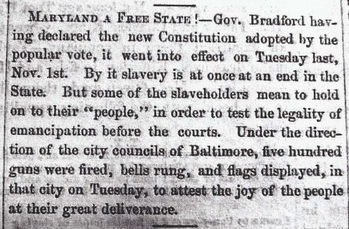

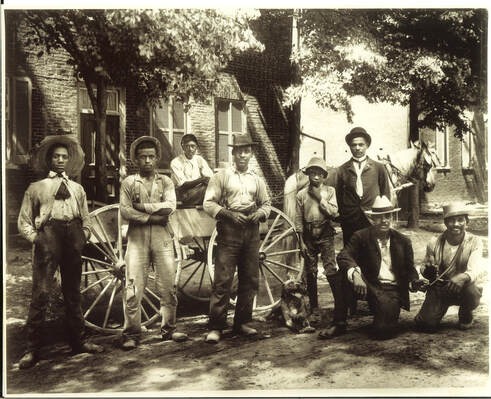

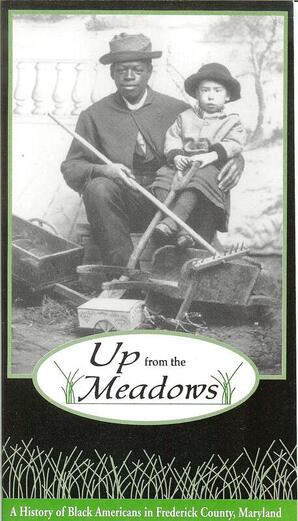

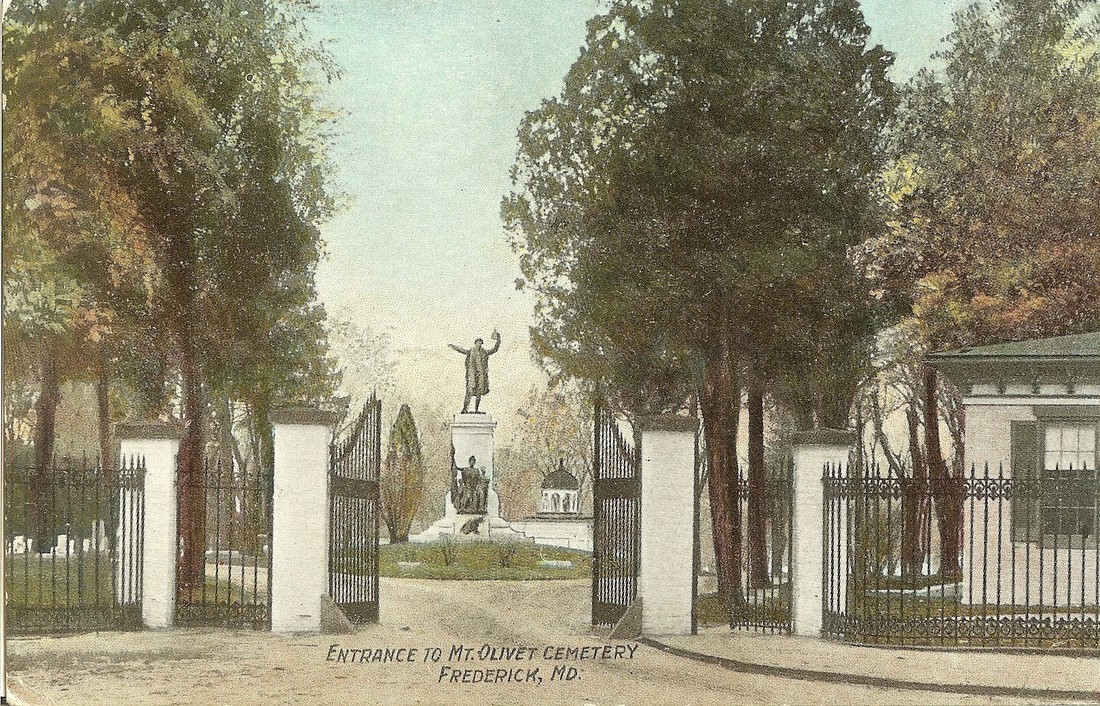

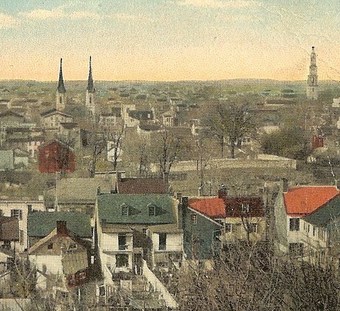

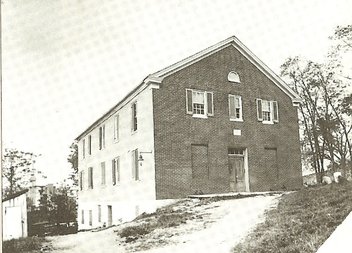

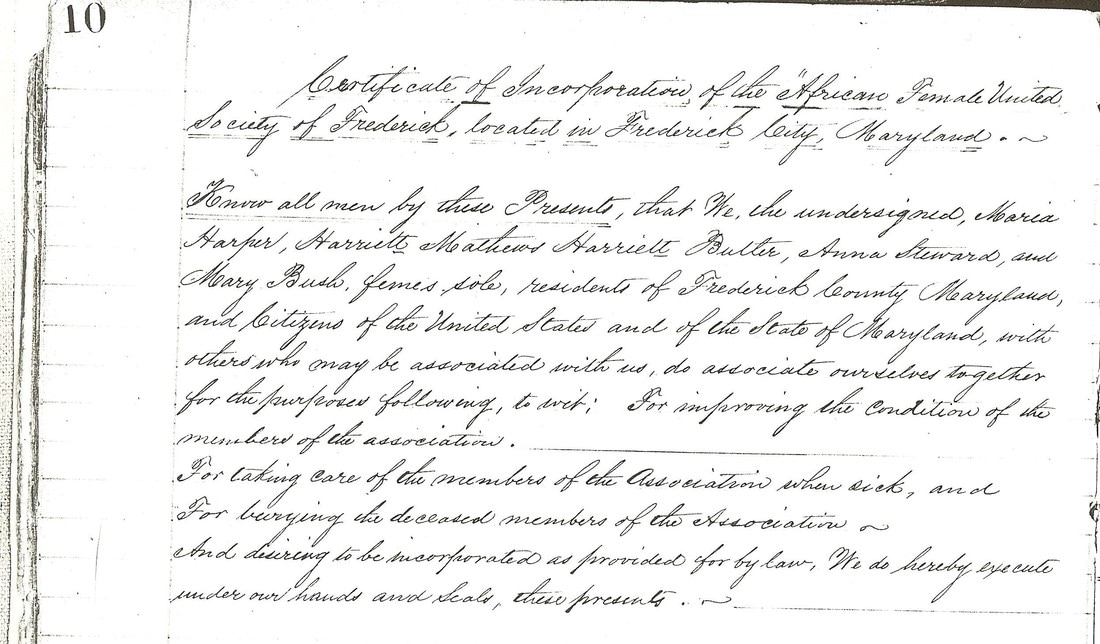

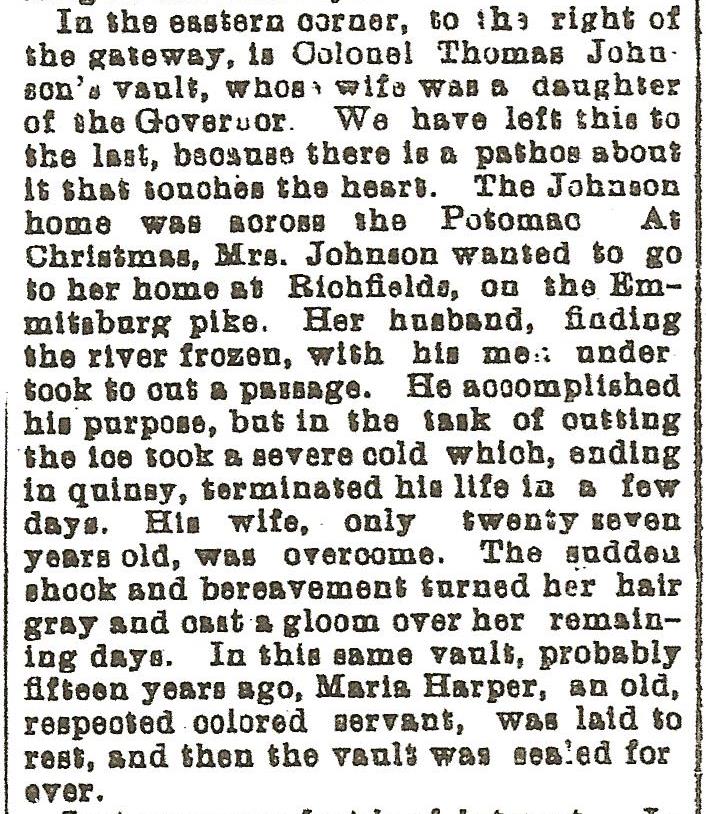

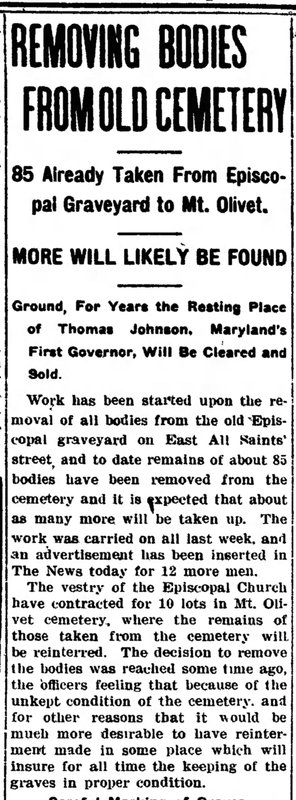

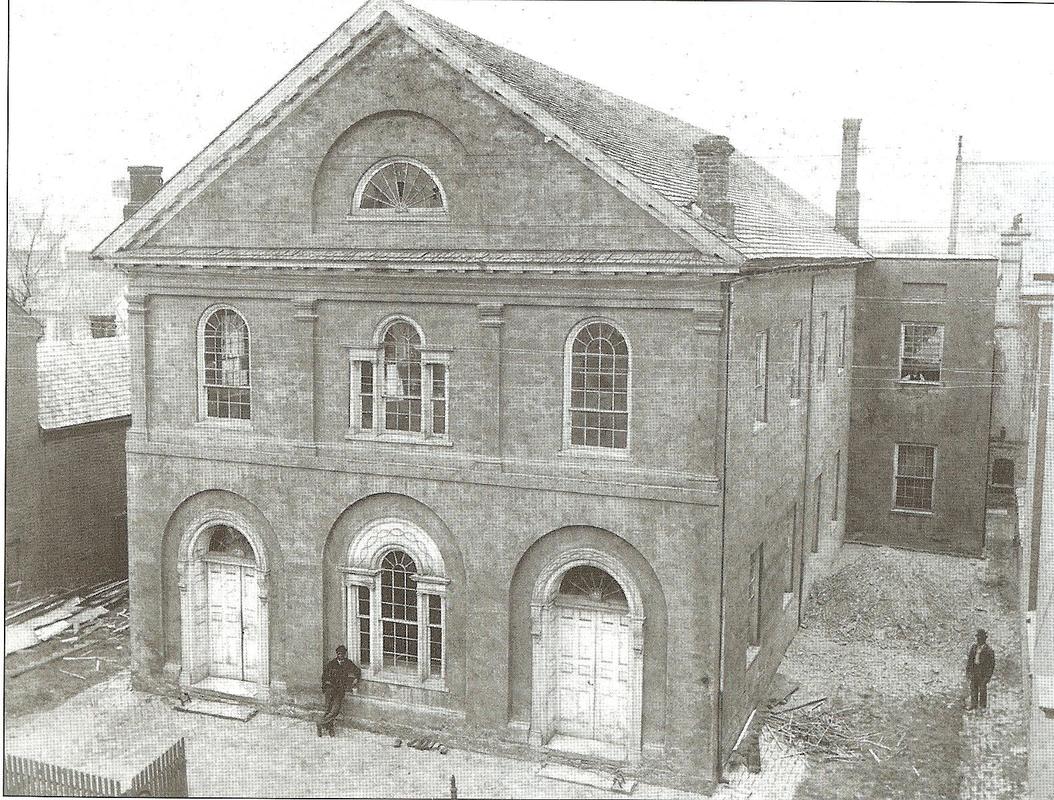

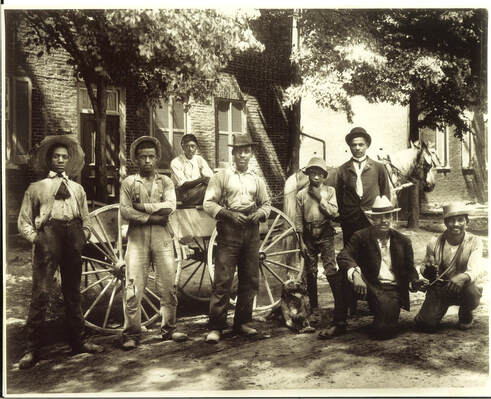

A clipping from the Commonwealth newspaper (Boston, Mass) dated Nov. 5, 1864 A clipping from the Commonwealth newspaper (Boston, Mass) dated Nov. 5, 1864 In honor of both Black History Month and Women’s History Month, I offer a three-part story to bridge February to March. I went in search of the first known burial of a person of color within Mount Olivet. In my research, I came upon three such interesting past residents, all women—and all of whom came into the Mount Olivet Cemetery in unorthodox ways. Of the three, one is the oldest known person of color here. Another was the first to be buried in the cemetery. Finally, the third remaining lady had the most controversial and arduous route ever taken to Mount Olivet, as it would entail a 34-year journey to travel a very short distance. I will share with you the story of one of these ladies this week, and the other two next week. First off, I must provide you with some important context about the times in which these women lived. Mount Olivet Cemetery was dedicated in 1854, ten years prior to the official state sanctioned abolishment of slavery. At this time, the population of Frederick County looked as follows: Total population Slaves/(%) Free Blacks/(%) 1850 40,987 3,913/(10%) 3,243/(7%) 1860 45,591 3,243/(7%) 4,957/(11%) Maryland lawmakers would meet in 1864, with the American Civil War continuing to rage. This was an effort to address, and strengthen, previous principles on how the state was to be governed. Actually, the 1864 Constitution was more so the product of strong Unionists, who had seized control of the state at the time. The document outlawed slavery, disenfranchised Southern sympathizers, and reapportioned the General Assembly based upon the number of white inhabitants. This provision further diminished the power of the small counties where the majority of the state's large former slave population lived. The framers' goal was to reduce the influence of Southern sympathizers, citizens who almost caused the state to secede in 1861. The constitution did emancipate the slaves, but this did not mean equality. The franchise was restricted to white males. Additionally, the Maryland legislature refused to ratify both the 14th Amendment, which conferred citizenship rights on former slaves, and the 15th Amendment, which gave the vote to blacks.  Frederick, county and city, had the unique situation of boasting both free and enslaved blacks living here during the Civil War era. By and large, the northern and north western reaches of the county had fewer instances of slavery due to the original settlement of German peoples in the prior century. These folks generally practiced family operated farms. This was counter-balanced by English/Scots-Irish settlers moving in and settling on the eastern, southern and southwestern areas of the county. Many of these people came from the original 17th century settlements of tidewater/southern Maryland. Slave plantations would take hold in places such as Carrollton Manor, Petersville, Urbana, New Market and Libertytown. As for Frederick City, this was a mixed bag. Household slaves could be found working in small industry and working in homes of wealthy Courthouse Square area English stock families such as the Potts, Murdochs, McPhersons and Tylers. In some instances, upper crust German families can also be found owning slaves. Examples include founding families such as the Getzendanners, Schleys, and Brunners. Even Barbara Fritchie owned slaves—the woman made world famous by the pen of one of the leading abolitionist in the land, John Greenleaf Whittier. The original bylaws and articles of incorporation for Mount Olivet say nothing about excluding burials of blacks within the cemetery. However, there was an unwritten rule of the times here in segregated Frederick. The community, itself, dictated that this not be attempted.  Hosselback Cemetery (Claggett Center, Adamstown) Hosselback Cemetery (Claggett Center, Adamstown) Before emancipation, most slaves were simply buried on the plantations where they lived and labored. Distinct slave cemeteries were prevalent. A surviving burial ground of this kind exists on the grounds of the Claggett Center in Adamstown, just below Buckeystown. Twenty years back, I began my video documentary entitled “Up from the Meadows: A history of Black Americans in Frederick County, Maryland” with video scenes of this humble burying ground, which certainly had more beneath the surface than above. A few field stones were evident, but nothing resembling an official grave marker or tombstones to be found. This is the site of the Hosselboch family cemetery, with provisions for at least two known family-owned slaves. The larger plantation would eventually turn into the Buckingham Industrial School for Boys, a boarding school for white youth, operated by the Baker brothers.  Ceres Bethel AME burying ground near Burkittsville. Ceres Bethel AME burying ground near Burkittsville. A more pronounced “slave cemetery” in Frederick County can be found in north county at Catoctin Furnace, below Thurmont. A roadway project associated with US 15 construction unearthed a cemetery containing nearly 35 souls associated with the iron furnace that began in the colonial era under the ownership of Thomas and James Johnson. Archeological study by the Smithsonian Institute on the remains is ongoing as the managing entity of the project is the Catoctin Furnace Historical Society. There were many other private slave and farm cemeteries across the county, most lost forever to residential and business development. Fortunately, we have several surviving black cemeteries that started to appear in post-emancipation communities and enclaves. These are most commonly located adjacent early rural Black churches such as Hope Hill, Sunnyside, Oldfields, Silver Hill and Ebenezer. Here you will find former slaves buried alongside freedmen. Luckily, community interest and activism has kept many of these burying grounds in satisfactory and respectable condition, especially in the light of longtime burial inactivity and the discontinuation of churches. However, just as many of these need help and protection. As for the smaller towns of the county, separate black cemeteries exist in places such as Middletown, Brunswick, New Market and Libertytown. More times than not, these cemeteries are/were associated with nearby black religious congregations. In other cases, blacks could be found worshipping in traditional white congregations, thus allowing for potential burial in those respective cemeteries. This usually took place in a designated “colored subsection” within a larger cemetery. Examples include Catholic cemeteries such as St. Mary’s in Petersville, St. Anthony’s (atop Catoctin Mountain behind Mount St. Mary’s College in Emmitsburg), St. Timothy’s in Libertytown, St. Joseph’s on Carrollton Manor near Buckeystown, and St. John’s Catholic Cemetery in downtown Frederick.  Amos Tecumseh "Tup" Lucas Amos Tecumseh "Tup" Lucas Back in 1996, an old mentor of mine, Marie Erickson, pointed out to me the grave of Amos ”Tecumseh” Lucas (1848-1917) in Thurmont’s Weller United Brethren, (now United Methodist) Church cemetery. Lucas was well-known by his nickname of “Tup” and served as a tonsorial expert (barber). He practiced his trade in Thurmont for nearly 40 years. The former slave came to town after the Civil War, from Lovettsville in Loudoun County, (VA) with Dr. J.J. Hanshew. He was the only self-proclaimed man of color to live in the Mechanicstown District for nearly 30 years, and serves as an overwhelming minority within the cemetery. "Tup" Lucas was buried in the Hanshew family lot upon his death in 1917. One other black individual, Ms. Helen Hammond, a popular camp counselor on the mountain, would also have Weller UM cemetery as a final resting place in 1977. In Frederick City, four cemeteries were utilized as exclusive burying grounds for black residents. In eras of slavery and segregation, beneficial societies also formed in order to provide burial opportunities for persons of color. The oldest known burying ground for blacks in Frederick City was the All Saints' Church Cemetery, once located on the northern slope of the "Old Hill," between Carroll Creek and East All Saints Street. Today, the Maxwell Place Condominiums occupy the former burial site, and the hill is virtually gone at this site, however can be found again with the creek amphitheater area just to the east. This locale was the original site of the All Saints' Protestant Episcopal Church structure. Many of the leading members of town (along with their slaves) worshipped, and were buried, here. Graves would eventually surround the original church structure. When the All Saints' congregation moved out in the early 1800’s (to locate closer to the Courthouse Square area), a new worship place for blacks and whites was constructed just west of the former location. This became known as the "Old Hill Church.” It sometimes gets confused for the original All Saints' church building, however, that structure was dismantled around 1813 with elements being used for a new home for the All Saint's parishioners on Court Street. Over time, the "Old Hill" congregation eventually came under total black leadership and evolved into Asbury Methodist Episcopal Church (around 1870). Adjacent the church, was a ground lot that contained earlier burials of slaves which had been placed outside the brick-walled All Saints' Cemetery. These dated to the 1700's. When the All Saints' congregation left, free blacks and others began being buried here and around the Old Hill Church structure. By the 1860’s, most burial activity had ceased at the white East All Saints' burying ground. The new Mount Olivet “garden design” Cemetery provided a welcome alternative for All Saints’ white parishioners. Almost immediately, families of means bought lots at Mount Olivet, and had loved ones reinterred—dug up, moved, and reburied. The All Saints' Cemetery started its steady descent, as did other congregational graveyards located downtown. The Old Hill burial situation would also be impacted at this time by the creation of two, new cemeteries, started by local black beneficial groups in the mid to late 1800’s. As for the "Old Hill" church, the Asbury ME congregation purchased land in 1912 at the northwest corner of West All Saint’s and Brewer’s Alley. Here is where they would build their new house of worship (which opened in 1922). In 1913, the All Saints' and Asbury ME trustees put their neighboring properties up for sale, as this was highly coveted real estate. Bodies of the dead had to be moved elsewhere. One such was a former slave and later emancipated woman. Her name was Mrs. Maria Harper. Maria Harper was no stranger to funerals and cemeteries during her lifetime as she was one of the five founding members of the “African Female United Society of Frederick,” known to many as simply "the Mothers." Incorporated in 1868, the aim of this benevolent association was to “take care of the members of the Association when sick, and for burying the deceased members of the Association.”  Furnace Mountain in Loudoun County (VA) as seen from Point of Rocks atop Catoctin Mountain. The Johnson-owned furnace was in this vicinity. Furnace Mountain in Loudoun County (VA) as seen from Point of Rocks atop Catoctin Mountain. The Johnson-owned furnace was in this vicinity. Mrs. Harper’s own burial took place in All Saints' Cemetery on October 3rd, 1884. She had been placed in one of six vaults that resided on the grounds. Her supposed “final resting place” would be the crypt associated with Col. Thomas James Johnson (1777-1815), son of Col. James Johnson of Springfield Manor near Lewistown (and the original furnace master of Catoctin Furnace). This would make Thomas James Johnson the nephew of Frederick’s favorite son, Gov. Thomas Johnson, Jr. Interestingly, our vault owner would also refer to Maryland’s first governor as not only an uncle, but also his father-in-law because he had married TJ’s daughter Rebecca Johnson. Let’s not judge here as this kind of thing happened regularly in those days. Plus it had its benefits such as making family holidays more manageable, not to mention the hassles associated with legal name change, etc.—but I digress. The couple of Col. Thomas James and Rebecca Johnson lived on the Loudoun County shore of the Potomac, operating the Bush Creek Forge, directly across from Point of Rocks. Entitled Ancient “God’s Acre,” a local newspaper article about the All Saints' Cemetery appeared back in November of 1894, and reported Maria Harper’s placement within the Col. Thomas James Johnson vault, after which it was “sealed forever.” (An excerpt of that article appears below) Apparently, forever would be short-lived (pardon my pun), as the tomb would be re-opened in the fall of 1913. At this time, 324 bodies in the All Saints' burying ground were in the process of being removed by the Vestry of All Saints'. They were destined for Mount Olivet, where the All Saints' vestry had purchased multiple lots within Area MM for reburial. Unfortunately, due to earlier vandalism of tombstones, coupled with the problem of missing or incomplete records, only 70 bodies could be properly identified. In addition, individuals placed within family crypts had become co-mingled, in some cases vandals were to blame. As a result, all members of the Johnson family, along with Maria Harper, were re-interred together within a new, large vault at Mount Olivet. This crypt lays underground and directly in front of the large Gov. Thomas Johnson, Jr. monument, and adjacent tombstones of Col. James Johnson and wife Margaret (to the right of the monument). Thankfully a careful documenting of the All Saints' Cemetery was performed by the congregation’s Ernest Helfenstein before the reburial process commenced back in 1913. He was able to record the contents of a number of tombstones, many of which were broken and required Helfenstein to piece together sections in an effort to decipher the information. One of the stones captured at that time belonged to Maria Harper and read as follows: Maria Harper Born Dec 23, 1806 Died Oct 1st, 1884 Aged 77 years 9 months And 8 days Only about 10 headstones were re-erected in Area MM at Mount Olivet along with associated known bodies. Most of the remains were reburied in a mass grave. This mound area lies a few yards beyond the Gov. Thomas Johnson monument. The balance of the tombstones from All Saints' were said to have been buried along with the remains, here. The cemetery apparently objected to the deteriorated condition of these stones, and required them below, and not above, ground—out of public view. Unfortunately, Maria Harper’s monument was one of these.

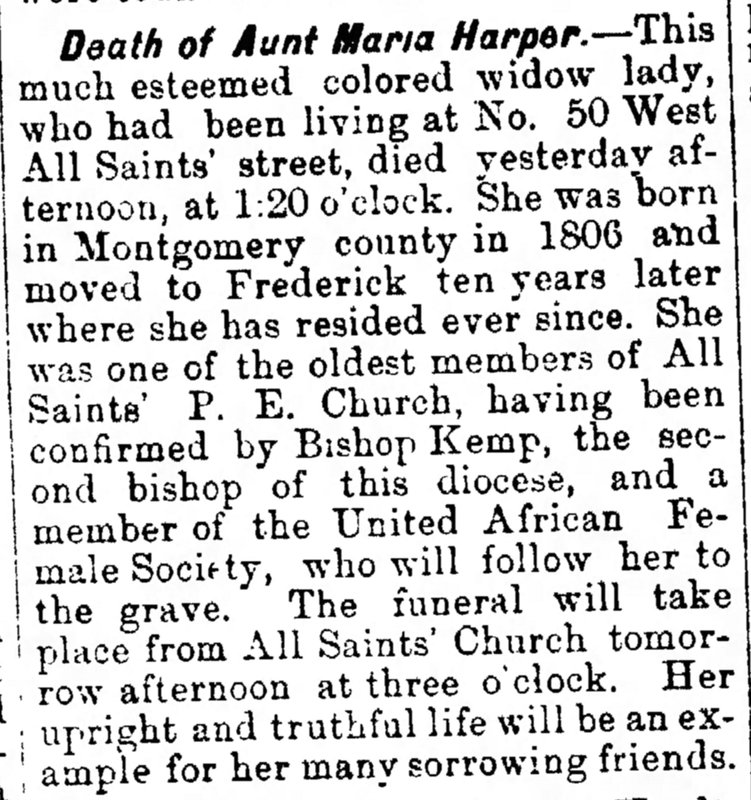

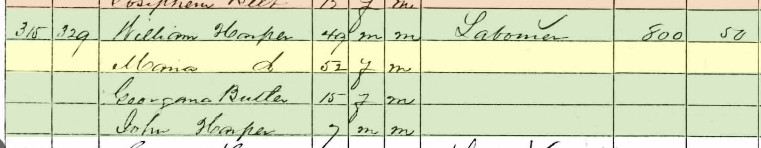

Mrs. Harper’s death was quite noteworthy at the time. Her obituary, and other related articles affectionately refer to her as “Aunt Maria.” At the time of her death, Maria resided at 50 West All Saints Street. She was listed as a “wash woman” in the 1870 census and was noted in her obituary as being one of the oldest members of the All Saints' Protestant Episcopal congregation. It seems that she was beloved by Frederick residents, both black and white.  Anne Grahame (McPherson) Ross (1827-1896) Anne Grahame (McPherson) Ross (1827-1896) The executrix of Mrs. Harper’s estate was Anne Grahame Ross, a luminary from Frederick’s past. Mrs. Ross was the wife of Worthington Ross and lived on Record Street. She had grown up in the Courthouse Square area on adjacent Council Street in the large mansion built by her paternal grandfather, Col. John McPherson. Mrs. Ross’ father, Col. John McPherson II, had married Frances “Fannie” Johnson, granddaughter of Gov. Thomas Johnson, Jr. To come full circle, Fannie’s father was Thomas Jennings Johnson, an older brother to Rebecca Johnson, whom I introduced you to earlier as the wife of Col. Thomas James Johnson—namesake for the funerary vault that Maria Harper was originally buried within. The best I could glean with researching local papers and census records is that Maria was classified as a mulatto, and had married William Harper, three years her junior. This appears in the 1860 census. The All Saints’ archives report this gentleman as Wilson Harper, and records show that the couple was married by Rev. Joshua Peterkin on March 18th, 1847. Within the 1860 census, Maria and William(Wilson) are living in Frederick City with 15-year old Georgeanna Butler and 7-year old son John Harper. By the next census in 1870, Maria appears as a widowed head of household, living with 16-year old son John Harper and 72-year old Alice Fowler. The All Saints' archives show that Maria had been a member of the congregation since 1816, and was actually married twice within the church. She had originally come to Frederick from Montgomery County in the year 1816 as Maria Waters. The ten year-old was a slave, the property of Rebecca Johnson. You may recall that Rebecca’s husband had tragically passed the previous year in 1815, leaving her with three small children. It’s likely that young Maria could have worshipped from the East Gallery of All Saints’ Church's second home, built on Court Street. She also may have participated in the congregations’ “Colored Sabbath School” as well. Maria Waters would marry the first time in February, 1832. Her first husband’s name was Robert Smith, and it is thought that the couple lived in Loudoun County with the Rebecca Johnson family.  McPherson-Ross Mansion (c. 1936) on Frederick's Council Street across from the current-day Frederick City Hall. McPherson-Ross Mansion (c. 1936) on Frederick's Council Street across from the current-day Frederick City Hall. Upon Rebecca Johnson’s death, Maria would return to Frederick in 1837, likely sans Robert Smith, who may have died. I venture to guess that she became the property of the McPherson family, but I have no concrete proof other than the 1840 census shows that the McPhersons had three female slaves living with them at the time, and Maria fits the age range perfectly. Maybe she was brought in to serve as a nanny to Ann Grahame McPherson, who would have been 10-years old in 1837? Maria remarried in 1847, as Miss McPherson turned 20. Was husband William(Wilson) Harper a slave of the McPhersons as well? I bring this up only due to the existence of a female slave named Ruthie Harper in the McPherson family. (She was written about by legendary Underground Railroad conductor William Still, having escaped slavery and Mr. McPherson in 1858. ) Anne Grahame McPherson would marry Worthington Ross in January, 1850. I assume Maria must have had an equally strong relationship with Anne’s aunt, Rebecca Johnson. This all can explain the indelible bond between these women, with major differences reflected by age and race. It would also give credence to the “Aunt Maria” moniker, not to mention the tremendous clout needed to have a former slave buried within the white All Saints' Cemetery and the prominent Johnson family crypt of her former owner. And to think, for over the past 100 years, Maria's remains reside alongside Gov. Thomas Johnson, Jr. within the same vault. Whatever the case, I pronounce that Maria Waters Harper is most likely the oldest/earliest born black resident of Mount Olivet Cemetery—but I need to caution that she wasn’t the first.  History Shark Productions Presents: "UP FROM THE MEADOWS: The Class" Are you interested in learning more about the incredible African-American heritage story of Frederick City and Frederick County, Maryland? Check out this author's latest, in-person, course offering: Chris Haugh's "Up From the Meadows: The Class" as a 4-part/week course on Tuesday evenings starting March 12th, 2024 (March 12, 19, 26 and April 2). These will take place from 6-8:00pm at Mount Olivet Cemetery's Key Chapel. Cost is $79 (includes all 4 classes). For more info and course registration, click the button below!

4 Comments

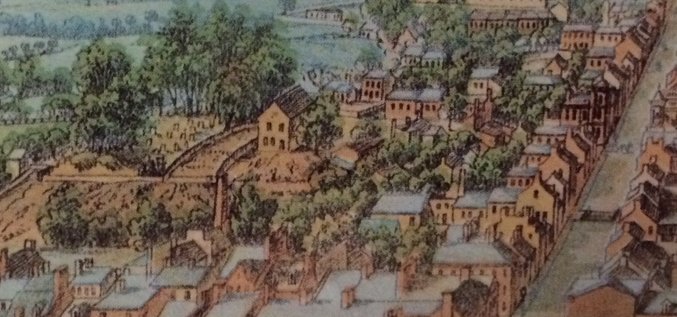

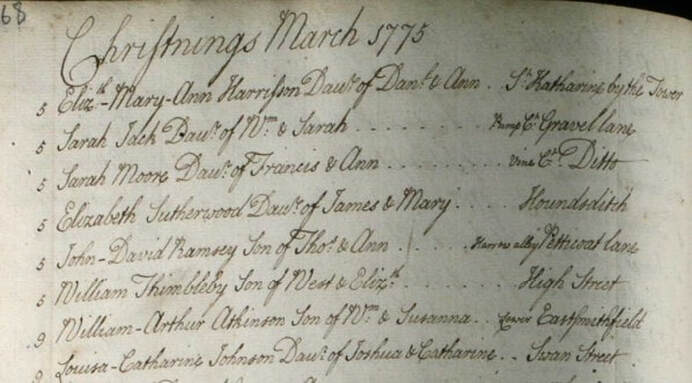

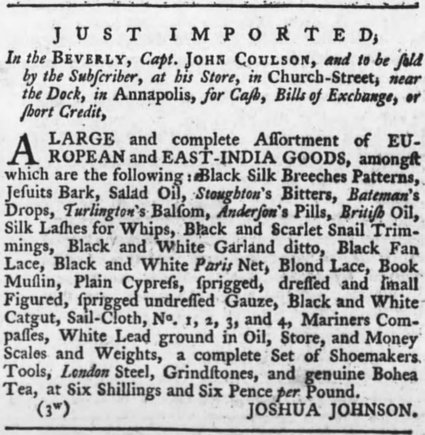

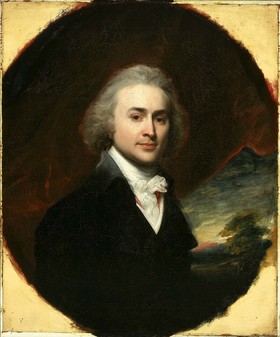

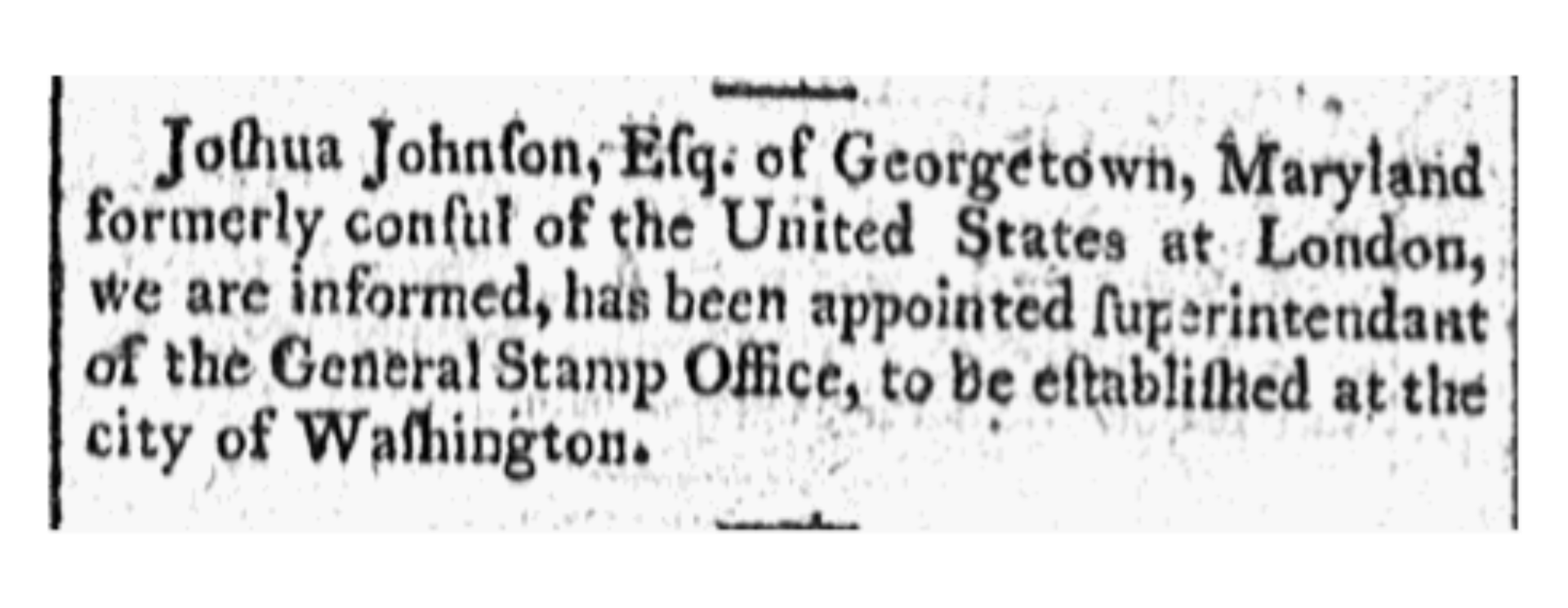

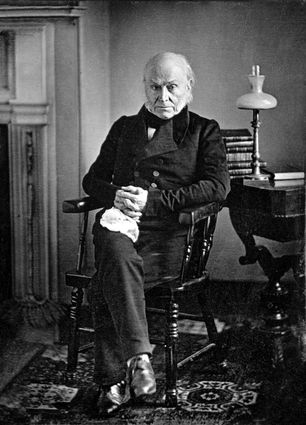

Thomas Johnson, Jr. (1732-1819) Thomas Johnson, Jr. (1732-1819) You won’t find a gravestone or monument. No interpretive wayside panel or mention in a brochure. Not even a portrait or likeness can be found. Regardless, Mount Olivet is the final resting place for a gentleman who personally knew several of our founding fathers and early US presidents. As a matter of fact, he was even a father-in-law to one of them. Joshua Johnson was born on June 25, 1742 at his father’s plantation located on St. Leonard’s Creek and the Patuxent River in southwestern Calvert County (Maryland). His parents were Dorcas and Thomas Johnson, Sr., the latter a name that may sound a little familiar to Frederick residents. Joshua was one of 10 children, half of which are buried in Mount Olivet. His brother, Thomas Johnson, Jr., holds the distinction of not only having a local high school named after him, but was Maryland’s first elected governor. A member of the Continental Congress, Thomas Johnson, Jr. should have been a signer of the Declaration of Independence, however he was back home in Maryland raising troops and supplies for the war effort, or so the story goes. Joshua’s elder brother did plenty of great stuff and boasts a pretty impressive resume that also includes starting the Catoctin Iron Furnace, supervising the building of the Hessian Barracks, leading Maryland troops into battle during the Revolutionary War, laying out Washington, DC, and serving as one of the country’s first Supreme Court justices.  Joshua Johnson Joshua Johnson Joshua Johnson was certainly no slouch himself. By the age of 25, he had firmly established himself as one of the leading merchants of Annapolis. Four years later, he entered into a partnership with two other men to establish Wallace, Davidson and Johnson, the first American tobacco firm to operate independently of British middlemen. He would also play a role in expanding the tobacco trade to France, in turn, marketing French goods to the colonies in the waning years of the American Revolution. Joshua Johnson had gone to London in 1771. While there, he met Catherine Nuth and apparently married the teenage Englishwoman in 1772. Or at least we think so, as existing documentation shows that the two did not officially marry until 1785. Whatever the case, Johnson and his young bride were blessed with a daughter named Anne in January, 1773—the first of nine children. Another daughter named Louisa Catherine would be born two years later in February, 1775. After the birth of a third child, named Carolina Virginia Maryland, Joshua felt it was in his family’s best interest to leave Great Britain. It was 1778, and the three namesakes for his recently-born daughter, along with ten other American colonies, were entrenched in war against the mother country. The Johnsons went to France, and would make their home in the port city of Nantes.  John Adams John Adams While here, the Johnsons lived quite well. They entertained many Americans, including leading merchants, expatriates, allies and diplomats. One such guest to visit the Johnson household was the famed John Adams of Massachusetts. Adams had served on the Continental Congress with Joshua’s brother, Thomas. As a diplomat in Europe, he would help negotiate the eventual peace treaty with Great Britain and acquired vital governmental loans from bankers in Amsterdam (Holland). Adams was accompanied on his European journey by his son, then-twelve year old John Quincy. This was the first encounter between children who would be future “man and wife,” as John Quincy Adams would marry Joshua’s daughter Louisa.  Thomas Jefferson Thomas Jefferson Following the American Revolution, Joshua Johnson and his family went back to London, where he again took up the merchant profession. As the colonies would further evolve into the United States under the guidance of the Constitution, Johnson would receive an important correspondence written in late summer, 1790. It came from his home country’s first Secretary of State, Thomas Jefferson, writing on behalf of George Washington from the new nation’s capital of New York: August 7th, 1790 Sir, The President of the United States, desirous of availing his country of the talents of it’s best citizens in their respective lines, has thought proper to nominate you Consul for the U.S. at the port of London. The extent of our commercial and political connections with that country marks the importance of the trust he confides to you, and the more as we have no diplomatic character at that court. I shall say more to you in a future letter on the extent of the Consular functions, which are in general to be confined to the superintendance and patronage of commerce, and navigation; but in your position we must desire somewhat more. Political intelligence from that country is interesting to us in a high degree. We must therefore ask you to furnish us with this as far as you shall be able; to send us moreover the gazette of the court, Woodfall’s parliamentary paper, Debrett’s parliamentary register: to serve sometimes as a center for our correspondencies [with] other parts of Europe, by receiving and forwarding letters sent to your care. It is desireable that we be annually informed of the extent to which the British fisheries are carried on within each year, stating the number and tonnage of the vessels and the number of men employed in the respective fisheries: to-wit the Northern, and Southern whale fisheries, and the Cod-fishery. I have as yet no statement of them for the year 1789. With which therefore I will thank you to begin.—While the press of seamen continues, our seamen in ports nearer to you than to Liverpool (where Mr. Maury is Consul) will need your protection. The liberation of those impressed should be desired of the proper authority, with due firmness, yet always in temperate and respectful terms, in which way indeed all applications to government should be made. The public papers herein desired may come regularly once a month by the British packet, and intermediately by any vessels bound directly either to Philadelphia or New York. All expences incurred for papers, and postages shall be paid at such intervals as you chuse either here on your order, or by bill on London whenever you transmit to me an account. There was a bill brought into the legislature for the establishment of some regulations in the Consular offices: but it is postponed to the next session. That bill proposed some particular fees for particular services. They were however so small as to be no object. As there will be little or no legal emolument annexed to the office of Consul, it is of course not expected that it shall render any expence incumbent on him. I have the honor to be with great esteem, Sir Your most obedient & most humble servant, Thomas Jefferson [Original source: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 17, 6 July–3 November 1790, ed. Julian P. Boyd. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1965, pp. 119–120.] Joshua Johnson would hold the post of US consul to London from 1790-1797. Life seemed to be very good to Joshua until 1796. It was at this time that he would experience a series of professional and personal “ups and downs.” His daughter Louisa had become recently re-acquainted with an old family friend—John Quincy Adams. The son of John Adams, current sitting vice-president under George Washington, John Quincy was serving as a US diplomat to the Netherlands, often going back and forth between the Hague (Netherlands) and Great Britain. He proposed to Louisa and the couple duly married in London in July, 1797. Though John Quincy Adams wanted to return to private life back home in Massachusetts at the end of his appointment, President Washington had made him minister to Portugal in 1796, where he was soon appointed to the Berlin Legation. Though his talents were far greater than his desire to serve, he was finally convinced to remain in public service when he learned how highly Washington thought of his abilities. Washington called Adams "the most valuable of America's officials abroad.”  February 21, 1797 ad in the Sentinel of Liberty (Georgetown, District of Columbia) February 21, 1797 ad in the Sentinel of Liberty (Georgetown, District of Columbia) On the eve of his daughter’s marriage, Joshua Johnson’s business failed. He had lost a large East India Company trading ship at sea, plunging him into financial disaster. The proud Marylander found himself in the embarrassing situation of owing heavy debts, not to mention not having the ability to provide the dowry promised his new son-in -law, a rising star on the world stage. Add to this the fact that his daughter’s new father-in-law won the US presidential election of 1796, and would become the country’s second president in 1797. While the Adams family may have found it necessary to work to improve Joshua’s image, daughter Louisa adored her father and was proud of him. Amanda Mathews Norton of the Massachusetts Historical Society wrote: “Louisa entered marriage with the anxiety and shame that her husband and others would think that she and her father had conned John Quincy into marrying her with false promises; it was a sensitivity that never went away. But for Louisa, her father had been entirely blameless, and this belief she also carried throughout her life. Fortune was unkind. His partners had cheated him.”  Joshua Johnson (a miniature from the NPS' Adams collection) Joshua Johnson (a miniature from the NPS' Adams collection) The best option for Joshua Johnson at this time was to resign his post as consul and return to his native home. He moved to Georgetown within the confines of the District of Columbia, the new national capital. He had the support of his brother Thomas and others from nearby Maryland, along with his new family thanks to daughter Louisa. President John Adams appointed Joshua Superintendent of Stamps, the overseer of the US General Stamp Office. Some citizens and politicians saw this as a form of nepotism, harboring distrust and dislike of Johnson who they thought had taken the easy way out during the American Revolution. After all, Joshua had made a fortune trading with the enemy (Great Britain), married an English woman and lived the high-life in Europe while others put their lives, and fortunes, on the line during the “great revolution.” He seems to have had an awkward relationship with Thomas Jefferson, the man who wrote to offer him the US consul position a decade earlier. In 1800, it was Jefferson, then sitting Vice President, who cast the deciding vote in Congress to break a tie vote, thus renewing Johnson’s appointment as Superintendent of Stamps. One year later, Jefferson would hastily dismiss Johnson of this position. Some claim that this fall-out-of-favor was the catalyst for Johnson’s severe depression and subsequent death the following year at the age of 60. Suffering from a severe fever, Joshua Johnson died on April 17th, 1802 while here in Frederick.  Birdseye view south of the Old All Saint's Church burying ground as it appears to the left of this inset from the Sachse 1854 lithograph image of Frederick. The Johnson crypt was said to have been on the eastern (left) side of the colonial era cemetery once located near the present site of the Carroll Creek amphitheater. (Note Market Street on right side of image.) Joshua Johnson would be laid to rest in the burying ground of All Saints Episcopal Church, adjacent Carroll Creek and East All Saints Street. In 1913, the Vestry of All Saints Church would reinter bodies from this cemetery to Mount Olivet Cemetery. The co-mingled contents of the larger Johnson family crypt would be buried within a vault that now lies in the cemetery’s Area MM, under the large memorial monument placed to honor Thomas Johnson, Jr. Unfortunately, Joshua’s sudden passing left little provisions for his family. His wife Catherine died in her mid-fifties, less than a decade later in 1811. She is buried in Rock Creek Cemetery, located in northwest Washington, DC. Joshua would not have the chance to witness his daughter Louisa faithfully assist husband John Quincy in the decades following his death. Back in America, Louisa’s husband entered congressional politics, elected as a US Senator for Massachusetts. After a few terms, the Adams’ would return to Europe in 1809 as John Quincy would fulfill duties as the first US minister to Russia, followed by an appointment as envoy to Great Britain. John Quincy (and Louisa) came back to the United States after being appointed to the position of Secretary of State in 1817 under President James Monroe. He held this position until 1825, when he was elected as the 6th President of the United States. In doing so, Joshua Johnson’s daughter became the first-lady of the nation. At age 65, Louisa Adams wrote her memoirs entitled “Adventures of a Nobody”—she was the “first” first-lady to do such a thing. The following passage from Joshua Johnson’s well-known daughter seems a most fitting tribute to a man of worldly experience and family values—yet forgotten to time.

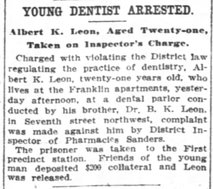

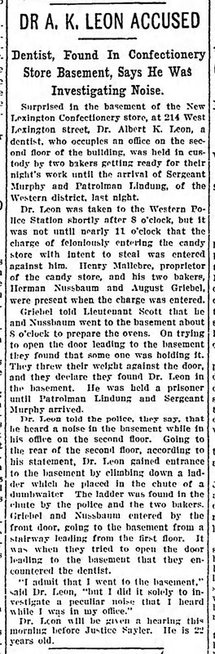

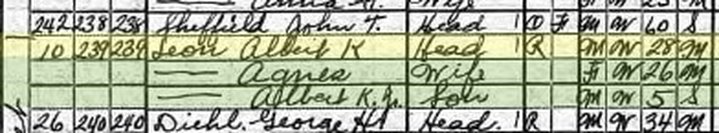

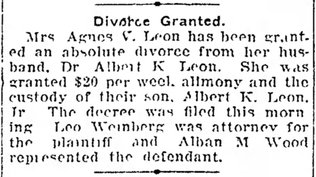

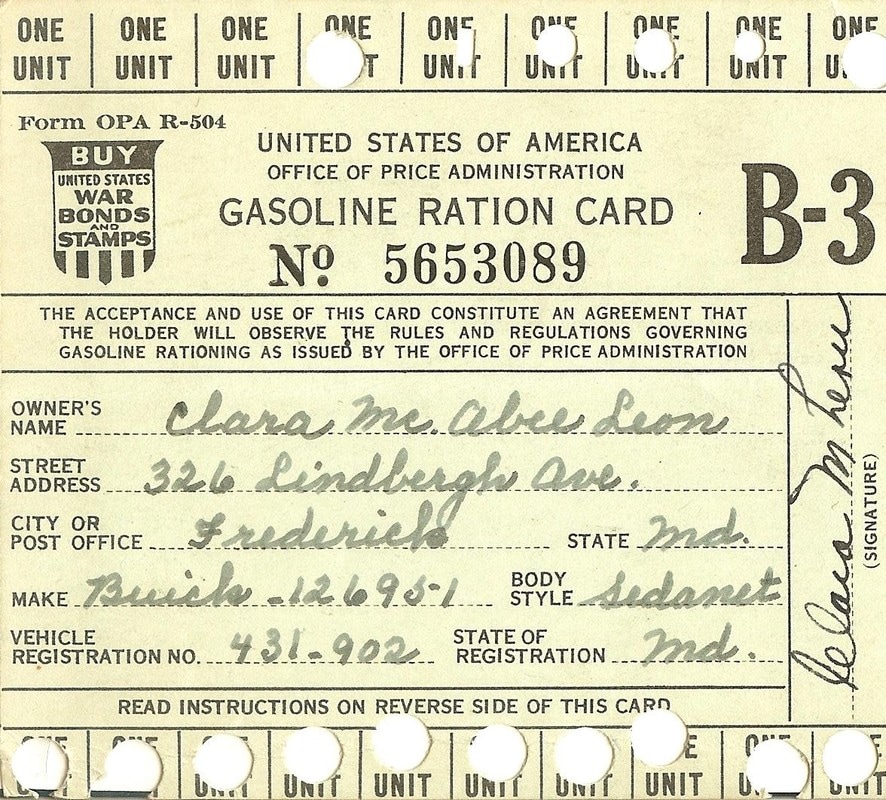

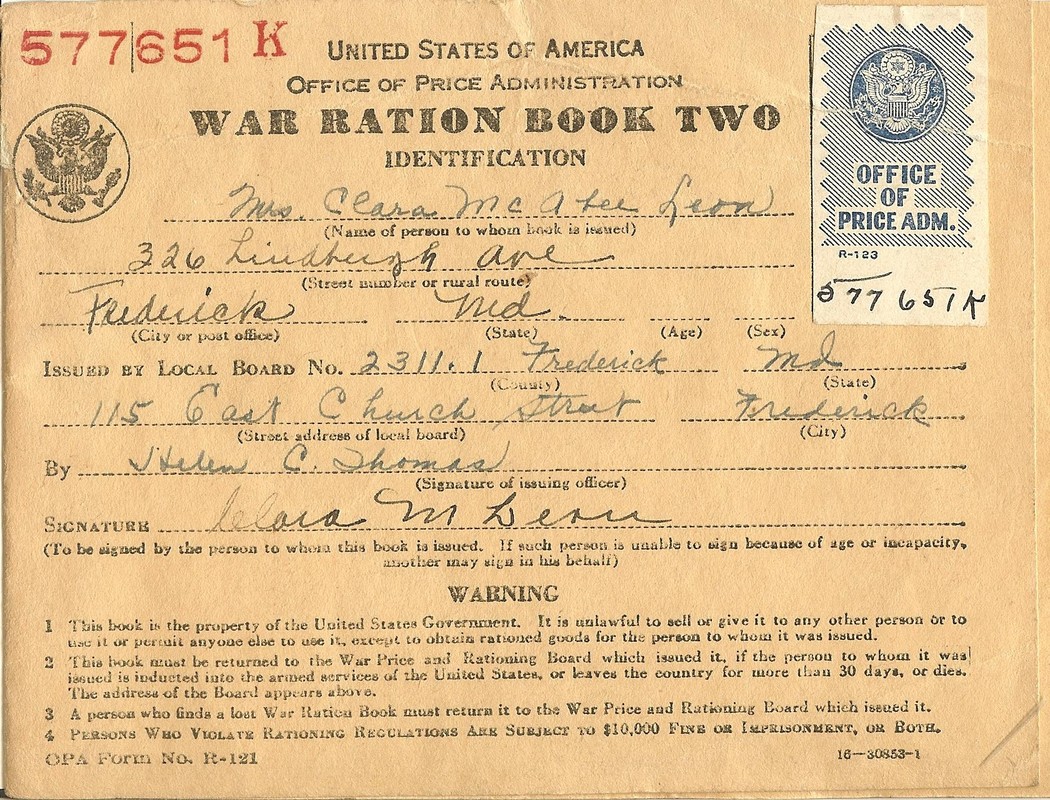

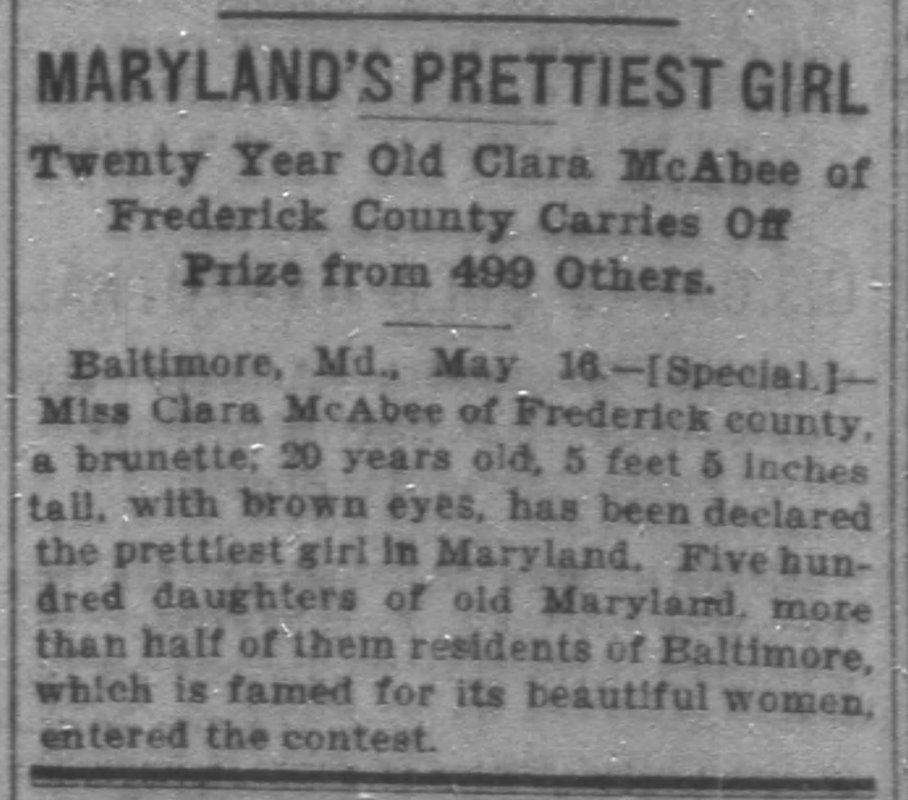

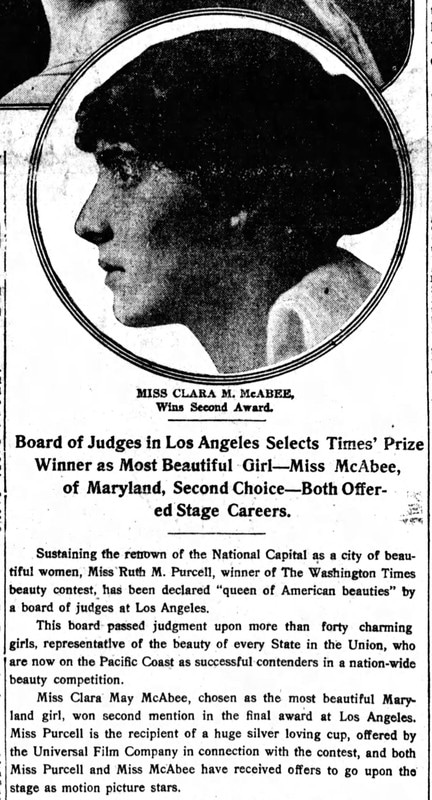

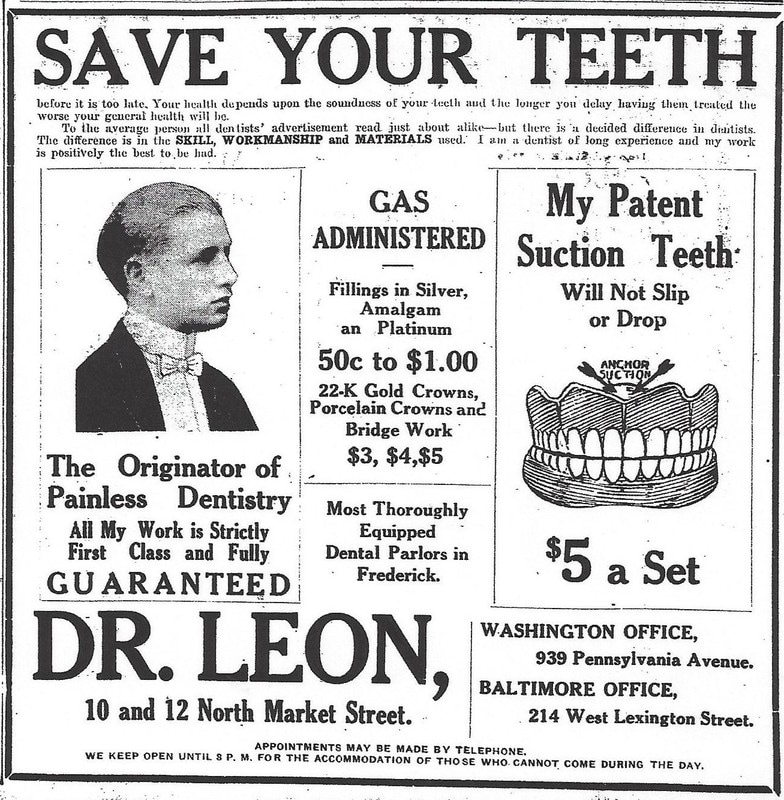

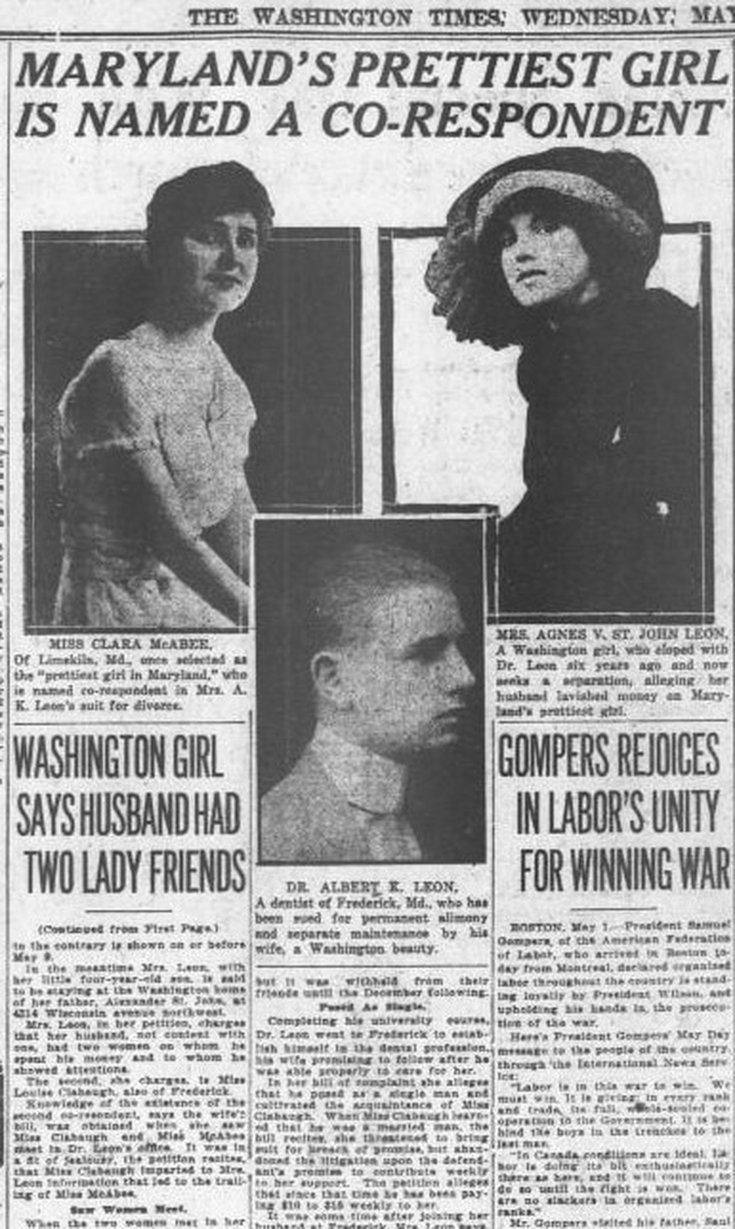

“The qualities of the heart and of the mind, excited a higher aim; and a romantic idea of excellence, the model of which seemed practically to exist before my eyes, in the hourly exhibition of every virtue in my almost idolized Father; had produced an almost mad ambition to be like him; and though fortune has blasted his fair fame; and evil report has assailed his reputation; still while I live I will do honour to his name, and speak of his merit with the honoured love and respect which it deserved—As long as he lived to protect them, his Children were virtuous and happy—amidst poverty and persecution.” Louisa Johnson Adams  William J. Grove (1854-1937) William J. Grove (1854-1937) It was about 25 years ago when I stumbled upon a certain yellowed publication within the boundless stacks of the Wonder Book & Video Store. It was the History of Carrollton Manor written by William Jarboe Grove in 1922. I had a tough time figuring out what it was in rough shape and devoid of a cover, held together by just a few rusty staples. As I flipped through the nearly 300 pages, I instantly became mesmerized by this history of southern Frederick County, as told by a lifelong resident. William J. Grove wrote this book while in his late sixties, colorfully recounting stories related to his childhood memories of events and neighbors on the manor. Included were stories relating to farming, industry and the Civil War. The Grove family were quite prominent during the late 19th century, as William’s father, Manassas Grove was a successful industrialist. The elder Grove was responsible for the quaint hamlet of Lime Kiln, aptly named after the booming lime production operation he created. Son William would carry on management after his father’s death, and stayed quite active in Frederick affairs and politics. Sufficed to say, I bought this tattered book and was excited to start exploring a part of the county I hadn’t known much about. It still remains my personal favorite Frederick history book. One of the “Carrollton Manor characters” introduced to readers is Clara McAbee—proclaimed as “Maryland’s prettiest girl.” The short passage on her by Mr. Grove reads as follows: May 17, 1915, Lime Kiln loomed up through the United States when Miss Clara May McAbee was selected as the prettiest girl in Maryland, and was given a trip to California where she entered the nationwide beauty contest, and there came out second after a close contest. In a letter written May 18th, 1915, by William J. Grove to the Baltimore News, he says: “The beauty contest put the little village of Lime Kiln, Frederick County, on the map, nestled as it is on historic ground, Carrolton Manor, once owned by Charles Carroll of Carrollton, the signer of the Declaration of Independence. Why should not this beautiful girl win out, surrounded by the beauties of this old historic manor and softened by southern breezes from the Potomac?” S.C. Malone, the leading fine art engraver of America says of Miss McAbee, “I am frank to admit as an artist of international reputation that she is indeed beautiful in every sense of the word. It seems as if Mother Nature has enveloped her in all the patriotic panorama that has made the natural scenery of Frederick County famous.”  Former residence of Clara McAbee Leon located at 326 Lindbergh Avenue, Frederick, MD Former residence of Clara McAbee Leon located at 326 Lindbergh Avenue, Frederick, MD About five years after buying this book, I found myself pecking around an antique store in Emmitsburg, busily looking for local history collectibles. I soon came upon some World-War II era ration books from Frederick. I did a double-take when I read the name of the owner of these items—Clara McAbee Leon. It took me a minute to conjure up Clara McAbee, “the prettiest girl” I had read about back in Mr. Grove’s book years before. Examining these documents, I discovered Clara’s married name of Leon, and a residential address of 326 Lindbergh Avenue, located in the College/Baker Park area northwest of Downtown Frederick. She was in her late forties at this time. Twenty more years go by, and I now find myself in the employ of Mount Olivet Cemetery, writing weekly blog posts on interesting inhabitants of the cemetery. A few months ago, I consulted The History of Carrollton Manor while helping a cemetery patron conducting family research. The first page I opened up to was page 46, the one about Clara McAbee which jogged my memory. I simply looked in our burial database and found that Clara McAbee Leon is buried here at Mount Olivet in Area GG, Lot 29! So that is the magical inspiration behind my quest for attempting to learn more about “Maryland’s prettiest girl.” Unfortunately, I must confess, I didn’t find a great deal as Clara would not have any children of her own. She served as a step-mother to her husband’s son from an earlier marriage—but as you will soon see, that must have been a complicated relationship at best.  “Maryland’s Prettiest Girl” Clara Mae McAbee (Leon) was born October 3rd, 1894 in the vicinity of Lime Kiln, a small village that sits adjacent the original route 15 south, today known as Maryland route 85/Buckeystown Pike. The once booming industrial complex can be found just south of English Muffin Way, and roughly one mile north of Buckeystown. Clara was the daughter of Joseph F. McAbee and Eliza C. Funk, the second of eight children. The McAbees operated a general store out of the front of their Lime Kiln household, located north of Lime Kiln where the old B&O railroad intersected the Buckeystown Pike. In 1915, twenty-year old Clara was chosen by a local newspaper to participate in a competition to pick Maryland’s most beautiful young lady. It’s interesting to point out that this was one of the first “beauty pageants” of this kind, held six years before the first “Miss America” pageant was held in Atlantic City in 1921. The Maryland event occurred May 16th in Baltimore, and was hosted by the Sun Newspaper Company. Clara Mae was chosen the winner from a large field of 500 contestants, half of which hailed from Charm City. This was quite an accomplishment from a small-town girl, and that’s even a stretch to give Lime Kiln credit for being a small town.  Newspapers near and far tried to describe the young lady in words. One such offered the following: “a black–haired beauty, with oval features, and Latinish mold of expression.” S. C. Malone went to work on behalf of his home state. He joined with the Frederick News in fundraising efforts to send young Miss McAbee to Los Angeles, California where a nationwide pageant was slated for mid-June. This competition was being sponsored by the Universal Film Company, known today as Universal Studios. For the motion picture pioneer, the event presented a great opportunity to gauge “visual talent” from across the land—the winner promised to receive a high-salaried film contract. Of course, visual appearance was “paramount,” (over straight-up acting ability) in this era of silent movies. Instant stardom was on the line for attractive young ladies representing nearly all the states in the country. When she departed Frederick on June 3rd, Clara’s reputation had preceded her to California, as she was listed among the favorites to win. As for the trans-Atlantic trek, the young Frederick Countian went first to New York City to meet with fellow Eastern contestants. From there, train travel took Clara and other contestants to Chicago to rendezvous with Midwest state champions. The caravan departed thence to the west coast.  Universal City, Los Angeles County, California (c. 1915) Universal City, Los Angeles County, California (c. 1915) The contest was maintained to be decided by merit, as the bulk of the judges were artists. Many of the competition categories were held at Universal City during the second week of June, 1915. All the while, the girls were treated to lavish dinners, shopping trips and excursions to nearby California sites and cities. The winner was announced June 12th after a lavish parade of the beauties. Washington DC’s Ruth Purcell won with a score of “93.45% perfect.” Clara McAbee was the runner-up with a score of “93% perfect.” Rounding out the top six were young ladies representing New Jersey, New Hampshire, Minnesota and Nebraska. As a consolation, the Frederick belle was also offered a motion picture contract. The top girls chosen next embarked on a goodwill tour across the country. Along the way, Clara began receiving marriage proposals. This was reported in Moving Pictures Magazine at the time. One matrimony offer came from a mine owner living in Las Vegas, another from a rancher whom she met at the Grand Canyon. On the subject, Clara playfully told a reporter: “I have been receiving letters from every city at which we have stopped and telegrams are also coming in from them. I’ll have to marry one of them to get rid of both.” Once back in Maryland, Clara was treated as a celebrity. She drew crowds, whenever, and wherever, she appeared in public. She was invited to many parties and dances throughout the region. In fact, the beauty queen was given a year pass of free movies from the Empire Theater in Frederick. The owners knew it would be good for business. Unfortunately, not much more is documented about Clara’s foray into the film industry. But what is known is that brown-haired beauty would play a starring role in a local drama to be played out in area courts and papers less than three years later. These events would feature all the love, scandal, and intrigue usually found in a Hollywood box office smash hit.  Washington Herald (1/27/1913) Washington Herald (1/27/1913) This was his second such offense.A trip to the Dentist Not usually pegged for a role in movies, our story’s leading man was a dentist by profession. His name, Dr. Albert K. Leon, a blonde-haired, blue-eyed native of Philadelphia, born in 1890. The son of Russian immigrants, Leon and his siblings had relocated to Washington DC. Dr. Leon’s father was a tailor and successful inventor who imparted on his children the importance of good dental hygiene. Like Albert, the bulk of his siblings (including an older sister) took up the dental profession. Albert was the youngest son and a bit of a rebel. Whether willingly of not, he completed dental school at Georgetown in 1911 and set out to start his career. That’s about the time he met Agnes V. St. John, a stylish young lady of the District of Columbia. Young Albert was “playing with fire” with Miss St. John. She was a devout Catholic, a “no—no” for a boy of Jewish faith for the times, not to mention his parents being even more strict to tradition as first generation immigrants. Whatever the case, Albert would bring embarrassment to the family in more ways than just a religious faux pa. In January of 1912, he was caught practicing dentistry without the necessary license needed in the nation’s capital. He did this while using the Washington, DC office of his older brother (Benjamin). Just a few month’s later, he eloped with girlfriend Agnes after telling his family he would be taking in a movie in Baltimore. The bi-religious couple were married on Easter Eve by Monsignor C. F. Thomas. This wedding would be kept secret by the couple for eight months, at which time the duo learned that Agnes was pregnant. The news shared with family was not well received well by either set of parents.  Baltimore Sun (12/2/1913) Baltimore Sun (12/2/1913) Albert’s family simply cut the cord on their youngest son, perhaps indirectly instigating his next big misstep by year’s end. Albert opened a dental office in Baltimore on West Lexington Street in October. In the early morning hours of December 2nd, Dr. Leon was caught in the basement of a candy store located below his office. He was arrested and charged with burglary, made even more sensational through newspaper coverage and the irony of a dentist caught robbing a confectionary. He claimed that he was simply investigating a noise, however the access for Dr. Leon required the help of a ladder placed within a dumb waiter chamber between floors. Albert Leon successfully sidestepped a candy store conviction to encounter two new life changes in 1914. First and foremost, Agnes gave birth to a baby boy in late August. He was named Albert K. for his father. Three months later (November of 1914), Dr. Leon announced in the Frederick newspaper that he had opened a dental office at 10-12 N. Market Street. He continued to boast locations in Baltimore and Washington, but Frederick would become his base of operations. Whether by design or not, Albert convinced Agnes that it was in the family’s best interest to have him firmly establish his practice in Frederick. This would require him to live in Frederick, while leaving his wife and son in DC with her parents. He claimed this would give him the time necessary to build a proper home for his wife and child. Leon’s innovative advertisements began appearing in the Frederick papers almost immediately. Interestingly, these included a self-photograph, something that strikes one as odd, especially done by a dentist. Perhaps there was an ulterior motive?  Former location of Dr. Leon's Dental Parlor at 10 & 12 N. Market Street, Frederick, MD (today the site of the Curious Iguana Book Store and Voila Tea Shop ) Former location of Dr. Leon's Dental Parlor at 10 & 12 N. Market Street, Frederick, MD (today the site of the Curious Iguana Book Store and Voila Tea Shop ) Dr. Leon seems to have been progressing well in Frederick by the size and scope of his advertising throughout 1915, the same year Clara McAbee was competing in pageants. Albert continued staying in Frederick during the week, and likely went home to Agnes and Albert Jr. in Washington on weekends. However, the long weeks could certainly open the doors of temptation—especially for a guy with a track record of proven sly behavior, getting caught with his hand in the candy jar, both literally and figuratively. However, this was nothing compared to what was to come. Somewhere along the line, Albert Leon became smitten with a young, vivacious patient named Louise M. Claybaugh, an employee of the Union Knitting Mills. Plenty of dental-themed double entendres could be used here, but I will refrain. Let’s just say that Louise received more than “a routine cleaning” from the good doctor. Claybaugh claimed later that Dr. Leon had misrepresented himself, claiming to have been unmarried. She made this discovery when Agnes and Albert, Jr. came to live in Frederick sometime in 1917. Claybaugh was enraged and threatened to bring suit against Albert. He calmed her with hush money, offering to pay her a weekly stipend for her silence and cooperation. She relented.  Reports claim that Frederick residents had marveled at the stylish, big-city fashions worn by Agnes when visiting her husband at his workplace. However, not to be outdone, a jilted Louise began copying the fashions of Mrs. Agnes Leon, obtaining and modeling many of the same outfits. The competition was on, however Louise would find out that she had more than one rival for Dr. Leon’s heart. Well, as if a love triangle wasn’t enough of a challenge for Albert Leon, the cunning periodontist decided to up the ante. Somehow, “Maryland’s prettiest girl,” Clara McAbee, would wind up in his dental chair. With his lack of self-restraint and love of teeth, it seems unfair that he could pass up the “prettiest” smile he would ever lay eyes on. One thing led to another and now he was successfully cheating on his mistress with the lovely girl from Lime Kiln. However, it was him who was about to go into the “kiln” as the jealous Miss Claybaugh was tracking his movements. She caught Dr. Leon and Miss McAbee in a compromising position in his office on October 12th, 1917. Claybaugh attacked Clara in a fit of rage. Claybaugh admitted that if it hadn’t been for the intercession of Dr. Leon, she would have inflicted serious bodily harm on “the prettiest girl.” After stewing a bit on what to do, Louise Claybaugh wrote an apology letter to Albert for her actions—then decided to make an unholy alliance with Agnes Leon. She confronted Albert’s wife on the subject. Oh to be a fly on the wall for that conversation. Louise divulged her role with the doctor, and then brought up his recent episode with “prettiest girl in Maryland.”  Agnes was devastated and on Christmas Eve, packed up her stuff and Albert, Jr. to head to her parent’s house in Washington, threatening to never return. A few days later, Albert apparently received a draft notice in the mail (as this was the height of World War I). Dr. Leon was no dummy, and persuaded Agnes and the draft board that his wife and son were dependent on him. It worked, and Agnes gave the seemingly repentant dentist another chance. She and Albert Jr. returned to Frederick. Everything was going as swimmingly as possible until late April 1918—that’s when “the toothpaste hit the fan,” so to speak. The Frederick and Baltimore papers were afire with the scandal of a “love quadrangle.” Agnes had issued a bill of complaint with the court outlining the altercation between misses Claybaugh and McAbee the previous October, and a titillating new wrinkle from March, 1918. On March 16th, Dr. Leon and Miss McAbee had “registered as husband and wife and remained at a hotel in Rockville all night occupying the same room.” Mrs. Leon had hired noted attorney Leo Weinberg and sued for court costs, that of her counsel and demanded a $100/month alimony payment starting immediately. This was duly granted by Judge Hammond Urner. She openly shared her story, and frustration (with her three-timing husband) with the newspapers. Once again, Clara McAbee found herself on the front page, but for the “unprettiest” of reasons.  The Leon family as they appeared living together in Frederick, Maryland for the 1920 US census. The Leon family as they appeared living together in Frederick, Maryland for the 1920 US census. Dr. Leon gave his side of the story a week later, not admitting or denying his guilt. He said it was simply a big misunderstanding. He pledged to Agnes that he would sever all ties with Claybaugh and McAbee. And somehow, it worked, the couple once again reconciled. It must have been divine intervention, but of a more technical kind. I’m thinking it was Agnes’ dedication to Catholicism and the sacrament of reconciliation, compounded with the church’s firm standing on divorce. Louise Claybaugh gave up the ghost and actually received positive attention for her role played in the affair. She also received marital offers E. Roy Kaufmann of Washington DC. The couple married just a few months later on September 11th, 1918. Forgiveness is a great virtue and Agnes Leon should be given all the credit in the world. But, alas it wouldn’t last. The Leon family of three persevered for a time, as they can be found living together in Frederick in the 1920 census, on South Market Street. Meanwhile, Clara Mae McAbee can be found still living at home in Lime Kiln within the same census. However, Agnes would find that she could not keep her husband and Clara apart.  In 1923, Agnes Leon and 9 year-old son Albert, Jr. left Frederick once and for all. She sued for divorce, stating that her husband could not keep his pledge of fidelity to her. The guilty accessory to Dr. Leon’s downfall was not announced at first, but soon would be revealed as Miss McAbee. In April, Agnes was granted an absolute divorce. She had returned to Washington and would live with her parents, raising young Arthur, Jr. as a single mother. She would never remarry, dying in 1969. Son Arthur K. Leon, Jr. followed in his father’s professional footsteps, becoming a successful dentist, last serving in Boca Raton, FL. I guess you could say that “Maryland’s prettiest girl,” was once again victorious, beating other beautiful contestants! Clara Mae McAbee had won Dr. Leon’s heart, and would marry him in the mid 1920’s. The couple resided at 326 Lindbergh Avenue, but would have no children together. Dr. Albert K. Leon continued his successful dental practice in Frederick for over 50 years. He was noted in his field, serving as president of the Frederick County Dental Society and presented with a life membership in the Maryland state Dental Association. He also busied himself with charitable and civic work. The couple remained together, without known issue, until Albert’s death in April, 1966 at the age of 74. Dr. Leon’s passing made front page news in the Frederick paper, but this time he was duly heralded for his many contributions to the Frederick Community over his lifetime.  As for Clara, I know she did her part during World War II in respect to rationing, but outside of that, but I failed to learn much more. She died on March 20th, 1983, nearly 65 years to the day of her infamous night spent with Dr. Leon in a Rockville hotel. Clara was 86 years old. Her obituary appeared in the Frederick News a few days following her death. It mentions her late husband, described as Albert K. Leon, prominent Frederick dentist. A bevy of nieces and nephews are mentioned but nothing else. No mention of her one-time title as “Maryland’s prettiest girl.” No mention of the honor of runner-up for Universal Film Company’s national beauty competition in 1915, or potential film foray. Sadly the obit just tells readers that there would be no visitation hours at the funeral home, and graveside services would be private. She was laid to rest beside Albert on March 24, 1983 in Mount Olivet’s Area GG, lot 229.  I was surprised to find that Louise Claybaugh (Kaufman) is also buried in the cemetery, about 150 yards away in Area S. She died in 1949 at the age of 52. Louise Claybaugh Kaufmann would live in Washington most of her adult life after marrying E. Roy Kaufmann. Upon her death in October, 1949, her body was returned to Frederick and buried in a lot next to her parents (Area S/Lot 10). Corinthians 13:4-8 reads “Love is patient, love is kind. It does not envy, it does not boast, it is not proud. It does not dishonor others, it is not self-seeking, it is not.” I don’t know how to exactly apply this bible passage to this sordid story, as it may be more fitting to take inspiration from song titles such as “Love is a many splendored thing,” “Love is strange,” and best of all “Love is a Battlefield.” In this case, pain and heartbreak was unfortunately experienced, but Dr. Albert K. Leon and Clara Mae McAbee were destined to be together. Their love for each other took hold in 1917 and would withstand the test of time. It just goes to show that true Valentines belong together. However, I would strongly advise that love is a great deal sweeter if you can spare the pain and embarrassment to ex-lovers, family friends and self—and 4 out of 5 dentists should be able to tell you the same. Special thanks to Paula Feldman of the University of South Carolina. Ms. Feldman is a literary historian, English professor and great niece of Dr. Albert K. Leon, Sr.

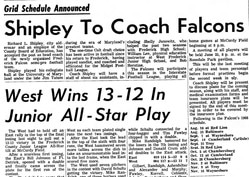

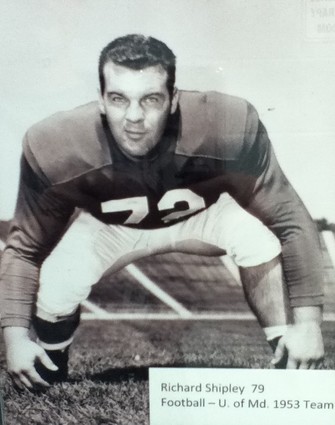

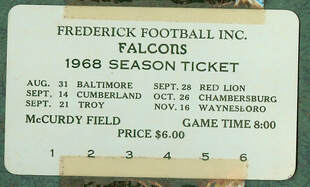

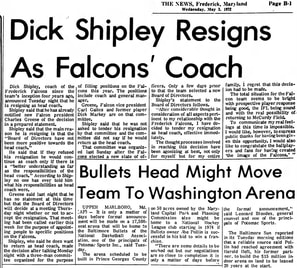

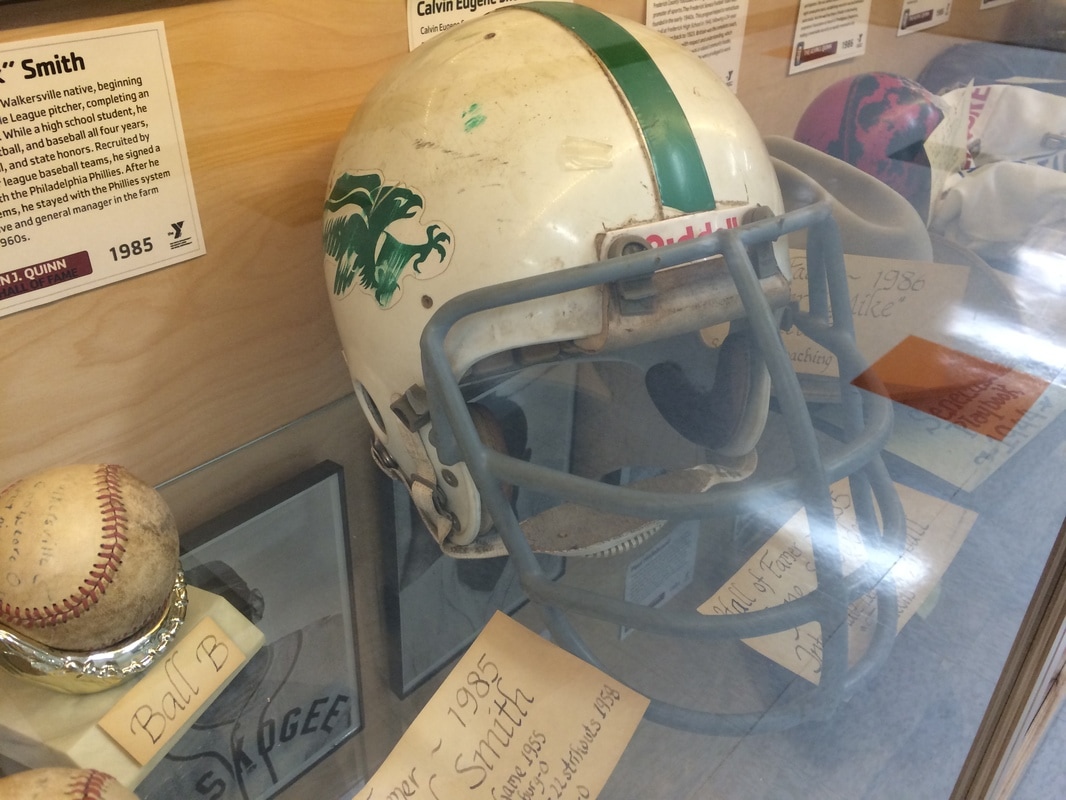

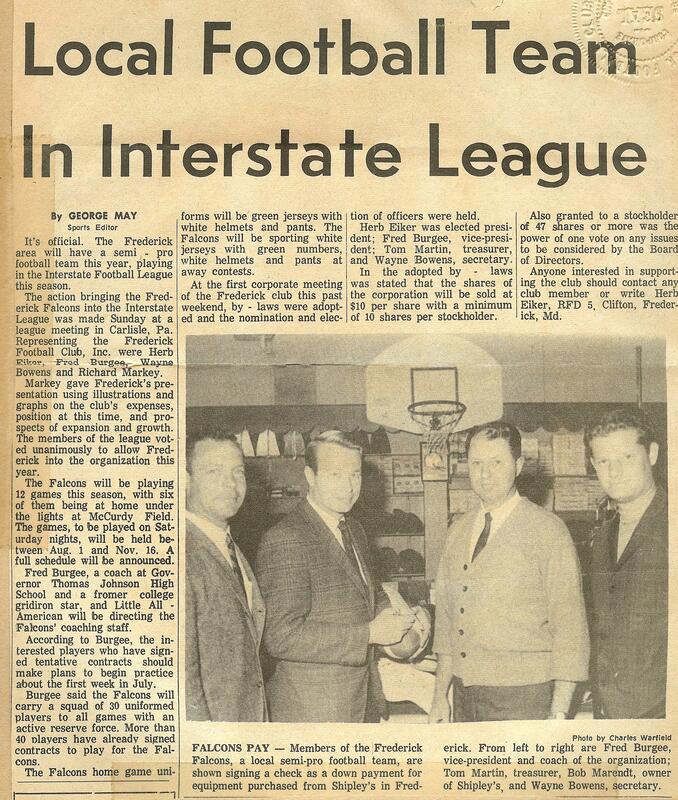

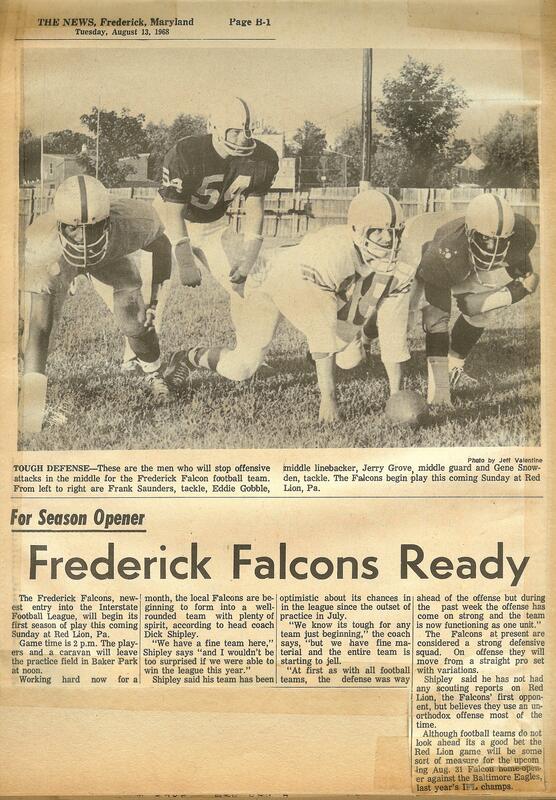

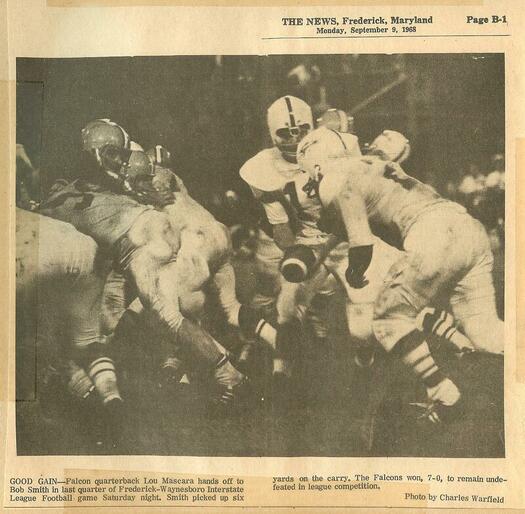

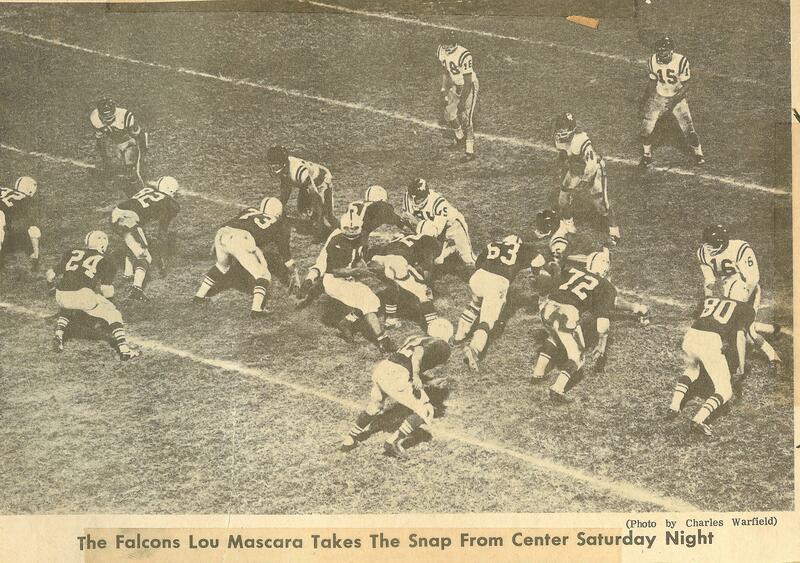

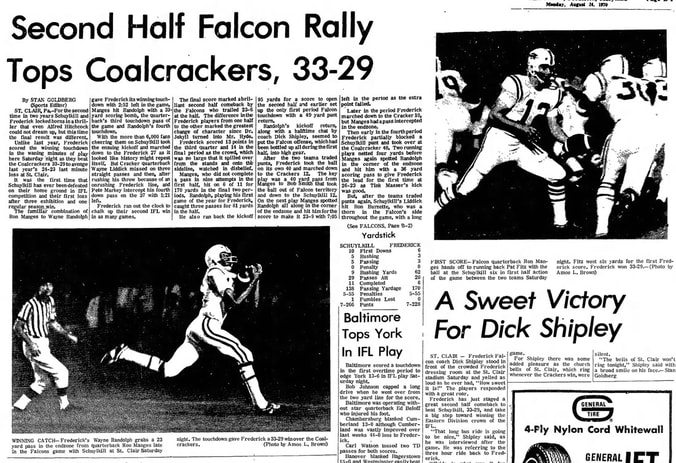

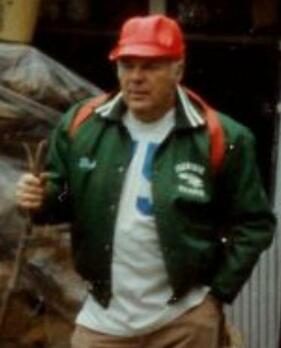

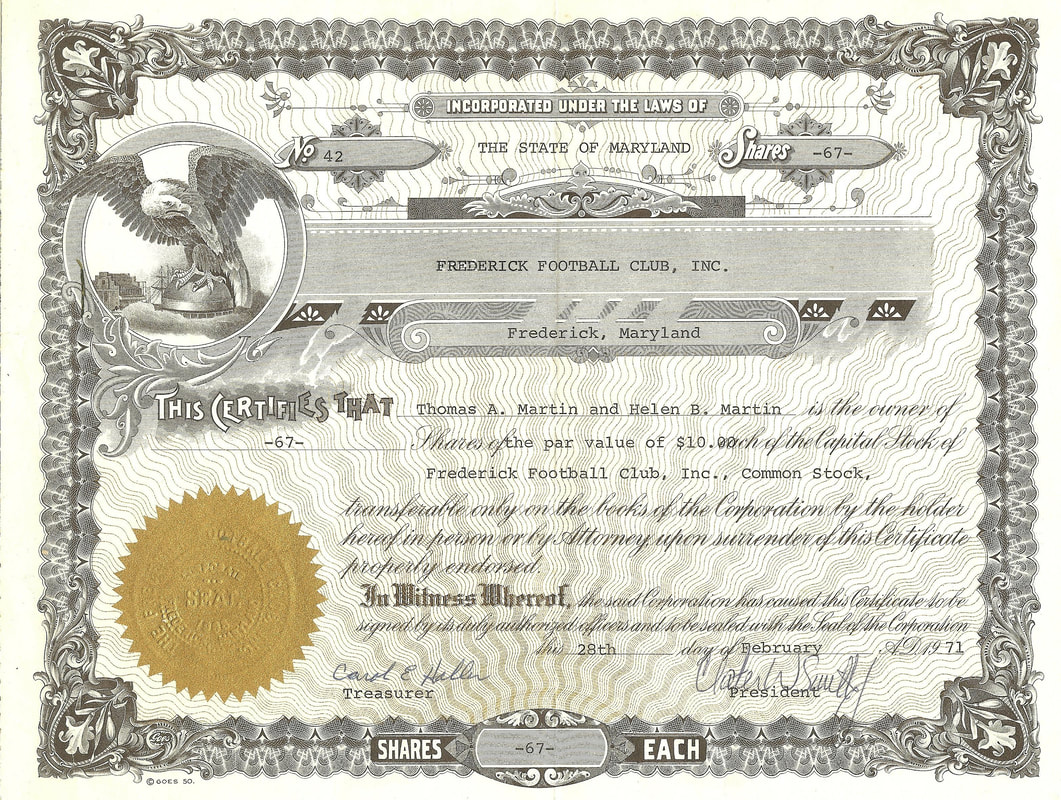

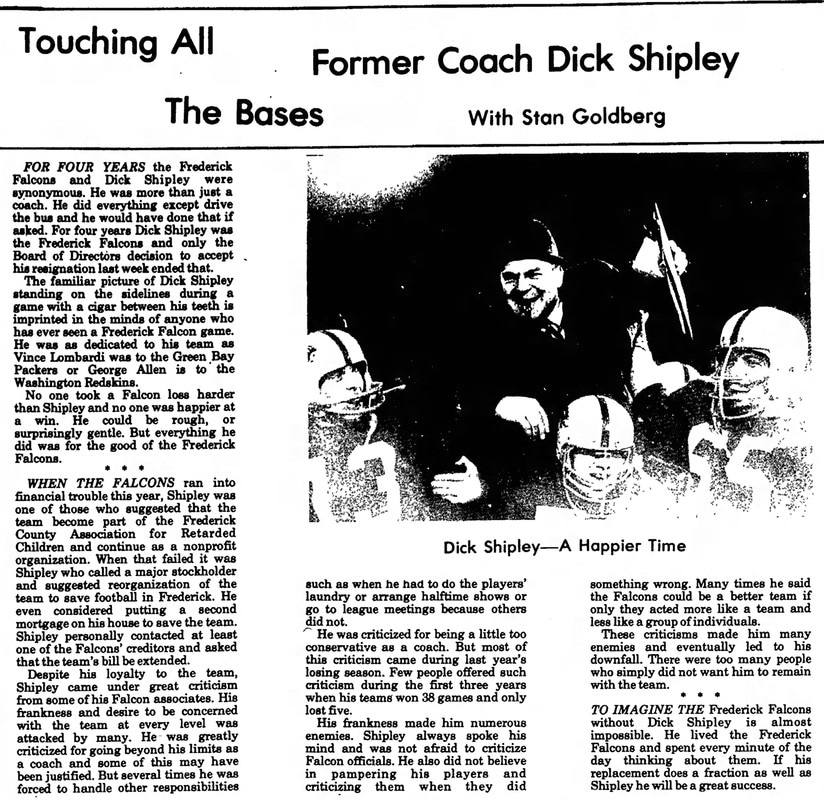

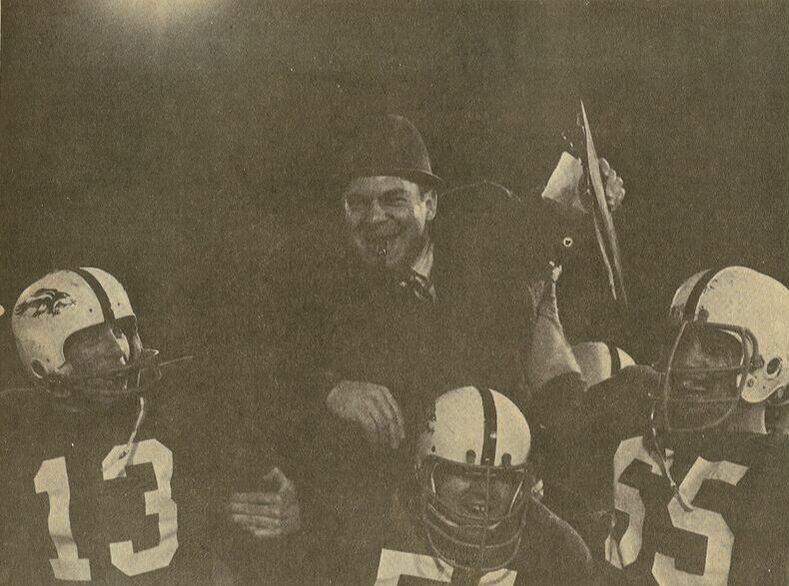

If you have anything to share, especially photographs or reminisces of Clara McAbee, Dr. Leon et al, please leave comment or contact the author. Thank you!  A scene from Super Bowl I, held at the Los Angeles Coliseum in January, 1967. A scene from Super Bowl I, held at the Los Angeles Coliseum in January, 1967. Are you ready for some football? It’s the Patriots vs. the Falcons, ironically two names very common to Frederick-area football. Super Bowl Sunday weekend, the annual post-Christmas ripple of heightened commercial marketing has no shortage of football-themed advertisements, viewing parties, and game prognostications. The whole thing has certainly turned into a cultural frenzy over the past half-century. Fifty years ago, the first ever Super Bowl was simply a major game between reigning champions of competing professional football leagues—the NFL (National Football League) and the AFL (American Football League). The game was played on January 15th, 1967 and featured the Green Bay Packers (NFL) and the Kansas City Chiefs (AFL). Although the Packers of the NFL were victorious, the game had a tinge of “David and Goliath” to it. The NFL had already been around for over 40 years when the upstart AFL, and its eight teams, began play in 1960. The established NFL had successfully fended off several other rival leagues in the past, and wrote off the AFL as a collection of second-rate misfits and rejects, not good enough to play at their level. NFL officials thought that fans would not accept these new teams and the players that filled their rosters. Contrary to popular belief, many of these players were good--very good in fact. The AFL would soon put themselves in a position to bid against the NFL for top free agents, college prospects and coaches. The AFL had arrived! Unfortunately, the AFL hadn’t completely "arrived" yet for that first Super Bowl as they experienced a 35-10 "beatdown" by Green Bay, led by quarterback/game MVP Bart Starr. The heavily favored Packers were also coached by the legendary Vince Lombardi, a coach so good they later would name the Super Bowl championship trophy after him.  Announcement of Shipley's hiring in the Frederick News (June 22, 1968) Announcement of Shipley's hiring in the Frederick News (June 22, 1968) Even in its infancy, the Super Bowl generated a heightened interest in professional football, giving hope to athletes, coaches and communities throughout the country that perhaps one day, they, themselves, could break into the big time, perhaps even playing in the “Big Game” itself one day. The stage was set for locals here in Frederick, Maryland to "strike while the iron was hot."We got ourselves a team! The Frederick Falcons were first organized in November, 1967 by Wayne Bowens and Herbert R. Eiker, Jr. A key component was hiring the right head coach. And this was done when they chose Richard L. “Dick” Shipley, Frederick’s version of Coach Lombardi—not to mention having a bit of Bill Belichick, Bill Walsh, and Bill Parcells sprinkled in.  Richard Lee Shipley, a father of three was a Supervisor of Operations for Frederick County Public Schools. He was also twice elected to serve as a member of the City of Frederick’s Board of Alderman at the time. Shipley knew how to work and motivate people, young and old. He also knew football. Born March 11th, 1933, Dick Shipley was an athletic standout at Frederick High School, playing from 1949 to 1951. He was named to the Maryland state high school All-Star team in 1951. Dick Shipley’s football career continued at the University of Maryland. His 1953 Terrapins team won the national championship after posting an undefeated regular season. The offensive lineman went on to play in the Blue and Gray Football Classic game in 1954. He entered the US Army and continued playing football while in the service. Once home, and starting a family with wife Eleanor Heston, he returned to football as one of the original coaches in the Frederick Midget Football League, a post he kept for five years. Then, in June of 1968, Shipley was hired to coach the Frederick Falcons.  Falcon Season for 1968 ticket showing all home games played at McCurdy Field Falcon Season for 1968 ticket showing all home games played at McCurdy Field Plans for the semi-professional team had come to fruition over the winter months. The Falcons would play as a member of the Interstate Football League which featured in-state rival teams from Baltimore and Cumberland, along with Pennsylvania mainstays Waynesboro and Chambersburg. The Falcons games were played at Frederick's McCurdy Field, with practices first held in Baker Park. The team was led by QB Ron Manges and receiver “Wonderful” Wayne Randolph. Coach Shipley was buttressed with other notables such as former college standout Fred Burgee, who doubled as both Falcon assistant coach and player. Two more assistants of note were William O. Lee and Richard “Bing” Keeney. Local radio legend Tommy Grunwell even played for the team as a stand-in for quarterback Manges while the latter was on summer camp active duty with the Marines. The team had players ranging in age from 17 to 41, plus had three deaf members. The first game took place at Red Lion, (PA) on August 18th, with the Falcons as 6-0 victors. The winning would continue, but Coach Shipley was dealt a challenge from the get-go, as he lost his starting quarterback in the second game of the season. He had to rely on 2nd string quarterback, Lou Mascara, who played admirably in relief of QB Manges. The Falcons would finish with an 11-0-1 record, dethroning the reigning champion Baltimore Eagles. It was a miraculous season that opened the eyes and hearts of Frederick Football fans. The Falcon(s) had landed! How do you repeat the surprise success of 1968? With another great season, of course! Shipley coached the 1969 Falcons to a 13-2 record. They unfortunately lost in the final championship game to the Chambersburg Cardinals by a score of 33-28. Year three for the Frederick team was much of the same, boasting a great record (14-3), however the last game was a tough loss to the Schuylkill Coalcrackers for the IFL championship in November 1970. Dick Shipley found himself with a coaching record of 38-5-1 as he entered his fourth season. Meanwhile, the Falcons had made a move to a new league—the Seaboard League, billed as the top minor-league football entity in the country. Coach Shipley and his Falcons were challenged both on, and off, the field. They finished 4-9, and were shut out in their last game against the Carroll County Chargers. The true problem came with other teams paying some of its star players, not just recruiting hometown talent from within. Shipley longed for the IFL days, having a team of local, unpaid players, and not having as far to travel. New teams from Long Island and Norfolk (VA) had joined the league, and players were now being lured to rival teams, something Coach Shipley did not think that this was in the best interest of Frederick. With all of this going on, the Falcons realized that it was harder to come by money to operate, especially in a more competitive league. They lost $13,000 during the previous season. For this reason, the team sought, and came into, the new ownership of a bonafide local non-profit entity in February, 1972. The Frederick County Association of Retarded Children was now responsible for administering Frederick’s football Falcons and solidified the team’s non-profit status and ability to accept donations and grants. (To note, these funds were separate from the central aim of FCARC.)  Frederick News (May 3, 1972) Frederick News (May 3, 1972) Coach Shipley came under fire from team management for being so vocal about the return to the IFL, and lobbing accusations against the Seaboard League. Some players became discouraged as well, thinking this move was a step down. Management was conflicted, and perhaps slightly intimidated, by the power and passion Coach Shipley wielded in regards to the Falcons. It was then and there that Shipley would surprisingly step down as coach in May of 1972. His resignation read as follows: “After considerable thought in consideration of all aspects pertinent to my relationship with the Frederick Falcons, I have decided to tender my resignation as head coach, effective immediately. The thought processes involved in reaching this decision have been agonizing at best, not only for myself but for my entire family, I regret that this decision had to be made. ….To communicate my real feelings at this time is impossible, I would like, however, to express public thanks for having been given this opportunity, I would also like to congratulate the ballplayers and fans for having created “the image of the Falcons.” It appears that his resignation was more a protest stemming from a disagreement with the team’s Board of Directors. He would defect to the Falcons top rival, the Chambersburg Cardinals, serving as their offensive line coach. Shipley also brought with him Frederick's star player, Wayne Randolph. Stan Goldberg, my old colleague from the Great Southern Printing and Manufacturing Company, wrote a bold editorial about the whole affair in the May 9th, 1972 Frederick News-Post.  Among the items within the fine collection of the YMCA's "Alvin J. Quinn Hall of Fame" are Dick Shipley's University of Maryland championship season varsity letter and his Falcon's jacket. Among the items within the fine collection of the YMCA's "Alvin J. Quinn Hall of Fame" are Dick Shipley's University of Maryland championship season varsity letter and his Falcon's jacket. Shipley and his new team (Chambersburg) would go to the Seaboard League's championship game in 1972 and 1973, winning the latter. At the time, the Seaboard League would be the second-highest ranked professional football league behind the NFL. The league folded after the 1974 season with the founding of the World Football League, which deprived them of talent. The Falcons would rejoin the Intersate Football League and fly on into the future with great coaches such as former player Tom Kent and Shipley’s one time player/coaching assistant Bing Keeney, who would later coach the team to three straight championships from 1987-89. Shipley even came back to the Falcons for head coaching and assistant coaching stints along the way. The team eventually disbanded in 1992 due to financial reasons. As for Dick Shipley, his name will be forever synonymous with Frederick football and the Frederick Falcons. He was inducted into the Alvin J. Quinn Hall of Fame in 1979.  Richard L. Shipley 1933-1985 (courtesy of Find-a-Grave website) Richard L. Shipley 1933-1985 (courtesy of Find-a-Grave website) Coach Shipley's last football assignment came with announcing high school games as a color commentator with WFMD. Shipley’s final broadcast featured coverage of a state championship loss by his high school alma-mater, Frederick High School. This event was fittingly played at the University of Maryland, his collegiate alma-mater. Just two days later on December 2nd, 1985, Dick Shipley was taking part in an annual hunting trip to Sterling Run, PA with friend Elgin Etchison. Sterling Run is located near Emporium in the north central part of the state. As the story goes, Etchison was on one hill talking with his son, when he turned to spot Shipley’s progress in traversing another nearby hill with an extremely steep grade. Etchison waved to Shipley, and he (Shipley) returned the favor, but then collapsed. Etchison rushed to his friend's aid, performing CPR for 15-20 minutes before leaving to seek help from the closest house, about a half-mile away. Dick Shipley was gone at the age of 52. His death made front page news here in Frederick the next day. A friend of mine is Tom Martin, who served as the first treasurer for the Frederick Falcons organization. He fondly recounted how the Falcons would pack the stadiums for both home and away games. In fact, one time he said, when the team played in Baltimore, they had so many Falcon supporters on hand for one game that a portion of the visiting teams grandstands collapsed from the weight. Now that's dedication! Tom also said that Coach Shipley's influence as an alderman also brought a few interesting perks. He said that management would take in extremely favorable gate receipts at McCurdy Field on tickets sold, plus made additional money with hot dog and other concession sales. As treasurer, he had to properly account for, and safeguard this income. The alderman/coach thus arranged for Martin to have a police escort after each home game in an effort to bring "a large pile of cash and coins" to the treasurer's home, then located on E. 14th Street. Tom said although people thought the organization brought in a great deal of money, it was a break-even endeavor. Each week's windfall was short-lived because as soon as it came in, it went out in check form to pay health insurance premiums for the players. Another lasting legacy, courtesy of Coach Shipley, was the naming of Falcon Lane, a twelve foot alley that once stretched from E. Patrick Street, adjacent the Frederick Fairgrounds, to E. South St. Falcon Lane still exists, however was shortened in the early 1970's to better facilitate and protect the city's publlc works department yard. It’s fitting here to share a story that occurred a couple weeks ago to me. I was taking a few pictures of Coach Shipley's grave marker. I looked up and saw what I thought could be an eagle flying over the cemetery’s western section. I was soon corrected by a co-worker that it wasn’t an eagle, but something else instead. Yes, you guessed it, the winged creature was a falcon. Perhaps it was simply just paying respects to the old gridiron coach, whose name will ever be synonymous with the bold and brash bird of prey, and more so, Frederick County football. Authors Note: Special thanks to Tom Martin with help with compiling this article.

|

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed