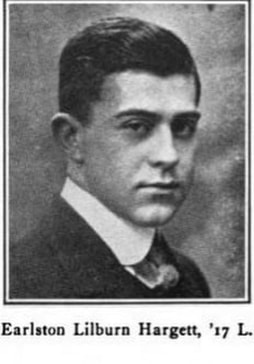

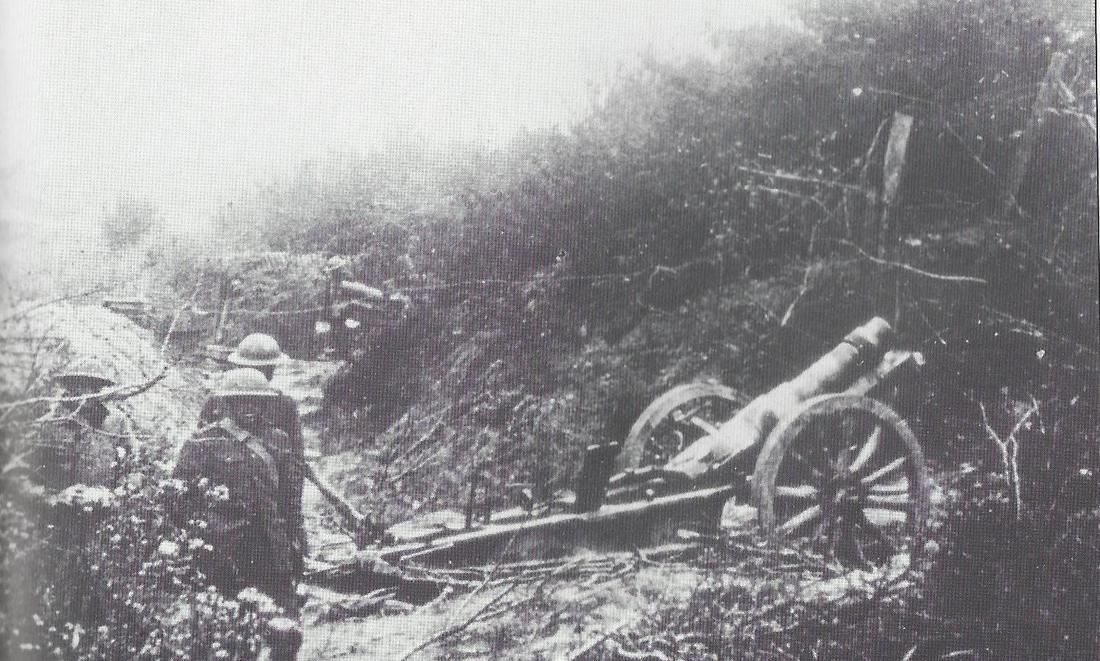

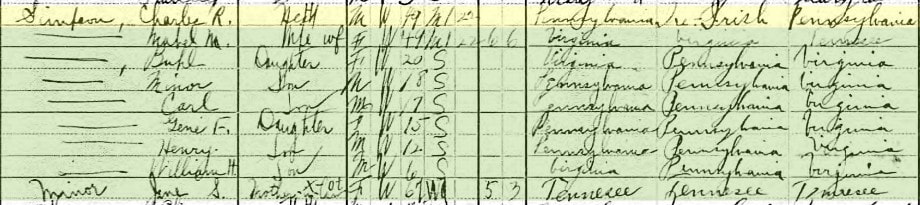

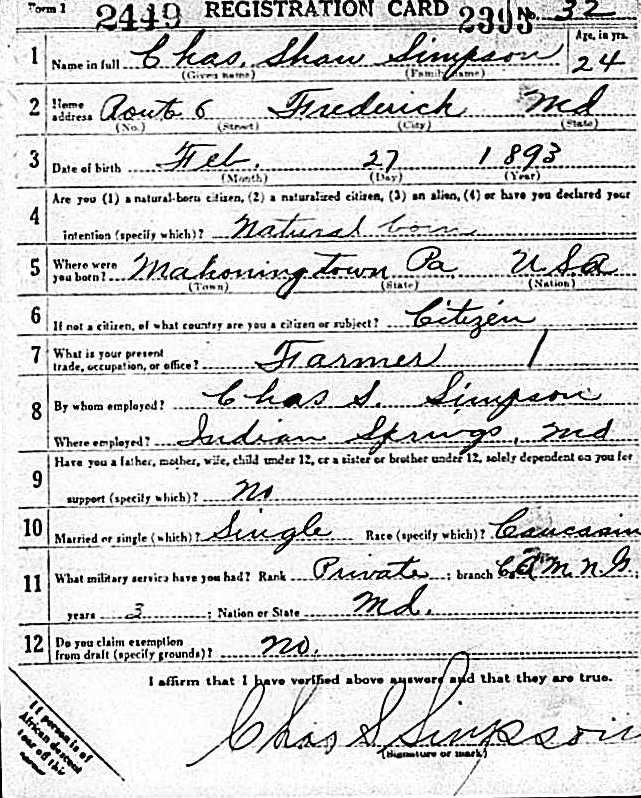

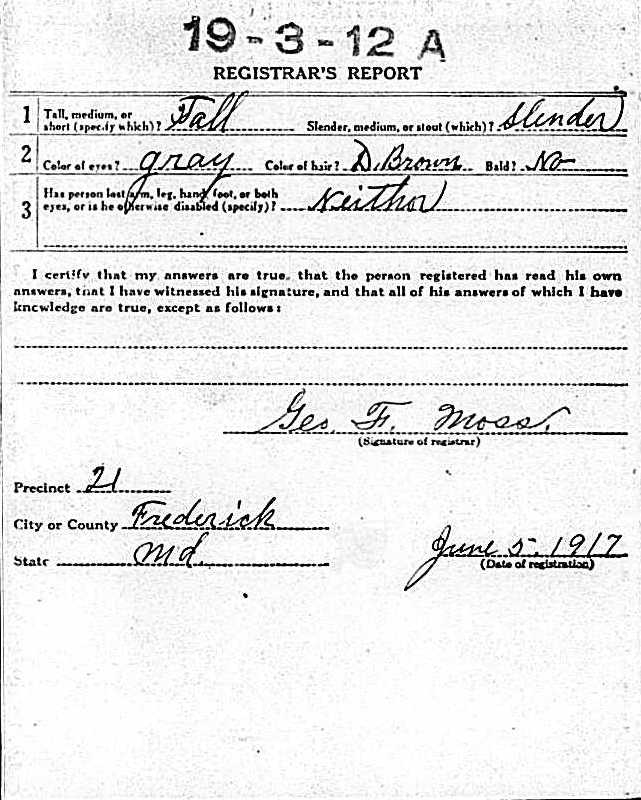

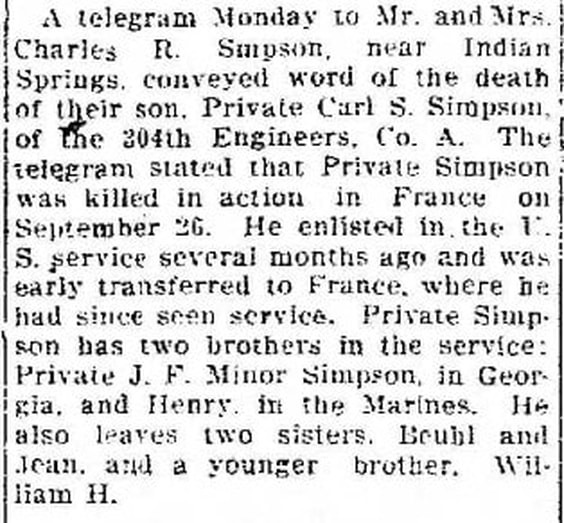

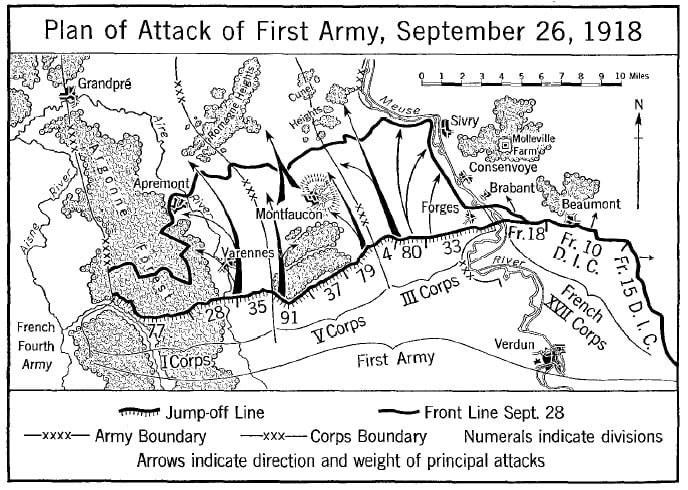

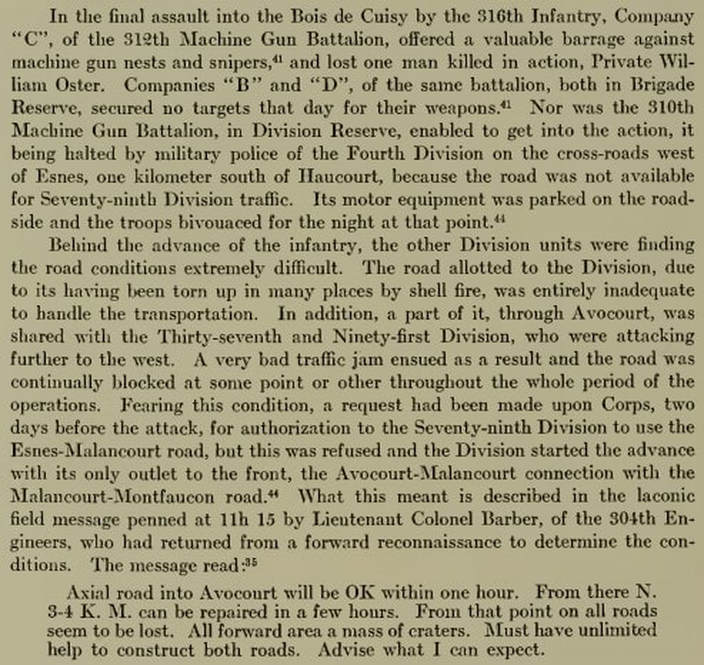

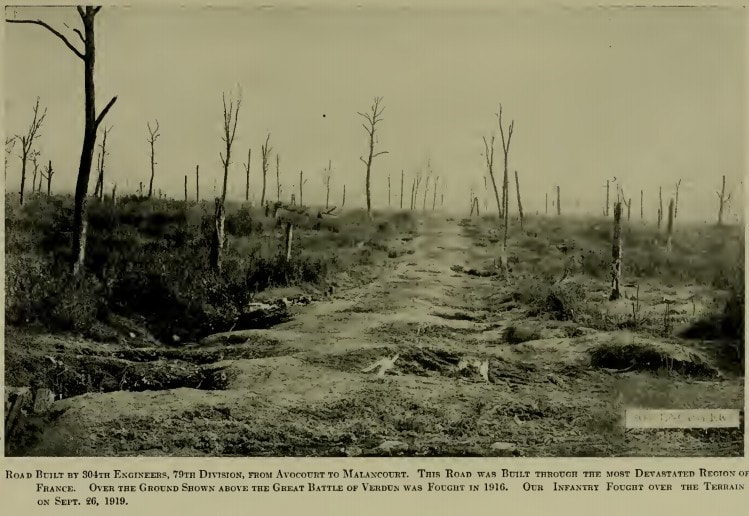

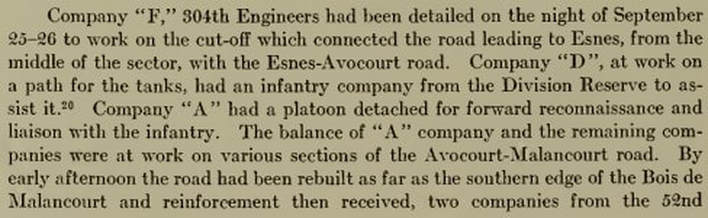

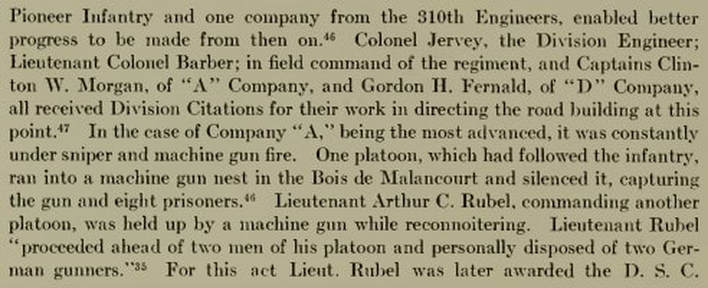

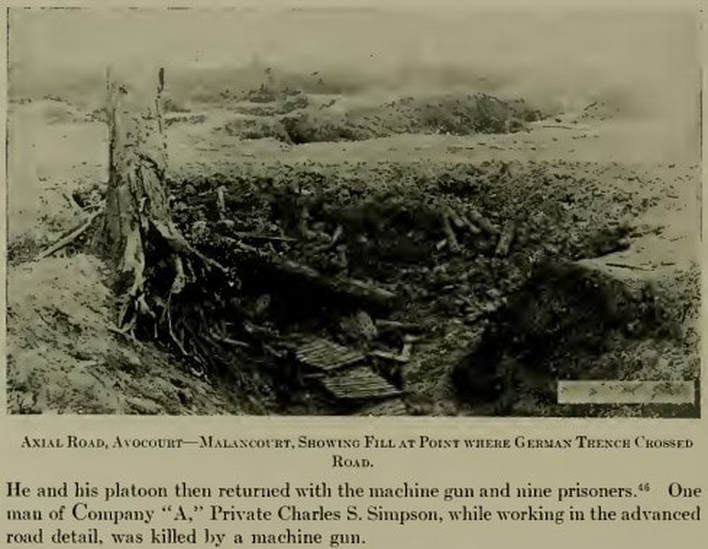

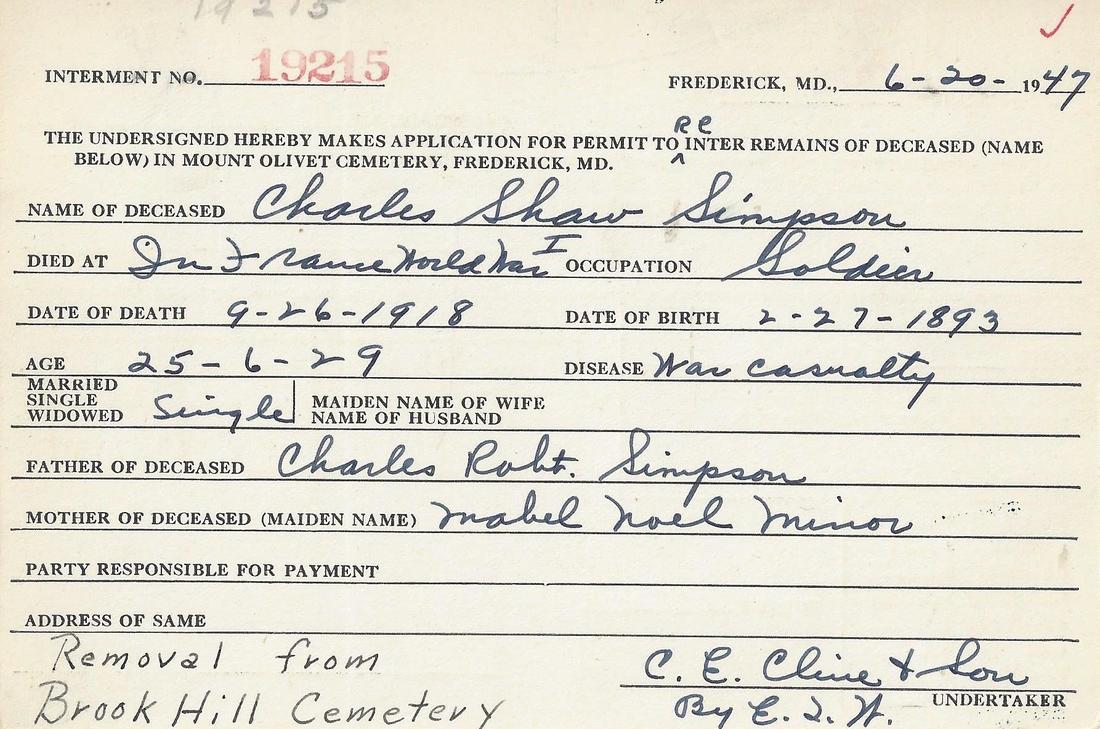

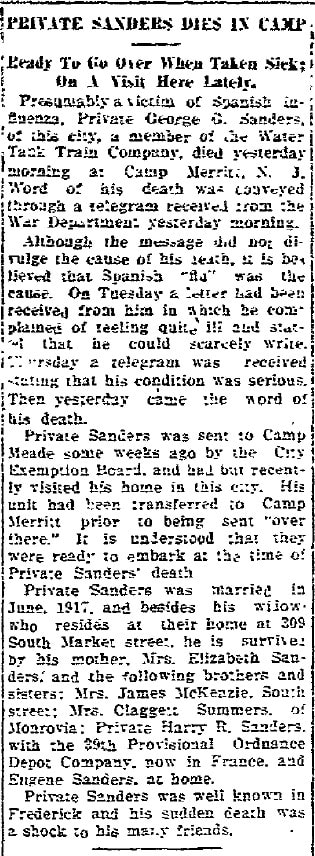

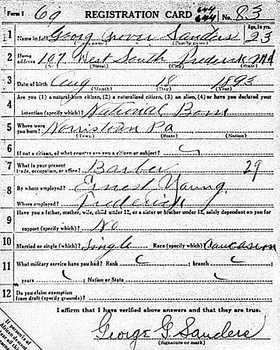

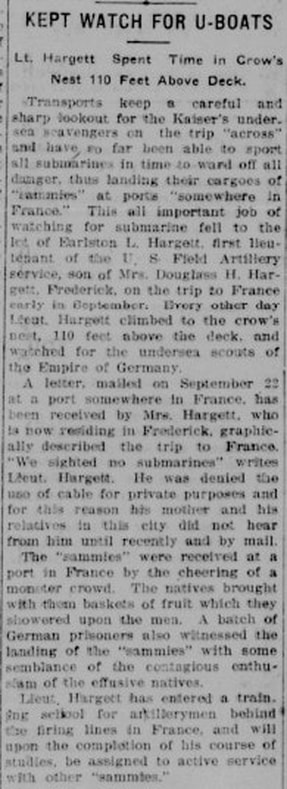

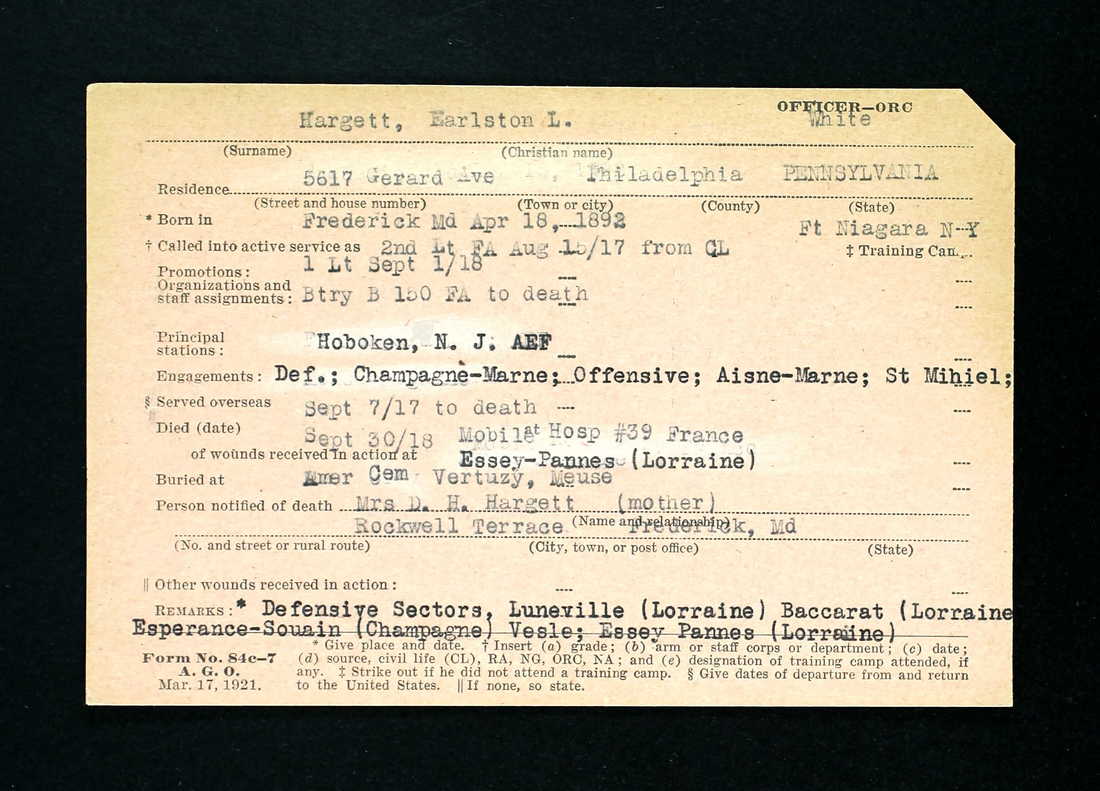

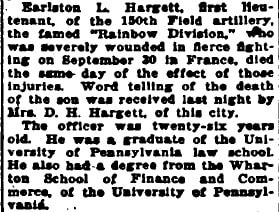

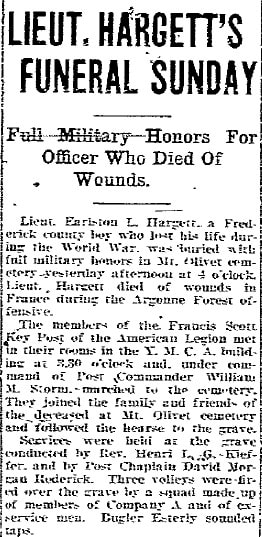

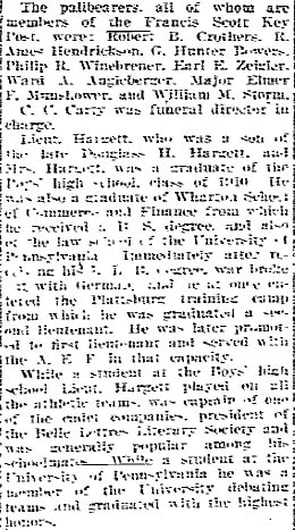

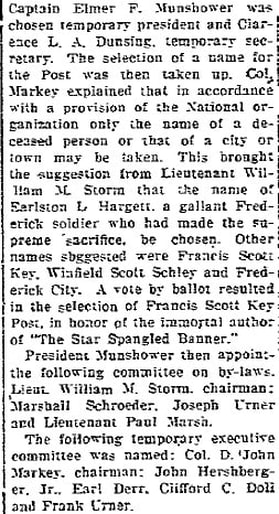

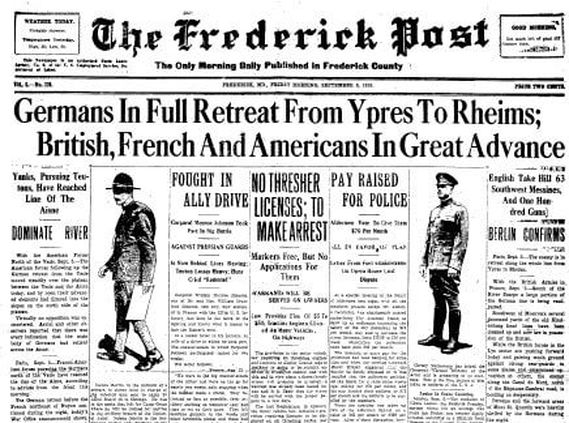

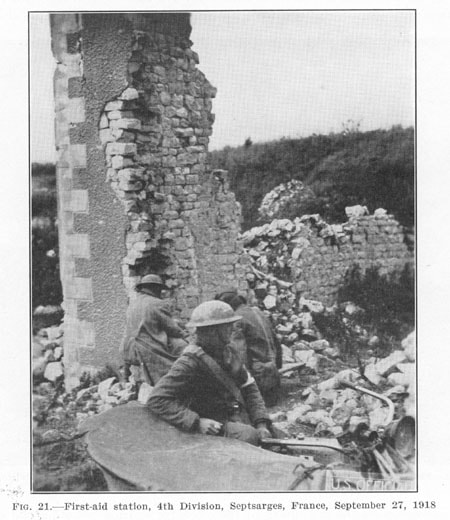

Col. R. H. Tyndall would receive the Distinguished Service Medal during the war and rose to the rank of Major General afterward. Later he would serve as the mayor of Indianapolis from 1942 until his death in 1947. Col. R. H. Tyndall would receive the Distinguished Service Medal during the war and rose to the rank of Major General afterward. Later he would serve as the mayor of Indianapolis from 1942 until his death in 1947. Mrs. D. H. Hargett, 303 Rockwell Terrace Frederick, Md. My Dear Mrs. Hargett: Allow me at this time to express my deep and most sincere sympathy for the great loss you have suffered in the death of your son, 1st Lieutenant Earlston L. Hargett. Being wounded by an enemy shell while performing his duties with his Battery, on September 30, 1918, he died later in the hospital, giving all that a man can give in this great cause. He was admired and respected by all his officers and comrades, and his Battery realizes the great loss of such a man, not only to our organization, but to his Country. You, as his mother, have made the greatest sacrifice that a mother can make, and no doubt you feel great pride in knowing that your son died while fighting civilization’s common enemy. I personally was talking to Lieutenant Hargett a few hours before his death. He was unusually spry and very much interested in the particular work he was doing at the time. I can assure that it was quite a shock to me to learn of his death. His grave will be marked with a cross and the emblem of the Rainbow Division, where it will stand as a monument that will inspire future generations with the willingness of the sacrifice made by this young man. Sincerely yours, Robert H. Tyndall Colonel USA 150th Field Artillery, Commanding  Over 2017-2018, I have placed a great deal of time into researching and writing about military veterans of World War I. There are 500 of these individuals resting here within Frederick’s Mount Olivet Cemetery. Earlston L. Hargett is one of these. Others such as John Reading Schley, Charlotte Berry Winters, Harry Burke, Jacob Holdcraft and Miriam Apple have been fodder for other “Stories in Stone” articles, while the entire group of 500 comprises much of the current content of Mount Olivet’s secondary website: www.mountolivetvets.com. One of the biggest historical events of this year (2018) will be the 100th anniversary of the end of that First World War. The November 1918 armistice, which took effect on ‘the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month,’ ended the four-year conflict and marked a victory for the Allied Expeditionary Forces. Will people take notice on the national, state or local level?  April 2016 April 2016 "Leroy Pence," None the Richer At the front half of our current decade, we had the opportunity to commemorate the bicentennial of the War of 1812, and the sesquicentennial (150th) of the American Civil War. At best, there was lukewarm interest shown, but these anniversaries failed to garner overwhelming appeal. I should know, not only because I’m a bonafide “history geek,” but more so because I had a hand in the design and management of several related, commemorative events in my former capacity with Visit Frederick/The Tourism Council of Frederick County. I dragged my sons to several activities, and for the most part, I think they learned some important lessons. One of the best was on July 9th, 2014 right here at Mount Olivet. My 8-year-old son, Eddie, and I spent the day traipsing across the farms comprising Monocacy Battlefield, part of incredible, “real-time” historical walks led by NPS rangers. Just prior to the last one tour in the vicinity of the Thomas Farm, children were instructed to make their way to NPS staff carrying backpacks. Each kid was to reach in the pack and take a small envelope for him or herself, but asked to refrain from opening this casing until after the tour. Each envelope had the name of a participating soldier in “the Battle that Saved Washington.” This was written on the outside, along with info ranging from age, hometown, marital status/children, and military rank and company. A card within the envelope would give the soldier’s fate after the battle. Eddie drew Confederate soldier Leroy Pence, a corporal in the 60th Georgia Infantry Regiment. He was 40-years-old and hailed from Gilmer County, Georgia (about 40 miles north of Atlanta). Pence had a wife named Ann, and nine children. After the tour, we got in my car and proceeded to drive to Mount Olivet Cemetery for a solemn roll call of Monocacy soldiers who were laid to rest in the “garden cemetery” in the days, weeks, months and years following the July 9th, 1864 battle. Along the way, Eddie asked if he could open up the envelope which he had received from the ranger. I obliged and with trepidation, Eddie carefully opened the small packet, and read the contents—"Leroy Pence was wounded in the Battle of Monocacy and captured the next day, July 10th. Sadly, he died of his wounds on September 12th and was buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery." Well, we soon arrived at the cemetery, and made our way to Confederate Row, the staging area for the evening program. I exchanged pleasantries with some of the rangers and other friends and acquaintances gathered. Meanwhile, Eddie ventured off a few yards to look at headstones in Confederate Row. Within a few brief minutes, Eddie called from about 30 yards away, “Dad, come here, I found Leroy!” I made my way to the specific gravesite, with two rangers and an NPS photographer in tow. When asked what this was all about, I explained to the others that Eddie had drawn an envelope at the battlefield with Leroy Pence’s name. As Eddie reverently gloated over his find, the rest of us history professionals stood in amazement—the envelope lesson exercise had worked. History came alive (so to speak) for Eddie that day. He also understands that past wars were not glamorous, but rather terrible events where the ultimate sacrifice was made by participants. And therein lies the most important part. From that day on, Eddie will forever remember Corporal Pence, as will his father, as I drive by the fallen soldier's grave each and every work day. Eddie usually stops at the grave every chance he gets. A few years back, he had opportunity to place a flower during a Confederate Decoration Day ceremony. Uncertain Septembers History die-hards, like myself, do make time for heritage commemorations. It’s pretty amazing to wonder how people of the past reacted to the events going on around them. We can appreciate, empathize and ponder their apprehension of what would come next in times of intense chaos and change. I look at Frederick and so many uncertain Septembers from our past, such as: *September, 1745 and the founding of Frederick Town by Daniel Dulany. People could have thought to themselves, "Was this little village on the western frontier going to make it?" S*eptember, 1781 and the beginning of the Battle of Yorktown against the British. Gen. Lafayette arrives in the nick of time to help George Washington and the Continental Army defeat Lord Cornwallis. *September, 1814 had attorney Francis Scott Key wondering if he was really seeing the US flag still flying high atop Fort McHenry during the War of 1812—a rematch against Britain for American Independence. Had the ragtag Defenders of Baltimore saved the city, and country? Or will we go back to drinking tea in the afternoon, and paying high prices to import the stuff? *September, 1862 and Gen. Robert E. Lee had brought his Army of Northern Virginia for the first time to a substantial Union/Northern town. You guessed it—Frederick, Maryland, home of several flag-waving Union heroines no less. In the weeks to follow, major conflicts would be fought nearby on South Mountain and Antietam. The introductory letter(at the beginning of this article) sent to Mrs. Emma Hargett typifies the mood of Frederick 100 years ago. However, it’s hard to emphasize the true desperation of times past, with today's lens within today’s society. As for World War I, we today we live in a global society. “Over There” is not the same big deal as it was in 1918. World War I, and the Planet Earth, in the late teens just isn’t as romantic or exciting as the World War II era. The same can be said for the star personalities: WWI’s Gen. Pershing, Kaiser Wilhelm, President Woodrow Wilson vs. WWII's Gens. Eisenhower & Patton, Adolph Hitler, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Winston Churchill, etc.). World War I gets overshadowed by World War II because it’s not as marketable. That’s what drives attention these days. If not, we as a society these days are simply numb to this stuff. It’s hard to believe that we can’t empathize with folks living a century ago. At least, we Americans as a whole, showed compassion 17 years ago in September, 2001 during and after the catastrophic events of the 11th day of that fateful month. Now that was a downright, scary September. Sorry to go off on an opinion-laden rant. It' just that one of my all-time favorite quotes comes from author Victor Hugo (1802-1875). He said: “What is history? An echo of the past in the future; a reflex from the future on the past.” This is the essence of what I am trying to do with this blog, and more so, this incredible cemetery and all those memorialized within it. Numbers, numbers, numbers: Frederick and the Reality of War in September, 1918 Speaking of Hugo, conflict, France, and all things “Les Miserables,” let’s get back to World War I. The total number of military and civilian casualties in World War I was about 40 million: estimates range from 15 to 19 million deaths and about 23 million wounded military personnel, ranking it among the deadliest conflicts in human history. The total number of deaths includes from 9 to 11 million military personnel. The civilian death toll was about 8 million, including about 6 million due to war-related famine and disease. The Triple Entente (also known as the Allies—short for Allied Expeditionary Forces) lost about 6 million military personnel while the Central Powers (the bad guys in our minds) lost about 4 million. At least 2 million died from diseases and 6 million went missing, presumed dead. About two-thirds of military deaths in World War I were in battle, unlike the conflicts that took place in the 19th century when the majority of deaths were due to disease. Nevertheless, disease, including the 1918 flu pandemic and deaths while soldiers were held as prisoners of war, still caused about one third of total military deaths for all belligerents. How did the US fare? Well in a country boasting 92 million people at the time, combat deaths and those missing in action totaled 53,402. Total military deaths from all causes came in at 116,708. Even though the war was fought “Over There” on the European continent, the killing effects of war reached our civilians in the form of a deadly flu epidemic known more commonly as the Spanish Influenza. Frederick City and County were not spared in either case (military members and non-combatant civilians). Mount Olivet Cemetery sadly bears witness to several interments of both camps. The Frederick newspaper included a countywide roll of honor on Page 5 of each edition during the war period. Daily tallies showed casualties in varying scenarios ranging from killed in action to accidental deaths and those from disease. All in all, Frederick County lost 87 military personnel out of nearly 2000 that served, and197 civilians due to the flu that ravaged our area in fall of 1918. Here in Mount Olivet we have 13 gravesites representing known war related casualties, an unlucky number any way you look at it. One of these however is simply a memorial but more on that in a minute. We also have several interments thanks to the Spanish Flu, but more on that with a story I’m working on for next month. An Important Midpoint Since we are making some comparisons to Septembers of the past, I can tell you that 38 of our tally of 500 veterans in Mount Olivet passed in the month of September. Four, out of that number of 13, actually died in September of 1918. I know this because I have been creating memorial pages for each of these soldiers to display on our www.mountolivetvets.com website. I chose to enter these into the site by death date/week. While preparing my entries for late September, I knew I was entering into the period of service related deaths over the last week of September 1918. This also marked the midpoint of the famed 100 Day Offensive. The Hundred Days Offensive (August 8th to November 11th, 1918) was an Allied offensive that ended the World War I. Beginning with the Battle of Amiens (August 8-12) on the Western Front, the Allies pushed the Central Powers back after their gains from the Spring Offensive. The Germans were eventually retreated to the Hindenburg Line, culminating in the Armistice of November 11th, 1918. The term "Hundred Days Offensive" does not refer to a battle or strategy, but rather the rapid series of Allied victories against which the German armies had no reply. The Meuse-Argonne Offensive was the largest of its kind in United States military history, involving 1.2 million American soldiers. Under the command of John J. Pershing, this was also the bloodiest operation of World War I for the American Expeditionary Force (AEF). “The Hundred Days Offensive” would also serve as the second-deadliest battle in American history, behind World War II’s Battle of Normandy. American losses were heightened by the inexperience of many of the troops, and tactics used during the early phases of the operation. The battle cost 28,000 German lives, 26,277 American lives and an unknown number of French lives. Meanwhile, Frederick would lose four local boys over the five-day period of September 26-30th, 1918. September 26th, 1918 —Charles Shaw Simpson Although the news was not known locally until mid-November, 1918, Charles “Carl” Shaw Simpson of my childhood home stomping grounds of Indian Springs (northwest of Frederick) had died on September 26th. Better known by the nickname of "Carl," Private Simpson was a native of Mahoningtown, Pennsylvania, located near Newcastle and northwest of Pittsburgh. Carls’ father, Charles Robert Simpson, purchased the Indian Springs Farm in 1907 and cultivated chestnuts. Carl’s mother, Mabel Noel-Minor, was from southwest Virginia, the daughter of a Confederate captain of the Civil War. Carl Simpson was inducted into the Army on January 10th, 1918. He began as a member of the 154th Depot Brigade's 24th Company. On January 28th, he was transferred to Company A of the 304th Engineers. Private Simpson would board a transport ship bound for France on July 9th. Meanwhile, two of Simpson's siblings were also engaged in the war effort. A telegram appeared in town on November 19th, 1918 announcing that Charles had been killed in action in France almost two months earlier. I conducted some research in an effort to find more specific details about Carl Simpson’s death. As a member of Company A of the 304th Engineers, the 25-year-old private would find himself under the umbrella of the 79th Division on September 26th, 1918. This particular day was also notable as the launch of the First phase of the Meuse-Argonne offensive near the remains of the destroyed village of Avocourt in northeast France. The key objective of this day, and those to follow, was to capture Montfaucon, a steep-sided 500-foot height that was the key to the Giselher Stellung, the first German line of defense. This fortress had to be seized quickly by the 79th Division if V Corps had any hope of taking Romagne and other strong points in the Kreimhilde Stellung, the second defense line. Unfortunately, “green” draftees from Pennsylvania and Maryland became badly confused as the fighting intensified. German machine-gunners, feigning to be dead, suddenly came to life and started shooting up the American rear areas. Men kept charging the machine guns en masse, enabling a single gun to mow down an entire platoon. Front-line elements lost all contact with their artillery. Not until dusk did one battalion of the 79th Division’s 313th Regiment get close enough to Montfaucon to make an attack.  Some of my prior knowledge of this assault came from looking into the death of Frederick resident Harry Burke who was fighting nearby Simpson as a member of Company L, 313th Infantry Regiment comprised of Maryland boys. Carl Simpson and his fellow engineers had the task of creating roads out of a war-torn terrain, and constantly assess the up to the minute volatility of these transportation corridors for other parts of the larger Allied fighting machine. I found a small reference to Private Simpson in a vintage history book about the 79th Division, published in 1922. I have included some book passages that provide context to Simpson’s assignment and subsequent death on that fateful day of September 26th, 1918. Originally buried on the field of battle near where he died, the body of Charles “Carl” Shaw Simpson was brought back home sometime after the war and buried in a family lot in Brook Hill cemetery in Yellow Springs, near the family farm. It appears that Carl’s siblings bought a lot in Mount Olivet (AA/92) in June, 1947. On the 20th of that month, Carl, parents Charles R. and Mable, and Carl’s maternal grandmother Sarah J. Minor were re-interred in Mount Olivet from Brook Hill. September 27th, 1918 —George Grover Sanders, Jr. George Grover Sanders, Jr. was inducted into the Army in late June, 1918. The native of Norristown, PA had been living at 309 S. Market St. with his bride of one year—Marie Frances Severa. He worked as a barber in the shop of owner Ernest Young. Private Sanders would become part of Company B of the 301st Water Tank Train Company. Sanders had originally been serving at Camp Meade and was said to have made a brief visit home to Frederick around this time. Meanwhile, Sanders’ camp had been transferred to Camp Merritt (New Jersey) prior to being disembarked over the prime summer months. A telegram from the US War Department would alert Sanders’ wife and family of the soldier’s sudden demise. He was thought to have contracted the Spanish Influenza. George G. Sanders would die on September 27th, 1917. Three days later, Sanders would be buried in Area T/Lot 126. He left behind a young widow, aged 23. A native of Czechoslovakia, Marie Sanders would remarry in 1922 and would continue to reside at 309 S. Market St. She wed another local WWI vet in Charles Smith Hobbs, Jr. of New Market. Hobbs was a wagoner and served overseas with Company D of the 103rd Ammunition train. He saw plenty of action, including activity at Meuse-Argonne.The couple would have at least one child, Charles Smith Hobbs, Jr. September 29th, 1918 —Harry Burke I previously mentioned Harry Burke in reference to Carl S. Simpson’s death while trying to take Montfaucon. Burke was reported “missing in action” just three days later. Back last February 2018), I wrote a full article on Harry C. Burke. He was born at Pearl, just east of Frederick in the vicinity of what locals know was the old Jug Bridge Seafood Restaurant on MD144, opposite the major development of Spring Ridge. Burke was with Company L of the 313th Infantry Regiment. At this time, the 313th was playing a major part in the principal engagement of the war—the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. Harry C. Burke was one of the casualties as he went missing in action on September 29th. The folks at home in Frederick wouldn’t learn this fact until November 11th, 1918—Armistice Day. In the meantime, an earlier written letter by Burke had made it back to town, here. The Frederick native participated in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive’s “First phase,” which took place from September 26th to October 3rd, 1918. The 79th Division was assigned the deepest, first-day objective of any division of the Army even though it was facing some of the most difficult terrain in the Meuse-Argonne region. Private Burke’s body would be recovered in early November. Subsequently, his remains were placed at the US Meuse-Argonne Military Cemetery in Romagne, France. Burke’s father bought a gravesite in Mount Olivet (Area U/Lot 12), and, at least by November of 1923, a wreath and flowers were placed on the young boy’s grave during Memorial Day commemorations. Although Burke’s corpse still remains in France, Mr. Burke erected a large granite block monument in the 1920’s. (http://www.mountolivetcemeteryinc.com/stories-in-stone-blog/finding-private-burke)  September 30th, 1918 —1st Lt. Earlston Lilburn Hargett You were introduced to this young man at the onset. Born April 18, 1892, this was truly a talented and promising individual, cut down before he could leave an even bigger imprint on the world. Here is the contents of an article from the local newspaper regarding his death. The Frederick Daily News, November 2nd, 1918 EARLSTON L. HARGETT, first lieutenant of the 150th Field Artillery, the famed "Rainbow Division," who was severely wounded in fierce fighting on September 30 in France, died the same day from the effect of those injuries. The following telegram was received last night (October 16th, 1918) by his mother, Mrs. D. H. Hargett, Rockwell Terrace: "Deeply regret to inform you that it is officially reported that Lieutenant Earlston L. Hargett, Field Artillery, died September 30 from wounds received in action. Harris, the Adjutant General" Lieutenant Hargett was 26 years of age. Despite his youth he was an LLB, being a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania law school and also a graduate of the Wharton School of Finance and Commerce of the University of Pennsylvania. His early education was received in the public schools of Frederick and at the Boys High School, where he was a graduate. During his course at the University of Pennsylvania he participated in intercollegiate debates, being an orator of exceptional skill. Fought At Chateau Thierry Lieutenant Hargett was commissioned a second lieutenant at the Fort Niagara training school, and was promoted to first lieutenant while in France. He participated in the fighting at Chateau Thierry, coming out of the battle without a scratch. Having served in France for about a year, he wrote a number of interesting and entertaining letters of camp and trench life. His letters were distinguished by keen humor and graphic bits of description. These articles were widely read and were among the most interesting sent home by Yankees in France.

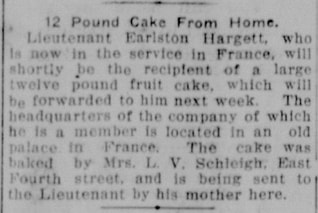

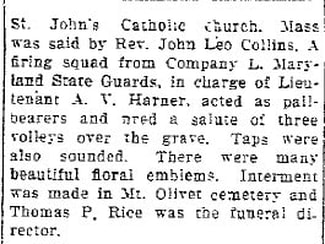

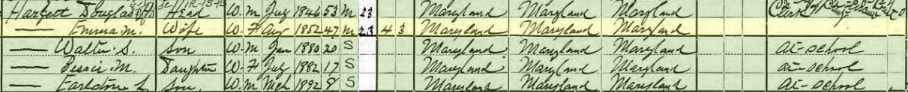

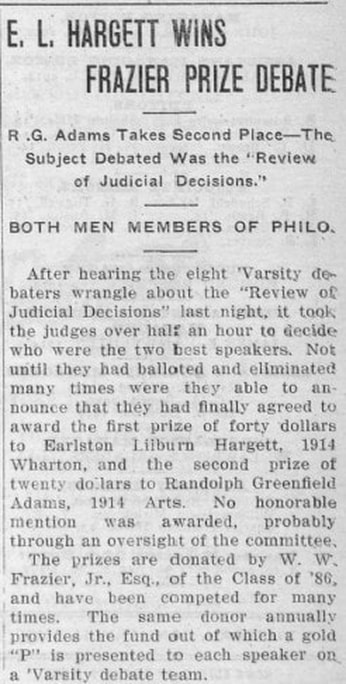

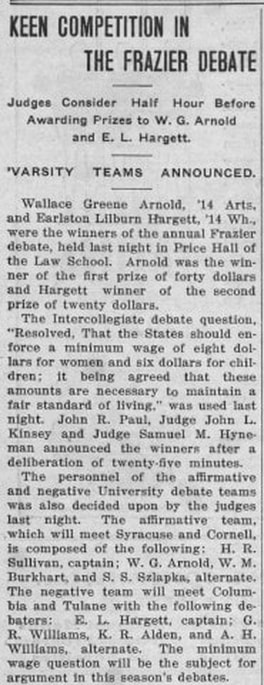

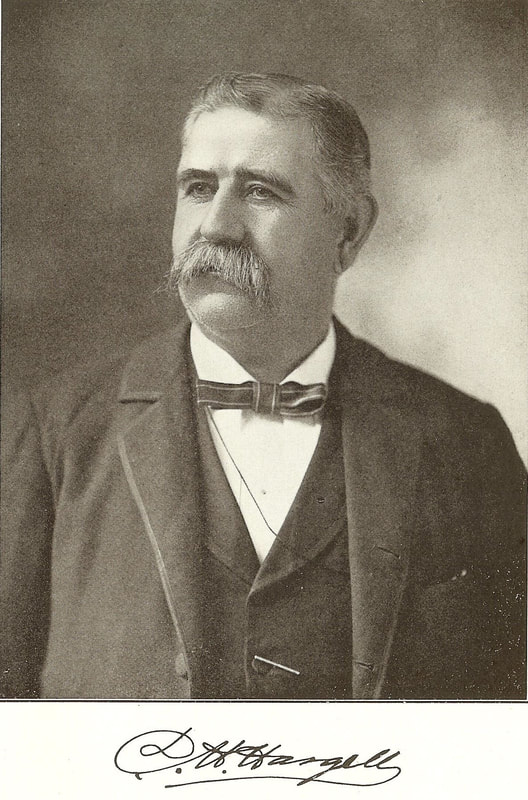

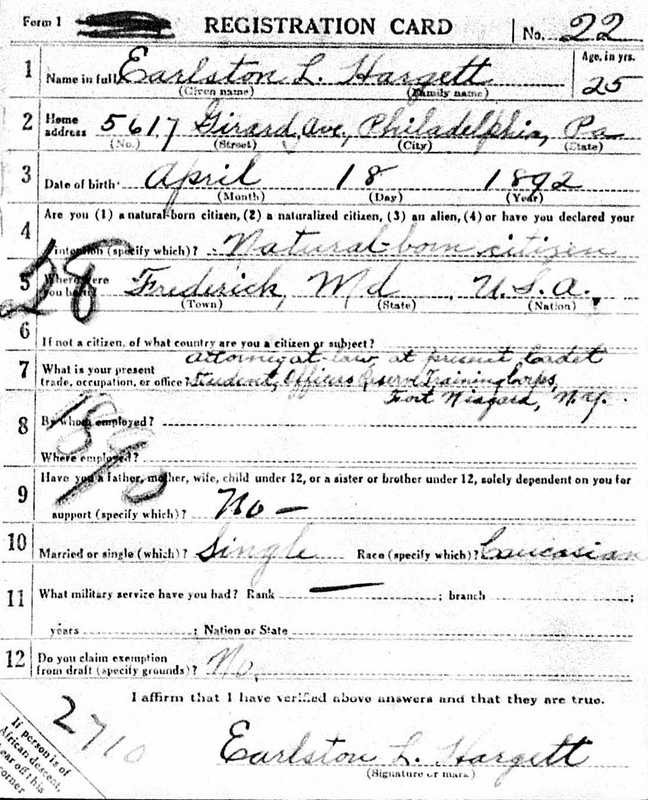

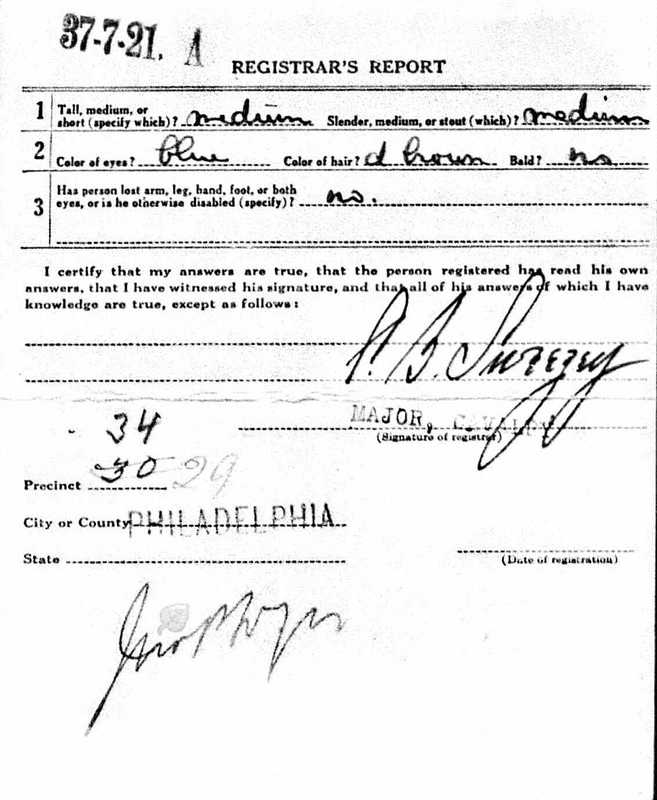

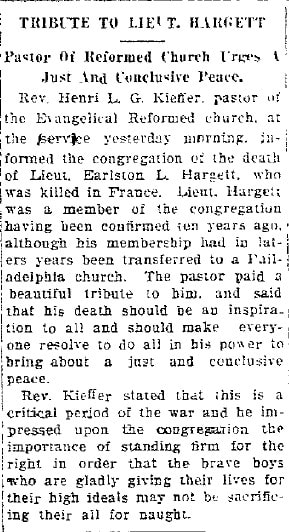

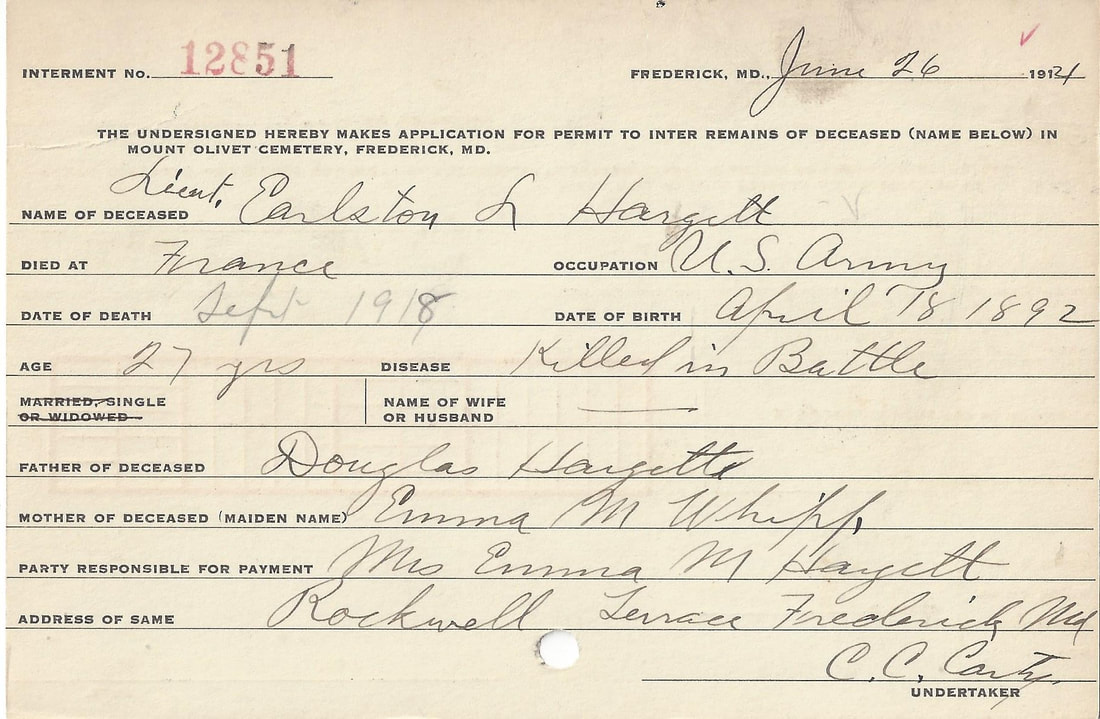

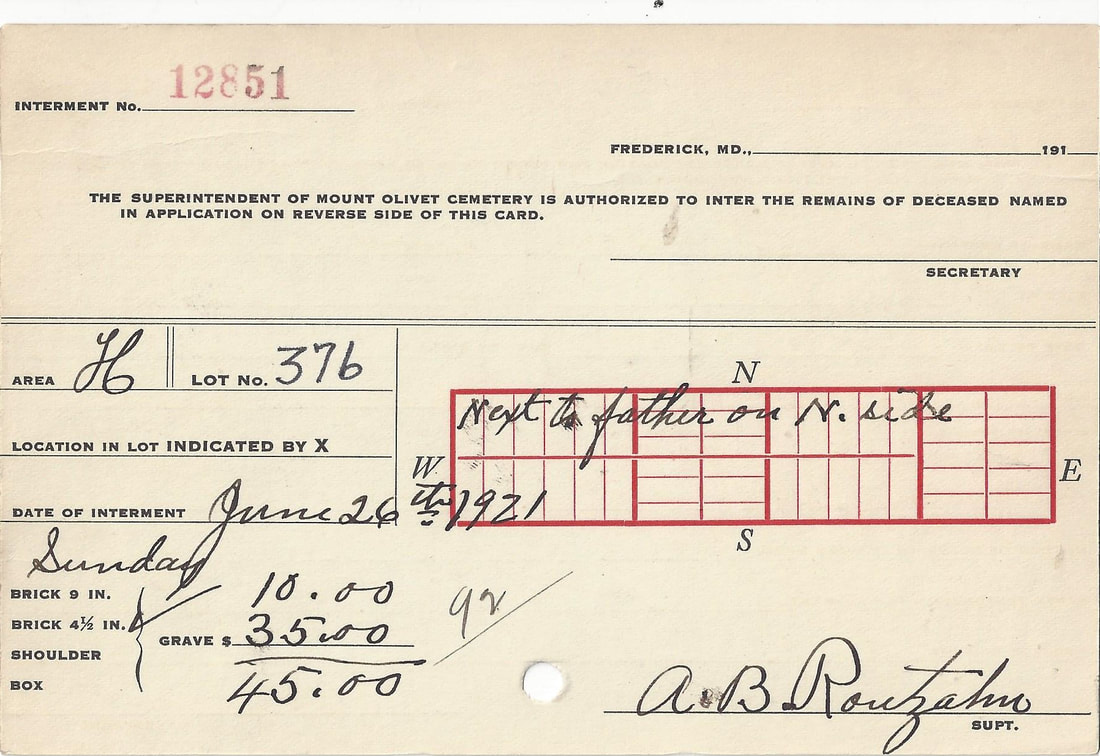

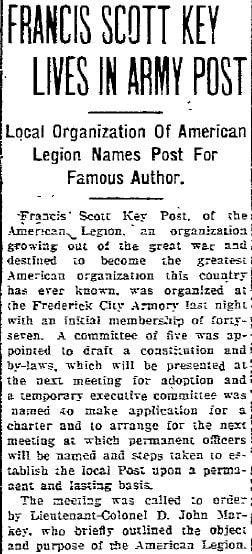

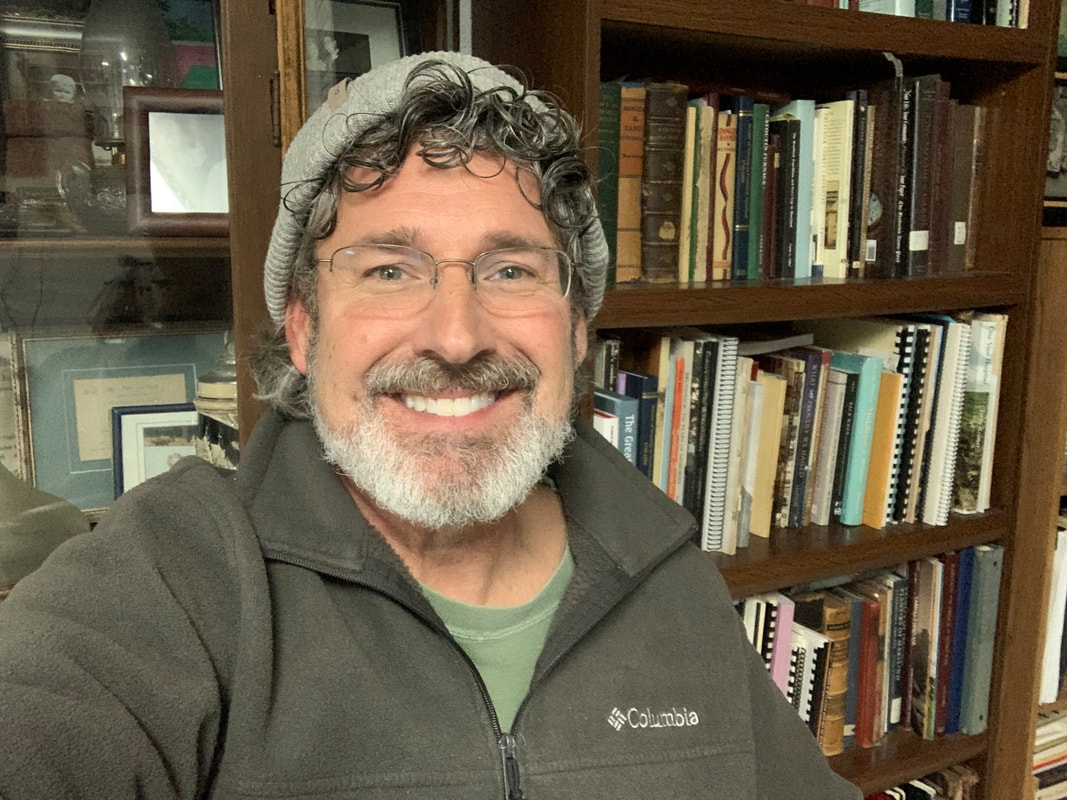

Frederick Post (Oct 27, 1917) Frederick Post (Oct 27, 1917) Before entering the Army, Hargett was living in Philadelphia and working as a attorney. Earlier he had attended Frederick Boys’ School and learned under the likes of Professor Amon Burgee. Hargett was one of the top cadets of his class and graduated in 1910. Sadness had engulfed the family a year prior in 1908 when Earlston’s father, Douglas L. Hargett, a local merchant and clerk of the circuit court died on September 29th, 1908. Mrs Hargett was left with Earlston and a sister named Bessie M. (Clapp). An older brother, Dr. Walter S. Hargett, had already moved out of the house and was living in Philadelphia. The family had endured heartache nearly 20 years earlier when Earlston's older brother, Burns, had died at 12 years of age in a farming accident back. Earlston had two strong uncles looking out for him, P. L. Hargett and Schaeffer T. Hargett, leading farmers and operators of a successful grain and milling business in town. A gifted student, Earlston excelled in grade school, and equally in college at the University of Pennsylvania, graduating with high honors. Earlston’s mother was the former Emma M. Whipp (1852-1931). She adored her youngest child and it can be assumed was worried throughout his wartime absence. I found an article in the newspaper from October, 1927 in which she had a special culinary surprise delivered to him while in Europe. He enlisted on August 15th, 1917, finding himself now a student cadet at Fort Niagara as part of the Officers Training Reserve Corps. Hargett was given the rank of 2ndLt of Field Artillery and shipped out to Europe a month later. Lt. Hargett would be promoted to 1st Lieutenant, a year later, on September 1, 1918. He found himself quite busy staging for the largest, and costliest, military offensive in American history. Just a few days before he went into the battle, in which he received the wounds which caused his death, Lieutenant Hargett wrote home describing his camp quarters. On September 26, just four days before his death, he sent his Christmas label, with a brief note attached. The letters: Piano at Field Camp Letter written Sept. 24: “Time has been skipping by so quickly that I hardly know when I wrote you last but think it has been about a week: a very busy one too for me. After our successful offensive, when we gained all our objectives, took more than 13,000 prisoners, and gained more than 130 square miles of territory, we are now resting and are stabilizing the lines for winter. I am in charge of the “echelon” or combat train. We are occupying a camp in the woods which the Germans constructed. There are barracks for the men, stables for the horses and splendid quarters for the officers. Some o the buildings were burned by the Germans before they left. There are enough remaining to accommodate our battery. We even have a piano which they were compelled to leave behind. I am living in a little building which is very attractively decorated with papered walls and mission work furnishings. Being the senior officer at the echelon, I am entitled to the best piano. I have a big mirror, four feet long, and two and a half feet wide with a gold frame. I have a splendid German stove and in camp there are about twenty cords of fine oak wood which the Germans cut and about fifteen tons of their coal. So we are well fixed for the winter if we are compelled to stay here. They had running water and even electric lights but neither of these are working now. One supply I wish they had not left as plentiful and that is German fleas. They have almost eaten us up since we have been here but I suppose they will quiet down after a while. I have not found any “cooties” recently and that is some consolation for the fleas. Oh, yes, we also have a big kettle which we use for a bath tub so that I will not now have to go eight weeks without a bath, as I did at one point this summer. Tell all the folks that I have not much time to write, but if all goes well, we will have things organized in a week or two and I can write again to everyone.” On September 26, a short letter was received advising what to enclose in the Christmas package and ending by saying: “I just wrote you day before yesterday. As I was up all last night, I am pretty tired now, I will get to bed now and write you again in a few days.” Earlston L. Hargett would not have the opportunity to follow up on his promise to write to his mother again. The distress and uncertainty she must have felt as days turned to weeks without word from her son. A Pennsylvania compensation records shows that Lt. Hargett was fatally wounded at a Essey-Panes (Lorraine) on September 30th. He succumbed of his wounds later that day at Mobile Hospital #39, and was buried at the American Cemetery at Vertuzey, within Aulnois-Sous, Department of Meuse. The newspaper article concluded by saying: "The death of Lieutenant Hargett brings the county’s honor roll up to 65 men, of this number, eight were killed in action; 4 died of wounds; one was killed in an accident; one died at sea; 28 died of disease; 20 were wounded in action and three were missing in action. The honor roll appears on page five of the morning edition." More casualties would be added to the Frederick Honor Roll in the weeks and months to follow. A few final notes on 1st Lt. Hargett. He was originally buried in a military cemetery at Vertuzey, France. In 1921, his body would be brought back home and he would be buried by his father’s side in Mount Olivet’s Area H/Lot 376. This occurred in a formal ceremony on June 26th, 1921. The planning and logistical work was performed by Frederick’s American Legion Post #11, formed in July 1919. As a matter of fact, during the initial planning sessions for that organization, a discussion ensued about naming the Post after a deserving figure in history. Interesting entries were put forth, but most interesting was a strong suggestion by W.L. Storm. He lobbied for Post 11 to become the Earlston Lilburn Hargett Post #11 of the American Legion. The name however went to Francis Scott Key, an equally deserving veteran and patriot from an uncertain September, 100 years earlier. The planning and logistical work was performed by Frederick’s American Legion Post #11, formed in July 1919. As a matter of fact, during the initial planning sessions for that organization, a discussion ensued about naming the Post after a deserving figure in history. Interesting entries were put forth, but most interesting was a strong suggestion by W.L. Storm. He lobbied for Post 11 to become the Earlston Lilburn Hargett Post #11 of the American Legion. The name however went to Francis Scott Key, an equally deserving veteran and patriot from an uncertain September, 100 years earlier. Interested in learning more Frederick History from this author? Check out Chris Haugh's latest, in-person, course offerings including : "Prehistoric Frederick" (starting Monday, October 2nd) and "Indian Tribes, Explorers & Fur Traders in the Monocacy Valley." (begins Monday, November 6th). These will take place at Mount Olivet Cemetery's historic Key Chapel. For more info and course registration, click the yellow link below! More class offerings (and walking tours) to come! http://www.historysharkproductions.com/more-frederick-history-courses.html

0 Comments

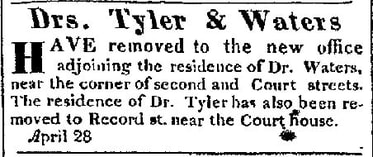

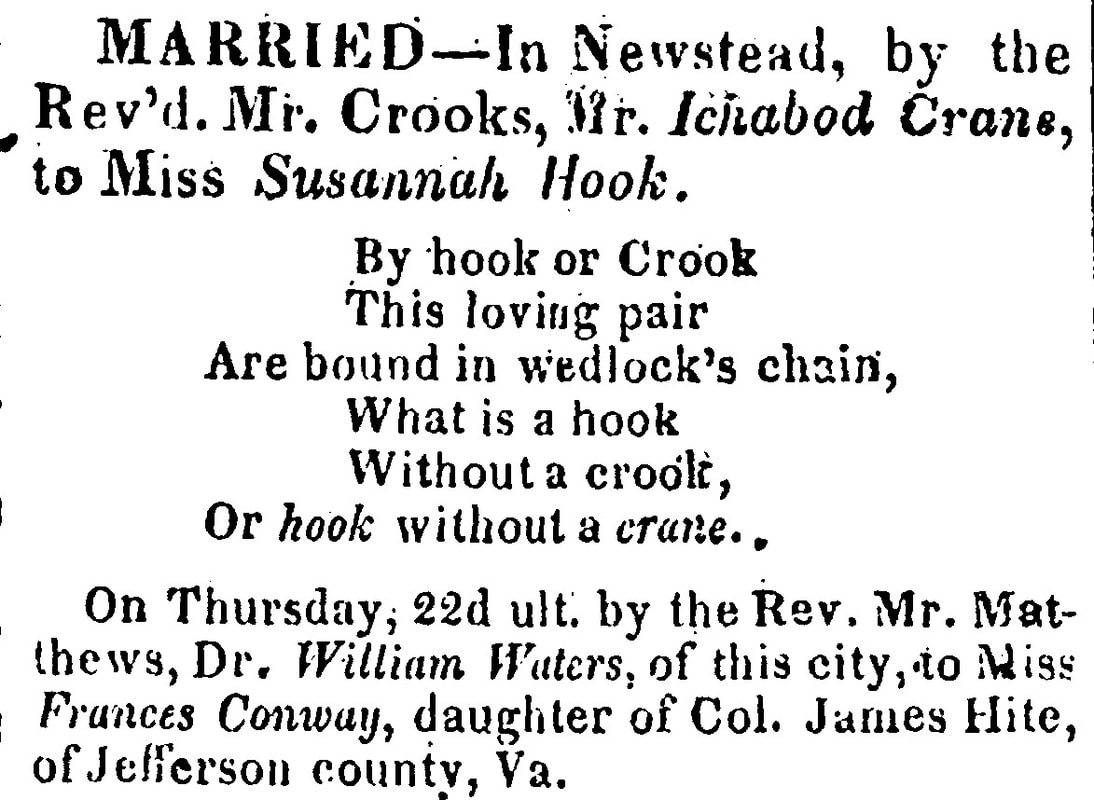

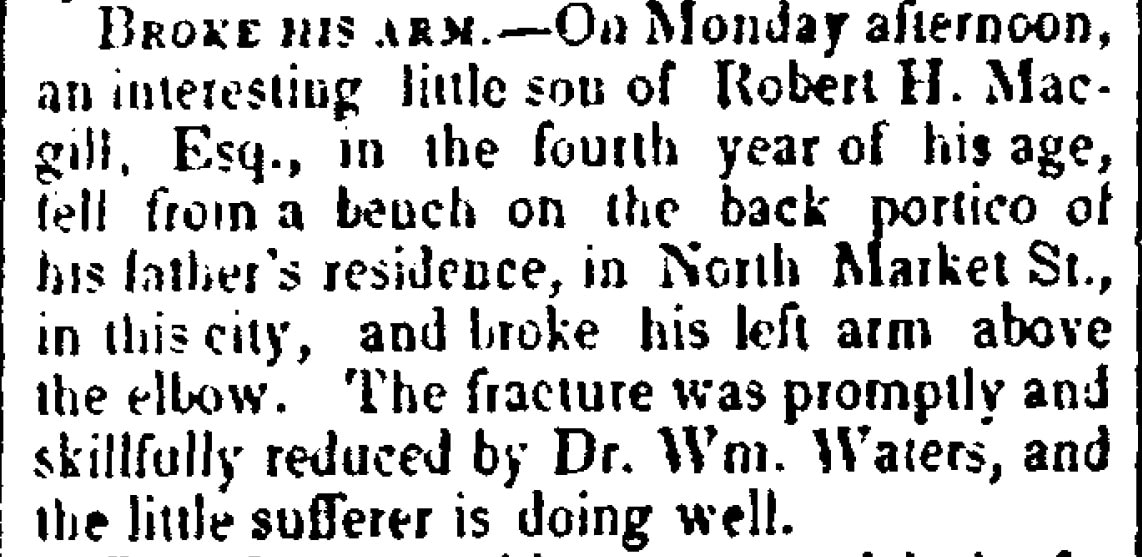

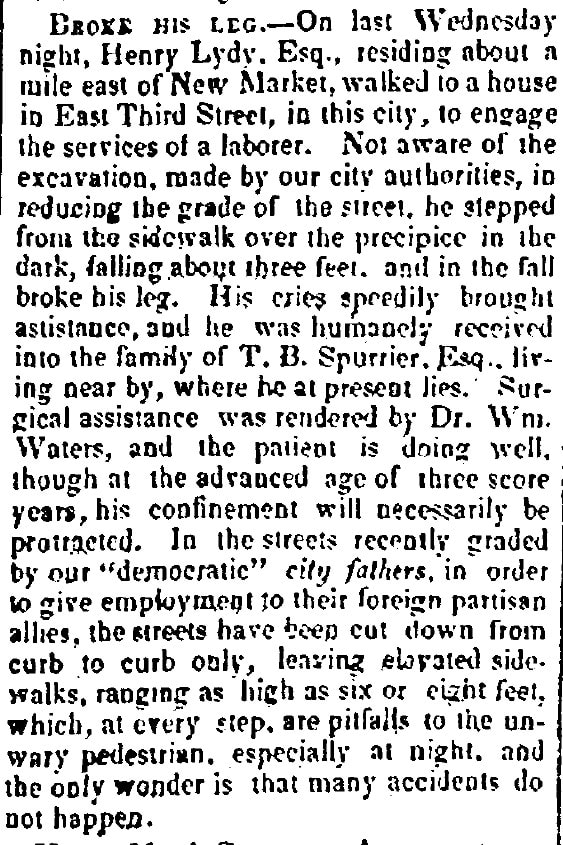

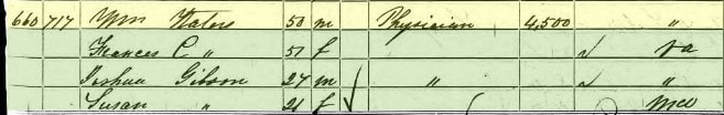

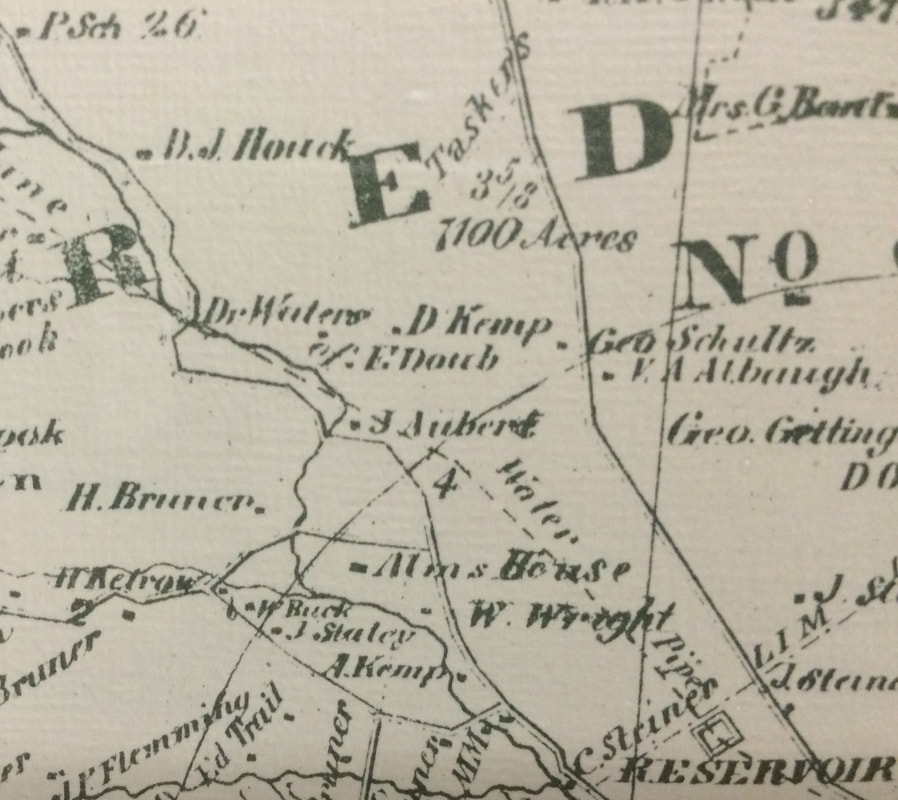

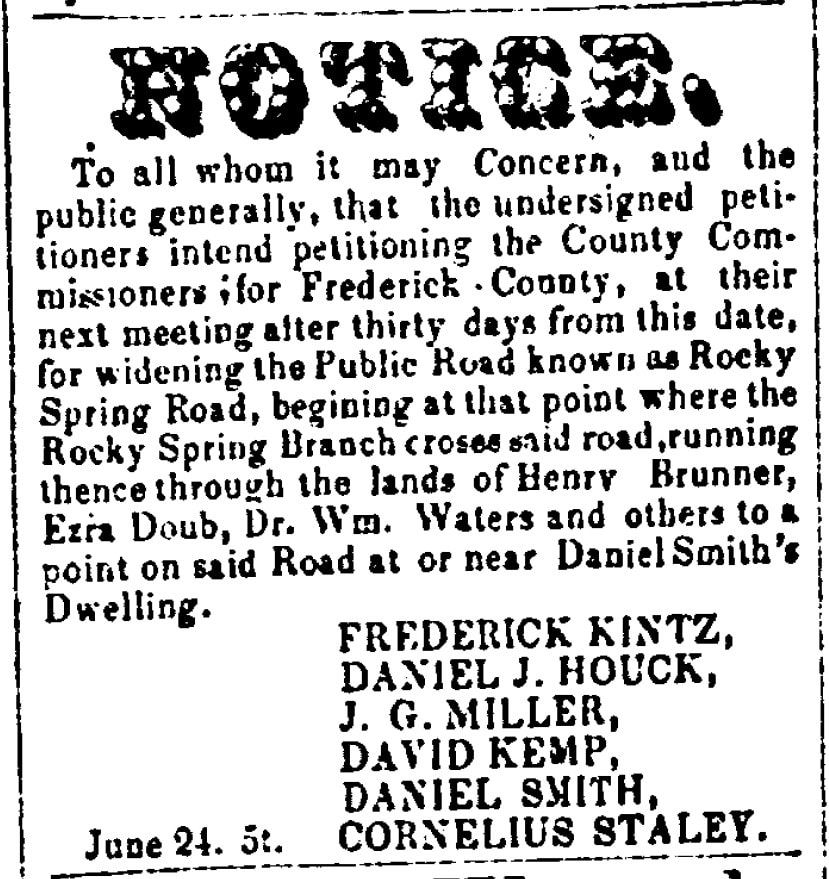

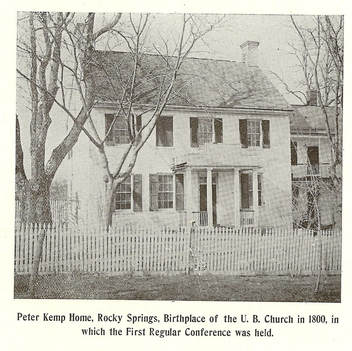

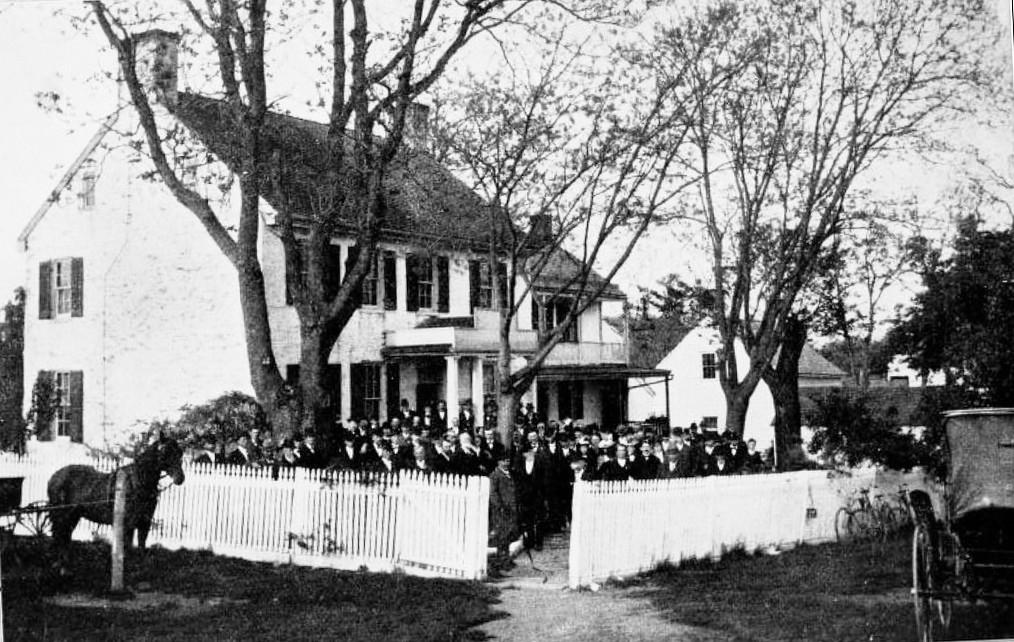

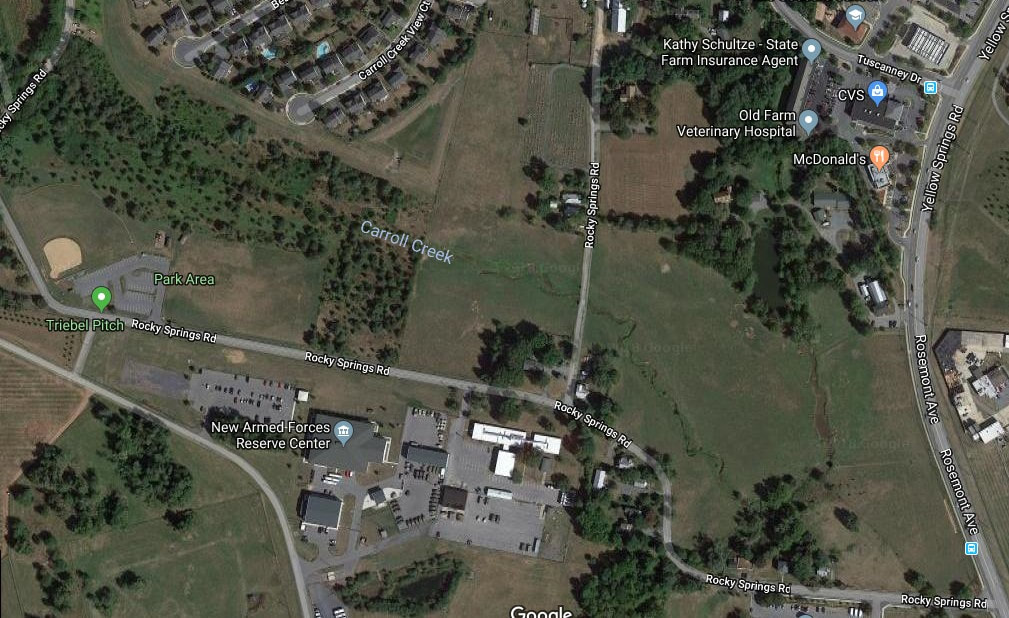

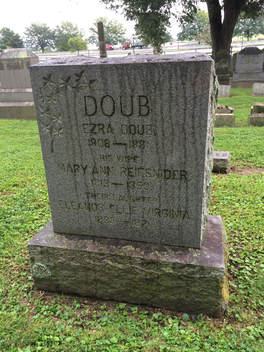

Here comes that rainy day feeling again And soon my tears they will be falling like rain It always seems to be a Monday Left over memories of Sunday always spent with you Before the clouds appeared and took away my sunshine Our weather "Fortunes" of late have been most, unfortunate. It's been a cruel, wet summer for many of my Frederick neighbors over the past several months. On the bright side, the continued weather woes have given inspiration to this week's story. While driving through the cemetery during a downpour last week, I coyly took note of an aged tandem of monuments in Area E with the name "Waters" carved on their marble faces. I don't know if this is a shining example of serendipity, but it was enough to provide guidance for my next research foray into another interesting former citizen, a physician who helped build the Frederick we know and love today. When delving into the research of this Waters family, I soon experienced the fitting adage of “When it rains, it pours,” as there were interesting connections galore. Basil Waters (1761-1844), the father of our subject (Dr. William Waters), was the son of the aforementioned William Waters of Brookeville. He married Anne Pottinger Magruder on March 19th, 1797. The bride was the daughter of Revolutionary War patriot, Zadok Magruder, a colonel who commanded the militia of lower Frederick County which at the time stretched to Georgetown. Col. Magruder, (Dr. Waters maternal grandfather), helped establish the early governmental framework for Montgomery County and is still remembered today with a high school named in his honor. Basil Waters built a house on 200 acres of land which he had inherited from his father, and located in the vicinity of today’s Germantown. He named the farm Pleasant Fields. The house still stands, now part of the Montgomery County Parks and Recreation system. Waters Special House Park sits on a 3.9 acre parcel on Milestone Manor Lane. It serves home to Montgomery Parks offices and Heritage Montgomery, a non-profit organization that seeks to promote heritage tourism, foster historic preservation, and provide associated educational programming. Imagine my surprise when I realized that I have actually spent time in this structure! I attended a few Maryland State Heritage Authorities meetings here when I worked for the Frederick County Tourism Council (2007-2015). My last visit to the Waters homestead was in September, 2014. I was in the process of returning a collection of War of 1812 uniforms borrowed for our "Home of the Brave" commemorative event which celebrated Frederick veterans in the 1812 conflict and the 200th anniversary of the writing of “The Star-Spangled Banner” by Francis Scott Key.  Residents of Pleasant Fields plantation in the early decades of the 19th century included Dr. William Waters, born December 28th, 1799 and five siblings: - Mary Waters [1802–1803] - Zadok Magruder Waters [1803–1892] - Susanna Waters [1806–1824] - Zachariah Waters [1809–1871] - Robert Pottinger Magruder Waters [1815–1824] William Waters would pursue studies in the medical field, attending the University of Maryland. Here, he was a classmate of Frederick City’s William Tyler (1784-1872), a longtime resident of Record Street. Waters would graduate in 1824, and afterwards became part of the state’s Medical and Chirurgical Faculty. The year 1824 would serve as a bittersweet pill for young Dr. Waters. In April, tragedy struck the Waters family when a Black Measles epidemic took the lives of Dr. Waters' siblings, 18-year-old Susanna, 9-year-old Robert, and his mother Anne.  Frederick Herald (May 5, 1832) Frederick Herald (May 5, 1832) Dr. Waters practiced in Montgomery County for two years before making his way to Frederick City, perhaps at the urging of his school chum, Dr. Tyler. In fact, the two would practice medicine together here in Frederick for seven years. On the personal side of life, William Waters would marry in December, 1825. His bride was Miss Frances Conway Hite, hailing from Berkeley County, VA (later WV). Frances’ great-grandfather was Jost Hite, an early German immigrant to this country who led 16 colonial era immigrant families from Pennsylvania to the site of today’s Winchester, VA. Along the way, Hite convinced the families of Jacob and Isaac Van Metre (the earliest European settlers to live on the Tasker's Chance parcel, land that would become Frederick City) to accompany him west. As early as 1725, the Van Metres had been living along Carroll Creek (then known as Beaver Creek) in the southeastern area of today's Downtown Frederick, roughly from today's S. Market St. to the Frederick Fairgrounds.  Jacob Engelbrecht (1798-1878) Jacob Engelbrecht (1798-1878) Dr. and Mrs. Waters had four children: Juliet Ann Waters (b. 1826) Susanna Waters (b. 1828) Amanda Baker Waters (b. 1830) Frances Courtney Waters (b. 1834) Ann Pottinger Waters (b.1837) Frederick diarist Jacob Engelbrecht has several mentions of Dr. Waters in his writings over the years. In particular, the good doctor made several house calls to the Engelbrecht residence. On September 1st, 1834, Jacob Engelbrecht penned this entry into his legendary diary: "Phillip Melancthon & myself have been sick the past week, he with the bilious (slight) & chills & fever, & myself with the chills & fever. But going through a regular course of medicine, we have thus far, thank God, recovered, though we dare not talk too fast yet. Dr. William Waters attended us." Here are a few articles which stand testament to Waters' medical "handiwork" in service to other Frederick City residents.  The three ledger (flat) stones in Area E/Lot 150 mark the graves of the Waters' children that were originally buried in the All Saints' Church burying ground The three ledger (flat) stones in Area E/Lot 150 mark the graves of the Waters' children that were originally buried in the All Saints' Church burying ground Sadly Jacob Engelbrecht also notes in his diary the premature deaths of three of Dr. Waters' children: Juliet in 1831 (age 4), Amanda in 1833 (age 3) and Frances (age 1) in 1835. Originally buried in All Saints' Protestant Episcopal burying ground, these bodies would be moved to Mount Olivet in 1854, the year the cemetery opened. Dr. Waters purchased several grave spaces in Area E/Lot 150. William and Frances' other two daughters, Susanna and Ann, would reach adulthood and marry physicians. Susanna would marry Dr. Joshua Gregg Gibson of Shepherdstown and Ann wed Dr. Harry W. Dorsey of New Market. Dr. Waters was a leading member of the Medical and Chirurgical Faculty of Maryland, holding various positions of leadership including Vice-President from 1857-58, and was regularly called on as an orator to the group for key meetings. The Doctor's Brethren I wanted to find out more about the physician's home residence. I uncovered a few references, one connecting him to a town home in downtown Frederick on W. Second Street, "across Court Street." A brief description can be found in C. Sue Markell's unpublished manuscript Short Stories of Life in Frederick in 1830: "Across the public thoroughfare, subsequently known as Dill's Alley (Court Street), stands, as then, the substantial old homestead of Dr. William Waters. Of the office adjoining, during her husband's absence, Mrs. waters always assumed charge; administering her quasi-professional duties with such ability and fidelity as to acquire the sobriquet of "Dr. Fannie." Many of our older citizens may yet be able to recall this lady's beaming countenance, with its environment of gingham or cambric ruffling—for she never appeared without a corded or "slip" bonnet of diminutive size perched upon the top of her head." Of equal interest, a reference from Jacob Engelbrecht in 1870 states that Dr. Waters had been the owner of the property by George Murdock, located roughly a mile and a half northwest of town. In fact, Dr. Waters home, labeled on the 1858 Bond Map, was part of the parcel named Rocky Spring, namesake of Rocky Springs Road which survives today. I would learn from my friend Debby Moone, (President of the Historic Rocky Springs Chapel Inc.), that the Waters family likely lived in, or near, the famed home built by early German settler Frederick Kemp. Dr. Waters appears to have been paying a mortgage on the farm, later to be known as Sandy Spring, to Capt. Ezra Doub. Doub was a former soldier, gentleman farmer and businessman who earned his military title through serving as an officer over a militia group which he personally raised for the Mexican War in the 1840's. Doub also owned, and farmed, a great deal of land in the Frederick area. The Rocky Springs parcel came via his parents Valentine Doub and Esther Kemp. Miss Kemp was the daughter of Rev. Peter Kemp, whose father, Frederick, built the house as I said earlier. Frederick Kemp hosted Reformed Church conferences out of his house, held under the leadership of Pastor Philip William Otterbein. One such gathering, in the year 1800, served as the organization meeting for the impetus of the United Brethren in Christ. I guess you could say that the U.B. Church had its "baptism" in the Rocky Spring which feeds Carroll Creek. It comes as no surprise that Frederick Kemp's son, Peter Kemp, would become a United Brethren minister, and several religious pilgrimages would be made to this vicinity into the future by church leaders and others. As for Capt. Ezra Doub, he produced farm implements through his operation of the Vulcan Iron Works on East Patrick Street at the site of the later Union Knitting Mills. Doub also served as president of the Junior Fire Company, #2 from 1851-1856, and was also a Whig candidate for the Maryland General Assembly. The captain would relocate to Baltimore in the early, 1860's and just a few years later experienced a "shock of paralysis," which would debilitate him until his death in 1881. Eventually religious services were held on Sundays in the Rocky Springs one-room schoolhouse located a half mile north on Rocky Springs Road. This structure was built in the late 1830's and still survives today. A formal chapel came to fruition in 1882, and both of these important buildings serve as priceless links to our area's rich German-Swiss settlement heritage. The above mentioned Rocky Springs Chapel non-profit organization focuses on this fact, and is under the leadership of a fine group of folks including Debby Moon and her mother JaNeen Smith. Many may recall that Mrs. Smith was the first director of our National Museum of Civil War History. To learn more about the Rocky Springs area, not to mention ongoing preservation projects and efforts, check out the Historic Rocky Springs Chapel Inc. website. The group has turned their attention of late to the Rocky Springs Cemetery, which has come under encroachment by new housing development activity. The cemetery began as the family burying plot for the Kemps dating to the 1700's, and still remains in use. This makes it the oldest cemetery in the City of Frederick. The Kemp family name yielded to the name of Rocky Springs Cemetery, however the family moniker lives on through another nearby thoroughfare—Kemp Lane. The Doub name has also been associated to this cemetery as well. This old Kemp and Doub homestead would make its way into Dr. Waters' hands in 1857. A detailed description of the house and property is featured in the equity papers of Frederick County connected to Dr. Waters after his death. Land - "Rocky Spring", 220+ acres; from Ezra DOUB (executor of Valentine DOUB and trustee of Valentine DOUB Jr) and William H. DOUB (executor of Joshua DOUB who was an heir of Valentine DOUB) in 1857. Adjoins tracts, "County Seat", David KEMP's "Safest Way". Mortgaged to Ezra DOUB, surviving executor of William DOUB and trustee of Esther DOUB, widow of William DOUB, in 1857. Improvements were 2-story stone house of nine rooms and kitchen attached with a first-rate cellar under the house and kitchen; a tenant house near the mansion of five rooms; two dairies, summer and winter; large stone Switzer barn with stabling underneath for 12 horses and 12 cattle; a double corn house, storing up to 300 barrels of corn with granary above it to store 1500 bushes of grain; wagon shed to accommodate two wagons and other vehicles; hog pen with crib above to hold 75 barrels of corn; fine carriage house to house two carriages; a smoke house, blacksmith shop, well within six yards of the kitchen and large spring near the barnyard and running water to supply the stock of the entire farm; also an orchard of choice fruit. The death of his wife likely prompted Dr. Waters to make his town house a primary residence. The house and farm would be auctioned off in 1859. For years Dr. Waters played a major role in local and state politics. He was active in the Democratic party serving as part of the county and state's leadership for the highly controversial Presidential election of 1860. He also was quite vocal throughout the Presidential Election of 1860, and meetings challenging representation for the state in secession-based hearings. William Waters would unexpectedly join his wife and children in the family plot at Mount Olivet Cemetery. This would occur just two months before Gen. Robert E. Lee would cross the waters of the Potomac to the Maryland shore and bring his Confederate Army and leading officers to Frederick in early September, 1862. The following tributes clearly show the standing of Dr. William Waters in the Frederick community at the time of his passing. In closing, I want to state that I have been unable to find Dr. Waters in the 1860 US Census, and any legitimate clue as to the identity of a second wife mentioned in the above obituary. My search continues!

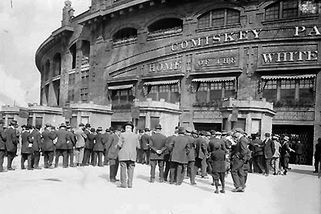

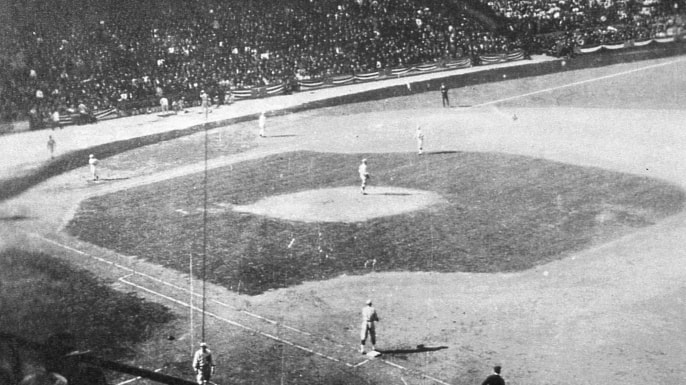

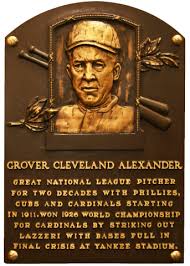

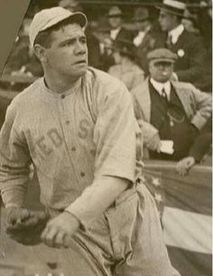

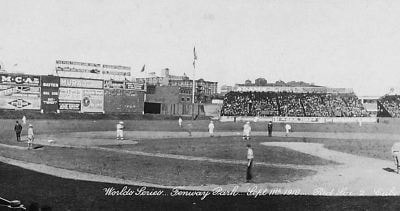

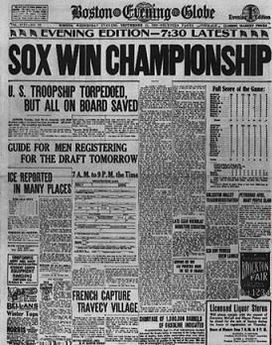

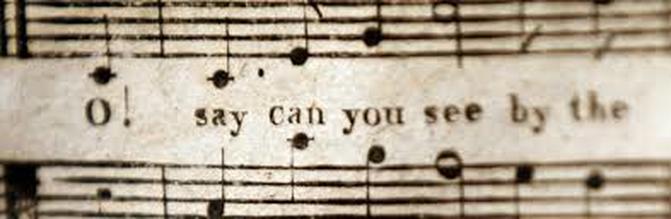

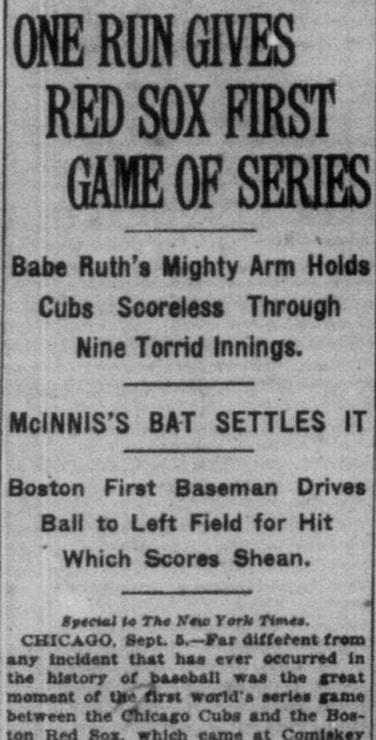

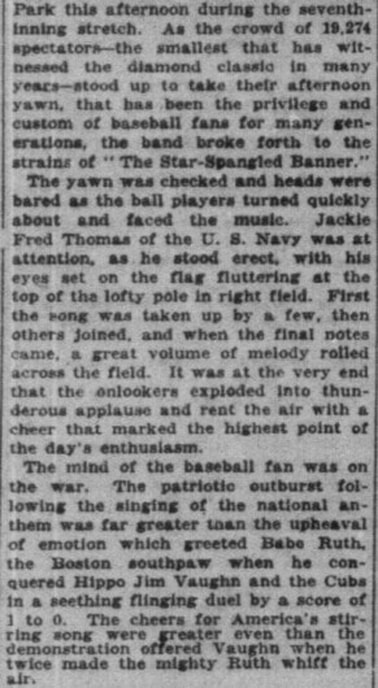

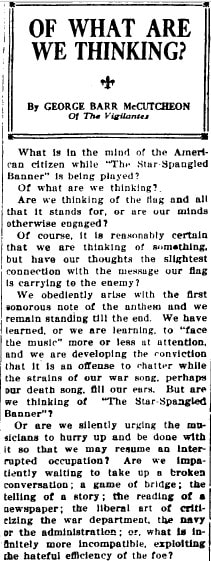

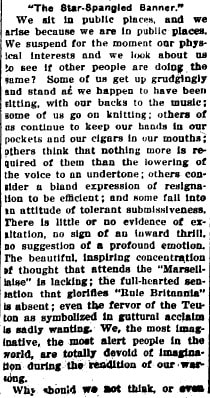

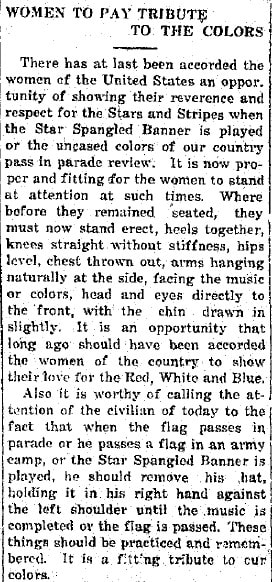

I'd like to end this story inspired by rain, about a man named Waters, who actually lived near Rocky Spring which served as the baptismal font of the United Brethren religion with a H2O reference. It comes from another diary entry from the physician's trusted patron, Jacob Engelbrecht. "Death, Doctor William Waters—This gentleman died of apoplexy last night a little before 9 o'clock. He had been nearly as well as usual & had just returned from visiting a patient & was sitting on the sofa in the passage talking with his wife, when in raising from his seat he staggered & fell down and instantly expired. He will be buried this evening at 6 o'clock as they cannot keep him longer. No ice in town, none got last winter." -July 8th, 1862  There are many rewards to working at a place like Frederick’s Mount Olivet Cemetery, so steeped in history. And I’m not just talking about the history of our fair city and county, but more so, the United States of America. One such perk is the unique opportunity to hear “The Star-Spangled Banner” being sung next door at Nymeo Field at Harry Grove Stadium. This is the home of our minor-league baseball team—the Frederick Keys. Now to be specific, our cemetery grounds are spacious, encompassing 100 acres adjacent the neighboring ballpark. The best place to be for this patriotic occurrence is in the shadow of the Francis Scott Key Monument near the front entrance off S. Market Street. This site doubles as the final resting place of the man who authored the legendary song, all the while being held captive aboard a British ship in Baltimore Harbor during the Battle of Fort McHenry on September 13-14th, 1814. Nowadays, the national anthem can be played about anywhere, especially where sports live and breed. When it comes to the gravesite of this guy who gave us the song (played at the Olympic Games and synonymous with “kicking off” most professional sporting events), the Frederick Keys are by far the closest in proximity. They are also named for him for goodness sake! And baseball and “The Star-Spangled Banner” seem to go together like peanut butter and jelly, don’t they? “The Star-Spangled Banner” has traditionally held high honor as the anticipated lead-in to major sports championships, and is usually performed by high profile musical artists. Who can forget Whitney Houston’s amazing rendition before Super Bowl XXV in late January 1991, made all the more meaningful as our country was entrenched in the Persian Gulf War at the time. A decade later, the song would take on heightened importance before games and matches of all kinds in the aftermath of the tragic 9-11 terrorist attacks. A “Star-Spangled Time” Exactly one century ago to the day (Thursday, September 5th, 1918), the country was embroiled in World War I. Frederick City and towns across the county had sent their boys into action. Many of these were in Europe, strangely taking on a major aggressor in German—a familiar country whom many here drew their heritage from in earlier generations. As an aside, Frederick Town (and later county) was so named in 1745 for Prince Frederick, Prince of Wales (1707-1751). This was the son of King George II and hailed from the House of Hanover. His mother, Caroline of Ansbach, was also of German extraction. This was employed as a brilliant marketing strategy by town and county founder Daniel Dulany to attract German immigrants, some from Europe and others already settled in Pennsylvania. By September, 1918, Frederick County had already heard the news that 7 of its citizens had already made the ultimate sacrifice in the Great War. Only 53 years removed from the American Civil War, this location, along with our entire country experienced a wave of patriotism like never seen before. It had been 17 months since we entered the war and 100,000 American deaths had been recorded as a result. Many more would follow in the next few months. This was said to be “the war to end all wars” and boasted unified population in cause and effort. One could say that the collective “we” was very confident in the abilities of our “fighting team,” but at the time, it is safe to say that “we” were equally scared and nervous about the state of the union. This was a tough opponent, and warfare during this time had grown into a particularly ugly and non-Romantic affair as compared to how folks drew on the Civil War and American Revolution for inspiration. The fighting was rough, involving improved side weapons and artillery, trench warfare, poison gas attacks and flamethrowers. Many fighting men died from the disease, primarily the Spanish Influenza. This deadly “12th man” of the enemy even made its way back home that fall, killing thousands of US civilian, with hundreds right here in Frederick County. Many Americans, here at home, simply looked to the game of baseball as a tension release. Who would know at the time, and more importantly on that particular day of September 5th, 1918, that the sport would become synonymous with national pride and patriotism from this point forward? The national pastime would earn its “national” billing. And to think it was all primarily due to a nod to the song written by Mount Olivet Cemetery’s perennial greeter, Francis Scott Key. A “World” Series to Remember September 5th, 1918 and the scene was Comiskey Park in Chicago, Illinois as the hometown Cubs hosted the Boston Red Sox for Game 1 of the World Series. The fabled “October Classic” was in its 16th year and had purposely been moved up to September due to the war. The federal government’s Selective Service Division had issued a “work or fight” order requiring all able-bodied men to either serve in the military or work in a “necessary” civilian occupation. Professional athletes were not immune. The regular season had been shortened for this fact, having ended on September 1st.  Sgt. Grover Cleveland Alexander Sgt. Grover Cleveland Alexander Interestingly, the Chicago Cubs best pitcher, Grover Cleveland Alexander had already spent most of the 2018 baseball season with the US Army in France for the war effort as a sergeant with the 342nd Field Artillery. While he was serving in France, he was exposed to German mustard gas and a shell exploded near him, causing partial hearing loss and triggering the onset of epilepsy. Following his return from the war, Alexander suffered from shell shock and was plagued with epileptic seizures, which exacerbated a drinking problem. Although people often misinterpreted his seizure-related problems as drunkenness, Alexander hit the bottle particularly hard as a result of the physical and emotional injuries inflicted by the war, which plagued him to his grave. Meanwhile, the starting pitcher for the Red Sox was a man named Ruth—Herman “Babe” Ruth to be exact. The Babe was as dominant on the mound as he was at the plate. He would pitch a shutout in Game 1, with his Red Sox winning 1 to 0. He would win his second outing in Game 4 and the Red Sox would go on to win the World Series by a count of 4 games to 2. This was Boston’s third World Series win in four years as they had also won 5 out of the first 15 baseball championships. Many are familiar with the interesting things to follow in the realm of baseball as Babe Ruth would be traded to the Yankees and go down as one of the greatest human beings to ever play the game. We even have a youth sports organization in our community named for the man. Players ages 13 to 19 play on diamonds such as Loats Field, also located adjacent Mount Olivet and the grave of Francis Scott Key. As for the Red Sox, they would not win another World Series for 86 years. The Chicago Cubs went on to lose World Series in 1929, 1932, 1935, 1938 and 1945. After a drought of 71 years, the Cubs finally made it to another World Series in 2016. This time, the seemingly cursed franchise made the most of it by defeating the Cleveland Indians. Speaking of Cleveland, Sgt. Grover Cleveland Alexander would at least have the opportunity to come back to the United States, and more so, play professional baseball after his service overseas. Eight of his fellow major leaguers did not have this chance, having been killed overseas during World War I. Seventh-Inning Stretch The most notable thing to happen during that Game 1 of the 1918 World Series actually had nothing to do with the baseball action on the field. No, it was clearly something that was generated from the stands. It was something that would have an everlasting effect on the fans, players, baseball and the entire gamut of American sports. That something was “The Star-Spangled Banner” written by Frederick’s native son Francis Scott Key.  This wasn’t the first time “The Star-Spangled Banner” was played at a sporting event. Apparently it has been documented as having been played at a baseball game in 1862 during the Civil War. It was also played in the 1890’s, on several occasions during the time of the Spanish American War. The events of September 5th, 1918 served as a major lynchpin—a tradition was born. Key’s song was played again in Chicago during Games 2 and 3. When the Series moved to Boston for Game 4, the Red Sox played the song during pregame festivities and paired it with the introduction of wounded soldiers, a theatrical move by Red Sox owner Harry Frazee. “The Star-Spangled Banner” quickly became the nation’s de facto anthem not long after. Congress made it official in 1931, after World War I vets had been lobbying for it for years. The song was still not played at all games in those days as team owners didn’t have bands on-hand to play the song. However, it was a staple of large events such as Opening Days and playoff and championship games. Another technology non-existent at this time was that of public address and credible sound systems. These would, however, be put in place by World War II, and the tradition was popularized to regular games.  The rest, as they call it, is history. Unfortunately, you may have heard that in recent years, the patriotic ditty has somehow gotten caught up in controversy. Some folks have different perceptions of what the song means, along with its place in national importance, and its role in the sporting event realm. I won’t be the first to tell you that we can learn a great deal from our past, as my livelihood has depended on this notion for many years. This project was as interesting as it is timely with the advent of another professional football season. More importantly, we are approaching the 204th anniversary of the writing of our anthem by Mr. Key (September 14), and the 100th anniversary of the end of World War I with the Armistice of November 11th, 1918.  I came across several evocative articles in doing a newspaper “key word” search for “Star-Spangled Banner” on the same day of September 6th, 1918—the day newspapers reported what occurred between sides of the seventh inning of Game 1 of the 1918 Series. I found several accounts of the song being played at patriotic sendoffs of troops from railroad platforms and ship docks across the country. I also uncovered references to its sounding in small town park rallys and memorial services throughout the land. A few other articles really caught my eye, and I felt that I should include as an addendum for your reading pleasure. History is a great thing, a true roadmap for the future. It also represents music to this humble writer’s ears—sort of like hearing the national anthem being sung at Grove Stadium, from the vantage of Francis Scott Key’s gravesite in Mount Olivet Cemetery. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed