I have no ambition in this world but one, and that is to be a fireman. The position may, in the eyes of some, appear to be a lowly one; but we who know the work which the fireman has to do believe that his is a noble calling. Our proudest moment is to save lives. Under the impulse of such thoughts, the nobility of the occupation thrills us and stimulates us to deeds of daring, even of supreme sacrifice. —Chief Edward F. Croker (1863-1951), FDNY

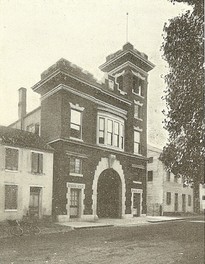

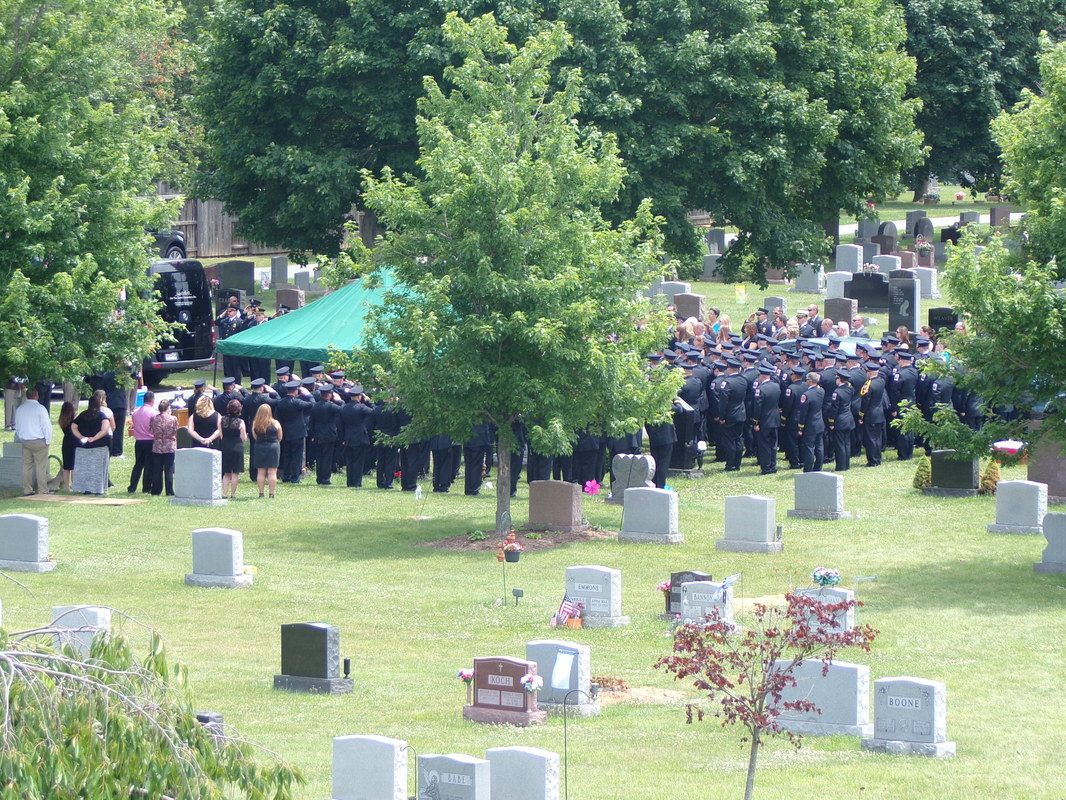

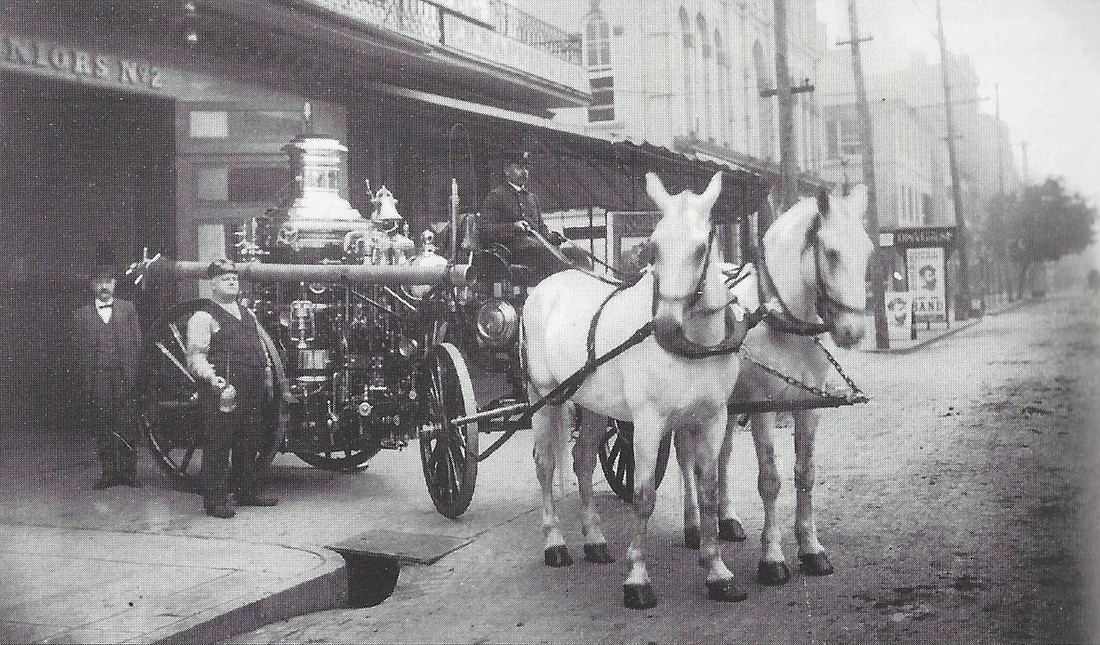

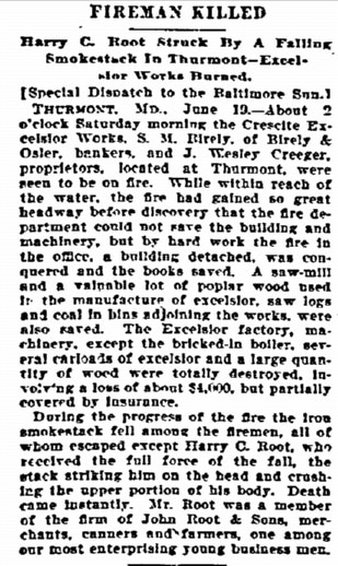

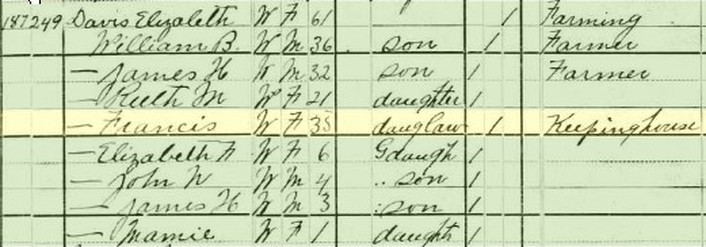

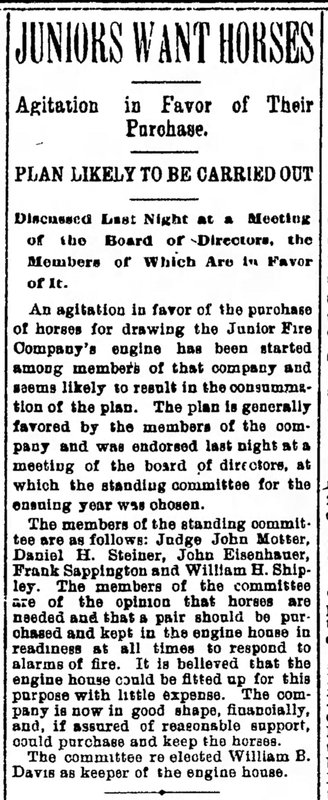

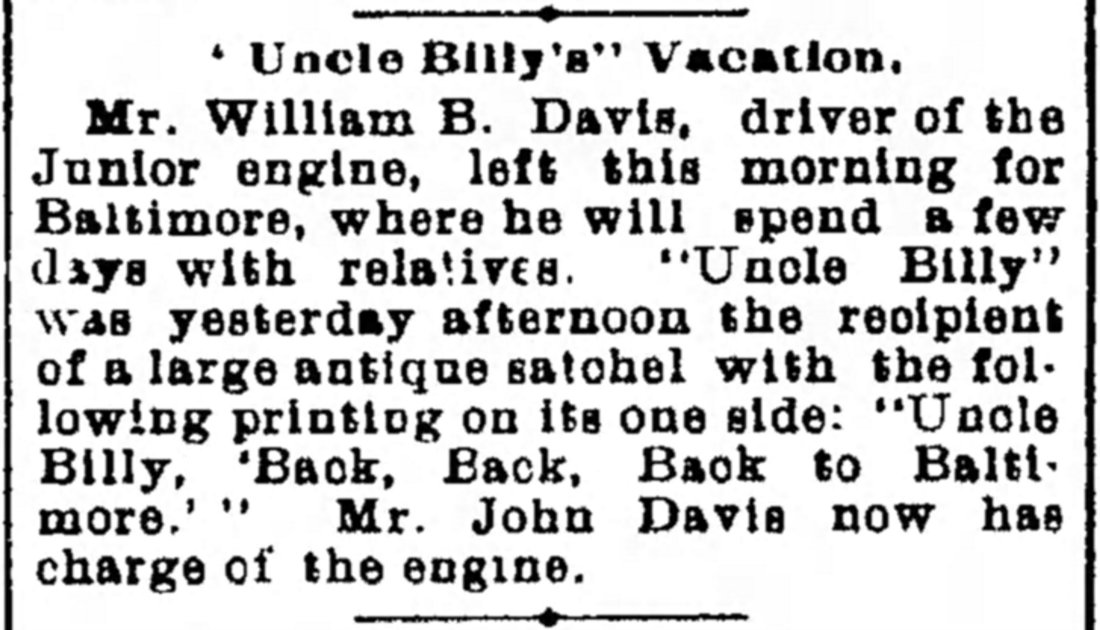

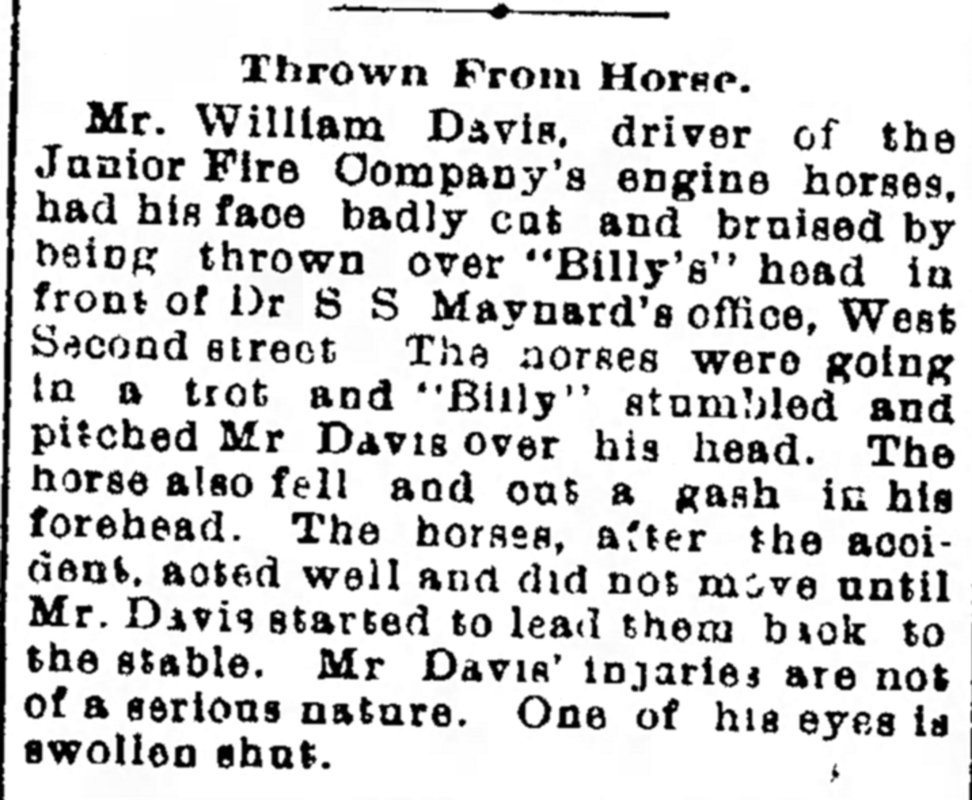

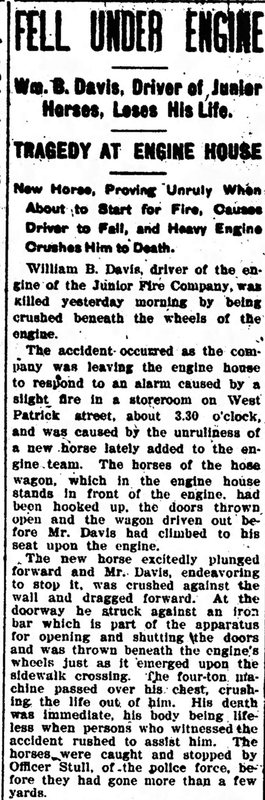

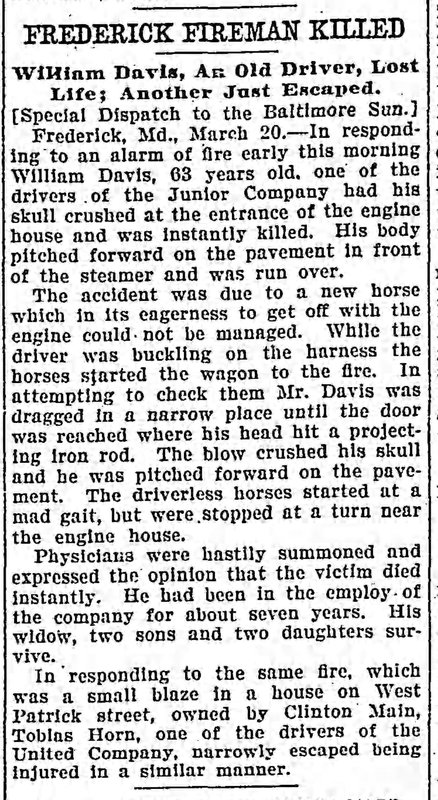

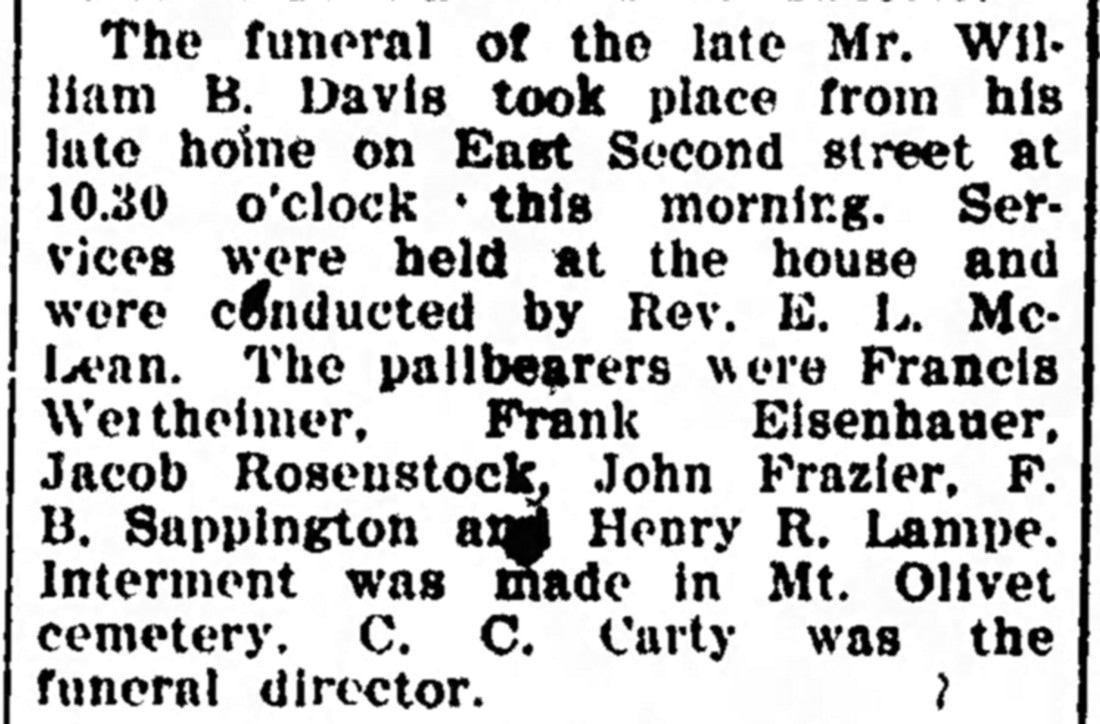

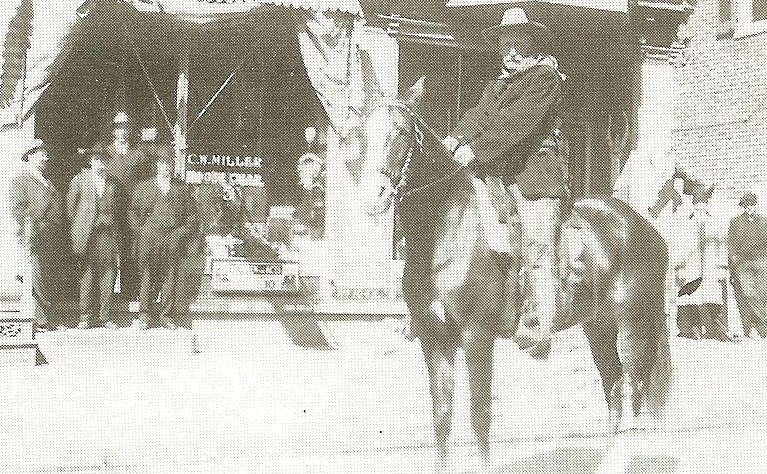

The wait for the next fireman’s death “in the line of duty” would take a relative fraction of time. Barely a a decade would pass. The victim had certainly taken his lumps over the years, dodging several work-related injuries along the way. Sadly, his last accident would prove fatal. He would be killed on March 20th, 1910, just steps in front of his own firehouse, a week before his 66th birthday. “Uncle Billy” Two of the first three firefighting casualties in Frederick County history involved members of the Junior Fire Company #2. The third name listed on Mount Olivet’s Fallen Firefighters Memorial of Frederick County is that of William Basil Davis. Davis was born in Frederick on March 29, 1844—four years after the death of Fireman William F. Charlton. He was the son of Nathan Davis and Elizabeth Delashmutt, operators of a farm located south of Frederick City. Unlike Charlton, Davis had been married for 38 years. His wife Virginia Frances Staley (1845-1926) joined her husband’s family in operating the farm after their marriage in 1872. The couple had four children, two boys (John and James) and two girls Elizabeth and Mamie). Mr. Davis led the proud life of a farmer, before trading in “country life” for “city life” and serving the community in various fashions. He was appointed a member of Frederick City’s police force and served from 1898-1901 under Mayor William F. Chilton. The family lived in a rented row house located at 56 E. Fourth Street. William Davis, and son, John became volunteer members of the Junior Steam Fire Company as well. In 1900, Davis was elected assistant foreman. He was beloved by his fellow company members, and affectionately earned the nickname “Uncle Billy.” Davis would eventually hold the title of Keeper of the Engine House. His advanced age dictated a role more suited to his physical abilities. The 59-year-old became the driver of the Juniors’ engine in 1903—a paid position. At this time, horses were introduced into the Juniors’ operation to improve response time in pulling the engine. In prior years, the firemen themselves pulled and pushed their engines to various fires in, and around, Frederick. Representatives of the company had visited Baltimore on a fact-finding mission to improve firefighting methods. They came back with ideas that resulted in the remodeling of their engine house, located within the first block of N. Market Street for the entire duration of William B. Davis’ life. The company’s name was changed to the Junior Steam Fire Engine Company #2. Two grey horses were put into service, one named “Dan,” the other “Billy." William Davis worked day and night shifts with his employment. He proudly took part in driving these horses and the company’s 1876 Silsby Steamer. In his inaugural year on the job, he took part in parading up and down Market Street as the Maryland State Firemen’s Convention was held in Frederick (1903). Large arches were erected across the street and in front of the three engine houses of downtown at that time (Juniors, Uniteds and Independents).  Chemical and hose wagon of the Juniors Chemical and hose wagon of the Juniors In August of 1904, the Juniors purchased a new piece of equipment. It was a combination chemical and hose wagon, manufactured by the American LaFrance Fire Engine Company of Elmira, NY. It was described as “maroon and black in color, and capable of holding 35 gallons of chemicals, 200 feet of chemical hose, and 1000 feet of water hose. The apparatus weighed 3,600 pounds and cost $2,000.” Another horse named “Frank” was brought on staff to help the company. William Davis happily drove the original Juniors tandem of “draft,” or better named “backdraft,” horses. However, one can’t say that Davis’ career was devoid of drama. There seems to be a history of the driver’s name making the pages of the local paper from time to time. In November, 1904, Davis’ face was badly cut and bruised resulting in an eye swelling shut. This was the result of being thrown forward when of his horses stumbled. Just over a year later, William B. Davis received an unwanted holiday present in December, 1905. This was the gift of mashed toes when one of the horses stepped on the driver’s foot quite hard. Months later in April of 1906, the unlucky fireman made news again when he accidentally burned his hands quite badly while charging the lighter of the engine. Supposedly chemicals in a bottle exploded. In 1908, William Davis was put in charge of another new piece of equipment. Also purchased from the American LaFrance Company of Elmira, a Combination Metropolitan Steam Engine was bought for $4,500 to replace the aging Silsby unit that Davis had tugged for five years. A few pictures exists of Mr. Davis at the helm in the carriage seat of the new Steamer unit. The weight of the vehicle eventually led to the forced retirement of one of the horse corps because of disability. This occurred in December of 1909. The change called for a replacement horse in the Juniors’ stable. Unfortunately, the new animal led to the final appearance of William B. Davis’ name in the Frederick News—his obituary 1910 and the Ides of March came and went. However, should have been aware of Sunday, March 20th instead. A fire had broken out in the storeroom of Clinton Main of W. Patrick Street. This occurred around 3:30am with most of Frederick sleeping. William Davis got the horses hitched up to the steam engine and began to start the departure process from the fire house. Tragically, the rogue horse became excited due to a fire alarm, and Mr. Davis would not make it with his steam engine to N. Market Street, just a few yards out the garage door—although the horses and engine would. The grisly accident was shared in the pages of the Frederick News and the Baltimore Sun over the next few days.  Christie tractor Christie tractor Prompted by the death of William B. Davis, a meeting was held to make major decisions that would have long-term positive effects on the Junior Steam Fire Engine Company, No. 2. Among these was decision to end the era of using horses. They would be sold to a fire department in Washington, D. C. Ironically, one of the horses involved in Davis' demise was killed in an accident while on duty in the nations' capital. The Juniors voted to purchase a Christie tractor to attach to the front of the 1908 LaFrance steam fire engine. This vehicle pushed and pulled the steamer into and out of the engine bay of the company's headquarters. Also at this time, a decision to sell the original engine house was made, and the building of a new fire house commenced near the corner of 6th and Market streets.  This new Juniors Company home opened in December 1913, and both fallen comrades, William Charlton and William B. Davis, were fondly remembered for their unselfish commitment to their duties, the Junior Company, and the Frederick, Maryland community. Their memory lives on here at Mount Olivet through respective grave monuments and the Frederick County Fallen Firefighter Memorial. Just this week, Mount Olivet played host to the funerals of two funerals for Frederick County fireman. I’d like to think that the spirits of the two Williams were amongst the throng saluting their departed brothers.  A few scenes from a modern day funeral at Mount Olivet of a Frederick County firefighter, more than a century after that of William B. Davis in 1910. This service took place on June 22, 2017 and honored Capt. Andrew "Andy" Pryce (1975-2017) formerly of the Walkersville Fire Company and Frederick County Fire/Rescue Services.

3 Comments

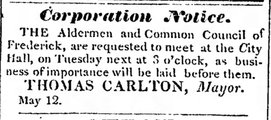

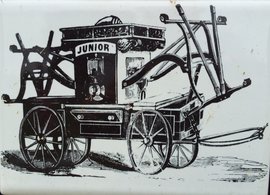

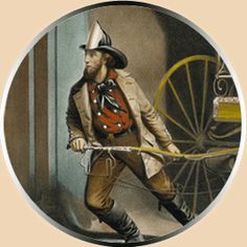

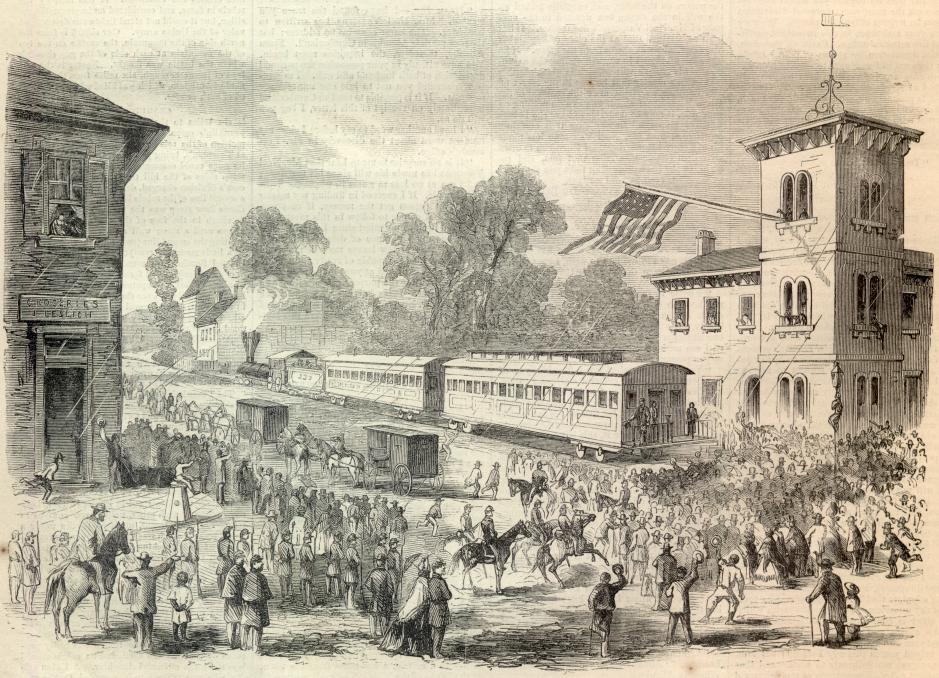

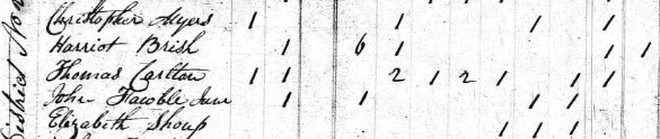

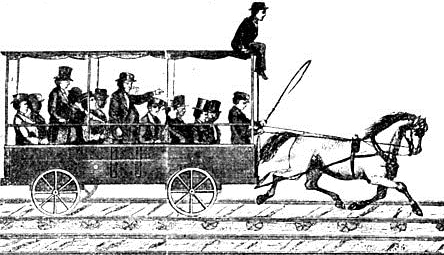

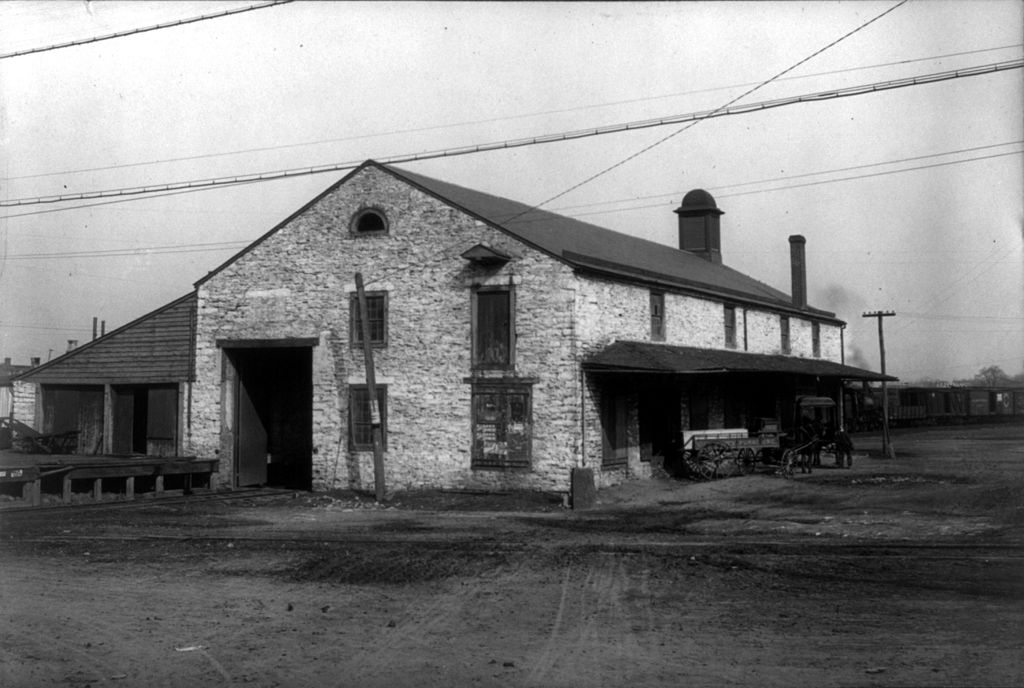

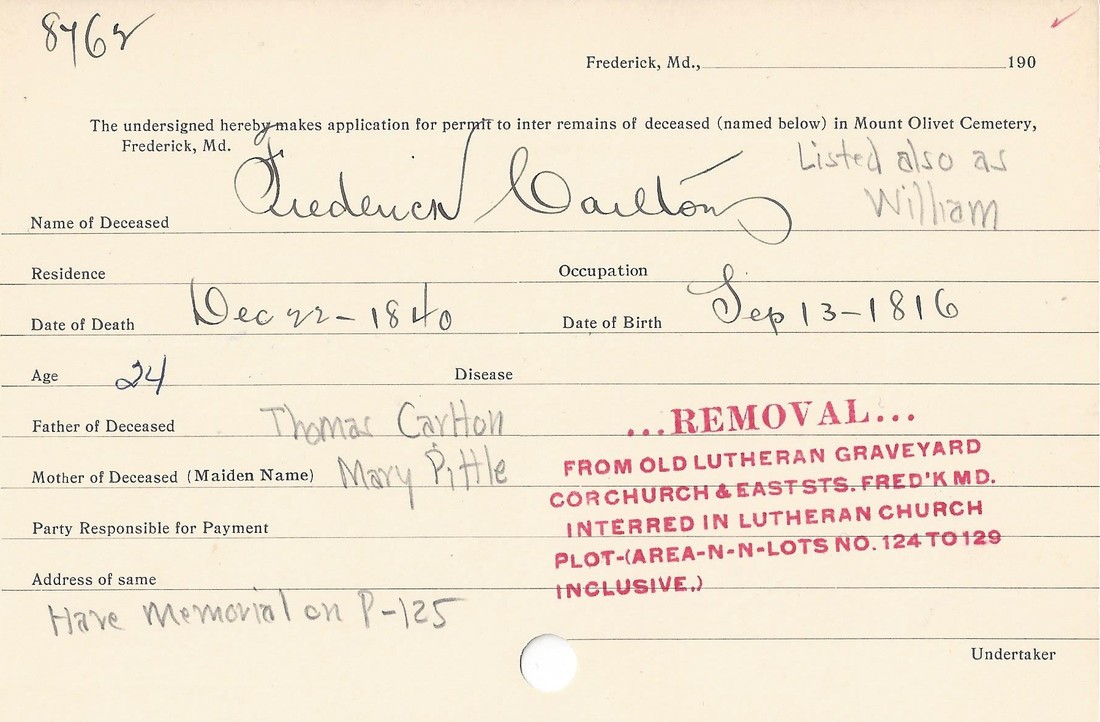

"Firemen are going to get killed. When they join the department they face that fact. When a man becomes a fireman his greatest act of bravery has been accomplished. What he does after that is all in the line of work. They were not thinking of getting killed when they went where death lurked. They went there to put the fire out, and got killed. Firefighters do not regard themselves as heroes because they do what the business requires." —Chief Edward F. Croker (1863-1951), FDNY In June 2000, a very special monument was erected in Mount Olivet Cemetery. It is located in front of the mausoleum complex to the rear of the historic burying ground. Known as the Fallen Firefighters Memorial of Frederick County, the polished collective of granite currently lists the names of 21 men and women who died in the line of duty. Two of the first three individuals listed on this monument served with the town’s second fire company, better known as the Junior Fire Company, No. 2.  The Junior Fire Company was organized in 1838, and incorporated in March of 1840 by an act of the General Assembly of Maryland. The “Juniors” trace their origin back to a chance meeting of three townspeople meeting at Dr. Alexander Mantz’s drugstore on the Square Corner (corner of Market and Patrick streets) and discussing the recent destruction of the home of Horatio Waters and others on S. Market Street by fire. These men came to the agreement that something needed to be done, and set about the movement to create another fire fighting entity in addition to the Independent Hose Company, officially organized in 1818 as the Frederick Hose Company. The three founders Dr. Alexander K. Mantz, George F. Webster and William Carlton issued the call for volunteers for a “Young Men’s Fire Company” through the town’s weekly newspaper entitled The Frederick-Town Herald. In the months that followed, local men answered the call to serve, and officers were elected. This was a company of younger, or junior, residents of town. Among these were William Pitts, President and William Carlton, Vice President.  Frederick-Town Herald, May 12, 1832) Frederick-Town Herald, May 12, 1832) Vice President William Carlton was well-connected in Frederick. His late father, Thomas Carlton (1783-1835), was a veteran of the War of 1812 had served two terms as Sheriff of Frederick County a decade later in the 1820’s. His public life continued with two terms as town mayor from 1829-1835. Mayor Carlton’s main claim to fame came in 1831 when he was influential in brokering the deal to have the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad come to town. This was the nation’s first railroad, and an argument can be made that Frederick-Town was the first major town the fabled transportation line would reach from its center of origin in Baltimore. Frederick resident and diarist extraordinaire Jacob Engelbrecht captured the historical moment with an entry dated Thursday, December 1, 1831, 5 PM: “Opening of the railroad—The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was opened this day as far as Frederick City. Five cars came from Baltimore this day, in which came passengers, the president (Philip E. Thomas), and directors of the railroad, the Mayor & City Council (both branches), and the Governor of Maryland (George Howard Esquire) together with other officers of the company being upward of seventy in number. The citizens of Frederick gave them a dinner at Talbott’s hotel. The arrival of the cars was announced by the firing of cannon, ringing of the bells, & C, & C. It was a proud day for Frederick. The “car Frederick” was first. Mayor Thomas Carlton was responsible for the “Deep Cut” through All Saints Street which allowed the train to make its way to Market. Apparently, railroad tracks would eventually stretch up Frederick’s principal commercial street all the way to Fourth Street, as horse drawn train cars ran on tracks placed on wooden stringers. As a compliment to Mayor Carlton, a special car was sent to the front of Carlton’s home dwelling (located at the northwest corner of West Fourth and Market) on the occasion of his daughter Ann’s wedding to Lewis A. Brengle in 1834. Bride and groom were taken from here to the railroad depot (the present day site of the E. All Saints Parking Deck and Wm. Donald Schaefer Government Services building intersection of Carroll and Commerce streets).  Mayor Carlton’s son William Frederick Carlton was born September 13th, 1816 and grew up in Frederick. He and his colleagues with the new fire company venture contracted with the John Rodgers Company of Baltimore for an engine that cost $1,000. Local resident Henry Boteler provided hose reels, and hoses were gotten from another Baltimore firm named Dukehart’s. The engine, known as Rodger’s “Junior” model, made its debut in town in August, 1839. It was vermillion red in color, and was considered a “beauty.” It was immediately exhibited to the public with a show as it threw a stream of water 150 feet in the air over the town clock, located atop Trinity Church. The new apparatus was the centerpiece of the company that came to be known as the Juniors, and devoid of a fire house structure at the time, this was kept in a vacant lot in the rear of the original Farmers & Mechanics Bank location on the southwest corner of N. Market and 2nd streets. The year 1840 promised to be a great one for the 23-year old. He had accomplished the task of creating another fire company in town. He also had a fulfilling regular job as City Register, which we today generally call the Register of Wills. This individual is responsible for appointing personal representatives to administer decedent’s estates and for overseeing the proper and timely administration of these proceedings. On Saturday June 27th, 1840, Jacob Engelbrecht wrote in his diary: Married on Thursday evening last 25th instant by Reverend John L. Pitts, Mr. William Carlton (Register of this City) to Miss Mary P. Neill, daughter of the late John W. Neill of Philadelphia.  The summer of 1840 must have been one of bliss for the newlywed couple. Fall came, and perhaps with it, talk of starting a family of his own? Whatever the case, the remembrance of family would certainly play heavy on his mind with end of year holidays. His father, Thomas Carlton, was resting in peace in the new Evangelical Lutheran burying ground, once located at the southeast corner of East Street and E. Church Street extended (also known as the Gas House Pike). Next to his father was buried older brother Edward Alexander Carlton (1806-1834). Perhaps William visited this cemetery on December 20th, 1840, the sixth anniversary of his brother’s death? Whatever the case, he likely never imagined that he would join these loved ones in just a matter of days. Two days before Christmas, Jacob Engelbrecht would again put pen to paper regarding a member of the Carlton family: Died last evening in the year of his age, Mr. William Carlton, Register of this city, son of the late Thomas Carlton. His death was very sudden. There was a cry of fire in town about 6 or half past 6 o'clock PM (Colonel John McPherson’s chimney) and was running with the engine (Juniors Company of which he was a member) and when they got to Brien’s Row, Court Street, he became exhausted, fell down, and in short time, thereafter expired. Wednesday, December 23, 1840 12 o’clock Midnight  Frederick County Courthouse fire of 1842 Frederick County Courthouse fire of 1842 William Carlton would be the first firefighter in the State of Maryland to die in the line of duty. His body was placed next to his father and brother in the new Lutheran Graveyard on the east side of town. He had only been married for six months, leaving wife Mary to celebrate Christmas as a widow. The Junior Fire Company would live on. Two years following the death of their co-founder, the “Juniors” would take part in extinguishing one of the worst fires in Frederick history. Ironically, this would take place in the vicinity of Court House Square within feet of where William Carlton took his last breath. A fire had broken out at the Record Street home of Dr. William Tyler on March 31st 1842. Strong winds blew burning embers through the air, causing additional fires to start in adjacent structures including the Court House itself, when the cupola ignited and soon became engulfed in flames. A fire engine house for Company No. 2 would be built by the City Council four years later in 1846. The location was donated by the Farmers & Mechanics National Bank next to the same lot where the company’s engine had already been stored. The structure fronted N. Market Street, and had another prominent neighbor to the south in the old Market House, which also housed the town offices. Today, Brewers Alley stands on the Market House site.

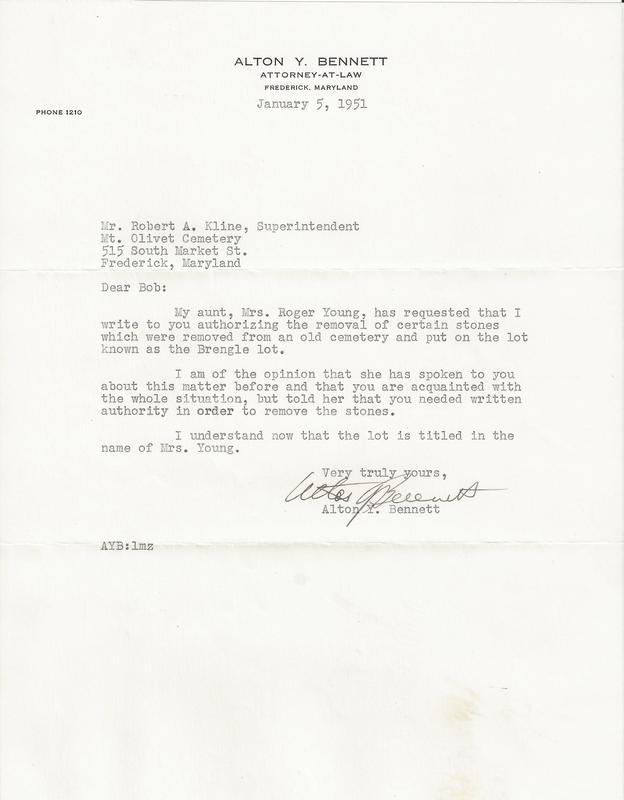

For those wanting to visit the grave of William Carlton to pay respects, there is a bit of a snafu. His gravesite, along with father Thomas, brother Edward and mother Mary is unmarked—at least in Area NN. Supposedly, the Carlton headstones were once here in the cemetery, but in a completely different area. They once adorned a lot in Area P owned by the son of Lewis A. Brengle and wife Ann (Carlton) Brengle. You may recall that Ann was William’s sister, the one who got the free train ride down Market Street on her wedding day. Ann had died in 1852 but was originally laid to rest in the German Reformed Cemetery of town (today’s site of Memorial Park on the corner of Bentz and W. Second streets). Lewis would pass in 1879, and buried next to Ann. However, both would be reinterred in 1881 and moved to Mount Olivet (Area P/Lot 125).

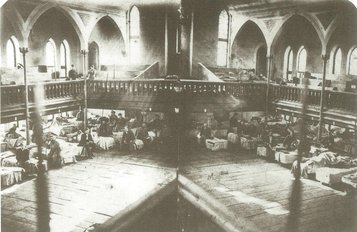

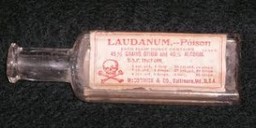

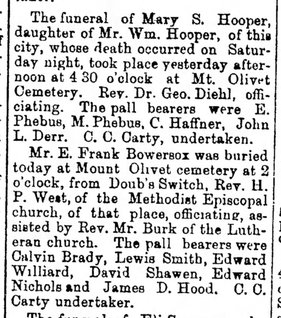

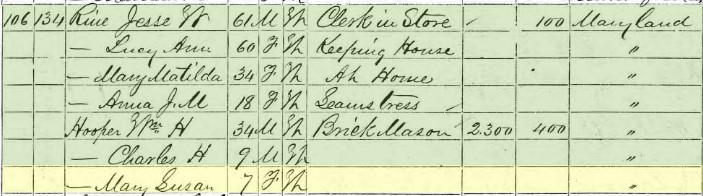

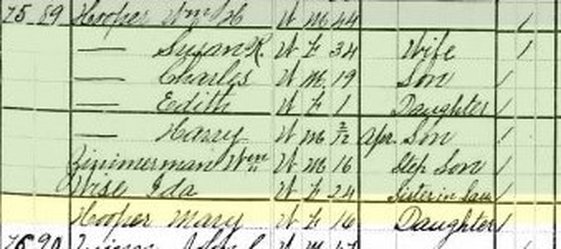

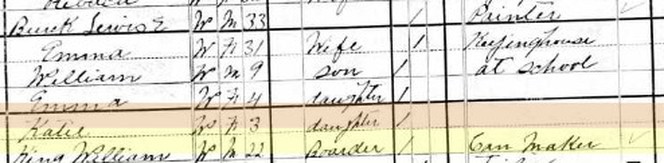

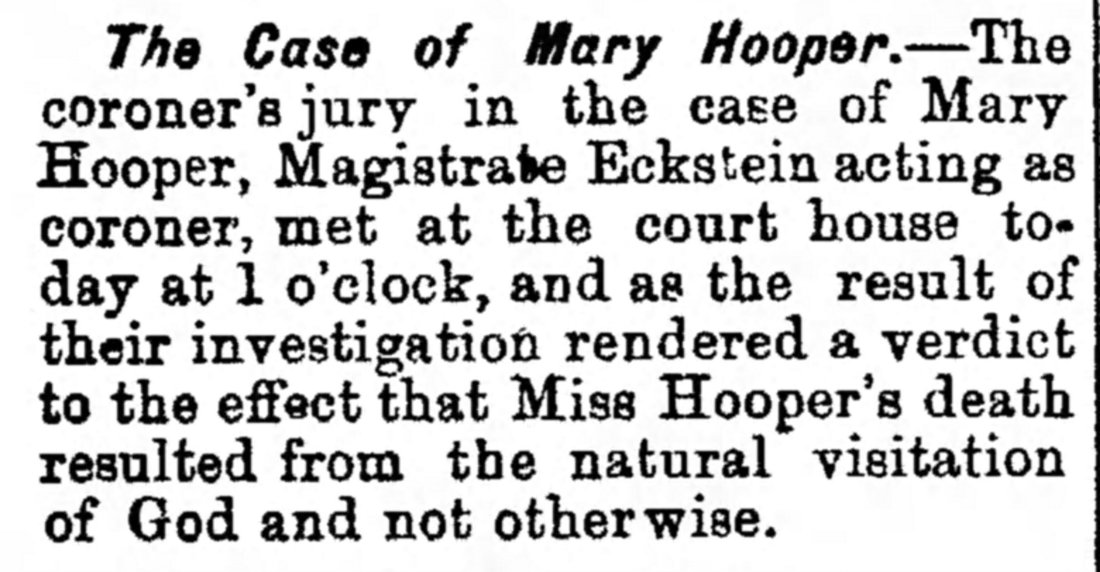

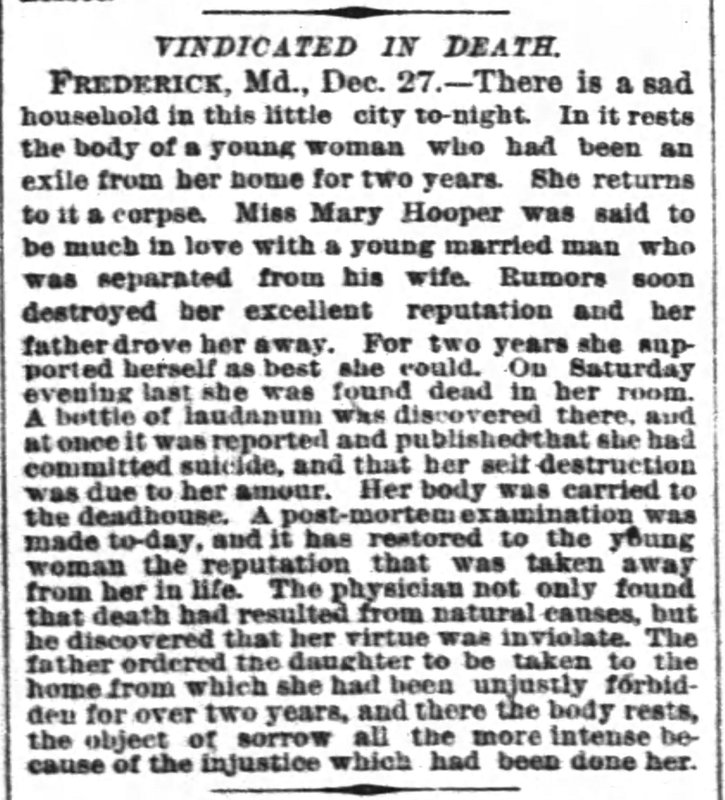

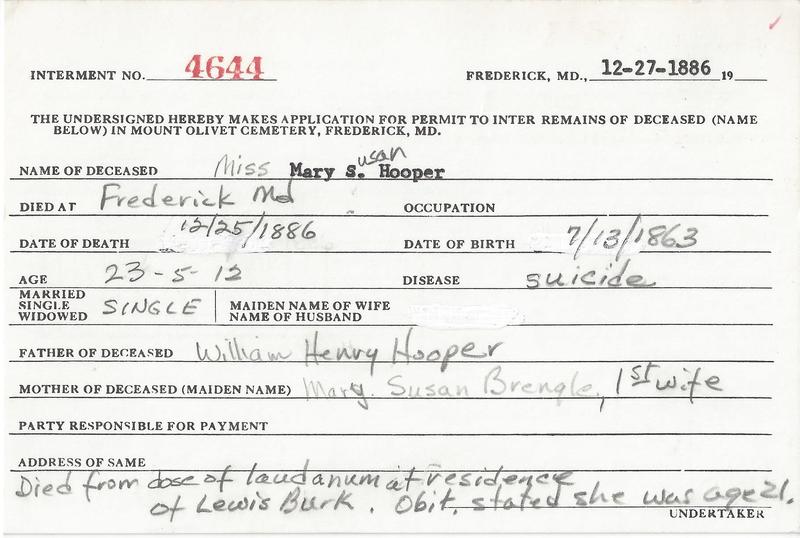

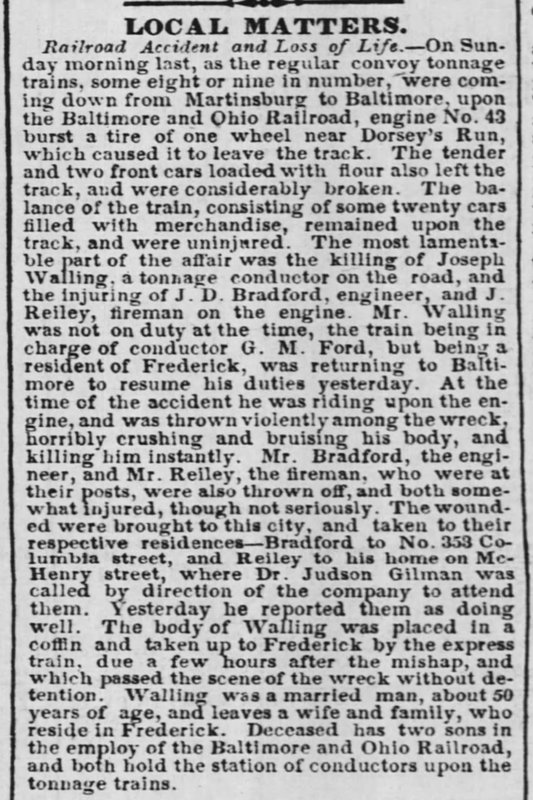

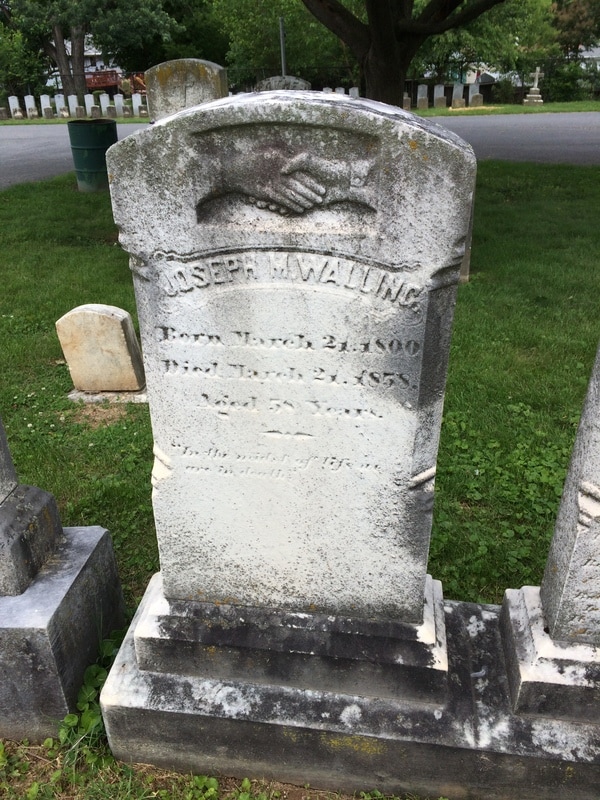

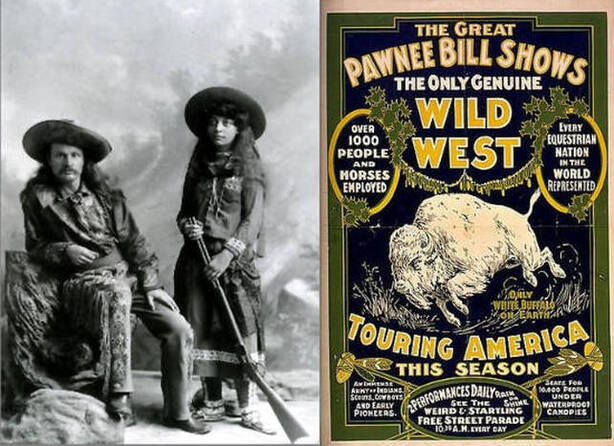

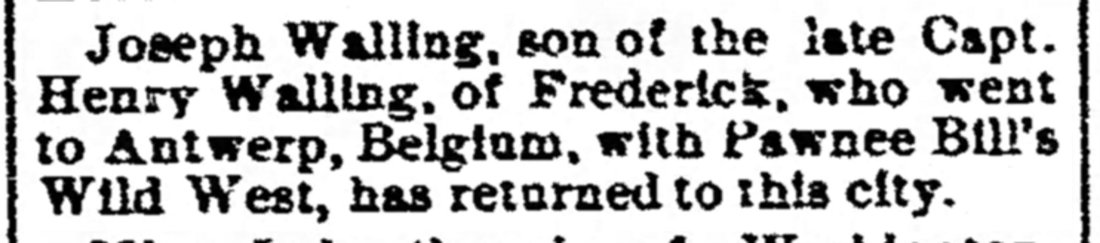

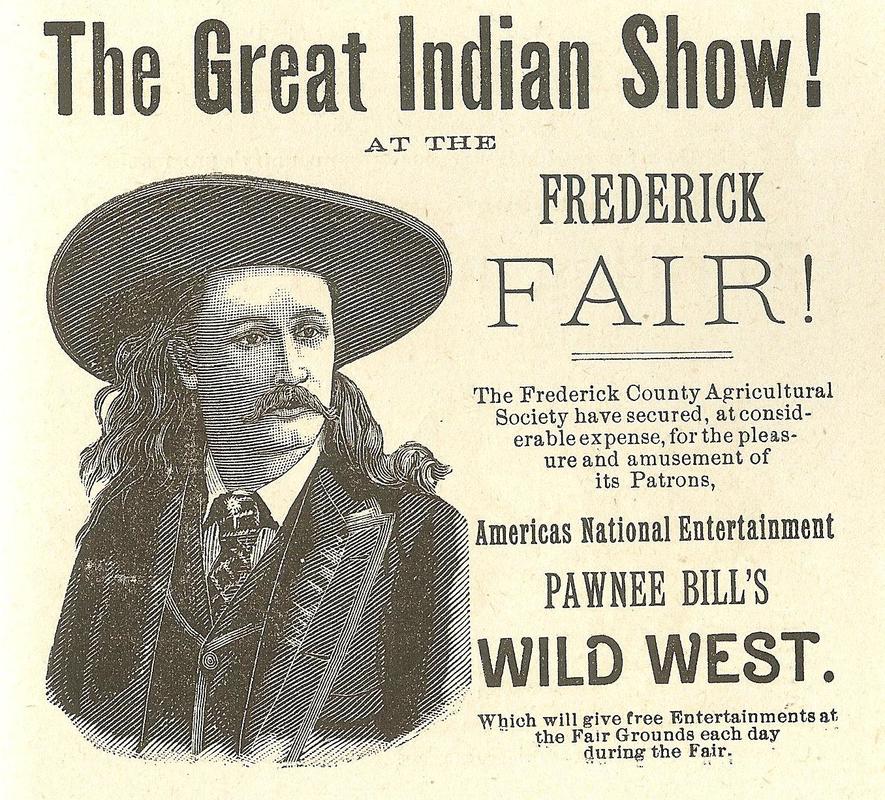

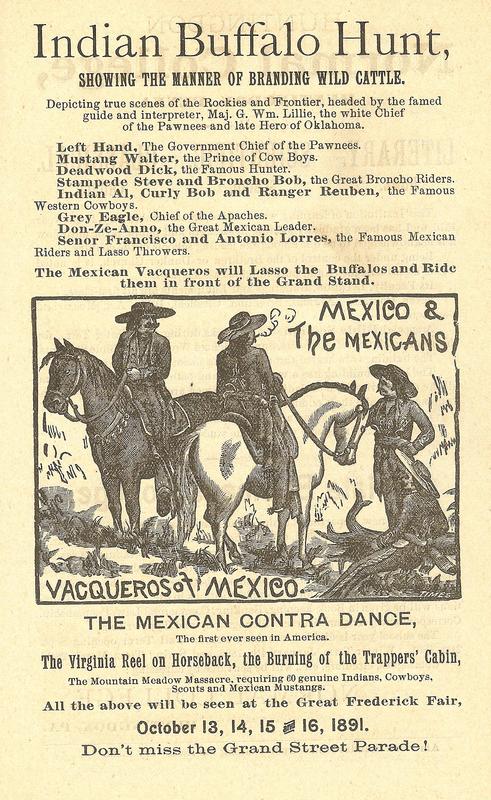

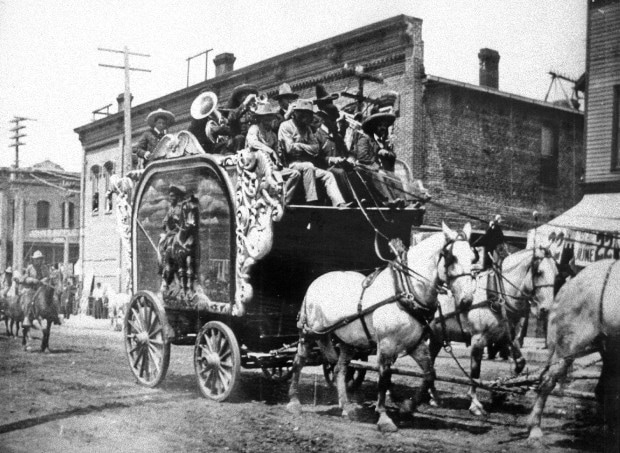

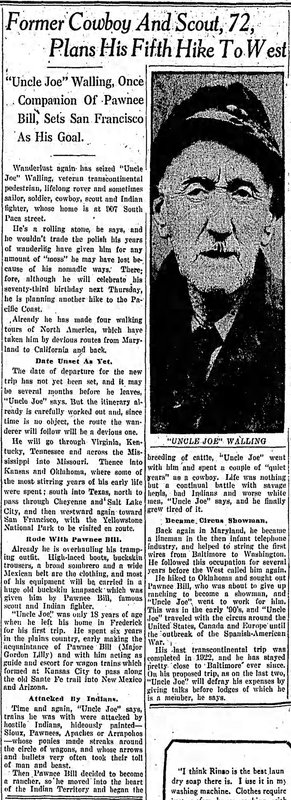

The word “misjudge” is defined as having formed a wrong opinion or conclusion about someone, thing or action. It happens all the time, sometimes a person is given a false estimation simply by their appearance. Others are assessed based on past “track record,” and not given credit for the ability to accomplish a current task at hand. We often see this in sports with “upset” victories by misjudged team thought to be lesser in talent, heart or drive. Most often, an individual’s action or response could be perceived in such a way to give an onlooker a wrong or negative idea. Misinformation and yellow journalism, and the newly coined concept of “fake news,” can easily aid in the misjudgment of people, companies, and events. This is a result of sloppy research work by news media. Other times it could be done by design to boost ratings, print sales or an attempt to cause a firing or dismissal. With the emergence of social media, good-old fashioned gossip can be presented as fact in print, photo or video form and distributed to the world thanks to the internet.  The cast of Three's Company The cast of Three's Company Oftentimes, misjudgments can end up as harmless misunderstandings, with valuable lessons learned. I can look back at popular television comedies from my childhood that featured this theme such as The Brady Bunch and Gilligan’s Island. Probably the best example I can think of is Three’s Company. This sitcom aired for eight seasons on ABC from 1977 to 1984 and revolved around three single roommates: Janet Wood (Joyce DeWitt), Chrissy Snow (Suzanne Somers), and Jack Tripper (John Ritter), who all platonically live together in a Santa Monica, California apartment building owned by Stanley Roper (Norman Fell) and Helen Roper (Audra Lindley). The show is best described as a comedy of errors. It chronicles the escapades and hijinks of the roommate trio's constant misjudgments, misunderstandings, social lives, and financial struggles, such as keeping the rent current, living arrangements and keeping up deception. Oftentimes, one simple misunderstanding would lead to a misjudgment which would spiral into several more. Three's Company was quite popular in its day, and still can be seen in syndication. It also brought controversy at times with the use of risqué subject matter, adult topics and double entendre. The program seems very tame compared to today’s television standards. This is a sign of the times as things such as fashion and social norms have relaxed over time, or gained acceptance. In the past, a lady showing a bare ankle in the 1800’s would be the focus of strict judgment, as would a divorcee or homosexual. This could lead to public or family shunning, loss of work, and tarnished reputations. Worse of all, the misjudgment could follow an individual to their grave. This week’s article is a bit paradoxical in nature, as I want to be careful not to wrongly “misjudge” William H. Hooper, the father of our subject Mary S. Hooper. However, as you will soon see, Mr. Hooper appears guilty of serious misjudgment himself—one that would lead to the tragic downfall of his daughter, eventually culminating in wrong opinions being formed by the local news media and the Frederick community as a whole. A cemetery record that survives until today shows evidence of this misjudgment. It’s time to set the record straight.  Evangelical Lutheran Church during the Civil War Evangelical Lutheran Church during the Civil War Mary S. Hooper Mary Susan Hooper was born July 13th, 1863, just over a week after the famed Battle of Gettysburg. Frederick was still in turmoil as Gen. Lee’s retreating Confederates were penned up at Williamsport, not able to cross back into the safety of Virginia because of a raging Potomac River in flood stage. Wounded soldiers from both armies were being brought to town, and Union soldiers were highly visible. Mary’s father, William H. Hooper, was a well-known brick mason, credited for crafting the original walkways in front of the Frederick County Courthouse that was currently under construction at this time, the former courthouse having been destroyed by fire in May of 1861. He would later build the front walk leading up to the Maryland School for the Deaf. Mary was named for her mother, Mary Susan Brengle. Mary S. Hooper had an older sibling named Charles (b. 1861) and a sister Florence (b. 1858). Florence celebrated her 5th birthday, just four days after the birth of her baby sister on July 17th (1863). Sadly, the young girl would die less than two months later. Although unknown, I could only imagine the conflicted feelings of the Hooper parents—happy to have a healthy second child while heartbroken over the tragic loss of their first. Maybe this caused a delay in Mary’s christening, deferred to January of 1864. However, another prime reason could be the Civil War activity of the time as the family’s house of worship, the Evangelical Lutheran Church, was in heavy use as a makeshift hospital for wounded and sick soldiers. Mary’s mother would give birth to a third child a year later in February, 1865. Her mother gave her husband a son, and (now two-and-a half year-old) Mary, a brother. He was named Eugene. The war soon ended, hostilities subsided, and William H. Hooper found his employment steadier as peaceful times prevailed once again. Mrs. Hooper had two youngsters to attend to. Tragedy visited the family’s East South Street door once again in late summer of 1868. This time, the grim reaper took Eugene to the grave. Whether disease, or deep stress, the second death of a child likely took its toll on mother Mary Hooper. She would soon die before the year’s end on December 31st, 1868. At just five years of age, Mary’s mother, brother and sister Florence laid in rest beneath a large marble obelisk in Mount Olivet Cemetery’s Area B, lot 84. The 1870 census shows William H. Hooper, along with Charles and Mary, cohabitating with the Jesse W. Rine family. Where, three had been company for the Hooper family, the dynamic would change drastically a decade later to eight. The 1880 census shows the family living on W. Patrick Street. William H. Hooper had remarried—Susan R. (Wise) Zimmerman, and Mary Hooper now had three step-siblings: 16-year-old William, one year-old Edith and two-month-old Harry. Stepmother Susan’s sister, Ida, was also here in residence. I failed to glean any more information on Mary S. Hooper, on the verge of womanhood at the time of her 17th birthday in 1880. She carried quite a burden with her, but how did this affect her relationship with God, educational studies, and personal relationships? Was she introverted or extroverted? We will likely never know. Nothing more can be surmised until six years later. The year 1886 brought with it great misjudgment, or should I say, misjudgments. Mary's brother Charles was known to have worked at the Lewis McMurray Canning Factory located off W. South Street. A co-worker was a fellow named William H. King, a can-maker. Apparently Mary, described as “a very pretty and prepossessing young lady,” had either shown an interest in William or vice-versa. Perhaps some sort of liaison occurred between the two. This likely happened two years earlier in 1884. Whatever it was, news reached Mary’s father—and he was none too pleased. The matter was compounded due to the fact that William King was a newly married man. The story or misjudgment was that Mary had intercourse with Mr. King, aiding in him now labeled as an adulterer by co-workers and townspeople. Mary fell from grace, and most tragically in the eyes of her father.  It was 1884 when Mr. Hooper promptly kicked Mary out of the family household and disowned her. She sought refuge at the home of Mr. Lewis Burck of 464 W. South Street. I immediately sought out information on Mr. Burck, to see if he was a relative of some sort. I found that he was a 40-year-old house painter. The family home is located close to the intersection of W. South Street and the aptly named Burck Street which came about around 1884, as well as Madison Street which it bisects to the south. Lewis Burck’s wife was named Emma. Interestingly, Emma Burck was the former Emma King, older sister to William H. King, the object of all this controversy. As a matter of fact, William was living in this same house at the time of the 1880 US census.  So to review, 23-year-old Mary had been kicked out of her family’s home, and in 1886 is living with the sister of the man she was accused of having an affair with. Seems like a crazy Three’s Company episode to me. Now I will take you to Christmas Day, 1886. Here is the story as told by the Frederick Daily News from Monday, December 27th(1886). “At a late hour on Saturday afternoon she went upstairs and dressed herself to go out, her intention being to take Mrs. Burck’s children for a walk. As she came downstairs, she met Mrs. Burck, to whom she remarked that she did not feel very well. Mrs. Burck advised her to go in the room and lie down on the bed, which she did. She had been lying down a few minutes when Mrs. Burck entered the room and found her hands cold and stiff. When asked how she felt, Miss Hooper believed she was better. She came downstairs and sat down to converse with the family. Fearing that something serious might be the matter with the girl, Dr. Long was sent for, In the meantime, Miss Hooper showed signs of being in extreme pain and fell from the chair. She was picked up and placed on a sofa and the doctor again sent for. She immediately became unconscious and expired before the arrival of the physician. A few moments after her death, her body turned black and began to swell perceptibly. This led to the supposition that she had committed suicide by taking poison for it was known that her alliance with King was a source of trouble for her.”  The file in Mount Olivet Cemetery for Mary S. Hooper (1863-1886) states that she died from “suicide by taking laudanum." If you were to go back to the late 1800’s, you would find laudanum being sold without a prescription over the counter. It was commonly used as a painkiller, cough suppressant and served as a remedy for the treatment of diarrhea. Laudanum is a tincture of opium and highly addictive. Until the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act of 1914 restricted the manufacture and distribution of opiates, including laudanum, and coca derivatives in the US, you could purchase it almost anywhere without a prescription. Today it is not normally used for medical purposes, although it has a proven record as a pain reliever.  Even a holiday could not stop word from traveling throughout town that night and next day: Jilted lover Mary Hooper had taken her own life. And, no less, on a day associated with great joy and appreciation—especially for family. Mary’s lifeless body was immediately removed from the Burck family household, shortly after the recorded time of death of 8:30pm. It was brought back home to the home of her father. On Sunday morning (December 26th), Magistrate Christian H. Eckstein summoned a coroner’s inquest due to the inability of Dr. W. A. Long to give a legitimate reason for the 24-year old’s sudden death. Dr. Franklin B. Smith was requested to perform an autopsy. This was done at 3pm and three major misjudgments would be discovered through the findings. The body was then transported to the Mount Olivet Cemetery vault, where it had to rest until Dr. Smith gave his findings at a hearing scheduled for 1pm on December 27th at the Frederick Courthouse. First, and foremost, Miss Hooper did not take laudanum or any other poison. She had not committed suicide as had been thought. Instead, Mary had died from natural causes. Secondly, Mary specifically died from a cerebral hemorrhage, an internal bleeding within the brain tissue or ventricles. Symptoms can include headache, one-sided weakness, vomiting, seizures, decreased level of consciousness, and neck stiffness. Often symptoms get worse over time. Fever is also common. This is generally caused by head trauma, but also happens naturally due to aneurysms and brain tumors. Third, and most shocking of all, Mary Susan Hooper was still a virgin. The newspaper reported this delicately using the description: “her purity of life was unmolested.”  Funeral of Mary S. Hooper in Frederick News (December 27, 1886) Funeral of Mary S. Hooper in Frederick News (December 27, 1886) Mary Susan Hooper was buried in the family plot the very next day. She would be laid next to her mother, Florence, and Eugene. I would imagine that Mary’s father felt some pretty deep guilt. He would move out of Frederick with his wife and young family to Washington, DC in April, 1887. However, Mr. Hooper would die suddenly in March the following year (1888). Five years later, Charles A. Hooper (Mary’s older brother) would pass just one month before his 32nd birthday. He was the last remaining member of the original Hooper nuclear family. All five are buried in Area B/lot 84, their names adorning the monument in the center of the lot. Thank goodness for that coroner’s inquest, or Mary’s reputation in death, would mimic what many people believed to be true while she was living. Rest in peace Mary Hooper, I’m truly sorry you had to experience the pain you endured.  Horace L. Greeley (1811-1872) Horace L. Greeley (1811-1872) How did the concept of Manifest Destiny play to Frederick residents just three months after the close of the American Civil War? On July 13th, 1865, Horace Greeley, Editor of the New York Tribune newspaper, wrote an editorial promoting the Homestead Act which President Lincoln had signed earlier on May 20th, 1862. Young men working in Washington D.C. had complained about the cost of living and the low wages paid by the government. Greeley wrote: “Washington is not a place to live in. The rents are high, the food is bad, the dust is disgusting and the morals are deplorable. Go West, young man, go West and grow up with the country.” One young man was just too darn young to act on any impulse in 1865—but years later he would, multiple times. Eleven-year old Joseph Walling knew little of the world outside of his hometown, but appreciated the modes of travel afforded local residents wanting to see more of the country that had just been preserved by the recent four-year conflict. The young man’s father (Capt. Henry Jefferson Walling) was a popular passenger conductor for the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, making trips to Charm City and elsewhere on a daily basis. Joe Walling would also understand the dangers involved in travel as well. His grandfather and namesake, Joseph M. Walling, was also an employee of the mighty B&O. He was tragically killed in a railroad derailment accident in March, 1858. Maybe travel was just in Joe Walling’s blood, and his childhood exposure to the carnage of the Civil War simply made him numb to danger? This can be hypothesized because Walling’s long-“road” ahead would be defined by two things: westward travel and engaging in risky professions and hobbies. Joseph Henry Jefferson Walling was born September 21st, 1853 in Frederick, Maryland. His family lived in a two story dwelling on East All Saints Street, located between the B&O Railroad Depot to the east, and the B&O Passenger Station to the west. "Joe" was five when his grandfather lost his life heading to work one day en-route to Baltimore. At eight, the American Civil War erupted, and Frederick would be visited by both major armies, North and South. Throughout the duration, wounded, sick and dying soldiers could be easily seen as they were brought for care to Frederick’s “one-vast hospital.”  The Walling family residence can be seen in this wartime sketch depicting the October 4, 1862 visit of Abraham Lincoln to Frederick which appeared in Harpers Weekly magazine. This is the old B&O Passenger Station located at the southeast corner of E. All Saints and S. market streets. The two-story Walling home appears on the south side of All Saints Street (just beyond the locomotive)  Wagon train on the Santa Fe Trail Wagon train on the Santa Fe Trail At 15, Joe followed in a first responder role, shared with both his father and grandfather as he joined the United Fire Company. He would spend the next 75 years in service to various fire companies, one day earning the moniker as “the oldest volunteer firefighter in the United States.” In 1871, Joe made his first big move and took up residence in Baltimore and worked for the railroad. Shortly thereafter, he earned a job as an Indian scout, guide and escort assisting wagon trains delivering shipments from Kansas City to points in the “Wild West.” Most of these were along the famed Santa Fe Trail, taking him to New Mexico and Arizona. He lived in the plains country for six years between 1872-1878. In between trips, he had proposed to the love of his life, Laura Staley. The couple married in 1876, but the life change didn’t seem to slow down Joe Walling one bit, as he would have plenty of stories to tell in the future of his western experiences. Nearly 70 years later, a newspaper writer of the Frederick News would write of Joe: “He could describe the markings painted on the faces of the Apaches and the sound of their battle cries as they attacked the wagon trains. He knew the Pawnee, the Arapahoes and the Sioux. Many a time their ponies streaked in lightning circles around the massed covered-wagons he protected, and he swapped bullets with the best of them.” Joe next ventured into the heart of Indian Territory (Oklahoma Territory) and became a bona-fide cowboy. For two years (1879-1880) he would ride the range, keeping a lookout for cattle rustlers and other unsavory men of the Old West. It was here that he met a young adventurer much like himself and named Gordon William Lillie. Lillie would later become a well-known American showman and performer under the name Pawnee Bill. He and wife May, a female marksman in the style of Annie Oakley, specialized in Wild West shows, including a short partnership with Maj. William F. Cody—Buffalo Bill. By June of 1880, Joe was back east in Frederick with wife Laura and son Henry Jefferson, who were living with Joe’s parents and grandmother in the family home on E. All Saints Street. He gained employment again with the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad as a brakeman. The job of the freight train brakeman was a solitary one and was especially dangerous. Before the widespread use of airbrakes in the late 19th century, trains were stopped through the manual application of brakes on each of the train’s cars. Even after the airbrake came into universal use, the brakeman still had to be ready to climb atop the train to manually set the brakes when the airbrakes failed to work or when a section of cars had to be cut from the train. In the interest of train safety, the middle brakeman, if there was one, would ride out in the open in order to be ready to manually apply the brakes if the need arose. Middle brakemen were most frequently used on long freight trains as well as on local freight lines where freight cars had to be cut loose or added on regularly.

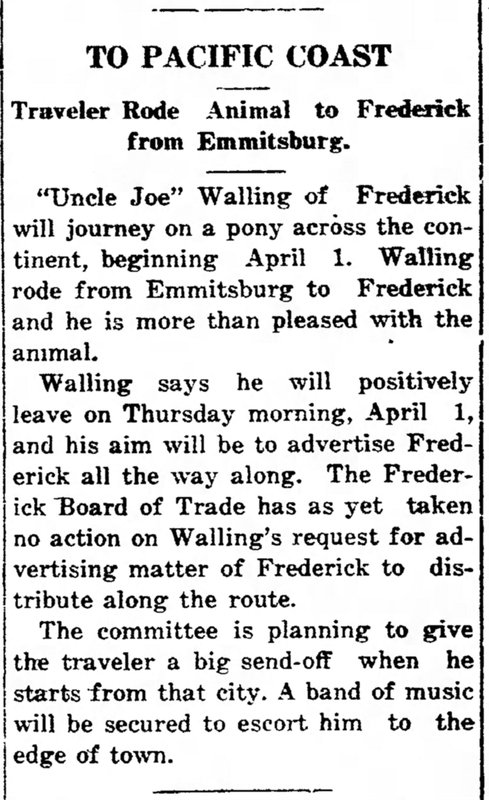

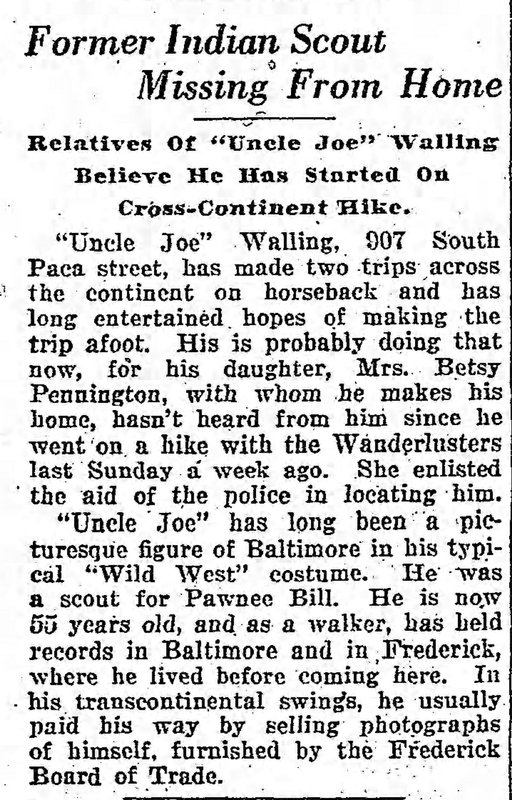

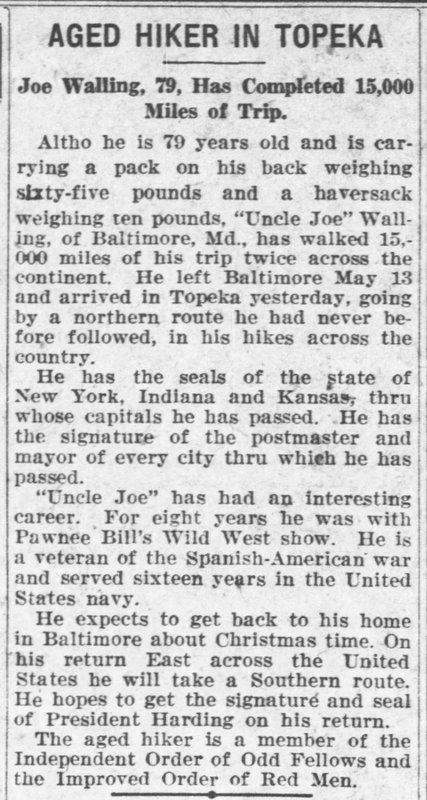

One month later, Joe Walling would experience another tragic event with the death of wife Laura. His four children were grown, but the pain was no less. He took up residence with his daughter Betty Pennington, and lived under her roof at 907 S. Paca Street in Baltimore, only a few blocks west of the current day sports stadium complex of Camden Yards and M&T Bank Stadium. Joe Walling’s personal storytelling ability to family and friends was legendary. He had a welcome invitation to visit and “conduct court” at a plethora of fire houses across Charm City. This is likely how he earned the nickname of “Uncle Joe.” Joe needed something to fill his desire for travel and danger. He was working for a Baltimore ironworks at this time, and his chief hobby was that of a member of the Baltimore Wanderlust Club, an organization that conducted hiking outings. Joe loved this group and regularly walked long distances to towns across the region, including many trips to and from Frederick on foot. As Joe was trying to fill the major void created in his life following the loss of Laura, he decided to head west once again, as he had done in his youth. However, he wasn’t going to stay out west, he just wanted to visit, and come back to Maryland. In 1910, Joe embarked on the first of five known transcontinental trips he would attempt over the next 22 years. To San Francisco and back on foot was “Uncle Joe’s” first major feat. It also brought him notoriety and standing as one of the state’s most colorful characters. In 1915, Joe Walling planned another transcontinental trip, but this time aboard a pony. Escorted by policemen and drum corps, Joe set out on his journey from Frederick on April 1st. Unfortunately, the trek had to be aborted later in the month. After traveling 300 miles, the 62 year-old rider was thrown from his mount near Wheeling, WV. He suffered a broken leg but remained in good spirits, determined to try again in the spring of 1916.

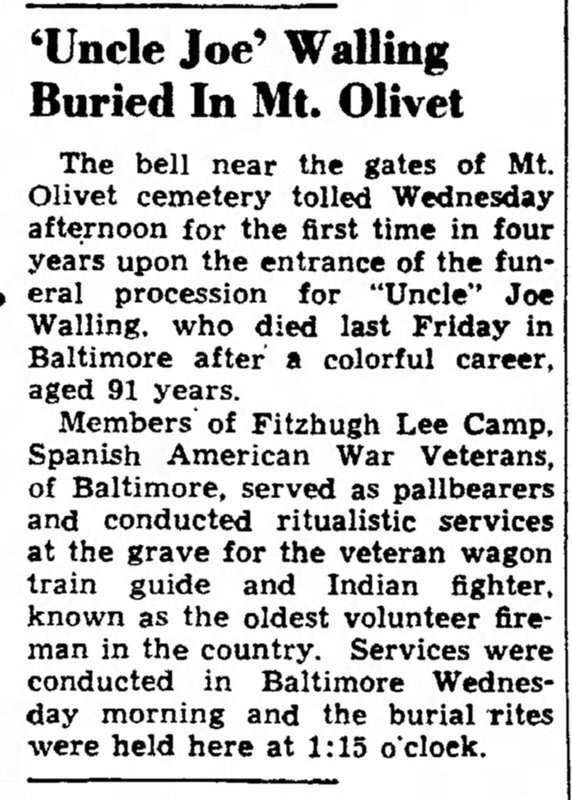

In his eighties, he would continue to walk all over Baltimore, but would not attempt another cross-country sojourn. His last decade of life found Uncle Joe in the familiar role as raconteur as he told the tales of a storied life, full of adventure, duty to others, travel and the romance of the famed “Wild West.” Joseph J. Walling died quietly in Baltimore on July 2nd, 1944 at the age of 91. The “old warrior” made one last trip west to his native Frederick, where he would be laid to rest in the family plot in Mount Olivet Cemetery. He would take his place next to wife Laura, with his parents and grandparents close at hand. His monument reads:

“Here he lies where he longed to be. Home is the sailor, home from the sea.” |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed