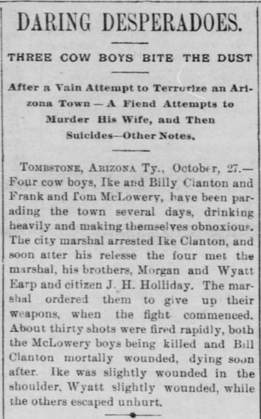

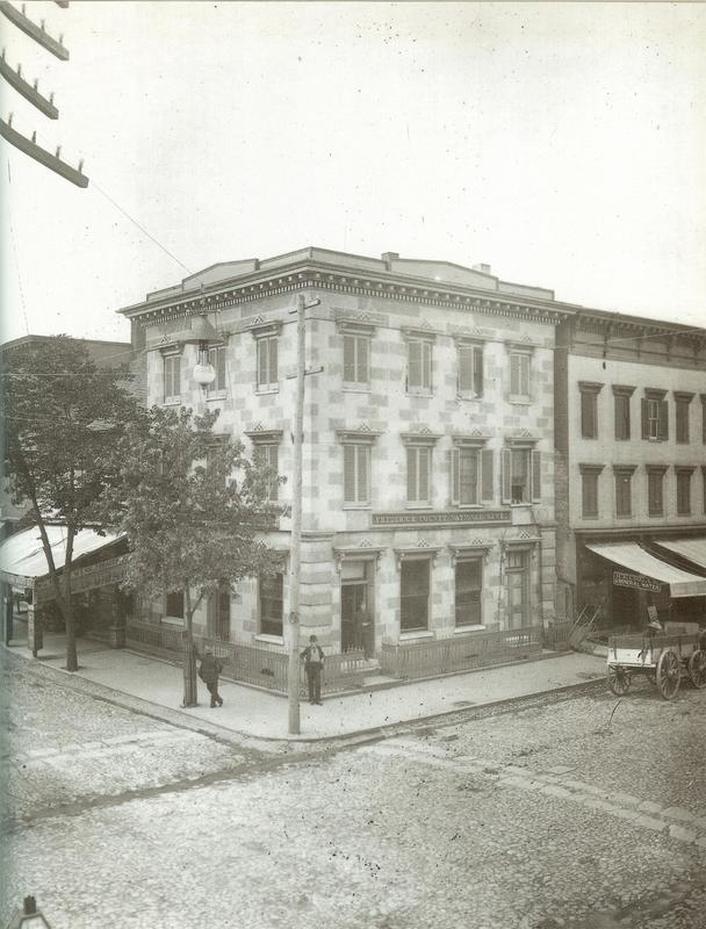

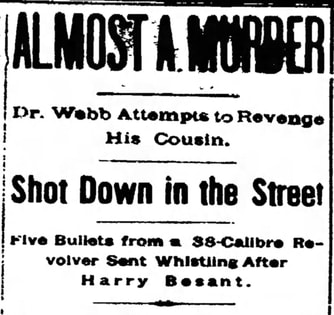

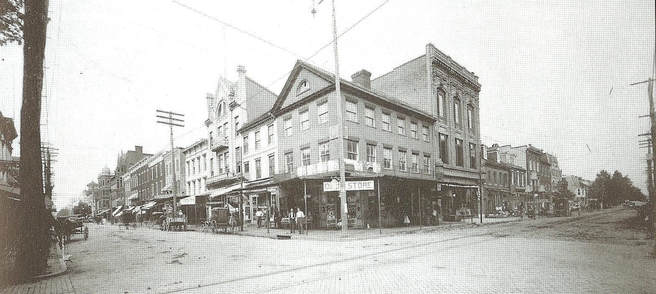

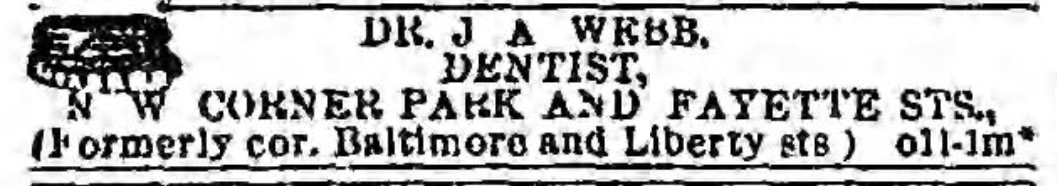

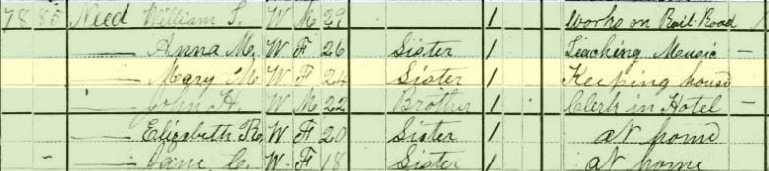

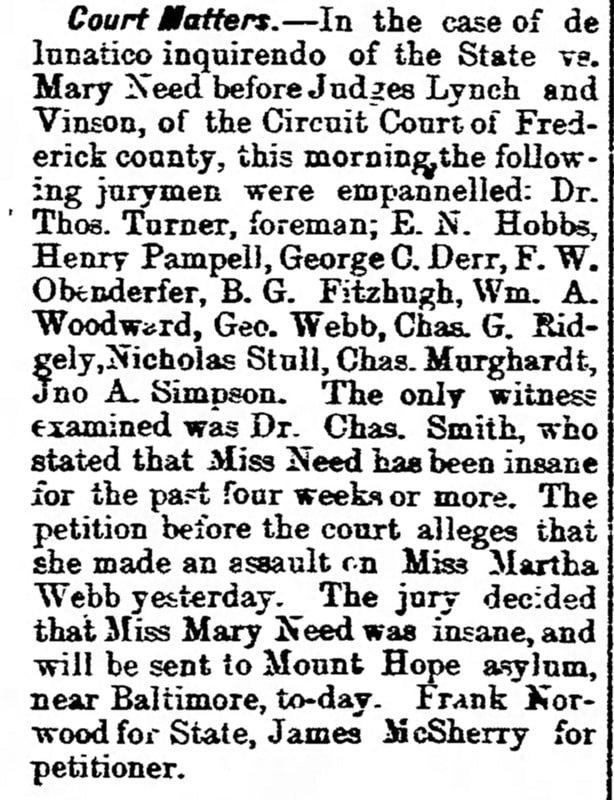

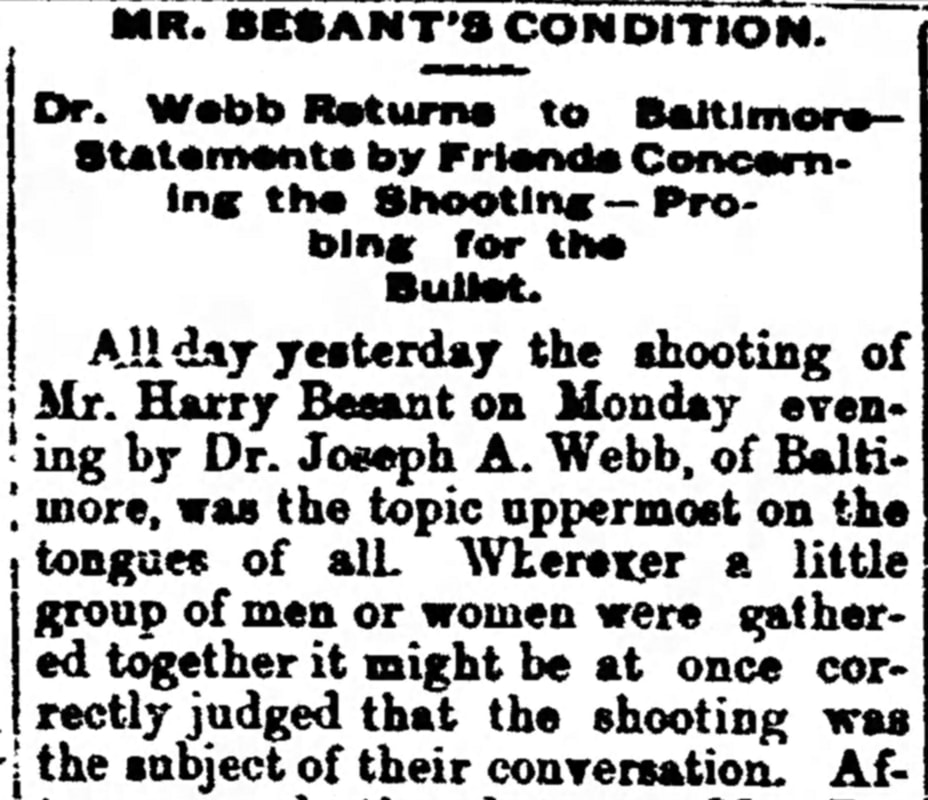

Leavenworth (KS) Times (Oct. 28, 1881 Leavenworth (KS) Times (Oct. 28, 1881 Generally regarded as the most famous gun shootout in American history, the “Gunfight at the O.K. Corral” occurred in Tombstone, Arizona Territory between lawmen and an outlaw group called the Cowboys. The legendary event that made Wyatt Earp a legend lasted only 30 seconds. It took place at about 3:00pm, Wednesday, October 26th, 1881. Forgotten to time, is a shootout that occurred nearly five years later in the heart of Downtown Frederick’s Square Corner. The major take away from this event that occurred on the Fourth of July (1886) was the fact that two lucky men, each bearing the first name of Henry, escaped with their lives. Thankfully, Mount Olivet Cemetery had to wait. Perhaps “shootout” is a strong term to describe this event, as forays of this variety usually involve two opposing foes utilizing firepower. In our Frederick instance, only one side had a weapon, the other side was unarmed. Maybe it would be better described as an “ambush.” It also appears that there wasn’t a clear-cut “good guy” or “bad guy,” but certainly wrongdoers on both sides. There were no deputized lawmen (like the Earp brothers) involved here, however, the vigilante aggressor was a dentist, much like the legendary Doc Holliday who played a starring role at Tombstone back in ‘81. This gentleman viewed his rival as a ruthless “cowboy,” who had wronged his beloved cousin. His feud had simmered quickly to a boil, with the combatants knowing virtually nothing of each other before this dark day. In fact they didn't know what each other looked like until the moment of the incident. Meanwhile, Fourth of July festivities were taking place throughout the town.  City Hotel on W. Patrick Street (c. 1880) City Hotel on W. Patrick Street (c. 1880) Dr. Joseph A. Webb was born in Pennsylvania in March, 1840. Sadly, Webb was orphaned at an early age, along with sisters Mary Jane, Susan and Martha. The children were taken in, and raised, by maternal aunt Mary (Trainer) Need in Maryland. This was the Emmitsburg household of Mary and husband John Need. A decade later (in 1857), the Needs would become owners of Frederick’s top hostelry—the City Hotel. They ran this operation during the turbulent years of the American Civil War. Mr. Need would also serve as Frederick County’s Deputy Collector of Taxes, and worked for several years as a clerk of the county court. John Need’s brother, William, also lived in the household as a widower. He was the original publisher of the Catoctin Clarion, Thurmont’s principal newspaper of the period. Joseph Webb and his sisters developed close bonds with their cousins/step-parents, and a slew of cousins/step-siblings. As far as I could tell the children were raised in the Catholic faith tradition of the Needs, and likely received a Catholic-based education at nearby St. John’s and the Visitation Academy. After grade school graduation, Joseph trained to become a dentist at the Baltimore College of Dental Surgery. He would open a practice on Market Street in the 1860’s, and was known to have a quiet and mild-mannered disposition. Dr. Webb married wife Fannie (Carter) and became the father of four children of his own. He practiced in Baltimore in the early 1870's but returned to Frederick. He eventually moved back to Baltimore in the early 1880’s, and quickly became as respected in “Charm City” as he was in his adopted home of Frederick. On July 3rd, 1886, Dr. Webb learned a disturbing story—one which shone a light on the true reason his cousin, Mary Need, (daughter of John and Mary), had been recently sentenced to a Baltimore insane asylum four months earlier. Overcome with emotion, Webb would soon take the law into his own hands. On the afternoon of July 4th, he purchased a revolver and quietly left his Baltimore home, boarding a train bound for Frederick. Mary Need, born in 1856, had once been a popular young lady in Frederick—her fall from grace would be swift. In the 1880 census, Mary can be found living with her siblings in a house on East 2nd Street, her parents having died a few years earlier. She would go to live with her brother John in Sharpsburg for a year. While there, poor Mary had supposedly fallen under the spell of a young Frederick man named Henry Reid Besant, known more commonly as Harry Besant. Besant, born in Point of Rocks in 1862, enjoyed a privileged upbringing, the son of Frederick County court justice James H. Besant. Harry Besant is said to have had a particular friendship with Jane Need, Mary’s younger sister. When Jane left for Washington, DC in fall of 1884, Besant began having secret sexual encounters with Mary, six years his senior. This resulted in an accidental pregnancy, which was painstakingly concealed from the Frederick community and general public. The child was born in Baltimore on July 12th, 1885. Both Miss Need and Harry Besant were practicing Catholics. Besant turned to a church institution for assistance upon the birth of the baby. It was taken to an orphanage for safekeeping, apparently a chance to allow the young couple to regroup. Mary returned to Frederick to live with her siblings and return to work as a milliner. Meanwhile, one thing led to another and the child somehow died within three months on October 21st, 1885. Besant was notified of this fact, but withheld information from Mary at first. When he finally let her know of the tragic circumstance, Mary became very depressed as could be expected. Ironically, in Mary Need’s greatest “time of need,” Besant decided to make his exit strategy, and abruptly broke things off with Mary. A newspaper account in the Baltimore Sun (dated July 7, 1886) said: “At its (baby’s) death, Besant became open to the attentions of other ladies. This is said to have weighed heavily upon her (Mary Need’s) mind. She went to Mr. Besant’s mother and told her the story. She finally grew violent and it became necessary to restrain her.” This was the proverbial "straw that broke the camels’ back." Twenty eight year-old Mary snapped and had a nervous breakdown and required confinement after apparently got into some sort of altercation with Dr. Webb’s younger sister, Martha Webb. This led to her arrest and subsequent court hearing. A local jury found Mary Webb to be insane, and sentenced the young woman to the Mount Hope Asylum in west Baltimore. Dr. Webb's train arrived in Frederick at 4:30pm on July 4th. He made his way through the familiar streets of town to the house of his older sister, Mary Jane Walsh, and husband William. Mr. Walsh, an Irish immigrant, had served as a clerk for the Frederick County National Bank for over two decades. The Walsh’s lived above the bank, at its location on the northwest corner of Frederick’s “Square Corner,” the intersection of Market and Patrick streets. Dinner was served, but Dr. Webb had no appetite for food, rather information. Suddenly the dinner conversation centered on Dr. Webb’s recent discovery regarding cousin Mary Need. Mrs. Walsh stayed tight-lipped about the whole affair as Dr. Webb pressed for more details. Finally, getting none, Dr. Webb excused himself in order to smoke a cigar across the street. He promptly went to David O. Thomas’ Cigar Shop.  The general vicinity of the 1886 Fourth of July shootout, northwest corner of the Square Corner intersection of Patrick (left) and Market (right)streets. Frederick County National Bank (with the Walsh residence upstairs) is in the center of this (c. 1890) photograph. To the right of the bank is the D. H. Markey Store which specialized in selling shoes, boots and hats. The left most storefront window (under the awning) was the victim of Dr. Webb's first bullet. Curiosity seekers came from all over the county to personally witness the sensational crime scene. Mr. Thomas, himself, was among the witnesses that provided testimony at the inquest hearing on July 7th, 1886. “I was sitting in front of my cigar store around 6 o’clock when Messrs. Besant and Debring came along. Dr. Webb asked Samuel Brubaker who they were. Mr. Brubaker told them, and when the two had crossed the street at the crossing, Dr. Webb arose and began walking toward them. He drew his pistol at the same time and began firing at Besant when he was about at the middle of the street. The first shot went through the glass window. The second cut the brim off Mr. DeBring’s hat, the third shot hit Besant, and as he stooped over and partly turned about, a fourth ball passed over him. A great many fire-crackers were being exploded at the time, and the shooting attracted little notice until it had become known that Mr. Besant had been shot. The excitement spread quickly, and the details of the old scandal were revived.”  Frederick News headline from July 6, 1886 Frederick News headline from July 6, 1886 The “Shootout at the Square Corner” took place on the north side of the square. Less than two hours after his train arrival, Dr. Webb had prevailed with his mission. He was thinking and acting with a cool and controlled head, albeit a tad irrational in the big picture. After Webb had fired his last shot, while being accosted by police officers and civilians, he willingly gave up his pistol, replying that he no longer had use for it. His accuracy as a dentist seems to have surpassed his talent as a marksman. Public outcry was mixed as this was a time period when reputation and chivalrous conduct meant everything. In the court proceedings to follow, it was learned that Mary’s brother William had intended to kill Besant the previous May, but failed to act. Besant is also lucky that Mary’s brother John stood down as well, as I found that he would spend the final years of his life in California’s San Quentin Prison after being charged with a felony. And speaking of brotherly love, one of the most spectacular actions associated with this event came from William H. Besant—Harry’s older brother, and a longtime personal friend of Joseph Webb. He actually told the authorities that the shooting was somewhat justified, and that the Besant family did not want to press charges against Dr. Webb.

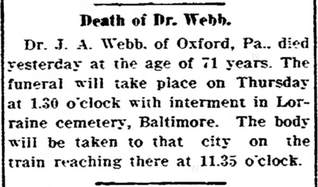

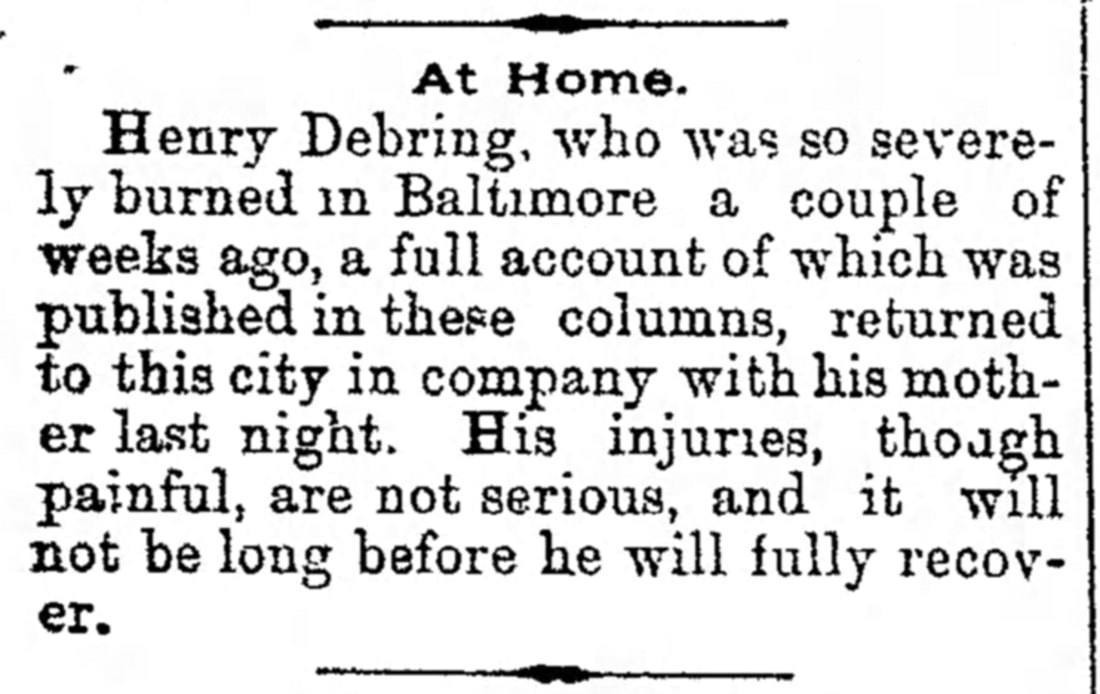

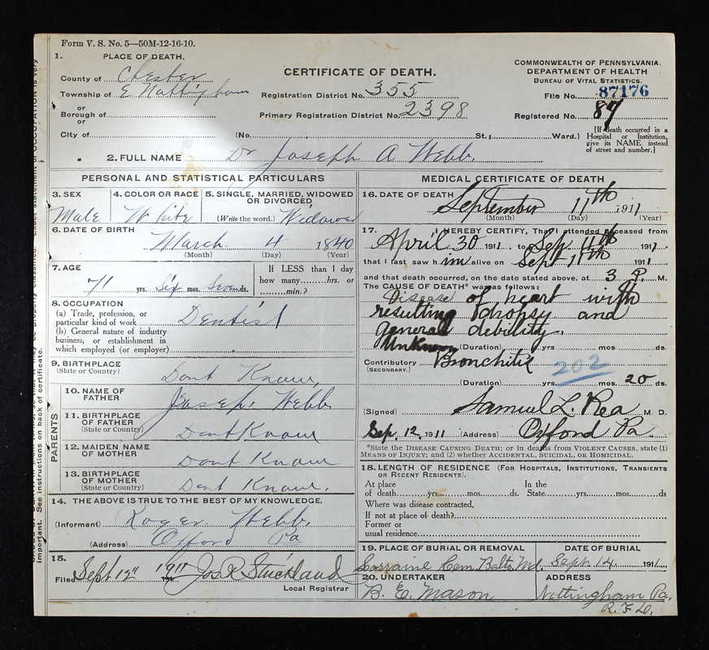

On the night of May 24th, 1904, Harry Besant retired to the bedroom of his E. Church Street home after dinner. He was in apparent good health and spirits. When Minnie tried to awake her husband the next morning, he is said to have “breathed heavily and expired.” Cause of death was found to be heart failure, super-induced by an attack of acute indigestion. Could it also have been a delayed result from being shot at the Square Corner nearly 18 years earlier? We’ll never know. The 42 year-old was laid to rest in Mount Olivet’s Area L/Lot 240, after a well-attended funeral mass at St. Johns Catholic Church. Harry’s buddy, Henry B. DeBring, would count his lucky stars on that July 4th, 1886 evening, for he had come out unscathed. His hat, however, wasn’t as fortunate. Less than one year later, Henry was living in Baltimore and worked as a firefighter. On June 13th, DeBring and his colleagues would respond to a business fire. While attempting to put out the blaze, he was severely injured by a gasoline explosion. Like his friend Besant the previous year, Henry DeBring would go on to make a full recovery, having cheated the grim reaper two years in a row. He would marry Verna Burg, raise a family in Baltimore and tell these tales for the next 47 years before being buried in Mount Olivet’s Area S in November, 1934.  Frederick Post (Sept. 12, 1911) Frederick Post (Sept. 12, 1911) Although he immediately regretted the fact that he did not fully succeed in completing his goal of killing Harry Besant, Dr. Joseph Webb was remorseful for his disrespectful conduct towards friend, William T. Besant, the older brother of his victim. He was also touched by the tremendous outpouring of support received by Frederick residents who sided with him in his actions. Charges were dropped, and Dr. Webb went back to Baltimore, unfortunately never to make a permanent return to Frederick. Dr. Webb went back to work as a dentist. He stayed active in his church, and Elks Club through the remainder of his life, while continuing his dental practice. As a widower, he would eventually retire to Oxford, Pennsylvania to live with his son Roger. This is where he died in 1911 of heart disease. And what of Miss Mary Need, the root cause of Dr. Webb’s vigilante-type action, and Harry Besant’s near death experience? Unfortunately, the shooting episode created sensational media attention, causing Mary’s private heartbreak to become known to countless thousands as the story was picked up by newspapers across the country. She would spend the next 37 years within the Mount Hope Asylum up to her death at age 65. She died two days before Christmas, December 23rd, 1923.

Just as Mary Need had been forgotten in life, her fate in death was quite the same, as I couldn’t find mention of it in any newspaper. Her body was laid to rest in the Need family lot within St. John’s Catholic Cemetery in Frederick. She is buried in an unmarked grave, only a stone's throw away from Harry Besant's parents. Oh, how her life could have been so different.

3 Comments

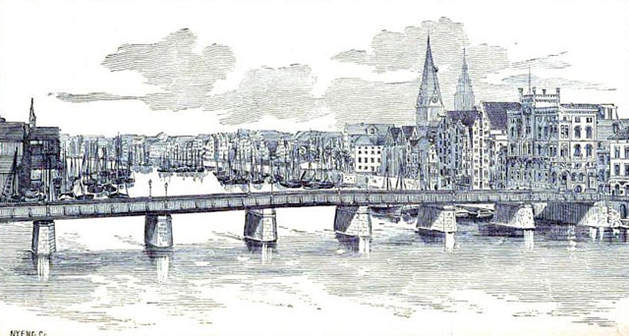

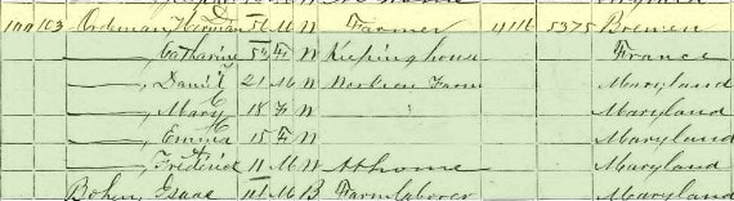

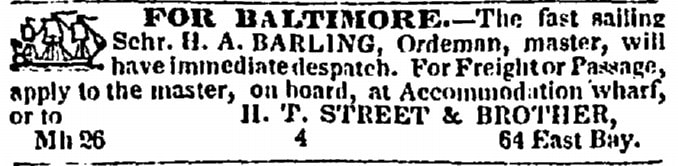

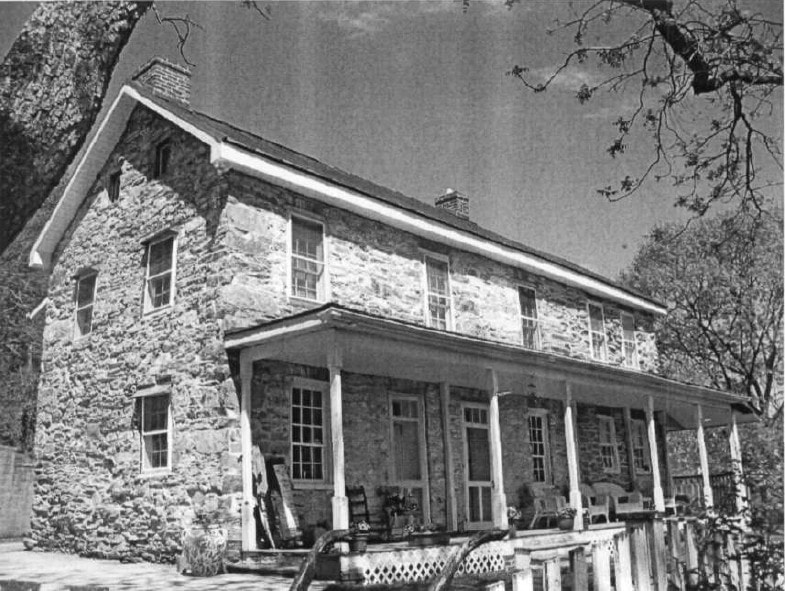

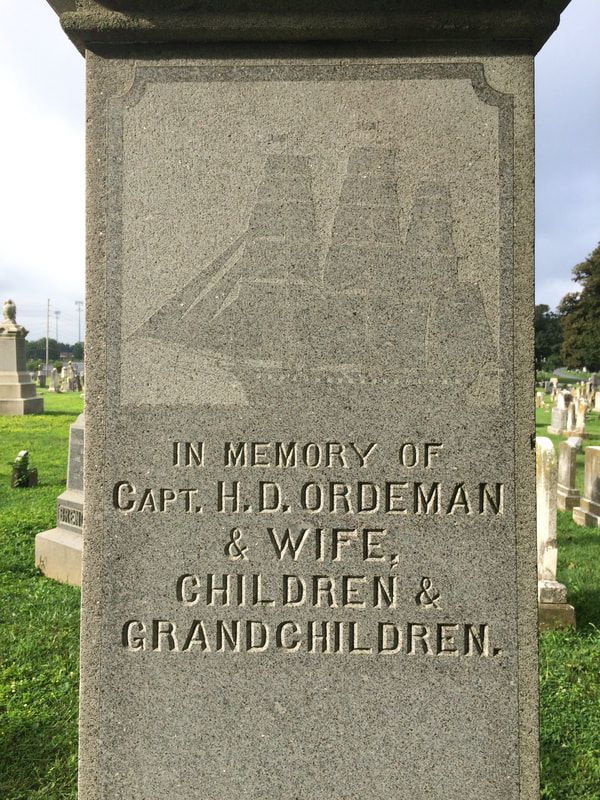

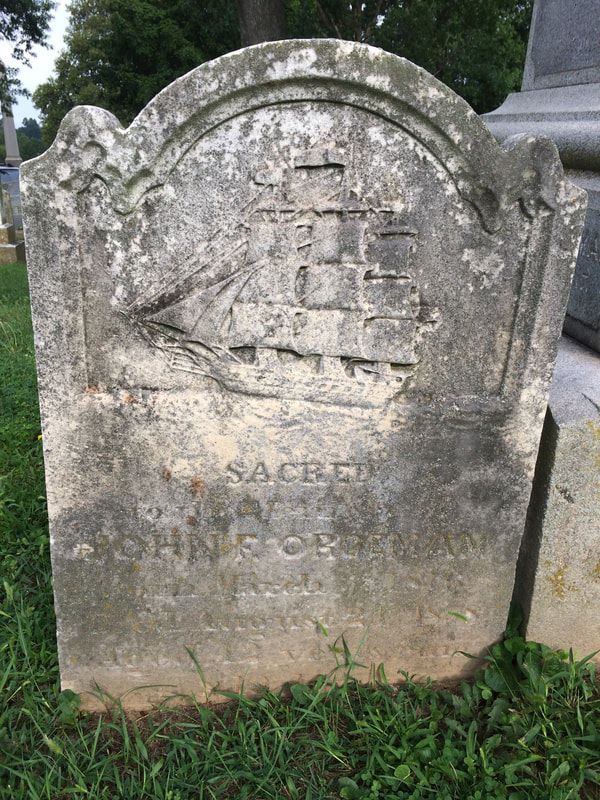

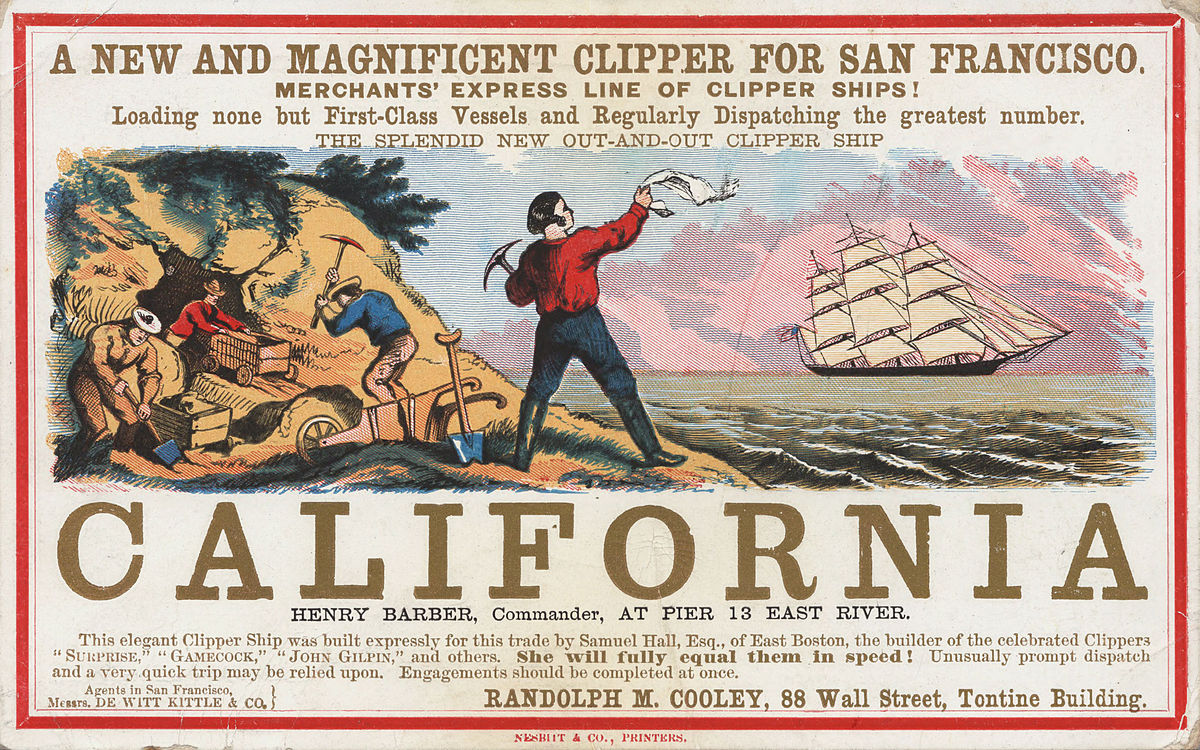

The beach is the perfect vacation spot for many of us. There are many factors at its core, having virtually nothing to do with additional recreational perks such as boardwalks, seafood, water slides, miniature-golf, or caramel popcorn. The true essence of “salt life” for beachcombers includes several sensory experiences—feeling the warmth of the sun, sand and soft breezes; smelling the rich salt air; hearing seagulls sing against the background of a lapping surf; and most importantly, the sight of cresting waves tumbling over themselves. And this doesn’t even account for the joy of actually getting in the water. Doctors and psychologists have praised the recuperative powers of visiting the ocean. Some have even commented on the body’s return to water as being a key factor. With 60% of our body made up of H2O, the natural pull toward the beach could have ties to evolution. As many are drawn to the sea, visitors to Mount Olivet are often drawn to one particular monument which stands out like a buoy in a surrounding “sea of gravestones.” It belongs to H. D. Ordeman and is adorned with nautical imagery, however you won’t find any sand, warm salt-air or waves. You will find an etching of a clipper ship on the front face, and topped with an anchor. There exist many examples of grave monuments with anchors in the cemetery, but this one has a true connection to the ocean, where many others have the anchor as an iconic, religious symbol representing hope. This was a popular gravestone adornment utilized during the Victorian era. The Catholic Encyclopedia explains:  “The anchor, because of the great importance in navigation, was regarded in ancient times as a symbol of safety. The Christians therefore, in adopting the anchor as a symbol of hope in future existence, merely gave a new and higher significance to a familiar emblem. In the teachings of Christianity, the virtue of hope occupies a place of great importance; Christ is the unfailing hope of all who believe in Him. St. Peter, St. Paul, and several of the early Fathers speak in this sense, but the Epistle to the Hebrews for the first time connects the idea of hope with the symbol of the anchor. The writers says that we have "Hope" set before us "as an anchor of the soul, sure and firm" (Hebrews 6:19-20). The hope here spoken of is obviously not concerned with earthly, but with heavenly things, and the anchor as a Christian symbol, consequently, relates only to the hope of salvation. It ranks among the most ancient of Christian symbols. St. Ambrose evidently had this symbol in mind when he wrote (In. Ep. ad Hebrews 6): "As the anchor thrown from a ship prevents this from being borne about, but holds it securely, so faith, strengthened by hope," etc.” In respect to a “nautical practicality” explanation, the anchor was a popular symbol because it was not only part of a ship, but because, just like Christians, sailors liked the connection this symbol had to stability and strength. Putting down an anchor also represented the safe end of a long journey—a very fitting punctuation mark for a past life memorialized at a cemetery. The Captain Herman Dietrich Ordeman(n) has been described as “a highly respected, honorable and handsome gentleman, loved by everybody.” This compliment came from his son-in law and Frederick merchant John E. Price. More important to our story here is the fact that Ordeman was a sea captain who spent 39 years in his particular trade before retiring to Frederick County in the mid 1850’s. Richard "Skip" Ordeman, a direct descendant of Captain Ordeman, of Oakwood, Ohio was kind enough to pass on some biographical information. This was compiled by two of the mariner’s grandsons. Capt. Herman Ordeman was a native of Bremen, Germany. Born November 30th, 1812, his life was greatly influenced by his old hometown. Bremen is the second most populated city in northern Germany and stands as a renowned commercial and industrial hub with a major port on the River Weser.  Bremen’s geographical location is 37 miles south of the mouth of the Weser on the North Sea. Just prior to Herman D. Ordeman’s birth, Napolean invaded Bremen in 1811 and integrated it as the capital of the Department of the Mouths of the Weser (within the new French State). In 1813, the French retreated and withdrew from Bremen. It soon became a sovereign republic. The first German steamship was manufactured in 1817 in the Bremen shipyard of Johann Lange. Ten years later, Bremen mayor, Johann Smidt, purchased land from the Kingdom of Hanover, to establish the city of Bremerhaven (Port of Bremen) as an outpost of Bremen because the river Weser was silting up. The shipping industry continued to blossom. Herman Dietrich Ordeman was the son of Heinrich Ordemann and Gesche Margrete Helmers. He attended primary schools in the village of Hunterbrueck (located northwest of Bremen) and a secondary school (likely in Bremen). Young Henry left school and went to nearby Berne, Germany (a few miles from Hunterbrueck) in order to escape compulsory military training. Then about 16 years old, he apprenticed on a sailing vessel and made his first trip. This was to the United States—Baltimore, Maryland. For the next five years, Ordeman climbed the ladder quickly, sailing as a seaman, third officer, second officer and first officer between practically every major port in Europe and North America.  In 1835, Herman Ordeman settled in Baltimore and began the process of becoming a naturalized US citizen. He would later accomplish this task in 1840, a week after his 28th birthday. As first officer on the barque John A. Robb, Ordeman sailed from Baltimore to Valparaiso, Chile and on his return in 1836 received his masters papers “for all oceans, all tonnages”. Later he commanded the barkentine Alexandria, schooner Henry A. Barling, barque Texadora (later Buena Vista), barque Aleyandra (built in Chile) and the barque George A. Henry. The latter two ships were registered under the Chilean flag. Herman D. Ordeman’s first love was the sea, but his second soon became a Parisian transplant named Catherine Schmaul (b. 1818 d. 1889). The couple would be wed in Baltimore on September 13th, 1838, and went on to become the parents of seven children (John Ordeman 1839-1904), Charles Henry Ordeman (1840-1862), Georgianna Ordeman (1848-1891), Daniel Thomas Ordeman Sr. (1848-1907), Mary Catherine Ordeman (1850-1932), Emma O. Ordeman (Hughes) (1855-1941), and Frederick A. Ordeman (1857-1924). Capt. Ordeman soon owned two ships that sailed internationally. Advertisements in vintage papers show him sailing to Liverpool, England and visiting American ports including Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Charleston and New Orleans. It has been said that the majority of his latter career was spent traveling between Baltimore and the west coast of South America, rounding Cape Horn twice a year. He sailed into places such as Santa Cruz and Rio de Janiero, Argentina and Talcahuano, Chile. He carried passengers, mail and such things as guano for fertilizer.  "Montevino" "Montevino" Dropping Anchor in Frederick In 1856, the good captain decided to move inland from his home in Baltimore. Capt. Ordeman moved to the vicinity of Park Mills (namesake of Park Mills Road) in the Urbana District of southeastern Frederick County. He purchased a farm containing 335 acres. This property wasn’t far from water, as it was located on the south side of Bennett’s Creek. He also owned a parcel on the north side of the creek of 30 acres on which stood a grist mill. A pot still distillery was added to the mill site in 1858, and for many years operated at a capacity of 175 gallons per day. The whiskey was said to have been carted to Frederick Junction on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad and shipped to Baltimore for storage in bonded warehouse. Capt. Ordeman would add to his real estate holdings a few years later in 1858 by purchasing an adjoining parcel that boasted a direct connection to his hometown of Bremen. This was the John Frederick Amelung property named Montevino, consisting of 1200 acres on the north side of Bennett’s Creek. The 100-room Georgian manor house was constructed by Amelung around 1784-85 as part of his New Bremen Glassworks operation. John Frederick Amelung was born and raised in Bremen, Germany. He had arrived in Baltimore in 1784, with 68 workers and enough glassmaking equipment to establish a factory. An agent and 14 additional workers arrived later in the year, and the group quickly established their New Bremen settlement and glass factory upon Bennett’s Creek. An early Colonial era pioneer in this endeavor, John Amelung is credited with producing “some of the most beautiful glass ever made in America.” He had agents in Baltimore and New York, but his fortunes came to a halt less than a decade later as Amelung declared bankruptcy. Fine examples of New Bremen glass work can be seen at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City; the Corning Museum of Glass in Corning, New York; and Winterthur Museum in Winterthur, Delaware. Herman D. Ordeman preferred to keep residence on his original purchased parcel, as he came into Amelung’s Motevino at a time when it was in a bad state of repair. He leased out farm shares from 1860 until the early 90's with several tenant families living in the old building. About 1893 the farm was taken over by the captain’s youngest son, Frederick A. Ordeman, and farmed by him until his death in 1924." From the time he was made a shipmaster, he shared ownership in the vessels he commanded. On his retirement from shipping he owned the Aleyandria and seventy percent of the George and Henry. He disposed of all interests except forty percent of the Aleyandria which he held until 1860.  Descendant Skip Ordeman's home-based shrine to ancestor Capt. H. D. Ordeman featuring a model of the Aleyandra (one of captain's last ships) and a wrought-iron nameplate that once adorned a fence in the backyard of a (Ordeman) family property outside of Frederick City. He surmises this could be a relic from an earlier ornamental fence that once surrounded the Ordeman grave lot (Area A/Lot 120) in Mount Olivet Capt. Ordeman was now content to live the life of a country gentleman and farmer. He might have left the ocean, but the ocean had never left him. Family, friends and neighbors would be thoroughly entertained by the captain’s telling of seafaring tales and adventures. One such was William Jarboe Grove (1854-1937), author of The History of Carrollton Manor. In this book, written in 1925, Grove recounts: "As a boy it was very interesting for me to hear him tell my father his experiences on the ocean. He was a jovial character and a splendid talker. His son Fred and grandchildren live in Frederick. Mr. Ordeman was a Southern sympathizer and his sons, John and Charles, served in the Confederate army.” Herman D. Ordeman was active in local affairs and politics, running for Frederick County commissioner in 1873. He was a member of the Frederick Odd Fellows Chapter as well. In early 1883, Capt. Ordeman began feeling the effects of a stomach tumor. It was cancer. He battled this affliction for 18 months before succumbing on September 12th, 1884. He was laid to rest in Mount Olivet Cemetery the next day, his funeral well-attended by family and the many friends and acquaintances, quickly made, in his new home of Frederick. The old captain was placed next to the grave of his brother, John Frederick Ordeman (1816-1858), who had passed 26 years earlier. He, too, was a man of the sea, making regular trips from Germany to Baltimore from the 1830’s through the 1850’s. I guess you could say, Mount Olivet serves as the final port of call for these brothers from Bremen.

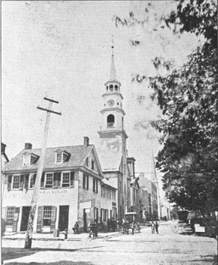

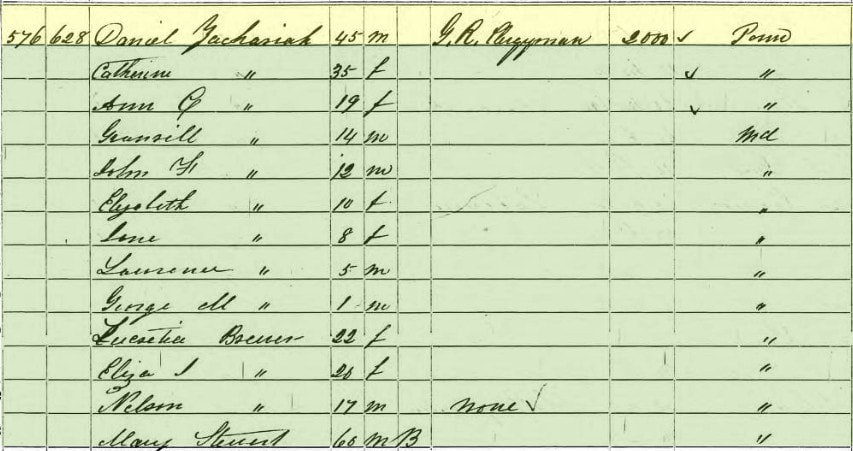

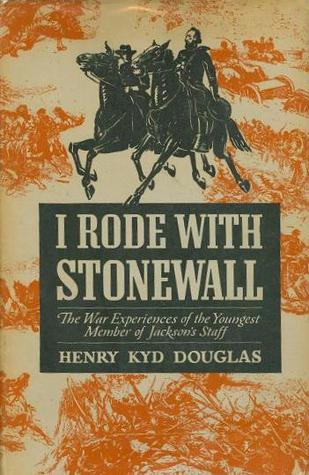

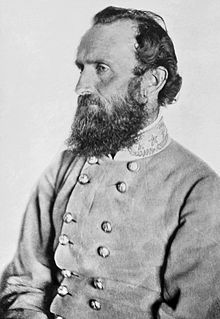

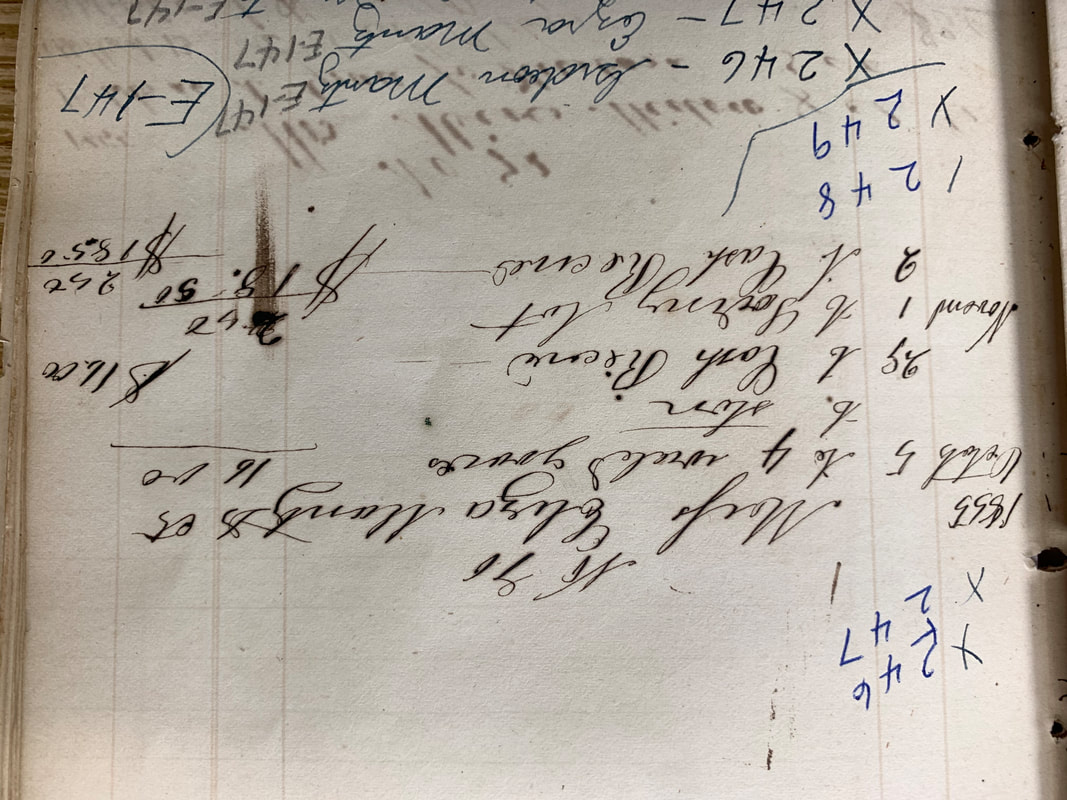

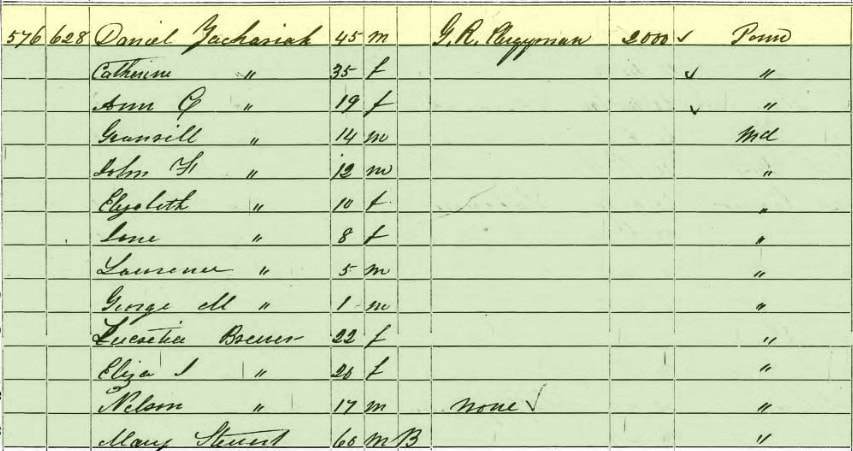

W. Church Street (Looking west from N. Market) with Trinity Chapel in background (c. 1890) W. Church Street (Looking west from N. Market) with Trinity Chapel in background (c. 1890) “It is a most instructive and refreshing exercise to sit down and gather around us all the biography of a period–all the journals–all the contemporaneous spiritual history of it, to bring all this together, review it carefully, analyze, sift and digest it, till the heart begins to burn within us. Shall we be unmindful of those who have gone before us? Shall we forget them or their deeds? No brethren, the good and the great can never be held too much in remembrance. Let us therefore, remember those who through faith and patience have gone before us.” These were the words coming from the pulpit of Frederick’s German Reformed Church, Trinity Chapel, on the occasion of the congregation’s centennial festivities which took place on May 21st (Whit-Monday), 1847. They were delivered as part of the opening of Rev. Daniel Zacharias’ sermon. Rev. Daniel Zacharias, D. D. (Doctor of Divinity) exhibited a life dedicated to “faith and patience.” He came to Frederick in the “prime of early manhood.” He was said to have exhibited “energy and great endurance.” Before his entrance, Frederick’s Evangelical Reformed Church had been experiencing turmoil with previous pastors. T.J.C. Williams’ “History of Frederick County” (1910) includes a passage from a letter explaining the early 1830’s period in which Rev. Zacharias was called to town: “There had been an unhealthy commotion and much dissatisfaction in the church during the past two pastorates. This was especially so during the administration of the Rev. Reighly—1833-1835. His ministry was forced to a conclusion as the direct result of his misdeeds. This served in a great measure to wean his friends from him, so that now the congregation with great unanimity turned a second time to Rev, Daniel Zacharias, of Harrisburg, Pa., who was elected pastor by a large majority, his first acceptance being impossible on account of the difficulties caused by Reighly.” Daniel Zacharias was a native of nearby Washington County, MD. Born in the vicinity of Clear Spring on January 14, 1805, he was the son of John George (Christopher) Zacharias and Catherine Kirschner. His grandfather was a German immigrant from North Rhine-Westphalia, who came to the US around 1753 and first settled near Berks County, PA. He would serve in the American Revolution. Young Daniel received a classical education at the Hagerstown Academy, followed by attending Jefferson College in Canonsburg, PA. He remained here through the end of his junior year, at which time he transferred to the Theological Seminary at Carlisle (PA). Zacharias received his academic degree in divinity (Doctor of Divinity), was licensed and ordained in 1828 within the German Reformed Church, an early Protestant denomination brought to this country by German and Swiss immigrants in the 18th century. He was given a charge in York County. Two years later, he was called to congregations in Harrisburg and Schupps, where he would remain here for nearly five years, at which time he moved to Frederick.  Jacob Engelbrecht (1797-1878) Jacob Engelbrecht (1797-1878) Daniel Zacharias’ entrance to Frederick was documented by noted diarist Jacob Engelbrecht (1797-1878) in a post dated April 5, 1835: “The Reverend Zacharias, late of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, arrived here one day last week (with his family) to take charge of the German Reformed Congregation of this city & neighborhood. Yesterday he preached his first sermon. Vice, Reverend Charles Reighley going to Michigan.” Engelbrecht traced the earliest work-related moves of the new minister and in town. Zacharias conducted his first funeral service on April 5, 1835 when he administered the burial of 40-year-old William Quynn in the Mantz Graveyard on W. 4th Street Earlier that day, the reverend preached his inaugural sermon at Evangelical Reformed on April 5th. This took place in the “old church,” known today as Trinity Chapel on the south side of W. Church St. Twelve days later, Dr. Zacharias performed his first marriage in town. This matrimonial union joined George W. Jacobs and Ann Margaret Hamilton. Daniel Zacharias soon learned that he had a charge that included other congregations located outside of the city of Frederick— Carrollton Manor, Mt. Zion and Bethel. Rev. Zacharias had already experienced personal heartbreak before coming to Frederick. His first wife, Jane Hays, had died in late 1831. The couple wed in Carlisle in June 1829 and had only been married for roughly two-and-a-half years before her untimely passing at age 22. He later began courting Catherine Zinn Forney of Harrisburg. They married in March, 1834. When the couple arrived in Frederick in spring 1835, Catherine was two months pregnant. Past difficulties at Evangelical Reformed soon dissipated and Rev. Zacharias received credit for unifying the congregation, something that would last for 38 years, the duration of Zacharias’ tenure at the church, among the longest in the history of Evangelical Reformed Church of Frederick. Under Rev. Zacharias, a new church structure would be built across the street from Trinity Chapel. This building, erected in 1848, cost $24,000. This building still stands today as the Evangelical Reformed Church, United Church of Christ, located at 15 W. Church Street. A German (language) congregation retained the old church for their sole purposes.  Kemp Hall on the SW corner of N. Market and E. Church streets (c. 1870) Kemp Hall on the SW corner of N. Market and E. Church streets (c. 1870) An additional, multi-purpose building was constructed a block to the east of Trinity Chapel at the corner of N. Market and E. Church streets. This structure would provide Sunday school amenities and a social hall for the growing congregation. Commercial storefronts on the ground level of Market Street were rented out in order to collect funds to pay for the whole of the building. This was also built under Rev. Zacharias leadership. A new burying ground was also opened on the corner of N. Bentz and W. Second streets. At one time this cemetery had stone walls built around it (1857). In fall of 1860, the Consistory of the church ordered the steeple on the old church to be repaired and painted. The job fell to church elder Abraham Kemp. Upon finishing the job to thorough expectations, he waved his fee of $742.42 and instead offered his work as a donation to the church. By way of showing appreciation, the Consistory gave their building complex, a block away, the moniker of Kemp Hall. Then came the American Civil War, the most trying time of Rev. Zacharias’ professional career here in Maryland. He had to work extra hard to calm the fears of parishioners. One of the first incidents of war involved the church, and specifically, the newly-named Kemp Hall. This structure served in the capacity as Maryland’s capitol during the spring and summer of 1861, as the state came perilously close to leaving the Union. Because Virginia had seceded in April of 1861, President Lincoln could not have Maryland fall to the Confederacy as this would have surrounded the U.S. capital of Washington, D.C. Two weeks after the Confederate capture of Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor (South Carolina), Maryland’s governor, Thomas H. Hicks, called the General Assembly into special session. The state capital, Annapolis, was southern leaning and seething with resentment over the recent Federal occupation of that city. The decision came for the body to meet here in Frederick, a strongly Unionist city, to debate secession. Both the Senate and the House of Delegates began the session on April 26th, 1861, in the former Frederick County Courthouse building located a block west of the church. The next day, the senators and delegates moved down the street to Kemp Hall, as this structure boasted a better meeting space. As early as June 20th, under Lincoln’s suspension of the writ of habeas corpus, Federal troops began arresting suspected pro-secession legislators, starting with Delegate Ross Winans of Baltimore, who was stopped on his way home from the session here. He, like several other lawmakers, was confined under Lincoln’s orders. Some would be incarcerated at Baltimore’s Fort McHenry, while others found themselves destined or Fort Warren in Boston Harbor. The legislature continued to meet here at Kemp Hall throughout the summer of 1861. Finally, lacking a quorum—primarily because of the arrest of so many secession-leaning senators and delegates—it adjourned in September without ever considering a secession bill. Rev. Zacharias was likely relieved and happy with this outcome. He would be identified as being an ardent Unionist in our “border county within a border state.” Conventional thinking would make one think that the German Reformed congregation would be Union leaning in nature, but there were Southern leaning parishioners here as well. Rev. Zacharias had to unite his flock in faith, regardless of political sides favored. However, Zacharias is best known for a Civil War period incident which would bear witness to his legacy as a Union man “through and through.” Gen. Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson, Robert E. Lee's trusted general, came to Frederick in September 1862 with the Army of Northern Virginia. They had recently been victors at the Second Battle of Bull Run in Manassas, (VA). Gen. Jackson, along with Gen. Lee and other leading officers camped south of town at the Best Farm. In his autobiography entitled "I Rode With Stonewall," Jackson’s aide-de-camp, Henry Kyd Douglas, delivers an amazing story involving our subject, Rev. Zacharias. Henry Kyd Douglas grew up at his parent’s plantation of Ferry Hill, overlooking the Potomac and Shepherdstown (WV) from the east on the Maryland side of the river. His father, Rev. Robert Douglas, was a retired minister in the German Reformed Church and he knew Rev. Zacharias personally.  Rev. Dr. Zacharias in the pulpit of Frederick's German Reformed Church (c. 1860) Rev. Dr. Zacharias in the pulpit of Frederick's German Reformed Church (c. 1860) According to the story, Gen. Jackson asked Douglas and another aide to go to church with him in Frederick. Gen. Jackson had recently been thrown from a horse and was slightly injured, so he rode into Frederick in an army ambulance wagon while his aides rode their horses. Because Presbyterian services were not being held that Sunday night, Gen. Jackson elected to go to the Reformed Church on West Church Street. “The minister, Dr. Zacharias, a man with deep-set eyes and a musical voice, was said to be good preacher, but as usual, the General went to sleep at the beginning of the sermon," Mr. Douglas wrote, “and a very sound slumber it was.” "His cap, which he held in his hand on his lap, dropped to the floor, and his head dropped upon his breast, the prayer of the congregation did not awaken him, and only the voice of the choir and the deep tones of the organ broke his sleep." “The Rev. Zacharias, whose son was serving as a Confederate surgeon, prayed for President Lincoln during the service and was greatly admired in Frederick for doing so in front of Gen. Jackson.” Mr. Douglas wrote that "The general didn't hear it; but if he had I've no doubt he would have joined in it heartily." Dr. Zacharias was one of the most revered ministers in his faith denomination, regularly being called for his leadership over synod committees and ecclesiastical assemblies. Here in Frederick, he gave the address at the laying of the cornerstone for the Female Seminary (later to become the Frederick Woman’s College) and was for many years the President of the Board of Visitors for the Frederick Academy.

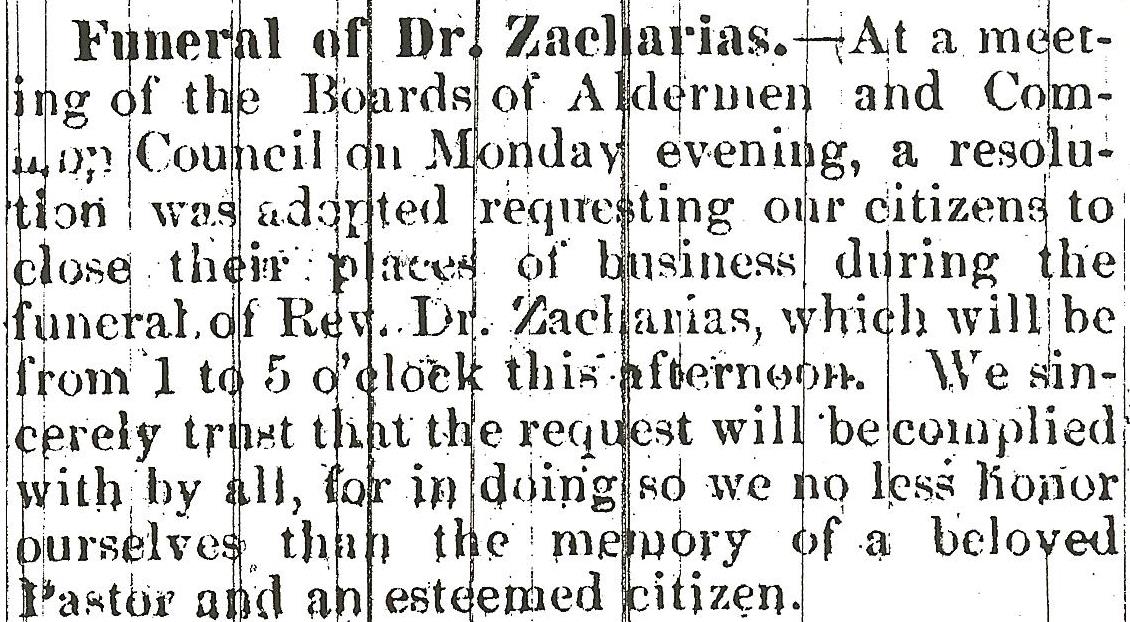

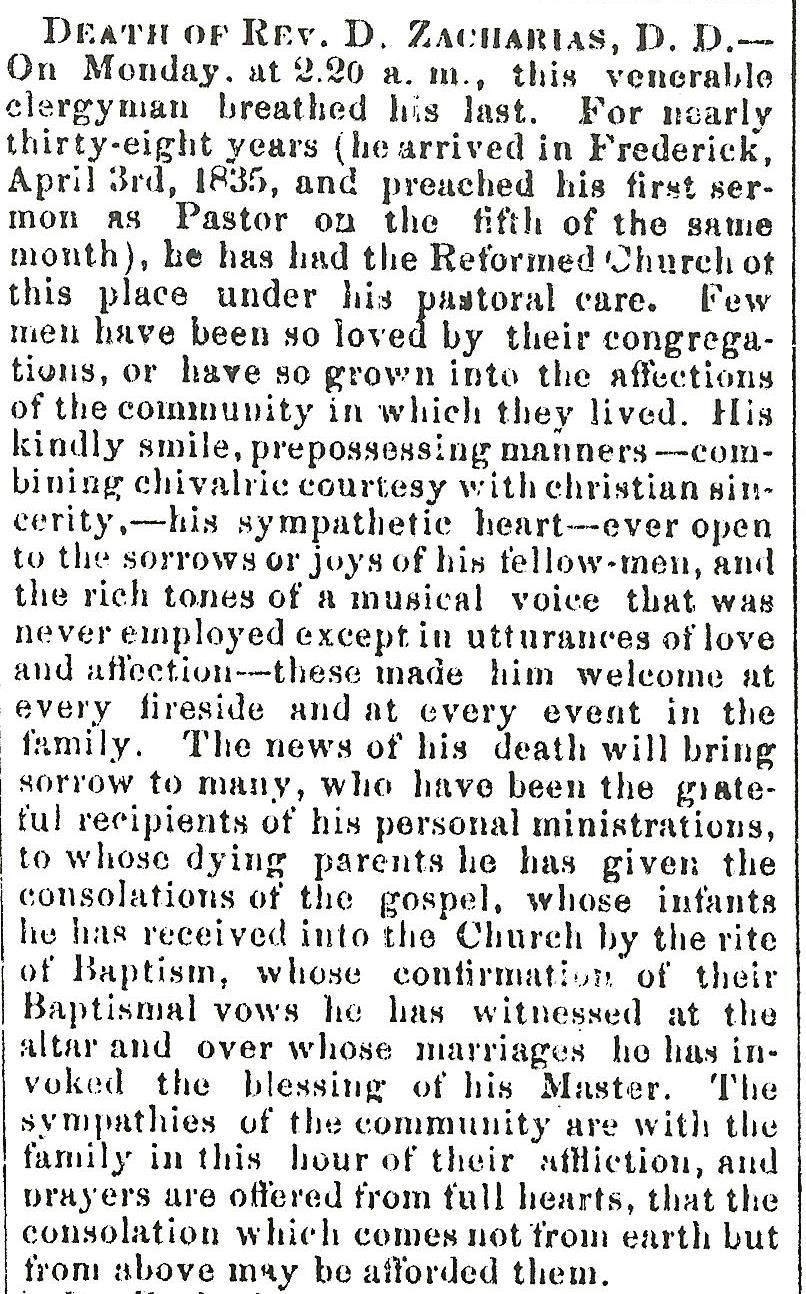

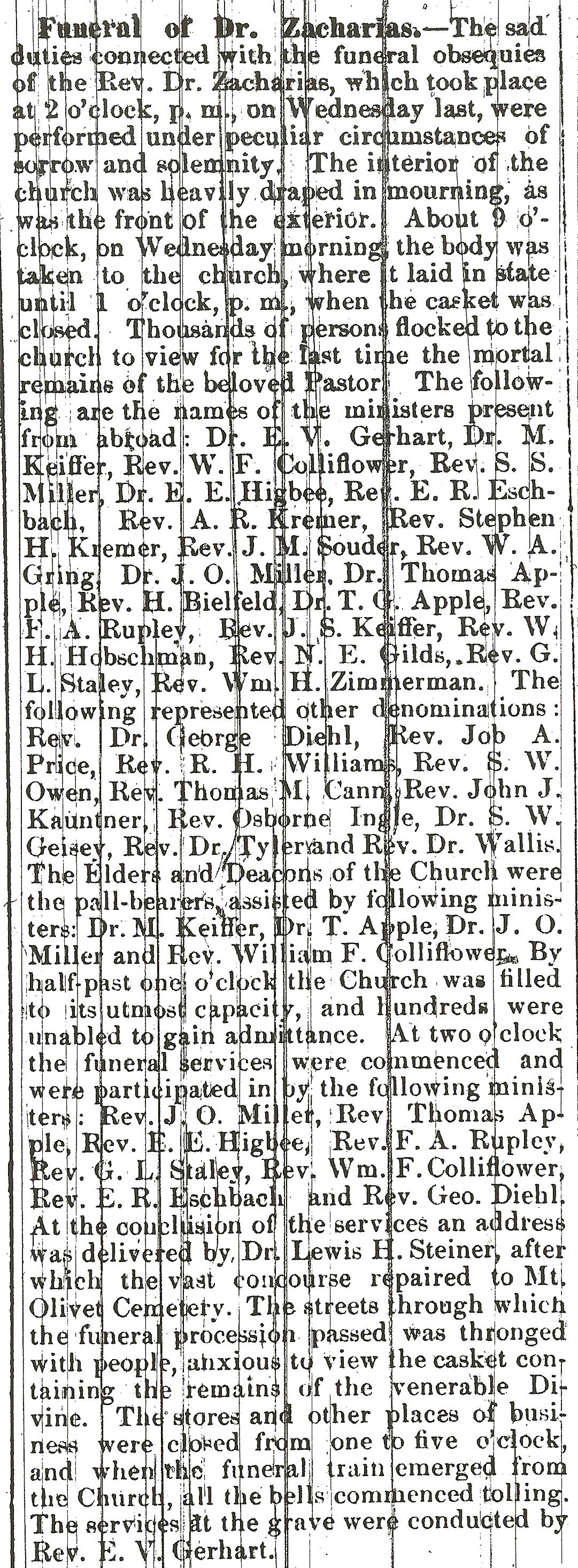

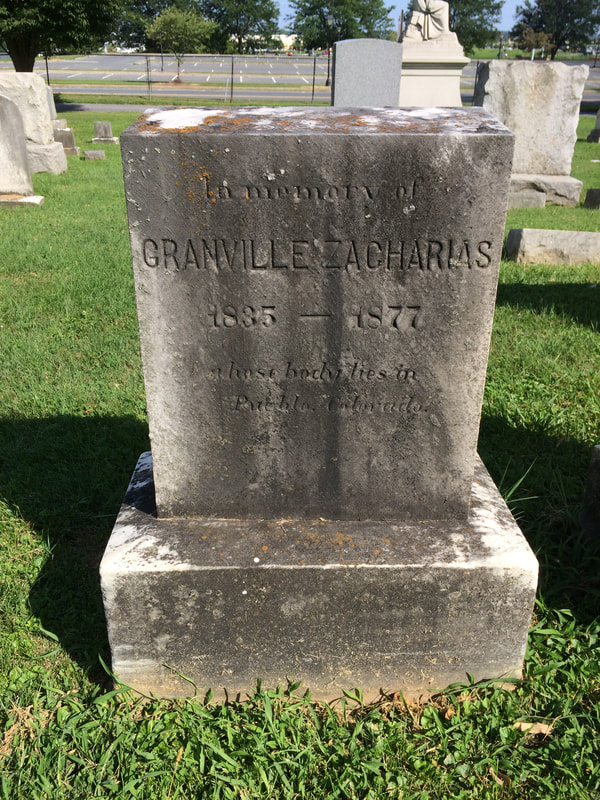

Rev. Dr. Zacharias’ funeral would take place at Mount Olivet Cemetery on April 2nd, 1873. A resolution had been passed two nights prior as the Frederick Boards of Alderman and Common Council requested citizens to close their places of business during the four-hour event. Twenty ministers from the German Reformed Church, including his successor Rev. Edmund R. Eschbach, would be in attendance. Dr. Zacharias body was placed on display for a public viewing in his home church that morning in a service that lasted from 9am until 1pm. Jacob Engelbrecht estimated that “one half of the town & also people from the country went to see him.“ The funeral sermon would be given by Rev. Thomas G. Apple, Professor of the Theological Seminary at Lancaster (PA) and president of Franklin & Marshall College. Rev. Apple’s nephew, Joseph H. Apple, would have another major impact on Frederick into the near future, in his presidency (1897-1934) of the Woman's College of Frederick, operated by the Potomac Synod of the Reformed Church in the United States. This entity would evolve into Hood College. Nine ministers from other Protestant churches were also in attendance at his funeral. It has been said that all the bells in town, Protestant and Roman Catholic, were rung that day during the time of Rev. Zacharias’ interment. An immense concourse of Frederick’s citizenry, and then some, made a procession to the cemetery. T.J.C. Williams would sum up his life in the following manner: “Eminently a man of peace, Dr. Zacharias would rather endure a wrong than contend for his convictions of right. Here in Frederick his memory will ever be green, for all about us are the monuments of his faithfulness, and his works to follow him.” At the time of Rev. Zacharias’ death, the Consistory purchased a desirable lot in Mount Olivet, and gave this to his family. It is located near the southern perimeter in Area C/Lot 137. In 1875, the sum of $1,034.15 was collected by a committee solely created for the purpose of raising an appropriate memorial monument at his grave “a massive shaft of marble, suitably inscribed.” The committee in their concluding remarks state: “The monument, we think, is in keeping with the character and tastes of him whose memory it is designed to perpetuate.” So beloved was Rev. Zacharias that he was memorialized once again with a tablet placed in the main vestibule of Frederick's German Reformed Church. This occurred in late February, 1899—nearly 26 years after his passing in 1873. It's fair to say that he is the true cornerstone of this structure, and the congregation he helped forge throughout his time in Frederick. One-hundred and eighteen years later, the plaque remains on display at the church, now known as the United Church of Christ. Dr. Zacharias’s monument in Mount Olivet stands tall, surrounded by his familial flock including his wife Catherine (1815-1895) and son Granville (1835-1877), a sheep herder who perished from an accidental shooting in Pueblo, Colorado. Another son George Merle (1848-1910) would follow in his father’s footsteps and become a clergyman. Zacharias’ other children would rest in the shadow of the monument and include Confederate veteran John Forney Zacharias (1837-1904), Jane Zacharias (1843-1906), Lawrence Brengle Zacharias (1844-1923), Merle Herbine Zacharias (1846-1847), Edwin Daniel Zacharias (1851-1915) and William Zacharias (1855-1927).

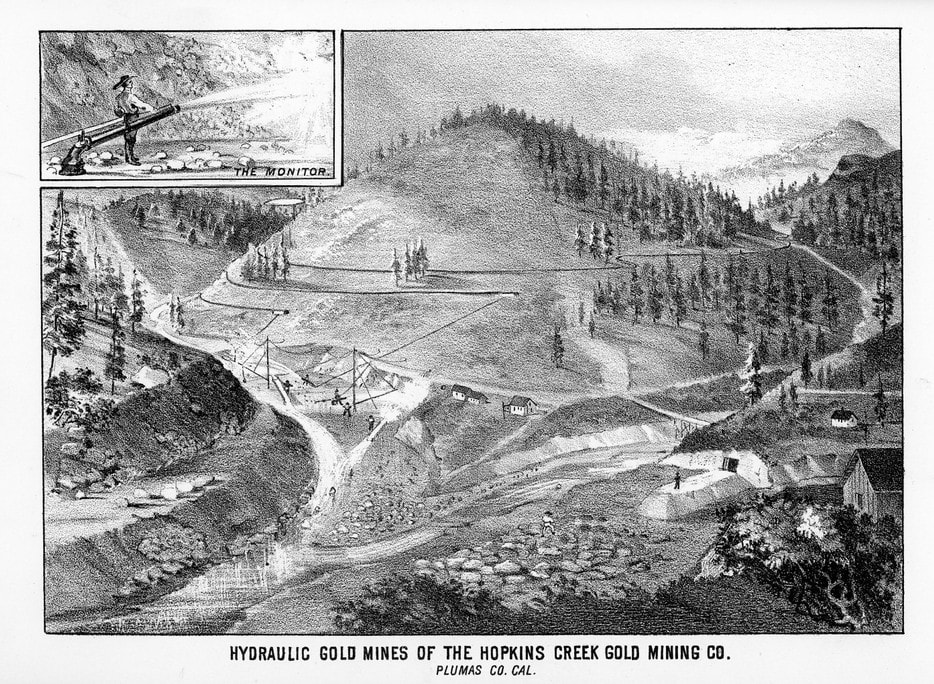

When I was a kid, there were often commercials on television and radio that introduced me to the mystical destination of Pueblo, Colorado. These were usually seen or heard on weekday afternoons and Saturday mornings. Viewers, like me, were introduced to the wonderful world of free, printed advice and information from our U.S. Government via these public service announcements. It was just so easy, all you had to do was call the given telephone number, or write a letter to the address shown on the screen—Consumer Information Catalog, Pueblo, Colorado 81009. Free information, what a great thing to have! This famous Pueblo location is actually one of two distribution facilities operated by the U.S. Government Printing Office’s Agency Distribution Services. Its mission is to store and ship out government publications on behalf of Federal agencies to the public. The other distribution site is in Laurel, Maryland, but this destination doesn’t intrigue me in the least. Perhaps Colorado residents had the same feeling about Laurel, similar to what the rest of us felt toward Pueblo? This was years before any of us had heard the word internet. Nowadays, free information and advice is readily available at your fingertips. As for the U.S. Government Printing Office’s Agency Distribution Services, the Consumer Information Center continues to pump out the goods. In a visit to the GPO’s website (https://pueblo.gpo.gov/Publications/PuebloPubs.php), I learned that the number of distributed material bundles recently reached an incredible milestone—one billion and one thousand million. I haven’t thought about Pueblo, Colorado until recently seeking “information and advice” on an individual buried here at Mount Olivet Cemetery in Frederick, Maryland. This was something distinctly connected to Pueblo, so I had no reason to go to nearby Laurel instead. My research focused on a 42-year-old former native and resident of Frederick named Granville Zacharias. His marble grave monument is not ornate, or outstanding in any way. As a matter of fact, his rectangular, upright stone is pretty uniform, standing in a row of others just the same. This group consists of siblings of the deceased, all dying in various stages in life. They all stand in the shadow of a large 13-foot monument dedicated to the memory of their parents, Daniel and Catherine Zacharias. Granville’s father was the Rev. Dr. Daniel Zacharias, a legend in church annals, and an individual who led Frederick’s Evangelical German Reformed Church for 38 years (1835 and 1873). I soon discovered an amazing irony between father and son as both men were charged with maintaining “flocks of sheep”—both figuratively and literally. Both men would be involved in this endeavor up until the times of their death.  The third home to the Evangelical German Reformed Church, dedicated in 1850 (photo c. 1895) The third home to the Evangelical German Reformed Church, dedicated in 1850 (photo c. 1895) I will share more about Dr. Zacharias in next week’s blog entry, but for now, I’d like to share what little I know about Granville Zacharias. For this I need to take you to Pueblo, Colorado and the year 1877. But first, a scant bit of backstory. Granville Zacharias was born on November 16, 1835. His father had just come to Frederick, a busy crossroads town on the National Road that had just gotten busier thanks to the arrival of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad in town a few years prior. Frederick was not only a center for talented craftsmen and light industry, it was a hub oasis surrounded my rich farmland in every direction. Being the son of a clergyman had its advantages as well as disadvantages surely. I'm assuming the family lived on Church Street in close proximity to the church, if not next to it. Granville was the second oldest of eight children, the oldest male. He would receive his early education in the church, as well as the Frederick Academy located a block from his W. Patrick Street home.  Just days into the new year of 1877, and Granville Zacharias found himself 1,650 miles from home. Colorado had just been admitted as a state five months before. The minister’s son was working diligently to erase debts that he had wrung up earlier in California, where he had formerly lived for many years. He had recently purchased sheep from a Dr. Smallwood and Mr. T.T. Hershberger. He was giving the gentlemen chattel mortgages in payment. He had been raised in a large family, one made even larger based on his father’s profession. Now, he was alone with no one at all. He never had want of anything in younger days, but now found that he had little more than the clothes on his back and his health. Soon, he would lose the latter in the blink of an eye. A horrible accident was to blame, one that was nobody’s fault. Granville Zacharias was just attempting to be a good shepherd, something his father ingrained in his mind, body and soul over his lifetime. January 11, 1877 would be his last. An early “publication” from Pueblo, Colorado gave me the information and advice that I was seeking. The following account was found in the town’s Daily Chieftain newspaper, dated January 14th, 1877 under the headline “Death of Granville Zacharias”: Mr. Granville Zacharias died in this city on Thursday morning from a wound in his leg, caused by the accidental discharge of his own pistol. The deceased kept a flock of sheep, and having lost some of them, was engaged in hunting the stray animals on the prairie this side of the Chico. When in a lonesome place several miles from any settlement, a rabbit jumped up in front of him and he drew his pistol to shoot it. The animal disappeared from view and Mr. Zacharias attempted to return the weapon – a large dragoon pistol, to the scabbard, neglecting to let down the hammer. The pistol was discharged, the ball entering the rear of the leg above the knee and ranging downward, how far is not known. The shooting happened in the morning and the deceased managed to walk about half a mile from the scene of the accident towards his camp. He was able to go no further and towards evening was discovered by one of his own herders who was also in search of sheep. Mr. Zacharias had had some high words with this man a few days before about some sheep that had been smothered, and the herder feared that the wounded man might die before any third party could arrive, and he (the herder) would be accused of having killed him. The herder gave Mr. Zacharias his blankets and coat and made him as comfortable as possible, while the former ran with all possible speed to the camp, secured a team and brought the unfortunate man in. The sufferer was brought to town so that he might have good surgical attendance. Mortification soon set in and in a few days death supervened. His physician would have amputated the wounded limb but the condition of the patient was such that certain death would have resulted. In August 1871, Granville’s mother had bought lot 187 within the cemetery's Area C. This is where the gravestone of Granville Zacharias resides today. But does Granville, himself, lie below the surface? He’s listed in our records as being here, but I can’t find definitive proof that he does, but surely could. I have since located information online saying that the ill-fated sheep herder could be buried in what is known as Pioneer Cemetery on the north edge of Pueblo, Colorado. This was Pueblo’s first, permanent burying ground established in 1870 when a Masonic Lodge purchased 80 acres from the US Government. No stone exists at this place, but apparently this is where Granville’s lifeless body was laid to rest on that lonely day in January, 1877. Perhaps I should contact the Consumer Information Center in Pueblo for assistance? In closing, I guess it could be safe to venture that Granville, himself, could be the rogue sheep that got away from Frederick’s beloved Zacharias flock. We may never know the truth, but at least his life and memory continued to be cherished by family members and friends within the confines of Frederick’s “Cemetery Beautiful.” Header image for story: Vincent Van Gogh's Shepherd with a Flock (1884)

|

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed