|

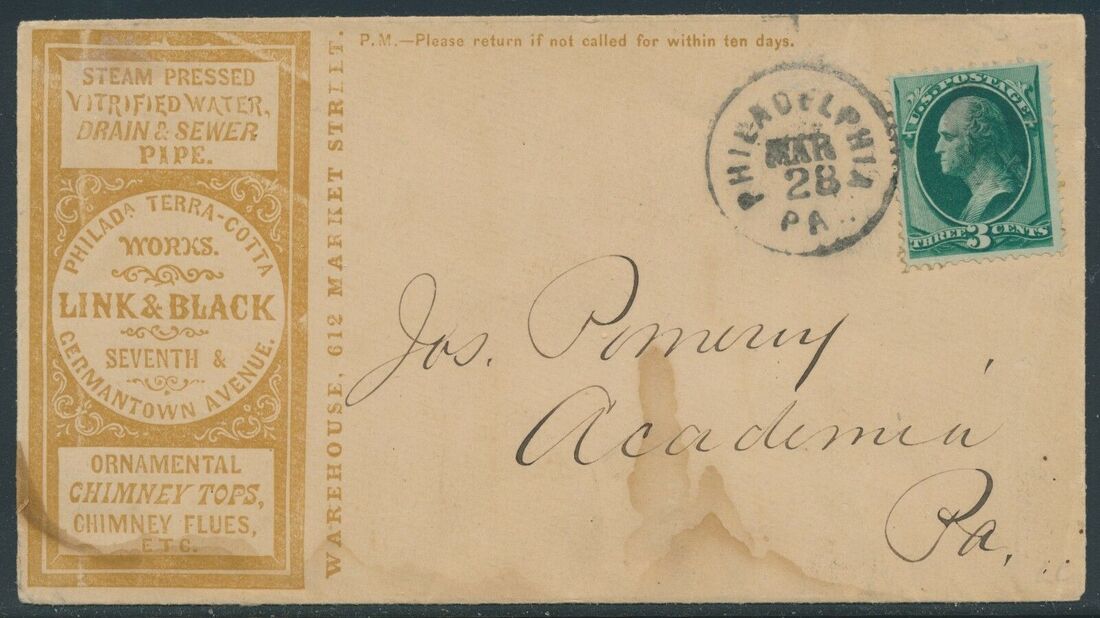

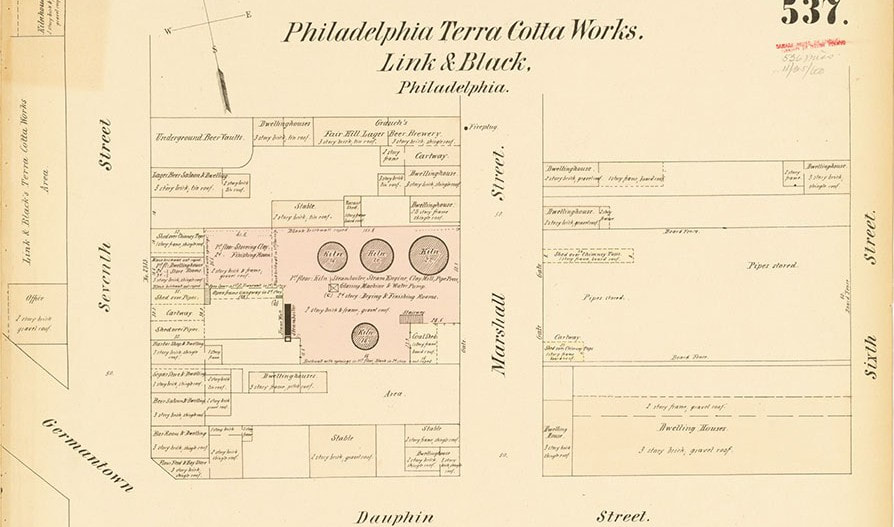

One of the smallest grave monuments within Mount Olivet is also the most thought provoking. In addition, this final resting place of a child, who died in 1874, is among the most eye-catching, as it clearly stands out against a backdrop of 40,000 other gravesites. The memorial in question is not made of marble or granite, and deceives some into thinking that it could be an above ground crypt—crafted in the shape of a small sarcophagus from ancient time. Before receiving a thorough cleaning a few years back from cemetery superintendent J. Ronald Pearcey, you wouldn’t have even noticed this memorial to Arfue Brooks. And if, indeed, you did find it, an attempt to read the name carved on the exterior would have been a futile and frustrating chore—but not anymore. A bas-relief figure of a sleeping child conjures up a melancholy feeling as the onlooker is tipped off to the occupant’s age and innocence. In contrast, a sudden feeling of warmth (in any season) may follow, thanks in part to the brown-orange hue of the monument— a diversion from the vast sea of whites, grays that can be found throughout the grounds. As far as I know, this is the only terracotta monument of this color and design within the cemetery. Terracotta is a type of ceramic pottery, used to make flower-pots, pipes, bricks, and sculptures. The word (Terracotta) comes from the Italian words for “baked earth.”

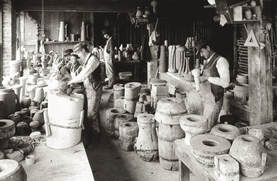

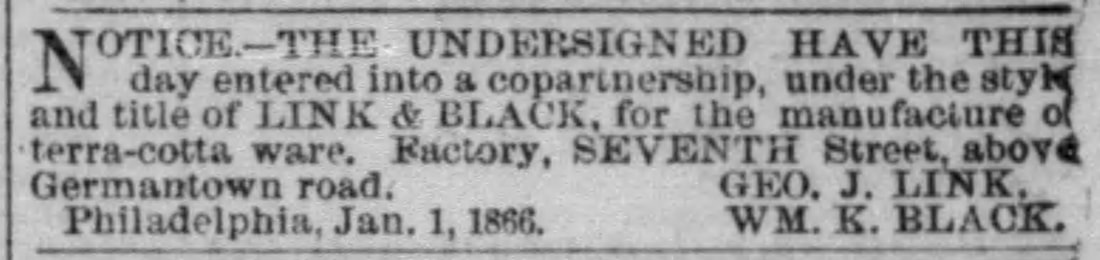

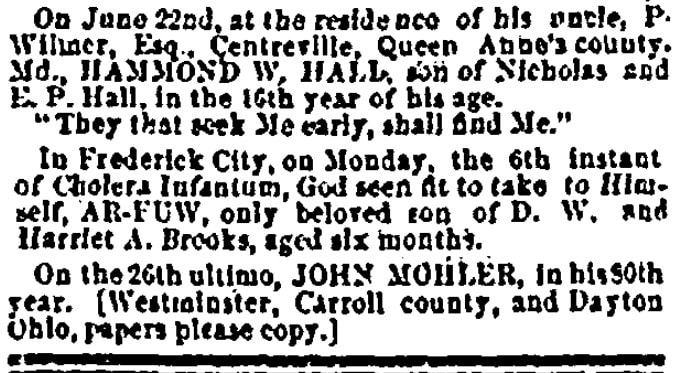

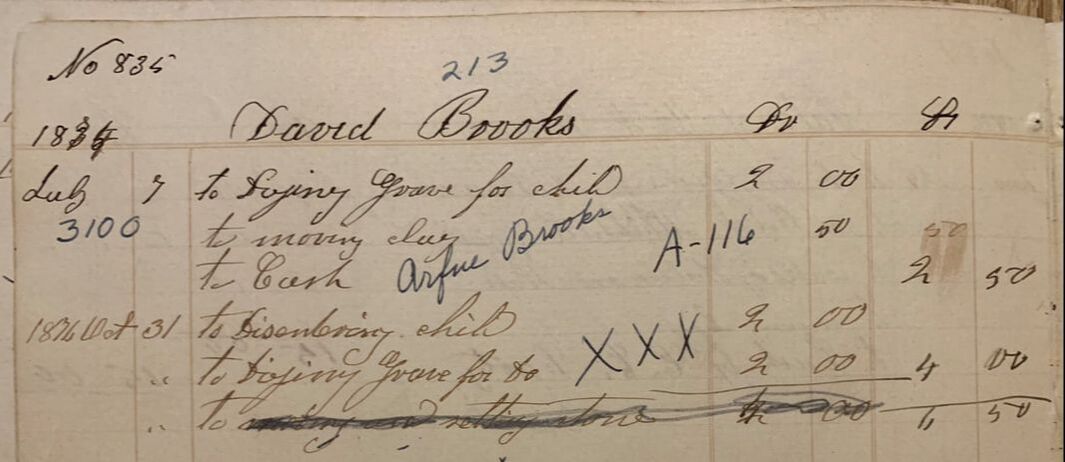

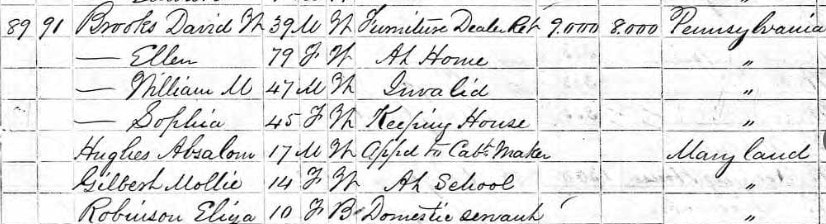

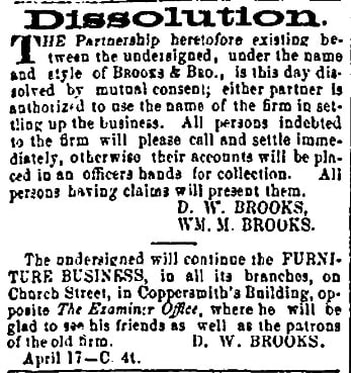

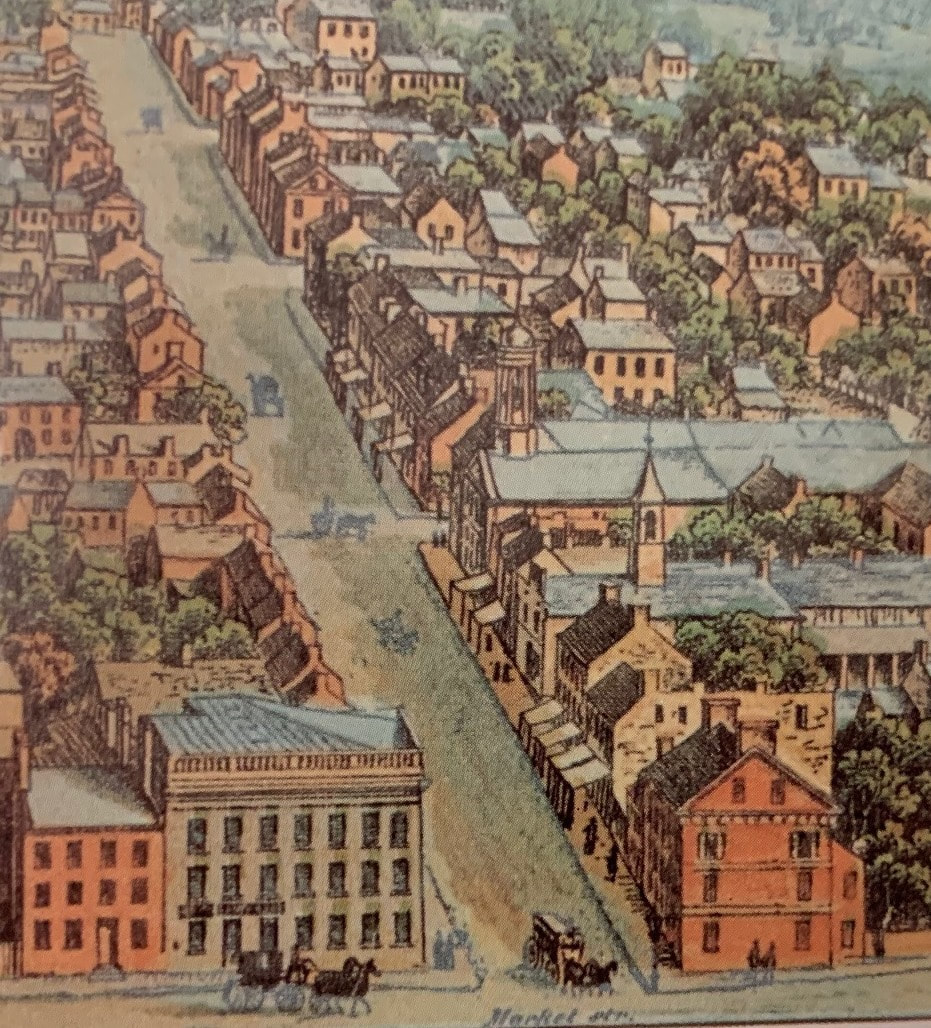

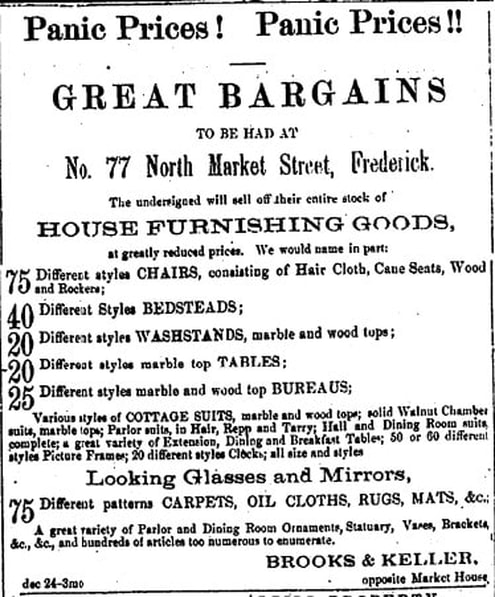

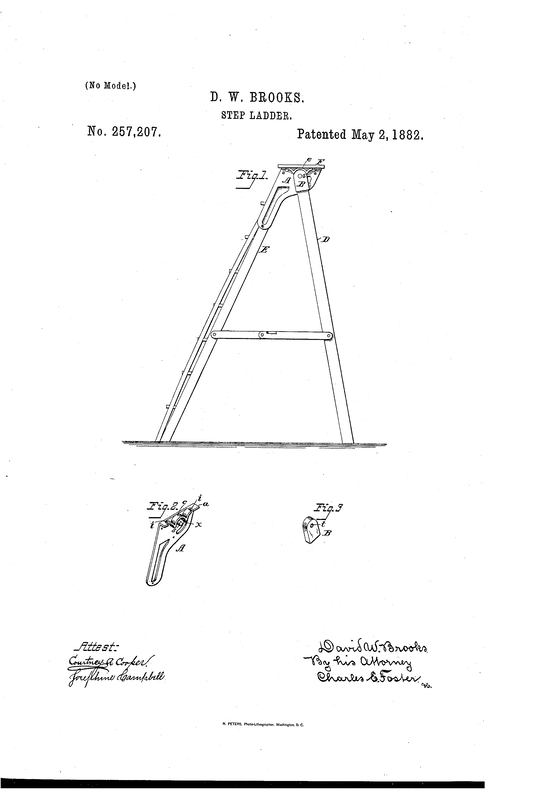

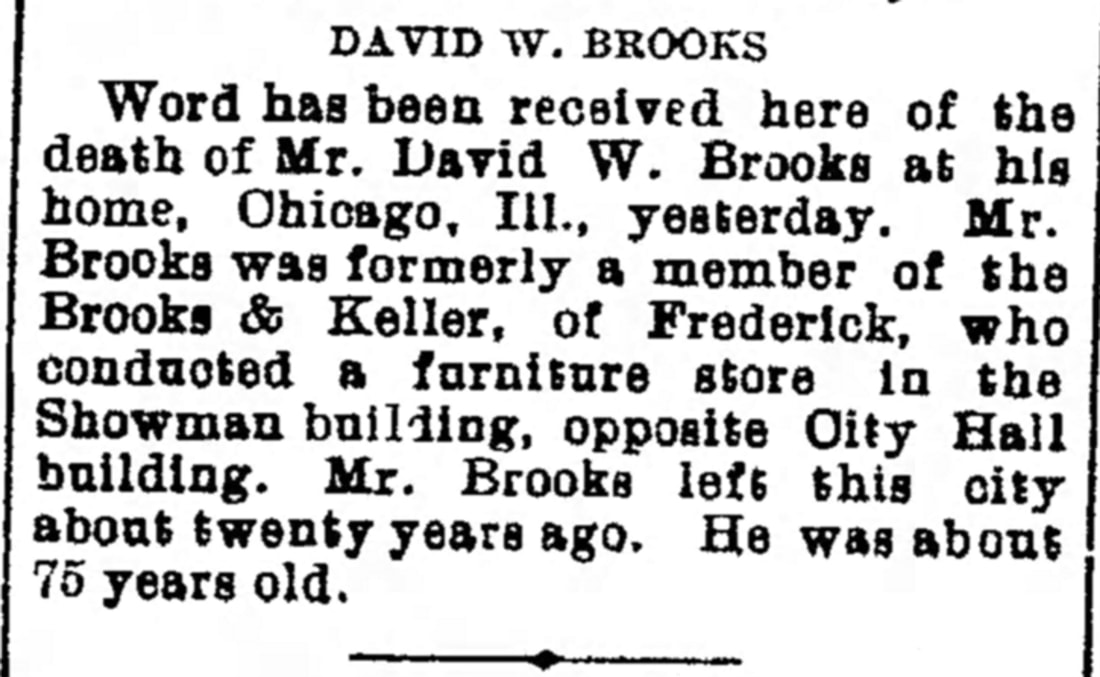

The terracotta comprising grave markers is not simply the brick-red composition of flowerpots and utilitarian redwares. It is called architectural terracotta, a form of ornamental ceramic cladding made from sculpted and molded clay. The body has a fine texture that allows it to be molded, sculpted, and glazed. Terracotta was often made in the form of hollow blocks with internal webbing or supports that allowed it to be both strong and light. Nineteenth-century architects viewed terracotta as a sort of “wonder material.” Less expensive than stone, it could be mass produced to exacting specifications, easily took glaze, was fireproof, could be sculpted and molded, was easy to clean, and billed as lasting forever. I found a study of these memorials online and the researcher had documented 175 terracotta grave-markers in New Jersey and adjacent parts of New York State. Other examples have been reported from upstate New York, near the site of a terracotta factory, as well as from California, Louisiana, and Ireland. The markers were produced in a variety of forms and sizes, most of which fall within the standard canon of Victorian mourning art. They include crosses, tablets, pedestals surmounted by urns, obelisks, and statues. Small marble tablets were often attached with personal information about the deceased. The earliest terracotta grave-markers date from the 1870s and 1880s. They gradually grew in popularity from the 1870s until roughly 1910. Then, they exploded in popularity. After 1920, they rapidly lost their appeal. The latest examples date from the 1930s. Some grave-markers appear to have been sculpted, whereas others were molded. The latter were made in plaster molds, reinforced with strap iron or wires, which could be reused over and over. Pressing the clay into the molds took great strength. After a mold was filled, the pressers would set it aside to dry. The piece was then removed and allowed to sit for several days. Next it was finished by rubbing and trimming. It was then taken to a drying room heated to about eighty-five degrees Fahrenheit. After two days of drying, glazes and slips were applied to the hardened unfired body. Red, buff, and gray was the triumvirate of colors on which the industry initially built its strength. In the 1880s a variety of new colors was introduced. The Brooks terracotta marker here in the cemetery’s Area A/Lot 116 is thought to be one of the earliest of the trade. The decedent, Arfue Brooks, died on July 6th, 1874. A small obituary mention can be found in the Frederick Examiner newspaper dated July 15th (1874) and mentions that Arfue was only six months old and died from cholera infantum (infant cholera). For those, like me, who don’t completely understand this malady, it is defined as an acute noncontagious intestinal disturbance of infants formerly common in congested areas of high humidity and temperature. Although rare today, it was a common form of death back in the day and was nicknamed “the blue death.” I will spare you the explanation, however. A common question we receive from visitors who happen upon Arfue Brooks' grave marker is whether or not Arfue's body was placed within the terracotta crypt which sits about 1 foot off the ground. The answer is a resounding "No," as the decedent was placed in a dug (and back-filled) grave below the monument. Arfue Brooks was the child of a local cabinetmaker from Pennsylvania named David William Brooks (1831-1904). Mr. Brooks operated a successful furniture business with his brother (William M. Brooks) once located at Coppersmith's Hall on the corner northeast corner of Church and Market streets. David and William dissolved the partnership in 1863, but the former would take on a new colleague shortly thereafter and continued operation of his retail store at 77 N. Market intothe 1870’s. Brooks and new partner, John H. Keller, sold a wide variety of household wares and continued to from a new location across from old City Hall on N. Market St. (today’s Brewer’s Alley). David W. Brooks got married in February, 1873. His bride was Miss Harriet Ann Rice, born in 1835, the daughter of George Rice, Jr. and Harriet Trego. Harriet kept the family household located at 417 N. Market St., and soon found herself expecting the couple's first child in January, 1874. Unfortunately, we already know the sad set of circumstances that beset the couple in regard to Arfue's death that following summer. The couple would not have any other children. Mr. Brooks seems to have continued with focus on his business with Mr. Keller, but also appears to have been aspiring to get to new heights—both literally and figuratively. Along these lines, I found an article in a Frederick newspaper from May, 1886 that reported that Mr. and Mrs. Brooks were moving to Otsego, Michigan. Here, David would be engaged in the manufacture of stepladders.

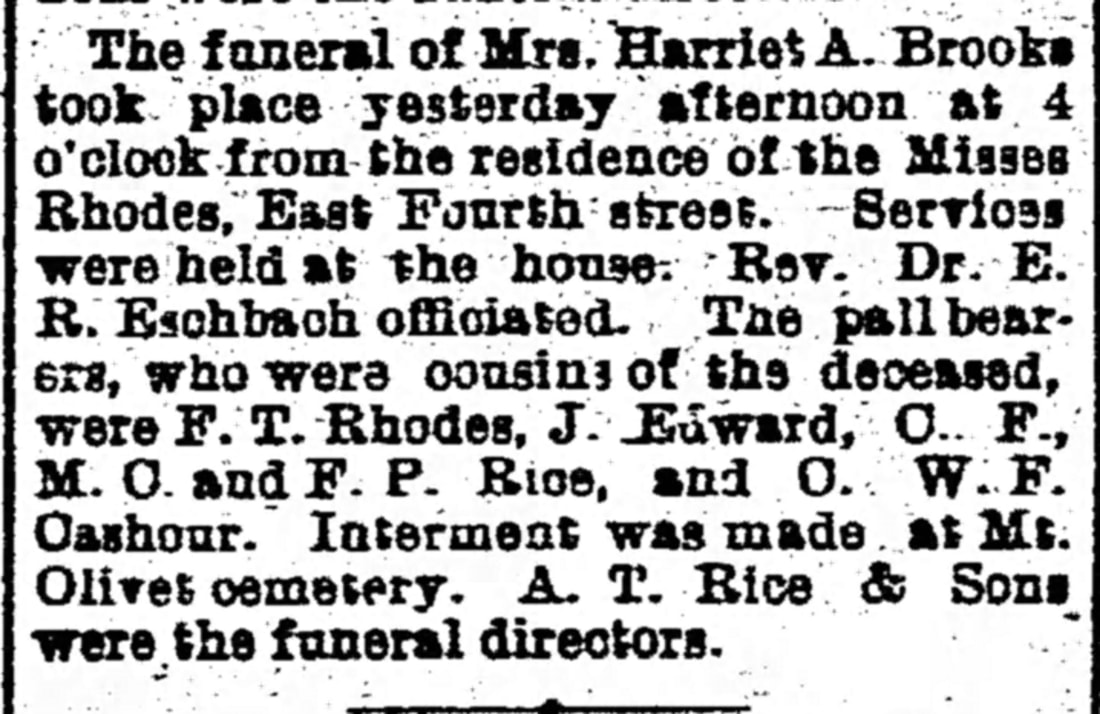

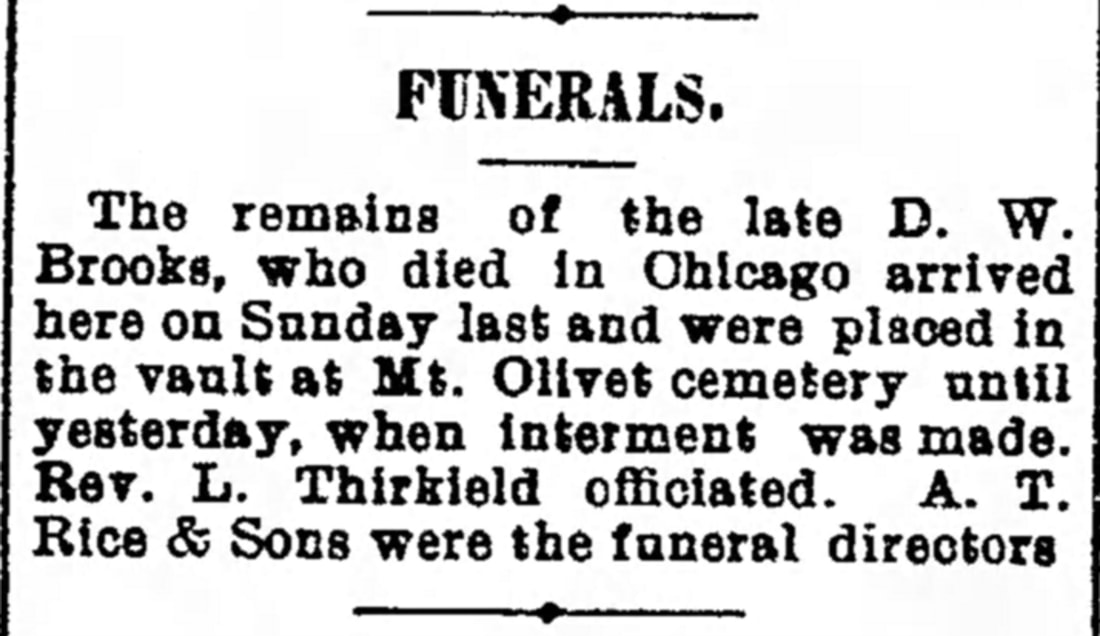

Of the time the couple spent living and working in Michigan, I know not. I hope it was fruitful as we don’t have the 1890 census to give us any clues. A decade later, I found the couple living in the Hyde Park area of Chicago in the 1900 census. Here the couple took up residence in the "Windy City's" south side at an address listed as 82 Avenue L. Daniel’s profession is listed as a cabinetmaker as it appears he had come “full circle” in his professional life. Harriet died in late August of 1902. Her body was returned back home to Frederick, where it was interred a few feet away from son Arfue’s which had been placed here nearly 30 years earlier. As for David W. Brooks, he would live the following two years as a widower at Chicago’s aptly named “Old Peoples Home.” Here he would die on August 15th, 1904. David, too, would return to Frederick and the Brooks family lot in Mount Olivet's Area A/Lot 116 containing the magnificent terracotta grave marker of the son he only had the chance to father for six months.

8 Comments

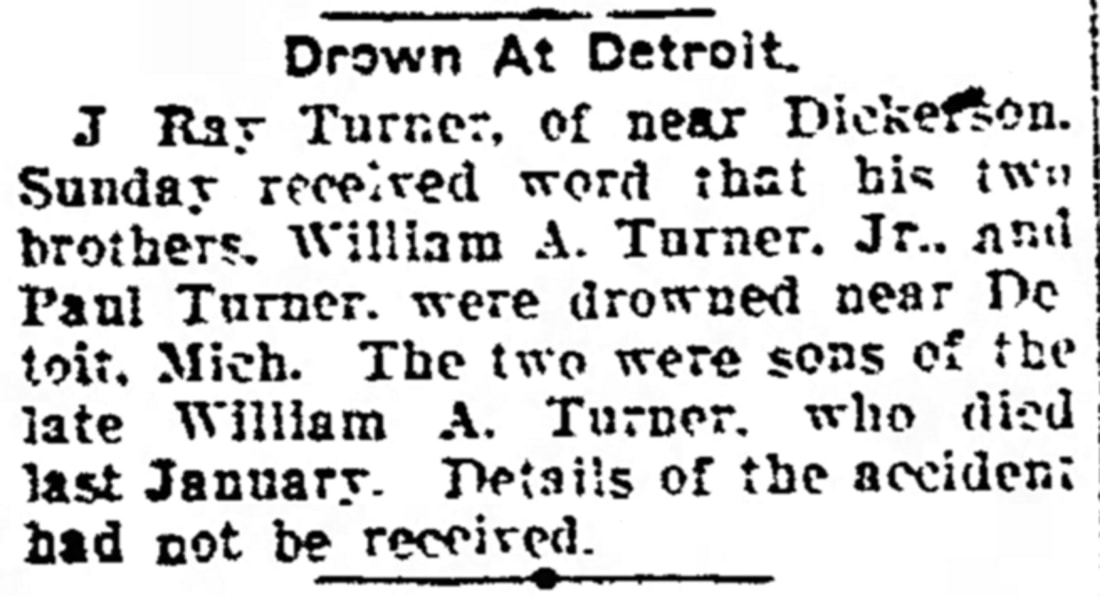

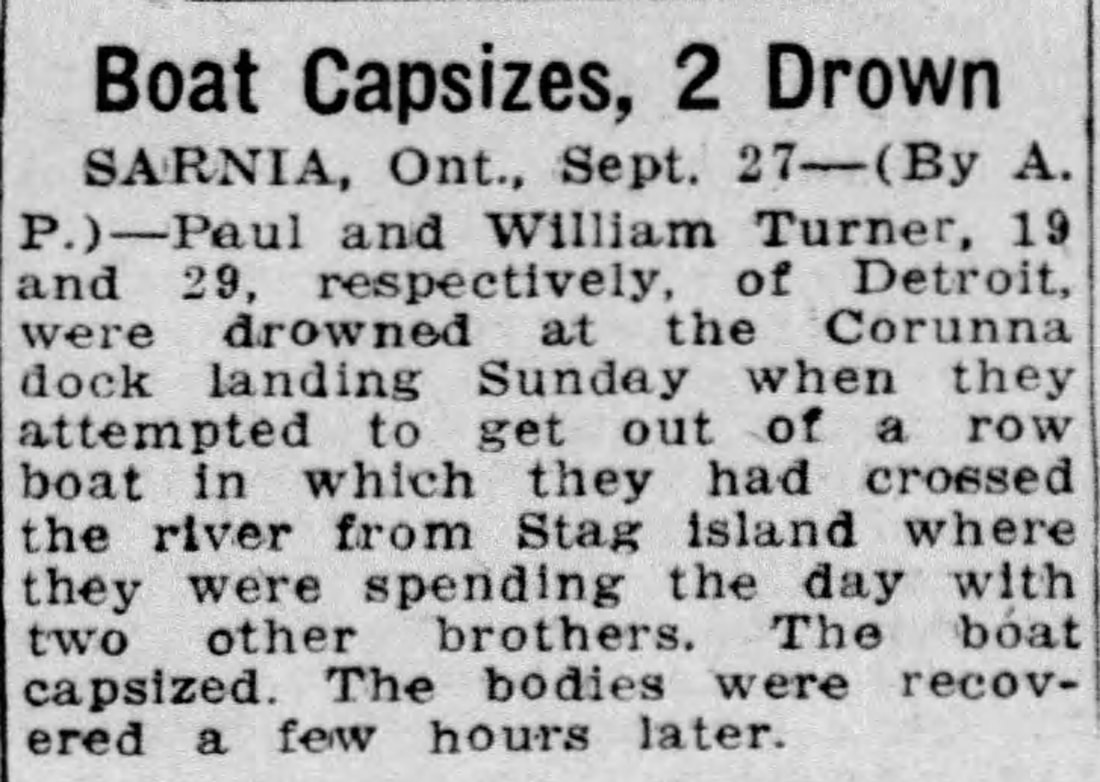

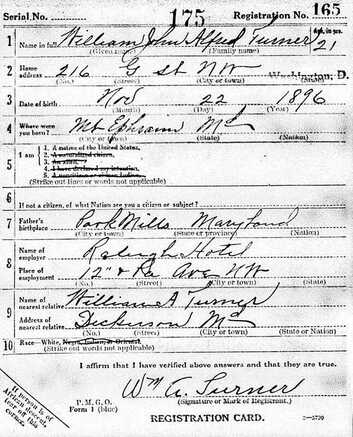

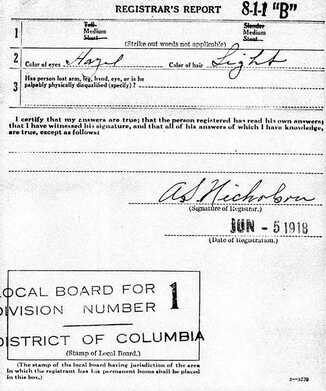

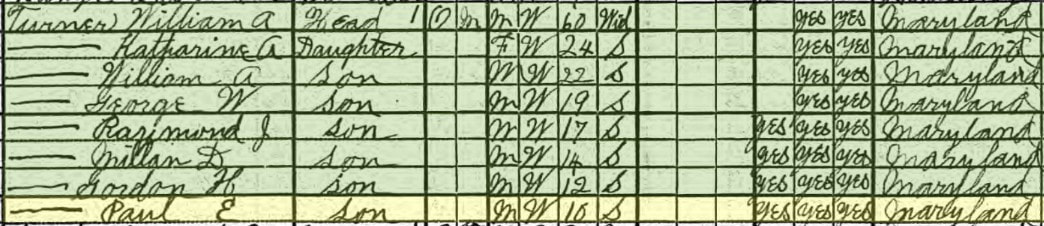

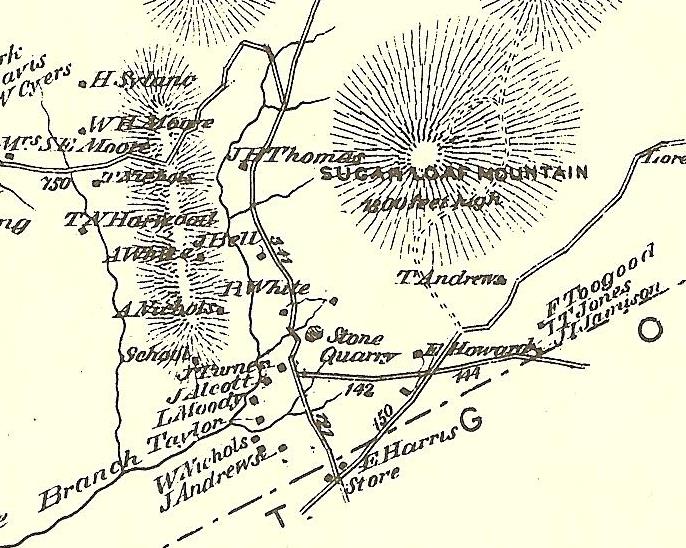

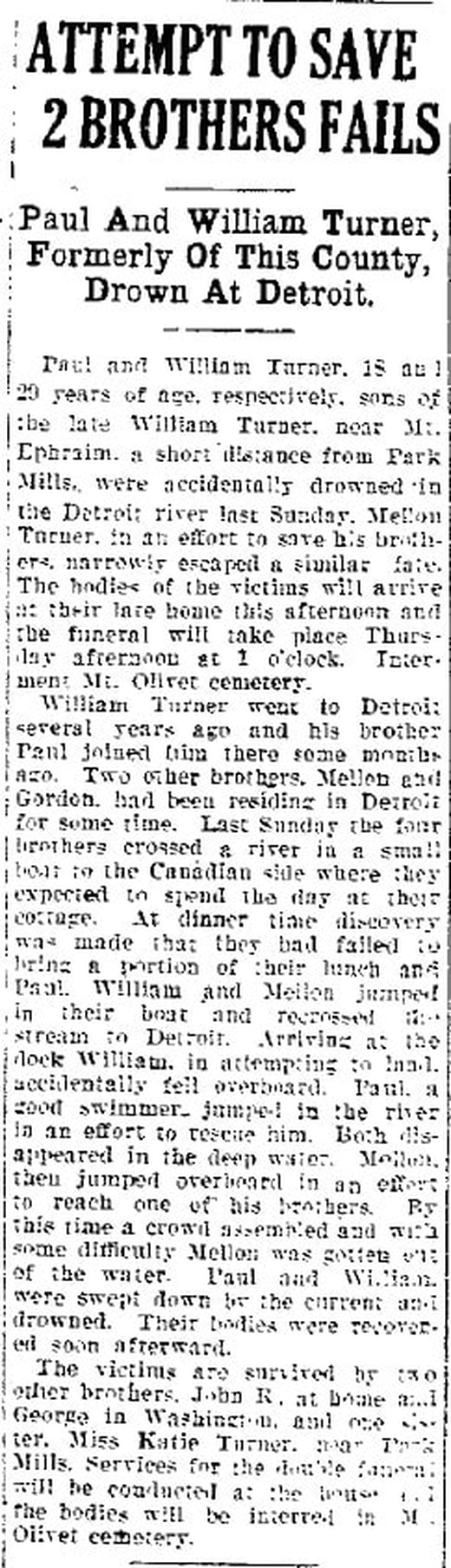

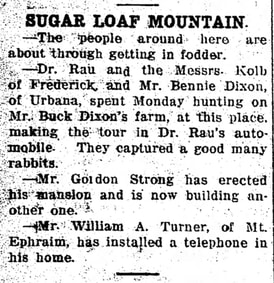

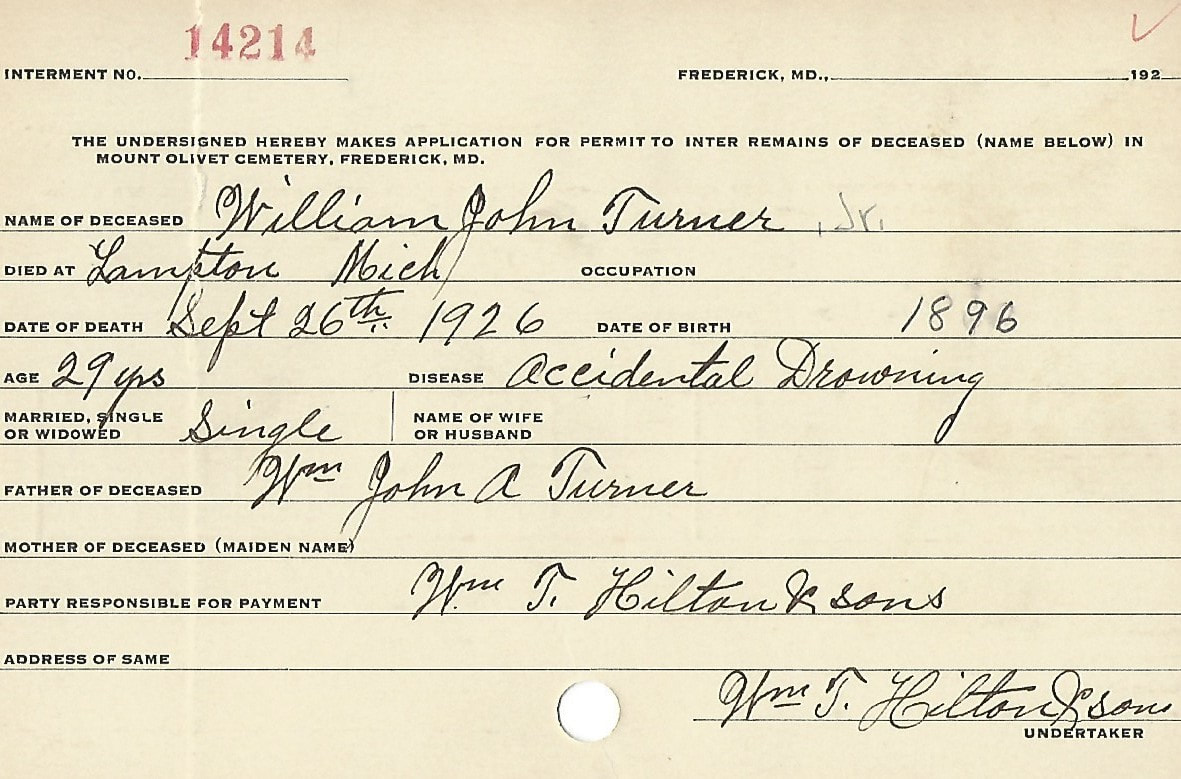

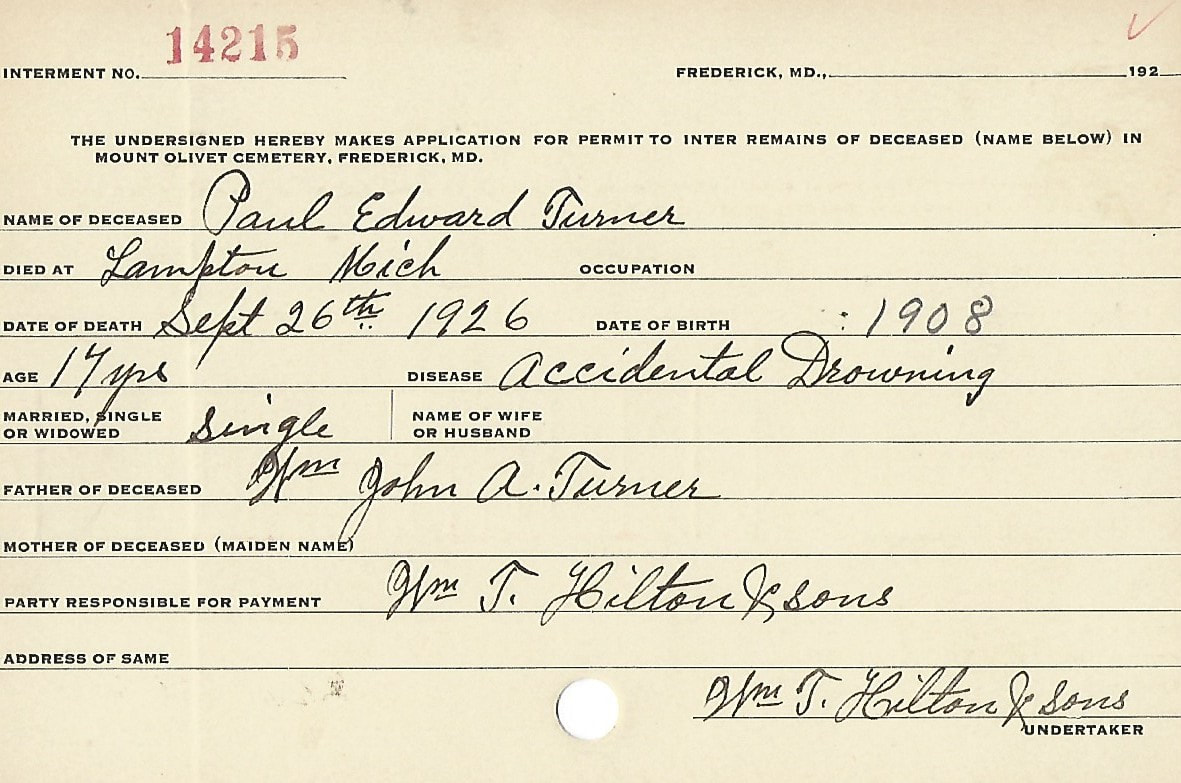

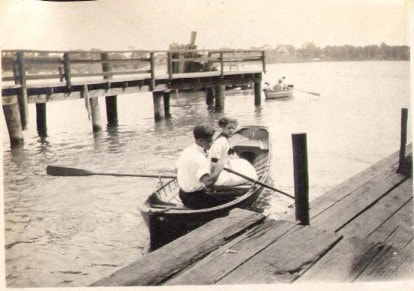

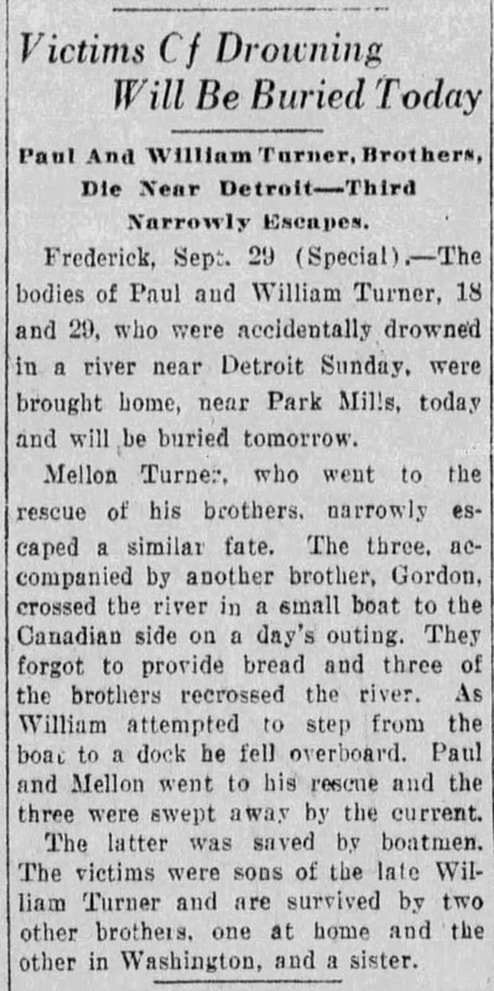

Canoes on the Potomac on Nolands Island Canoes on the Potomac on Nolands Island For the last few summers, I have participated as a history guide for a middle school-aged outdoor activity camp. It is a product of the Journey Through Hallowed Ground Heritage Area, a partnership I worked with closely during my time at the Tourism Council of Frederick County. This group is headquartered in Waterford, VA and comprises “historic” real estate stretching from Gettysburg to Frederick and down to Charlottesville. My primary role for these camps is to provide historical context associated with the Potomac River while the participants are engaged in a peaceful canoe sojourn from Lander to the Monocacy Aqueduct near Dickerson, affording a beautiful view of nearby Sugarloaf Mountain. My talk revolves around the early geology and peoples of the environs, with major emphasis on the earliest inhabitants in the form of the Piscataway and Tuscarora Indian tribes. I have to say the highlight for me is retracing the research and videography steps I took back in the late 1990’s while producing a film documentary on the subject. My favorite sites are part of the tour and include Heaters Island (home to the Piscataway Tribe from 1699-1712)and the Mouth of the Monocacy, where a French Canadian fur trader named Martin Chartier once operated a trading post and a contingent of Tuscarora Indians would come up from North Carolina and settle nearby from 1712-1724. The experience has been quite rewarding for me, but not just because of the history aspect. The natural beauty of the area and getting glimpses of ospreys and bald eagles is the proverbial “icing on the cake.” I’ve also recaptured an appreciation for paddling and the expertise practiced by river guides. We’ve been “on the river” in a variety of situations, from static flat water under sunny blue skies, to summer rain storms, one of which cut our trip short as it brought with it “an electrical component.“ That brings us to this week’s “Story in Stone,” set in the year 1926 amidst the backdrop of a river and what was supposed to have been a carefree day of picnicking and pleasure on an island “sandwiched” between east-central Michigan and the western border of Ontario, Canada. Below is the first article I could find which appeared in the Frederick News a few days after the tragedy. I found out a bit more about the accident in the following Michigan paper out of Lansing. I originally stumbled upon this melancholy tale about a year ago. It involves two former Frederick County residents, one having been a veteran of World War I. What struck me more is the fact that William Turner, Jr. was a Navy veteran who would be promoted to Seaman 2nd Class. I just assumed he would be a strong swimmer since he was stationed on and adjacent water. William John Alfred Turner, Jr. was born on November 22nd, 1896 and Paul Edward Turner in 1909. They were among seven children of William John Alfred Turner, Sr. and wife Margaret Virginia “Jennie” H. Kanode. The Turner family resided in the hamlet of Mt. Ephraim near Bell’s Chapel at the southwestern foot of Sugarloaf Mountain. The specific location is just west of the intersection of Comus and Mt. Ephraim roads. The property appears on the 1873 Titus Atlas.

Details (on earlier life for the boys) have been hard to find. The Turner children presumably worked on the farm and attended local schools. Apparently, William would obtain a job as a hotel clerk in Frederick. On July 5th, 1918, 21-year-old William Jr. would join the Navy as the United States ramped up its staging and began amassing its great force in eastern France in the fall of that year. He was sent to a Naval training Station in Newport, RI. Two months later, William was assigned to a Receiving Ship in Boston. He remained here for four months before being admitted to a hospital in Chelsea, MA. Next, I found William receiving an honorable discharge for physical reasons on March 14th, 1919. Another article about the boating accident, from the local Frederick paper of record, explains that the two Turner boys had recently moved to Detroit to join two other brothers, Millan David Turner (1904-1967) and Gordon Henry Turner (1906-1968), already living in “the Motor City.” I would discover that both were employed as auto body mechanics at the time of their deaths. The surmise the reason for their move could be related to the fact that the young men lost their father earlier that year in January. The aforementioned Mr. Turner died of acute indigestion, and was laid to rest in a family plot on January 7th, 1926 beside his wife who had passed back in November, 1917.

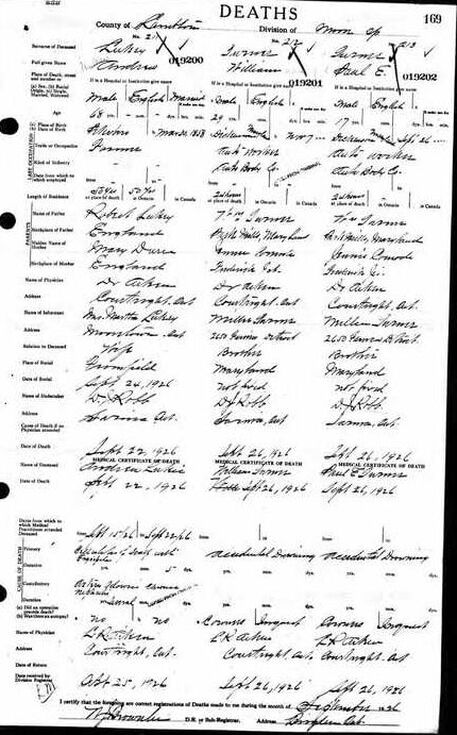

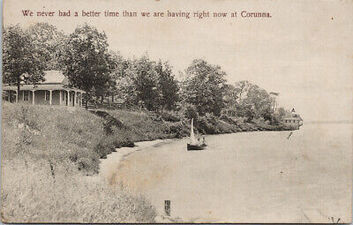

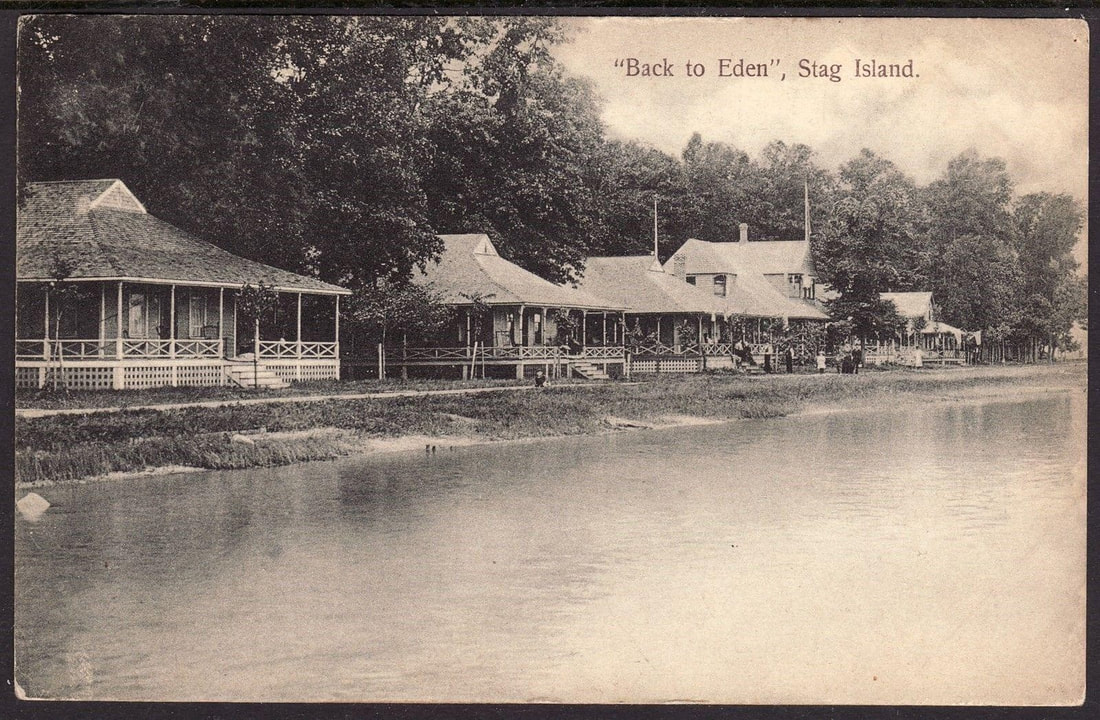

As for the melancholy drownings in the St. Clair River, I sought to learn more about the area, and any particulars on the cause of the accident. Stag Island is a private Canadian island that today boasts over 100 cottages and once featured a casino. The island is accessed by Marysville, Michigan on the west and Corunna, Ontario to the east. The St. Clair River drains the famed “Great Lake” Huron, with the waterway’s mouth located just upstream from Stag Island. This surely explains the potential for dangerous currents, such as that which swept the Turner brothers to their early demise. The quartet of brothers were apparently vacationing on the Ontario side of the river in Corunna. On September 26th, they had obtained a rowboat and ventured to spend the day on Stag Island. While there, three of the brothers decided to make a quick trip back to their vacation cottage at Corunna in hopes to return right back a short-time later. Gordon Turner remained on Stag Island to “hold down” the proverbial fort in his brothers’ absence. The largest nearby town is Sarnia, on the Canadian side, within Lambton County. From death records, I found that this was the location of a coroner’s inquest on the bodies of both William and Paul. I even found the original coroner’s report on Ancestry.com. This was a boon, especially due to the fact that our original cemetery interment cards were scant and even mistakenly listed Lambton County as being in Michigan. I found several vintage images of Stag Island, Corunna and Sarnia. These helped me visualize to a degree, the scene of drownings. From my own recent experiences on the river, it’s somewhat hard to believe that a place of such beauty and tranquility can be tarnished in an instant by such a tragic event. A final article found in newspaper research came within a funeral announcement in the September 30th edition of the Baltimore Sun. This article tipped me off to a prime catalyst and cause for the horrific events of September 26th, 1926. It appears that the fateful “chain of events” was put into motion by a simple error in packing the picnic basket for the island excursion—someone forgot the bread. Somehow, I was reminded of the passage found in the Bible, Ecclesiastes 11:1-10, known commonly as “Cast thy bread upon the waters." The bodies of William and Paul Turner were shipped back to Frederick, and the young men would be buried in the family plot in Area OO/Lot 36. In time, they would be joined by Millan, the brother who was luckily saved from the jaws of the St. Clair River back in early fall, 1926. He would stay in Detroit for the rest of his life, working as a merchant. I assume he painfully relived the site of that terrible day for 41 years before his death in November, 1967. Remaining brother, Gordon, returned home to the family farm. He worked as a carpenter, never married and would join his siblings in death a year after Millan in 1968. The lot also includes sister Catharine “Katie” (Turner) Smith and an additional brother named George (1900-1946). Interestingly, our cemetery records list George’s profession as that of a cable-splicer with C & P Telephone. I wonder if he was inspired by the advent of the telephone earlier in life, as he was 13 when it was installed in his home. "Cast thy bread upon the waters: for thou shalt find it after many days.

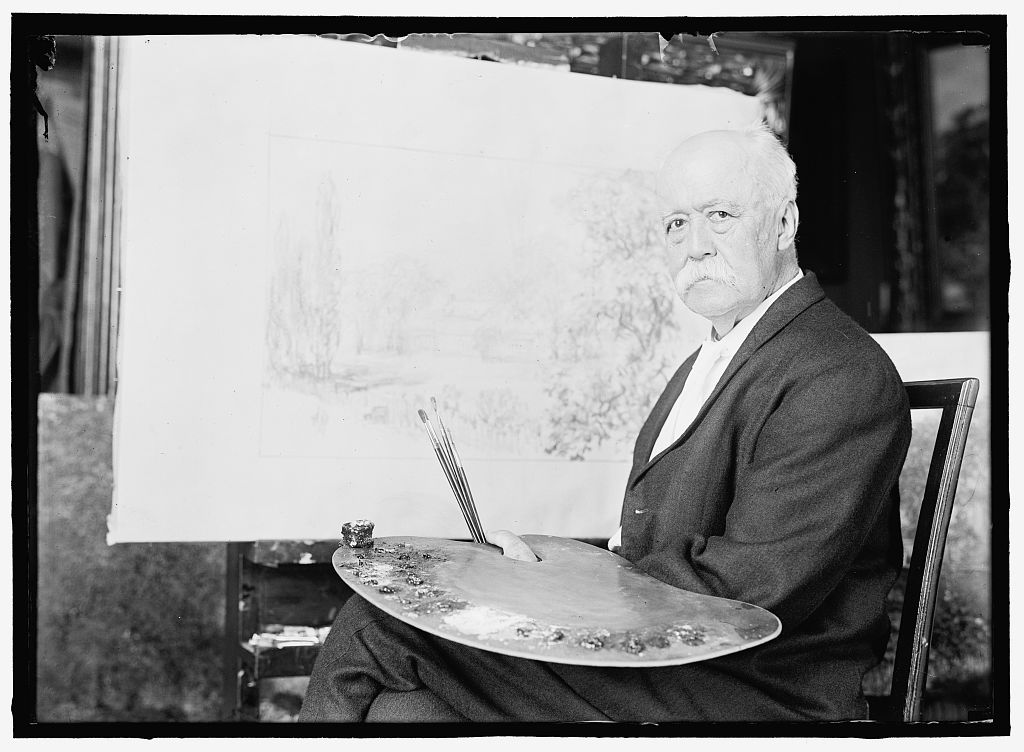

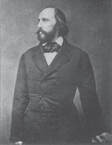

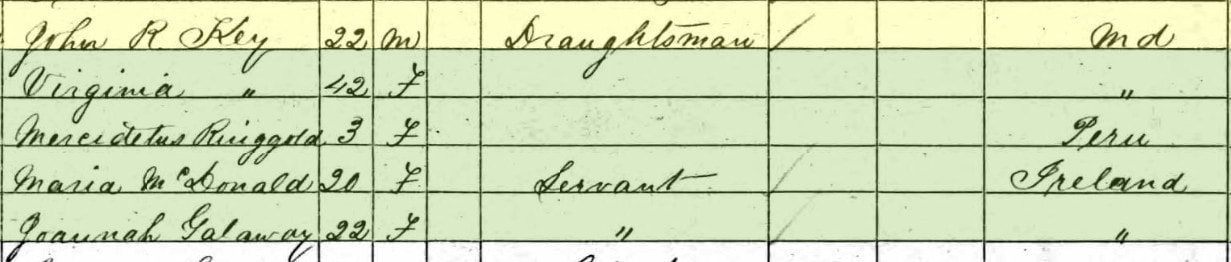

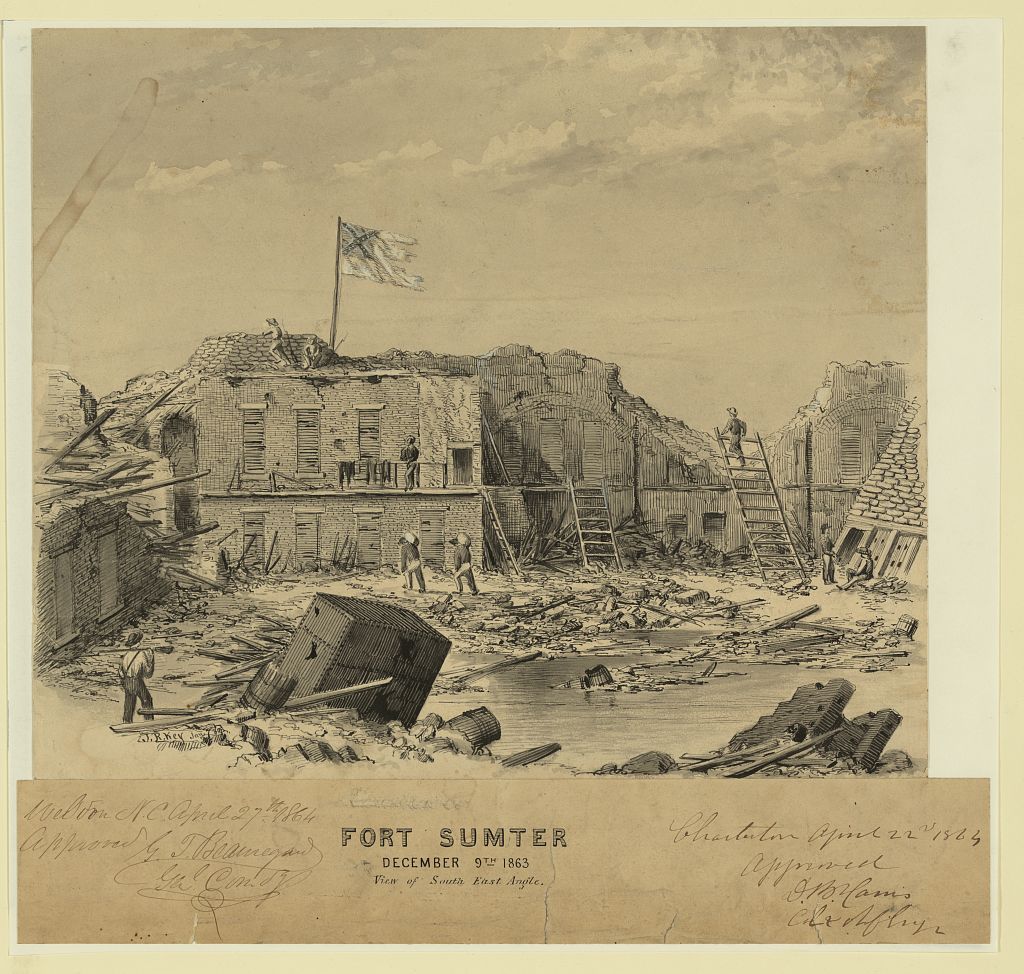

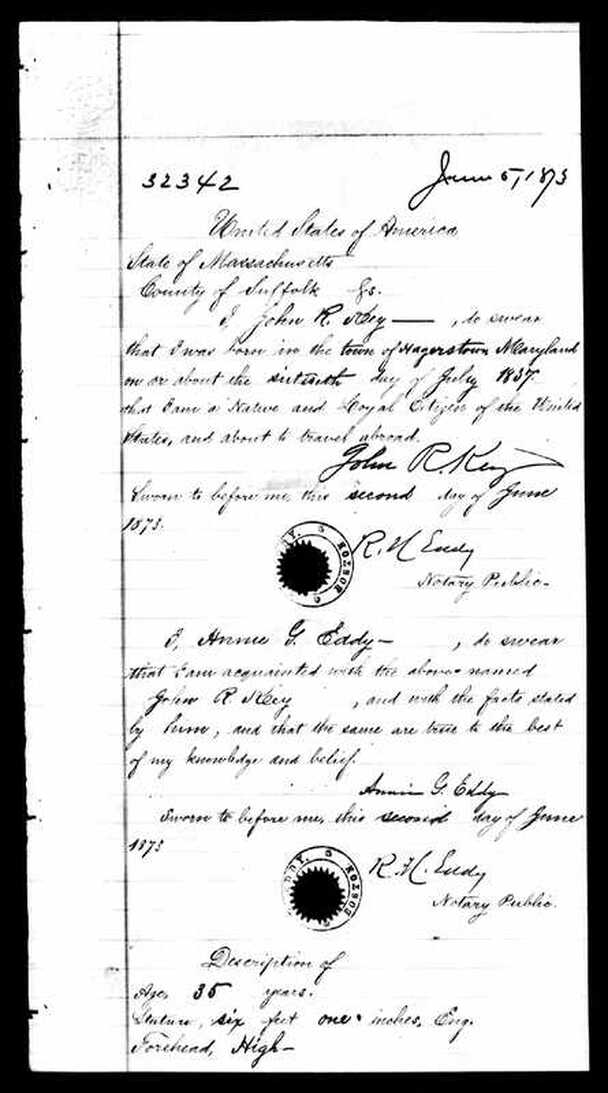

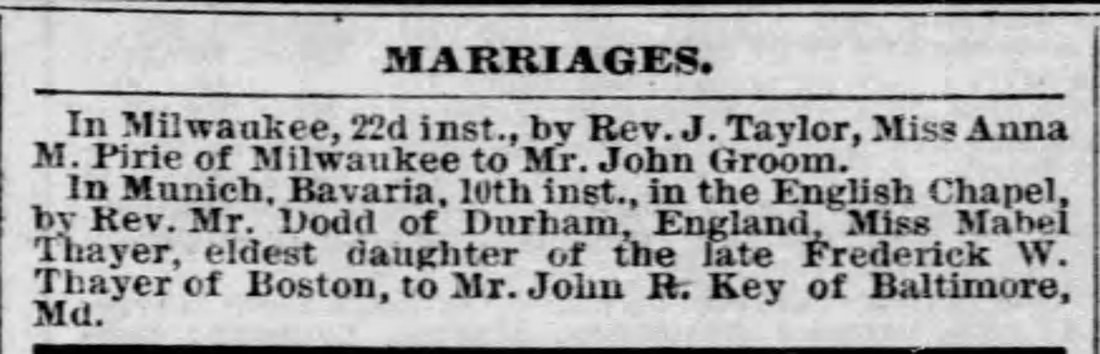

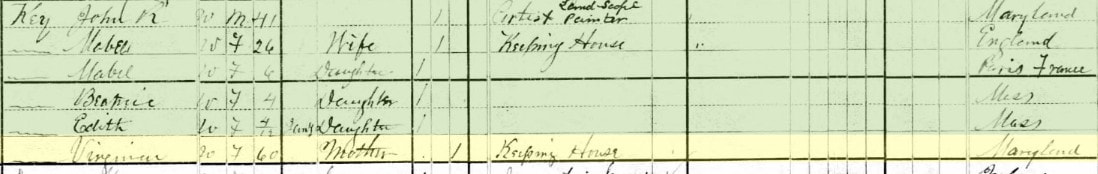

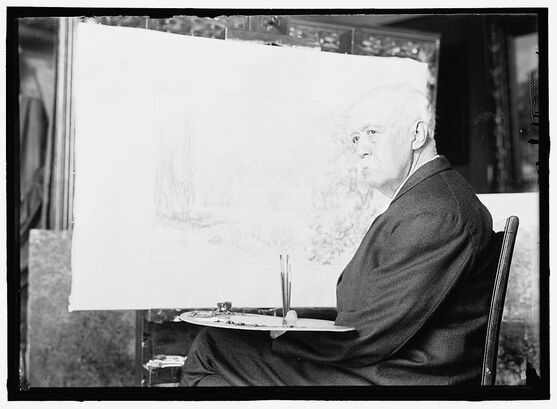

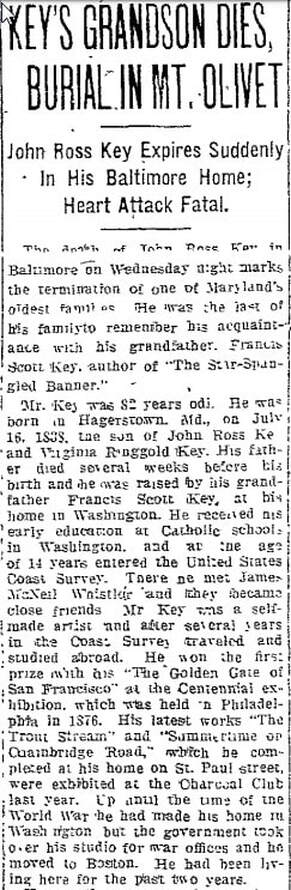

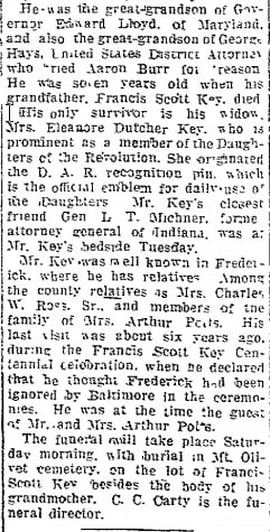

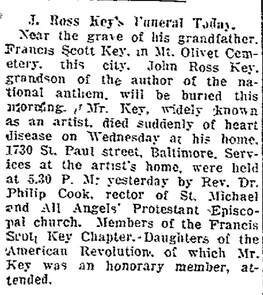

Give a portion to seven, and also to eight; for thou knowest not what evil shall be upon the earth. If the clouds be full of rain, they empty themselves upon the earth: and if the tree fall toward the south, or toward the north, in the place where the tree falleth, there it shall be. He that observeth the wind shall not sow; and he that regardeth the clouds shall not reap. As thou knowest not what is the way of the spirit, nor how the bones do grow in the womb of her that is with child: even so thou knowest not the works of God who maketh all. In the morning sow thy seed, and in the evening withhold not thine hand: for thou knowest not whether shall prosper, either this or that, or whether they both shall be alike good. Truly the light is sweet, and a pleasant thing it is for the eyes to behold the sun: But if a man live many years, and rejoice in them all; yet let him remember the days of darkness; for they shall be many. All that cometh is vanity. Rejoice, O young man, in thy youth; and let thy heart cheer thee in the days of thy youth, and walk in the ways of thine heart, and in the sight of thine eyes: but know thou, that for all these things God will bring thee into judgment. Therefore remove sorrow from thy heart, and put away evil from thy flesh: for childhood and youth are vanity." -Ecclesiastes 11:1-10 In addition to being the grandson of Mount Olivet’s most famous resident, Francis Scott Key, author of “The Star-Spangled Banner," John Ross Key III was a world class artist. He was born in Hagerstown on July 16th, 1837, two months after the death of his father, John Ross Key II (1809-1837). Young Key’s mother, Virginia Ringgold (1815-1903), was a native of Washington County and daughter of Brigadier Gen. Samuel Ringgold, a veteran of the War of 1812 and a US congressman. John Ross Key III was the third such in the illustrious family to hold the name, the first being the father of Francis Scott Key who served as a captain in the American Revolutionalso buried at Mount Olivet. We will tell his life tale another day. As for the subject of this week’s “Story in Stone,” John Ross Key III would be brought up in Georgetown, District of Columbia, until the age of five by his famous grandfather (Francis Scott Key). The family home had a back yard that stretched to the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal and Potomac River. This house no longer stands today, however the site is marked with a small park on the southern approach to the aptly named Francis Scott Key Bridge (“Key Bridge”) built in 1923 and connecting Georgetown with Rosslyn, Virginia on the other side of the river. John had an older brother Clarence and another sibling, Caroline who appears to have died in childhood. As a teenager, John Ross Key III was forced to go to work to support his widowed mother. He showed an early talent for drawing, in which he was mostly self-taught. Key’s talent led to a job as a topographical artist and draftsman with the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey where James McNeill Whistler was a colleague in the department. Whistler would achieve later fame as an artist living abroad in Paris, his most well-known work being “Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1,” best known under its colloquial name “Whistler’s Mother.

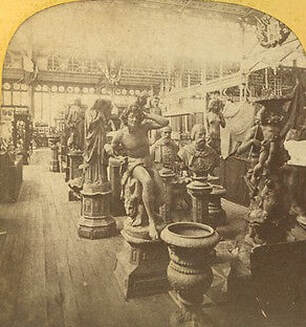

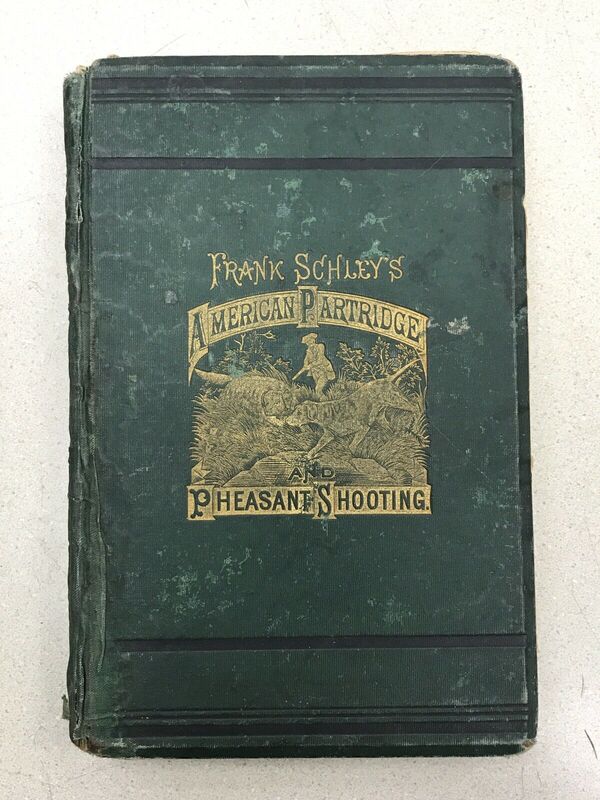

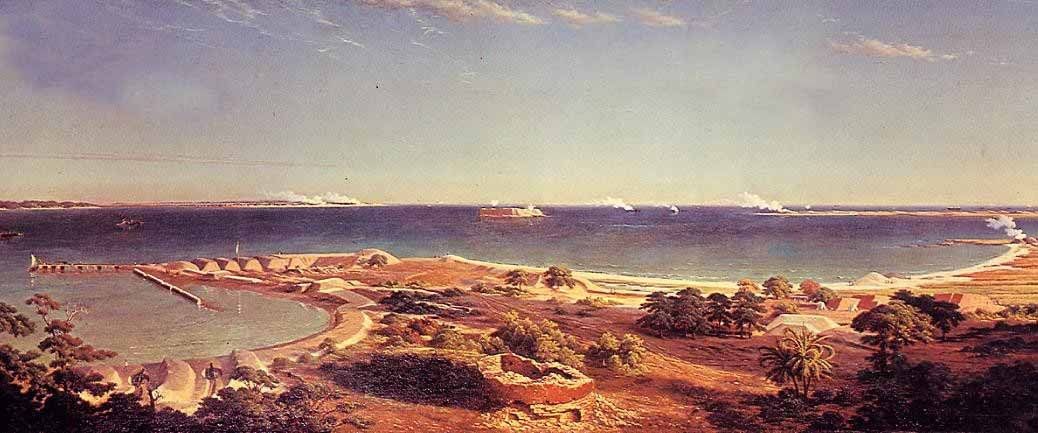

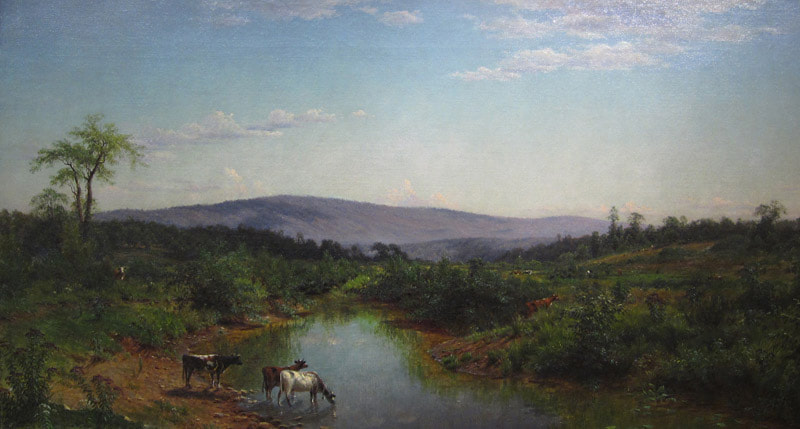

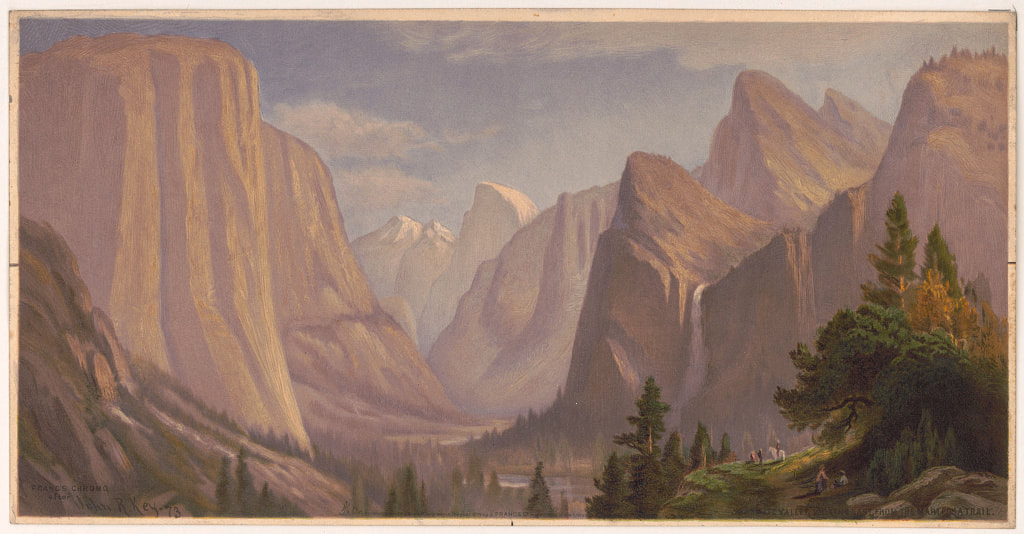

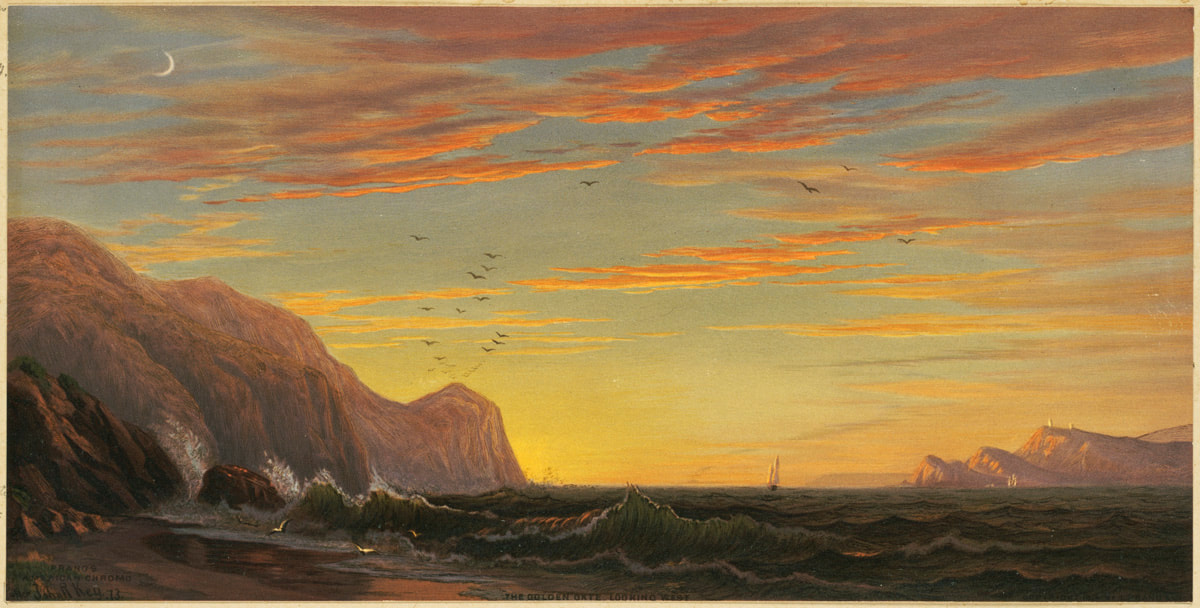

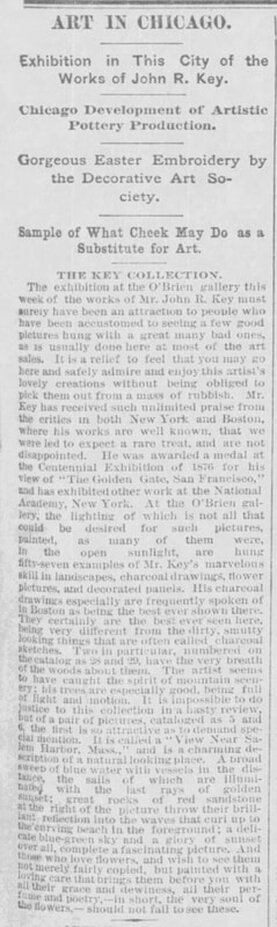

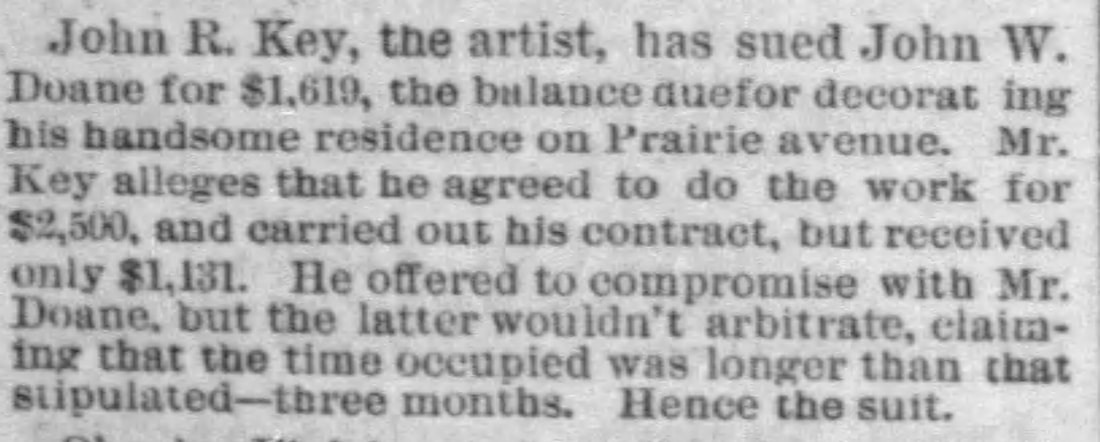

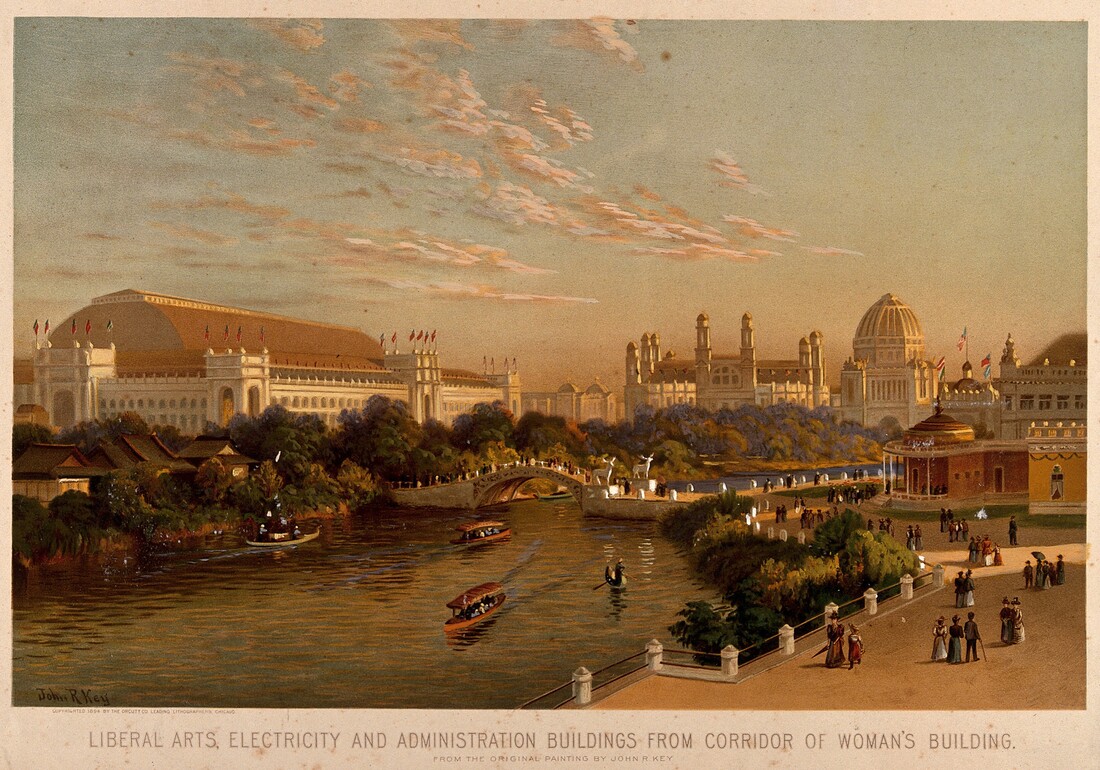

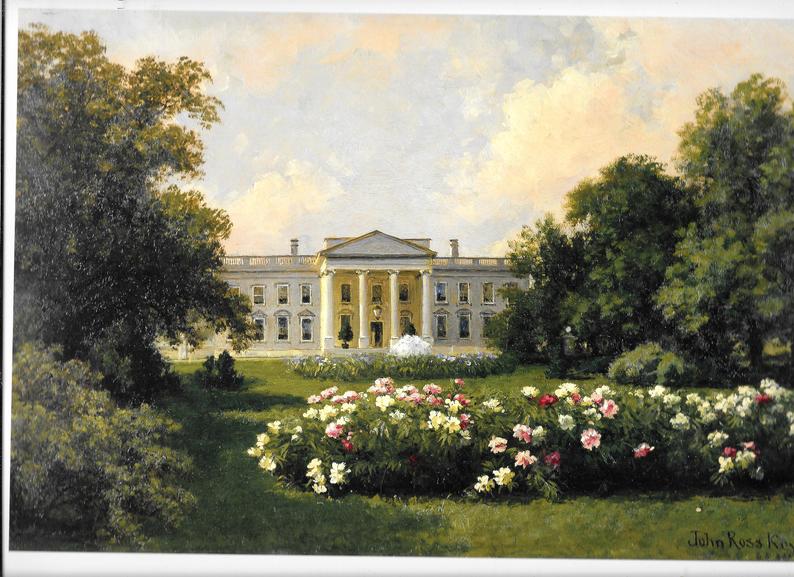

A train departs Oakland in the 1800's A train departs Oakland in the 1800's Professional Artist At war’s end, John Ross Key settled in Baltimore where his war scenes found a sympathetic audience and critical acclaim. He soon launched into a career as a landscape painter and divided his time between Baltimore and New York City. During the summers of 1867 and 1868, he retreated to the rustic Key-Howard family cottage at Oakland, Maryland in Garrett County on the far western end of the state. Here, John was accompanied by his mother. Oakland had become a popular summer resort for prominent families trying to escape the summer heat of Baltimore. The Keys and Ringgolds were among the firsts, making this a fashionable resort area easily accessible by the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. The area's popularity would grow into the greater tourist destination we know today as Deep Creek Lake.  Key-Howard cottage (Oakland) Key-Howard cottage (Oakland) Among relatives in the area were Key’s maternal aunt, Nancy Ringgold Schley, and her husband, Maryland state senator William Schley. They owned “Herrington Manor,” a 2,000 acre tract about five miles from Oakland that the Keys had named “the Glade.” John painted several versions of this work, showing Herrington Creek and Snaggy Mountain, a view on the Schley’s property. One of these, smaller and slightly different, is in the collection of the Maryland Historical Society, Baltimore. The Herrington Creek depicted in these paintings has become Herrington Lake, the result of a dam built in the 1950s. In 1869, Key headed west again and lived in San Francisco. He traveled throughout California, painting dramatic scenic views of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, Point Lobos and the Golden Gate. The latter oil painting would be awarded a gold medal at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia and many of his California-themed paintings were made into chromolithographs by publisher/printer Louis Prang in the 1870’s. John Ross Key kept painting Allegheny mountain scenes later in his career, based on studies done in the late 1860s. In 1872, an art critic of the Boston Evening Transcript reported that Key had almost finished “three or four rugged glimpses of the Allegheny Mountain region in Maryland… a section almost unknown on canvas in our locality, but quite as worthy of attention as the well-worn White Mountain region.” (February 17, 1872). Later that year, the same critic wrote: “John R. Key has a spirited view among the Alleghenies, the foreground of which is rich in color and strong in effect. The water and shadows are finely rendered, and the cattle careful studies.” (March 23, 1872). These are said to be extremely rare and beautiful exhibition paintings in the Hudson River school style of seldom portrayed parts of America. About the year 1873, John traveled to Europe to study art in Munich and Paris. Here, he would meet and marry, Mabel Thayer (b. 1852), a native of Boston living in England. The couple had their first child, named Mabel, in 1874 while living in Paris. They would return stateside the following year as Key would establish a studio in Boston. The family settled in Stockbridge, Massachusetts in Berkshire County. John’s mother, Virginia, would reside with the family which grew with the additions of daughters Beatrice (1876) and Edith (1880) and Marian (1883).  "Resting Cows" "Resting Cows" At this time, John Ross Key primarily worked in Boston where he showed over 100 works in 1877 at the Boston Athenaeum. Critics praised a selection of his charcoal drawings as “firm and masterly, strong and graceful.” Over his career, he would also exhibit at the National Academy of Design, the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, and the Boston Art Club. In the early 1880’s, John seems to have created a great stir in Chicago with his artwork. An article in the Chicago Tribune newspaper gives a tremendous review of Key’s artwork in an article appearing in mid-April, 1881. He would have another stellar exhibition in 1882 and received commissions for special pieces and painting home-based murals from wealthy Chicago patrons. This prompted a move by the Key family to “the Windy City.” John Ross Key opened his own office and art studio in town. In 1888, Key helped decorate the famous Chicago Club with his art pieces. The prominent social club had been ravaged by fire. A few years later, Key was commissioned to make portraits of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, also known as the Chicago World’s Fair. This opportunity would make him a favorite adopted son to Chicago, and led to other expositions/fairs taking the country and world by storm. He would produce more scenes of this historic event over the remaining years of the decade. As John Ross Key's fame grew, so did that of wife Mabel Key, John’s wife. She became a central figure in Chicago’s social scene, and regularly made the newspapers’ society page write-ups. Sadly she would die in 1897 at the age of 44, after what the newspapers referred to as a long illness. She would be laid to rest in Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

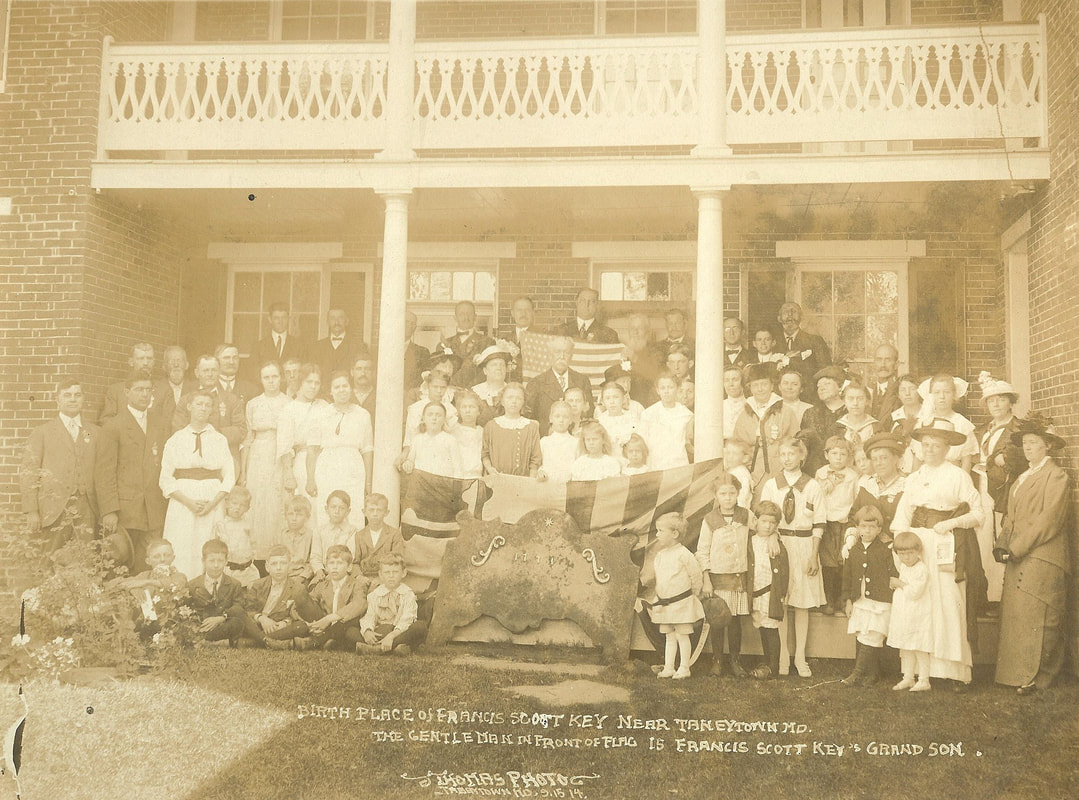

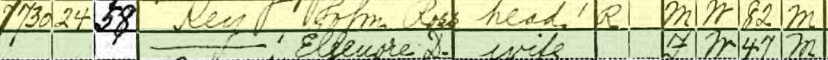

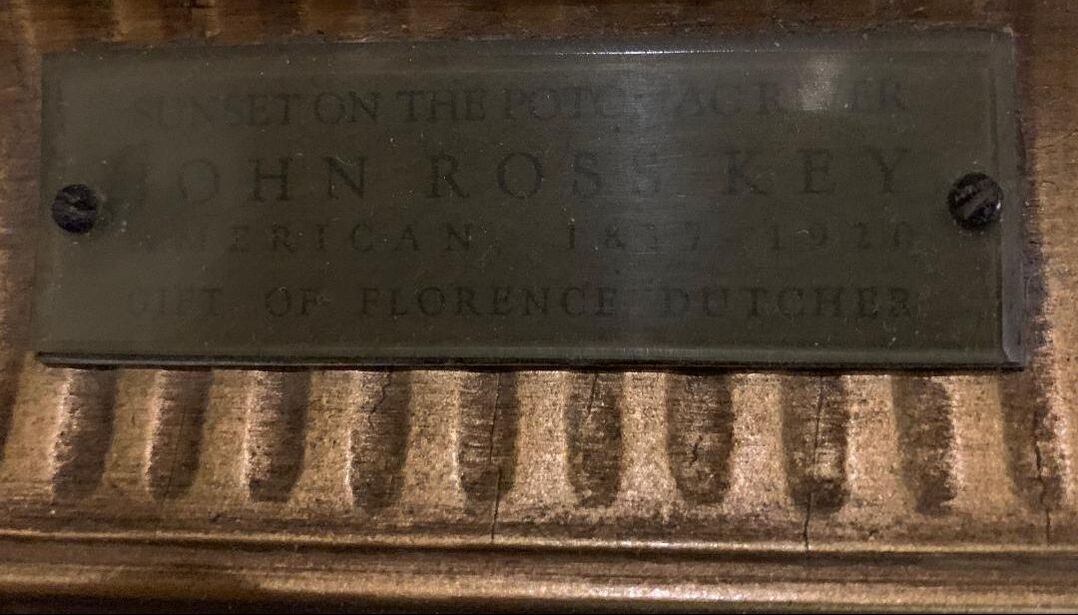

Miss Dutcher was a resident of Omaha, Nebraska and worked for a regional rail line and served as a leading member of the DAR chapter there. At the Eighth Continental Congress in 1899, Ellenore proposed the adoption of an official emblem of suitable size for the organization’s daily use. She was concerned how the larger, existing pin would get caught on clothing and had become somewhat of a safety issue. She explained that this new pin could provide funds in which to help the DAR in their goal of building Memorial Continental Congress Hall in Washington DC (Constitution Hall). This resulted in the creation of the DAR Recognition pin, which each member may purchase today upon admission. At the 10th Continental Congress in 1901, the design proposed by Miss Dutcher was adopted as the official emblem for daily use. It is worn over the left breast in accordance with the guidelines set forth in the DAR Handbook and National Bylaws. Each pin is engraved with the owner’s unique membership number—the lower the number, the older the pin. In 1900, Key traveled to Paris, accompanied by Miss Dutcher, where his scenes of the Chicago World’s Fair were exhibited to European audiences as part of the Exposition Universelle. The following year these same pieces were featured in the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo. He was revered for new works depicting both these events. The couple of John and Ellenore would marry in 1902 in Chicago, and relocate to Key’s earlier home of Washington, DC. The artist, now 65 years old, seemed to preoccupy his time with creating landscapes of the nation’s capital and other nearby places, however he seldom sold any of these works with the hopes of one day having a large exhibition of his works. He would eventually move to Baltimore and took up residence in the Mount Vernon neighborhood. John Ross Key was back home for a very important event that occurred in 1914. It was the centennial anniversary of his grandfather’s writing of “the Star-Spangled Banner.” He took part in commemorative events in Baltimore and also here in Frederick and in Mount Olivet on September 15th, 1914. John R. Key would be the guest of honor at the groundbreaking ceremony for a new monument to his grandfather placed on the grounds of the Terra Rubra, childhood home of the famed songwriter located near Keymar in Carroll County. John Ross Key’s family heritage proved very important, especially in his waning years. He would be inspired to paint scenes of both of his grandfather’s primary residences including the plantation birthplace of Terra Rubra and the Key home in Georgetown. He did these from memory. John Ross Key died in Baltimore on March 24th, 1920, a victim of heart disease. He would be buried in the original Key family lot in Mount Olivet’s Area H. This is where Francis Scott Key and wife Mary had been placed 54 years earlier in October, 1866 after being reinterred from Baltimore’s Old St. Paul’s Burying Ground. Five years after the death of her husband, Ellenore worked to organize the largest exhibition of John's more recent work. This was “a Star-Spangled success" to say the least. John Ross Key’s works have been represented in important exhibitions over the following decades since his death, including the National Academy of Design, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and Corcoran Gallery. They can be found all over the world and originals, as well as prints are still being sold and can even be found on eBay. JOhn Ross Key’s works are represented in important museum collections across the country, including the White House Historical Association, Fine Art Museums of San Francisco, University of Michigan Art Museum, Missouri History Museum, Morris Museum of Art, and Greenville County (SC) Museum of Art. If you’d like to see a John Ross Key work in person, stop by Frederick City Hall as you can find one of his original landscapes entitled "Sunset on the Potomac" adorning a wall along the stairs leading to the second floor.

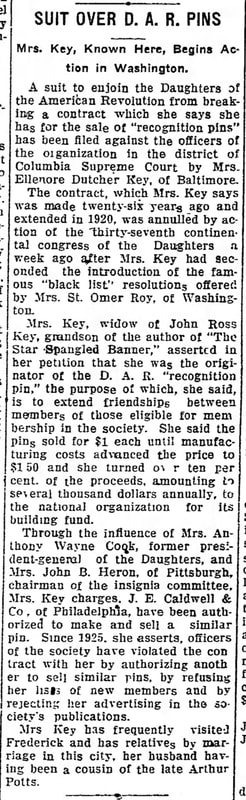

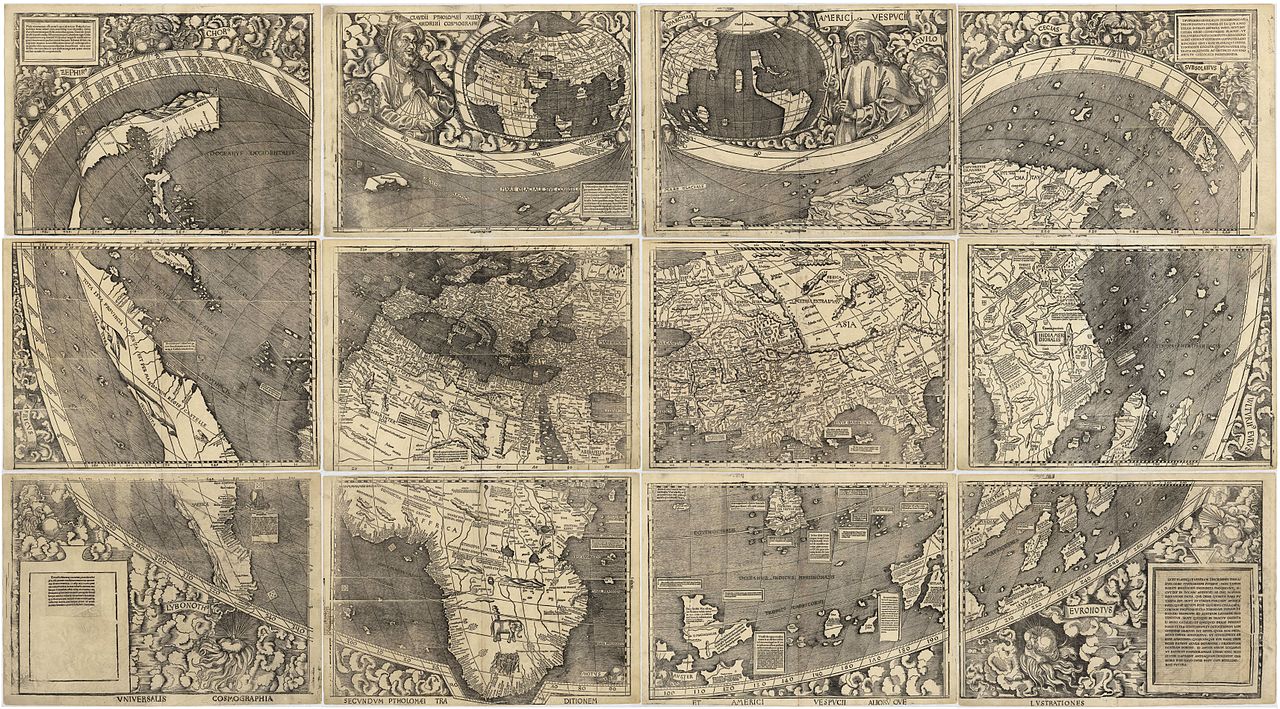

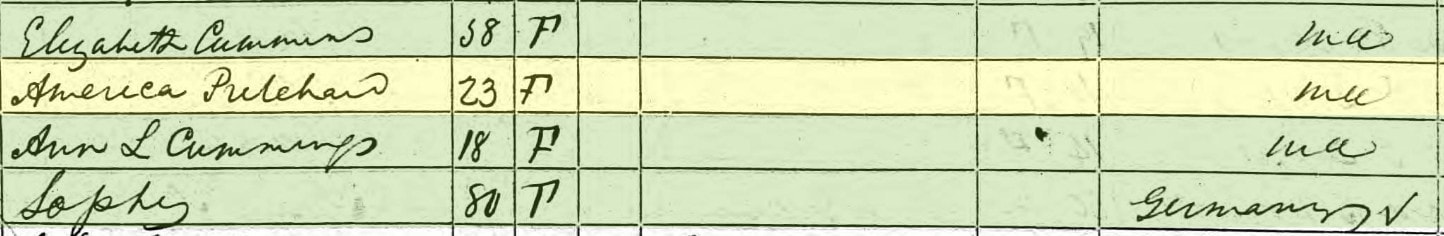

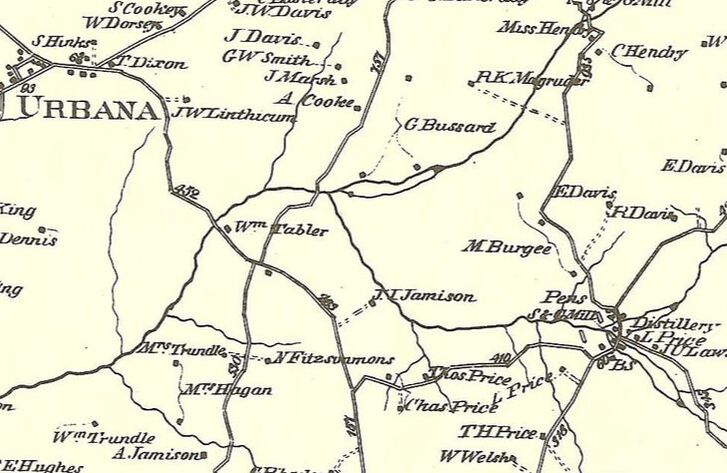

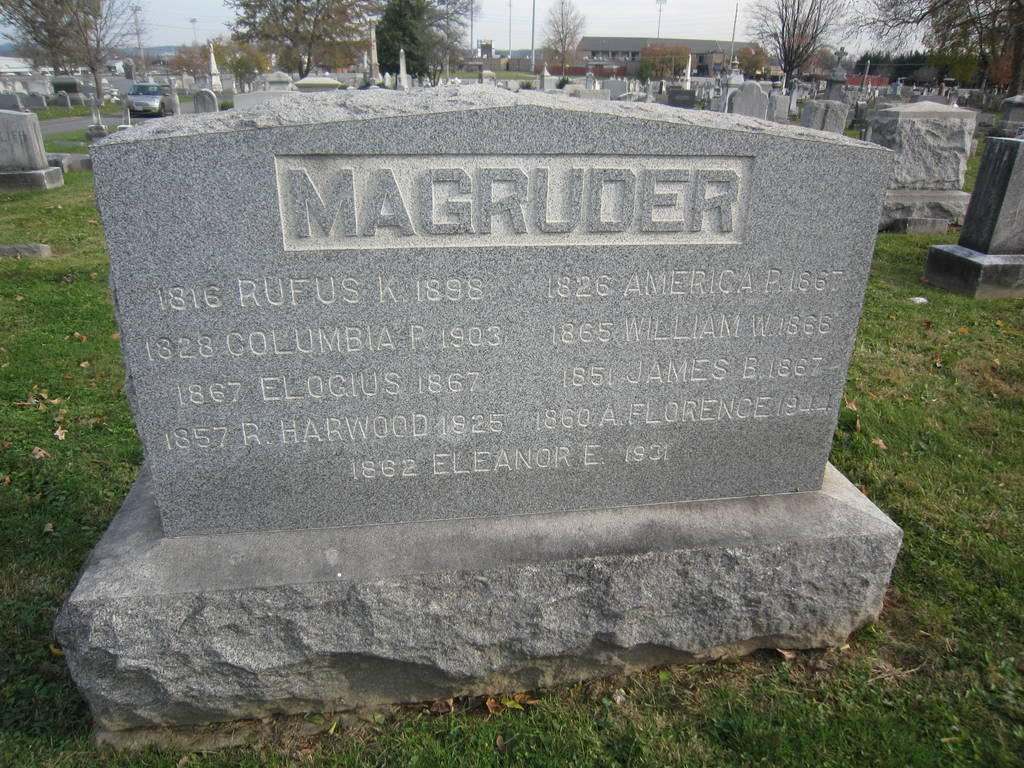

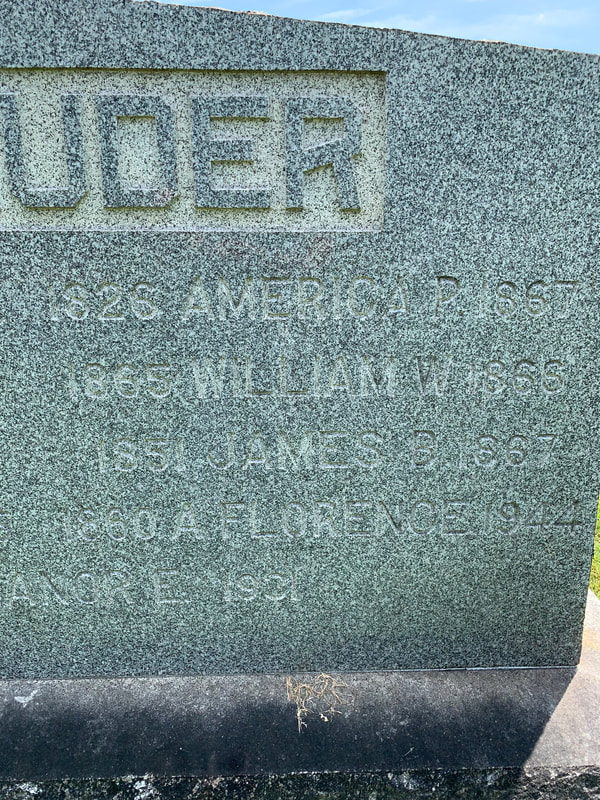

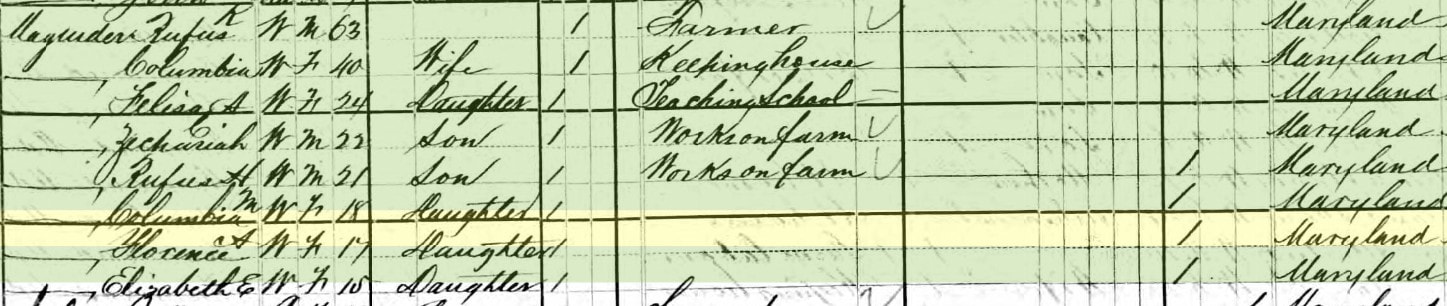

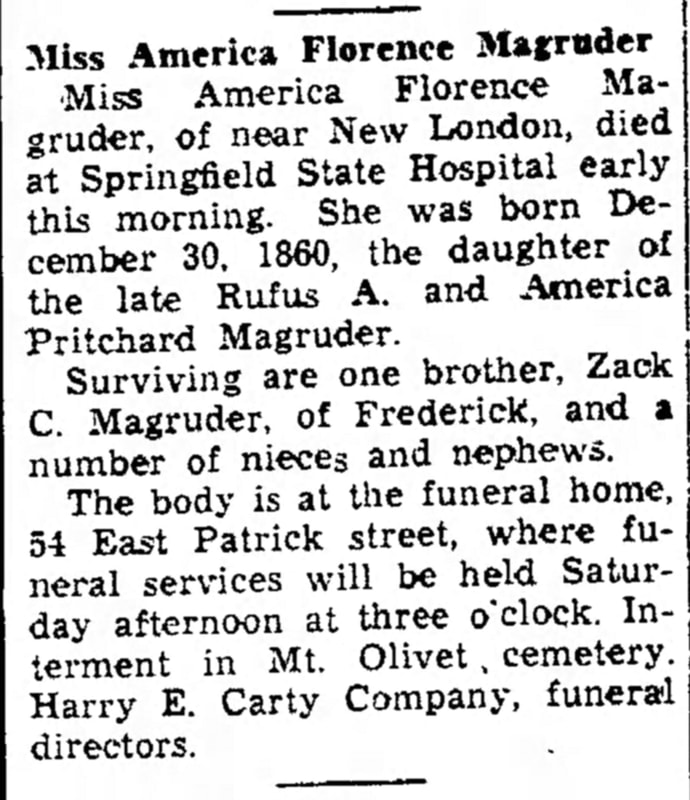

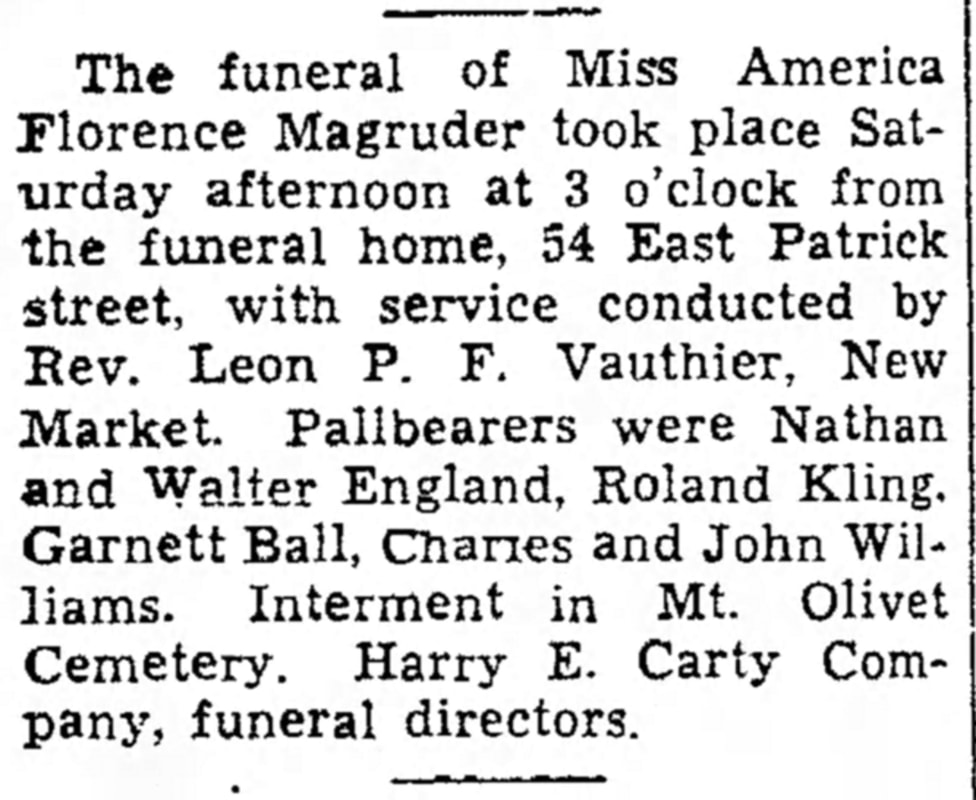

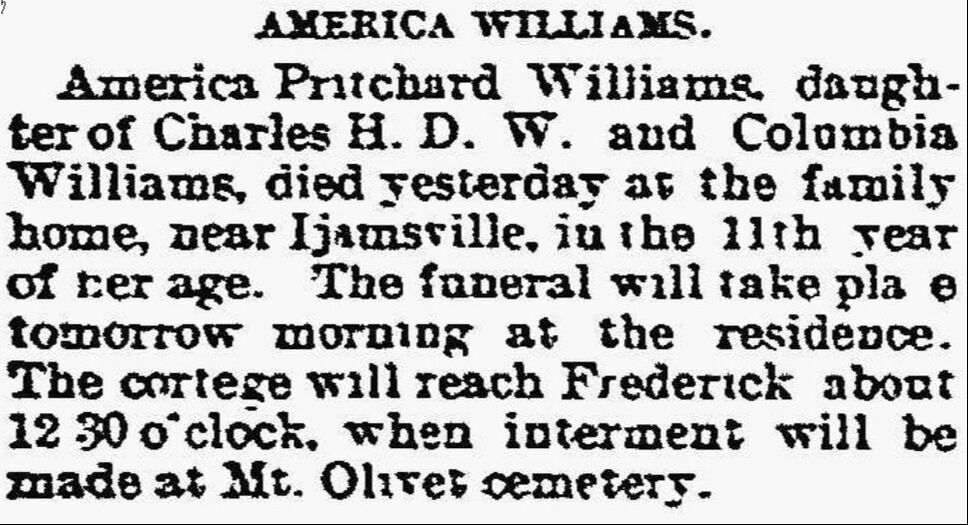

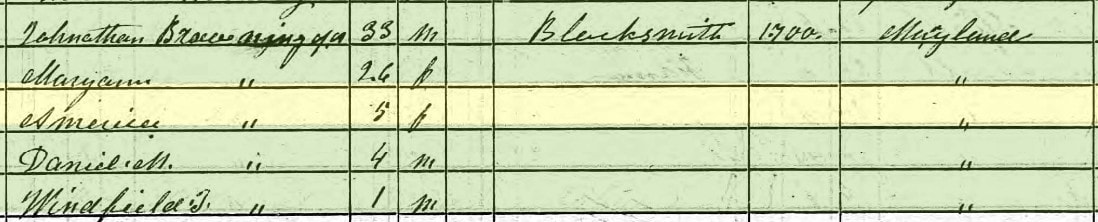

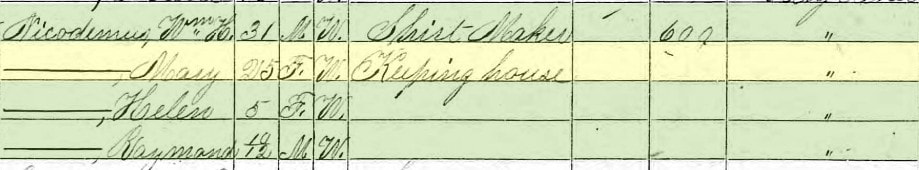

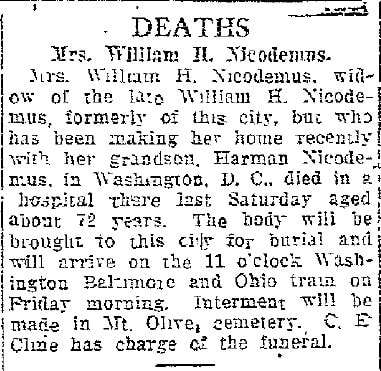

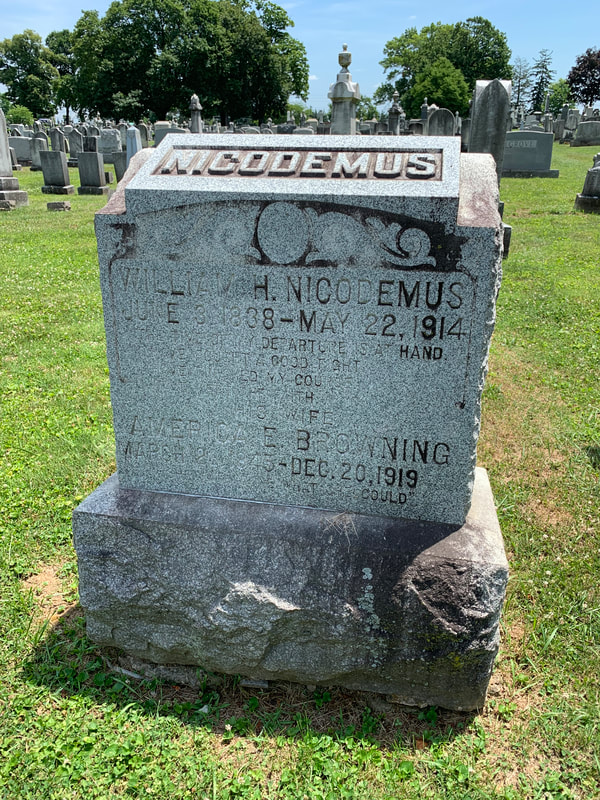

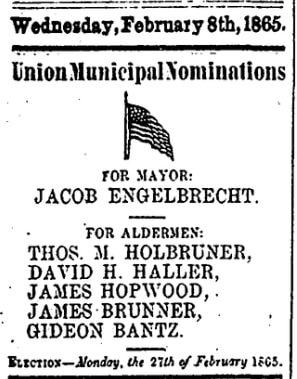

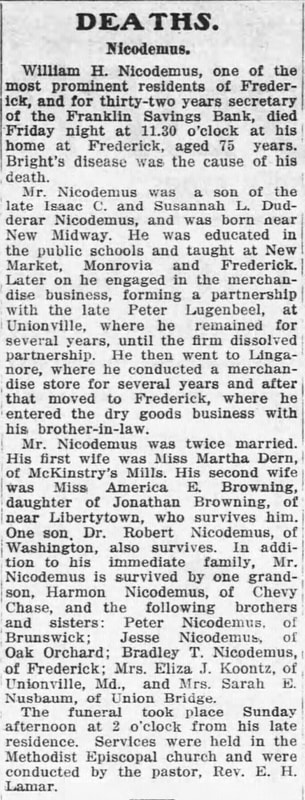

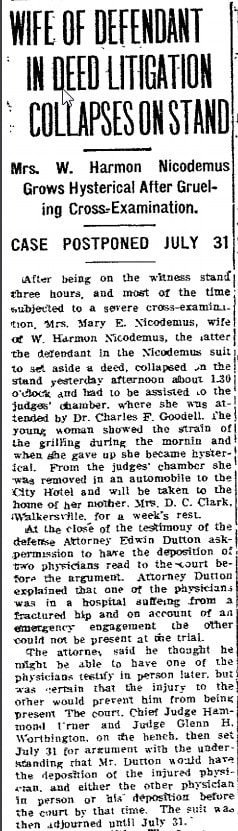

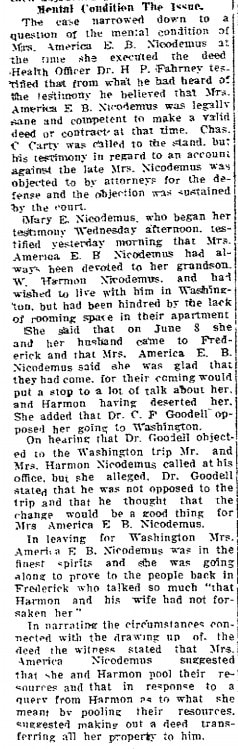

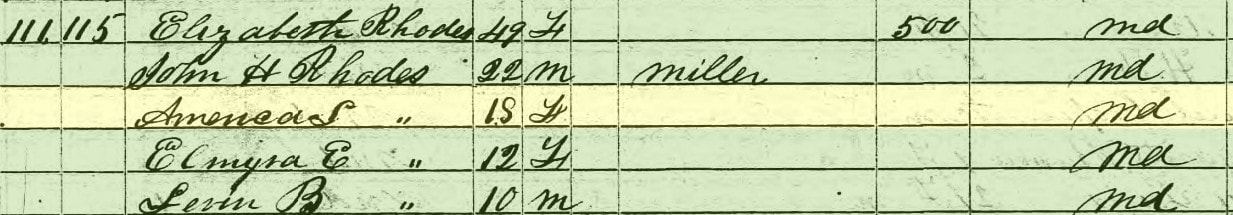

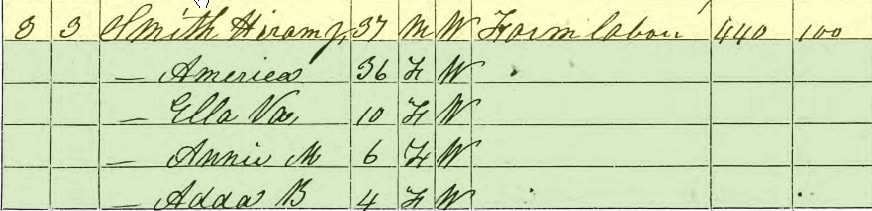

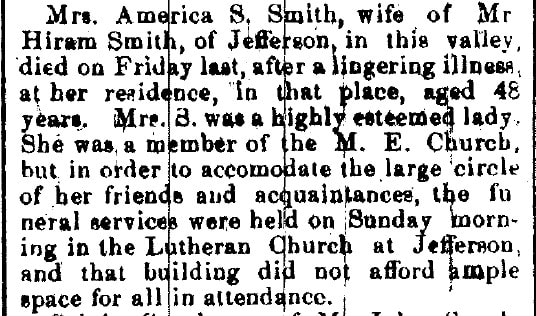

Well, well, well... the 4th of July is here once again—that special day in which we celebrate American Independence Day each, and every, year. Of course, this date is predicated on the magical day in our history when the members of the Continental Congress followed the lead of John Hancock in affixing their signatures to a piece of parchment under a fine essay penned by Virginia’s Thomas Jefferson. The document was destined to be sent to Great Britain’s King George III, son of Frederick, Prince of Wales—namesake of our fine city and county! This event constitutes the birth of the United States of America. Well, we had to win a war first, but it eventually worked out for us in the end. We, the people, went from a collection of separate, provincial colonies under provincial government rule dictated by a royal ruling family and British Parliament located across the Atlantic Ocean on another continent. The founders had successfully assembled a confederation of newly called “states” that were united together at a location in the middle of our own continent. Best of all, they were united as one against their former oppressor. This was quite an accomplishment, but one thing that surely bound us together (at that time, and ever since) was the fact that we have continually given homage to our “home continent” as it’s even included in our former name (USA). Now, I know that Canada was slow to get the memo (see the Statute of Westminster in 1931) but they would eventually sidestep British Parliament’s rule as well. Canadians choose to celebrate their independence on July 1st each year, a date that commemorates the uniting of Canada, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick in the year 1867. Meanwhile, our neighbors to the immediate south, Mexico, celebrate two annual holidays marking “independence” from former European continent invaders--Cinco de Mayo (commemorating the triumph over French and Austrian invaders, and 16 de Septiembre (getting out from under Spain). I guess you could say that the continent of America successfully escaped European dominance over itself.  An American in Italy? Now how did that continent name of America come about in the first place? It was coined by Martin Waldseemüller, a German cartographer. He and Matthias Ringmann are credited with the first recorded usage of the word America. This occurred in 1507, as the gentlemen produced a map entitled “Universalis Cosmographia” in honor of the Italian explorer Americus Vespucius, the Latinized version of the name of Amerigo Vespucci (1454–1512). Vespucci was an Italian explorer who mapped what we today known as South America's east coast, along with the Caribbean Sea in the early 16th century. Through his voyages, made between 1499-1504, Vespucci was able to demonstrate that there existed a separate land mass or “super continent” that eventually came to be referred to as the New World. An article appearing on the Library of Congress’ website adds: The map celebrated Vespucci's understanding that a new continent had been uncovered following Columbus' and subsequent voyages in the late 15th century. An edition of 1,000 copies of the large wood-cut print was reportedly printed and sold, but no other copy is known to have survived. It was the first map, printed or manuscript, to depict clearly a separate Western Hemisphere, with the Pacific as a separate ocean. The map reflected a huge leap forward in knowledge, recognizing the newly found American landmass and forever changing mankind's understanding and perception of the world itself.  So there you have it, our continent is named for an Italian who sailed under both a Spanish and Portuguese flag and eventually received citizenship from Spain—and this, thanks to a pair of German mapmakers. Ironically, the cavalcade of European connections here is also at the core of helping to create the “politically correct” name that has recently been affixed to the continent’s first, indigenous inhabitants—Native Americans. I, of course, say this with a tinge of sarcasm. Europeans at the time of Christopher Columbus' voyage often referred to all of South and East Asia as "India" or "the Indias/Indies", sometimes dividing the area into "Greater India", "Middle India", and "Lesser India.” The oldest surviving terrestrial globe, fashioned by Martin Behaim in 1492 (before Columbus' voyage), labels the entire Asian subcontinent region as "India". When Columbus landed in the Antilles, he referred to the resident peoples he encountered there as "Indians" reflecting his purported belief that he had reached the Indian Ocean. The name stuck and for centuries the native people of the Americas were collectively called "Indians" in various European languages. This misnomer was perpetuated in place naming as the islands of the Caribbean were named the West Indies. The 19th century brought many immigrants to our middle portion of the continent, especially from Europe—the continent that formerly “dogged” our land mass. Of course, immigrants from other continents such came here as well. The term “America” began to take on greater meaning than merely being a fancy name for our mainland. The old explorer’s name now represented an ideal, and would mean different things to different people. This included such things as independence from oppression, a place of peace and prosperity, or the chance to achieve success and fortune. The name America had the overarching connotation of something good, something positive. That being said, it should come as no surprise that the continent name (of America) would also gain popularity as a baby moniker. Today, many may think it an odd an awkward choice for a person’s name, but just compare this with other evocative choices of the post-colonial period Federal period to follow (roughly 1790-1830). During this time, a keen sense of nationalism arose, and government leaders looked to the classical ages of Greece and Rome for inspiration in forging an identity for the new American Republic. Children were given the names of Liberty and Columbia, personifications of the United States of America with the latter owing its origin to that other famed Italian explorer. In addition, a host of virtue-related names were being used such as Charity, Chastity, Hope, Justice, Mercy, Patience, Faith, Grace, and the name “Virtue,” itself.  America Ferrara pictured in her role as Betty Suarez of the "Ugly Betty" television sitcom America Ferrara pictured in her role as Betty Suarez of the "Ugly Betty" television sitcom The name “America” waned in popularity a bit in the Antebellum Era but seems to have made a comeback in 1876 during the time of our country's Centennial celebration. This resurgence continued through the end of the century and beginning of the 20th century to follow. A website entitled www.OhBabyNames.com recounts the history of the name America, one primarily given to females: The name would drop off the charts in 1910 and not re-emerge for another 88 years. “America’s” reappearance took place in 1998 but we’re not sure what prompted the return. We do know later in 2002, the American actress of Honduran descent, America Ferrera, established herself as an up-and-coming talent thanks to her role in the successful indie film “Real Women Have Curves,” followed by the starring role in a television show called “Ugly Betty.” It seems Ferrera has had some positive impact on the usage of her uncommon first name. In more recent years, however, America has fallen substantially further down the charts so her heyday may be behind her (the name, not the actress). In fact, the actress was quoted in Time Magazine regarding how she got her name: “I'm named after my mother. In Latin America, April 14 is Day of the Americas, and my mother was born on April 14, so my grandpa named her America.” From this perspective, America might be a good choice for a U.S. baby born on the 4th of July. Really, it’s hard to find a name more patriotic than America (Liberty comes close). It is also a “place” name much in the same vein as Asia, India or Africa (not to mention London, Paris and Brooklyn). So what’s the controversy with America? Seems that a lot of people who claim to love America feel this is just going too far. Yet the name appears to be more common among immigrants coming to the country from South and Central America; they have a different perspective of and respect for America in general. For them, it’s more of a celebration, which we find lovely. This is not a name for everyone, but there is something special about it that’s hard to deny. So with all that said, I decided to be "an explorer" myself, and took a voyage through our fair cemetery of Mount Olivet in search of "Americas." Here are my findings. America Pritchard Magruder (Dec. 7, 1826-July 15, 1867) I could not find an obituary for America Pritchard Magruder, who died at the age of 40 on July 15, 1867. I was, however, able to find out a little about her. She was the daughter of Benjamin and Elizabeth (Lewis) Pritchard and grew up in Clarksburg, Montgomery County, MD. She married Rufus King Magruder, a prominent farmer of Montgomery County, on October 18th, 1850. The couple would live first in Clarksville, but would relocate to a 230-acre farm just east of Urbana. I was surprised to find that the Magruder farm was directly north and bordering the farm of Miel Burgee on Prices Distillery Road. My last "Story in Stone" centered on Professor Amon Burgee, son of Miel, what are the odds of that?! Apparently the county road here was originally called Magruder Road. Rufus and America had eight children, however only five would reach maturity. Two of these children would receive patriotic names (America and Columbia). Following America P. Magruder's death, Rufus would remarry. His new wife was his former sister-in-law and namesake for daughter Columbia. This was Columbia Pritchard (1828-1903). All three individuals are buried in Mount Olivet's Area Q/Lot118, and their names are etched in stone on the Magruder family monument that stands here. America Florence Magruder (Dec 30, 1860-March 23, 1944) Another woman by the name of America rests in Area Q's Magruder lot. This is America Pritchard Magruder's daughter, America. Her given birth name is America Florence Magruder and it appears she chose to avoid confusion by preferring to go by the name of Florence. She would be raised into adulthood in the Urbana/Ijamsville area by aunt/step-mother Columbia Pritchard Magruder. America Pritchard Williams (1889-April 9, 1899) On the opposite, east face of the above shown Magruder family monument, one will find the names of America Pritchard Williams and brother H. Magruder Williams. These were the children of Charles A. D. Williams (1859-1938) and wife Columbia Matilda (Magruder) Williams (1828-1903). Mrs. Williams was a daughter of the fore-mentioned America Pritchard Magruder who is buried in the same lot. As you can see by birth and death dates, both of Columbia's children died young. America Eugenia (Browning) Nicodemus (March 23, 1845-Dec 20, 1919) First off, I was ecstatic that this America was not related to the Magruder family, as it was getting very tough to keep a handle on all those Americas and Columbias. America Eugenia Browning Nicodemus was born in Frederick to blacksmith, Jonathan Browning and wife Maryann Clary. The family lived in the vicinity of N. Bentz and W. Third streets in downtown Frederick. America would leave her parents upon marriage in 1863. America's husband, William H. Nicodemus (1838-1914), was a pretty successful businessman who listed his occupation as shirt-maker in the 1870 US census. America is listed in this record as "Mary." Children were born to the couple, a girl, Helen, in 1864, and a son, A. Hammond in 1869. (I ventured whether the "A" stood for "you know what," but wasn't able to find out.) Both would die in childhood before spring of 1880. A third son, however, was born in 1877 and would reach adulthood, Robert C. Nicodemus. He would become a doctor and moved to the nation's capital. By 1880, the family lived at 514 N. Market St. and William worked as a bank secretary. America is listed as A. Eugenia, so the passing fancy of Mary must have worn off, but upon closer inspection "Mary" is a good nickname for a woman named America. Mr. Nicodemus accumulated great wealth and real estate over his professional career. He died in 1914 and Mrs. Nicodemus appears to have been well taking care of. At this time, the couple resided at 119 W. Third Street. However, upon her death five years later in 1919, the local newspapers are filled with articles about a highly contested case involving Mrs. Nicodemus' fortune. Apparently a grandson and his wife had taken the invalid widow into their home in Washington DC. and left these individuals the bulk of her estate. Questions were raised by other family members over the legitimacy of this claim and whether or not America Nicodemus was of sound mind when her grandson had her rework her will. The case would not be settled until 1922. America Nicodemus' gravestone in Area H (Lot362) sits along the main drive, opposite Confederate Row. It has the following quote written at the bottom: "She Hath Done What She Could." America Susanna Rhoades Smith (March 5, 1832 –Aug 6, 1880) America S. Rhoades was born in Jefferson, Maryland on March 5th, 1832 to Henry and Elizabeth Susannah (Titlow) Rhoades. She would marry Hiram Joshua Smith of Jefferson, and the couple had at least four known children. Sadly, America would die of consumption at the age of 48. She left a widowed husband and four children. Our cemetery records state that she was originally buried in Jefferson Methodist Episcopal Cemetery but later re-interred to Mount Olivet's Area L/Lot71 on December 1st, 1906.  "Babs" Fritchie is in good company! "Babs" Fritchie is in good company! So on this particular Independence Day, I humbly dedicate this blog to five, former “Miss Americas” of Frederick County who are buried here within Mount Olivet. I’m sure each proudly wore her moniker, even though they could have also gone by nicknames such as Amie or Erica as well. Regardless, I hope that each inspired a patriotic spirit among family and friends, especially on the many “4th of Julys” that came and went over their lifetime on earth, and more particularly, the great namesake continent that shares their name, not to mention the amazing country we all should celebrate on this sacred day—the United States of America. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed