|

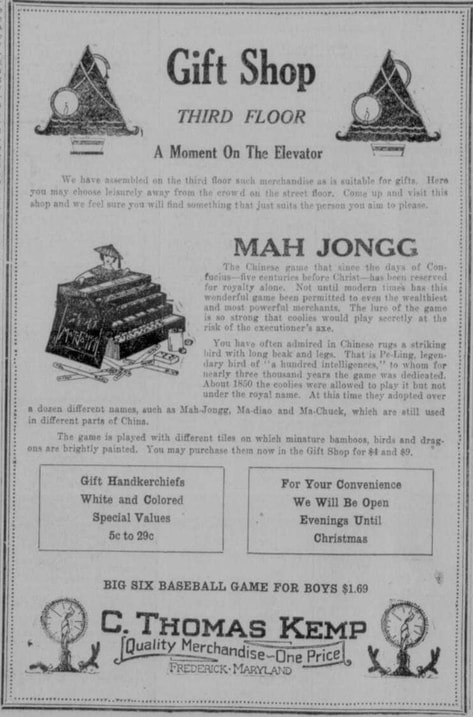

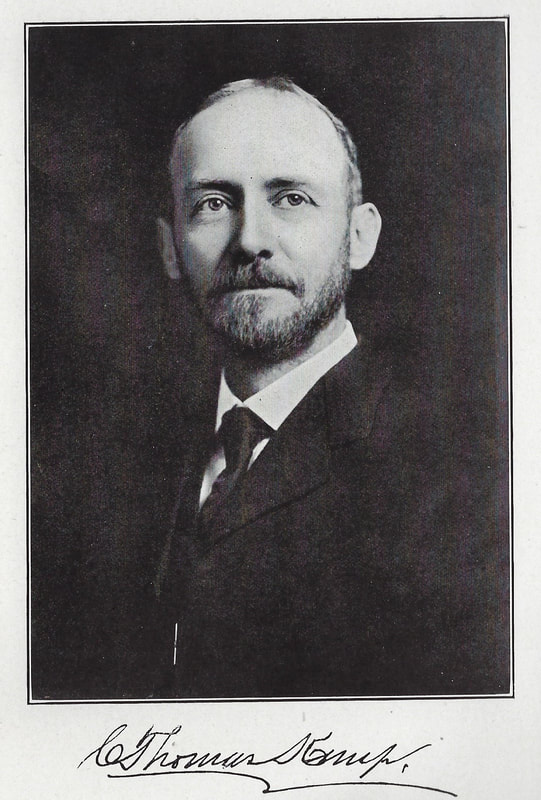

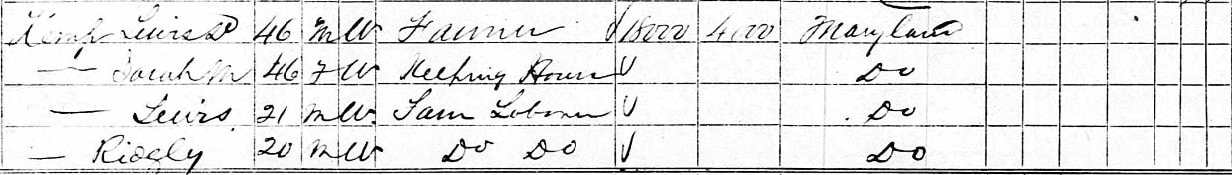

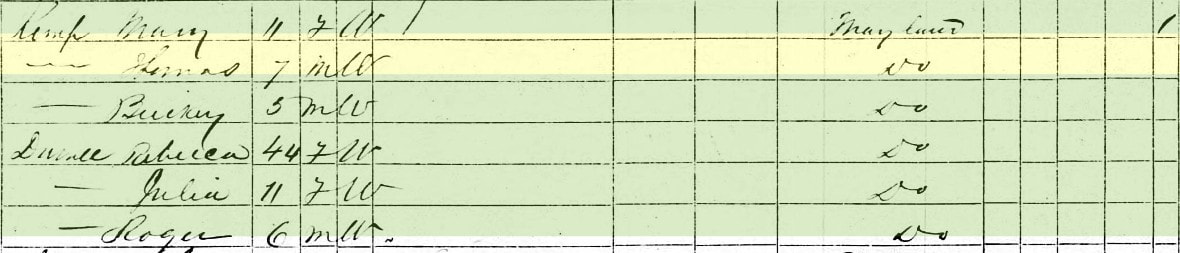

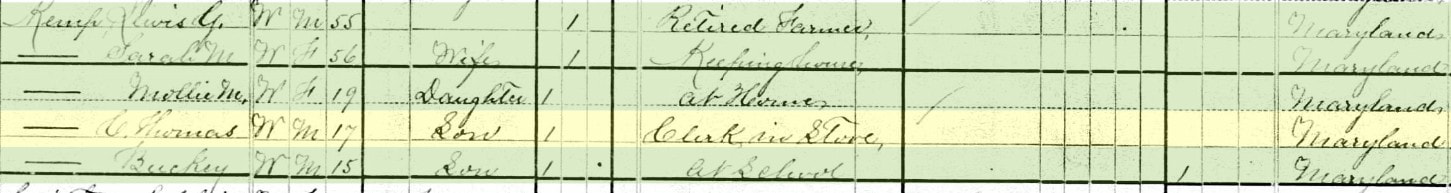

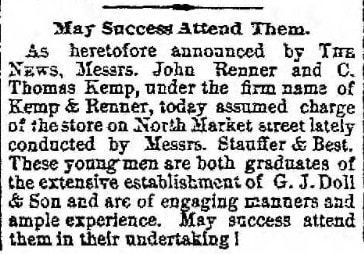

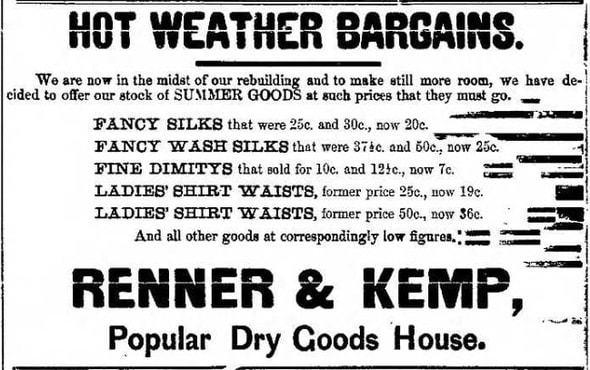

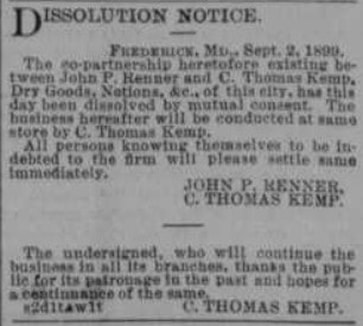

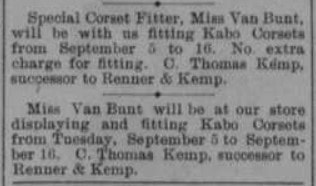

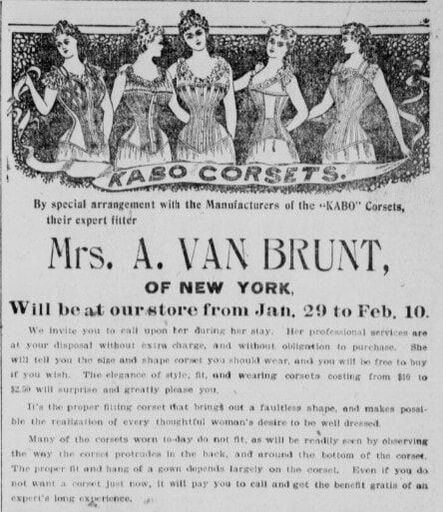

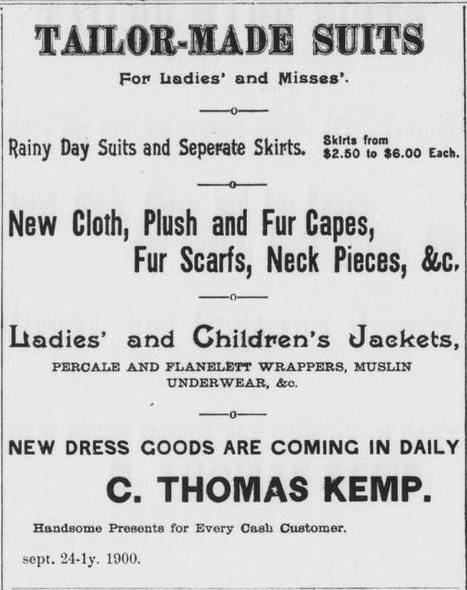

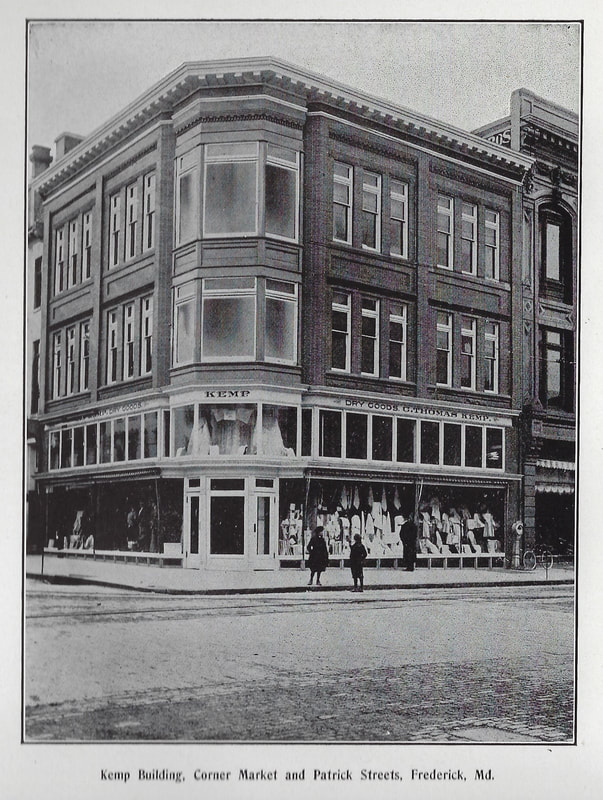

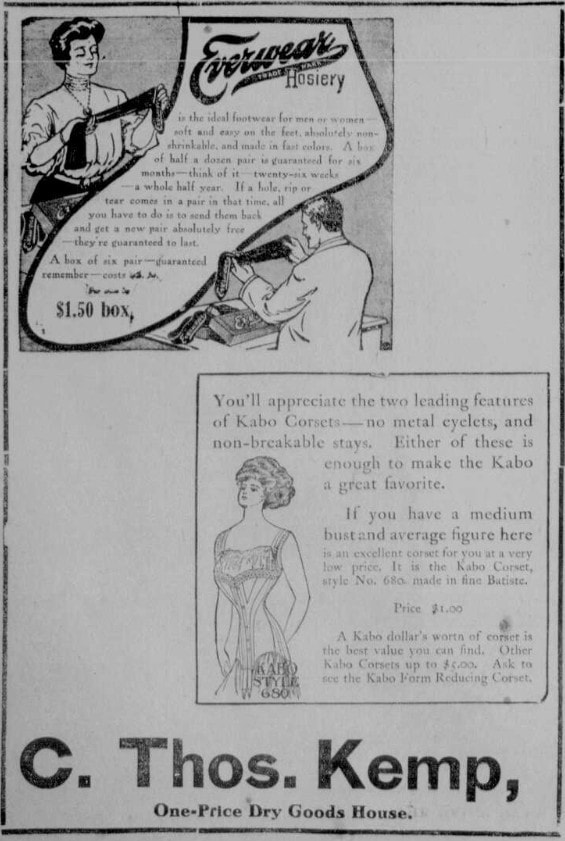

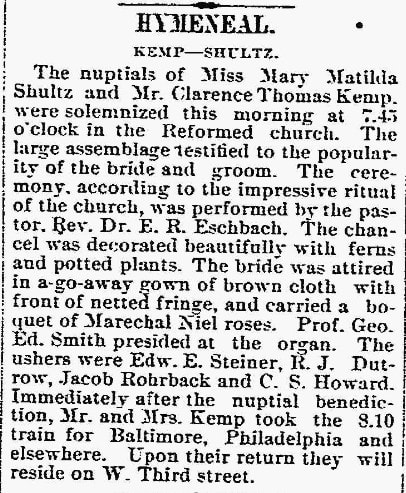

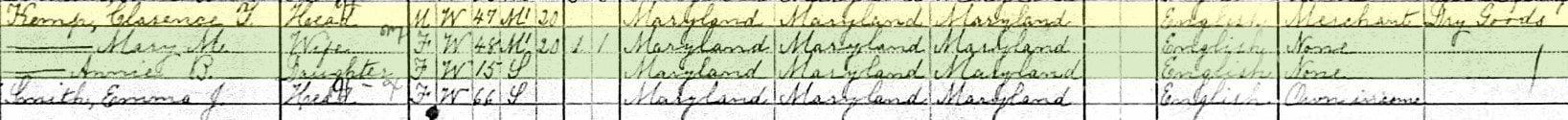

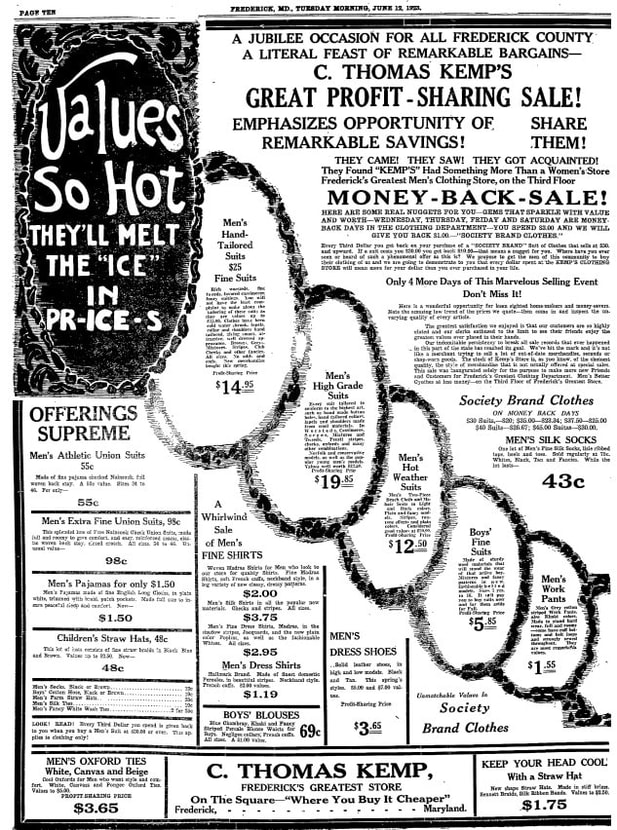

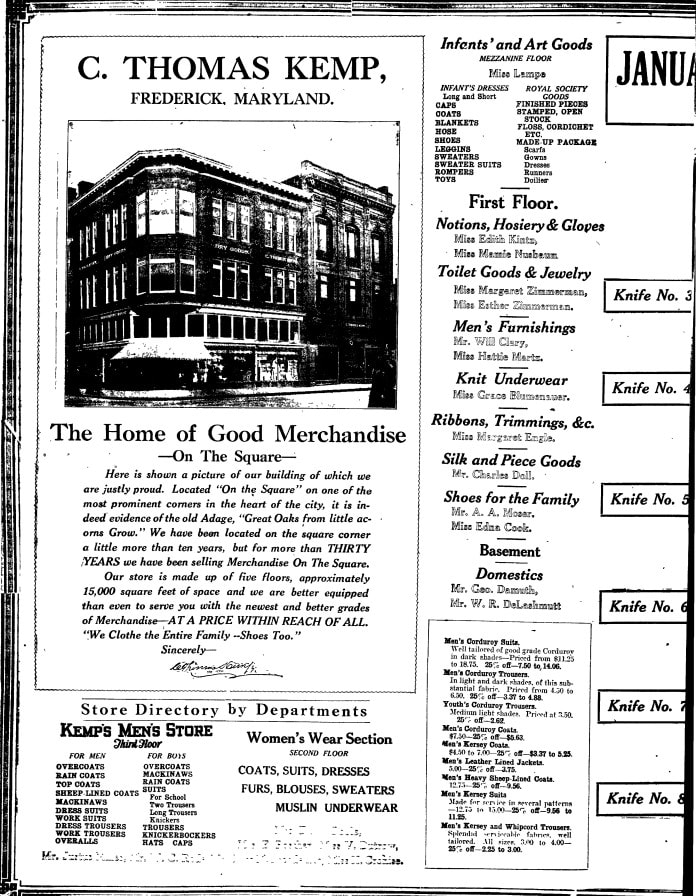

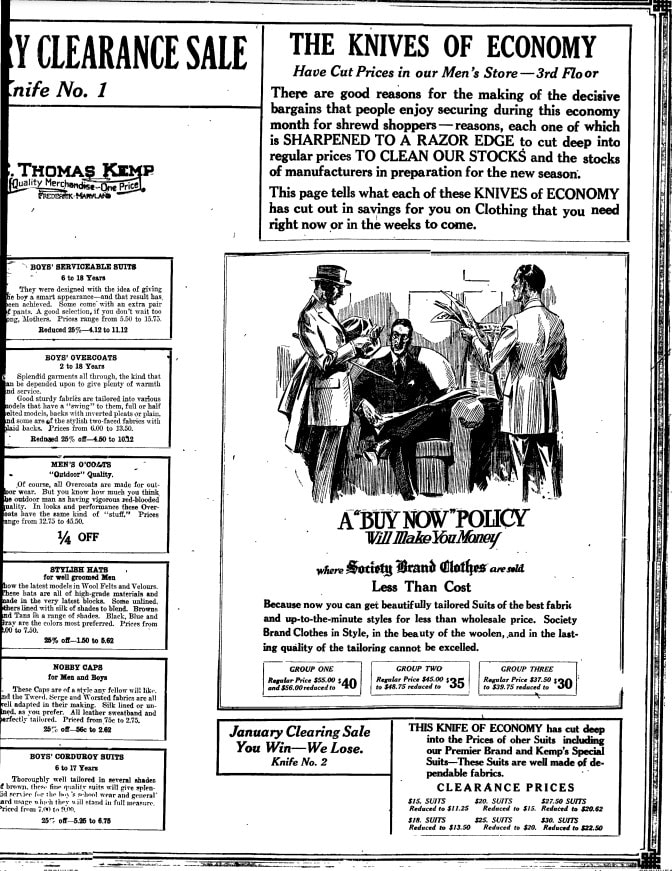

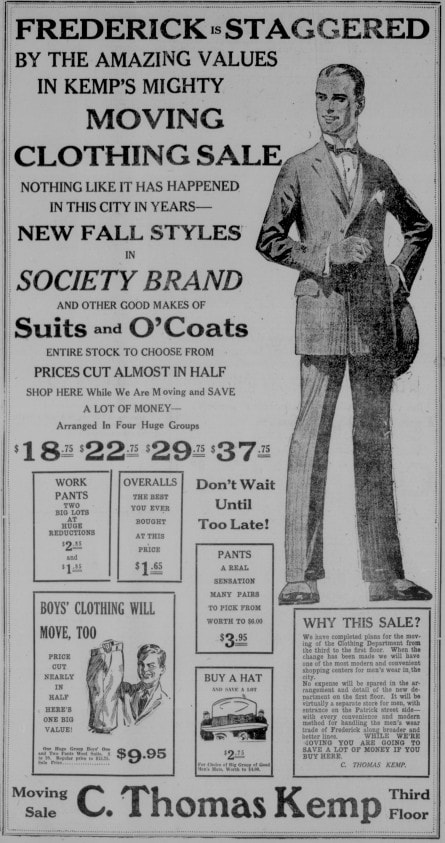

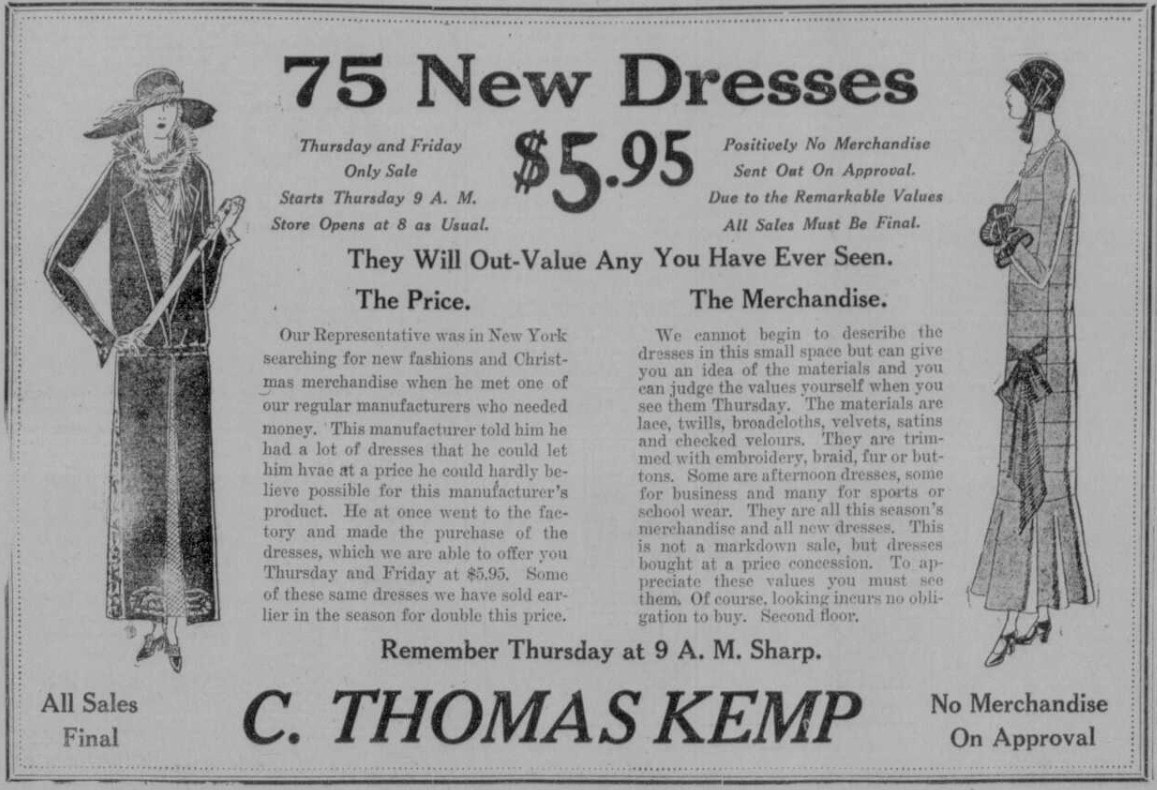

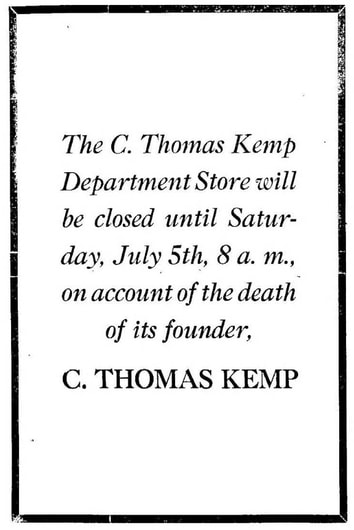

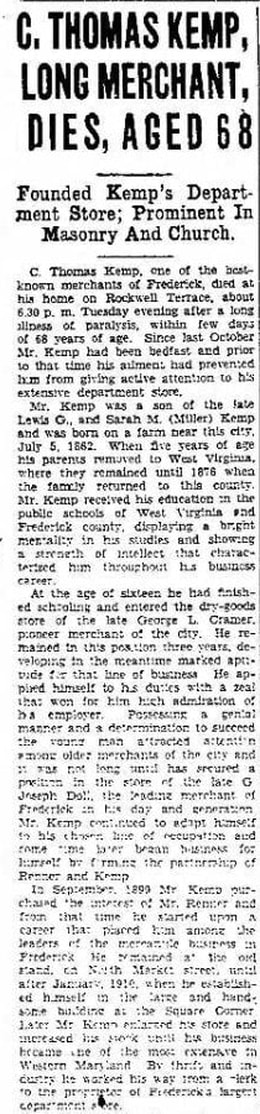

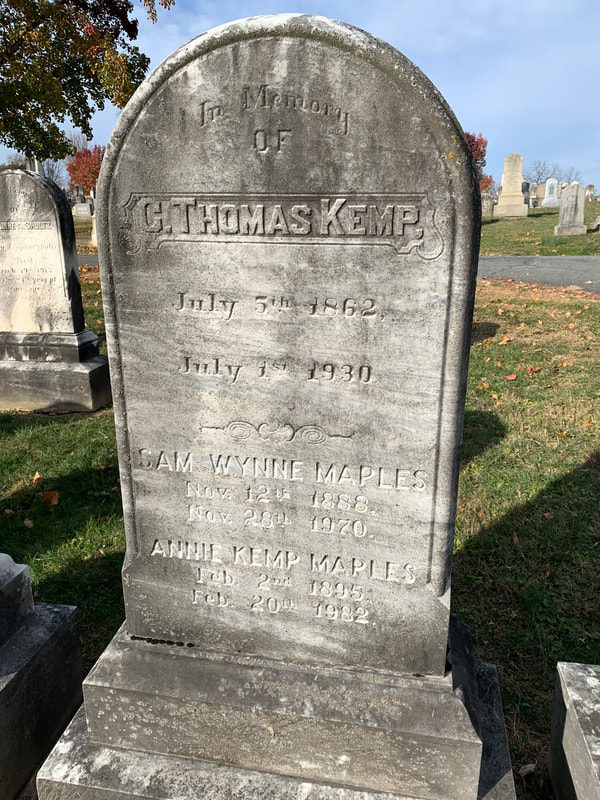

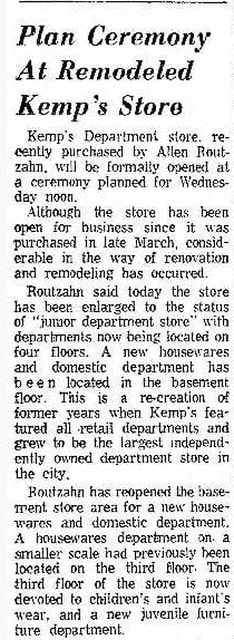

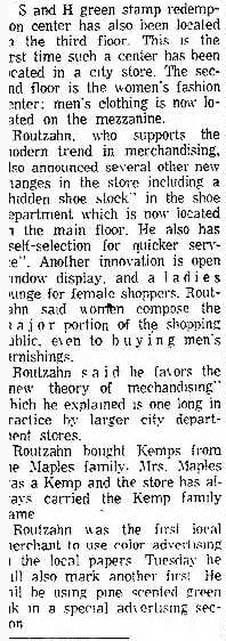

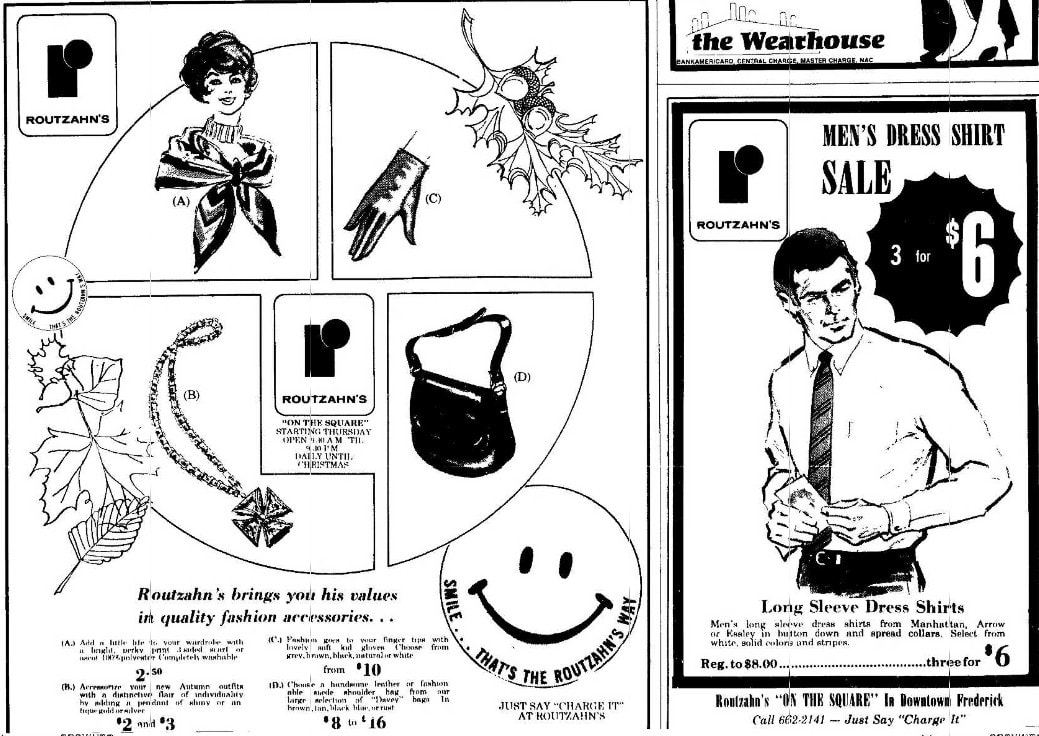

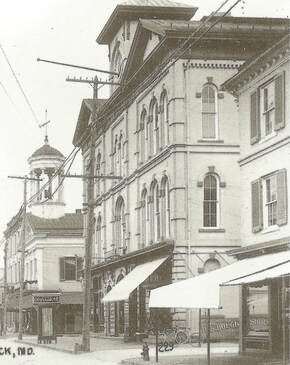

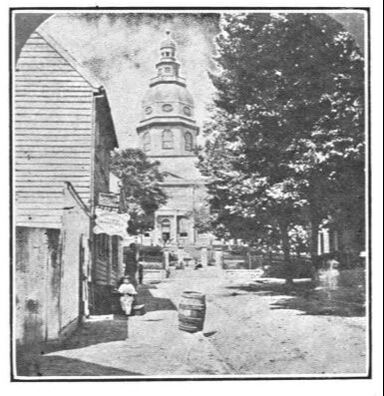

Well, maybe that’s not the best title choice for a blog article coming from a cemetery, but it certainly describes the days and weeks following Thanksgiving in which a central activity for many becomes the frantic pursuit of gifts for Christmas. The “Olympic Games of Commerce” boast, as their opening ceremony, the unofficial holiday of “Black Friday,” which now extends through the entire weekend. This is book-ended by “Cyber Monday,” the online version of the previous three days. If you still see your own shadow without presents for all on your list, you better not pout because there are nearly four more weeks of shopping before “Santa Claus” comes to town. I decided to look at the Frederick News of a century ago to study this phenomenon "back in the day" as they say. A logical place to start was December 1st, 1923, as I wanted to see what shopping options were available (here in Frederick) long before there was something called “Black Friday.” As a matter of fact, this particular year of 1923 came six years before the infamous “Black Thursday” of October 24th, 1929—the day of the largest sell-off of shares in U.S. history causing the Great Stock Market Crash. Let's get back to the topic of holiday shopping. The answer was clear back then—your best strategy for scoring Christmas deals was keeping a keen eye on advertisements in the "local" newspaper, and getting to the "local" store as fast as possible. Usually this required a trip to downtown Frederick, because this was the prime hub for almost everything in the realm of commercially bought gifts. As I hearken back to the time period of the “Roaring 20s," it’s important to recall that all presents did not come from stores or shipping warehouses as the majority do today. Back then, a popular alternative included handmade, and homemade, gifts. These could come in many forms and included specialty crafts, clothing and valued antiques. However, not everyone had the talent, time or know-how. I found an article touting holiday shopping in downtown Frederick in the November 20th edition of the Frederick News. This appeared five days prior to Thanksgiving that particular year. Frederick had several nice shops to choose from ranging from Doll Brothers to Bennett’s, Hamburgers to Hendrickson’s. However, there was one additional store that particularly stood out from the rest. This was Kemp’s. Perhaps it was the marketing acumen of owner Clarence Thomas Kemp, or maybe it was his location on the northeast corner of the town square, known better as “the Square Corner” at the intersection of Market and Patrick streets. Whatever the case, this endeavor offered not just the customary ground floor browsing, but the addition of a second and third floor. Talk about a store of many departments! And come holiday time, the third floor would be transformed into a magical oasis of Christmas gift offerings. Kemp’s was the place, and as the advertisement above makes mentions, it even boasted an elevator to assist customers to those upper floors. A busy venue all-year round, Kemp’s Dry Goods and Notions Store was Santa’s workshop for “kids from 1 to 94” as Karen Carpenter would sing. And if you, like me, are curious to the commercial meaning of notions, they are small objects and accessories such as buttons, snaps, and collar stays used in sewing and haberdashery. Notions also include the small tools used in sewing, such as needles, thread, pins, marking pens, elastic and seam rippers. Oh, the lost art of sewing and "at-home" alteration of "hand-me down" clothing! Clarence Thomas Kemp Although previously familiar with this leading merchant of Frederick’s rich past, I knew I had a short cut waiting for me in respect to compiling a biography of his life, or at least part of it. Clarence Thomas Kemp's biography appears in Volume 2 of T. J. C. Williams’ History of Frederick County, published in 1910. The following passage is taken from that work, and paints a robust picture of Mr. Kemp, whose early ancestors hailed from Germany and Switzerland as is well-documented in genealogical work of Frederick County. In fact, his great-grandfather, Lt. Col. Henry Kemp (1763-1833) led soldiers in the War of 1812 and resides in our cemetery in Area NN. Henry's father, John Ludwig served as a member of the Committee of Observation during the American Revolution here in Frederick. You may also be familiar with a road connected to this early family, located just north of downtown Frederick as it links Rocky Springs Road with Shookstown Road on a northwestern perimeter of Fort Detrick property—Kemp Lane. Here's that promised biography: “C. Thomas Kemp, one of the leading citizens of Frederick, Md., proprietor of one of the most successful drygoods and notion houses, situated on the northeast corner of Market and Patrick streets of the city, began life as a poor boy and owes his present eminence in the community to his own earnest efforts. By good management and close application to his business interests, coupled with strict integrity, and fair dealing in his relations with others, he has acquired a reputation and a general regard that are most creditable. Mr. Kemp, who was born July 5th, 1862, is a son of Lewis G. and Sarah M. (Miller) Kemp. The Kemp family traces its ancestry to reputable lineage in its old home in Germany. The founder of the American branch of the family (Conradt Kemp (1685-1765)) was one of the early settlers of Frederick County, Md. Lewis G. Kemp, father of C. Thomas Kemp, was for many years an active farmer. Later in life, he moved to Frederick. He is now about eighty-five years old, and with his wife resides in Frederick. Mr. Kemp is a member of the Reformed Church. For the past sixty-five years he has been connected with the Democratic party, whose ticket he has constantly supported. His wife, Sarah M. Miller, is a descendant of the well-known Miller family. Three of their children are living: Mary Margaret, unmarried, resides in Frederick; C. Thomas; and B. M., of Chicago, Ill. C. Thomas Kemp, son of Lewis G. and Sarah M. (Miller) Kemp, grew up on the home farm where he was born. When he was five years old, his parents removed to West Virginia where they remained until 1876, when they returned to their native county, bringing their son with them. Mr. Kemp was educated in the public schools of West Virginia and Frederick, displaying a bright mentality in his studies, and exhibiting that strength of intellect which subsequently characterized him in his business career. At the age of sixteen, he entered the drygoods store of George L. Cramer, of Frederick, where he remained as clerk for about three and a half years, showing a marked aptitude for that line of effort, and applying himself to the duties assigned him with a zeal that won for him the high regard of his employer. Mr. Kemp was next employed by G. J. Doll, when he began business for himself, forming a partnership with Mr. Renner. The firm of Renner and Kemp did a general retail business in drygoods and notions, and speedily became known as one of the most reliable business firms in Frederick. In September 1899, Mr. Kemp bought out Mr. Renner’s share of the enterprise, and conducted the business under the old stand until January, 1910, under the name of C. Thomas Kemp. He has an extensive trade in drygoods and notions, making a specialty of women’s and children’s ready-made wear. No similar house bears a more enviable reputation and the success attained is directly traceable to the business ability shown by Mr. Kemp in its management. He is progressive in his methods, his integrity as a merchant is unquestioned, and he has built up the extended trade enjoyed by his house through fair and liberal dealing that has gained for him an enviable reputation. He is a man of sound judgment, keen foresight, untiring effort, and stands high in the community as a worthy citizen of a genuine public spirit, and unquestioned usefulness. Mr. Kemp is a director in the Fredericktown Savings Institution. Mr. Kemp is a Democrat and has always been an active advocate of the principles of the party, although he has never aspired to public office, having no taste in that direction, preferring to be numbered among the rank and file rather than to aspire to political preferment. Mr. Kemp is well known in fraternal circles being a leading member of the Lynch Lodge, No. 163 A. F. and A. M. of Frederick; of Enoch Royal Arch Chapter, No. 23, Royal Arch Masons; and of Jacques de Molay Commandery, No. 4, Knights Templar. He stands high in the Masonic order as one of the most popular gentlemen allied therewith. Mr. Kemp is an active and earnest member of the Evangelical Reformed Church, in the work of which he takes a prominent part, promoting its interest in every way possible. C. Thomas Kemp was married, March 18, 1890 to Matilda, daughter of Theodore Shultz, deceased of Frederick. They have one daughter, Annie Brunner Kemp. C. Thomas Kemp lived primarily at three locations in Frederick City. In 1880, he lived with his parents at 297 West Patrick. From here he would reside at today's 20 West 3rd Street by 1900, likely moving here after his marriage in 1895. He would be residing here in 1910 when the biography appeared in Williams’ History of Frederick County. Interestingly, his next door neighbor in that census was Frederick City Hospital foundress Emma J. Smith. The original site of Kemp and John P. Renner's dry goods store was 15 North Market Street. This structure no longer stands and is the current site of District Arts. Kemp would relocate to the northeast corner of "the Square Corner" at the intersection of Market and Patrick streets, so named because it was the town square of Frederick. This site had many previous usages, including that of a drugstore in the picture above. A previous "Story in Stone" on Daniel M. Grumbine illustrated its use for a tailoring business, and I also learned of a Milton A. Woodward who was a grocer, and the name of the structure was once familiar to residents as the Woodward Building. Mr. Kemp would enlarge the brick building to three stories in 1908, and it would soon be billed as "the Square Store at Square Corner." C. Thomas Kemp added men's and boy's clothing departments to his initial offerings of women's and children's apparel. A long list of items were sold here ranging from shoes, silk hosiery, handkerchiefs, jewelry, neckwear and corsets. Mr. Kemp went on to purchase the adjacent Rosenstock building on East Patrick Street in 1921 and expanded even further. By June of 1923, he was running advertisements which touted Kemp’s as “Frederick’s Greatest Store.” Year-in and year-out, Kemp worked hard to keep his operation humming. As mentioned earlier, it appears that he put extra effort into his marketing messages and advertisements. A key area of interest revolves around newspaper-based holiday ads, and more specific, Christmas advertising. My case study involved careful scrutiny of Mr. Kemp's work leading up to Christmas, 1923—a century ago. I found C. Thomas Kemp as one of the earliest businessmen to really “sell” the holiday. He continued his successful marketing strategy and clearly flexed the Kemp's brand. In addition, C. Thomas Kemp counterbalanced his advertising with a specific new department for his store during the holiday season. In December of 1923, we see the third floor, which had usually served as home to men’s clothing, becoming the "Gift Shop.” The "ramp up" week to Christmas included a second ad, in the daily newspaper, designed to provide special gift ideas to the Frederick populace. I was curious about the entire campaign of 1923, so I researched each day and found these gems from December 18th-22nd. Not quite the 12 days of Christmas, but a brilliant marketing campaign nonetheless. C. Thomas Kemp topped off each holiday with a heartfelt message to his customers and community. He did this on each major holiday, and here in 1923, he accentuated ads for Christmas and New Years. Since I had the Christmas Eve edition of the local paper in hand, I thought I'd share the front page and a few interesting articles from said front page that pertain to Santa Claus coming to Frederick. This should get you in the Christmas spirit! C. Thomas Kemp had worked his way up from the bottom and was enjoying the fruits of his labor. His personal life would eventually center around a new home for him and wife Mary in one of Frederick’s finest neighborhood—Rockwell Terrace. Kemp's ads would continue to attract customers up through the proprietor's death in 1930. As a matter of fact, I was interested to find an advertisement announcing to the community that the business would be closed for several days on account of Mr. Kemp's death in early July. A great sign of respect among business owners came that same week as his competitors shared their condolences. C. Thomas Kemp actually passed on July 1st, 1930. He died at his home at 208 Rockwell Terrace, just four days shy of his 68th birthday. His obituary states that he had been ill for quite some time, suffering from Parkinson’s Disease. C. Thomas Kemp was buried in Mount Olivet’s Area C/Lot 138/140 beside his in-laws, Theodore and Mary (Dill) Shultz. Wife Mary Matilda Kemp would join him here upon her passing in 1941. Mr. Kemp’s parents Lewis (1824-1913) and Sarah (1821-1912) are only about 75 yards up the hill in Area E/39, and other early Kemp family members are in this section too. C. Thomas Kemp's former business partner, John P. Renner, and other friends in the dry goods business such as Charles J. Doll (1859-1930), who died the day after Mr. Kemp, are buried nearby as well. Kemp’s Department Store would continue to operate for decades after C. Thomas Kemp’s passing. Daughter Annie, and son in-law, Sam Maples, would operate the store until the early 1960s. Routzahn & Sons, Inc., owners of a furniture, television and appliance store at 24-26 East Patrick Street would purchase the store and property in 1961. They continued to operate under the Kemp's moniker before eventually changing it to Routzahn’s Department Store. The rest, as they say, is history. Thank you Mr. Kemp for outfitting and assisting with "the spirit of giving" during the holidays for so many past (and present) Fredericktonians.

0 Comments

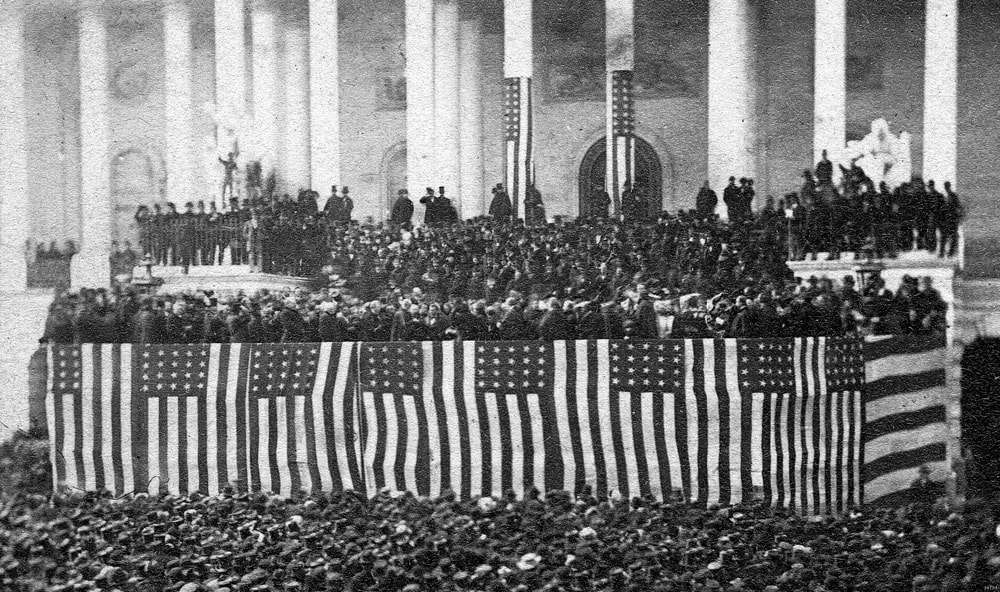

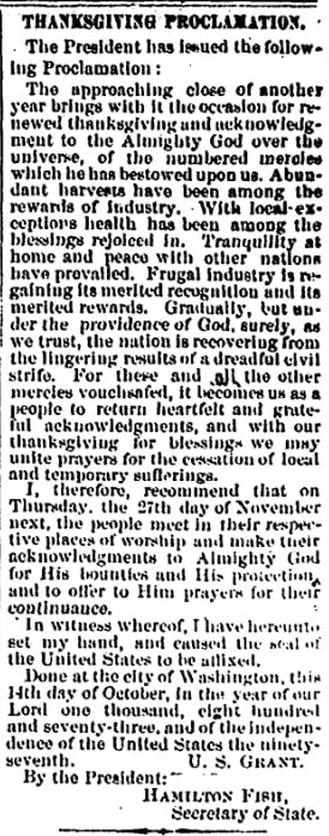

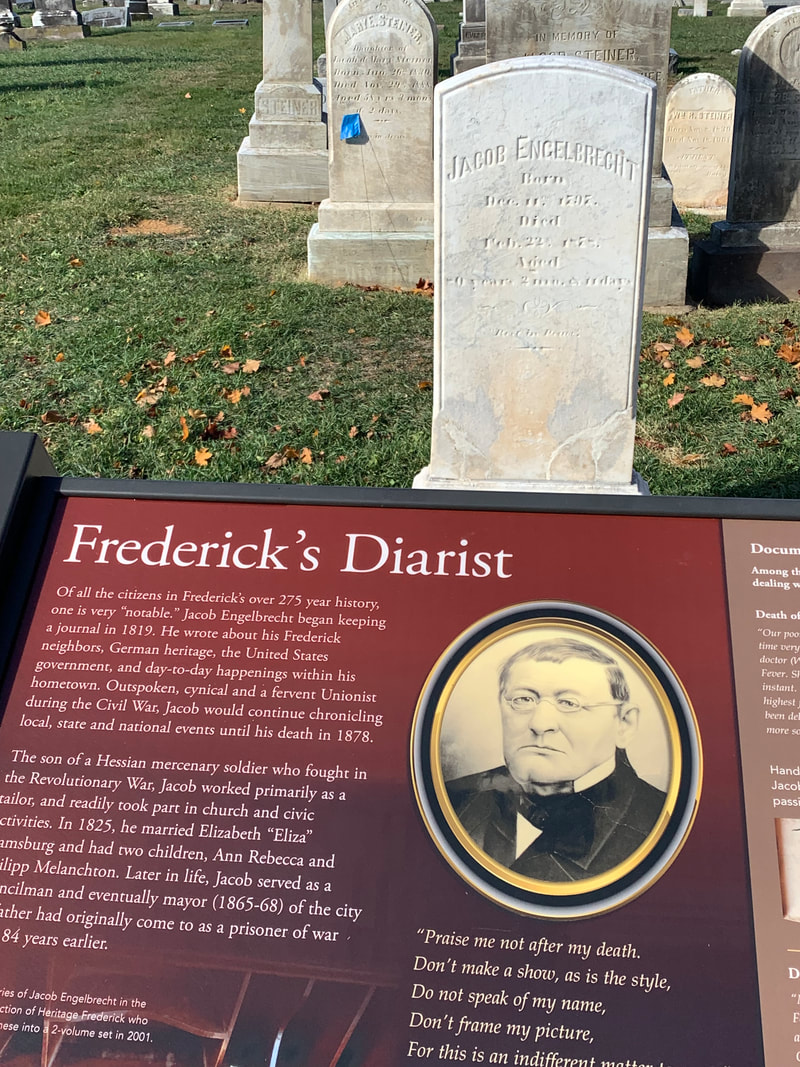

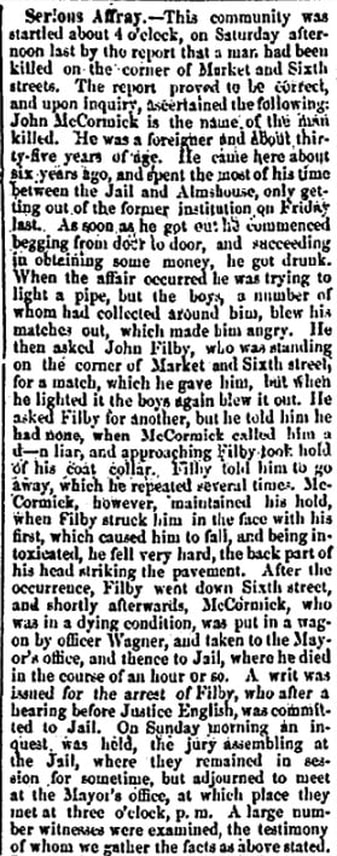

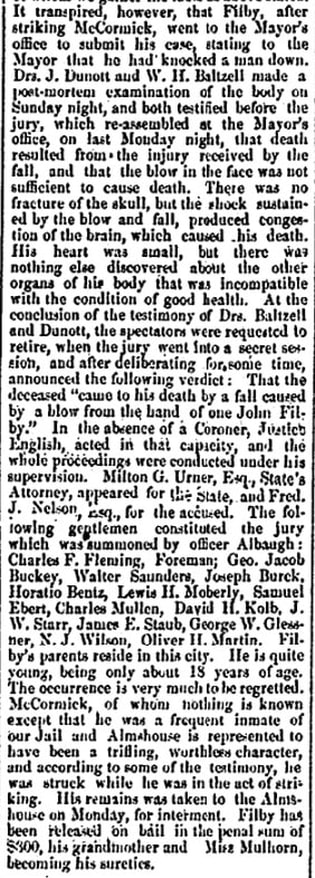

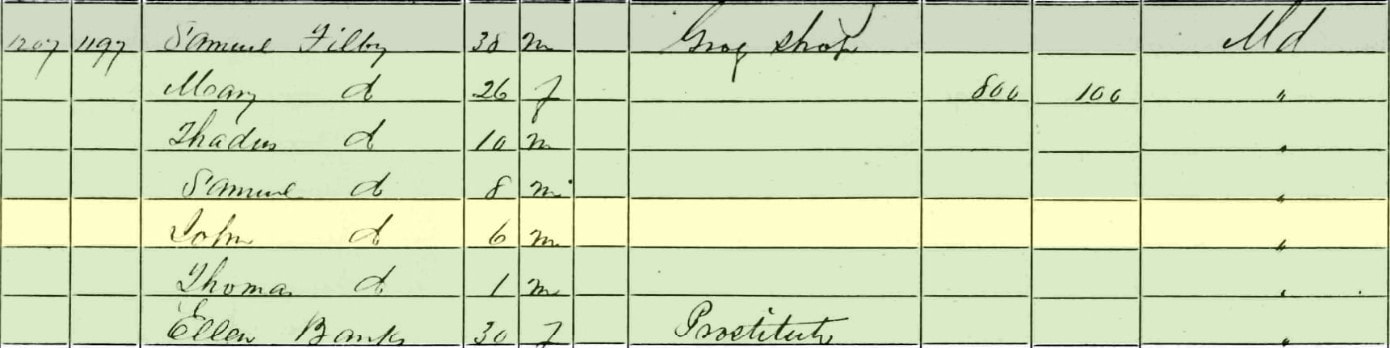

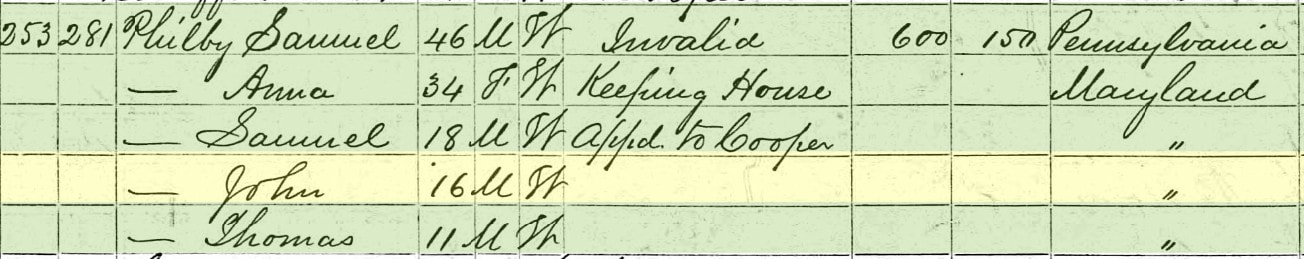

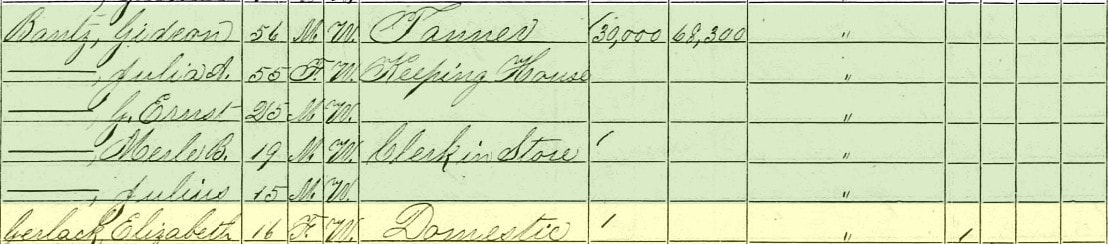

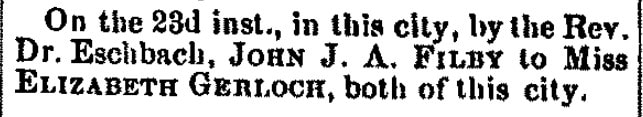

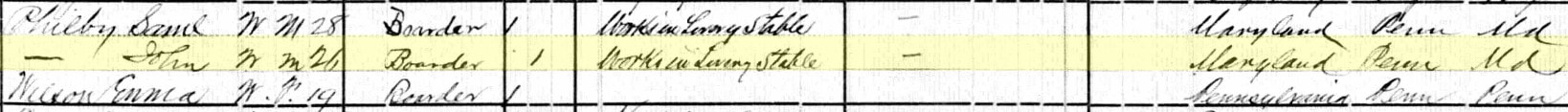

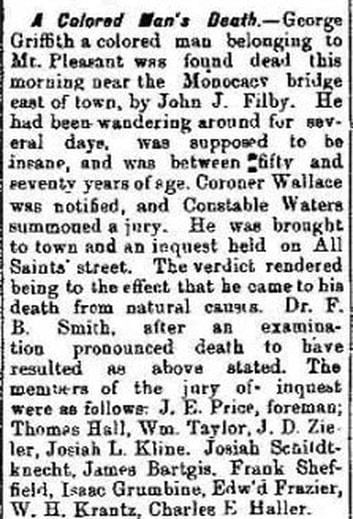

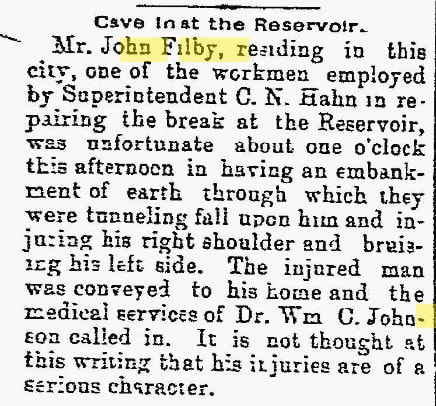

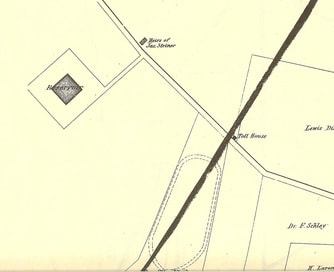

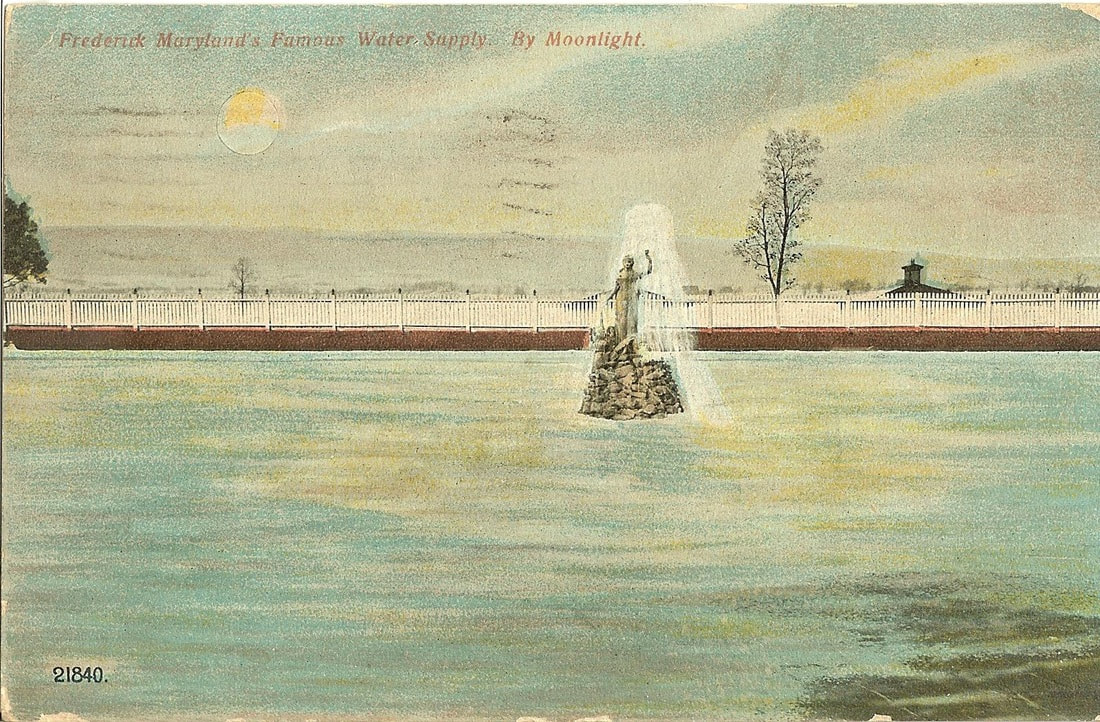

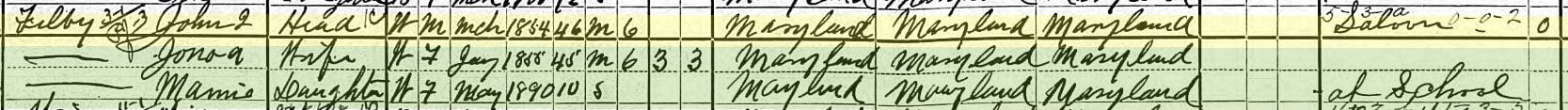

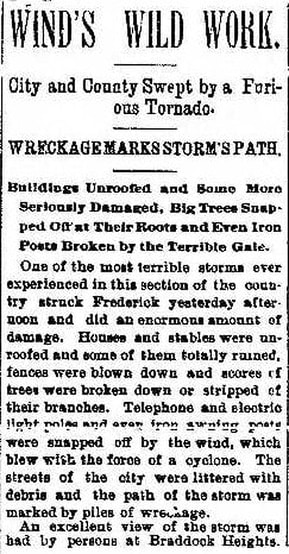

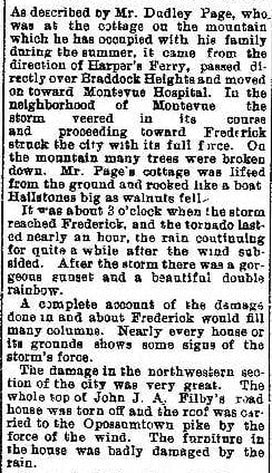

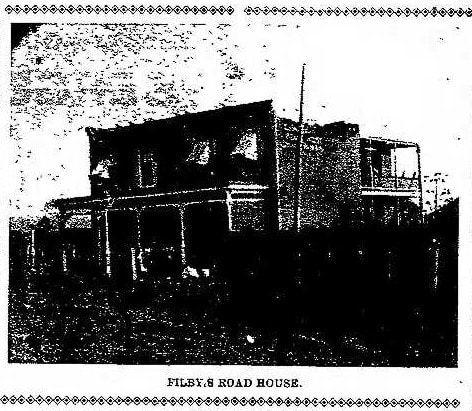

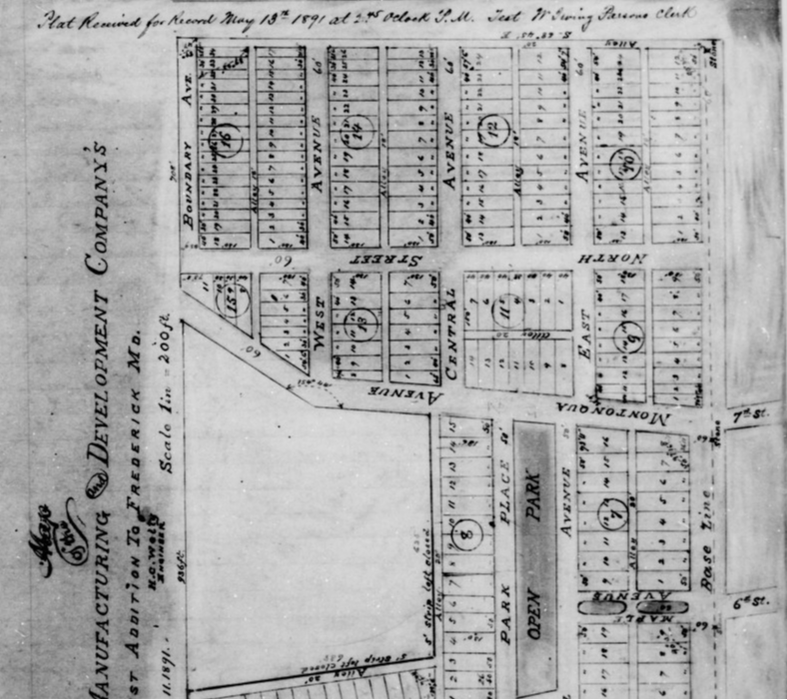

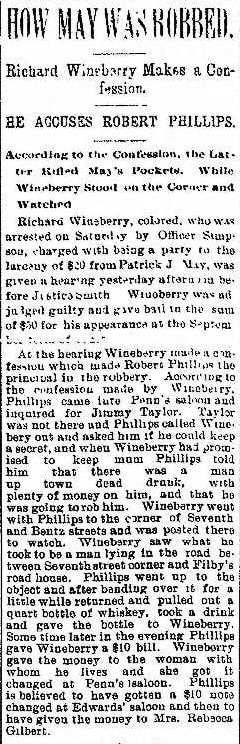

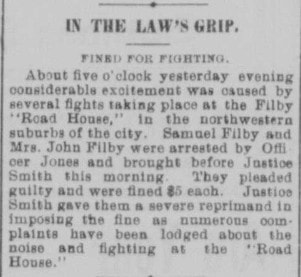

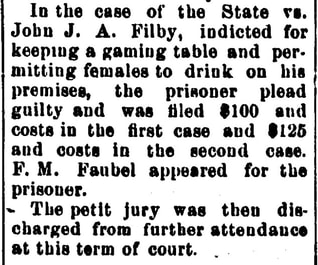

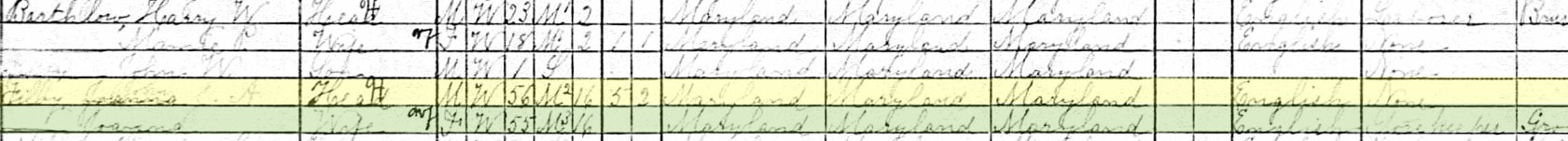

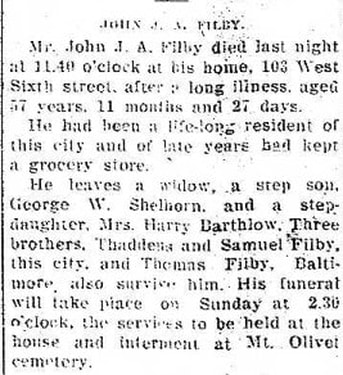

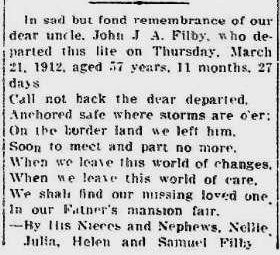

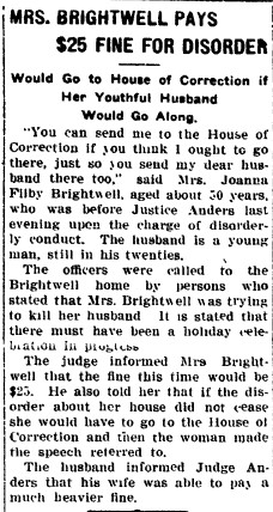

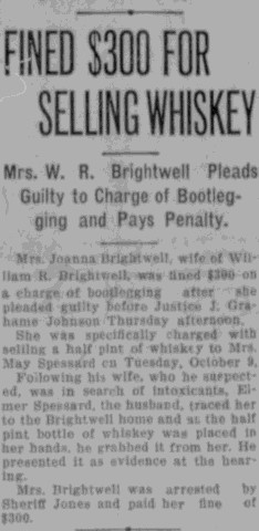

So with Thanksgiving at hand, I decided to take a look into what was happening in my hometown of Frederick, Maryland for the "Turkey Day" back this week, 150 years ago. According to my calculations, that puts us into the third week of November, 1873. Jacob Engelbrecht (b. 1797) was alive and well at this time. I immediately decided to consult his legendary diary, the greatest single, documentary of our city's rich history (kept from 1819 until the author's death in 1878). This would be a particularly sad time for Jacob, as he lost his wife, Eliza, at the very end of 1872. He would move from his home on West Patrick Street to that of his son Phillip on South Market Street only a few blocks from Mount Olivet's front gate the previous May. This would be his first Thanksgiving as a widower, and away from his longtime home next to the Carroll Creek, (and across from the original site of the Barbara Fritchie house). Outside of that, it was a quiet year that saw Ulysses S. Grant start his second term as U.S. President. Jacob commented on March 4th (the time of Grant's inauguration) that he hoped that Grant "would conduct himself as he had done in his first four years, and we'll be alright." He went on to write, "I think he managed as well taking all in all as good as a man possibly could. He's a good President." On the local level, the big news of the year was the corporation's decision to replace the old Market House, dating from 1769. This landmark on North Market Street was home to municipal government and would be replaced with a commodious building of brick at a cost of $8,000. The size and scope of the project necessitated additional properties on both sides, and behind, to be purchased. The demolition occurred in spring of 1873. Throughout the summer, residents saw the new structure, which would include a theater on the backside to accommodate lectures, concerts and theatrical productions, take shape. Of course this would become the City Opera House. I found Engelbrecht's diary entry of September 8th to be very ironic based on the structure's current use 150 years later: "New City Hall & Market House - On Saturday last September 6, 1873 the masons finished the brickwork on the above building, and on the strength of it, they had two kegs of "lager bier" and basket full of cakes for all hands concerned." You know this locale today as the site of Brewer's Alley Restaurant. Thanksgiving was celebrated by the fabled Pilgrims and Indians of eastern Massachusetts in fall 1621. In 1873, the "holiday" was not a given as we have today, 252 years later. Proclamations by both the United States President and individual state governors actually had to be made to recognize these days as special and worthy of closing banks and businesses, while encouraging the citizenry to get into church and be "thankful" for their blessings. I researched the history going back to George Washington and the time of the Nation's founding to learn that Thanksgiving has been celebrated nationally on and off since 1789, with a proclamation by our first president after a request by Congress. President Thomas Jefferson chose not to observe the holiday, and its celebration was intermittent until President Abraham Lincoln, in 1863. Honest Abe proclaimed a national day of "Thanksgiving and Praise to our beneficent Father who dwelleth in the Heavens", calling on the American people to also, "with humble penitence for our national perverseness and disobedience ..... fervently implore the interposition of the Almighty hand to heal the wounds of the nation." Just remember this as you are watching the Lions and Cowboys tomorrow, or as you are carving the turkey. Lincoln declared a day of Thanksgiving to be held the last Thursday in November. On June 28th, 1870, President Ulysses S. Grant signed into law "The Holidays Act" that made Thanksgiving a yearly appointed federal holiday in Washington, D.C. On that last Friday of November, 1873, Jacob Engelbrecht would write in his diary: "Day of thanksgiving —Yesterday was Thanksgiving day by proclamation of President Grant and Governor Whyte of Maryland and was generally observed in our town. The different churches had divine service." In case you were curious, this practice of political proclamations would continue until 1885. Another irony of history because an act of Congress would thereby make Thanksgiving, and other federal holidays, a paid holiday for all federal workers throughout the United States. This legislation would be enacted on January 6th of that year (1885). Perhaps, that's a better way for all of us to remember the importance of January 6th—instead of another "questionable" narrative involving the capitol and congress on that day? Jacob Engelbrecht did not write anything more on that first Thanksgiving without his beloved Eliza. Studying this man, I'm sure he found plenty in life to be thankful for, as it had been a wonderful one thus far. And like George Bailey, where would historians, genealogists and others be without this great Fredericktonian who kept his diary from 1819 until his death in 1878. In addition to serving a term as Frederick mayor, he was more importantly a friend to many. Thanksgiving week of 1873 however had started off pretty unnerving. This was due to a fatal incident on West 6th Street that left a man dead. "Killed or murdered —Last evening a man (stranger) named John McCormick was struck with a "slug shot" by John Philby from which he died soon thereafter. It occurred in Sixth Street. Philby was released on bail ($200). The coroner's jury was that he was injured by the fall on the pavement." Jacob Engelbrecht Sunday, November 3rd, 1873 Who was this John Filby? Who was John McCormick? I immediately was intrigued when I learned that Mr. Philby (or Filby) was buried here in Mount Olivet in Area H/Lot 134 nearly four decades later. McCormick would be buried in a potter's field at Montevue, the county almshouse, north of town. Consulting the newspapers of the day, stories of this event could be found in papers involving the Baltimore Sun, Cumberland Daily News, and Montgomery County Sentinel. The local papers of the day, the Maryland Union and the Frederick Examiner gave a much more thorough account of events as you can imagine.  Jennie Wade (1843-1863) Jennie Wade (1843-1863) Just what more could I find out about John Filby, a man who, like our friend Jacob Engelbrecht, I clearly presume had an equally tough Thanksgiving in November of 1873? John J. A. Filby John Jacob Astor Filby was born March 24th, 1854. He was the son of Samuel Thaddeus Filby (1823-1886) and Mary Anna (Mulhorn) Filby (1836-1894). It appears that John's father was from the Gettysburg, Pennsylvania area originally. In fact, Samuel's sister, Mary Ann (Filby) Wade, was the mother of Gettysburg's most famous resident during the famed American Civil War. This was Mary Virginia "Jennie/Ginnie" Wade, who was killed by an errant bullet on July 3rd, 1863 while in the process of kneading bread. This would make Jennie/Ginnie our subject John's first cousin. Our cemetery records list Samuel Filby as a stagecoach driver, something I confirmed in the 1850 US Census as it showed him in residence at Keefer's Hotel on West Church and Court streets. The Filby's, interchangeably spelled Philby, lived on West Sixth Street in Frederick near the intersection with North Bentz Street. The 1860 Census record perhaps speaks a bit toward young John's upbringing. The family residence appears to have been a "Grog House." If you don't know what this is, it's a tavern or bar, with "grog" defined as spirits/alcohol. This locale is made even more colorful by the tenancy of one Ellen Banks, her profession listed as prostitute. Alrighty then!  John Jacob Astor John Jacob Astor It was tough sledding to find out more about John Filby. As I gleaned a bit of his early life up until the day he literally knocked John McCormick's "lights out" in November of 1873 at age 19, one thing was definitely clear—his life would certainly not compare to that of his namesake John Jacob Astor (1763-1848). The German-born American businessman, merchant, real estate mogul, and investor died six years before John Filby's birth, and I have no idea why any parents would be so fond of the wealthy gentleman. This was a confusing name to give to a newborn because its well-known that Astor made his fortune in "sketchy" ways which included a fur trade monopoly, by smuggling opium into China, and by investing in real estate in and around New York City. He was the first prominent member of the Astor family and the first multi-millionaire in the United States. John Filby was only 11 years old when President Lincoln was assassinated and the Civil War ended in April of 1865. He can be found living at home on West Sixth Street in the 1870 census. John would marry his first wife, Miss Elizabeth Gerloch (Gerlach), in January, 1879. I found this woman, an immigrant, working as a domestic servant for wealthy mill owner and the Frederick Fair Board's first president, Gideon Bantz, in the 1870 census. Our subject likely worked as a laborer according to census records, and the few news articles I found. I had difficulty locating him in the 1880 Census, but located a person named John Philby of his age working alongside older brother Samuel at a horse livery on the north side of High Street in Baltimore. I was confused as to the whereabouts of the former Miss Gerloch, John's wife. I assume she could have died shortly after the marriage because I can't find her anywhere, including Mount Olivet. There was another instance of John Filby and a dead man in his path so to speak. One such story from the 1880s places him at the site of the water reservoir that used to be on West Seventh Street. Today this area is encompassed within Max Kehne Park. John J. A. Filby's parents are both buried here in Mount Olivet, but in different areas of the cemetery. Samuel passed just before Thanksgiving of 1886 (November 20th to be exact) and can be found in Area Q/Lot 218. Likewise, Annie (Linton) Filby died a week before Thanksgiving as well (on November 17th), 1894 making for another emotional Thanksgiving for our subject. Annie was laid to rest in Area H/lot 182. The 1890s are always problematic with a lack of the 1890 Census records, lost in a fire. I did not even come across any articles to bridge the gap to the 1900 census. I would however be able to place John at West Sixth Street in the first decade of the new century. He had remarried Joanna (Stimmel) Burrall. around 1893/94 and the couple would be living with a daughter from his new bride's former relationship. This was Joanna's third marriage as she originally been married to a gentleman named Anton Shelhorn. I reveled in seeing a new profession noted for John J. A. Filby, one that followed in his father's footsteps. He was a keeper of a saloon. I soon found other mentions of this establishment located on Montonqua Avenue, aka West Seventh Street. This was known as Filby's Road House and was considered to be on the outskirts of town at the time. It was positioned at the intersection of Montclaire Avenue and near the site of the old toll house. In 1901, a terrible windstorm took off the establishment's roof. It apparently made its way to the Oppossumtown Pike, the name for North Bentz Street above Seventh Street before the name of Motter Avenue would be applied. The occasion called for a photograph to be placed in the local newspaper as well giving us a visual. This structure, despite the damage, still stands today! It's now home to La Villa Nail Salon and Mackie's Barbecue Co. at 325 & 327 West Seventh Street. It's directly across from the hospital. Under Filby's ownership, the Road House often found itself in the center of controversy and bawdy conduct. The Filby Road House was sold around 1906/07. Newspaper advertisements show that Joanna, not John was the true owner or purse strings of the Road House. Joanna would also own several build-able lots on West Seventh. The 1910 census shows shows John without a job, or simply enjoying his retirement. However, Joanna is listed as operating a grocery store. I'm thinking this was done utilizing the couple's home domicile. John Jacob Astor Filby was reported ill in a few of the February News editions. He would be dead within a month, passing on March 21st, 1912. Filby would be buried not far from the grave of his mother in Mount Olivet's Area H/Lot 134. A sizeable dark gray monument stands over his grave. As I thought I had things nicely buttoned up on this story about a Frederick man who inadvertently killed another man, an apparent vagabond, just days before Thanksgiving, 1873, I couldn't help but think of John's wife Joanna Filby having to endure a lonely Thanksgiving in November, 1912. Regardless of how that went down, she appears relatively "grief free" by Thanksgiving of 1913. To my great surprise, Joanna had worked relatively quickly in getting remarried once again. This time her husband was in his early twenties, while she was 50. Forget turkey talk, we have a cougar on our hands "By George!" This was a future World War I vet by the name of William R. Brightwell. The articles below help illustrate the couple's interesting relationship. Apparently Joanna dabbled in a few other "questionable" endeavors as well. Months after her divorce, Joanna would suffer a major life setback as her home was consumed in a fire on West Sixth on October 24th, 1925. During this event, six homes in the neighborhood burned. These homes were seen as part of a slum area. The opportunity came for the City to rebuild public housing here in years to come as the John Hanson Apartments. The exciting life and times of Joanna (Filby) Brightwell would come to a close on February 23rd, 1928. She had been living with her daughter in the vicinity of Rose, Michigan at the time of her death caused by heart disease. She would be buried with her "old," both literally and figuratively, husband John J. A. Filby in Area H. Sadly, no one took the opportunity to ever apply her death date on her gravestone. Happy Thanksgiving, and smokers out there, I suggest you carry your own lighter and matches. Don't always count on the goodwill of others to offer you a light, as you may get more than you bargained for like John McCormick that Thanksgiving week of 1873.

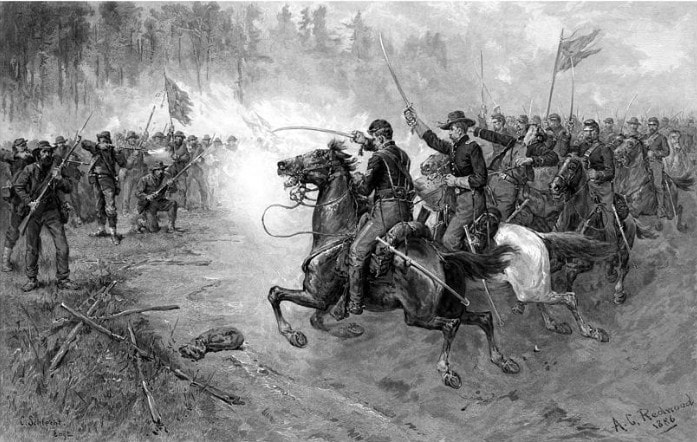

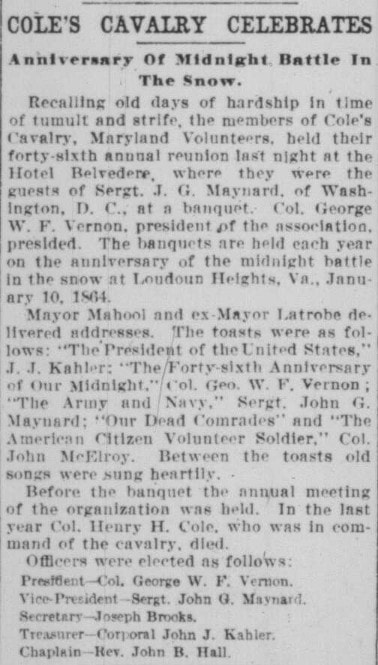

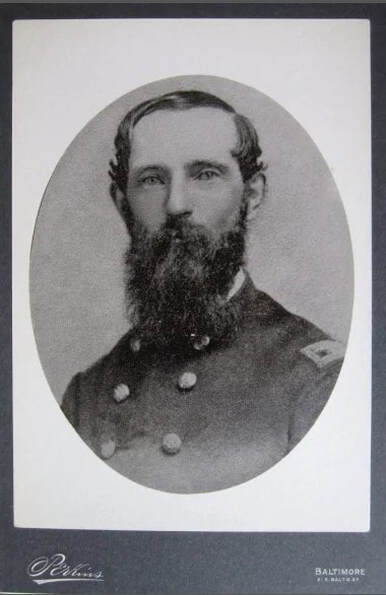

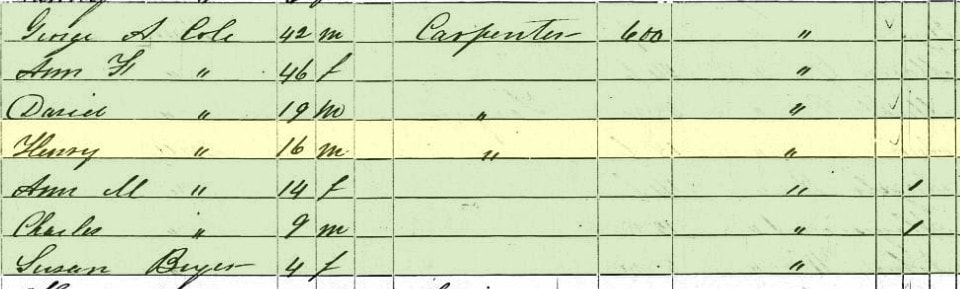

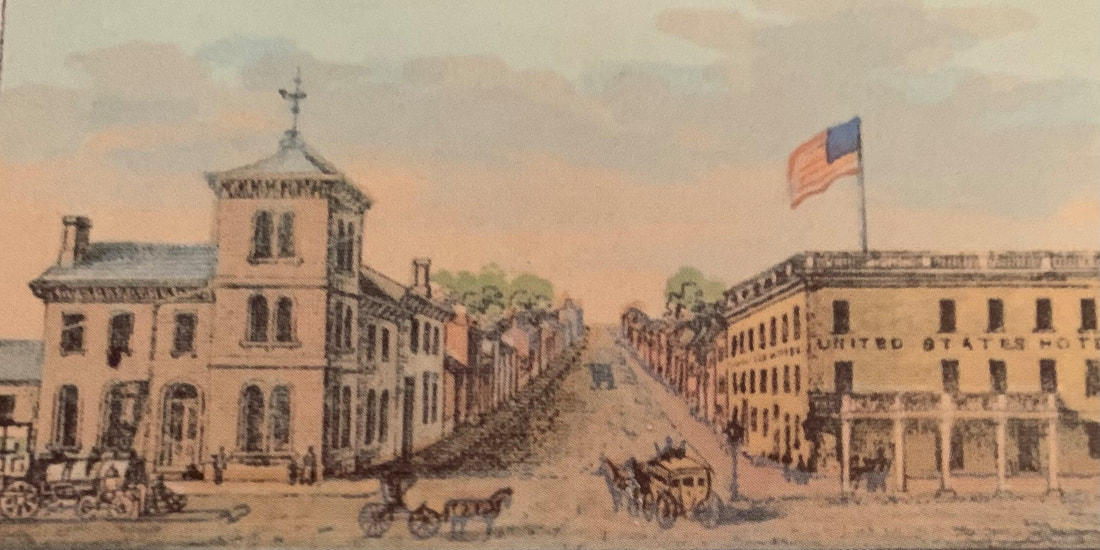

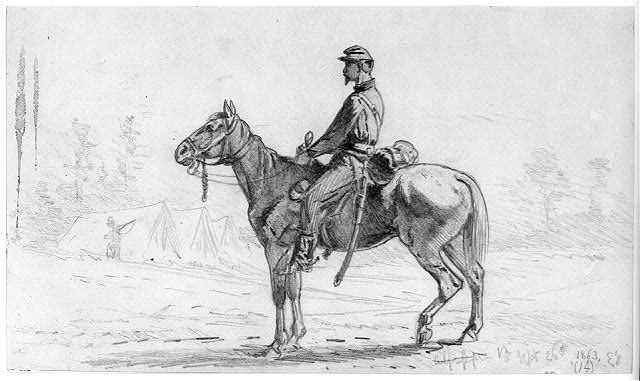

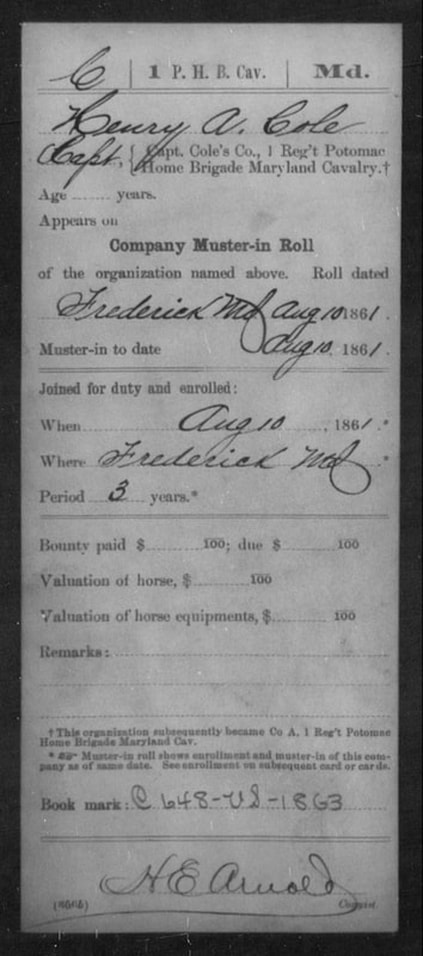

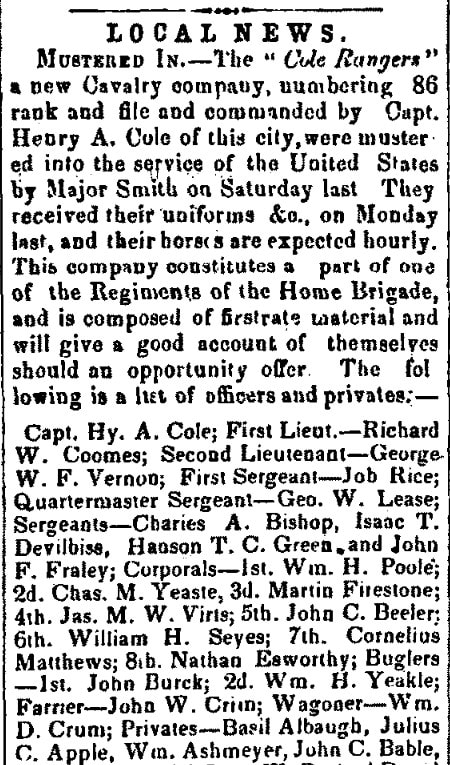

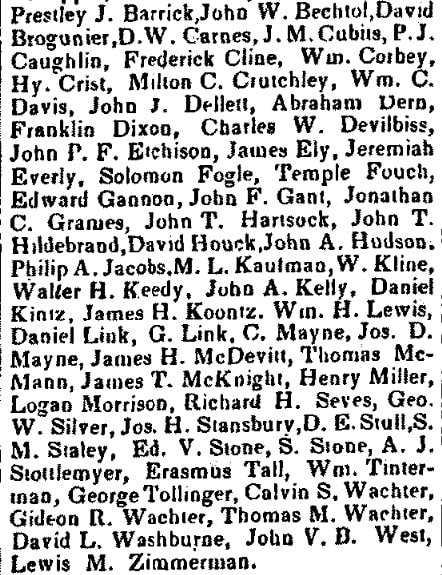

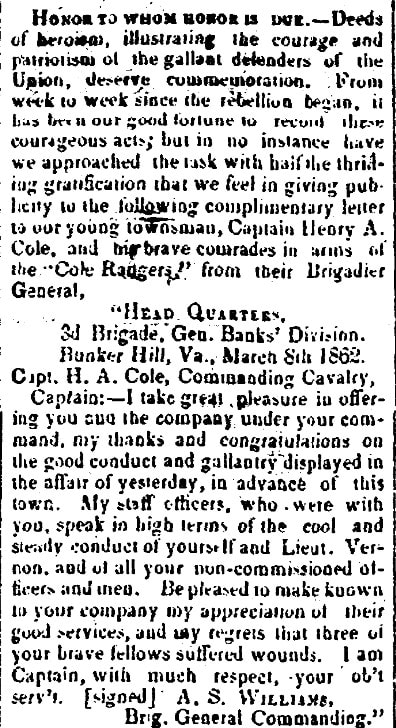

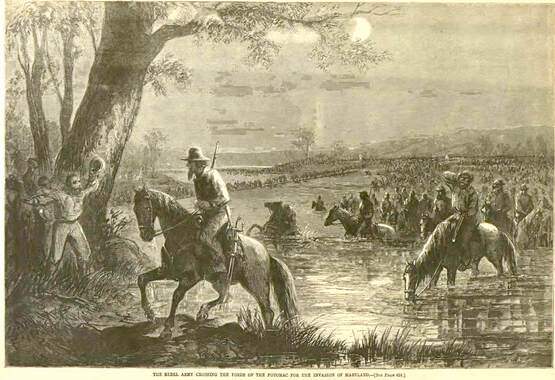

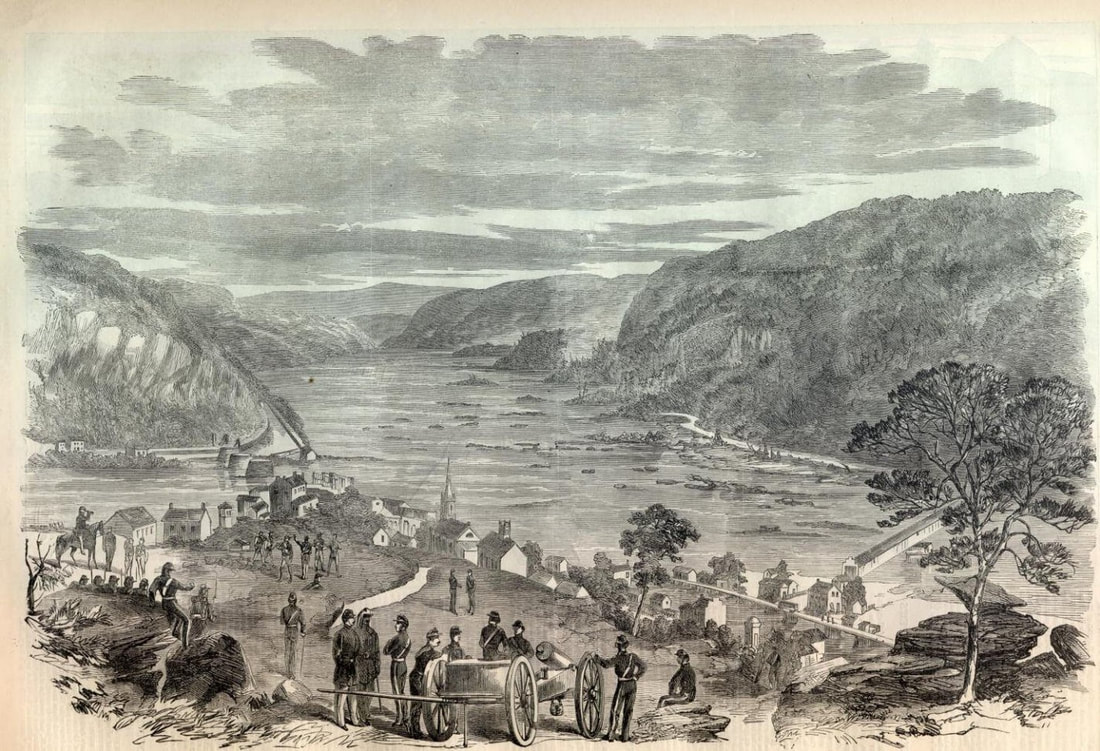

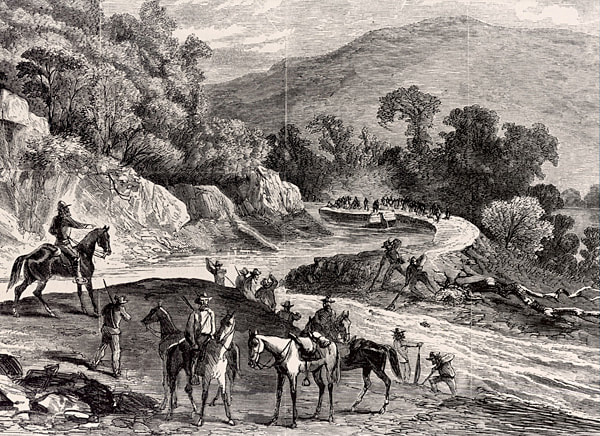

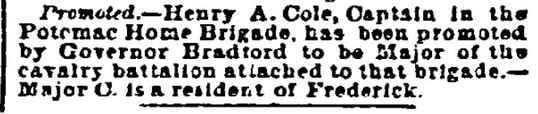

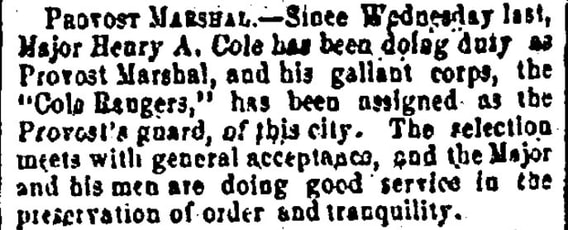

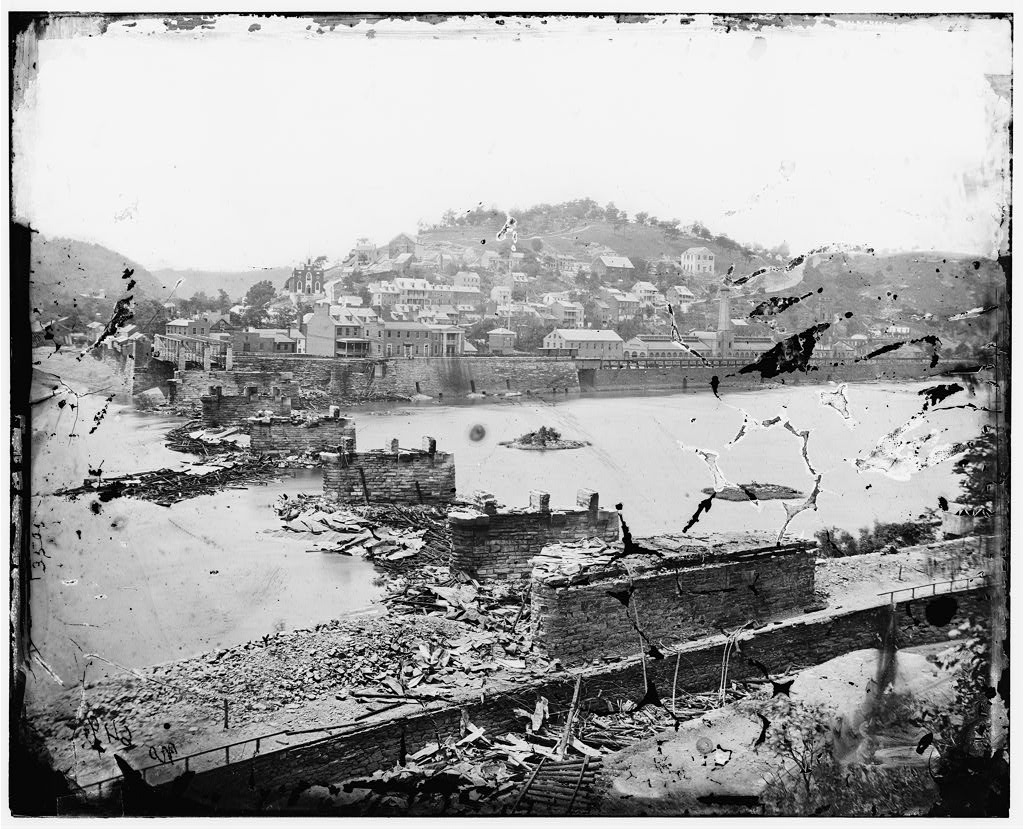

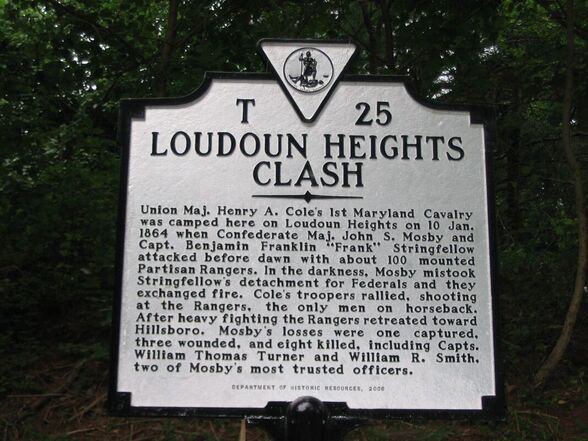

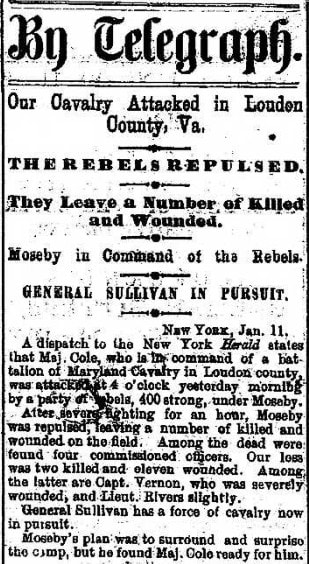

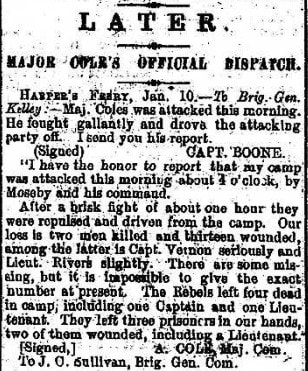

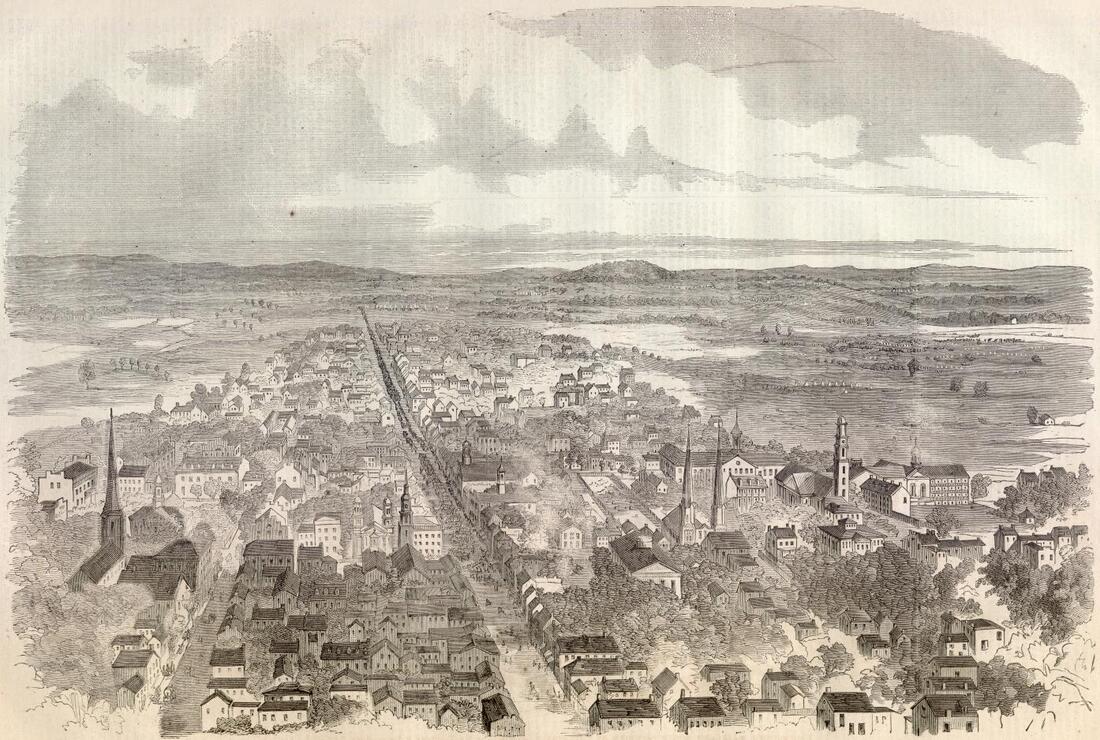

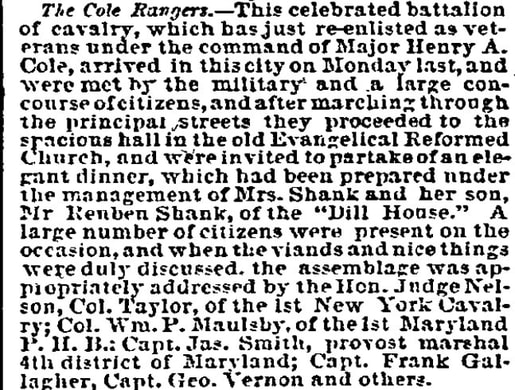

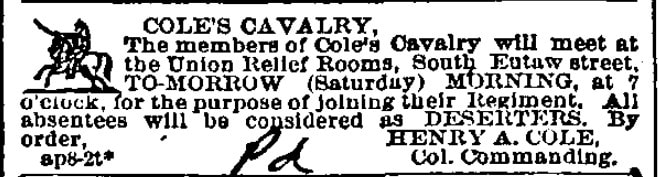

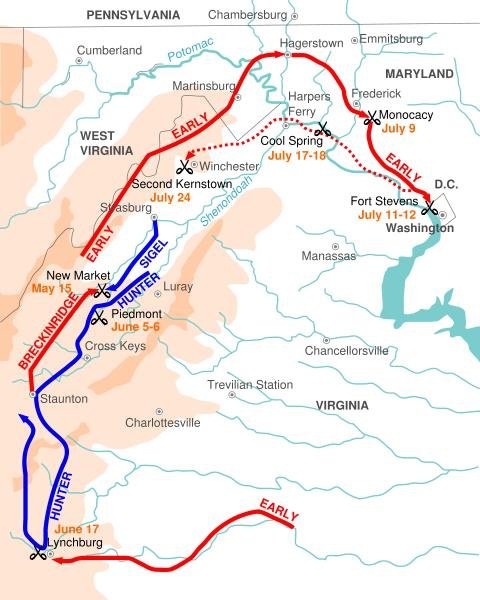

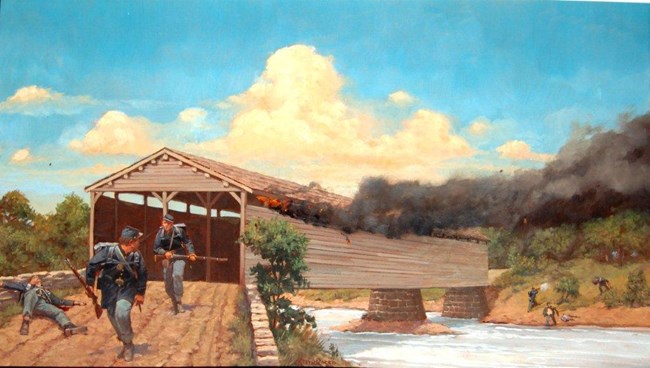

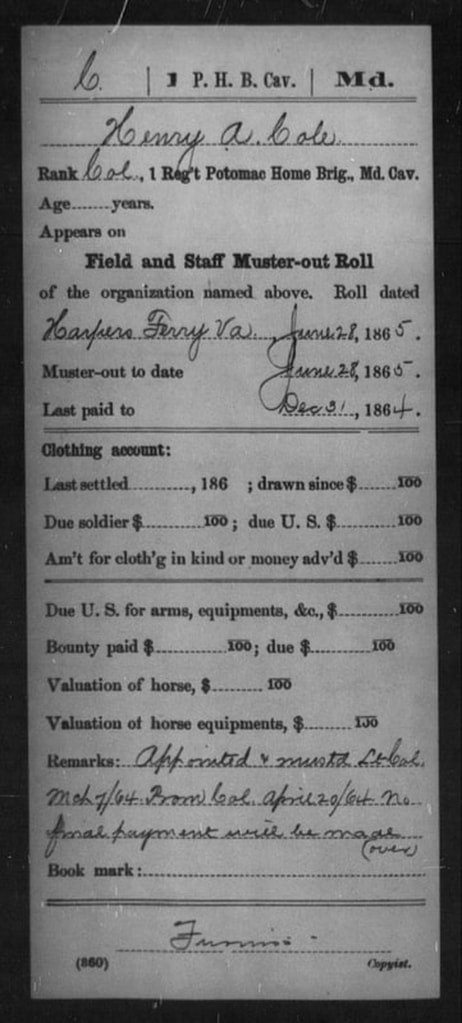

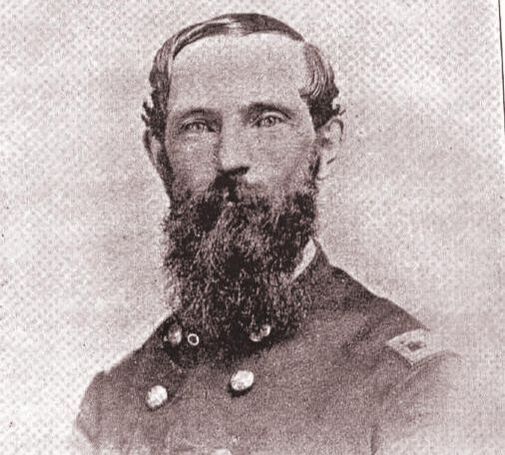

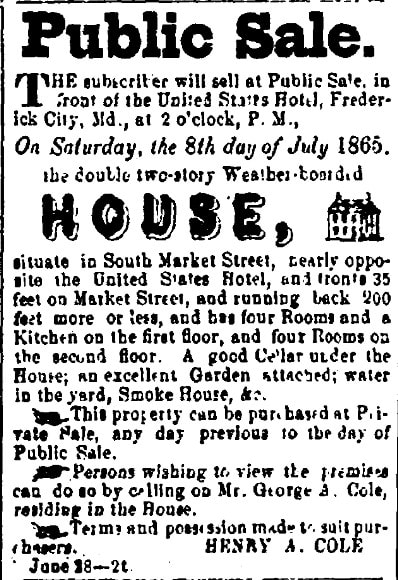

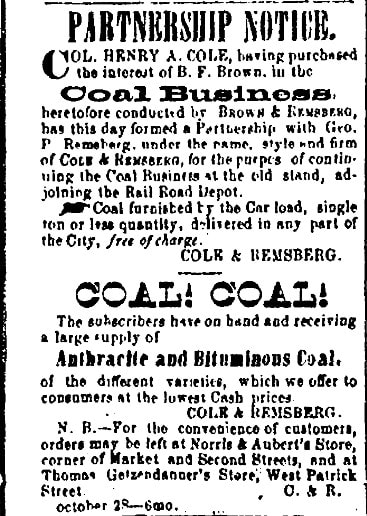

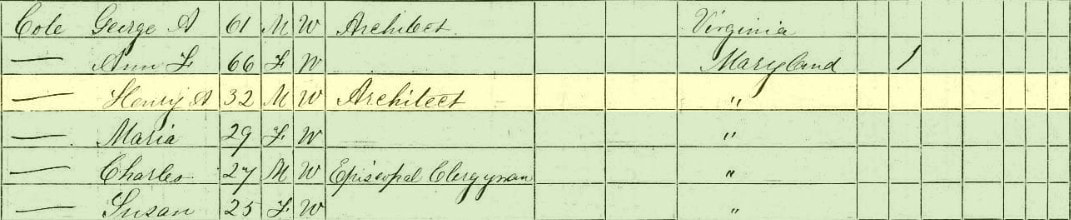

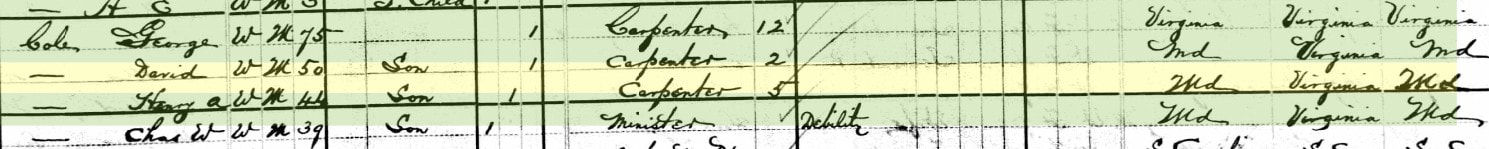

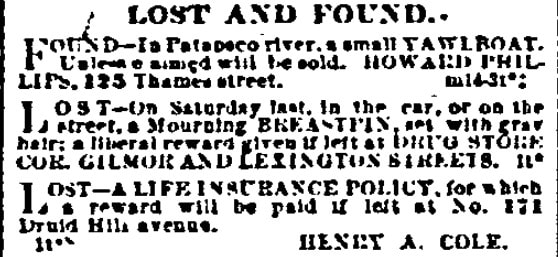

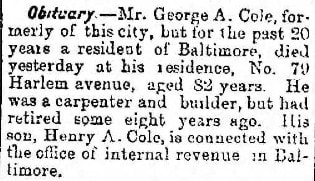

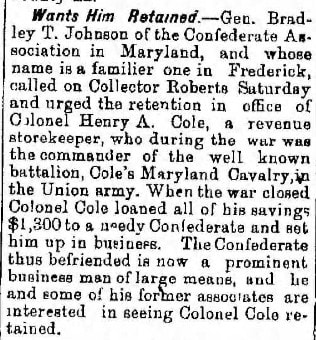

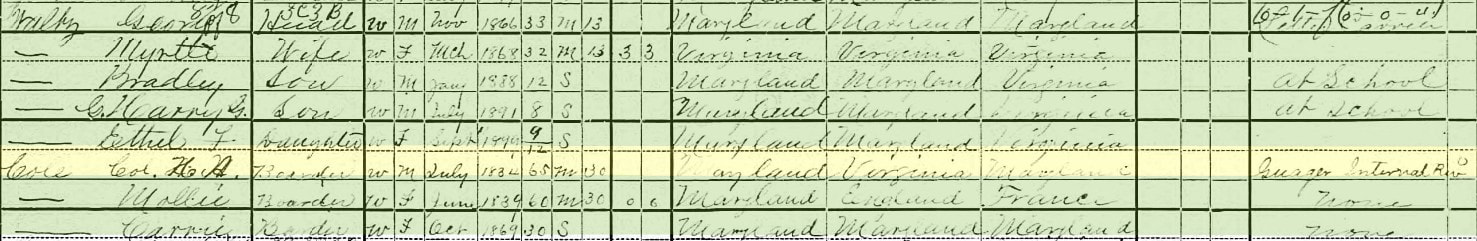

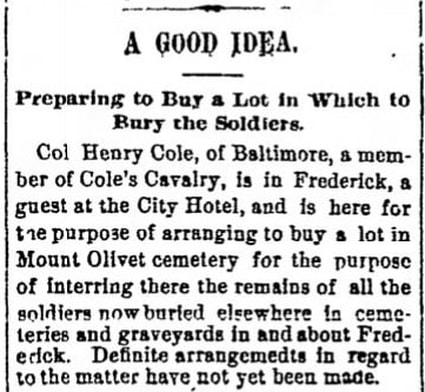

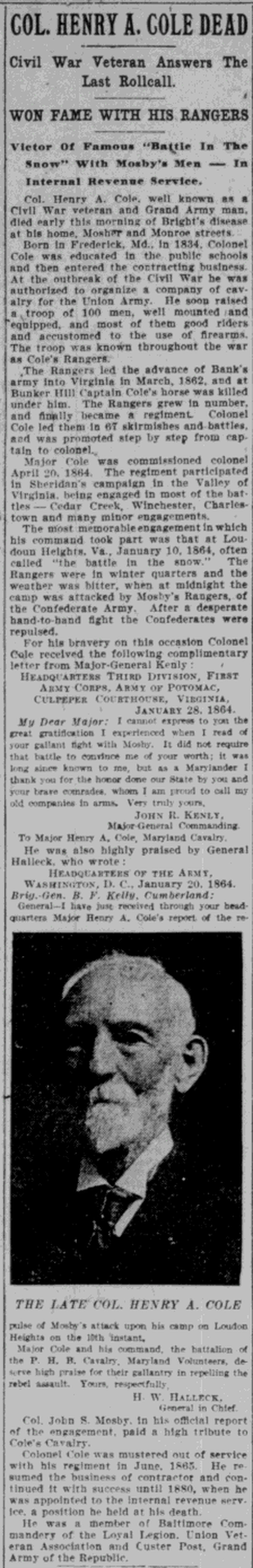

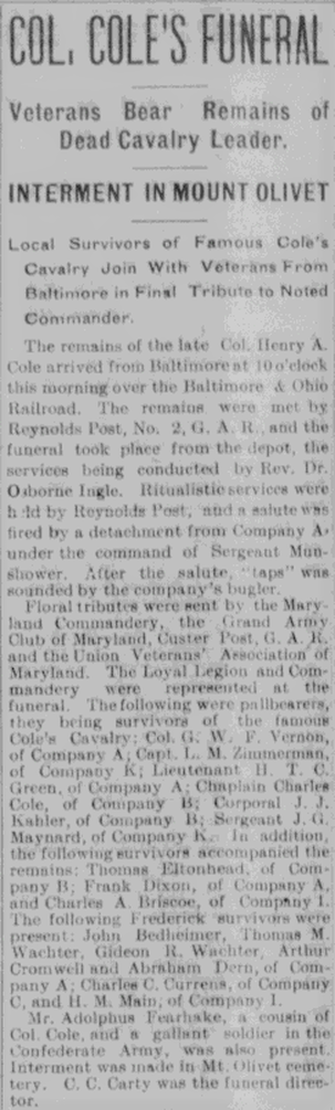

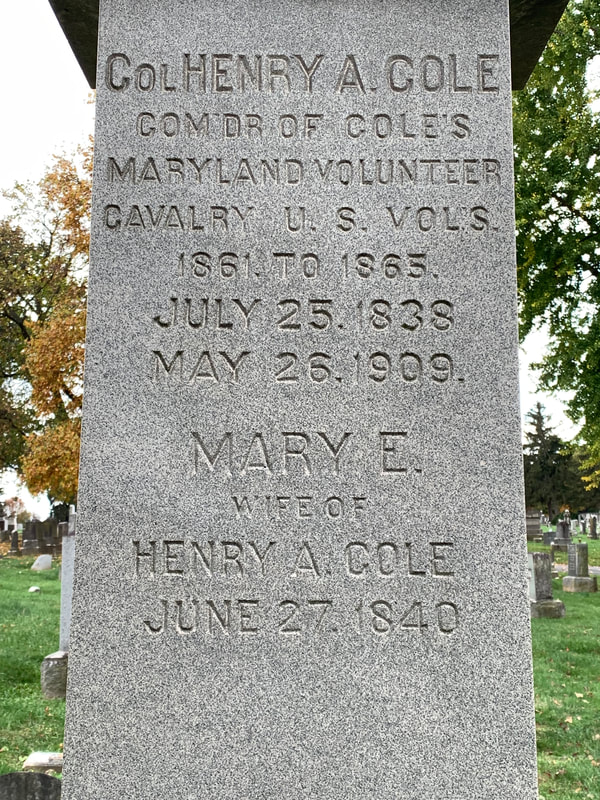

The Belvedere Hotel made its formal debut in 1903, taking its name from the estate of John Eager Howard (his son Charles would marry Francis Scott Key’s daughter Elizabeth in 1825.) Located at 1 Chase Street in downtown Baltimore, this was the center of Charm City’s social scene for many years. The structure still stands today, however its primary usage today is boasting luxury condos. In its heyday as a hotel, the Belvedere hosted many famous celebrities ranging from movie stars and musicians to politicians and three U.S. presidents. The hotel’s majestic ballroom was used nightly for formal dinners and fanciful galas. An event that occurred here on the night of Monday, January 11th, 1910, did not possess the glitz and glamour of a Hollywood party, nor did it have the stuffy air of a formal state dinner. No, on this particular night, a group of Union veterans of the American Civil War once again gathered together to reminisce about days of old, and enjoy each other’s company during times of peace—something they had been doing since their inaugural edition of these annual reunions decades before. This group was known as Cole’s Cavalry, a military outfit of volunteers that had been formed 49 years earlier in 1861 at the outset of “the War between the States.” Although the event was well-attended and went off without a hitch, there was something noticeably different in comparison with previous gatherings of this set of cavalrymen attached to a military unit known as the Potomac Home Brigade. Plain and simply, absent was the group’s wartime leader and namesake—Col. Henry A. Cole, a Frederick, Maryland native. Col. Cole had died the previous May. In 1861, Henry Alexander Cole rose to the rank of American colonel and bravely commanded the 1st Maryland Cavalry Battalion, Potomac Home Brigade in operations across his home state of Maryland and Virginia during the American Civil War. An 1881 newspaper article appearing in a newspaper called the Carbon Advocate (Lehighton, PA) spoke of our subject: “Maj. Henry A. Cole of Frederick, Md., was the commander, and it is needless to say that he was a man of great dash and courage. From the first fight in which he led his four companies of brave mountaineers, down to the close of the war, the cavalry he commanded bore his name and I doubt if there was ever one of those sturdy veterans who did not take pride in saying that he belonged to Cole’s Cavalry.” Henry Alexander Cole was born on July 25th, 1838, in Frederick. He was the third son of George A. Cole (1806-1886) and wife Ann F. (Hilton) Cole (1803-1877). One of eight children, Henry was educated in local schools and took on the trade of carpenter like his father before him. Over the next decade, Henry used his skills in the contracting and construction of residential, commercial and public structures. The Cole family lived on South Market Street, just south of the intersection with All Saints St. They had a house on the east side of Frederick’s principal north-south thoroughfare, and this was three doors down from the B&O Railroad passenger station (across Market Street from the US Hotel). With the winds of war prominently blowing on Frederick in the spring of 1861, local residents had seen events such as the fall of Fort Sumter (SC), the fall of Harpers Ferry and defection of Virginia from the Union, the Pratt Street Riots in Baltimore, and the capital of Maryland temporarily moved from Annapolis to downtown Frederick. An early war zone would soon constitute our county’s southern border. This was the Potomac River, true dividing line between North and South, the Union and the Confederacy. Before the war, Henry A. Cole was a commissioned "Major" in Maryland’s Militia on May 1st, 1861. He would serve as Aide-de-camp on the staff of Major General Anthony Kimmel (commander of militia in the western part of the state.) On July 19th, 1861, US Congressman from Maryland, Francis Thomas, received authorization from Edwin Stanton, President Abraham Lincoln’s Secretary of War, to provide for the raising of four regiments of infantry for the protection of persons and property in the area. In addition to the four companies of infantry, Representative Thomas also planned to raise four regiments of cavalry who would prove useful for the exact services that the brigade was being raised for – scouting, patrolling river crossings, and anti-guerrilla operations. Secretary Stanton’s order was brought to Frederick and a request for volunteers was called for with interested parties asked to assemble at the old Hessian Barracks site on South Market Street, a stone’s throw from Mount Olivet Cemetery. The day was August 10th, 1861. As this was a volunteer unit, most of the men who answered the call were young and had come from local farms, bringing their own horses for use in the war effort to preserve the Union. This would be the same day that Henry A. Cole enlisted in the Union Army. Like the men under him, he was mustered into the military for three years’ service. Just over three months later on November 27th, 1861, Cole would be appointed captain of Company A of the 1st Maryland Cavalry Battalion, Potomac Home Brigade. In short time, this outfit, made up primarily of Frederick men, would take the name of its charismatic recruiter, becoming “Cole’s Rangers” and/or "Cole's Cavalry.” Henry A. Cole made a true name for himself on March 7th, 1862 as his men led the advance of Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks division into Virginia. Cole would have his horse killed under him at the battle of Bunker Hill (north of Winchester). Luckily, our subject would not be injured in the incident. He was able to quickly liberate one of the many horses the Rebels had captured/stolen for his own use, allowing him to lead a defeat of the Confederate units under renowned cavalry Gen. Turner Ashby (1828-1862.) Cole and his men would take many prisoners in the days to follow. Capt. Cole and his men would participate in the Battle of Kernstown on March 22nd, 1862 and the following day's Battle of Winchester in which Gen. James Shields faced off against soldiers under Gen. T. J. "Stonewall" Jackson and his stalwart brigade. In the months to follow that spring, the Frederick men in Company A would see action at Edinburg and Charles Town, both in Virginia. On August 1st, 1862, Companies A, B, C, and D were consolidated within the 1st Maryland. The whole regiment now took Cole’s moniker. Henry Cole would be officially promoted to the rank of major a few months later in October. In late summer, Cole's Cavalry would participate in the Second Battle of Bull Run/Manassas, operating against the left flank of the Confederates. After Gen. Robert E. Lee’s victory in this major engagement, the Confederates headed north into Maryland. They crossed the Potomac River at Conradt’s Ferry and soon would be traversing Carrollton Manor. Frederick would be the first substantial, northern town to which the fabled general would bring his Army of Northern Virginia. This was early September of 1862. Meanwhile, Cole’s Rangers attacked Southern cavalry units near Leesburg. They did encounter a surprise attack in the Battle of Mile Hill on September 2nd of 1862 in which Cole lost roughly 60 men. Two days later, Cole's Cavalry was active at skirmishes at Edwards Ferry and Monocacy Creek along the Potomac. They provided reconnaissance of troop movements in the Lovettsville area as the Rebel forces converged on Frederick. From here, Cole was ordered to participate at the Battle of Harpers Ferry (Sept. 12-15) of the Maryland Campaign. A cavalry breakthrough of enemy lines was necessary at the final stages of the battle. Cole’s Cavalry were tasked to deliver an important dispatch from the beleaguered garrison of Col. Dixon Miles to Gen. George B. McClellan, in charge of the Union’s Army of the Potomac. Major Cole , with three men on foot, succeeded in eluding the Confederate forces, and reached McClellan's headquarters east of Burkittsville. Once there, he reported the condition of affairs at Harpers Ferry, and was assured by the general "that he felt confident that by that time Gen. Miles had been relieved" by Gen. Franklin. Unfortunately, this would not happen resulting in a major surrender by Miles. Over 12,000 men laid down their arms in what became the largest surrender of US forces until the Second World War. The captured men were paroled and were soon on their way to Camp Parole near Annapolis, where they would wait out their exchanges. Cole's Cavalry had lost about a dozen men around the Harpers Ferry area through the whole episode and days leading up to it. Regardless, Henry Cole would receive personal thanks for the mission. The battles of South Mountain and Antietam would occur at this same time. Afterwards, Henry Cole would remain in Northern Virginia to square-off against one of his key rivals—Confederate Col. John S. Mosby (1833-1916). Mosby’s operations in Northern Virginia, and regular attacks across the Potomac on the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal and Baltimore & Ohio River, are legendary. During the Gettysburg campaign of June/July, 1863, Maj. Cole was connected with the division of Gen. French. Cole's Cavalry would be sent to Frederick where Cole, himself, would serve as provost marshal. After the Battle of Gettysburg, Cole's command was sent to Harpers Ferry to destroy the bridge to prevent Rebels from crossing at that point. This was a mission that was successfully accomplished with small loss to Cole's unit. With well over a year of solid experience and services under its belts, the decimated ranks of Cole’s Cavalry needed to be refilled due to losses due to capture and casualty. Soon replenished to full strength, the battalion drew the assignment to range up and down the Shenandoah Valley, keeping a watchful eye on the movements of Gen. Lee. For a short time, the battalion was broken up, however in the fall of 1863 the command was reunited and assigned to pursue Lee and his Army. During the autumn and winter, Cole’s Cavalry fought the Confederates at Leesburg, Upperville, Charlestown, Woodstock, Front Royal, Edinburg, New Market, Harrisonville, and Romney. The old battalion was placed in a “Brigade” with the First New York Cavalry within the 34th Massachusetts Infantry. The New York cavalrymen and Cole’s cavalrymen became devoted friends. Each command had the highest opinion of the brave qualities of the other. Rations and powder were practically shared. Going to the following winter of 1863 – 1864, the New Yorkers and the Marylanders engaged in horse racing and other sports at Brigade headquarters at nearby Charlestown, which seems all but fitting. Maj. Cole would go on to participate at the Battle of Loudoun Heights (VA) and was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel for his dramatic victory at the engagement on January 10th, 1864. This would often be referred to as “the battle in the snow.” Mosby’s Rangers would attack Maj. Cole’s command in the middle of the night. Cole’s men fought them off in the snow wearing only their night clothes (ie: pajama equivalent). After a desperate hand-to-hand combat, the Confederates were repulsed. This event would be commemorated each year on January 10th by Cole and his men, setting the date for the annual reunion banquets like the one mentioned at the outset of this particular "Story in Stone" on January 10th, 1910. (NOTE: For a detailed description of this event, see Travis' "A River Divided" blog article.) Celebrated in Frederick The heroics at Loudoun Heights by Cole's Cavalry won its commander much attention, not to mention personal thanks from Gen. H. W. Halleck, commander-in-chief of the United States armies. The bravery of Cole's Cavalry had been published in newspapers across the country. In February, 1864, three fourths of the command reenlisted for the duration of the war. They were granted a furlough for the period of 30 days. The cavalrymen were given a warm reception by the people Frederick. Citizens flocked to the outskirts of town in order to greet them, all the while bells of the fire engine companies and the churches were ringing. The soldiers marched through the streets of Frederick amidst waving flags welcoming Cole’s cavalrymen back, and were eventually escorted into City Hall on North Market Street to the strains of the song "Home Again." A patriotic address was then made by Judge Madison Nelson, associate judge of the Maryland court of appeals. The ceremony was followed by a banquet, after which the members of the battalion hurried to their homes. At this same time, Maryland Governor Augustus W. Bradford had taken great interest in Cole’s Cavalry, and suggested the major enlarge his battalion to full regiment. This unit had proven so useful to Federal commanders during the campaigns of 1862 and 1863 that the organization was further expanded in February 1864. Eight additional companies were created, raising the battalion to a full regimental strength. The governor had no difficulty in getting the necessary authorization from President Lincoln’s War Department. Maj. Cole was commissioned lieutenant colonel in March, and then fully promoted to colonel the following month on April 20th, 1864. The veterans of the first Battalion, who were fully equipped, were ordered to report to Gen. Franz Sigel as part of Gen. Phil Sheridan's campaign in the Shenandoah Valley. On May 15th, 1864, Cole’s Cavalry took part in the disastrous fight at New Market, Virginia. Losses were heavy for the Union side as Gen. Sigel was defeated, and many soldiers were captured by the brigade of brave young cadets from the Virginia Military Institute located in Lexington, Virginia. Gen. Sigel’s movements have been subject to criticism. Unfortunately, he failed to thwart a secret mission headed by Rebel Gen. Jubal A. Early a month later, allowing Early's force to arrive in Martinsburg by train from Lynchburg, VA while the Union had the capital of Richmond under siege, as well as Petersburg. This "Hail Mary" plan of Robert E. Lee's involved a sneak attack on Washington, DC from the northwest, or so it would play out that way in early July, 1864. With Cole's Cavalry out in the Shenandoah Valley, a clear path to Frederick without opposition had been laid out to Gen. Early. He would levy ransoms on Hagerstown, Middletown and finally Frederick. You likely have heard the story of Frederick's city officials and local banks cobbling together $200,000 at that time in effort to "save the town" from the supposed torch of Early and his men. The Battle of Monocacy would immediately follow on July 9th as heavily outnumbered Union forces under Gen. Lew Wallace met Gen. Early along the banks of the Monocacy River south of town at the site of the Frederick railroad junction. If not for this little engagement, and the delay it caused allowing the city of Washington to be re-fortified, our nation's capital might have been captured by Early's force. Later in 1864, Cole’s cavalrymen took part in the engagements at Keedysville, Charlestown, Halltown, Summit Point, Berryville, and Winchester. The area was soundly kept in check by the forces under Gen. Phil Sheridan. The regiment of Col. Cole was afterwards ordered into the newly-formed/named) state of West Virginia to guard lines of communication until the war's end in the spring of 1865 when Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered to Union Gen. Ulysses S. Grant on April 9th. Col. Henry A. Cole would be relieved of command a few weeks later in Martinsburg on May 3rd. Cole's Cavalry was officially mustered out of the service at Harpers Ferry on June 28th, 1865. Over the course of the war, at least 1,616 officers and men served under the Frederick native. During the period of nearly four years from August 1861 to June 28th, 1865, the regiment had fought in nearly 200 engagements and captured more than 1000 prisoners. Some of Col. Cole's men had covered 7000 miles criss-crossing the Potomac region. After the war, Henry A. Cole applied for a position in the U.S. Cavalry and was informed by the U.S. Secretary of War (Edwin Stanton) that he had been appointed Captain of the 7th U.S. Cavalry by the President of the United States (Andrew Johnson), and was sworn-in on October 11th, 1866. He was examined and was found physically competent, but shortly after that, he failed the examination by the Cavalry Board and his appointment was canceled. Two advertisements appear in Frederick Examiner newspapers in 1865 regarding his personal home, and a business venture into the "coal" business. Henry A. Cole would soon move to Baltimore, and start a home contracting business. building a number of houses on Madison Avenue in the west part of the city. He is listed as an architect in business directories of the period, as well as the 1870 US Census. In the US Census of that year, it appears that Col. Cole’s parents moved with him to Baltimore as well, along with his younger siblings. He would soon met Mary E. Smith (1840-1927) of Baltimore, and the couple were married in 1870. Cole would build a number of houses on Madison Avenue in west Baltimore. He soon met Mary E. Smith (1840-1927) here in the city and the couple wed on 1870. Henry's profession would change in 1880 when our subject accepted an appointment to the United States Internal Revenue Service, which position he held at the time of his death. One source says he was a US Internal Revenue Storekeeper (1881-1890), and a US Internal Revenue Gauger (1890-1909). The 1890 veterans schedule shows Col. Cole living at 1420 Argyle Avenue in Baltimore. He would appear in the 1900 census living here as well, with Argyle Ave. located in the Upton neighborhood of the city (slightly northwest of center city). Henry was found to be living as a boarder to the George J. Waltz family. Mr. Waltz was a druggist.  The last home of Col. Cole was the building to the right (yellow) at 1831 W. Mosher St and Monroe St. It was likely the site of Mr. Waltz drugstore back in the first decade of the 1900s. The Waltz' can be found living here in the 1910 US Census, having moved from Argyle Ave. Today it is Jemella's Cut Rate Liquors. Often called “modest and kindly,” Col. Henry A. Cole's benevolence was put on display by our local newspaper back in 1891. The same article appeared in the Baltimore Sun the following day. Cole was a prominent member of the (G.A.R) Grand Army of the Republic, the largest of all Union veterans' organizations. This may have been the genesis of the G.A.R. plot in Mount Olivet that currently exists at the south end corner of Area C (Lots 1 & 2) today. Here, you will find a collection of Union soldiers buried by themselves in adjoining gravesites. A few members of Cole's Cavalry are here as well, John A. Hudson and Charles J. Reynolds. Col. Henry A. Cole would join his former soldiers and family members in 1909. He would pass days before Memorial Day on May 25th 1909 at his home on West Mosher Street in Baltimore. He had been ill for a time, and his obituary states Bright's Disease as the cause for his death at age 70. Col. Cole's body would return to his hometown of Frederick for burial in the family lot in Area R/Lot 98. Here, he would join his parents (George and Anna) and siblings David, George, William, Maria and Sue Boyer. The pall bearers for the burial were all former members of “Cole’s Cavalry” from the Frederick area. The Frederick G.A.R. Reynolds Post #2, performed the ritual services at the grave and many Civil War veterans groups were part of the ceremonies, Then a final salute was fired over the grave, and “Taps” were sounded. A fitting, large, granite monument adorns the site. It is topped with a sphere and a decorative staircase leads up to the monument placed on a small bluff. This seems like it could be on a battlefield and its placement reminded me of the colonel's heroism in battle at Loudoun Heights back in January, 1864. I found it interesting that there is no mention whatsoever of Col. Cole's wife, Mary, in his obituary. I actually had trouble finding any reference to her in newspapers and census records, and their supposed wedding in 1870. I also surmise they had no children. Mary died on November 7th, 1927, and is buried next to the colonel in Area R. Veterans' Day 2023 marks the debut of our American Civil War "Union soldier collection" on MountOlivetVets.com. Many thanks to Marilyn Veek and several other volunteers over the last several years who have helped us research these soldiers, and now you can explore these memorial pages of Mount Olivet's Union soldiers. We hope to have Confederate soldiers up by next Veteran's Day, if not sooner. The button below will take you directly to the Civil War portal on the site.

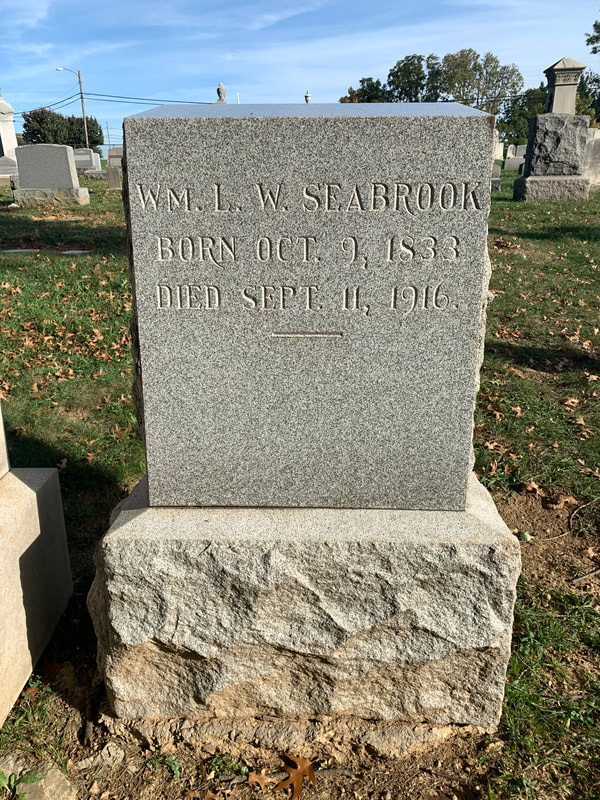

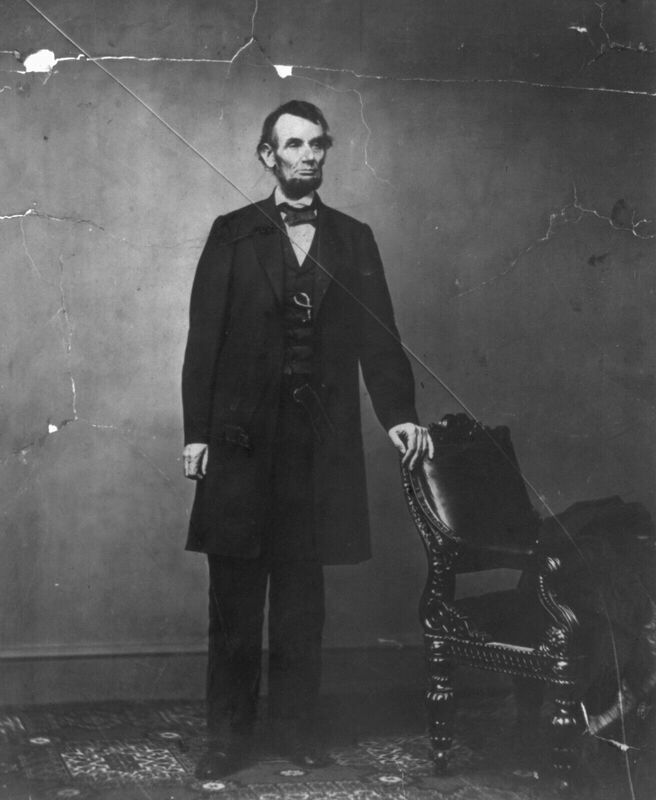

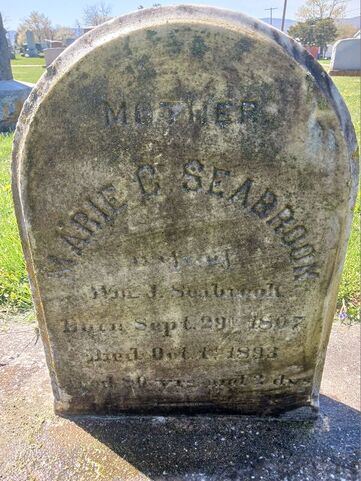

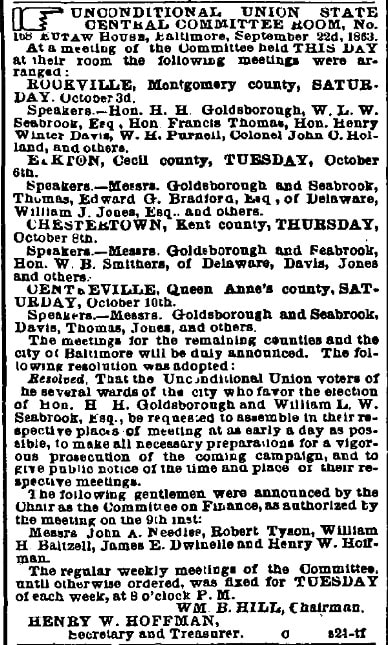

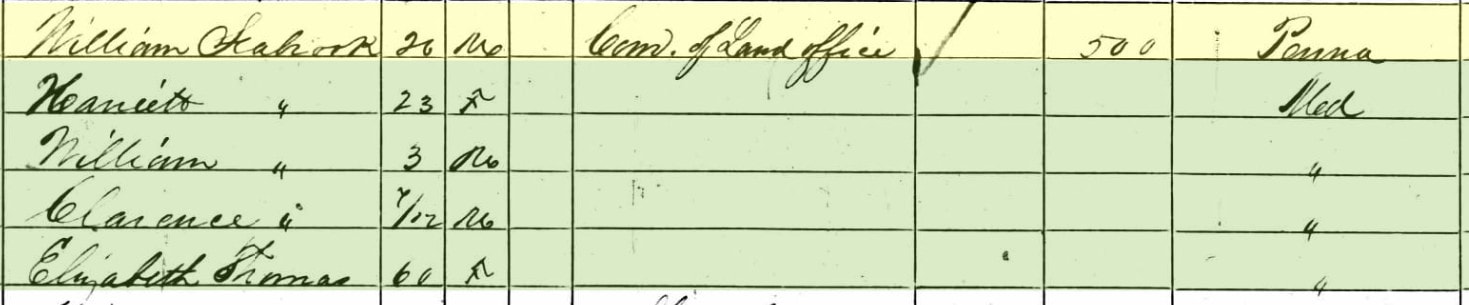

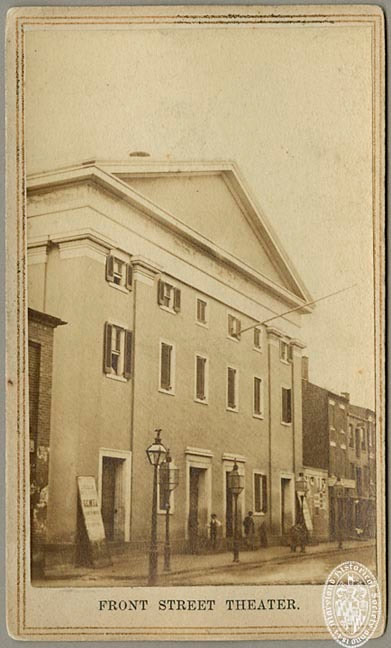

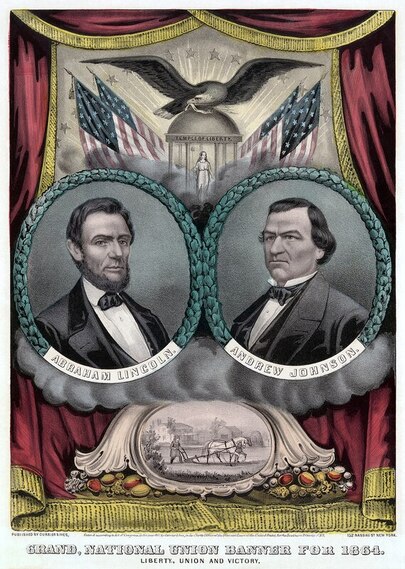

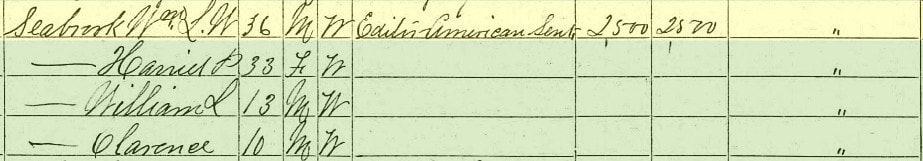

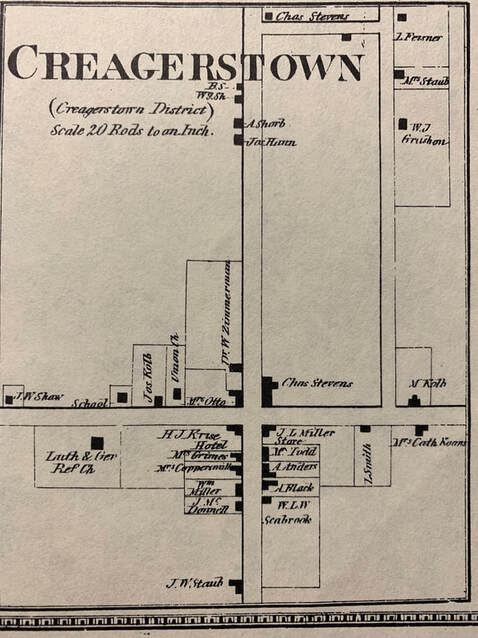

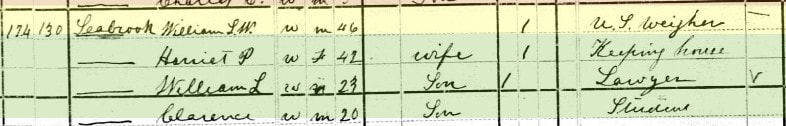

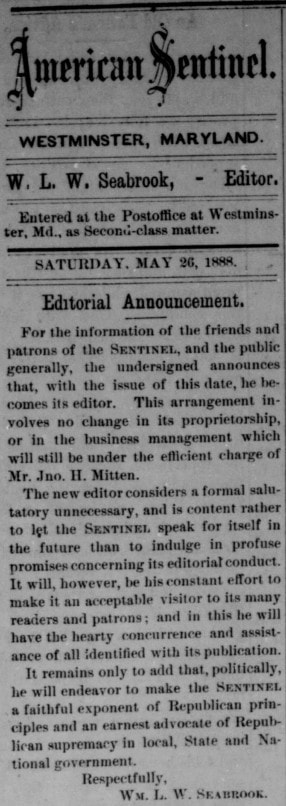

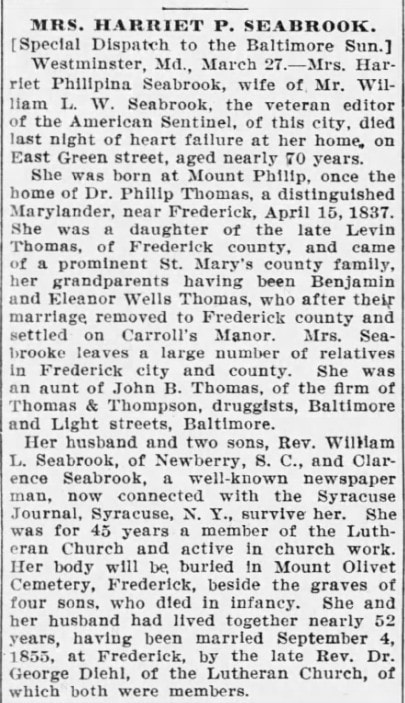

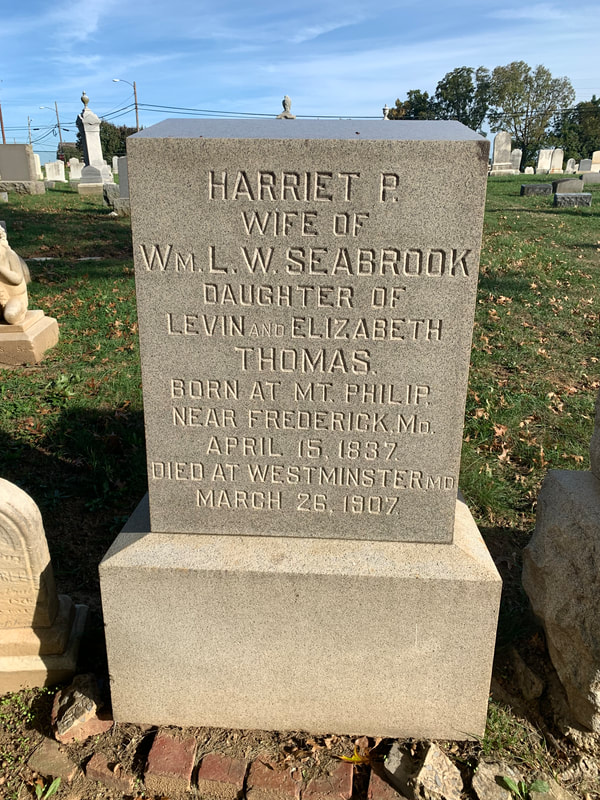

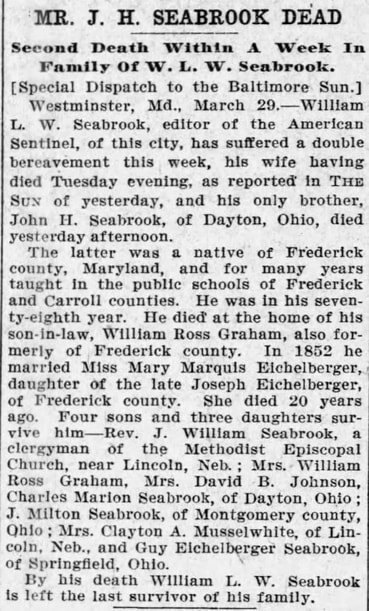

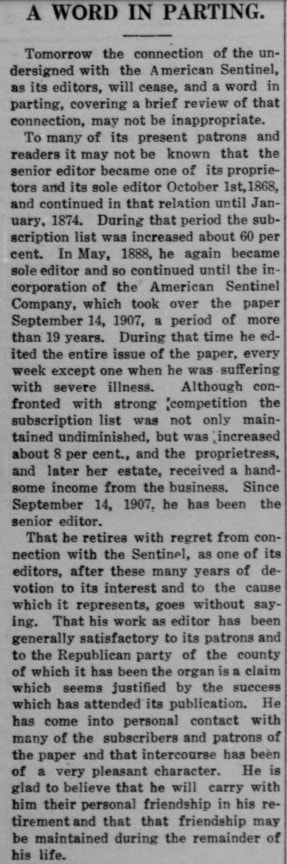

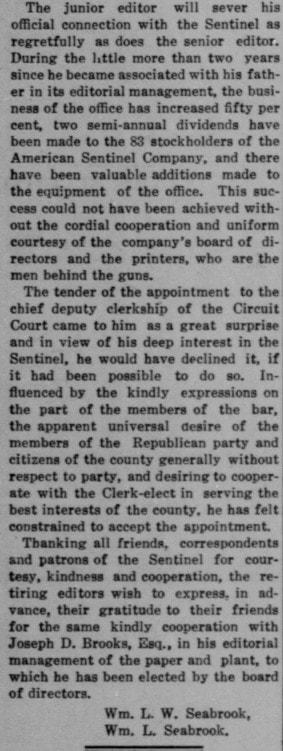

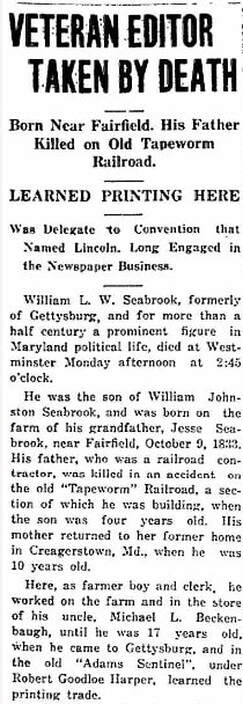

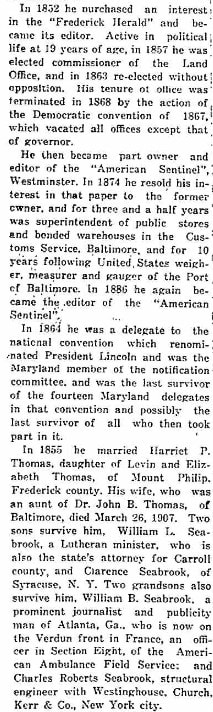

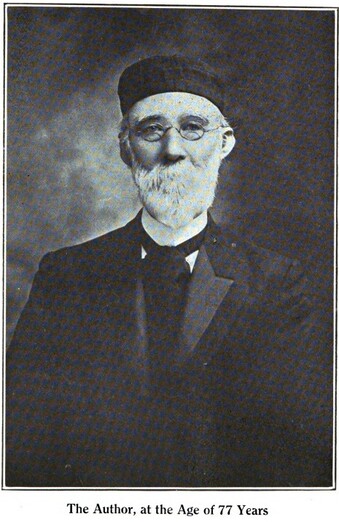

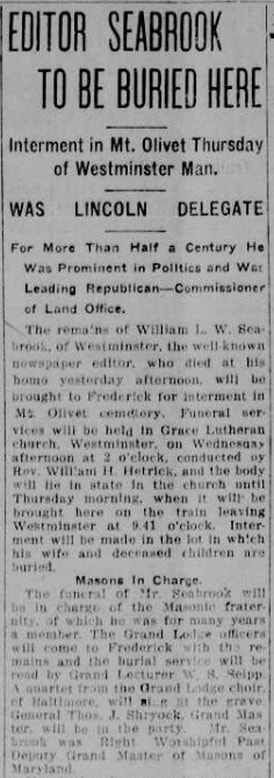

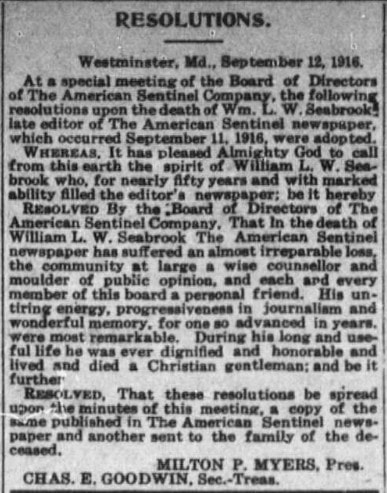

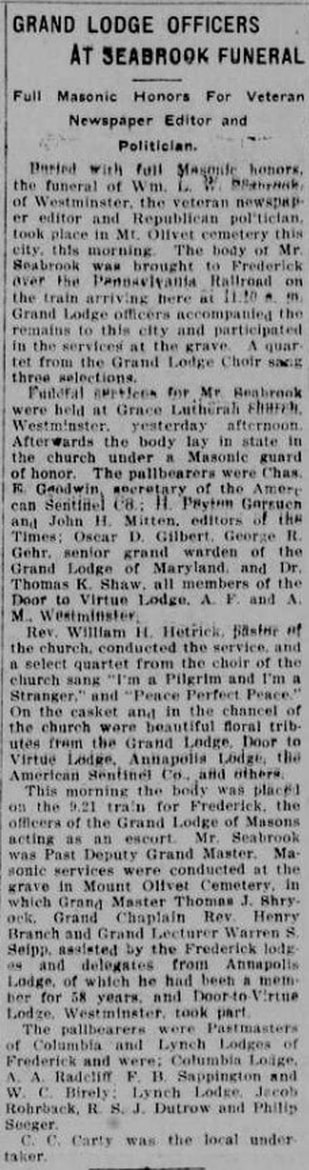

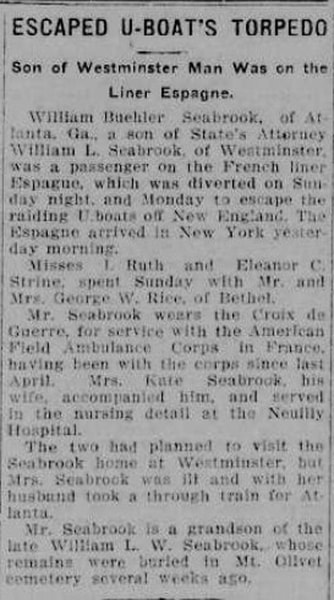

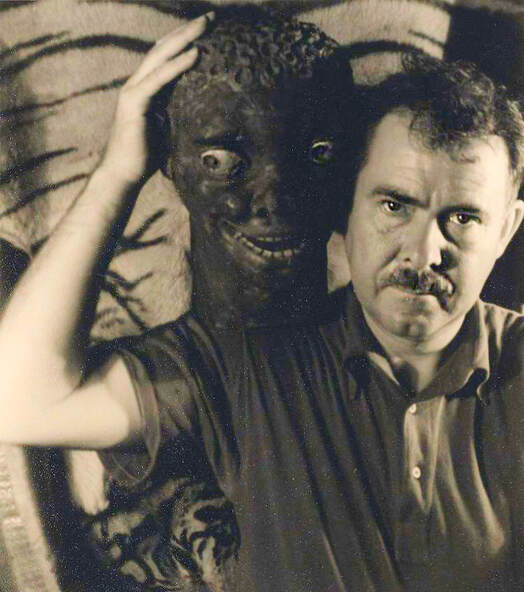

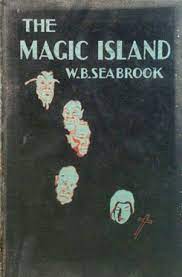

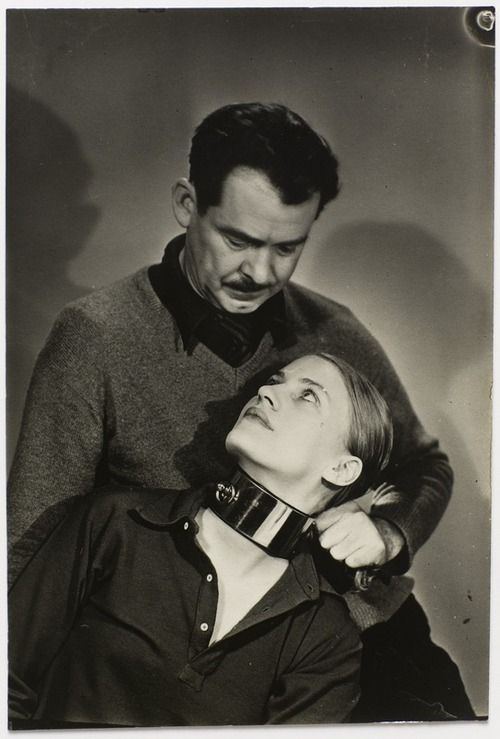

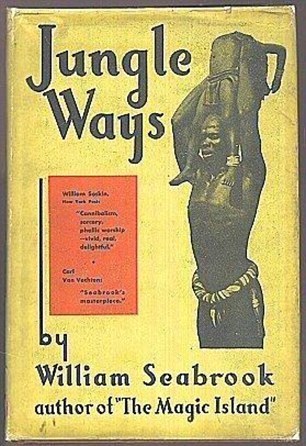

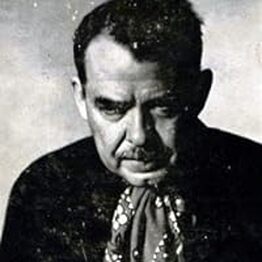

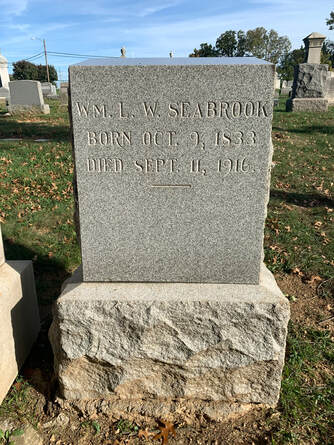

A special little monument depicting a child praying recently introduced me to an equally interesting man named William L. W. Seabrook. The Seabrooks are buried not far from the entrance of the cemetery in Area A, within plain sight of the Francis Scott Key Monument in one direction, and the aptly named Key Memorial Chapel in another. Here also, the visitor will find Mrs. Harriet Philipina (Thomas) Seabrook buried along with five additional young children who died rather young between the years of 1863 through 1872. The fore-mentioned child figure monument marks the grave of an infant simply known in our records as L.S. I’ve deduced this to denote the name of Luther Stanley. Four siblings of L. S. can be found in separate graves—all sharing a central miniature obelisk. Interestingly, the least appealing grave monument in this plot belongs to the family patriarch and original purchaser (of the cemetery ground). His name was William L. W. Seabrook and his life story and accomplishments are very impressive. Seabrook's obituary in the Frederick News, American Sentinel, Baltimore Sun and Gettysburg Times and several other regional papers in September 1916 reads as a well-crafted biography. I will include that here later, thinking perhaps that this man, himself, could have been responsible for writing it as he made his mark as a long-time newspaper editor.

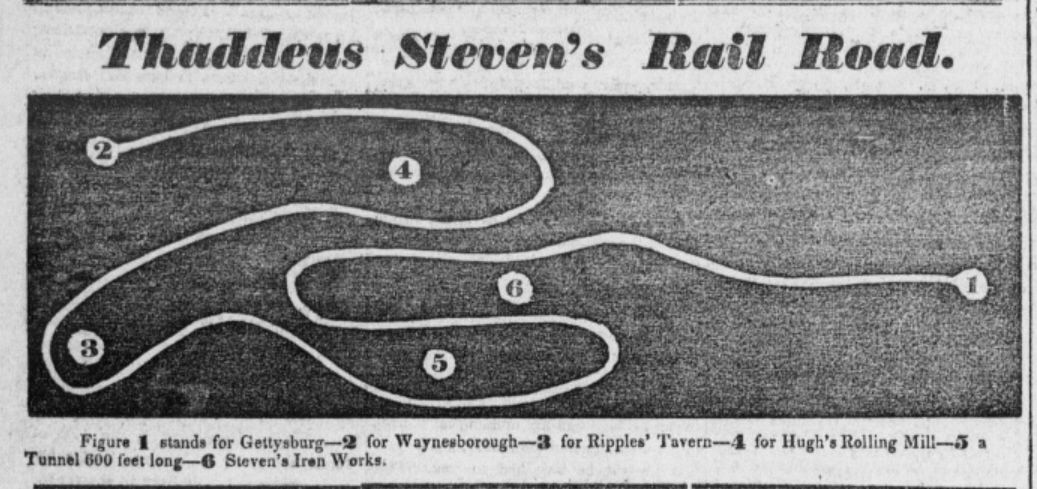

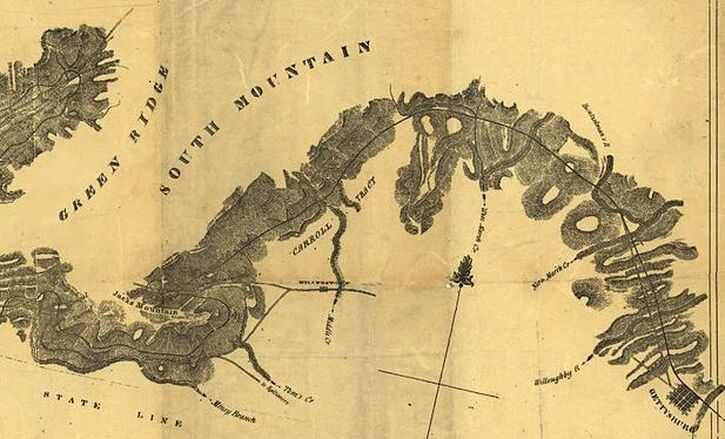

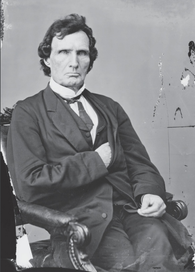

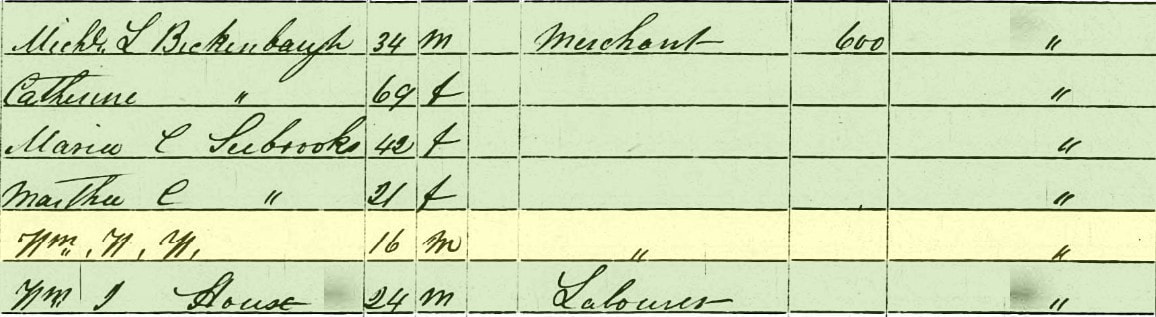

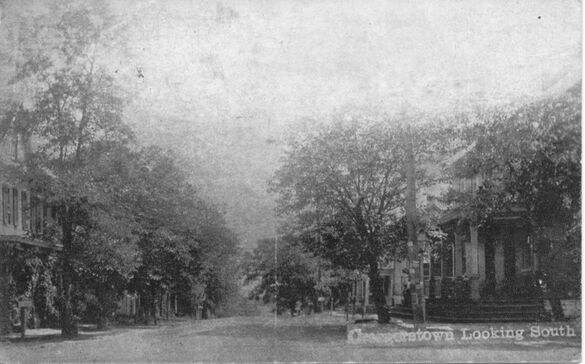

The Gettysburg Railroad line which Mr. Seabrook was building was also known as “Tapeworm Railroad.” It had been planned by Congressman Thaddeus Stevens, who began his law career in Gettysburg. The transportation line was given this odd nickname by opponents who ridiculed its planned lengthy serpentine layout (of switchbacks) connecting several forges and furnaces. One of these was owned by Mr. Stevens himself and called Maria Furnace. Its ancient remains can still be found around the Green Ridge of South Mountain. This very early railroad, not to mention its connections to Thaddeus Stevens, intrigued me. In 1836, a man named Herman Haupt had surveyed the "road from Gettysburg across South Mountain to the Potomac" and in 1838, the rail "bed" was "graded for a number of miles, but never got further than Monterey.” No train ever traveled on "the Tapeworm," and no rails were ever laid but the route was surveyed and graded in Adams County. The right-of-way was later used by the Susquehanna, Gettysburg and Potomac Railway and its successor, the Baltimore and Harrisburg Railway to build a line from Gettysburg west to Highfield, Maryland. Some may recognize a highly visible part of this line on the northwest portion of the Gettysburg Battlefield property at McPherson Ridge with its memorable railway cut through surrounding reddish-brown sandstone. Heavy fighting during the battle took place here, and also around the Seminary Ridge railway cut, on July 1st, 1863. As for Thaddeus Stevens (1792 – 1868), he was an American politician who served as a member of the United States House of Representatives from Pennsylvania, being one of the leaders of the Radical Republican faction of the Republican Party during the 1860s. As chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee during the American Civil War, he played a leading role, focusing his attention on defeating the Confederacy, financing the war with new taxes and borrowing, crushing the power of slave owners, ending slavery, and securing equal rights for the freedmen. He was a fierce opponent of slavery and discrimination against black Americans, and sought to secure their rights during Reconstruction, leading the opposition to U.S. President Andrew Johnson. I found this fascinating as our subject, and his father, were acquainted with this man, especially considering their respective ties to Gettysburg and the Republican Party as you will soon learn. William L. W. Seabrook would also have a strong connection to another Republican politician with indelible ties to Stevens, the abolition of slavery, and Gettysburg—Abraham Lincoln. Let’s get back to Fairfield and the childhood days of our subject. Nearly six years after the death of his father, William L. W. Seabrook’s mother, Harriet P. (Beckenbaugh) Seabrook, made the decision to move back to her former home in Frederick County’s Creagerstown. The boy, now 10, would attend school here and work on the family farm. He would also learn to perform clerk duties in the store of his uncle, Michael Beckenbaugh. The family attended the Lutheran Church there. Around 1850, William L. W. Seabrook moved to Gettysburg and learned the printing trade under a gentleman named Robert Goodloe Harper, Jr. Harper published the Adams Sentinel. Two years later, at age 19, Seabrook continued his foray into publishing by purchasing an interest in a newspaper in our neck of the woods entitled the Frederick Herald. He would become its editor in chief in 1852. In 1855, William L. W. Seabrook married a local Frederick girl named Harriet Philippina Thomas. She was the daughter of Robert Levin Thomas (1786-1842) and Elizabeth (Dill) Thomas (1800-1866). Her name likely was given as a result of being born on the Mount Philip plantation located west of Frederick City and accessed by the road that today still carries its name. The original builder of this estate at the foot of Catoctin Mountain was a relative, Dr. Philip Thomas, one of Frederick’s earliest (and legitimate) physicians. Dr. Thomas was also highly active in the war for independence. The children of this union mentioned at the outset of this article, buried as youngsters in the family plot here in Mount Olivet, include: Stanley (d. 1861) at 5 months old; Stanley Charles (d. 1863); Frankie (d. 1864 at 3 months old); L. S. (d. 1867); and Claude (d. 1872 at 5 months old). Two sons, born earlier than the others, reached adulthood and had full lives. William Levin Seabrook (1856-1931) became a noted Lutheran minister and later state’s attorney for Carroll County. Clarence Seabrook (1859-1924) moved to Syracuse, New York and followed in his father’s footsteps by having a career in the newspaper business. In March of 1856, Frederick diarist Jacob Engelbrecht notes that William L. W. Seabrook was elected teacher of the Primary School No. 72 located on the east side of North Market Street. I assume he performed this job in tandem with that of the newspaper which naturally would pull Mr. Seabrook into the wonderful world of politics. In 1857, William L. W. Seabrook left the teaching and newspaper professions as he would be elected commissioner of the Maryland State Land Office, and was subsequently re-elected six years later in 1863. This also precipitated an eventual move to Annapolis. This was his lot during the period of the American Civil War, in which Seabrook staunchly supported the Union through his Republican leanings. I guess you could say that William L. W. Seabrook had more than “leanings,” as he campaigned on behalf of President Abraham Lincoln throughout the entire state. I found that he wrote a book on his experiences in state government service during the Civil War. Most interesting was his relationship with Gov. Thomas Holiday Hicks who made the decision to move Maryland's General Assembly sessions to Frederick in the summer of 1861. Seabrook used this opportunity to praise his political party for keeping Maryland, a staunch Democratic state, in the Union and not seceding to the south. One of William L. W. Seabrook's chief claims to fame is that he had a warm friendship with Abraham Lincoln. He would serve as an advisor over the pulse of Maryland during the Civil War, culminating in playing an important role as a delegate to the national convention which re-nominated President Lincoln in the election of 1864. Seabrook was the Maryland member of the notification committee, and would live to be the last surviving member of the 14-person Maryland delegation to that 1864 presidential convention, and has been said to have possibly outlived all the men that took part in the entire convention. I found a detailed review of Seabrook's experiences of that time, written in his own hand. (NOTE: I will include at the end of this story). Seabrook voted against Lincoln’s running mate Andrew Johnson, a Democrat, for Vice President in 1864, and this explains why Seabrook’s position as Land Office commissioner would be terminated in 1868 by the action of the Democratic convention of 1867. You may recall that Andrew Johnson ascended to the presidency following the April, 1865 assassination of President Lincoln, and would hold the office until 1869. In that same year, however, Seabrook became part owner and editor of the American Sentinel newspaper of Westminster. He would work here for seven years before reselling his interest in the paper to the former owner in 1874. William L. W. and Harriet had resided in Westminster at the Montour boarding house during this time, but I also found them associated with a house in Creagerstown. This could have been his mother's house, but kept in W. L. W. Seabrook's name. William would switch professional gears completely becoming superintendent of public stores and bonded warehouses for the United States Customs Service in Baltimore. He would soon move on to a job with the Port of Baltimore in the role of "United States weigher, measurer and gauger." In 1886, our subject returned to the newspaper business and Westminster to serve a second tenure as editor of the American Sentinel. He finally settled into this career, and life in Carroll County. He was active in civic life, and especially the Masons, where he would serve in several leadership positions. In 1900, Seabrook ran unsuccessfully for Congress’ second district here in Maryland, but lost in the primary. He would continue to work as editor at the American Sentinel and was highly respected for his standing as one of the country’s oldest newspaper men, in age and experience. William L. W. Seabrook lost his beloved wife, “Pina,” in 1907. She would be buried in Frederick in the family plot where the couple’s children had been buried nearly 40 years earlier. Just days later, Seabrook would learn of a second death, that of his brother. It was around this time that William would be joined in Westminster by his son, William L. Seabrook, the Lutheran minister. Rev. Seabrook helped his father with his household, and the newspaper. A few years later, William L. W. would call it quits. Nearly 60 years after first entering the newspaper business, Mr. Seabrook would retire in November of 1909 after 41 years with the American Sentinel. Surrounded by family, William L. W. Seabrook would live out his final years in Westminster. His death would come on September 11th, 1916. His obituary would appear in newspapers near and far, as he was a well-known, and respected, figure in his field. The Frederick News would be among this group, and I’m sure the Delaplaine brothers were acquainted with their fellow industry-man. Their paper would run a detailed article in their September 14th addition chronicling the scene in Westminster and Mount Olivet on the occasion of Mr. Seabrook’s funeral services, handled by the Masonic Fraternal Order. Though not buried here, I became interested in two grandchildren mentioned in Mr. Seabrook’s obituary. Both would have their names in the Frederick newspaper in the months immediately following their paternal grandfather’s death. First would be William B. Seabrook, as he would successfully escape death twice during the time of his grandfather's passing. Raised for a time by William L. W. and Harriet Seabrook in Westminster, William would participate in World War I. While on the French warfront, his first encounter involved being wounded by deadly gas. Removed from the front, he almost got killed on his way back home to America. I want to say more about this man in a minute, but let me complete my earlier thought by relaying that William L. W.’s granddaughter made the Delaplaine’s newspaper pages with an announcement of her engagement in November of 1916. Her name was Frances Seabrook and she wed Ralph Whitman, a civil engineer in the US Navy. He would eventually achieve the rank of Rear Admiral and had a storied career and much notoriety in military duty, and the pair are buried at Arlington Cemetery. Speaking of careers and notoriety however, let's get back to Frances’ brother William. His career would be an evocative one as I found myself going down the proverbial rabbit hole after seeing countless references to him after a simple Google search. To my surprise, I found that he is more famous, or shall I say infamous, than his namesake grandfather. He’s been labeled as having been terrible, a drunkard, abominable, tormented, perverted, crazy and an all-out whacko. Oh, how I wish he was buried here in Mount Olivet! In her article for Atavest Magazine, author Emily Matchar describes the grandson of William L. W. Seabrook as "the writer who introduced zombies to America." The following link to her online article is a great resource, as it paints a picture of Harriet P. (Thomas) Seabrook. It reveals that William B. "Willy" Seabrook held his grandmother “Piny” in high regard, although his assessment of his father and grandfather was not kind. Here is a link to that article: https://magazine.atavist.com/the-zombie-king/ William Buehler Seabrook was born in Westminster in 1884. Apparently his father (William L. Seabrook) and mother left him in the care of his grandparents when he was eight years old. He had great resentment for this action (and his parents in general) based on the gentleman's later writings. He wasn't overly crazy about William L. W. Seabrook either. The only family member for whom William B. Seabrook had any affection was his grandmother, who he called "Piny," (pronounced "pee-nee") a nickname stemming from her middle name of Philippina. Our cemetery records back up this claim, however ours incorrectly reads as "Ponie." William B. Seabrook described his grandmother as being a soul barely of this world. He wrote in his memoirs: "She was born on a Maryland plantation in the caul (the amniotic sac unbroken around her, which was said to impart on a child a supernatural aura), and nursed by an Obeah slave girl. Piny possessed “visions and powers” since childhood but was married off as a teen to Seabrook’s “white-bearded” grandfather, who brought her to Westminster and forced her to live an unhappy life among the tedious bourgeoisie. To feed her opium addiction, she hid a bottle of laudanum in the crook of a backyard tree." Seabrook believed that his grandmother saw something in him (self described as "her odd, morose grandson"). They were kindred spirits, and he went on to say, “Another little soul which, like herself, found normal, ordinary life unbearable.” It was through his beloved Piny that he had his first experience with the “unexplained,” and supernatural. This would serve as a subject that would occupy his mind for the rest of his life. Ms. Matchar illustrates in her article that, "He and Piny would often walk together in Shreiver’s Woods, just outside Westminster. Seabrook knew the woods well; he would often go there to gather chinquapin nuts or fish for minnows in the stream. But one day, Seabrook wrote, while he was strolling with Piny, the woods became strange. They arrived at a clearing he didn’t recognize. Suddenly, the trees surrounding him were not trees but the legs of 'beautiful bright-plumaged roosters, which were as tall as houses.' Taking him by the hand, Piny led him beneath the legs of the roosters as the enormous birds shuffled and crowed." I assume that "Willy" Seabrook was here in Mount Olivet's Area A/Lot 95 for the funeral of his grandmother in 1907. Perhaps she brought him here on occasion to visit the graves of the children "Piny" lost decades earlier? Maybe he visited his grandfather's grave after returning from the war? Regardless, this is some strange stuff indeed, but get ready for tales of cannibalism, witchcraft and human bondage. William B. Seabrook began a respectable career as a reporter and City Editor of the Augusta Chronicle in Georgia, worked at the New York Times, and later became a partner in an advertising agency in Atlanta. He is well-known for his later writing on, and engaging in, cannibalism. Seabrook's 1929 book The Magic Island, which documents his experiences with Haitian Vodoo in Haiti, is considered the first popular English-language work to describe the concept of zombies. That’s right, the grandson of William L. W. Seabrook and wife Harriet Philippina (Thomas) Seabrook is responsible for what we know as zombies. Cue Michael Jackson’s “Thriller,” and fire up a Netflix binge-watch of the Walking Dead. William B. Seabrook would die of suicide by drug overdose in 1945. There is plenty written about this man to be found on the internet, and many of his books, and a few biographies are available in print. Be sure to check eBay because they have a great selection to choose from. If anything else, I guess the old saying, "Don't judge a book by its cover," surely fits the gravestone and life story of William B.'s grandfather, William Luther Wesley Seabrook.

|

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed