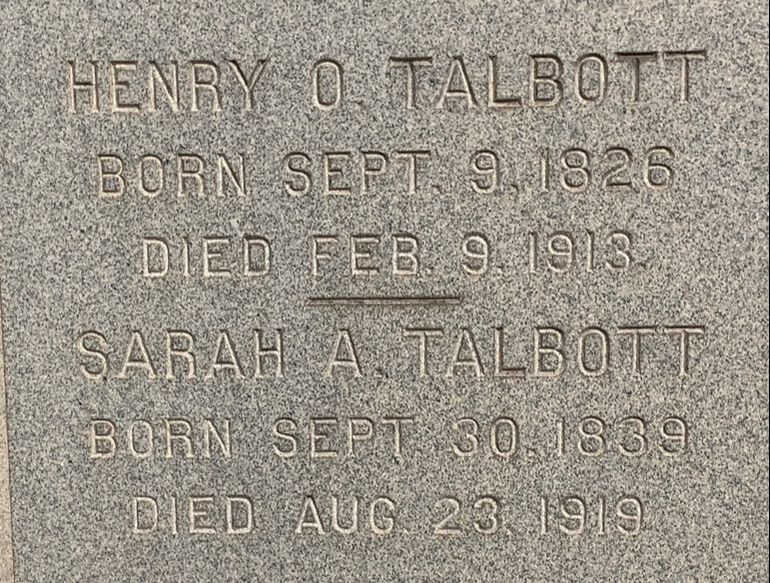

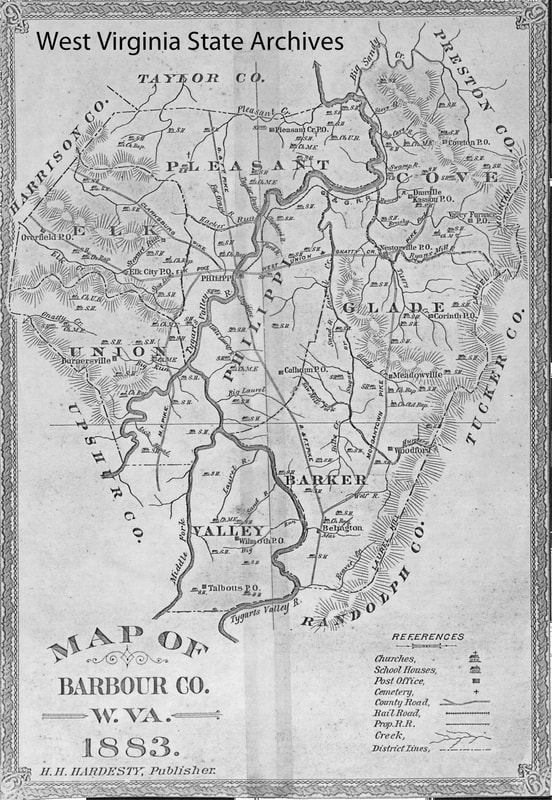

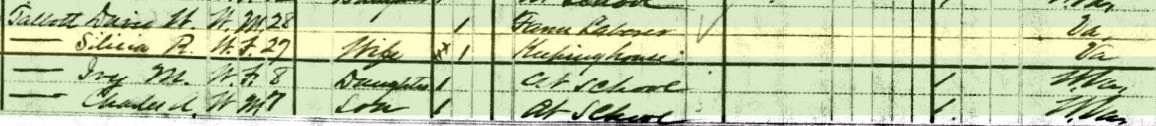

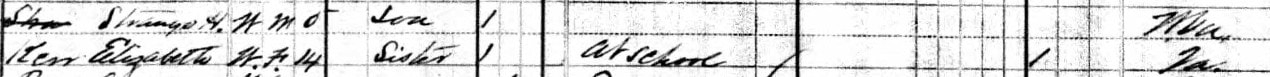

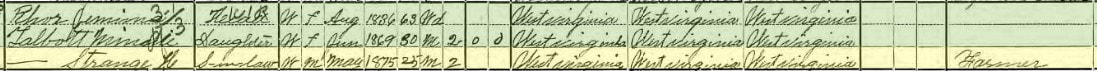

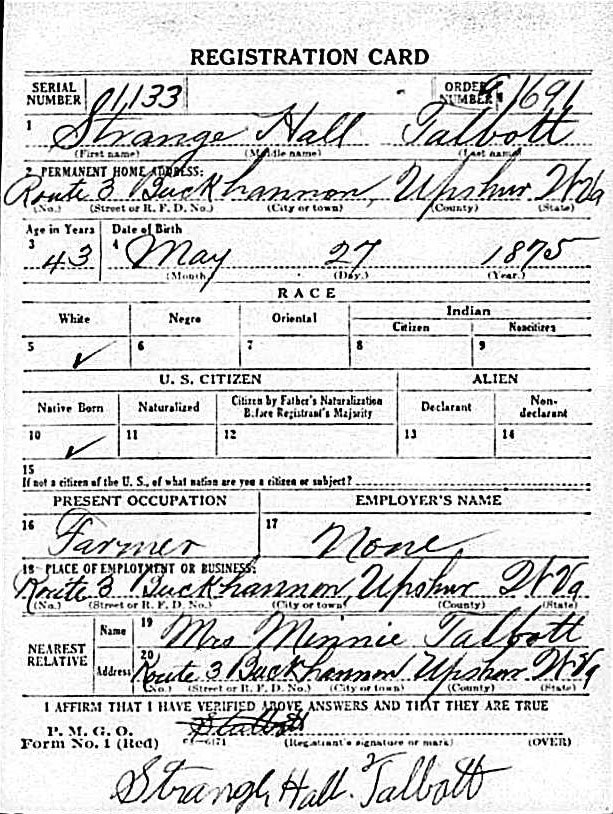

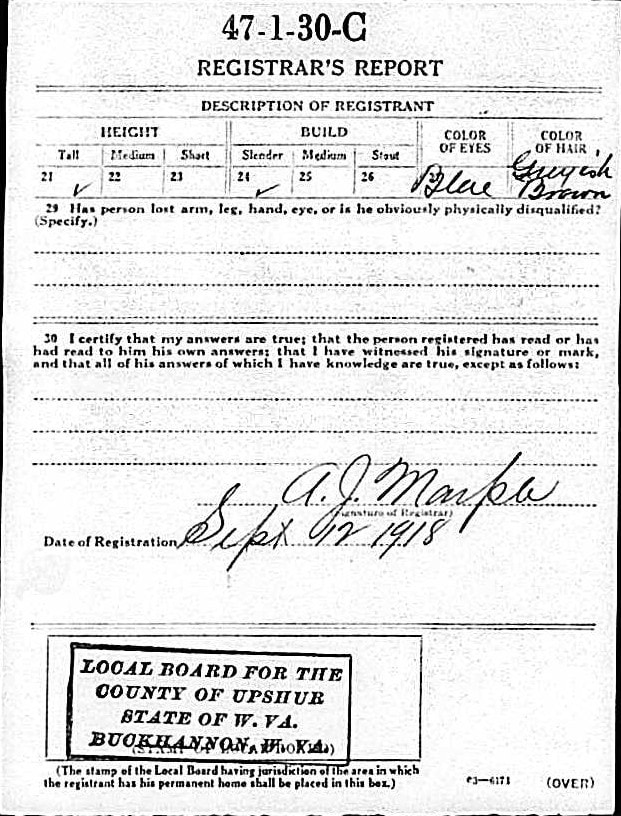

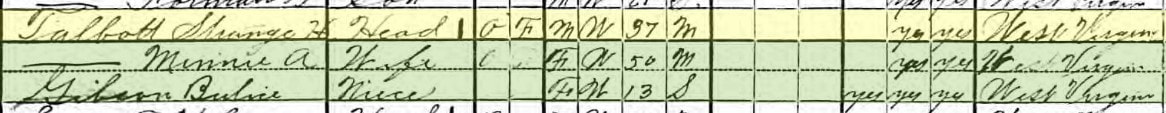

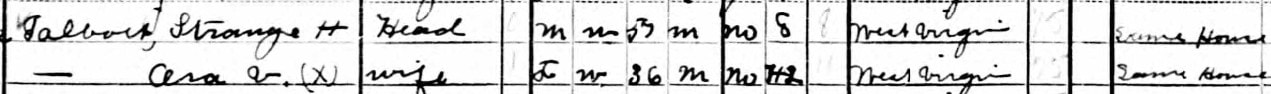

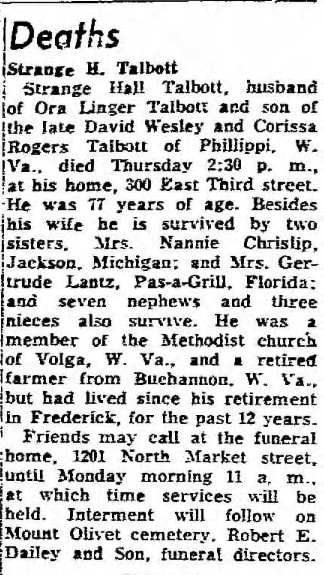

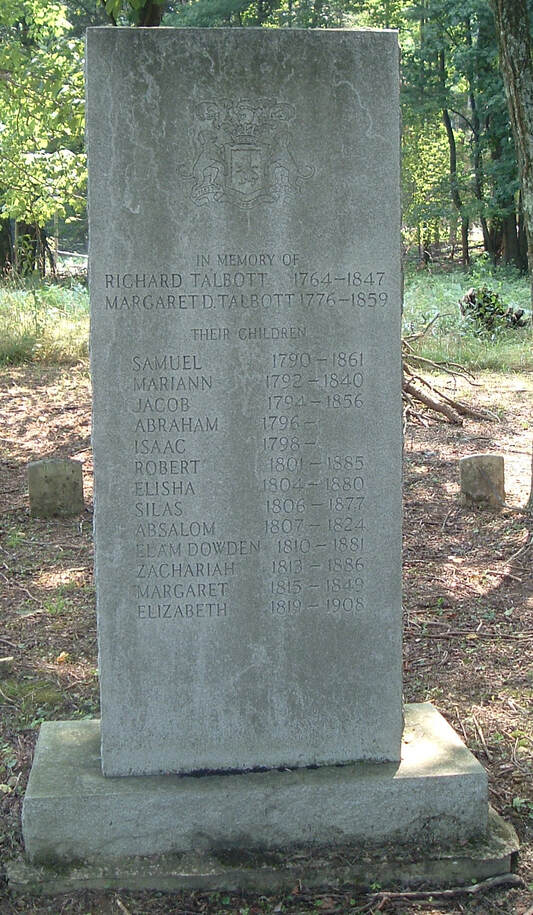

Our names—oh, those unique identifiers. They are varied. They are special. They are unique, unless, of course, you hold the moniker of John Smith. I say that only in jest, because not all John Smiths are created equal, and that is the ultimate beauty of individuality in a society that is slowly becoming more and more homogenized. That may be okay for milk, but I’m not a big fan of globalization and sameness among people, places and experiences. I like authenticity (the quality of being authentic or genuine) and diversity (the presence of differences within a given setting). That’s what makes Frederick so special, and in the same breath, the same can be said about Mount Olivet Cemetery. Back to the name business, nowhere can the originality of the subject of diversity be seen more clearly than at a cemetery. Thousands of names are etched upon gravestones, markers and monuments, everywhere you look. In some cases, you may spot ones that are distinctly “Frederick,” meaning they have been handed down for generations from original settlers dating back to the town and county’s founding in the mid-1700s. Other times, enlightenment comes with a name you’ve never seen before. This usually pertains to surnames, but can surely include first names too. A stroll through this place can supply expectant couples plenty of options. Don’t laugh, throwback names from yesteryear are just as great as the trendy names offered by today’s “social influencers.” The jury may still be out on Orville, Milton, Gilmer, Hiram, Viola, Hester, Cora, or Bertha, but I’ve got four sons with names that are a little different from their respective college and high school classmates. These include Jack (John), Nick (Nicholas), Vinnie (Vincent) and Eddie (Edwin). I’ve been asked what’s the strangest first name I’ve encountered during my time here. Up until recently, three immediately come to mind in Gamaliel Easterday, Lycurgus Hedges and Confederate Row’s Raisin Pitts. However, I have seen a new light with the discovery of the absolute, strangest first name in Mount Olivet—Strange. That’s right it’s actually the name “Strange,” itself. Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, I present the gravestone of the decedent found in Area X/Lot 82. The grave of Strange Hall Talbott surely will elicit a doubletake. I was curious to learn more, but could not find a definitive rationale for the name as there could be a clever story of association that has been lost in time. Maybe this individual looked “strange” as a baby? Maybe the pregnancy came under questionable (strange) circumstances? Was his birth unusual or abnormal? At first glance, I thought my subject was related to the local family connected to the oft-mentioned Talbott’s Tavern that once sat at the west end of West Patrick Street’s first block. This was purchased by Mr. Talbott in the 1820s from Catherine Kimboll, who had kept an ordinary here for quite some time. The site would continue its history as a popular inn as it would eventually become the famed City Hotel. Frederick Diarist Jacob Engelbrecht and our local newspapers of the time document the fact that notable historical figures would stay here while visiting our fair town. These included such persons as Andrew Jackson, Henry Clay, Davy Crockett, James Polk and Zachary Taylor. Many of these distinguished visitors chose Joseph Talbott’s tavern for their personal lodging, which may indicate that it was one of the finer establishments in town. In the year 1824, Talbott’s Tavern/Hotel welcomed French general Marquis de Lafayette during his grand tour of the United States. While here, Lafayette received and greeted the public. Several celebrations were held, including a public dinner and ball for the great hero of the American Revolution. Joseph Talbott’s tavern was rebranded the City Hotel around 1831, and demolished in the 1920s to make way for the Francis Scott Key Hotel, which eventually became luxury apartments. Joseph can be found living in Baltimore in the 1850s and appears to be running a guesthouse. Interestingly, I took note that his next-door neighbor was merchant Samuel Hinks, who is buried here and the subject of one of these “Stories in Stone” back in April of 2018. Hinks would serve as “Mobtown’s” mayor from 1854-1856, and would later retire to the Landon House located in nearby Urbana. A final note regarding Joseph Talbott is that he would die in 1857, and is buried next to his wife Jane (nee Daniel) in an unmarked grave within Mount Olivet Cemetery in Baltimore. We have three of Joseph’s grandchildren buried here in Frederick’s Mount Olivet, all the children of Mahlon Talbott, who had a career as a lawyer both here and in Baltimore. Two of the three children died before Mount Olivet opened and were originally buried in All Saints Protestant Episcopal burying ground along Carroll Creek. These bodies were moved here by local shopkeeper/grocer Basil Norris, who is responsible for moving his own two daughters’ bodies to the Norris family plot (F9-12) when the cemetery officially opened in 1854. As a matter of fact, it was Mr. Norris who erected the very first monument here in Mount Olivet to the memory of his teenage girls.  Basil Norris' Lot 10 in Area F contains the graves (and gravestones) of three of Mahlon Talbott's children located to the right of the taller twin-columned monument (the very first in the cemetery). From left to right are the graves of Joseph Henry Clay Talbott (1837-1852), John Charlton Talbott (1834-1835) and Annie Elizabeth Talbott (1833-1856). The boys' deaths predated Mount Olivet's opening and they were reinterred here from All Saints' Protestant Episcopal Cemetery in June 1854. Annie was 22 years of age when she died in 1856 in Baltimore. There are 28 Talbotts buried here in Mount Olivet to date. I recall recently seeing the grave of Dr. Henry Thomas Talbott (1866-1909), a physician of Charles Town, West Virginia who married Lilian B. Hedges (1865-1892), daughter of the fore-mentioned Lycurgus Hedges. I pointed out Lilian’s beautifully carved stone with floral design to participants of a spring/garden-themed walking tour for our Friends of Mount Olivet this past April. Dr. Talbott’s father has a large monument on Area R/Lot 108. Henry Odel Talbott (1826-1913) was a former banker who spent most of his career in Charles Town as well. These Talbotts hailed from the Beallsville area just across the Montgomery County border to our south. Henry Odel’s father (Henry Warren Talbott 1780-1859) and grandfather (Nathan Talbott 1763-1839) are buried in the old Monocacy Cemetery located at the southern foot of Sugarloaf Mountain. Nathan was a Revolutionary War Patriot who apparently enlisted here in Frederick. His father (William Talbott 1715-1781) came to Frederick, (today’s Montgomery) County from Prince Georges County and established a plantation here near present-day Poolesville. He was among a group of white settlers who attempted to grow tobacco as they had successfully done in southern Maryland. The family had been in Maryland since the early 1700s, hailing from Yorkshire, England. Our subject, Strange Hall Talbott, had roots in West Virginia, and came to Frederick later in life. He spent his retirement at an iconic -looking house located on the southeast corner of East Third and East streets. This is diagonally across from St. John’s Catholic Cemetery.  Strange Hall Talbott was born on May 27th, 1882 to parents David Wesley Talbott and Celise Ruth Rogers. In case you were curious, the meaning of Celise is “the one who takes God as the oath.” The family was living in Philippi, West Virginia, a town of 3,000 people, county seat of Barbour County and the site of a Civil War battle in 1861. Although a minor skirmish, the Battle of Philippi is considered the earliest notable land action of the American Civil War. For over a century, Philippi has been home to Alderson Broaddus University, a four-year liberal-arts school affiliated with the American Baptist Churches. I was delighted to learn that Philippi also served as the childhood home to actor Ted Cassidy (1932–1979), who played the roles of two of the “strangest” characters in television history. These included "Lurch" and "Thing" on the 1960s TV show The Addams Family. Mr. Cassidy was raised in Philippi, graduating from Philippi High School around 1950.  I couldn’t find much on Strange Hall Talbott and his life in Philippi outside of census records. I scoured his family tree and on original attempt couldn’t find “Strange” as a first, or last name. Upon further research, I found a few early (West) Virginia settlers who had the combination of “Strange Hall” in their names. In particular, I discovered a Jonathan Strange Hall (1797-1875) who settled in the “Collins Settlement” in what would later become Lewis County, WV. This was to the southwest of Barbour County. Jonathan Strange Hall had 12 children, with the sixth being Mary Hall, born at Skin Creek in 1827. Mary would wed David J. Talbott (1822-1898) in 1845. In looking into the Talbott family, which appears also as Tolbert, I found the couple living in Buckhannon, Upshur County, which neighbored both Barbour and Lewis counties. This group, the Talbotts, were also early settlers of this area in the 1700s when the region was still part of Virginia. West Virginia would not become a separate state until 1864. There is a gray area in the genealogical record involving this family with a generation connection. Ancestry.com trees and a few census records show a man named Enoch Talbott as our subject’s father, however, our Mount Olivet cemetery records and those pertaining to our subject show his father as David Wesley Talbott (1852-1917), a resident of Philippi. My “David Talbotts” don’t simply have the “strange” connection I was hoping for. David Wesley Talbott (father of Strange) is shown to be the son of Enoch Talbott (1832-1901) and wife Susan O’ Neal. Perhaps a relative can bail me out on this? Regardless, Strange Talbott worked on the family farm during his youth and attended school. He married Minnie Ella Rohr on November 25th, 1898, in Barbour County and lived south of Philippi in the village of Union for about 10 years. The family would have no children and relocated to Buckhannon, Upshur County by late summer 1918. Strange did not serve in World War I, but registered for the draft as was mandatory. The census of 1920 shows Strange running a truck farm. The same would hold true ten years later in 1930. Minnie would die in 1931, and our subject remarried Ora V. Linger (b. February 12th, 1904) in 1934. She was the daughter of a schoolteacher, John C. Linger and lived nearby outside Buckhannon. As a fitting aside, Ora is a name of Latin origin meaning "prayer.” The couple continued living off the Brushy Fork Road southwest of Buckhannon. Strange retired in 1947 and would come to Frederick with his wife of 14 years. This move east could have been precipitated by Ora’s sister and parents living in nearby Hagerstown. Another brother lived in Martinsburg. The Talbotts were deeded their property here on August 26th, 1947 by P. Luther Rice of Frederick. The 1950 US Census gives us a little clue to what the couple were up to, along with a few boarders found living with them at this time. Strange Hall Talbott did not make the papers as far as I can see. He didn’t get in trouble or do anything newsworthy either. His name finally appears in late June upon his death on 18 June 1959 at the age of 77. He would be buried in front of a row of Hemlock trees in Area X/Lot 82. Ora died a week shy of her 61st birthday on February 5th, 1965. I found it only fitting that the paper would boldly refer to her as "Mrs. Strange H. Talbott" in the header instead of Ora L. Talbott.  Talbott Family History In looking again at the Talbott family, I see a major branch in Maryland, and of course another in Virginia/West Virginia. Strange’s family was a shining example of the early “wild west” and westward migration, although he would reverse that trend with his move east 150 years later. I found out more about his ancestors in Barbour County from some old histories of the area republished online. There is even a community named Talbott in honor of founder Robert R. Talbott, who moved here in the year 1846. This is located off Route 48 midway between Elkins and Buckhannon. Robert R. Talbott came from a few miles north of Philippi and built his cabin before he brought the family of a wife and one small child. Supposedly, it took them two days to walk from their former home, and Mr. Talbott carried all of his property on his back while his wife carried their child. Earlier ancestors had come to this part of Virginia from Richmond County at the time of the American Revolution, likely as payment for military service. “The first white settlement in present-day Barbour County was established in 1780 by Richard Talbott – along with his brother Cotteral and sister Charity – about three miles downriver from the future site of Philippi. At this time, the region was still a part of Monongalia County, Virginia. The region had had no permanent Indian settlements and so conflicts with Native Americans were relatively infrequent in the early days. Nevertheless, the Talbotts were obliged to leave their homestead several times for safety and twice found it necessary to retreat back east of the Alleghenies, returning each time. No member of this eventually large family was ever killed by Indian attacks. Over time, parts of the future Barbour County were included in the newly created Harrison (1784), Randolph (1787), and Lewis (1816) Counties. Barbour County, itself, was created in 1843 and named for the late Virginia politician and jurist Philip P. Barbour (1783–1841). (Barbour had served as a U.S. Congressman from Virginia, Speaker of the House, and Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court.) The settlement of Philippi – formerly "Anglin's Ford" and "Booth's Ferry" – was platted, named, and made the county seat in the same year; it was chartered in 1844. By the 1850s, when a major covered bridge was constructed at Philippi to service travelers on the Beverly-Fairmont Turnpike, the county's population was approaching 10,000 people.” My assistant Marilyn Veek attempted to close the gap on the Talbott-Strange connection through Mary Hall and David J. Talbott as I mentioned earlier. She found a not-so-well documented familysearch.org tree which traced Mary’s father, Jonathan Strange Hall to his father Joseph Hall (1745-1824) and mother Mary Anne Hitt (1756-1813). Mary Anne Hitt had been previously married to a man named William George Strange (1760-1795). This would have made her the widow Mary Anne Strange who later married Joseph Hall.

Apparently, there is a legend about Mary Anne’s former husband, William George Strange. This was written by David Sibray this past January and published in West Virginia Explorer Magazine. It’s worth the read, although very “strange” as you can imagine.

0 Comments

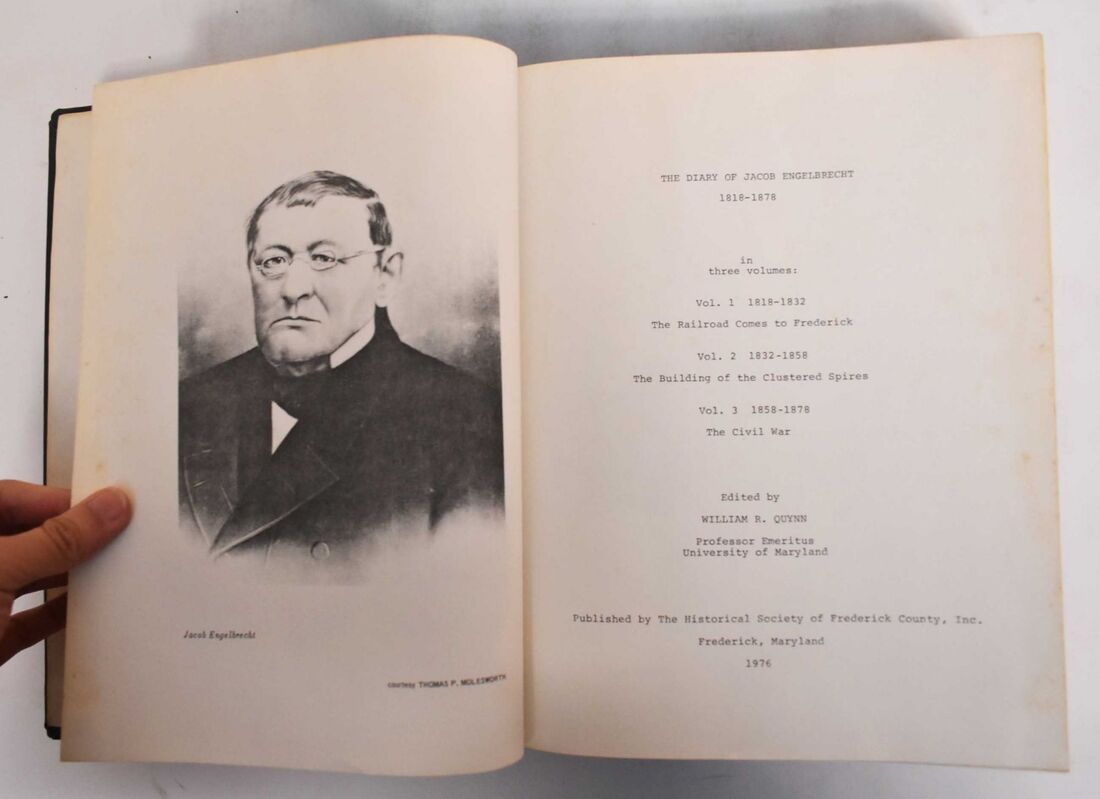

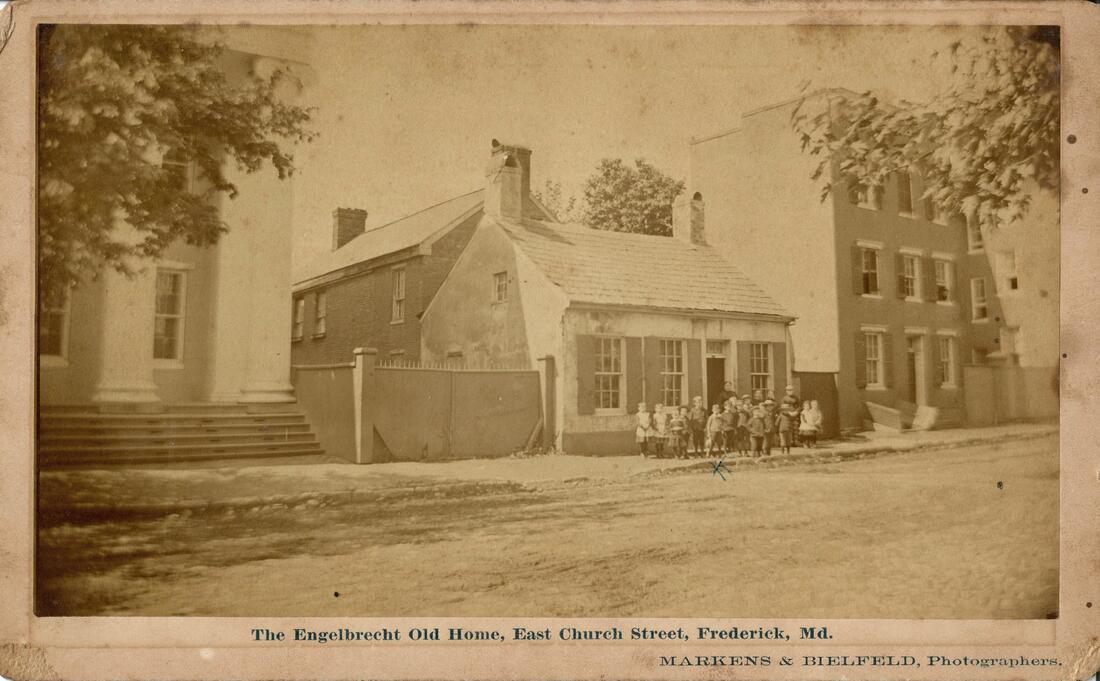

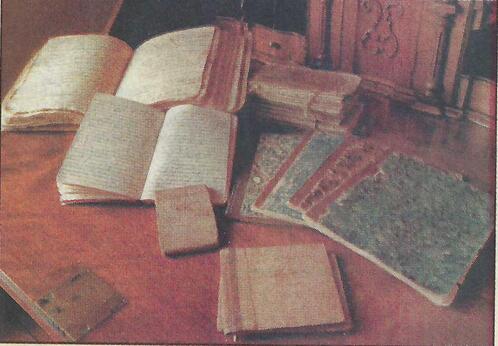

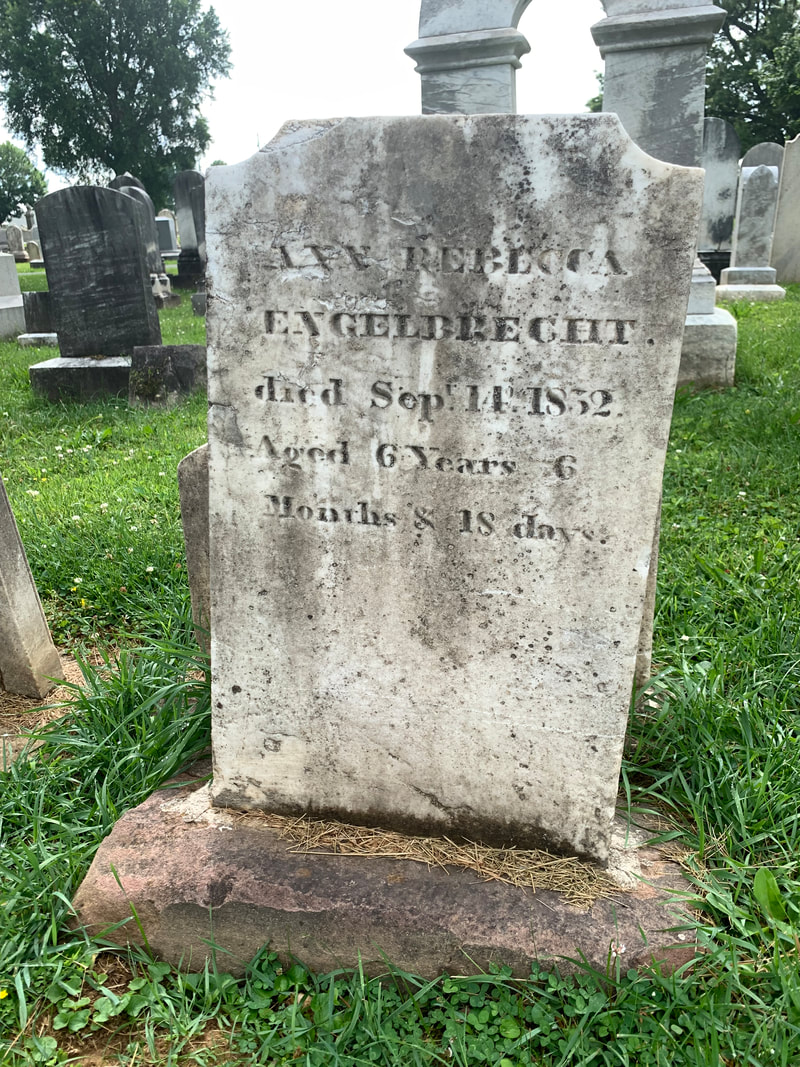

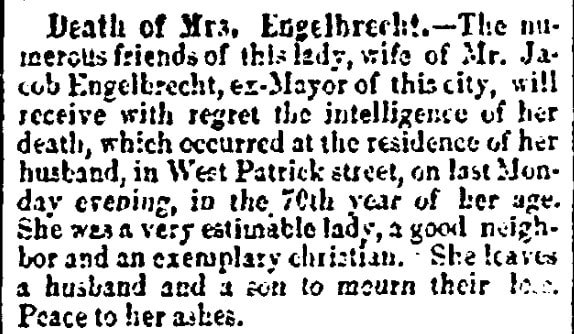

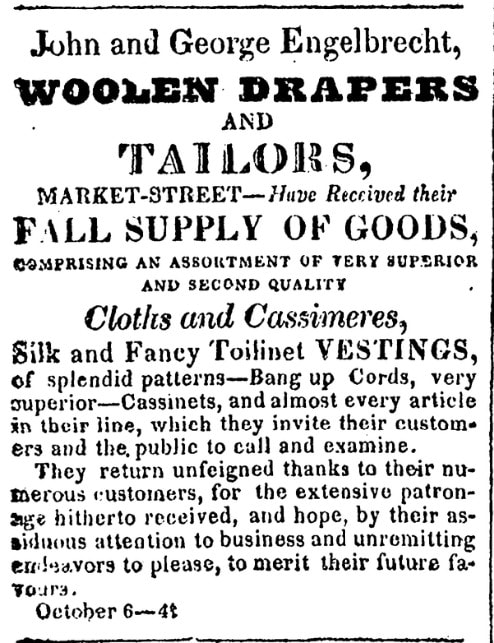

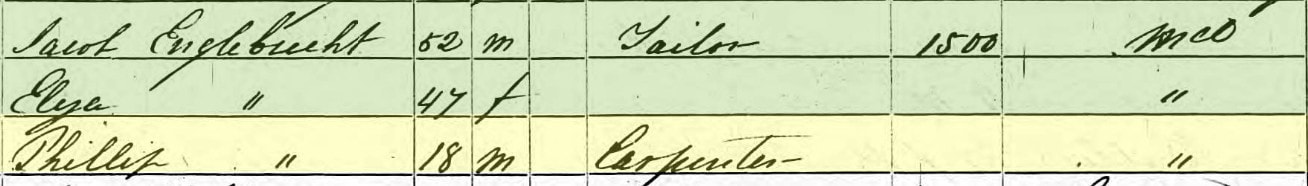

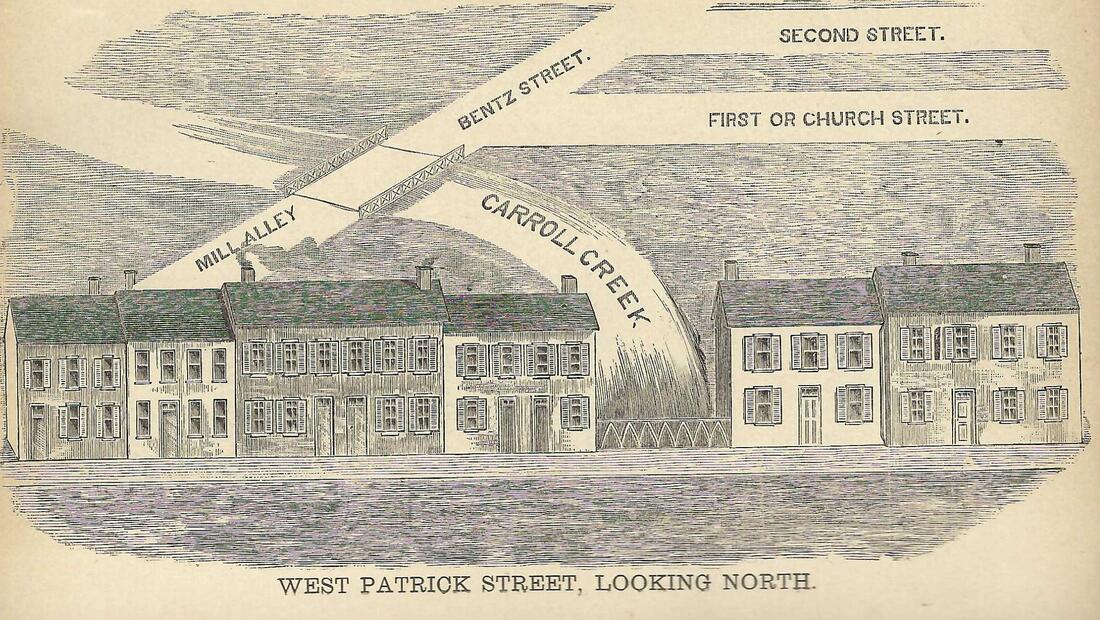

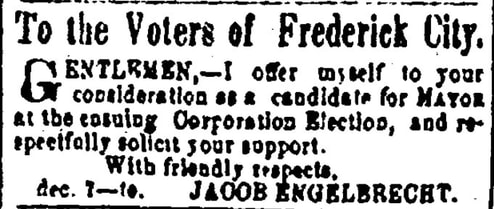

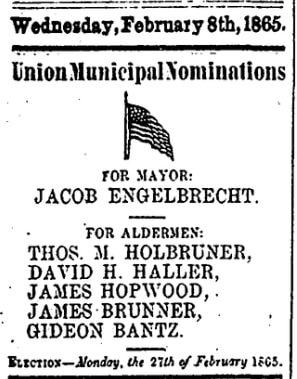

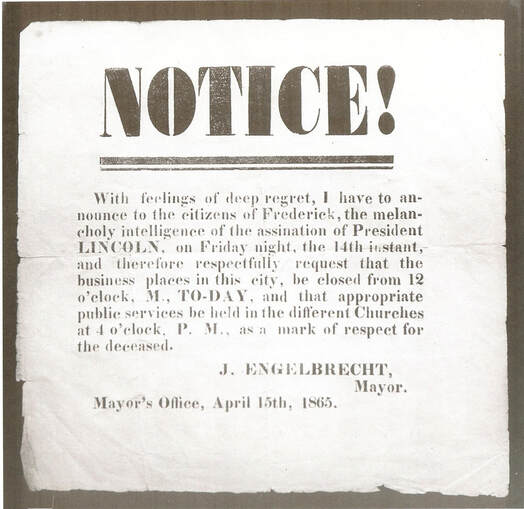

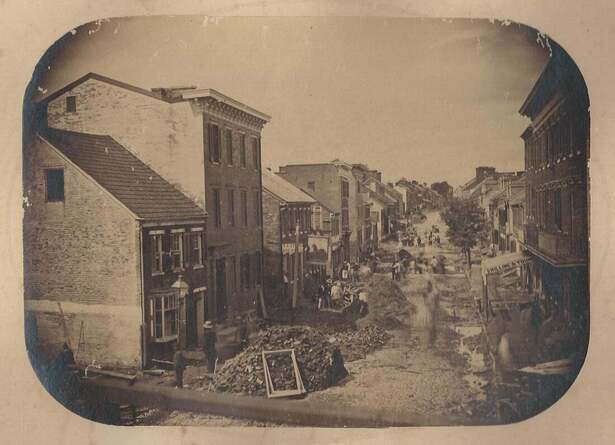

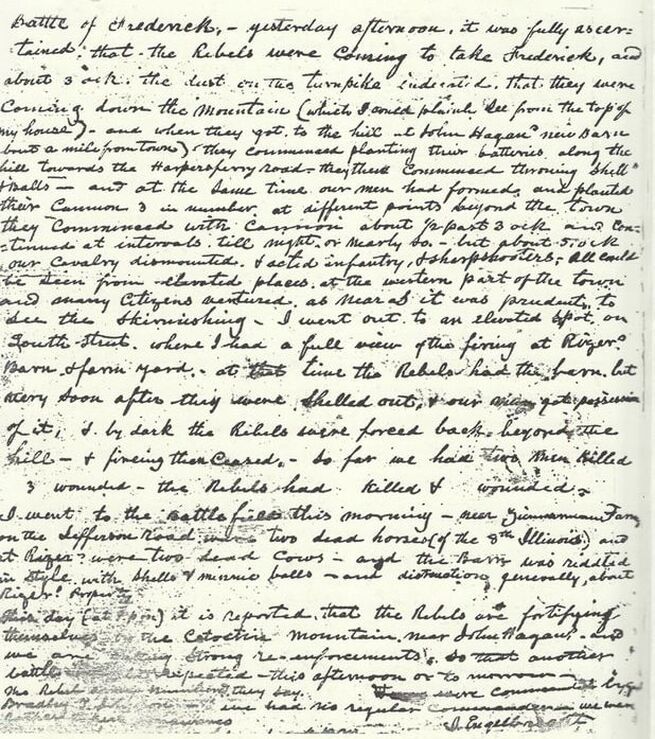

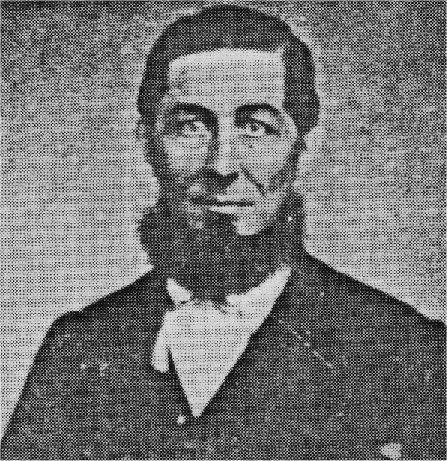

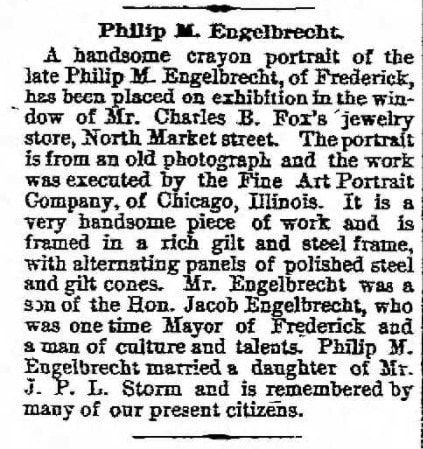

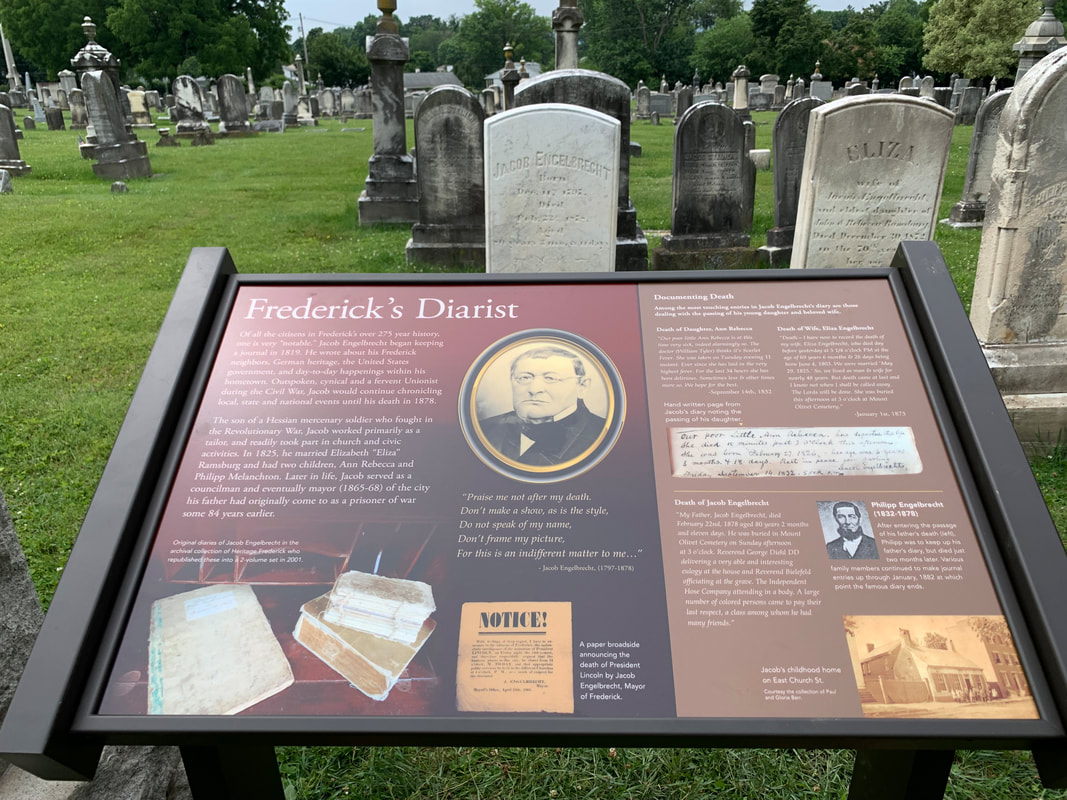

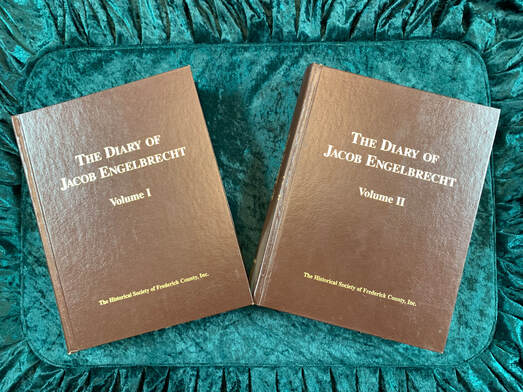

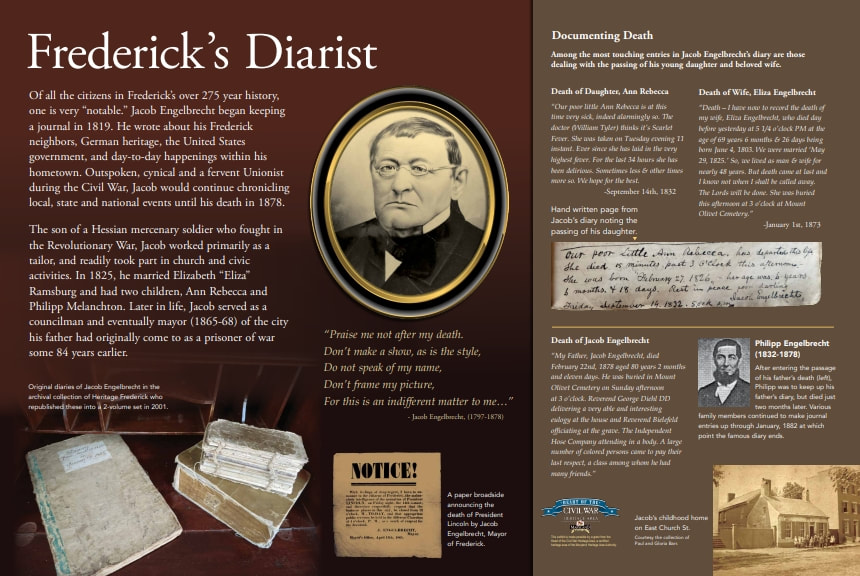

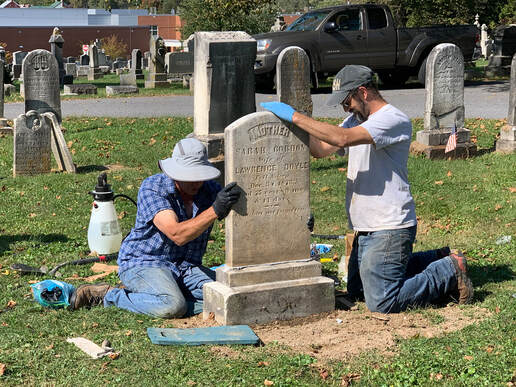

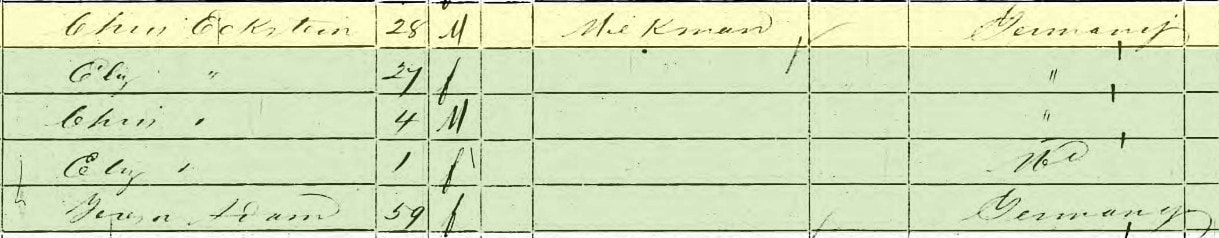

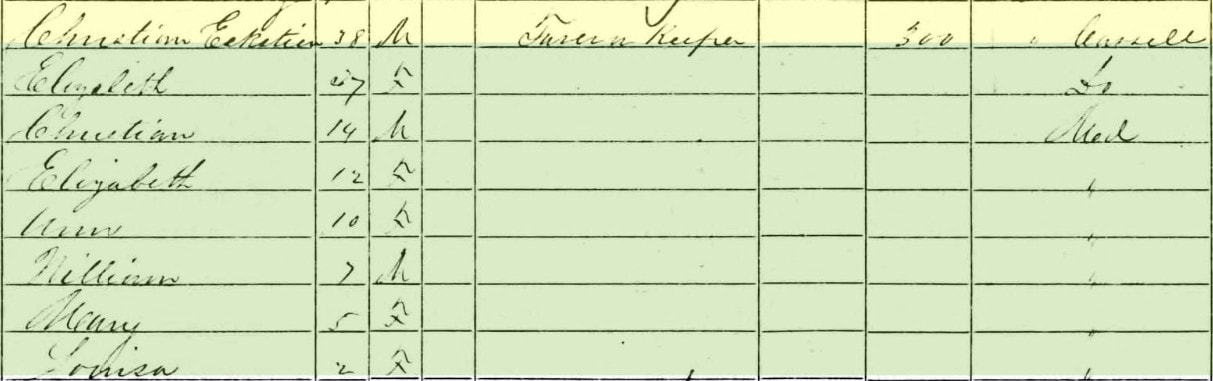

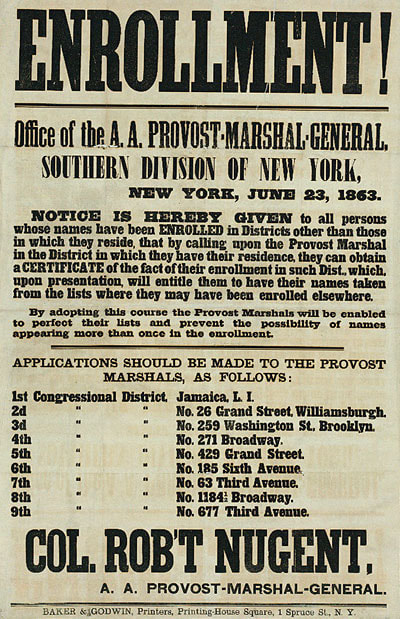

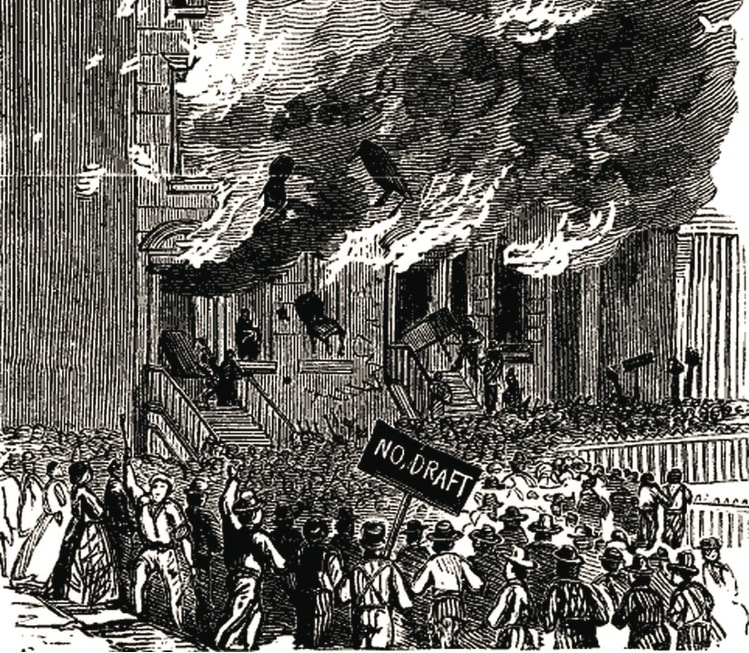

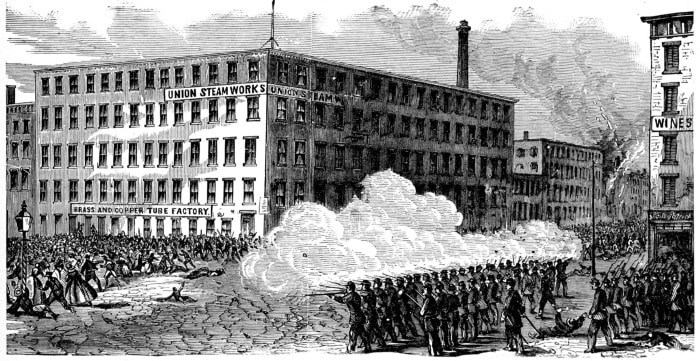

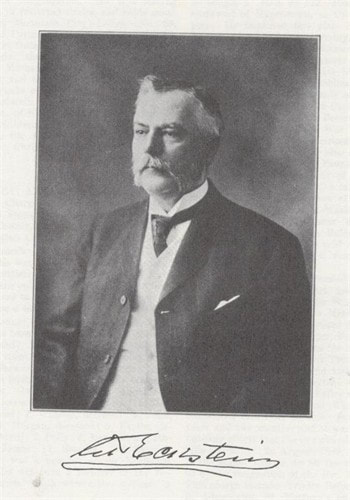

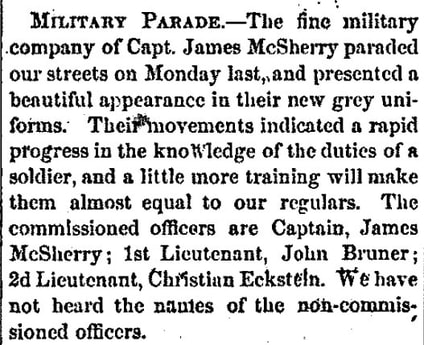

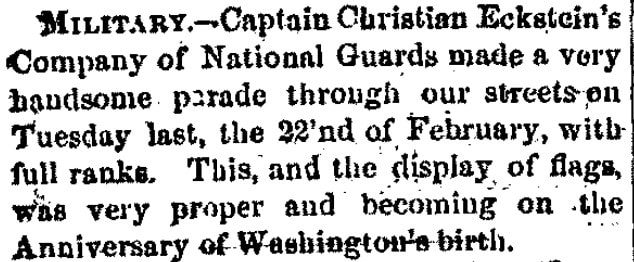

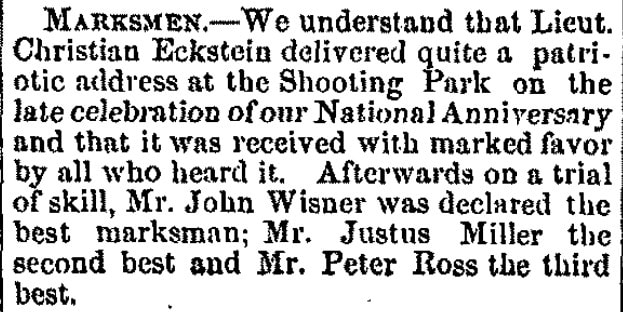

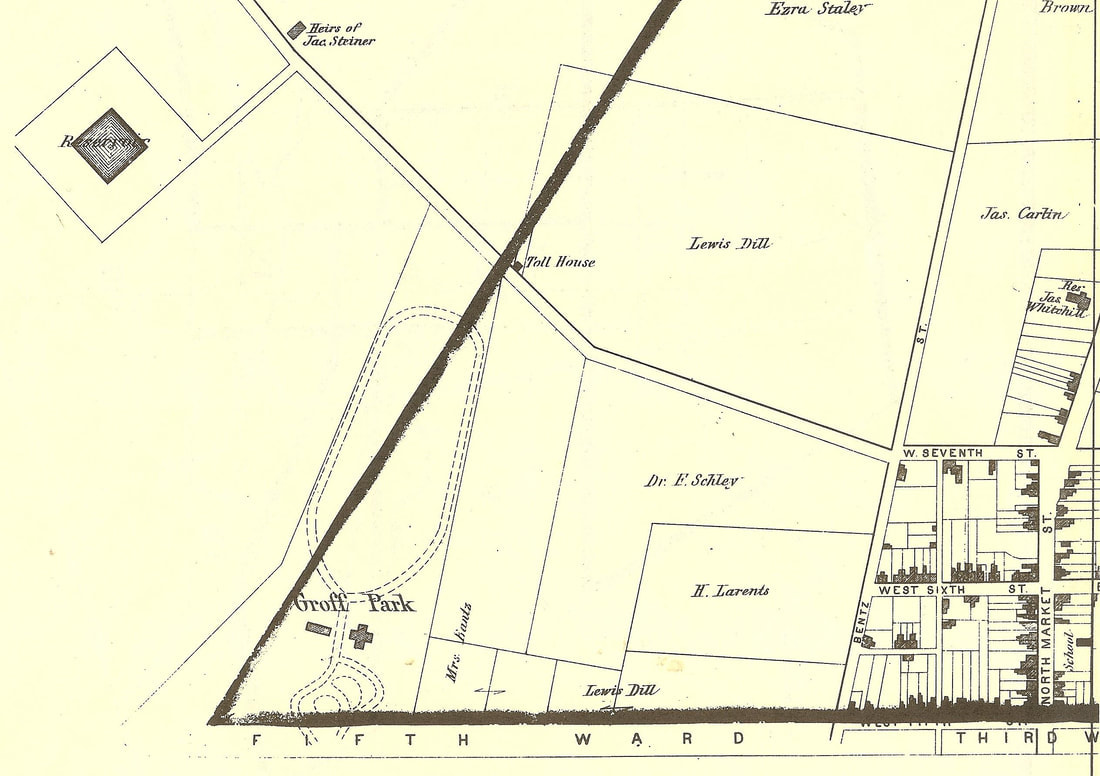

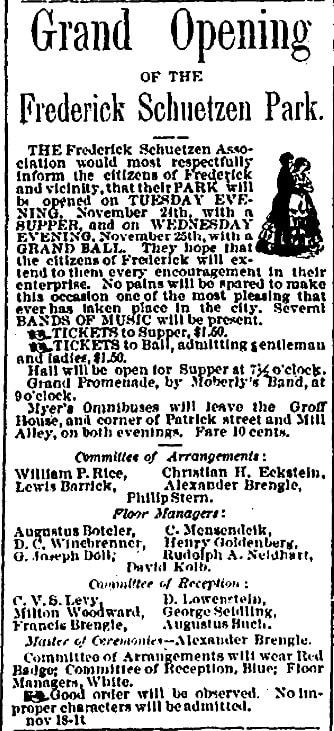

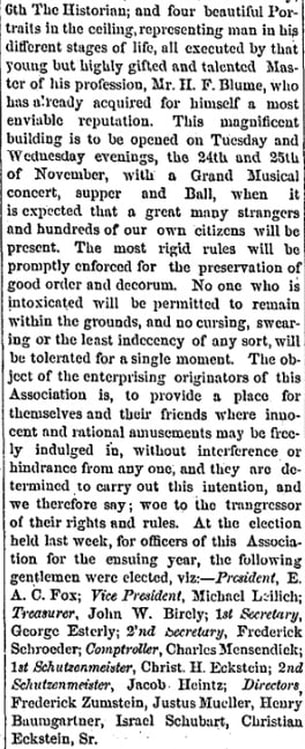

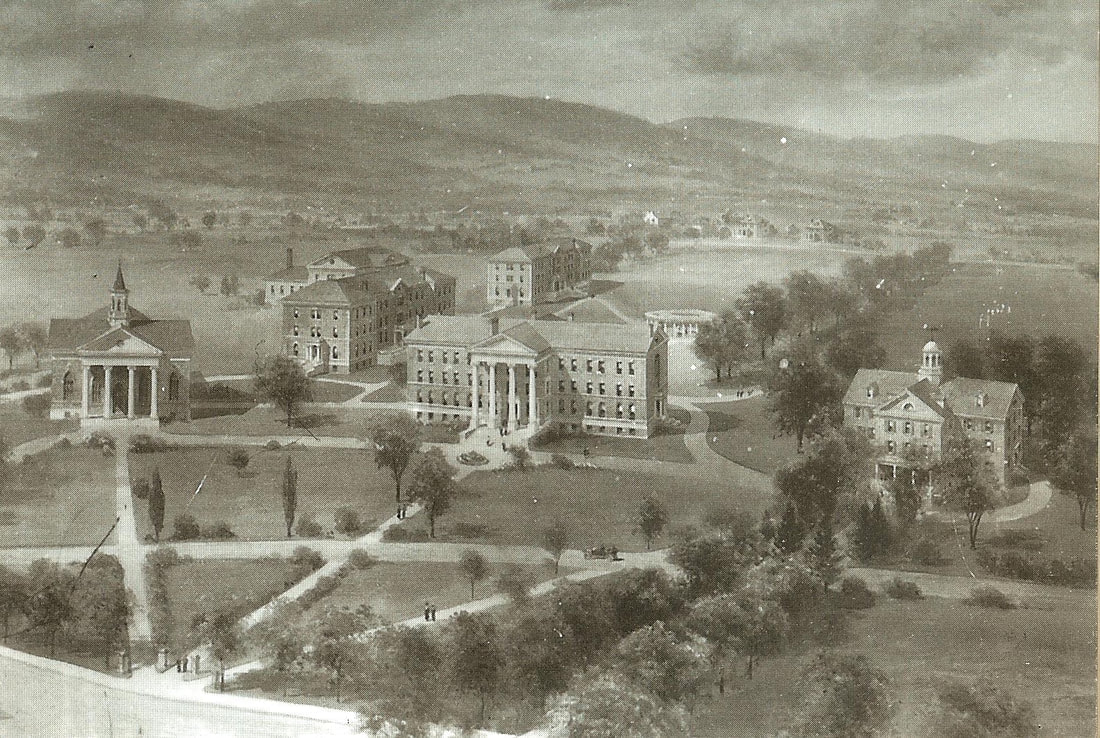

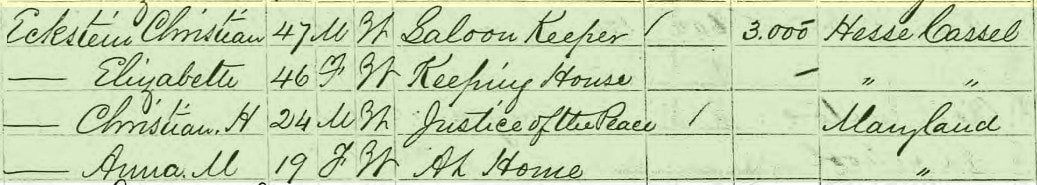

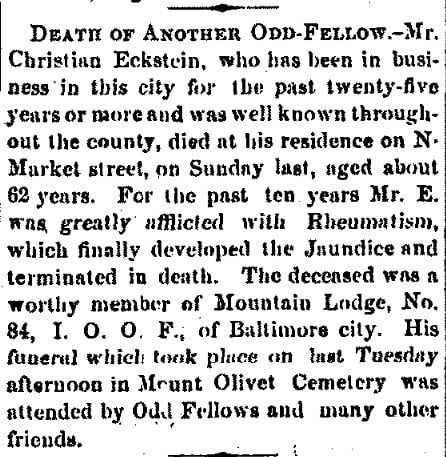

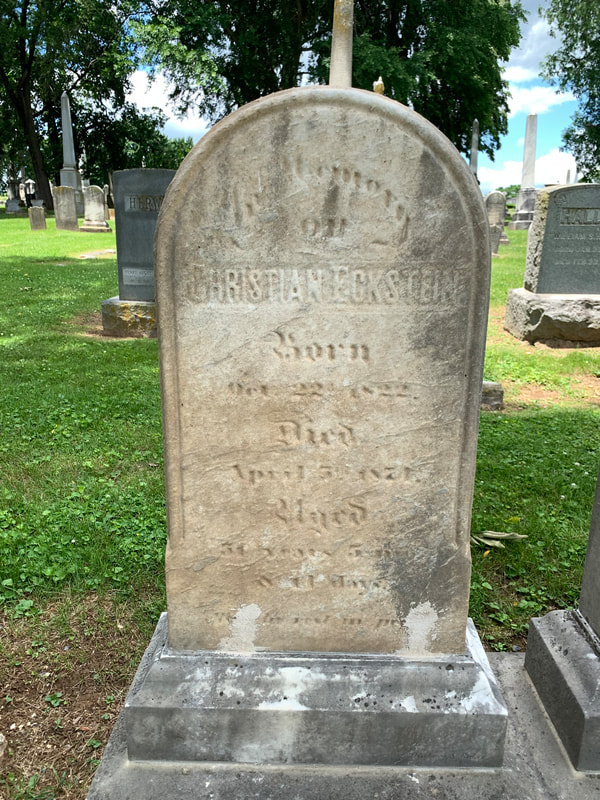

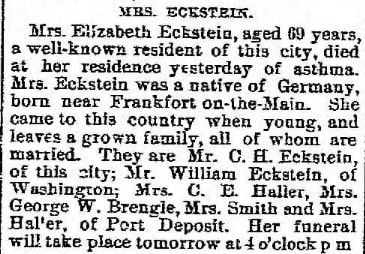

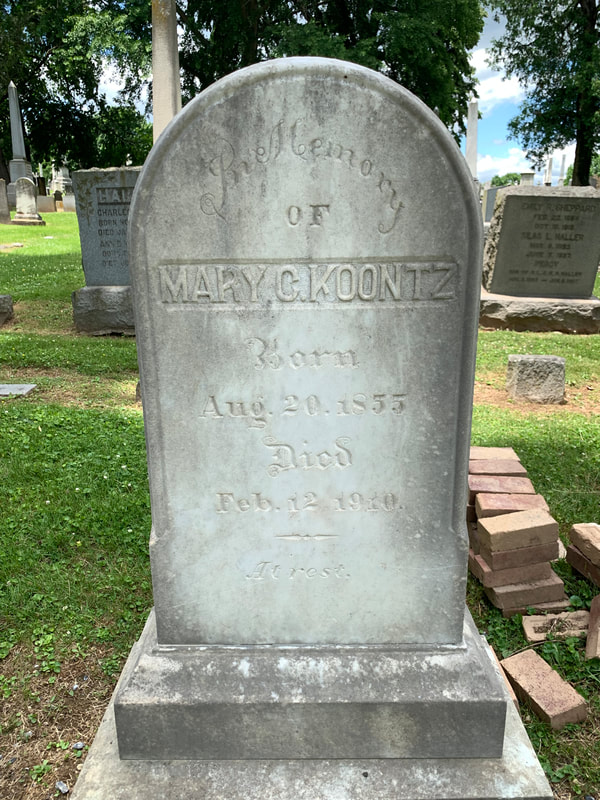

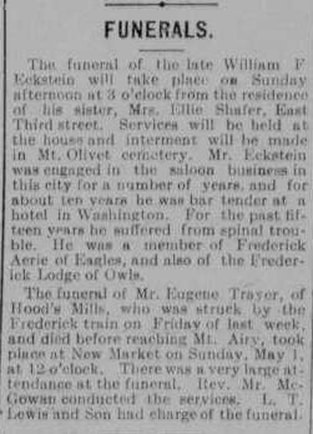

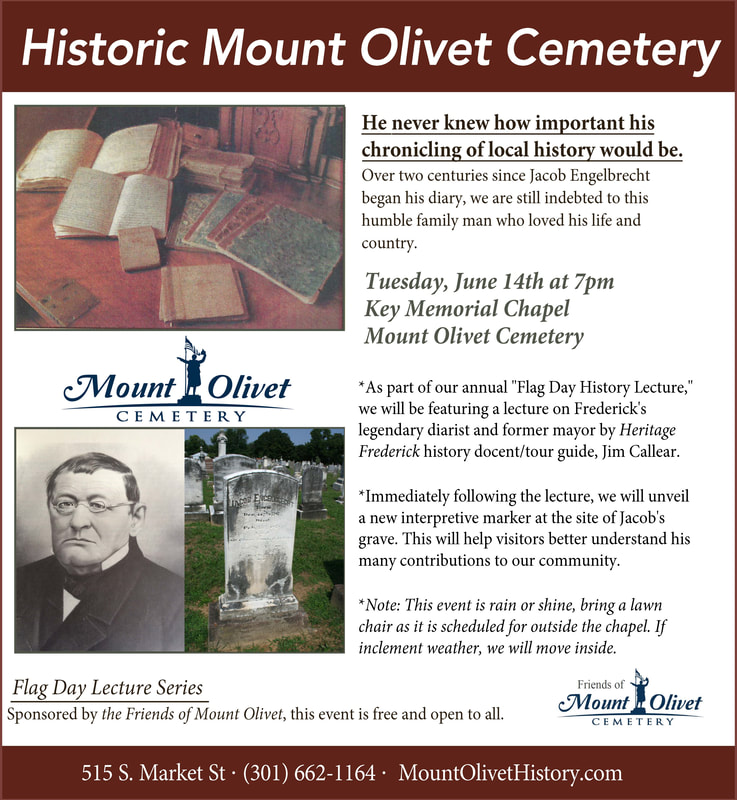

Tuesday, June 14th marked "Flag Day," the annual observation that celebrates the day in 1777 when the United States approved the design for its first flag. Although not a federal holiday, the observance dates back to the 1880s, although there is a claim that it could have started with a first formal celebration in 1861. In 1916, President Woodrow Wilson proclaimed June 14th as the official date for Flag Day, and in 1949 the U.S. Congress permanently established the date as National Flag Day. One more interesting fact is that Pennsylvania celebrates Flag Day as a state holiday. Last year, in 2021, our Friends of Mount Olivet membership group thought it important to recognize Flag Day with some sort of commemoration on site at the cemetery within clear view of the US flag, the same that gave inspiration for our most famous decedent to write what, in time, would become our national anthem. Of course we are talking about Francis Scott Key. We went one step further with creating a Flag Day lecture tradition in which we would feature a local author who has written something connected to Mount Olivet or those buried within. Last year, it was Lori Swerda who wrote a novel called Star-Spangled Scandal about the murder of Francis Scott Key's son, Phillip Barton Key. The dastardly act of 1859 was performed by a sitting congressman from New York, who would later lead troops at the Battle of Gettysburg. This was Daniel Sickles, who eventually beat the charge with the first successful use of the temporary insanity plea. This year's lecture focused on a true Frederick patriot and one-time mayor, whose father came to Frederick in "literal" chains as a prisoner of the American Revolution. Jacob Engelbrecht's father was a mercenary soldier from the German state of Hesse, what we would call a Hessian soldier. He was housed only a block and a half from our cemetery at the Frederick Barracks, which have held the title of the Hessian Barracks since housing these soldiers in the early 1780s. Within a century, the name of Engelbrecht would gain great reputation and respect in the Frederick community. Jacob had a big hand in "turning lemons into lemonade" through his work as a tailor and civic involvement. Interestingly, his neighbor Barbara Fritchie helped the public relations aspect of her last name as well because her father-in-law was on the wrong side of history during the Revolution as a Tory Loyalist. He unfortunately was executed for his treason, where the Hessian soldiers were welcomed warmly into the community with definitive German settlement origins dating back to the 1730s and 1740s. June 14th, 2022 was a beautiful night to salute the flag and learn about a gentleman who kept a diary of Frederick events from 1819 up through his death in 1878. To recount his life story and achievements, Heritage Frederick docent and tour guide Jim Callear prepared a nice speech to share with our participants. It was so nice and original, in my humble appraisal, that I asked Jim, a professional antique appraiser, himself, if I could republish here as the crux of a "Story in Stone" article. The following is a transcript of Jim Callear's presentation on Jacob Engelbrecht. I am honored to be speaking on Jacob Engelbrecht and his diaries on this special occasion. Before I address Engelbrecht and his work, I want to acknowledge the work of those who ensured that his diaries could be printed and accessible to the public: his family, who preserved the diaries and made them publicly available; Professor William Quynn who first published the diaries in 1976; Paul and Rita Gordon, whose tireless efforts led to the republication of the diaries in the current, expanded format; Mark Hudson, executive director of Heritage Frederick; and others who handled all phases of the editorial work that went into moving the words from Englebrecht’s handwritten diaries to the printed page. Even without the diaries, the Engelbrecht family would have merited our attention because of their role in the early settlement of Frederick. Jacob’s father, Johann Conrad Engelbrecht, was born in Bavaria, fought for the British, and came to Frederick by way of Yorktown, where he became a prisoner of war in 1781. After marching from Virginia to Maryland, he joined other prisoners at the Hessian Barracks. After news of the peace treaty with Great Britain reached the colonies in 1783, the Hessian Barracks prisoners were given the choice of staying in this country or going back to Europe. Engelbrecht stayed and soon married the daughter of a local schoolmaster. They went on to have 10 children, one of whom was Jacob. The story of Conrad, Jacob, and their succeeding generations embody the assimilation and success of many of the immigrant settlers in Frederick. I want to turn to the diaries now. In his forward to the diaries, Paul Gordan noted that Jacob Engelbrecht had several occupations – tailor, shopkeeper, cabinet maker, council member, and mayor – but had many other “preoccupations.” We know of his passion for music – he was both a member of a choir and a band member, playing the French horn. He loved to garden and he was an expert in the care and development of fruit trees, frequently telling us of his experiments in grafting the branch of one fruit tree to another. He was a traveler going to other cities on the East Coast, where he would act as his own tour guide, finding churches, government buildings and historic sites to visit and observe. And, of course, he liked wandering around Frederick. In reading Engelbrecht’s diaries, one thing is clear: he had an insatiable curiosity about his world and the people in it. I am going to briefly explore five areas where Engelbrecht recorded facts that reveal something about his world. Not only do we learn about the people and places he recorded, but we also learn what kind of person Englebrecht was. First and foremost, Englebrecht was a dispassionate recorder of facts, particularly when it came to the weather, prices of food items, deaths and marriages. We might be told whether the bride or groom was an immigrant from Europe, or the son or daughter of a family in Frederick, and who the officiating minister was. With regard to deaths, there are few character judgments and even less on how the individual deaths may have affected him. An exception to this was his diary entry regarding his daughter who died at the age of 6 from scarlet fever. “Rest in peace poor darling.” (9/14/1832). His brief entry hides the real pain he must have felt because on September 14, 1861, he wrote, “This day it is 29 years since the death of my little daughter Ann Rebecca . . . . Were she now alive, she would be 35 years 6 months & 18 days old. She died of scarlet fever.” His wife’s death was recorded with a few more details than his usual death entries but with more apparent acceptance than his daughter’s death because of his wife’s age. (1/1/1873). Another death that warranted more than his usual factual recitation was that of Roger Brooke Taney, whom he tells us was buried “in first rate Catholic style.” (10/15/1864). Another area where Engelbrecht is very guarded in what he tells us is his work. What is clear from the diaries is that Engelbrecht is very good about separating his work life from his personal life (or as Paul Gordan stated his “preoccupations”). There are few entries that deal his work as a tailor or shop keeper. One entry documents that Engelbrecht sold the contents of his shop and returned to tailoring with his brothers in the shop that his father formerly ran. (5/7/1841). Another entry describes how he had to stay up late to finish work on mourning clothes for a customer who had to attend a funeral the next day. (11/26/1821). But, Engelbrecht does not tell us much about who his customers were, where he bought his supplies, or whether he had help in his shop. He had several apprentices, but he records only when they came to work for him and when they left. Third, there were areas of Engelbrecht’s life that he was deeply passionate about: politics, abolishing slavery, and preserving the Union. He was a diehard Republican and kept score on wins and losses in both local and national elections. Engelbrecht’s views on slavery were clear. When the new Maryland constitution was adopted in 1864, Engelbrecht writes, “From this day forward and forever . . . Maryland is free from the foul blot of slavery – until yesterday there were more than 90,000 slaves . . . (& about 80,000 free blacks). ‘All men are created free.’” (11/1/1864). His view on the Union and its preservation are equally unequivocal. Just prior to the Civil War, he recorded the secession of several southern states and stated, “Maryland will never leave our glorious union, at any rate not by my consent.” (1/21/1861). At a Union pole raising signifying opposition to secession, he wrote, “The Constitution and the Union, now and forever, one and Indivisible.” (1/21/1861). Four years later at the end of the Civil War, Engelbrecht noted that the cost of the war was $2,600,000. He concluded, “the Union of this government is cheap even at that price . . .. In the gloomiest time, I did not believe that God would forsake our government & country.” (8/8/1865). Fourth, we see glimpses of his humor, his interests in entertainment, and his humanity in his diaries. Engelbrecht’s efforts at humor were sporadic and subtle: “There is an eclipse of the moon . . . at twelve o’clock, but I can’t think of staying up to see . . . a corner of the moon off. If I get sleepy, I’ll eclipse it to bed that’s better.” (2/5/1822). “Yesterday morning I bought a half ticket to the ‘Maryland State Lottery’. . . . So I have half a chance to win nothing.” (7/31/1821). Engelbrecht showed us that Frederick was not just a place where people worked – they also played (at least a little bit). There were domesticated snakes at Talbot’s Tavern (10/4/1822); there was rope dancing with Jacob Engelbrecht and his band providing the musical accompaniment (8/29/1822); and lions, tigers, and talking parrots on North Market Street (4/7/1835) – all available at low admission prices. It seems that we must include in the entertainment category, public executions. One in particular was noteworthy – John Markley, who murdered 6 people in the Newey house, was hung at the barracks before a crowd of three or four thousand, Engelbrecht estimated. (6/24/1831). I am not sure whether this rates as humor or entertainment, but as I was looking through the index under Engelbrecht’s wife’s name, I saw “weight” listed as a diary item. In fact, there were two entries. Well, to my surprise, getting weights taken back then was no easy matter – there were no bathroom scales were there? Jacob, his wife and their daughter made a trip to a local mill and were weighed, and if you need to know Jacob weighed in at 160 lbs. and his wife at 113 lbs. (4/18/1826). Humanity is defined as one’s compassion to his fellow man. We see incidents of Engelbrecht’s humanity in his diary entries. He tells us of an enslaved boy of 13 who was in his shop, and Engelbrecht learned that he did not have a name. “I took the liberty with his consent of naming him . . . . I gave him the name on a piece of paper which he promised to preserve and be governed accordingly.” (12/21/1824). On another occasion, Engelbrecht appeared before a lawyer to verify under oath that an African American was free and had been born to parents who were free. The purpose of this was to enable the man to obtain a certificate of freedom from the clerk of the Frederick County Court. 7/12/1825. Finally, where Engelbrecht excels as a diarist was in recording events in Frederick. For instance, there are nine diary entries pertaining to the flooding of Carroll Creek. Engelbrecht describes how Barbara Fritchie’s original house on the creek was torn down so the creek could be widened. (4/8/1869). Who knew the city’s flood control efforts started back them? Engelbrecht used that diary entry to write that the flag waving incident, memorialized in the poem by Whittier, “is not true.” (4/8/1869). Another interesting event he recorded was the beginning of the McMurray Canning Co., which he said many had predicted would fail. Engelbrecht’s response was that it might as well fail in Frederick Co. as else any other county. (3/27/1869). Of course, McMurray went on to employ nearly 1000 workers and produce 1 million cans of corn in one season. Of tremendous importance are his diary excepts that relate to the Civil War, Antietam, and the Battle of Monocacy, because they illustrate Engelbrecht’s view of major events going on around him that also affected the city, state, and nation. These diary entries reminded me of a program in the early days of television where news anchor Walter Cronkite would be at history-making events during the past centuries. At the end of the program, after Cronkite summarized what had happened and stated, "What sort of day was it? A day like all days, filled with those events that alter and illuminate our times... all things are as they were then, except you were there." That is the way these diary entries affect me. Jacob Englebrecht’s diaries are a gift to us, because they are our unique connection to the history of Frederick, Maryland, and the nation for a span of 60 years. I have come to understand that my appreciation for the diaries rests on their being a very personal connection to Frederick’s past, more so than our historic houses and the antiques in them. For this, we owe Jacob Englebrecht our recognition and gratitude. In addition to giving us a connection to our history, he also shows us what it means to be connected to a community, not only through his words in the diaries, but through his life, his public service, his loyalty to his city and country, and his humanity. It is fitting that we honor him as we do today. In conclusion, I will simply say as Engelbrecht did in many of his early diary entries, “So we rub along.” 5/22/1822 Jacob died on February 22nd, 1878 at his home in Frederick along Carroll Creek on W. Patrick Street. He would be buried in the family plot (Area H/Lot 276) alongside his wife and daughter. His son Philipp would take up the charge of recording this event in his father’s diary: “My Father, Jacob Engelbrecht, died February 22nd, 1878 aged 80 years 2 months and eleven days. The immediate disease of which he died, inflammation of the bowels. He was buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery on Sunday afternoon at 3 o'clock. Reverend George Diehl DD delivering a very able and interesting eulogy at the house and Reverend Bielefeld officiating at the grave. The funeral was largely attended. The Independent Hose Company attending in a body. A large number of colored persons came to pay their last respect, a class among whom he had many friends.” Philipp was to keep up his father’s diary, but died just two months after Jacob. Various family members continued to make journal entries up through January, 1882 at which point the famous diary ends. After Jim's lecture presentation, participants were invited to take part in a special wayside interpretive marker unveiling at Jacob's gravesite. The honors (of unveiling) were done by Beth Molesworth, Jim Callear and the marker's graphic designer Ruth Bielobocky of Ion Design (Charles Town, WV). Ms. Molesworth is a descendant of Jacob Engelbrecht and helped make the marker possible, with additional monetary support in the form of a mini-grant from the Heart of the Civil War Heritage Area. She was kind enough to say a few words about her famous ancestor, and gave thanks on behalf of her family that the famed diarist's story would be shared with visitors, tourists, lot-holders and local residents alike through this cemetery amenity. Ms. Molesworth shared that her uncle, also named Jacob L. "Jake" Engelbrecht was the one who inherited the diaries, and later donated them to the Historical Society. This gentleman was the grandson of the diarist and made this gift to the Society in 1958. In 1976, the diaries were transcribed and published for the first time. They would be republished in 2001. Our story title is sure to attract attention, but won't likely make sense until you finish this article. On the last day of April, we hosted a workshop in conjunction with Preservation Maryland. Folks from around the region representing a number of cemeteries, big and small, were on-hand to learn best practices associated with cleaning and repairing gravestones. As many of our readers know, this certainly wasn’t our first “rodeo,” as we (ironically) “live and breathe” cemetery preservation here, usually holding annual workshops of this kind. I relish the opportunity of having Mount Olivet play the role of “restoration classroom,” because we benefit greatly. Each session brings the promise of repairing a handful of our unfortunate collection of downed, and damaged, stones. They are either brought back to their original state, or at least, a highly acceptable one state based on the damage suffered over the decades. A great article on this workshop appeared the following Monday (after our Saturday session) in our local newspaper. It certainly helped raise awareness to not only the problem that besets old, historic cemeteries in regard to preservation, but more so, the message was conveyed that we can make a difference simply by an effort being made to garner time, money, know-how and volunteers. Gravestones can be cleaned, fixed and repaired if an effort is made.  Jonathan Appell, Atlas Preservation Jonathan Appell, Atlas Preservation The News-Post reporter, Mary Grace Keller, was very enthusiastic during her short time with us, and I can say with surety that she perfectly captured the spirit of what we are trying to do. And how could she not with “yours truly” in one ear, and more so, the distinguished experts we had on hand to lead the workshop. Ms. Keller had the chance to briefly interview three others who are among the tops in the respective preservation game on a state and national level. The session on this day was being led by our old friends Jonathan Appell and Moss Rudley. As one of the nation’s foremost gravestone restoration experts, Jonathan operates Atlas Preservation out of his home headquarters in Southington, Connecticut. As I write this article, he is currently in Nebraska, as part of his “48 State Tour” in which he is presenting workshops of this nature in cemeteries in all 48 continental states of the country.  Moss Rudley, NPS Moss Rudley, NPS Based here in Frederick as the superintendent of the National Park Service’s Historic Preservation Training Center, Moss is well known both locally and nationally, and equally well-traveled throughout the U.S. and highly respected. For those not familiar with this unique NPS unit, headquartered here in Frederick, I will share this part of its mission statement from the center’s webpage: “The HPTC utilizes historic preservation projects as the main vehicle for teaching preservation philosophy and building crafts, technology, and project management skills. Their experiential learning approach emphasizes flexibility in addressing the unknown conditions encountered during projects and ensures that the goals of preservation are met.” The operation serves NPS historic sites throughout the country and has its executive headquarters at the Gambrill Mansion on Monocacy National Battlefield, and a workshop facility on Commerce Street, immediately next to my old stomping grounds of the Frederick Visitor Center.  Last, but certainly not least, we had Nicholas Redding here with us on site at the time Mary Grace observed the workshop. Nick is a Walkersville resident and also the individual primarily responsible for setting this special session up in the first place. He serves as president and CEO of Preservation Maryland, a non-profit based in Baltimore that works to protect the state’s heritage and historic structures. Mary Grace had a front row seat to view these master craftsmen and volunteers in action. At this time in the program, they were working on a gravesite in Mount Olivet’s Area C. Two large dyes (principal piece of monuments with information inscribed) had toppled, likely years ago. This commonly occurs due to unsound foundations. Today, grave monuments are usually placed atop substantial concrete foundations poured over well compacted earth. The same “terra firma” covers sound, concrete lined burial vaults which contain the caskets. Concrete vaults further improved upon the use of perma-crete vault liner kits introduced in the 1930s. However, in yesteryear, fixed compartments containing the casket were not always the norm. Interestingly, the absence of a vault for many graves in our historic parts of the cemetery doesn’t seem to cause many future issues. This is relative when you think about it due to the fact that if you had little to spend on the burial, you likely had little to spend on the grave monument. Small monuments cause small problems, as opposed to medium and large-sized gravestones. We commonly see vintage era children’s graves covered by small stones. However, gravesites with vaults and dirt shoulders are a potential problem, and, in many instances, have not been able to last an eternity. For an explanation, a dirt-shouldered grave is one in which a rectangular hole accepted the casket, and a piece of slatestone serves as a lid being supported by opposing ledges of dirt. A step up from this practice came with a request for a brick-lined vault, which called for a mason to build four walls to accept the casket. Sometimes cement was used to join the bricks, however there were many more that just had bricks stacked to form walls with no joining agent whatsoever. In some cases, a floor was actually laid, other times not. Regardless, a piece of slatestone was also employed here as a ceiling topper for this custom-made casket vault. After the graveside services and placement of the coffin in the respective vault, dirt was shoveled back in the hole to cover the slatestone and entirety of the brickwork up to surface level. Lastly, after allowing for settling and more compaction, a heavy monument was added in the same vein a cherry is added to a sundae. Over time, the slatestone covering of the vault, or the brick walls can fail, collapsing earth into the casket and vault cavity below. With this ground shift, a monument above and once level, now leans or has fallen over. This may be enough to topple some large monuments, especially multi-piece structures that are simply stacked pieces relying on the laws of gravity. If the monument doesn’t collapse at first, the occurrence into an angled position, may allow water (in the form of rain or snow) to reach iron pins that traditionally connect a base stone to the upright backboard (called a dye). The pins can expand and contract based on weather conditions and commonly fracture marble tombstones toward the base. These eventually will rust as more water reaches the pin at open fracture points. The pins become brittle and eventually break, causing the dye to fall over—hopefully not into another gravestone. After that laborious explanation, I will say that the repair at hand, captured in the News-Post photo in Area C/Lot 22, did not involve the level of complexity needed for the stone situations pictured above. Those would need extraction of old pins (which is pretty tricky), pin replacement, and filling fractures, etc. The current repair featured two stones that were not joined by pins. these had simply leaned to a point of toppling over. Our repair involved the addressing of the ground level foundation with dirt and gravel, first and foremost. With the base stone now put to a perfectly level position, a special tripod was used to lift the dye into place (atop the leveled base below). Lead strips were used to re-set the monuments. Christian Eckstein The reporter asked if I knew who the decedents connected to these specific gravestones were? I asked her to give me a minute as I had no idea, John and Moss simply decided to spotlight these graves for the afternoon repair. I did some quick, on the spot, research courtesy on my phone and learned that the plot owner was one Christian Eckstein, who died in 1874. His wife, Elizabeth, was to his right and had passed in 1892. A stone to the left of Christian was illegible, with the dye actually broken in half with a diagonal fracture. I would later find this to be William F. Eckstein (1856-1910). One more individual, Mary C. (Eckstein) Koontz (1856-1910) is buried to the right of Elizabeth and was a married daughter of the couple whose grave monument is in perfect shape. Both Christian and Elizabeth were natives of Germany. Christian was born on October 22nd, 1822 in Dernichein in Hesse-Kassel, Germany. His wife, the former Elizabeth Kepple, was also from Derniechein as well. The couple married on April 26th, 1841. Four years later in 1845, they immigrated to America, landing in Baltimore. This is where we find the Ecksteins in the 1850 US Census. They would welcome their first-born child, Christian Henry, on October 10th, 1845. The couple would go on to have even children from my research. Christian is listed as a milkman, a “milchmann” in the Eckstein’s native tongue. I would find his son Christian H. Eckstein’s biography in T. J.C. William’s History of Frederick County (published in 1910). It said that Christian Eckstein “successfully followed the dairy business until 1854, in which year he removed to Frederick.” In the 1860 census, Christian is listed as operating a tavern. I learned that he may have started at the noted Dill House that once sat at the corner of West Church and Court Street. I did an earlier story on the origins of this location, now represented by a stellar, macadam parking lot serving the Paul Mitchell Temple and M&T Bank. I was fascinated to learn that, although German, Christian was outspoken during the American Civil War. Where most Germans and Irish immigrants backed the Union, I don’t think many were particularly excited to fight a war. Just check out the 2002 Academy Award ® winning film of the year by Martin Scorsese, The Gangs of New York, for proof of this statement. The film includes a scene dealing with the infamous New York City Draft Riots of mid-July, 1863. This occurred a few weeks after Gettysburg as President Lincoln instituted a mandatory draft. This did not sit well with the Bowery Boys and others. Of course, dissenting stories of valor surround immigrants in local action such as the famed Irish Brigade (69th NY Infantry) at Antietam, and heroics of Paddy O’Rorke at Little Round Top in the Battle of Gettysburg. In this blog, I’ve also chronicled the bravery of Capt. Joseph Groff of Frederick, extremely proud of his German heritage, as he fought for the Union in the Potomac Home Brigade. In doing more study, I theorize Christian could have seen war much the same as Leonardo DiCaprio’s character of Amsterdam Vallon. You escaped mayhem in the “old world” to come to this country, and you’re trying hard to eke out a living here. Then you get drafted and forced to fight a “rich man’s” war in which the politicians and wealthy, who have the most to gain, can get their son’s a replacement soldier to fight in their place. Eckstein was from Hesse-Cassel, the German state known for the famed Hessian soldiers. These mercenary soldiers were rented out by Frederick II of Hesse to Great Britain to fight us in the Revolutionary War. Many of these Germans stayed here after the war instead of going back to a country. Why not, their former leader forced them into servitude. One such Hessian who stayed was Francis Klinehart, namesake of Klinehart Alley. He was a tavern keeper whose daughter married Joshua Dill, founder of the tavern that took his name. Anyway, Eckstein surprised me because he was outspoken in his support of the South. An article found in 1861 lays claim to this fact as Christian voiced his opposition to President Lincoln in a church service at the German Reformed Congregation (Trinity Chapel). Perhaps this was in response to pacifying southern leaning clientele at the tavern, located just a few doors down the street from the church. I’m assuming that Christian also wanted to keep in good grace with the many firefighters who doubled as militia, and frequented his popular tavern. He was also a member of the Junior Fire Company. Either way it seems he did his best on behalf of the Southern Cause in the form of getting Union soldiers drunk. Eckstein had opened his own bar by 1862, which would take his name. This was located on the northwest corner of North Market and third streets. This location at 301 North Market Street, also doubled as his home residence as far as I could tell. Diarist Jacob Engelbrecht notes the following event in his diary on July 14th, 1862: “Lager beer saloon—Mr. Christian Eckstein, who keeps a lager beer saloon at the corner of Market and 3rd Street, was called on by the Provost Marshal & his posse with a wagon, & took 21 kegs of lager beer other article in his line. Government reason, selling liquor to the soldiers. This happened on Saturday evening last 12th instant.” The war came and went, and I’m sure Mr. Eckstein sold plenty more alcohol to the various soldiers of both armies who visited our city along the way. Weeks after the surrender at Appomattox in April, 1865, Christian Eckstein embarked on a sojourn back to his native homeland (Germany) accompanied by a friend and fellow resident named Jacob Schmidt, who kept the Black Horse Tavern located on the famed bend in the second block of West Patrick Street. They left town by train on May 15th and returned on August 30th after a pleasant trip. Upon his return, Eckstein saw his eldest son, the fore-mentioned Christian H. Eckstein (1845-1917), join the Frederick Bar in 1866, and pursue politics. Like is father, he was an ardent member of the Conservative Democrat Party who would become one of Frederick’s most outstanding citizens of his time as a longtime Justice of the Peace appointee. Our subject's son Christian H. Eckstein was appointed to the Board of Trustees to the Almshouse (Montevue Home) in 1866 and again in 1868. A clipping from a paper, that latter year, shows that the family came close to needing services from the emergency hospital at Montevue. This was certainly not not the best weekend to frequent Eckstein's Saloon. Our subject Christian was a leading member of the International Order of Odd Fellows and assisted in starting a German Building Company here in Frederick. He also stayed busy as a lieutenant in a local militia outfit and took great pride in participating with this group in parades and special functions. In addition to slinging beer, Mr. Eckstein was an avid marksman. Jacob Engelbrecht makes mention to Herr Eckstein again in reference to an interesting purchase of land on Fredericks’ northwest side: “Deutsche Scheutzen park—This park adjoining our city was sold at public sale on Saturday last March 12, 1870 to Christian Eckstein for fifteen-thousand one hundred dollars ($15,100). It contains 28 and ½ acres of sand and was formerly part of the farm of Mr. Stephen Ramsburg but lately to Doctor William Tyler from whom the “Scheutzen Gesellschaft” purchased it.” For quite sometime, I have had a particular interest in this curious organization of German origin. I first stumbled upon the Deutche Sheutzen Gesellschaft in context to the local German Civil War soldier Joseph Groff. His name would be applied to Groff Park which was synonymous with Frederick Scheutzen Park. You know this locale better today as the campus of Hood College, northwest of Frederick’s downtown center. The Deutche Scheutzen Gesellschaft was in essence a private membership stock company that featured shooting and drinking for its members boasting German heritage. Eckstein and Groff were leading organizers and members of this early example of the many German-American social clubs that can be found throughout our country today. Frederick has always been proud of its strong German ties, with origins dating back to the 1730s/1740s with many of its first families of settlers hailing from Deutchland such as the Schleys, Steiners, Mantzs, Ramsburgs, Brunners and Getzendanners. “Scheutzen” translates to shooting, and “gesellschaft” means organization. Frederick’s Scheutzen Park began as a shooting range, and what better means of celebrating cultural heritage are there than drinking and shooting—just hopefully done responsibly. I’ve read that Scheutzen Park was noted for its social events including fine dinners and dancing were available in a grand ballroom, especially German cuisine. The large social hall was constructed in 1868, and the local members were aided in laying the cornerstone for this impressive building with the help of the Adam Masonic Lodge and the mayor of Baltimore accompanied by a contingent of like organization members from “Charm City.” I was pleased to find that Christian delivered the opening remarks for this interesting event in July of that year. Construction would be done over the summer and fall, with a grand opening gala in November. Take note that Christian H. Eckstein was on the committee of arrangements, but also held the position of "First Sheutzenmeister" (translates to first shooting master.) The Gesellschaft didn’t last long, but the main building still stands proud today on the Hood campus, and boasts plenty of revelry in the form of music played within over its life. This is Brodbeck Hall, home of the college’s music department, after serving as the clubhouse for the German social club, which came complete with an old-fashioned beer garden to accommodate stockholders. Something went awry as the Scheutzen Park was put up for public sale not long after its grand opening. Christian Eckstein would purchase this property in 1869, and sold it shortly thereafter to Capt. Groff, who was the former proprietor of the Arlington House Hotel on North Market, and later the Groff House Hotel on North Market Street at Seventh Street and by the fountain. This is when the property was renamed Groff Park. The grounds with its many lanes offered an oasis for scenic carriage rides and social and athletic events to be held on its spacious grounds. The Groff family would split time living here and used the vicinity to grow gardens of produce that would be used to feed guests staying in their hotel. The couple's oldest son, David, would grow flowers here for his successful career as a local florist. Eventually, Groff Park would be sold to Margaret Scholl Hood in the 1890s. Mrs. Hood would later deed the former Groff Park to Dr. Joseph Henry Apple and the Frederick Women's College and in 1915, this would comprise the newly named seat of higher education for women named Hood College. In case you were curious, "Brodbeck" is an occupational name and translates to "Baker of bread." As for Christian and family, we find he and his wife still operating their saloon in the 1870 census. Son Charles would make an unsuccessful run for Maryland’s House of Delegates as a Democratic candidate in 1871. The saloon on North Market would continue to be a favorite watering hole for members of the Conservative Democrat Party however. Christian Eckstein died on April 5th, 1874. His obituary mentions a ten-year battle with Rheumatism, which resulted in him being an invalid in the few years preceding his death. I find it remarkable that he continued with his shooting and military ceremonial events amidst great pain. He would be buried in Mount Olivet on April 7th. His gravesite would see activity upon the funerals of his wife and two children here, but there was quite a lull until our April 30th workshop and repairing his stone to its original glory as had been done 148 years before. Oh, and I almost forgot to tell you what Eckstein translates from German to English. "Eck" means corner and "stein" means stone—cornerstone. Now that was fitting to be the signature "fix" as a focal point for a gravestone preservation workshop.

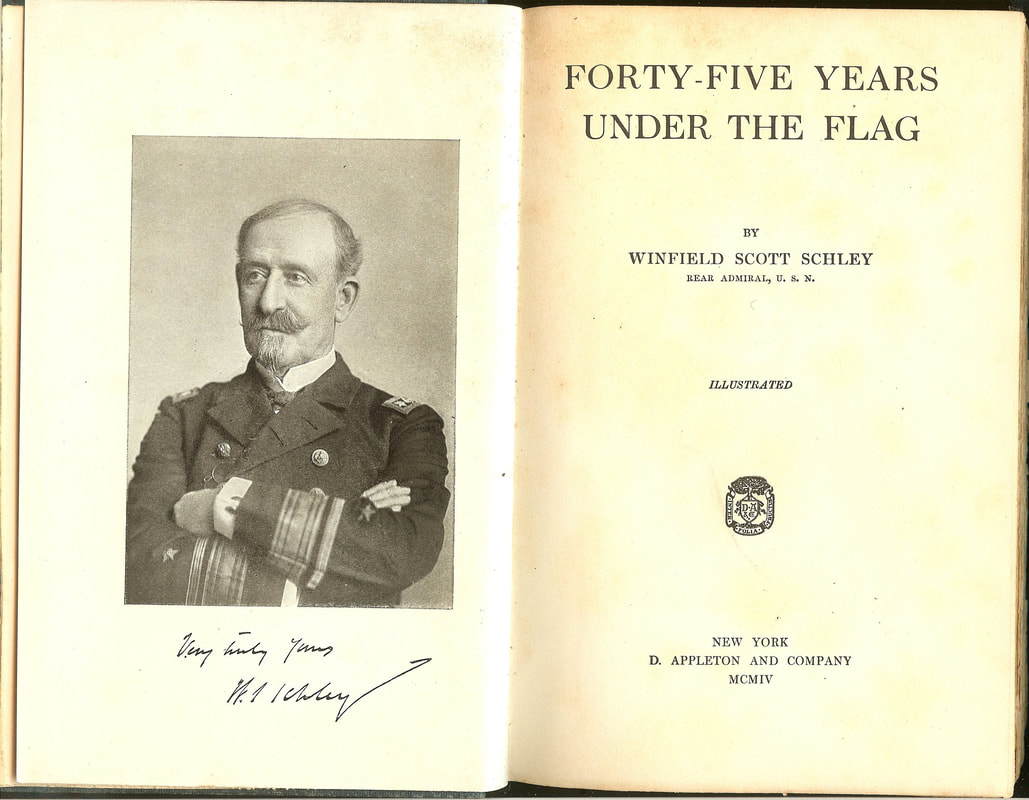

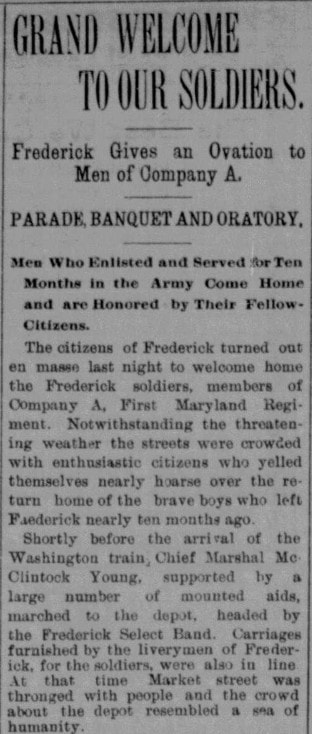

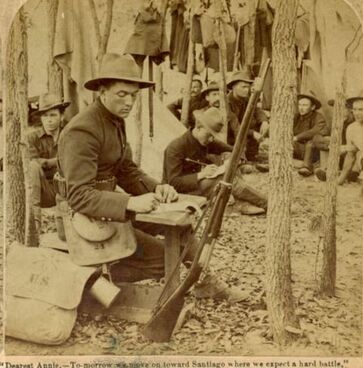

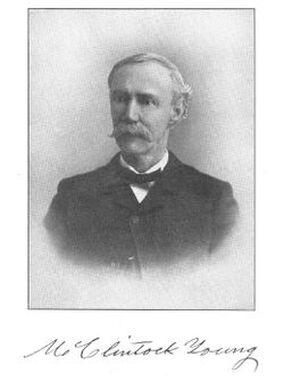

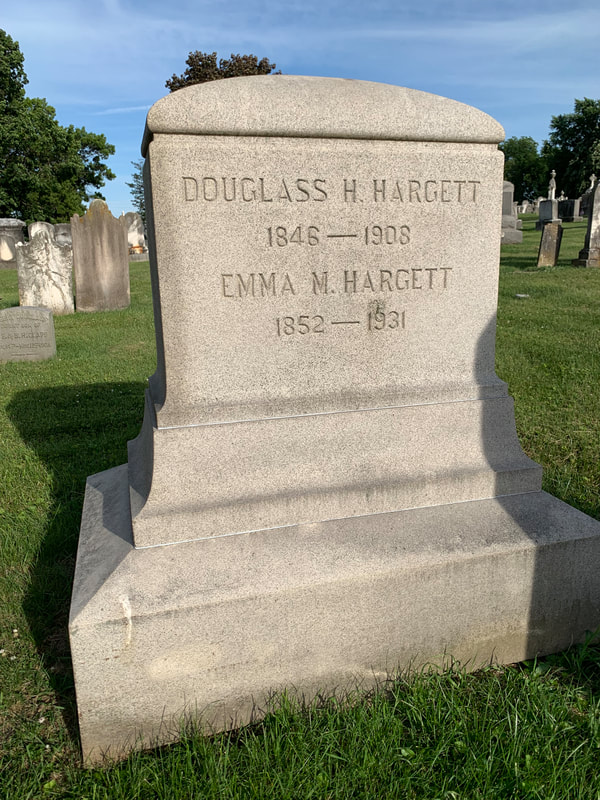

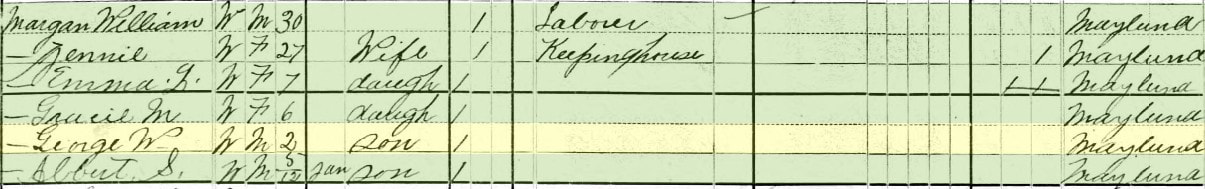

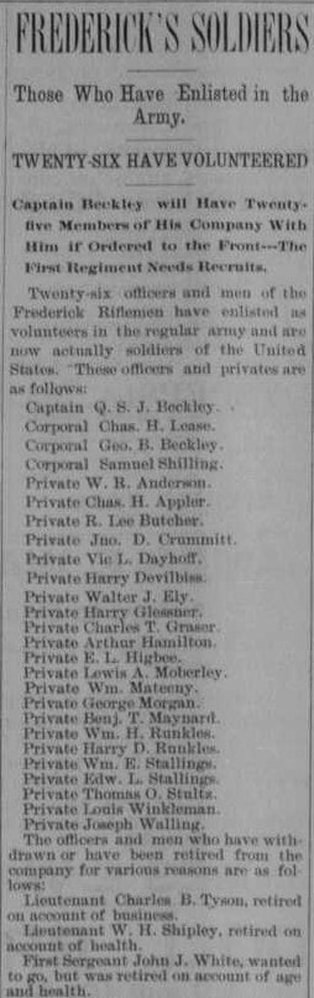

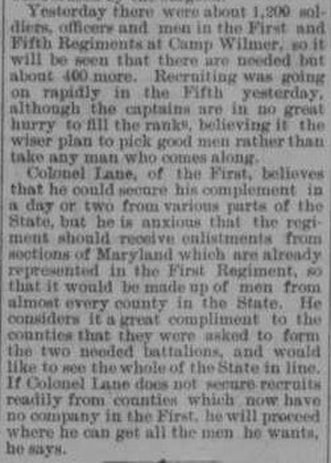

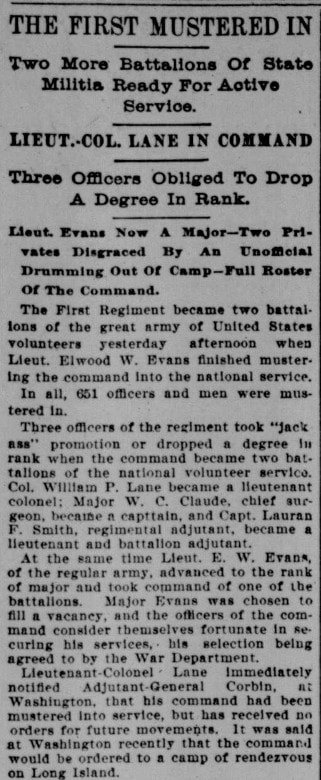

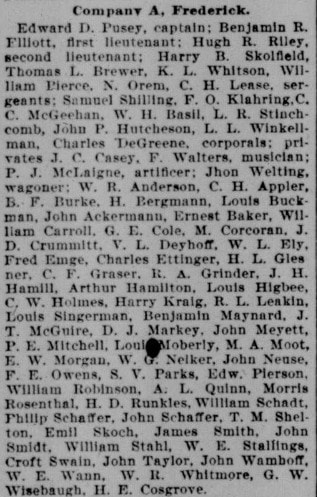

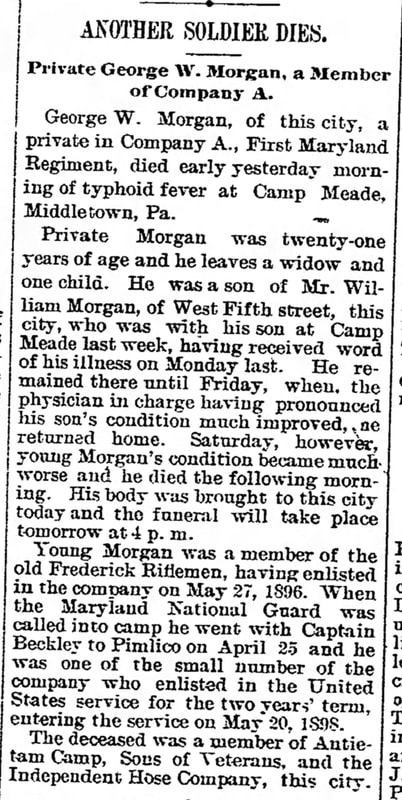

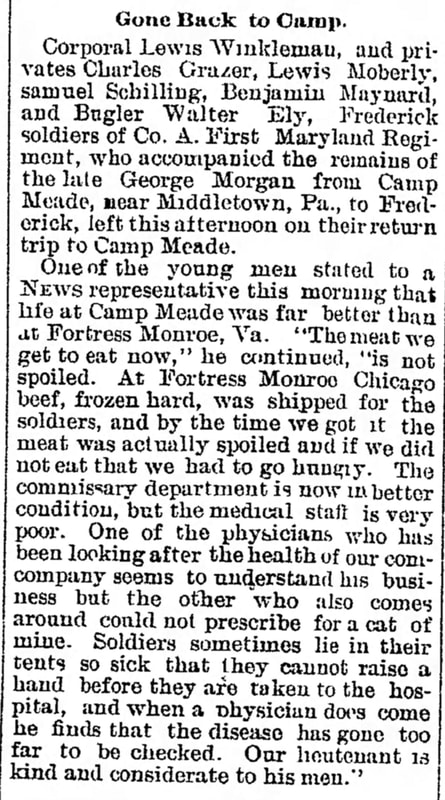

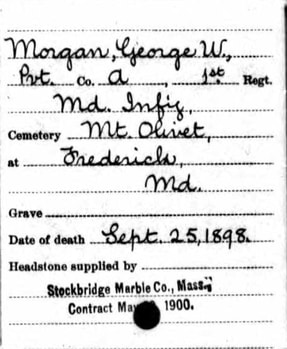

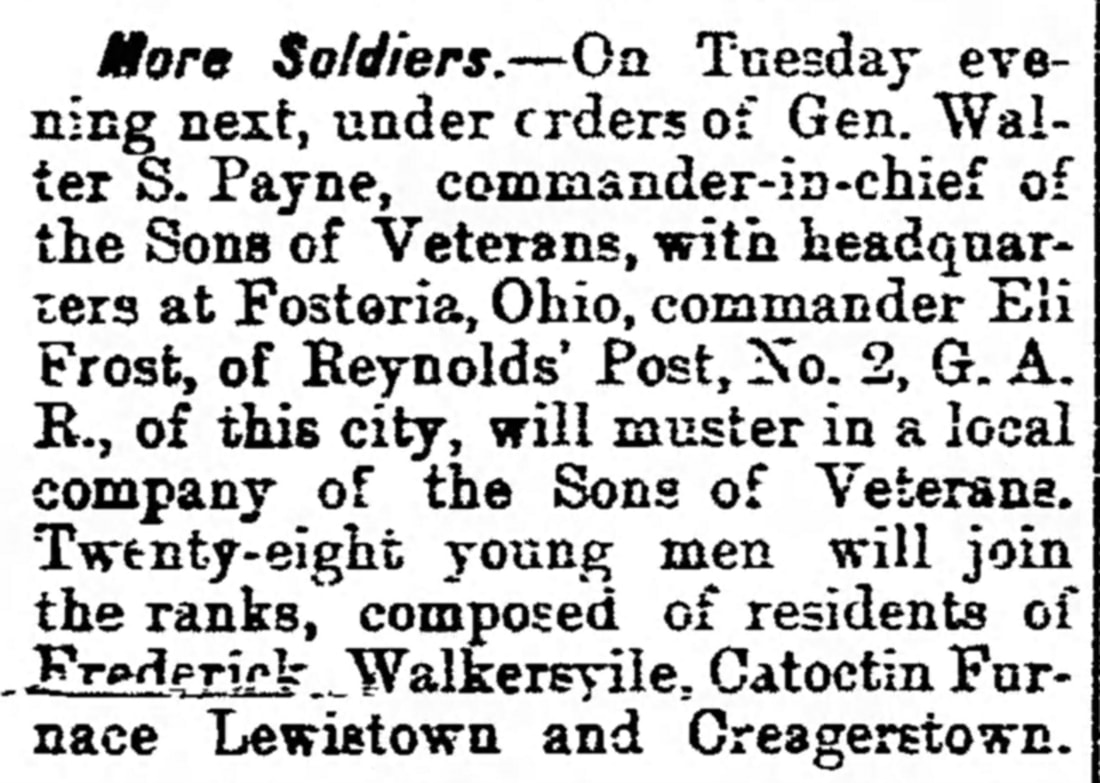

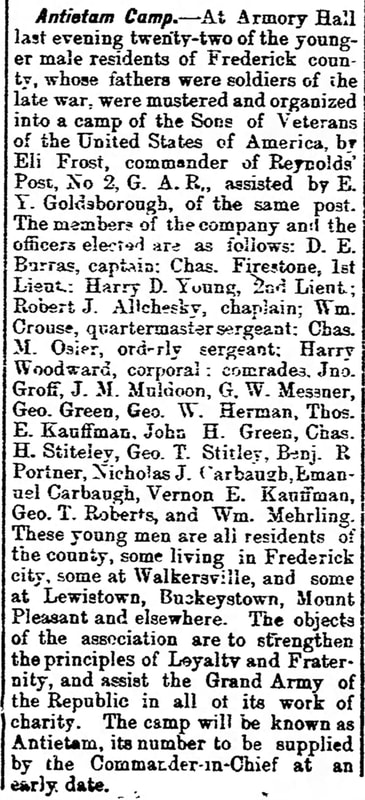

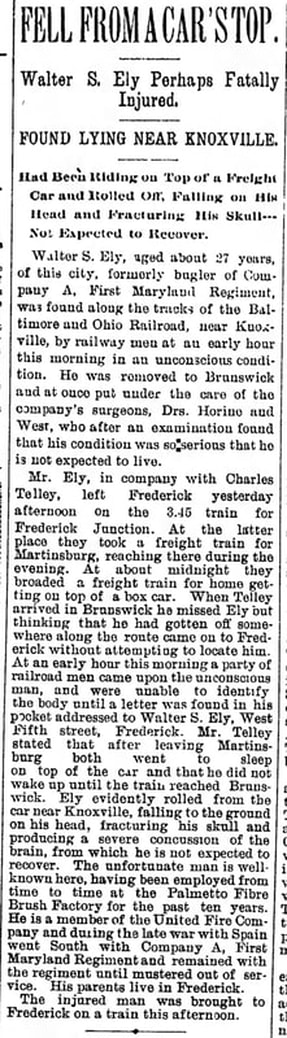

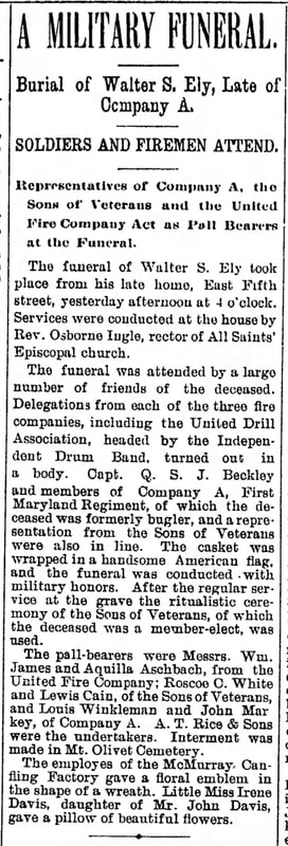

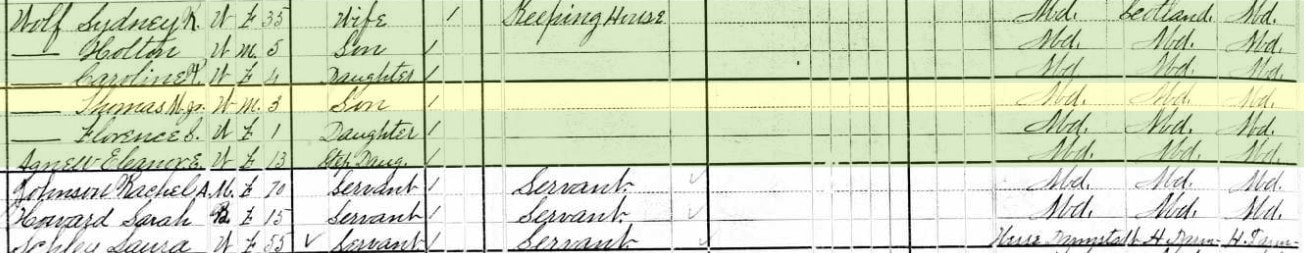

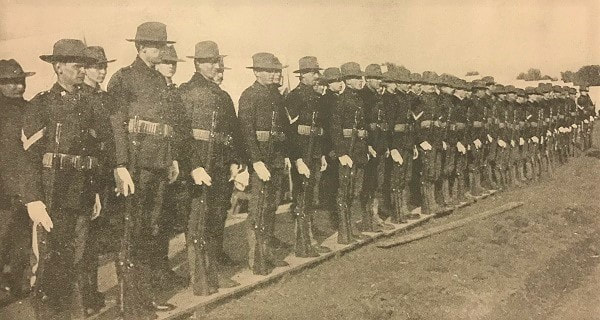

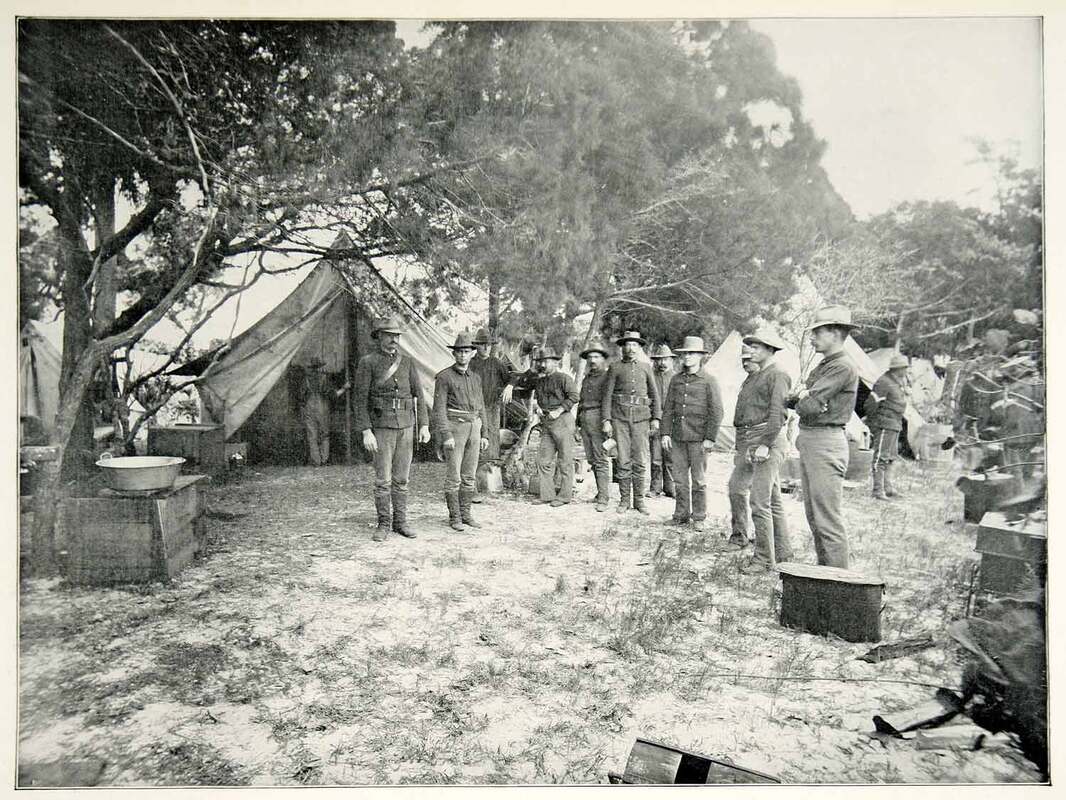

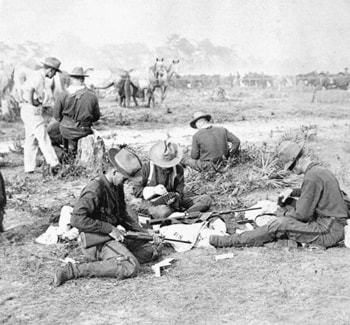

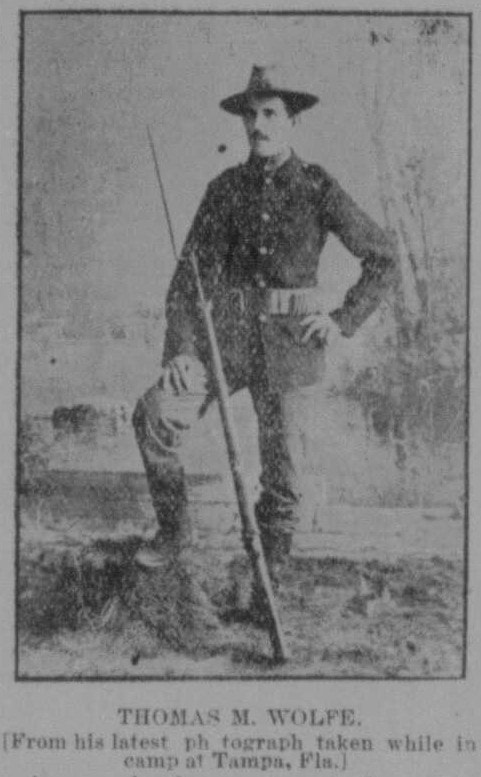

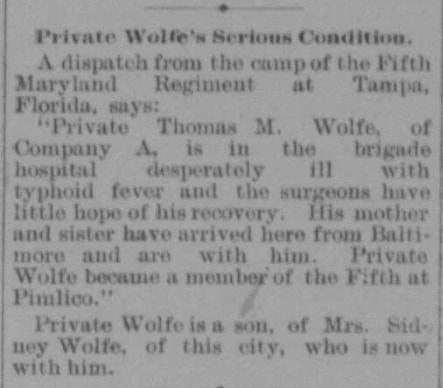

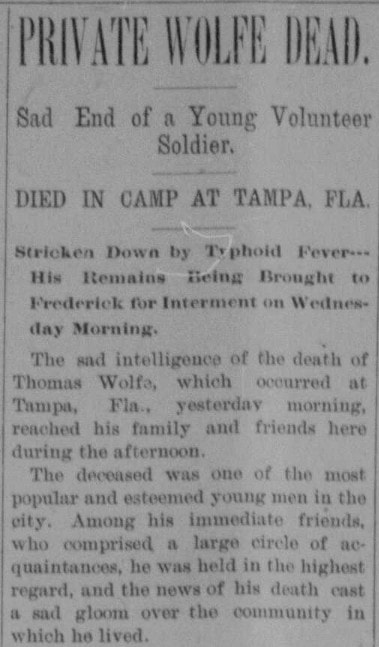

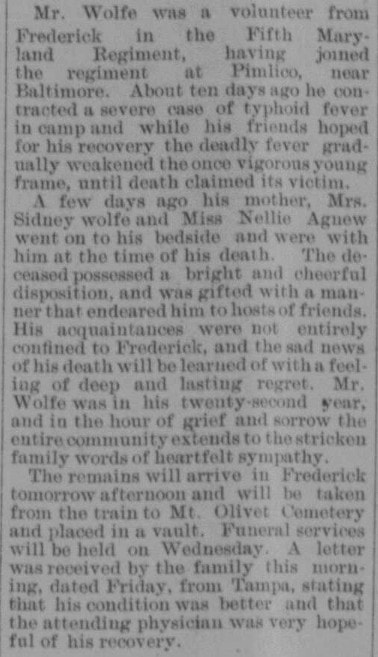

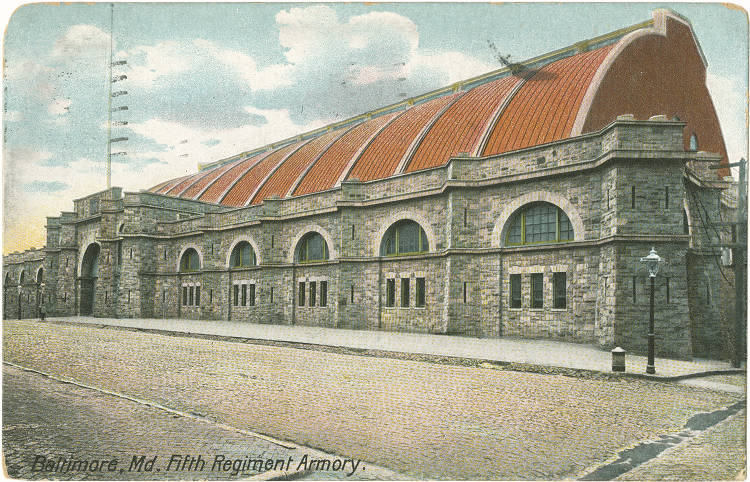

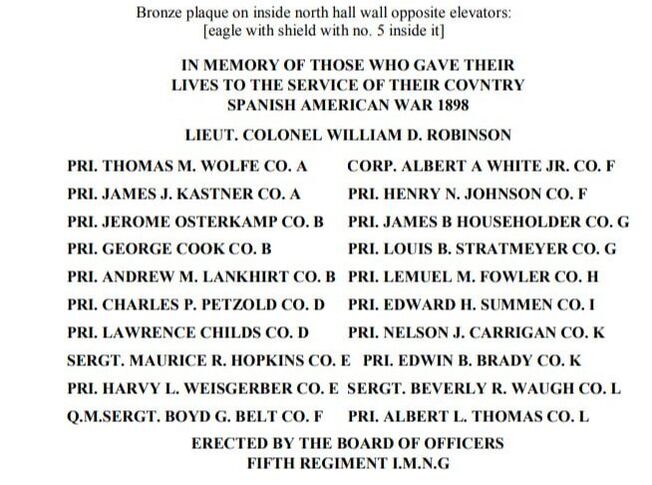

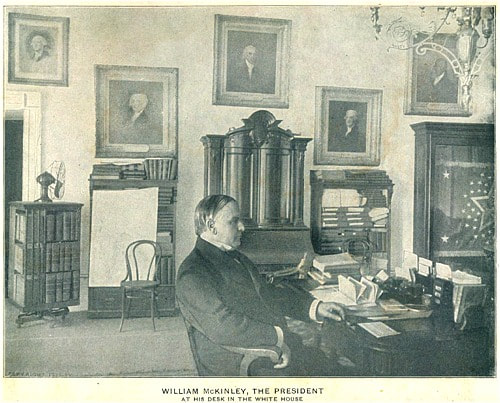

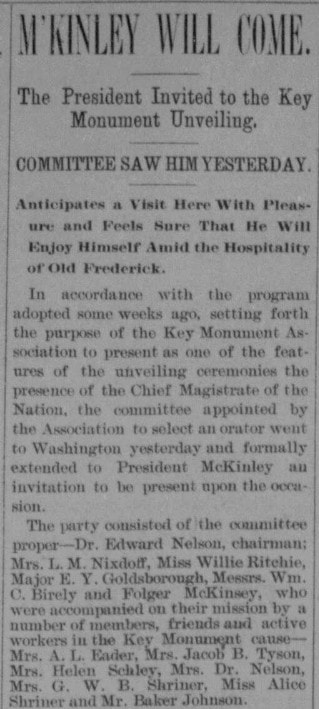

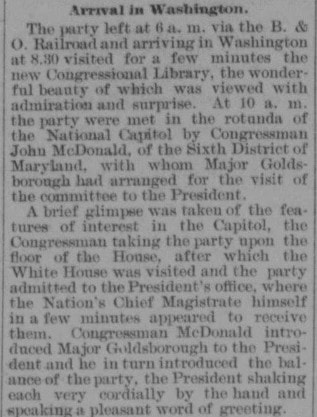

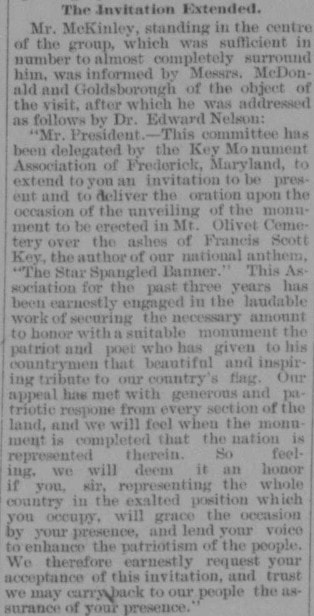

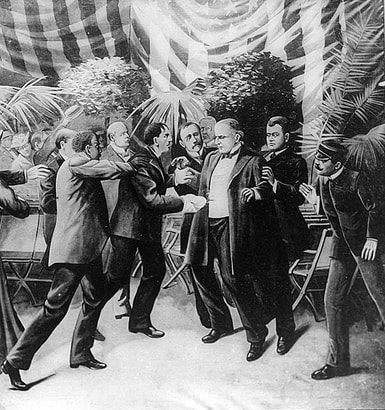

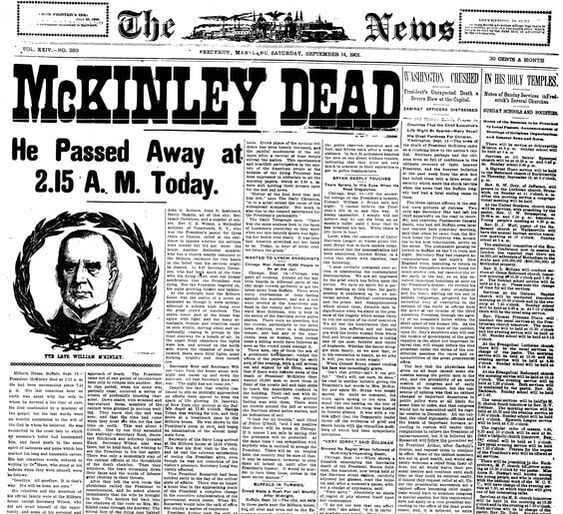

Memorial Day weekend has passed us by, but it’s hard not to be in a patriotic mood when you work as the historian of a cemetery like ours that boasts nearly 4,700 veterans. We still have flag-covered gravesites for a few more days, as the grounds are still humming in the aftermath of fine annual ceremonies by our Daughters of the America Revolution chapters and the Francis Scott Key American Legion Post 11. Speaking of Francis Scott Key, the mortal remains of the man who helped “immortalize” the US flag are here in Mount Olivet, as is the great flag-waver, herself, Barbara Fritchie of Civil War fame, albeit a bit sketchy. We are only a week away from Flag Day (June 14th) and our annual patriotic lecture at the Key Chapel which kicks off at 7pm. (NOTE: This year, our subject will be Frederick diarist Jacob Engelbrecht, who will be the recipient of an upcoming “Story in Stone.”) When I think of the US flag and its relation to Frederick, how can FSK and Barbara Fritchie not come to mind? Perhaps this is a question easily answered by native and long-time residents only, but don’t worry Frederick newcomers, our goal is to indoctrinate you into this frame of thinking as well. Like Mount Olivet, Frederick is a very patriotic place. So much so, we made sure Francis and Barbara were strategically located by the front door entrance of the Frederick Visitor Center on South East Street. I know, because I worked on that project with my esteemed former colleagues of the Tourism Council of Frederick County in John Fieseler and Liz Shatto. One other hero who has the flag, per se, to thank for his fame, was Admiral Winfield Scott Schley (b. 1839). As a matter of fact, he named his memoirs Forty-Years Under the Flag, published in 1904. If you are not familiar with Admiral Schley, the namesake of Schley Avenue (between Rosemont and West Seventh Street), he was a rear admiral in the United States Navy. More so, Schley was the hero of the Battle of Santiago de Cuba during the Spanish–American War on July 3rd, 1898. His actions while in command of Admiral Thomas Dewey’s flagship, the USS Brooklyn, helped destroy the Spanish naval fleet, thus cutting off supplies and support to the Spanish infantry forces on land who were defeated by Gen. Joseph Wheeler featuring his legendary cavalry group— “the Rough Riders” under the command of one Teddy Roosevelt. Their eternal fame came with the Battle of San Juan Hill. One of these "Rough Riders" was Jesse Clagett, buried here in Mount Olivet’s Area P/Lot 36. (See Story) Back to Admiral Winfield Scott Schley, he can be found on a postage stamp and also had a fine drink (Admiral Schley Punch) named in his honor. He died in 1911 but is not buried in Mount Olivet, but rather Arlington Cemetery. I will tell you more about him in a later story I plan to write in context with his family as his parents and siblings are buried here in Area P/Lot 9. This is directly adjacent the grave plot of Jesse Claggett and his family. A few weeks back, I came across an article that mentioned Admiral Schley and the immortal "Rough Riders." Most interesting was the article’s description of Frederick as being the “Home of Heroes.” This really resonated with me, but probably because I’m also used to hearing the fore-mentioned Francis Scott Key’s line, “Home of the Brave.” The Francis Scott Key monument had been unveiled amidst great fanfare just a month after Schley and Clagett’s “heroics” in Cuba, and seven months previous to the article’s publication. I’m sure local residents were beaming with patriotism as their city and county were recognized on the national stage as being the home to Schley, Key and Fritchie. The article in question makes mention to participants of the Spanish-American War. Overshadowed by the Revolutionary War, Civil War and World Wars to follow, the “Span-Am” War is usually relegated to B-League history along with the War of 1812 and Mexican War (which both preceded it). To give the Readers Digest version of this conflict, I present the Wikipedia synopsis: The Spanish–American War (April 21 – August 13, 1898) was a period of armed conflict between Spain and the United States. Hostilities began in the aftermath of the internal explosion of USS Maine in Havana Harbor in Cuba, leading to United States intervention in the Cuban War of Independence. The war led to the United States emerging predominant in the Caribbean region, and resulted in U.S. acquisition of Spain's Pacific possessions. It led to United States involvement in the Philippine Revolution and later to the Philippine–American War. The main issue was Cuban independence. Revolts had been occurring for some years in Cuba against Spanish colonial rule. The United States backed these revolts upon entering the Spanish–American War. There had been war scares before, as in the Virginius Affair in 1873. But in the late 1890s, American public opinion swayed in support of the rebellion because of reports of concentration camps set up to control the populace. Yellow journalism exaggerated the atrocities to further increase public fervor and to sell more newspapers and magazines. This is an interesting passage, and gives us a unique lens in which to view current events that we continue to experience up through this day. It’s a recipe consisting of politics, power, money and the media. Author, astronomer, educator Carl Sagan (1934-1996) said it best when he wrote in his signature work Cosmos in 1980: “You have to know the past to understand the present.” In the local Frederick news article referenced earlier (from 1899), I was interested to see the names of the local boys in Company A. I also took note that Frederick’s greatest inventor on record was chosen as parade marshal. Today his name, McClintock Young, adorns a local distillery on East Church Street, not far from the Ox Fibre Company where some of his creations help produce fine palmetto hand brushes. Mr. Young is buried in Area H, not far from the toastmaster mentioned in this article for the banquet welcoming the soldiers back home. This was Douglas Henry Hargett (1846-1908) who rests only a short distance from the inventor in Area H /Lot 483. Hargett was a resident of East Church Street and a successful merchant. As the article mentions, he served as Clerk of the Frederick County Court in 1898. Interestingly, Mr. Hargett was the father of Lt. Earlston Lilburn Hargett (1892-1918), one of two men buried in Mount Olivet that were actually killed in battle during World War I. I found this particularly ironic, because this article pointed out to me the fact that we had two local boys die during the “Span-Am” War, and they both are here in Mount Olivet. They did not die in battle, but rather of sickness. Nine such World War I soldiers buried here in Mount Olivet died in this fashion during the war, and their malady was the Spanish Flu Pandemic. Alas, Spain is to blame in some form or fashion! The young gentlemen in question were George W. Morgan and Thomas Melvin Wolfe, Jr. You could not have two more different socio-economic backgrounds as what you have with these two boys. Finding information on both was a challenge to say the least, but they did appear in the 1880 census as youngsters. The 1890 census was lost, and they wouldn’t survive past the war year of 1898 to be counted among the living in 1900. George W. Morgan George William Morgan was born September 4, 1871 here in Frederick, the son of Jennie and husband William V. Morgan (1840-1905). The elder Morgan was a veteran of the American Civil War, serving in Company H of the Union’s Potomac Home Brigade. In the 1880 census, six-year old George can be found living at what was 304 West Patrick St. with his parents and three siblings. Again not much can be gleaned from local resources aside from George entering military service into Maryland’s 1st Infantry Regiment, Company A. His name is among 26 who volunteered for military duty in this outfit in early May, 1898. A few weeks later, this group, comprising Company A militiamen, would be mustered into active duty on the national level. Morgan’s initials were erroneously typed as E. W. Morgan instead of G. W. Morgan. The soldiers would be sent to Fort Monroe in Hampton, Virginia for their initial training, before being transferred to Camp George Meade near Middletown, Pennsylvania in Dauphin County. Middletown is south of Harrisburg and conveniently located three miles north of the infamous Three-Mile Island of nuclear reactor meltdown fame when I was a kid. I learned that Camp George Meade was established on August 24th, 1898, and soon thereafter was occupied by the Second Army Corps, of about 22,000 men under command of Maj. Gen. William M. Graham, which had been moved from Camp Alger in an attempt to outrun the typhoid fever epidemic. Camp Meade was visited by President William McKinley on August 27th, 1898. More on him in a little later. Apparently, the camp had its own issue with typhoid fever that dreadful year. It’s no wonder, as this was commonplace as large numbers of men were detained in cramped quarters during wartime. The number of typhoid deaths up through October 11th, 1898 would be 64. One of these victims would be Frederick’s George W. Morgan. He died on September 25th. Morgan's death made the local papers, and his body was escorted for burial in Mount Olivet by fellow Fredericktonians of Morgan's company. Camp Meade was inspected November 3rd and 4th, and found to be spacious and well laid out. The water supply was obtained from artesian wells, and was piped to every organization. It was both good and abundant. The hospitals were commodious, and well equipped and conducted. The bathing facilities for the men were ample. The sanitary and other conditions were of high order, and the camp, as a whole, was open to but little criticism. The testimony of a number of officers and men was taken, and the troops and camp inspected. In November this camp was discontinued and the troops—not mustered out—distributed to the various camps in the South. The installation was abandoned about November 17, 1898. The 3rd Brigade of the 2nd Division of the Second Army Corps was relocated to Camp Fornance, Columbia, South Carolina, and a brigade of the 1st Division, Second Corps to Camp Marion, Summerville, South Carolina. "Sons of Veterans" Private Morgan was buried in an interesting little burial plot in Area P/Lot 164. This lot was owned by the "Sons of Veterans." This organization was formed here in Frederick with a chapter in July of 1886. It was overseen by the local G.A.R. (Grand Army of the Republic) Post which had been formed years earlier and named in honor of Gen. John B. Reynolds, a Union officer who was killed at the Battle of Gettysburg just a few days after visiting Frederick in late June of 1863. With national headquarters in Fostoria, Ohio, the "Sons of Veterans" included sons of Union Civil War soldiers. The local chapter would purchase a grave plot here in Mount Olivet for use by its members. George’s family members are buried in adjoining Lot 163, where a civilian headstone also bears the Span-Am War casualty’s name. I quickly recognized the name of another Spanish-American war vet buried in the "Sons of Veterans" lot and located to the immediate left of Private Morgan's gravesite. This is the burial spot of Walter J. Ely (1872-May 13, 1899). In the article above recounting Morgan's funeral, Ely is said to have accompanied the body from Camp Meade (PA) to Frederick, and was responsible for giving ceremonial bugle calls at the military funeral on September 28th, 1898 here in Mount Olivet. I was surprised to see that Ely would be occupying his own grave in less than six months. This piqued my curiousity, so I made a quick inquiry to learn of his demise at the age of 27. Forrest Gump said "Life is like a box of chocolates, you never know what you're going to get." In doing research at a cemetery for "a living," I can attest to "death," also, being like a box of chocolates. Thomas M. Wolfe, Jr. A more affluent upbringing involved Thomas Melvin Wolfe Jr, who died a little over a month before George W. Morgan. Wolfe was the son of Thomas M. Wolfe and wife Sydney and grew up in a fine residence on Record Street at Courthouse Square. His father was a veteran of the Civil War as well, having served as quartermaster of the Potomac Home Brigade. Mr. Wolfe was a successful businessman and civil servant having been appointed Postmaster by President Andrew Johnson immediately after the war. He would also serve as a Frederick Alderman. Our decedent in this case, attended local schools, likely the Frederick Academy, and enlisted for service in Baltimore where he served in Company A of Maryland’s Fifth Regiment. I found the following regimental history online on a site called spanamwar.com: The Fifth Maryland Volunteer Infantry, apparently formed around a Maryland National Guard unit, assembled at Pimlico, Maryland on April 25th, 1898. Several weeks later, on May 14th, the regiment was mustered into federal service. At the time of mustering in, the regiment consisted of forty-eight officers and 935 enlisted men. Five days after being mustered in, the regiment was sent south, to the large training camp forming on the grounds of the old Civil War battlefield of Chickamauga in Georgia. The new camp was named Camp Thomas. The regiment arrived at Camp Thomas on May 21st, but, luckily for the men, the unit shipped out for Tampa, Florida shortly thereafter on June 2nd. Camp Thomas was to become greatly over crowded and very unsanitary, resulting in a large number of deaths. The 5th Maryland arrived in Tampa on June 5th. On July 31st, the regiment was shifted slightly to Tampa Heights. It remained here until August 18th. The regiment was in this location when Spain and the U.S. agreed to an armistice, ending the war's fighting, though the war would not officially end until December 10, 1898, when the Treaty of Paris was signed. On August 18th, 1898, the regiment proceeded to Huntsville, Alabama. Again, its stay was short, and on September 5th, it was ordered home to Baltimore, Maryland. The regiment was furloughed for one month, beginning on September 11th. On October 22nd, the Fifth Maryland Volunteer Infantry was mustered out of service. At the time of mustering out, the regiment consisted of forty-nine officers and 1,229 enlisted men. During its term of service, the regiment had one officer and nineteen enlisted men die of disease. In addition, eight men were discharged on disability, one man was court-martialed, and three men deserted. The regiment has one of the lower desertion rates experienced by regiments during the war. We are lucky to have a photograph of Private Wolfe as this was taken shortly before his death and included with news of his death in the Frederick newspaper. Private Wolfe had become sick with typhoid fever, and was cared for in a Red Cross hospital that had been set up by Clara Barton herself. Wolfe's mother and a sister had the means to travel to Tampa to assist in the care of him. News of his illness was printed in the local paper, and it appeared he would make a recovery. Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, and is a disease caused by Salmonella serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over several days. This is commonly accompanied by weakness, abdominal pain, constipation, headaches, and mild vomiting. Some people develop a skin rash with rose colored spots. In severe cases, people may experience confusion. Unfortunately Thomas M. Wolfe's rally was only temporary as he would succumb to this prevalent wartime ailment on August 21st, 1898. Private Wolfe was buried "a stone's throw away" from his brother in arms, George W. Morgan. He was laid to rest in the Wolfe family plot in Area Q/Lot 149. His father had been buried here since 1890. Wolfe’s name is among those soldiers lost to the Fifth Maryland during the war. It can be found on a bronze plaque hanging on a wall within the Fifth Regiment Armory located in Baltimore. This structure can be found between Preston, Howard, Hoffman and Bolton streets. I had earlier mentioned President McKinley who had visited Camp George Meade in Pennsylvania in late August, 1898, just three days after Thomas Wolfe's funeral here in Frederick on the 24th. I'm assuming that Private George W. Morgan had the opportunity to see, hear and possibly meet the chief executive on the occasion at Camp Meade that preceded his death by 28 days. Interestingly, the president should have been here at Mount Olivet two weeks earlier on August 9th, as he was the recipient of a very important invitation to attend the unveiling ceremony of the Francis Scott Key Monument. He had been to Frederick before, but this was in wartime as a participant of the Battle of South Mountain. He served with an Ohio Regiment under his future mentor, and president, Rutherford B. Hayes. I have included an elaborate newspaper article that discussed the circumstances of the Key monument invitation the previous winter by a delegation sent to the White House for the very purpose. Naturally, the events of the Spanish-American War likely precluded President McKinley’s visit on that 9th day of August, 1898. It would have made a great photo-op however. He would be assassinated just over three years later on September 6th, 1901. The 25th president of the United States, was shot on the grounds of the Pan-American Exposition at the Temple of Music in Buffalo, New York, six months into his second term. He was shaking hands with the public when anarchist Leon Czolgosz shot him twice in the abdomen. He seemed to have been making a recovery but died of a gangrene infection on September 14th—oddly enough, the 87th anniversary of the writing of “the Star-Spangled Banner” by Francis Scott Key.

|

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed