|

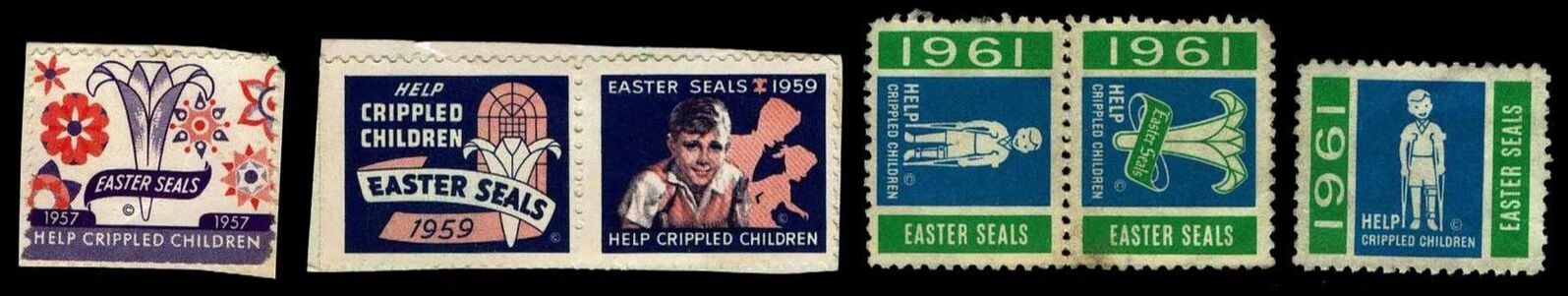

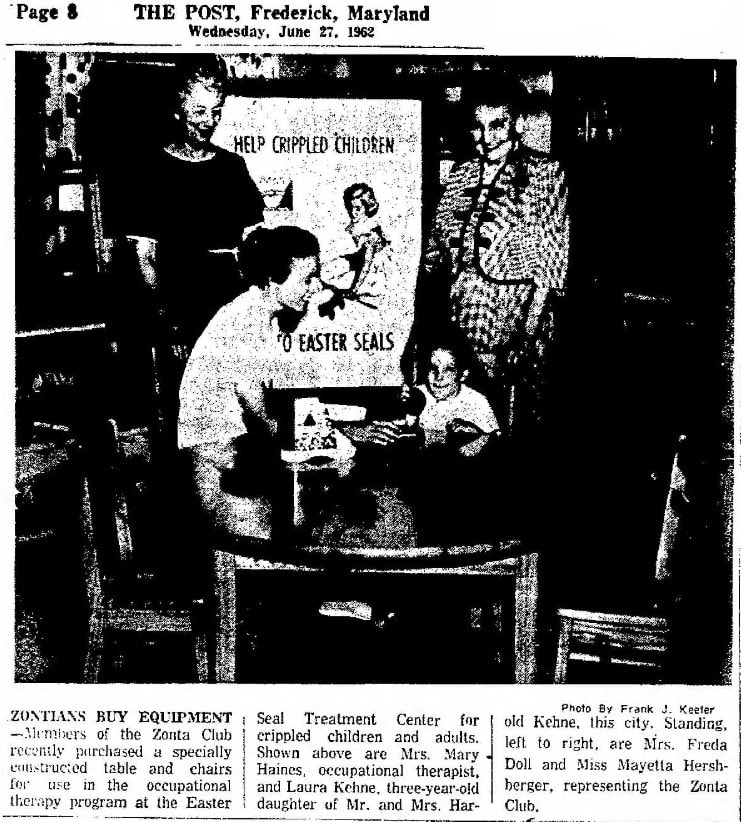

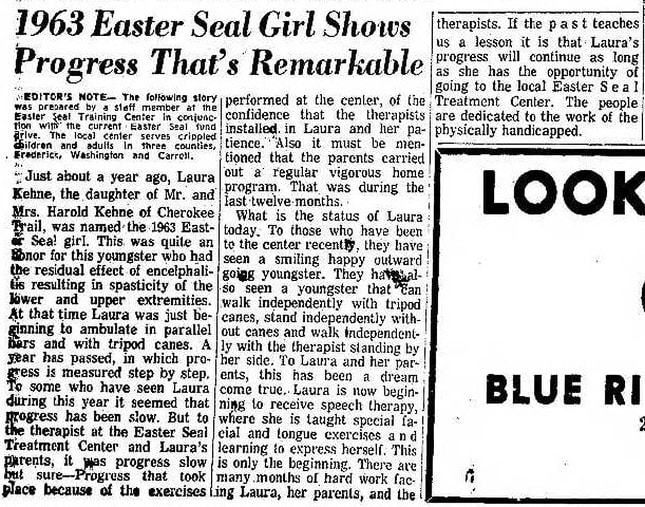

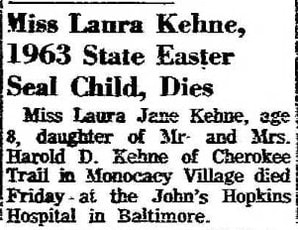

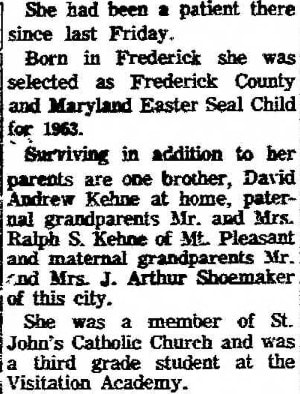

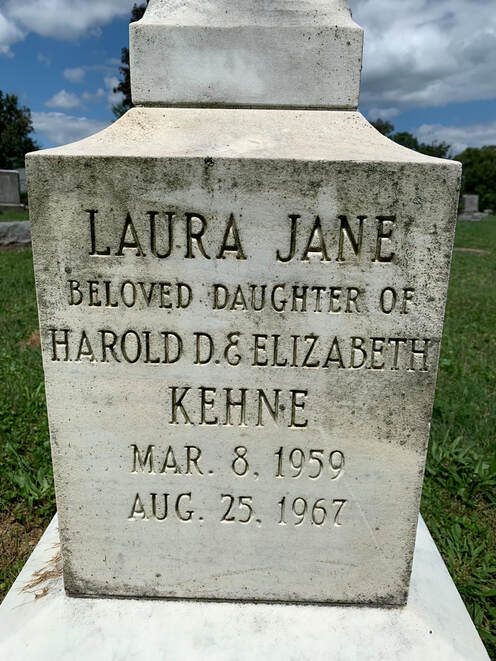

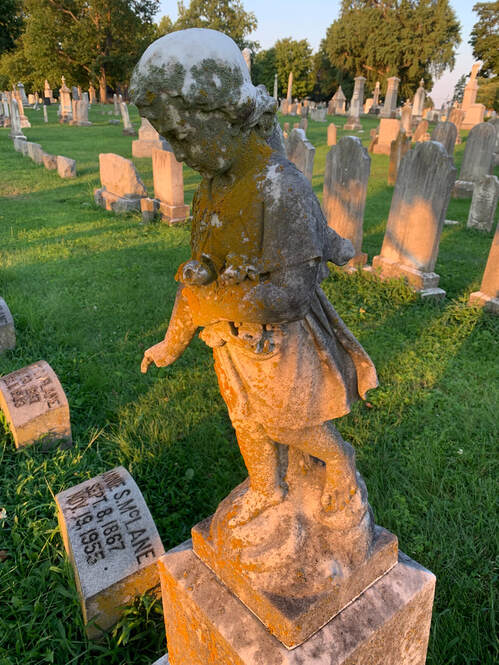

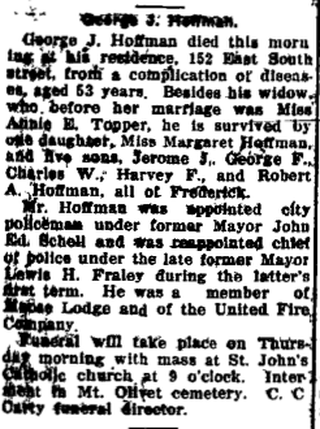

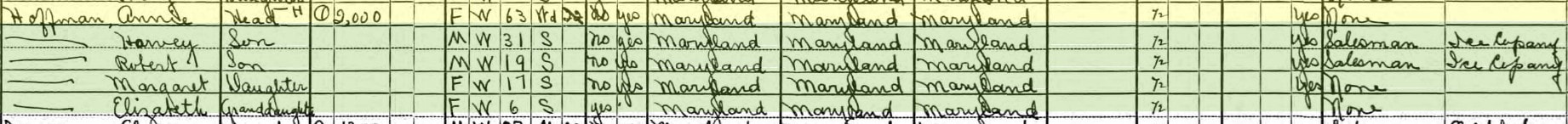

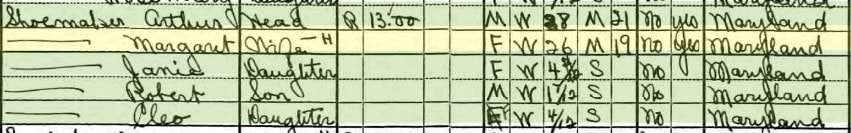

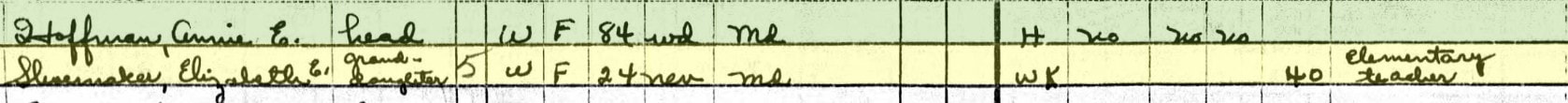

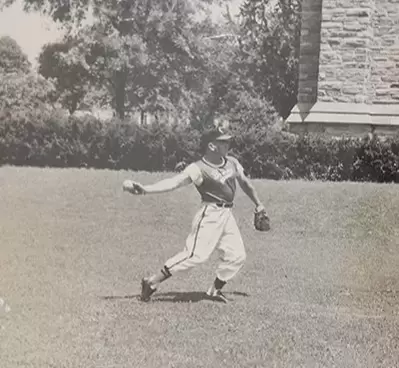

“Angelic Bookends,” that’s what they are. These two funerary pieces can be found in Mount Olivet’s Area U/Lot 123. They mark the graves of Laura Jane and Ann Elizabeth Kehne, two sisters who died in their early youth and just a decade apart from one another. The pieces in question employ a “throwback,” or vintage, design of a cherub commonly referred to as a “child-angel.” This iconic figure from the Victorian era is a symbol of innocence and immortality. In cemeteries, monuments of this type usually denote the grave of a baby or a child. When they adorn the grave of an adult, their meaning might be more representative of the soul’s entrance into paradise than a connection to childhood. I assumed available information on these decedents would be light as these two youngsters spent a combined 14 years of existence in this world. Hopefully, someone out there reading this piece will add more about them (and the family) in the comment section (at the end of this article) as the girls’ parents have both passed within the last 20 years. The extent of information on Ann Elizabeth Kehne can be found in her obituary and funeral notice in the local newspaper from 1957. Born January 6th, 1955, Ann only attained the age of two, dying three days after her birthday on January 9th, 1957. Our cemetery records show that although the family was living in Frederick’s Monocacy Village (912 Cherokee Trail) at the time, the toddler died of encephalitis while hospitalized in Baltimore. Just over a year after Ann Elizabeth’s death, the Kehnes had reason to rejoice as they were blessed with the birth of a second daughter on March 3rd, 1958. She was given the name Laura Jane. I wasn’t expecting to find much about this youngster in the newspaper either, but I was wrong as I immediately found a photograph of her in an edition of the Frederick Post from October 17th, 1962. It shows Laura Jane undergoing ambulation therapy. For those not familiar with the term, “ambulation” is the ability to walk without the need for any kind of assistance.  The picture’s caption said that this therapy had taken place at the Frederick Easter Seals Health Center. This facility opened in 1957 and was once located at the Odd Fellows Home on North Market Street. It served not only Frederick County, but our neighboring counties as well. Now, some of our younger readers may be asking, “What is/are Easter Seals?” Easterseals (formerly known as Easter Seals) is a charity founded in 1919 as the National Society for Crippled Children. It is a 501(c)3 nonprofit organization providing disability services, with additional support areas serving veterans and military families, seniors, and caregivers. The name "Easter Seals" came from an earlier fundraising program begun in 1934 with colorful adhesive seals, the size of postage stamps being sold around Easter. Purchasers could stick these on the back of mailed envelopes, as a popular tradition was to send cards to friends and family both at Christmas and Easter seasons. Because of the program's success, the organization changed its name from "the National Society for Crippled Children" to "Easter Seals." Another photograph of little Laura had appeared a few months earlier in the Frederick newspaper. It showed Laura, with her mother (Elizabeth), receiving assistance from Frederick’s Zonta Club. I would find another at the end of 1963 with a visit from Santa. Right when I began thinking that my young subject (Laura) could have been some sort of posterchild for children with disabilities, I read the heartwarming news on January 3rd, 1964 that Laura had been named Maryland’s Easter Seal Child. An informative article appeared in March of 1964. Laura was making great progress and was a shining example and ambassador for the work the Easter Seals organization was doing. I found nothing more at hand during my cursory checks of old newspapers and the internet, save for some school class pictures appearing in newspaper. Laura would go on to attend the Visitation Academy from what I could see. Sadly, the last mention of Laura Jane Kehne came in the form of her obituary in late August of 1967. She, like her sister, died in Baltimore. This occurred on August 25th of that year at the tender age of 8. Laura would be buried a few days later in Mount Olivet, roughly five yards away from the “older” sister she never had the chance to know. A “child-angel” monument was added to mark her final resting place, just like the one that had been placed on Ann Elizabeth Kehne’s grave a decade earlier.  Visiting the sisters graves this week, I sought to learn more about the basis of these particular funerary monuments. In their online blog entitled Cemetery Insights and Beyond, authors Dave and Linda Vichiola-Coppola state that: “Cherubs appear in the Book of Genesis and are ranked as one of the highest orders of angels. As the Bible story goes, after Adam and Eve’s banishment from the garden of Eden, God stationed a cherub holding a flaming sword to guard the entrance. It was not hard for the faithful of long ago to imagine the cherubim as sentinels. The traditional image of a cherub was not cute or childlike at all. In modern times we find it difficult to envision a winged infant (or a young child) holding a flaming sword and assuming a strong stance to ward of intruders. Our perception of the cherub was changed by two important developments during the 19th Century: archaeological discoveries and a set of new social values. In the mythology of ancient Greece and Rome, the god of love was depicted as a young boy. Yet, neither the Greek god Eros or the Roman god Cupid is depicted as a baby. Lin Vertefeuille of Ringling Docents.org points out that the image of the cherub as a baby more closely resembles a nature spirit known in ancient Greek and Roman mythology as genius/genii. The same images of the winged babies appeared in masterpieces of art from the Renaissance and Baroque periods, but they were called putti (putto, singular). During the Victorian era, there was a revival of classical art sparked by major archaeological excavations that were taking place in Greece. The winged baby image of the genii decorated the artifacts that were unearthed. The image appealed to the Victorians because of its resemblance to the infant angels that were depicted in masterworks of art from the Renaissance and Baroque periods. The Coppolas go on to say, “While archaeology played a role in the cherub’s physical characteristics of the 1800’s, a growing cultural concern over the well-being of children made the cherub a popular cemetery monument. Prior to the 20th century, the death rates for children and infants were staggering. Before the time of major medical advancements, many infants died at birth and those that survived had to make it through childhood without succumbing to infectious diseases. Poverty levels in industrialized areas and the lack of child labor laws made children more prone to life-threatening health problems.” Annette Stott, a writer for the website Nineteenth Century Art-Worldwide, explains, “High mortality rates boosted the value of children….an ideal of childhood arose that stressed the natural innocence and joyfulness of children.” Advocates of child labor laws during the late 1800’s helped prompt growing social concerns over the well-being of children. The treasured values of childhood were frequently depicted in Victorian art and literature. The images of the putti that decorated the Greek artifacts resembled a baby angel, just as the Roman and Greek god(s) of love (Cupid and Eros) resembled an angel child. So, when a child died, the Victorian cherub served as an appropriate graveside symbol of innocence and youth. Today, the Victorian cherub remains a popular cemetery icon to mark the graves of children and infants. Many examples exist within the historic section of the cemetery. A more modern angel can be found close to the Kehne sister on the east side of Area U as the prime marker for a unique section called “Babyland.” I know the name catches some off guard, but this is a specific area designated for infants and toddlers. Young children of this age were originally buried in Area M, also known as “Stranger’s Row,” a charitable area where bodies of deceased visitors to town (without family elsewhere) could be buried, as well as indigent persons, or those widowing wives and orphaning children with little to no means to bury their loved one. Many infants were buried here in economical, “smaller designed” lots—helping to relieve a financial strain from families not having family plots (or planning for them in the prime of life as young adults). When photographing the Kehne “child-angel” monuments for this story, I struggled to find the girls’ parents anywhere nearby. I simply found a large family marker for the lot-holding Hoffman family. Once back in the office, our database revealed that parents Harold Dorsey Kehne and Elizabeth Eloise “Boots” (Shoemaker) Kehne were buried in Area FSK/Lot 105. This is a section to the immediate north of the Mausoleum/Office complex in the back section of Mount Olivet. This is nowhere close to Area U where Ann and Laura are located. A secondary question came to me in addition to “Who were these young “angels?” — “Why are these girls not buried with their parents in the same location?” I soon found the Hoffmans to be the maternal great-grandparents of Laura Jane and Ann Elizabeth Kehne (grandparents to the fore-mentioned Elizabeth (Shoemaker) Kehne. This took a little detective work—fitting because original lot-holder George Jacob Hoffman (b. 1868) was a Frederick City policeman. Mr. Hoffman died at age 53 at his home at 152 East South Street in 1922. He would be the first of his immediate family to be buried here in a plot shared with his great-granddaughters. George’s widow, Annie Hoffman would continue living in her home on Frederick’s southside off East South Street. This a fairly recognizable rowhouse that still stands today across from the Frederick County Public Schools headquarters building on the northwest corner of East South and South East streets. The house at #152 is the easternmost townhome here, just down from Winchester Street. Regular readers of this blog may recall that the name of this street comes from Benjamin F. Winchester who opened a brick manufactory in this vicinity. This would eventually become Frederick Brick Works. Benjamin was the brother of Hiram Winchester, a New England schoolteacher who was responsible for the Frederick Female Seminary on East Church Street in the 1840s. This is today known as Winchester Hall and serves home to our local Frederick County Government.  Shoemaker gravesite in Area FF/Lot 294 Shoemaker gravesite in Area FF/Lot 294 Back to our Kehne sisters and their great-grandmother Annie (buried between them), Mrs. Hoffman is listed as head of household in the 1930 census. Her sons worked as salesmen for a nearby ice plant operation, while her daughter, Margaret, and granddaughter, Elizabeth, also lived here. The puzzling thing for me here came in the realization that six-year-old Elizabeth Shoemaker was listed as “Elizabeth Hoffman” and that her supposed mother, Margaret Hoffman was only 11 years her senior at age 17? I thought that perhaps Margaret was simply an aunt and that there was a missing, or deceased, son of Mrs. Annie Hoffman who could be the father of Elizabeth prompting the name Hoffman here in this census record. Her mother would be missing as well. Our cemetery records did not provide me with the names of Elizabeth’s parents, however, my research assistant Marilyn Veek answered these questions for me. She showed me that George and Annie Hoffman's daughter, Margaret Laura Hoffman, married a man named Jacob Arthur Shoemaker, Sr. and that Elizabeth was the daughter of Margaret Hoffman. I checked our database and found Margaret and Jacob Arthur buried here in Mount Olivet (Area FF/Lot 294). Our records show Margaret’s birthdate as February 15th, 1904, thus proving that the 1930 census showing of her age as 17 was erroneous. She was actually 27 and plenty capable of having a six-year-old daughter in 1930. When I looked for Mr. Shoemaker in the 1930 Census, I found him also living with Margaret, but at a location around the corner at #10 Winchester Street—and they had other children too! In Ancestry.com, I found the R.L. Polk Frederick City directory from 1928-1929 that listed both Jacob and Margaret Shoemaker as living at 152 E. South Street, the former Hoffman family home. They must have moved nearby shortly thereafter. Margaret was a machine operator at a tailoring business and Jacob was an electrician with Frederic Iron and Steel Company. As an aside, I found a small article in a paper from 1916 that stated that Jacob had run away from home, but not for long. This occurred just months after the youth was “stunned” by a bolt of lightning that struck near his church in Braddock Heights. Naturally, I expected to find Elizabeth living with her mother and Mr. Shoemaker in the 1940 census. Instead, Elizabeth was still residing with her grandmother and maternal uncles on Winchester Street. Maybe the house on Winchester wasn’t big enough? Or perhaps Elizabeth got along better with her grandmother than mother, we may never know? Meanwhile, Margaret Hoffman Shoemaker can be found living at #10 Winchester Street with three children: Jane, Jacob Arthur, Jr., and Cleora. Elizabeth can be found once again living with her grandmother Hoffman in spring of 1950, and she is listed as an elementary school teacher. She had graduated from Frederick High School in 1940 and from State Teachers College at Towson in 1944. She would later earn her master's degree from University of Maryland at College Park. Just a few months after this census was taken, she would be married in the month of July in a double wedding ceremony with a younger sister named Cleora (Cleo) Shoemaker (1930-2015). Mr. Kehne was a former veteran of World War II and may be remembered for owning a gas station, Kehne’s Citgo on the corner of East and East 13th Streets, not far from his family’s home in Monocacy Village. He owned this from 1957-1974 and That station still exists today as the East Street Liberty. The Kehnes would have three children, the fore-mentioned Ann and Laura, and a son David. Harold Dorsey Kehne, age 86, of Frederick, passed away at Frederick Memorial Hospital. He was a graduate of Frederick High School (class of 1943). After selling his business, Mr. Keene attended the University of Maryland and studied education, likely inspired by his wife. He taught at Middletown High School, West Frederick Middle School, and New Market Middle School, until his retirement in 1986. A teacher for 31 years, Mrs. Kehne first taught at Emmitsburg Junior High School and at several other schools including Elm Street School and Frederick High School. When she returned to teaching after having children, she taught at Frederick Academy of the Visitation and then returned to teaching public school. An early advocate for special needs students, she started the county's physical education program at Harmony Grove School and then moved to Rock Creek School when it opened in 1972. This would lead to her election into the Alvin G. Quinn Sports Hall of Fame. Her unselfish service and belief in impaired students led her to strive for successful creation of the Frederick County Special Olympics. She coached students to numerous championships in various sports and created for her teams and students the opportunity to achieve beyond all expectations. Somewhere along the way, she picked up the nickname “Boots.” Elizabeth’s brother-in-law, Max S. Kehne, is also a member of this prestigious group of local athletes and sports pioneers recognized in the Quinn Hall of Fame (housed at the Frederick County YMCA). Max Kehne is still remembered as most famous softball pitcher in Frederick County history, and a member of the Maryland Softball Hall of Fame. He was also a key area sports promoter and a member of Frederick City Board of Aldermen at the time of his untimely death due to an automobile accident. Max S. Kehne Park on West 7th Street is named in his honor. Elizabeth S. Kehne retired in 1986. She was active in the Frederick City Recreation Council, serving for many years as the council's secretary. Following her retirement, she was a volunteer tutor with the Literacy Council of Frederick and enjoyed spending time with family and friends in Frederick and in Rehoboth, Delaware. I found that surviving son David helped establish the Harold D. and Elizabeth S. Kehne Scholarship Fund in 2015 with the Community Foundation of Frederick County. The fund’s purpose is to provide scholarships to graduates of Frederick High School or Gov. Thomas Johnson High School pursuing a career in education. Preference is given but not limited to students attending Towson University, University of Maryland College Park, or one of these educational institutions’ extension campuses. Since the fund was created, it has helped students pursue careers in education just as the Kehnes did. So, there it is. I figured out who the interesting monuments in Area U were “bookending,” so far from the gravesite of their educator parents. I had become intrigued with Elizabeth’s challenges throughout her life. Her resilience as evidenced by her educational pursuits and achievement are evident that she persevered despite any initial setbacks. I will say that knowing this information about Elizabeth’s childhood and professional career, certainly makes me respect her even more knowing that she lost Ann Elizabeth at such an early age, and was forced to endure the incredible stress of having Laura and working so dutifully as a mother with assisting her daughter in the everyday challenges revolving around disabilities. As we know, this would end with Laura’s untimely death as well. I never knew Elizabeth Eloise (Shoemaker) Kehne, but when I visited her gravesite here in Mount Olivet, several hundred yards from that of her daughters, I thought to myself that perhaps there should be one more “child-angel” monument placed here on her grave as well.

0 Comments

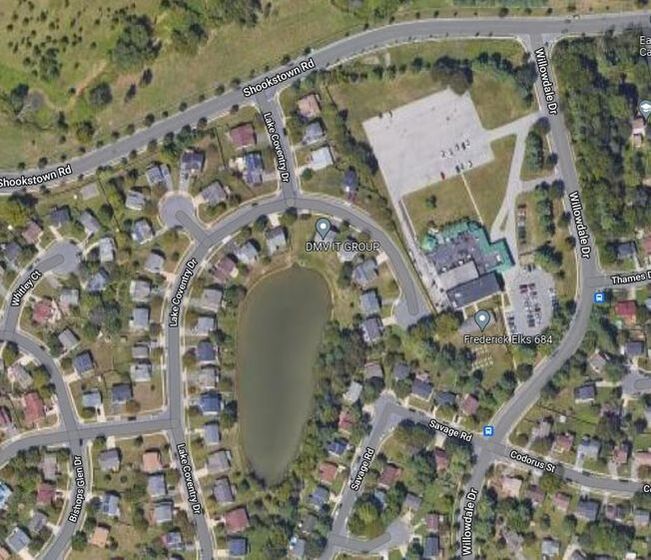

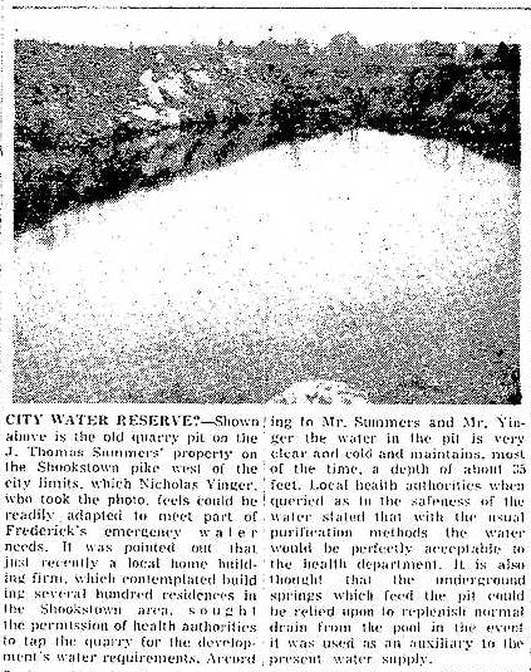

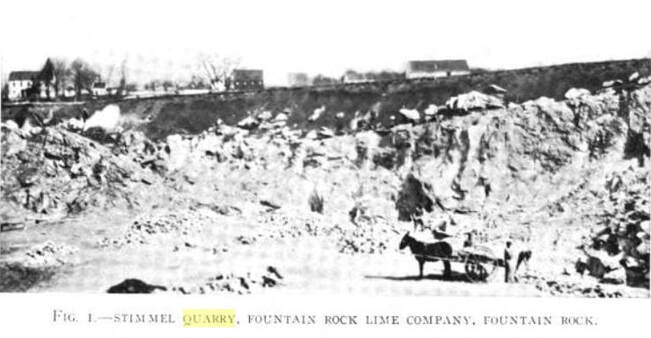

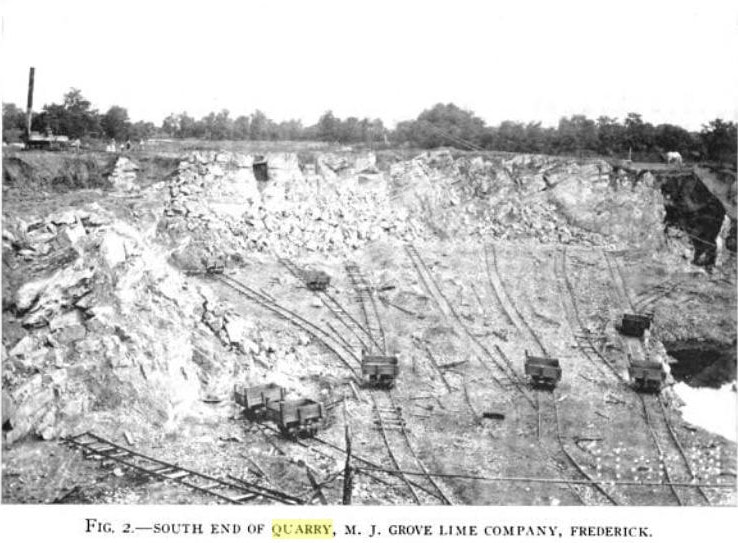

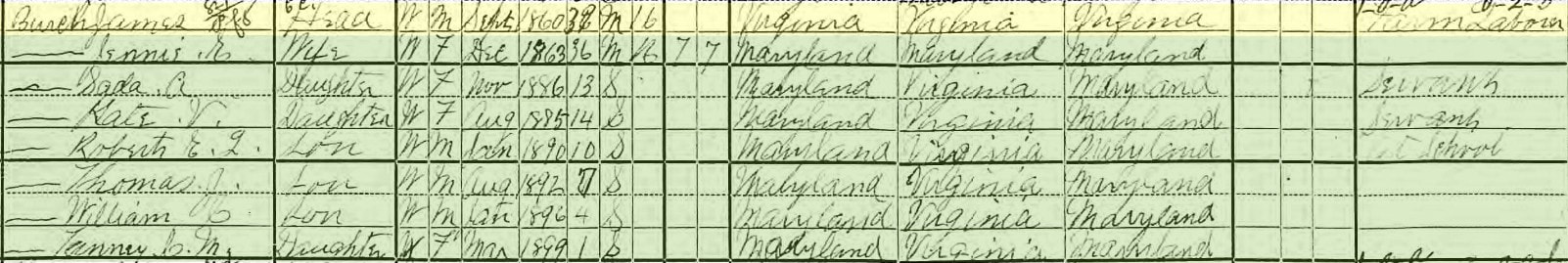

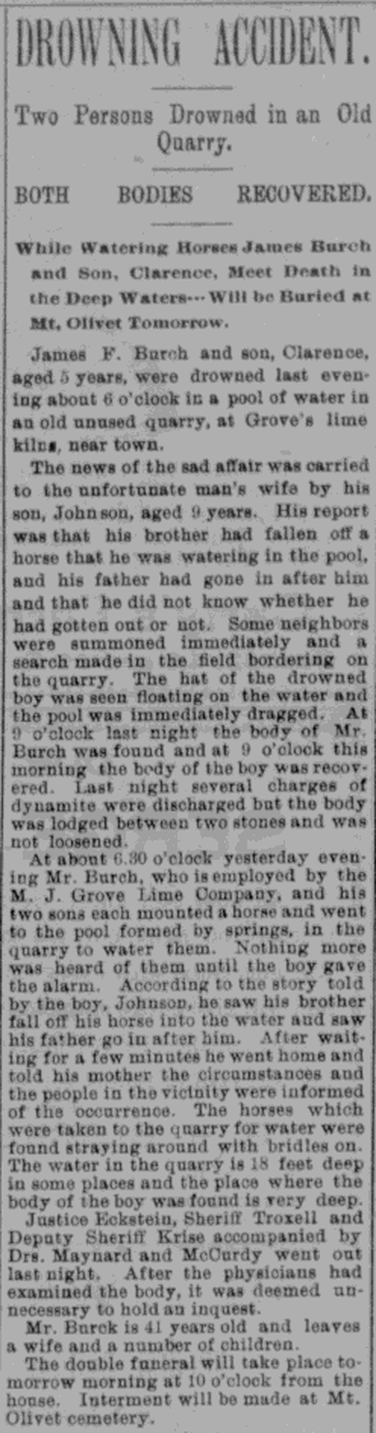

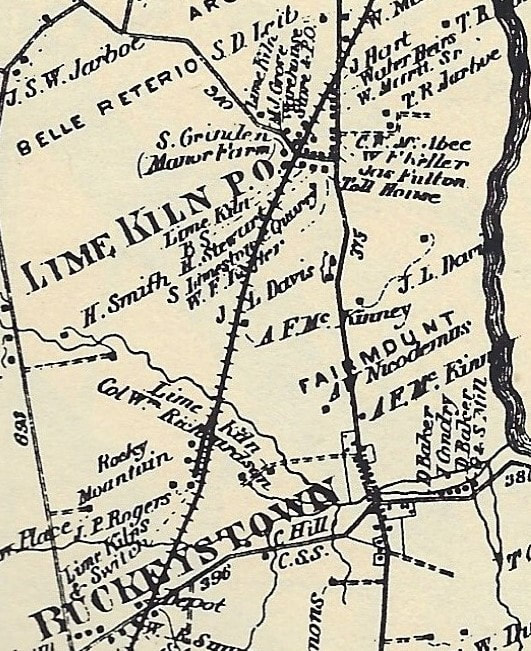

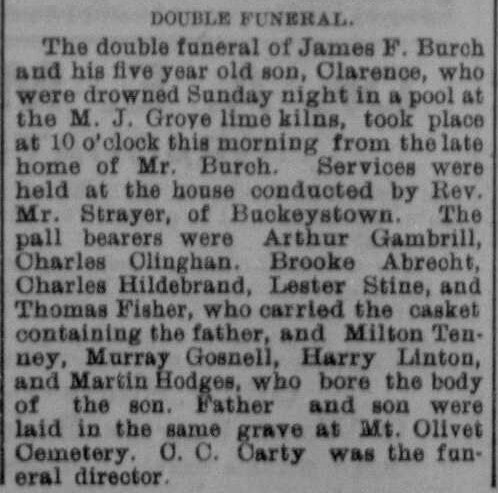

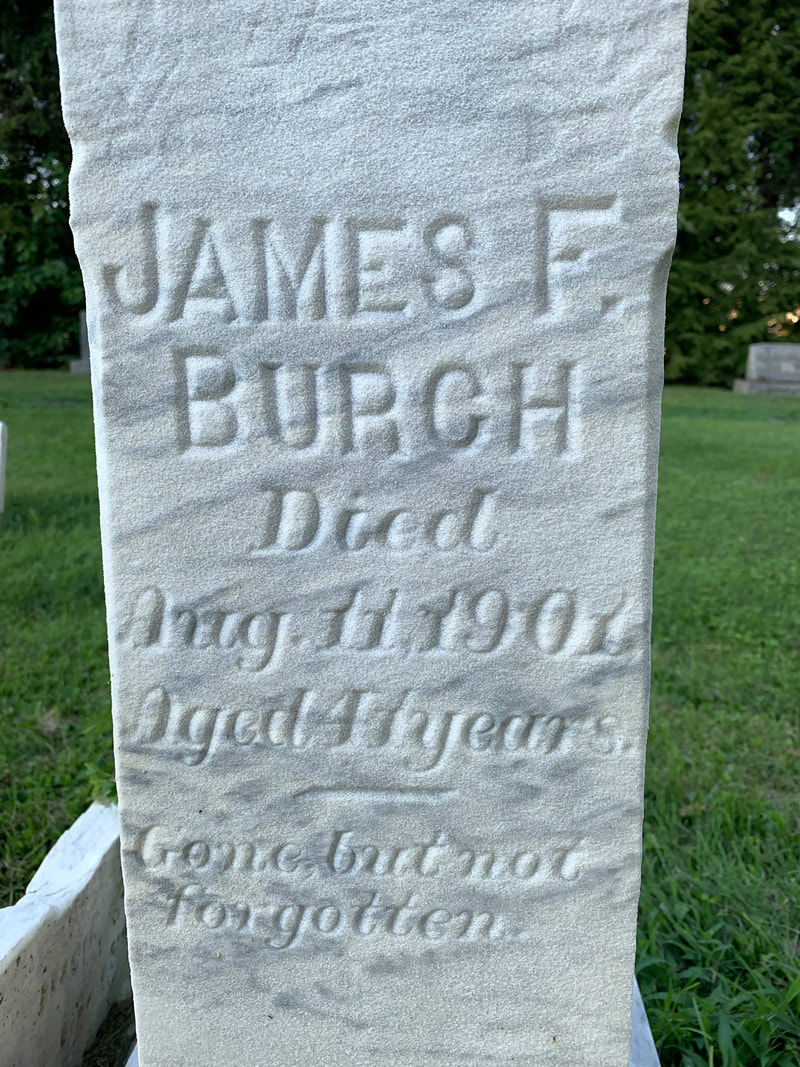

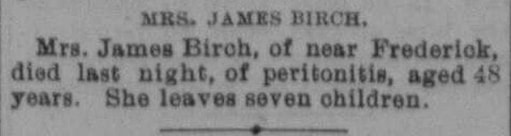

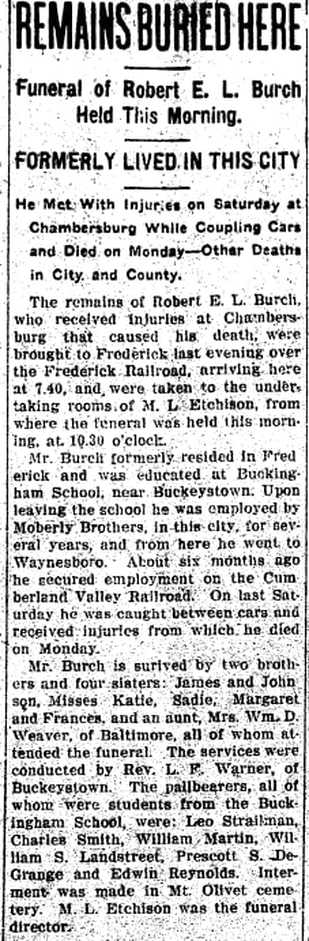

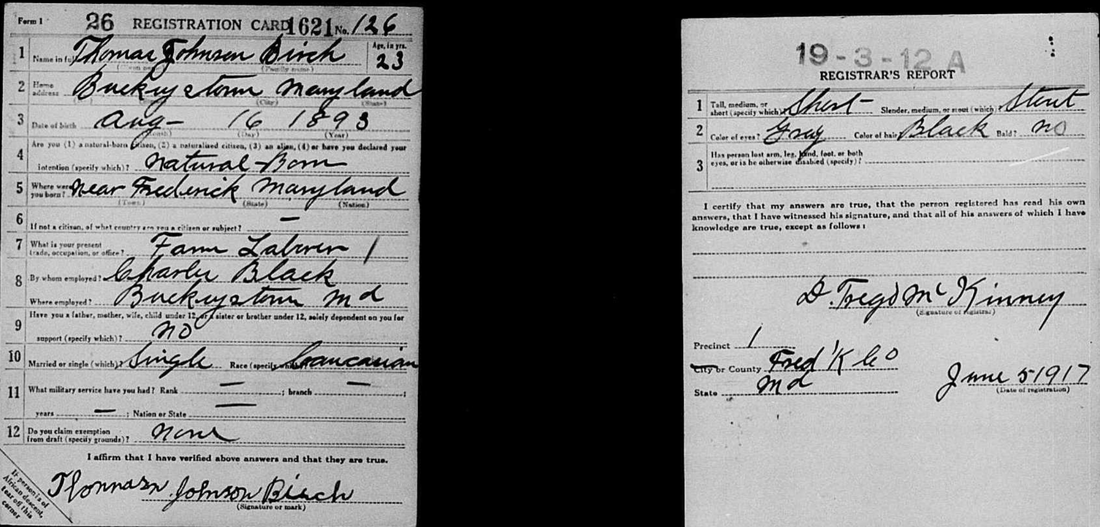

Fountain Rock Park Fountain Rock Park In my professional past, I've had the opportunity (on more than one occasion) to visit rock quarries. I was working on a documentary back in the late 1990s which I named Monocacy: the Pre-history of Frederick County, Maryland. This project involved an investigation into the geologic history of our region, and what better way to see the rocks deep below the ground surface of today, than visiting a quarry? In addition to the old LeGore (current-day Barrick Quarry) near Woodsboro, I also filmed at another large operation north of Buckeystown--the former Essroc Quarry, now known as the Vulcan Materials Company. Of course we have the Martin Marietta Quarry (formerly LaFarge) only a mile from Mount Olivet Cemetery to the southeast. This comprises an earlier quarry known as the M. J. Grove Lime Company. Gravestone conservators like Jonathan Appell have told me that the daily blasts at this site have caused movement to some of our taller, ornate, multi-piece grave monuments over the years. Of course, we all know that East South Street/Reichs Ford Road is no stranger to sinkholes as well thanks to this operation from time to time . In fact, my former in-laws had to have one of their Golden Retrievers rescued after falling into a sinkhole on the Maryland School for the Deaf property north of Monocacy Boulevard. I was also introduced to smaller rock quarries from our past, sprinkled throughout the county, including, of course, the visitor-friendly, former site of the Fountain Rock Quarry. This is a county park today and has a nature center to compliment the remains of lime kilns and a nice boardwalk in which to traverse the water- filled quarry cavity. My kids loved it. From my vast experience in researching Frederick history, I know of many more places once mined for limestone on local farms. A while back, I wrote a "Story in Stone" that featured the Schley Quarry, once located north of the Frederick Fairgrounds property and today's Highland Street. The first quarry that I ever heard of, comes from my youth growing up in the Rocky Springs area northwest of Frederick City. Although I never tried it for myself, I heard stories of kids swimming at a quarry positioned south of Shookstown Road. It's still around, and today is more commonly referred to as Lake Coventry. It's tucked within the residential community of Willowdale, just west of the Frederick Elks Club. At one time, this location was discussed as a possible water reservoir to feed Frederick City but this idea never materialized. This location was infamously memorable to me as I recall the news while I was in high school of a fellow teen, only a couple years older than me, drowning in the old quarry. That was enough to make me leery of quarry swimming for a lifetime. The Shookstown Quarry like others had flooded out many years before from aquifers seeping water through its lowest levels. Many local kids used it as our “swimming hole" for decades. Robin Lee Zimmerman was buried at Resthaven Memorial Gardens. I found an article in the Frederick paper just four months later that reported a car was retrieved from this quarry. I've never seen a quarry used to dispose of stolen vehicles while watching my children play GTA ("Grand Theft Auto" video game series), but apparently it was a thing back in the day. That would be one more reason not to jump in a quarry, as you may land on a car! Not to mention the gas, oil and anti-freeze from the vehicle that now comprises the soothing water. The newspaper articles regarding Mr. Zimmerman's death cite earlier fatalities here at Shookstown in 1977 and 1955. I even read an online recollection from a former co-worker (Jack Spinnler) at Frederick Visitor Center in which he said that he almost lost his life there at the Shookstown Quarry site when he was 16, due to a diving mishap. The deceased in the 1977 incident at Shookstown was a 29 year-old Howard County resident named Emmanuel Lee Wells, Jr. In each of my filming and research sojourns, I asked for, and was duly granted, permission to do what I was doing. I was also accompanied by someone who knew the lay of the land as well. This was an obvious need for the large commercial operations, but I understood the dangers involved with the extant, historic sites, long since abandoned. My greatest takeaway from the experience of visiting these scenic and seemingly peaceful settings--quarries are dangerous places! A site called Geology.com reports that in a typical year, several people die in accidents that occur in abandoned mines across the United States. Some of these deaths could have been prevented if citizens knew the danger of these properties, and if landowners had made better efforts to warn and limit access to said bodies of water. The website also speaks to government's role in having improved programs for reclaiming or regulating these places. The stern warning is as clear as the water in some quarries, "If you are a mineral collector, hiker, recreational vehicle rider, swimmer, or curious person, you have no business entering an abandoned or inactive mine or quarry. In almost every instance, you will be trespassing because abandoned mines and quarries are almost always on private property." Drowning is the number one cause of death in abandoned mining locations. Most people involved in this type of accident originally went to a quarry for swimming or ATV riding. Quarries are extremely dangerous places to swim. Steep drop-offs, deep water, sharp rocks, flooded equipment, submerged wire, and industrial waste make swimming risky. Another risk factor is the very cold water. Many quarry operations excavate to depths below the water table and use pumps to keep the mine dry while it is in operation. When mining stops, the pumps are turned off and the quarry floods by the inflow of cold groundwater. This groundwater inflow can keep the quarry water very cold, even in late summer. Jumping or falling into cold water can be fatal--even for a young healthy person. Here is a quote from the National Institute of Health on how the human body responds to sudden immersion in cold water: "A fall in skin temperature elicits a powerful cardiorespiratory response, termed "cold shock," comprising an initial gasp, hypertension, and hyperventilation despite a profound hypocapnia. The respiratory responses to skin cooling override both conscious and other autonomic respiratory controls and may act as a precursor to drowning." I also wrote a "Story in Stone" about the previously mentioned Grove family tied to multiple quarries. Although focusing on baseball with a pivot point of Harry Grove, namesake of our local stadium, I recalled the family's successful business endeavor at Frederick and another location at Lime Kiln, located on MD route 85 just above Buckeystown. The M.J. Grove Lime Company was one of the largest and most successful companies of its kind. It was founded in 1860 by Manassas J. Grove with his son William. Grove, a Frederick County native born in 1824, worked as a teacher, merchant, surveyor, and postmaster until he decided to capitalize on the increasing use of lime for agricultural purposes. He purchased a tract of limestone land along the main line of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, five miles south of Frederick, which became the village of Lime Kiln, and began manufacturing lime. In 1889, the company purchased the property known as the Brengle Lime Kilns from Thomas Schley and Raymond Reich, as well as the lime kilns of Samuel Hoke, which were located at the southeast edge of the city, near present day Interstate 70 and Reich’s Ford Road. The property included six lime quarries with 14 iron clad kilns for burning. In November, 2020, The City Of Frederick's Preservation Planner, Lisa Mroszczyk Murphy, wrote about Frederick's quarries in her amazing Preservation Matters series found in the Frederick News-Post. She had this to say about the father of our stadium namesake (Harry Grove): "In 1902, the M.J. Grove Lime Company erected a stone crushing mill at the Frederick plant to supply crushed stone for railroad ballast and hard surfaced roads. In 1905 the company entered into road building and bridge construction and went on to build one of the first concrete roads in the state. By 1906, the company was producing 1,000,000 bushels of lime yearly and established itself as one of the largest industries in the county. The company also established quarries in Buckeystown, Stevens City, Virginia, and Washington, D.C. M.J. Grove died in 1907 and his sons continued to operate the company well into the 20th century. In 1910, a report by the Maryland Geological Survey described the Frederick quarry of the M.J. Grove Lime Company as the largest near Frederick. It also reported that they operated 17 kilns and had other steel-clad kilns under construction. Notable projects by the company included supplying stone for the White House grounds and for water filtration at McMillan Reservoir in Washington, D.C. In 1925, a concrete and cinder block plant was constructed at the Frederick location in order to utilize the fines from the crushed stone plant. In 1960, the company became a division of the Flintkote Company." So back to abandoned quarries, I recently came across an early tragedy involving the site tied to the Grove's operation at Lime Kiln. This event involved a father and son, James F. Burch, a Virginia native from Loudoun County, and his five-year-old son, William Clarence. This event occurred in August, 1901. I immediately wanted to locate this quarry and went to an atlas map and Google Earth for clarification. James and Clarence were laid to rest in Mount Olivet's Area K on the northern boundary of the cemetery near the Key Chapel location. During the Civil War, this exact location was the site of "a Union Row" of graves of northern soldiers who died of wounds suffered at nearby battlefields or of disease/illness. Many of these grave spots were repurposed as single grave lots, many going to destitute persons and infant decedents after the vast majority of soldiers were relocated to the national cemetery at Sharpsburg which opened in 1868. I was interested to learn more about Mr. Burch and his backstory. We didn't find much. James F. Burch's parents were Francis E. Burch and Henrietta P. Newton Burch. He was born in Loudoun Co, VA, but the family moved to the Poolesville area in the 1870s. His parents and various other aunts, uncles and relatives are buried at Monocacy Cemetery in Beallsville. James didn't own property, and worked as a laborer for the Grove Lime Company. My assistant Marilyn could not pinpoint exactly where he and his family were living, but it was likely Lime Kiln or neighboring Buckeystown to the south. Speaking of south, the Findagrave record for Francis Burch says that he was a Confederate Veteran, 1861-1865 (American Civil War), as a member of "Jacob's Mounted Riflemen", Mounted Infantry, VA. There are no military records of his service with the Confederate States of America (CSA) that we could find. Henrietta Burch died in 1906 in Washington, DC. Two of her children also lived in DC. James F. Burch's siblings included Henry Clay Burch and Robert Lee Burch, (historical figure names) as well as a sister Margaret (Burch) Dove. As an aside, one of Margaret Dove's daughters became Sister Mary Ignatius Loyola Dove, and is buried at the Visitation Convent Cemetery here in Frederick. Another sibling of James F. Burch was John Lewis Burch, who died after jumping off a railroad bridge in Washington, DC in 1909. As if the loss of her husband and young son wasn't terrible enough, Jennie (Carson) Burch would be widowed and now found herself as the single parent of seven children. To add to the family's plight, Jennie died just nine months later, perhaps due to complications of childbirth with son James Francis (b. April 22nd, 1902). She would be buried in an adjoining lot (K67) and her name carved on the same monument with her husband and son. I became very curious of what became of the orphaned children including Johnson who eye-witnessed the deaths of his father and younger brother at the quarry back in August, 1901. James and Jennie Burch's surviving children were: 1.) Katherine Virginia Burch (Aug. 1885-1934, married Charles Martin Paris in 1913 in Washington, DC). 2.) Mildred Alice Burch (Nov. 1886 - 1942) is buried here in Mount Olivet near her parents grave in Area X/Lot 1. 3.) Robert E. L. Burch (Jan. 1889 - Dec. 4th, 1911) - funeral notice attached; it says that he attended Buckingham School and that he died as a result of injuries from his railroad job. Buried at Mount Olivet in the same grave lot as James and William Clarence (Area K/Lot 64), however his name was not placed on the monument. 4.) Thomas Johnson Burch (Aug. 16th, 1892/1893 - May 7th, 1930) who is buried at Mount Olivet under the name Johnson Burch. I couldn't find him in the 1910 census or later, but did locate his WW1 draft registration. The Charles Black for whom he was working in 1917 is probably the Charles N. Black (1886-1983) buried at Mount Olivet in Area L. Johnson died of pneumonia and is recorded as being buried in Area K/Lot 51, a few yards away from other family members in an unmarked grave. 5. )William Clarence Burch was the original victim of the Grove Quarry accident of 1901. 6.) Frances C. Burch (Mar 1899-1960) - in 1910 she was in the Loats Asylum. In 1918, she married George Washington Grantham in Washington, DC. Apparently after he died in 1940, she married Charles Woods Adams. 7.) James Francis Burch (April 22nd, 1902 - Aug. 28th, 1971) was born after his father's death. As mentioned above, his mother died May 16th 1902, perhaps due to complications of his birth. In the 1910 census, he is shown as an orphan in the household of Richard Carlisle in Barnesville. In the 1920 census, he is listed as the adopted son of Richard Carlisle. By 1930, he was married, but his wife (Francis E. Johnson) died shortly thereafter, and in 1940 James was lodging with Lucy Carlisle (daughter of Richard Carlisle) in Boyds. His youngest son, Robert Lee Burch, was an Army corporal in WWII and is buried at Riverside National Cemetery in California. Isn't it fascinating (and extremely troubling) how a sudden, unexpected accident at a quarry can change a family's fortunes forever? This particular situation with the Burch family would not be considered careless, but just terribly unfortunate. Regardless, please seek the tranquil waters of a pool or ocean if you can, lifeguards are given that name for a reason. Special bonus below, click to see Frederick quarry footage east of MD Route 355.

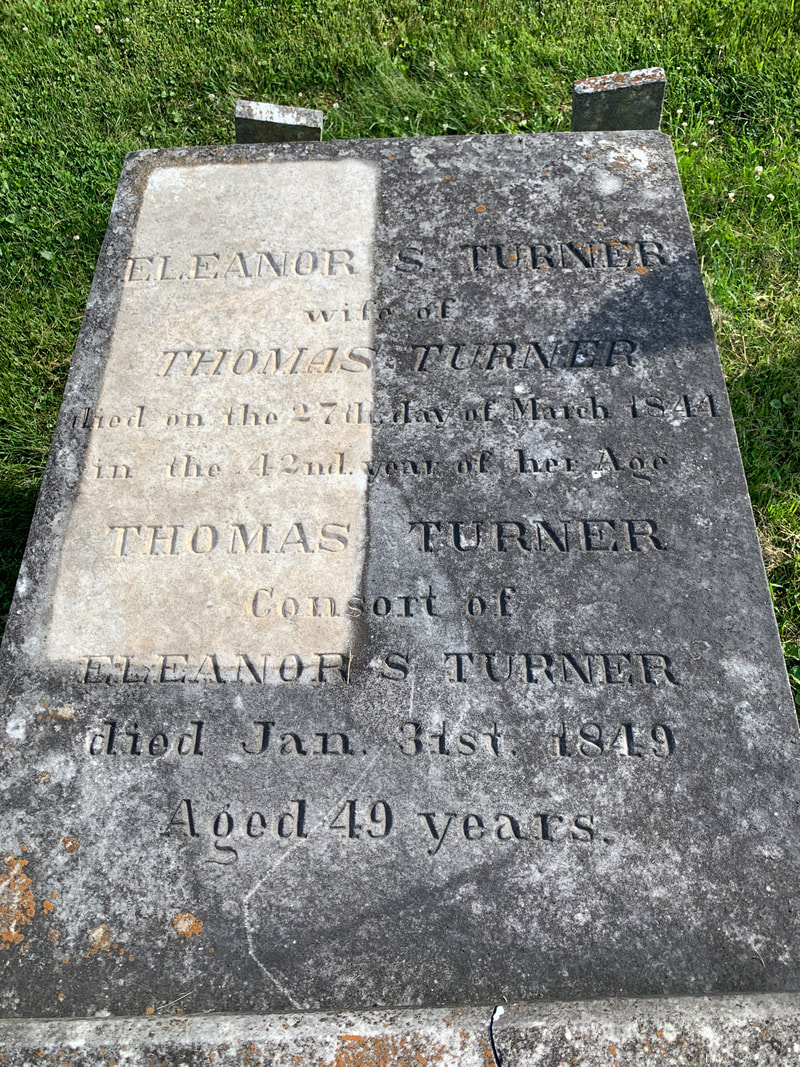

I came across a very odd sight in the cemetery while conducting a tour a few weeks ago for a throng of middle-schoolers attending a history camp. No need to brace yourself, as it has nothing to do with anything disturbing or macabre. Rather, it was simply a discoloration of a section of a ledger-style gravestone. Or should I say, it can be better described as a rare preservation of a portion of a ledger gravestone. The history session immediately turned into a science lab in which I was describing why this lasting memorial to Eleanor S. (Pratt) Turner (1842-1844) and her consort, Thomas Turner (1799-1849), had a big, white rectangle on its face. I had to stop my presentation and think a minute, but the answer was crystal clear—It was all about aging and exposure to outside elements. Although old age does a number on all gravestones (as it does most decedents), the Maryland climate with four seasons also plays a major factor on our memorials. Blame this on such things as algae, lichen, moss, mold, or mildew growth and stains. These growths develop on the surface, making headstones look dark, dirty, and downright creepy. Most grave monuments sit outside naturally, and are constantly subjected to moist, humid conditions. Unfortunately, these situations promote unsightly growths to take hold and grow. This is especially true in the southern part of the country where high humidity is common.

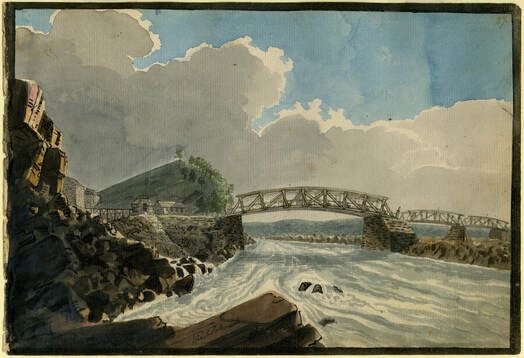

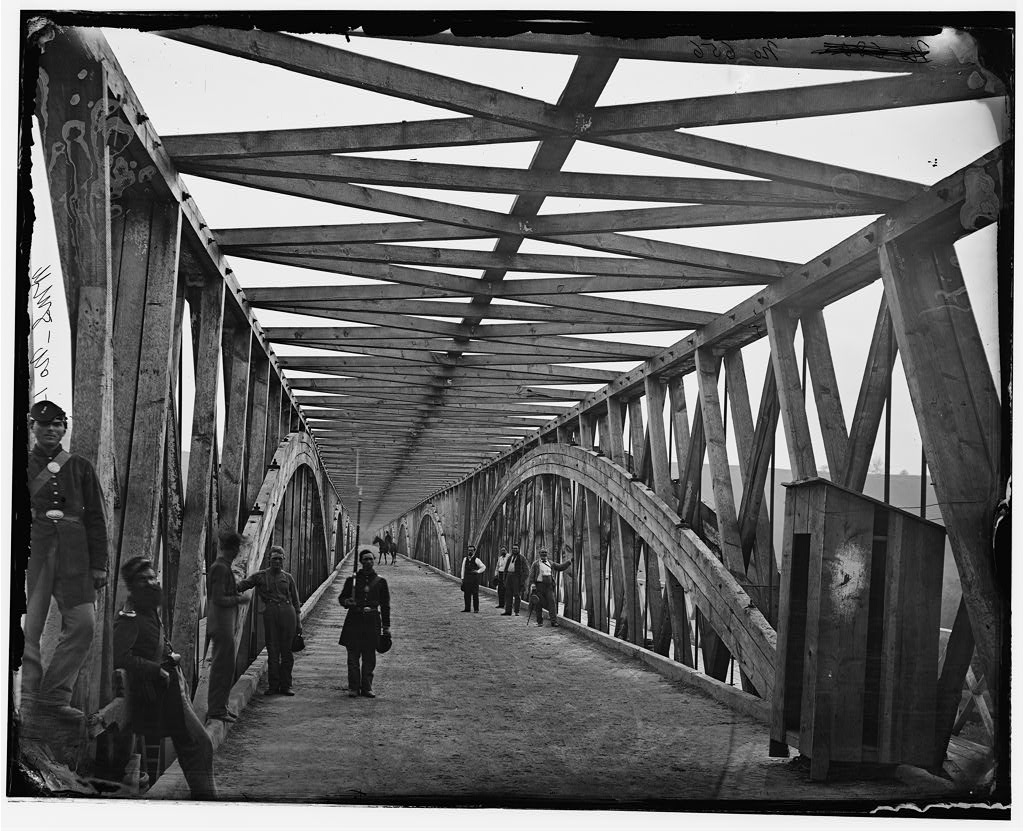

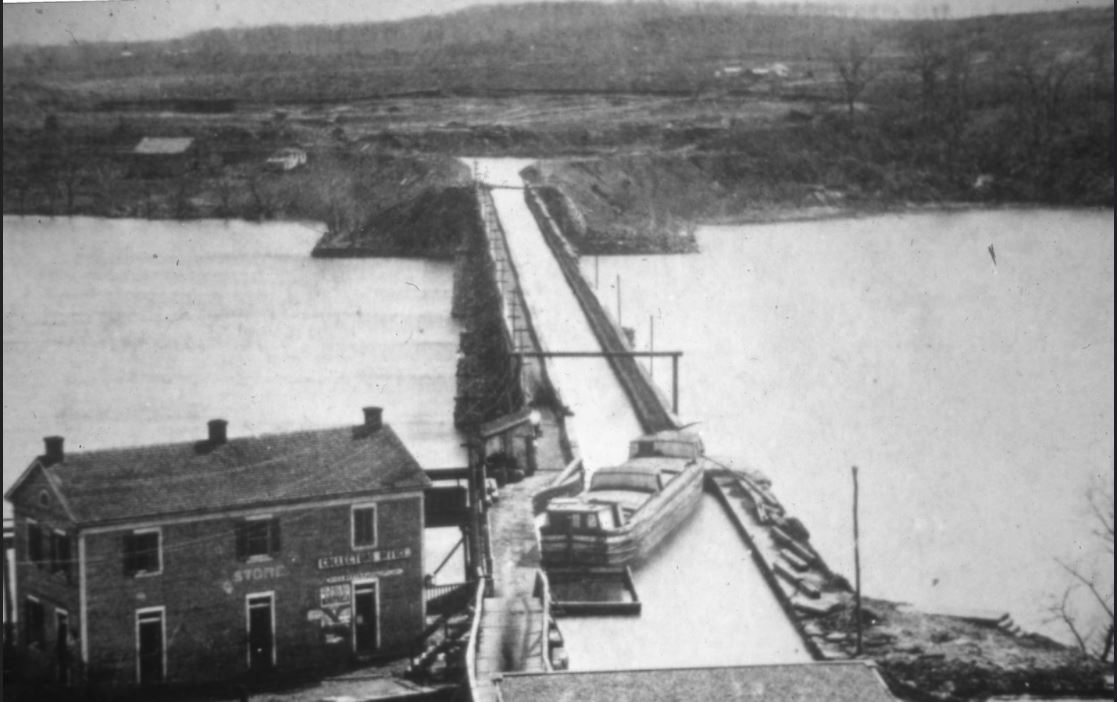

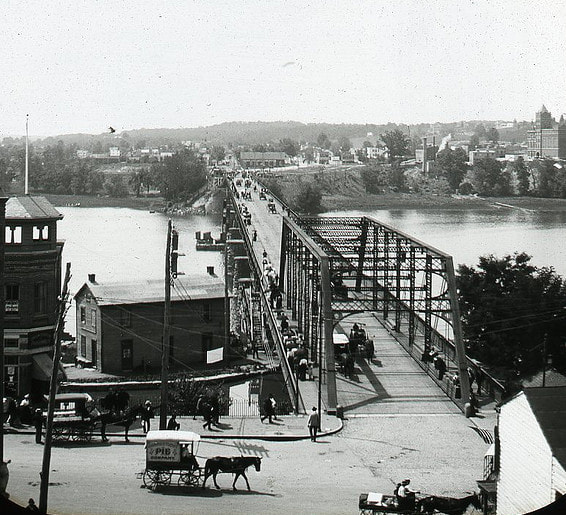

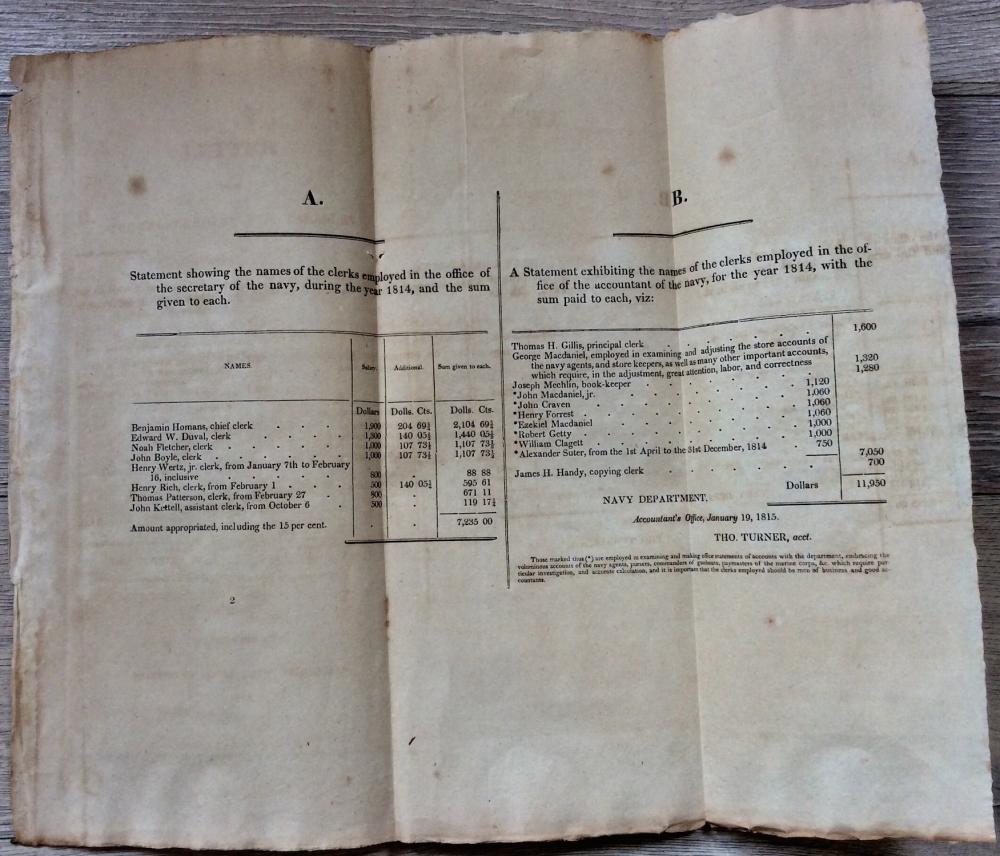

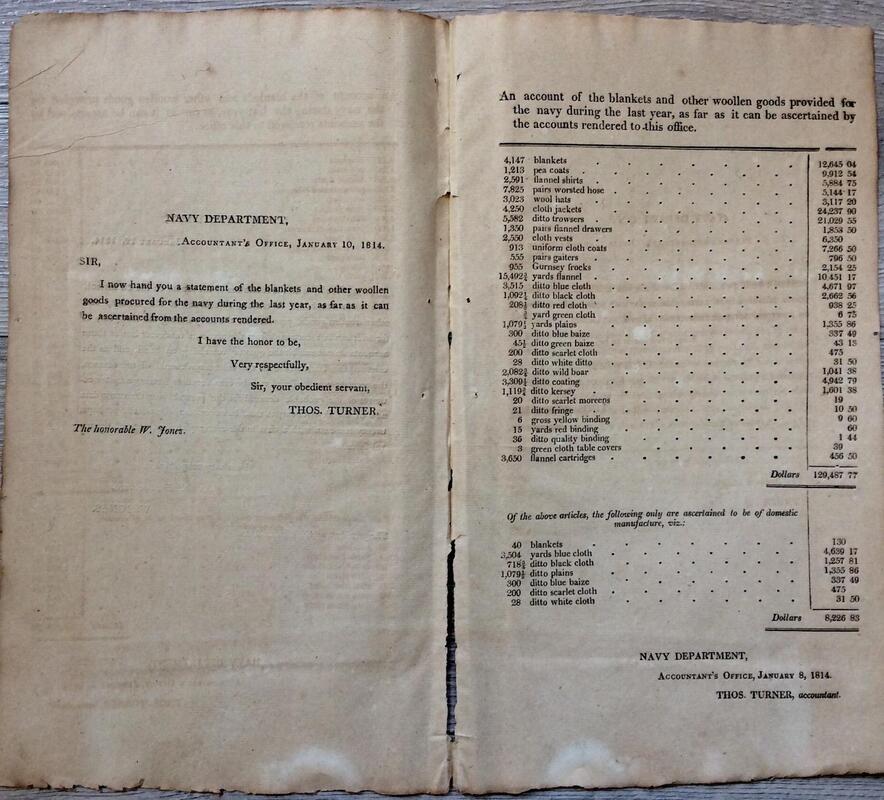

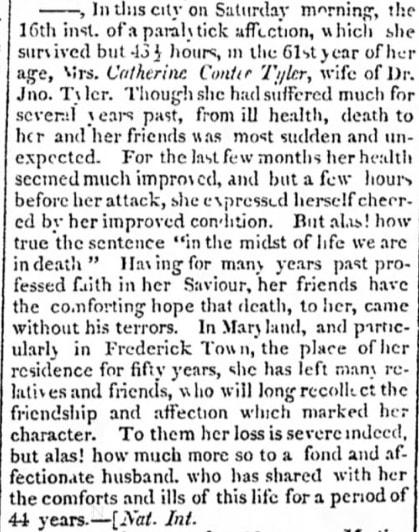

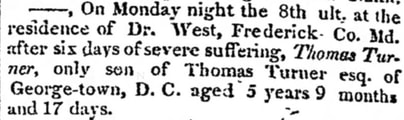

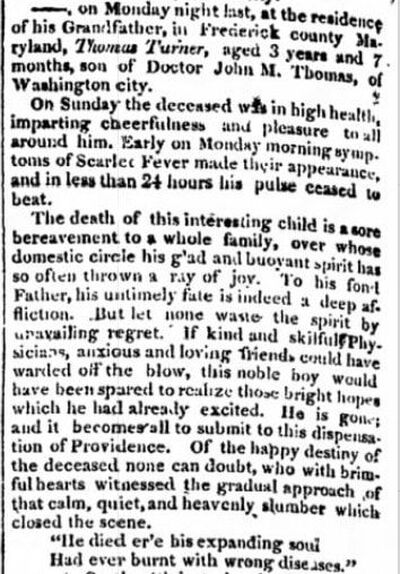

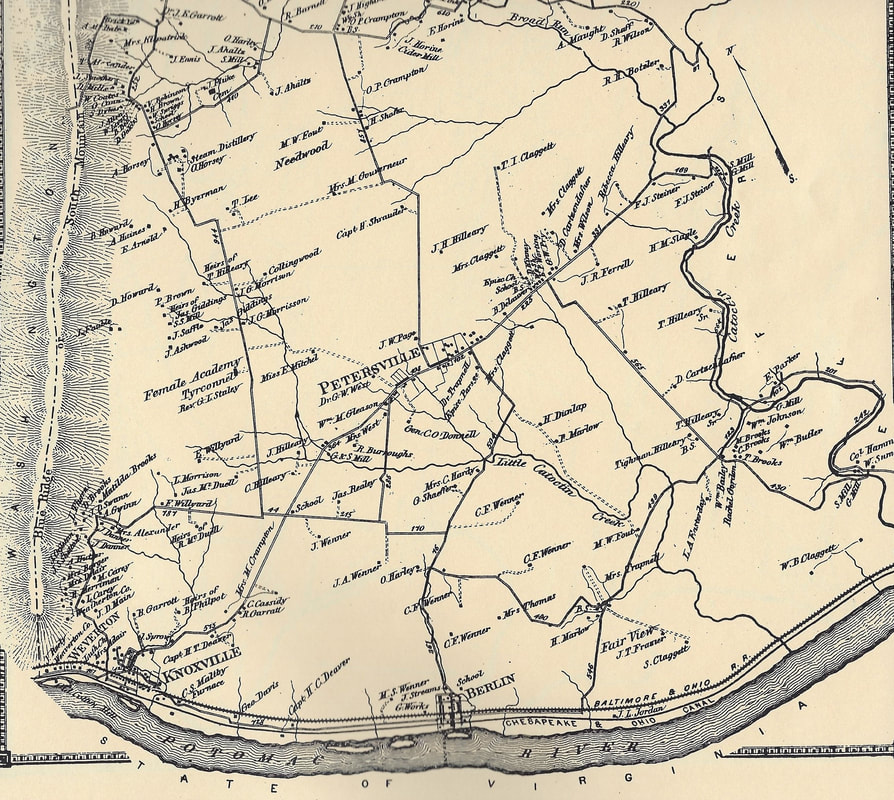

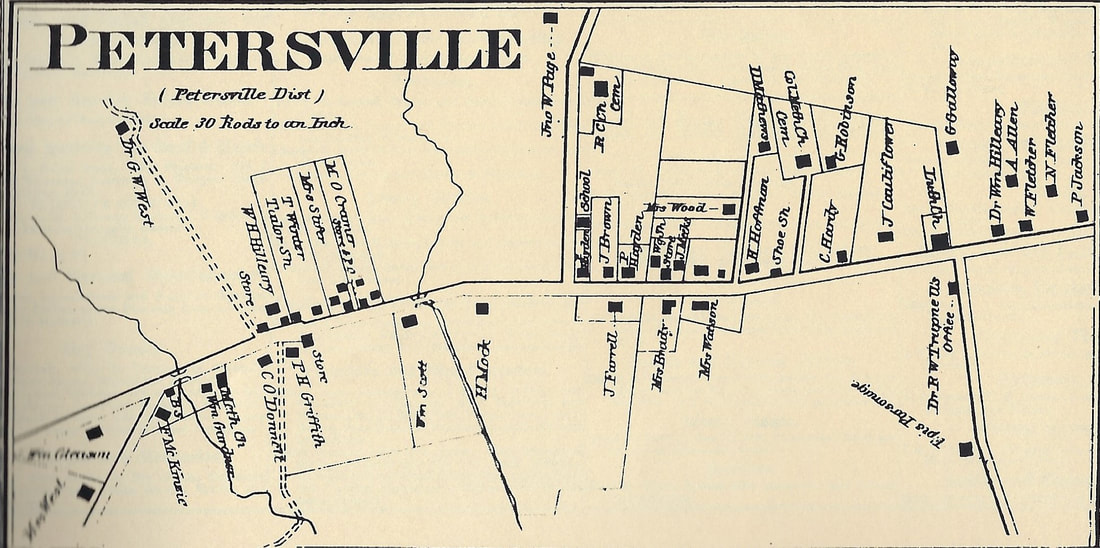

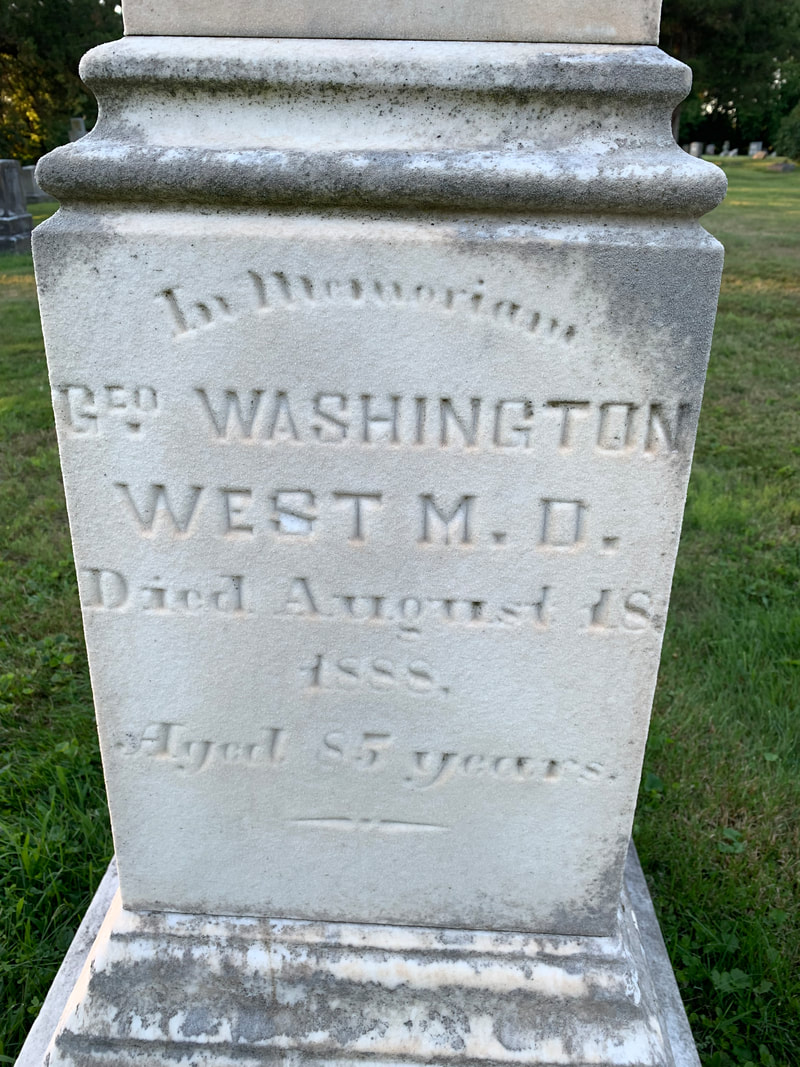

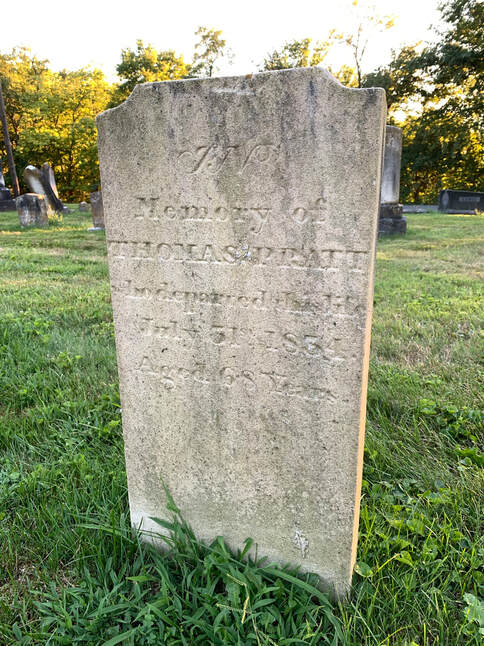

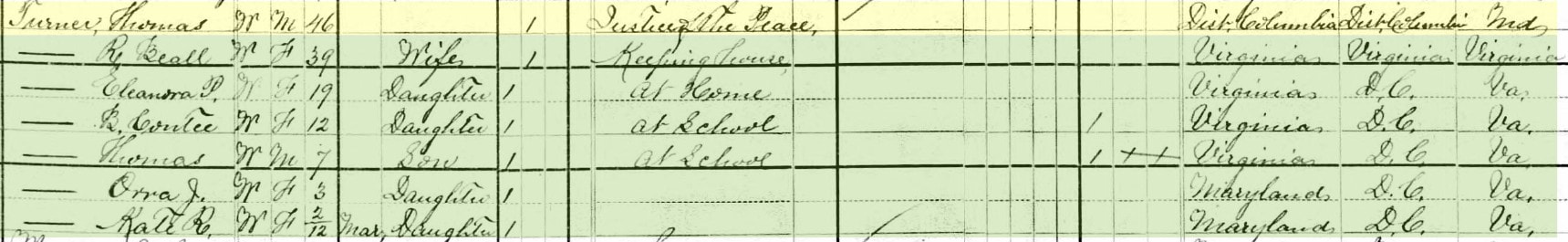

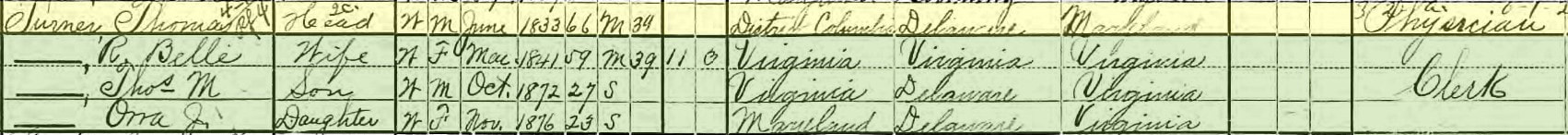

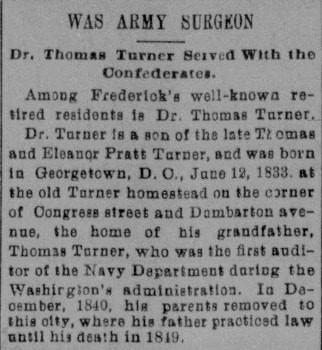

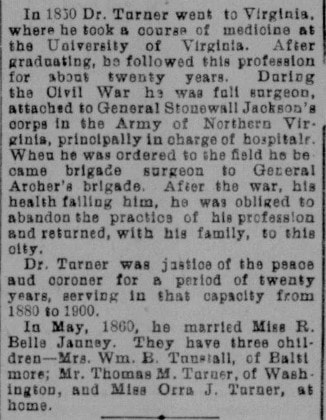

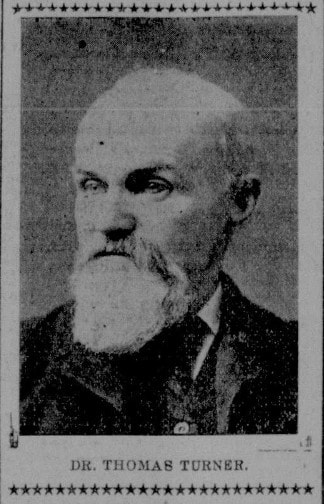

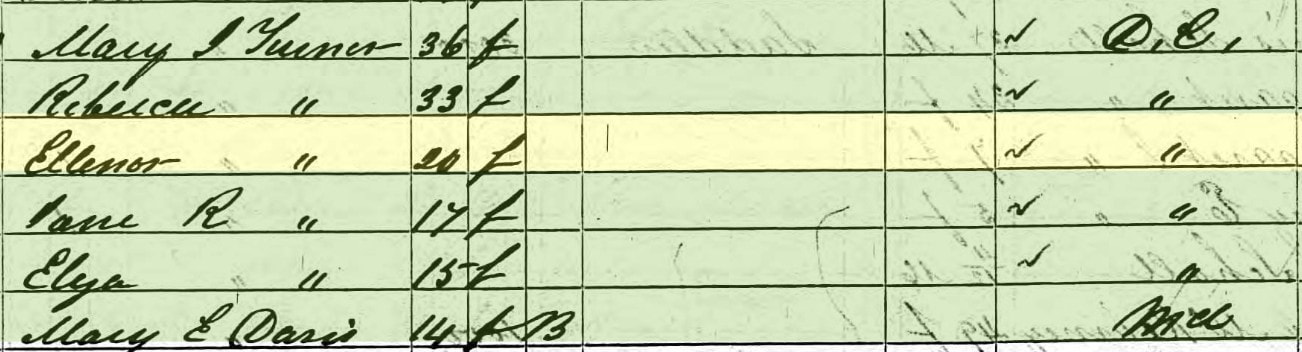

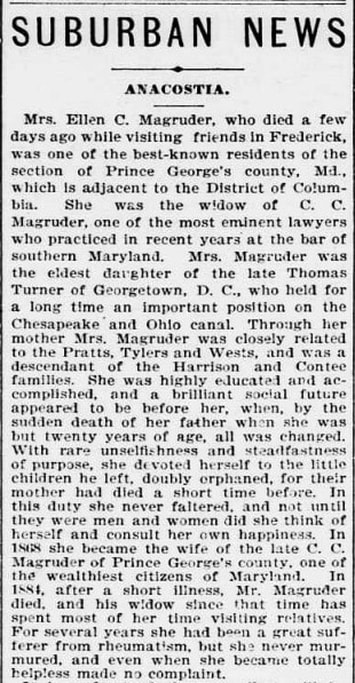

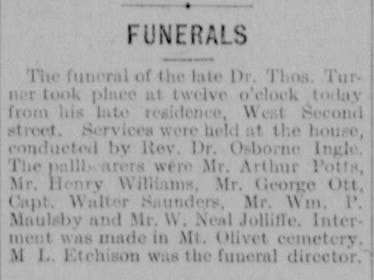

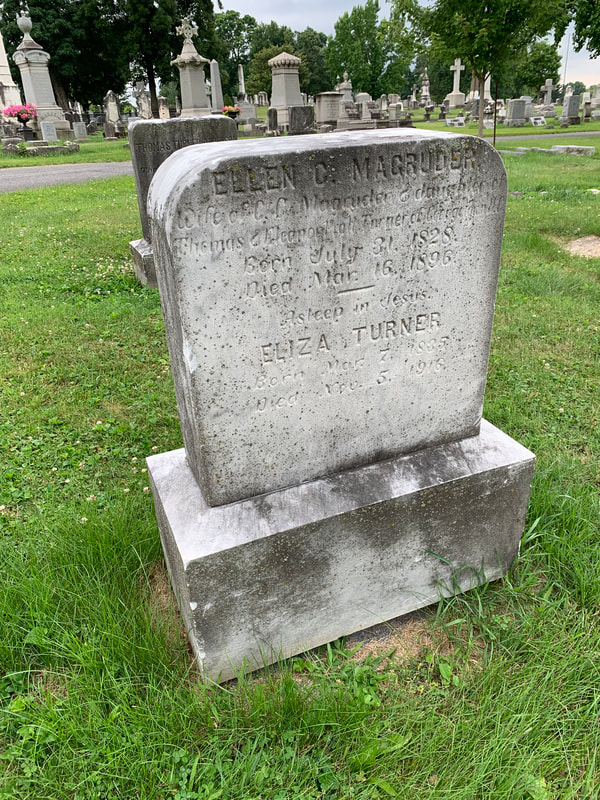

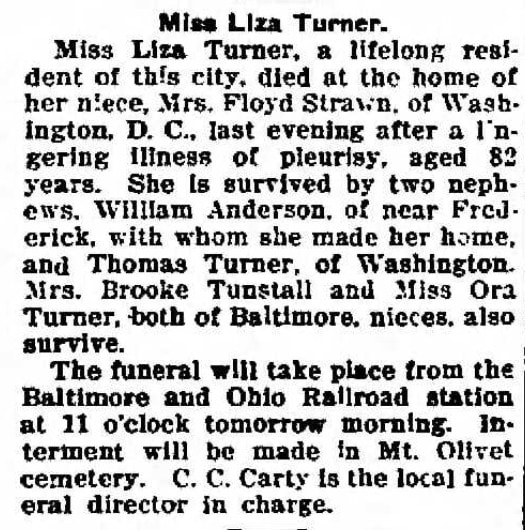

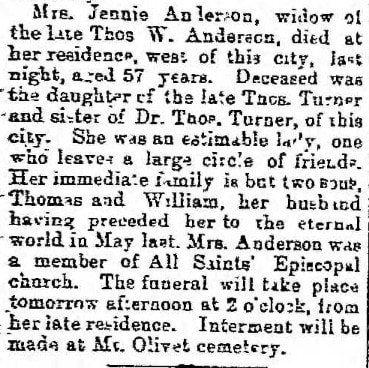

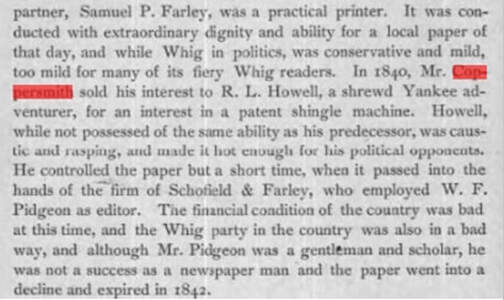

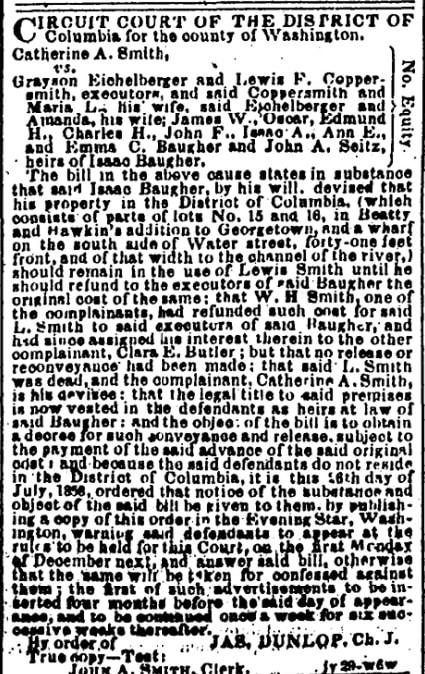

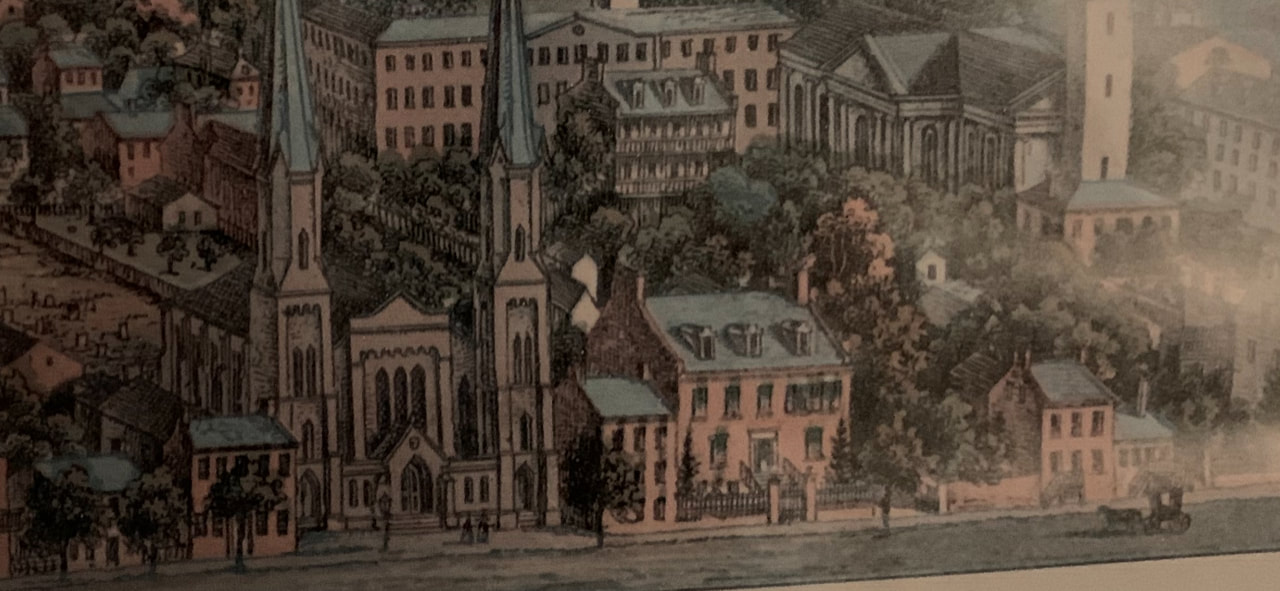

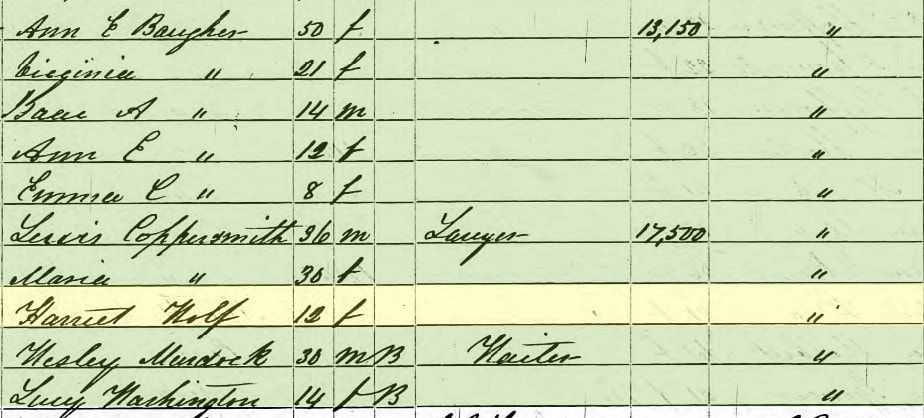

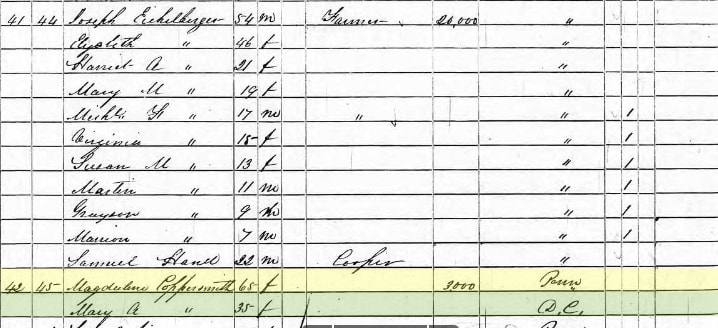

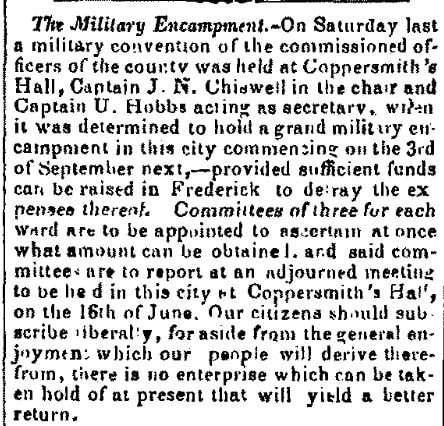

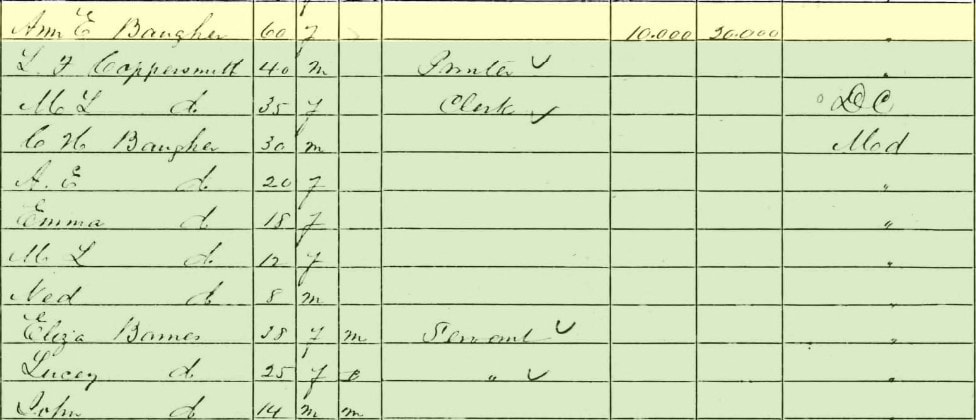

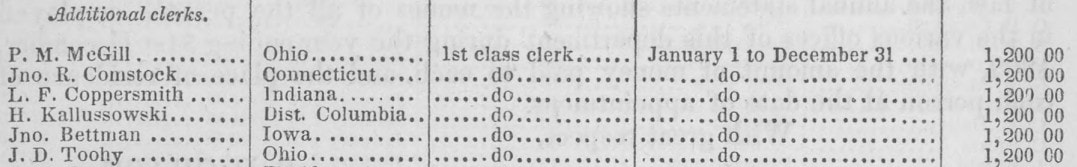

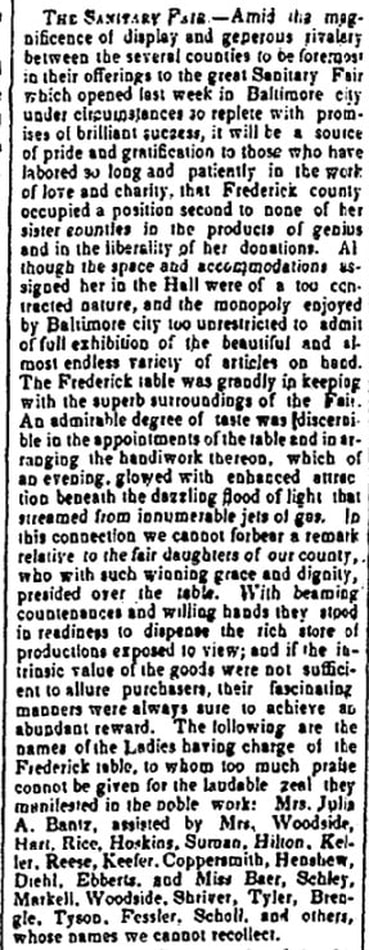

The D/2 Biological solution kills the lichen and whitens the stone, especially effective in the case of marble grave markers. This was the dominant material utilized in the early decades of the cemetery. D/2 is sprayed on the damp gravestone and one can see immediately things start to happen. You may question yourself as to why the gravestone is turning pink? Don't worry—as its normal for the stone to turn a subtle color of pinkish-orange, gray or purplish brown in other cases after applying the solution. This color change is the result of the biological organisms reacting to the solution. Not all stones react this way, but some will—and this discoloration is only temporary. When it does, it will generally take 24-48 hours before the discoloration disappears. So, the only downside is that you may have to come back after a few days to take some good "after cleaning" pictures. I give plenty of lectures and programs to civic and social groups around the county and talk about our continued preservation and fundraising efforts and am often asked, "Why do you want to clean the monuments as the wear and soiling gives them a unique character." I ask the question back of them saying "Why do we clean our cars, marble countertops, or power-wash decks and patios?" I tell them not to worry, just give it time and they will eventually be dirty again one day. More so, I explain the importance of cleaning as a necessary maintenance to preserve the longevity of the stone, especially in each monument's legibility. Let's just say, "A clean stone is a happy stone." If you are curious about the process and want to see it happening live, I invite you to come out some Thursday morning and see for yourself. Perhaps we may even recruit you to our ranks with a membership in our FOMO Group? (Contact me for more info if interested). Nan Markey, our "Chief Stoner," (pictured below) would love to have you as she has been leading our organized process section by section for the past two years. We are lucky to have this level of detail from the retired Registrar of Hood College, and plenty of other talented folks who care about Mount Olivet. So, what’s the deal with Eleanor and Thomas Turner’s headstone in Area H/Lot 399? Why would somebody only clean a small section of a large ledger stone? Au contraire, this is not the case at all! First off, let me explain the term “ledger stone” to those who may not be familiar with it. A ledger stone, or ledgerstone, is an inscribed stone slab usually laid into the floor of a church to commemorate or mark the place of the burial of an important deceased person. The term "ledger" derives from the Middle English words lygger, ligger or leger, themselves derived from the root of the Old English verb liċġan, meaning to lie (down). Think of accounting ledgers, and ledger paper and notepads—long and narrow. Ledger stones may also be found as slabs forming the tops of chest tombs. An inscription is usually incised into the stone within a ledger line running around the edge of the stone in the same manner a ledger book contains stacked rows of recorded information and numbers. Such inscription may continue within the central area of the stone, which may be decorated with relief-sculpted or incised coats of arms, or other appropriate decorative items such as skulls, hourglasses, etc. Stones with inset brasses first appeared in the 13th century.  An upright stone in the fashion of an olde world ledger stone of Europe is cleaned by preservation expert Jonathan Appell of Connecticut. This is the oldest formal gravestone in Frederick, likely the county as well. It belongs to Jacob Steiner/Stoner (1713-1748), one of Frederick's first settlers in the mid 18th century. Gravestones of this type are generally found in older, “colonial-era” cemeteries in New England and English-settled places like Williamsburg, Virginia or New Castle, Delaware. They also were a preferred grave marker of the wealthy. We have many examples here at Mount Olivet, some predating our cemetery and coming from other downtown graveyards. There are also instances of more recent decedents simply fancying this unique, throwback-style of monument. In the case of the Turners, here is a ledger stone that is propped up off the ground with four rounded-pillars. These appear to be standing on a flat rock, purposely put in place to be used as a foundation, as not to allow the pillars to sink into the earth below. This creates an optic looking like legs supporting a table or an altar. Regardless, you want to put something between the stone and the ground, so as to keep it from eventually sinking and being engulfed into the ground over time. The grave (stone and decedent) in question was moved here in 1859 from the former All Saints’ Protestant Episcopal Church Graveyard along Carroll Creek. Eleanor Turner died on March 28th, 1844. This took a little research as the All Saints’ Parish Burial Records (Register #3) states: “Ellen or Eleanor S. Turner, wife of Thomas (of D.C.), died March 28th, 1844, while her headstone recorded her death as March 27th, 1844.” As for Eleanor’s husband (or consort), I was fascinated to learn that Thomas Turner was the editor and publisher of the Frederick Town Herald, immediately before Lewis F. Coppersmith, the subject of our last “Story in Stone.” Coppersmith continued his predecessor’s role throughout the 1850s. What are the odds of that? As I’ve said many times, I love discovering these unique “connections” within these stories as it’s not just connections across family lines, but almost anything imaginable in some cases. Thomas Turner had begun a newspaper in Georgetown in 1837 called the Potomac Advocate and Metropolitan Intelligencer. Like Coppersmith, Mr. Turner also practiced law and served as a clerk as well for the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal. He died on January 31st, 1849 and his obituary appeared in multiple papers in Maryland and around the nation’s capital. One way or another, the Turner’s fashionable stone was apparently used as a makeshift table to hold another family member’s stone, or a portion thereof. This was Mr. Turner’s sister, Catharine Contee (Turner) Thomas. She died at age 30 on September 22nd, 1831. Jacob Engelbrecht made mention of this death as well in his famous diary. Like her brother and sister-in-law, Catharine is what we call “a removal,” and was brought here from All Saints Protestant Episcopal Graveyard as well. We learn that Catharine’s father (Thomas Turner, Sr.) was an "Accountant of the Navy Department" from the inscription on her headstone. The stone also records the fact that she was married to Dr. John M. Thomas. John M. is not buried here with her, as he died on December 28th, 1835, in St. Louis, Missouri, about the age of 38. Dr. Thomas was in the U.S. Army, but I cannot locate a burial for him here locally, in Maryland, Missouri, or the District of Columbia. Catharine’s mini-ledger stone must have sat on the Turner’s stone for quite some time as it protected/blocked the area directly underneath from the elements and pollutants. For reasons unknown, somebody recently moved Catherine’s stone toward the bottom of her brother’s ledger. Perhaps it was a descendant or interested genealogist who wanted to see what was written on the area of Eleanor and Thomas’ stone that was covered for all those years? Apparently, the Turners never bought a home in Frederick, unfortunately. Deeds found by my assistant, Marilyn Veek, for Thomas Turner involved bringing enslaved persons from Washington, D.C. into Maryland when he moved here. These included one in 1840 for a Negro girl named Emily (age 18) and a girl Phoebe (age 10). Other deeds were written in 1842 (a Negro girl Rachel age 11-12) and in 1844 (a Mulatto woman Letty Henson aged 30-35 and her infant child Maria Victoria aged about 15 months). I did, however, find the Turner’s former home when they lived in northwest Washington, D.C. It still stands and is in Georgetown, on the southeast corner of current day 31st Street, N.W. (formerly known as Congress Street) and Dumbarton Avenue. The Turners had a long history in Georgetown prior to moving to Frederick. Thomas Turner, Sr. (father of our “multi-colored stone” subjects) was clerk of the corporation of Georgetown prior to 1791 and was elected mayor on January 5th, 1795. Also in 1795, Thomas, Sr. was appointed by the governor of Maryland to a committee to assess the impact of constructing a road from Georgetown to a bridge to be built over the Potomac at Little Falls. The bridge would become a reality and featured several stone abutments and wooden cross sections that went across the Potomac. Little Falls is the place on the river where Washington, D.C., Maryland, and Virginia meet. You may recognize this structure as “Chain Bridge,” which originally was a covered wooden bridge completed on July 3rd, 1797. It apparently rotted and collapsed by 1804, and a replacement of the same design burned around 1805. Numerous bridges have been built in the same position since then. Speaking of bridges, Thomas Sr.’s son, Thomas Turner (Eleanor's husband), was on a committee that petitioned the U.S. Senate to build a bridge in connection with the aqueduct for the Alexandria Canal Company. This was the first Aqueduct Bridge, built in 1830 to carry the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal across the Potomac to connect with the Alexandria Canal on the Virginia shore. The bridge was later converted into a roadway during the American Civil War. In 1866, the canal was restored, and a new wooden roadway built over it atop trestles. The 1830 bridge was torn down in 1884, and a new structure was built, opening in 1889. This would be named for an individual who once lived on the Georgetown side of the bridge that takes motorists across the river to Rosslyn (VA)—the Francis Scott Key Bridge and is more commonly referred to the Key Bridge. The Washington and Virginia abutments for the original crossing still survive. Both are located a short distance west of the Key Bridge. Between the two abutments, a pier also remains in the river near the Virginia shore. How’s that for “bridging” history? In January of 1800, Thomas Turner, Sr. (the father of Thomas Turner and Catharine Thomas) was nominated by John Adams to be Fourth Auditor (accountant of the U.S. Navy) in the Treasury Department and served for 16 years. As mentioned earlier, this position is noted on daughter Catherine Contee (Turner) Thomas’ ledger headstone. Fitting that a ledger stone connects to a ledger entry about an accountant, isn’t it? Mr. Turner had his hands full with the new branch of our young country's armed forces. He would serve in this position throughout the duration of the War of 1812, and was likely very familiar with fellow Georgetown resident and notable war personality Francis Scott Key and his catchy tune about the flag over Baltimore's Fort McHenry. Examples of Thomas Turner Sr.'s accounting prowess with these published reports on US Navy expenditures at the time of the War of 1812. Eleanor Pratt and Thomas Turner were married in 1825 in Allegany County, which seems odd at first glance, but both had ties to Cumberland as a home thanks to the construction of the C & O Canal. Not a great deal is known about Eleanor, but there is a definitive connection to Frederick through her mother, Christiana B. (Tyler) Pratt (1767-1825), a sister of Dr. John Tyler (1763-1841). We will review the accomplished life of Dr. Tyler another time as he is buried here in Mount Olivet, but many are familiar with the fact that he was one of our country’s first accomplished ophthalmologists and receives credit as one of the first physicians to perform cataract surgery. His majestic home of West Church Street still survives and is known as the Tyler-Spite House. Catharine (Turner) Thomas is named for Dr. Tyler’s wife, the former Catharine Contee Harrison (1770-1831). Both Dr. and Mrs. Tyler are buried in Area MM/Lot 52. There is yet another family link as our subject Thomas Turner’s mother was a sister to Mrs. Tyler in the form of Eleanor Contee Harrison who married Thomas Turner, Sr. 1n 1792. When Dr. Tyler died intestate in 1841, there was an equity court case. Thomas Turner was one of the trustees appointed in the case to handle the sale of Tyler's property but, refrained from buying any of it himself. Eleanor’s father was Thomas George Pratt, born in the year 1769. He removed from his native Prince Georges County to Allegany County (Maryland) and eventually afterwards lived in southwestern Frederick County at a point about five miles from Harper's Ferry. This was a 245-acre plantation bought in 1830 from the estate of Daniel Leakins which included part of Fielderia Manor on the eastern slope of Catoctin Mountain east of Jefferson (near the intersection of MD 180 and Mount Zion Road). Unfortunately, Pratt got himself into debt and had to sell this property off in 1832. After that, he apparently lived with his son-in-law, a man named George Washington West (1803-1888) who married his daughter Eliza. The same year of 1832, a year after the death of Catherine (Turner) Thomas, saw more heartache for Mr. Pratt, the Turners and recent widower Dr. John M. Thomas—all connected to our Mount Olivet “Stonehenge of stacked ledgers” in form of a table in Area H. Thomas Turner’s first-born son, named Thomas Turner, would die of Scarlet Fever at the home of Dr. West on October 8th. One week later, Thomas Turner Thomas, only child of Dr. Thomas, would pass of likely the same ailment at the same location. Both obituaries appeared in the October 8th edition of the Frederick Town Herald. In 1834, Pratt sold West two enslaved persons; the deed includes the following language: "I Thomas Pratt fully aware of the trouble inconvenience and expense to which Doct. George W. West and his family have been subjected by the board of and attention to myself during the four last years & that the same will continue so long as I may live, and being willing and desirous some compensation to the said Doct. George W. West for the services so rendered and to be rendered by himself and family.” And here is another amazing connection, but perhaps more so for me, because of a personal link. I recently became interested in the George W. West family through my son’s girlfriend who lives on a parcel that was once part of the larger West plantation known as Westhill Farm. This is located just “west” of Petersville, a small hamlet located on the fore-mentioned MD180, the original road from Frederick to Harpers Ferry which at one time was a turnpike. Westhill Farm is quite picturesque and can be seen from MD 340 as well, with its stone manor house, barn buildings and an adjacent pond. Thought to be built around 1800 by Thomas H. West, the house passed to his son, Dr. George Washington West (1803-1888), in an 1832 partition of real property following his death. Dr. West was a prominent local physician and former graduate of the University of Maryland in 1825. George W. West would own the farm for more than 50 years and his name is shown on both the 1858 Bond Atlas and 1873 Titus Atlas of Frederick County. Since I rarely get to speak on Petersville, the village grew as a stop along the turnpike with businesses to serve travelers as well as local farmers. The land on which Petersville is situated was originally patented by Captain John Colvill as the "Merryland Tract" on November 5th, 1731, containing over 6,000 acres. Shortly after the Revolutionary War, Petersville began to develop as a village, with lots facing the turnpike route and four cross streets. The village also sat at the crossroads of one of the valley's north-south roads leading from Middletown to Berlin (today Brunswick). The 1808 Varle Map of Maryland shows Petersville as well. Five years later, in October 1813, the Petersville Post Office was established (it closed in 1909). The Maryland General Assembly established the Petersville District in 1829. In his will, Thomas Pratt had intended to leave his own plantation at Fielderia (part of the former site of a short-lived, colonial era furnace operation by Fielder Gantt) to his son John Wilkes Pratt, who was named executor. Unfortunately, by the time Thomas died in 1834, he had lost the property. John Wilkes Pratt declined to return to Maryland to be executor as he had gone to Cass County, Illinois for health reasons. While there, the brother of the fore-mentioned Eleanor (Turner) and Catherine (Thomas) worked as a lawyer, served in the State Legislature, and performed duties as Cass County’s first County Clerk. Not living to see it, Thomas Pratt would've been proud of the fact that his son excelled where he, himself, fell short. Mr. Pratt’s grandson (John Wilkes Pratt’s son) Thomas George Pratt was even more accomplished. The young man studied law and returned to his father’s native state to settle in Prince Georges County. He would serve in the House of Delegates and State Senate for several years before becoming Maryland’s governor from 1845-48. Two years later in 1850, Thomas and Eleanor Turner’s nephew, Thomas G. Pratt, was elected to the U.S. Senate to represent the Western Shore of Maryland. As for the governor’s namesake, I found Eleanor (Pratt) Turner’s father buried next to his daughter Eliza and husband George W. West in St. Mark’s Apostolic Church Cemetery on the “east” side of Petersville. After Eleanor and Thomas passed in the mid to late 1840s, their children were split up. Son Thomas became a physician at age 17 and went to live with Samuel Turner, his uncle (also a physician) in Clarke County, VA. Thomas was still living in Clarke County in 1860, but I could not locate him in 1870, as he was possibly lying low after the American Civil War since he served with the Confederacy as a surgeon. In 1880, Dr. Turner and his family were living on South Market Street in Frederick. In 1900 the family was living at what is now 125 W. Second St, in a house owned by George Nixdorf. The younger Thomas Turner never bought any real estate of his own, but in the late 1890s held a mortgage from Bettie Ritchie on the house then known as 50-52 W. Church St. She defaulted on the mortgage, and he sold the property at 50 West Church Street to Otho Keller and 52 West Church Street to Henrietta Maulsby. Today these properties are labeled as 116-118 W. Church Street. We did a story on Mrs. Ritchie a few years back as she was the foundress of our original Frederick Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution. Eleanor and Thomas Turner’s daughters remained in Frederick. In the 1850 census, the head of household was Mary Jane Turner, age 36. The others were Rebecca, age 33, Ellenor “Ellen”, age 20, Jane R. age 17, Eliza, age 15. An obituary for oldest daughter Ellenor (aka Ellen/Eleanor Contee (Turner) Magruder) from the Washington Star says she was very prominent later in life after showing selflessness in caring for her younger siblings after the parents died. Mary Jane Turner (1814-1867) and Rebecca Turner (1817-1877) are aunts of Eleanor, Jane “Jennie” Rebecca and Eliza—making them sisters of our subject Thomas Turner. These ladies bought what is now 211-213 East Second St in 1855. The property was sold in 1879 after Rebecca's death (the current building is more recent, however). I couldn’t determine where they were living in 1850 but, did discover that Rebecca had employment with the U.S. Navy. Here in Mount Olivet’s Area H/Lot 399, Mary Jane, Rebecca and Dr. Thomas Turner are buried next to Thomas and Eleanor Turner’s table-resembling memorial. The physician died on September 6th, 1908 from "a pulmonary affection." Within adjoining lot #403, one can find grave markers for Thomas and Eleanor’s daughters: Ellen C. (Turner) Magruder (1828-1896), Eliza Turner (1835-1916) and Jane "Jennie" (Turner) Anderson (1831-1888). Frankly, all these stones could use a good cleaning, and hopefully they will match the small, pearly white rectangle that can be found on Thomas and Eleanor’s discolored grave ledger!