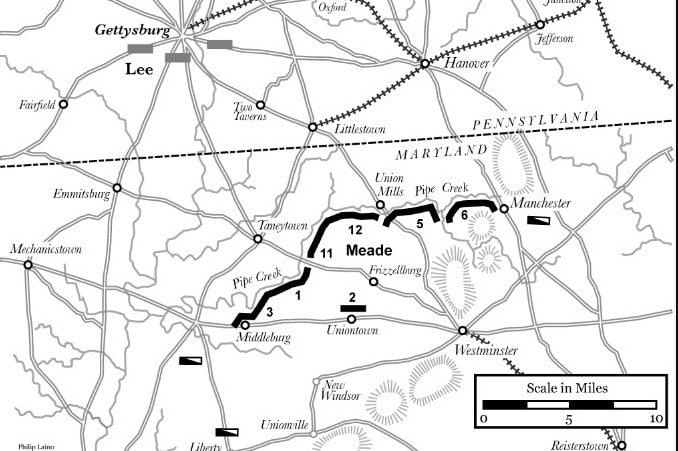

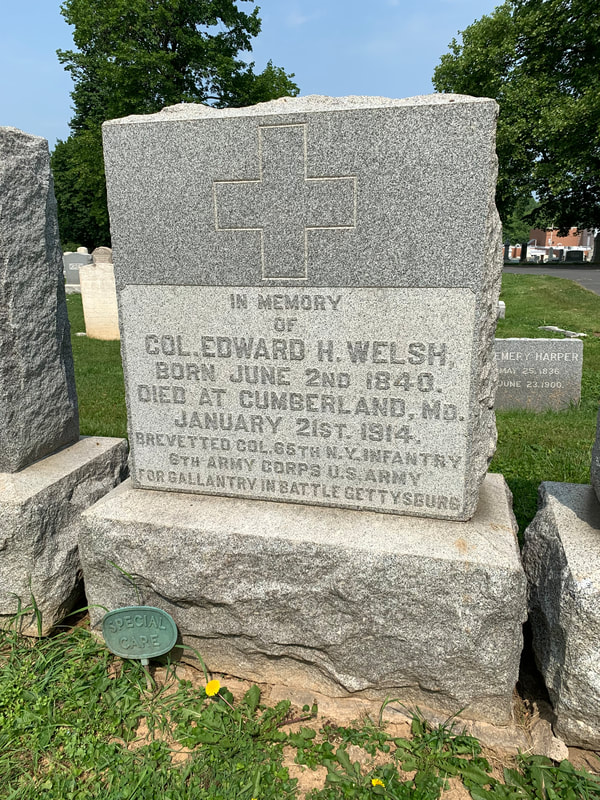

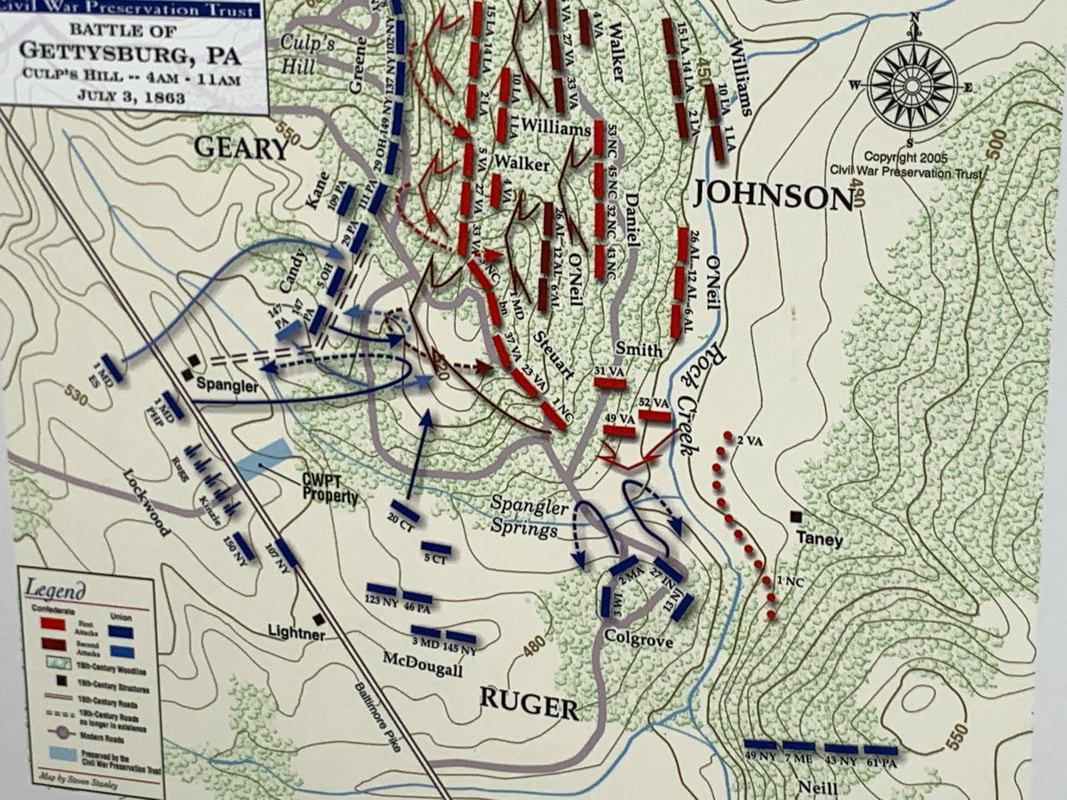

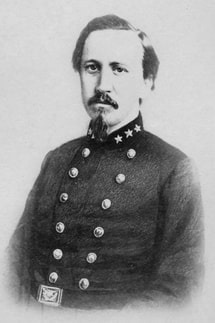

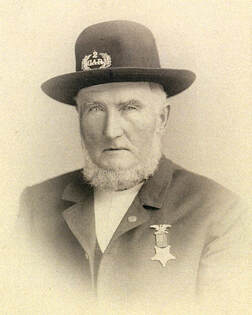

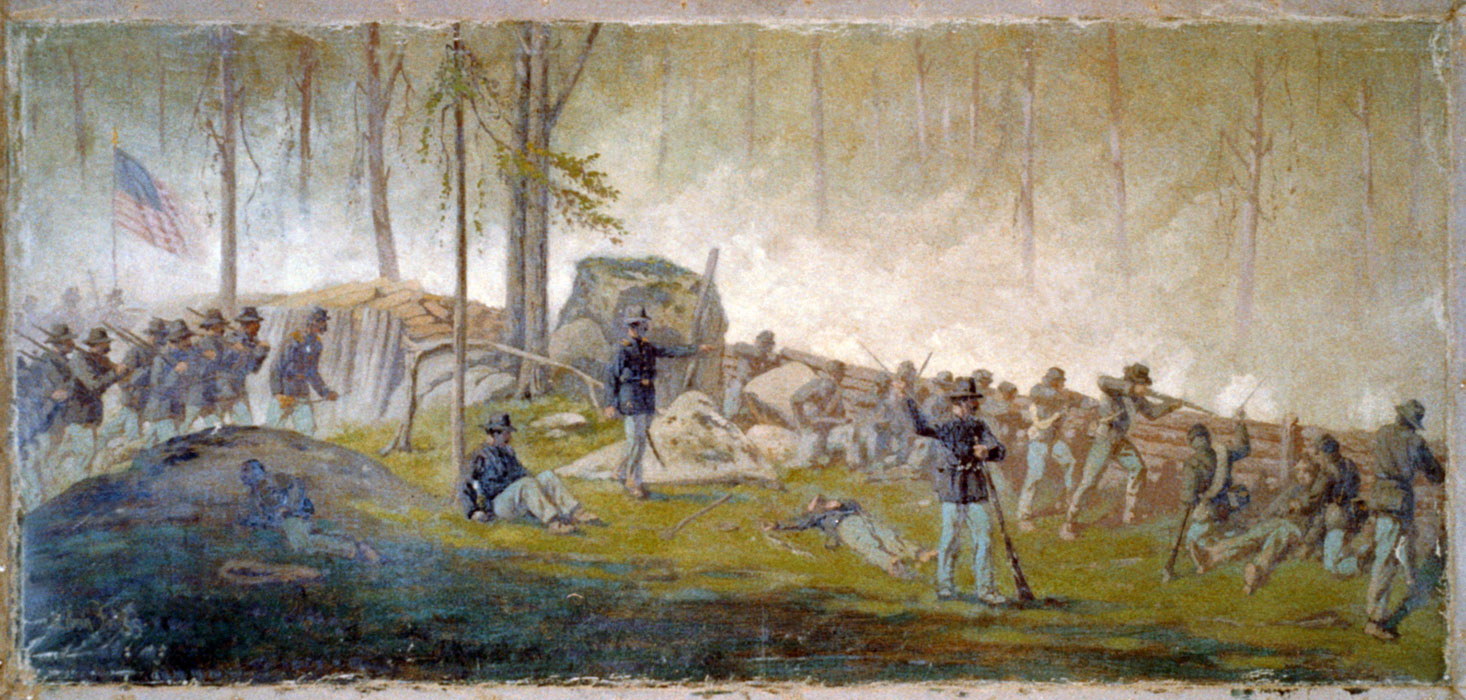

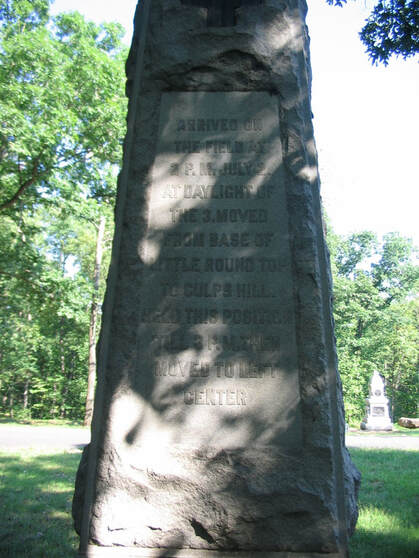

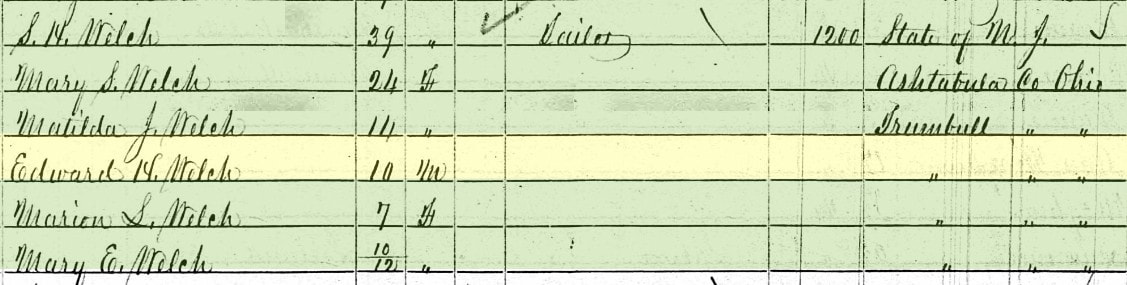

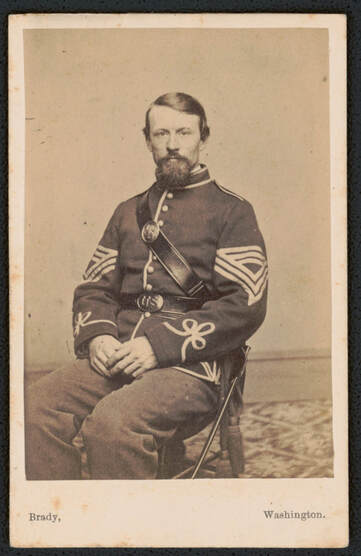

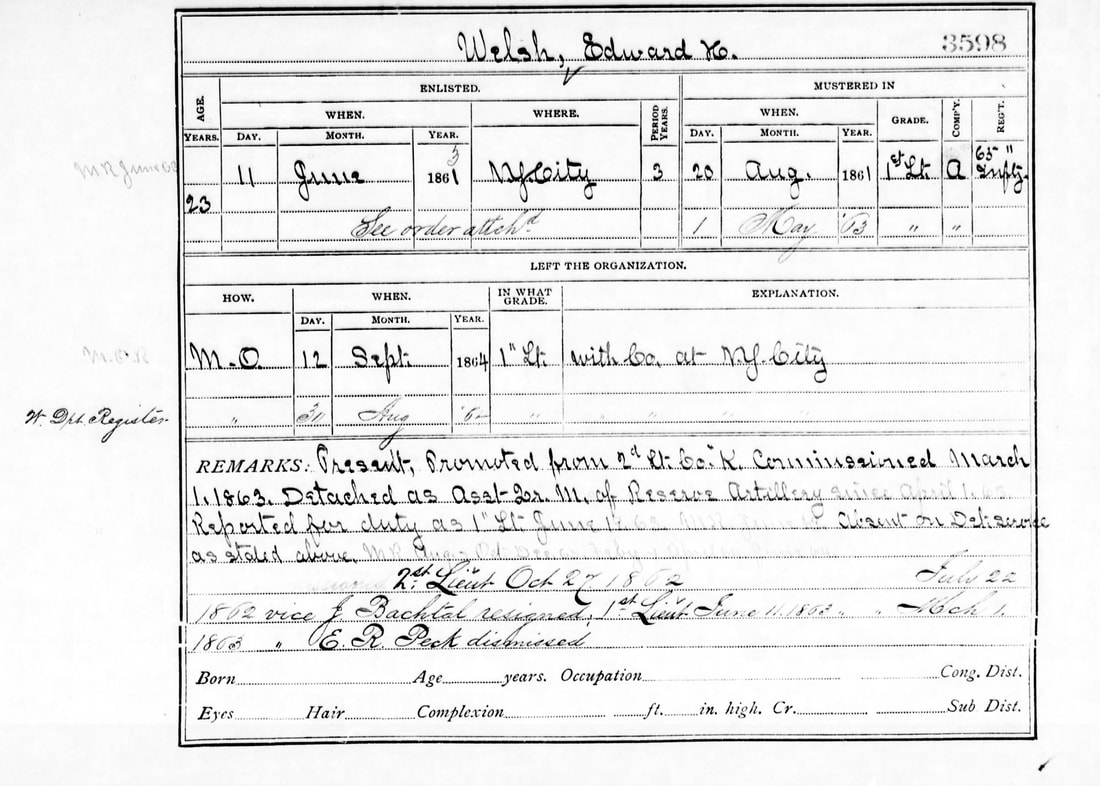

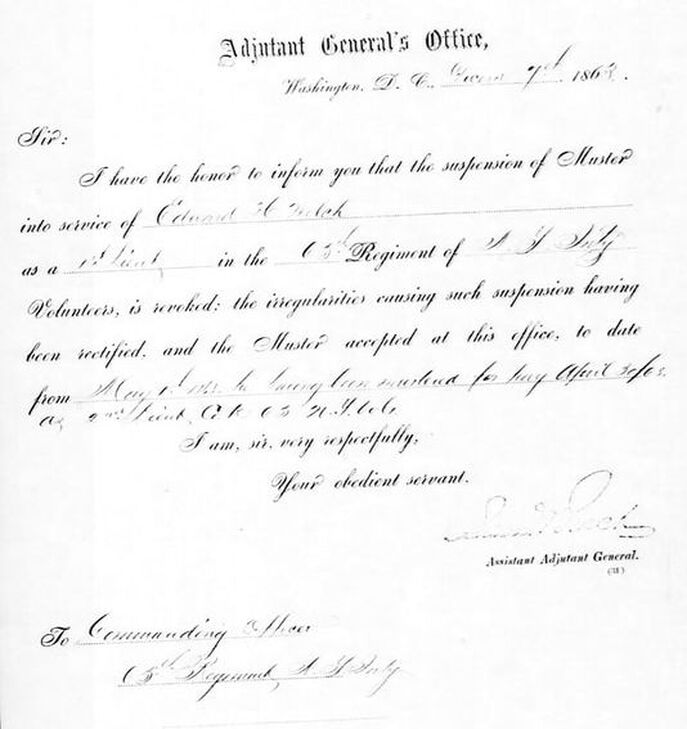

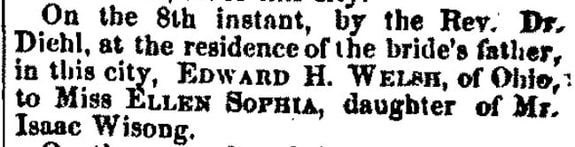

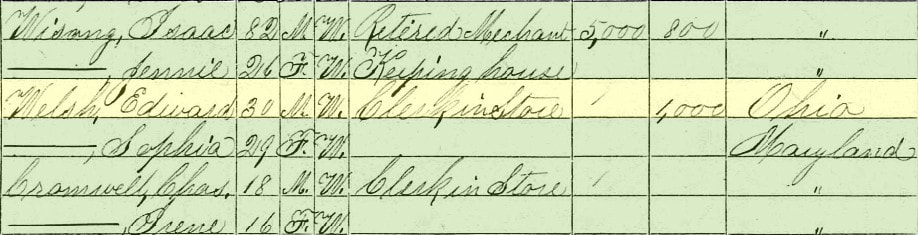

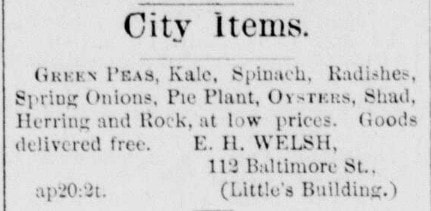

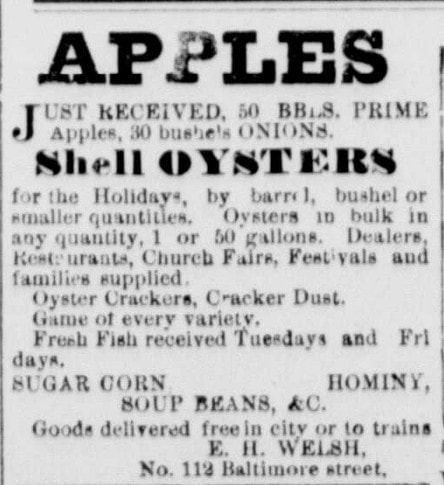

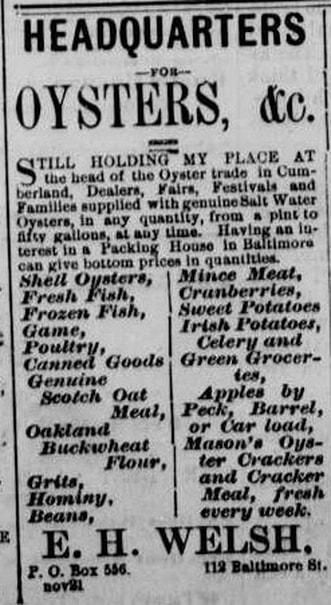

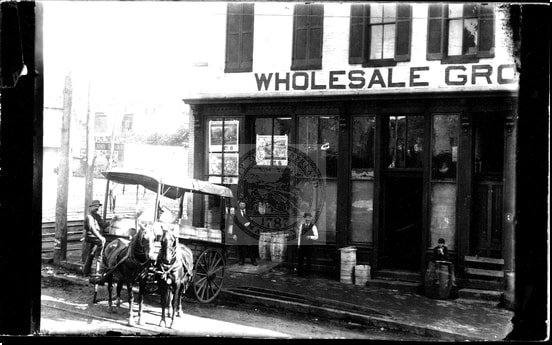

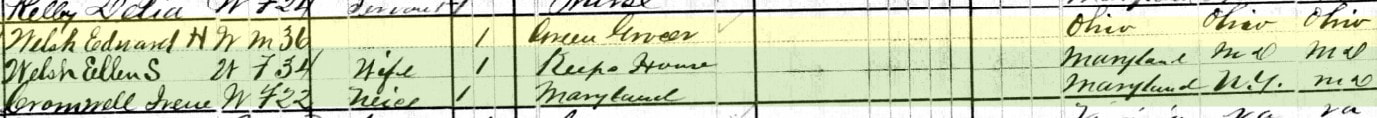

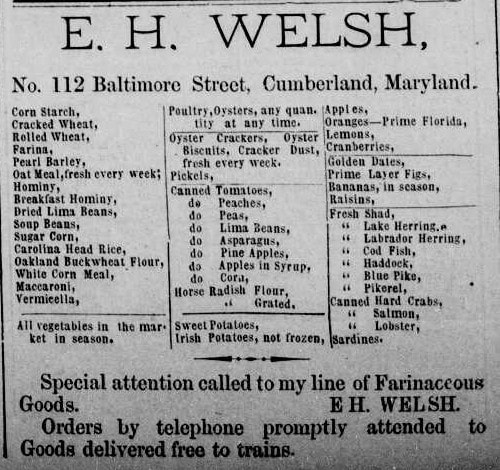

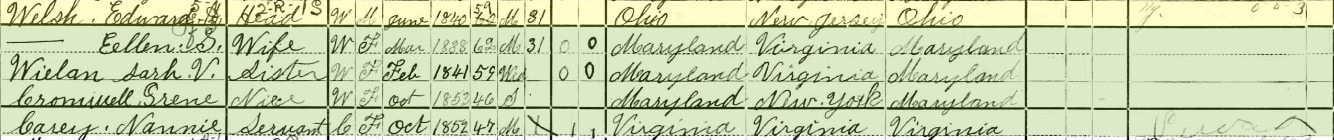

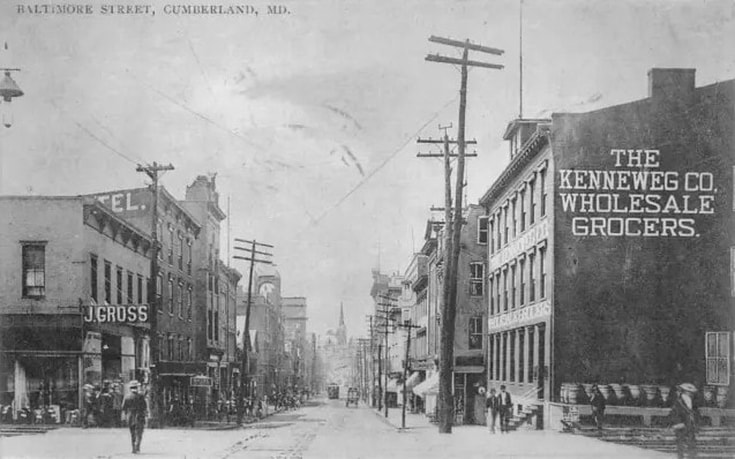

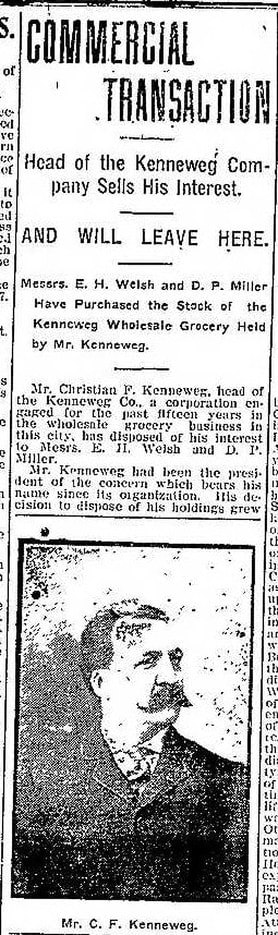

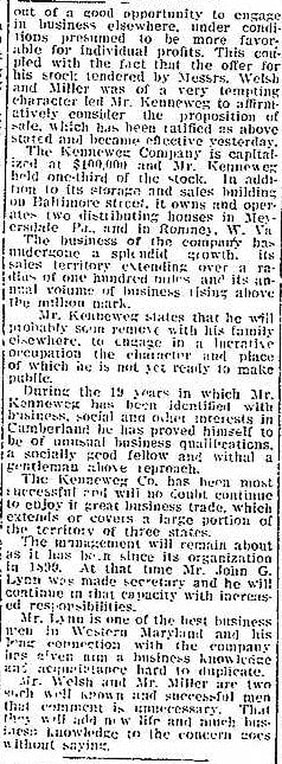

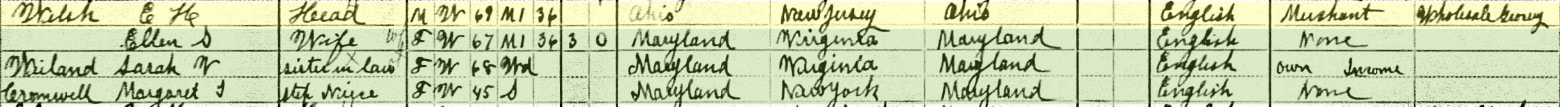

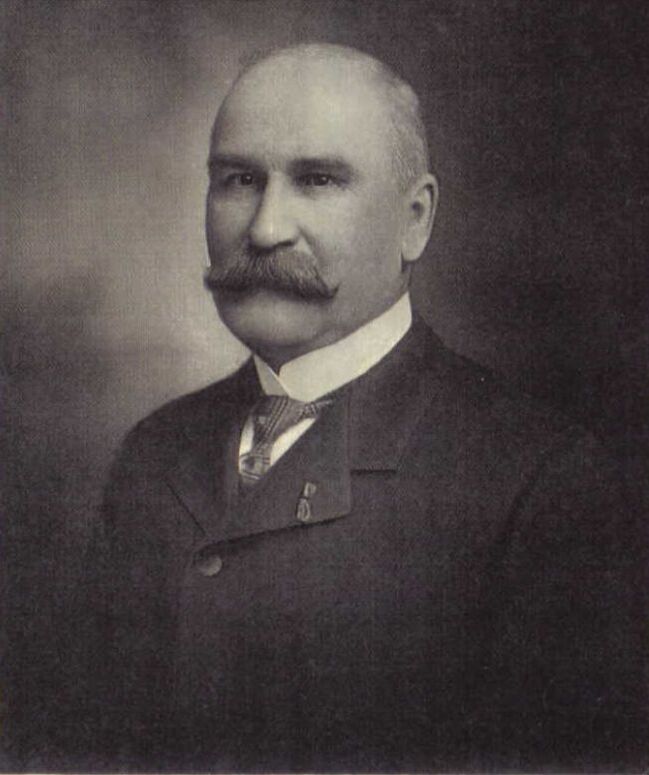

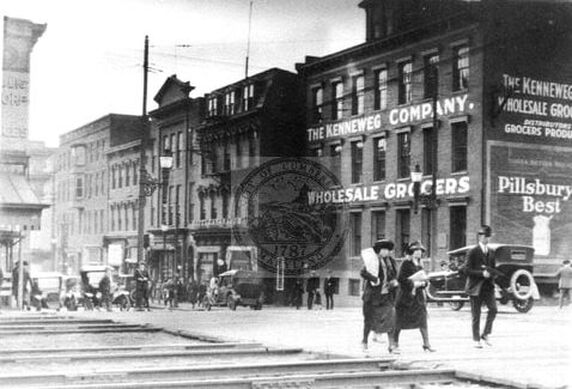

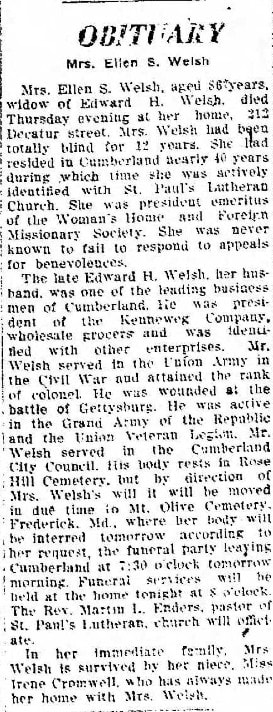

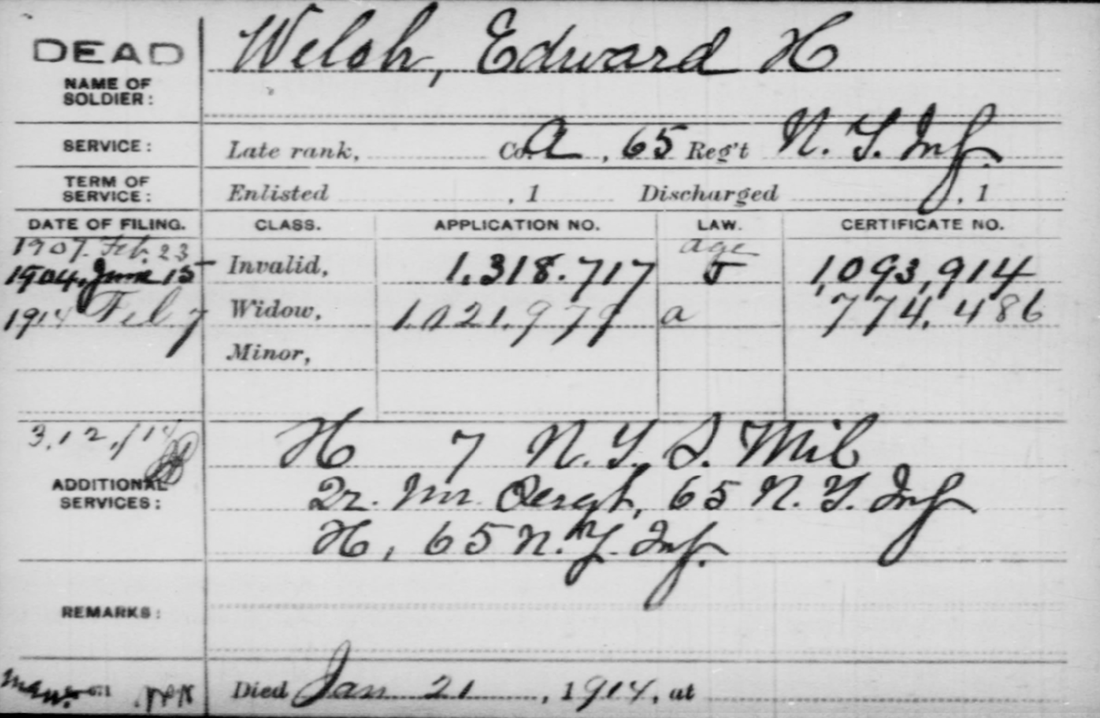

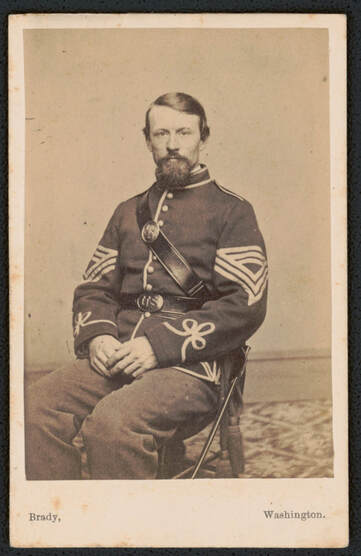

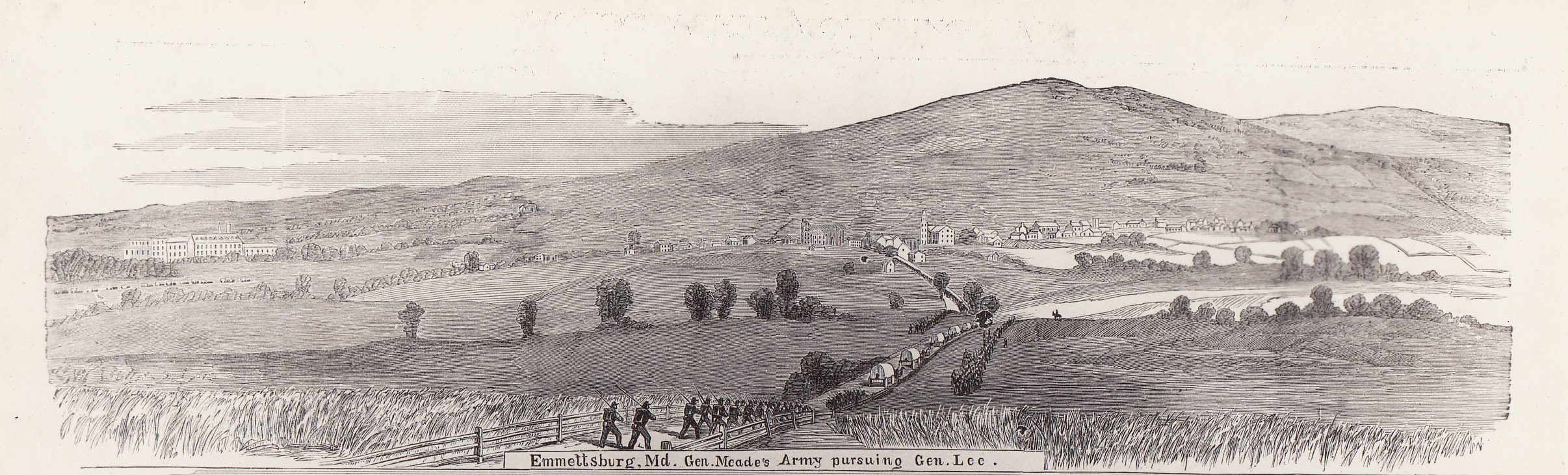

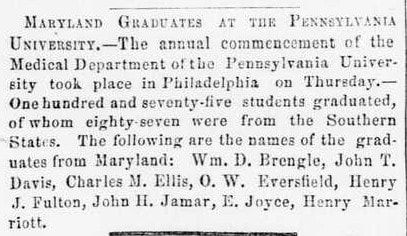

With the 160th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg upon us, I thought it would be fitting to highlight a participant of that legendary conflict for this week’s story subject. His name is Col. Edward H. Welsh, and his gravestone in Frederick’s historic Mount Olivet spells out the fact that he was brevetted for gallantry shown in battle at Gettysburg in early July, 1863. And in case you are not familiar with the word “brevet,“ here is the definition: In many of the world's military establishments, a brevet was a warrant giving a commissioned officer a higher rank title as a reward for gallantry or meritorious conduct but may not confer the authority, precedence, or pay of real rank. An officer so promoted was referred to as being brevetted. Those of you who read last week’s “Story in Stone” know that the Union Army of the Potomac spent a few days in Frederick in late June, 1863. With Gen. Joseph J. Hooker in command, the Army was in pursuit of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee who had crossed the Potomac into Maryland a few weeks earlier with Rebel forces. Lee’s objectives were unknown to the Union forces and the leadership in Washington as this marked his furthest foray into northern territory. Cities such as Washington, Baltimore, Harrisburg and Philadelphia found themselves on high alert. Meanwhile back in Frederick, a messenger had been sent to town with an order from President Lincoln to relieve Gen. Hooker of his duties, and put Gen. George G. Meade in his place atop the Army of the Potomac. Meade and his men of the 5th Corps were encamped at Arcadia, a fine manor house on the Buckeystown Pike, located just north of the small hamlet of Lime Kiln. The actual change of command would occur at Gen. Hooker’s temporary quarters in the early morning hours of June 28th, at Prospect Hall a few miles to the northwest. With little time to plan strategy, Gen. Meade gathered his army which had been encamped in and around Frederick City, and marched them northwards toward the Mason-Dixon Line and Pennsylvania where intelligence reported Gen. Lee and his men to be. Every major roadway leading north from Frederick was utilized by the expansive Union force. Meade would make his next headquarters at Middleburg (Carroll County) on the 29th, and then northeast of Taneytown on the Shunk Farm where he directed the early concentration of his forces between June 30th and July 1st. Ironically, Meade had come from the south northward to meet his rival (coming from the north). His initial plan was one of a defensive nature requiring the spreading out of his troops across a series of entrenchments in northwestern Carroll County utilizing Pipe Creek as a line of demarcation. This has an interesting connection to Mount Olivet, and our most famous resident in Francis Scott Key who grew up along Pipe Creek near Keymar (MD). Key’s birthplace was the family plantation of Terra Rubra. What if the battle had been fought here and not Gettysburg? Could it have spilled over into northeastern Frederick County such as Thurmont (known then as Mechanicstown) or Graceham or Emmitsburg? What if? Instead, the greatest battle of the American Civil War would be fought July 1st–3rd, 1863, in and around the small town of Gettysburg just over the Pennsylvania border. In the conflict, Gen. Meade's Army defeated attacks by Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia, halting Lee's invasion of the North. The battle involved the largest number of casualties of the entire war and is often described as the war's turning point due to the Union's decisive victory and concurrence with its victorious Siege of Vicksburg. There are soldiers here in Mount Olivet that found themselves in Gettysburg on the field of battle in early July, 1863. One of them was a gentleman named Edward H. Welsh. His gravesite is marked by a substantial chunk of granite located adjacent the Key Memorial Chapel in Area H/Lot 5. The gravestone employs a mixed exterior of both polished surface along with rough-hewn sides and base. The lower face of his gravestone has raised, polished lettering and a simple cross. The cross, however, has nothing to do with traditional religion per se, but has a special military meaning as I would soon find out. The simple cross on Col. Welsh’s gravestone can be found throughout Gettysburg National Battlefield Park and signifies the Union Army of the Potomac’s 6th Corps. The 6th Corps had 37 infantry regiments and 8 artillery batteries at the Battle of Gettysburg, organized into 3 divisions of two or three brigades each and an artillery brigade. The military cross that appears on Col. Welsh’s gravestone in Mount Olivet, also appears on a very special monument on the battlefield on Culp’s Hill. As an aside, please check out a website called CivilWarCycling.com in which author Sue Thibodeaux has written an article (geared towards bicycle-bearing tourists) about the monument shapes and symbols at Gettysburg. It is a key to unlocking the symbols on regimental monuments that honor the Army of the Potomac. Sue has written books about other Civil War battlefield sites as well. The 65th New York Monument on Slocum Avenue honors Maj. Gen. John Sedwick’s 6th Corps. (Gen. Henry Slocum, of whom the avenue is named, was in command of the army’s right wing, which included Sedwick’s Corps.) The geographical location of the battlefield here is Culp’s Hill, as mentioned earlier. Particularly interesting for us locally, the action that involved the 6th Corps here occurred on the Union Army’s right on Day 2 and Day 3 of the battle (July 2nd and 3rd), and featured Marylanders of the Union Army pitted against Marylanders of the Confederate Army. On the second day of battle, most of both armies had assembled. The Union line was laid out in a defensive formation resembling a fishhook. In the late afternoon of July 2nd, Lee launched a heavy assault on the Union left flank, and fierce fighting raged at Little Round Top, the Wheatfield, Devil's Den, and the Peach Orchard. On the Union right, Confederate demonstrations escalated into full-scale assaults on Culp's Hill and Cemetery Hill. All across the battlefield, despite significant losses, the Union defenders held their lines. In addition to Edward H. Welsh, two prominent Frederick men were on opposing sides at Culp’s Hill—Bradley Tyler Johnson and Joseph Groff. Brigadier Gen. Bradley Tyler Johnson was a former attorney from Frederick who left town after gathering men to fight for the Confederacy. He would be among the most prominent Marylanders who fought for the South, and led the 1st Maryland Regiment, C.S.A. (Confederate States of America). He is descended from the Tyler and Johnson families of town with roots going back to Baker Johnson, brother of Gov. Thomas Johnson. Bradley Tyler Johnson was born in 1829, the son of Charles Worthington Johnson and Eleanor Murdock Tyler and graduated from Princeton in 1849. He read law with William Ross of Frederick, and finished his legal degree at Harvard. He was admitted to the bar in 1851. Johnson is not buried here, but rather in Loudon Park Cemetery in Baltimore. About 100 yards directly behind (and west) of Edward H. Welsh’s grave is that of Capt. Joseph Groff of the Union’s Potomac Home Brigade. This outfit was made up of local men from our area. I wrote a “Story in Stone” on Captain Groff and you can read more on him at your leisure. On the third day of battle, fighting resumed on Culp's Hill, and cavalry battles raged to the east and south, but the main event was a dramatic infantry assault by around 12,000 Confederates against the center of the Union line on Cemetery Ridge, known as Pickett's Charge. The charge was repelled by Union rifle and artillery fire, at great loss to the Confederate army. Lee led his army on a torturous retreat back to Virginia. Between 46,000 and 51,000 soldiers from both armies were casualties in the three-day battle, the most costly in US history. Both Capt. Groff and Lt. Welsh would be wounded at Culp’s Hill, not far from Spangler’s Spring. The landmark is down below the hill from the 65th New York Infantry Monument marking the ground Welsh, and his fellow soldiers, stood upon 160 years ago. One side panel of the monument reads: “Arrived on the field at 2 P.M. on July 2. At daylight of the 3rd, moved from the base of Little Round Top to Culp’s Hill. Held this position til 3 P.M. then moved to the left center.” The 65th’s brigade commander, Col. Alexander Shaler, was relatively new in his position. His recent promotion came following heroics at the Battle of Salem Heights (VA) in which he, himself, displayed gallantry under fire leading him to earn the Medal of Honor, the United States Armed Forces' highest military decoration. Lt. Colonel Joseph E. Hamblin was promoted to colonel as a result, and took direct command of the regiment. At Gettysburg, he had brought 319 men to the field, including Lt. Welsh. Hamblin lost 4 men killed and 5 wounded during the three-day engagement between July 1st-3rd, 1863. One of those wounded was our subject Edward H. Welsh. Edward Horace Welsh was born on June 2nd, 1840 in North Bloomfield, Trumbull County, Ohio. His parents were Samuel H. Welsh (1811-1900) and Matilda (Flower) Welsh (1815-1846). A biography of Col. Welsh can be found in the History of Allegany County, Maryland by James Thomas and Thomas J. C. Williams (published 1923). It reads: “He was reared and educated in his native state. When still a lad, moved to Cleveland, Ohio, and later became a member of the Cleveland Grays, a company organized in that city. When war broke out between the States, he enlisted as a member of the Seventh New York Militia, and served with it until it was mustered out ninety days later, and he then enlisted, with the First Regiment of United States Chasseurs, also called the Sixty-fifth New York Volunteer Infantry, and July 11, 1861, was appointed quartermaster-sergeant of this regiment because of his patriotism and valor. At the time of this later enlistment he was only twenty years of age, and yet in spite of his youth served with distinction throughout the entire campaign. At the battle of Fair Oaks, or Seven Pines, as it is sometimes called, he was wounded in the breast, leg and ankle, and, as a reward for meritorious service, was made a second lieutenant. On October 28, 1863, Mr. Welsh was appointed first lieutenant of the Sixth Artillery, New York State Volunteers, and served with distinction during the three days battle of Gettysburg, and was very active in the placing of artillery at strategic points, and for this splendid service was brevetted colonel. A monument in honor of the service performed by his regiment now stands near the entrance to the Gettysburg National Cemetery. Subsequently he was assigned to the personal staff of General Hunt, of the Artillery of the Army of the Potomac, where he served with distinction until the close of the war. In spite of his severe wounds he never drew a pension, nor did he ever apply for one, "it being his pleasure that he served his country and was wounded in its service because of his patriotic love for it, and not for any material reward.” The History of Allegany County biography continues: “After his honorable discharge, Mr. Welsh went to Frederick City, Maryland. On November 8th, 1869, Mr. Welsh married Ellen Sophie (Wisong) (1838-1923) of Frederick City. She grew up in a house found on East Patrick Street.” Welsh supposedly came to Frederick and sold lightning rods. After marrying, the couple lived together with Ellen’s widowed father, Isaac Wisong, and sister Jennie. Also living here were Ellen’s 16-year-old niece Margaret Irene Cromwell and nephew 18-year-old Charles Cromwell. The men (Edward and Charles) are listed as working as store clerks, and I would bet they worked at the Excelsior Stove House of N. J. Wilson located on E. Patrick Street. which featured a lightning rod department; or in either of grocery stores, as two were located near their home in the 100 block of East Patrick Street. (The Wisongs lived at 117 E. Patrick according to records). These groceries were Holbrunner’s Grocery and Plummer’s Grocery at the time (1870). Welsh worked as a hotel clerk in Cumberland as early as 1873. Another excerpt from the biography found in the History of Allegany County by Williams and Thomas tells of Welsh's move from Frederick to western Maryland but mentions the job he would "leave the hotel" for: “In 1873, he came to Cumberland, and established himself in the wholesale and retail green grocery business on Baltimore Street, and later became associated with the Kenneweg Company, wholesale grocers, was its president for a number of years until his death January 21st, 1914. He was a director of the First National Bank, and the Cumberland Dry Goods & Notion Company, both of Cumberland, and never lost his deep interest in the welfare of the city, and the development of its enterprises. Mr. Welsh took an active part in the operation of the Allegany Building, Loan & Savings Company, and demonstrated his faith in the city and county by investing in their different enterprises. A strong Republican, he was honored by being the successful candidate of his party for the office of city councilman, and was returned to that office after serving one term.” Let’s break this published bio down a bit, shall we? In the 1890 Cumberland Directory, the Welshs lived on Baltimore Street, next door to their grocery business. Ads from 1889 say that the E. H. Welsh Grocery was located at 150 Baltimore Street. Perhaps a renumbering occurred, or a move to a different building occurred. Regardless, they would re-locate from this home at some point before the 1900 census was taken, as they can be found living in a house they owned on Decatur Street. Edward was active in the National Civil War Veterans fraternal organization known as the Grand Army of the Republic, or G.A.R. for short. In 1903, Edward H. Welsh was appointed as an Aide-de-Camp of the National Commander in Chief of the G.A.R., and in 1905 he could be found serving as Commander of the Tyler Post #5 in Cumberland. Welsh represented the Department of Maryland at the National Encampment of the G.A.R. in Denver, Colorado in September, 1905. He also represented the Cumberland G.A.R. Post at the annual Department Encampment in Baltimore in April, 1906. In business, our subject was re-elected as a director of the Inter-State Trust Company in 1907, and again in 1909. In 1907, Edward and a business associate bought the large Kenneweg Company Wholesale Grocery store, a chain store affiliate of the Pittsburgh firm of the same name. Mr. Christian Kenneweg had come to town in the late 1880s, and Col. Welsh seems to have kept his composure and competed for years without issue. Mr. Kenneweg likely saw something in Welsh to eventually sell the location/franchise to him.

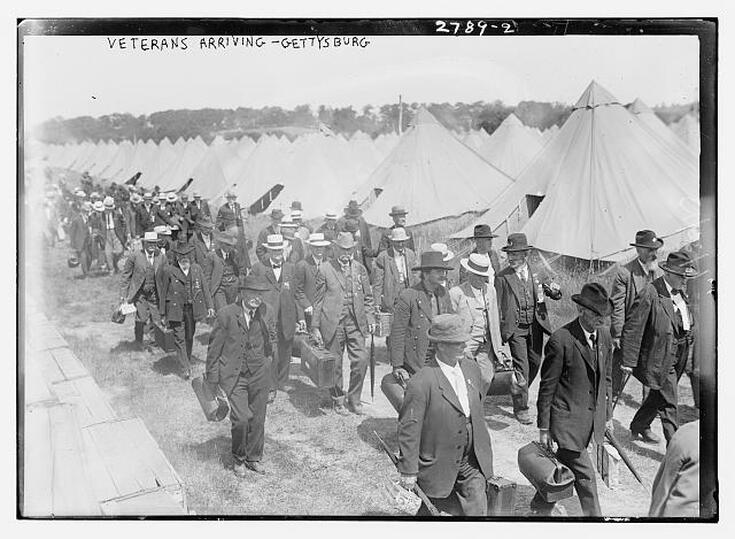

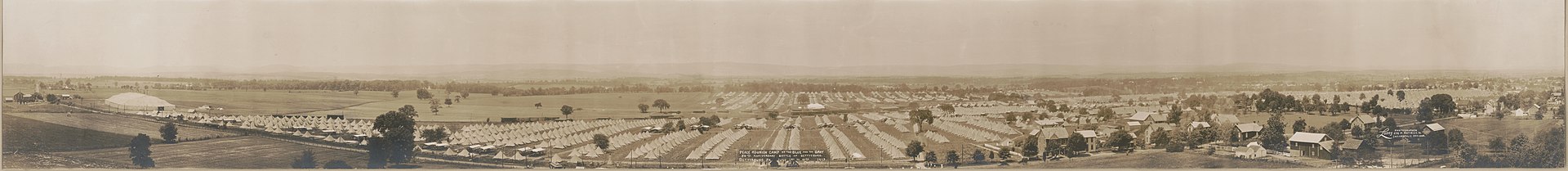

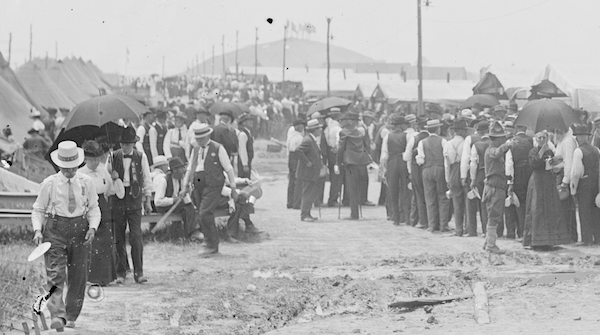

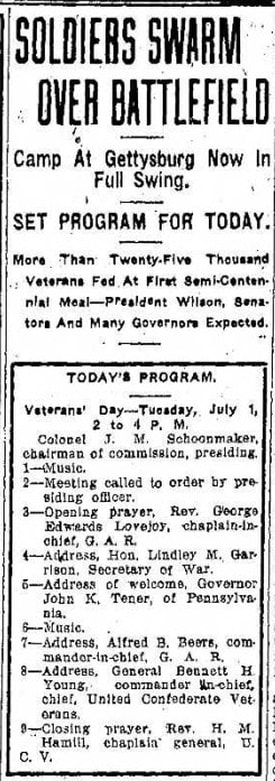

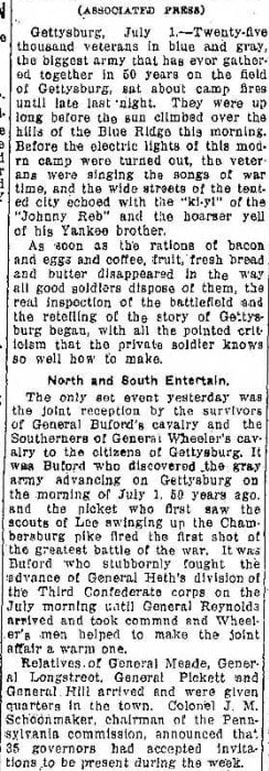

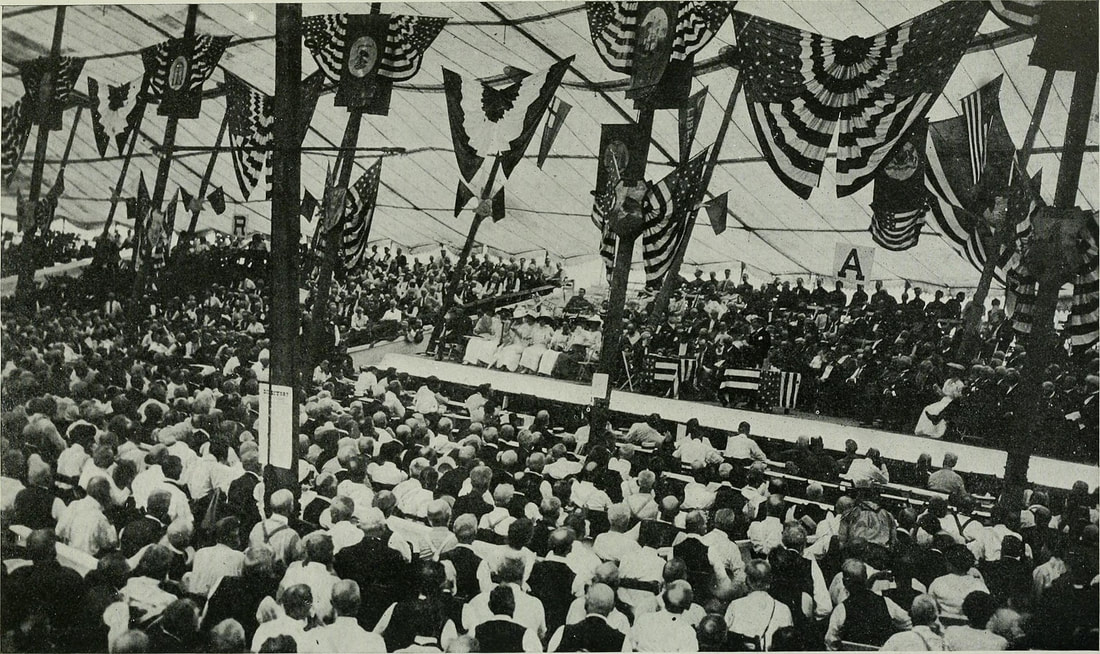

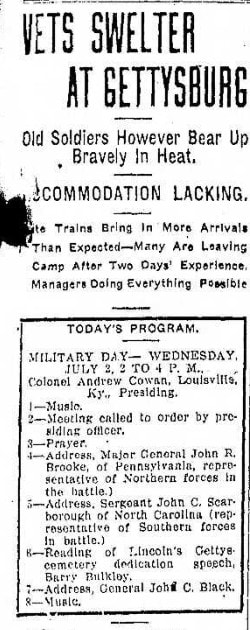

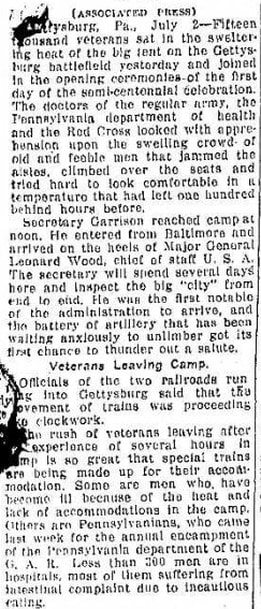

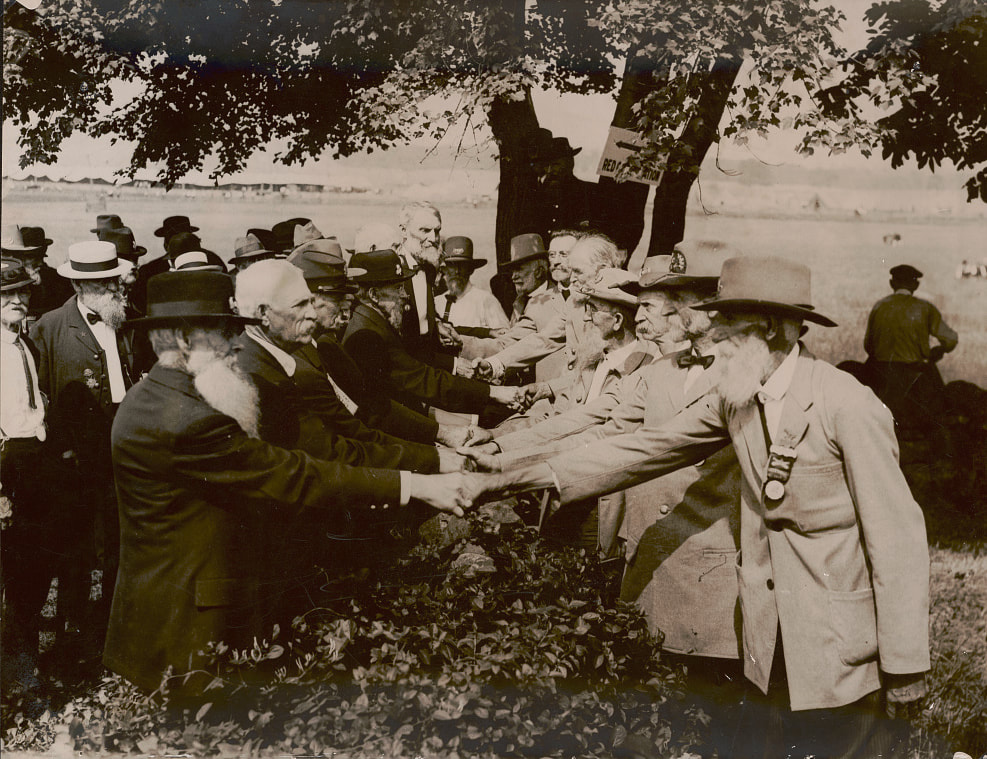

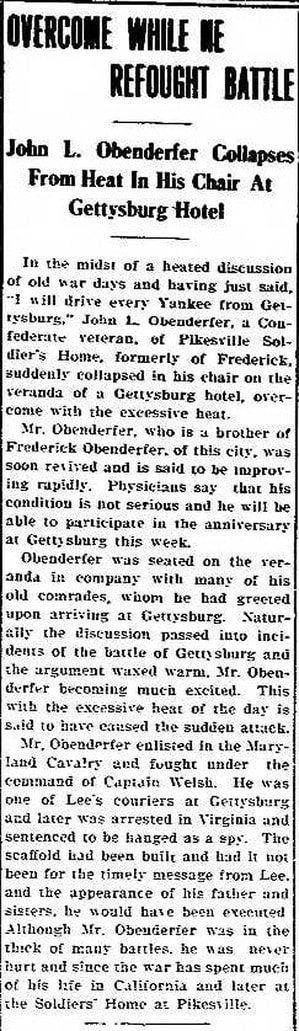

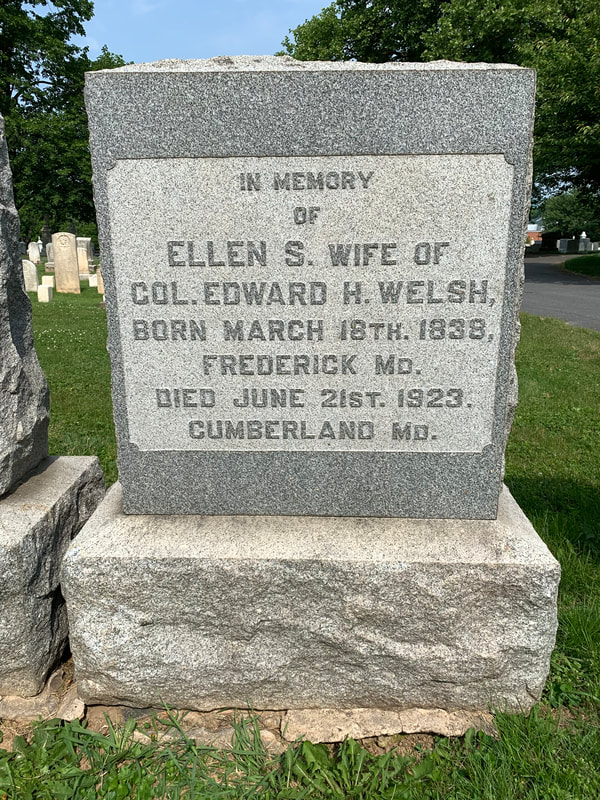

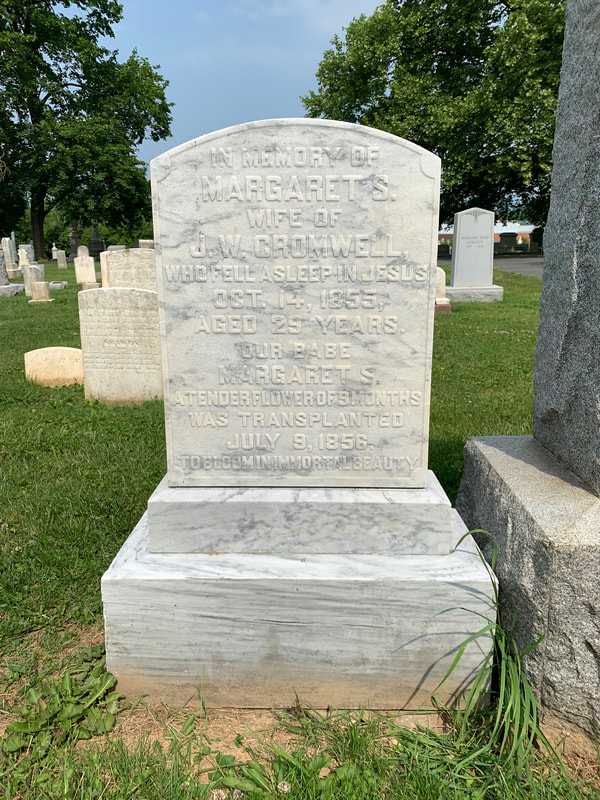

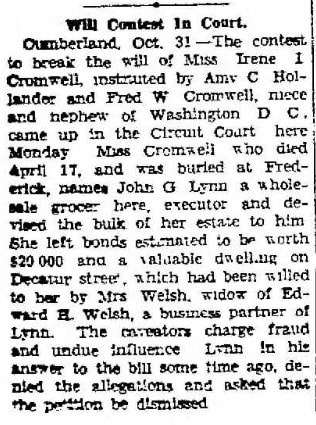

Col. Welsh was now 70 years of age by early July, 1910 and the 47th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg. He continued his activities in business, civic and personal life. I searched the local papers for any mention of Col. Welsh’s participation in the activities marking the 50th anniversary of the most famous battle fought on American soil. This was a big deal as thousands of soldiers gathered in the central Pennsylvania town to participate in commemorative events marketed as "The Great Peace Reunion." It would be held in sweltering heat, and was attended by President Woodrow Wilson, former officers of the battle and other dignitaries. I would have to assume that Col. Welsh was there in Gettysburg with old friends and foes from 1863 for that amazing commemoration. Here was a man very proud of his military service, exemplified by participation at the highest leadership levels in the G.A.R. activities, and having a gravestone that makes special note of his participation in the Battle of Gettysburg. I’d bet money that Edward H. Welsh was there in Gettysburg from July 1st-4th, 1913. I thought I had something when a Frederick newspaper online search provided me with a Welsh result pertaining to the Gettysburg commemoration of 1913. However, I soon deducted that this gentleman was not our Edward H. Welsh. The article centered on another former resident named John L. Obenderfer who once reported to a “Capt. Welsh” in the Confederate ranks. It is a comically written story so I decided to share with you nonetheless. Getting back to our Col. Welsh of Frederick and Cumberland, I am happy to think that he had this amazing experience in Gettysburg of attending the 50th anniversary commemoration. This is even more poignant because five months later, Edward H. Welsh would be gone. He died on January 21st, 1914 in Cumberland. The History of Allegany County states: “For about a year prior to his demise Mr. Welsh was in poor health, but his death came as a shock to his many friends in the city and county. His funeral was largely attended by the leading citizens of this region, who flocked to honor one who in life had rendered so public-spirited a service, and set so high an example of honorable living. Interestingly, interment was not made here in Mount Olivet. Instead, Col. Welsh was interred in Cumberland’s Rose Hill Cemetery.” Ellen S. Welsh continued living in the couple’s home in Cumberland. She also would receive her late husband's pension. Her live-in companion remained niece Margaret Irene Cromwell. She died in 1923 at the age of 85 in Cumberland, however her body was brought to her native home for burial. She would be laid to rest in her family plot in Area H/Lot 5 just outside Key Memorial Chapel, newly constructed less than a decade before. Mrs. Welsh left quite an estate behind, a testimonial to her late husband’s business acumen. It was worth an estimated $200,000 according to her will. Without any direct heirs, the majority of the estate would go to niece Margaret Irene Cromwell. Mrs. Welsh’s last wishes directed that the body of her late husband Edward be exhumed and re-interred next to her in Mount Olivet at the time of her death. This would be completed six months after Ellen’s funeral . Edward’s body arrived at the cemetery on November 23rd, 1923. An additional bequest included $200 to be paid to Mount Olivet for the upkeep of the family plot. Margaret Cromwell had started her life in Frederick, but would stay in Cumberland living in the home on Decatur Street until her death in 1933. Margaret's executors would sell the former Welsh family home to Allegany Hospital of the Sisters of Charity in 1935. Ms. Cromwell's body would be brought back to Frederick like the Welshs. She would be buried next to Col. Welsh and Ellen, her adopted parents for the bulk of her life one could say. A final person of note in this plot was Margaret’s mother of the same name. She was Ellen Welsh’s sister who died at age 29 in October 1855. This was less than two weeks before daughter Margaret’s second birthday. So on this 160th observance of the Battle of Gettysburg, let us not forget that "freedom is not free." The idiom expresses gratitude for the service of members of the military, implicitly stating that the freedoms enjoyed by many citizens in many democracies are possible only through the risks taken and sacrifices made by those in the military, drafted or not. The saying pertains to Col. Welsh and thousands of others in Mount Olivet who participated in conflicts that allow us to attend baseball games, eat hotdogs and drink beer at family picnics, go to the beach, and watch fireworks this holiday weekend if we so please. So be sure to give the colonel's "illustrative" gravestone a nod of respect if you happen to be in the cemetery anytime soon. AUTHOR'S NOTE: Special thanks to Karl "Woody" Woodcock and Gary L. Dyson for the advance research work both gentleman have done on our Civil War soldiers at Mount Olivet. Some of that research was utilized in pulling together this story. History Shark Productions presents:

Chris Haugh's "Frederick History 101" Are you interested in Frederick history? Want to learn more from this award-winning author and documentarian? Check out his latest, in-person, course offering: Chris Haugh's "Frederick History 101," with a 4-part/week course on Tuesday evenings in late August/early September, 2023 (Aug. 22, 29 & Sept 5, 12). These will take place from 6-8:30pm at Mount Olivet Cemetery's Key Chapel. Cost is $79 (includes 4 classes). In addition to the lecture class above, four unique "Frederick History 101 Walking Tour-Classes" in Mount Olivet Cemetery will be led by Chris this summer. These are available for different dates (July 11, July 25th, Aug. 8th and Aug 23rd) Cost $20. For more info and course registration, click the button below! (More courses to come)

0 Comments

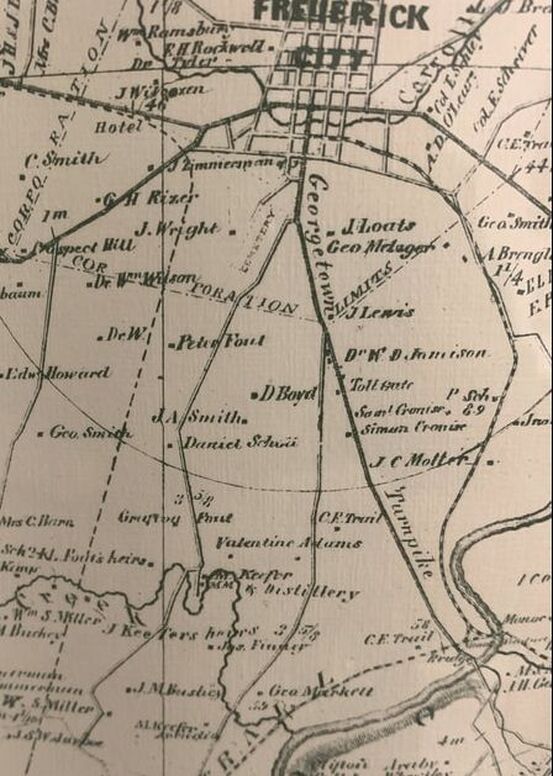

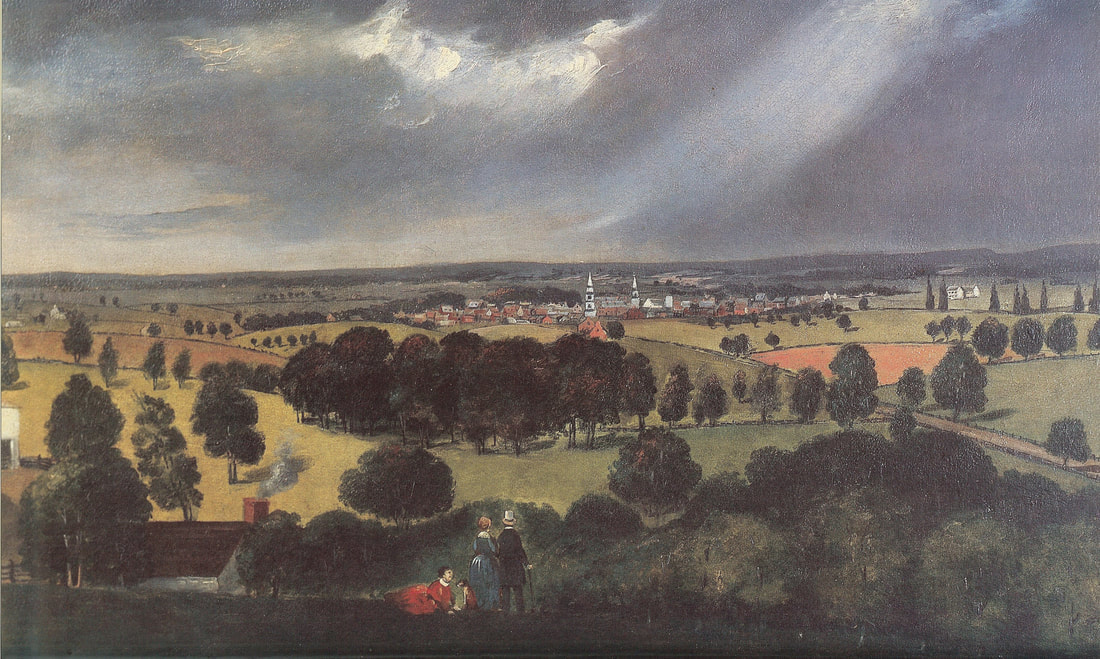

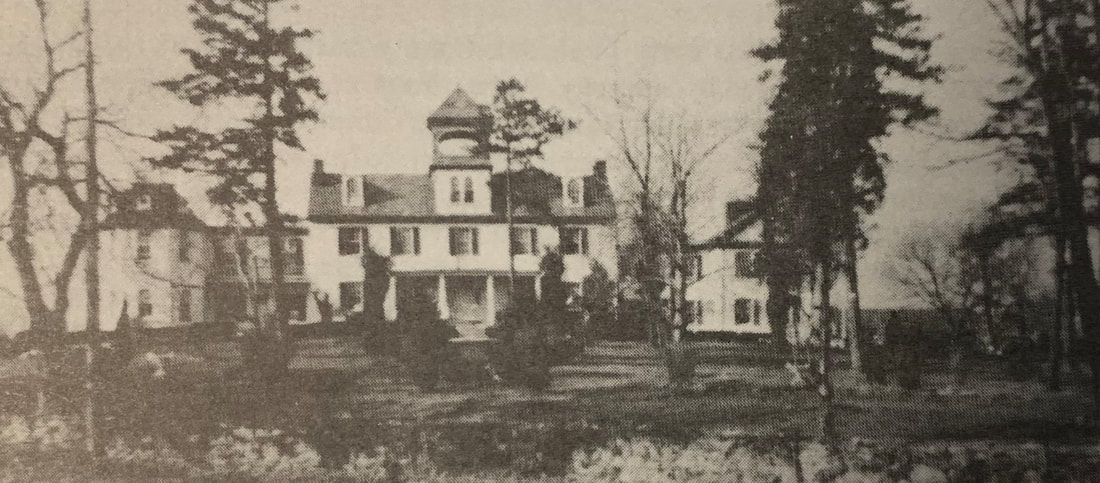

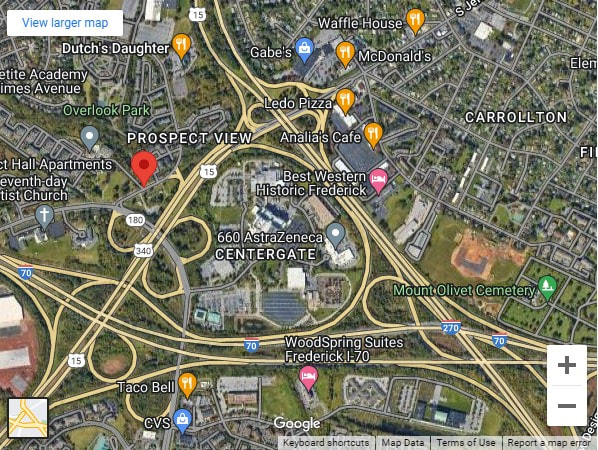

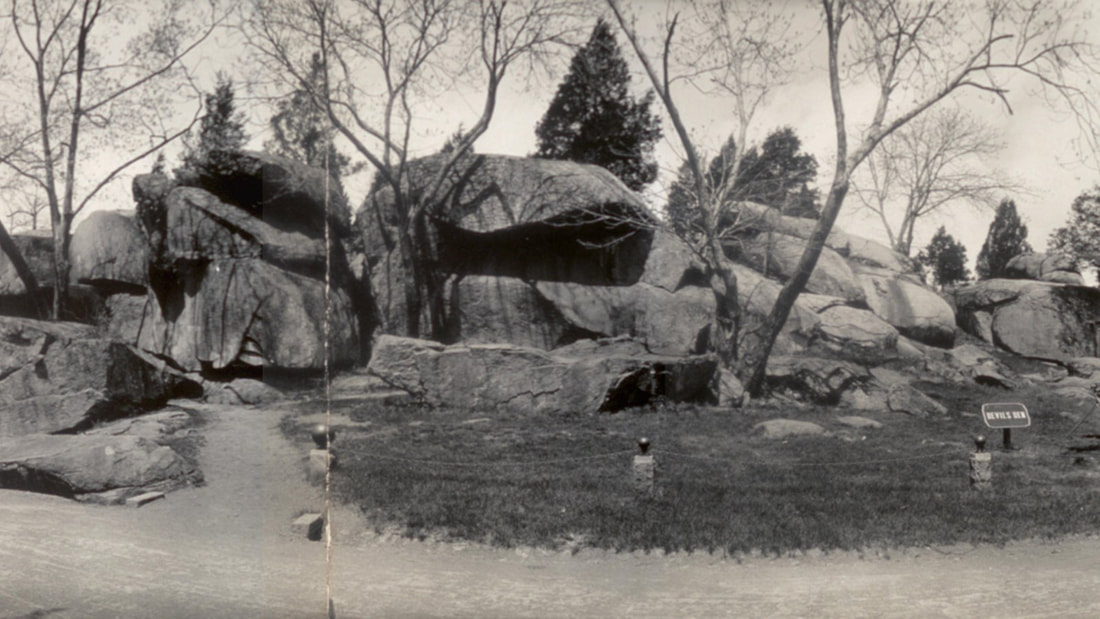

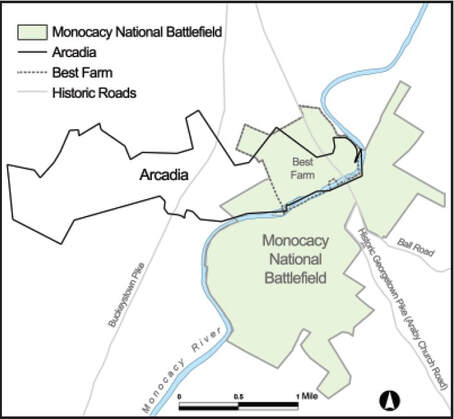

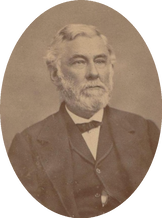

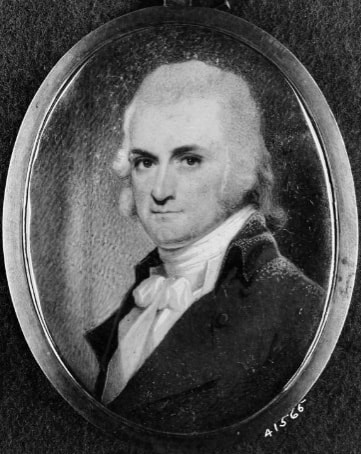

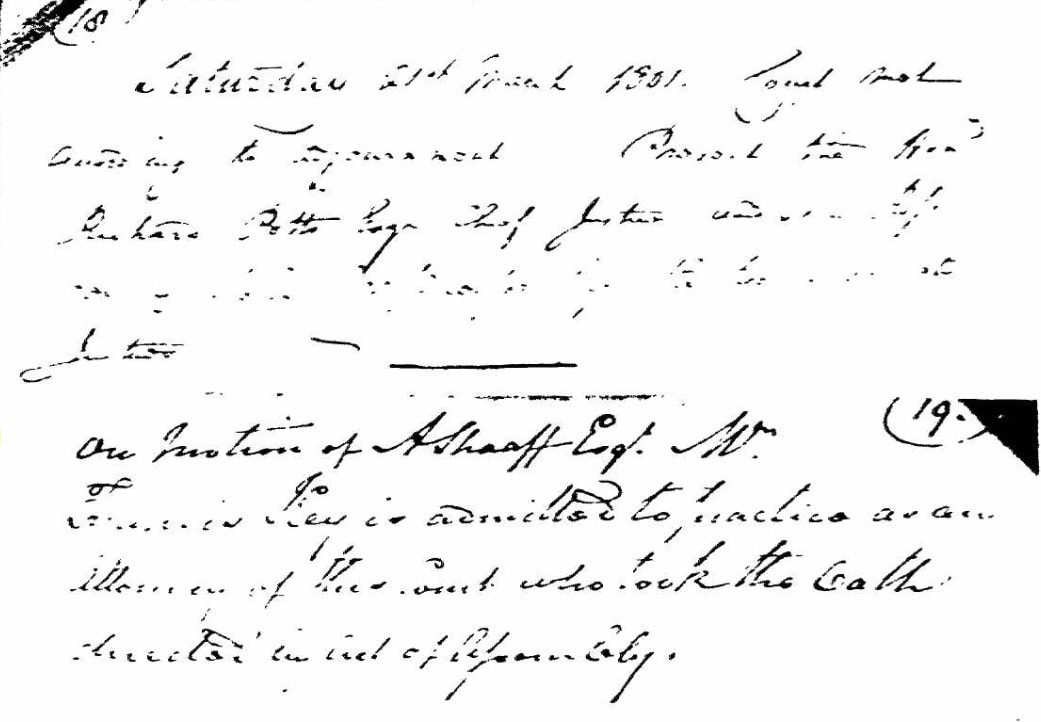

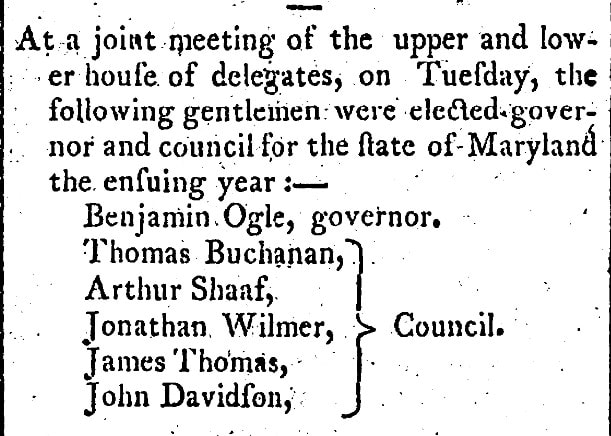

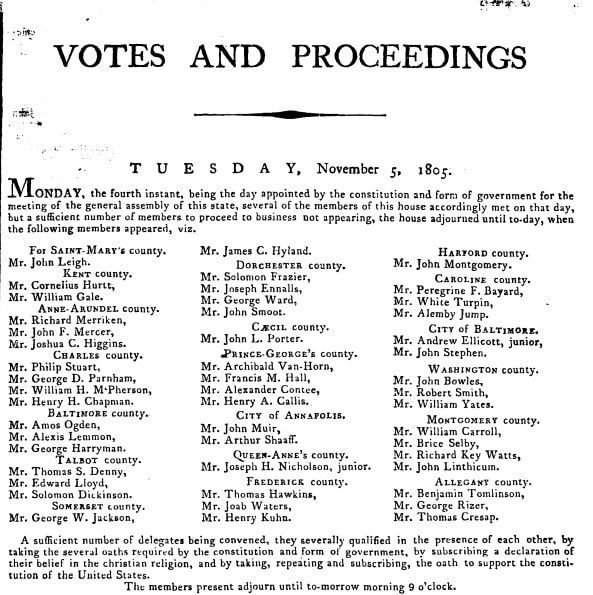

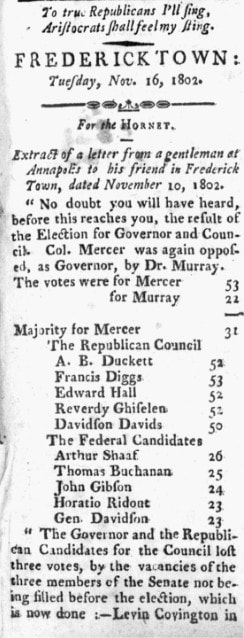

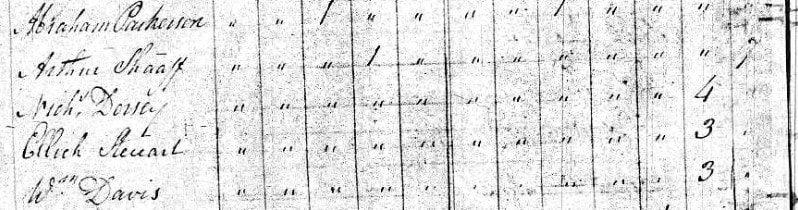

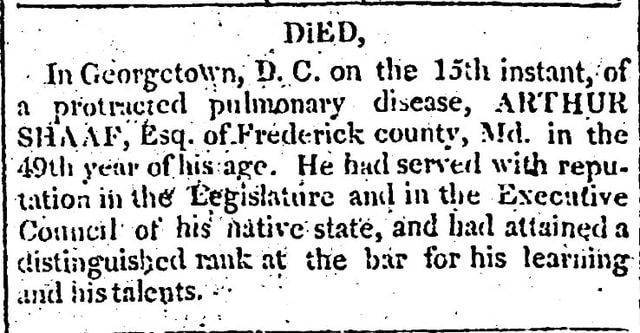

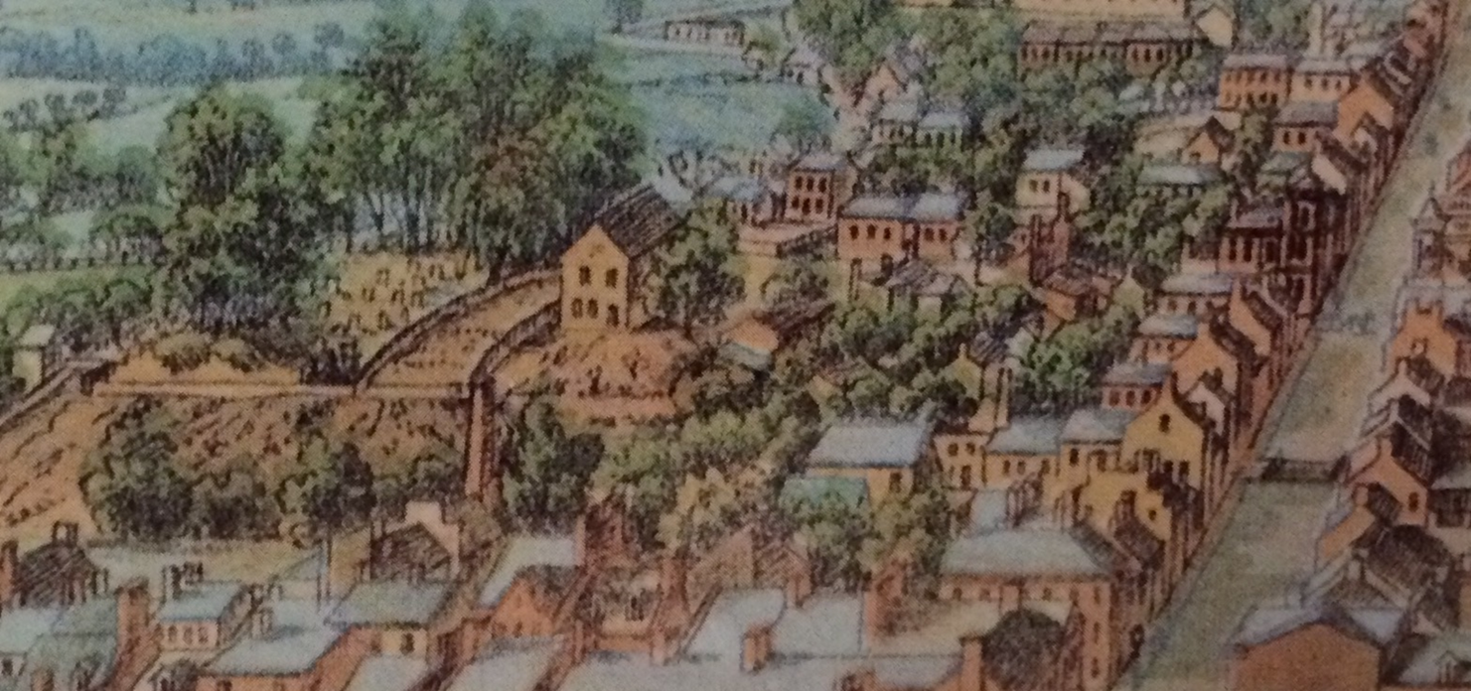

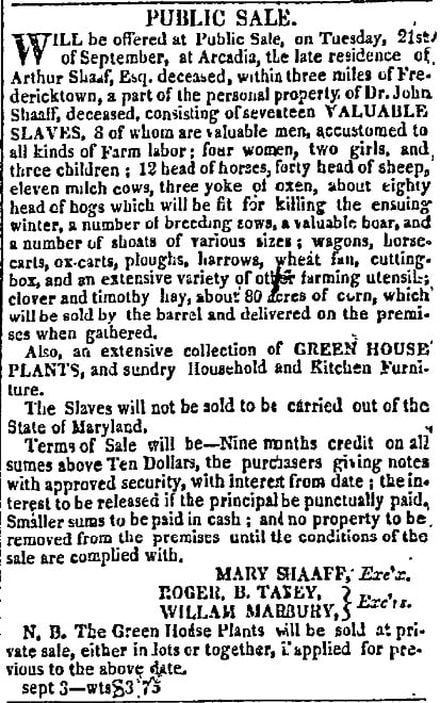

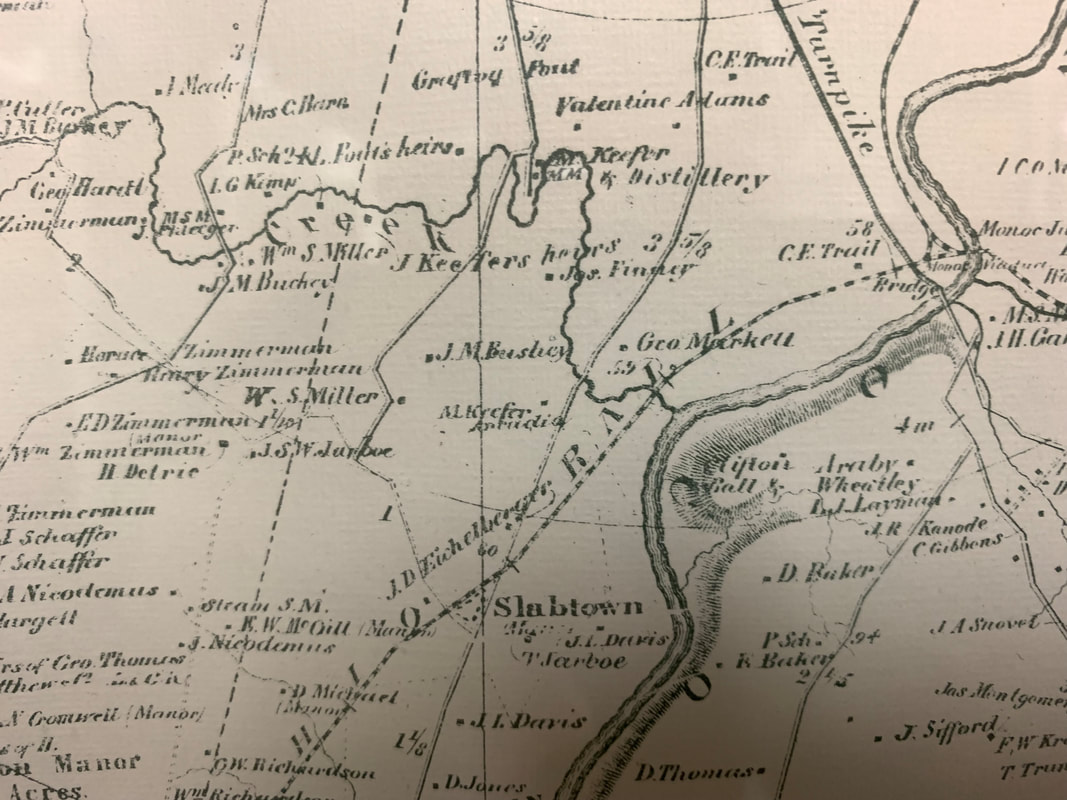

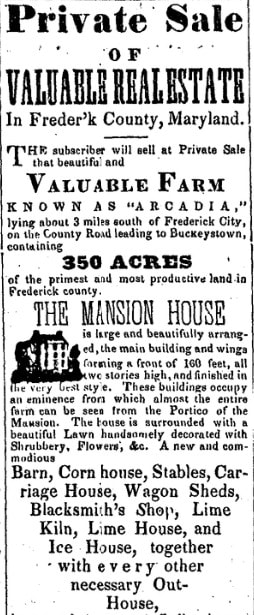

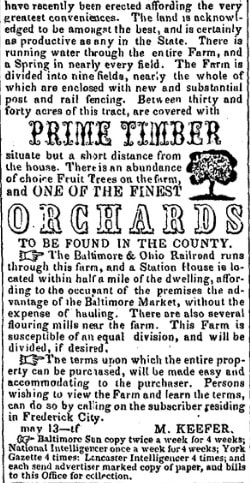

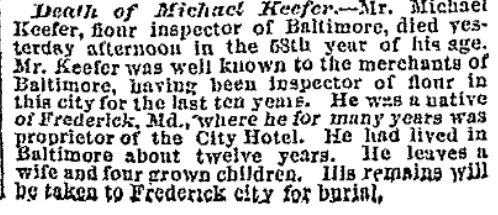

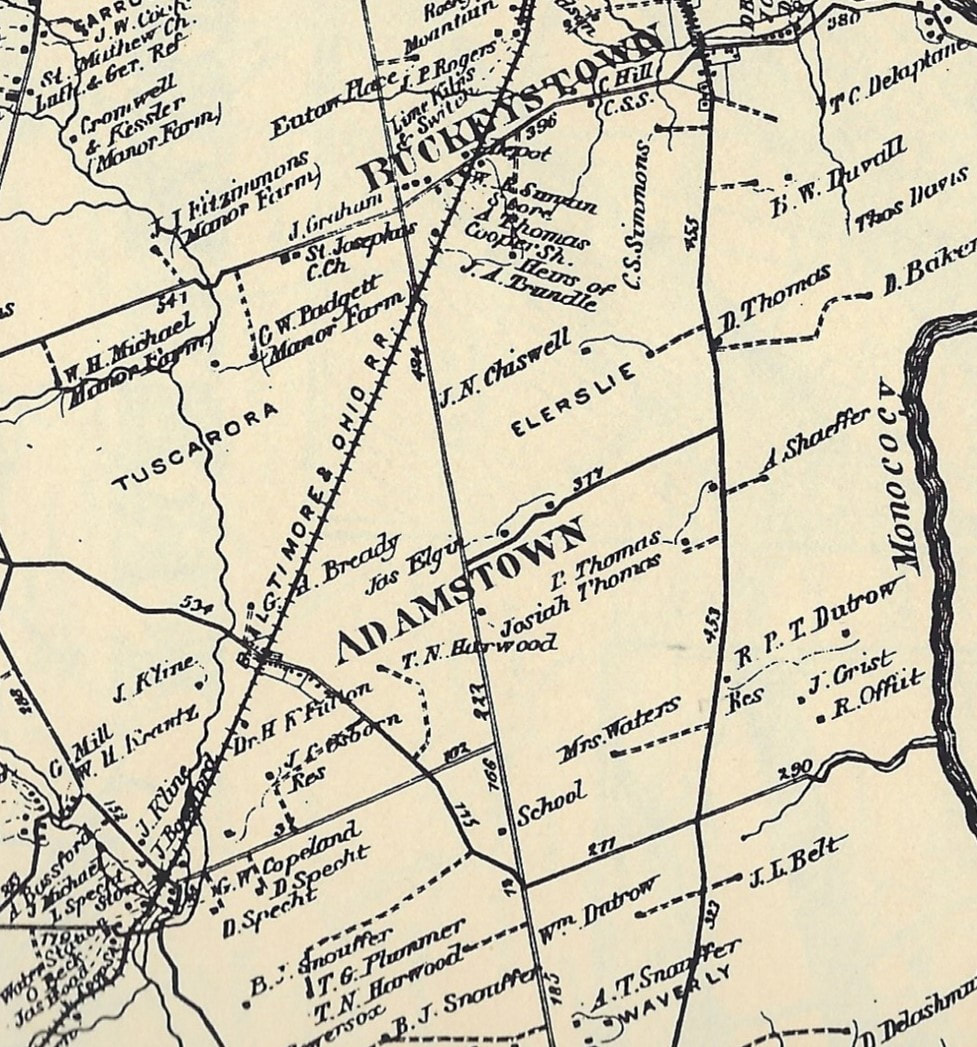

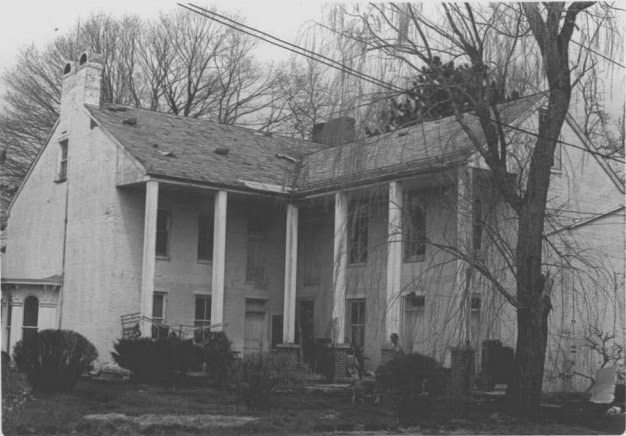

Anyone who reads this blog on a regular basis knows that I am no stranger to a wide variety of monuments and gravestones, and the “stories” behind them. As a matter of fact, rocks (primarily of granite and marble) are the “basis” of this ongoing “Stories in Stone” series. However, our interest in rocks is centered on history and geneaology instead of geology and the science that deals with the earth’s physical structure and substance. An interesting point to make here is that rocks last forever. With the assignment to represent the “physical footprint” of a human being, place or event, the memory (of said person, place or event) should last equally as long as “the rock,” shouldn't it? That’s what memorialization is all about, and why gravestones and monuments hold value to those of us who care about learning from things from our past. Going back even earlier in time, before the recording of history by cultures, we study rocks to understand early peoples and the planet itself (ie: Native American spearpoints, monadnocks like Sugarloaf Mountain, Stonehenge and petroglyphs). As we near the end of June, I can’t help but think about a unique, local specimen that proves my “point of rocks” serving as solid, lasting reminders. This particular one captures a legendary event from Frederick’s past that did not occur on Mount Olivet’s property, but was in very close proximity from a geographic sense. Years ago, this locale would have been reached by a short walk of about 500 hundred yards from my office at the cemetery. This would be similar to a walk from the back of Mount Olivet to our front gate on South Market. These days, with residential, commercial and transportation growth over the last century, getting there requires greater effort, and is best made by automobile. I’m talking about “the Gen. Meade Change of Command Monument” at Prospect Hill. Considered to be on the outskirts of southwest Frederick, the “Change of Command” monument is often missed. It is located along Himes Avenue at the foot of the hill and service road leading up to the Prospect Hall mansion, formerly the site of St. Johns Regional High School. The marker’s visibility and accessibility have improved greatly in recent years thanks to the Civil War Trails program in which wayside interpretive markers have been placed next to the rock in question, which had previously been partially hidden by shrub growth, and difficult to access by automobile. The granite monument marks the vicinity where the command of the Union Army of the Potomac passed from Gen. Joseph Hooker to Gen. George B. Meade on June 28th, 1863. This was done by order of President Abraham Lincoln at a critical time during the American Civil War. The significance of this event was not known at the time, as just days later, Gen. Meade would be engaged in the most famous battle ever to take place on American soil, perhaps only rivaled by Lexington & Concord or the Battle of Yorktown of the American Revolution. This is not a native rock to Frederick, but fittingly hails from Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. More specifically, it comes from the infamous “Devil's Den” on the battlefield. For those not familiar, Devils’ Den is a boulder-strewn hill on the south end of Houck’s Ridge below Big Round Top. On the second day of battle (July 2nd, 1863), “the Den” was skillfully used by Confederate artillery and sharpshooters to shoot at the commanding Union position above on the ridge. Why don't we bring science into this story this week, just for fun. The Gettysburg National Military Park website gives readers the following geologic background on the rock composing Devil's Den and our local monument : Approximately 180 million years ago during the late Triassic Period, the Gettysburg Formation comprising sandstone, siltstone, and shale was deposited in a large carved-out basin in the Gettysburg area. These lowlands were broken by hills and ridges that were formed as a result of geologic activity when a dense 2,000-foot thick slab of igneous (molten) rock called the Gettysburg Sill and also two 50-foot dikes were thrust into the Gettysburg Formation. One of the dikes underlies Seminary Ridge in a north to south orientation while the other parallels the ridge to the west. Sills are responsible for the topographically-high areas of the Round Tops, Culp's Hill, and Cemetery Ridge and Hill. The intrusion dikes are composed of very fine-grained, dense diabase rock very resistant to weathering. The composition of these rocks indicates that the molten masses cooled very rapidly. The Gettysburg Sill is coarse-grained diabase, an igneous rock otherwise known as granite. The Sill also contains a large amount of feldspar. Two bronze plaques are attached to a granite boulder. The first plaque marked the original dedication in 1930, and the other is from the re-dedication in 1963 as part of the American Civil War Centennial activities.  1963 "Change of Command" plaque unveiling and 100th anniversary commemoration with three known attendees to the right of the monument. These include (L-R) E. Lease Bussard (Chairman of the Frederick Centennial Committee), unidentified woman, Judge Edward S. Delaplaine (noted historian/author), and Sen. Charles McCurdy "Mac" Mathias. From natural history, let's return to American history. Gen. Meade formally assumed command of the Army in the dining room of Prospect Hall on June 29th, just two days before the fateful Battle of Gettysburg. Gen. Joseph “Fighting Joe” Hooker was the Union Army General who succeeded General Ambrose Burnside as commander of the Army of the Potomac in 1863, despite his grandiose notions of becoming a dictator. He had a reputation for being aggressive in pursuit of war, women, and liquor. Interestingly, Gen. Hooker is best known for having his name attached to the female camp followers—the first “hookers” of record. Prospect Hall has a much richer history than simply this singular event in the Civil War. I hope to talk about other episodes involving Prospect Hall in future stories involving various former owners dating back to the 1700s. Prospect Hall may not as durable as a rock or boulder down the hill, but we are blessed to have such a historical “monument” still standing.  The area directly below Frederick City is depicted here from the 1858 Isaac Bond Atlas map. Note "Prospect Hill" (location of Prospect Hall where Hooker had his headquarters in June, 1863) in the upper left. To the southeast of Prospect Hill (at the center-bottom of this image), you can see labeled "M. Keefer-Arcadia." This is where Meade had made his headquarters in late June, 1863. Another interesting part of the “Meade Change of Command” story involves another “structural witness to history.” This landmark mansion can be found still standing a few miles to the southeast of Prospect Hall. This is known as Arcadia, and you may have driven by it before while on Buckeystown Pike. Or perhaps you’ve heard of it because its name has appeared in the news a great deal of late because it may be demolished. Arcadia is important to local history for a variety of reasons. In particular, for our recounting of the “change of command,” this property is part of our larger story as it is the location where Gen. Meade was encamped when he learned the news of his military promotion. The order for a change of command from President Lincoln was carried by Gen. James A. Hardie, a 40-year-old West Point graduate who served as Secretary of War Edwin Stanton's Chief of Staff. According to the account by Judge Edward S. Delaplaine in the souvenir program issued on the occasion of the centennial anniversary of the war, the messenger arrived from Washington at the train station on South Market among a throng of Union soldiers in the streets of Frederick: "Hardie made the journey in mufti (civilian clothes). In Frederick he heard that Meade's headquarters was located near the Harper's Ferry road about a mile from the city. Hiring a buggy and driver, he made his way at night with difficulty past army wagons and crowds of soldiers, reaching Meade's tent on Sunday, June 28 at three o'clock in the morning.” Meade took command reluctantly because he was concerned about changing leaders in the middle of a campaign. Additionally, he felt his longtime friend Gen. John F. Reynolds was more capable and more deserving of the assignment. Gen. Meade described his appointment in a letter back home to his wife Margaret: "At 3:00 a.m., I was aroused from my sleep by an officer from Washington entering my tent, and after waking me up, saying he had come to give me trouble. At first, I thought it was either to relieve me or arrest me.... He then handed me a communication to read; which I found was an order relieving Hooker of command and assigning me to it.... As a soldier, I had nothing to do but accept and exert my utmost abilities to command success... I am moving at once against [Confederate Gen. Robert E.] Lee, who I am in hopes [Gen. Darius N.] Couch will at least check for a few days; if so, a battle will decide the fate of our country and our cause." Meade's prediction proved true. Just hours after his promotion, the general found himself with little to no time to calculate his next moves. During the day of the 29th, he moved the Army of the Potomac forward (and northward) towards the enemy. By that evening, Gen. Meade had established his headquarters in Middleburg, Maryland. He wrote again to his wife: “We are marching as fast as we can to relieve Harrisburg, but have to keep a sharp lookout that the rebels don’t turn around us and get at Washington and Baltimore in our rear. They have a cavalry force in our rear, destroying railroads, etc., with the view of getting me to turn back; but I shall not do it. I am going straight at them, and will settle this thing one way or the other. The men are in good spirits; we have been reinforced so as to have equal numbers with the enemy, and with God’s blessing I hope to be successful. Good-by!”  Jim Hueting in front of Prospect Hall Jim Hueting in front of Prospect Hall Both armies would soon be fully engaged on the farm fields and woods surrounding Gettyburg for the first three days of July, 1863. This would be the turning point of the Civil War, and Meade had found himself in a much different situation from when he had laid his head down to go to sleep in his tent beside peaceful Ballenger Creek at Arcadia just a few days earlier. If interested, please take a look at the following blog by Gettysburg Battlefield Guide Jim Hueting made back in 2009. He has some excellent photographs of Arcadia and Prospect Hall to help frame the scene of that fateful night Meade took command. Arcadia The word arcadia is defined as “a region or scene of simple pleasure and quiet.” I guess this was also the marketing message of National Bohemian beer, which was brewed and enjoyed “in the land of pleasant living” here in Maryland? The Arcadia mansion and former manor site is located between Frederick and Buckeystown. The extensive plantation, in its original form, included land stretching eastward across the Monocacy River. The manor house is said to have been erected around 1790, or the years immediately after. According to histories of Frederick, the mansion was the meeting place of the local gentry who gathered to play cards, dance, race horses and fox hunt. History books from the early 20th century make comment that, “the splendid mansion is one of the finest in Western Maryland. It is of colonial style and is situated on a high rolling elevation, surrounded by all kinds of beautiful trees and flowers. This estate is one of the best country homes in the county.” Today the house overlooks adjacent Buckeystown Pike (MD Route 85) and offers a commanding view of the surrounding area including Monocacy National Battlefield, in the distance to the east. Arcadia was extensively altered in the late 19th century, and now possesses an elaborate balconied tower. The interior was also extensively updated at that time as well. Historians and architectural experts agree that Arcadia is significant for its historical associations and as an interesting mix of architectural features which have made it a bonafide local landmark. The house played other roles during “the war between the states” in addition to hosting Gen. Meade and his soldiers in late June, 1863. Ten months earlier, in September, 1862, Confederate colonel (later general) William N. Pendleton stayed at Arcadia. This was during the Antietam Campaign and Pendleton was certainly no stranger to Frederick. He was actually a former resident, having served as rector of the city’s All Saints Episcopal Church from 1847-1853. He left town in a huff after resigning his post due to a dispute with the church vestry. He had urged the vestry to build a new church to replace the aging facility on Court Street. They refused, at least until after he left town. The new church would go under construction later that decade and front on West Church Street. In 1864, Arcadia was utilized during the Battle of Monocacy. It actually encompassed the Best Farm at one point of time (as the map above shows). Rebel Gen. Jubal Early formed his troops here to cross the Monocacy and go into battle. Arcadia would also serve as a makeshift, field hospital for wounded Confederate soldiers during the famed “Battle that Saved Washington.” There have been a number of owners of Arcadia over the years as you can imagine. I’d like to highlight a handful that are buried here in Mount Olivet. First off, there is Arthur Shaaff, credited with originally building the mansion along (Henry) Ballenger's Creek south of town. Arthur Shaaf Arthur Shaaff was born in Frederick County on October 7th, 1768 and died on May 15th, 1817. Named for his grandfather, Arthur Charlton, he was the son of Caspar Shaaff (?-1799) and Alice Charlton (b. 1743-1775). Mrs. Shaaff was the daughter of Arthur Charlton (1722-1771) and Eleanor (Harrison) Charlton (1723-1770), well-known tavern operators in Frederick’s past. Caspar Shaaff and Alice Charlton were married in November, 1759. The couple had four children: Mary, John Thomas, Arthur, and Caspar. The Charlton family was of English descent and arrived in Frederick County during the early eighteenth century. They had direct ties to the Keys of Terra Rubra. Caspar Shaaff was of German descent and worked as a merchant and carpenter. In 1754, Shaaff (also found to be spelled Shaaf and Shoaf) acquired 275 acres of land surveyed originally for Joseph Chaplaine under the name of "The Resurvey on Exchange" in the vicinity of Fox’s Gap atop South Mountain. During the period 1757-1758, Caspar Shaaff filed legal petitions in the local court to collect debts owed to him. He is shown as head of household in Frederick County in the 1790 US Census. It is thought that he lived here locally in 1796, because Mr. Shaaff assisted in settling his mother-in-law, Mrs. Eleanor Charlton's estate. In 1797, Caspar Shaaff of Frederick Town was appointed "agent for the late Daniel Dulany, in the counties of Montgomery, Frederick, and Washington, to accept rents, etc." Caspar’s son, Arthur Shaaff, could be found living primarily in Annapolis by century’s end. He had become a prominent lawyer in Maryland, and would play a role in the early careers of two other Frederick esquires. Shaaff practiced law in Frederick, Annapolis, and Hagerstown. Roger Brooke Taney identified Arthur Shaaff as one of the prominent and distinguished members of the Maryland Bar when Taney, himself, was a law student in Annapolis between 1796-1799. Taney recalled Shaaff as a mentor and a colleague. He (Taney) prepared cases both with Arthur Shaaff, and opposing the gifted attorney.  Francis Scott Key (1779-1843) Francis Scott Key (1779-1843) Taney related that Shaaff assisted him when he moved to Frederick City in 1801 to practice law. "Mr. Shaaff, who still practiced in Frederick, having invited me to take part in one of his cases, in order to give me the opportunity of appearing in public.” Arthur Shaaff’s practice included real estate management, property disputes, property transfers, and estate settlement. In some cases, Shaaff, Roger Brooke Taney, and a cousin, Francis Scott Key, collaborated. I’ve been under the impression for years that the fabled joint law office of Taney and Key, once found in Courthouse Square (and fronting Court Street), was actually the law office of Arthur Shaaff. In 1806, Roger Brooke Taney married Ann Phoebe Charlton Key, the sister of Francis Scott Key, and became a cousin by marriage to Arthur Shaaff. Shaaff’ s mother (Alice (Charlton) Shaaff) was sister of Ann Phoebe Penn (Charlton) Key—the mother of the Key siblings, Ann Phoebe Penn Dagworthy (Charlton) Key and Francis Scott Key. Like he had done with Taney, Arthur Shaaff is credited with presenting young Francis Scott Key to the Frederick County Court, and moved for his admission to the bar. The formal ceremony was noted as follows in the records of Clerk William Ritchie: “On motion of A. Shaaff, Esq., Mr. Francis Key is admitted to practice as an Attorney of this Court who took the Oath directed by Act of Assembly.”  Wide view from Council St giving contect. Faux Law office to the right of historic brick house (denoted by marker) and original Shaaff, Taney, Key office was to the left of said house. The three story, duplex with dormers was built in the early 1900s in keeping with the guidelines of the Historic Preservation Commission several decades before there even was a designated historic district in Frederick. It's just too bad we lost the original dwelling, which prompted the "building/labeling" of the faux office for tourism sake not unlike the rebuilt Fritchie House. Historian William Jarboe Grove (1854-1937) wrote in his “History of Carrollton Manor” of 1922: "In the summer, Mr. Taney would sometimes retire, with his family, a few miles from Frederick to Arcadia, the country-seat of the eminent lawyer Arthur Shaaff, a bachelor, and a cousin of Mrs. Taney, to recruit his overtasked mind in the serenities of the country.” Although Arthur Shaaff practiced law in Frederick County, he was not recorded in the 1800 and 1810 censuses as residing in Frederick County. His primary residence was in Annapolis, Maryland. However, Shaaff also was not recorded in the Annapolis census data for 1800. The 1800 census listed his brother John T. Shaaff as head of household in Annapolis, Maryland. The household contained 2 free white males between the ages of 26 and 44 (presumably John T. and Arthur), one free white female between the ages of 26 and 44, and seven slaves (U.S. Census 1800). By 1810, both Arthur Shaaff and John T. Shaaff were listed as separate heads of household living in Annapolis. Arthur Shaaff died on May 15th, 1817 at approximately 49 years of age. He would be buried in All Saints’ Protestant Episcopal Cemetery, originally located between Carroll Creek and East All Saints Street. On September 30th, 1854, one of Mount Olivet’s founding board members, Richard Marshall, handled plans to re-inter Shaaff’s body in newly opened Mount Olivet Cemetery. Marshall was a leading lawyer in town, and formerly mentored by Roger Brooke Taney. Marshall also moved the bodies of Mrs. Ann Taney and her parents (Ann and John Ross Key) to the south end of his lot. This gravesite was originally known as the Marshall Lot, but is now better known as the Potts Lot, as the Marshall’s married into this family. The Arcadia Mansion and associated property were inherited by John Thomas Shaaff, the elder brother of Arthur Shaaff. John T. Shaaff was a doctor by profession who practiced in Annapolis. He was the Treasurer of Medical and Chirurgical Faculty of Maryland from 1799 to 1801 and a member of the Governor's Council from 1798-1800. He moved his practice to Georgetown after 1810. While in D.C., he served as the Vice-President of Columbia Institute and was a founder of the Medical Society of the District of Columbia in 1819. When John T. Shaaff died on May 3rd, 1819, the executors of his estate were his wife Mary Shaaff of Georgetown, William Marbury of Georgetown, and Roger Brooke Taney of Baltimore. (Frederick Examiner 1851, July 23). In 1826, the executors of the estate of John T. Shaaff sold Arcadia to Col. John McPherson (1760-1829) of Frederick for $29,000. McPherson transferred the property to teenage grandson John McPherson Brien (1807-1850), who transferred the property to his father, John Brien (1766-1834)in 1833. In 1835, the estate of John Brien sold the property to Col. Griffin Taylor, described as a large slaveholder living the lavish "southern plantation lifestyle" and incurring debts that required him to sell off sections of the property. William Jarboe Grove referenced account books containing gaming debts that were found in the attic by later owners. In the 1850 census, Taylor was recorded with 18 enslaved persons. In 1851, Mr. Taylor offered his real and personal property for sale stating that he intended to remove to the West. A footnote on Col. Taylor is that he relocated to Cincinnati, but died four years later in October, 1855 and was laid to rest in St. Johns’ Catholic Cemetery in Frederick. The estate was described as containing 1,015 acres and was offered as a single farm or for subdivision into three or four farms. The estate contained three dwelling houses, as well as Arcadia Mansion where Col. Taylor resided. The mansion was described as a large brick house with "wings handsomely finished, and the gardens and grounds about the house are handsomely laid off and improved with evergreens". Griffin offered the mansion with about 280 acres as one farm. Frederick resident Jacob Engelbrecht reported in his diary entry of September 9th, 1851 the sale of Arcadia Farm and Mansion by Griffin Taylor to Michael Keefer for $18,000. At the time, Keefer (1815-1876) was the proprietor of Frederick’s City Hotel on West Patrick Street. In 1858, Michael Keefer assigned his real estate, including Arcadia, and personal property to Edward Shriver to act as his trustee to sell advantageously at private or public sale to clear Keefer's debts. In October 1858, Shriver sold Arcadia, then containing approximately 338 acres, to Thomas and Cynthia Clagett. The deed was recorded in 1862. Both men are buried here at Mount Olivet.

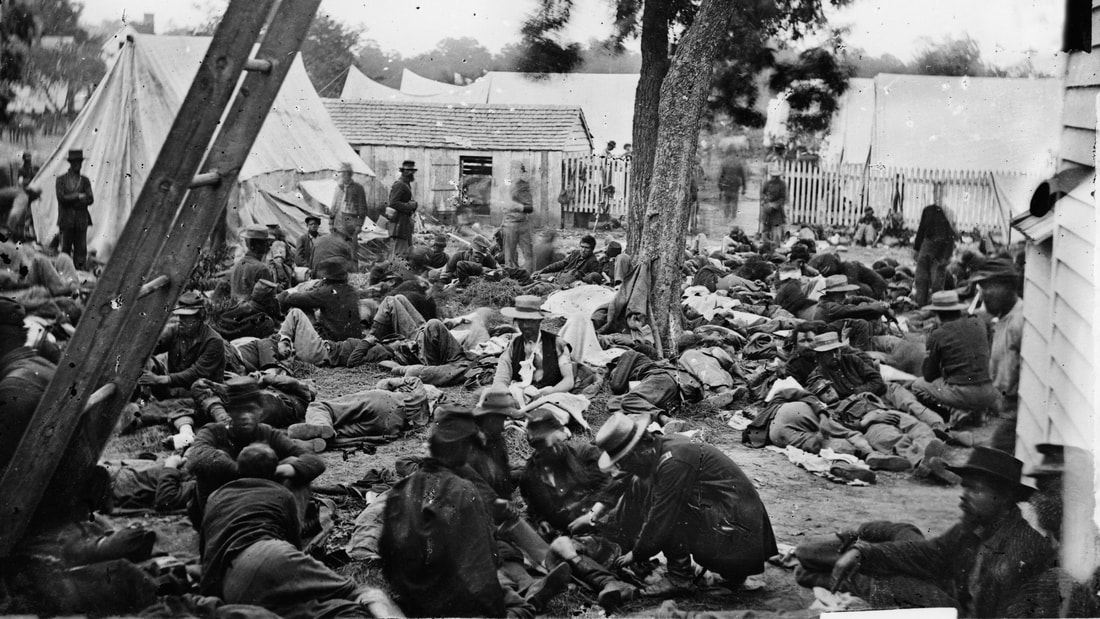

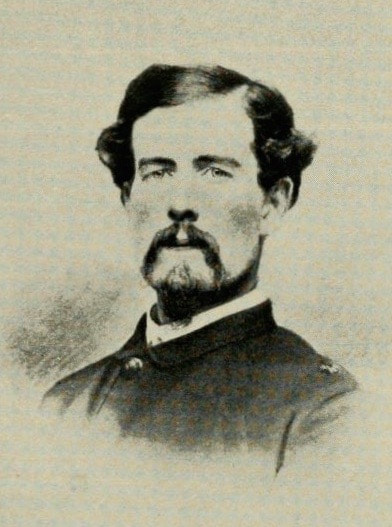

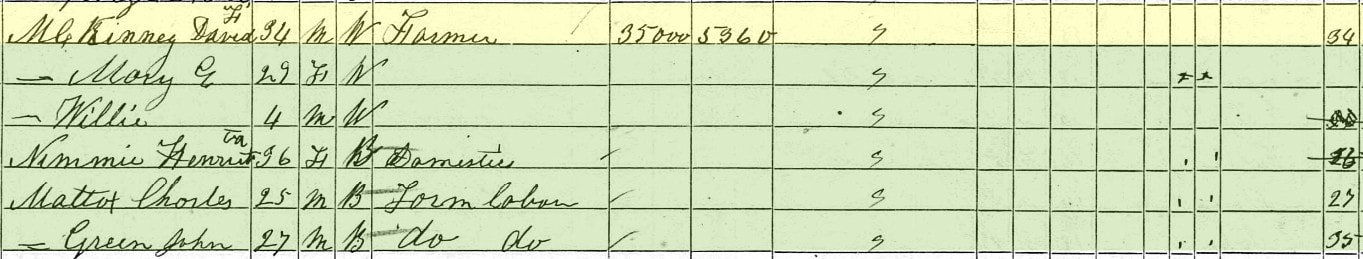

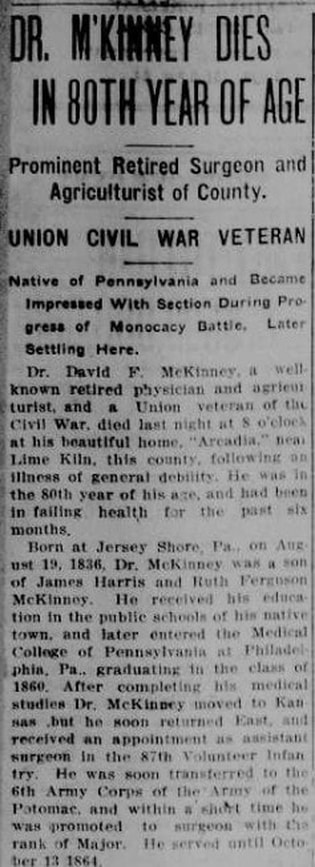

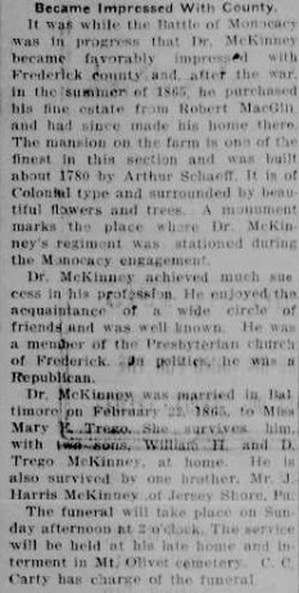

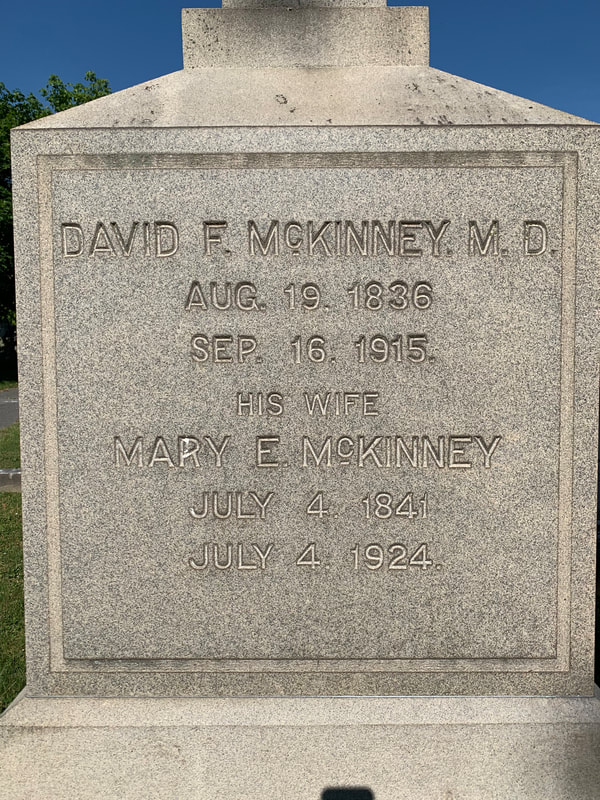

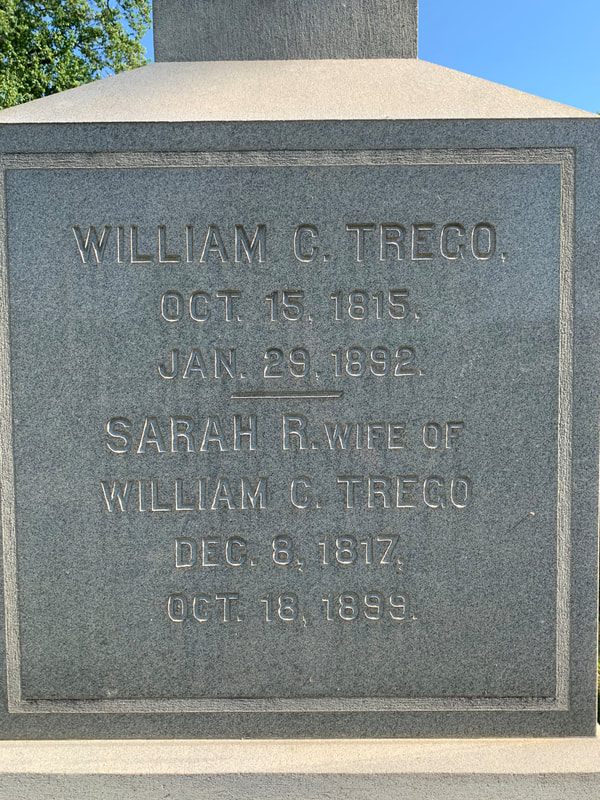

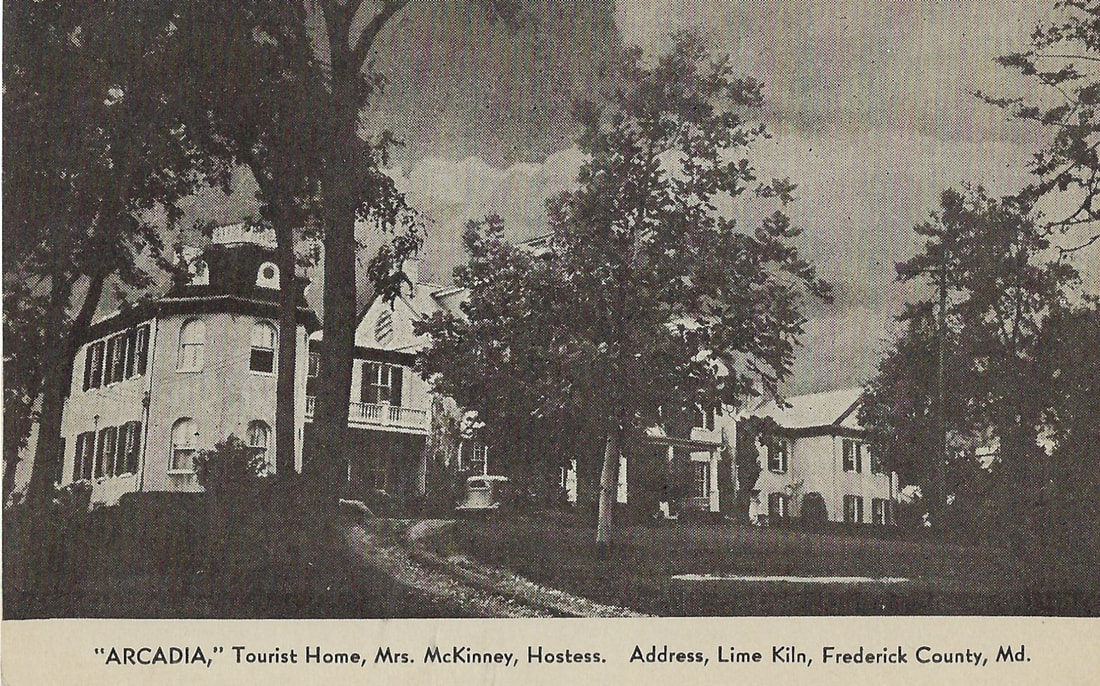

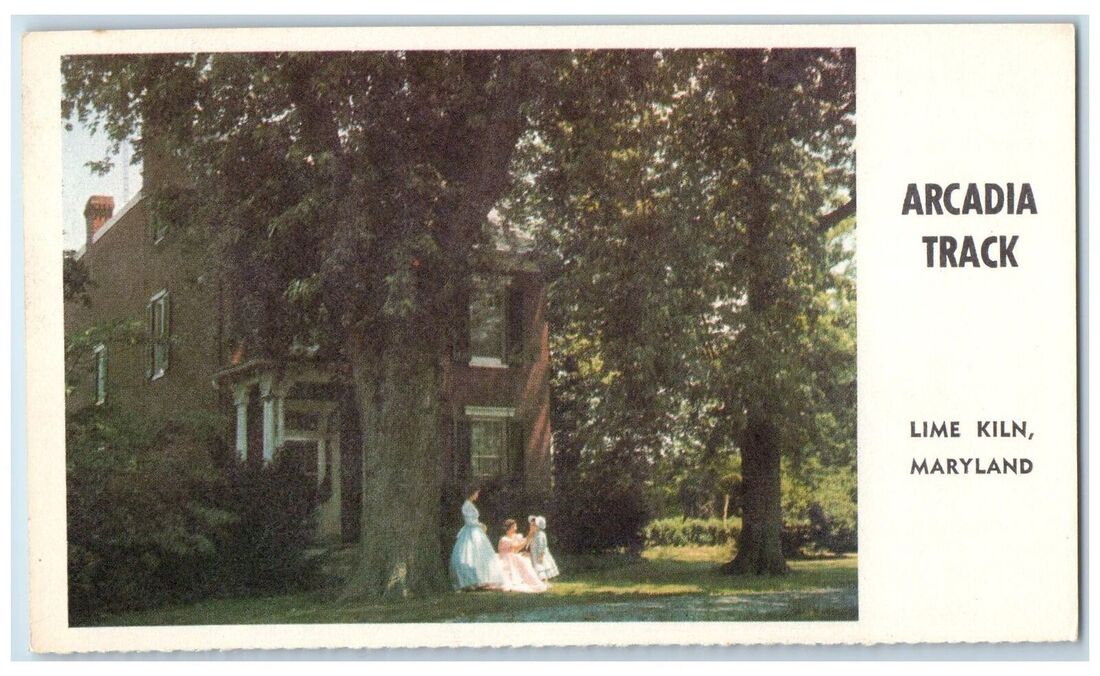

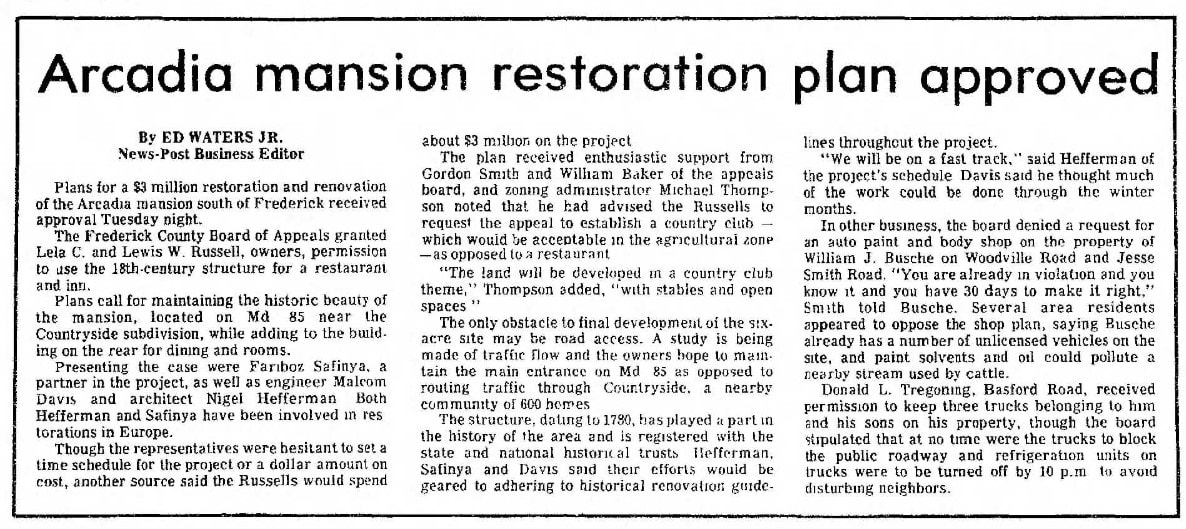

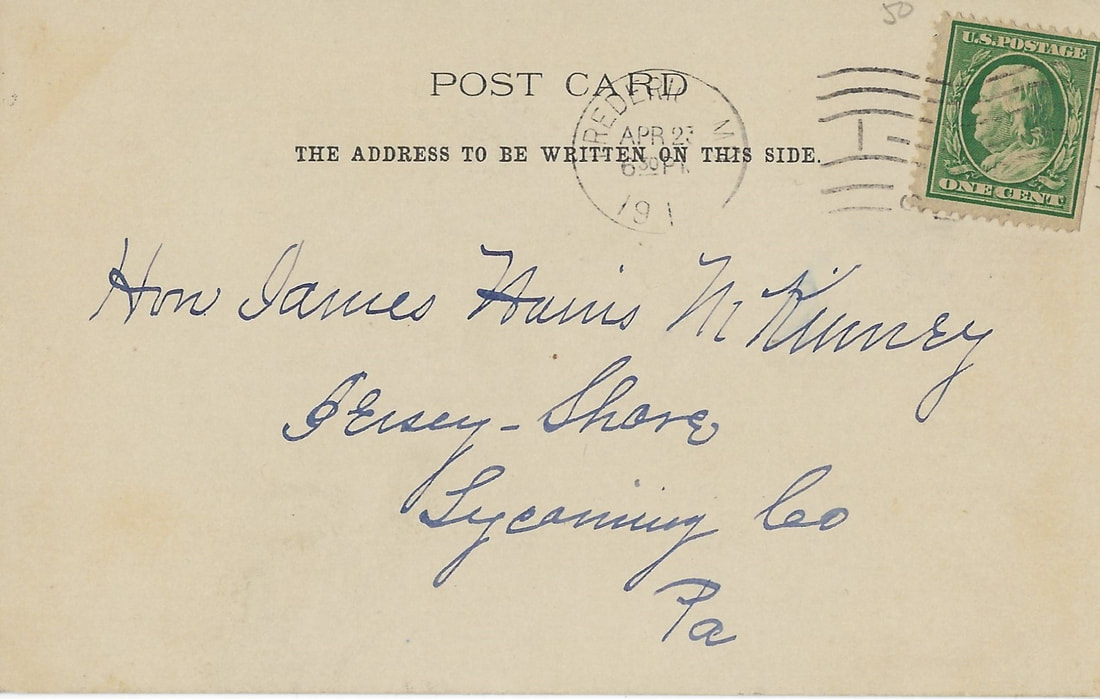

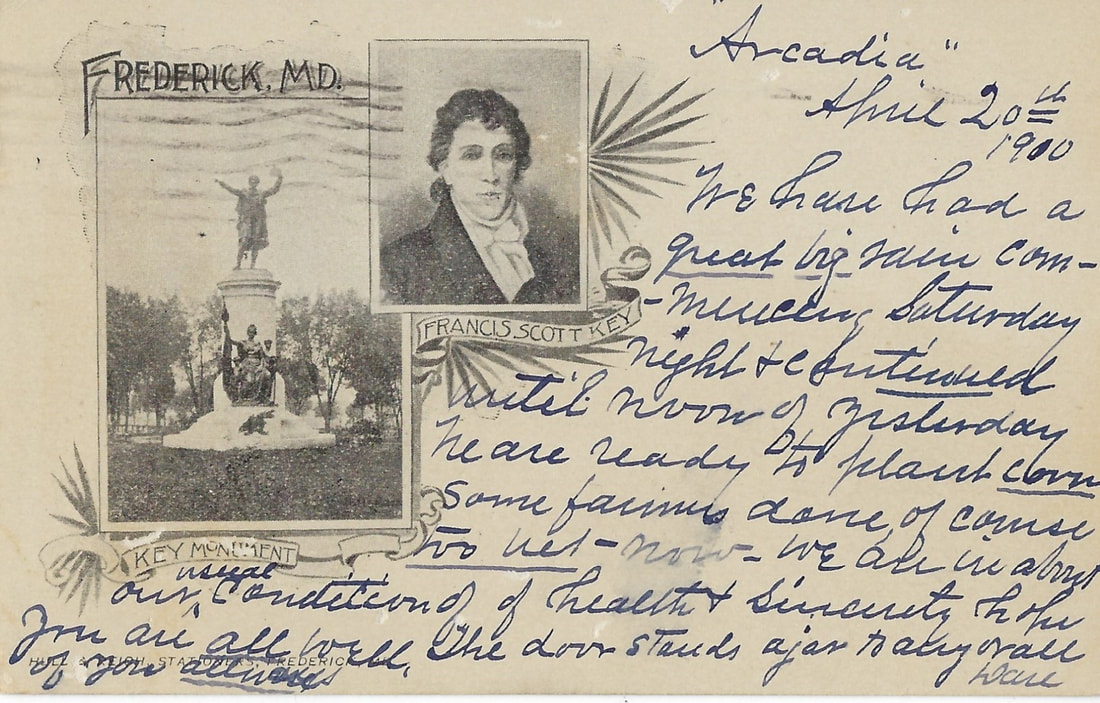

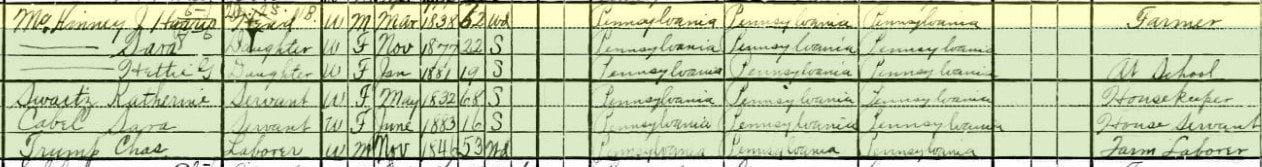

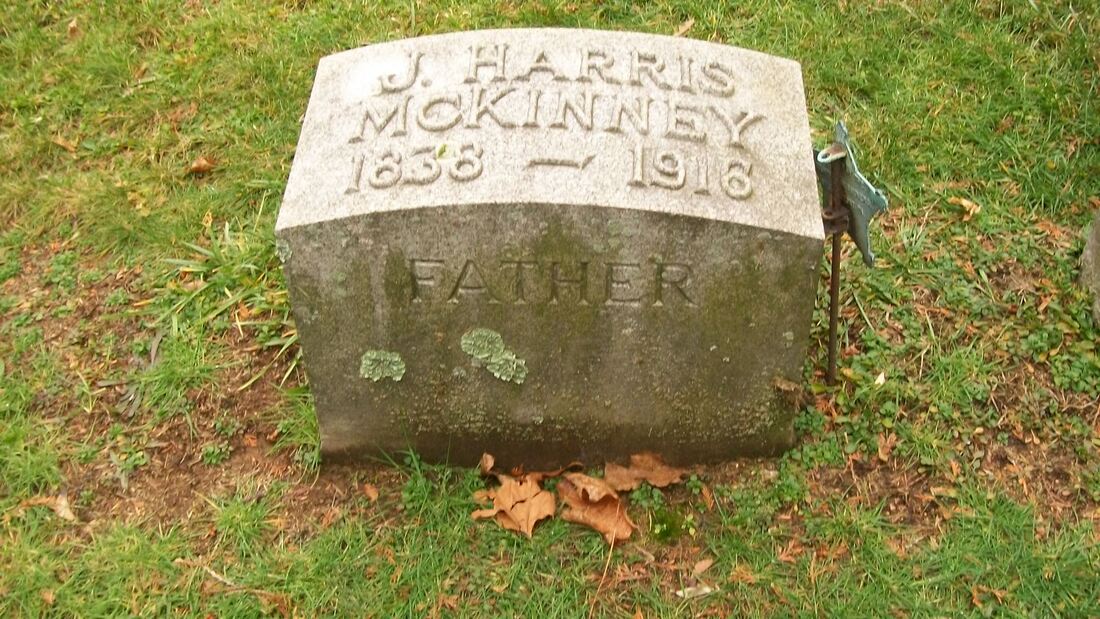

Thomas Clagett resided on a large estate near Kemptown and used Arcadia as a fox hunting retreat. In residence in 1860 were Thomas Clagett, age 22, with the occupation of farmer and a laborer, J. Dunloff, and 4 slaves. Mr. Grove recalled that his father lived at Arcadia under Clagett's ownership and boarded his son. In 1862, Thomas Clagett sold Arcadia Mansion and 210 acres of land to Robert Henry MacGill, Sr. (1821-1876). He wouldn't be here for long, however. MacGill and McKinney It was Mr. MacGill who hosted Gen. Meade and the Union soldiers in late June 1863. A year later, William Jarboe Grove recalled that, as a ten-year old boy, he watched the ambulances bringing Confederate wounded from the battlefield. His father was pressed into service to carry stretchers. Arcadia was used as a temporary field hospital, with operations conducted in the central room on the first floor. While Confederate wounded were taken to Arcadia, Union wounded were taken to another farmhouse nearby. That hospital, on the George Markell property, was under the charge of David F. McKinney, a surgeon with the 6th Army Corps of the Army of the Potomac. Dr. McKinney reportedly was so taken with the area that he purchased 277 acres containing the Arcadia Mansion in 1865 from Robert MacGill. McKinney continued to work as a physician in Frederick County and became an agriculturalist. Dr. David Ferguson McKinney was born in 1836 in Clinton County, Pennsylvania near Loch Haven. He was educated in public schools and received a degree from Jefferson College in Canonsburg, PA. He entered the Pennsylvania Medical College of Philadelphia and graduated in 1860. Soon after graduation, McKinney was appointed as assistant surgeon in the 87th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. He was transferred to the 6th Army Corps of the Potomac and was shortly thereafter promoted to surgeon with the rank of major. He served for three years and was discharged in October 1864. Dr. McKinney was married in 1865 and brought his new bride, Mary (Trego) McKinney, to live at Arcadia. The former Mary Trego (b. 1841) was the daughter of a successful iron manufacturer from Baltimore. David and Mary McKinney improved Arcadia Mansion during their tenure. It was reported that Dr. McKinney replaced the blood-stained floorboards in the first floor center room, the family’s dining room. The room had been used as the operating room when Arcadia was used for a short period of time as a Confederate field hospital. Other alterations that occurred were the raising of the one-story hyphens to two stories. William Jarboe Grove reported that "the north wing is as it was originally built except the two center rooms, a story was added by Dr. McKinney. The small rooms connecting the main and end wings were formerly one story high." The McKinneys added the viewing tower on the front of the east elevation of the building. The McKinneys would reside at Arcadia for half a century. Both David, who died in 1915, and Mary E. McKinney (d. 1924) are buried here in Mount Olivet Cemetery. They have one of the only surviving lots with marble "curbing" delineating their gravesite. A massive cross is the central feature with corresponding footstones for family members listed on the base of the cross. Here too are Dr. McKinney's Trego in-laws and his sons William and David who would assume Arcadia after his death. Both gentlemen would farm and manage the estate with their respective wives. I have a very nice collection of vintage Frederick postcards. In a thrift shop in Hagerstown, I found a few cards showing our Arcadia. I bought both. The first card talked of Arcadia serving as a tourist home near Lime Kiln with Mrs. McKinney as a hostess and appears to be from the 1930s/40s by the car in the driveway. I assumed this to be William McKinney's wife, Grace McSherry McKinney, and not Dr. McKinney's wife Mary (Trego) McKinney. The second card doesn't even look like the house in question, but I bought it anyway. It probably hails from the 1960s during the Civil War Centennial period. I would soon learn that the McKinneys began to take in tourists in the 1930s. Author Nancy Bodmer wrote in her Buckeystown and Other Historical Sites that this was "not only for monetary benefits but because they enjoyed sharing Arcadia with other people. One of the first to stay for the summer months was Miss Mary Neighbours, who was born in Buckeystown. In 1939 she came to Arcadia for a rest in the country from the hot and hectic Frederick. She stayed 27 years, leaving only when the house was sold. Hardly a night would go by that the rooms would not be occupied." In April 1966, heirs of the McKinney family sold 277 acres south of the mansion to a group of investors who would construct the Countryside development. The mansion and remaining land has been bought and sold many times over. Plans along the way have even included a country club, but that did not come to fruition. Years ago, I bought another old postcard on eBay, dated 1900, with the Francis Scott Key monument on its face. I was particularly interested in this card because it was actually written at Arcadia. The author was Dr. McKinney who signed his correspondence with “Dave.” It was penned on April 20th, 1900 to the former physician’s brother James Harris McKinney living in Jersey Shore, Pennsylvania (located in Lycoming County and nowhere close to the Atlantic Ocean). (Written Transcript) “Arcadia,” April 20th, 1900 We have had a big rain commencing Saturday night and continued until noon of yesterday. We are ready to plant clover. Some farmers done, of course too wet-now-We are in about our usual condition of health and sincerity. Hope you all are well. The door stands ajar to any or all of you. Always, Dave For good measure, I searched for James Harris McKinney and found his name in the 1900 Census and final resting place up in Pennsylvania. This is one of my longest stories to date and actually inspired by my acquisition of that antique postcard. Made of paper, it's a miracle it even survived and somehow started in the hands of David F. McKinney at Arcadia 123 years ago, was sent to Jersey Shore, PA, and wound up in my hands all these years later. This humble (and long) "Story in Stone" is not just a testament to several owners of a singular property that happened to be buried in the local cemetery.It's also not just about a beautiful mansion from Frederick’s past, that still survives. No, it’s much more than that—Arcadia is a common thread of Frederick’s history through hundreds of years, and and serves as a touchstone to legendary figures in our local and national history including Gen. George Gordon Meade, Roger Brooke Taney and Francis Scott Key. Those men, along with lessor known characters such as Arthur Shaaff, Robert MacGill and Dr. David F. McKinney, are long-gone as well. But steadfast Arcadia is still here, weathering the test of time, not unlike a rock formed millions of years ago. The home was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1978, and the subject of postcards throughout the 20th century. Many county residents would even refer to Ballenger Creek as "Shoaff's Creek," giving credit to the early builder of the mansion. Sadly, Arthur's surname has silently slipped away, but his mansion home has not. I know that Frederick County continues to grow, and progress does not stand still. However, as the name of the mansion suggests, I pray that the parcel and beautiful house located at 4720 Buckeystown Pike remains untouched, and like a gravestone in a cemetery, has the opportunity to continue standing as a testament to the owners and events of the past as a reminder of “a region or scene of simple pleasure and quiet.” AUTHOR'S NOTE: Key sources of information were compiled in the Maryland Historical Trust Maryland Inventory of Historical Properties Survey Form (Inventory No. F-l-172) and Nancy Wilmann Bodmer's "The Past Revisited: Buckeystown and Other Historical Sites" published in 1990. The latter is where the early period image comes from.

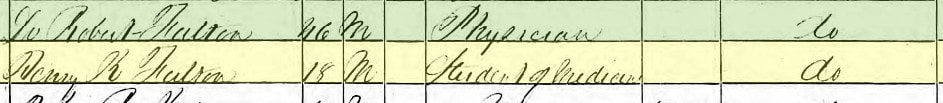

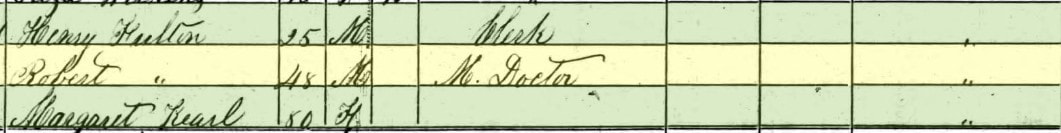

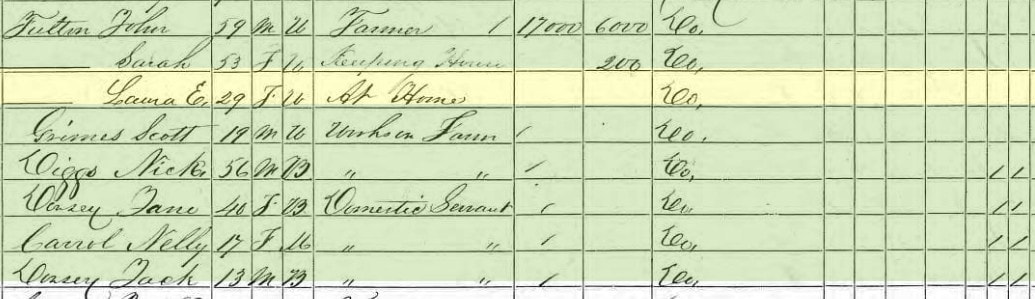

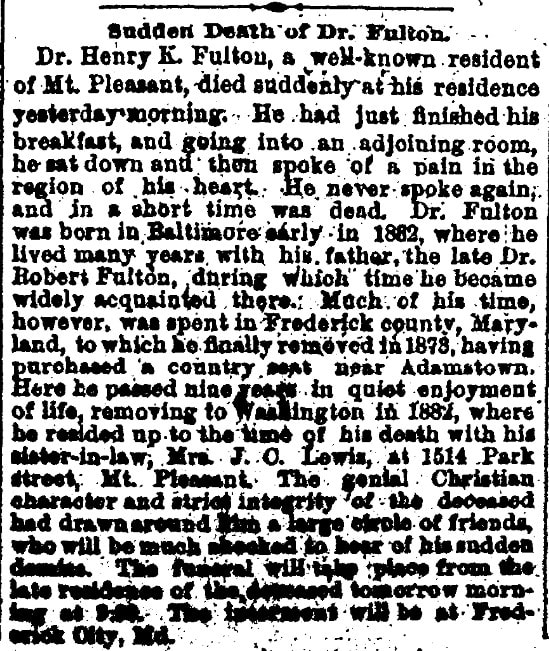

False Advertising 101 is what I have done here with my cover photo, as this has absolutely nothing to do with current events. I'm sure it has lured many curious readers into my sinister "history web." As can be seen upon closer inspection, there is snow in this photo, one taken by yours truly on January 29th, 2019. That late afternoon, we had the most amazing sunset, one that painted the sky an "emblazoned orange." This came out of nowhere, as the entire day had been cloud-covered with falling snow most of the duration. FaceBook and Instagram erupted with similar pictures to mine, taken throughout the greater Frederick region. I just happened to be shooting obligatory "cemetery in snow" pictures, when this rare phenomenon occurred. Talk about being at the right place at the right time? Speaking of rare, and strange, occurrences, we certainly experienced one this time last week over a few day period, and featuring orange skies. Certainly not as pretty, but noteworthy and a cause for alarm by some as those with respiratory conditions were cautioned to stay indoors. A few events were canceled such as Frederick's Alive at Five, and our regularly scheduled Thursday gravestone-cleaning session for our Friends of Mount Olivet. Off the top of my head, I can think of only one thing more daunting than the media-hyped spectacle captivating much of the east part of our country (including little old Frederick) and thanks to the Canadian wildfires bringing hazy and smog-like conditions, bad air-quality index and a hint of woodfire smoke about. That one thing that comes to mind (after a painfully long tease) would be a song about a magic horse on a cold Nebraska night. That's right, I'm talking about the one, and only, Wildfire by Michael Martin Murphey. The hit single reached #3 on the Billboard "Hot 100" Music Chart in June, 1975. Interestingly, the name of the album this song came from is Blue Sky-Night Thunder. All I could think of when I discovered the album name for this story was Orange Sky-Night Coughing. At least the air quality on the album cover looked a bit like it did last week. From one Michael to another, I was fascinated by the drone pictures and video obtained by the talented videographer Michael DeMattia for the popular Frederick Scanner website (www.frederickscanner.com) and complementary FaceBook site. These "orange skies" weren't the same orange skies commonly only seen at dawn and dusk. They were eerily prevalent all day long on Wednesday, June 7th and June 8th as we were under a Code Red Air Quality warning. For those unaware of this rare occurrence, it was the result of the smoke from over 400 fires, more than 700 miles away from Frederick, having already burned land 20 times the acreage of our county. While all of this was happening Thursday, I recall looking out my office window and thinking that it looked like it could rain, but there was no chance for precipitation at all. It was all so strange. Since I couldn't take any "glamour gravestone shots" on my I-phone for upcoming stories, (yes, I'm now thinking that sounds equally strange), I started looking at some photos on my phone that I've taken over the last several months. After perusing through a few dozen, I became transfixed on a monument belonging to the Fulton family in Area F/Lot 71. I don't know about "night thunder," but the blue sky in the background of this photo made me leave "sodbustin' behind" (part of a lyric in the fore-mentioned Wildfire song) and truly appreciate brilliant, clear sky days like I never have thought of before. Why, this now reminds me of another song from the 1970s which seems very apropos here —ELO's "Mr. Blue Sky" which hit its peak of #35 on the Billboard Chart in June, 1978. Interesting it was from an album similar in name to Mr. Murphey's entitled Out of the Blue. This lot contains four members of the Fulton family, with Dr. Henry K. Fulton (1832-1891) and wife Laura (1841-1922) on the monument in the picture. A few feet away are John (1810-1845) and Sarah Fulton (1817-1898). I decided to go out and explore the lot a little closer, and contextualize the situation. I assumed that John and Sarah were either parents of Dr. Fulton, or at the very least John was a brother. I was wrong. After some "hazy"research, I realized that John and Sarah Fulton were the parents of Dr. Fulton's wife Laura. "Uh-oh," I thought, I've got more than "kissin' cousins" on my hands here. Who am I to judge, I certainly became more curious about the symbolism projected by the funerary monument of Dr. Henry K. Fulton and Laura. Traditionally, a broken column signifies "a life cut short." Dr. Fulton lived to age 59, but that doesn't illustrate "being cut down before your prime."

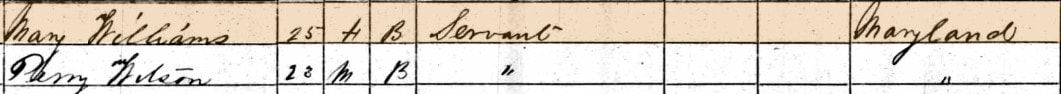

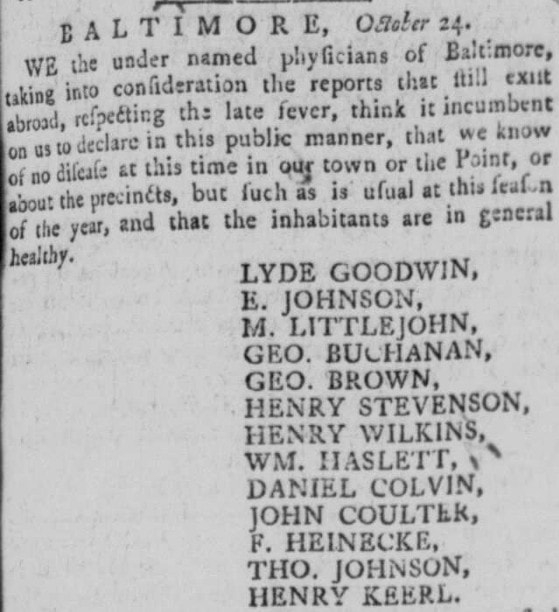

From a book entitled From the Medical Annals of Maryland 1799-1899 published in 1903 for the Maryland Chirurgical Society, I learned that father Robert Fulton was born in Frederick County in 1803 and was a pupil of Dr. John Baltzell, whose home is today's Heritage Frederick on East Church Street. He attended the University of Maryland, graduating in 1827. Robert is said to have always resided and practiced in Baltimore, dying there in May of 1880. He is buried in Greenmount Cemetery. Henry is working as a clerk at this point of time on the eve of the American Civil War. I would later learn that the father and son were joined by Henry's maternal grandmother, Margaret Keerl. Henry's mother, Amelia Henrietta (Keerl) Fulton, had died at the tender age of 21 in the year 1832. Now there is someone who deserved a broken column monument. I was impressed with Amelia's grave nonetheless, seeing it on Find-a-Grave's Greenmount Cemetery memorial pages. The page also included a transcript of her obituary which provided more insight on my Dr. Henry K. Fulton. "Obituary, Baltimore Gazette and Daily Advertiser (Baltimore, MD), January 30, 1832: "This morning at half past 5 o'clock, AMELIA HENRIETTA, wife of Doctr. Robert Fulton, and only daughter of the late Dr. Henry Keerl, of this city, aged 21 years 5 months and 15 days." I now learned what the "K" stands for in our central subject's middle name, along with his first-name namesake Henry (his maternal grandfather, who I would discover was a physician as well.)

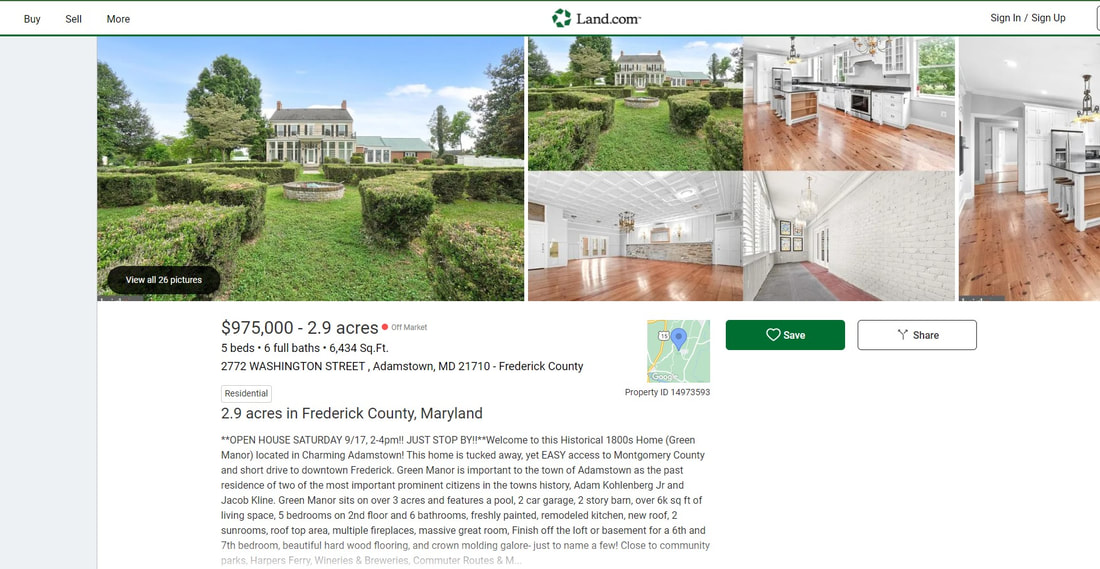

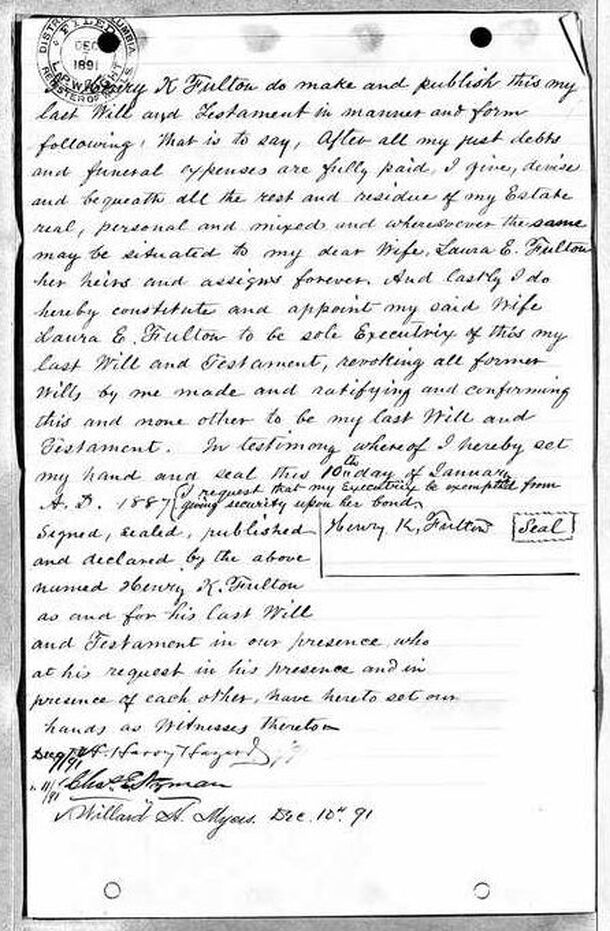

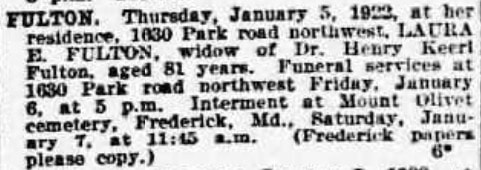

Even though things are out of order in my line of discovery, this article from the Baltimore Sun solidified my subject's heritage to the Hessian physician. I tried to make a connection to our Frederick Barracks, but was unsuccessful in doing so. Dr. Keerl invested heavily in real estate and garnered a large fortune, one that would be shared with his family upon his death in 1827. It's no surprise that his son-in-law (Dr. Robert Fulton) and grandson (Dr. Henry K. Fulton) would live comfortable lives. I found an article in the Baltimore Sun from 1851 showing that Henry owned property as a minor, certainly proving my postulate. I read that Dr. Henry attended the University of Maryland for his training, but found an article from 1861 that shows his graduation from the University of Pennsylvania's Medical School. Even though the article has a "J" for his middle initial here (instead of a K), this lines up chronologically and perhaps he attended both schools as it's not like he was without the means to do so. Since I was poking around in Baltimore's Greenmount Cemetery anyway, I thought I'd share a look at Dr. Henry's father's grave monument. Dr. Robert Fulton would pass in May, 1880. It appears that he remarried sometime after 1860. She was a Baltimore widow named Caroline (Lloyd) Starr. Henry Fulton wound up here in Frederick by the early 1870s from what I've seen. I was frustrated in not being able to find Henry and his father (Dr. Robert) in the 1870 US Census. This would have given be a better context of his permanent arrival in Frederick. I do know that Laura Fulton was living with her parents in the vicinity of Woodsboro in 1870. My research assistant Marilyn found this part of Frederick County as the home of many of the Fulton family, and likely the place where Henry's father (Dr. Robert Fulton) was born and raised before re-locating to Baltimore. Apparently, young Henry spent a great deal of time in Frederick County with extended family while growing up. This is understandable considering the premature loss of his mother. To confuse things, I found a Charles Henry Fulton (1834-1915), farmer at Glade in the greater Walkersville vicinity and buried at the Glade Cemetery. He was known by the name Henry Fulton and appears regularly in the papers as a leading member of his neighborhood. I assume he was a cousin. And speaking of cousins, Laura can be found in the 1870 census living with her parents near Woodsboro. She would marry Dr. Henry K. Fulton the following year. A living legacy of Dr. and Laura Fulton is a house they once owned in Adamstown. This is Green Manor and may have been their only residence here in Frederick County, as they would eventually re-locate to the Mount Pleasant neighborhood or northwest Washington, D.C. by 1882. Located at the west end of Washington Street, Green Manor was the home of Adamstown's namesake, Adam Kohlenberg. Kohlenberg served as the first railway agent and postmaster, and established a storage warehouse near the original Davis warehouse (demolished) which was built about 1835. In 1856, another man, Daniel Rhoads, laid out 12 lots on the south side of the main road which was the first stage of its development. Green Manor is important to the town of Adamstown as the past residence of two of the most prominent citizens in the town's history, the fore-mentioned Adam Kohlenberg Jr., and later Jacob Kline. By 1864, a brick dwelling house was standing on twenty-five acres on the periphery of the developing Adamstown. Upon Kohlenberg's death, the house was sold to Dr. Henry K. Fulton, who lived there until 1882. Three years later Jacob Kline bought the property for $5,200. He lived at "Green Manor" for more than twenty years and during that time platted and sold lots, "Jacob Kline's Addition" to Adamstown which today comprises the largest area of Adamstown. The Fultons moved to 1514 Park Street in northwest Washington, DC. I didn't learn much of Dr. Fulton's work, if any, as a physician, and the same about their personal interests. All I saw were a few newspaper mentions that they were happily spending summers in Bar Harbor, Maine. In less than a decade from moving from Adamstown, Dr. Fulton would be dead. On November 26th, 1891 was not a good Thanksgiving for Laura Fulton, This would be the day she lost her husband. Dr. Henry K. Fulton would be placed in the family burial plot of his wife's family at Mount Olivet the following day (January 28th)in Area F/Lot 71. Our records show that this plot was purchased in 1864. I found his last will online as well and have shared it here. As can be seen, Laura outlived her husband by 31 years. She died in Washington on January 5th, 1922. A rare find came in the form of an ad for the monument company that constructed the Fulton's monument. I had noticed earlier that the maker's mark of J. F. Manning Wash, D.C. was stamped/carved on the base of our monument. When I found Laura's obit in the Washington Evening Star, an advertisement for J. F. Manning appeared in the very next column. If anything else, I think you will agree that we have a bit "clearer" view of a monument and its decedents located in Mount Olivet's Area F. In doing so, I pulled on the help of the "ROY G. BIV" acronym as we focused on at least one primary color in blue, and two secondary colors in orange and green.

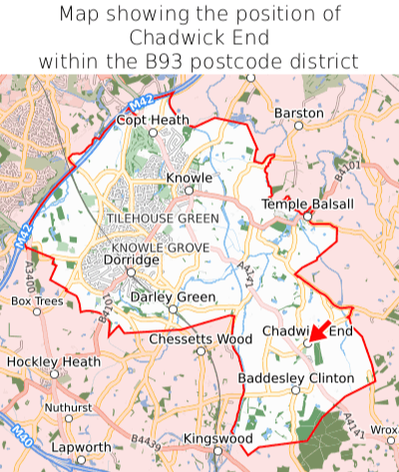

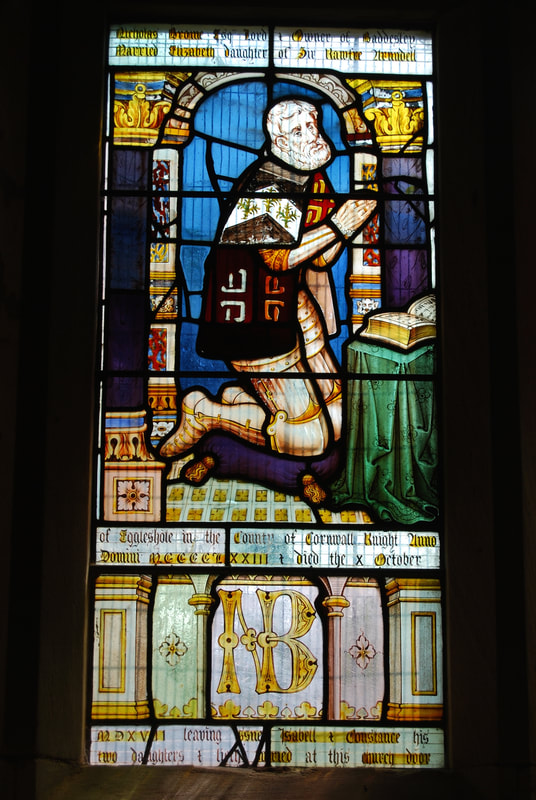

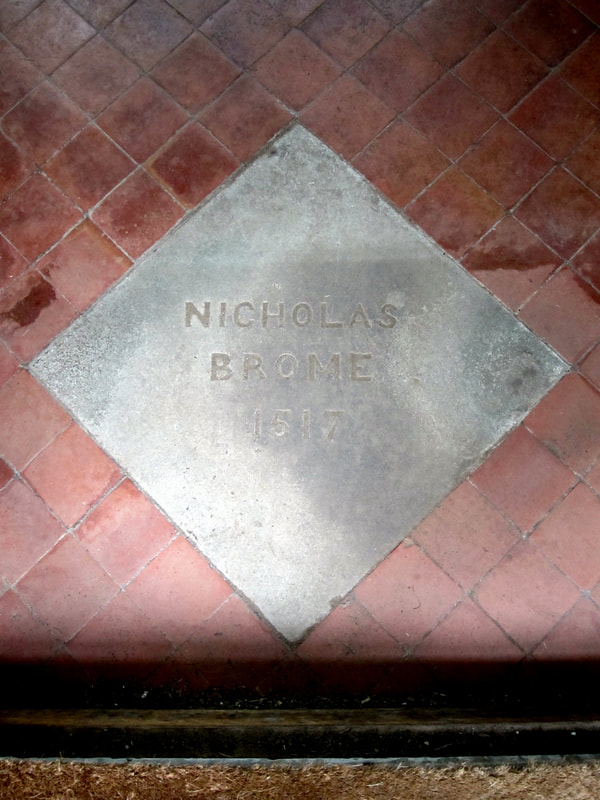

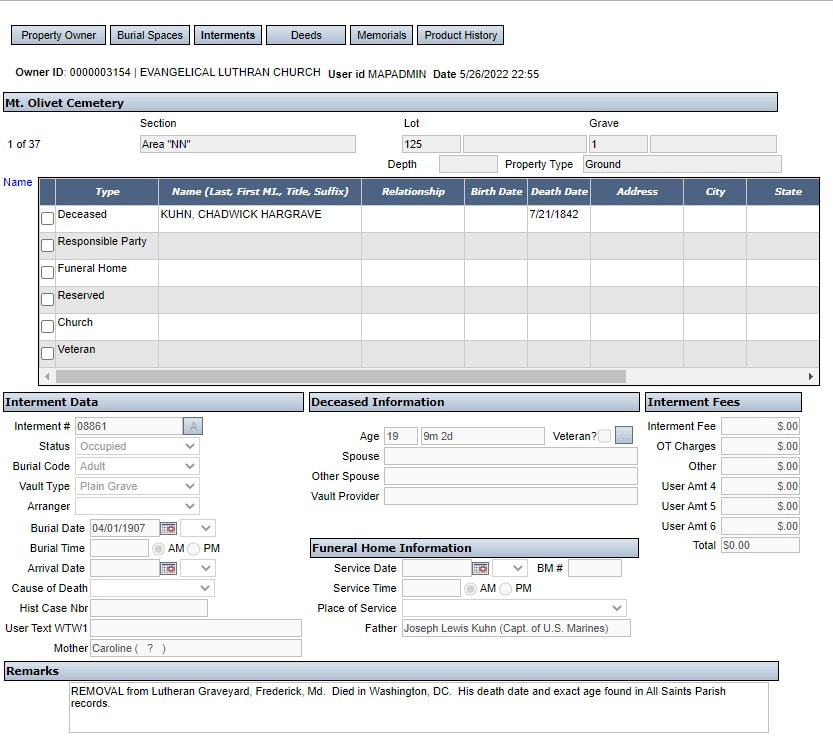

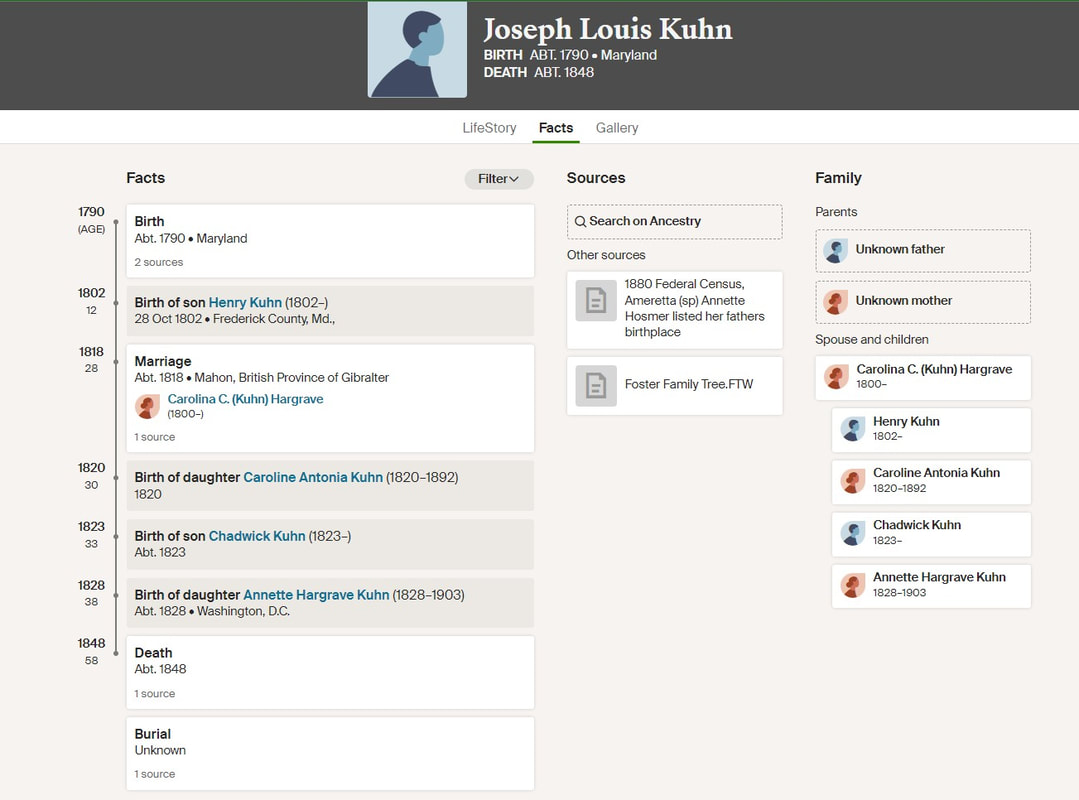

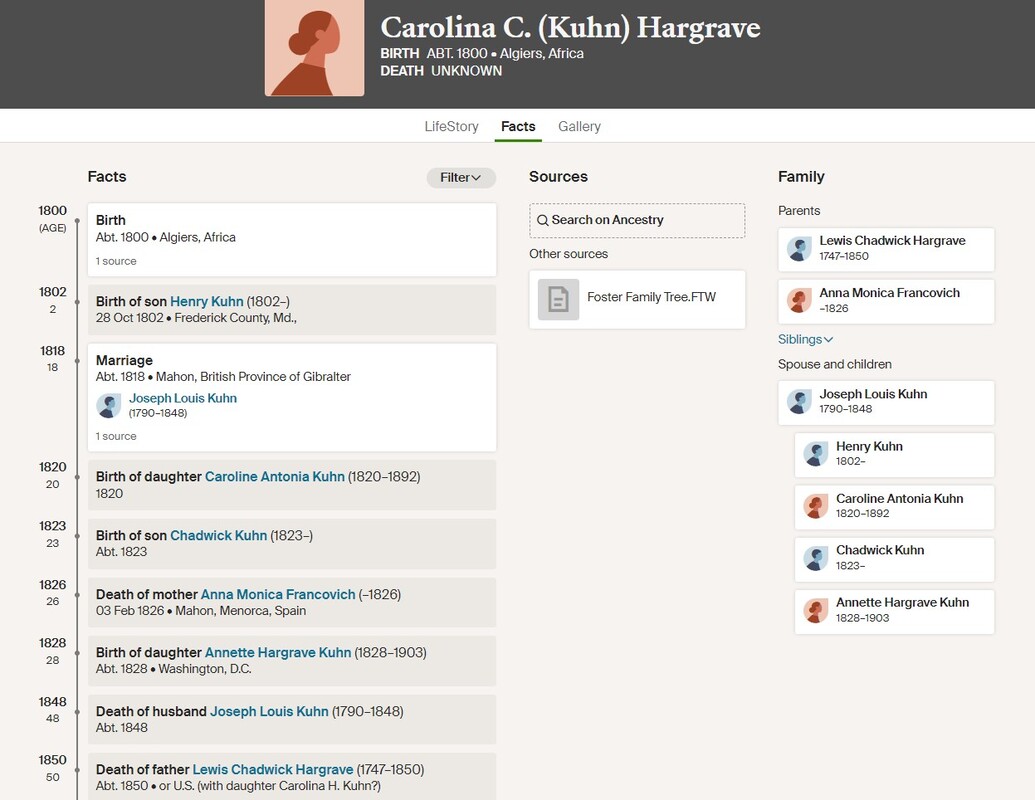

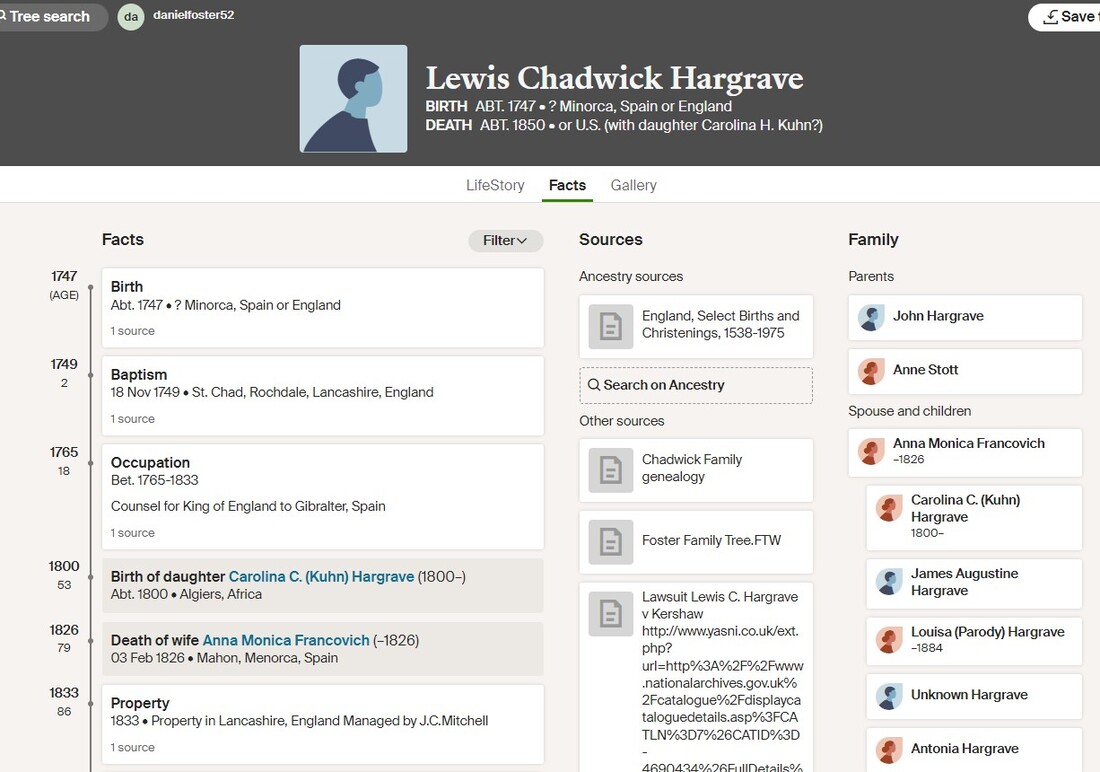

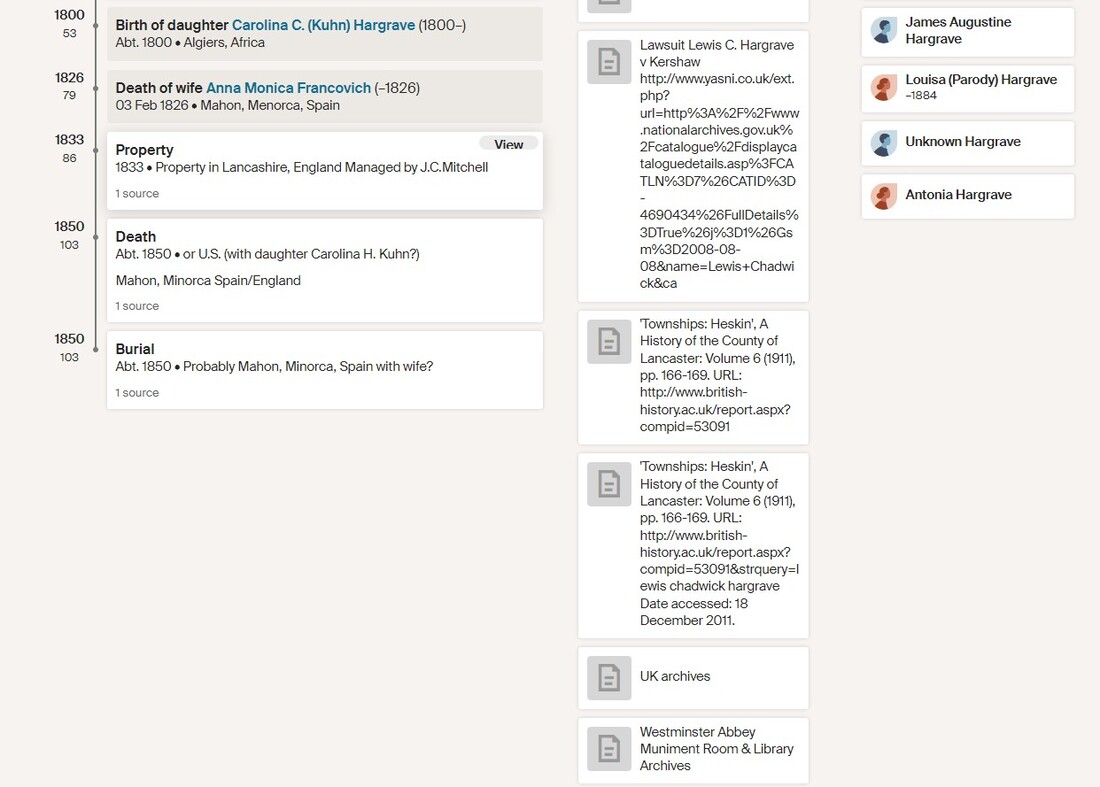

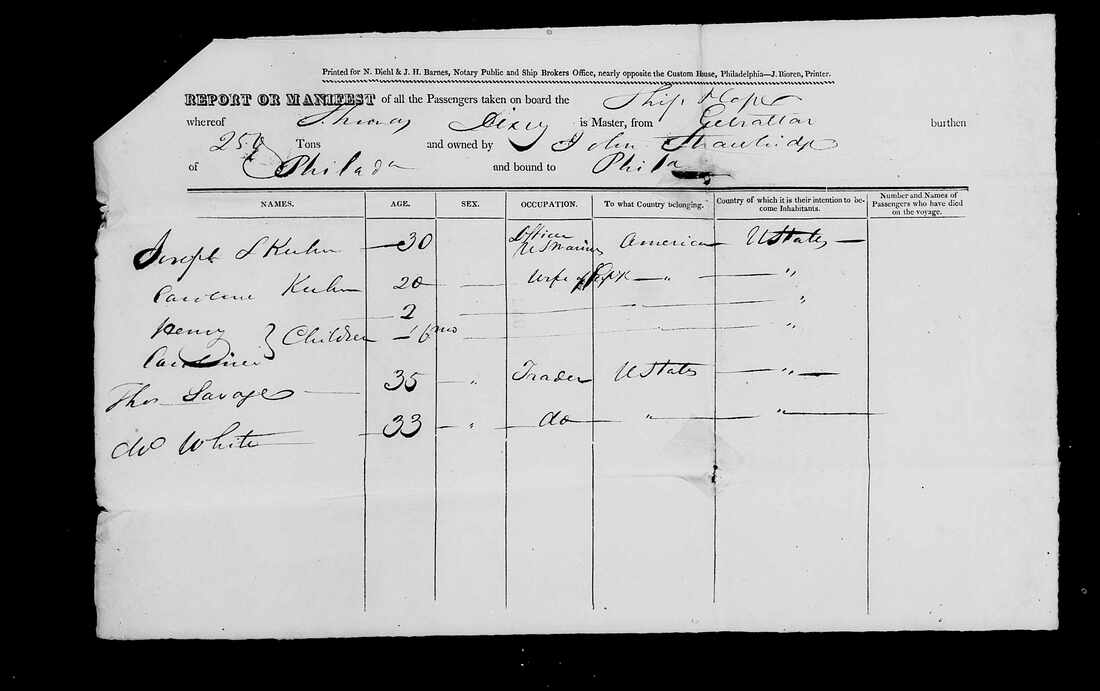

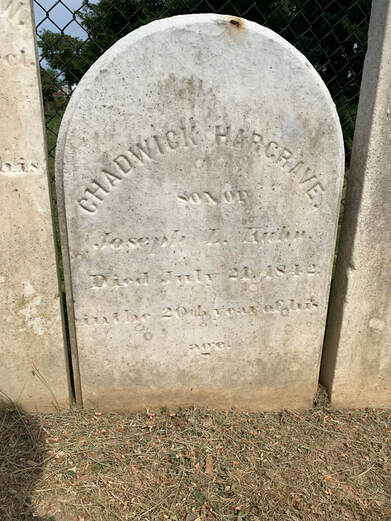

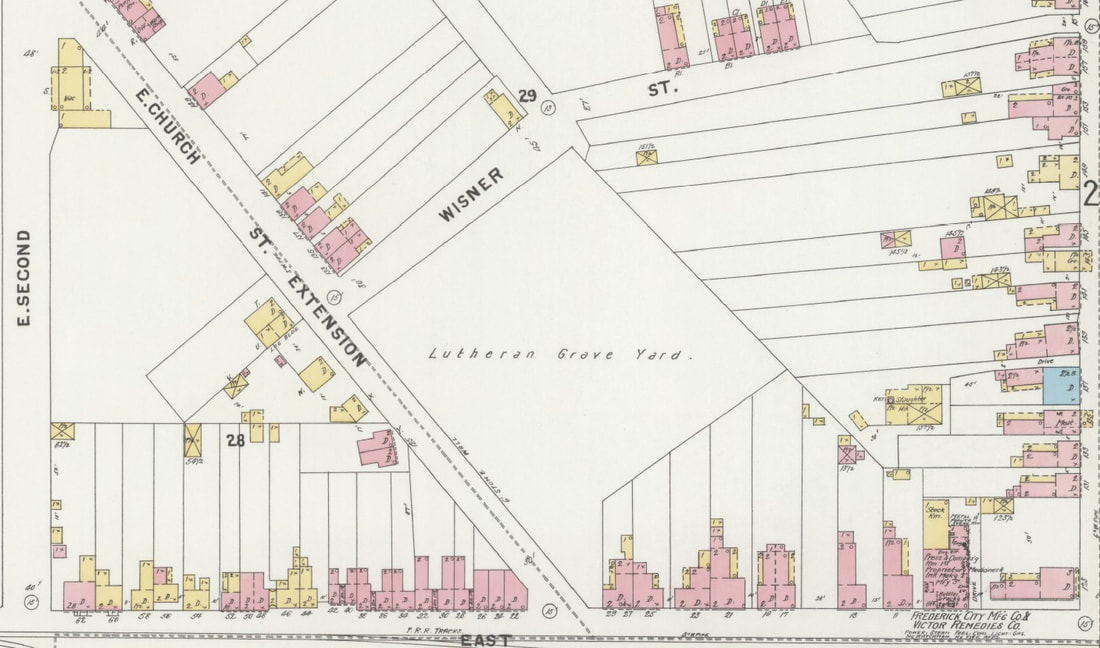

As usual, these are the ramblings of a curious and strange mind in a quest to gain greater understanding of those who eternally rest here at one of Maryland's most historic burial grounds.  An old cottage in Chadwick End along the Warwick Road An old cottage in Chadwick End along the Warwick Road A web search recently landed me on a website with the address of www.solihull.gov.uk. I was searching for a small, rural village in Warwickshire, England called Chadwick End. Just by looking at this url, one can spot that this page is hosted by the government of Great Britain. In particular, the information I would gain on Chadwick End could be found as part of a larger information portal for the Metropolitan Borough of Solihull in the West Midlands, England, one of seven metropolitan districts (in the West Midlands) and one of 36 in the metropolitan counties of England. Now I've never had the opportunity to travel to Great Britain, but hope to one day. Chadwick End is not a place on my "bucket list" at all, but I stumbled over it while researching a unique first name found in Frederick's historic Mount Olivet. As a matter of fact, I just learned that Chadwick is ranked #5,568 in popularity according to the website thebump.com. More about him in a moment. Here is what I learned from the "worldwide web" on my village quest, for those interested: "Chadwick means 'farm near a spring'. Chadwick End is approximately 6 miles south-east of Solihull town centre and is in the parish of Balsall, itself previously in the parish of Hampton-in-Arden. The village is not a traditional village in terms of a cluster of houses situated around a village green with a church and a public house. Rather, it is a crossroads settlement that has expanded over time with a ribbon of development along the A41. It lies astride this trunk road between Birmingham and Warwick, some 3 miles from Knowle, and its position on this established route probably accounts for its development. Most of Chadwick End falls into Solihull although part is in Warwickshire; sometimes the houses may be in Solihull and the gardens in Warwickshire! There are close links between Chadwick End, Baddesley Clinton, which is in Warwickshire, and the cluster of properties formerly known as Bedlam's End. Traditionally a small village that supported a farming community, between 1905 and 1960 the settlement of Chadwick End, together with the adjacent Bedlam's End and Baddesley Clinton, grew considerably." I have to admit that I instantly became interested in a potential visit to Chadwick End's sister-city Bedlam's End! if nothing else, I'd go there just to obtain a souvenir tee-shirt. I got sidetracked with this "squirrel distraction" as I desperately looked for more info on Chadwick End's neighboring village. That's when I learned that the term "bedlam" comes from the name of a hospital in London, “Saint Mary of Bethlehem,” which was devoted to treating the mentally ill in the 1400s. Over time, the pronunciation of “Bethlehem” morphed into bedlam and the term came to be applied to any situation where pandemonium prevails. Who says that these "Stories in Stone" are nothing more than biographical tributes to the deceased? I sure pride myself on providing my viewers with the knowledge to expand horizons and wow friends, family and co-workers. But I digress. I tried to find a good photo of Chadwick End for my story's cover image (at top of the article). There was nothing of interest (or historic sex appeal) to be found. However, the big tourist draw in this area is the British National Trust' Baddesley Clinton Manor located nearby Chadwick End (and Bedlam's End) in the greater Solihull area. I lost track of the project at hand (this article) as I read a story about a former lord of this manor named Nicholas Brome. One of the "must sees" found within this attraction include stains on the floorboards said to be blood, and left in 1483 when Mr. Brome stabbed the local priest. It seems a "big time" sin in breaking commandments (Thou Shall not Kill) until one learns that the said priest was actually breaking another. Brome's rage boiled over when the clergyman was "being overly familiar with his wife." Tests on the stains suggest that they are comprised of pig's blood, but the murder probably did take place somewhere in Baddesley Clinton on account of this "unsaintly" conduct by both individuals. Brome went on to rebuild the nearby parish church, dedicated to St. Michael, as a penance for having murdered the parish priest. It doesn't end there though. Mystery and intrigue continues to invoke interest in Nicholas Brome's gravesite. Apparently, Brome demanded to be buried "standing up" in the doorway of the St. Michael's Church at Baddesley Clinton. Sadly his marker stone often gets covered by a doormat, but hey, remember that he did stab a priest to death in cold-blood. So what does any of this have to do with Mount Olivet Cemetery in Frederick, Maryland? Nothing in particular, save for a "catchy" obituary header for a decedent buried in our Area NN. A slight alteration of Chadwick End would have provided our local newspaper with "Chadwick's End," fitting to run above the fold and photograph of our decedent's gravestone that still sits over his traditional, horizontal burial. However, photography hadn't quite made its way to Frederick yet by 1842, and this certainly would not have appeared in our Frederick newspapers until much later in the 19th century. Regardless of that, I'd like to finally introduce you to our main subject this week, Chadwick Hargrave Kuhn (1822-1842). So I've talked before about the sources used in compiling these stories. One of the first places consulted is Mount Olivet's digital burial database. Here was the result of my search for this random stone that caught my eye on a walk of the grounds back in late March. With some quick computing, I deducted that Chadwick's birthdate was November 19th, 1822. As a 19-year-old, I assumed that I wouldn't find much on this youngster. I did my initial searches in other source materials at hand, but found nothing. I was also frustrated by the fact that I did not have immediate access to local newspapers of this period either. So Chadwick had me looking in other directions. First, I wanted to track down his parents, who sadly are not buried here in Mount Olivet. I had their names in Chadwick's data with father being Joseph Lewis Kuhn, and the unique inclusion of our records of his military duty. I soon found that Chadwick's mother was the former Caroline/Carolina Hargrave. A family tree on Ancestry.com helped further, as it had been uploaded on the website by a descendant of one of Chadwick's sisters. I soon found myself at a " dead end, pardon the pun, on the Kuhn family line going backwards. However, a look at the Hargrave line certainly piqued my curiosity. If anything else, I felt good about discovering the source of more than just Chadwick's middle name "Hargrave." Yep, our subject's first name comes from his grandfather's middle name and likely a family surname before that in an earlier generation. Lewis Chadwick Hargrave, Chadwick's grandfather, was a politically important man of his times who apparently served as "Counsel for the King of England to Gibralter, Spain," according to Ancestry.com. Deeper investigation showed that Lewis Chadwick Hargrave was the Britannic Majesty's Consul General for the Balearic Isles of London. Hargrave died in 1837 and his daughter Caroline is mentioned in his will which I was able to find thanks to the internet and a genealogical board: "Lewis Chadwick Hargrave now devised his moiety in trust to Charles Bowdler of Doctors Commons, George Henry Malcom Wagner of Hurstmonceux Place Sussex and John Chadwick the younger of Rochdale Lancaster merchant for use of his son James Augustine Hargrave for life. And in trust to raise £ 4000 the interest to his daughter Louisa Maria wife of John Parody of Gibraltar And also £ 4000 the interest to the children of his deceased daughter Caroline Catherine late wife of Joseph Louis Kuhn now in America. After the decease of James Augustine Hargrave proceeds of moiety for use of his children." Our subject unfortunately did not get much of a chance to spend his inheritance from his noteworthy grandfather. I see three siblings listed for Chadwick in Henry, Caroline and Antoinette. However, I strongly think Henry's supposed birth date of 1802 (as listed in this family tree) is erroneous, as this is impossible because Joseph L. Kuhn married Caroline/Carolina Hargrave around 1818. In performing a Google search, I found a town history that revealed that Chadwick's older sister (Caroline) lived the majority of her life in Tiffin, Ohio (within Seneca County) as Mrs. Caroline Pennington. She married in 1842, and Mr. Pennington's biography states that Caroline A. Kuhn was a native of the island of Minorca (a province of Spain). It also said that she was a daughter of Joseph L. Kuhn, of the United States Navy, and a granddaughter of Lewis Chadwick Hargrave, late British consul-general to the Spanish Balearic Islands. This was a nice vetting process for me, and I also have seen that many former Frederick residents would make Tiffin, Ohio their home back in the early 19th century. So, I may never learn how Chadwick and Caroline's parents first met, but it's safe to assume they were married and living in Minorca, or Menorca as it is known today. Now here is a place that is a tourism "keeper" at first glance, unlike Chadwick End! I went in search of its history and learned that in November 1798, a British expedition captured the island of Menorca (historically called "Minorca" by the British) from Spain. A large force under Gen. Charles Stuart landed on the island and forced its Spanish garrison to surrender in eight days with minimal bloodshed. The British occupied the island for four years, using it as a major naval base, before handing it back to Spain following the Treaty of Amiens in 1802. My research assistant Marilyn Veek was summoned by yours truly, to find out more about Joseph L. Kuhn. I was getting nowhere fast with him, however, I found scant mentions in Jacob Engelbrecht's diary, kept from 1819-1878. More on that momentarily as I'd like to share Marilyn's findings done on abbreviated time before she headed off on a "birding" trip to the west coast. She actually found a ship manifest for Joseph L. Kuhn and his family from Gibraltar to Philadelphia in the year 1821. Unfortunately, for me, this was just before Chadwick's birth in November of the following year. However, it confirmed Henry Kuhn as a sibling (born c. 1819) to Chadwick, along with a time of passage to the United States.  Dr. Henry Kuhn, 1st mayor of Tiffin, OH Dr. Henry Kuhn, 1st mayor of Tiffin, OH A reader (Deborah Ward) pointed out to me this poignant Jacob Engelbrecht entry from July 2nd, 1821: “Lieutenant Joseph L. Kuhn of the United States Marines arrived in town on Thursday evening last 28 of June 1821 from Port Mahon Island of Manorca, in the Mediterranean Sea. After an absence of nine years he brought with him his lady & two children. He arrived in Philadelphia his welcome return.” I had assumed that the Kuhns lived in Philadelphia but a definitive home by 1830 would be Washington, DC. Jacob Engelbrecht writes in his diary on December 16th, 1830, the following entry: "Died at Washington City on the 10th instant in the year of her age Mrs Caroline Kuhn consort of Captain Joseph L. Kuhn of the United States Marines." The question that begs asking here is, "Why would Engelbrecht write this? Did he know the Kuhn family? If so, did they live in Frederick between 1821 and 1830? Or, was Capt. Kuhn a Frederick native to begin with?" I found a Joseph L. Kuhn (1798-1855) who lived in the Creagerstown area in the 1850 census, but he had a wife, Sarah, and slew of kids. This is not our father of Chadwick because Engelbrecht also wrote of Capt. Kuhn's death in 1836: "Died at Washington City on the 7th instant in the year of his age, Captain Joseph L. Kuhn, late of the United States marines, a native of our town. Son of the late Henry Kuhn, Esquire, Second Mayor of our city. (January 12, 1836)." And this is why I love history! Captain Joseph L. Kuhn was the son of our second mayor, Henry Kuhn, no way! Henry Kuhn (1761-1834) was a longtime judge of the Orphans Court for Frederick County and died at his farm in Graceham in north county. So perhaps the Henry Kuhn I saw linked to Thurmont is a distant cousin to Chadwick somehow? A Google search of "Mayor Kuhn and Frederick" led me to a Dr. Henry Kuhn of Ohio. This was a brother of Captain Joseph who holds the distinct honor of being a town's first mayor. Interestingly, that town is none other than the fore-mentioned Tiffin, Ohio. Dr. Kuhn was born and raised here in Frederick, and Engelbrecht made a note in his diary of Dr. Kuhn's marriage on Nov. 17, 1825 to Catherine Baltzell, daughter of Charles Baltzell. Marilyn found a land transaction done three years before Joseph L. Kuhn's death. In 1833, Joseph L. Kuhn of Washington City, bought from the estate of Peter Mantz, a 32-acre tract called "Stovers Good Luck". I think it may have been located in the vicinity of Tuscarora but don't quote me on that. Looking through Jacob Engelbrecht's Diary longer, led me to another obituary for the family. This was the death of Chadwick's brother whose birthdate given in the Ancestry.com family tree I disputed. "Died in Washington, DC on the 26th instant in the year of his age Mr. Henry Hargrave Kuhn, son (eldest) of the late Joseph L. Kuhn of the United States Marine Corps. He was born on the island of Minorca, Mediterranean Sea. (April 29, 1841)." As much as I achieved in chasing down the story of this family through fine resources at hand, I have yet to find the final resting places of Captain Joseph L. Kuhn, wife Caroline and son Henry. I'm also puzzled that Engelbrecht failed to write about Chadwick's end, I mean death—well you know what I mean. I scoured the diary to no avail. I also checked the online database of Frederick's Evangelical Lutheran Church and they don't have a clear record of his burial in their graveyard. However they have a record of his reburial from the second Lutheran burying ground at the corner of E. Church and East Street to Mount Olivet in 1907. Our records are dependable in this regard and backed up by Evangelical Lutheran in their database. He was re-interred in Mount Olivet's Area NN/Lot 125 on April 1st, 1907. Not my first choice for a dependable date (April 1), but I will trust in the system of record keeping. Its now been 116 years here in our humble cemetery within Frederick, Maryland far from Chadwicks End and Gibralter, native home of our subject's mother. Chadwick Hargrave Kuhn is buried among a row of strangers, with no one from his nuclear family in the cemetery as well. At least his paternal grandfather was a big wheel here in Frederick in his lifetime. |

STORIES

|

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed