|

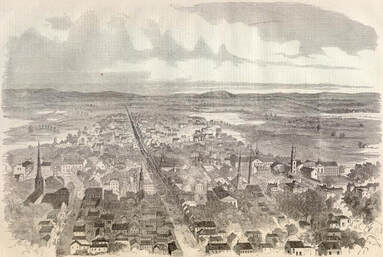

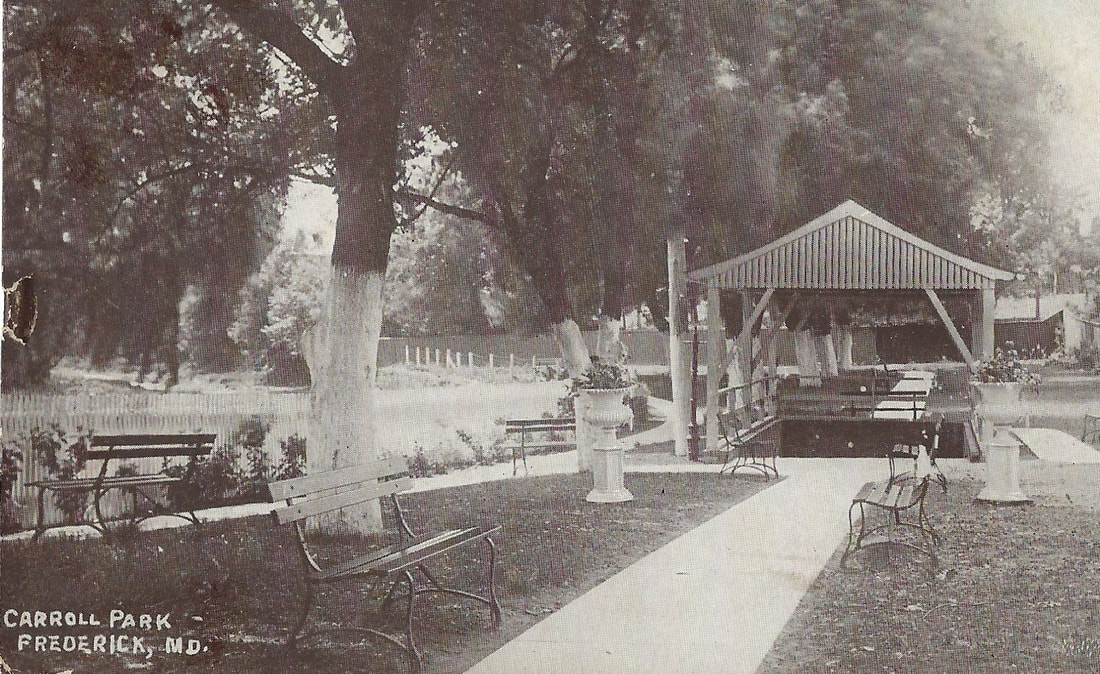

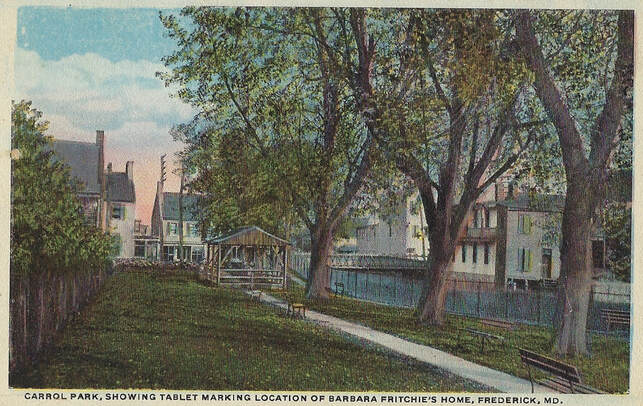

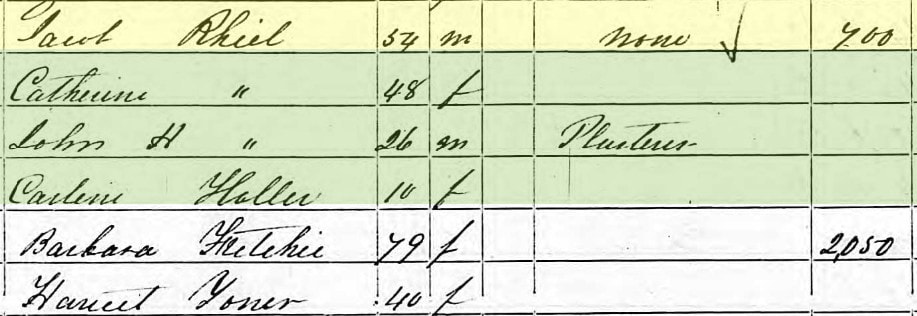

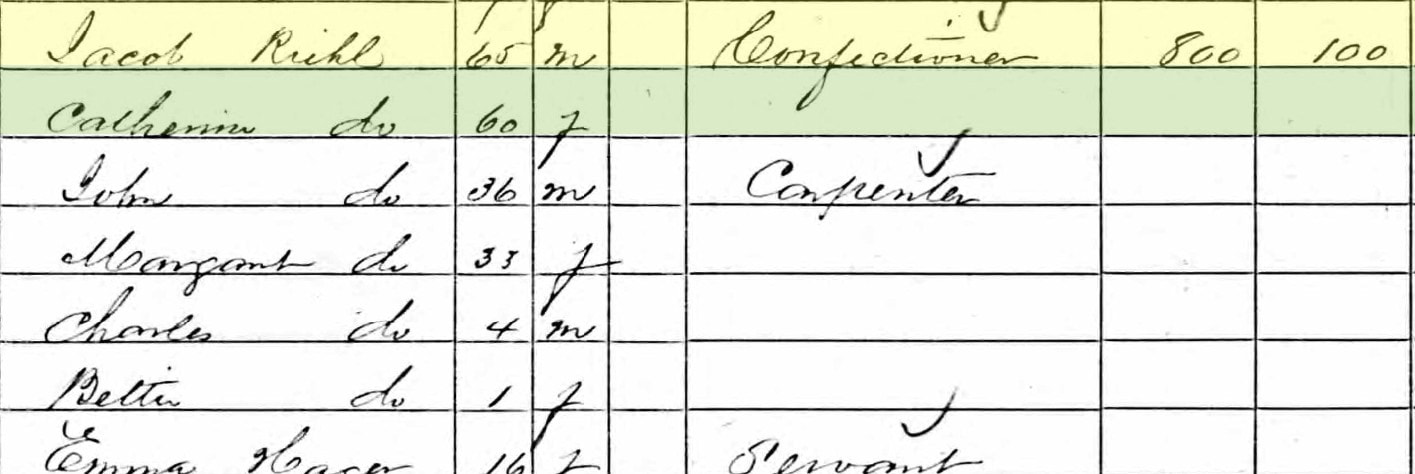

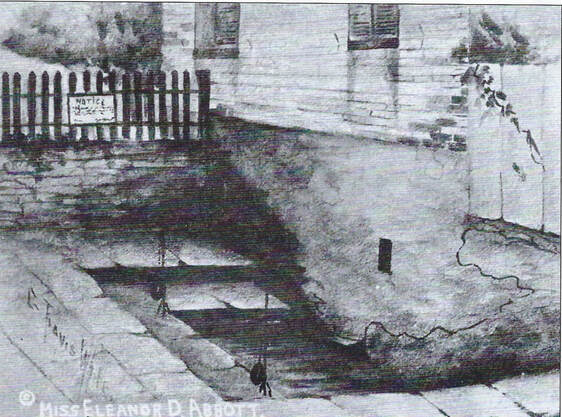

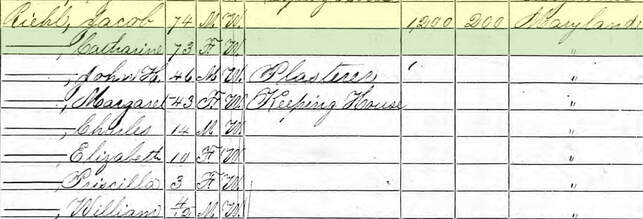

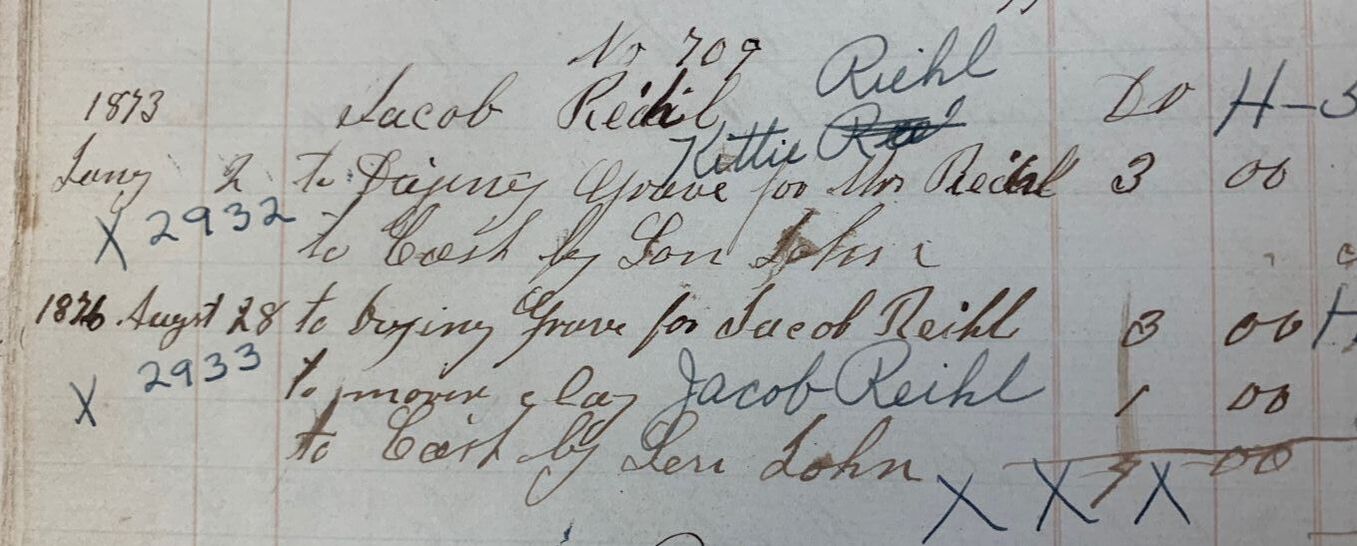

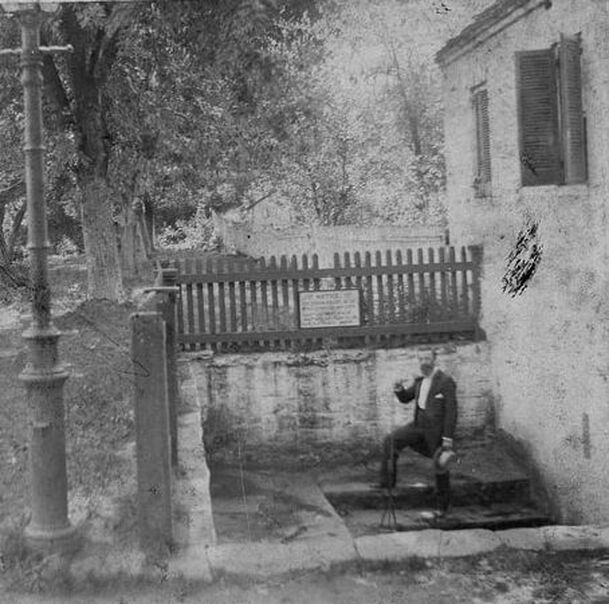

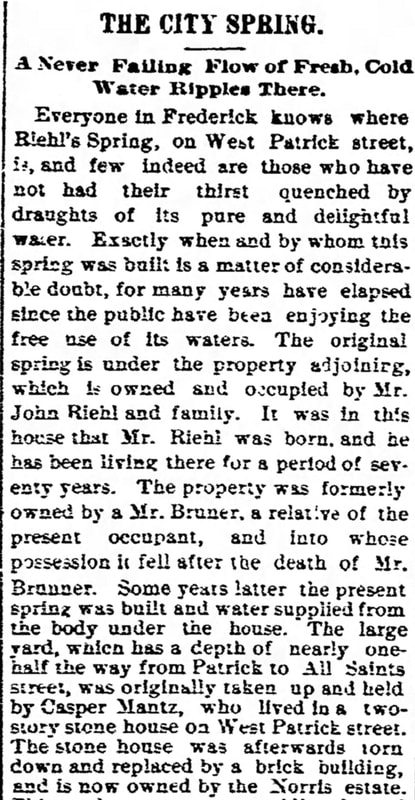

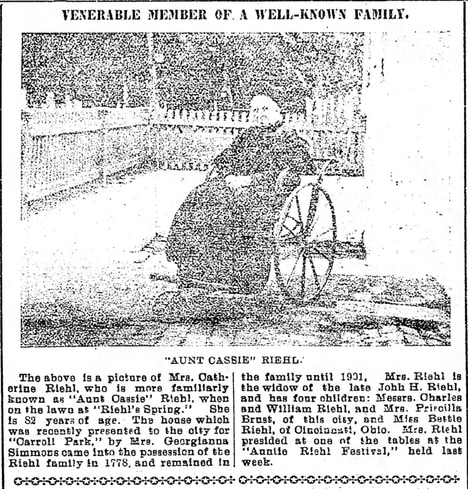

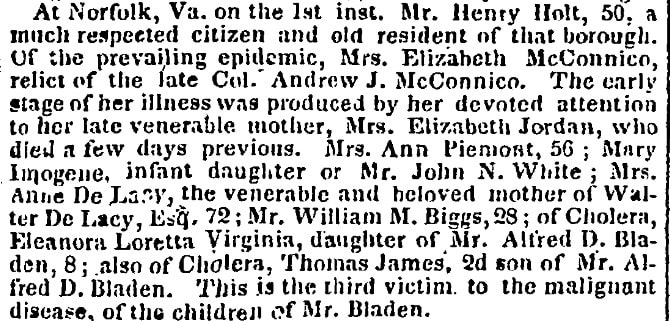

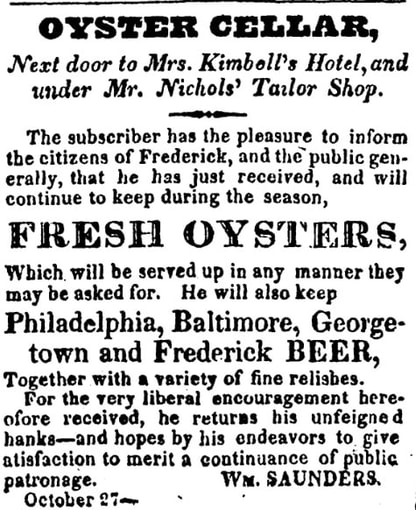

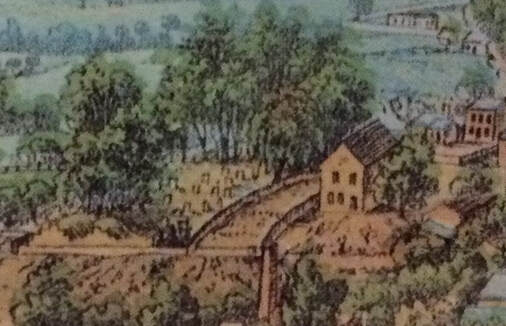

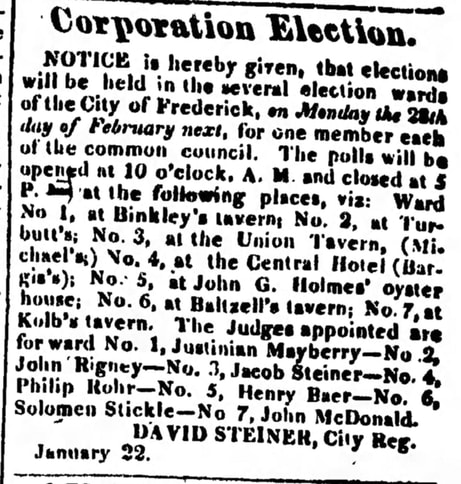

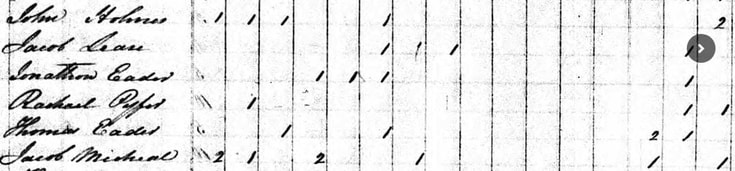

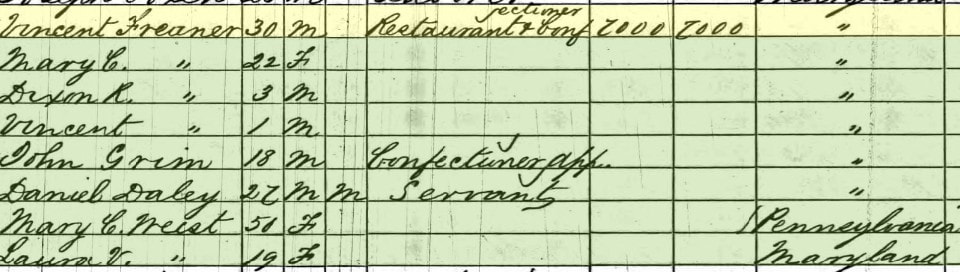

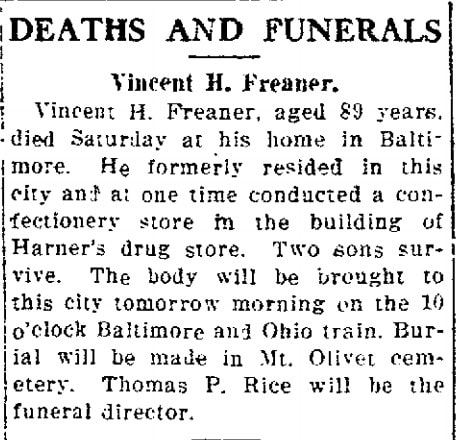

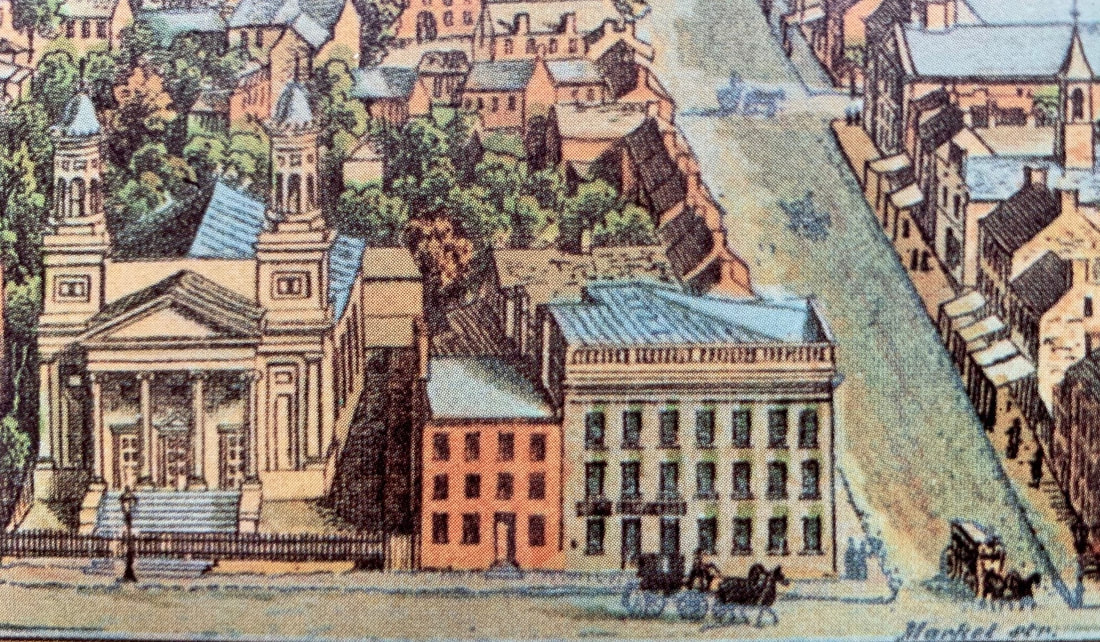

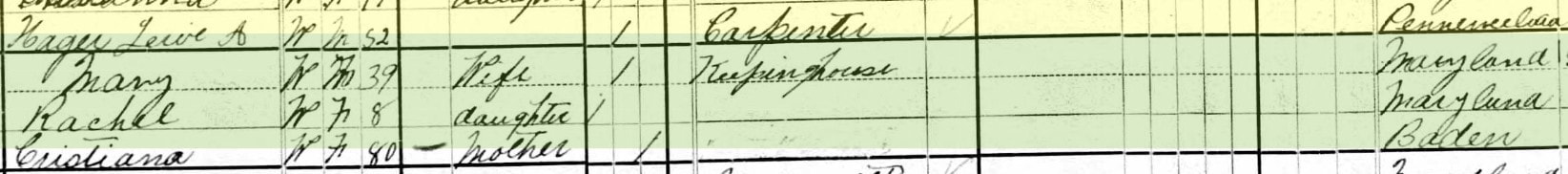

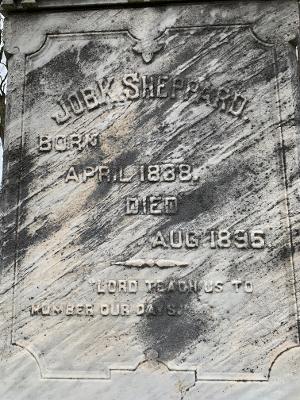

Well, this was a spring to forget. It officially began on Friday, March 20th—the day a state quarantine was issued due to the coronavirus pandemic. Social distancing and self-hibernation took the place of baseball games, public Easter Egg hunts and church services, and graduation ceremonies. Most mom’s got short-changed on their very own day (Mother’s Day), and we even lost the opportunity to enjoy Spring Break! At least there was no excuse for us not to get spring cleaning chores completed. In doing some research of late I got to thinking about the confusion inherent with our English language and those pesky words with multiple meanings. In particular, I thought of the word spring which above I have used according to the definition as the season after winter and before summer, in which vegetation begins to appear, in the northern hemisphere from March to May and in the southern hemisphere from September to November. But what about “the resilient device, typically a helical metal coil, that can be pressed or pulled but returns to its former shape when released, used chiefly to exert constant tension or absorb movement.” Ironically, I always received a Slinky® in my Easter basket as a kid, what does that say about the universe? Back to the word spring, what about its usage as a verb? —“To move or jump suddenly or rapidly upward or forward.” Last, but not least, we can’t forget spring as an origin of water, a point at which H2O flows from an aquifer to the Earth's surface.  "The Spring" "The Spring" Hey, you don’t have to tell me about the latter springs! In addition to the multitude of Slinkys® obtained in the Aprils of my youth, I couldn’t avoid them from a geographic reference. I grew up in what is officially known as Bootjack Springs northwest of Frederick City, in a house located 100 yards from the intersection of Indian Springs Road and Rocky Springs Road. I even went to Yellow Springs Elementary School. My Dad actually took me once a month to “The Spring,” at which place an iron (or dare I say lead) pipe emitted from a rock outcropping located somewhere off Hamburg Road where we would diligently fill empty milk jugs with salubrious “spring” water. Sadly, something that cannot be enjoyed today in the same fashion, but back then was there even such a thing as bottled spring water outside Perrier? This week’s “Story in Stone,” connects a person/family with one of the more famous springs in our area. Known as Riehl's Spring, it does not exist today, but it was a focal point of town for centuries. Riehl’s Spring was a Godsend for the people of downtown. It lay directly beside two downtown landmarks: Carroll Creek and the original Barbara Fritchie house on West Patrick Street. It was used by locals since the 1700s for its seemingly endless supply of cold, clean refreshment. According to myths and legends that were bantered around in the early 20th century, the spring was said to have possibly been the location for everything from Native American treaty signing ceremonies to a watering hole for George Washington and patriotic militiamen. Neither of these happenings have been proven so far.  Engelbrecht Engelbrecht Frederick diarist, Jacob Engelbrecht (1798-1878) lived diagonally across the street from the aqua-source and gives us a good description as a journal entry from July 13th, 1825: “Riehl’s Spring” The spring about 200 feet south from the Bentztown Bridge, was until the last 4 years called “Zimmeryergel’s Spring.” It first derived its name from the original proprietor George Schneider who was a carpenter by profession and small in stature. Carpenter in German is “Zimmer” and “Yergel” means “Small George” & he was generally called “Zimmeryergel.” Mrs. Riehl is the present proprietess, is his daughter. The “Mrs. Riehl” that Engelbrecht refers to here passed away the following November (1825). She was Elisabeth Schneider Riehl (b. 1763), the wife of Johann George Riehl (1763-1801). I want to think that the spring is named for her, and not her husband, since it dates back to her family’s ownership which began in 1778. It could have taken the moniker of Schneider’s Spring, but let’s face it, Riehl’s Spring rattles off the tongue much easier than Zimmeryergel’s Spring. I can’t tell you much more about the Schneider family, but I did find that Elisabeth apparently bought the property from her father in 1812. The property began 12 feet west from the west end of the West Patrick Street Bridge over Carroll Creek, fronted 25.5 feet on West Patrick and ran back 268.5 ft. This is the easternmost portion of a property George Snider bought from John Hanson Jr in 1778 (the entire property stretched 181.5 ft along what is now West Patrick). As for her husband’s family, Mr. (George) Riehl descended from Johann Fredrich Riehl (or Ruhl to begin with) who originally came to America from the area of Strasburg, Germany. The Riehl family can be found settled in the area of Middletown by the early 1760s and are found to be early parishoners of the fabled Monocacy Lutheran Church. Other sons appear to be Frederick Riehl (1760-1828) and Johann Jacob Riehl died at the age of 14 in 1792. George and Elisabeth married in 1788 and from this union came four children: Sophia (1789-1792/died of Typhoid Fever); Johannes (b. 1791); Anna (1791-1794); and Jacob (b. 1795). This youngest child would be the only one who would grow into adulthood and assumed the family property in question.  Battle of Baltimore in 1814 Battle of Baltimore in 1814 Jacob Riehl Jacob Riehl was born on October 5th, 1795 in Frederick, and baptized at Evangelical Lutheran Church. His father died when he was only six. If this didn’t force an early adulthood, I’m sure warfare did as he would participate as a soldier in the War of 1812. Private Jacob Riehl served in the 1st Regiment, Maryland Militia under the command of Captain John Brengle from August 25 through September 19, 1814 when the unit was discharged. He was among those “minutemen” gathered hastily when Capt. Brengle and Lutheran minister David F. Schaeffer rode through the streets of town that late august of 1814 in an effort to pull together a company to help rescue Washington under attack by the British. Plans quickly changed, and these volunteers helped secure victory with the successful defense of Baltimore on September 13-14. In the process, Mount Olivet’s front-gate greeter won fame by doodling a little ditty while held in captivity within eye and earshot of Fort McHenry—a story for another day of course. Jacob married Catherine Boswell on December 9th, 1821 in Frederick. The couple had four known children, but only two would live into adulthood: George Valentine Riehl (1822-1824); John Henry Riehl born January 9th, 1824; Charles William Riehl born September 3rd, 1825; and George Henry Riehl (1829-1831). Elizabeth Riehl willed the family property on West Patrick Street, including the spring, to son Jacob in 1825. Outside of that, I didn’t glean a great deal about Jacob’s early life, however he was the talk of the town in fall of 1826. Again, we can learn a great deal from Mr. Engelbrecht and his diary: “Cactus Triangilaris or night blooming Cerius” belonging to Mr. Jacob Riehl of this city was in bloom last night. 14 flowers opened & there are several other buds that will open this or tomorrow evening. Mr. Riehl had it beautifully illuminated and exposed in his yard for the inspection of the public. In fall of 1830, a fund drive was taken up for repairing Riehl’s Spring including the paving of walks and reconstruction of steps. Apparently the Corporation of Frederick City would attempt to acquire this site for decades as a source of clean water for the town. The superintendents were John Ebert, John C. Fritchie (husband of Barbara), and Jacob Engelbrecht. The corporation chipped in $10 and a host of citizens put forth money for the site holding the position as city spring. Others in town donated needed building supplies instead of money such as flagstone and bricks. Jacob and Catherine, or “Aunt Kittie” as she would become known, can be found in the census records of yore. No job is listed for Jacob in 1850, as I assume he was retired. I seem to recall reading somewhere that he was a carpenter. His son John Henry Riehl is found living with his parents in the successive censuses of 1860 and 1870 and lists plasterer as a profession. So, perhaps, like father, like son, Jacob could have dabbled in this profession as well. Either way, carpenter or plasterer, they both make “zimmers,” what I learned in school was the German word for rooms.  In that same 1860 census, Jacob is listed as a confectioner. Jacob served his country, or at least city, with the call to arms in spring 1861, shortly after the fall of Fort Sumter. He became a member of the Brengle Home Guards, formed in April of that year. The unit named for his old commander in 1814, the 65-year-old performed local militia duties on behalf of the Union Army during the American Civil War such as providing protection for state legislators and guarding supplies, etc. In 1861, a fire destroyed the second Frederick County Courthouse. Some speculate that it could have been Southern Sympathizers but that has never been proven. Regardless, it would take two years to complete demolition as it was wartime and Frederick played an active role. On October, 1863, the Frederick County Court commenced for the first time in a new courthouse, the one we know today as our home to Frederick City’s mayor and municipal staff. A new bell had been installed in the cupola atop the structure. The honor of ringing the bell that day to signify that court was once again in session was given to Jacob Riehl as he was titled, the keeper of the court-house. The vicinity of Riehl’s Spring was the scene of Civil War legend as it was adjacent to the famed home of Barbara Fritchie. One of the many stories of Frederick’s patriotic dame says that at least on one occasion, Barbara hastily swept out Rebel interlopers who decided to hang out enjoying the delicious, cool libations the spring had to offer. Adding insult to injury, these Confederates were “spouting” off derogatory talk about Ms. Fritchie’s beautiful Union, and this did not sit well to the nonagenarian flag-waver. Although it is highly unlikely that famed Gen. Stonewall Jackson took notice of Riehl’s Spring, we are likely to have an illustration dated from the late 1870s that shows the Riehl’s home on the west side of Carroll Creek. Catherine Riehl died on January 1st, 1873 at the family home on West Patrick Street. Three and a half years later on August 28th, 1876, Jacob died at the family home on West Patrick Street. They are buried at Mount Olivet Cemetery in Section H, Lot 52. The Riehl family home went to Jacob’s son, John Henry (of plastering fame) and daughter-in-law Catherine (Stone) (1826-1909). The Riehl’s still lived here in 1880. They had four children: Charles and William Riehl; Pricilla (Riehl) Brust, of this city; and Miss Bessie Riehl, later of Cincinnati, Ohio. John Henry Riehl died in 1895, and I’m not quite sure what his widow was doing in the decade before his death. Catherine (Stone) Riehl would die over a decade later. Known as "Aunt Cassie," we are fortunate to have a photo of her at the spring as a reporter included her in a story touting Carroll Park. She would pass in 1909. In 1901, the Riehl heirs sold the property to Arabella Faubel. She sold it to Georgianna Simmons in 1907, who then sold to the City of Frederick. It was a long wait, but set the stage for a municipal park. As an aside, Miss Simmons donated two other city lots to Frederick City Hospital which would become the site of the aptly named Georgianna Simmons Nurses Home. Carroll Park This was the original, “old school” portion of the Carroll Creek Linear Park. In 1907, Frederick alderman, and successful downtown merchant, David Lowenstein suggested putting a monument in the vicinity of where the Barbara Fritchie house had once stood. The legendary home had been partially destroyed in the Great Flood of 1868, and subsequently removed completely a short time later in an effort to widen the creek. Alderman Lowenstein went one step further by suggesting that a park be built on the west side of Carroll Creek surrounding Riehl’s Spring. This would become known as Carroll Park, a frequent scene of band concerts, camp meetings and unruly teenagers. Colloquially it also had the name of “Barbara Fritchie Park.” The Barbara Fritchie Home Association, which was responsible for building the nearby recreation of the heroine’s home, installed the wooden canopy. An article in Frederick Magazine years ago states: “The park itself welcomed residents and visitors for decades, though the once-vibrant spring became little more than a trickle over the succeeding years.” The article concluded by saying that by the 1980s, the once abundant spring was nothing more than “a small pool of dirty water which had collected in the spring pit, and had become a target for litterers.”

The spring was then redirected and became part of the Carroll Creek Linear Park project, which was built to thwart any future flood devastation from Downtown Frederick. Riehl’s Spring was perfect inspiration for what would come decades later. Pedestrian sidewalks today skirt the town creek and have become a pedestrian friendly asset in recreating and exploring the creek as it winds through downtown.

2 Comments

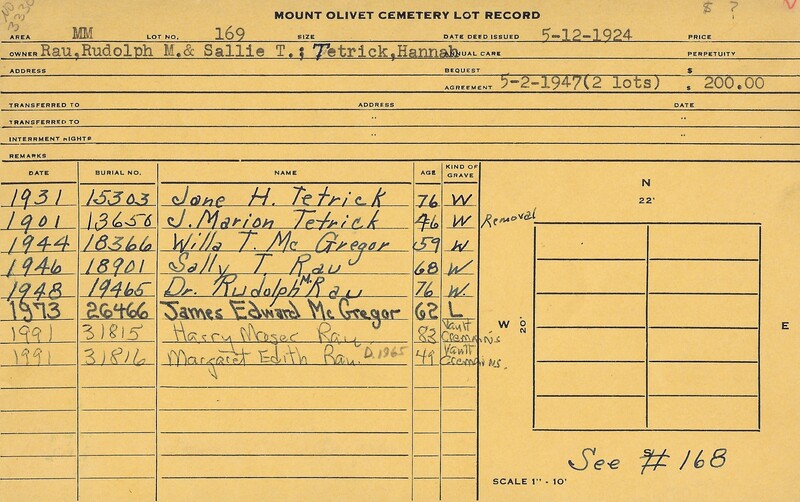

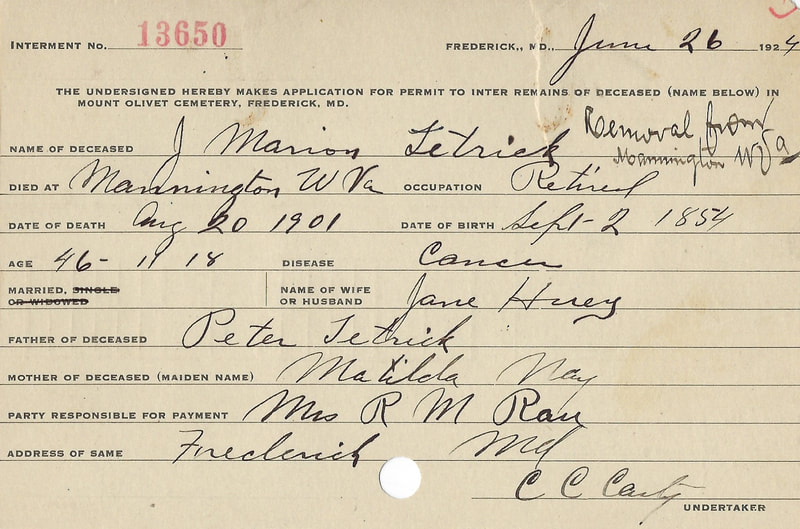

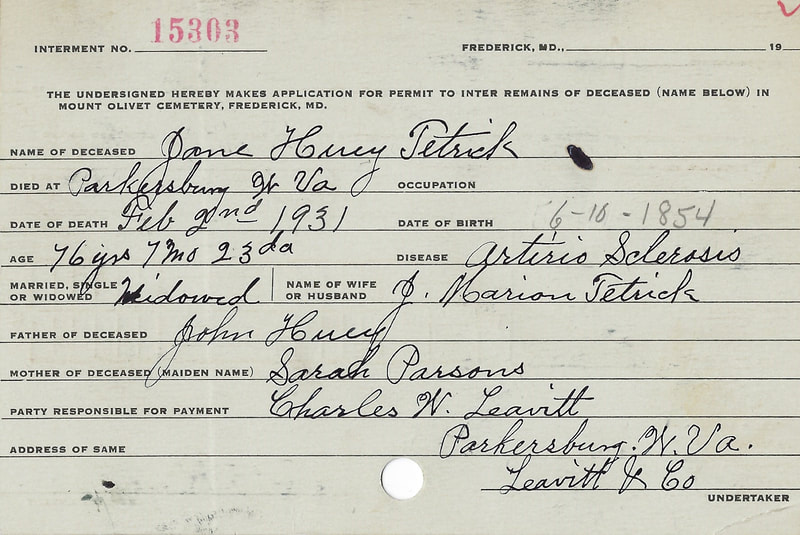

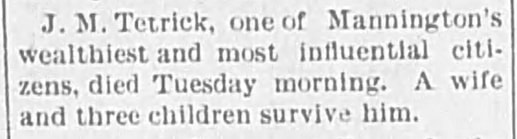

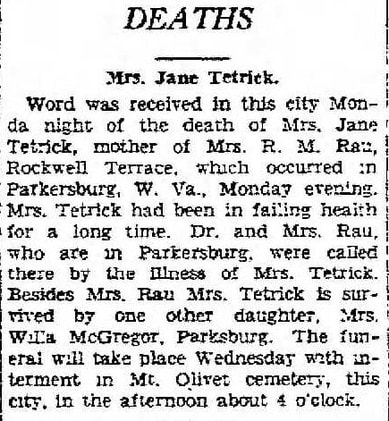

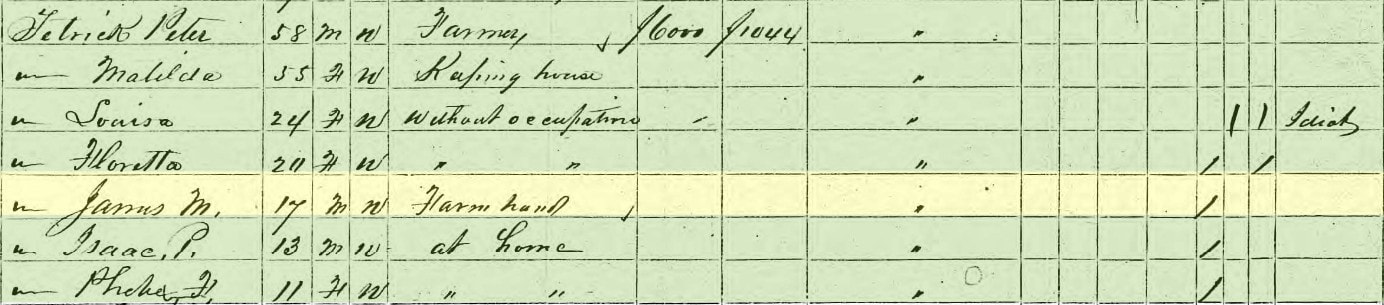

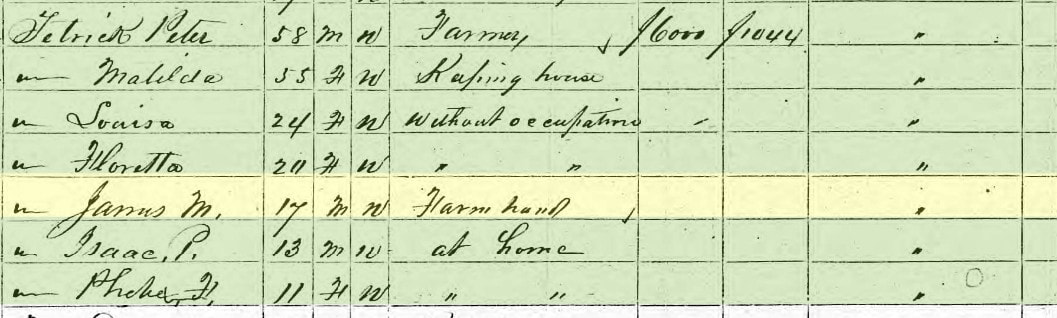

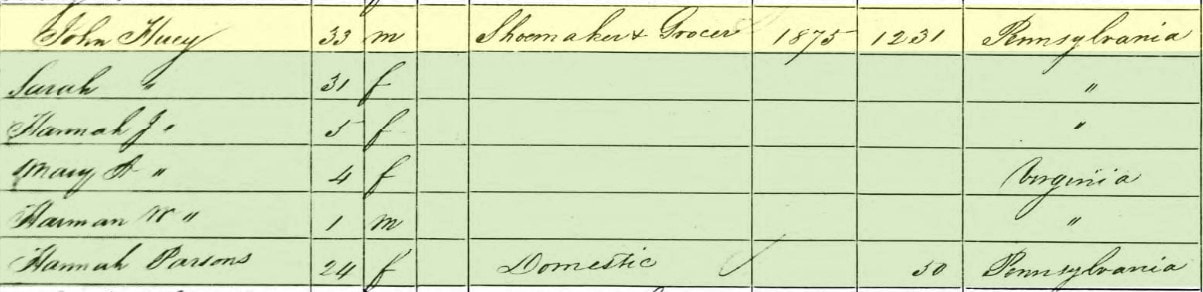

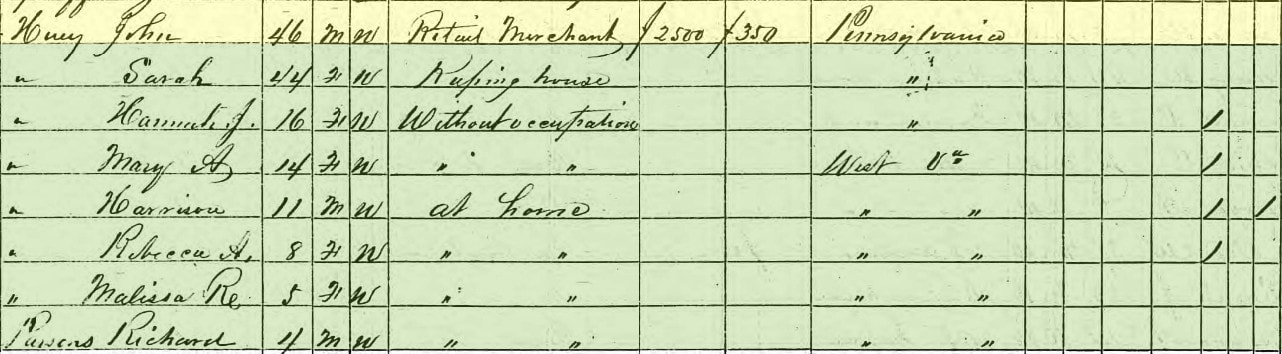

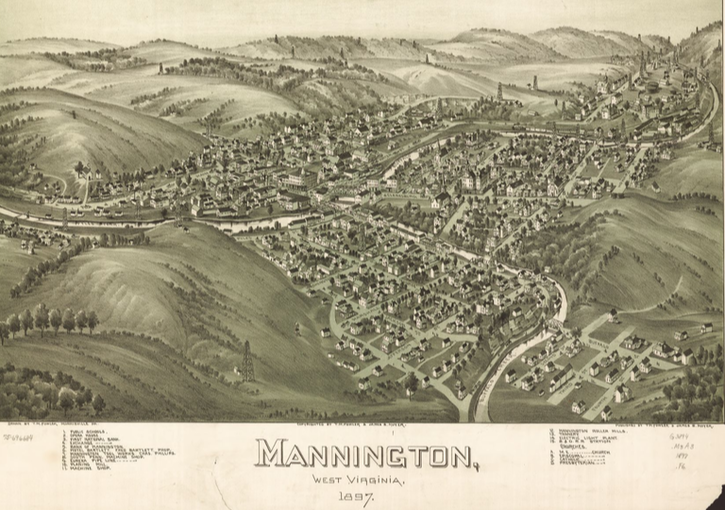

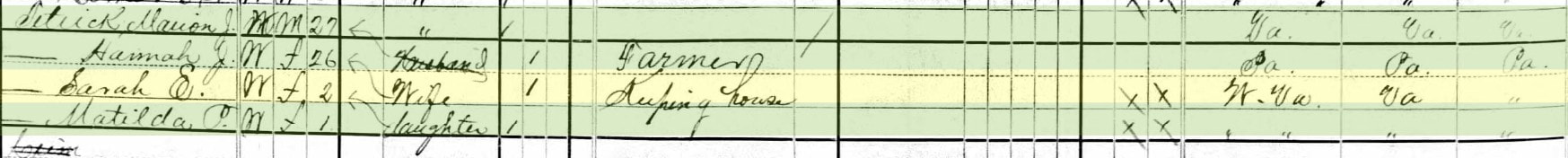

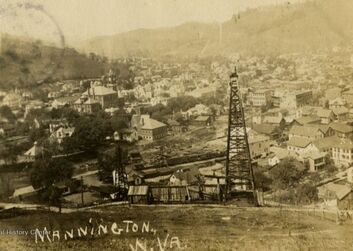

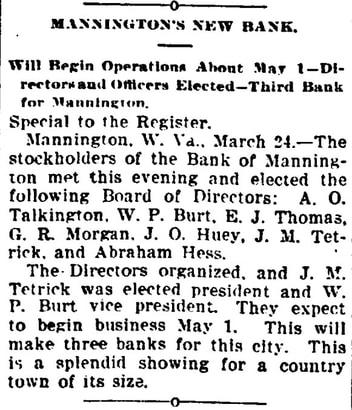

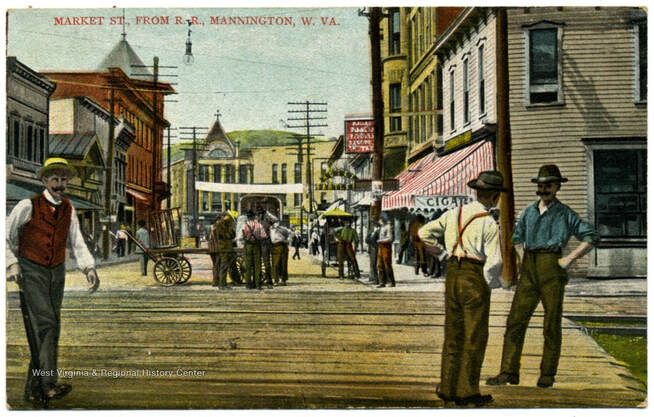

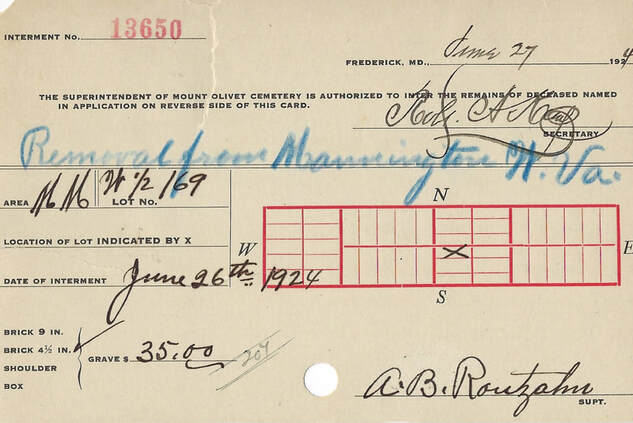

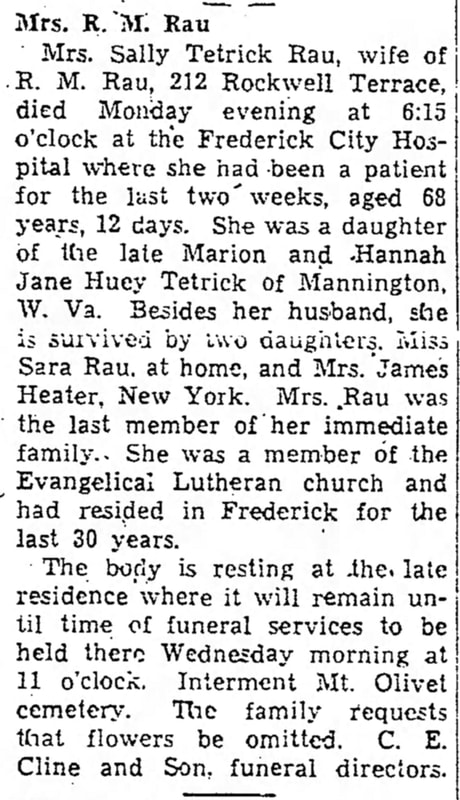

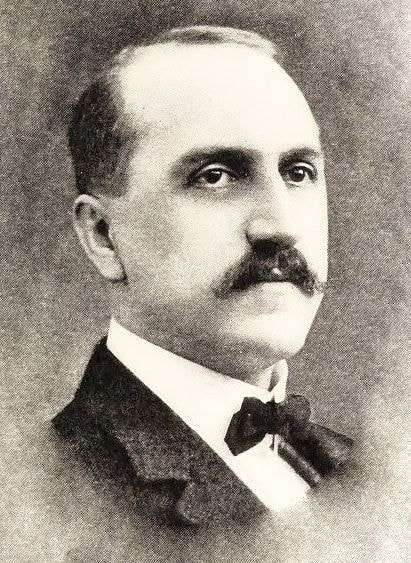

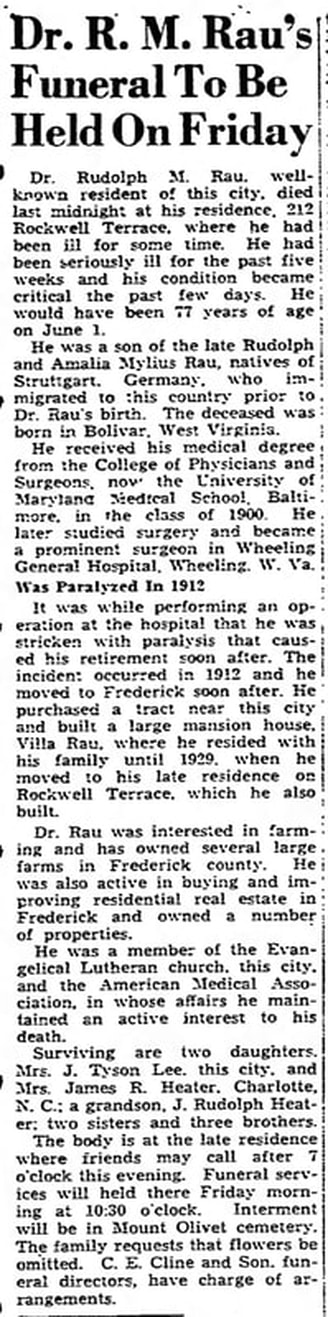

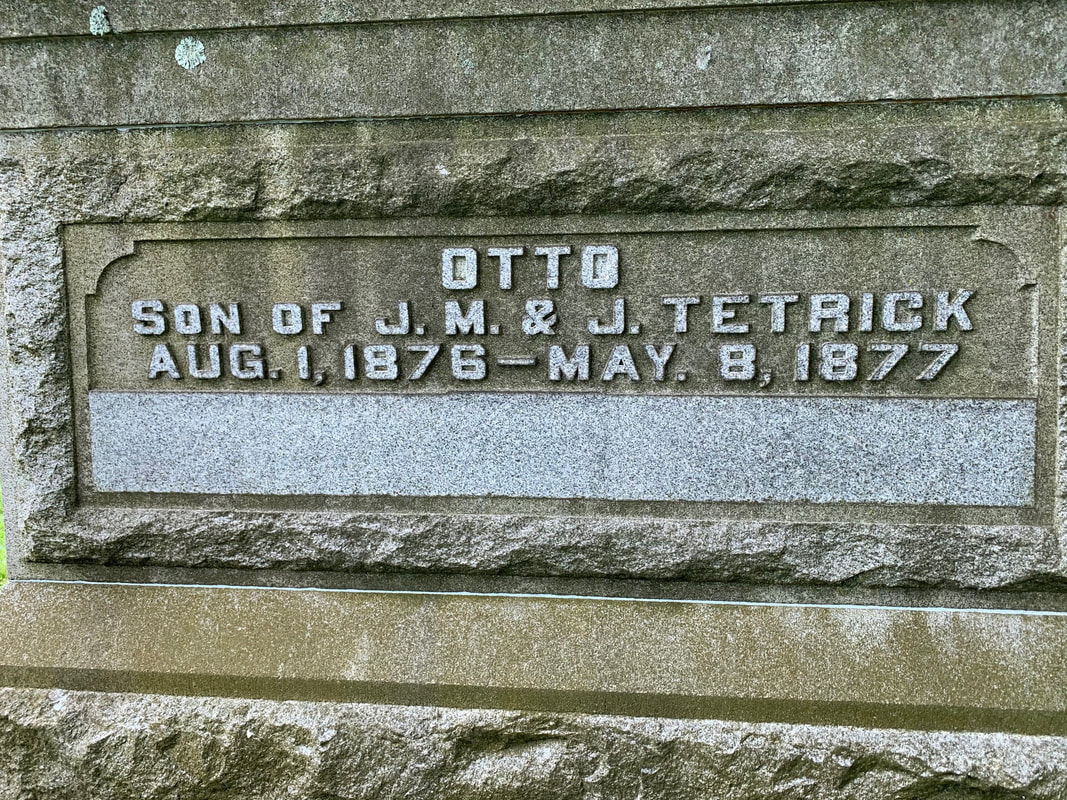

So, when you work at a cemetery, there are certain monuments that catch your eye on a daily basis. Yes, some are utterly unique or incredibly artistic. Others may be marking the grave of an outstanding citizen from our past, or have a familiar, Frederick-centric name carved on their faces. For this week’s “Story in Stone,” I chose a monument that always jumps out at me, solely for the fact that I have never seen the family surname anywhere locally, or in our local history books. I was intrigued because the memorial in question is quite large, and I was particularly curious as to the decedent’s background, having died in 1901 and not recognizing the name at all. The gravestone in question is that of James Marion Tetrick and wife Hannah “Jane” (Huey) Tetrick. I would soon learn that neither individual ever lived here in Frederick, or Maryland for that matter. When I first saw their grave, I actually thought it said Detrick but had to do a double-take. Interestingly, I would find a couple connections to Detrick in name and place. It is fashioned in the style of a sarcophagus, a popular style of the late 19th century and found throughout Mount Olivet. A sarcophagus is a box-like funeral receptacle for a corpse, most commonly carved in stone, and usually displayed above ground, though it may also be buried. Although not as ornate as others of this ilk found here, the final place is certainly well-marked with a substantial piece of granite. From time to time, I get asked if bodies are actually placed within these monuments as was done in ancient times. The answer is a resounding no, as these are strictly ornamental. And speaking of ornamental, my research on the couple buried beneath this stone did not reveal as much as I had hoped, however, along the way, I would find another vintage memorial in stone to the Tetricks—one which I never expected to stumble upon. The Search I’ve started research from scratch like this plenty of times before, and am fortunate to have cemetery records at my fingertips. In our Mount Olivet database, I found the Tetricks and corresponding information as to vital dates, parents’ names and exact grave location. I next pulled the lot card for Area MM/Lot 169 and found the original owners to be Mrs. Tetrick and a daughter (Sallie) and a son-in-law named Dr. Rudolph M. Rau. The threesome also owned the adjoining Lot 168, both properties having been purchased in May of 1924. I next located the all-important interment cards for both Mr. and Mrs. Tetrick. The interment cards usually provide “place of death” and “cause of death.” Things now ramped up as I cut to the chase by looking for obituaries for Jane and James (Tetrick). Starting with James, I learned he had died of cancer in August, 1901. I, however, only found a scant mention of death in a Wheeling, West Virginia newspaper from 1901. In the case of Jane Tetrick, I successfully garnered a local obit in the Frederick paper from February, 1931. Although she was living in Parkersburg, WV at the time of her death, the sole reason for local coverage was due to the fact that daughter Sallie (Tetrick) Rau was living in Frederick at 212 Rockwell Terrace at the time. Dr. Rau was listed as a medical surgeon and mental therapeutist. The newspaper makes mention of how Mr. and Mrs. Rau abruptly left town to be with the ailing Mrs. Tetrick in West Virginia. I checked for info on the Tetricks in online newspaper archives, Findagrave.com and Ancestry.com. I netted various census records showing both husband and wife to have lived most of their lives in north-central West Virginia. Mr. Tetrick was born in Virginia, as this particular area (Marion County) was not West Virginia until the new state was established during the American Civil War in the year 1864. James was born on September 2nd, 1852. He was the son of Peter Tetrick and wife Matilda Nay and grew up on the family farm located along the Buffalo River outside of Mannington in a nearby hamlet named Worthington. His father served as a county justice in the 1850s and was descended from a German immigrant named Henry Christoph Tetrick, born between 1720-1730 in Bavaria, Germany. Henry (d.1814 in Harrison county, VA), our subject’s great-grandfather, immigrated to Virginia sometime around 1740, possibly with brothers named George and Jacob, and his name was Anglicized from De Ryck. Jane’s Huey family had come from Pennsylvania a few years after her birth in about 1854. She first appears in the 1860 census with her family living in Mannington and her father listed as a shoemaker and grocery store merchant. As said earlier, Mannington is located in north central West Virginia and is within Marion County. This town, northwest of Fairmont, has a current population of 2,124 and was originally known as Forks of Buffalo due to its location on Buffalo Creek. The town site was first settled around 1840, and in 1856 it was renamed Mannington in honor of Charles Manning, a civil engineer with the newly constructed Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) Railroad. Perhaps James and Jane knew each other from childhood and school days as both were only a few years apart in age. The couple married on September 2nd, 1875. The 1880 census has them living on the family farm of Peter Tetrick. James profession here is listed as that of a farmer, but it would change drastically by the end of the century. The couple has two daughters at this point in time—Matilda Pearl (b. 1877) and Sarah Sallie (b. 1878). A son named Otto died at nine months of age. His name adorns the back of the Tetrick monument here in Mount Olivet, but he is not noted being here anywhere in our records as he died and was originally buried in West Virginia. A new chapter in Mannington's history began in 1889 with the first oil drilling, following recommendations made by Dr. I. C. White, a geologist from Morgantown. Although many felt that the area was unfavorable for oil reserves, White persisted and soon gained enough local support to drill. Following the first strike, late in 1889, real estate prices soared 100% in two days in a boom-town mentality. Dr. White pushed for natural gas exploration. It was this venture, more successful than any before or since, that was most responsible for Mannington's growth. Of course, we are not aided by the presence of an 1890 census record because all were lost in a horrific fire. I did find a small advertisement that listed J.M. Tetrick as a druggist in Mannington that same year. As the town grew, so did the need for banks and Mr. Tetrick can be found on the board of directors for a third bank in the vicinity organized in 1896. James Marion Tetrick was duly elected the bank’s first president. Oh, what an exciting time to be in Mannington! The population would increase from approximately 700 people in the late 1800s to over 4,000 by 1917. By 1900, Mannington was a thriving town, complete with its own trolley system, electricity, theaters, schools, fire department, telephones and other amenities. James M. Tetrick even ran for the state’s House of Delegates, but came up short of election.

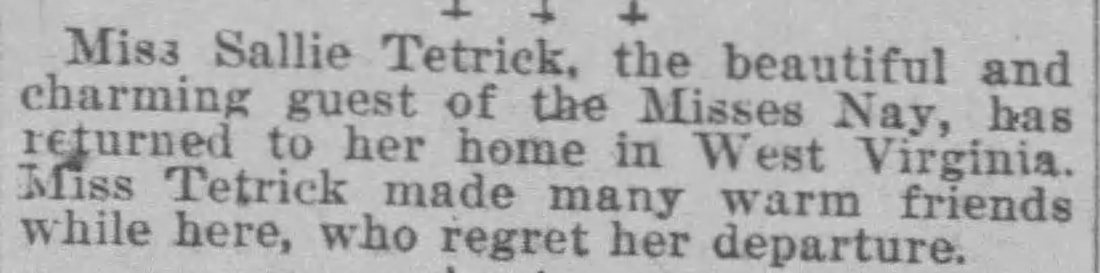

Of the many things in death, missed by Mr. Tetrick, was the discovery of oil on his former farm, as evidenced by this news clipping from 1907. The body of James Marion Tetrick would repose in Mannington until the year 1924. For one reason or another, his widow would make plans to have his body moved to Mount Olivet in Frederick, Maryland—some 194 miles away. The reburial here in Area MM was performed on June 26th, 1924. This info is clearly written on the back of the interment card, in bold blue pencil, I may add. As for the rest of the Tetrick family, Jane would join her husband here in Mount Olivet upon her death in 1931 as referenced earlier. Daughter Willa (Tetrick) McGregor (1884-1944), a resident of Parkersburg, WV, would be buried here in the family plot upon her death in February, 1944. The Tetrick's other daughter, Sallie, has an interesting story herself. As a Frederick resident since 1911, she and her husband, Dr. Rudolph Rau (1871-1948), have left us some interesting proof of their habitation here in Frederick. Mr. Rau met Miss Tetrick, said to have been quite a beautiful young lady, in West Virginia. He was a native of nearby Bolivar, (WV) in Jefferson County but practiced in Wheeling at which place he and his wife resided before coming here. The physician apparently suffered paralysis while conducting a surgery. Forced into an early retirement, the Raus came to Frederick after purchasing a property northwest of the city which once contained the former St. Joseph's Villa located east of today's Rosemont Avenue/Yellow Springs Road near the intersection with Rocky Springs Road. The Jesuits had used this site as a retreat center for aspiring priests and their teachers associated with the Frederick Novitiate Academy, once located on East Second Street. The two-storey, 80 by 60 ft villa they built included a small chapel, recreation room, kitchen, and dormitories. A porch extended around 3 sides, and occupants could sit on chairs and enjoy the cool mountain breezes. The Jesuits stopped using the villa in January 1903, when the Novitiate Academy moved to New York. St. Joseph’s Villa was torn down sometime afterwards. In 1911, Francis T. Lakin sold a 99-acre parcel to Rudolph and Sallie Tetrick Rau. Rau built a 3 storey, Greek Revival-style mansion and carriage house, and also extensively landscaped the property. The imposing mansion had two storey columns and a ballroom on the third floor. The garden and estate fit with the early 20th century gardening trend away from ornate Victorian designs. The Raus would rename their country home Villa Rau. According to his obituary, Rau was interested in farming and owned several large farms in Frederick County. Dr. Rau and his family sold the property to Robert S. Bright on January 31st, 1929. Bright used the house as a summer residence until his death in 1943. The 4.5 acre site of the mansion eventually was sold to Macie S. King, and Bright sold the surrounding property to Harry M. Free. The United States government obtained both properties in 1946 as they became part of Fort Detrick. The Rau mansion housed post commanders until it was demolished for safety reasons in 1977. The carriage house was demolished in 1993. They stayed here until 1929, at which time the couple built a near duplicate at 212 Rockwell Terrace and moved in town. I'm assuming the Tetrick "oil money proceeds" were put to good use as the Raus would buy several properties in and around Frederick while here. Sally Rau, died in 1946 and was memorialized with a fine ledger monument that sits in the front row of Area MM adjacent the central driveway through the heart of Mount Olivet. Mrs. Rau’s husband, Dr. Rudolph M. Rau, would die in 1948 and be placed by her side. Old Mannington The 1929 stock market crash and the Depression severely affected Mannington's economy. The trolley ceased operation in 1933, factory workers left as demand for products decreased, and the town's population began to decline. The oil and gas boom has long passed, but coal mining became a principal industry in the 1950s. Although many of these industries left the area, the wealth that they brought to the community is still reflected in its handsome historic homes and public buildings. Many are included in the Mannington Historic District, which is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. While doing some online sightseeing, one building certainly caught my eye, much like the Tetrick sarcophagus burial monument had done to me in the first place. I found a beautiful photograph found on the Flickr website, taken by a Joseph A. from Pittsburgh. It was a streetscape scene which prominently included the former sight of the Mannington Bank, more commonly known as the “Tetrick Building.” The 1898 building located on 102 Buffalo Street has seen better days, as it is in deplorable condition. High atop its face, within its gable, one can see a memorial to the bank’s first president, elected in 1896— J. M. Tetrick. Just as the name Tetrick caught my eye here in Mount Olivet, inspiring me to write this story, I’m betting it has caught countless more as it sits high atop Mannington, WV. A true testament to a life once lived.

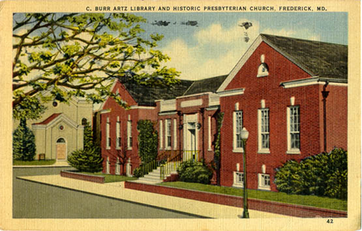

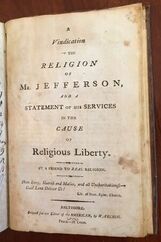

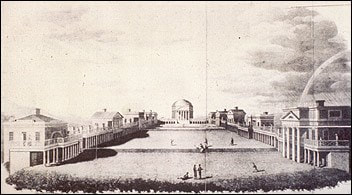

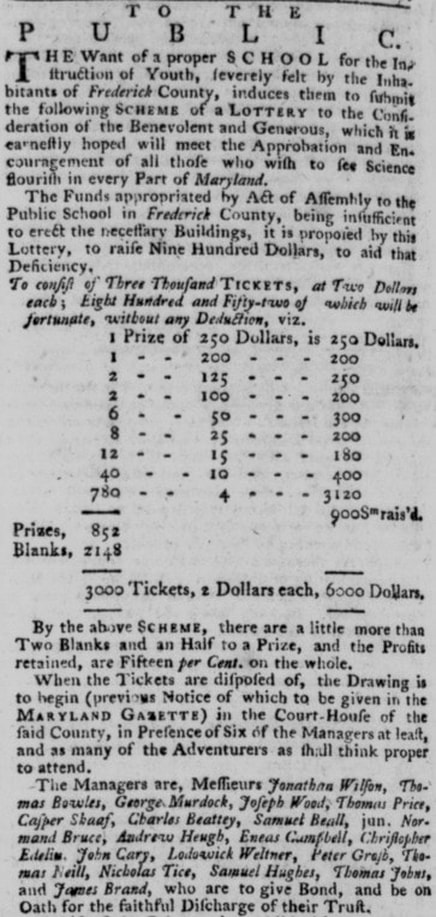

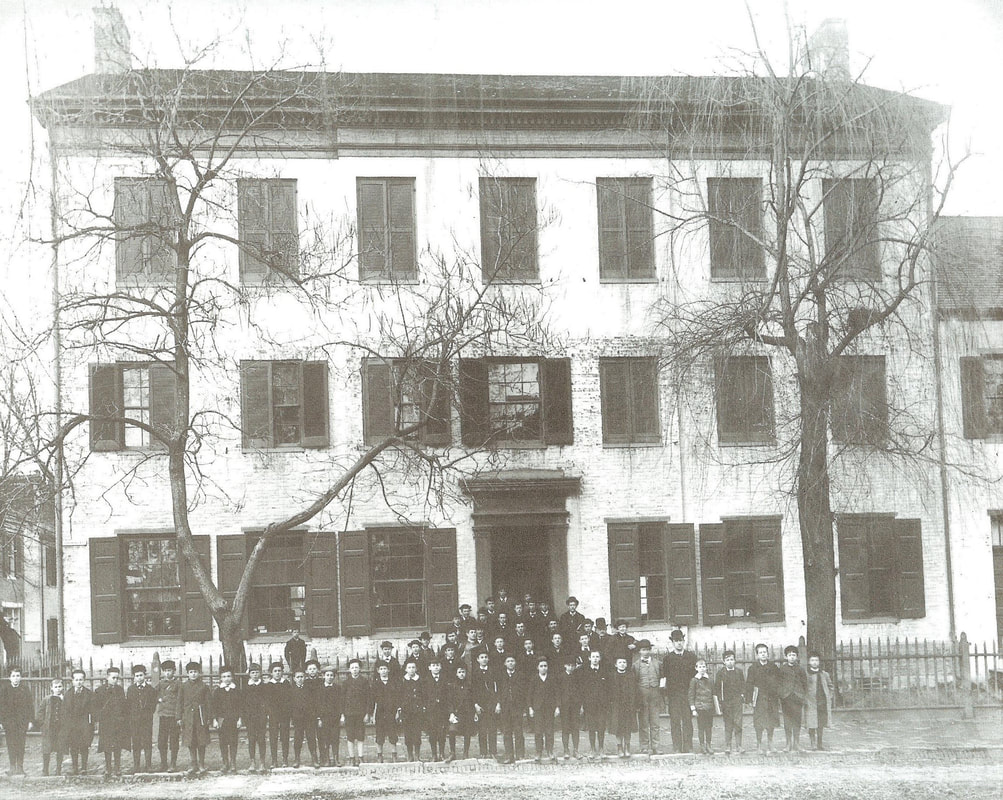

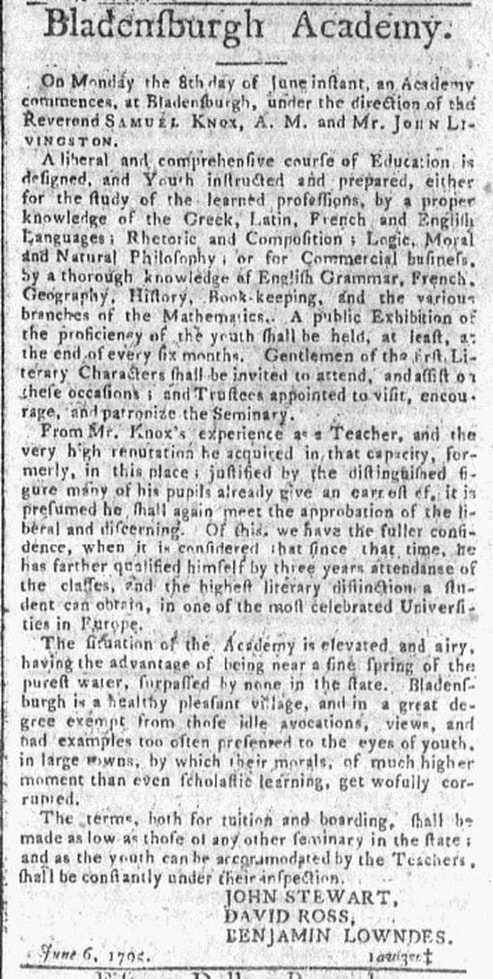

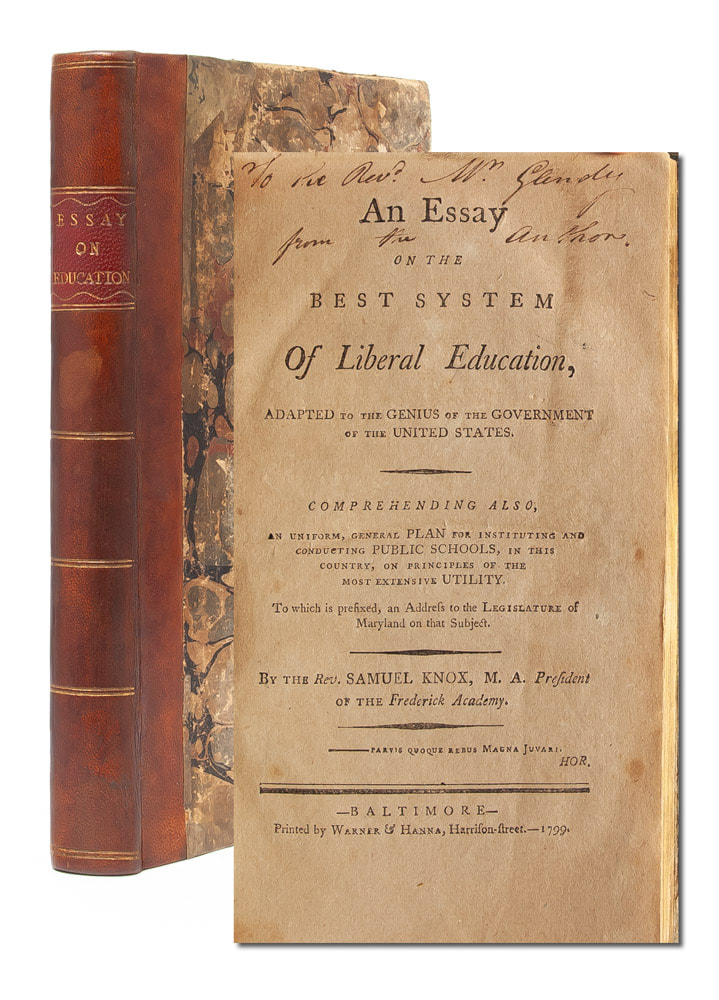

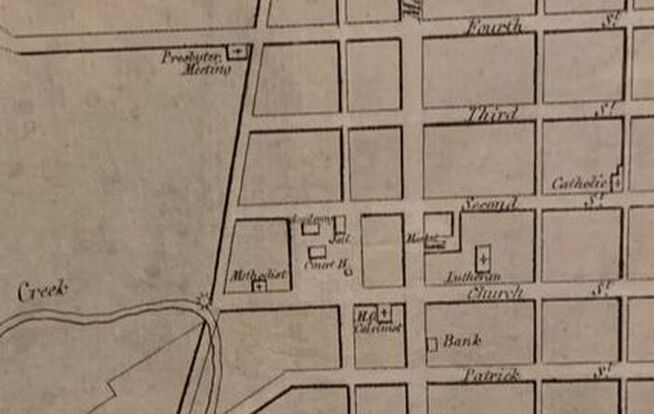

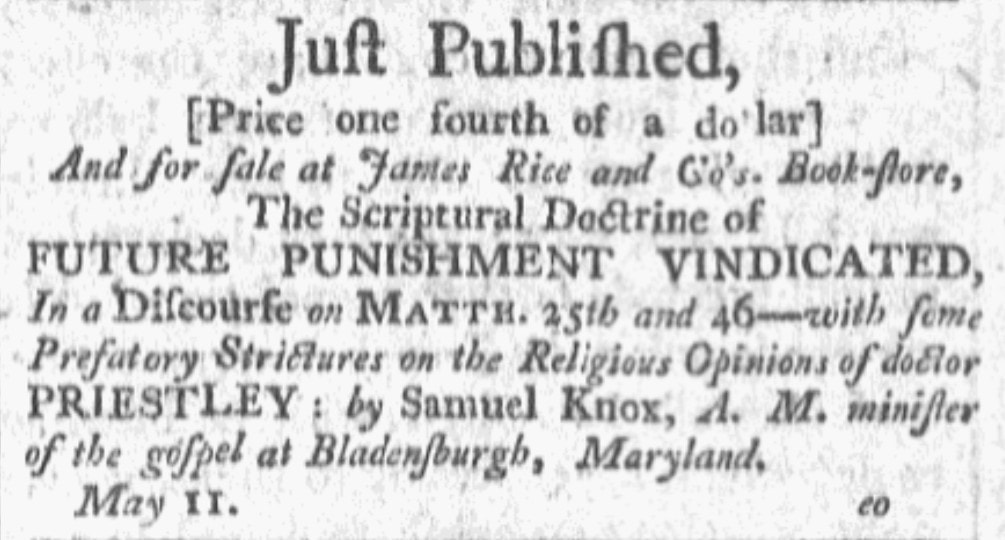

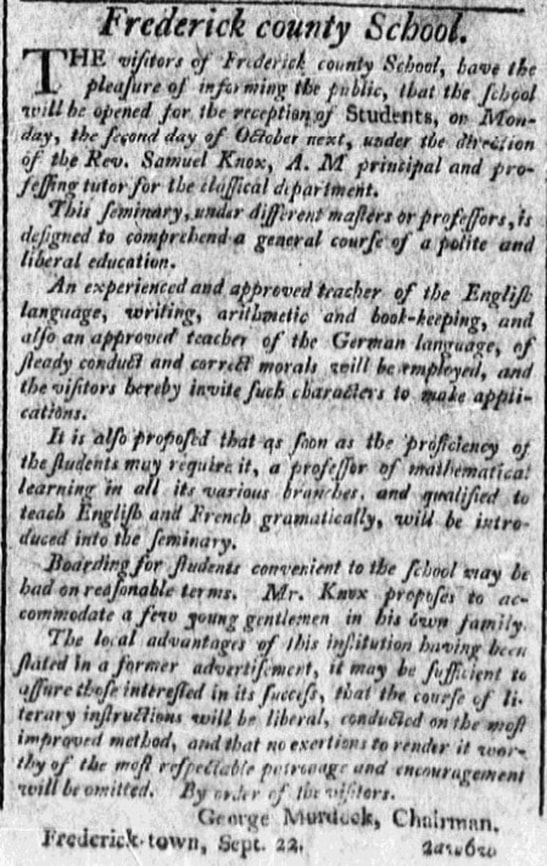

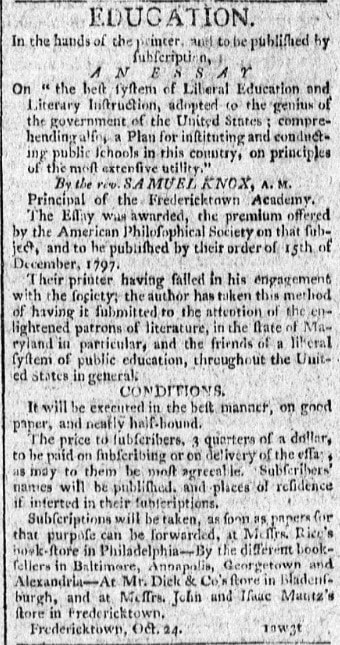

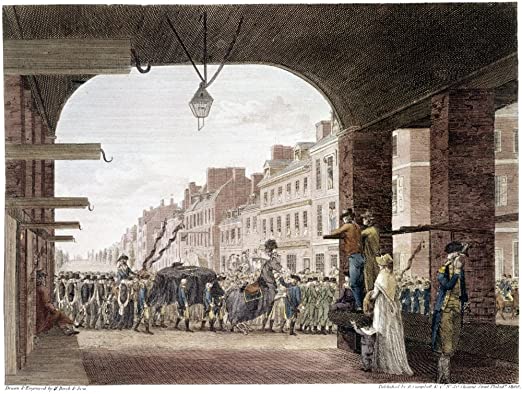

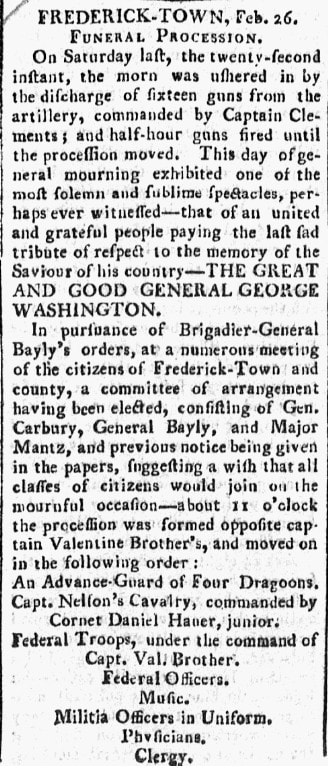

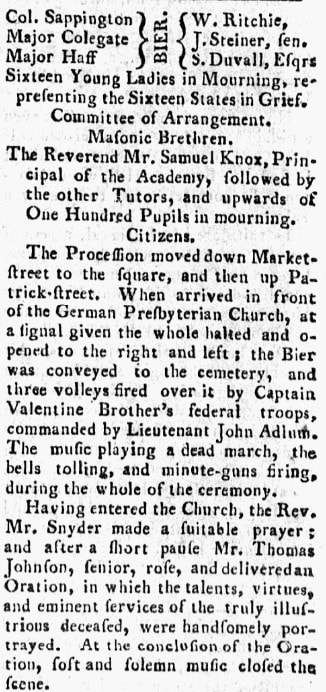

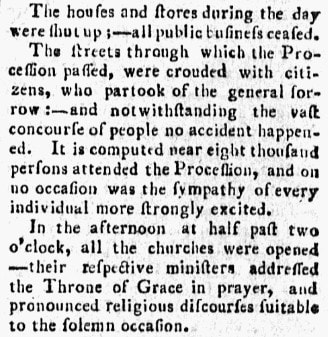

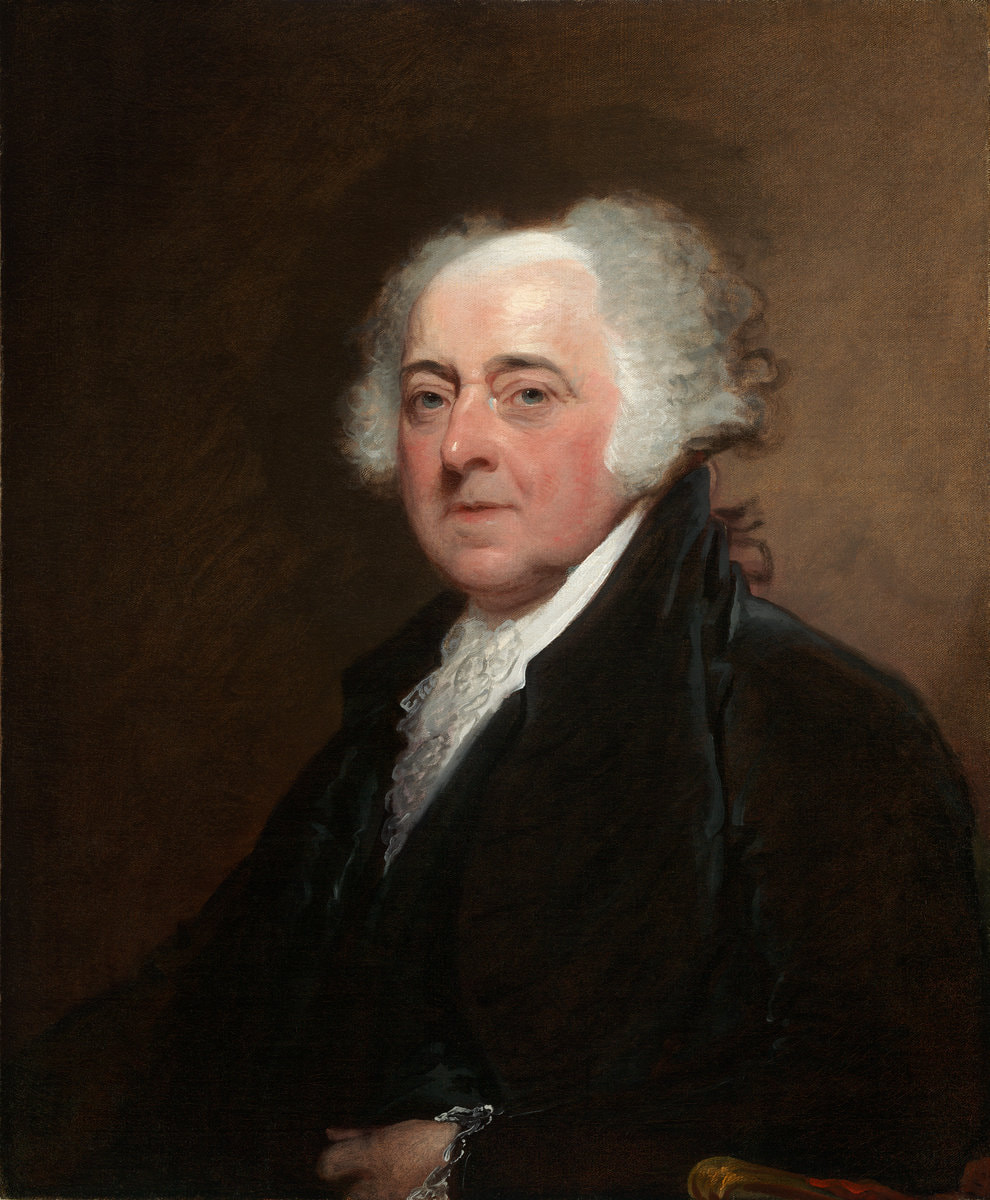

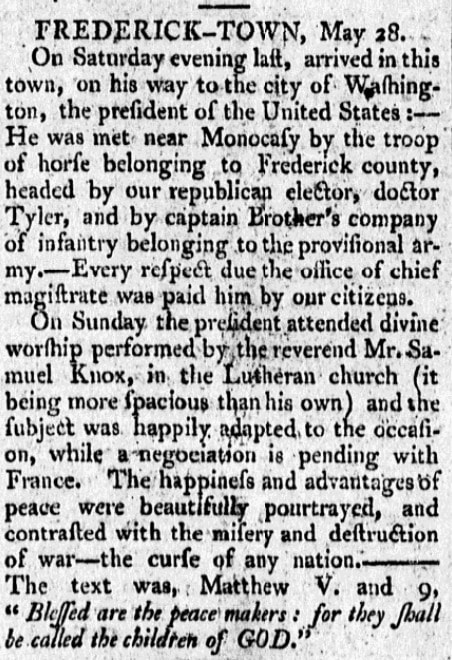

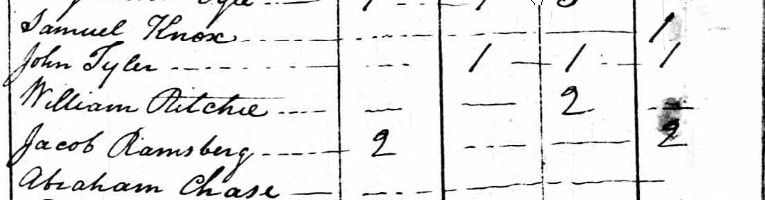

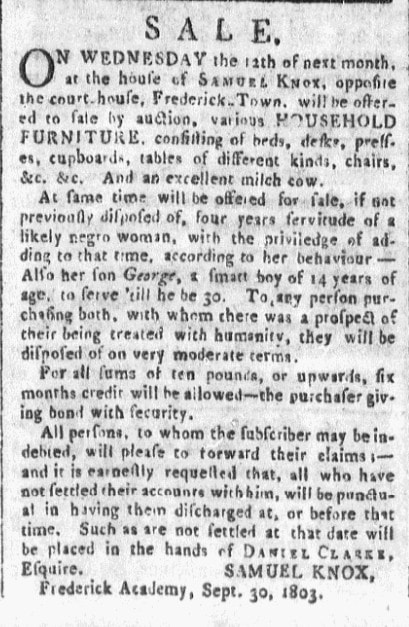

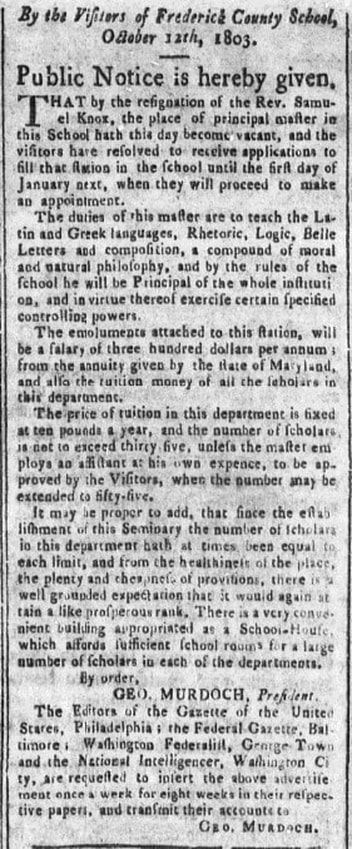

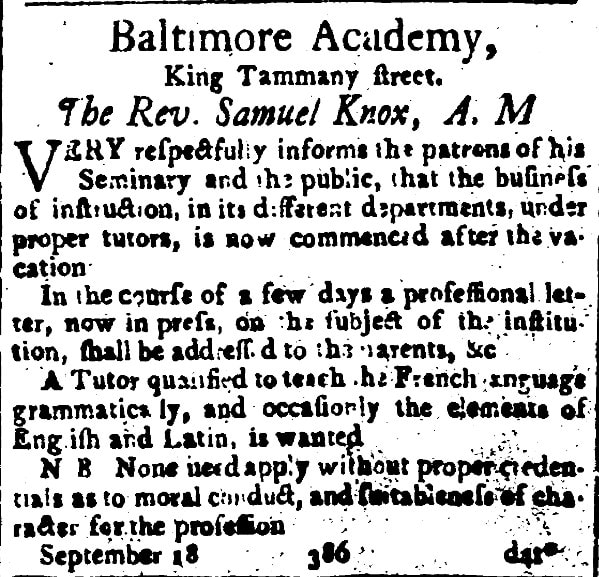

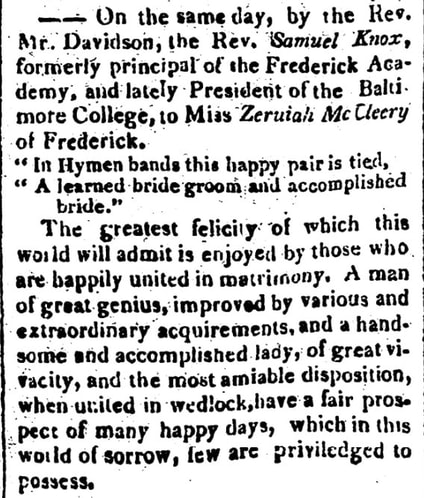

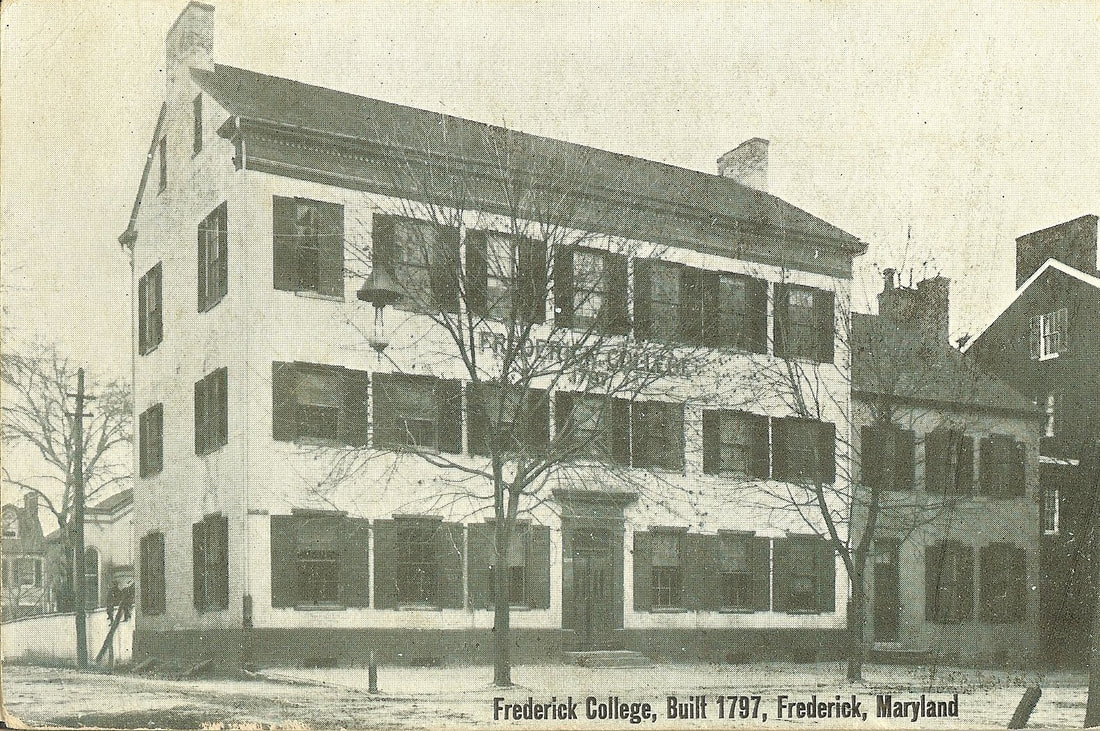

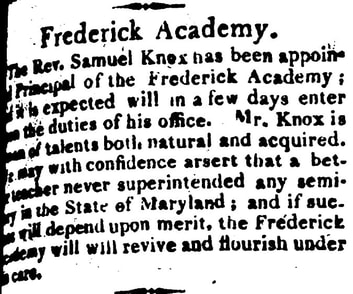

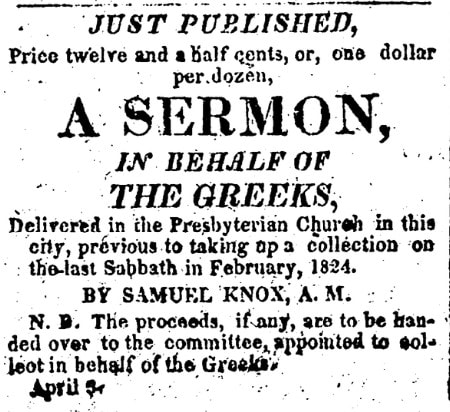

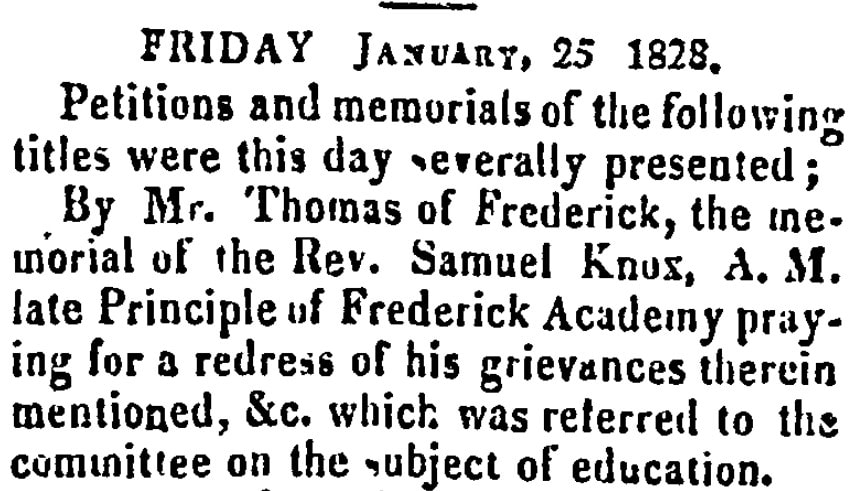

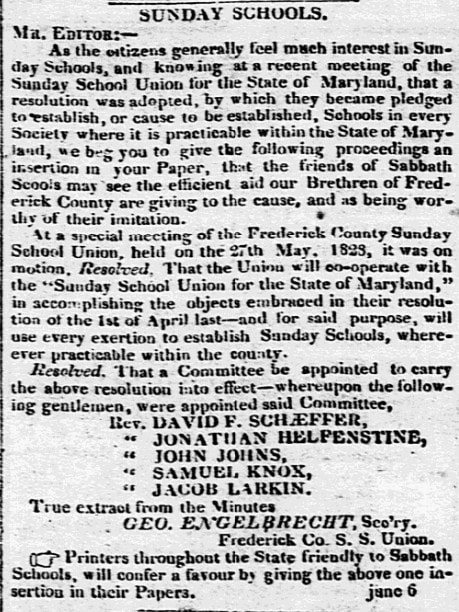

It’s mid-May and we are in the throes of graduation season, primarily celebrating the final step toward receiving a high school or college diploma. The earliest institution in Frederick’s rich educational history was Frederick College, once located on the corner of Counsel (Council) and Record streets in the Court Square neighborhood of downtown Frederick. It played a pivotal role as a model for the nation’s early educational facilities. The school represented both a college and high school, as few people would ascertain this higher level of learning at the time of its founding in the late 1700s. The school's first principal is buried here in Mount Olivet, along several other former administrators and teachers. His name is Samuel Knox With its publication in 1910, T.J.C. Williams’ History of Frederick County chronicled the background of this school, affectionately referred to as “the old Academy” by former students and townspeople alike. “As early as 1763, when this territory was largely wilderness, the (Maryland General) Assembly granted a charter to the Frederick County School and College. Thomas Cresap, Thomas Beatty, Nathan Magruder. Capt. Joseph Chapline, John Darnall, Colonel Samuel Beall and Rev. Thomas Bacon were named as the first Board of Visitors. Strenuous times followed in an effort to realize practically the good sought in the establishment of this pioneer institution. The years of the Revolutionary War put an effective stop to much effort in this direction, and it was not until 1796 that appreciable headway was made, when, partly through the aid of a lottery (a recognized means in those days), the public-spirited generosity of the community was rewarded by seeing erected the first building which is still used as the College. In 1797 a grant was made by the Assembly, and the School was opened with Samuel Knox, a Presbyterian minister, as its first Principal. It is interesting to note in this connection that it was from Dr. Knox that Thomas Jefferson got his scheme and plans for the University of Virginia. As the years went by the School prospered under the unremitting vigilance and fostering care of the Visitors, who invariably were our leading citizens, and who thought no attention and effort were too big a price to pay for the fostering of this School, which was to be a blessing to our boys  Chase Chase The records of the early hours of work (as early as 6 A. M. in the Summer months) with the three sessions a day, the almost continuous course from the last of August to the last of July, the daily exhortation to right living and the hour of prayer would make many of our boys of today glad that they did not live in those times, and yet some of the strongest men in the State and Nation came from the walls of the old Academy equipped for life's battles as many of our day are not. Duels were fought and punishment inflicted in the early years of the last century, and the boys took what came to them like men. A fact not generally known is that in 1824, a place on the faculty was sought by a young man from New Hampshire, who was on his way to Ohio; he failed to secure the desired position and continued on his way West and years afterward came East and became known to the Nation in many capacities as Salmon P. Chase. (NOTE: Chase (1808-1873) was a U.S. politician and jurist who served as the sixth Chief Justice of the United States. He also served as the 23rd Governor of Ohio, represented Ohio in the United States Senate, and served as the 25th United States Secretary of the Treasury.) In 1830 a Collegiate charter was granted by the Assembly, and under it ever since good work has been done. Eight scholars are educated by the College absolutely without charge and ministers and missionaries, physicians and lawyers, merchants and farmers have here secured at no cost to them, the education and training that gave them their place in the world. During the Civil War, the buildings were used, as were most of our churches, for a hospital after the battle of Antietam.  For years Jesse Stapleton Bonsall was Principal, and was known probably to more students than any one teacher that filled that position. Severe, stern, unsparing of self, devoted to his work, the very soul of a high honor, he instilled into his boys the very essence of his life, and by his life and teaching imbued them with the spirit of the School as set forth in its motto: “Non scholae sed vitae; vitae utrique,”—Not for school but for life, both lives. To call a roster of the boys trained here would read like a census list of this place, and the surrounding country, and would include the names of many long since scattered to the uttermost parts of the United States. The old institution, a pioneer in 1797, a vigorous factor for sound education and morality for more than one hundred years, a blessing and a pride to our community, still wears its venerable smile as it hears of the well-doing of its children, and listen with concern as they come back to tell of the buffetings they have received from the hard, material world. Frederick with its rich historic heritage of great men and stirring events, serenely resting amid the rush and clamor of present day strenuous endeavor, is a fit setting for this old School, grown hoary with the accumulated memories of more than three generations of men. Frederick College would be supplanted by Boys’ High School as the area’s top place for education in the early years of the 20th century. In 1916, the old Academy structure became the new home of the Frederick County Free Library which had opened in 1914 and moved in here in 1916. The library would operate at this location for the next 23 years before donating its collection to the town’s new C. Burr Artz Library which opened in 1938. In building the new library, the Academy building would be razed in 1936. Rev. Samuel Knox Samuel Knox was born in the year 1756 in County Armagh, Ireland. Apparently, he was from a poor Scotch-Irish Presbyterian family and little else is known about his childhood. He married Grace Gilman in Dublin in 1774. The couple were the parents of four daughters. The Knox family arrived in Maryland by 1786 and was known to be living in Bladensburg. Here, he taught at a grammar school from 1788-1789. Knox returned to Europe in 1789, and received a Master of Arts from the University of Glasgow in 1792. While there he received Greek and Latin scholarships. After the Presbytery of Belfast licensed him for the ministry, he returned to the United States and was assigned by the Baltimore Presbytery to the Bladensburg pastorate (1795–1797). In 1796, the American Philosophical Society held a contest to design the best system of education for the United States. Samuel Knox entered, proposing a system of national instruction particularly designed for this “wide extent of territory, inhabited by citizens blending together almost all the various manners and customs of every country in Europe.” Providing elementary education for both girls and boys, uniform training and salaries for teachers, standard textbooks produced by a national university press, with a college in every state each charging the same fees and tuition, and at “the fountain head of science” a national university, Knox’s ambitious plan won second prize. Rev. Knox performed the dual duties associated with rural Presbyterian ministers of the time. He was a schoolteacher and a “supply pastor,” charged with the religious congregation in Frederick, which he served from 1797–1803. Old papers are full of wedding announcements performed by the Irish clergyman.  At first, Knox was a heralded figure in Frederick. His reputation preceded him. He was accomplished as a writer of not only award-winning essays and published works. In addition to his religious and educational duties, Knox engaged in the political debates of the day, writing pamphlets in 1798 on English Separatist theologian Joseph Priestley’s “avowed Religious Principles.” In 1800, Knox wrote A Vindication of the Religion of Mr. Jefferson and a Statement of his Services in the Cause of Religious Liberty. Herein, Knox approved of Thomas Jefferson’s Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom. Speaking of founding fathers, Knox exchanged correspondences with other men of mark including our George Washington. The following is a letter penned by Knox to President Washington in October 1798.  Washington Washington Sir, Being About to publish, by subscription an Essay on the best Method of Introducing an Uniform System of Education adapted to the United States, I Beg leave to solicit the favour of your permission to prefix to it an Introductory address to you. Though I own this Request is dictated by a share of vanity in presuming to be ambitious of so high a recommendatory sanction to my Essay; yet I truly declare that, what has chiefly prompted me thereto arises from a desire to express, on a Subject of that Nature, How much I Consider the Cause of Education indebted to your patronage through the whole of your publick Character. The Essay I am about to publish, obtain’d the premium offer’d by the Philosophical Society of Philadelphia, on that subject, together with one written by a Mr Smith of that place. The Society passed a Resolution to publish them; but were disappointed by the Printer who had Undertaken that Business. On being inform’d of this by their Secretary, And that the publication would be, on this Account, long retarded, by the advice of some friends I was induc’d to publish it, by subscription, in this State—from the view of its, probably, having some effect in turning the attention of our State-Legislature to that Subject. From this view I have Received the Manuscript from the Secretary of the Phil[adelph]ia Philosophical Society; And shall proceed to publish [as] soon as I Can ascertain whether I am to Have the Honour of dedicating or addressing it to you. Two or three weeks since I was at Alexandria, designing to have personally waited on you; And if necessary to have given you some view of the Essay—Doctor Steuart near that place who has long known me, promised doing me the favour of introducing me to you; But learning that the State of your Health, at that time, forbade any such trouble, I flatter’d myself that this mode of application might be equally as proper—especially, as I have had the pleasure of seeing it announc’d to the Publick that your Health is again perfectly restor’d. I Have Spent more than twenty years of my Life in the Education of youth. A considerable part of that time I Resided at Bladensburgh in this State—and remember having once had the Honour of being Introduc’d to you by Coll Fitzgerald of Alexandria—at a publick Examination of the youth in that Academy. Since that time I Study’d four years at one of the most celebrated Universities in Britain—and recd a Master of Art’s Degree, from the view of being Useful to Myself; this Country in particular; and Society in general—in the line of my profession as a Teacher of Youth—and a Minister of the Gospel. On my return to this Country I was offer’d the Charge of the Alexandria-Academy by its Visitors or Trustees with a Salary of 200 pounds Currency per Annum. But having a family to Support, I did not Consider their terms sufficiently liberal; or promising me a sufficient Compensation for the preparatory expence I Had been at in qualifying Myself for the Business. I take the Liberty of Mentioning these circumstances merely from the view of informing you that in presuming to Solicit the Sanction of your Name to my Publication; and in venturing to lay My thoughts before an enlighten’d Publick on so important a Subject, It has not been without long experience in, as well as mature attention to the most improved Methods of publick Education. Joining in the general tribute of sincere Congratulation; and thanks to Divine Providence for the restoration of your Health, I am, Sir, your Most devoted Obedt Hble Servt, Saml Knox (Source: National Archives’ Founders Online website - www.founders/archives.gov) Upon Washington’s death in December, 1799, Knox was held in esteem here locally along with others like Thomas Johnson, Jr., a longtime friend of our first president. In March, Knox and his students from the academy would take part in a memorial funeral procession for George Washington through the streets of town and culminating at Frederick’s Presbyterian Church, once located at the southwest corner of North Bentz Street and Dill Avenue. Knox would deliver the funeral oration. In late May, 1800, Knox would have the distinct honor of delivering a sermon for a church service with our second president of the United States—John Adams. Adams was traveling through Frederick County and stayed the night. Rev. Knox home church structure being too small, services were conducted in the more spacious Lutheran church in town here. Rev. Knox was no stranger to speaking his mind and ruffling feathers. Late in 1802, Knox wrote an open letter to the 16 trustees of the Frederick Town Academy lamenting the fact that none of them had attended the December 23rd examination at the school. He went on to give the full results of the exams and attributed the absence of many trustees to political party spirit. In this letter that was published in the Dec 31st edition of Bartgis’s Republican Gazette, Rev. Knox also gave himself a big pat on the back by including a December 14th letter from the faculty of the College of New Jersey (later Princeton University) affirming that the performance of Knox’s former students who had enrolled at the college was “creditable to themselves and honorable to their instructor.” It comes as no surprise that Samuel Knox’ days in Frederick would be numbered. He would resign in the late summer of 1803 and left town, holding an auction of his household items, including servants, in late September. He and his wife had been living in a house on Counsel Street that adjoined the school. Knox would move on from Frederick to a place called Soldier’s Delight Hundred, near present day Owings Mills in Baltimore County as the principal of a private academy which would merge with Baltimore College. This school would apparently merge with another academy and become Baltimore College.  University of Virginia University of Virginia Rev. Knox had established a firm reputation of one of the country’s top academics. He had a correspondence with Thomas Jefferson’s proposed system of education for the state Virginia. Knox had proposed a similar system for Maryland, with the same lack of success that Jefferson had across the Potomac River. However, Jefferson may have been influenced by Knox’ essays when he designed the University of Virginia in 1816. One year later, the Frederick Academy’s former principal was offered a professorship in languages and belles lettres at the University of Virginia, but the plans fell through. Knox would stay at Baltimore College until 1819. In personal life, Rev. Knox’s wife, Grace, died in Baltimore in November, 1812. Ten years later, the feisty minister married a woman with a biblical name in Zeruiah McCleery. Zeruiah, whose name crudely translates to “pain,” was the daughter of Henry and Martha McCleery. Mr. McCleery and Zeruiah’s brother, Andrew, were accomplished architects with lasting connections to noted Frederick structures such as the second Frederick County courthouse, the second All Saints Church building on N. Court Street, and the Ross and Mathias mansions on Counsel (Council) Street. Knox and Miss McCleery were married on April 17th, 1822—the good reverend was 66 at the time and she was 39. Rev. Knox and Zeruiah would have no children. Perhaps the former Miss McCleery’s influence brought back to her hometown as Knox would return to Frederick and Frederick College in 1823. Rev. Knox continued his publication work and that with the church as well. However, his stay at Frederick College would be short as he was fired in 1827. Unfortunately, his demise here in western Maryland came because of a dispute with the trustees over retention of the Lancastrian method of instruction, which he had been utilizing. The Lancastrian, or "Lancasterian," system was devised by Joseph Lancaster (1778-1838) and has also been called the monitorial method in which more advanced students taught less advanced ones, enabling a small number of adult masters to educate large numbers of students at low cost in basic and often advanced skills. From about 1798 to 1830 it was highly influential, but would be displaced by the "modern" system of grouping students into age groups taught using the lecture method, led by such educators as Horace Mann, and later inspired by the assembly-line methods of Frederick Taylor, although Lancaster's methods continue to be used and rediscovered today. History summarizes Samuel Knox as a dedicated reformer with visionary plans for America’s future, however his downfall lay in the fact that he was also a despotic teacher and unable to bring his grandest schemes to fruition. Ideas of his, such as standardized textbooks, are things that are still with us today. Knox made final waves in early 1828 when he memorialized his trials by submitting to the state legislature an account of the treatment he received from the school's board of trustees with reference to his termination as principal. Knox retired in 1827 and busied himself with local activities such as leadership given to the Frederick County Sunday School Union. In trying to find a retirement home, my assistant Marilyn found that Mrs. Knox bought a property formerly owned by her father and today numbered as 29 East Second Street. Rev. Knox lived in Frederick until his death on August 31st, 1832. He was originally buried in Frederick’s Presbyterian burial ground once located at the southwest corner of N. Bentz Street and Dill Avenue. His wife, Zeruiah died in 1839 and was placed by his side. In September, 1863, both Rev. Samuel and Zeruiah Knox would be re-interred to Mount Olivet in the McCleery family lot, number 374 within Area H. For your reading pleasure, the following letter was written by Rev. Samuel Knox to Thomas Jefferson in November, 1818 while the former was still in the employ of Baltimore College. Baltre College Novr 30th 1818.