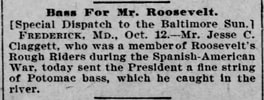

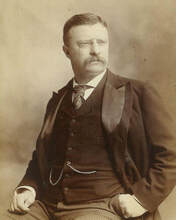

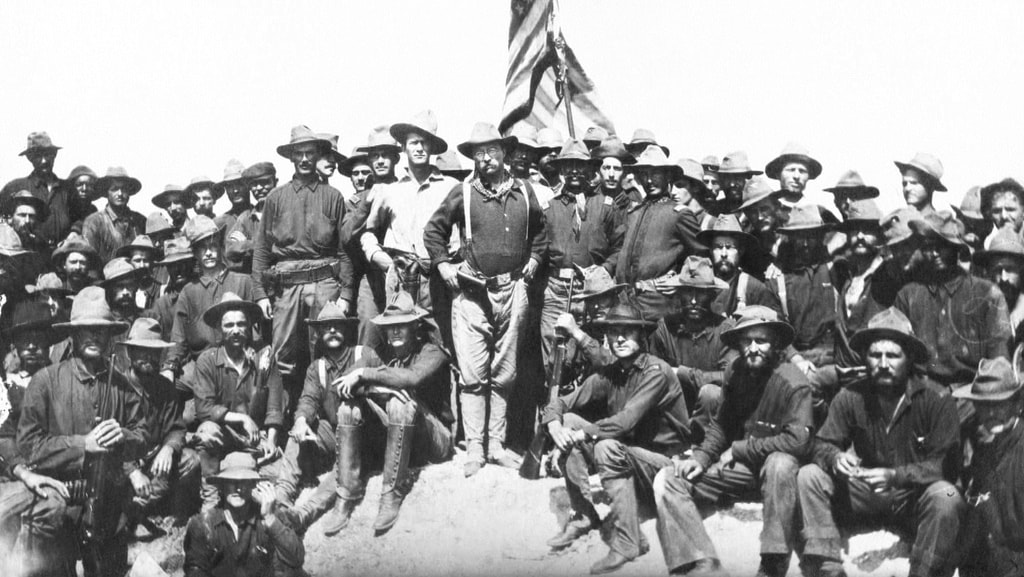

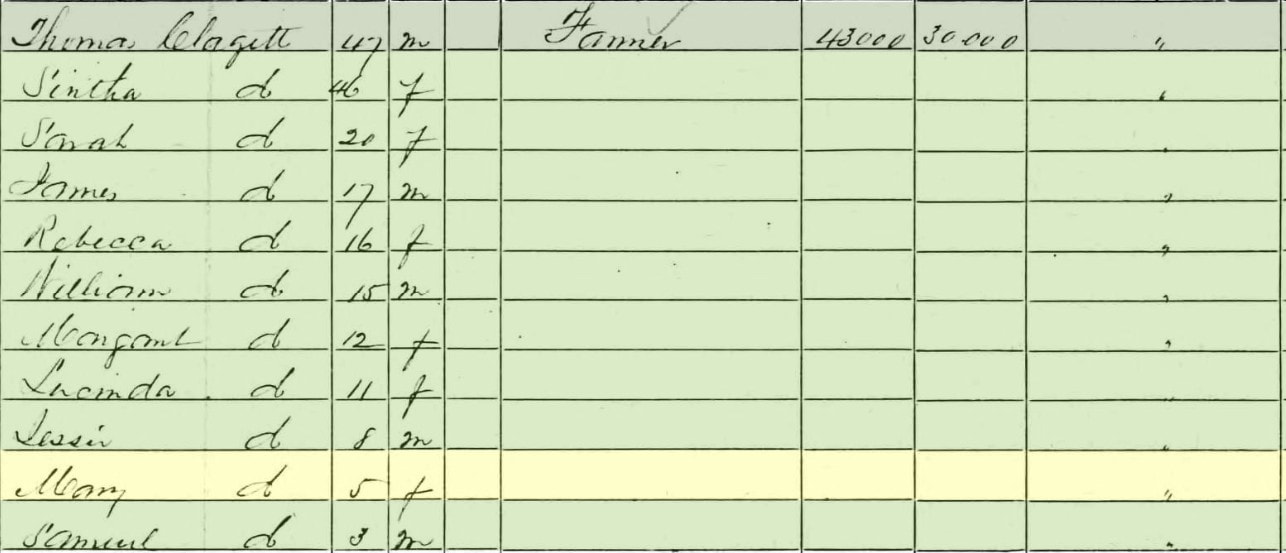

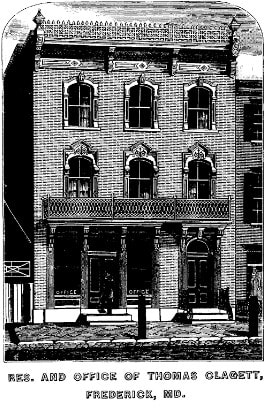

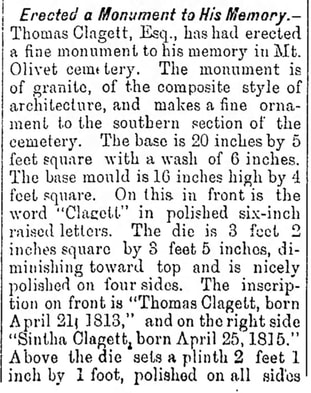

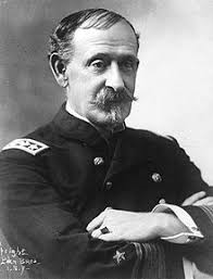

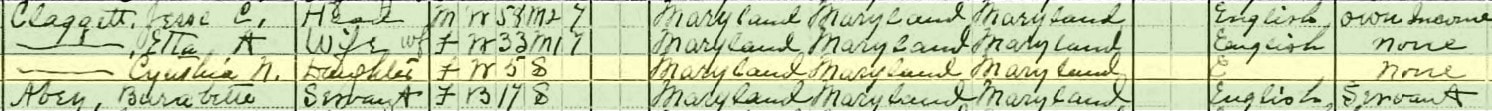

Memorial Day weekend or not, curiosity can certainly be piqued when finding a small news article like this in an old edition of the Baltimore Sun. It dates back to October 13th, 1901 and involves two veterans of the Spanish-American War. One of these men was among the most colorful characters in our nation’s history, while the other was a well-known resident of Frederick County during his day. Few, if any, know anything about this latter gentleman today.  President Theodore Roosevelt President Theodore Roosevelt The news article comes less than a month from the day that Theodore Roosevelt was inaugurated as our country’s 26th US president. Many are familiar with the legacy of this vivacious man and war hero. Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (1858 – 1919) was a statesman, politician, conservationist, naturalist, and writer. He served as president from 1901 to 1909. He previously served as the 25th vice president of the United States from March to September 1901 and as the 33rd governor of New York from 1899 to 1900. As a leader of the Republican Party during this time, he became a driving force for the Progressive Era in the United States in the early 20th century. He helped start what we know as today’s National Park Service and, fittingly, his face is depicted on Mount Rushmore, alongside those of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and Abraham Lincoln. In polls of historians and political scientists, Roosevelt is generally ranked as one of the five best presidents. Over 120 years ago, on July 1, 1898, Theodore Roosevelt could be found racing up Santiago, Cuba’s San Juan Hill in a decisive military offensive that would help define the Spanish-American War. With Capt. Roosevelt on that fateful day was the aforementioned fisherman—Jesse C. Claggett. He was a member of Troop K of the 1st US Army Cavalry. Claggett is significant in the fact that he was the only Marylander to participate in the storming of San Juan Hill as a member of the immortal Rough Riders—an event that would soon take on mythical proportions. Jesse C. Clagett Once again, I am most fortunate to have found some “ready-made” research on my subject, courtesy of T.J.C. Williams’ and Folger McKinsey’s masterful work published in 1910: The History of Frederick County, Maryland. The biographical supplement includes the following entry for Jesse C. Clagett: Jesse C. Clagett, a well-known citizen of Motters, Emmitsburg District, Frederick County, Md., son of Thomas and Cynthia (Norwood) Clagett, both deceased, was born on his father’s plantation, Urbana District, Frederick County, Md., May 15, 1851. Jesse C. Clagett is the eighth child and the third son of his parents. He attended the country schools until his parents removed to Frederick when he was sent to Mount St. Mary’s College, where he spent four years under Father McCaffrey and Father McCloskey. However, Jesse was of a restless, roving disposition, and left school against his father’s wishes to go to Texas, where he became a cowboy on a ranch in McLennan County. He rode into Dallas when it was a straggling village with one old countrified hotel with steps on the outside leading into it. He spent four years in Texas and, after a short visit at his home in Maryland, went to St. Louis, Mo., where he secured a situation as night clerk in a hotel. Not long after this, he was taken sick with typhoid fever, and was removed to the Sisters’ Hospital on Grand Ave. When he was discharged, at the end of nine weeks, he secured a position with a firm of wholesale grocers to build up their city trade. Some time after this, Mr. Clagett accepted a position as street broker for a firm dealing largely in tea and coffee. He soon decided that he could sell for himself as well as for others, and began business for himself, and was very successful. He was finally made a partner in the first firm which he had served, the firm being, Churchil, Rearick & Clagett. This partnership lasted almost three years, when Mr. Clagett withdrew from the firm after making the largest coffee deal ever made in St. Louis, at that time, through B. C. Arnold & Co, of New York, then known as the Coffee King of Wall Street. Mr. Clagett now went to New York, speculated in Wall Street and lost, returning to his home in Frederick City, and afterwards going to Baltimore to seek a position. There he approached Levering & Co., large dealers in coffee, without success. However while at the old "Maltby House," he was offered a position as salesman for a dealer in paper collars at $75 per month and expenses. This offer he accepted and remained with the firm for five or six years. Mr. Clagett was next employed by a firm in Troy, N. Y., to sell shirts and linen collars. After having spent twenty-one years as traveling salesman, Mr. Clagett gave up the business and, returning to Maryland, settled in Frederick City. About 1890 he purchased his present home, a farm of 40 acres, known as "Windy Castle." At the breaking out of the Spanish-American War, Mr. Clagett responded to the call for volunteers and enlisting in the Rough Riders under Col. Roosevelt, served until the close of the war and, after the surrender, was taken sick with yellow fever. He is a member of the Society of the Army of Cuba. Mr. Clagett was a Democrat, but left the party at the time it divided on the silver issue, and is now an independent voter. Jesse C. Clagett was married in 1880 to Miss Price, daughter of the late Thomas W. Price, of Philadelphia, Pa. They have two children, Thomas, aged twenty-seven, and Jesse, deceased. On November 5th, 1903, Mr. Clagett was married to Mrs. Etta L. Spicer, daughter of Mrs. Florence Shipley, of Baltimore, Md. They have one child, Cynthia Norwood, born on October 4th, 1904.  Thomas Clagett Thomas Clagett The Clagett family has an extremely rich heritage in Maryland. The spelling of this surname sometimes includes two “G”s and two “T”s as it varies in in both public records and newspaper articles. However, family gravestones and monuments at Mount Olivet pertaining to this particular family utilize the spelling “Clagett.” Jesse Charles Clagett was one of 15 children born to Thomas Clagett (1813-1887) and wife Cynthia Norwood (1815-1895). Cynthia’s gravestone, and many records, spell her name as Syntha which was likely a nickname or pet name given by Mrs. Clagett’s husband. Jesse’s father was a native of Clarksburg in Montgomery County. The son of Ninian Clagett of Prince George’s County, Thomas grew up on a farm and busied himself in like pursuits as an adult. His mother, Margaret Burgess, was the daughter of a Revolutionary War Continental Army captain. Thomas Clagett came to Frederick County in 1839, two years after his marriage to the former Miss Norwood, first settling in Urbana, where he would grow tobacco and engage in shipping. Cynthia Norwood’s father was a native Englishman, who had immigrated to Frederick County. In 1866, the Clagetts moved to Frederick City, living at 17 E. Patrick Street, not far from the intersection with Market St. This building (now housing the children’s toy store called The Dancing Bear) doubled as Mr. Clagett’s business office. Here, Thomas changed his profession from commercial shipping to that of broker and banker. The Clagetts were also active in St. John’s Catholic Church here. Thomas Clagett died on August 7th, 1887 after a several year illness of dropsical effusion—the local paper includes several articles of Mr. Clagett’s trials with medical operations beginning in 1885. Jesse’s father was buried a day after his death in Mount Olivet’s Area P/Lot34. At the time of his passing, he was reported to have been worth a half-million dollars and considered the wealthiest man in the county. His elaborate grave monument, erected earlier in 1884, stands proof to the power and prestige of Mr. Clagett. Cynthia Clagett died eight years later in 1895.

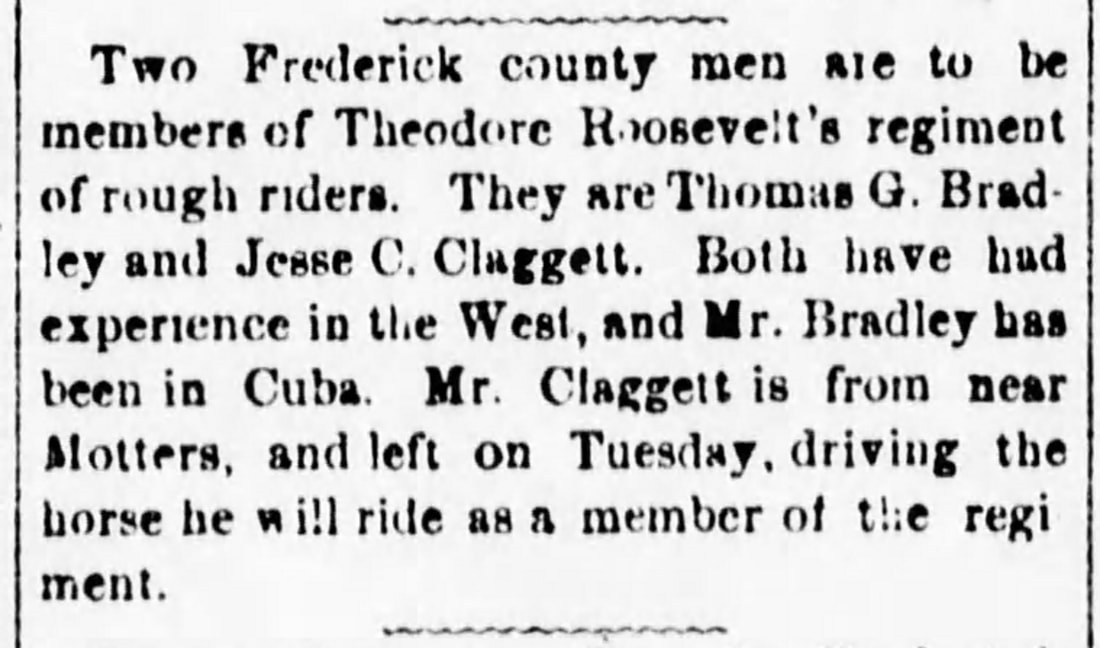

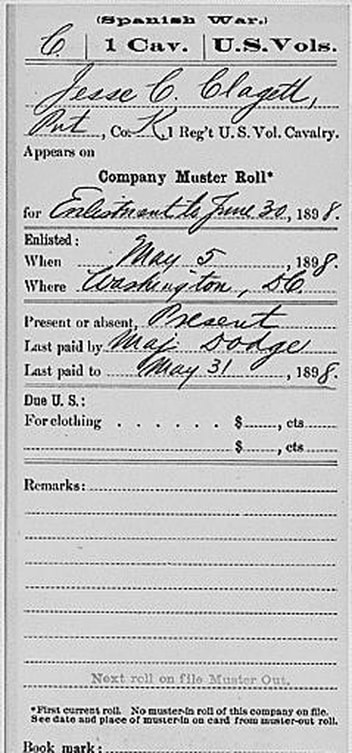

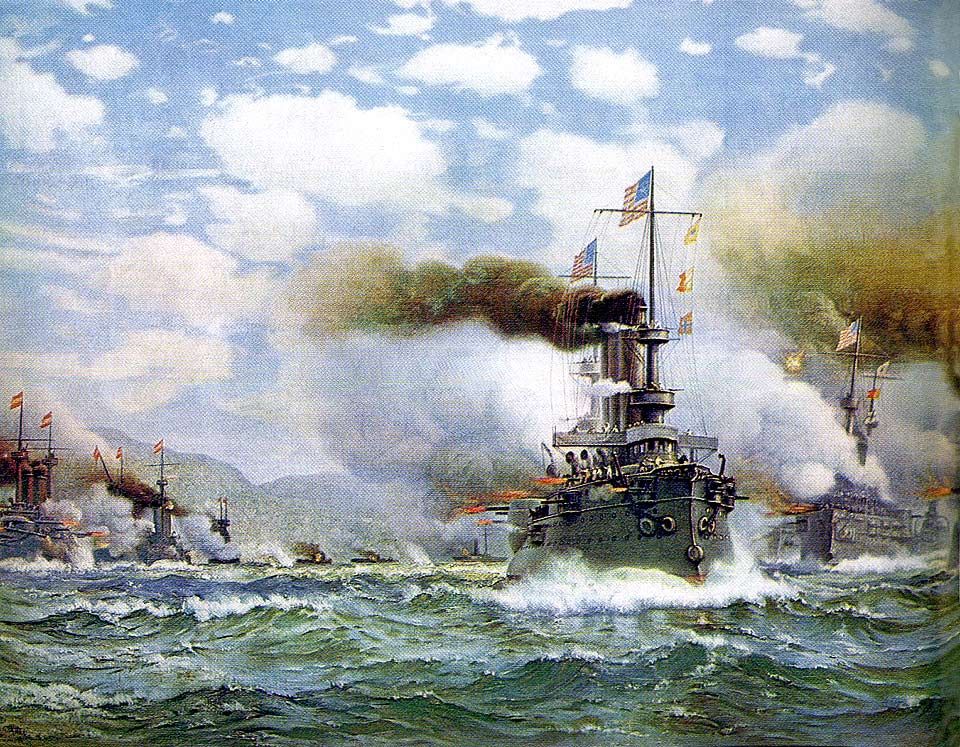

On a crisp spring day in early May, 1898, Jesse would take his favorite horse for a ride into destiny. One week before his 47th birthday, Clagett departed from his “Windy Trails Farm” near Emmitsburg with a destination of Washington, DC. Here he would join to the 1st United States Volunteer Cavalry. The Rough Riders The Rough Riders was a nickname given to the 1st United States Volunteer Cavalry, one of three such regiments raised in 1898 for the Spanish-American War and the only one to see action. The United States Army was small, understaffed, and disorganized in comparison to its status during the American Civil War roughly thirty years prior. Following the sinking of the USS Maine, President William McKinley needed to muster a strong ground force military group swiftly. This was accomplished by calling upon 125,000 volunteers to assist in the war efforts. The United States was fighting against Spain over Spain's colonial policies with Cuba. Applications to serve (in the 1st US Volunteer Cavalry) flooded in from all over the country. Clagett’s request was accepted and he would soon be serving in the regiment also called "Wood's Weary Walkers" in honor of its first commander, Colonel Leonard Wood. This nickname served to acknowledge that despite being a cavalry unit they ended up fighting on foot as infantry. Wood's second in command was the former Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Theodore Roosevelt. Roosevelt was a strong advocate in support of the Cuban War of Independence. When Col. Wood became commander of the 2nd Cavalry Brigade, the Rough Riders then became "Roosevelt's Rough Riders." That term was familiar in 1898, from Buffalo Bill who called his famous western show "Buffalo Bill's Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World." The original plan for this unit called for filling it with men accustomed to fighting within the Indian Territory in places such as New Mexico, Arizona, and Oklahoma. Frederick’s Jesse Clagett fit right in as his earlier time in Texas and abroad as a cowboy had served him well. He would be assigned to Troop K.  The Rough Riders aboard the USS Yucatan heading for Cuba (June, 1898) The Rough Riders aboard the USS Yucatan heading for Cuba (June, 1898) The regiment trained for several weeks in San Antonio, Texas, and in his autobiography, Teddy Roosevelt wrote that his prior experience with the New York National Guard had been invaluable, in that it enabled him to immediately begin teaching his men basic soldiering skills. The Rough Riders used some standard issue gear and some of their own design, purchased with gift money. Diversity characterized the regiment, which included Ivy Leaguers, professional and amateur athletes, upscale gentlemen, cowboys, frontiersmen, Native Americans, hunters, miners, prospectors, former soldiers, tradesmen, and sheriffs. The Rough Riders were part of the cavalry division commanded by former Confederate general Joseph Wheeler, which itself was one of three divisions in the V Corps under Lieutenant General William Rufus Shafter. Lt. Col. Roosevelt and his men landed in Daiquiri, Cuba, on June 23rd, 1898, and marched to the nearby village of Siboney. Wheeler sent parts of the 1st and 10th Regular Cavalry on the lower road northwest and sent the "Rough Riders" on the parallel road running along a ridge up from the beach. To throw off his infantry rival, Wheeler left one regiment of his Cavalry Division, the 9th, at Siboney so that he could claim that his move north was only a limited reconnaissance if things went wrong.  San Juan Heights (1898) San Juan Heights (1898) Roosevelt was promoted to colonel and took command of the volunteer regiment when Col. Wood was put in command of the brigade. The Rough Riders had a short, minor skirmish known as the Battle of Las Guasimas in which they fought their way through Spanish resistance and, together with the Regulars (professional soldiers), forced the Spaniards to abandon their positions. Under Roosevelt’s leadership, the Rough Riders became famous for the charge up Kettle Hill, part of the San Juan Heights, on July 1st, 1898, while supporting the Regulars. Private Jesse Clagett is said to have been the sole Marylander in the engagement. Roosevelt had the only horse, and rode back and forth between rifle pits at the forefront of the advance up Kettle Hill (San Juan Hill), an advance that he urged despite the absence of any orders from superiors. He was forced to walk up the last part of Kettle Hill, because his horse had been entangled in barbed wire. The victories came at a cost of 200 killed and 1,000 wounded. Roosevelt commented on his role in the battles: "On the day of the big fight I had to ask my men to do a deed that European military writers consider utterly impossible of performance, that is, to attack over open ground an unshaken infantry armed with the best modern repeating rifles behind a formidable system of entrenchments. The only way to get them to do it in the way it had to be done was to lead them myself." He always recalled the Battle of Kettle Hill as "the great day of my life" and "my crowded hour.” Likewise, it was the greatest moment of Jesse C. Claggett’s life, as well. He could easily identify with Roosevelt as both came from wealthy and comfortable upbringings, but had a secret yearning for adventure, danger and “roughing” it with comrades of varied economic backgrounds and lifestyles. Roosevelt and his Rough Riders were a colorful group of characters and received the most publicity of any unit in the army. A few days after the legendary charge up San Juan Hill, the Spanish fleet was virtually all but destroyed in Santiago Harbor. Thanks in part went to another Frederick Countian, Winfield Scott Schey. Schley’s leadership in command of Admiral Dewey’s flagship, the USS Brooklyn, made him a household name and hero across the nation. It was just a matter of weeks before the war had ended and the U.S. was victorious. Two of Frederick’s native sons were at the forefront. In August, Roosevelt and other officers demanded that the soldiers be returned home. Thanks to newspaper headlines, the colonel’s writing ability and the retelling of the courageous charge by veterans themselves, soldiers like Jesse Clagett became seen as men among men, once home. Private Jesse Clagett became a hero and celebrity of sorts back home in Frederick County.

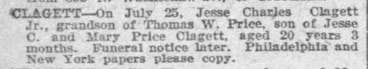

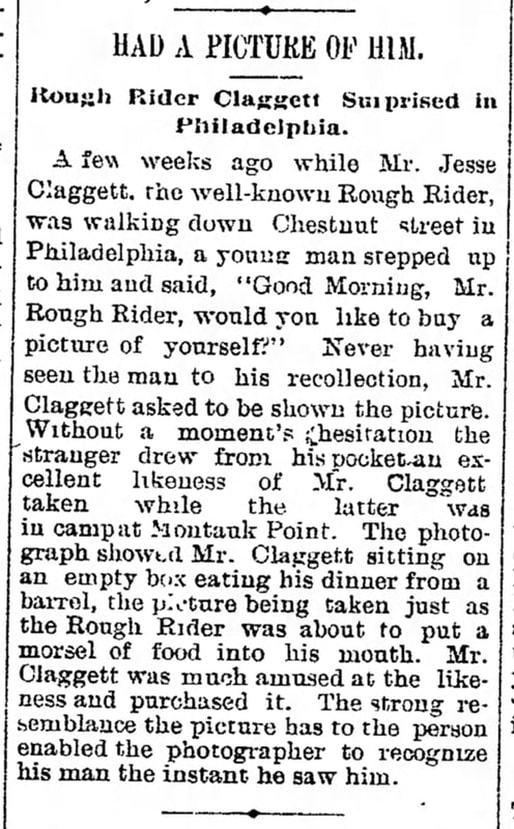

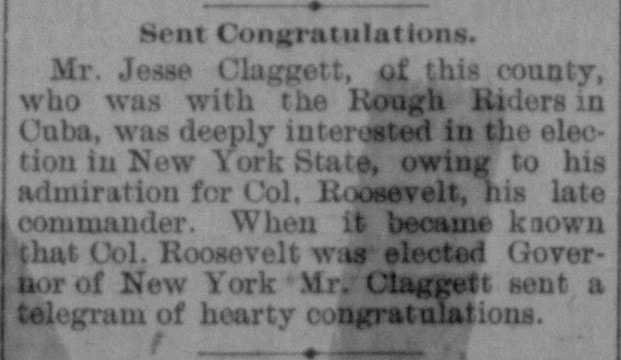

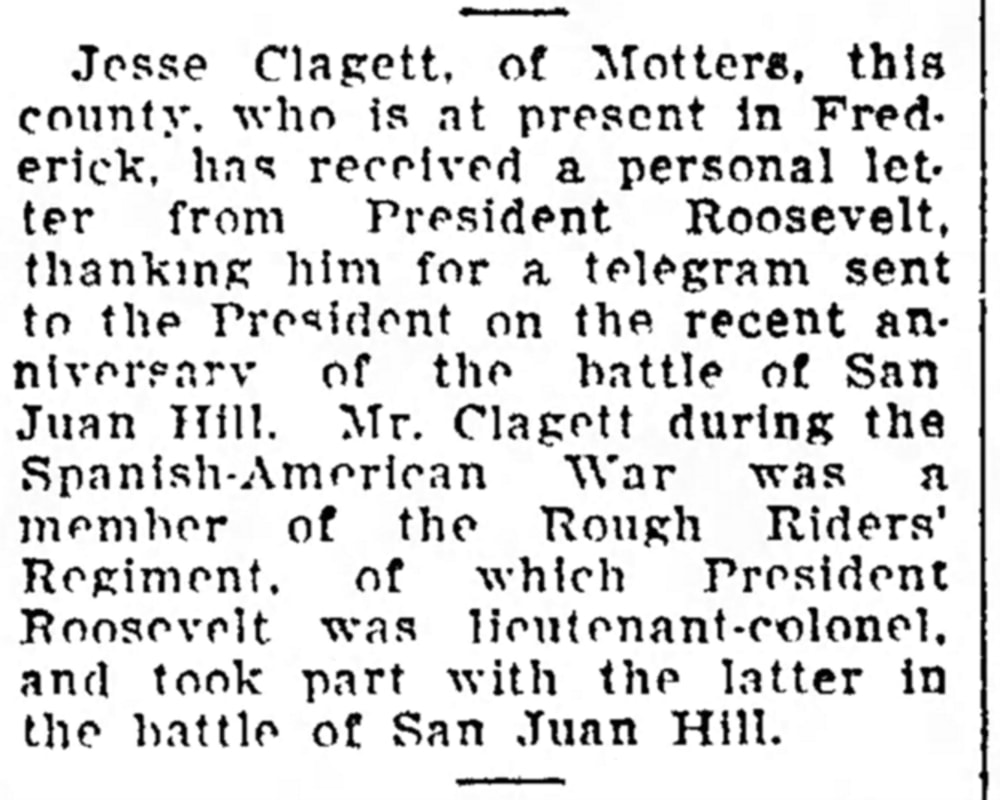

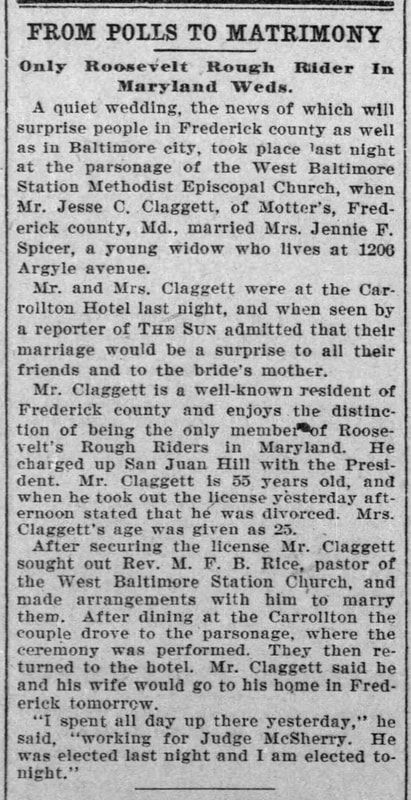

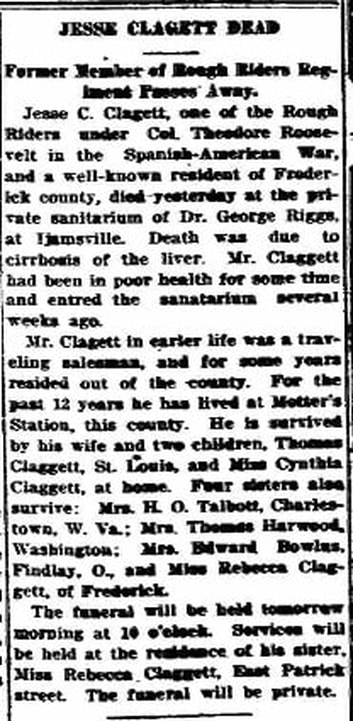

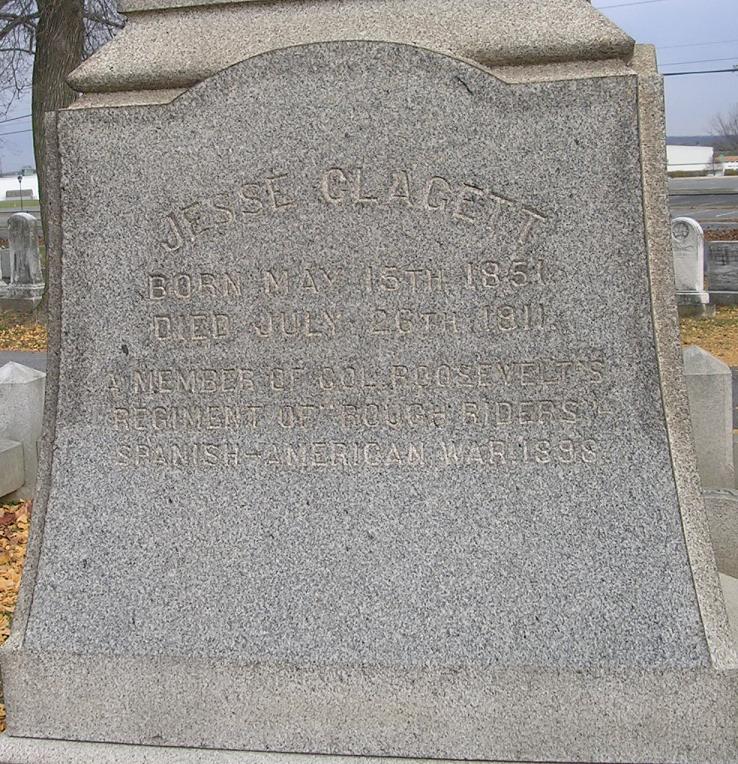

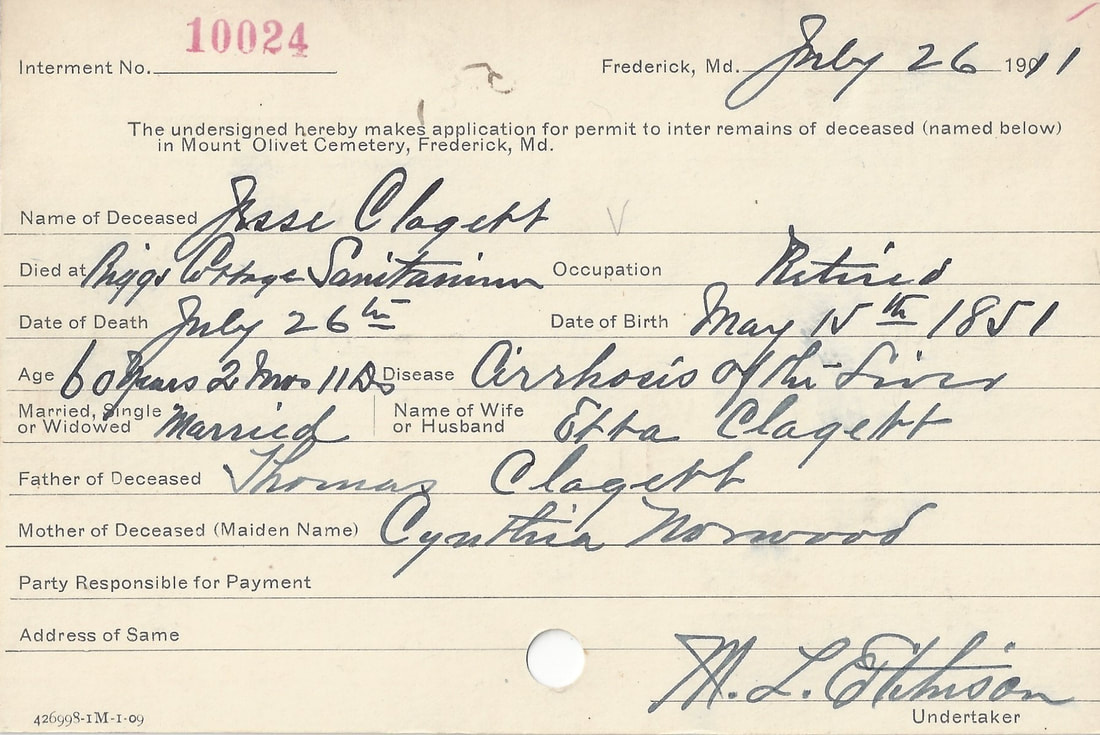

Heroes Return By the end of August, Jesse Clagett would make a triumphant return to his home in northern Frederick County while on furlough. Jesse came back to Frederick for good that fall, and rejoiced in telling his tale of combat, made all the more special when his former commander was elected governor of New York in early November (1898). The Emmitsburg citizen/soldier was now in high demand to perform honorary equestrian duties, possessing an even more impressive resume based on his US Cavalry experience. The Rough Rider was singled out to be chief aid to Capt. Walter Saunders, Chief Marshall for a victory parade held in Frederick for the Spanish American War’s other local hero, Admiral Winfield Scott Schley. This occurred on November 20th, 1898. Clagett was getting recognized everywhere for his gallantry, or should I venture “praise by association.” There was even one occasion in which he was identified by a stranger on a city street in Philadelphia. Philadelphia was the home of his wife (Mary S. Price), or should I say his first wife, whom he would request an absolute divorce from in the fall of 1900. Meanwhile, Jesse’s old commander was uncertain about whether to begin strategising for a 1904 presidential election run, or to serve another term as New York’s governor. Roosevelt eventually joined President William McKinley's reelection campaign ticket as the Republican vice-presidential nominee (as McKinley's first vice president had passed away, leaving an opening). The tandem were victorious in the November (1900) election. President McKinley would die in September, 1901, the result of an assassin's bullet. Roosevelt would be propelled to the office of president, the nation's youngest at age 42. Weeks later, Jesse Clagett sent the new president a “fine string” of fish he had recently caught in the Potomac River. This was just another example of the friendship and correspondence between these two men. By fall of 1903, Jesse was 55 years old, but still kept a youthful outlook on life. Someone who certainly helped in this arena was Etta Leister (Shipley) Spicer of Baltimore. Mrs. Spicer, a 26-year-old widow, had lost her husband two years earlier. In November, Jesse and Etta would elope, and marry in the parsonage of the West Baltimore Station Methodist Episcopal Church in Baltimore in November. Interestingly, it was said that Claggett had principally been in town for the purpose of helping with a political campaign for a friend on election day. He would bring Etta back to his 40-acre farm at Motters Station. The following October (1904), Etta would give birth to a daughter, Cynthia Norwood Clagett, named for Jesse’s mother.  Chicago Tribune (July 29, 1905) Chicago Tribune (July 29, 1905) Sadly, Jesse would lose his namesake son from his earlier marriage. Jesse Charles Clagett, Jr. died in July 1905 while living in Chicago. Another son, however, was living in St. Louis. This was Thomas “Tom” H. Clagett who was working as a shipping agent for the railroad at the time. A few years later, Jesse was given command of his own local, ceremonial “Rough Rider” unit. This consisted of 125 men and performed drills for onlookers at local patriotic events and carnivals. In 1909, they would be one of the main entertainment attractions at a large home-coming festival in Emmitsburg. This would be one of Clagett’s last public appearances.  Riggs Cottage in Ijamsville (known to many as the restaurant Gabriel's Inn) Riggs Cottage in Ijamsville (known to many as the restaurant Gabriel's Inn) Jesse’s health soon began to fail and he was forced to decline social invitations. His condition further declined, forcing him to enter the Riggs Cottage Sanitarium for Nervous and Mental Diseases. This facility was located in Ijamsville, originally constructed by local carpenter and slate mine owner Christopher Riggs in 1862 for use by Welsh mining families. Riggs's son, Dr. George Henry Riggs (a local family physician and psychiatrist), converted the structure into a "sanatorium for nervous and mental health disorders" in 1896. Jesse C. Clagett died on July 26th, 1911. Cause of death given was cirrhosis of the liver. I hope he, at least, had the capacity to reflect on his climb of Kettle Hill on the occasion of the 13th anniversary at the beginning of the month. Clagett’s obituary appeared in the Frederick Post of July 27th, 1911. Clagett was buried in the family plot, and his name appears on the west face of the large obelisk his father had placed here a few decades earlier. His life's greatest moment is carved in stone for eternity:

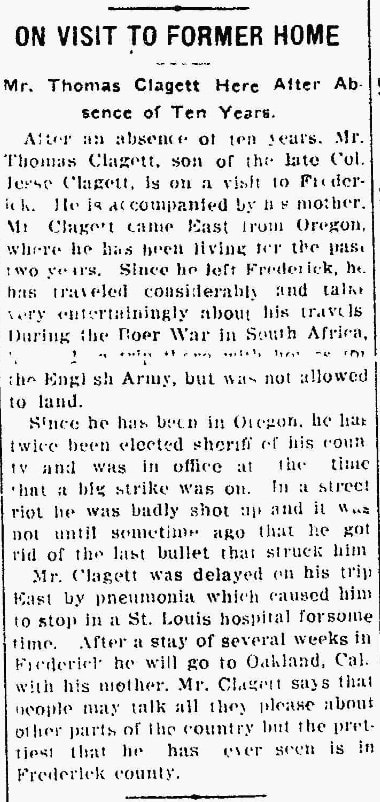

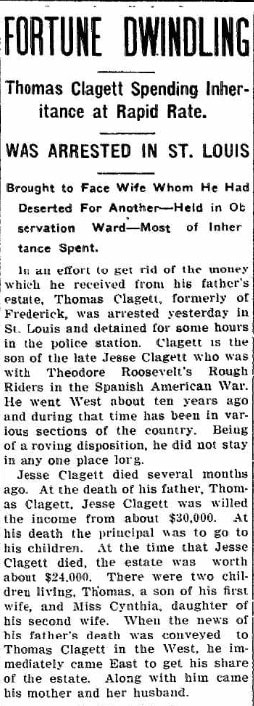

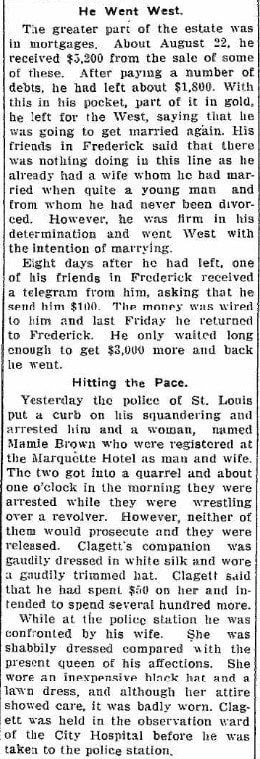

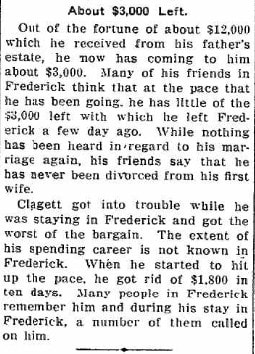

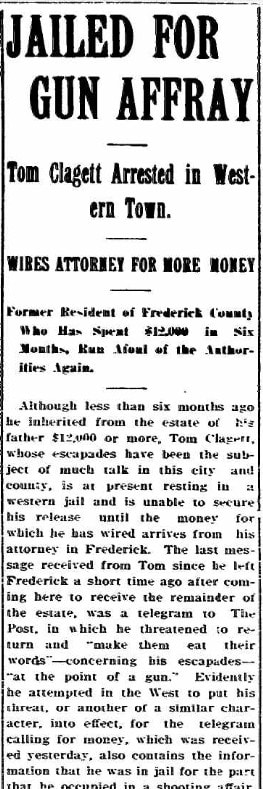

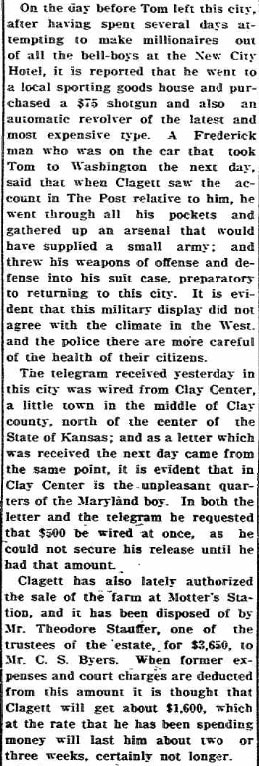

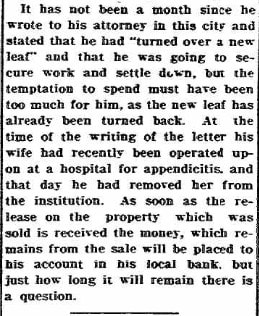

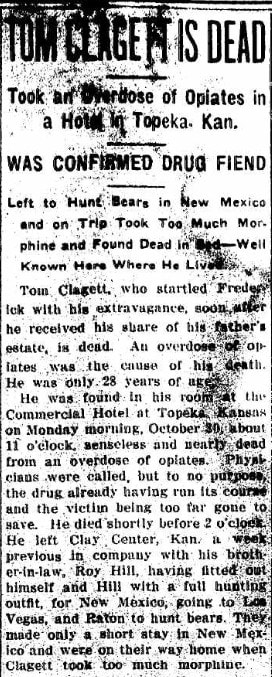

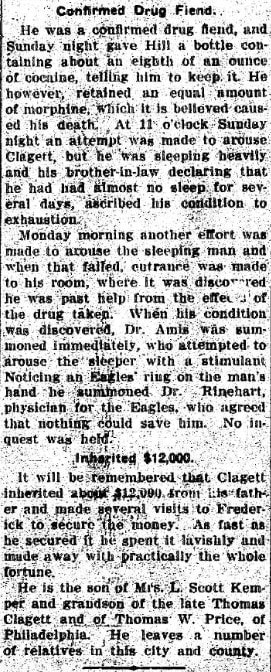

A member of Col. Roosevelt's Regiment of Rough Riders Spanish-American War 1898 In his will, Jesse took care of his wife and children with his accrued wealth, not to mention his military pension. Wife Etta would leave Frederick for sunny Florida, primarily because Jesse had left his farm to his son (Thomas). She would not remarry, but spent the majority of her remaining years in Miami with daughter Cynthia (Clagett) Daisey. The fate of Jesse’s son, Thomas, is a story unto itself as his father’s estate became a curse instead of a blessing. Although not buried here, I have included clippings of Tom Clagett’s “rough ride” and subsequent demise below. It's just a shame that Jesse Clagett didn't live another year as President Roosevelt visited Frederick on May 4th, 1912 as part of a barnstorming election tour as he attempted to run for a third term as president. He spoke to residents from the steps of the Frederick County Courthouse (today's City Hall). Had Private Clagett been on hand, it is certain who would have held the title of Grand Marshal for the president's visit.

6 Comments

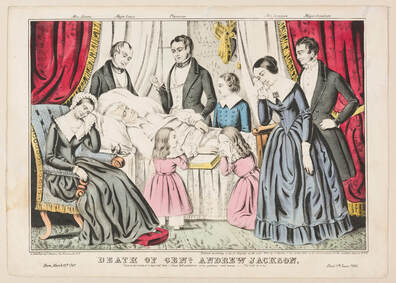

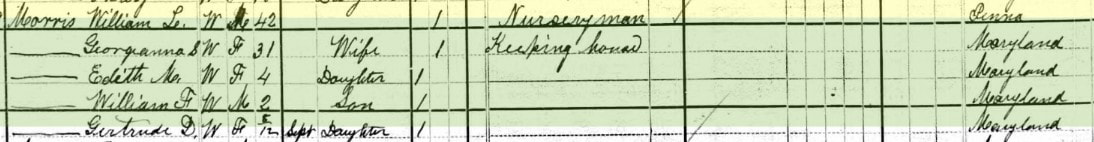

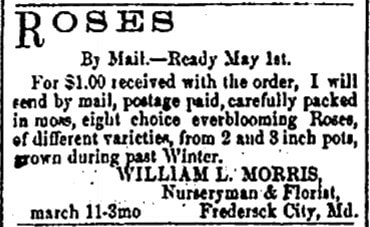

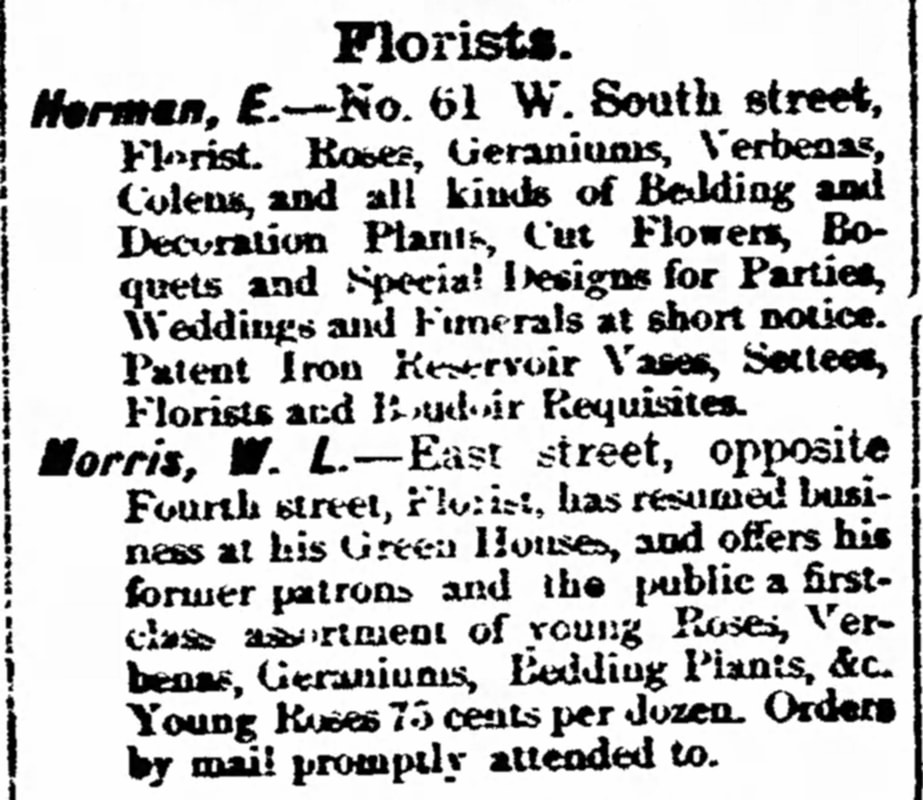

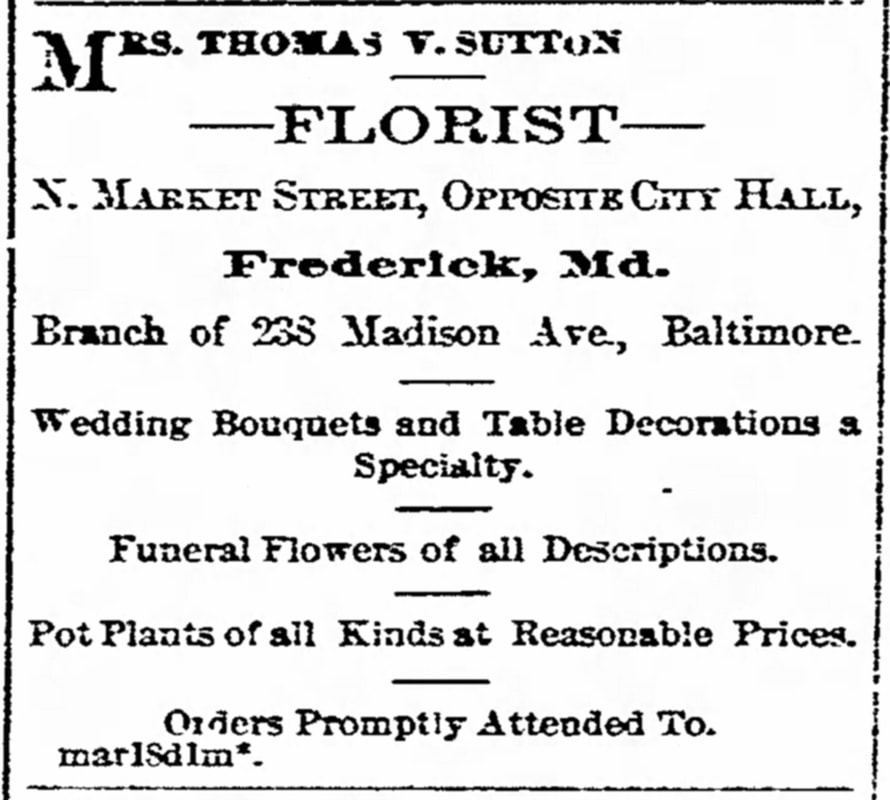

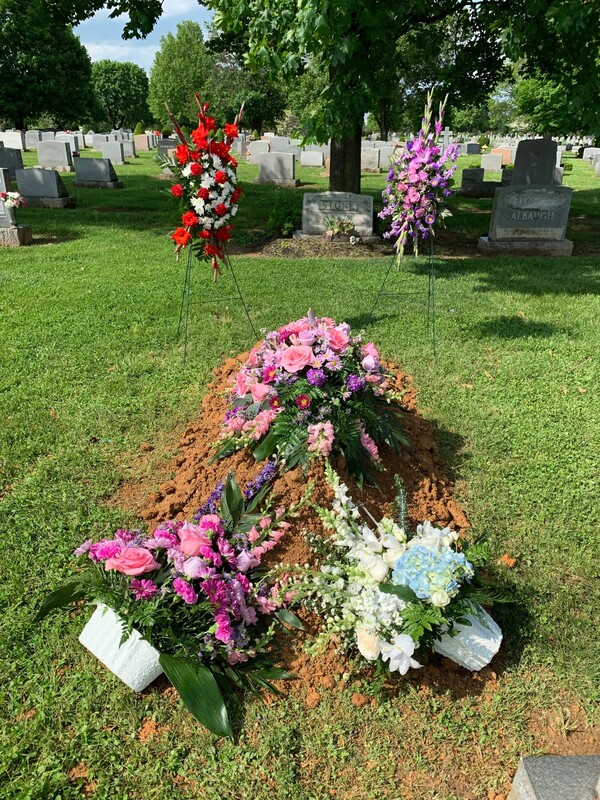

It’s Mother's Day, and the florist trade in Frederick, Maryland has been well-tested once again. Among the major recipients of florists' handiwork on this special holiday are cemeteries. For many burying grounds, such as Mount Olivet, Mother's Day is traditionally the day with the highest visitation totals each and every year. While Mother's Day includes the introduction of hundreds of new floral arrangements into the cemetery, others appear daily to commemorate birthdays and anniversaries. The most common occurrence of flowers in the cemetery however is quite obvious—funerals. Some of the most recognizable names for local flower fashions over the last century were Sharpe and Zimmerman, two family run operations that closed their doors in the last decade after “four score plus” of serving the needs of our community. Their story was told last week. We have a bit of a special mission with this week's blog as we’ll try to answer three questions: * Why are flowers synonymous with cemeteries and funerals? *Who were some of our earliest artisans in this trade? *What’s the deal with this week’s blog title?  Flowers & Funerals Flowers have always been a potent symbol for expressing many deep feelings. For both those who are gifted communicators, be it verbally or written, there’s not much of a problem. However, for others, flowers can do the talking for us. Just think about the greeting card industry as a perennial “lifesaver” as well. While flowers have long been traditionally given at many different times to help express feelings of sympathy or condolence, sending flower arrangements to a funeral have also served an ulterior motive for many centuries. Sending flowers to a funeral is not a modern custom. In fact, according to The Funeral Source, archaeologists have discovered evidence dating back to 60,000 BC of flower fragments surrounding corpses at ancient burial sites. It is unsure exactly what purpose these flowers served, but researchers hypothesize that the flowers were used in a type of burial ritual or ceremony.  In more recent history, flowers were used for their fragrance. Things get a little more delicate with this explanation as the art of embalming has certainly evolved over the centuries. In ancient times flowers were not only tokens of respect, but they were also used as a means to help cover up the unpleasant odors of decomposition. Depending on the environment, condition of the body and delay of the actual burial from the time of death, flowers were used in varying quantities to allow mourners to tolerate the smell of the dead as they grieved and paid final respects to the body before it was interred. An interesting case in point was that of our illustrious seventh US president, Andrew Jackson. The website My Funky Funeral recounts his post-mortem story: “He died at the age of 78 and by the time the funeral took place his body had begun to severely decompose. The stench from the closed coffin was so horrible that the undertaker at the time used a literal mound of flowers to cover up the entire coffin to contain it. The potent fragrance of the hundreds of flowers was just enough to overpower the stench for attendees to sit through the service. This particular act highlighted just how important flowers are for their beauty and scent.” I’ve now given you a colorful story to share the next time you pull a $20 bill out of your purse or wallet! I also learned another interesting fact involving President Jackson's funeral in that his beloved pet parrot had to be removed from the service due to incessant cursing. Aside from the practical use in covering up odors, flowers have also always served as sentimental tokens for the bereaved and by the mourning. In the Victorian era, emotions were not readily discussed or shared. Surrounding the casket with flowers served as a silent expression of emotion. This deep interconnection still survives today as flowers can convey what we can’t—the secret language of condolence that expresses everything that is too painful to speak of. They can also help create a beautiful final memory at the funeral service.  Flowers & Frederick In searching the old town newspapers, I came across the first floral experts of Frederick. One of the earliest was a gentleman named William L. Morris. He was a Civil War veteran from Lancaster, Pennsylvania who fought with Company A of the 97th Pennsylvania Regiment. Morris came to Frederick prior to 1870 and would begin advertising his services as a nurseryman and florist in the local papers in 1874. He would soon marry a local girl, Georgeanna S. Dill, whose family Dill Avenue is named. Morris appears in the 1880 census and was continuing his work with plants and flowers here in Frederick at a location on East Street across from E. 4th Street. The Morris family would re-locate to Nashville, TN by 1900. William died in 1918, and is buried in another Mount Olivet—the famed Mount Olivet Cemetery of Nashville.

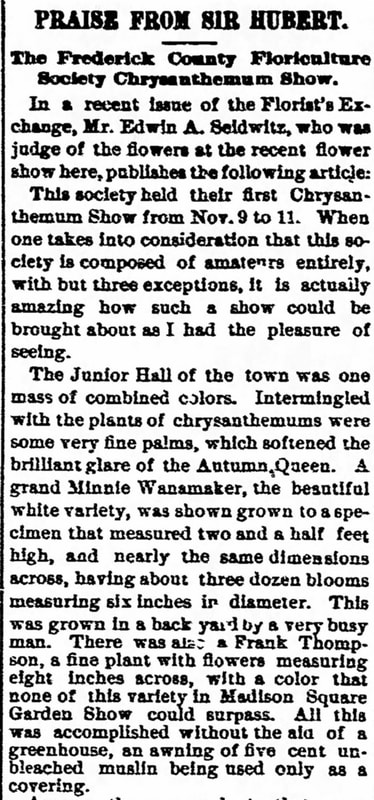

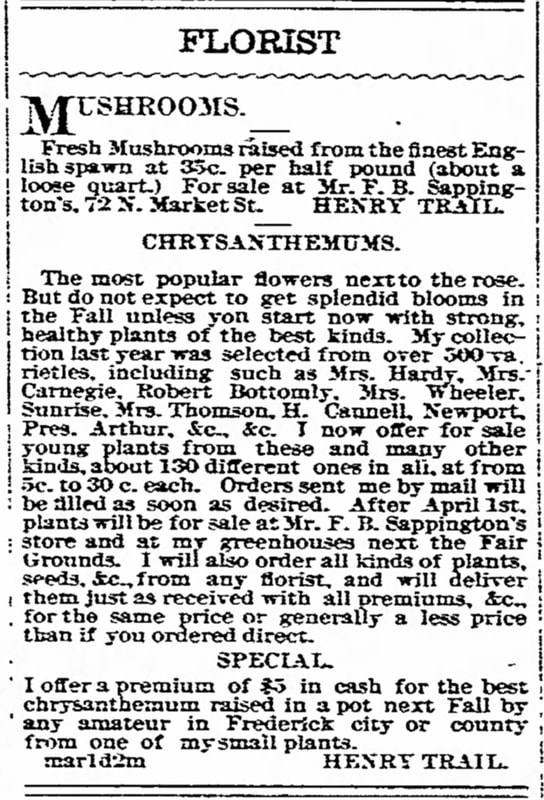

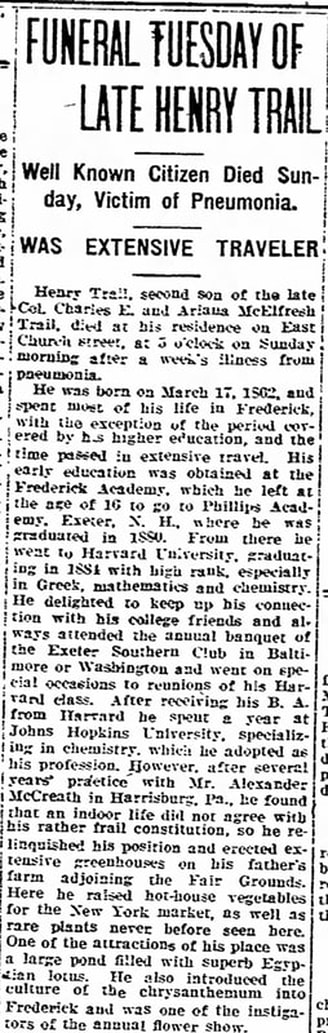

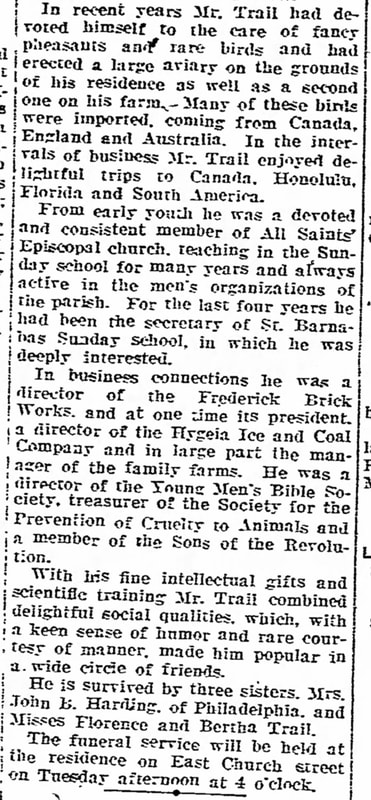

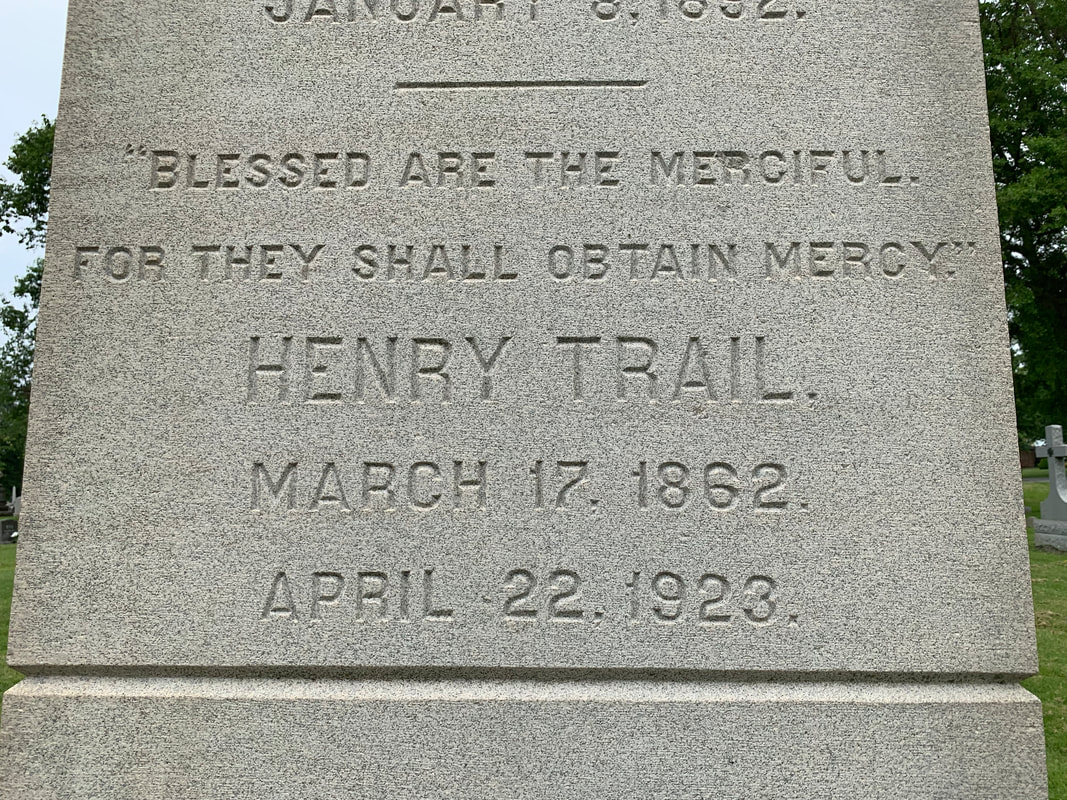

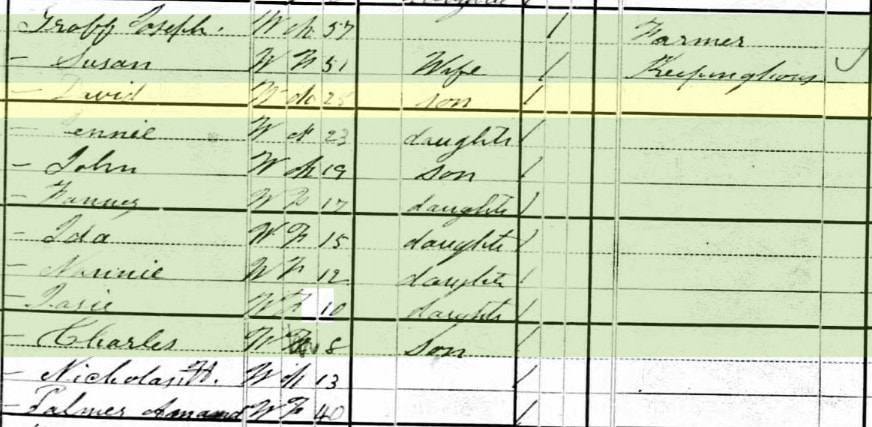

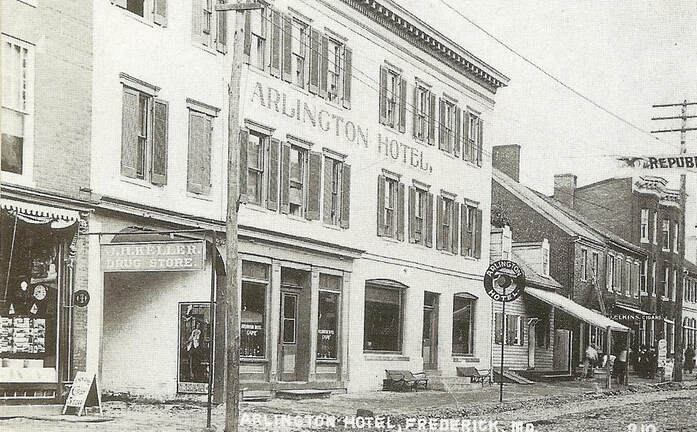

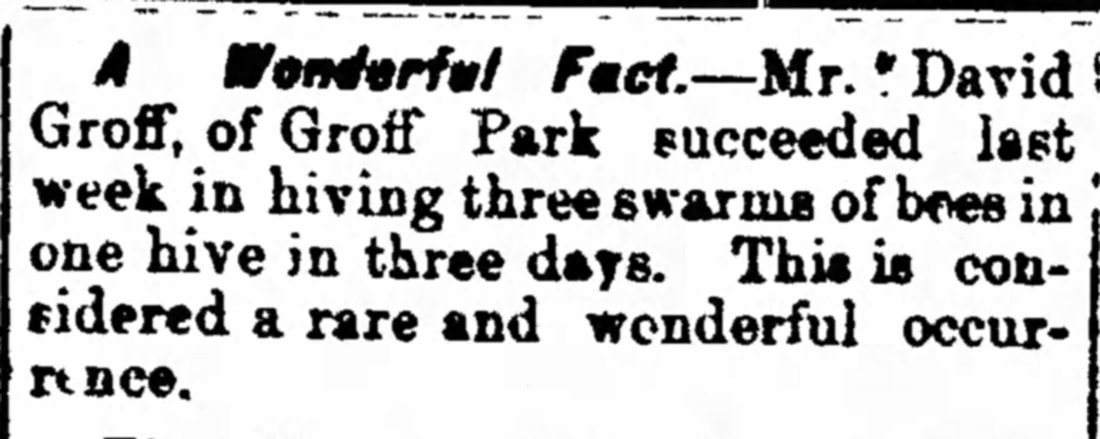

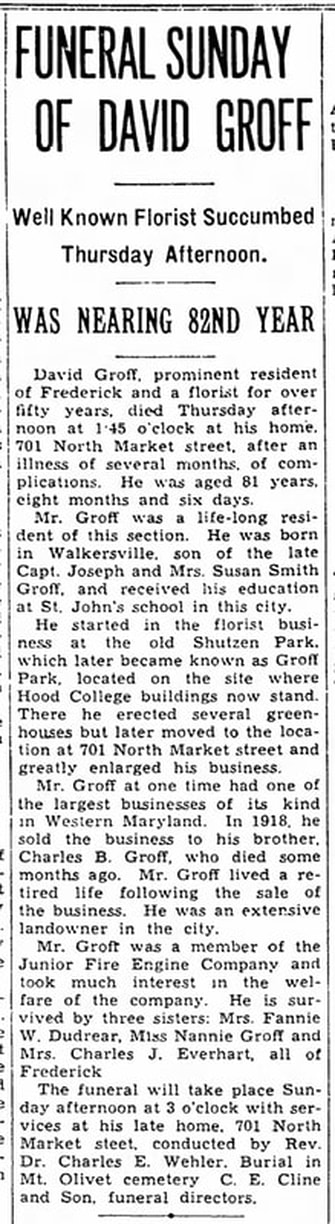

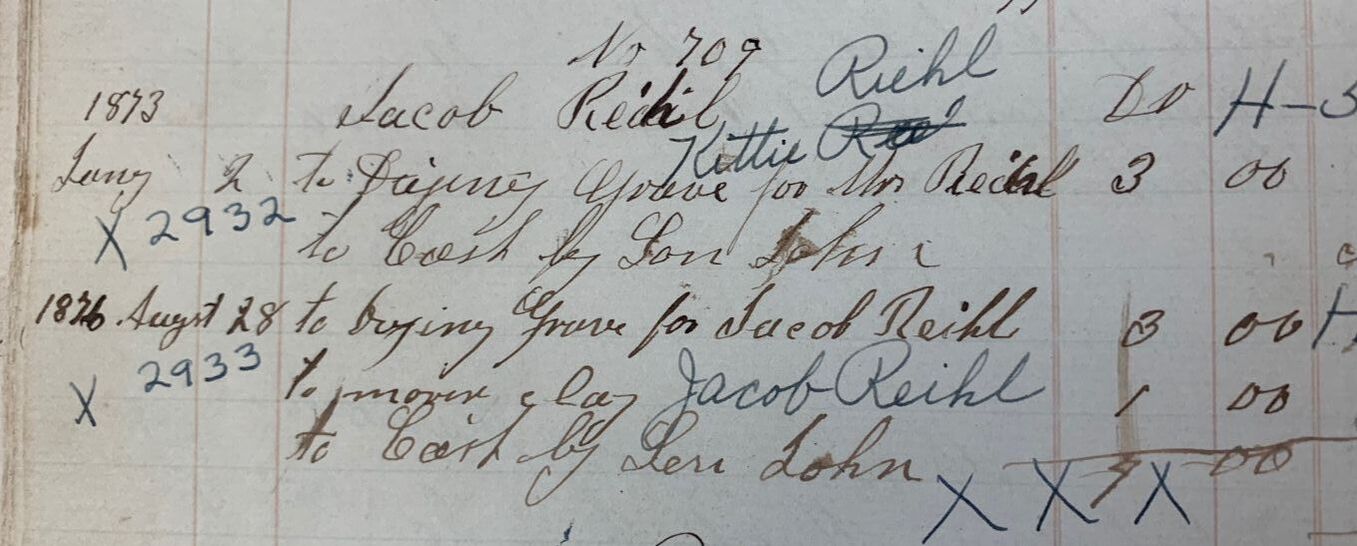

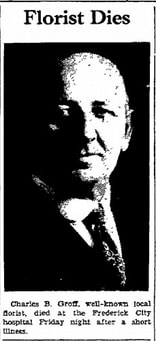

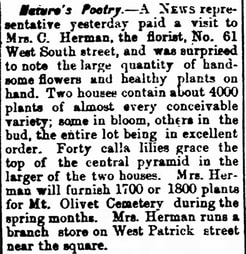

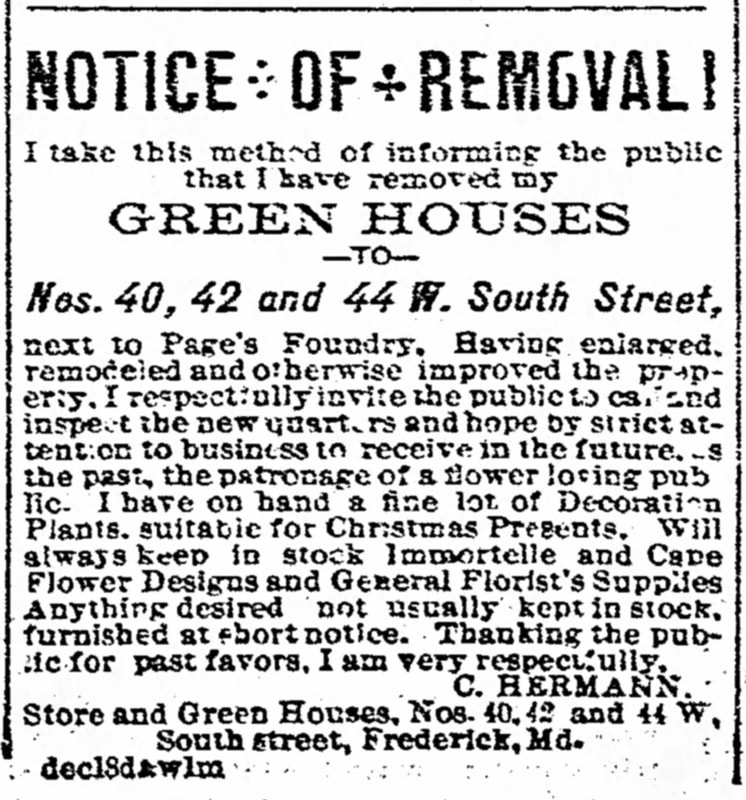

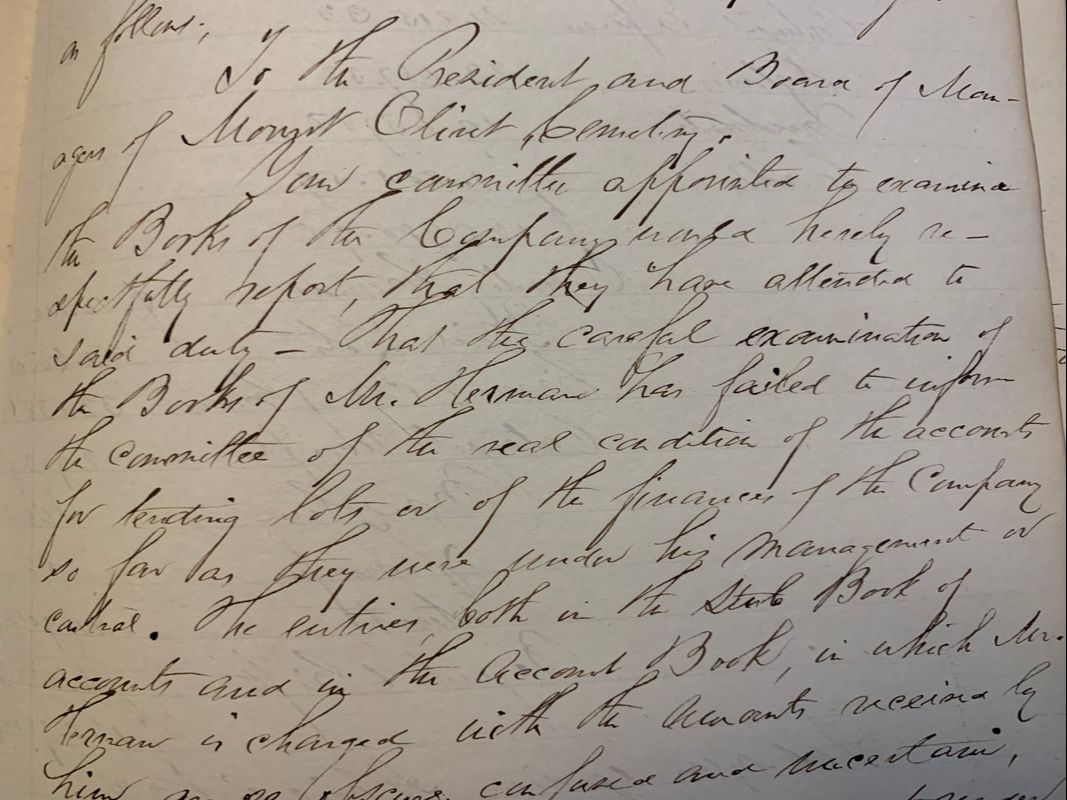

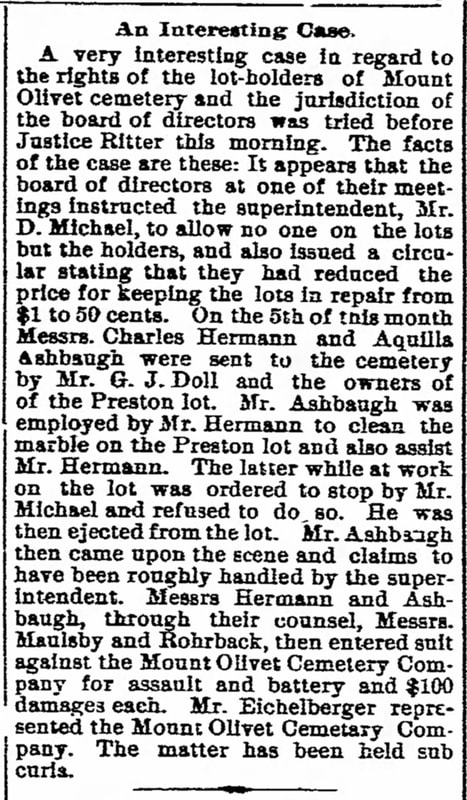

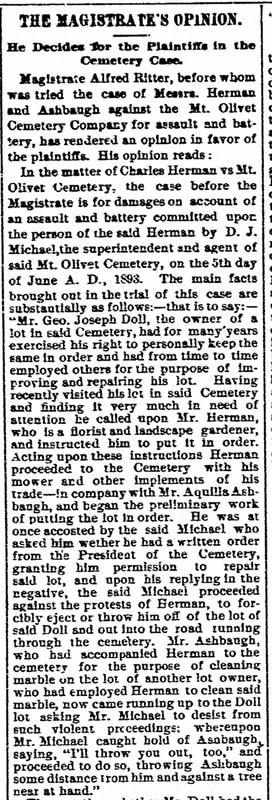

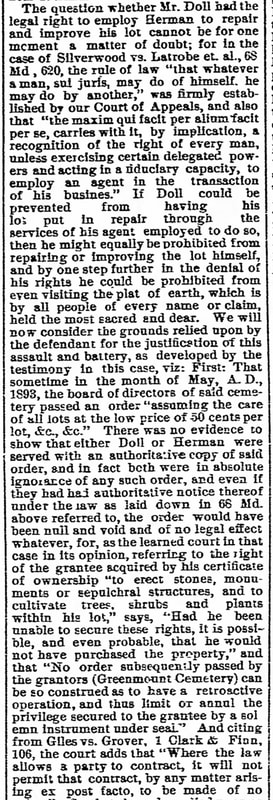

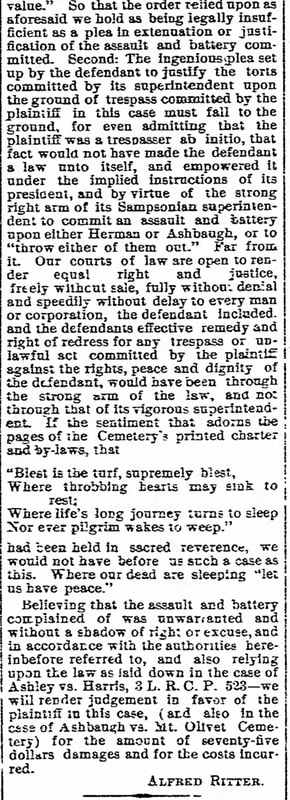

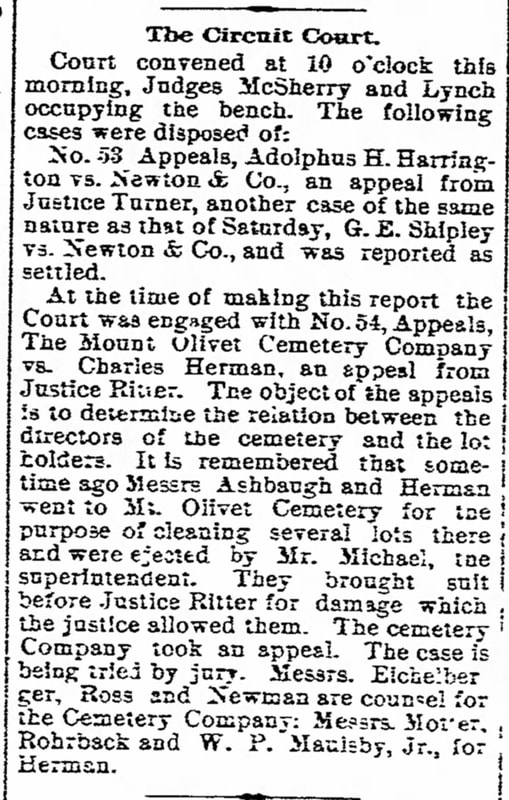

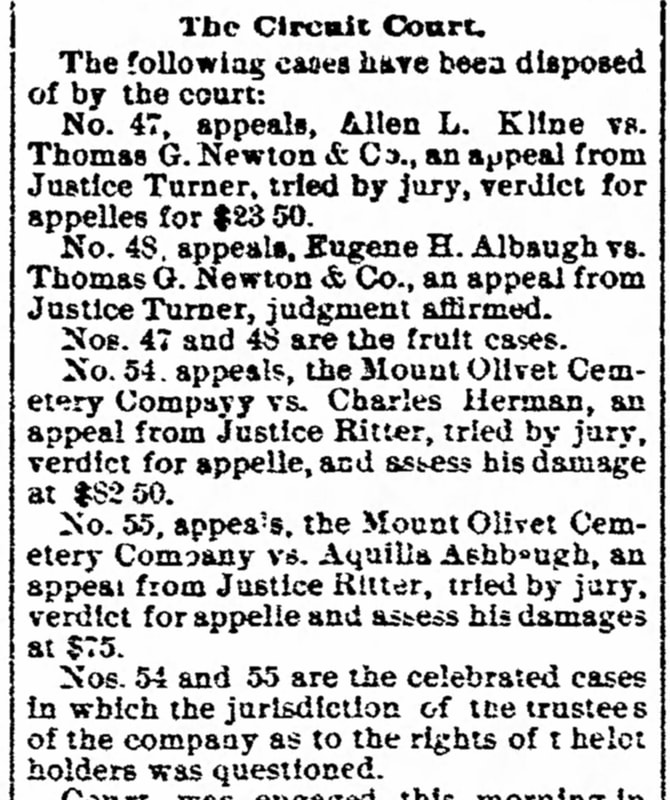

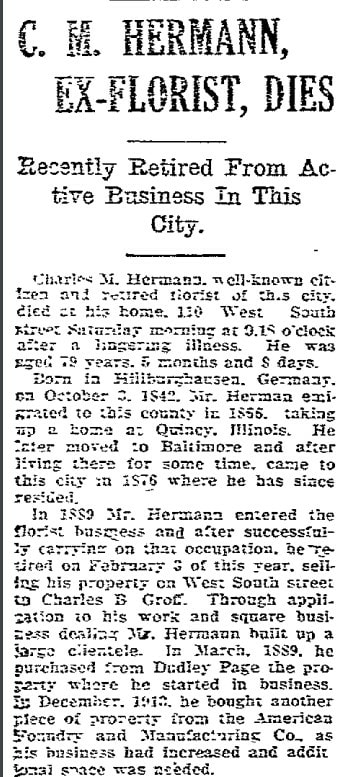

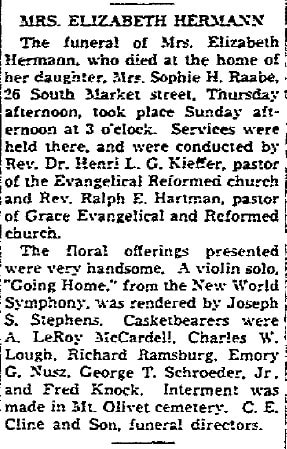

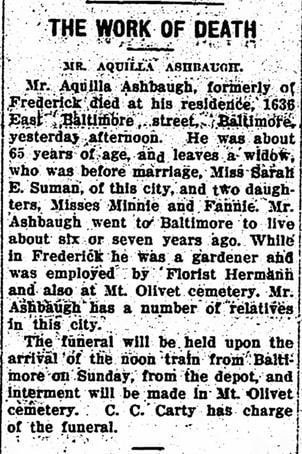

Henry Trail was the son of one of the cemetery’s founders, Col. Charles E. Trail. Col. Trail was a highly successful businessman who built the Italianate mansion on E. Church Street that today serves home to the Keeney & Basford Funeral Home. Henry was born March 17th, 1862 and lived his entire life at the Trail family mansion at 106 E. Church Street. He was a Harvard graduate who at one-time worked as a chemist at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore and traveled the world over his life of 61 years. Henry grew produce which would be sent to the finest restaurants of New York City and grew exotic flowers never before seen here in Frederick. This was done in “extensive greenhouses” that were erected on his father’s farm that adjoined the Frederick Fairgrounds on the east side of town. Henry Trail lived the life of a gentlemen and left the growing business of exotic plants in favor to raising exotic birds. Many Fredericktonians have heard stories of pheasants and peacocks strolling the grounds of the old Trail Mansion, at which Henry constructed a large aviary structure to be used for his hobby. He died of pneumonia on April 22nd, 1923 and is buried beneath the outstanding monument that adorns the Trail family lot on Area H/Lot 110. David Groff was born on Christmas Day, 1855 in Walkersville. His parents are known in the annals of Frederick history as prominent hoteliers and local heroes of the Civil War. Joseph and Susan Groff ran the Arlington House, located on N. Market Street during the turbulent era of the 1860’s. David’s father was a shrewd businessman who also ran a brickyard and dabbled in real estate acquisition. One such property was the site of a former German social club called Scheutzen Park. The site would come to be known as Groff Park and the former social group’s main club house would become the family’s new personal residence. In the next century, Groff Park would become the new site of the Frederick Woman’s College, renamed Hood College. David Groff’s childhood home was none other than Brodbeck Hall, the central facility associated with Hood College’s music department. Groff Park and Brodbeck would serve as the family residence until 1894, at which time they re-located to another stately dwelling at the intersection of 7th and N. Market Street. Here they would open a new hotel by the name of the Groff House. This location would later serve as the home of WFMD. David attended St. John’s School and began taking a keen interest in growing things from a young age. Groff Park was his showplace, and he would turn a hobby into a profitable profession. It was here (in Groff Park) where the family grew extensive gardens in which they harvested produce and flowers for their hotel guests. Greenhouses were built here for the express purpose. Locals were invited to see David’s handiwork as the location became known as somewhat of a “poor man’s” botanical garden—one that preceded Baker Park by nearly 50 years as a scenic destination for picnicking, leisurely strolls and carriage rides. The park would become a prime location for “drives” with the advent of the automobile in the 1890’s. The 1873 Titus Atlas of Frederick illustrates the lanes within Groff Park, and I assume that they were paved as the family-owned brickyard specialized its marketing efforts on advertising pavers for streets, alleys and driveways. David’s job was to run this family business, which was anchored in the 700 block of N. Market Street not far from the Groff House Hotel which was originally constructed by Captain Groff in 1884. David seems to have extended his floral hobby to competitions in the early 1890’s and was a prominent member of the Frederick Floriculture Club. He is mentioned in a newspaper article in November 1892 which talks about the Chrysanthemum Show in which he entered 20 varieties of the flower. Articles regularly appeared in the local newspaper boasting David Groff’s floral artistry and special growing experiments. When the family left Groff Park around 1897, David took charge of selling off properties for building lots on the eastern edge closer to town. He took up residence at 701 N. Market Street adjacent the family-run hotel. He would build greenhouses here that would help supply a florist business ran out of his new residence.  Charles B. Groff (c. 1889) Charles B. Groff (c. 1889) The florist operation of David Groff thrived and became his life’s work as he never married or would have children. David would run the business until early 1916, at which time the reins were handed to his younger brother Charles Benjamin Groff (b. 1873). The younger Groff had worked as a county clerk but assisted David for years. He, too, would make his mark as well on the community over the next 18 years until his death in December, 1936. An article appearing in the April 5th, 1917 edition of the Weekly Journal of Florists, Seedsmen and Nurserymen contained a small mention of the Groff-run business: “A grower whose long suit is performance and who has a reputation as a teetotaler, will find a good market for his services if he happens down Frederickway and stops in at Charles B. Groff’s stand where everything is grown, and grown well.” David Groff never stopped growing things. He devoted his time to selling family-owned land, newly constructed homes and renting apartments within the old Groff House (after the hotel closed as a business). In 1927, he ran advertisements for things such as potted tomato plants and celery. He died nine months after his brother at the age of 81 (August 26, 1937). His passing, and subsequent funeral were the source for a few nice articles that appeared on the pages of the Frederick News-Post. Of special notes was the fact that “floral offerings were beautiful and numerous.” One of his pallbearers was Alfred G. Zimmerman (1891-1961), the progenitor of Zimmerman Florists. David Groff is buried next to his parents in Area L/Lot 247. His kid brother can be found in Area Q/Lot 127. Not that far from the gravesite of Charles B. Groff is buried a true early giant in the field of Frederick floristry—Charles Hermann. He even became known as “Hermann, the Florist,” a slogan that can be found in several old news articles and advertisements. Charles Maximilian Hermann was a German transplant to Frederick who earned the nickname of “Hermann the Florist” by the mid 1880’s. Actually, I found that a good deal of this gentleman’s success should be given to his wife, Elizabeth (Diehl) Hermann. Evidence comes in the form of a news article that appeared in the Frederick News in mid-December 1883. I saw ads referencing Mrs. Hermann and her business and greenhouse located at 61 W. South Street in Frederick up through mid-1888. She is said to have had a branch office located on W. Patrick near the Square Corner and in 1885 was preparing to furnish Mount Olivet with 1700-1800 plants. In December of that year, her husband Charles announced that the Hermann floral business had moved to a new home down the street from their home and next to the old Page agricultural implements foundry that sat on the SW corner of the intersection of W. South and Broadway Street. Back in the day, Broadway Street was called Mantz Street and the Page foundry location is the home of the Gary L. Rollins Funeral home with an address of 110 W. South Street. Whether by design or accident, Mr. Hermann shared his talents with Mount Olivet Cemetery in more ways than a flower vendor. On March 16th, 1887, he was given the title of assistant superintendent of the cemetery, the first time such a position would exist after 33 years of operation as a burying ground. I searched to see if Hermann had been working for the cemetery in any other capacity before this date, but came up unsuccessful. So I deem it a case of “chicken or the egg.” Was Hermann hired for his special expertise in gardening and floral creation, or did he hone his skills here at the cemetery, which in turn, would benefit the business apparently started by his wife, Elizabeth? Interestingly, Mr. Hermann’s immediate supervisor, Edward Herwig, started in his position on March 16th, 1887—the same day Hermann began his duties as assistant super. Herwig was filling big shoes, as he would be the second superintendent ever chosen for the position, following inaugural cemetery head William T. Duvall who served from February 6th, 1854 until the day of his death on September 19th, 1886. Regardless, things seem to have “taken bloom” for the Hermann family business here in Frederick, perhaps tied to an increase in orders connected to Mount Olivet Cemetery. Was this a case of “double-dipping?” And I’m certainly not talking about ice-cream. As said, everything was coming up roses for Charles B. Hermann until one fateful day in early November, 1892. A special meeting of the cemetery board of directors had been called with the death of Board President Lycurgus Hedges. At this meeting, the Board secretary, Thomas M. Markell, was instructed to notify Superintendent Herwig that “his service would be disposed with after the first day of January next.” This was roughly a 8-week notice, and the board subsequently authorized interim president Lewis C. Clingan to find a new man to take Herwig’s place. Charles Hermann was not even considered for the job, but there was good reason as he could been a prime reason for Herwig’s downfall. The accounting associated with the cemetery’s books was in question as things weren’t quite matching up—floral and shrubbery expenses were way up.  Frederick News (Dec 6, 1892) Frederick News (Dec 6, 1892) Just over a week later, Mr. D. Jerome Michael was unanimously elected to become the cemetery’s third superintendent, a position he would hold for the next 14 years. In conducting research, I was more than pleased to find a celebration of sorts held at the Michael residence a few week’s after being awarded his new post at the cemetery. This would certainly not be the last “pound” party that Superintendent Michael would take part in.  Mr. Michael assisted the Board of Directors with research into the accounting and management issues discovered under the Herwig regime. Apparently, the trouble came under the purview of Mr. Hermann in the daily performance of his duties as assistant superintendent. It came as no surprise that Mr. Hermann was given the proverbial “pink slip” on January 1st, as his service was promptly disposed with as well. Superintendent Michael, the new sheriff in town so to speak, continued his research over the winter months. The Board of Directors reconvened for their annual meeting in early May, 1893. A special committee would be appointed by the Board to explore the cemetery books more in depth with a goal of “placing things in a satisfactory and intelligible shape.” Assistance would come from the Board’s secretary and treasurer as well. On May 22nd, a special meeting was called in which Board member Mr. Charles M. Tyson presented a report on the special committee’s finding. the following passage comes from the Mount Olivet Minute Book records: May 22, 1893 report To the President and Board of Managers of Mount Olivet Cemetery: Your Committee appointed to examine the books of the Company would hereby respectfully report that they have attended the said duty that the careful examination of the Books of Mr. Hermann has failed to inform the Committee of the real condition of the accounts for tending lots or of the finances of the Company so far as they were under his management or control. The entries, both in the Book of accounts and in the Account Book, in which Mr. Hermann is charged with the amounts received by him, are so obscure, confused and uncertain and the calculations so inaccurate, as to render it impossible to say what the status of this department. What was happening in the cemetery, behind the scenes, had been brought to light by the new superintendent and likely corroborated by existing grounds employees—Charles Hermann was not only using his personal business as a major vendor for the cemetery (for plants, shrubs and flowers), he was likely recommending his personal business services to lot-holders over the capable individuals on the Mount Olivet payroll. He was poaching customers for personal gain—a clear-cut case of conflict of interest. At another Board of Managers meeting, held May 31st, 1893, Mr. Edward S. Eichelberger made a pivotal motion. Eichelberger was one of the three Board members assigned to the special committee of inquest into the matter. His motion ordered that “no one other than Employees of the Company be allowed to take care of Lots, unless he files with the Superintendent of the Cemetery, a separate written authority from each lot holder of whose lots he is to have charge, which authority shall be countersigned by the President of the Company and which shall be kept by the Superintendent, as a defense against any complaint of the lot holders for any alleged neglect. “ Mr. Eichelberger went on to add that “the President be instructed to obtain a list of those persons whose lots have been placed in Mr. Hermann’s charge, and notify them of the above order, and correct any misapprehension as to the facts in regard to the lots, and the Secretary is instructed to send a written copy of the above order to Mr. Herman. It appears that Mr. Hermann had decided to continue accommodating “his” lot-holding friends and cronies by providing special services to them and their respective lots in the spring after his termination. The Board was not amused. They also understood the ramifications that they would be liable for the conduct, or better—misconduct or “neglect” of an outside vendor performing work in their cemetery—especially work they were plenty capable of doing themselves with their own staff. Well, just five days later, let’s just say that the “flowers” hit the fan so to speak. Mr. Hermann and a hired hand named Aquilla Ashbaugh came to Mount Olivet to perform work on lots, contrary to the recent order set forth and communicated by the Board of Managers. These lots belonged to local department store owner Joseph Doll (1829-1895), and another owned by the hiers/family of William T. Preston (1811-1879). Our minutes book say nothing of the incident that occurred on this day, however a vivid depiction of events was printed in the Frederick newspaper two weeks later as part of a court case that went before local magistrate Alfred Ritter. The case can be seen from two different vantage points. First and foremost was the obvious “assault and battery” on Hermann and Ashbaugh as Superintendent Michael decided to host another “Pound” party on June 5th as he threatened (and succeeded somewhat) in pummeling his adversaries. The other part centered on cemetery lot-holder rights vs the cemetery corporation’s authority and responsibilities of operating a cemetery. Judge Ritter ruled in favor of the plaintiffs, but simply looked at the case from the perspective of the unjustified act of assault and battery on these gentlemen at the hands of Superintendent Michael. Each plaintiff was awarded $75 and their court costs were paid by Mount Olivet. (For your reading pleasure, I have included below the full verdict as reported in the newspaper) It didn’t end there, as the case would be appealed by the cemetery. In late August, 1893, a jury listened to the facts of the case and ruled in favor of the cemetery. The end result was a study into the ultimate responsibilities of the Cemetery Board, and their standing as being nominated and duly elected to represent the mass congregate of active lot-holders. The jury found the cemetery “not guilty” of wrongdoing, and rewarded them back $82.50 in both cases (involving both men—Hermann and Ashbaugh).  Frederick News (June 12, 1893) Frederick News (June 12, 1893) The Hermann-Michael "Battle Royale of 1893" solidified a rule that still stands today under Article 31 of our official Mount Olivet booklet of rules and regulations published by the cemetery: “No one other than employees of the cemetery will be allowed to take care of lots, including but not limited to the mowing, trimming and watering of grass on their lots.” While Charles Hermann lost $75, court costs, and future earning potential with personal lot renovation work, it is important to know that he kept working. As a matter of fact, he would continue to have success in the floral business and would be appointed overseer of St. John’s Catholic Burying Ground off E. 3rd and N. East Street in June, 1893. Hermann would grow the business with the guidance of Elisabeth and help of his son (Charles) who he brought into the business. Charles eventually sold the family business upon his retirement in February, 1922. This would go to friend and fellow florist Charles B. Groff, brother of David Groff, whom we discussed earlier. Charles M. Hermann died on March 11th, 1922. He would be buried on a corner lot in Area H, directly across from Confederate Row. Wife Elizabeth, the unsung and original floral artist of the couple, died in 1941 at the age of 95. Hermann’s faithful sidekick, Aquilla Ashbaugh, is also buried in Mount Olivet with his wife Minnie. In finding his obituary, I was surprised to find that Mr. Ashbaugh was a former employee of the cemetery. This means that he left with Hermann when the latter was fired in January, 1893. Sadly, the Ashbaugh gravesite is devoid of an identifying marker or monument (Area B/Lot44). Must have been confusing for friends and relatives to find his grave in order to place flowers... “In joy or sadness, flowers are our constant friends”

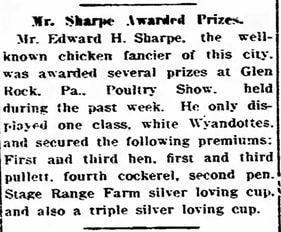

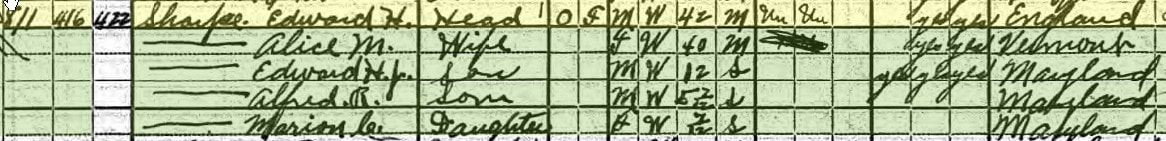

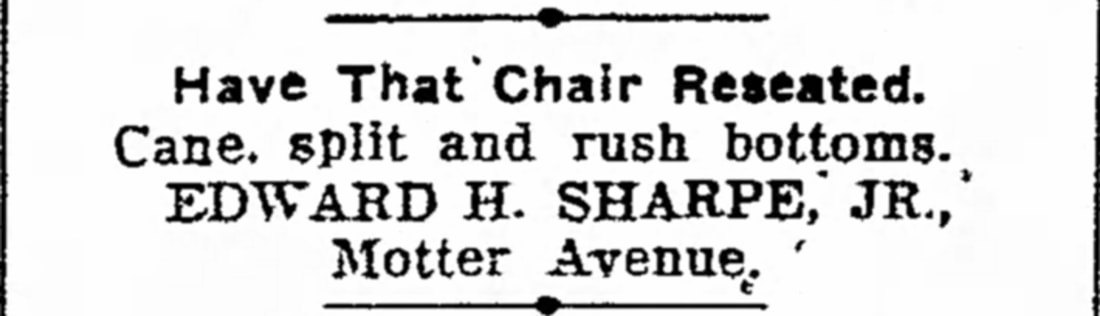

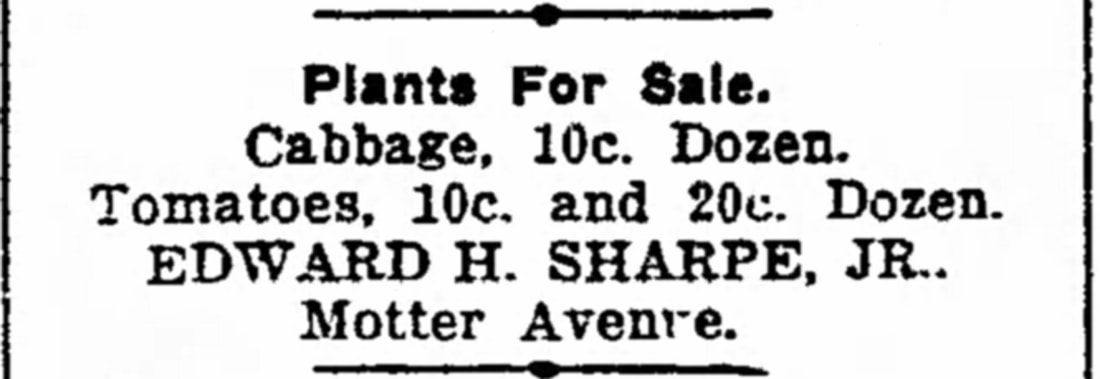

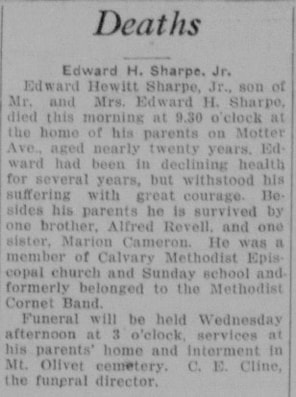

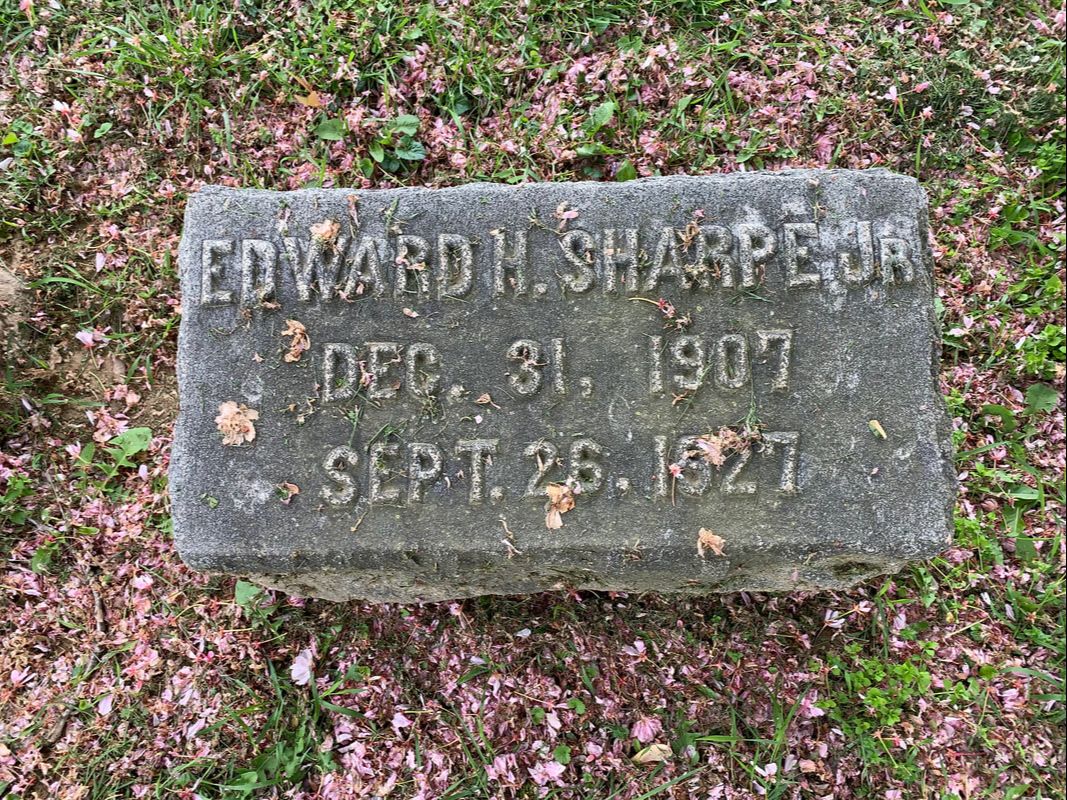

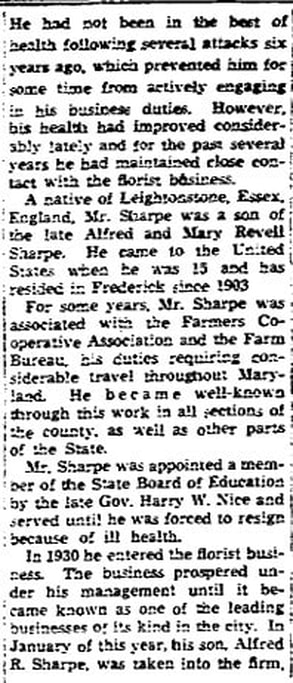

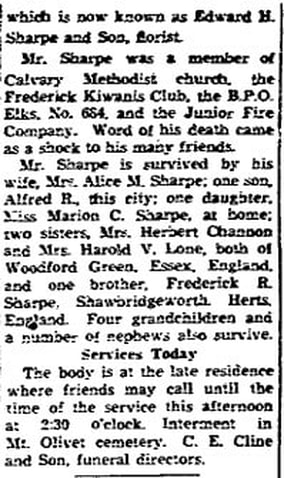

-Okakura Kakuzo  Thomas Tusser Thomas Tusser April showers bring May flowers — or so we’ve been told. Rainfall last spring was exceptionally memorable, but not so much for the lush floral scenery, but more so for the frustration brought to kids, adults, parents and grandparents who hoped to participate/attend spring sports such as baseball games, and the annual host of festivals and special events that occur this time of year. Even though its officially May at the time of this writing, Mother Nature continues to dump on us here in the Mid-Atlantic, ensuring make-up games and a spike in umbrella and rain poncho sales. Hopefully, it will also be guaranteeing an above average flower harvest as well! So, where does this expression (“April showers bring May flowers” ) come from, and what does it mean in both a literal and figurative sense? According to George Latimer Apperson’s “Dictionary of Proverbs,” we can trace the phrase “April showers bring May flowers” to an 1886 saying — “March winds and April showers bring forth May flowers” — which might have even deeper roots to a 16th century poem written by Thomas Tusser (1524-1580) which features the verse: "Sweet April showers/Do spring May flowers". The phrase is even referenced in the General Prologue of Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales: "Whan that Aprill, with his shoures soote The droghte of March hath perced to the roote.”  April is typically a wet month here in our part of the country. I can say with surety that our plants are likely not aware of this proverb, but rarely have to worry about having enough water in the spring to start growing and producing flowers especially because the water itself isn’t the key factor which dictates flowering times. Many researchers have studied rain and the general effect it has on timing and abundance of flowering, but have found that for most species, the first flowering is more closely tied to temperature than to rain. The figurative meaning of our proverb is a life lesson in “cause and effect,” and dictates that a period of discomfort can provide the basis for a period of happiness and joy. We can certainly visualize and feel this as winter turns to spring and higher temperatures change snow to rain, and brown grass and leafless trees turn to backdrops of green (even helping out the baseball fields). “Viva the flowers,” adding the punctuation of vibrant color (yellow, pink, red, orange, purple, blue) everywhere. It’s a happy time as we can once again play and recreate outside again without wearing an abundance of uncomfortable layers. It’s also a joyous time for florists, individuals whose job involves arranging and selling cut flowers. Although Christmas and Valentine’s Day represent a welcomed spike in business, especially in the sale of poinsettias and roses, it is two holidays in springtime that bring the most work and stress for florists—Easter and Mother’s Day. They also bring in the most money. Spring is also wedding season, and flowers are a must! These profitable days of “cause and effect” certainly illustrate “a period of discomfort providing the basis for a period of happiness and joy.” Flowers are also seen as a source of appreciation when received on an anniversary, or inspiration, when one is recovering in a hospital bed or convalescing at home. Sadly, the flowers both myself and my work colleagues see the most are those expressly sent as an offering of comfort, condolence and sympathy. Such is the case among employees of cemeteries and funeral homes everywhere. We must remember that cemeteries should not be perceived as places of sadness, but places of remembrance. The spirit and memory of our deceased loved ones continue to live on as long as we keep them in mind and heart. Decorating gravesites with flowers is certainly a big way to do this. Florists of Yore Here in Frederick, we have plenty of reputable florists at hand, and in the ever-changing electronic world we live in, the simple act of a 1-800 call, or visit to the internet, can send a beautiful floral arrangement to a recipient anywhere in the world. However, it’s still a nice experience to walk into a flower shop, and be dazzled with a plethora of beautiful specimen everywhere you look. And there is a sense of special accomplishment in picking out the exact flowers to be utilized for a gift offering or arrangements, and in some cases, working with the folks primarily responsible for growing these flowers. Of course, there are the special experiences to be had such as the awkward nervousness associated with having to write romantic or sympathetic prose under the watchful eye of a florist for flowers to be delivered, or the possible mayhem related to self-delivery as it relates to properly balancing a vase of flowers without saturating a car seat or loosing/mashing precious petals in transport. Mount Olivet Cemetery is proud to have interred many of the greatest florists ever to do business in Frederick, Maryland. In fact there names are almost synonymous with Mount Olivet. This is due to the simple fact that a large portion of their flower harvests were destined to decorate the graves herein. In recent memory, two names stand above the rest—Sharpe and Zimmerman.  Frederick Post (Dec 9, 1911) Frederick Post (Dec 9, 1911) Mr. Sharpe Edward Hewitt Sharpe, Sr. was fittingly born on May 1st, 1877 to Alfred Sharpe and wife Mary Revell. A native of Leytonstone, Essex, England, his father worked as a merchant. Edward came to the US in 1892 at the age of 15. He attended, and graduated, from the Massachusetts Agricultural School in Amherst, Massachusetts and met his future wife, Alice N. Hyde while there. Miss Hyde was a native of Poultney, Vermont and attended the Northfield Seminary in Northfield, Massachusetts for her schooling. Sharpe graduated around 1901 and came to Frederick in 1903. The couple of Edward and Alice married on November 15th, 1905. In the 1910 census, the Sharpes can be found residing at 811 N. Market Street with two-year old son, Edward H. Sharpe, Jr. At this time, Edward, Sr. was working as a commercial trader for a biscuit company, likely Frederick’s G & L Bakery. His name regularly made the paper for his competitive hobby of raising champion poultry. In 1917, he was working as a salesman for Frederick C. Knott’s grocery store (known formerly as Besant & Knott). By 1920, the Sharpe family consisted of two additional children Alfred Revell (b. 1914) and infant daughter Marion Cameron (b. 1919). They would relocate their home residence to nearby 720 Motter Avenue, basically their former backyard.

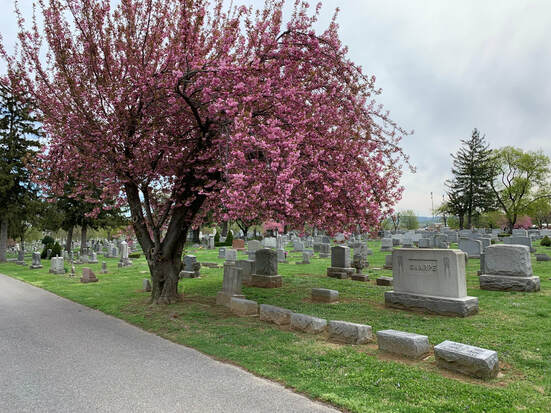

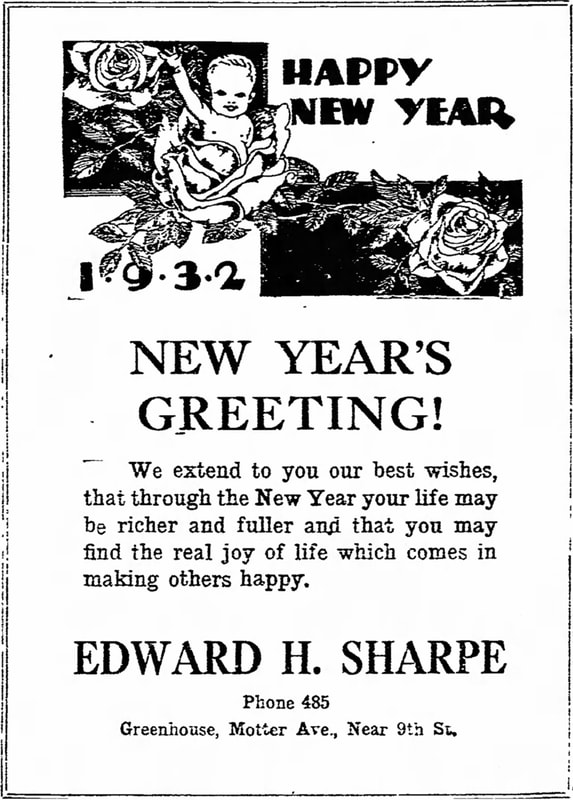

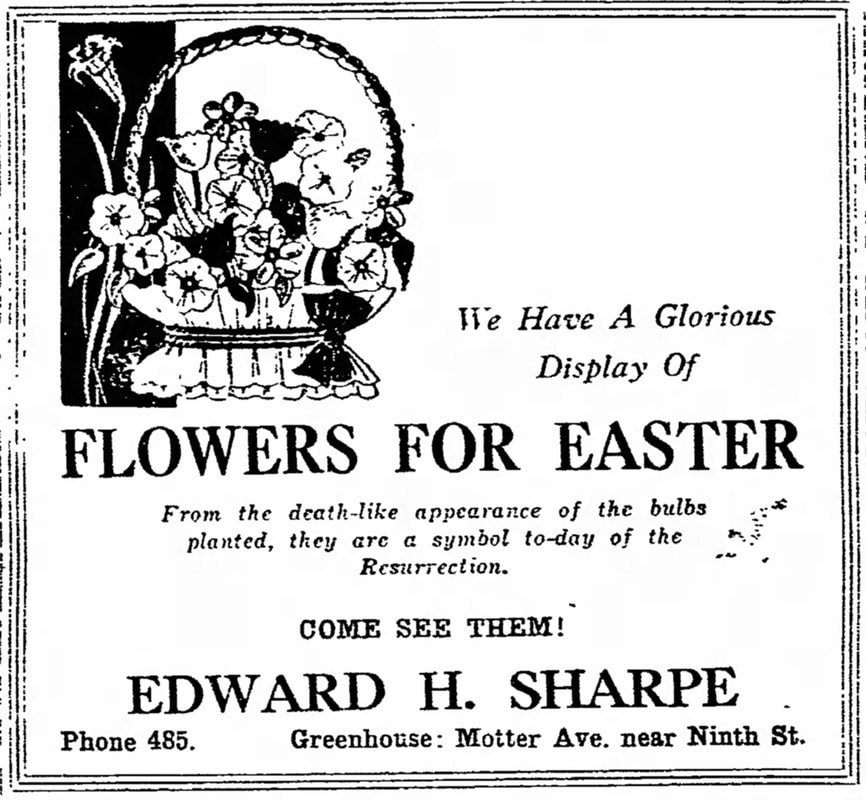

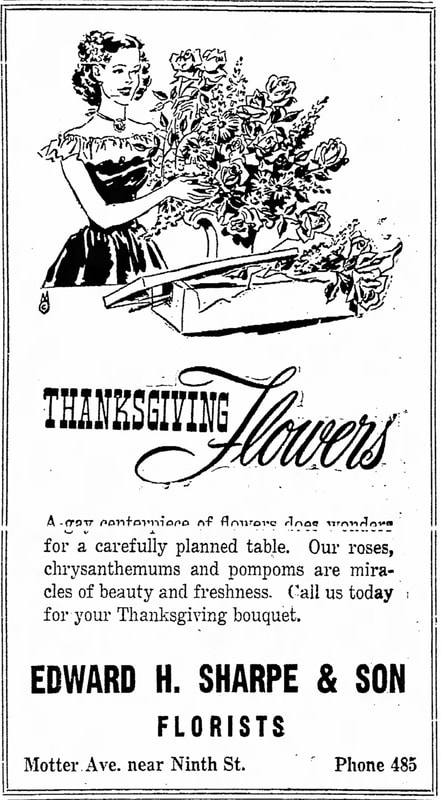

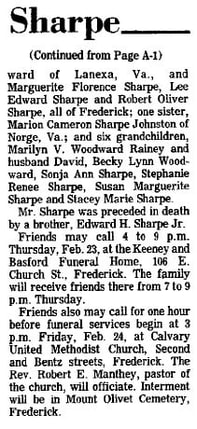

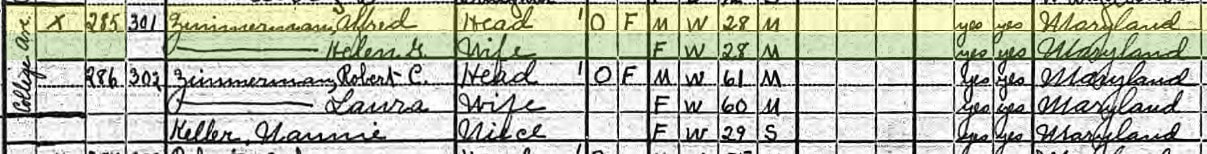

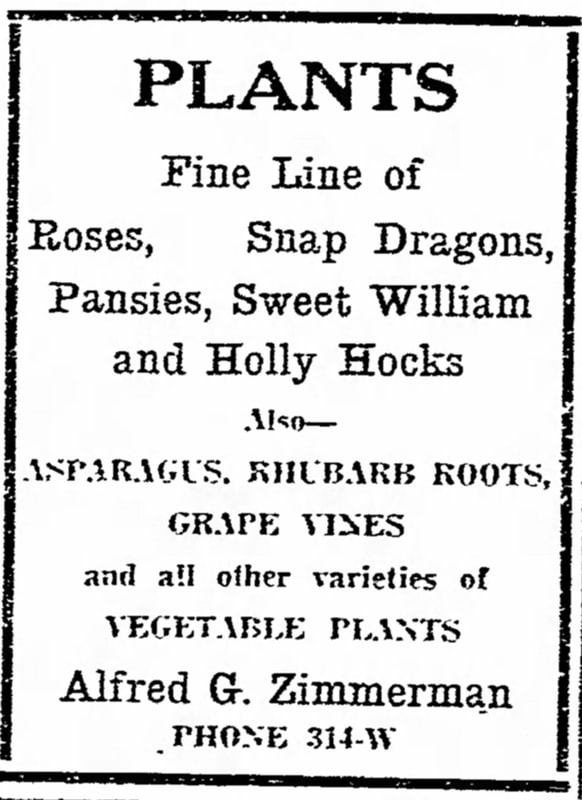

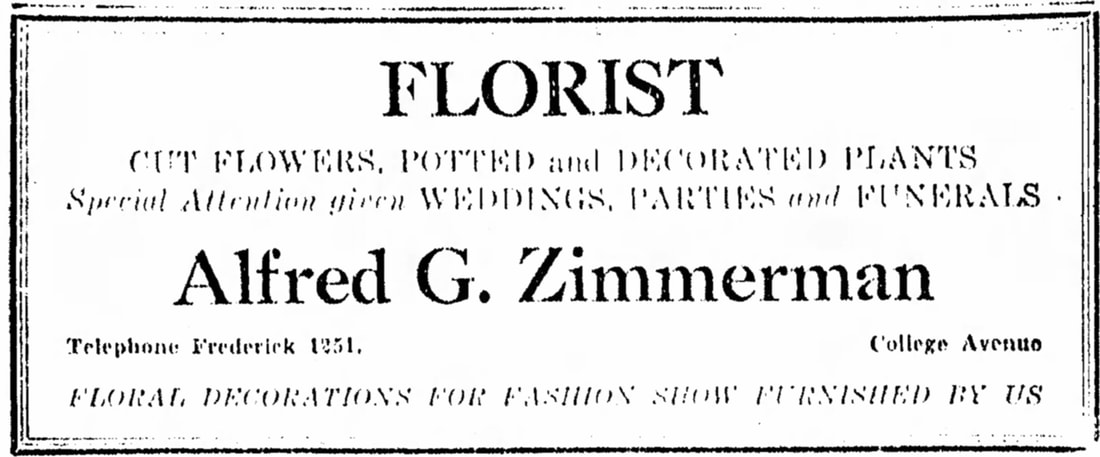

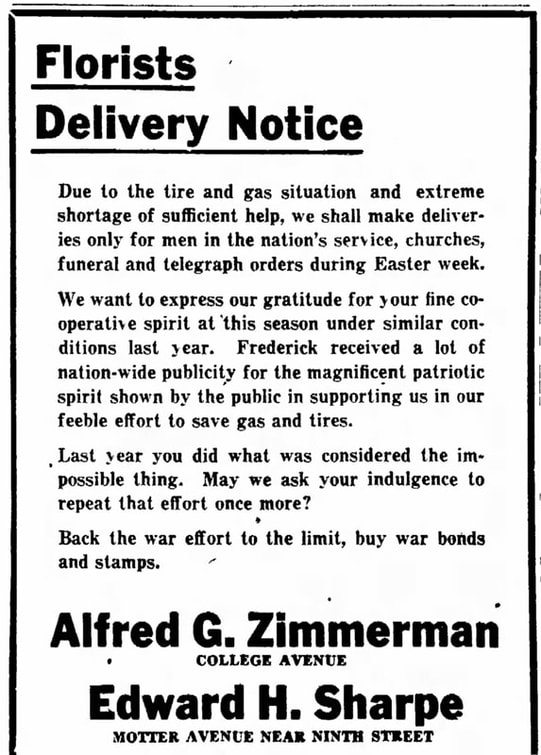

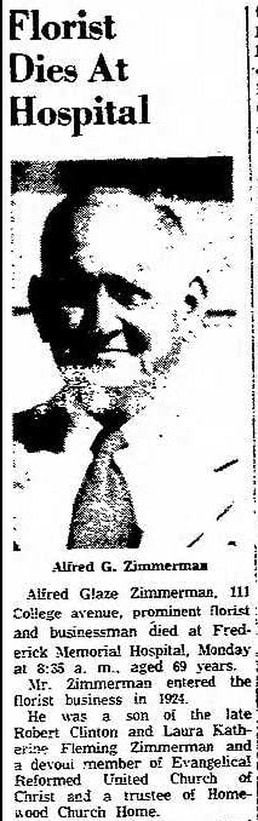

A few lonely years passed as Edward H. Sharpe performed commercial salesman duties for the Frederick Farm Bureau. He would be hired by the state to serve as a field agent to the Maryland Farm bureau. He likely tired of the travel required across the state. In August, 1930, Edward would find himself following somewhat in his deceased son’s footsteps. He was now selling flowers and plants as the proprietor of a floral shop located directly behind his home residence and known as Edward H. Sharpe, Florist. A greenhouse and walk-in business office would be built here in due time, fronting Motter Avenue. The business grew during the lean years of the great depression and World War II. In spring, 1930, Mr. Sharpe’s second son, Alfred, had graduated from Frederick High School. After a few month respite, the young man would assist his father in the Edward H. Sharpe Florist operation. In time, it came to be known as Edward H. Sharpe & Son. Edward H. Sharpe, Sr. had successfully created an enterprise that would last 84 years—one day to be run solely by son Alfred, and eventually by his grandson. Mr. Sharpe died at the age of 69 on June 8th, 1946. His death was front page news in the local paper, a testament to his business acumen and community involvement. He would be laid to rest next to son Edward in Mount Olivet’s Area LL. Alfred was now the sole operator of Sharpe’s Florist at the age of 32. He was assisted by his wife, Mary Florence Winebrenner, and later his son, Robert. In 1972, Alfred incorporated the business, changing the name to Sharpe’s Flowers since that is what most patrons had been calling the business. Alfred R. Sharpe died on February 23rd, 1995, and just like his father, the florist’s passing made the front page of the Frederick News-Post. He too is buried in Area LL/Lot 80. At this time, Robert , took over the family business. Sharpe’s Flowers operated until May, 2014, at which time it was discontinued. The old greenhouse and business showroom still stand on Motter Avenue. Meanwhile, over in Mount Olivet, the family burial plot is located under a beautiful Cherry Blossom tree that rains a beautiful shower of pink and white blossoms on this special “floral family’s” gravestones each spring. Mr. Zimmerman Born on October 30th, 1891, Alfred Glaze Zimmerman was the son of Frederick City farmer Robert Clinton Zimmerman and wife Laura K. Fleming. After attending public school, Alfred spent time at the Frederick Academy. In early 1916, he undertook special courses on horticulture at the Maryland Agricultural College (later known as the University of Maryland). Zimmerman operated as a farmer’s market gardener early in his career before going into the florist business as a retailer and wholesaler in 1924. A publication stated that Mr. Zimmerman grew his products under about 35,000 square feet of glass. Alfred Zimmerman married Helen Brunner Gittinger, daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Samuel Gittinger on July 3rd, 1917. Interestingly, Helen’s father bought the Sharpe’s first residence located at 811 N. Market Street in 1919. The couple would not have children. Mrs. Zimmerman would assist her husband in his floriculture pursuits from the very start. In the early 1920’s, newspaper advertisements boasted the sale of shrubbery, celery and finally a virtual grab-bag of various potted plants and vegetables.  1929 aerial photograph looking northwest from downtown Frederick. The center of photo is Baker Park with College Avenue bisecting from left to right. At the intersection with an extended W. 2nd St., one can make out the Zimmerman Florist greenhouses to the right and to the left, the old Zimmerman farmhouse within the copse of trees. The Zimmerman’s originally lived at 207 College Avenue. A greenhouse would be constructed here as well. To the south was Alfred’s original home, having been born in this house on the western outskirts of Frederick City. W. Second Street would eventually extend through the Zimmerman farm property, dividing Alfred’s adult home from that of his childhood home in which his parents still resided. In 1935, the couple would move across W. 2nd Street and take up Albert’s childhood home of 111 College Avenue as their new abode. The home on 207 could now be solely used for the home and office of the florist business. Over the next decade, the Zimmermans would make additional money as they subdivided lots on the old family farm and sold these. Most lots had frontage on W. 2nd Street, and these stretched clear down to Culler Lake. An interesting find from the World War II era is an advertisement in which both Alfred Zimmerman and Edward H. Sharpe, Sr. worked together in helping the war effort here at home. The floral giants addressed tire and gas rationing by limiting flower deliveries to soldiers and their families during Easter. They also made a unified plea for residents to buy war bonds.

The former Zimmerman greenhouses were dismantled, and the old storefront and office was renovated, remodeled and sold as a private residence a few years ago. The larger Zimmerman farm property remnant at the northwest corner of College Avenue and W. 2nd Street was purchased by a local builder and subdivided. Today, you will find a row of luxury homes, each selling for top dollar—not unlike what occurred eighty years ago on the other side of the street. Edward Sharpe and Alfred Zimmerman provided Frederick with flowers through nine decades. They actually produced more more than flowers, they grew livelihoods for themselves and future generations. Stay tuned next week for Part II of this story on early Frederick floral entrepreneurs. I will show you how April showers bring May flowers...and how May flowers can bring June court cases of assault and battery! One such happened in 1893 and featured a prominent florist and a cemetery superintendent

|

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed