|

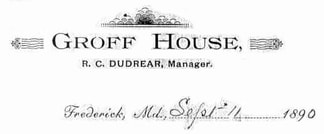

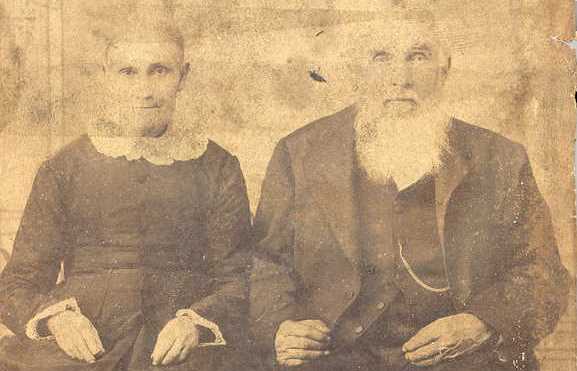

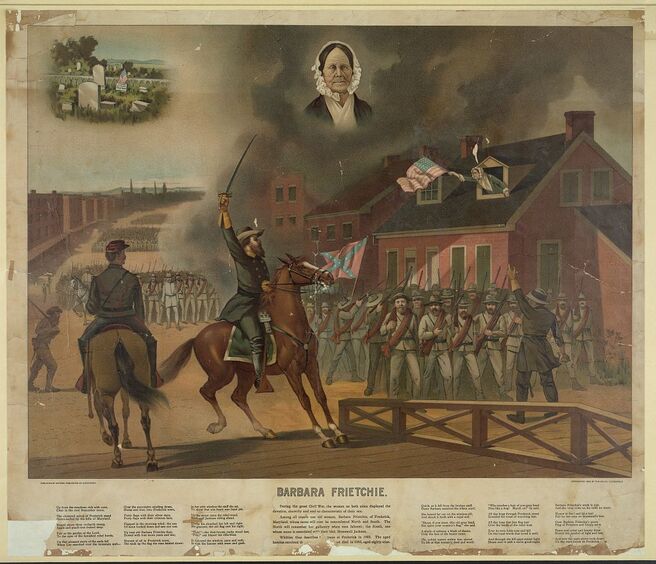

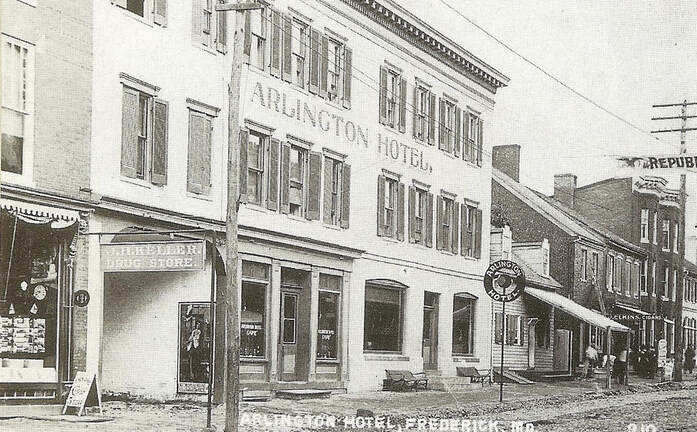

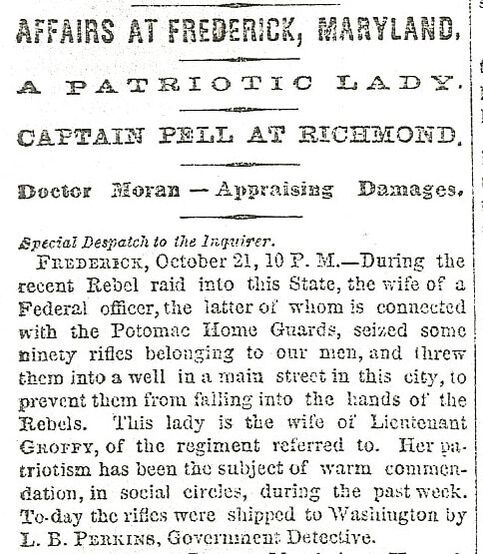

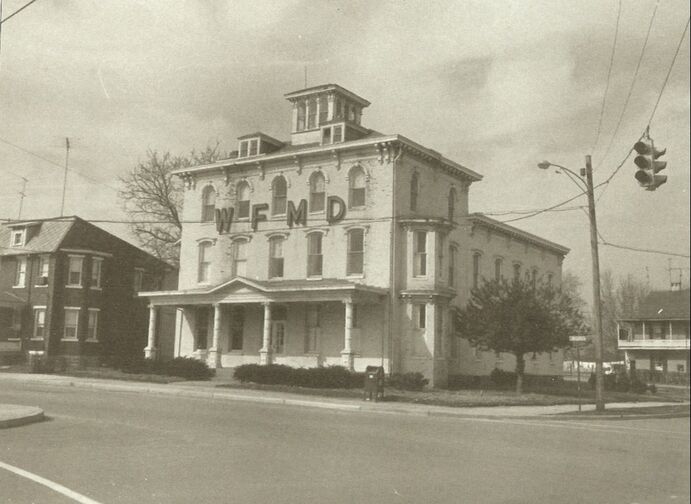

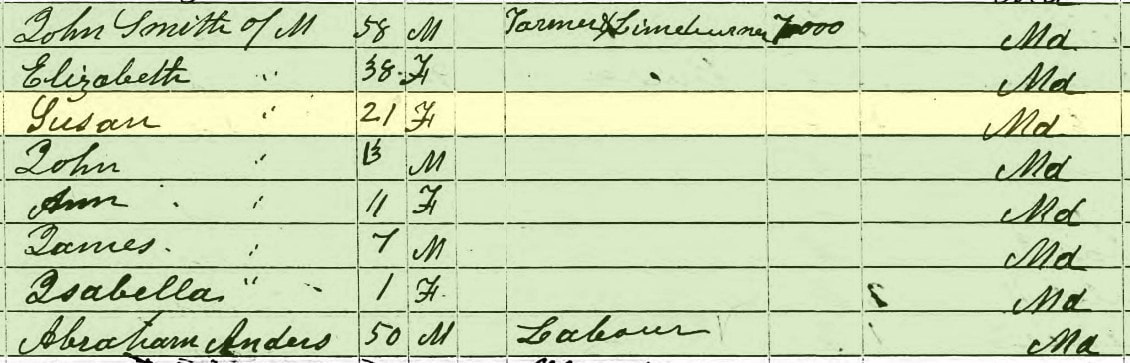

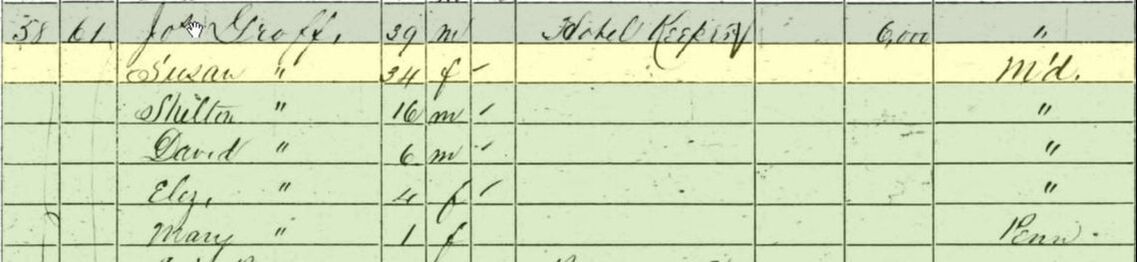

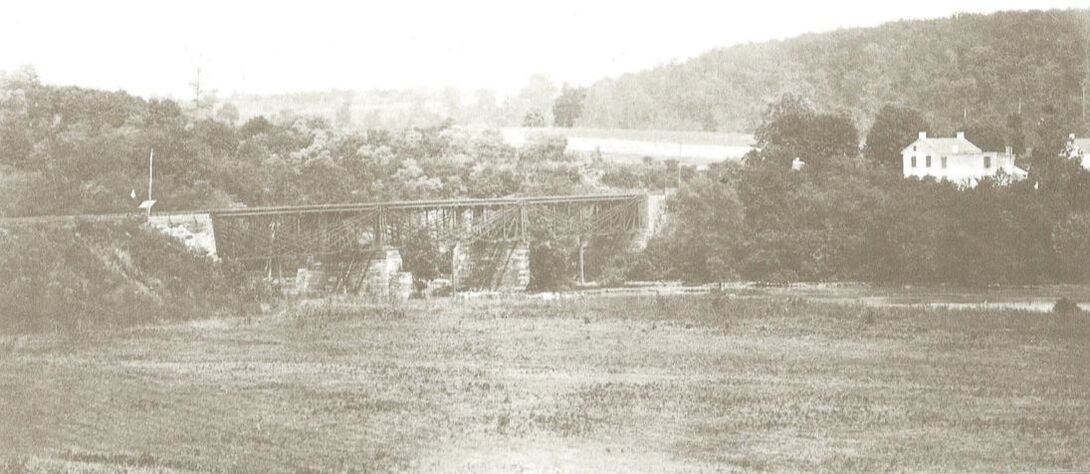

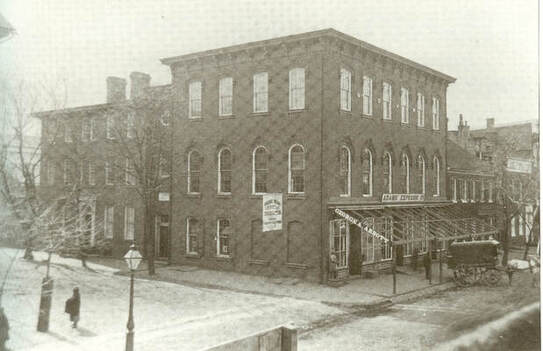

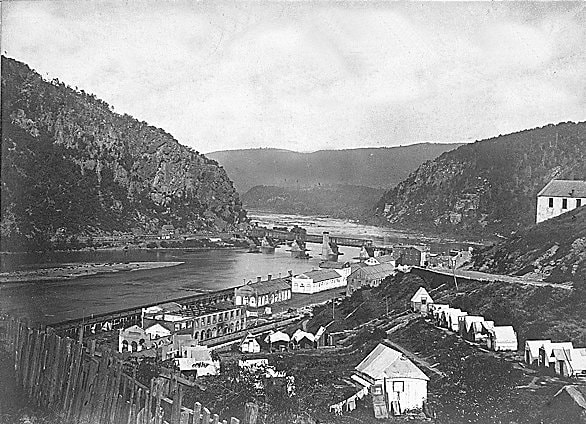

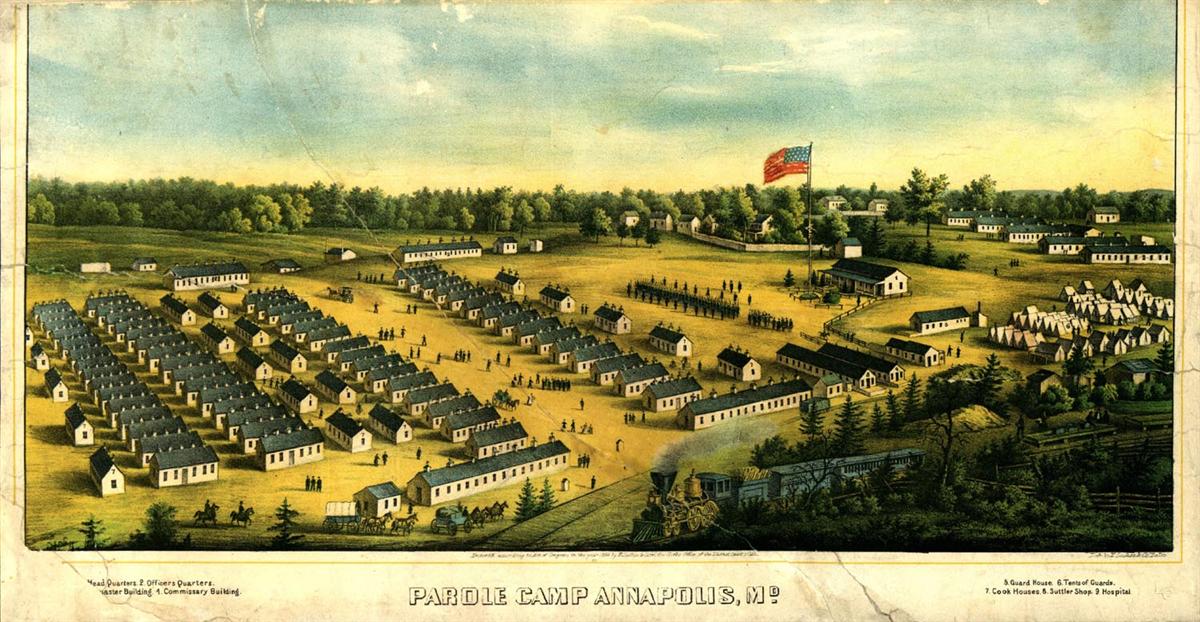

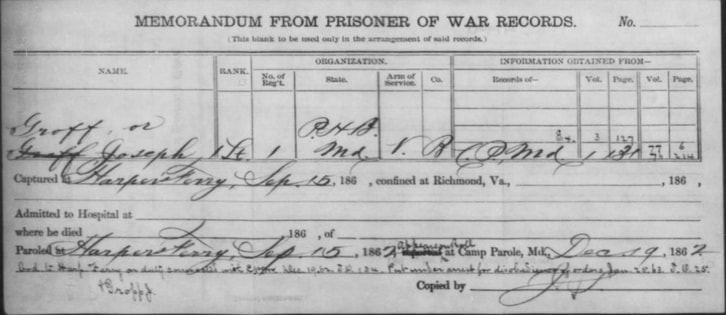

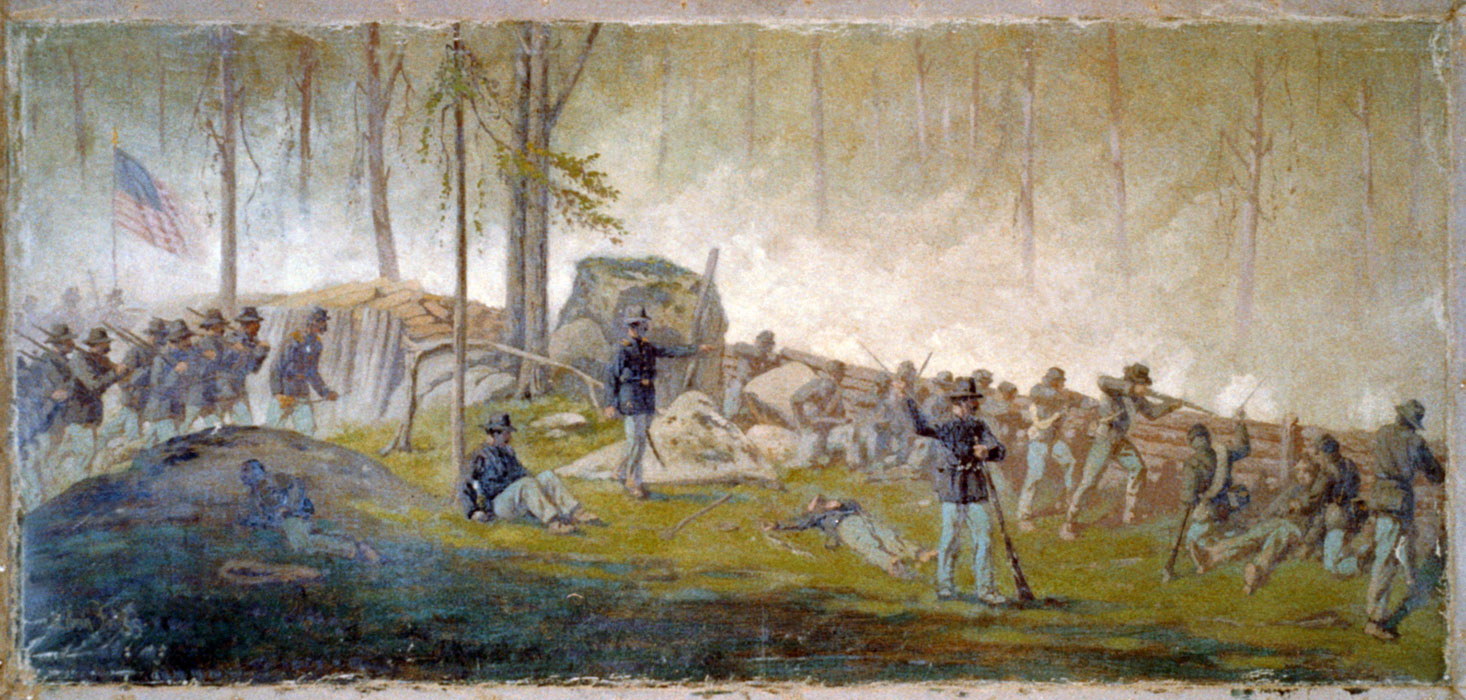

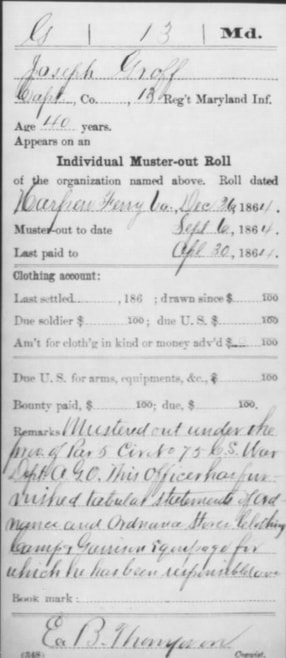

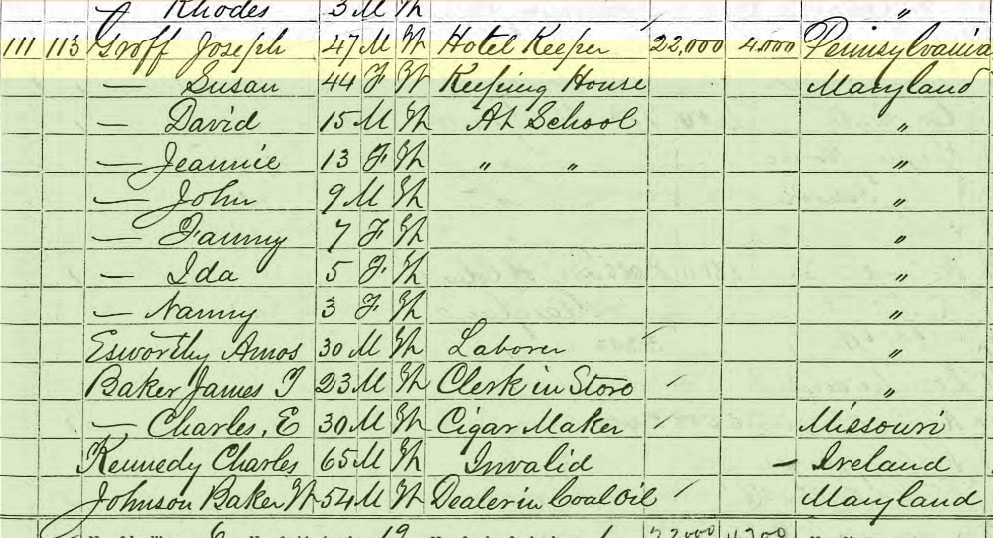

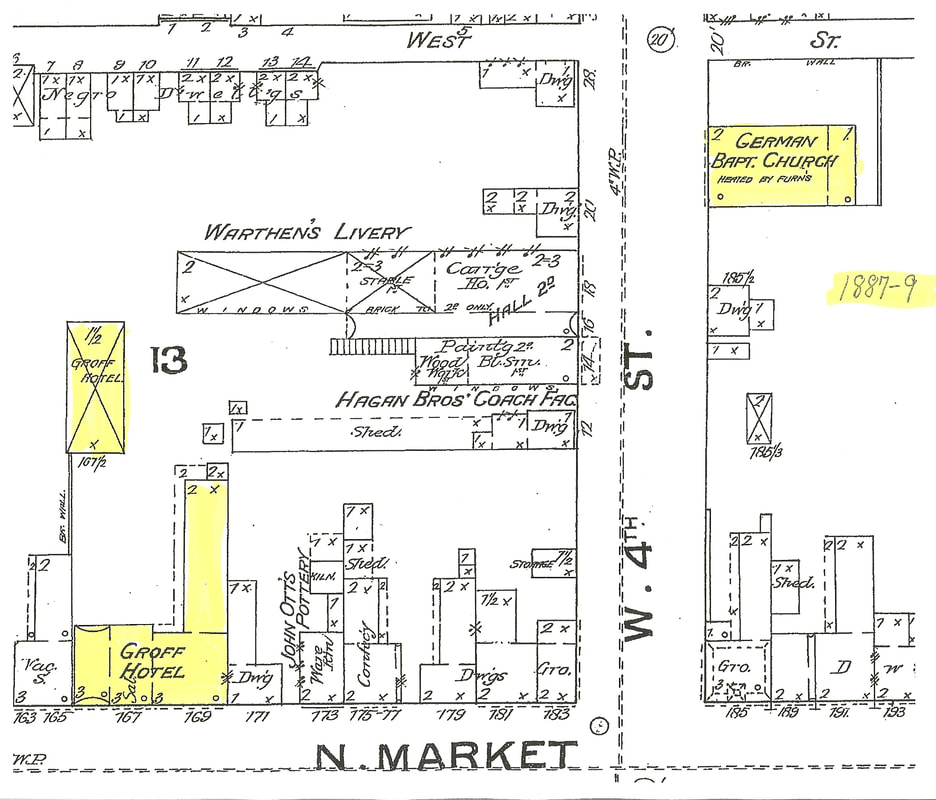

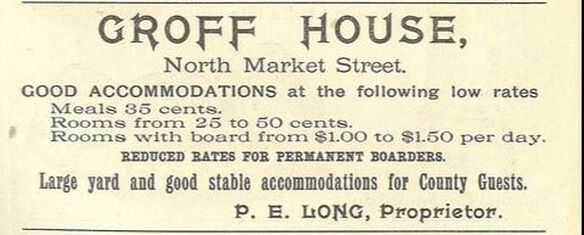

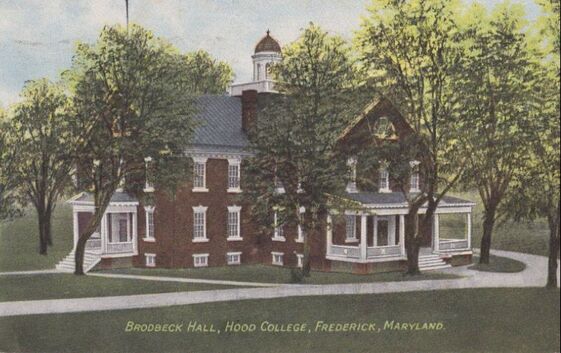

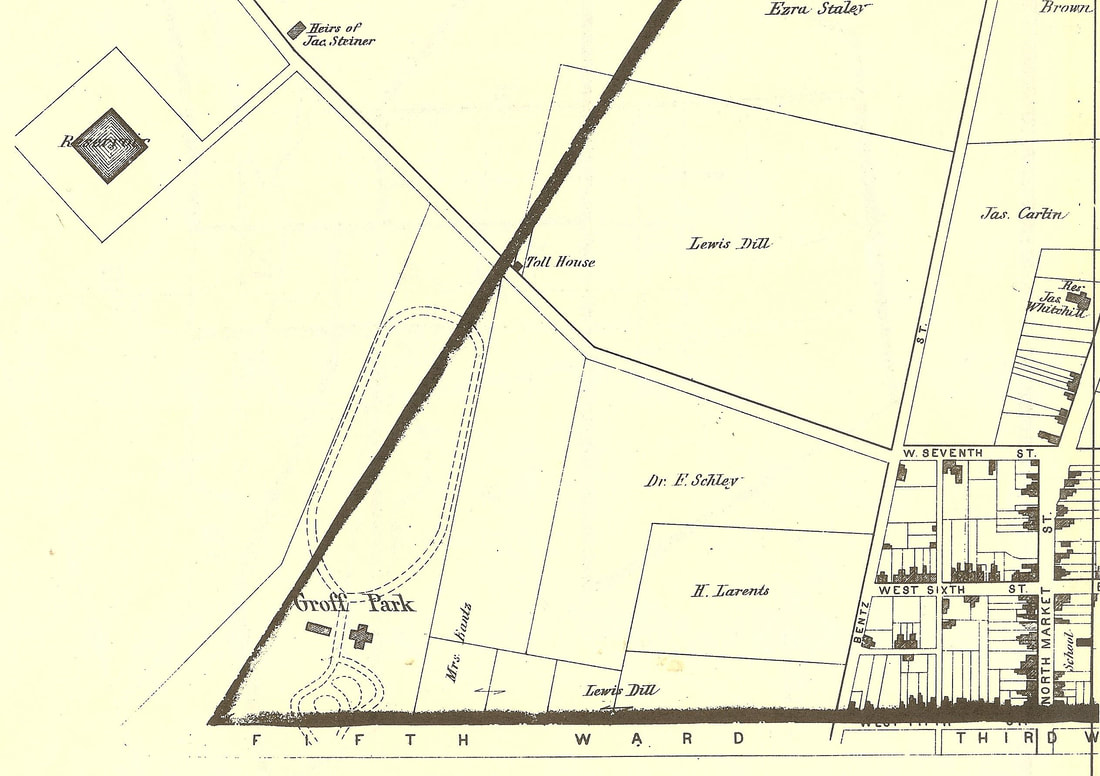

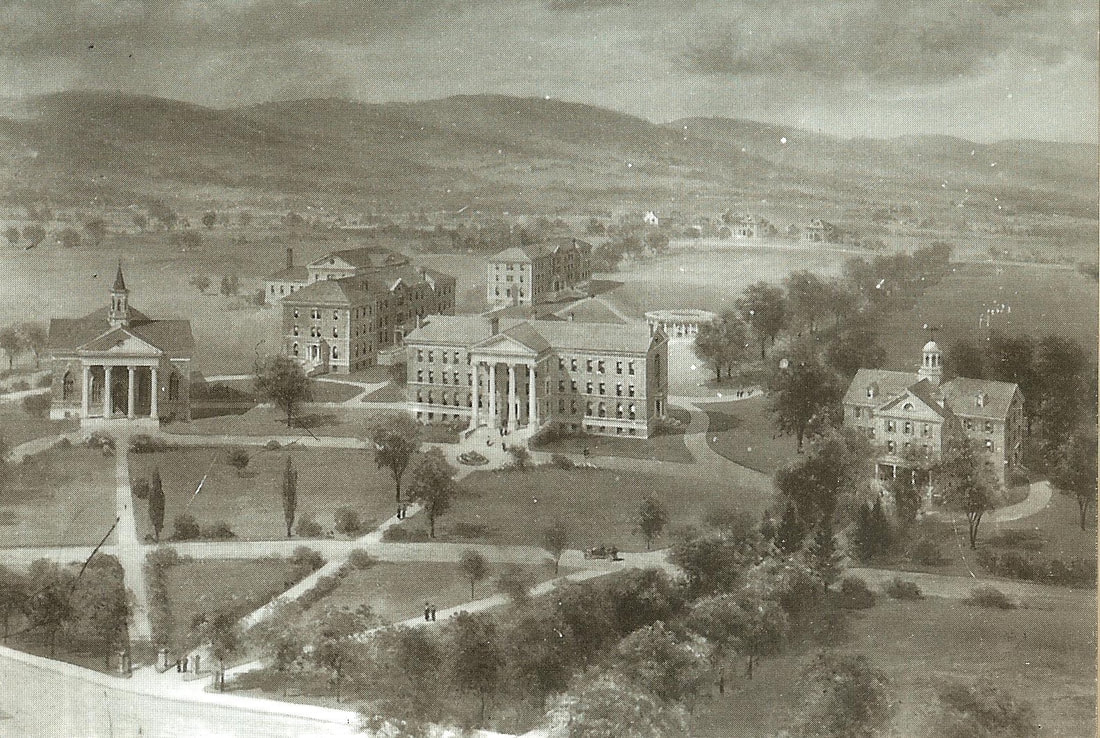

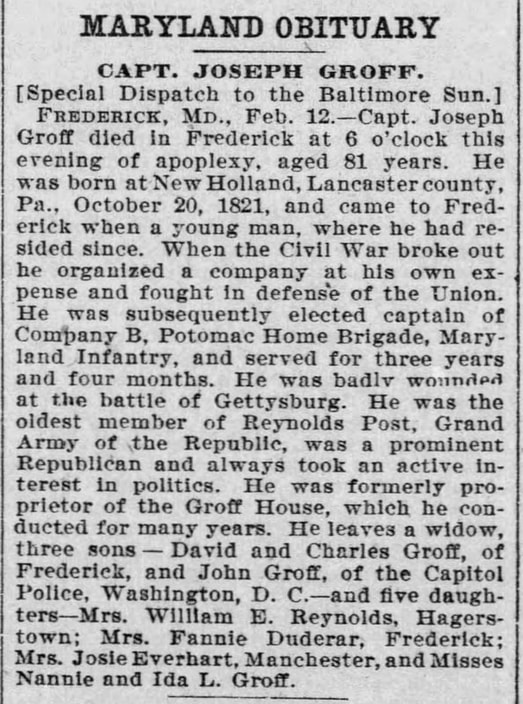

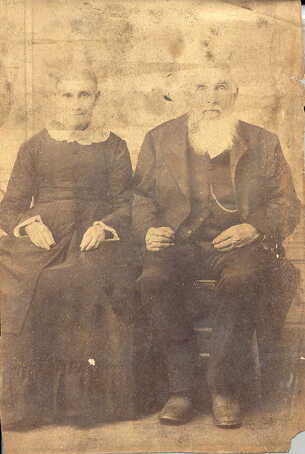

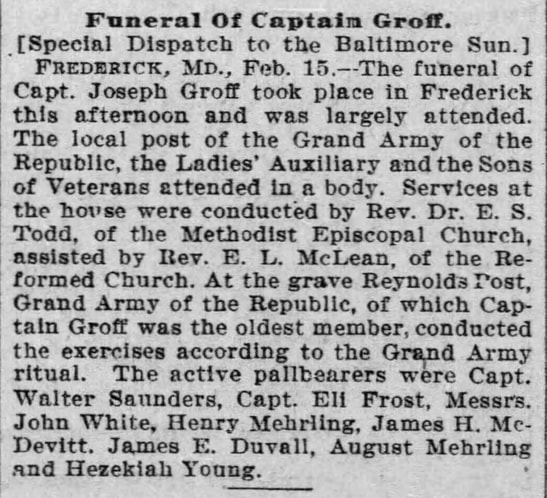

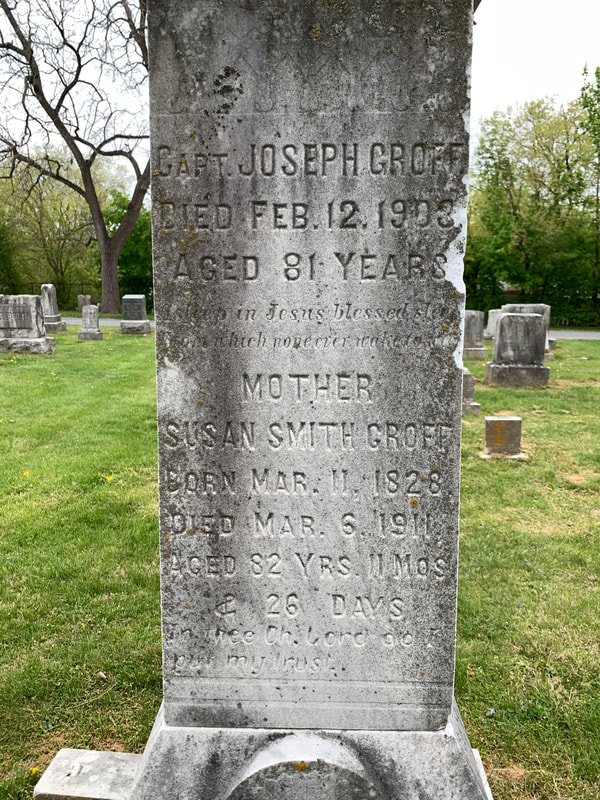

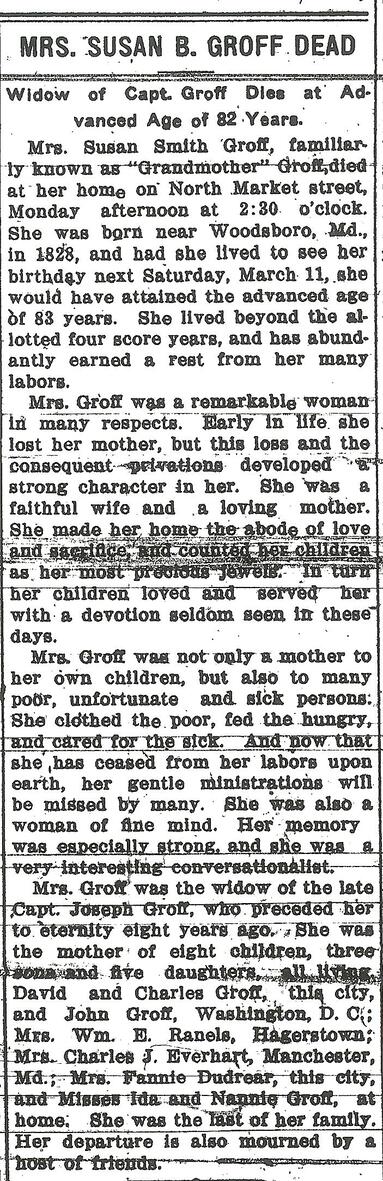

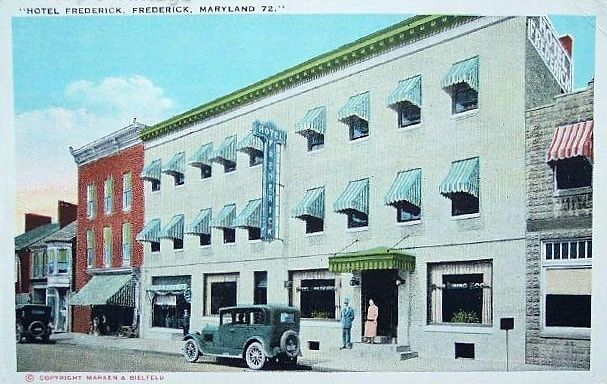

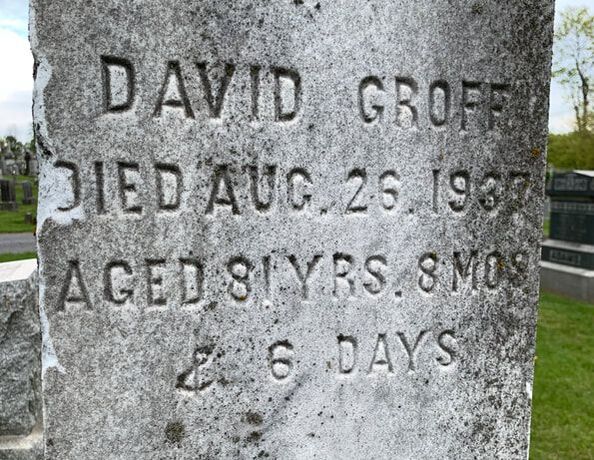

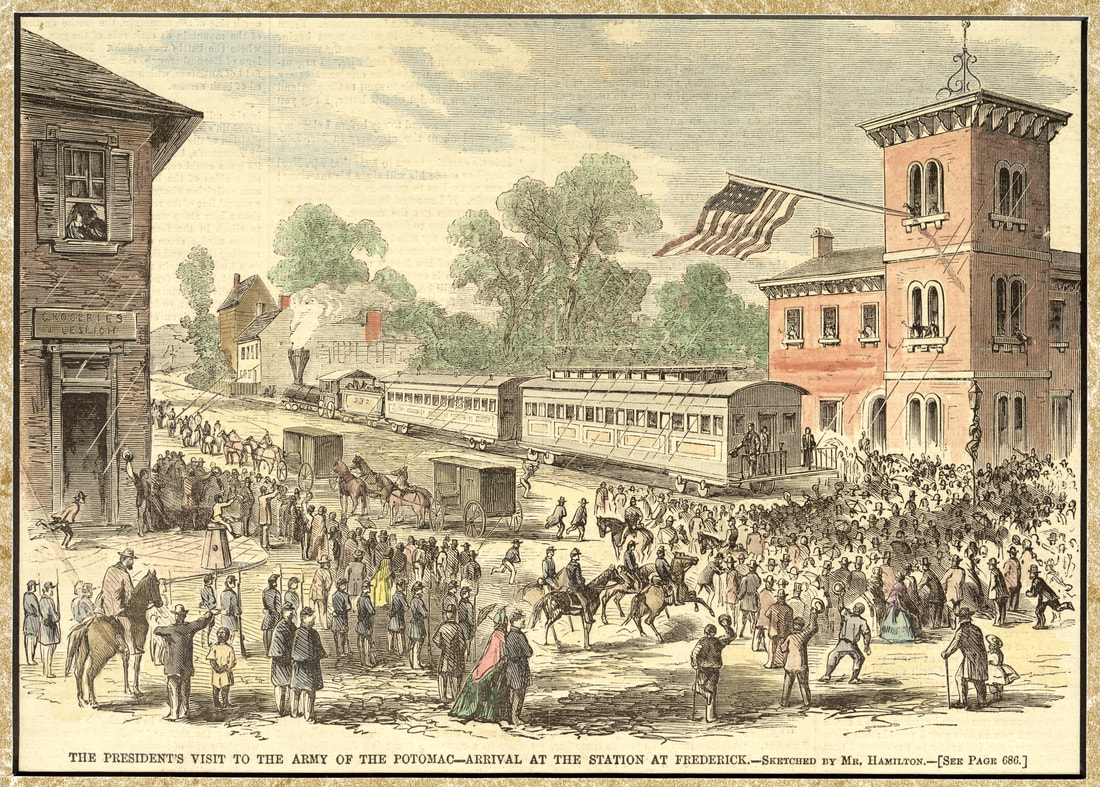

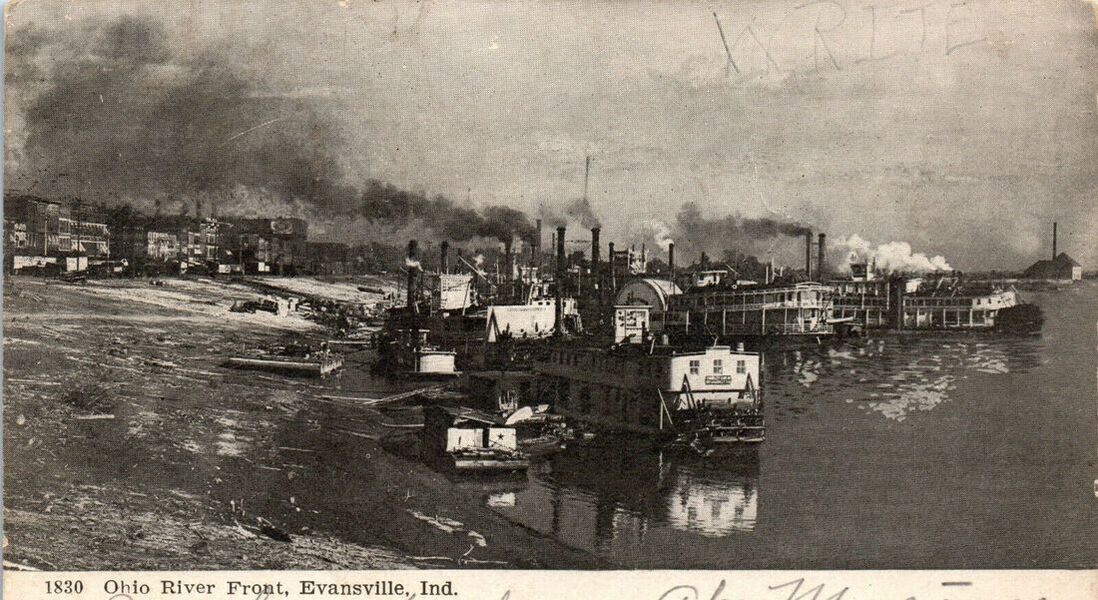

Back in 2007, I made the acquaintance of a historical writer and genealogist named Alice L. Luckhardt of Stuart, Florida. I met Alice via the internet as I was conducting research for a presentation that I was invited to give for the Frederick Master Docent Series (sponsored by the Frederick County Historic Sites Consortium). My topic was “Myth-busting and Frederick History,” and I had a variety of Frederick stories in mind such as John Hanson as first POTUS, George Washington’s alleged headquarters on W. All Saints’ Street and the legendary Snallygaster of the Middletown Valley. Above all these, however, my headliner would be exploration into the famed Barbara Fritchie-Stonewall Jackson incident on W. Patrick Street during the American Civil War.  The Ballad of Barbara Frietchie, a poem, written by a Quaker poet from Massachusetts (and published a year later in October of 1863) would give posthumous fame to the former Frederick resident. However, with all the success this work would garner, including a great shot in the arm for Frederick tourism, more questions than answers would come due to the fact that this monumental event had no legitimate eye-witnesses. That’s right, no one could vouch for “Ms. F.” actually waving a flag out of her second-story dormer window at the Confederate Army on September 10th, 1862. Many saw her wave a flag at the Union soldiers marching by her house the following day, but that was not nearly as daring a deed as the one John Greenleaf Whittier recorded for posterity with his poem. Through my intensive research of the event between 2007-2012, I carefully explored other “Barbara Fritchies” in our midst—patriotic women here in Frederick (city and county) during that turbulent test to our union of states. I found other former female residents who should hold like-fame to that of Barbara’s through their displays of bravery in exhibiting Yankee pride. These included Mary Quantrill, a woman who lived less than two blocks west of Barbara Fritchie and Carroll Creek on W. Patrick Street; Nannie (Nancy Crouse) Bennett, the famed “Valley Maid” of Middletown and star of a poem written by Thomas Chalmers Harbaugh; and another whose moniker has never graced local history books as a legitimate heroine for the Northern cause—Susan (Smith) Groff. Perhaps the reason why I had never heard of this Woodsboro native is that she was clearly overshadowed by her husband, Captain Joseph Groff, who was larger than life, and a true character in the sense of the word. Mr. Groff was a local businessman and Union officer assigned to the 1st Maryland Infantry Regiment, Potomac Home Brigade. During the Civil War, Mrs. Groff ran the couple’s hotel located in the 400 block of N. Market Street in Frederick City. Known as the Groff Hotel, it would take the name of the Arlington House in the early 1900s, and later the Hotel Frederick. I was first introduced to the Groffs by pure accident in 2007 through an eBay auction of all things. While searching for collectibles pertaining to Frederick history, I saw an item advertised as a Civil War era newspaper featuring an account of a patriotic lady from Frederick, Maryland. It was dated October 22nd, 1862 and reported a noteworthy event during the recent Maryland campaign. I immediately clicked to view this vintage paper item, thinking that it had a connection to Barbara Fritchie, or perhaps Mary Quantrill, the 38-year-old schoolteacher and fellow flag-waver, who lived up the street from the feisty nonagenarian. This edition of the Philadelphia Inquirer would not have the mention of either woman’s name, and one more, Nancy Crouse for that matter. To my surprise, I quickly learned that the lady being heralded by this Philadelphia newspaper account was Susan (Smith) Groff (not Groffy as the paper inadvertently reads). She acted in a patriotic fashion by hiding rifles in a well on her property, as not to allow them to fall into the hands of the invading Rebel army under Gen. Robert E. Lee. This contingent of the Army of Northern Virginia would spend nearly a week in town in early September before moving westward and engaging Union troops in heated battle at South Mountain (September 14th, 1862) and Antietam (September 17th, 1862). This was the only newspaper article that appeared during the fall of 1862 pertaining to any of the four patriotic women of note (including Dame Fritchie). The Groffs are best remembered for the large Victorian guest house/hotel built on the northwest corner of N. Market and Seventh Street in 1884. This building would become the first home of WFMD in the next century and was later razed in March, 1973 to make way for a parking lot. Susan Groff was born Susan Christina Smith on March 11th, 1828 in nearby Woodsboro. She was the daughter of John Smith and Susan Ebert and married Joseph Groff on January 1st, 1852. The couple took up residence in Walkersville for a short time afterwards. This is where the fore-mentioned Alice Luckhardt comes into the story as she aided me greatly with the backstory on Susan’s husband, Captain Joseph Groff. I learned that Mr. Groff was born in New London near Lancaster (PA) in 1822, and came to Frederick as a young man, perhaps attracted by shipping opportunities with the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal. He had married Rebecca Beichtel on October 28th, 1842 in Hollidaysburg, Blair County, Pennsylvania. They moved to Harper's Ferry, (VA) in 1844 and had two children, William Shelton and Rebecca. Joseph’s wife died August 1850, precipitating him to relocate to Frederick County's Woodsboro where he would meet his second wife. Joseph and Susan were the parents of several children including David, Jennie, John, Fannie, Ida, Minnie, Nannie, Josie and Charles. David and John are buried here in Mount Olivet and were the focus of two of my earlier “Stories in Stone” articles. By 1858, the Groffs were living in Philadelphia where they ran a hotel and kept a stockyard, and another stock room of Groffs was apparently located in western Virginia at Parkersburg. The spring of 1861 saw the Groff family back in Frederick, primarily because Virginia had seceded from the Union. The Groffs opened a store here which sold various goods at public auction. They later turned this venture into a hotel located on the west side of Market Street between 3rd and 4th streets known later as the Arlington Hotel and Hotel Frederick (today the site of another parking lot and formerly that of Carmack-Jays grocery store). The Groffs are said to have been ardent Unionists and Mr. Groff and his sons participated in the famed “war between the states.“ The previously mentioned Alice L. Luckhardt wrote a story about her great, great grandfather (Joseph) for the June/July 2007 edition of History Magazine. The article was entitled “The Defiant Flag Waver,” and depicts Captain Groff involved in Frederick City’s first recorded flag-related incident of the four-year conflict. In the Spring of 1861, Joseph Groff reportedly placed his 20-ft long Union flag over N. Market Street for all to see, attaching one end to his business establishment on one side of the street and the other to an adjacent building across the street. Joseph Groff explains the situation in a memoir written later for the Grand Army of the Republic: “When I came to Frederick from Philadelphia in 1861, I brought with me a large U.S. flag which I strung across the street from my storeroom, which was at what is now the Groff House. It caused much excitement and the secessionists secured a Mr. Poffinberger to come to town to take it down, and to thrash me also. When I heard of it, I stopped upon the pavement and said that if any man took that flag he would have me to whip first, and if that man came in to do it, I would meet him –he never came.” Joseph Groff must have made a good impression on his fellow residents, as he would soon be showcasing his love of flag and country through military service. Home Guard units had been in place in Washington, Frederick and Carroll counties throughout the summer of 1861. Union Maryland regimental units were authorized and men began volunteering. The best-known local unit was the 1st Regiment Infantry, Potomac Home Brigade, Maryland Volunteers. This group would serve with distinction under the command of Col. William P. Maulsby, a Frederick attorney. Joseph Groff would enlist at Frederick’s old Market House, and took his 17-year-old son, William Shelton, with him. Since the previous spring, both father and son had served in a state militia company known as Sander’s Independent Rifle Company. Their assignments had included guard duty of the Monocacy Junction railroad bridge for the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad and keeping watch over Kemp Hall during the Special Session of the Legislature. During the latter duty, the elder Groff was stationed in the Senate room, and both men were given orders to arrest the secession element of the Legislature. Joseph Groff helped raise the Potomac Home Brigade’s Company B, and was immediately made First Lieutenant. He raised 62 men for his company. They were mustered into service on August 20th, 1861 and would soon be quartered at the Old Hessian Barracks. For good luck, Groff supposedly took his supersized flag with him into military service. By the end of the Civil War, Groff would rise to the rank of captain. During the winter of December 1861-April 1862, the regiment was led by General Nathaniel P. Banks. They trained and were quartered on Barracks Hill near Frederick (Maryland School for the Deaf). In the winter of 1861, they left the barracks and wintered at Camp Worman, north of Frederick (today’s site of the Wormans Mill neighborhood). All of the 1st Potomac Home Brigade were quartered there for the winter. By the springtime of 1862, the forces marched up (which actually in a southerly fashion in this case) the Shenandoah Valley as far as Winchester. From here, the 1st PHB (Potomac Home Brigade) was assigned to guarding the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad line. Gen. Banks and his troops were eventually driven out of the Shenandoah Valley and stayed in the Harper's Ferry area. Joseph Groff knew the area quite well since he had lived here earlier for a decade from 1840-1850. After the second battle of Bull Run, Gen. Lee would bring his Army of Northern Virginia across the Potomac River to northern soil. The first major Union city he would come was Frederick. While her husband and son were "off at war," Susan ran the affairs of the family's Frederick hotel. This first week of September (1862) was the time of General Lee’s invasion of Maryland, and more importantly for us with this biographical exploration of the Groffs, the time Susan found herself busily hiding those guns in a nearby water well. After five days, the main column of the Rebel army would head westward past Barbara Fritchie’s house on the National Pike to points west and the battles of South Mountain (September 14th, 1862) and Antietam (September 17th, 1862). As for the Groffs, their regiment guarded the passages along the Potomac River near the mouth of the Monocacy, and later concentrated its efforts at Harper's Ferry. The Potomac Home Brigade’s Company B would participate at the siege of Harper's Ferry and Battle of Maryland Heights (across the Potomac River) from September, 12-15th. “On Thursday, September 10th, we were ordered to Solomon Heights where we found the enemy in ambush. My First Corporal, Charles Oursler, was killed there by the enemy. We fell back to Maryland Heights. On Friday the fight on Loudoun took place. On Saturday after spiking the siege guns on Maryland Heights we were ordered to the Ferry, Colonel Ford was in command at the Heights. On Sunday the Garibaldi Rifles returned to the Heights, securing the brass guns and brought them to the Ferry. We were fired upon all day Sunday.” -Lt. Joseph Groff It was here that the regiment was surrendered on September 15th, 1862 after being surrounded by the Confederate forces. Both father and son would be captured and eventually “paroled” in, of all places, Parole, Maryland (Anne Arundel County). While I’m at it, I should note that this cleverly named suburb of Annapolis continues to be a location where several major roads intersect at the western edge of the state capital. The neighborhood is so named because it was a parole camp, where Union and Confederate prisoners of war were brought for mutual exchange and eventual return to their respective homes. Today this area boasts the Annapolis Mall, and a number of other large shopping centers, and the Anne Arundel Medical Center. After Groff was paroled, he saw duty at Point Lookout in St. Mary’s County, and later saw action at Gettysburg in July, 1863. Alice shared a family story that Capt. Groff stopped in Woodsboro on his way to Gettysburg to kiss his daughter (Rebecca) good-bye. At the Battle of Gettysburg (July 1-3, 1863), the regiment was part of Gen. Lockwood's brigade. On July 2nd the regiment fought on Culp's Hill and worked with Sickles Corps to repulse the Confederates under Gen. Longstreet. Capt. Joseph Groff fought at Spangler's Spring in command of his company against Maryland-born Confederates. In the early hours of July 3rd, 1863, he was wounded by a bullet lodged just above his foot. Not trusting the battlefield surgeons at hand, the captain received special permission to go to his home in Frederick to have his personal doctor care for his wound. After being given time by the Army to mend his wound, he returned to his company and active duty in early September 1863. Capt. Groff’s military career would soon be coming to an end because over the next several months, the effect of explosives had caused deafness in Joseph's ears. He was also unable to do physical labor after a year. This is the reason that the captain would not participate in the Battle of Monocacy in early June, 1864. However, Joseph's son, William Shelton, who had been promoted to corporal, did take part in “the Battle that Saved Washington” on July 9th, and came out of it unscathed in the defeat of Lew Wallace’s grossly outnumbered soldiers. By September 6th, 1864 (even while the war still raged on), Joseph was released from his three-year military service and then honorably discharged in Washington, DC in December, 1864. His son, William, was mustered out of his company at Harper's Ferry on the same September day as his father. Immediately after the war, Joseph Groff continued supervision of the hotel with Susan for a few years before hiring managers to run the operation at different times. Additional time and assistance was required for launching a newly opened brickyard business (Eighth and Market streets) and a social club named Groff Hall (W. Fourth Street) which also catered to the town's Black population. Joseph and Susan's family situation was just as busy as they were in the midst of raising eight children into adulthood. The entire Groff clan resided in the hotel and can be found here the 1870 and 1880 censuses. Through her research, family historian Alice Luckhardt compiled a list of activities involving the Groffs and taken from the pages of local newspapers, court documents and Jacob Engelbrecht’s diary: *Thursday - Feb. 21, 1867 --- At a public sale Capt. Groff offered his tavern stand for rent at a public sale. It went for $1,285 rent a year. *Friday - Jan. 27, 1871 and Sat. - Feb. 4, 1871 - the Union or Republican Party made nomination for councilmen, Mayor and Alderman at "Groff Hall" located on West 4th Street. *1878 - Frederick had a population of about 10,000. Joseph Groff ran one of the city's hotel and William (his son) made mattresses and upholstered furniture. *In December 1883, the Groff Hotel was enlarged by 20 feet in front. On the property was also a livery stable, which Joseph Groff rented out to individuals over the years. By 1886, a small barbershop was set up by John F. Yingling on the first floor with an entrance onto North Market Street. *By the mid-1880s, Joseph had built a grand new home for his family at 7th and North Market streets, a few blocks north of the hotel. *Between 1889 and 1895, Groff had a couple of his daughters along with a son-in-law, Richard C. Dudrear manage the hotel. Room rates were generally $1.50 a day. *During the 1880s, the hotel was always decorated for various holidays. Celebrations during the 4th of July were always special with U. S. flags on display everywhere. Also during the latter part of the 19th century, the Groff Hotel was the scene for many weddings. Included was the April 1885 wedding of Capt Groff's daughter, Jennie Groff and William E. Ranels and in June 1890, the wedding of Capt. Groff’s youngest daughter, Josie Groff to Charles Everhart. *Over the years and into the 20th century the hotel was the gathering place for many civic and community organizations to meet. Before the Civil War, Joseph Groff was a prominent member of the Deutsches Schuetzen Gesellschaft Park, a social and stock endeavor formulated by leading German descended residents. Present day Brodbeck Hall (on the campus of Hood College) served as the clubhouse for the group, which came complete with an old-fashioned beer garden to accommodate stockholders. The war and lean times caused financial woes that the club could not rebound from, and apparently Capt. Groff purchased the locale. The property was renamed Groff Park. The Groff family would split time living here and used the vicinity to grow gardens of produce that would be used to feed guests staying in their hotel. The couple's oldest son, David, would grow flowers here for his successful career as a local florist. Eventually, Groff Park would be sold to Margaret Scholl Hood in the 1890s. Mrs. Hood would later deed the former Groff Park to Dr. Joseph Henry Apple and the Frederick Women's College and in 1915, this would comprise the newly named seat of higher education for women named Hood College  *1879 - Joseph Groff applied in Nov. 24, 1879 and received a veteran’s pension (#180772 - 281584) of $15 a month. *1880 census - had Nicholas H. Groff living with his family. Nicholas - age 13, born about 1867 in MD as were his parents. Listed on the census was that he could not read or write but had attended school in the last year. *Feb. 2, 1881 -- Capt Groff purchased two large Poland China hogs from Mr. Joseph Harp. The hogs weighed 2,350 pounds. *Early 1885 - partners in a "Frederick Colored Rink" - skating rink on 4th St. Groff Hall for the 'colored' population (blacks). Had his future son-in-law, Charles Everhart as ticket taker. *April 1885 - very successful rink - Capt. Groff very strict in running it. Sept. 12, 1885 - Sole ownership of the skating rink with a big grand opening. *1886 - owned a bull dog. *Nov. 1886 - David Cronin worked for Capt. Groff at the Hotel. On Oct. 1886 - Cronin shot his wife after a disagreement. They had married about 1863 in Frederick. Cronin then joined the Union Army and to war. He remained away from Frederick until about 1885 and then came back to his wife (lived on West 4th St.) *May 1887 - Mr. P. E. Long Baltimore, MD - rented the Groff Hotel from Capt. Groff, the captain and family moved to Groff Park at the north end of the city. *Oct. 10, 1887 - in newspaper - Levi L. Groff (brother of Capt. Joseph Groff) - his ex-wife (Nancy S. Waltz - 'Nannie') remarried to Capt. Alfred Schley. Levi may have tried to stop the wedding. *Aug. 1889 - Capt Groff was in West Virginia, (Jefferson County) to supervise the construction of the Shepherd Turnpike. *June 5, 1890 - 8:30 pm - the wedding of Josie Groff and Charles Everhart in the Groff Hotel. *March 1890 - David Groff took over ownership of the Groff brickyard. *April 1890 -- An advertisement appeared in the Frederick newspaper - about Groff Hotel, owned by Misses Groff (Joseph's daughters) and managed by Dudrear. Cost $1.50 per day for a room (1st class). *May 1890 - John Groff has ownership of North End Livery and Sales Stables. *Sept. 28, 1890 - a floor put in the bar room of the Groff Hotel. *1891 - Morse Fountain built by M. P. Morse at North Market St. across from Groff home--a large iron four-tier fountain *April 30, 1891 - quote in News by Capt. Groff - "I have lived in Frederick a long time and have seen many changes wrought, but the bustle and activity here this spring are greater than I ever saw before. The old town is certainly waking up at last." *June 1891 - selling large lots of property at Groff Park - 30 acres (west of Frederick). Possibly big sale to a gentleman from Washington, DC. No sale then. Groff Park also known as Scheutzen Park. Placed many newspaper ads for sale of Park, Hotel and Hall in late 1891. *Nov. 1892 - Capt Groff owned North End Livery Stables, his son, John Groff previously. *June 1896 - home robbery at night while family slept. Only money taken. His sister, Elizabeth was visiting at the time. *Sept. 19, 1899 - Capt. Joseph Groff's first son, William Shelton Groff - died of TB at his home in PA. *Oct. 2, 1899 - Frederick, MD - Capt. Groff was selected President of the Rossbourg Club - for Maryland Agricultural College. Captain Joseph Groff died on February 12th, 1903 at the age of 81. His death notice would appear here, Baltimore and his hometown of Lancaster, PA. Captain Joseph Groff would be laid to rest in a lot located in Area L/Lot 247. Susan Groff died on March 11th, 1911 and is interred with her husband. Her obituary included an impressive list of pallbearers from the Potomac Home Brigade’s top leadership including Major Edward Y. Goldsborough, Col. William P. Maulsby and Capt. Eli Frost among others. Her patriotism was remembered until the very end. What became of the Groff properties? By 1910, the Groff family has leased the operation of the Groff Hotel to Joseph F. Beacht, who was a former grocer in town. In 1906, Beacht was manager of the City Opera House and in 1907, manager of the Frederick Baseball Club before taking over the Groff Hotel. Things changed for Beacht in July 1913 when the Groff family, (with a deal completed by David and Charles Groff), sold the hotel for $20,000. Beacht’s lease on the hotel expired April 1st, 1914. He had about ten months before the new owner would take over operation. The Groff Hotel was next purchased by William H. Ramsburg, a wholesale grocer here in town. He would rename it the Arlington Hotel. By March 1st, 1914, Ramsburg was able to take full charge of Groff Hotel. He wanted to increase the number of rooms from 30 to about 50 rooms. Also added were the sale of special amenities such as cigars and railroad tickets. In 1920, Michael Joseph Croghan became the new owner of the hotel, leasing it first and then to purchasing it from William Ramsburg. Croghan was born in April 21st, 1889 in Ireland, coming to the U.S. in 1908. He worked at the Stewart Hotel in Frederick on East Patrick St. and the New City Hotel in Frederick.  Mike Croghan, Jr. (1921-2006) Mike Croghan, Jr. (1921-2006) Croghan had many plans for changes and improvement to the old hotel, including making it more modern, enlarging the dining room and adding 25 additional rooms. The Café on the left side (facing the Hotel) would become a cafeteria. The building was to be painted inside and out with new lighting installed. He also added a new restaurant to the Hotel. The biggest change would be the name changed from ‘Arlington Hotel’ to ‘Hotel Frederick’. The hotel was closed during its remodeling. To help clear out some of the older items, he held an auction in May 1920 of many of the furnishings; including doors, bedding, wash basins, electric fixtures, glassware and china. Most of the changes were completed by the Spring of 1920. The new restaurant at the hotel charged 40 to 60 cents for lunches and 75 cents to $1.00 for dinners. During the 1920s, Mr. Croghan also managed (held leases) on the Hotel Braddock, in the summer months. By July 5th, 1923, Croghan made the final purchase of Arlington Hotel / Hotel Frederick. Into the 1930s and 1940s, Michael Croghan continued running the Hotel Frederick and managing the Hilltop Hotel in Harper’s Ferry in West Virginia. By the 1950s, his son, Michael J. Croghan Jr. was assisting the Hotel Frederick operation. Croghan Sr. died October 1960. Mike, Jr., who I had the pleasure of knowing myself, continued ownership and operation of the Hotel Frederick and its catering services until 1972. In early 1972, the Croghan family decided to sell the old hotel (building and property) to the City of Frederick. In June of that same year, an auction was held to sell off items from the hotel. One year later, June 1973, the City had the fine, old hotel torn down and sold the land to Carmack Jays Supermarket to construct a parking lot. Since the deaths of Captain Joseph and Susan Groff, some of the couple's children are buried here with them in Area L/ Lot 247: John (d. 1921), David (d. 1937), and Fannie G. (d. 1953). Here are links to stories involving John (an early secret service agent), and David (a local florist).  As a final aside, I looked intently for the site of Mrs. Groff’s daring deed. Unfortunately, there is no specific location given for the Frederick "well" in which Mrs. Groff hid the Union firearms for safekeeping. Perhaps the original site could have been on the hotel property or maybe somewhere in Groff Park. Or, just maybe, the said well morphed into the famous fountain at the head of N. Market Street, situated in front of the later built Groff House? That would have been a good three block hike for Mrs. Groff, but could serve as a romantic ending and commemoration spot for an untold act of bravery connected to the Rebel invasion/occupation of Frederick in September 1862. INTERESTED IN LEARNING MORE LOCAL HISTORY FROM THIS AUTHOR? Join History Shark Productions and Chris Haugh for a new local history class coming this September: “Frederick in the Civil War” This 4-part course will explore the war and its effect on the landscape and residents of Frederick, MD including the nearby battles of South Mountain and Monocacy, Barbara Fritchie, the 1861 Maryland General Assembly session, Lincoln’s visit in 1862, the Ransom of Frederick and Meade’s Change of Command. Lecture classes will meet 6-8pm on Tuesdays (Sept. 10, 17, 24 and Oct. 1) at Mount Olivet’s Key Memorial Chapel. The last class will include a two-hour walking tour of interesting gravesites and monuments associated with Civil War soldiers and citizens. $79 for the entire 4-part course. Begins on Tuesday, September 10th @6-8pm! For more info and registration details, click the button below:

2 Comments

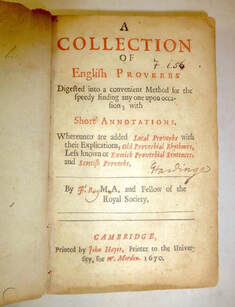

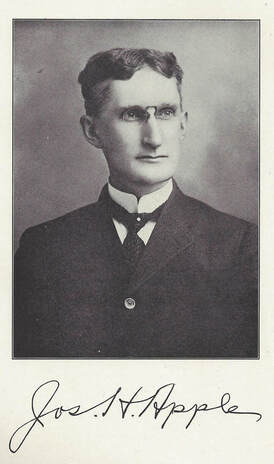

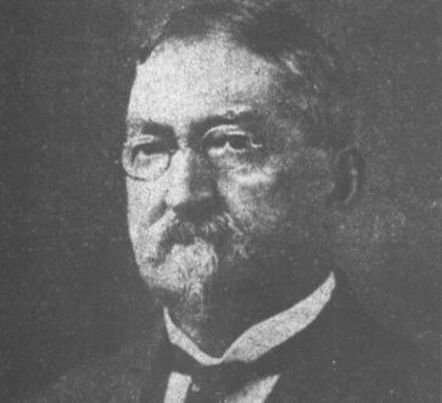

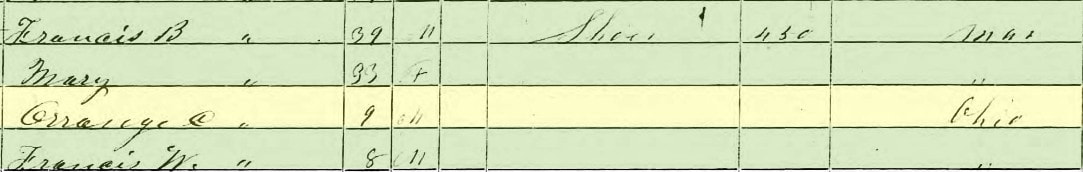

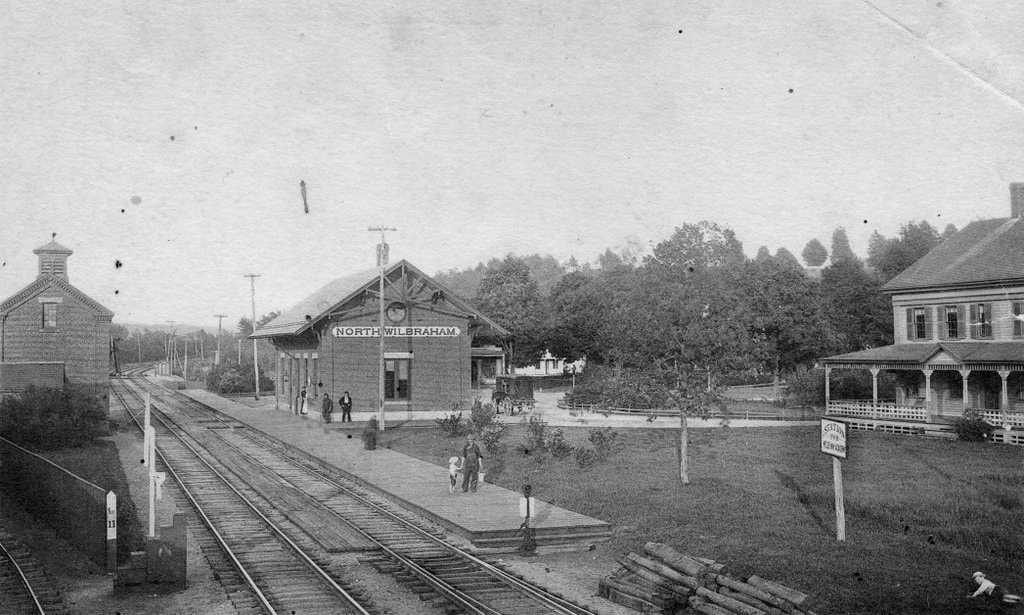

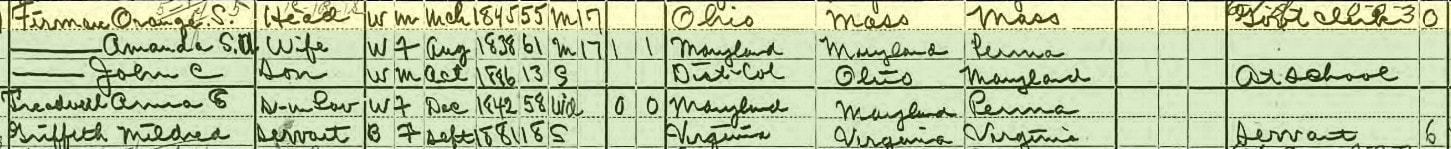

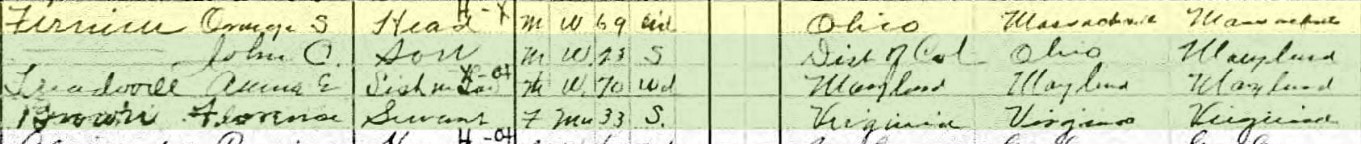

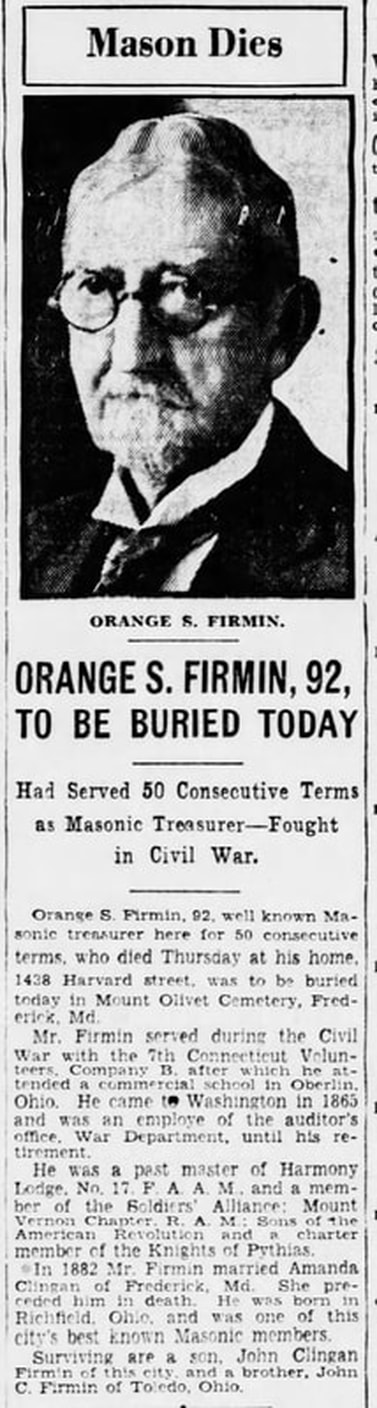

John Ray's 1670 work John Ray's 1670 work Making comparisons, we do it all the time. Being employed in the field of research, public history, and memorialization, I often find myself measuring persons’ lives according to the times in which they lived, and the things in which they experienced and accomplished. In many situations, I encounter what I believe to be unfair analogies of persons who cannot fairly be matched to one another, life stories that are completely different yet sharing like things such as generation, education, profession, and military experience. And the greatest likenesses of all, especially in our specific context here, are the givens of once having lived in Frederick and afterwards being laid to rest here in Mount Olivet. Many know that I’m an idiot for idioms, and I can’t help using the old fruit-themed adage of “apples to oranges.” Maybe you’ve heard of this expression before, maybe you haven’t. In doing a little research on the saying’s origin, I found that the idiom “apples to oranges” was first known as “apples to oysters” in John Ray’s proverb collection of 1670. The original expression referred to oysters on behalf of oranges as something which can never be compared with the apples. This seems a little random and blunt, but does express the definition at hand of items possessing non-identical attributes. Leave it to the purveyors of Romance languages to “class-up” the old idiom as the French are credited with using the expression “apples to oranges” dating back to 1889. Meanwhile, the Spanish used another member of the fruit group, with their variation “apples to pears.” While on a sojourn in the cemetery a few weeks back, my attention was drawn to a large, granite stone in Mount Olivet’s Area A, the oldest known section of the cemetery. This locale naturally hosted the cemetery’s first burial in late May, 1854, that of a woman named Ann Crawford. Only 15 yards away, I was intrigued by the decedent whose name was etched on this large block of stone. That’s right, Mr. Orange Scott Firmin, now that is a unique first name if ever there was one. I also liked the middle name of Scott, having a fitting, patriotic ring to it for some unknown reason. I immediately took a few pictures and thought this worthy of further exploration. I did have to laugh to myself as I had written a former “Story in Stone,” on a gentleman buried in Area CC who also boasted a “fruity” name if you will, Dr. Joseph Henry Apple, whose name is “immortal” and can be found easily within the annals of Frederick’s rich history. The first president of the Frederick Woman’s College and builder of its successor, Hood College, Dr. Apple also has a street named for him on Frederick’s west side. (Dr. Apple's Story in Stone from January, 2018) Sadly, I would safely bet that no one has ever heard of our new person of interest O. S. Firmin, save a handful of family historians perhaps. Regardless, he will serve as our subject du jour. The cemetery is filled with tens of thousands of monuments, markers and plaques at the very least keeping the names of their decedents above ground while their mortal remains remain below, or a crypt and urn does the same behind a plaque or nameplate in a mausoleum or columbarium. I’ve shared the adage in which it has been said that we all experience two deaths. The first is when we encounter physical death and thus require the services of places like Mount Olivet. The second, and final death, is when no one ever says our name, or remembers our face. Our time and accomplishments (big or small) on earth are forgotten. The markers and monuments can lead us to these “lost souls” if we take the time to notice. Well I would certainly hate to compare “Apples and Oranges,” because Mr. Firmin seems to be in clear need of “resuscitation” with a brief life history lesson. I find myself once again having the responsibility to operate the proverbial “defibrillator,” but it definitely falls on you readers to assist me in this biographical séance. I must say though, that I was selfishly hoping to find that a contributing factor to Mr. Firmin’s death was scurvy, but I couldn’t have been that lucky! Here goes anyway. Orange Scott Firmin Orange Scott Firmin was born on March 28th, 1841, in Richfield, Summit County, Ohio. I went to a website called behindthename.com and found the following about the moniker “Orange”: First found as a girl's name in medieval times, in the forms Orenge and Orengia. The etymology is uncertain, and may be after the place in France named Orange. This is a corruption of Arausio, the name of a Celtic water god whose name meant "temple (of the forehead)." Later it was conflated with the name of the fruit, which comes from the Sanskrit for "orange tree," naranga. The word was used to describe the fruit's color in the 16th century. Orange can be used as a surname, which may be derived from the medieval female name, or directly from the French place name. First used with the modern spelling in the 17th century, apparently due to William, Prince of Orange, who later became William III. His title is from the French place name. Orange Firmin was the second oldest of seven children born to Frances Bugbee Firmin (1809-1881) and wife Mary Colby Chapin (1817-1903). He lived the majority of his youth and teenage years in Wilbraham, Hampden County, Massachusetts, today an eastern suburb of Springfield. The Bay State had served home for previous generations of his Firmin relatives dating back to the early 1600s. Orange’s 5th great-grandfather (John Firmin 1588-1642) had come to Massachusetts with his parents from Nayland, Sussex, England. As one can imagine, he possessed a number of direct ancestors from Massachusetts who participated in the American Revolution. Mr. Firmin would serve in the American Civil War with his native Union. He was a Private in Company B., 7th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry, from Aug. 19th, 1861 to September 7th, 1864. Immediately following his military service, he was given employment by the War Department where he served as a clerk and auditor. Orange married Amanda Susan Ada Clingan (b. August 7, 1844) on October 24th, 1882, in Washington, DC. Amanda worked in the US Treasury Office in DC, but was born in Frederick back in 1844. She is our portal to Mount Olivet as the Firmins are buried in a lot owned by her parents. As early as the 1870 census, Amanda can be found boarding at the house of William Farrow, a clerk at the US Treasury in Washington, DC, and husband of her sister Ann. Both members of this couple, Orange and Amanda, had great jobs with the US Government and appear to have been paid handsomely. They resided in northwest DC and in late October, 1886, became the proud parents of John Clingan Firmin. Mr. Firmin was quite active in the Sons of the American Revolution and Freemasonry. He remained quite active in his working career, celebrated for his above-average dedication to the US Government, his employer. An article in a Washington newspaper in 1905 recognized Mr. Firmin on the occasion of his 40th anniversary with the War Department. Amanda died on August 27th, 1909. She would be buried in her parents' burial plot, not far from the noted monument dedicated to the memory of Francis Scott Key just 11 years prior. As for Orange, he would never re-marry as he seemed to keep himself more than ever with his dedicated service to the US Government. In 1919, ten years later, another article would appear in a December issue of the Washington Evening Times. A few more details were brought forward on our subject. Orange Scott Firmin died of pneumonia on December 28th, 1933. The previous year, I found a small mention in the Frederick News that Mr. Firmin had traveled to Orlando, Florida to spend some time. I assume this visit was recreational in nature and likely more so taken for health reasons. I just find it interesting since Orlando is the county seat of Orange County, so named because of the prized fruit industry that took hold there long before a guy named Disney showed up with a mouse in tow from California.  Although Frederick, Maryland was never his home in life, it would serve as Orange's home in death as he has been here for over 87 years now. Orange and Amanda's only child John would die in June of 1942. He enjoyed an early career as a draftsman, and finished his working days as a trademark examiner for the federal government. John would not be buried in Mount Olivet, being laid to rest in Fort Lincoln Cemetery located in Brentwood in Prince Georges County, Maryland. Mount Olivet has decedents who worked as lawyers and doctors, served as politicians and captains of industry, ran businesses, won awards and accolades, served in the military and acted on stage and played sports. There should be no need to compare apples or oranges here, as we should be judged the same in the end, simply as humans who lived a life the best they could. A higher power will take care of the rest. As long as you lived a life, you should take solace in knowing when it comes to cemeteries, you will be memorialized for that "body of work" that comprises the dash between your birth and death years on a gravestone's face. And, suffice it to say, Mr. Firmin did just fine.

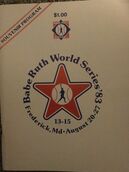

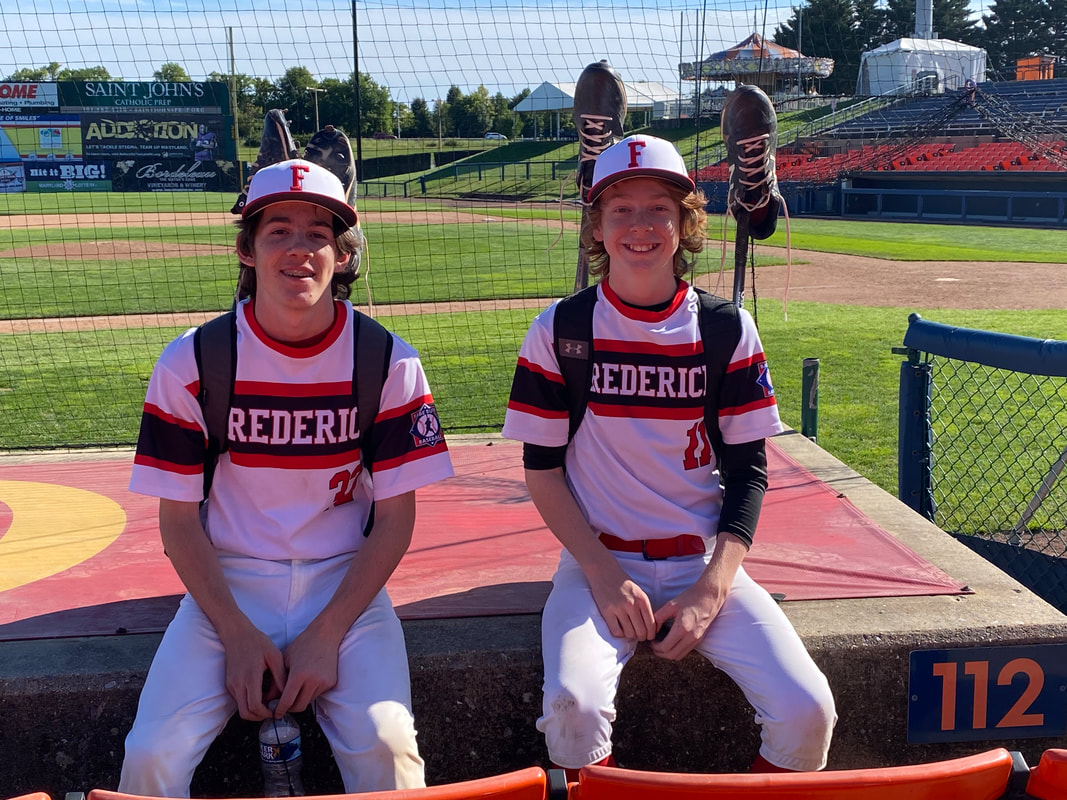

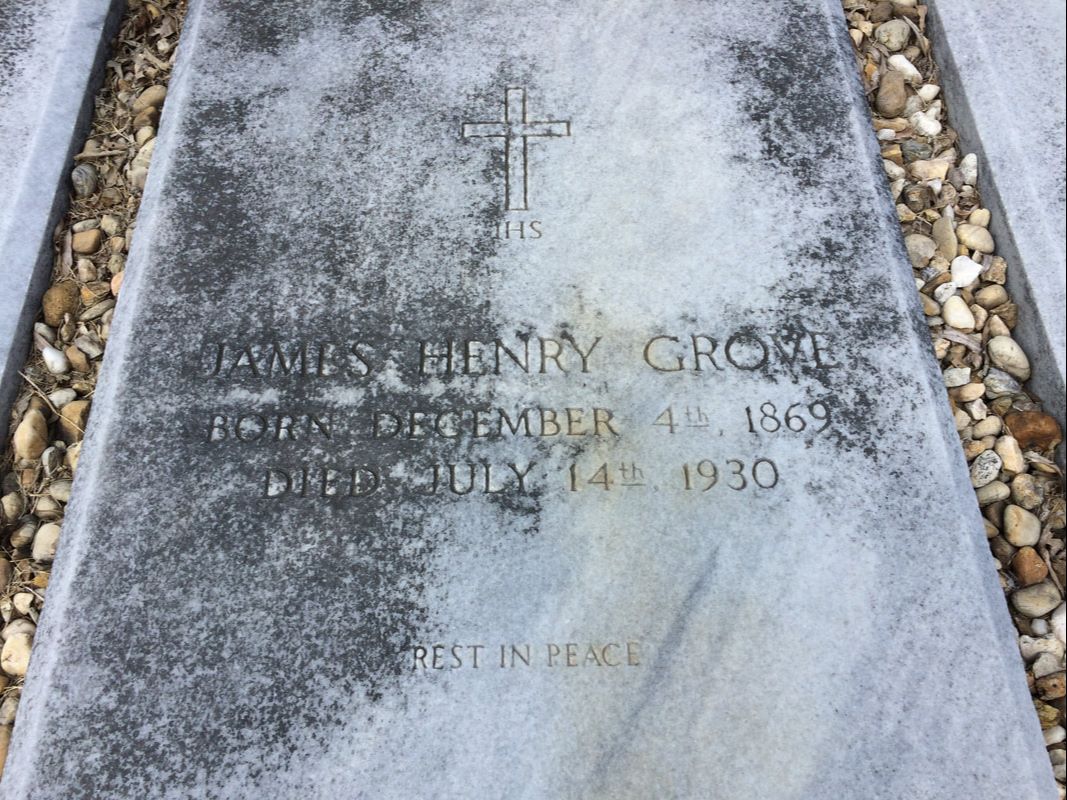

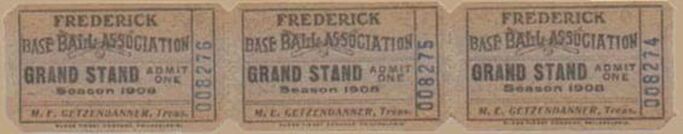

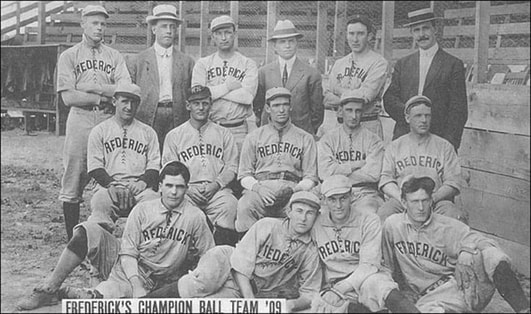

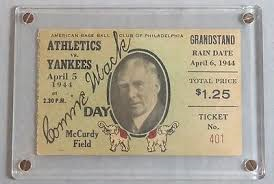

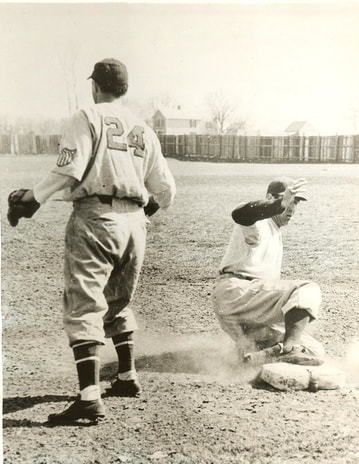

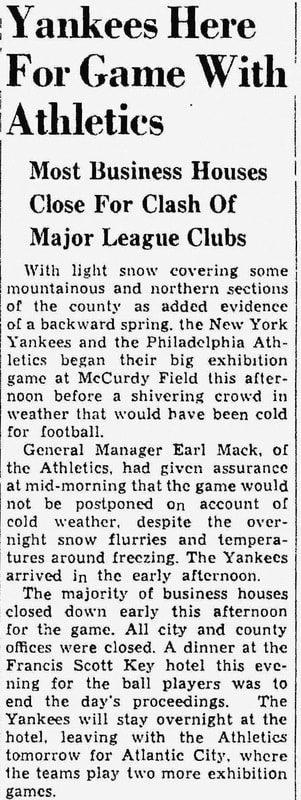

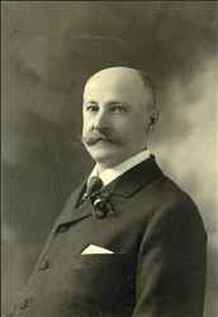

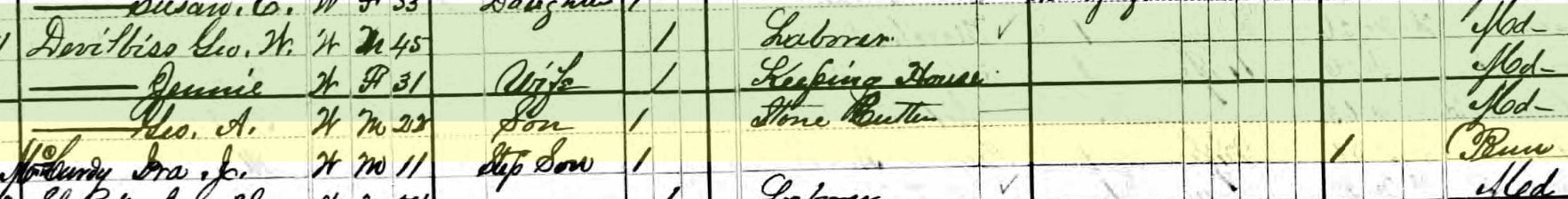

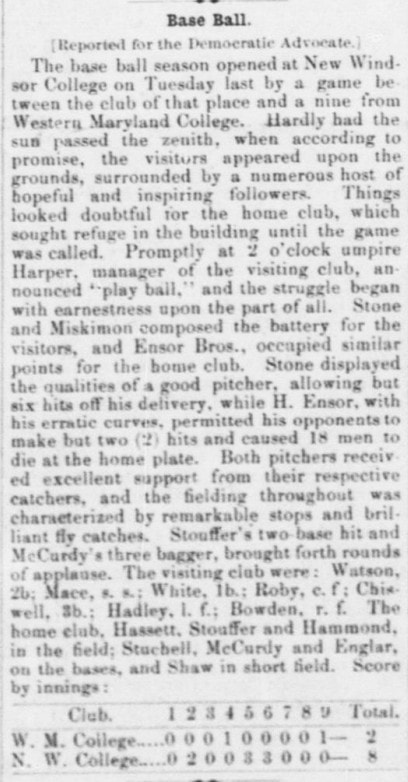

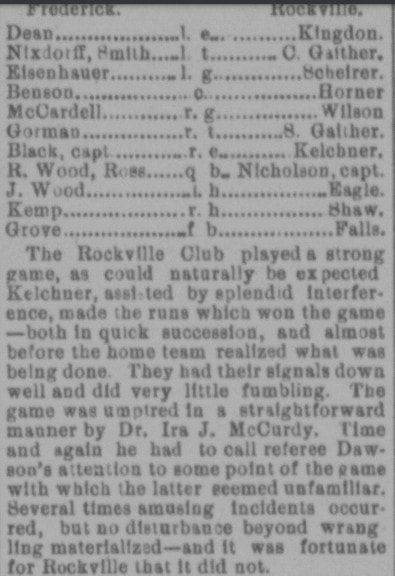

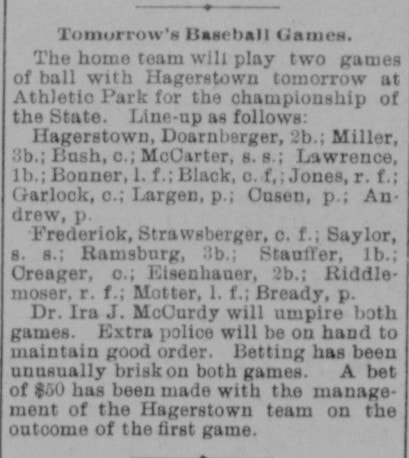

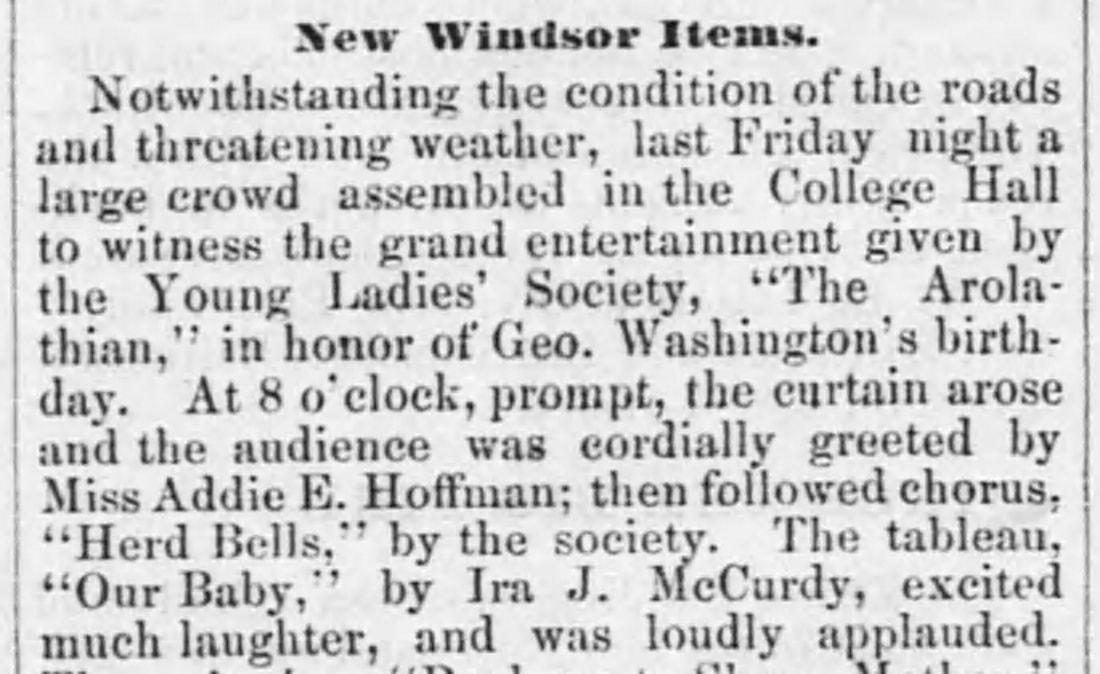

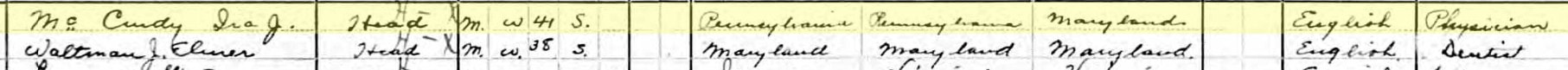

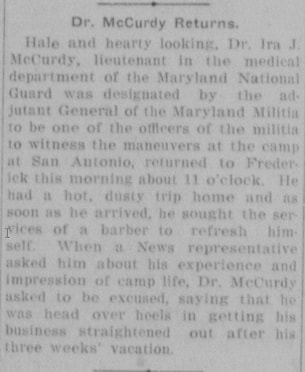

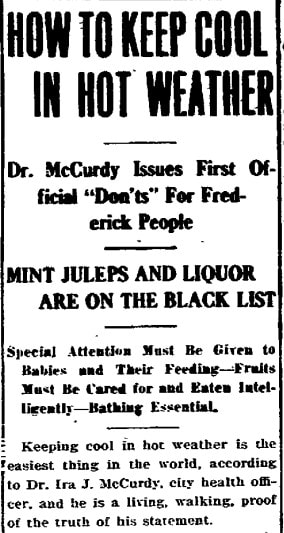

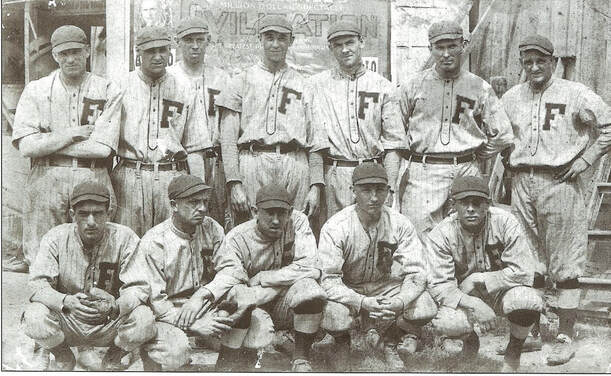

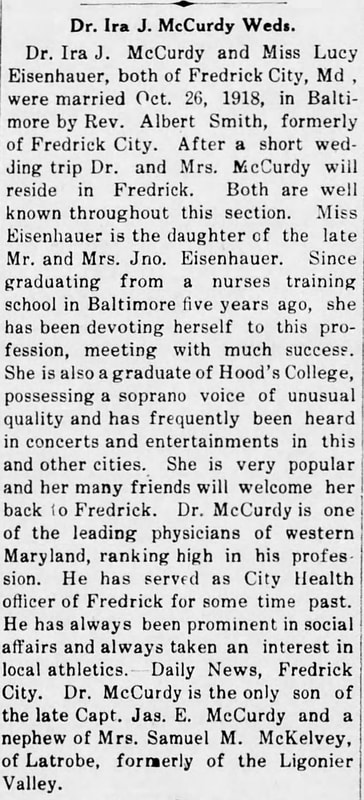

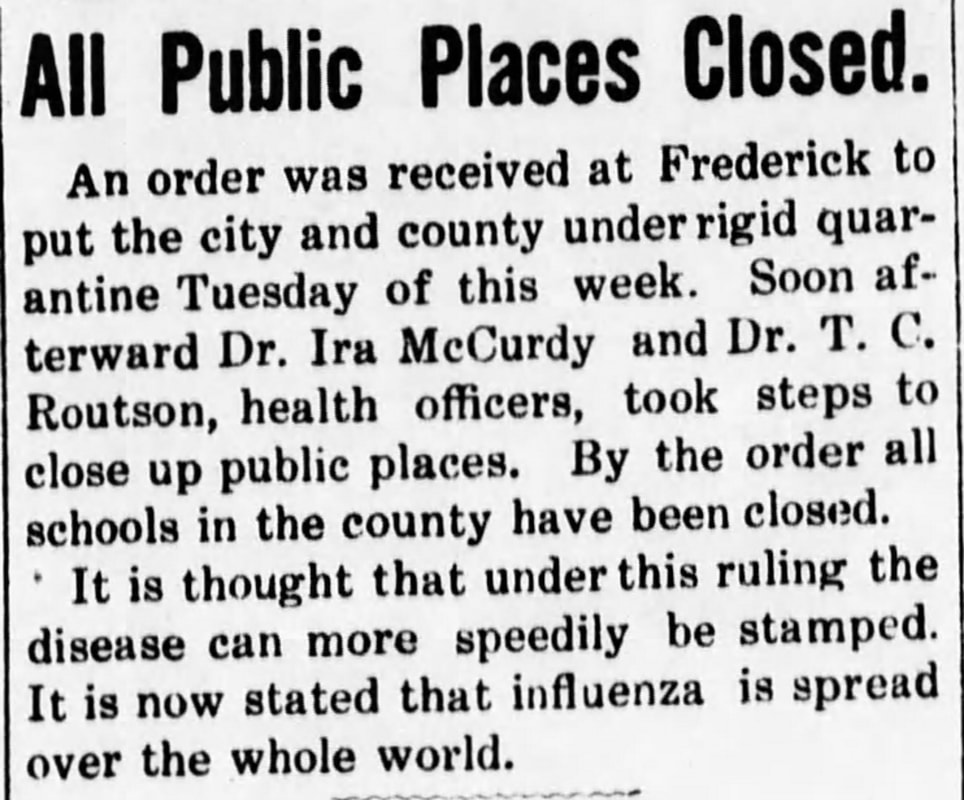

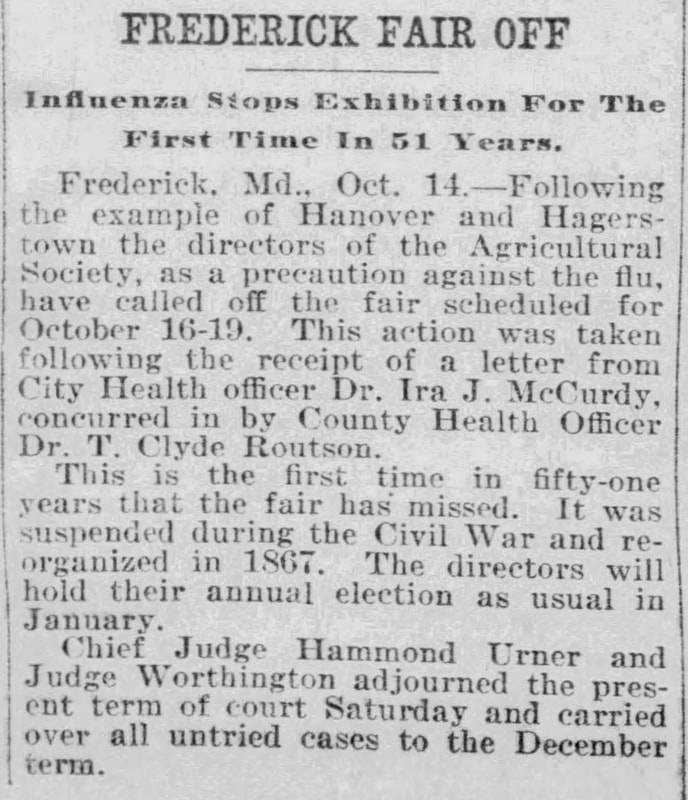

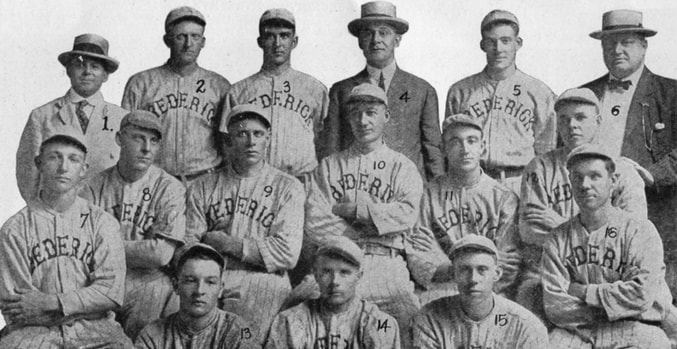

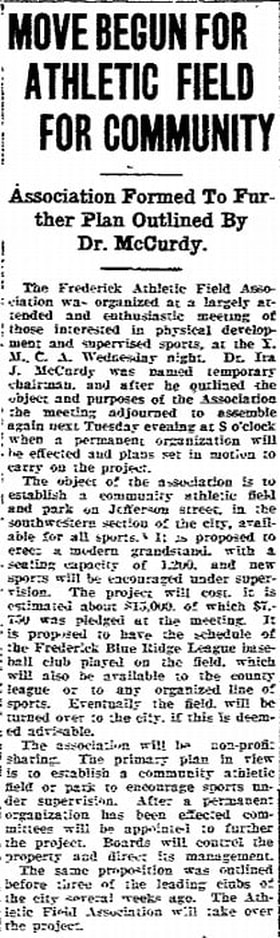

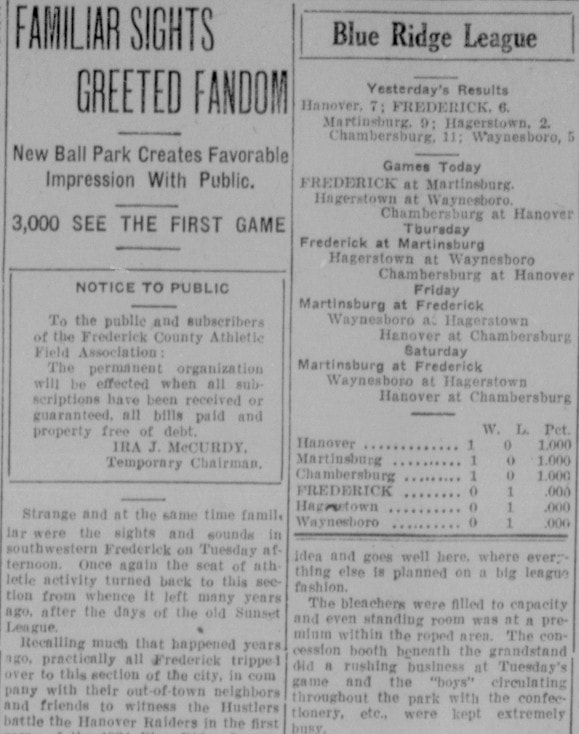

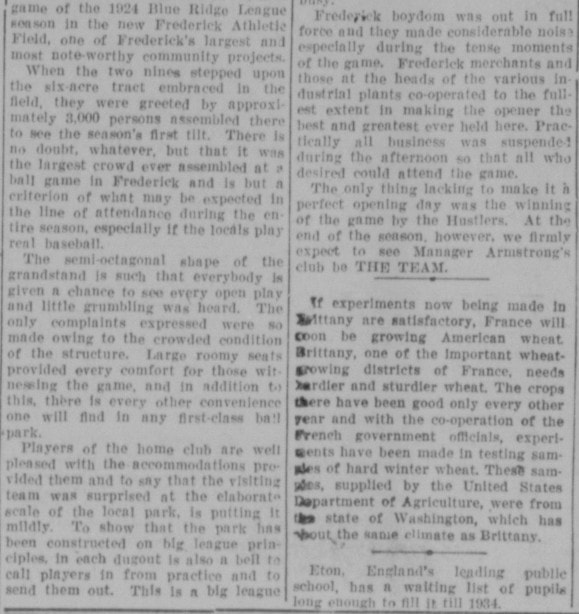

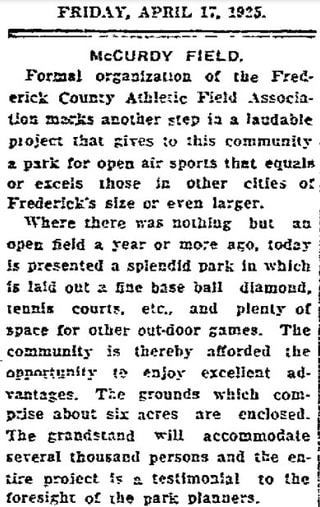

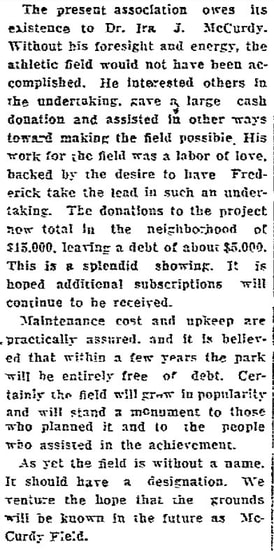

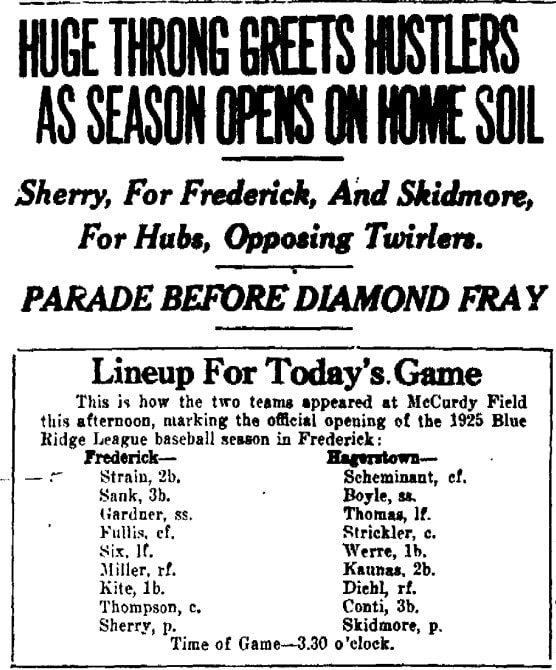

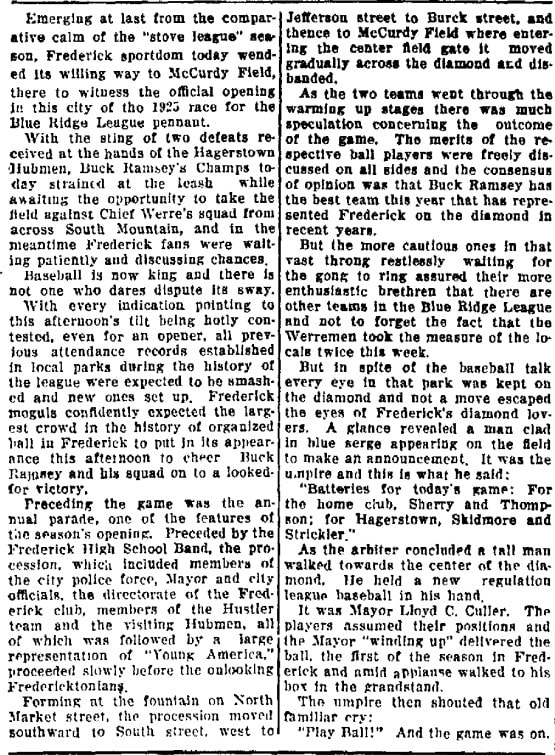

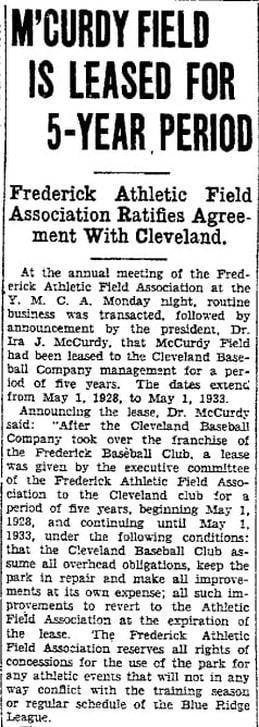

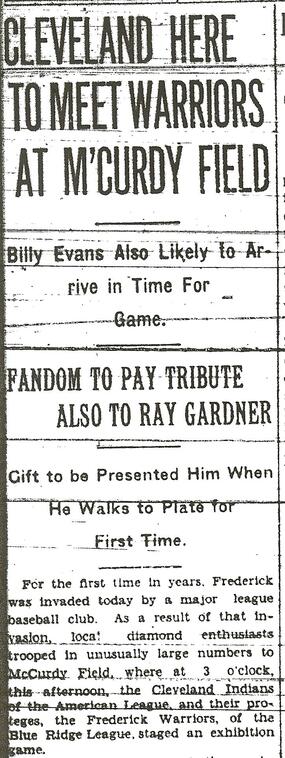

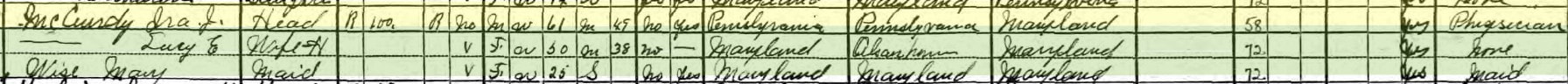

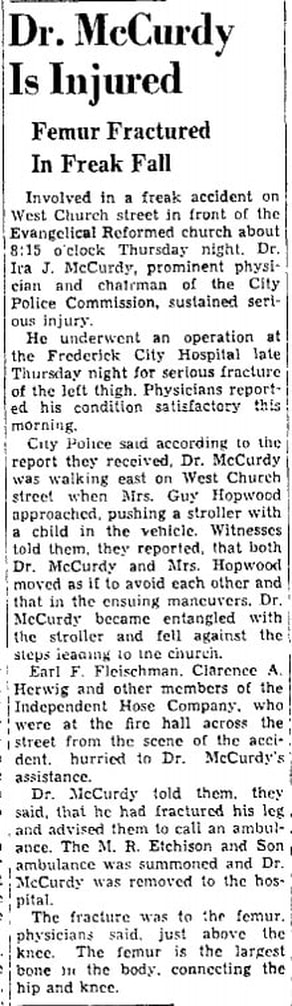

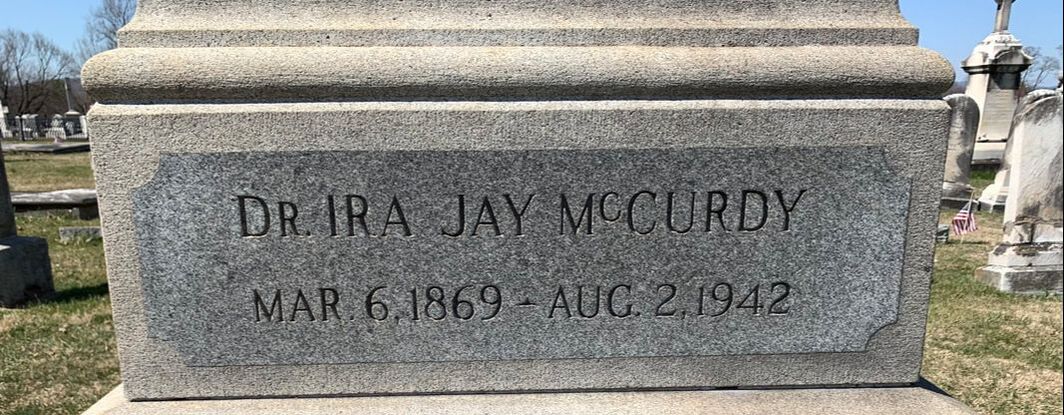

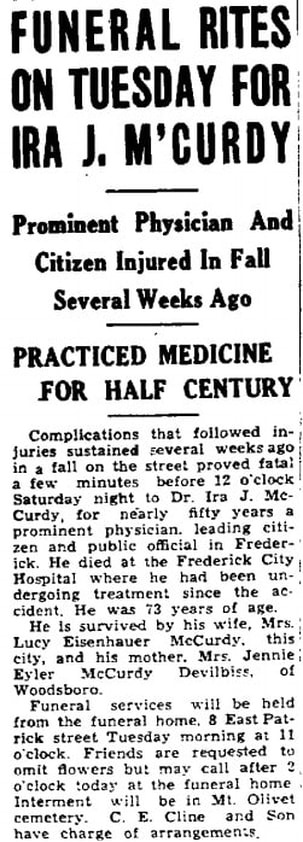

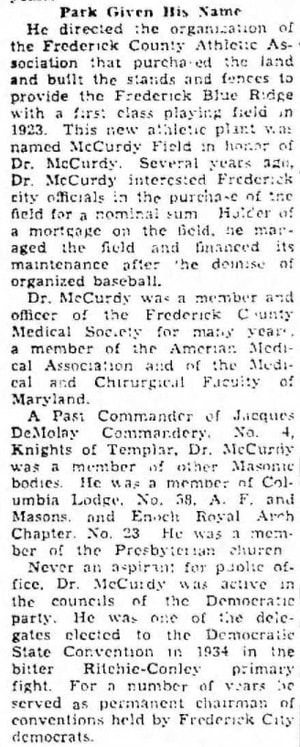

It’s baseball season and I was desperately searching for the end of what I thought was a quote commonly heard for years starting with: “Hear the crack of the bat and the smell of the __________________!” I could not exactly fill in the blank, thinking it was possibly grass, but doubting my own thought process. I did a Google search thinking I would find an exact quote and author for this “baseball-themed invitation” by plugging in the front end of the quote in the popular internet search engine. Soon, a myriad of word options filled my page, thus allowing me to complete the phrase—all courtesy of previously published articles and other content copy. These “olfactory offerings” ranged from grass, leather, pine tar, peanuts and crackerjacks, dirt, grilled hot dogs, and I even found “a freshly-poured beer.” Here in Frederick, our local team, the Keys, did not take the field in 2020 at neighboring Harry Grove Stadium at Nymeo Field due to the Covid-19 pandemic. It’s been a long, strange year for everything, but it was extremely odd to have more noise coming from the cemetery, on evenings last spring and summer, than hearing upcoming batter announcements, walk up music and the roar of the crowd after a hit or good play from our next-door neighbor. I am being a bit sarcastic as baseball returned to the location in the form of youth baseball late last summer and fall. Among these players, were two teenage kids of my own. I had the opportunity to see my sons Eddie and Vinnie play at Grove Stadium, and more regularly on their home diamond of Loats Field, as part of a team belonging to the Frederick City Babe Ruth Baseball league. This baseball field, along with a smaller little league field, are beyond Grove Stadium’s left field wall, and all three baseball venues are part of the City’s Parks & Rec Department Loat's complex located off Stadium Drive. They sit on the footprint of an old farm estate that once belonged to a gentleman named John Loats, buried here in Mount Olivet’s Area E. This former farmer-businessman's gravesite offers a commanding view of his former property. Another fitting family plot within eye and ear shot of these fields is that of James Henry “Harry” Grove. The stadium’s namesake helped originally bring professional baseball to town a century ago, and his son later donated money towards the building of the Key’s stadium which opened in 1990. Mr. Grove is among those family members buried in a lot on the southeast corner of Area LL/Lot 210, and was the focus of one of these “Stories in Stone” back in 2018. When it comes to baseball history of our Frederick professional and semi—pro teams, I truly revere the work of longtime FNP sports editor/reporter Stan Goldberg, statistics and local athlete guru Sheldon Shealer, historian-author Bob Savitt of Middletown (who wrote The Blue Ridge League), and Mark Ziegler, a diligent student of baseball history and former Keys employee at the time our former Carolina League, Single A affiliate of the Baltimore Orioles came to town over three decades ago in the spring of 1989. All these guys have researched, written and spoken on Frederick’s baseball history dating back to the 19th century. Ziegler even created a website BlueRidgeLeague.org that I invite you to check out. Interestingly, Mark would go on to later work in the marketing department with the Great Frederick Fair. The fairgrounds located off East Patrick Street on the outskirts of town, was the site of Frederick’s first reputable baseball stadium, fittingly known as Agricultural Field—so-named due to its connection to the agricultural fair of course. Here is where the Frederick Hustlers played many a fabled game going back to their semi-professional days with the Sunset League and culminating with their introduction into the Blue Ridge League back in 1915. In reference to baseball and this unique site, Mark found that the planning for the first organized baseball field here started in 1903, and by 1908, a wood stadium with a grandstand was built at the site for the semi-pro Sunset League. Trees were planted along East Patrick Street, in front of the Fairground property, and to the rear corner, surrounding the back of the grandstand area. There were organized leagues that played here with the Sunset League from 1908 to 1911, the semi-pro Tri-City League in 1914, and the Class D, Blue Ridge League from 1915 to 1923. We’ve had three professional/semi-professional teams in our history: the Keys (1989-present), the Warriors (1929-30) and the HustIers (1915-1928). One field, and one field alone, hosted games featuring all three of these teams—and the ballpark’s namesake as laid to rest here in Mount Olivet like the early mentioned Mr. Grove. Of course, I’m talking about McCurdy Field located on the southwest side of town, at the intersection of Jefferson Street and the newly named Scottys Bus Lane. (AUTHOR’S NOTE: And for those that experienced Raymond Scott and his magical, brown, culinary bus, this was certainly a place where one could "Hear the crack of the bat, and the smell of Scotty Dogs,” with the latter lingering in the air whether there was a game going on at the stadium or not!) In early 1924, a fund-raising committee was formed with the mission to build a modern baseball park in Frederick as a significant upgrade from the existing Agricultural Field. The ”modern and up-to-date” facility, known then as Frederick County Athletic Field, opened just months later after a cost of $15,000. It boasted 1,300 grandstand seats and 1,200 bleacher seats, along with a ten-foot high fence running around a massive playing field. This spectacle of the time would eventually take the name of McCurdy Field. In 1937, the NFL's Washington Redskins (just having relocated from Boston) needed a place to play their first exhibition, and played here. The Hustlers and Warriors professional team came and went, leaving a semi-professional version of the Frederick Hustlers. In 1943 and 1944, the American League’s Philadelphia Athletics, under the immortal Connie Mack, held spring training here (due to the limits on travel during World War II). Lights were installed in 1947, and in 1968, the old wooden grandstand was condemned and torn down in 1971, leaving just the field, and a sub-par home for Frederick youth and amateur baseball. Deciding that this was now a poor site for baseball, local businessman Bob Marendt headed a campaign to renovate this park. He raised $50,000 in donations, and federal and state government kicked in the rest. A renovated concrete and steel park opened in 1974 with metal bleachers that sat 1,500 and clubhouse facilities. The park was the home of Frederick City Babe Ruth Baseball and was even reputable enough to host the Babe Ruth national organization’s World Series tournaments back in the early-mid1980s. Some of the best young baseball talent in the country came to Frederick in August, 1982 and played at McCurdy Field as part of the 13-year-old Babe Ruth World Series, hosted by the Frederick Babe Ruth League. There were nine teams in the tournament including Frederick, which as the host city got an automatic bid. Teams came from as far away as California, Idaho and Arkansas. The tournament began on August 14th and ended a week later with Nashville, Tennessee, beating Brooklyn, NY, 6-1 for the national title. The tournament was a big success with a total of 42,290 fans attending the games.  This was one of three Babe Ruth World Series held here as the 13-15 championship tournament took place the following year with the host Frederick team reaching the semifinals. In 1984, the 16-18 tier World Series was played here at McCurdy Field. Less than five years later, the stage had been set for McCurdy to host an electric night in April, 1989 in which the Frederick Keys would play their very first home game here in Frederick. Fittingly it was against a minor league affiliate of the Cleveland Indians, from Kinston, North Carolina. The City of Frederick had successfully lured the Orioles Class A affiliate, the Hagerstown Suns, with the promise of a new stadium, but they would have to play one season here while Harry Grove Stadium was under construction. In studying the McCurdy Field of 1924, and the same of 1989, the place was in desperate need of “doctoring” or medical attention, so to speak. In ’24, this “doctoring” came in the literal form of a well-respected physician who headed up the drive for the stadium. His tenacity and ultimate success brought him the distinct honor of having his surname grace the stadium to this day, nearly a century later. As for the figurative meaning (of doctoring) in respect to McCurdy Field, Mark Ziegler and others can attest to the fact that it was a poor facility for minor league baseball nearly 70 years later (in 1989). There had to be a trailer brought in for the teams to dress, and folding chairs doubled for box seats. Regardless, the Keys drew well in their inaugural season, and that opening night was sold out. Currently this facility is used for American Legion and assorted other youth baseball. So just who was this Dr. McCurdy, namesake of the stadium that has seen nearly a century of baseball here in Frederick? His name was Dr. Ira Jay McCurdy, born on New Years Day, 1869. Dr. Ira Jay McCurdy I will submit one of the obituaries that ran in local papers at the time of this man’s death in 1942, seven months before the Philadelphia Athletics would train/play here in March, 1943. This obit comes from the Frederick Post’s August 4th, 1942 edition: On Saturday night death claimed Dr. IRA J. McCURDY, one of Frederick's leading physicians, who has practiced here for about half a century. He was a skilled general practitioner and an excellent diagnostician. Hundreds of patients can testify to his ability and recall the valuable professional services he rendered throughout the years. His distinguished figure and serious manner inspired confidence in the sickroom. And he had a remarkable insight into human ailments and realized the scope of his medical aids and treatment. He was quick to recognize when specialized service, beyond his field, was necessary. This community can ill afford to lose a family doctor of his experience and ability, especially at a time when physicians due to war requirements are so greatly in demand. Dr. McCurdy was a most useful citizen, beyond the realm of his medical practice. He was a man of strong convictions and great determination. Through his leadership, Frederick secured a modern milk ordinance, requiring pasteurization and supervision of this important product. He stood firmly for other important health measures for the city, and his strong influence was always for the protection of the health of the community. He took an interest in other civic affairs and was prominent in the movement to place the city police force on high standards. He was the first liquor license commissioner for Frederick County and fearlessly blazed the path for rigid supervision of the sale of intoxicants. For his diversion, Dr. McCurdy found pleasure and relaxation in sports. He was an ardent supporter of baseball for many years, and it is an appropriate tribute to his memory that the city's athletic park, in which he was so greatly interested, bears his name. There you have it, the simple story of how a stadium and Frederick landmark got its name. But let’s find out a little more about this well-revered citizen whose gravesite is adorned with a tall obelisk and located in Area E only yards from that of John Loats (mentioned earlier). It, too, also affords a press-box level view of “the new stadium” that would supplant McCurdy Field as Frederick City’s top baseball venue. I submit to you a biography of our subject, published in 1910 as part of T.J.C. Williams’ History of Frederick County (Volume II). Ira Jay McCurdy, M.D., one of the well-known and leading practitioners of Frederick City, is a native of York, Pa. He is a son of James Crawford and Jennie (Eyler) McCurdy. The McCurdy family is one of the oldest in Western Pennsylvania. The first of the name in this country were three brothers, James, John and Charles McCurdy, who were Scotch Covenanters. George McCurdy, the grandfather of Dr. Ira J. McCurdy, was a native of Westmoreland County, Pa., in 1837, and died there in 1871. He was a farmer and was also engaged in the coal mining business. He was principal of a high school at Ligonier, in Westmoreland County, Pa. He served for the cause of the Union during the Civil war and made a very credible record. He was Captain of Company E, of the Eleventh Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, and was in active service for three years and three months. He was in the various campaigns in Virginia and participated in the many hard-fought battles. He took part in the battle of Fredericksburg, Va., where he was stricken with rheumatism, and was soon afterwards mustered out of service. After the expiration of his duties as a soldier, Captain McCurdy engaged in commercial pursuits, which he followed until his death. He was married to Jennie Eyler. They were the parents of one son, Ira J. Ira J. McCurdy, son of Captain James Crawford and Jennie (Eyler) McCurdy, spent his childhood with his mother at Woodsboro, Md. He later entered New Windsor College, of Carroll County, Md., from which he graduated in 1889. He then went to New York, where he became a student in the Bellevue Hospital Medical College, from which institution he was graduated in the spring of 1892. Dr. McCurdy next took a special course in the New York Eye and Ear Hospital. In the fall of 1892, he located in Frederick City, where he has since remained in active practice of his profession. Dr. McCurdy is well known and has acquired a large clientele. He has been very successful in the exacting field to which he was devoted himself. He is well liked by all who have come into contact with him. Dr. McCurdy is surgeon for the Pennsylvania Railroad; for the Frederick Railroad, and the United Fire Engine Company of Frederick. In 1907, he was appointed city health officer of Frederick for a term of three years and reappointed in 1910. He was commissioned by Governor Crothers in July, 1910, as First Lieutenant Medical Corps, M.N.G., and was assigned to First Regiment Infantry, M.N.G. Dr. McCurdy is a member of the Frederick County Medical Society, of which he is the First Vice-President; was Secretary for ten years; a member and on the Legislative Committee of the American Medical Association; and a member of the Medico Chirurgical Faculty of Maryland. Fraternally, Dr. McCurdy is a well-known Mason, being a member of Columbia Lodge, No. 58, A. F. and A. M., Enoch Royal Arch Chapter, No. 23, and Jacques de Molay Commandery, No. 4, Knights Templar, of Frederick, and holds position as Generalissimo. He also holds membership in the Buomi Temple of the Ancient Order of Nobles of the Mystic Shrine, of Baltimore City; in Frederick Lodge, No. 684, B.P.O.E., and Mountain City Lodge, No. 29, Knights of Pythias. Dr. McCurdy is also connected with the Frederick City Country Club and “Camp Le-Mid” Association, of Ontario, Can., a camping and fishing association. Politically, he is a Democrat. Dr. McCurdy has never married. As I stated, this biography dates to 1910. A little more information can be gleaned from an obituary found in the Carroll County Times (May 10th, 1946) of Dr. McCurdy’s mother, Jennie (Eyler) McCurdy Devilbiss who would remarry after the death of her first husband, James.  Mrs. Jennie McCurdy Devilbiss, widow of George Devilbiss, died at her home in Woodsboro on Sunday, May 5th, 1946. She was 97 years of age and had been stricken with paralysis. She was the daughter of the late Peter and Mary Engle Eyler of Frederick County and is survived by nieces and nephews, one of whom, Melvin J. Anders, made his home with her. Dr. Ira J. McCurdy, her son by her first marriage to Captain James McCurdy, predeceased his mother by four years. Dr. McCurdy was a popular student and athlete at New Windsor College class 1889. He enjoyed a busy and successful life in Frederick as a physician. Mrs. Devilbiss had been a life-long member of the Woodsboro Lutheran church and was also active in the Missionary Society of that church. The funeral was held from the late home in Woodsboro on Wednesday at 1:30 p. m. Rev. Herbert H. Schmidt officiated, assisted by Rev. R. S. Poffenberger. Interment was in Mt. Olivet Cemetery, Frederick. Powell and Martzler, funeral directors. After reading this, I immediately wondered if Dr. McCurdy was an accomplished ballplayer, himself—hence explaining a lifelong love of baseball? He played in his youth and made a fine showing in his New Windsor days as the school’s first baseman. I also found an article stating that Ira McCurdy stayed near the game in the capacity of umpiring. I also searched local newspapers of the late 1800s and first decade of the 1900s to learn a little more of the education and early career of Doc McCurdy. I found Ira J. McCurdy living in a hotel on Frederick’s West Patrick Street in the 1910 US Census. I strongly feel that this was the Park Hotel, which formerly went by the name of the Carlin House, and Dill House earlier yet in the early 19th century. It should come as no surprise that a bachelor professional of the period would keep permanent residence in a hotel as large apartment complexes and luxury condos were not even dreamed about at that time. Dr. McCurdy was a member of the Maryland National Guard. Countless newspaper mentions at the time speak to the respect his community had for him. One of the most insightful articles I read was a 1914 piece in which he gave tips to the citizenry on how to stay cool in summer. Dr. McCurdy joined with associates Guy Motter and Frank Schmidt in starting the Frederick Baseball Association which gave Frederick its first professional team, the Hustlers in 1915. As mentioned earlier, they played at Agricultural Field against other clubs from Hagerstown, Martinsburg, Gettysburg, Chambersburg and Hanover. Well, the good doctor wouldn’t stay a bachelor into the next decade, marrying a Frederick native living in Baltimore at the time, but engaged in the medical profession, nonetheless. This occurred in the fall of 1918. I marvel at the timing of this wedding, as the date was October 26th, 1918. For the previous year, Dr. McCurdy was a member of the local draft board evaluating local men for service in a World War. As for the wedding date of October 26th, it is quite significant as being in the middle of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive (Sept 28-Nov 11), the major, and final, part of the Allied offensive of World War I. But that isn’t what really surprised me. This date was at the height of the Spanish Flu pandemic that ravaged the country and county that particular fall. Dr. McCurdy’s profession as a physician was put to the test, now seeing something in a deadly flu virus that our doctors had never seen before. More than that, McCurdy held the pivotal role as Frederick City’s Health Inspector at the time—our local Dr. Fauci if you will. Well throughout this war-time period, you can imagine the impact on professional baseball and its players. Life eventually returned to normal the following year as the war was over, and the flu was gone. Sadly, many Frederick County lives were lost but McCurdy did his best to comfort loved ones of both war casualties and flu victims. In the 1920 census, the McCurdys can be found living on West Church Street. They would have no children, Dr. McCurdy was 51 at this juncture and put energy into civic affairs and his professional endeavors instead of child rearing. Perhaps his fix was watching youth play baseball? Whatever the case, he was a leading force in elevating Frederick's first professional team in the Hustlers. With the success of the stadium effort, many wanted to honor the local physician in some way. The local newspaper helped lead the way in promoting that the new baseball park should take Dr. McCurdy's name. This would become a reality for the 1925 season. Dr. McCurdy was also a key player in forging a relationship with the Cleveland Indians of the Major League of baseball. Earlier in 1929, the Cleveland Indians purchased the Frederick Hustlers, and the new “farm” team changed its name to the Warriors to connect more with its parent team. On July 24th, 1929, a special exhibition game was played at McCurdy Field featuring the Warriors versus the Indians. The Indians won 11-5, but it marked a great day in which a big-time team came to town—one on which a local boy named Ray Gardner played. Imagine that happening today? Dr. Ira McCurdy continued practicing medicine here, and stayed very active in both social and civic affairs. He took a special interest in the local police force based on some of the articles I read. He was still practicing at age 60 with an office at 32 North Court Street in town. This would place his office in the vicinity of the parking lot next to the present day M&T Bank location. However, back then this would have been a perfect location for a physician as it was the site of Frederick's original YMCA of which Dr. McCurdy was an avid supporter and proponent. He and Lucy lived a few blocks away at 5 S. Market. This was an apartment over the old F&M Bank (today's Colonial Jewelers on the Square Corner). Our subject would continue on practicing through the Great Depression Era, and would live long enough to see the beginning of the Second World War, but not its conclusion. Sadly, his physical demise occurred as a result of complications a month after breaking his leg during a freak accident while walking down West Church Street. Ira J. McCurdy spent his final weeks in Frederick City Hospital, somewhat fitting for a man with such a rich medical background. Dr. Ira Jay McCurdy never fully recovered from this accident. He died on August 2nd (1942) and was laid to rest on Area E/Lot 52. His funeral on August 4th was well attended as one would imagine. His faithful mother would join him here in 1946, and wife Lucy as well in 1958. The fine monument certainly marks the final resting place of one of Frederick’s men of mark. In a quieter Frederick, at the time of his death and for a few decades after, I bet you could hear “the crack of the bat, and the pop of the ball” in the distance coming from his namesake field. It still may be possible today, but there are more competing sounds. Regardless, it’s not even a question that these sounds are once again heard now as the “boys of spring and summer” have again taken up residence on the fields to the immediate east of Mount Olivet. As for McCurdy Field, it’s "still in play" and under the City of Frederick’s purview. I experienced a historical rush when our kids’ Frederick City Babe Ruth team played here last August against a Frederick Legion squad. That particular evening, I saw my boys hit, field and pitch on the same diamond used by former members of the Hustlers, Warriors and Keys, including visiting legends of the Blue Ridge League who went on to the big leagues like local product Ray Gardner and Hall of Famers Lefty Grove (Martinsburg), Hack Wilson (Martinsburg), and Eddie Plank (Gettysburg). Others such as Walter Johnson played in exhibition games here, while the immortal Connie Mack coached and managed here. Half a decade later, the Baltimore Orioles top draft pick in 1989, pitcher Ben MacDonald, made his professional debut here with the Keys. Mix in the fact that high schools, colleges and travel teams have played here too. That's just McCurdy's baseball legacy, as there’s been plenty of football played here too. I said earlier that the Washington Redskins played their first exhibition game here. This was followed by a myriad of games ranging from youth football to high school, and who can forget this venue as the home to the semi-pro Frederick Falcons?

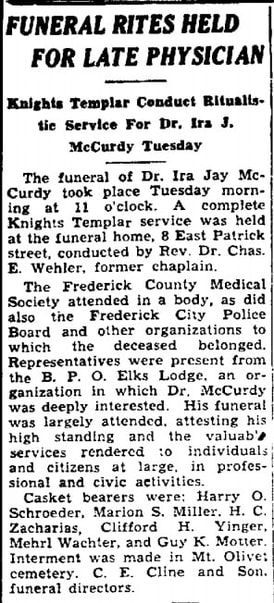

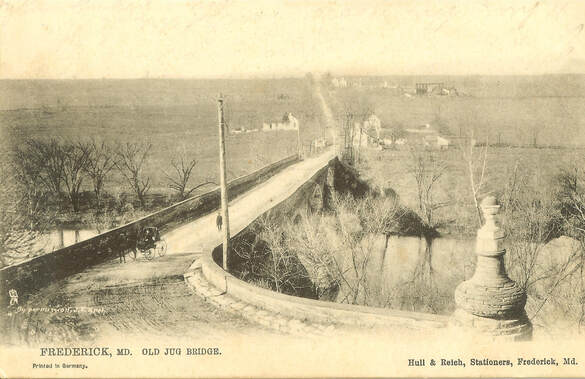

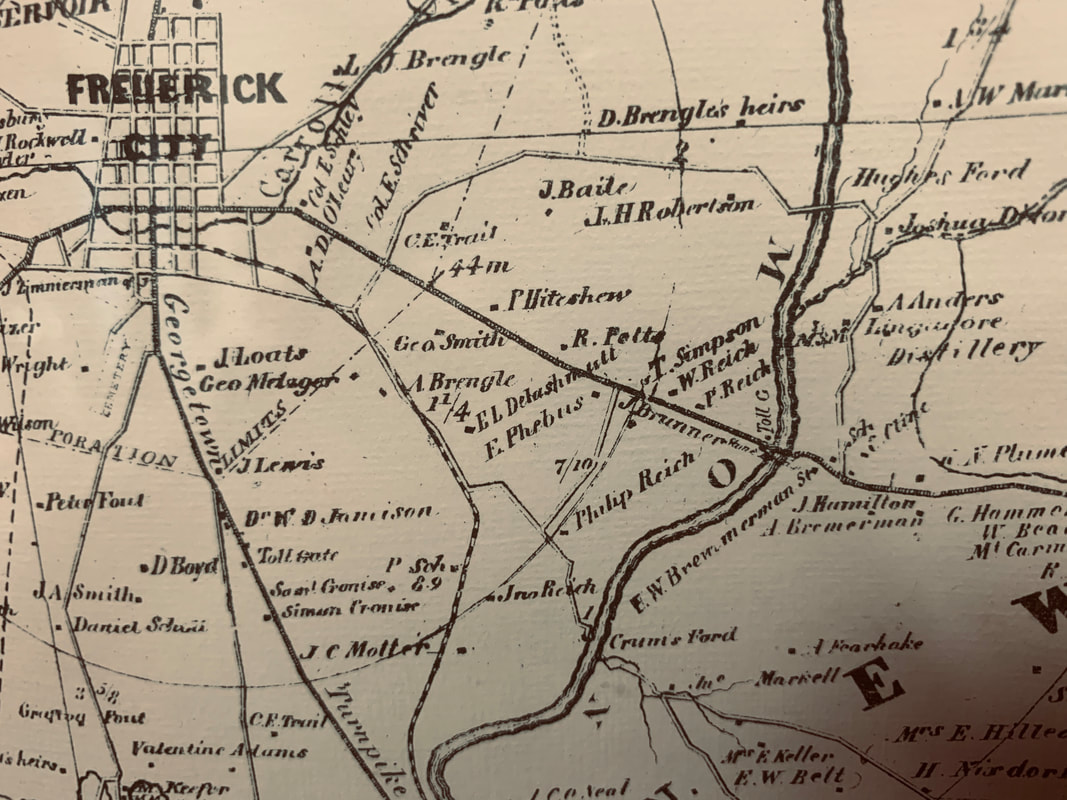

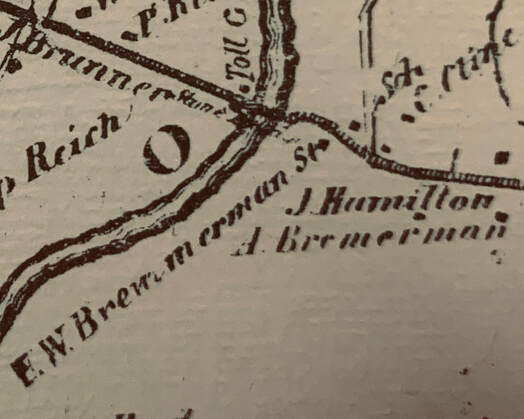

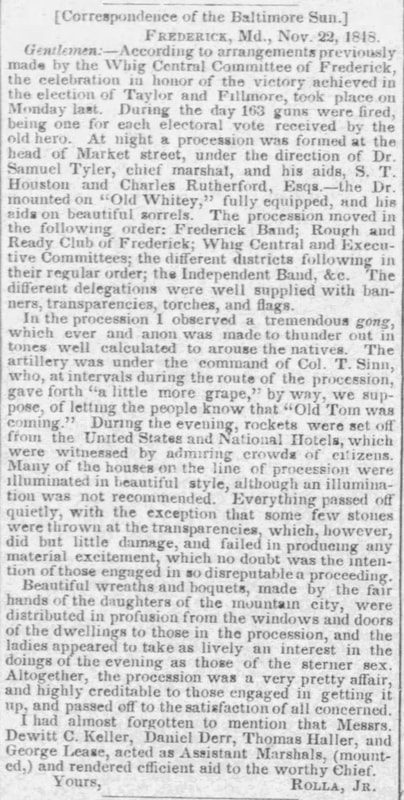

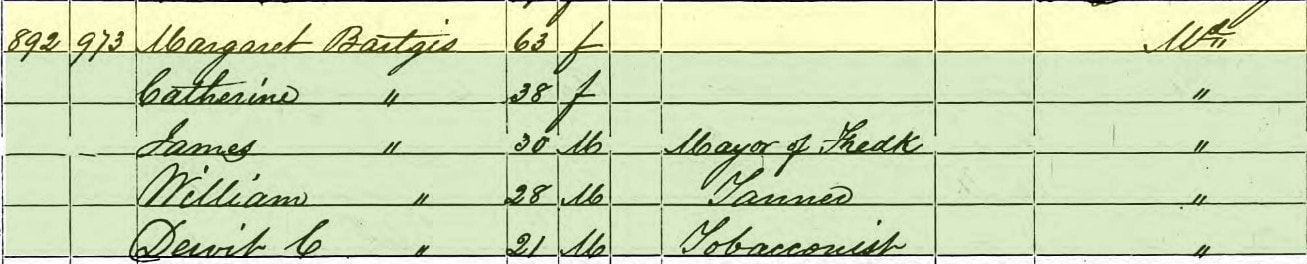

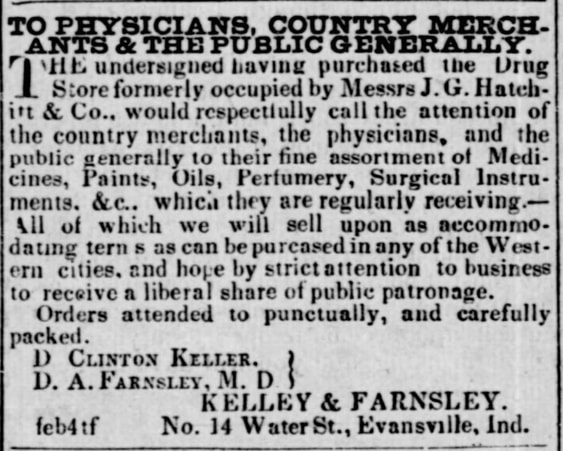

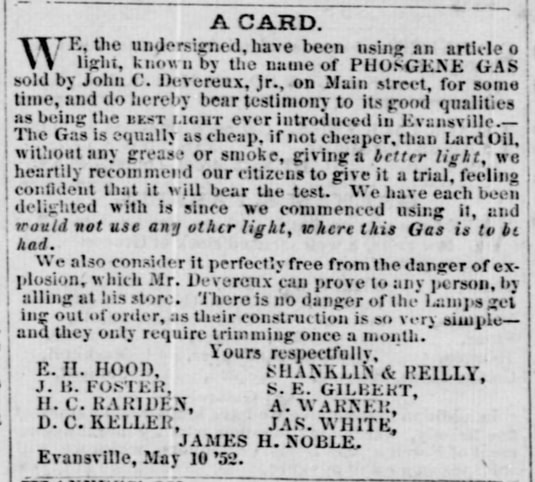

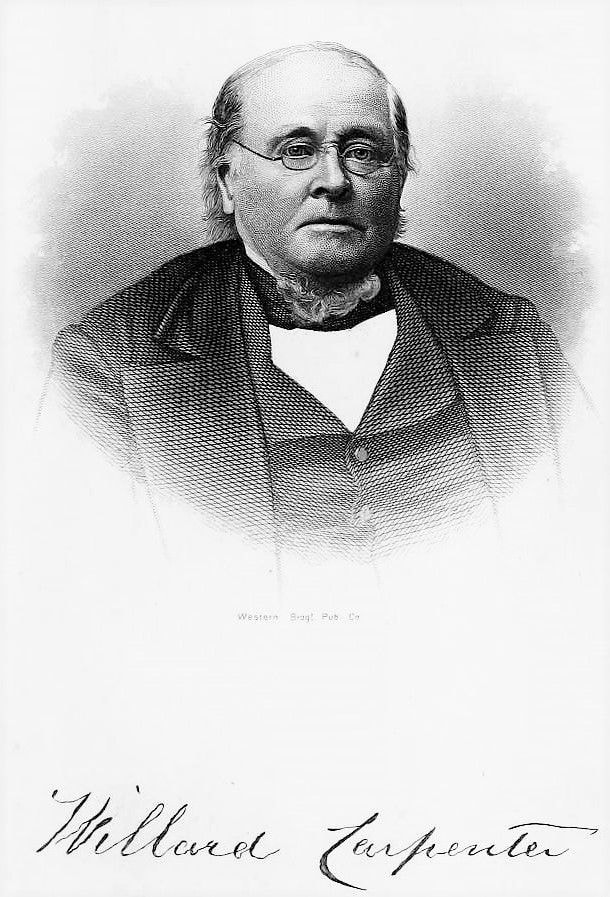

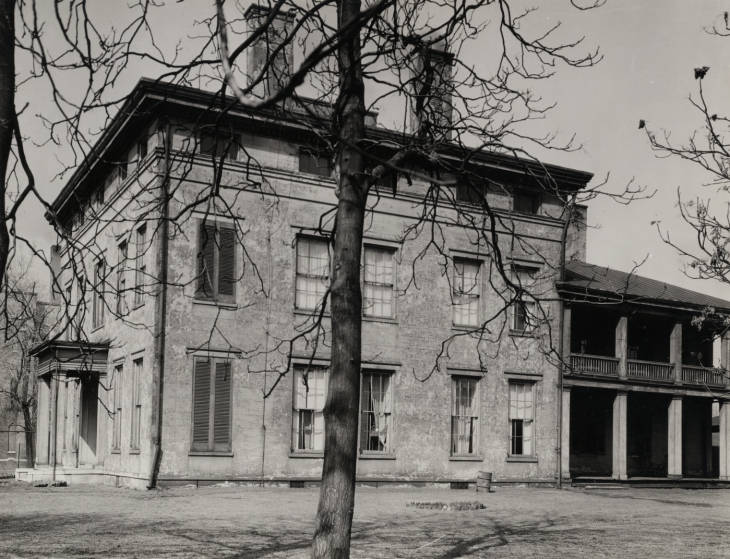

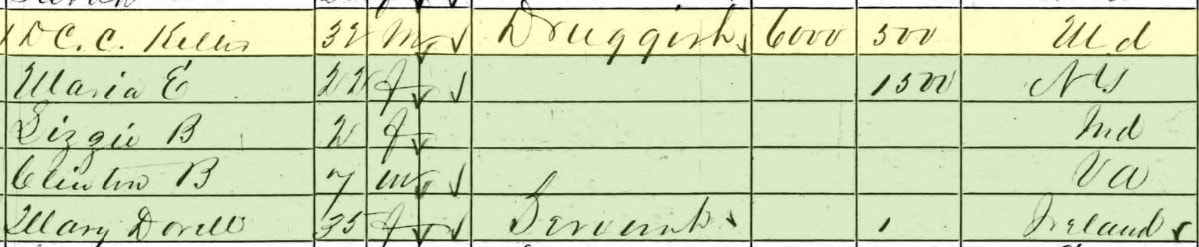

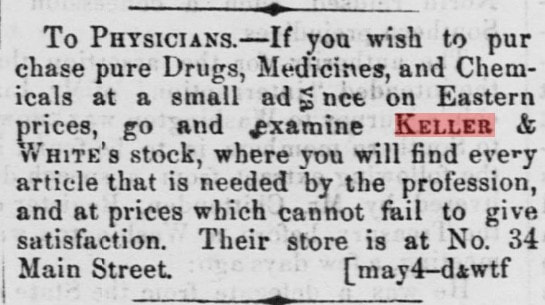

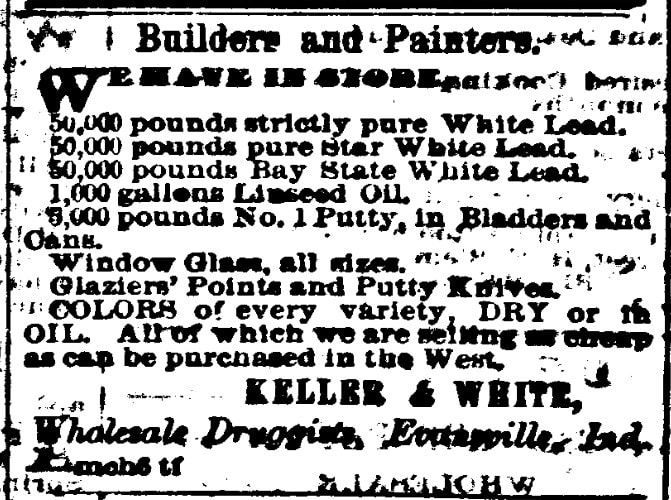

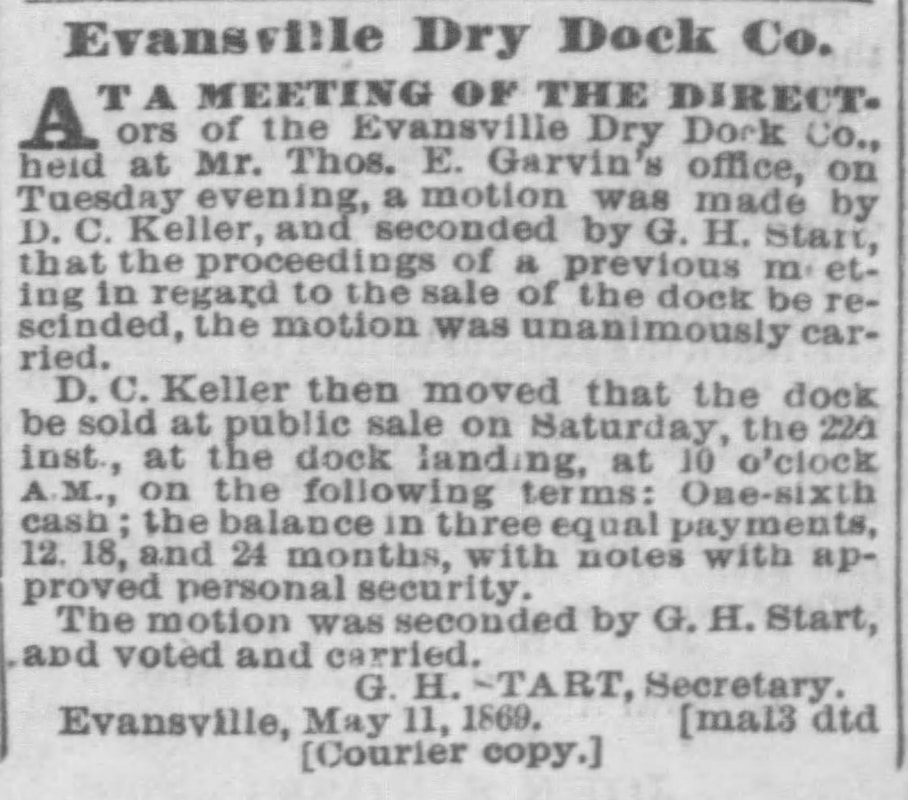

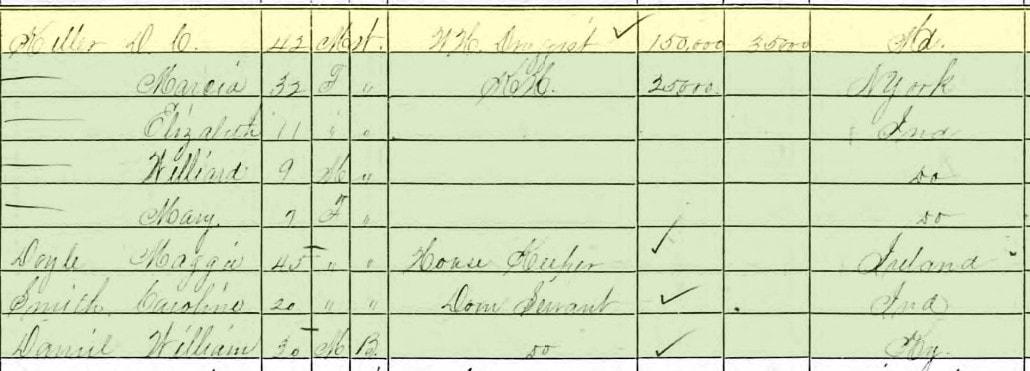

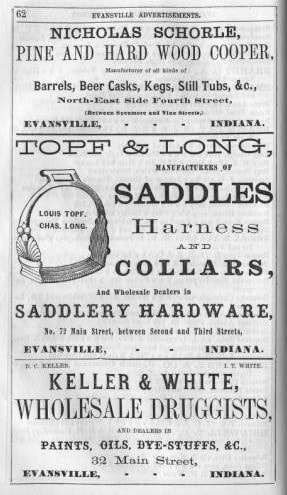

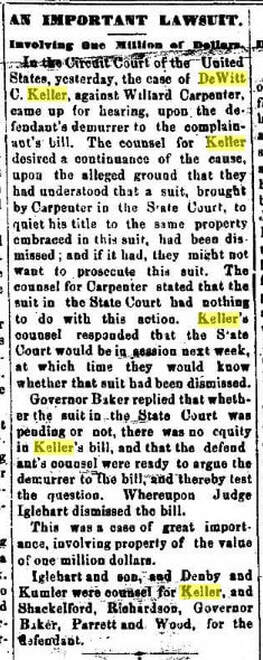

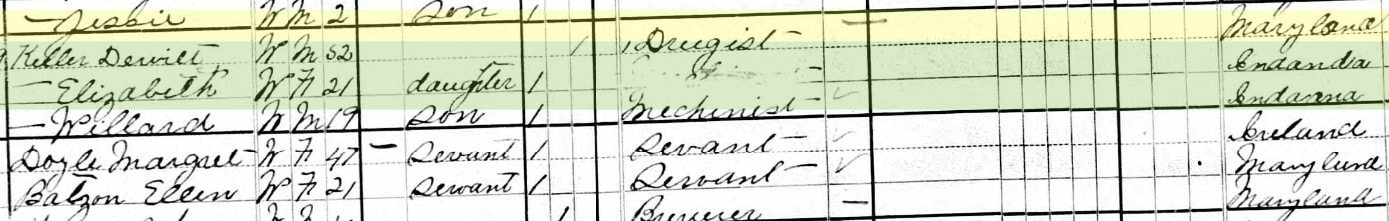

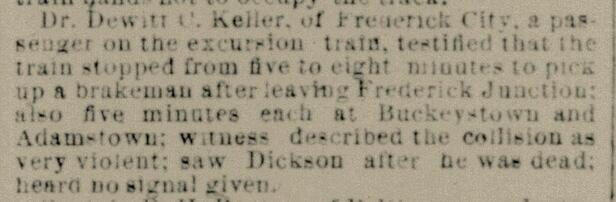

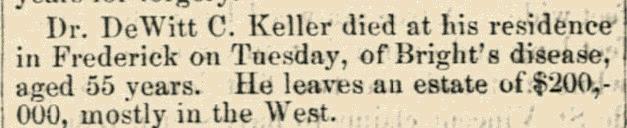

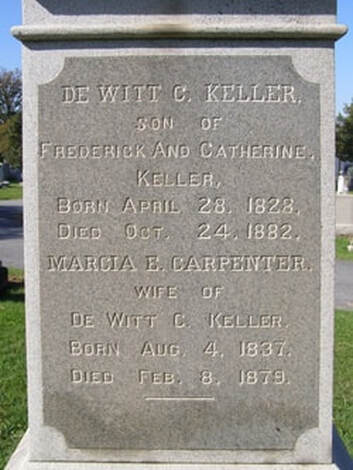

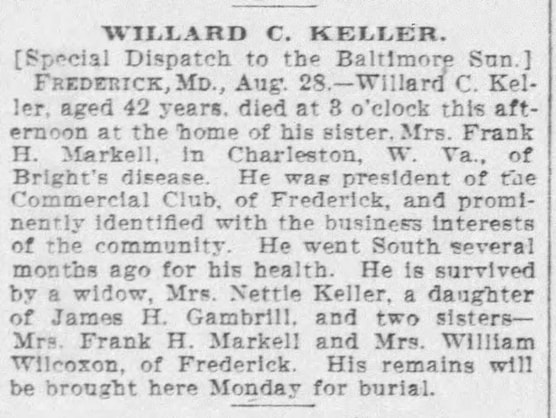

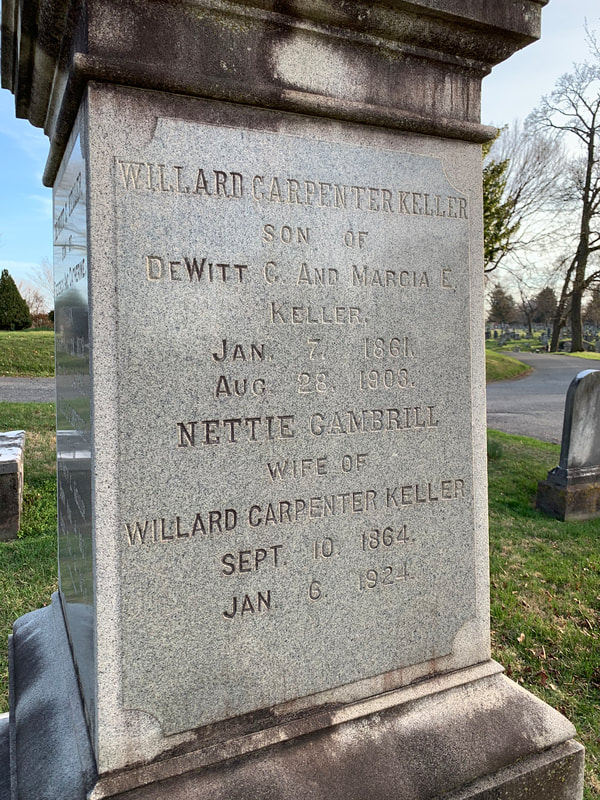

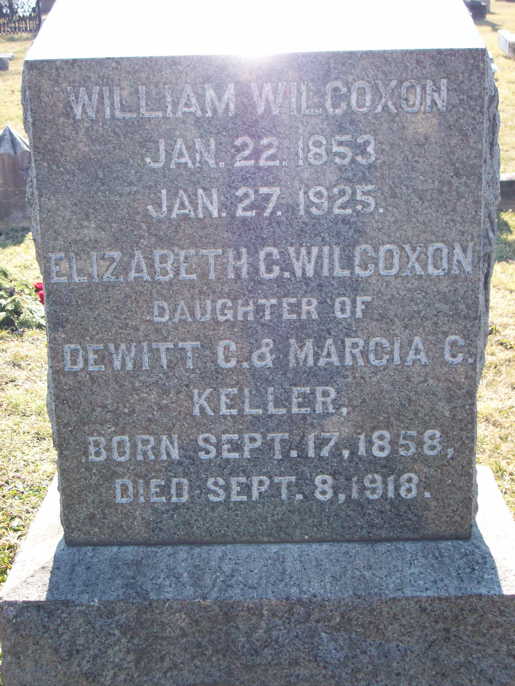

We can thank old Doc McCurdy for "prescribing" the perfect medicine in the form of this athletic park for Frederick players and sport enthusiasts to enjoy over the last century. McCurdy Field is more than simply a "Field of Dreams," it's a place of rich memories and Frederick history.  Happy Easter 2021! It’s so amazing how fast time passes as it just seems like yesterday that I was acknowledging 2020’s Easter weekend. We were a few weeks into the initial Covid-19 virus quarantine, and under the impression that we would be attempting to help “flatten the curve” for two weeks. Oh my, if we only knew then what we know now. As the mandated quarantines were extended in most places, there still existed a hope that we would be able to attend Easter Sunday services in person. Now, most churches can’t congregate for the holiday serve a full year later! I kid you not when I say that I have had the Rolling Stones song “Time Waits for No One” in my head for the last few weeks, a song recorded 47 years ago in April of 1974—the same month my family moved to Frederick from Delaware. I’m not a big Stones fan, but this song has captivated me for a variety of reasons of late. A key one comes with reflecting back on the past year and all that should have been experienced, but wasn’t because of Covid-19—be them in-person church services, school graduation ceremonies, sporting events, weddings, concerts, annual events and in some cases, vacation trips and even family holiday get-togethers. Another attraction to this song came as a result of me finding myself killing off quarantine time for half of March, 2021 after being diagnosed positive for the coronavirus. Luckily, my symptoms were mild, but the time warp was very strange as I had to stay in the basement away from the rest of my family. Fourteen days went slow as a whole as I was disappointed about missing things in the outside world. Oddly, the days seemed like the movie “Groundhog Day”—monotonous, but seemingly fast moving. It was one of the strangest, paradoxical situations I’ve ever experienced. All in all, I was blessed to make it through unscathed and fully recovered, as compared to many others who have not had as easy a road over the last year, including an old friend of mine from high school (Mike Hernick) who passed a few nights ago as a complete and utter surprise. You could say that we had a year of lent, sacrificing and giving up things much more critical than the candy and soda I recall bypassing for 40 days in my youth. This current culmination of the Lenten season has been a time to reflect on loss and resurrection, not only as it pertains to Christian religion and Biblical history, but on the time of Covid-19, and hopefully soon, a time without. When leaving the cemetery on Good Friday last year, I distinctly took notice of a monument I passed every workday, but had never investigated and taken in fully. This same monument is the one you see above as the header of this week’s “Story in Stone.” On that evening of April 10th (2020), I was compelled to stop and take a picture with my I-phone, one that would fittingly, featuring a cross-bearer. As I took my shot while looking in a westerly direction, the clouds had parted in the distance, showing a burst of sunshine. This was around dusk. I was suddenly reminded of the beautiful oil painting of Calvary behind the alter in St. John the Evangelist Catholic Church here in Frederick—the congregation of my youth. Calvary is the hill outside Jerusalem which is traditionally held to be the location of the crucifixion of Jesus. So who was the recipient of this wondefully scenic, and Bible-friendly, final monument you may ask? De Witt C. Keller We are compelled to believe that the owner of this outstanding monument in Area G/Lot 31 was a person of faith. I found him to be Dr. De Witt C. Keller, a druggist by trade, who once ran what we would call pharmacies in southwestern Indiana in the mid nineteenth-century. De Witt Clinton Keller was born April 28th, 1828 in Frederick. He was the son of Frederick Keller (1790-1832) and Catherine Hughes (1799-1835), and named for De Witt Clinton (1769-1828), an American politician and naturalist who served as a United States Senator, Mayor of New York City, and as the sixth Governor of New York. Our “Frederick County De Witt Clinton” grew up near the old Jug Bridge over the Monocacy. His father (Frederick Keller) built the house that we referred to as the Bremerman/Waters house in our former story on Civil War general (and inspiration for the movie Glory) Robert Gould Shaw. Shaw actually spent time in this exact house, at one time located on the eastern approach to Jug Bridge. This was in winter of 1862 as the Union soldier from Massachusetts had drawn the assignment of guard duty here at the very strategic water crossing. http://www.mountolivethistory.com/stories-in-stone-blog/fredericks-glory-part-i DeWitt’s mother, Catherine, apparently operated a tavern, either here or across the river on her father’s property, after her husband’s death in 1832. Frederick Keller also owned a larger piece of property on the west side of Linganore Road, midway between Linganore Creek and Gas House Pike, one that likely belonged to his parents originally. DeWitt grew up in a time that would see transportation explode as the National Pike passed by his front door, and the railroad and canal would reach Frederick County in the early 1830s. Sadly, De Witt’s mother passed away on Sept. 25th, 1835. She died intestate and Chancery court proceedings followed in which her land would be sold off. At that time, the four children of Mrs. Keller were still minors, and Mathias Bartgis of Frederick was appointed their guardian. De Witt was just seven years old at the time and I assume he attended local schools. I found that he lived in the vicinity of Court House Square with the Bartgis family, so I assume he attended the Frederick Academy. He would work as a tobacconist and later a druggist, but I'm not sure when or where he received his training. The first newspaper reference to Mr. Keller comes in the form of a newspaper article from 1848 in the Baltimore Sun recounting a recent parade held in Frederick by representatives of the Whig political party. De Witt C. Keller, only 20 years-old at the time, was mentioned as an assistant marshal in this event that celebrated the recent presidential victory run of Zachary Taylor and his vice presidential running mate, Millard Fillmore. Frederick diarist Jacob Engelbrecht mentioned DeWitt C. Keller a number of times in his fabled work, however the journal entry of most interest to me occurred on May 2nd, 1850: “Mssrs. Doctor Charles Boyd, Doctor Fairfax Schley & John R. Baltzell, Esquire leave our town this forenoon in the western cars, the former to locate in Texas and the 2 latter to seek a location in one of the western states. Dewitt Clinton Keller left town yesterday and will join them at Cumberland & proceed with them for Iowa or Minnesota. Success attend them.” In early 1851, De Witt C. Keller is found partnering with a gentleman named Farnsley and operating a wholesale drugstore which also sold an array of items that CVS and Walgreen stores are not known for today. Mr. Keller was becoming active in Evansville’s civic and business affairs as well. Keller’s sojourn west paid off personally as much as it did professionally. De Witt married Marcia Ellen Carpenter, a native of Indiana on December 10th, 1857. Ms. Carpenter’s father was a highly successful man in Evansville, (Vanderburgh County). Willard Carpenter was one of Evansville's leading citizens and greatest entrepreneurs. He made his fortune in real estate, was a member of the city council, and built one of the town's first railroads. And speaking of railroads, Mr. Carpenter was an abolitionist and participant on the Underground Railroad by using his home to harbor slaves escaping to their freedom. He would build Willard Library which is still in operation today. The Carpenter family home also still exists and is used by WNIN, the local PBS station. As you can see, De Witt married into money. Based on census records and some other news clippings, it seems that the couple lived between Frederick and Evansville for the majority of their marriage, one in which they would raise the following children: Elizabeth Carpenter Keller (1858-1915), Willard Clinton Keller (1861-1903) and Mary Louise Keller (1863-1944). I found a couple references on Ancestry.com that said that Mr. Keller served in the American Civil War. I don’t believe this to be true as there was another gentleman here in town by the name of Clinton Keller who served in Company E of the 7th Regiment of Maryland Volunteers under Col. Edwin H. Webster. This group of soldiers was mustered into service on August 26th, 1862. Now I’m not ruling this out completely as here is a bit about that military outfit. A history of the 7th Maryland reports the following of the regiment’s activity: After serving guard duty in the defenses of Washington, the regiment was sent to the Shenandoah Valley for operations. Their first combat came on March 13, 1863, when they repulsed a charge by the 5th Virginia Infantry regiment. They were sent to V Corps, Army of the Potomac. At the Battle of Gettysburg, they were forced to withdraw from the Peach Orchard early on the second day. They were among the units who repelled Pickett's charge. The unit was stationed for garrison duty in southern Pennsylvania and was involved in skirmishes against some of Jubal Early's infantry units. Because of heavy losses at the Battle of Cold Harbor, they were sent as replacements to IV corps, Army of the Potomac. They suffered heavy casualties during the Siege of Petersburg, having to repel six charges by counterattacking units of the 15th Georgia Volunteer Infantry. They marched in the Grand review and were mustered out of service on June 3, 1865. This unit suffered the loss of 389 men, who were 23 officers and 366 enlisted men, and 65 of those men died of disease. 13 men were captured at Gettysburg, 5 of which perished at Libby Prison. Unit was noted by President Lincoln for being "very effective in combat and showing utmost loyalty to the cause of the great republic." One of the reasons why I dispute this theory is the fact that De Witt seemed to be quite busy in Evansville, having had a change of partners from Mr. Farnsley a decade earlier. It also would make sense to get his family out of Frederick, a place whose residents certainly saw more than their share of rival armies traveling and battling through the county, not to mention viewing the carnage of war as we became a hospital center. Post war, more articles are found within Indiana newspapers of Mr. Keller’s land and real estate transactions. A city directory for Evansville from 1876 states that Dr. Keller’s residence was outside Frederick, MD, however he was continuing to partner in business with Isaac T. White in the firm located in Evansville and called Keller & White. The directory lists this operation as “Wholesale Druggists and dealers in Paints, Varnishes, Dye Stuffs, &c.” It was located on Main Street. I began wondering what the real reason behind the move back to Maryland was after I found an article involving a lawsuit between Dr. Keller and his father-in-law from fall of 1872. According to later obituaries, Dr. Keller apparently relocated back to Frederick primarily due to poor health. Marcia Keller, however, predeceased him, dying in 1879 and was buried here in Mount Olivet. He had apparently made his fortune, of course aided by his wife’s father and an inheritance to boot, in Indiana, as his estate was reportedly worth $200,000. Interestingly, the widowed pharmacist can be found as head of household living in Frederick in a rented home, as he would not buy property on his return to Frederick. Based on the 1880 census and who his neighbors were, he is believed to have lived on that block of West Patrick Street where the courthouse stands now. My assistant Marilyn Veek found that Mr. Keller’s daughter, Mary Louise (1863-1944), apparently married the “boy next door,” a gentleman named Francis/Frank Markell (1863-1944). Mary’s older sister, Lizzie, would marry local lawyer William W. Wilcoxon. Marcia would be buried in Mount Olivet in a family plot that Dr. Keller had purchased six years earlier in 1873 as he would arrange to have his parents buried here. His father, Frederick, died in 1832 and was buried in the town’s Baptist graveyard which no longer exists today. It was located on West All Saints Street, on the north side of the thoroughfare, and adjacent Carroll Creek. Frederick’s wife, Catherine died in 1835 and was buried in the All Saints Graveyard, located a few blocks to the east on East All Saints Street. As a side note, the former Ms. Hughes was a daughter of Levi Hughes of whom Hughes Ford was named who once owned considerable real estate west of the Monocacy River stretching from the airport to MD route 144 as I-70 bisects it. While De Witt was engaged in moving his parents, he would have his paternal grandmother, Elizabeth Stallings Keller (1772-1831) and later, grandfather Conrad Keller (1765-1821) also brought from the ancient Baptist burying ground. The 4 transplanted bodies are buried in a row with a fine ledger/tablet style stone laid atop their final resting places. Dr. Keller had cheated death a few years before his wife. Marilyn Veek found that in the category of "all these Frederick “Stories in Stone” seemed at times to be linked somehow" comes the fact that Dr. Keller was on the train involved in the terrible Point of Rocks crash in 1877, which took the lives of five local residents. You can read this one later, but here is a link to my earlier story written in June, 2018. http://www.mountolivethistory.com/stories-in-stone-blog/the-accident-at-point-of-rocks The following newspaper account features a statement from our subject. De Witt would eventually meet his maker on October 24th, 1882. I don’t know exactly the date of this fine marker but it was either erected by Dr. Keller or son Willard who is also buried here with his wife, Nettie Gambrill and a two year-old son, Willard, Jr. (1895-1897). Willard had made a career out of building things, and had his own cement paving business. Willard Keller was one of the partners in the South Park Villa Company, which developed Clarke Place located a block from our front gate. It was also Willard who purchased the Loats Female Asylum property for the development. He was the secretary and general manager of the company, while Dr. Joseph Williamson was president and Harry Bowers was VP/treasurer. Marilyn learned that although the property was outside the Frederick city limits at the time, the company signed an agreement with the mayor and Alderman in which they would be exempt from city/municipal taxes for 10 years if the property was annexed (an annexation would benefit the city in terms of revenue and taxes) and that the city would pay for/buy the private street the company planned to build (which became Clarke Place). This agreement was later sanctioned by the state legislature. Willard's home was at what is now 16 Clarke Place. He did not own property in Frederick prior to that. Nettie Keller was the daughter of miller James H. Gambrill, (builder of the Delaplaine Center) and brother of park namesake James H. Gambrill, Jr. She grew up in her parent's mansion home within the confines of today's Monocacy Battlefield property on the east side of the namesake river. It appears that Nettie was somehow incapacitated late in life, as when Willard sold the house in 1903 she was identified as "temporarily in Baltimore", and in an equity case in 1905, when certain of the lots were sold by the company to Harry Bowers to settle Willard's estate, the grantors were a "committee" consisting of Mary Markell trustee for the benefit of Nettie G. Keller, Mary and Francis Markell, and James Gambrill. In the 1910 census, Nettie was enumerated at Relay Sanitarium/St. Agnes Hospital in Baltimore county. De Witt C. Keller’s two daughters married and lived out their lives here in Frederick and both are buried here at Mount Olivet. Elizabeth Carpenter (Keller) Wilcoxon passed in 1915 and is buried nearby her parents in Area G. Mary Louise (Keller) Markell lived up through 1944 and her gravesite can be found in Area R. I found a few newspaper articles which say that Mrs. Markell sent portraits of her parents and maternal grandparents to the Willard Library back in Evanston in 1944. One final soul rests here in Area G/Lot 31. This is Margaret Doyle, who we found to be a domestic servant of the family. She hailed from Ireland and lived with the family in Indiana, before coming to Frederick. Better known as Maggie, her grave monument fits perfectly with our Easter theme. With all the research performed for this story, I never did find the exact religious denomination of Dr. De Witt Clinton Keller. Special thanks to our Hood College intern Katelyn Klukosky who did a great job gathering resources for me to put this story together in short order. Also thanks to Stan Schmidt and Greg Hager of the Willard Library in Evansville, Indiana for sharing images of the Keller and Carpenter families from portraits belonging to the library collection.

|

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed